The Study of Man

GA 293

22 August 1919, Stuttgart

Lecture II

In the future all teaching must be founded on a real psychology—a psychology which has been gained through an anthroposophical knowledge of the world. Of course it has been widely recognised that instruction and education generally must be built up on psychology, and you know that Herbartian pedagogy, for instance, which has influenced great numbers of people, founded its educational standards on Herbartian psychology. Now during the last few centuries and up to recent times there has been something present in the life of man which prevents a real practical psychology from coming into being. This can be traced to the fact that in the age in which we now are, the age of the Consciousness Soul, man has not yet reached the spiritual depth which would enable him to come to a real understanding of the human soul. But those concepts which have been built up in past times in the sphere of psychology—the science of the soul—out of the old knowledge of the fourth Post-Atlantean period, have become more or less devoid of content to-day: they have become mere words. Anyone who takes up psychology or anything to do with psychological concepts will find that there is no longer any real content in the books on the subject. They will have the feeling that psychologists only play with concepts. Who is there to-day for instance who develops a really clear conception of what mental picture or will is? In psychologies and theories of education you can find one definition after another of mental picture and of will, but these definitions will not be able to give you a real mental picture, a real idea, either of mental picture itself or of will. Psychologists have completely failed—owing to an external, historical necessity, it is true—to make any connection between the soul life of the individual human being and the whole universe. They were not in a position to understand how the soul-life of man stands in relation to the whole universe. It is only by perceiving the connection between the individual human being and the whole universe that it is possible to arrive at the idea of the being “man.”

Let us look at what is ordinarily called mental picture. We must develop this, as well as feeling and willing, in the children, and to this end we must first of all gain a clear conception of the mental picture. Anyone who looks with an open mind at what lives in men as this activity will at once be struck by its image character. The mental picture is of the nature of an image. And those who try to find in it the character of existence or being are subject to a great illusion. What would it be for us if it were “being”? We certainly have elements of being in us also. Think only of our bodily elements of being: to take a somewhat crude example: your eyes, they are elements of being, your nose or your stomach, that is an element of being. It will be clear to you that you live in these elements of being, but you cannot make mental pictures with them. You flow out with your own nature into the elements of being, and you identify yourself with them. The possibility of understanding, of grasping something with your mental pictures arises from the fact that they have an image character, that they do not so merge into us that we are in them. For indeed, they do not really exist, they are mere images. One of the great mistakes of the last period of man's evolution during the last few centuries, has been to identify being with thought as such. Cogito ergo sum (I think therefore I am), is the greatest error that has been put at the summit of recent philosophy, for in the whole range of the Cogito there lies not the sum but the non sum. That is to say, as far as my knowledge reaches I do not exist, but there is only image.

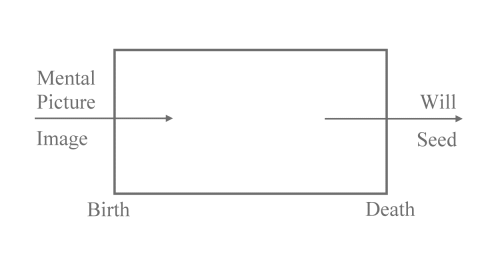

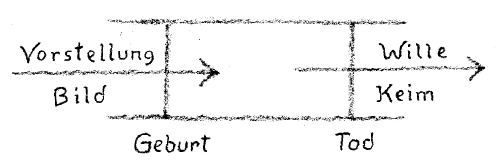

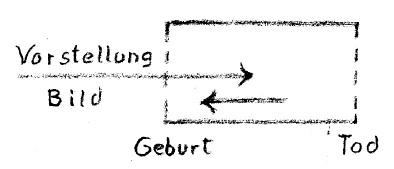

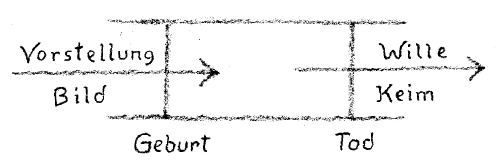

Now when you consider the image character of mental picturing you must above all think of it qualitatively. You must consider its mobility, one might almost say its activity of being, but that might give too much the impression of being, of existence, and we must realise that even activity of thought is only an image activity. Everything which is purely movement in mental picturing is a movement of images. But images must be images of something; they cannot be merely images as such. If you think of the comparison of mirror images you can say to yourselves: out of the mirror there appear mirror images, it is true, but what is in the mirror images is not behind the mirror, it exists independently somewhere else. It is of no consequence to the mirror what is to be reflected in it; all sorts of things can be reflected in it. When we have thus clearly grasped that the activity of mental picturing is of this image nature, we must next ask: of what is it an image? Naturally no outer science can tell us this, but only a science founded on Anthroposophy. Mental picturing is an image of all the experiences which we go through before birth, or rather conception. You cannot arrive at a true understanding of it unless it is clear to you that you have gone through a life before birth, before conception. And just as ordinary mirror images arise spatially as mirror images, so your life between death and re-birth is reflected in your present life and this reflection is mental picturing. Thus when you look at it diagrammatically you must mentally picture the course of your life to be running between the two horizontal lines bounded on the right and left by birth and death.

You must then further represent to yourself that mental picturing is continually playing in from the other side of birth and is reflected by the human being himself. And it is because the activity which you accomplish in the spiritual world before birth or conception is rejected by your bodily nature that you experience mental picturing. For true knowledge this activity is a proof, because it is an image, of life before birth.

I want to place this first before you as an idea (we shall come back to a real explanation of these things later) in order to show you that we can get away from the mere verbal explanations which you find in psychologies and theories of education, and arrive at a true understanding of what the activity of mental picturing is, by learning to know that in it we have a reflection of the activity which was carried on by the soul before birth or conception, in the purely spiritual world. All other definitions of mental picturing are of absolutely no value, because they give us no true idea of what it is.

We must now investigate will in the same way. For the ordinary consciousness will is really a very great enigma. It is the crux of psychologists simply because to the psychologist will appears as something very real but basically without content. For if you examine what content psychologists give to will you will always find that this content comes from mental picturing. As for will itself it has no immediate real content of its own. Then again the fact is that there are no definitions of will: these definitions of will are all the more difficult because it has no real content. But what is will really? It is nothing else but the seed in us of that which after death will be reality of spirit and of soul. Thus when you picture to yourself what will be our spirit-soul reality after death, and picture it as seed within us, then you have will. In our drawing our life's course ends with death on the one side, and will passes over beyond it.

Thus we have to picture to ourselves: mental picturing on the one hand, which we must conceive of as an image from pre-natal life; and will, on the other hand, which we must conceive of as the seed of something which appears later. I beg you to bear clearly in mind the difference between seed and image. For a seed is something more than real, and an image is something less than real; a seed does not become real until later, it carries within it the ground of what will appear later as reality; so that the will is indeed of a very spiritual nature. Schopenhauer had a feeling for this truth, but naturally he could not advance to the knowledge that will is a seed of the Spirit-Soul as it unfolds after death in the spiritual world.

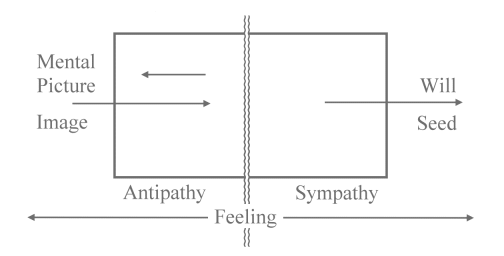

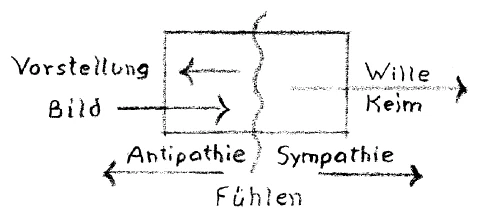

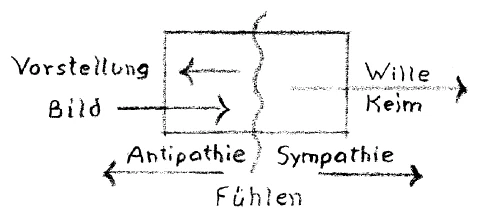

Now we have divided man's soul-life into two spheres, as it were: into mental picturing, which is in the nature of image, and will, which is in the nature of seed, and between image and seed there lies a boundary. This boundary is the whole life of the physical man himself who reflects back the pre-natal, thus producing the images of mental picturing, and who does not allow the will to fulfil itself, thereby keeping it continually as seed, allowing it to be nothing more than seed. Now we must ask: what are the forces that really bring this about?

We must be quite clear that in man there are certain forces which reflect back the pre-natal reality and hold the after death reality in seed. And now we come to the most important psychological concepts of facts which are reflections of the forces described in my book Theosophy—reflections of sympathy and antipathy. Because we can no longer remain in the spiritual world (and here we come back to what was said yesterday) we are brought down into the physical world. In being brought down into the physical world we develop an antipathy for everything spiritual so that we radiate back the spiritual, pre-natal reality in an antipathy of which we are unconscious. We bear the force of antipathy within us, and through it transform the pre-natal element into a mere mental picture or image. And we unite ourselves in sympathy with that which radiates out towards our later existence as the reality of will after death. We are not immediately conscious of these two, sympathy and antipathy, but they live unconsciously in us, and they signify our feeling, which consists continually of a rhythm, of an alternating between sympathy and antipathy.

We develop within us all the world of feeling, which is a continual alternation—systole, diastole—between sympathy and antipathy. This alternation is continually within us. Antipathy on the one hand changes our soul life into picture image: sympathy, which goes in the other direction, changes our soul life into what we know as our will for action, into that which holds in germ what after death is spiritual reality. Here we come to the real understanding of the life of soul and spirit. We create the seed of the soul life as a rhythm of sympathy and antipathy.

Now what is it that you ray back in antipathy. You ray back the whole life, the whole world, which you have experienced before birth or conception. That has in the main the character of cognition. Thus you really owe your cognition to the shining in, the raying in of your pre-natal life. And this cognising, which possesses great reality before birth or conception, is weakened to such a degree through antipathy that it becomes only a picture image. Thus we can say: this cognising comes up against antipathy and is thereby reduced to mental picture.

If antipathy is sufficiently strong something very remarkable happens. For in ordinary life after birth we could not picture mentally if we did not do it in a measure with the very force which has remained in us from the time before birth. When you use this faculty to-day as physical man you do not do it with a force which is in you, but with a force which comes from a time before birth, and which still works on in you. You might suppose it ceased with conception, but it remains active, and we make our mental pictures with this force which continues to ray into us. You have it in you, continually living on from pre-natal times, only you have the force in you to ray it back. You have this force in your antipathy. When in your present life you make mental pictures, each such process meets antipathy, and if the antipathy is sufficiently strong a memory image arises. So that memory is nothing else but a result of the antipathy that holds sway within us. Here you have the connection between the purely feeling nature of antipathy which rays back in an indefinite manner, and the definite raying back, the raying back of the activity of perception in memory, an activity which is carried out in a pictorial way. Memory is only heightened antipathy. You could have no memory if you had so great a sympathy for your mental pictures that you could devour them; you have a memory only because you have a kind of “disgust” for them, you fling them back and in this way make them present. That is their reality.

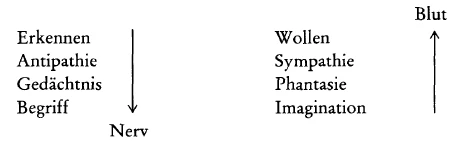

When you have gone through this whole process, when you have produced a mental picture, reflected this back in the memory, and held fast the image element, then there arises the concept. This then is one side of the soul's activity: antipathy, which is connected with our pre-natal life.

Now we will take the other side, that of willing, which is in the nature of a germ in us and belongs to the life after death. Willing is present in us because we have sympathy with it, because we have sympathy with this seed which will not be developed until after death. Just as our thinking depends upon antipathy, so our willing depends on sympathy. Now if this sympathy is sufficiently strong—as strong as the antipathy which enables mental picturing to become memory—then out of sympathy there arises imagination. Just as memory arises out of antipathy so imagination arises out of sympathy. And if your imagination is sufficiently strong (which only happens unconsciously in ordinary life), if it is so strong that it permeates your whole being right down into the senses, then you get the ordinary picture forms* through which you make mental pictures of outer things. This activity has its starting point in the will. People are very much mistaken when in speaking psychologically they constantly say: “We look at things, then we make them abstract, and thus we get the mental picture.” This is not the case. The fact that chalk is white to us is a result of the application of the will, which by way of sympathy and imagination has become picture form.1Imaginationen But when we form a concept, on the other hand, it has quite a different origin; for the concept arises from memory.

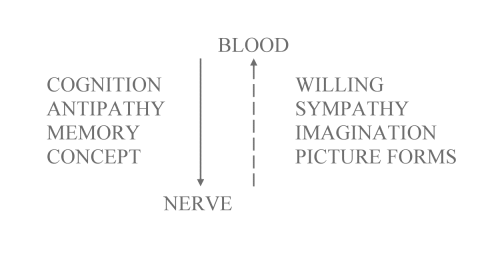

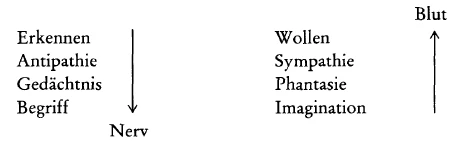

Here I have described to you the soul processes. It is impossible for you to comprehend the being of man unless you understand the difference between the elements of sympathy and antipathy in man. These elements, as I have described, find their full expression in the soul world after death. There sympathy and antipathy hold sway undisguised. I have been describing the soul-man who, on the physical plane, is united with the bodily man. Everything pertaining to the soul is expressed and revealed in the body, so that on the one hand we find revealed in the body what is expressed in antipathy, memory and concept. All this is bound up with the nerves in the bodily organisation. While the nervous system is being formed in the body all that belongs to the pre-natal life is at work there. The pre-natal life of the soul works into the human body through antipathy, memory and concept, and hereby creates the nerves. This is the true concept of nerves. All talk of classifying nerves as sensory and motor is meaningless, as I have often explained to you.

Similarly, in a certain sense, the activity of willing, sympathy, picture-forming and imagination works out of the human being. This is bound to the seed condition; it can never really come to completion but must perish at the moment it arises; it has to remain as a seed, and the seed must not evolve too far. Thus it must perish in the moment of arising. Here we come to a very important fact about the human being. You must learn to understand the whole man, spirit, soul and body. Now in man there is something continually being formed which always has the tendency to become spiritual. But because out of our great love, albeit selfish love, we want to hold it fast in the body, it never can become spiritual; it loses itself in its bodily nature. We have something within us which is material but which is always wanting to pass over from its material condition and become spiritual. We do not let it become spiritual, and therefore we destroy it in the very moment when it is striving to become spiritual—I refer to blood, the opposite of the nerves.

Blood is really a “very special fluid.” For it is the fluid which would whirl away as spirit if we were able to remove it from the human body so that it still remained blood and was not destroyed by other physical agencies—an impossibility while it is bound to earthly conditions. Blood has to be destroyed in order that it may not whirl away as spirit, in order that we may retain it within us as long as we are on the earth, up to the moment of death. For this reason we have perpetually within us: formation of blood—destruction of blood—formation of blood—destruction of blood: through in-breathing and out-breathing.

We have a polaric process within us. We have those processes within us which, working through the blood and blood-vessels, continually have the tendency to lead our being out into the spiritual. To talk of motor nerves, as has become customary, does not correspond to the facts, because the motor-nerves would really be blood-vessels. In contrast to the blood all nerves are so constituted that they are constantly in the process of dying, of becoming materialised. What lies along the nerve-paths is really extruded, rejected material. Blood wants to become ever more spiritual—nerve ever more material. Herein consists the polaric contrast. In the later lectures we shall follow these fundamental principles further and we shall see how this can give us help to arrange our teaching in a hygienic way, so that we can lead a child to health of soul and body, and not to decadence of spirit and soul. The amount of bad education now prevalent is because so much is unknown. Although physiology believes it has discovered a truth when it talks of sensory and motor nerves, it is nevertheless only playing with words. Motor nerves are spoken of because of the fact that when certain nerves are injured, i.e. those which go to the legs, a man cannot walk when he wants to do so. It is said that he cannot walk because he has injured the nerves which, as motor nerves, set the leg in motion. In reality the reason why he cannot walk is that he has no perception of his own legs. This age in which we live has been obliged to entangle itself in a mass of errors, so that, through having to disentangle ourselves from them, we may become independent human beings.

Now you will have seen, from what I have here developed, that really the human being can only be understood in connection with the cosmos. For when we make mental pictures we have what is cosmic within us. We were in the cosmos before we were born, and our experience there is now mirrored in us; we shall be in the cosmos again when we have passed through the gate of death, and our future life is expressed in seed form in what rules our will. What works unconsciously in us works in full consciousness for higher knowledge in the cosmos.

We have a threefold expression of this sympathy and antipathy revealed in our physical body. We have, as it were, three centres where sympathy and antipathy interplay. First we have a centre of this kind in the head, in the working together of blood and nerves, whereby memory arises. At every point where the activity of the nerves is broken off, at every point where there is a gap, there is a centre where sympathy and antipathy interplay. Another gap of this kind is to be found in the spinal marrow; for instance, when one nerve passes in towards the posterior horn of the spinal marrow and another passes out from the anterior horn. And again there is such a gap in the little bundles of ganglia, which are embedded in the sympathetic nerves. We are by no means such simple beings as it might seem. In three parts of our organism, in the head, in the chest and in the lower body, there are boundaries at which antipathy and sympathy meet. In perceiving and willing it is not that something leads round from a sensory to a motor nerve, but a direct stream springs over from one nerve to another, and through this the soul in us is touched; in the brain and in the spinal marrow. At these places where the nerves are interrupted we unite ourselves with our sympathy and antipathy to the soul-life; and we do so again where the ganglia systems are developed in the sympathetic nervous system.

We are united with our experience with the cosmos. Just as we develop activities which have to be continued in the cosmos, so does the cosmos constantly develop with us the activity of antipathy and sympathy. When we look upon ourselves as men, then we see ourselves as the result of the sympathies and the antipathies of the cosmos. We develop antipathy from out of ourselves, the cosmos develops antipathy together with us; we develop sympathy, the cosmos develops sympathy with us.

Now as human beings we are manifestly divided into the head system, the chest system, and the digestive system with the limbs. But please notice that this division into organised systems can very easily be combated, because when men make systems to-day they want to have the separate parts neatly arranged side by side. If we say that a man is divided into a head system, chest system, and a system of the lower body with the limbs, then people expect each of these systems to have a fixed boundary. People want to draw lines where they divide, and that cannot be done when dealing with realities. In the head we are principally head, but the whole human being is head, only what is outside the head is not principally head. For though the actual sense organs are in the head, we have the sense of touch and the sense of warmth over the whole body. Thus in that we feel warmth we are head all over. In the head only are we principally head, but we are secondarily head in the rest of the body. Thus the parts are intermingled, and we are not so simply divided as the pedants would have us be. The head extends everywhere, only it is specially developed in the head proper. The same is true of the chest. Chest is the real chest but only principally, for again the whole man is chest. For the head is also to some extent chest as is the lower body with the limbs. The different parts are intermingled. And it is just the same in the lower body. Some physiologists have noticed that the head is “lower body.” For the very fine development of the head-nerve system does not really lie within the outer brain layer of which we are so proud; it does not lie within but below the outer layer of the brain. For the outer covering of the brain is, to some extent, a retrogression; this wonderful artistic structure is already on the retrograde path; it is much more a system of nourishment. So that in a manner of speaking, we may say a man has no need to be so conceited about the outer brain for it is a retrogression of the complicated brain into a brain more used for nourishment. We have the outer layer so that the nerves which are connected with knowing may be properly supplied with nourishment. And the reason that our brain excels the animal brain is only that we supply our brain nerves better with nourishment. We are only able to develop our higher powers of cognition because we are able to nourish our brain nerves better than the animals are able to do. Actually the brain and the nervous system have nothing to do with real cognition but only with the expression of cognition in the physical organism.

Now the question is: why have we the contrast between the head system (we will leave the middle system out of account for the present) and the polaric limb system with the lower body? We have this contrast because at a certain moment the head system is breathed out by the cosmos. Man has the form of his head by reason of the antipathy of the cosmos. When the cosmos has such aversion for what man bears within him that it pushes it out, then the image or copy arises. In the head man really bears the copy of the cosmos in him. The roundly formed head is such a copy. The cosmos, through antipathy, creates a copy of itself outside itself. That is our head. We can use our head as an organ for freedom because it has been pushed out by the cosmos. We do not regard the head correctly if we think of it as incorporated in the cosmos as intensively as is our limb-masses system, in which are included the sexual organs. Our limb system is incorporated in the cosmos and the cosmos attracts it, has sympathy with it, just as it has antipathy towards the head. In the head our antipathy meets the antipathy of the cosmos; there they come into collision. And in the rebounding of our antipathies upon those of the cosmos our perceptions arise. All inner life which rises on the other side of man's being has its origin in the loving sympathetic embrace between the cosmos and the limb system of man.

Thus the human bodily form expresses how a man, even in his soul nature, is formed out of the cosmos, and also what he then takes from the cosmos. If you look at it from this point of view you will more easily see that there is a great difference between the formation of the mental picture and the formation of will. If you work exclusively and one-sidedly on the building up of the former, then you really point the child back to his pre-natal existence, and you will harm him if you are educating him rationalistically, because you are coercing his will into what he has already done with—the pre-natal life. You must not introduce too many abstract concepts into what you bring to the child. You must rather introduce imaginative pictures. Why is this? Imaginative pictures stem from picture-forming and sympathy. Concepts, abstract concepts, are abstractions; they go through memory and antipathy, and they stem from the pre-natal life. If you use many abstractions in teaching a child, you involve him too intensely in the production of carbonic acid in the blood, namely in processes of the hardening of the body, and decay. If you bring to the child as many imaginations as possible, if you educate him as much as possible by speaking to him in images, then you are actually laying in the child the germ for the preservation of oxygen, for continuous growth, because you point to the future, to what comes after death. In educating we take up again in some measure the activities which were carried out with us men before birth. We must realise that mental picturing is an activity connected with images, originating in what we have experienced before birth or conception. The spiritual Powers have so dealt with us that they have planted within us this image activity which works on in us after birth, If in our education we ourselves give the children images we are taking up this cosmic activity again. We plant images in them which can become germs, seeds, because we plant them into a bodily activity. Therefore, whilst as educators we acquire the power to work in images we must continually have the feeling: you are working on the whole man; it echoes, as it were, through the whole human being, if you work in images.

If you yourselves continually feel that in all education you are supplying a kind of continuation of pre-natal super-sensible activity, then you will give to all your education the necessary consecration, for without this consecration it is impossible to educate at all.

To-day we have learnt of two systems of concepts: cognition, antipathy, memory, concept: willing, sympathy, picture-forming, imagination: two systems which we shall be able to apply practically in all that we have to do in our educational work. We will speak further of this tomorrow.

Zweiter Vortrag

Jeder Unterricht in der Zukunft wird gebaut werden müssen auf eine wirkliche Psychologie, welche herausgeholt ist aus anthroposophischer Welterkenntnis. Daß der Unterricht und das Erziehungswesen überhaupt auf Psychologie gebaut werden müsse, erkannte man selbstverständlich an den verschiedensten Orten, und Sie wissen ja wohl, daß zum Beispiel die in der Vergangenheit in sehr weiten Kreisen wirkende Herbartsche Pädagogik ihre Erziehungsmaßnahmen auf die Herbartsche Psychologie aufgebaut hat. Nun liegt heute und auch in der Vergangenheit der letzten Jahrhunderte eine gewisse Tatsache vor, welche eigentlich eine wirkliche, eine brauchbare Psychologie gar nicht aufkommen ließ. Das muß darauf zurückgeführt werden, daß in dem Zeiitalter, in welchem wir jetzt sind, in dem Bewußtseinsseelenzeitalter, bisher noch nicht eine solche geistige Vertiefung erreicht worden ist, daß man wirklich zu einer tatsächlichen Erfassung der menschlichen Seele hätte kommen können. Diejenigen Begriffe aber, die man sich früher auf psychologischem Gebiete, auf dem Gebiete der Seelenkunde gebildet hatte aus dem alten Wissen noch des vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraumes heraus, diese Begriffe sind eigentlich heute mehr oder weniger inhaltleer, sind zur Phrase geworden. Wer heute irgendeine Psychologie oder auch nur irgend etwas in die Hand nimmt, das mit Psychologiebegriffen zu tun hat, der wird finden, daß ein wirklicher Inhalt heute in solchen Schriftwerken nicht mehr drinnen ist. Man hat das Gefühl, daß die Psychologen nur mit Begriffen spielen. Wer entwickelt heute zum Beispiel einen richtigen deutlichen Begriff von dem, was Vorstellung, was Wille ist? Sie können heute Definition nach Definition aus Psychologien und Pädagogiken nehmen über Vorstellung, über Wille: eine eigentliche Vorstellung über die Vorstellung, eine eigentliche Vorstellung vom Willen werden Ihnen diese Definitionen nicht geben können. Man hat eben vollständig versäumt - natürlich aus einer äußeren geschichtlichen Notwendigkeit heraus -, den einzelnen Menschen anzuschließen auch seelisch an das ganze Weltenall. Man war nicht imstande zu begreifen, wie das Seelische des Menschen in Zusammenhang steht mit dem ganzen Weltenall. Erst dann, wenn man den Zusammenhang des einzelnen Menschen mit dem ganzen Weltenall ins Auge fassen kann, ergibt sich ja eine Idee von der Wesenheit Mensch als solcher.

Sehen wir einmal auf das, was man gewöhnlich die Vorstellung nennt. Wir müssen ja Vorstellen, Fühlen und Wollen bei den Kindern entwickeln. Also wir müssen zunächst für uns einen deutlichen Begriff gewinnen von dem, was Vorstellung ist. Wer wirklich unbefangen das anschaut, was als Vorstellung im Menschen lebt, dem wird wohl sogleich der Bildcharakter der Vorstellung auffallen: Vorstellung hat einen Bildcharakter. Und wer einen Seins-Charakter in der Vorstellung sucht, wer eine wirkliche Existenz in der Vorstellung sucht, der gibt sich einer großen Illusion hin. Was sollte für uns aber auch Vorstellung sein, wenn sie ein Sein wäre? Wir haben zweifellos auch SeinsElemente in uns. Nehmen Sie nur unsere leiblichen Seins-Elemente, nehmen Sie nur das, was ich jetzt sage, ganz grob: zum Beispiel Ihre Augen, die Seins-Elemente sind, Ihre Nase, die ein Seins-Element ist, oder auch Ihren Magen, der ein Seins-Element ist. Sie werden sich sagen, in diesen Seins-Elementen leben Sie zwar, aber Sie können mit ihnen nicht vorstellen. Sie fließen mit Ihrem eigenen Wesen in die Seins-Elemente aus, Sie identifizieren sich mit den Seins-Elementen. Gerade das ergibt die Möglichkeit, daß wir mit den Vorstellungen etwas ergreifen, etwas erfassen können, daß sie Bildcharakter haben, daß sie nicht so mit uns zusammenfließen, daß wir in ihnen sind. Sie sind also eigentlich nicht, sie sind bloße Bilder. Es ist der große Fehler gerade im Ausgange der letzten Entwickelungsepoche der Menschheit in den letzten Jahrhunderten gemacht worden, das Sein mit dem Denken als solchem zu identifizieren. «Cogito, ergo sum» ist der größte Irrtum, der an die Spitze der neueren Weltanschauung gestellt worden ist; denn in dem ganzen Umfange des «cogito» liegt nicht das «sum», sondern das «non sum». Das heißt, soweit meine Erkenntnis reicht, bin ich nicht, sondern ist nur Bild.

Nun müssen Sie, wenn Sie den Bildcharakter des Vorstellens ins Auge fassen, ihn vor allem qualitativ ins Auge fassen. Sie müssen auf die Beweglichkeit des Vorstellens sehen, müssen sich gewissermaßen einen nicht ganz zutreffenden Begriff vom Tätigsein machen, was ja anklingen würde an das Sein. Aber wir müssen uns vorstellen, daß wir auch im gedanklichen Tätigsein nur eine bildhafte Tätigkeit haben. Also alles, was auch nur Bewegung ist im Vorstellen, ist Bewegung von Bildern. Aber Bilder müssen Bilder von etwas sein, können nicht Bilder bloß an sich sein. Wenn Sie reflektieren auf den Vergleich mit den Spiegelbildern, so können Sie sich sagen: Aus dem Spiegel heraus erscheinen zwar die Spiegelbilder, aber alles, was in den Spiegelbildern liegt, ist nicht hinter dem Spiegel, sondern ganz unabhängig von ihm irgendwo anders vorhanden, und es ist für den Spiegel ziemlich gleichgültig, was sich in ihm spiegelt; es kann sich alles mögliche in ihm spiegeln. - Wenn wir genau in diesem Sinne von der vorstellenden Tätigkeit wissen, daß sie bildhaft ist, so handelt es sich darum, zu fragen: Wovon ist das Vorstellen Bild? Darüber gibt natürlich keine äußere Wissenschaft Auskunft; darüber kann nur anthroposophisch orientierte Wissenschaft Auskunft geben. Vorstellen ist Bild von all den Erlebnissen, die vorgeburtlich beziehungsweise vor der Empfängnis von uns erlebt sind. Sie kommen nicht anders zu einem wirklichen Begreifen des Vorstellens, als wenn Sie sich darüber klar sind, daß Sie ein Leben vor der Geburt, vor der Empfängnis durchlebt haben. Und so wie die gewöhnlichen Spiegelbilder räumlich als Spiegelbilder entstehen, so spiegelt sich Ihr Leben zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt in dem jetzigen Leben drinnen, und diese Spiegelung ist das Vorstellen. Also Sie müssen sich geradezu vorstellen — wenn Sie es sich bildhaft vorstellen -, Ihren Lebensgang verlaufend zwischen den beiden horizontalen Linien, begrenzt rechts und links durch Geburt und Tod. Sie müssen sich dann weiter vorstellen, daß fortwährend von jenseits der Geburt das Vorstellen hereinspielt und durch die menschliche Wesenheit selber zurückgeworfen wird. Und auf diese Weise, indem die Tätigkeit, die Sie vor der Geburt beziehungsweise der Empfängnis ausgeführt haben in der geistigen Welt, zurückgeworfen wird durch Ihre Leiblichkeit, dadurch erfahren Sie das Vorstellen. Für wirklich Erkennende ist einfach das Vorstellen selbst ein Beweis des vorgeburtlichen Daseins, weil es Bild dieses vorgeburtlichen Daseins ist.

Ich wollte dies zunächst als Idee hinstellen — wir kommen auf die eigentlichen Erläuterungen der Dinge noch zurück -, um Sie darauf aufmerksam zu machen, daß wir auf diese Weise aus den bloßen Worterklärungen, die Sie in den Psychologien und Pädagogiken finden, herauskommen und daß wir zu einem wirklichen Ergreifen dessen, was vorstellende Tätigkeit ist, kommen, indem wir wissen lernen, daß wir im Vorstellen die Tätigkeit gespiegelt haben, die vor der Geburt oder Empfängnis von der Seele in der rein geistigen Welt ausgeübt worden ist. Alles übrige Definieren des Vorstellens nützt gar nichts, weil man keine wirkliche Idee von dem bekommt, was das Vorstellen in uns ist.

Nun wollen wir uns in derselben Art nach dem Willen fragen. Der Wille ist eigentlich für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein etwas außerordentlich Rätselhaftes; er ist eine Crux der Psychologen, einfach aus dem Grunde, weil dem Psychologen der Wille entgegentritt als etwas sehr Reales, aber im Grunde genommen doch keinen rechten Inhalt hat. Denn wenn Sie bei den Psychologen nachsehen, welchen Inhalt sie dem Willen verleihen, dann werden Sie immer finden: solcher Inhalt rührt vom Vorstellen her. Für sich selber hat der Wille zunächst einen eigentlichen Inhalt nicht. Nun ist es wiederum so, daß keine Definitionen da sind für den Willen; diese Definitionen sind beim Willen um so schwieriger, weil er keinen rechten Inhalt hat. Was ist er aber eigentlich? Er ist nichts anderes, als schon der Keim in uns für das, was nach dem Tode in uns geistig-seelische Realität sein wird. Also wenn Sie sich vorstellen, was nach dem Tode geistig-seelische Realität von uns wird, und wenn Sie es sich keimhaft in uns vorstellen, dann bekommen Sie den Willen. In unserer Zeichnung endet der Lebenslauf auf der Seite des Todes, und der Wille geht darüber hinaus (siehe Zeichnung S. 34).

Wir haben uns also vorzustellen: Vorstellung auf der einen Seite, die wir als Bild aufzufassen haben vom vorgeburtlichen Leben; Willen auf der anderen Seite, den wir als Keim aufzufassen haben für späteres. Ich bitte, den Unterschied zwischen Keim und Bild recht ins Auge zu fassen. Denn ein Keim ist etwas Überreales, ein Bild ist etwas Unterreales; ein Keim wird später erst zu einem Realen, trägt also der Anlage nach das spätere Reale in sich, so daß der Wille in der Tat sehr geistiger Natur ist. Das hat Schopenhauer geahnt; aber er konnte natürlich nicht bis zu der Erkenntnis vordringen, daß der Wille der Keim des Geistig-Seelischen ist, wie dieses Geistig-Seelische sich nach dem Tode in der geistigen Welt entfaltet.

Nun haben Sie in einer gewissen Weise das menschliche Seelenleben in zwei Gebiete zerteilt: in das bildhafte Vorstellen und in den keimhaften Willen; und zwischen Bild und Keim liegt eine Grenze. Diese Grenze ist das ganze Ausleben des physischen Menschen selbst, der das Vorgeburtliche zurückwirft, dadurch die Bilder der Vorstellung erzeugt, und der den Willen nicht sich ausleben läßt und dadurch ihn fortwährend als Keim erhält, bloß Keim sein läßt. Durch welche Kräfte, so müssen wir fragen, geschieht denn das eigentlich?

Wir müssen uns klar sein, daß im Menschen gewisse Kräfte vorhanden sein müssen, durch welche die Zurückwerfung der vorgeburtlichen Realität und das Im-Keime-Behalten der nachtodlichen Realität bewirkt wird; und hier kommen wir auf die wichtigsten psychologischen Begriffe von den Tatsachen, die Spiegelung desjenigen sind, was Sie aus dem Buche «Theosophie» schon kennen: Spiegelungen von Antipathie und Sympathie. Wir werden - und jetzt knüpfen wir an das im ersten Vortrage Gesagte an -, weil wir nicht mehr in der geistigen Welt bleiben können, herunterversetzt in die physische Welt. Wir entwickeln, indem wir in diese herunterversetzt werden, gegen alles, was geistig ist, Antipathie, so daß wir die geistige vorgeburtliche Realität zurückstrahlen in einer uns unbewußten Antipathie. Wir tragen die Kraft der Antipathie in uns und verwandeln durch sie das vorgeburtliche Element in ein bloßes Vorstellungsbild. Und mit demjenigen, was als Willensrealität nach dem Tode hinausstrahlt zu unserem Dasein, verbinden wir uns in Sympathie. Dieser zwei, der Sympathie und der Antipathie, werden wir uns nicht unmittelbar bewußt, aber sie leben in uns unbewußt und sie bedeuten unser Fühlen, das fortwährend aus einem Rhythmus, aus einem Wechselspiel zwischen Sympathie und Antipathie sich zusammensetzt.

Wir entwickeln in uns die Gefühlswelt, die ein fortwährendes Wechselspiel - Systole, Diastole - zwischen Sympathie und Antipathie ist. Dieses Wechselspiel ist fortwährend in uns. Die Antipathie, die nach der einen Seite geht, verwandelt fortwährend unser Seelenleben in ein vorstellendes; die Sympathie, die nach der anderen Seite geht, verwandelt uns das Seelenleben in das, was wir als unseren Tatwillen kennen, in das Keimhafthalten dessen, was nach dem Tode geistige Realität ist. Hier kommen Sie zum realen Verstehen des geistig-seelischen Lebens: wir schaffen den Keim des seelischen Lebens als einen Rhythmus von Sympathie und Antipathie.

Was strahlen Sie nun in der Antipathie zurück? Sie strahlen das ganze Leben, das Sie durchlebt, die ganze Welt, die Sie vor der Geburt beziehungsweise vor der Empfängnis durchlebt haben, zurück. Das hat im wesentlichen einen erkennenden Charakter. Also Ihre Erkenntnis verdanken Sie eigentlich dem Hereinscheinen, dem Hereinstrahlen Ihres vorgeburtlichen Lebens. Und dieses Erkennen, das in weit höherem Maße vorhanden ist, als Realität vorhanden ist vor der Geburt oder der Empfängnis, wird abgeschwächt zum Bilde durch die Antipathie. Daher können wir sagen: Dieses Erkennen begegnet der Antipathie und wird dadurch abgeschwächt zum Vorstellungsbild.

Wenn die Antipathie nun genügend stark wird, dann tritt etwas ganz Besonderes ein. Denn wir könnten auch im gewöhnlichen Leben nach der Geburt nicht vorstellen, wenn wir es nicht doch auch mit derselben Kraft in gewissem Sinn täten, die uns geblieben ist aus der Zeit vor der Geburt. Wenn Sie heute als physische Menschen vorstellen, so stellen Sie nicht mit einer Kraft vor, die in Ihnen ist, sondern mit der Kraft aus der Zeit vor der Geburt, die noch in Ihnen nachwirkt. Man meint vielleicht, die habe aufgehört mit der Empfängnis, aber sie ist noch immer tätig, und wir stellen vor mit dieser Kraft, die noch immer in uns hereinstrahlt. Sie haben das Lebendige vom Vorgeburtlichen fortwährend in sich, nur haben Sie die Kraft in sich, es zurückzustrahlen. Die begegnet Ihrer Antipathie. Wenn Sie nun jetzt vorstellen, so begegnet jedes solche Vorstellen der Antipathie, und wird die Antipathie genügend stark, so entsteht das Erinnerungsbild, das Gedächtnis, so daß das Gedächtnis nichts anderes ist als ein Ergebnis der in uns waltenden Antipathie. Hier haben Sie den Zusammenhang zwischen dem rein Gefühlsmäßigen noch der Antipathie, die unbestimmt noch zurückstrahlt, und dem bestimmten Zurückstrahlen, dem Zurückstrahlen der jetzt noch bildhaft ausgeübten Wahrnehmungstätigkeit im Gedächtnis. Das Gedächtnis ist nur gesteigerte Antipathie. Sie könnten kein Gedächtnis haben, wenn Sie zu Ihren Vorstellungen so große Sympathie hätten, daß Sie sie «verschlucken» würden; Sie haben Gedächtnis nur dadurch, daß Sie eine Art Ekel haben vor den Vorstellungen, sie zurückwerfen - und dadurch sie präsent machen. Das ist ihre Realität.

Wenn Sie diese ganze Prozedur durchgemacht haben, wenn Sie bildhaft vorgestellt haben, dies zurückgeworfen haben im Gedächtnis und das Bildhafte festhalten, dann entsteht der Begriff. Auf diese Weise haben Sie die eine Seite der Seelentätigkeit, die Antipathie, die zusammenhängt mit unserem vorgeburtlichen Leben.

Jetzt nehmen wir die andere Seite, die des Wollens, was Keimhaftes, Nachtodliches in uns ist. Das Wollen lebt in uns, weil wir mit ihm Sympathie haben, weil wir mit diesem Keim, der nach dem Tode sich erst entwickelt, Sympathie haben. Ebenso wie das Vorstellen auf Antipathie beruht, so beruht das Wollen auf Sympathie. Wird nun die Sympathie genügend stark - wie es bei der Vorstellung war, die durch Antipathie zum Gedächtnis wird -, dann entsteht aus Sympathie die Phantasie. Genau ebenso wie aus der Antipathie das Gedächtnis entsteht, so entsteht aus Sympathie die Phantasie. Und bekommen Sie die Phantasie genügend stark, was beim gewöhnlichen Leben nur unbewußt geschieht, wird sie so stark, daß sie wieder Ihren ganzen Menschen durchdringt bis in die Sinne, dann bekommen Sie die gewöhnlichen Imaginationen, durch die Sie die äußeren Dinge vorstellen. Wie der Begriff aus dem Gedächtnis, so geht aus der Phantasie die Imagination hervor, welche die sinnlichen Anschauungen liefert. Die gehen aus dem Willen hervor.

Es ist der große Irrtum, dem sich die Menschen hingeben, daß sie fortwährend in der Psychologie erzählen: Wir schauen die Dinge an, dann abstrahieren wir und bekommen so die Vorstellung. - Das ist nicht der Fall. Daß wir zum Beispiel die Kreide weiß empfinden, das ist hervorgegangen aus der Anwendung des Willens, der über die Sympathie und Phantasie zur Imagination wird. Wenn wir uns dagegen einen Begriff bilden, so hat dieser einen ganz anderen Ursprung, denn der Begriff geht aus dem Gedächtnis hervor.

Damit habe ich Ihnen das Seelische geschildert. Sie können unmöglich das Menschenwesen erfassen, wenn Sie nicht den Unterschied ergreifen zwischen dem sympathischen und antipathischen Element im Menschen. Diese, das sympathische und das antipathische Element, kommen zum Ausdruck an sich — wie ich es geschildert habe - in der Seelenwelt nach dem Tode. Dort herrscht unverhüllt Sympathie und Antipathie.

Ich habe Ihnen den seelischen Menschen geschildert. Der ist verbunden auf dem physischen Plan mit dem leiblichen Menschen. Alles Seelische drückt sich aus, offenbart sich im Leiblichen, so daß sich auf der einen Seite alles das im Leiblichen offenbart, was sich ausdrückt in Antipathie, Gedächtnis und Begriff. Das ist gebunden an die Leibesorganisation der Nerven. Indem die Nervenorganisationen gebildet werden im Leibe, wirkt darin für den menschlichen Leib alles Vorgeburtliche. Das seelisch Vorgeburtliche wirkt durch Antipathie, Gedächtnis und Begriff herein in den menschlichen Leib und schafft sich die Nerven. Das ist der richtige Begriff der Nerven. Alles Reden von einer Unterscheidung der Nerven in sensitive und motorische ist, wie ich Ihnen schon öfter auseinandergesetzt habe, nur ein Unsinn.

Und ebenso wirkt Wollen, Sympathie, Phantasie und Imagination in gewisser Beziehung wieder aus dem Menschen heraus. Das ist an das Keimhafte gebunden, das muß im Keimhaften bleiben, darf daher eigentlich nie zu einem wirklichen Abschluß kommen, sondern muß im Entstehen schon wieder vergehen. Es muß im Keime bleiben, es darf der Keim in der Entwickelung nicht zu weit gehen; daher muß es im Entstehen vergehen. Hier kommen wir zu etwas sehr Wichtigem im Menschen. Sie müssen den ganzen Menschen verstehen lernen: geistig, seelisch und leiblich. Nun wird im Menschen fortwährend etwas gebildet, das immer die Tendenz hat, geistig zu werden. Aber weil man es in großer Liebe, allerdings in egoistischer Liebe, im Leibe festhalten will, kann es nie geistig werden; es zerrinnt in seiner Leiblichkeit. Wir haben etwas in uns, was materiell ist, aber aus dem materiellen Zustand fortwährend in einen geistigen Zustand übergehen will. Wir lassen es nicht geistig werden; daher vernichten wir es indem Moment, wo es geistig werden will. Es ist das Blut - das Gegenteil der Nerven.

Das Blut ist wirklich ein «ganz besonderer Saft». Denn es ist derjenige Saft, welcher, wenn wir ihn aus dem menschlichen Leibe entfernen könnten — was innerhalb der irdischen Bedingungen nicht geht -, so daß er noch Blut bliebe und durch die anderen physischen Agenzien nicht vernichtet würde, dann als Geist aufwirbeln würde. Damit nicht das Blut als Geist aufwirbele, damit wir es so lange, als wir auf der Erde sind, bis zum Tode in uns behalten können, deshalb muß es vernichtet werden. Daher haben wir immerwährend in uns: Bildung des Blutes - Vernichtung des Blutes, Bildung des Blutes - Vernichtung des Blutes und so weiter durch Einatmung und Ausatmung.

Wir haben einen polarischen Prozeß in uns. Wir haben diejenigen Prozesse in uns, die längs des Blutes, der Blutbahnen laufen, die fortwährend die Tendenz haben, unser Dasein ins Geistige hinauszuleiten. Von motorischen Nerven so zu reden, wie dies üblich geworden ist, ist ein Unsinn, weil die motorischen Nerven eigentlich die Blutbahnen wären. Im Gegensatz zum Blut sind alle Nerven so veranlagt, daß sie fortwährend im Absterben, im Materiellwerden begriffen sind. Was längs der Nervenbahnen liegt, das ist eigentlich ausgeschiedene Materie; der Nerv ist eigentlich abgesonderte Materie. Das Blut will immer geistiger werden, der Nerv immer materieller; darin besteht der polarische Gegensatz.

Wir werden in den späteren Vorträgen diese hiermit gegebenen Grundprinzipien weiter verfolgen und werden sehen, wie ihre Verfolgung uns wirklich das geben kann, was uns auch in bezug auf die hygienische Gestaltung des Unterrichtes dienlich sein wird, damit wir das Kind zur seelischen und leiblichen Gesundheit heranerziehen und nicht zur geistigen und seelischen Dekadenz. Es wird deshalb so viel mißerzogen, weil so vieles nicht erkannt wird. So sehr die Physiologie glaubt, etwas zu haben, indem sie von sensitiven und motorischen Nerven spricht, so hat sie darin doch nur ein Spiel mit Worten. Von motorischen Nerven wird gesprochen, weil die Tatsache besteht, daß der Mensch nicht gehen kann, wenn gewisse Nerven beschädigt sind, zum Beispiel die, welche nach den Beinen gehen. Man sagt, er könne das nicht, weil er die Nerven gelähmt hat, die als «motorische» die Beine in Bewegung setzen. In Wahrheit ist es so, daß man in einem solchen Fall nicht gehen kann, weil man die eigenen Beine nicht wahrnehmen kann. Dieses Zeitalter, in dem wir leben, hat sich eben notwendigerweise in eine Summe von Irrtümern verstricken müssen, damit wir wieder die Möglichkeit haben, uns aus diesen Irrtümern herauszuwinden, selbständig als Menschen zu werden.

Nun merken Sie schon an dem, was ich jetzt hier entwickelt habe, daß eigentlich das Menschenwesen nur begriffen werden kann im Zusammenhange mit dem Kosmischen. Denn indem wir vorstellen, haben wir das Kosmische in uns. Wir waren im Kosmischen, ehe wir geboren wurden, und unser damaliges Erleben spiegelt sich jetzt in uns; und wir werden wieder im Kosmischen sein, wenn wir die Todespforte durchschritten haben werden, und unser künftiges Leben drückt sich keimhaft aus in dem, was in unserem Willen waltet. Was in uns unbewußt waltet, das waltet sehr bewußt für das höhere Erkennen im Kosmos.

Wir haben allerdings selbst in der leiblichen Offenbarung einen dreifachen Ausdruck dieser Sympathie und Antipathie. Gewissermaßen drei Herde haben wir, wo Sympathie und Antipathie ineinanderspielen. Zunächst haben wir in unserem Kopf einen solchen Herd, im Zusammenwirken von Blut und Nerven, wodurch das Gedächtnis entsteht. Überall, wo die Nerventätigkeit unterbrochen ist, überall, wo ein Sprung ist, da ist ein solcher Herd, wo Sympathie und Antipathie ineinanderspielen. Ein weiterer solcher Sprung findet sich im Rückenmark, zum Beispiel wenn ein Nerv nach dem hinteren Stachel des Rückenmarks hingeht, ein anderer Nerv von dem vorderen Stachel ausgeht. Dann ist wieder ein solcher Sprung in den Ganglienhäufchen, die in die sympathischen Nerven eingebettet sind. Wir sind gar nicht so unkomplizierte Wesen, wie es scheinen mag. An drei Stellen unseres Organismus, im Kopf, in der Brust und im Unterleib, spielt das hinein, da sind Grenzen, an denen Antipathie und Sympathie sich begegnen. Es ist mit Wahrnehmen und Wollen nicht so, daß sich etwas umleitet von einem sensitiven Nerven zu einem motorischen, sondern ein gerader Strom springt über von einem Nerven auf den anderen, und dadurch wird in uns das Seelische berührt: in Gehirn und Rückenmark. An diesen Stellen, wo die Nerven unterbrochen sind, sind wir eingeschaltet mit unserer Sympathie und Antipathie in das Leibliche; und dann sind wir wieder eingeschaltet, wo die Ganglienhäufchen sich entwickeln im sympathischen Nervensystem.

Wir sind mit unserem Erleben in den Kosmos eingeschaltet. Ebenso wie wir Tätigkeiten entwickeln, die im Kosmos weiter zu verfolgen sind, so entwickelt wieder mit uns der Kosmos fortwährend Tätigkeiten, denn er entwickelt fortwährend die Tätigkeit von Antipathie und Sympathie. Wenn wir uns als Menschen betrachten, so sind wir wieder selbst ein Ergebnis von Sympathien und Antipathien des Kosmos. Wir entwickeln Antipathie von uns aus: der Kosmos entwickelt mit uns Antipathie; wir entwickeln Sympathie: der Kosmos entwickelt mit uns Sympathie.

Nun sind wir ja als Menschen, indem wir uns äußerlich offenbaren, deutlich gegliedert in das Kopfsystem, in das Brustsystem und in das eigentliche Leibessystem mit den Gliedmaßen. Nun bitte ich aber zu berücksichtigen, daß diese Einteilung in gegliederte Systeme sehr leicht angefochten werden kann, weil die Menschen, wenn sie heute systematisieren, die einzelnen Glieder hübsch nebeneinander haben wollen. Wenn man also sagt: Man unterscheidet am Menschen ein Kopfsystem, ein Brustsystem und ein Unterleibssystem mit den Gliedmaßen, dann muß nach Ansicht der Menschen jedes System eine strenge Grenze haben. Die Menschen wollen Linien ziehen, wenn sie einteilen, und das kann man nicht, wenn man von Realitäten spricht. Wir sind im Kopf hauptsächlich Kopf, aber der ganze Mensch ist Kopf, nur ist das andere nicht hauptsächlich Kopf. Denn wie wir im Kopfe die eigentlichen Sinneswerkzeuge haben, so haben wir über den ganzen Leib ausgebildet zum Beispiel den Tastsinn und den Wärmesinn; indem wir daher Wärme empfinden, sind wir ganz Kopf. Wir sind nur im Kopfe hauptsächlich Kopf, sonst sind wir «nebenbei» Kopf. So gehen also die Teile ineinander, und wir haben es nicht so bequem mit den Gliedern, wie es die Pedanten haben möchten. Der Kopf setzt sich also fort; er ist nur im Kopfe besonders ausgebildet. Ebenso ist es mit der Brust. Brust ist die eigentliche Brust, aber nur hauptsächlich, denn der ganze Mensch ist wiederum Brust. Also auch der Kopf ist etwas Brust und auch der Unterleib mit den Gliedmaßen. Die Glieder gehen also ineinander über. Und ebenso ist es mit dem Unterleib. Daß der Kopf Unterleib ist, haben einige Physiologen bemerkt, denn die sehr feine Ausbildung des Kopf-Nervensystems liegt eigentlich nicht in dem, was unser Stolz ist, im Gehirn, in der äußeren Hirnrinde, sondern die liegt unter der äußeren Hirnrinde,. Ja, der kunstvollere Bau, die äußere Hirnrinde, ist gewissermaßen schon eine Rückbildung; da ist der komplizierte Bau schon in Rückbildung begriffen; es ist vielmehr schon ein Ernährungssystem im Gehirnmantel vorliegend. So daß der Mensch, wenn man das so vergleichsweise ausdrücken will, sich auf seinen Gehirnmantel gar nichts Besonderes einzubilden braucht; der ist ein Zurückgehen des komplizierteren Gehirns in ein mehr ernährendes Gehirn. Wir haben den Gehirnmantel mit dazu, daß die Nerven, die mit dem Erkennen zusammenhängen, ordentlich mit Nahrung versorgt werden. Und daß wir das über das tierische Gehirn hinausgehende bessere Gehirn haben, das ist nur aus dem Grunde, weil wir die Gehirnnerven besser ernähren. Nur dadurch haben wir die Möglichkeit, unser höheres Erkennen zu entfalten, daß wir die Gehirnnerven besser ernähren, als die Tiere es können. Aber mit dem eigentlichen Erkennen hat das Gehirn und das Nervensystem überhaupt nichts zu tun, sondern nur mit dem Ausdruck des Erkennens im physischen Organismus.

Nun fragt es sich: Warum haben wir den Gegensatz zwischen Kopfsystem — lassen wir zunächst das mittlere System unberücksichugt und dem polarischen Gliedmaßensystem mit dem Unterleibssystem? Wir haben ihn, weil das Kopfsystem in einem bestimmten Zeitpunkte «ausgeatmet» wird durch den Kosmos. Der Mensch hat durch die Antipathie des Kosmos seine Hauptesbildung. Wenn dem Kosmos sozusagen gegenüber dem, was der Mensch in sich trägt, so stark «ekelt», daß er es ausstößt, so entsteht dieses Abbild. Im Kopfe trägt wirklich der Mensch das Abbild des Kosmos in sich. Das rund geformte menschliche Haupt ist ein solches Abbild. Durch eine Antipathie des Kosmos schafft der Kosmos ein Abbild von sich außerhalb seiner. Das ist unser Haupt. Wir können uns unseres Hauptes als eines Organs zu unserer Freiheit deshalb bedienen, weil der Kosmos dieses Haupt zuerst von sich ausgestoßen hat. Wir betrachten das Haupt nicht richtig, wenn wir es etwa in demselben Sinne intensiv eingegliedert denken in den Kosmos wie unser Gliedmaßensystem, mit dem die Sexualsphäre ja zusammengehört. Unser Gliedmaßensystem ist in den Kosmos eingegliedert, und der Kosmos zieht es an, hat mit ihm Sympathie, wie er dem Haupt gegenüber Antipathie hat. Im Haupte begegnet unsere Antipathie der Antipathie des Kosmos, die stoßen dort zusammen. Da, in dem Aufeinanderprallen unserer Antipathien mit denen des Kosmos, entstehen unsere Wahrnehmungen. Alles Innenleben, das auf der anderen Seite des Menschen entsteht, rührt her von dem liebevollen sympathischen Umschlingen unseres Gliedmaßensystems durch den Kosmos.

So drückt sich in der menschlichen Leibesgestalt aus, wie der Mensch auch seelisch aus dem Kosmos heraus gebildet ist und was er in seiner Trennung wiederum aufnimmt aus dem Kosmos heraus. Sie werden daher auf Grundlage solcher Betrachtungen leichter einsehen, daß ein großer Unterschied ist zwischen der Willensbildung und der Vorstellungsbildung. Wirken Sie besonders auf die Vorstellungsbildung, wirken Sie einseitig auf die Vorstellungsbildung, so weisen Sie eigentlich den ganzen Menschen auf das Vorgeburtliche zurück, und Sie werden ihm schaden, wenn Sie ihn rationalistisch erziehen, weil Sie dann seinen Willen einspannen in das, was er eigentlich schon absolviert hat: in das Vorgeburtliche. Sie dürfen nicht zuviel abstrakte Begriffe in das einmischen, was Sie in der Erziehung an das Kind heranbringen. Sie müssen mehr Bilder darin einmischen. Warum? Das können Sie an unserer Zusammenstellung ablesen. Bilder sind Imaginationen, gehen durch die Phantasie und Sympathie. Begriffe, abstrakte Begriffe, sind Abstraktionen, gehen durch das Gedächtnis und durch die Antipathie, kommen vom vorgeburtlichen Leben. Wenn Sie also beim Kinde viele Abstraktionen anwenden, werden Sie fördern, daß das Kind sich besonders intensiv verlegen muß auf den Prozeß des Kohlensäurewerdens, Kohlensäurebildens im Blute, auf den Prozeß der Leibesverhärtung, des Absterbens. Wenn Sie dem Kinde möglichst viele Imaginationen beibringen, wenn Sie es möglichst so ausbilden, daß Sie in Bildern zu ihm sprechen, dann legen Sie in das Kind den Keim zum fortwährenden Sauerstoffbewahren, zum fortwährenden Werden, weil Sie es auf die Zukunft, auf das Nachtodliche hinweisen. Wir nehmen gewissermaßen, indem wir erziehen, die Tätigkeiten, die vor der Geburt mit uns Menschen ausgeübt werden, wieder auf. Wir müssen uns heute gestehen: Vorstellen ist eine Bildtätigkeit, die herrührt von dem, was wir vor der Geburt oder Empfängnis erlebt haben. Da ist mit uns von den geistigen Mächten so verfahren worden, daß Bildtätigkeit in uns gelegt wurde, die in uns nachwirkt noch nach der Geburt. Indem wir den Kindern Bilder überliefern, fangen wir im Erziehen damit an, diese kosmische Tätigkeit wieder aufzunehmen. Wir verpflanzen in sie Bilder, die zu Keimen werden können, weil wir sie hineinlegen in eine Leibestätigkeit. Wir müssen daher, indem wir uns als Pädagogen die Fähigkeit aneignen, in Bildern zu wirken, das fortwährende Gefühl haben: du wirkst auf den ganzen Menschen, eine Resonanz des ganzen Menschen ist da, wenn du in Bildern wirkst.

Dieses in das eigene Gefühl aufnehmen, daß man in aller Erziehung eine Art Fortsetzung der vorgeburtlichen übersinnlichen Tätigkeit bewirkt, dies gibt allem Erziehen die nötige Weihe, und ohne diese Weihe kann man überhaupt nicht erziehen.

So haben wir uns zwei Begriffssysteme angeeignet: Erkennen, Antipathie, Gedächtnis, Begriff - Wollen, Sympathie, Phantasie, Imagination; zwei Systeme, die uns dann im speziellen Anwenden für alles dienen können, was wir praktisch auszuüben haben in unserer pädagogischen Tätigkeit. Davon wollen wir dann morgen weitersprechen.

Second Lecture

All teaching in the future will have to be based on a real psychology derived from anthroposophical knowledge of the world. The fact that teaching and education must be based on psychology was recognized in many different places, and you are well aware that, for example, Herbart's pedagogy, which had a very wide influence in the past, based its educational measures on Herbart's psychology. Now, today and also in the past centuries, there is a certain fact that has actually prevented a real, useful psychology from emerging. This must be attributed to the fact that in the age in which we now live, the age of the consciousness soul, such spiritual depth has not yet been achieved that it has been possible to truly comprehend the human soul. However, the concepts that were previously formed in the field of psychology, in the field of soul science, from the ancient knowledge of the fourth post-Atlantean period, are now more or less empty of content and have become mere phrases. Anyone who picks up any psychology book today, or even anything that has to do with psychological concepts, will find that such works no longer contain any real content. One has the feeling that psychologists are just playing with concepts. Who today, for example, develops a correct and clear concept of what mental image or will is? Today, you can take definition after definition from psychology and pedagogy about mental image and will: these definitions will not be able to give you a real mental image of imagination or a real idea of will. We have completely failed – naturally out of an external historical necessity – to connect the individual human being spiritually to the whole universe. People were unable to comprehend how the human soul is connected to the entire universe. Only when we can grasp the connection between the individual human being and the entire universe can we arrive at an idea of the essence of the human being as such.

Let us look at what is commonly called mental image. We must develop mental image, feeling, and will in children. So we must first gain a clear understanding of what mental image is. Anyone who looks impartially at what lives as mental image in human beings will immediately notice the pictorial character of the mental image: the mental image has a pictorial character. And anyone who seeks a character of being in the mental image, who seeks a real existence in the mental image, is indulging in a great illusion. But what would the mental image be for us if it were a being? We undoubtedly also have elements of being within us. Take, for example, our physical elements of being, take only what I am saying now, very roughly: for example, your eyes, which are elements of being, your nose, which is an element of being, or even your stomach, which is an element of being. You will say to yourself that you live in these elements of being, but you cannot form a mental image with them. You flow out with your own being into the elements of being, you identify with the elements of being. This is precisely what makes it possible for us to grasp something with our mental images, to comprehend something, that they have an image-like character, that they do not flow together with us in such a way that we are in them. So they are not really, they are mere images. It is the great mistake that has been made, especially at the end of the last epoch of human development in the last centuries, to identify being with thinking as such. “Cogito, ergo sum” is the greatest error that has been placed at the forefront of the modern worldview; for in the whole scope of ‘cogito’ lies not “sum,” but “non sum.” That is, as far as my knowledge extends, I am not, but only an image.

Now, when you consider the pictorial character of mental image, you must above all consider it qualitatively. You must look at the mobility of mental image, you must, in a sense, form a not entirely accurate concept of activity, which would indeed echo being. But we must imagine that even in mental activity we only have pictorial activity. So everything that is movement in mental image is movement of images. But images must be images of something; they cannot be images merely in themselves. If you reflect on the comparison with mirror images, you can say to yourself: the mirror images appear from the mirror, but everything that lies in the mirror images is not behind the mirror, but exists somewhere else, quite independently of it, and it is quite indifferent to the mirror what is reflected in it; anything can be reflected in it. If we know in this very sense that the mental image activity is pictorial, then the question is: What is the mental image? Of course, no external science can provide information about this; only anthroposophically oriented science can provide information about this. The mental image is an image of all the experiences we had before birth or before conception. You cannot truly understand imagination unless you are clear that you lived a life before birth, before conception. And just as ordinary mirror images arise spatially as mirror images, so your life between death and new birth is reflected in your present life, and this reflection is the mental image. So you must imagine — if you imagine it pictorially — your life course running between the two horizontal lines, bounded on the right and left by birth and death. You must then further imagine that your mental image continually plays in from beyond birth and is reflected back by the human being itself. And in this way, as the activity you carried out before birth or conception in the spiritual world is reflected back through your physicality, you experience a mental image. For those who truly recognize this, a mental image itself is simply proof of pre-birth existence, because it is an image of this pre-birth existence.

I wanted to present this as an idea first — we will come back to the actual explanations of things — in order to draw your attention to the fact that in this way we move beyond the mere explanations of words that you find in psychology and pedagogy, and that we come to a real grasp of what mental image activity is by learning that in forming mental images we have mirrored the activity that was exercised by the soul in the purely spiritual world before birth or conception. Any other definition of the mental image is useless, because it does not give us a real idea of what the mental image is within us.

Now let us ask ourselves about the will in the same way. The will is actually something extremely mysterious for ordinary consciousness; it is a crux for psychologists, simply because the will confronts the psychologist as something very real, but which, when it comes down to it, has no real content. For if you look at what content psychologists give to the will, you will always find that such content stems from a mental image. The will itself does not initially have any actual content. Now, it is also the case that there are no definitions for the will; these definitions are all the more difficult with the will because it has no real content. But what is it actually? It is nothing other than the seed within us for what will be our spiritual-soul reality after death. So when you form the mental image of what will become of us spiritually and soul-wise after death, and when you form it as a seed within us, then you get the will. In our drawing, the course of life ends on the side of death, and the will goes beyond it (see drawing on p. 34).

So we have to imagine: on the one hand, a mental image that we have to understand as an image of pre-birth life; on the other hand, will, which we have to understand as a seed for later life. I ask you to really consider the difference between a seed and an image. For a seed is something super-real, an image is something sub-real; a seed only later becomes real, so it carries within it the potential for later reality, so that the will is in fact very spiritual in nature. Schopenhauer sensed this; but of course he could not advance to the realization that the will is the seed of the spiritual-soul, as this spiritual-soul unfolds in the spiritual world after death.

Now you have, in a certain sense, divided human soul life into two areas: the pictorial mental image and the embryonic will; and there is a boundary between image and germ. This boundary is the whole life of the physical human being itself, which rejects the pre-birth reality, thereby creating the images of mental image, and which does not allow the will to live itself out, thereby continually preserving it as a seed, allowing it to be merely a seed. We must ask ourselves, through what forces does this actually happen?

We must be clear that certain forces must be present in the human being through which the rejection of the prenatal reality and the preservation of the post-mortem reality in the germ are effected; and here we come to the most important psychological concepts of the facts, which are reflections of what you already know from the book “Theosophy”: reflections of antipathy and sympathy. We will — and now we are following on from what was said in the first lecture — because we can no longer remain in the spiritual world, be transferred down into the physical world. As we are transferred down into this world, we develop antipathy toward everything spiritual, so that we reflect back the spiritual pre-birth reality in an antipathy that is unconscious to us. We carry the power of antipathy within us and through it transform the pre-birth element into a mere mental image. And we connect with sympathy to that which radiates out into our existence as will reality after death. We are not immediately aware of these two, sympathy and antipathy, but they live within us unconsciously and they represent our feelings, which are constantly composed of a rhythm, an interplay between sympathy and antipathy.

We develop within ourselves a world of feelings that is a constant interplay—systole, diastole—between sympathy and antipathy. This interplay is constantly present within us. The antipathy that goes in one direction continually transforms our soul life into a mental image one; the sympathy that goes in the other direction transforms our soul life into what we know as our will to act, into the germination of what is spiritual reality after death. Here you come to a real understanding of spiritual-soul life: we create the seed of soul life as a rhythm of sympathy and antipathy.

What do you now radiate back in antipathy? You radiate back the whole life you have lived through, the whole world you lived through before birth or before conception. This has essentially a cognitive character. So you actually owe your knowledge to the shining in, the radiating in of your pre-birth life. And this recognition, which is present to a far greater extent than reality is present before birth or conception, is weakened to an image by antipathy. Therefore, we can say: this recognition encounters antipathy and is thereby weakened to a mental image.

When antipathy becomes strong enough, something very special happens. For we could not imagine this in ordinary life after birth if we did not do so with the same power that has remained with us from the time before birth. When you form a mental image of things today as physical human beings, you do not form an image with a power that is within you, but with the power from the time before birth, which still has an effect on you. One might think that it ceased with conception, but it is still active, and we imagine with this power that still shines within us. You have the vitality of the prenatal life continually within you, only you have the power within you to reflect it back. This encounters your antipathy. If you now imagine something, every such mental image encounters antipathy, and if the antipathy becomes strong enough, the memory image, the memory, arises, so that memory is nothing other than a result of the antipathy reigning within us. Here you have the connection between the purely emotional, the antipathy that still radiates back indeterminately, and the definite radiation back, the radiation back of the now still pictorially exercised activity of perception in memory. Memory is only heightened antipathy. You could not have memory if you had such great sympathy for your mental images that you would “swallow” them; you only have memory because you have a kind of disgust for the mental images, you reject them—and thereby make them present. That is their reality.

Once you have gone through this whole procedure, once you have mentally imaged it as a pictorial image, rejected it in your memory, and retained the pictorial image, then the concept arises. In this way, you have one side of the soul's activity, antipathy, which is connected with our pre-birth life.

Now let us take the other side, that of will, which is germinal, post-mortem in us. Will lives in us because we sympathize with it, because we sympathize with this germ, which only develops after death. Just as the mental image is based on antipathy, so volition is based on sympathy. If sympathy becomes strong enough — as was the case with the mental image, which becomes memory through antipathy — then sympathy gives rise to fantasy. Just as memory arises from antipathy, so fantasy arises from sympathy. And if your imagination becomes strong enough, which in ordinary life happens only unconsciously, it becomes so strong that it permeates your whole being, right down to your senses, and then you acquire the ordinary imaginations through which you form mental images of external things. Just as the concept arises from memory, so imagination arises from the imagination, which provides the sensory perceptions. These arise from the will.

It is a great mistake that people indulge in when they constantly say in psychology: We look at things, then we abstract and thus obtain the mental image. That is not the case. For example, the fact that we perceive chalk as white arises from the application of the will, which becomes imagination through sympathy and fantasy. When we form a concept, on the other hand, it has a completely different origin, for the concept arises from memory.

I have thus described the soul to you. You cannot possibly understand the human being if you do not grasp the difference between the sympathetic and antipathetic elements in the human being. These elements, the sympathetic and the antipathetic, express themselves—as I have described—in the soul world after death. There, sympathy and antipathy reign undisguised.

I have described the soul-being to you. It is connected on the physical plane with the physical human being. Everything of the soul expresses itself, reveals itself in the physical, so that on the one hand everything that is expressed in antipathy, memory, and concept is revealed in the physical. This is bound to the physical organization of the nerves. As the nerve organization is formed in the body, everything prenatal works within the human body. The prenatal soul works into the human body through antipathy, memory, and concept, and creates the nerves. That is the correct concept of the nerves. All talk of a distinction between sensitive and motor nerves is, as I have often explained to you, nonsense.

And in a certain sense, will, sympathy, fantasy, and imagination also work out of the human being again. This is bound to the embryonic, must remain in the embryonic, and therefore must never actually come to a real conclusion, but must pass away again as soon as it arises. It must remain in the seed; the seed must not go too far in its development; therefore, it must pass away in its emergence. Here we come to something very important in the human being. You must learn to understand the whole human being: spiritually, soulfully, and physically. Now, something is constantly being formed in the human being that always has the tendency to become spiritual. But because we want to hold it in the body with great love, albeit selfish love, it can never become spiritual; it dissolves in its physicality. We have something within us that is material, but that constantly wants to transition from the material state to a spiritual state. We do not allow it to become spiritual; therefore, we destroy it the moment it wants to become spiritual. It is the blood — the opposite of the nerves.

Blood is truly a “very special juice.” For it is the juice which, if we could remove it from the human body—which is not possible under earthly conditions—so that it would remain blood and not be destroyed by other physical agents, would then swirl up as spirit. In order to prevent the blood from swirling up as spirit, so that we can keep it within us as long as we are on earth, until death, it must be destroyed. Therefore, we have within us a perpetual process: formation of blood — destruction of blood, formation of blood — destruction of blood, and so on, through inhalation and exhalation.

We have a polar process within us. We have those processes within us that run along the blood, the blood vessels, which constantly tend to lead our existence out into the spiritual realm. To speak of motor nerves, as has become customary, is nonsense, because the motor nerves would actually be the blood vessels. In contrast to blood, all nerves are predisposed to constantly die off and become material. What lies along the nerve pathways is actually excreted matter; the nerve is actually secreted matter. Blood always wants to become more spiritual, the nerve always more material; this is the polar opposition.

In later lectures, we will continue to pursue these basic principles and see how their pursuit can really give us what will also be useful in terms of the hygienic design of teaching, so that we can raise the child to mental and physical health and not to spiritual and mental decadence. There is so much poor education because so much is not recognized. As much as physiology believes it has something when it speaks of sensory and motor nerves, it is only playing with words. Motor nerves are mentioned because it is a fact that humans cannot walk if certain nerves are damaged, for example, those that go to the legs. It is said that they cannot do so because they have paralyzed the nerves that, as “motor” nerves, set the legs in motion. In truth, in such a case, one cannot walk because one cannot perceive one's own legs. The age in which we live has necessarily become entangled in a sum of errors so that we may once again have the opportunity to extricate ourselves from these errors and become independent as human beings.

Now you can see from what I have just explained that the human being can only be understood in connection with the cosmic. For when we form a mental image, we have the cosmic within us. We were in the cosmic realm before we were born, and our experiences there are now reflected in us; and we will be in the cosmic realm again when we have passed through the gates of death, and our future life is expressed in embryonic form in what governs our will. What governs us unconsciously governs very consciously for higher knowledge in the cosmos.

However, even in our physical manifestation we have a threefold expression of this sympathy and antipathy. In a sense, we have three centers where sympathy and antipathy interact. First, we have such a center in our head, in the interaction of blood and nerves, which gives rise to memory. Wherever nerve activity is interrupted, wherever there is a break, there is such a center where sympathy and antipathy interact. Another such break is found in the spinal cord, for example, when one nerve goes to the posterior horn of the spinal cord and another nerve emanates from the anterior horn. Then there is another such break in the ganglion clusters embedded in the sympathetic nerves. We are not as uncomplicated beings as we may seem. This plays a role in three places in our organism, in the head, in the chest, and in the abdomen, where there are boundaries where antipathy and sympathy meet. With perception and volition, it is not the case that something is diverted from a sensory nerve to a motor nerve, but rather a direct current jumps from one nerve to another, and this touches the soul within us: in the brain and spinal cord. At these points, where the nerves are interrupted, we are connected with our sympathy and antipathy to the physical; and then we are connected again where the ganglion clusters develop in the sympathetic nervous system.