The Study of Man

GA 293

4 September 1919, Stuttgart

Lecture XIII

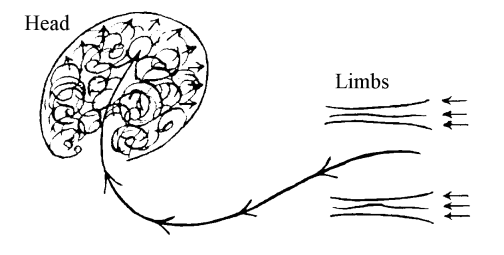

The insight we have won through these lectures will enable us to understand man in his relationship to the world around him. It will enable us also to deal with the child in his relationship to the world. It is only a question of being able to apply this insight in life in the right way. We have to think of the relation of man to the outside world as twofold, for we have found that the constitution of the limb man is in complete contrast to that of the head man. We must accustom ourselves to the difficult thought that the only way to understand the forms of the limb man is to imagine the head forms turned inside out like a glove or stocking. And in this is an expression of something of great significance in the whole life of man. If we were to draw it as a diagram we might say: the head is formed as though it were pressed outwards from within, is “bulged” outwards from within. The limbs of man we can picture as pressed inwards from without through being turned inside out at the forehead. (This turning inside out is a process of great significance in the life of man.) Consider your forehead, and imagine that your inner being is striving from within outwards towards your forehead. Now on the palm of your hand or on the sole of your foot, a kind of pressure is being exercised, like the pressure on your forehead from within, only in the reverse direction. So that when you hold your hand with the palm facing outwards, or when you place the sole of your foot on the ground, there streams from without through your sole, or through your palm, what streams towards your forehead from within. This is a fact of remarkable importance. It is so very important because it enables us to see the actual disposition of the spiritual-soul element in man.

This spirit-soul element, as you now see, is a stream. The spirit-soul passes through man as a stream, as a current.

And what is man in respect to this soul and spirit? Imagine a flowing stream of water stopped by a dam, so that it is checked and floods back on itself. So does the spirit and soul gush over in man. The human being is like a dam for the spirit and soul. They might flow through him unhindered, but he retards and keeps them back. Man causes spirit and soul to be dammed up within him. Now this process, which I have likened to a stream, is a very remarkable one. I have likened the active flow of spirit and soul through man to a stream. But actually—what is it from the point of view of the external bodily nature? It is a perpetual suction of the human being. Man confronts the external world. Spirit and soul are continuously striving to absorb him, to suck him in. This is why we continuously shed flakes and bits of ourselves. And if the spirit is not strong enough to do it we have to cut off bits of ourselves, e.g. the finger nails—because the spirit, coming from without, seeks to devour and destroy them. The spirit destroys everything, and the body checks this destructiveness of the spirit. And in man a balance must be created between the destructive spirit and soul and the continually constructive activity of the body. The chest abdomen system is inserted amidst this stream. And it is this chest abdomen system which throws itself against the destructive onset of spirit and soul, and which permeates the human being with the material substance it produces. From this you will see that the limbs of man which reach out beyond the chest abdomen system are really the most spiritual thing of all, for there is less of the substance-creating process going on in the limbs than anywhere else in man. The only thing that brings a material element into the limbs is that part of the metabolic process which is sent into the limbs by the chest abdomen system. Our limbs are spirit to a high degree, and it is the limbs which consume our body when they move.

And the task of the body is to develop in itself what is potentially in man from his birth. If the limbs move too little or move in the wrong way, they do not consume enough of the body. The abdomen chest system is then in the fortunate position—fortunate, that is, for itself—that an insufficient quantity of it is consumed by the limbs. It uses what is left over to produce surplus substantiality in man. This surplus substantiality then permeates what is native to man from his birth, that is, the bodily nature proper to him as a being born of spirit and soul. It permeates what he ought to have with something he ought not to have, with a substantiality which belongs to his earthly nature only, a substantiality having no tendency to spirit and soul in the true sense of the words: it permeates him with fat. Now when this fat is deposited in man to an abnormal extent it causes too much obstruction to the incoming consuming process of spirit and soul; with the result that the path of this spirit and soul process to the head system is made difficult. For this reason it is not right to allow children to have too much fat producing food. It causes their heads to be separated off from the soul-spiritual stream. For fat obstructs soul and spirit, and renders the head empty. It is a question of having the tact to co-operate with the child's home life and see to it that he does not get too fat. Later in life getting fat depends on all kinds of other things, also some abnormally constituted children tend to get fat because they are weak—but with normal children it is always possible to prevent excessive fat by giving a suitable diet.

We shall not, however, have the right feeling of responsibility towards these things unless we appreciate their very great significance. We must realise that if we allow the child to accumulate too much fat we are encroaching on the work of the world process. The world has a purpose to achieve in man, which it signifies by letting soul and spirit flow through him. We definitely encroach on a cosmic process if we let the child get too fat.

Now something very remarkable happens in man's head: as all spirit and soul is dammed up there it splashes back like water meeting a weir. It is like this: the spirit and soul brings matter with it, as the Mississippi brings sand, and this matter sprays back right inside the brain; thus where spirit and soul is dammed up we have streams surging one over the other. And in this beating back of the material element matter is continually perishing in the brain. And when matter, which is still permeated with life, collapses and is driven back, as I described, there then arises the nerve. Nerve comes into existence wherever matter which has been driven through life by the spirit perishes and decays within the living organism. Hence nerve is decayed matter within the living organism: life gets jammed, as it were, gets dammed up in itself, matter crumbles away and decays. Hence arise channels in all parts of the body filled with decayed matter, these are the nerves. Here spirit and soul can play back into man. Spirit and soul sprays through man along the nerves; for spirit and soul makes use of the decayed matter. It causes matter to decay, to flake off on the surface of man's body. Indeed spirit and soul will not enter man's body and permeate it until matter has died within it. The spirit and soul element in man moves within him along the nerve channels of lifeless matter.

In this way we can see how spirit and soul actually operates in man. We see it pressing upon him from outside, developing, as it does so, a devouring, consuming activity. We see it penetrating into him. We see how it is checked, how it splashes back, how it kills matter. We see how matter decays in the nerves, and how this enables the spirit and soul to make its way even to the skin, from within outwards, along the pathways of its own making. For spirit and soul cannot pass through what has organic life.

Now, how can you picture the organic, the living element? You can picture it as something that takes up spirit and soul into itself, that does not let them through. And you can picture the dead material, mineral element as something that lets the spirit and soul through. So that you can get a kind of definition for the living-organic element and a definition for the bone-nerve element, and indeed for the material-mineral element as a whole. For the living-organic element is impermeable for the spirit. The dead physical element is permeable for the spirit. “Blood is a very special fluid,” for as opaque matter is to light, so is blood to the spirit. It does not let the spirit through. It retains the spirit within it. Nerve substance is a very special substance, also. It is to spirit as transparent glass is to light. As transparent glass lets the light through, so, too, physical matter, material nerve substance lets the spirit through.

Here we have the difference between two component parts of the human being, that in him which is mineral, which is permeable to the spirit, and that in him which is more animal, more of a living organism, and which retains the spirit within him—that which causes the spirit to produce the forms which shape the organism.

From this many things follow for the treatment of the human being. For example, when a man does bodily work he moves his limbs. This means he is entirely immersed, he is swimming about in the spirit. This is not the spirit that has dammed itself up within him, this is the spirit that is outside him. If you chop wood, or if you walk—whenever you move your limbs in work of some sort—whether useful or not—you are constantly splashing about in spirit; you are concerned constantly with spirit. This is very important. And, further it is important to ask ourselves: What if we are doing spiritual work, if we are thinking or reading—how is it then? Well, this is a concern of the spirit and soul that is within us. Now it is not we who splash about in spirit with our limbs, but the spirit and soul is at work in us and continuously makes use of our bodily nature; that is, spirit and soul come to expression wholly as a bodily process within us. And here within us by means of this damming up, matter is constantly being thrown back upon itself. In spiritual work the activity of the body is excessive, in bodily work, on the other hand, the activity of the spirit is excessive. We cannot do spiritual work, work of soul and spirit, except with the continuous participation of the body. When we do bodily work the spirit and soul within us takes part only in so far as our thoughts direct our walking, or guide our work. But the spirit and soul nature takes part in it from without. We continuously work into the spirit of the world, we continuously unite ourselves with the spirit of the world when we do bodily work. Bodily work is spiritual; spiritual work is bodily, its effect is bodily upon and within man. We must understand this paradox and make it our own, namely that bodily work is spiritual and spiritual work bodily, both in man and in its effects on man. Spirit is flooding round us when do bodily work. Matter is active within us when we do spiritual work.

We must know such things, my dear friends, if we are to think with understanding about work—whether spiritual or bodily work—and about recreation and fatigue. We can only do this if we have a thorough grasp of what I have just described. For, suppose a man works too much with his limbs, that he does too much bodily work, what is the result? It brings him too much into relation with the spirit. For spirit continually floods round him when he does bodily work; consequently the spirit gains too much power over man, the spirit that comes from outside. We make ourselves too spiritual when we do too much bodily work. From without we let ourselves be made too spiritual. And it follows that we need to give ourselves up to the spirit for too long, in other words, we have to sleep too long. And too much sleep in turn promotes too much bodily activity, the bodily activity of the chest abdomen, not of the head system. This activity over-stimulates life, we become feverish, too hot. Our blood pulses in us too strongly its activity in the body cannot be assimilated, if we sleep too much. Nevertheless through excessive bodily work we produce in ourselves the desire to sleep too much.

But what about lazy people who love to sleep, and who sleep so much? Why are they like this? It is due to the fact that man can never really stop working. When a lazy person sleeps it is not because he works too little, for a lazy person has to move his legs all day long, and he flourishes his arms about, too, in some fashion or other. Even a lazy person does something. From an external point of view he really does no less than an industrious person—but he does it without sense or purpose. The industrious man turns his attention to the outside world, He introduces meaning into his activities. That is the difference. Senseless activities such as a lazy person carries on are more conducive to sleep than are activities with a purpose in them. In intelligent occupation we do not merely splash about in the spirit: if there is meaning in the movements we carry out in our work we gradually draw the spirit into us. When we stretch out our hand with a purpose we unite ourselves with the spirit; and the spirit, in its turn, does not need to work so much unconsciously in sleep, because we are working with it consciously. Thus it is not a question of whether man is active or not, for a lazy man too is active, but the question is how far man's actions have a purpose in them. To be active with a purpose—these words must sink into our minds if we would be teachers. Now when is a man active without purpose? He is active without purpose, senselessly active, when he acts only in accordance with the demands of his body. He acts with purpose when he acts in accordance with the demands of his environment and not merely in accordance with those of his own body. We must pay heed to this where the child is concerned. It is possible, on the one hand, to direct the child's outer bodily movements more and more to what is purely physical, that is, to physiological gymnastics, where we simply enquire of the body what movements shall be carried out. But we can also guide the child's outer movements so that they become purposeful movements, movements penetrated with meaning, so that the child does not merely splash about in the spirit in his movements, but follows the spirit in his aims. So we develop the bodily movements into Eurythmy. The more we make the child do purely physical gymnastics the more he will be at the mercy of excessive desire for sleep; and of an excessive tendency to fat. We must not entirely neglect the bodily side, for man must live in rhythm, but having swung over to this side we must swing back again to a kind of movement which is permeated with purpose—as in Eurythmy, where every movement expresses a sound and has a meaning—the more we can alternate gymnastics with Eurythmy the more we shall bring harmony into the need for sleeping and waking; the more, too, shall we maintain normal life in the child's will, in his relations to the outer world. That gymnastics, moreover, has become void of all sense or meaning, that we have made it into an activity that follows the body entirely, is a characteristic phenomenon of the age of materialism. And the fact that we seek to “raise” this activity to the level of sport, where the movements to be performed are derived solely from the body, and not only lack all sense and meaning, but are contrary to sense and meaning—this fact is typical of the endeavour to drag man down even beyond the level of materialistic thinking to that of brute feeling. The excessive pursuit of sport is Darwinism in practice. Theoretical Darwinism is to assert that man comes from the animals. Sport is practical Darwinism, it proclaims an ethic which leads man back again to the animal.

One must speak of these things to-day in this radical manner because the present-day teacher must understand them; for, not only must he be the teacher of those children entrusted to his care, he must also work socially, he must work back upon mankind as a whole to prevent the increasing growth of things which would tend indeed to have an animalising effect upon humanity. This is not false asceticism. It comes from the objectivity of real insight, and is as true as any other scientific knowledge.

Now what is the position with regard to spiritual work? Spiritual work, thinking, reading and so on, is always accompanied by bodily activity and by the continual decay and dying of organic matter. When we are too active in spirit and soul we have decayed organic matter within us. If we spend our entire day in learned work we have too much decayed organic matter in us by the evening, This works on in us, and disturbs restful sleep. Excessive spiritual work disturbs sleep just as excessive bodily work makes one sleep-sodden. But when we exert ourselves too much over soul-spiritual work, when, for instance, we read something difficult, and really have to think as we read (not exactly a favourite occupation nowadays), if we do too much difficult reading we fall asleep over it. Or if we listen, not to the trite platitudes of popular speakers or others who only say what we already know, but to people whose words we have to follow with our thoughts because they are telling us what we do not yet know—we get tired and sleep-sodden. It is well known that people who go to a lecture or concert because it is “the thing to do”, and do not give real thought or feeling to what is put before them, fall asleep at the first word, or the first note. Often they will sleep all through the lecture or concert which they have attended only from a sense of duty or of social obligation.

Now here again are two kinds of activity. Just as there is a difference between outward activity which has meaning and purpose and that which has no meaning, so there is a difference between the inner activity of thought and perception which goes on mechanically and that which is always accompanied by feelings. If we so carry out our work that continuous interest is combined with it, this interest and attention enlivens the activity of our breast system and prevents the nerves from decaying to an excessive degree. The more you merely skim along in your reading, the less you exert yourselves to take in what you read with really deep interest—the more you will be furthering the decay of substance within you. But the more you follow what you read with interest and warmth of feeling the more you will be furthering the blood activity, that is, that activity which keeps matter alive. And the more, too, you will be preventing mental activity from disturbing your sleep. When you have to cram for an examination you are assimilating a great deal in opposition to your interest. For if we only assimilated what aroused our interest we should not get through our examinations under modern conditions. It follows that cramming for an examination disturbs sleep and brings disorder into our normal life. This must be specially borne in mind where children are concerned. Therefore for children it is best of all, and most in accordance with an educational ideal, if we omit all cramming for examinations. That is, we should omit examinations altogether and let the school year finish as it began. As teachers we must feel it our duty to ask ourselves: why should the child undergo a test at all? I have always had him before me and I know quite well what he knows and does not know. Of course under present-day conditions this must remain an ideal for the time being. And I must beg you not to direct your rebel natures too forcibly against the outside world. Your criticism of our present-day civilisation you must turn inwards like a goad, so that you may work slowly—for we can only work slowly in these things—towards making people learn to think differently; then external social conditions will change their present form.

But you must always remember the inner connection of things. You must know that Eurythmy, external activity permeated with purpose, is a spiritualising of bodily activity, and the arousing of interest in one's teaching (provided it is genuine) is literally a bringing of life and blood into the work of the intellect.

We must bring spirit into external work, and we must bring blood into our inward, intellectual work. Think over these two sentences, and you will see that the first is of significance both in education and in social life, and that the second is of significance both in education and in hygiene.

Dreizehnter Vortrag

Wir können den Menschen in seinem Verhalten zur Außenwelt begreifen und können Einblick gewinnen, wie wir uns zum Kinde bezüglich seines Verhaltens zur Außenwelt verhalten sollen, wenn wir solche Einsichten zugrunde legen, wie wir sie in diesen Vorträgen uns verschafft haben. Es handelt sich nur darum, diese Einsichten in entsprechender Weise im Leben anzuwenden. Bedenken Sie, daß wir geradezu ein zweifaches Verhalten des Menschen zur Außenwelt ins Auge fassen müssen dadurch, daß wir sprechen können von einer ganz entgegengesetzten Gestaltung des Gliedmaßenmenschen zum Kopfmenschen.

Wir müssen uns die schwierige Vorstellung aneignen, daß wir die Formen des Gliedmaßenmenschen nur begreifen, wenn wir uns vorstellen, daß die Kopfformen wie ein Handschuh oder wie ein Strumpf umgestülpt werden. Das, was damit zum Ausdruck kommt, ist von einer großen Bedeutung im ganzen Leben des Menschen. Wenn wir es schematisch hinzeichnen, so ist es so, daß wir uns sagen können: Die Kopfform wird so gebildet, daß sie gewissermaßen von innen nach außen gedrückt wird, daß sie aufgeplustert wird von innen nach außen. Wenn wir uns die Gliedmaßen des Menschen denken, so können wir uns vorstellen, daß sie von außen nach innen gedrückt werden, durch die Umstülpung - das bedeutet sehr viel im Leben des Menschen - an Ihrer Stirne. Und vergegenwärtigen Sie sich, daß Ihr inneres Menschliches hinstrebt von innen aus nach Ihrer Stirne. Besehen Sie sich Ihre innere Handfläche und besehen Sie sich Ihre innere Fußfläche: es wird auf diese fortwährend eine Art von Druck ausgeübt, der gleich ist dem Druck, der auf Ihre Stirne von innen ausgeübt wird, nur in der entgegengesetzten Richtung. Indem Sie also Ihre Handfläche der Außenwelt entgegenhalten, indem Sie Ihre Fußsohlenfläche auf den Boden aufsetzen, strömt von außen durch diese Sohle dasselbe ein, was von innen strömt gegen die Stirne zu. Das ist eine außerordentlich wichtige Tatsache. Es ist deshalb so wichtig, weil wir dadurch sehen, wie es eigentlich mit dem Geistig-Seelischen im Menschen ist. Dieses GeistigSeelische, das sehen Sie ja daraus, ist eine Strömung. Es geht eigentlich dieses Geistig-Seelische als Strömung durch den Menschen durch.

Und was ist denn der Mensch gegenüber diesem Geistig-Seelischen ? Denken Sie sich, ein Wasserstrom fließt hin und wird durch ein Wehr aufgehalten, so daß er sich staut und in sich zurückwellt. So übersprudelt das Geistig-Seelische sich im Menschen. Der Mensch ist ein Stauapparat für das Geistig-Seelische. Es möchte eigentlich ungehindert durch den Menschen durchströmen, aber er hält es zurück und verlangsamt es. Er läßt es in sich aufstauen. Nun ist aber allerdings diese Wirkung, die ich als Strömung bezeichnet habe, eine sehr merkwürdige. Ich habe Ihnen diese Wirkung des Geistig-Seelischen, das da den Menschen durchströmt, als eine Strömung bezeichnet, aber was ist es eigentlich gegenüber der äußeren Leiblichkeit? Es ist ein fortwährendes Aufsaugen des Menschen.

Der Mensch steht der Außenwelt gegenüber. Das Geistig-Seelische strebt danach, ihn fortwährend aufzusaugen. Daher blättern wir außen fortwährend ab, schuppen ab. Und wenn der Geist nicht stark genug ist, müssen wir uns Stücke, wie zum Beispiel die Fingernägel, abschneiden, weil der Geist sie, von außen kommend, saugend zerstören will. Er zerstört alles, und der Leib hält diese Zerstörung des Geistes auf. Und es muß im Menschen ein Gleichgewicht geschaffen werden zwischen dem zerstörenden Geistig-Seelischen und dem fortwährenden Aufbauenden des Leibes. Es ist eingeschoben in diese Strömung das Brust-Bauchsystem. Und das Brust-Bauchsystem ist dasjenige, welches sich entgegenwirft der Zerstörung des eindringenden Geistig-Seelischen und welches von sich aus den Menschen durchdringt mit Materiellem. Daraus aber ersehen Sie, daß die Gliedmaßen des Menschen, die hinausragen über das Brust-Bauchsystem, wirklich auch das Geistigste sind, denn da in den Gliedmaßen wird noch am wenigsten der Materie erzeugende Prozeß im Menschen vorgenommen. Nur dasjenige, was vom Bauch-Brustsystem hineingeschickt wird an Stoffwechselvorgängen in die Glieder, das macht, daß unsere Glieder materiell sind. Unsere Glieder sind in hohem Grade geistig, und sie sind es, welche an unserem Leib zehren, wenn sie sich bewegen. Und der Leib ist darauf angewiesen, in sich dasjenige zu entwickeln, wozu der Mensch eigentlich veranlagt ist von seiner Geburt an. Bewegen sich die Glieder zuwenig oder bewegen sie sich nicht entsprechend, dann zehren sie nicht genug am Leibe. Das Brust-Bauchsystem ist dann in der glücklichen Lage - in der für es glücklichen Lage -, daß ihm nicht genügend weggezehrt wird von den Gliedern. Das, was es so übrig behält, verwendet es dazu, um überschüssige Materialität im Menschen zu erzeugen. Diese überschüssige Materialität durchdringt dann dasjenige, was im Menschen veranlagt ist von seiner Geburt aus, was er also eigentlich haben sollte zu der Leiblichkeit, weil er als seelisch-geistiges Wesen geboren wird. Es durchdringt das, was er haben sollte, mit etwas, was er nicht haben sollte, was er nur als irdischer Mensch hat materiell, was nicht geistig-seelisch veranlagt ist im wahren Sinne des Wortes; es durchdringt ihn immer mehr und mehr mit Fett. Wenn aber dieses Fett in abnormer Weise eingelagert wird in den Menschen, dann stellt sich ja eigentlich dem geistig-seelischen Prozeß, der als ein Saugprozeß, als ein verzehrender Prozeß eindringt, zuviel entgegen, und dann wird ihm sein Weg erschwert zum Kopfsystem hin. Daher ist es nicht richtig, wenn man den Kindern erlaubt, zuviel fetterzeugende Nahrung zu nehmen. Dadurch wird ihr Kopf abgegliedert vom Geistig-Seelischen. Denn das Fett legt sich in den Weg des Geistig-Seelischen, und der Kopf wird leer. Es handelt sich darum, daß man den Takt entwickelt, so zusammenzuwirken mit der gesamten sozialen Lage des Kindes, daß das Kind in der Tat nicht zu fett wird. Später im Leben hängt ja das Fettwerden von allerlei anderen Dingen ab, aber in der Kindheit hat man es bei nicht abnorm gebildeten, das heißt besonders schwach gebildeten Kindern, die, weil sie schwach sind, leicht fett werden, also bei normal gebildeten Kindern immerhin in der Hand, nachzuhelfen durch eine entsprechende Ernährung gegen das zu starke Fettwerden.

Aber man wird diesen Dingen gegenüber nicht die rechte Verantwortlichkeit haben, wenn man nicht ihre ganz große Bedeutung ermißt; wenn man nicht ermißt, daß man in dem Fall, wo man dem Kinde erlaubt, zuviel Fett ansammeln zu lassen, dem Weltenprozeß, der etwas vorhat mit dem Menschen, was er zum Ausdruck bringt dadurch, daß er sein Geistig-Seelisches durchströmen läßt durch den Menschen, daß man da diesem Weltenprozeß ins Handwerk pfuscht. Man pfuscht tatsächlich dem Weltenprozeß ins Handwerk, wenn man das Kind zu fett werden läßt.

Denn, sehen Sie, in diesem Haupt des Menschen, da geschieht etwas höchst Merkwürdiges: indem da sich alles staut im Menschen von dem Geistig-Seelischen, spritzt es zurück wie das Wasser, wenn es an ein Wehr kommt. Das heißt, es spritzt dasjenige, was das Geistig-Seelische von der Materie mitträgt, so wie der Mississippi den Sand, auch im Inneren des Gehirns zurück, so daß da sich überschlagende Strömungen im Gehirn sind, wo das Geistig-Seelische sich staut. Und im Zurückschlagen des Materiellen, da fällt im Gehirn fortwährend Materie in sich selbst zusammen. Und wenn Materie, die noch vom Leben durchdrungen ist, in sich selbst zusammenfällt, also so zurückschlägt, wie ich es Ihnen gezeigt habe, dann entsteht der Nerv. Der Nerv entsteht immer, wenn vom Geiste durch das Leben getriebene Materie in sich selbst zusammenfällt und im lebendigen Organismus drinnen abstirbt. Deshalb ist der Nerv im lebendigen Organismus drinnen abgestorbene Materie, so daß sich also das Leben verschiebt, sich in sich selbst staut, Materie abbröckelt, zusammenfällt. So entstehen Kanäle im Menschen, die überall hingehen, die ausgefüllt sind von erstorbener Materie: die Nerven; da kann dann das Geistig-Seelische zurücksprudeln in den Menschen. Längs der Nerven sprudelt das Geistig-Seelische durch den Menschen durch, weil das Geistig-Seelische die zerfallende Materie braucht. Es läßt die Materie an der Oberfläche des Menschen zerfallen, bringt sie zum Abschuppen. Dieses Geistig-Seelische läßt sich nur darauf ein, den Menschen zu erfüllen, wenn in ihm die Materie zuerst erstirbt. Längs der materiell erstorbenen Nervenbahnen bewegt sich im Inneren das Geistig-Seelische des Menschen.

Auf diese Weise sieht man hinein in die Art, wie das Geistig-Seelische eigentlich im Menschen arbeitet. Man sieht es herandringen von außen, saugende, zehrende Tätigkeit entwickelnd. Man sieht es eindringen; man sieht, wie es gestaut wird, wie es zurückbrodelt, wie es die Materie ertötet. Man sieht, wie die Materie zerfällt in den Nerven und dadurch von innen heraus das Geistig-Seelische nun auch an die Haut dringen kann, indem es sich selbst Wege bereitet, durch die es durch kann. Denn durch das, was organisch lebt, geht das GeistigSeelische nicht durch.

Wie können Sie sich denn also das Organische, das Lebendige vorstellen? Sehen Sie, das Lebendige können Sie sich auch vorstellen wie etwas, was das Geistig-Seelische aufnimmt, was es nicht durchläßt. Das Tote, Materielle, das Mineralische können Sie sich vorstellen wie etwas, was das Geistig-Seelische durchläßt, so daß Sie eine Art Definition des Leiblich-Lebendigen und eine Definition des KnöcherigNervösen, wie überhaupt des Mineralisch-Materiellen bekommen können: Das Lebendig-Organische ist geistundurchlässig; das PhysischTote ist geistdurchlässig. - «Blut ist ein ganz besonderer Saft», denn es ist so gegenüber dem Geiste, wie undurchsichtige Materie gegenüber dem Lichte ist; es läßt den Geist nicht durch, es behält ihn in sich. Nervensubstanz ist eigentlich auch eine ganz besondere Substanz. Sie ist wie durchsichtiges Glas gegenüber dem Lichte. Wie durchsichtiges Glas das Licht durchläßt, so läßt materiell physische Materie, auch Nervenmaterie, den Geist durch.

Sehen Sie, da haben Sie den Unterschied zwischen zwei Bestandteilen des Menschen: zwischen dem, was in ihm Mineral ist, was geistdurchlässig ist, und dem, was in ihm mehr tierisch, mehr organischlebendig ist, was den Geist aufhält in ihm, was den Geist veranlaßt, die Formen hervorzubringen, die den Organismus gestalten.

Nun folgt aber daraus für die Behandlung des Menschen allerlei. Wenn der Mensch, sagen wir körperlich arbeitet, so bewegt er seine Glieder, das heißt, er schwimmt ganz und gar im Geiste herum. Das ist nicht der Geist, der sich in ihm schon gestaut hat; das ist der Geist, der draußen ist. Ob Sie Holz hacken, ob Sie gehen, wenn Sie nur Ihre Glieder bewegen, indem Sie Ihre Glieder zur Arbeit bewegen, zur nützlichen oder unnützlichen Arbeit bewegen, plätschern Sie fortwährend im Geiste herum, haben es fortwährend mit dem Geiste zu tun. Das ist sehr wichtig. Und wichtig ist ferner, sich zu fragen: Wenn wir nun geistig arbeiten, wenn wir denken oder lesen oder dergleichen, wie ist es dann? — Ja, da haben wir es mit dem Geistig-Seelischen zu tun, das in uns drinnen ist. Da plätschern nicht wir mit unseren Gliedern im Geiste, da arbeitet das Geistig-Seelische in uns und bedient sich fortwährend unseres Leiblichen, das heißt, es kommt ganz in uns in einem leiblich-körperlichen Prozeß zum Ausdruck. Da wird fortwährend drinnen durch dieses Stauen Materie in sich zurückgeworfen. Bei der geistigen Arbeit ist unser Leib in einer übermäßigen Tätigkeit; bei der körperlichen Arbeit ist dagegen unser Geist in einer übermäßigen Tätigkeit. Wir können nicht geistig-seelisch arbeiten, ohne daß wir fortwährend mit unserem Leib innerlich mitarbeiten. Wenn wir körperlich arbeiten, da ist höchstens, indem wir uns durch die Gedanken die Richtung zum Gehen geben, durch die Gedanken orientierend wirken, unser Geistig-Seelisches im Inneren beteiligt; aber das Geistig-Seelische von außen ist beteiligt. Wir arbeiten fortwährend in den Geist der Welt hinein. Wir verbinden uns fortwährend mit dem Geiste der Welt, indem wir körperlich arbeiten. Körperliche Arbeit ist geistig, geistige Arbeit ist leiblich, am und im Menschen. Dieses Paradoxon muß man sich aneignen und es verstehen, daß körperliche Arbeit geistig und geistige Arbeit leiblich ist im Menschen und am Menschen. Der Geist umspült uns, indem wir körperlich arbeiten. Die Materie ist bei uns tätig, rege, indem wir geistig arbeiten.

Diese Dinge muß man wissen in dem Augenblick, wo man verständnisvoll denken will über Arbeit, sei es nun geistige oder leibliche Arbeit, über Erholung und Ermüdung. Man kann nicht verständig denken über Arbeit und Erholung und Ermüdung, wenn man nicht das wirklich verständig durchschaut, was wir eben besprochen haben. Denn denken Sie einmal, meine lieben Freunde, ein Mensch arbeite zuviel mit seinen Gliedern, er arbeite zuviel körperlich, was wird denn das für eine Folge haben? Das bringt ihn in eine zu große Verwandtschaft mit dem Geiste. Es umspült ihn ja der Geist fortwährend, wenn er körperlich arbeitet. Die Folge davon ist, daß der Geist über den Menschen eine zu große Gewalt gewinnt, der Geist, der von außen an den Menschen herankommt. Wir machen uns zu geistig, wenn wir zuviel körperlich arbeiten. Von außen machen wir uns zu geistig. Die Folge davon ist: wir müssen uns zu lange dem Geiste übergeben, das heißt, wir müssen zu lange schlafen. Arbeiten wir zuviel körperlich, so müssen wir zu lange schlafen. Und zu langer Schlaf fördert wiederum zu stark die leibliche Tätigkeit, die vom Brust-Bauchsystem ausgeht, die nicht vom Kopfsystem ausgeht. Sie wirkt zu stark das Leben anregend, wir werden zu fiebrig, zu heiß. Das Blut wallt zu sehr in uns, es kann nicht verarbeitet werden in seiner Tätigkeit im Leibe, wenn wir zuviel schlafen. Demnach erzeugen wir die Lust, zuviel zu schlafen, durch übermäßige körperliche Arbeit.

Aber die Trägen, die schlafen doch so gerne und schlafen so viel; woher kommt denn das? Ja, das kommt davon her, daß der Mensch eigentlich gar nicht die Arbeit unterlassen kann. Er kann sie gar nicht unterlassen. Der Träge hat seinen Schlaf nicht davon, weil er zuwenig arbeitet, denn der Träge muß ja auch den ganzen Tag seine Beine bewegen, und irgendwie fuchtelt er doch mit seinen Armen herum. Fr tut auch etwas, der Träge; er tut eigentlich, äußerlich angeschaut, gar nicht weniger als der Fleißige, aber er tut es sinnlos. Der Fleißige wendet sich an die Außenwelt; er verbindet mit seinen Tätigkeiten einen Sinn. Und das ist der Unterschied. Sinnloses Sich-Betätigen, wie es der Träge tut, das ist dasjenige, was mehr zum Schlaf verleitet, als sinnvolles Sich-Betätigen. Denn sinnvolles Sich-Betätigen läßt uns nicht nur im Geiste herumplätschern, sondern indem wir uns sinnvoll bewegen mit unserer Arbeit, ziehen wir den Geist auch allmählich hinein. Indem wir die Hand ausstrecken zu sinnvoller Arbeit, verbinden wir uns mit dem Geiste, und der Geist braucht wiederum nicht zuviel unbewußt arbeiten im Schlafe, weil wir bewußt mit ihm arbeiten. Also nicht darauf kommt es an, daß der Mensch tätig ist, denn das ist auch der Träge, sondern darauf kommt es an, inwiefern der Mensch sinnvoll tätig ist. Sinnvoll tätig — diese Worte müssen uns auch schon durchdringen, indem wir Erzieher des Kindes werden. Wann ist der Mensch sinnlos tätig? Sinnlos tätig ist er, wenn er nur so tätig ist, wie es sein Leib erfordert. Sinnvoll tätig ist er, wenn er so tätig ist, wie es seine Umgebung erfordert, wie es nicht bloß sein eigener Leib erfordert. Darauf müssen wir beim Kinde Rücksicht nehmen. Wir können auf der einen Seite die äußere Leibestätigkeit des Kindes immer mehr und mehr überführen zu dem, was bloß nach dem Leiblichen hin liegt, nach dem physiologischen Turnen, wo wir bloß den Leib fragen: Welche Bewegungen sollen wir ausführen lassen? - Und wir können die äußere Bewegung des Kindes hinführen zu sinnvollen Bewegungen, zu sinndurchdrungenen Bewegungen, so daß es mit seinen Bewegungen nicht plätschert im Geiste, sondern dem Geiste in seinen Richtungen folgt. Dann entwickeln wir die Leibesbewegungen hinüber nach der Eurythmie. Je mehr wir bloß leiblich turnen lassen, desto mehr verleiten wir das Kind dazu, eine übermäßige Schlafsucht zu entfalten, eine übermäßige Tendenz nach der Verfettung zu entfalten. Je mehr wir abwechseln lassen dieses Hinüberschwingen nach dem Leiblichen - was wir natürlich nicht ganz vernachlässigen dürfen, weil der Mensch im Rhythmus leben muß -, je mehr wir dieses Hinüberschwingen nach dem Leibe wiederum zurückschwingen lassen nach dem sinnvollen Durchdrungensein der Bewegungen wie in der Eurythmie, wo jede Bewegung einen Laut ausdrückt, wo jede Bewegung einen Sinn hat: je mehr wir abwechseln lassen das Turnen mit der Eurythmie, desto mehr rufen wir Einklang hervor zwischen dem Schlaf- und Wachbedürfnis; desto normaler erhalten wir von der Willensseite her, von der Außenseite her das Leben auch des Kindes. Daß wir allmählich auch das Turnen bloß sinnlos gemacht haben, zu einer Tätigkeit, die bloß dem Leibe folgt, das war eine Begleiterscheinung des materialistischen Zeitalters. Daß wir es gar erhöhen wollen zum Sport, wo wir nicht bloß sinnlose Bewegungen, bedeutungslose, bloß vom Leibe hergenommene Bewegungen sich auswirken lassen, sondern auch noch den Widersinn, den Gegensinn hineinlegen - das entspricht dem Bestreben, den Menschen nicht nur bis zum materiell denkenden Menschen, sondern ihn herunterzuziehen bis zum viehisch empfindenden Menschen. Übertriebene Sporttätigkeit ist praktischer Darwinismus. Theoretischer Darwinismus heißt behaupten, der Mensch stamme vom Tier ab. Praktischer Darwinismus ist Sport und heißt, die Ethik aufstellen, den Menschen wiederum zum Tiere zurückzuführen.

Man muß diese Dinge heute in dieser Radikalität sagen, weil der heutige Erzieher sie verstehen muß, weil er sich nicht bloß zum Erzieher der ihm anvertrauten Kinder machen muß, sondern weil er auch sozial wirken soll, weil er zurückwirken soll auf die ganze Menschheit, damit nicht solche Dinge mehr und mehr aufkommen, welche eigentlich auf die Menschheit nach und nach wirklich vertierend wirken müssen. Das ist nicht falsche Askese, das ist etwas, was aus dem Objektiven der wirklichen Einsicht herausgeholt ist und was durchaus so wahr ist wie irgendeine andere naturwissenschaftliche Erkenntnis.

Wie ist es denn mit der geistigen Arbeit? Mit der geistigen Arbeit, also mit Denken, Lesen und so weiter ist es so, daß sie fortwährend begleitet ist von leiblich-körperlicher Tätigkeit, von fortwährendem innerem Zerfall der organischen Materie, von Totwerden der organischen Materie. Wir haben daher, indem wir uns zuviel geistig-seelisch beschäftigen, zerfallende organische Materie in uns. Verbringen wir unseren Tag restlos nur in gelehrter Tätigkeit, so haben wir am Abend zuviel zerfallene Materie in uns, zerfallene organische Materie. Die wirkt in uns. Die stört uns den ruhigen Schlaf. Übertriebene geistig-seelische Arbeit zerstört ebenso den Schlaf, wie übertriebene körperliche Arbeit einen schlaftrunken macht. Aber wenn wir uns zu stark geistig-seelisch anstrengen, wenn wir Schwieriges lesen, so daß wir beim Lesen auch denken müssen — was ja bei den heutigen Menschen nicht gerade beliebt ist -, wenn wir also zuviel denkend lesen wollen, schlafen wir darüber ein. Oder wenn wir nicht dem wasserklaren Geschwafle der Volksredner oder anderer Leute zuhören, die nur das sagen, was man schon weiß, sondern wenn wir zuhören denjenigen Leuten, deren Worten man mit seinem Denken folgen muß, weil sie einem etwas sagen, was man noch nicht weiß, dann wird man müde und schlaftrunken. Es ist ja eine bekannte Erscheinung, daß die Menschen, wenn sie, weil es «sich so gehört», in Vorträge, in Konzerte gehen und nicht gewohnt sind, wirklich denkend und empfindend das zu erfassen, was ihnen geboten wird, beim ersten Ton oder beim ersten Wort einschlafen. Sie verschlummern oft den ganzen Vortrag oder das ganze Konzert, dem sie pflichtgemäß oder standesgemäß beigewohnt haben.

Nun, da ist wiederum ein Zweifaches vorhanden. Wie ein Unterschied ist zwischen der sinnvollen äußeren Tätigkeit und der sinnlosen äußeren Geschäftigkeit, so ist auch ein Unterschied zwischen der mechanisch verlaufenden inneren Denk- und Anschauungstätigkeit und zwischen der fortwährend mit Gefühlen begleiteten inneren Denk- und Anschauungstätigkeit. Wird unsere geistig-seelische Arbeit so getrieben, daß wir fortwährendes Interesse mit ihr verbinden, dann belebt das Interesse, belebt die Aufmerksamkeit unsere Brusttätigkeit und läßt die Nerven nicht im Übermaße absterben. Je mehr Sie bloß dahinlesen, je weniger Sie sich bemühen, das Gelesene in sich mit tiefgehendem Interesse aufzunehmen, desto mehr fördern Sie das Absterben Ihrer inneren Materie. Je mehr Sie mit Interesse, mit Wärme alles verfolgen, desto mehr fördern Sie die Bluttätigkeit, das Lebendigerhaltenwerden der Materie, desto mehr verhindern Sie auch, daß Ihnen die geistige Tätigkeit den Schlaf stört. Wenn man dem Examen entgegenbüffeln muß — man kann auch ochsen sagen, je nach dem Klima -, nimmt man eben viel auf gegen das Interesse. Denn würde man nur nach seinem Interesse aufnehmen, dann würde man - nach den heutigen Zeitverhältnissen mindestens — durchfallen. Die Folge ist, daß einem das Büffeln oder Ochsen zum Examen den Schlaf zerstört, daß es in unser normales Menschendasein Unordnung hineinbringt. Das muß insbesondere bei Kindern beachtet werden. Daher ist es bei Kindern am allerbesten, und es wird dem Ideal der Erziehung am meisten entsprechen, wenn wir überhaupt das sich aufstauende Lernen, das immer vor dem Examen getrieben wird, ganz weglassen, das heißt, die Examina ganz weglassen; wenn das Ende des Schuljahres geradeso verläuft wie der Anfang. Wenn wir uns als Lehrer die Verpflichtung auferlegen, uns zu sagen: Wozu soll denn das Kind geprüft werden? Ich habe das Kind ja immer vor Augen gehabt und weiß ganz gut, was es weiß oder nicht weiß. - Natürlich kann das unter den heutigen Verhältnissen vorläufig bloß ein Ideal sein, wie ich Sie überhaupt bitte, nicht Ihre Rebellennatur zu stark nach außen zu kehren. Kehren Sie zunächst dasjenige, was Sie vorzubringen haben gegen unsere gegenwärtige Kultur, wie Stacheln nach innen, damit Sie langsam dahin wirken — denn auf diesem Gebiet können wir nur langsam wirken -, daß die Menschen anders denken lernen, dann werden auch die äußeren sozialen Verhältnisse in andere Formen eintreten, als sie jetzt sind.

Aber man muß alles im Zusammenhang denken. Man muß wissen, daß Eurythmie von Sinn durchzogene äußere Tätigkeit, Vergeistigen der körperlichen Arbeit und Interessantmachen des Unterrichts in nicht banaler Weise, Beleben - wörtlich genommen -, Beleben, Durchbluten der intellektuellen Arbeit ist.

Wir müssen die Arbeit nach außen vergeistigen, wir müssen die Arbeit nach innen, die intellektuelle Arbeit, durchbluten! Denken Sie über diese zwei Sätze nach, dann werden Sie sehen, daß der erstere eine bedeutsame erzieherische und auch eine bedeutsame soziale Seite hat; daß der letztere eine bedeutsame erzieherische und auch eine bedeutsame hygienische Seite hat.

Thirteenth Lecture

We can understand human beings in their behavior toward the outside world and gain insight into how we should behave toward children with regard to their behavior toward the outside world if we base our actions on the insights we have gained in these lectures. It is simply a matter of applying these insights in an appropriate way in life. Consider that we must take into account a twofold behavior of human beings toward the outside world, in that we can speak of a completely opposite configuration of the limb-oriented human being and the head-oriented human being.

We must acquire the difficult mental image that we can only understand the forms of the limb-oriented person if we imagine that the head forms are turned inside out like a glove or a stocking. What this expresses is of great significance in the whole of human life. If we sketch it schematically, we can say that The shape of the head is formed in such a way that it is, as it were, pressed from the inside out, that it is puffed up from the inside out. When we think of the limbs of the human being, we can form a mental image of them being pressed from the outside in, through the turning inside out – which means a great deal in human life – at your forehead. And remember that your inner humanity strives from within toward your forehead. Look at the inside of your palm and look at the inside of your foot: a kind of pressure is constantly exerted on them, which is the same as the pressure exerted on your forehead from within, only in the opposite direction. So when you hold your palm out to the outside world, when you place the soles of your feet on the ground, the same thing that flows from within toward your forehead flows in from outside through these soles. This is an extremely important fact. It is so important because it allows us to see how the spiritual-soul aspect actually works in human beings. As you can see, this spiritual-soul aspect is a current. This spiritual-soul aspect actually flows through human beings as a current.

And what is the human being in relation to this spiritual-soul aspect? Imagine a stream of water flowing along and being held back by a weir, so that it accumulates and flows back into itself. In the same way, the spiritual-soul flows over in human beings. Human beings are a kind of dam for the spiritual-soul. It actually wants to flow unhindered through human beings, but they hold it back and slow it down. They allow it to accumulate within themselves. Now, however, this effect, which I have described as a stream, is a very strange one. I have described this effect of the spiritual-soul forces flowing through human beings as a stream, but what is it actually in relation to the outer physical body? It is a constant absorption of the human being.

Human beings stand in relation to the outside world. The spiritual-soul strives to constantly absorb them. That is why we constantly peel away, shedding our outer layers. And if the spirit is not strong enough, we have to cut off parts of ourselves, such as our fingernails, because the spirit, coming from outside, wants to destroy them by sucking them away. It destroys everything, and the body holds back this destruction of the spirit. And a balance must be created in the human being between the destructive spiritual-soul and the constant building up of the body. The chest-abdomen system is inserted into this current. And the chest-abdomen system is that which opposes the destruction of the invading spiritual-soul and which, of its own accord, permeates the human being with material substance. From this, however, you can see that the limbs of the human being, which protrude beyond the chest-abdomen system, are truly the most spiritual, for it is in the limbs that the least material-producing process takes place in the human being. Only that which is sent from the abdomen-chest system to the limbs in metabolic processes makes our limbs material. Our limbs are highly spiritual, and it is they that consume our body when they move. And the body is dependent on developing within itself that which the human being is actually predisposed to from birth. If the limbs move too little or do not move appropriately, then they do not consume enough of the body. The chest-abdomen system is then in the fortunate position — fortunate for it — that it is not sufficiently consumed by the limbs. It uses what it has left over to create excess materiality in the human being. This excess materiality then permeates what is predisposed in the human being from birth, what he should actually have in terms of physicality, because he is born as a soul-spiritual being. It permeates what they should have with something they should not have, something they only have materially as earthly human beings, something that is not predisposed in the true sense of the word spiritually and soulfully; it permeates them more and more with fat. But when this fat is stored in an abnormal way in humans, it actually opposes the spiritual-soul process, which penetrates as a sucking process, as a consuming process, and then its path to the head system is made more difficult. Therefore, it is not right to allow children to eat too much fat-producing food. This disconnects their head from the spiritual-soul. For the fat gets in the way of the spiritual-soul, and the head becomes empty. It is a matter of developing the tact to work together with the child's entire social situation so that the child does not actually become too fat. Later in life, becoming fat depends on all sorts of other things, but in childhood, in the case of children who are not abnormally developed, that is, particularly weakly developed children who, because they are weak, easily become fat, in other words, in the case of normally developed children, it is still possible to help prevent them from becoming too fat by providing them with an appropriate diet.

But one will not have the right responsibility towards these things if one does not appreciate their great importance; if one does not realize that in allowing a child to accumulate too much fat, one is interfering with the world process that has something in mind for human beings, which it expresses by allowing its spiritual-soul forces to flow through human beings. You are indeed interfering with the world process when you allow the child to become too fat.

For, you see, something most remarkable happens in the human head: as everything spiritual and soul-related accumulates in the human being, it splashes back like water when it reaches a weir. That is, what the spiritual-soul carries along with the material, like the Mississippi carries sand, splashes back inside the brain, so that there are overturning currents in the brain where the spiritual-soul accumulates. And in the backlash of the material, matter continually collapses into itself in the brain. And when matter that is still permeated by life collapses into itself, rebounding as I have shown you, then the nerve arises. The nerve always arises when matter driven by the spirit through life collapses into itself and dies within the living organism. Therefore, the nerve is dead matter within the living organism, so that life shifts, accumulates within itself, matter crumbles and collapses. This creates channels in the human being that go everywhere, filled with dead matter: the nerves; then the spiritual-soul can bubble back into the human being. The spiritual-soul flows through the human being along the nerves, because the spiritual-soul needs the decaying matter. It causes the matter on the surface of the human being to decay, causing it to flake off. This spiritual-soul will only agree to fill the human being when the matter within them first dies. The spiritual-soul element of the human being moves inwardly along the materially dead nerve pathways.

In this way, one can see how the spiritual-soul element actually works in the human being. One sees it approaching from outside, developing a sucking, consuming activity. One sees it penetrating; one sees how it is dammed up, how it bubbles back, how it kills matter. One sees how matter decays in the nerves and how, as a result, the spiritual-soul can now also penetrate the skin from within, preparing paths for itself through which it can pass. For the spiritual-soul does not pass through what is organically alive.

So how can you form a mental image of the organic, the living? You see, you can also form a mental image of the living as something that absorbs the spiritual-soul, that does not allow it to pass through. You can form a mental image of the dead, the material, and the mineral as something that allows the spiritual-soul to pass through, so that you can arrive at a kind of definition of the physical-living and a definition of the bony-nervous, as well as of the mineral-material in general: the living-organic is impervious to the spirit; the physically dead is permeable to the spirit. “Blood is a very special juice,” because it is to the spirit what opaque matter is to light; it does not allow the spirit to pass through, it keeps it within itself. Nervous substance is actually also a very special substance. It is like transparent glass in relation to light. Just as transparent glass allows light to pass through, so does material physical matter, including nervous matter, allow the spirit to pass through.

You see, there you have the difference between two components of the human being: between what is mineral in him, what is permeable to the spirit, and what is more animalistic, more organically alive in him, what holds the spirit within him, what causes the spirit to produce the forms that shape the organism.

Now, however, all sorts of things follow from this for the treatment of human beings. When human beings do physical work, for example, they move their limbs, which means that they are completely immersed in the spirit. This is not the spirit that has already accumulated within them; it is the spirit that is outside. Whether you are chopping wood or walking, if you are only moving your limbs, moving your limbs to work, to useful or useless work, you are constantly splashing around in the spirit, constantly dealing with the spirit. This is very important. And it is also important to ask ourselves: When we work mentally, when we think or read or do similar things, what happens then? — Yes, then we are dealing with the spiritual-soul within us. We do not splash about with our limbs in the spirit; the spiritual-soul works within us and constantly makes use of our physical body, that is, it is expressed entirely within us in a physical-bodily process. There, matter is constantly thrown back inside by this congestion. In mental work, our body is in a state of excessive activity; in physical work, on the other hand, our spirit is in a state of excessive activity. We cannot work spiritually and soulfully without our body constantly cooperating internally. When we work physically, our spiritual and soulful nature is involved internally at most in that we use our thoughts to guide us in the direction we are going, to orient ourselves; but the spiritual and soulful nature is involved externally. We are constantly working into the spirit of the world. We are constantly connecting with the spirit of the world through our physical work. Physical work is spiritual, spiritual work is physical, in and on the human being. We must grasp this paradox and understand that physical work is spiritual and spiritual work is physical in and on the human being. The spirit surrounds us when we work physically. Matter is active and lively in us when we do spiritual work.

These things must be known when one wants to think intelligently about work, whether spiritual or physical, about rest and fatigue. One cannot think intelligently about work, rest, and fatigue unless one truly understands what we have just discussed. For think about it, my dear friends, if a person works too much with their limbs, if they work too much physically, what will be the consequence? It brings them into too close a relationship with the spirit. The spirit constantly surrounds them when they work physically. The result is that the spirit gains too much power over the person, the spirit that approaches the person from outside. We become too spiritual when we work too much physically. We become too spiritual from outside. The result is that we have to surrender ourselves to the spirit for too long, that is, we have to sleep too long. If we do too much physical work, we have to sleep too long. And too much sleep in turn promotes too much physical activity, which originates in the chest-abdomen system, not in the head system. It stimulates life too strongly, we become too feverish, too hot. The blood surges too much within us, it cannot be processed in its activity in the body if we sleep too much. Accordingly, we create the desire to sleep too much through excessive physical work.

But the lazy, who love to sleep and sleep so much; where does that come from? Yes, it comes from the fact that human beings cannot actually refrain from work. They cannot refrain from it at all. The lazy person does not get their sleep from working too little, because the lazy person also has to move their legs all day long, and somehow they still wave their arms around. The lazy person also does something; outwardly, they actually do no less than the hard-working person, but they do it pointlessly. The diligent person turns to the outside world; he connects his activities with meaning. And that is the difference. Meaningless activity, as practiced by the lazy person, is what leads to sleep more than meaningful activity. For meaningful activity not only allows us to splash around in the spirit, but by moving meaningfully with our work, we also gradually draw the spirit in. By reaching out to meaningful work, we connect with the spirit, and the spirit in turn does not need to work too much unconsciously in sleep, because we are consciously working with it. So it is not important that a person is active, because even the lazy person is active, but rather that a person is meaningfully active. Meaningfully active — these words must also permeate us as we become educators of children. When is a person meaninglessly active? A person is meaninglessly active when they are only active in the way that their body requires. They are meaningfully active when they are active in the way that their environment requires, not just in the way that their own body requires. We must take this into account with children. On the one hand, we can increasingly transfer the child's external physical activity to what is purely physical, to physiological gymnastics, where we only ask the body: What movements should we perform? And we can guide the child's external movement toward meaningful movements, toward movements imbued with meaning, so that its movements do not splash about in the spirit, but follow the spirit in its directions. Then we develop the physical movements toward eurythmy. The more we let children do purely physical gymnastics, the more we tempt them to develop an excessive sleepiness, an excessive tendency toward obesity. The more we alternate this swinging over to the physical – which we must not neglect entirely, of course, because human beings must live in rhythm – the more we allow this swinging over to the physical to swing back again to a meaningful permeation of the movements, as in eurythmy, where every movement expresses a sound, where every movement has a meaning: the more we alternate gymnastics with eurythmy, the more we bring about harmony between the need for sleep and the need to be awake; the more normal we make the life of the child from the point of view of the will, from the outside. The fact that we have gradually made gymnastics meaningless, an activity that merely follows the body, was a side effect of the materialistic age. That we even want to elevate it to a sport, where we not only allow meaningless movements, movements that are meaningless and merely taken from the body, to take effect, but also add absurdity and contradiction to them – this corresponds to the endeavour not only to reduce human beings to materially thinking human beings, but to drag them down to human beings with animalistic feelings. Excessive sporting activity is practical Darwinism. Theoretical Darwinism means claiming that humans are descended from animals. Practical Darwinism is sport and means establishing an ethic that reduces humans back to animals.

These things must be said in such radical terms today because today's educators must understand them, because they must not only educate the children entrusted to them, but also because they must have a social impact, because they must have an effect on humanity as a whole, so that things do not arise more and more which must actually have a gradually dehumanizing effect on humanity. This is not false asceticism; it is something that has been drawn from the objective reality of true insight and is just as true as any other scientific discovery.

What about intellectual work? Intellectual work, that is, thinking, reading, and so on, is constantly accompanied by physical activity, by the continuous inner decay of organic matter, by the death of organic matter. Therefore, when we engage in too much mental and spiritual activity, we have decaying organic matter within us. If we spend our entire day engaged solely in scholarly activity, by evening we have too much decayed matter within us, decayed organic matter. This has an effect on us. It disturbs our peaceful sleep. Excessive mental and emotional work destroys sleep just as much as excessive physical work makes one sleepy. But if we exert ourselves too much mentally and emotionally, if we read difficult material that requires us to think while reading — which is not exactly popular with people today — if we try to read while thinking too much, we fall asleep. Or when we do not listen to the crystal-clear chatter of popular speakers or other people who only say what we already know, but when we listen to those people whose words we have to follow with our minds because they tell us something we do not yet know, then we become tired and sleepy. It is a well-known phenomenon that when people go to lectures or concerts because “it is the done thing” and are not used to really thinking and feeling what is being offered to them, they fall asleep at the first sound or the first word. They often sleep through the entire lecture or concert that they have attended out of a sense of duty or social obligation.

Now, there is again a twofold difference here. Just as there is a difference between meaningful external activity and meaningless external busyness, so there is also a difference between mechanical internal thinking and perception and internal thinking and perception that is continually accompanied by feelings. If our mental and spiritual work is carried out in such a way that we are constantly interested in it, then this interest and attention stimulates our chest activity and prevents our nerves from dying off excessively. The more you simply read, the less you try to absorb what you read with deep interest, the more you promote the dying off of your inner matter. The more you follow everything with interest and warmth, the more you promote blood activity and keep your inner substance alive, and the more you prevent your mental activity from disturbing your sleep. When you have to cram for an exam — you could also say “plow” depending on the climate — you absorb a lot that is not of interest to you. Because if you only absorbed what interested you, you would fail — at least under today's circumstances. The result is that cramming or plowing for exams destroys your sleep and brings disorder into our normal human existence. This must be taken into account especially with children. Therefore, it is best for children, and it will correspond most closely to the ideal of education, if we completely eliminate the accumulated learning that always takes place before exams, that is, if we eliminate exams altogether; if the end of the school year proceeds just as the beginning did. If we as teachers impose on ourselves the obligation to ask ourselves: Why should the child be tested? I have always had the child in front of my eyes and know very well what he or she knows or does not know. Of course, under today's circumstances, this can only be an ideal for the time being, and I ask you not to reveal your rebellious nature too strongly. First, turn what you have to say against our current culture like thorns inward, so that you can slowly work toward it — because in this area we can only work slowly — so that people learn to think differently, then the external social conditions will also take on different forms than they do now.

But one must think of everything in context. One must know that eurythmy is an external activity imbued with meaning, spiritualizing physical work and making teaching interesting in a non-trivial way, enlivening — taken literally — enlivening, breathing life into intellectual work.

We must spiritualize our external work, we must invigorate our internal work, our intellectual work! Think about these two sentences, and you will see that the former has a significant educational and also a significant social aspect; that the latter has a significant educational and also a significant hygienic aspect.