The Study of Man

GA 293

26 August 1919, Stuttgart

Lecture V

Yesterday we discussed the nature of will in so far as will is embodied in the human organ. Today we will use this knowledge of man's relationship to will to fructify our consideration of the rest of the human being.

You will have noticed that in treating of the human being up to now I have chiefly drawn attention to the intellectual activity, the activity of cognition, on the one hand, and the activity of will on the other hand. I have shown you how the activity of cognition has a close connection with the nerve nature of the human being, and how the activity of will has a close connection with the activity of the blood. If you think this over you will also want to know what can be said with regard to the third soul power, that is, the activity of feeling. We have not yet given this much consideration, but today, by thinking more of the activity of feeling, we shall have the opportunity of entering more intensively into an understanding of the two other sides of human nature, namely cognition and will.

Now there is one thing that we must be clear about, and this I have already mentioned in various connections. We cannot put the soul powers pedantically side by side, separate from each other, thus: thinking, feeling, willing, because in the living soul, in its entirety, one activity is always merging into another.

Consider the will on the one hand. You will realise that you cannot bring your will to bear on anything that you do not represent to yourself as mental picture, that you do not permeate with the activity of cognition. Try in self-contemplation, even superficially, to concentrate on your willing, you will find that in every act of will the mental picture is present in some form. You could not be a human being at all if mental picturing were not involved in your acts of will. And your willing would proceed from a dull instinctive activity, if you did not permeate the action which springs forth from the will with the activity of thought, of mental picturing.

Just as thought is present in every act of will, so will is to be found in all thinking. Again, even a purely superficial contemplation of your own self will show you that in thinking you always let your will stream into the formation of your thoughts. In the forming of your own thoughts, in the uniting of one thought with another, or passing over to judgments and conclusions—in all this there streams a delicate current of will.

Thus actually we can only say that will activity is chiefly will activity and has an undercurrent of thought within it; and thought activity is chiefly thought activity and has an undercurrent of will. Thus, in considering the separate faculties of soul, it is impossible to place them side-by-side in a pedantic way, because one flows into the other.

Now this flowing into one another of the soul activities, which is recognisable in the soul, is also to be seen in the body, where the soul activity comes to expression. For instance, let us look at the human eye. If we look at it in its totality we shall see that the nerves are continued right into the eye itself; but so also are the blood vessels. The presence of the nerves enables the activity of thought and cognition to stream into the eye of the human being; and the presence of the blood vessels enables the will activity to stream in. So also in the body as a whole, right into the periphery of the sense activities, the elements of will on the one hand and thought or cognition on the other hand are bound up with each other. This applies to all the senses and moreover it applies to the limbs, which serve the will: the element of cognition enters into our willing and into our movements through the nerves, and the element of will enters in through the blood vessels.

But now we must also learn the special nature of the activities of cognition. We have already spoken of this, but we must be fully conscious of the whole complex belonging to this side of human activity, to thought and cognition. As we have already said, in cognition, in mental picturing lives antipathy. However strange it may seem, everything connected with mental picturing, with thought, is permeated with antipathy. You will probably say, “Yes, but when I look at something I am not exercising any antipathy in this looking.” But indeed you do exercise it. When you look at an object, you exercise antipathy. If nerve activity alone were present in your eye, everything you looked at would be an object of disgust to you, would be absolutely antipathetic to you. But the will, which is made up of sympathy, also pours its activity into the eye, that is, the blood in its physical form penetrates into the eye, and it is only by this means that the feeling of antipathy in sense-perception is overcome in your consciousness, and the objective, neutral act of sight is brought about by the balance between sympathy and antipathy. It is brought about by the fact that sympathy and antipathy balance one another, and by the fact also that we are quite unconscious of this interplay between sympathy and antipathy.

If you take Goethe's Theory of Colour, to which I have already referred in this connection, and study especially the physiological-didactic part of it, you will see that it is because Goethe goes more deeply into the activity of sight that there immediately enters into his consideration of the finer shades of colour the elements of sympathy and antipathy. As soon as you begin to enter into the activity of a sense organ you discover the elements of sympathy and antipathy which arise in that activity. Thus in the sense activity itself the antipathetic element comes from the actual cognitive part, from mental picturing, the nerve part—and the sympathetic element comes from the will part, from the blood.

As I have often pointed out in general anthroposophical lectures there is a very important difference between animals and man with regard to the constitution of the eye. It is a significant characteristic of the animal that it has much more blood activity in its eye than the human being. In certain animals you will even find organs which are given up to this blood activity, as for example the ensiform cartilage, or the “fan.” From this you can deduce that the animal sends much more blood activity into the eye than the human being, and this is also the case with the other senses. That is to say, in his senses the animal develops much more sympathy, instinctive sympathy with his environment than the human being does. The human being has in reality more antipathy to his environment than the animal only this antipathy does not come into consciousness in ordinary life. It only comes into consciousness when our perception of the external world is intensified to a degree of impression to which we react with disgust. This is only a heightened impression of all sense-perceptions; you react with disgust to the external impression. When you go to a place that has a bad smell and you feel disgust within the range of this smell, then this feeling of disgust is nothing more than an intensification of what takes place in every sense activity, only that the disgust which accompanies the feeling in the sense impression remains as a rule below the threshold of consciousness. But if we human beings had no more antipathy to our environment than the animal, we should not separate ourselves off so markedly from our environment as we actually do. The animal has much more sympathy with his environment, and has therefore grown together with it much more, and hence he is much more dependent on climate, seasons, etc., than the human being is. It is because man has much more antipathy to his environment than the animal has that he is a personality. We have our separate consciousness of personality because the antipathy which lies below the threshold of consciousness enables us to separate ourselves from our environment.

Now this brings us to something which plays an important part in our comprehension of man. We have seen how in the activity of thought there flow together thinking (nerve activity as expressed in terms of the body) and willing (blood activity as expressed in terms of the body). But in the same way there flow together in actions of will the real will activity and the activity of thought. When we will to do something, we always develop sympathy for what we wish to do. But it would get no further than an instinctive willing unless we could bring antipathy also into willing, and thus separate ourselves as personalities from the action which we intend to perform. But the sympathy for what we plan to do is predominant, and a balance is only effected by the fact that we bring in antipathy also. Hence it comes about that the sympathy as such lies below the threshold of consciousness, and part of it only enters consciously into that which is willed. In all the numerous actions that we perform not merely out of our reason but with real enthusiasm, and with love and devotion, sympathy predominates so strongly in the will that it penetrates into the consciousness above the threshold, and our willing itself appears charged with sympathy, whereas as a rule it merely unites us with our environment in an objective way. Just as it is only in exceptional circumstances that our antipathy to the environment may become conscious in cognition, so our sympathy with the environment (which is always present) may only become conscious in exceptional circumstances, namely, when we act with enthusiasm and loving devotion. Otherwise we should perform all our actions instinctively. We should never be able to relate ourselves properly to the objective demands of the world, for example in social life. We must permeate our will with thinking, so that this will may make us members of all humanity and partakers in the world's process itself.

Perhaps it will be clear to you what really happens if you think what chaos there would be in the human soul if we were perpetually conscious of all this that I have spoken of. For if this were the case man would be conscious of a considerable amount of antipathy accompanying all his actions. This would be terrible! Man would then pass through the world feeling himself continually in an atmosphere of antipathy. It is wisely ordered that this antipathy as a force is indeed essential to our actions, but that we should not be aware of it, that it should lie below the threshold of consciousness.

Now in this connection we touch upon a wonderful mystery of human nature, a mystery which can be felt by any person of perception, but which the teacher and educator must bring to full consciousness. In early childhood we act more or less out of pure sympathy, however strange this may seem; all a child does, all its romping and play, it does out of sympathy with the deed, with the romping. When sympathy is born in the world it is strong love, strong willing. But it cannot remain in this condition, it must be permeated with thought, by idea, it must be continuously illumined as it were by the conscious mental picture. This takes place in a comprehensive way if we bring ideals, moral ideals, into our mere instincts. And now you will understand better the true significance of antipathy in this connection. If the impulses that we notice in the little child were throughout our life to remain only sympathetic, as they are sympathetic in childhood, we should develop in an animal way under the influence of our instincts. These instincts must become antipathetic to us; we must pour antipathy into them. When we pour antipathy into them we do it by means of our moral ideals, to which the instincts are antipathetic, and which for our life between birth and death bring antipathy into the childlike sympathy of instincts. For this reason moral development is always somewhat ascetic. But this asceticism must be rightly understood. It always betokens an exercise in the combating of the animal element.

This can show us to what a great extent willing in man's practical activity is not merely willing but is also permeated with idea, with the activity of cognition, of mental picturing.

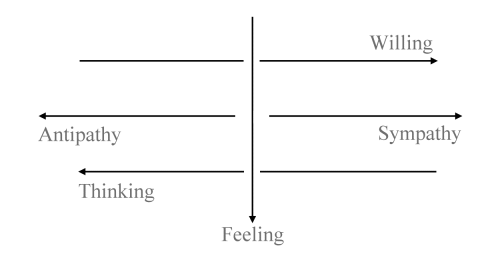

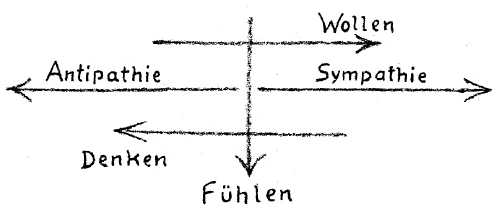

Now between cognition or thinking on the one hand and willing on the other hand we find the human activity of feeling. If you picture to yourselves what I have now put forward as willing and as thinking, you can say: From a certain central boundary there stream forth on the one hand all that is sympathy, willing, and on the other hand all that is antipathy, thinking. But the sympathy of willing also works back into thinking, and the antipathy of thinking works over into willing. Thus man is a unity because what is developed principally on the one side plays over into the other. Now between the two, between thinking and willing, there lies feeling, and this feeling is related to thinking on the one hand and to willing on the other hand. In the soul as a whole you cannot keep thought and will strictly apart, and still less can you keep the thought and will elements apart in feeling. In feeling, the will and thought elements are very strongly intermingled.

Here again you can convince yourselves of the truth of these remarks by even the most superficial self-examination. What I have already said will lead you to this conviction, for I told you that willing, which in ordinary life proceeds in an objective way, can be intensified to an activity done out of enthusiasm and love. Then you will clearly see willing as permeated with feeling—that willing which otherwise springs forth from the necessities of external life. When you do something which is filled with love or enthusiasm, that action flows out of a willing which you have allowed to become permeated by a subjective feeling. But if you examine the sense activities closely—with the help of Goethe's theory of colour—you will see how these are also permeated by feeling. And if the sense activity is enhanced to a condition of disgust, or on the other hand to the point of drinking in the pleasant scent of a flower, then you have the feeling activity flowing over directly into the activity of the senses.

But feeling also flows over into thought. There was once a philosophic dispute which—at all events externally—was of great significance—there have indeed been many such in the history of philosophy—between the psychologist Franz Brentano and the logician Sigwart, in Heidelberg. These two gentlemen were arguing about what it is that is present in man's power of judgment. Sigwart said: “When a man forms a judgment, and says, for example, ‘Man should be good’; then feeling always has a voice in a judgment of this kind; decision concerns feeling.” But Brentano said, “Judgment and feeling (which latter consists of emotions) are so different that the faculty of judgment could not be understood at all if one imagined that feeling played into it.” He meant that in this case something subjective would play into judgment, which ought to be purely objective.

Anyone who has a real understanding for these things will see from a dispute of this kind that neither the psychologists nor the logicians have discovered the real facts of the case, namely that the soul activities are always flowing into one another. Now consider what it is that should really be observed here. On the one hand we have judgment, which must of course form an opinion upon something quite objective. The fact that man should be good must not be dependent on our subjective feeling. The content of the judgment must be objective. But when we form a judgment something else comes into consideration which is of a different character. Those things which are objectively correct are not on that account consciously present in our souls. We must first receive them consciously into our soul. And we cannot consciously receive any judgment into our soul without the co-operation of feeling. Therefore, we must say that Brentano and Sigwart should have joined forces and said: True, the objective content of the judgment remains firmly fixed outside the realm of feeling, but in order that the subjective human soul may become convinced of the rightness of the judgment, feeling must develop.

From this you will see how difficult it is to get any kind of exact concepts in the inaccurate state of philosophic study which prevails to day. One must rise to a different level before one can reach such exact concepts, and there is no education in exact concepts to-day except by way of spiritual science. External science imagines that it has exact concepts, and rejects what anthroposophical spiritual science has to give, because it has no conception that the concepts arrived at by spiritual science are by comparison more exact and definite than those commonly in use to-day, since they are derived from reality and not from a mere playing with words.

When you thus trace the element of feeling on the one hand in cognition, in mental picturing, and on the other hand in willing, then you will say: feeling stands as a soul activity midway between cognition and willing, and radiates its nature out in both directions. Feeling is cognition which has not yet come fully into being, and it is also will which has not yet fully come into being; it is cognition in reserve, and will in reserve. Hence feeling also, is composed of sympathy and antipathy, which—as you have seen—are only present in a hidden form both in thinking and in willing. Both sympathy and antipathy are present in cognition and in will, in the working together of nerves and blood in the body, but they are present in a hidden form. In feeling they become manifest.

Now what do the manifestations of feeling in the body look like? You will find places all over the human body where the blood vessels touch the nerves in some way. Now wherever blood vessels and nerves make contact feeling arises. But in certain places, e.g., in the senses, the nerves and the blood are so refined that we no longer perceive the feeling. There is a fine undercurrent of feeling in all our seeing and hearing, but we do not notice it, and the more the sense organ is separated from the rest of the body, the less do we notice it. In looking, in the eye's activity, we hardly notice the feelings of sympathy and antipathy because the eye, embedded in its bony hollow, is almost completely separated from the rest of the organism. And the nerves which extend into the eye are of a very delicate nature and so are the blood vessels which enter into the eye. The sense of feeling in the eye is very strongly suppressed.

In the sense of hearing it is less suppressed. Hearing has much more of an organic connection with the activity of the whole organism than sight has. There are numerous organs within the ear which are quite different from those of the eye, and the ear is thus in many ways a true picture of what is at work in the whole organism. Therefore the sense activity which goes on in the ear is very closely accompanied by feeling. And here even people who are good judges of what they hear find it difficult to discriminate clearly—especially in the artistic sphere—between what is purely thought-element and what is really feeling. This fact explains a very interesting historical phenomenon of recent times, one which has even influenced actual artistic production.

You all know the figure of Beckmesser in Richard Wagner's “Meistersinger.” What is Beckmesser really supposed to represent? He is supposed to represent a musical connoisseur who quite forgets how the feeling element in the whole human being works into the thought element in the activity of hearing. Wagner, who represented his own conceptions in Walther, was, quite one-sidedly, permeated with the idea that it is chiefly the feeling element that should dwell in music. In the contrast between Walther and Beckmesser, arising out of a mistaken conception—I mean mistaken on both sides—we see the antithesis of the right conception, viz. that feeling and thinking work together in the hearing of music. And this came to be expressed in a historical phenomenon, because as soon as Wagnerian art appeared, or became at all well known, it found an opponent in the person of Eduard Hanslick of Vienna, who looked upon the whole appeal to feeling in Wagner's art as unmusical. There are few works on art which are so interesting from a psychological point of view as the work of Eduard Hanslick On Beauty in Music. The chief thought in this book is that whoever would derive everything in music from a feeling element is no true musician, and has no real understanding for music: for a true musician sees the real essence of what is musical only in the objective joining of one tone with another, and in Arabesque which builds itself up from tone to tone, abstaining from all feeling. In this book, On Beauty in Music Hanslick then works out with wonderful purity his claim that the highest type of music must consist solely in the tone-picture, the tone Arabesque. He pours unmitigated scorn upon the idea which is really the very essence of Wagnerism, namely that tunes should be created out of the element of feeling. The very fact that such a dispute as this between Hanslick and Wagner could arise in the sphere of music is a clear sign that recent psychological ideas about the activities of the soul have been completely confused, otherwise this one-sided idea of Hanslick's could never have arisen. But if we recognise the one-sidedness and then devote ourselves to the study of Hanslick's ideas which have a certain philosophical strength in them, we shall come to the conclusion that the little book On Beauty in Music is very brilliant.

From this you will see that, regarding the human being for the moment as feeling being, some senses bear more, some less of this whole human being into the periphery of the body, in consciousness.

Now in your task of gaining educational insight it behoves you to consider something which is bringing chaos into the scientific thinking of the present day. Had I not given you these talks as a preparation for the practical reforms you will have to undertake, then you would have had to plan your educational work for yourselves from the pedagogical theories of to-day, from the existing psychologies and systems of logic and from the educational practice of the present time. You would have had to carry into your schoolwork the customary thoughts of the present day. But these thoughts are in a very bad state even with regard to psychology. In every psychology you find a so-called theory of the senses. In investigating the basis of sense-activity the psychologist simply lumps together the activity of the eye, the ear, the nose, etc., all in one great abstraction as “sense-activity.” This is a very grave mistake, a serious error. For if you take only those senses which are known to the psychologist or physiologist of to-day and consider them in their bodily aspect alone, you will notice that the sense of the eye is quite different from the sense of the ear. Eye and ear are two quite different organisms—not to speak of the organisation of the sense of touch which has not been investigated at all as yet, not even in the gratifying manner in which eye and ear have been investigated. But let us keep to the consideration of the eye and ear. They perform two quite different activities so that to class seeing and hearing together as “general sense-activity” is merely “grey theory.” The right way to set to work here would be to speak from a concrete point of view only of the activity of the eye, the activity of the ear, the activity of the organ of smell, etc. Then we should find such a great difference between them that we should lose all desire to put forward a general physiology of the senses as the psychologies of to-day have done.

In studying the human soul we only gain true insight if we remain within the sphere which I have endeavoured to outline in my Truth and Science, and also in The Philosophy of Freedom. Here we can speak of the soul as a single entity without falling into abstractions. For here we stand upon a sure foundation; we proceed from the point of view that man lives his way into the world, and does not at first possess the whole of reality. You can study this in Truth and Science, and in The Philosophy of Freedom. To begin with man has not the whole reality; he has first to develop himself further, and in this further development what formerly was not yet reality becomes true reality for him through the interplay of thinking and perception. Man first has to win reality. In this connection Kantianism, which has eaten its way into everything, has wrought the most terrible havoc. What does Kantianism do? First of all it says dogmatically: we look out upon the world that is round about us, and within us there lives only the mirrored image of this world. And so it comes to all its other deductions. Kant himself is not clear as to what is in the environment which man perceives. For reality is not within the environment, nor is it in phenomena: only gradually, through our own winning of it, does reality come in sight, and the first sight of reality is the last thing we get. Strictly speaking, true reality would be what man sees in the moment when he can no longer express himself, the moment in which he passes through the gateway of death.

Many false elements have entered into our civilisation, and these work at their deepest in the sphere of education. Therefore we must strive to put true conceptions in the place of the false. Then, also, shall we be able to do what we have to do for our teaching in the right way.

Fünfter Vortrag

Wir haben gestern die Wesenheit des Willens besprochen, insofern der Wille in den menschlichen Organismus eingegliedert ist. Wir wollen nun die Beziehungen des Willens zum Menschen, die wir kennengelernt haben, fruchtbar machen für die Anschauung der übrigen Wesenheit des Menschen.

Sie werden bemerkt haben, daß ich bei den bisherigen Besprechungen der menschlichen Wesenheit hauptsächlich Rücksicht genommen habe auf die intellektuelle, auf die Erkenntnistätigkeit auf der einen Seite und auf die Willenstätigkeit auf der anderen Seite. Ich habe Ihnen ja auch gezeigt, wie die Erkenntnistätigkeit im Zusammenhang steht mit dem Nervenwesen des Menschen, wie die Willensstärke im Zusammenhang steht mit der Bluttätigkeit. Sie werden, wenn Sie über die Sache nachdenken, sich fragen: Wie steht es denn nun mit der dritten Seelenfähigkeit, mit der Gefühlstätigkeit? - Die haben wir bisher noch wenig berücksichtigt. Aber gerade indem wir die Gefühlstätigkeit heute mehr ins Auge fassen, wird sich uns auch die Möglichkeit bieten, die anderen beiden Seiten der Menschennatur, die erkennende und die willensmäßige, intensiver zu durchdringen.

Wir müssen uns nur über eines noch klar werden, das ich ja in verschiedenen Zusammenhängen schon erwähnt habe. Man kann nicht die Seelenfähigkeiten so pedantisch nebeneinanderstellen: Denken, Fühlen, Wollen — weil in der ganzen lebendigen Seele die eine Tätigkeit immer in die andere übergeht.

Betrachten Sie einmal auf der einen Seite den Willen. Sie werden sich bewußt sein können, daß Sie nicht zu wollen imstande sind, was Sie nicht durchdringen mit Vorstellung, also mit erkenntnismäßiger Tätigkeit. Versuchen Sie in einer, wenn auch nur oberflächlichen Selbstbesinnung, auf Ihr Wollen sich zu konzentrieren. Sie werden immer finden: in dem Willensakt steckt immer irgendwie Vorstellen drinnen. Sie würden gar nicht Mensch sein, wenn Sie in dem Willensakt nicht Vorstellen drinnen hätten. Sie würden aus einer stumpfen, instinktiven Tätigkeit heraus alles das vollziehen, was aus Ihrem Willen strömt, wenn Sie nicht die Handlung, die aus dem Willen hervorquillt, mit vorstellender Tätigkeit durchdringen würden.

Ebenso nun wie in aller Willensbetätigung das Vorstellen steckt, so steckt in allem Denken der Wille drinnen. Wieder wird Ihnen eine, wenn auch nur recht oberflächliche Betrachtung Ihres eigenen Selbstes die Erkenntnis liefern, daß Sie, indem Sie denken, immer in das Gedankenbilden den Willen hineinströmen lassen. Wie Sie Gedanken selber formen, wie Sie einen Gedanken mit dem anderen verbinden, wie Sie zu Urteil und Schluß übergehen, das alles ist von einer feineren Willenstätigkeit durchströmt.

Daher können wir eigentlich nur sagen: Die Willenstätigkeit ist hauptsächlich Willenstätigkeit und hat in sich die Unterströmung der Denktätigkeit; die Denktätigkeit ist hauptsächlich Denktätigkeit und hat in ihrer Unterströmung Willenstätigkeit. Also ein pedantisches Nebeneinanderstellen ist schon für die Beobachtung der einzelnen Seelenbetätigungen nicht möglich, weil eben die eine in die andere überfließt.

Was Sie für die Seele erkennen können: das Ineinanderfließen der Seelentätigkeiten, das sehen Sie auch ausgeprägt in dem Leib, in dem sich die Seelentätigkeit offenbart. Betrachten Sie zum Beispiel das menschliche Auge. In das Auge hinein, wenn wir es in seiner Ganzheit betrachten, setzen sich fort die Nerven; aber es setzen sich in das Auge auch die Blutbahnen fort. Dadurch, daß sich die Nerven in das menschliche Auge hinein fortsetzen, strömt die Gedanken-, die Erkenntnistätigkeit ins Auge ein; dadurch, daß sich die Blutbahnen ins Auge fortsetzen, strömt die Willensbetätigung in das Auge ein. So ist bis in die Peripherie der Sinnesbetätigungen auch im Leibe Willensgemäßes und Vorstellungs- oder Erkenntnisgemäßes miteinander verbunden. Das ist für alle Sinne so, ist aber auch für alle Bewegungsglieder, die dem Wollen dienen, eben so: in unser Wollen, in unsere Bewegungen geht durch die Nervenbahnen das Erkenntnisgemäße und durch die Blutbahnen das Willensgemäße.

Nun müssen wir aber auch die besondere Art der Erkenntnistätigkeit kennenlernen. Wir haben schon darauf hingewiesen, aber wir müssen uns voll bewußt werden, was in diesem ganzen Komplex von menschlicher Tätigkeit, der nach der Erkenntnis-, der Vorstellungsseite hinneigt, alles liegt. Wir haben schon gesagt: Im Erkennen, im Vorstellen lebt eigentlich Antipathie. So sonderbar es ist, alles, was nach dem Vorstellen hinneigt, ist durchdrungen von Antipathie. Sie werden sich sagen: Ja, wenn ich etwas anschaue, so übe ich in diesem Anschauen doch nicht Antipathie aus! — Doch, Sie üben sie aus! Sie üben Antipathie aus, indem Sie einen Gegenstand ansehen. Würde in Ihrem Auge nur Nerventätigkeit sein, so würde Ihnen jeder Gegenstand, den Sie mit Ihren Augen ansehen, zum Ekel sein, er wäre Ihnen antipathisch. Nur dadurch, daß sich in die Augentätigkeit hinein auch die Willenstätigkeit ergießt, die in Sympathie besteht, dadurch daß sich leiblich in Ihr Auge hineinerstreckt das Blutmäßige, nur dadurch wird für Ihr Bewußtsein die Empfindung der Antipathie im sinnlichen Anschauen ausgelöscht, und es wird durch einen Ausgleich zwischen Sympathie und Antipathie der objektive, gleichgültige Akt des Sehens hervorgerufen. Er wird da hervorgerufen, indem Sympathie und Antipathie sich ins Gleichgewicht stellen und uns dieses Ineinanderspielen von Sympathie und Antipathie gar nicht bewußt wird.

Wenn Sie die Goethesche Farbenlehre, auf die ich in diesem Zusammenhang schon einmal aufmerksam gemacht habe, studieren, namentlich in ihrem physiologisch-didaktischen Teil, dann werden Sie sehen: weil Goethe eingeht auf die tiefere Tätigkeit des Sehens, so kommt dadurch für seine Betrachtung in den Farbennuancen gleich zum Vorschein das Sympathische und das Antipathische. Sie brauchen nur ein wenig hineindringen in die Tätigkeit eines Sinnesorgans, dann finden Sie sogleich das Sympathische und das Antipathische in der Sinnestätigkeit auftauchen. Es rührt eben auch in der Sinnestätigkeit das Antipathische her von dem eigentlichen Erkenntnisteil, von dem Vorstellungsteil, dem Nerventeil, und das Sympathische rührt her von dem eigentlichen Willensteil, von dem Blutteil.

Es gibt einen bedeutungsvollen Unterschied, den ich auch schon in den allgemeinen anthroposophischen Vorträgen öfter hervorgehoben habe, zwischen den Tieren und den Menschen mit Bezug auf die Einrichtung des Auges. Es ist sehr eigentümlich, daß das Tier viel mehr von Bluttätigkeit im Auge hat als der Mensch. Bei gewissen Tieren finden Sie sogar Organe, welche dieser Bluttätigkeit dienen, wie den «Schwertfortsatz» und den «Fächer». Daraus können Sie entnehmen, daß das Tier viel mehr von Bluttätigkeit auch ins Auge hineinsendet - und so ist es auch bei den übrigen Sinnen - als der Mensch. Das heißt, das Tier entwickelt in seinen Sinnen viel mehr Sympathie, instinktive Sympathie mit der Umwelt als der Mensch. Der Mensch hat in Wirklichkeit mehr Antipathie zu der Umwelt als das Tier, aber sie kommt im gewöhnlichen Leben nicht zum Bewußtsein. Sie kommt nur zum Bewußtsein, wenn sich das Anschauen der Umwelt steigert bis zu dem Eindruck, auf den wir mit dem Ekel reagieren. Das ist nur ein gesteigerter Eindruck alles sinnlichen Wahrnehmens: Sie reagieren mit dem Ekel auf den äußeren Eindruck. Wenn Sie an einen Ort gehen, der übel riecht, und Sie empfinden in der Sphäre dieses Übelriechens Ekel, so ist dieses Ekelempfinden nichts anderes als eine Steigerung desjenigen, was bei jeder Sinnestätigkeit stattfindet, nur bleibt die Begleitung der Empfindung durch den Ekel in der gewöhnlichen Sinnesempfindung unter der Bewußtseinsschwelle liegend. Wenn wir Menschen aber nicht mehr Antipathie hätten zu unserer Umgebung als das Tier, so würden wir uns nicht so stark absondern von unserer Umgebung, als wir uns tatsächlich absondern. Das Tier hat viel mehr Sympathie mit der Umgebung, ist daher viel mehr mit der Umgebung zusammengewachsen, und es ist deshalb auch viel mehr angewiesen auf die Abhängigkeit vom Klima, von den Jahreszeiten und so weiter als der Mensch. Weil der Mensch viel mehr Antipathie hat gegen die Umgebung, deshalb ist er eine Persönlichkeit. Der Umstand, daß wir uns durch unsere unter der Schwelle des Bewußtseins liegende Antipathie absondern können von der Umgebung, diese Tatsache bewirkt unser gesondertes Persönlichkeitsbewußtsein.

Damit aber haben wir auf etwas hingewiesen, was zur ganzen Auffassung des Menschen ein sehr Wesentliches beiträgt. Wir haben gesehen, wie in der Erkenntnis- oder Vorstellungstätigkeit zusammenfließen: Denken - Nerventätigkeit, leiblich ausgedrückt; und Wollen Bluttätigkeit, leiblich ausgedrückt.

So aber fließen auch zusammen in der Willensbetätigung vorstellende und eigentliche Willenstätigkeit. Wir entwickeln immer, wenn wir irgend etwas wollen, Sympathie mit dem Gewollten. Aber es würde immer ein ganz instinktives Wollen bleiben, wenn wir uns nicht auch durch eine in die Sympathie des Wollens hineingeschickte Antipathie absondern könnten als Persönlichkeit von der Tat, von dem Gewollten. Nur überwiegt jetzt eben durchaus die Sympathie zu dem Gewollten, und es wird nur ein Ausgleich mit dieser Sympathie dadurch geschaffen, daß wir auch die Antipathie hineinschicken. Dadurch bleibt aber die Sympathie als solche unter der Schwelle des Bewußstseins liegend, es dringt nur etwas von dieser Sympathie ein in das Gewollte. In den ja nicht sehr zahlreichen Handlungen, die wir nicht bloß aus Vernunft vollbringen, sondern die wir in wirklicher Begeisterung, in Hingabe, in Liebe ausführen, da überwiegt die Sympathie so stark im Wollen, daß sie auch hinaufdringt über die Schwelle unseres Bewußtseins und unser Wollen selber uns durchtränkt erscheint von Sympathie, während es uns sonst als ein Objektives verbindet mit der Umwelt, sich uns so offenbart. Geradeso wie uns nur ausnahmsweise, nicht immer, unsere Antipathie mit der Umwelt ins Bewußtsein kommen darf im Erkennen, so darf uns unsere immer vorhandene Sympathie mit der Umwelt nur in Ausnahmefällen, in Fällen der Begeisterung, der hingebenden Liebe, zum Bewußtsein kommen. Sonst würden wir alles instinktiv ausführen. Wir würden uns niemals in das, was objektiv, zum Beispiel im sozialen Leben, die Welt von uns fordert, eingliedern können. Wir müssen gerade das Wollen denkend durchdringen, damit dieses Wollen uns eingliedert in die Gesamtmenschheit und in den Weltenprozeß als solchen.

Sie werden sich das, was dabei geschieht, vielleicht klarmachen können, wenn Sie bedenken, welche Verheerungen es in der menschlichen Seele eigentlich anrichten würde, wenn im gewöhnlichen Leben diese ganze Sache, von der ich jetzt gesprochen habe, bewußt wäre. Wenn diese Sache im gewöhnlichen Leben fortwährend in der menschlichen Seele bewußt wäre, dann wäre dem Menschen ein gut Stück Antipathie bewußt, das bei allen seinen Handlungen begleitend wäre. Das wäre furchtbar! Der Mensch ginge dann durch die Welt und fühlte sich fortwährend in einer Atmosphäre von Antipathie. Das ist weise eingerichtet in der Welt, daß diese Antipathie als eine Kraft zwar notwendig ist zu unserem Handeln, daß wir uns ihrer aber nicht bewußt werden, daß sie unter der Schwelle des Bewußtseins bleibt.

Nun schauen Sie da, ich möchte sagen, in ein merkwürdiges Mysterium der menschlichen Natur hinein, in ein Mysterium, das eigentlich jeder bessere Mensch empfindet, das aber der Erzieher und Unterrichter sich ganz zum Bewußtsein bringen sollte. Wir handeln ja, indem wir zuerst Kinder werden, mehr oder weniger aus bloßer Sympathie. So sonderbar es klingt: aber alles, was das Kind tut und tobt, ist aus Sympathie zu dem Tun und Toben vollbracht. Wenn die Sympathie geboren wird in der Welt, so ist sie starke Liebe, starkes Wollen. Aber sie kann nicht so bleiben, sie muß durchdrungen werden vom Vorstellen, sie muß gewissermaßen fortwährend erhellt werden vom Vorstellen. Das geschieht in umfassender Weise, indem wir eingliedern in unsere bloßen Instinkte die Ideale, die moralischen Ideale. Und jetzt werden Sie besser begreifen können, was eigentlich auf diesem Gebiete die Antipathie bedeutet. Blieben uns die Instinktimpulse, die wir in dem kleinen Kinde bemerken, durch das ganze Leben nur sympathisch, wie sie dem Kinde sympathisch sind, so würden wir uns unter dem Einfluß unserer Instinkte animalisch entwickeln. Diese Instinkte müssen uns antipathisch werden, wir müssen Antipathie in sie hineingießen. Dann, wenn wir Antipathie in sie hineingießen, tun wir das durch unsere moralischen Ideale, denen die Instinkte antipathisch sind und die zunächst für unser Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod Antipathie in die kindliche Sympathie der Instinkte hineinsetzen. Daher ist moralische Entwickelung immer etwas Asketisches. Es muß nur dieses Asketische im richtigen Sinne gefaßt werden. Es ist immer ein Üben in der Bekämpfung des Animalischen.

Das alles soll uns lehren, in wie hohem Grade Wollen nicht nur Wollen in der praktischen Betätigung des Menschen ist, sondern inwiefern Wollen durchaus auch von Vorstellen, von erkennender Tätigkeit durchdrungen ist.

Nun steht zwischen Erkennen, Denken und Wollen mitten drinnen die menschliche Gefühlstätigkeit. Wenn Sie sich das vorstellen, was ich jetzt als Wollen und Denken entwickelt habe, so können Sie sich sagen: Von einer gewissen mittleren Grenze strömt auf der einen Seite alles das aus, was Sympathie ist: Wollen; auf der anderen Seite strömt aus alles, was Antipathie ist: Denken. Aber die Sympathie des Wollens wirkt auch zurück in das Denken hinein, und die Antipathie des Denkens wirkt auch in das Wollen hinein. Und so wird der Mensch ein Ganzes, indem das, was sich auf der einen Seite hauptsächlich entwickelt, auch in die andere Seite hineinwirkt. Zwischendrinnen nun, zwischen Denken und Wollen, liegt das Fühlen, so daß das Fühlen nach der einen Richtung hin verwandt ist mit dem Denken, nach der anderen Richtung hin mit dem Wollen. Wie Sie schon in der ganzen menschlichen Seele nicht streng auseinanderhalten können erkennende oder denkerische Tätigkeit und Willenstätigkeit, so können Sie noch weniger auseinanderhalten im Fühlen das denkerische Element von dem Willenselement. Im Fühlen fließen ganz stark ineinander Willenselemente und Denkelemente.

Auch hier können Sie wieder durch die bloße Selbstbeobachtung, wenn Sie diese auch nur oberflächlich ausüben, sich von der Richtigkeit des eben Gesagten überzeugen. Schon was ich bis jetzt gesagt habe, führt Sie auf die Anschauung von dieser Richtigkeit, denn ich sagte Ihnen: Das Wollen, das im gewöhnlichen Leben objektiv verläuft, steigert sich bis zur Tätigkeit aus Enthusiasmus, aus Liebe heraus. Da sehen Sie ganz deutlich ein sonst von der Notwendigkeit des äußeren Lebens hervorgebrachtes Wollen durchströmt vom Fühlen. Wenn Sie etwas Enthusiastisches oder Liebevolles tun, so tun Sie das, was aus dem Willen fließt, indem Sie es durchdrungen sein lassen von einem subjektiven Gefühl. Aber auch bei der Sinnestätigkeit können Sie sehen, wenn Sie genauer zusehen — eben durch die Goethesche Farbenlehre -, wie sich in die Sinnestätigkeit hineinmischt das Fühlen. Und wenn sich die Sinnestätigkeit bis zum Ekel steigert oder auf der anderen Seite bis zum Einsaugen des angenehmen Blumenduftes, so haben Sie auch dabei die Gefühlstätigkeit in die Sinnestätigkeit ohne weiteres überfließend.

Aber auch in die Denktätigkeit fließt die Gefühlstätigkeit hinein. Es war einmal ein, äußerlich wenigstens, sehr bemerkenswerter philosophischer Streit — es gab ja in der Geschichte der Weltanschauungen viele philosophische Streitigkeiten - zwischen dem Psychologen Franz Brentano und dem Logiker Sigwart in Heidelberg. Die beiden Herren stritten miteinander über das, was in der Urteilstätigkeit des Menschen liegt. Sigwart meinte: Wenn der Mensch urteilt - sagen wir, er fällt das Urteil: Der Mensch soll gut sein -, so spräche in einem solchen Urteil immer ein Gefühl mit; die Entscheidung trifft das Gefühl. — Brentano meinte: Urteilstätigkeit und Gefühlstätigkeit, die in Gemütsbewegungen bestehen, seien so verschieden, daß die Urteilsfunktion, die Urteilsbetätigung gar nicht begriffen werden könnte, wenn man nur glaube, das Gefühl spiele da hinein. Er meinte, dadurch käme etwas Subjektives in das Urteil hinein, während doch unser Urteil objektiv sein wolle.

Ein solcher Streit zeigt dem Einsichtigen nur, daß weder die Psychologen noch die Logiker auf das gekommen sind, worauf sie kommen sollten — auf das Ineinanderfließen der Seelentätigkeiten. Bedenken Sie, was hier wirklich beobachtet werden muß. Wir haben auf der einen Seite die Urteilsfähigkeit, die natürlich entscheiden muß über etwas ganz Objektives. Daß der Mensch gut sein muß, darf nicht von unserem subjektiven Gefühl abhängen. Also der Inhalt des Urteils muß objektiv sein. Aber wenn wir urteilen, kommt ja noch etwas ganz anderes in Betracht. Die Dinge, die objektiv richtig sind, sind ja deshalb noch nicht bewußt in unserer Seele. Wir müssen sie erst bewußt in unsere Seele hereinbekommen. Und bewußt bekommen wir kein Urteil in unsere Seele herein, ohne daß die Gefühlstätigkeit mitwirkt. Daher müssen wir sagen, Brentano und Sigwart hätten sich dahin einigen müssen, daß sie beide gesagt hätten: Ja, der objektive Inhalt des Urteils steht außerhalb der Gefühlstätigkeit fest; damit aber in der subjektiven Menschenseele die Überzeugung von der Richtigkeit des Urteils zustande komme, muß die Gefühlstätigkeit sich entwickeln.

Sie sehen daraus, wie schwer es ist bei der ungenauen Art der philosophischen Betrachtungen, wie sie gegenwärtig gepflogen werden, überhaupt zu genauen Begriffen zu kommen. Zu solchen genauen Begriffen muß man sich ja erst erheben, und es gibt heute keine andere Erziehung zu genauen Begriffen als die durch Geisteswissenschaft. Die äußere Wissenschaft meint, sie habe genaue Begriffe, und sie ergeht sich sehr hochnäsig über das, was anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft liefert, weil sie keine Ahnung hat, daß die von dieser Seite gelieferten Begriffe gegenüber den heute gebräuchlichen viel genauer und exakter sind, weil sie aus der Wirklichkeit hergeholt sind, nicht aus dem bloßen Spiel mit den Worten.

Indem Sie so das gefühlsmäßige Element nach der einen Seite verfolgen in dem Erkennenden, in dem Vorstellenden, und auf der anderen Seite in dem Willensgemäßen, werden Sie sich sagen: Das Gefühl steht als die mittlere Seelenbetätigung zwischen Erkennen und Wollen drinnen und strahlt seine Wesenheit nach den beiden Richtungen aus. — Gefühl ist sowohl noch nicht ganz gewordene Erkenntnis, wie noch nicht ganz gewordener Wille, zurückgehaltene Erkenntnis und zurückgehaltener Wille. Daher auch ist das Fühlen zusammengesetzt aus Sympathie und Antipathie, die sich nur verstecken, wie Sie gesehen haben, sowohl im Erkennen wie im Wollen. Beide, Sympathie und Antipathie, sind im Erkennen und Wollen vorhanden, indem leiblich Nerventätigkeit und Bluttätigkeit zusammenwirken, aber sie verstekken sich. Im Fühlen werden sie offenbar.

Wie schauen denn daher die leiblichen Offenbarungen des Fühlens aus? Sie werden ja im menschlichen Leibe überall finden, wie die Blutbahnen mit den Nervenbahnen in irgendeiner Weise sich berühren. Und überall dort, wo Blutbahnen mit Nervenbahnen sich berühren, entsteht eigentlich Gefühl. Nur ist, in den Sinnen zum Beispiel, sowohl der Nerv wie das Blut so verfeinert, daß wir nicht mehr das Gefühl spüren. Von einem leisen Gefühl ist all unser Sehen und Hören durchzogen, aber wir spüren es nicht; wir spüren es um so weniger, als das Sinnesorgan abgegrenzt, abgetrennt ist von dem übrigen Leib. Beim Sehen, bei der Augentätigkeit, spüren wir das gefühlsmäßige Sympathisieren und Antipathisieren fast gar nicht, weil das Auge, in der Knochenrundung eingebettet, fast ganz vom übrigen Organismus abgesondert ist. Und sehr verfeinert sind die Nerven, die sich ins Auge hineinerstrecken und auch die Blutbahnen, die sich ins Auge hineinerstrecken. Es ist das gefühlsmäßige Empfinden im Auge sehr unterdrückt. -— Weniger unterdrückt ist das Gefühlsmäßige beim Sinn des Hörens. Das Hören steht viel mehr als das Schauen mit der Gesamttätigkeit des Organismus in einem organischen Zusammenhang. Indem sich zahlreiche Organe im Ohre befinden, die ganz andersgeartet sind als die Organe des Auges, ist das Ohr in vieler Beziehung ein getreues Abbild desjenigen, was im ganzen Organismus vor sich geht. Daher wird das, was im Ohr als Sinnestätigkeit vor sich geht, sehr stark begleitet von Gefühlstätigkeit. Und hier wird es selbst Menschen, die sich gut auf das verstehen, was gehört wird, schwer, wirklich zur Klarheit zu kommen, was im Gehörten, besonders beim künstlerisch Gehörten, bloßes Erkennen und was Gefühlsmäßiges ist. Darauf beruht eine sehr interessante Erscheinung der neueren Zeit, die auch in die unmittelbare künstlerische Produktion hineingespielt hat.

Sie kennen alle in Richard Wagners «Meistersinger» die Figur des Beckmesser. Was sollte Beckmesser eigentlich darstellen? Er sollte darstellen einen musikalisch Auffassenden, der ganz vergißt, wie auch das gefühlsmäßige Element des ganzen Menschen in das Erkenntnismäßige der Gehörtätigkeit hineinwirkt. Wagner, der seine eigene Auffassung in dem Walter dargestellt hat, war wiederum ganz einseitig davon durchdrungen, daß hauptsächlich das Gefühlsmäßige im Musikalischen leben müsse. Was da im Walter und im Beckmesser aus einer mißverständlichen Auffassung - ich meine: bei beiden mißverständlichen Auffassung — sich gegenübergestellt wird, im Gegensatz zu der richtigen Auffassung, wie Gefühlsmäßiges und Erkenntnismäßiges im musikalischen Hören zusammenwirken, das kam in einer historischen Erscheinung dadurch zum Ausdruck, daß die Wagnersche Kunst bei ihrem Auftreten, namentlich aber bei ihrem Bekanntwerden einen Gegner fand in der Person von Eduard Hanslick in Wien, der alles, was in der Gefühlssphäre aufströmt in der Wagnerschen Kunst, als unmusikalisch ansah. Es gibt vielleicht wenig psychologisch so interessante Schriften auf dem Gebiete des Künstlerischen wie die «Vom MusikalischSchönen» von Eduard Hanslick. Darin wird hauptsächlich ausgeführt, daß der kein wahrer Musiker ist, keinen wahren musikalischen Sinn hat, der alles vom Gefühlsmäßigen in der Musik herholen möchte, sondern nur derjenige, der in der objektiven Verbindung von Ton zu Ton den eigentlichen Nerv des Musikalischen sieht, in der alles Gefühlsmäßige entbehrenden Arabeske, die sich zusammenfügt von Ton zu Ton. Mit einer wunderbaren Reinlichkeit wird da die Forderung, daß das höchste Musikalische nur im Tonbilde, in der Tonarabeske bestehen darf, ausgeführt in dem Buche «Vom Musikalisch-Schönen» von Eduard Hansliick, und es wird aller mögliche Spott über das ergossen, was gerade den Nerv des Wagnertums ausmacht als das Schaffen des Tonlichen aus dem Gefühlselemente heraus. Daß überhaupt ein solcher Streit wie der zwischen Hanslick und Wagner auftreten konnte auf dem Gebiete des Musikalischen, das bezeugt eben, daß psychologisch die Ideen über die Seelenbetätigungen in der neueren Zeit durchaus im unklaren waren, sonst hätte gar nicht eine solch einseitige Neigung, wie sie bei Hanslick hervortrat, entstehen können. Durchschaut man aber das Finseitige und gibt man sich dann hin den philosophisch starken Auseinandersetzungen von Hanslick, dann wird man sagen: das Büchelchen «Vom Musikalisch-Schönen» ist ein sehr geistreiches.

Sie sehen daraus, daß bei dem einen Sinne mehr, bei dem anderen weniger von dem ganzen Menschen, der zunächst als Gefühlswesen lebt, in die Peripherie hineindringt, erkenntnismäßig.

Das wird und muß auch Sie gerade zum Behufe pädagogischer Einsicht auf etwas aufmerksam machen, was eine große Verheerung im wissenschaftlichen Denken der Gegenwart anrichtet. Hätten wir hier nicht vorbereitend gesprochen und sprächen wir nicht vorbereitend über das, was Sie hinüberleiten soll zu einer reformatorischen Tätigkeit, so müßten Sie aus den jetzigen vorhandenen Pädagogiken, aus den bestehenden Psychologien und Logiken und aus den Erziehungspraktiken sich das zusammensetzen, was Sie in Ihrer Schultätigkeit ausüben wollen. Sie müßten das, was außen üblich geworden ist, in die Schultätigkeit hineintragen. Nun leidet aber das, was heute üblich geworden ist, von vornherein an einem großen Übelstand schon mit Bezug auf die Psychologie. Sie finden ja in jeder Psychologie zunächst eine sogenannte Sinneslehre. Indem man untersucht, worauf die Sinnestätigkeit beruht, gewinnt man die Sinnestätigkeit des Auges, des Ohres, der Nase und so weiter. Man faßt alles in einer großen Abstraktion «Sinnestätigkeit» zusammen. Das ist ein großer Fehler, ist ein beträchtlicher Irrtum. Denn nehmen Sie nur diejenigen Sinne, die zunächst dem heutigen Physiologen oder Psychologen bekannt sind, so werden Sie, wenn Sie zunächst nur auf das Leibliche sehen, beobachten können, daß eigentlich der Sinn des Auges etwas ganz anderes ist als der Sinn des Ohres. Auge und Ohr sind zwei ganz verschiedene Wesen. Und dann erst die Organisation des Tastsinnes, die überhaupt noch gar nicht erforscht ist, auch nicht in nur so befriedigender Weise, wie es beim Auge und Ohr der Fall ist! Aber bleiben wir beim Auge und Ohr stehen. Sie sind zwei ganz verschiedene Tätigkeiten, so daß die Zusammenfassung des Sehens und Hörens in eine «allgemeine Sinnestätigkeit» eine graue Theorie ist. Man müßte, wollte man richtig hier zu Werke gehen, mit einem konkreten Anschauungsvermögen zunächst überhaupt nur sprechen von der Betätigung des Auges, von der Betätigung des Ohres, von der Betätigung des Geruchsorgans und so weiter. Dann würde man eine so große Verschiedenheit finden, daß einem die Lust verginge, eine allgemeine Sinnesphysiologie, wie sie die heutigen Psychologien haben, aufzustellen.

Man kommt in der Betrachtung der menschlichen Seele nur zu einer Einsicht, wenn man auf dem Gebiete stehenbleibt, das ich zu begrenzen versuchte in meinen Auseinandersetzungen sowohl in «Wahrheit und Wissenschaft» wie in der «Philosophie der Freiheit». Dann kann man von der einheitlichen Seele sprechen, ohne daß man dabei in Abstraktionen verfällt. Denn da steht man auf einem sicheren Boden; da geht man davon aus, daß der Mensch sich in die Welt hineinlebt und nicht die ganze Wirklichkeit hat. Sie können das in «Wahrheit und Wissenschaft» und in der «Philosophie der Freiheit» nachlesen. Der Mensch hat anfangs nicht die ganze Wirklichkeit. Er entwickelt sich erst weiter, und im Weiterentwickeln wird ihm das, was vorher noch nicht Wirklichkeit ist, durch das Ineinandergehen von Denken und Anschauung erst zur wahren Wirklichkeit. Der Mensch erobert sich erst die Wirklichkeit. In dieser Beziehung hat der Kantianismus, der sich in alles eingefressen hat, die furchtbarsten Verheerungen angerichtet. Was tut denn der Kantianismus? Er sagt von vornherein dogmatisch: Die Welt, die uns umgibt, haben wir zunächst anzuschauen, und in uns lebt eigentlich nur das Spiegelbild von dieser Welt. So kommt er zu allen seinen anderen Deduktionen. Kant ist sich nicht im klaren darüber, was in der wahrgenommenen Umgebung des Menschen ist. Denn die Wirklichkeit ist nicht in der Umgebung, ist auch nicht in der Erscheinung, sondern es ist so, daß die Wirklichkeit erst nach und nach auftaucht durch unser Frobern dieser Wirklichkeit, so daß das Letzte, was an uns herantritt, die Wirklichkeit erst ist. Im Grunde genommen wäre das die richtige Wirklichkeit, was der Mensch in dem Augenblicke erschaut, wo er sich nicht mehr aussprechen kann, in jenem Augenblicke nämlich, wo er durch die Pforte des Todes geht.

Es sind sehr viele falsche Elemente eingeflossen in die neuere Geisteskultur, und das wirkt am einschneidensten auf dem Gebiete der Pädagogik. Daher müssen wir bestrebt sein, an die Stelle der falschen Begriffe die richtigen zu setzen. Dann werden wir das, was wir für den Unterricht zu tun haben, auch in der richtigen Weise ausüben können.

Fifth Lecture

Yesterday we discussed the nature of the will insofar as it is integrated into the human organism. We now want to make use of the relationships between the will and the human being that we have learned about in order to gain insight into the rest of the human nature.

You will have noticed that in my previous discussions of the human essence, I have mainly considered intellectual activity, or cognition, on the one hand, and volitional activity on the other. I have also shown you how cognitive activity is related to the human nervous system, and how strength of will is related to blood activity. If you think about it, you will ask yourself: What about the third faculty of the soul, the activity of feeling? We have paid little attention to this so far. But precisely by focusing more on the activity of feeling today, we will also have the opportunity to penetrate more deeply into the other two sides of human nature, the cognitive and the volitional.

We just need to be clear about one thing, which I have already mentioned in various contexts. You cannot pedantically juxtapose the soul's faculties: thinking, feeling, willing — because in the whole living soul, one activity always merges into the other.

Consider the will on the one hand. You will realize that you are not able to will what you do not penetrate with a mental image, that is, with cognitive activity. Try to concentrate on your will in a self-reflection, even if only superficial. You will always find that the act of will always involves a mental image in some way. You would not be human if you did not have a mental image in the act of will. You would carry out everything that flows from your will out of a dull, instinctive activity if you did not penetrate the action that springs from the will with a mental image.

Just as the mental image is involved in all acts of will, so too is will involved in all thinking. Once again, even a very superficial observation of your own self will reveal to you that, when you think, you always allow your will to flow into the formation of your thoughts. The way you form thoughts yourself, the way you connect one thought with another, the way you proceed to judgment and conclusion—all of this is permeated by a finer activity of the will.

Therefore, we can only say: the activity of the will is mainly the activity of the will and has the undercurrent of the activity of thinking; the activity of thinking is mainly the activity of thinking and has the activity of the will as its undercurrent. Thus, a pedantic juxtaposition is not possible even for the observation of the individual activities of the soul, because one flows into the other.

What you can recognize for the soul: the interflowing of soul activities, you can also see clearly in the body, in which soul activity manifests itself. Consider, for example, the human eye. When we look at the eye in its entirety, we see that the nerves continue into it, but the blood vessels also continue into the eye. Because the nerves continue into the human eye, the activity of thought and cognition flows into the eye; because the blood vessels continue into the eye, the activity of the will flows into the eye. Thus, even in the periphery of sensory activity, the will and the activity of the mental image or cognition are connected with each other in the body. This is true for all the senses, but it is also true for all the limbs that serve the will: through the nerve pathways, the cognitive flows into our will and our movements, and through the blood vessels, the volitional flows into them.

Now, however, we must also learn about the special nature of cognitive activity. We have already pointed this out, but we must become fully aware of everything that lies within this whole complex of human activity that tends toward cognition and mental image. We have already said that antipathy actually lives in cognition and mental image. Strange as it may be, everything that tends toward mental image is permeated with antipathy. You will say to yourself: Yes, when I look at something, I do not express antipathy in this looking! — But you do express it! You express antipathy when you look at an object. If there were only nervous activity in your eye, every object you looked at with your eyes would be disgusting to you, it would be antipathetic to you. Only because the activity of the will, which consists of sympathy, pours into the activity of the eyes, only because the blood extends physically into your eyes, only then is the feeling of antipathy in sensory seeing erased from your consciousness, and the objective, indifferent act of seeing is brought about by a balance between sympathy and antipathy. It is brought about by sympathy and antipathy balancing each other out, and we are not even aware of this interplay of sympathy and antipathy.

If you study Goethe's theory of colors, to which I have already drawn attention in this context, particularly in its physiological-didactic part, you will see that because Goethe goes into the deeper activity of seeing, the sympathetic and the antipathetic immediately come to the fore in his observation of color nuances. You only need to delve a little into the activity of a sensory organ to immediately find the sympathetic and the antipathetic emerging in sensory activity. In sensory activity, too, the antipathetic arises from the actual cognitive part, from the imaginative part, the nervous part, and the sympathetic arises from the actual volitional part, from the blood part.

There is a significant difference, which I have often emphasized in general anthroposophical lectures, between animals and humans with regard to the structure of the eye. It is very peculiar that animals have much more blood activity in the eye than humans. In certain animals, you even find organs that serve this blood activity, such as the “sword-like appendage” and the “fan.” From this you can see that animals send much more blood activity into the eye—and this is also true of the other senses—than humans do. This means that animals develop much more sympathy, instinctive sympathy with their environment, in their senses than humans do. In reality, humans have more antipathy toward the environment than animals, but this does not come to consciousness in everyday life. It only comes to consciousness when the perception of the environment intensifies to the point where we react with disgust. This is only an intensified impression of all sensory perception: you react with disgust to the external impression. If you go to a place that smells bad and you feel disgust in the sphere of this bad smell, this feeling of disgust is nothing more than an intensification of what takes place in every sensory activity, only the accompaniment of the sensation by disgust remains below the threshold of consciousness in ordinary sensory perception. But if we humans did not have more antipathy toward our environment than animals do, we would not separate ourselves from our environment as strongly as we actually do. Animals have much more sympathy for their environment, are therefore much more integrated with it, and are therefore much more dependent on the climate, the seasons, and so on than humans. Because humans have much more antipathy toward their environment, they are personalities. The fact that we can separate ourselves from our surroundings through our antipathy, which lies below the threshold of consciousness, is what causes our separate sense of personality.But in doing so, we have pointed to something that contributes very significantly to the whole conception of the human being. We have seen how the following converge in the activity of cognition or mental image: thinking—nerve activity, expressed physically; and willing—blood activity, expressed physically.

But in the activity of the will, too, imaginative and actual volitional activity converge. Whenever we want something, we always develop sympathy for what we want. But it would always remain a completely instinctive wanting if we could not also separate ourselves as personalities from the act, from what we want, by sending antipathy into the sympathy of wanting. Only now does sympathy for what we want predominate, and a balance with this sympathy is created only by sending antipathy into it as well. As a result, however, sympathy as such remains below the threshold of consciousness; only something of this sympathy penetrates into the will. In the few actions that we perform not merely out of reason, but with real enthusiasm, devotion, and love, sympathy predominates so strongly in our will that it also rises above the threshold of our consciousness, and our will itself appears to us to be imbued with sympathy, whereas otherwise it connects us with the environment as an objective entity and reveals itself to us in this way. Just as our antipathy toward the environment may only exceptionally, not always, come to our consciousness in recognition, so our ever-present sympathy with the environment may only come to our consciousness in exceptional cases, in cases of enthusiasm, of devoted love. Otherwise, we would do everything instinctively. We would never be able to integrate ourselves into what the world objectively demands of us, for example in social life. We must think through our will in order for this will to integrate us into humanity as a whole and into the world process as such.

You may be able to understand what happens here if you consider the devastation it would actually cause in the human soul if, in ordinary life, this whole thing I have just spoken about were conscious. If this matter were constantly conscious in the human soul in everyday life, then human beings would be conscious of a great deal of antipathy that would accompany all their actions. That would be terrible! People would then go through life feeling constantly surrounded by an atmosphere of antipathy. It is wisely arranged in the world that this antipathy is necessary as a force for our actions, but that we are not aware of it, that it remains below the threshold of consciousness.

Now look, I would like to say, into a strange mystery of human nature, a mystery that every better person actually feels, but which educators and teachers should bring to their full consciousness. When we first become children, we act more or less out of sheer sympathy. As strange as it may sound, everything a child does and raves about is done out of sympathy for doing and raving. When sympathy is born in the world, it is strong love, strong will. But it cannot remain so; it must be permeated by the mental image, it must, so to speak, be continually illuminated by the mental image. This happens in a comprehensive way when we integrate ideals, moral ideals, into our mere instincts. And now you will be able to understand better what antipathy actually means in this area. If the instinctive impulses that we observe in small children remained sympathetic to us throughout our lives, as they are sympathetic to the child, we would develop in an animalistic way under the influence of our instincts. These instincts must become antipathetic to us; we must pour antipathy into them. Then, when we pour antipathy into them, we do so through our moral ideals, which are antipathetic to the instincts and which, at first, for our life between birth and death, place antipathy into the childlike sympathy of the instincts. Therefore, moral development is always something ascetic. This asceticism must only be understood in the right sense. It is always an exercise in combating the animalistic.

All this should teach us to what extent willing is not only willing in the practical activity of human beings, but also to what extent willing is thoroughly permeated by mental image, by cognitive activity.

Now, human emotional activity stands between cognition, thinking, and willing. If you form a mental image of what I have now developed as willing and thinking, you can say to yourself: from a certain middle boundary, on the one hand, everything that is sympathy flows out: willing; on the other hand, everything that is antipathy flows out: thinking. But the sympathy of the will also has an effect on thinking, and the antipathy of thinking also has an effect on the will. And so the human being becomes a whole, in that what develops mainly on one side also has an effect on the other side. In between, between thinking and willing, lies feeling, so that feeling is related to thinking in one direction and to willing in the other. Just as you cannot strictly distinguish between cognitive or thinking activity and volitional activity in the whole human soul, so you can even less distinguish between the thinking element and the volitional element in feeling. In feeling, elements of will and elements of thinking flow very strongly into one another.

Here, too, you can convince yourself of the truth of what has just been said through mere self-observation, even if you practice it only superficially. What I have said so far already leads you to the realization of this truth, for I told you: the will, which in ordinary life proceeds objectively, intensifies to the point of activity out of enthusiasm, out of love. Here you can clearly see a will that is otherwise produced by the necessities of external life, permeated by feeling. When you do something enthusiastic or loving, you do what flows from the will by allowing it to be permeated by a subjective feeling. But even in sensory activity, if you look more closely — precisely through Goethe's theory of colors — you can see how feeling mixes into sensory activity. And when sensory activity intensifies to the point of disgust or, on the other hand, to the point of inhaling the pleasant scent of flowers, you also have the activity of feeling overflowing into sensory activity without further ado.

But feeling also flows into thinking. Once upon a time, there was a very remarkable philosophical dispute, at least outwardly — there have been many philosophical disputes in the history of worldviews — between the psychologist Franz Brentano and the logician Sigwart in Heidelberg. The two gentlemen argued with each other about what lies in human judgment. Sigwart believed that when a person judges—let's say they make the judgment that a person should be good—a feeling always plays a part in such a judgment; the decision is made by the feeling. Brentano believed that judgment and emotion, which consist of mental processes, are so different that the function of judgment, the act of judgment, cannot be understood at all if one believes that emotion plays a role in it. He believed that this would introduce something subjective into judgment, whereas our judgment should be objective.

Such a dispute only shows the discerning observer that neither psychologists nor logicians have arrived at what they should have arrived at — the intertwining of mental activities. Consider what really needs to be observed here. On the one hand, we have the ability to judge, which naturally has to decide on something completely objective. The fact that a person must be good must not depend on our subjective feelings. So the content of the judgment must be objective. But when we judge, something else entirely comes into play. The things that are objectively correct are not yet consciously present in our soul. We must first consciously bring them into our soul. And we cannot consciously bring a judgment into our soul without the involvement of emotional activity. Therefore, we must say that Brentano and Sigwart should have agreed that they both said: Yes, the objective content of the judgment is established outside of emotional activity; but in order for the conviction of the correctness of the judgment to arise in the subjective human soul, emotional activity must develop.

You can see from this how difficult it is to arrive at precise concepts at all, given the imprecise nature of philosophical considerations as they are currently practiced. One must first rise to such precise concepts, and today there is no other education in precise concepts than that provided by spiritual science. External science believes it has precise concepts and is very snobbish about what anthroposophically oriented spiritual science has to offer, because it has no idea that the concepts provided by this side are much more precise and exact than those commonly used today, because they are drawn from reality, not from mere word games.

By tracing the emotional element on the one hand in the cognitive, in the mental image, and on the other hand in the volitional, you will say to yourself: Emotion stands as the middle soul activity between cognition and volition and radiates its essence in both directions. — Feeling is both knowledge that has not yet fully developed and will that has not yet fully developed, restrained knowledge and restrained will. Therefore, feeling is also composed of sympathy and antipathy, which, as you have seen, are only hidden in both cognition and will. Both sympathy and antipathy are present in cognition and volition, in that physical nerve activity and blood activity interact, but they are hidden. In feeling, they become apparent.

What, then, do the physical manifestations of feeling look like? You will find everywhere in the human body how the blood vessels and the nerve pathways touch each other in some way. And wherever blood vessels and nerve pathways touch, feeling actually arises. However, in the senses, for example, both the nerves and the blood are so refined that we no longer feel the sensation. All our seeing and hearing is permeated by a subtle sensation, but we do not feel it; we feel it all the less because the sense organ is separated and isolated from the rest of the body. When we see, when our eyes are active, we hardly feel any emotional sympathy or antipathy at all, because the eye, embedded in the curve of the bone, is almost completely separated from the rest of the organism. And the nerves that extend into the eye and the blood vessels that extend into the eye are very refined. Emotional perception is very suppressed in the eye. Emotional perception is less suppressed in the sense of hearing. Hearing is much more organically connected to the overall activity of the organism than seeing. Because there are numerous organs in the ear that are completely different from the organs of the eye, the ear is in many ways a faithful reflection of what is going on in the whole organism. Therefore, what goes on in the ear as sensory activity is very strongly accompanied by emotional activity. And here, even people who are well versed in what is heard find it difficult to really clarify what in what is heard, especially in what is heard artistically, is mere recognition and what is emotional. This is the basis for a very interesting phenomenon of recent times, which has also played a role in immediate artistic production.

You are all familiar with the character of Beckmesser in Richard Wagner's “Meistersinger.” What was Beckmesser actually supposed to represent? He was supposed to represent a musically perceptive person who completely forgets how the emotional element of the whole human being also influences the cognitive aspect of hearing. Wagner, who portrayed his own view in Walter, was in turn completely imbued with the one-sided idea that it is mainly the emotional that must live in music. What is contrasted in Walter and Beckmesser from a misunderstood view — I mean: a misunderstood view in both cases — in contrast to the correct view of how the emotional and the cognitive interact in musical listening, This was expressed in a historical phenomenon in that Wagner's art, when it first appeared, but especially when it became known, found an opponent in the person of Eduard Hanslick in Vienna, who regarded everything that arises in the sphere of emotion in Wagner's art as unmusical. There are perhaps few writings in the field of art that are as interesting psychologically as Eduard Hanslick's “On the Beautiful in Music.” In it, he mainly argues that a true musician is not someone who wants to draw everything from the emotional in music, but rather someone who sees the true essence of music in the objective connection between tone and tone, in the arabesque devoid of all emotion that is formed by the combination of tone and tone. With wonderful clarity, the book “On the Beautiful in Music” by Eduard Hanslick argues that the highest musical expression can only exist in the sound image, in the arabesque of sound, and it pours scorn on everything that constitutes the essence of Wagnerism, namely the creation of sound from emotional elements. The fact that such a dispute as that between Hanslick and Wagner could arise in the field of music testifies to the fact that, psychologically speaking, ideas about the activities of the soul in modern times were thoroughly unclear; otherwise, such a one-sided inclination as that which emerged in Hanslick could not have arisen. But if one sees through the superficial and then surrenders to Hanslick's philosophically powerful arguments, one will say: the little book “On the Beautiful in Music” is very witty.

You can see from this that in one sense more, and in the other less, of the whole human being, who initially lives as an emotional being, penetrates into the periphery in terms of knowledge.

This will and must also draw your attention, for the sake of pedagogical insight, to something that is wreaking great havoc in contemporary scientific thinking. If we had not spoken preparatory here and if we were not speaking preparatory about what is to lead you to a reformatory activity, you would have to piece together from the current pedagogies, from the existing psychologies and logics, and from the educational practices, what you want to practice in your school activity. You would have to bring what has become common practice outside into your school activities. However, what has become common practice today suffers from a major flaw from the outset, particularly with regard to psychology. In every psychology, you will first find what is known as sensory theory. By examining what sensory activity is based on, you arrive at the sensory activity of the eye, the ear, the nose, and so on. Everything is summarized in a broad abstraction called “sensory activity.” This is a major mistake, a considerable error. For if you take only those senses that are currently known to physiologists or psychologists, you will observe, if you look only at the physical, that the sense of sight is actually something quite different from the sense of hearing. The eye and the ear are two very different entities. And then there is the organization of the sense of touch, which has not yet been researched at all, not even in a satisfactory manner, as is the case with the eye and ear! But let us stick with the eye and ear. They are two completely different activities, so that summarizing seeing and hearing as a “general sensory activity” is a vague theory. If one wanted to proceed correctly here, one would have to speak only of the activity of the eye, the activity of the ear, the activity of the olfactory organ, and so on, with a concrete power of observation. Then one would find such great diversity that one would lose the desire to establish a general sensory physiology, as is the case in today's psychology.

One can only gain insight into the human soul by remaining within the field that I have attempted to define in my discussions in both “Truth and Science” and “The Philosophy of Freedom.” Then one can speak of the unified soul without falling into abstractions. For there one stands on solid ground; there one proceeds from the assumption that human beings live their way into the world and do not possess the whole of reality. You can read about this in “Truth and Science” and in “The Philosophy of Freedom.” Human beings do not have the whole of reality at the beginning. They first develop further, and in the course of this development, what was not yet reality before becomes true reality through the intertwining of thinking and intuition. Human beings first conquer reality. In this respect, Kantianism, which has eaten its way into everything, has caused the most terrible devastation. What does Kantianism do? It dogmatically states from the outset: we must first look at the world around us, and only the reflection of this world actually lives within us. This is how it arrives at all its other deductions. Kant is not clear about what is in the perceived environment of man. For reality is not in the environment, nor is it in appearance, but rather reality emerges gradually through our grasping of it, so that the last thing that approaches us is reality itself. Basically, the true reality would be what humans see at the moment when they can no longer speak, namely at the moment when they pass through the gate of death.

Many false elements have found their way into modern intellectual culture, and this has had the most drastic effect in the field of education. We must therefore strive to replace false concepts with correct ones. Then we will be able to carry out our teaching duties in the right way.