The Study of Man

GA 293

27 August 1919, Stuttgart

Lecture VI

Up to now we have tried to understand the human being from the point of view of the soul, in so far as this understanding is necessary in the education of the child. We must keep the three standpoints distinct—the standpoints of spirit, of soul and of body, and, in order to arrive at a complete anthropology, we shall study the human being from all three. The first to be taken is the psychic, or soul point of view because this is nearest to man in his ordinary life. And you will have felt that in taking sympathy and antipathy as principal concepts for the understanding of man we have been directing our attention to the soul. It will not answer our purpose if we pass straight over from the psychical to the physical, for we know, from what spiritual science has told us, that the physical can only be understood when it is looked upon as a revelation of the spiritual and also of the soul. Therefore to what we have already sketched in general lines as a study of the soul we will now add a contemplation of the human being from the point of view of spirit, and finally we shall come to a real “anthropology,” as it is now called, a consideration of the human being as he appears in the external physical world.

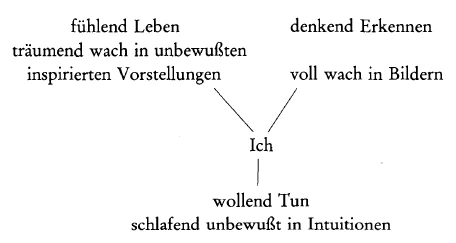

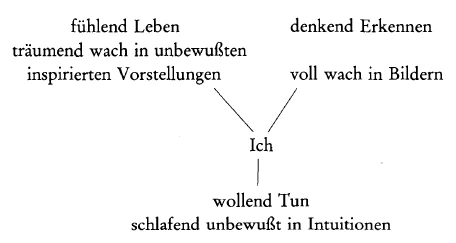

If you want to examine the human being effectively from any point of view you must return again and again to the separation of man's soul activities into cognition (which takes place in thought) and into feeling and willing. Up till now we have considered thinking (or cognition), feeling and willing in the light of antipathy and sympathy. Now we will study willing, feeling and cognition from the point of view of the spirit.

From the spiritual point of view, also, you will find a difference between willing, feeling and thinking-knowing. If I may speak pictorially (for the pictorial element will help us to form the right concepts): when you have knowledge through thought you must feel that in a certain way you are living in the light. You cognise, and you feel yourself with your ego right in the midst of this activity of cognition. It is as though every part, every bit of the activity which we call cognition, were there within all that your ego does; and again what your ego does is there within the activity of cognition. You are entirely in the light; you live in a fully conscious activity, if I may express myself in such a concept. And it would be bad indeed if you were not in a fully conscious activity in cognising. Suppose for a moment that you had the feeling that while you were forming a judgment something happened to your ego somewhere in the subconscious and that your judgment was the result of this process. For instance you say: “That man is a good man,” thus forming a judgment. You must be conscious that what you need in order to form this judgment—the subject “man” the predicate “is good”—are parts of a process which is clearly before you and which is permeated by the light of consciousness. If you had to assume that some demon or some mechanism of nature had tangled up the man with the “being good” while you were forming the judgment, then you would not be fully, consciously present in this act of thought, of cognition: in some part of the judgment you would be unconscious. That is the essential thing about thinking cognition, that you are present in complete consciousness in the whole warp and woof of its activity.

That is not the case in willing. You know that when you perform the simplest kind of willing, for instance walking, you are only really fully conscious in your mental picture of the walking. You know nothing of what takes place in your muscles whilst one leg moves forward after the other; nothing of what takes place in the mechanism and organism of your body. Just think of what you would have to learn of the world if you had to perform consciously all the arrangements involved when you will to walk. You would have to know exactly how much of the activity produced by your food in the muscles of your legs and other parts of your body is used up in the effort of walking. You have never reckoned out how much you use up of what your food brings to you. You know quite well that all this happens unconsciously in your bodily nature. When we “will” there is always something deeply, unconsciously present in the activity. This is not only so when we look at the nature of willing in our own organism. What we accomplish when we extend our will to the outer world, that, too, we do not by any means completely grasp with the light of consciousness.

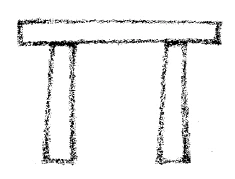

Suppose you have here two posts set up like pillars. (See drawing.)

Imagine you lay a third post across the top of them. Now notice carefully, please, how much fully conscious knowing activity there is in what you have done; how much fully conscious activity such as there is when you pass the judgment “a man is good,” where you are right in the midst of it with your knowledge. Distinguish, please, what is present as the activity of cognition here from that of which you know nothing although you had to do it with all your will: why these two pillars through certain forces support the beam that is lying on them? Up to now physics has only hypotheses concerning this, and if men believe that they “know” why the two pillars support the beam they are under an illusion. All the concepts that exist of cohesion, adhesion, forces of attraction and repulsion are, at bottom, only hypotheses on the part of external knowledge. We count upon these external hypotheses in our actions; we are convinced that the two posts supporting the beam will not give way if they are of a certain thickness. But we cannot understand the whole process which is connected with this, any more than we can understand the movements of our legs when we move forwards. Here, too, there is in our willing an element that does not reach into our consciousness. Willing in all its different forms has an unconscious element in it.

And feeling stands midway between willing and thinking-cognition. Feeling is also partly permeated by consciousness, and partly by an unconscious element. In this way feeling on the one hand shares the character of cognition-thinking, and on the other hand the character of feeling or felt will. What is this then really from a spiritual point of view?

You will only arrive at a true answer to this question if you can grasp the facts characterised above in the following way. In our ordinary life we speak of being awake, of the waking condition of consciousness. But we only have this waking condition of consciousness in the activity of our knowing-thinking. If therefore you want to say absolutely correctly how far a human being is awake you will be obliged to say: A human being is really only awake as long and in so far as he thinks of or knows something.

What then is the position with regard to the will? You all know the sleep condition of consciousness—you can also call it, if you like, the condition of unconsciousness—you know that what we experience while we sleep, from falling asleep until we wake, is not in our consciousness. Now it is just the same with all that passes through our will as an unconscious element. In so far as we as human beings are beings of will, we are “asleep” even when we are awake. We are always carrying about with us a sleeping human being—that is, the willing man—and he is accompanied by the waking man, by the man of cognition and thought: in so far as we are beings of will we are asleep even from the time we wake up until we fall asleep. There is always something asleep in us, namely: the inner being of will. We are no more conscious of that than we are of the processes which go on during sleep. We do not understand the human being completely unless we know that sleep plays into his waking life, in so far as he is a being of will.

Feeling stands between thinking and willing, and we may now ask: How is it with regard to consciousness in feeling? That too is midway between waking and sleeping. You know the feelings in your soul just as you know your dreams, only that you remember your dreams and have a direct experience of your feelings. But the inner mood and condition of soul which you have with regard to your feelings is just the same as you have with regard to your dreams. Whilst you are awake you are not only a waking man in that you think and know, and a sleeping man in that you will: you are also a “dreamer” in that you feel. Thus we are really immersed in three conditions of consciousness during our waking life: the waking condition in its real sense in thinking and knowing, the dreaming condition in feeling, and the sleeping condition in willing. Seen from the spiritual point of view ordinary dreamless sleep is a condition in which a man gives himself up in his whole soul being to that to which he is given up in his willing nature during his daily life. The only difference is that in real sleep we “sleep” with the whole soul being, and when we are awake we only sleep with our will. In dreaming as it is called in ordinary life we are given up with our whole being to the condition of soul which we call the “dream” and in waking life we only give ourselves up in our feeling nature to this dreaming soul condition.

If you look at the matter in this way, from the educational point of view, you will not wonder that the children differ with regard to awakeness of consciousness. For you will find that children in whom the feeling life predominates are dreamy children; if thought is not fully aroused in such children they will certainly incline to dreaminess. This must be an incentive to you to work upon such children through strong feeling. And you can reasonably hope that these strong feelings will awaken clear thought in them, for, following the rhythm of life, everything that is asleep has the tendency sometime to awaken. If we have such a child, who broods dreamily in his feeling life, and we approach him with strong feelings, after some time these feelings awaken of themselves as thoughts.

Children who brood still more and are even dull in their feeling life, will reveal specially strong tendencies in their will life. By studying these things you bring knowledge to bear on many a problem in child life. You may get a child in school who behaves like a true dullard. If you were immediately to decide “That is a weak-minded, a stupid child,” if you tested him with experimental psychology, with wonderful memory tests and all the other things which are done now in psychological pedagogical laboratories, and if you then said, “stupid child in his whole disposition; belongs to the school for the feeble-minded, or to the now popular schools for backward children,” you would be very far from understanding the real nature of the child. It may be that the child has special powers in the region of the will; he may be one of those children who, out of his choleric nature will develop active energy in his later life. But at present the will is asleep. And if the thinking cognition in the child is destined not to appear until later, then he must be treated appropriately so that in his later life he may be able to work with active energy. At first he seems to be a veritable dullard, but it may be that he is not that at all. And you must know how to awaken the will in a child of this kind. That means that you must work into his waking sleep-condition, his will, in such a way that later on—because all sleeping has a tendency to change into waking—this sleep is gradually wakened up into conscious will, a will that is perhaps very strong, only it is at present overpowered by the sleeping element. You must treat a child of this kind by building as little as possible on his powers of knowing, on his understanding, but by “hammering” in some things which will work strongly on the will, by letting him walk while he speaks. You will not have many such children, but in a case of this kind you can call the child out from the class—which will be stimulating to the other children, and educative for the child himself—and get him to say sentences and accompany his words by movements. Thus: “The (step) man (step) is (step) good (step).” In this way you combine the whole human being in the will element with the merely intellectual element in cognition, and you can gradually bring it about that the will is awakened into thought in such a child. It is not until we realise that in the waking human being we have to do with different conditions of consciousness, with waking, dreaming, and sleeping, that we are brought to a true knowledge of our task with regard to the growing child.

But now we can put this question: How is the true centre of the human being, the ego, related to these different conditions? The easiest way to arrive at a true answer to this is to postulate—what is indeed undeniable—that what we call the world, the cosmos, is a sum of activities. These activities express themselves for us in the different spheres of elemental life. We know that forces are at work in this elemental life. Life-force, for instance, is at work all around us. And between the elemental forces and life-force there is inwoven all that warmth and fire produces. Just think what an important part fire plays in our environment.

In certain parts of the world, for instance in South Italy, you only need to light a ball of paper and immediately great clouds of smoke will begin to rise out of the earth. Why does this happen? It happens because when you light the ball of paper and thus produce warmth you rarefy the air in this place, and what is usually at work in the forces under the surface of the earth becomes perceptible through the ascending smoke: the very moment you light the paper ball and throw it on the earth, you are standing in a cloud of smoke. That is an experiment that can be made by every traveler who goes into the neighbourhood of Naples. This is an example to show you that if we do not look at the world superficially we must recognise that our whole environment is permeated by forces.

Now there are also higher forces than warmth. They too are round about us. We walk among them continually in going about the world as physical men. Indeed our physical bodies are so constituted that we can endure this, though we are unaware of it in our ordinary knowledge. With our physical body we can pass through the world in this way.

With our ego, the youngest member of the human being, we could not pass through these world forces if this ego were to give itself up directly to them. This ego cannot give itself up to all that is round it and in the midst of which it is placed. This ego must still be guarded from having to pour itself out into the world forces. In course of time it will evolve so that it will be able to enter into these world forces. But it cannot do so yet. It is necessary, therefore, that in our fully awakened ego we be not forced to enter into the real world that is around us, but only into the image of that world. Hence in our thinking-cognition we have only images of the world—as already described when speaking from the point of view of the soul. Now we view it also from the point of view of spirit.

In thinking-cognition we live in images; and, in our present stage of evolution, while we live between birth and death in our fully wakened ego—it is only in images of the cosmos that we human beings can live, not yet in the real cosmos. Therefore when we are awake our body has to produce images of the cosmos for us. And then our ego dwells in these images.

Psychologists take endless trouble to define the relation between body and soul: they speak of the interplay between body and soul, of psycho-physical parallelism and many other things. All these are in reality childish concepts. For the process really at work is this: when the ego in the morning passes over into the waking condition, it enters into the body, but not into the physical processes of the body, only into the world of images, which the body creates from out of the external processes in the very depths of its being. In this way thinking-cognition is communicated to the ego.

In feeling it is different. There the ego does enter into the real body, not only into the images. But if, as it enters into the body, it were fully conscious, then (remember this is spoken now of the soul) it would literally “burn up” in the soul. If the same thing happened to you in feeling that happens to you in thinking when you penetrate with your ego into the images which your body has produced in you, you would burn up in your soul. You could not bear it. This penetration which is proper to feeling can only be experienced by you in a dreaming, dulled condition of consciousness. It is only in a dream that you can bear what really happens in your body in the process of feeling.

And what happens in willing you can only experience in a sleeping condition. You would experience something most terrible if in your ordinary life you were obliged to participate in all that happens when you will. The most terrible pain would lay hold of you if, for instance, as I have already indicated, you really had to experience how the forces brought to your organism by your food are used up in your legs when you walk. It is lucky for you that you do not experience this, or rather that you only experience it in a condition of sleep. For if you were awake it would mean the greatest pain imaginable, a fearful pain.

Hence you will understand it if I now characterise the life of the ego during what is usually called waking consciousness—which comprises: complete waking, dreaming-waking, sleeping-waking—you will understand it if I characterise what the ego actually experiences while it is living in the body in the ordinary waking condition. This ego lives in “thinking-cognition” in that it wakes up into the body; here it is fully awake. But it lives in it only in images. Hence man between birth and death lives in images only, when using his thinking-cognition unless he does such exercises as are indicated in my book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and How to Attain It.

Next the ego, in awaking, also sinks into those processes which condition feeling. In feeling life we are not fully awake, but dreaming-awake. How do we actually experience what we go through in feeling in this dream-waking condition? We actually experience it as what has been called “Inspiration,” inspired—unconsciously inspired—mental pictures. In the artist this is the centre whence rises all that comes out of the feelings into waking consciousness. There it is first worked through. There too are worked through all those “inklings,” which turn to image in waking consciousness. The “Inspirations” spoken of in my book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and How to Attain It are the same as these; only that the experience of the unconscious inspirations deep within the feeling life of every man is lifted, in these, into clarity and full consciousness.

And when especially gifted people speak of their inspirations they really speak of that which the world has laid into their feeling life and has avowed to come into their fully awake consciousness by means of their capacities. It is a matter of world content, no less than thought content is world content. But in the life between birth and death these unconscious inspirations reflect world processes which we can only experience in dreaming, for if we experienced them otherwise our ego would burn up in these processes, or rather it would suffocate. You sometimes find suffocation setting-in in abnormal conditions. Suppose you have a nightmare. This means that the interplay between man and the outer air has come into consciousness in an abnormal way because something in this interplay is out of order. In trying to enter the ego consciousness it does not become conscious as a normal mental picture, but as a tormenting picture, as a nightmare. And just as this abnormal breathing in a nightmare is tormenting, so the breathing process as a whole would be torment if man experienced his breathing with full consciousness. He would experience it in feeling, but it would be torment to him. For this reason it is dulled, and so it is not experienced as a physical process, but only in the dreamlike feeling.

And as to the processes which take place in willing as I have already indicated to you they would mean fearful pain. So that we can add a third statement: the ego in action of the will is asleep. What a man really experiences in such action, with a greatly dimmed consciousness (a sleeping consciousness in fact), is unconscious intuitions. A human being has unconscious intuitions continually; but they live in his will. He is asleep in his will. Therefore in ordinary life he cannot call up these intuitions; it is only at auspicious moments in life that they well up. Then in a dim way the human being participates in the spiritual world.

Now there is something remarkable in the ordinary life of man. We all know the full consciousness in complete awakeness that we have in our thinking-cognition. Here we are, so to speak, in the clear light of consciousness; here we find certitude. But you know that people when thinking about the world, sometimes say: “We have intuitions.” Vague feelings emanate from these intuitions. What people then relate is often very confused, but it can also be, unconsciously, quite well-ordered. Finally when a poet speaks of his intuitions, that is entirely right for he does not produce them immediately from the region nearest to him—from the inspired representations of his feeling life—but he brings them forth, these completely unconscious intuitions, from the region of his sleeping will.

Anyone who looks deeply into these things sees that what appear as the chances of life, are governed by deep laws. For instance, when you read the second part of Goethe's “Faust” you want to study deeply how the structure of this remarkable verse could be achieved. Goethe was already old when he wrote the second part of his “Faust”—at least the greater part of it. This was how it was written: His secretary John sat at the writing table and wrote what Goethe dictated. If Goethe had had to write it down himself he would probably not have been able to produce such marvelously chiseled verses in the second part of his “Faust.” While he was dictating in his little room in Weimar, Goethe continuously walked up and down, and this walking up and down is part and parcel of the conception of the second part of “Faust.” While Goethe was producing this unconscious willed activity in walking, something of his intuitions pressed upwards and this outer motion brought to light what the other man wrote down for him on paper.

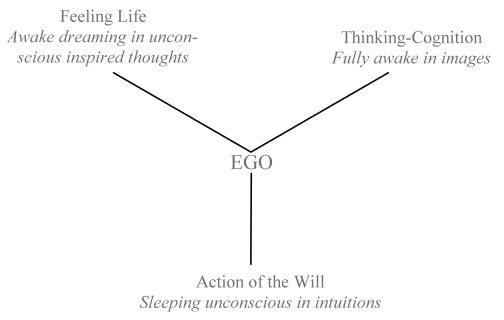

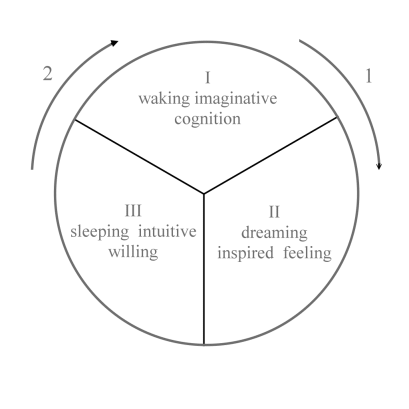

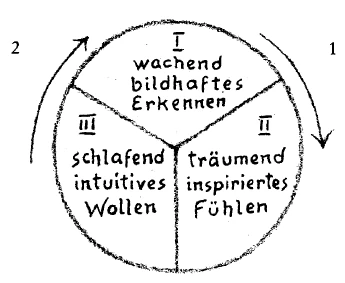

If you want to make a diagram of the life of the ego in the body it is possible to make it in the following way:

| i. | Waking | ... | ... | Knowing in images |

| ii. | Dreaming | ... | ... | Inspired feeling |

| iii. | Sleeping | ... | ... | Intuitive or “intuited” willing |

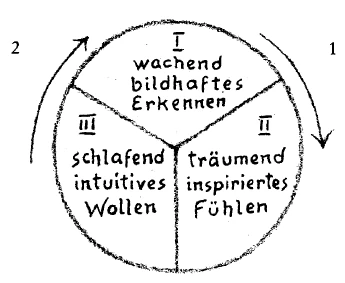

but if you do this you will not be able to make it clear why intuition, of which men speak instinctively, comes up more readily to the image knowing of every day than the inspired feeling which lies nearer to us. If you now want to draw the diagram correctly (for the above is not correct) you must draw it in the following way, and then you will be able to understand the facts more easily. For then you will say: knowing in images descends in the direction of arrow 1 into inspirations, and it comes up again out of intuitions (arrow 2). But this knowing, which is indicated by arrow 1 is the descent into the body.

And now observe yourself; you are at first quite quiet, sitting or standing, giving yourself up to thinking-cognition, to the observation of the external world. There you live in images. What further the ego experiences in the outward processes descends into the body—first into the feeling, then into the will. You do not notice what is in your feeling; neither at first do you notice what is in your will. Only, when you begin to walk, when you begin to act, what you first observe outwardly is not the feeling but the will. And then in the descent into the body and the re-ascent, which happens in the direction of arrow 2, it is nearer for intuitive willing to come to the image consciousness than for the dreaming inspired feeling. Hence you will find that people so often say: “I have a vague intuition.” In such a case what are called intuitions in my book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and How to Attain It are being confused with the superficial intuition of ordinary consciousness.

Now you will be able to understand something of the formation of the human body. Imagine to yourself for a moment that you are walking but observing the world. Imagine to yourself that it was not your lower body that was walking with your legs, but that your head had your legs directly attached to it and that it had to walk itself. Then your observing of the world and your willing would be woven into a unity, and the result would be that you could only walk in a sleeping condition. Because your head is placed upon your shoulders and upon the remaining part of your body, it is at rest there. It is at rest, and since you only move with these other parts of your body, you carry your head. Now the head must be able to rest on the body, otherwise it could not be the organ of thinking-cognition. It must be withdrawn from the sleeping-willing; for the moment you brought it into movement, brought it out of relative rest into independent movement, it would fall asleep. It allows the body to carry out the real willing, and it lives in this body as in a carriage and allows itself to be conveyed by this carriage. And it is only because the head allows itself, as in a carriage, to be conveyed by the body, and because it acts while it is being conveyed during the resting condition, that the human being is awake in action. It is only when you see things in such connections as these that you can come to a true understanding of the form of the human body.

Sechster Vortrag

Wir haben bisher versucht, den Menschen zu begreifen, insofern uns dieses Begreifen für die Erziehung des Kindes notwendig ist, vom seelischen Standpunkte aus. Wir werden ja die drei Standpunkte auseinanderhalten müssen — den geistigen, den seelischen und den physischen Standpunkt — und werden, um eine vollständige Anthropologie zu bekommen, von jedem dieser Standpunkte aus den Menschen betrachten. Es liegt am nächsten, die seelische Betrachtung zu vollziehen, weil dem Menschen im gewöhnlichen Leben eben das Seelische am nächsten liegt. Und Sie werden auch empfunden haben, daß wir, indem wir zu diesem Begreifen des Menschen als Hauptbegriffe verwendet haben Antipathie und Sympathie, damit auf das Seelische hingezielt haben. Es wird sich für uns nicht entsprechend erweisen, wenn wir vom Seelischen gleich auf das Leibliche übergehen, denn wir wissen aus unseren geisteswissenschaftlichen Betrachtungen heraus, daß das Leibliche nur gefaßt werden kann, wenn es als eine Offenbarung des Geistigen und auch des Seelischen aufgefaßt wird. Daher werden wir zu der seelischen Betrachtung, die wir in allgemeinen Linien skizziert haben, jetzt hinzufügen eine Betrachtung des Menschen vom geistigen Gesichtspunkte aus, und wir werden dann erst auf die eigentliche, jetzt so genannte Anthropologie, auf die Betrachtung des Menschenwesens, wie es sich in der äußeren physischen Welt zeigt, näher eingehen.

Wenn Sie von irgendeinem Gesichtspunkt aus den Menschen zweckmäßig betrachten wollen, so müssen Sie immer wieder und wieder zurückgehen auf die Gliederung der menschlichen Seelentätigkeiten in Erkennen, das im Denken verläuft, in Fühlen und in Wollen. Wir haben bis jetzt Denken oder Erkennen, Fühlen und Wollen in die Atmosphäre von Antipathie und Sympathie gerückt. Wir wollen jetzt einmal eben vom geistigen Gesichtspunkte aus Wollen, Fühlen und Erkennen ins Auge fassen.

Sie werden auch vom geistigen Gesichtspunkte aus einen Unterschied finden zwischen Wollen, Fühlen und denkendem Erkennen. Betrachten Sie nur das Folgende. Indem Sie denkend erkennen, müssen Sie empfinden — wenn ich mich zunächst bildlich ausdrücken darf, aber das Bildliche wird uns zu Begriffen verhelfen -, daß Sie gewissermaßen im Lichte leben. Sie erkennen und fühlen sich ganz drinnen mit Ihrem Ich in dieser Tätigkeit des Erkennens. Gewissermaßen jeder Teil, jedes Glied derjenigen Tätigkeit, die Sie Erkennen nennen, ist drinnen in alledem, was Ihr Ich tut; und wieder: was Ihr Ich tut, ist drinnen in der Tätigkeit des Erkennens. Sie sind ganz im Hellen, Sie leben in einer vollbewußten Tätigkeit, wenn ich mich begrifflich ausdrücken darf. Es wäre auch schlimm, wenn Sie beim Erkennen nicht in einer vollbewußten Tätigkeit wären. Denken Sie einmal, wenn Sie das Gefühl haben müßten: während Sie ein Urteil fällen, geht mit Ihrem Ich irgendwo im Unterbewußten etwas vor, und das Ergebnis dieses Vorganges sei das Urteil! Nehmen Sie an, Sie sagen: Dieser Mensch ist ein guter Mensch -, fällen also ein Urteil. Sie müssen sich bewußt sein, daß das, was Sie brauchen, um dieses Urteil zu fällen — das Subjekt «der Mensch», das Prädikat «er ist ein guter» -, Glieder sind eines Vorganges, der Ihnen ganz gegenwärtig ist, der für Sie ganz vom Lichte des Bewußtseins durchzogen ist. Müßten Sie annehmen, irgendein Dämon oder ein Mechanismus der Natur knäuele zusammen den «Menschen» mit dem «Gutsein», während Sie das Urteil fällen, dann wären Sie nicht vollbewußt in diesem erkennenden Denkakt drinnen, und Sie wären immer mit etwas vom Urteil im Unbewußten. Das ist das Wesentliche beim denkenden Erkennen, daß Sie in dem ganzen Weben der Tätigkeit beim denkenden Erkennen mit Ihrem vollen Bewußtsein drinnenstecken.

Nicht so ist es beim Wollen. Sie wissen ganz gut, wenn Sie das einfachste Wollen, das Gehen, entwickeln, so leben Sie eigentlich vollbewußt nur in der Vorstellung von diesem Gehen. Was innerhalb Ihrer Muskeln sich vollzieht, während Sie ein Bein nach dem anderen vorwärts bewegen, was da im Mechanismus und Organismus Ihres Leibes vorgeht, von dem wissen Sie nichts. Denken Sie nur, was Sie alles zu lernen haben würden von der Welt, wenn Sie alle die Vorrichtungen bewußt vollziehen müßten, welche beim Wollen des Gehens notwendig sind! Sie müßten dann genau wissen, wieviel von den Tätigkeiten, welche die Nahrungsstoffe in den Muskeln Ihrer Beine und in den anderen Körpermuskeln hervorrufen, verbraucht wird, während Sie sich anstrengen, zu gehen. Sie haben das nie ausgerechnet, wieviel Sie von dem verbrauchen, was Ihnen die Nahrung zuführt. Sie wissen ganz gut: Das alles geschieht in Ihrer Körperlichkeit sehr, sehr unbewußt. Indem wir wollen, mischt sich fortwährend in unsere Tätigkeit ein tiefes Unbewußtes hinein. Das ist nicht etwa bloß so, wenn wir das Wesen des Wollens an unserem eigenen Organismus betrachten. Auch was wir vollbringen, wenn wir unser Wollen auf die äußere Welt erstrecken, auch das umfassen wir keineswegs vollständig mit dem Lichte des Bewußtseins.

Nehmen Sie an, Sie haben zwei säulenartige Pflöcke. Sie nehmen sich vor, Sie legen einen dritten Pflock quer darüber. Unterscheiden Sie jetzt genau, was in alledem, was Sie da getan haben, als vollbewußte erkennende Tätigkeit lebt, von dem, was in Ihrer vollbewußten Tätigkeit lebt, wenn Sie das Urteil fällen: Ein Mensch ist gut -, wo Sie mit Ihrem Erkennen ganz drinnenstecken. Unterscheiden Sie bitte, was darin als erkennende Tätigkeit lebt, von dem, wovon Sie nichts wissen, trotzdem Sie es mit Ihrem vollen Willen zu tun hatten: Warum stützen diese zwei Säulen durch gewisse Kräfte diesen darüberliegenden Balken? Dafür hat ja die Physik bis heute nur Hypothesen. Und wenn die Menschen glauben, daß sie wissen, warum die beiden Pflöcke den Balken tragen, so bilden sie es sich nur ein. Alles, was man hat als Begriffe der Kohäsion, der Adhäsion, der Anziehungs- und Abstoßungskraft, sind im Grunde genommen für das äußere Wissen nur Hypothesen. Wir rechnen mit diesen äußeren Hypothesen, indem wir handeln; wir rechnen damit, daß die beiden Pflöcke, die den Balken tragen sollen, nicht zusammenknicken werden, wenn sie eine gewisse Dicke haben. Aber durchschauen können wir den ganzen Vorgang, der damit zusammenhängt, nicht, geradesowenig wie wir unsere Beinbewegungen durchschauen können, wenn wir vorwärts streben. So mischt sich auch hier in unser Wollen ein nicht in unser Bewußtsein hineinreichendes Element hinein. Das Wollen hat im weitesten Umfange ein Unbewußtes in sich,

Und das Fühlen steht zwischen Wollen und denkendem Erkennen mitten drinnen. Beim Fühlen ist es auch so, daß es zum Teil von Bewußtsein durchzogen wird, zum Teil von einem Unbewußten. Das Fühlen nimmt auch in dieser Weise teil an der Eigenschaft eines erkennenden Denkens, auf der anderen Seite an der Eigenschaft eines fühlenden oder gefühlten Wollens. Was liegt denn nun da eigentlich vom geistigen Gesichtspunkte aus vor?

Sie kommen nur zurecht, wenn Sie sich vom geistigen Gesichtspunkte aus die oben charakterisierten Tatsachen in der folgenden Art zum Begreifen bringen. Wir reden in unserem gewöhnlichen Leben vom Wachen, von dem wachen Bewußtseinszustande. Aber wir haben diesen wachen Bewußtseinszustand nur in der Tätigkeit des erkennenden Denkens. Wenn Sie also ganz genau davon reden wollen, inwiefern der Mensch wacht, so müssen Sie sagen: Wirklich wachend ist der Mensch nur, solange und insofern er ein denkender Erkenner von irgend etwas ist.

Wie steht es nun mit dem Wollen? Sie kennen alle den Bewußtseinszustand — nennen Sie es meinetwillen auch Bewußtseinslosigkeitszustand — des Schlafes. Sie wissen, während wir schlafen, vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen, ist das, was wir erleben, nicht in unserem Bewußtsein drinnen. Geradeso ist es aber auch mit alledem, was als Unbewußtes unser Wollen durchzieht. Insofern wir wollende Wesen sind als Menschen, schlafen wir, auch wenn wir wachen. Wir tragen immer mit uns einen schlafenden Menschen, nämlich den wollenden Menschen, und begleiten ihn mit dem wachenden, mit dem denkend erkennenden Menschen; wir sind, insofern wir wollende Wesen sind, auch vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen schlafend. Es schläft immer etwas in uns mit, nämlich die innere Wesenheit des Wollens. Der sind wir uns nicht stärker bewußt, als wir uns derjenigen Vorgänge bewußt sind, die sich mit uns abspielen während des Schlafes. Man erkennt den Menschen nicht vollständig, wenn man nicht weiß, daß das Schlafen in sein Wachen hereinspielt, indem der Mensch ein Wollender ist.

Das Fühlen steht in der Mitte, und wir dürfen uns jetzt fragen: Wie ist das Bewußtsein im Fühlen? — Das steht nun auch in der Mitte zwischen Wachen und Schlafen. Gefühle, die in Ihrer Seele leben, kennen Sie gerade so, wie Sie Träume kennen, nur daß Sie die Träume erinnern und die Gefühle unmittelbar erleben. Aber die innere Seelenverfassung und Seelenstimmung, die Sie haben, indem Sie von Ihren Gefühlen wissen, ist keine andere als die, welche Sie gegenüber Ihren Träumen haben. Sie sind im Wachen nicht nur ein wachender Mensch, indem Sie denkend erkennen, und ein schlafender, insofern Sie wollen, Sie sind auch ein träumender, insofern Sie fühlen. So sind also tatsächlich drei Bewußtseinszustände während unseres Wachens über uns ergossen: das Wachen im eigentlichen Sinne im denkenden Erkennen, das Träumen im Fühlen, das Schlafen im Wollen. Der gewöhnliche traumlose Schlaf ist vom geistigen Gesichtspunkte aus angesehen nichts anderes als die Hingabe des Menschen mit seiner ganzen Seelenwesenheit an das, woran er hingegeben ist mit seinem Wollen, während er seinen Tageslauf vollbringt. Es ist nur der Unterschied, daß wir im eigentlichen Schlafen mit unserem ganzen Seelenwesen schlafen, daß wir im Wachen nur schlafen mit unserem Wollen. Beim Träumen, was man im gewöhnlichen Leben so nennt, ist es so, daß wir mit unserem ganzen Menschen an den Seelenzustand hingegeben sind, den wir Traum nennen, und daß wir im Wachen nur als fühlender Mensch an diesen träumerischen Seelenzustand hingegeben sind.

Pädagogisch betrachtet werden Sie sich jetzt nicht mehr verwundern, wenn Sie die Sache so ansehen, daß die Kinder verschieden sind mit Bezug auf die Wachheit ihres Bewußtseins. Denn Sie werden finden, daß Kinder, bei denen das Gefühlsleben der Anlage gemäß überwiegt, träumerische Kinder sind, so daß solche Kinder, bei denen in der Kindheit eben das volle Denken noch nicht aufgewacht ist, leicht hingegeben sein werden an ein träumerisches Wesen. Das werden Sie dann zum Anlaß nehmen, um durch starke Gefühle auf ein solches Kind zu wirken. Und Sie werden dann die Hoffnung haben können, daß diese starken Gefühle bei ihm auch das helle Erkennen erwecken werden, denn alles Schlafen hat dem Lebensrhythmus gemäß die Tendenz, nach einiger Zeit aufzuwachen. Wenn wir nun ein solches Kind, das träumerisch im Gefühlsleben dahinbrütet, mit starken Gefühlen angehen, dann werden diese in das Kind versetzten starken Gefühle nach einiger Zeit von selbst als Gedanken aufwachen.

Kinder, die noch mehr brüten, die sogar stumpf sind gegenüber dem Gefühlsleben, die werden Ihnen offenbaren, daß sie besonders im Willen stark veranlagt sind. Sie sehen da: wenn Sie dies bedenken, können Sie erkennend vor manchem Rätsel im kindlichen Leben stehen. Sie können ein Kind in die Schule hereinbekommen, das sich ausnimmt wie ein echter Stumpfling. Wenn Sie da gleich das Urteil fällen: Das ist ein schwachsinniges, ein stumpfsinniges Kind -, wenn Sie es mit experimenteller Psychologie untersuchen würden, schöne Gedächtnisprüfungen vornähmen und allerlei, was ja jetzt auch schon in psychologisch-pädagogischen Laboratorien gemacht wird, und dann sagen würden: Stumpfes Kind seiner ganzen Anlage nach, gehört in die Schwachsinnigen-Schule oder auch in die jetzt beliebte Wenigerbefähigten-Schule, so würden Sie mit solchem Urteil nicht dem Wesen des Kindes nahekommen. Vielleicht aber ist dieses Kind besonders stark im Willen veranlagt, vielleicht ist es eines jener Kinder, die im späteren Leben aus ihrer Cholerik zu tatkräftigem Handeln übergehen. Aber der Wille schläft zunächst. Und wenn das denkende Erkennen bei diesem Kinde verurteilt ist, später erst hervorzutreten, dann muß es auch in der entsprechenden Weise behandelt werden, damit es dann später berufen sein kann, etwas Tatkräftiges zu vollbringen. Vorerst erscheint es als ein rechter Stumpfling, der ist es aber vielleicht gar nicht. Und man muß dann den Blick dafür haben, bei einem solchen Kinde den Willen zu erwecken; das heißt, man muß so in seinen wachen Schlafzustand hineinwirken, daß es nach und nach dahinkommt — weil ja jeder Schlaf die Tendenz hat, zum Erwachen zu kommen -, seinen Schlaf als Willen, der vielleicht sehr stark ist, der aber nur jetzt schläft, vom schlafenden Wesen übertönt wird, im späteren Lebensalter aufzuwecken. Ein solches Kind muß so behandelt werden, daß Sie möglichst wenig auf sein Erkenntnisvermögen, auf sein Begreifen bauen, sondern ihm gewissermaßen einhämmern einige recht stark auf den Willen wirkende Sachen, daß Sie es, indem es spricht, zu gleicher Zeit gehen lassen. Sie nehmen ein solches Kind, Sie werden ja nicht sehr viele davon haben, aus der Klasse heraus und - für die anderen Kinder wird es anregend sein, für dieses Kind ist es bildend - lassen es, indem es Sätze spricht, die Worte mit Bewegungen begleiten. Also: Der (Schritt) - Mensch (Schritt) - ist (Schritt) — gut! — Auf diese Weise verbinden Sie den ganzen Menschen im Willenselement mit dem bloß Intellektuellen im Erkennen, und Sie können es nach und nach dahin bringen, daß bei einem solchen Kinde der Wille zum Gedanken erwacht. Erst die Einsicht, daß man es im wachenden Menschen schon zu tun hat mit verschiedenen Bewußtseinszuständen — mit Wachen, Träumen und Schlafen -, erst diese Einsicht bringt uns zu einer wirklichen Erkenntnis unserer Aufgaben gegenüber dem werdenden Menschen.

Wir können aber jetzt etwas fragen. Wir können fragen: Wie verhält sich das eigentliche Zentrum des Menschen, das Ich, zu diesen verschiedenen Zuständen? Sie kommen am leichtesten dabei zurecht, wenn Sie zunächst, was ja unleugbar ist, voraussetzen: Was wir Welt, was wir Kosmos nennen, das ist eine Summe von Tätigkeiten. Für uns drücken sich diese Tätigkeiten aus auf den verschiedenen Gebieten des elementaren Lebens. Wir wissen, daß in diesem elementaren Leben Kräfte walten. Die Lebenskraft waltet zum Beispiel um uns herum. Und zwischen den elementaren Kräften und der Lebenskraft eingesponnen ist alles, was zum Beispiel die Wärme und das Feuer bewirkt. Denken Sie nur, wie sehr wir in einer Umgebung stehen, in der durch das Feuer sehr vieles bewirkt wird.

In gewissen Gegenden der Erde, zum Beispiel in Süditalien, brauchen Sie nur eine Papierkugel anzuzünden, und in demselben Augenblick fängt es an, aus der Erde heraus mächtig zu rauchen. Warum geschieht das? Es geschieht, weil Sie durch das Anzünden der Papierkugel und die sich dadurch entwickelnde Wärme die Luft an dieser Stelle verdünnen, und das, was sonst unter der Erdoberfläche an Kräften waltet, wird durch den nach aufwärts gerichteten Rauch nach oben gezogen, und in dem Augenblick, wo Sie die Papierkugel anzünden und auf die Erde werfen, stehen Sie in einer Rauchwolke. Das ist ein Experiment, das jeder Reisende machen kann, der in die Gegend von Neapel kommt. Das habe ich als ein Beispiel dafür angeführt, daß wir, wenn wir die Welt nicht oberflächlich betrachten, uns sagen müssen: Wir leben in einer Umgebung, die überall von Kräften durchzogen ist.

Nun gibt es auch höhere Kräfte als die Wärme. Die sind auch in unserer Umgebung. Durch sie gehen wir immer durch, indem wir als physische Menschen durch die Welt gehen. Ja, unser physischer Körper, ohne daß wir es im gewöhnlichen Erkennen wissen, ist so geartet, daß wir das vertragen. Mit unserem physischen Körper können wir so durch die Welt schreiten.

Mit unserem Ich, das die jüngste Bildung unserer Evolution ist, könnten wir nicht durch diese Weltenkräfte schreiten, wenn dieses Ich sich unmittelbar an diese Kräfte hingeben sollte. Dieses Ich könnte nicht an alles sich hingeben, was in seiner Umgebung ist und worin es selbst drinnen ist. Dieses Ich muß jetzt noch davor bewahrt werden, sich ergießen zu müssen in die Weltenkräfte. Es wird sich einmal dazu entwickeln, in die Weltenkräfte hinein aufgehen zu können. Jetzt kann es das noch nicht. Deshalb ist es notwendig, daß wir für das völlig wache Ich nicht versetzt werden in die wirkliche Welt, die in unserer Umgebung ist, sondern nur in das Bild der Welt. Daher haben wir in unserem denkenden Erkennen eben nur die Bilder der Welt, was wir vom seelischen Gesichtspunkte aus schon angeführt haben.

Jetzt betrachten wir es auch vom geistigen Gesichtspunkte aus. Im denkenden Erkennen leben wir in Bildern; und wir Menschen auf der gegenwärtigen Entwickelungsstufe innerhalb von Geburt und Tod können mit unserem vollwachenden Ich nur in Bildern von dem Kosmos leben, noch nicht in dem wirklichen Kosmos. Daher muß, wenn wir wachen, unser Leib uns zuerst die Bilder des Kosmos hervorbringen. Dann lebt unser Ich in den Bildern von diesem Kosmos.

Die Psychologen geben sich furchtbar viel Mühe, die Beziehungen zwischen Leib und Seele zu konstatieren. Sie reden von Wechselwirkung zwischen Leib und Seele, reden vom psychophysischen Parallelismus und auch von anderen Dingen noch. Alle diese Dinge sind im Grunde genommen kindliche Begriffe. Denn der wirkliche Vorgang dabei ist der: Wenn das Ich des Morgens in den Wachzustand übergeht, so dringt es in den Leib ein, aber nicht in die physischen Vorgänge des Leibes, sondern in die Bilderwelt, die bis in sein tiefstes Inneres der Leib von den äußeren Vorgängen erzeugt. Dadurch wird dem Ich das denkende Erkennen übermittelt.

Beim Fühlen ist es anders. Da dringt schon das Ich in den wirklichen Leib ein, nicht bloß in die Bilder. Wenn es aber bei diesem Eindringen voll bewußt wäre, dann würde es - nehmen Sie das jetzt seelisch — buchstäblich seelisch verbrennen. Wenn Ihnen dasselbe passierte beim Fühlen, was Ihnen passiert beim Denken, indem Sie in die Bilder, die Ihnen Ihr Leib erzeugt, mit Ihrem Ich eindringen, dann würden Sie seelisch verbrennen. Sie würden es nicht aushalten. Sie können dieses Eindringen, welches das Fühlen bedeutet, nur träumend, im herabgedämpften Bewußtseinszustande erleben. Nur im Traume halten Sie das aus, was beim Fühlen in Ihrem Leib eigentlich vor sich geht.

Und was beim Wollen sich abspielt, das können Sie überhaupt nur erleben, indem Sie schlafen. Das wäre etwas ganz Schreckliches, was Sie erleben würden, wenn Sie im gewöhnlichen Leben alles miterleben müßten, was mit Ihrem Wollen vor sich geht. Der entsetzlichste Schmerz ergriffe Sie zum Beispiel, wenn Sie, was ich schon andeutete, wirklich erleben müßten, wie sich die durch die Nahrungsmittel dem Organismus zugeführten Kräfte beim Gehen verbrauchen in Ihren Beinen. Es ist schon Ihr Glück, daß Sie das nicht erleben beziehungsweise nur schlafend erleben. Denn wachend dies erleben, würde den denkbar größten Schmerz bedeuten, einen furchtbaren Schmerz. Man könnte sogar sagen: Könnten wir den Wachzustand im Wollen erreichen, so würde der Schmerz, der sonst latent bleibt, betäubt wird durch den Schlafzustand im Wollen, ins Bewußtsein treten.

Daher werden Sie verstehen, wenn ich Ihnen jetzt das Leben des Ich charakterisiere während dessen, was man im gewöhnlichen Leben Wachzustand nennt — was also umfaßt: voll Wachen, träumend Wachen, schlafend Wachen -, wenn ich charakterisiere, was das Ich, indem es im gewöhnlichen Wachzustande im Leibe lebt, eigentlich in Wirklichkeit durchlebt. Dieses Ich lebt im denkenden Erkennen, indem es aufwacht in den Leib; da ist es voll wach. Es lebt darin aber nur in Bildern, so daß der Mensch in seinem Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod, wenn er nicht solche Übungen macht, wie sie in meinem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» angedeutet sind, fortwährend nur in Bildern durch sein denkendes Erkennen lebt.

Dann senkt sich erwachend das Ich auch ein in die Vorgänge, die das Fühlen bedingen. Fühlend leben: da sind wir nicht voll wach, sondern da sind wir träumend wach. Wie erleben wir denn eigentlich das, was wir da im träumenden Wachzustande fühlend durchmachen? Das erleben wir tatsächlich in dem, was man immer genannt hat Inspirationen, inspirierte Vorstellungen, unbewußt inspirierte Vorstellungen. Da ist der Herd von alledem, was aus den Gefühlen beim Künstler hinaufsteigt in das wache Bewußtsein. Dort wird es zuerst durchgemacht. Dort wird auch alles das durchgemacht, was beim wachen Menschen oftmals als Einfälle hinaufsteigt ins Wachbewußtsein und dann zu Bildern wird.

Was in meinem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» Inspirationen genannt wird, das ist nur das zur Helligkeit, zum Vollbewußtsein heraufgehobene Erleben desjenigen, was bei jedem Menschen unten im Gefühlsleben unbewußt an Inspirationen vorhanden ist. Und wenn besonders veranlagte Leute von ihren Inspirationen sprechen, so sprechen sie eigentlich von dem, was die Welt in ihr Gefühlsleben hineingelegt hat und durch ihre Anlagen heraufkommen läßt in ihr volles Wachbewußtsein. Es ist das ebenso Weltinhalt, wie der Gedankeninhalt Weltinhalt ist. Aber in dem Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod spiegeln diese unbewußten Inspirationen solche Weltenvorgänge, die wir nur träumend erleben können; sonst würde unser Ich in diesen Vorgängen sich verbrennen oder es würde ersticken, namentlich ersticken. Dieses Ersticken beginnt auch manchmal beim Menschen in abnormen Zuständen. Denken Sie nur einmal, Sie haben Alpdruck. Dann will ein Zustand, der sich abspielt zwischen Ihnen und der äußeren Luft, wenn bei einem Menschen in diesem Wechselverhältnis nicht alles in Ordnung ist, in abnormer Weise übergehen in etwas anderes. Indem das übergehen will in Ihr Ich-Bewußtsein, wird es Ihnen nicht als eine normale Vorstellung bewußt, sondern als eine Sie quälende Vorstellung: als der Alpdruck. Und so qualvoll wie das abnorme Atmen im Alpdruck, so qualvoll wäre das gesamte Atmen, wäre jeder Atemzug, wenn der Mensch das Atmen vollbewußt erleben würde. Er würde es fühlend erleben, aber qualvoll wäre es für ihn. Es wird daher abgestumpft, und so wird es nicht als physischer Vorgang, sondern nur in dem träumerischen Gefühl erlebt.

Und gar die Vorgänge, die sich beim Wollen abspielen, ich habe es Ihnen schon angedeutet: furchtbarer Schmerz wäre das! Daher können wir weiter sagen als drittes: Das Ich im wollenden Tun ist schlafend. Da wird das erlebt, was erlebt wird mit stark herabgedämpftem Bewußtsein — eben im schlafenden Bewußtsein — in unbewußten Intuitionen. Unbewußte Intuitionen hat der Mensch fortwährend; aber sie leben in seinem Wollen. Er schläft in seinem Wollen. Daher kann er sie auch nicht im gewöhnlichen Leben heraufholen. Sie kommen nur in Glückszuständen des Lebens herauf; dann erlebt der Mensch ganz dumpf die geistige Welt mit.

Nun ist etwas Eigentümliches beim gewöhnlichen Leben des Menschen vorhanden. Das Vollbewußtsein im vollen Wachen beim denkenden Erkennen, das kennen wir ja alle. Da sind wir sozusagen in der Helligkeit des Bewußtseins, darüber wissen wir Bescheid. Manchmal fangen dann die Menschen an, wenn sie über die Welt etwas nachdenken, zu sagen: Wir haben Intuitionen. Unbestimmt Gefühltes bringen die Menschen dann aus diesen Intuitionen heraus vor. Was sie da sagen, kann manchmal etwas sehr Verworrenes sein, aber es kann auch unbewußt geregelt sein. Und schließlich, wenn der Dichter von seinen Intuitionen spricht, so ist das durchaus richtig, daß er sie zunächst nicht herausholt aus dem Herd, wo sie ihm am nächsten liegen, aus den inspirierten Vorstellungen des Gefühlslebens, sondern er holt hervor seine ganz unbewußten Intuitionen aus der Region des schlafenden Wollens.

Wer in diese Dinge hineinsieht, der sieht selbst in scheinbaren Zufälligkeiten des Lebens tiefe Gesetzmäßigkeiten. Man liest zum Beispiel den zweiten Teil von Goethes «Faust», und man möchte sich ganz gründlich davon unterrichten, wie gerade diese merkwürdigen Verse in ihrem Bau hervorgebracht werden konnten. Goethe war schon alt, als er den zweiten Teil seines «Faust» schrieb, wenigstens den größten Teil davon. Er schrieb ihn so, daß John, sein Sekretär, am Schreibtische saß und das schrieb, was Goethe diktierte. Hätte Goethe selber schreiben müssen, so hätte er wahrscheinlich nicht so merkwürdig ziselierte Verse für den zweiten Teil seines «Faust» hervorgebracht. Goethe ging, während er diktierte, in seiner kleinen Weimarer Stube fortwährend auf und ab, und dieses Auf- und Abgehen gehört mit zur Konzeption des zweiten Teiles des «Faust». Indem Goethe dieses unbewußte wollende Tun im Gehen entwickelte, drängte aus seinen Intuitionen etwas herauf, und in seiner äußeren Tätigkeit offenbarte sich dann dasjenige, was er durch einen anderen auf das Papier schreiben ließ.

Wenn Sie sich ein Schema machen wollen von dem Leben des Ich im Leibe, und Sie machen es sich in der folgenden Weise:

I. wachend — bildhaftes Erkennen

II. träumend - inspiriertes Fühlen

III. schlafend - intuitierendes oder intuitiertes Wollen

dann werden Sie sich nicht recht begreiflich machen können, warum das Intuitive, von dem die Menschen instinktiv sprechen, leichter heraufkomme ins bildhafte Erkennen des Alltags als das näherliegende inspirierte Fühlen. Wenn Sie sich nun das Schema jetzt richtig zeichnen - denn hier oben ist es falsch gezeichnet —, wenn Sie es in der Weise machen, wie in der Zeichnung, dann werden Sie die Sache leichter begreifen. Denn dann werden Sie sich sagen: In der Richtung des Pfeils (1) steigt das bildhafte Erkennen hinunter in die Inspirationen, und es kommt wieder herauf aus den Intuitionen (Pfeil 2). Aber dieses Erkennen, das mit dem Pfeil 1 angedeutet ist, ist das Hinuntersteigen in den Leib. Und jetzt betrachten Sie sich; Sie sind zunächst ganz ruhig, sitzend oder stehend, geben sich nur dem denkenden Erkennen hin, der Betrachtung der Außenwelt. Da leben Sie im Bilde. Was sonst das Ich erlebt an den Vorgängen, steigt hinunter in den Leib, erst ins Fühlen, dann ins Wollen. Was im Fühlen ist, beachten Sie nicht, was im Wollen ist, beachten Sie zunächst auch nicht. Nur wenn Sie anfangen zu gehen, wenn Sie anfangen zu handeln, dann betrachten Sie äußerlich nicht zuerst das Fühlen, sondern das Wollen. Und da, beim Hinuntersteigen in den Leib und beim Wiederheraufsteigen, was in der Richtung des Pfeiles 2 vor sich geht, da hat das intuitive Wollen es näher, zum bildhaften Bewußtsein zu kommen, als das träumende inspirierte Fühlen. Daher werden Sie finden, daß die Menschen so oft sagen: Ich habe eine unbestimmte Intuition. — Da wird dann das, was in meinem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten ?» Intuitionen genannt wird, mit der oberflächlichen Intuition des gewöhnlichen Bewußtseins verwechselt.

Jetzt werden Sie etwas begreifen von der Gestalt des menschlichen Leibes. Denken Sie sich jetzt einmal einen Augenblick gehend, aber die Welt betrachtend. Denken Sie sich: Nicht Ihr Unterleib müßte mit den Beinen gehen, sondern Ihr Kopf würde direkt die Beine haben und müßte gehen. Da würde in eins verwoben sein Ihr Weltbetrachten und Ihr Wollen, und die Folge wäre, daß Sie nur schlafend gehen könnten. Indem Ihr Kopf aufgesetzt ist auf die Schultern und auf den übrigen Leib, ruht er auf dem übrigen Leibe. Er ruht, und Sie tragen Ihren Kopf, indem Sie sich nur mit dem anderen Leib bewegen. Der Kopf muß aber auf dem Leibe ruhen können, sonst könnte er nicht das Organ des denkenden Erkennens sein. Er muß dem schlafenden Wollen entzogen werden, denn in dem Augenblick, wo Sie ihn in die Bewegung überführen, wo Sie ihn aus der relativen Ruhe in eine selbstgemachte Bewegung überführen würden, da würde er zum Schlafen kommen. Das eigentliche Wollen läßt er den Leib vollziehen, und er lebt in diesem Leibe drinnen wie in einer Kutsche und läßt sich von diesem Wagen weiterbefördern. Nur dadurch, daß sich der Kopf wie in einer Kutsche von dem Wagen des Leibes weiterbefördern läßt und während dieses Weiterbeförderns, während dieses Ruhens handelt, ist der Mensch wachend handelnd. Nur wenn Sie die Dinge so zusammenhalten, kommen Sie auch zu einem wirklichen Begreifen der Gestalt des menschlichen Leibes.

Sixth Lecture

So far, we have tried to understand human beings from a spiritual point of view, insofar as this understanding is necessary for the education of the child. We will have to distinguish between the three points of view — the spiritual, the soul, and the physical — and, in order to obtain a complete anthropology, we will consider human beings from each of these points of view. It is most natural to begin with the soul, because in ordinary life the soul is closest to human beings. And you will also have sensed that, in using antipathy and sympathy as the main concepts for understanding human beings, we have been aiming at the soul. It would not be appropriate for us to move straight from the soul to the physical, because we know from our spiritual scientific observations that the physical can only be understood if it is regarded as a revelation of the spiritual and also of the soul. Therefore, we will now add to the soul-based consideration that we have outlined in general terms a consideration of the human being from a spiritual point of view, and only then will we go into more detail about what is now called anthropology, the consideration of the human being as it appears in the outer physical world.

If you want to consider human beings purposefully from any point of view, you must return again and again to the division of human soul activities into cognition, which takes place in thinking, feeling, and willing. So far, we have placed thinking or cognition, feeling, and willing in the atmosphere of antipathy and sympathy. Let us now consider willing, feeling, and cognition from a spiritual point of view.

From a spiritual point of view, you will also find a difference between willing, feeling, and thinking cognition. Just consider the following. When you recognize through thinking, you must feel — if I may express myself figuratively at first, but the figurative will help us to understand — that you are, in a sense, living in the light. You recognize and feel yourself completely immersed in this activity of recognition with your I. In a sense, every part, every limb of that activity you call cognition is within everything your ego does; and again, what your ego does is within the activity of cognition. You are completely in the light, you live in a fully conscious activity, if I may express myself conceptually. It would also be bad if you were not in a fully conscious activity when you cognize. Just imagine if you had to feel that while you were making a judgment, something was going on with your ego somewhere in your subconscious, and the result of this process was the judgment! Suppose you say: This person is a good person — in other words, you make a judgment. You must be aware that what you need to make this judgment — the subject “the person,” the predicate “he is a good person” — are elements of a process that is completely present to you, that is completely permeated by the light of consciousness. If you had to assume that some demon or mechanism of nature tangled together “person” with “goodness” while you were making the judgment, then you would not be fully conscious in this act of cognitive thinking, and you would always have something of the judgment in your unconscious. The essential thing in thinking cognition is that you are fully conscious in the whole weaving of activity in thinking cognition.

This is not the case with willing. You know very well that when you develop the simplest form of willing, walking, you actually live fully consciously only in the mental image of this walking. You know nothing about what is going on inside your muscles as you move one leg after the other forward, what is going on in the mechanism and organism of your body. Just think how much you would have to learn about the world if you had to consciously perform all the processes that are necessary when you want to walk! You would then have to know exactly how much of the activity caused by the nutrients in the muscles of your legs and other body muscles is consumed while you are exerting yourself to walk. You have never calculated how much of what you consume in food you actually use. You know very well that all this happens very, very unconsciously in your physical body. When we will, a deep unconsciousness constantly interferes with our activity. This is not only the case when we consider the nature of willing in our own organism. What we accomplish when we extend our will to the external world is also not completely comprehended by the light of consciousness.

Suppose you have two column-like pegs. You decide to place a third peg across them. Now distinguish precisely what lives in all that you have done as a fully conscious, cognitive activity from what lives in your fully conscious activity when you make the judgment: A person is good — where you are completely immersed in your cognition. Please distinguish between what lives in this as a cognitive activity and what you know nothing about, even though you were fully involved in it with your will: Why do these two columns support the beam above them through certain forces? To this day, physics has only hypotheses for this. And when people believe they know why the two pegs support the beam, they are only imagining it. Everything we have in terms of cohesion, adhesion, attraction, and repulsion are basically just hypotheses for external knowledge. We reckon with these external hypotheses when we act; we reckon that the two pegs that are supposed to support the beam will not buckle if they are of a certain thickness. But we cannot see through the whole process involved, just as we cannot see through the movements of our legs when we strive forward. Here, too, an element that does not reach into our consciousness interferes with our volition. Volition has an unconscious element in it to the greatest extent.

And feeling stands in the middle between volition and thinking cognition. Feeling is also partly permeated by consciousness and partly by the unconscious. In this way, feeling also participates in the quality of cognitive thinking on the one hand and in the quality of feeling or felt volition on the other. What is actually present here from a spiritual point of view?

You will only succeed if you understand the facts characterized above from a spiritual point of view in the following way. In our everyday life, we speak of waking, of the waking state of consciousness. But we only have this waking state of consciousness in the activity of cognitive thinking. So if you want to talk very precisely about the extent to which human beings are awake, you must say: human beings are only truly awake as long as and to the extent that they are thinking cognizers of something.

What about volition? You are all familiar with the state of consciousness—call it, if you like, the state of unconsciousness—of sleep. You know that while we sleep, from the moment we fall asleep until we wake up, what we experience is not in our consciousness. But it is exactly the same with everything that permeates our will as the unconscious. Insofar as we are volitional beings as human beings, we sleep even when we are awake. We always carry a sleeping human being with us, namely the volitional human being, and accompany him with the waking, thinking, knowing human being; insofar as we are volitional beings, we are also asleep from waking up to falling asleep. Something always sleeps within us, namely the inner essence of volition. We are no more aware of this than we are of the processes that take place within us during sleep. One cannot fully understand human beings without knowing that sleep plays into their waking life, in that human beings are beings of will.

Feeling stands in the middle, and we may now ask ourselves: What is consciousness like in feeling? — It also stands in the middle between waking and sleeping. You know the feelings that live in your soul just as you know dreams, except that you remember dreams and experience feelings directly. But the inner state of mind and mood you have when you are aware of your feelings is no different from that which you have toward your dreams. When you are awake, you are not only a waking person in that you recognize through thinking, and a sleeping person in that you will, you are also a dreaming person in that you feel. So there are actually three states of consciousness that pervade us during our waking hours: waking in the true sense of thinking and recognizing, dreaming in feeling, and sleeping in willing. From a spiritual point of view, ordinary dreamless sleep is nothing more than the devotion of the human being with his whole soul to that to which he is devoted with his will while he goes about his daily business. The only difference is that in actual sleep we sleep with our whole soul, while in waking life we sleep only with our will. In dreaming, as it is called in ordinary life, we are devoted with our whole being to the state of soul we call dreaming, and when awake we are devoted to this dreamlike state of soul only as feeling human beings.

From an educational point of view, you will no longer be surprised when you consider that children differ in terms of the alertness of their consciousness. For you will find that children in whom the emotional life predominates according to their disposition are dreamy children, so that such children, in whom full thinking has not yet awakened in childhood, will easily be devoted to a dreamy nature. You will then take this as an opportunity to influence such a child through strong feelings. And you will then be able to hope that these strong feelings will also awaken clear recognition in them, for all sleep has a tendency, according to the rhythm of life, to awaken after a while. If we now approach such a child, who broods dreamily in their emotional life, with strong feelings, then these strong feelings instilled in the child will, after a while, awaken of their own accord as thoughts.

Children who brood even more, who are even dull to emotional life, will reveal to you that they are particularly strong-willed. You see, if you consider this, you can face many of the mysteries of childhood with understanding. You may have a child in school who seems like a real dullard. If you immediately judge that this is a feeble-minded, dull child, if you examine it using experimental psychology, carry out memory tests and all sorts of other things that are already being done in psychological and educational laboratories, and then say: This dull child, based on its entire disposition, belongs in a school for the mentally disabled or even in the now popular school for the less able, then you would not be getting close to the essence of the child with such a judgment. Perhaps this child has a particularly strong will, perhaps it is one of those children who, in later life, will transform their choleric nature into energetic action. But the will is dormant at first. And if this child's thinking and cognitive abilities are doomed to emerge only later, then it must also be treated in an appropriate manner so that it can later be called upon to accomplish something energetic. For the time being, it appears to be a real dullard, but perhaps it is not at all. And one must then have the insight to awaken the will in such a child; that is, one must work into its waking sleep state in such a way that it gradually comes to — because every sleep has a tendency to awaken — awaken its sleep as a will, which may be very strong but is only now asleep, drowned out by the sleeping being, at a later age. Such a child must be treated in such a way that you rely as little as possible on its cognitive abilities, on its comprehension, but rather hammer into it, as it were, certain things that have a strong effect on the will, so that you let it go at the same time as it speaks. You take such a child, and you will not have very many of them, out of the class and — for the other children it will be stimulating, for this child it will be educational — let it accompany the words with movements while speaking sentences. So: The (step) – human being (step) – is (step) – good! – In this way, you connect the whole human being in the element of will with the purely intellectual in cognition, and you can gradually bring about the awakening of the will to think in such a child. Only the insight that in the waking human being we are already dealing with different states of consciousness — with waking, dreaming, and sleeping — only this insight brings us to a real understanding of our tasks toward the developing human being.

But now we can ask a question. We can ask: How does the actual center of the human being, the I, relate to these different states? The easiest way to deal with this is to start from the undeniable premise that what we call the world, what we call the cosmos, is a sum of activities. For us, these activities are expressed in the various areas of elementary life. We know that forces are at work in this elementary life. The life force, for example, is at work around us. And woven between the elementary forces and the life force is everything that causes, for example, warmth and fire. Just think how much we are surrounded by an environment in which fire causes so much.

In certain areas of the earth, for example in southern Italy, you only need to light a ball of paper, and at that very moment, powerful smoke begins to rise from the earth. Why does this happen? It happens because when you light the ball of paper and the heat that develops dilutes the air at that point, the forces that otherwise prevail beneath the earth's surface are drawn upward by the upward-moving smoke, and the moment you light the ball of paper and throw it on the ground, you are standing in a cloud of smoke. This is an experiment that any traveler who comes to the Naples area can do. I have cited this as an example of how, if we do not view the world superficially, we must say to ourselves: We live in an environment that is permeated by forces everywhere.

Now there are also higher forces than heat. They are also in our environment. We always pass through them as we go through the world as physical human beings. Yes, our physical body, without us knowing it in our ordinary consciousness, is so constituted that we can tolerate this. With our physical body, we can thus stride through the world.

With our ego, which is the most recent formation of our evolution, we could not walk through these world forces if this ego were to surrender itself directly to these forces. This ego could not surrender itself to everything that is in its environment and in which it itself is contained. This ego must now still be protected from having to pour itself into the world forces. It will one day develop the ability to merge with the forces of the world. It cannot do so yet. That is why it is necessary that we, with our fully awake ego, are not transported into the real world that surrounds us, but only into the image of the world. Therefore, in our thinking cognition, we have only the images of the world, as we have already mentioned from a spiritual point of view.

Now let us also consider it from a spiritual point of view. In thinking cognition, we live in images; and we humans at the present stage of development between birth and death can only live with our fully awakening ego in images of the cosmos, not yet in the real cosmos. Therefore, when we are awake, our body must first produce the images of the cosmos for us. Then our ego lives in the images of this cosmos.

Psychologists go to great lengths to establish the relationships between body and soul. They talk about the interaction between body and soul, about psychophysical parallelism, and about other things as well. All these things are basically childish concepts. For the real process is this: when the ego passes into the waking state in the morning, it penetrates the body, but not into the physical processes of the body, but into the world of images that the body produces from external processes in its deepest interior. Through this, thinking cognition is transmitted to the ego.

With feeling, it is different. Here, the ego penetrates the real body, not just the images. But if it were fully conscious of this penetration, it would — take this now in a spiritual sense — literally burn up spiritually. If the same thing happened to you when feeling as happens when thinking, when you penetrate with your ego into the images produced by your body, you would burn spiritually. You would not be able to bear it. You can only experience this penetration, which is what feeling means, in a dream, in a state of subdued consciousness. Only in dreams can you endure what actually happens in your body when you feel.

And what happens when you will can only be experienced when you are asleep. It would be a terrible thing to experience if you had to witness everything that happens with your will in everyday life. For example, you would be seized by the most terrible pain if, as I have already indicated, you really had to experience how the forces supplied to the organism by food are consumed in your legs when you walk. It is your good fortune that you do not experience this, or rather that you only experience it when you are asleep. For to experience this while awake would mean the greatest pain imaginable, a terrible pain. One could even say: if we could achieve the waking state in our will, the pain that otherwise remains latent, numbed by the sleeping state in our will, would enter our consciousness.

Therefore, you will understand when I now characterize the life of the I during what is called the waking state in ordinary life — which includes: fully awake, dreaming awake, sleeping awake — when I characterize what the I actually experiences in reality while living in the body in the ordinary waking state. This I lives in thinking cognition by awakening in the body; there it is fully awake. However, it lives in it only in images, so that in his life between birth and death, unless he does exercises such as those indicated in my book “How to Attain Knowledge of Higher Worlds,” man lives continuously only in images through his thinking cognition.

Then, upon awakening, the ego also sinks into the processes that condition feeling. Living feeling: here we are not fully awake, but rather awake in a dreamlike state. How do we actually experience what we go through feeling in this dreamlike waking state? We actually experience this in what has always been called inspirations, inspired mental images, unconsciously inspired mental images. There is the source of everything that rises from the artist's feelings into waking consciousness. That is where it is first experienced. That is also where everything is experienced that often rises into the waking consciousness of the waking person as ideas and then becomes images.

What is called inspiration in my book “How to Attain Knowledge of Higher Worlds” is only the experience, raised to brightness and full consciousness, of what is unconsciously present in every human being's emotional life as inspiration. And when particularly gifted people speak of their inspirations, they are actually speaking of what the world has placed in their emotional life and, through their predispositions, allows to rise into their full waking consciousness. It is just as much part of the world as the content of our thoughts is part of the world. But in the life between birth and death, these unconscious inspirations reflect world events that we can only experience in our dreams; otherwise, our ego would burn itself up in these events or it would suffocate, literally suffocate. This suffocation sometimes also begins in people in abnormal states. Just think, for example, that you are having a nightmare. Then a state that takes place between you and the outside air, if everything is not in order in this interrelationship in a human being, wants to transition into something else in an abnormal way. As it wants to transition into your ego consciousness, it does not become conscious to you as a normal mental image, but as a tormenting mental image: as a nightmare. And as agonizing as abnormal breathing is in nightmares, so agonizing would be all breathing, every breath, if a person were to experience breathing fully consciously. They would experience it emotionally, but it would be agonizing for them. It is therefore dulled, and so it is not experienced as a physical process, but only in a dreamlike feeling.

And even the processes that take place in willing, as I have already indicated to you: that would be terrible pain! Therefore, we can say further, as a third point: the I in willing action is asleep. What is experienced there is experienced with greatly dulled consciousness — precisely in sleeping consciousness — in unconscious intuitions. Human beings have unconscious intuitions all the time, but they live in their will. They sleep in their will. That is why they cannot bring them up in ordinary life. They only come up in states of happiness in life; then human beings experience the spiritual world in a very dull way.

Now there is something peculiar about the ordinary life of human beings. We are all familiar with full consciousness in full wakefulness during thinking and recognizing. There we are, so to speak, in the brightness of consciousness, and we know about that. Sometimes, when people think about the world, they begin to say: We have intuitions. People then express vague feelings based on these intuitions. What they say can sometimes be very confusing, but it can also be unconsciously regulated. And finally, when the poet speaks of his intuitions, it is quite true that he does not initially draw them from the source where they are closest to him, from the inspired mental images of his emotional life, but rather he draws his completely unconscious intuitions from the realm of the sleeping will.Those who look into these things see deep laws even in the apparent coincidences of life. For example, one reads the second part of Goethe's “Faust” and wants to learn thoroughly how these remarkable verses could have been produced in their structure. Goethe was already old when he wrote the second part of his “Faust,” at least most of it. He wrote it in such a way that John, his secretary, sat at his desk and wrote down what Goethe dictated. If Goethe had had to write it himself, he probably would not have produced such strangely chiseled verses for the second part of his “Faust.” While dictating, Goethe paced continuously back and forth in his small room in Weimar, and this pacing is part of the conception of the second part of Faust. As Goethe developed this unconscious volitional activity while walking, something emerged from his intuitions, and his external activity then revealed what he had another person write down on paper.

If you want to make a diagram of the life of the ego in the body, you can do so in the following way:

I. awake — pictorial recognition

II. dreaming — inspired feeling

III. asleep — intuitive or intuited volition

then you will not be able to understand why the intuitive, which people instinctively speak of, comes more easily into the pictorial recognition of everyday life than the more obvious inspired feeling. If you now draw the diagram correctly — because it is drawn incorrectly above — if you do it in the way shown in the drawing, then you will understand the matter more easily. For then you will say to yourself: in the direction of arrow (1), pictorial recognition descends into inspirations, and it rises again from intuitions (arrow 2). But this recognition, indicated by arrow 1, is the descent into the body. And now consider yourself; you are initially completely calm, sitting or standing, devoting yourself only to thinking cognition, to observing the outside world. You live in the image. What else the I experiences in the processes descends into the body, first into feeling, then into willing. You do not pay attention to what is in feeling, nor do you initially pay attention to what is in willing. Only when you begin to walk, when you begin to act, do you first observe not feeling, but willing. And there, as it descends into the body and ascends again, what happens in the direction of arrow 2, intuitive willing is closer to reaching pictorial consciousness than dreaming, inspired feeling. That is why you will find that people so often say: I have a vague intuition. — What is called intuition in my book “How to Attain Knowledge of Higher Worlds” is then confused with the superficial intuition of ordinary consciousness.