The Study of Man

GA 293

3 September 1919, Stuttgart

Lecture XII

When we consider the human body, we must relate it to the physical sense-world that surrounds it and maintains it, for there is a constant interplay between the physical body and the world, through which it is sustained. When we look out into the physical sense-world around us, we perceive mineral beings, plant beings, animal beings. Our physical body is related to the beings of the minerals, plants and animals. But the peculiar nature of this relationship is not immediately evident to superficial observation; we must penetrate deeply into the character of the kingdoms of nature if we are to understand this relationship.

When we regard the human being as physical body, what we first perceive is his solid bony frame and his muscles. When we penetrate further into him we perceive the circulation of the blood with the organs which belong to it. We perceive the breathing, we perceive the processes of nourishment. We see how, the organs are built up out of the most varied vascular forms—as they are called in natural science. We perceive brain and nerves, the sense organs. We have now to co-ordinate these various organs of the human being and their functions with the external world.

Let us begin with that part of the human being which at first appears to be the most perfect (we have already seen how the matter really stands), let us begin with the brain and nervous system which is closely linked with the sense organs. This part of the human organisation shows the longest earthly evolution behind it, so that it has passed beyond the form which the animal world has developed. Man has passed through the animal world, as it were, in relation to this, his head system, and he has gone beyond the animal system to the real human system—which indeed is most clearly expressed in the formation of the head.

Now we spoke yesterday of how far the formation of the head takes part in individual human evolution, how far the shape, the form of the human body proceeds from the forces which are to be found in the head. And we saw how the work of the head reaches a kind of conclusion with the change of teeth towards the seventh year. We should make clear to ourselves what really happens through the interplay between the human head, the chest organs and the limb organs. We should answer the question: what does the head really do in carrying out its work in connection with the chest-trunk system and the limb-system? It is continually forming, shaping. Our life really consists in this, that in the first seven years an intense forming force streams from the head right down into the physical form; and the head continues its aid by preserving the form, by ensouling it, by spiritualising it.

The head is involved in shaping the human form. But does the head build up our truly human shape? No, indeed it does not. You must learn to accept the view that your head is constantly trying, in secret, to make something different out of you from what you are. There are times when the head would like to shape you so that you would look like a wolf; at other times it would like to shape you so that you would look like a lamb. Then again, so that you would look like a serpent; it would like to make you into a serpent, a dragon.

All the shapes which your head really designs in you, you find spread out in nature, in the different animal forms. If you look at the animal kingdom you can say to yourself: that am I; but when the head produces the wolf form, for instance, my trunk system and my limb system constantly do me the favour of changing this wolf form into the human form. They are perpetually within themselves overcoming the animal element. They so master it as to prevent it attaining complete existence within them, they metamorphose it, they transform it. Thus the human being has a relationship to the animal world around him through the head system. But it is such that he is continually carried beyond the animal world in the creation of his body. What, then, really remains in you? You can look at a human being. Imagine that you have a man before you: you can make this interesting observation. You can say: there is the man. There is his head, and in the head a wolf is actually stirring, but it does not develop into a wolf; it is immediately dissolved by the trunk and the limbs. In the head a lamb is actually stirring; it is dissolved by the trunk and the limbs.

The animal forms are continually moving supersensibly in the human being, and are being dissolved. What would happen if there were a super-sensible photographer who could retain this process, who could preserve this process on a photographic plate, or on a series of photographic plates? What should we see on these plates? We should then see the thoughts of man. These thoughts of the human being are indeed a super-sensible correlate to that which does not come to expression in the sense-world. This continual metamorphosis out of the animal, streaming down from the head, is not expressed in the senses, but it works in man supersensibly as the process of thought. In reality this is present as a super-sensible process. Your head is not merely the lazy-bones on your shoulders, it is that which would really like to maintain you in animality. It gives you the forms of the whole animal kingdom; it would like animal kingdoms continually to arise. But by means of your trunk and your limbs you prevent a whole animal kingdom from arising through you in the course of your life: you transform this animal kingdom into your thoughts. Such is our relationship to the animal kingdom. We allow this animal kingdom to arise supersensibly within us, and then we do not allow it to come to sensible reality, but hold it back in the super-sensible. The trunk and the limbs do not allow these evolving animal forms to enter their sphere. If the head has too strong an inclination to produce something of this animal nature, the remaining organism struggles against accepting it, and then the head has to resort to migraine or to some similar head complaint in order to exterminate it again.

The trunk system is also related to our environment—not in this case, to the animal world but to the whole range of the plant kingdom. There is a mysterious connection between the trunk system of man, the chest system, and the plant world. The most important processes in the circulation of the blood, also in breathing and nourishment, all take place in the chest or trunk system. All these processes are in active interchange with what takes place outside in the physical sense-world of the plants, but in a very special way.

Let us first take the breathing. What does a man do in breathing? You know that he takes in oxygen, and through his life processes he changes oxygen into carbon dioxide by connecting it with carbon. Carbon is in the organism from the transformed foodstuffs. This carbon takes up the oxygen, and carbon dioxide gas arises through the union of the oxygen with the carbon. Now when man has the carbon dioxide within him it would be a splendid opportunity for him not to let it out, but to keep it there. And if he could free the carbon again from the oxygen, what would happen? Let us say that a man breathes in oxygen through his life processes, and allows it to form carbon dioxide by uniting with carbon; if now he were in a position to separate off the oxygen again within, and to work upon the carbon, what would then arise in the man? The plant world. The whole vegetable kingdom would suddenly grow up in man. It really could grow there.

For if you consider a plant, what does it do? Of course it does not breathe in oxygen in the same regular way as man, but it assimilates carbon dioxide. By day the plant is bent on getting carbon dioxide, it gives up oxygen. It would be bad if it did not do this; for then neither we nor the animals would have it. But the plant retains carbon, and out of this it forms starch and sugar and everything else it consists of. From this it builds up its whole organism. The plant world arises by building itself up from carbon which plants in their process of assimilation separate off from the carbon dioxide. When you look at the plant world, it is metamorphosed carbon, which is separated off by the process of assimilation, and this process corresponds to the human process of breathing. The plants also breathe to a certain extent, but it is different from the breathing process in man. The plant does breathe a little, especially in the night, but to say that plants can really breathe shows a superficial observation, and is like saying: “Here is a razor, I will cut meat with it.” The process of breathing in plants is different from the process of breathing in men and in animals, just as the razor is different from the table knife. The human process of breathing corresponds in the plants to the reverse process, that of assimilation.

From this you will understand that if you continued in yourself the process by which carbon dioxide has arisen, that is, if the oxygen could be given up again and the carbon dioxide could be transformed into carbon, as is done by nature in the world around you, then you could let the whole vegetable world grow up in you. You would have the materials for this within yourself and you could bring it about that you would suddenly blossom forth as plant world. You would disappear and the whole plant world would arise. This capacity of producing a plant world is indeed inherent in man, but he does not allow it to come to this point. His chest system has a strong inclination continually to produce the plant world. Head and limbs do not allow this to happen, they defend themselves against it. And so man drives out the carbon dioxide, and does not allow the plant kingdom to arise within himself. He allows the plant kingdom to arise out of the carbon dioxide in the outside world.

This is a remarkable interplay between the trunk-chest system and the sense physical world around us; for outside there is the kingdom of the vegetables, and the human being is continually having to prevent the process of vegetation from arising within him; if it does arise he must immediately send it out again so that he may not become a plant. Thus, in so far as the chest-trunk system is concerned, man is able to create the counter kingdom to the plant world. If you conceive the plant kingdom as positive, then man produces the negative of the plant kingdom. He produces, as it were, reversed plant kingdom.

What happens when the plant kingdom begins to behave badly in him, and head and limbs have not the power to nip it in the bud, to drive it out? Then the man becomes ill. The internal illnesses which come from the trunk system are ultimately due to this, that a man is too weak to check the plant-like growth as soon as it begins to arise within him. The moment there arises in us even a vestige of plant-like nature, the moment we fail to ensure that the plant kingdom which endeavours to grow in us shall be cast out to form its kingdom outside us—in that moment we become ill. And thus the essential nature of disease must be sought in this tendency towards plant growth in man. Naturally it is not true plants that grow, for after all the human interior is not a very pleasant surrounding for a lily. But through a weakening of the other systems of the trunk there can result a tendency towards the growth of the plant kingdom, and then man becomes ill.

Thus if we look at the whole plant world of man's environment we must say to ourselves: in a certain sense the plant kingdom presents pictures of all our illnesses. It is the wonderful secret in man's relationship to surrounding nature that not only (as we have shown on other occasions) do the plants represent pictures of his development up to adolescence, but in the plants around him, especially in so far as these plants are fruit bearing, he can see the pictures of his illnesses. This is a thing we may perhaps not like to hear, because it is natural to love the plant world aesthetically; and, when the plant unfolds in the world outside, this aesthetic attitude is justified. But the moment the plant seeks to unfold within man, the moment vegetation sets up within him, then what works outside in the many-coloured beautiful plant kingdom, works in man as the cause of illness. Medicine will become a science when it is able to show how each individual illness corresponds with some form in the plant world. Actually it is true that when man breathes out carbonic acid gas, he is, for the sake of his own existence, constantly breathing out the whole of the plant world which wants to arise in him. Hence it need not seem strange to you that when the plant begins to extend—beyond its ordinary plant nature, and produces poisons, these poisons are bound up with the processes of man's health and sickness. At the same time all this is bound up with the normal process of nourishment.

Indeed, nourishment, like the process of breathing, takes place in the chest-trunk system, at least in its initial stages, and must be considered in exactly the same way as breathing. In the processes of nourishment man also takes in substances from the world around him, but he does not leave them as they are; he changes them. He changes them with the help of the oxygen which he breathes in. As man transforms the substances taken up in nourishment, they combine with oxygen. This appears as a process of combustion, and it looks as though the human being were constantly burning within. This moreover is what natural science frequently says, that a process of combustion is going on in the human being. But it is not true. What takes place in the human being is no true process of combustion, but is a process of combustion (notice this carefully)—it is a process of combustion which lacks both beginning and end. It is merely the middle stage of the process of combustion; it lacks the beginning and end of it. The beginning and the end of the process of combustion must never take place in the human body, only the intervening part. It is destructive to the human being if the first stages of the process of combustion, such as take place in the forming of fruit, are carried on in the human organism; for instance when a man eats unripe fruit. The human being cannot carry out this initial process similar to combustion. The human being cannot endure this in himself, it makes him ill. And if he can eat a great deal of unripe fruit, like strong country people for instance, then he must be very closely related to the nature around him, for otherwise he would not be able to digest unripe apples and pears as he can the fruit which has been ripened by the sun. Thus it is only the middle process which he can carry out. In the processes of digestion the human being can only take part in the middle stage of all the combustion processes. Again, if the process is carried to its conclusion, to where, in the outer world, the ripe fruit would rot, the human being can have no part in it. Thus he cannot take part in the end stage either. He must excrete the food stuffs before this stage is reached. It is actually the case that the human being does not carry on the processes of nature as they take place around him, but he only goes through the middle part; within himself he cannot fulfil the beginning or the end.

Now we will look at something most remarkable. Consider breathing. It is the opposite to everything which takes place in the plant world around us. It is in a certain way the anti-plant kingdom. The breathing of man is the anti-plant kingdom, and it is inwardly connected with the process of nourishment which is the middle stage of the combustion process of the outer world. You see, there are two processes in our bodily chest-trunk system; this anti-plant process, which takes place through the breathing, is always at work in connection with the central portion of the other external processes. These two are constantly interrelated in their work. Here, you see, body and soul are combined. That which takes place through the breathing unites with the remaining nature processes, which however, as they take place in man, represent only the middle portion of Nature's processes. And this means that the soul life, which is the anti-plant process, unites with the humanised bodily life, namely the middle portion of the processes of Nature. Science may well search for a long time for the mutual relationship between body and soul unless it seeks it in the mysterious connection between the breath, which has become soul, and the middle part of the processes of Nature, which has become body. These processes of Nature neither arise nor decay in man. They take their rise outside him and only after he has excreted them should they decompose. Man unites himself in body with a central part only of the processes of Nature; and in the breathing processes he fills these Nature processes with soul.

Here there arises that delicate inter-weaving of processes to which the medicine and the hygiene of the future will have to devote very special attention. The hygiene of the future will have to ask: how are the different degrees of warmth interrelated in the world outside? How does warmth act when passing from a cooler place to a warmer, and vice versa? There are warmth processes at work in the external world; how does such a warmth process act in the human organism when this organism is placed into it? Man finds an interplay of air and water in the external process of vegetation. He will have to study how that works on the human being when he is placed in it, and so forth.

With regard to things of this kind the medicine of to-day has only made the very smallest beginning, scarcely even a beginning. When there is an illness the medicine of to-day sets the greatest value on finding the bacilli, the kind of bacteria which causes the illness. Then, when it has found that, it is satisfied. But it is much more important to know how it comes about that, at a particular moment of a man's life, he is prone to develop some suggestion of a vegetative process, so that the bacilli scent a comfortable place of sojourn. The important thing is to keep our bodily constitution in such a condition that it is not an agreeable hostelry for all vegetable pests; if we do this, these gentlemen will not be able to bring about too great a devastation in us.

Now there remains the question: in considering the human being physically in his relation to the outer world, what part do the bony skeleton and muscles really play in the human life process as a whole?

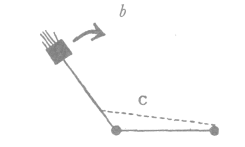

We now come to something which, in the science of today, is hardly regarded at all; but it is absolutely essential that you should grasp it if you want to understand the human being. Please notice what happens when you bend your arm. Through the contraction of the muscle which bends your forearm you are bringing into play a machine-like process. Imagine that it simply comes about in the following way. First of all, you have a position where upper and lower arm (or two corresponding laths or poles) lie in one and the same direction (drawing a).

Then this position (drawing b) represents the bent arm.

Suppose now you stretch a band (c) and then begin to roll it up. This lath here would carry out the movement indicated by the arrow in the drawing. It is a thoroughly machine-like movement. You also carry out mechanical movements of this kind when you bend your knee and when you walk. For in walking the whole mechanism of your body is brought into continuous movement, and forces are continuously at work. They are pre-eminently forces of leverage, but forces are actually at work. Imagine to yourselves that by some kind of photographic trick you could arrange that, when a man was walking, all the forces and nothing of the man, should be photographed; I mean the forces which he applies to raise his knee, to put it down again, to bring the other leg in front.

Nothing of the man would be photographed except the forces. If in the photograph you could see these forces developing, it would be a photograph of a shadow, and even in walking itself you would have a whole series of shadows. You make a great mistake if you believe that you live with your ego in your muscles and flesh. Even when you are awake you do not live with your ego in your muscles and flesh, you live with your ego principally in the shadow which you photograph in this way, in the forces used by your body when it moves. Grotesque though it may sound, when you sit down and press your back against the back of the chair, you live with your ego in the force which is developed in this pressure.

When you stand up you live in the force with which your feet press the ground. You live continually in forces. It is not in the least true that we live with our ego in our visible body. We live with our ego in forces. We only carry our visible body about with us; drag it along with us during our physical earth life until death. Even in the waking condition we live only in a force body. And what does this force body really do? It continually sets itself a peculiar task.

It is true, is it not, that when you are eating you take in all kinds of mineral substances? Even if you do not make your soup very salty, the salt is nevertheless in the food, and you are taking in mineral substance. It is necessary that you should take in mineral substance. What do you do with it? Your head cannot do much with it. Neither can your trunk-chest system. But your limb system prevents these mineral substances from taking on their own crystal forms in you. If you did not develop the forces of your limb system, then when you ate salt you would become a salt crystal. Your limb system, your skeleton and your muscular system have a constant tendency to work against the mineral formation of the earth, that is, to dissolve the minerals. The forces which dissolve the minerals in the human being come from the limb system. If a morbid disturbance goes beyond the merely vegetable process, that is, if the body has the tendency not only to allow plant life to appear, but also the process of mineral crystallisation, then a more severe, a more destructive form of illness is set up; for instance, diabetes. Then the body is not able to apply the force of the limbs which it receives from the universe to dissolve the mineral. In reality it should be constantly dissolving the mineral. If to-day men cannot master those forms of illness which arise from unhealthy mineralisation in the human body, it is largely because we cannot adequately apply the antidote which we must find in connection with the sense organs, the brain, the nerve fibres, etc. In order to overcome gout, diabetes and similar illnesses, we ought to be able to use in some form the apparent substances (* German: Scheinstoge)—I call them apparent substances advisedly—we ought to use this decaying matter, which is in the sense organs, in the brain and nerves. What is really healing for humanity in this sphere will only be reached when the relationship between man and nature has been thoroughly investigated from the point of view which I have given you to-day.

The human body is only to be explained when we know the processes that take place in it: when we know that the human being must dissolve within him the mineral, must reverse within him the plant kingdom, must raise above him, that is, must spiritualise, the animal kingdom. And all that a teacher ought to know about the evolution of the body has—as its foundation—what I have placed before you here in these anthropological, anthroposophical considerations.

Zwölfter Vortrag

Wenn wir den menschlichen Leib betrachten, müssen wir ihn in Beziehung bringen zu unserer physisch-sinnlichen Umwelt, denn mit der steht er in einem fortwährenden Wechselverhältnis, durch die wird er unterhalten. Wenn wir hinausblicken in unsere physisch-sinnliche Umwelt, dann nehmen wir in dieser physisch-sinnlichen Umwelt wahr mineralische Wesen, pflanzliche Wesen, tierische Wesen. Mit den Wesen des Mineralischen, des Pflanzlichen, des Tierischen ist unser physischer Leib verwandt. Aber die besondere Art der Verwandtschaft wird nicht ohne weiteres durch eine Oberflächenbetrachtung klar, sondern es ist notwendig, da tiefer in das Wesen der Naturreiche überhaupt einzudringen, wenn man die Wechselbeziehung des Menschen mit seiner physisch-sinnlichen Umgebung kennenlernen will.

Wir nehmen am Menschen, insofern er physisch-leiblich ist, wahr zunächst sein festes Knochengerüst, seine Muskeln. Wir nehmen dann, wenn wir weiter in ihn eindringen, den Blutkreislauf wahr mit den Organen, die zum Blutkreislauf gehören. Wir nehmen die Atmung wahr. Wir nehmen die Ernährungsvorgänge wahr. Wir nehmen wahr, wie aus den verschiedensten Gefäßformen — wie man es in der Naturlehre nennt — die Organe sich herausbilden. Wir nehmen wahr Gehirn und Nerven, die Sinnesorgane, und es entsteht die Aufgabe, diese verschiedenen Organe des Menschen und die Vorgänge, die sie vermitteln, in die äußere Welt, in der er drinnensteht, hineinzugliedern.

Gehen wir da aus von demjenigen, was am Menschen zunächst als das Vollkommenste erscheint — wie es sich in Wirklichkeit damit verhält, haben wir ja schon gesehen -, gehen wir aus von seinem GehirnNervensystem, das sich zusammengliedert mit den Sinnesorganen. Wir haben ja darin diejenige Organisation des Menschen, die die längste zeitliche Entwickelung hinter sich hat, so daß sie hinausgeschritten ist über die Form, welche die Tierwelt entwickelt hat. Der Mensch ist gewissermaßen durchgeschritten durch die Tierwelt in bezug auf dieses sein eigentliches Hauptsystem, und er ist hinweggeschritten über das Tiersystem zu dem eigentlich menschlichen System, das ja am deutlichsten in der Hauptesblidung zum Ausdruck kommt.

Nun haben wir gestern davon gesprochen, inwiefern unsere Hauptesbildung an der individuellen menschlichen Entwickelung teilnimmt, inwiefern die Formung, die Gestaltung des menschlichen Leibes ausgeht von den Kräften, die im Haupte, im Kopfe veranlagt sind. Und wir haben gesehen, daß gewissermaßen dem Kopfwirken eine Art Schlußpunkt gesetzt wird mit dem Zahnwechsel gegen das siebente Jahr zu. Wir sollten uns klar werden, was da eigentlich geschieht, indem der menschliche Kopf in Wechselwirkung steht mit den Brustorganen und mit den Gliedmaßenorganen. Wir sollten die Frage beantworten: Was tut denn eigentlich der Kopf, indem er seine Arbeit verrichtet in Zusammenhang mit dem Brust-Rumpfsystem und dem Gliedmaßensystem? Er formt, er gestaltet fortwährend. Unser Leben besteht eigentlich darin, daß in den ersten sieben Lebensjahren eine starke Gestaltung von ihm ausgeht, die sich auch bis in die physische Form hineinergießt, daß dann aber der Kopf immer noch nachhilft, die Gestalt erhält, die Gestalt durchseelt, die Gestalt durchgeistigt.

Der Kopf hängt mit der Gestaltbildung des Menschen zusammen. Ja aber - bildet der Kopf unsere eigentliche Menschengestalt? Das tut er nämlich nicht. Sie müssen sich schon bequemen zu der Anschauung, daß der Kopf fortwährend im geheimen etwas anderes aus Ihnen machen will, als Sie sind. Da gibt es Augenblicke, in denen Sie der Kopf so gestalten möchte, daß Sie aussehen wie ein Wolf. Da gibt es Augenblicke, in denen Sie der Kopf so gestalten möchte, daß Sie aussehen wie ein Lamm, dann wiederum, daß Sie aussehen wie ein Wurm; zum Wurm, zum Drachen möchte er Sie machen. All die Gestaltungen, die eigentlich Ihr Haupt mit Ihnen vorhat, die finden Sie ausgebreitet draußen in der Natur in den verschiedenen Tierformen. Schauen Sie das Tierreich an, so können Sie sich sagen: Das bin ich selbst, nur erweist mir mein Rumpfsystem und mein Gliedmaßensystem die Gefälligkeit, fortwährend, indem vom Kopf ausgeht zum Beispiel die Wolfsgestalt, diese Wolfsgestalt umzuwandeln zur Menschenform. Sie überwinden in sich fortwährend das Animalische. Sie bemächtigen sich seiner so, daß Sie es in sich nicht ganz zum Dasein kommen lassen, sondern es metamorphosieren, umgestalten. Es ist also der Mensch durch sein Kopfsystem mit der tierischen Umwelt in einer Beziehung, aber so, daß er in seinem leiblichen Schaffen über diese tierische Umwelt fortwährend hinausgeht. Was bleibt denn da eigentlich in Ihnen? Sie können einen Menschen anschauen. Stellen Sie sich den Menschen vor. Sie können die interessante Betrachtung anstellen, daß Sie sagen: Da ist der Mensch. Oben hat er seinen Kopf. Da bewegt sich eigentlich ein Wolf, aber es wird kein Wolf; er wird gleich durch den Rumpf und die Gliedmaßen aufgelöst. Da bewegt sich eigentlich ein Lamm; es wird durch den Rumpf und die Gliedmaßen aufgelöst.

Fortwährend bewegen sich da übersinnlich die tierischen Formen im Menschen und werden aufgelöst. Was wäre es denn, wenn es einen übersinnlichen Photographen gäbe, der diesen Prozeß festhielte, der also diesen ganzen Prozeß auf die Photographenplatte oder auf fortwährend wechselnde Photographenplatten brächte? Was würde man denn da auf der Photographenplatte sehen? Die Gedanken des Menschen würde man sehen. Diese Gedanken des Menschen sind nämlich das übersinnliche Korrelat desjenigen, was sinnlich nicht zum Ausdruck kommt. Sinnlich kommt nicht zum Ausdruck diese fortwährende Metamorphose aus dem Tierischen, vom Kopfe nach unten strömend, aber übersinnlich wirkt sie im Menschen als der Gedankenprozeß. Als ein übersinnlich realer Prozeß ist das durchaus vorhanden. Ihr Kopf ist nicht nur der Faulenzer auf den Schultern, sondern er ist derjenige, der Sie eigentlich gerne in der Tierheit erhalten möchte. Er gibt Ihnen die Formen des ganzen Tierreiches, er möchte gerne, daß fortwährend Tierreiche entstehen. Aber Sie lassen es durch Ihren Rumpf und die Gliedmaßen nicht dazu kommen, daß durch Sie ein ganzes Tierreich im Laufe Ihres Lebens entsteht, sondern Sie verwandeln dieses Tierreich in Ihre Gedanken. So stehen wir zum Tierreich in Beziehung. Wir lassen übersinnlich dieses Tierreich in uns entstehen und lassen es dann nicht zur sinnlichen Wirklichkeit kommen, sondern halten es im Übersinnlichen zurück. Rumpf und Gliedmaßen lassen diese entstehenden Tiere in ihr Gebiet nicht herein. Wenn der Kopf zu sehr die Neigung hat, etwas von diesem Tierischen zu erzeugen, dann sträubt sich der übrige Organismus, das aufzunehmen, und dann muß der Kopf zur Migräne greifen, um es wiederum auszurotten, und zu ähnlichen Dingen, die sich im Kopfe abspielen.

Auch das Rumpfsystem steht zur Umgebung in Beziehung. Aber es steht nicht zu dem Tiersystem der Umgebung in Beziehung, sondern es steht in Beziehung zu dem gesamten Umfang der Pflanzenwelt. Eine geheimnisvolle Beziehung ist zwischen dem Rumpfsystem des Menschen, dem Brustsystem und der Pflanzenwelt. In dem Rumpfsystem, in dem Brustsystem, Rumpf-Brustsystem spielt sich ja ab das Hauptsächlichste des Blutkreislaufes, die Atmung, die Ernährung. All diese Prozesse sind in einer Wechselbeziehung zu dem, was draußen in der physisch-sinnlichen Natur, in der Pflanzenwelt vor sich geht, aber in einer sehr eigenartigen Beziehung.

Nehmen wir zunächst die Atmung. Was tut der Mensch, indem er atmet? Sie wissen, er nimmt den Sauerstoff auf, und er verwandelt durch seinen Lebensprozeß den Sauerstoff, indem er ihn verbindet mit dem Kohlenstoff, zur Kohlensäure. Der Kohlenstoff ist im Organismus durch die umgewandelten Ernährungsstoffe. Dieser Kohlenstoff nimmt den Sauerstoff auf. Dadurch, daß sich der Sauerstoff mit dem Kohlenstoff verbindet, entsteht die Kohlensäure. Ja, jetzt wäre eine schöne Gelegenheit in dem Menschen, wenn er die Kohlensäure da in sich hat, diese nicht herauszulassen, sondern sie drinnen zu behalten. Und wenn er jetzt den Kohlenstoff wiederum loslösen könnte vom Sauerstoff — ja, was würde denn dann geschehen? Wenn der Mensch zunächst durch seinen Lebensprozeß den Sauerstoff einatmet und ihn da drinnen sich verbinden läßt mit dem Kohlenstoff zur Kohlensäure und wenn der Mensch jetzt in der Lage wäre, innerlich den Sauerstoff wieder fortzuschaffen, auszuschalten, aber den Kohlenstoff drinnen zu verarbeiten, was würde denn da im Menschen entstehen? Die Pflanzenwelt. Im Menschen würde plötzlich die ganze Vegetation wachsen. Sie könnte wachsen. Denn wenn Sie die Pflanze ansehen, was tut sie denn? Die atmet nämlich nicht in derselben regelmäßigen Weise wie der Mensch den Sauerstoff ein, sondern sie assimiliert die Kohlensäure. Die Pflanze ist bei Tage erpicht auf die Kohlensäure, den Sauerstoff gibt sie ab. Es wäre schlimm, wenn sie es nicht tun würde; wir hätten ihn dann nicht, und auch die Tiere hätten ihn nicht. Aber den Kohlenstoff behält sie zurück. Daraus bildet sie sich Stärke und Zukker und alles, was in ihr ist; daraus baut sie sich ihren ganzen Organismus auf. Die Pflanzenwelt entsteht eben dadurch, daß sie sich aufbaut aus dem Kohlenstoff, den sich die Pflanzen durch ihre Assimilation absondern von der Kohlensäure. Wenn Sie die Pflanzenwelt ansehen, ist sie metamorphosierter Kohlenstoff, der abgesondert ist aus dem Assimilationsprozeß, der dem menschlichen Atmungsprozeß entspricht. Die Pflanze atmet auch etwas, aber das ist etwas anderes als beim Menschen. Nur eine äußerliche Betrachtung sagt, die Pflanze atme auch. Sie atmet zwar ein wenig, namentlich in der Nacht; aber das ist gerade so, wie wenn einer sagt: Da ist ein Rasiermesser, ich werde Fleisch damit schneiden. -— Der Atmungsprozeß ist bei den Pflanzen anders als beim Menschen und bei den Tieren, wie das Rasiermesser etwas anderes ist als das Tischmesser. Dem menschlichen Atmungsprozesse entspricht bei den Pflanzen der umgekehrte Prozeß, der Assimilationsprozeß.

Daher werden Sie es begreifen: wenn Sie in sich den Prozeß fortsetzen, wodurch Kohlensäure entstanden ist, das heißt, wenn Sauerstoff wieder weggegeben würde und die Kohlensäure in Kohlenstoff umgewandelt würde, wie die Natur es draußen macht — die Stoffe hätten Sie auch dazu in sich -, dann könnten Sie in sich die ganze Vegetation wachsen lassen. Sie könnten es bewirken, daß Sie plötzlich aufgingen als Pflanzenwelt. Sie verschwänden, und die ganze Pflanzenwelt entstünde. Diese Fähigkeit ist nämlich im Menschen, daß er fortwährend eine Pflanzenwelt erzeugt; er läßt es nur nicht dazu kommen. Sein Rumpfsystem hat stark die Neigeng, fortwährend die Pflanzenwelt zu erzeugen. Kopf und Gliedmaßen lassen es nicht dazu kommen; sie wehren sich dagegen. Und so treibt der Mensch die Kohlensäure heraus und läßt das Pflanzenreich in sich nicht entstehen. Er läßt draußen das Pflanzenreich entstehen aus der Kohlensäure.

Es ist das eine merkwürdige Wechselbeziehung zwischen dem BrustRumpfsystem und der sinnlich-physischen Umgebung, daß da draußen das Reich der Vegetabilien ist und daß der Mensch fortwährend genötigt ist, damit er nicht zur Pflanze wird, den Vegetationsprozeß nicht in sich aufkommen zu lassen, sondern, wenn er entsteht, ihn gleich nach außen zu schicken. Wir können also sagen: Mit Bezug auf das BrustRumpfsystem ist der Mensch in der Lage, das Gegenreich des Pflanzlichen zu schaffen. Wenn Sie sich das Pflanzenreich vorstellen als positiv, so erzeugt der Mensch das Negativ vom Pflanzenreich. Er erzeugt gewissermaßen ein umgekehrtes Pflanzenreich.

Und was ist es denn, wenn das Pflanzenreich in ihm beginnt, sich schlecht aufzuführen und Kopf und Gliedmaßen nicht die Kraft haben, sein Entstehen im Keime gleich zu ersticken, es wegzuschicken? Dann wird der Mensch krank! Und im Grunde genommen bestehen die inneren Erkrankungen, die herrühren vom Brust-Rumpfsystem, darin, daß der Mensch zu schwach ist, um die in ihm entstehende Pflanzlichkeit sogleich zu verhindern. In dem Augenblick, wo nur ein bißchen in uns entsteht, was nach dem Pflanzenreich hintendiert, wo wir nicht in der Lage sind, gleich dafür zu sorgen, daß das, was als Pflanzenreich in uns entstehen will, herauskommt und draußen sein Reich aufrichtet, in dem Augenblick werden wir krank. So daß man das Wesen der Erkrankungsprozesse darin suchen muß, daß Pflanzen im Menschen anfangen zu wachsen. Sie werden natürlich nicht zu Pflanzen, weil schließlich für die Lilie das menschliche Innere keine angenehme Umgebung ist. Aber die Tendenz, daß das Pflanzenreich entsteht, kann durch eine Schwäche der anderen Systeme sich ergeben, und dann wird der Mensch krank. Richten wir daher unseren Blick auf die ganze pflanzliche Umwelt unserer menschlichen Umgebung, so müssen wir uns sagen: In einem gewissen Sinne haben wir in der pflanzlichen Umwelt auch die Bilder unserer sämtlichen Krankheiten. Das ist das merkwürdige Geheimnis im Zusammenhang des Menschen mit der Naturumwelt, daß er nicht nur, wie wir bei anderen Gelegenheiten ausgeführt haben, in den Pflanzen zu sehen hat Bilder seiner Entwickelung bis zur Geschlechtsreife, sondern daß er in den Pflanzen draußen, namentlich insofern diese Pflanzen in sich die Anlage tragen zum Fruchtwerden, die Bilder zu sehen hat seiner Erkrankungsprozesse. Das ist etwas, was vielleicht der Mensch gar nicht gerne hört, weil er selbstverständlich die Pflanzenwelt ästhetisch liebt und weil, wenn die Pflanzenwelt ihr Wesen außerhalb des Menschen entfaltet, der Mensch mit dieser Ästhetik recht hat. In dem Augenblick aber, wo die Pflanzenwelt innerhalb des Menschen ihr Wesen entfalten will, in dem Augenblick, wo es im Menschen anfangen will zu vegetarisieren, in dem Augenblick wirkt das, was draußen in der farbenschönen Pflanzenwelt wirkt, im Menschen als Krankheitsursache. Die Medizin wird dann einmal eine Wissenschaft sein, wenn sie jede einzelne Krankheit in Parallele bringen wird zu irgendeiner Form der Pflanzenwelt. Es ist einmal so, daß, indem der Mensch die Kohlensäure ausatmet, er im Grunde genommen um seines eigenen Daseins willen die ganze Pflanzenwelt fortwährend ausatmet, die in ihm entstehen will. Daher braucht es Ihnen auch nicht verwunderlich zu sein, daß dann, wenn die Pflanze beginnt, über ihr gewöhnliches Pflanzendasein hinauszugehen und Gifte in sich zu erzeugen, daß diese Gifte auch zusammenhängen mit den Gesundheits- und Erkrankungsprozessen des Menschen. Aber es hängt ja auch mit dem normalen Ernährungsprozeß zusammen.

Ja, meine lieben Freunde, die Ernährung, die sich ebenso vollzieht im Brust-Rumpfsystem, wenigstens ihrem Ausgangspunkt nach, wie der Atmungsvorgang, sie muß in einer ganz ähnlichen Art betrachtet werden wie die Atmung. Bei der Ernährung nimmt der Mensch auch die Stoffe seiner Umwelt in sich auf, aber er läßt sie nicht so, wie sie sind; er verwandelt sie. Er verwandelt sie gerade mit Hilfe des Sauerstoffes der Atmung, Es verbinden sich die Stoffe, die der Mensch durch seine Ernährung aufnimmt, nachdem er sie verwandelt hat, mit dem Sauerstoff. Das sieht so aus wie ein Verbrennungsprozeß, und es sieht aus, als ob der Mensch in seinem Inneren fortwährend brennen würde. Das sagt auch vielfach die Naturwissenschaft, daß im Menschen ein Verbrennungsprozeß wirke. Es ist aber nicht wahr. Es ist kein wirklicher Verbrennungsprozeß, was da im Menschen vorgeht, sondern es ist ein Verbrennungsprozeß - beachten Sie das wohl -, dem der Anfang und das Ende fehlt. Es ist bloß die mittlere Stufe des Verbrennungsprozesses;, es fehlt ihm der Anfang und das Ende. Im menschlichen Leibe darf niemals Anfang und Ende des Verbrennungsprozesses vor sich gehen, sondern nur das Mittelstück des Verbrennungsprozesses. Es ist für den Menschen zerstörend, wenn die allerersten Stadien eines Verbrennungsprozesses, wie er in der Fruchtbereitung vor sich geht, im menschlichen Organismus vollzogen werden; zum Beispiel, wenn der Mensch ganz unreifes Obst genießt. Diesen Anfangsprozeß, der der Verbrennung ähnlich ist, den kann der Mensch nicht durchmachen. Das gibt es nicht in ihm, das macht ihn krank. Und kann er viel unreifes Obst essen, wie die starken Landleute zum Beispiel, dann muß er schon sehr, sehr viel von Verwandtschaft mit der umgebenden Natur haben, daß er die unreifen Apfel und Birnen in sich so verdauen kann, wie er das schon von der Sonne reifgekochte Obst verdaut. Also nur den mittleren Prozeß kann er mitmachen. Von allen Verbrennungsprozessen kann der Mensch im Ernährungsvorgang nur den mittleren Prozeß mitmachen. Wird der Prozeß zu seinem Ende getrieben, kommt es dahin, wohin es zum Beispiel das reife Obst draußen bringt, daß es fault, das darf der Mensch nicht mehr mitmachen. Also das Ende darf er auch nicht mitmachen; da muß er vorher die Ernährungsstoffe ausscheiden. Der Mensch vollzieht tatsächlich nicht die Naturprozesse so, wie sie sich in der Umgebung abspielen, sondern er vollzieht nur das Mittelstück; Anfang und Ende kann er nicht in sich vollziehen.

Und jetzt sehen wir etwas höchst Merkwürdiges. Betrachten Sie die Atmung. Sie ist das Gegenstück zu alledem, was in der Pflanzenwelt draußen vor sich geht. Sie ist gewissermaßen das Anti-Pflanzenreich. Die Atmung des Menschen ist das Anti-Pflanzenreich, und sie verbindet sich innerlich mit dem Ernährungsprozeß, der ein Mittelstück zu dem Prozeß draußen ist. Sehen Sie, da lebt zweierlei in unserem leiblichen Brust-Rumpfsystem: dieser Anti-Pflanzenprozeß, der sich da abspielt durch die Atmung, wirkt immer zusammen mit dem Mittelstück der übrigen Naturprozesse draußen. Das wirkt durcheinander. Da, sehen Sie, hängen zusammen Seele und Leib. Da ist der geheimnisvolle Zusammenhang zwischen Seele und Leib. Indem sich dasjenige, was sich durch den Atmungsprozeß abspielt, verbindet mit den übrigen Naturprozessen, deren Ausführung nur in ihrem Mittelstück erfolgt, da verbindet sich das Seelische, das der Anti-Pflanzenprozeß ist, mit dem menschlich gewordenen Leiblichen, das immer das Mittelstück ist der Naturprozesse. Die Wissenschaft kann lange nachdenken, welches die Wechselbeziehung zwischen Leib und Seele ist, wenn sie sie nicht sucht in dem geheimnisvollen Zusammenhange zwischen dem seelisch gewordenen Atmen und dem leiblich gewordenen Dasein des Mittelstückes der Naturprozesse. Diese Naturprozesse entstehen im Menschen nicht und vergehen im Menschen nicht. Ihr Entstehen läßt er außerhalb; ihr Vergehen darf erst sein, wenn er sie ausgeschieden hat. Der Mensch verbindet sich leiblich nur mit einem mittleren Teil der Naturprozesse, und er durchseelt diese Naturprozesse im Atmungsprozeß.

Hier entsteht jenes feine Gewebe von Vorgängen, welches die Zukunftsmedizin, die Zukunftshygiene ganz besonders wird studieren müssen. Die Zukunftshygiene wird sich fragen müssen: Wie wirken im Weltall draußen die verschiedenen Wärmeabstufungen ineinander? Wie wirkt die Wärme beim Übergang von einem kühleren Ort zu einem wärmeren und umgekehrt? Und wie wirkt das, was da draußen wirkt als Wärmevorgang, im menschlichen Organismus, wenn er in diesen Wärmevorgang hineingestellt ist? — Ein Zusammenspiel von Luft und Wasser findet der Mensch im äußeren Vegetationsprozeß. Er wird studieren müssen, wie das auf den Menschen wirkt, wenn der Mensch da hineingestellt ist und so weiter.

Mit Bezug auf solche Dinge ist die Medizin von heute ein ganz klein wenig im Anfang, aber kaum noch im Anfang. Die Medizin von heute legt zum Beispiel viel größeren Wert darauf, daß sie, wenn irgend so etwas da ist wie eine Krankheitsform, den Krankheitserreger aus der Bazillen- oder Bakterienform findet. Dann, wenn sie ihn hat, ist sie zufrieden. Es kommt aber viel mehr darauf an, zu erkennen, wie es kommt, daß der Mensch imstande ist, in einem Augenblick seines Lebens ein klein wenig einen Vegetationsprozeß in sich zu entwickeln, so daß die Bazillen darin dann einen angenehmen Aufenthaltsort wittern. Es kommt darauf an, daß wir unsere Leibeskonstitution so erhalten, daß für all das vegetabilische Gezücht kein angenehmer Aufenthaltsort mehr da ist; wenn wir das tun, dann werden diese Herrschaften nicht allzugroße Verheerungen bei uns selbst anrichten können.

Nun bleibt uns noch die Frage: Wie stehen nun eigentlich Knochengerüst und Muskeln zum gesamten menschlichen Lebensprozeß, wenn wir den Menschen betrachten leiblich in seiner Beziehung zur Außenwelt?

Sehen Sie, da kommen wir auf etwas, was Sie unbedingt begreifen müssen, wenn Sie den Menschen verstehen wollen, worauf aber in der gegenwärtigen Wissenschaft fast gar nicht gesehen wird. Beachten Sie einmal, was geschieht, indem Sie den Arm beugen. Da bewirken Sie ja durch die Muskelanziehung, die den Vorderarm beugt, einen ganz maschinellen Vorgang. Stellen Sie sich jetzt vor, das wäre einfach dadurch geschehen, daß Sie zuerst gehabt hätten eine Stellung wie diese (siehe erste Zeichnung).

Sie würden nun ein Band spannen (c) und würden es zusammenrollen; dann würde diese Stange diese Bewegung ausführen (siehe zweite Zeichnung). Es ist eine ganz maschinelle Bewegung. Solche maschinelle Bewegungen führen Sie auch aus, wenn Sie Ihr Knie beugen und auch, wenn Sie gehen. Denn beim Gehen kommt fortwährend die ganze Maschinerie Ihres Leibes in Bewegung, und fortwährend wirken Kräfte. Es sind vorzugsweise Hebelkräfte, aber es wirken eben Kräfte. Denken Sie sich jetzt einmal, Sie könnten durch irgendeinen kniffligen photographischen Vorgang bewirken, daß, wenn der Mensch geht, vom Menschen nichts photographiert würde, aber all die Kräfte, die er anwendet, photographiert würden. Also die Kräfte, die er anwendet, um das Bein zu heben, es wieder aufzustellen, das andere Bein nachzusetzen. Vom Menschen würde also nichts photographiert als nur die Kräfte. Es würde da zunächst, wenn Sie diese Kräfte sich würden entwickeln sehen, ein Schatten photographiert und beim Gehen sogar ein ganzes Schattenband. Sie sind groß im Irrtum, wenn Sie glauben, daß Sie mit Ihrem Ich in Muskeln und Fleisch leben. Sie leben mit Ihrem Ich, auch wenn Sie wachen, nicht in Muskeln und Fleisch, sondern Sie leben mit Ihrem Ich hauptsächlich in diesem Schatten, den Sie da abphotographieren, in den Kräften, durch die Ihr Leib seine Bewegungen ausführt. So grotesk es Ihnen klingt: wenn Sie sich setzen, dann drücken Sie Ihren Rücken an die Stuhllehne an; mit Ihrem Ich leben Sie in der Kraft, die sich in diesem Zusammendrücken entwickelt. Und wenn Sie stehen, leben Sie in der Kraft, mit der Ihre Füße auf die Erde drücken. Sie leben fortwährend in Kräften. Es ist gar nicht wahr, daß wir in unserem sichtbaren Körper mit unserem Ich leben. Wir leben mit unserem Ich in Kräften. Unseren sichtbaren Körper tragen wir nur mit; den schleppen wir nur mit während unseres physischen Erdenlebens bis zum Tode. Wir leben aber auch im wachen Zustand lediglich in einem Kraftleib. Und was tut denn eigentlich dieser Kraftleib? Er setzt sich fortwährend eine sonderbare Aufgabe.

Nicht wahr, indem Sie sich ernähren, nehmen Sie auch auf allerlei mineralische Stoffe. Auch wenn Sie sich nicht stark Ihre Suppe salzen — das Salz ist ja in den Speisen drinnen -, nehmen Sie mineralische Stoffe auf. Sie haben auch das Bedürfnis, mineralische Stoffe aufzunehmen. Was tun Sie denn mit diesen mineralischen Stoffen? Ja, sehen Sie, Ihr Kopfsystem kann nicht viel mit diesen mineralischen Stoffen anfangen. Ihr Rumpf-Brust-System auch nicht. Aber Ihr Gliedmaßensystem; das verhindert, daß diese mineralischen Stoffe in Ihnen die ihnen eigene Kristallform annehmen. Wenn Sie nicht die Kräfte Ihres Gliedmaßensystems entwickeln, so würden Sie, wenn Sie Salz essen, zum Salzwürfel werden. Ihr Gliedmaßensystem, das Knochengerüst und das Muskelsystem haben die fortwährende Tendenz, der Mineralbildung der Erde entgegenzuwirken, das heißt, die Minerale aufzulösen. Die Kräfte, die die Mineralien auflösen im Menschen, die kommen vom Gliedmaßensystem.

Wenn der Krankheitsprozeß über das bloß Vegetative hinausgeht, das heißt, wenn der Körper die Tendenz hat, nicht nur das Pflanzliche in sich beginnen zu lassen, sondern auch den mineralischen Kristallisationsprozeßs, dann ist eine höhere, sehr zerstörerische Form von Krankheit vorhanden, zum Beispiel Zuckerkrankheit. Dann ist der menschliche Leib nicht in der Lage, aus der Kraft seiner Gliedmaßen heraus, die er von der Welt aufnimmt, das Mineral, das er fortwährend auflösen soll, wirklich aufzulösen. Und wenn heute die Menschen gerade jener Krankheitsformen, die vielfach von krankhaftem Mineralisieren im Menschenleibe herrühren, nicht Herr werden können, so rührt das vielfach davon her, daß wir nicht genügend anwenden können die Gegenmittel gegen diese Erkrankungsform, die wir alle hernehmen müßten aus den Zusammenhängen der Sinnesorgane oder des Gehirns, der Nervenstränge und dergleichen. Wir müßten die Scheinstoffe - ich nenne sie aus gewissen Gründen Scheinstoffe -, die in den Sinnesorganen sind, die in Gehirn und Nerven sind, diese zerfallende Materie, die müßten wir in irgendeiner Form verwenden, um solcher Krankheiten Herr zu werden wie Gicht, Zuckerkrankheit und dergleichen. Auf diesem Gebiete kann erst das wirklich der Menschheit Heilsame erreicht werden, wenn einmal der Zusammenhang des Menschen mit der Natur ganz durchschaut wird von dem Gesichtspunkte aus, den ich Ihnen heute angegeben habe.

Der Leib des Menschen wird auf keine andere Weise erklärlich, als indem man zuerst seine Vorgänge, seine Prozesse kennt, indem man weiß, daß der Mensch in sich auflösen muß das Mineral, in sich umkehren muß das Pflanzenreich, über sich hinausführen muß, das heißt, vergeistigen muß das Tierreich. Und alles dasjenige, was der Lehrer wissen soll über die Leibesentwickelung, das hat zur Grundlage eine solche anthropologische, anthroposophische Betrachtung, wie ich sie hier mit Ihnen angestellt habe. Was nun pädagogisch darauf aufgebaut werden kann, das wollen wir morgen weiterbesprechen.

Twelfth Lecture

When we consider the human body, we must relate it to our physical and sensory environment, because it is in constant interaction with this environment, which sustains it. When we look out into our physical and sensory environment, we perceive mineral beings, plant beings, and animal beings in this physical and sensory environment. Our physical body is related to the beings of the mineral, plant, and animal kingdoms. But the special nature of this relationship is not immediately apparent from a superficial observation; rather, it is necessary to penetrate more deeply into the essence of the natural kingdoms in order to understand the interrelationship between human beings and their physical and sensory environment.

Insofar as human beings are physical and corporeal, we first perceive their solid skeleton and muscles. Then, as we delve deeper into them, we perceive the blood circulation and the organs that belong to it. We perceive breathing. We perceive the processes of nutrition. We perceive how the organs develop from the most diverse vascular forms, as they are called in natural science. We perceive the brain and nerves, the sensory organs, and the task arises of integrating these various human organs and the processes they mediate into the external world in which the human being stands.

Let us start with what initially appears to be the most perfect thing in the human being — we have already seen how things really are — let us start with the brain and nervous system, which is connected to the sensory organs. Here we have the human organism that has undergone the longest period of development, so that it has progressed beyond the form developed by the animal world. In a sense, the human being has passed through the animal world in relation to this, his actual main system, and has progressed beyond the animal system to the actual human system, which is most clearly expressed in the formation of the head.

Yesterday we spoke about the extent to which our head formation participates in individual human development, the extent to which the formation and shaping of the human body proceeds from the forces that are predisposed in the head. And we have seen that, in a sense, the activity of the head is brought to a kind of conclusion with the change of teeth around the age of seven. We should be clear about what actually happens when the human head interacts with the chest organs and the limb organs. We should answer the question: What does the head actually do when it performs its work in connection with the chest-torso system and the limb system? It continuously shapes and forms. Our life actually consists of the fact that in the first seven years of life, a strong shaping force emanates from it, which also pours into the physical form, but that the head then continues to help, to maintain the form, to imbue the form with soul, to imbue the form with spirit.The head is connected with the formation of the human form. Yes, but does the head actually form our human form? No, it does not. You must come to terms with the idea that the head is constantly trying to secretly make you into something other than what you are. There are moments when the head wants to shape you so that you look like a wolf. There are moments when the head wants to shape you so that you look like a lamb, then again so that you look like a worm; it wants to turn you into a worm, into a dragon. All the shapes that your head actually has in mind for you can be found spread out in nature in the various animal forms. If you look at the animal kingdom, you can say to yourself: That is me, only my torso and my limbs do me the favor of constantly transforming this wolf-like form, which emanates from my head, for example, into a human form. You are constantly overcoming the animalistic within yourself. You take control of it in such a way that you do not allow it to fully come into being within you, but rather metamorphose it, transform it. So, through their head system, humans are connected to the animal environment, but in such a way that they continually transcend this animal environment in their physical activity. What actually remains within you? You can look at a human being. Form a mental image of the human being. You can make the interesting observation that you say: There is the human being. At the top he has his head. There is actually a wolf moving there, but it does not become a wolf; it is immediately dissolved by the torso and the limbs. There is actually a lamb moving there; it is dissolved by the torso and the limbs.

The animal forms in the human being are constantly moving in a supersensible way and are dissolved. What would it be like if there were a supersensible photographer who captured this process, who brought this whole process onto the photographic plate or onto constantly changing photographic plates? What would one see on the photographic plate? One would see the thoughts of the human being. These thoughts of the human being are the supersensible correlate of that which is not expressed sensually. This continuous metamorphosis from the animal, flowing down from the head, is not expressed sensually, but it works supersensibly in the human being as the thought process. As a supersensible real process, it is definitely present. Your head is not just the lazybones on your shoulders, but it is the one that would actually like to keep you in animality. It gives you the forms of the entire animal kingdom; it would like to see animal kingdoms continually emerging. But you do not allow your torso and limbs to create an entire animal kingdom in the course of your life; instead, you transform this animal kingdom into your thoughts. This is how we relate to the animal kingdom. We allow this animal kingdom to arise within us supersensibly and then do not allow it to become a sensory reality, but hold it back in the supersensible realm. The torso and limbs do not allow these emerging animals into their domain. If the head is too inclined to produce something of this animal nature, then the rest of the organism resists accepting it, and then the head must resort to migraine to eradicate it, and to similar things that take place in the head.

The trunk system also relates to the environment. But it does not relate to the animal system of the environment, rather it relates to the entire scope of the plant world. There is a mysterious relationship between the human trunk system, the chest system, and the plant world. The torso system, the chest system, and the torso-chest system are where the most important aspects of blood circulation, respiration, and nutrition take place. All these processes are interrelated with what is happening outside in the physical-sensory nature, in the plant world, but in a very peculiar relationship.

Let us first consider breathing. What does a person do when they breathe? As you know, they take in oxygen and, through their life process, transform the oxygen by combining it with carbon to form carbon dioxide. The carbon is present in the organism through the converted nutrients. This carbon absorbs the oxygen. When oxygen combines with carbon, carbon dioxide is produced. Now, it would be a wonderful opportunity for humans, when they have carbon dioxide inside them, not to let it out, but to keep it inside. And if they could then separate the carbon from the oxygen again — well, what would happen then? If humans first inhale oxygen through their life process and allow it to combine with carbon to form carbon dioxide, and if humans were now able to remove the oxygen internally, to eliminate it, but to process the carbon internally, what would then arise in humans? The plant world. All vegetation would suddenly grow in humans. It could grow. Because when you look at a plant, what does it do? It does not breathe in oxygen in the same regular way as humans do, but assimilates carbon dioxide. During the day, the plant is eager for carbon dioxide and releases oxygen. It would be bad if it did not do so; we would not have it, and neither would the animals. But it retains the carbon. From this it forms starch and sugar and everything that is in it; from this it builds its entire organism. The plant world arises precisely because it builds itself up from the carbon that plants secrete from carbon dioxide through their assimilation. When you look at the plant world, it is metamorphosed carbon that has been secreted from the assimilation process, which corresponds to the human respiratory process. Plants also breathe something, but it is different from humans. Only an external observation says that plants also breathe. They do breathe a little, especially at night, but that is just like saying: There is a razor, I will cut meat with it. — The respiratory process in plants is different from that in humans and animals, just as a razor is different from a table knife. The human respiratory process corresponds to the reverse process in plants, the assimilation process.

Therefore, you will understand: if you continue the process within yourself that produces carbon dioxide, that is, if oxygen were to be released again and the carbon dioxide were to be converted into carbon, as nature does outside — you would also have the substances for this within yourself — then you could grow all vegetation within yourself. You could cause yourself to suddenly blossom into a plant world. You would disappear, and the entire plant world would emerge. This ability is inherent in human beings, that they can continuously produce a plant world; they just don't allow it to happen. Their trunk system has a strong tendency to continuously produce the plant world. The head and limbs prevent this from happening; they resist it. And so humans expel carbon dioxide and do not allow the plant kingdom to arise within themselves. They allow the plant kingdom to arise outside themselves from carbon dioxide.

There is a strange interrelationship between the chest-torso system and the sensory-physical environment, in that the plant kingdom exists outside and human beings are constantly compelled, in order not to become plants, not to allow the process of vegetation to arise within themselves, but, when it does arise, to send it outwards immediately. We can therefore say that, with regard to the chest-torso system, humans are capable of creating the opposite of the plant kingdom. If you have in your mind the mental image of the plant kingdom as positive, then humans create the negative of the plant kingdom. In a sense, they create a reverse plant kingdom.

And what happens when the plant kingdom within him begins to misbehave and his head and limbs do not have the strength to nip its emergence in the bud, to send it away? Then the human being becomes ill! And basically, the internal diseases that originate in the chest-torso system consist in the fact that the human being is too weak to immediately prevent the plant kingdom from emerging within him. The moment something arises in us that tends toward the plant kingdom, and we are unable to immediately ensure that what wants to arise in us as the plant kingdom comes out and establishes its kingdom outside, at that moment we become ill. So the essence of the disease process must be sought in the fact that plants begin to grow in humans. Of course, they do not become plants, because after all, the human interior is not a pleasant environment for the lily. But the tendency for the plant kingdom to arise can result from a weakness in the other systems, and then the human being becomes ill. If we therefore turn our gaze to the entire plant environment of our human surroundings, we must say to ourselves: in a certain sense, we also have the images of all our illnesses in the plant environment. This is the remarkable secret in the connection between human beings and the natural environment: not only, as we have explained on other occasions, do they see in plants images of their development to sexual maturity, but they also see in the plants outside, especially insofar as these plants have the potential to bear fruit, images of their disease processes. This is something that humans may not like to hear, because they naturally love the plant world aesthetically and because, when the plant world unfolds its essence outside of humans, humans are right about this aesthetic. But at the moment when the plant world wants to unfold its essence within humans, at the moment when it wants to begin to vegetate within humans, at that moment, what works outside in the colorful plant world works within humans as a cause of disease. Medicine will one day be a science when it brings every single disease into parallel with some form of the plant world. It is the case that, by exhaling carbon dioxide, humans are essentially exhaling the entire plant world that wants to arise within them for the sake of their own existence. Therefore, it should come as no surprise to you that when the plant begins to go beyond its normal plant existence and produce toxins within itself, these toxins are also related to the health and disease processes of humans. But it is also related to the normal nutritional process.

Yes, my dear friends, nutrition, which takes place in the chest-torso system, at least in terms of its starting point, just like the breathing process, must be viewed in a very similar way to breathing. During nutrition, humans also absorb substances from their environment, but they do not leave them as they are; they transform them. They transform them with the help of the oxygen from respiration. The substances that humans take in through nutrition, after they have been transformed, combine with the oxygen. This looks like a combustion process, and it looks as if humans were constantly burning inside. Natural science also often says that a combustion process is at work in humans. But this is not true. What takes place within the human being is not a real combustion process, but rather – note this carefully – a combustion process that lacks a beginning and an end. It is merely the middle stage of the combustion process; it lacks a beginning and an end. The beginning and end of the combustion process must never take place in the human body, only the middle part of the combustion process. It is destructive for humans when the very first stages of a combustion process, as occurs in fruit ripening, take place in the human organism; for example, when humans consume completely unripe fruit. Humans cannot go through this initial process, which is similar to combustion. It does not exist within them; it makes them ill. And if they can eat a lot of unripe fruit, as strong country folk do, for example, then they must have a great deal in common with the surrounding nature in order to be able to digest unripe apples and pears in the same way as they digest fruit that has been ripened by the sun. So they can only participate in the middle process. Of all the combustion processes, humans can only participate in the middle process in the nutritional process. If the process is driven to its end, it comes to the point where, for example, ripe fruit outside rots, and humans can no longer participate in that. So they cannot participate in the end either; they must excrete the nutrients beforehand. Humans do not actually carry out the natural processes as they take place in the environment, but only the middle part; they cannot carry out the beginning and the end within themselves.

And now we see something most remarkable. Consider breathing. It is the counterpart to everything that goes on in the plant world outside. It is, in a sense, the anti-plant kingdom. Human breathing is the anti-plant kingdom, and it is internally connected to the nutritional process, which is a middle part of the process outside. You see, there are two things living in our physical chest-torso system: this anti-plant process, which takes place through breathing, always works together with the centerpiece of the other natural processes outside. This has a confusing effect. You see, the soul and the body are connected. There is the mysterious connection between soul and body. As that which takes place through the breathing process connects with the other natural processes, the execution of which takes place only in their centerpiece, the soul, which is the anti-plant process, connects with the physical, which has become human and is always the centerpiece of the natural processes. Science can ponder at length what the interrelationship between body and soul is, if it does not seek it in the mysterious connection between the soul-become breathing and the body-become existence of the centerpiece of natural processes. These natural processes do not arise in man and do not pass away in man. Their arising is outside him; their passing away can only be when he has excreted them. Human beings connect physically only with a middle part of the natural processes, and they animate these natural processes in the breathing process.

This is where the delicate fabric of processes arises that future medicine and future hygiene will have to study in particular. Future hygiene will have to ask itself: How do the various gradations of heat interact in the universe outside? How does heat act when moving from a cooler place to a warmer one and vice versa? And how does what acts as a heat process out there act in the human organism when it is placed in this heat process? — Humans find an interaction of air and water in the external vegetation process. They will have to study how this affects humans when they are placed in it, and so on.

With regard to such things, today's medicine is still in its infancy, but hardly in its infancy anymore. Today's medicine, for example, attaches much greater importance to finding the pathogen in the form of a bacillus or bacterium when there is something like a form of disease. Then, once it has found it, it is satisfied. But it is much more important to recognize how it comes about that the human being is able, at a moment in his life, to develop a small vegetative process within himself, so that the bacilli then sense a pleasant place to stay. It is important that we maintain our physical constitution in such a way that there is no longer a pleasant place for all these vegetative organisms to live; if we do that, then these creatures will not be able to cause too much damage to ourselves.

Now we are left with the question: How do the skeleton and muscles actually relate to the entire human life process when we consider the human being physically in relation to the outside world?

You see, this brings us to something that you absolutely must understand if you want to understand the human being, but which is almost completely overlooked in current science. Notice what happens when you bend your arm. By contracting the muscles that bend the forearm, you are causing a completely mechanical process. Now imagine that this happened simply because you first had a position like this (see first drawing).

You would now stretch a band (c) and roll it up; then this rod would perform this movement (see second drawing). It is a completely mechanical movement. You also perform such mechanical movements when you bend your knee and also when you walk. Because when you walk, the entire machinery of your body is constantly in motion, and forces are constantly at work. These are primarily lever forces, but forces are at work nonetheless. Now imagine that, through some tricky photographic process, you could ensure that when a person walks, nothing of the person is photographed, but all the forces they apply are photographed. In other words, the forces they apply to lift their leg, put it back down, and move the other leg forward. Nothing of the person would be photographed except the forces. At first, if you could see these forces developing, a shadow would be photographed, and when walking, even a whole band of shadows. You are greatly mistaken if you believe that you live with your ego in muscles and flesh. Even when you are awake, you do not live with your ego in muscles and flesh, but you live with your ego mainly in this shadow that you photograph, in the forces through which your body performs its movements. As grotesque as it may sound to you: when you sit down, you press your back against the back of the chair; with your ego, you live in the force that develops in this pressing together. And when you stand, you live in the force with which your feet press down on the earth. You live continuously in forces. It is not true at all that we live with our ego in our visible body. We live with our ego in forces. We only carry our visible body with us; we only drag it along during our physical life on earth until death. But even when we are awake, we live only in a force body. And what does this force body actually do? It constantly performs a strange task.

Isn't it true that when you eat, you also absorb all kinds of mineral substances? Even if you don't add much salt to your soup — the salt is already in the food — you still absorb mineral substances. You also have a need to absorb mineral substances. What do you do with these mineral substances? Well, you see, your head system cannot do much with these mineral substances. Neither can your torso-chest system. But your limb system prevents these mineral substances from taking on their characteristic crystal form within you. If you do not develop the powers of your limb system, you would turn into a cube of salt if you ate salt. Your limb system, your skeleton, and your muscular system have a constant tendency to counteract the mineral formation of the earth, that is, to dissolve minerals. The forces that dissolve minerals in humans come from the limb system.

If the disease process goes beyond the merely vegetative, that is, if the body has a tendency not only to allow the vegetative to begin within itself, but also the mineral crystallization process, then a higher, very destructive form of disease is present, for example, diabetes. Then the human body is unable to truly dissolve the mineral it is supposed to continuously dissolve using the power of its limbs, which it absorbs from the world. And if people today cannot cope with precisely those forms of disease that often result from pathological mineralization in the human body, this is often because we cannot sufficiently apply the antidotes to this form of disease, which we should all take from the connections between the sense organs or the brain, the nerve cords, and the like. We would have to use the apparent substances — I call them apparent substances for certain reasons — that are in the sense organs, that are in the brain and nerves, this decaying matter, we would have to use it in some form to overcome diseases such as gout, diabetes, and the like. In this area, what is truly beneficial to humanity can only be achieved once the connection between humans and nature is fully understood from the perspective I have outlined to you today.

The human body can only be explained by first understanding its processes, by knowing that the human being must dissolve the mineral within themselves, must transform the plant kingdom within themselves, and must transcend, that is, spiritualize, the animal kingdom. And everything that teachers need to know about physical development is based on the kind of anthropological, anthroposophical consideration that I have presented to you here. Tomorrow we will continue our discussion of what can be built upon this from an educational perspective.