The Evolution of the Earth and Man

and the Influence of the Stars

GA 354

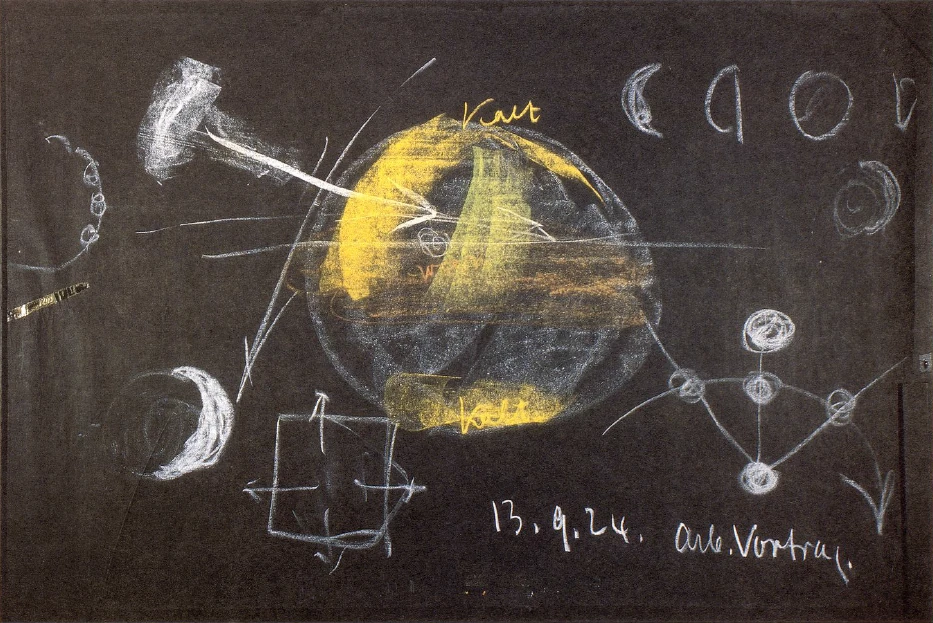

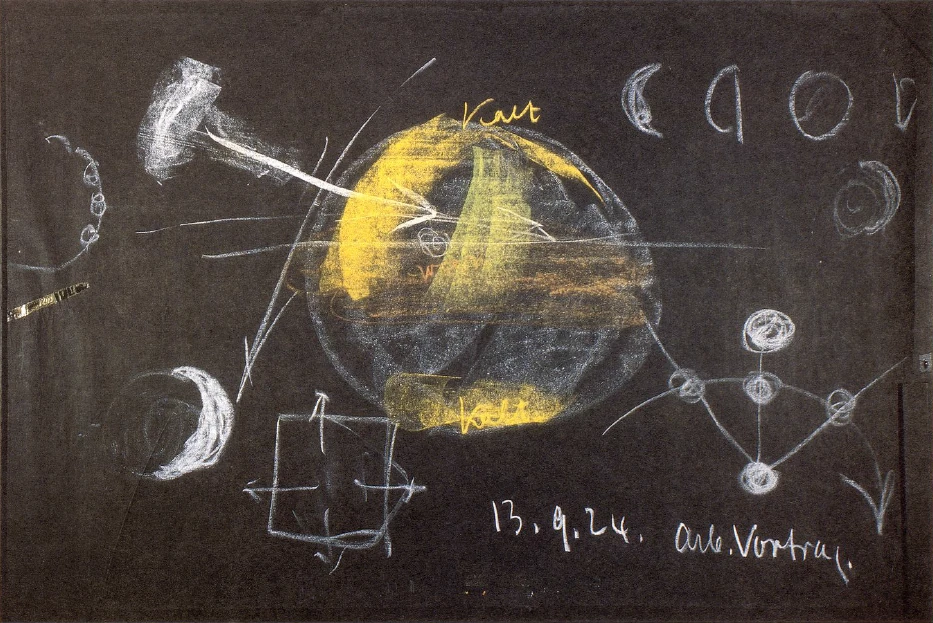

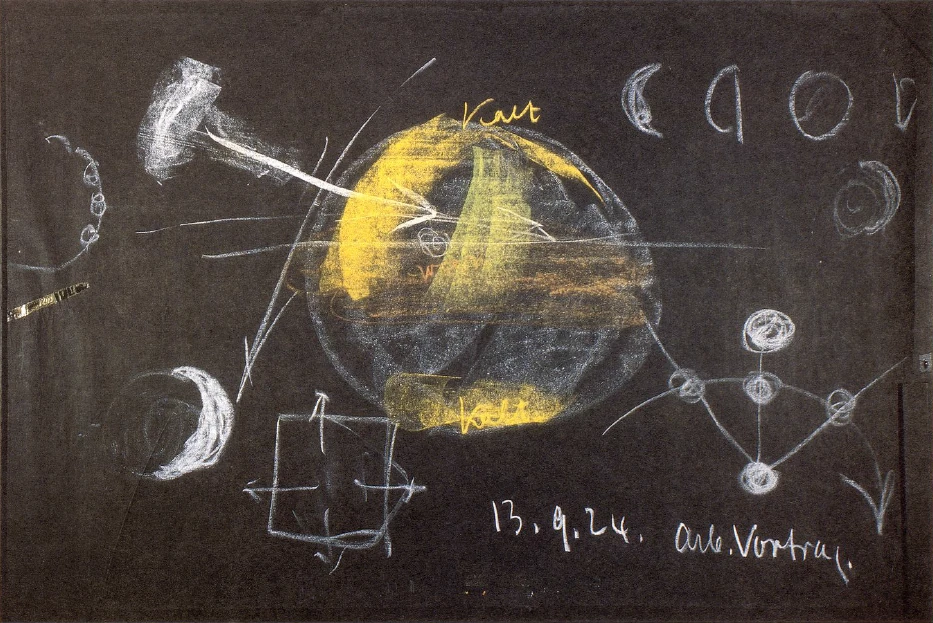

13 September 1924, Dornach

Lecture XI

Rudolf Steiner: Good morning, gentlemen! Does anyone have a question?

Question: Has Mars' proximity to the earth anything to do with the weather? The summer has been so unbelievably bad! Have planetary influences in general any effect upon the weather?

Dr. Steiner: The weather conditions which have shown such irregularities through the years, particularly recent years, do have something to do with conditions in the heavens, but not specifically with Mars. When these irregularities are observed we must take very strongly into consideration a phenomenon of which little account is usually taken, although it is constantly spoken of. I mean the phenomenon of sunspots. The sunspots are dark patches, varying in size and duration, which appear on the surface of the sun at intervals of about ten or eleven or twelve years. Naturally, these dark patches impede the sun's radiations, for, as you can well imagine, at the places where its surface is dark, the sun does not radiate. If in any given year the number of such dark patches increases, the sun's radiation is affected. And in view of the enormous significance the sun has for the earth, this is a matter of importance.

In another respect this phenomenon of sunspots is also noteworthy. In the course of centuries their number has increased, and the number varies from year to year. This is due to the fact that the position of the heavenly bodies changes as they revolve, and the aspect they present is therefore always changing. The sunspots do not appear at the same place every year, but—according to how the sun is turning—in the course of years they appear in that place again. In the course of centuries they have increased enormously in number and this certainly means something for the relationship of the earth to the sun.

Thousands of years ago there were no spots on the sun. They began to appear, they have increased in number, and they will continue to increase. Hence there will come a time when the sun will radiate less and less strongly, and finally, when it has become completely dark, it will cease to radiate any light at all. Therefore we have to reckon with the fact that in the course of time, a comparatively long time, the source of the light and life that now issues from the sun will be physically obliterated for the earth. And so the phenomenon of the sunspots—among other things—shows clearly that one can speak of the earth coming to an end. Everything of the earth that is spiritual will then take on a different form, just as I have told you that in olden times it had a different form. Just as a human being grows old and changes, so the sun and the whole planetary system will grow old and change.

The planet Mars, as I said, is not very strongly connected with weather conditions; Mars is more connected with phenomena that belong to the realm of life, such as the appearance and development of the grubs and cockchafers every four years. And please do not misunderstand this. You must not compare it directly with what astronomy calculates as being the period of revolution of Mars,21The “synodic” revolution, that is, the time between two successive conjunctions or oppositions to the sun, varies with Mars between 2 years 34 days and 2 years 80 days, the average time therefore being 2 years 50 days. because the actual position of Mars comes into consideration here. Mars stands in the same position relatively to the earth and the sun every four years, so that the grubs which take four years to develop into cockchafers are also connected with this. If you take two revolutions of Mars—requiring four years and three months—you get the period between the cockchafers and the grubs, and the other way around, between the grubs and the cockchafers. In connection with the smaller heavenly bodies you must think of the finer differentiations in earth phenomena, whereas the sun and moon are connected with cruder, more tangible phenomena such as weather, and so on.

A good or bad vintage year, for example, is connected with phenomena such as the sunspots, also with the appearance of comets. Only when they are observed in connection with phenomena in the heavens can happenings on the earth be studied properly.

Now of course still other matters must be considered if one is looking for the reasons for abnormal weather. For naturally the weather conditions—which concern us so closely because health and a great deal else is affected by them—depend upon very many factors. You must think of the following. Going back in the evolution of the earth we come to a time of about six to ten thousand years ago. Six to ten thousand years ago there were no mountains in this region where we are now living. You would not have been able to climb the Swiss mountains then, because you would not have existed in the way you do now. You could not have lived here or in other European lands because at that time these regions were covered with ice. It was the so-called Ice Age. This Ice Age was responsible for the fact that the greatest part of the population then living in Europe either perished or was obliged to move to other regions. These Ice Age conditions will be repeated, in a somewhat different form, in about five or six or seven thousand years—not in exactly the same regions of the earth as formerly, but there will again be an Ice Age.

It must never be imagined that evolution proceeds in an unbroken line. To understand how the earth actually evolves it must be realized that interruptions such as the Ice Age do indeed take place in the straightforward process of evolution. What is the reason? The reason is that the earth's surface is constantly rising and sinking. If you go up a mountain which need by no means be very high, you will still find an Ice Age, even today, for the top is perpetually covered with snow and ice. If the mountain is high enough, it has snow and ice on it. But it is only when, in the course of a long time, the surface of the earth has risen to the height of a mountain that we can really speak of snow and ice on a very large scale. So it is, gentlemen! It happens. The surface of the earth rises and sinks. Some six thousand or more years ago the level of this region where we are now living was high; then it sank, but it is now already rising again, for the lowest point was reached around the year 1250. That was the lowest point. The temperature here then was extremely pleasant, much warmer than it is today. The earth's surface is now slowly rising, so that after five or six thousand years there will again be a kind of Ice Age.

From this you will realize that when weather conditions are observed over ten-year periods, they are not the same; the weather is changing all the time.

Now if in a given year, in accordance with the height of the earth's surface a certain warm temperature prevails over regions of the earth, there are still other factors to be considered. Suppose you look at the earth. At the equator it is hot; above and below, at the Poles it is cold. In the middle zone, the earth is warm. When people travel to Africa or India, they travel into the heat; when they travel to the North Pole or the South Pole, they travel into the cold. You certainly know this from accounts of polar expeditions.

Think of the distribution of heat and cold when you begin to heat a room. It doesn't get warm all over right away. If you would get a stepladder and climb to the top of it, you would find that down below it may still be quite cold while up above at the ceiling it is already warm. Why is that? It is because warm air, and every gaseous substance when it is warmed, becomes lighter and rises; cold air stays down below because it is heavier. Warmth always ascends. So in the middle zone of the earth the warm air is always rising. But when it is up above it wafts toward the North Pole: winds blow from the middle zone of the earth toward the North Pole. These are warm winds, warm air. But the cold air at the North Pole tries to warm itself and streams downward toward the empty spaces left in the middle zone. Cold air is perpetually streaming from the North Pole to the equator, and warm air in the opposite direction, from the equator to the North Pole. These are the currents called the trade winds. In a region such as ours they are not very noticeable, but very much so in others.

Not only the air, but the water of the sea, too, streams from the middle zone of the earth toward the North Pole and back again. That phenomenon is, naturally, distributed in the most manifold ways, but it is nevertheless there.

But now there are also electric currents in the universe; for when we generate wireless electric currents on the earth we are only imitating what is also present in some way in the universe. Suppose a current from the universe is present, let's say, here in Switzerland, where we have a certain temperature. If a current of this kind comes in such a way that it brings warmth with it, the temperature here rises a little. Thus the warmth on earth is also redistributed by currents from the universe. They too influence the weather.

In addition, however, you must consider that such electromagnetic currents in the universe are also influenced by the sunspots. Wherever the sun has spots, there are the currents which affect the weather. These particular influences are of great importance.

Now in regard to the division of the seasons—spring, summer, autumn, winter—there is a certain regularity in the universe. We can indicate in our calendar that spring will begin at a definite time, and so on. This is regulated by the more obvious relationships in which the heavenly bodies stand to one another. But the influences resulting from this are few. Not many of the stars can be said to have an influence; most of them are far distant and their influence is only of a highly spiritual character.

But in regard to weather conditions the following may be said. Suppose you have a disc with, let's say, four colors on it—red, yellow, green, blue. If you rotate the disc slowly, you can easily distinguish all the four colors. If you rotate it more quickly, it is difficult but still possible to distinguish the colors. But if you rotate the disc very rapidly indeed, all the colors run into each other and you cannot possibly distinguish one from the other. Likewise, the seasons of spring, summer, autumn and winter can be distinguished because the determining factors are more or less obvious. But the weather depends upon so many circumstances that the mind cannot grasp all of them; it is impossible, therefore, to mark anything definite in the calendar in regard to it—while this is obviously quite possible in regard to the seasons. The weather is a complicated matter because so many factors are involved.

But in old folklore something was known about these things. Old folklore should not be cast aside altogether. When the conditions of life were simpler, people took an interest in things far more than they do today. Today our interest in a subject lasts for 24 hours ... then the next newspaper comes and brings a new interest! We forget what happens—it is really so! The conditions of our life are so terribly complicated. The lives of our grandparents, not to speak of our great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents, were quite different. They would sit together in a room around and behind the stove and tell stories, often stories of olden times. And they knew how the weather had been a long time ago, because they knew that it was connected with the stars; they observed a certain regularity in the weather. And among these great-grandparents there may have been one or two “wiseacres”, as they are called. By a “wiseacre” I mean someone who was a little more astute than the others, someone who had a certain cleverness. Such a person would talk in an interesting way. A “wiseacre” might have said to a grandchild or great-grandchild: Look, there's the moon—the moon, you know, has an influence on the weather. This was obvious to people in those days, and they also knew that rainwater is better for washing clothes than water fetched from the spring. So they put pails out to collect the rainwater to wash the clothes—my own mother used to do this. Rainwater has a different quality, it has much more life in it than ordinary water; it absorbs bluing and other additives far better. And it wouldn't be a bad idea if we ourselves did the same thing, for washing with hard water can, as you know, ruin your clothes.

So you see, these things used to be known; it was science in the 19th century that first caused people to have different views. Some of you already know the story I told once about the two professors at the Leipzig University:22Matthias Jakob Schleiden, 1804–1881. Naturalist. Gustav Theodor Fechner, 1801–1887. Naturalist; founder of psychophysics. See his publication “Professor Schleiden und der Mond,” Leipzig 1856. one was called Schleiden and the other Fechner. Fechner declared that the moon has an influence on the earth's weather. He had observed this and had compiled statistics on it. The other professor, Schleiden, was a very clever man. He said: That is sheer stupidity and superstition; there is no such influence. Now when professors quarrel, nothing very much is gained by it and that's mostly the case also when other people quarrel! But both these professors were married; there was a Frau Professor Schleiden and a Frau Professor Fechner. In Leipzig at that time people still collected rainwater for washing clothes. So Professor Fechner said to his wife: That man Schleiden insists that one can get just as much rainwater at the time of new moon as at full moon; so let Frau Professor Schleiden put out her pail and collect the rainwater at the time of the next new moon, and you collect it at the time of full moon, when I maintain that you will get more rainwater. Well, Frau Professor Schleiden heard of this proposal and said: Oh no! I will put my pail out when it is full moon and Frau Professor Fechner shall put hers out at the time of new moon! You see, the wives of the two professors actually needed the water! The husbands could squabble theoretically, but their wives decided according to practical needs.

Our great-grandparents knew these things and said to their grandchildren: The moon has an influence upon rainwater. But remember this: everything connected with the moon is repeated every 18 or 19 years. For example, in a certain year, on a certain day, there are sun eclipses and on another day moon eclipses; this happens regularly in the course of 18 to 19 years. All phenomena connected with the positions of the stars in the heavens are repeated regularly. Why, then, should not weather conditions be repeated, since they depend upon the moon? After 18 or 19 years there must be something in the weather similar to what happened 18 or 19 years before. So as everything repeats itself, these people observed other repetitions too, and indicated in the calendar certain particulars of what the weather had been 18 or 19 years earlier, and now expected the same kind of weather after the lapse of this period. The only reason the calendar was called the Hundred-Years' Calendar was that 100 is a number which is easy to keep in mind; other figures too were included in the calendar according to which predictions were made about the weather. Naturally, such things need not be quite exact, because again the conditions are complicated. Nevertheless, the predictions were useful, for people acted accordingly and did indeed succeed in producing better growing conditions. Through such observations something can certainly be done for the fertility of the soil. Weather conditions do depend upon the sun and moon, for the repetitions of the positions of the moon have to do with the relation of these two heavenly bodies.

In the case of the other stars and their relative positions, there are different periods of repetition. One such repetition is that of Venus, the morning and evening star. Suppose the sun is here and the earth over there. Between them is Venus. Venus moves to this point or that, and can be seen accordingly; but when Venus is here, it stands in front of the sun and covers part of it. This is called a “Venus transit”.23There is a period of 243 years 2 days in which the intervals between the Venus transits are 8 years, 121.5 years, 8 years and 105.5 years. The last transit took place December 6, 1882. According to astronomical calculation the next transit will be on June 7, 2004. (Venus, of course, looks much smaller than the moon, although it is, in fact, larger.) These Venus transits are very interesting because for one thing they take place only once every hundred years or so, and for another, very significant things can be observed when Venus is passing in front of the sun. One can see what the sun's halo looks like when Venus is standing in front of the sun. This event brings about great changes. The descriptions of it are very interesting. And as these Venus transits take place only once in about a hundred years, they are an example of the phenomena about which science is obliged to say that it believes some things that it has not actually perceived! If the scientists declare that they believe only things they have seen, an astronomer who was born, say, in the year 1890 could not lecture today about a Venus transit, for that has not occurred in the meantime, and presumably he will have died before the next Venus transit, which will apparently take place in the year 2004. There, even the scientist is obliged to believe in something he does not see!

Here again, when Venus is having a special effect upon the sun because it is shutting out the light, an influence is exercised upon weather conditions that occurs only once about every hundred years. There is something remarkable about these Venus transits and in earlier times they were regarded as being extraordinarily interesting.

Now when the moon is full, you see a shining orb in the sky; at other times you see a shining part of an orb. But at new moon, if you train your eyes a little—I don't know whether you know this—you can even see the rest of the new moon. If you look carefully when the moon is waxing, you can also see the other part of the moon—it appears bluish-black. Even at new moon a bluish-black disc can be seen by practiced eyes; as a rule it is not noticed, but it can be seen. Why is it that this disc is visible at all? It is because the part of the moon that is otherwise dark is still illuminated by the earth. The moon is about 240,000 miles from the earth and is not, properly speaking, illuminated by it; but the tiny amount of light that falls upon the moon from the earth makes this part of the moon visible.

But now no light at all radiates from the earth to Venus. Venus has to rely upon the light of the sun; no light streams to it from the earth. Venus is the morning and evening star. It changes just as the moon changes but not within the same periods. Only the changes are not seen because Venus is very far away and all that is visible is a gleaming star. Looked at through a darkened telescope Venus can be seen to change, just as the moon changes. But in spite of the fact that Venus cannot be illuminated from the earth, part of it is always visible as a dull bluish light. The sun's light is seen at the semi-circle above—but this is not the whole of Venus; where Venus is not being shone upon by the sun, a bluish light is seen.

Now, gentlemen, there are certain minerals—for instance, in Bologna—which contain barium compounds. Barium is a metallic element. If light is allowed to fall on these minerals for a certain time, and the room is then darkened, you see a bluish light being thrown off by them.

One says that the mineral, after it has been illuminated, becomes phosphorescent. It has caught the light, “eaten” some of the light, and is now spitting it out again when the room is made dark. This is of course also happening before the room is dark, but the light is then not visible to the eye. The mineral takes something in and gives something back. As it cannot take in a great deal, what it gives back is also not very much, and this is not seen when the room is light, just as a feeble candle-light is not seen in strong sunlight. But the mineral is phosphorescent and if the room is darkened, one sees the light it radiates.

From this you will certainly be able to understand where the light of Venus comes from. While it receives no light from this side, Venus is illuminated from the other side by the sun, and it eats up the sun's light, so to say. Then, when you see it on a dark night, it is throwing off the light, it becomes phosphorescent. In days when people had better eyes than they have now, they saw the phosphorescence of Venus. Their eyes were really better in those days; it was in the 16th century that spectacles first began to be used, and they would certainly have come earlier if people had needed them! Inventions and discoveries always come when they are needed by human beings. And so in earlier times the changes that come about when phosphorescent Venus is in transit across the sun were also seen. And in still earlier times the conclusion was drawn that because the sun's light is influenced at that time by Venus, this same influence will be there again after about a hundred years; and so there will be similar weather conditions again in a region where a transit of Venus is seen to be taking place. (As you know, eclipses of the sun are not visible from everywhere, but only in certain regions.) In a hundred years, therefore, the same weather conditions will be there—so the people concluded—and they drew up the Hundred Years' Calendar accordingly.

Later on, people who did not understand the thing at all, made a Hundred Years' Calendar every year, then they found that the details given in the calendar did not tally with the actual facts. It could just as well have said: “If the cock crows on the dunghill, the weather changes, or stays as it is!” But originally, the principle of the thing was perfectly correct. The people perceived that when Venus transits the sun, this produces weather conditions that are repeated somewhere after a hundred years.

Since the weather of the whole year is affected, then the influences are at work not only during the few days when Venus is in transit across the sun but they last for a longer period. So you see from what I have said that to know by what laws the weather is governed during some week or day, one would have to ask many questions: How many years ago was there a Venus transit? How many years ago was there a sun-eclipse? What is the present phase of the moon? I have mentioned only a few points. One would have to know how the trade winds are affected by magnetism and electricity, and so on. All these questions would have to be answered if one wanted to determine the regularity of weather conditions. It is a subject that leads to infinity! People will eventually give up trying to make definite predictions about the weather. Although we hear about the regularity of all the phenomena with which astronomy is concerned—astronomy, as you know, is the science of the stars—the science that deals with factors influencing the weather (meteorology, as it is called) is by no means definite or certain. If you get hold of a book on meteorology, you'll be exasperated. You'll be exclaiming that it's useless, because everyone says something different. That is not the case with astronomy.

I have now given you a brief survey of the laws affecting wind and weather and the like. But still it must be added that the forces arising in the atmosphere itself have a tremendously strong influence on the weather. Think of a very hot summer when there is constant lightning out of the clouds and constant thunder growling: there you have influences on the weather that come from the immediate vicinity of the earth. Modern science holds a strange view of this. It says that it is electricity that causes the lightning to flash out of the clouds. Now you probably know that electricity is explained to children at school by rubbing a glass rod with a piece of cloth smeared with some kind of amalgam; after it has been rubbed for some time, the rod begins to attract little scraps of paper, and after still more rubbing, sparks are emitted, and so on. Such experiments with electricity are made in school, but care has to be taken that everything has been thoroughly wiped beforehand, because the objects that are to become electric must not even be moist, let alone wet; they must be absolutely dry, even warm and dry, for otherwise nothing will be got out of the glass rod or the stick of sealing-wax. From this you can gather that electricity is conducted away by water and fluids. Everyone knows this, and naturally the scientists know it, for it is they who make the experiments. In spite of this, however, they declare that the lightning comes out of the clouds—and clouds are certainly wet!

If it were a fact that lightning comes out of the clouds, “someone” would have had to rub them long enough with a gigantic towel to make them quite dry! But the matter is not so simple. A stick of sealing wax is rubbed and electricity comes out of it; and so the clouds rub against one another and electricity comes out of them! But if the sealing wax is just slightly damp, electricity does not come out of it. And yet electricity is alleged to come out of the clouds—which are all moisture! This shows you what kind of nonsense is taught nowadays. The fact of the matter is this: You can heat air and it becomes hotter and hotter. Suppose you have this air in a closed container. The hotter you make the air, the greater is the pressure it exerts against the walls of the container. The hotter you make it, the sooner it reaches the point where, if the walls of the container are not strong enough, the hot air will burst them asunder. What's the usual reason for a child's balloon bursting? It's because the air rushes out of it. Now when the air becomes hot it acquires the density, the strength to burst. The lightning process originates in the vicinity of the earth; when the air gets hotter and hotter, it becomes strong enough to burst. At very high levels the air may for some reason become intensely hot—this can happen, for example, as the result of certain influences in winter when somewhere or other the air has been very strongly compressed. This intense heat will press out in all directions, just as the hot air will press against the sides of the container. But suppose you have a layer of warm air, and there is a current of wind sweeping away the air. The hot air streams toward the area where the air is thinnest.

Lightning is the heat generated in the air itself that makes its way to where there is a kind of hole in the surrounding air, because at that spot the air is thinnest. So we must say: Lightning is not caused by electricity, but by the fact that the air is getting rid of, emptying away, it's own heat.

Just because of this intensely violent movement, the electric currents that are always present in the air receive a stimulus. It is the lightning that stimulates electricity; lightning itself is not electricity.

All this shows you that warmth is differently distributed in the air everywhere; this again influences the weather. These are influences that come from the vicinity of the earth and operate there.

You will realize now how many things influence the weather and that today there are still no correct opinions about these influences—I have told you about the entirely distorted views that are held about lightning. A change must come about in this domain, for spiritual science, anthroposophy, surveys a much wider field and makes thinking more mobile.

We cannot, of course, expect the following to be verified in autopsies, but if one investigates with the methods of spiritual science, one finds that in the last hundred years human brains have become much stiffer, alarmingly stiffer, than they were formerly. One finds, for example, that the ancient Egyptians thought quite definite things, of which they were just as sure as we ourselves are sure of the things we think about. But today we are less able to understand things in the winter than in the summer. People pay no attention to such matters. If they would adjust themselves to the laws prevailing in the world, they would arrange life differently. In school, for instance, different subjects would be studied in the winter than in the summer. (This is already being done to some extent in the Waldorf School.)24The Waldorf School, Stuttgart, Germany, opened in 1919 under Rudolf Steiner's guidance. There are now more than 300 schools in the international Waldorf School movement. It is not simply a matter of taking botany in the summer because the plants bloom then, but some of the subjects that are easier should be transferred to the winter, and some that are more difficult to the spring and autumn, because the power to understand depends upon this. It is because our brains are harder than men's brains were in earlier times. What we can think about in a real sense only in summer, the ancient Egyptians were able to think about all year round. Such things can be discovered when one observes the various matters connected with the seasons of the year and the weather.

Is there anything that is not clear? Are you satisfied with what has been said? I have answered the question at some length. The world is a living whole and in explaining one thing one is naturally led to other things, because everything is related.

Question: Herr Burle says that his friends may laugh at his question—he had mentioned the subject two or three years ago. He would like to know whether there is any truth in the saying that when sugar is put into a cup of coffee and it dissolves properly, there will be fine weather, and when it does not dissolve properly there will be bad weather.

Dr. Steiner: I have never made this experiment, so I don't know whether there is anything in it or not. But the fact of the sugar dissolving evenly or unevenly might indicate something—if, that is to say, there is anything in the statement at all. I speak quite hypothetically, because I don't know whether there is any foundation for the statement, but we will presume that there is.

There is something else that certainly has meaning, for I have observed it myself. What the weather is likely to be can be discovered by watching tree frogs, green tree frogs. I've made tiny ladders and observed whether they ran up or down. The tree frog is very sensitive to what the weather is going to be. This need not surprise you, for in certain places it has happened that animals in their stalls suddenly became restless and tried to get out; those that were not tethered ran away quickly. Human beings stayed where they were. And then there was an earthquake! The animals knew it beforehand, because something was already happening in nature in advance. Human beings with their crude noses and other crude senses do not detect anything, but animals do. So naturally the tree frog, too, has a definite “nose” for what is coming. The word Witterung (weather) is used in such a connection because it means “smelling” the weather that is coming.

Now there are many things in the human being of which he himself has no inkling. He simply does not observe them. When we get out of bed on a fine summer day and look out the window, we are in quite a different humor than when a storm is raging. We don't notice that this feeling penetrates to the tips of our fingers. What the animals sense, we also sense; it is only that we don't bring it up to our consciousness.

So just suppose, Herr Burle, that although you know nothing about it, your fingertips, like the tree frogs, have a delicate feeling for the kind of weather that is coming. On a day when the weather is obviously going to be fine and you are therefore in a good humor, you put the sugar into your coffee with a stronger movement than on another day. So the way the sugar dissolves does not necessarily depend upon the coffee or the sugar, but upon a force that is in yourself. The force I'm speaking of lies in your fingertips themselves; it is not the force that is connected with your consciously throwing the sugar into the coffee. It lies in your fingertips, and is not the same on a day when the weather is going to be fine as when the weather is going to be bad. So the dissolving of the sugar does not depend upon the way you consciously put it into your coffee but upon the feeling in your fingertips, upon how your fingertips are “sensing” the weather. This force in your fingertips is not the same as the force you are consciously applying when you put the sugar into your coffee. It is a different force, a different movement.

Think of the following: A group of people sits around a table; sentimental music, or perhaps the singing of a hymn, puts them into a suitable mood. Then delicate vibrations begin to stir in them. Music continues. The people begin to convey their vibrations to the table, and the table begins to dance. This is what may happen at a spiritualistic séance. Movements are set going as the effect of the delicate vibrations produced through the music and the singing. In a similar fashion the weather may also cause very subtle movements, and these in turn may influence what happens with the sugar in the coffee. But I am speaking quite hypothetically because, as I said, I don't know whether it is absolutely correct in the case of which you are speaking. It is more probable that it is a premonition which the person himself has about the weather that affects the sugar—although this is not very probable either. I am saying all this as pure hypothesis.

A spiritual scientist has to reject such phenomena until he possesses strict proof of their validity. If I were to tell you in a casual way the things I do tell you, you really wouldn't have to believe any of it. You should only believe me because you know that things which cannot be proved are not accepted by spiritual science. And so as a spiritual scientist I can only accept the story of the coffee if it is definitely proved. In the meantime I can make the comment that one knows, for instance, of the delicate vibrations of the nerves, also that this is how animals know beforehand of some impending event—how even the tree frog begins to tremble and then the leaves on which it sits also begin to tremble. So it could also be—I don't say that it is, but it could be—that when bad weather is coming, the coffee begins to behave differently from the way it behaves when the weather is good.

So—let us meet next Wednesday.25This lecture was postponed to Thursday, September 18th After that, I think we'll be able to have our sessions regularly again.

Elfter Vortrag

Nun, meine Herren, vielleicht ist Ihnen noch etwas auf der Seele, was Sie heute gern beantwortet haben wollen?

Frage: Ob die Erdnähe des Mars mit dem Wetter zusammenhängt, weil so ein schlechter Sommer gewesen ist, wie man es sich kaum denken kann — oder überhaupt die Planeteneinflüsse da hereinspielen?

Dr. Steiner: Nun, nicht wahr, die Witterungsverhältnisse, wie sie sich im Laufe der Jahre, überhaupt in letzter Zeit als wenig regelmäßig erwiesen haben, sie haben schon etwas zu tun mit den Himmelsverhältnissen, aber nicht eigentlich direkt mit dem Mars, sondern wenn wir diese Unregelmäßigkeiten beobachten, so müssen wir vor allen Dingen auf eine Erscheinung sehr stark Rücksicht nehmen, die ja auch wenig berücksichtigt wird sonst, aber von der doch immerhin gesprochen wird: das ist die Erscheinung der Sonnenflecken. Die Sonnenflecken sind Erscheinungen, welche in Abständen von zehn, elf, zwölf Jahren immer wiederum in einer bestimmten Veränderung auftreten. Man sieht, wenn man die Fläche der Sonne beobachtet, dunkle Flecken auftreten. Diese dunklen Flecken beeinträchtigen natürlich die Ausstrahlungen der Sonne, denn, wo es dunkel ist, strahlt sie nicht aus. So daß Sie sich denken können, daß wenn einmal in einem Jahre mehr solche Sonnenflecken vorhanden sind, dann in einem solchen Jahre eine geringere Ausstrahlung stattfindet. Und bei der sehr großen Bedeutung - von der ich Ihnen gesprochen habe -, die die Sonne schon einmal für die Erde hat, ist das schon wichtig.

Und diese Erscheinung der Sonnenflecken ist ja auch noch in einer anderen Richtung sehr bemerkenswert. Es muß durchaus zugegeben werden, daß im Laufe der Jahrhunderte die Zahl der Sonnenflecken sich vermehrte. Sie erscheinen also durchaus nicht jedes Jahr in der gleichen Menge. Das rührt davon her, daß die Stellung der Himmelskörper eine andere ist. Wenn sich die Himmelskörper drehen, so wird die Stellung eine andere; dadurch wird der Anblick, den ein Himmelskörper bietet, immer anders. Wenn also an einer bestimmten Stelle die Sonnenflecken sind, so erscheinen sie nicht jedes Jahr an derselben Stelle, sondern je nachdem sich die Sonne dreht; sie erscheinen dann im Laufe der Jahre wiederum an derselben Stelle. Aber im Laufe der Jahrhunderte haben sie sich wesentlich vermehrt, und es ist so, daß diese Vermehrung der Sonnenflecken schon für die Auffassung desjenigen, was eigentlich im Verhältnis der Erde zur Sonne vorgeht, etwas bedeutet.

Wenn wir Jahrtausende zurückgehen, so sind sozusagen noch gar keineSonnenflecken da. Die Sonnenflecken sind entstanden, vermehrten sich und werden sich immer weiter vermehren. Daher ist die Sache so, daß die Sonne einmal überhaupt weniger strahlen wird und zuletzt, wenn sie ganz schwarz geworden ist, verfallen sein wird, gar kein Licht mehr ausstrahlen wird. So daß wir also tatsächlich damit zu rechnen haben, daß da wirklich in verhältnismäßig langer Zeit die Quelle von Licht und Leben, die von der Sonne ausgeht, physisch für die Erde erlischt. Wir können also auch aus der Erscheinung der Sonnenflecken — was ja auch sonst, nicht wahr, klar ist — von einem Erdenende sprechen. Dann wird alles dasjenige, was geistig ist an der Erde, andere Formen annehmen, wie ich Ihnen schon erzählt habe, daß es andere Formen gegeben hat in älteren Zeiten. Aber geradeso wie ein Mensch alt wird und auch sich verändert, so wird die Sonne mit dem ganzen Planetensystem alt und verändert sich.

Mars selber hat eigentlich nicht mit diesen Erscheinungen — das sagte ich schon das letzte Mal — einen starken Zusammenhang, sondern mit solchen mehr lebendigen, dem Leben angehörenden Erscheinungen wie dem Ablauf des Erscheinens der Engerlinge und Maikäfer alle vier Jahre. Da müssen Sie auch die Sache natürlich nicht mißverstehen. Mit dem, was man in der Astronomie ausrechnet als Umlaufszeit des Mars, dürfen Sie das nicht ohne weiteres vergleichen, weil die Stellung in Betracht kommt. Dieselbe Stellung, die der Mars zur Erde und zur Sonne hat, die kommt alle vier Jahre so zustande, daß die Engerlinge, die also vier Jahre leben, bis sie Maikäfer werden, auch damit zusammenhängen. Aber wenn Sie zwei Marsumläufe nehmen — die also vier Jahre drei Monate sind -, dann bekommen Sie heraus die Zeit, die da liegt zwischen den Maikäfern und den Engerlingen, und umgekehrt zwischen den Engerlingen und Maikäfern. So daß Sie also bei diesen kleineren Himmelskörpern auch an die feineren Erscheinungen auf der Erde denken müssen, währenddem bei der Sonne und dem Mond durchaus an die gröberen, also an die Witterungserscheinungen und dergleichen zu denken ist.

Aber so etwas wie die Sonnenflecken hängt zum Beispiel dann auch wiederum damit zusammen, ob ein gutes oder schlechtes Weinjahr ist, was aber auch wiederum mit den Kometenerscheinungen und dergleichen zusammenhängt. Wirklich richtig studieren kann man dasjenige, was auf der Erde vorgeht, eben nur dann, wenn man es im Zusammenhang mit den Himmelserscheinungen beobachtet.

Es kommen jetzt natürlich noch andere Fragen in Betracht, wenn wir ins Auge fassen wollen, warum abnorme Witterungserscheinungen eintreten. Denn dasjenige, was wir Witterungserscheinungen nennen und was uns als Menschen so naheliegt, weil davon Gesundheit und alles mögliche abhängt, das hängt natürlich von sehr vielen Verhältnissen ab. Da müssen Sie bedenken: Wenn wir zurückgehen in der Entwickelung der Erde, so kommen wir zu einer Zeit zurück, die etwa sechstausend Jahre oder so etwas zurückliegt, sechstausend bis zehntausend Jahre zurückliegt. Ja, wenn Sie in der Zeit unsere Gegenden betrachten, sechs- bis zehntausend Jahre zurückliegend, da würden Sie natürlich nicht so, wie es heute ist, da draußen die Berge haben. Sie würden überhaupt nicht die Schweizer Berge besteigen können, weil sie so, wie Sie heute leben, überhaupt nicht vorhanden wären! Sie könnten nicht hier leben, könnten auch nicht in den anderen Ländern Europas leben, denn dazumal waren diese Gegenden im wesentlichen von Eis bedeckt, vereist. Es war die sogenannte Eiszeit. Diese Erscheinung der Eiszeit, die hat bewirkt, daß der größte Teil der früher schon in Europa vorhandenen Bevölkerung entweder physisch zugrunde gegangen ist, oder andere Gegenden aufsuchen mußte. Diese Eiszeit, die wird sich wiederholen, in einer gewissen Weise anders gestaltet, und zwar wiederum so in fünf-, sechs-, siebentausend Jahren; sie wird nicht genau auf derselben Stelle der Erde sein, wie sie dazumal war, aber es wird wiederum eine Eiszeit geben.

Sehen Sie, man darf sich eben durchaus nicht vorstellen, daß sich alles so glatt entwickelt, sondern solche Unterbrechungen wie durch die Eiszeit, die finden schon statt! Und wenn man verstehen will, wie die Erde sich eigentlich entwickelt, so muß man eben sich sagen: Es finden fortdauernd solche Unterbrechungen der glatten Entwickelung statt. Nun, woher kommt denn so etwas? So etwas kommt davon her, daß die Erdoberfläche sich ja fortwährend hebt und senkt. Ja, wenn Sie auf den Berg hinaufgehen, der ja gar nicht einmal so besonders hoch zu liegen braucht, so finden Sie schon heute auch noch eine Eiszeit; es bleibt etwas Schnee und Eis oben. Nun ist es so, daß wenn der Berg heute so hoch ist, so ist hier Schnee und Eis. Wenn aber im Laufe der Zeit sich die Oberfläche der Erde so hebt, daß sie gerade so hoch ist als der Berg, so ist da erst recht Schnee und Eis. Auf der Oberfläche der Erde liegt dann Eis und Schnee. Und das findet statt, meine Herren. Es findet statt, daß sich die Oberfläche der Erde hebt und senkt. Und die Erde vor sechstausend Jahren war hoch in der Fläche, wo wir jetzt sind. Jetzt ist sie heruntergesunken, ist schon wieder im Aufsteigen, denn der tiefste Punkt war etwa im Jahr 1250. Das war der tiefste Punkt. Da war es hier in den Gegenden von einer Temperatur, die außerordentlich wohlig war, viel wärmer war, als die heutige ist. Nun ist es schon wiederum auf dem Rückgang und bewegt sich langsam hinauf, so daß nach fünf- bis sechstausend Jahren wiederum eine Art von Eiszeit da sein wird.

Daraus können Sie schon wissen, daß, wenn man von zehn zu zehn Jahren die Witterung beobachtet, sie nicht gleich bleibt; sie verändert sich fortwährend.

Nun aber wiederum, das ist eines, was die Witterung beeinflußt. Aber, meine Herren, bedenken Sie einmal, wenn, sagen wir, in einem bestimmten Jahre bei dieser Höhe der Erdenoberfläche über der Erde eine bestimmte Temperatur wäre, so daß das Wetter dadurch von der Wärmeseite aus so gelegen wäre, so ist ja noch etwas anderes bei der Erde der Fall. Sehen Sie, bei der Erde ist es so: Wenn ich hier die Erde aufzeichne (es wird gezeichnet), so ist die Erde hier, wie man sagt, durch den Äquator warm. Oben und unten auf den Polen ist die Erde kalt. In der Mitte ist die Erde warm. Wenn die Leute nach Afrika oder Indien reisen, so reisen sie in die Hitze hinein. Oben, auf dem Nordpol - und so ist es auch auf dem Südpol - reist man in die Kälte hinein. Sie haben ja die Polarfahrtenbeschreibungen gelesen.

Sie brauchen bloß zu beachten, wie es mit der Wärme- und Kälteverteilung in einem Zimmer ist, das wir anfangen einzuheizen: Wenn Sie anfangen ein Zimmer einzuheizen, so werden Sie bemerken, daß es anfangs nicht gleich warm wird; es dauert eine gewisse Zeit, bis das Zimmer warm wird. Wenn Sie aber eine Leiter nehmen würden und heraufsteigen würden, so würden Sie finden, daß es unten noch ganz kalt sein kann, und oben am Plafond ist es schon warm. Wovon rührt das her? Das rührt davon her, daß die Wärme, die warme Luft, jeder luftförmige, gasförmige erwärmte Körper hinaufsteigt, leichter wird. Alles, was kalte Luft ist, das hält sich unten, weil das schwerer ist; alle warme Luft steigt nach oben, weil sie leichter ist. Nun ist fortwährend die warme Luft hier in dieser Gegend und die kalte Luft hier. Diese Wärme steigt fortwährend in die Höhe, so daß hier in der Mitte der Erde fortwährend die warme Luft aufsteigen will. Wenn sie aber oben ist, weht sie hinauf gegen den Nordpol, und es entstehen solche Winde, die von der Mitte der Erde nach dem Nordpol gehen, und die stellen dar hinaufgehende warme Luft. Die kalte Luft aber wiederum, die will sich erwärmen, geht in die leere Stelle, in die Mitte hinein: kalte Luft strömt herunter; so daß fortwährend vom Nordpol nach der Mitte der Erde kalte Luft strömt, und vom Äquator, von der Mitte der Erde nach dem Nordpol, warme Luft strömt. Man nennt das ja die Passatwinde, die sich in solchen Gegenden, wie die unsrigen sind, verfangen, nicht so bemerkbar sind, aber in anderen Gegenden eben durchaus bemerkbar sind.

Aber das ist nicht nur der Fall für die Luft, sondern auch das Meerwasser zeigt solche Strömungen von der Mitte der Erde nach dem Nordpol und wieder herunter. Das verteilt sich natürlich in der mannigfaltigsten Weise, aber es ist eben da.

Nun denken Sie einmal, wenn nun gerade eine Strömung, eine elektrische Strömung — elektrische Strömungen sind immer vorhanden im Weltenall, denn nicht nur wir bringen drahtlose elektrische Wellen auf der Erde zustande; da ahmen wir ja nur das nach, was im Weltenall in irgendeiner Weise auch vorhanden ist —, wenn gerade eine solche Strömung da ist, sagen wir, in der Schweiz ist: In der Schweiz hat es eine bestimmte Kälte; geht aber eine solche Strömung so her, daß die Wärme hergetragen wird, so wird es etwas wärmer. Und so wird die Wärme durch Weltenströmungen wiederum verteilt. Das beeinflußt die Witterung.

Nun, denken Sie sich aber, daß wiederum solche Strömungen, elektrisch-magnetische Strömungen im Weltenall abhängig sind von den Sonnenflecken. Wenn die Sonne gerade hier ihre Flecken hat (es wird gezeichnet), so sind da die Strömungen - die Folge davon ist das Wetter. Es sind das ja ganz bedeutsame Einflüsse. Und so ist es einfach so, daß wir sagen können: In bezug auf die Verteilung der Jahreszeiten Frühling, Sommer, Herbst und Winter, da ist eine gewisse Regelmäßigkeit im Weltenall. Das können wir im Kalender einteilen. Der Frühling beginnt zu einer bestimmten Zeit und so weiter. Das richtet sich nach den groben Verhältnissen unter den Himmelskörpern. Aber da sind auch wenige Einflüsse. Es sind ja nicht so viei Sterne da, die Einfluß haben; die meisten sind ja weit und haben nur auf das Allergeistigste auf der Welt einen Einfluß. Aber nun mit Bezug auf die Witterungsverhältnisse, meine Herren, da ist es so. Denken Sie sich einmal, Sie haben eine Scheibe, darauf sind Farben, Sie drehen die Scheibe; da können Sie, wenn Sie langsam drehen, noch alle Farben — sagen wir, es sind vier Farben darauf: rot, gelb, grün, blau — gut unterscheiden. Sie können schneller drehen: Es wird Ihnen schon schwerer, aber Sie können doch noch unterscheiden. Drehen Sie aber ganz schnell, dann schwimmt alles durcheinander; da können Sie nichts mehr unterscheiden. Aber es ist auch so, daß man sagen kann: Bei groben Erscheinungen wie Frühling, Sommer, Herbst und Winter, da kann man noch übersehen, von was es abhängt. Aber da sind so viele Dinge, von denen die Witterung abhängt, daß man sie nicht mehr überdenken kann, so daß man die Sache im Kalender in bezug auf die Witterung nicht mehr einschreiben kann, wie: Frühling, Sommer und so weiter — da wird es kompliziert, weil es sich eben verwirrt.

Aber auch da sind alte Volksanschauungen vorhanden. Man muß alte Volksanschauungen nicht so ohne weiteres abweisen; die beruhen darauf, daß sich die Leute, als die Verhältnisse noch einfacher waren, wirklich viel mehr für die Sachen interessiert haben. Heute, wo wir uns höchstens vierundzwanzig Stunden lang für eine Sache so recht interessieren, weil nach vierundzwanzig Stunden wieder eine neue Zeitung kommt, und wir durch die neue Zeitung ein anderes Interesse kriegen, heute vergessen wir ja alles, was geschieht. Es ist ja so! Und außerdem, wie sind unsere Lebensverhältnisse kompliziert geworden; es ist Ja alles schauderbar kompliziert. So war es nicht einmal bei unseren Großvätern, geschweige denn bei unseren Ururgroßvätern. Die saßen schon so in der Stube und hinterm Ofen, saßen zusammen und erzählten sich, erzählten sich aber auch von alten Zeiten und wußsten, wie in alten Zeiten manchmal die Witterung war, weil sie sie zusammenhängend wußten mit den Gestirnen, und dadurch haben sie gesehen, wahrgenommen, daß doch eine gewisse Regelmäßigkeit in der Witterung liegt. Und sehen Sie, es gab ja unter diesen Urgroßvätern auch sogenannte «verflixte Kerle», wissen Sie — ich meine mit einem «verflixten Kerl» einen, der nicht ganz dumm ist, sondern der auch ein bißchen gescheiter ist als die anderen, der so etwas Gescheites hat -, es gab solche verflixten Kerle mit einer gewissen Gescheitheit. Ja, meine Herren, wenn man diesen verflixten Kerlen zuhören würde, dann würde man sie ganz interessant reden hören! Wollen wir einmal hören, wie so ein recht alt gewordener, verflixter Kerl zu seinem Ururenkel oder Urenkel gesagt hätte. Der hätte gesagt: Ja, sieh einmal, wenn du den Mond beobachtest — du weißt ja, der Mond, der hat auf die Witterung Einfluß. - Das haben die Leute also einfach gesehen. Sie wußten ganz gut, das Regenwasser ist besser zum Wäschewaschen als das gewöhnliche Wasser, das man aus dem Brunnen herholt. Deshalb haben sie die Eimer aufgestellt. Das hat meine Mutter auch noch gemacht: Eimer aufgestellt, Regenwasser gesammelt und zum Waschen das Regenwasser verwendet! Es ist eben ein anderes Wasser, das Regenwasser, hat eine gewisse Lebendigkeit in sich, nimmt auch die Waschbläue und anderes, was man braucht als Zusatz beim Waschen, viel mehr auf als das gewöhnliche Wasser. Und gar nicht so schlecht wäre, wenn wir das auch täten, denn mit dem harten Wasser waschen, das hat schon etwas Zerstörerisches für vieles, was Sie anziehen.

Also, meine Herren, das hat man früher gewußt; darüber hat man erst durch die Wissenschaft im 19. Jahrhundert andere Ansichten bekommen. Ich habe Ihnen einmal erzählt - ein Teil der Herren weiß es schon — von den zwei Professoren an der Leipziger Universität; der eine hieß Schleiden, der andere hieß Fechner. Fechner behauptete, weil er das beobachtet hatte, statistische Aufzeichnungen gemacht hatte: Der Mond hat auf die Erde Einfluß, auf das Wetter der Erde Einfluß. Schleiden war der ganz Gescheite; der sagte: Das ist eine Dummheit, ein Aberglaube; das gibt es nicht. - Nun, wenn Professoren streiten, so kommt nicht viel dabei heraus; wenn andere Leute sich streiten, kommt meistens auch nicht viel dabei heraus! Aber nun waren die zwei Professoren verheiratet, und es gab auch eine Frau Professor Schleiden und eine Frau Professor Fechner. Und es war noch in jener Zeit, in der man in Leipzig das Regenwasser noch gesammelt hat zum Waschen der Wäsche. Da hat der Fechner zu seiner Frau gesagt: Nun ja, gut, wenn mein Kollege, der Schleiden, sagt, daß man bei Neumond ebensoviel Regenwasser kriegt wie bei Vollmond, da soll die Frau Professor Schleiden bei Neumond ihre Eimer herausstellen und Wasser sammeln, und du sammelst bei Vollmond, wo ich sage, daß du mehr Wasser kriegst! -— Nun das hat die Frau Professor Schleiden gehört, diesen Vorschlag, und hat gesagt: Nein, da wird nichts draus, ich will meine Eimer bei Vollmond herausstellen, und die Frau Professor Fechner soll ihre Eimer bei Neumond herausstellen! — Sehen Sie, die Frauen haben anders entschieden, weil die das Wasser brauchten! Die Professoren können ruhig über das Wasser herumstreiten, aber die Frauen brauchen das Wasser.

Das wußte auch dieser Urgroßvater noch und wußte, daß der Urenkel das auch weiß, und sagte: Sieh einmal das an, der Mond beeinflußt das Wasser. Aber schau dir einmal an, wie das ist mit dem Mond: Alle achtzehn, neunzehn Jahre wiederholt sich für den Mond alles, was es nur gibt für ihn.Wir haben zum Beispiel in einem bestimmten Jahr, an einem bestimmten Tag Sonnen- und an einem bestimmten Tag Mondenfinsternisse. Das wiederholt sich im Lauf von achtzehn, neunzehn Jahren regelmäßig. So ist der Kreislauf. Und so wiederholen sich alle Erscheinungen nach der Stellung der Sterne im Weltenall. Warum könnte nicht auch - so sagte er - sich alles in der Witterung wiederholen, da es doch vom Mond abhängt? Es muß also nach achtzehn, neunzehn Jahren eine Ähnlichkeit in der Witterung mit derjenigen vor achtzehn, neunzehn Jahren sein.

Und wiederum, sehen Sie, wenn alles sich wiederholt, so schauten diese Leute dann auf andere Wiederholungen, und verzeichneten im Kalender gewisse Witterungen in früheren Jahren, vor achtzehn, neunzehn Jahren, und erwarteten, daß ähnliche Witterungen kommen wiederum.nach achtzehn, neunzehn Jahren. Man hat also nur den Kalender den Hundertjährigen Kalender genannt, weil hundert so eine Zahl ist, die man leicht behalten kann; aber es waren andere Zahlen eingeschrieben, nach denen man die Witterung vorausgesagt hat. — Nur natürlich, so ganz zu stimmen braucht ja das nicht, weil wiederum die Verhältnisse kompliziert sind; aber im praktischen Leben hat das doch den Leuten Dienste getan, denn sie haben sich danach gerichtet und haben dadurch in der Tat bessere Fruchtbarkeitsverhältnisse für die Erde bekommen. So daß man sagen kann: Aus solchen Beobachtungen heraus kann man schon für die Fruchtbarkeitsverhältnisse wiederum etwas tun. — Aber diese Witterungsverhältnisse haben eben durchaus wiederum eine Abhängigkeit von Sonne und Mond, denn diese Wiederholungen der Mondesstellungen, die beziehen sich eben auf Sonne und Mond.

Für andere Sterne in ihren Verhältnissen sind andere Wiederholungen da. Eine interessante Wiederholung ist ja diejenige, die sich auf die Venus bezieht, auf den Morgen- und Abendstern. Nicht wahr, wenn da die Sonne ist und da die Erde (es wird gezeichnet), so ist zwischen Sonne und Erde die Venus, die sich bewegt. Wenn die Venus da steht, so sieht man so heraus; wenn die Venus da steht, sieht man so heraus; wenn die Venus aber da steht, bedeckt die Venus die Sonne. Es ist von der Venus, die natürlich nur viel kleiner ausschaut wie der Mond, wenn sie auch größer ist, die Sonnenscheibe ein Stückchen bedeckt. Man nennt das einen Venusdurchgang. Diese Venusdurchgänge sind deshalb sehr interessant, weil sie eigentlich nur ungefähr alle hundert Jahre einmal stattfinden, und weil, wenn so die Venus vor der Sonne vorbeigeht, also vor der Sonne durchgeht, man da sehr wichtige Sachen beobachten kann. Man kann beobachten, wie sich ringsherum der Lichtschein der Sonne ausnimmt, wenn die Venus davorsteht. Das verursacht große Veränderungen. Das ist sehr interessant. Diese Venusdurchgänge, die werden beschrieben; und da sie nur ungefähr alle hundert Jahre stattfinden, kann man sagen: sie gehören zu demjenigen, wo die Wissenschaft sagen müßte, sie glaube auch andere Sachen als die, die sie gesehen habe. Denn wenn die Wissenschafter sagen, sie glauben nur diejenigen Dinge, die sie gesehen haben, so könnte niemals ein Astronom, der im Jahre 1890 geboren ist und heute vorträgt, über einen Venusdurchgang sprechen, denn den kann er in der Zeit gar nicht wahrgenommen haben, und vermutlich wird er früher sterben, bevor der nächste Venusdurchgang ist, der eben wahrscheinlich im Jahre 2004 stattfinden wird. Da muß auch der Wissenschafter glauben, was er nicht sieht! Das kann er nicht wahrnehmen.

Aber wiederum haben wir da, weil ja die Venus jetzt die Sonne beeinflußt, weil sie das Licht abhält, einen Einfluß auf die Witterungsverhältnisse — einen Einfluß, der ungefähr nur alle hundert Jahre stattfindet. Diese Venusdurchgänge, die hat man gerade in alten Zeiten außerordentlich interessant gefunden.

Und da ist etwas sehr Merkwürdiges. Sehen Sie, meine Herren, wenn Sie den Mond anschauen: Sie finden den Mond auf dem Himmel stehen, wenn Vollmond ist, als eine Scheibe, sonst als einen Kipfel, eine Halbscheibe und so weiter — da glänzt er in seinem Licht. Dann gibt es aber Neumond. Wenn Sie aber ein bißchen geübte Augen haben - ich weiß nicht, ob Sie das wissen —, können Sie auch den Neumond sehen; namentlich können Sie das Stückchen Mond sehen, wenn dahier zunehmender Mond ist. So kann man schon, wenn man genauer hinschaut, auch das andere vom Mond sehen, so schwarz-bläulich. Und wie gesagt, wenn man geübte Augen hat, kann man auch bei Neumond eine so schwarz-bläuliche Scheibe noch sehen; man gibt nur nicht acht darauf, man kann sie aber sehen. Ja, woher kommt das, daß das überhaupt sichtbar wird beim Mond? Das kommt davon her, weil dieses Stück Mond, das sonst finster ist, noch von der Erde etwas beleuchtet wird. Der Mond ist ja ungefähr fünfzigtausend Meilen von der Erde entfernt, wird nicht eben von der Erde beleuchtet; aber dieses kleine Licht, das von der Erde auf den Mond hinstrahlt, macht uns dieses Stück Mond sichtbar. Aber bis zur Venus strahlt gar kein Licht von der Erde. Die Venus ist angewiesen auf das Sonnenlicht; es strahlt kein Licht auf sie von der Erde. Nun ist die Venus der Morgen- und Abendstern. Der ist ja auch so, daß er sich so verändert wie der Mond, nur nicht in derselben Zeit. Es gibt Zeiten, in denen die Venus so ausschaut (es wird gezeichnet), so, und wieder so, dann wiederum so. Die Venus hat auch diese Veränderung, man sieht das nur nicht; die Venus ist weit weg, und man sieht eben nur einen glänzenden Stern. Man muß sie abblenden und muß sie dann mit dem Fernrohr anschauen, dann sieht man, daß die Venus auch sich in dieser Weise verändert wie der Mond. Da aber, bei der Venus, ist es so, daß nun, trotzdem sie von der Erde nicht mehr beleuchtet werden kann, dieses Stück außerdem in einem matten, bläulichen Licht noch immer sichtbar ist. Das Sonnenlicht, das sieht man an der Venusphase, wie man sagt, an dem «Kipfel» oben — nicht der ganzen Venus, aber da, wo die Venus nicht von der Sonne beschienen ist, da sieht man ein bläuliches Licht.

Nun, meine Herren, es gibt zum Beispiel gewisse Steine, die Bologneser Leuchtsteine, die eine Bariumverbindung — Barium ist ein metallischer Stoff — enthalten. Wenn Sie diese Steine eine Zeitlang beleuchten, also Licht auffallen lassen, dann das Zimmer verfinstern, dann sehen Sie, wie der Stein noch ein bläuliches Licht zurückwirft. Man sagt, der Stein, nachdem er beleuchtet ist, phosphoresziert. Er hat das Licht gewissermaßen auch bekommen, etwas gefressen von dem Licht, und jetzt speit er es wiederum von sich, wenn es finster ist. Er tut das natürlich auch, wenn es hell ist; er nimmt immer etwas auf, gibt immer etwas zurück. Weil er nicht viel aufnehmen kann, so ist es natürlich auch wenig, was er zurückgibt; man sieht es daher nicht, wenn es hell ist, geradeso wie man ein schwaches Kerzenlicht nicht wahrnimmt, wenn Sonnenlicht da ist; aber wenn man das Zimmer verfinstert, dann phosphoresziert der Stein, dann sieht man das Licht, das von ihm ausgeht.

Nun, sehen Sie, meine Herren, wenn Sie dieses Licht am Stein beobachten, so ist es Ihnen ja erklärlich, woher das Licht der Venus kommt. Die Venus wird auf der anderen Seite, wenn sie hier nicht beschienen wird, von der Sonne beschienen, sie frißt also gleichsam das Sonnenlicht auf, und wenn Sie sie dann anschauen in der finsteren Nacht, wo sie nicht beschienen ist, da speit sie es aus, phosphoresziert. In der Zeit, als der Mensch alles besser gesehen har als jetzt — die Menschen haben ja alles besser gesehen, bessere Augen gehabt in früheren Zeiten -, hat er das auch gesehen. Sie wissen, die Brillen sind ja erst im 16. Jahrhundert aufgekommen; sie wären sicher früher aufgekommen, wenn der Mensch sie gebraucht hätte! Die Erfindungen und Entdeckungen kommen immer dann, wenn die Menschen sie brauchen. Die Menschen haben schon bessere Augen gehabt, und sie haben dieses Phosphoreszieren der Venus gesehen. Aber außerdem haben sie die Veränderung, die bewirkt wird, wenn die phosphoreszierende Venus da in die Sonne hereinkommt, auch wahrgenommen. Und daraus haben sie in ganz alten Zeiten den Schluß gezogen, daß, weil da das Sonnenlicht einen Einfluß von der Venus hat, dieser selbe Einfluß nach ungefähr hundert Jahren wieder da ist; dann wird da auch eine ähnliche Witterung sein. So daß in einer solchen Gegend, wo man den Venusdurchgang sehen wird — Sie wissen ja, Sonnenfinsternisse sieht man auch nicht in allen Gegenden, sondern nur in gewissen Gegenden -, wieder eine ähnliche Witterung sein wird in hundert Jahren. Sehen Sie, daraus bildeten sie dann in gewissen Jahren einen Hundertjährigen Kalender. Dann haben die Leute, die nichts mehr verstanden haben von der Sache, in jedem Jahr einen Hundertjährigen Kalender gemacht. Dann finden sie in jedem Jahr: der Hundertjährige Kalender sagt das. Das stimmt nicht! Das geht dann nach der Lebensregel: Wenn der Hahn kräht auf dem Mist, ändert sich’s Wetter oder’s bleibt, wie’s ist. — Aber darauf beruht die Sache überhaupt, daß ursprünglich ganz richtige Dinge da waren: Die Leute haben gesehen, wenn die Venus durch die Sonne durchgeht, dann bewirkt das eine Witterung, die sich dann irgendwo wiederholt nach ungefähr hundert Jahren.

Und weil das so ist bei der Witterung, daß das das ganze Jahr sich gegenseitig beeinflußt, so ist das nicht nur während der Tage, während derer die Venus durchgeht, sondern es ist ausgedehnt durch längere Zeit. Und so sehen Sie: nach dem, was ich Ihnen schon gesagt habe, müßte man eigentlich ja nachdenken darüber, wenn man die Gesetzmäßigkeit der Witterung wissen wollte für irgendeine Woche oder einen Tag: Vor wieviel Jahren war ein Venusdurchgang? Wie steht jetzt der Mond? Vor wieviel Jahren war eine Sonnenfinsternis, dieselbe wie jetzt? — Das sind aber nur wenige Dinge, die ich Ihnen gesagt habe. Man muß wissen: Wie werden durch den Magnetismus oder die Elektrizität die Passatwinde vertragen? Alle diese Fragen müßte man beantworten, wenn man die Regelmäßigkeit der Witterung bestimmen wollte. Ja, meine Herren, das ist etwas, wo man eben ins Unendliche hineinkommt! Daher wird man es aufgeben, darüber irgendwie etwas Bestimmtes zu sagen, welche Witterung unbedingt eintreten müßte. So regelmäßig alle Erscheinungen sind, die die Astronomie behandelt - Astronomie ist die Lehre, welche den Himmelseinfluß der Sterne behandelt -, so wenig eigentlich ist die Wissenschaft bestimmt, die die gegenseitigen Verhältnisse der Einflüsse auf die Witterung behandelt, die sogenannte Meteorologie. In der Meteorologie, da werden Sie finden, wenn Sie heute ein Buch in die Hand nehmen, das etwas von Meteorologie enthält: Donnerwetter, da kann ich gar nichts daraus lernen, denn eigentlich behauptet jeder etwas anderes. — Das ist bei der Astronomie nicht der Fall.

Damit habe ich Ihnen wohl einen Überblick gegeben über das, wie man über die Gesetzmäßigkeit von Wind und Wetter und so weiter sprechen kann. Dazu kommt noch dieses, daß auf die Witterung ungeheuer starken Einfluß haben die Kräfte, die in der Atmosphäre selber entstehen. Sie brauchen nur an den Sommer zu denken, an den heißen Sommer, wo die Blitze aus den Wolken kommen und die Donner rollen: da haben Sie wiederum Einflüsse auf die Witterung ausgedrückt, die aus der unmittelbaren Erdennähe herkommen. Über diese Geschichte hat ja die heutige Wissenschaft eine merkwürdige Ansicht. Sie sagt: Ja, das ist die Elektrizität, die da bewirkt, daß der Blitz aus der Wolke schlägt. - Nun, Sie wissen ja vielleicht, daß man in der Schule anfängt, die Elektrizität zu erklären, indem man eine Glasstange nimmt und mit einem Tuchlappen reibt, der etwas mit Amalgam geschmiert ist. Man kann dann finden, daß die Glasstange kleine Papierschnitzel anzieht und so weiter; man kann soweit reiben, daß dann auch Funken entstehen und so weiter. Man macht solche Versuche in der Schule mit der Elektrizität. Aber, meine Herren, es ist notwendig, wenn man solche Versuche mit der Elektrizität macht, daß man alles sorgfältig abwischt, denn die Gegenstände, die elektrisch werden sollen, die dürfen gar nicht irgendwie feucht oder naß sein, müssen ganz trocken sein, warm-trocken sein, sonst kriegt man nichts heraus aus dem Glas oder Siegellack. Daraus würden Sie wissen können: Die Elektrizität wird vertrieben durch Wasser und Flüssigkeit. Das weiß jeder, wissen natürlich auch die Gelehrten, denn die machen es ja. Trotzdem behaupten sie, daß der Blitz aus den Wolken herauskommt, und die sind doch ganz gewiß naß!

Soll denn wirklich der Blitz aus den Wolken herauskommen, dann müßte man ja zuerst die Wolken mit einem riesigen Handtuch abreiben und alles trocken machen, wenn der Blitz aus den Wolken kommen soll! Aber man sagt es so einfach: Man reibe eine Siegellackstange, dann kommt Elektrizität heraus: die Wolken reiben sich auch aneinander, es kommt Elektrizität heraus. Wenn aber die Siegellackstange ein bißchen naß ist, kommt keine Elektrizität heraus. Nun soll aus den Wolken, die ja nur naß sind, Elektrizität kommen! Daraus sehen Sie aber, was für Dinge Sie eigentlich heute lernen, die ganz innerlich unsinnig sind. Die Sache ist eben diese, sehen Sie: Wenn Sie Luft haben, können Sie die warm machen, sie wird dann immer heißer und heißer. Nun denken Sie sich einmal, Sie haben Luft eingeschlossen in einem Kessel. Man kann sagen: Diese Luft wird dichter, denn je heißer und heißer Sie sie machen, desto mehr drückt sie auf die Kesselwände, immer mehr und mehr drückt sie auf die Kesselwände. Je heißer Sie sie machen, desto mehr kommt es an den Punkt, wo unter Umständen, wenn die Kesselwände nicht dick genug sind, die heiße Luft die Kesselwände auseinandersprengt. Warum zerspringt denn solch ein Ball meistens, den die Kinder zum Spielen haben? Weil die Luft herausgeht. Ja nun, meine Herren, daraus können Sie sehen, daß die Luft, wenn sie warm wird, durch das Heißerwerden die Tendenz bekommt, die Kraft bekommt, auseinanderzugehen. So bleibt die Geschichte in der Nähe der Erde. In der Nähe der Erde bekommt die Luft so eine Kraft, auseinanderzugehen. Geht man aber in recht hohe Schichten hinauf und wird in recht hohen Schichten die Luft durch irgend etwas sehr, sehr warm — was zum Beispiel auch durch irgendwelche Einflüsse im Winter geschehen kann, wenn sie zuerst irgendwo sehr stark zusammengedrückt wird -, dann kriegt sie furchtbare Hitze in sich. Nicht wahr, wenn Sie einen Kessel haben und dadrinnen Luft (es wird gezeichnet), dann drückt es nach allen Seiten. Wenn Sie aber hier eine warme Luftschicht haben, und hier weht, durch irgend etwas bewirkt, ein Wind vorbei, so daß er die Luft hier wegfängt - hier ist irgendwie eine dickere Luft, weil es sich zusammenschoppt -, dann kann es nicht hier hinaus, sondern geht hier herüber: die wärmende Hitze der Blitze strömt nach der Seite, wo es am leichtesten ist. Die Blitze, das ist die Hitze, die die Luft in sich selber erzeugt und die dahin geht, wo gewissermaßen dadurch, daß die Luft dort am dünnsten ist, eine Art Loch ist in der umgebenden Luft. Man muß sagen: Der Blitz entsteht nicht durch Elektrizität, sondern der Blitz entsteht dadurch, daß die Luft ihre eigene Hitze ausleert.

Aber nun dadurch, daß diese furchtbar starke Bewegung geschieht, . dadurch werden wiederum die immerfort in der Luft, namentlich in der warmen Luft vorhandenen elektrischen Strömungen erregt. Der Blitz erregt erst die Elektrizität. Er ist noch keine Elektrizität.

Und wiederum sehen Sie da, daß überall in der Luft eine andere innere Wärmeverteilung ist. Das beeinflußt wiederum die Witterung. Das sind Witterungseinflüsse, die von der Nähe der Erde kommen, die in der Nähe der Erde selber sich abspielen.

Aus alledem sehen Sie, wie viele Dinge da sind, die die Witterung beeinflussen, und wie heute — wie Sie sehen, hat man ja über den Blitz ganz verdrehte Ansichten, wie ich Ihnen gesagt habe — über alle diese Einflüsse eben noch durchaus keine richtigen Ansichten da sind. In dieser Beziehung muß wirklich, weil die Geisteswissenschaft, die Anthroposophie, eine größere Übersicht erreicht, das Denken überhaupt beweglicher macht, ein Umschwung eintreten.

Denn, sehen Sie — natürlich kann man das nicht im heutigen Seziersaal nachweisen —, wenn man eben mit den Mitteln der Geisteswissenschaft forscht, so findet man, daß die Gehirne der Menschen in den letzten Jahrhunderten furchtbar viel steifer geworden sind, als sie vorher waren, furchtbar viel steifer. Denn man findet zum Beispiel, sagen wir, die alten Ägypter haben ganz bestimmte Dinge gedacht, die ihnen gerade so sicher waren wie uns unsere Dinge. Aber der Mensch kann sie heute, wenn er richtig Obacht gibt, im Winter weniger verstehen als im Sommer. Man gibt nur nicht acht auf solche Dinge; man gibt wirklich nicht acht auf solche Dinge. Und würde man in manchen Dingen sich recht richten können nach dem, was eigentlich gesetzmäßig in der Welt drinnen ist, dann würde man sich anders einrichten. Man würde zum Beispiel selbst in der Schule — was in gewissem Sinne schon in der Waldorfschule beobachtet wird - in den Winter andere Gegenstände verlegen als in den Sommer. Nicht nur, daß man da Botanik nimmt, weil ja die Pflanzen da sind, sondern manches, was leichter zu verstehen ist, sollte man in den Winter verlegen, manches was schwerer zu verstehen ist, sollte man in den Frühling und Herbst verlegen, weil das Verstehen schon auch von diesen Dingen abhängig ist. Das kommt davon her, weil wir härtere Gehirne gekriegt haben und die früheren Menschen weichere Gehirne gehabt haben. Was wir nur im Sommer denken können, haben die Ägypter im ganzen Jahre denken können. — Ja, alle diese Dinge gibt es. Auf alle diese Dinge kommt man, wenn man eben Jahreszusammenhänge, Witterungszusammenhänge und so weiter beobachtet.

Ist vielleicht jemandem noch etwas nicht klar? Sind Sie befriedigt über die Sache? Ich habe es natürlich etwas ausführlicher beantwortet. Nicht wahr, die Welt ist ein Ganzes, ein Wesen, und man kommt dann natürlich, wenn man eines erklären will, in die andere Sache selbstverständlich hinein, weil alles voneinander abhängt.

Frage: Herr Burle sagt, er möchte etwas darüber fragen, ob daran etwas sei — seine Kollegen werden wahrscheinlich lachen, er habe vor zwei, drei Jahren schon einmal davon gesprochen —, daß man sagt, wenn man Kaffee hat, und tut Zucker in den Kaffee, der sich dann auflöst so, daß es schön in der Mitte bleibt: Es wird schönes Wetter — oder umgekehrt, wenn er sich schlecht auflöst, zerfließt: Es wird schlechtes Wetter — und so ähnlich?

Dr. Steiner: Ja, nicht wahr, dieses Experiment habe ich in der Weise noch nicht gemacht. Ich weiß es also nicht, ob da etwas dahintersteckt oder nicht. Aber es könnte schon sein, daß es etwas zu bedeuten hat, wenn sich der Zucker gleichmäßig oder weniger gleichmäßig auflöst — wenn es überhaupt etwas zu bedeuten hat. Aber nehmen wir an, es hätte etwas zu bedeuten; ich will unter dieser Voraussetzung: Es hat etwas zu bedeuten — hypothetisch reden.

Nehmen wir aber etwas anderes an, das etwas an sich hat, denn das habe ich genügend beobachtet: Das ist die Ergründung des nächsten kommenden Wetters durch die Laubfrösche, die grünen Laubfrösche. Das habe ich genügend gemacht: Kleine Leitern gemacht und den Laubfrosch beobachtet, ob er herauf oder herunter geht. Da finden Sie, daß der Laubfrosch in der Tat eine sehr feine Empfindung dafür hat, was da für Wetter kommt. Das braucht Sie nicht zu verwundern, denn in gewissen Gegenden kommt manchmal folgendes vor: Die Menschen müssen beobachten, wie plötzlich die Tiere in den Ställen unruhig werden, fort wollen; und diejenigen, die fort können, die freigebundenen Tiere, machen sich schnell davon. Die Menschen bleiben zurück: es kommt ein Erdbeben! Die Tiere haben das voraus gewußt, daß sich schon früher etwas in der Natur vollzieht. Es verändert sich alles in der Natur schon vorher. Die Menschen nehmen das durch ihre Nasen und anderen groben Sinne nicht wahr; die Tiere nehmen es wahr. Ich habe das schon einmal ausgeführt. So hat natürlich auch der Laubfrosch eine bestimmte Witterung für dasjenige, was da kommt. Man nennt das sogar «Witterung», was man da riecht, weil es sich auf das Zukünftige bezieht.

Nun sehen Sie, im Menschen sind auch recht viele Dinge, von denen er gar nichts weiß. Ja, meine Herren, das ist schon so: Im Menschen sind recht viele Dinge, von denen man nichts weiß! Man beobachtet es einfach nicht. Wenn es ein schöner Sommertag ist, dann sind wir unter Umständen, wenn wir aufgestanden sind und zum Fenster hinausschauen, ganz anders aufgelegt, als wenn es furchtbar wettert. Wir beobachten nicht, daß das bis in unsere Fingerspitzen hineingeht. Und das, was die Tiere können, können wir schon auch; wir bringen es uns nur nicht zum Bewußtsein.

Also denken Sie einmal, Herr Burle, wenn die Sache so wäre, daß Sie, nicht irgendwo anders, aber in dem Feingefühl Ihrer Fingerspitzen, wovon Sie nichts wissen, wittern, so wie der Laubfrosch, die kommende Witterung, dann tun Sie instinktiv an dem Tage, wo Sie durch eine günstige Witterung besser aufgelegt sind, den Zucker mit einer größeren Kraft in den Kaffee hinein - am anderen Tag weniger. Also es braucht nicht abzuhängen vom Kaffee und Zucker, sondern von Ihrer Kraft, mit der Sie ihn hineinwerfen. Aber dieseKraft, die ich jetzt meine, die ist ja nicht diese, daß Sie stark oder schwach bewußt hineinwerfen, sondern die ist in Ihren Fingerspitzen. In Ihren Fingerspitzen liegt das eben so, daß Sie, wenn günstige Witterung kommt, anderes in Ihren Fingerspitzen haben, als an einem anderen Tag, wo trübes Wetter kommt. Das hängt nicht ab von der Kraft, wie stark oder schwach Sie hineinwerfen, sondern von dem, wie in Ihren Fingerspitzen miterlebt wird die Witterung. Davon hängt es ab, nicht von dem, wie Sie mit Ihrem Bewußtsein hineinwerfen, sondern wie Sie in Ihren Fingerspitzen das haben! Das ist ja eine etwas andere Kraft, eine andere Bewegung.

Denn, sehen Sie, nehmen Sie einmal die Sache so: Da sitzt eine Gesellschaft, sie setzt sich um einen Tisch herum; man macht zunächst irgend etwas Sentimentales, singt ein heiliges Lied, bringt die Gesellschaft in Stimmung. Dann fangen -es ist eine feine, nicht eine grobe Wendung -, dann fangen dadrinnen Schwingungen an. Womöglich kommt dann Musik. Weiter schwingt es; dann fangen die Leute an und geben um den Tisch alle diese feinen Erzitterungen an den Tisch weiter. Das summiert sich und der Tisch fängt an zu tanzen. Es ist die spiritistische Sitzung zustandegekommen durch diese kleinen, durch Musik und Gesang erregten Bewegungen. So verursacht schon auch die Witterung feinere Bewegungen. Von diesen feineren Bewegungen kann das wieder beeinflußt sein, was da stattfindet — ich sage es nur hypothetisch; ich kann nicht sagen, daß das absolut stimmt. Aber wahrscheinlicher ist es, daß da dasjenige, was der Mensch selber ahnt über die Witterung, sich ausdrückt, als daß das auf den Zucker einen besonderen Eindruck gemacht hat, was eben nicht gerade sehr wahrscheinlich ist; ich sage es ja selbst nur als eine Hypothese. Aber derjenige, der auf dem Standpunkt der Geisteswissenschaft steht, der muß unbedingt eine solche Erscheinung solange abweisen, bis er den striktesten Beweis hat. Sehen Sie, wenn ich Ihnen leichten Herzens erzählen würde über die Dinge, die ich Ihnen hier erzähle, so brauchten Sie mir eigentlich gar nichts zu glauben. Nur dadurch können Sie mir glauben, daß Sie wissen: Solange die Dinge nicht bewiesen sind, werden sie nicht in der Geisteswissenschaft aufgenommen. So kann ich die Geschichte mit dem Kaffee auch dann nur in die Geisteswissenschaft aufnehmen, wenn sie wirklich bewiesen ist. Vorher kann man nur sagen, daß man zum Beispiel etwas weiß von den feinen Wellenschwingungen der Nerven, die ja auch die Ursache sind, daß die Tiere die Wirkung vorauswissen — auch der Laubfrosch, denn der kommt in Erzitterung; und wenn er in Erzitterung kommt, dann werden Sie auch sehen, wie die Blätter, auf denen er sitzt, anfangen zu zittern. Und so kann das auch - ich sage nicht, daß es so ist, aber es könnte - viel wahrscheinlicher davon abhängen, daß der Kaffee anders zu erzittern anfängt, wenn schlechte Witterung kommt, als wenn bessere Witterung kommt, je nachdem.

Das nächste Mal dann am nächsten Mittwoch. Aber ich denke schon, daß ich dann regelmäßig wieder die Stunden einhalten kann.

Eleventh Lecture

Well, gentlemen, is there anything else on your minds that you would like to have answered today?

Question: Is Mars' proximity to Earth related to the weather, because we've had such a bad summer, as one can hardly imagine — or do planetary influences play a role at all?

Dr. Steiner: Well, it is true that weather conditions, which have proven to be rather irregular over the years, especially recently, do have something to do with celestial conditions, but not directly with Mars. When we observe these irregularities, we must first and foremost take into account a phenomenon that is otherwise rarely considered, but which is nevertheless discussed: the phenomenon of sunspots. Sunspots are phenomena that occur at intervals of ten, eleven, twelve years, always in a certain variation. When you observe the surface of the sun, you see dark spots appearing. These dark spots naturally impair the sun's radiation, because where it is dark, it does not radiate. So you can imagine that if there are more sunspots in a given year, then there will be less radiation in that year. And given the great importance – which I have already mentioned – that the sun has for the Earth, this is indeed significant.

And this phenomenon of sunspots is also very remarkable in another respect. It must be admitted that over the centuries the number of sunspots has increased. So they do not appear in the same quantity every year. This is because the position of the celestial bodies is different. When the celestial bodies rotate, their position changes, and as a result, the view of a celestial body is always different. So when sunspots are in a certain place, they do not appear in the same place every year, but rather depending on the rotation of the sun; they then reappear in the same place over the course of the years. But over the centuries, they have increased significantly, and this increase in sunspots is significant for our understanding of what is actually happening in the relationship between the Earth and the sun.