The Mystery of the Trinity

Part 1: The Mystery of Truth

GA 214

28 July 1922, Dornach

Lecture II

In various and complicated ways, we have already seen that the human being can only be understood within the context of the entire universe, out of the whole cosmos. Today we will consider this relationship of the human being to the cosmos from a rather simpler standpoint in order to bring the subject to a certain culmination in later lectures.

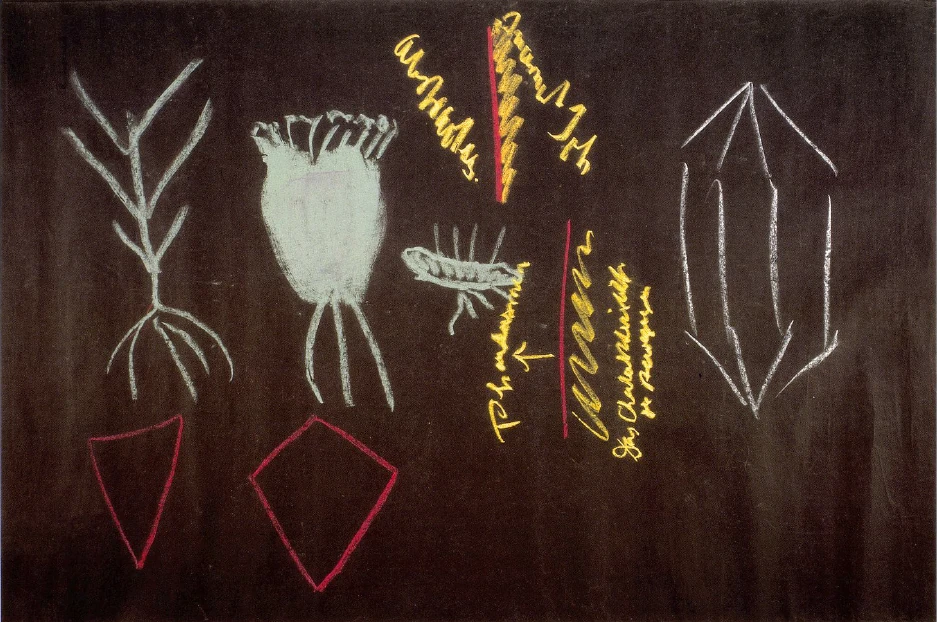

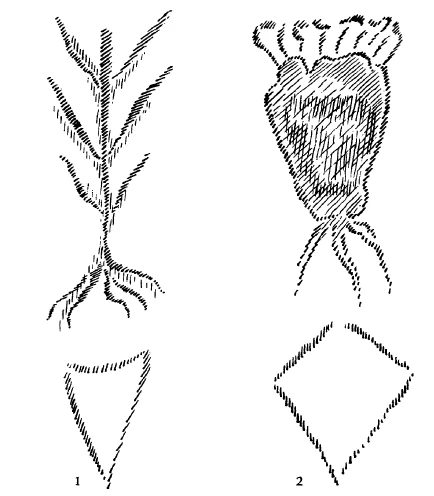

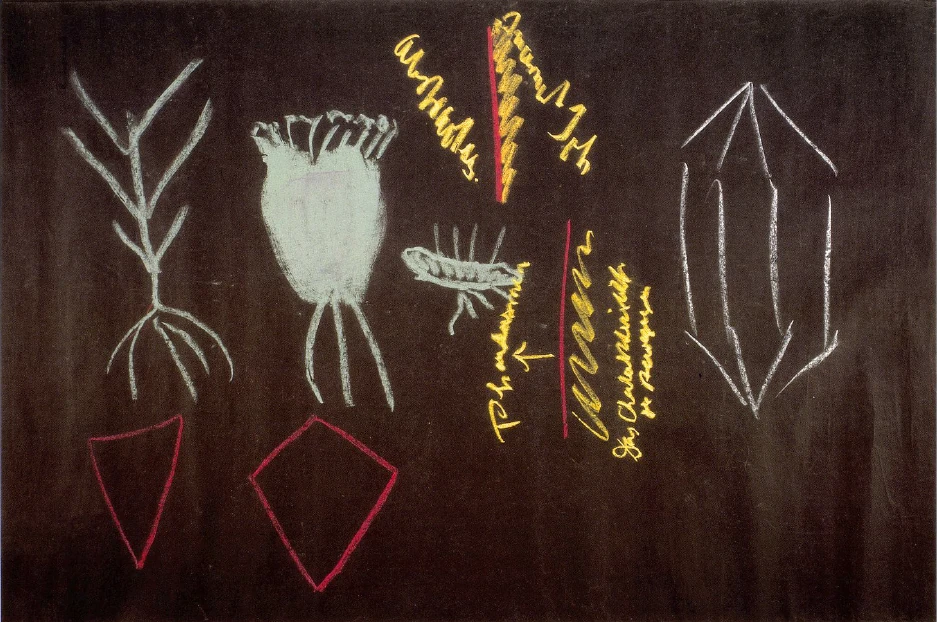

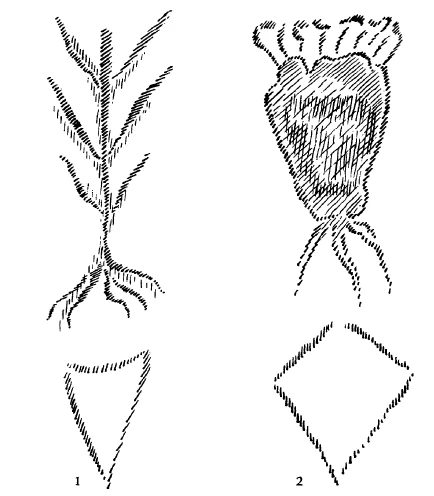

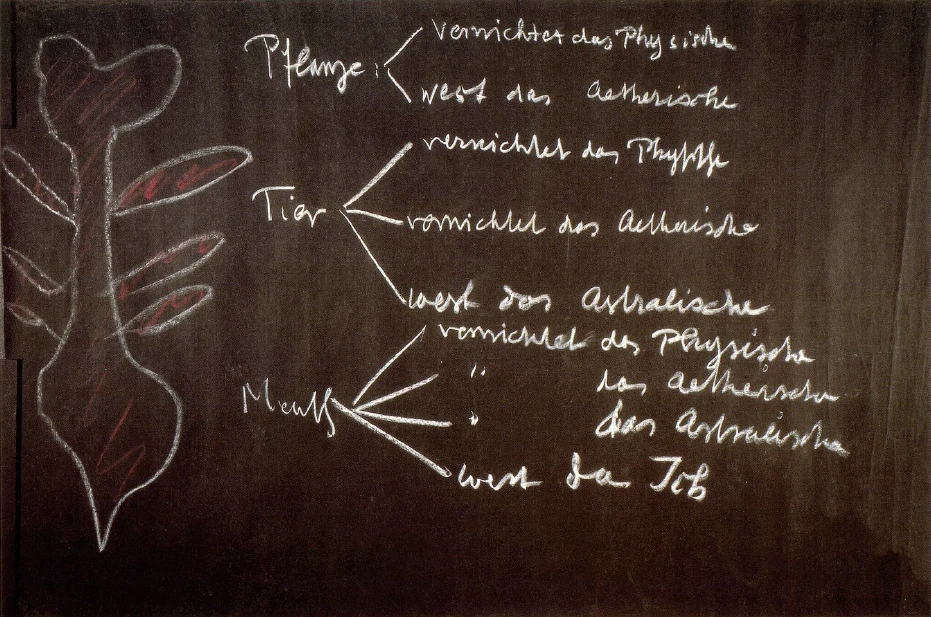

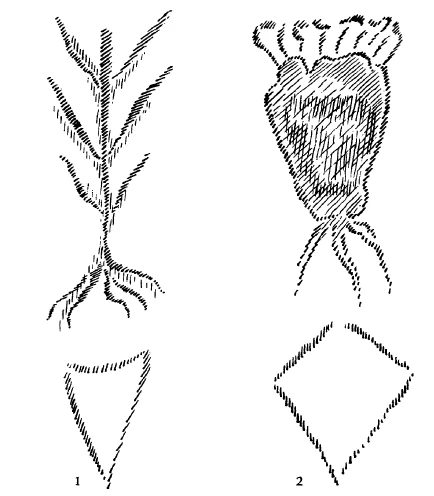

The most immediate part of the cosmos surrounding us is, to begin with, what appears to us as the physical world. But this physical world actually comes to meet us as the mineral kingdom, at least it confronts us only there in its intrinsic, primal form. Considering the mineral kingdom in the wider sense to include water, air, the phenomena of warmth and the warmth ether, we can study within the mineral kingdom the forces and the essential being of the physical world. This physical world manifests its workings, for instance, in gravity and in magnetic and chemical phenomena. In reality we can only study the physical world within the mineral kingdom. As soon as we come to the plant kingdom, the ideas and concepts we have formed for the physical world are no longer adequate. In modern times no one has felt this truth as intensely as Goethe.15Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), German poet and thinker. Published Metamorphosis of Plants in 1790; in this book he shows the leaf as the primeval organ of the plant out of which all other plant organs evolved. As a relatively young man he became acquainted with the plant world from a scientific point of view and sensed immediately that the plant world must be understood with a very different kind of thought and observation than is applicable to the physical world. He encountered the science of plants in the form developed by Linnaeus.16Karl von Linne (Linnaeus) (1107–1778), Swedish naturalist, father of modern systematic botany. This great Swedish naturalist developed botany by observing, above all, the external and minute forms to be found in the individual species and genera. Following these forms he evolved a system in which plants with similar structural characteristics are grouped into genera, so that the various genera and species stand next to each other in the same way as the objects of the mineral kingdom are organized. Goethe was repelled by this aspect of the Linnaean system, by this grouping of individual plant forms. This, said Goethe to himself, is how one observes the minerals and everything of a mineral nature. A different kind of perception must be used for plants. In the case of plants, said Goethe, one would have to proceed in the following way: Here, let us say, is a plant which develops roots, then a stem, then leaves on the stem, and so forth (drawing 1). But it does not always have to be that way. For example, Goethe said to himself, it could be like this (drawing 2):

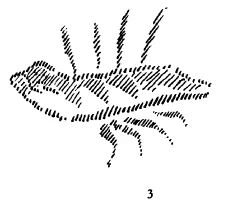

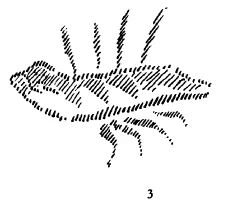

Here is the root—but the force that in the first plant (drawing 1) began to develop right in the root is held back here (drawing 2), still enclosed in itself, and therefore does not develop a slender stem that immediately unfolds its leaves but a thick bulbous stem instead. In this way the forces of the leaves go into the thick stem structure and very little remains over to start new leaves or, with time, blossoms. Or again, it may be that a plant develops its roots very sparingly; some of the forces of the roots are left. Such a development would look like this (drawing 3):

Then there would be few stalk and leaf starts developing from the plant. All these examples are, however, inwardly the same. In one case the stem is slender and the leaves strongly developed (drawing 1); in another (drawing 2), the stem becomes bulbous and the leaves grow sparingly. The basic idea is the same in all the plants but the idea must be kept inwardly mobile in order to be able to move from one form to the other. Here I must create this form: weak stem, distinct leaves, concentrated leaf force (drawing 1). With the same idea I get a second form: concentrated root force (drawing 2). And again with the same idea I find another, a third form. And so I must create a flexible, mobile concept, through which the whole system of plants becomes a unity.

Whereas Linnaeus set the different forms side by side and observed them as he would observe mineral forms, Goethe, by means of mobile ideas, wanted to grasp the whole system of plant growth as a unity—so that he slipped out of one plant form, as it were, into another form by metamorphosing the idea itself. This kind of observation with mobile ideas was, in Goethe, doubtless the initial impulse toward an imaginative way of observing. Thus we may say that when Goethe approached the system of Linnaeus, he felt that the usual object-oriented way of knowing, although very useful when applied to the physical world of the mineral kingdom, was not adequate for the study of plant life. Confronted with the Linnaean system he felt the necessity for an imaginative means of observation.

In other words, Goethe said to himself: When I look at a plant it is not the physical that I see or, at any rate, that I should see; in a manner of speaking, the physical has become invisible, and I must grasp what I see with ideas very different from those applicable to the mineral kingdom. It is extraordinarily important for us to appreciate this distinction. If we see it in the right way we can say that in the mineral kingdom nature is outwardly visible all around us, while in the plant kingdom physical nature has become invisible. Of course, gravity and all the other forces of physical nature are still at work in the plant kingdom; but they have become invisible while a higher nature has become visible—a higher nature that is inwardly mobile all the time, inwardly alive. What is really visible in the plant is the etheric nature. And we are wrong if we say that the physical body of the plant is visible. The physical body of the plant has actually become invisible. What we see is the etheric form.

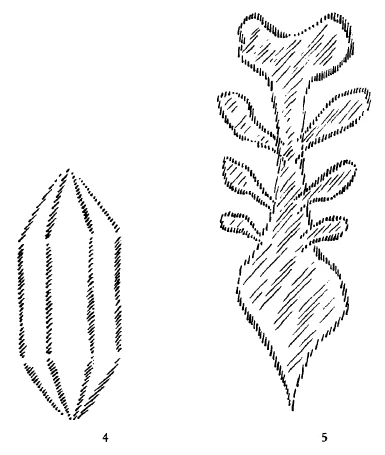

How then does the visible part of the plant really come into being? If you have a physical body, for instance, a quartz crystal, you can see the physical in an unmediated way. But with a plant you do not really see the physical, you see the etheric form. This etheric form is filled out with physical matter; physical substances live within it. When the plant loses its life and becomes carbon in the earth you see how the substance of physical carbon remains. It is contained in the plant. We can say, then, that the plant is filled out with the physical but dissolves the physical through the etheric. The etheric is what is actually visible in the plant form. The physical is invisible.

Thus the physical becomes visible for us in the mineral world. In the world of the plants the physical has already become invisible, for what we see is really the etheric made visible through the agency of the physical. We would not, of course, see the plants with our ordinary eyes if the invisible etheric body did not carry within it little granules (an overly simplified and crude expression, to be sure) of physical matter. Through the physical the etheric form becomes visible to us; but this etheric form is what we are really seeing. The physical is, so to speak, only the means whereby we see the etheric. So that the etheric form of a plant is an example of an Imagination, but of an Imagination that is not directly visible in the spiritual world but only becomes visible through physical substances.

If you were to ask, what is an Imagination?—We could answer that the plants are all Imaginations, but as Imaginations they are visible only to imaginative consciousness. That they are also visible to the physical eye is due to the fact that they are filled with physical particles whereby the etheric is rendered visible in a physical way to the physical eye. But if we want to speak correctly we should never say that in the plant we are seeing something physical. In the plants we are seeing genuine Imaginations. We have Imaginations all around us in the forms of the plant world.

But if we now ascend from the world of plants to that of animals, it is no longer sufficient for us to turn to the etheric. Here we must go a step further. In a sense we can say of the plant that it nullifies the physical and makes manifest the being of the etheric.

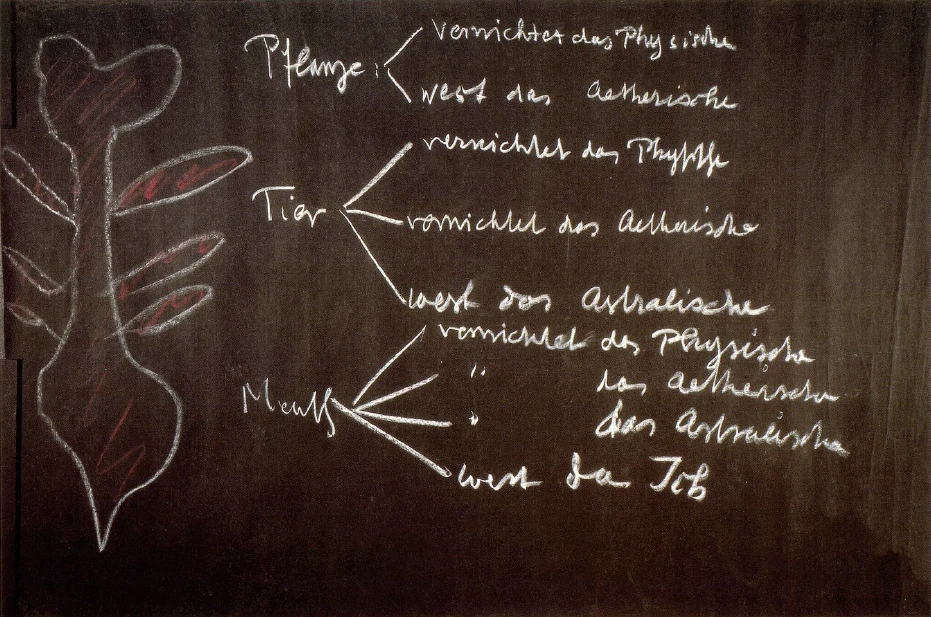

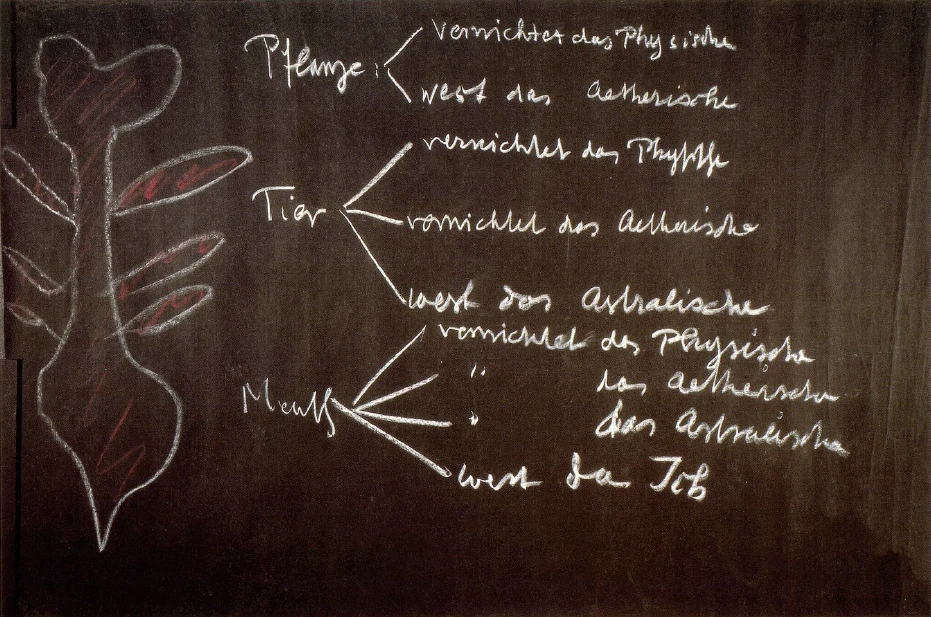

Plant: nullifies the physical and manifests the being of the etheric.

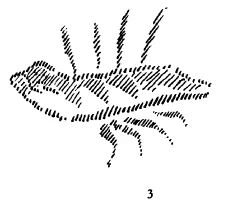

But when we ascend to the animal, we are not allowed to hold onto the etheric; we must imagine the animal form with the etheric now also nullified. Thus we can say that the animal nullifies the physical (the plant does this too) and also nullifies the etheric: the animal manifests that which can assert itself when the etheric is nullified. When the physical is nullified by the plant the etheric can assert itself. If then the etheric too, is only a filling, granules (again, a crude expression), then the astral, which is not within the world of ordinary space but works in ordinary space, can make its being manifest. Therefore we must say that in the animal the being of the astral is made manifest.

Animal: nullifies the physical, nullifies the etheric, and manifests the being of the astral.

Goethe strove with all his power to acquire mobile ideas, mobile concepts, in order to behold this fluctuating life in the world of the plants. In the plants the etheric is before us because the plant, as it were, drives the etheric out onto the surface. The etheric lives in the form of the plant. But in animals we must recognize the existence of something that is not driven to the surface. The very fact that a plant must remain at the place where it has grown shows that there is nothing in the plant that does not come to the surface and make itself visible. The animal moves about freely. There is something in the animal that does not come to the surface and become visible. This is the astral in the animal, something which cannot be grasped by merely making our ideas mobile, as I explained previously, by merely showing how we move from form to form in the idea itself. This does not suffice for the astral. If we want to understand the astral we must go further and say that something enters into the etheric and is then able, from within outward, to enlarge the form—for example, to make the form nodular or tuberous. In the plant you must always look outside for the cause of the variation in form, for the reasons why the form changes. You must be flexible with your idea. But the merely mobile is not enough to comprehend the animal. To comprehend the animal you have to bring something else into your concepts. If you want to understand how the conceptual activity appropriate for understanding animals must differ from that for plants, then you need more than a mobile concept capable of assuming different forms; the concept itself must receive something inwardly, must take into itself something that it does not contain of itself. This something could be called Inspiration in the forming of concepts. In the organic activity that takes place below our breathing we remain in the activity, so to speak, within ourselves. But when we breathe in, we receive the air from outside; so too if we would comprehend the animal we not only need to have mobile concepts but we must take into these mobile concepts something from the “outside.”

Let me explain the difference in another way. If we really want to understand the plant, then we can remain standing still, as it were; we can regard ourselves, even in thought, as stationary beings. And even if we were to remain stationary our whole life long we would still be able to make our concepts mobile enough to grasp the most varied forms in the plant world. But we could never form the idea, the concept of an animal, if we ourselves could not move about. We must be able to move around ourselves if we want to form the concept of an animal. And why?

When you transform the concept of a plant (drawing 1) into a second concept (drawing 2) then you yourself have transformed the concept. But if you then begin running, your concept becomes different through the very act of your running; you yourself must bring life into the concept. That infusion of life is what makes a merely imagined concept into an inspired concept. When it is a plant that is concerned, you can picture yourself inwardly at rest and merely changing the concepts. But if you want to think a true concept of an animal (most people do not like to do this at all because the concept must become inwardly alive; it wriggles within) then you must take the Inspiration, the inner liveliness, into yourself, it is not enough to externally weave sense perceptions from form to form. You cannot think an animal in its totality without taking this inner liveliness into the concept.

This conception of the animal was something which Goethe did not achieve. He did reach the point of being able to say that the plant world is a sum total of concepts, of Imaginations. But with the animals something has to be brought into the concept; with the animal we ourselves have to make the concept inwardly alive. In the case of a plant the Imagination is not itself actually living. This can be seen from the fact that as the plant stands in the ground and grows, its form changes only as the result of external stimuli, and not because of any inner activity. But the animal is, in a manner of speaking, the moving, living concept; with the animal we have to bring in Inspiration, and only through Inspiration can we penetrate to the astral.

When, finally, we ascend to the human being we have to say that he nullifies the physical, the etheric, and the astral and makes the being of the I manifest.

Humanity: nullifies the physical, nullifies the etheric, nullifies the astral, and manifests the being of the I.

With an animal we must say that what we see is really not the physical but a physically appearing Inspiration. This is the reason why, when the inspiration or breathing of a person is disturbed in some way it very easily assumes an animal form. Try sometime to remember some of the figures that appear in nightmares. Very many of them appear in animal forms. Animal forms are forms filled with Inspirations.

The human I we can only grasp through Intuition. Truly, in reality, the human I can only be grasped through Intuition. In the animal we see Inspiration; in the human being we actually see the I, the Intuition. We speak falsely when we say that we see the physical body of an animal. We do not see the physical body at all. It has been dissolved away, nullified, it merely makes the Inspiration visible to us; and the etheric body has likewise been dissolved away, nullified. With an animal we are actually seeing the astral body externally by means of the physical and the etheric. And with the human being we perceive the I or ego. What we actually see there before us is not the physical body, for it is invisible—and so too are the etheric body and the astral body. What we see in a human being is the I externally formed, formed in a physical way. And this is why people appear to visual, external perception in their flesh color—a color found nowhere else, just as the I is not found in any other being. Therefore, if we want to express ourselves correctly, we should say that we can only completely comprehend the human being when we think of him as consisting of physical body, etheric body, astral body, and the I. What we see before us is the I, while invisibly within are astral body, etheric body, and physical body.

Now, we really only comprehend the human being if we consider the matter a little more closely. What we see to begin with is merely the “outside” of the I. But the I is perceptible in its true form only inwardly, only through Intuition. But something of this I is also noticed by the human being in his ordinary, conscious life—that is, in his abstract thoughts which the animal does not have because it does not have an I. The animal does not have the ability to abstract thoughts because it does not have an I. Therefore, we can say that in the human form and figure we see externally the earthly incarnation of the I; and when we experience ourselves from within, in our abstract thoughts, there we have the I. But they are merely thoughts; they are pictures, not realities.

If now we consider the astral body, which is present although nullified, we come to the member that cannot be seen externally but that we can see if we look at a person in movement and out of their movements begin to understand their form. Here we need to practice the following kind of observation: Think of a small, dwarflike, thickset person who walks about on short legs. You will understand his movement if you observe his stout legs, which he thrusts forward like little pillars. A tall, lanky man with very long legs will move very differently. Observing in this way you will see unity between movement and form. You can train yourself to observe this unity in other aspects of human movement and form. For example, a man with a forehead sloping backward and a very prominent chin moves his head differently than someone with a receding chin and a strikingly projecting forehead. Everywhere you will see a connection between the form and movement of a human being if you simply observe him as he stands before you and get an impression of his flesh, of its color, and of how he holds himself when in repose. You are observing his I when you watch what passes over from his form into his movements and back again into his form.

Study the human hand sometime. How differently people with long or short fingers handle their tools. Movement passes over into form, form into movement. Here you are visualizing, as it were, a shadow of the astral body expressed through external, physical means. But, you see, as I am describing it to you now, it is a primitive inspiration. Most people do not think of observing people who walk about, as, for example, Fichte walked the streets of Jena.17Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814), German idealist philosopher. Important for the development of anthroposophy. See Rudolf Steiner: Truth and Science and The Riddle of Man. Anyone who saw Fichte walking through the streets of Jena could also have sensed the movement and the formative process which were in his speech organs and which came to expression particularly when he wanted his words to carry conviction although they were in his speech organs all the time. Inspiration, at least in an elementary form, is required in order to see this.

But when we see from within what we have thus seen from without, which I have told you is perceptible by means of a primitive kind of inspiration, what we find is, in essence, the human life of fantasy permeated with feeling. It is the realm where abstract thoughts are inwardly experienced. Memory pictures, too, when they arise, live in this element.

Seen from without the I expresses itself, for example, in the flesh color but also in other forms, for example, in the countenance. Otherwise we would never be able to speak of a physiognomy. If, for example, the corners of one's mouth droop when one's face is in repose, this is definitely connected karmically with the configuration of one's I in this incarnation. Seen from the inside, however, abstract thoughts are present here. The astral body reveals itself externally in the character of the movements, inwardly in fantasy or in the pictures of fantasy that appear to the human being. The astral body itself more or less avoids observation, the etheric body still more so.

The etheric body is really not visible from outside, or at most only becomes visible in physical manifestation in very exceptional cases. It can, however, become externally visible when a person sweats—when a person sweats the etheric body becomes visible outwardly. But you see, Imagination is required in order to relate the process of sweating to the whole human being. Paracelsus18Paracelsus (1493–1541), Renaissance alchemist, doctor, and philosopher. Cf. Rudolf Steiner: Mysticism at the Dawn of the Modern Age, Origins of Modern Science (Lecture Eight). was one who made this connection. For him, not only the manner but the substance of the sweat differed in individual human beings. For Paracelsus, the whole human being—the etheric nature of the entire human being—was expressed in this way. Generally speaking, then, there is very little external expression of the etheric. Inwardly, on the other hand, it is experienced all the more, namely in feeling. The whole life of feeling, inwardly experienced, is what is living in the etheric body when this body is active from within, so that one experiences it from within. The life of feeling is always accompanied by inner secretion. To observation of the etheric body in the human being it appears that the liver, for instance, sweats, that the stomach sweats—that every organ sweats and secretes. The etheric life of the human being lives in this process of inner secretion. Around the liver, around the heart, there is a cloud of sweat, all is enveloped in mist and cloud. This needs to be understood imaginatively. When Paracelsus spoke about the sweat of the human being he did not say that it is only on the surface. He said rather that sweat permeates the whole human being, that it is his etheric body that is seen when the physical is allowed to fall away from sight. This inner experience of the etheric body is, as I have said, the life of feeling.

And the external experience of the physical body—this, too, is by no means immediately perceptible. True, we become aware of the physical part of human corporeality when, for example, we take a child into our arms. It is heavy, just as a stone is heavy. That is a physical experience; we perceive something which belongs to the physical world. If someone gives us a box on the ears there is, apart from the moral experience, a physical experience, too—a blow, an impact. But as something physical it is actually only an elastic blow, as when one billiard ball impacts another. The physical element must always be kept separate from the other, the moral element. But if we go on to perceive this physical element inwardly, in the same way we inwardly perceive the external manifestation of the life of feeling, then in the merely physical processes we experience inwardly the human will. The human will is what brings the human being together with the cosmos in a simple, straightforward way.

You see, when we look around us for Inspiration we find it in the forms of the animals. The manifold variety of animal forms is the basis for our perceptions in Inspiration. You will realize from this fact that when Inspirations are seen in their pure, original form, without being filled with physical corporeality, that these Inspirations can then represent something essentially higher than animals. And they can, too. But Inspirations that are present in the spiritual world in their pure state may also appear to us in animal-like forms.

In the times of the old atavistic clairvoyance people sought to portray in animal forms the Inspirations that came to them. The form of the sphinx, for example, was intended to create a picture of something that had been seen in Inspiration. We are dealing, therefore, with superhuman beings when we speak of animal forms in the purely spiritual world. During the days of atavistic clairvoyance—and this continued in the first four Christian centuries, in any case, still at the time of the mystery of Golgotha—it was no mere symbolism in the ordinary sense, but a genuine inner knowledge that caused men to portray, in the forms of animals, spiritual beings who were accessible to Inspiration.

It was in complete accordance with this practice when the Holy Spirit was portrayed in the form of a dove by those who had received Inspiration. How must we think of it today when the Holy Spirit is said to have appeared in the form of a dove? We must say to ourselves: Those people who spoke in this way were inspired, in the old atavistic sense. They saw him in this form as an Inspiration in that realm of pure spirit where the Holy Spirit revealed himself to them.

And how would the contemporaries of the mystery of Golgotha who were endowed with atavistic clairvoyance have characterized the Christ? Perhaps they had seen him outwardly as a man. To see him as a human being in the spiritual world they would have needed Intuition. And people who were able to see his I in the world of Intuition were not present at the time of the mystery of Golgotha. That was not possible for them. But they could still see him in atavistic Inspiration. They would, then, have used animal imagery, even to express Christ. “Behold the Lamb of God!” was true and correct language for that time. It is a language we must learn to understand if we are to grasp what Inspiration is, or to see, by means of Inspiration, what can become manifest in the spiritual world. “Behold the lamb of God!” It is important for us to recognize once again what is imaginative, what is inspired, and what is intuitive, and thereby to find our way into the language that echoes down to us from olden times.

In terms of the ancient powers of vision this way of language presents us with realities. But we must learn to express such realities in the way they were still expressed, for example, at the time of the mystery of Golgotha, and to feel that they are justified and natural. Only in this way will we be able to grasp the meaning of what was represented, for example, over in Asia as the winged cherubim, in Egypt as the sphinx, and what is presented to us as a dove and even as Christ, the Lamb. In ancient times Christ was again and again portrayed through Inspiration, or better said, through inspired Imagination.

Zweiter Vortrag

[ 1 ] In mancherlei komplizierter Art haben wir bereits gesehen, wie der Mensch eigentlich nur begriffen werden kann aus dem ganzen Universum heraus, aus der Summe des Kosmos heraus. Wir wollen heute einmal, um dann die Sache in den nächsten Tagen nach einer besonderen Richtung hin gipfeln zu lassen, diese Beziehung des Menschen zu dem Kosmos uns in einer einfacheren Art vor die Seele führen. Wir haben als die nächste Umgebung des Kosmos das zu verzeichnen, was uns als die physische Welt erscheint. Aber diese physische Welt tritt uns eigentlich nur da entgegen, wo sie Mineralreich ist; wenigstens tritt sie uns nur da in ihrer ureigenen Form entgegen. Wir können, wenn wir innerhalb des Mineralreiches im weiteren Sinne, zu dem wir natürlich auch Wasser und Luft, die Wärmeerscheinungen, die Erscheinungen des Wärmeäthers rechnen, wir können innerhalb des mineralischen Reiches die Kräfte, das Wesenhafte der physischen Welt studieren. Diese physische Welt äußert ihre Wirkungen zum Beispiel in der Schwere, in den Erscheinungen, sagen wir des chemischen, des magnetischen Verhaltens und so weiter. Aber wir können doch eigentlich die physische Welt nur innerhalb der mineralischen Welt studieren; sobald wir in das Pflanzenreich heraufgehen, können wir mit den Ideen und Begriffen, die wir uns von der physischen Welt machen, nicht mehr zurechtkommen. Keiner empfand das eigentlich in der neueren Zeit in einer so intensiven Weise wie Goethe. Goethe, der als verhältnismäßig junger Mensch von der wissenschaftlichen Seite her mit der Pflanzenwelt bekanntgeworden ist, empfand auch sofort, daß die Pflanzenwelt mit einer anderen Art von Anschauung erfaßt werden müsse als die physische Welt. Er trat der Wissenschaft von den Pflanzen, in der Form, wie sie Linne ausgebildet hatte, entgegen. Dieser große schwedische Naturforscher hat ja die Pflanzenlehre so ausgebildet, daß er vor allen Dingen darauf gesehen hat, welche Formen im Äußeren und auch im Genaueren die einzelnen Pflanzenarten und Pflanzengattungen haben. Nach diesen Formen hat er ein Pflanzensystem aufgestellt, in dem die ähnlichen Pflanzen zu Gattungen zusammengestellt sind, so daß die Pflanzengattungen und -arten gleichsam nebeneinander stehen, wie wir sonst die Gegenstände der mineralischen Natur nebeneinander stellen. Deshalb war eben gerade Goethe von dieser Linneschen Art, die Pflanzen zu behandeln, abgestoßen, weil die einzelnen Pflanzenformen nebeneinander standen. So, sagte sich Goethe, sieht man die Mineralien an, das, was in der mineralischen Natur ist; bei den Pflanzen muß man eine andere Anschauungsweise anwenden. Bei den Pflanzen, sagte Goethe, müsse man zum Beispiel so vorgehen: Da ist, sagen wir, eine Pflanze, welche Wurzeln entwickelt, dann einen Stengel entwickelt (siehe Zeichnung), an dem Stengel Blätter und so weiter. Aber das muß nicht gerade so bei der Pflanze sein (Zeichnung 1), sagte sich Goethe, sondern es kann zum Beispiel auch so sein (Zeichnung 2). Hier ist die Wurzel; aber die Kraft, welche sich bei dieser Pflanzenform (Zeichnung 1) gleich an der Wurzel zu entwickeln beginnt, die bleibt hier (Zeichnung 2) noch in sich beschlossen und “entwickelt nicht einen dünnen Stamm, der sich gleich in Blätter teilt, sondern bildet einen dicken Stamm. Dadurch geht die Kraft der Blätter in diesem dicken Stamm auf, und es bleibt nur noch wenig Kraft, um dann Blätteransätze und daran vielleicht die Blüte zu entwickeln. Es kann aber auch so sein, daß die Pflanze nur ganz spärlich ihre Wurzel entwickelt. Von der Kraft der Wurzel bleibt noch etwas übrig. Das entwickelt sich so (Zeichnung 3), und dann entwickeln sich daran spärliche Blatt- und Stengelansätze. Das alles ist aber innerlich dasselbe. Hier ist schmächtig ausgebildet der Stengel und sind mächtig ausgebildet die Blätter (Zeichnung 1). Hier (Zeichnung 2) ist der Stengel knollig ausgebildet und spärlich ausgebildet die Blätter. Die Idee ist in allen drei Pflanzen dieselbe, aber man muß die Idee innerlich beweglich halten, um von einer Form in die andere hinüberzukommen. Ich muß hier (Zeichnung 1) diese Form ausbilden: schmächtige Stengel, einzelne Blätter; «Blätterkraft zusammennehmen»: in dieser Idee (Zeichnung 2) bekomme ich die andere Form; «Wurzelkraft zusammennehmen»: in dieser Idee bekomme ich wieder eine andere Form, die dritte. Und so muß ich einen beweglichen Begriff bilden und aus dem beweglichen Begriff wird mir das ganze Pflanzensystem eine Einheit.

[ 2 ] Während Linn die verschiedenen Formen nebeneinander zusammengestellt und sie beobachtet hat wie mineralische Formen, wollte Goethe das ganze Pflanzensystem als eine Einheit mit beweglichen Ideen fassen, so daß er gewissermaßen aus einer Pflanzenform mit dieser Idee herausschlüpft, und, indem er diese Idee selber verändert, in die andere Pflanzenform hineinschlüpft und so weiter.

[ 3 ] Diese Art der Betrachtungen, diese Art, mit beweglichen Ideen zu betrachten, das war bei Goethe durchaus der Ansatz zu imaginativer Betrachtungsweise. So daß man sagen kann: Als Goethe an das Linnesche Pflanzensystem herantrat, da fühlte er, wie man mit der gewöhnlichen gegenständlichen Erkenntnis, die in der physischen Welt des Mineralreiches gut anwendbar ist, nicht ausreicht im Pflanzenleben. Er fühlte dem Linneschen System gegenüber die Notwendigkeit der imaginativen Betrachtungsweise.

[ 4 ] Das heißt mit anderen Worten, Goethe sagte sich: Wenn ich eine Pflanze anschaue, dann ist es gar nicht das Physische, was ich sehe, was ich wenigstens sehen soll, sondern dieses Physische ist unsichtbar geworden, und das, was ich sehe, muß ich mit anderen Ideen erfassen, als es diejenigen des Mineralreiches sind. — Das ist außerordentlich wichtig, daß wir das ins Auge fassen. Denn wir können uns sagen, wenn wir uns das in der richtigen Weise vor die Seele stellen: Im mineralischen Reiche ist rings um uns herum äußerlich sichtbar die physische Natur. Im Pflanzenreich ist die physische Natur unsichtbar geworden. Natürlich wirkt die Schwere, alles, was in der physischen Natur ist, wirkt noch auf das Pflanzenreich; aber es ist unsichtbar geworden, und sichtbar geworden ist eine höhere Natur, ist dasjenige, was innerlich fortwährend beweglich ist, was innerlich lebendig ist. — Es ist die ätherische Natur in der Pflanze das eigentlich Sichtbare. Und wir tun nicht gut, wenn wir sagen: Der physische Leib der Pflanze ist sichtbar. -— Der physische Leib der Pflanze ist eigentlich unsichtbar geworden; und das, was wir sehen, das ist die ätherische Form.

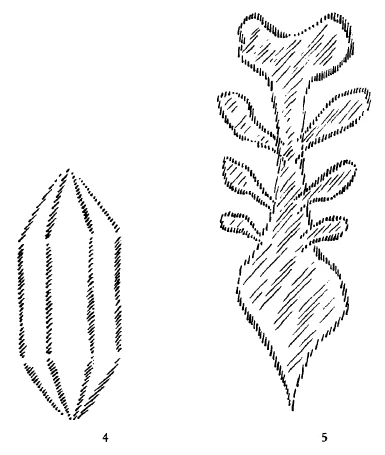

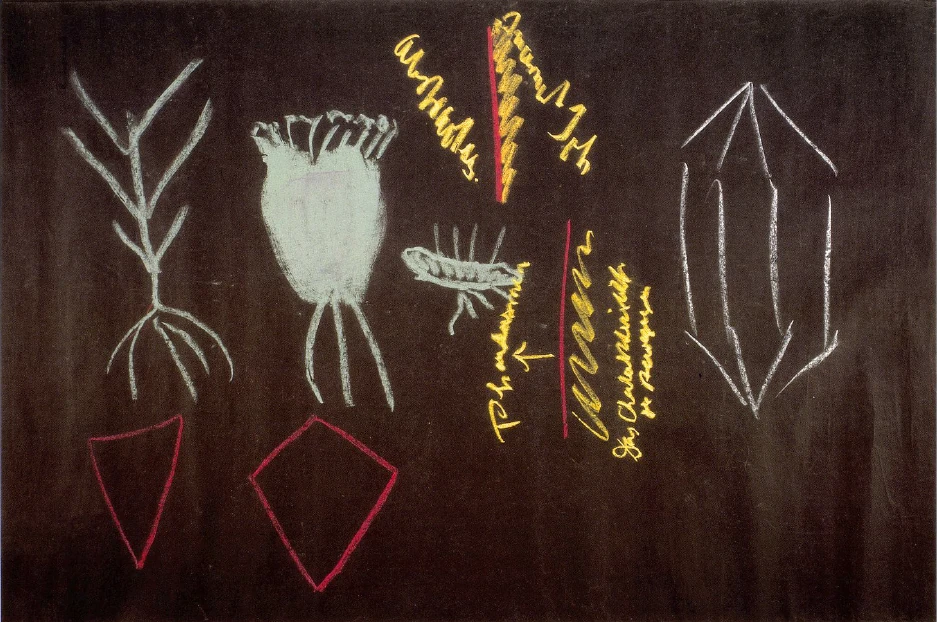

[ 5 ] Wie kommt denn eigentlich das Sichtbare bei der Pflanze zustande? Nun, wenn Sie einen physischen Körper haben, zum Beispiel einen Bergkristall, da sehen Sie unmittelbar das Physische (Zeichnung 4). Wenn Sie eine Pflanze haben, da sehen sie nicht das Physische; da sehen Sie an der Pflanze die ätherische Form (Zeichnung 5). Aber diese ätherische Form ist ausgefüllt mit Physischem, da drinnen leben physische Stoffe. Wenn die Pflanze ihr Leben verliert und in der Erde zu Kohle wird, so sieht man, wie der physische Kohlenstoff übrigbleibt: der ist in der Pflanze drinnen. Wir können also sagen: Die Pflanze ist ausgefüllt mit dem Physischen, aber sie löst das Physische auf durch das Ätherische. Das Ätherische ist dasjenige, was in der Pflanzenform eigentlich sichtbar ist. Unsichtbar ist das Physische.

[ 6 ] Also das Physische wird uns sichtbar in der mineralischen Natur. In der pflanzlichen Natur wird uns das Physische schon unsichtbar, denn alles, was wir sehen, ist eben nur durch das Physische sichtbar gemachtes Ätherisches. Wir würden natürlich nicht mit gewöhnlichen Augen die Pflanzen sehen, wenn nicht der unsichtbare Ätherleib physische, sagen wir, Körnchen, um grob zu reden, tragen würde. Durch das Physische wird uns die ätherische Form sichtbar; aber diese ätherische Form ist das, was wir eigentlich sehen, das Physische ist sozusagen nur das Mittel, damit wir das Ätherische sehen. So daß eigentlich die ätherische Form der Pflanze ein Beispiel ist für eine Imagination, nur für eine solche Imagination, die nicht unmittelbar in der geistigen Welt sichtbar wird, sondern die durch physische Einschlüsse sichtbar wird.

[ 7 ] Fragen Sie also, meine lieben Freunde: Was sind Imaginationen? — so kann man Ihnen antworten: Die Pflanzen sind alle Imaginationen. Nur sind sie als Imaginationen bloß dem imaginativen Bewußtsein sichtbar; daß sie dem physischen Auge auch sichtbar sind, das rührt davon her, daß die Pflanzen ausgefüllt sind mit physischen Teilchen, und dadurch wird das Ätherische auf eine physische Art dem physischen Auge sichtbar. Wir dürfen aber, wenn wir richtig sprechen wollen, gar nicht einmal sagen: Wir sehen in der Pflanze ein Physisches. — Wir sehen in der Pflanze eine richtige Imagination. Sie haben also die Imaginationen rings um sich herum in den Formen der Pflanzenwelt.

[ 8 ] Steigen wir jetzt herauf von der Pflanzenwelt zu der tierischen, da genügt es nicht mehr, daß wir uns an das Ätherische wenden. Da müssen wir einen Schritt weitergehen. Sehen Sie, bei der Pflanze können wir sagen: Sie vernichtet gewissermaßen das Physische und «west» das Ätherische — «wesen» als Verbum gebraucht.

Die Pflanze:

vernichtet das Physische

west das Ätherische

[ 9 ] Wenn wir zum Tierischen heraufschreiten, dann dürfen wir auch nicht mehr bloß an dem Ätherischen festhalten, sondern da müssen wir uns die tierische Bildung so vorstellen, daß nun auch das Ätherische vernichtet wird. So daß wir sagen können: Das Tier vernichtet das Physische —- das tut auch schon die Pflanze — es vernichtet aber auch das Ätherische, und es west in demjenigen, was dann sich geltend machen kann, wenn das Ätherische vernichtet wird. Wenn das Physische vernichtet wird durch die Pflanze, kann sich das Ätherische geltend machen. Wenn nun auch das Ätherische nur gewissermaßen, grob gesprochen, Ausfüllendes, Körniges ist, dann kann dasjenige, was nun nicht mehr im gewöhnlichen Raume ist, sondern im gewöhnlichen Raume wirkt, dann kann das Astralische wesen. Wir müssen also sagen: Im Tiere west das Astralische. - Wenn wir das Tier ansehen, so west in ihm das Astralische.

Das Tier:

vernichtet das Physische

vernichtet das Ätherische

west das Astralische

[ 10 ] Nun, Goethe strebte mit aller Gewalt danach, bewegliche Ideen, bewegliche Begriffe zu bekommen, um dieses fluktuierende Leben in der Pflanzenwelt zu durchschauen. Man hat in der Pflanzenwelt noch das Ätherische vor sich, weil die Pflanze in gewissem Sinne bis an die Oberfläche dieses Ätherische heraustreibt. Es lebt in der Form der Pflanze. Beim Tiere müssen wir uns sagen: Da ist etwas im Tiere, was sich nicht an die Oberfläche heraustreibt. Schon daß die Pflanze an dem Orte bleiben muß, wo sie angewachsen ist, das zeigt, daß da nichts in der Pflanze drinnen ist, was nicht auch an die Oberfläche heraustritt für die Sichtbarkeit. - Das Tier bewegt sich frei. Da ist etwas in ihm, was nicht an die Oberfläche heraustritt und sichtbar wird. Das ist das Astralische in dem Tiere. Das ist etwas, was nicht so erfaßt werden kann, daß wir unsere Ideen bloß beweglich machen, wie ich es Ihnen hier veranschaulicht habe, wo wir in der Idee selbst von Form zu Form gehen (siehe die drei ersten Pflanzenzeichnungen). Das genügt nicht für das Astralische. Wollen wir das Astralische erfassen, dann müssen wir weitergehen, dann müssen wir sagen: In das Ätherische, da geht noch etwas herein, und das, was da drinnen ist, das würde von innen heraus zum Beispiel die Form knollig machen und vergrößern können (Zeichnung 2). — Bei der Pflanze müssen Sie immer im Äußeren die Veranlassung suchen, warum die Form anders wird. Sie müssen mit Ihrer Idee beweglich sein. Aber dieses bloße Beweglichsein genügt nicht, um das Tier zu erfassen. Da müssen Sie in die Begriffe noch etwas anderes hineinbekommen.

[ 11 ] Wenn Sie sich klarmachen wollen, wie anders die begriffliche Tätigkeit sein muß beim Tiere als bei der Pflanze, so müssen Sie nicht nur einen beweglichen Begriff haben, der verschiedene Formen annehmen kann, sondern der Begriff muß innerlich etwas aufnehmen, was er nicht in sich selber hat. Es ist das, was man nennen kann: die Inspiration beim Begriffebilden. So wie wir bei unseren Inspirationen, bei unserer Einatmung von außen die Luft aufnehmen, während wir bei unserer sonstigen organischen Tätigkeit, die unterhalb des Atmens liegt, in der Tätigkeit in uns verbleiben, müssen wir, wenn wir das Tier begreifen wollen, nicht bloß bewegliche Begriffe haben, sondern in diese beweglichen Begriffe von außen her noch etwas hineinnehmen.

[ 12 ] Wir können -— wenn ich mich anders ausdrücken will -, wenn wir die Pflanze richtig verstehen wollen, stehenbleiben, können uns auch in Gedanken als stehenbleibendes Wesen betrachten. Und wenn wir das ganze Leben stehen würden, könnten wir dennoch unsere Begriffe so beweglich machen, daß sie die verschiedensten Pflanzenformen umfaßten; aber wir könnten niemals die Idee, den Begriff eines Tieres bilden, wenn wir nicht selber herumlaufen könnten. Wir müssen selber herumlaufen können, wenn wir den Begriff eines Tieres bilden wollen. Warum?

[ 13 ] Ja, wenn Sie, sagen wir, diesen Begriff der Pflanze haben (siehe Zeichnung 1) und ihn umformen in diesen zweiten, dann haben Sie selber diesen Begriff umgeformt. Wenn Sie aber laufen, dann wird Ihr Begriff durch das Laufen ein anderer. Sie selber müssen Leben hineinbringen in den Begriff. Das ist es, was einen bloß imaginierten Begriff zu einem inspirierten macht. Bei der Pflanze können Sie sich vorstellen, daß Sie selber innerlich ganz ruhig sind und die Begriffe nur verändern. Wenn Sie sich einen tierischen Begriff vorstellen wollen — die meisten Menschen tun es ja ganz gewiß nicht gern, weil der Begriff innerlich lebendig werden muß, es krabbelt in einem —, da nehmen Sie die Inspiration, die innere Lebendigkeit auf, nicht nur das äußere Sinnesweben von Form zu Form, sondern die innere Lebendigkeit. Sie können ein Tier nicht totaliter vorstellen, ohne daß Sie diese innere Lebendigkeit in den Begriff hineinnehmen.

[ 14 ] Das war etwas, was Goethe eben nicht mehr erreichte. Er erreichte, daß er sich sagen konnte: Die Pflanzenwelt ist eine Summe von Begriffen, von Imaginationen. Aber bei den Tieren muß man in den Begriff etwas hineinnehmen, da muß man den Begriff selber innerlich lebendig machen. — Daß die Imagination bei der einzelnen Pflanze nicht lebt, das können Sie schon daraus sehen, daß die Pflanze, wenn sie auf ihrem Boden steht und wächst, ihre Form durch äußere Anlässe verändert, aber innerlich verändert sie die Form nicht. Das Tier ist der wandelnde Begriff, der lebendige Begriff, und da muß man die Inspiration aufnehmen, und durch die Inspiration erst dringt man zum Astralischen vor.

[ 15 ] Und wenn wir zum Menschen aufsteigen, so müssen wir sagen: Er vernichtet das Physische, er vernichtet das Ätherische, er vernichtet das Astralische, und er west das Ich.

Der Mensch:

vernichtet das Physische

vernichtet das Ätherische

vernichtet das Astralische

west das Ich

[ 16 ] Bei dem Tier müssen wir uns sagen: Wir sehen eigentlich nicht das Physische, sondern wir sehen eine physisch erscheinende Inspiration. Daher wird auch sehr leicht die menschliche Inspiration, die Atmung, wenn sie irgendeiner Störung unterliegt, zur tierischen Form. Versuchen Sie nur einmal, sich zu erinnern an manche Alptraumgestalten: was Ihnen da für tierische Formen erscheinen! Die tierischen Formen sind durchaus inspirierte Formen.

[ 17 ] Das menschliche Ich können wir erst durch Intuition erfassen. In Wirklichkeit kann das menschliche Ich erst durch Intuition erfaßt werden. Beim Tiere sehen wir also die Inspiration, beim Menschen sehen wir eigentlich das Ich, die Intuition. Wir reden falsch, wenn wir beim Tiere sagen: Wir sehen den physischen Leib. — Wir sehen gar nicht den physischen Leib. Der ist aufgelöst, der ist vernichtet, der veranschaulicht uns bloß die Inspiration, ebenso der ätherische Leib. Wir sehen beim Tier eigentlich äußerlich durch das Physische und Ätherische den astralischen Leib. Und beim Menschen sehen wir schon das Ich. Was wir da sehen, ist nicht der physische Leib, der ist gerade unsichtbar; ebenso der ätherische Leib; ebenso der astralische Leib. Was wir beim Menschen sehen, ist — äußerlich geformt, auf physische Weise geformt — das Ich. Daher erscheint auch zum Beispiel für die Augenwahrnehmung, für die Sichtbarkeit, der Mensch nach außen in seinem Inkarnat in einer Farbe, die sonst nicht vorhanden ist, wie auch das Ich sonst nicht in den anderen Wesenheiten vorhanden ist. Wir müßten also, wenn wir uns richtig ausdrücken wollen, sagen: Den Menschen können wir nur dann ganz erfassen, wenn wir ihn bestehend denken aus physischem Leib, Ätherleib, astralischem Leib und Ich. Das, was wir vor uns sehen, ist das Ich, und unsichtbar darinnen ist der astralische Leib, der Ätherleib und der physische Leib.

[ 18 ] Nun aber erfassen wir den Menschen doch nur, wenn wir noch etwas genauer auf die Sache hinschauen. Es ist ja zunächst nur die Außenseite des Ich, die wir sehen. Aber innerlich würde ja das Ich in seiner wahren Gestalt nur durch Intuition wahrzunehmen sein. Aber etwas von diesem Ich merkt der Mensch auch im gewöhnlichen Leben, im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein: Das sind seine abstrakten Gedanken; die hat das Tier nicht, weil es noch kein Ich hat. Abstraktionsfähigkeit hat das Tier nicht, weil es noch kein Ich hat. Wir können also sagen: Wir sehen äußerlich in der menschlichen Gestalt die irdische Verkörperung des Ich. Und wenn wir uns von innen erleben in unseren abstrakten Gedanken, da haben wir das Ich; aber das sind eben nur Gedanken, das sind keine Realitäten; das sind Bilder.

[ 19 ] Steigen wir jetzt beim Menschen zu dem in ihm befindlichen, aber in ihm vernichteten astralischen Leib hinunter, dann kommen wir zu dem im Menschen, was nun nicht mehr von außen gesehen werden kann, was wir aber sehen, wenn wir den Menschen in Bewegung sehen und wenn wir seine Form aus der Bewegung begreifen. Dazu ist folgende Anschauung notwendig. Denken Sie sich einmal einen kleinen, zwerghaften Menschen, so einen recht dicklichen, der mit kurzen Beinen dahingeht, Sie schauen seine Bewegung an: Sie werden aus seinen kurzen Beinen, die er fast wie kleine Säulen vorwärtsschiebt, seine Bewegung begreifen. Ein langer Rix mit langen Beinen wird sich anders bewegen. Sie werden in Ihrer Anschauung eine Einheit sehen zwischen der Bewegung und den Formen. Sie werden auch diese Einheit finden, wenn Sie sich in solchen Dingen schulen. Wenn Sie sehen, daß irgend jemand eine nach rückwärts verlaufende Stirne, ein vorstehendes Kinn hat, so ist er auch in der Bewegung des Kopfes anders als jemand, der ein zurückliegendes Kinn und eine weit nach vorne gehende Stirne hat. Sie werden überall beim Menschen einen Zusammenhang sehen zwischen seiner Form und seiner Bewegung, wenn Sie ihn einfach so, wie er vor Ihnen steht, anschauen und einen Eindruck bekommen von seinem Inkarnat, von dem, wie er sich selbst in Ruhe erhält. Sie schauen auf sein Ich, wenn Sie auf dasjenige achten, was von seiner Form in die Bewegung übergeht, und was von der Bewegung gleichsam wiederum zurückläuft.

[ 20 ] Suchen Sie einmal an der menschlichen Hand zu studieren, wie jemand mit langen Fingern anders dachselt mit den Fingern als derjenige, der kurze Finger hat. Die Bewegung geht in die Form über, die Form in die Bewegung: Da machen Sie sich noch, ich möchte sagen, einen Schatten von seinem astralischen Leib klar, allerdings durch äußere physische Mittel ausgedrückt. Aber Sie sehen, so wie ich Ihnen das beschreibe, ist es eine primitive Inspiration. Die meisten Menschen sehen es zum Beispiel solchen Menschen nicht an, die so gehen, wie Fichte durch die Straßen von Jena gegangen ist; sehen nicht, was in ihnen liegt. Wer Fichte durch die Straßen von Jena gehen sah, der empfand auch jene Bewegung und Formung, die in seinen Sprachorganen war, und die insbesondere dann, wenn er überzeugend wirken wollte, in der Formung der Sprachorgane sich ausgedrückt hat, und in der Formung der Sprachorgane schon drinnen war. Es gehört eine primitive Inspiration dazu, um das zu sehen.

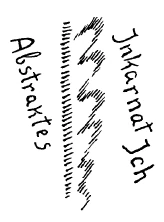

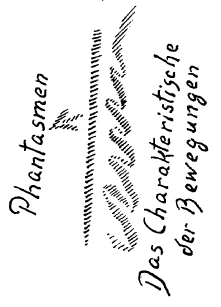

[ 21 ] Aber wenn wir jetzt von innen anschauen, was man so von außen sieht und was ich Ihnen eben beschrieben habe als wahrnehmbar durch diese primitive Inspiration, so ist das im wesentlichen das menschliche, vom Gefühl durchdrungene Phantasieleben, dasjenige, wo schon innerlich erlebt werden die abstrakten Gedanken. Auch die Gedächtnisvorstellungen als Bilder, wenn sie herantreten, leben in diesem Elemente. Wir können sagen: Von außen angesehen drückt sich zum Beispiel im Inkarnat das Ich aus, aber auch in den anderen Formen, die da auftreten. Wir würden sonst von keiner Physiognomie sprechen können. Sehen wir zum Beispiel jemanden, der herabgezogene Mund winkel hat, wenn er das Gesicht ruhig hält, so liegt das durchaus karmisch in seiner Ich-Gestaltung in dieser Inkarnation. Nach innen ge sehen sind das aber die abstrakten Gedanken.

[ 22 ] Nehmen wir den astralischen Leib, so ist es nach außen das Charakteristische der Bewegungen, nach innen die Phantasmen oder Phantasiebilder, was ihn kundgibt; der eigentliche astralische Leib entzieht sich schon mehr oder weniger der Beobachtung. Noch mehr entzieht sich beim Menschen der ätherische Leib der Beobachtung. Der ätherische Leib ist sozusagen von außen nicht mehr so richtig sichtbar, oder höchstens in absonderlichen Fällen sichtbar in physischen Manifestationen. Er kann es auch werden, wenn zum Beispiel jemand — mit Respekt zu vermelden — schwitzt, dann ist das ein Sichtbarwerden des ätherischen Leibes nach außen. Aber sehen Sie, dazu gehört schon Imagination, um das Schwitzen mit dem ganzen Menschen in Zusammenhang zu bringen. Paracelsus hat das durchaus getan. Für ihn war nicht nur die Art, sondern das Substantielle des Schwitzens bei einem Menschen nicht dasselbe wie beim anderen Menschen. Für ihn war darin der ganze Mensch ausgedrückt, das Ätherische des ganzen Menschen. Also da tritt schon das Äußerliche sehr stark zurück; aber innerlich tritt das im Erleben um so mehr hervor, nämlich im Fühlen. Das Gefühl innerlich erlebt, das ganze Gefühlsleben ist eigentlich das, was im ätherischen Leibe lebt, wenn er von innen wirkt, so daß man ihn von innen erlebt. Es ist ja auch immer das Gefühlsleben von der Sekretion nach innen begleitet. Und im wesentlichen stellt sich ja auch die Anschauung des ätherischen Leibes beim Menschen so dar — verzeihen Sie, jetzt wiederum mit Respekt zu vermelden —, daß zum Beispiel die Leber schwitzt, der Magen schwitzt, daß alles schwitzt, daß alles sekretiert. Gerade in diesem inneren Sekretieren lebt das ätherische Leben des Menschen. Die Leber hat um sich einen fortwährenden Schwitznebel, ebenso hat das Herz einen fortwährenden Schwitznebel: alles das ist Nebel, in Wolken eingehüllt. Das muß imaginativ erfaßt werden.

[ 23 ] Wenn Paracelsus vom Schwitzen des Menschen gesprochen hat, so hat er nicht gesagt: Das ist nur an der Oberfläche -, sondern da sagt er: Nein, das durchdringt den ganzen Menschen -, das ist sein Ätherleib, was man sieht, wenn man absieht von dem Physischen. Dieses innerliche Erlebnis also des Ätherleibes ist das Gefühlsleben.

[ 24 ] Und das äußerliche Erlebnis des physischen Leibes, das ist schon tatsächlich so ohne weiteres nicht wahrnehmbar. Wir nehmen es immerhin wahr, das Physische der Körperlichkeit, wenn wir zum Beispiel ein Kind auf den Arm nehmen: Es ist schwer, wie der Stein schwer ist. Das ist physisches Erlebnis, das ist dasjenige, was der physischen Welt angehört, was wir da wahrnehmen. Wenn uns jemand eine Ohrfeige gibt, so ist außer dem moralischen Erlebnis noch ein physisches da, ein Stoß; aber als Physisches ist es eigentlich nur ein elastischer Stoß, wie wenn eine Billardkugel an eine andere stößt. Wir müssen durchaus das Physische dabei von dem anderen richtig sondern. Aber wenn wir dieses Physische nach innen wahrnehmen in derselben Weise, wie ich vorhin gesagt habe, daß wir das Äußere vom Gefühlsleben nach innen wahrnehmen, dann ist in den physischen Vorgängen, in den bloßen physischen Vorgängen, innerlich erlebt, der menschliche Wille. Der menschliche Wille, das ist dasjenige, was in einer einfacheren Weise den Menschen mit dem Kosmos zusammenbringt.

[ 25 ] Nun, Sie sehen, wenn wir also Inspiration rings um uns herum suchen, so haben wir sie in den Tierformen gegeben. Die Mannigfaltigkeit der tierischen Formen wirkt auf uns für unsere Wahrnehmungen in Inspiration. Sie können daraus erkennen, daß ja dann, wenn wir Inspirationen rein sehen, ohne daß sie ausgefüllt sind mit physischer Körperlichkeit, daß dann diese Inspirationen etwas wesentlich Höheres als Tiere darstellen können. Das können sie auch. Aber es werden uns auch rein in der geistigen Welt vorhandene Inspirationen in tierähnlichen Formen auftreten können.

[ 26 ] In den Zeiten des älteren atavistischen Hellsehens haben die Menschen versucht, die Inspirationen, die sie hatten, in geistiger Weise hinzustellen in tierischen Formen; zum Beispiel die Sphinx hat ihre Form dadurch, daß sie eigentlich etwas nachbilden soll, was man inspiriert gesehen hat. Wir haben es also schon mit übermenschlichen Wesenheiten zu tun, wenn wir von tierischen Formen in der rein geistigen Welt sprechen. Während der Zeit des atavistischen Hellsehens, wie es noch vorhanden war in den ersten vier christlichen Jahrhunderten, also jedenfalls noch zur Zeit des Mysteriums von Golgatha, da war es nicht bloß eine äußerlich stroherne Symbolik, sondern ein wirklich inneres Wissen, das höhere geistige Wesenheiten, die zugänglich werden der Inspiration, in tierischen Formen ausdrückte.

[ 27 ] Und es ist durchaus diesem entsprechend, wenn der Heilige Geist von denen, die auf Inspiration aufmerksam machten, in der Gestalt einer Taube angedeutet wurde. Wie müssen wir heute es auffassen, wenn uns von dem Heiligen Geiste als in der Gestalt einer Taube gesprochen wird? Wir müssen es so auffassen, daß wir sagen: Diejenigen, die so sprachen, waren im alten atavistischen Sinne inspirierte Leute. Sie sahen in derjenigen Region, in der sich für sie rein geistig der Heilige Geist zeigte, ihn in dieser Form als Inspiration. Und wie werden diese mit atavistischer Inspiration ausgestatteten Zeitgenossen des Mysteriums von Golgatha charakterisiert haben den Christus?

[ 28 ] . Sie haben ihn vielleicht äußerlich gesehen, da haben sie ihn als Menschen gesehen. Um in der geistigen Welt ihn als Menschen zu sehen, dazu hätten sie Intuitionen haben müssen. Solche Menschen aber, die ihn als Ich sehen konnten in der intuitiven Welt, waren auch in der Zeit des Mysteriums von Golgatha nicht da; das konnten sie nicht. Aber sie konnten ihn noch in atavistischer Inspiration sehen. Dann werden sie auch tierische Formen gebraucht haben, um selbst den Christus auszudrücken. «Siehe, das ist das Lamm Gottes», das ist für jene Zeit eine richtige Sprache, eine Sprache, in die wir uns hineinfinden müssen, wenn wir wiederum darauf kommen, was Inspiration ist, beziehungsweise wie man durch Inspiration dasjenige sieht, was in der geistigen Welt auftreten kann: «Siehe, das Lamm Gottes!» Das ist wichtig, daß wir wiederum erkennen lernen, was imaginativ, was inspiriert, was intuitiv ist, und daß wir dadurch lernen, uns in die Sprachweise zu versetzen, die aus älteren Zeiten zu uns herauftönt.

[ 29 ] Diese Sprachweise stellt in bezug auf die älteren Anschauungen Wirklichkeiten dar; aber wir müssen uns erst da hineinfinden, diese Wirklichkeiten so auszudrücken, wie sie zum Beispiel noch zur Zeit des Mysteriums von Golgatha ausgedrückt wurden, und sie als selbstverständlich zu empfinden. Nur so werden wir in den Sinn desjenigen einrücken, was zum Beispiel drüben in Asien in den geflügelten Cherubim, was in Ägypten als die Sphinx dargestellt worden ist, was uns im Heiligen Geist als eine Taube dargestellt wird, was uns selbst in dem Christus als das Lamm dargestellt wird, was ja Inspiration, oder besser gesagt, inspirierte Imagination war, in der immer wieder in den ältesten Zeiten der Christus abgebildet worden ist.

Second Lecture

[ 1 ] In many complicated ways, we have already seen how human beings can only really be understood from the perspective of the entire universe, from the sum of the cosmos. Today, we want to present this relationship between humans and the cosmos in a simpler way, so that we can then focus on a specific aspect of it over the next few days. We can identify what appears to us as the physical world as the immediate environment of the cosmos. But this physical world only really confronts us in its mineral form; at least, it only confronts us in its most basic form. If we look within the mineral realm in the broader sense, which of course also includes water and air, the phenomena of heat, the phenomena of the heat ether, we can study the forces, the essence of the physical world. This physical world expresses its effects, for example, in gravity, in the phenomena of, say, chemical and magnetic behavior, and so on. But we can really only study the physical world within the mineral world; as soon as we ascend to the plant kingdom, we can no longer cope with the ideas and concepts we have formed of the physical world. No one in modern times has felt this as intensely as Goethe. Goethe, who became acquainted with the plant world from a scientific perspective at a relatively young age, immediately sensed that the plant world must be understood with a different kind of perception than the physical world. He opposed the science of plants as developed by Linnaeus. This great Swedish natural scientist developed botany in such a way that he focused above all on the external and more precise forms of the individual plant species and plant genera. Based on these forms, he established a plant system in which similar plants are grouped into genera, so that the plant genera and species stand side by side, as we otherwise place objects of mineral nature side by side. This is precisely why Goethe was repelled by Linnaeus's way of treating plants, because the individual plant forms stood side by side. Goethe said to himself, this is how we look at minerals, at what is in the mineral world; with plants, we must use a different approach. With plants, Goethe said, we must proceed as follows: Let us say there is a plant that develops roots, then a stem (see drawing), and on the stem there are leaves, and so on. But that does not have to be exactly how it is with plants (drawing 1), Goethe said to himself, but it can also be like this, for example (drawing 2). Here is the root; but the force that begins to develop at the root in this plant form (drawing 1) remains here (drawing 2) still contained within itself and "does not develop a thin stem that immediately divides into leaves, but forms a thick stem. As a result, the power of the leaves goes into this thick trunk, and only a little power remains to develop leaf buds and perhaps flowers. But it can also be the case that the plant develops only very sparse roots. Some of the power of the root remains. This develops as shown (drawing 3), and then sparse leaf and stem buds develop. However, internally, it is all the same. Here, the stem is thin and the leaves are thick (drawing 1). Here (drawing 2), the stem is bulbous and the leaves are sparse. The idea is the same in all three plants, but you have to keep the idea flexible internally in order to move from one form to another. Here (drawing 1) I have to form this shape: thin stems, individual leaves; “bring the leaf force together”: in this idea (drawing 2) I get the other shape; “bring the root force together”: in this idea I get yet another shape, the third one. And so I have to form a flexible concept, and from this flexible concept the whole plant system becomes a unity for me.

[ 2 ] While Linnaeus arranged the different forms side by side and observed them as mineral forms, Goethe wanted to grasp the entire plant system as a unity with flexible ideas, so that he could, as it were, slip out of one plant form with this idea and, by changing this idea himself, slip into another plant form, and so on.

[ 3 ] This type of observation, this way of looking at things with flexible ideas, was Goethe's approach to imaginative observation. So one can say that when Goethe approached Linnaeus's plant system, he felt that the usual objective knowledge, which is well applicable in the physical world of the mineral kingdom, was not sufficient for plant life. He felt that Linnaeus' system required an imaginative approach.

[ 4 ] In other words, Goethe said to himself: When I look at a plant, it is not the physical that I see, or at least that I should see, but rather that the physical has become invisible, and what I see must be grasped with ideas other than those of the mineral kingdom. It is extremely important that we keep this in mind. For we can say to ourselves, if we visualize this correctly: In the mineral kingdom, physical nature is visible around us. In the plant kingdom, physical nature has become invisible. Of course, gravity, everything that is in physical nature, still affects the plant kingdom; but it has become invisible, and a higher nature has become visible, that which is constantly moving within, that which is alive within. — It is the etheric nature in the plant that is actually visible. And we are not doing well when we say: The physical body of the plant is visible. — The physical body of the plant has actually become invisible; and what we see is the etheric form.

[ 5 ] How does the visible actually come about in plants? Well, if you have a physical body, for example a rock crystal, you see the physical immediately (drawing 4). When you have a plant, you do not see the physical; what you see in the plant is the etheric form (drawing 5). But this etheric form is filled with the physical; physical substances live inside it. When the plant loses its life and turns to coal in the earth, you see the physical carbon remaining: it is inside the plant. We can therefore say that the plant is filled with the physical, but it dissolves the physical through the etheric. The etheric is what is actually visible in the plant form. The physical is invisible.

[ 6 ] So the physical becomes visible to us in mineral nature. In plant nature, the physical is already invisible to us, because everything we see is only the etheric made visible through the physical. Of course, we would not see plants with our ordinary eyes if the invisible etheric body did not carry physical, let us say, grains, to put it roughly. Through the physical, the etheric form becomes visible to us; but this etheric form is what we actually see; the physical is, so to speak, only the means by which we see the etheric. So that the etheric form of the plant is actually an example of an imagination, only of an imagination that is not immediately visible in the spiritual world, but becomes visible through physical inclusions.

[ 7 ] So ask yourselves, my dear friends: What are imaginations? — and you can answer: Plants are all imaginations. But as imaginations they are visible only to the imaginative consciousness; the fact that they are also visible to the physical eye stems from the fact that plants are filled with physical particles, and this makes the etheric visible to the physical eye in a physical way. But if we want to speak correctly, we cannot even say that we see something physical in the plant. We see in the plant a true imagination. You therefore have the imaginations around you in the forms of the plant world.

[ 8 ] Let us now ascend from the plant world to the animal world, where it is no longer sufficient to turn to the etheric. We must go one step further. You see, with plants we can say: they destroy the physical and “west” the etheric — “wesen” is used as a verb.

The plant:

destroys the physical

west the etheric

[ 9 ] When we ascend to the animal realm, we can no longer cling to the etheric alone, but must imagine animal formation in such a way that the etheric is also destroyed. So we can say: the animal destroys the physical — as does the plant — but it also destroys the etheric, and it is in that which can then assert itself when the etheric is destroyed. When the physical is destroyed by the plant, the etheric can assert itself. If the etheric is also, in a certain sense, roughly speaking, something filling, something granular, then that which is no longer in ordinary space but works in ordinary space can be the astral. We must therefore say: the astral is in the animal. When we look at the animal, the astral is in it.

The animal:

destroys the physical

destroys the etheric

is the astral

[ 10 ] Now, Goethe strove with all his might to obtain moving ideas, moving concepts, in order to understand this fluctuating life in the plant world. In the plant world, we still have the etheric before us, because in a certain sense the plant pushes this etheric out to the surface. It lives in the form of the plant. With animals, we have to say: there is something in animals that does not push itself to the surface. The very fact that plants have to remain where they have grown shows that there is nothing inside them that does not also emerge to the surface to be seen. Animals move freely. There is something in them that does not emerge to the surface and become visible. That is the astral in the animal. It is something that cannot be grasped by merely making our ideas mobile, as I have illustrated here, where we move from form to form within the idea itself (see the first three plant drawings). That is not enough for the astral. If we want to grasp the astral, we must go further, we must say: Something else enters into the etheric, and what is inside there could, for example, make the form tuberous and enlarge it from within (drawing 2). — In plants, you must always look for the cause of the change in form in the external world. You must be flexible with your ideas. But this mere flexibility is not enough to grasp the animal. You have to get something else into the concepts.

[ 11 ] This is what can be called inspiration in concept formation. Just as we take in air from outside when we breathe in during our inspirations, while we remain within ourselves during our other organic activities that lie below breathing, so, if we want to understand animals, we must not merely have flexible concepts, but must also take something from outside into these flexible concepts.

[ 12 ] We can—if I may express myself differently—if we want to understand the plant correctly, we can stand still and also consider ourselves in our thoughts as beings that are standing still. And if we were to stand still for our entire lives, we could still make our concepts so flexible that they would encompass the most diverse plant forms; but we could never form the idea, the concept of an animal, if we could not run around ourselves. We must be able to run around ourselves if we want to form the concept of an animal. Why?

[ 13 ] Yes, if you have, say, this concept of a plant (see drawing 1) and transform it into this second one, then you yourself have transformed this concept. But when you walk, your concept becomes different through walking. You yourself must bring life into the concept. That is what makes a merely imagined concept an inspired one. With the plant, you can imagine that you yourself are completely calm inside and are only changing the concepts. If you want to imagine an animal concept — most people certainly don't like to do this because the concept has to come alive inside you, it crawls around inside you — then you take the inspiration, the inner liveliness, not just the outer sensory web of form to form, but the inner liveliness. You cannot imagine an animal in its totality without incorporating this inner liveliness into the concept.

[ 14 ] That was something Goethe was unable to achieve. He managed to say to himself: The plant world is a sum of concepts, of imaginations. But with animals, you have to take something into the concept, you have to make the concept itself alive within you. You can see that imagination does not live in individual plants from the fact that when a plant stands on the ground and grows, its form changes due to external influences, but internally it does not change its form. The animal is the changing concept, the living concept, and there you have to take in inspiration, and only through inspiration can you penetrate to the astral.

[ 15 ] And when we ascend to the human being, we must say: He destroys the physical, he destroys the etheric, he destroys the astral, and he is the I.

The human being:

destroys the physical

destroys the etheric

destroys the astral

is the I.

[ 16 ] With animals, we must say to ourselves: We do not actually see the physical, but rather we see a physically appearing inspiration. Therefore, when subjected to any disturbance, human inspiration, or breathing, very easily takes on an animal form. Just try to remember some of the figures in your nightmares: what animal forms appear there! Animal forms are entirely inspired forms.

[ 17 ] We can only grasp the human ego through intuition. In reality, the human ego can only be grasped through intuition. In animals, we see inspiration; in humans, we actually see the ego, intuition. We are wrong when we say of animals: We see the physical body. We do not see the physical body at all. It is dissolved, destroyed; it merely illustrates inspiration to us, as does the etheric body. In animals, we actually see the astral body externally through the physical and etheric bodies. And in humans, we already see the I. What we see there is not the physical body, which is invisible; the same is true of the etheric body and the astral body. What we see in humans is — outwardly formed, physically formed — the I. That is why, for example, in terms of visual perception, in terms of visibility, humans appear to the outside world in their incarnate form in a color that does not otherwise exist, just as the I does not otherwise exist in other beings. So, if we want to express ourselves correctly, we must say: We can only fully comprehend the human being if we think of him as consisting of a physical body, an etheric body, an astral body, and the I. What we see before us is the I, and invisible within it are the astral body, the etheric body, and the physical body.

[ 18 ] But we can only truly understand human beings if we look at the matter more closely. At first, we only see the outer side of the ego. But inwardly, the I in its true form can only be perceived through intuition. However, human beings also notice something of this I in their ordinary lives, in their ordinary consciousness: these are their abstract thoughts; animals do not have these because they do not yet have an I. Animals do not have the capacity for abstraction because they do not yet have an I. We can therefore say: Outwardly, in the human form, we see the earthly embodiment of the ego. And when we experience ourselves from within in our abstract thoughts, we have the ego; but these are only thoughts, they are not realities; they are images.

[ 19 ] If we now descend in the human being to the astral body that is within him but has been destroyed in him, we come to that in the human being which can no longer be seen from outside, but which we see when we see the human being in motion and when we comprehend his form from his motion. The following view is necessary for this. Imagine a small, dwarfish person, quite plump, walking along with short legs. You watch his movement: you will understand his movement from his short legs, which he pushes forward almost like little pillars. A tall person with long legs will move differently. You will see a unity between movement and form. You will also find this unity if you train yourself in such things. If you see that someone has a receding forehead and a protruding chin, their head movements will also be different from someone who has a receding chin and a forehead that protrudes far forward. You will see a connection everywhere in human beings between their form and their movement if you simply look at them as they stand before you and get an impression of their incarnate being, of how they maintain themselves at rest. You look at their I when you pay attention to what passes from their form into movement and what, as it were, runs back again from movement.

[ 20 ] Try studying the human hand to see how someone with long fingers moves their fingers differently from someone with short fingers. The movement passes into form, the form into movement: in this way, you make clear, I would say, a shadow of his astral body, albeit expressed through external physical means. But you see, as I describe it to you, it is a primitive inspiration. Most people do not see it, for example, in people who walk as Fichte walked through the streets of Jena; they do not see what lies within them. Anyone who saw Fichte walking through the streets of Jena also felt the movement and shaping that was in his speech organs, which, especially when he wanted to appear convincing, was expressed in the shaping of his speech organs and was already present in the shaping of his speech organs. It takes a primitive inspiration to see this.

[ 21 ] But if we now look from within at what can be seen from without, and what I have just described to you as perceptible through this primitive inspiration, then this is essentially the human life of imagination, permeated by feeling, in which abstract thoughts are already experienced inwardly. Memories as images, when they arise, also live in this element. We can say that, viewed from the outside, the ego expresses itself in the incarnate form, but also in the other forms that appear there. Otherwise, we would not be able to speak of physiognomy. If, for example, we see someone who has a downturned mouth when their face is calm, this is entirely karmic in their ego formation in this incarnation. Seen inwardly, however, these are abstract thoughts.

[ 22 ] If we take the astral body, it is the characteristic movements that reveal it to the outside world, while the phantasms or fantasy images reveal it inwardly; the actual astral body is more or less hidden from observation. The etheric body is even more elusive to observation in humans. The etheric body is, so to speak, no longer really visible from the outside, or at most visible in physical manifestations in rare cases. It can also become visible when, for example, someone—with all due respect—sweats; this is when the etheric body becomes visible to the outside world. But you see, it takes imagination to connect sweating with the whole human being. Paracelsus certainly did that. For him, not only the nature but also the substance of sweating was not the same in one human being as in another. For him, it expressed the whole human being, the etheric of the whole human being. So the external recedes very strongly, but internally it emerges all the more in experience, namely in feeling. The feeling experienced inwardly, the whole emotional life, is actually what lives in the etheric body when it works from within, so that one experiences it from within. The emotional life is always accompanied by secretion inward. And essentially, this is also how the etheric body appears in humans — forgive me once again with respect — that, for example, the liver sweats, the stomach sweats, that everything sweats, that everything secretes. It is precisely in this inner secretion that the etheric life of the human being lives. The liver is surrounded by a continuous mist of sweat, and the heart also has a continuous mist of sweat: all of this is mist, enveloped in clouds. This must be grasped imaginatively.

[ 23 ] When Paracelsus spoke of human sweating, he did not say: “That is only on the surface,” but rather, “No, that permeates the whole human being—that is his etheric body, which can be seen when one disregards the physical.” This inner experience of the etheric body is therefore the life of feeling.

[ 24 ] And the external experience of the physical body is indeed not immediately perceptible. We do perceive the physicality of the body, however, when we pick up a child, for example: it is heavy, like a stone is heavy. That is physical experience, that is what belongs to the physical world, what we perceive there. If someone slaps us in the face, there is a physical experience in addition to the moral experience, a blow; but as a physical phenomenon, it is actually only an elastic blow, like when one billiard ball hits another. We must distinguish the physical from the other. But when we perceive this physical aspect inwardly in the same way as I said earlier, that we perceive the external from the emotional life inwardly, then the human will is experienced inwardly in the physical processes, in the mere physical processes. The human will is that which, in a simpler way, brings the human being together with the cosmos.

[ 25 ] Now, you see, when we seek inspiration around us, we find it in animal forms. The diversity of animal forms acts upon our perceptions in inspiration. You can see from this that when we see inspiration in its pure form, without it being filled with physical corporeality, then this inspiration can represent something much higher than animals. It can do that. But inspiration that exists purely in the spiritual world can also appear to us in animal-like forms.

[ 26 ] In the days of older atavistic clairvoyance, people tried to represent the inspirations they had in a spiritual way in animal forms; for example, the sphinx has its form because it is actually supposed to represent something that was seen in inspiration. So we are already dealing with superhuman beings when we speak of animal forms in the purely spiritual world. During the time of atavistic clairvoyance, as it still existed in the first four Christian centuries, that is, at least at the time of the Mystery of Golgotha, it was not merely an outward straw symbolism, but a real inner knowledge that expressed higher spiritual beings, which become accessible to inspiration, in animal forms.

[ 27 ] And it is entirely consistent with this when the Holy Spirit was symbolized in the form of a dove by those who drew attention to inspiration. How should we understand today when we are told that the Holy Spirit appears in the form of a dove? We must understand it to mean that those who spoke in this way were inspired people in the old, atavistic sense. They saw the Holy Spirit in this form as inspiration in the region where He appeared to them in a purely spiritual way. And how would these contemporaries of the mystery of Golgotha, endowed with atavistic inspiration, have characterized Christ?

[ 28 ] . They may have seen him outwardly, they saw him as a human being. In order to see him as a human being in the spiritual world, they would have had to have intuition. But even at the time of the Mystery of Golgotha, there were no people who could see him as an I in the intuitive world; they were incapable of doing so. However, they could still see him in atavistic inspiration. They would then have needed animal forms to express Christ himself. “Behold, this is the Lamb of God” is the right language for that time, a language we must find our way into if we want to understand what inspiration is, or rather how inspiration enables us to see what can appear in the spiritual world: "Behold, the Lamb of God!It is important that we learn again to recognize what is imaginative, what is inspired, what is intuitive, and that we thereby learn to put ourselves into the language that echoes down to us from earlier times.

[ 29 ] This language represents realities in relation to older views; but we must first find our way into it, express these realities as they were still expressed, for example, at the time of the Mystery of Golgotha, and feel them as self-evident. Only in this way will we enter into the meaning of what, for example, has been represented in Asia in the winged cherubim, in Egypt as the sphinx, in the Holy Spirit as a dove, and in Christ himself as the lamb, which is inspiration, or rather, inspired imagination, in which Christ was repeatedly depicted in the most ancient times.