Third Scientific Lecture-Course:

Astronomy

GA 323

4 January 1921, Stuttgart

Lecture IV

If I had the task of presenting my subject purely according to the methods of Spiritual Science, I should naturally have to start from different premises and we should be able to reach our goal more quickly. Such a presentation, however, would not fulfill the special purpose of these lectures. For the whole point of these lectures is to throw a bridge across to the customary methods of scientific thought. Admittedly, I have chosen just the material which makes the bridge most difficult to construct, because the customary mode of thought in this realm is very far from realistic. But in contending against an unreal point of view, it will become apparent how we can emerge from the unsatisfying nature of modern theories and came to a true grasp of the facts in question. Today, then, I should like to consider the whole way in which ideas have been formed in modern times about the celestial phenomena.

We must, however, distinguish two things in the formation of these ideas. First, the ideas1Note by translators: In the first few pages of this lecture, the word Vorstellungen has been translated, either as “mental pictures” or “thought-pictures”, or by the word “ideas” as in Prof. Hoernle's original English edition of Dr. Steiner's Philosophie der Freiheit. In other translations, including the later editions of this book, the word is rendered “representations”, or again, “Mental presentations”. Dr. Steiner's use of Vorstellung corresponds, we believe, to the colloquial, work-a-day meaning of the word “idea” in current English. (Where Idea is meant in its deeper, more spiritual meaning—German Idee—it can be distinguished by the use of a capital.) are derived from observation of the celestial phenomena, and theoretical explanations are then linked on to the observations. Sometimes very far-reaching, spun-out theories have been linked on to relatively few observations. That is the one thing, namely, that a start is made from observations out of which certain ideas have been developed. The other is that, the ideas having been reached, they are further elaborated into hypotheses. In this creating of hypotheses,—a process which ends in the setting up of some definite cosmology,—much arbitrariness prevails, since in the setting-up of theories, any preconceived ideas existing in the minds of those who put forward the theory, make themselves strongly felt.

I will therefore first call your attention to something which will perhaps strike you as paradoxical, but which, when carefully examined, will none the less prove fruitful in the further course of our studies.

In the whole mode of thought of modern Science there prevails what might be called, and indeed has been called, the ‘Regula philosophandi’. It consists in saying: What has been traced to definite causes in one realm of reality, is to be traced to the same causes in other realms. In setting up such a ‘regula philosophandi’ the starting-point is as a rule apparently self-evident. It will be said—scientists of the Newtonian school will certainly say—that breathing must have the same causes in man as in the animal, or again, that the ignition of a piece of wood must have the same cause whether in Europe or in America. Up to this point the thing is obvious enough. But then a jump is made which passes unnoticed,—is taken tacitly for granted. Those who are wont to think in this way will say, for example, that if a candle and the Sun are both of them shedding light the same causes must surely underlie the light of the candle and the light of the Sun. Or again, if a stone falls to Earth and the Moon circles round the Earth, the same causes must underlie the movement of the stone and the movement of the Moon. to such an explanation they attach the further thought that if this were not so, we should have no explanations at all in Astronomy. The explanations are based on earthly things. If the same causality did not obtain in the Heavens as on Earth, we should not be able to arrive at any theory at all.

Yet when you come to think of it, this regula philosophandi is none other than a preconceived idea. Who in the world will guarantee that the causes of the shining of a candle and of the shining of the Sun are one and the same? Or that in the falling of a stone, or the falling of the famous apple from the tree by which Newton arrived at his theory, there is the same underlying cause as in the movements of the heavenly bodies? This would first have to be established. As it is, it is a mere preconceived idea. Prejudices of this kind enter in, when, having first derived theoretical explanations and thought—pictures inductively from the observed phenomena, people rush headlong into deductive reasoning and construct world-systems by deductive methods.

What I am now describing thus abstractly has, however, become a historical fact. There is a continuous line of development from what the great thinkers at the opening of the modern age—Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo—concluded from comparatively few observations. Of Kepler—notably of his third Law, quoted yesterday—it must be said that his analysis of the facts which were available to him is a work of genius.

It was a very great intensity of spiritual force which Kepler brought to bear when, from the little that lay before him, he discovered this ‘law’ as we call it, or better, this ‘conceptual synthesis’ of the phenomena of the universe. Then however, by way of Newton a development set in which was not derived from observation but from theoretical constructions, including concepts of force and mass and the like, which we must simply omit if we only want to hold to what is given. The development in this direction reaches a culminating point—conceived, admittedly, with genius and originality—in Laplace, where it leads to a genetic explanation of the entire cosmic system (as you will convince yourselves if you read his famous book Exposition du Systeme du Monde ), or again in Kant, in his Natural History and Theory of the Heavens. In all that has followed in this trend we see the effort constantly made to come to conclusions based on the thought pictures that have thus been conceived of the connections of the celestial movements, and resulting in such explanations of the origin of the universe as the nebular theory and so on.

It must be noted that in the historical development of these theories we have something which is put together from inductions made, once again, with no little genius in this domain—and from subsequent deductions in which the special predilections of their authors were included. Inasmuch as a thinker was imbued with materialism it was quite natural for him to mingle materialistic ideas with his deductive concepts. Then it was no longer the facts which spoke, for one proceeded on the basis of the theories which had emerged from the deductions. Thus, for example, inductively men first arrived at the mental pictures which they summed up in the notion of a central body, the Sun, with the planets revolving around it in ellipses according to a certain law, namely: the radius-vectors describe equal areas in equal periods of time. By observing the different planets of a solar system, it was moreover possible to summarize their mutual relations in Kepler's third law: ‘For different planets the squares of the periods of revolution are proportional to the cubes of the radius-vectors’. Here was a certain picture. The question, however, was not decided, whether this picture completely fitted the reality. It was in truth an abstraction from reality; to what extent it related to the full reality, was not established. From this picture—not from reality, but from this picture—people deduced what then became a whole genetic system of Astronomy. All this must be borne in mind. Modern man is taught from childhood as if the theories which have been reached in the past few centuries by deductive reasoning were the real facts. We will therefore, while taking our start from what is truly scientific, disregard as far as is possible all that is merely theoretical and link on to those ideas which only depart from reality to the extent that we shall still be able to discover in them a connection with what is real. It will be my task, in all that I give to-day, to follow the direction of modern scientific thought only up to those ideas and concepts which still permit one to find the way back again into reality. I shall not depart so far from reality that the concepts become crude enough to allow of the deduction of nebular hypotheses.

Proceeding in this way,—pursuing the modern method of forming concepts in this particular field,—we must first form a concept which presented itself inductively to Kepler and was then developed further I repeat expressly, I will only go so far in these concepts that even if the picture in the form in which it was conceived should be mistaken, it has departed only so far from reality that it will be possible to eliminate the mistake and return to what is true. We need to develop a certain flair for reality in the concepts we entertain. We cannot proceed in any other way if we wish to throw a bridge across from the reality to the spun-out theories of modern scholarship and science.

Here then, to begin with, is a concept which we must examine. The planets have eccentric orbits,—they describe ellipses. This is something with which we can begin. The planets have eccentric orbits and describe ellipses, in one focus of which is the Sun. They describe the ellipses in accordance with the law that the radius—vectors describe equal areas in equal periods of time.

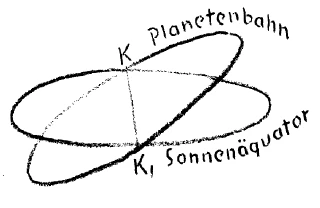

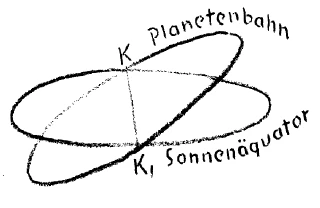

A second essential for us to hold to is the idea that each planet has its own orbital plane. Although the planets carry out their evolutions in the neighborhood of each other, so to speak, yet for each planet there is the distinct plane of its orbit, more or less inclined to the plane of the Sun's equator: If this depicts the plane of the Sun's equator (Fig.1), an orbital plane of a planet would be thus; it would not coincide at all with the plane of the Sun's equator.2Note by Editor: This plane is inclined at an angle of about seven degrees to the plane of the ecliptic.

These are two very significant mental pictures, to be formed from the facts of observation. And yet, in the very forming of them we must take note of something in the real world-picture, which as it were, rebels against them. For instance, if we are trying to understand our solar system in its totality, and only base it upon the picture of the planets moving in eccentric orbits, the orbital planes being inclined at varying degrees to the plane of the solar equator, we shall be in difficulties if we also take into account the movements of the comets. The moment we turn our attention to the cometary movements, the picture no longer suffices. The outcome will be better understood from the historical facts than from any theoretical explanations.

Upon these two thought-pictures,—that the orbital planes of the planets lie in the proximity of the plane of the Sun's equator, and that the orbits are eccentric ellipses,—Kant, Laplace and their successors built up the nebular hypothesis. Follow what emerges from this. At a pinch, and indeed only at a pinch, it is a way of imagining the origin of the solar system. But the astronomical system thus constructed contains no satisfactory explanation of the part played by the cometary bodies. They always fall out of the theory. This discordance of the comets with the theories which were formed, as described, in the course of scientific history, proves that the cometary life somehow rebels against a concept formed, not from the whole but only from a part of the whole. We must be clear, too, that the paths of the comets frequently coincide with those of other bodies which also play into our system and present a riddle precisely through their association with the comets. These are the meteoric swarms, whose paths very frequently—perhaps even always—coincide with the cometary paths. Here, my dear friends, taking into account the totality of our system, we are led to say: A sea of ideas has gradually been formed from the study of our planetary system as a whole,—ideas with which we cannot do justice to the seemingly irregular and almost arbitrary paths of the comets and meteoric swarms. They simply refuse to be included in the more abstract pictures that have been reached. I should have to give you long historical descriptions to show in detail how many difficulties have arisen in connection with the concrete facts, when the investigators—or rather, thinkers—approached the comets and meteoric swarms with their astronomical theories.

I wish only to point out the directions in which a sound understanding can be sought. We shall come to such an understanding if we pay attention to yet another aspect.

Starting in this way from concepts which still have a remnant of reality in them, we will now try to go back a little towards what is real. It is indeed always necessary to do this in relation to the outer world, in order that our concepts may not stray too far from reality,—for this is a strong propensity of man. We must go back again and again to the reality.

There is already no little danger in forming such a concept as that the planets move in ellipses, and then beginning at once to build a theory upon this concept. It is far better, after forming such a concept, to turn back to reality in order to see if the concept does not need correcting, or at least modifying. This is important. It is very clearly seen in astronomical thinking. Also in biological and especially in medical thought, the same failing has led people very far astray. They do not take into account, how necessary it is directly they have formed a concept, to go back to reality in order to make sure that there is no reason to modify it.

The planets, then, move in ellipses. But these ellipses vary; they are sometimes more circular, sometimes more elliptical. We find this if we return to reality with the ellipse idea. In the course of time the ellipse becomes more bulging, more like a circle, and then again more like an ellipse. So I by no means include the whole reality if I merely say, ‘the planets move in ellipses’. I must modify the concept and say: The planets move in paths which continually struggle against becoming a circle or remaining one and the same ellipse. If I were now to draw the elliptic line, to be true to the reality I should have to make it of india-rubber, or form it flexibly in some way, continually altering it within itself. For if I had formed the ellipse which is there in one revolution of the planet, it would not do for the next revolution, and still less for the following one. It is not true that when I pass from reality to the rigid concept I still remain within the real. That is the one thing.

The other is: We have said that the planes of the planetary orbits are inclined to the plane of the Sun's equator. Where the planets cross the point of intersection of their orbits (with the Ecliptic) in an upward or downward direction, they are said to form Nodes. The lines, joining the two Nodes (K-K 1 in Fig. 1), are variable. So too are the inclinations of the planes to one-another, so that even these inclinations, if we try to express them in a single concept, bring us to a rigid concept which we must immediately modify in face of the reality. For if an orbit is inclined at one time in one way, and at another time in another way, the concept we deduce in the first instance must afterwards be modified. To be sure, once such a point has been reached, we can take an easy line and say that there are ‘disturbances’ and that the reality is only grasped ‘approximately’ with our concepts. We then go on swimming comfortably in further theories. But in the end we swim so far that the fanciful and theoretic pictures we are constructing no longer correspond to the reality, though they are meant to do so.

It is easy to agree that this mutability of the eccentric orbits, and of the mutual inclination of the planes of the orbits, must somehow or other be connected with the life of the whole planetary system, or shall we say, with its continuing activity. It must be connected in some way with the living activity of the whole planetary system. That is quite evident. Starting from this, one might again try to form the concept, saying: Well now, I will bring such mobility into my thoughts that I picture the ellipses continually bulging out and contracting, the planes of the orbits ascending, descending and rotating, and then from this starting-point I will build up a world-system according to reality. Good. But if you think the idea through to the end, then precisely as the outcome of such logical thought, the result is a planetary system which cannot possibly go on existing. Through the summation of the disturbances which arise especially through the variability of the Nodes, the planetary system would move towards its own ultimate death and rigidity. Here there comes in what philosophers have pointed out again and again. While such a system can be thought out, in reality it would have had ample time to reach the ultimate finale. There is no reason why it should not. The infinite possibility would have been fulfilled; rigidity would long ago have set in.

We enter here into a realm where thought apparently comes to a standstill. Precisely by following my thinking through to the very last, I arrive at a world-system which is still and rigid. But that is not reality.

Now, however, we come to something else, to which we must pay special attention. In pursuing these things further—you can find the theory of it in the work of Laplace; I will only relate the phenomena—one finds that the reason why the system has not actually reached rigidity under the influence of the disturbances—the variability of the Nodes, etc.,—is that the ratios of the periods of revolution of the planets are not commensurable. They are incommensurable quantities, numbers with decimals to an infinite number of places. Thus we must say: If we compare the periods of revolution of the planets in the sense of Kepler's Third Law, the ratios of these periods cannot be given in integers, nor in finite fractions, but only in incommensurable numbers. Modern Astronomy is clear on this. It is to the incommensurability of the ratios between the periods of revolution of the several planets (in Kepler's third Law) that the planetary system owes its continued mobility. Otherwise, it must long ago have come to a standstill.

Observe now, what has happened. In the last resort, we are obliged to base our thoughts about the planetary system upon numbers which in the end elude our grasp. This is of no little importance.

We are therefore led, by the very requirements of scientific development, to think of the planetary system mathematically in such a way that the mathematical results are no longer commensurable. We are at the place, where in the mathematical process itself we arrive at incommensurable numbers. We have to let the number stand,—we come to a stop. We can write it in decimals no doubt, but only up to a certain place. Somewhere or other we must leave off when we come to the incommensurable. The mathematicians among you will be clear about this. You will see that in dealing with incommensurable number I reach the point where I must say: I calculate up to here and then I can go no further. I can only say (forgive my using a somewhat amusing comparison for a serious subject) that this coming to an inevitable halt in mathematics reminds me of a scene in which I was once a participator in Berlin. A fashion in Variety-entertainment came about through certain persons, one of whom was Peter Hill. He had founded a kind of Cabaret and wanted to read his own poems there. He was a very lovable person, in heart and soul a Theosophist, he had rather gone to seed in Bohemian circles. I went to a performance in which he read his own poems. The poem had got so far that single lines were finished, and so he read it aloud:

The Sun came up. ... etc. (The first line.)

The Moon rose. ... etc. (That was the second line.)

At each line he said ‘etc.’ That was a reading I once attended. As a matter of fact it was most stimulating. Everyone could finish the line as he chose! Admittedly with incommensurable numbers [you] cannot do this, yet here too you can only indicate the further process. You can say that the process continues in a certain direction, but nothing is given by which you might form an idea as to what numbers may yet be coming. It is important that precisely in the astronomical field we are led into incommensurabilities. We are forced by Astronomy to the very limits of mathematising; here the reality escapes us. Reality escapes us, we can say nothing else; reality eludes our grasp.

What does this mean? It means that we apply the most secure of our sciences, Mathematics, to the celestial phenomena, and in the last resort the celestial phenomena do not submit; the moment comes where they elude us. Precisely where we are about to reach their very life, they slip away into the incommensurable realm. Here then, our grasp of reality comes to an end at a certain point and passes over into chaos.

We cannot say without more ado, what this reality, which we are trying to follow mathematically, actually does when it slides away into the incommensurable. Undoubtedly this is related to its power of continued life. To enter the full astronomical reality we must take leave of what we are able to master mathematically. The calculation plainly shows this; the very history of science shows it.

Such are the points which we must work towards, if we would proceed in a realistic spirit. Now I would like to set before you the other pole of the matter. If you follow it physiologically you can begin from any point you like in embryonic development, whether it be from the development of the human embryo in the third or second month,—or the embryo of some other creature. You can follow the development back as far as ever you can with the means of modern science. (it is in fact only possible to a limited extent, as those of you who have studied it will know.) You can trace it back to a certain point, from which you cannot get much further, namely to the detachment of the ovum—the fertilized ovum. Picture to yourselves how far you can go back. If you wished to go still further back you would be entering the indeterminate realm of the whole maternal organism. This means that in going back you come into a kind of chaos. You cannot avoid this, and the fact that it cannot be avoided is shown by the course of scientific development. Think of such scientific hypotheses as the theory of “Panspermia” for instance, where they speculated as to whether the single germ-cell was prepared out of the forces of the whole organism, which was more the point of view of Darwin, or whether it developed in a more segregated way in the purely sexual organs. You will see when you study the course of scientific development in this field that no little fantasy was brought to bear on the attempt to explain the underlying genesis, when tracing backward the arising of the germ cell from the maternal organism. You come into a completely indeterminate realm. There is little but speculation in the external science of today as to the connection between the germ-cell and the maternal organism.

Then at a certain point in its development this germ appears in a very definite way, in a form which can be grasped at least approximately by mathematical or at any rate geometrical means. Diagrams can be made from a certain point onward. Many such diagrams exist in Embryology. The development of the germ-cell and other cells can be delineated more or less exactly. So one begins to picture the development in a geometrical way, representing it in forms similar to purely geometrical figures. Here we are following up a reality which in a way is the reverse of what we had in Astronomy. There we pursued a reality with our cognitional process and came to incommensurable numbers; the whole thing slips into chaos through the process of knowledge itself. In Embryology we slip out of chaos. From a certain moment onward we can grasp what emerges from chaos through forms that are like purely geometrical forms. Thus in effect, in employing Mathematics in Astronomy we come at one point into chaos. And by pure observation in Embryology we have at a certain point nothing before us but chaos; it all seems chaotic at first, observation is impossible. Then we come out of chaos into the realm of Geometry. It is therefore an ideal of certain biologists—a very justifiable ideal—to grasp in a geometrical form what presents itself in Embryology; not merely to make illustrations of the growing embryo naturalistically, but to construct the forms according to some inherent law, similar to the laws underlying geometrical figures. It is a justifiable ideal.

Now therefore we can say: When in Embryology we try to follow up the real process by observation, we emerge out of a sphere which lies about as near to our understanding as that which is beyond the incommensurable numbers. In Astronomy on the one hand, we proceed with our understanding up to the point where we can no longer follow mathematically. In Embryology on the other hand our understanding begins at a certain point, where we are first able to set to work with something resembling Geometry.

Think the thought through to its conclusion. You can do so, since it is a purely ‘methodological’ thought, that is to say the reality of it is in our own inner life.

If in arithmetic we reach the incommensurable numbers,—that is, we reach a point where the reality is no longer represented by a number that can be shown in its complete form—then we should also begin to ask whether the same thing may not happen with geometrical form as with arithmetical analysis. (We shall speak more of this in the next lecture.) The analytical process leads to incommensurable number. Now let us ask: How do geometrical forms image the celestial movements? Do not these images perhaps lead us to a certain point. Similar to that to which arithmetical analysis is leading when we reach incommensurable number? Do we not in our study of the heavenly bodies—namely the planets—come to a boundary, at which we must admit we can no longer use geometrical forms as a means of illustration; the facts can no longer be grasped with geometrical forms? Just as we must leave the region of commensurable numbers, it may well be that we must leave the region where reality can still be clothed in geometrical (or again arithmetical, algebraic, analytical) forms, such as in drawings of spirals and other figures derived from Geometry. So, in Geometry too, we should be coming into the incommensurable realm. In this sense it is indeed remarkable that in Embryology, though arithmetical analysis is not yet of much use, Geometry makes its presence felt pretty strongly the moment we begin to take hold of the embryological phenomena as they emerge from chaos. Here we are dealing, not indeed with incommensurable number but with something that tends to pass from incommensurable into commensurable form.

We have thus sought to grasp reality at two poles: On the one hand where the process of cognition leads through analysis into the incommensurable, and on the other where observation leads out of chaos to a grasping of reality in ever more commensurable forms. It is essential that we bring these things before our minds with full clarity, if we would add reality to what is presented by the external science of today. In no other way can we reach this end.

I should now like to add a methodical reflection, from which we can tomorrow make our way into more realistic problems.

In all that we have spoken of hitherto, we have been taking it for granted that the cosmic phenomena have been approached from the standpoint of Mathematics. It appeared that at one point the mathematician comes up to a limit—a limit he encounters too in purely formal Mathematics. Now there is something underlying our whole way of thinking in this realm, which perhaps passes unnoticed because it always wears the mask of the ‘obvious’ and we therefore never really face the problem. I mean the whole question of the application of mathematics to reality. How do we proceed? We develop Mathematics as a formal science and it appears to us absolutely cogent in its conclusions; then we apply it to reality, without giving a thought to the fact that we are really doing so on the basis of certain hypotheses. Today however, sufficient ground has already been created for us to see that Mathematics is only applicable to outer reality on the basis of certain premises. This becomes clear when we try to continue Mathematics beyond certain limits. First, certain laws are developed,—laws which are not obtained from external facts, as for example are Kepler's Laws, but from the mathematical process itself. They are in fact inductive laws, developed within Mathematics. They are then employed deductively; highly elaborate mathematical theories are built upon them.

Such laws are those encountered by anyone who studies Mathematics. In lectures given recently in Dornach by our friend Dr. Blumel, significant indications were given of this line of mathematical research. One of the laws in question is termed the Commutative Law. It can be expressed in saying: It is obvious that \(a+b\) equals \(b+a\), or \(a \cdot b\) equals \(b \cdot a\). This is a self-evident fact so long as one remains within the realm of real numbers: But it is merely an inductive law derived from the use of the implicit postulates in the arithmetic of real numbers.

The second law is the Associative Law. It is expressed as \((a + b) + c = a + (b + c)\). Again this is a law, simply derived by working with the implicit postulates in the arithmetic of real numbers.

The third is the so-called Distributive Law, expressible in the form: \(a (b + c) = ab + ac\). Once more, it is a law obtained inductively by working with the implicit postulates in the arithmetic of real numbers.

The fourth law may be expressed as follows: ‘A product can only equal zero if at least one of the factors equals zero.’ This law again is only an inductive one, derived by working with the implicit postulates in the arithmetic of real numbers.

We have, then, these four laws; the commutative law, the associative law, the distributive law, and this law about the product being equal to zero. These laws underlie the formal Mathematics of today, and are used as a basis for further work. The results are most interesting, there is no question of that. But the point is this: These laws hold good so long as we remain in the sphere of real numbers and their postulates. But no thought is ever given to the question, to what extent the real facts are in accord with them. Within our ordinary formal modes of experience it is true, no doubt that \(a + b = b + a\), but does it also hold good in outer reality? There is no ascertainable reason why it should. We might be very astonished one day to find that it did not work if we applied to some real process the idea that \(a + b\) equals \(b + a\). But there is another side to it. We have within us a very strong inclination to cling to these laws; with them therefore. We approach reality and everything that does not fit in escapes our observation. That is the other side.

In other words: We first set up postulates which we then apply to reality and take them as axioms of the reality itself. We ought only to say: I will consider a certain sphere of reality and see how far I get with the statement \(a + b = b + a\). More than that, I have no right to say. For by approaching reality with this statement we meet what answers to it, and elbow aside anything that does not. We have this habit too in other fields. We say for example, in elementary physics: Bodies are subject to the law of inertia. We define ‘inertia’ as consisting in the fact that bodies do not leave their position or alter their state of motion without a definite impelling force. But that is not an axiom; it is a postulate. I ought only so say: I will call a body which does not alter its own state of motion ‘inert’, and now I will seek in the real world for whatever answers to this postulate.

In that I form certain concepts, I am therefore only forming guiding lines with which to penetrate reality, and I must keep the way open in my mind for penetrating other facts with other concepts. Therefore I only regard the four basic laws of number in the right way if I see them as something which gives me a certain direction, something which helps me regulate my approach to reality. I shall [be] wrong if I take Mathematics as constituting reality, for then in certain fields, reality will simply contradict me. Such a contradiction is the one I spoke of, where incommensurability enters in, in the study of celestial phenomena.

Vierter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Würde ich die Aufgabe haben, das Darzustellende nach den Methoden der Geisteswissenschaft selber darzustellen, so müßte ich natürlich von anderen Voraussetzungen ausgehen und würde gewissermafßen zu dem Ziele, dem wir zusteuern wollen, auch schneller kommen können. Aber eine solche Auseinandersetzung würde Ihnen nicht die Absicht gerade dieser Vorträge erfüllen können. Denn in diesen Vorträgen soll es sich darum handeln, eine Brücke zu schlagen zu demjenigen, was die gewohnte wissenschaftliche Denkweise ist, wenn ich auch gerade für diese Darstellungen Kapitel ausgesucht habe, bei denen diese Brücke deshalb schwer zu schlagen ist, weil die gewohnte Denkweise sehr weit von einem wirklichkeitsgemäßen Standpunkte abliegt. Aber wenn auch der unwirklichkeitsgemäße Standpunkt bekämpft werden muß, so wird gerade in diesem Bekämpfen ersichtlich sein, wie man herauskommt aus dem Unbefriedigenden der modernen Theorien und hineinkommt in eine wirklichkeitsgemäße Erfassung der in Frage kommenden Tatsachen. Ich möchte heute deshalb anknüpfen an die Art, wie sich die Vorstellungen über die Himmelserscheinungen im Laufe der neueren Zeit gebildet haben.

[ 2 ] Wir müssen ja beim Bilden dieser Vorstellungen zweierlei unterscheiden: Erstens, daß diese Vorstellungen hergeleitet sind von Beobachtungen, von Beobachtungen der Himmelserscheinungen, und daß dann theoretische Erwägungen geknüpft worden sind an diese Beobachtungen. Manchmal wurden ja sehr weit ausgesponnene Theorien geknüpft an verhältnismäßig sehr wenige Beobachtungen. Das ist das eine, daß von Beobachtungen ausgegangen worden ist und man dadurch zu bestimmten Vorstellungen gekommen ist. Das andere ist aber, daß man dann, indem man zu bestimmten Vorstellungen gekommen ist, diese Vorstellungen weiter zu Hypothesen ausgebildet hat. Und in diesem Ausbilden zu Hypothesen, die dann landen bei der Aufstellung eines ganz bestimmten Weltbildes, waltet zumeist eine außerordentliche Willkür deshalb, weil in dem Ausbauen der Theorien sich durchaus dasjenige geltend macht, was als Vorurteil bei der einen oder anderen Persönlichkeit vorhanden ist, die solche Theorien ausbaut.

[ 3 ] Ich will Sie da zunächst auf etwas aufmerksam machen, was Ihnen vielleicht anfänglich paradox erscheinen könnte, was aber immerhin, wenn es präzise ins Auge gefaßt wird, im weiteren Verlauf des Forschens sich durchaus fruchtbar erweisen muß. Sehen Sie, in dem ganzen neueren Denken der Naturwissenschaft herrscht ja dasjenige, was man nennen könnte, und übrigens auch genannt hat, die regula philosophandi. Sie besteht darin, daß man sagt: Was man in irgendeinem bestimmten Gebiete der Realität auf bestimmte Ursachen zurückgeführt hat, das muß auch in anderen Gebieten des Daseins, der Realität, auf dieselbe Ursache zurückgeführt werden. Man geht, indem man eine solche regula philosophandi aufstellt, gewöhnlich von etwas sehr Einleuchtendem, etwas Selbstverständlichem aus. So, wenn man etwa sagt, wie das die Newtonianer immer tun: Der Artmungsptozeß muß dieselben Ursachen beim Tier und beim Menschen haben. Das Entzünden eines Spanes muß dieselbe Ursache haben, ob es in Europa oder in Amerika erfolgt. - Bis hierher bleiben die Dinge durchaus in der Sphäre der Selbstverständlichkeit. Dann wird aber ein gewisser Sprung gemacht, den man aber nicht merkt, sondern als etwas Selbstverständliches annimmt. Das charakterisiert sich uns, wenn wir etwas sehen, was eben gerade bei solchen Persönlichkeiten, die mit dieser Denkweise behaftet sind, angeschlossen wird. Da wird gesagt: Wenn eine Kerze leuchtend wird und wenn die Sonne leuchtet, so muß dem Leuchten der Kerze und dem Leuchten der Sonne dieselbe Ursache zugrunde liegen. Wenn ein Stein zur Erde fällt und wenn der Mond um die Erde kreist, so muß der Bewegung des Steines und der Bewegung des Mondes dieselbe Ursache zugrunde liegen. - Man schließt an eine solche Auseinandersetzung dann auch noch etwas anderes an: Man käme zu keinen Erklärungen in der Astronomie, wenn das nicht der Fall wäre, denn man kann Erklärungen eben nur von dem Irdischen gewinnen. Wenn also nicht im weiten Himmelsraum dieselbe Kausalität herrschen würde wie auf der Erde, könnte man nicht zu einer Theorie kommen.

[ 4 ] Aber bitte berücksichtigen Sie, daß das, was hier als regula philosophandi ausgesprochen wird, doch nichts weiter ist als ein Vorurteil. Denn wer bürgt denn irgendwie in der Welt dafür, daß nun wirklich die Ursachen des Leuchtens einer Kerze und die Ursachen des Leuchtens der Sonne dieselben sind? Oder daß beim Fallen des Steines oder beim Fallen des berühmten Apfels vom Baume, durch den Newton zu seiner Theorie gekommen ist, dieselben Ursachen zugrunde liegen wie den Bewegungen der Weltenkörper? Das war ja etwas, worauf man erst kommen mußte. Das ist durchaus nur ein Vorurteil. Und solche Vorurteile fließen durchaus überall da ein, wo man zuerst induktiv gewisse theoretische Erwägungen, gewisse Bildvorstellungen anknüpft an Beobachtungen und wo man dann einfach blindwütig ins Deduzieren hineinkommt und Weltensysteme durch dieses Deduzieren konstruiert.

[ 5 ] Dasjenige, was ich Ihnen hier so abstrakt charakterisiere, ist aber historische Tatsache geworden. Denn sehen Sie, es ist eine kontinuierliche Entwickelung zu verfolgen in demjenigen, was aus wenigen Beobachtungen gezogen haben die großen Geister am Ausgang der neueren Zeit, Kopernikus, Kepler, Galilei. Insbesondere bei Kepler wird man sagen müssen, daß in dem dritten, gestern angeführten Gesetz etwas ganz Außerordentliches liegt in bezug auf die Analyse der Tatsachen, die ihm allein vorliegen konnten. Es ist eine ungeheure geistige Spannkraft, die da in Tätigkeit versetzt wurde bei Kepler, wenn er aus dem Wenigen, was ihm vorlag, dieses, sagen wir, «Gesetz» — besser wäre zu sagen: diese begriffliche Zusammenfassung - über die Welterscheinungen gefunden hat. Aber dann setzt eine Entwickelung ein, die über Newton geht und die nicht eigentlich ausgeht von wirklichen Beobachtungen, sondern die im Grunde genommen schon von dem Theoretischen ausgeht und die allerlei Kraft- und Massenbegriffe konstruiert, die wir einfach weglassen müssen, wenn wir bei der Realität bleiben wollen. Und dann setzt sich das fort. Und es erscheint, ich möchte sagen, auf einem gewissen Höhepunkt durchaus mit Scharfsinn, mit Genialität erfaßt da, wo es zu einer genetischen Erklärung führt für das Weltsystem, wie bei Zap/ace, wovon Sie sich überzeugen können, wenn Sie durchlesen sein berühmtes Buch «Exposition du systeme du monde» oder bei Kart in seiner «Naturgeschichte und Theorie des Himmels». Und in alledem, was dann in der Entwickelung weiter gefolgt ist, sehen wir, wie versucht wird aus dem heraus, was man sich als Vorstellungen machte über den Zusammenhang der Himmelsbewegungen, rückschließend auch die Entstehung dieses Weltsystems zu erklären, aus der Nebularhypothese heraus und so weiter.

[ 6 ] Das muß durchaus berücksichtigt werden, daß hier im historischen Gang der Entwickelung etwas liegt, was sich zusammensetzt aus Induktionen, die allerdings gerade in diesem Gebiet in genialer Weise gemacht worden sind, und aus nachfolgenden Deduktionen, in denen aber durchaus mitgenommen ist dasjenige, was die betreffenden Persönlichkeiten gerade als in ihrer Vorliebe liegend angesehen haben. So daß man sagen kann: Insofern irgend jemand materialistisch dachte, war es für ihn ganz selbstverständlich, in den deduktiven Begriff hinein materialistische Vorstellungen zu mischen. Denn da sprachen nicht mehr die Tatsachen. Da konnte man jetzt ausgehen von demjenigen, was sich erst durch die Deduktion als eine Theorie ergeben hatte. Und so kann man sagen: Es bildete sich zum Beispiel durchaus induktiv die Vorstellung aus, die man jetzt zusammenfassen mußte in den Begriff: Zentralkörper Sonne, die Planeten in Ellipsen umgehend nach einem bestimmten Gesetz, die Radienvektoren beschreiben in gleichen Zeiten gleiche Sektoren. - Und indem man den Blick auf die einzelnen Planeten des Sonnensystems lenkte, konnte man wiederum zusammenfassen das gegenseitige Verhältnis durch das dritte Keplersche Gesetz: Für verschiedene Planeten verhalten sich die Quadrate der Umlaufzeiten wie die Kuben der mittleren Entfernungen von der Sonne. - Das ergab ein gewisses Bild. Die Frage war aber nicht entschieden, ob dieses Bild nun eine völlige Deckung in sich enthielt mit der Realität, sondern es war eine Abstraktion, die herausgenommen war aus der Realität. Wie sich dieses Bild zur Totalität des Realen verhält, das war damit ja nicht gegeben. Aber aus diesem Bilde heraus, durchaus nicht aus der Realität, sondern aus diesem Bilde heraus deduzierte man alles das, was dann im Grunde eine genetische Astronomie geworden ist. Das ist dasjenige, was durchaus ins Auge gefaßt werden muß. Und der Mensch der Gegenwart wird von Kindheit auf so unterrichtet, als ob das, was seit einigen Jahrhunderten deduziert worden ist, irgend welchen Realitäten entsprechen würde.

[ 7 ] Wir wollen daher, durchaus anknüpfend an das wirklich Wissenschaftliche, so gut es irgend geht, absehen von alledem, was in diesem Entwickelungsgang drinnen ist an rein Hypothetisch-Theoretischem, und wollen an die Vorstellungen anknüpfen, die sich nur soweit von der Realität wegbegeben, daß man in ihnen noch die Beziehung zur Realität später wird entdecken können. Das wird also in der ganzen heutigen Darstellung meine Aufgabe sein, daß ich mich nur so lange bewege in der Richtung, in der sich das neuere Denken auf diesen Gebieten bewegt hat, daß ich, um eben gerade im Wissenschaftlichen drinnen stehenzubleiben, mitgehen werde bis zu der Gestalt der Begriffe, die dann, wenn man sie als Begriffe nimmt, noch gestatten, den Weg in die Realität wiederum zurückzufinden. Ich will mich also nicht so weit von der Realität entfernen, daß die Begriffe so grob werden, daß man Nebularhypothesen aus ihnen deduzieren kann.

[ 8 ] Wollen wir in dieser Weise heute in unserer Betrachtung verfahren, dann können wir sagen: Wenn wir diese neuere Begriffsbildung auf dem uns interessierenden Felde verfolgen, so haben wir zuerst einen Begriff zu bilden, der sich nun wirklich induktiv gerade dem Kepler ergeben hat, der dann auch weiter ausgebildet worden ist und den man zunächst ins Auge zu fassen hat. Ich bemerke noch einmal ausdrücklich, ich will in diesen Begriffen nur so weit gehen, daß selbst wenn dieser Begriff, so wie er konzipiett ist, falsch sein sollte, er sich nur so wenig von der Realität entfernt hat, daß man in ihm das Falsche eliminieren und auf das Richtige wird zurückführen können. Es handelt sich darum, daß wir einen gewissen Takt entwickeln für dasjenige, was noch wittert die Realität in den Begriffen, die man ausbildet. Anders kann man nämlich nicht vorgehen, wenn man eine Brücke schlagen will zwischen dem, was wirklichkeitsgemäß ist, und der in die neueren Theorien so eingesponnenen W issenschaftlichkeit.

[ 9 ] Da ist zunächst ein Begriff, auf den wir eingehen müssen: Die Planeten haben exzentrische Bahnen, beschreiben Ellipsen. Das ist etwas, was wir zunächst vertreten können: Die Planeten haben exzentrische Bahnen und beschreiben Ellipsen; in einem Brennpunkt steht die Sonne, und zwar beschreiben sie diese Ellipsen eben nach dem Gesetz, daß die Radienvektoren in gleichen Zeiten gleiche Sektoren beschreiben.

[ 10 ] Ein zweites Wichtiges ist es, daß wir festhalten an der Vorstellung, daß für jeden Planeten eine eigene Bahnebene vorhanden ist. Wenn also auch im allgemeinen die Planeten, ich möchte sagen, in der Nachbarschaft ihre Umdrehungen vollführen, so ist doch für jeden Planeten eine bestimmte eigene Bahnebene vorhanden, welche geneigt ist gegen die Ebene des Sonnenäquators. Also einfach, wenn das die Ebene des Sonnenäquators charakterisieren würde (Figur), so würde eine Bahnebene eines Planeten so sein, und nicht in irgendeiner Weise zusammenfallen etwa mit der Ebene des Sonnenäquators.

[ 11 ] Das sind zwei sehr wichtige, bedeutsame Vorstellungen, die man sich aus den Beobachtungen heraus bilden muß. Und sogleich, indem man sich diese Vorstellungen bildet, muß man Rücksicht nehmen auf etwas, was gegen diese Vorstellungen, so möchte ich sagen, im wirklichen Weltenbilde sich auflehnt. Wenn man nämlich versucht, einfach unser Sonnensystem in seiner Totalität zusammenzudenken und man würde dabei nur diese zwei Vorstellungen zugrunde legen: Die Planeten bewegen sich in exzentrischen Bahnen und die Bahnebenen sind in verschiedenen Graden gegen die Ebene des Sonnenäquators geneigt -, so würde man, indem man dieses als Gesetz ausdehnen wollte, nicht mehr in irgendeiner Weise zurechtkommen in dem Augenblick, wo man die Kometenbewegungen ins Auge fassen wollte. Sobald man diese ins Auge faßt, reicht man nicht mehr aus, man kommt nicht zurecht. Und die Folgen mögen Sie lieber durch historische Tatsachen einsehen als durch theoretische Erwägungen.

[ 12 ] Aus den Vorstellungen heraus, daß annähernd in der Ebene des Sonnenäquators die Bahnebenen der Planeten liegen, daß die Bahnen exzentrische Ellipsen sind, aus dieser Vorstellung heraus haben ja Kant, Laplace und ihre Nachfolger eben die Nebularhypothese gebildet. Nun verfolgen Sie einmal dasjenige, was da zutage getreten ist. Es ist zur Not - auch nur zur Not, übrigens - eine Art Entstehungsgeschichte des Sonnensystems darstellbar. Aber dasjenige, was da als Weltensystem herauskonstruiert worden ist, das enthält eigentlich niemals eine irgendwie befriedigende Erklärung über den Anteil, den die Kometenkörper dabei haben. Die fallen immer aus der Theorie heraus. Dieses Herausfallen aus den Theorien, wie man sie auf dem historischen Wege gewinnt, ist nichts anderes als ein Beweis der Auflehnung des kometarischen Lebens gegen das, was nicht aus der Totalität, sondern nur aus einem Teil der Totalität heraus als Begriff konstruiert worden ist. Dann müssen wir ja uns klar sein darüber, daß die Kometen in ihren Bahnen ja vielfach wiederum zusammenfallen mit andern Körpern, die auch in unser System hereinspielen und die eben gerade durch ihre Eigenschaft als Begleiter der Kometen ein Rätsel abgeben. Das sind die Meteoritenschwärme, die sehr häufig, wahrscheinlich immer, in ihren Bahnen zusammenfallen mit den Kometenbahnen. Wir sehen also da etwas hereinspielen in die Totalität unseres Systems, was uns dazu führt, daß wir uns sagen: Es hat sich allmählich aus der Betrachtung der Totalität unseres Systems eine Summe von Vorstellungen gebildet, mit denen man nicht bewältigen kann dasjenige, was uns nun, durch dieses System sehr unregelmäßig, fast willkürlich durchgehend, die Kometen und Meteoritenschwärme darstellen. Diese entziehen sich durchaus demjenigen, was man noch umfassen kann mit den abstrakten Vorstellungen, die man gewonnen hat. Ich müßte Ihnen eine lange historische Auseinandersetzung geben, wenn ich im einzelnen darstellen wollte, wie Schwierigkeiten immer im Konkreten vorliegen, wenn aus astronomischen Theorien heraus die Forscher, oder besset gesagt, die Denker, auf die Kometen und Meteoritenschwärme kommen. Aber ich will ja überall nur auf die Richtungen hinweisen, in denen das Gesunde gesucht werden kann. Wir kommen zu diesem Gesunden, wenn wir noch etwas anderes berücksichtigen.

[ 13 ] Sehen Sie, jetzt wollen wir einmal versuchen aus Begriffen, die nun real geblieben sind, das heißt, noch einen Rest von Realität in sich haben, wiederum ein bißchen zurückzuwandern. Das muß man ja überhaupt immer tun in bezug auf die äußere Welt, damit man sich nicht zu stark mit seinen Begriffen von der Realität entfernt. Es ist ja menschlicher Hang, das zu tun. Man muß immer wiederum zurück. Es ist schon etwas außerordentlich Gefährliches, wenn man den Begriff gebildet hat: Die Planeten bewegen sich in Ellipsen, und nun anfängt, auf diesen Begriff eine Theorie aufzubauen. Es ist viel besser, wenn man, nachdem man einen solchen Begriff gebildet hat, wiederum zurückkehrt zur Realität, um nun zu probieren, ob man diesen Begriff nicht korrigieren oder wenigstens modifizieren muß. Das ist das allerwichtigste. Im astronomischen Denken zeigt es sich so ganz klar. Im biologischen und namentlich im medizinischen Denken wird dieser Fehler so stark gemacht, daß man das Richtige überhaupt schon nicht mehr macht, daß man niemals Rücksicht nimmt darauf, wie notwendig es ist, sofort wenn man einen Begriff gebildet hat, wiederum zurückzuwandern zur Realität, um zu sehen, ob man ihn nicht modifizieren muß.

[ 14 ] Also die Planeten bewegen sich in Ellipsen, aber diese Ellipsen sind veränderlich, sie sind manchmal mehr Kreis, manchmal mehr Ellipse. Das finden wir wiederum, wenn wir nun wieder mit dem Ellipsenbegriff zur Realität zurückgehen. Im Lauf der Zeit wird eine Ellipse mehr ausgebaucht, wird mehr zu einem Kreis, dann wiederum mehr zu einer Ellipse. Also es umfaßt gar nicht die totale Wirklichkeit, wenn ich sage: Die Planeten bewegen sich in Ellipsen, sondern ich muß den Begriff modifizieren. Ich muß sagen: Die Planeten bewegen sich in Bahnen, die fortwährend dagegen kämpfen, ein Kreis zu werden oder eine Ellipse zu bleiben. Wenn ich die Linie nun ziehe (Ellipse), muß ich eigentlich, um dem Begriff gerecht zu werden, die Linie aus Kautschuk oder wenigstens beweglich bilden, ich müßte sie in sich fortwährend verändern. Denn wenn ich mir einmal die Ellipse ausgebildet habe, die für eeze Umgehung des Planeten da ist, so paßt sie schon wieder nicht auf die nächste Umgehung und noch weniger auf die folgende. Also die Geschichte ist nicht so, daß, wenn ich übergehe von der Realität in die Starrheit des Begriffes, ich noch in der Realität bleiben kann. Das ist das eine.

[ 15 ] Das andere ist: Wir haben gesagt, die Ebenen der Planetenbahnen sind geneigt gegen die Ebene des Sonnenäquators. Weil die Planeten an den Schnittpunkten nach oben oder nach unten gehen, sagt man, sie bilden Knoten. Diese sind aber auch nicht feste Punkte. Es sind die Linien, die solche Knoten verbinden (Figur 5. 80, KK,) beweglich, ebenso die Neigungen der Ebenen zueinander. Also auch diese Neigungen, wenn wir sie aussprechen in Begriffszusammenfassungen, bringen uns wiederum zum starren Begriff, den wir gleich modifizieren müssen an der Wirklichkeit. Denn wenn einmal eine Bahn in einer bestimmten Weise geneigt ist, ein andermal wieder anders geneigt ist, modifiziert sich dadurch alles dasjenige, was man zunächst als Begriff herausbringt. Gewiß, man kann jetzt anfangen, wenn man an einen solchen Punkt gekommen ist, bequem zu werden und kann sagen: Ganz gewiß, in der Wirklichkeit sind Störungen vorhanden, die Wirklichkeit wird mit unseren Begriffen nur approximativ umfaßt. - Und dann kann man bequem fortschwimmen in den Theorien. Dann schwimmt man aber so weit, daß, sobald man phantastischerweise aus den Theorien Bilder zu konstruieren versucht, die der Wirklichkeit entsprechen sollen, diese der Wirklichkeit nicht entsprechen.

[ 16 ] Das ist ja natürlich leicht zuzugeben, daß zusammenhängen muß irgendwie mit dem Leben des ganzen Planetensystems oder, sagen wir, mit der Wirksamkeit im ganzen Planetensystem dieses Veränderliche der exzentrischen Bahnen, der Neigungen der Bahnebenen. Das muß mit der ganzen Wirksamkeit irgendwie zusammenhängen, muß dazugehören. Das ist ja ganz selbstverständlich. Aber wenn man nun von da aus wiederum den Begriff sich bildet, das heißt, wenn man sich sagt: Nun ja, ich will also mein Denken so weit in Bewegung bringen, daß ich mir die Ellipse fortwährend ausbauchend und zusammenziehend denke, die Bahnebene auf- und absteigend, sich drehend denke, dann kann man von da ausgehend sich wiederum ein Planetensysten konstruieren als Wirklichkeit. Schön. Aber wenn Sie den Begriff zu Ende denken, dann bekommen Sie gerade bei konsequentem Denken ein Planetensystem, das nicht bestehen kann. Durch die Summierung der Störungen, die entstehen, besonders auch durch die Veränderlichkeit der Knoten, würde das Planetensystem fortwährend seinem Tode entgegengehen, seiner Starrheit. Dann aber tritt das ein, was Philosophen immer betont haben: Wenn man ein solches System sich ausmalt, so hat ja die Wirklichkeit nun wirklich Zeit genug gehabt, bis zum Endpunkte zu kommen. Es ist kein Grund vorhanden, warum das nicht wahr sein sollte. Wir hätten es zu tun mit erfüllter Unendlichkeit, und es müßte die Starrheit schon da sein. Wir kommen da in ein Gebiet hinein, das sollte uns klar sein, welches schon scheinbar so dasteht, daß das Denken stillestehen bleibt. Denn gerade indem ich mein Denken bis zum letzten Punkt verfolge, kriege ich ein Weltsystem heraus, das ruhig und starr ist. Es ist aber nicht das wirkliche, was ich vor mir habe.

[ 17 ] Nun kommt man aber noch auf etwas anderes, und das ist dasjenige, was wir ganz besonders berücksichtigen müssen. Man kommt darauf, indem man diese Dinge weiter verfolgt — besonders bei Laplace können Sie es verfolgen, ich will nur die Erscheinungen immer angeben -, daß deshalb dieses Weltsystem unter dem Einflusse der Störungen durch die Veränderlichkeit der Knoten und so weiter nicht zur Starrheit gekommen ist, weil die Verhältniszahlen der Umlaufzeiten der Planeten nicht kommensurabel sind, weil sie inkommensurable Größen sind, Zahlen mit unendlich vielen Dezimalen. Also kommen wir dazu, uns zu sagen: Wenn wir vergleichen die Umlaufzeiten der Planeten im Sinne des dritten Keplerschen Gesetzes, dann sind die Verhältnisse dieser Umlaufzeiten nicht angebbar durch ganze Zahlen, auch nicht durch endliche Brüche, sondern nur durch inkommensurable Zahlen, durch Zahlen, die nicht irgendwie aufgehen. Deshalb ist sich die heutige Astronomie auch klar darüber, daß diesem Umstande der Inkommensurabilität der Verhältnisse zwischen den Umlaufzeiten auch im dritten Keplerschen Gesetz das Planetensystem seine weitere Beweglichkeit verdankt, sonst müßte es längst zum Stillstand gekommen sein.

[ 18 ] Aber jetzt halten wir uns das ganz genau vor Augen. Wir kommen zuletzt dazu, festhalten zu müssen dasjenige, was wir an Begriffen über das Planetensystem ausgebildet haben, in Zahlen, die sich überhaupt nicht mehr fassen lassen. Das ist etwas außerordentlich Bedeutsames. Durch die Notwendigkeit des wissenschaftlichen Entwickelungsganges selber kommen wir also dazu, über das Planetensystem mathematisch so zu denken, daß dieses Mathematische nicht mehr kommensurabel ist. Und wo Inkommensurabilität eintritt, da stehen wir doch gerade an dem Ort, in jenem Moment, wo wir doch landen müssen in der mathematischen Entwickelung bei einer kommensurablen Zahl. Wir lassen die inkommensurable Zahl stehen, schreiben den Dezimalbruch hin, aber nur bis zu einer gewissen Stelle. Irgendwo verlassen wir das, was wir da treiben, wenn wir zum Inkommensurablen kommen. Die Mathematiker unter Ihnen mögen sich das klar machen. Sie werden schen, daß da etwas vorliegt bei der inkommensurablen Zahl, wo ich sage: Ich mathematisiere bis hierher und muß dann sagen: Hier geht es nicht weiter. - Ich kann es nicht anders sagen - verzeihen Sie, wenn ich für ein Ernstes einen etwas komischen Vergleich gebrauche -, als daß mich dieses Stehenbleibenmüssen in der Mathematik sehr erinnert an eine Szene, die ich in Berlin einmal mitgemacht habe. Es kam damals auf die Mode der Überbrettl durch einige Männer, und ein solcher Mann war Peter Hille. Er hatte auch ein Überbrettl gegründet und wollte dort seine Gedichte vorlesen. Er war sehr liebenswürdig, er war in seinem Innern durchaus Theosoph, aber er ist etwas im Bohemienleben aufgegangen. Ich kam einmal zu einer Darstellung, wo er seine eigene Dichtung vortrug im Überbrettl. Diese Dichtung war so weit gediehen, daß einzelne Zeilen fertig waren, und so las er die Dichtung vor:

«Es kam die Sonne ... und so weiter» - die erste Zeile.

[ 19 ] «Der Mond ging auf... und so weiter» — das war die zweite Zeile. Bei jeder Zeile sagte er: und so weiter, und dergleichen! Das war eine Vorlesung, die ich einmal mitgemacht habe. Es war im Grunde außerordentlich anregend. Jeder konnte die Zeile ergänzen, wie er wollte. Das ist bei den inkommensurablen Zahlen zwar nicht der Fall. Aber es ist doch so etwas, sobald man in die Inkommensurabilität hineinkommt, daß man den weiteren Prozeß nur andeuten kann. Man kann nur sagen: In der Richtung geht es nun weiter. Es ist nichts gegeben, wodurch man eine Vorstellung sich macht, was da noch alles für Zahlen kommen. Das ist wichtig, daß wir gerade auf dem Gebiet der astronomischen Betrachtung in die Inkommensurabilität hineingeführt werden, daß wir also gar nicht anders können, als mit der Astronomie an die Grenze des Mathematisierens zu kommen, daß einfach einmal uns die Wirklichkeit durchgeht. Es geht uns die Wirklichkeit durch, anders können wir nicht sagen. Es entfällt uns die Wirklichkeit.

[ 20 ] Ja, was bedeutet das aber? Wir wenden das, was unsere sicherste Wissenschaft ist, die Mathematik, an auf die Himmelserscheinungen, aber diese Himmelserscheinungen beugen sich nicht dieser sichersten Wissenschaft, sie entschlüpfen uns an einem Punkte. Gerade da, wo es ihnen ans Leben geht, da schlüpfen sie hinein in das Gebiet der Inkommensurabilität. So daß wir also da die Erscheinung haben, daß das Ergreifen der Wirklichkeit an einem bestimmten Punkte aufhört und die Wirklichkeit in Chaos hineingeht. Wir können nicht von vorneherein sagen: Was macht denn nun eigentlich diese Wirklichkeit, die wir da mathematisierend verfolgen, wo sie ins Inkommensurable hineinschlüpft? - Sie macht da drinnen ganz gewiß etwas, was mit ihrer Lebensfähigkeit zusammenhängt. Wir müssen also heraus aus demjenigen, was wir mathematisch beherrschen, wenn wir in die astronomische Wirklichkeit hineinwollen. Das zeigt einfach der Kalkül selber, das zeigt die Entwickelung der Wissenschaft selber. Auf solche Punkte muß man hinarbeiten, wenn man wirklichkeitsgemäß Geist entfalten will.

[ 21 ] Und jetzt möchte ich Ihnen den anderen Pol der Sache hinstellen. Sehen Sie, wenn Sie es physiologisch verfolgen, da können Sie ausgehen von irgendeinem Punkt der embryonalen Entwickelung, sei es der der Entwickelung des menschlichen Embryos im dritten, im zweiten Monat, sei es eines andern Lebewesens. Sie können sie zurückverfolgen und Sie können dann, soweit das mit den heutigen Hilfsmitteln der Wissenschaft möglich ist - es ist ja in sehr, sehr eingeschränktem Mafe möglich, wie die, die sich damit befaßt haben, wissen werden -, Sie können, soweit einigermaßen gültige Vorstellungen darüber gemacht worden sind, sehen: Es wird eben zurückgegangen bis zu einem bestimmten Punkte, zu dem Punkte - und viel weiter kommt man nicht zurück - der Ablösung der Eizelle, der unbefruchteten Eizelle. Stellen Sie sich vor, wie weit Sie da zurückgehen können. Sie müssen aber, wenn Sie noch weiter zurückgehen wollen, in das Unbestimmte des ganzen mütterlichen Organismus zurückgehen. Das heißt, Sie kommen da im Zurückgehen in eine Art Chaos hinein. Das können Sie gar nicht vermeiden, und daß man das nicht kann, zeigt Ihnen wieder der Gang der wissenschaftlichen Entwickelung. Ich bitte Sie, verfolgen Sie doch nur dasjenige, was da als wissenschaftliche Hypothese aufgetreten ist in der Panspermie und ähnlichen Dingen, wo darüber spekuliert worden ist, ob aus den Kräften des ganzen Organismus, was mehr Darwins Ansicht ist, sich vorbildet der einzelne Eikeim, oder ob sich dieser Eikeim mehr abgesondert in den bloßen Sexualorganen entwickelt und so weiter. Sie werden sehen, wenn Sie den Gang der wissenschaftlichen Entwickelung auf diesem Gebiet verfolgen, daß da zutage getreten ist eine reiche Fülle von Phantasie sogar, wie es sich verhält mit dem, was da der Genesis zugrunde liegt, wenn man sie nach rückwärts verfolgt im Hervorgehen des Eikeimes aus dem mütterlichen Organismus. Da kommen Sie ins völlig Unbestimmte hinein. Heute ist überhaupt kaum mehr da in der äußeren Wissenschaft über diese Sache als Spekulationen über den Zusammenhang des Eikeimes mit dem mütterlichen Organismus.

[ 22 ] Dann aber tritt dieser Eikeim in einem bestimmten Punkte sehr determiniert auf in etwas, das Sie wenigstens annähernd ganz gut fassen können mathematisierend, wenn auch nur geometrisierend. Sie können Zeichnungen machen von einem bestimmten Punkte an. Solche Zeichnungen sind in der Embryologie ja auch vorhanden. Den Eikeim, die Zelle können Sie zeichnen, können die Entwickelung verfolgen, real verfolgen mehr oder weniger. So kann man anfangen etwas darzustellen, was Geometrie-ähnlich ist, was man in Formen bringen kann. Man verfolgt hier eine Realität. Sie ist in einer gewissen Weise umgekehrt demjenigen, was wir in der Astronomie gesehen haben. Da verfolgen wir erkennend eine Realität und wir kommen in die inkommensurable Zahl hinein. Die ganze Sache entschlüpft uns in das Chaos durch den Erkenntnisprozeß selber; in der Embryologie schlüpfen wir aus dem Chaos heraus. In einem gewissen Punkte können wir dasjenige, was aus dem Chaos hervorgeht, erfassen mit gewissen Formen, die der Geometrieform ähnlich sind. Gewissermaßen können wir sagen: Mathematisierend kommen wir ins Chaos hinein durch die Astronomie im Erkenntnisprozeß; und im bloßen Beobachten in der Embryologie haben wir gar nichts vor uns als ein Chaos, es wird ein Chaos, wenn die Beobachtung nicht mehr möglich ist. Da kommen wir aus dem Chaos heraus und kommen ins Geometrisieren hinein. Und es ist daher ein Ideal gewisser Biologen und ein sehr berechtigtes Ideal sogar, dasjenige, was sich darstellt in der Embryologie, in einer geometrisierenden Weise zu fassen. Die Figuren nicht nur als naturalistische Abbildungen des werdenden Embryos hinzumalen, sondern sie aus einer inneren Gesetzmäßigkeit, die ähnlich ist der Gesetzmäßigkeit geometrischer Figuren, zu konstruieren, das ist ein berechtigtes Ideal.

[ 23 ] Nun, da können wir also sagen: Indem wir die Wirklichkeit beobachtend verfolgen, kommen wir aus etwas heraus, was zunächst unserem Erkennen ebenso wenig nahe liegt wie dasjenige, was da (in der Astronomie) die inkommensurable Zahl ist. Wir haben gewissermaßen unser Erkennen nach der einen Seite geführt bis dahin, wo wir mit der Mathematik nicht mehr mitkommen; und wir haben unser Erkennen an einem bestimmten Punkte angefangen in der Embryologie, wo wir erst einsetzen können mit etwas, was ein Geometrie-Ähnliches ist. Bitte, denken Sie den Gedanken zu Ende. Sie können es, weil er ja ein methodologischer Gedanke ist, das heißt, seine Wirklichkeit in uns liegt.

[ 24 ] Wenn wir mit dem Rechnen bei der inkommensurablen Zahl ankommen, das heißt an einem bestimmten Punkte, wo wir das Reale nicht mehr hereinbringen in die Zahl, die wir abschließend darstellen können, dann muß unser Nachforschen darüber beginnen und das ist dasjenige, wozu wit uns im nächsten Vortrag wenden werden -, ob es nicht auch mit den geometrischen Gebilden so ist wie mit den arithmetischen Gebilden, den analytischen Gebilden. Das analytische Gebilde führt zur inkommensurablen Zahl. Setzen wir zunächst einmal die Frage hin: Wie bilden die geometrischen Formen die Himmelsbewegungen ab? Führt uns nicht vielleicht dieses Abbilden an einen bestimmten Punkt ähnlich dem, wohin uns die Analysis führt, indem wir in die inkommensurable Zahl hinein müssen? Kommen wir nicht vielleicht, indem wir die Weltenkörper, die Planeten verfolgen, an einer Grenze an, wo wir sagen müssen: Jetzt können wir nicht mehr in geometrischen Formen darstellen, jetzt ist das nicht mehr mit geometrischen Formen zu umfassen? Gerade so, wie wir das Gebiet der faßbaren Zahl verlassen müssen, kann es sein, daß wir das Gebiet desjenigen verlassen müssen, wo wir in die geometrischen — auch arithmetischen, algebraischen, analytischen - Formen, in Spiralen und so weiter, die Wirklichkeit mit der Zeichnung einfassen können. Da kommen wir ins Inkommensurable auch geometrisch hinein. Und so ist immerhin der folgende Tatbestand merkwürdig. Sehen Sie, Analysis kann man noch nicht viel anwenden in der Embryologie, aber die Geometrie erscheint schon sehr spukend da, wo wir anfangen, aus dem Chaos heraus die embryologischen Tatsachen zu entwickeln. Da erscheint an diesem Ende nicht so sehr das zahlenmäßig Inkommensurable, sondern das, was sich herausarbeitet aus dem formenhaft Inkommensurablen in die kommensurable Form hinein.

[ 25 ] Wir haben jetzt an zwei Polen die Wirklichkeit zu erfassen versucht: da, wo uns der Erkenntnisprozeß hinausführt aus der Analysis in das Inkommensurable hinein; da, wo uns das Beobachten hinführt aus dem Chaos zu einem Erfassen der Wirklichkeit in immer kommensurableren und kommensurableren Formen. Das sind die Dinge, die man sich unbedingt zunächst einmal mit völliger Klarheit vor die Seele führen muß, wenn man überhaupt eine wirklichkeitsgemäße Betrachtung anknüpfen will an dasjenige, was heute in der äußeren Wissenschaft vorliegt.

[ 26 ] Daran möchte ich nun eine methodologische Betrachtung anknüpfen, damit wir morgen mehr in Realeres hineinkommen können. Ich will anknüpfen an das Folgende. Sehen Sie, alles was wir bis jetzt dargestellt haben, hat ja in einer gewissen Weise zur Voraussetzung gehabt, daß man sich immerzu als Mathematiker an die Erscheinungen der Welt heranbegeben hat. Dann hat sich herausgestellt, daß an einem Punkt der Mathematiker an eine Grenze kommt, eine Grenze, an die er auch in der formalen Mathematik kommt. Nun liegt nämlich unserer Denkweise etwas zugrunde, was vielleicht am allerwenigsten bemerkt wird, weil es sozusagen in die Maske der Selbstverständlichkeit fortdauernd sich hüllt und wir das Problem nicht eigentlich an seiner richtigen Ecke anfassen. Das bezieht sich auf das Problem des Anwendens der Mathematik überhaupt auf die Wirklichkeit. Wie gehen wir dann da eigentlich vor? Wir bilden die Mathematik aus als eine formale Wissenschaft, und dann - sie erscheint uns absolut gewiß in ihren Folgerungen — wenden wir die Mathematik auf die Realität an und denken nicht daran, daß wir sie eigentlich im Grunde unter gewissen Voraussetzungen anwenden. Nun ist heute durchaus auch schon eine Basis dafür geschaffen, einzusehen, wie sehr wir die Mathematik eigentlich nur unter gewissen Voraussetzungen anwenden auf die äußere Wirklichkeit. Das stellt sich heraus, wenn man die Mathematik nun über gewisse Grenzen hinaus erweitern will. Da geht man davon aus, daß man auch gewisse Gesetze, die man eigentlich nun nicht, wie ich es vorhin dargestellt habe bei der Zusammenfassung der Keplerschen Gesetze, an der äußeren Wirklichkeit gewinnt, sondern an dem mathematischen Prozeß selbst, daß man gewisse Gesetze ausbildet, die eigentlich nichts anderes sind als induktive Gesetze, an dem Mathematischen ausgebildet. Die verwendet man dann deduktiv, indem man auch da nun weitergeht und weit ausgesponnene mathematische Theorien darauf baut.

[ 27 ] Solche Gesetze sind ja diejenigen, denen heute jeder, der sich mit Mathematik befaßt, begegnet. Es ist schon in Dornacher Vorträgen von unserem Freund Blümel auf diesen Gang der mathematischen Untersuchungen bedeutsam hingewiesen worden. Eines der Gesetze, um die es sich handelt, ist zunächst dasjenige, das man das kommutative Gesetz nennt. Das kann ja ausgesprochen werden damit, daß man sagt: Es ist selbstverständlich \(a + b = b + a\) oder \(a \cdot b = b \cdot a\).

[ 28 ] Es ist eine Selbstverständlichkeit, solange man innerhalb reeller Zahlen bleibt. Aber es ist eben nur ein induktives Gesetz, aus der Handhabung der Rechnungspostulate mit reellen Zahlen abgeleitet.

Das zweite Gesetz ist das assoziative Gesetz. Es würde sich etwa so aussprechen lassen:

$$(a+b)+c = a+(d+c)$$

Wiederum ein Gesetz, das eben einfach abgeleitet ist aus der Handhabung der Rechnungspostulate mit reellen Zahlen.

Das dritte Gesetz ist das sogenannte distributive Gesetz. Es ließe sich aussprechen etwa in der Form, daß man sagt:

$$a \cdot ( b + c ) = ab + ac$$

Wiederum ein Gesetz, das eben einfach induktiv gewonnen ist an der Handhabung der Rechnungspostulate mit reellen Zahlen.

[ 29 ] Das vierte Gesetz ist dasjenige, das man etwa so aussprechen muß: Es kann ein Produkt nur gleich Null werden, wenn einer der Faktoren gleich Null ist. — Dieses Gesetz ist aber wiederum nur ein induktives Gesetz, aus der Handhabung der Rechnungspostulate mit reellen Zahlen abgeleitet. Wir haben also diese vier Gesetze: Das kommutative Gesetz, das assoziative Gesetz, das distributive Gesetz und dieses Gesetz vom Nullwerden des Produktes. Diese Gesetze werden nun heute in der formalen Mathematik zugrunde gelegt, und es wird weiter mit ihnen verfahren. Man kommt da zu außerordentlich interessanten Dingen, das ist gar nicht abzuleugnen. Aber die Frage ist nun diese: Diese Gesetze gelten, solange man im Gebiet der reellen Zahlen und ihrer Postulate bleibt. Aber es ist dabei nie eine Rücksicht darauf genommen, ob die Wirklichkeit dem entspricht. Wir können sagen, innerhalb unserer formalen Erfahrungsarten gilt \(a+b=b+a\), aber gilt das auch innerhalb der Wirklichkeit? Es ist gar kein Grund aufzufinden, warum das nun innerhalb der äußeren Wirklichkeit gelten soll. Wir könnten ja sehr gut einmal überrascht werden damit, daß wir nicht zurecht kommen, wenn wir sagen wollten, bei einem Prozeß der Wirklichkeit wäre \(a+b=b+a\). Aber die Sache hat eine andere Seite. Wir haben in uns das Hängen an dieser Gesetzmäßigkeit und mit dieser Gesetzmäßigkeit gehen wir daher an die Wirklichkeit heran; aus unserer Beobachtung fällt heraus, was dieser Gesetzmäßigkeit nicht entspricht. Das ist die andere Seite. Mit anderen Worten: Wir stellen Postulate auf, die wir auf die Wirklichkeit anwenden und halten sie für Axiome der Wirklichkeit selber. Wir dürften nur sagen: Ich betrachte ein gewisses Gebiet der Wirklichkeit und schaue nach, wie weit ich komme mit dem Satz \(a+b=b+a\). Mehr darf ich nicht sagen. Denn indem ich mit diesem Satz an die Wirklichkeit herantrete, wird sich alles finden, was dem entspricht. Und dasjenige stoße ich mit den Ellbogen beiseite, was dem nicht entspricht. Diese Gewohnheit haben wir auch auf anderen Gebieten. Wir sagen zum Beispiel in der elementaren Physik: Die Körper haben ein Beharrungsvermögen, eine Trägheit, und wir definieren dann, die Trägheit bestünde darin, daß die Körper ohne bestimmten Anstoß den Ort nicht verlassen, an dem sie sind, oder daß sie ihre Bewegung nicht ändern. Aber das ist kein Axiom, sondern ein Postulat. Ich dürfte nur sagen: Ich nenne einen Körper, bei dem ich finde, daß er seinen Bewegungszustand nicht ändert, träge, und ich untersuche nun in der Wirklichkeit, was diesem Postulat entspricht. — Also, indem ich mir gewisse Begriffe bilde, bilde ich mir eigentlich nur Richtlinien, um die Wirklichkeit in einer gewissen Weise mit diesen Begriffen zu durchsetzen, und ich muß mir den Weg offen halten, andere Tatsachen mit anderen Begriffen zu durchsetzen. Ich denke eben die vier Grundgesetze der Zahlenlehre nur dann richtig, wenn ich sie ansehe als etwas, was mir Richtung gibt; als etwas, was mich befähigt, in regulativer Weise einzudringen in die Wirklichkeit. Aber ich befinde mich auf falschem Wege, wenn ich die Mathematik als konstitutiv für die Wirklichkeit annehme. Denn da wird mir die Wirklichkeit durchaus widersprechen in gewissen Gebieten. Und ein solcher Widerspruch ist der, von dem ich gesprochen habe, wo die Inkommensurabilität bei der Betrachtung der Himmelsetscheinungen eintritt.

Fourth Lecture

[ 1 ] If I had the task of presenting the subject matter myself using the methods of the humanities, I would naturally have to start from different premises and would, in a sense, be able to reach the goal we are aiming for more quickly. But such a discussion would not fulfill the purpose of these lectures. For these lectures are intended to build a bridge to the usual scientific way of thinking, even though I have chosen chapters for these presentations in which this bridge is difficult to build because the usual way of thinking is very far removed from a realistic point of view. But even if the unrealistic point of view must be combated, it is precisely in this combating that it will become apparent how to escape from the unsatisfactory nature of modern theories and arrive at a realistic understanding of the facts in question. Today, I would therefore like to follow up on the way in which mental images about celestial phenomena have developed in recent times.

[ 2 ] In forming these mental images, we must distinguish between two things: first, that these mental images are derived from observations, from observations of celestial phenomena, and that theoretical considerations have then been linked to these observations. Sometimes, far-fetched theories were linked to relatively few observations. That is one thing: observations were taken as a starting point and certain mental images were arrived at as a result. The other thing, however, is that once certain mental images had been arrived at, these mental images were then developed further into hypotheses. And in this development into hypotheses, which then lead to the establishment of a very specific worldview, there is usually an extraordinary degree of arbitrariness, because in the development of theories, the prejudices of the individuals who develop such theories come to the fore.

[ 3 ] I would first like to draw your attention to something that may seem paradoxical at first, but which, when viewed precisely, must prove fruitful in the further course of research. You see, in all recent scientific thinking, what one might call, and indeed has been called, the regula philosophandi prevails. This consists in saying that whatever has been traced back to certain causes in any particular area of reality must also be traced back to the same cause in other areas of existence, of reality. In establishing such a regula philosophandi, one usually starts from something very obvious, something self-evident. For example, when one says, as Newtonians always do, that the process of respiration must have the same causes in animals and in humans. The ignition of a splinter must have the same cause, whether it occurs in Europe or in America. Up to this point, things remain entirely within the sphere of the self-evident. But then a certain leap is made, which one does not notice, but accepts as something self-evident. This becomes apparent to us when we see something that is connected precisely with such personalities who are afflicted with this way of thinking. It is said: When a candle glows and when the sun shines, the same cause must underlie the glow of the candle and the shine of the sun. When a stone falls to the earth and when the moon circles the earth, the movement of the stone and the movement of the moon must have the same cause. - One then adds something else to such a discussion: one would not be able to explain anything in astronomy if this were not the case, because one can only obtain explanations from the earthly realm. So if the same causality did not prevail in the vast expanse of space as it does on Earth, it would be impossible to arrive at a theory.

[ 4 ] But please bear in mind that what is expressed here as regula philosophandi is nothing more than a prejudice. For who in the world can guarantee that the causes of the light of a candle and the causes of the light of the sun are really the same? Or that the fall of a stone or the fall of the famous apple from the tree, which led Newton to his theory, are based on the same causes as the movements of the celestial bodies? That was something that had to be discovered first. It is nothing more than a prejudice. And such prejudices arise wherever certain theoretical considerations and certain images are first linked inductively to observations, and where one then simply rushes blindly into deduction and constructs world systems through this deduction.

[ 5 ] What I am describing to you here in such abstract terms has, however, become historical fact. For you see, there is a continuous development to be traced in what the great minds at the dawn of modern times, Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, drew from a few observations. In Kepler's case in particular, it must be said that the third law mentioned yesterday is something quite extraordinary in terms of the analysis of the facts that were available to him alone. It is an enormous intellectual energy that was set in motion in Kepler when he discovered this, let us say, “law” — or rather, this conceptual summary — about the phenomena of the world from the little that was available to him. But then a development sets in that goes beyond Newton and does not actually start from real observations, but basically starts from the theoretical and constructs all kinds of concepts of force and mass that we simply have to leave out if we want to remain with reality. And then it continues. And it appears, I would say, at a certain climax, to be grasped with acuity and genius, where it leads to a genetic explanation for the world system, as in Zap/ace, which you can see for yourself if you read his famous book “Exposition du systeme du monde” or in Kart's “Natural History and Theory of the Heavens.” And in everything that followed in the course of development, we see how attempts were made to explain the origin of this world system by extrapolating from mental images about the connection between the movements of the heavens, based on the nebular hypothesis and so on.