The Cycle of the Year

GA 223

2 April 1923, Dornach

Lecture III

We should not underestimate the significance it once held for mankind to focus the whole attention during the year on a festival-time. Although in our time the celebration of religious festivals is largely a matter of habit, it was not always so. There were times when people united their consciousness with the course of the year; when, let us say, at the beginning of the year, they felt themselves standing within the course of time in such a way that they said to themselves: “There is such and such a degree of cold or warmth now; there are certain relationships among the other weather conditions, certain relationships also between the growth or non-growth in plants or animals.”—People experienced along with Nature the gradual changes and metamorphoses she went through. But they shared this experience with Nature in such a way—when their consciousness was united with the natural phenomena—that they oriented this consciousness toward a specific festival. Let us say, at the beginning of the year, through the various feeling perceptions associated with the passing of winter, the consciousness was directed toward the Easter time, or in the fall, with the fading away of life, toward Christmas. Then men's souls were filled with feelings which found expression in the way they related themselves to what the festivals meant to them.

Thus people partook in the course of the year, and this participation meant for the most part permeating with spirit not only what they saw and heard around them but what they experienced with their whole human being. They experienced the course of the year as an organic life process, just as in the human being when he is a child we relate the utterances of the childish soul with the awkward movements of a child, or its imperfect way of speaking. As we connect specific soul-experiences with the change of teeth, other soul experiences with the later bodily changes, so men once saw the ruling and weaving of the spiritual in the successive changes of outer nature, in growth and decline, or in a waxing followed by a waning.

Now all this cannot help affecting the whole way man feels himself as earthly man in the universe. Thus we can say that in that period at the beginning of our reckoning of time, when the remembrance of the Event of Golgotha began to be celebrated which later became the Easter festival—in that period in which the Easter festival was livingly felt and perceived, when man still took part in the turning of the year as I have just described it—then it was in essence so, that people felt their own lives surrendered, given over to the outer spiritual-physical world. Their feeling told them that in order to make their lives complete, they had need of the vision of the Entombment and the Resurrection, of that sublime image of the Mystery of Golgotha.

But it is from filling the consciousness in such a way that inspirations arise for men. People are not always conscious of these inspirations, but it is a secret of human evolution that from these religious attitudes toward the phenomena of the world, inspirations for the whole of life proceed.

First of all, we must understand clearly that during a certain epoch, during the Middle Ages, the people who oriented the spiritual life were priests, and those priests were concerned above all with the ordering of the festivals. They set the tone for the celebration of the festivals. The priesthood was that group of men who presented the festivals before the rest of mankind, before the laity, and who gave the festivals their content. In so doing the priests themselves felt this content very deeply; and the entire soul-condition that resulted from the inspiring effect of the festivals was expressed in the rest of the soul-life.

The Middle Ages would not have produced what is called Scholasticism—the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas and Albertus Magnus and the other Scholastics—if this philosophy, this world conception, with all its social consequences, had not been inspired by the most important thought of the Church, by the Easter thought. In the vision of the descending Christ, Who lives for a time in man on Earth and then goes through the Resurrection, that soul impulse was given which led to the particular relation between faith and science, between knowledge and revelation which was agreed upon by the Scholastics. That out of man himself, only knowledge of the sensible world can be acquired, whereas everything connected with the super-sensible world has to be gained through revelation—this was determined basically by the way the Easter thought followed upon the Christmas thought.

And if, in turn, the idea-world of natural science today is totally the product of Scholasticism, as I have often explained to you, we must then say: “Although the natural science of the present is not aware of it, its knowledge is essentially a direct imprint of the Easter thought which prevailed in the early Middle Ages and then became paralyzed in the later Middle Ages and in modern times.” Notice the way natural science applies in its ideas what is so popular today and indeed dominates our culture: it devotes its ideas entirely to dead nature; it considers itself incapable of rising above dead nature. This is a result of that inspiration which was stimulated by viewing the Laying in the Grave.

As long as people were able to add the Resurrection to the Entombment as something to which they looked up, they then added also the revelation concerning the super-sensible to mere outer sense-knowledge. But as it became more and more common to view the Resurrection as an inexplicable and therefore unjustifiable miracle, revelation—that is, the super-sensible world—came to be repudiated. The present-day natural scientific view is inspired solely by the conception of Good Friday and lacks any conception of Easter Sunday.

We need to recognize this inner connection: The inspired element is always that which is experienced within all the festival moods in relation to Nature. We must come to know the connection between this inspiring element and all that comes to expression in human life. When we once gain an insight into the intimate connection that exists between this living-oneself-into the course of the year and what men think, feel, and will, then we shall also recognize how significant it would be if we were to succeed, for example, in making the Michael festival in autumn a reality; if we were really to succeed, out of spiritual foundations, out of esoteric foundations, in making the autumn Michael festival something that would pass over into men's consciousness and again work inspiringly.

If the Easter thought were to receive its coloration through the fact that to the Easter thought “He has been laid in the grave and is arisen” the other thought is added, the human thought, “He is arisen and may be laid in the grave without perishing”—If this Michael thought could become living, what tremendous significance just such an event could have for men's whole perceiving (Empfindung), and feeling and willing—and how this could “live itself into” the whole social structure of mankind!

My dear friends, all that people are hoping for from a renewal of the social life will not come about from all the discussions and all the institutions based on what is externally sensible. It will be able to come about only when a mighty inspiration-thought goes through mankind, when an inspiration-thought takes hold of mankind through which the moral-spiritual element will once again be felt and perceived along with the natural-sensible element.

People today are like earthworms, I might say, looking for sunlight under the ground, while to find the sunlight they need to come forth above the surface of the earth. Nothing in reality will be accomplished by all of today's organizations and plans for reform; something can be achieved only by the mighty impact of a thought-impulse drawn out of the spirit. For it must be clear to us that the Easter thought itself can only attain its new “nuance” through being complemented by the Michael thought.

Let us consider this Michael thought somewhat more closely. If we look at the Easter thought, we have to consider that Easter occurs at the time of the bursting and sprouting life of spring. At this time the Earth is breathing out her soul-forces, in order that these soul-forces may be permeated again by the astral element surrounding the Earth, the extra-earthly, cosmic element. The Earth is breathing out her soul. What does this mean?

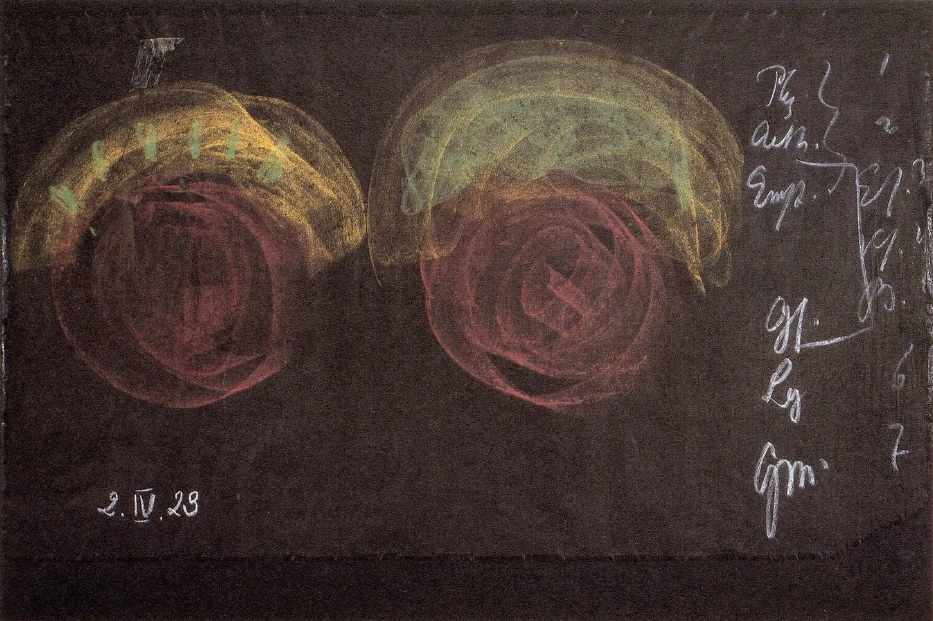

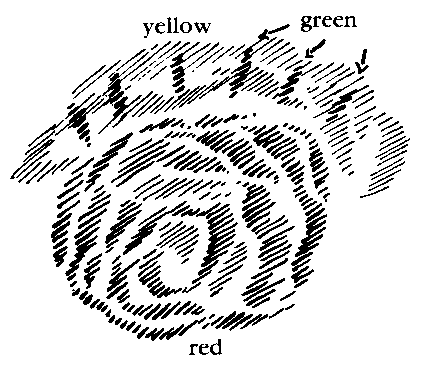

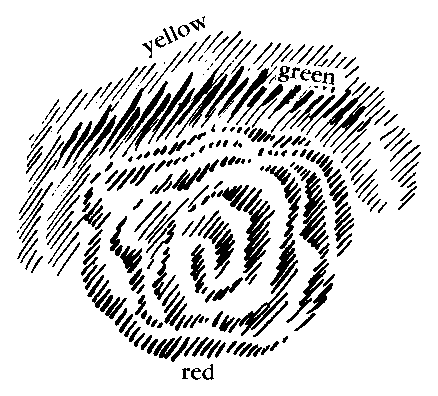

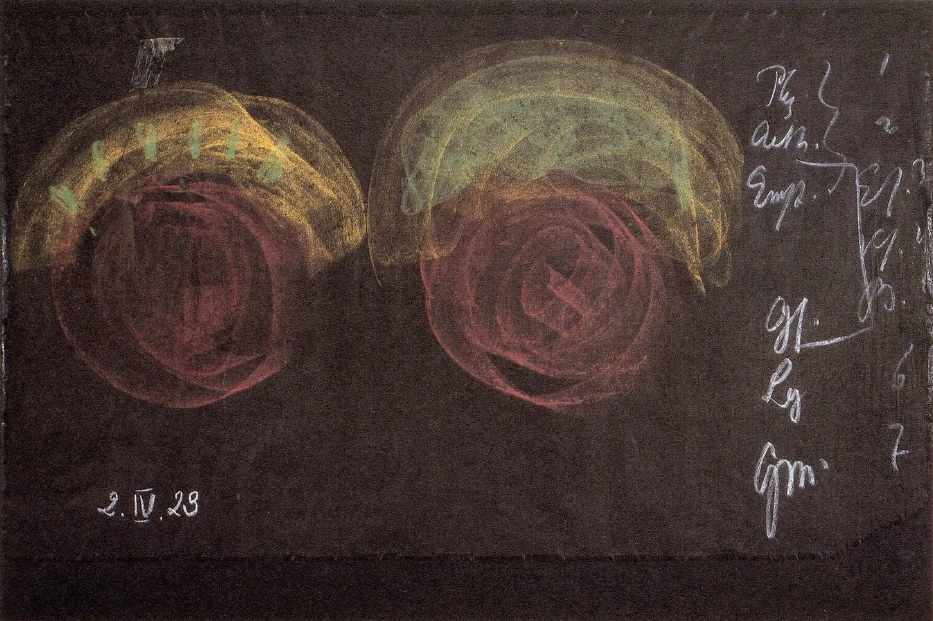

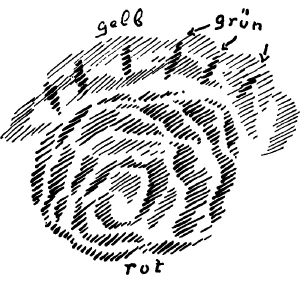

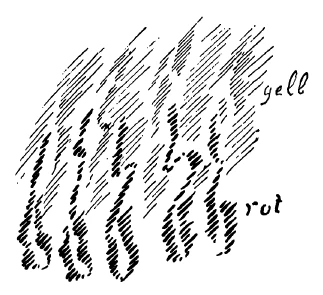

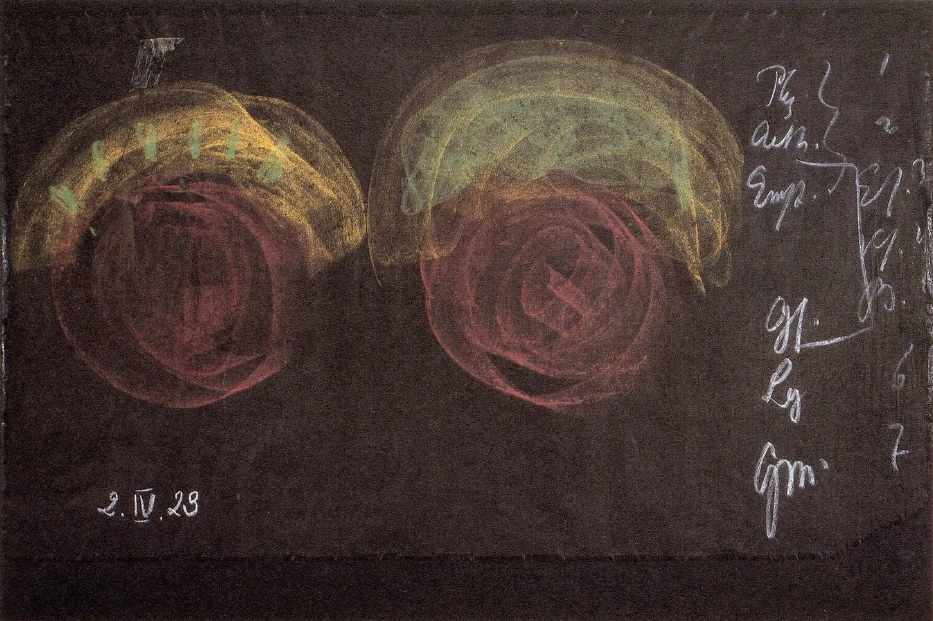

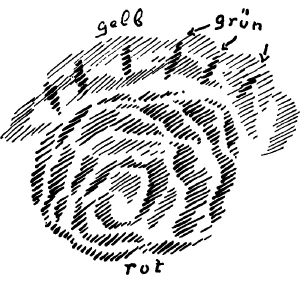

It means that certain elemental beings which are just as much in the periphery of the Earth as the air is or as the forces of growth are—that these unite their own being with the out-breathed Earth soul in those regions in which it is spring. These beings float and merge with the out-breathed Earth soul. They become dis-individualized; they lose their individuality and rise in the general earthly soul element. We see countless elemental beings in spring just around Easter time in the final stage of the individual life which was theirs during the winter. We see them merging into the general earth soul element and rising like a sort of cloud (red, yellow, with green). I might say that during the wintertime these elemental beings are within the soul element of the Earth, where they had become individualized; before this Easter time they had a certain individuality, flying and floating about as individual beings. During Easter time we see them come together in a general cloud (red), and form a common mass within the Earth soul (green). But by so doing these elemental beings lose their consciousness to a certain degree and enter into a sort of sleeping condition. Certain animals sleep in the winter; these elemental beings sleep in summer. This sleep is deepest during St. John's time, when they are completely asleep. Then they begin once more to individualize, and when the Earth breathes in again at Michaelmas, at the end of September, we can see them already as separate beings again.

Man needs these elemental beings... This is not in his consciousness, but man needs them nonetheless, in order to unite them with himself, so that he can prepare his future. And man could unite these elemental beings with himself, if at a certain festival time—it would have to be at the end of September—he could perceive with a special inner soul-filled liveliness how Nature herself changes toward the autumn; if he could perceive how the animal and plant life recedes, how certain animals begin to seek their shelters against the winter; how the plant leaves get their autumn coloring; how all Nature fades and withers.

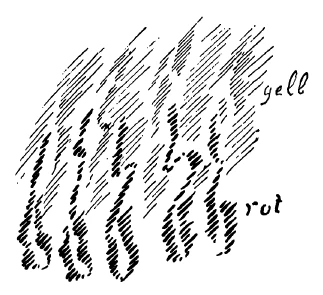

It is true that spring is fair, and it is a fine capacity of the human soul to perceive the beauty of the spring, the growing, sprouting, burgeoning life. But to be able to perceive also when the leaves fade and take on their fall coloring, when the animals creep away—to be able to feel how in the sensible which is dying away, the gleaming, shining, soul-spiritual element arises—to be able to perceive how with the yellowing of the leaves there is a descent of the springing and sprouting life, but how the sensible becomes yellow in order that the spiritual can live in the yellowing as such—to be able to perceive how in the falling of the leaves the ascent of the spirit takes place, how the spiritual is the counter-manifestation of the fading sense-perceptible; this should as a perceptive feeling for the spirit—ensoul the human being in autumn! Then he would prepare himself in the right way precisely for Christmastide.

Man should become permeated, out of anthroposophical spiritual science, by the truth that it is precisely the spiritual life of man on Earth which depends on the declining physical life. Whenever we think, the physical matter in our nerves is destroyed; the thought struggles up out of the matter as it perishes. To feel the becoming of the thought in one's self, the gleaming up of the idea in the human soul, in the whole human organism of man to be akin to the yellowing leaves, the withering foliage, the drying and shriveling of the plant world in Nature; to feel the kinship of man's spiritual “being-ness” with Nature's spiritual “being-ness”—this can give man that impulse which strengthens his will, that impulse which points man to the permeation of his will with spirituality.

In so doing, however, in permeating his will with spirituality, the human being becomes an associate of the Michael activity on earth. And when man lives with Nature in this way as autumn approaches and brings this living-with-Nature to expression in an appropriate festival content, then he will be able truly to perceive the completing (Erganzung) of the Easter mood. But by means of this, something else will become clear to him.—You see, what man thinks, feels, and wills today is really inspired by the Easter mood, which is actually one-sided. This Easter mood is essentially a result of the sprouting, burgeoning life, which causes everything to merge as in a pantheistic unity. Man is surrendered to the unity of Nature, and to the unity of the world generally. This is also the structure of our spiritual life today. Man wants everything to revert to a unity, to a monon; he is either a devotee of universal spirit or universal nature; and he is accordingly either a spiritualistic Monist or a materialistic Monist. Everything is included in an indefinite unity. This is essentially the spring mood.

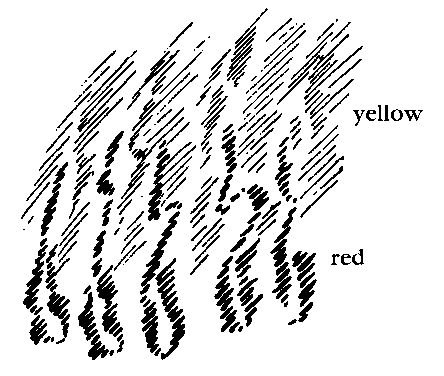

But when we look into the autumn mood, with the rising and becoming free of the spiritual, and the dropping away and withering of the sensible (red), then we have a view of the spiritual as such, and the sensible as such.

The sprouting plant in the spring has the spiritual within its sprouting and growing; the spiritual is mingled with the sensible; we have essentially a unity. The withering plant lets the leaf fall, and the spirit rises; we have the spirit, the invisible, super-sensible spirit, and the material falling out of it. I would say that it is just as if we had in a container, first, a uniform fluid in which something is dissolved, and then by some process we should cause this to separate from the fluid and fall to the bottom as sediment. We have now separated the two which were united, which had formed a unity.

The spring tends to weave everything together, to blend everything into a vague, undifferentiated unity. The view of the autumn, if we only look at it in the right way, if we contrast it in the right way with the view of the spring, calls attention to the way the spiritual works on the one side and the physical-material on the other. The Easter thought loses nothing of value if the Michaelmas thought is added to it. We have on the one side the Easter thought, where everything appears—I might say—as a pantheistic mixture, a unity. Then we have what is differentiated; but the differentiation does not occur in any irregular, chaotic fashion. We have regularity throughout.

Think of the cyclic course: joining together, intermingling, unifying; an intermediate state when the differentiating takes place; the complete differentiation; then again the merging of what was differentiated within the uniform, and so forth. There you see always besides these two conditions yet a third: you see the rhythm between the differentiated and the undifferentiated, in a certain way, between the in-breathing of what was differentiated-out and the out-breathing again, an intermediate condition. You see a rhythm: a physical-material, a spiritual, a working-in-each-other of the physical-material and the spiritual: a soul element.

But the important thing is this: not to stop with the common human fancy that everything must be led back to a unity; thereby everything, whether the unity is a spiritual or a material one, is led back to the indefiniteness of the cosmic night. In the night all cows are gray; in spiritual Monism all ideas are gray; in material Monism they are likewise gray. These are only distinctions of perceiving; they are of no concern for a higher view. What matters is this: that we as human beings can so unite ourselves with the cosmic course that we are in a position to follow the living transition from the unity into the trinity, the return from trinity into unity. When, by complementing the Easter thought with the Michael thought in this way we have become able to perceive rightly the primordial trinity in all existence, then we shall take it into our whole attitude of soul. Then we shall be in a position to understand that actually all life depends upon the activity and the interworking of primordial trinities. And when we have the Michael festival inspiring such a view in the same way that the one-sided Easter festival inspired the view now existing, then we shall have an inspiration, a Nature/Spirit impulse, to introduce threefoldness, the impulse of threefoldness into all the observing and forming of life. And it depends finally and only upon the introduction of this impulse, whether the destructive forces in human evolution can be transformed once more into ascending forces.

One might say that when we spoke of the threefold impulse it was in a certain sense a test of whether the Michael thought is already strong enough so that it can be felt how such an impulse flows directly out of the forces that shape the time. It was a test of the human soul, of whether the Michael thought is strong enough as yet in a large number of people. Well, the test yielded a negative result. The Michael thought is not strong enough in even a small number of people for it to be perceived truly in all its time-shaping power and forcefulness. And it will indeed hardly be possible, for the sake of new forces of ascent, to unite human souls with the original formative cosmic forces in the way that is necessary, unless such an inspiring force as can permeate a Michael festival—unless, that is to say, a new formative impulse—can come forth from the depths of the esoteric life.

If instead of the passive members of the Anthroposophical Society, even only a few active members could be found, then it would become possible to set up further deliberations to consider such a thought. It is essential to the Anthroposophical Society that while stimuli within the Society should of course be carried out, the members should actually attach primary value, I might say, to participating in what is coming to pass. They may perhaps focus the contemplative forces of their souls on what is taking place, but the activity of their own souls does not become united with what is passing through the time as an impulse. Hence, with the present state of the Anthroposophical Movement, there can of course be no question of considering as part of its activity anything like what has just now been spoken of as an esoteric impulse. But it must be understood how mankind's evolution really moves, that the great sustaining forces of humanity's world-evolution come not from what is propounded in superficial words, but from entirely different quarters.

This has always been known in ancient times from primeval elementary clairvoyance. In ancient times it was not the custom for the young people to learn, for example, that there are so and so many chemical elements; then another is discovered and there are then 75, then 76; another is discovered and there are 77. One cannot anticipate how many may still be discovered. Accidentally, one is added to 75, to 76, and so on. In what is adduced here as number, there is no inner reality. And so it is everywhere. Who is interested today in anything that would bring to revelation, let us say, that a systematic threefoldness or trinity prevails in plants! Order after order is discovered, species after species; and they are counted just as though one were counting a chance pile of sticks or stones. But the working of number in the world rests on a real quality of being, and this quality must be fathomed. Only think how short a time lies behind us since knowledge of substance was led back to the trinity of the salty, the mercurial, and the phosphoric; how in this a trinity of archetypal forces was seen; how everything that appeared as individual had to be fitted into one or another of the three archetypal forces.

And it is different again when we look back into still earlier times in which it was easier for people to come to something like this because of the very situation of their culture; for the Oriental cultures lay nearer to the Torrid Zone, where such things were more readily accessible to the ancient elementary clairvoyance. Today, however, it is possible to come to these things in the Temperate Zone through free, exact clairvoyance.... Yet people want to go back to the ancient cultures! In those days people did not distinguish spring, summer, autumn, winter. To distinguish spring, summer, autumn, winter leads us to a mere succession because it contains the “four.” It would have been quite impossible for the ancient Indian culture, for example, to think of something like the course of the year as ruled by the four, because this contains nothing of the archetypal forms underlying all activity.

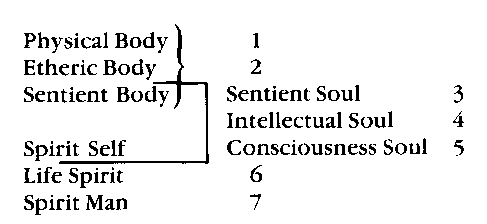

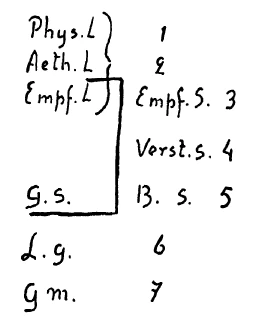

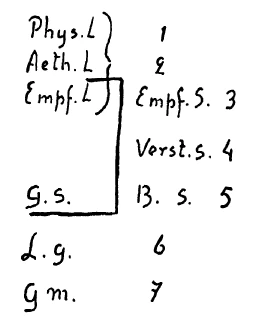

When I wrote my book, Theosophy, it was impossible simply to list in succession physical body, etheric body, astral body, and ego, although we can summarize it this way once the matter is before us, once it is inwardly understood. I had therefore to arrange them according to the number three: physical body, ether body, astral body, forming the first trinity. Then comes the trinity interwoven with it: sentient soul, intellectual soul, consciousness soul; then the trinity interwoven with this: spirit self, life spirit, spirit man—three times three interwoven with one another in such a way as to become seven.

Only when we look at the present stage of mankind's evolution does the four appear, which is really a secondary number. If we want to see the inwardly active principle, if we want to see the formative process, we must see forming and shaping as associated with threefoldness, with trinity.

Hence, the ancient Indian view was of a year divided into a hot season, which would approximate our months of April, May, June, July; a wet season, comprising approximately our months, August, September, October, November; and a cold season, which would include our months, December, January, February, March. The boundaries do not need to be rigidly fixed according to the months but are only approximate; they can be thought of as shifting. But the course of the year was thought of according to the principle of the “three.”

And thus man's whole state of soul would be imbued with the predisposition to observe this primal trinity in all weaving and working, and hence to interweave it also into all human creating and shaping. We can even say that it is only possible to have true ideas of the free spiritual life, the life of rights, the social-economic life, when we perceive in the depths this triple pulse of cosmic activity, which must also permeate human activity.

Any reference to this sort of thing today is regarded as some sort of superstition, whereas it is considered great wisdom simply to count “one” and again “one,” “two,” “three,” and so on. But Nature does not take such a course. If we look, however, only at a realm in which everything is woven together, as is the case with Nature in springtime—which of course we must look at if we want to observe the interweaving of things—then we can never restore the pulse of three.

But when anyone follows the whole course of the year, when he sees how the “three” is organized, how the spiritual and the physical-material life are present as a duality, and the rhythmic interweaving of the two as the third, then he perceives this three-in-one, one-in-three, and learns to know how the human being can place himself in this cosmic activity: three to one, one to three.

It would become the whole disposition of the human soul to permeate the cosmos, to unite itself with cosmic worlds, if once the Michael thought could awaken as a festival thought in such a way that we were to place a Michael festival in the second half of September alongside the Easter festival; if to the thought of the resurrection of the God after death could be added the thought, produced by the Michael force, of the resurrection of man from death, so that man through the Resurrection of Christ would find the force to die in Christ. This means, taking the risen Christ into one's soul during earthly life, so as to be able to die in Him—that is, to be able to die, not at death but when one is living.

Such an inner consciousness as this would result from the inspiring element that would come from a Michael service. We can realize full well how far removed from any such idea is our materialistic time, which is also a time grown narrow-minded and pedantic. Of course, nothing can be expected of us, so long as it remains dead and abstract. But if with the same enthusiasm with which festivals were once introduced in the world when people had the force to form festivals,—if such a thing happens again, then it will work inspiringly. Indeed it will work inspiringly for our whole spiritual and our whole social life. Then that which we need will be present in life: not abstract spirit on one hand and spirit-void nature on the other, but Nature permeated with spirit, and spirit forming and shaping naturally. For these are one, and they will once again weave religion, science, and art into oneness, because they will understand how to conceive the trinity in religion, science, and art in the sense of the Michael thought, so that these three can then be united in the right way in the Easter thought, in the anthroposophical shaping and forming. This can work religiously, artistically, cognitionally, and can also differentiate religiously, cognitionally. Then the anthroposophical impulse would consist in perceiving in the Easter season the unity of science, religion, and art; and then at Michaelmas perceiving how the three—who have one mother, the Easter mother—how the three become “sisters” and stand side by side, but mutually complement one another. Then the Michael thought which should become living as a festival in the course of the year, would be able to work inspiringly on all domains of human life.

With such things as these, which belong to the truly esoteric, we should permeate ourselves, at least in our cognition, to begin with. If then the time could come when there are actively working personalities, such a thing could actually become an impulse which singly and alone would be able, in the present condition of humanity, to replace the descending forces with ascending ones.

Dritter Vortrag

Wir dürfen nicht unterschätzen, welche Bedeutung für die Menschheit so etwas hat wie die Hinlenkung aller Aufmerksamkeit auf eine Festeszeit des Jahres. Wenn auch in unserer Gegenwart das Feiern der religiösen Feste mehr ein gewohnheitsmäßiges ist, so war es doch nicht immer so, und es gab Zeiten, in denen die Menschen ihr Bewußtsein verbanden mit dem Verlauf des ganzen Jahres, indem sie bei Jahresbeginn sich so im Zeitenverlaufe stehend fühlten, daß sie sich sagten: Es ist ein bestimmter Grad von Kälte oder Wärme da, es sind bestimmte Verhältnisse der sonstigen Witterung da, es sind bestimmte Verhältnisse da im Wachstum oder Nichtwachstum der Pflanzen oder der Tiere. - Und die Menschen lebten dann mit, wie allmählich die Natur ihre Verwandlungen, ihre Metamorphosen durchmachte. Sie lebten das aber so mit, indem ihr Bewußtsein sich mit den Naturerscheinungen verband, daß sie gewissermaßen dieses Bewußtsein hinorientierten nach einer bestimmten Festeszeit, sagen wir also: im Jahresbeginne durch die verschiedenen Empfindungen hindurch, die mit dem Vergehen des Winters zusammenhingen nach der OÖsterzeit hin, oder im Herbste mit dem Hinwelken des Lebens nach der Weihnachtszeit hin. Dann erfüllten die Seele jene Empfindungen, die sich eben ausdrückten in der besonderen Art, wie man sich zu dem stellte, was einem die Feste waren.

So erlebte man also den Jahreslauf mit, und dieses Miterleben des Jahreslaufes war ja im Grunde genommen ein Durchgeistigen desjenigen, was man um sich herum nicht nur sah und hörte, sondern mit seinem ganzen Menschen erlebte. Man erlebte den Jahreslauf wie den Ablauf eines organischen Lebens, so wie man etwa im Menschen, wenn er ein Kind ist, die Äußerungen der kindlichen Seele in Zusammenhang bringt mit den ungelenken kindlichen Bewegungen, mit der unvollkommenen Sprechweise des Kindes. Wie man bestimmte seelische Erlebnisse zusammenbringt mit dem Zahnwechsel, andere seelische Erlebnisse mit späteren Veränderungen des Körpers, so sah man das Walten und Weben von Geistigem in den Veränderungen der äußeren Naturverhältnisse. Es war ein Wachsen und Abnehmen.

Das aber hängt zusammen mit der ganzen Art und Weise, wie sich der Mensch überhaupt als Erdenmensch innerhalb der Welt fühlt. Und so kann man sagen: In der Zeit, in der im Beginne unserer Zeitrechnung angefangen wurde, die Erinnerung an das Ereignis von Golgatha zu feiern, das dann zum Osterfest geworden ist, in der Zeit, in der das Osterfest im Laufe des Jahres lebendig empfunden worden ist, in der man den Jahreslauf so miterlebte, wie ich es eben gekennzeichnet habe, da war es im wesentlichen so, daß die Menschen ihr eigenes Leben hingegeben fühlten an die äußere geistig-physische Welt. Sie fühlten, daß sie, um ihr Leben zu einem vollständigen zu machen, bedürftig waren der Anschauung der Grablegung und Auferstehung, des grandiosen Bildes vom Ereignis von Golgatha.

Von solchem Erfüllen des Bewußtseins aber gehen Inspirationen für die Menschen aus. Die Menschen sind sich dieser Inspirationen nicht immer bewußt, aber es ist ein Geheimnis der Menschheitsentwickelung, daß von diesen religiösen Einstellungen gegenüber den Welterscheinungen Inspirationen für das ganze Leben ausgehen. Zunächst müssen wir uns ja klar sein darüber, daß während eines gewissen Zeitalters, während des Mittelalters, die Menschen, die das geistige Leben orientiert haben, die Priester waren, jene Priester, welche vor allen Dingen auch damit zu tun hatten, die Feste zu regeln, tonangebend zu sein im Feste-Feiern. Die Priesterschaft war diejenige Körperschaft innerhalb der Menschheit, welche vor die übrige Menschheit, die Laienmenschheit, die Feste hinstellte, den Festen ihren Inhalt gab. Damit aber fühlte die Priesterschaft diesen Inhalt der Feste ganz besonders. Und der ganze Seelenzustand, der sich dadurch einstellte, daß solche Feste inspirierend wirkten, der drückte sich dann aus im übrigen Seelenleben.

Man hätte im Mittelalter nicht dasjenige gehabt, was man die Scholastik nennt, was man die Philosophie des Thomas von Aguino, des Albertus Magnus und anderer Scholastiker nennt, wenn diese Philosophie, diese Weltanschauung und alles, was sie sozial in ihrem Gefolge hatte, nicht inspiriert gewesen wäre gerade von dem wichtigsten Kirchengedanken: von dem Ostergedanken. In der Anschauung des heruntersteigenden Christus, der im Menschen ein zeitweiliges Leben auf Erden führt, der dann durch die Auferstehung geht, war jener seelische Impuls gegeben, der dazu führte, jenes eigentümliche Verhältnis zwischen Glauben und Wissen, zwischen Erkenntnis und Offenbarung zu setzen, das eben das scholastische ist. Daß man aus dem Menschen heraus nur die Erkenntnis der sinnlichen Welt bekommen kann, daß alles, was sich auf die übersinnliche Welt bezieht, durch Offenbarung gewonnen werden muß, das war im wesentlichen durch den Ostergedanken, wie er sich an den Weihnachtsgedanken anschloß, bestimmt.

Und wenn wiederum die heutige naturwissenschaftliche Ideenwelt eigentlich ganz und gar ein Ergebnis der Scholastik ist, wie ich oftmals hier auseinandergesetzt habe, so muß man sagen: Ohne daß es die naturwissenschaftliche Erkenntnis der Gegenwart weiß, ist sie im wesentlichen ein richtiger Siegelabdruck, möchte ich sagen, des Ostergedankens, so wie er geherrscht hat in den älteren Zeiten des Mittelalters, wie er dann abgelähmt worden ist in der menschlichen Geistesentwickelung im späteren Mittelalter und in der neueren Zeit. Schauen wir darauf hin, wie die Naturwissenschaft in Ideen das verwendet, was heute ja populär ist und unsere ganze Kultur beherrscht, sehen wit, wie die Naturwissenschaft ihre Ideen verwendet: sie wendet sie an auf die tote Natur; sie glaubt sich nicht erheben zu können über die tote Natur. Das ist ein Ergebnis jener Inspiration, die angeregt war durch das Hinschauen auf die Grablegung. Und solange man zu der Grablegung hinzufügen konnte die Auferstehung als etwas, zu dem man aufsah, da fügte man auch die Offenbarung über das Übersinnliche zu der bloßen äußeren Sinneserkenntnis hinzu. Als immer mehr und mehr die Anschauung aufkam, die Auferstehung wie ein unerklärliches und daher unberechtigtes Wunder hinzustellen, da ließ man die Offenbarung, also die übersinnliche Welt, weg. Die heutige naturwissenschaftliche Anschauung ist sozusagen bloß inspiriert von der Karfreitagsanschauung, nicht von der Ostersonntagsanschauung.

Man muß diesen inneren Zusammenhang erkennen: Das Inspirierte ist immer das, was innerhalb aller Festesstimmungen miterlebt wird gegenüber der Natur. Man muß den Zusammenhang erkennen zwischen diesem Inspirierenden und dem, was in allem Menschenleben zum Ausdrucke kommt. Wenn man erst einsieht, welch inniger Zusammenhang besteht zwischen diesem Sich-Einleben in den Jahreslauf und dem, was die Menschen denken, fühlen und wollen, dann wird man auch erkennen, von welcher Bedeutung es wäre, wenn es zum Beispiel gelänge, die Herbstes-Michael-Feier zu einer Realität zu machen, wenn es wirklich gelänge, aus geistigen Untergründen heraus, aus esoterischen Untergründen heraus die Herbstes-Michael-Feier zu etwas zu machen, was nun in das Bewußtsein der Menschen überginge und wiederum inspirierend wirkte. Wenn der Östergedanke seine Färbung bekäme dadurch, daß sich zu dem Ostergedanken: Et ist ins Grab gelegt worden und auferstanden - hinzufügte der andere Gedanke, der menschliche Gedanke: Er ist auferstanden und darf in das Grab gelegt werden, ohne daß er zugrunde geht -, wenn dieser Michael-Gedanke lebendig werden könnte, welche ungeheure Bedeutung würde gerade solch ein Ereignis haben können für das gesamte Empfinden und Fühlen und Wollen der Menschen! Wie würde sich das einleben können in das ganze soziale Gefüge der Menschheit!

Alles, was die Menschen erhoffen von einer Erneuerung des sozialen Lebens, es wird nicht kommen von all den Diskussionen und von all den Institutionen, die sich auf Äußerlich-Sinnliches beziehen, es wird allein kommen können, wenn ein mächtiger Inspirationsgedanke durch die Menschheit geht, wenn ein Inspirationsgedanke die Menschheit ergreift, durch welchen wiederum Moralisch-Geistiges unmittelbar im Zusammenhange gefühlt und empfunden wird mit dem NatürlichSinnlichen. Die Menschen suchen heute, ich möchte sagen, wie die unter der Erde befindlichen Regenwürmer das Sonnenlicht, während man, um das Sonnenlicht zu finden, eben über die Oberfläche der Erde hervorkommen muß. Mit allen Diskussionen und Reformgedanken von heute ist nichts zu machen in Wirklichkeit; allein von dem mächtigen Einschlage eines aus dem Geiste heraus geholten Gedankenimpulses ist etwas zu erreichen. Denn man muß sich klar sein darüber, daß gerade der Ostergedanke seine neue Nuance bekommen würde, wenn er ergänzt würde durch den Michael-Gedanken.

Betrachten wir diesen Michael-Gedanken einmal näher. Wenn wir den Blick auf den Ostergedanken hinwerfen, so haben wir zu beachten, daß Ostern in die Zeit des aufsprießenden und sprossenden Frühlingslebens fällt. In dieser Zeit atmet die Erde ihre Seelenkräfte aus, damit diese Seelenkräfte im Umkreise der Erde sich durchdringen mit dem, was astralisch um die Erde herum ist, mit dem außerirdischen Kosmischen. Die Erde atmet ihre Seele aus. Was bedeutet das? Das bedeutet, daß gewisse elementare Wesenheiten, welche ebenso im Umkreise der Erde sind wie die Luft oder wie die Kräfte des Pflanzenwachstums, ihr eigenes Wesen mit der ausgeatmeten Erdenseele verbinden für die Gegenden, in denen eben Frühling ist. Es verschwimmen und verschweben diese Wesenheiten mit der ausgeatmeten Erdenseele. Sie entindividualisieren sich, sie verlieren ihre Individualität, sie gehen in dem allgemein Irdisch-Seelischen auf. Zahlreiche Elementarwesen schaut man im Frühling gerade um die Osterzeit, wie sie aus dem letzten Stadium ihres individuellen Daseins, das sie während der Winterzeit gehabt haben, wolkenartig verschwimmen und aufgehen im allgemein Irdisch-Seelenhaften. Ich möchte sagen:

Diese Elementarwesen waren während der Winterzeit innerhalb des Seelenhaften der Erde, wo sie sich individualisiert hatten (siehe Zeichnung: grün im gelb). Die sind vor dieser Osterzeit noch mit einer gewissen Individualität behaftet, fliegen, schweben gewissermaßen herum als individuelle Wesenheiten. Während der Osterzeit sehen wir, wie sie in allgemeinen Wolken zusammenlaufen und eine gemeinsame Masse bilden innerhalb der Erdenseele (grün im gelb). Dadurch aber verlieren bis zu einem gewissen Grade diese Elementarwesen ihr Bewußtsein. Sie kommen in eine Art schlafähnlichen Zustand. Gewisse Tiere führen einen Winterschlaf; diese Elementarwesen führen einen Sommerschlaf. Das ist am stärksten während der Johannizeit, wo sie vollständig schlafen. Dann aber fangen sie wiederum an, sich zu individualisieren, und man sieht sie schon als besondere Wesen in dem Einatmungszug der Erde klar zur Michaeli-Zeit, Ende des September.

Aber diese Elementarwesen sind diejenigen, die der Mensch nun braucht. Das alles liegt ja nicht in seinem Bewußtsein, aber der Mensch braucht sie trotzdem, um sie mit sich zu vereinigen, damit er seine Zukunft vorbereiten kann. Und der Mensch kann diese Elementarwesen mit sich vereinigen, wenn er zu einer Festeszeit, die in das Ende des September fiele, mit einer besonderen inneren seelenvollen Lebendigkeit empfinden würde, wie die Natur gerade gegen den

Ar Herbst zu sich verändert; wenn der Mensch empfinden könnte, wie da das tierisch-pflanzliche Leben zurückgeht, wie gewisse Tiere sich anschicken, ihre schützenden Orte aufzusuchen für den Winter, wie die Pflanzenblätter ihre Herbstesfärbungen bekommen, wie das ganze Natürliche verwelkt. Gewiß, der Frühling ist schön, und die Schönheit des Frühlings, das wachsende, sprießende und sprossende Leben des Frühlings zu empfinden, ist eine schöne Eigenschaft der menschlichen Seele. Aber auch empfinden zu können, wenn die Blätter sich bleichen, ihre Herbstesfärbungen annehmen, wenn die Tiere sich verkriechen, fühlen zu können, wie im absterbenden Sinnlichen ersteht das glitzernde, glänzende Geistig-Seelische, empfinden zu können, wie mit dem Gelbfärben der Blätter ein Untergang des sprießenden, sprossenden Lebens da ist, aber wie das Sinnliche gelb wird, damit das Geistige in dem Gelbwerden als solches leben könne, empfinden zu können, wie in dem Abfallen der Blätter das Aufsteigen des Geistes stattfindet, wie das Geistige die Gegenoffenbarung des verglimmenden Sinnlichen ist: das sollte als eine Empfindung für den Geist den Menschen in der Herbsteszeit beseelen. Dann bereitet er sich in der richtigen Weise gerade auf die Weihnachtszeit vor.

Durchdrungen sollte der Mensch werden aus der anthroposophischen Geisteswissenschaft heraus von der Wahrheit, daß gerade das geistige Leben des Menschen auf Erden zusammenhängt mit dem absteigenden physischen Leben. Indem wir denken, geht ja unsere physische Materie in dem Nerv zugrunde. Der Gedanke ringt sich aus der zugrunde gehenden Materie auf. Das Werden der Gedanken in sich selber, das Aufglänzen der Ideen in der Menschenseele und im ganzen menschlichen Organismus Sich-verwandt-Fühlen mit den sich gelbfärbenden Blättern, mit dem welkenden Laub der Pflanzen, mit dem Dürrwerden der Pflanzen, dieses Sich-verwandt-Fühlen des menschlichen Geistseins mit dem Naturgeistsein: das kann dem Menschen jenen Impuls geben, der seinen Willen verstärkt, jenen Impuls, der den Menschen hinweist auf die Durchdringung des Willens mit Geistigkeit.

Dadurch aber, daß der Mensch seinen Willen mit Geistigkeit durchdringt, wird er ein Genosse der Michael-Wirksamkeit auf Erden. Und wenn der Mensch in dieser Weise gegen den Herbst zu mitlebt mit der Natur und dieses Mitleben mit der Natur in einem entsprechenden Festesinhalt zum Ausdrucke bringt, dann kann er jene Ergänzung der Osterstimmung wirklich empfinden. Dadurch aber wird ihm noch etwas anderes klar. Sehen Sie, was der Mensch heute denkt, fühlt und will, ist ja inspiriert von der einseitigen Osterstimmung, die noch dazu eine abgelähmte ist. Diese Osterstimmung ist im wesentlichen ein Ergebnis des sprossenden, sprießenden Lebens, das alles wie in eine pantheistische Einheit aufgehen läßt. Der Mensch ist hingegeben an die Einheit der Natur und an die Einheit der Welt überhaupt. Das ist ja auch das Gefüge unseres Geisteslebens heute. Man will alles auf eine Einheit, auf ein Monon zurückführen. Entweder ist einer Anhänger des Allgeistes oder der Allnatur: danach ist er entweder ein spiritualistischer Monist oder ein materialistischer Monist. Es wird alles in einem unbestimmten All-Einen gefaßt. Das ist im wesentlichen Frühlingsstimmung.

Schaut man hinein in die Herbstesstimmung mit dem aufsteigenden freiwerdenden Geistigen (gelb), mit dem, ich möchte sagen, abtropfenden, welkwerdenden Sinnlichen (rot), dann hat man den Ausblick auf das Geistige als solches, auf das Sinnliche als solches.

Die frühlingsprießende Pflanze hat in ihrem Wachstum, in ihrem Tafel 5, Sprossen und Wachsen das Geistige darinnen. Das Geistige ist mit dem Sinnlichen durchmischt, man hat im wesentlichen eine Einheit. Die verwelkende Pflanze läßt das Blatt fallen und der Geist steigt auf: man hat den Geist, den unsichtbaren, übersinnlichen Geist, und herausfallend das Materielle. Es ist so, wie wenn man in einem Gefäß zuerst eine einheitliche Flüssigkeit hätte, in der irgend etwas aufgelöst ist, und man dann durch irgendeinen Vorgang es bewirken würde, daß sich aus dieser Flüssigkeit etwas absetzt, was als 'Trübung herunterfällt. Da hat man die zwei, die miteinander verbunden waren, die ein einziges bildeten, nun getrennt.

Der Frühling ist geeignet, alles ineinander zu verweben, alles in eine undifferenzierte, unbestimmte Einheit zu vermischen. Die Herbstesanschauung, wenn man nur richtig auf sie hinschaut, wenn man sie in der richtigen Weise kontrastiert mit der Frühlingsanschauung, sie macht einen aufmerksam darauf, wie Geist auf der einen Seite wirkt, Physisch-Materielles auf der andern Seite. Und man darf natürlich dann nicht einseitig bei dem einen oder bei dem andern stehenbleiben. Der Ostergedanke verliert ja nicht an Wert, wenn man den MichaelGedanken hinzufügt. Man hat auf der einen Seite den Ostergedanken, wo alles, ich möchte sagen, in einer Art pantheistischer Vermischung auftritt, in einer Einheit. Man hat dann das Differenzierte, aber die Differenzierung geschieht nicht in irgendeiner unregelmäßigen, chaotischen Weise. Wir haben durchaus eine Regelmäßigkeit. Denken Sie sich den zyklischen Verlauf: Ineinanderfügung, Ineinandermischung, Vereinheitlichung, einen Zwischenzustand, wo die Differenzierung geschieht, die vollständige Differenzierung; dann wiederum das Aufgehen des Differenzierten im Einheitlichen und so fort. Da sehen Sie immer außer diesen zwei Zuständen noch einen dritten: da sehen Sie den Rhythmus zwischen dem Differenzierten und dem Undifferenzierten, gewissermaßen zwischen dem Einatmen des Herausdifferenzierten und dem Wiederausatmen. Einen Rhythmus sehen Sie, einen Zwischenzustand, ein Physisch-Materielles, ein Geistiges; ein Ineinanderwirken von Physisch-Materiellem und Geistigem: ein Seelisches. Sie lernen sehen im Naturverlaufe die Natur durchsetzt von der Urdreiheit: von Materiellem, von Geistigem, von Seelischem.

Das aber ist das Wichtige, daß man nicht stehenbleibt bei der allgemein-menschlichen Träumerei, man müsse alles auf eine Einheit zurückführen. Dadurch führt man alles, ob nun die Einheit eine spirituelle, ob sie eine materielle ist, auf das Unbestimmte der Weltennacht zurück. In der Nacht sind alle Kühe grau, im spirituellen Monismus sind alle Ideen grau, im materiellen Monismus sind sie ebenso grau. Das sind nur Empfindungsunterschiede. Darauf kommt es gar nicht an für eine höhere Anschauung. Worauf es ankommt, ist, daß wit als Menschen mit dem Weltenlauf uns so verbinden können, daß wir das lebendige Übergehen von der Einheit in die Dreiheit, das Zurückgehen von der Dreiheit in die Einheit zu verfolgen in der Lage sind. Dann, wenn wir dadurch, daß wir den Ostergedanken in dieser Weise ergänzen durch den Michaeli-Gedanken, uns in die Lage versetzen, die Urdreiheit in allem Sein in der richtigen Weise zu empfinden, dann werden wir sie in unsere ganze Seelenverfassung aufnehmen. Dann werden wir in der Lage sein, einzusehen, daß in der Tat alles Leben auf der Betätigung und dem Ineinanderwirken von Urdreiheiten beruht. Und dann werden wir, wenn wir das Michael-Fest so inspirierend haben, für eine solche Anschauung, wie das einseitige Osterfest inspirierend war für die Anschauungen, die nun einmal heraufgekommen sind, dann werden wir eine Inspiration, einen Natur-Geistimpuls haben, um in alles zu beobachtende und zu gestaltende Leben die Dreigliederung, den Dreigliederungsimpuls einzuführen. Und von der Einführung dieses Impulses hängt es doch zuletzt einzig und allein ab, ob die Niedergangskräfte, die in der menschlichen Entwickelung sind, wiederum in Aufgangskräfte verwandelt werden können.

Man möchte sagen, als von dem Dereigliederungsimpuls im sozialen Leben gesprochen worden ist, da war das gewissermaßen eine Prüfung, ob der Michael-Gedanke schon so stark ist, daß gefühlt werden kann, wie ein solcher Impuls unmittelbar aus den zeitgestaltenden Kräften herausquillt. Es war eine Prüfung der Menschenseele, ob der Michael-Gedanke in einer Anzahl von Menschen stark genug ist. Nun, die Prüfung hat ein negatives Resultat ergeben. Der Michael-Gedanke ist noch nicht stark genug in auch nur einer kleinen Anzahl von Menschen, um wirklich in seiner ganzen zeitgestaltenden Kraft und Kräftigkeit empfunden zu werden. Und es wird ja kaum möglich sein, die Menschenseelen für neue Aufgangskräfte so mit den urgestaltenden Weltenkräften zu verbinden, wie es notwendig ist, wenn nicht ein solch Inspirierendes wie eine Michael-Festlichkeit durchdringen kann, wenn also nicht aus den Tiefen des esoterischen Lebens heraus ein neugestaltender Impuls kommen kann.

Wenn sich statt der passiven Mitglieder der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft nur wenige aktive Mitglieder fänden, so würden über einen solchen Gedanken Erwägungen angestellt werden können. Das Wesentliche der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft besteht ja darin, daß allerdings Anregungen innerhalb der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft ausgelebt werden, daß aber die Mitglieder eigentlich hauptsächlich den Wert darauf legen, teilzunehmen an dem, was sich abspielt; daß sie wohl ihre betrachtenden Seelenkräfte hinwenden zu dem, was sich abspielt, daß aber die Aktivität der eigenen Seele nicht verbunden wird mit demjenigen, was als ein Impuls durch die Zeit geht. Daher kann natürlich bei dem gegenwärtigen Bestande der anthroposophischen Bewegung nicht davon gesprochen werden, daß so etwas wie dieses, was jetzt gewissermaßen wie ein esoterischer Impuls ausgesprochen wird, in seiner Aktivität erwogen werden kann. Aber verstehen muß man doch, wie eigentlich der Gang der Menschheitsentwickelung geht, wie nicht aus dem, was man in oberflächlichen Worten äußerlich ausspricht, die großen tragenden Kräfte der Weltentwickelung der Menschheit kommen, sondern wie sie, ich möchte sagen, aus ganz andern Ecken heraus kommen.

Alte Zeiten haben das immer gewußt aus ursprünglichem, elementarischem, menschlichem Hellsehen heraus. Alte Zeiten haben es nicht so gemacht, daß die jungen Leute zum Beispiel lernen: So und so viele chemische Elemente, dann wird eins entdeckt zu den fünfundsiebzig, dann sind es sechsundsiebzig, dann wird wieder eins entdeckt, dann sind es siebenundsiebzig. Man kann nicht absehen, wie viele noch entdeckt werden können. Zufällig fügt sich eins zu fünfundsiebzig, zu sechsundsiebzig und so weiter. In dem, was da als Zahl angeführt wird, ist keine innere Wesenhaftigkeit. Und so ist es überall. Wen interessiert heute, was, sagen wir in der Pflanzensystematik, irgendwie eine Art von Dreiheit zur Offenbarung bringen würde! Man entdeckt Ordnung neben Ordnung oder Art neben Art. Man zählt ab so, wie man zufällig hingeworfene Bohnen oder Steinchen abzählt. Aber das Wirken der Zahl in der Welt ist ein solches, das auf Wesenhaftigkeit beruht, und diese Wesenhaftigkeit muß man durchschauen.

Man denke zurück, wie kurz die hinter uns liegende Zeit ist, wo dasjenige, was Stoffeserkenntnis war, zurückgeführt wurde auf die Dreiheit: auf das Salzige, das Merkurialische, das Phosphorartige, wie da eine Dreiheit von Urkräftigem geschaut wurde, wie alles, was sich als einzelnes fand, eben in irgendeine der Urkräfte der Drei hineingefügt werden mußte. Und anders noch ist es, wenn wir zurückblicken in noch ältere Zeiten, in denen es übrigens auch durch die Lage der Kultur den Menschen leichter war, auf so etwas zu kommen, denn die orientalischen Kulturen lagen mehr der heißen Zone zugeneigt, wo das dem älteren elementaren Hellsehen leichter möglich war. Heute ist es der gemäßigten Zone allerdings möglich, in freier, exakter Hellsichtigkeit zu diesen Dingen zu kommen; aber man will ja zurück in alte Kulturen! Damals unterschied man nicht Frühling, Sommer, Herbst und Winter. Frühling, Sommer, Herbst und Winter zu unterscheiden, verführt, weil man darinnen die Vier hat, zu einem bloßen Aneinanderreihen. So etwas wie den Jahreslauf beherrscht von der Vier zu denken, wäre zum Beispiel der altindischen Kultur ganz unmöglich gewesen, weil da nichts von den Urgestalten alles Wirkens darinnen liegt.

Als ich mein Buch «Theosophie» schrieb, da konnte ich nicht einfach aneinanderreihen: physischer Leib, ätherischer Leib, astralischer Leib und Ich, wie man es zusammenfassen kann, wenn die Sache schon da ist, wenn man die Sache innerlich durchschaut. Da mußte ich nach der Dreizahl anordnen: physischer Leib, Ätherleib, Empfindungsleib; erste Dreiheit. Dann die damit verwobene Dreiheit: Empfindungsseele, Verstandesseele, Bewußtseinsseele; dann die damit verwobene Dreiheit: Geistselbst, Lebensgeist, Geistesmensch, drei mal drei, ineinander verwoben (siehe Schema), dadurch wird es zu sieben. Aber die Sieben ist eben drei mal drei ineinander verwoben. Und nur, wenn man auf das gegenwärtige Stadium der Menschheitsentwickelung blickt, kommt die Vier heraus, die eigentlich im Grunde genommen eine sekundäre Zahl ist.

Will man auf das innerlich Wirksame, auf das sich Gestaltende sehen, muß man auf die Gestaltung im Sinne der Dreiheit schauen. Daher hat die alte indische Anschauung gehabt: heiße Jahreszeit, ungefähr würde das umfassen unsere Monate April, Mai, Juni, Juli; feuchte Jahreszeit, die würde ungefähr umfassen unsere Monate August, September, Oktober, November; und die kalte Jahreszeit würde umfassen unsere Monate Dezember, Januar, Februar, März, wobei die Grenzen gar nicht so festzustehen brauchen nach Monaten, sondern nur approximativ sind. Das kann verschoben gedacht werden. Aber der Jahreslauf wurde gedacht in der Dreiheit. Und so würde überhaupt die menschliche Seelenverfassung sich durchdringen mit der Anlage, diese Urdreiheit in allem Webenden und Wirkenden zu beobachten, dadurch aber auch allem menschlichen Schaffen, allem menschlichen Gestalten diese Urdreiheit einzuverweben. Man kann schon sagen, reinliche Ideen zu haben auch von dem freien Geistesleben, von dem Rechtsleben, von dem sozial-wirtschaftlichen Leben ist nur möglich, wenn man diesen Dreischlag des Weltenwirkens, das auch durch das Menschenwirken gehen muß, in der Tiefe durchschaut.

Heute gilt alles, was auf solche Dinge sich beruft, als eine Art von Aberglaube, währenddem es als hohe Weisheit gilt, einfach zu zählen: eins und wieder eins, zwei, drei und so weiter. Aber so verfährt ja die Natur nicht. Wenn man aber seine Anschauung lediglich darauf beschränkt, auf dasjenige hinzuschauen, in dem sich alles verwebt, zum Beispiel auf das Frühlingshafte allein, auf das man natürlich hinschauen muß, um zu sehen, wie sich alles verwebt, so kann man eben nicht den Dreischlag wiedergeben. Wenn man aber den ganzen Jahreslauf verfolgt, wenn man sieht, wie sich die Drei gliedert, wie das Geistige und das physisch-materielle Leben als Zweiheit vorhanden ist und das rhythmische Ineinanderweben von beiden als das Dritte, dann nimmt man wahr dieses Drei in Eins, Eins in Drei, und lernt erkennen, wie der Mensch sich selber hineinstellen kann in dieses Weltenwirken: drei zu eins, eins zu drei.

Das würde menschliche Seelenverfassung werden, weltendurchdringende, mit Welten sich verbündende menschliche Seelenverfassung, wenn der Michael-Gedanke als Festesgedanke so erwachen könnte, daß wirklich dem Osterfest an die Seite gesetzt würde in der zweiten Septemberhälfte ein Michael-Fest, wenn dem Auferstehungsgedanken des Gottes nach dem Tode hinzugefügt werden könnte der durch die Michael-Kraft bewirkte Auferstehungsgedanke des Menschen vor dem Tode. So daß der Mensch durch die Auferstehung Christi die Kraft finden würde, in Christus zu sterben, das heißt, den auferstandenen Christus in seine Seele aufzunehmen während des Erdenlebens, damit er in ihm sterben könne, das heißt, nicht tot, sondern lebendig sterben kann.

Solches inneres Bewußtsein würde hervorgehen aus dem Inspirierenden, das aus einem Michael-Dienst kommen würde. Man kann sehr wohl einsehen, wie unserer materialistischen Zeit, die aber identisch ist mit einer ganz und gar philiströs gewordenen Zeit, so etwas ferne liegt. Gewiß, man kann auch nichts davon erwarten, wenn es ein Totes, Abstraktes bleibt. Aber wenn mit demselben Enthusiasmus, mit dem einmal in der Welt Feste eingeführt worden sind, als man die Kraft hatte, Feste zu gestalten, wiederum so etwas geschieht, dann wird es inspirierend wirken. Dann wird es aber auch inspirierend wirken für unser ganzes geistiges und für unser ganzes soziales Leben. Dann wird dasjenige im Leben stehen, was wir brauchen: nicht abstrakter Geist auf der einen Seite, geistlose Natur auf der andern Seite, sondern durchgeistigte Natur, natürlich gestaltender Geist, die eines sind, und die auch wiederum Religion, Wissenschaft und Kunst in eines verweben werden, weil sie verstehen werden, die Dreiheit im Sinne des Michael-Gedankens in Religion, Wissenschaft und Kunst zu fassen, damit sie in der richtigen Weise vereinigt werden können im Ostergedanken, im anthroposophischen Gestalten, das religiös, künstlerisch, erkenntnismäßig wirken kann, das auch wiederum religiös, erkenntnismäßig differenzieren kann. So daß eigentlich der anthroposophische Impuls darin bestehen würde, in der Osterzeit zu empfinden Einheit von Wissenschaft, Religion und Kunst; in der Michaelzeit zu empfinden, wie die Drei — die eine Mutter haben, die Ostermutter -, wie die Drei Geschwister werden und nebeneinander stehen, aber sich gegenseitig ergänzen. Und auf alles menschliche Leben könnte der Michael-Gedanke, der festlich lebendig werden sollte im Jahreslauf, inspirierend wirken.

Von solchen Dingen, die durchaus dem real Esoterischen angehören, sollte man sich durchdringen, wenigstens zunächst erkenntnismäßig. Wenn dann einmal auch die Zeit kommen könnte, wo es aktiv wirkende Persönlichkeiten gibt, so könnte so etwas tatsächlich ein Impuls werden, der doch so, wie die Menschheit ist, einzig und allein wiederum Aufgangskräfte an die Stelle der Niedergangskräfte setzen könnte.

Third Lecture

We must not underestimate the importance for humanity of something like the focusing of all attention on a festive time of the year. Even if in our present time the celebration of religious festivals is more of a habitual one, it was not always so, and there were times when people connected their consciousness with the course of the whole year, in that at the beginning of the year they felt themselves to be in the course of time in such a way that they said to themselves: There is a certain degree of cold or warmth, there are certain conditions of other weather, there are certain conditions in the growth or non-growth of plants or animals. - And people then witnessed how nature gradually underwent its transformations, its metamorphoses. But they lived through it in such a way that their consciousness connected with the natural phenomena, that they oriented this consciousness, so to speak, towards a certain festive season, let us say: at the beginning of the year through the various sensations connected with the passing of winter towards the Easter season, or in autumn with the withering away of life towards the Christmas season. Then the soul was filled with those feelings that expressed themselves in the particular way in which one related to what the festivals were to one.

So one experienced the course of the year, and this co-experience of the course of the year was basically a spiritualization of what one not only saw and heard around oneself, but experienced with one's whole being. One experienced the course of the year like the course of an organic life, just as one associates the expressions of the child's soul with the child's awkward movements and imperfect way of speaking when he is a child. Just as one associates certain spiritual experiences with the change of teeth, and other spiritual experiences with later changes in the body, so one saw the activity and weaving of the spiritual in the changes in the external conditions of nature. It was a waxing and waning.

But this is connected with the whole way in which man feels himself as an earthly human being within the world. And so we can say that at the time when, at the beginning of our era, the memory of the event of Golgotha was first celebrated, which then became Easter, at the time when Easter was felt to be alive in the course of the year, when the course of the year was experienced in the way I have just described, it was essentially the case that people felt their own lives to be devoted to the outer spiritual-physical world. They felt that in order to make their lives complete, they needed to see the burial and resurrection, the grandiose image of the event of Golgotha.

Inspirations for people emanate from such a fulfillment of consciousness. People are not always aware of these inspirations, but it is a secret of human development that these religious attitudes towards world phenomena provide inspiration for the whole of life. First of all, we must be clear about the fact that during a certain age, during the Middle Ages, the people who oriented spiritual life were the priests, those priests who above all had to regulate the festivals, to set the tone in the celebration of festivals. The priesthood was the body within humanity that placed the festivals before the rest of humanity, lay humanity, and gave the festivals their content. Thus, however, the priesthood felt this content of the festivals in a very special way. And the whole state of soul that arose as a result of the inspiring effect of such festivals was then expressed in the rest of the soul's life.

In the Middle Ages we would not have had what is called scholasticism, what is called the philosophy of Thomas of Aguino, Albertus Magnus and other scholastics, if this philosophy, this world view and everything that it had socially in its wake had not been inspired by the most important church idea: the idea of Easter. In the view of the descending Christ, who leads a temporary life on earth in man, who then passes through the resurrection, there was that spiritual impulse which led to the establishment of that peculiar relationship between faith and knowledge, between cognition and revelation, which is precisely the scholastic relationship. The fact that man can only gain knowledge of the sensory world, that everything that relates to the supersensible world must be gained through revelation, was essentially determined by the Easter idea, as it followed on from the Christmas idea.

And if, again, today's scientific world of ideas is actually entirely a result of scholasticism, as I have often explained here, then it must be said: without the scientific knowledge of the present knowing it, it is essentially a true seal impression, I would like to say, of the Easter idea as it prevailed in the older times of the Middle Ages, as it was then paralyzed in the human spiritual development in the later Middle Ages and in more recent times. If we look at how natural science uses in ideas what is popular today and dominates our whole culture, we see how natural science uses its ideas: it applies them to dead nature; it does not believe it can rise above dead nature. This is a result of that inspiration which was stimulated by looking at the Entombment. And as long as the resurrection could be added to the burial as something to look up to, the revelation of the supersensible was also added to the mere external sense knowledge. As more and more the view arose that the resurrection was an inexplicable and therefore unjustified miracle, revelation, i.e. the supersensible world, was omitted. Today's scientific view is, so to speak, merely inspired by the Good Friday view, not the Easter Sunday view.

You have to recognize this inner connection: That which is inspired is always that which is experienced within all festive moods in relation to nature. One must recognize the connection between this inspiring and that which is expressed in all human life. Once you realize what an intimate connection there is between this settling into the course of the year and what people think, feel and want, then you will also realize what significance it would be if, for example, it were possible to make the autumn Michaelmas celebration a reality, if it were really possible to make the autumn Michaelmas celebration out of spiritual backgrounds, out of esoteric backgrounds, into something that would now pass into people's consciousness and in turn have an inspiring effect. If the Easter thought were given its coloring by the fact that the other thought, the human thought, was added to the Easter thought: He was laid in the grave and rose again: He rose again and may be laid in the grave without perishing - if this Michael thought could come to life, what tremendous significance such an event could have for the entire feeling and sensibility and will of people! How it would be able to settle into the whole social fabric of humanity!

Everything that people hope for from a renewal of social life will not come from all the discussions and from all the institutions that relate to the external-sensual, it will only be able to come if a powerful inspirational thought goes through humanity, if an inspirational thought takes hold of humanity, through which in turn the moral-spiritual is directly felt and sensed in connection with the natural-sensual. People today, I would like to say, seek the sunlight like earthworms underground, whereas in order to find the sunlight one has to come above the surface of the earth. Nothing can be achieved in reality with all the discussions and reform ideas of today; only the powerful impact of a thought impulse drawn from the spirit can achieve anything. For one must be clear about the fact that the Easter thought in particular would take on a new nuance if it were supplemented by the Michael thought.

Let us take a closer look at this Michael thought. When we look at the Easter thought, we have to bear in mind that Easter falls in the time of the budding and sprouting life of spring. At this time the earth breathes out its soul forces, so that these soul forces in the earth's orbit interpenetrate with what is astral around the earth, with the extra-terrestrial cosmic. The earth exhales its soul. What does that mean? It means that certain elemental beings, which are just as much in the earth's orbit as the air or the forces of plant growth, connect their own being with the exhaled earth-soul for the regions in which it is spring. These entities blur and merge with the exhaled earth soul. They de-individualize themselves, they lose their individuality, they merge into the general earthly soul. Numerous elemental beings can be seen in spring, especially around Easter time, as they blur like clouds from the last stage of their individual existence, which they had during the winter time, and merge into the general earthly-soulful. I would like to say:

These elemental beings were during the winter time within the soulfulness of the earth, where they had individualized themselves (see drawing: green in yellow). Before this Easter time they are still afflicted with a certain individuality, flying, floating around, so to speak, as individual entities. During the Easter period we see how they converge in general clouds and form a common mass within the earth soul (green in yellow). As a result, however, these elemental beings lose their consciousness to a certain extent. They enter a kind of sleep-like state. Certain animals hibernate in winter; these elemental beings hibernate in summer. This is strongest during St. John's Day, when they are completely asleep. But then they begin to individualize again, and you can already see them as special beings in the inhalation procession of the earth clearly at Michaelmas time, at the end of September.

But these elemental beings are the ones that man now needs. All this is not in his consciousness, but man still needs them in order to unite them with himself so that he can prepare his future. And man can unite these elemental beings with himself if at a festive time, which would fall at the end of September, he would feel with a special inner soulful vitality how nature changes just towards the

If man could feel how animal and plant life declines, how certain animals prepare to seek out their protective places for the winter, how the plant leaves take on their autumn colors, how the whole natural world withers. Certainly, spring is beautiful, and to feel the beauty of spring, the growing, sprouting and budding life of spring, is a beautiful quality of the human soul. But also to be able to feel when the leaves turn pale, when they take on their autumn colors, when the animals crawl away, to be able to feel how the glittering, shining spiritual-soul arises in the dying sensual, to be able to feel how with the yellowing of the leaves there is a decline of the sprouting life, But how the sensual becomes yellow so that the spiritual can live as such in the yellowing, to be able to feel how the rising of the spirit takes place in the falling of the leaves, how the spiritual is the counter-revelation of the fading sensual: this should animate man in the autumn season as a sensation for the spirit. Then he prepares himself in the right way for the Christmas season.

Man should be imbued with the truth from anthroposophical spiritual science that the spiritual life of man on earth is connected with the descending physical life. When we think, our physical matter perishes in the nerve. Thought emerges from the perishing matter. The becoming of thought in itself, the shining forth of ideas in the human soul and in the whole human organism, the feeling of being related to the yellowing leaves, to the withering foliage of the plants, to the withering of the plants, this feeling of the human spiritual being being related to the natural spiritual being: this can give man that impulse which strengthens his will, that impulse which points man towards the permeation of the will with spirituality.

But through the fact that man permeates his will with spirituality he becomes a comrade of Michael's activity on earth. And when man lives together with nature in this way towards autumn and expresses this living together with nature in a corresponding festive content, then he can really feel that addition to the Easter mood. But this makes him realize something else. You see, what people think, feel and want today is inspired by the one-sided Easter mood, which is also a paralyzed one. This Easter mood is essentially a result of the sprouting, budding life that allows everything to merge into a pantheistic unity. Man is devoted to the unity of nature and to the unity of the world in general. This is also the structure of our spiritual life today. One wants to trace everything back to a unity, to a monon. Either one is a follower of the All-Spirit or the All-Nature: then he is either a spiritualist monist or a materialist monist. Everything is subsumed in an indeterminate All-One. This is essentially a spring mood.

If one looks into the autumnal mood with the ascending spiritual becoming free (yellow), with the, I would like to say, dripping off, wilting sensual (red), then one has the view of the spiritual as such, of the sensual as such.

The spring sprouting plant has the spiritual within it in its growth, in its sprouting and growth. The spiritual is intermingled with the sensual; there is essentially a unity. The withering plant lets the leaf fall and the spirit rises: one has the spirit, the invisible, supersensible spirit, and the material falls out. It is as if you first had a uniform liquid in a vessel, in which something is dissolved, and then through some process you would cause something to settle out of this liquid, which falls down as 'turbidity. So the two that were joined together, that formed one, have now been separated.

Spring is capable of interweaving everything, of blending everything into an undifferentiated, indeterminate unity. The autumnal view, if one only looks at it correctly, if one contrasts it in the right way with the spring view, it makes one aware of how the spirit works on the one side and the physical-material on the other. And, of course, one must not remain one-sidedly with the one or the other. The Easter idea does not lose its value if you add the Michael idea. On the one hand you have the Easter idea, where everything, I would say, appears in a kind of pantheistic mixture, in a unity. We then have the differentiated, but the differentiation does not happen in some irregular, chaotic way. We definitely have a regularity. Think of the cyclical progression: Interlocking, intermixing, unification, an intermediate state where differentiation occurs, complete differentiation; then again the merging of the differentiated into the unified, and so on. In addition to these two states, you always see a third: you see the rhythm between the differentiated and the undifferentiated, between the inhalation of the differentiated and the exhalation again, so to speak. You see a rhythm, an intermediate state, a physical-material, a spiritual; an interaction of the physical-material and the spiritual: a soul. In the course of nature you will learn to see nature interspersed with primordial freedom: material, spiritual and mental.

But that is the important thing, that one does not stop at the general human reverie that everything must be reduced to a unity. In this way everything, whether the unity is spiritual or material, is reduced to the indeterminacy of the night of the world. In the night all cows are gray, in spiritual monism all ideas are gray, in material monism they are just as gray. These are only differences in perception. That is not important for a higher view. What matters is that we as human beings can connect ourselves with the course of the world in such a way that we are able to follow the living transition from unity to trinity, the return from trinity to unity. Then, if by supplementing the Easter thought in this way with the Michaelmas thought, we put ourselves in a position to feel the primordial freedom in all being in the right way, then we will absorb it into our whole soul constitution. Then we will be able to realize that all life is indeed based on the activity and interaction of primal freedoms. And then, when we have the Michaelmas festival as inspiring for such a view as the one-sided Easter festival was inspiring for the views that have now come up, then we will have an inspiration, a nature-spirit impulse, to introduce the threefoldness, the threefoldness impulse, into all life that is to be observed and shaped. And ultimately it depends solely on the introduction of this impulse whether the forces of decline in human development can in turn be transformed into forces of ascent.

We would like to say that when we spoke of the impulse of disintegration in social life, it was to a certain extent a test of whether the Michael thought is already so strong that it can be felt how such an impulse springs directly from the forces that shape the times. It was a test of the human soul as to whether the Michael-thought is strong enough in a number of people. Well, the test produced a negative result. The Michael-thought is not yet strong enough in even a small number of people to really be felt in all its time-shaping power and strength. And it will hardly be possible to connect the human souls for new emergence forces with the primordial world forces in the way that is necessary if such an inspiring thing as a Michael-festivity cannot penetrate, that is, if a new formative impulse cannot come from the depths of esoteric life.

If, instead of the passive members of the Anthroposophical Society, there were only a few active members, such a thought could be considered. The essence of the Anthroposophical Society consists in the fact that suggestions are lived out within the Anthroposophical Society, but that the members actually place the main value on participating in what is happening; that they turn their contemplative soul forces towards what is happening, but that the activity of their own souls is not connected with that which goes through time as an impulse. Therefore, of course, in the present state of the anthroposophical movement it cannot be said that something like this, which is now, so to speak, expressed as an esoteric impulse, can be considered in its activity. But one must understand how the course of human development actually proceeds, how the great supporting forces of humanity's world development do not come from what is expressed outwardly in superficial words, but how they come, I would like to say, from quite different corners.

Old times have always known this from original, elementary, human clairvoyance. Ancient times did not teach young people, for example, that there are so and so many chemical elements, then one is discovered among the seventy-five, then there are seventy-six, then another one is discovered, then there are seventy-seven. You can't predict how many more will be discovered. By chance, one adds up to seventy-five, seventy-six and so on. There is no inner essence in what is cited as a number. And it's like that everywhere. Who is interested today in what, let us say in plant systematics, would somehow reveal a kind of trinity! One discovers order next to order or species next to species. One counts off in the same way as one counts off randomly thrown beans or stones. But the work of number in the world is one that is based on essentiality, and this essentiality must be seen through.

Think back how short a time lies behind us when that which was knowledge of matter was traced back to the trinity: to the salty, the Mercurial, the phosphoric, how there was seen a trinity of primal forces, how everything that was found as an individual had to be inserted into one of the primal forces of the three. And it is even different when we look back to even older times, when it was also easier for people to come up with such things due to the location of the culture, because the oriental cultures were more inclined towards the hot zone, where it was easier for the older elementary clairvoyance. Today, however, it is possible for the temperate zone to come to these things in free, exact clairvoyance; but we want to go back to old cultures! Back then, no distinction was made between spring, summer, fall and winter. Distinguishing between spring, summer, fall and winter is tempting because the four of them are simply strung together. To think of the course of the year as being dominated by the four would have been quite impossible in ancient Indian culture, for example, because there is nothing of the primal forms of all activity in it.

When I wrote my book “Theosophy”, I could not simply string together: physical body, etheric body, astral body and I, as one can summarize it when the matter is already there, when one sees through the matter inwardly. I had to arrange them according to the trinity: physical body, etheric body, sensory body; first trinity. Then the trinity interwoven with it: sensory soul, intellectual soul, consciousness soul; then the trinity interwoven with it: spirit self, life spirit, spirit man, three times three, interwoven (see diagram), thus it becomes seven. But the seven is interwoven three times three. And only when you look at the current stage of human development does the four emerge, which is actually basically a secondary number.

If you want to look at what is inwardly effective, at what is being formed, you have to look at the formation in the sense of the trinity. Therefore, the old Indian view had: the hot season would roughly encompass our months of April, May, June, July; the humid season would roughly encompass our months of August, September, October, November; and the cold season would encompass our months of December, January, February, March, whereby the boundaries need not be so fixed according to months, but are only approximate. This can be thought of as shifted. But the course of the year was conceived as a trinity. And in this way the human constitution of the soul would permeate itself with the disposition to observe this primordial freedom in everything that weaves and works, and thereby also to interweave this primordial freedom into all human creation, all human forms. One can say that it is only possible to have pure ideas about free spiritual life, legal life and socio-economic life if one has a deep understanding of this threefold action of the world, which must also pass through human activity.

Today, everything that refers to such things is regarded as a kind of superstition, whereas it is considered high wisdom to simply count: one and again one, two, three and so on. But that is not how nature works. But if one limits one's view merely to looking at that in which everything is interwoven, for example at the springtime alone, which of course one must look at in order to see how everything is interwoven, then one cannot reproduce the three-stroke. But if one follows the whole course of the year, if one sees how the three is structured, how the spiritual and the physical-material life are present as a duality and the rhythmic interweaving of both as the third, then one perceives this three in one, one in three, and learns to recognize how man can place himself in this working of the world: three to one, one to three.