The Cycle of the Year

GA 223

7 April 1923, Dornach

Lecture IV

I have frequently referred recently to the connection the course of the year has with various aspects of human life, and during the Easter days I pointed especially to the connection with the celebration of festivals. Today I should like to go back to very ancient times and say more on this subject, just in relation to the ancient Mysteries. This can perhaps deepen in one way or another what we have spoken of before.

To the people of very ancient periods on Earth, the festivals that took place during the year formed a very significant part of their lives. We know that in those ancient times the human consciousness worked in an entirely different way from that of later times. We might ascribe a somewhat dreamy nature to this old form of consciousness. And indeed it was out of this dream condition that those insights arose in the human soul, in the human consciousness, which then took on the form of myths and in fact became mythology.

Through this dreamy, or we can also say instinctively clairvoyant consciousness people saw more deeply into the spiritual environment. But precisely through this more intensive kind of participation, not just in the sensible workings of Nature, as is the case today, but also in the spiritual events, people were all the more involved with the phenomena connected with the cycle of the year, with the differing aspects of Nature in spring and in autumn. I have pointed to this just in recent days.

Today I want to share something entirely different with you in this regard, and that is, how the festival of Midsummer, which has become our St. John's festival, and the Midwinter festival, which has become our Christmas, were celebrated in connection with the old Mystery teachings. To begin with, we must be quite clear that the humanity of the ancient times of which we are speaking did not have a full ego-consciousness, as we do today. In the dreamlike consciousness, a full ego-consciousness was lacking; and when this is the case, people do not perceive precisely that which present-day humanity is so proud of. Thus the people of that period did not perceive what existed in dead nature, in the mineral nature.

Let us keep this firmly in mind, my dear friends: It was not a consciousness that flowed along in abstract thoughts, but it lived in pictures; yet it was dreamlike. These people entered into, for example, the sprouting, burgeoning plant-life and plant-nature in spring far more than is the case today. Again, they felt the shedding of the leaves, their drying up in autumn, the whole dying away of the plant world; felt deeply also the changes the animal world lived through during the course of the year; felt the whole human environment to be different when the air was filled with butterflies fluttering and beetles humming. They felt their own human weaving in a certain way as being alongside the weaving and being of the plants and animal existence. But they not only had no interest, they had no proper consciousness for the mineral realm, for the dead world outside them. This is one side of the earlier human consciousness.

The other side is this: that no interest existed among this ancient humanity for the form of man in general. It is very difficult today to imagine what the human perception was in this regard, that people in general took no particular interest in the human figure as a space-form. They had, however, an intense interest in what pertains to race. And the farther back we go into ancient cultures, the less do we find people with the common consciousness interested in the human form. On the other hand, they were interested in the color of the skin, in the racial temperament. This is what people noticed. On the one side man was not interested in the dead mineral world, nor, on the other, in the human form. There was an interest, as we have said, in what pertains to race, rather than in the universally human, including the outer form of man.

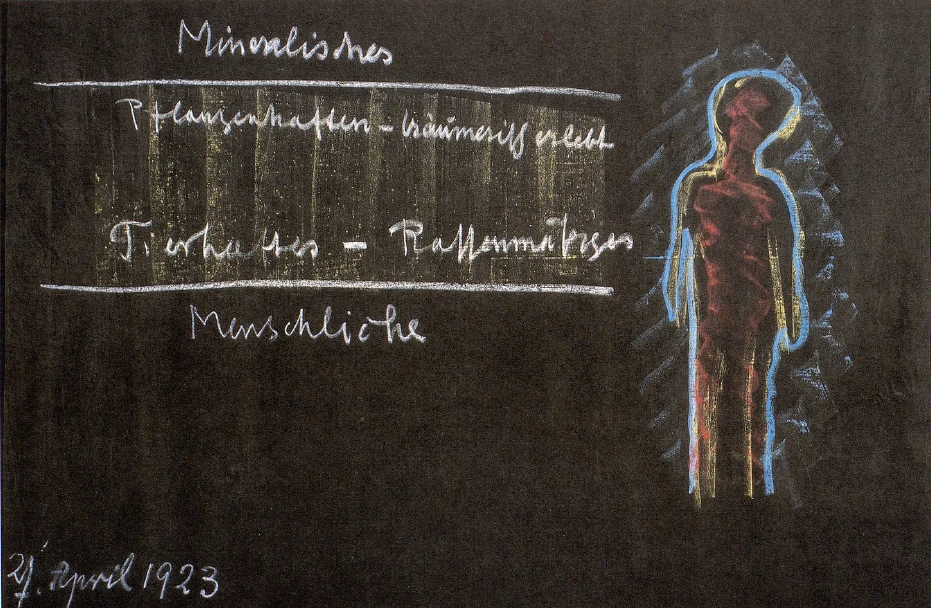

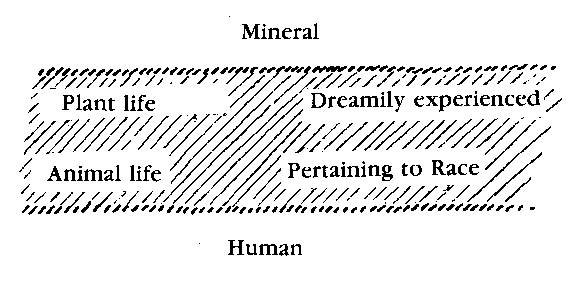

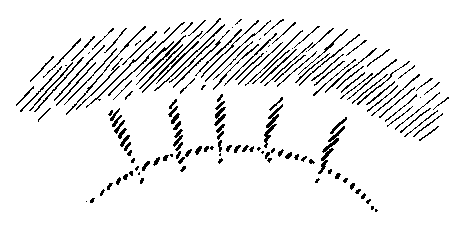

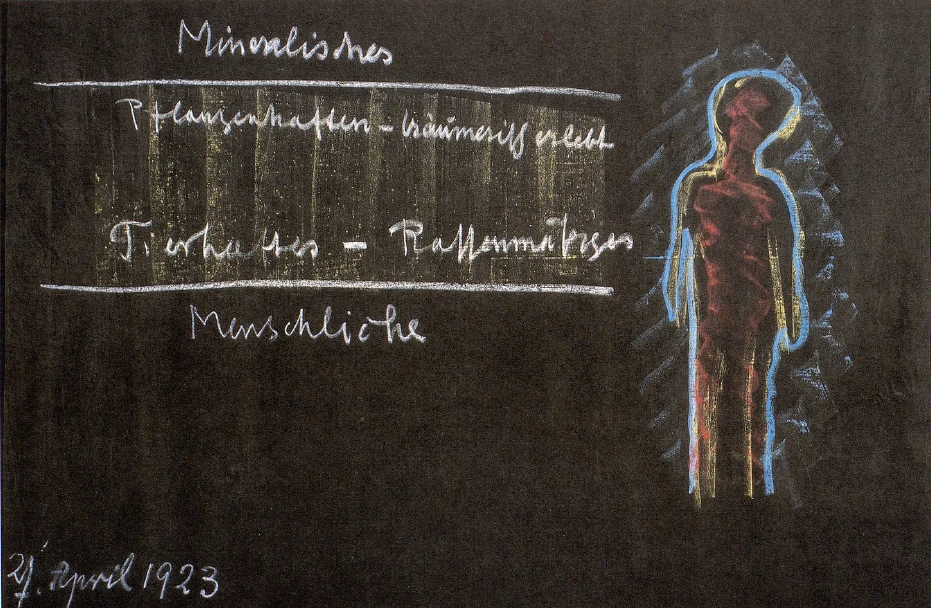

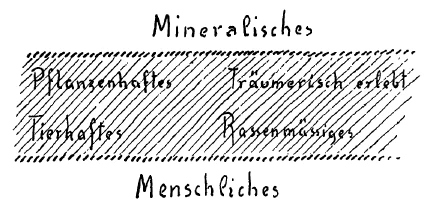

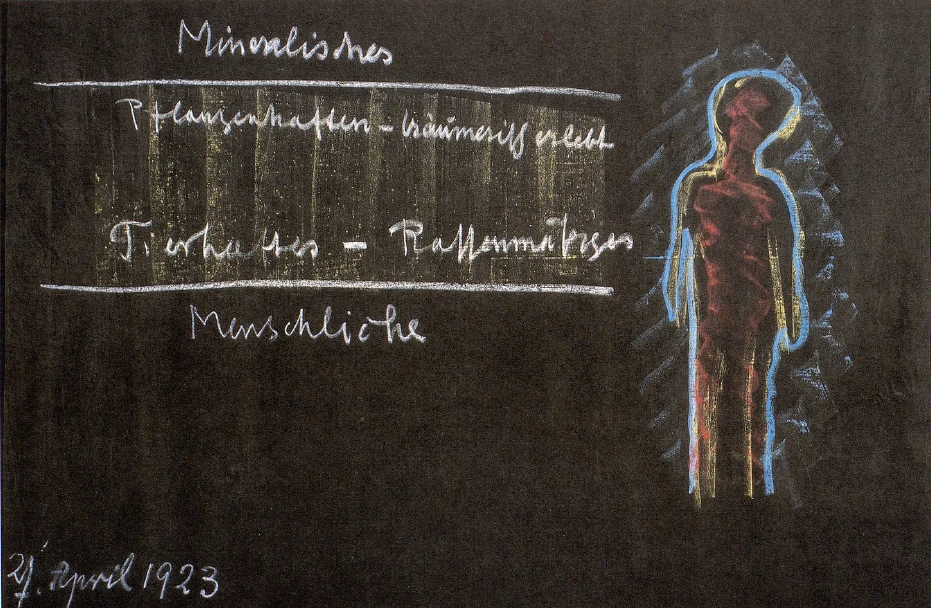

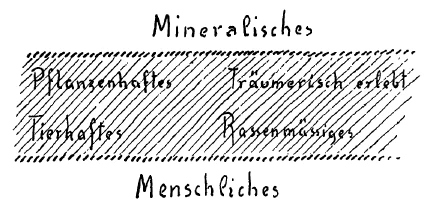

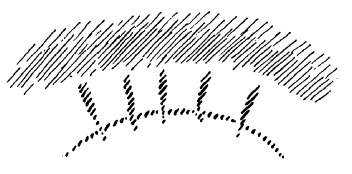

The great teachers of the Mysteries simply accepted this as a fact. How they thought about it, I will show you graphically in a drawing. They said to themselves: “The people have a dreamlike consciousness by means of which they perceive very clearly the plant life in their environment.”—In their dream-pictures these people indeed lived with the plant life; but their dream consciousness did not extend to the comprehension of the mineral world. So the Mystery teachers said to themselves: “The human consciousness reaches on the one side to the plant life [see drawing], which is dreamily experienced, but not to the mineral; this lies outside human consciousness. And on the other side, men feel within them what still binds them with the animal world, that is, what pertains to race, what is typical of the animal. [See drawing]. On the other hand, what makes man really man, his upright form, the space form of his being, lies outside of human consciousness.”

Thus, the specifically human lay outside the interest of these people of ancient times. We can characterize the human by thinking of it, in the sense of this ancient humanity, as enclosed within this space [shaded portion in drawing], while the mineral and the specifically human lay outside the realm of knowledge generally accessible to those people who carried on their lives outside the Mysteries.

But what I have just said applies only in general. With his own forces, with what man experienced in his own being, he could not penetrate beyond this space [see drawing], to the mineral on the one side, to the human on the other. But there were ceremonies originating in the Mysteries which brought to man in the course of the year something approximating the human ego-consciousness on the one side and the perception of the general mineral kingdom on the other.

Strange as it may sound to people of the present time, it is nevertheless true that the priests of the ancient Mysteries arranged festivals by whose unusual effects man was lifted out above the plant-like to the mineral, and thereby at a certain time of year experienced a lighting up of his ego. It was as if the ego shone into the dream-consciousness. You know that even in a person's dreams today, one's own ego, which is then seen, often constitutes an element of the dream.

And so at the time of the St. John's festival, through the ceremonies that were arranged for those among the people who wanted to take part in them, ego-consciousness shone in just at the height of summer. And at this time of midsummer people could perceive the mineral realm at least to the extent necessary to help them attain a kind of ego-consciousness, whereby the ego appeared as something that entered into dreams from outside. In order to bring this about, the participants in the oldest midsummer festivals—those of the summer solstice which have become our St. John's festival—the participants were led to unfold a musical-poetic element in round dances having a strong rhythmic quality and accompanied by song. Certain presentations and performances were filled with distinctive musical recitative accompanied by primitive instruments. Such a festival was completely immersed in the musical-poetic element. What man had in his dream-consciousness he poured out into the cosmos, as it were, in the form of music, in song and dance.

Modern man can have no true appreciation of what was accomplished by way of music and song during those intense and widespread folk festivals of ancient times, which took place under the guidance of men who in turn had received their guidance from the Mysteries. For what music and poetry have come to be since then is far removed from the simple, primitive, elemental form of music and poetry which was unfolded in those times at the height of summer under the guidance of the Mysteries. For everything the people did in performing their round-dances, accompanied by singing and primitive poetic recitations, had the single goal of bringing about a soul mood in which there occurred what I have just called the shining of the ego into the human spirit.

But if those ancient people had been asked how they came to form such songs and such dances, by means of which there could arise what I have described, they would have given an answer highly paradoxical to modern man. They would have said, for example: “Much of it has been given to us by tradition, for those who went before us have also done these things.” But in certain ancient times they would have said: “One can learn these things also today without having any tradition, if one simply develops further what manifests itself. One can still learn today how to make use of instruments, how to form dances, how to master the singing voice”—and now comes the paradox in what these ancient people would have said. They would have said: “It is learned from the songbirds.”—For they understood in a deep way the whole import of the songbirds' singing.

My dear friends, mankind has long ago forgotten why the songbirds sing. It is true that men have preserved the art of song, the art of poetry, but in the age of intellectualism in which the intellect has dominated everything, they have forgotten the connection of singing with the whole universe. Even someone who is musically inspired, who sets the art of music high above the commonplace, even such a man, speaking out of this later intellectualistic age, says: “I sing as the bird sings who dwells in the branches. The song that issues from my throat is my reward, and an ample reward it is.” Indeed, my dear friends, the man of a certain period says this. The bird, however, would never say such a thing. He would never say: “The song that issues from my throat is my reward.” And just as little would the pupils of the ancient Mystery schools have said it. For when at a certain time of year the larks and the nightingales sing, what is thereby formed streams out into the cosmos, not through the air, but through the etheric element; it vibrates outward in the cosmos up to a certain boundary... then it vibrates back again to Earth, to be received by the animal realm—only now the divine-spiritual essence of the cosmos has united with it.

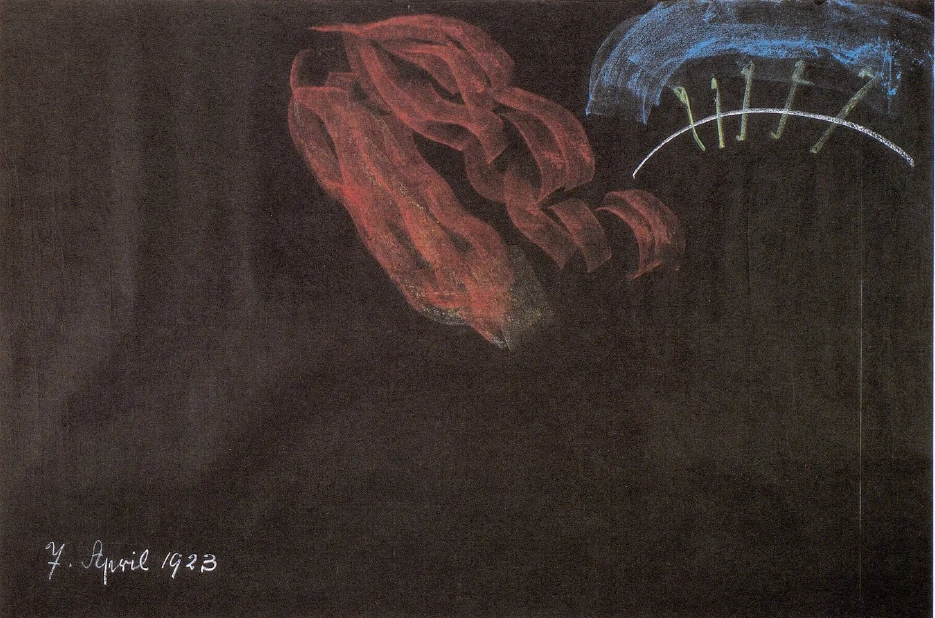

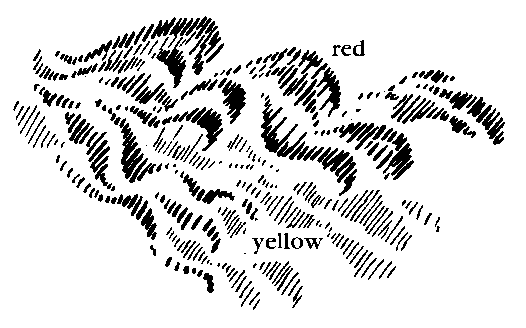

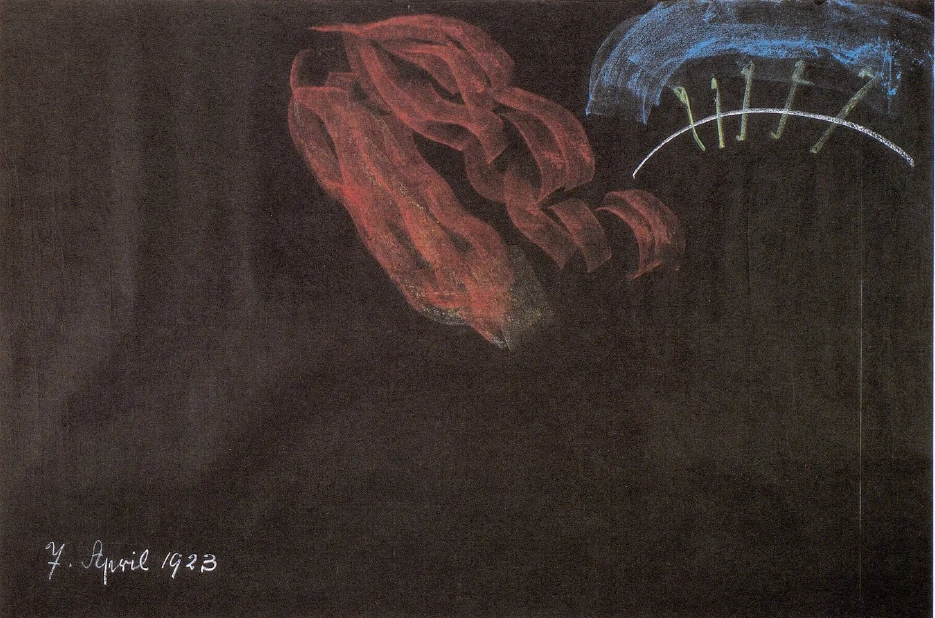

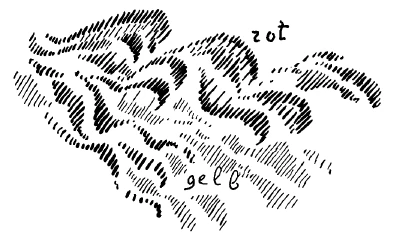

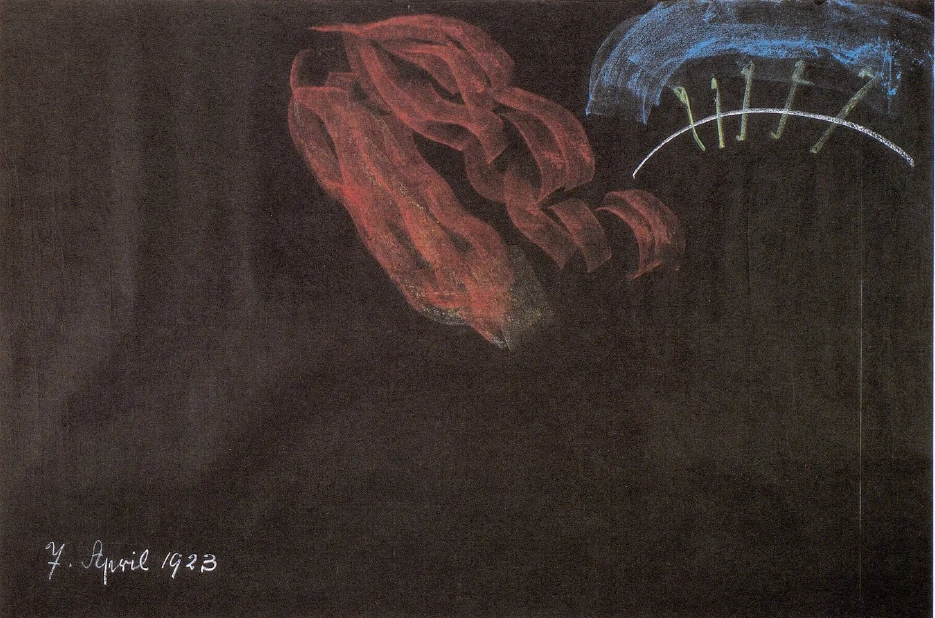

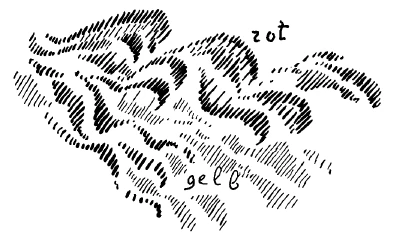

And thus it is that the nightingales and the larks send forth their voices into the universe (red) and that what they thus send forth comes back to them etherically (yellow), for the time during which they do not sing;

but in the meantime it has been filled with the content of the divine-spiritual. The larks send their voices out over the cosmos, and the divine spiritual, which takes part in the forming, in the whole configuration of the animal kingdom, streams back to the Earth on the waves of what had streamed out in the songs of the larks and the nightingales.

Therefore if anyone speaks, not from the standpoint of the intellectualistic age, but out of the truly all-encompassing human consciousness, he really cannot say: “I sing as the bird sings who dwells in the branches. The song that issues from my throat is my reward, and an ample reward it is.” Rather, he would have to say: “I sing as the bird sings who dwells in the branches. And the song which streams forth from his throat into the cosmic expanses returns to the Earth as a blessing, fructifying the earthly life with divine spiritual impulses which then work on in the bird world and which can only work in the bird world because they find their way in on the waves of what has been ‘sung out’ to them into the cosmos.”

Now of course not all creatures are nightingales and larks; also of course not all of them send out song; but something similar even though it is not so beautiful, goes out into the cosmos from the whole animal world. In those ancient times this was understood, and therefore the pupils of the Mystery-pupils were instructed in such singing and dancing as they could then perform at the St. John's festival, if I may call it by the modern name. Human beings sent this out into the cosmos, of course not now in animal form, but in humanized form, as a further development of what the animals send out into cosmic space.—And there is something else yet that belonged to those festivals: not only the dancing, the music, the song, but afterward, the listening. First, there was the active performance in the festivals; then the people were directed to listen to what came back to them. For through their dances, their singing, and all that was poetic in their performances, they had sent forth the great questions to the divine spiritual of the cosmos. Their performance streamed up, as it were, into cosmic spaces as the water of the earth rises, forming clouds above and dropping down again as rain. Thus, the effects of the human festival performances arose and came back again—of course not as rain, but as something which manifested itself to man as ego-power. And the people had a sensitive feeling for that particular transformation which took place in the air and warmth around the Earth, just about the time of the St. John's festival. Of course the man of the present intellectualistic age disregards anything like this. He has something else to do than people of olden times. In these times, as also in others, he has to go to five o'clock teas, to coffee parties; he has to attend the theater, and so on; he simply has something else to do which is not dependent on the time of year. In the doing of all this, man forgets that delicate transformation which takes place in the Earth's atmospheric environment.

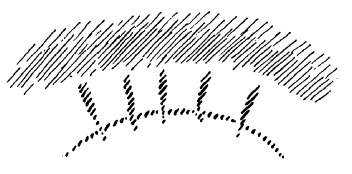

But these people of olden times did feel how different the air and warmth become around St. John's time, at the height of summer, how these take on something of the plant nature. Just consider what kind of a perception that was—this sensitive feeling for all that goes on in the plant world. Let us suppose that this is the Earth, and everywhere plants are coming out of the Earth.

The people then had a subtle feeling awareness of what is developing there in the plant, of what lives in the plant. They had in the spring a general feeling of nature, of which an after-echo is still retained in our language. You will find in Goethe's Faust the expression “es gruenelt” (It is beginning to get green). Who notices nowadays when it is growing green, when the greenness rising up out of the Earth in the spring, wells and wafts through the air? Who notices when it grows green and when it blossoms? Well, of course people see it today; the red and the yellow of the flowers please them; but they do not notice that the air becomes quite different when the flowers bloom, and again when the fruit is formed. Such living participation in the plant world no longer exists in our intellectualistic age, but it did exist for the people of ancient times.

Hence they were aware of it in their perceptive feeling when the “greening,” blooming and fruiting came toward them—not now out of the Earth, but out of the surrounding atmosphere; when air and warmth themselves streamed down from above like something akin to plant nature (shaded in drawing). And when air and warmth became thus plant-like, the consciousness of those people was transported into that sphere in which the “I” then descended, as answer to what they had sent out into the cosmos in the form of music and poetry.

Thus the festivals had a wonderful, intimate, human content. This was a question to the divine-spiritual universe. Men received the answer because—just as we perceive the fruiting, the blossoming, the greening of the Earth today—they felt something plant-like streaming down from above out of the otherwise merely mineral air. In this way there entered into the dream of existence, into the ancient dreamy consciousness also the dream of the ego.

And when the St. John's festival was past and July and August came again, the people had the feeling “We have an ego, but this ego remains up there in heaven and speaks to us only at St. John's time. Then we become aware that we are connected with heaven. It has taken our ego into its protection. It shows it to us when it opens the great window of heaven at St. John's time. But we must ask about it. We must ask as we carry out the festival performances at St. John's time, as in these performances we find our way into the unbelievably close and intimate musical and poetic ceremonies.”—Thus these ancient festivals already established a communication, a union, between the earthly and the heavenly.

You see this whole festival was immersed in the musical, in the musical-poetic. I might say that in the simple settlements of very ancient peoples, suddenly, for a few days at the height of summer, everything became poetic—although it had been thoroughly prepared beforehand by the Mysteries. The whole social life was plunged into this musical-poetic element. The people believed that they needed this for life during the course of the year, just as they needed daily food and drink; that they needed to enter into this mood of dancing, music and poetry, in order to establish their communication with the divine-spiritual powers of the cosmos. A relic of this festival remained in a later age, when a poet said, for example; “Sing, O Muse, of the wrath of Achilles, the son of Peleus,” because he still remembered that once upon a time the great question was put before the deity, and the deity was expected to give answer to the question of men.

Just as these festivals at St. John's time were carefully prepared in order to pose the great question to the cosmos so that the cosmos might assure man at this time that he has an ego, which the heavens have taken into their protection, so likewise was prepared the festival at the time of the winter solstice, in the depths of winter, which has now become our Christmas festival. But while at St. John's time everything was steeped in the musical-poetic, in the dance element, now in the depths of winter everything was first prepared in such a way that the people knew they must become still and quiet, that they must enter into a more contemplative element. And then there was brought forth—in these ancient times of which outer history provides no record, of which we can only know through spiritual science—all that during the summer had been in the forming and shaping and imaging elements which reached a climax in the festivals in music and dance. During that time these ancient people, who in a certain way went out of themselves in order to unite with the ego in the heavens, were not involved in learning anything. Besides the festival, they were occupied in doing what was necessary for their subsistence. Instruction waited for the winter months, and this reached its culmination, its festival expression, at the time of the winter solstice, in the depth of winter, at Christmas time.

Then began the preparation of the people, again under the guidance of pupils of the Mysteries, for various spiritual celebrations which were not performed during the summer. It is difficult to describe in modern terms what the people did from our September/October to our Christmas time, because everything was so very different from what is done now. But they were guided in what we would perhaps call riddle-solving, in answering questions that were put in a veiled form so that people had to discover a meaning in what was given in signs. Let us say that the Mystery-pupils gave to those who were learning in this way some kind of symbolic image, which they were to interpret. Or they gave what we would call a riddle to be solved, or some kind of incantation. What the magic saying contained, they were to apply to Nature, and thus divine its meaning.

But especially there was careful preparation for what later took on the most varied forms among the different peoples; for example, for what was known in northern countries at a later time as the throwing of the runic wands so that they formed shapes which were then deciphered. People devoted themselves to these activities in the depth of winter; but above all, those things were cultivated that then led to a certain art of modeling, in a primitive form of course.

Among these ancient forms of consciousness was a most singular one, paradoxical as it sounds to modern people, and it was as follows: With the coming of October, an urge for some sort of activity began to stir in people's limbs. In the summer a man had to accommodate the movements of his limbs to what the fields demanded of him; he had to put his hands to the plough; he had to adapt himself to the outer world. When the harvest had been gathered in, however, and his limbs were rested, then a need stirred in them for some other form of activity, and his limbs took on a longing to knead. Then people derived a special satisfaction from all kinds of plastic, moulding activity. We might say that just as an intensive urge had arisen at the time of the St. John's festival for dancing and music, so toward Christmas time an intensive urge arose to knead, to mould, to create, using any kind of pliant substance available in nature. People had an especially sensitive feeling, for example, for the way water begins to freeze. This gave them the specific impulse to push it in one direction and another, so that the ice-forms appearing in the water took on certain shapes. Indeed people went so far as to keep their hands in the water while the shapes developed and their hands grew numb! In this way, when the water froze under the waves their hands cast up, it assumed the most remarkable artistic shapes, which of course again melted away.

Nothing remains of all this in the age of intellectualism except at most the custom of lead-casting on New Year's Eve, the Feast of St. Sylvester. In this, molten lead is poured into water, and one discovers that it takes on shapes whose meaning is then supposed to be guessed. But that is the last abstract remnant of those wonderful activities that arose from the impelling force in Nature experienced inwardly by the human being, which expressed itself for example as I have related: that a person thrust his hand into water which was in process of freezing, the hand then becoming numb as he tested how the water formed waves, so that the freezing water then “answered” with the most remarkable shapes. In this way the human being found the answers to his questions of the Earth. Through music and poetry at the height of summer, he turned toward the heavens with his questions, and they answered by sending ego-feeling into his dreaming consciousness. In the depth of winter he turned for what he wanted to know not now toward the heavens, but to the earthly, and he tested what kind of forms the earthly element can take on. In doing this he observed that the forms which emerged had a certain similarity to those developed by beetles and butterflies. This was the result of his contemplation. From the plastic, formative element that he drew out of the nature processes of the Earth, there arose in him the intuitive observation that the various animal forms are fashioned entirely out of the earthly element. At Christmas man understood the animal forms. And as he worked, as he exerted his limbs, even jumped into the water and made certain movements, then sprang out and observed how the solidifying water responded, he noticed in the outer world what sort of form he himself had as man. But this was only at Christmas time, not otherwise; at other times he had a perception only of the animal world and of what pertains to race. At Christmas time he advanced to the experience of the human form as well.

Just as in those times of the ancient Mysteries the ego-consciousness was mediated from the heavens, so the feeling for the human form was conveyed out of the Earth. At Christmas time man learned to know the Earth's form-force, its sculptural shaping force; and at St. John's time, at the height of summer he learned to know how the harmonies of the spheres let his ego sound into his dream-consciousness.

And thus at special festival seasons the ancient Mysteries expanded the being of man. On the one side the environment of the Earth extended out into the heavens, so that man might know how the heavens held his “I” in their protection, how his “I” rested there. And at Christmas time the Mystery teachers caused the Earth to give answer to the questioning of man by way of plastic forms, so that man gradually came to have an interest in the human form, in the flowing together of all animal forms into the human form. At midsummer man learned to know himself inwardly, in relation to his ego; in the depth of winter he learned to feel himself outwardly, in relation to his human form. And so it was that what man perceived as his being, how he actually felt himself, was not acquired simply by being man, but by living together with the course of the year; that in order for him to come to ego-consciousness, the heavens opened their windows; that in order for him to come to consciousness of his human form, the Earth in a certain way unfolded her mysteries. Thus the human being was inwardly intimately linked with the course of the year, so intimately linked that he had to say to himself: “I know about what I am as man only when I don't live along stolidly, but when I allow myself to be lifted up to the heavens in summer, when I let myself sink down in winter into the Earth mysteries, into the secrets of the Earth.”

You see from this that at one time the festival seasons with their celebrations were looked upon as an integral part of human life. A man felt that he was not only an earth-being but that his essential being belonged to the whole world, that he was a citizen of the entire cosmos. Indeed he felt himself so little to be an earth-being that he actually had first to be made aware of what he was through the Earth by means of festivals. And these festivals could be celebrated only at certain seasons because at other times the people who experienced the course of the year to some degree would have been quite unable to experience it at all. For all that the people could experience through the festivals was connected with the related seasons.

Mark you, after man has once achieved his freedom in the age of intellectualism, he can certainly not come again to this sharing in the life of the cosmos in the same way that he experienced it in primitive ages. But he can nevertheless come to it even with his modern constitution, if he applies himself once more to the spiritual.

We might say that in the ego consciousness which mankind has had for a long time now, something has been drawn in which could be attained only through the windows of heaven in summer. But just for that reason man must be learning to understand the cosmos, acquire for himself something else which in turn lies beyond the ego. It is natural today for people to speak of the human form in general. Those who have entered into the intellectual age no longer have a strong feeling for the animalistic-racial element. But just as this feeling formerly came over man, I should like to say as a force, as an impulse, which could be sought only out of the Earth, so today, through an understanding of the Earth which cannot be gained by means of geology or mineralogy but only once more in a spiritual way, man must come again to something more than the mere human form.

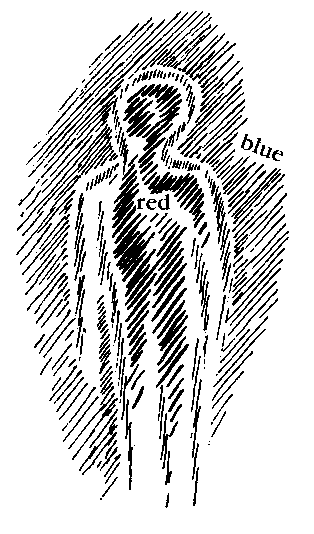

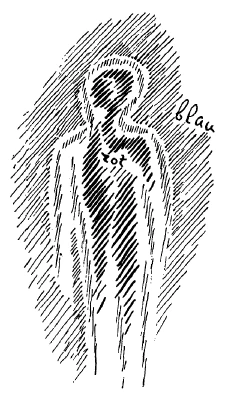

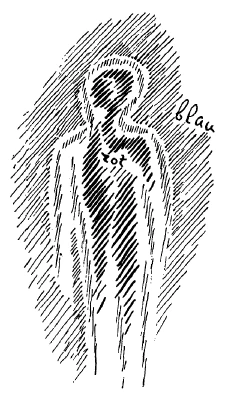

If we consider the human form we can say: In very ancient times man felt himself within this form in such a way that he felt only the external racial characteristics connected with the blood, but failed to perceive as far as the skin itself (red in drawing); he did not notice what formed his outline.

Today man has come so far that he does notice his outline, his bodily limits. He perceives his contour indeed as the typically human feature of his form (blue). Now, however, man must come out beyond himself; he must learn to know the etheric and astral elements outside himself. This he can do only through the deepening of spiritual science.

Thus we see that our present-day consciousness has been acquired at the cost of losing much of the former connection of our consciousness with the cosmos. But once man has come to experience his freedom and his world of thought, then he must emerge again and experience cosmically.

This is what Anthroposophy intends when it speaks of a renewal of the festivals, even of the creating of festivals like the Michael festival in autumn of which we have recently spoken. We must come once more to an inner understanding of what the cycle of the year can mean to man in this connection; it can then be something even loftier than it was for man long ago, as we have described it.

Vierter Vortrag

In der letzten Zeit habe ich oftmals hinweisen müssen auf den Zusammenhang des Jahreslaufes mit irgendwelchen menschlichen Verhältnissen, und ich habe ja während der Ostertage hingewiesen auf den Zusammenhang des Jahreslaufes mit der Begehung menschlicher Feste. Ich möchte heute in sehr alte Zeiten zurückgehen, um gerade im Zusammenhange mit dem Mysterienwesen der Menschheit in alten Zeiten etwas über diesen Zusammenhang des Jahreslaufes mit menschlichen Festen noch zu sagen, das vielleicht dasjenige, was wir schon besprochen haben, nach der einen oder andern Seite noch vertiefen kann.

Die Festlichkeiten während des Jahres bedeuteten den Menschen sehr alter Erdenzeiten eigentlich ein Stück von ihrem ganzen Leben. Wir wissen, daß in diesen alten Zeiten das menschliche Bewußtsein in ganz anderer Weise wirkte als später. Man möchte diesem alten Bewußtsein etwas Träumetisches zuschreiben. Und aus diesem Träumerischen sind ja diejenigen Erkenntnisse des menschlichen Bewußtseins, der menschlichen Seele hervorgegangen, die dann die Mythenform angenommen haben, die auch zur Mythologie selber wurden. Durch dieses mehr träumerische, man kann auch sagen, instinktiv-hellseherische Bewußtsein schauten die Menschen tiefer hinein in dasjenige, was geistig in der Umgebung des Menschen ist. Aber gerade dadurch, daß die Menschen auf diese Art intensiv teilnahmen nicht nur an dem Sinnenwirken der Natur, wie das heute der Fall ist, sondern an den geistigen Geschehnissen, gerade dadurch waren die Menschen auch mehr hingegeben an die Erscheinungen des Jahreslaufes, an die Verschiedenheit des Wirkens in der Natur im Frühling und im Herbste. Ich habe auch darauf gerade in der letzten Zeit hingewiesen.

Heute aber will ich Ihnen einiges andere darüber mitteilen: wie namentlich das Hochsommerfest, das dann zu unserem Johannifeste geworden ist, und das Tiefwinterfest, das zu unserem Weihnachtsfest geworden ist, im Zusammenhange mit den alten Mysterienlehren begangen wurden. Da müssen wir allerdings uns klarmachen, daß jene Menschheit, von der wir für ältere Erdenzeiten sprechen, nicht in derselben Weise zu einem vollen Ich-Bewußtsein kam, wie wir das heute tun. Im traumhaften Bewußtsein liegt nicht ein volles Ich-Bewußtsein; und wenn kein volles Ich-Bewußtsein da ist, nehmen die Menschen auch nicht dasjenige wahr, worauf gerade die Menschheit der heutigen Zeit so stolz ist. Die Menschen jener Zeit nahmen nicht wahr, was in der toten Natur, in der mineralischen Natur lebte.

Halten wir das durchaus fest: Das Bewußtsein war ein solches, das nicht in abstrakten Gedanken verlief, das in Bildern lebte, aber es war traumhaft. Dadurch lebten sich die Menschen viel mehr ein, als das jetzt der Fall ist, sagen wir im Frühling in das sprießende, sprossende Pflanzenleben und Pflanzenwesen. Wiederum fühlten sie, könnte man sagen, das Entblättern im Herbste, das Welkwerden der Blätter, das ganze Hinsterben der pflanzlichen Welt, fühlten auch tief mit die Veränderungen, welche die Tierwelt im Laufe des Jahres durchmachte, fühlten die ganze menschliche Umgebung anders, wenn die Luft von Schmetterlingen durchflattert, von Käfern durchsurrt wurde. Sie fühlten gewissermaßen ihr eigenes menschliches Weben zusammen mit dem Weben und Wesen des pflanzlich-tierischen Daseins. Aber sie hatten nicht nur kein Interesse, sondern auch kein rechtes Bewußtsein von dem Mineralischen, von dem Toten draußen. Das ist die eine Seite dieses alten menschlichen Bewußtseins.

Die andere Seite ist diese, daß auch kein Interesse vorhanden war bei dieser alten Menschheit für die Gestalt des Menschen im allgemeinen. Es ist das heute sogar recht schwierig vorzustellen, wie nach dieser Richtung hin das menschliche Empfinden war; allein ein starkes Interesse für die menschliche Gestalt in ihrer Raumesform hatten die Menschen im allgemeinen nicht. Sie hatten aber ein intensives Interesse für das Rassenhafte des Menschen. Und je weiter wir in alten Kulturen zurückgehen, desto weniger interessiert eigentlich den Menschen so für das allgemeine Bewußtsein die menschliche Gestalt; dagegen interessiert die Menschen, wie die Farbe der Haut ist, wie das Rassentemperament ist. Auf das schauen diese Menschen hin. Auf der einen Seite also interessiert diese Menschen das Tote, Mineralische Tafel 6

nicht, und auf der andern Seite interessiert sie nicht die menschliche Gestalt. Es war ein Interesse vorhanden, wie gesagt, für das Rassige, nicht aber für das allgemein Menschliche, auch nicht in bezug auf die äußere Gestalt.

Das nahmen eben als eine Tatsache die großen Lehrer der Mysterien hin. Wie sie darüber dachten, das will ich Ihnen dutch eine graphische Zeichnung darlegen. Sie sagten: Die Menschen haben ein traumhaftes Bewußtsein; dadurch gelangen sie dazu, das Pflanzenleben in der Umgebung scharf aufzufassen. — Durch ihre Traumesbilder lebten ja diese Menschen das Pflanzenleben mit, aber es reichte dieses Traumbewußtsein nicht bis zu der Auffassung des Mineralischen. So daß die Mysterienlehrer sich sagten: Nach der einen Seite geht das menschliche Bewußtsein zum Pflanzenhaften (siehe Schema), das träumerisch erlebt wird, aber nicht bis zum Mineralischen; das liegt außerhalb des menschlichen Bewußtseins. Und nach der andern Seite fühlt der Mensch in sich das, was ihn noch mit der Tierheit verbindet, das Rassenmäßige, das Tierhafte (siehe Schema). Dagegen liegt außerhalb des menschlichen Bewußtseins das, was den Menschen durch seine aufrechte Gestalt, durch die Raumesform seines Wesens eigentlich zum Menschen macht.

Also das eigentlich Menschliche liegt außerhalb dessen, was diese Menschen in alten Zeiten interessierte. Wir können also das menschliche Bewußtsein dadurch bezeichnen, daß wir es im Sinne dieser alten Menschheit innerhalb dieses Raumes eingeschlossen denken (siehe Schema, schraffiert), während das Mineralische und das eigentlich Menschliche außer dem Bereich dessen lagen, wovon im Grunde genommen diese alte Menschheit, die außerhalb der Mysterien ihr Dasein verbrachte, etwas wußte.

Aber was ich jetzt ausgesprochen habe, galt nur so im allgemeinen. Durch seine eigenen Kräfte, durch das, was der Mensch in seinem Wesen erlebte, konnte er nicht bis jenseits dieses Raumes zum Mineralischen auf der einen Seite, zum Menschlichen auf der andern Seite dringen. Aber es gab von den Mysterien ausgehende Einrichtungen, welche im Laufe des Jahres den Menschen, wenigstens annähernd, so etwas brachten wie das menschliche Ich-Bewußtsein einerseits und Anschauung des allgemein Mineralischen auf der andern Seite. So sonderbar es dem Menschen der heutigen Zeit klingt, so ist es doch so, daß die alten Mysterienpriester Feste eingerichtet haben, durch deren besondere Verrichtungen die Menschen sich über das Pflanzenhafte hinaus zum Mineralischen erhoben und dadurch in alten Zeiten in einer gewissen Jahreszeit ein Aufleuchten des Ich hatten. Wie wenn in das Traumbewußtsein das Ich hereinleuchtete, so war es. Sie wissen, daß auch in den Träumen der Menschen von heute das eigene Ich, das die Menschen dann schauen, manchmal noch einen Bestandteil des Traumes bildet.

Und so leuchtete zum Johannifest durch die Verrichtungen, die für einen Teil der Menschheit, die eben daran teilnehmen wollte, veranstaltet wurden, so leuchtete herein das Ich-Bewußtsein eben zu dieser Hochsommerzeit. Und zu dieser Hochsommerzeit konnten die Menschen wenigstens so weit das Mineralische wahrnehmen, daß sie mit Hilfe dieses Mineralwahrnehmens eine Art Ich-Bewußtsein bekamen, wobei ihnen allerdings das Ich als etwas erschien, das von außen her in die Träume hereinkam. Und um das zu bewirken, wurden in den ältesten Hochsommerfesten, in den Festen zur Sommersonnenwendezeit, die dann unsere Johannifeste geworden sind, die Teilnehmer angeleitet, ein musikalisch-poetisches Element zu entfalten voll von Gesang begleiteter, streng rhythmisch angeordneter Reigentänze. Erfüllt von eigentümlichen musikalischen Rezitativen, die von primitiven Instrumenten begleitet wurden, waren gewisse Darstellungen und Aufführungen. Solch ein Fest war durchaus in Musikalisch-Poetisches getaucht. Der Mensch strömte das, was er in seinem Traumbewußtsein hatte, in musikalisch-sanglicher, in tanzartiger Weise wie in den Kosmos hinaus.

Was dazumal unter der Anleitung derjenigen Menschen, die selber wieder ihre Anleitung von den Mysterien hatten, für solche mächtige, weit ausgebreitete Volksfeste der alten Zeiten an Musikalischem, an Gesanglichem geleistet worden ist, dafür kann der moderne Mensch nicht ein unmittelbares Verständnis haben. Denn was dann später Musikalisches, Poetisches geworden ist, das steht weit ab von jenem primitiven, elementaren, einfach Musikalisch-Poetischen, das zur Hochsommerzeit unter der Anleitung der Mysterien in jenen alten Zeiten entfaltet wurde. Alles zielte darauf hin, daß, während die Menschen ihre von Gesang und primitiven poetischen Aufführungen begleiteten Reigentänze machten, sie in eine Stimmung kamen, durch die eben dasjenige geschah, was ich jetzt genannt habe das Hereinleuchten des Ich in die menschliche Sphäre.

Aber wenn man diese alten Menschen, die die Anleitungen hatten, gefragt hätte: Ja, wie kommt man denn eigentlich darauf, solche Gesänge, solche Tänze zu bilden, durch welche das, was ich geschildert habe, entstehen kann? - dann hätten diese alten Menschen wiederum eine für den modernen Menschen höchst paradoxe Antwort gegeben. Sie hätten zum Beispiel gesagt: Ja, vieles ist überliefert, vieles ist schon da, das haben noch ältere gemacht! - Aber in gewissen alten Zeiten hätten die Menschen so gesagt: Man kann es auch heute noch lernen, ohne daß man etwas auf eine Tradition gibt, wenn man nur das, was sich offenbart, weiter ausbildet. Man kann auch heute noch lernen, wie man sich der primitiven Instrumente bedient, wie man die Tänze formt, wie man die Gesangsstimme meistert. - Und nun kommt eben das Paradoxe, was diese alten Leute gesagt hätten. Sie würden gesagt haben: Das lernt man von den Singvögeln. - Aber sie haben eben in einer tiefen Weise verstanden den ganzen Sinn dessen, warum eigentlich die Singvögel singen.

Das ist ja längst vergessen worden von der Menschheit, warum die Singvögel singen. In der Zeit, in der der Verstand alles beherrscht, in der die Menschen intellektualistisch wurden, gewiß, die Menschen haben sich ja auch da Gesangskunst, poetische Kunst bewahrt, aber den Zusammenhang des Singens mit dem ganzen Weltenall haben sie in der Zeit des Intellektualismus vergessen. Und selbst jemand, der begeistert ist für die musische Kunst, der die musische Kunst hinausstellt über alles Banausisch-Menschliche, der sagt aus diesem späteren intellektualistischen Zeitalter heraus:

Ich singe, wie der Vogel singt,

Der in den Zweigen wohnet.

Das Lied, das aus der Kehle dringt,

Ist Lohn, der reichlich lohnet.

Ja, das sagt der Mensch eines gewissen Zeitalters. Der Vogel selber würde es nämlich niemals sagen. Der Vogel würde niemals sagen: «Das Lied, das aus der Kehle dringt, ist Lohn, der reichlich lohnet.» Und ebensowenig hätten es die alten Mysterienschüler gesagt. Denn wenn in einer bestimmten Jahreszeit die Lerchen, die Nachtigallen singen, dann dringt das, was da gestaltet wird, nicht durch die Luft, aber durch das ätherische Element in den Kosmos hinaus, vibriert im Kosmos hinaus bis zu einer gewissen Grenze; dann vibriert es zurück auf die Erde, und dann empfängt die Tierwelt dieses, was da zurückvibriert, nur hat sich dann mit ihm das Wesen des Göttlich-Geistigen des Kosmos verbunden. Und so ist es, daß die Nachtigallen, die Lerchen ihre Stimmen hinausrichten in das Weltenall (rot) und daß dasjenige, was sie hinaussenden, ihnen ätherisch wieder zurückkommt (gelb) für den Zustand, wo sie nicht singen, aber das ist dann durchwellt von dem Inhalte des Göttlich-Geistigen. Die Lerchen senden ihre Stimmen hinaus in die Welt, und das Göttlich-Geistige, das an der Formung, an der ganzen Gestaltung des Tierischen teilnimmt, das strömt auf die Erde wiederum herein auf den Wellen dessen, was zurückströmt von den hinausströmenden Liedern der Lerchen und Nachtigallen.

Man kann also, wenn man nicht aus dem intellektualistischen Zeitalter heraus, sondern aus dem wirklichen, allumfassenden menschlichen Bewußtsein heraus redet, eigentlich nicht sagen: «Ich singe, wie der Vogel singt, der in den Zweigen wohnet. Das Lied, das aus der Kehle dringt, ist Lohn, der reichlich lohnet», sondern man müßte dann sagen: Ich singe, wie der Vogel singt, der in den Zweigen wohnet. Das Lied, das aus der Kehle hinausströmt in Weltenweiten, kommt als Segen der Erde wiederum zurück, befruchtend das irdische Leben mit den Impulsen des Göttlich-Geistigen, die dann weiterwirken in der Vogelwelt, und die nur deshalb in der Vogelwelt der Erde wirken können, weil sie den Weg hereinfinden auf den Wellen desjenigen, was ihnen hinausgesungen wird in die Welt.

Nun sind ja nicht alle TiereNachtigallen und Lerchen; es singen auch selbstverständlich nicht alle hinaus, aber etwas Ähnliches, wenn es auch nicht so schön ist, geht von der ganzen tierischen Welt in den Kosmos hinaus. Das verstand man in jenen alten Zeiten, und deshalb wurden die Schüler der Mysterienschulen angeleitet, solches Gesangliche, solches Tänzerische zu erlernen, das sie dann aufführen konnten am Johannifest, wenn ich es mit dem modernen Ausdruck nennen darf. Das sandten die Menschen in den Kosmos hinaus, natürlich in einer jetzt nicht tierischen, sondern vermenschlichten Gestalt, als eine Weiterbildung dessen, was die Tiere in den Weltenraum hinaussenden.

Und es gehörte noch etwas anderes zu jenen Festen: nicht nur das Tänzerische, nicht nur das Musikalische, nicht nur das Gesangliche, sondern hinterher das Lauschen. Erst wurden die Feste aktiv aufgeführt, dann gingen die Anleitungen dahin, daß die Menschen zu Lauschern wurden dessen, was ihnen zurückkam. Sie hatten die großen Fragen an das Göttlich-Geistige des Kosmos gerichtet mit ihren Tänzen, mit ihren Gesängen, mit all dem Poetischen, das sie aufgeführt hatten. Das war gewissermaßen hinaufgeströmt in die Weiten des Kosmos, wie das Wasser der Erde hinaufströmt, das oben die Wolken bildet und als Regen wieder hinabträufelt. Also erhoben sich die Wirkungen der menschlichen Festesverrichtungen und kamen jetzt zurück, selbstverständlich nicht als Regen, aber als etwas, was sich als die Ich-Gewalt dem Menschen offenbarte. Und es hatten die Menschen eine feine Empfindung für jene eigentümliche Umwandelung, welche gerade um die Johannifesteszeit mit der um die Erde herum befindlichen Luft und Wärme geschieht.

Darüber geht natürlich der heutige Mensch der intellektualistischen Zeit hinweg. Er hat etwas anderes zu tun als die Menschen der alten Zeiten. Er muß zu diesen Zeiten, wie auch zu andern Zeiten, zum Five o’clock tea gehen, zu Kaffees gehen, muß ins Theater gehen und so weiter. Er hat eben etwas anderes zu tun, was nicht von der Jahreszeit abhängt. Über alldem, was man da treibt, vergißt man jene leise Umwandelung dessen, was sich in der atmosphärischen Umgebung der Erde vollzieht.

Es ist nämlich so, daß diese Menschen der alten Zeit gefühlt haben, wie Luft und Wärme anders werden um die Johannizeit, um die Hochsommerzeit, wie sie etwas Pflanzenhaftes bekommen. Denken Sie einmal, was das für eine Empfindung war: eine feine Empfindung für alles, was in der Pflanzenwelt vorgeht. Nehmen wir an, das sei hier die Erde, und aus der Erde überall kommen die Pflanzen heraus; da hatten die Menschen eine feine Empfindung für alles, was mit der Pflanze sich heranentwickelt, was in der Pflanze lebt. Im Frühling hatte man so ein allgemeines Naturgefühl, das höchstens noch in der Sprache erhalten ist. Sie finden im Goetheschen «Faust» das Wort: es «grunelt». Wer merkt denn heute, wenn es grunelt, wenn die Grünheit, die im Frühling aus der Erde herauskommt, die Luft durchweht und durchwellt? Wer merkt denn, wenn es grunelt und wenn es blüht! Nun ja, heute sehen das die Menschen. Da gefällt ihnen das Rote, das Gelbe, das da blüht; aber sie merken es nicht, daß da die Luft etwas ganz anderes wird, wenn es blüht, oder gar wenn es fruchtet. Also dieses Miterleben mit der Pflanzenwelt ist weg für die intellektualistische Zeit. Für diese Menschen aber war es vorhanden. Daher konnten sie auch empfinden, wenn ihnen jetzt nicht von der Erde heraus das Gruneln, das Blühen, das Fruchten, sondern wenn ihnen das aus der Umgebung, aus der Luft kam, wenn Luft und Wärme selber von oben herunter (schraffiert) etwas wie Pflanzenhaftes ausströmten. Und dieses Pflanzenhaftwerden von Luft und Wärme, das versetzte das Bewußtsein hinein in jene Sphäre, wo dann das Ich herunterkam als Antwort auf dasjenige, was man musikalisch-dichterisch in den Kosmos hinaussandte.

Also diese Feste hatten einen wunderbaren intimen menschlichen Inhalt. Es war eine Frage an das göttlich-geistige Weltenall. Die Antwort bekam man, weil man so, wie man das Fruchtende, das Blühende, das Grunelnde der Erde empfindet, von oben herunter aus der sonst bloß mineralischen Luft etwas Pflanzenhaftes empfand. Dadurch trat in den Traum des Daseins, in dieses träumerische alte Bewußtsein auch der Traum des Ich herein.

Und wenn dann das Johannifest vorüber war und der Juli und August wieder kamen, dann hatten die Menschen das Gefühl: Wir haben ein Ich; aber das Ich bleibt im Himmel, das ist da oben, das spricht nur zur Johannizeit zu uns. Da werden wir gewahr, daß wir mit dem Himmel zusammenhängen. Der hat unser Ich in Schutz genommen. Der zeigt es uns, wenn er das große Himmelsfenster öffnet; zur Johannizeit zeigt er es uns! Aber wir müssen darum bitten. Wir müssen bitten, indem wir die Festesverrichtungen der Johannizeit aufführen, indem wir da bei diesen Festesverrichtungen uns in die unglaublich traulichen, intimen musikalisch-poetischen Veranstaltungen hineinfinden. So waren schon diese alten Feste die Herstellung einer Kommunikation, einer Verbindung des Irdischen mit dem Himmlischen. Und Sie spüren, meine lieben Freunde: Dieses ganze Fest war in Musikalisches getaucht, in Musikalisch-Poetisches, es wurde plötzlich in der Hochsommerzeit für ein paar Tage - aber es war gut von den Mysterien her vorbereitet —, es wurde plötzlich in den einfachen Ansiedlungen der Urmenschen überall poetisch. Das ganze soziale Leben war in dieses musikalisch-poetische Element getaucht. Die Menschen glaubten eben, sie brauchten das, wie das tägliche Essen und Trinken, zu dem Leben im Jahreslaufe, daß sie da in diese tänzerisch-musikalisch-poetische Stimmung hineinkamen und auf diese Weise ihre Kommunikation mit den göttlich-geistigen Mächten des Kosmos herstellten. Von diesem Feste blieb dann das, was in der späteren Zeit kam: daß, wenn ein Mensch dichtete, er zum Beispiel sagte: Sing’ mir, o Muse, vom Zorn des Peleiden Achilleus -, weil man sich da noch erinnerte, daß einstmals die große Frage an das Göttliche gestellt worden war und das Göttliche antworten sollte auf die Frage der Menschen.

Ebenso, wie sorgfältig vorbereitet wurden diese Feste zur Johannizeit, um die große Frage an den Kosmos zu stellen, damit der Kosmos zu dieser Zeit dem Menschen verbürge, daß er ein Ich hat, das nur eben die Himmel in Schutz genommen haben, so wurde in derselben Weise vorbereitet das Wintersonnenwendefest, das 'Tiefwinterfest, das jetzt zu unserem Weihnachtsfest geworden ist. Aber wie zur Johannizeit alles getaucht war in das musikalisch-poetische Element, in das tänzerische Element, so war in der Tiefwinterzeit alles zunächst so vorbereitet, daß die Menschen wußten: sie müssen still werden, sie müssen in ein mehr beschauliches Element hineinkommen. Und dann wurde hervorgeholt alles, was in alten Zeiten, von denen die äußere Geschichte ja nichts berichtet, von denen man nur wissen kann durch die Geisteswissenschaft, was in alten Zeiten da war während der Sommerzeit an verbildlichten Elementen, an plastisch verbildlichten Elementen, die ihren Höhepunkt erreichten in jenen tänzerischen, musikalischen Festen, von denen ich Ihnen soeben gesprochen habe. Während jener Zeit kümmerte sich die alte Menschheit, die gewissermaßen da aus sich herausging, um sich mit dem Ich in den Himmeln zu vereinigen, nicht um dasjenige, was man damals lernte. Außerhalb des Festes hatten sie ja zu tun mit der Besorgung all dessen, was eben in der Natur für den menschlichen Unterhalt zu besorgen war. Das Lehrhafte fiel in die Wintermonate, und das erlangte auch seine Kulmination, seinen Festesausdruck eben zur Wintersonnenwende, zur tiefen Winterzeit, zur Weihnachtszeit.

Da fing man an, die Menschen, welche wiederum unter der Anleitung der Mysterienschüler standen, vorzubereiten darauf, allerlei geistige Verrichtungen zu tun, die während des Sommers nicht getan wurden. Es ist schwierig, weil natürlich die Dinge sich von dem, was heute getan wird, sehr unterscheiden, mit heutigen Ausdrücken das zu benennen, was die Menschen so von unserer September-Oktoberzeit an bis zu unserer Weihnachtszeit hin trieben. Aber sie wurden angeleitet zu dem, was wir etwa heute nennen würden Rätselraten, Fragen beantworten, die in irgendeiner verhüllten Gestalt gegeben wurden, so daß sie aus dem, was in Zeichen gegeben war, einen Sinn herausfinden sollten. Sagen wir, die Mysterienschüler gaben denen, die so etwas lernen sollten, irgendein symbolisches Bild; das sollten sie deuten. Oder sie gaben ihnen, was wir ein Rätsel nennen würden; das sollten sie auflösen, Sie gaben ihnen irgendeinen Zauberspruch. Was der Zauberspruch enthielt, sollten sie auf die Natur beziehen und es damit auch erraten. Aber namentlich wurde sorgfältig vorbereitet, was dann bei den verschiedenen Völkern verschiedenste Formen angenommen hat, was zum Beispiel in nordischen Ländern dann in einer späteren Zeit gelebt hat als das Hinwerfen der Runenstäbe, so daß sie Formen bildeten, die dann enträtselt wurden. Diesen Betätigungen gab man sich zur Tiefwinterzeit hin, aber insbesondere wurden solche Dinge gepflegt, allerdings in der alten primitiven Form, die dann zu einer gewissen primitiven plastischen Kunst führten.

Bei diesen alten Bewußtseinsformen war nämlich das Eigentümliche - so paradox es wieder für den heutigen Menschen klingt — das Folgende: Wenn der Oktober heranrückte, so machte sich in den menschlichen Gliedern etwas geltend, was nach irgendeiner Betätigung strebte. Im Sommer mußte der Mensch sich im Bewegen seiner Glieder dem fügen, was der Acker von ihm forderte; er mußte die Hand an den Pflug legen, er mußte das oder jenes tun. Da mußte er sich an die Außenwelt anpassen. Wenn die Ernte vorüber war und die Glieder ausruhten, dann regte sich in ihnen das Bedürfnis nach irgendeiner Betätigung, und dann bekamen die Glieder die Sehnsucht, zu kneten. Man hatte an allem plastischen Bilden seine besondere Befriedigung. So wie zur Johannizeit ein intensiver Trieb nach Tanz, nach Musik auftauchte, so tauchte gegen die Weihnachtszeit hin ein intensiver Trieb auf, zu kneten, zu bilden, aus allerlei weichen Massen, die da waren, zu bilden, auch alles Natürliche dazu benützend. Namentlich hatte man eine feine Empfindung für die Art und Weise, wie zum Beispiel das Wasser anfing zu gefrieren. Da gab man ganz besondere Impulse. Man stieß nach dieser oder jener Richtung. Dabei bekamen die Eisformen, die sich im Wasser bildeten, eine besondere Gestalt, und man brachte es dahin, daß man, mit der Hand im Wasser drinnen, Formen ausführte, während einem die Hand erstarrte, so daß dann, wenn das Wasser gefror unter den Wellen, die man da aufwarf, das Wasser die sonderbarsten künstlerischen Formen annahm, die dann natürlich wiederum zerschmolzen.

Von alledem ist ja nichts mehr geblieben im intellektualistischen Zeitalter als höchstens das Bleigießen in der Silvesternacht. Da wird noch Blei in das Wasser hineingegossen, und man findet, daß es Formen annimmt, die man dann erraten soll. Aber das ist das letzte abstrakte Überbleibsel von jenen wunderbaren Betätigungen der inneren menschlichen Triebkraft in der Natur, die sich zum Beispiel so äußerte, wie ich es beschrieben habe: daß der Mensch die Hand in das Wasser steckte, das schon im Gefrieren war, daß er die Hand erstarrt bekam und nun probierte, wie er das Wasser in Wellen formte, so daß das gefrierende Wasser dann mit den wunderbarsten Gestalten antwortete.

Der Mensch bekam auf diese Weise die Fragen heraus an die Erde. Durch die Musik, durch die Poesie wandte er sich in der Hochsommerzeit mit seinen Fragen an die Himmel, und die antworteten ihm, indem sie ihm das Ich-Gefühl hereinsandten in sein träumendes Bewußtsein. In der Tiefwinterzeit wandte er sich für das, was er jetzt wissen wollte, nun nicht hinaus an die Himmel, sondern er wandte sich an das irdische Element, und er probierte, was das irdische Element für Formen annehmen kann. Und an diesem merkte er, daß die Formen, die da herauskamen, sich in einer gewissen Weise ähnlich verhielten den Formen, welche die Käfer, die Schmetterlinge bildeten. Das ergab sich für seine Anschauung. Aus der Plastik, die er herausholte aus dem Naturwirken der Erde, ergab sich für ihn die Anschauung, daß überhaupt aus dem irdischen Elemente die verschiedenen Tierformen herausgebildet werden. Zur Weihnachtszeit verstand der Mensch die Tierformen. Und indem er arbeitete, seine Glieder anstrengte, sogar ins Wasser sprang, gewisse Beinbewegungen machte, dann heraussprang und probierte, wie das Wasser antwortete, das erstarrende Wasser, da merkte er an der Außenwelt, welche Gestalt er als Mensch selber hat. Das war aber nur zur Weihnachtszeit, nicht sonst; sonst hatte er nur für das Tierische, für das Rassenhafte eine Empfindung. Zur Weihnachtszeit kam er dann auch an das Erleben der menschlichen Gestalt heran.

So wie also in jenen alten Mysterienzeiten vermittelt wurde das IchBewußtsein von den Himmeln herein, so wurde die menschliche Gestaltempfindung vermittelt aus der Erde heraus. Der Mensch lernte zur Weihnachtszeit die Erde in ihrer Formkraft, in ihrer plastisch bildnerischen Kraft kennen und lernte erkennen, wie ihm die Sphärenharmonien sein Ich hereinklangen in sein Traumbewußtsein zur Johannizeit im Hochsommer. Und so erweiterten zu besonderen Festeszeiten die alten Mysterien das Menschenwesen. Auf der einen Seite wuchs die Umgebung der Erde in den Himmel hinaus, damit der Mensch wissen konnte, wie die Himmel sein Ich in Schutz halten, wie da sein Ich ruht. Und zur Weihnachtszeit ließen die Mysterienlehrer die Erde auf die Anfrage der Menschen auf dem Wege durch das plastische Bilden antworten, damit der Mensch da allmählich das Interesse bekam für die menschliche Gestalt, für das Zusammenfließen aller tierischen Gestalt in die menschliche Gestalt. Der Mensch lernte sich innerlich seinem Ich nach in det Hochsommerzeit kennen; der Mensch lernte sich äußerlich in bezug auf seine Menschenbildung erfühlen in der tiefen Winterzeit. Und so war das, was der Mensch als sein Wesen empfand, wie er sich eigentlich fühlte, nicht allein zu erlangen dadurch, daß man einfach Mensch war, sondern daß man mit dem Jahreslauf mitlebte, daß einem, um zum Ich-Bewußtsein zu kommen, die Himmel die Fenster öffneten, daß, um zum Bewußtsein der menschlichen Gestalt zu kommen, die Erde gewissermaßen ihre Geheimnisse entfaltete. Da war der Mensch eben innig, intim verbunden mit dem Jahreslaufe, so intim verbunden, daß er sich sagen mußte: Ich weiß ja von dem, was ich als Mensch bin, nur dann, wenn ich nicht stumpf dahinlebe, sondern wenn ich mich erheben lasse im Sommer zu den Himmeln, wenn ich mich einsenken lasse im Winter in die Erdenmysterien, in die Erdengeheimnisse.

Sie sehen daraus, daß es einmal schon so war, daß die Festeszeiten in ihren Verrichtungen eben als etwas aufgefaßt wurden, das zum menschlichen Leben gehört. Der Mensch fühlte sich nicht nur als Erdenwesen, sondern er fühlte sich als Wesen, das der ganzen Weltangehörte, das ein Bürger der ganzen Welt war. Ja, er fühlte sich so wenig als Erdenwesen, daß er auf das, was er durch die Erde selbst war, eigentlich erst aufmerksam gemacht werden mußte durch Feste, die nur zu einer bestimmten Jahreszeit begangen werden konnten, weil zu andern Jahreszeiten die Menschen, die mehr oder weniger den Jahreslauf erlebten, es gar nicht hätten miterleben können. Es war eben alles, was man durch Feste erfahren und miterleben konnte, an die betreffende Jahreszeit gebunden.

In dieser Weise, wie es einmal in primitiven Zeiten war, kann der Mensch, nachdem er seine Freiheit im intellektualistischen Zeitalter errungen hat, gewiß nicht wiederum zum Miterleben mit dem Kosmos kommen. Aber er kann dazu kommen auch mit seiner heutigen Konstitution, wenn er sich wiederum einläßt auf das Geistige. In dem IchBewußtsein, das ja jetzt die Menschheit schon lange hat, ist etwas eingezogen, was früher nur durch das Himmelsfenster im Sommer zu erlangen war. Aber deshalb muß der Mensch sich gerade etwas anderes, was wiederum über das Ich hinausliegt, durch das Verständnis des Kosmos aneignen.

Es ist heute dem Menschen natürlich, von der menschlichen Gestalt im allgemeinen zu sprechen. Wer in das intellektualistische Zeitalter eingetreten ist, hat nicht mehr ein so starkes Gefühl von dem TierischRassenhaften. Aber wie das früher als eine Kraft, als ein Impuls, der nur aus der Erde heraus gesucht werden konnte, über den Menschen gekommen ist, so muß heute durch das Verständnis der Erde, das nicht durch Geologie oder Mineralogie, sondern wiederum nur auf geistige Art gegeben werden kann, der Mensch wiederum zu etwas anderem kommen als bloß zur menschlichen Gestalt.

Wenn man die menschliche Gestalt nimmt, so kann man sagen: In sehr alten Zeiten hat der Mensch sich innerhalb dieser Gestalt so gefühlt, daß er nur das Äußerlich-Rassenhafte, das im Blute liegt, fühlte, daß er nicht bis zu der Haut hin empfunden hat (siehe Zeichnung, rot); er war nicht aufmerksam auf die Grenze. Heute ist der Mensch so weit, daß er auf die Umgrenzung aufmerksam ist. Er empfindet die Umgrenzung als das eigentlich Menschliche an seiner Gestalt. Aber der Mensch muß nun über sich hinauskommen. Er muß das Ätherisch-Astralische außer sich kennenlernen (blau). Das kann er eben durch geisteswissenschaftliche Vertiefung.

So sehen wir, daß das gegenwärtige Bewußtsein dadurch erkauft worden ist, daß allerdings vieles von dem Zusammenhang des Bewußtseins mit dem Kosmos verlorengegangen ist; aber nachdem der Mensch einmal zum Erleben dessen gekommen ist, was seine Freiheit und seine Gedankenwelt ist, muß er wiederum hinauskommen und muß kosmisch erleben. Das ist dasjenige, was die Anthroposophie will, wenn sie so von einer Erneuerung der Feste spricht, ja gar von dem Kreieren von Festen wie dem Michaelfest im Herbste, von dem neulich gesprochen worden ist. Man muß wiederum ein inneres Verständnis dafür haben, was in dieser Beziehung der Jahreslauf dem Menschen sein kann. Und er wird dann etwas Höheres sein können, als er einstmals in der geschilderten Weise dem Menschen war.

Fourth Lecture

In recent times I have often had to point out the connection between the course of the year and some human circumstances, and during Easter I pointed out the connection between the course of the year and the celebration of human festivals. Today I would like to go back to very ancient times in order to say something about this connection between the course of the year and human festivals, especially in connection with the mystery system of humanity in ancient times, which may perhaps deepen what we have already discussed in one way or another.

The festivities during the year actually meant a piece of their whole life to the people of very old times on earth. We know that in those ancient times human consciousness worked in a completely different way than later. One would like to attribute something dreamy to this old consciousness. And it was from this dreamy quality that those insights of human consciousness, of the human soul, emerged which then took the form of myths, which also became mythology itself. Through this more dreamy, one could also say instinctive, clairvoyant consciousness, people looked deeper into that which is spiritual in man's environment. But precisely because people participated intensively in this way not only in the sensory effects of nature, as is the case today, but also in spiritual events, people were also more devoted to the phenomena of the course of the year, to the diversity of activity in nature in spring and autumn. I have also referred to this recently.

Today, however, I want to tell you something else about it: how the high summer festival, which then became our St. John's festival, and the low winter festival, which became our Christmas festival, were celebrated in connection with the ancient mystery teachings. However, we must realize that the humanity of which we speak for earlier times on earth did not attain full ego-consciousness in the same way as we do today. There is no full I-consciousness in dreamlike consciousness; and if there is no full I-consciousness, people do not perceive that of which the humanity of today is so proud. The people of that time did not perceive what lived in dead nature, in mineral nature.

Let's be clear: the consciousness was one that did not run in abstract thoughts, that lived in images, but it was dreamlike. As a result, human beings became much more involved than is the case now, let us say in spring, in the sprouting, sprouting plant life and plant beings. Again, one could say, they felt the defoliation in autumn, the withering of the leaves, the whole dying away of the plant world, they also felt deeply the changes that the animal world underwent in the course of the year, felt the whole human environment differently when the air was fluttered through by butterflies, buzzed through by beetles. In a sense, they felt their own human weaving together with the weaving and essence of plant and animal existence. But not only did they have no interest, they also had no real awareness of the mineral, of the dead outside. That is one side of this old human consciousness.

The other side is that this ancient humanity also had no interest in the form of man in general. Today it is even quite difficult to imagine what human feeling was like in this direction; people generally did not have a strong interest in the human form in its spatial form. They did, however, have an intense interest in the racial nature of man. And the further back we go in ancient cultures, the less people are actually interested in the human form for the general consciousness; on the other hand, people are interested in the color of the skin, in the racial temperament. That is what these people look at. On the one hand, therefore, these people are not interested in the dead, mineral Plate 6

not, and on the other hand they are not interested in the human form. There was an interest, as I said, in the racy, but not in the generally human, not even in relation to the outer form.

The great teachers of the Mysteries accepted this as a fact. I will show you what they thought by means of a graphic drawing. They said: "People have a dreamlike consciousness; this enables them to perceive the plant life in their surroundings clearly. - Through their dream images these people lived the plant life, but this dream consciousness did not reach as far as the perception of the mineral. So that the Mystery Teachers said to themselves: On the one hand, human consciousness goes to the plant-like (see diagram), which is experienced dreamily, but not as far as the mineral; that lies outside human consciousness. And on the other side, man feels within himself that which still connects him with animality, the racial, the animal-like (see diagram). On the other hand, that which actually makes man human through his upright form, through the spatial form of his being, lies outside of human consciousness.

So what is actually human lies outside what interested these people in ancient times. We can therefore designate human consciousness by thinking of it in terms of this ancient humanity as being enclosed within this space (see diagram, shaded), while the mineral and the actually human lay outside the realm of what this ancient humanity, which spent its existence outside the Mysteries, actually knew something about.

But what I have now said was only true in general terms. Through his own powers, through what man experienced in his being, he could not penetrate beyond this space to the mineral on the one side, to the human on the other. But there were institutions emanating from the Mysteries which in the course of the year brought to man, at least approximately, something like the human ego-consciousness on the one hand and a view of the general mineral on the other. Strange as it may sound to modern man, it is nevertheless the case that the ancient mystery priests instituted festivals by means of whose special ceremonies men raised themselves beyond the vegetable to the mineral, and thus in ancient times had in a certain season a lighting up of the ego. As when the I shone into the dream consciousness, so it was. You know that even in the dreams of people today, their own ego, which people then see, sometimes still forms a component of the dream.

And so the I-consciousness shone in at this midsummer time through the activities that were organized for a part of humanity that wanted to participate. And at this time of midsummer people were at least able to perceive the mineral world to such an extent that with the help of this mineral perception they acquired a kind of ego-consciousness, although the ego appeared to them as something that came into their dreams from outside. And in order to achieve this, in the oldest midsummer festivals, in the festivals at the time of the summer solstice, which then became our Johanni festivals, the participants were instructed to unfold a musical-poetic element full of strictly rhythmically arranged round dances accompanied by singing. Certain representations and performances were filled with peculiar musical recitatives accompanied by primitive instruments. Such a festival was steeped in musical poetry. Man poured out what he had in his dream consciousness into the cosmos in a musical-singing, dance-like manner.

Modern man cannot have a direct understanding of what was then achieved in music and song under the guidance of those people who themselves had their guidance from the Mysteries for such powerful, widespread folk festivals of ancient times. For what later became musical and poetic is far removed from that primitive, elementary, simply musical and poetic which was developed at midsummer under the guidance of the Mysteries in those ancient times. Everything was aimed at the fact that, while people were doing their round dances accompanied by singing and primitive poetic performances, they entered into a mood through which precisely that happened which I have now called the shining in of the I into the human sphere.

But if one had asked these old people who had the instructions: Yes, how does one actually come to form such songs, such dances, through which what I have described can arise? - then these ancient people would have given an answer that is highly paradoxical for modern man. They would have said, for example: Yes, much has been handed down, much is already there, it was done by even older people! - But in certain ancient times, people would have said: You can still learn it today without relying on tradition, if you only continue to develop what is revealed. You can still learn today how to use primitive instruments, how to form dances, how to master the singing voice. - And now comes the paradox of what these old people would have said. They would have said: You learn that from the songbirds. - But they understood in a deep way the whole meaning of why songbirds actually sing.

Humanity has long forgotten why songbirds sing. In the age when the intellect dominated everything, when people became intellectualists, people certainly preserved the art of singing, poetic art, but in the age of intellectualism they forgot the connection between singing and the whole universe. And even someone who is enthusiastic about the musical arts, who places the musical arts above everything banal and human, says from this later intellectualistic age:

I sing as the bird sings,

That dwells in the branches.

The song that comes from the throat,

Is reward that richly rewards.

Yes, that is what the man of a certain age says. For the bird itself would never say it. The bird would never say: “The song that comes from the throat is a reward that is richly worthwhile.” And neither would the old mystery students have said it. For when in a certain season the larks, the nightingales sing, then that which is formed there does not penetrate through the air, but through the etheric element out into the cosmos, vibrates out in the cosmos up to a certain limit; then it vibrates back to the earth, and then the animal world receives that which vibrates back, only then the essence of the divine-spiritual of the cosmos has united with it. And so it is that the nightingales, the larks, send out their voices into the universe (red) and that what they send out comes back to them etherically (yellow) for the state where they do not sing, but that is then permeated by the content of the divine-spiritual. The larks send their voices out into the world, and the divine-spiritual, which participates in the forming, in the whole shaping of the animal, flows back into the earth on the waves of that which flows back from the outflowing songs of the larks and nightingales.

Thus, if one does not speak out of the intellectualistic age, but out of the real, all-encompassing human consciousness, one cannot actually say: "I sing as the bird sings that dwells in the branches. The song that comes from the throat is a reward that is richly worthwhile“, but one would then have to say: ”I sing as the bird sings that dwells in the branches. The song that flows out of the throat into the world comes back as a blessing of the earth, fertilizing earthly life with the impulses of the divine-spiritual, which then continue to work in the bird world, and which can only work in the bird world of the earth because they find their way in on the waves of that which is sung out to them into the world.

Now not all animals are nightingales and larks; of course not all of them sing out, but something similar, even if it is not so beautiful, goes out from the whole animal world into the cosmos. This was understood in those ancient times, and that is why the pupils of the Mystery Schools were taught to learn such singing and dancing, which they could then perform on the Feast of St. John, if I may use the modern expression. People sent this out into the cosmos, not in an animal but in a humanized form of course, as a further development of what the animals send out into the universe.

And there was something else to those festivals: not just the dancing, not just the music, not just the singing, but the listening afterwards. First the festivals were actively performed, then the instructions were given so that people became listeners to what came back to them. They had addressed the great questions to the divine-spiritual of the cosmos with their dances, with their songs, with all the poetry they had performed. This had, as it were, flowed upwards into the vastness of the cosmos, just as the water of the earth flows upwards, forming the clouds above and trickling down again as rain. So the effects of human festive activities rose up and now returned, not as rain of course, but as something that revealed itself to man as the power of the ego. And people had a keen sense of the peculiar transformation that happens to the air and warmth around the earth at the time of St. John's Day.

Of course, today's intellectualists ignore this. He has something different to do than the people of old. At these times, as at other times, he has to go to five o'clock tea, go to coffee, go to the theater and so on. He has something else to do that does not depend on the season. Above all that one does, one forgets the quiet transformation of what is taking place in the earth's atmospheric environment.

The fact is that these people of old felt how the air and warmth change around St. John's Day, around midsummer, how they take on a plant-like quality. Just think what kind of feeling that was: a fine feeling for everything that happens in the plant world. Let's assume that this is the earth here, and that plants come out of the earth everywhere; then people had a fine feeling for everything that develops with the plant, everything that lives in the plant. In spring, people had a general feeling for nature that is at best still preserved in language. In Goethe's “Faust” you will find the word: it “grunts”. Who notices today when it grunts, when the greenery that emerges from the earth in spring blows and ripples through the air? Who notices when it grunts and when it blooms! Well, people see that today. They like the red, the yellow that blooms, but they don't realize that the air becomes something completely different when it blooms, or even when it bears fruit. So this co-experience with the plant world is gone for the intellectualistic age. But for these people it was there. That is why they were also able to feel when they did not experience the greening, the blossoming, the fruiting from the earth, but when it came to them from the surroundings, from the air, when air and warmth themselves emanated something plant-like from above (hatched). And this plant-like quality of air and warmth transported the consciousness into that sphere where the ego came down in response to what was sent out into the cosmos in musical and poetic form.

So these festivals had a wonderfully intimate human content. It was a question to the divine-spiritual universe. The answer was given because, just as one senses the fruitfulness, the blossoming, the rumbling of the earth, one felt something plant-like from above in the otherwise merely mineral air. Thus the dream of the ego also entered into the dream of existence, into this dreamy old consciousness.

And when St. John's festival was over and July and August came again, people had the feeling: We have an ego; but the ego remains in heaven, it is up there, it only speaks to us at St. John's time. That's when we realize that we are connected to heaven. He has taken our I under his protection. He shows it to us when he opens the great heavenly window; at St. John's time he shows it to us! But we have to ask for it. We must ask by performing the festivities of St. John's Day, by entering into the incredibly intimate musical and poetic events during these festivities. These ancient festivals were already the establishment of a communication, a connection between the earthly and the heavenly. And you sense, my dear friends: this whole festival was immersed in music, in music-poetry, it suddenly became poetic for a few days in the height of summer - but it was well prepared by the Mysteries - it suddenly became poetic everywhere in the simple settlements of primitive man. The whole social life was immersed in this musical-poetic element. The people believed that they needed this, like the daily eating and drinking, for life in the course of the year, that they could get into this dancing-musical-poetic mood and in this way establish their communication with the divine-spiritual powers of the cosmos. From this festival then remained what came in later times: that when a man wrote poetry, he said, for example: Sing to me, O Muse, of the wrath of the Peleid Achilles - because one still remembered that once the great question had been put to the divine and the divine was to answer the question of man.

Just as these festivals were carefully prepared at the time of St. John in order to put the great question to the cosmos, so that the cosmos at this time would guarantee to man that he has an I, which only the heavens have just taken into protection, so the winter solstice festival, the 'deep winter festival, which has now become our Christmas festival, was prepared in the same way. But just as in the time of St. John everything was immersed in the musical-poetic element, in the dancing element, so in the time of deep winter everything was first prepared in such a way that people knew: they must become quiet, they must enter into a more contemplative element. And then everything was brought out that was there in ancient times, of which external history tells us nothing, of which we can only know through spiritual science, that was there in ancient times during the summer time in visualized elements, in plastic visualized elements, which reached their climax in those dancing, musical festivals of which I have just spoken to you. During that time, the old humanity, which to a certain extent went out of itself in order to unite with the ego in the heavens, did not concern itself with what was learned at that time. Outside of the feast they had to deal with everything that had to be done in nature for human sustenance. The teaching fell into the winter months, and this also reached its culmination, its festive expression at the winter solstice, in the depths of winter, at Christmas time.

Then they began to prepare the people, who were again under the guidance of the Mystery students, to do all kinds of spiritual activities that were not done during the summer. It is difficult, because of course things are very different from what is done today, to describe in today's terms what people did from our September-October time until our Christmas time. But they were led to do what we would call today guessing, answering questions that were given in some veiled form so that they could make sense of what was given in signs. Let us say that the students of the Mysteries gave some symbolic image to those who were to learn such things; they were to interpret it. Or they gave them what we would call a riddle; they were supposed to solve it, they gave them some kind of spell. They were to relate what the spell contained to nature and thus also guess it. But in particular, careful preparations were made for what then took on the most varied forms among the different peoples, for example, what lived in Nordic countries at a later time than the throwing down of the runic sticks, so that they formed shapes which were then unraveled. People indulged in these activities in the deep winter time, but in particular such things were cultivated, albeit in the old primitive form, which then led to a certain primitive plastic art.