Agriculture

GA 327

15 June 1924, Koberwitz

Lecture VII

My dear friends,

In the remainder of the time at our disposal, I wish to say something about farm animals, orchards and vegetable gardening. We have not much time left; but in these branches of farming, too, we can have no fruitful starting-point unless we first bring about an insight into the underlying facts and conditions. We shall do this to-day, and pass on tomorrow to the more practical hints and applications.

To-day I must ask you to follow me in matters which lie yet a little farther afield from present-day points of view. Time was, indeed, when they were thoroughly familiar to the more instinctive insight of the farmer; to-day they are to all intents and purposes terra incognita. The entities occurring in Nature (minerals, plants, animals—we will leave man out for the moment) are frequently studied as though they stood there all alone.

Nowadays, one generally considers a single plant by itself. Then, from the single plant, one proceeds to consider a plant-species by itself; and other plant-species beside it. So it is all prettily pigeonholed into species and genera, and all the rest that we are then supposed to know. Yet in Nature it is not so at all. In Nature—and, indeed, throughout the Universal being—all things are in mutual interaction; the one is always working on the other.

In our materialistic age, scientists only follow up the coarser effects of one upon the other—as for instance when one creature is eaten or digested by another, or when the dung of the animals comes on to the fields. Only these coarse interactions are traced. But in addition to these coarse interactions, finer ones, too, are constantly taking place—effects transmitted by finer forces and finer substances too—by warmth, by the chemical-ether principle that is for ever working in the atmosphere, and by the life-ether.

We must take these finer interactions into account. Otherwise we shall make no progress in certain domains of our farm-work. Notably we must observe these more intimate relationships of Nature when we are dealing with the life, together on the farm, of plant and animal. Here again, we must not only consider those animals which are undoubtedly very near to us—like cattle, horses, sheep and so on. We must also observe with intelligence, let us say, the many coloured world of insects, hovering around the plant-world during a certain reason of the year. Moreover, we must learn to look with understanding at the birds.

Modern humanity has no idea how greatly farming and forestry are affected by the, owing to the modern conditions of life, of certain kinds of birds from certain districts. Light must be thrown upon these things once more by that macrocosmic method which Spiritual Science is pursuing—for we may truly call it macrocosmic. Here we can apply some of the ideal we have already let work upon us; we shall thus gain further insight.

Look at a fruit-tree—a pear-tree, apple-tree or plum-tree. Outwardly Seen, to begin with, it is quite different from a herbaceous plant or cereal. Indeed, this would apply to any tree—it is quite different. But we must learn to perceive in what way the tree is different; otherwise we shall never understand the function of fruit in Nature's household (I am speaking now of such fruit as grows on trees).

Let us consider the tree. What is it in the household of Nature? If we look at it with understanding, we must include in the plant-nature of the tree any more than grows out of it in the thin stalks—in the green leaf-bearing stalks—and in the flowers and fruit. All this grows out of the tree, as the herbaceous plant grows out of the earth. The tree is really “earth” for that which grows upon its boughs and branches. It is the earth, grown up like a hillock; shaped—it is rate—in a rather more living way than the earth out of which our herbaceous plants and cereals spring forth.

To understand the free, we must say: There is the thick tree trunk (and in a sense the boughs and branches still belong to this). Out of all this the real plant grows forth. Leaves, flowers and fruit grow out of this; they are the real plant—rooted in the trunk and branches of the tree, as the herbaceous plants and cereals are rooted in the Earth.

Here the question will at once arise: Is this “plant” which grows on the tree—and which is therefore describable as a parasitic growth, more or less—is it actually rooted? An actual root is not to be found in the tree. To understand the matter rightly, we must say: This plant which grows on the tree—unfolding up there its flowers and leaves and Stems—has lost its roots. But a plant is not whole if it has no roots. It must have a root. Therefore we must ask ourselves: Where is the root of this plant?

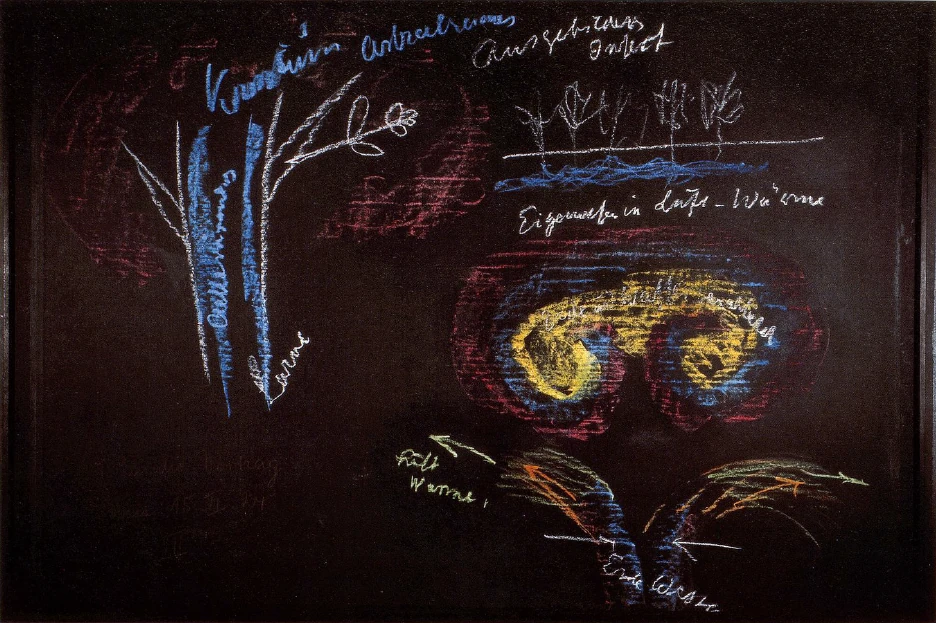

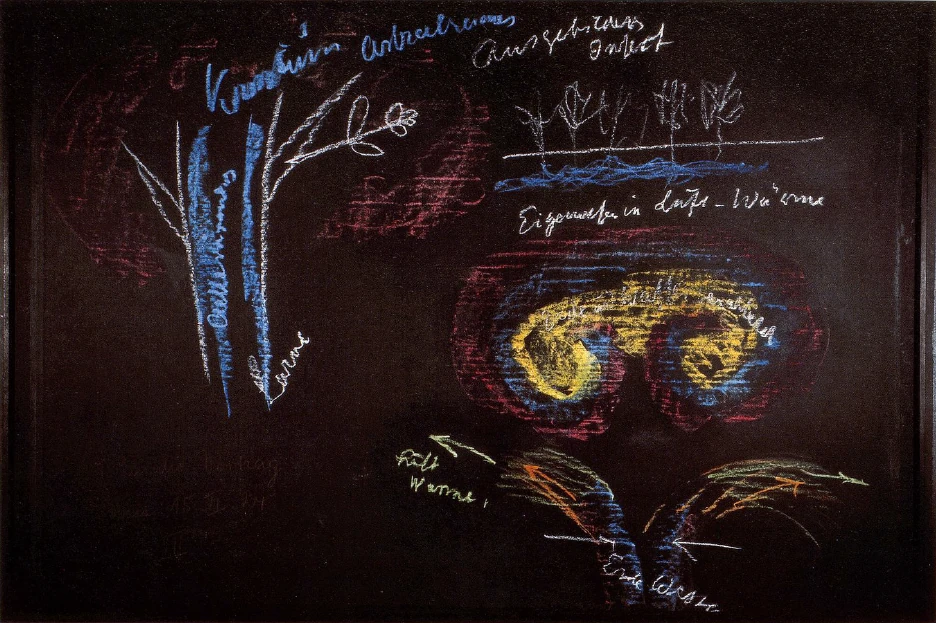

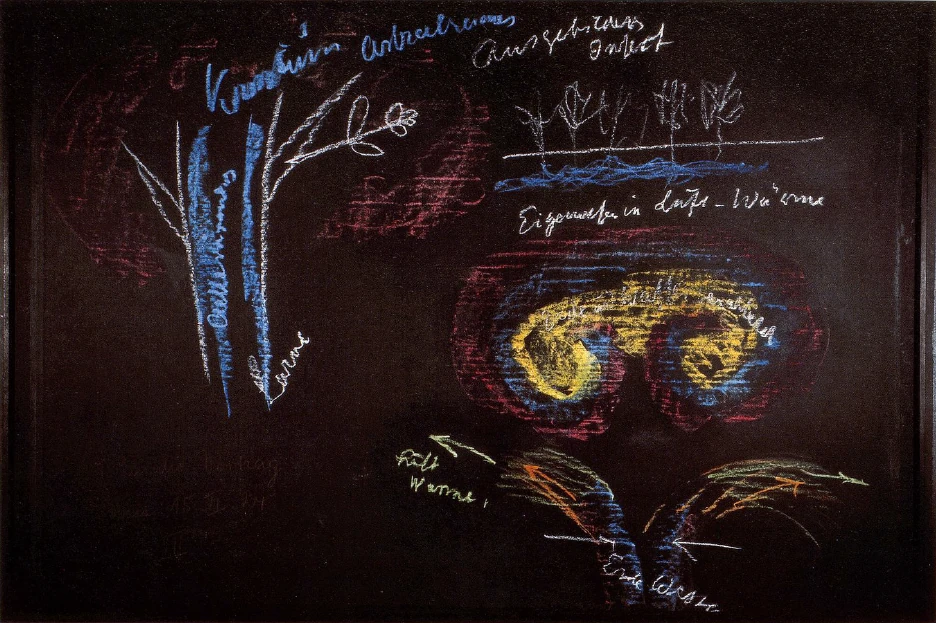

The point is simply that the root is invisible to crude external observation. In this case we must not merely want to see a root we must understand what a root is. A true comparison will help us forward here. Suppose I were to plant in the soil a whole number of herbaceous plants, very near together, so that their roots intertwined, and merged with one another—the one root winding round the other, until it all become a regular mush of roots, merging one into another. As you can well imagine, such a complex of roots would not allow itself to remain a mere tangle; it would grow organised into a single entity. Down there in the soil the saps and fluids would flow into one another. There would be an organised root-complex—roots flowing into one another. We could not distinguish where the several roots began or ended. A common root-being would arise for these plants (Diagram 15).

So it would be. No such thing need exist in reality, but this illustration will enable us to understand. Here is the soil of the earth: here I insert all my plants. Down there, all the roots coalesce, until they form a regular surface—a continuous root-stratum. Once more, you would not know where the one root begins and the other ends.

Now the very thing I have here sketched as an hypothesis is actually present in the tree. The plant which grows on the free has lost its root. Relatively speaking, it is even separated from its root—only it is united with it, as it were, in a more ethereal way. What I have hypothetically sketched on the board is actually there in the tree, as the cambium layer—the cambium. That is how we must regard the roots of these plants that grow out of the tree: they are replaced by the cambium. Although the cambium does not look like roots, it is the living, growing layer, constantly forming new cells, so that the plant-life of the free grows out of it, just as the life of a herbaceous plant grows up above out of the root below.

Here, then, is the free with its cambium layer, the growing formative layer, which is able to create plant-cells. (The other layers in the free would not be able to create fresh cells). Now you can thoroughly see the point. In the tree with its cambium or formative layer, the earth-realm itself is actually bulged out; it has grown outward into the airy regions. And having thus grown outward into the air, it needs more inwardness, more intensity of life, than the earth otherwise has, i.e. than it has where the ordinary root is in it. Now we begin to understand the free. In the First place, we understand it as a strange entity whose function is to separate the plants that grow upon it—stem, blossom and fruit—from their roots, uniting them only through the Spirit, that is, through the ethereal. We must learn to look with macrocosmic intelligence into the mysteries of growth. But it goes still further. For I now beg you observe: What happens through the fact that a free comes into being? It is as follows:

That which encompasses the free has a different plant-nature in the air and outer warmth than that which grows in air and warmth immediately on the soil, unfolding the herbaceous plant that springs out of the earth directly (Diagram 16). Once more, it is a different plant-world. For it is far more intimately related to the surrounding astrality. Down here, the astrality in air and warmth is expelled, so that the air and warmth may become mineral for the Bake of man and animal. Look at a plant growing directly out of the soil. True, it is hovered-around, enshrouded in an astral cloud. Up there, however, round about the free, the astrality is far denser. Once more, it is far denser. Our trees are gatherings of astral substance; quite clearly, they are gatherers of astral substance.

In this realm it is easiest of all for one to attain to a certain higher development. If you make the necessary effort, you can easily become esoteric in these spheres. I do not say clairvoyant, but you can easily become clair-sentient with respect to the sense of smell, especially if you acquire a certain sensitiveness to the diverse aromas that proceed from plants growing on the soil, and on the other hand from fruit-tree plantations—even if only in the blossoming stage—and from the woods and forests! Then you will feel the difference between a plant-atmosphere poor in astrality, such as you can smell among the herbaceous plants growing on the earth, and a plant-world rich in astrality such as you have in your nostrils when you sniff what is so beautifully wafted from the treetops.

Accustom yourself to specialise your sense of smell—to distinguish, to differentiate, to individualise, as between the scent of earthly plants and the scent of trees. Then, in the former case you will become clair-sentient to a thinner astrality, and in the latter case to a denser astrality. You see, the farmer can easily become clair-sentient. Only in recent times he has male less use of this than in the time of the old clairvoyance. The countryman, as I said, can become clair-sentient with regard to the sense of smell.

Let us observe where this will lead us. We must now ask: What of the polar opposite, the counterpart of that richer astrality which the plant—parasitically growing on the tree—brings about in the neighbourhood of the tree? In other words, what happens by means of the cambium? What does the cambium itself do?

Far, far around, the free makes the spiritual atmosphere inherently richer in astrality. What happens, then, when the herbaceous life grows out of the free up yonder? The tree has a certain inner vitality or ethericity; it has a certain intensity of life. Now the cambium damps down this life a little more, so that it becomes slightly more mineral. While, up above, a rich astrality arises all around the tree, the cambium works in such a way that, there within, the ethericity is poorer.

Within the tree arises poverty of ether as compared to the plant. Once more, here within, it will be somewhat poorer in ether. And as, through the cambium, a relative poverty of ether is engendered in the tree, the root in its turn will be influenced. The roots of the tree become mineral—far more so than the roots of herbaceous plants. And the root, being more mineral, deprives the earthly soil—observe, we still remain within the realms of life—of some of its ethericity. This makes the earthly soil rather more dead in the environment of the free than it would be in the environment of a herbaceous plant.

All this you must clearly envisage. Now whatever arises in this way will always involve something of deep significance in the household of Nature as a whole. Let us then enquire: what is the inner significance, for Nature, of the astral richness in the tree's environment above, and the etheric poverty in the realm of the free-roots? We only need Look about us, and we can find how these things work themselves out in Nature's household. The fully developed insect, in effect, lives and moves by virtue of this rich astrality which is wafted through the tree-tops.

Take, on the other hand, what becomes poorer in ether, down below in the soil. (This poverty of ether extends, of course, throughout the tree, for the Spiritual always works through the whole, as I explained yesterday when speaking of human Karma). That which is poorer in ether, down below, works through the larvae. Thus, if the earth had no trees, there would be no insects on the earth. The trees make it possible for the insects to be. The insects fluttering around the parts of the tree which are above the earth—fluttering around the woods and forests as a whole—they have their very life through the existence of the woods. Their larvae, too, live by the very existence of the woods.

Here you have a further indication of the inner relationship between the root-nature and the sub-terrestrial animal world. From the tree we can best learn what I have now explained; here it becomes most evident. But the fast is: What becomes very evident in the tree is present in a more delicate way throughout the whole plant-world. In every plant there is a certain tendency to become tree-like. In every plant, the root with its environment strives to let go the ether; while that which grows upward tends to draw in the astral more densely. The free-becoming tendency is there is every plant.

Hence, too, in every plant the same relationship to the insect world emerges, which I described for the special case of the tree. But that is not all. This relation to the insect-world expands into a relation to the whole animal kingdom. Take, for example, the insect larvae: truly, they only live upon the earth by virtue of the tree-roots being there. However, in times gone by, such larvae have also evolved into other kinds of animals, similar to them, but undergoing the whole of their animal life in a more or less larval condition. These creatures then emancipate themselves, so to speak, from the tree-root-nature, and live more near to the rest of the root-world—that is, they become associated with the root-nature of herbaceous plants.

A wonderful fast emerges here: Certain of these sub-terrestrial creatures (which, it is true, are already somewhat removed from the larval nature) develop the faculty to regulate the ethereal vitality within the soil whenever it becomes too great. If the soil is tending to become too strongly living—if ever its livingness grows rampant—these subterranean animals see to it that the over-intense vitality is released. Thus they become wonderful regulators, safety-valves for the vitality inside the Earth. These golden creatures—for they are of the greatest value to the earth—are none other than the earth-worms.

Study the earth-worm—how it lives together with the soil. These worms are wonderful creatures: they leave to the earth precisely as much ethericity as it needs for plant-growth. There under the earth you have the earth-worms and similar creatures distantly reminiscent of the larva. Indeed, in certain soils—which you can easily tell—we ought to take special care to allow for the due breeding of earth-worms. We should soon see how beneficially such a control of the animal world beneath the earth would react on the vegetation, and thus in turn upon the animal world in general, of which we shall speak in a moment.

Now there is again a distant similarity between certain animals and the fully evolved, i.e. the winged, insect-world. These animals are the birds. In course of evolution a wonderful thing has taken place as between the insects and the birds. I will describe it in a picture. The insects said, one day: We do not feel quite strong enough to work the astrality which sparkles and Sprays around the trees. We therefore, for our part, will use the treeing tendency of other plants; there we will flutter about, and to you birds we will leave the astrality that surrounds the trees. So there came about a regular division of labour between the bird-world and the butterfly-world, and now the two together work most wonderfully.

These winged creatures, each and all, provide for a proper distribution of astrality, wherever it is needed on the surface of the Earth or in the air. Remove these winged creatures, and the astrality would fail of its true service; and you would soon detect it in a kind of stunting of the vegetation. For the two things belong together: the winged animals, and that which grows out of the Earth into the air. Fundamentally, the one is unthinkable without the other. Hence the farmer should also be careful to let the insects and birds flutter around in the right way. The farmer himself should have some understanding of the rare of birds and insects. For in great Nature—again and again I must say it—everything, everything is connected.

These things are most important for a true insight: therefore let us place them before our souls most clearly. Through the flying world of insects, we may say, the right astralisation is brought about in the air. Now this astralisation of the air is always in mutual relation to the woods or forests, which guide the astrality in the right way just as the blood in our body is guided by certain forces. What the wood does—not only for its immediate vicinity but far and away around it (for these things work over wide areas)—what the wood does in this direction has to be done by quite other things in unwooded districts. This we should learn to understand. The growth of the soil is subject to quite other laws in districts where forest, Field and meadow alternate, than in wide, unwooded stretches of country.

There are districts of the Earth where we can tell at a glance that they became rich in forests long before man did anything—for in certain matters Nature is wiser than man, even to this day. And we may well assume, if there is forest by Nature in a given district, it has its good use for the surrounding farmlands—for the herbaceous and graminaceous vegetation. We should have sufficient insight, on no account to exterminate the forest in such districts, but to preserve it well. Moreover, the Earth by and by changes, through manifold cosmic and climatic influences.

Therefore we should have the heart—when we see that the vegetation is becoming stunted, not merely to make experiments for the fields or on the fields alone, but to increase the wooded areas a little. Or if we notice that the plants are growing rampant and have not enough seeding-force, then we should set to work and make some clearings in the forest—take certain surfaces of wooded land away: In districts which are predestined to be wooded, the regulation of woods and forests is an essential part of agriculture, and should indeed be thought of from the spiritual side. It is of a far-reaching significance.

Moreover, we may say: the world of worms, and larvae too, is related to the limestone—that is, to the mineral nature of the earth; while the world of insects and birds—all that flutters and flies stands in relation to the astral. That which is there under the surface of the earth—the world of worms and larvae—is related to the mineral, especially the chalky, limestone nature, whereby the ethereal is duly conducted away, as I told you a few days ago from another standpoint. This is the task of the limestone—and it fulfils its task in mutual interaction with the larva- and insect-world.

Thus you will see, as we begin to specialise what I have given, ever new things will dawn on us—things which were undoubtedly recognised with true feeling in the old time of instinctive clairvoyance. (I should not trust myself to expound them with equal certainty.) The old instincts have been lost. Intellect has lost all the old instincts—nay, has exterminated them. That is the trouble with materialism—men have become so intellectual, so clever. When they were less intellectual, though they were not so clever, they were far wiser; out of their feeling they knew how to treat things, even as we must learn to do once more, for in a conscious way we must learn once more to approach the Wisdom that prevails in all things. We shall learn it by something which is not clever at all, namely, by Spiritual Science. Spiritual Science is not clever: it strives rather for Wisdom.

Nor can we rest content with the abstract repetition of words: “Man consists of physical body, etheric body,” etc., etc., which one can learn off by heart like any cookery-book. The point is for us to introduce the knowledge of these things in all domains—to see it inherent everywhere. Then we are presently guided to distinguish how things are in Nature, especially if we become clairvoyant in the way I explained. Then we discover that the bird world becomes harmful if it has not the “needle-wood” or coniferous forests beside it, to transform what it brings about into good use and benefit. Thereupon our vision is still further sharpened, and a fresh relationship emerges. When we have recognised this peculiar relation of the birds to the coniferous forests, then we perceive another kinship. It emerges clearly. To begin with, it is a fine and intimate kinship—fine as are those which I have mentioned now. But it can readily be changed into a stronger, more robust relationship.

I mean the inner kinship of the mammals to all that does not become tree and yet does not remain as a small plant—in other words, to the shrubs and bushes—the haze-lnut, for instance. To improve our stock of mammals in a farm or in a farming district, we shall often do well to plant in the landscape bushes or shrub-like growths. By their mere presence they have a beneficial effect. All things in Nature are in mutual interaction, once again. But we can go farther. The animals are not so foolish as men are; they very quickly “tumble to it” that there is this kinship. See how they love the shrubs and bushes. This love is absolutely inborn in them, and so they like to get at the shrubs to eat them. They soon begin to take what they need, which has a wonderfully regulating effect on their remaining fodder.

Moreover, when we trace these intimate relationships in Nature, we gain a new insight into the essence of what is harmful. For just as the coniferous forests are intimately related to the birds and the bushes to the mammals, so again all that is mushroom—or fungus-like—has an intimate relation to the lower animal world—to the bacteria and such-like creatures, and notably the harmful parasites. The harmful parasites go together with the mushroom or fungus-nature; indeed they develop wherever the fungus-nature appears scattered and dispersed.

Thus there arise the well-known plant-diseases and harmful growths on a coarser and larger scale. If now we have not only woods but meadows in the neighbourhood of the farm, these meadows will be very useful, inasmuch as they provide good soil for mushrooms and toadstools; and we should see to it that the soil of the meadow is well-planted with such growths. If there is near the farm a meadow rich in mushrooms—it need not even be very large—the mushrooms, being akin to the bacteria and other parasitic creatures, will keep them away from the rest. For the mushrooms and toadstools, more than the other plants, tend to hold together with these creatures. In addition to the methods I have indicated for the destruction of these pests, it is possible on a larger scale to keep the harmful microscopic creatures away from the farm by a proper distribution of meadows.

So we must look for a due distribution of wood and forest, orchard and shrubbery, and meadow-lands with their natural growth of mushrooms. This is the very essence of good farming, and we shall attain far more by such means, even if we reduce to some extent the surface available for tillage.

It is no true economy to exploit the surface of the earth to such an extent as to rid ourselves of all the things I have here mentioned in the hope of increasing our crops. Your large plantations will become worse in quality, and this will more than outweigh the extra amount you gain by increasing your tilled acreage at the cost of these other things. You cannot truly engage in a pursuit so intimately connected with Nature as farming is, unless you have insight into these mutual relationships of Nature's husbandry.

The time has come for us to bring home to ourselves those wider aspects which will reveal, quite generally speaking, the relation of plant to animal-nature, and vice versa, of animal to plant-nature. What is an animal? What is the world of plants? (for the world of plants we must speak rather of a totality—the plant-world as a whole.) Once more, what is an animal, and what is the world of plants? We must discover what the essential relation is; only so shall we understand how to feed our animals. We shall not feed them properly unless we see the true relationship of plant and animal. What are the animals? Well may you look at their outer forms! You can dissect them, if you will, till you get down to the skeleton, in the forms of which you may well take delight; you may even study them in the way I have described. Theo you may study the musculature, the nerves and so forth.

All this, however, will not lead you to perceive what the animals really are in the whole household of Nature. You will only perceive it if you observe what it is in the environment to which the animal is directly and intimately related. What the animal receives from its environment and assimilates directly in its nerves-and-senses system and in a portion of its breathing system, is in effect all that which passes first through air and warmth. Essentially, in its own proper being, the animal is a direct assimilator of air and warmth—through the nerves-and-senses system.

Diagrammatically, we can draw the animal in this way: In all that is there in its periphery, in its environment—in the nerves-and-senses system and in a portion of the breathing system—the animal is itself. In its own essence, it is a creature that lives directly in the air and warmth. It has an absolutely direct relation to the air and warmth (Diagram 17).

Notably out of the warmth its bony system is formed—where the Moon- and Sun-influences are especially transmitted through the warmth. Out of the air, its muscular system is formed. Here again, the forces of Sun and Moon are working through the air. But the animal cannot relate itself thus directly to the earthy and watery elements. It cannot assimilate water and earth thus directly. It must indeed receive the earth and water into its inward parts; it must therefore have the digestive tract, passing inward from outside. With all that it has become through the warmth and air, it then assimilates the water and the earth inside it—by means of its metabolic and a portion of its breathing system.The breathing system passes over into the metabolic system. With a portion of the breathing and a portion of the metabolic system, the animal assimilates “earth” and “water” In effect, before it can assimilate earth and water, the animal itself must be there by virtue of the air and warmth. That is how the animal lives in the domain of earth and water. (The assimilation-process is of course, as I have often indicated, an assimilation more of forces than of substances).

Now let us ask, in face of the above, what is a plant? The answer is: the plant has an immediate relation to earth and water, just as the animal has to air and warmth. The plant—also through a kind of breathing and through something remotely akin to the sense system—absorbs into itself directly all that is earth and water; just as the animal absorbs the air and warmth. The plant lives directly with the earth and water.

Now you may say: Having recognised that the plant lives directly with earth and water, just as the animal does with air and warmth, may we not also conclude that the plant assimilates the air and the warmth internally, even as the animal assimilates the earth and water? Ne, it is not so. To find the spiritual truths, we cannot merely conclude by analogy from what we know. The fact is this: Whereas the animal consumes the earthy and watery material and assimilates them internally, the plant does not consume but, on the contrary, secretes—gives off—the air and warmth, which it experiences in conjunction with the earthy soil. Air and warmth, therefore, do not go in—at least, they do not go in at all far. On the contrary they go out; instead of being consumed by the plant, they are given off, excreted, and this excretion-process is the important point.

Organically speaking, the plant is in all respects an inverse of the animal—a true inverse. The excretion of air and warmth has for the plant the same importance as the consumption of food for the animal. In the same sense in which the animal lives by absorption of food, the plant lives by excretion of air and warmth. This, I would say, is the virginal quality of the plant. By nature, it does not want to consume things greedily for itself, but, on the contrary, it gives away what the animal takes from the world, and lives thereby. Thus the plant gives, and lives by giving.

Observe this give and take, and you perceive once more what played so great a part in the old instinctive knowledge of these things. The saying I have here derived from anthroposophical study: “The plant in the household of Nature gives, and the animal takes,” was universal in an old instinctive and clairvoyant insight into Nature. In human beings who were sensitive to these things, some of this insight survived into later times.

In Goethe you will often find this saying: Everything in Nature lives by give and take. Look through Goethe's works and you will soon find it. He did not fully understand it any longer, but he revived it from old usage and tradition; he felt that this proverb describes something very true in Nature. Those who came after him no longer understood it. To this day they do not understand what Goethe meant when he spoke of “give and take.” Even in relation to the breathing process—its interplay with the metabolism—Goethe speaks of “give and take.” Clearly-unclearly, he uses this word.

Thus we have seen that forest and orchard, shrubbery and bush are in a certain way regulators to give the right form and development to the growth of plants over the earth's surface. Meanwhile beneath the earth the lower animals—larvae and worm-like creatures and the like, in their unison with limestone—act as a regulator likewise.

So must we regard the relation of tilled fields, orchards and cattle-breeding in our farming work. In the remaining hour that is still at our disposal, we shall indicate the practical applications, enough for the good Experimental Circle to work out and develop.

Siebenter Vortrag

Meine lieben Freunde!

[ 1 ] Ich möchte nun anreihen an die Betrachtungen, die wir angestellt haben, noch einiges in dem Reste der Zeit, der uns zur Verfügung steht, über Tierzucht, Obst- und Gemüsekultur.

[ 2 ] Es wird ja natürlich nicht allzu viel Zeit dazu zur Verfügung stehen, aber es ist dieses Gebiet der landwirtschaftlichen Tätigkeit von einem fruchtbaren Ausgangspunkt nicht zu betrachten, wenn man nicht auch hier wieder alles tut, um ein Verständnis, eine Einsicht in die einschlägigen Verhältnisse herbeizuführen. Das wollen wir dann heute tun, und morgen wiederum zu einigen praktischen Winken in der Anwendung übergehen.

[ 3 ] Ich werde Sie bitten, heute zu versuchen, die Dinge zu verfolgen mit mir, die etwas, ich möchte sagen, abgelegener sind, weil sie, trotzdem sie ganz geläufig waren einmal einer mehr instinktiven landwirtschaftlichen Einsicht, heute geradezu wie vollständig unbekanntes Land dastehen. Die in der Natur vorkommenden Wesenheiten, Mineralien, Pflanzen, Tiere - wir wollen jetzt vom Menschen absehen -, die in der Natur vorkommenden Wesen, sie werden ja sehr, sehr häufig bloß so betrachtet, als ob sie allein dastünden. Man ist heute gewohnt, eine Pflanze für sich anzuschauen sogar, und dann, von dieser ausgehend, eine Pflanzenart zu betrachten für sich, eine andere Pflanzenart daneben wiederum für sich. Man ordnet das so hübsch in Schachteln, in Arten und Gattungen gegliedert, ein, in dasjenige, was dann eben von den Dingen gewusst werden soll. Aber so ist es ja nicht in der Natur. In der Natur, im Weltenwesen überhaupt steht alles in Wechselwirkung miteinander. Es wirkt immer das eine auf das andere. Heute, in der materialistischen Zeit, verfolgt man nur die groben Wirkungen des einen auf das andere; wenn das eine durch das andere gefressen, verdaut wird, oder wenn der Mist von den Tieren auf die Äcker kommt. Diese groben Wechselwirkungen verfolgt man allein.

[ 4 ] Es finden ja außer diesen groben auch durch feinere Kräfte und auch durch feinere Substanzen, durch Wärme, durch in der Atmosphäre fortwährend wirkendes Chemisch-Ätherisches, durch Lebensäther, fortwährend Wechselwirkungen statt. Und ohne dass man diese feineren Wechselwirkungen berücksichtigt, kommt man für gewisse Teile des landwirtschaftlichen Betriebes nicht vorwärts. Wir müssen namentlich auf solche, ich möchte sagen, naturintimeren Wechselwirkungen hinschauen, wenn wir es zu tun haben mit dem Zusammenleben von Tier und Pflanze innerhalb des landwirtschaftlichen Betriebes. Und wir müssen da hinschauen nicht bloß wiederum auf diejenigen Tiere, die uns zweifellos nahestehen, wie Rinder, Pferde, Schafe und so weiter, sondern wir müssen auch in verständiger Weise hinschauen, sagen wir zum Beispiel auf die bunte Insektenwelt, welche die Pflanzenwelt während einer gewissen Zeit des Jahres umflattert. Ja, wir müssen sogar verstehen, in verständiger Weise hinzuschauen auf die Vogelwelt. Darüber macht sich heute die Menschheit noch nicht richtige Begriffe, welchen Einfluss die Vertreibung gewisser Vogelarten aus gewissen Gegenden durch die modernen Lebensverhältnisse für alles landwirtschaftliche und forstmäßige Leben eigentlich hat. In diese Dinge muss wiederum durch eine geisteswissenschaftliche, man könnte ebenso gut sagen, durch eine makrokosmische Betrachtung hineingeleuchtet werden. Nun können wir einiges von dem, was wir auf uns haben wirken lassen, jetzt verwenden, um zu weiteren Einsichten zu kommen.

[ 5 ] Wenn Sie einen Obstbaum ansehen, einen Birnbaum oder einen Apfel-, Pflaumenbaum, so ist der ja eigentlich etwas ganz anderes, jeder Baum ist eigentlich zunächst äußerlich etwas ganz anderes als eine krautartige Pflanze oder eine getreideartige Pflanze. Und man muss ganz sachgemäß darauf kommen, inwiefern er etwas anderes ist, der Baum, sonst wird man niemals die Funktion des Obstes im Haushalt der Natur verstehen. Ich rede jetzt natürlich zunächst von demjenigen Obst, das auf Bäumen wächst.

[ 6 ] Nun schauen wir uns den Baum an. Was ist er denn eigentlich im ganzen Haushalt der Natur? Wenn wir ihn nämlich verständig anschauen, so können wir zunächst zum eigentlich Pflanzlichen nur rechnen beim Baum dasjenige, was in dünnen Stängeln, in den grünen Blätterträgern, in Blüten, in Früchten herauswächst. Das wächst aus dem Baum heraus, wie die Krautpflanze aus der Erde wächst.

[ 7 ] Der Baum ist nämlich wirklich für dasjenige, was da an den Zweigen wächst, die Erde. Er ist die hügelig gewordene Erde, nur die etwas lebendiger gestaltete Erde als diejenige, aus der unsere Kraut- und Getreidepflanzen herauswachsen.

[ 8 ] Wollen wir also den Baum verstehen, müssen wir sagen, nun ja, da ist der dicke Stamm des Baumes, in gewissem Sinne gehören auch noch die Äste und Zweige dazu. Von da ab also wächst zunächst die eigentliche Pflanze heraus, Blätter, Blüten wachsen da heraus. Das ist die Pflanze, die in den Stamm und in die Zweige des Baumes so eingewurzelt ist, wie die Kraut- und Getreidepflanzen in die Erde eingewurzelt sind. Da entsteht sogleich die Frage: Ist dann auch diese, also dadurch mehr oder weniger Schmarotzer zu nennende Pflanze am Baum, ist sie dann auch in Wirklichkeit eingewurzelt?

[ 9 ] Eine richtige Wurzel am Baum können wir nicht entdecken. Und wollen wir das richtig verstehen, so müssen wir sagen: Ja, diese Pflanze, die da wächst, die ja dort oben ihre Blüten und Blätter entwickelt, auch ihre Stängel, die hat die Wurzeln verloren, indem sie auf dem Baum aufsitzt. Aber eine Pflanze ist nicht ganz, wenn sie keine Wurzeln hat. Sie braucht eine Wurzel. Wir müssen uns also fragen: Wo ist denn nun eigentlich die Wurzel dieser Pflanze?

[ 10 ] Nun sehen Sie, die Wurzel ist nur nicht so für das grobe äußerliche Anschauen sichtbar. Man muss die Wurzel nicht nur anschauen wollen in diesem Falle, sondern man muss sie verstehen. Man muss sie verstehen, was heißt das? Denken Sie sich einmal - wollen wir durch einen realen Vergleich vorwärtskommen -, ich pflanzte so nahe aneinander in einem Boden lauter Krautpflanzen nebeneinander, die in ihren Wurzeln verwachsen, wo eine Wurzel um die andere sich herumschlingt und das Ganze eine Art ineinander verlaufender Wurzelbrei würde. Sie könnten sich denken, dieser Wurzelbrei würde es nicht gestatten, etwas Unregelmäßiges zu sein, er würde sich organisieren zu einer Einheit, und die Säfte würden ineinanderfließen da unten. Dort wäre Wurzelbrei, der organisiert ist, wo man nicht unterscheiden kann, wo die Wurzeln aufhören oder anfangen. Eine gemeinsame Wurzelwesenheit in der Pflanze würde entstehen.

[ 11 ] So etwas, was es doch zunächst gar nicht zu geben braucht, was uns aber etwas verständlich machen kann, würde dies sein: Da wäre der Erdboden. Pflanze ich nun alle meine Pflanzen ein - so! - und jetzt da unten, da wachsen die Wurzeln alle so ineinander. Nun bildet sich eine ganz flächenhafte Wurzelschichte. Wo die einen aufhören und die anderen anfangen, weiß man nicht. Nun, dasjenige, was ich Ihnen hier als hypothetisch aufgezeichnet habe, das ist tatsächlich im Baum vorhanden. Die Pflanze, die auf dem Baum wächst, hat ihre Wurzel verloren, sie hat sich sogar relativ von ihr getrennt und ist nur mit ihr verbunden, ich möchte sagen, mehr ätherisch. Und das, was ich hier hypothetisch aufgezeichnet habe, ist im Baum drinnen die Kambiumschichte, das Kambium, sodass wir die Wurzeln dieser Pflanze eben nicht anders anschauen können, als dass sie durch das Kambium ersetzt werden.

[ 12 ] Das Kambium sieht nicht wie Wurzeln aus. Es ist die Bildungsschichte, die immer neue Zellen bildet, aus der heraus sich das Wachstum immer wieder entfaltet, so wie sich aus einer Wurzel unten das krautartige Pflanzenleben oben entfalten würde. Wir können so recht sehen dann, wie im Baum mit seiner Kambiumschichte, die die eigentliche Bildungsschichte ist und die die Pflanzenzellen erzeugen kann - die anderen Schichten des Baumes würden ja nicht frische Zellen erzeugen können -, tatsächlich das Erdige sich aufgestülpt hat, hinausgewachsen ist in das Luftartige [und] dadurch mehr Verinnerlichung des Lebens braucht, als die Erde sonst in sich hat, indem sie die gewöhnliche Wurzel noch in sich hat. Und wir fangen an, den Baum zu verstehen. Zunächst verstehen wir den Baum als ein merkwürdiges Wesen, als dasjenige Wesen, das dazu da ist, die auf ihm wachsenden «Pflanzen»: Stängel, Blüten, Frucht und deren Wurzel auseinanderzutrennen, sie voneinander zu entfernen und nur durch den Geist zu verbinden, respektive durch das Ätherische zu verbinden.

[ 13 ] In dieser Weise ist es notwendig, makrokosmisch verständig in das Wachstum hineinzuschauen. Aber das geht noch viel weiter. Was geschieht denn dadurch, dass der Baum entsteht? Was da geschieht, ist das Folgende: Dasjenige, was da oben an dem Baum wächst, das ist in der Luft und in der äußeren Wärme ein anderes Pflanzenhaftes als dasjenige, was unmittelbar auf dem Erdboden in Luft und Wärme aufwächst und dann ausbildet die aus dem Erdboden herauswachsende krautartige Pflanze.

[ 14 ] Es ist eine andere Pflanzenwelt, es ist eine Pflanzenwelt, die viel innigere Beziehungen hat zu der umliegenden Astralität, die in Luft und Wärme ausgeschieden ist, damit Luft und Wärme mineralisch sein können, wie es der Mensch und das Tier dann brauchen. Und so ist das der Fall, dass, wenn wir die auf dem Boden wachsende Pflanze anschauen, sie von Astralischem, wie ich gesagt habe, umschwebt und umwölkt ist. Hier aber, an dem Baum, ist diese Astralität viel dichter. Da ist sie dichter, sodass unsere Bäume Ansammlungen sind von astralischer Substanz. Unsere Bäume sind deutlich Ansammler von astralischer Substanz.

[ 15 ] Auf diesem Gebiete ist es eigentlich am leichtesten, ich möchte sagen, zu einer höheren Entwicklung zu kommen. Wenn man auf diesen Gebieten sich bestrebt, so kann man sehr leicht auf diesen Gebieten esoterisch werden. Man kann nicht geradezu hellsichtig werden, aber man kann sehr leicht hellriechend werden, wenn man sich aneignet nämlich einen gewissen Geruchsinn für die verschiedenen Aromen, die ausgehen von Pflanzen, die auf der Erde sind, und die ausgehen von Obstpflanzungen, auch wenn diese erst blühen, vom Walde gar. Dann wird man den Unterschied empfinden können zwischen einer astralärmeren Pflanzenatmosphäre, wie man sie bei den Krautpflanzen, die auf der Erde wachsen, riechen kann, und zwischen einer astralreichen Pflanzenwelt, wie man sie haben kann in der Nase, wenn man schnüffelt dasjenige, was in einer so schönen Weise von den Kronen der Bäume her gerochen werden kann. Und gewöhnen Sie sich auf diese Weise an, den Geruch zu spezifizieren, zu unterscheiden, zu individualisieren zwischen Erdpflanzengeruch und Baumgeruch, so haben Sie im ersteren Fall Hellriechigkeit für dünnere Astralität, im zweiten Fall Hellriechigkeit für dichtere Astralität. - Sie sehen, der Landwirt kann leicht hellriechig werden. Er hat die Sache in den letzten Zeiten nicht so benützt, wie es in der alten instinktiven Hellseherzeit war. Der Landmann kann hellriechend werden, wie ich sagte.

[ 16 ] Wenn wir dasjenige nun ins Auge fassen, wohin das weiterführen kann, so müssen wir uns nun doch fragen: Ja, wie ist es denn nun mit demjenigen, was gewissermaßen polarisch entgegensteht demjenigen, was da die auf dem Baum wachsende parasitische Pflanze als Astralisches in der Baumumgebung bewirkt? Was geschieht denn durch das Kambium, was tut denn das?

[ 17 ] Sehen Sie, weit um sich herum macht der Baum die geistige Aumosphäre astralreicher in sich. Was geschieht denn da, wenn das Krautartige oben auf dem Baum wächst? [Dann hat er eine bestimmte innere Vitalität, Ätherizität, ein gewisses starkes Leben in sich.] Das Kambium dämpft nun dieses Leben etwas mehr herunter, sodass es mineralähnlicher wird. Dadurch wirkt das Kambium also so: Währenddem oben Astralreiches um den Baum entsteht, wirkt das Kambium so, dass im Innern Ätherisch-Ärmeres als sonst da ist, Ätherarmut gegenüber der Pflanze entsteht im Baum. Ätherärmeres entsteht hier. Dadurch aber, dass da im Baum durch das Kambium Ätherärmeres entsteht, wird auch die Wurzel wiederum beeinflusst. Die Wurzel im Baum wird Mineral, viel mineralischer, als die Wurzeln der krautartigen Pflanzen sind.

[ 18 ] Dadurch aber, dass sie mineralisierter wird, entzieht sie dem Erdboden aber jetzt in dem, was im Lebendigen drinnen bleibt, etwas von seiner Ätherizität. Sie macht den Erdboden etwas mehr tot in der Umgebung des Baumes, als er sein würde in der Umgebung der krautartigen Pflanze. Das muss man ganz strikte ins Auge fas: Aber was so in der Natur entsteht, das wird immer auch im Haushalt der Natur eine bedeutsame, eine innere Naturbedeutung haben. Deshalb müssen wir diese innere Naturbedeutung von dem Astralreichtum in der Baumumgebung und der Ätherarmut im Baumwurzelgebiet aufsuchen.

[ 19 ] Und wenn wir Umschau halten, so finden wir, wie das nun weiter im Haushalt der Natur geht. Von demjenigen, was da als Astralreiches durch die Bäume hindurchgeht, lebt und webt das ausgebildete Insekt. Und dasjenige, was da unten ätherärmer wird im Erdboden und als Ätherarmut sich durch den ganzen Baum natürlich erstreckt, so wie Geistiges immer über das Ganze wirkt, wie ich gestern in Bezug auf das Karma beim Menschen ausgeführt habe, dasjenige, was da unten wirkt, wirkt über die Larven, sodass also, wenn die Erde keine Bäume hätte, auf der Erde überhaupt keine Insekten wären. Denn die Bäume bereiten den Insekten die Möglichkeit, zu sein. Die um die oberirdischen Teile der Bäume herumflatternden Insekten, also die um den ganzen Wald so herumflatternden Insekten leben dadurch, dass der Wald da ist, und ihre Larven leben auch dadurch, dass der Wald da is

[ 20 ] Sehen Sie, da haben wir dann einen weiteren Hinweis auf eine innigere Beziehung alles Wurzelwesens zu der unterirdisch-tierischen Welt. Denn, ich möchte sagen, am Baum kann man das besonders lernen, was wir jetzt ausgeführt haben. Da wird es deutlich. Aber das Bedeutsame ist, dass dasjenige, was am Baum eklatant und deutlich wird, dass das nun wiederum nuanciert bei der ganzen Pflanzenwelt vorhanden ist, sodass in jeder Pflanze etwas drinnen lebt, was baumhaft werden will. In jeder Pflanze strebt eigentlich die Wurzel mit ihrer Umgebung danach, den Äther zu entlassen, und in jeder Pflanze strebt dasjenige, was nach oben wächst, danach, das Astralische dichter heranzuziehen. Das Baum-werden-Wollen ist eigentlich in jeder Pflanze enthalten. Daher stellt sich bei jeder Pflanze diese Verwandtschaft zur Insektenwelt heraus, die ich beim Baum besonders charakterisiert habe. Aber es dehnt sich auch aus diese Verwandtschaft zur Insektenwelt zu einer Verwandtschaft zur ganzen Tierwelt. Die Insektenlarven, die eigentlich zunächst auf der Erde nur leben können dadurch, dass Baumwurzeln vorhanden sind, die entwickelten sich zu anderen Tierarten, die ihnen ähnlich sind, die ihr ganzes Tierleben mehr oder weniger in einer Art von Larvenzustand durchmachen und die dann sich gewissermaßen von der Baumwurzelhaftigkeit emanzipieren, um nach der anderen Wurzelhaftigkeit auch der krautartigen Pflanzen hin zu leben und mit ihr zusammenzuleben.

[ 21 ] Nun stellt sich das Eigentümliche heraus, dass wir schen können, wie, allerdings schon von dem Larvenwesen sehr entfernt, unterir dische Tiere nun wiederum die Fähigkeit haben, zu regulieren im Erdboden die ätherhafte Lebendigkeit, wenn sie zu groß wird. Wenn der Erdboden sozusagen zu stark lebendig werden würde und die Lebendigkeit in ihm überwuchern würde, dann sorgen diese unterirdischen Tiere dafür, dass aus dem Erdboden heraus die zu starke Vitalität entlassen werde. Sie werden dadurch wunderbare Ventile und Regulatoren für die in der Erde vorhandene Vitalität. Diese goldigen Tiere, die dadurch für den Erdboden ihre ganz besondere Wichtigkeit haben, das sind die Regenwürmer. Die Regenwürmer, die sollte man eigentlich in ihrem Zusammenleben mit dem Erdboden studieren. Denn sie sind diese wunderbaren Tiere, welche der Erde gerade so viel Ätherizität lassen, als sie für das Pflanzenwachstum braucht.

[ 22 ] So haben wir unter der Erde diese, an die Larven nur noch erinnernden Regenwürmer und ähnliches Getier. Und eigentlich müsste man für gewisse Böden, denen man ja das ansehen kann, für eine in ihnen sich befindende günstige Regenwürmerzucht sogar sorgen. Dann würde man sehen, wie wohltätig eine solche Beherrschung dieser Tierwelt unter der Erde auch auf die Vegetation und dadurch wiederum — wie wir noch aufmerksam machen werden - auf die Tierwelt wirkt.

[ 23 ] Nun gibt es wiederum eine entfernte Ähnlichkeit von Tieren mit der Insektenwelt, wenn diese Insektenwelt ausgebildet ist und herumfliegt. Das ist die Vogelwelt. Nun ist aber bekanntlich zwischen den Insekten und den Vögeln im Laufe der Erdentwicklung etwas Wunderbares vor sich gegangen. Man möchte das möglichst bildhaft sagen, wie es vor sich gegangen ist. Die Insekten nämlich haben eines Tages gesagt: Wir fühlen uns nicht stark genug, die Astralität richtig zu bearbeiten, die um die Bäume herumsprüht. Wir benutzen daher unsererseits das Baumhaft-sein-Wollen der anderen Pflanzen und umflattern diese, und euch Vögeln überlassen wir in der Hauptsache dasjenige, was an Astralität die Bäume [umflattert]. Und so ist eine richtige Arbeitsteilung in der Natur zwischen dem Vogelwesen und dem Schmetterlingswesen eingetreten, und beides zusammen wirkt in einer ganz wunderbaren Weise wiederum so, dass dieses Fluggetier in der richtigen Weise die Astralität überall verbreitet, wo sie auf der Oberfläche der Erde, in der Luft gebraucht wird. Nimmt man dieses Fluggetier weg, so versagt die Astralität eigentlich ihren ordentlichen Dienst, und man wird das in einer gewissen Art von Verkümmerung der Vegetation erblicken. Das gehört zusammen: Fluggetier und dasjenige, was aus der Erde in die Luft hineinwächst. Eins ist ohne das andere letzten Endes gar nicht denkbar. Daher müsste innerhalb der Landwirtschaft auch ein Auge darauf geworfen werden, in der richtigen Art Insekten und Vögel herumflattern zu lassen. Der Landwirt selber müsste auch etwas von Insektenzucht und Vogelzucht zu gleicher Zeit verstehen. Denn in der Natur - ich muss das immer wieder betonen - hängt doch alles, alles zusammen.

[ 24 ] Diese Dinge sind ganz besonders wichtig für die Einsicht in die Sache, deshalb wollen wir sie uns ganz genau vor die Seele hinstellen. Wir können sagen: Durch die fliegende Insektenwelt ist die richtige Astralisierung der Luft bewirkt. Sie steht, diese Astralisierung der Luft, im Wechselverhältnis zum Wald, der die Astralität in der richtigen Weise so leitet, wie in unserem Körper das Blut in der richtigen Weise durch gewisse Kräfte geleitet wird. Dasjenige, was der Wald tut in seiner weiten Nachbarschaft - die Dinge wirken auf sehr weite Flächen hin - nach dieser Richtung hin, das muss durch ganz andere Dinge getan werden da, wo waldleere Gegenden sind. Und man sollte verstehen, dass eigentlich das Bodenwachstum in Gegenden, wo Wald und Feldflächen und Wiesen abwechseln, ganz anderen Gesetzen unterliegt, als in weithin waldlosen Ländern.

[ 25 ] Es gibt ja nun gewisse Gegenden der Erde, bei denen man von vornherein sieht, dass sie waldreich gemacht worden sind, als der Mensch noch nichts dazu tat - denn in gewissen Dingen ist die Natur noch immer gescheiter als der Mensch -, und man kann schon annehmen, wenn naturhaft der Wald in einer gewissen Landesgegend da ist, so hat er seinen Nutzen für die umliegende Landwirtschaft, die umliegende krautartige und halmartige Vegetation. Man sollte daher die Einsicht haben, in solchen Gegenden den Wald ja nicht auszurotten, sondern ihn gut zu pflegen. Und da die Erde aber auch durch allerlei klimatische und kosmische Einflüsse sich nach und nach verändert, sollte man das Herz dazu haben, dann, wenn man erblickt, die Vegetation wird kümmerlich, nicht allerlei Experimente bloß auf den Feldern und für die Felder zu machen, sondern die Waldflächen in der Nähe etwas zu vermehren. Und wenn man bemerkt, die Pflanzen wuchern und haben nicht genügend Samenkraft, dann sollte man allerdings dazu schreiten, im Walde Flächen auszusparen, herauszunehmen. Die Regulierung des Waldes in Gegenden, die schon einmal für Bewaldung bestimmt sind, gehört einfach mit zur Landwirtschaft und muss im Grunde genommen von der geistigen Seite her nach ihrer ganzen Tragweite betrachtet werden.

[ 26 ] Dann können wir wieder sagen, auch die Würmer- und Larvenwelt, sie steht in einer Wechselwirkung zum Kalk der Erde, also zum Mineralischen, die Insekten- und Vogelwelt, alles dasjenige, was da flattert und fliegt, das steht im Wechselverhältnis zu dem Astralischen. Das, was unter der Erde ist, die Würmer- und Larvenwelt, steht im Wechselverhältnis zum mineralischen und namentlich zum kalkigen Wesen, und dadurch wird in der richtigen Weise das Ätherische abgeleitet, was ich Ihnen von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte vor ein paar Tagen gesagt habe. Es obliegt dem Kalk diese Aufgabe, aber er übt diese Aufgabe in Wechselwirkung mit der Larven- und Würmerwelt aus.

[ 27 ] Sehen Sie, wenn man das, was da angeführt worden ist von mir, mehr spezialisiert, dann kommt man noch auf andere Dinge, die durchaus einmal - ich würde sie mir nicht mit einer solchen Sicherheit auszuführen getrauen - in der instinktiven Hellseherzeit gefühlsmäßig ganz richtig angewendet worden sind. Nur hat man dafür die Instinkte verloren. Der Intellekt hat eben alle Instinkte verloren, der Intellekt hat eben alle Instinkte ausgerottet. Die Schuld des Materialismus ist es, dass die Menschen so gescheit, so intellektuell geworden sind. In der Zeit, in der sie weniger intellektuell waren, waren sie nicht so gescheit, aber viel weiser, und sie wussten aus dem Gefühl heraus die Dinge so zu behandeln, wie wir sie wieder bewusst behandeln müssen, wenn wir nun durch etwas, was auch wieder nicht gescheit ist - Anthroposophie ist nicht gescheit, sie strebt mehr nach Weisheit -, wenn wir so auf diese Weise vermögen, uns der Weisheit für alle Dinge zu nähern, nicht bloß in dem abstrakten Geleier von Worten «Der Mensch besteht aus physischem Leib, Ätherleib und so weiter», das man auswendig lernen und ableiern kann wie ein Kochbuch. Aber darum handelt es sich nicht, sondern es handelt sich darum, dass man die Erkenntnis dieser Dinge wirklich überall einführt, dass man sie überall drinnen sieht, und dann wird man angeleitet - namentlich, wenn man in der Weise, wie ich es Ihnen auseinandergesetzt habe, wirklich hellsichtig wird -, nun wirklich zu unterscheiden in der Natur, wie die Dinge sind.

[ 28 ] Und dann findet man, dass die Vogelwelt dann schädlich wird, wenn sie nicht an ihrer Seite den Nadelwald hat, damit dasjenige, was sie vollbringt, ins Nützliche umgewandelt werde. Und jetzt wiederum wird der Blick weiter geschärft, und man bekommt eine andere Verwandtschaft heraus. Hat man diese merkwürdige Verwandtschaft der Vögel gerade mit den Nadelwäldern erkannt, dann bekommt man eine andere Verwandtschaft heraus, die sich deutlich einstellt, die zunächst eine feine Verwandtschaft ist, in solcher Feinheit, wie diejenige, die ich angeführt, die sich aber sogar in eine gröbere umsetzen kann. Nämlich zu all dem, was nun zwar nicht Baum wird, aber auch nicht kleine Pflanze bleibt, zu den Sträuchern, zum Beispiel Haselnusssträuchern, da haben die Säugetiere eine innere Verwandtschaft, und man tut daher gut, zur Aufbesserung seines Säugetierwesens in einer Landwirtschaft in der Landschaft strauchartige Gewächse anzupflanzen. Einfach schon dadurch, dass die strauchartigen Gewächse da sind, üben sie einen günstigen Einfluss aus. Denn in der Natur steht alles in Wechselwirkung.

[ 29 ] Aber man gehe weiter. Die Tiere sind ja nicht so töricht wie die Menschen, die merken nämlich sehr bald, dass diese Verwandtschaft da ist. Und wenn sie merken, dass sie die Sträucher lieben, dass ihnen die Liebe dazu angeboren ist, dann bekommen sie auch diese Sträucher zum Fressen gern, und sie fangen an, das Nötige davon zu fressen, was ungeheuer regulierend wirkt auf das andere Futter. Aber man kann, wenn man so diese intime Verwandtschaft in der Natur verfolgt, von da aus wiederum Blicke gewinnen für das Wesen des Schädlichen. So wie der Nadelwald eine intime Beziehung zu den Vögeln hat, die Sträucher eine intime Beziehung zu den Säugetieren haben, so hat wiederum alles Pilzige eine intime Beziehung zu der niederen Tierwelt, zu Bakterien und ähnlichem Getier, zu den schädlichen Parasiten nämlich. Und die schädlichen Parasiten halten sich mit dem Pilzartigen zusammen, sie entwickeln sich ja dort, wo das Pilzartige in Zerstreuung auftritt. Und dadurch entstehen jene Pflanzenkrankheiten, entstehen auch gröbere Schädlichkeiten bei den Pflanzen. Bringen wir es aber dahin, nicht nur Wälder zu haben, sondern Auen in entsprechender Nachbarschaft der Landwirtschaft, so werden diese Auen dadurch ganz besonders wirksam werden für die Landwirtschaft, dass in ihnen ein guter Boden vorhanden ist für Pilze. Und man sollte darauf sehen, dass die Auen besetzt sind in ihrem Boden mit Pilzen. Und da wird man das Merkwürdige erleben, dass, wo eine Aue, eine pilzreiche Aue, wenn auch vielleicht gar nicht von starker Größe, in der Nähe einer Landwirtschaft ist, dass da dann diese Pilze nun durch ihre Verwandtschaft mit den Bakterien und dem anderen parasitären Getier dieses Getier abhalten von dem anderen. Denn die Pilze halten mehr zusammen mit diesem Getier, als das die anderen Pflanzen tun. Neben solchen Dingen, wie ich sie angeführt habe zur Bekämpfung solcher Pflanzenschädlinge, besteht auch noch die Möglichkeit, im Großen die Möglichkeit, durch Anlegung von Auen das schädliche Kleingetier, das schädliche Kleinviehzeug von der Landwirtschaft abzuhalten.

[ 30 ] In der richtigen Verteilung von Wald, Obstanlagen, Strauchwerk, Auen mit einer gewissen natürlichen Pilzkultur liegt so sehr das Wesen einer günstigen Landwirtschaft, dass man wirklich mehr erreicht für die Landwirtschaft, wenn man sogar die nutzbaren Flächen des landwirtschaftlichen Bodens etwas verringern müsste. Jedenfalls übt man keine ökonomische Wirtschaft aus, wenn man die Fläche des Erdbodens so weit ausnutzt, dass alles das hinschwindet, wovon ich gesprochen habe, und man darauf spekuliert, dass man dadurch mehr anbauen kann. Das, was man da mehr anbauen kann, wird eben in einem höheren Grade schlechter, als dasjenige beträgt, was man durch die Vergrößerung der Flächen auf Kosten der anderen Dinge erreichen kann. Man kann eigentlich in einem Betriebe, der so stark ein Naturberrieb ist wie der landwirtschaftliche, gar nicht darinnen stehen, ohne in dieser Weise Einsichten zu haben in den Zusammenhang des Naturberriebs, die Wechselwirkung des Naturberriebs.

[ 31 ] Jetzt ist auch noch die Zeit, diejenigen Gesichtspunkte zu unserer Einsicht zu bringen, die uns überhaupt das Verhältnis des Pflanzlichen zum Tierischen und umgekehrt, des Tierischen zum Pflanzlichen, vor die Seele stellen. Was ist denn eigentlich ein Tier, und was ist eigentlich die Pflanzenwelt?

[ 32 ] Bei der Pflanzenwelt muss man mehr von der gesamten Pflanzenwelt sprechen. Was ist eigentlich ein Tier, und was ist die Pflanzenwelt? Dass das als Verhältnis aufgesucht werden muss, das geht daraus hervor, dass man nur, wenn man etwas davon versteht, auch vom Füttern der Tiere etwas verstehen kann. Denn das Füttern ist ja nur dann richtig zu vollziehen, wenn es im Sinne des richtigen Verhältnisses von Pflanze und Tier eben gehalten ist. Was sind Tiere?

[ 33 ] Ja, da schaut man die Tiere so an, seziert sie wohl auch, hat dann die Knochengerüste, an deren Formen man sich ja erfreuen kann, die man auch so studieren kann, wie ich es angeführt habe. Man studiert wohl auch das Muskel-, das Nervenwerk, aber was die Tiere eigentlich drinnen sind im ganzen Haushalt der Natur, bekommt man dadurch doch nicht heraus. Das bekommt man nur heraus, wenn man hinsieht auf dasjenige, womit das Tier in einer ganz unmittelbar intimen Wechselwirkung steht in Bezug auf seine Umgebung. Sehen Sie, da ist es so, dass das Tier unmittelbar verarbeitet aus seiner Umgebung in seinem Nerven-Sinnes-System und einem Teile seines Atmungssystems alles dasjenige, was erst geht durch Luft und Wärme. Das Tier ist im Wesentlichen, insofern es ein eigenes Wesen ist, ein unmittelbarer Verarbeiter von Luft und Wärme durch sein Nerven-Sinnes-System [und durch sein Atmungssystem].

[ 34 ] Sodass wir das Tier schematisch so zeichnen. In alledem, was in seiner Peripherie, Umgebung liegt, in seinem Nerven-Sinnes-System und in einem Teile seines Atmungssystems ist das Tier ein eigenes Wesen, das unmittelbar lebt in Luft und Wärme. Zu Luft und Wärme hat das Tier einen ganz unmittelbaren Bezug, und eigentlich aus der Wärme heraus ist sein Knochensystem geformt, indem Mond- und Sonnenwirkungen durch die Wärme namentlich vermittelt werden. Aus der Luft ist sein Muskelsystem geformt, in dem wiederum die Kräfte von Sonne und Mond auf dem Umwege durch die Luft wirken.

[ 35 ] In unmittelbarer Weise dagegen, so in unmittelbarer Verarbeitung, kann das Tier sich nicht verhalten zu dem Erdigen und zu dem Wässrigen. Erde und Wasser kann das Tier so unmittelbar nicht verarbeiten. Es muss Erde und Wasser in sein Inneres aufnehmen, muss also von außen nach innen gehend den Verdauungskanal haben und verarbeitet in seinem Innern alles dann mit dem, was es geworden ist durch Wärme und Luft, verarbeitet Erde und Wasser mit seinem Stoffwechselsystem und einem Teil seines Atmungssystems. Das Atmungssystem geht dann über in das Stoffwechselsystem. Mit einem Teil seines Atmungs- und einem Teil seines Stoffwechselsystems verarbeitet es Erde und Wasser. Es muss also das Tier schon da sein durch Luft und Wärme, wenn es Erde und Wasser verarbeiten soll. $o lebt das Tier im Bereiche der Erde und im Bereiche des Wassers. Natürlich geschieht die Verarbeitung, so wie ich es angedeutet [habe], mehr im kraftmäßigen Sinne als im Substanziellen. Fragen wir demgegenüber, was ist nun eine Pflanze?

[ 36 ] Sehen Sie, die Pflanze hat nun ebenso einen unmittelbaren Bezug zu Erde und Wasser, wie das Tier zu Luft und Wärme; sodass wir bei der Pflanze haben, dass sie auch durch eine Art von Atmung und durch etwas, was dem Sinnessystem entfernt ähnlich ist, unmittelbar in sich aufnimmt alles dasjenige - wie unmittelbar das Tier Luft und Wärme aufnimmt -, was Erde und Wasser ist. Die Pflanze lebt also unmittelbar mit Erde und Wasser.

[ 37 ] Nun werden Sie sagen: Nun ja, jetzt kann man ja weiter wis nachdem man eingesehen hat, die Pflanze lebt unmittelbar mit Erde und Wasser, so wie das Tier mit Luft und Wärme, so müsste die Pflanze jetzt in ihrem Innern Luft und Wärme so verarbeiten, wie das Tier Erde und Wasser verarbeitet.

[ 38 ] Das ist aber nicht der Fall. Man kann nun nicht von dem, was man einmal weiß, durch Analogie schließen, wenn man auf die geistigen Wahrheiten kommen will; sondern es ist so, dass, während das Tier aufnimmt Irdisches und Wässriges und in sich verarbeitet, die Pflanze gerade Luft und Wärme ausscheidet, indem sie mit dem Erdboden zusammen sie erlebt. Also Luft und Wärme gehen nicht hinein, oder sind wenigstens nicht wesentlich weit hineingegangen, sondern es gehen heraus Luft und Wärme und werden, statt aufgezehrt von der Pflanze, ausgeschieden.

[ 39 ] Und dieser Ausscheidungsprozess ist dasjenige, um das es sich handelt. Die Pflanze ist in Bezug auf das Organische in jeder Beziehung ein Umgekehrtes von dem Tier, ein richtig Umgekehrtes. Was beim Tier die Nahrungsaufnahme ist in ihrer Wichtigkeit, das ist bei der Pflanze die Ausscheidung von Luft und Wärme, und die Pflanze lebt in dem Sinne, wie das Tier aus der Nahrungsaufnahme lebt, so lebt die Pflanze in dem Sinne aus der Ausscheidung von Luft und Wärme. Das ist das, man möchte sagen, Jungfräuliche an der Pflanze, dass sie nicht gierig etwas aufnehmen will durch ihre eigene Wesenheit, sondern eigentlich das gibt, was das Tier nimmt aus der Welt, und dadurch lebt. So gibt die Pflanze und lebt vom Geben.

[ 40 ] Wenn Sie dieses Geben und Nehmen ins Auge fassen, dann haben Sie etwas wiederum erkannt, was in einer alten instinktiven Erkenntnis von diesen Dingen eine große Rolle spielte. Der Satz, den ich hier aus der anthroposophischen Betrachtung heraushole: «Die Pflanze gibt, das Tier nimmt im Haushalt der Natur», der war einstmals in einer instinktiven hellseherischen Einsicht in die Natur überhaupt gang und gäbe. Und manches ist bei besonders für diese Sache sensitiven Menschen bis in spätere Zeiten geblieben, und Sie finden just noch bei Goethe den öfteren Gebrauch dieses Satzes: «In der Natur lebt alles durch Geben und Nehmen.» Sie werden ihn schon, wenn Sie Goethes Werke durchgehen, finden. Er hat ihn nicht mehr richtig verstanden, aber er hat ihn aus alten Gebräuchen, Traditionen, wieder aufgenommen und hatte ein Gefühl dafür, dass man mit diesem Satze etwas Wahres in der Natur bezeichnete. Diejenigen, die nachgekommen sind, haben nun gar nichts mehr davon verstanden, verstehen auch nicht dasjenige, was Goethe damit gemeint hat, wenn er von Geben und Nehmen spricht. Er spricht auch vom Atmen, insofern das Atmen mit dem Stoffwechsel in Wechselwirkung steht, von Nehmen und Geben. Klar - unklar hat er dieses Wort angewendet. Nun, Sie sehen, dass in einer gewissen Weise die Wälder und Obstgärten, das Strauchwerk über der Erde, Regulatoren sind, um das Pflanzenwachstum in der richtigen Weise zu gestalten. Und wiederum unter der Erde ist ein ähnlicher Regulator dasjenige, was im Verein mit dem Kalk die niederen Larven, wurmartigen und so weiter Tiere sind. So sollte man anschauen das Verhältnis von Feldwirtschaft, Obstwirtschaft, Viehzucht und sollte daraus dann in die Praxis eintreten. Das werden wir dann versuchen in der letzten Stunde, die uns noch zur Verfügung steht, soweit zu tun, dass wirklich die Dinge von dem schönen Versuchsring weiterverarbeitet werden können.

Seventh Lecture

My dear friends!

[ 1 ] I would now like to continue the observations we have made and, in the time remaining, say a few words about animal husbandry and fruit and vegetable cultivation.

[ 2 ] Of course, we will not have much time for this, but this area of agricultural activity cannot be considered a fruitful starting point unless we do everything we can to promote understanding and insight into the relevant conditions. That is what we want to do today, and tomorrow we will move on to some practical pointers for application.

[ 3 ] I would ask you today to try to follow me in considering things that are, I would say, somewhat remote because, although they were once quite familiar to a more instinctive agricultural understanding, they now seem like completely unknown territory. The entities that occur in nature, minerals, plants, animals—we will leave humans aside for now—the beings that occur in nature are very, very often viewed as if they existed alone. Today, we are accustomed to looking at a plant on its own and then, starting from this, to consider one plant species on its own and another plant species next to it on its own. We arrange them neatly in boxes, divided into species and genera, into what we want to know about things. But that is not how it is in nature. In nature, in the universe as a whole, everything interacts with everything else. One thing always affects another. Today, in our materialistic age, we only pursue the gross effects of one thing on another; when one thing is eaten and digested by another, or when animal manure is spread on the fields. We pursue only these gross interactions.

[ 4 ] In addition to these gross interactions, there are also finer forces and finer substances, such as heat, chemical-etheric forces constantly at work in the atmosphere, and the life ether, which are constantly interacting. And without taking these finer interactions into account, it is impossible to make progress in certain areas of agriculture. We must look in particular at such, I would say, more intimate interactions with nature when we are dealing with the coexistence of animals and plants within the agricultural enterprise. And we must not only look at those animals that are undoubtedly close to us, such as cattle, horses, sheep, and so on, but we must also look intelligently at, say, the colorful world of insects that flutter around the plant world during a certain time of the year. Yes, we must even understand how to look intelligently at the world of birds. Today, humanity does not yet have a proper understanding of the impact that the displacement of certain bird species from certain areas due to modern living conditions actually has on all agricultural and forestry life. These things must be examined from a spiritual scientific perspective, or, one might just as well say, from a macrocosmic perspective. Now we can use some of what we have allowed to influence us to gain further insights.

[ 5 ] When you look at a fruit tree, a pear tree or an apple or plum tree, it is actually something completely different. Every tree is, at first glance, something completely different from a herbaceous plant or a cereal plant. And you have to come to a proper understanding of how the tree is different, otherwise you will never understand the function of fruit in the household of nature. I am, of course, talking first of all about the fruit that grows on trees.

[ 6 ] Now let's look at the tree. What is it actually in the whole household of nature? If we look at it intelligently, we can initially only count as part of the actual plant in the tree that which grows out of it in thin stems, in the green leaf carriers, in flowers, in fruits. This grows out of the tree, just as the herbaceous plant grows out of the earth.

[ 7 ] The tree is really the earth for what grows on its branches. It is the earth that has become hilly, only a little more lively than the earth from which our herbaceous plants and grain plants grow.

[ 8 ] So if we want to understand the tree, we have to say, well, there is the thick trunk of the tree, and in a certain sense the branches and twigs also belong to it. From there, the actual plant grows out, leaves and flowers grow out of it. This is the plant that is rooted in the trunk and branches of the tree, just as the herbaceous plants and grain plants are rooted in the earth. This immediately raises the question: Is this plant on the tree, which can be called a parasite to a greater or lesser extent, also actually rooted?

[ 9 ] We cannot discover a real root on the tree. And if we want to understand this correctly, we must say: Yes, this plant that grows there, which develops its flowers and leaves up there, and also its stems, has lost its roots by sitting on the tree. But a plant is not complete if it has no roots. It needs a root. So we must ask ourselves: Where is the root of this plant?

[ 10 ] Now you see, the root is just not visible to the naked eye. In this case, it is not enough to simply look at the root; you have to understand it. You have to understand it. What does that mean? Let's think about it—let's use a real-life comparison to help us understand. I planted a bunch of herbaceous plants close together in the ground, and their roots grew together, with one root twisting around another, and the whole thing became a kind of intertwined root mash. You might think that this root mush would not allow anything irregular to exist, that it would organize itself into a single entity, and that the juices would flow into each other down there. There would be organized root mush, where you couldn't tell where the roots ended or began. A common root entity would emerge in the plant.

[ 11 ] Something like this, which does not need to exist at first, but which can help us understand, would be this: There is the ground. Now I plant all my plants—like this!—and down there, the roots all grow into each other. Now a completely flat root layer forms. You don't know where one ends and the other begins. Well, what I have described to you here as a hypothetical scenario actually exists in trees. The plant growing on the tree has lost its roots; it has even separated itself from them relatively and is only connected to them, I would say, in a more ethereal way. And what I have hypothetically drawn here is the cambium layer inside the tree, the cambium, so that we cannot see the roots of this plant in any other way than as being replaced by the cambium.

[ 12 ] The cambium does not look like roots. It is the formative layer that constantly forms new cells, from which growth unfolds again and again, just as the herbaceous plant life would unfold from a root below. We can then see clearly how, in the tree with its cambium layer, which is the actual formative layer and can produce plant cells—the other layers of the tree would not be able to produce fresh cells— it is in fact the earthy part that has pushed itself up, grown out into the airy part [and] thereby needs more internalization of life than the earth otherwise has within itself, since it still has the ordinary root within itself. And we begin to understand the tree. At first, we understand the tree as a strange being, as the being that is there to separate the “plants” growing on it: stems, flowers, fruit, and their roots, to remove them from each other and connect them only through the spirit, or rather through the etheric.

[ 13 ] In this way, it is necessary to look at growth in a macrocosmic way. But it goes much further than that. What happens when the tree comes into being? What happens is this: what grows up there on the tree is, in the air and in the external warmth, a different plant entity from that which grows directly on the ground in air and warmth and then forms the herbaceous plant growing out of the ground.

[ 14 ] It is a different plant world, a plant world that has much more intimate relationships with the surrounding astrality that is excreted into the air and warmth so that air and warmth can be mineral, as humans and animals then need. And so it is that when we look at the plant growing on the ground, it is surrounded and clouded by astral matter, as I have said. Here, however, on the tree, this astrality is much denser. It is denser here, so that our trees are accumulations of astral substance. Our trees are clearly accumulators of astral substance.

[ 15 ] In this area, it is actually easiest, I would say, to attain a higher level of development. If one strives in these areas, one can very easily become esoteric. One cannot become clairvoyant, but one can very easily become clairscentient if one acquires a certain sense of smell for the various aromas that emanate from plants on the earth, from fruit plantations, even when they are only in bloom, and from the forest. Then you will be able to sense the difference between a plant atmosphere that is poorer in astral substance, as you can smell it in the herbaceous plants that grow on the earth, and between a plant world that is rich in astral substance, as you can smell it in your nose when you sniff what can be smelled in such a beautiful way from the crowns of the trees. And in this way, if you accustom yourself to specifying, distinguishing, and individualizing the smell between the smell of earth plants and the smell of trees, you will have, in the former case, a clear sense of smell for thinner astrality, and in the latter case, a clear sense of smell for denser astrality. - You see, farmers can easily become clairvoyant. They have not used this ability in recent times as they did in the old days of instinctive clairvoyance. Farmers can become clairvoyant, as I said.

[ 16 ] If we now consider where this might lead, we must ask ourselves: What about that which is, in a sense, polar opposite to what the parasitic plant growing on the tree causes as astral in the tree's environment? What happens through the cambium, what does it do?

[ 17 ] You see, far around itself, the tree makes the spiritual atmosphere more astral. What happens when the herbaceous plant grows on top of the tree? [Then it has a certain inner vitality, ethereality, a certain strong life within itself.] The cambium dampens this life a little more, so that it becomes more mineral-like. The cambium therefore has the following effect: while the astral realm develops around the tree at the top, the cambium acts in such a way that there is less ether than usual inside, and the tree becomes ether-depleted in relation to the plant. A more ether-poor substance is created here. However, because the cambium creates a more ether-poor substance in the tree, this in turn influences the root. The root in the tree becomes mineral, much more mineral than the roots of herbaceous plants.

[ 18 ] However, as it becomes more mineralized, it now draws something of its ethericity from the soil in what remains inside the living organism. It makes the soil around the tree somewhat more dead than it would be around the herbaceous plant. This must be strictly taken into account: But what arises in nature will always have a significant, inner natural meaning in the economy of nature. Therefore, we must seek out this inner natural meaning of the astral richness in the tree environment and the ether poverty in the tree root area.

[ 19 ] And when we look around, we find how this continues in the economy of nature. The developed insect lives and weaves from what passes through the trees as the astral realm. And that which becomes poorer in ether down below in the ground and naturally extends through the whole tree as ether poverty, just as the spiritual always works upon the whole, as I explained yesterday in relation to karma in human beings, that which works down below works upon the larvae, so that if the earth had no trees, there would be no insects on earth at all. For the trees provide the insects with the possibility of being. The insects fluttering around the above-ground parts of the trees, that is, the insects fluttering around the entire forest, live because the forest is there, and their larvae also live because the forest is there.

[ 20 ] You see, this gives us another indication of the intimate relationship between all root systems and the underground animal world. For I would say that what we have just explained can be learned particularly well from trees. There it becomes clear. But what is significant is that what becomes striking and clear in the tree is also present in a nuanced way in the entire plant world, so that something lives inside every plant that wants to become tree-like. In every plant, the root actually strives with its environment to release the ether, and in every plant, that which grows upward strives to draw the astral more densely toward itself. The desire to become a tree is actually contained in every plant. This is why every plant has this relationship to the insect world, which I have particularly characterized in trees. But this relationship to the insect world also extends to the entire animal world. Insect larvae, which can initially only live on the earth because tree roots are present, developed into other animal species that are similar to them, which spend their entire animal life more or less in a kind of larval state and then, in a sense, emancipate themselves from their tree root nature in order to live on the roots of herbaceous plants and coexist with them.

[ 21 ] Now we see the peculiarity that we can observe how underground animals, although very distant from the larval state, have the ability to regulate the etheric vitality in the soil when it becomes too great. If the soil were to become too alive, so to speak, and the vitality within it were to become overgrown, these underground animals would ensure that the excess vitality is released from the soil. They thus become wonderful valves and regulators for the vitality present in the earth. These golden animals, which are therefore of particular importance to the soil, are earthworms. Earthworms should really be studied in their coexistence with the soil. For they are these wonderful animals that allow the earth just as much ethericity as it needs for plant growth.

[ 22 ] So, underground, we have these earthworms and similar creatures, which are only reminiscent of larvae. And actually, for certain soils, where this can be seen, we should even ensure favorable conditions for earthworm breeding. Then we would see how beneficial such control of the animal world underground is for vegetation and, in turn, as we will point out later, for the animal world.