Education as a Social Problem

GA 296

15 August 1919, Dornach

IV. Education as a Problem Involving the Training of Teachers

From the various matters we have considered here you will have gathered that among the many problems under discussion today that of education is the most important. We had to emphasize that the entire social question contains as its chief factor, education. From what I indicated a week ago about the transformation of education it will have become clear to you that within the whole complex of this subject the training of teachers is the most important auxiliary question. When we consider the character of the epoch that has run its course since the middle of the fifteenth century it becomes evident that during this period there passed through mankind's evolution a wave of materialistic trials. In the present time it is necessary that we work our way out of this materialistic wave and find again the path to the spirit. This path was known to humanity in ancient cultural epochs, but it was followed more or less instinctively, unconsciously. Finally, it was lost in order that men might seek it out of their own impulse, their own freedom. This path must now be sought in its full consciousness.

The transition through which mankind had to pass after the middle of the fifteenth century is what might be called the materialistic test of mankind. If we observe the character of this materialistic period and the development of culture of the last three or four centuries right up to our time, we shall see that this materialistic wave has most intensively and quite particularly taken hold of teacher training. Nothing could have such a lasting effect as the permeation of educational philosophy by materialism. We only need to look at certain details in present-day education to appreciate the great difficulties in the way of progress. Those who today consider themselves well-versed in the problems of education say again and again that all instruction, even in the lowest grades, must be in the form of object lessons. In the teaching of arithmetic, for instance, mechanical aids to calculating are introduced. The greatest value is placed upon having the child see everything first, and then form his own inner concepts about it. To be sure, the urge for such objectivity in education is in many respects fully justified. Nevertheless, it raises the question, what becomes of a child if he only receives object lessons? He becomes psychically dried up; the inner dynamic forces of his soul gradually die out. His whole being unites with the objective surroundings, and what should sprout from his inmost soul is gradually deadened. The way material is presented in much of our education today is connected with this deadening of the soul. People do not realize that one kills the soul, but it really happens. And the consequence is what we experience with people today. How many are problem-laden personalities! How many are unable in their later years to produce out of their own inner resources that which could give them consolation and hope in difficult times and enable them to cope with the vicissitudes of life! We see at present many shattered natures. At important moments we ourselves are doubtful as to the direction we should take.

All this is connected with the deficiencies in our educational system, particularly in teacher training. What then do we have to strive for in order to have the right teacher training in future? The fact that a teacher knows the answers to what is asked in his examinations is a secondary matter, for he is mostly asked questions for which he could prepare himself by looking them up in a handbook. The examiners pay no attention to the general soul-attitude of the teacher, and that is what constantly has to pass from him to his students. There is a great difference between teachers as they enter a classroom. When one steps through the door the students feel a certain soul-relationship with him; when another enters they often feel no such relationship at all, but, on the contrary, they feel a chasm between them and are indifferent to him. This expresses itself in a variety of ways, even to ridiculing and sneering at him. All these nuances frequently lead to ruining any real instruction and education.

The burning question, therefore, is, how can teacher training be transformed in future? It can be transformed in only one way, and that is, that the teacher himself absorb what can come from spiritual science as knowledge of man's true nature. The teacher must be permeated by the reality of man's connection with the supersensible worlds. He must be in the position to see in the growing child evidence that he has descended from the supersensible world through conception and birth, has clothed himself with a body, and wishes to acquire here in the physical world what he cannot acquire in the life between death and a new birth, and in which the teacher has to help.

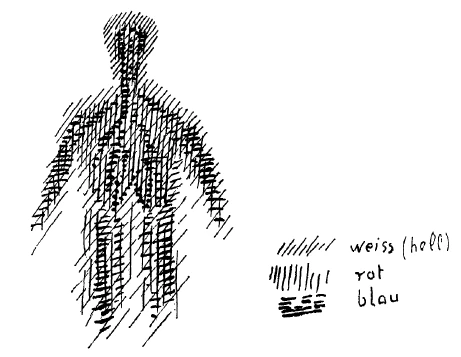

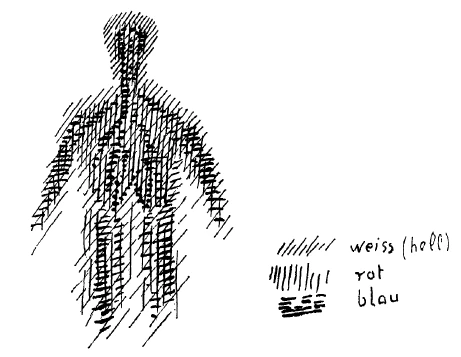

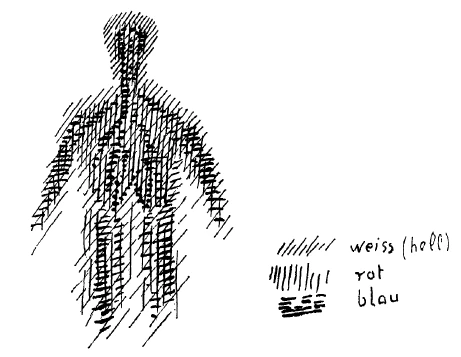

Every child should stand before the soul of the teacher as a question posed by the supersensible world to the sense world. This question cannot be asked in a definite and comprehensive way in regard to every individual child unless one employs the knowledge that comes from spiritual science concerning the nature of man. In the course of the last three or four centuries we gradually acquired the habit of observing man only in regard to his outer, bodily constitution, physiologically. This concept is detrimental, most of all for the educator. It will, therefore, be necessary above everything else for an anthropology resulting from anthroposophy to become the basis for education in the future. This, however, can only happen if man is considered from the points of view we have frequently touched upon here, that characterize him in many respects as a threefold being. But one must make up one's mind to grasp this three-foldness with penetrating insight. From various aspects I have drawn your attention to the fact that man as he confronts us is, first, a man of nerves and senses; popularly expressed he is a head-man. As a second member we have seen, externally, that part in which the rhythmical processes take place, the chest-man; and thirdly, connected with the entire metabolism is the limb-man, metabolic man. What man is as an active being is externally brought to completion in the physical configuration of these three members of his whole organism:

Head-man, or nerve-sense man;

Chest-man, or rhythmical man;

Limb-man, or metabolic man.

It is important to understand the differences between these three members, but this is very uncomfortable for people today because they love diagrams. If one says that man consists of head-man, chest-man, limb-man, he would like to make a line here at the neck, and what is above it is headman. Likewise, he would like to draw a line in order to limit the chest-man, and so he would have the three members neatly arranged, side by side. Whatever cannot be arranged in such a scheme is just of no interest to modern man.

But this does not correspond to reality. Reality does not make such outlines. To be sure, man above the shoulders is chiefly head-man, nerve-sense man, but he is not only that. The sense of touch and the sense of warmth, for instance, are spread over the whole body, so that the head-system permeates the entire organism. Thus, one can say, the human head is chiefly head. The chest is less head but still somewhat head. The limbs and everything belonging to the metabolic system are still less head, but nevertheless head. One really has to say that the whole human being is head, but only the head is chiefly head. The chest-man is not only in the chest; he is chiefly expressed, of course, in those organs where the rhythms of the heart and breathing are most definitely shown. But breathing also extends into the head; and the blood circulation in its rhythm continues on into the head and limbs.

So, we can say that our way of thinking is inclined to place these things side by side, and in this we see how little our concepts are geared to outer reality. For here things merge; and we have to realize that if we separate head, chest, and metabolic man we must think them together again. We must never think them as separated but always think them together again. A person who wishes only to think things separated resembles a man who wishes only to inhale, never to exhale.

Here you have something that teachers in future will have to do; they must quite specially acquire for themselves this inwardly mobile thinking, this unschematic thinking. For only by doing so can their soul forces approach reality. A person will not come near to reality if he is unable to conceive of approaching it from a larger point of view, as a phenomenon of the age. One has to overcome the tendency to be content with investigating life in its details, a tendency that has been growing in scientific studies. Instead one must see these details in connection with the great questions of life.

One question will become important for the entire evolution of spiritual culture in future, namely, the question of immortality. We must become clear about the way a great part of humanity conceives of immortality, particularly since the time when many have come to a complete denial of it. What lives in most people today who, still on the basis of customary religion, want to be informed about immortality? In these people there lives the urge to know something about what becomes of the soul when it has passed through the portal of death.

If we ask about the interest men take in the question of the eternity of man's essential being, we come to no other answer than this, that the main interest they have is connected with man's concern about what happens to him when he passes through death. Man is conscious of being an ego. In this ego his thinking, feeling, and willing live. The idea that this ego might be annihilated is unbearable to him. Above all then he is interested in the possibility of carrying the ego through death, and in what happens to it afterward. Most religious systems, in speaking about immortality, chiefly bear in mind this same question: What becomes of the human soul when man passes through death?

Now you must feel that the question of immortality, put in this manner, takes on an extraordinarily egotistical character. Basically, it is an egotistical urge that arouses man's interest in knowing what happens to him when he passes through death. If men of the present age would practice more self-knowledge, take counsel with themselves, and not surrender to illusions as they do now, they would realize the strong part egotism plays in the interest they have in knowing something about the destiny of the soul after death.

This kind of feeling has become especially strong in the last three to four centuries when the trials of materialism have come upon us. What has thus taken hold of human souls as a habit of thought and feeling cannot be overcome through abstract theories or doctrines. But must it remain so? Is it necessary that only the egotist in human nature speak when the question of the eternal core of man's being is raised?

When we consider everything connected with this problem we must say: The fact that man's soul-mood has developed as we have just indicated stems from the way religions have neglected to observe man as he is born, as he grows into the world from his first cry, as his soul in such miraculous fashion permeates the body more and more; their neglect to observe how in man there gradually develops that part of him which has lived in the spiritual world before birth. How little do people ask today: When man is born, what is it that continues on from the spiritual world into man as a physical being?

In future primary attention will have to be paid to this. We must learn to listen to the revelation of spirit and soul in the growing child as they existed before birth. We must learn to see in him the continuation of his sojourn in the spiritual world. Then our relationship to the eternal core of man's being will become less and less egotistical. For if we are not interested in what continues in physical life from out the spiritual world, if we are only interested in what continues after death, then we are egotistical. But to behold what continues out of the spiritual into physical existence in a certain way lays the basis for an unegotistical mood of soul.

Egotism does not ask about this continuation because it is certain that man exists, and one is satisfied with that fact. But he is uncertain whether he still exists after death, therefore he would like to have this proved. Egotism urges him on to this. But true knowledge does not accrue to man out of egotism, not even out of the sublimated egotism that is interested in the soul's continuation after death. Can one deny that the religions strongly reckon with such egotism? This must be overcome. He who is able to look into the spiritual world knows that from this conquest not only knowledge will result but an entirely different attitude toward one's human environment. We will confront the growing child with completely different feelings when we are aware that here we have the continuation of what could not tarry any longer in the spiritual world.

From this point of view just consider how the following takes on a different aspect. One could say that man was in the spiritual world before he descended into the physical world. Up there he must no longer have been able to find his goal. The spiritual world must have been unable to give to the soul what it strives for. There the urge must have arisen to descend into the physical world, to clothe oneself with a body in order to search in that world for what no longer could be found in the spiritual world as the time of birth approached.

It is a tremendous deepening of life if we adopt such a point of view in our feelings. Whereas the egotistical point of view makes man more and more abstract, theoretical, and inclines him toward head-thinking, the unegotistical point of view urges him to understand the world with love, to lay hold of it through love. This is one of the elements which must be taken up in teacher training; to look at prenatal man, and not only feel the riddle of death but also the riddle of birth.

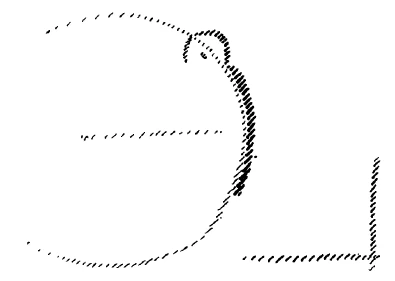

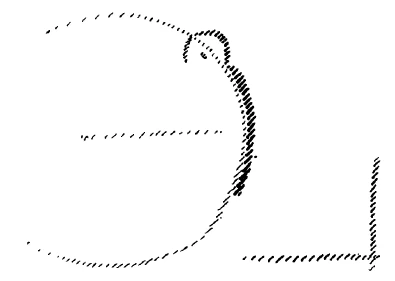

Then, however, we must learn to raise anthropology to the higher level of anthroposophy, by acquiring a feeling for the forms that express themselves in three-membered man. I said recently that the head in its spherical form is, so to say, merely placed on top of the rest of the organism. And the chest-man, he appears as if we could take a piece of the head, enlarge it, and we would have the spine. While the head bears its center within itself, the chest-man has its center at a great distance from itself. If you were to imagine this as a large head, this head then would belong to a man lying on his back. Thus, if we were to consider this spine as an imperfect head we would have a man lying horizontally, and a man standing vertically.

If we consider metabolic man, matters become still more complicated, and it is not possible to draw this in two dimensions. In short, the three members of the human organism, observed as to their plastic form, appear very different from one another. The head, we may say, is a totality; the chest-man is not a totality but a fragment; and metabolic man is much more so.

Now why is it that the human head appears self-enclosed? It is because this head, of all the members of man's organism, is to the greatest degree adapted to the physical world. This may appear strange to you because you are accustomed to consider the human head as the noblest member of man. Yet it is true that this head is to the greatest degree adapted to physical existence. It expresses physical existence in the highest degree. Thus, we may say, if we wish to characterize the physical body in its main aspects we must look toward the head. In regard to the head, man is mostly physical body. In regard to the chest organs, the organs of rhythm, man is mostly ether body. In regard to the metabolic organs, he is mostly astral body. The ego has no distinct expression in the physical world as yet.

Here we have arrived at a point of view which is very important to consider. We must say to ourselves, if we look at the human head we see the chief part of the physical body. The head expresses to the highest degree what is manifest in man. In the chest-man the ether body is more active; therefore, physically, the chest of man is less perfect than the head. And metabolic man is still less perfect, because in it the ether body is but little active and the astral body is most active. I have often emphasized that the ego is the baby; as yet it has practically no physical correlate.

So, you see we may also describe man in the following way: He consists of the physical body, characterized mostly by the sphere-form of the head; he consists of the ether body, characterized mostly by the chest section; he consists of the astral body, characterized mostly by metabolic man. We can hardly indicate anything for the ego in physical man. Thus, each of the three members—the nerve-sense system, the rhythmic system, the metabolic system—becomes an image of something standing behind it: The head the image for the physical body; the chest for the ether body; metabolism for the astral body. We must learn to observe this, not in the manner of research clinics where a corpse is investigated, and no attention is paid to the question of whether a piece of tissue belongs to the chest or the head. We must learn to realize that head, chest, and metabolic man have different relationships to the cosmos and express in picture form different principles standing behind them. This will extend the present anthropological mode of observation into the anthropomorphic one. Observed purely physically, chest and head organs have equal value. Whether you dissect the lung or the brain, from the physical aspect both are matter. From the spiritual aspect, however, this is by no means the case. If you dissect the brain you have it quite distinctly before you. If you dissect the chest, let us say the lungs, you have them quite indistinctly before you, because the ether body plays its important role in the chest while man is asleep.

What I have just discussed has its spiritual counter-image. One who has advanced through meditation, through the exercises described in our literature, gradually comes to the point where he really experiences man in his three members. You know that I speak of this threefold membering from a certain point of view in the chapter of my book, Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its Attainment, where I indicate the Guardian of the Threshold. But one can also bring about a picture of this three-membering through strong concentration upon one's self, by separating head-man, chest-man, and metabolic-man. Then one will notice what it is that makes the head into this head we have. If through inner concentration we withdraw the head from its appendage, the rest of the organism, and have it before us without the influence of the other members, the head is dead; it is no longer alive. It is impossible, clairvoyantly, to separate the head from the rest of the organism without perceiving it as a corpse. With the chest-system this is possible; it remains alive. And if you separate the astral body by separating the metabolic system, it runs away from you. The astral body does not remain in its place, it follows the cosmic movements.

Now imagine you stand before a child with the knowledge I have just developed for you, and you look at him in an unbiased way. You observe his head, how it carries death in itself. You look at the influence of the chest upon the head; it comes alive. You see the child as he starts to walk. You notice that it is the astral body that is active in walking. Now the child becomes something inwardly transparent to you. The head—a corpse; the outspreading life in him when he stands still, is quiet. The moment he begins to walk you notice that it is the astral body that walks. Man can walk because this astral body uses up substances in moving, metabolism is active in a certain way. How can we observe the ego?—for everything now has been exhausted, so to say. You observe the head-man, the life-giving element of the chest-man, the walking. What remains by which we might observe the ego externally? I have already stated that the ego hardly has an external correlate. You can see the ego only if you observe a child in his increasing growth. At one year he is very little; at two he is bigger, and so on. As you connect your impressions of him year after year, then join in your mind what he is in the successive years, you see the ego physically. You never see the ego in a child if you merely confront him, but only when you see him grow. If men would not surrender to illusions but see reality they would be aware of the fact that when they meet a person they cannot physically perceive his ego, only when they observe him in the various periods of his life. If you meet a man again after twenty years you will perceive his ego vividly in the change that has taken place in him; especially if twenty years ago you saw him as a child.

Now I beg you not to ponder just theoretically what I have said. I ask you to enliven your thoughts and consider this when you observe man: Head—corpse; chest—vitalization; the astral body in walking; the ego through growing. Thus, the whole man comes alive who previously confronted you like a wax doll. For what is it that we ordinarily see of man with our physical eyes and our intellect? A wax doll! It comes alive if you add what I have just described.

In order to do this, you need to have your perception permeated by what spiritual science can pour into your feelings, into your relationship to the world. A walking child discloses to you the astral body. The gesture of his walking—every child walks differently—stems from the configuration of his astral body. Growth expresses something of the ego.

Here karma works strongly in man. As an example, somewhat removed from our present age, take Johann Gottlieb Fichte. I have characterized him for you from various aspects, as a great philosopher, as a Bolshevist, and so on. Now let us look at him from another point of view, imagining him as he passed us by on the street and we watched him as he went. We would see a man, stocky, not very tall. What does the manner in which he has grown, disclose? He is stunted. He puts his feet, heels first, firmly on the ground. The whole Fichte-ego expresses itself in this. Not a detail of the man do we miss when we observe him so—his growth stunted by hunger in his youth, stocky, putting his heels down firmly. We could hear the manner of his speech by observing him in this way from behind.

You see, a spiritual element can enter into the externalities of life, but this does not occur unless men change their attitude. For people today, such observation of their fellowmen might be an evil indiscretion, and it would not be very desirable if this were to spread. People have been so influenced by ever-growing materialism that they, for instance, refrain from opening letters that do not belong to them only because it is prohibited; otherwise they would do it. With such an attitude, things cannot change. But the more we grow toward the future the more must we learn to take in spiritually what surrounds us in the sense world. The start must be made with the pedagogical activity of the teacher in regard to the growing child. Physiognomic pedagogy; the will to solve the greatest riddle, MAN, in every single individual, through education.

Now you can feel how strong is the test for mankind in our times. What I have discussed here really presses forward toward individualization, toward the consideration of every human being as an entity in himself. As a great ideal the thought must hover before us that no one person duplicates another; every single individual is a being in himself. Unless we learn to acknowledge that everyone is an entity in himself mankind will not attain its goal on earth. But how far removed we are today from the attitude that strives for this goal! We level human beings down. We do not test them in regard to their individual qualities. Hermann Bahr, of whom I have often spoken to you, disclosed once how the education of our times tends to do away with individualization. He participated in the social life of the 1890's in Berlin, and one evening at a dinner party he was seated of course with one lady at his right, another at his left. The next evening he sat again between two ladies, but only from the place cards could he gather that they were two different ladies. He did not look at them very attentively because, after all, the lady of yesterday and the lady of today did not look any different. What he saw in them was exactly the same. The culture of society, and especially of industry, makes every human being appear the same, externally, not permitting the individuality to emerge. Thus, present-day man strives for leveling, whereas the inmost goal of man must be his striving for individualization. We cover up individuality, whereas it is most important to seek it.

In his instruction the teacher must begin to direct his insight toward the individuality. Teacher training has to be permeated by an attitude which strives to find the individuality in men. This can only come about through an enlivening of our thoughts about man as I have described it. We must really become conscious of the fact that it is not a mechanism that moves one forward, but the astral body; it pulls the physical body along. Compare what thus can arise in your souls as an inwardly enlivened and mobile image of the whole human being, with what ordinary science offers today—a homunculus, a veritable homunculus! Science says nothing about man, it preaches the homunculus. The real human being above everything else must come into pedagogy, for now he is completely outside of it.

The question of education is a question of teacher training, and as long as this fact is not recognized nothing fruitful can come into education. You see, from a higher point of view things so belong together that one can make a true connection between them. Today one strives to develop man's activities as subjects side by side. A student learns anthropology, he learns about religion; the subjects have nothing to do with each other. In fact, as you have seen, what one observes about man borders on the question of immortality, of the eternal essence of human nature. We had to link this question to one's immediate perception of man. It is this mobility of soul experience which must enter education. Then, inner faculties quite different from those developed today in teacher training schools will come into being. This is of great importance.

Today I wished to put before you the fact that the science of the spirit must permeate everything, and that without it the great social problems of the present time cannot be solved.

Vierter Vortrag

Aus den letzten Betrachtungen, die wir hier angestellt haben, werden Sie ersehen haben, daß innerhalb der vielen Fragen, die die Gegenwart beschäftigen, die Erziehungsfrage die allerwichtigste ist. Wir haben ja betonen müssen, daß die ganze soziale Fragestellung in sich schließt als hauptsächlichstes Moment gerade die Erziehungsfrage. Und nachdem ich einiges vor acht Tagen angedeutet habe über die Umgestaltung, die Umwandlung des Erziehungswesens, werden Sie es begreiflich finden, daß wiederum innerhalb der Erziehungsfrage die bedeutsamste Unterfrage die nach der Bildung der Lehrer selbst ist. Wenn man den Charakter der Zeitepoche, die verflossen ist in genauer Abgrenzung seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts, auf sich wirken läßt, so bekommt man ja, wie Sie wissen, den Eindruck: durch die Menschheitsentwickelung ging hindurch in dieser Zeit die Welle der materialistischen Prüfungen. Und wir leben in der Gegenwart in der Notwendigkeit, aus der materialistischen Welle uns herauszuarbeiten und den Weg zum Geiste zurückzufinden; den Weg zum Geiste, der ja in älteren Kulturepochen der Menschheit bekannt war, der aber damals gegangen wurde von der Menschheit mehr oder weniger instinktiv, unbewußt, der verloren worden ist, damit die Menschheit ihn aus eigenem Antriebe, aus eigener Freiheit heraus suchen könne, und der nun bewußt, voll bewußt gesucht werden muß.

Der Übergang, durch den die Menschheit durchgehen mußte seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts, ist eben das, was man nennen könnte die materialistische Prüfung der Menschheit. Läßt man den Charakter dieser materialistischen Zeit auf sich wirken und betrachtet man dann mit dem, was man dadurch einsieht, die Kulturentwickelung in den letzten drei bis vier Jahrhunderten und bis in unsere Zeit herein, dann findet man, daß am meisten ergriffen worden ist von der materialistischen Welle, am intensivsten in Anspruch genommen worden ist von dieser materialistischen Welle gerade die Lehrerbildung. Alles übrige würde einen so nachhaltigen Eindruck nicht üben können wie die Durchsetzung der pädagogisch-didaktischen Anschauung mit materialistischer Gesinnung. Man braucht nur in verständiger Weise auf Einzelheiten zu sehen in unserem gegenwärtigen Unterrichtswesen, und man wird die ganze Schwierigkeit, die für einen wirklich fruchtbaren Fortschritt vorliegt, ins Auge fassen können. Bedenken Sie, daß immer wieder und wieder wiederholt wird gerade bei denjenigen Menschen, die heute glauben, besonders gut in Erziehungsfragen sprechen zu können, aller Unterricht müsse schon von der untersten Schulstufe ab anschaulich sein — was man eben so anschaulich nennt. Ich habe Sie ja öfter darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie man zum Beispiel den Rechenunterricht anschaulich machen will: Rechenmaschinen stellt man in der Schule auf! Man legt einen großen Wert darauf, daß gewissermaßen das Kind schon alles anschauen könne und dann aus der Anschauung sich erst Vorstellungen aus dem eigenen Inneren seiner . Seele heraus bilde. Dieser Trieb nach Anschaulichkeit im Erziehungswesen, er ist gewiß auf sehr vielen Gebieten der Pädagogik voll berechtigt. Aber er zwingt doch die Frage aufzuwerfen: Was wird aus dem Menschen, wenn er nur durch einen Anschauungsunterricht durchgeht? Wenn der Mensch nur durch einen Anschauungsunterricht durchgeht, dann wird er seelisch völlig ausgedörrt, dann ersterben nach und nach die inneren Triebkräfte der Seele; dann bildet sich eine Verbindung der ganzen menschlichen Wesenheit mit der anschaulichen Umgebung. Und dasjenige, was aus dem Innern der Seele sprießen sollte, das wird allmählich in der Seele ertötet. Und auf Ertötung des Seelischen geht vieles gerade wegen der Anschaulichkeit des gegenwärtigen Unterrichts aus. Man weiß natürlich nicht, daß man die Seele ertötet, aber man ertötet sie in Wirklichkeit. Und die Folge davon ist das - ich habe das von anderen Gesichtspunkten aus schon erwähnt -, was wir an den Menschen der Gegenwart erleben. Wie viele Menschen der Gegenwart sind eigentlich problematische Naturen. Wie viele Menschen der Gegenwart wissen in reiferen Jahren nicht aus ihrem eigenen Innern herauszuholen das, was ihnen in schwierigen Zeiten Trost und Hoffnung bieten könnte, um den verschiedenen Lagen des Lebens gewachsen zu sein. Wir sehen in der Gegenwart viele gebrochene Naturen, und uns selber kommt es wohl in besonderen Augenblicken an, wie wir uns nicht zurechtfinden können.

Das alles hängt zusammen mit den Mängeln unseres Erziehungswesens und namentlich mit den Mängeln der Lehrerbildung. Was wäre nun für eine gedeihliche Zukunft gerade in bezug auf die Lehrerbildung anzustreben? Sehen Sie, daß der Lehrer schließlich dasjenige weiß, was er gewöhnlich abgefragt wird bei den Prüfungen, das ist eigentlich eine untergeordnete Sache, denn da wird er ja zumeist über Dinge gefragt, die er vor den Stunden in irgendeinem Handbuch sich aufschlagen könnte, auf die er sich, wenn er sie braucht, vorbereiten könnte. Dasjenige aber, worauf bei den Prüfungen gar nicht gesehen wird, das ist die allgemeine Seelenverfassung des Lehrers, das ist dasjenige, was geistig immerfort übergehen muß von ihm auf seine Schüler. Es ist ein großer Unterschied, ob der eine Lehrer das Klassenzimmer betritt oder der andere. Wenn der eine Lehrer durch die Tür des Klassenzimmers tritt, so fühlen die Kinder oder die Schüler eine gewisse Verwandtschaft mit der eigenen Seelenstimmung; wenn ein anderer Lehrer die Klasse betritt, fühlen die Kinder oder die Schüler oftmals eine solche Verwandtschaft gar nicht; im Gegenteil, sie fühlen eine Kluft zwischen sich und dem Lehrer, und alle möglichen Schattierungen von Gleichgültigkeit bis zu dem, was sich ausspricht im Komischfinden des Lehrers, in dem Spotten über den Lehrer. Alle die Nuancen, die dazwischen liegen, finden sich oftmals recht sehr zum Ruinieren des wirklichen Unterrichtes und der wirklichen Erziehung.

Die Frage ist daher in erster Linie brennend: Wie kann die Lehrerbildung in die Zukunft hinein umgewandelt werden? Sie kann nicht anders umgewandelt werden als dadurch, daß der Lehrer aufnimmt in sich dasjenige, was aus der Geisteswissenschaft kommen kann an Erkenntnissen über die Natur des Menschen. Der Lehrer muß durchdrungen sein von dem Zusammenhang des Menschen mit den übersinnlichen Welten. Er muß in der Lage sein, in dem heranwachsenden Kinde das Zeugnis dafür zu sehen, daß dieses Kind heruntergestiegen ist aus der übersinnlichen Welt durch Empfängnis oder Geburt und daß das, was heruntergestiegen ist, sich mit dem Leib umkleidet hat, sich etwas aneignet, wozu er zu helfen hat hier in der physischen Welt, weil das Kind sich es nicht aneignen kann in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt.

Als Frage der übersinnlichen Welt an die sinnliche, so sollte eigentlich vor dem Gemüte des Lehrenden oder Erziehenden jedes Kind stehen. Diese Frage wird man sich nicht im konkreten, im umfassenden Sinne aufwerfen können, namentlich nicht jedem einzelnen Kinde gegenüber, es sei denn, daß man die Erkenntnisse verwenden kann, die über die Natur des Menschen aus der Geisteswissenschaft kommen. Die Menschheit hat sich allmählich im Laufe der drei bis vier letzten Jahrhunderte immer mehr und mehr angewöhnt, den Menschen zu sehen, ich möchte sagen, bloß physiologisch, bloß auf seine äußere leibliche Konstitution hin. Am schädlichsten ist diese Anschauung vom Menschen für den Erzieher, für den Unterrichter. Daher wird vor allen Dingen notwendig sein, daß eine in der Anthroposophie sich ergebende Anthropologie die Grundlage der Zukunftspädagogik werde. Das kann aber nicht anders geschehen als dadurch, daß der Mensch wirklich von den Gesichtspunkten aus ins Auge gefaßt wird, die wir öfter hier berührt haben und die ihn in mancherlei Beziehung charakterisieren als ein dreigliedriges Wesen. Aber man muß sich entschließen dazu, diese Dreigliederung wirklich innerlich zu erfassen. Ich habe Sie wiederholt von den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten aus darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie der Mensch, so wie er vor uns steht, zerfällt in das, was er zunächst als Nerven-Sinnes-Mensch ist, wasman populär so ausdrücken kann, daß man sagt: Zunächst ist der Mensch Kopfmensch, Hauptesmensch. Als zweites Glied der menschlichen Wesenheit, äußerlich betrachtet, haben wir denjenigen Menschen, in dem sich hauptsächlich die rhythmischen Vorgänge abspielen, den Brustmenschen; und dann, wie Sie ja wissen, zusammenhängend mit dem ganzen Stoffwechselsystem den Gliedmaßenmenschen, den Stoffwechselmenschen, in dem sich eben der Stoffwechsel als solcher abspielt. Dasjenige, was der Mensch als tätiges Wesen ist, das erschöpft sich äußerlich in der Bildgestalt, in der physischen Bildgestalt des Menschen in diesen drei Gliedern der menschlichen Gesamtnatur.

Notieren wir uns einmal diese drei Glieder der menschlichen Gesamtnatur: Kopfmensch oder Nerven-Sinnes-Mensch, Brustmensch oder rhythmischer Mensch und dann Gliedmaßenmensch, im weitesten Sinne natürlich, oder Stoffwechselmensch.

Nun handelt es sich darum, daß man diese drei Glieder der menschlichen Natur in ihrem Unterschiede voneinander erfaßt. Das ist ja für den Menschen der Gegenwart unbequem, denn der Mensch der Gegenwart liebt schematische Einteilungen. Er möchte sich, wenn man sagt: der Mensch besteht aus Kopfmensch, Brustmensch, Gliedmaßenmensch, am liebsten da einen Strich machen am Halse, was drüber ist, ist Kopfmensch. Dann möchte er sich wieder anderswo einen Strich machen, eine Linie ziehen, um den Brustmenschen zu begrenzen, und so möchte er die eingeteilten Glieder nebeneinander haben. Was sich nicht so schematisch nebeneinanderstellen läßt, darauf läßt sich der Mensch der Gegenwart nicht gerne ein.

Aber so ist es in der Wirklichkeit nicht; die Wirklichkeit macht nicht solche Striche. Der Mensch ist zwar über den Schultern hauptsächlich Kopfmensch, Nerven-Sinnes-Mensch. Aber er ist nicht allein über den Schultern Nerven-Sinnes-Mensch; zum Beispiel der Gefühlssinn, der Wärmesinn sind über den ganzen Leib ausgedehnt, so daß der Kopf über den ganzen Leib wiederum reicht. Also man kann, wenn man so sprechen will, sagen: der menschliche Kopf ist hauptsächlich Kopf. Und die Brust ist eben weniger Kopf, aber auch noch Kopf. Die Gliedmaßen oder alles, was Stoffwechselsystem ist, sind noch weniger Kopf, aber auch Kopf. So daß man also eigentlich sagen muß: der ganze Mensch ist Kopf, nur der Kopf ist hauptsächlich Kopf. Wollte man also schematisch zeichnen, so müßte man etwa, wenn man wollte den Kopfmenschen zeichnen, ihn so zeichnen (siehe Zeichnung, helle Schraffur).

Der Brustmensch ist wiederum nicht bloß in der Brust, er ist hauptsächlich in den Brustorganen, in den Organen, in denen sich das Herz und der Atmungsrhythmus am deutlichsten ausdrücken. Aber die Atmung setzt sich auch in den Kopf hinein fort, die Blutzirkulation in ihrem Rhythmus setzt sich in den Kopf hinein fort und in die Gliedmaßen. So daß man sagen kann: der Mensch ist Brust allerdings in dieser Gegend; aber er ist auch hier - zwar weniger — Brust (siehe Zeichnung, mittlere Schraffur) und hier — wiederum weniger Brust. Also wiederum der ganze Mensch ist Brust, aber in der Hauptsache ist das die Brust, das der Kopf.

Und wiederum der Gliedmaßen- und Stoffwechselmensch, ja er ist schon in der Hauptsache dieses (siehe Zeichnung, dunkle Schraffur); aber diese Gliedmaßen setzen sich wiederum so fort, daß sie weniger sind in der Brust und am wenigsten im Kopfe.

Also ebenso wahr, wie man sagen kann: der Kopf ist Kopf, kann man sagen: der ganze Mensch ist Kopf. Ebenso wahr, wie man sagen kann: die Brust ist Brust, kann man sagen: der ganze Mensch ist Brust und so weiter. Die Dinge schwimmen ineinander in der Wirklichkeit. Und unser Begreifen ist so veranlagt, daß wir gerne so nebeneinanderstellen die Teile, die Glieder. Dieses zeigt uns, wie wenig wir mit Bezug auf unsere Erkenntnisvorstellungen verwandt sind der äußeren Wirklichkeit. In der äußeren Wirklichkeit schwimmen die Dinge ineinander. Und wir müssen, wenn wir auf der einen Seite trennen; Kopf-, Brust-, Stoffwechselmensch, uns bewußt sein, daß wir dann die getrennten Glieder wieder zusammendenken müssen. Wir dürfen eigentlich niemals bloß auseinanderdenken, wir müssen immer auch wieder zusammendenken. Ein denkender Mensch, der nur auseinanderdenken wollte, der gleicht einem Menschen, der nur einatmen, nicht aber ausatmen wollte.

Damit haben Sie gleich etwas gegeben, was eintreten muß namentlich für das Denken der Lehrer der Zukunft; die müssen ganz besonders in sich aufnehmen dieses innerlich bewegliche Denken, dieses unschematische Denken. Denn nur dadurch, daß sie dieses unschematische Denken in sich aufnehmen, kommen sie mit ihrer Seele der Wirklichkeit nahe. Aber man wird der Wirklichkeit nicht naliekommen, wenn man nicht dieses Nahekommen von einem gewissen größeren Gesichtspunkte aus als Zeiterscheinung aufzufassen in der Lage ist. Man muß die Vorliebe, welche man gegen die Gegenwart herein immer mehr entwickelt hat, sich an die Details des Lebens zu halten, wenn man Wissenschaftliches ins Auge faßt, man muß diese Vorliebe überwinden und muß dahin kommen, die Details des Lebens an die großen Lebensfragen anzuknüpfen.

Und bedeutsam wird eine Frage werden für alle Entwickelung der Geisteskultur in die Zukunft hinein: das ist die Unsterblichkeitsfrage. Man wird sich klar werden müssen darüber, wie eigentlich ein großer Teil der Menschheit diese Unsterblichkeit auffaßt, namentlich seit der Zeit, in welcher viele Menschen sogar schon bis zur Leugnung der Unsterblichkeit gekommen sind. Was lebt eigentlich in den meisten Menschen, die heute noch aus den Untergründen der gebräuchlichen Religionen heraus über Unsterblichkeit sich unterrichten wollen, was lebt in diesen Menschen? Es lebt in diesen Menschen der Drang, etwas zu wissen darüber, was mit der Seele wird, wenn der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes durchgegangen ist.

Wenn wir fragen nach dem Interesse, das die Menschen nehmen an der Unsterblichkeitsfrage, besser gesagt, an der Frage nach der Ewigkeit des menschlichen Wesenskernes, so bekommen wir keine andere Antwort, als: das hauptsächlichste Interesse an der Ewigkeit des menschlichen Wesenskernes knüpft sich eben daran: Was wird mit dem Menschen, wenn er die Pforte des Todes durchschreitet? Der Mensch ist sich bewußt: er ist ein Ich. In diesem Ich lebt sein Denken, Fühlen und Wollen. Der Gedanke ist ihm unerträglich, dieses Ich etwa vernichtet zu wissen. Daß er es durch den Tod tragen kann, und was mit dem Ich nach dem Tode wird, das interessiert die Menschen vor allen Dingen. Daß es so mit diesem Interesse gekommen ist, das beruht im wesentlichen darauf, daß ja die, wenigstens für uns hier zunächst in Betracht kommenden Religionssysteme, wenn sie von der Unsterblichkeit sprechen, von der Ewigkeit des menschlichen Wesenskernes hauptsächlich im Auge haben eben die Frage: Was wird mit der Menschenseele, wenn der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes geht?

Nun müssen Sie fühlen, daß man der Unsterblichkeitsfrage, wenn man sie so stellt, einen außerordentlich stark egoistischen Beigeschmack gibt. Es ist im Grunde genommen ein egoistischer Trieb, der dem Menschen das Interesse einflößt, zu wissen, was mit seinem Wesenskern wird, wenn er die Pforte des Todes durchschreitet. Und würden die Menschen der Gegenwart, mehr als sie das tun, so recht Selbsterkenntnis üben, würden sie mit sich zu Rate gehen und sich nicht so stark Illusionen hingeben, als das der Fall ist, dann würden die Menschen schon einsehen, wie stark der Egoismus mitwirkt bei dem Interesse, etwas über das Schicksal der Seele nach dem Tode zu wissen.

Diese Art der Seelenstimmung ist nun ganz besonders stark wiederum geworden in der Zeit der materialistischen Prüfung in den letzten drei bis vier Jahrhunderten. Und man kann das, was so die Seele des Menschen wie eine innere Empfindungs- und Denkgewohnheit ergriffen hat, nicht etwa durch Theorien oder Lehren überwinden, wenn diese Theorien oder Lehren nur abstrakte Form haben. Aber die Frage muß doch aufgeworfen werden: Kann es so bleiben? Darf bei der Frage nach dem ewigen Wesenskern des Menschen nur Egoistisches in der Menschennatur sprechen?

Wenn man alles, was mit diesem Fragenkomplex zusammenhängt, ins Auge faßt, dann muß man sich sagen: Daß das so geworden ist mit der menschlichen Seelenstimmung, wie ich es eben charakterisiert habe, das rührt im wesentlichen davon her, daß von den Religionen vernachlässigt worden ist der andere Gesichtspunkt: anzuschauen den Menschen, indem er geboren wird, indem er hereinwächst in die Welt vom ersten kindlichen Schrei, in dieser wunderbaren Weise, wie sich immer mehr und mehr die Seele hineindrängt in die Körperlichkeit, anzuschauen den Menschen, wie da in ihm sich herauflebt das, was vorgeburtlich in der geistigen Welt gelebt hat. Wie oft wird denn heute die Frage aufgeworfen: Was setzt sich fort aus dem geistigen Gebiete, wenn der Mensch geboren wird, mit dem physischen Menschen? Danach frägt man immer wieder und wieder: Was setzt sich fort, wenn der Mensch stirbt? Danach aber frägt man wenig: Was setzt sich fort, wenn der Mensch geboren wird?

Darauf ist die Hauptaufmerksamkeit zu richten in der Zukunft. Wir müssen gewissermaßen lernen, abzulauschen dem heranwachsenden Menschen die Offenbarung des Geistig-Seelischen, wie es war vor der Geburt oder vor der Empfängnis. Wir müssen lernen, in dem heranwachsenden Kinde die Fortsetzung seines Aufenthaltes in der geistigen Welt zu sehen: dann wird unser Verhältnis zu dem ewigen Wesenskern des Menschen immer unegoistischer und unegoistischer werden. Wenn einen nämlich nicht interessiert, was sich fortsetzt mit dem physischen Leben aus der geistigen Welt heraus, sondern nur interessiert, was sich fortsetzt hinter dem Tode, dann ist man innerlich egoistisch. Es begründet in einer gewissen Weise eine unegoistische Seelenstimmung, auf dasjenige hinzuschauen, was sich aus dem Geistigen fortsetzt in das physische Dasein hinein.

Der Egoismus, der frägt aus dem Grunde nicht nach dieser Fortsetzung, weil er ja dessen gewiß ist, daß er da ist, der Mensch, und er ist zufrieden damit, daß er da ist. Er ist nur dessen nicht gewiß, daß er auch noch nach dem Tode da ist; daher möchte er sich das beweisen lassen. Dazu treibt ihn der Egoismus. Aber die wahre Erkenntnis wird nicht dem Menschen aus dem Egoismus heraus, auch nicht aus jenem sublimierten Egoismus, den wir jetzt eben charakterisiert haben als erzeugend das Interesse an der Fortsetzung des seelischen Daseins nach dem Tode. Und ist es denn eigentlich zu leugnen, daß die Religionen gar sehr spekulieren auf diesen eben gekennzeichneten Egoismus? Dieses Spekulieren auf den eben gekennzeichneten Egoismus, das muß überwunden werden. Und der, welcher hineinschaut in die geistige Welt, der weiß, daß diese Überwindung mit sich bringen wird nicht bloß Erkenntnisse — diese Überwindung wird mit sich bringen eine ganz andere Einstellung des Menschen zu seiner menschlichen Umgebung. Man wird ganz anders fühlen und empfinden mit dem kindlich heranwachsenden Menschen, wenn man immer darauf hinschaut, wie sich fortsetzt das, was nicht mehr bleiben konnte in der geistigen Welt.

Bedenken Sie doch nur einmal, wie sehr sich eine Frage gerade von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus verschiebt. Man könnte sagen: Der Mensch war in der geistigen Welt, bevor er durch Empfängnis oder Geburt heruntergestiegen ist in die physische Welt. Da oben muß es also gewesen sein, daß er sein jeweiliges Ziel nicht mehr gefunden hat. Die geistige Welt muß ihm das nicht mehr gegeben haben, was die Seele anstrebt. Und aus der geistigen Welt heraus muß sich der Drang ergeben haben, herunterzusteigen in die physische Welt, sich mit einem Leib zu umkleiden, um das in der physischen Welt zu suchen, was nicht mehr in der geistigen Welt gesucht werden konnte, als die Zeit nahe der Geburt zuging.

Es ist eine ungeheure Vertiefung des Lebens, wenn man den Gesichtspunkt so — aber jetzt fühlend und empfindend — zu nehmen weiß. Während der eine Gesichtspunkt, der egoistische, immerzu den Menschen dazu drängt, abstrakter und abstrakter zu werden, ins Theoretische einzulaufen, dem Kopfdenken sich zuzuneigen, wird das, was nach dem anderen, dem unegoistischen Gesichtspunkte hingeht, den Menschen immer mehr und mehr dazu drängen, die Welt in Liebe zu erkennen und durch Liebe zu begreifen. Das ist eines der Elemente, die in der Lehrerbildung werden aufgenommen werden müssen: hinzuschauen auf den vorgeburtlichen Menschen, nicht also nur das Rätsel des Todes zu empfinden, sondern auch zu empfinden dem Leben gegenüber das Rätsel der Geburt.

Dann aber muß gelernt werden, Anthropologie zu erhöhen zu Anthroposophie dadurch, daß man nun wirklich ein Gefühl sich aneignet für die Formen, die sich in dem dreigegliederten Menschen ausdrücken. Ich sagte schon neulich: Ja, ist denn nicht dieses Haupt des Menschen, das, was hauptsächlich Haupt ist, in einer ganz anderen Form kugelig, nur aufgesetzt dem übrigen Organismus? (siehe Zeichnung). Und wiederum, wenn wir den Brustmenschen nehmen, wie erscheint er uns? Er erscheint uns eigentlich so, daß wir ein Stück des Kopfes nehmen könnten, es nun vergrößern, und hier das Rückgrat haben würden (siehe Zeichnung). Während der Kopf seinen Mittelpunkt in sich trägt, trägt der Brustmensch den Mittelpunkt sehr weit von sich weg. Und würden Sie sich das gleichsam wie einen großen Kopf denken, so würde er, dieser große Kopf, angehören etwa einem auf dem Rücken liegenden Menschen. So daß wir haben würden, wenn wir die Wirbelsäule wie einen unvollkommenen Kopf betrachten, einen horizontal liegenden Menschen, und einen vertikal stehenden Menschen.

Noch komplizierter, so daß man gar nicht in der Lage ist, das in die Ebene zu zeichnen, wird das, wenn wir den Stoffwechselmenschen ins Auge fassen würden. Kurz, für eine Formbetrachtung, für eine Betrachtung der plastischen Form, stellen sich die drei Glieder der menschlichen Natur ganz verschieden vor. Der Kopf ist gleichsam eine Totalität, der Brustmensch ist keine Totalität, das ist ein Fragment; und gar erst der Stoffwechselmensch!

Nun, wodurch ist der menschliche Kopf, das menschliche Haupt, dieses in sich Abgeschlossene? Dieses in sich Abgeschlossene ist das menschliche Haupt dadurch, daß von allen Gliedern des Menschen dieses menschliche Haupt am meisten angepaßt ist der physischen Welt. So sonderbar Ihnen das scheinen mag, weil Sie ja gewohnt sind, das menschliche Haupt als das edelste Glied des Menschen zu betrachten, so richtig ist es doch, daß dieses menschliche Haupt am meisten angepaßt ist dem physischen Dasein. Das Haupt drückt am meisten vom physischen Dasein aus. So daß man sagen kann: Will man den physischen Leib in der Hauptsache charakterisieren, so muß man nach dem Kopfe hinschauen. In bezug auf den Kopf ist der Mensch am meisten physischer Leib. In bezug auf die Brustorgane, auf die Rhythmusorgane ist der Mensch am meisten Ätherleib; in bezug auf die Stoffwechselorgane ist der Mensch am meisten astralischer Leib. Und das Ich, das hat überhaupt noch nichts Deutliches in der physischen Welt ausgeprägt.

Hier sind wir bei einem Gesichtspunkte angelangt, der außerordentlich wichtig ist ins Auge zu fassen. Sie müssen sich diesen Gesichtspunkt so zurechtlegen, daß Sie sich sagen: Sehe ich das menschliche Haupt an, also das, was ich weiß gezeichnet habe (siehe Zeichnung Seite 72, helle Schraffur), so habe ich das Hauptsächlichste auch vom physischen Leib. Das Haupt bringt am meisten zum Ausdrucke, was im Menschen offenbar ist. Im Brustmenschen, da ist der Ätherleib mehr tätig. Im Kopf ist der Ätherleib am wenigsten tätig, in der Brust ist der Ätherleib viel mehr tätig. Daher ist physisch genommen der Brustteil des Menschen unvollkommener als der Kopf. Physisch genommen ist er unvollkommener. Und erst recht unvollkommen ist der Stoffwechselmensch, weil da wiederum der Ätherleib ganz wenig tätig ist und der astralische Leib am meisten tätig ist. Und wie ich oftmals betont habe: Das Ich ist ja noch das Baby, hat noch kaum ein physisches Korrelat.

Also Sie sehen, man kann den Menschen auch so beschreiben, daß man sagt: Der Mensch besteht aus dem physischen Leib. Willst du dir die Frage beantworten: Was ist am ähnlichsten dem physischen Leib des Menschen? so lautet die Antwort: Die Kopfkugel. Der Mensch besteht aus dem Ätherleibe. Was ist am ähnlichsten dem Ätherleibe? Das Brustfragment. Der Mensch besteht aus astralischem Leib. Was ist am ähnlichsten dem astralischen Leib? Der Stoffwechselmensch. Für das Ich hat man kaum auf etwas hinzudeuten im physischen Menschen. So wird jedes der drei Glieder des Menschen, Kopf, Nerven-Sinnes-Mensch, der Brustmensch, der rhythmische Mensch und der Stoffwechselmensch zum Bilde für etwas Dahinterstehendes: der Kopf zum Bilde für den physischen Leib, die Brust zum Bilde für den ÄÄtherleib, der Stoffwechsel zum Bilde für den astralischen Leib. Das wird man lernen müssen, nicht so zu betrachten, wie man heute den Menschen betrachtet, indem man den Leichnam in der Klinik untersucht, ein Stück als Gewebe oder so etwas betrachtet, gleichgültig ob es in der Brust oder im Kopfe ist. Man wird lernen müssen, sich zu sagen: Kopf-, Brust- und Stoffwechsel-Mensch stehen in verschiedenen Beziehungen zum Kosmos, drücken bildhaft verschiedenes Dahinterstehendes aus. Das wird erweitern die heutige bloß anthropologische Betrachtungsweise ins Anthroposophische hinein. Rein physisch betrachtet sind Brustorgane und Kopforgane gleichwertig. Ob Sie schließlich die Lunge sezieren oder das Gehirn sezieren, physisch genommen ist das eine wie das andere Materie. Geistig genommen ist dies keineswegs der Fall. Geistig genommen ist das so, daß, wenn Sie das Gehirn seziieren, Sie wirklich das ziemlich deutlich vor sich haben, was Sie sezieren. Wenn Sie die Brust sezieren, zum Beispiel die Lunge, da haben Sie das schon recht undeutlich vor sich, was Sie sezieren, denn da spielt der Ätherleib eine eminent wichtige Rolle darinnen, während der Mensch schläft.

Die Sache, die ich eben jetzt auseinandergesetzt habe, hat ihr geistiges Gegenbild. Derjenige, der etwas vorgeschritten ist durch Meditation, durch solche Übungen, wie Sie sie beschrieben finden in unserer Literatur, der kommt allmählich dazu, den Menschen wirklich dreizugliedern. Sie wissen, ich spreche von dieser Dreigliederung von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus in dem Kapitel meines Buches «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?», wo auf den Hüter der Schwelle hingedeutet wird. Aber man kann die Dreigliederung so auch vollziehen durch starke Konzentration auf sich selbst: daß man nun wirklich Kopfmenschen (siehe Zeichnung, helle Schraffur), Brustmenschen (mittlere Schraffur) und Stoffwechselmenschen (dunkle Schraffur) trennt. Dann merkt man, wodurch der Kopf dieser Kopf eigentlich ist, den wir haben. Sehen Sie, wenn Sie durch innere Konzentration den Kopf herausziehen mit seinem Anhange, herausziehen aus dem übrigen menschlichen Organismus und dann als wirklichen Kopf unbeeintlußt von den anderen Gliedern der Menschennatur vor sich haben, dann ist er tot, dann lebt er nicht mehr. Sie können hellseherisch unmöglich den Kopf abgliedern von dem übrigen menschlichen Organismus, ohne daß Sie ihn als Leichnam wahrnehmen. Beim Brustmenschen können Sie das, der bleibt lebendig. Und wenn Sie den astralischen Leib abtrennen dadurch, daß Sie abtrennen den Stoffwechselmenschen, dann läuft er Ihnen davon, der astralische Mensch, dann bleibt er nicht an dem Orte, dann folgt er den kosmischen Bewegungen, denn er hat das Astralische in sich.

Und jetzt denken Sie sich einmal, Sie stehen vor einem Menschenkinde, Sie schauen es mit solchen Erkenntnissen unbefangen und vernünftig an, wie ich sie eben auseinandergesetzt habe. Dann blicken Sie hin auf das menschliche Haupt: es trägt den Tod in sich; Sie blicken hin auf dasjenige, was das Haupt beeinflußt von der Brust aus: es belebt alles. Sie blicken hin, wenn das Kind anfängt zu laufen, Sie merken: das ist der astralische Leib eigentlich, der da im Laufen drinnen tätig ist. Jetzt wird Ihnen die menschliche Wesenheit etwas innerlich Durchschaubares. Der Kopf — Leichnam; das sich ausbreitende Leben in dem Menschen stillstehend, wenn er ganz ruhig sein würde. Im Augenblick, wo er zu laufen beginnt, merken Sie sogleich: der astralische Leib ist es eigentlich, der läuft; und er kann laufen, weil dieser astralische Leib beim Laufen, beim Bewegen Stoffe verbraucht, der Stoffwechsel ist tätig in einer gewissen Weise. Das Ich, wie kann man das beobachten? Es ist eigentlich jetzt schon alles erschöpft. Wenn Sie verfolgen den Kopf-Leichnam, das Belebende des Brustmenschen, das Laufen, was bleibt noch übrig, um das Ich äußerlich anzuschauen? Ich sagte Ihnen, das Ich hat kaum ein physisches Korrelat. Sie schauen das Ich nur an, wenn Sie den Menschen in seinem aufsteigenden Wachstum betrachten. Mit einem Jahr, da ist er ganz klein, mit zwei Jahren größer und so weiter. Wenn Sie ihn so größer und größer werden sehen, wenn Sie zusammenfügen dasjenige, was er in den aufeinanderfolgenden Zeiten ist, dann sehen Sie physisch das Ich an. Sie sehen das Ich niemals im Menschen, wenn Sie ihm nur gegenüberstehen, sondern das Ich sehen Sie erst dadurch, daß Sie den Menschen wachsen sehen. Würden sich die Menschen nicht Illusionen hingeben, sondern die Wirklichkeit sehen, dann würden sie sich klar sein darüber, daß sie in dem Menschen, der einem nur so einfach begegnet, physisch gar nicht das Ich so ohne weiteres wahrnehmen, daß sie das Ich eigentlich nur wahrnehmen, wenn sie den Menschen in verschiedenen Lebensaltern betrachten. Wenn Sie aber einen Menschen später wiedersehen nach zwanzig Jahren, dann nehmen Sie sehr stark sein Ich wahr an der Veränderung, die mit ihm vorgegangen ist, insbesondere wenn Sie ihn vor zwanzig Jahren als Kind gesehen haben.

Nun bitte ich Sie, das, was ich gesagt habe, nicht theoretisch bloß zu durchdenken, sondern ich bitte, beleben Sie Ihre Vorstellungen und überlegen Sie sich, wenn Sie so den Menschen betrachten: Kopf Leichnam, Brust — Belebung, Laufen des astralischen Leibes, Größerwerden durch das Ich - wie sich der ganze Mensch belebt, der vorher wie eine Wachspuppe vor Ihnen stand.

Was ist denn schließlich das, was man gewöhnlich mit seinen physischen Augen und auch mit seinem Verstande vom Menschen sieht? Eine Wachspuppe! und die belebt sich, wenn Sie das hinzufügen, was ich eben jetzt auseinandergesetzt habe!

Dazu brauchen Sie allerdings die Durchsetzung Ihrer Anschauung _ durch dasjenige, was Geisteswissenschaft in die Empfindungen, in die Gefühle, in das ganze Verhältnis des Menschen zur Welt hineingießen kann. Ein laufendes Kind verrät Ihnen den astralischen Leib. Und das, was in der Geste des Laufens liegt — jedes Kind läuft ja anders —, das kommt von der Konfiguration der verschiedenen astralischen Leiber her. Und dasjenige, was im Wachsen liegt, das prägt etwas vom Ich aus.

Sehen Sie, da wirkt das Karma sehr stark in den Menschen hinein. Nehmen wir ein Beispiel, das der Gegenwart nicht mehr naheliegt: Fichte, Johann Gottlieb Fichte. Ich habe Ihnen von den verschiedensten Seiten Johann Gottlieb Fichte charakterisiert. Ich habe ihn Ihnen charakterisiert einmal als großen Philosophen, ich habe ihn Ihnen charakterisiert einmal als Bolschewisten, und so weiter, nicht wahr. Wollen wir ihn aber einmal noch von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte aus ins Auge fassen. Sie erinnern sich ja wohl, daß ich auch gezeigt habe, wie Johann Gottlieb Fichte durchaus unter die Bolschewisten gerechnet werden kann; nun wollen wir ihn von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte ins Auge fassen. Nehmen wir einmal an, wir stünden so auf der Straße und Fichte ginge vorüber, wir schauen ihm nach: ein nicht sehr großer Mann, stämmig. Was verrät die Art, wie er gewachsen ist? Zurückgehaltenes Wachstum. Stark aufsetzend die Füße, besonders stark die Fersen aufsetzend, so, wenn man ihm nachschaut, geht er dahin. Das ganze Fichte-Ich ist dadrinnen. Keine Nuance dessen, was der Mann war, kann einem entgehen, wenn man ihn so anschaut mit dem durch etwas Hungern in der Jugend zurückgehaltenen Wachstum, stämmig, den Körper zurückgehalten, stark die Fersen aufsetzend. Man hörte, wie er sprach, indem man ihn so von rückwärts bemerkte!

Sie sehen, in die Äußerlichkeiten des Lebens kann ein geistiges Element hineinkommen. Es kann allerdings nicht hineinkommen in die ÄAußerlichkeiten des Lebens, wenn nicht die Menschen etwas anderes, als heute noch in der Seelenverfassung ist, an Gesinnung in sich aufnehmen. Für die heutigen Menschen wäre ja das Anschauen ihrer Mitmenschen von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus eine recht böse Indiskretion. Man möchte es nicht sehr wünschen, daß das sich verbreitete, denn die Menschen von heute sind ja zumeist so geartet durch den Materialismus, wie er sich immer mehr und mehr ausgebreitet hat, daß sie nur deshalb, weil es verboten ist, nicht Briefe aufmachen, die ihnen nicht gehören, sonst würden sie es nämlich tun. Aber bei einer solchen Menschengesinnung ist es nicht tunlich, daß mit den Menschen alles anders werde. Dennoch, die Erde hat mit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts dasjenige erfüllt, was die Menschen auf andere Weise sich im Erdendasein nicht aneignen konnten, als dadurch, daß Mensch dem Menschen bis ins Physische hinein geistig entgegenkommt. Und je mehr wir der Zukunft entgegenwachsen, desto mehr müssen wir alles dasjenige, was sinnlich um uns herum ist, lernen geistig aufzufassen. Und angefangen muß das werden mit der pädagogischen Betätigung des Lehrers gegenüber dem heranwachsenden Kinde. Physiognomische Pädagogik: Wille, dieses größte Rätsel Mensch in jedem einzelnen Exemplar Mensch durch die Erziehung zu lösen!

Nun können Sie fühlen, wie stark eigentlich in unserer Zeit das ist, was ich als Prüfung der Menschheit auseinandergesetzt habe. Eigentlich drängt dasjenige, was ich auseinandergesetzt habe, dahin: immer mehr und mehr zu individualisieren, jeden Menschen als ein Wesen für sich zu betrachten. Das muß uns ja eigentlich als großes Ideal vorschweben: Keiner gleicht dem andern, jeder, jeder ist ein Wesen für sich. Würde die Erde an ihr Ziel kommen, ohne daß wir uns aneignen würden als Menschen, anzuerkennen jeden Menschen als ein Wesen für sich, die Menschheit würde auf der Erde nicht ihr Ziel erreichen. Aber wie weit sind wir heute von der Gesinnung entfernt, die nach diesem Ziele hinstrebt! Wir nivellieren ja heute die Menschen. Wir sehen die Menschen so an, daß wir sie gar nicht stark auf ihre individuellen Eigenschaften hin prüfen, Hermann Bahr, von dem ich Ihnen öfter erzählt habe, hat einmal in Berlin verraten, wie die Zeitbildung dahin geht, gar nicht mehr zu individualisieren. Als Hermann Bahr in den neunziger Jahren eine Zeitlang in Berlin lebte und mitmachte das Berliner Gesellschaftsleben, hatte er natürlich an jedem Abend rechts eine Tischdame und links eine Tischdame neben sich, nicht wahr. Aber wenn er wiederum am nächsten Abend zwischen zwei Tischdamen saß, da konnte er höchstens aus der Einladungskarte entnehmen, daß das andere Damen waren: er schaute sie sich nämlich gar nicht so genau an, denn im Grunde genommen war die Dame von gestern und die Dame von heute ganz dasselbe. Was er von ihnen sah, war ganz dasselbe. Und die gesellschaftliche, namentlich industrielle Kultur, die macht auch äußerlich aus den Menschen gleiche, läßt die Individualitäten nicht herauskommen. Und so strebt man in der Gegenwart nach Nivellement, während das innerste Ziel des Menschen sein muß, nach Individualisierung zu streben. Wir verdecken am meisten die Individualität in der Gegenwart und haben es am nötigsten, die Individualität aufzusuchen.

Beginnen, den inneren Seelenblick voll auf die Individualität hinzulenken, das muß im Unterricht des Menschen kommen. In die Lehrerbildung muß die Gesinnung aufgenommen werden: Individualitäten in den Menschen zu finden. Das können wir nur dadurch, daß wir unsere Vorstellung vom Menschen so beleben, wie ich es dargestellt habe; daß wir uns wirklich bewußt werden: Es ist nicht ein Mechanismus, der sich vorwärtsbewegt, es ist der astralische Leib, der sich vorwärtsbewegt, und der den physischen Leib mitzieht. Und vergleichen Sie mit dem, was in Ihrer Seele entstehen kann als innerlich belebtes und sich bewegendes Bild des ganzen Menschen, vergleichen Sie damit das, was heute die gebräuchliche Wissenschaft gibt: den Homunkulus, einen richtigen Homunkulus! Die Wissenschaft sagt nichts vom Menschen, predigt nur den Homunkulus. Der wirkliche Mensch, das ist derjenige, der vor allen Dingen in die Pädagogik einziehen muß. Aber er ist ganz heraußen aus der Pädagogik.

Also die Erziehungsfrage ist eine Lehrerbildungsfrage, und so lange sie nicht als das betrachtet wird, ist man nicht so weit, daß irgend Ersprießliches in der Erziehung geschehen kann. Sie sehen, alles gehört von den höheren Gesichtspunkten aus betrachtet so zusammen, daß man das eine wirklich an das andere anschließt. Heute möchte man am liebsten auch die menschlichen Tätigkeiten, innerlichen Tätigkeiten als Fächer nebeneinander ausbilden. Da lernt der Mensch Menschenkunde, dann Religion — die Dinge haben nicht viel miteinander zu tun. In Wahrheit grenzt, wie Sie gesehen haben, dasjenige, was man am Menschen betrachtet, an die Unsterblichkeitsfrage, an die Frage nach dem ewigen Wesen der Menschennatur. Und wir mußten die Frage nach dem ewigen Wesen der Menschennatur mit dem unmittelbaren Anschauen des Menschen zusammenbringen. Dieses Bewegliche des seelischen Erlebens, das muß insbesondere in die Pädagogik hinein. Dann werden ganz andere innere Fähigkeiten entwickelt, als sie heute durch die Lehrerbildungsanstalten entwickelt werden. Und das ist von ganz besonderer Wichtigkeit.

Ich wollte Ihnen durch die heutige Betrachtung nahebringen, wie Geisteswissenschaft eigentlich alles durchdringen muß, und wie man ohne Geisteswissenschaft die großen sozialen Probleme der Gegenwart nicht lösen kann.

Fourth Lecture

From the last considerations we have made here, you will have seen that among the many issues that concern the present, the question of education is the most important. We have had to emphasize that the whole social question includes as its most important element precisely the question of education. And after I indicated a few days ago something about the reorganization, the transformation of the educational system, you will understand that within the question of education, the most important sub-question is that of the training of teachers themselves. If one considers the character of the era that has passed, precisely defined as the period since the middle of the 15th century, one gets the impression, as you know, that during this time a wave of materialistic trials swept through human development. And we live in the present with the necessity of working our way out of the materialistic wave and finding our way back to the spirit; the path to the spirit, which was known in earlier cultural epochs of humanity, but which was then followed by humanity more or less instinctively, unconsciously, which was lost so that humanity could seek it out of its own impulse, out of its own freedom, and which must now be sought consciously, fully consciously.

The transition that humanity has had to go through since the middle of the 15th century is precisely what could be called the materialistic test of humanity. If we allow the character of this materialistic age to sink in and then consider, with the insight this gives us, the development of culture over the last three to four centuries and up to our own time, we find that it is teacher training that has been most affected by the materialistic wave, that has been most intensively claimed by this materialistic wave. Nothing else could have made such a lasting impression as the implementation of the pedagogical-didactic view with a materialistic attitude. One need only look intelligently at the details of our current education system to see the whole difficulty that stands in the way of truly fruitful progress. Consider that it is repeated over and over again, especially by those who today believe they are particularly well qualified to speak on educational matters, that all teaching must be vivid from the lowest school level onwards — what is called vivid. I have often pointed out to you how, for example, arithmetic lessons are to be made vivid: calculators are set up in schools! Great importance is attached to the idea that children should be able to see everything, so to speak, and then form mental images from their own inner soul based on what they have seen. This drive for vividness in education is certainly justified in many areas of pedagogy. But it does raise the question: What becomes of a person who only receives visual instruction? If a person only receives visual instruction, then their soul becomes completely parched, and the inner driving forces of the soul gradually die out; then a connection is formed between the whole human being and the visual environment. And that which should spring from within the soul is gradually killed in the soul. And much of the killing of the soul is due precisely to the visual nature of present-day teaching. Of course, one does not know that one is killing the soul, but in reality one is killing it. And the result of this is what we experience in people today, as I have already mentioned from other points of view. How many people today are actually problematic natures? How many people today, in their mature years, do not know how to draw from within themselves what could offer them comfort and hope in difficult times, in order to cope with the various situations of life? We see many broken natures in the present, and in special moments we ourselves find that we cannot find our way.

All this is connected with the shortcomings of our education system and, in particular, with the shortcomings of teacher training. What should we strive for in order to ensure a prosperous future, especially with regard to teacher training? You see, the fact that teachers ultimately know what they are usually asked in exams is actually a secondary matter, because they are mostly asked about things that they could look up in a handbook before class and prepare for when they need them. But what is not looked at at all in the exams is the general state of mind of the teacher, which is what must constantly be transferred from him to his students. There is a big difference between one teacher entering the classroom and another. When one teacher walks through the classroom door, the children or students feel a certain affinity with their own state of mind; when another teacher enters the classroom, the children or students often do not feel such an affinity at all; on the contrary, they feel a gap between themselves and the teacher, and all possible shades of indifference up to what is expressed in finding the teacher funny, in mocking the teacher. All the nuances in between are often found to be quite ruinous to real teaching and real education.

The burning question is therefore: How can teacher training be transformed for the future? It can only be transformed if teachers take on board the insights into human nature that can come from spiritual science. Teachers must be imbued with an understanding of the connection between human beings and the supersensible worlds. They must be able to see in the growing child the evidence that this child has descended from the supersensible world through conception or birth and that what has descended has clothed itself in the body, is acquiring something that they must help it to acquire here in the physical world, because the child cannot acquire it in the life between death and a new birth.

As a question from the supersensible world to the sensory world, this should actually be before the mind of every teacher or educator. It is not possible to pose this question in a concrete, comprehensive sense, especially not in relation to each individual child, unless one can apply the insights into human nature that come from spiritual science. Over the last three to four centuries, humanity has gradually become more and more accustomed to seeing human beings, I would say, merely physiologically, merely in terms of their external physical constitution. This view of human beings is most harmful to the educator, to the teacher. Therefore, it will be necessary above all that an anthropology arising from anthroposophy become the basis of future education. But this can only happen if human beings are truly viewed from the perspectives we have often touched upon here, which characterize them in many ways as threefold beings. But we must resolve to truly grasp this threefold structure inwardly. I have repeatedly drawn your attention, from various points of view, to how the human being, as he stands before us, can be divided into what he is first and foremost as a nerve-sense being, which can be expressed in popular terms as follows: First and foremost, the human being is a head being, a head person. As the second member of the human being, viewed externally, we have the human being in whom mainly the rhythmic processes take place, the chest human being; and then, as you know, connected with the whole metabolic system, the limb human being, the metabolic human being, in whom metabolism as such takes place. What human beings are as active beings is exhausted externally in the image, in the physical image of human beings in these three members of the whole human nature.

Let us note these three members of the whole human nature: the head human or nerve-sense human, the chest human or rhythmic human, and then the limb human, in the broadest sense of course, or metabolic human.

Now it is a matter of grasping these three members of human nature in their differences from one another. This is inconvenient for people today, because people today love schematic divisions. When you say that human beings consist of head people, chest people, and limb people, they would prefer to draw a line at the neck, so that everything above is head people. Then they would like to draw another line somewhere else to delimit the chest person, and so they would like to have the divided parts side by side. People today do not like to deal with anything that cannot be placed side by side in such a schematic way.

But that is not how it is in reality; reality does not draw such lines. Above the shoulders, humans are mainly head people, nerve-sense people. But they are not only nerve-sense people above the shoulders; for example, the sense of feeling and the sense of warmth extend over the whole body, so that the head in turn extends over the whole body. So, if you like, you could say that the human head is mainly head. And the chest is less head, but still head. The limbs, or everything that is part of the metabolic system, are even less head, but still head. So you actually have to say that the whole human being is head, only the head is mainly head. If one wanted to draw a diagram, one would have to draw the head person like this (see drawing, light hatching).

The chest person, in turn, is not only in the chest, but mainly in the chest organs, the organs in which the heart and the breathing rhythm are most clearly expressed. But breathing also continues in the head, and the rhythm of blood circulation continues in the head and in the limbs. So one can say that the human being is indeed a chest in this area, but he is also a chest here — albeit to a lesser extent — (see drawing, middle hatching) and here — again to a lesser extent. So again, the whole human being is chest, but mainly it is the chest that is the head.

And again, the limb and metabolism human is mainly this (see drawing, dark hatching); but these limbs continue in such a way that they are less in the chest and least in the head.

So just as it is true to say that the head is the head, it is also true to say that the whole human being is the head. Just as it is true to say that the chest is the chest, it is also true to say that the whole human being is the chest, and so on. In reality, things flow into one another. And our understanding is such that we like to juxtapose the parts, the limbs. This shows us how little we are related to external reality in terms of our concepts of knowledge. In external reality, things flow into one another. And when we separate them on the one hand—head, chest, metabolic human being—we must be aware that we then have to think the separate parts together again. We must never just think them apart; we must always think them together again. A thinking person who only wants to think separately is like a person who only wants to inhale but not exhale.

With this, you have immediately given something that must be taken into account, especially for the thinking of the teachers of the future; they must take this internally flexible thinking, this non-schematic thinking, particularly to heart. For it is only by absorbing this unschematic thinking that they can come close to reality with their soul. But one cannot come close to reality unless one is able to understand this closeness from a certain broader perspective as a phenomenon of our time. One must overcome the preference that has increasingly developed in the present day for sticking to the details of life when considering scientific matters, and one must come to link the details of life to the great questions of life.

And one question will become significant for all future development of intellectual culture: the question of immortality. We will have to become clear about how a large part of humanity actually understands this immortality, especially since the time when many people have even come to deny immortality. What actually lives in most people who still want to learn about immortality from the foundations of common religions today? What lives in these people? What lives in these people is the urge to know something about what happens to the soul when a person has passed through the gate of death.

When we ask about people's interest in the question of immortality, or rather, in the question of the eternity of the human core, we get no other answer than this: the main interest in the eternity of the human core is linked to the question: What happens to a person when they pass through the gate of death? Human beings are aware that they are an “I.” Their thinking, feeling, and willing live in this “I.” The thought of this ‘I’ being destroyed is unbearable to them. Whether they can carry it through death, and what becomes of the “I” after death, is what interests human beings above all else. The reason this interest has arisen is essentially because the religious systems that are relevant to us here, at least for the time being, when they speak of immortality, of the eternity of the human core, mainly have in mind the question: What happens to the human soul when a person passes through the gate of death?

Now you must realize that when the question of immortality is posed in this way, it takes on an extremely strong egoistic connotation. It is basically an egoistic impulse that instills in human beings an interest in knowing what will become of their core being when they pass through the gate of death. And if people today were to practice self-knowledge more than they do, if they were to consult with themselves and not indulge in illusions as much as they do, then they would realize how strongly egoism influences their interest in knowing something about the fate of the soul after death.

This kind of soul mood has become particularly strong again in the materialistic era of the last three to four centuries. And what has taken hold of the human soul as an inner habit of feeling and thinking cannot be overcome by theories or teachings if these theories or teachings are only abstract in form. But the question must be raised: Can it remain this way? When it comes to the question of the eternal core of human nature, should only egoistic impulses be allowed to speak?