The Human Soul in Relation to World Evolution

GA 212

27 May 1922, Dornach

7. Modern and Ancient Spiritual Exercises

I spoke yesterday about how man's etheric and astral bodies develop. Today I want to indicate how during different epochs man attained knowledge of this kind. A description of how higher knowledge is attained provides insight into man's being from various aspects and also into his relation to the world. It is by no means necessary that everyone should be able to repeat these practices, but a description of how higher knowledge was arrived at in the past and how it is arrived at now will throw light on matters of vital importance for every individual.

The paths by which in very remote times men acquired supersensible knowledge were very different from those appropriate today. I have often drawn attention to the fact that in ancient times man possessed a faculty of instinctive clairvoyance. This clairvoyance went through many different phases to become what may be described as modern man's consciousness of the world, a consciousness out of which a higher one can be developed. In my books Occult Science—an Outline and Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and its Attainment and other writings is described how man at present, when he understands his own times, can attain higher knowledge. Today I want to describe these things from a certain aspect with reference to what was said yesterday.

When we look back to the spiritual strivings of man in a very distant past we find among others the one practiced in the Orient within the culture known later as the Ancient Indian civilization. Many people nowadays are returning to what was practiced then because they cannot rouse themselves to the realization that, in order to penetrate into supersensible worlds, every epoch must follow its own appropriate path.

On previous occasions I have mentioned that, from the masses of human beings who lived during the period described in my Occult Sciences as the Ancient Indian epoch, certain individuals developed, in a manner suited to that age, inner forces which led them upwards into supersensible worlds. One of the methods followed is known as the path of Yoga; I have spoken about this path on other occasions.

The path of Yoga can best be understood if we first consider the people in general from among whom the Yogi emerged—that is to say, the one who sets out to attain higher knowledge by this path. In those remote ages of mankind's evolution, human consciousness in general was very different from what it is today. In the present age we look out into the world and through our senses perceive colors, sounds and so on. We seek for laws of nature prevailing in the physical world and we are conscious that if we attempt to experience a spirit-soul content in the external world then we add something to it in our imagination. It was different in the remote past for then, as we know, man saw more in the external world than ordinary man sees today. In lightning and thunder, in every star, in the beings of the different kingdoms of nature, the men of those times beheld spirit and soul. They perceived spiritual beings, even if of a lower kind, in all solid matter, in everything fluid or aeriform. Today's intellectual outlook declares that these men of old, through their fantasy, dreamed all kinds of spiritual and psychical qualities into the world around them. This is known as animism.

We little understand the nature of man, especially that of man in ancient times, if we believe that the spiritual beings manifesting in lightning and thunder, in springs and rivers, in wind and weather, were dream-creations woven into nature by fantasy. This was by no means the case. Just as we perceive red or blue and hear C sharp or G, so those men of old beheld realities of spirit and soul in external objects. For them it was as natural to see spirit-soul entities as it is for us to see colors and so on. However, there was another aspect to this way of experiencing the world; namely, that man in those days had no clear consciousness of self.

The clear self-consciousness which permeates the normal human being today did not yet exist. Though he did not express it, man did not, as it were, distinguish himself from the external world. He felt as my hand would feel were it conscious: that it is not independent, but an integral part of the organism. Men felt themselves to be members of the whole universe. They had no definite consciousness of their own being as separate from the surrounding world. Suppose a man of that time was walking along a river bank. If someone today walks along a river bank downstream he, as modern, clever man, feels his legs stepping out in that direction and this has nothing whatever to do with the river. In general, the man of old did not feel like that. When he walked along a river downstream, as was natural for him to do, he was conscious of the spiritual beings connected with the water of the river flowing in that direction. Just as a swimmer today feels himself carried along by the water—that is, by something material—so the man of old felt himself guided downstream by something spiritual. That is only an example chosen at random. In all his experiences of the external world man felt himself to be supported and impelled by Gods of wind, river, and all surrounding nature. He felt the elements of nature within himself. Today this feeling of being at one with nature is lost. In its place man has acquired a strong feeling of his independence, of his individual `I'.

The Yogi rose above the level of the masses whose experiences were as described. He carried out certain exercises of which I shall speak. These exercises were good and suitable for the nature of humanity in ancient times; they have later fallen into decadence and have mainly been used for harmful ends. I have often referred to these Yoga breathing exercises. Therefore, what I am now describing was a method for the attainment of higher worlds that was suitable and right only for man in a very ancient oriental civilization.

In ordinary life breathing functions unconsciously. We breathe in, hold the breath and exhale; this becomes a conscious process only if in some way we are not in good health. In ordinary life breathing remains for the most part in unconscious process. But during certain periods of his exercises the Yogi transformed his breathing into a conscious inner experience. This he did by timing the inhaling, holding and exhaling of the breath differently and so altered the whole rhythm of the normal breathing. In this way the breathing process became conscious. The Yogi projected himself, as it were, into his breathing. He felt himself one with the indrawn breath, with the spreading of the breath through the body and with the exhaled breath. In this way he was drawn with his whole soul into the breath.

In order to understand what is achieved by this let us look at what happens when we breathe: When we inhale, the breath is driven into the organism, up through the spinal cord, into the brain; from there it spreads out into the system of nerves and senses. Therefore, when we think, we by no means depend only on our senses and nervous system as instruments of thinking. The breathing process pulsates and beats through them with its perpetual rhythm. We never think without this whole process taking place, of which we are normally unaware because the breathing remains unconscious.

The Yogi, by altering the rhythm of the breath, drew it consciously into the process of nerves and senses. Because the altered breathing caused the air to billow and whirl through the brain and nerve-sense-system the result was an inner experience of their function when combined with the air. As a consequence, he also experienced a soul element in his thinking within the rhythm of breathing.

Something extraordinary happened to the Yogi by this means. The process of thinking, which he had hardly felt as a function of the head at all, streamed into his whole organism. He did not merely think but felt the thought as a little live creature that ran through the whole process of breathing which he had artificially induced.

Thus, the Yogi did not feel thinking to be merely a shadowy, logical process, he rather felt how thinking followed the breath. When he inhaled he felt he was taking something from the external world into himself which he then let flow with the breath into his thinking. With his thoughts he took hold, as it were, of that which he had inhaled with the air and spread through his whole organism. The result of this was that there arose in the Yogi an enhanced feeling of his own T, an intensified feeling of self. He felt his thinking pervading his whole being. This made him aware of his thinking particularly in the rhythmic air-current within him.

This had a very definite effect upon the Yogi. When man today is aware of himself within the physical world he quite rightly does not pay attention to his thinking as such. His senses inform him about the external world and when he looks back upon himself he perceives at least a portion of his own being. This gives him a picture of how man is placed within the world between birth and death. The Yogi radiated the ensouled thoughts into the breath. This soul-filled thinking pulsated through his inner being with the result that there arose in him an enhanced feeling of selfhood. But in this experience, he did not feel himself living between birth and death in the physical world surrounded by nature. He felt carried back in memory to the time before he descended to the earth; that is, to the time when he was a spiritual-soul being in a spiritual-soul world.

In normal consciousness today, man can reawaken experiences of the past. He may, for instance, have a vivid recollection of some event that took place ten years ago in a wood perhaps; he distinctly remembers all the details, the whole mood and setting. In just the same way did the Yogi, through his changed breathing, feel himself drawn back into the wood and atmosphere, into the whole setting of a spiritual-soul world in which he had been as a spiritual-soul being. There he felt quite differently about the world than he felt in his normal consciousness. The result of the changed relationship of the now awakened selfhood to the whole universe, gave rise to the wonderful poems of which the Bhagavad Gita is a beautiful example.

In the Bhagavad Gita we read wonderful descriptions of how the human soul, immersed in the phenomena of nature, partakes of every secret, steeping itself in the mysteries of the world. These descriptions are all reproductions of memories, called up by means of Yoga breathing, of the soul—when it was as yet only soul—and lived within a spiritual universe. In order to read the ancient writings such as the Bhagavad Gita with understanding one must be conscious of what speaks through them. The soul, with enhanced feeling of selfhood, is transported into its past in the spiritual world and is relating what Krishna and other ancient initiates had experienced there through their heightened self-consciousness.

Thus, it can be said that those sages of old rose to a higher level of consciousness than that of the masses of people. The initiates strictly isolated the “self' from the external world. This came about, not for any egoistical reason, but as a result of the changed process of breathing in which the soul, as it were, dove down into the rhythm of the inner air current. By this method a path into the spiritual world was sought in ancient times.

Later this path underwent modifications. In very ancient times the Yogi felt how in the transformed breathing his thoughts were submerged in the currents of breath, running through them like little snakes. He felt himself to be part of a weaving cosmic life and this feeling expressed itself in certain words and sayings. It was noticeable that one spoke differently when these experiences were revealed through speech. What I have described was gradually felt less intensely within the breath; it no longer remained within the breathing process itself. Rather were the words breathed out and formed of themselves rhythmic speech. Thus, the changed breathing led, through the words carried by the breath, to the creation of mantras; whereas, formerly, the process and experience of breathing was the most essential, now these poetic sayings assumed primary importance. They passed over into tradition, into the historical consciousness of man and subsequently gave birth later to rhythm, meter, and so on, in poetry.

The basic laws of speech which are to be seen, for instance, in the pentameter1Pentameter: in prosody, a line scanning in five feet. and hexameter2Hexameter: Greek measure of six—in poetry, line scanning in six feet. as used in ancient Greece, point back to what had once long before been an experience of the breathing process. An experience which transported man from the world in which he was living between birth and death into a world of spirit and soul.

This is not the path modern man should seek into the spiritual world. He must rise into higher worlds, not by the detour of the breath, but along the more inward path of thinking itself. The right path for man today is to transform, in meditation and concentration, the otherwise merely logical connection between thoughts into something of a musical nature. Meditation today is to begin always with an experience in thought, an experience of the transition from one thought into another, from one mental picture into another.

While the Yogi in Ancient India passed from one kind of breathing into another, man today must attempt to project himself into a living experience of, for example, the color red. Thus, he remains within the realm of thought. He must then do the same with blue and experience the rhythm: red- blue; blue-red; red-blue and so on, which is a thought- rhythm. But it is not a rhythm which can be found in a logical thought sequence; it is a thinking that is much more alive.

If one perseveres for a sufficiently long time with exercises of this kind—the Yogi, too, was obliged to carry out his exercises for a very long time—and really experiences the inner qualitative change, and the swing and rhythm of: red- blue; blue-red; light-dark; dark-light—in short, if indications such as those given in my book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds are followed, the exact opposite is achieved to that of the Yogi in ancient times. He blended thinking with breathing, thus turning the two processes into one. The aim today is to dissolve the last connection between the two, which, in any case, is unconscious. The process by which, in ordinary consciousness, we think, and form concepts of our natural environment is not only connected with nerves and senses: a stream of breath is always flowing through this process. While we think, the breath continually pulsates through the nerves and senses.

All modern exercises in meditation aim at entirely separating thinking from breathing. Thinking is not on this account torn out of rhythm, because as thinking becomes separated from the inner rhythm of breath it is gradually linked to an external rhythm. By setting thinking free from the breath we let it stream, as it were, into the rhythm of the external world. The Yogi turned back into his own rhythm. Today man must return to the rhythm of the external world. In Knowledge of the Higher Worlds you will find that one of the first exercises shows how to contemplate the germination and growth of a plant. This meditation works toward separating thinking from the breath and to let it dive down into the growth forces of the plant itself.

Thinking must pass over into the rhythm pervading the external world. The moment thinking really becomes free of the bodily functions, the moment it has torn itself away from breathing and gradually united with the external rhythm, it dives down—not into the physical qualities of things—but into the spiritual within individual objects.

We look at a plant: it is green and its blossoms are red. This our eyes tell us, and our intellect confirms the fact. This is the reaction of ordinary consciousness. We develop a different consciousness when we separate thinking from breathing and connect it with what exists outside. This thinking yearns to vibrate with the plant as it grows and unfolds its blossoms. This thinking follows how in a rose, for example, green passes over into red. Thinking vibrates within the spiritual which lies at the foundation of each single object in the external world.

This is how modern meditation differs from the Yoga exercises practiced in very ancient times. There are naturally many intermediate stages; I chose these two extremes. The Yogi sank down, as it were, into his own breathing process; he sank into his own self. This caused him to experience this self as if in memory; he remembered what he had been before he came down to earth. We, on the other hand, pass out of the physical body with our soul and unite ourselves with what lives spiritually in the rhythms of the external world. In this way we behold directly what we were before we descended to the earth. This is the consequence of gradually entering into the external rhythm.

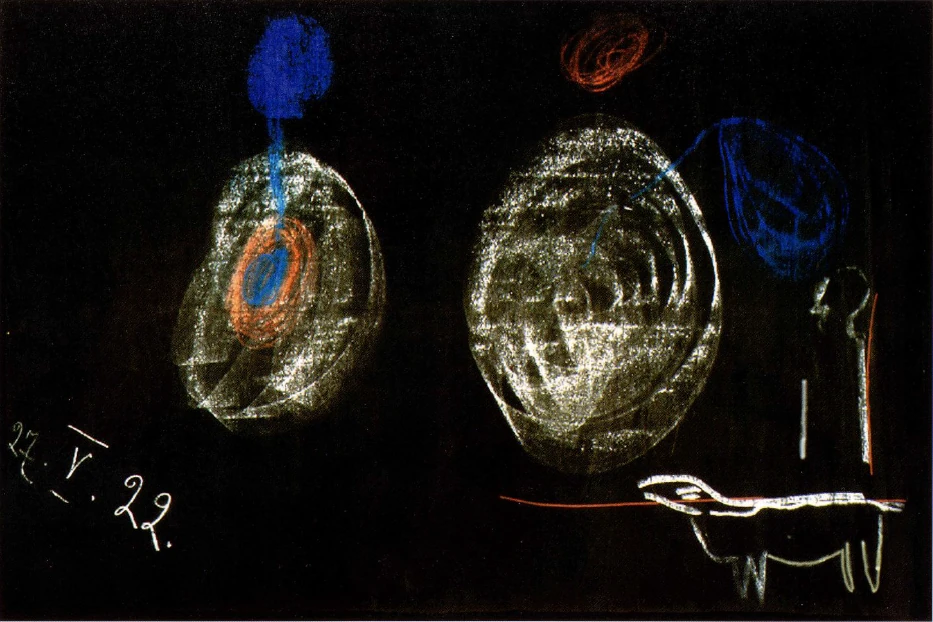

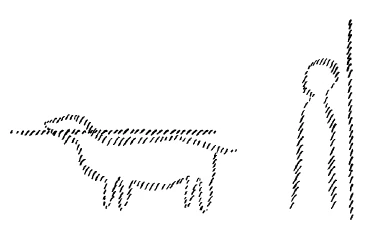

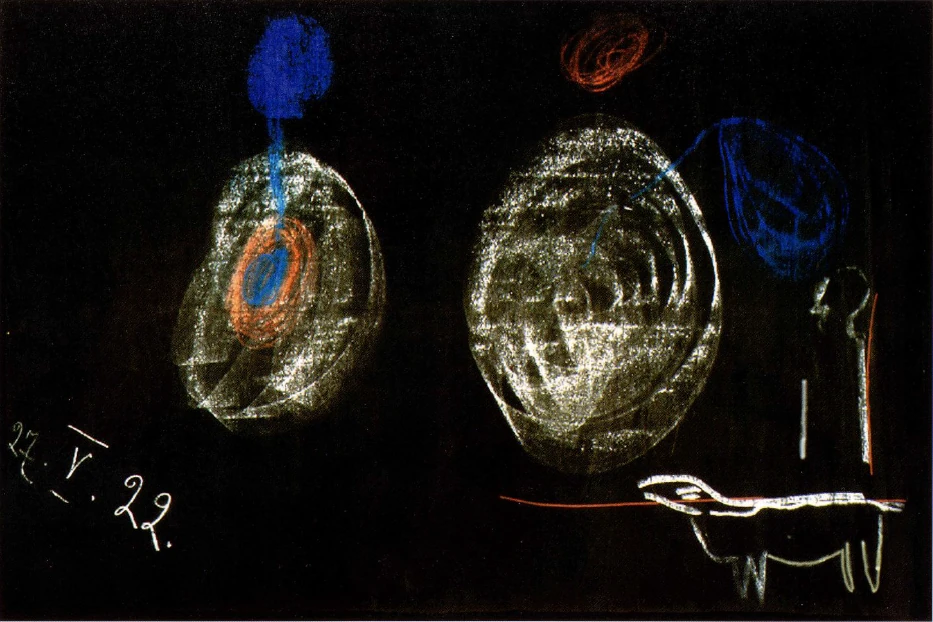

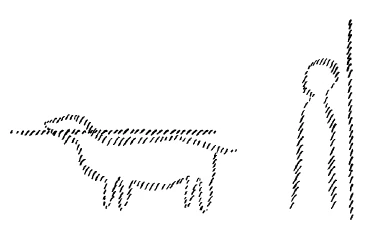

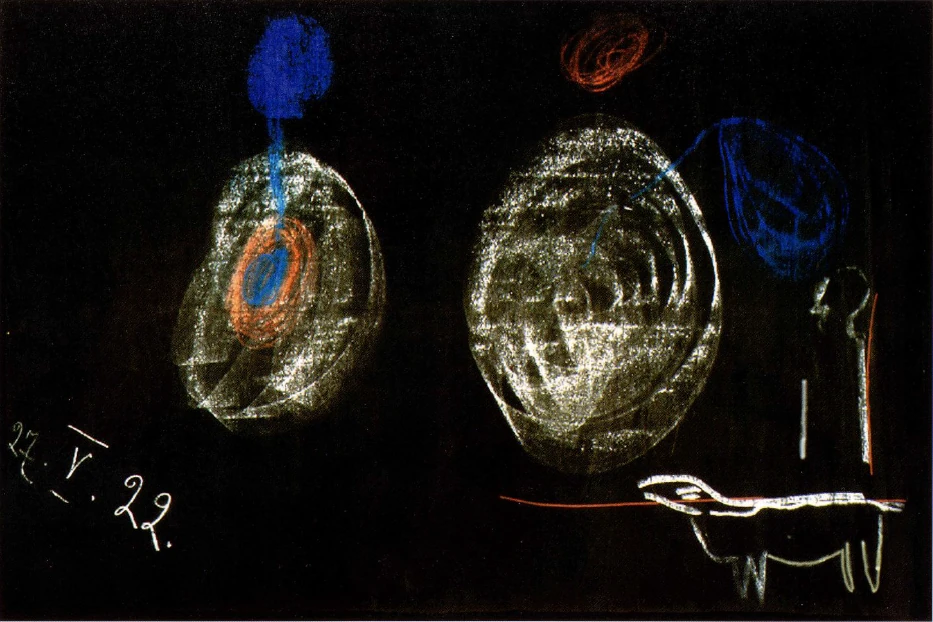

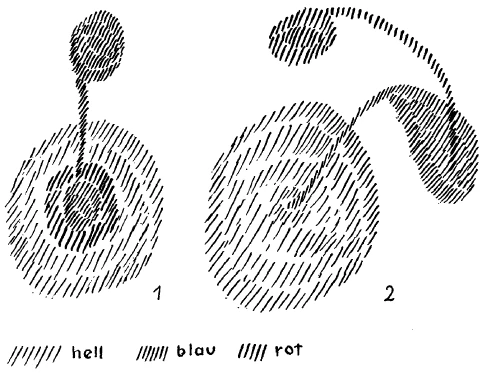

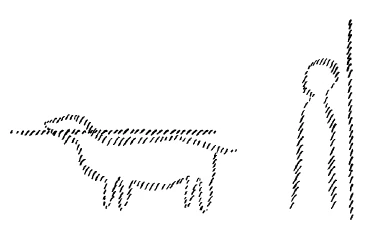

To illustrate the difference, I will draw it schematically: Let this be the Yogi (first drawing, white lines). He developed a strong feeling of his `I' (red). This enabled him to remember what he was, within a soul-spiritual environment, before he descended to earth (blue). He went back on the stream of memory.

Let this be the modern man who has attained supersensible knowledge (second drawing, white lines). He develops a process that enables him to go out of his body (blue) and live within the rhythm of the external world and behold directly, as an external object (red), what he was before he descended to earth.

Thus, knowledge of one's existence before birth was in ancient times in the nature of memory, whereas at the present time a rightly developed cognition of pre-birth existence is a direct beholding of what one was (red). That is the difference.

That was one of the methods by which the Yogi attained insight into the spiritual world. Another was by adopting certain positions of the body. One exercise was to hold the arms outstretched for a long time; or he took up a certain position by crossing his legs and sitting on them and so on. What was attained by this?

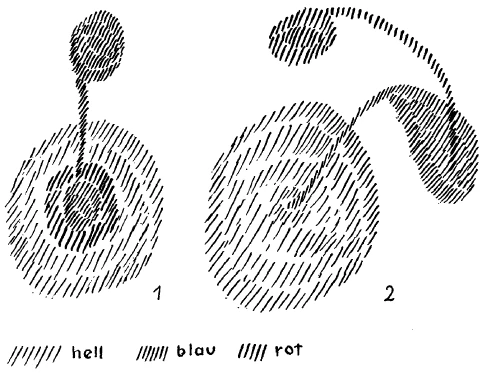

He attained the possibility to perceive what can be perceived with those senses which today are not even recognized as senses. We know that man has not just five senses but twelve. I have often spoken about this—for example, apart from the usual five he has a sense of balance through which he perceives the equilibrium of his body so that he does not fall to the right or left, or backwards or forwards. Just as we perceive colors, so we must perceive our own balance or we should slip and fall in all directions. Someone who is intoxicated or feels faint loses his balance just because he fails to perceive his equilibrium. In order to make himself conscious of this sense of balance, the Yogi adopted certain bodily postures. This developed in him a strong, subtle sense of direction. We speak of above and below, of right and left, of back and front as if they were all the same. The Yogi became intensely conscious of their differences by keeping his body for lengthy periods in certain postures. In this way he developed a subtle awareness of the other senses of which I have spoken. When these are experienced they are found to have a much more spiritual character than the five familiar senses. Through them the Yogi attained perception of the directions of space.

This faculty must be regained but along a different path. For reasons which I will explain more fully on another occasion the old Yoga exercises are unsuitable today. However, we can attain an experience of the qualitative differences within the directions of space by undertaking such exercises in thinking as I have described. They separate thinking from breathing and bring it into the rhythm of the external world. We then experience, for instance, what it signifies that the spine of animals lies in the horizontal direction whereas in man it is vertical. It is well known that the magnetic needle always points north-south. Therefore, on earth the north-south direction means something special, for the manifestation of magnetic forces, since the magnetic needle, which is otherwise neutral, reacts to it. Thus, the north-south direction has a special quality. By penetrating into the external rhythm with our thoughts we learn to recognize what it means when the spine is horizontal or vertical. We remain in the realm of thought and learn through thinking itself. The Indian Yogi learned it, too, but by crossing his legs and sitting on them and by keeping his arms raised for a long time. Thus, he learned from the bodily postures the significance of the invisible directions of space. Space is not haphazard but organized in such a way that the various directions have different values.

The exercises that have been described which lead man into higher worlds are mainly exercises in the realm of thought. There are exercises of an opposite kind; among them are the various methods employed in asceticism. One such method is the suppression of the normal function of the physical body through inflicting pain and all kinds of deprivations. It is practically impossible for modern man to form an adequate idea of the extremes to which such exercises were carried by ascetics in former times. Modern man prefers to be as firmly as possible within his physical body. But whenever the ascetic suppressed some function of the body by means of physical pain, his spirit-soul nature drew out of his organism.

In normal life the soul and spirit of man are connected with the physical organism between birth and death in accordance with the human organization as a whole. When the bodily functions are suppressed, through ascetic practices, something occurs which is similar to when today someone sustains an injury. When one knows how modern man generally reacts to some slight hurt then it is clear that there is a great difference between that and what the ascetic endured just to make his soul organism free. The ascetic experienced the spiritual world with the soul organism that had been driven out through such practices. Nearly all of the earlier great religious revelations originated in this way.

Those concerned with modern religious life make light of these things. They declare the great religious revelations to be poetic fiction, maintaining that whatever insight man acquires should not cause pain. The seekers of religious truths in former times did not take this view. They were quite clear about the fact that when man is completely bound up with his organism, as of necessity he must be for his earthly tasks—the gain was not to portray unworldliness as an ideal—then he cannot have spiritual experiences. The ascetics in former times sought spiritual experiences by suppressing bodily life and even inflicting pain. Whenever pain drove out spirit and soul from a bodily member that part which was driven out experienced the spiritual world. The great religions have not been attained without pain but rather through great suffering.

These fruits of human strivings are today accepted through faith. Faith and knowledge are neatly separated. Knowledge of the external world, in the form of natural science, is acquired through the head. As the head has a thick skull, this causes no pain, especially as this knowledge consists of extremely abstract concepts. On the other hand, those concepts handed down as venerable traditions are accepted simply through faith. It must be said though, that basically, knowledge and faith have in common the fact that today one is willing to accept only knowledge that can be acquired painlessly, and faith does not hurt any more than science, though its knowledge was originally attained through great pain and suffering.

Despite all that has been said, the way of the ascetic cannot be the way for present-day man. On some other occasion we will consider the reason. In our time it is perfectly possible, through inner self-discipline and training of the will, to take in hand one's development which is otherwise left to education and the experiences of life. One's personality can be strengthened by training the will. One can, for example, say to oneself: Within five years I shall acquire a new habit and during that time I shall concentrate my whole will power upon achieving it. When the will is trained in this way, for the sake of inner perfection, then one loosens, without ascetic practices, the soul-spiritual from the bodily nature. The first discovery, when such training of the will is undertaken for the sake of self-improvement, is that a continuous effort is needed. Every day something must be achieved inwardly. Often it is only a slight accomplishment, but it must be pursued with iron determination and unwavering will. It is often the case that if, for example, such an exercise as concentration each morning upon a certain thought is recommended, people will embark upon it with burning enthusiasm. But it does not last, the will slackens and the exercise becomes mechanical because the strong energy which is increasingly required is not forthcoming. The first resistance to be overcome is one's own lethargy; then comes the other resistance, which is of an objective nature, and it is as if one had to fight one's way through a dense thicket. After that, one reaches the experience that hurts because thinking, which has gradually become strong and alive, has found its way into the rhythm of the external world and begins to perceive the direction of space—in fact, perceive what is alive. One discovers that higher knowledge is attainable only through pain.

I can well picture people today who want to embark upon the path leading to higher worlds. They make a start and the first delicate spiritual cognition appears. This causes pain, so they say they are ill; when something causes pain one must be ill. However, the attainment of higher knowledge will often be accompanied by great pain, yet one is not ill. No doubt it is more comfortable to seek a cure than continue the path. Attempts must be made to overcome this pain of the soul which becomes ever greater as one advances. While it is easier to have something prescribed than continue the exercises, no higher knowledge is attained that way. Provided the body is robust and fit for dealing with external life, as is normally the case at the present time, this immersion in pain and suffering becomes purely an inner soul path in which the body does not participate. When man allows knowledge to approach him in this way, then the pain he endures signifies that he is attaining those regions of spiritual life out of which the great religions were born. The great religious truths which fill our soul with awe, conveying as they do those lofty regions in which, for example, our immortality is rooted, cannot be reached without painful inner experiences.

Once attained, these truths can be passed on to the general consciousness of mankind. Nowadays they are opposed simply because people sense that they are not as easy to attain as they would like. I spoke yesterday about how the changed astral body unites, within the heart, with the ether body. I also explained how all our actions, even those we cause others to carry out, are inscribed there. Just think how oppressive such a thought would be to many people. The great truths do indeed demand an inner courage of soul which enables it to say to itself: If you could experience these things you must be prepared to attain knowledge of them through deprivation and suffering. I am not saying this to discourage anyone, but because it is the truth. It may be discouraging for many, but what good would it do to tell people that they can enter higher worlds in perfect comfort when it is not the case. The attainment of higher worlds demands the overcoming of suffering.

I have tried today, my dear friends, to describe to you how it is possible to advance to man's true being. The human soul and spirit lie deeply hidden within him and must be attained. Even if someone does not set out himself on that conquest he must know about what lies hidden within him. He must know about such things as those described yesterday and how they run their course. This knowledge is a demand of our age. These things can be discovered only along such paths as those I have indicated again today by describing how they were trodden in former times and how they must be trodden now.

Tomorrow we shall link together the considerations of yesterday and those of today and in so doing penetrate further into the spiritual world.

Siebenter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Ich möchte heute auf die Art hinweisen, wie zu verschiedenen Zeiten Menschen dazu gekommen sind, Erkenntnisse zu gewinnen, wie ich sie gestern mit Bezug auf die Entwickelung des menschlichen ätherischen und des menschlichen astralischen Leibes hier dargelegt habe. Aus einer Schilderung, wie man zu solchen Anschauungen kommt, wird sich immerhin auch einiges erhellen können über das Wesen des Menschen, über das Verhältnis des Menschen zur Welt und so weiter. Es ist durchaus nicht nötig, daß etwa jeder solche Dinge gewissermaßen nachmachen kann, aber aus den Schilderungen, wie sie da oder dort vor sich gegangen sind oder noch vor sich gehen, wird man schon einiges gewinnen, das dann wiederum Licht zurückwirft auf die Ergebnisse, die für jeden Menschen so wichtig sind. Die Art und Weise, wie in sehr alten Zeiten die Menschen zu ihren übersinnlichen Erkenntnissen gekommen sind, und die Art und Weise, wie man heute solche Erkenntnisse gewinnt, sind durchaus voneinander verschieden. Ich habe ja öfter darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie in älteren Zeiten der Menschheit ein gewisses instinktives Hellsehen vorhanden war, wie dann dieses Hellsehen sich allmählich durch verschiedene Zwischenphasen zu der Anschauung von der Welt entwickelt hat, die heute der Mensch seine eigene nennen muß, und wie aus diesem allgemeinen Bewußtsein heraus dann ein gewisses höheres Bewußtsein entwickelt werden kann. Wie heute der Mensch, wenn er seine Zeit und sein Verhältnis zu dieser Zeit richtig erfaßt, zu höheren Erkenntnissen kommen kann, das ist geschildert im zweiten Teil meiner «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß», in dem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» und in anderen Schriften. Aber heute möchte ich Ihnen eine Schilderung von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus geben, gerade mit Rücksicht auch auf das, was ich gestern hier ausgeführt habe. Wenn wir in sehr alte Zeiten der Menschheitsentwickelung zurückgehen und das geistige Streben jener Zeiten ins Auge fassen, dann finden wir unter anderem das Geistesstreben, das im alten Orient vorhanden war, in derjenigen Kultur, deren spätere Zeit dann als die indische Kultur bekanntgeworden ist und zu der heute viele Menschen zurückkehren, weil sie sich nicht dazu aufschwingen können, einzusehen, daß jede Zeit eben ihren eigenen Weg gehen muß, um in die übersinnlichen Welten einzudringen.

[ 2 ] Ich habe schon einmal auch hier angedeutet, daß sich aus der Gesamtmasse der Menschen, die innerhalb jenes Zeitraumes gelebt haben, den ich in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft» den urindischen Zeitraum genannt habe, einzelne Persönlichkeiten so, wie es der damaligen Zeit angemessen war, innere Kräfte der menschlichen Wesenheit zur Entwickelung brachten, die sie dann hinaufführten in die übersinnlichen Welten. Einen dieser Wege, den ich in anderem Zusammenhange hier schon angedeutet habe, bezeichnet man als den Weg der Yoga.

[ 3 ] Der Yogaweg kann am besten begriffen werden, wenn man zunächst auf die übrigen Menschen hinschaut, aus denen heraus sich der Yogi, also derjenige, der auf diesem Wege zu höheren Erkenntnissen kommen wollte, heraushob. In jenen älteren Zeiten der Menschheitsentwickelung war das allgemeine Bewußtsein ein ganz anderes, als es heute ist. Wir Menschen von heute schauen in die Welt hinaus, nehmen durch unsere Sinne zum Beispiel die Farben, nehmen die Töne wahr und so weiter. Wir suchen in dieser sinnlichen Welt die Gesetzmäßigkeiten auf, aber wir sind uns bewußt, daß, wenn wir weitergehen, wenn wir uns in die äußeren Dinge gewissermaßen geistig-seelisch hineinleben wollen, daß wir dann aus unserer Phantasie heraus schöpfen. Das war in jenen älteren Zeiten nicht so. Da sahen die Menschen in der äußeren Welt, wie wir wissen, mehr, als der normale Mensch heute sieht. In Blitz und Donner, in allen einzelnen Gestirnen, in den Wesen der verschiedenen Naturreiche sahen die alten Menschen zugleich ein Geistig-Seelisches. Sie nahmen geistige Wesenheiten, wenn auch niederer Art, in allem Festen, in allem Flüssigen, im Luftförmigen und so weiter wahr. Heute sagt eine intellektualistische Gelehrsamkeit: Diese alten Menschen haben eben durch ihre Phantasie in die Umgebung, die sie geschaut haben, allerlei Geistig-Seelisches hineingeträumt. Man nennt das Animismus.

[ 4 ] Nun kennt man die menschliche Natur und vor allen Dingen die menschliche Natur jener älteren Zeiten schlecht, wenn man glaubt, daß diese Menschen aus ihrer Phantasie heraus allerlei Wesenheiten in Blitz und Donner, in Quelle und Fluß, in Wind und Wetter hineingeträumt hätten. Nein, das ist nicht der Fall. Sie haben sie gesehen. Geradeso wie wir Rot und Blau sehen oder cis und g hören, so haben diese älteren Menschen in den Dingen der Außenwelt Geistig-Seelisches gesehen. Es war ihnen so natürlich, dieses Geistig-Seelische zu sehen, wie es uns natürlich ist, Blau und Rot zu sehen. Aber damit war etwas anderes verknüpft. Damit war verknüpft, daß die Menschen kein deutliches Selbstbewußtsein hatten.

[ 5 ] Das deutliche Selbstbewußtsein, von dem wir heute als normale Menschen durchdrungen sind, das fehlte jenen älteren Zeiten. Der Mensch unterschied sich gewissermaßen nicht von der äußeren Welt. Was etwa meine Hand sehen würde, wenn sie ein Bewußtsein hätte, nämlich daß sie nicht selbständig ist, daß sie nur ein Glied meines Organismus ist, das haben, wenn sie es auch nicht ausgesprochen haben, jene älteren Menschen gefühlt. Sie fühlten sich als Glieder des ganzen Universums. Sie trennten ihre eigene menschliche Wesenheit gar nicht in intensiver Weise von der Umgebung ab. Solch ein älterer Mensch ging meinetwillen den Fluß entlang. Wenn wir heute einen Fluß entlanggehen in der Richtung, wie der Fluß fließt, dann haben wir als heutige gescheite Menschen selbstverständlich das Gefühl: wir schreiten mit unseren Beinen aus und bewegen uns nach abwärts; mit dem Fluß hat das nichts zu tun. — So fühlte im allgemeinen der ältere Mensch nicht. Wenn er an dem Ufer des Flusses stromabwärts ging — das ist ihm durchaus natürlich gewesen -, so fühlte er die geistigen Wesenheiten, die mit dem Strom-abwärts-Fließen des Flusses verbunden sind so, wie heute sich etwa der Schwimmer vom Wasser, also von einem Materiellen, getragen fühlt. So fühlte er sich von dem Geistigen hinuntergeführt. Das ist nur ein herausgegriffenes Beispiel. Es war alles, was der Mensch in der Außenwelt erlebte, so von ihm gedacht und empfunden, daß er sich von Wind-, von Stromesgöttern, von allem, was da draußen ist, getragen, getrieben, können wir sagen, fühlte. Er fühlte die Elemente der Natur in sich. Dieses Sich-Hineinfühlen in die Natur ist dem Menschen verlorengegangen. Er hat sich aber dafür auch sein intensives Selbständigkeitsgefühl, sein Ich-Gefühl allmählich erobert.

[ 6 ] Von der gesamten Masse der Menschen, die so fühlte, hob sich nun der Yogagelehrte, der Yogi, heraus. Er machte gewisse Übungen, und ich habe da von jenen Übungen zu sprechen, die in der späteren Zeit sehr in die Dekadenz gekommen sind, die, während sie einer älteren Menschennatur als etwas Gutes angepaßt waren, später fast bloß, ich möchte sagen, zu schädlichen Zwecken verwendet worden sind. Das sind die Übungen, die ich hier schon öfter angeführt habe: die Übungen des Yoga-Atmens. Was ich also jetzt schildere, gilt sozusagen nur für die Menschen einer sehr alten orientalischen Kultur als ein rechtmäßiger Weg, um in die höheren Welten hinaufzukommen.

[ 7 ] Im gewöhnlichen Leben verfließt das Atmen beim Menschen ja unbewußt. Der Mensch atmet ein, hält den Atem, atmet aus, und nur, wenn er in irgendeiner Weise nicht ganz gesund ist, wird ihm dieses Atmen bewußt. Im gewöhnlichen Leben bleibt es zum weitaus größten Teil ein unbewußter Vorgang. Der Yogi aber verwandelte durch gewisse Zeiten des Übens den Atem dadurch in einen bewußten inneren Vorgang, daß er die Zeitstrecken, in denen er einatmete, den Atem hielt und wieder ausatmete, daß er also den ganzen Rhythmus des Atmungsprozesses änderte. Er atmete eine längere Zeit ein, hielt den Atem länger, atmete wiederum anders aus in einer anderen Zeit, kurz, er gab sich einen anderen Atmungsrhythmus, als der gewöhnliche ist. Dadurch wurde ihm der ganze Atmungsprozeß ein bewußter. Er lebte sich sozusagen in sein Atmen hinein. Das Gefühl, das er von sich selbst bekam, war das eines fortwährenden Mitgehens mit dem Einatmen, mit dem Ausbreiten des Atems im Leibe und mit dem wiederum Ausatmen. Der Mensch zog sich dadurch mit seinem ganzen seelischen Wesen in das Atmen hinein.

[ 8 ] Wenn wir einsehen wollen, was dadurch eigentlich erreicht worden ist, so können wir sagen: Wenn wir zum Beispiel einatmen, so geht der Atemstoß in unseren Organismus hinein, er geht dann durch den Rückenmarkskanal in das Gehirn und breitet sich dort innerhalb derjenigen Vorgänge aus, welche sich im Nervenorganismus, im Sinnesorganismus vollziehen. Wenn wir also als Menschen denken, haben wir niemals etwa bloß die Sinne und den Nervenorganismus als Werkzeuge dieses Denkens, sondern Sinnes- und Nervenorganismus werden fortwährend durchrhythmisiert, durchschlagen, durchströmt, durchwellt von dem Atmungsprozeß, von dem Atmungsrhythmus. Wir denken nicht, ohne daß dieser Atmungsrhythmus unseren Nerven-Sinnesprozeß rhythmisch durchsetzt. Nur weil der ganze Atmungsprozeß beim heutigen normalen Menschen unbewußt bleibt, bleibt auch das natürlich unbewußt.

[ 9 ] Bei dem Yogi wurde dieser veränderte Atem bewußt in den Nerven-Sinnesprozeß hineingezogen. Dadurch erlebte der Yogi einen inneren Vorgang, der sich zusammensetzte aus dem, was durch den Nerven-Sinnesprozeß erfolgte, und dem, was durch das Gehirn und auch durch die Sinne hindurchwellte und hindurchwirbelte durch den veränderten Atmungsrhythmus. Er lebte dadurch aber auch das Seelische seines Denkens in den Atmungsrhythmus hinein.

[ 10 ] Dadurch kam an diesen Yogi etwas ganz Besonderes heran. Er strahlte gewissermaßen das Denken, das sonst kaum als ein Kopfesvorgang gefühlt wird, in seinen ganzen Organismus hinein. Er dachte nicht bloß, sondern er fühlte, wie der Gedanke, ich möchte sagen, wie so ein Tierchen durchlief durch den Atmungsvorgang, den er als einen künstlichen Vorgang hervorgerufen hatte.

[ 11 ] Fr fühlte also das Denken nicht nur als etwas so logisch Verlaufendes und Schattenhaftes, sondern er fühlte, wie das Denken mitging mit dem Atmungsprozeß. Wenn er einatmete, da fühlte er, da nimmt er etwas aus der Außenwelt herein; jetzt läßt er den Atmungsprozeß in sein Denken hineinfließen. Da greift er mit seinen Gedanken gewissermaßen dasjenige an, was er mit der Atemluft eingesogen hat, und jetzt verbreitet er das durch den ganzen Organismus. Dadurch aber kam über den Yogi ein erhöhtes Ich-Gefühl, ein erhöhtes Selbstgefühl. Er verbreitete sein Denken empfindungsgemäß über sein ganzes inneres Wesen. Er wurde sich dadurch seines Denkens in der Luft bewußt, und zwar in dem regelmäßigen Luftvorgang, der in seinem Inneren vor sich ging.

[ 12 ] Nun, das hatte für ihn eine ganz besondere Folge. Wenn sich der Mensch heute in der sinnlichen Welt fühlt, so ist das ja ganz richtig, daß er in seinem Denken etwas hat, auf das er kaum hinschaut. Seine Sinne unterrichten ihn schon über das, was in der Außenwelt ist, und wenn er zurückschaut auf sich, so sieht er wenigstens Teile von sich selber. Er bekommt dadurch ein Bild von der Art und Weise, wie der Mensch in der Außenwelt drinnensteht zwischen Geburt und Tod. Aber der Yogi, der strahlte gewissermaßen sein Seelisch-Gedankliches über den Atmungsprozeß aus. Er trieb mehr in sich hinein dieses ganze seelische Denken. Und die Folge davon war, daß jetzt aus seiner Seele ein besonderes Selbstgefühl, ein besonderes Ich-Gefühl auftauchte. Aber er fühlte das jetzt nicht als ein Mensch hier zwischen Geburt und Tod in der natürlichen Umgebung, sondern dadurch, daß er sein SeelischGedankliches in den Atmungsprozeß ausgestrahlt hatte, fühlte er sich wie zurückerinnert an die Zeit, bevor er heruntergestiegen war auf die Erde, an die Zeit, als er ein geistig-seelisches Wesen innerhalb einer geistig-seelischen Welt war. Geradeso wie der heutige Mensch bei normalem Bewußtsein- wenn er zum Beispiel eine besonders lebhafte Erinnerung hat an etwas, was vor zehn Jahren geschehen ist -, wie er sich da hineinfühlen kann in dieses Ereignis, aber auch meinetwillen in den Wald, in dem er dieses Ereignis erlebt hat, in die ganze Stimmung von dazumal, so fühlte sich der Yogi durch diesen veränderten Atmungsprozeß in die ganze Stimmung, in die ganze Umgebung hinein, in der er als geistig-seelisches Wesen innerhalb einer geistig-seelischen Welt gewesen war. Da fühlte er ganz anders gegenüber der Welt, als er hier als Mensch fühlte. Und aus dem, was ihn überkam, aus dem Verhältnis dieses jetzt erweckten Selbstes zu dem ganzen Universum, entstanden dann jene wunderbaren alten Dichtungen, von denen ein schönes Ergebnis zum Beispiel die Bhagavad Gita ist.

[ 13 ] Wenn Sie in der Bhagavad Gita diese wunderbaren Schilderungen von dem menschlichen Selbst lesen, wie es mitlebt mit allem, wie es untertaucht in alle Vorgänge der Natur, in alle einzelnen Geheimnisse der Welt, wie es in allem darinnen ist, so ist das eben die Wiedergabe jener durch den Yoga-Atmungsprozeß hervorgerufenen Erinnerungen an die Art, wie die Seele, als sie noch bloß Seele war, in einem geistigen Universum drinnen lebte. Und wenn Sie die Bhagavad Gita mit dem Bewußtsein lesen, daß eigentlich die in die geistige Welt zurückversetzte Seele mit dem erhöhten Selbstgefühl es war, die das alles sagt, was Krishna oder andere zu solchem Selbstgefühl gekommene alte Eingeweihte aushauchten, dann erst lesen Sie diese alten Dichtungen richtig.

[ 14 ] Man kann also sagen: Jene alten Weisen hoben sich heraus aus der Gesamtmasse der damaligen Bevölkerung und sonderten ihr Selbst streng ab von der Außenwelt. Sie sonderten es ab. Aber sie sonderten es nicht etwa durch egoistische Gedanken ab, sondern durch einen verwandelten Atmungsprozeß, der gewissermaßen mit dem Seelischen untertauchte in den inneren Luftrhythmus. Das war jene Art, in der in alten Zeiten ein Weg gesucht worden ist in die geistige Welt hinein.

[ 15 ] In späteren Zeiten wurde dieser Weg verändert. Man versetzte sich also in alten Zeiten in ein solch anderes Atmen. Man fühlte, wie die Gedanken durch die Atmungsströmungen gingen, und mit diesem Untertauchen der Gedanken, die da, ich möchte sagen, wie Schlangen durch die Atmungsströmungen gingen, fühlte man sein Selbst in dem Allweben der Welt drinnen, und man sprach dann das, was aus dieser Empfindung heraus sich offenbaren konnte, in gewissen Worten und Sprüchen aus. Man merkte, man redet anders, wenn man durch die Sprache offenbart, was in dieser Weise erlebt wurde. Und allmählich kam man davon ab, das, was ich geschildert habe, so stark, so intensiv zu erleben, daß das Erleben im Atmungsprozeß selbst drinnensteckte. Man erlebte nach und nach, wie sich die Worte aushauchten, wie sich die Worte von selber zu Sprüchen skandierten, von selber in das Rezitativ hineinkamen.

[ 16 ] Und so bildeten sich aus dem veränderten Atmungsprozeß heraus, indem man die Worte, die von diesem Atmungsprozeß getragen wurden, gewissermaßen abhob, so bildeten sich die mantrischen Sprüche heraus, die Mantrams. Und während in älteren Zeiten das Wesentliche der Atmungsprozeß und sein Erleben war, wurden es dann diese Sprüche. Das ging in die Tradition, das ging in das historische Bewußtsein der Menschen über, und daraus entstand im wesentlichen dann der spätere Rhythmus, Takt und so weiter der Dichtung.

[ 17 ] Wenn wir aber von dem, was in den älteren griechischen Zeiten zum Beispiel schon durchaus Gesetzmäßigkeit, zu erfühlende Gesetzmäßigkeit der Sprache war, was schon zum Hexameter, zum Pentameter geworden war, wenn wir von dem zurückgehen, so finden wir ein altes Atmungserlebnis. Das aber war bestimmt, den Menschen herauszutragen aus der Welt, in der er lebt zwischen Geburt und Tod, und hineinzutragen in eine geistig-seelische Welt.

[ 18 ] Es kann nicht die Aufgabe des heutigen Menschen sein, auf diese Weise, wie es in älteren Zeiten der Fall war, seinen Weg hinein in die geistige Welt zu suchen. Der heutige Mensch soll nicht auf dem Umwege durch das Atmen, sondern er soll auf einem seelischeren Wege, auf einem Wege mehr des Gedankens selber sich in die geistigen Welten hinaufleben. Daher ist es heute richtig, wenn der Mensch in der Meditation, in der Konzentration seiner Gedanken und Bilder das, was sonst bloßer logischer Zusammenhang ist, in einen, ich möchte sagen, musikalischen Zusammenhang innerhalb des Gedankens selbst verwandelt. Immer ist aber das heutige Meditieren zunächst ein Erleben in Gedanken, ein Übergang des einen Gedankens in den anderen, ein Übergang der einen Vorstellung in die andere.

[ 19 ] Während der alte indische Yogi von einer Atemart zu der anderen übergegangen ist, muß der heutige Mensch versuchen, lebendig sich mit seiner ganzen Seele zum Beispiel hineinzuleben in das Rot. Er bleibt also im Gedanklichen. Er lebt sich dann in das Blau hinein. Er macht den Rhythmus durch: Rot, Blau; Blau, Rot; Rot, Blau was ein Gedankenrhythmus ist, aber nicht so, wie er im logischen Denken abläuft, sondern als ein viel lebendigeres Denken.

[ 20 ] Wenn der Mensch genügend lange solche Übungen macht - genügend lange mußte auch der alte Yogi seine Übungen machen -, wenn er gewissermaßen den Schwung, den Rhythmus, die innere Qualitätsänderung: Rot, Blau; Blau, Rot; Hell, Dunkel; Dunkel, Hell erlebt kurz, wenn er solche Anweisungen befolgt, wie Sie ja einzelne in meinem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» finden; wenn der Mensch also stehenbleibend im Denken nun nicht gewissermaßen den Atem hineintreibt in den Nerven-Sinnesprozeß, sondern wenn er gleich beim Nerven-Sinnesprozeß beginnt und den Nerven-Sinnesprozeß selber in einen inneren Schwung und Rhythmus und in eine Qualitätsänderung hineinbringt, dann erlangt er gerade das Gegenteil von dem, was der alte Yogi erlangt hat. Der alte Yogi schaltete gewissermaßen den Denkprozeß mit dem Atmungsprozeß zusammen; er machte eines aus dem Denkprozeß und dem Atmungsprozeß. Wir versuchen heute den letzten Zusammenhang zwischen dem Atmungsprozeß und dem Denkprozeß, der ja ohnehin sehr unbewußt ist, noch zu lösen. Wenn Sie im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein sind, wenn Sie im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein nachdenken über Ihre natürliche Umgebung, so haben Sie niemals in Ihren Vorstellungen etwa einen bloßen Nerven-Sinnesprozeß, sondern da geht immer noch der Atem hinein. Sie denken, indem fortwährend Ihr Atem Ihren Nerven-Sinnesprozeß durchwellt und durchströmt.

[ 21 ] Alle Übungen des Meditierens der neueren Zeit gehen darauf aus, das Denken ganz loszulösen von dem Atmungsprozeß. Dadurch reißt man es aber nicht etwa aus dem Rhythmus heraus, sondern man reißt es nur aus einem Rhythmus heraus, der der innere Rhythmus ist. Aber man verbindet dann allmählich das Denken mit einem äußeren Rhythmus. Indem man das Denken loslöst vom Atmungsrhythmus — darauf gehen unsere heutigen Meditationen aus -, läßt man das Denken gewissermaßen hineinströmen in den Rhythmus der äußeren Welt. Der Yogi ging zu seinem eigenen Rhythmus zurück. Der heutige Mensch geht zu dem Rhythmus der äußeren Welt zurück. Lesen Sie gleich die ersten Übungen, welche ich angegeben habe in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?», wo ich zeige, wie man, sagen wir, das Keimen und das Wachsen einer Pflanze verfolgen soll. Die Meditation geht darauf hin, die Vorstellung, das Denken von dem Atmen loszulösen und es untertauchen zu lassen in die Wachstumskräfte der Pflanze selber.

[ 22 ] Das Denken soll in den Rhythmus hinausgehen, der die äußere Welt durchzieht. In dem Momente aber, wo das Denken wirklich in dieser Weise sich befreit von den leiblichen Funktionen, wo es sich losreißt vom Atem, wo es sich allmählich zusammenbindet mit dem äußeren Rhythmus, da taucht es unter, jetzt nicht in die sinnlichen Wahrnehmungen, in die sinnlichen Eigenschaften der Dinge, sondern da taucht es unter in das Geistige der einzelnen Dinge.

[ 23 ] Wenn Sie eine Pflanze anschauen - sie ist grün, sie ist in der Blüte rot. Das sagt Ihnen Ihr Auge. Darüber denkt dann Ihr Verstand nach. Von dem lebt unser gewöhnliches Bewußtsein. Ein anderes Bewußtsein entwickeln wir, wenn wir das Denken losreißen vom Atem, wenn wir es verbinden mit dem, was da draußen ist. Dieses Denken, das lernt mitvibrieren mit der Pflanze, wie sie heranwächst, wie sie sich in der Blüte entfaltet, wie sie, bei einer Rose zum Beispiel, aus dem Grün in das Rote hinübergeht. Das vibriert hinaus in das Geistige, das allen einzelnen Dingen der Außenwelt zugrunde liegt.

[ 24 ] Sehen Sie, das ist der Unterschied des modernen Meditierens von den Yogaübungen einer sehr alten Zeit. Dazwischen gibt es natürlich vieles, aber ich erwähne diese beiden Extreme. Und dadurch, daß der Mensch sich in diesen äußeren Rhythmus allmählich hineinlebt, geschieht nun folgendes.

[ 25 ] Der Yogi tauchte unter in seinen eigenen Atmungsprozeß. Er senkte sich selber in sich hinein. Dadurch bekam er das Selbst wie eine Erinnerung. Er erinnerte sich gewissermaßen an das, was er früher war, bevor er auf die Erde heruntergestiegen war. Wir gehen mit unserer Seele aus unserem Leibe heraus. Wir verbinden uns mit dem, was da draußen im Rhythmus, also geistig lebt. Dadurch schauen wir jetzt dasjenige an, was wir waren, bevor wir auf die Erde heruntergestiegen sind.

[ 26 ] Sehen Sie, das ist der Unterschied. Ich will es schematisch aufzeichnen: wenn das der Yogi war (Zeichnung 1, S. 138, hell), so entwickelte er sein starkes Ich-Gefühl (rot). Mit diesem Ich-Gefühl erinnerte er sich an dasjenige, was er war, bevor er auf die Erde heruntergestiegen ist, wo er in einer geistig-seelischen Umgebung war (blau). Es ging der Strom der Erinnerung zurück.

[ 27 ] Wenn das hier der moderne übersinnliche Erkenner ist (Zeichnung 2, S. 138, hell), so entwickelt er einen solchen Vorgang, daß er aus seinem Leibe herausgeht (blau), dadurch in dem Rhythmus der äußeren Welt lebt, und jetzt als einen äußeren Gegenstand dasjenige anschaut (rot), was er vorher war, bevor er auf die Erde heruntergestiegen ist.

[ 28 ] So ist die Erkenntnis des vorgeburtlichen Zustandes für die alten Zeiten etwas wie ein Erinnern gewesen. So ist das Erkennen des vorgeburtlichen Zustandes, wenn es richtig entwickelt wird, in der Gegenwart ein Anschauen dessen, wie man war (rot). Das ist der Unterschied.

[ 29 ] Nun ist das die eine Art gewesen, wodurch der Yogi sich in die geistigen Welten hinauflebte. Eine andere Art war diese, daß er seinem Leib bestimmte Stellungen gab. Er machte zum Beispiel die Übung: Mit seinen Armen ausgestreckt längere Zeit zu verharren, oder er nahm eine ganz bestimmte Stellung an, indem er ein Bein über das andere kreuzte und sich auf seine eigenen Beine setzte und so weiter. Was erlangte er dadurch?

[ 30 ] Dadurch, sehen Sie, kam er in die Möglichkeit hinein, wahrzunehmen, was diejenigen Sinne wahrnehmen, die man heute kaum berücksichtigt. Wir wissen ja, der Mensch hat nicht nur fünf, sondern zwölf Sinne. Er hat, wenn wir von den gewöhnlichen Sinnen absehen, zum Beispiel den Gleichgewichtssinn - ich habe über das öfter gesprochen -, durch den er wahrnimmt, wie er sich im Gleichgewicht erhält, daß er nicht nach links, rechts, rückwärts, vorne fällt. Geradeso wie man Farben wahrnimmt, so muß man auch sein Gleichgewicht wahrnehmen, sonst würde man nach allen Seiten gleiten und umfallen. Der Betrunkene oder der Ohnmächtige nimmt das eben nicht wahr, daher taumelt er auch. Nun, um sich diesen Gleichgewichtssinn zum Bewußtsein zu bringen, nahm der Yogi gewisse Attitüden des Organismus ein. Dadurch entwickelte er ein feines, starkes Gefühl für die Richtungen. Wir reden von Oben und Unten, Rechts und Links, Vorne und Hinten, als ob das alles ganz einerlei wäre. Das wurde für den Yogi allmählich etwas, was er sehr stark und fein empfand dadurch, daß er seinem Körper längere Zeit gewisse Stellungen gab. Er entwickelte dadurch gerade ein feines Gefühl für diese anderen Sinne, die ich außer den fünf Sinnen angeführt habe. Aber wenn diese anderen Sinne erlebt werden, haben sie einen viel geistigeren Charakter als die gewöhnlichen Sinne. Und der Yogi lebte sich dadurch wiederum hinein in ein Wahrnehmen für die Richtungen des Raumes.

[ 31 ] Das müssen wir uns wieder erringen, aber auf eine andere Weise. Wir können, aus Gründen, die ich bei einer anderen Gelegenheit weiter ausführen werde, nicht in solcher Weise üben, wie es in der alten Yoga geschah. Aber indem wir solche Übungen des Denkens vornehmen, wie ich sie eben beschrieben habe, die sich loslösen können vom Atmen, die sich einleben in den äußeren Rhythmus, da erleben wir auf diese Weise den Unterschied in den Richtungen. Wir erleben, was es heißt, daß das Tier lebenslänglich sein Rückgrat horizontal hat und daß der Mensch sein Rückgrat vertikal hat. Für die gewöhnliche unorganische Natur wissen die Menschen, daß die Magnetnadel nur nach der Richtung Nord-Süd weist, daß diese Nord-Süd-Richtung im Irdischen etwas Besonderes bedeutet für die Entwickelung der magnetischen Kraft, weil die Magnetnadel, die sich sonst neutral verhält, sich in diese Lage hineinfindet; daß das also eine besondere Richtung ist. Indem wir uns in den äußeren Rhythmus mit unseren Gedanken hineinfinden, lernen wir erkennen, wie anders es ist, die Horizontallinie mit dem Rückgrat einzuhalten als die Vertikallinie. Wir lernen das alles im Gedanken selber, indem wir im Gedanken bleiben. Der indische Yogi lernte das auch, indem er seine Beine kreuzte, sich auf die eigenen Beine setzte und dabei die Arme hoch hielt. Er lernte also aus dem Körperlichen heraus das unsichtbare Bedeutungsvolle von Raumrichtungen. Der Raum ist nicht ein beliebiges Nebeneinander, sondern nach allen Seiten hin so organisiert, daß die Richtungen verschiedenen Wert haben. Solche Übungen also, die den Menschen hineinführen in die höhere Welt, wie ich sie jetzt geschildert habe, sind mehr Übungen, die nach der Gedankenseite hingehen.

[ 32 ] Es gibt aber auch Übungen, die nach der anderen Seite hingehen, und da finden wir unter den mannigfaltigen Übungen, die auf diesem Felde vorhanden sind, die des asketischen Lebens, wo die Funktionen des physischen Leibes heruntergestimmt wurden, wo dem physischen Leibe geradezu allerlei Entbehrungen, Leidensvolles zugefügt wurde. Dadurch wurde der physische Leib gewissermaßen aus seinen normalen Funktionen herausgebracht. Was ältere Asketen nach dieser Richtung geleistet haben, davon macht sich der moderne Mensch keine Vorstellungen, denn der moderne Mensch, der will so gründlich als möglich in seinen Organismus hinein. Jedes Mal, wenn der alte Asket diese oder jene körperlichen Funktionen schmerzvoll unterdrückte, zog sich sein Geistig-Seelisches aus dem Organismus heraus.

[ 33 ] Nicht wahr, wenn Sie leben, so wie eben im normalen Leben gelebt wird, dann ist das Geistig-Seelische mit dem physischen Organismus so verbunden, wie das eben zwischen Geburt und Tod nach der menschlichen Organisation sein soll. Wenn Sie die körperlichen Funktionen in asketischer Weise herabdrücken, dann geschieht etwas Ähnliches, wie es heute in minderem Grade bei den Menschen geschieht, die sich irgendwo etwas verletzen.

[ 34 ] Nun, wenn man weiß, wie der heutige Mensch ist, wenn ihm nur ein klein wenig etwas weh tut, dann ist es klar, daß es von da ein weiter Abstand ist zu dem, was zuweilen alte Asketen ertrugen, um nur ihren seelischen Organismus freizubekommen. Dann erlebten sie aber mit dem seelischen Organismus, der durch die Askese aus dem Körper herausgetrieben wurde, in der geistigen Welt. Im wesentlichen sind eigentlich auf diesem Wege alle älteren großen Religionsvorstellungen gewonnen.

[ 35 ] Die modernen Erklärer des religiösen Bewußtseins machen sich die Sache etwas leicht. Sie erklären die religiösen Vorstellungen für eine Dichtung, weil sie vor allen Dingen an dem Satze festhalten: Dasjenige, was der Mensch über die Welt an solchen Erkenntnissen gewinnen soll, das darf nicht weh tun. — Auf diesem Standpunkt standen eben die alten Religionssucher nicht, sondern sie waren sich klar: Wenn der Mensch in seinem physischen Organismus voll drinnensteckt — was für seine irdische Arbeit selbstverständlich das Richtige ist; es soll nicht ein falsches, weltfremdes Wesen etwa als das Richtige geschildert werden -, kann er nichts erleben in der geistigen Welt. Dieses Erleben in der geistigen Welt, das suchten eben die alten Asketen dadurch, daß sie den Körper abstumpften, ihm sogar Schmerz zufügten. Denn jedesmal, wenn sie aus einem Glied durch Schmerz das Geistig-Seelische heraustrieben, erlebte dieses Stück Geistig-Seelisches in der geistigen Welt. Und die großen Religionen sind eben nicht schmerzlos errungen, sondern sie sind durch gründliches Erleiden errungen.

[ 36 ] Dasjenige, was sich da als Ergebnisse der menschlichen Entwickelung mitgeteilt hat, das wird heute durch den Glauben aufgenommen. Heute trennt man hübsch voneinander ab: Wissen auf der einen Seite, das Wissen soll Naturwissen der äußeren Welt sein. - Nun, das erwirbt man durch den Kopf. Der Kopf ist dickschädelig, dem tut das nicht weh, insbesondere weil auch die Erkenntnisse durch außerordentlich dünnmaschige Begriffe gewonnen werden. Und auf der anderen Seite: Was sich erhalten hat als ehrwürdige Traditionsvorstellungen, das nimmt man, wie man sagt, durch den Glauben auf. Aber eigentlich müßte man von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkt aus sagen: Der Unterschied zwischen dem Wissen und dem Glauben ist der, daß man heute den Willen hat, als Wissen nur dasjenige gelten zu lassen, was nicht weh tut, wenn man es erringt, und daß man durch den Glauben, der auch nicht weht tut, dasjenige zu erringen sucht, was einmal als ein Wissen, das allerdings nicht der sinnlichen Welt angehört, auf sehr schmerzvolle, leidvolle Art errungen worden ist.

[ 37 ] Nun, auch der asketische Weg kann nicht der Weg des Menschen der Gegenwart sein, trotz alledem, was ich eben gesagt habe. Warum, das werden wir bei einer anderen Gelegenheit betrachten. Aber es ist heute durchaus möglich, durch eine innere Selbstzucht, durch eine Willenszucht, dadurch, daß man seine Entwickelung, die sonst nur das Leben und die Erziehung bringt, selbst in die Hand nimmt, in der eigenen Persönlichkeit in die Willenswachstumskräfte einzugreifen. Wenn man sich zum Beispiel sagt: Du mußt in fünf Jahren dir etwas angewöhnt haben, und du willst diese fünf Jahre alle Gewalt deines Willens darauf lenken, dir dieses anzugewöhnen - wenn man dann so die Entfaltung des Willens nach der inneren Vervollkommnung treibt, dann löst man das Geistig-Seelische auch ohne Askese aus dem Leiblichen heraus, dann fühlt man zunächst das, was man in dieser Selbstvervollkommnung unternehmen muß, als etwas, was unter fortwährender Eigentätigkeit vollzogen werden soll.

[ 38 ] Jeden Tag muß man irgend etwas innerlich verrichten. Es sind manchmal kleine Verrichtungen, aber sie müssen mit eisernem Fleiß und mit einer unwiderstehlichen Geduld ausgeübt werden. Man kann es ja öfter erleben, daß, wenn man den Leuten solche Übungen empfiehlt wie: Du sollst zum Beispiel an jedem Morgen einen ganz bestimmten Gedanken haben -, sie voller Feuereifer sind, das zu tun. Aber es dauert nicht lange, da erlahmt wiederum alles, und da soll die Sache von selber gehen. Da merken Sie, das wird mechanisch, weil sie die stärkere Kraft, die immer mehr und mehr nötig wird, nun nicht anwenden wollen. Erstens hat man also diesen Widerstand der eigenen Trägheit zu überwinden; dann aber kommt der andere Widerstand, der von dem Objektiven herrührt. Es ist, wie wenn man sich durch etwas Dichtes hindurcharbeiten müßte, und dann kommt wirklich jenes innere Erlebnis, daß das Denken, das sich allmählich entwickelt hat, das lebendig geworden ist, das jetzt Raumrichtungen, überhaupt Lebendiges wahrnimmt, das in den Rhythmus der äußeren Welt sich hineinfindet, daß das einem weh tut, daß jede Erkenntnis, die errungen wird, schmerzt.

[ 39 ] Ich kann mir ganz gut moderne Menschen vorstellen, die den Weg in die höheren Welten hinein gehen wollen. Sie fangen an. Die allererste leise Erkenntnis kommt. Das tut weh. Also bin ich krank, sagen sie. Es ist selbstverständlich, wenn einem etwas weh tut, so ist man krank. Aber wenn man höhere Erkenntnisse erringt, dann kann es einem manchmal sehr vielweh tun, und man ist doch nicht krank. Es ist allerdings bequemer, anstatt fortzuschreiten auf dem Wege, den die höhere Erkenntnis notwendig macht - denn die seelischen Leiden werden immer größer -, es ist leichter, statt zu streben, diese seelischen Leiden zu überwinden, sich kurieren zu lassen. Man läßt sich etwas verschreiben, statt daß man aufdem Wege weitergeht. Selbstverständlich ist dies bequemer. Aber man kommt in der Erkenntnis nicht weiter dadurch. Für den modernen Menschen ist es so, daß auch dieses Hineintauchen in den Schmerz, in das Leiden ein innerer seelischer Weg wird, so daß es sich rein seelisch abspielt, daß der Körper daran zunächst nicht eigentlich teilnimmt, insofern als der Körper robust und stark und der Außenwelt gewachsen bleibt, wie er es sonst bei den Menschen heute ist. Dadurch aber, daß der Mensch beginnt, seine Erkenntnisse wie etwas an sich herankommen zu lassen, das Leid bedeutet, dadurch kommt er heute wiederum in diejenigen Regionen des geistigen Lebens hinein, aus denen einstmals die großen Religionswahrheiten geholt worden sind. Die großen Religionswahrheiten, das heißt diejenigen Wahrheiten, die religiös stimmen durch den Eindruck, den die höhere Welt, die übersinnliche Welt, die Welt, in der unsere Unsterblichkeit zum Beispiel wurzelt, macht, diese Wahrheiten können nicht ohne schmerzliche innere Erlebnisse errungen werden.

[ 40 ] Wenn sie so errungen werden, können sie dann wiederum dem allgemeinen Menschenbewußtsein übergeben werden. Die Menschen sträuben sich heute gegen solche Wahrheiten aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil sie den Dingen anspüren, sie sind nicht so, wie man es gerne haben möchte.

[ 41 ] Denken Sie doch nur einmal, daß manchem schon recht fatal sein könnte, daß ich gestern gesagt habe: In diesen sich umwandelnden Astralleib, der dann im Herzen eingreift in den Ätherleib, da wird alles eingeschrieben, was der Mensch an Tätigkeit vollbringt, sogar dasjenige, was er einem anderen aufträgt, schreibt sich ein. Schon dieser Gedanke macht manchen zappelig im Inneren. Und die großen Wahrheiten fordern eben auch in gewissem Sinne einen inneren Mut der Seele, der sich dazu aufschwingt, sich zu sagen: Erlebst du diese Dinge, dann muß du bereit sein, Erkenntnis dir zu erringen durch Entbehrung und Schmerz.

[ 42 ] Das soll nicht zur Entmutigung gesprochen sein, obwohl es heute für viele Menschen zur Entmutigung gesprochen ist, aber es ist eben einfach aus der Wahrheit heraus gesprochen. Was nützt es, den Menschen zu sagen, sie können im Wohlergehen in die höchsten Welten einziehen, wenn es doch nicht wahr ist, wenn das Eindringen in die höheren Welten erfordert, daß Überwindungen geschehen, daß Leidvolles überwunden werde.

[ 43 ] Und so versuchte ich Ihnen heute zu schildern, meine lieben Freunde, wie man zu dem Menschlichen vordringt. Dieses Menschlich-Seelisch-Geistige ist Ja tief innerlich im Menschen verborgen. Man muß erst zu ihm vordringen. Aber der Mensch muß auch, wenn er nicht selber vordringt, wissen, daß da in ihm ein Verborgenes ist, und er muß kennenlernen aus den Anforderungen der heutigen Zeit heraus, wie solche Dinge, wie sie gestern geschildert worden sind, in Wahrheit verlaufen.

[ 44 ] Finden kann man solche Dinge nur auf solchen Erkenntniswegen, wie ich sie heute wieder angedeutet habe und wie sie in verschiedener Weise gegangen worden sind in alten und in neuen Zeiten.

[ 45 ] Morgen wollen wir dann die gestrigen und die heutigen Betrachtungen verbinden in eine solche, die uns weiter hineinführen soll in die geistigen Welten, wie wir das auch heute versuchten.

Seventh Lecture

[ 1 ] Today I would like to point out the way in which, at different times, people have come to gain insights such as those I presented yesterday in relation to the development of the human etheric and astral bodies. From a description of how such views are arrived at, some light can be shed on the nature of the human being, on the relationship of the human being to the world, and so on. It is by no means necessary for everyone to be able to reproduce such things in a certain way, but from the descriptions of how they have taken place here and there, or are still taking place, one will already gain something that in turn sheds light on the results that are so important for every human being. The way in which people in very ancient times arrived at their supersensible insights and the way in which such insights are gained today are quite different from each other. I have often pointed out how, in earlier times, human beings possessed a certain instinctive clairvoyance, how this clairvoyance gradually developed through various intermediate stages into the view of the world that human beings today must call their own, and how a certain higher consciousness can then develop out of this general consciousness. How human beings today, when they correctly understand their time and their relationship to it, can attain higher knowledge is described in the second part of my “Outline of Secret Science,” in the book “How to Know Higher Worlds,” and in other writings. But today I would like to give you a description from a certain point of view, taking into account what I explained here yesterday. If we go back to very ancient times in human evolution and consider the spiritual striving of those times, we find, among other things, the spiritual striving that existed in the ancient Orient, in that culture whose later period became known as Indian culture and to which many people are returning today because they cannot bring themselves to understand that every age must go its own way in order to penetrate the supersensible worlds.

[ 2 ] I have already indicated here that from the total mass of human beings who lived during the period I have called the “primitive Indian period” in my “Secret Science,” individual personalities, in a manner appropriate to the time, developed inner forces of the human being which then led them up into the supersensible worlds. One of these paths, which I have already mentioned here in another context, is called the path of yoga.

[ 3 ] The path of yoga can best be understood by first looking at the rest of humanity, from whom the yogi, that is, the one who wanted to attain higher knowledge through this path, stood out. In those earlier times of human development, the general consciousness was very different from what it is today. We humans today look out into the world and perceive, for example, colors and sounds through our senses. We search for laws in this sensory world, but we are aware that if we go further, if we want to live ourselves into external things in a spiritual-soul way, so to speak, we are drawing on our imagination. That was not the case in those earlier times. As we know, people then saw more in the external world than normal people see today. In lightning and thunder, in all the individual stars, in the beings of the various natural kingdoms, the ancient people saw something spiritual and soul-like at the same time. They perceived spiritual beings, albeit of a lower order, in everything solid, in everything liquid, in the air, and so on. Today, intellectual scholarship says that these ancient people simply dreamed all kinds of spiritual and soul things into the environment they saw through their imagination. This is called animism.

[ 4 ] Now, one has a poor understanding of human nature, and especially of human nature in those earlier times, if one believes that these people dreamed all kinds of beings into lightning and thunder, into springs and rivers, into wind and weather out of their imagination. No, that is not the case. They saw them. Just as we see red and blue or hear C sharp and G flat, these older people saw spiritual and soulful beings in the things of the outer world. It was as natural for them to see these spiritual and soulful beings as it is natural for us to see blue and red. But there was something else connected with this. It was connected with the fact that people did not have a clear sense of self-awareness.

[ 5 ] The clear self-awareness that we as normal people today are imbued with was lacking in those older times. In a sense, human beings did not differ from the external world. What my hand would see if it had consciousness, namely that it is not independent, that it is only a limb of my organism, was felt by those older people, even if they did not express it. They felt themselves to be limbs of the whole universe. They did not separate their own human essence from their surroundings in any intense way. One such older person walked along the river for my sake. When we walk along a river today in the direction in which the river flows, we, as intelligent people of today, naturally have the feeling that we are stepping forward with our legs and moving downward; this has nothing to do with the river. Older people did not generally feel this way. When they walked along the bank of the river downstream — which was completely natural to them — they felt the spiritual beings connected with the downstream flow of the river in the same way that a swimmer today feels carried by the water, that is, by something material. They felt themselves being led down by the spiritual. This is just one example. Everything that humans experienced in the external world was thought and felt in such a way that they felt themselves carried and driven, we might say, by wind gods, river gods, by everything that was out there. They felt the elements of nature within themselves. This ability to empathize with nature has been lost to humans. But in return, they have gradually gained an intense sense of independence, a sense of self.

[ 6 ] From the entire mass of people who felt this way, the yoga scholar, the yogi, now stood out. He performed certain exercises, and I am referring here to those exercises that later fell into decadence, which, while they were well suited to an older human nature, were later used almost exclusively, I would say, for harmful purposes. These are the exercises I have mentioned here several times: the exercises of yogic breathing. What I am describing now applies, so to speak, only to people of a very ancient Oriental culture as a legitimate way of ascending to the higher worlds.

[ 7 ] In ordinary life, breathing in humans is unconscious. People breathe in, hold their breath, breathe out, and only when they are not completely healthy in some way do they become aware of this breathing. In ordinary life, it remains for the most part an unconscious process. Through certain periods of practice, however, the yogi transformed breathing into a conscious inner process by changing the time intervals during which he inhaled, held his breath, and exhaled, thus changing the entire rhythm of the breathing process. He inhaled for a longer period of time, held his breath longer, exhaled differently at a different time; in short, he gave himself a different breathing rhythm than the usual one. This made the entire breathing process more conscious to him. He lived, so to speak, into his breathing. The feeling he got from himself was that of constantly going along with the inhalation, with the spreading of the breath in the body, and with the exhalation. In this way, the person drew his entire soul into his breathing.

[ 8 ] If we want to understand what has actually been achieved by this, we can say: When we breathe in, for example, the breath enters our organism, then passes through the spinal canal into the brain, where it spreads within the processes that take place in the nervous system, in the sensory system. So when we think as human beings, we never have merely the senses and the nervous organism as tools of this thinking, but the sensory and nervous organisms are continually rhythmicized, permeated, flowed through, and undulated by the breathing process, by the breathing rhythm. We do not think without this breathing rhythm rhythmically permeating our nervous and sensory processes. It is only because the entire breathing process remains unconscious in normal people today that this also remains unconscious.

[ 9 ] In the yogi, this altered breath was consciously drawn into the nerve-sense process. As a result, the yogi experienced an inner process consisting of what took place through the nerve-sense process and what surged and swirled through the brain and also through the senses as a result of the altered breathing rhythm. In this way, however, he also lived the soul life of his thinking into the breathing rhythm.

[ 10 ] This brought something very special to this yogi. He radiated, as it were, the thinking that is otherwise hardly felt as a mental process, into his entire organism. He did not merely think, but felt how the thought, I might say, like a little animal, passed through the breathing process that he had brought about as an artificial process.

[ 11 ] Fr thus felt thinking not only as something logical and shadowy, but he felt how thinking went along with the breathing process. When he inhaled, he felt that he was taking something in from the outside world; now he let the breathing process flow into his thinking. In a sense, he attacked with his thoughts what he had inhaled with the air, and now he spread it throughout his entire organism. This gave the yogi a heightened sense of self, a heightened sense of self-awareness. He spread his thinking sensually throughout his entire inner being. He became aware of his thinking in the air, namely in the regular process of breathing that was taking place within him.

[ 12 ] Now, this had a very special consequence for him. When human beings today feel themselves in the sensory world, it is quite true that they have something in their thinking that they hardly notice. His senses already inform him about what is in the outer world, and when he looks back at himself, he sees at least parts of himself. This gives him a picture of the way in which human beings stand in the outer world between birth and death. But the yogi, in a sense, radiated his soul-thoughts through the breathing process. He drove all this soul thinking deeper into himself. And the result was that a special sense of self, a special sense of “I,” emerged from his soul. But he did not feel this as a human being here between birth and death in the natural environment. Rather, because he had radiated his soul-mind into the breathing process, he felt as if he were being reminded of the time before he had descended to earth, to the time when he was a spiritual-soul being within a spiritual-soul world. Just as the modern human being in normal consciousness—when he has, for example, a particularly vivid memory of something that happened ten years ago—can feel himself into that event, but also, for my sake, into the forest where he experienced this event, into the whole atmosphere of that time, so the yogi felt, through this altered breathing process, into the whole atmosphere, into the whole environment in which he had been as a spiritual-soul being within a spiritual-soul world. There he felt completely different toward the world than he felt here as a human being. And from what came over him, from the relationship of this now awakened self to the whole universe, arose those wonderful ancient poems, a beautiful result of which is, for example, the Bhagavad Gita.

[ 13 ] When you read in the Bhagavad Gita these wonderful descriptions of the human self, how it lives with everything, how it submerges itself in all the processes of nature, in all the individual mysteries of the world, how it is in everything within it, this is precisely the reproduction of those memories evoked by the yoga breathing process of how the soul, when it was still just a soul, lived in a spiritual universe. And when you read the Bhagavad Gita with the awareness that it was actually the soul, restored to the spiritual world with an elevated sense of self, that said all that Krishna or other ancient initiates who had attained such a sense of self uttered, only then will you read these ancient poems correctly.

[ 14 ] One can therefore say that those ancient sages distinguished themselves from the general population of their time and strictly separated their selves from the outside world. They separated it. But they did not separate it through selfish thoughts, but through a transformed breathing process, which, in a sense, submerged the soul into the inner rhythm of the air. That was the way in which, in ancient times, a path into the spiritual world was sought.

[ 15 ] In later times, this path was changed. In ancient times, people put themselves into such a different breathing state. They felt how their thoughts passed through the breathing currents, and with this submerging of the thoughts, which I would like to say, like snakes passing through the respiratory currents, one felt one's self within the universal web of the world, and one then expressed in certain words and sayings what could be revealed from this feeling. One noticed that one speaks differently when one reveals through language what has been experienced in this way. And gradually one ceased to experience what I have described so strongly, so intensely, that the experience was contained within the breathing process itself. One gradually experienced how the words breathed themselves out, how the words chanted themselves into sayings, how they entered into recitative of their own accord.

[ 16 ] And so, out of the changed breathing process, by lifting the words carried by this breathing process, so to speak, the mantric sayings, the mantrams, emerged. And while in earlier times the essence was the breathing process and its experience, it then became these sayings. This became tradition, it passed into the historical consciousness of the people, and from this essentially arose the later rhythm, meter, and so on of poetry.