The Cycle of the Year

GA 223

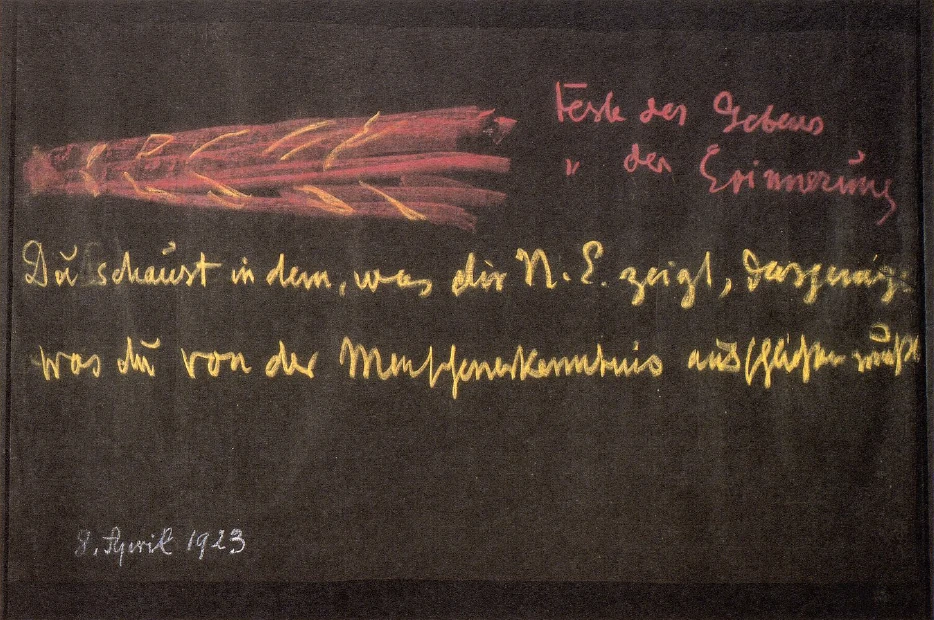

8 April 1923, Dornach

Lecture V

I should like to carry to a still wider horizon the reflections I have already made here concerning the relationship between man and the cycle of Nature which was formed in ancient times under the influence of the Mysteries, and to go into what was believed in those times with regard to all that one as man received from the cosmos through this cycle of Nature. You may have gathered from yesterday's lecture as well perhaps as from the recollection of much that I could still say about such matters during the past Christmas season, in the Goetheanum which has now been taken from us—you may have gathered that the cycle of the year in its phenomena was perceived, and indeed today can still be perceived, as a result of life, as something which in its external events is just as much the expression of a living being standing behind it as the actions of the human organism are the manifestations of a being, of the human soul itself.

Let us remind ourselves how, in midsummer, the time we know as St. John's, the people became aware under this ancient Mystery-influence of a certain relationship to their ego, an ego which they did not yet consider as exclusively their own, but which they viewed as resting still in the bosom of the divine-spiritual.

These people believed that by means of the ceremonies I have described, they approached their “I” at midsummer, although throughout the rest of the year it was hidden from them. Of course they thought of themselves as dwelling in their beings altogether in the bosom of the divine-spiritual; but they thought that during the other three-quarters of the year nothing was revealed to them of what belonged to them as their ego. Only in this one quarter, which reached its high point at St. John's, did the essential being of their own ego manifest itself to them as through a window opening out of the divine spiritual world.

Now this essence of the individual ego within the divine spiritual world in which it revealed itself was by no means regarded in such a neutral, indifferent—one may even say phlegmatic—way as is the case today. When the “I” is spoken of today, a person is hardly likely to think of it as having any special connection either with this world or any other. Rather, he thinks of his “I” as a kind of point; what he does rays out from it and what he perceives rays in. But the feeling a person has today in regard to his “I” is of an altogether phlegmatic nature. We cannot really say that modern man even feels the “egoity” of his “I”—in spite of the fact that it is his ego; for anyone who wants to be honest cannot really claim that he is fond of his “I.” He is fond of his body; he is fond of his instincts; he may be fond of this or that experience. But the “I” is just a tiny word which is felt as a point in which all that has been indicated is more or less condensed. But in that period in which, after long preparations had been made, the approach to this “I” was undertaken ceremonially, each man was enabled in a certain sense to meet his “I” in the universe. Following this meeting, then, the “I” was perceived to be once more gradually withdrawing and leaving the human being alone with his bodily and soul nature, or as we would say today, with his physical-etheric-astral being. In that period man felt the “I” perceptively as having a real connection with the entire cosmos, with the whole world.

But what was felt above all else with regard to the relationship of this “I” to the world was not something “naturalistic,” to use the modern term; it was not something received as an external phenomenon. Rather, it was something which was deemed to be the very center of the most ancient moral conception of the world. Men did not expect great secrets of Nature to be revealed to them at this season. To be sure, such Nature secrets were spoken of, but man did not direct his attention primarily to them. Rather, he perceived through his feeling that above all he was to absorb into himself as moral impulse what is revealed at this time of midsummer when light and warmth reach their highest point.

This was the season man perceived as the time of divine-moral enlightenment. And what he wanted above all to obtain from the heavens as “answer” to the performances of music, poetry and dancing that were carried on at this season, what he waited for was that there should be revealed out of the heavens in all seriousness what they required of him morally.

And when all the ceremonies had been carried out that I described yesterday as belonging to the celebration of these festivals during the time of the sun's sultry heat—if it sometimes happened that a powerful storm broke forth with thunder and lightning, then just in this outbreak of thunder and lightning men felt the moral admonition of the heavens to earthly humanity.

There are vestiges from this ancient time in conceptions such as that of Zeus as the god of thunder, armed with a thunderbolt. Something similar is linked with the German god, Donar. This we have on one side. On the other side, man perceptively felt Nature, I might say, as warm, luminous, satisfied in itself. And he felt that this warming, luminous Nature as it was during the daytime remained also into the night time. Only he made a distinction, saying to himself: “During the day the air is filled with the warmth-element, with the light-element. In these elements of warmth and light there weave and live spiritual messengers through whom the higher divine beings want to make themselves known to men, want to endow them with moral impulses. But at night, when the higher spiritual beings withdraw, the messengers remain behind and reveal themselves in their own way.”

And thus it was that especially at midsummer people perceived the ruling and weaving of Nature in the summer nights, in the summer evenings. And what they felt then seemed to them to be a kind of summer dream which they experienced in reality; a summer dream through which they came especially near to the divine-spiritual; a summer dream by which they were convinced that every phenomenon of Nature was at the same time the moral utterance of the gods, but that all kinds of elemental beings were also active there who revealed themselves to men in their own way.

All the fanciful embellishment of the midsummer night's dream, of the St. John's night dream, is what remained later of the wondrous forms conjured by human imagination that wove through this midsummer time on the soul-spiritual level. This then, in all particulars, was taken to be a divine-spiritual moral revelation of the cosmos to man.

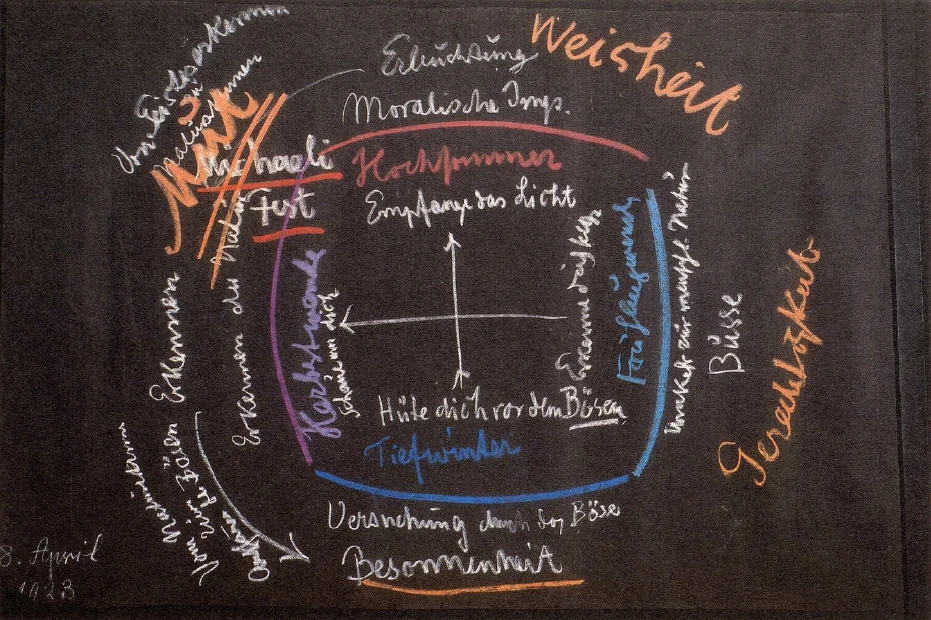

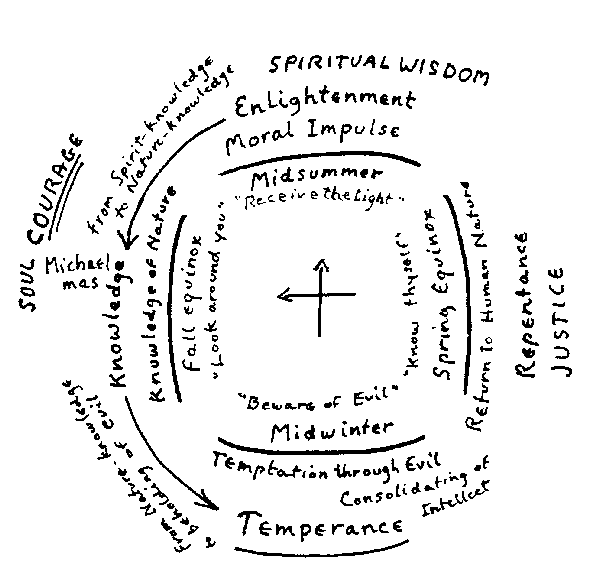

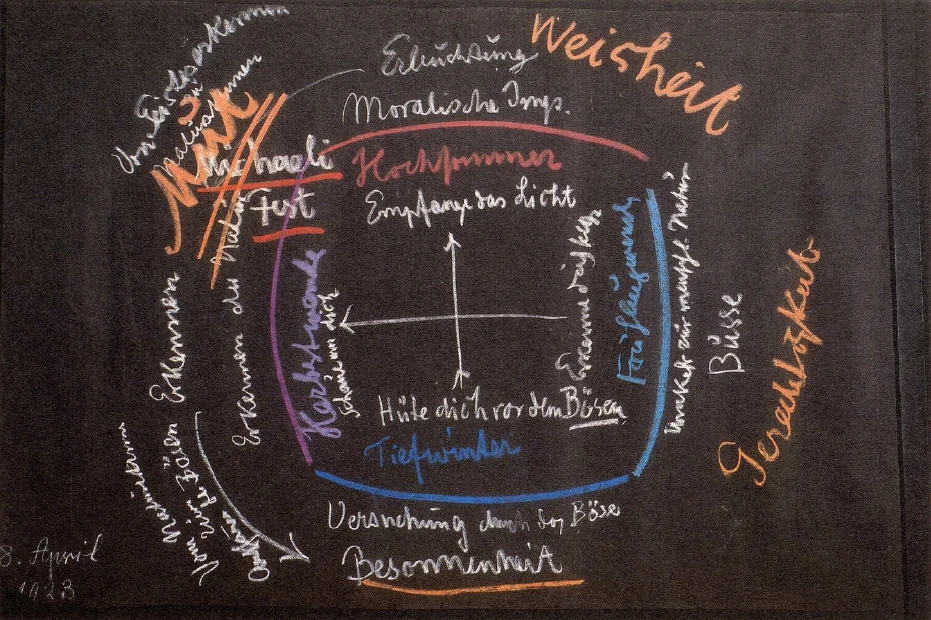

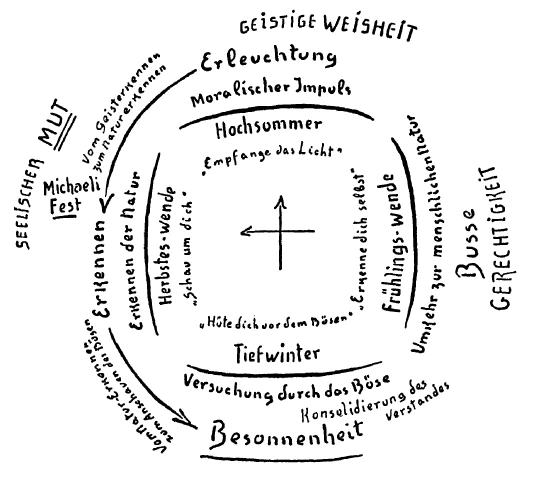

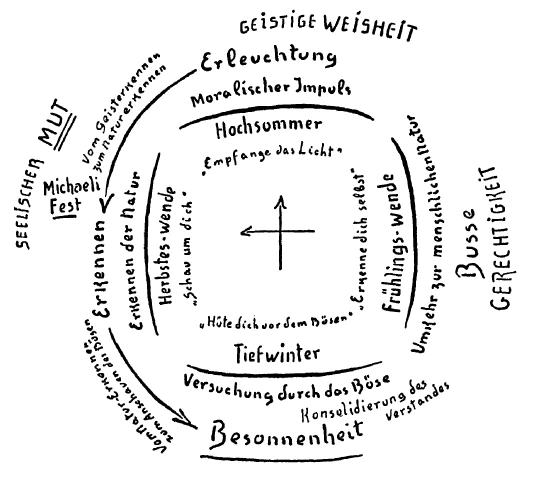

And so we may say that the conception underlying this was: at midsummer the divine-spiritual world revealed itself through moral impulses which were implanted in man as Enlightenment (see diagram). And what was felt in a quite special way at that time, what then worked upon man, was felt to be something super-human which played into the human order of things.

From his inner participation in the festivities celebrated in that time, man knew that he was lifted up above himself as he then was into the super-human, and that the Deity grasped the hand that man as it were reached toward him at this season. Everything that man believed to be divine-spiritual within him he ascribed to the revelations of this season of St. John's.

When the summer came to an end and autumn approached, when the leaves were withered and the seeds had ripened, when, that is, the full luxurious life of summer had faded and the trees become bare, then, because the insights of the Mysteries had flowed into all these perceptions, man felt: “The divine-spiritual world is withdrawing again from man.” He notices how he is directed back to himself; he is in a certain sense growing out of the spiritual into Nature.

Thus man felt this “living-into” the autumn as a “living-out-from” the spiritual, as a living into Nature. The tree leaves became mineralized; the seeds dried up and mineralized. Everything inclined in a certain way towards the death of Nature's year.

In being thus interwoven with what was becoming mineral on the Earth and around the Earth, man felt that he himself was becoming woven together with Nature. For in that period man still stood closer in his inner experience to what was going on outside. And he also thought, he pondered in his mind about how he experienced his being woven-together with Nature. His whole thinking took on this character. If we want to express in our language today what man felt when autumn came, we should have to say the following—I beg you, however, to realize that I am using present-day words, and that in those days man would not have been able to speak thus, for then everything rested on perceptive feeling and was not characterized through thinking—but if we want to speak in modern terms we shall have to say: With his particular trend of thinking, with his feeling way of perceiving, the human being experienced the transition from summer to autumn in such a way that he found in it a passing from spirit-knowledge to Nature-knowledge (see diagram). Toward autumn man felt that he was no longer in a time of spirit-knowledge but that autumn required of him that he should learn to know Nature. Thus at the autumn equinox we have, instead of moral impulse, knowledge of Nature, coming to know Nature.

The human being began to reflect about Nature. At this time also he began to take into account the fact that he was a creature, a being within the cosmos. In that time it would have been considered folly to present Nature-knowledge in its existing form to man during the summer. The purpose of summer is to bring man into relation with the spiritual in the world. With the arrival of what we today call the Michaelmas season, people said to themselves: “By everything that man perceives about him in the woods, in the trees, in the plants, he is stimulated to pursue nature-knowledge.” It was the season in which men were to occupy themselves above all with acquiring knowledge, with reflection. And indeed it was also the time when outer circumstances of life made this possible. Human life thus proceeded from Enlightenment to Knowledge. It was the right season for knowledge, for ever-increasing cognition.

When the pupils of the Mysteries received their instruction from the teachers, they were given certain mottoes of which we find adaptations in the maxims of the Greek sages. The “seven maxims” of the Seven Wise Men of Greece are, however, not actually those which originated in the primeval Mysteries.

In the very earliest Mysteries there was a saying associated with midsummer: “Receive the Light” (see diagram). By “Light,” spiritual wisdom was meant. It designated that within which the human being's own “I” shone.

For autumn (see diagram), the motto imprinted in the Mysteries as an admonition pointing to what should be carried on by the souls was: “Look around thee.”

Now there approached the next development of the year, and with it, what man felt within himself to be connected of itself with this year. The season of winter approached. We come to midwinter (see diagram), which includes our Christmas time. Just as the human being in midsummer felt himself lifted out above himself to the divine-spiritual existence of the cosmos, so he felt himself in midwinter to be unfolding downward below himself. He felt as if the forces of the Earth were washing around him and carrying him along. He felt as though his will nature, his instincts and impulses were infiltrated and permeated by gravity, by the force of destruction and other forces that are in the Earth. In these ancient times people did not feel winter as we feel it, that it merely gets cold and we have to put on warm boots, for example, in order not to get chilled. Rather, a man of that ancient time felt what was coming up out of the Earth as something that united itself with his own being. In contrast to the sultry, light-filled element, he felt what came up then in winter as a frosty element. We feel the chilliness today, too, because it is connected with the corporeality; but ancient man felt within his soul as a phenomenon accompanying the cold: darkness and gloom. He felt somewhat as if all around him, wherever he went, darkness rose up out of the Earth and enveloped him in a kind of cloud—only up to the middle of his body, to be sure, but this is the way he felt.

And he said to himself—again I have to describe it in more modern words—man said to himself: “During the height of summer I stand face to face with Enlightenment; then the heavenly, the super-terrestrial streams down into the earthly world. But now the earthly is streaming upward.”—Man already perceived and experienced something of the earthly during the autumnal equinox. But what he perceived and felt then of earthly nature was in conformity in a certain sense with his own nature; it was still connected with him. We might say: “At the time of the autumn equinox man felt in his Gemuet, in his realm of feeling, all that had to do with Nature. But now, in winter, he felt as though the Earth were laying claim to him, as if he were ensnared in his will nature by the forces of the Earth. He felt this to be the denial of the moral world order. He felt that together with the blackness that enveloped him like a cloud, forces opposed to the moral world order were ensnaring him. He felt the darkness rise up out of the Earth like a serpent and wind him about. But at the same time he was also aware of something quite different.”

Already during autumn he had felt something stirring within him that we today call intellect. Whereas in summer the intellect evaporates and there enters from outside a wisdom-filled moral element, during autumn the intellect is consolidated. The human being approaches evil but his intellect consolidates. Man felt an actual serpent-like manifestation in midwinter, but at the same time the solidification, the strengthening of shrewdness, of the reflective element, of all that made him sly and cunning and incited him to follow the principle of utility in life. All this he was aware of in this way. And just as in autumn the knowledge of nature gradually emerged, so in midwinter the Temptation of Hell approached the human being, the Temptation on the part of Evil. Thus he was aware of this. So when we write here: “Moral impulse, Knowledge of Nature” (see diagram), here (at midwinter) we must write “Temptation through Evil.”

This was just the time in which man had to develop what in any case was within him by way of Nature: everything associated with the intellect, slyness, cunning, all that was directed toward the utilitarian. This, man was to overcome through Temperance (Besonnenheit).1The third of the cardinal or “Platonic” virtues, called in Greek Sophrosyne, in English, Temperance or moderation, in German is Besonnenheit. According to Steiner, Besonnenheit is “enfilling one's impulses with the degree of consciousness possible.” “A man who rules his impulses through reflective thinking, feeling and perceiving is a man who is ‘besonnen.’” (From Das Raetsel des Menschen, 6th August, 1916). See also Spiritual Foundation of Morality by Steiner. This was the season then in which man had to develop—not an open sense for wisdom, which in accordance with the ancient Mystery wisdom had been required of him during the time of Enlightenment, but something else. Just in that season in which evil revealed itself as we have indicated, man could experience in a fitting way resistance to evil: he was to become self-controlled (besonnen—see preceding footnote). Above all else at the season of change which he passed through in moving on from Enlightenment to Cognition, from Knowledge of Spirit to Knowledge of Nature, he was to progress from Nature knowledge to the contemplation of Evil (see diagram, arrow on left). This is the way it was understood.

And in giving instructions to the pupils of the Mysteries which could become mottoes, the teachers said to them—just as at midsummer they had said: “Receive the Light,” and in autumn “Look around you”—now in midwinter it was said: “Beware of Evil.” And it was expected that through “Temperance,” through this guarding of oneself against evil, men would come to a kind of self-knowledge which would lead them to realize how they had deviated from the moral impulses in the course of the year.

Deviation from the moral impulses through the contemplation of evil, its overcoming through moderation—this was to come to man's consciousness just in the time following midwinter. Hence in this ancient wisdom all sorts of things were undertaken that induced men to atone for what they recognized as deviations from the moral impulses they had received through Enlightenment. With this, we approach spring, the spring equinox (see diagram).

And just as here (see diagram: midsummer, autumn, midwinter) we have Enlightenment, Cognition, Temperance, so for the spring equinox we have what was perceived as the activity of repentance. And in place of Cognition, and correspondingly, Temptation through Evil, there now entered something which we could call the Return—the reversion—to man's higher nature through Repentance. Where we have written here (see diagram: midsummer, autumn, winter): Enlightenment, Cognition, Temperance, here we must write: Return to Human Nature.

If you look back once more to what was in the depths of winter the Temptation by Evil, you will have to say: At that time man felt as though he were lowered into the abysmal deeps of the Earth; he felt himself entrapped by Earth's darkness. Just as during the height of summer man was in a sense torn out of himself, his soul-nature being then lifted up above him, so now, in order not to be ensnared by Evil during the winter, his soul-being made itself inwardly free.

Through this there existed during the depths of winter, I might say a counter-image to what was present during the height of summer. At midsummer the phenomena of Nature spoke in a spiritual way. People sought especially in the thunder and the lightning for what the heavens had to say. They looked at the phenomena of Nature, but what they sought in these phenomena was a spiritual language. Even in small things, they sought at St. John's-tide the spiritual message of the elemental beings, but they looked for it outside themselves. They dreamed in a certain sense outside the human being. During the depths of winter, however, people sank into themselves and dreamed within their own being. To the extent that they tore themselves loose from the entanglement of the Earth, that is, whenever they could free their soul-element, they dreamed within their own being. Of this there has remained what is connected with the visions, with the inner beholding, of the Thirteen Nights following the winter solstice. Everywhere recollections have remained of these ancient times. You can look on the Norwegian Song of Olaf [&Åsteson]2Because of Rudolf Steiner's lectures referring to “The Dream Song of Olaf &Åsteson” (December 26, 1911 and January 7, 1913), this unique poem of initiation experience has been translated into English. as a later development of what existed quite extensively in ancient times.

Then the springtime drew near. In our time the situation has shifted somewhat; in those days spring was closer to winter, and the whole year was viewed as being divided into three periods. Things were compressed. Nevertheless what I am sharing with you here was taught in its turn. Thus, just as at midsummer they said: “Receive the light;” and in autumn, at Michaelmas: “Look around you;” just as at midwinter, at the time that we celebrate Christmas, they said: “Beware of the Evil,” so for the time of return they had a saying which was then thought to have effect only at this time: “Know thyself”—placing it in exact polarity to the Knowledge of Nature.

“Beware of the Evil” could also be expressed: “Beware, draw back from Earth's darkness.” But this they did not say. Whereas during midsummer men accepted the external natural phenomenon of light as Wisdom, that is, at midsummer they spoke in a certain way in accordance with Nature, they would never have put the motto for winter into the sentence: “Beware of the darkness”—for they expressed rather the moral interpretation: “Beware of Evil.”

Echoes of these festivals have persisted everywhere, so far as they have been understood. Naturally everything was changed when the great Event of Golgotha entered in.

It was in the season of the deepest human temptation, in winter, that the birth of Jesus occurred. The birth of Jesus took place in the very time when man was in the grip of the Earth powers, when he had plunged down, as it were, into the abysses of the Earth. Among the legends associated with the birth of Jesus, you will even find one which says that Jesus came into the world in a cave, thus hinting at something that was perceived as wisdom in the most ancient Mysteries, namely, that there the human being can find what he has to seek in spite of being held fast by the dark element of the Earth, which at the same time holds the reason for his falling prey to Evil.

It is in accord with all of this, too, that the time of Repentance is ascribed to the season when spring is approaching.

The understanding for the midsummer festival has quite naturally disappeared to a still greater extent than that for the other side of the year's course. For the more materialism overtook mankind, the less people felt themselves drawn to anything such as Enlightenment.

And what is of quite special importance to present-day humanity is precisely that time which leads on from Enlightenment, of which man still remains unconscious, toward the season of autumn. Here lies the point where man, who indeed has to enter into knowledge of nature, should grasp in the nature-knowledge a picture, a reflection, of a knowledge of divine spirits. For this there is no better festival of remembrance than Michaelmas.

If this is celebrated in the right way, it must follow that mankind everywhere will take hold of the question: How is spirit knowledge to be found in the glorified nature-knowledge of the present? How can man transform nature-knowledge so that out of what the human being possesses as the fruits of this nature-knowledge, spirit knowledge will arise? In other words, how is that to be overcome which, if it were to run its course on its own, would entrap man in the subhuman?

A turnaround must take place. The Michael festival must take on a particular meaning. This meaning emerges when one can perceive the following: Natural science has led man to recognize one side of world evolution, for example, that out of lower animal organisms higher more perfect ones have evolved in the course of time, right up to man; or, to take another example, that during the development of the embryo in the mother's body the human being passes through the animal forms one after the other. That, however, is only one side. The other side is what comes before our souls when we say to ourselves: “Man had to evolve out of his original divine-human beginning.” If this (see drawing) indicates the original human condition (lighter shading), then man had to evolve out of it to his present state of unfoldment. First, he had gradually to push out of himself the lower animals, then, stage by stage what exists as higher animal forms. He overcame all this, separated it out, thrust it aside (darker shading). In this way he has come to what was originally predestined for him.

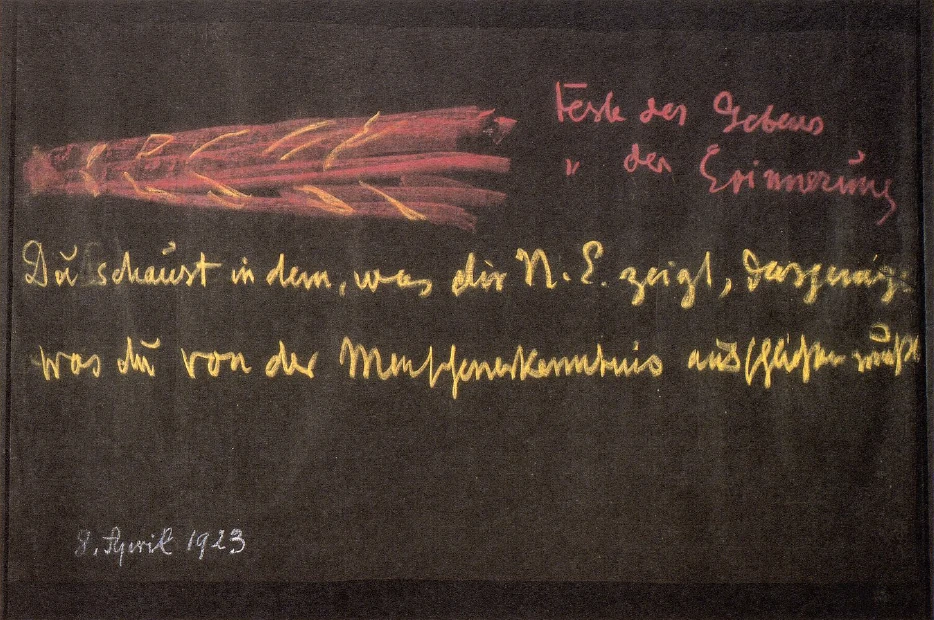

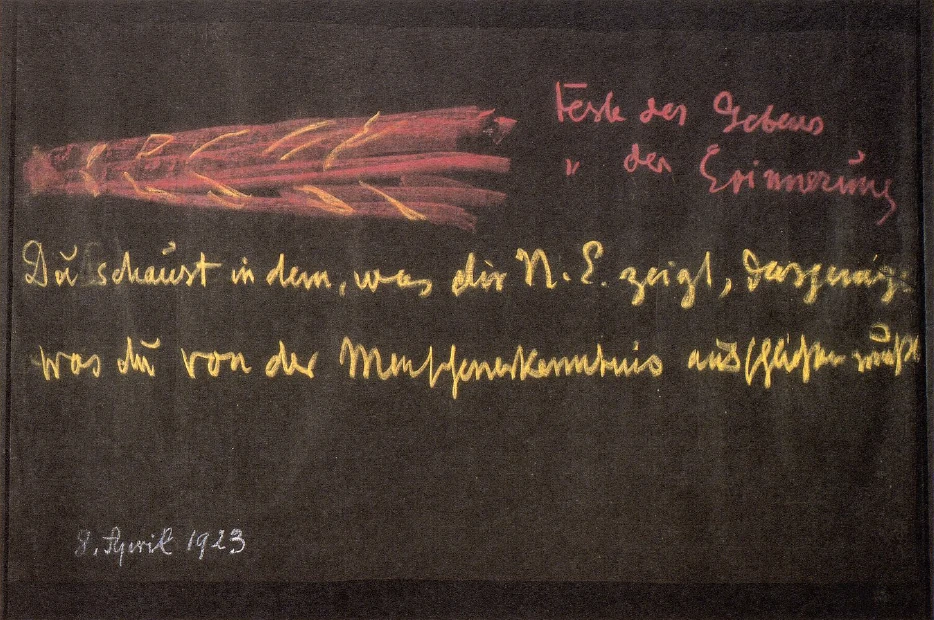

It is the same in his embryonic development. The human being rejects, each in its turn, everything that he is not to be. We do not, however, derive the real import of present-day nature-knowledge from this fact. What then is the import of modern nature-knowledge. It lies in the sentence: You behold in what nature-knowledge shows you that which you need to exclude from knowledge of man.

What does this imply? It implies that man must study natural science. Why?—When he looks into a microscope he knows what is not spirit. When he looks through a telescope into the far spaces of the universe, there is revealed to him what spirit is not. When he makes some sort of experiment in the physics or chemistry laboratory, what is not spirit is revealed to him. Everything that is not spirit is manifest to him in its pure form.

In ancient times when men beheld what is today nature, they still saw the spirit shining through it. Today we have to study nature in order to be able to say: “All that is not spirit.” It is all winter wisdom. What pertains to summer wisdom must take a different form. In order that man may be spurred toward the spirit, may get an impulse toward the spirit, he must learn to know the unspiritual, the anti-spiritual. And man must be sensible of things that no one as yet admits today. For example, everyone says today: “If I have some sort of tiny living creature too small to be seen with the naked eye and I put it under a microscope, it will be enlarged for me so that I can see it.”—Then, however, one must conceive: “This size is illusory. I have increased the size of the creature, and I no longer have it. I have a phantom. What I am seeing is not a reality. I have put a lie in place of the truth!”—This is of course madness from the present-day point of view, but it is precisely the truth.

If we will only realize that natural science is needed in order from this counter-image of the truth to receive the impulse toward the truth, then the force will be developed which can be symbolically indicated in the overcoming of the Dragon by Michael.

But something else is connected with this which already stands in the annals in what I might call a spiritual way. It stands there in such a form, however, that when man no longer had any true feeling for what lives in the year's changing seasons, he related the whole thing instead to the human being. What leads to “Enlightenment” was replaced by the concept of “Wisdom” [called “Prudence” in English practice]; then what leads to “Knowledge” was replaced by the concept of “Courage” [“Fortitude”]; “Temperance” stayed the same (see diagram 1); and what corresponded to “Repentance” was replaced by the concept “Justice.”

Here you have the four Platonic concepts of virtue: Wisdom [Prudence], Fortitude, Temperance, Justice. What man had formerly received from the life of the year in its course was now taken into man himself. It will come into consideration just in connection with the Michaelmas festival, however, that there will have to be a festival in honor of human courage, of the human manifestation of the courage of Michael. For what is it that holds man back today from spirit-knowledge?—Lack of soul courage, not to say soul cowardice. Man wants to receive everything passively, wants to set himself down in front of the world as if it were a movie, and wants to let the microscope and the telescope tell him everything. He does not want to temper the instrument of his own spirit, of his own soul, by activity. He does not care to be a follower of Michael. This requires inner courage. This inner courage must have its festival in Michaelmas. Then from the Festival of Courage, from the festival of the inwardly courageous human soul, there will ray out what will give the other festivals of the year also the right content.

We must in fact continue the path further; we must take into human nature what was formerly outside. Man is no longer in such a position that he could develop the knowledge of Nature only in autumn. It is already so that in man today things lie one within the other, for only in this way can he unfold his freedom. Yet it nevertheless holds true that the celebrating of festivals, I might say in a transformed sense, is again becoming necessary.

If the festivals were formerly festivals of giving by the divine to the earthly, if man at the festivals formerly received the gifts of the heavenly powers directly, so today, when man has his capacities within himself, the metamorphosis of the festival-thought consists in the festivals now being festivals of remembrance or admonition.3Feste der Erinnerungen (a plural form). Erinnerung has two shades of meaning. One is “recollection” or “remembrance”; the other “admonition” or “reminder.” Both elements seem to apply in this passage. In them man inscribes into his soul what he is to consummate within himself.

And thus again it will be best to have as the most strongly working festival of admonition and remembrance this festival with which autumn begins, the Michaelmas festival, for at the same time all Nature is speaking in meaningful cosmic language. The trees are becoming bare; the leaves are withering. The creatures, which all summer long have fluttered through the air, as butterflies, or have filled the air with their hum, as beetles, begin to withdraw; many animals fall into their winter sleep. Everything becomes paralyzed. Nature, which through her own activity has helped man during spring and summer—Nature, which has worked in man during spring and summer, herself withdraws. Man is referred back to himself. What must now awaken when Nature forsakes him is courage of soul. Once more we are shown how what we can conceive as a Michael festival must be a festival of soul-courage, of soul-strength, of soul-activity.

This is what will gradually give to the festival thought the character of remembrance or admonition, qualities already suggested in a monumental saying by which it was indicated that for all future time what previously had been festivals of gifts will become, or should become, festivals of remembrance. These monumental words, which must be the basis of all festival thoughts, also for those which will arise again,—this monumental saying is: “This do in remembrance of Me.” That is the festival thought which is turned toward the memory-aspect.

Just as the other thought that lies in the Christ-Impulse must work on livingly, must reform itself and not be allowed simply to remain as a dead product toward which we look back, so must this thought also work on further, kindling perceptive feeling and thought, and we must understand that the festivals must continue in spite of the fact that man is changing, but that because of this the festivals also must go through metamorphoses.

Fünfter Vortrag

Um die Betrachtung, die ich gestern hier angestellt habe über jenes Verhältnis, das sich in alten Zeiten unter dem Einfluß der Mysterien zwischen dem Menschen und dem Naturlauf ausgebildet hatte, auf einen noch weiteren Horizont zu bringen, will ich heute eingehen auf dasjenige, was in jenen alten Zeiten geglaubt worden ist in bezug auf alles, was man durch diesen Naturlauf als Mensch von dem Weltenall empfing. Sie haben ja aus dem gestrigen Vortrage entnehmen können — auch vielleicht in Erinnerung an manches, was ich über solche Dinge um die letzte Weihnachtszeit noch in dem uns nun entrissenen Goetheanum ausführen konnte -, daß der Jahreslauf in seinen Erscheinungen empfunden wurde, ja auch heute noch empfunden werden kann als ein Lebensablauf, als etwas, was in bezug auf den äußeren Verlauf ebenso der Ausdruck eines dahinterstehenden lebendigen Wesens ist, wie die Äußerungen des menschlichen Organismus solche Offenbarungen eines Wesens, der menschlichen Seele selber sind.

Erinnern wir uns daran, wie die Menschen unter diesem alten Mysterieneinfluß zur Hochsommerzeit, zu der Zeit, die wit heute als die Johannizeit empfinden, ein gewisses Verhältnis zu ihrem Ich empfunden haben; zu demjenigen Ich aber, das sie dazumal noch nicht sich selbst ausschließlich zuschrieben, sondern das sie noch versetzten in den Schoß des Göttlich-Geistigen. Diese Menschen glaubten eben, daß sie durch alle diese Verrichtungen, die ich geschildert habe, sich während der Hochsommerzeit ihrem Ich näherten, das sich durch den übrigen Jahreslauf hindurch vor den Menschen verbirgt. Natürlich dachten sich die Menschen als ganzes Wesen überhaupt im Schoße des Göttlich-Geistigen befindlich. Allein sie dachten, während der übrigen Dreiviertel des Jahres offenbart sich ihnen nichts von dem, was zu ihnen als ihr Ich gehört; nur in diesem einen Viertel, das seinen Höhepunkt zur Johannizeit hatte, da offenbart sich ihnen gewissermaßen durch ein Fenster, das hereinerrichtet war aus der göttlich-geistigen Welt, die Wesenheit ihres eigenen Ich.

Nun wurde aber diese Wesenheit des eigenen Ich innerhalb der göttlich-geistigen Welt, in der sie sich offenbarte, nicht in einem so neutralen, gleichgültigen, ja, man kann schon sagen phlegmatischen Erkenntniswege gedacht, wie das heute der Fall ist. Wenn heute von dem Ich gesprochen wird, so denkt ja der Mensch eigentlich dabei kaum irgendwelche wirkliche Beziehung zu dieser oder jener Welt. Er denkt sich das Ich gewissermaßen als einen Punkt, von dem ausstrahlt, was er tut, in den einstrahlt, was er erkennt. Aber es ist durchaus eine Art phlegmatischer Empfindung, die der Mensch heute gegenüber seinem Ich hat. Man kann nicht einmal sagen, daß der heutige Mensch in seinem Ich, trotzdem dieses ja das Ego ist, den eigentlichen Egoismus empfindet; denn wenn er ehrlich sein will, kann er sich ja gar nicht sagen, er habe sein Ich besonders gern. Er hat seinen Leib gern, er hat seine Instinkte gern, er hat diese oder jene Erlebnisse gern, Aber das Ich ist ja nur ein Wörtchen, das als Punkt empfunden wird, und in dem eben all das Angedeutete so mehr oder weniger zusammengefaßt wird. Aber in jener Zeit, in der die Annäherung an dieses Ich festlich begangen wurde, in der man schon lange Vorbereitungen machte, um gewissermaßen sein Ich im Weltenall zu treffen, in der Zeit, in der man dann wiederum empfand, wie dieses Ich sich allmählich zurückzog und den Menschen mit seinem leiblich-seelischen Wesen — was wir heute nennen würden physisch-ätherisch-astralisches Wesen - allein ließ, in jener Zeit empfand man das Ich wirklich in Beziehung zu dem ganzen Kosmos, zu der ganzen Welt.

Aber was man vor allen Dingen empfand gegenüber diesem Ich in seinem Verhältnis zur Welt, das war nicht etwas Naturalistisches, wenn wir das heutige Wort gebrauchen, das war nicht etwas, was nur als äußere Erscheinung aufgefaßt wurde, sondern es war etwas, was im wesentlichen als der Mittelpunkt der alten, der uralten moralischen Weltanschauung galt. Man nahm nicht an, daß dem Menschen große Naturgeheimnisse geoffenbart wurden in dieser Zeit. Gewiß, solche Naturgeheimnisse - wir haben sie gestern ausgesprochen -, auf die achtete der Mensch nicht in allererster Linie damals, sondern er hatte die Empfindung, daß vor allen Dingen dasjenige, was er als moralische Impulse in sich aufnehmen soll, sich in dieser Hochsommerzeit offenbart, in der Licht und Wärme ihren höchsten Stand erreichen. Es war die Zeit, die der Mensch empfand als die göttlich-moralische Erleuchtung. Und was man vor allen Dingen als Antwort von den Himmeln erhalten wollte durch die musikalischen, poetischen, tänzerischen Aufführungen, die damals gepflegt wurden, was man erwartete, das war, daß sich offenbarte aus den Himmeln in allem Ernste dasjenige, was die Himmel in moralischer Beziehung von den Menschen verlangten.

Wenn es sich einmal zutrug, daß alle diese Verrichtungen gepflogen wurden, die ich gestern beschrieben habe, daß in schwüler Sommerzeit diese Feste gefeiert wurden und dann ein mächtiges Gewitter hereinbrach mit Blitz und Donner, dann fühlte man gerade in dem Hereinbrechen von Blitz und Donner die moralische Ermahnung der Himmel an die Erdenmenschheit. Aus diesen alten Zeiten ist zurückgeblieben, was sich etwa in der Anschauung über den Zeus findet, daß er der Donnergott ist, der Gott, der mit dem Blitze ausgestattet ist. Ähnliches knüpft sich an den deutschen Donar-Gott an. Das auf der einen Seite, und auf der andern Seite das Folgende.

Man empfand ja da, ich möchte sagen, die in sich gesättigte, warme, leuchtende Natur, man empfand dasjenige, was leuchtende, wärmende Natur während des Tages war, auch in die Nachtzeit hinein und man machte nur den Unterschied, daß man sich sagte: Während des Tages ist die Luft angefüllt mit dem Wärmeelemente, mit dem Lichtelemente. Da weben und leben im Wärme- und im Lichtelemente die geistigen Boten, durch die sich die höheren göttlichen Wesenheiten den Menschen kundgeben wollen, sie ausstatten wollen mit moralischen Impulsen. Aber des Nachts, wenn sich zurückziehen die höheren geistigen Wesenheiten, dann bleiben die Boten und offenbaren sich auf ihre Weise. -— Und so empfand man besonders zu dieser Hochsommerzeit das Walten und Weben der Natur in den Sommernächten, in den Sommerabenden. Und was man da erlebte, war einem etwas wie ein in der Wirklichkeit erlebter Sommertraum, ein Sommertraum, durch den man sich der göttlich-geistigen Welt besonders genähert hatte; ein Sommertraum, von dem man überzeugt war, daß da alles, was Naturerscheinung war, zu gleicher Zeit moralische Sprache der Götter war, daß da aber auch allerlei Elementarwesen wirkten und sich auf ihre Art den Menschen zeigten.

Alles, was die Ausschmückung des Sommernachtstraumes, des Johanninachtstraumes ist, das ist dasjenige, was später geblieben ist von den wunderbaren Ausgestaltungen, welche die menschliche Imagination einmal vollzog für alles das, was geistig-seelisch diese Hochsommerzeit durchzog, was aber im großen und kleinen genommen wurde als eine geistig-göttlich-moralische Offenbarung des Kosmos an die Menschen. Und so dürfen wir sagen, daß die Vorstellung, die da zugrunde lag, diese war: In der Hochsommerzeit offenbarte sich die göttlich-geistige Welt durch moralische Impulse, die den Menschen eingepflanzt wurden in Erleuchtung (siehe Schema Seite 76). Und was man da ganz besonders empfand, was da wirkte auf die Menschen, das empfand man als ein, ich möchte sagen, Übermenschliches, das hereinspielte in die menschliche Ordnung. Der Mensch wußte aus dem Mitempfinden dieser Festlichkeiten, die da gefeiert wurden, daß er, so wie er nun einmal in jener Zeit war, über sich selber hinausgehoben wurde ins Übermenschliche, daß gewissermaßen die Gottheit die ihr von dem Menschen zu dieser Zeit entgegengestreckte Hand nahm. Alles, was man glaubte göttlich-geistig zu haben, das schrieb man den Offenbarungen dieser Johannizeit zu.

Wenn nun der Sommer zu Ende ging und die Herbsteszeit heraufkam, wenn die Blätter welk wurden, die Saaten reiften, wenn also das volle strotzende Leben des Sommers bleichte, die Bäume kahl wurden, dann empfand man, weil überall in diese Empfindungen hineingeströmt wurden die Erkenntnisse der Mysterien: Die göttlich-geistige Welt zieht sich wiederum von dem Menschen zurück. Er spürt, wie er auf sich selbst zurückgewiesen wird; er wächst gewissermaßen aus dem Geistigen heraus in die Natur hinein. - So empfand der Mensch dieses Hineinleben in den Herbst als ein Herausleben aus dem Geistigen, als ein Hineinleben in die Natur. Die Blätter der Bäume mineralisierten sich, die Saaten wurden dürr, mineralisierten sich. Alles neigte sich gewissermaßen nach dem Jahrestode der Natur hin.

In diesem Verwobensein mit dem Mineralischwerden dessen, was auf Erden war und die Erde umgab, empfand man ein Verwobenwerden des Menschen selber mit der Natur. Der Mensch stand dazumal in seinem inneren Erleben noch näher dem, was sich äußerlich zutrug. Und so dachte er auch, sann er auch in dem Sinne, wie er dieses Verwobenwerden mit der Natur erlebte. Sein ganzes Denken nahm diesen Charakter an. Würden wir heute in unserer Sprache das ausdrücken wollen, was da der Mensch empfand, wenn der Herbst kam, so müßten wir folgendes sagen. Ich bitte Sie aber, die Sache so aufzufassen, daß ich mit heutigen Worten spreche, daß man also dazumal natürlich nicht in der Lage gewesen wäre, so zu sprechen. Dazumal war ja alles durchaus Empfindung, man charakterisierte die Dinge ja nicht denkend. Wenn man aber in heutigen Worten, in unseren Worten sprechen wollte, so müßte man sagen: Der Mensch empfand diesen Übergang so, daß er mit seiner Denkrichtung, mit seiner Empfindungsart den Übergang fand vom Geisteserkennen zum Naturerkennen (siehe Schema Seite 76). Das empfand der Mensch, daß er gegen den Herbst zu nicht mehr im Geist-Erkennen war, sondern daß der Herbst von ihm verlangte, daß er die Natur erkennen sollte. So daß wir bei der Herbstwende nicht mehr die moralischen Impulse haben, sondern das Erkennen der Natur. Der Mensch fing an, über die Natur nachzudenken.

So war es auch in der Zeit, als man damit rechnete, daß der Mensch ein Geschöpf, ein Wesen innerhalb des Kosmos war. In jener Zeit hätte man es als einen Unsinn betrachtet, im Sommer Naturerkennen in der damaligen Form an den Menschen heranzubringen. Der Sommer ist da, um den Menschen in Beziehung zum Geistigen der Welt zu bringen. Wenn die Zeit begann, die wir heute die Michaelizeit nennen würden, da war es, daß man sagte: Aus alledem, was der Mensch um sich herum empfindet in den Wäldern, in den Bäumen, in den Pflanzen, da wird er angeregt, Naturerkenntnis zu treiben. — Es war überhaupt die Zeit, in welcher die Menschen dazu kommen sollten, Erkenntnis, Nachdenklichkeit zu ihrer Beschäftigung zu machen. Es war ja auch die Zeit, wo das die äußeren Lebensverhältnisse möglich machten. Also es ging über das menschliche Leben von der Erleuchtung in das Erkennen. Es war die Zeit der Erkenntnis, der immer sich steigernden Erkenntnis.

Wenn die Mysterienschüler ihren Unterricht empfingen von den Mysterienlehrern, dann gaben ihnen diese solche Sprüche mit, wie wir sie dann in den Sprüchen der griechischen Weisen irgendwie wieder nachgebildet finden. Aber es sind diese sieben Sprüche der sieben griechischen Weisen nicht die der ursprünglichen Mysterien. In den ursprünglichen Mysterien gab es für den Hochsommer den Spruch:

Empfange das Licht

und man bezeichnete mit dem Lichte eigentlich die geistige Weisheit. Man bezeichnete dasjenige, innerhalb dessen das eigene menschliche Ich strahlte.

Für den Herbst wurde der Spruch geprägt in den Mysterien, um zu ermahnen zu dem, was getrieben werden sollte von den Seelen:

Schaue um dich.

Nun näherte sich dann die Entwickelung des Jahres und damit auch dasjenige, was der Mensch in sich selber von sich verbunden mit diesem Jahre fühlte, es näherte sich das der Winterzeit. Wir kommen in den Tiefwinter hinein, der unsere Weihnachtszeit enthält. Ebenso wie sich der Mensch in der Hochsommerzeit über sich hinausgehoben fühlte zu dem göttlich-geistigen Dasein des Kosmos, so fühlte sich der Mensch in der Tiefwinterzeit wie unter sich herunterentwickelt. Er fühlte sich gewissermaßen wie von den Kräften der Erde umspült, von den Kräften der Erde mitgenommen. Er fühlte so etwas, wie wenn seine Willensnatur, seine Instinkt- und Triebnatur durchsetzt und dutchströmt wäre von Schwerkraft, von Zerstörungskraft und andern Kräften, die in der Erde sind. Der Mensch fühlte den Winter nicht so in diesen alten Zeiten, wie wir ihn fühlen, daß uns bloß kalt wird und daß wir zum Beispiel Stiefel anziehen, damit uns nicht kalt wird, sondern der Mensch fühlte das, was von der Erde heraufkam, als etwas, was sich jetzt mit seinem eigenen Wesen vereinigte. Er fühlte sozusagen den Gegensatz des schwülen, des lichtvollen Elementes als ein frostiges Element, das heraufkam. Das Frostige, das fühlen wir ja auch noch heute, denn das bezieht sich auf die Körperlichkeit, aber der alte Mensch fühlte seelisch als Begleiterscheinung des Frostigen das Dunkle, das Finstere. Er fühlte gewissermaßen, als ob sich überall, wo er ging, aus der Erde heraus das Finstere höbe und ihn wolkenförmig einschlösse, nur bis zu seiner Körpermitte herauf allerdings, aber so fühlte der Mensch. Und dann sagte er sich - ich muß das wiederum mit etwas neueren Worten charakterisieren -, dann sagte sich der Mensch: Während des Hochsommers stehe ich der Erleuchtung gegenüber, da strömt in diese Erdenwelt herein, was himmlischüberirdisch ist, jetzt strömt das Irdische herauf.

Aber etwas vom Irdischen hat der Mensch schon während der Herbstwende erlebt und empfunden. Da hat er aber von der Erdennatur etwas erlebt und empfunden, was ihm gewissermaßen noch konform war, was noch etwas mit ihm zu tun hatte. Wir könnten etwa auch sagen: Der Mensch fühlte in der Herbstwende das Natürliche in seinem Gemüte, in seiner Gefühlswelt. Jetzt aber fühlte er, wie wenn die Erde ihn in Anspruch nähme, wie wenn er umgarnt würde von den Kräften der Erde in bezug auf seine Willensnatur. Das fühlte er wie das Gegenteil der moralischen Weltordnung. Er fühlte zugleich mit dieser Schwärze, die ihn wolkenförmig einhüllte, die Gegenkräfte gegen das Moralische ihn umgarnen. Er fühlte die Finsternis schlangenförmig aus der Erde aufsteigen und ihn umwinden. Aber er fühlte zu gleicher Zeit mit diesem noch etwas anderes. Schon während des Herbstes hatte er gefühlt, daß sich etwas regt, was wir heute Verstand nennen. Während im Sommer der Verstand ausdünstet und von außen herein das Moralisch-Weisheitsvolle kommt, konsolidiert sich während des Herbstes der Verstand. Der Mensch nähert sich dem Bösen, aber sein Verstand konsolidiert sich. Man hat durchaus etwas wie eine Schlangenoffenbarung gefühlt in der Tiefwinterzeit, aber zugleich das Konsolidieren, das Stärkerwerden der Klugheit, des Nachdenklichen, dessen, was den Menschen schlau und listig machte, was ihn dazu anspornte, die Nützlichkeitsprinzipien im Leben zu verfolgen. Das alles empfand man in dieser Weise. Und so wie im Herbste allmählich die Erkenntnis der Natur heraufkam, so kam in der Tiefwinterzeit heran an die Menschen die Versuchung der Hölle, die Versuchung von seiten des Bösen. So empfand man das. So daß, wenn wir hier schreiben (siehe Schema Seite 76): Moralischer Impuls, Erkennen der Natur -, wir nun hier, bei Tiefwinter, schreiben müssen: Versuchung durch das Böse.

Und das war eben die Zeit, in der der Mensch entwickeln mußte, was sich in ihm ja ohnedies naturhaft zusammenschloß: das Verstandesmäßige, das Schlaue, das Listige, das auf das Nützliche Gerichtete. Das sollte der Mensch bezwingen durch die Besonnenheit. Es war die Zeit eben, in der der Mensch entwickeln mußte nun nicht den offenen Sinn für die Weisheit, den man von ihm im Sinne der alten Mysterienweisheit verlangte während der Zeit der Erleuchtung. Gerade in der Zeit, in der sich das Böse in der angedeuteten Weise offenbarte, konnte der Mensch den Widerstand gegen das Böse in entsprechender Weise empfinden: er sollte besonnen werden. Er sollte vor allen Dingen jetzt bei dieser Wendung, die er da durchmachte, während er von der Erleuchtung zum Erkennen übergegangen war, eben vom Geisteserkennen zum Naturerkennen, jetzt übergehen vom Naturerkennen zur Anschauung des Bösen. So faßte man das auf. Und den Schülern der Mysterien, denen man Lehren geben wollte, die ihnen Geleitworte sein konnten, wie man ihnen im Hochsommer sagte: Empfange das Licht -, wie man ihnen im Herbst sagte: Schaue um dich -, ihnen sagte man im Tiefwinter: Hüte dich vor dem Bösen.

Und man rechnete darauf, daß durch diese Besonnenheit, durch dieses Sich-Hüten vor dem Bösen die Menschen zu einer Art von Selbsterkenntnis kommen, die sie dann dazu führt, einzusehen, wie sie im Jahreslaufe abgewichen waren von den moralischen Impulsen.

Das Abweichen von den moralischen Impulsen durch das Anschauen des Bösen, seine Überwindung durch die Besonnenheit, das sollte den Menschen gerade in der Zeit, die auf die 'Tiefwinterzeit folgte, zum Bewußtsein kommen. Deshalb wurde in diese Weisheit allerlei aufgenommen, was die Menschen anleitete, Buße zu tun für dasjenige, wovon sie eingesehen hatten, daß es abweichend war von dem, was sie an moralischen Impulsen durch die Erleuchtung bekommen hatten.

Wir nähern uns dem Frühling, der Frühlingswende. Und ebenso wie wir hier (siehe Schema Seite 76: Hochsommer, Herbst, Tiefwinter) die Erleuchtung haben, das Erkennen, die Besonnenheit, so haben wir für die Frühlingswende dasjenige, was empfunden wurde als Bußetätigkeit. Und an die Stelle des Erkennens, beziehungsweise der Versuchung durch das Böse, trat jetzt etwas, was man nennen konnte die Umkehr, die Wiederhinwendung zu seiner höheren Natur durch die Buße. Haben wir hier geschrieben: Erleuchtung, Erkennen, Besonnenheit —, so müssen wir hier schreiben: Umkehr zur menschlichen Natur.

Wenn Sie noch einmal zurückblicken zu dem, was in der Tiefwinterzeit die Zeit der Versuchung durch das Böse war, so werden Sie sagen müssen: Da fühlte sich eben der Mensch wie versenkt in die Klüfte der Erde. Er fühlte sich umgarnt von der Erdenfinsternis. Da war es, wo gerade so, wie er gewissermaßen während der Hochsommerzeit aus sich herausgerissen war, wie sein Seelisches über ihn selbst erhoben wurde, wo sich jetzt innerlich, um nicht umgarnt zu werden von dem Bösen während der Tiefwinterzeit, das Seelische frei machte. Dadurch war während der Tiefwinterzeit, ich möchte sagen, ein Gegenbild da zu dem, was in der Hochsommerzeit da war.

In der Hochsommerzeit sprachen die Naturerscheinungen auf geistige Art. Man suchte in Blitz und Donner insbesondere die Sprache der Himmel. Man blickte auf die Naturerscheinungen hin, aber man suchte in den Naturerscheinungen geistige Sprache. Selbst in den Kleinigkeiten suchte man in der Johannizeit die geistige Sprache der Elementarwesen, aber außerhalb. Man träumte gewissermaßen außerhalb des Menschen.

In der Tiefwinterzeit nun versenkte man sich in sich und träumte innerhalb des Menschen. Indem man sich losriß von der Umgarnung der Erde, träumte man innerhalb des Menschen, wenn man sein Seelisches losreißen konnte. Und von diesem ist geblieben dasjenige, was sich knüpft an die Schauungen, an das innere Schauen der dreizehn Nächte nach der Wintersonnenwendezeit. Es sind überall an diese alten Zeiten Erinnerungen zurückgeblieben. Sie können geradezu das norwegische Olaf-Lied als eine spätere Ausbildung dessen ansehen, was in alten Zeiten in ganz besonderem Maße vorhanden war.

Dann nahte die Frühlingszeit. Heute hat sich die Sache etwas verschoben; die Frühlingszeit war damals mehr gegen den Winter zugeneigt. Überhaupt wurde das Ganze angesehen als in drei Jahresperioden gelegt. Es wurden auch die Dinge zusammengeschoben, aber dennoch, das, was ich Ihnen hier mitteile, wurde wiederum gelehrt. So wie man zur Hochsommerzeit sagte: Empfange das Licht -, zur Herbsteszeit, zur Michaelizeit: Schaue um dich -, so wie man in der Tiefwinterzeit, in derjenigen Zeit, wo wir das Weihnachtsfest haben, sagte: Hüte dich vor dem Bösen -, so hatte man für die Zeit der Umkehr einen Spruch, der nur für diese Zeit dazumal als wirksam gedacht worden ist:

Erkenne dich selbst

gerade gegenübergestellt dem Erkennen der Natur.

Hüte dich vor dem Bösen — könnte man auch so aussprechen: Hüte dich, zucke zurück vor dem Erdendunkel. — Aber das hat man nicht gesagt. Während man zur Hochsommerzeit die äußere Naturerscheinung des Lichtes für die Weisheit nahm, also zur Hochsommerzeit gewissermaßen auf naturhafte Weise sprach, so würde man den Spruch zur Winterzeit nicht hineingegossen haben in den Satz: Hüte dich vor der Finsternis -, sondern da sprach man die moralische Deutung aus: Hüte dich vor dem Bösen.

Überall sind dann die Anklänge an diese Feste geblieben, soweit man die Dinge verstanden hat. Natürlich ist alles anders geworden, als das große Ereignis von Golgatha eintrat. In die Zeit der tiefsten Menschenversuchung, in die Winterzeit hinein fiel die Geburt Jesu. Die Geburt Jesu fiel in die Zeit, in der der Mensch eben umklammert war von den Erdenmächten, gewissermaßen hinunterversenkt war in die Erdenklüfte. Sie finden unter den Sagen, die sich anschließen an die Geburt Jesu, auch eine, welche davon spricht, daß Jesus in einer Höhle zur Welt gekommen sei, womit eben hingedeutet wird auf etwas, was als Weisheit in den allerältesten Mysterien empfunden wurde: daß der Mensch da dasjenige, was er zu suchen hat, finden könne trotz seiner Umklammerung von dem Irdisch-Finsteren, das zugleich die Gründe enthält, warum der Mensch dem Bösen verfallen kann. Und ein Anklang an all das ist dann, daß in die Zeit, wo der Frühling herannaht, die Bußezeit gelegt wird.

Für das Hochsommerfest ist natürlich das Verständnis noch mehr geschwunden als für die andere Seite des Jahreslaufes. Denn je mehr der Materialismus über die Menschheit hereinbrach, desto weniger fühlte man sich hingezogen zur Erleuchtung oder dergleichen. Und was für die gegenwärtige Menschheit von ganz besonderer Wichtigkeit ist, das ist eben diejenige Zeit, die von der Erleuchtung, die zunächst den Menschen noch unbewußt bleibt, hinführt gegen die Herbsteszeit hin. Da liegt der Punkt, wo der Mensch, der ja in das Naturerkennen hinein muß, im Naturerkennen das Abbild eines Gottgeist-Erkennens erfassen soll. Dafür gibt es kein besseres Erinnerungsfest als das Michaeli-Fest. Von diesem muß ausgehen, wenn es in der richtigen Weise gefeiert wird, die allmenschliche Erfassung der Frage: Wie wird in dem gloriosen Naturerkennen der Gegenwart die GeistErkenntnis gefunden, wie metamorphosiert man die Naturerkenntnisse so, daß aus dem, was der Mensch als Naturerkenntnisse hat, ihm die Geist-Erkenntnis wird? - Wie wird, mit andern Worten, dasjenige besiegt, was, wenn es in sich verläuft, den Menschen mit dem Untermenschlichen umgarnen müßte?

Eine Wendung muß eintreten. Das Michaeli-Fest muß einen bestimmten Sinn bekommen. Der Sinn ergibt sich dann, wenn man das Folgende empfinden kann: Die Naturwissenschaft hat den Menschen dazu geführt, die eine Seite der Weltentwickelung zu erkennen, zum Beispiel, daß sich aus niederen tierischen Organismen höhere, vollkommenere und so weiter bis herauf zum Menschen ergeben haben im Laufe der Zeit, oder daß der Mensch während der Keimesentwickelung im Mutterleibe die Tierformen nacheinander durchmacht. Das ist aber nur die eine Seite. Die andere Seite ist die, welche vor unsere Seele tritt, wenn wir uns sagen: Der Mensch hat sich aus seiner ursprünglich göttlich-menschlichen Anlage herausentwickeln müssen. Wenn dieses (siehe Zeichnung) die ursprüngliche menschliche Anlage ist (hell schraffiert), so hat sich herausentwickeln müssen der Mensch zu seiner heutigen Entfaltung. Er hat nach und nach von sich abstoßen müssen zuerst die niederen Tiere, dann immer weiter und weiter alles das, was an Tierformen da ist. Das hat er überwunden, von sich herausgesetzt, abgestoßen (dunkel schraffiert). Dadurch ist er zu seiner ursprünglichen Bestimmung gekommen. Ebenso ist es bei seiner Embryonalentwickelung. Der Mensch stößt nach und nach alles ab, was er nicht sein soll. Dadurch aber bekommen wir den eigentlichen Sinn der heutigen Naturerkenntnis nicht. Was ist der Sinn der heutigen Naturerkenntnis? Der liegt in dem Satze: Du schaust in dem, was dir Naturerkenntnis zeigt, dasjenige, was du von der Menschenerkenntnis ausschließen mußt. — Was heißt das? Das heißt: Der Mensch muß heute Naturwissenschaft studieren. Warum? Wenn er in das Mikroskop hineinsieht, so weiß er, was nicht Geist ist. Wenn er durch das Teleskop in die Ferne des Weltenraumes sieht, so offenbart sich ihm dasjenige, was nicht Geist ist. Wenn er auf eine andere Weise im physikalisch-chemischen Laboratorium experimentiert, offenbart sich ihm, was nicht Geist ist. In seiner reinen Gestalt offenbart sich ihm alles, was nicht Geist ist.

In alten Zeiten haben die Menschen, wenn sie angeschaut haben, was heute Natur ist, noch den Geist durchscheinen gesehen. Heute müssen wir die Natur erkennen, um eben sagen zu können: Das alles ist nicht Geist, das ist Winterweisheit. Und alles, was Sommerweisheit ist, das muß andere Gestalt haben. - Damit der Mensch den Stoß bekommt, den Impuls bekommt zum Geist, muß er das Ungeistige, das Widergeistige erkennen. Und einsehen muß man solche Dinge, die heute noch kein Mensch zugibt. Heute sagt zum Beispiel jeder: Nun ja, wenn ich irgendein kleines Lebewesen habe, das man mit freiem Auge nicht sieht, so lege ich es unter das Mikroskop; da vergrößert es sich mir, dann sehe ich es. — Ja, aber man wird einsehen müssen: Diese Größe ist ja verlogen; ich dehne das Lebewesen aus, ich habe es nicht mehr, ich habe ein Gespenst. Das ist nicht mehr Wirklichkeit, was ich da sche. Ich habe eine Lüge an die Stelle der Wahrheit gesetzt! -— Es ist natürlich für die heutige Anschauung Wahnsinn, aber es ist gerade die Wahrheit. Wenn man einsehen wird, daß man Naturwissenschaft braucht, damit man an diesem Gegenbilde der Wahrheit den Stoß bekommt zur Wahrheit hin, dann wird die Kraft entwickelt sein, die symbolisch angedeutet werden kann in der Überwindung des Drachen durch den Michael.

Aber dazu gehört etwas, was nun eigentlich auch schon, ich möchte sagen, auf geistige Art in den Annalen steht, aber es steht so, daß dann, als man keine rechte Ahnung mehr hatte von dem, was im Jahreslauf lebt, man die Sache auf den Menschen bezog. Da setzte man auf dasjenige, was zur Erleuchtung hinführt, den Begriff der Weisheit; da setzte man auf dasjenige, was hinführt zum Erkennen, den Begriff des Mutes; bei der Besonnenheit blieb es (siehe Schema Seite 76), und auf das, was der Buße entsprach, setzte man den Begriff der Gerechtigkeit. Hier haben Sie die vier platonischen Tugendbegriffe: Weisheit, Mut, Besonnenheit, Gerechtigkeit. Es wurde in den Menschen hineingenommen, was der Mensch vorher aus dem Leben des Jahreslaufes empfing. Das aber wird beim Michael-Fest ganz besonders in Betracht kommen: daß das wird sein müssen ein Fest zu Ehren des menschlichen Mutes, der menschlichen Offenbarung des Michael-Mutes. Denn was ist es, was heute den Menschen von der Geist-Erkenntnis zurückhält? Seelische Mutlosigkeit, um nicht zu sagen seelische Feigheit. Der Mensch will passiv alles empfangen, will sich hinsetzen vor die Welt wie vor ein Kino und will sich alles sagen lassen durch das Mikroskop und Teleskop. Er will nicht in Aktivität härten das Instrument des eigenen Geistes, der eigenen Seele. Er will nicht Michael-Nachfolger sein. Dazu gehört innerer Mut. Dieser innere Mut, der muß sein Fest bekommen in dem Michael-Fest. Dann wird von dem Fest des Mutes, von dem Fest der inneren mutigen Menschenseele ausstrahlen, was auch den andern Festeszeiten des Jahres rechten Inhalt geben wird.

Ja, wir müssen sogar den Weg fortsetzen: wir müssen hereinnehmen in die menschliche Natur das, was früher draußen war. So steht es heute nicht mehr mit dem Menschen, daß er nut im Herbste das Erkennen der Natur und so weiter entwickeln könnte. Es steht schon so, daß im Menschen die Dinge heute ineinanderliegen, denn nur dadurch kann er seine Freiheit entfalten. Aber dabei bleibt es doch richtig, daß, ich möchte sagen, in einem verwandelten Sinne das Feste-Feiern wiederum notwendig wird. Waren die Feste ehemals Feste des Gebens des Göttlichen an die Irdischen, empfing der Mensch ehemals unmittelbar die Gaben der himmlischen Mächte bei den Festen, so besteht heute, wo er in sich die Fähigkeiten hat, die Metamorphosierung des Festgedankens darin, daß es Feste der Erinnerungen sind. So daß sich der Mensch in die Seele schreibt dasjenige, was er in sich vollbringen soll.

Und da wird es wiederum am besten sein, als das stärkstwirkende Fest der Erinnerung, dieses Fest, das den Herbst beginnt, das MichaelFest zu haben, denn da spricht zu gleicher Zeit die ganze Natur eine bedeutsame kosmische Sprache. Die Bäume werden kahl, die Blätter verwelken, die Tiere, die den Sommer hindurch als Schmetterlinge die Luft durchflatterten, als Käfer die Luft durchsurrten, ziehen sich zurück. Viele Tiere verfallen in den Winterschlaf. Alles lähmt sich ab. Die Natur, die durch ihre eigene Wirksamkeit dem Menschen geholfen hat durch Frühling und Sommer, die Natur, die im Menschen gewirkt hat durch Frühling und Sommer, zieht sich zurück. Der Mensch ist auf sich zurückgewiesen. Was jetzt erwachen muß, wo die Natur einen verläßt, das ist der Seelenmut. Wiederum werden wir hingewiesen, wie es ein Fest des Seelenmutes, der Seelenkraft, der Seelenaktivität sein muß, was wir als Michael-Fest auffassen können.

Das ist es, was allmählich dem Festesgedanken einen Erinnerungscharakter geben wird, der aber schon angedeutet worden ist mit einem monumentalen Worte, mit welchem darauf hingewiesen wurde, daß in aller Zukunft dasjenige, was vorher Feste der Gaben waren, Erinnerungsfeste werden oder werden sollen. Dieses monumentale Wort, das das Fundament für alle Festgedanken sein muß, also auch derjenigen, die wieder entstehen werden, dieses monumentale Wort ist: «Dieses tut zu meinem Angedenken.» Da ist der Gedanke des Festes nach der Erinnerungsseite hingewendet.

So wie das andere, was im Christus-Impuls liegt, lebendig fortwirken muß, sich gestalten muß, nicht bloß totes Produkt bleiben darf, zu dem man zurückschaut, so muß auch dieser Gedanke empfindungs- und gedankenzeugend weiterwirken, und man muß verstehen, daß die Feste bleiben müssen, trotzdem der Mensch sich ändert, und daß daher auch die Feste Metamorphosen durchmachen müssen. Die Anthroposophie und das menschliche Gemüt

Fifth Lecture

In order to broaden the horizon of the contemplation I made here yesterday about the relationship that developed in ancient times between man and the course of nature under the influence of the Mysteries, I want to go into more detail today about what was believed in those ancient times with regard to everything that one received as man from the universe through this course of nature. You were able to gather from yesterday's lecture - perhaps also in memory of some of what I was able to say about such things around the last Christmas time in the Goetheanum, which has now been torn away from us - that the course of the year in its manifestations was felt, indeed can still be felt today, as a course of life, as something which, in relation to the outer course, is just as much the expression of an underlying living being as the manifestations of the human organism are such revelations of a being, of the human soul itself.

Let us remember how, under the influence of the ancient Mysteries, people felt a certain relationship to their ego at the height of summer, at the time which we today perceive as the time of St. John; to that ego, however, which at that time they did not yet ascribe exclusively to themselves, but which they still placed in the bosom of the Divine-Spiritual. These people believed that through all these activities which I have described, they were approaching their ego during midsummer, which hides itself from people throughout the rest of the year. Naturally, men as whole beings thought themselves to be in the bosom of the divine-spiritual. But they thought that during the other three quarters of the year nothing of that which belongs to them as their ego was revealed to them; only in this one quarter, which had its climax at the time of St. John, did the essence of their own ego reveal itself to them, as it were, through a window that had been opened from the divine-spiritual world.

Now, however, this essence of the self within the divine-spiritual world, in which it revealed itself, was not thought of in such a neutral, indifferent, one could even say phlegmatic way of cognition as is the case today. When people speak of the ego today, they hardly think of any real relationship to this or that world. He thinks of the ego as a kind of point from which what he does radiates, into which what he recognizes radiates. But it is certainly a kind of phlegmatic feeling that man has towards his ego today. One cannot even say that today's man feels actual egoism in his ego, even though it is the ego; for if he wants to be honest, he cannot say to himself that he is particularly fond of his ego. He likes his body, he likes his instincts, he likes this or that experience, but the ego is only a little word that is perceived as a point and in which all that is indicated is more or less summarized. But in that time, in which the approach to this ego was festively celebrated, in which preparations had long been made to meet one's ego in the universe, so to speak, in the time in which one then again felt how this ego gradually withdrew and left the human being alone with his bodily-soul being - what we would today call physical-etheric-astral being - in that time one really felt the ego in relation to the whole cosmos, to the whole world.

But what was felt above all in relation to this ego in its relationship to the world was not something naturalistic, if we use today's word, it was not something that was only understood as an external appearance, but it was something that was essentially regarded as the center of the old, the ancient moral world view. It was not assumed that great natural secrets were revealed to man at that time. Certainly, such secrets of nature - we spoke of them yesterday - were not what man paid attention to in the first place at that time, but he had the feeling that above all that which he should absorb as moral impulses was revealed in this high summer time, when light and warmth reach their highest state. It was the time that man felt as the divine moral enlightenment. And what one wanted to receive above all as an answer from the heavens through the musical, poetic, dance performances that were cultivated at that time, what one expected, was that what the heavens demanded of man in moral terms would be revealed from the heavens in all seriousness.

When it once happened that all these activities were practiced, which I described yesterday, that these festivals were celebrated in sultry summer time and then a mighty thunderstorm broke in with lightning and thunder, then one felt just in the breaking in of lightning and thunder the moral admonition of the heavens to earth mankind. What has remained from these ancient times is to be found, for example, in the view of Zeus that he is the god of thunder, the god who is endowed with lightning. Something similar is connected with the German god Donar. That on the one hand, and on the other the following.

There one felt, I would like to say, the saturated, warm, luminous nature, one felt that which was luminous, warming nature during the day, also into the night time and one only made the difference that one said to oneself: During the day the air is filled with the warmth element, with the light element. There the spiritual messengers weave and live in the warmth and light elements, through which the higher divine beings want to make themselves known to men, want to endow them with moral impulses. But at night, when the higher spiritual beings withdraw, the messengers remain and reveal themselves in their own way. -- And so, especially at this time of high summer, one felt the activity and weaving of nature in the summer nights, in the summer evenings. And what one experienced there was something like a summer dream experienced in reality, a summer dream through which one had particularly approached the divine-spiritual world; a summer dream of which one was convinced that everything that was a natural phenomenon was at the same time the moral language of the gods, but that all kinds of elemental beings were also at work there and showed themselves to people in their own way.

Everything that is the embellishment of the Midsummer Night's Dream, of St. John's Night's Dream, is that which later remained of the wonderful formations that the human imagination once carried out for everything that spiritually and emotionally permeated this midsummer time, but which was taken on a large and small scale as a spiritual-divine-moral revelation of the cosmos to men. And so we may say that the underlying idea was this: In the time of midsummer the divine-spiritual world revealed itself through moral impulses which were implanted in people in enlightenment (see diagram on page 76). And what was felt there in a very special way, what had an effect on people, was perceived as something, I would like to say, superhuman, which played into the human order. Man knew from his experience of these festivities, which were celebrated there, that he, as he was at that time, was lifted above himself into the superhuman, that in a sense the deity took the hand extended to it by man at that time. Everything that was believed to be divine-spiritual was attributed to the revelations of this time of John.

When the summer came to an end and the autumn time came up, when the leaves withered, the seeds ripened, when the full bursting life of the summer faded, the trees became bare, then one felt, because everywhere in these sensations the knowledge of the mysteries flowed in: The divine-spiritual world in turn withdraws from man. He senses how he is rejected into himself; he grows, as it were, out of the spiritual into nature. - Thus man felt this living into autumn as a living out of the spiritual, as a living into nature. The leaves of the trees mineralized, the seeds became dry and mineralized. Everything leaned towards the annual death of nature, so to speak.

In this interweaving with the mineralization of what was on earth and surrounded the earth, man himself was felt to be interwoven with nature. At that time, man's inner experience was even closer to that which took place externally. And so he thought and pondered in the same way as he experienced this interweaving with nature. His entire thinking took on this character. If we wanted to express in our language today what man felt when autumn came, we would have to say the following. But I would ask you to understand the matter in such a way that I am speaking in today's words, i.e. that in those days one would naturally not have been able to speak in this way. In those days, everything was a matter of feeling, things were not characterized by thinking. But if one wanted to speak in today's words, in our words, one would have to say: Man felt this transition in such a way that he found the transition from the cognition of the spirit to the cognition of nature with his way of thinking, with his way of feeling (see diagram on page 76). Man felt that towards autumn he was no longer in the spirit-recognition, but that autumn demanded of him that he should recognize nature. So that at the turn of autumn we no longer have moral impulses, but the recognition of nature. Man began to think about nature.

This was also the case at the time when man was considered to be a creature, a being within the cosmos. At that time, it would have been considered nonsense to bring knowledge of nature to man in the summer in the form it was then. Summer is there to bring man into relationship with the spiritual world. When the time began that we would today call the Michaelmas period, it was said: From everything that man feels around him in the woods, in the trees, in the plants, he is stimulated to pursue knowledge of nature. - It was the time when people were supposed to make knowledge and contemplation their occupation. It was also the time when external living conditions made this possible. So human life went from enlightenment to cognition. It was the time of knowledge, of ever-increasing knowledge.

When the students of the Mysteries received their instruction from the Mystery Teachers, they were given such sayings, as we find them somehow reproduced in the sayings of the Greek sages. But these seven sayings of the seven Greek sages are not those of the original Mysteries. In the original mysteries there was the saying for midsummer:

Receive the light

and the light was actually used to refer to spiritual wisdom. It referred to that within which the human self shone.

For the autumn, the saying was coined in the Mysteries to admonish what should be done by the souls:

Look around you.

Now the development of the year approached and with it also that which man felt in himself connected with this year, the winter time approached. We are entering the deep winter, which contains our Christmas time. Just as man felt lifted above himself in the high summer time to the divine-spiritual existence of the cosmos, so in the low winter time man felt as if he had developed below himself. He felt as if he was being washed by the forces of the earth, taken along by the forces of the earth. He felt as if his will nature, his instinct and drive nature were permeated and flowed through by gravity, by destructive power and other forces that are in the earth. Man did not feel winter in those ancient times as we feel it, that we merely get cold and that we put on boots, for example, so that we do not get cold, but man felt what came up from the earth as something that now united with his own being. He felt, so to speak, the contrast of the sultry, light-filled element as a frosty element that came up. We still feel the frosty element today, because it relates to the body, but the old man felt the dark, the gloomy, as a side effect of the frosty element. He felt, as it were, as if everywhere he went the darkness rose up out of the earth and enveloped him in clouds, but only up to the center of his body. And then he said to himself - I must again characterize this with somewhat newer words - then man said to himself: During high summer I am facing enlightenment, there streams into this earthly world what is heavenly supernatural, now the earthly streams up.

But man has already experienced and felt something of the earthly during the turn of autumn. But then he experienced and felt something of the earthly nature that was in a sense still in conformity with him, that still had something to do with him. We could also say, for example, that at the turn of autumn man felt the natural in his mind, in his emotional world. Now, however, he felt as if the earth were claiming him, as if he were being ensnared by the forces of the earth in relation to his will nature. He felt that this was the opposite of the moral world order. At the same time as this blackness, which enveloped him like a cloud, he felt the opposing forces against morality ensnaring him. He felt the darkness rising like a snake from the earth and coiling around him. But he felt something else at the same time. Already during the fall he had felt that something was stirring which today we call mind. While in summer the intellect evaporates and the moral and wise come in from outside, in autumn the intellect consolidates itself. Man approaches evil, but his mind consolidates. Something like a serpent revelation was felt in the depths of winter, but at the same time the consolidation, the strengthening of wisdom, of thoughtfulness, of what made man clever and cunning, what spurred him on to pursue the principles of usefulness in life. All this was felt in this way. And just as in autumn the knowledge of nature gradually emerged, so in the depths of winter the temptation of hell, the temptation of evil, approached people. This is how it was felt. So that when we write here (see diagram on page 76): Moral impulse, recognition of nature - we must now write here, in Tiefwinter: Temptation by evil.

And that was precisely the time in which man had to develop what was naturally united in him anyway: the intellectual, the cunning, the cunning, the useful. Man was to conquer this through prudence. It was just the time when man had to develop the open sense of wisdom that was demanded of him in the sense of the old mystery wisdom during the time of enlightenment. It was precisely at the time when evil manifested itself in the manner indicated that man could feel the resistance to evil in a corresponding way: he should become prudent. Above all, he should now, at this turning point which he was undergoing, while he had passed from enlightenment to cognition, precisely from the cognition of the spirit to the cognition of nature, now pass from the cognition of nature to the perception of evil. This is how it was understood. And the disciples of the Mysteries, to whom one wanted to give teachings that could be words of guidance to them, as they were told in midsummer: Receive the light -, as they were told in fall: Look around you -, they were told in deep winter: Beware of evil.

And it was reckoned that through this prudence, through this guarding against evil, people would come to a kind of self-knowledge, which would then lead them to realize how they had deviated from moral impulses in the course of the year.

The deviation from moral impulses through the contemplation of evil, its overcoming through prudence, was to become conscious to people precisely in the time that followed the ‘time of deep winter’. That is why all sorts of things were included in this wisdom that instructed people to repent for what they had realized was deviant from the moral impulses they had received through enlightenment.

We are approaching spring, the vernal equinox. And just as we have here (see diagram on page 76: High Summer, Autumn, Deep Winter) enlightenment, recognition, prudence, so we have for the turning point of spring that which was felt as penitential activity. And in place of recognition, or the temptation of evil, there now came something that could be called conversion, the turning back to one's higher nature through repentance. Have we written here? Enlightenment, recognition, prudence - we must write here: Turning back to human nature.

If you look back again to the time of temptation by evil in the depths of winter, you will have to say: Man felt as if he had sunk into the crevices of the earth. He felt ensnared by the earth's darkness. There it was, just as he had been torn out of himself, as it were, during the high summer time, how his soul was lifted above himself, where now, in order not to be ensnared by the evil during the deep winter time, the soul freed itself. Thus, during the time of deep winter, there was, I would like to say, a counter-image to what was there in the time of high summer.

In midsummer, the natural phenomena spoke in a spiritual way. People looked for the language of the heavens in thunder and lightning. One looked at the natural phenomena, but one looked for spiritual language in the natural phenomena. In the time of St. John, the spiritual language of the elemental beings was sought even in the trifles, but outside of them. One dreamed, so to speak, outside of the human being.

Now, in the time of deep winter, one immersed oneself and dreamed within the human being. By tearing oneself away from the cloak of the earth, one dreamed within the human being, if one could tear away one's soul. And what remains of this is that which is linked to the vision, to the inner vision of the thirteen nights after the winter solstice. Memories of these old times have remained everywhere. You can almost see the Norwegian Olaf song as a later development of what was present to a very special degree in ancient times.