The Study of Man

GA 293

23 August 1919, Stuttgart

Lecture III

The teacher of the present day should have a comprehensive view of the laws of the universe as a background to all he undertakes in his school work. And clearly, it is particularly in the lower classes, in the lower school grades, that education demands a connection in the teacher's soul with the highest ideas of humanity. A real canker in school constitution of recent years has been the habit of keeping the teacher of younger classes in a kind of dependent position, in a position which has made his existence seem of less value than that of teachers in the upper school. Naturally this is not the place for me to speak in general of the spiritual branch of the social organism. But I must point out that in future everything in the sphere of teaching must be on an equal footing; and public opinion will have to recognise that the teacher of the lower grades, both spiritually and in other ways, has the same intrinsic value as the teacher of the upper grades. It will not surprise you, therefore, if we point out to-day in the background of all teaching—with younger children as with older—there must be something that one cannot of course use directly in one's work with the children, but which it is essential that the teacher should know if his teaching is to be fruitful.

In our teaching we bring to the child the world of nature on the one hand and the world of the spirit on the other. In so far as we are human beings on the earth, on the physical plane, fulfilling our existence between birth and death, we are intimately connected with the natural world on the one hand and the spiritual world on the other hand. Now the psychological science of our time is a very weak growth. It is still suffering from the after-effects of that dogmatic Church pronouncement of A.D. 869—to which I have often alluded—a decree which obscured an earlier vision resting on instinctive knowledge: the insight that man is divided into body, soul and spirit. When you hear psychologists speak to-day you will nearly always find that they speak only of the twofold nature of man. You will hear it said that man consists of matter and soul, or of body and spirit, however it may be put. Thus matter and body, and equally soul and spirit, are regarded as meaning much the same thing.1The words here translated as matter and body are Körper and Leib, for which we have no precise equivalent in English. Körper is equivalent to physical body. Leib denotes a living body, i.e. an organism penetrated with life. Nearly all psychologies are built up on this erroneous conception of the twofold division of the human being. It is impossible to come to a real insight into human nature if one adopts this twofold division alone. It is for this fundamental reason that nearly everything that is put forward to-day as psychology is only dilettantism, a mere playing with words.

This is chiefly due to that error, which reached its full magnitude only in the second half of the nineteenth century, and which arose from a misconception of a really great achievement of physical science. You know that the good people of Heilbronn have erected a memorial in the middle of their city to the man they shut up in an asylum during his life: Julius Robert Mayer. And you know that this personality, of whom the Heilbronn people are to-day naturally extremely proud, is associated with what is called the law of the Conservation of Energy or Force.

This law states that the sum of all energies or forces present in the universe is constant, only that these forces undergo certain changes, and appear, now as heat, now as mechanical force, or the like. This is the form in which the law of Julius Robert Mayer is presented, because it is completely misunderstood. For he was really concerned with the discovery of the metamorphosis of forces, and not with the exposition of such an abstract law as that of the conservation of energy.

Now, considered broadly and from the point of view of the history of civilisation, what is this law of the conservation of energy or force? It is the great stumbling-block to any understanding of man. For as soon as people think that forces can never be created afresh, it becomes impossible to arrive at a knowledge of the true being of man. For the true nature of man rests on the fact that through him new forces are continually coming into existence. It is certainly true that, under the conditions in which we are living in the world, man is the only being in whom new forces and even—as we shall hear later—new matter is being formed. But as modern philosophy will have nothing to do with the elements through which alone the human being can be fully comprehended, it produces this law of the conservation of energy; a law which, in a sense, does no harm when applied to the other kingdoms of nature, to the mineral, plant and animal kingdoms—but which applied to man destroys all possibility of a true understanding and knowledge.

As teachers it will be necessary for you on the one hand to give your pupils an understanding of nature, and on the other hand to lead them to a certain comprehension of spiritual life. Without a knowledge of nature in some degree, and without some relation to spiritual life, man cannot take his place in social life. Let us therefore first of all turn our attention to external nature.

Outer nature presents itself to us in two ways. On the one side, we confront nature in our thought life which as you know is of an image character and is a kind of reflection of our pre-natal life. On the other side we come into touch with that nature which may be called will-nature, which, as germ, points to our life after death. In this way we are continuously involved with nature. This might of course appear to be a two fold relationship between man and the world, and it has in point of fact given rise to the error of the twofold nature of man. We shall return to this subject later. When we confront the world from the side of thinking and of the mental picture, then we can really only comprehend that part of the world which is perpetually dying. This is a law of extraordinary importance. You must be very clear on this point: you may come across the most marvellous natural laws, but if they have been discovered by means of the intellect and the powers of the mental picture, then they will always refer to what is in process of dying in external nature.

When, however, the living will, present in man as germ, is turned to the external world, it experiences laws very different from those connected with death. Hence those of you, who still retain conceptions which have sprung from the modern age and the errors of present-day science, will find something difficult to understand. What brings us into contact with the external world through the senses—including the whole range of the twelve senses—has not the nature of cognition, but rather of will. A man of to-day has lost all perception of this. He therefore considers it childish when he reads in Plato that actually sight comes about by the stretching forth of a kind of prehensile pair of arms from the eyes to the objects. These prehensile arms cannot of course be perceived by means of the senses; but that Plato was conscious of them is proof that he had penetrated into the super-sensible world. Actually, looking at things involves the same process as taking hold of things, only it is more delicate. For example, when you take hold of a piece of chalk this is a physical process exactly like the spiritual process that takes place when you send the etheric forces from your eyes to grasp an object in the act of sight. If people of the present day had any power of observation, they would be able to deduce these facts from observing natural phenomena. If, for example, you look at a horse's eyes, which are directed outwards, you will get the feeling that the horse, simply through the position of his eyes, has a different attitude to his environment from the human being. I can show you the causes of this most clearly by the following hypothesis: imagine that your two arms were so constituted that it was quite impossible for you to bring them together in front, so that you could never take hold of yourself. Suppose you had to remain in the position of “Ah” in Eurythmy and could never come to “0,” that, through some resisting force, it were impossible for you by stretching your arms forward to bring them together in front. Now the horse is in this situation with respect to the super-sensible arms of his eyes: the arm of his right eye can never touch the arm of his left eye. But the position of man's eyes is such that he can continually make these two super-sensible arms of his eyes touch one another. This is the basis of our sensation of the Ego, the I—a super-sensible sensation. If we had no possibility at all of bringing left and right into contact; or if the touching of left and right meant as little as it does with animals, who never rightly join their fore-feet, in prayer for instance, or in any similar spiritual exercise—if this were the case we should not be able to attain this spiritualised sensation of our own self.

What is of paramount importance in the sensations of eye and ear is not so much the passive element, it is the activity, i.e. how we meet the outside world in our will. Modern philosophy has often had an inkling of some truth, and has then invented all kinds of words, which, however, usually show how far one is from a real comprehension of the matter. For example, the Localzeichen of Lotze's philosophy exhibit a trace of this knowledge that the will is active in the senses. But our lower sense organism, which clearly shows its connection with the metabolic system in the senses of touch, taste and smell, is indeed closely bound up with the metabolic system right into the higher senses—and the metabolic system is of a will nature.

You can therefore say: man confronts nature with his intellectual faculties and through their means he grasps all that is dead in Nature, and he acquires laws concerning what is dead. But what rises in Nature from the womb of death to become the future of the world, this is comprehended by man's will—that will which is seemingly so indeterminate, but which extends right into the senses themselves.

Think how living your relationship to Nature will become if you keep clearly in view what I have just said. For then you will say to yourselves: when I go out into Nature I have the play of light and colour continually before me; in assimilating the light and its colours I am uniting myself with that part of Nature which is being carried on into the future; and when I return to my room and think over what I have seen in Nature, and spin laws about it, then I am concerning myself with that element in the world which is perpetually dying. In Nature dying and becoming are continuously flowing into one another. We are able to comprehend the dying element because we bear within us the reflection of our prenatal life, the world of intellect, the world of thought, whereby we can see in our mind's eye the elements of death at the basis of Nature. And we are able to grasp what will come of Nature in the future because we confront Nature, not only with our intellect and thought, but with that which is of a will-nature within ourselves.

Were it not that, during his earthly life, man could preserve some part of what before his birth became purely thought life, he would never be able to achieve freedom. For, in that case, man would be bound up with what is dead, and the moment he wanted to call into free activity what in himself is related to the dead element in Nature, he would be wanting to call into free activity a dying thing. And if he wished to make use of what unites him with Nature as a being of will, his consciousness would be deadened, for what unites him as a will being with Nature is still in germ. He would be a Nature being, but not a free being.

Over and above these two elements—the comprehension of what is dead through the intellect, and the comprehension of what is living and becoming through the will—there dwells something in man which he alone and no other earthly being bears within him from birth to death, and that is pure thinking; that kind of thinking which is not directed to external nature, but is solely directed to the super-sensible nature in man himself, to that which makes him an autonomous being, something over and above what lives in the “less than death” and “more than life.” When speaking of human freedom therefore, one has to pay attention to this autonomous thing in man, this pure sense-free thinking in which the will too is always present.

Now when you turn to consider Nature itself from this point of view you will say: I am looking out upon the world, the stream of dying is in me, and also the stream of renewing: dying—being born again. Modern science understands but little of this process; for it regards the external world as more or less of a unity, and continually muddles up dying and becoming. So that the many statements about Nature and its essence which are common to-day are entirely confused, because dying and becoming are mixed up and confounded with one another. In order clearly to differentiate between these two streams in Nature the question must be asked: how would it be with the world if man himself were not within it?

This question presents a great dilemma for the philosophy of modern science. For, suppose you were to ask a truly modern research scientist: what would Nature be like if man were not within it? Of course he might at first be rather shocked, for the question would seem to be to him a strange one. Then, however, he would consider what grounds his science gives for answering such a question, and he would say: in this case, minerals, plants and animals would be on the earth, only man would not be there; and the course of the earth right through from the beginning, when it was still in the nebulous condition described by Kant and Laplace, would have been the same as it has been, only that man would not have been present in this progress. Practically speaking this is the only answer that could result. He might perhaps add: man tills the ground and so alters the surface of the earth, or he constructs machines and thereby also brings about certain alterations; but these are immaterial in comparison with the changes that are caused by Nature itself. In any case the gist of the scientist's answer would be that minerals, plants and animals would develop without man being present on the earth.

This is not correct. For if man were not present in the earth's evolution then the animals, for the most part, would not be there either; for a great many animals, and particularly the higher animals, have only arisen in the earth's evolution because man was obliged—figuratively speaking, of course—to use his elbows. The nature of man formerly contained many things which are not there now, and at a certain stage of his earthly development he had to separate out from himself the higher animals, to throw them off, as it were, so that he himself could progress. I will make a comparison to describe this throwing out: imagine a solution where something is being dissolved, and then imagine that this dissolved substance is separated out and falls to the bottom as sediment. In the same way man was united with the animal world in earlier conditions of his development and later he separated out the animal world like a precipitate, or sediment. The animals would not have become what they are to-day if man had not had to develop as he has done. Thus without man in the earth evolution the animal forms as well as the earth itself would have looked quite other than they do to-day.

But let us pass on to consider the mineral and plant world. Here we must be clear that not only the lower animal forms but also the plant and mineral kingdoms would long ago have dried up and ceased to develop if man were not upon the earth. And, again, present-day philosophy, based as it is on a one-sided view of the natural world, is bound to say: certainly men die, and their bodies are burned or buried, and thereby are given over to the earth, but this is of no significance for the development of the earth; for if the earth did not receive human bodies into itself it would take its course in precisely the same way as now, when it does receive these bodies. But this means that men are quite unaware that the continuous giving over of human corpses to the earth—whether by cremation or burial—is a real process which works on in the earth.

Peasant women in the country know much better than town women that yeast plays an important part in bread making, although only a little is added to the bread; they know that the bread could not rise unless yeast were added to the dough. In the same way the earth would long ago have reached the final stage of its development if there had not been continuously added to it the forces of the human corpse, which is separated in death from what is of soul and spirit. Through the forces present in human corpses which are thus received by the earth, the evolution of the earth itself is maintained. It is owing to this that the minerals can still go on producing their powers of crystallisation, a thing they would otherwise long ago have ceased to do; without these forces they would long ago have crumbled away or dissolved. Plants, also, which would long ago have ceased to grow are enabled, thanks to these forces, to go on growing to-day. And it is the same with the lower animals forms. In giving his body over to the earth the human being is giving the ferment, the yeast for future—development.

Hence it is by no means a matter of indifference whether man is living on the earth or not. It is simply untrue that the evolution of the earth with respect to its mineral, plant and animal kingdoms, would continue if man himself were not there. The process of Nature is a unified whole to which man belongs. We only get a true picture of man if we think of him as standing even in death in the midst of the cosmic process.

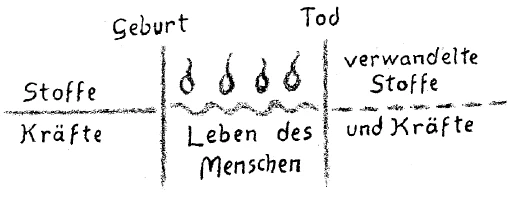

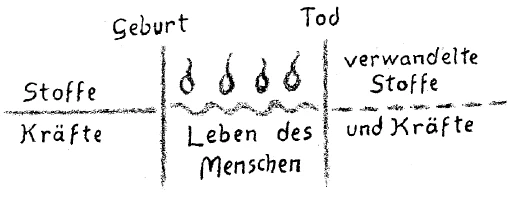

If you will bear this in mind then you will hardly wonder at what I am now going to say: when man descends from the spiritual into the physical world he receives his physical body as a garment. But naturally the body received as a child differs from the body as we lay it aside in death, at whatever age. Something has happened to the physical body. And what has happened could only come about because this body is permeated with forces of spirit and soul. For, after all, we eat what animals also eat. That is to say, we transform external matter just as the animals do; but we transform it with the help of something which animals have not got; something that came down from the spiritual world in order to unite itself with the physical body of man. Because of this we affect the substances in a different way than do animals or plants. And the substances given over to the earth in the human corpse are transformed substances, something different from what man received when he was born. We can therefore say: man receives certain substances and forces at birth; he renews them during his life and gives them up again to the earth process in a different form. The substances and forces which he gives up to the earth process at death are not the same as those which he received at birth. In giving them up he is bestowing upon the earth process something which continuously streams through him from the super-sensible world into the physical, sense-perceptible, earth process. At birth he brings down something from the super-sensible world; this he incorporates with the substances and forces which make up his body during his earthly life, and then at death the earth receives it. Man is thus the medium for a constant be-dewing of the physical sense world by the super-sensible. You can imagine, as it were, a fine rain falling continuously from the super-sensible on to the sense world; but these drops would remain quite unfruitful for the earth if man did not absorb them and pass them over to the earth through his own body. These drops which man receives at birth and gives up again at death, bring about a continual fructification of the earth by super-sensible forces; and through these fructifying super-sensible forces the evolutionary process of the earth is maintained. Without human corpses therefore, the earth would long ago have become dead.

With this presupposition we can now ask: what do the death forces do to human nature? The death-bringing forces which predominate in outer nature work into the nature of man; for if man were not continually bringing life to outer nature it would perish. Now how do these death-bringing forces work in the nature of man? They produce in man all those organisations which range from the bone system to the nerve system. What builds up the bones and everything related to them is of quite a different nature from what builds up the other systems. The death-bringing forces play into us. We leave them as they are, and thereby we become bone men. But the death-bringing forces play further into us and we tone them down, and thereby we become nerve men. What is a nerve? A nerve is something which is continually wanting to become bone, and is only prevented from becoming bone by being in a certain relationship to the non-bony, or non-nervous elements of human nature. Nerve has a constant tendency to ossify, it is constantly compelled towards decay; while bone in man is dead to a very large extent. With animal bones the conditions are different—animal bone is far more living than human bone. Thus you can picture one side of human nature by saying: the death-bringing stream works in the bone and nerve system. That is the one pole.

The other stream, that of forces continuously giving life, works in the muscle and blood system and in all that is connected with it. The only reason why nerves are not bones is that their connection with the blood and muscle system is such that the impulse in them to become bone is directly opposed by the forces working in the blood and muscle. The nerve does not become bone solely because the blood and muscle system stands over against it and hinders it from becoming bone. If during the process of growth bone develops a wrong relationship to blood and muscle, then the condition of rickets will result, which is due to the muscle and blood nature hindering a proper deadening of the bone. It is therefore of the utmost importance that the right alternation should come about in man between the muscle and blood system on the one hand and the bone and nerve system on the other. The bone nerve system extends into the eye, but in the outer covering the bone system withdraws, and sends into the eye only its weakened form, the nerve; this enables the eye to unite the will nature, which lives in muscles and blood, with the activity of mental picturing. Here again we come upon something which played an important role in ancient science, but which is scorned as a childish conception by the science of to-day. But modern science will come back to it again, only in another form.

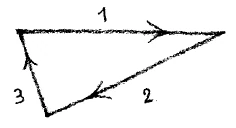

In the knowledge of ancient times men always felt a relationship between the nerve marrow, the nerve substance, and the bone marrow, the bone substance. And they were of the opinion that man thinks with his bone nature just as much as with his nerve nature. And this is true. All that we have in abstract science we owe to the faculty of our bone system. How is it, for instance, that man can do geometry? The higher animals have no geometry; that can be seen from their way of life. It is pure nonsense when people say: “Perhaps the higher animals have a geometry, only we do not notice it.” Now, man can form a geometry. But how, for example, does he form the conception of a triangle? If one truly reflects on this matter, that man can form the conception of a triangle, it will seem a marvellous thing that man forms a triangle, an abstract triangle—nowhere to be found in concrete life—purely out of his geometrical, mathematical imagination. There is much that is hidden and unknown behind the manifest events of the world. Now imagine, for example, that you are standing at a definite place in this room. As a super-sensible human being you will, at certain times, perform strange movements about which as a rule you know nothing; like this, for example: you go a little way to one side, then you go a little way backwards, then you come back to your place again. You are describing unawares in space a line which actually performs a triangular movement. Such movements are actually there, only you do not perceive them.

But since your backbone is in a vertical position, you are in the plane in which these movements take place. The animal is not in this plane, his backbone lies otherwise, i.e. horizontally; thus these movements are not carried out. Because man's backbone is vertical, he is in the plane where this movement is produced. He does not bring it to consciousness so that he could say: “I am always dancing in a triangle.” But he draws a triangle and says: “That is a triangle.” In reality this is a movement carried out unconsciously which he accomplishes in the cosmos.

These movements to which you give fixed forms in geometry—when you draw geometrical figures, you perform in conjunction with the earth. The earth has not only the movement which belongs to the Copernican system; it has also quite—different, artistic movements, which are constantly being performed; as are also still more complicated movements, such as those, for example, which belong to the lines of geometrical solids: the cube, the octahedron, the dodecahedron, the icosatetrahedron and so forth. These bodies are not invented, they are reality, but unconscious reality. In these and other geometrical solids lies a remarkable harmony with the subconscious knowledge which man has. This is due to the fact that our bone system has an essential knowledge; but your consciousness does not reach down into the bone system. The consciousness of it dies, and it is only reflected back in the geometrical images which man carries out in figures. Man is an intrinsic part of the universe. In evolving geometry he is copying something that he himself does in the cosmos.

Thus on the one hand we look into a world which encompasses ourselves and which is in a continuous process of dying. On the other hand we look into all that enters into the forces of our blood and muscle system; this is continuously in movement, in fluctuation, in becoming and arising: it is entirely seedlike, and has nothing dead within it. We arrest the death process within ourselves, and it is only we as human beings who can arrest it, and bring into this dying element a process of life, of becoming. If men were not here on the earth, death would long ago have spread over the whole earth process, and the earth as a whole would have been given over to crystallisation, though single crystals could not have maintained themselves. We draw the single crystals away from the general crystallisation process and preserve them, as long as we need them for our human evolution. And it is by doing so that we keep alive the being of the earth. Thus we human beings cannot be excluded from the life of the earth for it is we who keep the earth alive. Theodore Eduard von Hartmann hit on a true thought when, in his pessimism, he declared that one day mankind would be so mature that everybody would commit suicide; but what he further expected—viewing things as he did from the confines of natural science—would indeed be superfluous: for Hartmann it was not enough that all men should one day commit suicide, he expected in addition that an ingenious invention would blow the earth sky-high. Of this he would have no need. He need only have arranged the day for the general suicide and the earth would of itself have disintegrated slowly into the air. For without the force which is implanted into it by man, the evolution of the earth cannot endure. We must now permeate ourselves with this knowledge once again in a feeling way. It is necessary that these things be understood at the present time.

Perhaps you remember that in my earliest writings there constantly recurs a thought through which I wanted to place knowledge on a different footing from that on which it stands to-day. In the external philosophy, which is derived from Anglo-American thought, man is reduced to being a mere spectator of the world. In his inner soul process he is a mere spectator of the world. If man were not here on earth—it is held—if he did not experience in his soul a reflection of what is going on in the world outside, everything would be just as it is. This holds good of natural science where it is a question of the development of events, such as I have described, but it also holds good for philosophy. The philosopher of to-day is quite content to be a spectator, that is, to be merely in the purely destructive element of cognition. I wished to rescue knowledge out of this destructive element. Therefore I have said again and again: man is not merely a spectator of the world: he is rather the world's stage upon which great cosmic events continuously play themselves out. I have repeatedly said that man, and the soul of man, is the stage upon which world events are played. This thought can also be expressed in a philosophic abstract form. And in particular, if you read the final chapter about spiritual activity in my book Truth and Science. you will find this thought strongly emphasised, namely: what takes place in man is not a matter of indifference to the rest of nature, but rather the rest of nature reaches into man and what takes place in man is simultaneously a cosmic process; so that the human soul is a stage upon which not merely a human process but a cosmic process is enacted. Of course certain circles of people to-day would find it exceedingly hard to understand such a thought. But unless we permeate ourselves with such conceptions we cannot possibly become true educators.

Now what is it that actually happens within man's being? On the one hand we have the bone-nerve nature, on the other hand the blood-muscle nature. Through the co-operation of these two, substances and forces are constantly being formed anew. And it is because of this, because in man himself substances and forces are recreated, that the earth is preserved from death. What I have just said of the blood, namely that through its contact with the nerves it brings about re-creation of substances and forces—this you can now connect with what I said yesterday: that blood is perpetually on the way to becoming spiritual but is arrested on its way. To-morrow we shall link up the thoughts we have acquired in these two lectures and develop them further. But you can see already how erroneous the thought of the conservation of energy and matter really is, in the form in which it is usually put forward; for it is contradicted by what happens within human nature, and it is only an obstacle to the real comprehension of the human being. Only when we grasp the synthesizing thought, not indeed that something can proceed out of nothing, but that a thing can in reality be so transformed that it will pass away and another thing will arise, only when we substitute this thought for that of the conservation of energy and matter, will we attain something really fruitful for science.

You see what the tendency is which leads so much of our thinking astray. We put forward something, as for example, the law of the conservation of force and matter, and we proclaim it a universal law. This is due to a certain tendency of our thought life, and especially of our soul life, to describe things in a one-sided way; whereas we should only set up postulates on the results of our mental picturing. For instance, in our books on physics you will find the law of the mutual impenetrability of bodies set up as an axiom: at that place in space where there is one body no other body can be at the same time. This is laid down as a universal quality of bodies. But one ought only to say: bodies and beings of such a nature that in the place where they are in space no other similar object can be at the same time are “impenetrable” bodies. You ought only to apply your concepts to differentiate one province from another. You ought only to set up postulates, and not to give definitions which claim to be universal. And so we should not lay down a “law” of the conservation of force and substance, but we should find out what beings this law applies to. It was a tendency of the nineteenth century to lay down laws and say: this holds good in every case. Instead of this we should devote our soul powers to acquainting ourselves with things, and observing our experiences in connection with them.

Dritter Vortrag

Der gegenwärtige Lehrer müßte im Hintergrunde von allem, was er schulmäßig unternimmt, eine umfassende Anschauung über die Gesetze des Weltenalls haben. Es ist ja selbstverständlich, daß gerade der Unterricht in den unteren Klassen, in den unteren Stufen der Schule, einen Zusammenhang der Seele des Lehrenden mit den höchsten Ideen der Menschheit fordert. Ein Krebsschaden der bisherigen Schulkonstitution besteht wohl darin, daß man den Lehrer der unteren Schulstufen in einer gewissen, ich möchte sagen Abhängigkeit gehalten hat, namentlich daß man ihn in einer Sphäre gehalten hat, wodurch seine Existenz minderwertiger schien als die Existenz der Lehrer der höheren Schulstufen. Es obliegt mir hier natürlich nicht, über diese allgemeine Frage des geistigen Gliedes des sozialen Organismus zu sprechen. Aber darauf muß doch aufmerksam gemacht werden, daß in der Zukunft alles, was zur Lehrerschaft gehört, einander ebenbürtig sein muß und daß man ein starkes Gefühl in der Öffentlichkeit dafür wird haben müssen, daß der Lehrer der unteren Schulstufen durchaus gleichwertig ist, auch in bezug auf seine geistige Konstitution, dem Lehrer höherer Schulstufen. Daher wird es Sie nicht verwundern, wenn wir heute gerade darauf hinweisen, wie im Hintergrunde allen Unterrichtens — auch auf den untersten Schulstufen — dasjenige stehen muß, was man natürlich unmittelbar den Kindern gegenüber nicht verwenden kann, was man aber als Lehrer unbedingt wissen muß, denn sonst würde der Unterricht nicht ersprießlich sein können.

Wir bringen im Unterricht an das Kind heran auf der einen Seite die Naturwelt, auf der anderen Seite die geistige Welt. Wir sind als Menschen durchaus auf der einen Seite verwandt der Naturwelt, auf der anderen Seite verwandt der geistigen Welt, insofern wir eben Menschen hier auf der Erde, auf dem physischen Plane sind und unser Dasein zwischen Geburt und Tod vollenden.

Nun ist eben die Psychologie-Erkenntnis durchaus etwas, was in unserer Zeit außerordentlich schwach ausgebildet ist. Namentlich leidet die psychologische Erkenntnis unter der Nachwirkung jener kirchlichen dogmatischen Feststellung, die im Jahre 869 gefallen ist und in der eine ältere, auf einer instinktiven Erkenntnis beruhende Einsicht verdunkelt worden ist: die Einsicht, daß der Mensch gegliedert ist in Leib, Seele und Geist. Sie können ja fast überall, wo Sie heute von Psychologie reden hören, von einer bloßen Zweigliederung des Menschenwesens reden hören. Sie können davon reden hören, der Mensch bestehe aus Leib und Seele oder aus Körper und Geist, wie man es dann nennen will; man betrachtet dann Körper und Leib und ebenso auch Geist und Seele als ziemlich gleichbedeutend. Fast alle Psychologien sind auf diesem Irrtum der Zweigliederung des menschlichen Wesens aufgebaut. Man kann gar nicht zu einer wirklichen Einsicht in die menschliche Wesenheit kommen, wenn man sich nur dieser Zweigliederung als einem durchgreifend Gültigen zuwendet. Daher ist im Grunde genommen fast alles, was heute als Psychologie auftaucht, durchaus dilettantisch, manchmal auch nur ein Spiel mit Worten.

Das aber beruht ja im allgemeinen auf jenem großen Irrtum, der erst in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts so groß geworden ist, weil mißkannt worden ist eine eigentlich große Errungenschaft, welche die physikalische Wissenschaft zu verzeichnen hatte. Sie wissen Ja, daß die braven Heilbronner dem Manne inmitten ihrer Stadt ein Denkmal aufgerichtet haben, den sie zur Zeit seines Lebens ins Irrenhaus gesperrt haben: Julius Robert Mayer. Und Sie wissen, daß diese Persönlichkeit, auf die heute selbstverständlich die Heilbronner sehr stolz sind, verknüpft ist mit dem sogenannten Gesetz von der Erhaltung der Energie oder der Kraft. Dieses Gesetz besagt ja, daß die Summe aller im Weltenall vorhandenen Energien oder Kräfte eine konstante ist, daß sich diese Kräfte nur umwandeln, so daß etwa eine Kraft einmal als Wärme, ein andermal als mechanische Kraft erscheint und dergleichen. In diese Form kleidet man aber das Gesetz von Julius Robert Mayer nur dann, wenn man ihn gründlich mißversteht! Denn ihm war es zu tun um die Aufdeckung der Metamorphose der Kräfte, nicht aber um die Aufstellung eines so abstrakten Gesetzes, wie es das von der Erhaltung der Energie ist.

Was ist, in einem großen Zusammenhange angesehen, kulturgeschichtlich dieses Gesetz von der Erhaltung der Energie oder der Kraft? Es ist das große Hindernis, den Menschen überhaupt zu verstehen. Sobald man nämlich meint, daß niemals Kräfte wirklich neu gebildet werden, wird man nicht zu einer Erkenntnis des wahren Wesens des Menschen gelangen können. Denn dieses wahre Wesen des Menschen beruht gerade darin, daß fortwährend durch ihn neue Kräfte gebildet werden. Allerdings in dem Zusammenhange, in dem wir in der Welt leben, ist der Mensch das einzige Wesen, in welchem neue Kräfte und wie wir später noch hören werden - sogar neue Stoffe gebildet werden. Aber da die heutige Weltanschauung überhaupt nicht solche Elemente in sich aufnehmen will, durch welche auch der Mensch voll erkannt werden kann, so kommt sie dann mit diesem Gesetz von der Erhaltung der Kraft, das ja in einem gewissen Sinne nicht stört, wenn man nur die anderen Reiche der Natur - das Mineralreich, das Pflanzenreich und das Tierreich - ins Auge faßt, das aber sofort alles von wirklicher Erkenntnis auslöscht, wenn man an den Menschen herankommen will.

Sie werden als Lehrer die Notwendigkeit haben, auf der einen Seite Ihren Schülern die Natur verständlich zu machen, auf der anderen Seite sie hinzuführen zu einer gewissen Auffassung des geistigen Lebens. Ohne mit der Natur bekannt zu sein, wenigstens in einem gewissen Grade, und ohne ein Verhältnis zum geistigen Leben zu haben, kann sich heute der Mensch auch nicht in das soziale Leben hineinstellen. Wenden wir daher zunächst einmal unseren Blick der äußeren Natur zu.

Die äußere Natur wendet sich an uns so, daß gegenübersteht dieser äußeren Natur auf der einen Seite unser Vorstellungs-, Gedankenleben, das, wie Sie wissen, bildhafter Natur ist, das eine Art Spiegelung des vorgeburtlichen Lebens ist, und daß auf der anderen Seite sich der Natur zuwendet alles dasjenige, was willensartiger Natur ist, was als Keim hinweist auf unser nachtodliches Leben. In dieser Weise sind wir immer auf die Natur hingelenkt. Das scheint ja allerdings zunächst eine Hinordnung auf die Natur in zwei Gliedern zu sein, und sie hat auch hervorgerufen den Irrtum von der Zweigliederung des Menschen. Wir werden auf diese Sache noch zurückkommen.

Wenn wir der Natur so gegenüberstehen, daß wir ihr unsere Denkseite, unsere Vorstellungsseite zuwenden, dann fassen wir eigentlich von der Natur nur das auf, was in der Natur fortwährendes Sterben ist. Es ist dies ein außerordentlich gewichtiges Gesetz. Seien Sie sich ganz klar darüber: Wenn Sie noch so schöne Naturgesetze erfahren, die mit Hilfe des Verstandes, mit Hilfe der vorstellenden Kräfte gefunden sind, so beziehen sich diese Naturgesetze immer auf das, was in der Natur abstirbt.

Etwas ganz anderes als diese Naturgesetze, die sich auf das Tote beziehen, erfährt der lebendige Wille, der keimhaft vorhanden ist, wenn er sich auf die Natur richtet. Hier werden Sie, weil Sie ja wohl noch angefüllt sind mit mancherlei Vorstellungen, die aus der Gegenwart und den Irrtümern ihrer Wissenschaft entstammen, eine ziemliche Schwierigkeit Ihres Verständnisses finden. - Was uns zunächst in den Sinnen, ganz im Umfange der zwölf Sinne, in Beziehung bringt zur Außenwelt, das ist nicht erkenntnismäßiger, sondern willensmäßiger Natur. Dem Menschen der Gegenwart ist davon eigentlich die Einsicht ganz geschwunden. Daher betrachtet er es als etwas Kindliches, wenn er bei Plato liest, daß das Sehen eigentlich darauf beruhe, daß eine Art von Fangarmen aus den Augen ausgestreckt werde zu den Dingen hin. Diese Fangarme sind allerdings mit sinnlichen Mitteln nicht zu erkennen; aber daß Plato sich ihrer bewußt war, das beweist eben, daß er in die übersinnliche Welt eingedrungen war. Es ist in der Tat, indem wir die Dinge ansehen, nichts anderes als nur in feinerer Weise ein Vorgang vorhanden ähnlich demjenigen, der sich abspielt, wenn wir die Dinge angreifen. Wenn Sie zum Beispiel ein Stück Kreide anfassen, so ist dies ein physischer Vorgang ganz ähnlich dem geistigen Vorgange, der sich abspielt, indem Sie die Ätherkräfte aus Ihrem Auge senden, um den Gegenstand im Sehen zu erfassen. Wenn die Menschen überhaupt in der Gegenwart beobachten könnten, so würden sie aus den Naturbeobachtungen diese Tatsachen entnehmen können. Wenn Sie sich zum Beispiel die nach auswärts gestellten Pferdeaugen ansehen, dann werden Sie das Gefühl bekommen, daß einfach durch die Stellung seiner Augen das Pferd zu seiner Umgebung in eine andere Lage versetzt ist als der Mensch. Was da zugrunde liegt, kann ich Ihnen am besten dadurch klar machen, daß ich folgendes hypothetisch aufstelle. Denken Sie sich, Ihre beiden Arme wären so gestaltet, daß Sie in die Unmöglichkeit versetzt wären, die Arme nach vorn zusammenzubringen, so daß sie sich niemals übergreifen könnten. Sie müßten eurythmisch immer bei A stehenbleiben, könnten nie zum O kommen, es würde durch eine Widerstandskraft Ihnen unmöglich gemacht, durch die Vorwärtsrichtung der Arme diese vorne zusammenzubringen. Das Pferd ist nun in bezug auf die übersinnlichen Fangarme seiner Augen in dieser Lage: es kann niemals den Fangarm des linken Auges berühren lassen von dem Fangarm des rechten Auges. Der Mensch ist durch seine Augenstellung eben in der Lage, fortwährend diese zwei übersinnlichen Fangarme seiner Augen miteinander sich berühren zu lassen. Darauf beruht die Empfindung - die übersinnlicher Natur ist - von dem Ich. Würden wir überhaupt niemals in die Lage kommen, rechts und links miteinander in Berührung zu bringen, oder würde die Berührung von rechts und links eine so geringe Bedeutung haben, wie es bei den Tieren der Fall ist, die niemals so ganz richtig die Vorderpfoten, sagen wir, zum Gebet oder zu irgendeinem ähnlichen Geistigen verwenden, dann würden wir auch nicht zu einer vergeistigten Empfindung unseres Selbstes gelangen.

Was für die Sinnesempfindungen am Auge und Ohr überall wichtig ist, das ist nicht so sehr das Passive; es ist das Aktive, das, was wir willentlich den Dingen entgegenbringen. Die neuere Philosophie hat ja manchmal Ahnungen gehabt von etwas Richtigem und hat dann allerlei Worte erfunden, die aber in der Regel beweisen, wie weit man von der Erfassung der Sache entfernt ist. So sind in den Lokalzeichen der Lotzeschen Philosophie solche Ahnungen von Erkenntnis der Aktivität des Willens-Sinneslebens vorhanden. Aber unser Sinnesorganismus, der ja ganz deutlich in dem Tastsinn, Geschmackssinn, Geruchssinn sein Verbundensein mit dem Stoffwechsel zeigt, ist bis in die höheren Sinne mit dem Stoffwechsel verbunden, und der ist willensartiger Natur.

Daher können Sie sich sagen: Der Mensch steht, indem er der Natur gegenübersteht, durch sein Verstandesmäßiges der Natur gegenüber und faßt dadurch alles das von ihr auf, was in ihr tot ist und eignet sich von diesem Toten Gesetze an. Was aber in der Natur aus dem Schoße des Toten sich erhebt, um zur Zukunft der Welt zu werden, das faßt der Mensch auf durch seinen ihm so unbestimmt erscheinenden Willen, der sich bis in die Sinne hinein erstreckt.

Denken Sie sich, wie lebendig Ihnen Ihr Verhältnis zur Natur wird, wenn Sie das eben Gesagte ordentlich ins Auge fassen. Sie werden sich dann sagen: Wenn ich in die Natur hinausgehe, so glänzt mir entgegen Licht und Farbe; indem ich das Licht und seine Farben aufnehme, vereinige ich mit mir das von der Natur, was sie in die Zukunft hinübersendet, und indem ich dann in meine Stube zurückkehre und nachdenke über die Natur, Gesetze über sie ausspinne, da beschäftige ich mich mit dem, was in der Natur fortwährend stirbt. - In der Natur ist fortwährendes Sterben und Werden miteinander verbunden. Daß wir das Sterben auffassen, rührt davon her, daß wir in uns tragen das Spiegelbild unseres vorgeburtlichen Lebens, die Verstandeswelt, die Denkwelt, wodurch wir das der Natur zugrunde liegende Tote ins Auge fassen können. Und daß wir dasjenige, was in der Zukunft von der Natur da sein wird, ins Auge fassen können, rührt davon her, daß wir nicht nur unseren Verstand, unser Denkleben der Natur entgegenstellen, sondern daß wir ihr dasjenige entgegenstellen können, was in uns selbst willensartiger Natur ist.

Wenn der Mensch nicht etwas, was fortwährend ihm bleibt, retten könnte aus seinem vorgeburtlichen Leben durch sein Erdenleben hindurch, wenn er nicht etwas retten könnte von dem, was zuletzt während seines vorgeburtlichen Lebens zum bloßen Gedankenleben geworden ist, dann würde er niemals zur Freiheit kommen können. Denn der Mensch würde verbunden sein mit dem Toten, und er würde in dem Augenblick, wo er das, was in ihm selbst mit der toten Natur verwandt ist, zur Freiheit aufrufen wollte, ein Sterbendes zur Freiheit aufrufen wollen. Er würde, wenn er desjenigen sich bedienen wollte, was ihn als Willenswesen mit der Natur verbindet, betäubt werden; denn in dem, was ihn als Willenswesen mit der Natur verbindet, ist alles noch keimhaft. Er würde ein Naturwesen sein, aber kein freies Wesen.

Über diesen zwei Elementen — der Erfassung des Toten durch den Verstand und der Erfassung des Lebendigen, des Werdenden durch den Willen — steht im Menschen etwas, was nur er, kein anderes irdisches Wesen, von der Geburt bis zum Tode in sich trägt: das ist das reine Denken, dasjenige Denken, das sich nicht auf die äußere Natur bezieht, sondern das sich nur auf dasjenige Übersinnliche bezieht, was im Menschen selber ist, was den Menschen zum autonomen Wesen macht, zu etwas, was noch über demjenigen ist, was im Untertoten und im Überlebendigen ist. Will man daher von der menschlichen Freiheit reden, so muß man auf dieses Autonome im Menschen sehen, auf das reine, sinnlichkeitsfreie Denken, in dem immer auch der Wille lebt.

Wenn Sie aber von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus die Natur selbst betrachten, werden Sie sich sagen: Ich blicke hin auf die Natur, der Strom des Sterbens ist in mir und auch der Strom des Neuwerdens: sterben wiederum geboren werden. Von diesem Zusammenhang versteht die neuere Wissenschaft sehr wenig; denn ihr ist die Natur gewissermaßen eine Einheit, und sie puddelt fortwährend durcheinander das Sterbende und das Werdende, so daß alles, was heute vielfach ausgesagt wird über die Natur und ihr Wesen, etwas ganz Konfuses ist, weil Sterben und Werden fortwährend durcheinandergemischt werden. Will man reinlich diese beiden Strömungen in der Natur auseinanderhalten, so muß man sich schon fragen: Wie stünde es denn mit der Natur, wenn der Mensch nicht in dieser Natur wäre?

Gegenüber dieser Frage ist im Grunde genommen die neuere Naturwissenschaft mit ihrer Philosophie in einer großen Verlegenheit. Denn denken Sie einmal, Sie stellten einem richtigen neueren Naturforscher die Frage: Was wäre es mit der Natur und ihrem Wesen, wenn der Mensch nicht darin wäre? Er würde natürlich zunächst etwas schockiert sein, weil ihm die Frage sonderbar vorkommen würde. Aber er würde sich dann besinnen, welche Unterlagen zur Beantwortung dieser Frage ihm seine Wissenschaft gibt, und würde sagen: Dann wären auf der Erde Mineralien, Pflanzen und Tiere, nur der Mensch wäre nicht da, und der Erdenverlauf würde von dem Anfange an, wo die Erde noch im Kant-Laplaceschen Nebelzustande war, sich so vollzogen haben, daß alles so fortgegangen wäre, wie es gegangen ist; nur der Mensch wäre in diesem Fortgange nicht drinnen. - Eine andere Antwort könnte im Grunde genommen nicht herauskommen. Er könnte vielleicht noch hinzufügen: Der Mensch gräbt als Ackerbauer den Erdboden um und verändert so die Erdoberfläche, oder er konstruiert Maschinen und bringt dadurch Veränderungen hervor; aber das ist nicht so erheblich gegenüber den anderen Verwandlungen, welche durch die Natur selbst geschehen. Immer also würde der Naturforscher sagen: Es würden Miineralien, Pflanzen und Tiere sich entwickeln, ohne daß der Mensch dabei wäre.

Das ist nicht richtig. Wäre der Mensch nämlich nicht in der Erdenevolution vorhanden, dann wären die Tiere zum großen Teile nicht da; denn ein großer Teil, namentlich die höheren Tiere, ist nur dadurch in der Erdenevolution entstanden, daß der Mensch genötigt war - ich spreche jetzt natürlich bildlich -, seine Ellenbogen zu verwenden. Er mußte auf einer bestimmten Stufe seiner Erdenentwickelung aus seinem eigenen Wesen, in dem damals noch ganz anderes war, als jetzt in ihm ist, die höheren Tiere heraussondern, mußte sie abwerfen, damit er weiterkommen konnte. Ich möchte dies Abwerfen damit vergleichen, daß ich sage: Stellen Sie sich ein Gemisch vor, worin etwas aufgelöst ist, und stellen Sie sich vor, daß dann diese aufgelöste Substanz sich aussondert und zu Boden setzt. So war der Mensch in seinen früheren Entwickelungszuständen mit der Tierwelt zusammen und hat dann später die Tierwelt wie einen Bodensatz ausgeschieden. Die Tiere wären nicht in der Erdenentwickelung diese heutigen Tiere geworden, wenn der Mensch nicht hätte so werden sollen, wie er jetzt ist. Ohne den Menschen in der Erdenentwickelung würden also die Tierformen und die Erde ganz anders ausschauen, als es heute der Fall ist.

Aber gehen wir nun über zur mineralischen und pflanzlichen Welt. Da sollten wir uns darüber klar sein, daß nicht nur die niederen Tierformen, sondern auch die pflanzliche und die mineralische Welt längst erstarrt wären, nicht mehr im Werden wären, wenn der Mensch nicht auf der Erde wäre. Wiederum ist es notwendig für die heutige, auf einer einseitigen Naturanschauung fußenden Weltanschauung, zu sagen: Gut, die Menschen sterben, und ihre Körper werden verbrannt oder begraben und damit der Erde übergeben; aber das hat für die Erdenentwickelung keine Bedeutung; denn wenn die Erdenentwickelung nicht Menschenkörper aufnehmen würde, könnte sie gerade so verlaufen wie jetzt, da sie Menschenkörper aufnimmt. — Das heißt aber, man ist sich gar nicht bewußt, daß das fortwährende Übergehen menschlicher Leichname in die Erde, gleichgültig ob es durch Verbrennen oder durch Begraben geschieht, ein realer Prozeß ist, der fortwirkt.

Die Bäuerinnen auf dem Lande sind sich noch klarer, als es die Frauen in der Stadt sind, darüber, daß die Hefe für das Brotbacken eine gewisse Bedeutung hat, trotzdem nur wenig dem Brote zugesetzt wird; sie wissen, daß das Brot nicht gedeihen könnte, wenn nicht Hefe dem Teig zugesetzt würde. Ebenso aber wäre die Erdenentwickelung längst in ihren Endzustand hineingekommen, wenn ihr nicht fortwährend die Kräfte des menschlichen Leichnams, der mit dem Tode von dem Geistig-Seelischen abgesondert ist, zugeführt würden. Durch diese Kräfte, welche die Erdenentwickelung durch die Zuführung der menschlichen Leichname fortwährend bekommt, beziehungsweise der Kräfte, die in den Leichnamen sind, dadurch wird die Evolution der Erde unterhalten. Dadurch werden Mineralien dazu veranlaßt, ihre Kristallisationskräfte noch heute zu entfalten, die sie längst nicht mehr entfalten würden ohne diese Kräfte; sie wären längst zerbröckelt, hätten sich aufgelöst. Dadurch werden Pflanzen, die längst nicht mehr wachsen würden, veranlaßt, heute noch zu wachsen. Und auch mit Bezug auf die niederen Tierformen ist es so. Der Mensch übergibt der Erde in seinem Leibe das Ferment, gleichsam die Hefe für die Weiterentwickelung.

Daher ist es nicht bedeutungslos, ob der Mensch auf der Erde lebt oder nicht. Es ist einfach nicht wahr, daß die Erdenentwickelung in bezug auf das Mineralreich, Pflanzenreich und Tierreich auch dann vorwärtsgehen würde, wenn der Mensch nicht dabei wäre! Der Naturprozeß ist ein einheitlicher, ein geschlossener, zu dem der Mensch dazugehört. Der Mensch wird nur richtig vorgestellt, wenn er selbst noch mit seinem Tode als drinnenstehend in dem kosmischen Prozeß gedacht wird.

Wenn Sie dies bedenken, dann werden Sie sich kaum mehr wundern, wenn ich auch noch das Folgende sage: Der Mensch bekommt, indem er aus der geistigen Welt heruntersteigt in die physische, die Umkleidung seines physischen Leibes. Aber natürlich ist der physische Leib anders, wenn man ihn als Kind bekommt, als wenn man ihn in irgendeinem Lebensalter durch den Tod ablegt. Da ist etwas geschehen mit dem physischen Leibe. Was da mit ihm geschehen ist, das kann nur dadurch geschehen, daß dieser Leib durchdrungen ist von den geistigseelischen Kräften des Menschen. Nicht wahr, schließlich essen wir alle dasselbe, was die Tiere auch essen, das heißt, wir verwandeln die äußeren Stoffe so, wie die Tiere sie verwandeln, aber wir verwandeln sie unter der Mittätigkeit von etwas, was die Tiere nicht haben, von etwas, was aus der geistigen Welt heruntersteigt, um sich mit dem physischen Menschenleib zu vereinigen. Wir machen dadurch mit den Stoffen etwas anderes, als die Tiere oder Pflanzen mit ihnen machen. Und die Stoffe, welche im menschlichen Leichnam der Erde übergeben werden, sind verwandelte Stoffe, sind etwas anderes, als was der Mensch empfangen hat, als er geboren worden ist. Daher können wir sagen: Die Stoffe, welche der Mensch empfängt, und auch die Kräfte, welche er mit der Geburt empfängt, die erneuert er während seines Lebens und gibt sie in verwandelter Form an den Erdenprozeß ab. Es sind nicht dieselben Stoffe und Kräfte, die er bei seinem Tode an den Erdenprozeß abgibt, als diejenigen waren, die er bei seiner Geburt empfangen hat. Er übergibt damit also dem Erdenprozeß etwas, was durch ihn fortwährend aus der übersinnlichen Welt in den physisch-sinnlichen Erdenprozeß einfließt. Er trägt bei seiner Geburt aus der übersinnlichen Welt etwas herunter; das bekommt dann, indem er es einverleibt hat den Stoffen und Kräften, die während seines Lebens seinen Leib zusammensetzen, mit seinem Tode die Erde. Dadurch vermittelt der Mensch fortwährend das Herunterträufeln von Übersinnlichem an Sinnliches, an Physisches. Sie können sich vorstellen, daß gleichsam fortwährend etwas herunterregnet aus dem Übersinnlichen ins Sinnliche, daß aber diese Tropfen ganz unfruchtbar blieben für die : Erde, wenn der Mensch sie nicht aufnehmen würde und sie durch sich der Erde vermitteln würde. Diese Tropfen, die der Mensch aufnimmt bei der Geburt, die er abgibt bei seinem Tode, die sind ein fortwährendes Befruchten der Erde durch übersinnliche Kräfte, und durch diese befruchtenden, übersinnlichen Kräfte wird der Evolutionsprozeß der Erde erhalten. Ohne menschliche Leichname wäre daher die Erde längst tot. Geburt Tod

Wenn wir das vorausgeschickt haben, können wir nun fragen: Was machen nun die toten Kräfte mit der menschlichen Natur? Es wirken ja in die menschliche Natur herein die todbringenden Kräfte, die draußen in der Natur vorwaltend sind; denn gäbe der Mensch der äußeren Natur nicht fortwährend Belebung, so müßte sie absterben. Wie walten also diese todbringenden Kräfte in der menschlichen Natur? Sie walten so, daß der Mensch alle diejenigen Organisationen durch sie hervorbringt, die in der Linie vom Knochensystem bis zum Nervensystem liegen. Was die Knochen und alles, was mit ihnen verwandt ist, aufbaut, das ist ganz anderer Natur als dasjenige, was die anderen Systeme aufbaut. In uns spielen die todbringenden Kräfte herein: wir lassen sie, wie sie sind, und dadurch sind wir Knochenmenschen. In uns aber spielen weiter noch die todbringenden Kräfte herein: wir schwächen sie ab, und dadurch sind wir Nervenmenschen. -— Was ist ein Nerv? Ein Nerv ist etwas, was fortwährend Knochen werden will, was nur dadurch verhindert wird, Knochen zu werden, daß es mit nicht knochenmäßigen oder nicht nervösen Elementen der Menschennatur in Zusammenhang steht. Der Nerv will fortwährend verknöchern, er ist fortwährend gedrängt abzusterben, wie der Knochen im Menschen immer etwas in hohem Grade Abgestorbenes ist. Beim tierischen Knochen liegen die Verhältnisse anders, er ist viel lebendiger als der menschliche Knochen. - So können Sie sich die eine Seite der Menschennatur vorstellen, indem Sie sagen: Die todbringende Strömung wirkt im Knochen- und Nervensystem. Das ist der eine Pol.

Die fortwährend Leben gebenden Kräfte, die andere Strömung, wirkt im Muskel- und Blutsystem und in allem, was dazugehört. Nerven sind nur deshalb überhaupt keine Knochen, weil sie mit dem Blutund Muskelsystem so im Zusammenhang stehen, daß der Drang in ihnen, Knochen zu werden, den in Blut und Muskel wirkenden Kräften entgegensteht. Der Nerv wird nur dadurch nicht Knochen, weil ihm Blut- und Muskelsystem entgegensteht und sein Knochenwerden verhindert. Besteht im Wachstum eine falsche Verbindung zwischen Knochen einerseits und Blut und Muskeln andererseits, so kommt die Rachitis zustande, die ein Verhindern des richtigen Absterbens des Knochens durch die Muskel-Blutnatur ist. Es ist daher außerordentlich wichtig, daß im Menschen die richtige Wechselwirkung zustande kommt zwischen dem Muskel-Blutsystem auf der einen Seite und dem Knochen-Nervensystem auf der anderen Seite. Indem in unser Auge das Knochen-Nervensystem etwas hereinragt, in der Umhüllung das Knochensystem sich zurückzieht und nur seine Abschwächung, den Nerv, hineinschickt, kommt im Auge die Möglichkeit zustande, die willensartige Wesenheit, die in Muskel und Blut lebt, mit der vorstellungsmäßigen Tätigkeit, die im Knochen-Nervensystem liegt, zu verbinden. Da kommen wir wieder auf etwas, was in der älteren Wissenschaft eine große Rolle gespielt hat, was aber von der heutigen Wissenschaft als kindliche Vorstellung verlacht wird. Doch die neuere Wissenschaft wird schon wieder darauf zurückkommen, nur in anderer Form.

Die Alten haben in ihrem Wissen immer eine Verwandtschaft gefühlt zwischen dem Nervenmark, der Nervensubstanz und dem Knochenmark oder der Knochensubstanz, und sie sind der Meinung gewesen, daß man mit dem Knochenteil ebenso denkt wie mit dem Nerventeil. Das ist auch die Wahrheit. Wir verdanken alles, was wir an abstrakter Wissenschaft haben, der Fähigkeit unseres Knochensystems. Warum kann der Mensch zum Beispiel Geometrie ausbilden? Die höheren Tiere haben keine Geometrie; das sieht man ihrer Lebensweise an. Es ist nur ein Unsinn, wenn manche Leute sagen: Vielleicht haben die höheren Tiere auch Geometrie, man merkt es vielleicht nur nicht. — Der Mensch also bildet Geometrie aus. Wodurch aber bildet er zum Beispiel die Vorstellung eines Dreiecks aus? Wer wirklich über diese Tatsache nachdenkt, daß der Mensch die Vorstellung des Dreiecks ausbildet, der muß etwas Wunderbares darin finden, daß der Mensch das Dreieck, das abstrakte Dreieck, das im konkreten Leben nirgends vorhanden ist, rein aus seiner geometrisch-mathematischen Phantasie heraus ausbildet. Es liegt vieles Unbekannte zugrunde den Geschehnissen der Welt, die offenbar sind. Denken Sie sich zum Beispiel an einem bestimmten Platze dieses Zimmers stehend. Sie führen zu gewissen Zeiten als übersinnliches Menschenwesen merkwürdige Bewegungen aus, von denen Sie für gewöhnlich nichts wissen, ungefähr in der Art: Sie gehen ein Stückchen nach der einen Seite, dann gehen Sie ein Stückchen zurück, und dann kommen Sie wieder an Ihrem Platze an. Eine unbewußt bleibende Linie im Raume, die Sie beschreiben, verläuft tatsächlich als eine Dreiecksbewegung. Solche Bewegungen sind tatsächlich vorhanden, Sie nehmen sie nur nicht wahr, aber dadurch, daß Ihr Rückgrat in die Vertikale gerückt ist, sind Sie in der Ebene drinnen, in der diese Bewegungen verlaufen. Das Tier ist nicht in dieser Ebene drinnen, es hat sein Rückenmark anders liegen; da werden diese Bewegungen nicht vollführt. Indem der Mensch sein Rückenmark vertikal stehen hat, ist er in der Ebene, wo diese Bewegung ausgeführt wird. Zum Bewußtsein bringt er es sich nicht, daß er sich sagte: Ich tanze da fortwährend in einem Dreieck. — Aber er zeichnet ein Dreieck und sagt: Das ist ein Dreieck! - In Wahrheit ist das eine unbewußt ausgeführte Bewegung, die er im Kosmos vollführt.

Diese Bewegungen, die Sie in der Geometrie fixieren, indem Sie geometrische Figuren zeichnen, führen Sie mit der Erde aus. Die Erde hat nicht nur die Bewegung, welche sie nach der Kopernikanischen Weltansicht hat: sie hat noch ganz andere, künstlerische Bewegungen, die werden da fortwährend ausgeführt. Und noch viel kompliziertere Bewegungen werden ausgeführt, solche Bewegungen zum Beispiel, die in den Linien liegen, welche die geometrischen Körper haben: der Würfel, das Oktaeder, das Dodekaeder, das Ikosaeder und so weiter. Diese Körper sind nicht erfunden, sie sind Wirklichkeit, nur unbewußte Wirklichkeit. Es liegen in diesen und in noch anderen Körperformen merkwürdige Anklänge an dieses für die Menschen unterbewußte Wissen. Das wird dadurch herbeigeführt, daß unser Knochensystem eine wesentliche Erkenntnis hat; aber Sie reichen nicht mit Ihrem Bewußtsein bis zum Knochensystem hinunter. Das Bewußtsein davon erstirbt, es wird nur reflektiert in den Bildern der Geometrie, die der Mensch da als Bilder ausführt. Der Mensch ist recht sehr eingeschaltet in den Kosmos. Indem er die Geometrie ausbildet, bildet er etwas nach, was er selbst im Kosmos tut.

Da blicken wir auf der einen Seite in eine Welt hinein, die uns mitumfaßt und die fortwährend im Absterben ist. Auf der anderen Seite blicken wir in alles das hinein, was in die Kräfte unseres Blut-Muskelsystems hereinragt: das ist in fortwährender Bewegeng, in fortwährendem Fluktuieren, in fortwährendem Werden und Entstehen; das ist ganz keimhaft, da ist nichts Totes. Wir halten in uns den Sterbeprozeß auf, und nur wir als Menschen können ihn aufhalten und bringen in das Sterbende Werden hinein. Wäre der Mensch nicht hier auf der Erde, so würde eben längst das Sterben sich ausgebreitet haben über den Erdenprozeß, und die Erde wäre als Ganzes in eine große Kristallisation übergegangen. Nicht erhalten aber hätten sich die einzelnen Kristalle. Wir entreißen die einzelnen Kristalle der großen Kristallisation und erhalten sie, solange wir sie für unsere Menschenevolution brauchen. Wir erhalten aber damit auch das Leben der Erde rege. Wir Menschen sind es also, die das Leben der Erde rege halten, die nicht ausgeschaltet werden können vom Leben der Erde. Daher war es schon ein realer Gedanke von Eduard von Hartmann, der aus seinem Pessimismus heraus wollte, daß die Menschheit einmal eines Tages so reif wäre, daß alle Menschen sich selbst mordeten. Man braucht auch gar nicht das noch hinzuzufügen, was Hartmann aus der Beschränktheit der naturwissenschaftlichen Weltanschauung wollte: weil ihm nämlich das nicht genügt hätte, daß alle Menschen sich eines Tages selbst mordeten, wollte er auch noch die Erde durch eine großangelegte Unternehmung in die Luft sprengen. Das hätte er nicht gebraucht. Er hätte nur den Tag des großen Selbstmordens anordnen brauchen, und die Erde wäre von selbst langsam in die Luft gegangen! Denn ohne das, was vom Menschen in die Erde verpflanzt wird, kann die Erdenentwickelung nicht weitergehen. Von dieser Erkenntnis aus müssen wir uns wieder gefühlsmäßig durchdringen. Es ist notwendig, daß in der Gegenwart diese Dinge verstanden werden.

Ich weiß nicht, ob Sie sich erinnern, daß in meinen allerersten Schriften immer ein. Gedanke wiederkehrt, durch den ich die Erkenntnis auf eine andere Basis stellen wollte, als sie heute steht. In der äußeren Philosophie, die auf anglo-amerikanisches Denken zurückgeht, ist der Mensch eigentlich ein bloßer Zuschauer der Welt; er ist mit seinem inneren Seelenprozeß ein bloßer Zuschauer der Welt. Wenn der Mensch nicht da wäre, so meint man, wenn er nicht in der Seele wieder erlebte, was in der Welt draußen vor sich geht, so wäre doch alles so, wie es ist. Das gilt für die Naturwissenschaft in bezug auf jene Tatsachenentwickelung, die ich angeführt habe, es gilt aber auch für die Philosophie. Der heutige Philosoph fühlt sich sehr wohl als Zuschauer der Welt, das heißt, in dem bloß ertötenden Element des Erkennens. Aus diesem ertötenden Element wollte ich die Erkenntnis herausführen. Daher habe ich immer wiederholt: Der Mensch ist nicht bloß ein Zuschauer der Welt, sondern er ist Schauplatz der Welt, auf dem sich die großen kosmischen Ereignisse immer wieder und wieder abspielen. Ich habe immer wieder gesagt: Der Mensch ist mit seinem Seelenleben der Schauplatz, auf dem sich Weltgeschehen abspielt. So kann man das auch in philosophisch-abstrakte Form kleiden. Und besonders, wenn Sie das Schlußkapitel über Freiheit in meiner Schrift «Wahrheit und Wissenschaft» lesen, werden Sie finden, daß dieser Gedanke scharf betont ist: daß dasjenige, was sich im Menschen vollzieht, nicht etwas ist, was der übrigen Natur gleich ist, sondern daß die übrige Natur hereinragt in den Menschen und daß dasjenige, was im Menschen sich vollzieht, zugleich ein kosmischer Vorgang ist, so daß die menschliche Seele ein Schauplatz ist, auf dem sich ein kosmischer Vorgang abspielt, nicht bloß ein menschlicher. Damit wird man natürlich in gewissen Kreisen heute noch schwer verstanden. Aber ohne daß man sich mit solchen Anschauungen durchdringt, kann man unmöglich ein richtiger Erzieher werden.

Was geschieht denn tatsächlich in der menschlichen Wesenheit? Auf der einen Seite steht die Knochen-Nervennatur, auf der anderen Seite die Blut-Muskelnatur. Durch das Zusammenwirken beider werden fortwährend Stoffe und Kräfte neu geschaffen. Die Erde wird vor dem Tode dadurch bewahrt, daß im Menschen selber Stoffe und Kräfte neu geschaffen werden. Jetzt können Sie das, was ich eben gesagt habe: daß das Blut durch seine Berührung mit den Nerven Neuschöpfung von Stoffen und Kräften bewirkt, zusammenbringen mit dem, was ich im vorigen Vortrage sagte: daß das Blut fortwährend auf dem Wege zur Geistigkeit ist und dabei aufgehalten wird. Diese Gedanken, die wir in diesen zwei Vorträgen gewonnen haben, werden wir miteinander verbinden und dann weiter darauf aufbauen. Aber Sie sehen schon, wie irrtümlich der Gedanke der Erhaltung von Kraft und Stoff ist, wie er gewöhnlich vorgebracht wird: denn durch das, was im Inneren der Menschennatur geschieht, wird er widerlegt, und für eine wirkliche Auffassung der Menschenwesenheit ist er nur ein Hindernis. Erst wenn man wieder den synthetischen Gedanken bekommen wird, daß tatsächlich zwar nicht aus Nichts etwas hervorgehen kann, daß aber das eine so umgewandelt werden kann, daß es vergeht und das andere entsteht — erst wenn man diesen Gedanken an die Stelle des Gedankens von der Erhaltung der Kraft und des Stoffes gestellt haben wird, wird man etwas Gedeihliches für die Wissenschaft erhalten können.

Sie sehen, in welcher Richtung manches, was in unserem Denken lebt, verkehrt ist. Wir stellen etwas auf, wie zum Beispiel das Gesetz von der Erhaltung der Kraft und des Stoffes, und proklamieren es als ein Weltgesetz. Dem liegt zugrunde ein gewisser Hang unseres Vorstellungslebens, unseres Seelenlebens überhaupt, in einseitiger Weise zu beschreiben, während wir nur Postulate aufstellen sollten aus dem, was wir in unserem Vorstellen entwickeln. So finden Sie zum Beispiel in unseren Physikbüchern das Gesetz von der Undurchdringlichkeit der Körper als ein Axiom aufgestellt: An der Stelle im Raume, wo ein Körper steht, kann zu gleicher Zeit kein anderer sein. - Das wird als allgemeine Eigenschaft der Körper hingestellt. Man sollte aber nur sagen: Diejenigen Körperlichkeiten oder Wesenheiten, welche so sind, daß an der Stelle des Raumes, wo sie sind, zu gleicher Zeit kein anderes Wesen gleicher Natur sein kann, die sind undurchdringlich. - Man sollte bloß die Begriffe dazu verwenden, um ein gewisses Gebiet von einem anderen abzugliedern, man sollte bloß Postulate aufstellen, sollte keine Definitionen geben, die den Anspruch erheben, universell zu sein. So sollte man auch kein Gesetz von der Erhaltung der Kraft und des Stoffes aufstellen, sondern man sollte aufsuchen, für welche Wesenheiten dieses Gesetz eine Bedeutung hat. Das war gerade ein Bestreben im 19. Jahrhundert, daß man ein Gesetz aufstellte und sagte: Das gilt für alles — statt daß wir unser Seelenleben dazu verwenden, um an die Dinge heranzukommen und zu beobachten, was wir an ihnen erleben.

Third Lecture

The present teacher should have a comprehensive view of the laws of the universe in the background of everything he does in school. It goes without saying that teaching in the lower grades, in the lower levels of school, requires a connection between the soul of the teacher and the highest ideas of humanity. A cancerous flaw in the current school system is that teachers in the lower grades have been kept in a certain, I would say, dependency, namely that they have been kept in a sphere that makes their existence seem inferior to that of teachers in the higher grades. It is not my place here, of course, to discuss this general question of the spiritual link in the social organism. But attention must be drawn to the fact that in the future, everything that belongs to the teaching profession must be equal, and that there must be a strong public feeling that teachers in the lower grades are absolutely equal, also in terms of their intellectual constitution, to teachers in the higher grades. Therefore, it will not surprise you if we point out today that in the background of all teaching — even at the lowest school levels — there must be something that cannot, of course, be used directly with children, but which teachers must know, because otherwise teaching would not be fruitful.

In our teaching, we introduce the child to the natural world on the one hand and the spiritual world on the other. As human beings, we are closely related to the natural world on the one hand and to the spiritual world on the other, insofar as we are human beings here on earth, on the physical plane, and complete our existence between birth and death.

Now, psychological knowledge is something that is extremely poorly developed in our time. Psychological knowledge suffers in particular from the after-effects of the ecclesiastical dogmatic statement made in 869, which obscured an older insight based on instinctive knowledge: the insight that human beings are structured in body, soul, and spirit. Almost everywhere you hear people talking about psychology today, you hear them talking about a mere two-part division of the human being. You hear them say that man consists of body and soul or body and spirit, whatever you want to call it; body and spirit, as well as mind and soul, are then regarded as pretty much synonymous. Almost all psychology is based on this error of the two-part division of the human being. It is impossible to gain a real insight into the human essence if one only turns to this two-part division as something thoroughly valid. Therefore, basically, almost everything that appears as psychology today is thoroughly amateurish, sometimes even just a play on words.

But this is generally based on that great error, which only became so great in the second half of the 19th century because a truly great achievement of physical science was misunderstood. You know that the good people of Heilbronn erected a monument in the middle of their city to the man they had locked up in a madhouse during his lifetime: Julius Robert Mayer. And you know that this personality, of whom the people of Heilbronn are naturally very proud today, is associated with the so-called law of conservation of energy or force. This law states that the sum of all energies or forces present in the universe is constant, that these forces only transform themselves, so that one force appears as heat, another as mechanical force, and so on. However, Julius Robert Mayer's law can only be expressed in this way if it is thoroughly misunderstood! For he was concerned with uncovering the metamorphosis of forces, not with establishing such an abstract law as that of the conservation of energy.

Viewed in a broader context, what is the cultural-historical significance of this law of conservation of energy or force? It is the great obstacle to understanding human beings at all. For as soon as one believes that forces are never truly newly formed, one will not be able to arrive at an understanding of the true nature of human beings. For this true nature of human beings lies precisely in the fact that new forces are constantly being formed through them. Indeed, in the context in which we live in the world, human beings are the only beings in which new forces and, as we shall hear later, even new substances are formed. But since today's worldview does not want to accept elements through which human beings can be fully understood, it then comes up with this law of the conservation of energy, which in a certain sense does not interfere if one only considers the other kingdoms of nature—the mineral kingdom, the plant kingdom, and the animal kingdom—but which immediately obliterates all real knowledge when one wants to approach the human being.

As teachers, you will have the necessity, on the one hand, to make nature understandable to your students and, on the other hand, to lead them to a certain understanding of spiritual life. Without being familiar with nature, at least to a certain degree, and without having a relationship to spiritual life, human beings today cannot place themselves in social life. Let us therefore first turn our gaze to external nature.

External nature addresses us in such a way that, on the one hand, our mental images and thoughts, which, as you know, are pictorial in nature and are a kind of reflection of our pre-birth life, stand opposite this external nature, and on the other hand, everything that is volitional in nature, everything that points as a seed to our life after death, turns toward nature. In this way, we are always drawn to nature. At first glance, this seems to be a two-part orientation toward nature, and it has also given rise to the misconception of the two-part structure of the human being. We will come back to this point later.

When we face nature in such a way that we turn our thinking side, our imaginative side, toward it, then we actually only grasp that part of nature which is continuous dying. This is an extraordinarily important law. Be very clear about this: No matter how beautiful the laws of nature you discover with the help of your intellect and your mental images, these laws of nature always refer to what dies in nature.

The living will, which is present in embryonic form, experiences something quite different from these laws of nature that refer to what is dead when it turns its attention to nature. Here you will encounter considerable difficulty in understanding, because you are probably still filled with various mental images that originate from the present and the errors of its science. What initially connects us to the outside world in our senses, within the scope of the twelve senses, is not of a cognitive nature, but of a volitional nature. The insight into this has actually completely disappeared from the people of the present. Therefore, they consider it childish when they read in Plato that seeing is actually based on a kind of tentacles being extended from the eyes toward things. These tentacles cannot, of course, be perceived by the senses; but the fact that Plato was aware of them proves that he had penetrated into the supersensible world. In fact, when we look at things, there is nothing more than a process similar to that which takes place when we touch things, only in a more subtle way. For example, when you touch a piece of chalk, this is a physical process very similar to the mental process that takes place when you send the etheric forces from your eye to grasp the object in your vision. If people were able to observe in the present, they would be able to deduce these facts from their observations of nature. If you look at the outward-facing eyes of a horse, for example, you will get the feeling that simply through the position of its eyes, the horse is in a different position in relation to its surroundings than a human being. I can best explain the underlying principle by posing the following hypothetical situation. Imagine that your two arms were designed in such a way that you would be unable to bring them together in front of you, so that they could never overlap. You would always have to remain at A in eurythmy, you could never reach O, a resisting force would make it impossible for you to bring your arms together in front of you by moving them forward. The horse is now in this position with regard to the supersensible tentacles of its eyes: it can never allow the tentacle of the left eye to touch the tentacle of the right eye. The human being, through the position of his eyes, is in a position to allow these two supersensible tentacles of his eyes to touch each other continuously. This is the basis of the sensation — which is of a supersensible nature — of the I. If we were never able to bring the right and left into contact with each other, or if the contact between the right and left were as insignificant as it is in animals, which never really use their front paws, say, for prayer or any similar spiritual activity, then we would not be able to attain a spiritualized sense of our self.

What is important for the sensory perceptions of the eye and ear is not so much the passive; it is the active, what we willingly bring to bear on things. Recent philosophy has sometimes had inklings of something correct and has then invented all kinds of words, but these usually prove how far one is from grasping the matter. Thus, in the local signs of Lotze's philosophy, there are such inklings of knowledge of the activity of the will-sense life. But our sensory organism, which clearly shows its connection with metabolism in the senses of touch, taste, and smell, is connected to metabolism even in the higher senses, and that is of a volitional nature.

Therefore, you can say to yourself: when faced with nature, human beings stand opposite nature with their intellect and thereby grasp everything in nature that is dead and appropriate the laws of this dead matter. But what rises in nature from the womb of the dead to become the future of the world is grasped by man through his will, which seems so indefinite to him and extends into the senses.