The Study of Man

GA 293

1 September 1919, Stuttgart

Lecture X

We have spoken of the nature of man from the point of view of the soul and spirit. We have at least thrown some light on these two aspects. We shall have to supplement the knowledge thus gained by uniting the point of view of the body with that of the spirit and of the soul so that we may get a complete survey of man, and may be able to pass on from this to an understanding of his external bodily nature also.

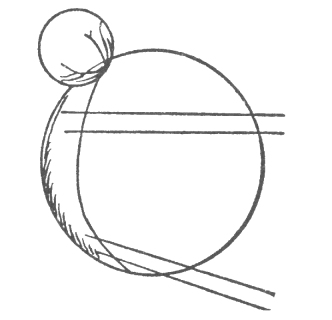

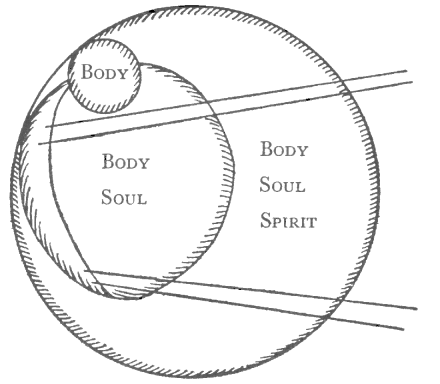

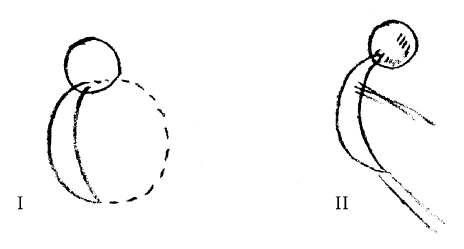

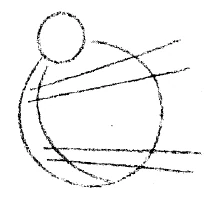

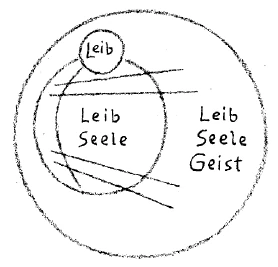

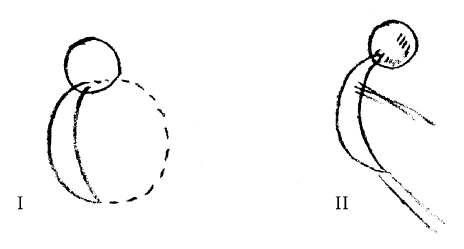

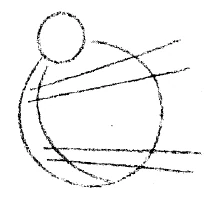

First we will recall—what must have struck us from various aspects—that the human being has different forms in the three members of his nature. We have pointed out that the head is essentially round; that the true nature of the bodily head is given in this spherical form. Next we pointed out how the chest part of man is a fragment of a sphere. Thus if we draw it diagrammatically we give the form of a sphere to the head, and a moon form to the breast—realising clearly that in this moon form a part of a sphere, a fragment of a sphere is contained. We must consequently, allow that the moon form of the chest can be completed. You will only rightly understand this central member of man's nature, the breast-form, when you regard it, too, as a sphere but as a sphere of which only one part, a moon, is visible, and the other part invisible.

From this it is perhaps apparent that in ancient times, when men had a greater capacity for seeing forms, they were not wrong in speaking of the sun as corresponding to the head, and of the moon as corresponding to the breast form. And just as when the moon is not full we see it only as a fragment of a sphere, so too we really only see in the breast form a fragment of the middle system of man. From this you can understand that the head form of man is a comparatively complete, self-enclosed thing. The head form reveals, physically, that it is a thing enclosed in itself. It is, so to speak, just what it appears. The head form is the one that conceals least of itself.

The breast part of the human being, on the other hand, conceals very much of itself. It leaves part of itself invisible. It is very important for a knowledge of man's nature to realise that a large part of the breast portion is invisible. We can say that the breast portion of man shows its bodily nature in one direction, that is, towards the back; but towards the front it passes over into the soul element. The head is altogether body; the breast portion of man is body towards the back, soul towards the front. Thus it is only in that we have our head resting on our shoulders that we carry about a real body. We consist of body and soul in so far as we separate out our breast from the visible part of the breast system and allow it to be worked upon and permeated by the soul.

Into these two members of the human being, head and breast (more obviously of course in the breast portion), the limbs are inserted. The third principle is the limb man. How can we understand the limb man? We can only understand this third member when we realise that certain parts of the spherical form remain visible, as with the breast portion, only in this case they are different parts. In the breast system a part of the periphery remains. In the limb system it is more an inner part consisting of the radii of a sphere that remains over; so that the inner parts of the sphere are inset as limbs.

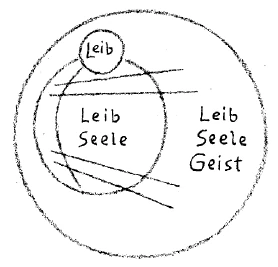

We never arrive at the truth—as I have often said to you on other occasions—if we only analyse things and divide them, into parts. We must always interweave one thing with another; for this is the nature of living things. We can say: we have the limb man, which consists of the limbs. But the head also has its limbs. If you look carefully at the skull you find, for example, that attached to the skull are the bones of the upper and lower jaws. They are properly attached like limbs. Thus the skull, too, has its limbs: the upper and lower jaws which are joined to it. Only in the skull the limbs are stunted. In the other parts of man they have developed to their proper size, but in the skull they are stunted and are only a kind of bone structure. There is yet another difference:

if you observe the limbs of the skull, that is, the upper and lower jaws, you will see that the essential thing in them is that the bone should perform its function. If you examine the limbs which are attached to our whole body, namely, when you consider the limb man proper, you find the essential fact is that they are surrounded by muscles and blood vessels. In a certain way the bones of our arms and legs, hands and feet are only inserted into our muscle and blood system. But in the upper and lower jaws—the limbs of the head—the muscles and blood vessels have shrunken. What does this mean? Muscles and blood are the organic instrument of the will, as we have already heard. Hence it is arms and legs, hands and feet that are principally developed for the will. Blood and muscles, which pre-eminently serve the will, are withdrawn, in a measure, from the limbs of the head, because what has to be developed in them is what tends to intellect, to thinking-cognition. If, then, you want to study how the will reveals itself in the outer bodily forms of the world, you must study the arms and legs, hands and feet. If you want to study how the intelligence of the world is revealed, then you must study the head, or rather the skull, as skeleton; you must see how the upper and lower jaws are attached to the head, and you must examine other parts of the head which are of a limb nature. You can regard all outer forms as revelations of what is within. And indeed you can only understand the outer forms when you look upon them as revelation of what is within.

I have always found that for most men there is a great difficulty in understanding the connection between the tubular bones of the arms and the legs and the shell-like bones of the head. Here it is particularly good for the teacher to master a conception remote from common life. And this brings us to a very, very difficult chapter, to the hardest, perhaps, of all the conceptions we have to gain in these educational lectures.

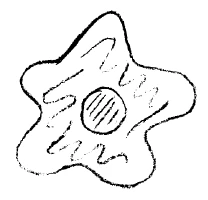

You know that Goethe was the first to turn his attention to the vertebral theory of the skull, as it is termed. What is meant by this? It means the application of the idea of metamorphosis to man and to his form. When we consider the human spinal column we perceive that one vertebra lies above another. We can take out the single vertebra, with its projections through which the spinal cord passes. Now Goethe was the first to observe (in a sheep skull, in Venice) how all head bones are transformed vertebrae. Imagine some organs puffed out and others indrawn—then you get the shell-like head bones out of the vertebral forms. This made a great impression on Goethe. It drove him to a conclusion of profound importance, namely: that the skull is a transformed, a more highly developed spinal column.

It is comparatively easy to see that the skull bones arise out of the vertebrae of the spine through transformation, through metamorphosis. It is very much harder, very difficult indeed, to see the limb bones—even the limbs of the head, the upper and lower jaws—as a metamorphosis, a transforming of the vertebral bones, or of the head bones (Goethe attempted to do this, but in an external way). Now why is this so difficult? The reason is that a tubular bone, wherever it may be, is indeed also a metamorphosis, a remodeling of a head bone, but a remodeling of a quite special nature. It is comparatively easy to think of a spinal vertebra metamorphosed into a head bone when you think of some parts of it being enlarged and some diminished. But you cannot so easily get the shell-shaped head bones out of the tubular bones of the arms and legs. To do this you have to adopt a certain procedure. You have to deal with the tubular bone of the arm or the leg as you do with a glove or stocking when you turn it inside out to put it on. Now it is comparatively easy to imagine what a glove or a stocking looks like turned inside out. But a tubular bone is not equal in all its parts; it is not so thin as to have the same form inside and out. The inside and outside are differently formed. If your stocking were of malleable material and you could give it an artistic form with all sorts of projections and indentations, and if you then turned it inside out you would no longer have the same form outside as that which would now be inside. And it is like this with the tubular bone. You must turn the inside outwards and the outside inwards and then you get the form of the head bone. Thus human limbs are not merely head bones metamorphosed, they are even more, head bones turned inside out. How does this come about? It is because the head has its centre somewhere within. It has its centre centrically, if I may put it so. Not so the breast. Its centre does not lie within the sphere. The breast has its centre very far away. (In the drawing this is only partially indicated because it would be too large if the whole were shown.) Thus the breast has its centre far away. Now where is the centre of the limb system? This brings us to the second difficulty. The limb system has its centre in the whole circumference. The centre of the limb system is a sphere; namely, the opposite of a point, the surface of a sphere. The centre is really everywhere; hence you can turn in every direction and radii ray in from all sides. They unite themselves with you.

What is in the head takes its rise in the head. What passes through the limbs unites itself within you. This is why I had to say in the other lectures that you must think of the limbs as inserted into the rest of our body. We are really a whole world, only what wants to enter into us from outside condenses at its end and becomes visible. A very minute portion of what we are becomes visible in our limbs. So that the limbs themselves are physical body, but the physical limbs are only the minutest atom of what is really in the limb system of man. Body, soul and spirit are in the limb system of man. The body is only indicated in the limbs, But in the limbs there is also a soul part; and there is within them, too, the spirit part which embraces the whole world.

Now we could also make another drawing of the human being. It could be said that man is, firstly a gigantic sphere which embraces the whole world: then a smaller sphere: and then a smallest sphere. Only the smallest sphere would be completely visible. The somewhat larger sphere would be partially visible. The largest sphere is only visible here at the end of it, where it rays in: the rest is invisible. Thus is the human form wrought by the whole world.

And again, in the middle system, the breast system, we have the union of the head system and the limb system. When you consider the spine with the ribs attached to it you will see that it tries to close up in front. At the back the whole is enclosed; in front an attempt only is made, it does not quite succeed. The nearer the ribs are to the head the more they succeed in making the enclosure, but the further down they are the more they fail. The last ribs do not meet because here the force which comes into the limbs from the outside is working against them.

Now the Greeks still had a very clear consciousness of this connection of the human being with the macrocosm. And the Egyptians knew of it also, but in a somewhat abstract way. Hence, when you look at Egyptian or, indeed, any sculpture of antiquity you can see that this thought of the cosmos is expressed. You can only understand the works of the ancients if you know that their work was an expression of their belief: they saw the head as a small sphere, a heavenly body in miniature; and the limbs as part of a great heavenly body which presses its radii into the human form. The Greeks had a beautiful, harmonious and perfect conception of this, hence they were good sculptors. No sculptor of human form can be a master in his art to-day unless he is conscious of this connection of man with the universe. Lacking this he will only make a clumsy copy of the forms of nature.

You will know from what I have said to you that the limbs are more inclined towards the world, the head more to the individual man. To what then will the limbs especially incline? They will incline towards the world, to that world in which man moves and in which he is continually changing his position. They will be related to the movement of the world. Please understand this quite clearly: the limbs are related to the movement of the world.

In that we move about the world and perform actions we are limb men. Now what kind of task has the head with respect to the movement of the world? It rests on the shoulders, as I told you when speaking in another connection. And further, it has the task of bringing the movement of the world continuously to rest within itself. Place yourself with your spirit inside your own head; you can get a picture of how you are then placed by thinking of yourself, for a time, as sitting in a railway train; the train is moving forwards, but you are quietly sitting in it. In the same way your soul sits in your head, which quietly allows itself to be carried forwards by the limbs, and brings the movement to rest inwardly. If you have room you may even lie down in the railway carriage, you can rest—though this rest is really a deception, for you are rushing in the train (in a sleeper perhaps) across the earth. Nevertheless you have the sensation of rest. Thus the head brings to rest in you what the limbs perform in the world by way of movement. And the breast system stands betwixt them. It mediates between the movement of the outer world and what the head brings into rest.

Now, as men, our purpose is to imitate, to absorb the movement of the world into ourselves through our limbs. What do we do then? We dance. This is true dancing. Other dancing is only fragmentary dancing. All true dancing has arisen from imitating in the limbs the movement carried out by the planets, by other heavenly bodies or by the earth itself.

But now, what part do our head and breast play in this dancing, this imitation of cosmic movement in the movement of our limbs? The movements we perform in the world are stemmed or stopped, as it were, in the head and in the breast. The movements cannot continue through the breast into the head, for the head, lazy fellow, rests on the shoulders and does not let the movements reach the soul. The soul must participate in the movements while at rest, because the head rests on the shoulders. What then does the soul do? It begins to reflect from within itself the dancing movements of the limbs. When the limbs execute irregular movements the soul begins to mumble; when the limbs perform regular movements it begins to whisper: when the limbs carry out the harmonious cosmic movements of the universe, it even begins to sing. Thus the outward dancing movement is changed into song and into music within.

The physiology of the senses will never succeed in understanding sensation unless it can accept man as a cosmic being. It will always say that vibrations of the air are outside and that man perceives sounds within: how the vibrations of the air are connected with the sounds it is impossible to know. This is what you find in books on physiology and psychology—in one of them it comes at the end, in the other at the beginning, that is the only difference.

Now why is this? It comes about because those who practise psychology and physiology do not know that a man's external movements are brought to rest in the soul, and through this begin to pass over into tones. The same is also true with regard to all other sense impressions. As the organs of the head do not take part in the outer movements, they ray these outer movements back into the breast, and make them into sounds and into the other sense impressions. Here lies the origin of sensation. Here, moreover, lies the connection between the arts. The poetic, the musical arts, arise out of the plastic, the architectural arts: for what the plastic and architectural arts are without, the musical arts are within. A reflecting back of the world from within outwards—such is the nature of the musical arts. Thus does man stand amidst the universe. You experience colour as movement come to rest. You do not perceive the movement externally—just as when lying down in a train you may have the illusion of being at rest. You let the train move on its outward course. Similarly you let your body participate in the outer world in fine movements of the limbs of which you are unaware, while you perceive colours and tones inwardly. This you owe to the circumstance that you let your head, in its physical form, be carried at rest by your limb system.

I said that what I had to speak to you about to-day was indeed a difficult matter. It is particularly difficult because in this age nothing whatever is done to facilitate our understanding of these things. Care is taken that the accepted culture of our time should leave man in ignorance of such things as I have described to you to-day. What is it that comes about through our present-day education? Well, a man cannot altogether know what a stocking or a glove is like unless he turns it inside out, for otherwise he never knows the part which touches his skin. He only knows the part turned outwards. Similarly, as the result of present culture man only knows what is turned outwards. He has concepts for one half of man only; he will never understand the limbs. For the limbs have been turned inside out by the spirit.

Another way of describing our subject would be as follows: if we consider man in all his fullness, as we meet him in the world and consider him in the first place as limb man he reveals spirit, soul and body. If we consider him as breast man he reveals soul and body. If we consider him as head man he reveals body alone. The large sphere (see drawing): spirit, body, soul. The smaller sphere: body and soul. And the smallest sphere: body only.

At the council of A.D. 869 the bishops of the Catholic Church forbade humanity to know anything about the large sphere. At that time they declared it a dogma of the Catholic Church that the middle sphere and the smallest sphere alone had existence, that man consists of body and soul only, spiritual characteristics being merely a quality of the soul. One part of the soul, it was held, was of a spiritual nature. Since the year A.D. 869 for Western culture derived from Catholicism there has been no spirit. But when relationship to the spirit was abolished the relationship of man to the world was abolished also. Man has been more and more driven in upon his egotism. Hence religion itself has become more and more egotistic. And to-day we live in an age when once again, if I may say so, from a spiritual observation we must learn man's relationship to the spirit, and through it to the world.

Who is actually to blame for the materialism of natural science? It is the Roman Catholic Church which is chiefly to blame for our scientific materialism, because at the council of Constantinople in A.D. 869 it abolished the Spirit. What actually came about at that time? Consider the human head. Its development in the course of natural evolution shows to-day that it is the oldest of man's principles. The head is evolved immediately from the higher animals, and, further back again, from the lower animals. With respect to our head we are descended from the animal world. There is no denying it—the head is only a further evolved animal. If we look for the ancestry of our head we go back to the lower animals. Our breast was not joined to the head until later; it is not so animal as the head. We only received the breast in a later age. And the organs we human beings received last of all are the limbs.

These are the most human of all. They are not remodeled from animal organs, they are added later. The animal organs were formed independently from out of the cosmos and given over to the animal, and the human organs were later formed independently and united with the breast. The Catholic Church concealed the knowledge of man's relationship to the universe from him: that is to say, it concealed from him the knowledge of the true nature of his limbs; and in so doing it handed on to succeeding generations an incomplete knowledge of the breast and a complete knowledge only of the head, of the skull. Thus, materialism made the discovery that the skull is descended from the animals: and now it claims that the whole human being is descended from the animals, whereas actually the breast organs and the limb organisation were only added later. By hiding from man the nature of his limbs, and hence this relation with the world, the Catholic Church caused the later materialistic age to apply to the whole human being what only holds good for the head. The Catholic Church is really the creator of materialism in this domain of the doctrine of evolution. It is the duty of the present-day teacher of youth to know these things. For he should take an interest in all that has happened in the world. And he should know the true grounds of the things which have happened in the world.

We have tried to-day to see clearly how it is that our age has become materialistic, taking our start from something quite different, from the spherical form, the moon form and the radial form of the limbs. That is to say, we began with something seemingly quite remote in order to make clear to ourselves a tremendous fact in the history of civilisation. But a teacher above all, if he is to do anything with the human being, must be in a position to grasp the fundamentals of civilisation. These are essential to him if he is to educate rightly out of the depths of his own nature through his unconscious and subconscious relations with the child. For then he will have due regard for the structure of man; above all he will perceive in it relationships to the macrocosm. How different is the outlook which sees the human form merely as the development of some little animal or other, a more highly developed animal body. Nowadays, for the most part, though some teachers may not admit it, the teacher meets the child with the distinct idea that he is a little animal and that he has to develop this little animal just a little further than Nature has done hitherto. He will feel differently if he says to himself: here is a man, and he has connections with the whole universe; and what I do with every growing child, the way I work with him, has significance for the whole universe. We are together in the classroom: in each child is situated a centre for the whole world, for the macrocosm. This classroom is a centre—indeed many centres—for the macrocosm. Think what it means when this is felt in a living way. How the idea of the universe and its connections with the child passes into a feeling which hallows all the varied aspects of our educational work. Without such feeling about man and the universe we shall not learn to teach earnestly and truly. The moment we have such feelings they pass over to the children by underground ways.

In another connection I said how it must always fill us with wonder when we see how wires go into the earth to copper plates and how the earth carries the electricity further without wires. If you go into the school with egotistic feelings you need all kinds of wires—words—in order to make yourself understood by the children. If you have great feelings for the universe which arise from ideas such as we have discussed to-day, then an underground current will pass between you and the child. Then you will be one with the children. Herein lies something of the mysterious relationship between you and the children as a whole. Pedagogy in the true sense must be built on feelings such as this. Pedagogy must not be a science, it must be an art. And where is the art which can be learned without dwelling constantly in the feelings? But the feelings in which we must live in order to practise that great art of life, the art of education, are only kindled by contemplation of the great universe and its relationships with man.

Zehnter Vortrag

Wir haben das Wesen des Menschen von dem seelischen und geistigen Gesichtspunkte aus besprochen. Wir haben wenigstens einige Streiflichter darauf geworfen, wie der Mensch zu betrachten ist vom geistigen, vom seelischen Gesichtspunkte aus. Wir werden dasjenige, was so von den zwei Gesichtspunkten aus betrachtet worden ist, dadurch zu ergänzen haben, daß wir zunächst verbinden die Gesichtspunkte des Geistigen, des Seelischen, des Leiblichen, damit wir einen vollständigen Überblick über den Menschen bekommen und dann übergehen können auf ein Erfassen, auf ein Begreifen auch der äußeren Leiblichkeit.

Zuerst wollen wir uns noch einmal ins Gedächtnis rufen, was uns von verschiedenen Seiten her aufgefallen sein muß: daß der Mensch in den drei Gliedern seines Wesens verschiedene Formen hat. Wir haben darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie im wesentlichen die Kopfform die Form des Kugeligen ist, wie in dieser kugeligen Kopfform das eigentliche leibliche Wesen des menschlichen Hauptes liegt. Wir haben dann darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß der Brustteil des Menschen ein Fragment einer Kugel ist, so daß also, wenn wir schematisch zeichnen, wir dem Kopfe eine Kugelform, dem Brustteil eine Mondenform geben und daß wir uns klar sind, daß in dieser Mondenform ein Kugelfragment, ein Teil einer Kugel enthalten ist. Daher werden wir uns sagen müssen: Wir können ergänzen die Mondform des menschlichen Brustgliedes. Und Sie werden nur dann dieses Mittelglied der menschlichen Wesenheit, die menschliche Brustform, richtig ins Auge fassen können, wenn Sie sie auch als eine Kugel betrachten, aber als eine Kugel, von der nur ein Teil, ein Mond sichtbar ist und der andere Teil unsichtbar ist [Abb. I]. Sie sehen daraus vielleicht, daß in denjenigen älteren Zeiten, in denen man mehr die Fähigkeit gehabt hat als später, Formen zu sehen, man nicht unrecht hatte, von Sonne dem Kopf entsprechend, von Mond der Brustform entsprechend zu sprechen. Und wie man dann, wenn der Mond nicht voll ist, von dem Mond eben nur ein Kugelfragment sieht, so sieht man von dem menschlichen Mittelgliede in der Brustform eigentlich nur ein Fragment. Daraus können Sie ersehen, daß die Kopfform des Menschen hier in der physischen Welt etwas verhältnismäßig Abgeschlossenes ist. Die Kopfform zeigt sich physisch als etwas Abgeschlossenes. Sie ist gewissermaßen ganz dasjenige, als was sie sich gibt. Sie verbirgt am allerwenigsten von sich.

Der Brustteil des Menschen verbirgt schon sehr viel von sich; er läßt etwas von seiner Wesenheit unsichtbar. Es ist sehr wichtig für die Erkenntnis der Wesenheit des Menschen, das ins Auge zu fassen, daß vom Brustteil ein gut Stück unsichtbar ist. Und so können wir sagen: Der Brustteil zeigt uns nach der einen Seite, nach rückwärts, seine Leiblichkeit; nach vorwärts geht er in das Seelische über. Der Kopf ist ganz Leib; der Brustteil des Menschen ist Leib nach rückwärts, Seele nach vorwärts. Wir tragen also einen wirklichen Leib nur an uns, indem wir unser Haupt auf den Schultern ruhen haben. Wir haben an uns Leib und Seele, indem wir unsere Brust herausgliedern aus dem übrigen Brustteil und sie durcharbeiten, durchwirken lassen von dem Seelischen.

Nun sind eingesetzt in diese beiden Glieder des Menschen, namentlich zunächst für die äußere Betrachtung in den Brustteil, die Gliedmaßen. Das dritte ist ja der Gliedmaßenmensch. Nun, wie können wir den Gliedmaßenmenschen eigentlich verstehen? Den Gliedmaßenmenschen können wir nur verstehen, wenn wir ins Auge fassen, daß andere Stücke übriggeblieben sind von der Kugelform als beim Brustteil. Beim Brustteil ist ein Stück von der Peripherie übriggeblieben. Bei den Gliedmaßen ist mehr übriggeblieben etwas von dem Inneren, von den Radien der Kugel, so daß also die inneren Teile der Kugel angesetzt sind als Gliedmaßen.

Man kommt eben nicht zurecht, wie ich Ihnen schon oftmals gesagt habe, wenn man nur schematisch eins ins andere gliedert. Man muß immer das eine mit dem anderen verweben, denn darin besteht das Lebendige. Wir sagen: Wir haben den Gliedmaßenmenschen, der besteht aus den Gliedmaßen. — Aber sehen Sie, auch der Kopf hat seine Gliedmaßen. Wenn Sie sich den Schädel ordentlich ansehen, dann finden Sie, daß zum Beispiel angesetzt sind an den Schädel die Knochen der oberen und der unteren Kinnlade [Abb. II]. Sie sind richtig eingesetzt wie Gliedmaßen. Der Schädel hat auch seine Gliedmaßen, und obere und untere Kinnlade sind als Gliedmaßen am Schädel angebracht. Sie sind nur am Schädel verkümmerrt. Sie sind richtig groß ausgebildet beim übrigen Menschen, am Schädel sind sie verkümmert, sind eigentlich nur Knochengebilde. Und noch einen Unterschied gibt es: wenn Sie die Gliedmaßen des Schädels betrachten, also obere und untere Kinnlade, so werden Sie sehen, daß es bei ihnen ankommt im wesentlichen darauf, daß der Knochen seine Wirksamkeit ausführt. Wenn Sie die Gliedmaßen, die an unserem gesamten Leib angesetzt sind, also die eigentliche Wesenheit des Gliedmaßenmenschen ins Auge fassen, dann werden Sie in der Umkleidung mit Muskeln und mit Blutgefäßen das Wesentliche suchen müssen. Gewissermaßen sind unserem Muskel- und Blutsystem für Arme und Beine, Hände und Füße nur eingesetzt die Knochen. Und gewissermaßen sind an der oberen und unteren Kinnlade als Gliedmaßen des Kopfes ganz verkümmert die Muskeln und die Blutgefäße. Was bedeutet das? — Sehen Sie, in Blut und Muskeln liegt die Organik des Willens, wie wir schon gehört haben. Daher sind ausgebildet für den Willen hauptsächlich Arme und Beine, Hände und Füße. Das, was dem Willen vorzugsweise dient, Blut und Muskeln, das ist ja, bis zu einem gewissen Grade, genommen den Gliedmaßen des Hauptes, weil in ihnen ausgebildet sein soll dasjenige, was zum Intellekt, zum denkerischen Erkennen hinneigt. Wollen Sie daher studieren, wie sich in den äußeren Leibesformen der Wille der Welt offenbart, so studieren Sie Arme und Beine, Hände und Füße. Wollen Sie studieren, wie sich das Intelligente der Welt offenbart, dann studieren Sie das Haupt als Schädel, als Knochengerüst, und wie sich dem Haupt angliedert obere Kinnlade, untere Kinnlade und auch anderes, was gliedmaßenähnlich aussieht am Haupte. Sie können nämlich überall die äußeren Formen als Offenbarungen des Inneren ansehen. Und Sie verstehen nur dann die äußeren Formen, wenn Sie sie als Offenbarungen des Inneren ansehen.

Nun, sehen Sie, ich habe immer gefunden, daß für die meisten Menschen eine große Schwierigkeit darin liegt, wenn sie begreifen sollen, welche Beziehung zwischen den Röhrenknochen der Arme und Beine und zwischen den Schalknochen des Kopfes, des Hauptes besteht. Es ist nun gerade für den Lehrer gut, hier sich einen Begriff anzueignen, der dem gewöhnlichen Leben fernliegt. Und wir kommen dabei an ein sehr, sehr schwieriges Kapitel, vielleicht das schwierigste für die Vorstellung, das wir zu überschreiten haben in diesen pädagogischen Vorträgen.

Sie wissen, Goethe hat zuerst seine Aufmerksamkeit zugewendet der sogenannten Wirbeltheorie des Schädels. Was ist damit gemeint? Damit ist gemeint die Anwendung des Metamorphosengedankens auf den Menschen und seine Gestalt. Wenn man die menschliche Wirbelsäule betrachtet, so liegt ja ein Knochenwirbel über dem anderen. Wir können so einen Knochenwirbel mit seinen Fortsätzen, in dem dann das Rückenmark durchgeht, herausnehmen (es wird gezeichnet). Nun hat Goethe an einem Schöpsenschädel in Venedig zuerst beobachtet, wie alle Kopfknochen umgebildete Rückenwirbelknochen sind. Das heißt, wenn man sich irgendwelche Organe aufgeplustert und andere zurückgegangen denkt, so bekommt man aus dieser Wirbelform den schalgeformten Kopfknochen. Auf Goethe hat das einen großen Eindruck gemacht, denn er hat daraus den Schluß ziehen müssen — was für ihn sehr bedeutungsvoll war -, daß der Schädel eine umgebildete, eine höhergebildete Wirbelsäule ist.

Man kann nun verhältnismäßig leicht einsehen, daß die Schädelknochen durch Umwandlung, durch Metamorphose aus den Wirbelknochen des Rückgrats hervorgehen. Aber nun wird es sehr schwierig, auch die Gliedmaßenknochen, schon die Gliedmaßenknochen des Kopfes, obere und untere Kinnlade — Goethe hat es versucht, aber auf äußerliche Weise noch — als Umformung, als Metamorphose der Wirbelknochen beziehungsweise der Kopfknochen aufzufassen. Warum ist das so? Ja, sehen Sie, das beruht darauf, daß ja allerdings ein röhriger Knochen, den Sie irgendwo haben, auch eine Metamorphose, eine Umwandlung des Kopfknochens ist, aber auf ganz besondere Art. Sie können verhältnismäßig leicht den Rückgratwirbel sich umgewandelt denken zum Kopfknochen, indem Sie sich einzelne Teile vergrößert, andere verkleinert denken. Aber Sie kriegen nicht so leicht aus dem Röhrenknochen der Arme oder der Beine heraus die Kopfknochen, die schaligen Kopfknochen. Da müssen Sie nämlich zuerst eine gewisse Prozedur vornehmen, wenn Sie die herausbekommen wollen. Sie müssen mit dem Röhrenknochen der Arme oder der Beine dieselbe Prozedur vornehmen, die Sie vornehmen würden, wenn Sie beim Anziehen eines Strumpfes oder eines Handschuhes das Innere zuerst nach außen wenden würden, also wenn Sie es umwenden würden. Nun ist es verhältnismäßig leicht, sich vorzustellen, wie ein Handschuh oder ein Strumpf aussieht, wenn das Innere nach außen gewendet wird. Aber der Röhrenknochen ist nicht gleichmäßig. Er ist nicht so dünn, daß er gleichmäßig im Inneren und außen gebaut wäre. Er ist verschieden im Inneren und außen gebaut. Würden Sie Ihren Strumpf so konstruieren und dann elastisch machen, daß Sie ihm äußerlich eine künstlerische Form geben würden mit allerlei Vorsprüngen und Einbuchtungen und ihn dann wenden, dann würden Sie nach außen nicht mehr dieselbe Form erhalten wie die, die dann im Inneren ist, wenn Sie ihn umgewendet haben. Und so ist es bei dem Röhrenknochen. Man muß das Innere nach außen und das Äußere nach innen kehren, dann kommt die Form des Kopfknochens heraus, so daß die menschlichen Gliedmafßen nicht nur umgewandelte Kopfknochen sind, sondern außerdem noch umgewendete Kopfknochen. Woher rührt das? Das rührt davon her, daß der Kopf seinen Mittelpunkt irgendwo im Inneren hat; er hat ihn konzentrisch. Nicht hat in der Mitte der Kugel die Brust ihren Mittelpunkt; die Brust hat den Mittelpunkt sehr weit weg. Das ist hier in der Zeichnung nur fragmentarisch angesetzt, denn es wäre sehr groß, wenn es ganz gezeichnet würde. Also weit weg hat die Brust den Mittelpunkt.

Und wo hat denn das Gliedmaßensystem den Mittelpunkt? Jetzt kommen wir auf die zweite Schwierigkeit. Das Gliedmaßensystem hat den Mittelpunkt im ganzen Umkreis. Der Mittelpunkt des Gliedmaßensystems ist überhaupt eine Kugel, also das Gegenteil von einem Punkt. Eine Kugelfläche. Überall ist der Mittelpunkt eigentlich; daher können Sie sich überallhin drehen und von überallher strahlen die Radien ein. Sie vereinigen sich mit Ihnen.

Was im Kopfe ist, geht vom Kopfe aus; was durch die Gliedmaßen geht, vereinigt sich in Ihnen. Deshalb mußte ich auch in den anderen Vorträgen sagen: Sie müssen sich die Gliedmaßen eingesetzt denken. Wir sind wirklich eine ganze Welt, nur daß dasjenige, was da von außen in uns herein will, an seinem Ende sich verdichtet und sichtbar wird. Ein ganz winziger Teil von dem, was wir sind, wird in unseren Gliedmaßen sichtbar, so daß die Gliedmaßen etwas Leibliches sind, das aber nur ein ganz winziges Atom ist von dem, was eigentlich da ist im Gliedmaßensystem des Menschen: Geist. Leib, Seele und Geist ist im Gliedmaßensystem des Menschen. Der Leib ist in den Gliedmaßen nur angedeutet; aber in den Gliedmaßen ist ebenso das Seelische drinnen, und es ist drinnen das Geistige, das im Grunde genommen die ganze Welt umfaßt.

Nun könnte man auch noch eine andere Zeichnung vom Menschen machen. Man könnte sagen: Der Mensch ist zunächst eine riesengroße Kugel, die die ganze Welt umfaßt, dann eine kleinere Kugel, und dann eine kleinste Kugel. Nur die kleinste Kugel wird ganz sichtbar; die etwas größere Kugel wird nur zum Teil sichtbar; die größte Kugel wird nur in ihren Einstrahlungen am Ende hier sichtbar, das übrige bleibt unsichtbar. So ist der Mensch aus der Welt heraus gebildet in seiner Form.

Und wiederum im mittleren System, im Brustsystem, haben wir die Vereinigung des Kopfsystems und des Gliedmaßensystems. Wenn Sie das Rückgrat mit den Ansätzen der Rippen betrachten, so werden Sie sehen, daß das der Versuch ist, sich abzuschließen nach vorne. Nach rückwärts ist das Ganze abgeschlossen, nach vorne ist nur der Versuch gemacht des Abschließens; er gelingt nicht ganz. Je mehr die Rippen dem Kopfe zugeneigt sind, desto mehr gelingt es ihnen, sich abzuschließen, aber je weiter nach unten gelegen, desto mehr mißlingt es ihnen. Die letzten Rippen kommen nicht mehr zusammen, weil ihnen da entgegenwirkt diejenige Kraft, die dann in den Gliedmaßen von außen kommt.

Von diesem Zusammenhang des Menschen mit dem ganzen Makrokosmos haben die Griechen noch ein sehr starkes Bewußtsein gehabt. Und die Ägypter wußten das sehr gut, nur wußten sie es etwas abstrakt. Daher können Sie sehen, wenn Sie ägyptische oder überhaupt ältere Plastiken anschauen, daß dieser Gedanke des Kosmos zum Ausdruck kommt. Sie verstehen sonst nicht, was die Menschen in alten Zeiten gemacht haben, wenn Sie nicht wissen, daß sie das gemacht haben, was ihrem Glauben entsprach: Der Kopf ist eine kleine Kugel, ein Weltkörper im Kleinen; die Gliedmaßen sind ein Stück vom großen Weltenkörper, wo er sich überall mit den Radien hineindrängt in die menschliche Gestalt. Die Griechen haben eine schöne, in sich harmonisch ausgebildete Vorstellung davon gehabt, daher waren sie gute Plastiker, gute Bildhauer. Und heute kann noch niemand die plastische Kunst der Menschen wirklich durchdringen, der sich nicht bewußt wird dieses Zusammenhanges des Menschen mit dem Weltall. Sonst patzt er immer nur äußerlich die Naturformen nach.

Nun werden Sie gerade aus dem, was ich Ihnen so gesagt habe, erkennen, meine lieben Freunde, daß die Gliedmaßen eben mehr der Welt zugeneigt sind, der Kopf mehr dem einzelnen Menschen zugeneigt ist. Wozu werden dann also die Gliedmaßen besonders neigen? Sie werden zur Welt neigen, in der der Mensch sich bewegt und selbst seine Stellung immerfort verändert. Sie werden zur Bewegung der Welt Beziehung haben. Fassen Sie das gut auf: die Gliedmaßen haben Beziehung zur Bewegung der Welt.

Indem wir in der Weit herumgehen, indem wir handelnd auftreten in der Welt, sind wir der Mensch der Gliedmaßen. Was hat denn nun der Bewegung der Welt gegenüber der Kopf, unser Haupt, für eine Aufgabe? Er ruht auf den Schultern, das habe ich Ihnen ja von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte aus gesagt. Er hat auch die Aufgabe, in sich fortwährend die Bewegung der Welt zur Ruhe zu bringen. Wenn Sie sich mit Ihrem Geiste in den Kopf hineinversetzen, so können Sie sich wirklich von diesem Sich-Versetzen ein Bild machen dadurch, daß Sie sich denken für eine Weile, Sie säßen in einem Eisenbahnzug; er bewegt sich vorwärts, Sie sitzen ruhig drinnen. So sitzt Ihre Seele im Kopf, der sich von den Gliedmaßen weiterbefördern läßt, ruhig drinnen und bringt die Bewegung innerlich zur Ruhe. Wie Sie sich sogar hinstrecken können, wenn Sie in dem Eisenbahnwagen Platz haben, und ruhen können, trotzdem diese Ruhe eigentlich eine Unwahrheit ist, denn Sie sausen ja in dem Zuge, vielleicht im Schlafwagen, durch die Welt; dennoch, Sie haben das Gefühl der Ruhe - so beruhigt in Ihnen der Kopf dasjenige, was die Gliedmaßen als Bewegung vollbringen können in der Welt. Und der Brustteil steht mitten darinnen. Der vermittelt die Bewegung der Außenwelt mit dem, was das Haupt, der Kopf zur Ruhe bringt.

Denken Sie sich jetzt: es geht geradezu unsere Absicht als Mensch darauf hin, die Bewegung der Welt durch unsere Gliedmaßen nachzuahmen, aufzunehmen. Was tun wir denn da? Wir tanzen. Sie tanzen in Wirklichkeit; das andere Tanzen ist nur ein fragmentarisches Tanzen. Alles Tanzen ist davon ausgegangen, Bewegungen, die die Planeten, die anderen Weltenkörper ausführen, die die Erde selbst ausführt, in den Bewegungen, in den Gliederbewegungen der Menschen zur Nachahmung zu bringen.

Aber wie ist denn das nun mit dem Kopfe und mit der Brust, wenn wir die kosmischen Bewegungen tanzend nachbilden in unseren Bewegungen als Mensch? Sehen Sie, da ist es so, im Kopfe und in der Brust, als wenn sich die Bewegungen, die wir in der Welt ausführen, stauen würden. Sie können sich nicht fortsetzen durch die Brust in den Kopf hinein, denn der Kerl ruht auf den Schultern, der läßt die Bewegungen nicht sich fortsetzen in die Seele hinein. Die Seele muß in Ruhe an den Bewegungen teilnehmen, weil der Kopf auf den Schultern ruht. Was tut sie daher? Sie fängt an, von sich aus dasjenige zu reflektieren, was die Glieder tanzend ausführen. Sie fängt an zu brummen, wenn die Glieder unregelmäßige Bewegungen ausführen; sie fängt an zu lispeln, wenn die Glieder regelmäßige Bewegungen ausführen, und sie fängt gar an zu singen, wenn die Glieder ausführen die harmonischen kosmischen Bewegungen des Weltalls. So setzt sich um die tanzende Bewegung nach außen in den Gesang und in das Musikalische nach innen.

Die Sinnesphysiologie wird es, wenn sie den Menschen nicht als kosmisches Wesen nimmt, nie dahin bringen, die Empfindung zu begreifen; sie wird immer sagen: Draußen sind die Bewegungen der Luft, im Inneren nimmt der Mensch den Ton wahr. Wie die Bewegungen der Luft mit dem Ton zusammenhängen, das kann man nicht wissen. - Das steht in den Physiologien und in den Psychologien, in den einen am Ende, in den anderen am Anfang; das ist der ganze Unterschied.

Woher rührt denn das? Das rührt davon her, daß die Leute, die Psychologie oder Physiologie ausüben, nicht wissen, daß das, was der Mensch äußerlich in Bewegungen hat, im Inneren der Seele zur Ruhe gebracht wird und dadurch anfängt, in Töne überzugehen. Und so ist es mit allen anderen Sinnesempfindungen auch. Weil die Hauptesorgane nicht mitmachen die äußeren Bewegungen, strahlen sie diese Bewegungen in die Brust zurück und machen sie zum Ton, zur anderen Sinnesempfindung. Da liegt der Ursprung der Empfindungen. Da liegt aber auch der Zusammenhang der Künste. Die musischen, die musikalischen Künste entstehen aus den plastischen und architektonischen Künsten, indem das, was plastische und architektonische Künste nach außen sind, die musikalischen Künste nach innen sind. Die Reflexion der Welt von innen nach außen, das sind die musikalischen Künste. - So steht der Mensch drinnen im Weltenall. Empfinden Sie eine Farbe als zur Ruhe gekommene Bewegung. Die Bewegung nehmen Sie äußerlich nicht wahr, wie wenn Sie in einem Eisenbahnzug hingestreckt liegen und die Illusion haben könnten, Sie seien in Ruhe. Sie lassen den Zug draußen sich bewegen. So lassen Sie Ihren Leib durch feine Bewegungen der Gliedmaßen, die Sie nicht wahrnehmen, mitmachen die äußere Welt, und Sie selbst nehmen drinnen die Farben und Töne wahr. Sie verdanken das dem Umstand, daß Sie Ihr Haupt als Form tragen lassen in Ruhe von dem Gliedmaßenorganismus.

Ich sagte Ihnen, es ist das, was ich Ihnen da mitteilte, eine gewisse schwierige Sache. Es ist das aus dem Grunde besonders schwierig, weil für das Begreifen dieser Dinge ja in unserer Zeit überhaupt nichts getan wird. Es wird durch alles das, was wir heute als Zeitbildung aufnehmen, dafür gesorgt, daß die Menschen über so etwas unwissend bleiben, wie es die Dinge sind, die ich Ihnen heute vorgebracht habe. Was geschieht denn eigentlich durch unsere heutige Bildung? Ja, der Mensch lernt wirklich nicht einen Strumpf oder Handschuh ganz kennen, wenn er ihn nicht einmal auch umdreht, denn er weiß dann nie, was eigentlich vom Strumpf oder vom Handschuh seine Haut berührt; er weiß nur dasjenige, was nach außen gewendet ist. So weiß durch unsere heutige Bildung der Mensch auch nur, was nach außen gewendet ist. Er bekommt nur Begriffe für den halben Menschen. Denn nicht einmal die Gliedmaßen kann er begreifen. Denn die hat schon der Geist umgewendert.

Wir können dasjenige, was wir heute dargestellt haben, auch so bezeichnen, wir können sagen: Betrachten wir den ganzen, vollen Menschen, wie er in der Welt vor uns steht, zunächst als Gliedmaßenmenschen, so zeigt er sich als solcher nach Geist, Seele und Leib. Betrachten wir ihn als Brustmenschen, so zeigt er sich uns als Seele und Leib. Die große Kugel (siehe Zeichnung $. 152): Geist, Leib, Seele; die kleinere Kugel: Leib, Seele; die kleinste Kugel: bloß Leib. Auf dem Konzil des Jahres 869 haben die Bischöfe der katholischen Kirche der Menschheit verboten, etwas über die große Kugel zu wissen. Sie haben dazumal erklärt, es sei Dogma der katholischen Kirche, daß nur vorhanden sei die mittlere Kugel und die kleinste Kugel, daß der Mensch nur bestehe aus Leib und Seele, daß die Seele nur als ihre Eigenschaft etwas Geistiges enthalte; die Seele sei nach der einen Seite auch geistartig. Geist gibt es seit dem Jahre 869 für die vom Katholizismus ausgehende Kultur des Abendlandes nicht mehr. — Aber mit der Beziehung zum Geiste ist abgeschafft worden die Beziehung des Menschen zur Welt. Der Mensch ist mehr und mehr in seine Egoität hineingetrieben worden. Daher wurde die Religion selbst immer egoistischer und egoistischer, und heute leben wir in einer Zeit, wo man, ich möchte sagen, wiederum aus der geistigen Beobachtung heraus die Beziehung des Menschen zum Geiste und damit zur Welt kennenlernen muß.

Wer hat denn eigentlich die Schuld, daß wir einen naturwissenschaftlichen Materialismus bekommen haben? Daß wir einen naturwissenschaftlichen Materialismus bekommen haben, daran hat die Hauptschuld die katholische Kirche, denn sie hat im Jahre 869 auf dem Konzil von Konstantinopel den Geist abgeschafft. Was ist damals eigentlich geschehen? Betrachten Sie den menschlichen Kopf. Er hat sich innerhalb der Tatsachenwelt des Weltgeschehens so ausgebildet, daß er heute das älteste Glied an dem Menschen ist. Der Kopf ist entsprungen zuerst aus höheren, dann weiter zurückgehend aus niederen Tieren. Mit Bezug auf unseren Kopf stammen wir ab von der Tierwelt. Da ist nichts zu sagen — der Kopf ist nur ein weiter ausgebildetes Tier. Wir kommen zur niederen Tierwelt zurück, wenn wir die Ahnen unseres Kopfes suchen wollen. Unsere Brust ist erst später dem Kopf angesetzt worden; die ist nicht mehr so tierisch wie der Kopf. Die Brust haben wir erst in einem späteren Zeitalter bekommen. Und die Gliedmaßen haben wir Menschen als die spätesten Organe bekommen; die sind die allermenschlichsten Organe. Die sind nicht umgebildet von den tierischen Organen, sondern die sind später angesetzt. Die tierischen Organe sind selbständig gebildet aus dem Kosmos zu den Tieren hin, und die menschlichen Organe sind später selbständig hinzugebildet zu der Brust. Aber indem die katholische Kirche das Bewußtsein des Menschen von seiner Beziehung zum Weltall, von der eigentlichen Natur seiner Gliedmaßen also, hat verbergen lassen, hat sie nur ein bißchen überliefert den folgenden Zeitaltern von der Brust und hauptsächlich vom Kopf, vom Schädel. Und da ist der Materialismus darauf gekommen, daß der Schädel von den Tieren abstammt. Und nun redet er davon, daß der ganze Mensch von den Tieren abstammt, während sich die Brustorgane und die Gliedmaßenorgane erst später hinzugebildet haben. Gerade indem die katholische Kirche dem Menschen verborgen hat die Natur seiner Gliedmaßen, seinen Zusammenhang mit der Welt, hat sie verursacht, daß die spätere materualistische Zeit verfallen ist in die Idee, die nur für den Kopf eine Bedeutung hat, die sie aber für den ganzen Menschen anwendet. Die katholische Kirche ist in Wahrheit die Schöpferin des Materialismus auf diesem Gebiet der Evolutionslehre. Es geziemt insbesondere dem heutigen Lehrer der Jugend, solche Dinge zu wissen. Denn er soll sein Interesse verknüpfen mit dem, was in der Welt geschehen ist. Und er soll die Dinge, die in der Welt geschehen, aus den Fundamenten heraus wissen.

Wir haben heute versucht, uns klarzumachen, wie es kommt, daß unsere Zeit materialistisch geworden ist, indem wir begonnen haben mit etwas ganz anderem: mit der Kugelform und Mondenform und mit der Radienform der Gliedmaßen. Das heißt, wir haben mit dem scheinbar ganz Entgegengesetzten begonnen, um eine große, gewaltige, kulturhistorische Tatsache uns klarzumachen. Das ist aber notwendig, daß insbesondere der Lehrer, der sonst mit dem werdenden Menschen gar nichts machen kann, die Kulturtatsachen aus den Fundamenten heraus zu erfassen in der Lage ist. Dann wird er etwas in sich aufnehmen, was notwendig ist, wenn er aus seinem Inneren heraus durch die un- und unterbewußten Beziehungen zum Kinde in der richtigen Weise erziehen will. Denn dann wird er vor dem Menschengebilde die richtige Achtung haben. Er wird in dem Menschengebilde überali die Beziehungen zur großen Welt sehen. Er wird anders an dieses menschliche Gebilde herantreten, als wenn er nur so etwas wie ein besser ausgebildetes Viehchelchen, einen besser ausgebildeten Tierleib im Menschen sieht. Heute tritt der Lehrer im Grunde genommen, wenn er sich auch manchmal in seinem Oberstübchen Illusionen darüber hingibt, er tritt mit dem deutlichen Bewußtsein vor den anderen Menschen hin, daß der aufwachsende Mensch ein kleines Viehchelchen, ein Tierlein ist und daß er dieses Tierlein zu entwickeln hat — etwas weiter, als es die Natur schon entwickelt hat. Anders wird er fühlen, wenn er sagt: Da ist ein Mensch, von dem gehen Beziehungen aus zur ganzen Welt, und in jedem einzelnen aufwachsenden Kind habe ich etwas, wenn ich daran etwas arbeite, tue ich etwas, was in der ganzen Welt eine Bedeutung hat. Wir sind da im Schulzimmer: in jedem Kinde liegt ein Zentrum von der Welt aus, vom Makrokosmos aus. Dieses Schulzimmer ist der Mittelpunkt, ja viele Mittelpunkte für den Makrokosmos. Denken Sie sich, lebendig das gefühlt, was das bedeutet! Wie da die Idee vom Weltenall und seinem Zusammenhang mit dem Menschen übergeht in ein Gefühl, welches durchheiligt alle einzelnen Vornahmen des Unterrichtes. Ohne daß wir solche Gefühle vom Menschen und vom Weltenall haben, kommen wir nicht dazu, ernsthaftig und richtig zu unterrichten. In dem Augenblick, wo wir solche Gefühle haben, übertragen sich diese durch unterirdische Verbindungen auf die Kinder. Ich habe Ihnen in anderem Zusammenhange gesagt, daß es auf einen immer wunderbar wirken muß, wenn man sieht, wie die Drähte in die Erde hinein zu Kupferplatten gehen und die Erde die Elektrizität ohne Drähte weiterleitet. Gehen Sie in die Schule hinein nur mit egoistischen Menschengefühlen, dann brauchen Sie alle möglichen Drähte - die Worte -, um sich mit den Kindern zu verständigen. Haben Sie die großen kosmischen Gefühle, wie sie entwickeln solche Ideen, wie wir sie eben entwickelt haben, dann geht eine unterirdische Leitung zu dem Kinde. Dann sind Sie mit den Kindern eins. Darin liegt etwas von geheimnisvollen Beziehungen von Ihnen zum Schulkinderganzen. Aus solchen Gefühlen heraus muß auch das aufgebaut sein, was wir Pädagogik nennen. Die Pädagogik darf nicht eine Wissenschaft sein, sie muß eine Kunst sein. Und wo gibt es eine Kunst, die man lernen kann, ohne daß man fortwährend in Gefühlen lebt? Die Gefühle aber, in denen man leben muß, um jene große Lebenskunst auszuüben, die Pädagogik ist, diese Gefühle, die man haben muß zur Pädagogik, die feuern sich nur an an der Betrachtung des großen Weltalls und seines Zusammenhanges mit dem Menschen.

Tenth Lecture

We have discussed the nature of the human being from a spiritual and soul perspective. We have shed at least some light on how the human being can be viewed from a spiritual and soul perspective. We will have to supplement what has been considered from these two points of view by first combining the spiritual, soul, and physical aspects so that we can obtain a complete overview of the human being and then move on to an understanding of the outer physical body.

First, let us recall what we must have noticed from various sides: that human beings have different forms in the three members of their being. We have pointed out how the shape of the head is essentially spherical, how the actual physical essence of the human head lies in this spherical shape. We then pointed out that the chest part of the human being is a fragment of a sphere, so that when we draw schematically, we give the head a spherical shape and the chest part a crescent shape, and that we are clear that this crescent shape contains a fragment of a sphere, a part of a sphere. Therefore, we must say to ourselves: we can supplement the crescent shape of the human chest member. And you will only be able to correctly visualize this middle member of the human being, the human chest form, if you also regard it as a sphere, but as a sphere of which only one part, a moon, is visible and the other part is invisible [Fig. I]. You may see from this that in those older times, when people had a greater ability to see forms than later, it was not wrong to speak of the sun corresponding to the head and the moon corresponding to the breast form. And just as, when the moon is not full, only a fragment of the sphere is visible, so too only a fragment of the human middle member is actually visible in the breast form. From this you can see that the shape of the human head here in the physical world is something relatively complete. The shape of the head appears physically as something complete. In a sense, it is entirely what it appears to be. It conceals the least of itself.

The chest part of the human being hides a great deal of itself; it leaves something of its essence invisible. It is very important for understanding the essence of the human being to realize that a good part of the chest is invisible. And so we can say: the chest shows us its physicality on one side, towards the back; towards the front, it transitions into the soul. The head is entirely physical; the chest area of the human being is physical toward the back and soul toward the front. We therefore only carry a real body with us when we rest our head on our shoulders. We have body and soul with us when we separate our chest from the rest of the chest area and allow it to be worked through and permeated by the soul.

Now, the limbs are inserted into these two parts of the human being, namely, for external observation, into the chest. The third is the limb-human. Now, how can we actually understand the limb-human? We can only understand the limb-human if we consider that other pieces remain from the spherical form than in the chest part. In the chest part, a piece of the periphery remains. In the limbs, more remains of the interior, of the radii of the sphere, so that the inner parts of the sphere are attached as limbs.

As I have often told you, it is not enough to simply schematically divide one thing into another. One must always interweave one thing with another, for that is what constitutes life. We say: we have the limb-bearing human being, who consists of limbs. — But you see, the head also has its limbs. If you look closely at the skull, you will see that, for example, the bones of the upper and lower jaw are attached to the skull [Fig. II]. They are correctly positioned like limbs. The skull also has its limbs, and the upper and lower jaws are attached to the skull as limbs. They are only atrophied on the skull. They are properly developed in other humans, but on the skull they are atrophied and are actually only bone structures. And there is another difference: if you look at the limbs of the skull, i.e., the upper and lower jaws, you will see that what is essential for them is that the bone performs its function. If you consider the limbs that are attached to our entire body, i.e., the actual essence of the limb-bearing human being, then you will have to look for the essential in the covering of muscles and blood vessels. In a sense, only the bones are attached to our muscle and blood system for arms and legs, hands and feet. And in a sense, the muscles and blood vessels are completely atrophied in the upper and lower jaws as limbs of the head. What does this mean? — You see, as we have already heard, the organic nature of the will lies in the blood and muscles. Therefore, it is mainly the arms and legs, hands and feet that are developed for the will. That which primarily serves the will, blood and muscles, is, to a certain extent, taken from the limbs of the head, because they are supposed to develop that which inclines toward the intellect, toward thinking and cognition. Therefore, if you want to study how the will of the world manifests itself in the outer forms of the body, study the arms and legs, hands and feet. If you want to study how the intelligence of the world manifests itself, then study the head as a skull, as a skeleton, and how the upper jaw, lower jaw, and other parts that look like limbs are attached to the head. You can see the external forms everywhere as manifestations of the inner. And you will only understand the outer forms if you regard them as manifestations of the inner.

Now, you see, I have always found that most people have great difficulty in understanding the relationship between the tubular bones of the arms and legs and the skull bones of the head. It is particularly good for teachers to acquire a concept here that is far removed from everyday life. And this brings us to a very, very difficult chapter, perhaps the most difficult for the mental image that we have to overcome in these educational lectures.

You know that Goethe first turned his attention to the so-called vertebral theory of the skull. What does this mean? It means applying the idea of metamorphosis to human beings and their form. If you look at the human spine, you see that one vertebra lies on top of another. We can remove such a vertebra with its processes, through which the spinal cord then passes (it is drawn). Goethe first observed on a sheep's skull in Venice how all the bones of the head are transformed vertebrae. This means that if one imagines some organs enlarged and others reduced, one obtains the shell-shaped skull bone from this vertebral form. This made a great impression on Goethe, because he had to conclude from this—which was very significant for him—that the skull is a transformed, higher-developed spine.

It is now relatively easy to see that the skull bones arise from the vertebrae of the spine through transformation, through metamorphosis. But now it becomes very difficult to understand the limb bones, even the limb bones of the head, the upper and lower jaws — Goethe tried, but still in an external way — as a transformation, as a metamorphosis of the vertebral bones or the skull bones. Why is that? Well, you see, this is based on the fact that a tubular bone that you have somewhere is also a metamorphosis, a transformation of the skull bone, but in a very special way. It is relatively easy to imagine the vertebrae of the spine transforming into the skull bone by imagining individual parts enlarged and others reduced in size. But it is not so easy to get the skull bones, the shell-like skull bones, out of the tubular bones of the arms or legs. You first have to perform a certain procedure if you want to get them out. You have to do the same thing with the long bones of the arms or legs that you would do if you were putting on a sock or a glove and turning the inside out first, that is, if you were turning it inside out. Now, it is relatively easy to form a mental image of what a glove or sock looks like when the inside is turned outwards. But the tubular bone is not uniform. It is not so thin that it is constructed uniformly inside and outside. It is constructed differently inside and outside. If you were to construct your sock in such a way and then make it elastic so that you could give it an artistic shape on the outside with all kinds of protrusions and indentations, and then turn it inside out, you would no longer have the same shape on the outside as you would on the inside after turning it inside out. And so it is with the tubular bone. You have to turn the inside out and the outside in, then the shape of the skull emerges, so that the human limbs are not only transformed skulls, but also inverted skulls. Where does this come from? It comes from the fact that the head has its center somewhere inside; it is concentric. The chest does not have its center in the middle of the sphere; the chest has its center very far away. This is only fragmentarily indicated here in the drawing, because it would be very large if it were drawn in its entirety. So the chest has its center far away.

And where is the center of the limb system? Now we come to the second difficulty. The limb system has its center in the entire circumference. The center of the limb system is actually a sphere, i.e., the opposite of a point. A spherical surface. The center is actually everywhere; therefore, you can turn anywhere and the radii radiate in from everywhere. They unite with you.

What is in the head emanates from the head; what passes through the limbs unites within you. That is why I had to say in the other lectures: you must imagine the limbs as being inserted. We are truly a whole world, except that what wants to enter us from outside becomes condensed and visible at its end. A tiny part of what we are becomes visible in our limbs, so that the limbs are something physical, but only a tiny atom of what is actually there in the limb system of the human being: spirit. Body, soul, and spirit are in the limb system of the human being. The body is only hinted at in the limbs; but the soul is also inside the limbs, and the spirit is inside, which basically encompasses the whole world.

Now one could also make another drawing of the human being. One could say: the human being is first of all a huge sphere that encompasses the whole world, then a smaller sphere, and then a smallest sphere. Only the smallest sphere is completely visible; the slightly larger sphere is only partially visible; the largest sphere is only visible in its rays at the end here, the rest remains invisible. This is how the human being is formed from the world in its shape.

And again, in the middle system, in the chest system, we have the union of the head system and the limb system. If you look at the spine with the beginnings of the ribs, you will see that this is an attempt to close off the front. The whole is closed off at the back, but at the front only an attempt is made to close it off; it does not quite succeed. The more the ribs are inclined towards the head, the more they succeed in closing themselves off, but the further down they are, the more they fail. The last ribs no longer come together because they are counteracted by the force that then comes from outside in the limbs.

The Greeks still had a very strong awareness of this connection between humans and the entire macrocosm. And the Egyptians knew this very well, only they knew it in a somewhat abstract way. Therefore, when you look at Egyptian or older sculptures, you can see that this idea of the cosmos is expressed. Otherwise, you will not understand what people did in ancient times if you do not know that they did what corresponded to their beliefs: the head is a small sphere, a miniature world body; the limbs are a part of the great world body, where it penetrates everywhere with its radii into the human form. The Greeks had a beautiful, harmoniously developed mental image of this, which is why they were good sculptors. And even today, no one can truly penetrate the plastic art of human beings without becoming aware of this connection between human beings and the universe. Otherwise, they will only ever imitate the forms of nature externally.

Now, my dear friends, from what I have told you, you will realize that the limbs are more inclined toward the world, while the head is more inclined toward the individual human being. So what will the limbs be particularly inclined toward? They will be inclined toward the world in which the human being moves and constantly changes his position. They will be related to the movement of the world. Understand this well: the limbs are related to the movement of the world.

As we walk around in the world, as we act in the world, we are the human beings of the limbs. What, then, is the task of the head, our head, in relation to the movement of the world? It rests on the shoulders, as I have told you from another point of view. It also has the task of continually bringing the movement of the world to rest within itself. If you put yourself in your head with your mind, you can really get an idea of this by imagining for a moment that you are sitting in a train; it is moving forward, you are sitting quietly inside. In the same way, your soul sits in your head, which is carried along by the limbs, sitting quietly inside and bringing the movement to rest within. You can even stretch out if you have room in the train car and rest, even though this rest is actually untrue, because you are rushing through the world in the train, perhaps in a sleeping car; nevertheless, you have the feeling of rest – in this way, the head calms within you what the limbs can accomplish as movement in the world. And the chest part stands in the middle. It mediates the movement of the outside world with what the head brings to rest.

Now think about this: it is our very intention as human beings to imitate and absorb the movement of the world through our limbs. What do we do to achieve this? We dance. You dance in reality; other forms of dancing are only fragmentary. All dancing is based on imitating the movements of the planets, the other celestial bodies, and the Earth itself in the movements, in the limb movements of humans.

But what about the head and the chest when we imitate the cosmic movements in our movements as humans through dancing? You see, it is as if the movements we perform in the world accumulate in the head and chest. They cannot continue through the chest into the head, because the head rests on the shoulders, which do not allow the movements to continue into the soul. The soul must participate in the movements at rest, because the head rests on the shoulders. So what does it do? It begins to reflect on its own what the limbs are doing as they dance. It begins to hum when the limbs perform irregular movements; it begins to lisp when the limbs perform regular movements, and it even begins to sing when the limbs perform the harmonious cosmic movements of the universe. Thus, the dancing movement is transformed outwardly into song and inwardly into music.

If it does not regard the human being as a cosmic being, sensory physiology will never be able to comprehend sensation; it will always say: Outside are the movements of the air, inside the human being perceives the sound. How the movements of the air are connected with the sound cannot be known. That is what is written in physiology and psychology, at the end of one and at the beginning of the other; that is the whole difference.

Where does this come from? It comes from the fact that people who practice psychology or physiology do not know that what humans have externally in movements is brought to rest within the soul and thereby begins to transform into sounds. And so it is with all other sensory perceptions. Because the main organs do not participate in external movements, they radiate these movements back into the chest and turn them into sound, into another sensory perception. That is the origin of sensations. But that is also the connection between the arts. The musical arts arise from the plastic and architectural arts, in that what the plastic and architectural arts are outwardly, the musical arts are inwardly. The reflection of the world from the inside out is the musical arts. This is how human beings stand within the universe. Perceive a color as movement that has come to rest. You do not perceive the movement externally, as when you lie stretched out in a train and could have the illusion that you are at rest. You let the train move outside. In this way, you allow your body to participate in the outer world through subtle movements of the limbs that you do not perceive, and you yourself perceive the colors and sounds inside. You owe this to the fact that you allow your head to be carried in peace by the limb organism.

I told you that what I am telling you is a rather difficult matter. It is particularly difficult because nothing is being done in our time to help people understand these things. Everything we learn in school today ensures that people remain ignorant of the things I have brought to your attention today. What actually happens as a result of our education today? Well, people do not really get to know a sock or a glove completely if they do not even turn it inside out, because then they never know what part of the sock or glove actually touches their skin; they only know what is on the outside. So, through our present-day education, people also only know what is turned outward. They only get concepts for half of the human being. For they cannot even comprehend the limbs. For the spirit has already turned them inside out.

We can also describe what we have presented today in this way: if we consider the whole, complete human being as he stands before us in the world, first as a limb-being, he reveals himself as such in spirit, soul, and body. If we consider him as a chest being, he appears to us as soul and body. The large sphere (see drawing): spirit, body, soul; the smaller sphere: body, soul; the smallest sphere: body only. At the Council of 869, the bishops of the Catholic Church forbade humanity from knowing anything about the large sphere. At that time, they declared it to be dogma of the Catholic Church that only the middle sphere and the smallest sphere existed, that human beings consisted only of body and soul, that the soul contained something spiritual only as its property, and that the soul was also spirit-like in one respect. Since 869, spirit has ceased to exist for Western culture, which originated in Catholicism. — But with the relationship to the spirit, man's relationship to the world has been abolished. Man has been driven more and more into his egoism. As a result, religion itself has become more and more egoistic, and today we live in a time when, I would say, we must once again learn about man's relationship to the spirit and thus to the world through spiritual observation.

Who is actually to blame for the fact that we have ended up with scientific materialism? The Catholic Church is mainly to blame for the fact that we have ended up with scientific materialism, because it abolished the spirit at the Council of Constantinople in 869. What actually happened back then? Consider the human head. It has developed within the factual world of world events in such a way that today it is the oldest part of the human being. The head first arose from higher animals, then, going further back, from lower animals. With regard to our head, we are descended from the animal world. There is no denying it — the head is just a more highly developed animal. We return to the lower animal world when we seek the ancestors of our head. Our chest was only added to the head later; it is no longer as animalistic as the head. We only acquired our chest in a later age. And we humans acquired our limbs as the latest organs; they are the most human organs. They are not transformed from animal organs, but were added later. The animal organs were formed independently from the cosmos to the animals, and the human organs were later added independently to the chest. But by concealing man's awareness of his relationship to the universe, that is, of the actual nature of his limbs, the Catholic Church has passed on only a little to subsequent ages about the chest and mainly about the head, about the skull. And so materialism came to the conclusion that the skull originated from animals. And now it claims that the whole human being originated from animals, while the chest organs and the limb organs were only formed later. Precisely because the Catholic Church has concealed from man the nature of his limbs, his connection with the world, it has caused the later materialistic age to fall into the idea that only the head has meaning, but applies this idea to the whole human being. The Catholic Church is in truth the creator of materialism in this field of evolutionary theory. It is particularly appropriate for today's teachers of young people to know such things. For they should link their interest with what has happened in the world. And they should know the things that happen in the world from their foundations.

Today we have tried to understand how our age has become materialistic by starting with something completely different: with the spherical shape and the shape of the moon and with the radial shape of the limbs. In other words, we started with something that seems to be the complete opposite in order to understand a great, powerful, cultural-historical fact. But it is necessary, especially for the teacher, who otherwise cannot do anything with the developing human being, to be able to grasp the cultural facts from the foundations. Then he will take in something that is necessary if he wants to educate in the right way from within himself through the unconscious and subconscious relationships with the child. For then they will have the right respect for the human being. They will see the relationships to the greater world in the human being. They will approach this human being differently than if they saw only something like a better-trained animal, a better-trained animal body in the human being. Today, even if teachers sometimes indulge in illusions about this in their minds, they basically approach other people with the clear awareness that the growing human being is a little animal, a little creature, and that they have to develop this little creature — a little further than nature has already developed it. He will feel differently when he says: There is a human being from whom relationships emanate to the whole world, and in every single growing child I have something; when I work on it, I am doing something that has meaning in the whole world. We are there in the classroom: in every child lies a center of the world, of the macrocosm. This classroom is the center, indeed many centers, for the macrocosm. Imagine feeling what that means! How the idea of the universe and its connection to human beings transforms into a feeling that permeates every single aspect of teaching. Without such feelings about human beings and the universe, we cannot teach seriously and correctly. The moment we have such feelings, they are transmitted to the children through underground connections. I have told you in another context that it must always have a wonderful effect on one to see how the wires go into the earth to copper plates and the earth transmits the electricity without wires. If you enter the school with only selfish human feelings, then you will need all kinds of wires – words – to communicate with the children. If you have the great cosmic feelings that develop ideas such as those we have just developed, then an underground connection to the child is established. Then you are one with the children. Therein lies something of the mysterious relationship between you and the schoolchildren as a whole. What we call pedagogy must also be built on such feelings. Pedagogy must not be a science, it must be an art. And where is there an art that can be learned without constantly living in feelings? But the feelings in which one must live in order to practice that great art of living that is pedagogy, these feelings that one must have for pedagogy, are only kindled by contemplating the great universe and its connection with human beings.