Ways to a New Style in Architecture

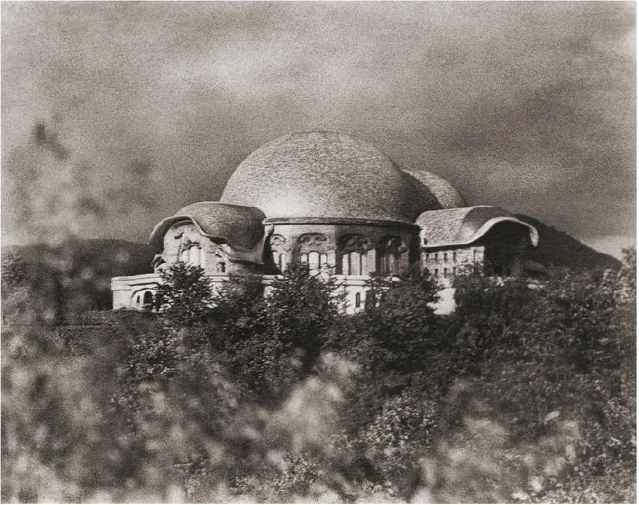

GA 286

7 June 1914, Dornach

4. The Acanthus Leaf

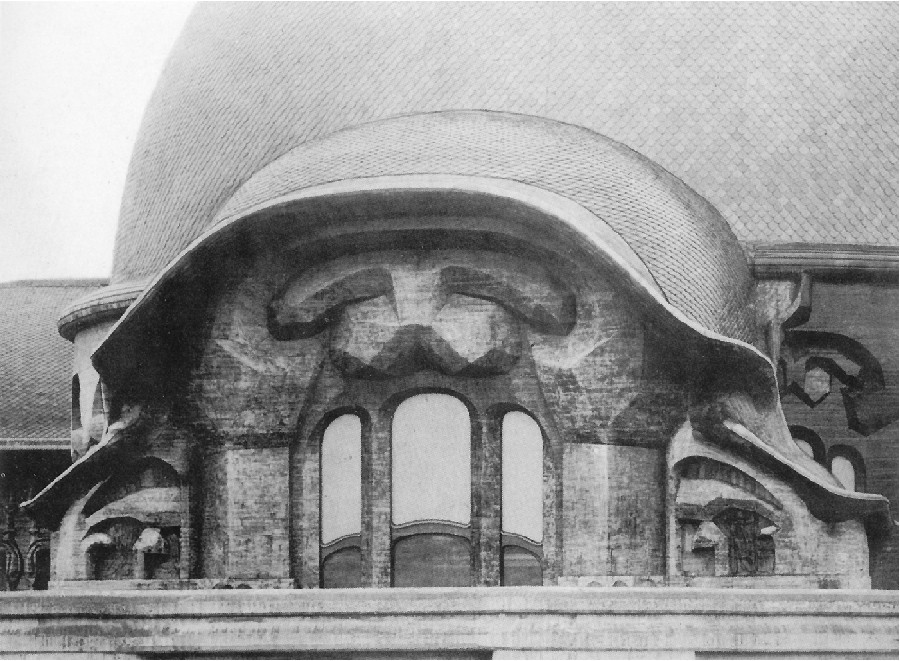

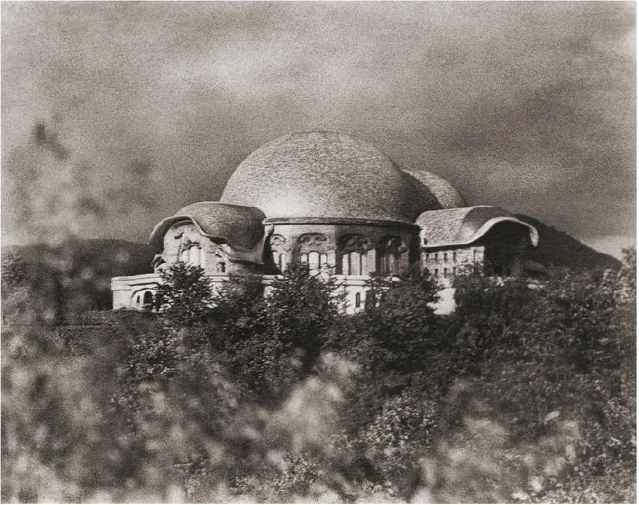

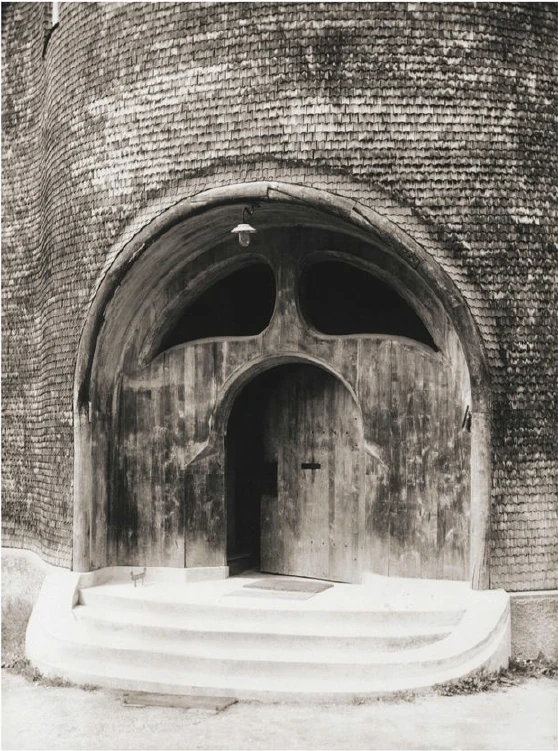

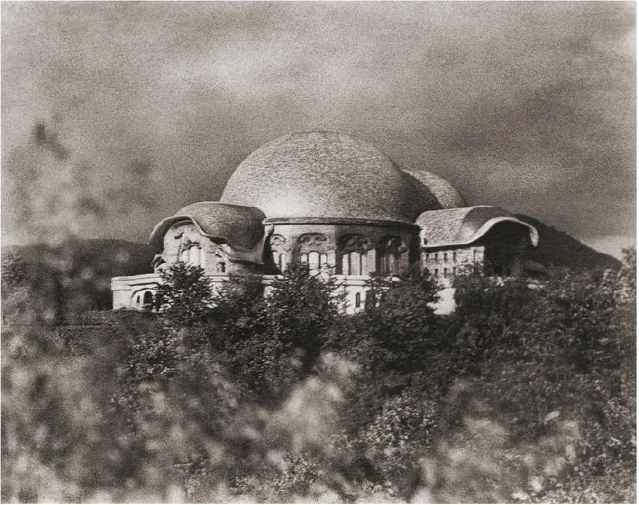

A thought that may often arise in connection with this building is that of our responsibility to the sacrifices which friends have made for its sake. Those who know how great these sacrifices have been, will realise that the only fit response is a strong sense of responsibility, for the goal at which we must aim is the actual fulfilment of the hopes resting in this building. Anyone who has seen even a single detail—not to speak of the whole structure, for no conception of that is possible yet—will realise that this building represents many deviations from other architectural styles that have hitherto arisen in the evolution of humanity and have been justified in the judgment of man. An undertaking like this can of course only be justified if the goal is in some measure attained. In comparison to what might be, we shall only be able to achieve a small, perhaps insignificant beginning. Yet, may be, this small beginning will reveal the lines along which a spiritual transformation of artistic style must come about in the wider future of humanity. We must realise that when the building is once there, all kind of objections will be made, especially by so-called ‘experts,’ that it is not convincing, perhaps even dilettante. This will not disconcert us, for it lies in the nature of things that ‘expert’ opinion is least of all right when anything claiming to be new is placed before the world. We shall not, however, be depressed by derogatory criticism that may be levelled at our idea of artistic creation, if we realise, as a compensation for our sense of responsibility, that in our age, the origin of the Arts and of their particular forms and motifs is greatly misunderstood by technical experts. And then, gradually, we shall understand that all we are striving to attain in this building stands much closer to primordial forces of artistic endeavour which are revealed when the eye of the Spirit is directed to the origin of the Arts, than do the conceptions of art claiming to be authoritative at the present time. There is now little understanding of what was once implied by the phrase “true artistic conception.” It need not therefore astonish us if a building like ours, which strives to be in harmony with primordial Will and in accordance with the origin of the arts, is not well or kindly received by those who adhere to the direction and tendency of the present age.

In order to bring home these thoughts to you, I should like to start to-day by considering a well-known motif in art—that of the so-called acanthus leaf—showing the sense in which our aims are in harmony with the artistic endeavours of humanity as expressed in the origin of this acanthus leaf as a decorative motif. Now because our endeavours are separated by many hundreds, nay even thousands of years, from the first appearance of this acanthus motif, they must naturally take a very different form from anything that existed in the days when, for instance, the acanthus leaf was introduced into the Corinthian capital.

If I may be permitted a brief personal reference here, let me say that my own student days in Vienna were passed during the time when the buildings which have given that city its present stamp, were completed—the Parliament Buildings, the Town Hall, the Votivkirche and the Burgtheatre. The famous architects of these buildings were still living: Hanson who revived Greek architecture, Schmidt who elaborated Gothic styles with great originality, Ferstel who built the Votivkirche. It is perhaps not known to you that the Burgtheatre in Vienna was built according to the designs of an artist who in the seventies and eighties of the last century was the leading influence in artistic appreciation and development of form in architecture and sculpture. The Burgtheatre was built according to the designs of the great Architect, Gottfried Semper.

At the Grammar School I myself had as a teacher a gifted admirer and disciple of Gottfried Semper, in the person of Josef Baier, so that I was able to live, as it were, in the whole conception of the world of architectural, sculptural and decorative form as inaugurated by the great Semper.

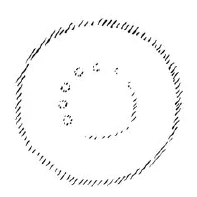

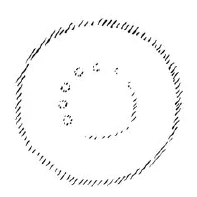

Now, in spite of all the genius that was at work, here was something that well-nigh drove one to despair in the whole atmosphere of the current conceptions of the historical development of art, on the one side, and of the way to artistic creation on the other. Gottfried Semper was undoubtedly a highly gifted being, but in those days the usual conception of man and the universe was an outcome of the materialistic interpretation of Darwin, and the doctrine of evolution was also apparent in the current ideas of art. Again and again this materialistic element crept into the conceptions of art. It was, above all, considered necessary to possess a knowledge of the technique of weaving and interlacing. Architectural forms were derived in the first place from the way in which substances were woven together, or fences constructed so that the single canes might interpenetrate and hold together. In short, people were saturated with the principle that decoration and ornamentation were forms of external technique. This subject of course might be further elaborated, but I only want to indicate the general tendency which was asserting itself at that time—namely, the tendency to lead everything artistic back to external technique. The standpoint had really become one of ultilitarianism and the artistic element was considered to be an outcome of the use to which things were put. All treatises on the subject of art, and especially on decoration, invariably made mention of the special idiosyncrasies of the different technical experts. This of course was a stream running parallel to the great flood of materialistic conceptions that swept over the 19th century, chief among them being the materialistic conception of art. The extent to which materialism asserted itself in all spheres of life during the second half of the 19th century was enough to drive one to despair. Indeed I still remember how many sleepless nights I had at that time over the Corinthian capital. Now the main feature, the principal decoration of the Corinthian capital—although in the days of which I am speaking it was almost forbidden to speak of such a thing as ‘decoration’—is the acanthus leaf. What could be more obvious than to infer that the acanthus leaf, on the Corinthian capital was simply the result of a naturalistic imitation of the leaf of the common acanthus plant? Now anyone with true artistic feelings finds it very difficult to conceive that a beginning was somewhere made by man taking a leaf of a weed, an acanthus leaf, working it out plastically and adding it to the Corinthian column. Let us think for a moment of the form of the acanthus leaf.  I will draw a rough sketch of the form of the Acanthus Spinoza. This was supposed to have been worked out plastically and then added to the Corinthian column. Now there is, of course, something behind this. Vitruvius, the learned compiler of the artistic traditions of antiquity, quotes a well-known anecdote, which led to the adoption of the “basket hypothesis” in connection with the Corinthian column. The expression is a good one, for what, according to the materialistic conception of art, was the origin of the decoration on the Corinthian capital? Little baskets of acanthus leaves that were carried about! When we enter more deeply into these things we realize that this is both symptomatic and significant. It becomes evident that their understanding of the finer spiritual connections of the evolutions of humanity has led investigators to a basket, to basket-work, and as a kind of token of it we have the “basket hypothesis” of the Corinthian column. Vitruvius says that Callimachos, the Corinthian Sculptor, once saw a little basket standing on the ground somewhere, with acanthus plants growing around it, and he said to himself: There is the Corinthian capital! This is the very subtlest materialism imaginable. Now let me show you the significance of this anecdote narrated by Vitruvius. The point is that in the course of the modern age the inner principle, the understanding of the inner principle of artistic creation has gradually been lost. And if this inner principal is not re-discovered, people simply will not understand what is meant and desired in the forms of our building, its columns and capitals. Those who hold fast to the basket hypothesis—in a symbolical sense of course—will never be able rightly to understand us.

I will draw a rough sketch of the form of the Acanthus Spinoza. This was supposed to have been worked out plastically and then added to the Corinthian column. Now there is, of course, something behind this. Vitruvius, the learned compiler of the artistic traditions of antiquity, quotes a well-known anecdote, which led to the adoption of the “basket hypothesis” in connection with the Corinthian column. The expression is a good one, for what, according to the materialistic conception of art, was the origin of the decoration on the Corinthian capital? Little baskets of acanthus leaves that were carried about! When we enter more deeply into these things we realize that this is both symptomatic and significant. It becomes evident that their understanding of the finer spiritual connections of the evolutions of humanity has led investigators to a basket, to basket-work, and as a kind of token of it we have the “basket hypothesis” of the Corinthian column. Vitruvius says that Callimachos, the Corinthian Sculptor, once saw a little basket standing on the ground somewhere, with acanthus plants growing around it, and he said to himself: There is the Corinthian capital! This is the very subtlest materialism imaginable. Now let me show you the significance of this anecdote narrated by Vitruvius. The point is that in the course of the modern age the inner principle, the understanding of the inner principle of artistic creation has gradually been lost. And if this inner principal is not re-discovered, people simply will not understand what is meant and desired in the forms of our building, its columns and capitals. Those who hold fast to the basket hypothesis—in a symbolical sense of course—will never be able rightly to understand us.

The basis of all artistic creation is a consciousness that comes to a standstill before the portals of the historical evolution of humanity as depicted by external documents. A certain consciousness that was once active in man, a remnant of the old clairvoyance, belonged to the fourth Post-Atlantean period, the Graeco-Roman. Although Egyptian culture belongs to the third Post-Atlantean epoch, all that was expressed in Egyptian art belongs to the fourth epoch. In the fourth epoch this consciousness gave rise to such intense inner feeling in men that they perceived how the movement, bearing and gestures of the human being, nay even the human form itself, develop outwards into the physical and etheric. You will understand me if you realise that in those times, when there was a true conception of artistic aim, the mere sight of a flower or a tendril was of much less importance than the feeling: ‘I have to carry something heavy; I bend my back and generate with my own form the forces which make me, as a human being, able to bear the weight.’ Men felt within themselves what they must bring to expression in their own postures. This was the sense in which they made movements when it was a question of taking hold of something or of carrying something in the hand. They were conscious of a sense of carrying, of weight, where it was necessary to spread the hands and finger outwards. Then there arose the lines and forms which passed over into artistic creation. It is as though one felt in humanity itself how man can indeed go beyond what he sees with his eyes and perceives with his other senses:—he can go beyond it when he enters into and adapts himself to a larger whole. Even in this case of a larger whole, when a man no longer merely lets himself go as he walks along, but is obliged to adapt himself to the carrying of a load—already here he enters into the organism of the whole universe.  And, from the feeling of the lines of force which man has to develop in himself, arose the lines that gave birth to artistic form. Such lines are nowhere to be found in external reality. Now spiritual research is often confronted by a certain wonderful akashic picture; it represents the joining together of a number of human beings into a whole, but a harmonious, ordered joining together. Imagine a kind of stage, and as an amphitheatre around it, seats with spectators; certain human beings are now to pass in a procession round and inside the circle. Something higher, super-sensible—not naturalistic—is to be presented to man.

And, from the feeling of the lines of force which man has to develop in himself, arose the lines that gave birth to artistic form. Such lines are nowhere to be found in external reality. Now spiritual research is often confronted by a certain wonderful akashic picture; it represents the joining together of a number of human beings into a whole, but a harmonious, ordered joining together. Imagine a kind of stage, and as an amphitheatre around it, seats with spectators; certain human beings are now to pass in a procession round and inside the circle. Something higher, super-sensible—not naturalistic—is to be presented to man.

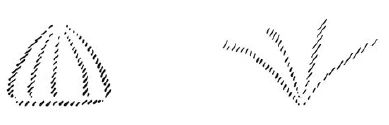

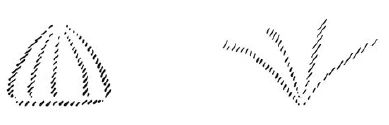

I have drawn it diagrammatically, from the side view: a number of men are walking one behind the other. They form the procession which then passes round inside the circle; others are sitting in the circle looking on.  Now the persons (in the procession) are to portray something of great significance, something that does not exist on the Earth, of which there are only analogies on the Earth; they are to represent something that brings man into connection with the great sphere of the cosmos. In those times it was a question of representing the relationship between the earthly forces and the sun forces. How can man come to feel this relationship of the earthly forces to the sun forces? By feeling it in the same way as, for instance, the state of carrying a load. He can feel it in the following way: all that is earthly rests upon the surface of the earth and as it rises away from the earth (this is only to be thought of in the sense of force) it runs to a point. So that man felt the state of being bound to the earth expressed in a form with a wide base, running upwards to a point. It was this and nothing else, and when man sensed this working of forces, he said to himself: ‘I feel myself standing on the earth.’

Now the persons (in the procession) are to portray something of great significance, something that does not exist on the Earth, of which there are only analogies on the Earth; they are to represent something that brings man into connection with the great sphere of the cosmos. In those times it was a question of representing the relationship between the earthly forces and the sun forces. How can man come to feel this relationship of the earthly forces to the sun forces? By feeling it in the same way as, for instance, the state of carrying a load. He can feel it in the following way: all that is earthly rests upon the surface of the earth and as it rises away from the earth (this is only to be thought of in the sense of force) it runs to a point. So that man felt the state of being bound to the earth expressed in a form with a wide base, running upwards to a point. It was this and nothing else, and when man sensed this working of forces, he said to himself: ‘I feel myself standing on the earth.’

In the same way he also became aware of his connection with the sun. The sun works in upon the earth and man expressed this by portraying the lines of forces in this way. The sun, in its apparent journey round the earth, sends its rays thus, running downwards to a point.

In the same way he also became aware of his connection with the sun. The sun works in upon the earth and man expressed this by portraying the lines of forces in this way. The sun, in its apparent journey round the earth, sends its rays thus, running downwards to a point.

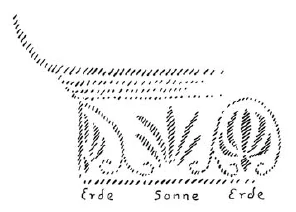

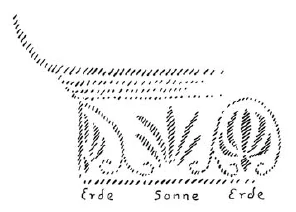

If you think of these two figures in alternation, you have the earth-motif and the sun-motif that were always carried by the people who formed the procession. This was one thing that in olden times was presented in circling procession. The people sat around in a circle and the actors passed around in a procession. Some of them carried emblems representing man's connection with the sun; and they alternated: earth-sun, sun-earth and so on:

Man sensed this cosmic power: earth-sun, and then he began to think how he could portray it. The best medium for purposes of art proved to be a plant or tree whose forms runs upwards to a point from a wider base. This was alternated with palms. Plants having a form like a wide bud were alternated with palms. Palms represented' the sun forces; bud-forms running upwards to a point, the earth forces.

Feeling his place in the cosmos, man created certain forms, merely using the plants as a means of expression. He used plants instead of having to invent some other device. Artistic creation was the result of a living experience of cosmic connections; this is in accordance with the evolution of the creative urge in man and the process is no mere imitation of outer phenomena of nature. The artistic representation of the elements of outer nature only entered into art later on. When men no longer realised that palms were used to express the sun forces, they began to think that the ancients simply imitated the palm in their designs. This was never the case; the ancients used the leaves of palms because they were typifying the sun forces. Thus has all true artistic creation arisen, from a ‘superabundance’ of forces in the being of man—forces which cannot find expression in external life, which strive to do so through man's consciousness of his connection with the universe as a whole. Now all contemplation and thought both in the spheres of natural science and art, have been misled and confused by a certain idea which it will be very difficult to displace. It is the idea that complexity has arisen from simplicity. Now this is not the case. The construction of the human eye, for instance, is much more simple than that of many of the lower animals. The course of evolution is often from the complex to the simple; it often happens that the most intricate interlacing finally resolves itself into the straight line. In many instances, simplification is the later stage, and man will not acquire the true conception of evolution unless he realises this.

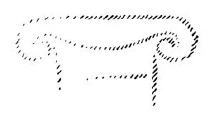

Now all that was presented to the spectators in those ancient times, when it was always a question of portraying living cosmic forces, was later on simplified into the decoration, the lines of which expressed man's living experience when he presented these things.  I might make the following design in order to express how man, from his conception of the course of evolution from the complex to the simple, developed the lines into a decoration. If you think of the lines in alternation you have a simplified reproduction of the circling procession of Sun-motif—Earth-motif, Sun-Motif—Earth-motif. That is what man experienced in the decorative motif. This decorative motif was already a feature of Mesopotamian art and it passed over into Greek art as the so-called Palmette, either in this or in a similar form, resembling the lotus petal.

I might make the following design in order to express how man, from his conception of the course of evolution from the complex to the simple, developed the lines into a decoration. If you think of the lines in alternation you have a simplified reproduction of the circling procession of Sun-motif—Earth-motif, Sun-Motif—Earth-motif. That is what man experienced in the decorative motif. This decorative motif was already a feature of Mesopotamian art and it passed over into Greek art as the so-called Palmette, either in this or in a similar form, resembling the lotus petal.

This alternation of Sun-motif, Earth-motif, presented itself to the artistic feeling of mankind as a decorative motif in the truest sense. Later on man no longer realised that he must see in this decorative motif a reproduction that had passed into the subconscious realm, of a very ancient dance motif, a ceremonial dance. This was preserved in the palmette motif. Now it is interesting to consider

the following:—On the decorations of certain Doric columns one often finds a very interesting motif which I will sketch thus.

Underneath what has to bear the capital we find

the following. Here we have the torus of the Doric column,

but underneath this we find, in certain Doric columns,

introduced as a painting around the pillar, the Earth-motif

somewhat modified, and the Sun-motif. Up above we have the

Doric torus and the decorative motif below as an ornament. We

actually find the palmette motif on certain Doric columns,

carried out in such a way that it forms a procession:

Sun-Earth, Sun-Earth and so on.

Underneath what has to bear the capital we find

the following. Here we have the torus of the Doric column,

but underneath this we find, in certain Doric columns,

introduced as a painting around the pillar, the Earth-motif

somewhat modified, and the Sun-motif. Up above we have the

Doric torus and the decorative motif below as an ornament. We

actually find the palmette motif on certain Doric columns,

carried out in such a way that it forms a procession:

Sun-Earth, Sun-Earth and so on.

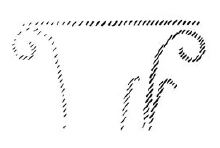

In Greece, that wonderful land where the fourth Post-Atlantean period was expressed in all its fulness, there was a union of what came over from Asia with all that I have now described and which, as an after-image is there, on Doric columns together with the truly dynamic-architectonic principle of weight-bearing. This union came about because it was in Greece that the Ego was fully realised within the human body, and therefore this motif could find expression in Greek culture.  The Ego, when it is within the body, must grow strong if it has to bear a load. It is this strengthening process that is felt in the volute. We see the human being, as he strengthens his Ego in the fourth Post-Atlantean period, expressed in the volute. Thus we come to the basic form of the Ionic pillar; it is as if Atlas is bearing the world, but the form is still undeveloped in that the volute becomes the weight bearer.

The Ego, when it is within the body, must grow strong if it has to bear a load. It is this strengthening process that is felt in the volute. We see the human being, as he strengthens his Ego in the fourth Post-Atlantean period, expressed in the volute. Thus we come to the basic form of the Ionic pillar; it is as if Atlas is bearing the world, but the form is still undeveloped in that the volute becomes the weight bearer.

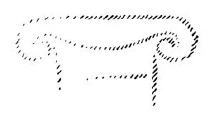

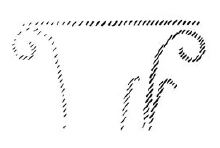

Now you need only imagine what is merely indicated in the Ionic pillars, the middle portion, developing downwards to the perfect volute and you have the Corinthian column.  The middle portion is simply extended downward, as it were, so that the character of weight bearing becomes complete. And now think of this weight bearing in the form of a plastic figure and you have the human force bent into itself—the Ego bent round, in this case bearing a weight. An artistic principle is involved when we reproduce in miniature anything that is worked out on a large scale, and vice-versa. If you now think of an elaboration of the Corinthian column with the volute bearing the abacus here, and repeat this artistic motif lower down where it only serves as a decoration, you have plastically introduced in the decoration something that is really the whole column. Now imagine that the Doric painting which grew out of the decorative representation of a very ancient motif, is united with what is contained in the Corinthian column and the intuition will arise that the decoration around it is the same as an earlier painting. The painting on the Doric column was worked out plastically—I can illustrate this to you by the diagram of the motif containing the the palmette—and the urge arose to bring the palmette into the later decorative motif. Here it was not a motif representing the bearing of a load; what was mere painting in the Doric column (and therefore flat) was worked out plastically in the Corinthian column and the palm leaves are allowed to turn downwards. To the left I have drawn a palmette and on the right the beginning of it that arises when the palmette is worked out plastically.

The middle portion is simply extended downward, as it were, so that the character of weight bearing becomes complete. And now think of this weight bearing in the form of a plastic figure and you have the human force bent into itself—the Ego bent round, in this case bearing a weight. An artistic principle is involved when we reproduce in miniature anything that is worked out on a large scale, and vice-versa. If you now think of an elaboration of the Corinthian column with the volute bearing the abacus here, and repeat this artistic motif lower down where it only serves as a decoration, you have plastically introduced in the decoration something that is really the whole column. Now imagine that the Doric painting which grew out of the decorative representation of a very ancient motif, is united with what is contained in the Corinthian column and the intuition will arise that the decoration around it is the same as an earlier painting. The painting on the Doric column was worked out plastically—I can illustrate this to you by the diagram of the motif containing the the palmette—and the urge arose to bring the palmette into the later decorative motif. Here it was not a motif representing the bearing of a load; what was mere painting in the Doric column (and therefore flat) was worked out plastically in the Corinthian column and the palm leaves are allowed to turn downwards. To the left I have drawn a palmette and on the right the beginning of it that arises when the palmette is worked out plastically.  If I were now to continue, the painted Doric palmette would thus pass over into the Corinthian plastic palmette. If I did not paint the palmette we should in each case have the acanthus leaf. The acanthus leaf arises when the palmette is worked out plastically; it is the result of an urge not to paint the palmette but to work it out plastically. People then began to call this form the acanthus leaf; in early times, of course, it was not called by this name. The name has as little to do with the thing portrayed as the expression ‘wing’ has to do with the lungs and lobes or ‘wings’ of the lungs. The whole folly of naturalistic imitation in the case of the acanthus leaf is exposed, because, in effect, what is called the acanthus leaf decoration did not arise from any naturalistic imitation of the acanthus leaf, but from a metamorphosis of the old Sun motif in the palmette that was worked out plastically instead of being merely painted. So you see that these artistic forms have proceeded from an inner perception and understanding of the postures of the human etheric body (for the movement of a line is connected with this)—postures which man has to set up in his own being.

If I were now to continue, the painted Doric palmette would thus pass over into the Corinthian plastic palmette. If I did not paint the palmette we should in each case have the acanthus leaf. The acanthus leaf arises when the palmette is worked out plastically; it is the result of an urge not to paint the palmette but to work it out plastically. People then began to call this form the acanthus leaf; in early times, of course, it was not called by this name. The name has as little to do with the thing portrayed as the expression ‘wing’ has to do with the lungs and lobes or ‘wings’ of the lungs. The whole folly of naturalistic imitation in the case of the acanthus leaf is exposed, because, in effect, what is called the acanthus leaf decoration did not arise from any naturalistic imitation of the acanthus leaf, but from a metamorphosis of the old Sun motif in the palmette that was worked out plastically instead of being merely painted. So you see that these artistic forms have proceeded from an inner perception and understanding of the postures of the human etheric body (for the movement of a line is connected with this)—postures which man has to set up in his own being.

The essential forms of art can no more arise from an imitation of nature than music can be created by an imitation of nature. Even in the so-called imitative arts, the thing that is imitated is fundamentally secondary, an accessory as it were. Naturalism is absolutely contrary to true artistic feeling. If we find that people think our forms here are grotesque we shall be able to comfort ourselves with the knowledge that this kind of artistic conception sees in the acanthus motive nothing but a naturalistic imitation. The acanthus motif, as we have seen, was created purely from the spirit and only in its late development came to bear a remote resemblance to the acanthus leaf. Artistic understanding in future ages will simply be unable to understand this attitude of mind which in our time influences not only the art experts who are supposed to understand their subject, but all artistic creation as well. The materialistic attitude of mind in Darwinism also confronts us in artistic creation, in that there is a greater and greater tendency to make art into a mere imitation of nature. My discovery of these connections in regard to the acanthus leaf has really been a source of joy to me, for it proves circumstantially that the primordial forms of art have also sprung from the human soul and not from imitation of external phenomena.

I was only able really to penetrate to the essence of art after I had myself moulded the forms of our building here. When one moulds forms from out of the very well-springs of human evolution, one feels how artistic creation has arisen in mankind. It was a strange piece of karma that during the time when I was deeply occupied with following up a certain artistic intuition (this was after the forms for the buildings had already been made)—an intuition that had arisen during the General Congress in Berlin—it happened that I began to investigate what I had created in these forms, in order to get a deeper understanding. One can only think afterwards about artistic forms; if one “understands” them first and then carries them out, they will have no value. If one creates from concepts and ideas nothing of value will ensue, and the very thing that I perceived so clearly in connection with the acanthus leaf, and have shown to be erroneous, is an indication of the inner connections of the art in our building.

I came upon a remarkable example which is purely the result of clairvoyant investigation. At one point I discovered a curious point of contact with Rigl, a fellow-countryman of mine. It is a curious name, not very aristocratic, but typically Austrian. This man Rigl did not achieve anything of great importance but while he was Curator of an Architectural Museum in Vienna he had an intuitive perception of the fact that these architectural decorations had not arisen in the way described by “Semperism” at the end of the 19th century. Rigl hit upon certain thoughts which are really in line with the metamorphosis of the palmette motif into that of the acanthus leaf. Quite recently, therefore, I have discovered a perfect connection between the results of occult investigation, and external research which has also hit upon this development of the so-called acanthus motif from the palmette. ‘Palmette’ is of course merely a name; what is really there in the palmette is the Sun-motif. In the first place, of course, one feels in despair about an idea like that of Rigl. He simply could not realise whence the palmette motif had originated and that it was connected with forces working and moving in man. Rigl remonstrates with the learned art critics who have brought Semper's ideas into everything and are for the most part mere naturalists, but in spite of this he did not get very far. He says that in regard to the acanthus leaf the learned art critics are still feeding upon the old anecdote quoted by Vitruvius. (It cannot be said that they are all feeding upon it, but it is true that they constantly quote it.) Rigl, however, only mentions this anecdote briefly; he does not think it worth while to go into all the details because it is too well known. What he leaves out is very characteristic. He says that Callimachos had seen a basket surrounded by acanthus leaves and that then the idea of the Corinthian column came to him. Rigl, too, leaves something out and this very thing shows that the typical conceptions of our age must despair of ever having real knowledge in this sphere. He leaves out the most important factor in the whole anecdote, which is that what Callimachos saw was over the grave of a Corinthian girl. That is the important thing, for it implies no less than that Vitruvius, although he wisely holds his tongue about it, intends to indicate that Callimachos was clairvoyant and saw, over a girl's grave, the Sun-motif struggling with the Earth-motif, and above this the girl herself, hovering in her etheric body. Here indeed is a significant indication of how the motifs of Sun and Earth came to be used on the capitals of columns. If we are able to see clairvoyantly what is actually present in the etheric world above the grave of a girl who had died, we realise that the palmette motif has arisen out of this, growing, as it were, around the etheric body that is rising like the sun. It seems as though men have never really understood the later Roman statues of Pytri-Clitia for they are nothing else than a clairvoyant impression that can be received over the graves of certain people; in these statues, the head of an extraordinarily spiritual, though not virginal Roman woman, seems to grow upwards as if from a flower chalice. Some time, my dear friends, we shall understand what really underlies the anecdote quoted by Vitruvius, but not until we grow out of the unfortunate habit which makes us perpetually ask, ‘What is the meaning of this or that?’ and is always looking for symbolic interpretations such as, ‘this signifies the physical body, that the etheric body, this or that the astral body.’ When this habit is eliminated from our Movement we shall really come to understand what underlies artistic form—that is to say, we shall either have direct perception of true spiritual movement, or of the corresponding etheric phenomenon.

It is actually the case that in clairvoyant vision the acanthus leaf can be seen, in its true form, above a grave.

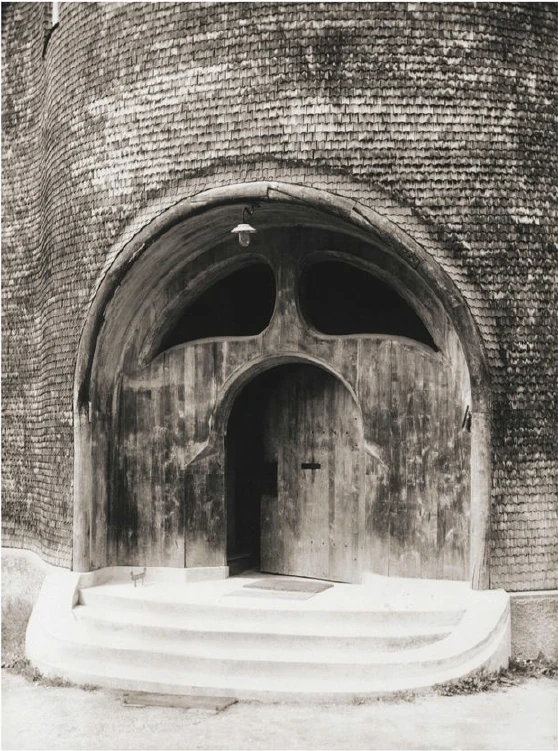

If you will consider all these things; my dear friends, you will realise how important it is to understand the forms in the interior of our building, the forms that should adorn it, and to know the artistic principle from which they have arisen. On previous occasions I used a somewhat trivial comparison, but it is only a question of understanding the analogy. Although it is trivial, it does, nevertheless, convey what it is intended to convey. When we are trying to understand what will be placed in the interior of the building in these two different sized spaces, we may with advantage think of the principle of the mould in which German cakes are baked.  The cake rises in the mould and when it is taken out its surface shows all the forms which appear on the sides of the mould in negative. The same principle may be applied in the case of the interior decoration of our building, only that of course there is no cake inside; what must live there is the speech of Spiritual Science, in its true form. All that is to be enclosed within the forms, all that is to be spoken and proclaimed, must be in correspondence, as the dough of the cake corresponds to the negative forms of the baking mould. We should feel the walls as the living negative of the words that are spoken and the deeds that are done in the building. That is the principle of the interior decoration. Think for a moment of a word, in all its primordial import, proceeding from our living Spiritual Science and beating against these walls. It seems to hollow out the form which really corresponds to it. Therefore I at least was satisfied from the very outset that we should work in the following way: with chisel and mallet we have a surface in mind from the beginning, for with the left hand we drive the driving chisel in the direction which will eventually be that of the surface. From the very outset we drive in this direction. On the other hand we hold the graver's chisel at right angles to the surface.

The cake rises in the mould and when it is taken out its surface shows all the forms which appear on the sides of the mould in negative. The same principle may be applied in the case of the interior decoration of our building, only that of course there is no cake inside; what must live there is the speech of Spiritual Science, in its true form. All that is to be enclosed within the forms, all that is to be spoken and proclaimed, must be in correspondence, as the dough of the cake corresponds to the negative forms of the baking mould. We should feel the walls as the living negative of the words that are spoken and the deeds that are done in the building. That is the principle of the interior decoration. Think for a moment of a word, in all its primordial import, proceeding from our living Spiritual Science and beating against these walls. It seems to hollow out the form which really corresponds to it. Therefore I at least was satisfied from the very outset that we should work in the following way: with chisel and mallet we have a surface in mind from the beginning, for with the left hand we drive the driving chisel in the direction which will eventually be that of the surface. From the very outset we drive in this direction. On the other hand we hold the graver's chisel at right angles to the surface.

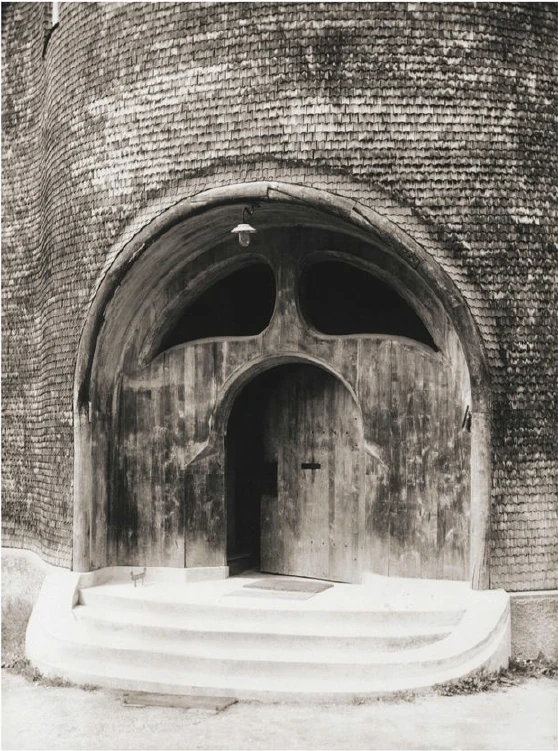

It would have been my wish—only it was not to be—that we should have had no such surfaces as these (pointing to an architrave). They will only be right—when something is taken away from them. This roundness here must be eliminated. It would have been better if from the very beginning we had worked with the graver's chisel for then there would have been no protuberance but only a surface. What we must do is to feel from the models how the interior decoration is the plastic vesture for the Spiritual Science that is given its in the building. Just as the interior decoration has the quality of being ‘in-carved,’ so the outer decoration will seem as though it is ‘laid on.’ The interior decoration must always have the character of being in-carved. One can feel this in the model, for the essential thing is a true inner feeling for form in space. It is this that leaves one unsatisfied even in such writings as those of a man like Hildebrandt. He has a certain idea of the workings of form but what he lacks is the inner feeling of form—the inner feeling that makes one live wholly within the form. He simply says that the eye should feel at home when it looks at form. In our building we must learn to experience the forms inwardly, so that, holding the chisel in a particular way, we learn to love the surface we are creating—the surface that is coming into being under the mallet. I, for my part, must admit that I always feel as if I could in some way caress such a surface. We must grow to love it, so that we live in it with inner feeling and not think of it as something that is merely there for the eye to look at.

Just recently someone told me after a lecture that a certain very clever man had accused us of straining after ‘externalities,’ as instanced by the fact that different kinds of wood have been used for the columns in the interior. This shows how little our work has been understood. Such a thing is considered to be a dreadful externality. This very intelligent man, you see, simply cannot realise that the columns must be of different woods. The real reason why he cannot understand, is that he has not paused to consider what answer he would have to make if he were asked: ‘Why must there be different strings on a violin? Would it not be possible simply to stretch four A strings instead?’ The use of different woods is a reality in just the same sense. We could no more use only one kind of wood than we could have only A strings on a violin. Real inner necessities are bound up with this. One can never do more than mention a few details in these matters. The whole conception of our building and what must be expressed in it, is based upon deep wisdom, but a wisdom that is at the same time very intimate. Of course there will be forms which are nowhere to be found in the outer physical world. If anything bears an apparent resemblance to a form in the animal or human body, this is simply due to the fact that higher Spirits who work in nature, create according to these forces; nature is expressing the same things as we are expressing in our building. It is not a question of an imitation of nature, but of the expression of what is there as pure etheric form. It is as though a man were to ask himself: ‘What idea must I have of my own being when I look away from the outer sense-world, and try to find an environment that will express my inner being in forms?’ I am sure that everyone will be struck by the plastic forms on the capitals and in the rest of the interior. Not a single one of these forms is without its own raison d'étre. Suppose anyone is carving the column just here (pointing to an architrave motif). At another place he will carve more lightly or deeper down into the wood. It would be nonsense to demand symmetry. There must be living progression, not symmetry. The columns and architraves in the interior are a necessary consequence of the two circular buildings with the two incomplete domes. And I cannot express this any more precisely than by saying that if the radius of the small dome were at all larger or smaller in proportion to the large dome, each of these forms would have to be quite different, just as the little finger of a dwarf is different from that of a giant. It was not only the differences in dimension, but the differences in the forms that called forth the overwhelming feeling of responsibility while we were erecting the building; down to the smallest detail it could not be other than it is. Each single part of a living organism has to exist within and in accordance with the whole living organism. It would be nonsense to say: I want to change the nose and put a different organ in the place where the nose now is.' It is a matter of actual fact that the big toe, and the small toe as well, would have to be different if the nose were different. Just as nobody in his senses would wish to re-model the nose, so it is impossible that the form here should be other than it is. If this form were different, the whole building would have to be different, for the whole is conceived in living, organic form. The advance we must make is this: all that was, in the early days of art, a kind of instinctive perception of a human posture transformed into artistic form must now enter with consciousness into the feeling life of man. In this way we shall have, in our interior decorations, etheric forms that are true and living, and we shall feel them to be the true expression of all that is to live in our building. It simply cannot be otherwise.

Now the other day I received two letters from a man who, ten years ago, it is true, did belong to the Anthroposophical Movement, but who since then has left it. He asked me if he could be allowed to make the windows, for he was so well qualified for the work. He was really very insistent. But when you see the windows you will understand that they could only be made by somebody who has followed our work right up to the present. Suppose I were to press my hand into a soft substance: the impress could only be that of my hand, it could not be the head of an ox for instance! It is Spiritual Science that must be impressed into the interior decoration; and Spiritual Science must let in the sunlight through the windows in a way that harmonises with its own nature. The whole building is really constructed—forgive this analogy—according to the principle of the cake mould, only of course instead of a rising cake, it is filled with Spiritual Science and all the sacred things that inspire us. This was always the case in art, and above all it was so in the days when men perceived in their dim, mystical life of feeling the alternation of the principles of earth and sun in the living dance and then portrayed the dance in the palmette motif. So it must be when it is a question of penetrating the outer sense- veil of natural and human existence and expressing in forms things that lie behind the realm of sense perception—if, that is to say, we are fortunate enough to be able to carry this building through. How inner progress is related to the symptoms of onward-flowing evolution—this is what will be expressed in the building, in the dimensional proportions, forms, designs and paintings.

I wanted to place these thoughts before you in order that you may not allow yourselves to be misled by modern conceptions of art, which have put all true understanding on one side. A good example of this is the belief that the Corinthian capital arose primarily from the sight of a little basket with acanthus leaves around it. The truth is that something springing from the very depths of human evolution has been expressed in the Corinthian capital. So also we shall feel that what surrounds us in our building is the expression of something living in the depths of human nature behind the experiences and events of the physical plane.

To-day I only wanted to speak of this particular detail in connection with our building and with a certain chapter in the history of art.

There may be opportunities during the coming weeks to speak to you of other things in connection with some of the motifs in the building. I shall seize every available opportunity to bring you nearer to what is indeed full of complexity, but yet absolutely natural and necessary, in a spiritual sense, for our building.

In our days it is not at all easy to speak about problems of art, for naturalism, the principle of imitation, really dominates the whole realm of art. So far as the artist himself is concerned, naturalism has arisen out of a very simple principle; so far as other people are concerned it seems to have arisen from something less simple. The artist, when he is learning must, of course, copy the productions of his master; he must imitate in order to learn. Man now imitates nature out of instinct—for he has made the principle of pupil into that of master and has then put the master on one side because he will brook no authority. This principle is very convenient for artists, for they do not want to get beyond an artistic reproduction of the models before them. The layman to-day understands the principle of naturalism as a matter of course. Where can he find anything to take hold of when he sees forms like those in our building? How are these forms to stimulate any thought at all? He will tear his hair and ask, with a shrug of his shoulders: ‘Whatever is this?’ And he will be lucky if he finds anything at all to take hold of, for instance, if he discovers that some detail has a slight resemblance, maybe to a nose! Although this may be negative, he is delighted that he has discovered anything at all. To-day the layman is pleased if when he finds in the different arts something that transcends the purely naturalistic element, he can say: ‘This has a resemblance to something or other.’ Art will most certainly be misunderstood if people continue to think that it is only legitimate to express things that resemble something or other in the external world. Real art does not ‘resemble’ anything at all; it is something in itself, sufficient unto itself. And again from this point of view it was despairing to find that as a result of the materialism of the second half of last century, painters (not to speak of sculptors) were asking themselves for instance: ‘How am I to get the effect of that mist in the distance?’ And then all kinds of attempts were made to reproduce nature by pure imitation. It really was enough to drive one to despair! Ingenious things were produced, it is true, but what is the value of them? It is all far better in nature herself. The artists were wasting their time in their efforts to imitate, for nature has it all in a much higher form. The answer to this problem is to be found in the Prologue to “The Portal of Initiation.” [The first of Dr. Steiner's Mystery Plays.]

Not long ago we happened to be going through the Luxemburg Gallery in Paris, and we saw a statue there. At first sight it was exceedingly difficult to make out what it was supposed to be, but by degrees it dawned on one that perhaps it was meant to represent a human figure. It was so distorted .... I will not imitate the posture, for it would be too much of a strain on the shoulders and knees! It is an absolutely hideous production, but I assure you that if it were to meet one in nature it would be much easier to understand than this “work of art.” People to-day do not realise the absurdity of giving plastic form to a motif that has been thought out, for there is, as a matter of fact, no real necessity to give it plastic form. That which is to be given plastic form must from the very beginning be there in itself and only conceived of plastically. No true sculptor will say that Rodin's productions are an expression of true plastic art. Rodin models non-plastic motifs very well, in an external sense, but true artistic feeling will always be prompted to ask if it amounts to anything, for true plastic conception is entirely lacking. All these things are connected, my dear friends. I have told you what happened in my young days, when I was about 24 or 25 years old, when I absorbed the doctrines of Semper. Already then they were enough to drive one to despair and their influence has not been got rid of yet. Therefore I ask you—and more particularly those who are working so devotedly and unselfishly at our building with all the sacrifices that their work entails—always to try to proceed from inner feeling for what this building ought to contain and to feel in life itself the forms which must arise, in order that we may free ourselves from the trammels of much so-called modern “art.” We must realise, in a new sense, that art is born from the depths of man's being. So greatly is this prone to be misunderstood in our age that people have taken the metamorphosis of of the Earth and Sun motifs to be an imitation of the acanthus leaf. If people will stop believing the anecdote quoted by Vitruvius, that Callimachos saw a basket strewn around with acanthus leaves and then used it as a motif on columns, and will listen to what he says about Callimachos having had a vision over the grave of a Corinthian girl, they will also realise that he had clairvoyant sight and they will have a better understanding of the evolution of art. They will realise that development of clairvoyance leads man to the realm lying behind the world of sense. Art is the divine child of clairvoyant vision—although it only lives as unconscious feeling in the soul. The forms that are seen by the clairvoyant eye in the higher worlds cast their shadow pictures, as it were, down to the physical plane.

When people understand all that lives in the Spirit—the Spirit which has the power to impress itself into what surrounds us here in our building, finding its expression in the outer framework around us—they will also understand the goal we have set ourselves, and see in the forms of art the impress of what has to be accomplished and proclaimed in living words in our building. It is a living word this building of ours!

Now that I have tried, scantily, it is true, to indicate something in regard to the interior we shall, before very long, be able to speak of the painting and also of the outside of the building.

4. Der Gemeinsame Ursprung der Dornacher Bauformen und des Griechischen Akanthusornamentes

Meine lieben Freunde! Ein Gedanke, der uns bei diesem Bau wohl oftmals kommen kann, das ist der Gedanke der Verantwortung, die wir zu tragen haben gegenüber den opferwillig dargebrachten Werten, welche unsere lieben Freunde zu diesem Bau zur Verfügung gestellt haben. Diejenigen, die sich einmal bekannt gemacht haben damit, wie groß eigentlich nach und nach diese Werte geworden sind, werden begreifen, daß gegenüber solcher Opferwilligkeit das richtige Äquivalent ein wirklich starkes Gefühl der Verantwortlichkeit sein muß, dahingehend, daß auch zustande gebracht wird dasjenige, was man erhoffen darf von diesem Bau.

Nun, jeder, der, ich möchte sagen, nur einmal einen Blick geworfen hat, gar nicht auf das Ganze, das man ja noch nicht überschauen kann, sondern nur auf das Einzelne, wird sich klar sein darüber, daß dieser Bau abweicht eigentlich von allem, was sich in der bisherigen Entwickelung der Menschheit als dieser oder jener Baustil darstellt, der nun einmal vor dem Urteil der Menschheit gerechtfertigt ist. Rechtfertigen kann ja eine solche Unternehmung selbstverständlich nur die Tatsache, daß das Gewollte annähernd gelingt. Aber jeder erste Anfang kann ja naturgemäß nichts anderes sein, als daß sozusagen das Gelingen nur in recht primitiver Weise eintreten kann. Gegenüber dem, was man etwa wollen könnte, wird dasjenige, was uns möglich sein wird zu vollbringen, nur ein kleiner, vielleicht winzig zu nennender Anfang sein. Aber man wird vielleicht doch in diesem Anfange die Linie sehen, nach welcher eine spirituelle Umgestaltung künstlerischer Stilmäßigkeit sich in der weiteren Zukunft der Menschheit vollziehen muß.

Allerdings müssen wir uns darauf gefaßt machen, meine lieben Freunde, daß wenn die Sache einmal fertig sein wird, insbesondere von sogenannter fachmännischer Seite die mannigfaltigsten Vorwürfe kommen werden und das hier Gemachte unsachgemäß, vielleicht sogar dilettantisch gefunden werden wird. Das alles wird uns aber nicht beirren können, denn es ist nur in der Natur der Tatsachen gelegen, daß fachmännische Urteile am wenigsten dann zurechtkommen, wenn irgend etwas als etwas Neues in die Welt gestellt worden ist. Wir werden uns aber nicht bedrückt fühlen gegenüber abfälliger Kritik, die gegenüber unserem künstlerischen Wollen auftreten könnte, wenn wir - ich möchte sagen, für uns selbst wie einen Trost für unser Verantwortlichkeitsgefühl - den Gedanken uns vor Augen führen, daß gerade in unserer Zeit im Grunde genommen die Entstehung der Künste, die Entstehung der einzelnen Formen und Motive der Künste, von fachmännischer Seite recht stark mißverstanden wird. Und da wird uns allmählich das Verständnis kommen, daß wir mit dem, was wir hier wollen mit diesem Bau, den, ich möchte sagen, «Urkräften künstlerischen Wollens» - wie es einem entgegentreten kann, wenn man auf die Entstehung der Künste einmal das geistige Auge lenkt - viel näher kommen, als ihm dasjenige nahekommt, was so vielfach als künstlerische Auffassung in der Gegenwart sich geltend macht. Man versteht heute wenig mehr von dem, was eigentlich einmal mit der künstlerischen Auffassung gemeint war im Entwickelungsgang der Menschheit. Daher braucht es nicht zu überraschen, wenn so etwas wie unser Bau, der wiederum im Einklang sein will mit dem Urwollen, mit der Entstehung der Künste, vielleicht gerade von denjenigen, die der Richtung und der Tendenz der Gegenwart huldigen, nicht gerade wohlwollend aufgenommen wird.

Ich möchte heute, um den Gedanken, den ich angedeutet habe, Ihnen näherzubringen, ausgehen von der Betrachtung eines sehr bekannten künstlerischen Motivs, des sogenannten Akanthusblattes, und möchte zeigen, wie das, was wir wollen, im vollen Einklang steht mit jenem Wollen sagen wir künstlerischem Wollen - der Menschheit, das sich ausdrückt in der Entstehung des Akanthusblattes. Nur muß das, was wir wollen, weil es selbstverständlich viele Jahrhunderte, ja Jahrtausende nach der Entstehung des Akanthusblattes liegt, eben etwas ganz anderes werden, als es damals geworden ist, da man das Akanthusblatt in die konrinthische Säule zum Beispiel eingefügt hat.

Meine lieben Freunde, wenn ich dabei kurz etwas Persönliches berühren darf, so möchte ich sagen, daß meine eigene Wiener Studienzeit gerade in diejenige Zeit der Wiener Entwickelung fiel, in welcher die großen Bauten, die Wien sein gegenwärtiges Gepräge gegeben haben - das Parlamentsgebäude, das Rathaus, die Votivkirche, das Burgtheater - ihre Vollendung gefunden haben. Die großen Baumeister dieser Bauten lebten noch: Hansen, der Regenerator, der Erneuerer der griechischen Architektur, Schmidt, der eigenartige Ausgestalter der Gotik, Ferstel, der die Votivkirche gebaut hat. Und bekannt wird ja vielleicht sein, daß das Burgtheater in Wien gebaut worden ist nach den Plänen desjenigen Künstlers, welcher dazumal in den siebziger, achtziger Jahren des vorigen Jahrhunderts für künstlerische Empfindung und künstlerische Ausgestaltung architektonischer, plastischer Formen tonangebend geworden ist: das Burgtheater ist ausgeführt nach den Plänen des großen Architekten Gottfried Semper. An der Hochschule hatte ich selbst zum Lehrer einen genialen Verehrer und Anhänger Gottfried Sempers in dem ausgezeichneten Ästhetiker Joseph Bayer, so daß ich dazumal leben durfte sozusagen in der ganzen Auffassung der Formenwelt, der architektonischen und plastischen Formenwelt und der Ornamentik, wie sie inauguriert worden ist durch den genialen Gottfried Semper.

Sehen Sie, meine lieben Freunde, es war dazumal etwas, ich möchte sagen, in der ganzen Atmosphäre der Anschauungen, die sich geltend machten auf der einen Seite, um zu begreifen das kunstgeschichtliche Werden, auf der andern Seite, um sich hineinzufinden in künstlerisches Gestalten, es war in der Atmosphäre der Auffassungen und Empfindungen dazumal etwas, das ich kurz so aussprechen möchte: es konnte einen zur Verzweiflung bringen trotz aller Genialität, die damals wirkte. Gottfried Semper war gewiß eine geniale Persönlichkeit, allein es hatte dazumal auch die ganze künstlerische Auffassung derjenige Zug der allgemeinen Menschheits- und Weltauffassung ergriffen, der hervorging aus der materialistischen Deutung des Darwinismus und der Entwickelungslehre. Und so konnte man immer wiederum das Materialistische auch in der Kunstauffassung dazumal hervortreten sehen. Da mußte man vor allen Dingen sich gut bekanntmachen mit den äußeren Techniken des Flechtens und Webens. Und aus der Art, wie, ich will sagen, Stoffe gewebt oder wie Zäune geflochten wurden, so daß man die einzelnen Stöcke in gewisser Weise ineinander zu stecken hatte, damit sie hielten und sich ineinander fügten, wurden erst abgeleitet die architektonischen Formen; so daß man förmlich eingepfropft bekam den Satz: das Ornament ist eine Form der äußeren Technik.

Ich deute damit etwas an, was weiter ausgeführt werden könnte, doch jetzt will ich nur auf merksam machen auf den Zug der Zeit, der sich damals geltend machte: alles, was künstlerisch ist, schließlich zurückzuführen auf das Äußere der Technik. Ich möchte sagen, man war auf einen gewissen Utilitätsstandpunkt gekommen, und das Künstlerische sah man an wie eine Weiterführung desjenigen, was sich ergab aus dem, wie man die Dinge gebrauchte. Daher hörte man in der damaligen Zeit auf Schritt und Tritt, wo es um künstlerische Themata sich handelte, besonders um Themata des Ornamentes, immer wiederum von den Eigenarten der Techniken sprechen.

Nun, das alles war gewissermaßen nur eine Nebenströmung der großen materialistischen Strömung, die im 19. Jahrhundert waltete und die man nennen könnte: die materialistische Auffassung des Künstlerischen überhaupt. Wie sich das Materialistische eben in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts auf allen Gebieten besonders geltend machte, das war eine Auffassung, die einen in der Tat zur Verzweiflung brachte. Denn wirklich, ich erinnere mich noch, wie viele schlaflose Nächte in jener Zeit mir das korinthische Kapital gemacht hat. Nicht wahr, dieses korinthische Kapital, das hat ja zu seinem Hauptteil, zu seinem Hauptschmuck sagen wir - obwohl es in der Zeit, von der ich spreche, fast verboten war, von Schmuck zu sprechen - das Akanthusblatt. Was lag selbstverständlich näher als zu sagen: Nun, das Akanthusblatt, auch das der korinthischen Säule, ist einfach entstanden durch naturalistische Nachahmung des Blattes der Akanthuspflanze, die man ja überall findet. - Nun, für denjenigen, der künstlerisches Empfinden hat, ist es wirklich ein hartes Stück, sich vorzustellen, daß irgendeinmal begonnen worden sein soll damit, daß man sozusagen ein Unkrautblatt genommen habe, eben ein Akanthusblatt, und daß man das plastisch ausgestaltet und an die korinthische Säule angeklebt habe.

Nehmen wir einmal, um uns zu orientieren, die Form des Akanthusblattes. Ich möchte es gewissermaßen schematisch aufzeichnen, dieses Akanthusblatt. So etwa ist dieses Blatt von Acanthus spinosus, der gewöhnlichen Bärenklaue, geformt:

Das soll also dazu gedient haben, plastisch ausgestaltet und in dieser Ausgestaltung an die korinthische Säule geklebt zu werden.

Nun kommt allerdings etwas anderes noch dazu. Nämlich Vitruv, der bedeutende Bearbeiter der künstlerischen Traditionen des Altertums, bringt eine Anekdote, die sehr bekannt ist, und diese Anekdote hat mit dazu geführt, die «Korbhypothese» des korinthischen Säulenkapitäls zu begründen. Man kann sie schon so nennen, denn wozu wurden nach und nach für die materialistische Kunstauffassung die Kapitale der korinthischen Säulen? Zu Körbchen, die ringsherum von Akanthusblättern getragen waren. Man kann, wenn man den Dingen genauer nachgeht, den Eindruck bekommen, daß hier etwas Symptomatisches, Bedeutsames vorliegt. Denn gerade an diesem Punkte zeigt es sich, daß das Verständnis der feineren spirituellen Zusammenhänge der Menschheitsentwickelung den nachforschenden Menschen einen «Korb» gegeben hat und gleichsam wie eine Art Denkmal dieses «Korbes»> steht diese Korbhypothese der korinthischen Säulenkapitäle da.

Was erzählt Vitruv denn eigentlich? Er erzählt, daß Kallimachos, der korinthische Bildhauer, einmal ein irgendwie zufällig dastehendes Körbchen gesehen habe, und am Grunde dieses Körbchens seien ringsherum diese Akanthusblätter gewachsen. - Also sagt man: Kallimachos habe angeschaut ein Körbchen, umgeben von Akanthusblättern, und habe gesagt: Ja, das gibt das korinthische Kapital. - Das ist der reinste Materialismus, den man sich denken kann. Nun, ich werde gleich nacher sagen, wie es sich mit dieser Vitruvanekdote eigentlich verhält, was sie für eine Bedeutung hat.

Die Hauptsache, die hier zugrunde liegt, ist diese, daß man allmählich - und im Laufe der neueren Zeit im Grunde genommen ganz - verloren hat das Verständnis für das innere Prinzipielle des künstlerischen Schaffens. Und wenn man dieses innere Prinzipielle des künstlerischen Schaffens nicht wieder finden wird, wird man eigentlich das, was mit den Formen gewollt ist, was den Formen unserer Kapitale, ja den Formen unseres ganzen Baues zugrunde liegt, niemals verstehen. Die Menschen, welche - jetzt symbolisch gesprochen - der «Korbhypothese» huldigen, werden uns niemals richtig verstehen können.

Dasjenige, was allem künstlerischen Schaffen zugrunde liegt, ist ein Bewußtsein, welches, ich möchte sagen, vor den Pforten der historischen Entwickelung der Menschheit - der äußeren historischen Entwickelung, die durch äußere Dokumente festgelegt ist - haltmacht. Ein gewisses Bewußtsein, das vor den Pforten dieser historischen Entwickelung im Menschen tätig war, und das noch ein Überbleibsel des alten Hellsehertums der Menschheit war, das war etwas, was ebenso dem vierten nachatlantischen Zeiträume angehörte. Wenn auch die ägyptische Kultur dem dritten nachatlantischen Zeiträume angehört, so ist doch das, was zur Kunst hintendiert in der ägyptischen Kultur, dem vierten nachatlantischen Zeiträume angehörig. Im vierten nachatlantischen Zeiträume hat sich dieses Bewußtsein so geltend gemacht, daß inneres Gefühl, innere Empfindung des Menschen Platz gegriffen hat, - so Platz gegriffen hat, daß man fühlte, wie die Bewegung des Menschen, wie Haltung und Geste die menschliche Form und die menschliche Figur herausentwickeln aus dem Ätherischen ins Physische.

Sie werden mich verstehen, wenn Sie sich darüber klar sind, daß für jene Zeiten mit einer, ich möchte sagen, richtigen Auffassung des künstlerischen Wollens, viel wichtiger als die Anschauung einer Blume oder einer Ranke das Gefühl war: ich muß etwas tragen, schwer tragen; ich beuge den Rücken und mache mit meiner menschlichen Figur die Kraftentwickelung, die mich Menschen nötigt, mich so zu bilden, um die Last zu tragen.

Man fühlte in sich gewissermaßen das gebildet, was man in der eigenen Geste ausführen muß. Und so führte man die Greifbewegung, so zum Beispiel auch das Tragen mit der Hand, aus. Man fühlt dieses Tragen mit den Händen, wo man nötig hat, die Hände nach auswärts zu spreizen. Da entstanden die Linien und Formen, die ins künstlerische Gestalten übergingen. Man fühlt sozusagen an der eigenen Menschlichkeit, wie der Mensch über das, was er mit den Augen sieht und mit den übrigen Sinnen wahrnimmt, hinausgehen kann, wenn er sich einfügt einem Allgemeinen. Und ich möchte sagen: schon bei diesem Allgemeinen, wenn man nicht mehr bloß hinzuschlendern braucht, sondern genötigt ist, sich zu fügen dem Tragen einer Last, da ordnet man sich ein dem Organismus der ganzen Welt. Und aus dem Fühlen solcher Linien, die man in sich selber zu bilden hat, entstanden jene Linien, die zur künstlerischen Gestalt führten. Das sind Linien, die nicht in der äußeren Wirklichkeit zu finden sind.

Nun tritt einem in der spirituellen Forschung eines oftmals entgegen. Ich möchte sagen, wie ein wunderbares Akashabild tritt einem immer wiederum entgegen das Einfügen einer Anzahl von Menschen in ein Ganzes, aber ein gesetzmäßiges, harmonisches Einfügen von Menschen in ein Ganzes. Denken Sie sich das etwa so: Wir hätten eine Art Bühne, rings herum, wie amphitheatralisch, Sitze, wo Zuschauer sind, und es würden Menschen einen Umgang formieren. Die gehen herum im Innern, sie haben einen Umgang zu formen. Nicht etwas naturalistisch Gebildetes, sondern etwas Höheres, Übersinnliches sollte vor des Menschen Auffassung treten. Denken Sie sich, das ist in der Aufsicht gezeichnet:

Ich zeichne es nun in der Seitenansicht, also schematisch: Eine Anzahl von hintereinander gehenden Menschen. Die bilden sozusagen den Umzug, der da im Kreise herumgeht; die andern sitzen im Kreise und schauen zu.

Nun handelt es sich darum, daß diese Personen etwas Wichtiges darstellen, etwas, was es sozusagen nicht ausgebildet gibt auf der Erde, sondern wovon es auf der Erde nur Analogien gibt, daß sie etwas darstellen, was den Menschen in Zusammenhang brachte mit dem großen Weltenzusammenhang. Und da liegt nun ja nahe, vor diesen Menschen der damaligen Zeit darzustellen das Verhältnis der Erdenwirkungen zu den Sonnenwirkungen. Wie kann der Mensch fühlen das Verhältnis der Erdenwirkungen zu den Sonnenwirkungen? Wenn er es ähnlich fühlt, wie man fühlen kann zum Beispiel das Getragensein, das heißt, wenn man eine Last trägt. Man kann also fühlen das Verhältnis der Erden- zu den Sonnenwirkungen so: Alles Irdische steht nur eben auf der Bodenfläche der Erde auf, und indem es sich von der Erde entfernt - das alles ist eigentlich nur in Kräften gedacht -, spitzt es sich zu. Also man fühlte sozusagen das Verbundensein des Menschen mit der Erde dadurch, daß man ein nach unten Breites und nach oben sich Zuspitzendes darstellte. Gar nichts anderes! Das heißt, indem man diese Kraftwirkung so fühlte, sagte man: ich fühle mich stehen auf der Erde.

Nun wurde der Mensch ebenso gewahr seine Zugehörigkeit zur Sonne. Dieses Hereinwirken der Sonne auf die Erde, man fühlte es, indem man die Kraftlinien eben so gestaltete, daß die Sonne, indem sie um die Erde herumgeht, in dieser Weise ihre Strahlen der Reihe nach hereinsendet, sie nach unten zuspitzend, weil die Sonne scheinbar um die Erde herumgeht.

Denken Sie sich diese beiden Darstellungen in Abwechslung, so können Sie sehen das Erdenund das Sonnenmotiv, das von diesen umhergehenden Menschen immer getragen wurde. Das gehörte zu dem, was in alten Zeiten im Umgang vorgeführt wurde. Da saßen die Menschen herum, und da gingen herum die Darsteller. Die einen trugen das Erdenmotiv, die andern gleichsam dasjenige, was man als Hinaufleben zur Sonne darstellte, denn so konnte man das Hereinstrahlen des Sonnenmäßigen auch darstellen. Und sie wechselten ab: Erde - Sonne, Erde - Sonne, und so weiter.

Diese Kraft, ich möchte sagen, diese kosmische Kraft: Erde - Sonne, fühlte man. Dann erst dachte man darüber nach, wie man das nun am besten machen könnte. Und da stellte sich heraus, daß man als Mittel, gleichsam als ein Kunstmittel, um das am besten zu machen, am besten eine solche Pflanze oder einen solchen Baum verwendet, der seine Wipfelentfaltung nach oben so hat, daß er unten breit ist und nach oben spitz zuläuft, und daß man dann abwechselt mit Palmen. So daß sich herausbildete das Hintereinandertragen von solchen Pflanzen, die etwas wie breite Knospen darstellen, welche sich nach oben zuspitzen, und von Palmen. Palmen als Entfaltung der sonnenhaften Kräfte, und nach oben sich zuspitzende Knospen als charakteristisch für die Erdenkräfte.

Man produzierte sozusagen, indem man fühlen lernte das Hineingestelltsein in den Kosmos als Mensch, gewisse Formzusammenhänge, und man benützte nur die pflanzlichen Mittel zur Darstellung. Man griff dabei, um das nicht künstlerisch erst fabrizieren zu müssen, zu den pflanzlichen Mitteln. Aus dem lebendigen Erfühlen des Weltenzusammenhanges heraus ist das künstlerische Schaffen entstanden, das deshalb auch einem Entfalten des Schaffensdranges entspricht, der im Menschen liegt, und nicht einer bloßen Nachahmung irgendeines bloß äußerlich Natürlichen entspricht. Alles äußerlich Natürliche ist lediglich, indem es künstlerisch nachgeahmt wurde, erst später in die Kunst hineingekommen. Als man nicht mehr gewußt hat, daß man Palmen genommen hat, um Sonnenkräfte auszudrücken, da hat man, indem man einen solchen Zweig aufgemalt hat, geglaubt, die Alten hätten die Absicht gehabt, eine Palme zu kopieren. Das war aber niemals der Fall, sondern sie haben die Palmen verwendet, weil sie die Sonnenkräfte darstellten. So ist alles wirkliche künstlerische Schaffen hervorgehend aus einer in der menschlichen Natur steckenden Überfülle von Kräften, die im äußeren Leben nicht zum Ausdruck kommen können, die sich daher ausleben wollen, indem der Mensch sich bewußt wird seines Zusammenhanges mit dem Weltenganzen.

Nun beirrte alles Nachdenken und Empfinden - sowohl gegenüber der Naturwissenschaft, wie auch gegenüber dem Künstlerischen -, es beirrte alles Empfinden und Vorstellen ein Gedanke, der aus der Menschheit recht schwer auszutreiben sein wird. Das ist der Gedanke, daß alles Komplizierte aus Einfachem entsteht. Das ist nicht wahr! Das menschliche Auge zum Beispiel ist in seiner Konstruktion viel einfacher als das Auge vieler niederer Tiere. Die Entwickelung geht vielfach so vonstatten, daß das Komplizierte vereinfacht wird, daß das Verschlungene zur geraden Linie abgerundet wird. Das Vereinfachte ist vielfach in der Entwickelung das Spätere. Erst wenn man das einsehen wird, wird man einen richtigen Begriff von wahrer Entwickelung erlangen.

Dasjenige, was sich nun damals den Menschen darbot, und was alles für die Zuschauer ringsherum dargestellt wurde und durchaus die Darstellung von lebendigen kosmischen Kräften war, das wurde später vereinfacht zu jenem Ornamente, in dessen Linie man zusammenfaßte dasjenige, was damals der Mensch, indem er diese Dinge darstellte, lebendig erfühlte. Und wenn ich darstellen wollte, wie man zusammengefaßt hat aus dem Komplizierten der Menschheitsentwickelung ins Einfache die Linie zu einem Ornament, das zum Schmucke dienen soll, so könnte ich mich folgender Zeichnung bedienen:

Denken Sie sich das abwechselnd, so haben Sie die vereinfachte Wiedergabe jenes Umganges, den ich angeführt habe als Erdenmotiv, Sonnenmotiv - Erdenmotiv, Sonnenmotiv. Da haben Sie das, was der Mensch erlebt hat, zusammengefaßt in das ornamentartige Motiv. Dieses ornamentartige Motiv figurierte schon in der mesopotamischen Kunst und ist auch in die griechische Kunst herübergekommen als die sogenannte Palmette, in dieser oder einer ähnlichen Form, die dem Lotosblatt ähnlich ist.

Diese Abwechslung von Erden- und Sonnenmotiv, die bot sich sozusagen dem menschlichen Empfinden dar als Schmuckmotiv, als richtiges ornamentales Schmuckmotiv. Daß man in diesem ornamentalen Schmuckmotiv eine ins Unbewußte übergegangene Nachbildung eines uralten Tanzmotives, eines feierlichen Tanzes zu sehen hat, das wußte man später nicht mehr. Aber erhalten hat sich das im Palmettenmotiv.

Nun ist es interessant, das Folgende ins Auge zu fassen. Wenn Sie gewisse dorische Säulen betrachten, so finden Sie da, wo die dorischen Säulen bemalt worden sind, ein höchst interessantes Motiv, das ich in dieser Weise zeichnen möchte. Unter dem, was das Kapital zu tragen hat, finden wir folgendes: Hier würde der obere Wulst der dorischen Säule sein, hier unten aber finden wir bei gewissen dorischen Säulen als Malerei rund um die Säule herum nur etwas modifiziert angebracht das Erdenmotiv und das Sonnenmotiv. Oben haben Sie den dorischen Wulst, unten ringsherum gemalt die ornamentalen Motive zum Schmuck der Säulen. So sehen Sie tatsächlich an gewissen dorischen Säulen unten gemalt die Palmette, so ausgeführt, daß sie wirklich einen Umgang gibt: Erde - Sonne, Erde - Sonne und so fort.

In Griechenland, dem vorzüglichsten Gebiete, in dem der vierte nachatlantische Zeitraum zu seinem vollen Ausdruck kam, vermählte sich nun das, was aus Asien herüberkam, mit all dem, was ich jetzt erzählt habe, und was in Griechenland an dorischen Säulen in Nachbildung sichtbar ist, mit dem eigentlich dynamisch-architektonischen Prinzip des Tragens, weil in Griechenland zunächst die Erfassung des Ich im menschlichen Leibe in vollkommenster Weise zum Ausdruck kam. Und deshalb war es in Griechenland, wo ein solches Motiv zum Ausdruck kommen konnte: daß das Ich, wenn es im Leibe ist, sich verstärken muß, wenn es eine Last trägt. Das Ganze fühlt man in der Volute:

Dieses Starkmachen, das ist dasjenige, was man in der Volute fühlt. Den Menschen, indem er sein Ich verstärkt im vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum, den sehen wir ausgedrückt in der Volute. Und so gewinnen wir die Grundform der ionischen Säule, ich möchte sagen, wie wenn der Atlas die Welt trägt, aber noch unausgebildet, indem die Volute zum Träger wird.

Nun brauchen Sie sich nur vorzustellen, daß das, was in der ionischen Säule nur angedeutet ist, das Mittelstück, nach unten sich zur vollständigen Volute ausbildet, dann haben Sie die korinthische Säule: nichts anderes, als die Mittelstücke gleichsam nach unten ausgedehnt, so daß die Natur des Tragens zur Vollständigkeit wird. Und nun denken Sie sich dieses Tragende als plastisches Gebilde, dann haben Sie gleichsam die in sich gekrümmte Menschenkraft. Das Ich umgebogen, hier Last tragend.

Ein künstlerisches Prinzip liegt nun darin, meine lieben Freunde, daß man dasjenige, was irgendwie ausgebildet ist im Großen, im Kleinen, en miniature wiederholt, oder umgekehrt. Wenn Sie sich nun die korinthische Säule so ausgebildet denken, daß sie hier die haupttragende Volute hat, und Sie wiederholen nun dieses künstlerische Motiv hier, wo es nur zum Schmuck dient, so haben Sie gleichsam plastisch eingefügt dasjenige, was das ganze Kapital ist, noch ringsherum im Schmuck. Und jetzt denken Sie sich, daß sich vermählt das dorische Malmotiv, das hervorgegangen ist aus der ornamentalen Nachmalerei des vorgeführten uralten Sonnenmotivs, vermählt mit dem, was an der korinthischen Säule angebracht ist, denken Sie sich, daß die Intuition entsteht, das, was ringsherum ist, ähnlich zu gestalten dem, was man früher gemalt hat: und man hat das Gemalte der dorischen Säule plastisch ausgestaltet. Ich kann das dadurch versinnlichen, daß ich das plastische Motiv zunächst Ihnen zeige, an das ich angemalt habe die Palmette [siehe Abbildung 8]. Der Drang ist entstanden, die Palmette zu sehen an dem Motiv, das sich hier so ergeben hat. Es ist aber nicht zu einem solchen Anmalen dieses Tragmotivs gekommen, sondern es ist dazu gekommen, daß man, was man dorisch bloß gemalt hat, korinthisch plastisch gestaltet hat; das heißt, man hat hier plastisch ausgestaltet, und ließ das Palmettenblatt bis unten hin gehen. Links habe ich gezeichnet eine Palmette [siehe Abbildung], rechts den Anfang, der entsteht, wenn die Palmette plastisch ausgestaltet wird. Da würde, wenn ich weiter fortfahren würde, die dorische gemalte Palmette in die korinthische plastische Palmette ausgestaltet. Und so würden wir, wenn ich nicht die Palmette malen würde, überall bekommen das Akanthusblatt.

Das Akanthusblatt entsteht, indem die Palmette plastisch umgewandelt wird. Also aus dem Drang, hier die Palmette nicht aufzumalen, sondern sie plastisch zu gestalten, ergibt sich diese Form; und aus dem bloßen Träger wird, indem man immer mehr in Komplikationen übergeht, dasjenige, wovon es einem Menschen ein Gefühl sein kann zu sagen: das hat eine gewisse Ähnlichkeit mit dem Akanthusblatt. Und man hat diese Sache, die man früher selbstverständlich nicht Akanthusblatt genannt hat, von da an Akanthusblatt genannt. Aber der Name hat mit dem, was dargestellt wurde, ebensoviel zu tun wie mit der Lunge und den Lungenflügeln der Ausdruck «Flügel». Und das ganze Unsinnige der naturalistischen Nachahmung des Akanthusblattes entfällt, weil dasjenige, was man Akanthusblatt nennt, gar nicht entstanden ist aus der naturalistischen Nachbildung des Akanthusblattes, sondern durch Umbildung des alten Sonnenmotivs, der Palmette, die man plastisch gemacht, statt daß man sie gemalt hat. So sehen Sie, daß aus einem inneren Erfassen desjenigen, was mit der Geste des menschlichen Ätherleibes zusammenhängt — denn damit hängt die Bewegung einer Kraftlinie zusammen, die man an sich selbst auszuführen hat -, durch die Wahrnehmung dessen, was aus dem menschlichen Ätherleib fließt, wirklich diese künstlerischen Formen geflossen sind.