The Mystery of the Trinity

Part 1: The Mystery of Truth

GA 214

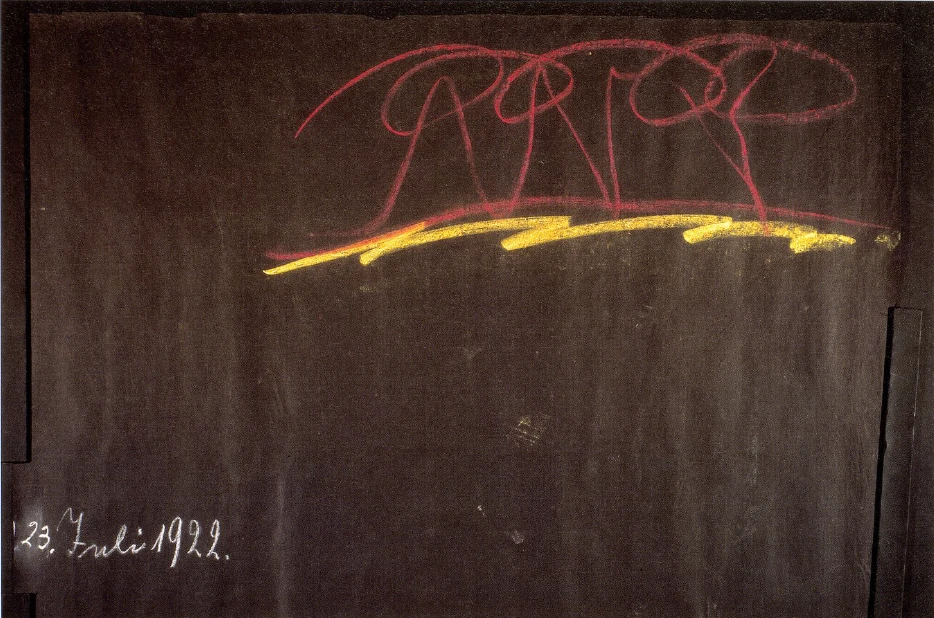

23 July 1922, Dornach

Lecture I

We have often drawn attention to the fact that the spiritual life of the first four Christian centuries has been completely buried, that everything written today about the views and knowledge of human beings living at the time of the mystery of Golgotha and during the four centuries thereafter is based on sources which have come to us essentially through the writings of the opponents of gnosticism. This means that the “backward seeing” of the spiritual researcher is necessary to create a more exact picture of what actually took place during these first four Christian centuries. In this sense I have recently attempted to present a picture of Julian the Apostate.1Julian, the Apostate (332–363), Roman Emperor (361–363). Steiner is referring to his lecture of July 16, 1922 (GA213). Cf. Rudolf Steiner: Occult History (Lecture Four), Building Stones for an Understanding of the Mystery of Golgotha (Lecture Seven), World History in the light of Anthroposophy (Lecture Six).

Now, we cannot say that the following centuries, as presented in the usual historical descriptions, are very clear to people today. What we could call the soul life of the European population from the fifth on into the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries remains completely unclear in the usual historical portrayals. What do we find, then, basically represented in these usual historical portrayals? And what do we find even if we look at the writings of facile, so-called dramatists and authors, writers such as Ernst von Wildenbruch,2 Ernst von Wildenbruch (1845–1909), German writer, author of historical dramas, novels, and verse. whose writings are, in essence, nothing more than the family histories of Louis the Pious or other similar personages, garnished with superficial pageantry, and then presented to us as history?

It is extremely important to look at the truth concerning European life during those times when so much of the present originated. If we want to understand anything at all concerning the deeper streams of culture, including the culture of recent times, we must understand the soul life of the European population in those times. Here I would like to begin with something which will, no doubt, be somewhat remote from many of you; we need, however, to address this subject because it can only be seen properly today in the light of spiritual science.

As you know there is something today called theology. This theology—basically all our present day European theology—actually came into being—in its fundamental structure, in its inner nature—during the time from the fourth and fifth centuries after Christ through the following very dark centuries up to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, when it was brought to a certain conclusion through scholasticism. From the point of view of this theology, which was really only developed in its essential nature in the time after Augustine, Augustine himself could no longer be understood; or, at best, he could barely be understood, while all that preceded him, for example, what was said about the mystery of Golgotha, could no longer be understood at all.3 St. Augustine, Bishop of Hippo (354–430). Early Latin church father. Exerted tremendous influence on later Christian thought. Cf. Rudolf Steiner: Christianity as Mystical Fact, Building Stones for an Understanding of the Mystery of Golgotha, (Lecture Seven). Let us consider the essence of this theology which developed precisely during the darkest times of the Middle Ages, darkest, that is, for our external knowledge. Above all, it becomes clear to us that this theology is something entirely different from the theology that came before it—if indeed what came before can be called theology. What theology had been before was actually only transplanted like a legacy into the times in which the theology I have just characterized arose. And you can get an impression of what earlier theology was like if you read the short essay on Dionysius the Areopagite in this week's edition of the Goetheanum,4 Steiner is here referring to an essay by Günther Wachsmuth on Dionysius the Areopagite and the doctrine of the hierarchies that appeared in Das Goetheanum, July 23 and July 30, 1922. There you will find a portrayal of the way in which human beings related to the world in the first Christian centuries, a way altogether different from that which came to prevail by the time of the ninth, tenth, and following centuries.

In contrast to the later, newer theology, the old theology—the theology of which Dionysius the Areopagite was a late product—saw everything that related to the spiritual world from within and had a direct view of what happens in the spiritual worlds. If we want to gain insight into the way adherents of this old theology actually thought, into the way the soul of this theology inwardly regarded things, then once again we can really only do so with the methods of present-day anthroposophical spiritual science.

We then come to the following results. (Yesterday, from another point of view I characterized something very similar.)5 Lecture of July 22, 1922 (GA213).

In the ascent to Imagination, in the entire process of climbing, ascending to imaginative knowledge, we notice more and more that we are dwelling suspended in spiritual processes. This “hovering” in spiritual processes with our entire soul life we experience as if we were coming into contact with beings who do not live on the physical plane. Perceptions from our sense organs cease, and we experience that, to a certain extent, everything that is sense perception disappears. But during the whole process it seems as if we were being helped by beings from a higher world. We come to understand these as the same beings that the old theology had beheld as angels, archangels, and archai. I could, therefore, say that the angels help us to penetrate up into imaginative knowledge. The sense world “breaks up,” just as clouds disperse, and we see into what is behind the sense world. Behind the sense world a capacity that we can call Inspiration opens up; behind this sense world is then revealed the second hierarchy, the hierarchy of the exusiai, dynamis, and kyriotetes. These ordering and creative beings present themselves to the inspired knowledge of the soul. And when we ascend further still, from Inspiration to Intuition, then we come to the first hierarchy, the thrones, cherubim, and seraphim. Through immediate spiritual training we can experience the realities that the older theologians actually referred to when they used such terms as first, second, and third hierarchy.

Now, it is just when we look at the theology of the first Christian centuries, which has been almost entirely stamped out, that we notice the following: in a certain way that early theology still had an awareness that when man directs his senses toward the usual, sensible, external world, he may see the things in that world and he may believe in their existence, but he does not actually know that world. There is a very definite consciousness present in this old theology: the consciousness that one must first have experienced something in the spiritual world before the concepts present themselves with which one can then approach the sense world and, so to speak, illuminate it with ideas acquired from the spiritual world.

In a certain way this also corresponds to the views resulting from an older, dreamlike, atavistic clairvoyance, under the influence of which people first looked into a spiritual world—though only with dreamlike perceptions—and then applied what they experienced there to their sense perceptions. If these people had had before them only a view of the sense world, it would have seemed to them as if they were standing in a dark room with no light. However, if they first had their spiritual vision, a result of pure seeing into the world of the spirit, and then applied it to the sense world—if, for example, they had first beheld something of the creative powers of the animal world and then applied that vision to the outer, physical animals—then they would feel as though they were walking into the dark room with a lamp. They would feel that they were walking into the world of the senses and illuminating it with a spiritual mode of viewing. Only in this way was the sense world truly known. This was the consciousness of these older theologians. For this reason the entire Christology of the first Christian centuries was actually viewed from within. The process which took place, the descent of Christ into the earthly world, was essentially seen not from the outside but rather from the inside, from the spiritual side. One first sought out Christ in spiritual worlds and then followed him as he descended into the physical, sensible world. That was the consciousness of the older theologians.

Then the following happened: the Roman world, which the Christian impulse followed in its greatest westward development, was permeated in its spiritual understanding with an inclination, a fondness, for the abstract. The Romans tended to translate perceptions, observations, and insights into abstract concepts. However, the Roman world was actually decaying and falling apart while Christianity gradually spread toward the west. And, in addition, the northern peoples were pushing from the eastern part of Europe into the west and the south. Now, it is remarkable that, at the very time Rome was decaying and the fresh peoples from the north were arriving, a college was created on the Italian peninsula, a collegium concerning which I spoke recently, which set for itself the task of using all these events to completely root out the old views and modes of seeing, to allow to survive for posterity only those writings which this college felt comfortable with.6 Lecture of July 16, 1922 (GA213).

History reports nothing concerning these events; nevertheless, they were real. If such a history did exist, it would point out how this college was created as a successor to the pontifical college of ancient Rome. Everything that this college did not allow was thoroughly swept away and what remained was modified before being passed on to posterity. Just as Rome invented the last will and testament as a part of its national economic order so that the dispositions of the individual human will could continue to work beyond the individual's life, so there arose in this college the desire to have the essence of Rome live on in the following ages of historical development if only as an inheritance, as the mere sum of dogmas that had been developed over many generations. “For as long as possible nothing new shall be seen in the spiritual world”—so decreed this college. “The principle of initiation shall be completely rooted out and destroyed. Only the writings we are now modifying are to survive for posterity.” If the facts were to be presented in a dry, objective fashion they would be presented in this way. Entirely different destinies would have befallen Christianity—it would have been entirely rigidified—had not the northern peoples come pushing into the west and the south. These northern peoples brought with them their own natural talent, a predisposition entirely different from that of the southern peoples, the Greeks and the Romans—different, that is, from that earlier southern predisposition that had originated the older theology.

In earlier times at least, the talent of the southern peoples had been the following: Among the earlier Romans and even more among the earlier Greeks there were always individuals from the mass of the people who developed themselves, who passed through an initiation and then could see into the spiritual world. With this vision the older theology arose, the theology that possessed a direct perception of the spiritual world. Such vision in its last phase is preserved in the theology of Dionysius the Areopagite. Let us consider one of the older theologians, say from the first or second century after the mystery of Golgotha, one of those theologians who still drew wisdom from the old science of initiation. If he had wanted to present the essence, I would like to say, the principles of his theology, he would have said: In order to have any relationship to the spiritual world, a human being must first obtain knowledge of the spiritual world, either directly through his own initiation or as the pupil of an initiate. Then, after acquiring ideas and concepts in the spiritual world he could apply these ideas and concepts to the world of the senses. Those were more or less the abstract principles of such an older theologian. The whole tendency of the older theological mood predisposed the soul to see the events in the world inwardly, first to see the spiritual and then to admit to oneself that the sensible world can only be seen if one starts from the spiritual. Such a theology could only result as the ripest product of an old atavistic clairvoyance, for atavistic clairvoyance was also an inner seeing or perception, though only of dreamlike imaginations.

But to begin with, the peoples coming down from the north had nothing of this older theological drive, that, as I said, was so strong in the Greeks. The natural abilities of the Gothic peoples, the Germanic, did not allow such a theological mood to rise up directly in the soul in an unmediated way. To properly understand the drive that these northern peoples brought into the development of Europe in the following ages (through the Germanic tribes, the Goths, the Anglo-Saxons, the Franks, and so forth) we must resort to spiritual scientific means, for recorded history reports nothing of this. Initiates, able to see directly into the spiritual world in order to survey from that vantage point the sense world, could not arise from within the ranks of these peoples storming down from the north because their inner soul disposition was different. These peoples were themselves still somewhat atavistically clairvoyant; they were actually still at an earlier, more primitive stage of humanity's development. These peoples—Goths, Lombards, and so forth—still brought some of the old clairvoyance with them. But this old clairvoyance was not related to inner perceptions—to spiritual perceptions, yes—but rather to spiritual perceptions of things outer. The northern peoples did not see the spiritual world from the inside, so to speak, as had the southern peoples. The Northerners saw the spiritual world from the outside.

What does it mean to say that these peoples saw the spiritual world from the outside? Say that these people saw a brave man die in battle. The life in which they saw this man spiritually from the outside was not at an end for them. Now, with his death, they could follow him—still from the outside spiritually speaking—on his path into the spiritual world. They could follow not only the way this man lived into the spiritual world but also the ways in which he continued to be active on behalf of human beings on the earth. And so these northern peoples could say: Someone or other has died, after this or that significant deed, perhaps, or after his having been the leader of this people or that tribe. We see his soul, how it continues to live, how (if he had been a soldier) he is received by the great soldiers in Valhalla, or how he lives on in some other way. This soul, this man, is still here. He continues to live and is actually present. Death is merely an event which takes place here on the earth. Such an experience, having come with the northern peoples, was present in the fourth and fifth on through the twelfth and thirteenth centuries before being essentially buried. This was the perception of the dead as actually always present, the awareness that the souls of human beings who were greatly venerated were still present, even for earthly human beings. They were even still able to lead in battle. People of that time thought of these souls as still present, as not disappearing for the earthly. With the forces given them by the spiritual world these souls continued, in a certain sense, the functions of their earthly lives. The atavistic clairvoyance of the northern peoples was such then, that, as they saw the activities of people here on the earth, they also beheld a kind of shadow world directly above people on earth. The dead were in this shadow world. One needed only to look—these people felt—to see that those from the last and next to last generation actually continue to live. They are here, we experience community with them. For them to be present we need only to listen up into their realm.

This feeling, that the dead are here, was present, was incredibly strong, in the time that followed the fourth century, when the northern culture mixed with the Roman. You see, the northern peoples took Christ into this way of perceiving. They looked first at this world of the dead, who were actually the truly living. They saw hovering above them entire populations of the dead, and they beheld these dead as being actually more alive than themselves. They did not seek Christ here on the earth among people walking in the physical world; they sought Christ there where these living dead were. There they sought him as one who is really present above the earth. And you will only get the proper feeling concerning the Heliand, which was supposedly written by a Saxon priest, if you develop these ways of perceiving.7 Heliand, a poem in alliterative verse on the Gospels written between 825 and 835 A.D. The descriptions in the Heliand follow these old German customs. You will understand the Heliand's concrete description of Christ among living human beings only if you understand that actually the scenes are to be transplanted half into the kingdom of shadows where the living dead are dwelling. You will understand much more, if you truly grasp this predisposition, this ability, which came about through the mixing of the northern with the Roman peoples.

There is something recorded in literary history to which people should actually give a great deal of thought. However, people of the present age have almost entirely given up the ability to think about such clearly startling phenomena found in the life of humanity. But pursuing literary history, you will find, for example, writings in which Charlemagne (742–814) is mentioned as a leader in the Crusades. Charlemagne is simply listed as a leader in the Crusades.8 E.g., Pèlerinage de Charlemagne (eleventh century), Gran Conquista de Ultramar (thirteenth century). Indeed, you will find Charlemagne described as a living person again and again throughout the entire time that followed the ninth century. People everywhere called upon him. He is described as if he were there. And when the crusades began, centuries after his death, poems were written describing Charlemagne as if he were with the crusaders marching against the infidels.

We only understand such writings properly if we know that in the so-called dark centuries of the Middle Ages, the true history of which is entirely obliterated, there was this awareness of the living multitudes of the dead, who lived on as shadows. It was only later that Charlemagne was placed in the Untersberg. Much later, when the spirit of intellectualism had grown strong enough for this life in the shadows to have ceased, then Charlemagne was transplanted into the Untersberg (and, as another example, Frederick Barbarossa, the Holy Roman Emperor, into Kyffhaeuserberg).9 Charlemagne (724–814), King of France and Roman Emperor. The Untersberg is a mountain ridge, full of caves, near Salzburg, Austria. Frederick Barbarossa (Redbeard) or Frederick I (1123–1190), Holy Roman Emperor. Esteemed by Germans as one of their greatest kings. Until that time people knew that Charlemagne was still living among them.

But wherein did these people, who atavistically saw the dead living above them, wherein did these people seek their Christianity, their Christology, their Christian way of seeing? They sought it in this way: they directed their sight toward what results when a living dead person like Charlemagne, who was revered in life, came before their souls with all those who were still his followers. And so through long ages Charlemagne was seen undertaking the first crusade against the infidels in Spain. But he was seen in such a way that the entire crusade was actually transplanted into the shadow world. The people of that time saw this crusade in the shadow world after it had been undertaken on the physical plane; they let it continue working in the shadow world—as an image of the Christ who works in the world. Therefore, Christ was described riding south toward Spain among the twelve paladins, one of whom was a Judas who eventually betrayed the entire endeavor.10Peers of Charlemagne's court. So we see how clairvoyant perception was directed toward the outside of the spiritual world—not, as in earlier times, toward the inside—but rather now toward the outside, toward that which results when one looks at the spirits from the outside just as one looked at them earlier from the inside. Now, the splendor of the Christ event was reflected onto all the most important things that took place in the world of shadows.

From the fourth to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries there lived in Europe the idea that people who had died, if they had accomplished important deeds in life, arranged their afterlife so as to enable themselves to be seen with something like a reflected splendor, an image, of the Christ event. One saw everywhere the continuation of the Christ event—if I may express myself so—as shadows in the air. If people had spoken of the things they felt, they would have said: Above us the Christ stream still hovers; Charlemagne undertook to place himself in this Christ stream and with his paladins he created an image of Christ with the twelve apostles; the deeds of Christ were continued by Charlemagne in the true spiritual world.

This was how people thought of these things in the so-called dark time of the Middle Ages. There was the spiritual world, seen from without, I would like to say, as if imaged after the sense world, like a shadow picture of the sense world (whereas in the earlier times, of which the old theology was only a weak reflection, the spiritual world was seen from within). For merely intellectual human beings the difference between this physical world and the spiritual world is such that an abyss exists between the two. This difference did not exist in the first centuries of the Middle Ages, in the so-called Dark Ages. The dead remained with the living. During the first period after their death, after they had been born into the spiritual world, especially outstanding and revered personalities underwent a novitiate to become saints.

For the people of those times to speak of these living dead as if they were real personalities after they had been born into the spiritual world—this was not unusual. And you see, a number of these living dead, especially chosen ones, were called to become guardians of the Holy Grail. Specially chosen living dead were designated as guardians of the Holy Grail. And the Grail legend could never be completely understood without the knowledge of who these guardians of the Grail actually were. To say: “Then the guardians of the Grail weren't real people” would have seemed laughable to the people of that time. For they would have said: Do you who are only shadow figures walking on the earth really believe that you are more real than those who have died and now are gathered around the Grail? To those who lived in those times it would have appeared laughable for the little figures here on the earth to consider themselves more real than the living dead. We must feel our way into the souls of that time, and this is simply how those souls felt. Their consciousness of this connection with the spiritual world meant much for the world, and much for their souls. They would have said to themselves: To begin with, the people here on the earth consist of nothing more than what they are, right now, directly here. But a human being of the present will only become something proper and good if he takes into himself what one of the living dead can give him.

In a certain sense, physical human beings on the earth were seen as though they were merely vehicles for the outer working of the living dead. It was a peculiarity of those centuries that one said: If the living dead want to accomplish something here on earth, for which hands are needed, then they enter into a physically incarnated human being and do it through him. Not only that, but there were, furthermore, people in those times who said to themselves: One can do no better than to provide a vehicle for human beings who were revered while living on the earth and who have now become beings of such importance in the realm of the living dead that it is granted to them to guard the Holy Grail. And the view existed among the people of those times that individuals could dedicate themselves to the Order of the Swan. Those people dedicated themselves to the Order of the Swan who wanted the knights of the Grail to be able to work through them here in the physical world. A human being through whom a knight of the Grail was working here in the physical world was called a Swan.

Now, think of the Lohengrin legend.11Lohengrin, a knight of the Grail, son of Parsifal. Led by a swan to rescue Princess Elsa of Brabant, he then marries her. When she asks his name, in violation of her pledge, he must return to the Grail Castle without her. Tale ascribed to Wolfram von Eschenbach (c. 1285–90); basis for Richard Wagner's opera, Lohengrin (1847). When Elsa of Brabant is in great need, the swan comes. The swan who appears is a member of the Knights of the Swan, who has received into himself a companion of the circle of the Holy Grail. One is not permitted to ask him about his secret. In that century, and also in the following centuries, princes such as Henry I of Saxony were happiest of all when, as in his campaign into Hungary, he was able to have this Knight of the Swan, this Lohengrin, in his army.12Henry I (c. 876–936), first German king from the House of Saxony, campaigned in Hungary in 933.

But there were knights of many kinds who regarded themselves primarily as only outer vehicles for those from the other side of death who were still fighting in the armies. They wanted to be united with the dead; they knew they were united with them. The legend has actually become quite abstract today. We can only evaluate its significance for the living if we live into the soul life of the people alive at that time. And this understanding, which, to begin with, looks simply and solely upon the physical world and sees how the spiritual man arises out of the physical man and afterward belongs to the living dead, this understanding ruled the hearts and minds of that time and was the most essential element in their souls. They felt that one must first have known a human being on the earth, that only then can one rise to his spirit. It was really the case that the whole understanding was reversed, even in the popular conceptions of the masses, over against the older views. In olden times people had looked first into the spiritual world; they strove, if possible, to see the human being as a spiritual being before his descent to earth. Then, it was said, one can understand what the human being is on earth. But now, the following idea emerged among these northern peoples, after they had mixed with Roman civilization: We understand the spiritual, if we have first followed it in the physical world, and it has then lifted itself out of the physical world as something spiritual. This was the reverse of what had prevailed before.

The reflected splendor of this view then became the theology of the Middle Ages. The old theologians had said: First one must have the ideas, first one must know the spiritual. The concept of faith would have been something entirely absurd for these old theologians, for they first recognized the spiritual before they could even begin to think of knowing the physical, which had to be illumined by the spiritual. Now, however, when in the world at large people were starting from the point of view of knowing the physical, it came to this, even in theology. Theologians began to think in this way: For knowledge one must start with the world of sense. Then, from the things of the senses one must extract the concepts—no longer bring the concepts from the spiritual world to the things of sense, but now extract the concepts from the things of sense themselves.

Now imagine the Roman world in its decline; and then imagine, within that world, what still remained as a struggle from the olden time: namely, the fact that concepts were experienced in the spiritual world and then brought to meet the things of the senses. This was felt by such a man as Martianus Capella, who in the fifth century wrote his treatise, De Nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii, wherein he wrestled still to find within the spiritual world itself that which was becoming increasingly abstract in the life of ideas.13Martianus Minneus Felix, Latin author of the fourth-fifth century, author of The Marriage of Philology and Mercury, the encyclopædic work in verse and prose that introduced the Seven Liberal Arts to the Middle Ages. But this old view went under because the Roman conspiracy against the spirit—in that college or committee I have told you about—had destroyed everything representing a direct human connection with the spirit. We see how that direct connection gradually vanished. The old vision ceased. Living in the old conception a human being knew: When I reach over into the spiritual world angels accompany me. If they were Greeks they called them “guardians.” A person who went forth on the path of the spirit knew he was accompanied by a guardian spirit.

That which in ancient times had been a real spiritual being, the guardian, was grammatica, the first stage of the seven liberal arts, at the time when Capella wrote. In olden times men had known that which lives in grammar, in words and syntax, can lead up into imagination. They knew that the angel, the guardian, was working in the relationships between words. If we read the old descriptions, nowhere would we ever find an abstract definition. It is interesting that Capella does not describe grammar as the later Renaissance did. To him grammar is still a real person. So, too, rhetoric at the second stage is still a real person. For the later Renaissance such figures became mere allegories—straw figures for intellectual concepts. In earlier times they had also been spiritual perceptions that did not merely edify as they did in Capella's writings. They had been creative beings, and the entry that they had initiated into the spirit was felt as a penetration into a realm of creative beings. Now with Capella they had become allegories; but nevertheless, at least they were still allegorical. Though they were no longer stately, though they had become very pale and thin, they were still ladies: grammatica, rhetorica, dialectica. They were very thin and weak. All that was left of them, as it were, was the bones of spiritual effort and the skin of concepts; nevertheless, they were still quite respectable ladies who carried Capella, the earliest to write on the seven liberal arts, into the spiritual world. One by one he made the acquaintance of these seven ladies: first the lady grammatica, then the lady rhetorica, the lady dialectica, the lady arithmetica, the lady geometria, the lady musica, and finally the heavenly lady astrologia, who towered over them all. These were certainly ladies, and as I said, there were seven of them. The sevenfold feminine leads us onward and upward, so might Capella have concluded when describing his path to wisdom. But think of what became of it in the monastery schools of the later Middle Ages. When these later writers labored at grammar and rhetoric they no longer felt that “the eternal feminine leads us onward and upward.” And that is really what happened: Out of the living being there first came the allegorical and then the merely intellectual abstraction.

Homer, who in olden times had sought the way from the humanly spoken word to the cosmic word, so that the cosmic word might pass through him, had to say: “Sing me, O muse, of Peleus' son, Achilles.” From the stage when a spiritual being led a person on to the point in the spiritual world at which it was no longer he himself but the muse who sang of the wrath of Achilles, from that stage to the stage when rhetoric herself was speaking in the Roman way, and then to the mingling of the Roman with the life that came downward from the north—was a long, long way. Finally, everything became abstract, conceptual, and intellectual. The farther we go toward the east and into olden times the more we find everything immersed in concrete spiritual life: the theologian of old had gone to the spiritual beings for his concepts, which he then applied to this world. But the theologian who grew out of what arose from the merging of the northern peoples with the Roman said: Knowledge must be sought here in the sense world; here we gain our concepts. But he could not rise into the spiritual world with these concepts. For the Roman college had thoroughly seen to it that although men might angle around down here in the world of sense, they could not get beyond this world. Formerly men had also had the world of the senses, but they had sought and found their concepts and ideas in the spiritual world; and these concepts then, helped them to illuminate the physical world. But now they extracted their concepts out of the physical world itself, and they did not get far—they only arrived at an interpretation of the physical world. They could no longer reach upward by an independent path of knowledge. But they still had a legacy from the past. It was written down or preserved in traditions embodied and rigidified in dogmas. It was preserved in the creed. Whatever could be said about the spirit was contained therein. It was there. They increasingly arrived at a consciousness that all that had been said concerning the realms above as a result of higher revelation must remain untouched. The revelations could no longer be checked. The kind of knowledge that can be checked now remained down below—our conceptual life must be obtained here in the physical world.

So in the course of time what had still been present in the first dark centuries of the Middle Ages persisted merely as a written legacy. For it had become quite another time when the medieval, atavistic clairvoyance of the Saxon “peasant,” as he is called (though, as the Heliand shows, he was, in any case, a priest, born of the peasantry) still existed in Europe. Simply looking at the human beings around him this Saxon peasant-priest had the faculty to see how the soul and spirit goes forth at death and becomes the dead and yet alive, living human being. Thus, in the train of those that hover over the earthly realm, he describes his vision of the Christ event in the poem, the Heliand.

But what was living here on the earth was drawn further and further down into the realm of the merely lifeless. Atavistic clairvoyant abilities came to an end, and people now only sought for concepts in the sense world. What kind of a view and attitude resulted? It was this: There is no need to pay heed to the super-sensible when it comes to knowledge. What we need is contained in the sacred writings and traditions. We need only refer to the old books and look into the old traditions. Everything we should know about the super-sensible is contained there. And now in the environment of the sense world, we are not confused if for knowledge we take into account only the concepts contained in the sense world itself.

More and more this consciousness came to life: The super-sensible is preserved for us and will so remain. If we want to do research we must limit ourselves to the sense world. Someone who remained entirely within this habit of mind, who continued, as it were, in the nineteenth century this activity of extracting concepts out of the sense world that the Saxon peasant-priest who wrote the Heliand had practiced, was Gregor Mendel.14Johann Gregor Mendel. Augustinian priest and botanist, creator of Mendelian genetics. Mendel did his famous breeding experiments in the monastery garden in 1856. Results published 1866. Not widely recognized until after 1910. Why should we concern ourselves with investigations of the olden times into matters of heredity? They are all recorded in the Old Testament. Let us look, rather, down into the world of sense and see how the red and the white sweet peas will cross with one another, giving rise to red, white, and speckled flowers and so forth. Thus you can become a mighty scientist without coming into conflict or disharmony with what is said about the super-sensible, which remains untouched. It was precisely our modern theology, evolved out of the old theology along the lines I have characterized, that impelled people to investigate nature in the manner of Gregor Mendel, whose approach was that of a genuine Catholic priest.

And then what happened? Natural scientists, whose science is so “free from bias,” subsequently canonized Gregor Mendel as a saint. Although this is not their way of speaking, we can describe Mendel's fate in these terms. At first they treated him without respect; now they canonize him after their fashion, proclaiming him a great scientist in all their academies. All this is not without its inner connections. The science of the present time is only possible inasmuch as it is constituted in such a way as to regard as a great scientist precisely one who stands so thoroughly upon the standpoint of medieval theology! The natural science of our time is through and through the continuation of the essence of scholastic theology—its subsequent proliferation, its diversification. It is the continuation into our time of the scholastic era. Hence it is quite proper for Johann Gregor Mendel to be subsequently recognized as a great scientist; that he is, but in the good Catholic sense. It made good Catholic sense for Mendel to look only at sweet peas as they cross with one another, it was following Catholic principle, because all that is super-sensible is contained in the sacred traditions and books. But we see that this does not make sense for natural scientists, none in the least—only if they are bent on stopping short at the stage of ignoramuses and giving themselves up to complete agnosticism would it make any sense to limit research to the sense world.

This is the fundamental contradiction of our time. This contradiction is what we must be attentive to. For if we fail to look at these spiritual realities we shall never understand the source of all the confusion, of all the contradictions and inconsistencies, in the endeavors of the present day. But the easygoing comfort of our time does not allow people to awaken and really to look into these contradictory tendencies.

Think what will happen when all that is said about today's world events becomes history. Posterity will get this history. Do you think they will get much truth? Certainly not. Yet history for us has been made in this very way. These puppets of history, which are described in the usual textbooks, do not represent what has really happened in human evolution. We have arrived at a time when it is absolutely necessary for people to learn to know what the real events are. It is not enough for all the legends to be recorded as they are in our current histories—the legends about Attila and Charlemagne, or Louis the Pious, where history begins to be altogether fabulous. The most important things of all are overlooked in these writings; for it is really only the histories of the soul that make the present time intelligible.

Anthroposophical spiritual science must throw light into the evolving souls of human beings. Because we have forgotten how to look into the spiritual, we no longer have any history. Anyone of sensibility can see that in Martianus Capella the old guides and guardians who used to lead people into the spiritual world have become very thin, very lean ladies. But those whom historians teach us to know as Henry I, Otto I, Otto II, Henry II, and so on—they appear as mere puppets of history, formed after the pattern of those who had grown into the thin and pale ladies, after grammar, rhetoric, dialectic, and the others. When all is said and done the personalities who are enumerated in succession in our histories have no more fat on them than those ladies.

Things must be seen as they really are. Actually the people of today should be yearning to see things as they are. Therefore, it is a duty to describe these things wherever possible, and they can be described today within the Anthroposophical Society. I hope that this society, at least, may some day wake up.

Erster Vortrag

[ 1 ] Es ist schon darauf hingewiesen worden, daß das Geistesleben der ersten vier christlichen Jahrhunderte im Grunde genommen ganz verschüttet ist, daß alles, was heute verzeichnet wird über die Anschauungen, über die Erkenntnisse der Menschen, die zur Zeit des Mysteriums von Golgatha gelebt haben und die auch noch in den vier nachfolgenden Jahrhunderten lebten, im Grunde genommen doch nur durch die Schriften der Gegner auf die Nachwelt gekommen ist; so daß schon der rückschauende Blick des Geistesforschers notwendig ist, um ein genaueres Bild von dem zu entwerfen, was in diesen ersten vier christlichen Jahrhunderten sich zugetragen hat. Und ich habe ja auch in der letzten Zeit versucht, mit einigen Strichen das Bild Julians des Abtrünnigen zu zeichnen.

[ 2 ] Nun aber können wir nicht sagen, daß nach den gewöhnlichen Geschichtsdarstellungen die folgenden Jahrhunderte in einer klareren Weise vor dem Menschen der Gegenwart stehen. Vom 5. bis etwa ins 12., 13., 14. Jahrhundert hinein bleibt eigentlich das, was man nennen könnte das Seelenleben der europäischen Bevölkerung, nach den gebräuchlichen geschichtlichen Darstellungen durchaus unklar. Was ist denn im Grunde genommen in diesen gebräuchlichen geschichtlichen Darstellungen da? Und was ist denn selbst dann da, wenn man auf die Dichtungen federflinker sogenannter Dramatiker oder Dichter, etwa vom Schlage des Herrn von Wildenbruch sieht, die in ihren Dichtungen im wesentlichen zu äußerlichen Popanzen die verschiedenen Familiengeschichten von Ludwig dem Frommen oder ähnlichen Menschen ausstaffierten, die dann als Geschichte fortgetragen werden?

[ 3 ] Dennoch ist es von außerordentlicher Wichtigkeit, einmal einen Blick in die Wahrheit des europäischen Lebens zu werfen für diejenigen Zeiten, aus denen ja noch so vieles in der Gegenwart stammt, und die man im Grunde doch, namentlich in bezug auf das Seelenleben der europäischen Bevölkerung, verstehen muß, wenn man überhaupt irgend etwas von den tieferen Kulturströmungen auch der späteren Zeit verstehen will. Und da möchte ich zunächst von etwas ausgehen, was ja vielen von Ihnen ein wenig fern liegen wird, was aber doch heute auch nur im geisteswissenschaftlichen Lichte richtig betrachtet werden kann und deshalb eben hierher gehört.

[ 4 ] Sie wissen ja, daß es jetzt so etwas gibt, was man Theologie nennt. Diese Theologie, wie man sie heute anschaut, im Grunde genommen alle heutige Theologie der europäischen Welt, sie ist in ihrer Grundstruktur, in ihrem innerlichen Wesen eigentlich entstanden in der Zeit vom 4., 5. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert, durch die folgenden, recht dunkel bleibenden Jahrhunderte hindurch, bis zum 12., 13. Jahrhundert hin, wo sie dann durch die Scholastik einen gewissen Abschluß gefunden hat. Wenn man nun diese Theologie betrachtet, die sich im Grunde genommen erst in der Zeit nach Augustinus in ihrem eigentlichen Wesen heranbildet — denn Augustinus kann mit Hilfe dieser Theologie nicht oder höchstens noch eben verstanden werden, während alles vorhergehende, was zum Beispiel auch über das Mysterium von Golgatha vorgebracht wurde, nicht mehr verstanden werden kann mit dieser "Theologie -, wenn man auf das Wesen dieser Theologie hinschaut, die da gerade in den dunkelsten Zeiten des Mittelalters - dunkel für unsere Erkenntnis, für unsere äußere Erkenntnis — entsteht, so muß einem vor allen Dingen klarwerden, wie diese Theologie etwas ganz anderes ist, als etwa die Theologie, oder was man sonst so nennen könnte, vorher war. Was vorher Theologie war, ist ja eigentlich nur, ich möchte sagen, wie eine Erbschaft hineinverpflanzt in die Zeiten, in denen dann die Theologie, wie ich sie jetzt charakterisiert habe, entstand. Und Sie können einen Eindruck gewinnen, wie vorher dasjenige ausgesehen hat, was dann zur Theologie geworden ist, wenn Sie nur den kurzen Aufsatz lesen, den Sie in der dieswöchentlichen Nummer des «Goetheanum» über Dionysius den Areopagiten finden, der ja auch noch eine Fortsetzung in einer der nächsten Nummern finden wird. Da finden Sie eben dargestellt die ganz andere Art, sich zu der Welt zu stellen in den ersten christlichen Jahrhunderten, als es später, sagen wir, etwa in der Zeit des 9., 10. Jahrhunderts und in den folgenden Jahrhunderten der Fall war.

[ 5 ] Wenn man in einer skizzenhaften Weise den ganzen Gegensatz nennen wir es jetzt der alten Theologie — der Theologie, wie sie sich in einem Spätprodukt, möchte man sagen, in Dionysius dem Areopagiten sogar ausspricht, zu der späteren neuen Theologie charakterisieren wollte, so müßte man sagen: Die ältere Theologie hat alles, was sich auf die geistige Welt bezieht, wie von innen angesehen, wie durch einen direkten Hinblick auf das, was in den geistigen Welten vorgeht. Wenn man Einblick gewinnen will, wie diese ältere Theologie gedacht hat, wie sie innerlich seelisch angeschaut hat, so kann man das eigentlich nur wiederum mit den Methoden der heutigen anthroposophischen Geisteswissenschaft suchen. Da kann man auf folgendes kommen. Ich habe gestern schon von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte ähnliche Sachen charakterisiert.

[ 6 ] Wenn man zur imaginativen Erkenntnis aufsteigt, so merkt man immer mehr und mehr, daß man mit diesem ganzen Vorgang des Aufsteigens zur imaginativen Erkenntnis in geistigen Vorgängen drinnen schwebt. Dieses Drinnenschweben mit seinem ganzen Seelenleben während des Aufsteigens zur imaginativen Erkenntnis, das stellt sich einem so dar, als ob man in Berührung käme mit Wesenheiten, die nicht auf dem physischen Plane leben. Die Anschauung der Sinnesorgane hört auf, und man erfährt, daß gewissermaßen alles, was sinnliche Anschauung ist, entschwindet. Aber der ganze Vorgang stellt sich einem so dar, als ob einem dabei Wesenheiten einer höheren Welt helfen würden, und man kommt darauf, daß man diese Wesenheiten als dieselben aufzufassen hat, welche in der älteren Theologie als die Angeloi, Archangeloi und Archai angesehen werden. Also ich könnte sagen, diese Wesenheiten helfen einem, um hinaufzudringen zu der imaginativen Erkenntnis. Dann teilt sich, wie sich Wolken auseinanderteilen, die Sinneswelt auseinander, und man schaut hinter die Sinneswelt. Und hinter der Sinneswelt tut sich dann auf dasjenige, was man Inspiration nennen kann; hinter dieser Sinneswelt offenbart sich dann die zweite Hierarchie, die Hierarchie der Exusiai, Dynamis, Kyriotetes. Diese ordnenden schöpferischen Wesenheiten, die stellen sich vor der inspirierten Erkenntnis der Seele dar. Und wenn dann ein weiteres Ansteigen erfolgt zur Intuition, dann kommt die erste Hierarchie, die Throne, Cherubim, Seraphim. Das sind Möglichkeiten, um jetzt wiederum durch unmittelbare geistige Schulung darauf zu kommen, was mit solchen Bezeichnungen, wie erste, zweite, dritte Hierarchie, bei älteren Theologien eigentlich gemeint war.

[ 7 ] Nun, gerade wenn man noch auf die ja zum größten Teile ausgerottete Theologie der ersten christlichen Jahrhunderte hinblickt, dann bemerkt man, daß sie in einer gewissen Beziehung noch etwas davon hat, daß eigentlich der Mensch, wenn er seine Sinne nach der gewöhnlichen sinnlichen Außenwelt richtet, zwar die Dinge sieht und an sie glauben muß, aber sie nicht erkennt. Es ist ein ganz bestimmtes Bewußtsein in dieser älteren Theologie vorhanden: das Bewußtsein, daß man erst etwas erlebt haben muß in der geistigen Welt, und daß mit dem, was man in der geistigen Welt erlebt hat, sich erst die Begriffe ergeben, mit denen man dann herangehen kann an die Sinneswelt und gewissermaßen die Sinneswelt mit diesen aus der geistigen Welt gewonnenen Ideen beleuchten kann. Dann erst wird etwas aus der Sinneswelt.

[ 8 ] Das entspricht auch in gewissem Sinne dem, was sich einem älteren, traumhaft atavistischen Hellsehen ergeben hat. Da haben ja auch die Menschen, wenn auch in traumhaften Vorstellungen, in eine geistige Welt zuerst hineingeschaut und haben das, was sie da drinnen erlebt haben, dann auf die Sinnesanschauung angewendet. Diese Menschen wären sich, wenn sie nur die Sinnesanschauung vor sich gehabt hätten, so vorgekommen wie jemand, der in einem finsteren Zimmer steht und kein Licht hat. Wenn sie aber ihre Geistesanschauung, das Ergebnis des reinen Hineinschauens in die Geisteswelt gehabt haben und es anwendeten auf die Sinneswelt, wenn sie zuerst etwas geschaut haben, sagen wir, von den schöpferischen Kräften der Tierwelt und das dann anwendeten auf die äußeren Tiere, dann fühlten sie sich, als wenn sie eben mit einer Lampe in ein finsteres Zimmer treten würden. So fühlten sie sich mit der geistigen Anschauung vor die Sinnesanschauung hintretend und sie beleuchtend. Dadurch wird sie erst erkannt. Das war durchaus das Bewußtsein dieser älteren Theologien. Daher ist die ganze Christologie in den ersten christlichen Jahrhunderten eigentlich immer von innen angeschaut worden. Man hat im Grunde genommen den Vorgang, der sich abgespielt hat, das Herunterkommen des Christus in die irdische Welt, nicht von außen angeschaut, man hat ihn von innen angeschaut, von der geistigen Seite her. Man hat erst den Christus in geistigen Welten aufgesucht und dann verfolgt, wie er heruntergestiegen ist in die physisch-sinnliche Welt. Das ist das Bewußtsein gewesen der älteren Theologie.

[ 9 ] Nun trat als Ereignis dieses ein: Die römische Welt, nach der sich als am weitesten nach Westen der christliche Impuls fortschob, war in ihrer geistigen Auffassung durchsetzt von der Neigung, von dem Hang für das Abstrakte und dafür, das, was Anschauungen waren, in abstrakte Begriffe zu bringen. Diese römische Welt war aber eigentlich, während das Christentum sich nach und nach gegen Westen schob, am Zugrundegehen, in Fäulnis. Und die nordischen Völker drangen vom Osten Europas herüber gegen Westen und gegen Süden vor. Nun ist es ein Eigentümliches, daß, während auf der einen Seite das römische Wesen in Fäulnis übergeht und die frischen Völker vom Norden herankommen, sich jenes Kollegium bildet auf der italienischen Halbinsel, von dem ich schon in diesen Zeiten hier gesprochen habe, das eigentlich sich zur Aufgabe setzte, alle Ereignisse dazu zu benützen, um die alten Anschauungen mit Stumpf und Stiel auszurotten und nur diejenigen Schriften auf die Nachwelt kommen zu lassen, die diesem Kollegium bequem waren.

[ 10 ] Über diesen Vorgang berichtet ja die Geschichte eigentlich gar nichts, und dennoch ist es ein realer Vorgang. Würde eine geschichtliche Darstellung davon vorhanden sein, so würde man eben einfach hinweisen auf jenes Kollegium, das sich als ein Erbe des römischen Pontifexkollegiums in Italien gebildet hat, das gründlich aufgeräumt hat mit allem, was ihm nicht genehm war, und das andere modifiziert und der Nachwelt übergeben hat. Geradeso wie man in Rom in bezug auf die nationalökonomischen Vorgänge das Testament erfunden hat, um hinauswirken zu lassen über den einzelnen menschlichen Willen dasjenige, über das der Wille verfügt, so entstand in diesem Kollegium der Trieb, das römische Wesen als bloße Erbschaft, eben als bloße Summe von Dogmen fortleben zu lassen in der folgenden Zeit der geschichtlichen Entwickelung durch viele Generationen hindurch. Solange als möglich soll nicht irgendwie Neues in der geistigen Welt erschaut werden, so hat dieses Kollegium gesagt. Das Initiationsprinzip soll mit Stumpf und Stiel ausgerottet werden. Was wir jetzt modifizieren, das soll als Schrifttum auf die Nachwelt übergehen.

[ 11 ] Würde man es trocken darstellen, so müßte es in dieser Tatsächlichkeit dargestellt werden. Und dem Christentum hätten noch ganz andere Schicksale geblüht, es wäre vollständig erstarrt, wenn eben nicht die nordischen Völker gekommen wären und sich hineingeschoben hätten, sowohl nach Westen hin wie auch nach dem Süden hin. Denn diese Völker brachten sich eine gewisse Naturanlage mit, die ganz anders war als die Anlage der südlichen, der griechischen und der römischen Völker.

[ 12 ] Die Anlage der südlichen Völker war immerhin, wenigstens in älteren Zeiten — bei den Römern wenig, bei den Griechen aber stark — dahingehend, daß sich aus der Gesamtheit der Völker immer einzelne Individuen herausentwickelten, die die Initiation durchmachten und in die geistige Welt hineinschauen konnten; so daß dann solche Theologien entstehen konnten, die eine unmittelbare Anschauung der geistigen Welt waren, wie sie dann in ihrer letzten Phase in der Theologie des Dionysius Areopagita erhalten ist.

[ 13 ] Aber die von Norden herunterkommenden Völker hatten zunächst nichts von diesem Triebe, der, wie gesagt, bei den Griechen sehr stark war. Sie hatten aber etwas anderes, diese nordischen Völker. Um aber recht zu verstehen, was da nun in den folgenden Zeiten gerade durch die nordischen Völker, durch die gotischen, germanischen Völker, durch die Angelsachsen, Franken und so weiter, in die europäische Entwickelung hineinkam, muß man sich das Folgende vor die Seele führen.

[ 14 ] Geschichtlich sind ja darüber keine Nachrichten vorhanden, aber geisteswissenschaftlich kann man so etwas finden. Nehmen wir einen älteren Theologen, kurze Zeit - etwa im 1., 2. Jahrhundert - nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha, einen derjenigen Theologen, die noch geschöpft haben aus der alten Initiationswissenschaft. Wenn der hätte darstellen wollen, was der Nerv, ich möchte sagen, die Prinzipien seiner Theologie waren, so würde er gesagt haben: Erst muß der Mensch, um überhaupt eine Beziehung zur geistigen Welt zu haben, entweder direkt, unmittelbar durch seine eigene Initiation oder als Schüler von Initiierten sich Kenntnis verschaffen von der geistigen Welt. Dann, wenn er in der geistigen Welt die Begriffe und Ideen gewonnen hat, kann er diese Begriffe und Ideen auf die Sinneswelt anwenden.

[ 15 ] Bitte, halten Sie das recht gut fest. Die Begriffe und Ideen hat diese ältere Theologie gesucht zuerst durch unmittelbares Eindringen in die geistige Welt. Dann, nahm sie an, kann man die aus der geistigen Welt geschöpften Begriffe und Ideen auf die Sinneswelt anwenden. Das waren etwa die abstrakten Prinzipien eines solchen älteren 'Theologen.

[ 16 ] Nun waren die Anlagen der gotischen, der germanischen Völker nicht so, daß eine solche theologische Stimmung unmittelbar hätte heraufkommen können; denn diese theologische Stimmung war ja ganz darauf veranlagt, innerlich die Vorgänge zu sehen, die in der Welt zu sehen sind, das Geistige eben zuerst zu sehen und sich zuzugeben, daß das Sinnliche erst gesehen werden kann, wenn man von dem Geistigen ausgeht. Solch eine Theologie konnte sich ja nur aus dem alten atavistischen Hellsehen heraus als das reifste Produkt ergeben, weil atavistisches Hellsehen ja auch ein innerliches Anschauen, wenn auch von traumhaften Imaginationen, war. Solche Inititerte, die unmittelbar hineinschauten in die geistige Welt, um dann von da aus die Sinneswelt zu überschauen, konnten nach den ganzen Anlagen dieser von Norden herstürmenden Völker innerhalb dieser Völker nicht entstehen. Diese Völker waren auch noch etwas atavistisch hellsehend; sie waren ja eigentlich noch auf einer früheren, primitiveren Stufe der menschheitlichen Entwickelung. Sie hatten noch etwas mitgebracht, diese Goten oder Langobarden und so weiter von dem alten Hellsehen. Aber dieses alte Hellsehen bezog sich durchaus nicht auf innerliches Anschauen, sondern zwar auf ein geistiges Anschauen, aber auf das Hinschauen mehr nach der Außenseite hin. Sie schauten gewissermaßen die geistige Welt von außen an, während die südlichen Völker daraufhin veranlagt waren, die geistige Welt von innen anzuschauen.

[ 17 ] Was heißt das, diese Völker schauten die geistige Welt von außen an? Das heißt, sie sahen zum Beispiel: Ein Mensch ist tapfer in der Schlacht, er stirbt in der Schlacht. Nun war für sie das Leben, indem sie das Äußerliche von diesem Menschen anschauten, nicht zu Ende, sondern sie verfolgten diesen Menschen weiter, wie er sich in die geistige Welt hineinlebte. Aber sie verfolgten nicht nur, wie sich dieser Mensch in die geistige Welt hineinlebte, sondern wie er auch noch immer weiter für die Erdenmenschen tätig war. Und so können diese nordischen Völker sagen: Da ist irgendeiner hingestorben, sei es nach dieser oder jener bedeutenden Tat, nachdem er Führer war eines Volkes oder Volksstammes. Wir schauen seine Seele, wie sie weiterlebt, wie sie, wenn er zum Beispiel ein Krieger war, empfangen wurde von den «Einheriern», oder wie er in einer anderen Weise weiterlebt. Aber eigentlich ist diese Seele, ist dieser Mensch noch da. Er ist da, er lebt weiter. Es ist der Tod nur ein Ereignis, das sich hier auf Erden abgespielt hat. Und das, was nun geradezu verschüttet ist für die Jahrhunderte vom 4., 5. an bis zum 12., 13. Jahrhundert, das ist, daß eigentlich immer die Anschauung vorhanden war: Die Seelen der Menschen, die große Verehrung genossen, sind noch immer auch für die irdischen Menschen gegenwärtig; sie führen sie, wenn sie Schlachten liefern, sogar noch an. Man stellte sich vor: Diese Seelen sind noch vorhanden, sie sind nicht entschwunden für die Irdischen; sie führen in gewissem Sinne mit den Kräften, die ihnen die geistige Welt gibt, die Funktionen ihres Erdenlebens weiter. Es war dieses atavistische Hellsehen der nordischen Völker so, daß sie gewissermaßen hier auf der Erde das Treiben der Menschen sahen, aber unmittelbar darüber eine Art von Schattenwelt hatten. In dieser Schattenwelt waren die Verstorbenen. Man braucht nur hinzuschauen — so hatten es diese Menschen im Gefühl -, dann leben eigentlich diejenigen, die in der vorigen und in der vorvorigen Generation waren, fort, die sind da, mit denen haben wir Gemeinsamkeit; wir brauchen nur hinaufzulauschen, so sind sie da. — Dieses Gefühl, daß die Toten da sind, das war in ungeheurer Stärke vorhanden in der Zeit, welche auf das 4. Jahrhundert folgte, wo sich die nordische Bildung mit der römischen Bildung mischte.

[ 18 ] Sehen Sie, in diese Anschauung nahmen die nordischen Völker den Christus herein. Sie blickten zuerst auf diese Welt der Toten, die aber eigentlich erst die richtigen Lebendigen waren. Sie sahen über sich schwebend ganze Bevölkerungen von Toten, die aber eigentlich die Lebendigen waren. Hier auf der Erde, unter den in der physischen Welt wandelnden Menschen suchten sie den Christus nicht; aber da suchten sie den Christus, wo diese lebendigen Toten waren, da suchten sie ihn wirklich als über der Erde vorhanden. Und das richtige Gefühl über den «Heliand», der von einem sächsischen Geistlichen gedichtet sein soll, bekommen Sie erst, wenn Sie diese Anschauungen entwickeln. Da begreifen Sie das völlig Konkrete: wie da geschildert wird der Christus unter den Mannen, und so ganz nach deutscher Sitte geschildert wird, wenn Sie verstehen, daß eigentlich das alles halb ins Schattenreich hineinversetzt ist, wo die lebendigen Toten leben. Aber Sie werden viel mehr begreifen, wenn Sie diese Anlage, die sich dann ausbildete durch die Vermischung der nordischen Völker mit dem römischen Volke, richtig ins Auge fassen. Da wird zum Beispiel in der äußeren Literaturgeschichte immer etwas verzeichnet, worüber die Menschen eigentlich nachdenken sollten, nur haben sich ja die Menschen in der Gegenwart das Nachdenkenkönnen über solche Erscheinungen, die gerade als frappierend im geschichtlichen Leben verzeichnet werden, fast ganz abgewöhnt. Da finden Sie zum Beispiel Dichtungen in der Literaturgeschichte verzeichnet, in denen Karl der Große als ein Anführer der Kreuzzüge erwähnt wird. Karl der Große wird einfach geschildert als ein Anführer innerhalb der Kreuzzüge; ja, überhaupt die ganze Zeit von dem 9. Jahrhundert durch die folgenden Jahrhunderte wird Karl der Große überall als ein Lebender geschildert. Die Leute berufen sich überall auf ihn. Er wird so geschildert, als ob er da wäre. Und als die Kreuzzüge herankommen, von denen Sie ja wissen, daß sie Jahrhunderte später stattfanden, da werden Gedichte gemacht, die Karl den Großen so schildern, als wenn er eben mit den Kreuzfahrern gegen die Ungläubigen zöge.

[ 19 ] Was da zugrunde liegt, das kann nur verstanden werden, wenn man eben weiß, daß in diesen sogenannten dunklen Jahrhunderten des Mittelalters, deren wahre Geschichte ganz ausgelöscht ist, vorhanden war dieses Bewußtsein von der lebendigen toten Schar, die da als Schatten fortlebt. Karl den Großen haben die Leute erst später in den Untersberg hineinversetzt. Nach längerer Zeit, als eben der Geist des Intellektualismus so stark war, daß dieses Schattenleben aufgehört hat, da haben sie ihn in den Untersberg oder den Barbarossa in den Kyffhäuserberg hineinversetzt. Bis dahin haben sie ihn lebend unter sich gewußt.

[ 20 ] Aber worin haben denn diese Menschen, die also eine lebendige Welt atavistisch unter sich gesehen haben, worin haben denn diese Menschen ihr Christentum gesucht, ihre Christologie, ihre christliche Anschauung? Ja, sie haben sie darin gesucht, daß sie den Blick gerichtet haben auf dasjenige, was sich ergibt, wenn so der lebendige Tote, der im Leben verehrt worden war, ihnen vor die Seele trat mit allem, was noch seine Gefolgschaft war. Und so hat man lange Zeiten hindurch Karl den Großen gesehen, wie er den ersten Kreuzzug gegen die Ungläubigen in Spanien unternommen hat; aber man hat ihn so gesehen, daß eigentlich dieser ganze Kreuzzug in die Schattenwelt versetzt war. Man hat ihn in der Schattenwelt gesehen, diesen Kreuzzug, nachdem er auf dem physischen Plan unternommen worden war, man hat ihn fortwirken lassen in der Schattenwelt, aber als ein Abbild des in der Welt wirkenden Christus. Daher wird geschildert, daß Christus unter zwölf Paladinen, unter denen ein Judas war, hinunterritt nach Spanien, und wie dieser dann die ganze Sache verrät. So sehen wir, wie der hellseherische Blick auf die Außenseite der geistigen Welt hin gerichtet wurde — nicht so wie früher ins Innere -, sondern jetzt auf die Außenseite, auf das, was sich ergibt, wenn man die Geister ebenso von außen ansieht wie früher von innen. Jetzt ergab sich für die wichtigsten Dinge alles, was da in der Schattenwelt sich abspielte, wie ein Abglanz des Christus-Ereignisses.

[ 21 ] Und so lebte eigentlich vom 4. bis zum 13., 14. Jahrhundert in Europa die Vorstellung, daß die Menschen, die gestorben sind, nachdem sie im Leben Wichtiges zu verrichten hatten, sich so anordnen in ihren nachtodlichen Taten, daß sie anzuschauen sind wie ein Abglanz, wie ein Abbild des Christus-Ereignisses. Man sah überall die Fortsetzung des Christus-Ereignisses — wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf - als Schatten in den Lüften. Wenn die Menschen ausgesprochen hätten die Dinge, die sie gefühlt haben, so würden sie gesagt haben: Über uns schwebt noch der Christus-Strom; Karl der Große hat unternommen, sich in diesen Christus-Strom hineinzuversetzen, und er hat sich mit seinen Paladinen ein Abbild geschaffen des Christus mit seinen zwölf Aposteln, er hat in der realen geistigen Welt fortgesetzt die Taten des Christus. — So haben es sich vorgestellt diese Menschen in der sogenannten dunklen Zeit des Mittelalters. Da war die geistige Welt von außen angesehen, ich möchte sagen, wie nachgebildet der Sinnenwelt, wie Schattenbilder der Sinnenwelt, während sie früher in denjenigen Zeiten, von denen ein Nachglanz die alte Theologie war, eben von innen angeschaut worden ist. Kurz, der Unterschied zwischen dieser physischen Welt und der geistigen Welt für die bloß intellektuellen Menschen ist ein solcher, daß ein Abgrund zwischen beiden besteht. Dieser Unterschied bestand in den ersten Jahrhunderten des Mittelalters nicht für die Menschen der sogenannten dunklen Zeit. Ich möchte sagen, die Toten blieben bei den Lebendigen, und besonders hervorragende verehrte Persönlichkeiten, sie machten in der ersten Zeit nach ihrem Tode, also in der ersten Zeit, nachdem sie für die geistige Welt geboren waren, gewissermaßen das Noviziat durch für das Heiligwerden.

[ 22 ] Und sehen Sie, eine Anzahl dieser Menschen, die lebendige Tote waren — es war für die Menschen der damaligen Zeit nichts Absonderliches, von diesen lebendigen Toten als von realen Persönlichkeiten zu sprechen, nachdem sie für die geistige Welt geboren worden waren -, sie wurden, wenn sie besondere Auserwählte waren, zu Hütern des Heiligen Grals bestellt. Besonders auserlesene lebende Tote wurden zu Hütern des Heiligen Grals bestellt. Und man wird die Gralssage niemals vollständig verstehen, wenn man nicht weiß, wer eigentlich die Hüter des Grals waren. Zu sagen etwa: Dann waren ja die Hüter des Grals keine wirklichen Menschen -, das wäre den Leuten der damaligen Zeit höchst lächerlich erschienen. Denn sie hätten gesagt: Glaubt ihr Schattenfiguren, die ihr auf der Erde wandelt, daß ihr mehr seid als diejenigen, die gestorben sind und sich nun um den Gral sammeln? — Das wäre denjenigen, die in diesen Zeiten lebten, ganz lächerlich vorgekommen, wenn sich diese Figuranten hier auf der Erde für etwas Realeres gehalten hätten als die lebendigen Toten. Man muß sich in die Seelen der damaligen Zeit durchaus hineinfühlen: so war es für diese Seelen. Und alles, was das für die Welt sein konnte dadurch, daß man das Bewußtsein von einem solchen Zusammenhang mit der geistigen Welt hatte, spielte sich auch in den Seelen ab. Daher sagte man sich: Ja, die Menschen, die hier auf Erden sind, die sind gewiß zunächst herausgebildet aus ihrer Unmittelbarkeit. Aber etwas Rechtes wird der Mensch der Gegenwart erst, wenn er in sich aufnimmt, was ihm ein lebendiger Toter geben kann. — In einem gewissen Sinne wurden physische Menschen auf der Erde so angesehen, als ob sie eigentlich nur die Hülle wären für lebendige Tote in ihrem äußeren Wirken. Das war eine Eigentümlichkeit dieser Jahrhunderte, daß man sagte: Wenn diese lebendigen Toten etwas hier auf Erden verrichten wollen, wozu man Hände braucht, dann gehen sie in einen physisch lebenden Menschen hinein und verrichten durch den etwas.

[ 23 ] Aber nicht nur das. Solche Menschen gab es überhaupt in der damaligen Zeit, die sich sagten: Man kann nichts Besseres tun, als solchen Menschen, die hier auf Erden verehrt worden sind und jetzt so bedeutsame Wesenheiten in der Welt der lebendigen Toten sind, daß sie den Gral hüten dürfen, eine Hülle zu geben. Und es gab in der damaligen Zeit durchaus diese Anschauung unter dem Volke, daß man sagte: Der hat sich gewidmet, sagen wir zum Beispiel dem Schwanenorden. Dem Schwanenorden haben sich diejenigen gewidmet, welche wollten, daß die Gralsritter durch sie hier in der physischen Welt wirken können. Und man nannte einen Schwan solch einen Menschen, durch den ein solcher Gralsritter hier in der physischen Welt wirkte.

[ 24 ] Und nun denken Sie an die Lohengrin-Sage. Denken Sie, wie diese Sage berichtet, daß, als Elsa von Brabant in großer Not ist, der Schwan kommt. Es ist der Schwan, das heißt der Angehörige des Schwanenritterordens, es ist der Schwan, der aufgenommen hat einen Mitgenossen aus der Runde des Heiligen Grals, der da erscheint; man darf ihn um sein eigentliches Geheimnis nicht fragen. Und am glücklichsten fühlten sich zum Beispiel in dem Jahrhundert, aber auch noch in den folgenden Jahrhunderten, sogar solche Fürsten wie Heinrich von Sachsen, der bei seinem Ungarnzuge diesen Schwanenritter, diesen Lohengrin, innerhalb seiner Heeresmasse haben konnte.

[ 25 ] Aber man hatte mancherlei solche Ritter, welche im Grunde genommen sich nur als die äußere Umhüllung anschauten derjenigen, die von jenseits des Todes herüber in den Heeren noch kämpften. Man wollte verbunden sein mit den Toten; man wußte sich mit ihnen verbunden. Welche Bedeutung für die Lebenden diese heute eigentlich ganz abstrakt gewordene Sage für die Realität hatte, das kann man nur ermessen, wenn man sich in die Seelenverfassung der damaligen Zeit hineinlebt. Und diese Auffassung, die einzig und allein zunächst auf die physische Welt hinschaute, wie aus dem physischen Menschen heraus sich hebt der geistige Mensch, der dann zu den lebenden Toten gehört, diese Anschauung beherrschte die Gemüter in der damaligen Zeit, die war das Wesentliche, was in der Seele lebte: Man muß einen Menschen zuerst auf der Erde gekannt haben, dann kann man hinaufkommen zu seinem Geiste. Es war wirklich so, daß nun gegenüber einer älteren Anschauung die Sache auch im äußeren populären Leben umgekehrt war. In der alten Zeit hatte man zuerst in die geistige Welt hineingeschaut. Man hatte womöglich das Bestreben, den Menschen als geistiges Wesen zu sehen, bevor er auf die Erde heruntergestiegen ist, und dann, sagte man, begreift man das, was er auf Erden ist. Jetzt, bei diesen nordischen Völkerschaften, nachdem sie sich mit dem Römertum vermischten, bildete sich die Anschauung aus: Man begreift das Geistige, nachdem man es zunächst auf der physischen Welt verfolgt hat, und es sich dann heraushebt aus der physischen Welt als Geistiges. Es war umgekehrt gegenüber dem Früheren.

[ 26 ] Der Abglanz von dieser Anschauung wird nun die Theologie des Mittelalters. Die alten Theologien sagten: Zuerst muß man die Ideen haben, zuerst muß man erkennen das Geistige. Der Glaubensbegriff wäre für diese alten Theologien etwas ganz Absurdes gewesen, denn das Geistige wurde zuerst erkannt, bevor man überhaupt daran denken konnte, das Physische zu erkennen. Das mußte man ja erst mit dem Geistigen beleuchten. Jetzt aber war man, nachdem man aus der breiteren Welt davon ausgegangen war, zuerst das Physische kennenzulernen, dazu gekommen, auch in der Theologie so zu denken: Man muß von der Sinneswelt mit Erkenntnis ausgehen, und dann aus den Sinnesdingen die Begriffe herausschälen; nicht die Begriffe aus der geistigen Welt an die Sinnesdinge herantragen, sondern aus den Sinnesdingen Begriffe herausschälen.

[ 27 ] Und jetzt stellen Sie sich einmal die untergehende römische Welt vor, und dann, was in dieser Welt noch als Kampf von der alten Zeit her da war: daß man die Begriffe noch in der geistigen Welt erlebte und an die Sinnesdinge herantrug. Das empfanden solche Leute wie, sagen wir Martianus Capella, der im 5. Jahrhundert seine Abhandlung schrieb: «De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii», in der er danach ringt, dieses, was immer abstrakter und abstrakter werden will in den Ideen, dennoch in der geistigen Welt zu suchen. Aber es geht diese alte Anschauung unter, weil die römische Verschwörung gegen den Geist in jenem Konsortium, von dem ich Ihnen gesprochen habe, eben alles, was unmittelbar menschlicher Zusammenhang mit dem Geiste ist, ausrottete.

[ 28 ] Wir sehen, wie das allmählich verschwimmt, wie die alte Anschauung aufhört. Jene alte Anschauung hatte noch gewußt: Dringe ich hinüber in die geistige Welt, begleiten mich die Engel. - Oder wenn es Griechen waren, haben sie diese «Wächter» genannt. Solch ein Mensch, der hinausgegangen ist auf dem Wege des Geistes, der wußte sich begleitet von einem Wächter.

[ 29 ] Das, was in alten Zeiten eine wirkliche geistige Wesenheit, der Wächter war, das war zu den Zeiten, als Capella schrieb, bereits die Grammatik, die erste Stufe der siebengliedrigen sogenannten freien Künste. In älteren Zeiten wußte man: Dasjenige, was in Grammatik lebt, was in den Worten und Wortzusammenhängen lebt, das ist etwas, was dann weiter hinaufführt in die Imagination. Man wußte im Wortzusammenhang den Engel wirksam, den Wächter.

[ 30 ] Würden wir die Darstellungen bei älteren Zeiten suchen, so würden wir nirgends eine stroherne Definition finden. Es ist ja interessant, daß Capella nicht etwa die Grammatik so schildert wie die spätere Renaissance, sondern die Grammatik ist da noch eine richtige Person, und die Rhetorik als zweite Stufe wiederum eine Person. Dort sind sie schon stroherne Allegorien, früher waren sie geistige Anschauungen, die nicht bloß eben etwas lehrten, wie zum Beispiel beim Capella gelehrt wird, sondern die schaffende Wesenheiten waren, und das Hineingehen zum Geiste war gefühlt als ein Hineindringen zu schaffenden Wesenheiten. Nun waren das Allegorien geworden, aber immerhin noch Allegorien. Es sind immerhin noch, wenn sie auch nicht mehr sehr stattlich sind, wenn sie auch schon ziemlich schmächtig geworden sind, es sind immerhin noch Damen, diese Grammatik, Rhetorik, Dialektik. Sie sind ja sehr mager und haben eigentlich nur noch, sagen wir, die Knochen der geistigen Anstrengung und die Haut der Begriffe, aber es sind immerhin noch respektable Damen, die diesen Capella, den ältesten Schriftsteller über die sieben freien Künste, hineintragen in die geistige Welt. Mit diesen sieben Damen macht er nach und nach sozusagen Bekanntschaft; zuerst mit der Dame Grammatik, dann mit der Dame Rhetorik, mit der Dame Dialektik, mit der Dame Arithmetik, mit der Dame Geometrie, mit der Dame Musik, und endlich mit der alles überragenden himmlischen Dame Astrologia. Es sind eben durchaus Damen. Wie gesagt, es sind ihrer sieben. Das siebenfach Weibliche zieht uns hinan so hätte er schließen können, der Capella, indem er seinen Weg zur Weisheit schilderte. Aber denken Sie daran, was daraus geworden ist! Denken Sie an die späteren mittelalterlichen Klosterschulen. Die haben gegenüber der Grammatik und Rhetorik, wenn sie gebüffelt haben, nicht mehr empfunden: Das ewig Weibliche zieht uns hinan! Es war tatsächlich so, daß aus dem Lebendigen herausgewachsen ist zuerst das Allegorische und dann das Intellektuelle.

[ 31 ] Von jener musenartigen Wesenheit, welche noch gewirkt hat bei demjenigen, der in alten Zeiten den Weg von dem menschlich gesprochenen Worte zu dem Weltenworte suchte, so daß es durch ihn gehen konnte, so daß er sagen mußte: «Singe, o Muse, vom Zorn mir des Peleiden Achilleus ... .», von dieser Bekanntschaft mit der Muse, die den Menschen hineinführt in die Geisteswelt, so daß nicht mehr er singt, sondern daß die Muse singt von dem Zorn des Peleiden Achilleus, von dieser Stufe bis zu derjenigen, wo dann die Rhetorik selber im römischen Wesen sprach, und später in der Vermischung mit dem vom Norden herziehenden Wesen, das ist eben ein weiter Weg; da wird alles abstrakt, da wird alles begrifflich, da wird alles intellektuell. Aber je weiter wir herankommen an den Osten und nach den alten Zeiten, desto mehr finden wir alles im konkreten geistigen Leben. Und so war es durchaus, daß der alte 'Theologe zu den geistigen Wesenheiten ging, um seine Begriffe zu holen. Die wandte er dann auf diese Welt hier an. Derjenige Theologe aber, der schon herausgewachsen war aus dem, was aus dem Zusammenfluß der nordischen Völker mit dem Römertum entstand, der sagte: Hier in der Sinneswelt muß die Erkenntnis gesucht werden, dann gewinnt man die Begriffe. - Da konnte man aber nicht hinaufkommen in eine geistige Welt. Jetzt aber war eben durch das römische Kollegium gut dafür gesorgt, daß zwar da unten die Menschen herumfischten in der sinnlichen Welt, aber nicht über diese sinnliche Welt hinauskamen. Während sie früher zwar diese sinnliche Welt auch hatten, hier oben (es wird gezeichnet) aber die Begriffe und Ideen aufsuchten in der geistigen Welt und dann die physische Welt beleuchteten, sogen sie jetzt aus der physischen Welt die Begriffe heraus. Die kamen nicht weit hinauf, die kamen nur zu einer Interpretation der physischen Welt. Aber es war ja die Erbschaft da. Man kam nicht mehr durch einen eigenen Erkenntnisweg da hinauf, aber es war ja noch die Erbschaft vorhanden. Die war niedergeschrieben oder durch Tradition erhalten, in Dogmen verkörpert und erstarrt. Das war also da oben (in der Zeichnung), und seine Bewahrung wurde nun die Konfession. Da drinnen war dasjenige erhalten, was über Geistiges zu sagen war. Das war da. Und immer mehr und mehr gelangte man zu dem Bewußtsein: Das muß unangetastet bleiben, was da gesagt worden ist für oben durch irgendwelche Offenbarungen, die nicht mehr nachgeprüft werden können. Die Erkenntnis aber, die muß unten bleiben: da muß man alles Begriffliche herausholen.

[ 32 ] Und so entstand allmählich auch die Erbschaft desjenigen, was noch in den ersten dunklen Jahrhunderten des Mittelalters vorhanden war. Sehen Sie, es war doch noch eine andere Zeit, als in Europa das mittelalterliche atavistische Hellsehen vorhanden war, wo zum Beispiel der sächsische — man nennt ihn einen Bauern, aber er war, das zeigt der «Heliand» selber, jedenfalls ein aus dem Bauernstande herausgeborener Geistlicher —, wo dieser sächsische Bauerngeistliche eben einfach hinschaute auf die Menschen seiner Umgebung und die Fähigkeit hatte, zu sehen, wie mit dem Tode das Geistig-Seelische herausgeht und zum tot-lebendigen Menschenwesen wird. Und so schildert er dann in dem Zuge, der da über dem Irdischen schwebt, dasjenige, was er als Anschauung entwickelt über das Christus-Ereignis in dem «Heliand».

[ 33 ] Aber was hier auf Erden lebt, das wurde immer mehr und mehr, ich möchte sagen, herabgezogen in das bloß Unlebendige. Die atavistischen Fähigkeiten hörten auf, und im Sinnlichen suchte man nur noch die Begriffe. Und was ergab sich da für eine Anschauung? Diese Anschauung ergab sich: Um das Übersinnliche brauchen wir uns ja mit der Erkenntnis nicht besonders zu kümmern. Das ist ja in den Schriften und in den Traditionen erhalten, wir brauchen nur aufzuschlagen die alten Bücher, nur nachzuschauen in den alten Traditionen. Da ist über das Übersinnliche alles enthalten, was man überhaupt wissen soll. Jetzt beirrt es uns auch nicht, wenn wir nun im Umkreis der Sinneswelt gerade die in der Sinneswelt selbst liegenden Begriffe nur allein für die Erkenntnis beachten.

[ 34 ] Und so wurde immer mehr und mehr das Bewußtsein lebendig: Das Übersinnliche bleibt ein Bewahrtes; will man forschen, muß man sich an die sinnliche Welt halten.

[ 35 ] Und ein solcher Geist, der ganz darinnensteckte, der, ich möchte sagen, dieses Herausschälen aus der Sinneswelt des sächsischen Bauerngeistlichen, der den «Heliand» geschrieben hat, fortsetzte, das war noch im 19. Jahrhundert Gregor Mendel. Was soll man sich kümmern um irgend etwas in bezug auf die Vererbung, wie es in alten Zeiten erforscht worden war! Das steht ja im alten Testament. Da schaue man hinunter auf die Sinneswelt, wie die roten Erbsen und die weißen Erbsen sich miteinander vermischen, wie das dann wieder rote und weiße und scheckige Erbsen gibt und so weiter. Da kann man ein gewaltiger Naturforscher werden, und mit dem, was über das Übersinnliche zu sagen ist, mit dem kommt man ja in gar keine irgendwie geartete Disharmonie, denn das bleibt ganz unangetastet.