Third Scientific Lecture-Course:

Astronomy

GA 323

7 January 1921, Stuttgart

Lecture VII

You will have seen how we are trying in these lectures to prepare the ground for an adequate World-picture. As I have pointed out again and again, the astronomical phenomena themselves impel us to advance from the merely quantitative to the qualitative aspect. Under the influence of Natural Science there is a tendency, in modern scholarship altogether, to neglect the qualitative side and to translate what is really qualitative into quantitative terms, or at least into rigid forms. For when we study things from a formal aspect we tend to pass quite involuntarily into rigid forms, even if we went to keep them mobile. But the question is, whether an adequate understanding of the phenomena of the Universe is possible at all in terms of rigid, formal concepts. We cannot build an astronomical World-picture until this question has been answered.

This proneness to the quantitative, abstracting from the qualitative aspect, has led to a downright mania for abstraction which is doing no little harm in scientific life, for it leads right away from reality. People will calculate for instance under what conditions, if two sound-waves are emitted one after the other, the sound omitted later will be heard before the other. All that is necessary is the trifling detail that we ourselves should be moving with a velocity greater than that of sound. But anyone who thinks in keeping with real life instead of letting his thoughts and concepts run away from the reality, will, when he finds them incompatible with the conditions of man's co-existence with his environment, stop forming concepts in this direction. He cannot but do so. There is no sense whatever in formulating concepts for situations in which one can never be.

To be a spiritual scientist one must educate oneself to look at things in this way. The spiritual scientist will always want his concepts to be united with reality. He does not want to form concepts remote from reality, going off at a tangent,—or at least not for long. He brings them back to reality again and again. The harm that is done by the wrong kinds of hypothesis in modern time is due above all to the deficient feeling for the reality in which one lives. A conception of the world free of hypotheses, for which we strive and ought to strive, would be achieved far more quickly if we could only permeate ourselves with this sense of reality. And we should then be prepared, really to see what the phenomenal world presents. In point of fact this is not done today. If the phenomena were looked at without prejudice, quite another world-picture would arise than the world-pictures of contemporary science, from which far-fetched conclusions are deduced to no real purpose, piling one unreality upon another in merely hypothetical thought-structures.

Starting from this and from what was given yesterday, I must again introduce certain concepts which may not seem at first to be connected with our subject, though in the further course you will see that they too are necessary for the building of a true World-picture. I shall again refer to what was said yesterday in connection with the Ice-ages and with the evolution of the Earth altogether. To begin with however, we will take our start from another direction.

Our life of knowledge is made up of the sense-impressions we receive and of what comes into being when we assimilate the sense-impressions in our inner mental life. Rightly and naturally, we distinguish in our cognitional life the sense-perceptions as such and the inner life of ‘ideas’—mental pictures. To approach the reality of this domain we must being by forming these two concepts: That of the sense-perception pure and simple, and of the sense-perception transformed and assimilated into a mental picture.

It is important to see without prejudice, what is the real difference between our cognitional life insofar as this is permeated with actual sense-perceptions and insofar as it consists of mere mental picture. We need to see these things not merely side by side in an indifferent way; we need to recognize the subtle differences of quality and intensity with which they come into our inner life.

If we compare the realm of our sense-perceptions—the way in which we experience them—with our dream-life, we shall of course observe an essential qualitative difference between the two. But it is not the same as regards our inner life of ideas and mental pictures. I am referring now, not to their content but to their inner quality. Concerning this, the content—permeated as it is with reminiscences of sense-perceptions—easily deludes us. Leaving aside the actual content and looking only at its inner quality and character—the whole way we experience it,—there is no qualitative difference between our inner life in ideas and mental pictures and our life of dreams. Think of our waking life by day, or all that is present in the field of our consciousness in that we open our senses to the outer world and are thereby active in our inner life, forming mental pictures and ideas. In all this forming of mental pictures we have precisely the same kind of inner activity as in our dream-life; the only thing that is added to it is the content determined by sense-perception.

This also helps us realize that man's life of ideation—his forming of mental pictures—is a more inward process than sense-perception. Even the structure of our sense-organs—the way they are built into the body—shows it. The processes in which we live by virtue of these organs are not a little detached from the rest of the bodily organic life. As a pure matter of fact, it is far truer to describe the life of our senses as a gulf-like penetration of the outer world into our body (Fig. 1) than as something primarily contained within the latter. Once more, it is truer to the facts to say that through the eye, for instance, we experience a gulf-like entry of the outer world. The relative detachment of the sense-organs enables us consciously to share in the domain of the outer world. Our most characteristic organs of sense are precisely the part of us which is least closely bound to the inner life and organization of the body. Our inner life of ideation on the other hand—our forming of mental pictures—is very closely bound to it. Ideation therefore is quite another element in our cognitional life than sense-perception as such. (Remember always that I am thinking of these processes such as they are at the present stage in human evolution.)

Now think again of what I spoke of yesterday—the evolution of the life of knowledge from one Ice-Age to another. Looking back in time, you will observe that the whole interplay of sense-perceptions with the inner life of ideation—the forming of mental pictures—has undergone a change since the last Ice-Age. If you perceive the very essence of that metamorphosis in the life of knowledge which I was describing yesterday, then you will realize that in the times immediately after the decline of the Ice-Age the human life of cognition took its start from quite another quality of experience than we have today. To describe it more definitely; whilst our cognitional life has become more permeated and determined by the senses and all that we receive from them, what we do not receive from the senses—what we received long, long ago through quite another way of living with the outer world—has faded out and vanished, ever more as time went on. This other quality—this other way of living with the world—belongs however to this day to our ideas and mental pictures. In quality they are like dreams. Fro in our dreams we have a feeling of being given up to, surrendered to the world around us. We have the same kind of experience in our mental pictures. While forming mental pictures we do not really differentiate between ourselves and the world that then surrounds us; we are quite given up to the latter. Only in the act of sense-perception do we separate ourselves from the surrounding world. Now this is just what happened to the whole character of man's cognitional life since the last Ice-Age. Self-consciousness was kindled. Again and again the feeling of the “I” lit up, and this became ever more so.

What do we come to therefore, as we go back in evolution beyond the last Ice-Age? (We are not making hypotheses; we are observing what really happened.) We come to a human life of soul, not only more dream-like than that of today, but akin to our present life of ideation rather than to our life in actual sense-perception. Now ideation—once again, the forming of mental pictures—is more closely bound to the bodily nature than is the life of the senses. Therefore what lives and works in this realm will find expression rather within the bodily nature than independently of the latter. Remembering what was said in the last few lectures, this will then lead you from the daily to the yearly influences of the surrounding world. The daily influences, as I showed, are those which tend to form our conscious picture of the world, whereas the yearly influences affect our bodily nature as such. Hence if we trace what has been going on in man's inner life, as we go back in time we are led from the conscious life of soul deeper and deeper into the bodily organic life.

In other works; before the last Ice-Age the course of the year and the seasons had a far greater influence on man than after. Man, once again, is the reagent whereby we can discern the cosmic influences which surround the Earth. Only when this is seen can we form true ideas of the relations—including even those of movement—between the Earth and the surrounding heavenly bodies. To penetrate the phenomena of movement in the Heavens, we have to take our start from man—man, the most sensitive of instruments, if I may call him so. And to this end we need to know man; we must be able to discern what belongs to the one realm, namely the influences of the day, and to the other, the influences of the year.

Those who have made a more intensive study of Anthroposophical Science may be reminded here of what I have often described from spiritual perception; the conditions of life in old Atlantis, that is before the last Ice-Age. For I was there describing from another aspect—namely from direct spiritual sight—the very same things which we are here approaching more by the light of reason, taking our start from the facts of the external world.

We are led back then to a kind of interplay between the Earth and its celestial environment which gave men an inner life of ideation—mental pictures—and which was afterwards transmuted in such a way as to give rise to the life of sense-perception in its present form. (The life of the senses as such is of course a much wider concept; we are here referring to the form it takes in present time.)

But we must make a yet more subtle distinction. It is true that self-consciousness or Ego-consciousness, such as we have it in our ordinary life today, is only kindled in us in the moment of awakening. Self-consciousness trikes in upon us the moment we awaken. It is our relation to the outer world—that relation to it, into which we enter by the use of our senses—to which we owe our self-consciousness. But if we really analyze what it is that thus strikes in upon us, we shall perceive the following. If our inner life in mental pictures retained its dream-like quality and only the life of the senses were added to it, something would still be lacking. Our concepts would remain like the concepts of fantasy or fancy (I do not say identical with these, but like them). We should not get the sharply outlined concepts which we need for outer life. Simultaneously therefore with the life of the senses, something flows into us from the outer world which gives sharp outlines and contours to the mental pictures of our every-day cognitional life. This too is given to us by the outer world. Were it not for this, the mere interplay of sensory effects with the forming of ideas and mental pictures would bring about in us a life of fantasy or fancy and nothing more; we should never achieve the sharp precision of every-day waking life.

Now let us look at the different phenomena quite simply in Goethe's way, or—as has since been said, rather more abstractly—in Kizchhoff's way. Before doing so I must however make another incidental remark, Scientists nowadays speak of a “physiology of the senses”, and even try to build on this foundation a “psychology of the senses”, of which there are different schools. But if you see things as they are, you will find little reality under these headings. In effect, our senses are so radically different from one-another that a “Physiology of the senses”, claiming to treat them all together, can at more be highly abstract. All that emerges, in the last resort, is a rather scanty and even then very questionable physiology and psychology of the sense of touch, which is transferred by analogy to the other senses. If you look for what is real, you will require a distinct physiology and a distinct psychology for every one of the senses.

Provided we remember this, we may proceed. With all the necessary qualifications, we can then say the following. Look at the human eye. (I cannot now repeat the elementary details which you can find in any scientific text-book.) Look at the human eye, one of the organs giving us impressions of the outer world,—sense-impressions and also what gives them form and contour. These impressions, received through the eye, are—once again—connected with all the mental pictures which we then make of them in our inner life.

Let us now make the clear distinction, so as to perceive what underlies the sharp outline and configuration which makes our mental images more than mere pictures of fancy, giving them clear and precise outline. We will distinguish this from the whole realm of imagery where this clarity and sharpness is not to be found,—where in effect we should be living in fantasies. Even through what we experience with the help of our sense-organs—and what our inner faculty of ideation makes of it—we should still be floating in a realm of fancies. It is through the outer world that all this imagery receives clear outline, finished contours. It is through something from the outer world, which in a certain way comes into a definite relation to our eye.

And now look around. Transfer, what we have thus recognized as regards the human eye, to the human being as a whole. Look for it, simply and empirically, in the human being as a whole. Where do we find—though in a metamorphosed form—what makes a similar impression? We find it in the process of fertilization. The relation of the human being as a whole—the female human body—to the environment is, in a metamorphosed form, the same as the relation of the eye to the environment. To one who is ready to enter into these things it will be fully clear. Only translated, one might say, into the material domain, the female life is the life of fantasy or fancy of the Universe, whereas the male is that which forms the contours and sharp outlines. It is the male which transforms the undetermined life of fancy into a life of determined form and outline. Seen in the way we have described in today's lecture, the process of sight is none other than a direct metamorphosis of that of fertilization; and vice-versa.

We cannot reach workable ideas about the Universe without entering into such things as these. I am only sorry that I can do no more than indicate them, but after all, these lectures are meant as a stimulus to further work. This I conceive to be the purpose of such lectures; as an outcome, every one of you should be able to go on working in one or other of the directions indicated. I only want to show the directions; they can be followed up in diverse ways. There are indeed countless possibilities in our time, to carry scientific methods of research into new directions. Only we need to lay more stress on the qualitative aspects, even in those domains where one has grown accustomed to a mere quantitative treatment.

What do we do, in quantitative treatment? Mathematics is the obvious example; ‘Phoronomy’ (Kinematics) is another. We ourselves first develop such a science, and we then look to find its truths in the external, empirical reality. But in approaching the empirical reality in its completeness we need more than this. We need a richer content to approach it with, than merely mathematical and phoronomical ideas. Approach the world with the premises of Phoronomy and Mathematics, and we shall naturally find starry worlds, or developmental mechanisms as the case may be, phoronomically and mathematically ordered. We shall find other contents in the world if once we take our start from other realms than the mathematical and phoronomical. Even in experimental research we shall do so.

The clear differentiation between the life of the senses and the organic life of the human being as a whole had not yet taken place in the time preceding the last Ice-Age. The human being still enjoyed a more synthetic, more ‘single’ organic life. Since the last Ice-Age man's organic life has undergone, as one might say, a very real ‘analysis’. This too is an indication that the relation of the Earth to the Sun was different before the last Ice-Age from what it afterwards became. This is the kind of premise from which we have to take our start, so as to reach genuine pictures and ideas about the Universe in its relation to the Earth and man.

Moreover our attention is here drawn to another question, my dear Friends. To what extent is ‘Euclidean space’—the name, of course, does not matter—I mean the space which is characterized by three rigid directions at right angles to each other. This, surely, is a rough and ready definition of Euclidean space. I might also call it ‘Kantian space’, for Kant's arguments are based on this assumption. Now as regards this Euclidean—or, if you will, Kantian—space we have to put the question: Does it correspond to a reality, or is it only a thought-picture, an abstraction? After all, it might well be that there is really no such thing as this rigid space. Now you will have to admit; when we do analytical geometry we start with the assumption that the X-, Y- and Z-axes may be taken in this immobile way. We assume that this inner rigidity of the X, Y and Z has something to do with the real world. What if there were nothing after all, in the realms of reality, to justify our setting up the three coordinate axes of analytical geometry in this rigid way? Then too the whole of our Euclidean Mathematics would be at most a kind of approximation to the reality—an approximation which we ourselves develop in our inner life,—convenient framework with which to approach it in the first place. It would not hold out any promise, when applied to the real world, to give us real information.

The question now is, are there any indications pointing in this direction,—suggesting, in effect, that this rigidity of space can not, after all, be maintained? I know, what I am here approaching will cause great difficulty to many people of today, for the simple reason that they do not keep step with reality in their thinking. They think you can rely upon an endless chain of concepts, deducing one thing logically from another, drawing logical and mathematical conclusions without limit. In contrast to this tendency in science nowadays, we have to learn to think with the reality,—not to permit ourselves merely to entertain a thought-picture without at least looking to see whether or not it is in accord with reality. So in this instance, we should investigate. Perhaps after all, by looking into the world of concrete things, there is some way of reaching a more qualitative determination of space.

I am aware, my dear Friends, that the ideas I shall now set forth will meet with great resistance. Yet it is necessary to draw attention to such things. The theory of evolution has entered ever more into the different fields of science. They even began applying it to Astronomy. (This phase, perhaps, is over now, but it was so a little while ago.) They began to speak of a kind of natural selection. Then as the radical Darwinians would do for living organisms, so they began to attribute the genesis of heavenly bodies to a kind of natural selection, as though the eventual form of our solar system had arisen by selection from among all the bodies that had first been ejected. Even this theory was once put forward. There is this p to the whole Universe the leading ideas that have once been gaining some particular domain of science.

So too it came about that man was simply placed at the latter end of the evolutionary series of the animal kingdom. Human morphology, physiology etc. were thus interpreted. But the question is whether this kind of investigation can do justice to man's organization in its totality. For, to begin with, it omits what is most striking and essential even from a purely empirical point of view. One saw the evolutionists of Haechel's school simply counting how many bones, muscles and so on man and the higher animals respectively possess. Counting in that way, one can hardly do otherwise than put man at the end of the animal kingdom. Yet it is quite another matter when you envisage what is evident for all eyes to see, namely that the spine of man is vertical while that of the animal is mainly horizontal. Approximate though this may be, it is definite and evident. The deviations in certain animals—looked into empirically—will prove to be of definite significance in each single case. Where the direction of the spine is turned towards the vertical, corresponding changes are called forth in the animal as a whole. But the essential thing is to observe this very characteristic difference between man and animal. The human spine follows the vertical direction of the radius of the Earth, whereas the animal spine is parallel to the Earth's surface. Here you have purely spatial phenomena with a quite evident inner differentiation, inasmuch as they apply to the whole figure and formation of the animal and man. Taking our start from the realities of the world, we cannot treat the horizontal in the same way as the vertical. Enter into the reality of space—see what is happening in space, such as it really is,—you cannot possibly regard the horizontal as though it were equivalent or interchangeable with the vertical dimension.

Now there is a further consequence of this. Look at the animal form and at the form of man. We will take our start from the animal, and please fill in for yourselves on some convenient occasion what I shall now be indicating. I mean, observe and contemplate for yourselves the skeleton of an mammal. The usual reflections in this realm are not nearly concrete enough; they do not enter thoroughly enough into the details.

Consider then the skeleton of an animal. I will go no farther than the skeleton, but what I say of this is true in an even higher degree of the other parts and systems in the human and animal body. Look at the obvious differentiation, comparing the skull with the opposite end of the animal. If you do this with morphological insight, you will perceive characteristic harmonies or agreements, and also characteristic diversities. Here is a line of research which should be followed in far greater detail. Here is something to be seen and recognized, which will lead far more deeply into realty than scientists today are wont to go.

It lies in the very nature of these lectures that I can only hint at such things, leaving out many an intervening link. I must appeal to your own intuition, trusting you to think it out and fill in what is missing between one lecture and the next. You will then see how all these things are connected. If I did otherwise in these few lectures, we should not reach the desired end.

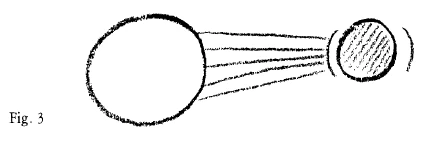

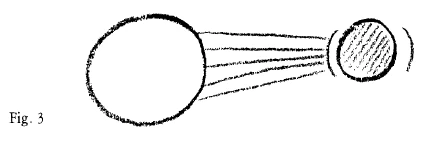

Diagrammatically now (Fig. 2), let this be the animal form. If after going into an untold number of intervening links in the investigation, you put the question: ‘What is the characteristic difference of the front and the back, the head and the tail end due to?’, you will reach a very interesting conclusion. Namely you will connect the differentiation of the front end with the influences of the Sun. Here is the Earth (Fig. 3). You have an animal on the side of the Earth exposed to the Sun. Now take the side of the Earth that is turned away from the Sun. In one way or another it will come about that the animal is on this other side. Here too the Sun's rays will be influencing the animal, but the earth is now between. In the one case the rays of the Sun are working on the animal directly; in the other case indirectly, inasmuch as the Earth is between and the Sun's rays first have to pass through the Earth (Fig. 3).

Expose the animal form to the direct influence of the Sun and you get the head. Expose the animal to those rays of the Sun which have first gone through the Earth and you get the opposite pole to the head. Study the skull, so as to recognize in it the direct outcome of the influences of the Sun. Study the forms, the whole morphology of the opposite pole, so as to recognize the working of the Sun's rays before which the Earth is interposed—the indirect rays of the Sun. Thus the morphology of the animal itself draws our attention to a certain interrelation between Earth and Sun. For a true knowledge of the mutual relations of Earth and Sun we must create the requisite conditions, not by the mere visual appearance (even though the eye be armed with telescopes), but by perceiving also how the animal is formed—how the whole animal form comes into being.

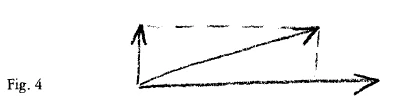

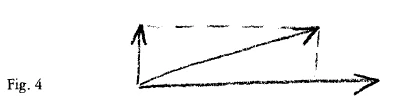

Now think again of how the human spine is displaced through right angle in relation to the animal. All the effects which we have been describing will undergo further modification where man is concerned. The influences of the Sun will therefore be different in man than in the animal. The way it works in man will be like a resultant (Fig. 4). That is to say, if we symbolize the horizontal line—whether it represent the direct or the indirect influence of the Sun—by this length, we shall have to say; here is a vertical line; this also will be acting. And we shall only get what really works in man by forming the resultant of the two.

Suppose in other words that we are led to relate animal formation quite fundamentally to some form of cosmic movement—say, a rotation of the Sun about the Earth, or a rotation of the Earth about its own axis. If then this movement underlies animal formation, we shall be led inevitably to attribute to the Earth or to the Sun yet another movement, related to the forming of man himself,—a movement which, for its ultimate effect, unites to a resultant with the first. From what emerges in man and in the animal we must derive the basis for a true recognition of the mutual movements among the heavenly bodies.

The study of Astronomy will thus be lifted right out of its present limited domain, where one merely takes the outward visual appearance, even if calling in the aid of telescopes, mathematical calculations and mechanics. It will be lifted into what finds expression in this most sensitive of instruments, the living body. The forming forces working in the animal, and then again in man, are a clear indication of the real movements in celestial space.

This is indeed a kind of qualitative Mathematics. How, then, shall we metamorphose the idea when we pass on from the animal to the plant? We can no longer make use of either of the two directions we have hitherto been using. Admittedly, it might appear as though the vertical direction of the plant coincided with that of the human spine. From the aspect of Euclidean space it does, no doubt (Euclidean space, that is to say, not with respect to detailed configuration but simply with respect to its rigidity.) But it will not be the same in an inherently mobile space. I mean a space, the dimensions of which are so inherently mobile that in the relevant equations, for example, we cannot merely equate the \(x\)- and the \(y\)-dimensions: \(y = ƒ(x)\). (The equation might be written very differently from this. You will see what I intend more from the words I use than from the symbols; it is by no means easy to express in mathematical form.) In a co-ordinate system answering to what I now intend, it would no longer be permissible to measure the ordinates with the same inherent measures as the abscissae. We could not keep the measures rigid when passing from the one to the other. We should be led in this way from the rigid co-ordinate system of Euclidean space to a co-ordinate system that is inherently mobile.

And if we now once more ask the question: How are the vertical directions of plant growth and of human growth respectively related?—we shall be led to differentiate one vertical from another. The question is, then, how to find the way to a different idea of space from the rigid one of Euclid. For it may well be that the celestial phenomena can only be understood in terms of quite another kind of space—neither Euclidean, nor any abstractly conceived space of modern Mathematics, but a form of space derived from the reality itself. if this is so, then there is no alternative; it is in such a space and not in the rigid space of Euclid that we shall have to understand them.

Thus we are led into quite other realms, namely to the Ice-Age on the one hand and on the other to a much needed reform of the Euclidean idea of space. But this reform will be in a different spirit than in the work of Minkowski and others. Simply in contemplating the given facts and trying to build up a science free of hypotheses, we are confronted with the need for a thoroughgoing revision of the concept of space itself. Of these things we shall speak again tomorrow.

Siebenter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Sie haben gesehen, die Bestrebungen dieser Vorträge gingen dahin, die Voraussetzungen für ein Weltbild zu finden. Und ich mußte Sie immer wiederum darauf verweisen, daß uns die astronomischen Erscheinungen selbst die Notwendigkeit auferlegen, aus dem bloßen Quantitativen heraus in das Qualitative hineinzukommen. Es ist ja in der neueten, von der Naturwissenschaft sehr beeinflußten Wissenschaftsbetrachtung die Neigung heraufgezogen, überall vom Qualitativen abzusehen und auch die Vorgänge im Qualitativen zu übersetzen durch Darstellungen, die dem Quantitativen oder wenigstens dem Formhaften, ich möchte sagen dem Starr-Formhaften, entsprechen. Denn an sich führt eine formhafte Betrachtung ja sehr leicht, selbst wenn man die Formen als bewegliche, in sich bewegliche betrachten will, ganz unwillkürlich in die Betrachtung des starren Formenhaften hinein. Und die Frage muß uns ja beschäftigen, ob wir mit start-formenhaften Begriffsgebilden irgendwie die Erscheinungen des Weltenalls erkenntnismäßig decken können. Bevor diese Frage beantwortet ist, ist kein Aufbau des astronomischen Weltenbildes möglich.

[ 2 ] Nun hat dieses Hinneigen zu dem Quantitativen, bei dem man abstrahiert von dem Qualitativen, auch zu einer gewissen Abstraktionssucht geführt, welche in gewissen Partien unseres Wissenschaftslebens außerordentlich schädlich zu werden beginnt, weil sie von der Wirklichkeit abführt. Man liebt es ja heute sogar auszurechnen, unter welchen Umständen man von zwei Schallquellen, die nacheinander Schall abgeben, den später abgegebenen Schall früher hören kann als den früher abgegebenen. Dazu ist ja nur die Kleinigkeit notwendig, nicht wahr, daß man sich selber mit einer größeren Geschwindigkeit bewegt als der Schall. Derjenige, der mit seinen Begriffen im wirklichen Leben drinnensteht, der nicht mit seinen Begriffen aus der Wirklichkeit herausgeht, der kann unmöglich anders, als in dem Augenblick, wo es sich darum handelt, die Bedingungen des Hineingestelltseins des Menschen in die Umwelt aufzuheben, auch mit seinen Begriffsbildungen aufhören. Es hat nicht den geringsten Sinn, Begriffsbildungen zu formulieren für Zustände, in denen man nicht sein kann. Zu dieser Art von Betrachtung muß ja der Geisteswissenschafter sich erziehen, der überall auch mit seinen Begriffen mit der Wirklichkeit verbunden sein will, der also niemals mit seinen Begriffsbildungen aus der Wirklichkeit herausgeht, wenigstens niemals stark, indem er immer wieder an die Wirklichkeit zurückgeht. Und alle Schädlichkeiten der neuzeitlichen Hypothesenbildung beruhen ja im Grunde genommen auf diesem mangelnden Sinn für das Verbundensein mit der Wirklichkeit. Man würde viel eher zu dem, was unbedingt angestrebt werden muß, zu einer hypothesenfreien Auffassung der Welt kommen, wenn man sich durchdringen würde mit diesem Wirklichkeitssinn. Allerdings muß man dann auch wirklich dasjenige, was in der Erscheinungswelt gegeben ist, betrachten wollen. Das tut man ja heute nicht in Wirklichkeit. Würde man vorurteilslos die Erscheinungen betrachten, dann würde sich ein ganz anderes Weltbild ergeben, als heute vielfach da ist in dem wissenschaftlichen Leben, aus dem dann allerlei Schlüsse und Konsequenzen gezogen werden, bei denen nichts herauskommen kann, weil sie Unwirkliches auf Unwirkliches bauen und man bloß in hypothetische Ideensysteme hineinkommt.

[ 3 ] Von diesem und von dem gestern hier Auseinandergesetzten ausgehend, muß ich noch auf einige Begriffe eingehen, die scheinbar wiederum nicht mit unserem Thema zusammenhängen, aber Sie werden ja sehen im weiteren Verlauf der Vorträge, wie das gerade zum Aufbau eines Weltbildes notwendig ist, was ich hier entwikkele. Ich muß weiter eingehen auf das, was ich Ihnen gestern in Anlehnung an die Erscheinungen der Eiszeiten und der sonstigen Erdenentwickelung dargestellt habe. Fangen wir wiederum an einem ganz andeten Ende an. Unser Erkenntnisleben setzt sich zusammen aus den gegebenen Sinneseindrücken und aus jenen Gebilden, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, die entstehen, indem wir die Sinneseindrücke innerlich verarbeiten. Wir trennen ja daher unser Erkenntnisleben in das der Sinneswahrnehmungen und in das eigentliche Vorstellungsleben. Ohne daß man sich zunächst diese zwei Begriffe bildet, den Begriff der noch unverarbeiteten Sinneswahrnehmung und den Begriff der innerlich verarbeiteten Sinneswahrnehmung, die zur Vorstellung geworden ist, kommt man der Wirklichkeit, die in diesem Gebiete vorliegt, nicht nahe. Nun handelt es sich darum, vorurteilslos zu erfassen, welches eigentlich der Unterschied ist zwischen dem Leben in der Erkenntnissphäre, insofern diese Erkenntnissphäre durchzogen ist von den Sinneswahrnehmungen und insofern sie bloße Vorstellungssphäre ist. Da handelt es sich darum, daß man beobachten kann nicht nur, wie man es heute gewöhnt ist, im Reiche des Nebeneinander, sondern auch beobachten kann in demjenigen, was seiner Intensität nach, seiner Qualität nach in verschiedener Art an uns herantritt.

[ 4 ] Wenn wir das Reich der Sinneswahrnehmungen, sofern wir drinnen stehen, vergleichen mit dem Traumleben, so können wir einen wesentlichen qualitativen Unterschied selbstverständlich bemerken. Diesen Unterschied muß man auch bemerken. Anders aber liegt die Sache, wenn Sie das Vorstellungsleben selbst nehmen, wenn Sie, ohne jetzt auf das Inhaltliche einzugehen, nur auf die ganze Qualität des Vorstellungslebens sehen. Darüber täuscht der Inhalt des Vorstellungslebens hinweg, weil er ja durchsetzt ist von den Reminiszenzen des Sinneslebens. Aber wenn Sie absehen von dem, was inhaltlich im Vorstellungsleben liegt, wenn Sie bloß darauf sehen, wie qualitativ das Vorstellungsleben im Menschen eben da ist, dann bekommen Sie einen qualitativen Unterschied des Vorstellungslebens als solchen von dem Traumleben nicht heraus. Es ist durchaus unser Tagesleben so, daß in demjenigen, was wir präsent haben in unserem Bewußtseinsfelde, wenn wir unsere Sinne nach außen öffnen und dadurch innerlich vorstellungsgemäß tätig sind, im Vorstellungsbilden dieselbe innere Tätigkeit vorliegt, die beim Träumen vorliegt, und daß alles dasjenige, was zu diesem Traumerlebnis hinzukommt, inhaltlich bedingt ist durch die Sinneswahrnehmung. Dadurch kommt man dazu zu verstehen, daß das Vorstellungsleben des Menschen mehr nach innen gelegen ist als das Sinnesleben. Unsere Sinnesorgane sind ja so einkonstruiert in den menschlichen Organismus, daß die Vorgänge, in denen wir durch sie leben, verhältnismäßig stark sich loslösen von dem sonstigen organischen Leben (Fig. 1). Das Sinnesleben ist ein Leben, das, wenn man es darstellen würde, besser dargestellt würde der reinen Tatsächlichkeit nach als ein golfartiges Hereinragen der Außenwelt in unseren Organismus denn als etwas, was von unserem Organismus umfaßt wird. Es ist durchaus dem beobachteten Tatbestand gemäß richtiger zu sagen: Wir erleben durch das Auge ein golfartiges Hereinragen der Außenwelt, wir erleben durch diese Absonderung der Sinnesorgane die Sphäre der Außenwelt mit. Es ist am wenigsten gebunden dasjenige, was gerade im ausgesprochensten Maße Sinnesorgan an uns ist, an die innere Organisation. Dagegen ist ganz gebunden an unsere innere Organisation dasjenige, was sich im Vorstellungsleben geltend macht. Wir haben also im Vorstellungsprozeß ein anderes Element innerhalb unseres Erkenntnislebens als im Sinneswahrnehmungs-Prozeß. Ich mache Sie dabei darauf aufmerksam, daß ich überall diese Prozesse so betrachte, wie sie im gegenwärtigen Stadium der Menschheitsentwickelung vorliegen.

[ 5 ] Nun, wenn Sie dasjenige noch einmal ins Auge fassen, was ich Ihnen gestern gesagt habe über die Erkenntnisentwickelung von Eiszeit zu Eiszeit, so werden Sie zurückblicken darauf, wie dieses ganze Zusammenströmen von Sinneswahrnehmungen und Vorstellungsleben eine Änderung erfahren hat seit der letzten Eiszeit. Und wenn Sie ganz erfassen die Art, wie ich zurückverfolgend gestern die Metamorphose des Erkenntnislebens dargestellt habe, so werden Sie sich sagen: Eigentlich ist unmittelbar nach dem Abfluten der Eiszeit das menschliche Erkenntnisleben von ganz anders erlebten Qualitäten ausgegangen, als es heute der Fall ist. Will man zu einer bestimmteren, konkteteren Vorstellung darüber kommen, muß man sagen: Es ist immer mehr hineingedrungen in unser Erkenntnisleben dasjenige, was wir von den Sinnen haben, und es ist immer mehr dasjenige geschwunden, was wir nicht von den Sinnen haben, sondern was wit einst hatten durch ein ganz andersgeartetes Zusammenleben mit der Außenwelt. Aber diesen Charakter des ganz andersgearteten Zusammenlebens mit der Außenwelt haben auch unsere Vorstellungen. Sie sind von der Dumpfheit des Traumlebens ihrer Qualität nach, aber sie sind durchaus so, daß wir in ihnen auch erleben das mehr Hingegebensein an die Umwelt, das wir im Traum erleben. Wir unterscheiden uns im Vorstellungsleben eigentlich nicht von unserer Umwelt. Wir sind im Vorstellungsleben an die Umwelt hingegeben. Wir sondern uns erst durch die Sinneswahrnehmung von der Umwelt ab. Es war also ein fortwährendes Aufleuchten des Ich, des Selbstbewußtseins, was sich herausbildete, indem das eben mit dem menschlichen Erkenntnisvermögen geschah, was seit der letzten Eiszeit geschehen ist.

[ 6 ] Auf was werden wir denn also zurückgehen - das ist nichts Hypothetisches, sondern ein einfaches Verfolgen der Vorgänge -, indem wir mit der Entwickelung hinter die letzte Eiszeit zurückgehen? Wir werden zurückgehen auf ein solches Seelenleben innerhalb des Menschen, welches zwar traumhafter ist, welches aber verwandter ist unserem Vorstellungsleben als unserem Sinnesleben. Nun ist aber das Vorstellungsleben mehr an unsere Organisation gebunden als das Sinnesleben. Es wird also auch dasjenige, was im Vorstellungsleben sich äußert, mehr in der Organisation sich äußern, als unabhängig von dieser Organisation. Dadurch werden wir aber geführt, wenn Sie das nehmen, was ich in den letzten Tagen auseinandergesetzt habe, von den Tageseinflüssen der umgebenden Welt zu den Jahreseinflüssen. Denn ich habe Ihnen ja gezeigt, die Tageseinflüsse sind eben diejenigen, welche unser Weltbild formen, die Jahreseinflüsse diejenigen, die unsere Organisation umändern. Also wir werden geführt von dem seelischen Erleben zu dem körperlichen, dem organischen Erleben, wenn wir auf dasjenige zurückgehen, was da innerlich im Menschen sich abspielt.

[ 7 ] Mit anderen Worten: Vor der letzten Eiszeit hat alles dasjenige, was im Jahreswechsel begründet ist, einen größeren Einfluß gehabt auf den Menschen, als es nach der letzten Eiszeit hat. Wir haben also wiederum in dem Menschen ein Reagens, um zu beurteilen, wie die um die Erde herumliegenden Einflüsse sind. Und erst wenn wir das haben, können wir uns Vorstellungen darüber machen, wie die Verhältnisse, auch die Bewegungsverhältnisse, zwischen der Erde und den umliegenden Himmelskörpern sind. Denn wir müssen durchaus von dem, ich möchte sagen, empfindlichsten Instrumente ausgehen, von dem Menschen selber, wenn wir die Bewegungserscheinungen des Himmels studieren wollen. Dazu müssen wir aber zuerst den Menschen kennen, müssen wirklich zuteilen können dasjenige, was zu dem einen Tatsachengebiet gehört, zu den Tageseinflüssen, und dasjenige, was zu dem anderen Gebiet der Tatsachen gehört, zu den Jahreseinflüssen. Diejenigen, die sich etwas ernster beschäftigt haben mit Anthroposophie, brauche ich ja nur darauf zu verweisen, wie ich aus der Anschauung heraus beschrieben habe die Verhältnisse der alten Atlantis, wie sie gelegen haben vor der letzten Eiszeit. Dann werden sie sehen, wie dort von einer anderen Seite her, also aus der unmittelbaren Anschauung heraus, dasjenige beschrieben ist, dem man sich nähert, wenn man, wie wir es jetzt tun, rein verstandesmäßig versucht, in den Tatsachen der Außenwelt zurechtzukommen. Wir kommen also zurück zu einer solchen Wechselwirkung der Erde mit ihrer Himmelsumgebung, die den Menschen gebracht hat zu dem Vorstellungsleben und die sich dann verwandelt hat, so daß das heutige Sinnesleben — natürlich nicht das Sinnesleben als solches, sondern die heutige Art - daraus entstanden ist.

[ 8 ] Nun müssen wir noch eine feinere Unterscheidung machen. Es ist richtig: Zu dem, was wir im gewöhnlichen Leben Selbstbewufßtsein nennen, Ich-Bewußtsein, kommen wir eigentlich erst immer im Moment des Aufwachens. Im Moment des Aufwachens schlägt das Selbstbewußtsein in uns ein. Die Beziehung, in die wir uns zur Welt setzen, indem wir unsere Sinne gebrauchen, ist also diejenige, die uns das Selbstbewußtsein gibt. Aber wenn wir nun tatsachengemäß analysieren dasjenige, was da einschlägt in uns, so kommen wit allerdings dazu, uns zu sagen: Bliebe das Vorstellungsleben bloß in der Qualität des Traumlebens, und schlüge bloß das Sinnesleben ein, so würde in unserem Vorstellen etwas fehlen. Wir würden bloß zu Begriffen kommen, die etwa den Phantasiebegriffen ähnlich sind nicht gleich, aber ähnlich sind -, aber wir würden nicht zu jenen scharf umgrenzten Begriffen kommen, die wir brauchen für das äußere Leben. Es fließt also mit dem Sinnesleben zu gleicher Zeit dasjenige in uns ein, was unseren gewöhnlichen Erkenntnisbildern die scharfen Umrisse, die scharfen Konturen gibt. Das ist etwas, das uns auch die Außenwelt gibt. Wir würden, wenn uns das die Außenwelt nicht geben würde, durch das Zusammenwirken der Sinneseffekte mit den Vorstellungseffekten ein bloßes Phantasieleben zustande bringen; wir würden nicht zustande bringen das scharf konturierte Tagesleben.

[ 9 ] Wenn man nun einfach die Erscheinungen im Goetheschen Sinne miteinander vergleicht - oder auch in dem Sinne, wie dann abstrakter Kirchhoff sich ausgedrückt hat -, dann bietet sich einem noch folgendes dar. Allerdings muß ich da eine Zwischenbemerkung machen: Heute ist man gewöhnt, von einer Sinnesphysiologie zu sprechen, und man baut darauf auch allerlei Sinnespsychologien auf. Wer auf die Dinge der Wirklichkeit eingeht, der kann nichts Wirklichkeitsgemäßes, weder in diesen Sinnesphysiologien noch in diesen Sinnespsychologien, finden, denn unsere Sinne sind so durchaus verschieden voneinander, daß wir in einer sie alle in einheitlicher Wesenheit behandelnden Sinnesphysiologie nur ein höchst abstraktes Gebilde haben. Es kommt auch kaum mehr heraus als eine spärliche und sehr fragwürdige Physiologie und Psychologie des Tastsinnes, die dann einfach durch Analogien auf die anderen Sinne übertragen wird. Derjenige, der auf diesem Gebiet das Wirklichkeitsgemäße sucht, der braucht für jeden einzelnen Sinn eine gesonderte Physiologie und eine gesonderte Psychologie.

[ 10 ] Wenn wir das voraussetzen, also uns dessen bewußt sind, dann können wir, selbstverständlich mit allen Einschränkungen, auch das Folgende sagen: Betrachten wir einmal das menschliche Auge. Ich kann natürlich nicht auf die elementaren Einzelheiten eingehen, die können Sie in jedem entsprechenden naturwissenschaftlichen Lehrbuch finden. Betrachten wir das menschliche Auge. Es ist eines der Organe, die uns überliefern Eindrücke der Außenwelt, Sinneseindrücke mit demjenigen, was diese Sinneseindrücke in bestimmter Weise konturiert. Und diese Eindrücke des Auges stehen wiederum in Verbindung mit dem, was wir innerlich zu Vorstellungen verarbeiten. Sondern wir jetzt einmal ordentlich dasjenige, was zugrunde liegt der scharfen Konturierung, was unsere Vorstellungen aus bloßen Phantasievorstellungen heraushebt und sie zu scharf konturierten Vorstellungen macht, sondern wir das einmal von dem, was wirkt, wenn wir diese scharfe Konturierung nicht finden, so daß wir in einem Phantasieleben sein würden. Wir würden durchaus durch dasjenige, was wir mit Hilfe der Sinnesorgane erleben und was das Vorstellungsvermögen innerlich daraus macht, in einer Art Phantasieleben sein. Scharfe Konturen bekommt dieses Leben durch die Außenwelt, durch etwas, was in einer bestimmten Art zu unserem Auge in einem Wechselverhältnis steht. Und sehen wir uns jetzt um. Übertragen wir dasjenige, was wir so für das Auge herausbekommen haben, auf den ganzen Menschen, suchen wir es einfach ganz empirisch auf im ganzen Menschen. Wo finden wir denn dasjenige, was uns, nur in einer metamorphosierten Form, ebenso entgegentritt? Wir finden es im Befruchtungsvorgang. Das Wechselverhältnis des ganzen Menschen, insofern er weiblicher Organismus ist, zu der Umgebung, ist metamorphosiert dasselbe, wie das Verhältnis des Auges zu der Umgebung. Es muß ohne weiteres demjenigen, der auf diese Dinge eingehen will, einleuchten, wie, man kann sagen, nur ins Materielle umgesetzt, das weibliche Leben das Phantasieleben des Universums ist, das männliche Leben dasjenige, was die Konturen bildet, was dieses unbestimmte Leben zu dem bestimmten, konturierten macht. Und wir haben im Sehvorgang, wenn wir ihn so betrachten, wie wir es heute getan haben, nichts anderes als die Metamorphose des Befruchtungsvorganges. Und umgekehrt.

[ 11 ] Solange man nicht auf diese Dinge eingehen wird, wird es unmöglich sein, überhaupt zu brauchbaren Vorstellungen über das Weltenall zu kommen. Es ist mir nur leid, daß ich diese Dinge bloß andeuten kann. Aber ich will Sie ja auch in diesen Vorträgen nur anregen. Dasjenige, was ich mir eigentlich als Aufgabe solcher Vorträge denke, das ist, daß als Ergebnis jeder einzelne von Ihnen dann soviel als möglich weiter arbeitet nach diesen Richtungen. Ich möchte eben nur die Richtungen angeben. Diese Richtungen können nach allen möglichen Seiten verfolgt werden. Es gibt heute unzählige Möglichkeiten, die Forschungsmethoden in neue Richtungen zu bringen, aber man muß gewissermaßen dasjenige, was man gewöhnt worden ist, bloß ins Quantitative hinüber zu treiben, ins Qualitative treiben. Dasjenige, was man so quantitativ treibt, man bildet es aus zunächst — die Mathematik ist das beste Beispiel, Phoronomie ist ein anderes Beispiel - und sucht es wieder in der empirischen Realität. Aber wir brauchen auch noch anderes, um die Mathematik und. Phoronomie empirisch real zu decken. Wir müssen mit reicherem Inhalt an die empirische Realität herantreten als bloß mit dem mathematischen und dem phoronomischen. Wir finden eben nichts anderes als phoronomisch und mathematisch angeordnete Weltenund Entwickelungsmechaniken, wenn wir bloß herangehen an die Welt mit den Voraussetzungen der Phoronomie und Mathematik. Aber wir finden anderes in der Welt, wenn wir auch mit der experimentellen Forschung von anderen Gebilden ausgehen als den mathematischen und phoronomischen.

[ 12 ] Es war also jene Differenzierung zwischen dem menschlichen Sinnesleben und dem menschlichen Gesamtleben, dem gesamten organischen Leben, vor der letzten Eiszeit eben noch nicht eingetreten, es war da noch ein viel synthetischeres, einheitlicheres organisches Leben des Menschen vorhanden. Seit der letzten Eiszeit haben wir eine reale Analyse für das menschliche organische Leben erlebt. Das weist uns darauf hin, daß wir uns die Beziehung der Erde zur Sonne anders zu denken haben vor der letzten Eiszeit als nach der letzten Eiszeit. Wir müssen von solchen Voraussetzungen ausgehen, um allmählich zu bildartigen Vorstellungen über das Weltenall in seinem Zusammenhang mit der Erde und dem Menschen zu kommen.

[ 13 ] Aber das weist Sie nach einer anderen Richtung hin; das weist Sie darauf hin, die Frage aufzuwerfen, inwiefern wir überhaupt für unsere Weltenbetrachtung den euklidischen Raum gebrauchen können. Ich nenne euklidischen Raum - es kommt nicht auf die Bezeichnung an - denjenigen, der charakterisiert wird durch drei aufeinander senkrechte, starre Richtungen. Das ist wohl dasjenige, was man als eine Art Definition des euklidischen Raumes geben kann. Ich könnte ihn auch den kantischen Raum nennen, denn was Kant gibt, wird unter der Voraussetzung gegeben, daß man es zu tun hat mit drei aufeinander senkrechten, starren Richtungen, nicht ineinander verschiebbaren Richtungen. Gegenüber demjenigen, was wit da als den euklidischen oder meinetwillen den kantischen Raum haben, muß auch durchaus die Frage aufgeworfen werden: Entspricht er einer Realität oder ist er ein Gedankenbild, eine Abstraktion? Es könnte ja sein, daß dieser starre Raum überhaupt nicht vorhanden ist. Ich bitte Sie aber zu bedenken, daß wir, wenn wir analytische Geometrie treiben, durchaus davon ausgehen, daß wir die \(x\), \(y\), \(z\)- Achse als in sich unbeweglich annehmen dürfen und daß wir irgendein Reales damit decken, wenn wir einfach das \(x\), \(y\), \(z\) in sich starr setzen. Wenn es nirgends im Reiche der Wirklichkeit so etwas gäbe, was uns erlaubte, die drei Achsen unseres gewöhnlichen Koordinatensystems in der analytischen Geometrie als starr anzunehmen, dann wäre ja unsere gesamte euklidische Mathematik eigentlich nur etwas, was wit gewissermaßen als eine Annäherung an die Wirklichkeit in uns ausbilden würden, als ein bequemes Mittel, diese Wirklichkeit zu umfassen. Aber sie wäre eigentlich nichts, was in der Anwendung auf die Wirklichkeit versprechen könnte, uns irgend etwas zu sagen über diese Wirklichkeit.

[ 14 ] Nun frägt es sich, ob wir irgendwo Anhaltspunkte dafür finden, daß der euklidische Raum nicht in dieser Starrheit eigentlich festgehalten werden darf. Ich komme da allerdings auf etwas, was den meisten Menschen heute die größten Schwierigkeiten machen wird, aus dem Grunde, weil sie eben nicht wirklichkeitsgemäß denken; weil sie immer glauben, man könne am Gängelband der Begriffe fortdeduzieren und -logisieren, -mathematisieren und so weiter. Das ist gerade dasjenige, was wir gegenüber den heutigen Wissenschaftsneigungen lernen müssen: aus der Wirklichkeit heraus zu denken; gar nicht uns zu erlauben, irgendein Bild bloß auszubilden, ohne daß wir nachsehen wenigstens, ob es der Wirklichkeit entsprechend ist. Man muß untersuchen, ob es, wenn wir auf das Konkrete eingehen, tatsächlich so etwas gibt wie eine Art qualitativer Bestimmung des Raumes. Ich weiß, daß diejenigen Vorstellungen, die ich jetzt entwickele, eigentlich den größten Widerstand finden müssen. Aber es ist nicht anders möglich, als auch auf solche Dinge aufmerksam zu machen. Sehen Sie, wenn man die Entwickelungslehre betrachtet, wie sie in der neueren Zeit immer mehr und mehr in das wissenschaftliche Gebiet sich hineinbegeben hat, so ist es ja in gewissen Kreisen - die Zeiten sind jetzt schon wiederum etwas vorüber, aber bis vor kurzem war es so -— üblich gewesen, diese Entwickelungslehre auch auf die Astronomie auszudehnen und auch da zu sprechen zum Beispiel von der Selektion, wie man sie in dem radikalen Darwinismus für die Organismen geltend gemacht hat. Es ist üblich geworden, auch da mit Bezug auf die Genesis der Himmelskörper von einer Art Selektion zu sprechen, so daß gewissermaßen dasjenige, was wir jetzt als unser Sonnen-Planetengebilde vor uns haben, entstanden wäre durch Auslese von alle dem, was herausgesondert worden ist. Auch diese Theorie ist ja vertreten worden. Man hat einmal die Gewohnheit, alles dasjenige, was man aus irgendeinem Tatsachengebiet gewinnt, auf den ganzen Umfang der Welt womöglich auszudehnen.

[ 15 ] So ist man auch dazu gekommen, den Menschen an das Ende der tierischen Entwickelungsreihe einfach heranzustellen, indem man ihn untersuchte in bezug auf seine Morphologie und Physiologie und so weiter. Nun handelt es sich darum, ob man durch eine solche Untersuchung tatsächlich die Totalität der menschlichen Organisation umfassen kann. Man muß bedenken, daß bei einer solchen Untersuchung etwas, was uns rein empirisch als ganz Wesentliches entgegentreten muß, einfach weggelassen wird. Man hat erleben können, wie die Haeckelianer einfach zählten, wieviel Knochen der Mensch hat, wieviel Muskeln und so weiter und wieviel die vollkommenen Tiere haben. Wenn man so zählt, wird man schwer anders können, als den Menschen an das Ende der Tierreihe zu stellen. Aber etwas ganz anderes ist es, wenn es ganz offen zutage liegt, daß des Menschen Rückgratlinie vertikal liegt, die des Tieres im wesentlichen horizontal. Das ist approximativ, aber nicht weniger deutlich ausgesprochen. Wo eine Abweichung ist bei einzelnen Tieren, da zeigt gerade diese Abweichung, wenn man sie im einzelnen empirisch untersucht, daß durch die Abweichung, das heißt durch die Vertikaldrehung der Rückgratlinie, auch Abänderungen in dem Tiere hervorgerufen werden, die von einer bestimmten Wichtigkeit sind. Im wesentlichen muß hingeschaut werden auf diesen charakteristischen Unterschied des Menschen von dem Tiere, der darin besteht, daß des Menschen Rückgratlinie in der Richtung des Erdradius, der Vertikalen liegt, des Tieres Rückgratlinie parallel der Erdoberfläche geht. Damit haben Sie auf Raumerscheinungen hingewiesen, die in sich offenbar differenziert sind, insofern wir sie anwenden auf die Gestalt, auf die Formation des Tieres und des Menschen. Wir dürfen nicht, wenn wir vom Konkreten ausgehen, die Horizontale in derselben Weise betrachten wie die Vertikale. Ich meine, wenn wir uns hineinstellen in den wirklichen Raum und sehen, was da drinnen im wirklichen Raum geschieht, so können wir nicht die Horizontale als gleichbedeutend mit der Vertikalen ansehen.

[ 16 ] Nun aber hat das etwas anderes im Gefolge. Sehen Sie die tierische Form an und sehen Sie die menschliche Form an. Gehen wir von der tierischen Form aus. Ich bitte Sie einmal dasjenige, was ich Ihnen jetzt darstellen werde, durch eine sinnvolle Betrachtung irgendeines Säugetierskeletts ordentlich für sich selber, für Ihr Anschauungsvermögen zu ergänzen. Die Betrachtungen, die man nach dieser Richtung hin anstellt, sind immer viel zu wenig konkret, das heißt viel zu wenig auf die Wirklichkeit eingehend. Wenn Sie das Skelett betrachten - ich will jetzt beim Skelett stehenbleiben, aber was ich vom Skelett sage, gilt in einem noch höheren Maße von den anderen Teilen der tierischen und menschlichen Organisation -, wenn Sie das Skelett eines Tieres betrachten, sehen Sie auf die Differenzierung hin, welche gegeben ist im Schädelskelett; sehen Sie sich an diese Differenzierung im Schädelskelett und vergleichen Sie diese mit dem anderen Pol des Tieres! Gehen Sie wirklich innerlich morphologisch dabei vor, so werden Sie charakteristische Einklänge und charakteristische Verschiedenheiten sehen. Es liegt hier eine Richtung der Forschung vor, die eben genauer verfolgt werden muß. Denn hier muß etwas durchschaut werden, was einen tiefer in die Wirklichkeit hineinbringt, als man es heute gewöhnt ist.

[ 17 ] Es liegt in der Natur dieser Vorträge, daß ich eben Dinge nur andeuten kann, gewissermaßen über Mittelglieder hinweggehen muß; daß ich appellieren muß an Ihre Intuition und voraussetzen muß, daß Sie zwischen zwei Vorträgen sich die Dinge zurechtlegen, damit Sie sehen, wie das eine mit dem andern zusammenhängt. Sonst würde ich in den paar Vorträgen, die ich halten kann, eben nicht zu einem Resultat kommen können.

[ 18 ] Ich will nun schematisch darauf hinweisen, wie die tierische Organisation sich gestaltet (Fig. 2). Wenn Sie sich fragen: Woher rührt denn eigentlich der charakteristische Unterschied von Vorne und Rückwärts? - dann kommen Sie nach Prüfung von unermetßlich vielen Zwischengliedern zu etwas sehr Merkwürdigem. Sie kommen dazu, die Differenzierung von Vorne mit den Wirkungen der Sonne zusammenzubringen. Sie haben da die Erde (Fig.3, rechts), Sie haben das Tier, ein Tier auf der Sonnenseite der Erde. Und nehmen Sie dann an, durch irgendwelche Vorgänge kommt zustande, daß das Tier dann auf der anderen, auf der abgewendeten Seite ist (Fig. 3, ganz rechts), dann haben Sie auch die Wirkung der Sonnenstrahlen auf das Tier, aber die Erde ist dazwischen. Sie haben also das eine Mal zu reden von der Wirkung der Sonnenstrahlen auf das Tier direkt, das andere Mal von der Wirkung der Sonnenstrahlen auf das Tier indirekt, indem die Erde dazwischen ist, indem die Sonnenstrahlen die Erde erst zu passieren haben. Exponieren Sie nun die Gestalt des Tieres der direkten Sonnenwirkung, so bekommen Sie den Kopf; exponieren Sie das Tier denjenigen Sonnenstrahlen, die erst dutch die Erde hindurchgehen, so bekommen Sie den entgegengesetzten Pol des Kopfes. Sie müssen studieren das Schädelskelett als ein Ergebnis der direkten Sonnenwirkung; Sie müssen studieren die Formen, die Morphologie des entgegengesetzten Poles als die Wirkung der Sonnenstrahlen, vor die sich die Erde gestellt hat, der indirekten Sonnenstrahlen. Es weist uns also die Morphologie des Tieres auf ein Wechselverhältnis zwischen Erde und Sonne hin. Wir müssen aus demjenigen, was sich im Tiere heranbildet, nicht aus dem bloßen Augenschein, auch wenn das Auge durch das Teleskop bewaffnet ist, die Vorbedingungen schaffen für das Erkennen der Wechselverhältnisse zwischen Erde und Sonne.

[ 19 ] Und bedenken Sie jetzt, daß die menschliche Rückgratlinie im Verhältnis zur tierischen um einen rechten Winkel gedreht ist, daß also hinzukommt eine wesentliche Modifikation dieser Wirkungen; daß wir im Grunde genommen etwas ganz anderes von Sonneneinflüssen haben im Menschen als im Tier; daß wir nötig haben, dasjenige, was im Menschen wirkt, im Sinne einer Resultierenden darzustellen (Fig.4). Wenn wir nämlich die Linie (parallel zur Erdoberfläche in Fig. 3), ob sie nun direkte oder indirekte Sonnenwirkung darstellt, symbolisch durch diese Länge darstellen (die Horizontale in Fig.4), so müssen wir uns sagen: Da wirkt auch eine Vertikale.

[ 20 ] Und erst wenn wir die Resultierende bilden, bekommen wir dasjenige, was im Menschen wirkt. Mit anderen Worten: Wenn wir etwa genötigt sein sollten, der Bildung der tierischen Form zugrunde zu legen, sei es eine Umdrehung der Sonne um die Erde, sei es eine Bewegung der Erde um ihre eigene Achse, so sind wir genötigt, noch eine andere Bewegung der Erde beziehungsweise der Sonne zuzuschreiben, eine Bewegung, die mit der menschlichen Bildung zusammenhängt und die im Effekt zu einer Resultierenden sich vereinigt mit der ersten Bewegung, die der tierischen Bildung zugrunde liegt. Das heißt: Wir müssen herausbekommen an dem, was sich im Menschen und im Tier äußert, die Grundlage für dasjenige, was etwaige gegenseitige Bewegungen der Weltenkörper sind. Wir müssen herausheben die astronomischen Betrachtungen aus den Dingen, die wir verfolgen können, wenn wir in der Sphäre der bloßen Anschauung bleiben, auch wenn wir mit dem Teleskop oder der Rechnung oder der Mechanik vorgehen. Wir müssen hineinheben das, was Astronomie ist, in dasjenige, was sich äußert in diesem empfindlichen Instrument, der Organisation. Denn offenbar weist uns auf Bewegungen im Himmelsraum dasjenige hin, was formend als Kräfte im Tiere wirkt, was formend im Menschen wirkt.

[ 21 ] Und bleiben wir jetzt innerhalb der Sphäre einer Art qualitativer Mathematik. Wenn wir vom Tiere übergehen zur Pflanze, wie müssen wir denn da gewissermaßen die Vorstellung umformen? Von diesen beiden Richtungen, die wir jetzt angegeben haben, können wir keine brauchen. Allerdings, es könnte scheinen, als ob die Vertikalrichtung der Pflanzen in derselben Lage ist wie die Vertikalrichtung des menschlichen Rückgrates. Für den euklidischen Raum ist das ja der Fall, selbstverständlich - jetzt nicht für den euklidischen Raum in seiner Figuralität, sondern in seiner Starrheit. Also, für den euklidischen Raum ist das der Fall, es muß aber deshalb nicht der Fall sein für einen Raum, der in sich nicht starr ist, sondern beweglich ist, dessen Dimensionen etwa so beweglich sind, daß, sagen wir, wir nicht einfach in den Gleichungen die \(y\)-Richtung und die \(x\)-Richtung gleich setzen können, von gleicher innerer Tragweite, sondern wo wir setzen müssen die \(y\)-Richtung als Vertikalrichtung und zu gleicher Zeit als eine Funktion der \(x\)-Richtung: \(y = f(x)\). Man könnte die Gleichung auch anders schreiben. Sie werden mehr aus den Worten ersehen, was ich sagen will, denn es ist eben mathematisch nicht so leicht auszudrücken. Hätten wir ein Koordinatensystem, das dem entsprechen würde, was ich jetzt sage, so würden wir von diesem Koordinatensystem verlangen müssen, daß wir nicht mit denselben inneren Maßen, denselben starr bleibenden Maßen die Ordinaten messen dürfen wie die Abszissen. Das ist dasjenige, was hinweisen würde von einem starren euklidischen Koordinatensystem auf ein in sich bewegliches Koordinatensystem.

[ 22 ] Wenn wir uns nun die Frage vorlegen: Wie verhält sich die Vertikale des Pflanzenwachstums zur Vertikalen des menschlichen Wachstums? - so kommen wir dazu, zwischen Vertikaler und Vertikaler zu unterscheiden und uns zu fragen: Welches ist der Weg zu einer anderen Vorstellung des Raumes, als es der starre euklidische Raum ist? Wenn nämlich unsere Himmelserscheinungen nur begriffen werden können etwa mit einem solchen Raum, der nicht der euklidische ist, allerdings auch nicht der ausgedachte Raum der neueren Mathematik, sondern ein wirklicher, ein der Wirklichkeit entnommener Raum, dann müssen wir auch die Himmelserscheinungen in diesem Raum begreifen und nicht in dem euklidischen Raum.

[ 23 ] Sie sehen, wir kommen in Vorstellungen hinein, die uns auf der einen Seite auf die Eiszeit hinführen, auf der anderen Seite zu einer Reform gewissermaßen des euklidischen Raumes, aber aus anderem Geiste heraus, als es Minkowski und andere tun. Wir kommen, rein indem wir die Tatsachen betrachten und eine hypothesenfreie Wissenschaft suchen, zu der Notwendigkeit, den Raumbegriff einmal ordentlich zu kritisieren. Davon wollen wir dann morgen weiter reden.

Seventh Lecture

[ 1 ] You have seen that the aim of these lectures was to find the prerequisites for a world view. And I had to keep pointing out to you that astronomical phenomena themselves impose on us the necessity of moving from the purely quantitative to the qualitative. In the latest scientific view, which is greatly influenced by natural science, there is a tendency to disregard the qualitative everywhere and to translate even qualitative processes into representations that correspond to the quantitative or at least to the formal, I would say the rigidly formal. For in itself, a formal consideration very easily leads, even if one wants to regard the forms as mobile, mobile in themselves, quite involuntarily to the consideration of rigid form. And we must ask ourselves whether we can somehow cover the phenomena of the universe cognitively with rigid, formal conceptual constructs. Until this question is answered, it is not possible to construct an astronomical world picture.

[ 2 ] Now, this tendency toward the quantitative, in which one abstracts from the qualitative, has also led to a certain addiction to abstraction, which is beginning to be extremely harmful in certain areas of our scientific life because it leads away from reality. Today, people even like to calculate the circumstances under which, of two sound sources that emit sound one after the other, the sound emitted later can be heard earlier than the sound emitted earlier. All that is necessary for this is the minor detail that one is moving at a greater speed than the sound, isn't it? Those who remain grounded in real life with their concepts, who do not depart from reality with their concepts, cannot help but cease their conceptualizations at the moment when it becomes necessary to suspend the conditions of human existence in the environment. It makes no sense whatsoever to formulate concepts for states in which one cannot exist. The humanities scholar must train himself to think in this way, wanting to remain connected to reality with his concepts at all times, never departing from reality with his concepts, at least not strongly, by always returning to reality. And all the harmfulness of modern hypothesis formation is basically based on this lack of sense of connection with reality. One would be much more likely to arrive at what must be striven for, a hypothesis-free view of the world, if one were to permeate oneself with this sense of reality. However, one must then also really want to observe what is given in the world of appearances. In reality, this is not done today. If one were to observe phenomena without prejudice, a completely different worldview would emerge than the one that is prevalent in scientific life today, from which all kinds of conclusions and consequences are drawn that cannot lead to anything because they build the unreal on the unreal and one merely enters into hypothetical systems of ideas.

[ 3 ] Starting from this and from what was discussed here yesterday, I must go into a few more concepts that may seem unrelated to our topic, but you will see in the course of the lectures how this is necessary for the development of a worldview, which I am developing here. I must go into more detail about what I presented to you yesterday in relation to the phenomena of the ice ages and other developments on Earth. Let us start again at a completely different end. Our life of cognition is composed of the given sensory impressions and, if I may express it this way, those structures that arise when we process the sensory impressions internally. We therefore divide our cognitive life into sensory perception and actual mental image. Without first forming these two concepts—the concept of unprocessed sensory perception and the concept of internally processed sensory perception that has become a mental image—one cannot come close to the reality that exists in this area. Now it is a matter of grasping without prejudice what the difference actually is between life in the sphere of cognition, insofar as this sphere of cognition is permeated by sensory perceptions, and insofar as it is merely a sphere of imagination. The point is that we can observe not only, as we are accustomed to doing today, in the realm of coexistence, but also in that which approaches us in different ways in terms of its intensity and quality.

[ 4 ] If we compare the realm of sensory perceptions, insofar as we are within it, with dream life, we can of course notice a significant qualitative difference. This difference must also be noted. But the situation is different when you take the life of imagination itself, when you look only at the whole quality of the life of imagination, without going into the content. The content of the life of imagination obscures this, because it is interspersed with reminiscences of sensory life. But if you disregard the content of the life of imagination and look only at the quality of the life of imagination in human beings, then you cannot discern any qualitative difference between the life of imagination as such and dream life. It is certainly the case in our daily life that in what we have present in our field of consciousness, when we open our senses to the outside world and are thereby internally active in our imagination, the same inner activity is present in the formation of images as is present in dreaming, and that everything that is added to this dream experience is conditioned in content by sensory perception. This leads us to understand that the imaginative life of human beings is more inwardly located than the sensory life. Our sensory organs are constructed in such a way in the human organism that the processes we experience through them are relatively strongly detached from the rest of our organic life (Fig. 1). Sensory life is a life that, if one were to describe it, would be better described in terms of pure reality as a wave-like intrusion of the outside world into our organism than as something that is encompassed by our organism. It is certainly more accurate, in accordance with the observed facts, to say: through the eye we experience a wave-like intrusion of the outside world; through this separation of the sense organs we experience the sphere of the outside world. That which is most distinctly our sense organ is least bound to our inner organization. On the other hand, that which asserts itself in our life of imagination is completely bound to our inner organization. Thus, in the process of imagination, we have a different element within our life of cognition than in the process of sensory perception. I would like to point out that I am considering these processes as they exist at the present stage of human development.

[ 5 ] Now, if you consider once again what I told you yesterday about the development of knowledge from ice age to ice age, you will look back on how this whole confluence of sensory perception and imaginative life has undergone a change since the last ice age. And if you fully grasp the way in which I traced the metamorphosis of the life of knowledge yesterday, you will say to yourself: Actually, immediately after the end of the Ice Age, human knowledge began with qualities that were experienced quite differently from what is the case today. If we want to arrive at a more definite, more concrete mental image of this, we must say: what we have from the senses has increasingly penetrated our life of cognition, and what we do not have from the senses, but what we once had through a completely different kind of coexistence with the outside world, has increasingly disappeared. But our mental images also have this character of a completely different kind of coexistence with the outside world. They are dull in quality, like dream life, but they are such that we also experience in them the greater devotion to the environment that we experience in dreams. In our imaginative life, we do not actually differ from our environment. In our imaginative life, we are devoted to the environment. It is only through sensory perception that we separate ourselves from the environment. So it was a continuous illumination of the ego, of self-consciousness, that developed as human cognitive ability evolved since the last ice age.

[ 6 ] So what will we return to – this is not hypothetical, but simply a tracing of events – when we go back in development beyond the last ice age? We will return to a kind of soul life within the human being that is more dreamlike, but more closely related to our life of imagination than to our sensory life. Now, however, the life of imagination is more closely linked to our organization than the life of the senses. So what is expressed in the life of imagination will also be expressed more in the organization than independently of this organization. But this leads us, if you take what I have explained over the last few days, from the daily influences of the surrounding world to the annual influences. For I have shown you that the daily influences are precisely those that shape our worldview, while the annual influences are those that change our organization. So we are led from the soul experience to the physical, organic experience when we go back to what is happening internally in the human being.

[ 7 ] In other words, before the last ice age, everything based on the changing of the seasons had a greater influence on human beings than it has since the last ice age. So we again have a reagent in human beings to assess what the influences surrounding the Earth are like. And only when we have that can we form mental images about the relationships, including the relationships of motion, between the Earth and the surrounding celestial bodies. For we must start from what I would call the most sensitive instrument, the human being itself, if we want to study the movements of the heavens. To do this, however, we must first know the human being, we must be able to distinguish between what belongs to the one realm of facts, the daily influences, and what belongs to the other realm of facts, the annual influences. For those who have studied anthroposophy more seriously, I need only refer to how I have described, based on my observations, the conditions of ancient Atlantis as they were before the last ice age. Then they will see how, from another perspective, that is, from direct observation, what one approaches when one tries, as we are doing now, to come to terms with the facts of the external world purely intellectually, is described. So we come back to this interaction between the earth and its celestial environment, which brought human beings to the life of imagination and then transformed itself so that today's sensory life — not sensory life as such, of course, but today's kind — arose from it.

[ 8 ] Now we must make a finer distinction. It is true: we actually only come to what we call self-consciousness in ordinary life, ego-consciousness, at the moment of waking up. At the moment of waking up, self-consciousness strikes us. The relationship we establish with the world by using our senses is therefore the one that gives us self-consciousness. But if we now analyze what actually strikes us, we come to the conclusion that if the mental image remained merely in the quality of dream life, and if only the life of the senses struck us, something would be missing in our mental image. We would only arrive at concepts that are similar to, but not identical with, fantasy concepts, but we would not arrive at those sharply defined concepts that we need for external life. So, at the same time as sensory life, something flows into us that gives our ordinary images of knowledge their sharp outlines and contours. This is something that the external world also gives us. If the external world did not give us this, the interaction of sensory effects with imaginative effects would result in a mere fantasy life; we would not achieve the sharply contoured daily life.

[ 9 ] If we now simply compare the phenomena in Goethe's sense—or also in the sense in which the more abstract Kirchhoff expressed himself—then the following becomes apparent. However, I must make an interjection here: today we are accustomed to speaking of sensory physiology, and all kinds of sensory psychology are built upon it. Anyone who looks at things in reality will find nothing realistic in either sensory physiology or sensory psychology, because our senses are so different from one another that a sensory physiology that treats them all as a unified entity is nothing more than a highly abstract construct. The result is little more than a sparse and highly questionable physiology and psychology of the sense of touch, which is then simply transferred to the other senses by analogy. Anyone who seeks reality in this field needs a separate physiology and a separate psychology for each individual sense.

[ 10 ] If we assume this, i.e., if we are aware of it, then we can also say the following, with all the necessary reservations, of course: Let us consider the human eye. Of course, I cannot go into the elementary details, which you can find in any relevant science textbook. Let us consider the human eye. It is one of the organs that convey impressions of the outside world to us, sensory impressions with what contours these sensory impressions in a certain way. And these impressions of the eye are in turn connected with what we process internally into mental images. But let us now properly examine what lies behind the sharp contouring, what lifts our mental images out of mere fantasy and makes them sharply contoured mental images, but let us examine what happens when we do not find this sharp contouring, so that we would be in a fantasy life. We would certainly be living in a kind of fantasy life through what we experience with the help of our sensory organs and what our imagination makes of it internally. This life is given sharp contours by the outside world, by something that interacts with our eyes in a certain way. And now let us look around us. Let us transfer what we have discovered for the eye to the whole human being, let us simply search for it empirically in the whole human being. Where do we find that which confronts us, only in a metamorphosed form? We find it in the process of fertilization. The interaction of the whole human being, insofar as he is a female organism, with the environment is metamorphosed into the same thing as the relationship of the eye to the environment. It must be immediately apparent to anyone who wants to explore these things how, one might say, translated into the material realm, female life is the imaginative life of the universe, while male life is that which forms the contours, which makes this indeterminate life into something definite and contoured. And in the process of seeing, when we look at it as we have done today, we have nothing other than the metamorphosis of the process of fertilization. And vice versa.