Spiritual Science and Medicine

GA 312

28 March 1920, Dornach

Lecture VIII

The mode of expression in which we use to abridge or to simplify somewhat our ideas, when we say etheric body, astral body, etc., can be traced back to the imprint of these higher bodies in the realm of physical functions. Nowadays, people are not very ready to link up expressions in the realm of physical functions with the spiritual foundations of existence. But this must be done if medical thinking and conception are to become permeated with Spiritual Science. For instance, it will be necessary to study in detail the exact manner of the interaction between what we term the etheric body and what we term the physical. You have learned that this interaction is at work in man and we have just dealt with its coming into a kind of disorder in relation to the influence of the astral body. But the same interaction also takes place in extra-human nature.

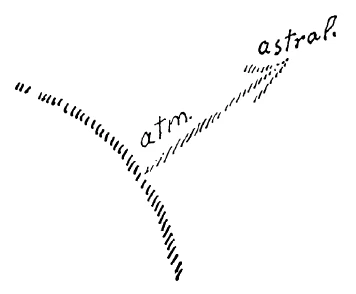

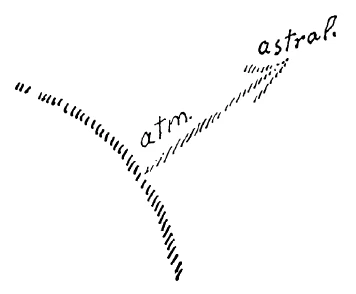

Think this out thoroughly to its conclusion, and then consider that you are gazing profoundly into the relationship between man and nature. Man is surrounded—let us choose this one thing to begin with—by all the earth's flora in their many species, which he perceives through his different senses. You can at least admit the possibility of an interplay between the flora and all that our earthly atmosphere contains, in the first place, and all that lies outside this earthly sphere, in the planetary and astral regions, in the second place. In considering the flora, suppose the earth's surface to be here (See Diagram 15)—then we can say that the plants refer us to the atmospheric and astral regions (in the literal sense of a pointing to the stars, to the extra-telluric). And even apart from occult research, we can intuitively sense a living interchange between what manifests in blossom-bearing and fruit, and what flows into them from the whole wide universe. (Of course you must make use of a certain intuition here; but as I have already remarked, you will not get very far in medicine without intuition.) Let us Suppose that having realised the external cosmic interplay, we turn our thoughts to our own inner being. There, too, we shall find a certain relationship to that which surrounds us. Just as the etheric and the physical are closely united in in the plant-world, so must we surmise a certain kinship between this union and the manner of connection of the etheric and the physical in man himself.

How then can we speak concretely about this relationship of the etheric with the physical? From the abstract point of view, we can say that the etheric is nearer to the astral than to the physical; for the etheric is open to the forces from above. But we must expect also some relationship between the etheric and the physical. So we must take this two-sided kinship and must look for something which guides us to it. I shall try to do this in the most concrete manner possible.

Walk through an avenue of lime trees in bloom, and try to visualise what happens as you pass between the trees, enveloped in the scent of the lime blossoms. Realise that something is taking place between this fragrance of the limes in flower and, so to speak, the nerve ramifications in your olfactory organs. Turning your conscious thought to this process of perception, you become aware of a certain opening-out or release of the capacity for smelling, which meets the scent of the lime blossom. And you conclude that a process takes place through which an internal sphere in yourself opens to meet something outside, and that the two combine in some way to produce something by virtue of their inner kinship. So you must say that what is diffused in the air as scent from the lime trees—arising without a doubt from an interplay between the flowers and the whole extra-terrestrial environment as they open out towards it—is inwardly felt by you through your sense of smell. There you undoubtedly have something that passes from the etheric body to the astral, for otherwise you could not perceive it, and there would only be the mere process of life. The perception of smell itself proclaims the participation of the astral body. And that which reveals the kinship with the external world, simultaneously shows that the production of the sweet fragrance of the lime blossoms is the polar process to that taking place in your olfactory organs. The fragrance flowing from the blossoms shows the interaction of the plant-etheric with the astral element that embraces it and fills the surrounding universe. So in our sense of smell, we have a process that enables us to take part in the relationship between the plant-life of the earth and the astral element outside the earth.

Now take the sense of taste, and, as an example, something not unlike the scent of the lime blossom, though appealing to another sense, say the flavour of liquorice or of sweet ripe grapes. Here we have to do with a process in our taste organ in contrast to that of smell. You know how closely related they are; and you will also realise the resemblance between what happens functionally in the two cases. But you must, at the same time, understand that tasting is a much more organic and internal process than smell. Smelling is far more a surface activity; a participation in extra-human processes widely diffused in space. But that is not so with taste. Taste reveals certain properties inherent in the substances themselves, and therefore closely interwoven with matter. You can learn more of the internal quality of plants by taste than by smell. Call some intuition to your aid and it will help you to know that all connected with the solidification of matter in plants, and all that is revealed in the organic processes of solidification, is disclosed if we taste the contents of the plant. The essential nature of the plant defends itself against solidification and this is manifested in the tendency of the plants to be fragrant. So you really cannot doubt that taste is a process associated with the relationships of the etheric and the physical.

Now compare smell and taste. As you react to the plant-world through both these senses, you experience the twofold relationship which the etheric has to the astral on one side and to the physical on the other. You literally enter the etheric, or its expression, if you study these two processes of taste and smell. Where they occur in man, there is a physical revelation of the etheric in its dual relationship to the physical and the astral. When we examine what takes place in the acts of tasting and smelling, we live, so to speak, near the surface of man. Our task today is to pass beyond the abstract, mystical view and to approach the concrete grasp of spiritual truth, so that a true science may be fertilised by spiritual science. What can it avail people to listen to perpetual talk of the need to grasp the Divine in man, if they only understand by that a purely abstract Divinity? This method of approach only becomes fruitful if we can consider concrete instances in detail, and trace, say, the interiorisation of outer processes. For example, if we trace in smell and taste the etheric element which is external yet related to man, we perceive, in what is, perhaps, the crudest of our upper sensory processes, the interiorisation of external processes. It is so extremely important for our time to get beyond mere abstract and mystical notions.

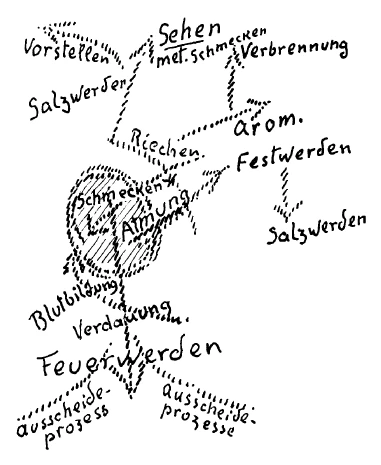

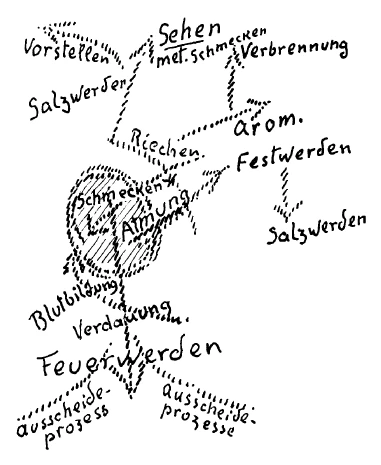

Now you are fully aware that in nature every process tends to pass over into another, to be metamorphosed into some other process. Take what we have just said, for instance, that the sense of smell is located more on the surface of our organism, (See Diagram 16) while that of taste is more inward (we are speaking here with reference to the plant-world). Both these sense activities occur within the etheric, which opens into the astral on the one hand and solidifies into the physical on the other. The sense of smell reaches outwards towards the evanescent scent of the flowers, while that of taste lives in the process that opposes aromatisation, and interiorises that which externally produces solidification. When we carefully examine smell and taste, we find that in them the outer and the inner merge, as it were.

But in nature, all processes merge into others. Consider again the aromatic qualities of plants, through which, in a certain sense, they tend away from solidification and towards diffusion even so to speak, going beyond their limits in striving towards the active the amateurish term—into the atmosphere, so that this bears in itself some of the plant existence in the aroma. The phantoms of the plants are still bound up with the aroma. What actually happens when the plant pours its fragrant phantoms into the air, frustrating the process of solidification, and sending forth from the blossoms something that tended to become blossoms too? Simply a process of combustion held back. If you picture to yourself the further metamorphosis of this aromatic activity, you reach the conclusion that it is a combustion that is held back. Compare the process of combustion proper, with the aromatisation of plants. They are two metamorphoses of the same unity. I would even say that combustion is aromatisation on another level.

Let us now see what is in plants that produces flavour. It is more deep-seated and does not urge the dispersal of formative forces into the air like a phantom, but gathers them together that they may be used to build up the internal structure. If you follow up this formative activity with your taste, you come to the process lying below solidification in plants, i.e. to salification, which is a metamorphosis, on another level, of solidification (See Diagram 16). In plants, therefore, we find a strange metamorphosis. The aroma-process directed upwards is, in a certain sense, suspended combustion, which may lead to the initial stages of combustion (for processes of efflorescence are combustion processes). While in the downward tendency you have solidification and salification, and what you taste is something that is held back on the way to salification. But if saline substance is deposited in the tissues of the plant itself, it is something that has gone a step beyond the path of plant-formation; the plant has pressed the phantom of its form down into its actual being.

Here we have the “ratio” for finding remedies and light is thrown on the whole plant-kingdom because one now begins to realise what takes place there. I must again emphasise that this consideration of concrete facts is the only thing that can help us.

To find the next step, you need only remember that wherever it is possible, and from motives of opportunism in a higher sense, I shall link up what I have to explain with current ideas. Thus you should be in a position to build the bridge between what spiritual science is able to give and what is taught by external science. Naturally the contents of the following paragraphs could be stated in a more strictly spiritual-scientific way. But I will connect my remarks with the customary ideas of modern science, because they exist. The physiologist today keeps to the material that lies before him; the spiritual scientist does not need this material before him in the same way, for he does not use the method of dissection. We need not imitate the methods which over-rate anatomical inspection, yet we must reckon with the fact that they have been used and that their results have been established for some time. They will only cease to be employed when natural science has been fertilised to some extent by spiritual science.

Let us examine the close relationship, to which spiritual science will give the key, between the process taking place within the eye, and the processes of smell and taste—particularly of the latter. Let us compare the ramifications of the nerve of taste into neighbouring tissues, with the optic nerve within the eyeball. The relationship is so close that we could hardly avoid looking for an analogy with the process of taste, if we wanted an inward characterisation of the process of sight. Of course the nerve of taste is not continued into anything like the highly intricate structure of the eye, which is situated in front of the retina, and therefore sight is in many ways different.

But what begins as the process of sight, behind the wonderful instrument of the physical eye, has a close inner relationship to the process of taste. I mean that in the act of seeing, we are performing a transformed tasting, metamorphosed because the organic processes of taste are supplemented by the processes due to the intricate structure of the eye. In each one of our senses, we must distinguish between what our organism brings to meet the outer world and what the outer world brings to meet our organism. We must look at the inner process that takes place when the blood runs into the choroid of the eye, where the organism works into the eye. This process is more pronounced in certain animals, which not only have our ocular apparatus but the pecten and the xiphoid processes as well. Now the latter are organs of the blood circulation thrusting the ego forward into the interior of the eye, whereas with us, the ego recedes leaving the eyeball inwardly free. But by means of the blood, our whole organism works through the eye into the whole process of vision. And there, within the process of vision, the transmuted tasting is present. Therefore we may call sight metamorphosed tasting. And in our diagram (See Diagram 16), we have to put sight as metamorphosed tasting above taste and smell.

The processes of taste and of sight correspond to something external that co-operates with something internal. Thus the, process of taste must metamorphose itself upwards; sight is the upper metamorphosis of taste. Now there must also be a complementary downward metamorphosis of the process of taste, diving down into the lower bodily sphere. In the visual process we raise ourselves to the external world; the eye is enclosed in a bony socket, it belongs to the outside; it is a very external organ, built in accordance with the external world. Now we turn to the opposite direction and imagine the metamorphosis of the process of taste downwards into the depths of the organism. Here we come to the opposite pole of the sense of sight; we find, as it were, what corresponds in the lower part to the visual process in the upper part of the body. And this will throw much light upon our further inquiries.

In tracing the metamorphosis of the process of taste downwards, we find the digestive function.

You can only come to an inner understanding of this function, by recognising it, on the one hand, as a metamorphosed continuation of the process of taste, and on the other, as the complete polar opposite of the exteriorised process of sight. For the exteriorised visual sense enables you to recognise what in the outer world around you corresponds to digestion, of what digestion is an organic interiorisation. On the other hand, you become aware to what extent digestion must be called akin to the process of taste. It is not possible to understand the more intimate activities of our organism, in so far as they focus in the digestive process, unless you visualise that entire process as follows: good digestion is founded on capacity to taste with the whole alimentary tract, and bad digestion results from an incapacity of the whole tract to carry out this function of tasting.

Let us remember now that the process we are considering divides itself into taste and smell. As we have pointed out, taste is more involved in the relationships of the etheric with the physical: and smell, on the other hand, in those of the etheric with the astral. The continuation of the process of taste downwards into the organism is likewise bifurcated. This appears in the tendency of the digestive function towards faecal excretion, while on the other hand, we have excretion through the kidneys in the form of urine.

The two bifurcations, upper and lower, are exactly complementary. There are two polar opposites, one dividing upwards into taste and smell, while downward you have the division into digestion proper, and into that function which separates from mere digestion and is based on the more intimate activity of the kidneys and is accessory to their work in the body.

Thus it becomes possible to regard all that happens within our bodies, bounded by the surface of our skin, as an introverted external region. Every continuation upwards leads into the external world; man opens himself up to the exterior in this region.

Now we can follow the matter up in another way. There is, again, a faculty in us which lives in our soul, but is bound to the organism, not bound indeed in any materialistic sense, but in that peculiar sense of which you know from other lectures. For in thinking and the forming of “representations,”1The term “representation” renders the German Vorstellung better than the usual translation “idea,” which is ambiguous. (see Diagram 16) we have a metamorphosed seeing, once more turned inward in a certain sense.

Just consider for a moment how many of the representations you use in thinking are simply continuations of visual images; compare for a moment the soul-life of the congenitally blind or deaf person with your own! In thinking we have an interiorised continuation of seeing. And we may even find light thrown upon the remarkable interaction between the anatomy of the head and brain, and the process of thought itself. (This would furnish fine material for medical essays!) When we carefully examine our thinking processes, especially the connection between the powers of combination and association and the cerebral structure, we come upon formations resembling a transformation of the olfactory nerve. So we may say that from an internal point of view, our discontinuous, analytic thinking is very like its counterpart, seeing. But the combination of “things seen,” the association of representations, resembles smell in its internal organic formation. This contrast is expressed in a remarkable way in the anatomical structure of the brain.

Thus we find thinking and representation as the one end of a metamorphosis. What then may be regarded as the complementary interiorised process? Remember the power of representation can be termed a transformed sight; something that is exteriorised in sight and radiates back into the interior in thought. In thinking we try to reverse our vision, as it were, and to direct it again into the organism. So its polar opposite will be a process that does not in any way try to lead into the interior, but to lead out. This polar opposite is the process of evacuation—the conclusion of digestion. (See Diagram 16). Thus evacuation becomes the counter-image of representation. Here you have in a more intimate aspect what I have already dealt with from the standpoint of Comparative Anatomy, when I tried to show the close relationship between the so-called mental (spiritual) capacities of man and the regulated or non-regulated process of excretion; basing my argument on anatomical structure and the existence of the flora of the intestines.

Here is the same truth revealed by another approach. In thought we have an internal continuation of sight, and in evacuation an external continuation of digestion. Now refer to what we said before, that the aroma process in plants is a suspended combustion, and their solidification a suspended salt-process. This again throws light on what takes place within the body! Only—we must be clear that a reversal takes place. In representation, we have the sense of sight reversed and turned inwards, while in the lower bodily sphere there is a reversal towards the outside. So we have to recognise the relationship of the upper process to salification and of the lower to combustion, or to “fire.” (See Diagram 16). So if you apply a suitable remedy containing aromatisation and suspended combustion in plants, to the hypogastrium, you will help and relieve it. Conversely, if you apply to the upper part of man what tends to keep back or to interiorise the salt-process within the plant, you will give help in this sphere also. This rule we shall have to discuss and apply in detail.

Thus the whole external world may reappear in our human interior. And the more deeply internal the process, the greater the need to find its external analogue. We must see something very closely akin to the aromatic and combustion processes—but akin in the sense of polarity—in the activities of the digestive organs, especially of the kidneys. Again in the upper region, from the lungs upward, through the larynx into the head, we must see something related to the tendency to salt formation in the plant; all this tends to salification in man. We might even say, or rather we can say, that if we have once acquired a knowledge of the different ways in which plants absorb and collect salt, we need only look for their analogies in the human organisation. We have dealt with this in general today, and we shall go on to consider it in detail.

With this you have a basic principle for the whole of plant therapy. You have a general picture of the whole process of mutual action and reaction between the interior and the exterior world. But you will already be able to see some specific applications. Take, for instance, some of the odours which even as such are linked with taste, so that they may be fully experienced if the plant is not only sniffed, but chewed. Then we find a synthesis of smell and taste, aroma and flavour, as for instance in balm or ground ivy. In such cases we find that in the scent there is already an element of salification; there is a collaboration between the saline and aromatic tendencies. And this is an indication of their correspondence in the organism, an indication that balm, for instance, is suitable for the external organs and the chest, whereas such very fragrant forms as lime or rose blossom are akin to that which lies deep within the abdomen or in the neighbourhood of the abdominal wall.

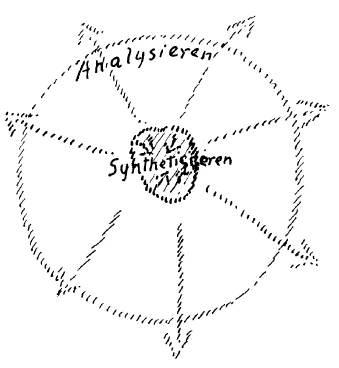

All the organs and functions of our upper sphere in the regions of the smell and taste activities, are interlocked with a life-process, which can be so termed in a deeper sense—i.e.—respiration (See Diagram 16). Let us look for the polar complementary activity; it must be something branching from the digestive process, before digestion passes into evacuation, and be the polar counterpart of “representation.” Yet it must be something organically adjacent to the process of digestion, just as respiration is organically adjacent to the process of smell and taste. So we find the converse of respiration in the lymph and blood processes, in the process of blood formation and especially in what branches off and is pushed inward from the digestion, i.e., the processes in the lymphatic glands and similar organs contributing to blood formation. Here then are two polar processes; the one branching from the digestive system, the other from the more external sensory processes; one, respiration, in the second line behind the sensory organs; and the other situated just in front of where the digestive process leads to excretion—the process of blood and lymph. It is remarkable how, starting from actual processes, we come to an insight into the whole human being, whereas in current medicine man is studied only from the organs, considered externally. Here, however, we take our start from the processes and we try to understand the individual person out of the whole relationship between man and the external world. We find interactions that directly depict the etheric activities in man; and these have been our object of study today. And the two processes of breathing and blood formation meet again in the human heart itself. The whole outside world (including man) appears as a duality that is dammed up in the heart, and in it strives for a kind of equilibrium.

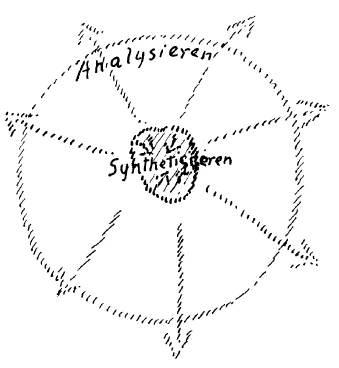

Thus we come to a remarkable picture, the picture of the human heart, with its interiorising character, its synthesis of everything that works from outside into our bodies. Outside in the world there is an analysis, a scattering, of all that is gathered together in the heart (See Diagram 17). You come here to an important conception that might be expressed thus: You look out into the world, face the horizon and ask:—What is in these outer surroundings? What works inwards from the periphery? Where can I find something in myself that is akin to it? If I look into my own heart. I find, as it were, the inverted heaven, the polar opposite. On the one hand you have the periphery, the point extended to infinity, on the other you have the heart, which is the infinite circle concentrated to a point. The whole world is within our heart. To use an illustration, perhaps one that is somewhat crude:—Picture to yourselves man standing looking on into the infinite expanses of the world; perhaps standing on a high hill, looking out and around. And suppose that the tiniest dwarf imaginable is put in the human heart. Try to realise that what the dwarf sees within the heart is the complete inverted image of the universe, contracted and synthesised. This is perhaps purely a picture, a kind of imagination. But if righty conceived and taken up, it can work as an orderly regulative picture, a regulative principle, that is able to guide us, and to help us rightly to combine our isolated attainments of knowledge.

Most of the foundations for our special studies and inquiries have now been laid down, and they will be the basis for answering the many questions you have addressed to me.

Achter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Die Ausdrucksweise, die wir ja schon, ich möchte sagen, mehr zur Verkürzung oder zur Vereinfachung unserer Ideen anwenden müssen, wenn wir sagen «Ätherleib», «Astralleib» und so weiter, kann durchaus zurückgeführt werden auf dasjenige, was sich von ihr gewissermaßen abdrückt im physischen Geschehen. Nur ist man heute nicht sehr geneigt, dasjenige, was sich im physischen Geschehen ausdrückt, wirklich in richtige Beziehung zu setzen zu der geistigen Grundlage des Daseins. Für eine Durchgeistigung des medizinischen Denkens und Anschauens wird aber das unbedingt geschehen müssen. Man wird unbedingt zum Beispiel darauf eingehen müssen, wie das Wechselspiel zwischen dem, was wir Ätherleib nennen, und dem, was wir physischen Leib nennen, eigentlich geschieht. Sie wissen, dieses Wechselspiel geschieht im Menschen, und wir haben gestern gesprochen von einer Seite dieses Wechselspiels, nämlich, wenn es in eine Art Unordnung kommt gegenüber den Einwirkungen des astralischen Leibes. Aber dieses Wechselspiel geschieht ja auch draußen in der außermenschlichen Natur.

[ 2 ] Nun bedenken Sie, daß Sie, wenn Sie diesen Gedanken ordentlich zu Ende führen, dann eigentlich recht gründlich hineinschauen in den Zusammenhang des Menschen mit der außermenschlichen Natur. Sie schauen hinaus in die außermenschliche Natur. Sie haben um sich — halten wir zunächst heute daran fest — die ganze Flora mit allen ihren einzelnen Arten, und Sie werden diese Flora durch Ihre verschiedenen Sinne gewahr. So können Sie, wenn Sie da hinausschauen, mit Ihren verschiedenen Sinnen die Flora gewahr werden, mindestens ahnen ein Wechselspiel zwischen dieser Flora und alledem, was erstens in der irdischen Atmosphäre ist, und alledem, was dann außerhalb dieser irdischen Sphäre im Planetarischen, im Astralischen liegt. Wir können gewissermaßen sagen, wenn wir die Flora der Erde betrachten, wenn hier (siehe Zeichnung Seite 158) Tafel 12

[ 3 ] die Erdoberfläche ist, so weist uns diese Flora hinaus auf das Atmosphärische, auf das Astralische, jetzt in diesem Sinne gemeint, daß es zu den Sternen hingeht, zu dem Außertellurischen, und wir können zunächst, auch wenn wir nicht auf Okkultes eingehen, ahnen, daß da draußen eine lebendige Wechselwirkung ist zwischen dem, was sich in der Flora, in dem Blüte- und dem Fruchtaufschießen zeigt, und dem, was da hereinwirkt aus dem ganzen weiten Weltenall.

[ 4 ] Wenn wir dann von alledem wegsehen und den Gedanken hineinleiten in unser Inneres — allerdings müssen Sie versuchen, bei dieser Anschauung etwas Intuition zu Hilfe zu nehmen, aber ich habe schon gesagt, ohne Intuition geht es in der Medizin absolut nicht ab —, wenn wir diesen Gedanken ableiten von diesem Äußeren und in unser eigenes Inneres hineinschauen, so finden wir mit demjenigen, was da draußen ist, eine gewisse Verwandtschaft. Und da wir uns sagen müssen: In der Flora ist eng verbunden das Ätherische mit dem Physischen, so müssen wir auch ahnen eine gewisse Verwandtschaft dieser Art von Verbindung des Ätherischen mit dem Physischen in der Flora und der Art der Verbindung des Ätherischen mit dem Physischen im Menschen selbst.

[ 5 ] Nun handelt es sich darum, daß wir uns Rechenschaft darüber geben, durch was wir äußerlich konkret sprechen können über diese Verwandtschaft des Ätherischen mit dem Physischen. Wir werden uns ja zunächst abstrakt sagen können: Das Ätherische steht dem Astralischen näher als dem Physischen, insofern es sich nach oben öffnet. Wir werden uns aber auch sagen müssen, daß das Ätherische irgendeine Beziehung zu dem Physischen hin hat. Wir werden also auf diese Doppelverwandtschaft hinschauen müssen, in der das Ätherische auf der einen Seite zu dem Physischen, auf der anderen Seite zu dem Astralischen steht, und wir werden etwas aufsuchen müssen, was uns gewissermaßen in diese Doppelverwandtschaft hineinführt. Nun möchte ich Ihnen zunächst möglichst konkret darstellen, wie Sie in diese Doppelverwandtschaft hineingeführt werden können.

[ 6 ] Gehen Sie einmal, sagen wir, durch eine Lindenblütenallee und versuchen Sie sich recht klarzumachen, wie Sie in dieser Lindenblütenallee durch den Duft der blühenden Linden hindurchgehen. Machen Sie sich klar, daß nun ein Prozeß sich abspielt zwischen all dem, was sich, sagen wir, nervenartig in Ihre Geruchsorgane ausbreitet, und diesem Lindenblütenduft. Dann haben Sie, wenn Sie auf diesen Prozeß des Wahrnehmens des Lindenblütenduftes hin Ihre Aufmerksamkeit wenden, gewissermaßen das Aufschießen des Innern, des Geruchsfähigen gegen den Lindenblütenduft, den Lindenblütengeruch, und Sie müssen sich sagen: Da spielt sich ein Prozeß ab, der ein Inneres einem Äußeren entgegenbringt, die irgendwie etwas miteinander vollbringen durch ihre innere Verwandtschaft. Und Sie müssen sich sagen: Dasjenige, was sich durch den Lindenblütenduft draußen zerstreut, was zweifellos auf einer Wechselwirkung der Flora mit der ganzen außerirdischen Umgebung beruht, der sich nach der außerirdischen Umgebung hin aufschlieBenden Flora, das wird gewissermaßen verinnerlicht in der Geruchswahrnehmung selber. Da haben Sie innerlich, weil Sie ja die Sache wahrnehmen, ganz zweifellos etwas gegeben, was vom Ätherleib aus auf den astralischen Leib wirkt, denn sonst könnten Sie nicht wahrnehmen, sonst wäre es ein bloßer Lebensprozeß. Der Geruchsvorgang selbst bezeugt einem, daß der astralische Leib daran beteiligt ist. Aber dasjenige, was Ihnen die Verwandtschaft enthüllt mit der Außenwelt, zeigt Ihnen zugleich, daß das Entstehen jenes süßlichen Geruches, den die Lindenblüten ausströmen, in einem gewissen Sinne verwandt ist, polarisch ist zu dem, was in Ihrem Geruchsorgan vor sich geht. Und in der Tat haben wir in diesem sich verbreitenden süßlichen Geruche der Lindenblüten die Wechselwirkung des Pflanzlich-Ätherischen mit dem Umliegenden gegeben, den allgemeinen Weltenraum durchfüllenden Astralischen. Wir haben daher in unserem Riechen einen Prozeß, der sich so abspielt, daß wir durch diesen Prozeß an dem teilnehmen, was verwandt ist in der Flora mit dem außertellurischen Astralischen.

[ 7 ] Wenn wir nun nehmen irgendeinen Geschmack, sagen wir, um wiederum etwas dem eben Angeführten Verwandtes zum Beispiel zu haben, den Geschmack des Süßholzes oder den Geschmack süßer Weintrauben, da haben wir etwas Ähnliches. Da haben wir es aber zu tun mit einem Vorgang, der sich abspielt in unserem Geschmacksorgan im Gegensatz zu den Vorgängen, die sich abspielen in unseren Geruchsorganen. Sie wissen, wie nahe verwandt das Geschmacksorgan dem Geruchsorgan ist, und Sie werden daher ohne weiteres eine Vorstellung davon haben müssen, wie nahe verwandt auch in bezug auf das ganze natürliche Geschehen dasjenige ist, was im Schmecken vor sich geht, mit dem, was im Riechen vor sich geht. Aber Sie müssen sich zugleich klar sein, daß das Schmecken ein viel organisch-innerlicherer Prozeß ist als das Riechen. Das Riechen spielt sich mehr an der Oberfläche ab. Das Riechen nimmt teil an den Prozessen des Außermenschlichen, die sich gewissermaßen ausbreiten, die im Raume ausgebreitet sind. So ist es beim Schmecken nicht der Fall. Durch das Schmecken kommen Sie mehr auf gewisse Eigenschaften, die innerlich in den Substanzen liegen müssen, die also mit dem Substantiellen selber verbunden sein müssen. Sie kommen mehr durch das Schmecken als durch das Riechen darauf, was die Dinge, die Pflanzen also in diesem Falle, im Innern sind. Und Sie brauchen einfach ein wenig Ihre Intuition zu Hilfe zu nehmen, so werden Sie sich sagen, daß alles dasjenige, was mit dem Festwerden in den Pflanzen, mit den organischen Prozessen des Festwerdens in den Pflanzen zusammenhängt, sich enthüllt, sich offenbart durch das Schmecken alles desjenigen, was in der Pflanze ist. Nun wehrt sich aber dieses Pflanzliche gegen das Festwerden. Das tritt uns hervor in dem, was die Pflanze veranlaßt, riechbar zu werden. Daher werden Sie nicht eigentlich zweifeln können, daß der Geschmack ein Vorgang ist, der zusammenhängt mit den Beziehungen des Ätherischen zum Physischen.

[ 8 ] Also nehmen Sie jetzt zusammen Riechen und Schmecken. Indem Sie im Riechen und Schmecken gegenüber der Flora leben, leben Sie eigentlich in jenen Beziehungen, welche das Ätherische nach den beiden Seiten hin hat, nach dem Astralischen und nach dem Physischen. Sie gehen so recht ins Ätherische hinein, das heißt in seinem Abdruck, wenn Sie zum Riechen und Schmecken mit Ihrer Aufmerksamkeit sich hinwenden. Da wo Riechen und Schmecken im Menschen ist, da ist im Grunde genommen eine in der physischen Welt befindliche Offenbarung des Ätherischen in seinen Beziehungen zum Astralischen und zum Physischen. Wir sind damit gewissermaßen selber an des Menschen Oberfläche, wenn wir so untersuchen, was sich im Riechen und Schmecken abspielt. Aber sehen Sie, es handelt sich wirklich heute darum, daß wir endlich zur Befruchtung der wirklichen Wissenschaft von seiten der Geisteswissenschaft über das Abstrakt-Mystische hinauskommen und zum konkreten Geist-Erfassen wirklich vordringen. Was nützt es denn wirklich, wenn die Leute immer fort und fort nur reden davon, es soll das Göttliche im Menschen erfaßt werden, wenn sie unter diesem Göttlichen höchstens irgendein ganz abstraktes Göttliches verstehen? Es wird diese Betrachtungsweise erst dann fruchtbar, wenn wir auf die konkreten Erscheinungen eingehen können, wenn wir in diesem konkreten Sinne das Innerlichwerden der äußeren Vorgänge betrachten, zum Beispiel also, indem wir im Riechen und Schmecken tatsächlich dasjenige, was äußerlich, verwandt dem Menschen, lebt, das Ätherische betrachten, wie das sich verinnerlicht, wie wir in diesem vielleicht gröbsten oberen Sinnesprozesse unmittelbar ein Innerlichwerden der äußeren Vorgänge sehen. Das ist für unsere Zeit so außerordentlich wichtig, hinauszukommen über das bloß Abstrakte, Mystische. Nun werden Sie aber sich klar sein darüber, daß in der Natur alles in fortwährendem Übergang zu etwas anderem ist, daß in der Natur alles so ist, daß ein Vorgang die Tendenz hat, in einen anderen überzugehen, sich zu metamorphosieren in einen anderen Vorgang hinein. Nehmen Sie also das, was wir eben gesagt haben: mehr an der Oberfläche gelegen das Riechen (siehe Zeichnung Seite 162), mehr in das Innere des Menschen hineinverlegt — alles das ist auf die Flora, die Pflanzen bezüglich — das Schmecken, den Geschmack, und diese, ich möchte sagen, verlaufend im Ätherischen, insofern sich das Ätherische gegen das Astralische aufschließt oder in das Physische hinein verfestigt, nach außen also gehend, nach alledem, was in der Flora geschieht im Verflüchtigen, im Aromatischwerden oder auch im sich dem Aromatischen Entziehen im Schmecken, alles dasjenige verinnerlichend, was im Außernführt zum Festwerden. Es fließen gewissermaßen zusammen das Äußerliche und das Innerliche, wenn wir die Aufmerksamkeit in bezug auf Riechen und Schmecken festhalten.

[ 9 ] Aber in der Natur geht immer ein Prozeß in den anderen über. Richten wir einmal unseren Sinn auf dieses Aromatische der Flora, auf alles dasjenige, wodurch die Flora sich gewissermaßen ihrem 'Festwerden entzieht, wo die Flora das Pflanzensein noch über sich hinaustreiben will, wo die Pflanze gewissermaßen noch — verzeihen Sie den Laienausdruck — ihre Geistigkeit hinaussetzt in die Atmosphäre, so daß die Atmosphäre in dem Riechstoff noch etwas von dem Pflanzensein in sich trägt. Es sind gewissermaßen noch die Schemen der Pflanzen in dem, was da draußen riecht. Nehmen Sie das. Was ist denn das eigentlich, was da draußen vorgeht, wenn die Pflanze ihre Riechschemen hinausschickt, wenn sie es nicht ganz zum verfestigten Pflanzensein kommen läßt, wenn sie aus der Blüte noch etwas hinaussendet, was zwar Blüte werden will, was sich aber diesem Blütewerden entzieht, was sich in dem Flüchtigsein erhält? Das ist nämlich nichts anderes als ein zurückgehaltener Verbrennungsprozeß. Sie kommen, wenn Sie sich dieses Aromatisieren metamorphosisch fortgesetzt denken, dahin, zu denken: dieses Aromatisieren ist eigentlich ein zurückgehaltener Verbrennungsprozeß. Sie sehen auf der einen Seite die Verbrennung und auf der anderen Seite das Aromatisieren der Pflanzenwelt an, dann erkennen Sie darinnen zwei Metamorphosen einer gemeinsamen Einheit. Ich möchte sagen: es ist einfach im Aromatisieren auf einer anderen Stufe das Verbrennen gegeben.

[ 10 ] Jetzt schauen wir auf dasjenige bei der Pflanze, was Anregung gibt zum Schmecken, was also in der Pflanze tiefer drinnen liegt, was in der Pflanze dazu Veranlassung gibt, daß sie nun nicht ihre Pflanzenbildekraft wie ein Schemen aus sich heraustreibt in die Umgebung hinein, sondern daß sie sie in sich zusammenhält, daß sie sie zur inneren Bildung verwendet. Da kommen Sie, weil Sie dieses innere Bilden im Schmecken mitmachen, zu demselben Prozeß, der unterhalb des Festwerdens des Pflanzlichen liegt, der aber eine Metamorphose ist auf dieser anderen Stufe zum Salzwerden, aber natürlich zum Salzwerden der Pflanze, denn wir reden von der Flora (siehe Zeichnung Seite 162).

[ 11 ] Denken Sie, Sie haben in der Pflanze eine merkwürdige Metamorphosierung gegeben. Sie haben in der Pflanze nach oben das Aromatisieren gegeben, das gewissermaßen ein zurückgehaltener Verbrennungsprozeß ist und schon auch zu dem Anfange der Verbrennungsprozesse führen kann; denn Prozesse des Blütigwerdens sind eben einfach Verbrennungsprozesse, die sich da hineingliedern. Nach unten haben Sie das Festwerden, das Salzwerden. Und das, was Sie in der Pflanze schmecken, ist dasjenige, was noch zurückgehaltenes Salzwerden ist. Aber wenn sich das Salz eingliedert und Sie das Salz in der Pflanze selber finden, also diese Pflanzensalze haben, so sind diese etwas, was in der Pflanze selbst über den Weg des Pflanzenwerdens hinausgeschritten ist, wo die Pflanze in ihr eigenes Wesen hineingepreßt ihren eigenen Schemen hat.

[ 12 ] Da ist die Ratio für das Heilmittel erkannt, da beginnt es, ich möchte sagen, in einem gewissen Sinne Licht zu werden in der Flora, weil man hineinschaut in dasjenige, was da geschieht. Auf dieses, ich muß es immer wieder betonen, konkrete Hineinschauen kommt es an.

[ 13 ] Nun brauchen Sie sich, um weiterzugehen, nur an folgendes zu erinnern: Ich will da, wo es geht, ich möchte sagen, rein aus höheren opportunistischen Gründen dasjenige, was auseinanderzusetzen ist, doch anknüpfen an das, was heute gang und gäbe ist, damit Sie auch in der Lage sind, die Brücke zu schlagen zwischen dem, was Geisteswissenschaft geben kann, und dem, was äußere Wissenschaft ist. Natürlich könnte ich jetzt auch das, was ich in den folgenden Sätzen auseinandersetzen werde, noch geisteswissenschaftlicher charakterisieren, aber ich will anknüpfen an gebräuchliche Vorstellungen der heutigen Wissenschaft, die eben schon da sind. Der Physiologe spricht heute von dem, was ihm vorliegt, was dem Geisteswissenschafter aus dem Grunde nicht vorzuliegen braucht, weil er nicht in diesem selben Sinne zu anatomisieren braucht. Aber knüpfen wir eben an die gebräuchlichen Vorstellungen an. Wir haben ja nicht nötig, die anatomisierenden Unfuge der anderen aufzunehmen, aber wir müssen doch mit dem Faktum rechnen, daß sie eben schon dagewesen sind und ihre Ergebnisse geliefert haben. Aufhören werden sie doch nur, wenn Naturwissenschaft etwas von Geisteswissenschaft befruchtet worden sein wird. Also prüfen wir einmal! Es wird dann aus der Geisteswissenschaft ganz klar werden, welch nahe Verwandtschaft, welch nahe Beziehung besteht zwischen jenem Prozeß, der sich im Auge abspielt, und dem Prozeß, der sich im Geruch und namentlich im Geschmack abspielt, in dem Ausbreiten des Geschmacksnervs in der übrigen Organsubstanz und in dem Ausbreiten des Augennervs im Auge. Da besteht eine so nahe Verwandtschaft, daß man eigentlich fast nicht umhin kann, wenn man das Innerliche des Sehvorganges charakterisiert, Analogien zum Geschmacksvorgang zu suchen. Natürlich, da beim Ausbreiten des Geschmacksnervs in der organischen Substanz sich nicht dasjenige anschließt, was die kunstvolle Bildung des Auges ist, die der Ausbreitung des Sehnervs in der organischen Substanz vorgelagert ist, so ist das Sehen etwas ganz anderes. Aber dasjenige, was gewissermaßen als Sehvorgang beginnt hinter dem kunstvollen Ausbau des physischen Auges, das ist schon sehr innerlich verwandt mit dem Geschmacksvorgang. Ich möchte sagen: Wir vollziehen im Sehen ein metamorphosiertes Schmecken, metamorphosiert dadurch, daß wir eben den Organvorgängen, die sich im Schmecken abspielen, all dasjenige vorgelagert haben, was durch den kunstvollen Bau des Auges bedingt ist.

[ 14 ] Nun müssen wir natürlich bei jedem Sinn unterscheiden zwischen dem, was unser Organismus der Außenwelt entgegenbringt, und dem, was die Außenwelt unserem Organismus entgegenbringt. Wir müssen also auf dasjenige hinschauen, was von innen als Vorgänge geschieht dadurch, daß das Blut ins Auge hineinstößt, daß also der Organismus ins Auge hineinwirkt. Das ist noch stärker bei gewissen Tieren, die zu unseren Organen hinzu noch im Auge den Fächer und den Schwertfortsatz haben, also Blutorgane, wodurch das Ego mehr hineingetrieben wird in den Augapfel, während bei uns sich das Ego zurückzieht und den Augapfel innerlich freiläßt. Aber es wirkt da hinein die ganze Organisation auf dem Umwege des Blutes durch das Auge in den ganzen Sinnenvorgang, und da drinnen im Sehvorgang ist gewissermaßen metamorphosiert der Geschmacksvorgang, so daß wir das Sehen ein metamorphosiertes Schmecken nennen können. Wir würden also gewissermaßen oberhalb des Schmeckens und Riechens das Sehen gelagert haben als metamorphosiertes Schmecken (siehe Zeichnung Seite 162). |

[ 15 ] Es entspricht also dem, was der gesamte Geschmacksvorgang sowohl wie Sehvorgang ist, etwas Äußeres, das mit dem Inneren zusammenwirkt. Es muß sich also der Vorgang gewissermaßen nach oben hin metamorphosieren. Eine Metamorphose des Schmeckvorganges ist der Sehvorgang. Aber es muß dann auch nach unten in den Körper hinein eine Metamorphose des Schmeckvorganges geben. Wir müssen, während wir im Sehvorgang mehr nach der Außenwelt steigen — das Auge ist eingeschlossen nur in der Knochenhöhle und wir kommen da nach außen, das Auge ist ein sehr äußerliches Organ, es wird der Sehvorgang mehr nach dem Äußeren hin organisiert —, jetzt nach der entgegengesetzten Seite uns die Metamorphose des Schmeckvorganges nach unten in den Organismus hineindenken. Wir kommen dann gewissermaßen zum anderen Pol des Sehens, zu dem, was im Organismus dem Sehvorgang entspricht, auf etwas, was uns ungeheuer viel Licht werfen wird in den folgenden Betrachtungen. Denn was ist nun da gegeben, wenn wir die Metamorphose des Geschmacksvorganges nach unten verfolgen? Da ist nämlich die Verdauung bedingt, und Sie kommen zu einem wirklichen innerlichen Verstehen der Verdauung nur, wenn Sie sich auf der einen Seite das Sehen als eine metamorphosierte Fortsetzung des Schmeckens vorstellen, auf der anderen Seite die Verdauung als metamorphosierte Fortsetzung des Schmeckens, aber so, daß Sie die Verdauung in ihrem vollen polarischen Gegensatz zu dem veräußerlichten Sehen aufzufassen vermögen, denn das veräußerlichte Sehen führt Sie gerade darauf hin, zu erkennen, was in der Außenwelt dieser Verdauung entspricht, von was die Verdauung organisch eine Verinnerlichung ist. Auf der anderen Seite werden Sie gewahr, wie der Verdauungsvorgang verwandt gedacht werden muß dem Schmeckvorgang. Sie können einfach die intimen Wirksamkeiten im menschlichen Organismus, insofern sie auf den Verdauungsprozeß hin lokalisiert sind, gar nicht verstehen, wenn Sie sich nicht den gesamten Verdauungsprozeß so vorstellen, daß das gute Verdauen auf einer Fähigkeit beruht, die gewissermaßen mit dem ganzen Verdauungstrakt zu schmecken versteht, daß das schlechte Verdauen gewissermaßen auf der Unfähigkeit beruht, mit dem ganzen Verdauungsapparat zu schmecken.

[ 16 ] Nun sondert sich der Vorgang, den wir da betrachtet haben, in Schmecken und Riechen. Da spaltet sich gewissermaßen ein Vorgang so, daß wir es einmal zu tun haben mit einem Prozeß, der mehr in Wechselwirkung des Ätherischen und des Physischen steht im Schmecken und auf der anderen Seite mit einem Vorgange, der mehr in den Beziehungen des Ätherischen zum Astralischen steht, was wir in dem Riechen vorliegen haben. Dasjenige, was wir als Fortsetzung des Schmeckens in den Organismus hinein haben, das haben wir der gleichen Spaltung unterworfen, indem wir auf der einen Seite das Verdauen hinneigend haben zu den Ausscheidungen durch den Darm, zu den fäkalen Ausscheidungen, und indem wir auf der anderen Seite die Ausscheidungen durch die Nieren, durch das Urinieren haben. Da haben Sie genau das Entsprechende in dem Unteren und in dem Oberen des Menschen. Sie haben ganz genau etwas, was vorliegt wie zwei polarische Gegensätze, indem Sie spalten zum Schmecken und Riechen und indem Sie spalten zum gewöhnlichen Verdauen und zu dem, was vom gewöhnlichen Verdauen sich abscheidet als alles dasjenige, was auf der intimeren Nierentätigkeit beruht, auf demjenigen, was der intimeren Nierentätigkeit zugeordnet ist.

[ 17 ] Da haben wir gewissermaßen die Möglichkeit, dasjenige, was im Innern des Organismus durch die Haut begrenzt geschieht, als ein Verinnerlichtes des Äußerlichen zu betrachten. Denn mit alledem, was wir da nach oben fortsetzen, kommen wir eben mehr ins ÄAußerliche hinein; da schließt sich der Mensch nach dem Äußerlichen auf. Jetzt haben wir die Sache so weiter zu verfolgen, daß wir in dem, was gewissermaßen in uns seelisch lebt, aber an den Organismus eben gebunden ist, nicht im materialistischen Sinne, sondern in einem anderen Sinne, den Sie ja aus den Vorträgen kennen, ein metamorphosiertes Sehen haben, wiederum nach einer gewissen Seite nach dem Innern gelegen, im Denken, im Vorstellen (siehe Zeichnung Seite 162), wobei wir uns zu denken haben diejenigen Organe, die zugrunde liegen den Vorstellungen, also die des menschlichen Innenhauptes als metamorphosierte Sehorgane nach einer gewissen Richtung. Bitte, orientieren Sie sich nur darüber, wie die meisten Ihrer Vorstellungen, die im Denken leben, einfach Fortsetzungen sind der Sehvorstellungen, Sie brauchen ja nur das seelische Leben des Blindgeborenen, des Taubgeborenen zu vergleichen. Wir haben eine Fortsetzung des Sehens nach dem Inneren im Denken. Und wir kommen so dazu, uns zu sagen, daß auch ein Licht geworfen wird auf das merkwürdige Wechselwirken, das ja zwischen der Anatomie des Kopfes, des Gehirnes und dem Denkvorgang selber besteht. Es ist ja zum Beispiel sehr eigentümlich, daß, wenn man ordentlich zu Leibe geht unseren Denkvorgängen — ein schönes Kapitel für eine medizinische Dissertation übrigens — und untersuchen will, wie mit dem zusammenfassenden Denken die Organisation des Gehirnes zusammenhängt, man sonderbarerweise auf Strukturen kommt, die sich wie eine Umbildung des Riechnervs ausnehmen. So daß man sagen könnte: unser zerstreutes, analytisches Denken ist, innerlich angesehen, in seinem Gegenbilde sehr ähnlich dem Sehen. Aber das Zusammenfassen des Gesehenen, das Assoziieren der Vorstellungen, ist eigentlich, innerlich organisch angesehen, sehr ähnlich dem Riechen. Das drückt sich nämlich in der anatomischen Struktur des Gehirnes sogar in einer sehr bemerkenswerten Weise aus. Wir kommen also jedenfalls da zum Vorstellen, zum Denken nach der einen Seite.

[ 18 ] Wohin kommen wir nun, wenn wir wiederum den innerlichen Prozeß suchen? Nicht wahr, im Vorstellen haben wir vom Sehen aus dasjenige, was veräußerlicht ist im Sehen, was wiederum gewissermaßen nach dem Inneren zurückstrahlt im Denken. Man bemüht sich, den Sehprozeß gewissermaßen umzukehren, nach dem Organismus wiederum zu leiten. Sein polarisch entgegengesetzter Prozeß wird daher darinnen bestehen, daß man sich nicht bemüht, dasjenige, was da Prozeß ist, nach dem Innern, sondern nach dem Äußeren zu leiten. Und das ist: der Verdauungsprozeß setzt sich fort in den Ausscheidungsprozeß (siehe Zeichnung Seite 162), der damit zum Gegenbilde des Vorstellens wird. Da haben Sie von einem anderen, intimeren Standpunkte aus das gesehen, was ich Ihnen mehr durch die vergleichende Anatomie gezeigt habe vor ein paar Tagen, wo ich Sie auch darauf hingewiesen habe, wie einfach der Bau des Menschen und namentlich das Auftreten der Darmflora in einer gewissen Weise darauf hindeuten, welch innige Verwandtschaft besteht zwischen den sogenannten geistigen Fähigkeiten des Menschen und seinem regulierten Ausscheideprozeß oder nichtregulierten Ausscheideprozeß. Da haben Sie das von einer anderen Seite. Da haben Sie also, wie wir nach innen eine Fortsetzung des Sehprozesses im Denkprozeß haben, nach außen eine Fortsetzung des Verdauungsprozesses im Ausscheidungsprozeß. Wenn wir nun zurückgehen auf dasjenige, was wir beobachtet haben vorhin gerade, daß das Aromatisieren ein zurückgehaltenes Verbrennen ist und das Festwerden der Pflanze ein zurückgehaltenes Salzwerden, so werden wir wiederum auf dasjenige Licht geworfen haben, was da nun im Innern geschieht, nur müssen wir uns klar sein darüber, daß ja eine Umkehrung geschieht. Hier (oben) ist eine Umkehrung des Sehens nach der Verinnerlichung, hier (unten) ist es eine Umkehrung nach der Veräußerlichung, daher werden wir hier (oben) zu der Anerkennung einer Verwandtschaft der Vorgänge mit dem Salzwerden kommen und hier (unten) zu einer Verwandtschaft der Vorgänge mit dem Feuerwerden oder mit dem Verbrennen, mit dem Feuer (siehe Zeichnung Seite 162). Leiten Sie also dasjenige, was geeignet ist, das Aromatisieren und den zurückgehaltenen Verbrennungsprozeß in den Pflanzen zu bewirken (siehe Hinweise), nach dem Unterleibe, so helfen Sie dem Unterleibe. Leiten Sie das, was in der Pflanze berufen ist, den Salzprozeß zurückzuhalten oder ihn in der Pflanze zu verinnerlichen, nach dem oberen Menschen, so helfen Sie den Vorgängen des oberen Menschen. Das werden wir im einzelnen dann durchzuführen haben.

[ 19 ] Da sehen Sie, wie gewissermaßen wieder auftreten kann das ganze Äußere im ganzen Inneren. Und je innerlicher wir in den Menschen hineinkommen, desto mehr müssen wir im Innern des Menschen das Äußerliche suchen. Wir müssen geradezu in dem, was sich in den Verdauungsorganen, namentlich in den Nieren, abspielt, etwas suchen, was sehr, sehr verwandt ist mit dem Aromatisierungs- und Verbrennungsprozeß, nur eben der andere Pol ist. Und wir müssen in dem, was sich abspielt in der Organisation des Menschen, von der Lunge angefangen nach oben durch Kehlkopf und Kopf, etwas suchen, was innerlich verwandt ist mit all dem, was in der Pflanze zum Salzwerden, was überhaupt in der menschlichen Natur zum Salzwerden hinneigt. Man möchte also sagen — das heißt, nicht nur man möchte es sagen, man kann es sagen: kennt man die verschiedenen Arten, wie die Pflanzen Salz in sich ansammeln, dann braucht man nur zu suchen das Entsprechende in der menschlichen Organisation. Im Großen haben wir es heute gesucht, im Speziellen werden wir es in den folgenden Vorträgen aufsuchen.

[ 20 ] Hier sehen Sie gewissermaßen die ganze Pflanzenheilkunde zunächst im Prinzip charakterisiert. Sie sehen, worauf sie beruht. Ich möchte sagen: Sie sehen in den ganzen realen Prozeß, der sich abspielt in seiner Wechselwirkung zwischen dem Inneren und dem Äußeren, hinein; Sie sehen aber auch ganz Spezielles schon. Nehmen Sie zum Beispiel diejenigen Gerüche, die, ich möchte sagen, schon als Gerüche mehr zum Geschmacklichen hinneigen, so daß man eigentlich, indem man die betreffende Pflanze kaut, erst auf den richtigen Geruch kommt und eigentlich eine Synthese zwischen Geruch und Geschmack wahrnimmt, wie bei der Melisse oder bei der Gundelrebe, dann finden wir, daß da drinnen schon etwas von Salzwerden liegt, daß da drinnen schon ein Zusammenwirken zwischen dem Salzwerden und dem Aromatisieren ist. Das weist uns darauf hin, daß die Organe, die zu diesen Pflanzen Verwandtschaft haben müssen, wie Melisse und so weiter, mehr nach dem Äußeren, nach der Brust zu liegen, während diejenigen Organe, die verwandt sein müssen mit dem, was stark aromatisch ist, wie, sagen wir, die Linde oder die Rose, verwandt sein müssen mit dem, was mehr in den Unterleib eingegraben ist oder mehr nach dem Unterleib hin liegt.

[ 21 ] Nun finden Sie, daß zwischen all dem, was da im oberen Menschen liegt in der Gegend des Riechens oder Schmeckens, organisch betrachtet, sich ein anderer Prozeß hineingliedert, der nun in einem etwas tieferen Sinne für den Menschen ein wichtiger Lebensprozeß ist; das ist der Atmungsprozeß, der sich hier hineingliedert (siehe Zeichnung Seite 162). Wir können zu diesem Atmungsprozeß nun auch den polarisch zugeordneten Prozeß suchen. Es muß derjenige Prozeß sein, der gewissermaßen sich so von dem Verdauungsprozeß abgliedert, insofern der Verdauungsprozeß zum Ausscheideprozeß führt und das Polarische ist zu dem organischen Vorstellungsprozeß. Es muß sich da auch etwas abgliedern, was noch naheliegt organisch dem Verdauungsprozeß, so wie naheliegt lokalisiert das Atmen dem Riech- oder Schmeckprozeß, organisch angesehen. Das ist alles das, was sich im Lymph- und Blutprozeß abspielt, im Blurbildungsprozeß, respektive was von der Verdauung nach innen geschoben wird, was also in den Organen liegt wie in den Lymphdrüsen und so weiter, in all den Organen, die an der Blutbildung beteiligt sind. Sie sehen also hier zwei polarische Prozesse, den einen abgespalten von der Verdauung, den anderen abgespalten von den mehr nach außen gelegenen Sinnesvorgängen, dasjenige, was gewissermaßen zurückliegt hinter den Sinnesvorgängen, die Atmung, und was vorgelagert ist der Verdauung, insofern diese Verdauung dann zur Ausscheidung führt, den Blutbildungs-Lymphbildungsprozeß. Es ist merkwürdig, wie wir da vom Prozesse aus in den ganzen Menschen hineinführen, währenddem man heute gewöhnlich nur von den vorliegenden Organen aus den Menschen betrachtet. Hier suchen wir von dem Prozesse aus und von dem ganzen Zusammenhang des Menschen mit der außermenschlichen Welt diesen Menschen zu erkennen, zu durchschauen, und wir finden in der Tat Zusammenhänge, die uns wirklich unmittelbar ein Bild sind des ganzen Ätherwirkens im Menschen, denn wir haben ja eigentlich in der heutigen Stunde die Ätherwirkung im Menschen studiert. Und die zwei Prozesse begegnen sich wiederum, Atmungsund Blutbildungsprozeß, und ihre Begegnung geschieht im menschlichen Herzen. Sie sehen, die ganze Außenwelt, insofern sie auch das Äußere des Menschen einschließt, tritt uns als eine Dualität entgegen, die sich im menschlichen Herzen staut, die im menschlichen Herzen zu einer Art von Ausgleich strebt.

[ 22 ] Und so können wir zu einem merkwürdigen Bilde kommen, zu dem Bilde des menschlichen Herzens mit seiner Innerlichkeit, mit seinem Synthetisieren desjenigen, was äußerlich auf uns nach dem ganzen Umfang des Leibes einwirkt, ein Synthetisieren, und in der Außenwelt ein Analysieren, ein überall Zerstreutsein desjenigen, was im Herzen, ich möchte sagen, zusammengeschoppt ist (siehe Zeichnung Seite 172). Sie kommen da zu der wichtigen Vorstellung, die man etwa so aussprechen könnte: Sie gucken in die Welt hinaus und sehen den Umkreis und fragen sich: Was ist da in diesem Umkreis, was wirkt aus diesem Umkreis herein? Wo finde ich irgend etwas in mir, was damit verwandt und gleicher Art ist? — Wenn ich in mein eigenes Herz hineinschaue! Da ist gewissermaßen der umgekehrte Himmel drinnen, das polarisch Entgegengesetzte. Während Sie hier das Peripherische haben, den, ich möchte sagen, ins Unendliche erweiterten Punkt, haben Sie den Kreis zusammengenommen im menschlichen Herzen. Die ganze Welt ist da drinnen. Wenn man ein grobes Bild gebraucht, so könnte man einfach sagen: Man denke sich, der Mensch steht auf einem Berge und guckt hinaus in den weiten Umkreis und sieht den weiten Umkreis der Welt. Und stellen Sie ein ganz winziges Zwerglein in das menschliche Herz hinein und versuchen sich zu vergegenwärtigen, was dieses Zwerglein da drinnen sieht, so sieht das da drinnen in Umkehrung das vollständige Bild der Welt zusammengezogen, synthetisiert. Das ist ja vielleicht eine bloß bildliche Vorstellung, eine Art von Imagination, allein, es ist zu gleicher Zeit dasjenige, was, wenn man es in der richtigen Weise aufnimmt, als ein ganz ordentliches, regulatives Bild, als regulatives Prinzip wirken kann und was uns anleiten kann, gerade das, was wir im einzelnen erkennen, in der richtigen Weise zusammenzufassen.

[ 23 ] Ich habe nun die meisten Grundlagen zu dem geschaffen, was spezielle Betrachtungen sein werden, was auch Grundlagen sein werden für die Beantwortung der mannigfaltig mir gestellten Fragen im einzelnen.

Eighth Lecture

[ 1 ] The expressions we use, which I would say are more for the purpose of shortening or simplifying our ideas, when we say “etheric body,” ‘astral body,’ and so on, can certainly be traced back to what is, in a sense, imprinted on it in physical events. However, today people are not very inclined to really relate what is expressed in physical events to the spiritual basis of existence. But for a spiritualization of medical thinking and perception, this will absolutely have to happen. For example, it will be essential to examine how the interaction between what we call the etheric body and what we call the physical body actually takes place. You know that this interaction takes place in human beings, and yesterday we spoke of one aspect of this interaction, namely when it becomes disordered in relation to the influences of the astral body. But this interaction also takes place outside, in nature beyond the human realm.

[ 2 ] Now consider that if you follow this thought through to its logical conclusion, you will actually gain a thorough insight into the connection between human beings and nature beyond the human realm. You look out into nature beyond the human realm. You have around you — let us stick to that for now — the entire flora with all its individual species, and you perceive this flora through your various senses. So when you look out there, you can perceive the flora with your various senses, or at least sense an interplay between this flora and everything that is first of all in the earthly atmosphere, and everything that then lies outside this earthly sphere in the planetary, in the astral. We can say, in a sense, that when we look at the flora of the earth, when here (see drawing on page 158)

[ 3 ] is the surface of the earth, this flora points us to the atmospheric, to the astral, now meant in the sense that it goes to the stars, to the extra-terrestrial, and we can first of all, even if we do not go into the occult, suspect that there is a living interaction out there between what is manifested in the flora, in the blossoming and fruiting, and what is working in from the whole wide universe.

[ 4 ] If we then look away from all this and turn our thoughts inward — you must try to use a little intuition to help you with this view, but I have already said that without intuition it is absolutely impossible to do medicine — if we derive this thought from the outside and look into our own inner being, we find a certain kinship with what is out there. And since we must say to ourselves that in flora, the etheric is closely connected with the physical, we must also suspect a certain kinship between this kind of connection between the etheric and the physical in flora and the kind of connection between the etheric and the physical in human beings themselves.

[ 5 ] Now it is a matter of giving ourselves an account of what we can say concretely about this relationship between the etheric and the physical. We can first say abstractly: the etheric is closer to the astral than to the physical, insofar as it opens upward. But we will also have to say that the etheric has some kind of relationship to the physical. So we will have to look at this dual relationship, in which the etheric stands on the one hand to the physical and on the other hand to the astral, and we will have to look for something that will lead us, as it were, into this dual relationship. Now I would like to show you as concretely as possible how you can be led into this dual relationship.

[ 6 ] Walk, for example, through an avenue of linden trees and try to make yourself quite clear how you walk through this avenue of linden trees through the scent of the blossoming linden trees. Realize that a process is now taking place between everything that spreads, let's say, like nerves into your olfactory organs, and this linden blossom scent. Then, when you turn your attention to this process of perceiving the scent of linden blossoms, you have, in a sense, the emergence of the inner, the olfactory, against the scent of linden blossoms, the smell of linden blossoms, and you must say to yourself: There is a process taking place that brings the inner and the outer together, which somehow accomplish something together through their inner kinship. And you must say to yourself: that which is dispersed outside through the scent of linden blossoms, which is undoubtedly based on an interaction between the flora and the entire external environment, the flora opening up to the external environment, is, in a sense, internalized in the perception of smell itself. Because you perceive the thing, you undoubtedly have something within you that acts from the etheric body on the astral body, for otherwise you could not perceive it; otherwise it would be a mere life process. The process of smelling itself testifies that the astral body is involved in it. But what reveals to you the relationship with the outside world also shows you that the emergence of that sweet smell emanating from the linden blossoms is, in a certain sense, related, polar to what is going on in your olfactory organ. And indeed, in this sweet smell of linden blossoms spreading through the air, we have the interaction of the plant-etheric with the surrounding astral, which fills the general space of the world. We therefore have a process in our sense of smell that takes place in such a way that through this process we participate in what is related in the flora to the extra-terrestrial astral.

[ 7 ] If we now take any taste, say, to have something related to what has just been mentioned, for example, the taste of licorice or the taste of sweet grapes, we have something similar. But here we are dealing with a process that takes place in our taste organ, in contrast to the processes that take place in our olfactory organs. You know how closely related the taste organ is to the smell organ, and you will therefore easily be able to form a mental image of how closely related, in terms of the whole natural process, what goes on in tasting is to what goes on in smelling. But at the same time, you must be aware that tasting is a much more organic, internal process than smelling. Smelling takes place more on the surface. Smelling participates in the processes of the non-human, which spread out, so to speak, and are spread out in space. This is not the case with tasting. Through tasting, you come more to certain qualities that must lie within the substances, that must therefore be connected with the substantial itself. Through tasting, more than through smelling, you come to what things, in this case plants, are like inside. And you simply need to use your intuition a little, and you will tell yourself that everything connected with the solidification in plants, with the organic processes of solidification in plants, is revealed, is disclosed through tasting everything that is in the plant. But this plant life resists solidification. This becomes apparent to us in what causes the plant to become smellable. Therefore, you cannot really doubt that taste is a process connected with the relationship between the etheric and the physical.

[ 8 ] So now take smelling and tasting together. By living in relation to flora through smelling and tasting, you actually live in those relationships that the etheric has on both sides, toward the astral and toward the physical. You really enter into the etheric, that is, into its imprint, when you turn your attention to smelling and tasting. Where smelling and tasting are in the human being, there is basically a revelation of the etheric in the physical world in its relationships to the astral and the physical. In a sense, we are ourselves on the surface of the human being when we examine what takes place in smelling and tasting. But you see, what is really important today is that we finally move beyond the abstract-mystical in order to fertilize real science from the side of spiritual science and really advance to concrete spiritual understanding. What good does it really do if people keep talking about grasping the divine in human beings when, at best, they understand this divine to be something completely abstract? This way of looking at things only becomes fruitful when we can respond to concrete phenomena, when we can observe the internalization of external processes in this concrete sense, for example, by actually observing in smelling and tasting that which lives externally, related to the human being, the etheric, how it becomes internalized, how we see in this perhaps crudest upper sense process an immediate internalization of external processes. This is so extraordinarily important for our time, to go beyond the merely abstract, the mystical. But now you will be clear that in nature everything is in constant transition to something else, that in nature everything is such that one process tends to transition into another, to metamorphose into another process. So take what we have just said: more on the surface, smelling (see drawing on page 162), more inside the human being — all this relates to flora, to plants — tasting, flavor, and these, I would say, taking place in the etheric, insofar as the etheric opens up to the astral or solidifies into the physical, thus going outward, according to everything that happens in the flora in the process of volatilization, in becoming aromatic or also in withdrawing from the aromatic in tasting, internalizing everything that leads to solidification in the external. In a sense, the external and the internal flow together when we hold our attention on smelling and tasting.

[ 9 ] But in nature, one process always merges into another. Let us turn our attention to the aromatic qualities of flora, to everything that enables flora to elude solidification, so to speak, where flora still wants to transcend its plant nature, where the plant still — forgive the layman's expression — projects its spirituality into the atmosphere, so that the atmosphere still carries something of the plant nature in the fragrance. In a sense, the outlines of the plants are still present in what smells out there. Consider this. What is actually happening out there when the plant sends out its scent patterns, when it does not allow itself to become completely solidified as a plant, when it sends out something from the flower that wants to become a flower but eludes this becoming, that preserves itself in its fleetingness? This is nothing other than a restrained combustion process. If you think of this aromatization as continuing metamorphically, you come to think: this aromatization is actually a restrained combustion process. You see combustion on the one hand and the aromatization of the plant world on the other, and then you recognize two metamorphoses of a common unity within them. I would say that aromatization is simply combustion on a different level.

[ 10 ] Now let us look at what it is in the plant that stimulates the sense of taste, what lies deeper within the plant, what causes the plant not to drive its plant image power out into the environment like a shadow, but to hold it within itself, to use it for inner formation. Because you participate in this inner formation in tasting, you arrive at the same process that lies beneath the solidification of the plant, but which is a metamorphosis at this other stage into salt, but of course into the salt of the plant, because we are talking about flora (see drawing on page 162).

[ 11 ] Consider that a remarkable metamorphosis has taken place in the plant. You have given the plant the upward movement of aromatization, which is, in a sense, a restrained combustion process and can already lead to the beginning of combustion processes; for the processes of flowering are simply combustion processes that are integrated into it. Downwards, you have the solidification, the saltification. And what you taste in the plant is what is still retained saltification. But when the salt is integrated and you find the salt in the plant itself, that is, when you have these plant salts, they are something that has gone beyond the process of becoming a plant in the plant itself, where the plant has its own schema pressed into its own being.

[ 12 ] Once the rationale for the remedy has been recognized, it begins, I would say, to become light in the flora, in a certain sense, because one looks into what is happening there. This concrete looking in, I must emphasize again and again, is what matters.

[ 13 ] Now, in order to continue, you only need to remember the following: Where possible, I would like to say, purely for higher opportunistic reasons, I would like to link what needs to be dealt with to what is common practice today, so that you are also in a position to bridge the gap between what spiritual science can offer and what external science is. Of course, I could now characterize what I am going to discuss in the following sentences in a more spiritual scientific way, but I want to tie in with the common mental images of today's science, which are already there. The physiologist today speaks of what is before him, which does not need to be before the spiritual scientist for the simple reason that he does not need to anatomize in the same sense. But let us tie in with the common mental images. We do not need to take up the anatomical nonsense of others, but we must reckon with the fact that they have already been there and delivered their results. They will only stop when natural science has been fertilized by spiritual science. So let us examine this! It will then become quite clear from spiritual science what a close relationship, what a close connection there is between the process that takes place in the eye and the process that takes place in smell and especially in taste, in the spread of the taste nerve in the rest of the organ substance and in the spread of the optic nerve in the eye. There is such a close relationship that one cannot help but seek analogies to the taste process when characterizing the inner workings of the visual process. Of course, since the spread of the taste nerve in the organic substance is not accompanied by the elaborate formation of the eye, which precedes the spread of the optic nerve in the organic substance, seeing is something completely different. But what begins, so to speak, as the process of seeing behind the artistic development of the physical eye is very closely related to the process of tasting. I would like to say that in seeing we perform a metamorphosed tasting, metamorphosed in that we have placed everything that is conditioned by the artistic construction of the eye in front of the organ processes that take place in tasting.

[ 14 ] Now, of course, with every sense we must distinguish between what our organism brings to the outside world and what the outside world brings to our organism. So we must look at what happens internally as processes through the blood entering the eye, that is, through the organism acting on the eye. This is even stronger in certain animals, which, in addition to our organs, also have the fan and the sword-like appendage in the eye, i.e., blood organs, through which the ego is driven more into the eyeball, while in us the ego withdraws and leaves the eyeball free internally. But the entire organism acts there indirectly through the blood through the eye in the entire sensory process, and inside the visual process, the taste process is metamorphosed, so to speak, so that we can call seeing a metamorphosed taste. So we would have vision stored above tasting and smelling, as metamorphosed tasting (see drawing on page 162).

[ 15 ] It therefore corresponds to what the entire process of tasting and seeing is, something external that interacts with the internal. The process must therefore undergo a metamorphosis upwards, so to speak. The process of seeing is a metamorphosis of the process of tasting. But there must also be a metamorphosis of the process of tasting downwards into the body. While we ascend more toward the external world in the process of seeing—the eye is enclosed only in the bone cavity and we come out there, the eye is a very external organ, the process of seeing is organized more toward the outside—we must now think about the metamorphosis of the process of tasting down into the organism on the opposite side. We then come, as it were, to the other pole of seeing, to what corresponds to the process of seeing in the organism, to something that will shed an enormous amount of light on the following considerations. For what is given when we follow the metamorphosis of the process of tasting downward? There is digestion, and you will only come to a real inner understanding of digestion if, on the one hand, you mentally image seeing as a metamorphosed continuation of tasting and, on the other hand, digestion as a metamorphosed continuation of tasting, but in such a way that you are able to understand digestion in its full polar opposition to externalized seeing, for externalized seeing leads you precisely to recognize what corresponds to this digestion in the external world, of which digestion is organically an internalization. On the other hand, you become aware of how the digestive process must be thought of as related to the process of tasting. You simply cannot understand the intimate workings in the human organism, insofar as they are localized to the digestive process, if you do not have in your mental image of the entire digestive process that good digestion is based on an ability to taste with the entire digestive tract, so to speak, and that poor digestion is based on an inability to taste with the entire digestive apparatus, so to speak.

[ 16 ] Now the process we have been considering divides into tasting and smelling. In a sense, a process splits so that we are dealing on the one hand with a process that is more in interaction between the etheric and the physical in tasting, and on the other hand with a process that is more in the relationship between the etheric and the astral, which we have in smelling. What we have in the organism as a continuation of tasting, we have subjected to the same division, in that on the one hand we have digestion tending toward excretion through the intestines, toward fecal excretion, and on the other hand we have excretion through the kidneys, through urination. There you have exactly the same thing in the lower and upper parts of the human being. You have something that is exactly like two polar opposites, in that you divide tasting and smelling, and you divide normal digestion and what is separated from normal digestion as everything that is based on the more intimate activity of the kidneys, on what is associated with the more intimate activity of the kidneys.

[ 17 ] Here we have, in a sense, the opportunity to regard what happens inside the organism, bounded by the skin, as an internalization of the external. For with everything we continue upwards, we enter more and more into the external; there the human being opens up to the external. Now we have to pursue the matter further in such a way that in what lives in us, so to speak, in our soul, but is bound to the organism, not in the materialistic sense, but in another sense, which you know from the lectures, we have a metamorphosed vision, again situated on a certain side towards the inner, in thinking, in mental image (see drawing on page 162), whereby we have to think of those organs that underlie the mental images, that is, those of the human inner head as metamorphosed organs of sight in a certain direction. Please just orient yourself to the fact that most of your mental images that live in thinking are simply continuations of visual mental images; you only need to compare the soul life of those born blind or deaf. We have a continuation of vision in our thinking. And this leads us to say that light is also shed on the remarkable interaction that exists between the anatomy of the head, the brain, and the thought process itself. It is very peculiar, for example, that when one properly tackles our thought processes — a fine chapter for a medical dissertation, by the way — and wants to investigate how summarizing thinking is related to the organization of the brain, one strangely comes across structures that look like a transformation of the olfactory nerve. So one could say that, viewed internally, our scattered, analytical thinking is very similar in its counterpart to seeing. But summarizing what we see, associating mental images, is actually, viewed internally and organically, very similar to smelling. This is expressed in a very remarkable way in the anatomical structure of the brain. In any case, this brings us to a mental image, to thinking on the one hand.