The Study of Man

GA 293

28 August 1919, Stuttgart

Lecture VII

Your task is to gain an insight into what the human being really is. Up to now in our survey of general pedagogy we have endeavoured to comprehend this nature of man first of all from the point of view of the soul and then from that of the spirit. To-day we will continue from the latter point of view. We shall of course continually have to refer to the conceptions of pedagogy, psychology and the life of the soul, which are current in the world to-day; for in course of time you will have to read and digest the books which are published on pedagogy and psychology, as far as you have time and leisure to do so.

If we consider the human being from the point of view of the soul, we lay chief stress on discovering antipathies and sympathies within the laws which govern the world; but if we consider the human being from the spiritual point of view, we must lay the chief stress on discovering the conditions of consciousness. Now yesterday we concerned ourselves with the three conditions of consciousness which hold sway in the human being: namely, the full waking consciousness, dreaming and sleeping: and we showed how the full waking consciousness is really only present in thinking-cognition; dreaming in feeling; and sleeping in willing.

All comprehension is really a question of relating one thing to another: the only way we can comprehend things in the world is by relating them to each other. I wish to make this statement concerning method at the outset. When we place ourselves into a knowing relationship with the world, we are first of all observing. Either we observe with our senses, as we do in ordinary life, or we develop ourselves somewhat further and observe with soul and spirit, as we can do in Imagination, Inspiration and Intuition. But spiritual observation too is “observation,” and all observation requires to be completed by our comprehension or conception. But we can only comprehend if we relate one thing to another in the universe and in our environment. You can form good conceptions of body, soul and spirit if you have the whole course of human life clearly before you. Only you must take into account that in this relating of things to each other, as I shall now explain, you have only the rudiments of comprehension. You will need to develop further the conceptions you arrive at in this manner.

For instance if you consider the child as he first comes into the world, if you observe his physical form, his movements, his expressions, his crying, his baby talk and so on—you will get a picture which is chiefly of the human body. But this picture will only be complete if you relate it to the middle age, and old age of the human being. In the middle age the human being is more predominantly soul, and in old age he is most spiritual. This last statement can easily be contended. People will certainly come and say: “But a great many old people become quite feeble-minded.” A favourite objection of materialism to those who speak of the soul and the spirit is that people get feeble-minded in old age, and, with true consistency, the materialists argue that even such a great man as Kant became feeble-minded in his old age. The statement of the materialists and the fact are quite right. Only they do not prove what they set out to prove. For even Kant, when he stood before the gate of death, was wiser than in his childhood; only in childhood his body was capable of receiving all that came out of his wisdom, and thereby it could become conscious in his physical life. But in old age the body became incapable of receiving what the spirit was giving it. The body was no longer a proper instrument for the spirit. Therefore on the physical plane Kant could no longer come to a consciousness of what lived in his spirit. In spite of the apparent force of the above-mentioned argument, then, we must be quite clear that in old age men become wise and spiritual and that they come near to the Spirits. Therefore in the case of people who, right into their old age, can preserve elasticity and life power for their spirit, we must recognise the beginnings of spiritual qualities. For there are such possibilities.

In Berlin there were once two professors. One was Michelet the disciple of Hegel, who was over ninety years old. And as he was considerably gifted he only got as far as being Honorary Professor, but although he was so old he still gave lectures Then there was another called Zeller, the historian of Greek philosophy. Compared with Michelet he was a mere boy, for he was only seventy. But everybody said how he was feeling the burden of age, how he could no longer give lectures, or, in any case, was always wishing to have them reduced. To this Michelet always said: “I can't understand Zeller; I could give lectures all day long, but Zeller, though still in his youth, is always saying that it is getting too much of a strain for him!” So you see one may find isolated examples only of what I have stated about the spirit in old age; yet it really is so.

If, on the other hand, we observe the characteristics of the human being in middle age, we shall get a first basis for our observations of the soul. For this reason, too, a man in middle life is more able, as it were, to belie the soul element. He can appear to be either soulless or very much imbued with soul. For the soul element lies within the freedom of man, even in education. The fact that many people are very soulless in middle life does not prove that middle age is not the age of the soul. If you compare the bodily nature of the child—kicking and sprawling and performing unconscious actions—with the quiet contemplative bodily nature of old age, you have on the one hand a body that shows its bodily side predominantly, in the child, and on the other hand you have a body that as it were withdraws its bodily side in old age, a body that to a certain degree belies its own bodily nature.

Now if we turn our attention more to the soul life we shall say: the human being bears within him thinking-cognition feeling and willing. When we observe a child the impression we get of the child's soul shows a close connection between willing and feeling. We might say that willing and feeling have grown together in the child. When the child kicks and tumbles about he is making movements which precisely correspond to his feelings at the moment; he is not capable of keeping his movements and his feelings separate.

With an old man the opposite is the case: thinking-cognition and feeling have grown together within him, and willing stands apart, independently. Thus human life runs its course in such a way that feeling, which is at first bound up with willing, gradually frees itself from it. And a good deal of education is concerned with this, with this freeing of the feeling from the will. Then the feeling which has been freed from willing unites itself with thinking-cognition. And this is the concern of later life. We can only prepare the child rightly for his later life if we bring about the proper release of feeling from willing; then in a later period of life as a grown man or woman he will be able to unite this released feeling with thinking-cognition, and thus be fitted for his life. Why is it that we listen to an old man, even when he is relating his life history? It is because in the course of his life he has united his personal feeling with his concepts and ideas. He is not telling us theories: he is really telling us about the feelings which he personally has been able to unite with his ideas and concepts. With the old man, who has really united his feelings with thinking-cognition, the concepts and ideas ring true; they are filled with warmth, and permeated with reality; they sound concrete and personal. Whilst with those who have ceased to develop beyond the stage of middle-aged manhood or womanhood the concepts and ideas sound theoretical, abstract, scientific. It is an essential factor of human life that the evolution of soul powers runs a certain course; for the feeling-willing of the child develops into the feeling-thinking of the old man. Human life lies between the two, and we can only give an education befitting this human life when our study of the soul includes this knowledge.

Now we must take notice that something arises straight-away whenever we begin to observe the world—indeed in all psychologies it is described as the first thing that occurs in observation of the external world; and that is sensation. When any one of our senses comes into touch with the environment, it has a sensation. We have sensations of colour, tones, warmth and cold. Thus sensation enters into our contact with our environment.

But you cannot get a true conception of sensation from the way it is described in current books on psychology. When the psychologists speak of sensation they say: in the external world a certain physical process is going on, vibrations in the light ether or waves in the air; this streams on to our sense organ and stimulates it. People speak of stimulus, and they hold to the expression they form, but will not make it comprehensible. For through the sense organ the stimulus releases sensation in our souls, the wholly qualitative sensation which is caused by the physical process (for example by the vibration of air waves in hearing). But how this comes about neither psychology nor present-day science can tell us. This is what we generally find in psychological books.

You will be brought nearer to an understanding of these things than you will by these psychological ideas, if, having insight into the nature of sensations themselves, you can yourself answer the question: to which of the soul forces is sensation really most closely related? Psychologists make light of it; they glibly connect sensation with cognition, without more ado, and say: first we have a sensation, then we perceive, then we make mental pictures, form concepts and so on. This indeed is what the process appears at first to be. But this explanation leaves out of account what the nature of sensation really is.

If we consider it with a sufficient amount of self-observation we shall recognise that sensation is really of a will nature with some element of feeling nature woven into it. It is not really related to thinking-cognition, but rather to feeling-willing or willing-feeling. It is of course impossible to be acquainted with all the countless psychologies there are in the world to-day, and I do not know how many of them have grasped anything of the relationship between sensation and willing-feeling or feeling-willing. It would not be quite exact to say that sensation is related to willing; rather it is related to willing-feeling or feeling-willing. But there is at least one psychologist, Moritz Benedikt of Vienna, who especially distinguished himself by his power of observation, and who recognised in his psychology that sensation is related to feeling.

Other psychologists certainly set very little store by this psychology of Moritz Benedikt, and it is true that there is something rather peculiar about it. Firstly, Moritz Benedikt is by vocation a criminal-anthropologist; and he proceeds to write a book on psychology. Secondly, he is a naturalist—and writes about the importance of poetic works of art in education, in fact he analyses poetic works of art to show how they can be used in education. What a dreadful thing! The man sets up to be a scientist, and actually imagines that psychologists have something to learn from the poets! And thirdly, this man is a Jewish naturalist, a scientific Jew, and he writes a book on Psychology and deliberately dedicates it to Laurenz Mullner, a priest, the Catholic philosopher of the theological faculty in the University of Vienna (for he still held this post at that time). Three frightful things, which make it quite impossible for the professional psychologists to take the man seriously. But if you were to read his books on psychology, you would find so many single apt ideas, that you would get much from them, although you would have to repudiate the structure of his psychology as a whole, his whole materialistic way of thought—for such it is indeed. You would get nothing at all from the book as a whole, but a great deal from single observations within it. Thus you must seek the best in the world wherever it is to be found. If you are a good observer of details, but are put off by the general tendency of Moritz Benedikt's work, you need therefore not necessarily repudiate the wise observations that he makes.

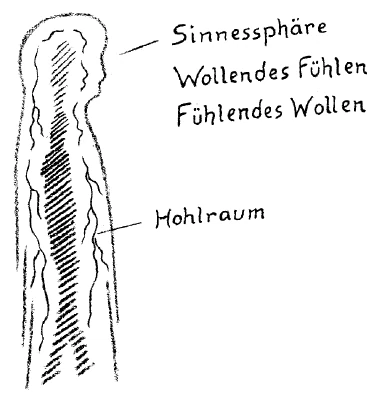

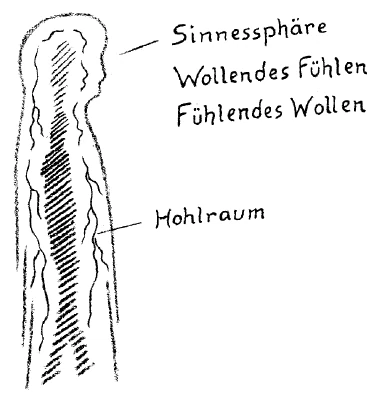

Thus sensation, as it appears within the human being, is willing-feeling or feeling-willing. Therefore we must say that where man's sense sphere spreads itself externally—for we bear our senses on the periphery of our body, if I may express it rather crudely—there some form of feeling-willing and willing-feeling is to be found. If we draw a diagram of the human being (and please note it is only a diagram) we have here on the outer surface, in the sphere of the senses, willing-feeling and feeling-willing. (see drawing further on) What then do we do on this surface when feeling-willing and willing-feeling is present, in so far as this surface of the body is the sphere of the senses? We perform an activity which is half-sleeping, half dreaming; we might even call it a dreaming-sleeping, a sleeping-dreaming. For we do not only sleep in the night, we are continually asleep on the periphery, on the external surface of our body, and the reason why we as human beings do not entirely comprehend our sensations, is because in these regions where the sensations are to be found we are only dreaming in sleep, or sleeping in dreams. The psychologists have no notion that what prevents them from understanding the sensations is the same thing as prevents us from bringing our dreams into clear consciousness when we wake in the morning. You see, the concepts of sleeping and dreaming have a meaning which differs entirely from that we would give them in ordinary life. All we know about sleeping in ordinary life is that when we are in bed at night we go to sleep. We have no idea that this sleeping extends much further, and that we are always sleeping on the surface of the body, although this sleeping is constantly being penetrated by dreams. These “dreams” are the sensations of the senses, before they are taken hold of by the intellect and by thinking-cognition.

You must seek out the sphere of willing and feeling in the child's senses also. This is why we insist so strongly in these lectures that while educating intellect we must also work continually on the will. For in all that the child looks at and perceives we must also cultivate will and feeling; otherwise we shall really be contradicting the child's sensations. It is only when we address an old man, a man in the evening of his life, that we can think of the sensations as having already been transformed. In the case of the old man sensation has already passed over from feeling-willing to feeling-thinking or thinking-feeling. Sensations have been somewhat changed within him. They have more of the nature of thought and have lost the restless nature of will—they have become more calm. Only in old age can we say that sensations approach the realm of concepts and ideas.

Most psychologists do not make this fine distinction in sensations. For them the sensations of old age are the same as those of the child, for sensations for them are simply sensations. That is about as logical as to say: the razor (Rasermesser) is a knife (Messer), so let us cut our meat with it, for a knife is a knife. This is taking the concept from the verbal explanation. This we should never do, but rather take the concept from the facts. We should then discover that sensation has life, that it develops, and in the child it has more of a will nature, in the old man more of an intellectual nature. Of course it is much easier to deduce everything from words; it is for this reason that we have so many people who can make definitions, some of which can have a terrible effect on you.

On one occasion I met a schoolfellow of mine, after we had for some time been separated and had gone our several ways. We had been at the same primary school together; I then went to the Grammar School (Realschule) and he to the Teachers' Training College, and what is more to a Hungarian College—and that meant something in the seventies. After some years we met and had a conversation about light. I had already learnt what could be learnt in ordinary physics, that light has something to do with ether waves, and so on. This could at least be regarded as a cause of light. My former schoolfellow then added: “We have also learnt what light is. Light is the cause of sight!” A hotchpotch of words! It is thus that concepts become mere verbal explanations. And we can imagine what sort of things the pupils were told when we learn that the gentleman in question had later to teach a large number of pupils, until at last he was pensioned off. We must get away from the words and come to the spirit of things. If we want to understand something we must not immediately think of the word each time, but we must seek the real connections. If we look up the derivation of the word Geist (spirit) in Fritz Mauthner's History of Language to discover what its original form was, we shall find it is related to Gischt (“froth” or “effervescence”) and to “gas.” These relationships do exist, but we should not get very far by simply building on them. But unfortunately this method is covertly applied to the Bible and therefore with most people, and especially present-day theologies, the Bible is less understood than any other book.

The essential thing is that we should always proceed according to facts, and not endeavour to get a conception of spirit from the derivation of the word, but by comparing the life in the body of a child with the life in the body of an old person. By means of this connecting of one fact with another we get true conception.

And thus we can only get a true conception of sensation if we know that it is able to arise as willing-feeling or feeling-willing in the bodily periphery of the child, because compared with the more human inward side of the child's being this bodily periphery is asleep and dreaming in its sleep. Thus you are not only fully awake in thinking-cognition, but you are also only awake in the inner sphere of your body. At the periphery or surface of the body you are perpetually asleep. And further: that which takes place in the environment, or rather on the surface of the body, takes place in a similar way in the head, and increases in intensity the further we go into the human being into the blood and muscle elements. Here, too, man is asleep and also dreaming. On the surface man is asleep and dreaming, and again towards the inner part of his body he is asleep and dreaming. Therefore what is more of a soul nature, willing-feeling, feeling-willing, our life of desires and so on, remain in the inner part of our body in a dreaming sleep.

Where then are we fully awake? In the intervening zone, when we are entirely wakeful. Now you see that we are proceeding from a spiritual point of view, by applying the facts of waking and sleeping to man even in a spatial way, and by relating this to his physical form so that we can say: from a spiritual point of view the human being is so constituted that at the surface of the body and in his central organs he is asleep and can only be really awake in the intervening zone, during his life between birth and death. Now what are the organs that are specially developed in this intervening region?

Those organs, especially in the head, that we call nerves, the nerve apparatus. This nerve apparatus sends its shoots into the zone of the outer surface and also into the inner region where they again disperse as they do on the surface: and between the two there are middle zones such as the brain, the spinal cord and the solar plexus. Here we have the opportunity of being really awake. Where the nerves are most developed, there we are most awake. But the nervous system has a peculiar relationship to the spirit. It is a system of organs which through the functions of the body continually has the tendency to decay and finally to become mineral. If in a living human being you could liberate his nerve system from the rest of the gland-muscle-blood nature and bony nature—you could even leave the bony system with the nerves—then this nerve system in the living human being would already be a corpse, perpetually a corpse. In the nerve system the dying element in man is always at work. The nerve system is the only system that has no connection whatever with soul and spirit. Blood, muscles, and so on always have a direct connection with soul and spirit. The nerve system has no direct connection with these: the only way in which it has such a connection at all is by constantly leaving the human organisation, by not being present within it, because it is continually decaying. The other members are alive, and can therefore form direct connections with the soul and spirit; the nerve system is continually dying out, and is continually saying to the human being: “You can evolve because I am setting up no obstacle, because I see to it that I with my life am not there at all.” That is the peculiar thing about it. In psychology and physiology you find the following put forward; the organ that acts as a medium for sensation, thinking and the whole soul and spirit element, is the nerve system. But how does it come to be this medium? Only by continually expelling itself from life, so that it does not offer any obstacles to thinking and sensation, forms no connections with thinking and sensation, and in that place where it is it leaves the human being “empty” in favour of the soul and spirit, Actually there are hollow spaces for the spirit and soul where the nerves are. Therefore spirit and soul can enter in where these hollow spaces are. We must be grateful to the nerve system that it does not trouble about soul and spirit, and does not do all that is ascribed to it by the physiologists and psychologists. For if it did this, if for five minutes only the nerves did what the physiologists and psychologists describe them as doing, then in these five minutes we should know nothing about the world nor about ourselves; in fact we should be asleep. For the nerves would then act like those organs which bring about sleeping, which bring about feeling-willing, willing-feeling.

Indeed it is no easy matter to state the truth about physiology and psychology to-day, for people always say: “You are standing the world on its head.” The truth is that the world is already standing on its head, and we have to set it on its legs again by means of spiritual science. The physiologists say that the organs of thinking are the nerves, and especially the brain. The truth is that the brain and nerve system can only have anything to do with thinking-cognition through the fact that they are constantly shutting themselves off from the human organisation and thereby allowing thinking-cognition to develop.

Now you must attend very carefully to what I am going to say, and please bring all your powers of understanding to bear upon it. In the environment of man, where the sphere of the senses is, there are real processes at work which play their part unceasingly in the life of the world. Let us suppose that light is working upon the human being through the eye. In the eye, that is, in the sphere of the senses, a real process is at work, a physical-chemical process is taking place. This continues into the inner part of the human body, and finally indeed into that inner part where, once again, physical-chemical processes take place (the dark shading in the drawing). Now imagine that you are standing opposite an illumined surface and that rays of light are falling from this surface into your eye. There again physical-chemical processes arise, which are continued into the muscle and blood nature within the human being. In between there remains a vacant zone. In this vacant zone, which has been left empty by the nerve organ, no independent processes are developed such as that in the eye or in the inner nature of the human being; but there enters what is outside: the nature of light, the nature of colour. Thus, at the surface of our bodies where the senses are, we have material processes which are dependent on the eye, the ear, the organs which can receive warmth and so on: similar processes also take place in the inner sphere of the human being. But not in between, where the nerves spread themselves out: they leave the space free, there we can live with what is outside us. Your eye changes the light and colour. But where your nerves are, where as regards life there is only hollow space, there light and colour do not change, and you yourself are experiencing light and colour. It is only with regard to the sphere of the senses that you are separated from the external world: within, as in a shell, you yourself live with the external processes. Here you yourself become light, you become sound, the processes have free play because the nerves form no obstacle as blood and muscle do.

Now we get some feeling of how significant this is: we are awake in a part of our being which in contrast to other living parts may be described as a hollow space, whilst at the external surface and in the inner sphere we are dreaming in sleep, and sleeping in dreams. We are only fully awake in a zone which lies between the outer and inner spheres. This is true in respect to space.

But in considering the human being from a spiritual point of view we must also bring the time element of his life into relationship with waking, sleeping and dreaming. You learn something, you take it in and it passes into your full waking consciousness. Whilst you are occupying yourself with this thing and thinking about it, it is in your full waking consciousness. Then you return to your ordinary life. Other things claim your interest and attention. Now what happens to what you have just learnt, to what was occupying your attention? It begins to fall asleep; and when you remember it again, it awakens again. You will only get the right point of view about all these things when you substitute real conceptions for all the rigmarole's you read in psychology books about remembering and forgetting. What is remembering? It is the awakening of a complex of mental pictures. And what is forgetting? It is the falling asleep of the complex of mental pictures. Here you can compare real things with real experiences, here you have no mere verbal definitions. If you ponder over waking and sleeping, if you look at your own experience or another's on falling asleep, you have a real process before you. You relate forgetting, this inner soul activity, to this real process—not to any word—and you compare the two and say: forgetting is only falling asleep in another sphere, and remembering is only waking up in another sphere.

Only so can you come to a spiritual understanding of the world, by comparing realities with realities. Just as you have to compare childhood with old age to find the real relationship between body and soul, at least the elements of it, so in the same way you can compare remembering and forgetting by relating it to something real, to falling asleep and waking up.

It is this that will be so infinitely necessary to the future of mankind; that men accustom themselves to enter into reality. People think almost exclusively in words today; they do not think in real terms. How could a present-day man get at this conception of awakening which is the reality about memory? In the sphere of mere words he can hear of all kinds of ways of defining memory; but it will not occur to him to find out these things from the reality, from the thing itself.

Therefore you will understand that when people hear of something like the Threefold Organism of the State, which springs entirely out of reality and not out of abstract conceptions, they find it incomprehensible at first because they are quite unaccustomed to produce things out of reality. They do not connect any of their conceptions with getting things out of reality. And the people who do this least are the Socialist leaders in their theories; they represent the last word, the last stage of decadence in the realm of verbal explanations. These are the people who most of all believe that they understand something of reality, but when they begin to talk they make use of the veriest husks of words.

This was only an interpolation with reference to the current trend of our times. But the teacher must understand also the times in which he lives, for he has to understand the children who out of these very times are entrusted to him for their education.

Siebenter Vortrag

Es kommt für Sie darauf an zu durchschauen, was das Menschenwesen eigentlich ist. Wir haben auf unserem bisherigen Gange durch die allgemeine Pädagogik versucht, zunächst vom seelischen, dann vom geistigen Gesichtspunkte aus dieses Menschenwesen zu begreifen. Das letztere wollen wir heute etwas fortsetzen. Wir werden uns selbstverständlich fortwährend beziehen müssen auf Begriffe, die über Pädagogisches, auch über Seelisches, Psychologisches in der Welt gang und gäbe sind; denn Sie werden sich ja durch Lektüre im Laufe der Zeit mit pädagogischer und psychologischer Literatur auseinanderzusetzen haben, soweit Sie dazu Zeit und Muße haben.

Betrachten wir vom seelischen Gesichtspunkte aus den Menschen, so legen wir das Hauptgewicht darauf, Antipathien und Sympathien innerhalb der Weltgesetzmäßigkeit zu entdecken; betrachten wir aber vom geistigen Gesichtspunkte aus den Menschen, so müssen wir das Hauptgewicht darauf legen, Bewußtseinszustände zu entdecken. Und wir haben uns ja gestern mit den im Menschen waltenden drei Bewußtseinszuständen beschäftigt: mit dem Vollwachsein, mit dem Träumen und mit dem Schlafen — und haben gezeigt, wie das Vollwachsein eigentlich nur im denkenden Erkennen vorhanden ist, das Träumen aber im Fühlen waltet und das Schlafen im Wollen.

Es ist alles Begreifen eigentlich ein Beziehen des einen auf das andere. Begreifen können wir aber in der Welt nicht anders, als daß wir das eine auf das andere beziehen. Diese methodische Bemerkung möchte ich vorausschicken. Indem wir uns zur Welt erkennend in Beziehung setzen, beobachten wir zunächst. Entweder beobachten wir mit unseren Sinnen, wie wir das im gewöhnlichen Leben tun, oder wir entwickeln uns etwas weiter und beobachten mit Seele und Geist, wie wir das im Imaginieren, in der Inspiration und in der Intuition können. Aber auch das geistige Beobachten ist eben ein Beobachten, und notwendig ist zur Ergänzung alles Beobachtens, daß wir begreifen. Begreifen aber können wir nur, wenn wir das eine auf das andere im Weltenall, in unserer Umgebung beziehen. Sie können sich gute Begriffe verschaffen von Leib, Seele und Geist, wenn Sie den ganzen menschlichen Lebenslauf ins Auge fassen. Nur müssen Sie berücksichtigen, daß Sie bei solchem Beziehen, wie ich es jetzt andeuten werde, immer nur die allerersten Anfangsgründe des Begreifens haben. Sie müssen dann die Begriffe, welche Sie auf diese Art bekommen, weiter ausbilden.

Betrachten Sie nämlich das erst in die Welt gekommene Kind, betrachten Sie es in seinen Formen, in seinen Bewegungen, in seinen Lebensäußerungen, im Schreien, im Lallen und so weiter, dann bekommen Sie ein Bild mehr des Menschenleibes. Aber Sie bekommen dieses Bild des Menschenleibes auch nur vollständig, wenn Sie es beziehen auf das mittlere und auf das greise Lebensalter des Menschen. Im mittleren Lebensalter ist der Mensch mehr seelisch, im Greisenalter ist er am meisten geistig. Das letztere könnte leicht angefochten werden. Selbstverständlich werden da manche sagen: Aber viele Greise werden doch wieder ganz schwachgeistig! — Das ist insbesondere ein Einwand des Materialismus gegen das Seelisch-Geistige, daß man im Alter wieder schwachgeistig wird, und mit einer wahren Beharrlichkeit dozieren ja die Materialisten, daß selbst ein so großer Geist wie Kant in seinem Alter schwachsinnig geworden wäre. Dieser Einwand der Materialisten und diese Tatsache sind richtig. Allein, was sie beweisen wollen, beweisen sie nicht. Denn auch Kant war, als er vor der Todespforte stand, weiser, als er in seiner Kindheit war; nur war in seiner Kindheit sein Leib imstande, alles aufzunehmen, was aus seiner Weisheit kam; dadurch konnte es bewußt werden im physischen Leben. Im Greisenalter dagegen war der Leib unfähig geworden, das auch aufzunehmen, was der Geist ihm lieferte. Es war der Leib kein richtiges Werkzeug des Geistes mehr. Daher konnte auf dem physischen Plan Kant nicht mehr zum Bewußtsein dessen kommen, was in seinem Geiste lebte. Trotz der scheinbaren Tragkraft des eben gekennzeichneten Einwandes muß man sich ja doch klar darüber sein, daß man im Alter weise, geistvoll wird, daß man sich den Geistern nähert. Daher wird man bei solchen Greisen, die sich bis ins hohe Alter hinein Elastizität und Lebenskraft für ihren Geist bewahren, die Eigenschaften des Geistigen in ihrem Anfange erkennen müssen. Es gibt ja auch solche Möglichkeiten.

In Berlin waren einmal zwei Professoren. Der eine war Michelet, der Hegelianer, der schon über neunzig Jahre war. Er hatte es, da er ziemlich geistvoll war, nur zum Honorarprofessor gebracht, aber er hielt noch, als er schon so alt war, seine Vorträge. Da war dann ein anderer, Zeller, der Geschichtsschreiber der griechischen Philosophie. Der war gegen Michelet ein Jüngling, denn er war erst siebzig Jahre. Von dem hörte man überall, daß er die Last des Alters fühle, daß er nicht mehr seine Vorlesungen halten könne, daß er vor allem aber seine Vorlesungen eingeschränkt wissen wollte. Dazu sagte Michelet immer: Ich begreife den Zeller nicht; ich könnte noch den ganzen Tag Vorlesungen halten, der Zeller aber in seiner Jugend redet immer davon, daß ihm das zu viel Anstrengung verursacht!

Also Sie sehen, man wird schon vielleicht nur in einzelnen Exemplaren äußerlich physisch das bewahrheitet finden, was hier über den Geist des Alters zugrunde gelegt wird. Aber es ist so.

Betrachten wir dagegen den Menschen in seinen Lebensäußerungen mehr in seinem mittleren Alter, so bekommen wir die Anfangsgründe für das Beobachten des Seelischen. Daher kann auch der Mensch in seinem mittleren Lebensalter, man möchte sagen, das Seelische mehr verleugnen. Er kann seelenlos oder sehr beseelt erscheinen. Denn das Seelische steht in der Freiheit des Menschen, auch in der Erziehung. Daß manche Menschen sehr seelenlos sind in ihrer mittleren Lebenszeit, beweist daher nichts dagegen, daß die mittlere Lebenszeit die eigentlich seelische ist. Wenn man vergleicht die mehr zappelnde, unbewußt sich betätigende Leibesnatur des Kindes mit der beschaulichen, ruhigen Leibesnatur des Alters, so hat man auf der einen Seite einen Leib, der besonders seinen Leib hervorkehrt im Kinde, und einen Leib, der den Leib als solchen zurücktreten läßt, der sich gewissermaßen als Leib selbst verleugnet, im Greisenalter.

Wenn wir diese Betrachtung mehr auf das Seelische anwenden, dann werden wir sagen: Der Mensch trägt in sich denkendes Erkennen, Fühlen und Wollen. Schauen wir das Kind an, dann haben wir in dem Bilde, das uns das Kind seelisch darbietet, eine enge Verknüpfung zwischen Wollen und Fühlen. Man möchte sagen, Wollen und Fühlen sind im Kinde zusammengewachsen. Wenn das Kind zappelt, strampelt, so macht es genau die Bewegungen, die seinem Fühlen in diesem Augenblicke entsprechen; es ist nicht imstande, die Bewegungen etwa von dem Gefühl auseinanderzuhalten.

Anders wird das beim Greise. Bei ihm ist das Entgegengesetzte der Fall: denkendes Erkennen und Fühlen sind zusammengewachsen, und das Wollen tritt in einer gewissen selbständigen Art auf. Es verläuft also der menschliche Lebensgang in der Weise, daß das Fühlen, welches zuerst an das Wollen gebunden ist, sich allmählich im Laufe des Lebens vom Wollen loslöst. Und damit haben wir es gerade vielfach im Erziehen zu tun: mit dem Loslösen des Fühlens vom Wollen. Dann verbindet sich das vom Wollen losgelöste Fühlen mit dem denkenden Erkennen. Damit hat es dann das spätere Leben zu tun. Wir haben das Kind für das spätere Leben nur dann richtig vorbereitet, wenn wir in ihm bewirken, daß das Fühlen sich gut loslösen kann von dem Wollen; dann wird es in einer späteren Lebensära als Mann oder Frau auch das losgelöste Fühlen mit dem denkenden Erkennen verbinden können und wird so dem Leben gewachsen sein. Warum hören wir dem Greise zu, auch wenn er uns von seinen Lebenserfahrungen erzählt? Weil er im Laufe seines Lebens sein persönliches Empfinden verbunden hat mit seinen Begriffen und Ideen. Er erzählt uns nicht Theorien, er erzählt uns das, was er persönlich an Gefühlen hat anknüpfen können an die Ideen und Begriffe. Bei dem Greise, der wirklich sein Fühlen mit dem denkenden Erkennen verbunden hat, klingen daher die Begriffe und Ideen warm, klingen wirklichkeitsgesättigt, konkret, persönlich; während bei dem Menschen, der mehr im Mannes- oder Frauenalter stehengeblieben ist, die Begriffe und Ideen theoretisch, abstrakt, wissenschaftlich klingen. Das gehört einmal zum menschlichen Leben, daß von den menschlichen Seelenfähigkeiten ein gewisser Gang durchgemacht wird, indem sich das fühlende Wollen des Kindes entwickelt zu dem fühlenden Denken des Greises. Dazwischen liegt das menschliche Leben, und wir werden zu diesem menschlichen Leben nur gut erziehen, wenn wir eine solche Sache psychologisch ins Auge zu fassen vermögen.

Nun müssen wir darauf Rücksicht nehmen, daß bei aller unserer Beobachtung der Welt etwas zuerst auftritt, auch alle Psychologien beschreiben es als das erste, das bei der Weltbeobachtung auftritt: das ist die Empfindung. Wenn irgendeiner unserer Sinne in Zusammenhang kommt mit der Umwelt, so empfinden wir. Wir empfinden die Farbe, die Töne, Wärme und Kälte. So tritt in unserem Wechselverkehr mit der Umwelt die Empfindung auf.

So, wie die Empfindung gewöhnlich in den landläufigen Psychologien beschrieben wird, bekommen Sie keine richtige Vorstellung von dem, was Empfindung eigentlich ist. Wenn die Psychologien von der Empfindung sprechen, so sagen sie: Draußen geht ein gewisser physischer Vorgang vor sich, Vibrationen im Lichtäther oder Schwingungen in der Luft, das strömt an unser Sinnesorgan, reizt dieses Sinnesorgan. — Man spricht dann wohl von dem Reiz, und man schwingt sich dann auf zu einem Ausdruck, den man bildet, aber nicht zum Verständnis bringen will. Denn der Reiz löst aus durch das Sinnesorgan in unserer Seele die Empfindung, die ganz qualitative Empfindung, welche zustande kommt aus dem physischen Vorgang, zum Beispiel durch Schwingungen der Luftwellen beim Hören. Wie das zustande kommt, darüber kann die Psychologie, kann die gegenwärtige Wissenschaft überhaupt noch keine Auskunft geben. Das steht ja gewöhnlich in den Psychologien.

Näher als durch solche psychologischen Betrachtungen werden Sie dem Verständnis dieser Dinge kommen, wenn Sie durch die Einsicht in die Natur der Empfindungen selber sich die Frage beantworten können: Welcher der Seelenkräfte ist denn eigentlich die Empfindung am meisten verwandt? - Die Psychologen machen sich die Sache leicht; sie rechnen die Empfindung glattweg zu dem Erkennen und sagen: Erst empfinden wir, dann nehmen wir wahr, dann machen wir uns Vorstellungen, bilden uns Begriffe und so weiter. - So scheint ja auch der Vorgang zunächst zu sein. Nur nimmt man dann darauf keine Rücksicht, welcher Wesenheit eigentlich die Empfindung ist.

Wenn man die Empfindung wirklich in genügender Selbstbeobachtung durchschaut, so erkennt man: die Empfindung ist willensartiger Natur mit einem Einschlag von gefühlsmäßiger Natur. Sie ist zunächst nicht verwandt mit dem denkenden Erkennen, sondern mit dem fühlenden Wollen oder dem wollenden Fühlen. Ich weiß nicht, wie viele Psychologien - man kann natürlich nicht alle die unzähligen Psychologien, die es in der Gegenwart gibt, kennen - irgend etwas von der Verwandtschaft der Empfindung mit dem wollenden Fühlen oder dem fühlenden Wollen eingesehen haben. Wenn man sagt, daß die Empfindung mit dem Wollen verwandt ist, so ist das nicht genau gesprochen, denn sie ist mit dem wollenden Fühlen und dem fühlenden Wollen verwandt. Aber daß sie mit dem Fühlen verwandt ist, hat wenigstens ein Psychologe, der sich durch eine besonders gute Beobachtung auszeichnete, Moriz Benedikt in Wien, in seiner Psychologie erkannt.

Diese Psychologie wird von den Psychologen allerdings weniger berücksichtigt. Es ist auch etwas Eigentümliches mit ihr. Erstens ist Moriz Benedikt seiner Fachstempelung nach Kriminalanthropologe; der schreibt nun eine Psychologie. Zweitens ist er Naturforscher, und er schreibt über die Wichtigkeit dichterischer Kunstwerke bei der Erziehung, analysiert sogar dichterische Kunstwerke, um zu zeigen, wie man sie in der Erziehung verwenden kann. Es ist etwas Schreckliches: der Mann will Wissenschafter sein und hält etwas davon, daß die Psychologen etwas lernen können von den Dichtern! Und drittens: Dieser Mann ist jüdischer Naturforscher und schreibt eine Psychologie und widmet diese ausgerechnet dem Priester, dem katholischen Philosophen der Theologischen Fakultät an der Wiener Universität — das war er damals noch -, Laurenz Müllner. Drei furchtbare Dinge, die unmöglich die Fachpsychologen veranlassen können, den Mann ernst zu nehmen. Aber Sie würden, wenn Sie seine Psychologie durchlesen würden, so viele wirklich treffende Aperçus im einzelnen finden, daß Sie davon viel hätten, trotzdem Sie den ganzen Aufbau dieser Psychologie, die ganze materialistische Denkweise Moriz Benedikts - denn in der steckt er doch - ablehnen müssen. Von dem Ganzen des Buches haben Sie nicht das Geringste, aber von den einzelnen Beobachtungen sehr viel. So muß man sich das Beste in der Welt dort suchen, wo es vorhanden ist. Wenn einer ein guter Beobachter im einzelnen ist und es ekelt einen vor der Gesamttendenz, die man bei Moriz Benedikt finden kann, dann braucht man darum nicht seine guten Beobachtungen im einzelnen abzulehnen.

Die Empfindung ist also, wie sie im Menschen auftritt, wollendes Fühlen oder fühlendes Wollen. Daher müssen wir sagen: Da, wo sich äußerlich die menschliche Sinnessphäre ausbreitet - die Sinne tragen wir ja an der Außenseite unseres Leibes, wenn man sich grob ausdrükken darf -, da ist im Menschen in gewisser Weise fühlendes Wollen, wollendes Fühlen vorhanden. Zeichnen wir uns skizzenhaft den Menschen schematisch auf, so können wir sagen: An der äußeren Oberfläche des Menschen - ich bitte zu berücksichtigen, daß das alles schematisch gemeint ist —, da haben wir die Sinnessphäre, da ist wollendes Fühlen, fühlendes Wollen vorhanden (siehe Zeichnung S. 114). Was tun wir denn an dieser Oberfläche, wenn fühlendes Wollen, wollendes Fühlen vorhanden ist, soweit diese Körperoberfläche Sinnessphäre ist? Wir verüben eine Tätigkeit, die halb Schlafen und halb Traum ist; ein träumendes Schlafen, ein schlafendes Träumen könnten wir es auch nennen. Denn wir schlafen nicht nur in der Nacht, wir schlafen fortwährend an der Peripherie, an der äußeren Oberfläche unseres Leibes, und wir durchschauen als Menschen deshalb die Empfindungen nicht ganz, weil wir in diesen Gegenden, wo die Empfindungen sind, nur schlafend träumen und träumend schlafen. Die Psychologen ahnen gar nicht, daß es derselbe Grund ist, warum sie die Empfindungen nicht erfassen können, der uns auch hindert, wenn wir des Morgens erwachen, die Träume uns klar zum Bewußtsein zu bringen. Sie sehen, die Begriffe von Schlafen und Träumen haben eine ganz andere Bedeutung noch als die, welche wir im gewöhnlichen Leben anwenden würden. Wir kennen das Schlafen im gewöhnlichen Leben nur dadurch, daß wir wissen: in der Nacht, wenn wir im Bette liegen, schlafen wir. Wir wissen gar nicht, daß dieses Schlafen etwas ist, was eine viel größere Verbreitung hat, was wir fortwährend auch tun an unserer Körperoberfläche; nur mischen sich an unserer Körperoberfläche in das Schlafen fortwährend Träume hinein. Diese «Träume» sind die Sinnesempfindungen, bevor sie vom Verstande und vom denkenden Erkennen erfaßt sind.

Sie müssen die Willens- und Fühlenssphäre beim Kinde auch in seinen Sinnen aufsuchen. Deshalb betonen wir so stark, daß wir, indem wir das Kind intellektuell erziehen, auch auf den Willen fortwährend wirken müssen; denn in allem, was das Kind anschauen muß, was es wahrnehmen muß, müssen wir auch den Willen und das Fühlen pflegen, sonst widersprechen wir ja eigentlich dem kindlichen Empfinden. Wir können erst zum Greise, erst am Lebensabend des Menschen so zu ihm sprechen, daß wir auch die Empfindungen auffassen als schon metamorphosiert. Beim Greise ist es so, daß auch schon die Empfindung übergegangen ist vom fühlenden Wollen zum fühlenden Denken oder denkenden Fühlen. Bei ihm ist die Empfindung etwas anderes geworden. Da haben die Empfindungen mehr Gedankencharakter und entbehren des unruhigen Willenscharakters, tragen größere Ruhe in sich. Beim Greise können wir erst sagen, die Empfindungen haben sich dem Begriffe, dem Ideencharakter angenähert.

Diesen feinen Unterschied in der Empfindung machen gewöhnlich die Psychologen nicht. Für sie ist Greisesempfindung dasselbe, was Kindesempfindung ist, denn Empfindung ist für sie Empfindung. Das ist ungefähr eine solche Logik, als wenn Sie ein Rasiermesser vor sich haben und sagen: Das Rasiermesser ist ein Messer, also schneiden wir damit das Fleisch, denn Messer ist Messer. - Da nimmt man von der Worterklärung den Begriff. Das sollte man aber niemals machen, sondern man sollte den Begriff von den Tatsachen nehmen. Bei der Empfindung würden wir finden, daß sie auch lebt, daß sie auch ein Werden im Leben durchmacht, daß sie beim Kinde mehr willensartigen Charakter hat, beim Greise mehr verstandesmäßig intellektuellen Charakter. Natürlich ist es für den Menschen leichter, alles aus den Worten herauszuklauben; daher haben wir so viele Worterklärer, und es kann manches ganz entsetzlich auf einen wirken.

Ich war einmal in der Lage, einem Mitschüler zuzuhören, nachdem wir beide etwas auseinandergekommen waren. Wir hatten dieselbe Volksschule besucht; ich kam auf die Realschule, er auf das Lehrerseminar, noch dazu auf ein ungarisches, und das wollte in den siebziger Jahren etwas heißen. Wir trafen uns nach einigen Jahren und besprachen uns über das Licht. Ich hatte schon gelernt, was man in der regulären Physik lernen konnte, daß also das Licht etwas zu tun habe mit Schwingungen im Äther und so weiter. Das konnte man wenigstens als eine Ursache des Lichtes ansehen. Mein ehemaliger Mitschüler sagte dazu: Wir haben auch gelernt, was das Licht ist: Licht ist die Ursache des Sehens! - Ein Wortgeplänkel! So werden die Begriffe zu bloßen Worterklärungen. Und man kann sich vorstellen, was damit den Schülern gegeben wurde, wenn man weiß, daß dieser betreffende Herr später selbst als Lehrer an zahlreiche Schüler den Unterricht zu erteilen hatte, bis er pensioniert worden ist. - Wir müssen von den Worten loskommen und müssen an den Geist der Dinge herankommen. Wir müssen nicht gleich, wenn wir etwas begreifen wollen, jedesmal an das Wort denken, sondern wir müssen die tatsächlichen Beziehungen aufsuchen. Wenn wir bei dem Worte «Geist» die Ursprünge dafür in Fritz Mauthners Sprachgeschichte aufsuchen und fragen: Wie tritt zuerst das Wort «Geist» auf? - so werden wir die Verwandtschaft des Wortes Geist mit «Gischt», mit «Gas» finden. Diese Verwandtschaften bestehen, aber es würde nichts Besonderes dabei herauskommen, wenn man bloß darauf bauen wollte. Leider wird gerade manchmal diese Methode kaschiert, umfassend kaschiert in der Bibelforschung angewendet. Daher ist die Bibel dasjenige Buch, das von den meisten Menschen, besonders von den gegenwärtigen Theologen, am allerschlechtesten verstanden wird.

Worum es sich handelt, das ist, daß wir überall sachgemäß vorgehen, daß wir also versuchen, nicht von der Wortgeschichte aus einen Begriff vom Geiste zu bekommen, sondern dadurch, daß wir die kindliche Leibesauslebung vergleichen mit der greisenhaften Leibesauslebung. Durch dieses Tatsachen-aufeinander-Beziehen bekommen wir reale Begriffe.

Und so bekommen wir auch nur einen realen Begriff von der Empfindung, wenn wir wissen: sie entsteht als wollendes Fühlen oder fühlendes Wollen berm Kinde noch in der Körperperipherie dadurch, daß diese Körperperipherie beim Kinde gegenüber dem mehr menschlichen Inneren schläft und dabei träumt. Sie sind also nicht nur im denkenden Erkennen voll wach, sondern Sie sind überhaupt nur im Inneren Ihres Leibes voll wach. An der Körperperipherie, an der Leibesoberfläche schlafen Sie auch fortwährend. Und weiter: Was da in der Umgebung des Leibes oder, besser gesagt, an der Oberfläche des Leibes stattfindet, das findet in ähnlicher Weise auch statt im Kopf, und am stärksten findet es statt, je weiter wir in das Innere des Menschen hineinkommen, in das Muskelhafte, das Bluthafte. Da drinnen schläft der Mensch wiederum und träumt dabei. An der Oberfläche schläft und träumt der Mensch, und auch mehr gegen sein Inneres zu schläft er und träumt wiederum dabei. Daher bleibt in unserem Inneren dasjenige, was mehr seelisch-wollendes Fühlen, fühlendes Wollen ist, unser Wunschleben und so weiter wiederum in einem träumenden Schlaf. Wo sind wir denn also nur voll wachend? In der Zwischenzone, wenn wir ganz wach sind.

Sie sehen, wir gehen jetzt vom geistigen Gesichtspunkte aus, indem wir die Tatsachen des Wachens und des Schlafens auch räumlich auf den Menschen anwenden und dies auf seine Gestaltung beziehen, so daß wir uns sagen können: Der Mensch ist vom geistigen Gesichtspunkte angesehen so, daß er an seiner Oberfläche und in seinen Innenorganen schläft und nur in der Zwischenzone im Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod jetzt wirklich ganz wach sein kann. Was für Organe sind denn in dieser Zwischenzone am meisten ausgebildet? Diejenigen Organe, besonders im Kopfe, die wir die Nerven nennen, der Nervenapparat. Dieser Nervenapparat sendet seine Ausläufer in die äußere Oberflächenzone hinein und wieder in das Innere; da verlaufen die Nerven, und zwischendrinnen sind solche Mittelzonen wie das Gehirn, namentlich das Rückenmark, auch das Bauchmark. Da ist uns Gelegenheit gegeben, so eigentlich recht wach zu sein. Wo die Nerven am meisten ausgebildet sind, da sind wir am meisten wach. Aber das Nervensystem hat zum Geiste eine eigentümliche Beziehung. Es ist ein Organsystem, das durch die Funktionen des Leibes fortwährend die Tendenz hat zu verwesen, mineralisch zu werden. Wenn Sie beim lebenden Menschen sein Nervensystem von der übrigen Drüsen-MuskelBlutwesenheit und Knochenwesenheit loslösen könnten — das Knochensystem könnten Sie sogar beim Nervensystem dabeilassen -, so wäre das beim lebenden Menschen schon Leichnam, fortwährend Leichnam. Im Nervensystem geht fortwährend das Sterben des Menschen vor sich. Das Nervensystem ist das einzige System, welches gar keine unmittelbare Beziehung zum Geistig-Seelischen hat. Blut, Muskeln und so weiter haben immer direkte Beziehungen zum Geistig-Seelischen, das nervöse System hat unmittelbar dazu gar keine Beziehungen; es hat nur dadurch Beziehungen zum Geistig-Seelischen, daß es sich fortwährend aus der menschlichen Organisation ausschaltet, daß es nicht da ist, weil es fortwährend verwest. Die anderen Glieder leben; deshalb bilden sie direkte Beziehungen aus zum Geistig-Seelischen. Das Nervensystem stirbt fortwährend ab; es sagt fortwährend zum Menschen: Du kannst dich entwickeln, weil ich dir kein Hindernis biete, weil ich mache, daß ich gar nicht da bin mit meinem Leben! — Das ist das Eigenartige. In der Psychologie und Physiologie finden Sie dargestellt: das vermittelnde Organ des Empfindens, des Denkens, des GeistigSeelischen überhaupt ist das Nervensystem. Wodurch ist es aber dieses vermittelnde Organ? Nur dadurch, daß es sich fortwährend aus dem Leben herausdrückt, daß es dem Denken und Empfinden gar keine Hindernisse bietet, daß es gar keine Beziehungen zum Denken und Empfinden anstiftet, daß es den Menschen leer sein läßt in bezug auf das Geistig-Seelische da, wo es ist. Für das Geistig-Seelische sind einfach dort, wo die Nerven sind, Hohlräume. Daher kann das GeistigSeelische dort hinein, wo die Hohlräume sind. Wir müssen dem Nervensystem dankbar sein, daß es sich nicht kümmert um das GeistigSeelische, daß es all das nicht tut, was ihm die Physiologen und Psychologen zuschreiben. Täte es das, geschähe nur fünf Minuten lang das, was die Nerven nach den Beschreibungen der Physiologen und Psychologen tun sollen, so würden wir gar nichts in diesen fünf Minuten von der Welt und von uns wissen: wir würden eben schlafen. Denn die Nerven machten es dann so wie jene Organe, die das Schlafen vermitteln, die das fühlende Wollen, das wollende Fühlen vermitteln.

Ja, es ist schon so, daß man es heute etwas hart hat, wenn man darauf kommt, was in der Physiologie und Psychologie die Wahrheit ist, denn die Leute sagen immer: Du stellst ja die Welt auf den Kopf. Die Wahrheit ist nur, daß sie auf dem Kopfe steht und daß man sie durch Geisteswissenschaft auf die Beine zu stellen hat. Die Physiologen sagen: Die Organe des Denkens sind die Nerven, insbesondere das Gehirn. — Wahr ist, daß Gehirn- und Nervensystem gerade nur dadurch mit dem denkenden Erkennen etwas zu tun haben, weil sie sich immerfort aus der Organisation des Menschen ausschließen und weil dadurch das denkende Erkennen sich entfalten kann.

Jetzt betrachten Sie etwas ganz genau und nehmen Sie, bitte, Ihre Verstandeskräfte gut zusammen. In der Umgebung des Menschen, wo die Sinnessphäre ist, geschehen reale Vorgänge, die sich immerfort hineinstellen in das Weltgeschehen. Nehmen Sie an, Licht wirke auf den Menschen durch das Auge. Im Auge, das heißt in der Sinnessphäre, geschieht ein realer Vorgang, es geschieht etwas, ein physisch-chemischer Vorgang. Der setzt sich fort in das Innere des menschlichen Leibes, und er kommt dann auch bis in jenes Innere hinein (das dunkel Schraffierte der Zeichnung), wo wiederum physisch-chemische Vorgänge vor sich gehen. Jetzt denken Sie sich, Sie stehen einer beleuchteten Fläche gegenüber, und Lichtstrahlen fallen von dieser beleuchteten Fläche aus in Ihr Auge. Dort entstehen wieder physisch-chemische Vorgänge, die sich fortsetzen in die Muskel-Blutnatur im Inneren des Menschen. Dazwischen bleibt eine leere Zone. In dieser leeren Zone, die durch das nervöse Organ leer gelassen ist, entwickeln sich keine solchen Vorgänge wie im Auge oder im Inneren des Menschen, die selbständige Vorgänge sind, sondern da hinein setzt sich fort, was draußen ist: die Natur des Lichtes, die Natur der Farben selber und so weiter. Wir haben also an unserer Körperoberfläche, wo die Sinne sind, reale Vorgänge, welche vom Auge, vom Ohr, vom Wärmeaufnahmeorgan und so weiter abhängen. Ähnliche Vorgänge sind auch im Inneren des Menschen. Aber dazwischen nicht, wo die Nerven sich eigentlich ausbreiten; die machen den Raum frei, dort können wir leben mit dem, was draußen ist. Das Auge verändert Ihnen Licht und Farbe. Dort aber, wo Sie Nerven haben, wo Sie hohl sind in bezug auf das Leben, da verändern sich Licht und Farbe nicht, da leben Sie Licht und Farbe mit. Sie sind nur in bezug auf die Sinnessphäre abgesondert von einer äußeren Welt, aber innen leben Sie wie in einer Schale die Außenvorgänge mit. Da werden Sie selbst zum Licht, da werden Sie selbst zum Ton, da breiten sich die Vorgänge aus, weil die Nerven dafür kein Hindernis sind wie das Blut und der Muskel.

Jetzt bekommen wir ein Gefühl davon, was das für eine Bedeutung hat: Wir wachen da mit Bezug auf einen im Verhältnis zum Leben in uns vorhandenen Hohlraum, während wir an der äußeren Oberfläche und im Inneren schlafend träumen und träumend schlafen. Wir wachen nur in einer Zone, die zwischen dem Äußeren und dem Inneren liegt, vollständig auf. Das mit Bezug auf den Raum.

Wir müssen aber, wenn wir den Menschen vom geistigen Gesichtspunkt betrachten, auch sein Zeitliches in Beziehung bringen zum Wachen und Schlafen und Träumen.

Sie lernen etwas; das nehmen Sie auf so, daß es hereingeht in Ihr Vollwachen. Während Sie sich damit beschäftigen und wenn Sie daran denken, ist es in Ihrem Vollwachen. Dann gehen Sie an das andere Leben. Anderes nimmt Ihr Interesse, Ihre Aufmerksamkeit in Anspruch. Was tut nun das, was Sie vordem gelernt haben und womit Sie sich beschäftigt haben? Es fängt an einzuschlafen, und wenn Sie sich wieder daran erinnern, dann wacht es wieder auf. Sie kommen mit allen diesen Dingen nur zurecht, wenn Sie all das Wortgeplänkel, das Sie in den Psychologien als Erinnern und Vergessen haben, ersetzen durch die realen Begriffe. Was ist Erinnern? Es ist das Aufwachen eines Vorstellungskomplexes. Und was ist das Vergessen? Das Einschlafen des Vorstellungskomplexes. Da können Sie Reales mit real Erlebtem vergleichen, da haben Sie keine bloßen Worterklärungen. Wenn Sie immer reflektieren auf Wachen und Schlafen, wenn Sie sich selber einschlafend erleben oder einen anderen einschlafen sehen, so haben Sie einen realen Vorgang. Sie beziehen das Vergessen, diese innere Seelentätigkeit, auf diesen realen Vorgang - nicht auf irgendein Wort -, vergleichen die beiden und sagen sich: Vergessen ist nur ein Einschlafen auf einem anderen Gebiete, und auch Erinnern ist nur ein Aufwachen auf einem anderen Gebiete.

Nur dadurch kommen Sie zum geistigen Weltbegreifen, daß Sie Reales mit Realem vergleichen. Wie Sie das kindliche Lebensalter mit dem Greisenalter vergleichen müssen, um Leib und Geist wirklich aufeinander beziehen zu können, wenigstens in den ersten Rudimenten, so vergleichen Sie Erinnern und Vergessen, indem Sie es auf ein Reales, auf Einschlafen und Aufwachen beziehen.

Das ist es, was für die Zukunft der Menschheit so unendlich notwendig werden wird: daß die Menschen sich bequemen, in die Realität, in die Wirklichkeit sich hineinzubegeben. Die Menschen denken heute fast nur in Worten, sie denken nicht in Wirklichkeit. Wo käme einem heutigen Menschen das Reale, was wir haben können, wenn wir vom Erinnern sprechen, das Aufwachen, in den Sinn? Er wird im Umkreise der Worte alles mögliche hören können, um das Erinnern zu definieren, aber er wird nicht daran denken, aus der Wirklichkeit, aus der Sache heraus diese Dinge zu finden.

Daher werden Sie es begreiflich finden, wenn man so etwas wie die Dreigliederung, was ganz aus der Wirklichkeit, nicht aus abstrakten Begriffen, herausgeholt ist, an die Menschen heranbringt, daß diese Menschen es zunächst unverständlich finden, weil sie gar nicht gewöhnt sind, die Dinge aus der Wirklichkeit herauszuholen. Sie verbinden gar keine Begriffe mit dem Herausholen der Dinge aus der Wirklichkeit. Und am wenigsten Begriffe mit dem Herausholen der Dinge aus der Wirklichkeit verbinden zum Beispiel die sozialistischen Führer in ihren Theorien; sie stellen das letzte Ende, die letzte Dekadenzerscheinung des Worterklärens dar. Die Leute glauben am allermeisten, etwas von der Wirklichkeit zu verstehen; wenn sie aber anfangen zu sprechen, dann kommen sie mit den allerleersten Worthülsen.

Das war nur eine Zwischenbemerkung, die namentlich mit dem Wesen unserer gegenwärtigen Zeitströmung zusammenhängt. Aber der Pädagoge muß auch die Zeit begreifen, in der er steht, weil er die Kinder begreifen muß, die ihm aus dieser Zeit heraus zum Erziehen übergeben werden.

Seventh Lecture

It is important for you to understand what the human being actually is. In our previous lectures on general education, we have attempted to understand the human being first from a psychological and then from a spiritual point of view. Today we will continue with the latter. Of course, we will have to continually refer to concepts that are commonplace in the world of education, as well as in the spiritual and psychological realms, because over time you will have to deal with educational and psychological literature, as far as you have the time and leisure to do so.

When we look at human beings from a psychological point of view, we place the main emphasis on discovering antipathies and sympathies within the laws of the world; but when we look at human beings from a spiritual point of view, we must place the main emphasis on discovering states of consciousness. Yesterday we dealt with the three states of consciousness that prevail in human beings: full wakefulness, dreaming, and sleeping — and we showed how full wakefulness is actually only present in thinking cognition, while dreaming prevails in feeling and sleeping in willing.

All understanding is actually a relating of one thing to another. But we cannot understand in the world other than by relating one thing to another. I would like to preface this with a methodological remark. By relating ourselves to the world in a cognitive way, we first observe. Either we observe with our senses, as we do in ordinary life, or we develop ourselves a little further and observe with our soul and spirit, as we can do in imagination, inspiration, and intuition. But even spiritual observation is still observation, and it is necessary to supplement all observation with understanding. But we can only understand if we relate one thing to another in the universe, in our environment. You can gain a good understanding of body, soul, and spirit if you consider the entire course of human life. However, you must bear in mind that in such a relationship, as I will now indicate, you will always have only the very first beginnings of understanding. You must then further develop the concepts you obtain in this way.

Consider the child who has just come into the world, consider it in its forms, in its movements, in its expressions of life, in its crying, in its babbling, and so on, and you will gain a more complete picture of the human body. But you will only obtain a complete picture of the human body if you relate it to the middle and old age of human beings. In middle age, human beings are more soulful, and in old age they are most spiritual. The latter could easily be contested. Of course, some will say: But many old people become very weak-minded again! — This is an objection of materialism against the soul-spiritual, that in old age one becomes weak-minded again, and with true persistence the materialists lecture that even a great mind like Kant became senile in his old age. This objection of the materialists and this fact are correct. However, what they want to prove, they do not prove. For even Kant, when he stood at death's door, was wiser than he had been in his childhood; only in his childhood was his body able to absorb everything that came from his wisdom; thus it could become conscious in physical life. In old age, on the other hand, the body had become incapable of absorbing what the spirit provided it. The body was no longer a proper tool of the spirit. Therefore, on the physical plane, Kant could no longer become conscious of what lived in his spirit. Despite the apparent weight of the objection just mentioned, one must nevertheless be clear that in old age one becomes wise and spiritual, that one approaches the spirits. Therefore, in such elderly people who retain elasticity and vitality for their spirit into old age, one must recognize the qualities of the spiritual in their beginnings. Such possibilities do exist.

There were once two professors in Berlin. One was Michelet, the Hegelian, who was already over ninety years old. Since he was quite spirited, he had only made it to honorary professor, but he still gave lectures even at his advanced age. Then there was another, Zeller, the historian of Greek philosophy. Compared to Michelet, he was a young man, for he was only seventy years old. Everyone said that he felt the burden of age, that he could no longer give his lectures, and that, above all, he wanted to limit his lectures. Michelet always said: “I don't understand Zeller; I could still give lectures all day long, but Zeller, in his youth, always talks about how it causes him too much effort!”

So you see, perhaps only in individual cases will one find outward physical evidence of what is assumed here about the spirit of old age. But that is how it is.

If, on the other hand, we consider human beings in their middle age in terms of their expressions of life, we obtain the basic principles for observing the soul. Therefore, people in middle age can, one might say, deny the soul more. They can appear soulless or very soulful. For the soul lies in human freedom, including in education. The fact that some people are very soulless in middle age therefore proves nothing against the fact that middle age is actually the age of the soul. If we compare the more restless, unconsciously active physical nature of the child with the contemplative, calm physical nature of old age, we have on the one hand a body that particularly emphasizes its physicality in the child, and on the other hand a body that allows the physicality to recede, that in a sense denies itself as a body in old age.

If we apply this observation more to the soul, then we will say: Human beings carry within themselves thinking, feeling, and willing. If we look at the child, then we see in the image that the child presents to us spiritually a close connection between willing and feeling. One might say that will and feeling have grown together in the child. When the child fidgets and kicks, it makes exactly the movements that correspond to its feelings at that moment; it is not able to separate the movements from the feeling.

The situation is different for the elderly. In their case, the opposite is true: thinking and feeling have grown together, and volition occurs in a certain independent way. The course of human life thus proceeds in such a way that feeling, which is initially bound to volition, gradually detaches itself from volition in the course of life. And this is precisely what we often have to deal with in education: the detachment of feeling from will. Then feeling, detached from will, connects with thinking and cognition. This is what later life has to do with. We have only properly prepared the child for later life if we enable it to detach its feelings from its will; then, in a later stage of life as a man or woman, it will also be able to connect detached feelings with thinking and cognition and will thus be able to cope with life. Why do we listen to the old man when he tells us about his life experiences? Because in the course of his life he has connected his personal feelings with his concepts and ideas. He does not tell us theories, he tells us what he personally has been able to connect with the ideas and concepts in terms of feelings. In the case of the old man who has truly connected his feelings with his thinking, the concepts and ideas sound warm, saturated with reality, concrete, personal; whereas in the case of the person who has remained more in the age of man or woman, the concepts and ideas sound theoretical, abstract, scientific. It is part of human life that the human soul undergoes a certain process, in which the feeling will of the child develops into the feeling thinking of the old man. Human life lies between these two stages, and we can only educate well for this human life if we are able to grasp such a thing psychologically.

Now we must take into account that in all our observations of the world, something occurs first, and all psychologies describe it as the first thing that occurs in the observation of the world: that is sensation. When any of our senses comes into contact with the environment, we feel. We perceive color, sounds, warmth, and cold. Thus, sensation arises in our interaction with the environment.

The way sensation is usually described in popular psychology does not give you a correct mental image of what sensation actually is. When psychologists talk about sensation, they say: a certain physical process is taking place outside, vibrations in the light ether or oscillations in the air, which flow to our sensory organ and stimulate it. — One then speaks of the stimulus, and one then swings to an expression that one forms, but does not want to understand. For the stimulus triggers through the sensory organ in our soul the sensation, the entirely qualitative sensation, which arises from the physical process, for example through vibrations of the air waves when hearing. Psychology and current science are still unable to provide any information about how this comes about. This is usually found in psychology books.

You will come closer to understanding these things than through such psychological considerations if you can answer the question yourself by gaining insight into the nature of sensations: Which of the soul's powers is actually most closely related to sensation? Psychologists make it easy for themselves; they simply attribute sensation to cognition and say: first we feel, then we perceive, then we form mental images, concepts, and so on. At first glance, this seems to be how the process works. But then they fail to take into account the nature of sensation itself.

If one really examines sensation through sufficient self-observation, one recognizes that sensation is of a volitional nature with an emotional element. It is not primarily related to thinking cognition, but to feeling volition or volitional feeling. I do not know how many psychologies—one cannot, of course, know all the countless psychologies that exist today—have recognized anything of the relationship between sensation and volitional feeling or feeling volition. To say that sensation is related to volition is not strictly accurate, because it is related to volitional feeling and feeling volition. But at least one psychologist, Moriz Benedikt in Vienna, who was particularly skilled at observation, recognized in his psychology that it is related to feeling.

However, this psychology is given less consideration by psychologists. There is also something peculiar about it. First, Moriz Benedikt is a criminal anthropologist by profession; he now writes a psychology. Second, he is a natural scientist, and he writes about the importance of poetic works of art in education, even analyzing poetic works of art to show how they can be used in education. It is something terrible: the man wants to be a scientist and believes that psychologists can learn something from poets! And thirdly: this man is a Jewish natural scientist and writes a psychology book and dedicates it, of all people, to the priest, the Catholic philosopher of the Faculty of Theology at the University of Vienna — which he still was at the time — Laurenz Müllner. Three terrible things that make it impossible for professional psychologists to take the man seriously. But if you were to read through his psychology, you would find so many truly apt insights in detail that you would gain a lot from it, even though you would have to reject the entire structure of this psychology, the entire materialistic way of thinking of Moriz Benedikt — because that is what it is. You gain nothing from the book as a whole, but you gain a great deal from the individual observations. So you have to look for the best in the world where it is to be found. If someone is a good observer in detail and you are repulsed by the overall tendency that can be found in Moriz Benedikt, then you don't have to reject his good observations in detail.

The sensation, as it occurs in humans, is therefore willing feeling or feeling willing. Therefore, we must say: where the human sensory sphere extends outward—we carry our senses on the outside of our body, if one may express it crudely—there is, in a certain sense, feeling willing and willing feeling present in humans. If we sketch a schematic diagram of the human being, we can say: on the outer surface of the human being — please bear in mind that this is all meant schematically — we have the sensory sphere, there is willing feeling, feeling willing (see drawing on p. 114). What do we do on this surface when feeling will and willing feeling are present, insofar as this body surface is the sensory sphere? We perform an activity that is half sleep and half dream; we could also call it dreaming sleep, sleeping dreams. For we do not only sleep at night, we sleep continuously at the periphery, at the outer surface of our body, and as human beings we do not fully understand sensations because in these areas where the sensations are, we only dream while sleeping and sleep while dreaming. Psychologists have no idea that the same reason why they cannot grasp sensations also prevents us, when we wake up in the morning, from bringing our dreams clearly into consciousness. You see, the concepts of sleeping and dreaming have a completely different meaning than the ones we would use in ordinary life. We know sleep in ordinary life only in that we know that at night, when we lie in bed, we sleep. We do not know that this sleeping is something that is much more widespread, something we also do continuously on the surface of our bodies; only on the surface of our bodies are dreams constantly mixed into our sleep. These “dreams” are the sensory perceptions before they are grasped by the mind and thinking cognition.

You must also seek out the sphere of will and feeling in the child's senses. That is why we emphasize so strongly that, while educating the child intellectually, we must also constantly influence the will; for in everything the child has to look at, everything it has to perceive, we must also cultivate the will and the feelings, otherwise we are actually contradicting the child's feelings. Only when we reach old age, only in the twilight of our lives, can we speak to others in such a way that we also perceive their feelings as already metamorphosed. In old age, feelings have already transitioned from feeling-willing to feeling-thinking or thinking-feeling. For the elderly, feelings have become something else. Their feelings have more of a thought-like character and lack the restless will-like character; they carry greater calm within themselves. Only in the elderly can we say that feelings have approached the concept, the idea-like character.

Psychologists do not usually make this subtle distinction in sensation. For them, the sensation of an elderly person is the same as that of a child, because for them, sensation is sensation. This is roughly the same logic as if you had a razor in front of you and said: The razor is a knife, so we use it to cut meat, because a knife is a knife. - Here, the concept is taken from the definition of the word. But one should never do that; instead, one should take the concept from the facts. In the case of sensation, we would find that it also lives, that it also undergoes a process of becoming in life, that it has a more volitional character in children and a more intellectual character in the elderly. Of course, it is easier for people to pick everything out of words; that is why we have so many word explainers, and some things can have a terrible effect on you.

I was once in a position to listen to a classmate after we had drifted apart somewhat. We had attended the same elementary school; I went on to secondary school, he to teacher training college, and a Hungarian one at that, which meant something in the 1970s. We met again after a few years and talked about light. I had already learned what could be learned in regular physics, that light had something to do with vibrations in the ether and so on. At least that could be seen as one cause of light. My former classmate said: We also learned what light is: Light is the cause of seeing! - A war of words! This is how concepts become mere explanations of words. And one can form a mental image of what was imparted to the students when one knows that this gentleman later had to teach numerous students himself until he retired. We must move away from words and approach the spirit of things. When we want to understand something, we must not immediately think of the word, but rather seek out the actual relationships. If we look for the origins of the word “spirit” in Fritz Mauthner's history of language and ask: How did the word “spirit” first appear? – we will find the relationship between the word spirit and ‘spray’ and “gas.” These relationships exist, but nothing special would come of it if one were to rely solely on them. Unfortunately, this method is sometimes concealed, comprehensively concealed in biblical research. That is why the Bible is the book that is least understood by most people, especially by contemporary theologians.

The point is that we proceed appropriately in all cases, that we try not to derive a concept of spirit from the history of the word, but by comparing the physical activity of a child with that of an elderly person. By relating these facts to each other, we arrive at real concepts.

And so we also only get a real concept of sensation when we know that it arises as willing feeling or feeling willing in children still in the body's periphery, because this body periphery in children sleeps and dreams in contrast to the more human inner self. So they are not only fully awake in thinking cognition, but they are only fully awake inside their bodies. At the periphery of the body, on the surface of the body, you are also constantly asleep. And further: what takes place in the environment of the body, or rather on the surface of the body, also takes place in a similar way in the head, and it takes place most strongly the further we go into the inner being of the human being, into the muscular, the bloody. There, the human being sleeps again and dreams. On the surface, the human being sleeps and dreams, and also sleeps and dreams again as he moves further inward. Therefore, what is more soul-willing feeling, feeling-willing, our life of desire, and so on, remains in our inner being in a dreaming sleep. So where are we fully awake? In the intermediate zone, when we are fully awake.