World Economy

GA 340

29 July 1922, Dornach

Lecture VI

You know, perhaps, that in my Threefold Commonwealth I endeavoured to express in a formula how we may arrive at a conception of “true price” (as we will call it to begin with) in the whole economic process. Needless to say—to begin with, such a formula is only an abstraction. And it is the object of these lectures (which, I believe, in spite of the shortness of the time, will really form a whole)—it is our very object in these lectures to work the whole science of Economics, at any rate in outline, into this abstraction.

The formula which I gave in my Threefold Commonwealth was as follows: “A ‘true price’ is forthcoming when a man receives, as counter-value for the product he has made, sufficient to enable him to satisfy the whole of his needs, including of course the needs of his dependants, until he will again have completed a like product.” Abstract as it is, this formula is none the less exhaustive. In setting up a formula it is always necessary that it should contain all the concrete details. I do believe, for the domain of economics, this formula is no less exhaustive than, say, the Theorem of Pythagoras is for all right-angled triangles. But the point is—just as we have to introduce into the Theorem of Pythagoras the varying proportions of the sides, so shall we have to introduce many, very many more variables into this formula. Economic Science is precisely an understanding of how the whole economic process can be included in this formula.

Today I intend to start from one essential feature of the formula. It is this. The formula does not point to what is past but to what is going to happen in the future, for I say in it, of set purpose, “the counter-value must satisfy the man's needs in the future—namely, until he will have made a like product again.” This is an absolutely essential feature of the formula. If we were to demand a counter-value, literally, for the product which the man has already finished—if we expected this to be true to the real economic facts—it might well happen that he would receive a value which would only satisfy his needs, say, for five-sixths of the time which he will take in finishing the new product. For the economic facts alter from the past into the future. He who imagines that he can draw up any kind of table from the past, will invariably go wrong in economics. Economic or business life essentially consists in setting future processes in motion with the help of what went before. But where past processes are thus used to set future ones in motion, it inevitably happens in some cases that the values are considerably shifted. Indeed they are constantly shifting. Hence in this formula it is essential to say: “If someone makes a pair of boots, the time he took to make them is not the determining factor in the economic sense. The determining factor is the time he will take to make the next pair of boots.” That is the point, and we must now try to understand its fuller implications within the whole economic process.

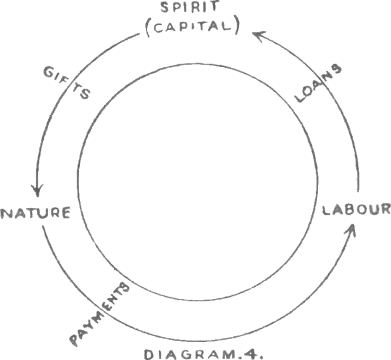

Yesterday we brought before our minds this cycle (see Diagram 3): Nature, Labour, Capital—that is, Capital endued with value by the Spirit. At this point I might just as well write (instead of “Capital”) “Spirit.” To begin with we followed out the economic process in this direction, counter-clockwise, and we found that at this point congestion must not be allowed to occur. On the contrary only so much must be allowed to go through as will act as a kind of seed to carry on the process. A state of economic congestion must not be allowed to arise through a fixation of Capital in ground rents. Now, as I said, fundamentally speaking, the return for land when it is sold—i.e., when land is given a value in the economic process—works in direct opposition to the interests of a person engaged in the manufacture of valuable goods. For if a man wishes to manufacture valuable goods with the help of Capital, it is to his interest that the rate of interest should be low. Having less interest to pay, he will be less hampered in his use of the Capital he has borrowed. The landowner, on the other hand (I may go fully into these things, as they are of economic significance), the landowner, or anyone who has an interest in the land becoming dearer, will be able to make it dearer simply by a reduction in the rate of interest. If he has a low rate of interest to pay, the value of his land will grow, it will become dearer and dearer. Whereas a man engaged in the manufacture of valuable commodities will be able to make them cheaper because of a low rate of interest. Commodities, therefore, which depend mainly on manufacture, become cheaper when the rate of interest is low. Land, on the other hand, which gives a yield without first having to be manufactured, becomes dearer when the rate of interest is low. You can easily work it out. It is an economic fact.

It would appear then to be necessary to arrange for two different rates of interest: We ought to have a rate of interest as low as possible for the installation of works for the production of valuable commodities; and a rate of interest as high as possible for everything that falls under the heading of “land.” This follows directly from what we said before. We want a rate of interest as high as possible for all that comes under the heading of “land.” But that is a thing which cannot easily be carried out in practice. A slightly higher rate of interest for Capital advanced on land might be practicable, but this would be of little help. A considerably higher rate of interest—say, for instance, the rate of interest which would keep the land at an ever constant value, namely, 100%—would be extremely difficult to realise in practice without taking additional steps. 100% interest for money borrowed on land would mend matters at once, but it cannot be carried out in practice. In all such cases, the first point is to see with full clarity into the economic process. When we do so, we soon realise that the life of Associations is the only thing that can make it healthy. Rightly to see the economic process will lead to our being able rightly to direct it.

In the economic process we must speak, as I indicated yesterday, of Production and Consumption. We must observe the producing and the consuming process. This contrast has played a great part recently in various much-canvassed economic theories which in due course have been used for purposes of agitation. There has especially been much dispute upon the question, whether spiritual or intellectual work, as such, is in any way value-creating in the economic sphere.

The spiritual worker is certainly a consumer. Whether he is also a producer in the economic sense is a question which has been much discussed. The extreme Marxists, for example, have again and again cited that luckless fellow, the Indian book-keeper, who has to keep the accounts for his village community. He does not till the fields or do any other productive work; he merely registers the productive work done by others. The Marxists deny him the faculty of producing anything. They declare that he is simply and solely maintained out of the surplus value which the productive workers create. This worthy book-keeper is worked as hard in Economics as Caius is in the formal Logic which we did at college. Caius's job is proving the mortality of man. You remember: “All men are mortal, Caius is a man, therefore Caius is mortal.” His everlasting function of proving the mortality of man has made him immortal in the world of Logic. The same thing has happened in Marxian literature to the Indian bookkeeper who is maintained simply by the surplus value of the productive workers. He has become a classic.

This question is, if I may say so, extraordinarily full of “snags,” in which we very easily get caught when we try to work it out economically. I mean the question: How far (if at all) spiritual work is economically productive? Now here it is especially important to distinguish between the past and the future. For if you consider, if you reflect statistically on, the past only, with respect to the past and to all that is only the unbroken continuation of the past, you will be able to prove that spiritual work is unproductive. From the past into the future within the material sphere, only purely material work and its effects can be held to be productive in the economic process. It is quite a different matter when you turn your eye to the future. And, as we said, to be engaged in economics is to be working from the past into the future.

You need only think of this simple instance. Assume that in some village a craftsman, who manufactures this or that, falls ill. Under certain given circumstances—let us say, if he falls into the hands of an unskilful doctor—he will have to lie in bed for three weeks, during which time he will be able to do nothing. He will disturb the economic process to no small extent. If he is a cobbler, for three weeks long the boots and shoes will not be brought to market—taking the word “market” in the widest sense. But now suppose he gets a very skilful doctor who makes him well in a week. He can go back to work again in a week. In all seriousness you can now decide the question: Who made the boots for the remaining 14 days, the cobbler or the doctor? In reality it was the doctor. And now the thing is altogether clear. As soon as you take into account the future from any given moment onward—towards the future—you can no longer call the Spiritual unproductive. In relation to the past, the Spiritual—or rather, those human beings who work in the spiritual sphere—are consumers only. In relation to the future they are decidedly productive, indeed they are the producers, for they transform the whole process of production and make it pronouncedly different for the economic life. You can see this from the example of the tunnel. What happens when tunnels are built nowadays? They could

not be built unless the differential calculus had been discovered. To this day, therefore, Leibnitz is helping to build all tunnels. The way prices work out in this case has really been determined by that exertion of his spiritual forces. You can never answer these questions in Economics if you consider the past in the same way as the future. But, ladies and gentlemen, life does not move towards the past, nor does it even prolong the past; it goes on into the future.

Hence no economic thought is real which does not reckon with what is done by spiritual work, if we may call it so, that is to say, fundamentally by thinking. But spiritual work is not an easy thing to grasp. It has its own peculiar properties which are not at all easy to grasp in economic terms. Spiritual work begins the moment work itself—that is to say, Labour—is organised. The organising work of thinking begins the very moment Labour itself is organised and divided. Thenceforward, it grows more and more independent. Consider the spiritual work of one who directs some undertaking within the material sphere. You will see that he applies an immense amount of spiritual work. Nevertheless he is still working with the resources with which the economic process provides him as from the past. But even on quite practical grounds you cannot get around the fact that the sphere of spiritual activity (if I may now call it “activity” instead of work or labour) also includes the entirely free kind of activity. When a man invents the differential calculus, and even more so when he paints a picture, there we have a case of entirely free spiritual activity. At any rate, relatively speaking, we can call it free. For whatever materials are derived from the past—the paints and the like—they no longer have the same significance in relation to the eventual products as do the raw products, for example, purchased for material manufacture.

Passing into this region, therefore (see Diagram 4), we come into the sphere of the completely free spiritual life. In this sphere we find, above all things, teaching and education. Those who have to teach and educate stand undoubtedly within the sphere of the completely free spiritual life. For the purely material economic process, it is especially the free spiritual workers who are, in relation to the past, absolutely and exclusively consumers. Of course, you may say, they produce something, and, if they are painters, for example, they are even paid something for what they have produced. In appearance, therefore, the economic process is the same as when I manufacture a table and sell it. And yet the process is essentially different as soon as we cease to consider the buying and selling of the individual and turn our attention to the economic organism as a whole—and this is what we must do in the present advanced stage of division of Labour.

Now there are also pure consumers of another kind within a social organism, namely, the young and the very old. Up to a certain age, the young are pure consumers; and those who have been pensioned off are again pure consumers. A very little reflection will suffice to convince you that if there were no pure consumers in the economic process—mere consumers who are not producers at all—the thing could not go forward at all. For if everyone were producing, all that is produced could not be consumed if the economic process were to go forward at all. It is so at any rate as human life is, and human life is not purely economics; it must be taken as a whole. The real advancement of the economic process is only possible if it includes pure consumers.

But I must now illumine from a different angle this fact: that we have pure consumers within the economic process.

You see, this circle (in the diagram) can be made very instructive. We can endow it with all manner of properties, and the question will always be, how to bring the several economic processes and facts into this circle, which represents for us the cycle of the economic process. Something very important happens when, in buying and selling in the market, I pay on the spot for what I get. The point is not that I pay for it with money; I might equally well barter it for a corresponding commodity which the other person was willing to accept. The point is that I pay at once. Indeed it is this that constitutes “paying” in the proper sense of the word. Now here once more we must pass from the ordinary, everyday conception to the true economic conception. For in the economic life the several concepts constantly play into one another. The total phenomenon, the total fact, results from the interplay of the most diverse factors. You may say: “It is conceivable that some regulation should be made, so that no one need ever pay cash down; then there would be no such thing as ‘paying at once’; one would only pay after a month or after some other interval of time.” But the point is this: We are forming our concepts altogether wrongly when we say: “Some-one hands me a suit of clothes and I pay for it after a month.” The fact is that after a month I no longer pay for this suit of clothes alone. In that moment I am paying for something quite different. I am paying for something which circumstances, by raising or lowering prices, may have made quite different. I am paying for an ideal element in addition. In fact, we cannot do without the concept of “immediate payment.” This is the concept which holds good in cases of simple purchase. Nay more, a thing becomes a commodity on the market through the very fact that it is paid for at once. This is generally the case with those commodities which are “Nature transformed by Labour.” For such commodities I pay. Here payment plays the essential part. There must be such payment. I pay at the very moment when I open my purse and give away my money; and the value is determined in the very moment at which I give away the money, or exchange my commodity for another. That is payment. That is one thing there must be in the economic process.

The second thing, which plays a similar part to payment, is the thing to which I drew attention yesterday. It is Lending. This, as I said, does not interfere with the concept of payment as such. Lending, once more, is an altogether different fact, a fact which simply exists. If I have money lent me, I can apply my Spirit to this loaned Capital. I become a debtor; but I also become a producer. In this way, lending plays a real economic part. If I have intellectual or spiritual capacities in some direction, it must be possible for me to obtain loaned Capital. No matter where I get it from, I must have it. Thus in addition to payment there must be loan (see >Diagram 4). Here then we have two very important factors in the economic process: Payment and Loan.

And now by a simple deduction—we must verify it here (see diagram)—by a very simple deduction you can find the third. You will not doubt for a moment what the third thing is. We have had Payment and Loan. The third thing is Gift. Payment, Loan and Gift—this is a real trinity of concepts, essential to a healthy economy. There is a prevailing disinclination to include “free gift ” in the economic process as such, but, ladies and gentlemen, if there is not a giving somewhere, the economic process cannot go on at all. Imagine for a moment what we should make of our children if we gave them nothing. We are constantly making free gifts to the children. If we consider the economic process as a whole—as a process that goes on and on continuously—Gift is part of it. There is no escaping the fact. It is wrong to regard the transfer of values from hand to hand, representing a process of free gift, as something inadmissible in the economic process as such. Precisely this one of the three is found—with horror by some people—worked out in my book, The Threefold Commonwealth, where it is shown how values are to be transferred, how means of production, for instance, are to be transferred, by a process really identical with giving, to one who has the faculties necessary for managing them further. Provision must, of course, be made that the giving is not done in a haphazard way. But in the economic sense they are none the less free gifts, and such gifts are absolutely necessary.

You will find it more and more to be an economic necessity. The trinity of payment, loan and gift is there in the economic process. Consider the matter thoroughly and you will say: In every economic process this must be contained. Otherwise it would be no economic process; it would lead to absurdities at every point.

People may rebel against these things for a time; but we must remember that economic wisdom is today not very great. Those especially who want to teach it should be under no illusions on this point. Modern economic knowledge is by no means great. People are little inclined to go into the real economic relationships. This is an obvious fact, so obvious that if you look in today's Basler Nachrichten you will find curiously enough a reflection on this very fact. Neither Governments nor private people nowadays, it says, are inclined to evolve real economic thinking. I think we may take it that anything expounded in the Basler Nachrichten is likely to be obvious. It is indeed a palpable fact and it is interesting to find it discussed in this way. The article is interesting, inasmuch as it endeavours to set in a glaring light the absolute impotence which prevails in the economic sphere; interesting, too, because it says that these things must be changed—it is time Governments and individuals began to think differently. But there the matter ends. How they are to think differently—on this you will, of course, find nothing in the Basler Nachrichten—which is also interesting!

Now it is possible to interfere in the economic process in a disturbing way, if one does not rightly relate the one thing with the other in this trinity. Many people today are enthusiastically demanding the taxation of legacies (which, of course, are also gifts), Such proposals have no deep economic significance. For we do not lessen the value of the inheritance if, say, it has a value V and we divide the value V into two parts, V1 and V2 giving V2 to some other party and leaving the legatee with V1 alone. All it means is that the two together will now do business with the original value V, and the question will be whether he who receives V2 will husband it as advantageously for the economic life as would the original legatee who would otherwise have received V1 and V2 together. Everyone of course may settle this question for himself according to his taste, whether a single clever man, receiving the whole legacy, will husband it better, or whether it will be better for one to receive only part while the State receives the other part, so that the individual is obliged to do business in conjunction with the State.

This sort of thing definitely leads us away from pure economic thinking. It is a thinking based on resentment, on feeling. People envy the rich heir. There may be reason for it, but we cannot look at it only from this point of view if we claim to be thinking in an economic sense. The point is, how must the thing be conceived in the economic sense, for whatever else has to be done must take its start from this. You can, of course, conceive a social organism becoming diseased through the fact that payment is not working together in an organic way with loan and gift, since one or the other is being obstructed and one or the other fostered. But they will still go on working together in some way. If you abolish giving on one side, you merely effect a redistribution, and the question to be decided is not whether this ought to be done, but whether it is necessarily advantageous. Whether the individual heir alone should receive the inheritance, or whether he must share it with the State, is a question which must first be settled on economic grounds. Which is more advantageous? That is the point.

The important thing is this: Free spiritual life arises almost of necessity out of the entry of the Spirit into the economic life. As a result of this free spiritual life, as I said just now, there will be pure consumers so far as the past is concerned. But what of the free spiritual life in relation to the future? Here it is productive—indirectly it is true—but none the less extraordinarily productive. Imagine the free spiritual life in the social organism really freed, so that the individual faculties were always able to evolve to the full. Then the free spiritual life will be able to exert an extremely fertilising influence on the half-free spiritual life—i.e., on that spiritual life which enters into the processes of material production. Considered in this light, the thing takes on a decidedly economic complexion.

Anyone who can observe life with an unbiased mind will say to himself that it is by no means a matter of indifference whether in a given region all who are active in the free spiritual life are exterminated (for instance, if they got nothing to consume, the right to live being admitted only for those who work directly into the material process) or whether really free spirits are allowed to exist within the social organism. For the free spirits have the peculiar property of loosening and liberating the spirituality, the “gumption” of the others. They make their thinking more mobile, and these others are thus able to work into the material process more effectively. But it is important to remember that the free spirits are living men. You must not try to refute me by pointing to Italy and saying: There is a great deal of free spiritual life there, yet the economic processes which proceed from spirit have not been stimulated to any unusual degree. Granted, it is a free spiritual life. But it is a free spiritual life handed down from the past. There are statues, museums and the like; but they do not have this effect. Only what is living is effectual—that is to say, what proceeds from the free spirit and passes on to other spiritual producers. This is what works as a productive factor into the future, even in the economic sense. It is certainly possible to exert a healing influence on the economic process by giving a free field of action to free spiritual workers.

Suppose now that we have a healthy Associative life in a community. The task of the Associations will be to arrange production in such a way that when too many people are working in any sphere they can be transferred to some other work. It is this vital dealing with men, this allowing the whole social order to originate from the insight of the Associations that matters. And when one day the Associations begin to understand something of the influence of free spiritual life on the economic process, we can give them a very good means of regulating the economic circuit. I mentioned this in my Threefold Commonwealth. The Associations will find that when free spiritual life declines, too little is being given freely; they will grasp the connection. They will see the connection between too little giving and too little free spiritual work. When there is not enough free spiritual work, they will realise that too little is being given. When too little is being given, they will notice a decline in free spiritual work.

There is then a very definite possibility of driving the rate of interest on Nature-property right up to 100% by transmitting as much Nature-property as possible in the shape of free gifts to those who are spiritually productive. In this way you can bring the Land question into direct connection with what works particularly into the future. In other words, the Capital which presses to be invested, the Capital which tends to march into mortgages and stay there, must be given an outlet into free spiritual institutions. That is the practical aspect. Let the Associations see to it that the money which tends to get tied up in mortgages finds its way into free spiritual institutions. There you have the connection of the Associative life with the general social life. Only when you try to penetrate the realities of economic life does it begin to dawn on you what must be done in the one case or in the other. I do not by any means wish to agitate that this or that must be done. I only wish to point out what is. And this is undoubtedly true: What we can never attain by legislative measures—namely, to keep the excess Capital away from Nature—we can attain by the life and system of Associations, diverting the Capital into free spiritual institutions. I only say: If the one thing happens, the other will happen too. Science, after all, has only to indicate the conditions under which things are connected.

Sechster Vortrag

Sie wissen vielleicht, daß ich in meinen «Kernpunkten der sozialen Frage» formelhaft zu bestimmen versuchte, wie man zu einer Vorstellung des, sagen wir zunächst richtigen Preises innerhalb des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses kommen kann. Natürlich ist mit einer solchen Formel ja nichts weiter gegeben als zunächst eine Abstraktion. Und in diese Abstraktion, ich möchte sagen, die ganze Volkswirtschaft wenigstens skizzenweise hineinzuarbeiten, ist ja eben unsere Aufgabe in diesen Vorträgen, die sich, ich denke doch, zu einem Ganzen schließen werden, wenn auch die Zeit eine kurze ist.

Ich habe also in den «Kernpunkten der sozialen Frage» als Formel das Folgende angegeben: Ein richtiger Preis ist dann vorhanden, wenn jemand für ein Erzeugnis, das er verfertigt hat, so viel als Gegenwert bekommt, daß er seine Bedürfnisse, die Summe seiner Bedürfnisse, worin natürlich eingeschlossen sind die Bedürfnisse derjenigen, die zu ihm gehören, befriedigen kann so lange, bis er wiederum ein gleiches Produkt verfertigt haben wird. Diese Formel ist, so abstrakt sie ist, dennoch erschöpfend. Es handelt sich ja beim Aufstellen von Formeln eben darum, daß sie wirklich alle konkreten Einzelheiten enthalten. Und ich meine, für das Volkswirtschaftliche ist diese Formel wirklich so erschöpfend wie, sagen wir, derPythagoräische Lehrsatz erschöpfend ist für alle rechtwinkeligen Dreiecke. Nur handelt es sich darum: ebenso wie man in diesen hineinbringen muß die Verschiedenheit der Seiten, so muß man unendlich viel mehr in diese Formel hineinbringen. Aber das Verständnis, wie man in diese Formel den ganzen volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß hineinbringt, das ist eben Volkswirtschaftswissenschaft.

Nun möchte ich heute gerade ausgehen von einem ganz Wesentlichen in dieser Formel. Das ist das, daß ich nicht hinweise in dieser Formel auf dasjenige, was vergangen ist, sondern auf dasjenige, was eigentlich erst kommt. Ich sage ausdrücklich: Der Gegenwert muß die Bedürfnisse in der Zukunft befriedigen, bis der Erzeuger wiederum ein gleiches Produkt verfertigt haben wird. Das ist etwas ganz Wesentliches in dieser Formel. Würde man einen Gegenwert verlangen für das Produkt, das er schon fertig hat, und dieser Gegenwert sollte entsprechen irgendwie den wirklichen volkswirtschaftlichen Vorgängen, so könnte es durchaus passieren, daß der Betreffende einen Gegenwert bekommt, der seine Bedürfnisse, sagen wir, nur zu fünf Sechsteln der Zeit befriedigt, bis er ein neues Produkt hergestellt hat; denn die volkswirtschaftlichen Vorgänge ändern sich eben von der Vergangenheit in die Zukunft hinein. Und derjenige, der da glaubt, von der Vergangenheit her allein irgendwelche Aufstellungen machen zu können, der muß immer im Volkswirtschaftlichen das Unrichtige treffen; denn Wirtschaften besteht eigentlich darinnen, daß man die künftigen Prozesse mit dem, was vorangegangen ist, ins Werk setzt. Wenn man aber die vergangenen Prozesse benützt, um die künftigen ins Werk zu setzen, dann müssen sich unter Umständen die Werte ganz bedeutend verschieben; denn fortwährend verschieben sie sich. Daher handelt es sich bei dieser Formel ganz wesentlich darum, daß ich sage: Wenn jemand ein Paar Stiefel verkauft, so ist die Zeit, in der er sie verfertigt hat, volkswirtschaftlich durchaus nicht maßgebend, sondern maßgebend ist die Zeit, in der er das nächste Paar Stiefel verfertigen wird. Das ist, worauf es in dieser Formel ankommt, und das müssen wir nun in breiterem Sinn innerhalb des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses verstehen.

Wir haben ja gestern uns den Kreislauf vor die Seele geführt (siehe Zeichnung 3): Natur - Arbeit - Kapital, das also vom Geiste verwertet wird. Ich könnte hier statt Kapital ebensogut herschreiben Geist. Und wir haben zunächst den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß in dieser Richtung — gegen den Uhrzeiger - verfolgt und gefunden, daß hier, bei der Natur, keine Stauung stattfinden darf, sondern daß eigentlich da nur durchkommen darf, was als eine Art Samen die Möglichkeit hat, den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß fortzusetzen, so daß also nicht durch eine Fixierung des Kapitals in der Bodenrente eine volkswirtschaftliche Stauung entsteht. Nun sagte ich Ihnen ja, daß im Grunde genommen der Ertrag von Grund und Boden beim Verkauf, also die Bewertung von Grund und Boden, widerspricht im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß den Interessen, die man hat bei der Herstellung von wertvollen Gütern. Derjenige, der mit Hilfe von Kapital wertvolle Güter herstellen will, hat ein Interesse daran, daß der Zinsfuß niedrig ist; denn er braucht dann weniger ‘Zins zurückzuzahlen und kann sich dadurch leichter bewegen mit dem, was er als Leihkapital bekommt. Derjenige aber, der Besitzer etwa ist - ich darf diese Dinge, weil sie innerhalb unserer Volkswirtschaft Bedeutung haben, durchaus besprechen -, derjenige, der ein Interesse daran hat, den Grund und Boden teurer zu machen, der macht ihn gerade dadurch teurer, daß der Zinsfuß ein niedriger ist. Hat er niedrigen Zins zu bezahlen, so wächst der Wert seines Grundes und Bodens, der wird immer teurer; während derjenige, der einen niedrigen Zinsfuß zu bezahlen hat, bei der Herstellung von wertvollen Waren die Waren billiger herstellen kann. Also Waren, bei denen es ankommt auf den Prozeß der Herstellung, werden bei niedrigem Zinsfuß billig: Grund und Boden, der einen Ertrag liefert, ohne daß man ihn erst herstellt, der wird teurer bei niedrigerem Zinsfuß. Sie können sich das einfach ausrechnen. Es ist das eine volkswirtschaftliche Tatsache.

Nun handelt es sich darum, daß also dann eigentlich die Notwendigkeit vorliegen würde, den Zinsfuß in zweifachem Sinn zu gestalten: man müßte also einen möglichst niedrigen Zinsfuß für das Installieren der Arbeit, des Erzeugens der wertvollen Warengüter haben, und man müßte einen möglichst hohen Zinsfuß haben für dasjenige, was Grund und Boden ist. Das folgt ja unmittelbar daraus. Man müßte einen möglichst hohen Zinsfuß haben für das, was Grund und Boden ist. Das ist etwas, was so ohne weiteres praktisch nicht leicht durchführbar ist. Ein etwas höherer Zinsfuß, der auch schon praktisch durchführbar wäre für Leihkapital, das auf Grund und Boden gegeben wird, würde nicht außerordentlich viel helfen, und ein wesentlich höherer Zinsfuß - ich will zum Beispiel sagen, der Zinsfuß, der einfach als Zinsfuß Grund und Boden immer auf einem gleichen Wert hielte, der Zinsfuß von hundert Prozent -, der würde auch praktisch außerordentlich schwierig so ohne weiteres durchführbar sein. Hundert Prozent für Beleihung von Grund und Boden würde ja sofort die Sache verbessern; aber es ist eben, wie gesagt, praktisch nicht durchführbar. Aber bei solchen Dingen handelt es sich darum, daß man klar und deutlich hineinschaut in den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß; und da merkt man dann, daß schon das Assoziationswesen dasjenige ist, was allein den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß gesund machen kann, weil nämlich der volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß, in der richtigen Weise angeschaut, dennoch dahin führt, daß man ihn auch in der richtigen Weise dirigieren kann.

Wir müssen ja reden im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß von Produktion und Konsum, wie ich schon gestern angedeutet habe. Wir müssen also sehen das Produzieren und das Konsumieren. Nun, das ist ja ein Gegensatz, der insbesondere in den neueren, vielfach geführten Diskussionen auf volkswirtschaftlichem Gebiet, die dann auch in die Agitation hineingegangen sind, eine große Rolle gespielt hat. Man hat namentlich über die Frage viel disputiert, ob die geistige Arbeit - einfach die geistige Arbeit als solche -, ob diese überhaupt auf wirtschaftlichem Gebiet werterzeugend sei.

Der geistige Arbeiter ist ja sicher ein Konsument. Ob er auch in dem Sinne, wie man es schon auf volkswirtschaftlichem Gebiet ansehen muß, ein Produzent ist, darüber ist ja viel diskutiert worden; und die extremsten Marxisten zum Beispiel haben ja immer und immer wiederum den unglückseligen indischen Buchhalter angeführt, der für seine Gemeinde die Bücher zu führen hat, der also nicht die Äcker besorgt oder eine andere produktive Arbeit verrichtet, sondern diese produktive Arbeit nur registriert, und sie sprechen diesem nun die Fähigkeit ab, irgend etwas zu produzieren. So daß sie konstatieren, daß er lediglich unterhalten wird aus dem Mehrwert, den die Produzenten erarbeiten. So daß wir diesen Prachtbuchhalter haben, wie er immer angeführt wird, wie wir ja auch den Cajus haben in der formalen Logik in den Gymnasien, der die Sterblichkeit der Menschen immer beweisen soll. Sie wissen ja: Alle Menschen sind sterblich, Cajus ist ein Mensch, also ist Cajus sterblich! — Dieser Cajus ist dadurch, daß er immerfort die Sterblichkeit des Menschen beweisen mußte, eine unsterbliche logische Persönlichkeit geworden. So ist es mit dem indischen Buchhalter, der nur vom Mehrwert der Produzenten erhalten wird; so ist es mit ihm in der marxistischen Literatur, wo man ihn sozusagen in Reinkultur findet.

Nun, diese Frage, die ist außerordentlich, ich möchte sagen, voll von allerlei solchen Schlingen, in denen man sich verfängt, wenn man sie volkswirtschaftlich durchführen will, diese Frage: Inwiefern ist - oder ist überhaupt - das geistige Arbeiten, die geistige Arbeit wirtschaftlich produktiv? — Sehen Sie, da kommt es eben sehr stark darauf an, daß man unterscheidet zwischen der Vergangenheit und der Zukunft. Wenn Sie nämlich bloß die Vergangenheit ins Auge fassen und bloß auf die Vergangenheit statistisch reflektieren, dann werden Sie beweisen können, daß die geistige Arbeit mit Bezug auf die Vergangenheit und alles dasjenige, was nur eine unmittelbare Fortsetzung der Vergangenheit ist, daß die geistige Arbeit dafür eigentlich unproduktiv ist. Von der Vergangenheit in die Zukunft ist an Materiellem nur die rein materielle Arbeit auch im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß produktiv zu denken mit ihrer Fortsetzung. Ganz anders ist es, wenn Sie die Zukunft ins Auge fassen - und Wirtschaften heißt eben, aus der Vergangenheit in die Zukunft hineinarbeiten. Da brauchen Sie ja nur an das einfache Beispiel zu denken: Sagen wir, irgendein Handwerker verfertigt irgend etwas in einem Dorf und er wird krank. Er wird, sagen wir, unter gewissen Verhältnissen, wenn er an einen ungeschickten Arzt kommt, drei Wochen im Bett liegen müssen und seine Dinge nicht verfertigen können. Da wird er den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß sehr wesentlich stören; denn es werden durch drei Wochen hindurch, wenn der Betreffende, sagen wir, Schuhe verfertigt hat, die Schuhe nicht auf den Markt gebracht werden - Markt im weitesten Sinne verstanden. Nehmen wir aber an, er kommt an einen sehr geschickten Arzt, der ihn in acht Tagen gesund macht, so daß er nach acht Tagen wieder arbeiten kann, dann können Sie die Frage in ernsthaftem Sinn entscheiden: Wer hat denn dann durch diese vierzehn Tage hindurch die Schuhe fabriziert? Der Schuhmacher oder der Arzt? Eigentlich hat der Arzt die Schuhe fabriziert. Und es ist ganz klar: Sobald Sie von irgendeinem Punkt an die Zukunft ins Auge fassen, können Sie nicht mehr sagen, daß das Geistige in die Zukunft hinein nicht produktiv wäre. Der Vergangenheit gegenüber ist das Geistige, das heißt, sind diejenigen Menschen, die im Geistigen arbeiten, nur konsumierend; in bezug auf die Zukunft sind sie durchaus produzierend, ja die Produzierenderen. Daß sie die Produzierenderen sind, in dem Sinn auch, daß sie den ganzen Produktionsprozeß umgestalten und ihn zu einem eminent anderen machen im volkswirtschaftlichen Sinn, das sehen Sie zum Beispiel, sagen wir, wenn heute Tunnels gebaut werden: sie können nicht gebaut werden, ohne daß die Differentialrechnung gefunden worden ist. Mit dieser Art Arbeit baut heute Leibniz noch an allen Tunnels mit, und wie sich da die Preise stellen, ist im wesentlichen durch diese Anspannung der geistigen Kräfte entschieden worden. So daß Sie niemals die Dinge so beantworten können, daß Sie in der volkswirtschaftlichen Betrachtung das Vergangene im gleichen Sinn betrachten wie das Zukünftige. Aber das Leben geht nicht nach der Vergangenheit hin, setzt auch die Vergangenheit nicht fort, sondern das Leben geht in die Zukunft hinein.

Daher ist keine volkswirtschaftliche Betrachtung eine reale, die nicht mit dem rechnet, was eben durch die geistige Arbeit - wenn wir sie so nennen wollen -, das heißt aber im Grunde genommen, durch das Denken geleistet wird. Aber diese geistige Arbeit, die ist nun wirklich recht schwer zu fassen; denn diese geistige Arbeit hat ganz bestimmte Eigentümlichkeiten, die sich wirtschaftlich zunächst außerordentlich schwer fassen lassen. Die geistige Arbeit, sie beginnt ja schon damit, daß die Arbeit durch organisierendes Denken organisiert, gegliedert wird. Sie wird aber immer selbständiger und selbständiger. Wenn Sie diese geistige Arbeit fassen bei demjenigen, der irgendein in der materiellen Kultur stehendes Unternehmen leitet, so wendet er eine große Summe von geistiger Arbeit auf, aber er arbeitet noch mit dem, was ihm der volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß aus der Vergangenheit liefert. Aber es ist ja nicht zu umgehen, rein auch aus ganz praktischen Interessen, daß innerhalb der geistigen Betätigung — so will ich es statt Arbeit nennen -, des geistigen Wirkens, auch das vollständig freie Wirken auftritt. Schon wenn man die Differentialrechnung erfindet, und gar erst, wenn man ein Bild malt, tritt eine vollständig freie geistige Betätigung auf. Mindestens kann man relativ von freier geistiger Betätigung sprechen, weil dasjenige, was aus der Vergangenheit verwendet wird, die Farben und dergleichen gegenüber dem, was zustande kommt, nun nicht mehr die Bedeutung hat wie etwa der Rohprodukteeinkauf bei der materiellen Fabrikation.

Wir kommen, indem wir da (siehe Zeichnung) herübergehen, in das Gebiet des vollständig freien Geisteslebens hinein und finden auf diesem Gebiet des freien Geisteslebens vor allen Dingen den Unterricht und die Erziehung. Diejenigen Menschen, die den Unterricht und die Erziehung zu leisten haben, die stehen eigentlich im völlig freien Geistesleben darin. Für den rein materiellen Fortgang des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses sind insbesondere diese freien Geistesarbeiter der Vergangenheit gegenüber durchaus Konsumenten, absolut Konsumenten nur. Nun, Sie können sagen: Sie produzieren ja etwas und bekommen für das, was sie produziert haben - wenn sie zum Beispiel Maler sind -, sogar etwas bezahlt. -— Also es spielt sich scheinbar derselbe volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß ab, wie wenn ich den Tisch fabriziere und verkaufe. Und doch ist es ein wesentlich anderer, sobald wir nicht auf den Kauf und Verkauf des einzelnen Menschen sehen, sondern beginnen, volkswirtschaftlich zu denken und auf den ganzen volkswirtschaftlichen Organismus unser Augenmerk zu lenken - und das müssen wir heute bei der so weit vorgeschrittenen Arbeitsteilung.

Außerdem aber sind innerhalb eines sozialen Organismus reine Konsumenten anderer Art noch da. Das sind die jungen Leute, die Kinder, und die alten Leute. Jene sind bis zu einer gewissen Altersstufe zunächst reine Konsumenten. Und diejenigen, die sich haben pensionieren lassen oder pensioniert worden sind, die sind wiederum reine Konsumenten.

Sie brauchen nur eine geringe Überlegung, so werden Sie sich sehr bald sagen: Ohne daß im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß reine Konsumenten da sind, die keine Produzenten sind, geht es gar nicht vorwärts, denn wenn alle produzieren würden, könnte nicht alles, was produziert wird, auch konsumiert werden, wenn der volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß überhaupt weitergehen soll - so wenigstens, wie es nun einmal im Menschenleben ist. Und das Menschenleben ist ja nicht bloß Volkswirtschaft, sondern ist als Ganzes zu nehmen. So ist der Fortschritt des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses nur möglich, wenn wir in ihm reine Konsumenten haben.

Nun, daß wir im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß reine Konsumenten haben, das muß ich Ihnen jetzt von einer ganz anderen Seite aus beleuchten.

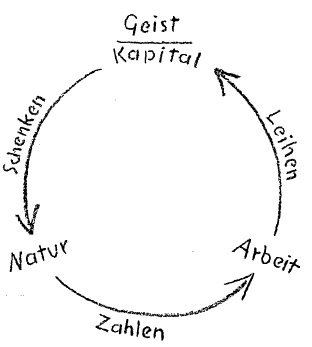

Wir können diesen Kreis hier (siehe Zeichnung 4), der sehr lehrreich sein kann, mit allen möglichen Eigenschaften ausstaffieren, und es wird immer die Frage sein, wie wir die einzelnen volkswirtschaftlichen Vorgänge, volkswirtschaftlichen Tatsachen in diesen Kreis, der uns eben der Kreisgang des volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesses ist, hineinbringen. - Da gibt es eine Tatsache, die spielt sich ab unmittelbar auf dem Markt bei Verkauf und Kauf, wenn ich dasjenige, was ich bekomme, gleich bezahle. Es kommt nicht einmal darauf an, daß ich es gleich mit Geld bezahle, ich kann es auch noch, wenn es Tauschhandel ist, mit der entsprechenden Ware bezahlen, die der Betreffende annehmen will. Es kommt darauf an, daß ich zunächst gleich bezahle, das heißt überhaupt zahle. Und jetzt haben wir wieder nötig, an dieser Stelle (siehe Zeichnung 4) von der gewöhnlichen trivialen Betrachtung zur volkswirtschaftlichen Betrachtung überzugehen. Es spielen nämlich in der Volkswirtschaft die einzelnen Begriffe fortwährend ineinander, und die Gesamterscheinung, die Gesamttatsache, ergibt sich aus dem Zusammenspiel der verschiedensten Faktoren. Sie können sagen: Es wäre ja auch denkbar, daß durch irgendeine Maßregel überhaupt niemand gleich bezahlen würde - dann gäbe es das Gleichzahlen nicht. Man würde also immer erst, sagen wir, nach einem Monat zahlen oder nach irgendeiner Zeit. Ja, es handelt sich nur darum, daß man dann in einer ganz falschen Begriffsbildung drinnen ist, wenn man sagt: Heute übergibt mir jemand einen Anzug und ich bezahle ihn nach einem Monat. Ich bezahle eben nach einem Monat nicht mehr diesen Anzug allein, sondern ich bezahle dann in diesem Moment etwas anderes: ich bezahle dasjenige, was unter Umständen durch eine Steigerung oder Erniedrigung der Preise etwas anderes ist, ich bezahle ein Ideelles dazu. Also der Begriff des A-tempo-Zahlens, der muß durchaus da sein, und der ist beim einfachen Kauf da. Und etwas wird eine Ware des Marktes dadurch, daß ich es gleich bezahle. So ist es im wesentlichen mit denjenigen Waren, die bearbeitete Natur sind. Da zahle ich, da spielt das Zahlen die wesentliche Rolle. Dieses Zahlen muß durchaus sein; denn zahlen tue ich dann, wenn ich meine Börse aufmache und Geld weggebe, und der Wert wird bestimmt in dem Moment, wo ich das Geld weggebe oder meine Ware gegen eine andere austausche. Da wird bezahlt. Dieses ist das eine, daß im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß gezahlt werden muß.

Das Zweite ist das, worauf ich gestern schon aufmerksam gemacht habe, was eine ähnliche Rolle spielt wie das Zahlen. Das ist das Leihen. Das tangiert, wie gesagt, das Zahlen als solches nicht; das Leihen ist wiederum eine ganz andere Tatsache, die doch da ist. Wenn ich Geld geliehen bekomme, kann ich meinen Geist anwenden auf dieses geliehene Kapital. Ich werde zum Schuldner; aber ich werde zum Produzenten. Da spielt das Leihen eine wirklich volkswirtschaftliche Rolle. Es muß möglich sein, daß ich, wenn ich geistig befähigt bin, dieses oder jenes zu tun, Leihkapital bekomme, ganz gleichgültig woher; aber ich muß es bekommen, es muß einfach Leihkapital geben. Es muß also zum Zahlen das Leihen kommen (siehe Zeichnung 4). Und damit haben wir zwei ganz wichtige Faktoren im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß darinnen: das Zahlen und das Leihen.

Und jetzt können wir wirklich durch eine einfache Deduktion - wir müssen sie nur da (siehe Zeichnung 4) verifizieren — das Dritte finden. Sie werden in keinem Moment im Zweifel sein, was dieses Dritte ist. Zahlen, Leihen - und das Dritte ist Schenken. Zahlen, Leihen, Schenken: Das ist tatsächlich eine Trinität von Begriffen, die in eine gesunde Volkswirtschaft hineingehört. Man hat eine gewisse Abneigung, das Schenken zum volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß zu rechnen; aber, wenn es das Schenken irgendwo nicht gibt, so kann überhaupt der volkswirtschaftliche Prozeß nicht weitergehen. Denn denken Sie sich doch einmal, was wir machen sollten aus den Kindern, wenn wir ihnen nichts schenken würden. Wir schenken fortwährend an die Kinder und, im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß darinnen gedacht, ist eben dann das Schenken da, wenn wir ihn vollständig betrachten, wenn wir ihn als einen fortlaufenden Prozeß betrachten. So daß der Übergang von Werten, die eine Schenkung bedeuten, eigentlich sehr mit Unrecht angesehen wird als irgend etwas, was nicht zulässig ist im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß. Sie finden daher - zum Horror sehr vieler Leute — in meinen «Kernpunkten der sozialen Frage» gerade diese Kategorie ausgebildet, wo die Werte übergehen, zum Beispiel die Produktionsmittel übergehen, im Grunde genommen durch einen Prozeß, der mit dem Schenken identisch ist, auf den, der dazu befähigt ist, sie weiter zu verwalten. Daß die Schenkung nicht in konfuser Weise gemacht wird, dafür muß eben vorgesorgt werden; aber im volkswirtschaftlichen Sinn ist das eine Schenkung. Diese Schenkungen sind durchaus notwendig.

Aber denken Sie sich jetzt einmal dieses, was Sie immer mehr finden werden als eine volkswirtschaftliche Notwendigkeit, daß die Trinität von Zahlen, Leihen und Schenken drinnen ist im volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, dann werden Sie sich eben sagen: Ja, sie muß in jedem volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß - sonst könnte er gar keiner sein, sonst würde er sich überall ins-Absurde hineinführen -, sie muß in jedem volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß drinnen sein.

Man kann sie zeitweilig bekämpfen; aber die volkswirtschaftlichen Kenntnisse sind heute keine sehr großen, und gerade diejenigen, die Volkswirtschaftswissenschaft lehren wollen, die müßten sich eigentlich ganz klar darüber sein, daß die volkswirtschaftlichen Kenntnisse heute keine sehr großen sind, daß man vor allen Dingen nicht sehr geneigt ist, in die wirklichen volkswirtschaftlichen Zusammenhänge hineinzugehen. Es ist ja mit Händen zu greifen, möchte ich sagen. So stark mit Händen zu greifen, daß Sie, wenn Sie heute die «Basler Nachrichten » lesen, kurioserweise heute in ihnen eine Betrachtung darüber angestellt finden, wie weder bei Regierungen noch bei Privaten heute die Neigung vorhanden ist, volkswirtschaftliches Denken zu entwickeln. Ich glaube ja nicht, daß Dinge, die nicht heute mit Händen zu greifen sind, just gerade in den «Basler Nachrichten » erörtert werden! Es ist schon mit Händen zu greifen. Und es ist immerhin interessant, daß das in dieser Weise besprochen wird; der Artikel ist interessant durch dieses, daß er einmal auf die absolute volkswirtschaftliche Impotenz ein grelles Licht zu werfen beginnt; und auch dadutch, daß er sagt: Das muß nun anders werden, die Regierungen und die Privaten müssen anfangen, nun endlich anders zu denken. — Damit schließt er aber auch. Wie sie anders denken sollen, darüber ist natürlich nichts zu finden in den «Basler Nachrichten». Das ist natürlich auch sehr interessant.

Nun, man kann störend eingreifen in den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, wenn man diese 'Trinität eben nicht in der richtigen Weise, das eine mit dem anderen in ein Verhältnis bringt. Es gibt heute viele Leute, die enthusiasmieren sich ganz besonders dafür, daß zum Beispiel Erbschaften, die auch Schenkungen sind, daß diese hoch besteuert werden müssen. Ja, das bedeutet ja nicht irgend etwas volkswirtschaftlich Bedeutsames; denn man entwertet die Erbschaft eigentlich nicht, wenn, sagen wir, sie einen \(Wert = W\) hat, und man teilt diesen \(Wert = W\) in zwei Teile, \(W\) \(1\) und \(W\) \(2\), und gibt dieses \(W\) \(2\) an jemand anderen ab und läßt dem einen nur das \(W\) \(1\), dann wirtschaften halt mit diesem Wert \(W\) die beiden zusammen, Und es handelt sich darum, ob derjenige, der das \(W\) \(2\) hat, ebenso günstig wirtschaften wird wie derjenige, der eventuell \(W\) \(1\) und \(W\) \(2\) zusammen bekommen hätte. Nicht wahr, es kann jeder selber nach seinem Geschmack das Folgende entscheiden: Ob nun ein gescheiter Einzelner, wenn er die Gesamterbschaft bekommt, besser wirtschaftet, oder ob besser wirtschaftet derjenige, der nur einen Teil der Gesamterbschaft bekommt und den anderen Teil der Staat, und der also mit dem Staat zusammen wirtschaften muß.

Das sind die Dinge, die ganz entschieden abführen von dem rein volkswirtschaftlichen Denken; denn es ist ein Denken des Ressentiments, ein Denken aus dem Gefühl heraus. Man beneidet eben die reichen Erben. Das mag ja begründet sein; aber von solchen Dingen allein kann man nicht reden, wenn man volkswirtschaftlich denken will. Darauf kommt es an, was im volkswirtschaftlichen Sinn gedacht werden muß; denn danach muß sich erst richten, was sonst einzutreten hat. So können Sie sich natürlich einen sozialen Organismus denken, der dadurch krank wird, daß in unorganischer Weise das Zahlen mit dem Leihen und dem Schenken zusammenwirkt, indem man gegen das eine oder andere auftritt oder das eine und das andere fördert. Irgendwie zusammenwirken tun sie doch. Denn schaffen Sie nur das Schenken auf der einen Seite ab, so lagern Sie es nämlich nur um. Und entscheidend ist nicht die Frage, ob man umlagern soll, sondern ob das Umlagern immer günstig ist; denn ob die Erbschaft der einzelne individuelle Erbe allein antritt oder mit dem Staat zusammen, das ist eine Frage, die erst volkswirtschaftlich entschieden werden muß. Ob das eine oder das andere günstiger ist, das ist es, worauf es ankommt.

Nun aber, das Wichtige ist nämlich dieses, daß wir vor der Tatsache stehen, daß ja das freie Geistesleben mit einer gewissen Notwendigkeit herausentsteht aus dem Eintritt des Geistes überhaupt in das Wirtschaftsleben. Und dieses freie Geistesleben - ich habe es vorhin gesagt -, es führt dazu, daß reine Konsumenten da sind für die Vergangenheit. Aber wie steht es denn mit diesem freien Geistesleben mit Bezug auf die Zukunft? Da ist es nämlich in einem gewissen Sinn mittelbar produktiv, aber außerordentlich produktiv. Wenn Sie sich nämlich dieses freie Geistesleben auch wirklich befreit denken im sozialen Organismus, so daß tatsächlich immer die Fähigkeiten sich voll entwickeln können, dann wird gerade dieses freie Geistesleben in der Lage sein, einen außerordentlich befruchtenden Einfluß auszuüben auf das halbfreie Geistesleben, auf dasjenige Geistesleben, das in das materielle Schaffen hineingeht. Und da, wenn wir das betrachten, beginnt die Sache eine durchaus volkswirtschaftliche Seite zu bekommen.

Wer das Leben unbefangen betrachten kann, der wird sich sagen: Es ist durchaus nicht gleichgültig, ob irgendwo auf einem Gebiet alle diejenigen, die sich im freien Geistesleben betätigen, nun ausgerottet sind — vielleicht dadurch, daß sie nichts mehr zum Konsumieren erhalten können undmandasRecht, da zu sein, nur denjenigen zuspricht, die in den materiellen Prozeß eingreifen -, oder ob innerhalb des sozialen Organismus wirklich freie Geistesmenschen existieren können. Diese freien Geistesmenschen haben nämlich die Eigenschaft, daß sie den «Gritzi», die Geistigkeit, bei den anderen loslösen, daß sie ihr Denken beweglicher machen, und daß dadurch die anderen besser in die materiellen Prozesse einzugreifen vermögen. Nur handelt es sich darum, daß es Menschen sind. Sie dürfen daher nicht etwa dasjenige, was ich jetzt sagen möchte, widerlegen wollen dadurch, daß Sie auf Italien hinweisen und sagen: In Italien ist ja wirklich sehr viel von freiem Geistesleben, aber die volkswirtschaftlichen Prozesse, die aus dem Geist herausgehen, wurden dadurch doch nicht in besonderer Weise angeregt. — Ja, es ist freies Geistesleben, aber freies Geistesleben, das aus der Vergangenheit stammt. Es sind Denkmäler, Museen und so weiter. Die machen es aber nicht aus. Ausgemacht wird es durch das, was lebendig ist. Und das ist dasjenige, was vom freien Geistesmenschen ausgeht auf die anderen geistig Produzierenden. Das ist dasjenige, was in die Zukunft hinein als ein auch volkswittschaftlich Produzierendes wirkt. Man kann also sagen: Es ist völlig die Möglichkeit gegeben, auf den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß gesundend einzuwirken, indem den freien Geistesarbeitern ihr Feld gegeben wird, das Feld freigegeben wird.

Nun denken Sie sich, Sie haben ein gesundes assoziatives Leben in einer sozialen Gemeinschaft. Es kommt ja bei diesem gesunden assoziativen Leben darauf an, daß man den Produktionsprozeß so ordnet, daß, wenn irgendwo auf einem Gebiet zu viele arbeiten, daß man sie auf etwas anderes hinüberleitet. Auf dieses lebendige Verhandeln mit den Menschen kommt es an, auf dieses Hervorgehenlassen der ganzen sozialen Ordnung aus den Einsichten der Assoziationen. Und wenn diese Assoziationen eines Tages anfangen, etwas zu verstehen von dem Einfluß des freien Geisteslebens auf den volkswirtschaftlichen Prozeß, dann kann man ihnen ein gutes Mittel übergeben - und darauf ist auch schon gedeutet in meinen «Kernpunkten der sozialen Frage» -, ein gutes Mittel, den Wirtschaftskreislauf zu regulieren. Sie werden nämlich finden, diese Assoziationen, daß wenn die freie Geistesarbeit zurückgeht, daß dann zuwenig geschenkt wird, und sie werden daraus, daß zuwenig geschenkt wird, den Zusammenhang erkennen. Sie werden den Zusammenhang zwischen dem ZuwenigSchenken und dem Mangel an freier Geistesarbeit erkennen. Wenn zuwenig freie Geistesarbeit da ist, werden sie merken, daß zuwenig geschenkt wird. Sie werden merken, daß die freie Geistesarbeit zurückgeht, wenn zuwenig geschenkt wird.

Es gibt nun die größte Möglichkeit, den Zinsfuß für den Naturbesitz geradezu auf hundert Prozent hinaufzutreiben dadurch, daß man möglichst viel von dem Naturbesitz in freier Schenkung vermittelt den geistig Produzierenden. Da haben Sie die Möglichkeit, die Bodenfrage in unmittelbaren Zusammenhang zu bringen mit demjenigen, was nun am meisten in die Zukunft hineinwirkt, das heißt mit anderen Worten: Dem Kapital, das angelegt werden will, das also die Tendenz hat, in die Hypotheken hineinzumarschieren, dem muß man den Ablauf schaffen in freie geistige Institutionen hinein. So nimmt sich das praktisch aus. Lassen Sie die Assoziationen dafür sorgen, daß das Geld, das die Tendenz hat, in die Hypotheken hineinzugehen, den Weg in freie geistige Institutionen hinein findet! Da haben Sie den Zusammenhang des assoziativen Lebens mit dem allgemeinen Leben. Sie sehen daraus, daß einem, wenn man nur versucht, in die Realitäten des wirtschaftlichen Lebens hineinzudringen, erst in Wirklichkeit aufgeht, was da zu tun ist, was mit dem einen oder anderen zu machen ist. Ich will gar nicht agitatorisch sagen, das oder jenes soll geschehen, sondern ich will nur darauf hinweisen, was ist. Und es ist der Fall, daß wir dasjenige, was wir durch einfache Gesetzesmaßregeln nie erreichen können, nämlich das überschüssige Kapital abzuhalten von der Natur, erreichen durch das assoziative Wesen, indem wir das Kapital ableiten in freie geistige Institute. Ich sage nur: Wenn das eine der Fall ist, so ist das andere der Fall. - Die Wissenschaft gibt ja die Bedingungen an, unter denen die Dinge zusammenhängen.

Sixth Lecture

You may know that in my “Key Points of the Social Question” I attempted to formulate a way of arriving at a concept of what we might initially call the correct price within the economic process. Of course, such a formula is nothing more than an abstraction at first. And it is precisely our task in these lectures, which I believe will form a coherent whole, even if time is short, to work this abstraction, I would say, at least in outline, into the entire economy.

In “Key Points of the Social Question,” I therefore stated the following formula: A correct price exists when someone receives so much in return for a product they have manufactured that they can satisfy their needs, the sum of their needs, which naturally includes the needs of those who belong to them, until they have manufactured the same product again. This formula, abstract as it is, is nevertheless exhaustive. The point of formulating formulas is precisely that they contain all the concrete details. And I believe that, for economics, this formula is as exhaustive as, say, the Pythagorean theorem is exhaustive for all right-angled triangles. The only thing is that just as one must include the difference in the sides in this theorem, one must include infinitely more in this formula. But understanding how to include the entire economic process in this formula is precisely what economics is all about.

Today, I would like to start with something very essential in this formula. That is, I am not referring in this formula to what has passed, but to what is actually yet to come. I say explicitly: the equivalent value must satisfy future needs until the producer has manufactured the same product again. That is something very essential in this formula. If one were to demand a countervalue for the product that has already been completed, and this countervalue were to correspond in some way to the actual economic processes, it could well happen that the person concerned would receive a countervalue that satisfies his needs, let's say, only five-sixths of the time until he has manufactured a new product; for economic processes change from the past into the future. And anyone who believes that they can make any kind of calculations based solely on the past will always be wrong in economic terms, because economic activity actually consists of putting future processes into action with what has gone before. But if one uses past processes to put future ones into action, then values may shift significantly under certain circumstances, because they are constantly shifting. Therefore, the essential point of this formula is that when someone sells a pair of boots, the time at which they were manufactured is not at all decisive in economic terms; what is decisive is the time at which the next pair of boots will be manufactured. That is what this formula is all about, and we must now understand this in a broader sense within the economic process.

Yesterday, we visualized the cycle (see Figure 3): nature – labor – capital, which is thus utilized by the mind. I could just as well write “mind” here instead of “capital.” And we first followed the economic process in this direction—counterclockwise—and found that here, in nature, there must be no congestion, but that only what has the potential to continue the economic process, like a kind of seed, should be allowed to pass through, so that the fixation of capital in ground rent does not cause economic congestion. Now, I told you that, basically, the yield from land when it is sold, that is, the valuation of land, contradicts the interests that one has in the production of valuable goods in the economic process. Those who want to produce valuable goods with the help of capital have an interest in keeping interest rates low, because then they need to pay back less interest and can therefore move more easily with the loan capital they receive. But those who are landowners—I am allowed to discuss these things because they are important within our economy—those who have an interest in making land more expensive make it more expensive precisely because the interest rate is low. If they have to pay low interest, the value of their land increases and becomes more and more expensive, while those who have to pay a low interest rate can produce valuable goods more cheaply. So goods that depend on the manufacturing process become cheaper when interest rates are low, while land that yields a return without first having to be manufactured becomes more expensive when interest rates are low. You can easily calculate this for yourself. It is an economic fact.

Now the point is that there would actually be a need to structure the interest rate in two ways: one would have to have the lowest possible interest rate for the installation of labor, the production of valuable goods, and one would have to have the highest possible interest rate for land. That follows directly from this. One would have to have the highest possible interest rate for land. This is something that is not easy to implement in practice. A slightly higher interest rate, which would already be practicable for loan capital given on land, would not help very much, and a significantly higher interest rate — for example, the interest rate that would simply keep land at the same value, the interest rate of one hundred percent – that would also be extremely difficult to implement in practice. One hundred percent for mortgaging land would immediately improve the situation, but as I said, it is not feasible in practice. But with such matters, it is important to take a clear and unambiguous look at the economic process; and then one realizes that it is association alone that can make the economic process healthy, because when viewed in the right way, the economic process nevertheless leads to a situation where it can also be directed in the right way.

We must talk about production and consumption in the economic process, as I already indicated yesterday. So we must look at production and consumption. Now, this is a contrast that has played a major role, especially in the more recent, frequently conducted discussions in the field of economics, which have also entered into the agitation. There has been much debate about the question of whether intellectual work – simply intellectual work as such – generates value in the economic sphere at all.

The intellectual worker is certainly a consumer. Whether he is also a producer in the sense that must be considered in the economic sphere has been the subject of much debate; and the most extreme Marxists, for example, have repeatedly cited the unfortunate Indian accountant who has to keep the books for his community, who does not work the fields or perform any other productive work, but only records this productive work, and they deny him the ability to produce anything. So they state that he is merely supported by the surplus value that the producers generate. So we have this splendid accountant, as he is always cited, just as we have Cajus in formal logic in high schools, who is always supposed to prove the mortality of human beings. You know: All human beings are mortal, Cajus is a human being, therefore Cajus is mortal! — Because he always had to prove the mortality of humans, this Cajus has become an immortal logical personality. The same is true of the Indian accountant, who is only supported by the surplus value of the producers; the same is true of him in Marxist literature, where he is found in his purest form, so to speak.

Now, this question is extraordinary, I would say, full of all kinds of snares in which one gets caught if one wants to apply it to economics: to what extent—if at all—is intellectual work, intellectual labor, economically productive? — You see, it is very important to distinguish between the past and the future. If you only consider the past and only reflect on the past statistically, then you will be able to prove that intellectual work is actually unproductive in relation to the past and everything that is merely a direct continuation of the past. From the past into the future, the only material work that can be considered productive in the economic process is purely material work and its continuation. It is quite different when you consider the future — and economic activity means working from the past into the future. Just think of a simple example: let's say a craftsman makes something in a village and he falls ill. Let's say that, under certain circumstances, if he ends up with an incompetent doctor, he will have to stay in bed for three weeks and will not be able to make his products. This will significantly disrupt the economic process because, for three weeks, if the person in question has been making shoes, for example, the shoes will not be brought to market—market in the broadest sense. But let us assume that he comes to a very skilled doctor who cures him in eight days, so that he can work again after eight days. Then you can seriously decide the question: Who made the shoes during those fourteen days? The shoemaker or the doctor? Actually, the doctor made the shoes. And it is quite clear: as soon as you look to the future from any point, you can no longer say that the spiritual is not productive in the future. In relation to the past, the spiritual, that is, those people who work in the spiritual, are only consuming; in relation to the future, they are thoroughly productive, indeed the more productive. That they are the more productive, also in the sense that they transform the entire production process and make it eminently different in an economic sense, can be seen, for example, when tunnels are built today: they cannot be built without the discovery of differential calculus. With this kind of work, Leibniz is still helping to build all tunnels today, and how prices are set has essentially been decided by this tension of intellectual forces. So you can never answer questions in such a way that, in economic terms, you view the past in the same way as the future. But life does not move toward the past, nor does it continue the past; rather, life moves toward the future.

Therefore, no economic analysis is realistic that does not take into account what is achieved through intellectual work—if we want to call it that—which basically means through thinking. But this intellectual work is really quite difficult to grasp, because it has very specific characteristics that are initially extremely difficult to grasp in economic terms. Intellectual work begins with the organization and structuring of work through organizing thinking. But it becomes more and more independent. If you consider this intellectual work in the case of someone who manages a company in the material culture, he expends a great deal of intellectual work, but he still works with what the economic process of the past has provided him with. But it is unavoidable, purely from practical interests, that within intellectual activity—I will call it that instead of work—intellectual work, completely free work also occurs. Even when one invents differential calculus, and even more so when one paints a picture, completely free intellectual activity occurs. At the very least, one can speak of relatively free intellectual activity, because what is used from the past, the colors and the like, no longer has the same significance for what is created as, for example, the purchase of raw materials in material manufacturing.

By crossing over there (see drawing), we enter the realm of completely free spiritual life, and in this realm of free spiritual life we find, above all, teaching and education. Those people who have to provide teaching and education are actually in the completely free spiritual life. For the purely material progress of the economic process, these free spiritual workers of the past are, in particular, consumers, absolutely consumers only. Now, you may say: they do produce something and even get paid for what they have produced—if they are painters, for example. — So it seems that the same economic process is taking place as when I manufacture and sell a table. And yet it is essentially different as soon as we stop looking at the buying and selling of individual people and begin to think in economic terms and focus our attention on the entire economic organism — and we must do this today with the division of labor being so advanced.

In addition, however, there are other types of pure consumers within a social organism. These are young people, children, and the elderly. The former are pure consumers up to a certain age. And those who have retired or been retired are, in turn, pure consumers.

With just a little thought, you will soon realize that without pure consumers who are not producers in the economic process, progress is impossible, because if everyone were to produce, not everything that is produced could be consumed if the economic process is to continue at all – at least as it is in human life. And human life is not just economics, but must be taken as a whole. Thus, progress in the economic process is only possible if we have pure consumers in it.

Now, I must now examine the fact that we have pure consumers in the economic process from a completely different angle.

We can adorn this circle here (see Figure 4), which can be very instructive, with all kinds of characteristics, and the question will always be how we bring the individual economic processes, economic facts, into this circle, which is precisely the cycle of the economic process. There is a fact that occurs directly on the market during sales and purchases when I pay immediately for what I receive. It does not even matter that I pay immediately with money; I can also pay with the corresponding goods that the other party is willing to accept if it is a barter transaction. What matters is that I pay immediately, that is, that I pay at all. And now we need to move again from the usual trivial consideration to the economic consideration (see Figure 4). In economics, the individual concepts constantly interact with each other, and the overall picture, the overall fact, results from the interaction of a wide variety of factors. You may say: It is also conceivable that, due to some measure, no one would pay immediately at all – then there would be no immediate payment. So one would always pay, say, after a month or after some period of time. Yes, it is just that one is then caught up in a completely false concept when one says: Today someone gives me a suit and I pay for it after a month. After a month, I am no longer paying for this suit alone, but I am paying for something else at that moment: I am paying for something that may be different due to an increase or decrease in prices; I am paying for something ideal. So the concept of immediate payment must definitely be there, and it is there in the case of a simple purchase. And something becomes a commodity on the market because I pay for it immediately. This is essentially the case with commodities that are processed natural products. I pay, and payment plays an essential role. This payment must be made, because I pay when I open my wallet and give away money, and the value is determined at the moment when I give away the money or exchange my goods for others. That is when payment is made. This is one thing that must be paid for in the economic process.

The second thing is what I pointed out yesterday, which plays a similar role to payment. That is borrowing. As I said, this does not affect payment as such; borrowing is a completely different matter, but it is there nonetheless. When I borrow money, I can apply my mind to this borrowed capital. I become a debtor, but I also become a producer. This is where borrowing plays a truly economic role. If I am mentally capable of doing this or that, it must be possible for me to obtain loan capital, regardless of where it comes from; but I must obtain it, there simply must be loan capital. So borrowing must accompany payment (see Figure 4). And with that, we have two very important factors in the economic process: payment and borrowing.

And now, through a simple deduction—we just have to verify it there (see Figure 4)—we can really find the third factor. You will have no doubt whatsoever as to what this third factor is. Paying, borrowing—and the third is giving. Paying, borrowing, giving: this is actually a trinity of concepts that belongs in a healthy economy. There is a certain aversion to including giving as part of the economic process; but if giving does not exist somewhere, then the economic process cannot continue at all. Just think for a moment what we would do with children if we did not give them anything. We constantly give gifts to children, and when we consider the economic process as a whole, gift-giving is part of it when we view it as a continuous process. So the transfer of values that constitute a gift is actually very wrongly regarded as something that is not permissible in the economic process. Therefore, to the horror of many people, you will find in my “Key Points of the Social Question” precisely this category developed, where values are transferred, for example, the means of production are transferred, basically through a process that is identical to giving, to those who are capable of continuing to manage them. Care must be taken to ensure that the gift is not made in a confused manner, but in economic terms it is a gift. These gifts are absolutely necessary.

But now consider this, which you will increasingly find to be an economic necessity, that the trinity of numbers, borrowing, and giving is inherent in the economic process, and then you will say to yourself: Yes, it must be part of every economic process — otherwise it could not be one at all, otherwise it would lead everywhere into absurdity — it must be part of every economic process.

One can fight it temporarily; but economic knowledge today is not very extensive, and precisely those who want to teach economics should be very clear that economic knowledge today is not very extensive, that above all, people are not very inclined to delve into the real economic context. It is obvious, I would say. So obvious that, if you read the Basler Nachrichten today, you will find, curiously enough, a commentary on how neither governments nor private individuals today are inclined to develop economic thinking. I don't believe that things that are not obvious today are discussed in the Basler Nachrichten! It is already tangible. And it is interesting that it is being discussed in this way; the article is interesting because it begins to shed a harsh light on the absolute economic impotence; and also because it says: This must now change, governments and private individuals must finally start to think differently. — But that is also where it ends. Of course, there is nothing in the Basler Nachrichten about how they should think differently. That is also very interesting, of course.

Well, you can interfere disruptively in the economic process if you don't bring this ‘trinity’ into the right relationship with each other. Today, there are many people who are particularly enthusiastic about the idea that inheritances, which are also gifts, should be heavily taxed. Yes, that doesn't mean anything significant in economic terms, because you don't actually devalue the inheritance if, say, it has a value of \(W\) and you divide this value of \(W\) into two parts, \(W\) \(1\) and \(W\) \(2\), and give this \(W\) \(2\) to someone else and leave only \(W\) \(1\) to the one, then the two of them will manage this value \(W\) together. And the question is whether the person who has \(W\) \(2\) will manage it as well as the person who might have received \(W\) \(1\) and \(W\) \(2\) together. Isn't it true that everyone can decide for themselves according to their own preferences whether a clever individual who receives the entire inheritance will manage it better, or whether the person who receives only part of the inheritance and the other part goes to the state, and who therefore has to manage it together with the state, will manage it better?

These are the things that definitely lead away from purely economic thinking, because it is a way of thinking based on resentment, a way of thinking based on emotion. People envy the rich heirs. That may well be justified, but you cannot talk about such things alone if you want to think economically. What matters is what must be considered in economic terms, because everything else that happens must be guided by this. Of course, you can imagine a social organism that becomes ill because payments interact with loans and gifts in an inorganic way, by opposing one or the other or promoting one or the other. Somehow they do interact. For if you abolish giving on the one hand, you are merely shifting it elsewhere. And the decisive question is not whether one should shift it, but whether shifting it is always beneficial; for whether the inheritance is taken up by the individual heir alone or together with the state is a question that must first be decided in economic terms. Whether one or the other is more favorable is what matters.