Third Scientific Lecture-Course:

Astronomy

GA 323

5 January 1921, Stuttgart

Lecture V

For the further progress of our studies I must today insert a kind of interlude, for we shall then understand more easily the real nature of our task. From a particular point of view we will reflect on the cognitional theory of Natural Science altogether. Let us link on to yesterday's lecture by calling to mind once more the provisional conclusions to which we came. The verification of them will emerge in the further course.

We have seen that in the study of celestial phenomena, in so far as these are expressed by our Astronomy in geometrical forms and arithmetical figures, we are led to incommensurable qualities. There is a moment in our process of cognition—in the attempt to understand the celestial phenomena—when we must come to a standstill, as it were, and can no longer declare the mathematical method to be competent. From a certain point onward, we simply cannot continue merely to draw geometrical lines, tracing the movements of the heavenly bodies. We can no longer employ mathematical analysis; we can only admit that analysis and geometry take us up to a certain point, whence we can go no further. At least provisionally, we come to the very significant conclusion that in reflecting on what we see, whether with the naked eye or with the aid of instruments, we can never fully compass it was geometrical figures or mathematical formulae. We do not contain the whole of the phenomena in algebra, analysis and geometry.

Think of the significance of this. If we are claiming to include the totality of the celestial phenomena, we must no longer imagine that we can do so by thinking of the Sun as moving in such a way that its movement can be represented by a definite geometry line, or that the Moon's movement can be so represented. Precise our most ardent wish must be renounced when we confront the phenomena in their totality. This is the more significant, since nowadays, the moment someone says ‘The Copernican System works no more satisfactorily than the Ptolemaic’, someone else will answer, ‘Let us then design another system’. We shall see the in the further course of these lectures, what must be put in the place of mere geometrical designs in order to comprehend the phenomena in their totality.

I must put this negative aspect before you first, before we can enter into the positive, for it is most important that we clear our thought in this respect.

On the other hand, we saw yesterday that what confronts us in Embryology emerges as if from indefinite, chaotic regions, and from a certain point onward can be grasped in picture-form, or even geometrically. As I said yesterday, in studying the celestial phenomena, through the very process of cognition we come to a point where we must recognize that the world is different from what this process of cognition might at first have led us to believe. And in the embryonic phenomena we are led to see that there must be something which preceeds the facts to which we still have access.

Now among other things there recently appeared a certain divergence of outlook among embryologists. (I will only give a rough description.) On the one hand there were the strict followers of biogenetic law, which states, as you know, that the development of the individual embryo is a kind of shortened recapitulation of the development of the race. These people wished to trace the cause of the development of the embryo to the development of the race. On the other hand, others came forward who would not hear of the derivation of the individual from the racial development, but held to a more or less mechanical conception of embryonic development saying that it was only necessary to take into account the forces directly present in what takes place in the embryo itself. For example, Oscar Hertwig left the strict biogenetic school of Haeckel and changed over to the more mechanical school. Now the mechanical needs to be grasped in a way that is at least similar to mathematics even though it be not pure mathematics. We therefore see, from the very history of Science, how front a certain stage onward (something as I said, must be presumed to have gone before this stage) embryological development is taken hold of by a mechanical, mathematical method of research. It is the history of these things to which I now wish to point.

All this appears in the field which one might call the theory of knowledge. On the one hand we are driven to a boundary in the cognitional process, where we can get no further with our favorite modern method of approach. On the other hand, in studying the embryonic life our only possibility of grasping it with ordinary methods is to start from a certain point: what goes before this has to be taken fro granted. We must admit that we find something in the realm of reality, the beginnings of which we must leave vague and unexplored; then from a certain point onward we can set to work, describing what we observe in terms of diagrams, formulas and relationships which are at least similar to those of mathematics and mechanics.

Bearing these things in mind, I deem it necessary in today's lecture to insert a kind of general reflection. As I have often pointed out, it is the ideal of modern scientific research to observe outer Nature as independently of man as possible,—to establish the phenomena in pure objectivity, as it were, excluding man altogether from the picture. We shall see that precisely through this method of excluding, it is impossible to transcend such barriers as we have now observed from two distinct sides.

This is connected with the fact that the principle of metamorphosis, which, as you know,was first conceived and presented in an elementary way by Goethe, ha so far hardly been followed up at all. It has no doubt been used to some extent in morphology, yet even here, as we saw yesterday, one essential principle is lacking. Morphology today cannot yet recognize the form and construction of a tubular or long bone, for example, in its relation to that of a skull-bone. To do this, we should have to reach a way of thinking whereby we should first study what is within, say, the inner surface of a tubular bone and then relate this to the outer surface of a skull-bone. This means a kind of inversion, as when a glove is turned inside-out; but at the same time there is an alteration of the form, an alteration of the surface-tensions through the reversing or turning of inside outward. Only if we follow the metamorphosis of forms in this way, though it may seem complicated, shall we reach true conclusions.

But when we leave the morphological and enter more into the functional domain, there are but the barest indications, in the existing ways of thought, towards a true pursuit of the idea of metamorphosis in this domain. Yet this is what is needed. A beginning was made in my book, “Riddles of the Soul”, wherein I indicated at least sketchily—the three-foldness of the being of man, recognized as a sum-total of interrelated functions. At least in outline, I explained how we must first distinguish those functions and processes in man which may be regarded as belonging to the nerves and senses; how we then have to recognize, as relatively independent processes, all that is rhythmical in the human organism; and how again we must recognize the metabolic processes as distinct. I pointed out that in these three forms of processes all that is functional in man is included. Anything else which appears functional in the human organism is derivable from these three.

It is essential to see that all phenomena in the organic realm although appearing outwardly side by side, are related to one-another through the principle of metamorphosis. People today are disinclined to look at things macroscopically. We must find our way back to the macroscopic aspect. Otherwise, through the very lack of synthetic understanding of what is living, problems will arise which are not inherently insoluble, but are made so by our methodical prejudices and limitations.

You see, in learning to understand man in this threefold aspect we must observe that he is connected with the outer world in a three fold way His life of nerves and senses is one way in which man is related to the outer world; through all rhythmic processes he is related to it in another way. It lies in the very nature of the rhythmical processes that they cannot be considered as isolated within man, apart from the rest of the world, for they depend upon the breathing,—a process of perpetual interchange between the human body and the outer world. Again, in the metabolism there is a very obvious process of interchange between man and the outer world. Also the nerves-and-senses process may be regarded as a continuation of the outer world into the inner man. This becomes easier to understand if the distinction is made between the actual perceptions, given to us through the senses, and the accompanying process of cognition—the forming of ideas and mental pictures. It is unnecessary here now to go into these things more deeply, for it is evident enough. In relation between man and the outer world during sense-perception the emphasis is more on the outer world, while the forming of ideas and mental pictures takes us more into the inner man. (I am referring to the bodily processes, not to the life of soul.)

Again, leaving aside for the moment the rhythmic system—breathing and blood-circulation—the metabolic system brings us to something else, which is in definite contrast to this inward-leading process from sense perception to ideation. A thorough study of the metabolic system establishes a connection between the inner metabolic processes and the functions of the human limbs. The limb-functions are connected with the metabolism.

If people would proceed more rationally than they are wont to be they would discover the essential connection between the metabolism, situated as it is more deeply within the body, and the processes by means of which we move our limbs. These too are metabolic. The actual organic functions which underlie the movements of the limbs are processes of metabolic. Consumption of material substances is what we find if we examine the organic functions here.

But we must not stop short at the metabolic process as such. There is a way in which this process leads as much from man towards the outer world, as sense-perception leads from the outer world towards the interior of the human body. (Such methods of research, which are really fundamental, need to be undertaken, otherwise no progress will be made in certain essential directions.)

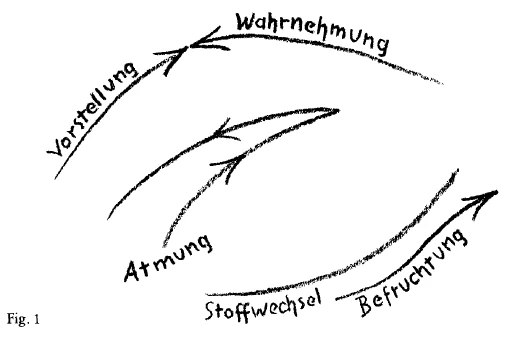

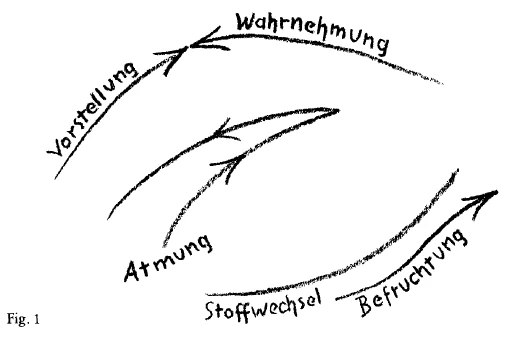

What is it that is directed outward from the metabolism even as something is directed inward from sense-perception to the creating ideas and mental pictures? It is the process of fertilization. Fertilization points in the opposite direction,—from the bodily organism outward. Representing it diagrammatically (Fig.1): In sense-perception the direction is from without inward; this in—coming process of sense-perception is then ‘fertilized’ by the organism and we get the forming of ideas. (Please do not take offense at the expression ‘fertilized’; we shall soon replace, what may look like a symbolical way of speaking, by the reality it indicates.) In the metabolic process the direction is from within outward, and we get actual fertilization. In what is manifested therefore at the two poles of threefold human nature, we are led in two opposite directions.

In the middle is all that belongs to the rhythmic system. Now we may ask, what in the rhythmic system is directed outward and what inward? Here it is not possible to find such precise distinctions as between the inner metabolism and fertilization, or between perception and ideation. The processes in the rhythmic system rather merge into one-another. In the in-breathing and out breathing the process is more of a unity. It cannot be distinguished quite so sharply, yet it is still possible to say (Fig.1): As sense perception comes from outside and fertilization goes outward, so too in inspiration and expiration there is a going inward and outward. Breathing is intermediate.

Here is a true example of metamorphosis: a single entity, underlying threefold human nature, organized now in one way, now in another.

In the upward direction this can be followed to some extent physiologically. (Some of you already know what I Shall now refer to.) Observe the breathing process. The intake of air influences the organism in a certain way; namely, in in-breathing, the cerebro—spinal fluid, in which the spinal cord and brain are stepped, is pressed upward. You must remember that the brain is in fact floating in cerebral fluid, and is thus buoyed up. We should not be able to live at all without this element of buoyancy. We will not go into that now, however, but only draw attention to the fact that here is an upward movement of the cerebral fluid in in-breathing and a downward movement in out-breathing. So that the breathing process actually plays into the skull, into the head. In this process we have a real interplay and co-operation of the nerves-and-senses system with the rhythmic system.

You see how the organs work, to bring about what we may call metamorphosis of functions. Then we can say, however hypothetical or only as a postulate: perhaps something similar will be found as regards metabolism and fertilization. But in this realm of the body we shall less easily reach a conclusion. This is indeed characteristic of the human organism; it is comparatively easy to understand the interpenetrating relation between the rhythmic system and the nerves-and-senses system in process accessible to thought, but we cannot so easily find an evident relation between the rhythmic system and the processes of metabolism and fertilization.

Call to your aid the physiological knowledge at your disposal, and the more exactly you go into the matter the better you will perceive this. Moreover it is quite obvious why it is so. Consider the regular alternation of sleeping and waking. Through sense-perception you are open to the outer world, continuously exposed to the outer world. Then you set to work with your thinking and ideation and bring a certain order and orientation into what you see around you in your waking life. It becomes ordered through an activity which works from within outward; the orientation comes from within. Actually we can say: We confront an external world which is already ordered according to its own laws, and we ourselves bring another order into it out of our own inner being. We think about the outer world, we put together the facts and phenomena according to our own liking—unhappily, often a very bad liking! From our inner being, something is introduced into the outer world which by no means necessarily corresponds to this outer world. If this were not so, we should never fall a victim to error. Out of our own inner being comes an arbitrary remolding of the world around us.

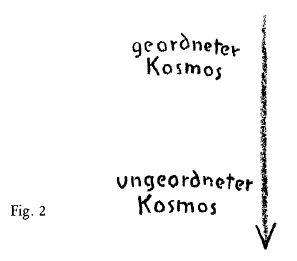

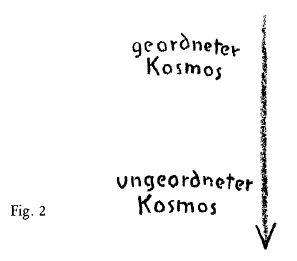

But now, looking at the other pole of human nature, you will agree that the disordering comes from without, both in metabolism and fertilization. For it is left very largely to our own arbitrary choice and free will, how we sustain our metabolism by taking food, and even more so, how we behave as regards fertilization. But here the arbitrary element has much to do with the outer world, which in the first place is foreign to us. We do at least feel at home in the arbitrary element we introduce, out of our own inner being, into the process of perception. But we do not feel familiar with all that we bring into ourselves from the outer world. We have, for instance but a very slight idea—at least, most people have very little idea of what actually happens in our relationship with the world when we eat or drink. And as to what happens in the intervals of time between our meals,—to this we pay very little attention, and even if we did it would not help as much. Here we come into an indefinite, impalpable region, I would say. Thus at the one place of man's being we have the ordered Cosmos which extends its gulfs, as it were, in our sense organs (Fig.2). (The world ‘ordered’ must not be misunderstood, it is only used to characterize the facts; we will not lose ourselves in philosophical arguments as to whether the Cosmos is really ordered or not, we want only o characterize the given facts.) The pole is in contrast to the other, which, we are bound to admit, is an un-ordered Cosmos, considering all that comes into us from without all that we stuff into ourselves, or again, how the process of fertilization is entered into in quite irregular intervals of time and so on. Contemplating this invasion of the metabolism by the outer world, we must admit that we are here confronted by an unordered Cosmos—un-ordered at least to begin with, so far as we are concerned.

And now we may put the question—from the more general aspects of the theory of human knowledge: How and to what extent are we really connected with the starry Heavens? In the first place, we see them. But you will have a vivid feeling by this time of the uncertainties which assail us when we being to think about the starry Heavens. Not only have the men of different ages felt convinced of the truth of the most diverse astronomical world—systems. As we saw yesterday, we have to face the fact that we cannot contain the totality of the starry Heavens in the mathematical and mechanical forms of thought in which we feel most secure.

Not only must we admit that we cannot trust to mere sensory appearances as regards the Heavens, but we must recognize that when we take our start from what we see and then work upon it with the life of thought, which, as we saw, belongs more to the inner man,we cannot ever really get at this world of stars. It is the truth, it is no mere comparison to say: The starry Heavens only present themselves to us in their totality—a relative totality, of course—through sense perception. Taking our start from sense-perception, when we as man try to go farther inward, to understand the starry Heavens, we feel somewhat foreign to them. We get a strong feeling of our inadequacy. And yet we feel that something intelligible must be there in the phenomenon which we behold.

Outside us, then , is the ordered Cosmos; it only presents itself to our senses. It most certainly does not at once reveal itself to our intellectual understanding. We have this ordered Cosmos on the one hand; with it, we cannot enter into man. We try to lead on from outer sense-perception of the Cosmos towards the inner man—the life of thought and ideation—and find we cannot enter. We must admit: Astronomy will not quite go into our head. This is not said in the least metaphorically. It is a demonstrable fact in the theory of knowledge. Astronomy will not go into the human head; it simply will not fit there.

What do we see now at the other pole—that of the unordered Cosmos? Let us but look at the facts; we do not want to set up theories or hypotheses, but only to see the facts clearly.

Look for what is in contrast, in the outer Universe to the astronomical domain, and in man to the processes of perception and ideation (the continuation of the ‘ordered Cosmos’ into man). In man you come into the realm of metabolism and fertilization—and Astronomy (Fig.2) and look downward in an analogous way, into what realm are you led? You are led into Meteorology—all the phenomena of the outer world once more, relating to Meteorology. For if you try to understand meteorological phenomena in terms of ‘natural law’, the amount of law you can bring in is to the ordered Cosmos of Astronomy in just the same proportion as is the temperamental region of metabolism and fertilization in man to the realm of sense perception, into which the whole starry Heaven sheds its light,—which only begins to get into disorder in our own inner life, namely in our forming of ideas.

If therefore we regard man not as an isolated being, but in connection with the whole of Nature, then we can place him into the picture in the following way. Through his head, he takes part in the astronomical, through his metabolism in the meteorological domain. Man is thus interwoven with the Cosmos on either hand.

Let us here add another thought. Yesterday we spoke of those processes which may be looked upon as an inner organic imagining of Moon-events, namely the processes in the female organism. In the female organism there is something like an alternation of phases, a succession of events, taking their course in 28 days. Although, as things are now, these events are not at all dependent on any actual Moon-events, yet they are somehow an inner reflection of the moon. I also drew your attention to the following psycho-physiological fact. If we really analyze human memory and take into account the underlying inner organic process, we cannot but compare it with this functioning of the female body. Only that in the latter the bodily nature is taken hold of more intensely than it is when holding fast in memory some outer experience which it has undergone. What comes to expression in these 28 days as a result of erstwhile our impressions is no longer contained within the individual life between birth and death, whereas the experiencing of outer events and the memory of them comes into a shorter period and takes its course between birth and death, within the single life of the individual. Considered in their psychological-physiological aspect, the two processes are however essentially the same—a functional reexperiencing of an external process or event. (In my ‘Occult Science’ I clearly hinted at this kind of experience in relation to the outer world.)

Now, study the functions of the ovum before fertilization and you will find that they are entirely involved in this 28-day inner rhythm; they belong to this process. But as soon as fertilization takes place, the processes in the ovum immediately fall out of this inner rhythmic life of the human being. A mutual relation with the outer world is at once established. Observing the process of fertilization, we are led to see that what is happening in the ovum from then onward no longer has to do with mere inner processes in the human body. Fertilization tears the ovum out of the purely inner organic process and leads it over into the realm of those processes which belong in common to the inner being of man and to the Cosmos,—a realm in which there are no barriers between what takes place within man and in the Cosmos. Therefore, what occurs after fertilization,—all that happens in the forming of the embryo,—must be studied in connection with external cosmic events, and not merely in terms of developmental mechanisms within the ovum itself in its successive stages.

Think what this means. All that goes on in the ovum before fertilization is, so to speak, within the domain of the human being's own inner organic process. But in what happens after fertilization and is brought about thereby—the human being opens himself to the Cosmos. Cosmic influences here prevail.

Thus on the one hand we have the Cosmos working in upon us up to the point where the life of ideas begins. We have, in sense—perception, a mutual relation, between man and the Cosmos. We investigate this relation, for example, by means of the laws of perception. The physiology of the senses and so on. The way in which we see an object must be investigated through such laws. Suppose we watch a railway-train traveling past us. We see the whole movement lengthwise. If, however, we are at a point directly in front of the train far enough away—however fast the train is going, we see it as if it were stationary. Pictorially, therefore, what takes place in us depends on the relation of the cosmos to us. We are in the midst of pictures and we ourselves belong to the picture. However, we become entangled in something chaotic,—for ultimately, our world systems are chaotic,—if we try to draw conclusions as to the real events from what we see externally.

On the other hand, in regard to fertilization, man is involved not in pictorial but in real cosmic processes.

Thus at the one role man is immersed in the Cosmos in a pictorial, and at the other in a real way. The very thing that eludes him when he looks out into the Cosmos, works in upon him when he undergoes the process of fertilization. Here therefore something, in itself a whole, is drawn apart into two members. In the one case a mere picture is before us and we cannot strike through to the reality. In the other the reality confronts us; through it a new man comes into being. But it does not become clear picture; it remains for us as devoid of law as do the manifestations of the weather, or meteorological conditions generally. Here we are face to face with a duality—here are two poles. From either side we receive half thrilled. It is as though we received the picture from the one side and the reality which underlies it from the other.

You see, the way man confronts the world is not as simple as one might assume in saying: The sensory picture of the world is given; now let us devise the reality by philosophical methods. This problem of finding the underlying reality in sense-perception is, of course, fundamental in the philosophic theory of cognition. But man is curiously balanced between the picture and reality in quite other ways than by mere philosophic speculation.

Now in the course of world-evolution, men have already tried to approach this secret through an experience of the intermediary realm: in-breathing and out-breathing. The ancient Indian wisdom which, as I often say, it would be wrong for us to imitate today—proceeded more or less instinctively from the following hypotheses. Sense-perceptions are of no use in the striving for reality; nor are the sexual processes or those of fertilization, for they give no clear picture. Therefore, let us keep to the middle region, which is metamorphosed at one time towards picture-forming and at another time towards reality. We must keep to the middle region, for through it the approach to reality and yet at one and the same time to the picture must in some way be possible. This is why the special breathing exercises of the Yoga system were perfected by the wisdom of Ancient India. Men sought to reach reality by experiencing the breathing process consciously, thus grasping at the same time both picture and reality. And if one asks why this should be, the answer is given: Breathing unites picture and reality. (The answer may be more or less instinctive, though not entirely so, as you can see if you will study, in the Indian philosophy itself, how this strange system of breathing-exercises arose.) Breathing unites picture and reality. The picture is experienced in its relation to the reality, if once the breathing process is lifted out of the unconscious into consciousness. We shall never understand what thus appeared in the historic evolution of mankind, unless we regard it from the point of view of the inner physiology of man. Looking at it in this light, you can say: There was a time when men sought to comprehend reality by turning to man himself. For pictures of the world, we have the senses; for the reality, something quite different. Therefore men turned to that part of the world human being which is neither shutoff in finished pictures, nor on the other hand in the mere experiencing of reality; they turned to what is not yet differentiated or divided—to the breathing process. And in so doing, they brought man into the Cosmos. They did not contemplate a world separate from man like the world of our Natural Science; they beheld a world for which man, as rhythmic man, became a real organ of perception. This world, they said, can be grasped neither by the nerves-and-senses man, nor by the metabolic man. In his life of nerves and senses, man becomes conscious in such a way that what presented itself to nerves and senses is thinned out to a mere picture; in the metabolism, reality meets him in such a way as not to be raised into consciousness at all. The interweaving of the real but unconscious experience with what is thinned out to a picture was sought by the wise men of ancient India in the regulated breathing process. Nor shall we ever understand the ancient cosmic systems, previous to the Ptolemaic, till we are able to divine how the Universe appears to man when in this was a synthesis, however undifferentiated, is achieved between the process of cognition on the one hand, and on the other the intense realty of the reproduction-process.

Consider now from this point of view the teachings about the creation of the world which are to be met with particularly in the Bible: teachings which, as things are today, are not so easy to see through. Consider the Bible story of the Creation, particularly as interpreted by those who still had the old traditions. Fundamentally, the Biblical story of Creation can only be understood if we are able to combine the genesis of the world which we derive by looking at the outer Universe, with that which we derive by Embryology. What is set forth in the Book of Genesis is in fact compounded of Embryology and of what is seen in the outward glory of the sense world. Hence the repeated attempts to interpret the Biblical story of Creation, even word for word, by embryological facts. Truly, it calls for such interpretation.

I introduced this today, my dear friends, for quite a definite reason.

You see, if our present studies—intended, as they are, to form a bridge between the external Science of today and Spiritual Science—are to have any meaning at all, we must first acquire a quite definite feeling and must permeate ourselves with this feeling otherwise we can get no further. We must become able to feel that certain modern ways of thought are superficial and external,—to feel this in a thoroughly deep way. We must learn to see the superficiality, on the one hand, of setting up pictures of the Universe which only try to make some slight corrections in the Copernican System, and on the other hand, of researching into the embryonic life in the ways which are customary today. One might say that Nietzsche's dictum: “The world is deeply thought and wrought; more deeply than the passing day”, proceeded from such a feeling. The impulses must be acquired not to seek explanations in the mere superficial acceptance of what presents itself directly, even if it be to the enhanced sight of telescope or microscope or X-ray apparatus. We must learn to have respect for explanations of another nature, aspiring to other faculties of knowledge, such as were sought by the old Indian sages in the Yoga System, so as to penetrate into reality and find the means of forming an adequate picture of reality.

Since we have now outgrown the Yoga system, we must feel impelled towards a new way of penetrating into the Universe by processes which still remain to be developed—which are not to be derived so simply from the habitual methods of today. For man is placed in the midst between the picture of the world,—a picture which presents itself to him in an overwhelmingly forceful way in the starry Heavens, the secrets of which will never be disclosed through the mere intellectual faculties,—and what meets him with ever—changing mood and temperament in the processes of reproduction, by virtue of which the human race exists. Into the midst of this great whole which is thus separated for him into two halves, man is placed. to find a connection between the two, he must look for a way of spiritual development, even as he did in an older form in the Yoga system,—a form no longer possible today.

Astronomy, practiced as hitherto, will never lead to a grasp of reality; it will only give us pictures. And Embryology, though in this realm we seize reality, will no enable us to penetrate the reality with ideas and mental pictures. Astronomical pictures of the world are poor in reality; embryological pictures are poor in idea—we fail to penetrate the facts with clear ideas. Thus in the theory of knowledge too we must approach the human being as a whole, instead of merely indulging in philosophical and psychological speculations about sense-perception. We must take our start from the whole of man. We must learn how to place man as a whole into the Universe. That is our task today.

It is very evident today, how on the one hand in Astronomy the ground of knowledge is being lost. And it is evident how on the other hand in Embryology, where knowledge fails to reach the well-springs of reality, all that results is a mere talking round and round the given facts, whether in terms of the biogenetic law or of developmental mechanisms. Amplification of our fundamental methods is quite evidently needed in both of these directions.

I had to put all this before you, so that we might understand each other better in what follows. For it will help you see that it would be no use if I were simply to add another formal picture of the Universe to the existing ones, although admittedly that is the kind of thing which people nowadays desire.

Fünfter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Es ist notwendig für den weiteren Fortgang unserer Betrachtungen, daß ich heute gewissermaßen etwas episodisch einschiebe. Wir werden uns dann in bezug auf unsere eigentliche Aufgabe leichter verständigen können. Ich möchte heute also eine allgemeinere Betrachtung über das Erkenntnistheoretische der Naturwissenschaft, allerdings von einem besonderen Gesichtspunkte aus, einschieben. Wir knüpfen insofern an das Gestrige an, als wir uns noch einmal vergegenwärtigen, zu welchen Resultaten wir gestern, wenigstens vorläufig, gekommen sind. Die Verifizierung dieser Resultate wird sich allerdings ja auch erst im Laufe der Vorträge ergeben können.

[ 2 ] Wir haben gesehen aus der Betrachtung der Himmelserscheinungen, insofern diese Himmelserscheinungen ausgedrückt werden von unserer Astronomie in geometrischen Formen oder auch zahlenmäßig verfolgt werden, daß man geführt wird zu inkommensurablen Größen. Das heißt, wie wir gestern auseinandergesetzt haben, daß es einen gewissen Moment in unserem Erkenntnisprozeß gibt, wenn wit diesen Erkenntnisprozeß auf die Himmelserscheinungen anwenden, wo wit gewissermaßen stille stehen müssen, wo wir aufhören müssen, die mathematischen Betrachtungen für kompetent zu erklären. Wir können einfach von einem bestimmten Punkte an nicht mehr fortfahren, Linien zu zeichnen, um Bewegungen von Himmelskörpern zu verfolgen, wir können auch nicht mehr fortfahren, die Analysis anzuwenden, sondern können nur sagen: Bis zu einem gewissen Punkte führen uns Analysis und geometrische Betrachtungsweise, aber von diesem Punkte an geht es nicht weiter. Daraus werden wir, allerdings zunächst auch wieder provisorisch, eine wichtige Folgerung ziehen müssen: daß wir dann, wenn wir dasjenige mathematisch betrachten, was wir sehen, sei es mit dem unbewaffneten oder mit dem bewaffneten Auge, es nicht in irgendwelche geometrische Figuren oder mathematische Formeln hineinbringen können. Wir umfassen also nicht die Totalität der Erscheinungen mit Algebra, Analysis oder Geometrie.

[ 3 ] Bedenken Sie, was sich daraus für Bedeutsames ergibt. Es ergibt sich, daß, wenn wir den Anspruch erheben, die Totalität der Himmelserscheinungen zu betrachten, wir darauf verzichten müssen, dies so zu tun, daß wir sagen: Die Sonne bewegt sich so, daß wir diese Bewegung in einer Linie nachzeichnen können; der Mond bewegt sich so, daß wir diese Bewegung in einer Linie nachzeichnen können. Also gerade auf dasjenige, was wir fortwährend als unseren sehnlichsten Wunsch empfinden, müssen wir im Grunde, wenn wir uns der Totalität der Erscheinungen gegenüberstellen, eigentlich verzichten. Es ist dies um so bedeutsamer, als ja heute in dem Augenblick, wo man sagt: Es genügt das kopernikanische Weltsystem so wenig als das ptolemäische -, jeder antwortet: Also zeichnen wir ein anderes auf. - Und wir werden erst im Verlauf dieser Vorträge sehen, was an die Stelle des Zeichnens gesetzt werden muß, wenn man die Totalität der Erscheinungen wirklich ins Auge fassen will.

[ 4 ] Ich muß zuerst dieses Negative vor Sie hinstellen, bevor wir in das Positive hineinkommen können, weil es außerordentlich wichtig ist, hier zu ganz klaren Begriffen vorzuschreiten. Auf der anderen Seite haben wir gestern gesehen, wie aus unbestimmten, chaotischen Regionen heraufsteigt dasjenige, was wir dann von einem bestimmten Punkte an bildhaft, also auch in einem gewissen Sinne geometrisch, erfassen können, nämlich dasjenige, was uns durch die Embryologie entgegentritt. Man möchte sagen: Wenn man im Erkenntnisprozeß - ich habe es auch gestern ausgesprochen - die Himmelserscheinungen verfolgt, so kommt man in diesem Erkenntnisprozeß an einen Punkt, wo man sich sagen muß, die Welt ist anders, als man mit diesem Erkenntnisprozeß sie zunächst auffassen möchte; wenn man die embryologischen Erscheinungen betrachtet, so muß man sagen, man muß irgend etwas voraussetzen, das vorangeht jener Wirklichkeit, die wir noch umfassen können.

[ 5 ] Nun trat ja außer anderen Dingen, ich will die Dinge nur ganz grob kennzeichnen, in der embryologischen Betrachtungsweise ein Zweifaches zutage in der neueren Zeit. Auf der einen Seite waren die Menschen noch stramme Anhänger des biogenetischen Grundgesetzes, welches ja besagt, daß die individuelle Entwickelung des Keimes eine Art verkürzter Stammesentwickelung ist. Diese Menschen wollten also gewissermaßen kausal zurückführen die Keimesentwickelung auf die Stammesentwickelung. Dagegen traten dann andere auf, welche von einer solchen Herleitung des IndividuellKeimhaften aus der Stammesentwickelung nichts wissen wollten und davon sprachen, daß man sich an die unmittelbar in den Erscheinungen des Embryonalen vorhandenen Kräfte halten müsse; welche, mit anderen Worten, von einer Art Entwickelungsmechanik sprachen. Man kann eigentlich sagen: Aus der strammen biogenetischen Schule Haeckels ist Oscar Hertwig hervorgegangen, der dann ganz übergegangen ist zur Anerkennung der Entwickelungsmechanik. Da man das Mechanische wenigstens Mathematik-ähnlich fassen muß, wenn man auch nicht zu einer genauen Mathematik kommt, so tritt uns da auch historisch entgegen - und auf die Dinge, wie sie sich historisch entwickelt haben, wollen wir ja hinweisen —, wie zuerst etwas anderes vorausgesetzt wird und dann eingesetzt wird mit einer Mechanik-Mathematik-ähnlichen Betrachtungsweise.

[ 6 ] Diese Dinge liegen zunächst, möchte ich sagen, mehr erkenntnistheoretisch vor. Auf der einen Seite werden wir im Erkenntnisprozeß an eine Grenze getrieben, wo wir nicht mehr weiterkommen mit der Betrachtungsweise, die wir zunächst als die uns beliebte haben; auf der anderen Seite kommen wir in der Beobachtung des Embryonalen nur dann zu irgendeiner Möglichkeit, die Sache in der gewöhnlichen Weise zu fassen, wenn wir Voraussetzungen machen, die wir zunächst liegen lassen; wenn wir uns also sagen: Im Gebiete des Wirklichen ist etwas, was wir zunächst liegen lassen im Unbestimmten, und an einem bestimmten Punkte fangen wir an, das Beobachtbare wenigstens in Formen und Verhältnissen anzuschauen, die Mathematik- und Mechanik-ähnlich sind.

[ 7 ] Diese Dinge machen es eben notwendig, daß wir heute eine Art allgemeiner Betrachtung einschieben. Ich habe schon darauf aufmerksarmn gemacht, daß die naturwissenschaftliche Betrachtung heute im Grunde genommen nach dem Ideal strebt, die äußere Natur möglichst unabhängig vom Menschen zu betrachten, die einzelnen Erscheinungen gewissermaßen in der Objektivität zu fixieren und den Menschen auszuschalten. Wir werden sehen, daß gerade durch diese Betrachtungsweise, die den Menschen ausschaltet, es unmöglich ist, über solche Schranken hinauszukommen, wie wir sie jetzt nach zwei Seiten hin haben bemerken können. Und das hängt damit zusammen, daß der Metamorphosengedanke, den ja Goethe, elementar zuerst, umfassend dargestellt hat, eigentlich noch recht wenig verfolgt worden ist. Er ist allerdings in bezug auf das Morphologische bis zu einem gewissen Grade verfolgt worden, allein auch da hat sich uns ja schon gezeigt, wie die Morphologie von heute aus dem Grunde zu keinem Ziel kommen kann, weil zum Beispiel die Formkonstruktion eines Röhrenknochens im Vergleich mit einem Schädelknochen nicht in der richtigen Weise angeschaut werden kann. Dazu müßte man ja vorschreiten zu Betrachtungen, welche uns dazu führen, das eine Mal das Innere, die innere Fläche des Knochens beim Röhrenknochen zum Beispiel zu verfolgen, und dann dieser inneren Fläche parallel zu stellen gerade die äußere Fläche des Schädelknochens, so daß man es da zu tun hat mit einer Umwendung, wie wenn man einen Handschuh umwendet, und zu gleicher Zeit mit einer Formänderung, also Änderung der FlächenSpannungsverhältnisse beim Umwenden, beim Kehren des Innern nach dem Äußeren. Erst wenn man die Metamorphose in dieser ja für manche kompliziert ausschauenden Weise verfolgt, kommt man in diesen Betrachtungen an ein Ziel.

[ 8 ] Aber wenn man herauskommt aus dem Morphologischen und mehr in das Funktionelle hineinkommt, dann sind erst ganz wenige Ansätze dazu vorhanden in dem heutigen menschlichen Vorstellen, den Metamorphosengedanken weiter zu verfolgen. Es wird unerläßlich sein, diese Metamorphosengedanken auch auf das Funktionelle des Organismus auszudehnen. Der Anfang ist gemacht an der Stelle, wo ich in meinem Buche «Von Seelenrätseln» wenigstens zunächst skizzenhaft angegeben habe die Anschauung von der Dreigliederung der menschlichen Wesenheit, insofern diese menschliche Wesenheit als eine Summe und als ein Ineinanderwirken von Funktionen aufgefaßt wird. Ich habe wenigstens skizzenhaft ausgeführt, wie wir zu unterscheiden haben am Menschen zunächst jene Funktionen, jene Vorgänge, Prozesse, die wir auffassen können als die Nerven-Sinnesprozesse; wie wir dann als verhältnismäßig selbständige Prozesse aufzufassen haben alle rhythmischen Prozesse im menschlichen Organismus; und wiederum als selbständige Prozesse aufzufassen haben die Stoffwechselprozesse. Und ich habe aufmerksam gemacht darauf, daß diese drei Prozeßformen eigentlich das Funktionelle am Menschen erschöpfen. Was sonst Funktionelles am menschlichen Organismus vorkommt, sind eigentlich Unterarten dieser drei Prozesse.

[ 9 ] Nun aber handelt es sich darum, daß man alles dasjenige, was im Organischen vorkommt, so aufzufassen hat, daß dasjenige, was scheinbar neben dem anderen steht, doch wiederum durch eine Metamorphose mit diesem anderen zu verbinden ist. Man ist heute abgeneigt, makroskopisch zu betrachten, allein in einer gewissen Weise muß man wiederum zum Makroskopischen zurückkommen, sonst wird man eben aus dem Mangel an jeder synthetischen Lebensbetrachtung überall zu Problemen kommen, die nicht an sich unmöglich zu lösen sind, sondern durch unsere methodologischen Vorurteile unlösbar werden.

[ 10 ] Wenn wir den Menschen nach dieser Dreigliederung betrachten, so haben wir zunächst in dieser Dreigliederung gegeben eine dreifache Art, wie der Mensch mit der Außenwelt in irgendeinem Verhältnis steht. In den Nerven-Sinnesvorgängen haben wir eine Art, wie der Mensch mit der Außenwelt in einem Verhältnis steht; in allen rhythmischen Vorgängen haben wir eine andere Art. Die rhythmischen Vorgänge sind durchaus so, daß sie nicht isoliert im Menschen betrachtet werden können, liegt ja doch den rhythmischen Vorgängen die Atmung zugrunde, die durchaus ein Wechselverhältnis des Innern des menschlichen Organismus mit der Außenwelt darstellt; und wiederum in alledem, was Stoffwechsel ist, liegt ja ganz klar ein Wechselverhältnis des Menschen mit der äußeren Welt vor. Die Nerven-Sinnesprozesse sind gewissermaßen nach dem Innern des Menschen eine Fortsetzung der Außenwelt. Auf diese Fortsetzung kommen wir, wenn wir unterscheiden zwischen der eigentlichen Wahrnehmung, die wesentlich durch die Sinne vermittelt wird, und dem, was sich dann für unsere menschliche Erkenntnis anschließt, dem Vorstellen. Wir brauchen uns jetzt nicht einzulassen auf tiefere Betrachtungen, sondern es wird von vorneherein ziemlich einleuchtend erscheinen müssen, daß dasjenige, was in der Sinneswahrnehmung vorliegt, ein mehr nach der Außenwelt gerichtetes Wechselverhältnis zwischen dem Menschen und seiner Außenwelt ist, als dasjenige, was in den Vorgängen des Vorstellens vorliegt. Zweifellos werden wir mehr nach dem Innern des Menschen gewiesen - ich spreche jetzt nur vom Organismus, nicht vom Seelischen - beim Vorstellen als bei der Sinneswahrnehmung.

[ 11 ] Und wiederum - wenn wir zunächst das rhythmische System, Atmung, Zirkulation, beiseite lassen - werden wir, wenn wir das Stoffwechselsystem betrachten, auf etwas anderes verwiesen, das in einer ganz bestimmten Weise ein Gegensatz ist zu diesem Nach-innengeführt-Werden von der Sinneswahrnehmung zum Vorstellen. Wenn man vollständig den Stoffwechsel studiert, dann muß man eine Verbindung herstellen zwischen demjenigen, was innere Stoffwechselvorgänge sind, und demjenigen, was die Funktionen der menschlichen Gliedmaßen sind. Diese Funktionen der Gliedmaßen hängen ja zusammen mit der Funktion des Stoffwechsels. Und würde man in diesen Dingen überhaupt rationeller verfahren, als man es gewöhnlich tut, dann würde man eben entdecken den Zusammenhang zwischen dem mehr nach innen gelegenen Stoffwechsel und den Vorgängen, denen wir uns unterwerfen, indem wir unsere Gliedmaßen entsprechend bewegen. Es sind immer Stoffwechselvorgänge, die als die eigentlichen organischen Funktionen den Bewegungen der Gliedmaßen zugrunde liegen. Verbrauch von Stoffen, das ist es, worauf wit zuletzt kommen, was uns das eigentliche organische Funktionieren dabei darstellt.

[ 12 ] Nun aber ist es nicht damit getan, daß wir stehenbleiben bei diesem Stoffwechselvorgang. Dieser führt uns vielmehr in einer gewissen Weise ebenso von dem Menschen aus nach der äußeren Welt, wie uns der Sinneswahrnehmungsvorgang von der äußeren Welt nach dem Inneren des Organismus führt. Solche Betrachtungen, die fundamental sind, müssen eben einmal angestellt werden, sonst kommt man nicht weiter auf bestimmten Gebieten. Und was ist es denn, was vom Stoffwechsel aus ebenso nach außen weist, wie etwas vom Sinnesvorgang aus zum Vorstellen nach innen weist? Das ist der Befruchtungsvorgang. Der Befruchtungsvorgang weist gewissermaßen nach der entgegengesetzten Richtung hin, von dem Organismus nach außen. Wenn Sie sich schematisch die Sinneswahrnehmung von außen nach innen vorstellen, dann wird dieser von außen nach innen gerichtete Sinneswahrnehmungsvorgang gewissermaßen - bitte stoßen Sie sich nicht an dem Ausdruck, wir werden schon später die Realität an die Stelle des vorläufig symbolisch Aussehenden setzen können - befruchtet durch den Organismus, und dadurch begegnet uns das Vorstellen (Fig. 1). Dasjenige, was wir Stoffwechselvorgänge nennen, das weist uns nach der anderen Seite, nach außen, und wir kommen zum Befruchtungsvorgang. So daß wir nunmehr schon in dem, was gewissermaßen an den zwei Polen der dreigliedrigen Menschennatur liegt, etwas haben, was wir nach den entgegengesetzten Richtungen hin betrachten können.

[ 13 ] In der Mitte liegt ja alles dasjenige, was dem rhythmischen System zugehört. Und wenn Sie sich fragen: Was weist im rhythmischen System nach außen? Was weist nach innen? - so werden Sie nicht so genaue Unterscheidungen finden können, wie zwischen innerem Stoffwechsel und Befruchtung oder Wahrnehmung und Vorstellung, sondern Sie werden mehr ineinanderschwimmend finden bei der Ein- und Ausatmung dasjenige, was hier der Prozeß ist. Er ist mehr ein einheitlicher Prozeß. Man kann da nicht in der gleichen Weise genau unterscheiden, aber man kann doch sagen (Fig. 1): Wie wir hier die Wahrnehmung von außen finden, hier die Befruchtung nach außen, so können wir in der Ein- und Ausatmung finden nach innen Gehendes und nach außen Gehendes. Wir haben gewissermaßen den Atmungsprozeß als einen mittleren Prozeß.

[ 14 ] Und jetzt werden Sie schon aufmerksam werden auf dasjenige, was sich hier ausnimmt wie eine Art Metamorphose, ein Einheitliches, das zugrunde liegt der dreigliedrigen Menschennatur, das sich das eine Mal nach einer bestimmten Weise hin bildet, das andere Mal nach einer anderen Weise hin bildet. Sie können gewissermaßen physiologisch nach der einen Richtung, nämlich nach oben, sehr gut verfolgen dasjenige, was hier eigentlich vorliegt. Eine Anzahl von Ihnen kennt schon dasjenige, um was es sich handelt. Wenn wir den Atmungsprozeß betrachten, so wird, indem wir die Luft aufnehmen, unser Organismus in einer gewissen Weise beeinflußt. Er wird so beeinflußt, daß durch die Atmung das aus Rückenmark und Schädelhöhle auslaufende Gehirnwasser nach oben gedrängt wird. Sie müssen ja berücksichtigen, daß wir unser Gehirn in Wirklichkeit durchaus schwimmend haben im Gehirnwasser, daß es dadurch einen Auftrieb hat und so weiter. Wir würden gar nicht leben können ohne diesen Auftrieb. Aber davon wollen wir jetzt nicht sprechen, sondern nur davon, daß wir ein gewisses Nachaufwärtsbewegen des Gehirnwassers beim Einatmen haben, ein Abwärtsbewegen beim Ausatmen. So daß also wirklich der Atmungsprozeß auch in unseren Schädel hineinspielt, in unseren Kopf hineinspielt, und daß dadurch ein Prozeß geschaffen wird, der durchaus ein Zusammenwirken, ein Ineinanderwirken darstellt desjenigen, was Nerven-Sinnesvorgänge sind, mit den rhythmischen Vorgängen.

[ 15 ] Sie sehen, wie die Organe arbeiten, um gewissermaßen die Metamorphose der Funktionen zustande zu bringen. Dann können wir zunächst ja gewissermaßen hypothetisch, oder vielleicht nur wie ein Postulat, sagen: Ja, vielleicht ist so etwas auch der Fall in bezug auf den Stoffwechsel und in bezug auf die Befruchtung. - Aber wir werden da nicht so leicht zurechtkommen, wenn wir ein solches Verhältnis aufsuchen. Und gerade das ist das Charakteristische, daß es uns verhältnismäßig leicht gelingt, in mit den Gedanken verfolgbaren Prozessen dasjenige zu erfassen, was Wechselverhältnis ist zwischen dem rhythmischen System und dem Nerven-Sinnessystem, daß wir aber nicht in der Lage sind, ein ebenso leicht durchschaubares Verhältnis zwischen dem rhythmischen und dem Stoffwechsel-Befruchtungsprozeß zu finden. Sie können alles, was Ihnen in der Physiologie zur Verfügung steht, aufrufen und Sie werden, je genauer Sie gerade auf die Dinge eingehen, desto besser dieses bemerken. Übrigens können Sie sich das ganz banal vor Augen halten, warum das so ist. Wenn Sie den regelmäßigen Wechsel von Schlafen und Wachen verfolgen, so werden Sie sich sagen: In bezug auf das Sinneswahrnehmen sind Sie eigentlich überall der Außenwelt ausgesetzt. Sie stehen immerfort der Außenwelt exponiert da. Nur wenn Sie mit dem Denken und Vorstellen eingreifen, dann wird das, was im wachen Zustand eigentlich um einen ist, geordnet, wird in einer gewissen Weise von innen aus orientiert. Also die Orientierung kommt von innen. Wir können eigentlich das sagen, wir stehen der in sich gesetzmäßig angeordneten Außenwelt gegenüber, und wir bringen eine andere Ordnung in dieselbe hinein aus unserem Innern. Wir denken über die Außenwelt, wir kombinieren die Verhältnisse der Außenwelt gewissermaßen nach unserem Belieben leider sehr häufig nach einem sehr schlechten Belieben. Aber da kommt etwas hinein von unserem Inneren in die Außenwelt, was gar nicht dieser Außenwelt zu entsprechen braucht. Wenn das nicht der Fall wäre, würden wir uns niemals einem Irrtum hingeben. Da kommt von unserem Inneren heraus ein gewisses Umgestalten der Außenwelt.

[ 16 ] Wenn wir den anderen Pol der menschlichen Natur anschauen, so werden Sie nach beiden Richtungen hin zugeben, daß da die Unordnung von außen kommt. Denn es ist in unsere Willkür gestellt, wie wir den Stoffwechsel unterhalten durch die Ernährung, und erst recht ist in unsere Willkür gestellt dasjenige, was Befruchtung genannt wird. Da werden wir also an die Außenwelt verwiesen, wenn es sich darum handelt, nach der Willkür hinzuschauen. Die Außenwelt ist uns zunächst ganz fremd. Mit jener Willkür, die wir hineinbringen in den Wahrnehmungsprozeß von innen, fühlen wir uns wenigstens vertraut; mit der Willkür, die wir von der Außenwelt in uns hineinbringen, da fühlen wir uns nicht sehr vertraut. Wir haben zum Beispiel in einem sehr geringen Grade — wenigstens die meisten Menschen in einem ganz außerordentlich geringen Grade eine Ahnung davon, was eigentlich geschieht in bezug auf unseren Zusammenhang mit der Welt, wenn wir dieses oder jenes essen, wenn wir dieses oder jenes trinken und so weiter. Und wie wir gar zusammenhängen mit der Welt in den Zeiten zwischen denjenigen, in denen wit unsern Stoffwechsel unterhalten, dem wird außerordentlich wenig Aufmerksamkeit zugewendet. Und wenn wir dem Aufmerksamkeit zuwenden würden, so würde uns das auch zunächst nicht besonders viel helfen. Wir kommen da in ein Unbestimmtes, in ein Ungreifbares, möchte ich sagen, hinein. So daß wir an dem einen Pole des Menschen haben den geordneten Kosmos, der gewissermaßen seine Golfe in unsere Sinne hereinerstreckt (Fig. 2). Das Wort «geordnet» braucht dabei nicht mißverstanden zu werden, es soll nur den Tatbestand charakterisieren, wir wollen uns nicht in philosophische Betrachtungen verlieren, ob der Kosmos als geordnet betrachtet werden darf oder nicht, sondern es soll nur der Tatbestand ausgedrückt werden. Diesem Pol steht der andere gegenüber, dasjenige, was wir wirklich den ungeordneten Kosmos nennen müssen, wenn wir die Vorgänge betrachten, die an uns selbst herantreten aus dem Kosmos, wenn wir alles übersehen, was wir in uns hereinpfropfen, oder wie die Menschen in unregelmäßigen Zeiträumen für die Befruchtung sorgen und so weiter. Wenn wir alle diese Vorgänge, die da an den Stoffwechsel von der Außenwelt herantreten, ins Auge fassen, müssen wir sagen: Da haben wir es zu tun mit dem zunächst für uns ungeordneten Kosmos.

[ 17 ] Sehen Sie, wir können daran jetzt anknüpfen, ich möchte sagen mehr universell erkenntnistheoretisch, die Frage - ich will das durchaus heute episodisch einschieben -: Inwiefern stehen wir denn mit dem Sternenhimmel in Verbindung? Ja, zunächst schauen wir ihn an. Und insbesondere werden Sie ein lebendiges Gefühl haben, wie unsicher die Dinge werden in bezug auf den Sternenhimmel, wenn wir anfangen, über ihn zu denken. Wir haben ja da nicht nur vorliegen, daß die verschiedensten astronomischen Weltsysteme den Menschen eingeleuchtet haben, sondern wir haben auch das, nach unserer gestrigen Betrachtungsweise, daß wir überhaupt mit demjenigen, was uns innerlich im Vorstellen das allergewisseste ist, dem mathematisch-mechanischen Betrachten, nicht die Totalität des Sternenhimmels umfassen können. Wir müssen nicht nur sagen, wir können uns dem Sternenhimmel gegenüber nicht auf den Sinnenschein verlassen, sondern wir müssen sogar sagen, wir erkennen, daß wir mit dem, was nun hier weiter innen liegt im Menschen, gar nicht an den Sternenhimmel herankommen, insofern wir ihn mit den Sinnen überschauen. Es ist durchaus real gesprochen, nicht irgendwie bloß vergleichsweise, wenn man sagt: Der Sternenhimmel liegt uns eigentlich in seiner Totalität - natürlich in seiner relativen Totalität - nur für die Sinneswahrnehmung vor. Denn wenn wir aus der Sinneswahrnehmung heraus mehr in das Innere kommen in der Auffassung des Sternenhimmels, müssen wir uns als Menschen dem Sternenhimmel gegenüber ziemlich fremd fühlen. Jedenfalls müssen wir stark das Gefühl bekommen, wir können ihn nicht erfassen. Aber wir müssen doch zugeben, daß irgend etwas, was einer Erfassung zugrunde liegen könnte, auch in dem enthalten ist, was wir da anschauen.

[ 18 ] Nun müssen wir also sagen: Außer uns liegt der geordnete Kosmos. Der bietet sich eigentlich nur dar unserer Sinneswahrnehmung. Er erschließt sich zunächst unserer Verstandeserkenntnis ganz gewiß nicht. Wir haben ihn auf der einen Seite, diesen geordneten Kosmos, und können nun nicht herein mit ihm in den Menschen. Wir sagen uns, wir werden gewiesen von der Sinneswahrnehmung nach dem Innern des Menschen, aber wir können mit dem Kosmos nicht in den Menschen hereinkommen. Astronomie ist also etwas, was eigentlich nicht in unseren Kopf hereingeht. Es ist das gar nicht vergleichsweise gesprochen, sondern ganz erkenntnistheoretisch gezeigt. Astronomie ist etwas, was nicht in den Kopf hereingeht. Sie paßt nicht herein.

[ 19 ] Was liegt denn auf der anderen Seite, wo wir den ungeordneten Kosmos haben? Wir wollen jetzt nur die Tatsachen ins Auge fassen, keine Theorien aufstellen, keine Hypothesen suchen, sondern nur die Tatsachen klarmachen. Sehen Sie, wenn Sie in der Welt den Gegensatz suchen zu dem Astronomischen, rein tatsachengemäß, und den Gegensatz im Menschen zu demjenigen, was da liegt im Wahrnehmungs- und Vorstellungsprozeß (als Fortsetzung der Außenwelt, des geordneten Kosmos), so werden Sie beim Menschen geführt zu dem Stoffwechselprozeß mit der Befruchtung, werden in ein Ungeordnetes hinausgeführt. Wenn ich ebenso hier in der Außenwelt beginne mit meiner Betrachtung (Fig.2), und ich will dann hier in der Außenwelt heruntergehen, gewissermaßen von der Astronomie herunterkommen, wo hinein werde ich denn da geführt? Ich werde geführt in die Meteorologie, in alles dasjenige, was mir nun auch in den äußeren Erscheinungen entgegentritt und was Gegenstand der Meteorologie ist. Wenn Sie nämlich die meteotologischen Erscheinungen auffassen und versuchen, eine Gesetzmäßigkeit hineinzubringen, so verhält sich das, was Sie da an Gesetzmäfßigkeit hereinbringen können, ganz genau so zu dem geordneten Kosmos in der Astronomie, wie sich verhält alles das, was da unten im Stoffwechsel- und Befruchtungssystem wetterwendisch ist, zu demjenigen, was da oben zunächst in der Wahrnehmung auftritt, in die ja der ganze Sternenhimmel hineinleuchtet, und was erst anfängt ungeordnet zu werden in unserem Innern, im Vorstellen.

[ 20 ] Sie sehen also: Wenn wir den Menschen nicht abgesondert betrachten wollen, sondern die äußere Naturordnung in Zusammenhang mit dem Menschen betrachten wollen, dann können wir ihn so hineinstellen, daß wir sagen: Der Mensch nimmt teil durch sein Haupt an dem Astronomischen, und er nimmt teil durch seinen Stoffwechsel an dem Meteorologischen. Da steht dann der Mensch nach beiden Seiten drinnen im ganzen Kosmos.

[ 21 ] Nun fügen Sie an diese Betrachtung eine andere an. Wir haben vorgestern gesprochen von jenen Vorgängen, die gewissermaßen eine innere organische Nachbildung der Mondenvorgänge sind, den Vorgängen im weiblichen Organismus. Wir haben im weiblichen Organismus gewissermaßen etwas wie einen Phasenwechsel, eine Aufeinanderfolge von Vorgängen, die in 28 Tagen ablaufen und die natürlich so, wie die Dinge jetzt sind, gar nicht zusammenhängen mit irgendwelchen Mondvorgängen, die aber innerlich diese Mondvorgänge nachbilden. Ich habe auch schon auf die psychologisch-physiologische Tatsache hingewiesen, die in der Erinnerung des Menschen vorliegt. Wenn man diese wirklich analysiert und den inneren organischen Prozeß nimmt, der der Erinnerung des Menschen zugrunde liegt, so muß man ihn parallelisieren, als einen organischen Prozeß, mit diesem Prozeß der weiblichen Funktionen. Dieser ergreift eben nur intensiver den Organismus, als der Organismus ergriffen wird, wenn er in der Erinnerung festhält irgend etwas, was er als äußere Erlebnisse gehabt hat. Es liegt nicht mehr im individuellen Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod dasjenige, was da als Ergebnis äußerer Eindrücke sich in diesen 28 Tagen zum Ausdruck bringt, während die Zusammenhänge zwischen dem Erleben von äußeren Vorgängen und der Erinnerung eben kurzfristiger sind und im individuellen Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod darinnenliegen. Aber es ist durchaus in bezug auf das Psychologisch-Physiologische dasselbe Prozeßerleben eines äußeren Vorganges. In meiner «Geheimwissenschaft» habe ich sehr deutlich auf dieses Erleben an der Außenwelt hingewiesen.

[ 22 ] Wenn Sie nun die Funktionen des Eikeimes bis zur Befruchtung verfolgen, dann werden Sie finden, daß diese Funktionen vor der Befruchtung durchaus einbezogen sind in diesen inneren, 28-tägigen Prozeß. Sie sind gewissermaßen zugehörig diesem Prozeß. Sofort fällt dasjenige, was im Eikeim vor sich geht, aus diesem Innern des Menschen heraus, wenn die Befruchtung eingetreten ist. Da wird sofort ein Wechselverhältnis zur Außenwelt hergestellt, so daß wir, wenn wit den Befruchtungsvorgang beobachten, dazu geführt werden einzusehen, daß er nichts mehr zu tun hat mit inneren Vorgängen im menschlichen Organismus. Der Befruchtungsvorgang entreißt den Eikeim dem bloßen inneren Vorgang und führt ihn hinaus in den Bereich jener Vorgänge, die dem menschlichen Inneren und dem Kosmischen gemeinschaftlich angehören, die keine Grenze setzen zwischen dem, was im menschlichen Inneren vorgeht und im Kosmischen. Was daher vorgeht nach der Befruchtung, was vorgeht in der Bildung des Embryos, muß man im Zusammenhang betrachten mit äußeren kosmischen Vorgängen, nicht mit irgendeiner bloßen Entwickelungsmechanik, die man am Eikeim und seinen aufeinanderfolgenden Stadien selbst betrachtet.

[ 23 ] Denken Sie, was man da eigentlich hat. Dasjenige, was im Eikeim vor sich geht bis zur Befruchtung, ist gewissermaßen eine Angelegenheit des menschlichen organischen Innern; dasjenige, was nach der Befruchtung vorgeht und schon durch die Befruchtung, das ist etwas, wodurch sich der Mensch öffnet dem Kosmos, was beherrscht wird von kosmischen Einflüssen.

[ 24 ] Jetzt haben wir also auf der einen Seite den Kosmos auf uns wirkend bis zu der Sphäre des Vorstellens hin. Wir haben in der Sinneswahrnehmung ein Wechselverhältnis zwischen dem Menschen und dem Kosmos. Wir untersuchen dieses Wechselverhältnis, meinetwillen durch das Gesetz der Perspektive und Ähnliches, durch die Gesetze der Sinnesphysiologie und dergleichen. Wie wir einen Gegenstand sehen, das muß durch solche Gesetze untersucht werden. Nicht wahr, wenn wir uns aufstellen hier, und hier fährt ein Eisenbahnzug an uns vorüber (quer zur Blickrichtung), so sehen wir diese ganze Bewegung, ich möchte sagen, der Länge nach. Wenn wir uns aber so aufstellen (mit Blick in Richtung des Zuges), so kann er geradeso schnell fahren, und wir schen ihn in völliger Ruhe, wenn der Zug genügend weit entfernt ist. Es hängt also dasjenige, was in uns bildhaft vorgeht, von Verhältnissen des Kosmos in bezug auf uns ab. Wir stehen drinnen in Bildvorgängen und gehören selber diesem Bilde an. Und Sie sehen, wir verwickeln uns in ein Chaotisches - denn schließlich sind die verschiedenen Weltsysteme etwas Chaotisches -, wenn wir nun einfach Schlüsse ziehen wollen aus dem, was wir äußerlich vorgehen sehen, auf die wahren Vorgänge.

[ 25 ] Auf der anderen Seite steht der Mensch mit der Befruchtung drinnen in realen, jetzt nicht bildhaften, sondern realen kosmischen Prozessen. Da haben Sie an einem Pol bildhaftes Drinnenstehen, an dem anderen Pol haben Sie reales Drinnenstehen. Gewissermaßen dasjenige, was sich Ihnen entzieht, wenn Sie den Kosmos anschauen, das wirkt auf den Menschen, wenn er dem Befruchtungsvorgang unterworfen ist. Wir sehen hier ein Einheitliches auseinandergezogen in zwei Glieder. Das eine Mal liegt uns bloß das Bild vor, und wir können nicht zur Realität durch. Das andere Mal liegt uns die Realität vor, denn durch diese entsteht der neue Mensch. Aber das wird nicht Bild, das bleibt ebenso im Ungesetzmäßigen für uns, wie es für uns im Ungesetzmäßigen bleibt, wenn wir das Wetter betrachten, überhaupt die meteorologischen Verhältnisse. Wir stehen hier wirklich zwei Polen gegenüber. Wir bekommen von zwei Seiten her zwei Hälften von der Welt, das eine Mal bekommen wir ein Bild, das andere Mal gewissermaßen die zugrunde liegende Realität.

[ 26 ] Sie sehen, das Gegenüberstehen des Menschen zur Welt ist nicht so einfach, wie man es sich philosophisch vorstellt, wenn man sagt: Ja, wir haben das Sinnesbild der Welt gegeben. Wir wollen jetzt philosophisch herausspintisieren, welches die Realität ist. - Die Frage, wie man die Realität in der Sinneswahrnehmung findet, das ist ja eine philosophische, erkenntnistheoretische Grundfrage. Wir sehen hier, daß die Einrichtung des Menschen als solchen sich zwischen das Bild und die Realität kurios hineinstellt. Wir müssen jedenfalls auf eine ganz andere Weise diese Vermittelung zwischen Bild und Realität suchen als dutch eine philosophische Spekulation.

[ 27 ] Sie wurde schon einmal im Weltengange gesucht, indem man sich gehalten hat an dasjenige, was Vermittelung ist: Einatmung und Ausatmung. Sehen Sie, die altindische Weisheit, die wir natürlich nicht nachmachen können, wie ich ja schon oftmals gesagt habe, sie ging mehr oder weniger instinktiv von der Voraussetzung aus: Mit der Sinneswahrnehmung ist nichts zu machen, wenn man in die Wirklichkeit hinein will; mit demjenigen, was die Befruchtung, die Sexualvorgänge sind, ist nichts zu machen, denn die geben kein Bild. Also halten wir uns an das Mittlere, welches gewissermaßen das eine Mal nach dem Bild-Erzeugenden hin metamorphosiert ist, das andere Mal nach der Realität hin metamorphosiert ist. Halten wir uns an das Mittlere, in welchem irgendwie eine Annäherung an die Wirklichkeit und zu gleicher Zeit an das Bild möglich sein muß. Daher bildete die altindische Weisheit diesen künstlichen Atmungsprozeß in dem Jogasystem aus und versuchte, den Atmungsprozeß in bewußter Weise durchzuführen in einer gewissen Realität, um im Atmungsprozeß zu gleicher Zeit Bild und Realität zu ergreifen. Und wenn man nach den Gründen frägt - wenn es auch nur eine mehr oder weniger instinktive Antwort ist, ist sie doch nicht bloß instinktiv; Sie können in der indischen Philosophie selber verfolgen, wie dieses sonderbare Atmungssystem entstanden ist —, wenn man nach den Gründen frägt, so ist einem die Antwort darauf so gegeben, daß man sagt: Die Atmung verbindet Bild und Realität miteinander. Man erlebt innerlich das Bild im Zusammenhang mit der Realität, wenn man den Atmungsprozeßß aus dem Unbewußten in das Bewußte hinauf erhebt. Man versteht durchaus dasjenige, was da im Laufe der geschichtlichen Entwickelung der Menschheit aufgetreten ist, nur, wenn man die Sache innerlich-physiologisch betrachtet.

[ 28 ] Wenn Sie dies ins Auge fassen, so werden Sie sich sagen können: Man hat einmal gesucht nach einem Erfassen des Wirklichen, indem man sich an den Menschen selbst gewendet hat. So wie man die äußeren Sinne für die Bilder hat, wie man aber für die Realität etwas ganz anderes hat, so hat man sich gewendet an dasjenige im Menschen, was weder abgeschlossen ist schon zur Bildauffassung, noch in sich abgeschlossen ist nach der anderen Seite zum Realitäterleben: an das Undifferenzierte des Atmungsprozesses. Aber man hat den Menschen dadurch eingeschaltet in den ganzen Kosmos. Man hat nicht die Welt betrachtet, die abgesondert ist vom Menschen wie diejenige unserer naturwissenschaftlichen Betrachtung, sondern man hat eine Welt betrachtet, für die durchaus der Mensch als rhythmischer Mensch Wahrnehmungsorgan wird. Man sagte sich gewissermaßen: Die kann der Mensch weder ergreifen als NervenSinnesmensch, noch als Stoffwechselmensch. - Als Nerven-Sinnesmensch wird er so bewußt, daß sich dasjenige, was dem NervenSinnesleben gegeben ist, zum Bild verdünnt; im Stoffwechsel liegt die Realität so vor, daß sie nicht zum Bewußtsein erhoben wird. Dieses Zusammenwirken des Realen, bloß unbewußt Erlebten und des bis zum Bild Verdünnten, das suchte der altindische Weise in dem regulierten Atmungsprozeß. Und man versteht auch dasjenige, was älter ist als das ptolemäische System, nur dann, wenn man eine Ahnung bekommt von dem, wie sich das Weltenall darstellt, wenn in einer solchen Weise eine allerdings undifferenzierte Synthese gebildet wird zwischen dem, was wir heute den Erkenntnisprozeß nennen, und dem, was die Realität des Fortpflanzungsprozesses ist.

[ 29 ] Und nun bitte ich Sie, von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus einmal diejenige Weltentstehungslehre zu betrachten, die Ihnen besonders entgegentritt in der Bibel, allerdings so, daß man die Sache, so wie die Dinge heute vorliegen, nicht sehr genau durchschauen kann. Betrachten Sie die Weltentstehungslehre der Bibel, namentlich da, wo sie interpretiert wird von denjenigen, die diese Weltentstehung eben noch nach den älteren Traditionen interpretiert haben. Sie haben im Grunde nur die Möglichkeit, die biblische Schöpfungsgeschichte zu verstehen, wenn Sie dasjenige, was sich als Genesis darstellen kann, wenn man die Welt anschaut, zusammendenken mit dem, was sich embryologisch darstellt. Es ist durchaus ein Zusammendrängen des Embryologischen mit dem, was der äußere Sinnenschein darbietet, was in der biblischen Genesis dargestellt ist. Daher immer wiederum der Versuch, bis auf das Wort hin biblische Schöpfungsgeschichte durch embryologische Tatsachen zu interpretieren. Diese Interpretation steckt durchaus darinnen.

[ 30 ] Ich habe dieses heute eingefügt aus einem ganz bestimmten Grunde. Wenn überhaupt diese Betrachtungen hier, die eine Brücke schlagen sollen zwischen der äußeren, heute getriebenen Wissenschaft und der Geisteswissenschaft, einen Sinn haben sollen, dann ist es notwendig, daß wir uns zunächst einmal ein ganz bestimmtes Gefühl aneignen. Von diesem Gefühl müssen wir uns durchdringen, sonst geht die Sache doch nicht weiter. Und dieses Gefühl, das müssen wir dadurch bekommen, daß wir die Möglichkeit finden, gewisse Methoden der heutigen Betrachtungsweise oberflächlich zu finden, äußerlich zu finden, aber in einem recht tiefen Sinn sie äußerlich zu finden. Wir müssen die Möglichkeit gewinnen, einzusehen die Oberflächlichkeit, die darin liegt, wenn man Weltenbilder aufstellt, die nur in der einen oder anderen Weise das kopernikanische System etwas korrigieren wollen, und wenn man auf der anderen Seite bloß solche Betrachtungen über das Embryologische anstellen würde, wie man sie heute gewöhnt ist anzustellen. Man möchte sagen: Aus einem solchen Gefühl ging ja wirklich das Nietzschesche Diktum hervor: Die Welt ist tief, und tiefer als der Tag gedacht. - Man muß einen Impuls bekommen, nicht in jenem oberflächlichen Hinnehmen desjenigen, was sich einem unmittelbar darbietet, sei es auch dem bewaffneten Auge im Teleskop, im Mikroskop, durch den Röntgenapparat, die Möglichkeit für Erklärungen zu suchen. Man muß einen gewissen Respekt bekommen für andere Arten der Erklärung, die nach anderem Erkenntnisvermögen hinstreben, wie der alte Inder gestrebt hat durch das Jogasystem, um in die Wirklichkeit einzudringen und um die Möglichkeit zu bekommen, ein adäquates Bild der Wirklichkeit zu schöpfen.

[ 31 ] Man muß von da aus, weil wir einmal entwachsen sind dem alten Jogasystem, den Drang bekommen nach einem neuen Eindringen in die Welt durch Vorgänge, die erst auszubilden sind, die sich nicht einfach einstellen mit demjenigen, was wir heute gewohnheitsmäßig haben. Denn der Mensch stellt sich mitten zwischen das Bild der Welt, das uns ganz besonders stark entgegentritt in dem Sternenhimmel, der sich uns gar nicht enträtseln will durch ein verstandesgemäßes Vorstellungsvermögen, und das, was uns wetterwendisch entgegentritt in den Vorgängen der Fortpflanzung, durch die ja das Menschengeschlecht da ist. In das, was sich uns da auseinanderlegt, da stellt sich der Mensch mitten hinein und er muß, um einen Zusammenhang zu finden, eben selber eine Entwickelung suchen, wie sie auf eine ältere, heute nicht mehr gangbare Art im Jogasystern gesucht worden ist.

[ 32 ] Astronomie, wenn wit sie betreiben wie bisher, führt uns durchaus niemals zu einem Ergreifen der Realität, sondern lediglich zu einem Ergreifen von Bildern; Embryologie führt uns zwar zum Ergreifen der Realität, aber niemals zur Möglichkeit, diese Realität mit irgendwelchen bildhaften Vorstellungen zu durchdringen. Astronomische Weltbilder sind realitätsarm; embryologische Bilder sind vorstellungsarm, wir können nicht durchdringen durch die Tatsachen mit den Vorstellungen. Man muß auch im Erkenntnistheoretischen an den ganzen Menschen herangehen, nicht bloß herumphantasieten durch irgendeine philosophisch-psychologische Erkenntnistheorie an den Sinneswahrnehmungen, sondern man muß an den ganzen Menschen herangehen. Und man muß in die Lage kommen, diesen ganzen Menschen in die Welt hineinzustellen. Man merkt durchaus auf der einen Seite, wie man den Erkenntnisboden verliert in der Astronomie. Man merkt durchaus auf der anderen Seite, wie gewissermaßen, wenn man aus der Realität heraus keine Erkenntnis schöpfen kann, alles nur ein Herumreden über die Tatsachen wird, sei es im Verfolgen des biogenetischen Grundgesetzes, sei es in der Entwickelungsmechanik. Man merkt ganz genau, daß da nach beiden Seiten hin etwas vorliegt, was einer Erweiterung bedarf.

[ 33 ] Ich mußte Ihnen dieses vorausschicken, damit wir uns in der Folge besser verständigen können. Denn Sie werden jetzt einsehen, daß es nichts nützen würde, wenn ich Ihnen zu den alten Weltenbildern nun irgendein neues hinzuzeichnen würde, was ja allerdings in der Gegenwart am meisten gewollt wird.

Fifth Lecture

[ 1 ] It is necessary for the further progress of our considerations that I insert something somewhat episodic today. This will make it easier for us to understand our actual task. So today I would like to insert a more general consideration of the epistemology of natural science, albeit from a particular point of view. We will tie in with yesterday's lecture by reviewing the results we arrived at yesterday, at least provisionally. The verification of these results will, of course, only be possible in the course of the lectures.

[ 2 ] We have seen from our consideration of celestial phenomena, insofar as these celestial phenomena are expressed by our astronomy in geometric forms or are also tracked numerically, that one is led to incommensurable quantities. This means, as we discussed yesterday, that there is a certain moment in our process of cognition, when we apply this process of cognition to celestial phenomena, where we must, so to speak, stand still, where we must cease to declare mathematical considerations to be competent. From a certain point on, we simply cannot continue to draw lines to track the movements of celestial bodies, nor can we continue to apply analysis, but can only say: up to a certain point, analysis and geometric observation guide us, but from that point on, we cannot go any further. From this we will have to draw an important conclusion, albeit provisionally at first: that when we look at what we see mathematically, whether with the naked eye or with the aid of instruments, we cannot translate it into geometric figures or mathematical formulas. We therefore cannot encompass the totality of phenomena with algebra, analysis, or geometry.

[ 3 ] Consider what is significant about this. It follows that if we claim to observe the totality of celestial phenomena, we must refrain from doing so in such a way that we say: The sun moves in such a way that we can trace this movement in a line; the moon moves in such a way that we can trace this movement in a line. So, when we confront the totality of phenomena, we must actually renounce precisely that which we continually feel to be our most ardent desire. This is all the more significant because today, when one says: The Copernican world system is just as inadequate as the Ptolemaic one, everyone responds: So let's draw up another one. And only in the course of these lectures will we see what must be put in place of drawing if one really wants to contemplate the totality of phenomena.

[ 4 ] I must first present this negative aspect to you before we can move on to the positive, because it is extremely important to proceed with very clear concepts here. On the other hand, we saw yesterday how, from indeterminate, chaotic regions, there arises that which we can then grasp pictorially, and thus also in a certain sense geometrically, from a certain point onward, namely that which confronts us through embryology. One might say: if, in the process of cognition — as I also said yesterday — one follows the phenomena of the heavens, one comes to a point in this process of cognition where one must say to oneself that the world is different from how one would initially like to perceive it with this process of cognition; if one considers the phenomena of embryology, one must say one must presuppose something that precedes the reality that we can still comprehend.

[ 5 ] Now, among other things, I will only describe the things very roughly, two things have come to light in recent times in the embryological view. On the one hand, people were still staunch supporters of the biogenetic law, which states that the individual development of the germ is a kind of abbreviated phylogenetic development. These people wanted, in a sense, to trace the development of the germ back causally to phylogenetic development. On the other hand, there were others who rejected such a derivation of the individual germ from the development of the species and argued that one must adhere to the forces immediately present in the phenomena of the embryo; in other words, they spoke of a kind of developmental mechanics. One can actually say that Oscar Hertwig emerged from Haeckel's strict biogenetic school and then completely switched to recognizing developmental mechanics. Since the mechanical must at least be understood in a mathematical way, even if one does not arrive at a precise mathematics, we are also confronted historically—and we want to point out how things have developed historically—with how something else is first assumed and then applied with a mechanical-mathematical approach.

[ 6 ] These things are, I would say, initially more epistemological in nature. On the one hand, in the process of cognition, we are driven to a limit where we can no longer proceed with the approach that we initially favored; on the other hand, in observing the embryonic, we can only arrive at any possibility of grasping the matter in the usual way if we make assumptions that we initially leave aside; if we say to ourselves: In the realm of the real, there is something that we initially leave undefined, and at a certain point we begin to view the observable at least in forms and relationships that are similar to mathematics and mechanics.