Practical Course for Teachers

GA 294

21 August 1919, Stuttgart

I. Introduction—Aphoristic remarks on Artistic Activity, Arithmetic, Reading, and Writing

To these lectures I wish to provide a kind of introduction; for even in our actual teaching methods we shall have to distinguish them—with all due modesty—from the methods which have evolved in our time on quite other assumptions than those which we must make. Our methods are not different from those others just because we want capriciously something “new” or “different,” but because the tasks of our particular age will compel us to realize the course which must be taken by education itself for humanity, if it is to answer in the future to the impulses towards development predestined in the human race by the universal world order.

Above all, we shall have to be aware, in our method, that we are concerned with a certain harmonizing of the spirit and soul with the physical-body. You will not, of course, be able to use the materials of study as they have been used hitherto. You will have to use them as the means of rightly developing the soul and body forces of the individual. And so you will not be concerned with the handing down of a province of knowledge as such, but with manipulating this province of knowledge in order to develop human abilities. You will have to distinguish, above all, between the material of knowledge which is really determined by convention, by human agreement—even if it is not admitted in so many words—and the materials of knowledge which depend on an understanding of human nature in general.

Just consider superficially the actual position, in general culture, of the reading and writing which you impart to the child to-day. We read, but the art of reading has naturally developed in the course of civilization. The letter-forms which have arisen, the combination of these various letter-forms, is all a matter determined by convention. In teaching the child the present form of reading, we teach him what, apart from the place of the individual within a quite definite culture, has no significance at all for the human entity. We must be aware that other practices of our physical culture have no direct meaning for super-physical humanity, for the super-physical world at all. It is quite wrong to believe, as spiritist circles sometimes do, that spirits wrote the human writing in order to bring it into the physical world. Human writing has arisen from human activity, from human convention on the physical plane. The spirits are not in the least interested in accommodating themselves to this physical convention. Even if the intervention of the spirits is a fact, it is in the form of special translation by means of intermediary human activity; it is not a direct gesture of the spirit itself, a communication into this form of writing or reading of its living essence. The reading and writing which you teach the child are determined by convention; they have arisen within the action of the physical body.

Teaching the child arithmetic is quite another thing. You will feel that here the most important thing is not the forms of the figures, but the reality that lives in the figure-forms. And this living reality alone is of more importance to the spiritual world than the reality living in reading and writing. And if we proceed further to teach the child certain activities which we must call artistic, we enter with them into the sphere which always has eternal significance, which reaches up into the activity of the spirit and soul in man. In teaching children reading and writing we are teaching in the domain of the most exclusively physical. Our teaching is already less physical in arithmetic, and we are really teaching the soul and the spirit when we teach the child music, drawing, or anything of that kind.

Now in a rationally pursued course of study we can combine these three impulses, the super-physical in the artistic activity, the semi-super-physical in arithmetic, and the entirely physical in reading and writing, and just this combination will bring about the harmonizing of the individual. Imagine that we approach the child in this way (this lecture is merely introductory, and only aphoristic individual instances will be given): we say: “You have already seen a fish. Now just try to get a clear idea of what it looked like—this fish that you saw. If I make this for you (see drawing) it looks very like a fish. What you saw as a fish looks something like what you see there on the board. Now just imagine that you are saying the word fish. What you say when you say ‘fish’ is expressed by this sign.

“Now just try not to say ‘fish,’ but only to start saying ‘fish.’ We now try to show the child that he must only begin saying ‘fish:’ F-f-f-f. Now look, you have started now to say ‘fish;’ and now picture to yourself that people gradually came to simplify what you see there. In starting to say ‘fish,’ F-f-f-f-, you are saying, and writing for it, this sign. And people call this sign ‘f’.

“So you have learned that what you say when you say ‘fish’ begins with f and now you write that as f. You always breathe f-f-f- when you start to say fish; in this way you learn what the sign was for saying fish in the very beginning.”

When you set about appealing to the child's nature in this way, you transport the child right back into earlier civilizations, for that is when writing first arose. Later the process passed into a mere convention, so that to-day we no longer recognize the connection between the abstract letter-forms and the images which arose purely as signs from the contemplation and imitation of what was observed. All letter-forms have arisen from pictorial shapes. And now think how, when you only teach the child the convention: “You are to make an f like this!” you are teaching him something quite disconnected, and out of its context with the human setting. Writing is then dislodged from its original setting: the artistic element. Therefore we must begin, in teaching to write, with the artistic drawing of the shapes—of the sound and letter-shapes—if we want to go so far back that the child is struck by the difference in shapes. It is not enough merely to form these shapes before the child with our mouth, for that makes people what they have become to-day. In dislodging the written shape from what is now convention and showing its original source, we compass the whole being and make it something quite different from what it would be if we simply appealed to perception. So we must not only think in abstracto. We must teach art in drawing, etc.; we must impart the psychic element in teaching arithmetic, and we must teach the conventional element of reading and writing artistically; we must permeate our whole teaching with the artistic element. Consequently, from the first we shall attach great importance to cultivating the artistic element in the child. The artistic element, as is well known, has a quite exceptional influence on the will. With its help we penetrate to something connected with the whole individual, whereas what is concerned with convention only affects the head, “head-man” (kopfmensch). Consequently, we proceed by letting every child cultivate something to do with drawing and painting. Thus we begin with drawing, the drawing-painting in the simplest way. But we begin, too, with the musical element, so that the child is accustomed from the first to handle an instrument, so that the artistic feeling is awakened in him. Then he will develop, as well, the power to feel with his whole being what is otherwise merely conventional.

It is our task in the study of method always to engage the whole individual. We could not do this without focussing our attention on the development of an artistic feeling with which the individual is endowed. This will also dispose the individual later to take an interest in the whole world as far as his nature permits. The fundamental error until now has always been that people have set themselves up in the world with nothing but their heads; they have at the most dragged the rest of their bodies after them. And the result is that the other parts now follow the lead of their animal impulses and live themselves out emotionally—as we are experiencing just now in the very curious wave of emotionalism which has spread from East Europe. This has occurred because the whole individual has not been cultivated. But it is not only that the artistic element must be cultivated, too, but the whole of our teaching must be drawn from the artistic element. All method must be immersed in the artistic element. Education and teaching must become a real art. Here, too, knowledge must not be more than the underlying basis.

Therefore we first extract from the element of drawing the written forms of the letters, then the printed forms. We build up reading on drawing. In this way you will soon see that we strike a chord to which the child-like soul loves to vibrate in harmony, because the child has then not only an external interest, but because, for instance, it sees, in actual fact, the coming to expression in reading and writing of its own breath.

We shall then have to rearrange much in our teaching. You will see that what we are aiming at in reading and writing can naturally not be built up exclusively in the way just described, but we shall only be able to awaken the forces necessary to such a superstructure. For if we were to try in modern life to build up all our teaching on the process of evolving reading and writing from a setting of drawing, we should need to spend the time up to the twentieth year over it; we should never finish in the school-life. We can only carry it out, then, first of all, in principle—and must, in spite of it, pass on, but while still remaining in the artistic element. When we have drawn out isolated instances in this way for a time, we must go on to make the child understand that grown-up people, when they have these peculiar forms in front of them, discover a meaning in them. While cultivating further what the child has learnt like this from isolated instances, we pass on—no matter whether the child understands the details or not—to write out sentences. In these sentences the child will then notice forms such as he has become familiar with in the f of fish. He will then notice other forms, next to these, which we are unable to show in their original setting for lack of time. We then proceed to draw on the board what the separate letters look like in print, and one day we write a long sentence on the board and say to the child: “Now grown-ups have all this in front of them when they have developed all that we have seen to be the f in fish, etc. Then we teach the child to copy writing. We lay stress upon his feeling with his hands whatever he sees, on his not merely reading with his eye, but on his following the shape with his hands, and on his knowing that he himself can shape all that is on the board, just so. He will then not learn to read without his hand following the shapes of what he sees, of the printed letters too. Thus we succeed—which is extraordinarily important—in seeing that reading is never done with the mere eye but that the activity of the eye passes mysteriously over into the entire activity of the human limbs. The children then feel unconsciously, right down into their legs, what they would otherwise only survey with the eye. We must endeavour to interest the whole being of the child in this activity.”

Then we go the opposite way: we split up the sentence we have written down, and show the other letter-shapes which we have not yet brought out of their element; we split up and divide, by atomizing, the words, and we go from the whole to the separate parts. For example, here stands the word “head.” The child first learns to write down “head,” just painting the word as a copy. Then we split the word “head” into h-e-a-d; we bring the separate letters out of the word, and thus go from the whole to the separate parts.

We continue, in fact, throughout our teaching to pass like this from the whole to the part. We divide, for instance, a piece of paper into a number of little paper shreds. Then we count these shreds; let us suppose that there are twenty-four. Then we say to the child: “Just look, I describe these paper shreds by what I have written on the board and call them: twenty-four paper shreds. [They might be beans just as well, of course.] Now notice that. Now I take a number of paper shreds away, I put them on a little pile; I make another little heap here, and there a third, and there a fourth; now I have made four little heaps out of the twenty-four paper shreds. Now watch: I will now count them; you can't do that yet, but I can, and what is lying on that little heap I call nine paper shreds, and what is lying on the second little heap I call five paper shreds, and what is lying on the third I call seven paper shreds, and what is lying on the fourth little heap I call three paper shreds. You see, before, I had a single heap: twenty-four paper shreds; now I have four little heaps: nine, five, seven, three paper shreds. That is all the same paper. The first time, when I have it altogether, I call it twenty-four; now I have divided it into four little heaps and call it, now nine, then five, then seven, and then three paper shreds.” Now I say: “Twenty-four paper shreds are, altogether, nine and five and seven and three.” Now I have taught the child to add up. That is, I have not started from the separate addenda and formed the sum from them. That is never the way of our original primitive human nature. (I refer you for this to my Outlines of a Theory of Knowledge Belonging to the Goethean World-Conception.) But the opposite process is the way of human nature: seeing the sum first, and then dividing it up into the separate addenda, so that we must teach the child to add in the opposite way to what is usually taught; we must start with the sum and then go to the addenda. Then the child will have a better idea of what “together” means, than he has had up to now from our picking the parts up and putting them together. Our teaching will have to be distinguished from teaching hitherto by the fact that we have to teach the child in more or less the opposite way what “sum” means in contrast to the “addenda.” Then we can rely on the response of a quite different understanding from that aroused by the opposite procedure. You will actually only see the full value of this from practice. For you will see the child enter quite differently into the subject; you will notice a quite different capacity for understanding in the child, if you go the way I have described.

You can then go the opposite way and continue your arithmetic. You can say: “Now I throw these paper shreds all together again, and make two little heaps, and I call the little heap which I have left quite separate, three. How have I got this three? By taking it away from the others. When it was still all together I called it twenty-four; now I have taken three away and now I call what is left twenty-one.” In this way you introduce the idea of subtraction. That is, again, you do not start from minuend and subtrahend, but from the remainder, from what is left, and you lead from this to what the remainder came from. Here, too, you proceed the opposite way. And—as we shall see later in the method of special subjects—you can apply to the whole art of arithmetic the process of going from the whole to the part. In this connection we shall doubtless have to accustom ourselves to adhere to a quite different course of instruction. We proceed here to cultivate, at the same time as “object lessons”—which we must never neglect, but which should not be too exclusively emphasized as they seem to be to-day—the sensitiveness to authority. For we are continually saying: I call that twenty-four. I call that nine. In emphasizing, in anthroposophical lectures, the point that between seven and fourteen years of age the feeling for authority should be cultivated, that does not mean that a training is required to produce this feeling for authority, but what is necessary can flow from the very method of instruction itself. Its influence is present like an undertone; when the child listens, he says: “Aha, he calls that nine, he calls that twenty-four,” etc. He obeys voluntarily, at once. Through listening like this to the person who uses this method the child is inoculated by what expresses itself as a sensitiveness to authority. That is the secret. Any artificial training of the feeling for authority must be excluded by the method or technique itself.

Then we must be quite clear that we always want to let three things work in unison: will, feeling, and thinking. When we teach on these lines, willing, feeling, and thinking are actually working together. The point is never to pervert the willing by false means into the wrong direction, but to secure the strengthening of the will by artistic means. To this end, from the first, teaching in painting, artistic instruction, and musical training, too, should be employed.

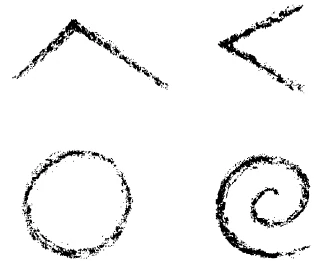

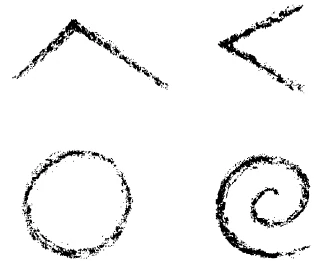

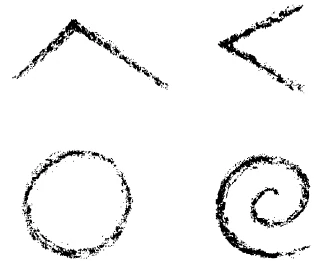

We shall notice incidentally that particularly in the first stage of the second period of his life, the child is most susceptible to authoritative teaching in the form of art and that we then can achieve the most for him with art. He will grow as if of himself into what we desire to pass on to him, and his greatest imaginable joy will be when he puts something down on paper in drawing or even in painting, which, however, must not be confused with any merely superficial imitation. Here, too, we must remember in teaching that we must transport the child, in a sense, into earlier cultural epochs, but that we cannot proceed as though we were still in these epochs. People were different then. You will transport the child into earlier cultural epochs now with quite a different disposition of soul and spirit. So, in drawing, we shall not be bent on saying: You must copy this or that, but we show him original forms in drawing; we show him how to make one angle like this, another like that; we try to show him what a circle is, what a spiral is. We then start with self-contained form, not with whether the form imitates this or that, but we try to awaken his interest in the form itself.

You may remember the lecture in which I tried to awaken a sense of the origin of the acanthus leaf. I then explained that the idea that people imitated the leaf of the acanthus plant in the form in which it appears in legend is quite false; the truth is that the acanthus leaf simply arose from an inner impulse to form, and people felt later: That resembles nature. Nature was not copied. We shall have to bear this in mind with drawing and painting. Then at last there will be an end of the fearful error which devastates human minds so sadly. When people meet with something formed by man, they say: It is natural—it is unnatural. But a mere correct imitation is of secondary importance. Resemblance to the external world should only appear as something secondary. Rather in man should live an impulse of becoming one with growing forces of the form itself. One must have, even when drawing a nose, some inner relation with the nose-form itself, and only later does the resemblance to the nose result. The inner meaning for forms one would never be able to awaken between the age of seven and fourteen by merely copying the forms outside. But one must realize the inner creative element which can be developed between seven and fourteen. If one misses this inner creative element at such a time, it never can be retrieved. The forces active at that time die away after; later, one can get at the most a makeshift, unless a transformation of the individual occurs in what we call “initiation,” natural or unnatural.

I am now going to say something unusual, we must go back to the principles of human nature if we wish to be teachers in the true sense to-day. There are exceptions, when an individual can still recover some omitted experience. But then he must have been through a severe illness, or must have suffered some deformation or other, have broken a leg, for instance, which is then not properly set; that is, he must have suffered a certain loosening of the etheric body from the physical body. That is, of course, dangerous. If it happens through Karma it must be accepted. But we cannot treat it as a calculable quantity, or give any guarantee for public life that a person can recover some thing thus missed—not to mention other things. The development of the individual is mysterious, and the aim of instruction and education must never be concerned with the abnormal, but always with the normal. Teaching is always a social matter. The problem must always be: In what year must the development of certain forces take place, so that this development establishes the individual securely in life? So we must reckon with the fact that it is only between the seventh and fourteenth year that certain abilities can be cultivated in such a way that the individual can stand his ground in the battle of life. If these abilities are not cultivated at this time, the individual concerned will not be equal to the battle of life, but will have to succumb to it, as most people do to-day.

This ability to secure an artistic footing in the world's rush must be our gift as educators to the child. We shall then notice that it is man's nature, up to a point, to be born a “musician.” If people had the right and necessary agility they would dance with all little children, they would somehow join in the movements of all children. It is a fact that the individual is born into the world with the desire to bring his own body into a musical rhythm, into a musical relation with the world, and this inner musical capacity is most active in children in their third and fourth years. Parents can do an enormous amount, if they only take care to build less on externally induced music than on the inducement of the whole body, the dancing element. And precisely in this third and fourth year infinite results could be achieved by the permeation of the child's body with an elementary Eurhythmy. If parents would learn to engage in Eurhythmy with the child, children would be quite different from what they are. They would overcome a certain heaviness which weighs down their limbs. We all to-day have this heaviness in our limbs. It would be overcome. And there would remain in the child when the first teeth are shed the disposition for the complete musical element. The separate senses, the musically attuned ear, the plastically skilled eye, arise first from this musical disposition; what we call the musical ear, or the eye for drawing or modelling, is a specification of the whole musical individual. Consequently, we must always cherish the idea that in drawing on the artistic element we assimilate into the higher man, into the nerve-sense-being, the disposition of the entire being. You elevate feeling into an intellectual experience in utilizing either the musical element or the element of drawing or modelling. That must be done in the right way. Everything to-day is in confusion, particularly where the artistic element is being cultivated. We draw with the hands, and we model with the hands—and yet the two things are completely different. This is most striking when we introduce children to art. When we introduce children to plastic art, we must pay as much attention as possible to seeing that they follow the plastic forms with the hands. When the child feels his own forming, when he moves his hand and makes something in drawing, we can help him to follow the forms with his eye—but with the will acting through the eye. It is in no way a violation of the naivety in the child to instruct him to feel this, to feel over the form of the body with the hollow of his hand. When, for instance, he is tracing the curves of a circle, we draw his attention to the eye, and tell him that he himself makes a circle with his eye. This is absolutely in no sense a violation of the child's naivety, but it engages the interest of the whole being. Consequently, we must realize that we are transporting the lower being of the individual into the higher being, into the nerve-sense-being.

In this way we shall win a certain deep-lying sense of method which we must develop in ourselves as educators and teachers, and which we cannot transfer directly to anyone else. Imagine that we have an individual before us to teach and educate—a child. In these days the vision of the growing being is completely disappearing from education; everything is in confusion. But we must accustom ourselves to distinguish between differences in our vision of this child. We must accompany, as it were, our teaching and educating with inner sensations, with inner feelings, even with inner stirrings of the will, which are only heard, as it were, in a lower octave, and which are not brought out. We must be conscious ourselves that in the growing child there evolve gradually the ego and the astral body; the etheric body and the physical body are already there, inherited.1See Rudolf Steiner, Theosophy, Occult Science. Now it is well for us to picture: The physical body and the etheric body are always particularly cultivated from the head downwards. The head radiates what really creates the physical man. If we follow the right course of education and instruction for the head, we best serve the growth-system. If we teach the child in such a way that we draw out the head-element from the whole being, the right experiences pass from his head into his limbs: the individual grows better, he learns how to walk better, etc. So we can say: the physical and etheric bodies stream downwards when we cultivate all that has relation to the higher man in a positive way. If, in teaching the child to read and write more intellectually, we have the feeling that the child, absorbing what we impart to him, comes to meet us, then this is passing from his head into the rest of his body. But the ego and the astral body are being developed from below upwards when the whole being is educated. A powerful ego sense would be awakened, for instance, if we taught the child elementary eurhythmy in the third and fourth years. The whole individual would be engaged, and a correct ego-sense would strike root in his being. And if he hears plenty of stories to rejoice over and even feel sad about, the astral body will develop from the lower individual upward. Just think back for a moment a little more intimately to your own experiences. I expect you will all have had this experience: In walking through the street and being startled by something, not only your head and your heart were startled, but in your limbs, too, you were startled and you re-lived the shock later. You will be able to agree from this experience that the surrender to something which disarticulates the feelings and the emotions, affects the whole being, not only the heart and the head.

This truth must be kept in view quite particularly by the educator and teacher. He must see that the whole being is moved. Think, then, from this point of view, of telling legends and fairy-tales, and if you have a real feeling for this, so that you convey your own mood when you tell the child stories, you will tell them so that the child re-lives with all his body what he has been told. In this way you really appeal to the child's astral body. The astral body radiates an experience into the head, to be felt there by the child. We must have the feeling that we are moving the whole child, and that only from the feelings, from the emotions we excite, must the understanding for the story come. Make it, therefore, your ideal, in telling the child fairy-tales or legends, or in drawing or painting with him, not to “explain,” or to act through concepts, but to let the whole being be stimulated, so that only afterwards when the child has gone away from you, understanding dawns on him. Try, then, to educate the ego and the astral body from below upwards, so that the head and the heart only come later. Try never to appeal in stories to the head and the understanding, but tell stories so that you evoke in the child—within limits—certain silent tremors of awe, so that you excite pleasures or sorrows which move his whole being so that these still linger and resound when the child has gone away, and only then understanding dawns on him and interest awakes in their meaning. Try to act through your whole intimacy with the children. Try not to excite interest artificially by relying on sensations, but try, by setting up an inner intimacy with the children, to let the interest grow from the child's own nature.

How can this be done with a whole class? It is comparatively easy to achieve with a single child. One only needs to love trying with him, one only needs to inspire one's work with love, to move the whole being, not only the heart and the head. With a whole class it is no harder if one is oneself moved by the subjects in question, but not only in the heart and the head. Take this example: I want to make clear to the child the continued life of the soul after death. I shall never make it clear to the child by theories, but shall only be deceiving myself. No kind of concept can make immortality mean anything to a child before fourteen. But I can say: “Just look at this butterfly's chrysalis. There is nothing inside it. The butterfly was inside it, but it has crept out.” I can show him the process, too, and it is a good thing to bring such metamorphoses before the child. Now I can draw the comparison: “Imagine you are a chrysalis like this yourself. Your soul is inside you; later it finds its way out; it will then find its way out like the butterfly from the chrysalis.” That is putting it naïvely, of course. Now you can talk about it for a long time. But if you do not believe yourself that the butterfly is like the human soul, you will not achieve much with the child through such comparison. You will not, of course, be guilty of introducing the blatant untruth that you only regard it as a man-made comparison. It is no such thing, but it is a fact of the divine ordering of the world. It is not the creation of our intellect. And if we have a right attitude to things, we learn to believe the fact that nature is full of symbols for spiritual-psychic experiences. If we become one with what we impart to the child, our action takes hold of the whole child. The loss of power to feel with the child, the belief in mere adjustment to a given ratio in which we ourselves do not believe, is responsible for the poverty of the child's education. Our own view of the facts must be such that, for instance, with the creeping out of the butterfly from the chrysalis, we introduce into the child's soul, not an arbitrary image, but an illustration, which we understand and believe to be furnished by the divine powers of the universe. The child must not understand what just passes from ear to ear, but what comes from soul to soul. If you notice this, you will go forward.

Erster Vortrag

Meine lieben Freunde, wir werden trennen müssen die Vorträge, die wir in diesen Kurs einbeziehen wollen, in die allgemein-pädagogischen und in diese mehr speziell methodisch-didaktischen. Auch zu diesen Vorträgen möchte ich eine Art von Einleitung sprechen, denn auch in der eigentlichen Methode, die wir anzuwenden haben, werden wir uns in aller Bescheidenheit unterscheiden müssen von den Methoden, die sich heute aus ganz andern Voraussetzungen herausgebildet haben, als denjenigen, die wir machen müssen. Wahrhaftig nicht deshalb werden sich die Methoden, die wir anwenden, von denjenigen unterscheiden, die bisher eingehalten worden sind, weil wir aus Eigensinn etwas Neues oder Anderes haben wollen, sondern weil wir aus den Aufgaben unseres besonderen Zeitalters werden erkennen sollen, wie eben der Unterricht wird verlaufen müssen für die Menschheit, wenn sie ihren Entwickelungsimpulsen, die ihr einmal von der allgemeinen Weltenordnung vorgeschrieben sind, in der Zukunft wird entsprechen sollen.

Wir werden vor allen Dingen einmal in der Handhabung der Methode uns bewußt sein müssen, daß wir es mit einer Harmonisierung gewissermaßen des oberen Menschen, des Geist-Seelenmenschen, mit dem körperleiblichen Menschen, mit dem unteren Menschen zu tun haben werden. Sie werden ja die Unterrichtsgegenstände nicht so zu verwenden haben, wie sie bisher verwendet worden sind. Sie werden sie gewissermaßen als Mittel zu verwenden haben, um die Seelen- und Körperkräfte des Menschen in der rechten Weise zur Entwickelung zu bringen. Daher wird es sich für Sie nicht handeln um die Überlieferung eines Wissensstoffes als solchen, sondern um die Handhabung dieses Wissensstoffes zur Entwickelung der menschlichen Fähigkeiten. Da werden Sie vor allen Dingen unterscheiden müssen zwischen jenem Wissensstoff, der eigentlich auf Konvention beruht, auf menschlicher Übereinkunft — wenn das auch nicht ganz genau und deutlich gesprochen ist -, und demjenigen Wissensstoff, der auf der Erkenntnis der allgemeinen Menschennatur beruht.

Betrachten Sie nur äußerlich, wenn Sie heute dem Kinde Lesen und Schreiben beibringen, wie dieses Lesen und Schreiben eigentlich in der allgemeinen Kultur drinnensteht. Wir lesen, aber die Kunst des Lesens hat sich ja im Laufe der Kulturentwickelung herausgebildet. Die Buchstabenformen, die entstanden sind, die Verbindung der Buchstabenformen untereinander, das alles ist eine auf Konvention beruhende Sache. Indem wir dem Kinde das Lesen in der heutigen Form beibringen, bringen wir ihm etwas bei, was, sobald wir absehen von dem Aufenthalt des Menschen innerhalb einer ganz bestimmten Kultur, für die Menschenwesenheit doch gar keine Bedeutung hat. Wir müssen uns bewußt sein, daß dasjenige, was wir in unserer physischen Kultur ausüben, für die überphysische Menschheit, für die überphysische Welt überhaupt keine unmittelbare Bedeutung hat. Es ist ganz unrichtig, wenn von manchen, namentlich spiritistischen Kreisen geglaubt wird, die Geister schrieben die Menschenschrift, um sie hineinzubringen in die physische Welt. Die Schrift der Menschen ist durch die Tätigkeit, durch die Konvention der Menschen auf dem physischen Plan entstanden. Die Geister haben gar kein Interesse daran, dieser physischen Konvention sich zu fügen. Es ist, auch wenn das Hereinsprechen der Geister richtig ist, eine besondere Übersetzung durch die mediale Tätigkeit des Menschen, es ist nicht etwas, was der Geist unmittelbar selbst ausführt, indem das, was in ihm lebt, in diese Schreibe- oder Leseform hereingeführt wird. Also was Sie dem Kinde beibringen als Lesen und Schreiben, beruht auf Konvention; das ist etwas, was entstanden ist innerhalb des physischen Lebens.

Etwas ganz anderes ist es, wenn Sie dem Kinde Rechnen beibringen. Sie werden fühlen, daß da die Hauptsache nicht liegt in den Zifferformen, sondern in dem, was in den Zifferformen von Wirklichkeit lebt. Und dieses Leben hat schon mehr Bedeutung für die geistige Welt, als was im Lesen und Schreiben lebt. Und wenn wir gar dazu übergehen, gewisse künstlerisch zu nennende Betätigungen dem Kinde beizubringen, dann gehen wir damit in die Sphäre hinein, die durchaus eine ewige Bedeutung hat, die hinaufragt in die Betätigung des GeistigSeelischen des Menschen. Wir unterrichten im Gebiete des Allerphysischesten, indem wir den Kindern Lesen und Schreiben beibringen; wir unterrichten schon weniger physisch, wenn wir Rechnen unterrichten, und wir unterrichten eigentlich den Seelengeist oder die Geistseele, indem wir Musikalisches, Zeichnerisches und dergleichen dem Kinde beibringen.

Nun können wir aber im rationell betriebenen Unterricht diese drei Impulse des Überphysischen im Künstlerischen, des Halbüberphysischen im Rechnen und des Ganzphysischen im Lesen und Schreiben miteinander verbinden, und gerade dadurch werden wir die Harmonisierung des Menschen hervorrufen. Denken Sie, wir gehen zum Beispiel — heute ist alles nur Einleitung, wo nur aphoristisch einzelnes vorgebracht werden soll - an das Kind so heran, daß wir sagen: Du hast schon einen Fisch gesehen. Mache dir einmal klar, wie das ausgesehen hat, was du als Fisch gesehen hast. Wenn ich dir dieses hier (siehe Zeichnung links) vormache, so sieht das einem Fisch sehr ähnlich. Was du als Fisch gesehen hast, sieht etwa so aus, wie das, was du da an der Tafel siehst. Nun denke dir, du sprichst das Wort Fisch aus. Was du sagst, wenn du Fisch sagst, das liegt in diesem Zeichen (siehe Zeichnung links). Jetzt bemühe dich einmal, nicht Fisch zu sagen, sondern nur anzufangen, Fisch zu sagen. - Man bemüht sich nun, dem Kinde beizubringen, daß es nur anfangen soll, Fisch zu sagen: F-f-f-f-. — Sieh einmal, jetzt hast du angefangen, Fisch zu sagen; und nun bedenke, daß die Menschen nach und nach dazugekommen sind, das, was du da siehst, einfacher zu machen (siehe Zeichnung rechts). Indem du anfängst, Fisch zu sagen, F-f-f-f-, drückst du das so aus, indem du es niederschreibst, daß du nun dieses Zeichen machst. Und dieses Zeichen nennen die Menschen f. Du hast also kennengelernt, daß das, was du in dem Fisch aussprichst, beginnt mit dem f - und jetzt schreibst du das auf als f. Du hauchst immer F-f-f- mit deinem Atem, indem du anfängst, Fisch zu schreiben. Du lernst also kennen das Zeichen für das Fischsprechen im Anfange.

Wenn Sie in dieser Weise beginnen, an die Natur des Kindes zu appellieren, so versetzen Sie das Kind richtig zurück in frühere Kulturepochen, denn so ist das Schreiben ursprünglich entstanden. Später ist der Vorgang nur in Konvention übergegangen, so daß wir heute nicht mehr den Zusammenhang erkennen zwischen den abstrakten Buchstabenformen und den Bildern, die rein zeichnerisch hervorgegangen sind aus der Anschauung und aus der Nachahmung der Anschauung. Alle Buchstabenformen sind aus solchen Bildformen entstanden. Und nun denken Sie sich, wenn Sie dem Kinde nur die Konvention beibringen: Du sollst das f so machen! — dann bringen Sie ihm etwas ganz Abgeleitetes bei, herausgehoben aus dem menschlichen Zusammenhang. Dann ist das Schreiben herausgehoben aus dem, woraus es entstanden ist: aus dem Künstlerischen. Und daher müssen wir, wenn wir Schreiben unterrichten, mit dem künstlerischen Zeichnen der Formen, der LautBuchstabenformen beginnen, wenn wir so weit zurückgehen wollen, daß das Kind ergriffen wird von dem Unterschiede der Formen. Es genügt nicht, daß wir das dem Kinde bloß mit dem Munde vorsagen, denn das macht die Menschen zu dem, wozu sie heute geworden sind. Indem wir die Schriftform herausheben aus dem, was heute Konvention ist und zeigen, woraus sie hervorgequollen ist, ergreifen wir den ganzen Menschen und machen aus ihm etwas ganz anderes, als wir aus ihm machen würden, wenn wir bloß an sein Erkennen appellieren. Daher dürfen wir nicht bloß in abstracto denken: Wir müssen Kunst lehren im Zeichnen und so weiter, wir müssen Seelisches lehren im Rechnen, und wir müssen auf künstlerische Art Konventionelles lehren im Lesen und Schreiben; wir müssen den ganzen Unterricht durchdringen mit einem künstlerischen Element. Daher werden wir von Anfang an einen großen Wert darauf zu legen haben, daß wir das Künstlerische im Kinde pflegen. Das Künstlerische wirkt ja ganz besonders auf die Willensnatur des Menschen. Dadurch dringen wir zu etwas vor, das mit dem ganzen Menschen zusammenhängt, während das, was mit dem Konventionellen zusammenhängt, nur mit dem Kopfmenschen zu tun hat. Daher werden wir so vorgehen, daß wir jedes Kind etwas Zeichnerisches und etwas Malerisches pflegen lassen. Wir beginnen also mit dem Zeichnerischen und Zeichnerisch-Malerischen in der einfachsten Weise. Aber auch mit Musikalischem beginnen wir, so daß das Kind sich von Anfang an gewöhnt, gleich irgendein Instrument zu handhaben, damit künstlerisches Gefühl in dem Kinde belebt werde. Dann wird es auch Gefühl dafür bekommen, etwas aus dem ganzen Menschen heraus zu fühlen, was sonst nur konventionell ist.

Es wird in der Methodik unsere Aufgabe sein, daß wir immer den ganzen Menschen in Anspruch nehmen. Wir würden das nicht können, wenn wir nicht auf die Ausbildung eines im Menschen veranlagten künstlerischen Gefühls unser Augenmerk richten würden. Damit werden wir auch für später den Menschen geneigt machen, seiner ganzen Wesenheit nach Interesse für die ganze Welt zu gewinnen. Der Grundfehler war bisher immer der, daß sich die Menschen nur mit ihrem Kopfe in die Welt hineingestellt haben; den andern Teil haben sie nur nachgeschleppt. Und die Folge ist, daß sich jetzt die andern Teile nach ihren animalischen Trieben richten, sich emotionell ausleben — wie wir es jetzt an dem erleben, was sich in so merkwürdiger Weise vom Osten Europas her ausbreitet. Das tritt dadurch ein, daß nicht der ganze Mensch gepflegt worden ist. Aber nicht nur, daß das Künstlerische auch gepflegt werden muß, sondern es muß das Ganze des Unterrichts herausgeholt sein aus dem Künstlerischen. Ins Künstlerische muß alle Methodik getaucht werden. Das Erziehen und Unterrichten muß zu einer wirklichen Kunst werden. Das Wissen darf auch da nur zugrunde liegen.

So werden wir herausholen aus dem zeichnerischen Element zuerst die Schreibformen der Buchstaben, dann die Druckformen. Wir werden das Lesen aufbauen auf dem Zeichnen. Sie werden auf diese Weise schon sehen, daß wir damit eine Saite anschlagen, mit der die kindliche Seele sehr gerne mitschwingen wird, weil das Kind dann nicht nur ein äußerliches Interesse hat, weil es zum Beispiel das, was es im Hauch hat, tatsächlich im Lesen und Schreiben zum Ausdruck kommen sieht.

Dann werden wir manches umkehren müssen im Unterricht. Sie werden sehen, daß wir das, was wir heute erreichen wollen im Lesen und Schreiben, natürlich nicht restlos in dieser Weise aufbauen können, wie wir das hier angedeutet haben, sondern wir werden nur die Kräfte erwecken können zu einem solchen Aufbau. Denn würden wir in dem heutigen Leben den ganzen Unterricht so aufbauen wollen, daß wir aus dem Zeichnen herausholen wollten das Lesen und Schreiben, dann würden wir damit die Zeit bis zum 20. Lebensjahr brauchen, wir würden nicht in den Schuljahren damit auskommen. Wir können das also zunächst nur im Prinzip ausführen und müssen dann trotzdem weitergehen, aber im künstlerischen Element verbleiben. Wenn wir also eine Zeitlang in dieser Weise einzelnes herausgehoben haben aus dem ganzen Menschen, dann müssen wir dazu übergehen, dem Kinde begreiflich zu machen, daß nun die großen Menschen, wenn sie diese eigentümlichen Formen vor sich haben, darin einen Sinn entdecken. Indem das weiter ausgebildet wird, was das Kind so an Einzelheiten gelernt hat, gehen wir dazu über - ganz gleichgültig, ob das Kind das einzelne versteht oder nicht versteht -, Sätze aufzuschreiben. In diesen Sätzen wird dann das Kind solche Formen bemerken, wie es sie hier als f am Fisch kennengelernt hat. Es wird dann andere Formen daneben bemerken, die wir jetzt aus Mangel an Zeit nicht herausholen können. Wir werden dann daran gehen, an die Tafel zu zeichnen, wie der einzelne Buchstabe im Druck aussieht, und wir werden eines Tages einen langen Satz an die Tafel schreiben und dem Kinde sagen: Dies haben nun die Großen vor sich, indem sie das alles ausgebildet haben, was wir besprochen haben als das f beim Fisch und so weiter. -— Dann werden wir das Kind nachschreiben lehren. Wir werden darauf halten, daß das, was es sieht, ihm in die Hände übergeht, so daß es nicht nur liest mit dem Auge, sondern mit den Händen nachformt, und daß es weiß: alles was es auf der Tafel hat, kann es selbst auch so und so formen. Also es wird nicht lesen lernen, ohne daß es mit der Hand nachformt, was es sieht, auch die Druckbuchstaben. So erreichen wir also das außerordentlich Wichtige, daß nie mit dem bloßen Auge gelesen wird, sondern daß auf geheimnisvolle Weise die Augentätigkeit übergeht in die ganze Gliedertätigkeit des Menschen. Die Kinder fühlen dann unbewußt bis in die Beine hinein dasjenige, was sie sonst nur mit dem Auge überschauen. Das Interesse des ganzen Menschen bei dieser Tätigkeit ist das, was von uns angestrebt werden muß.

Dann gehen wir den umgekehrten Weg: Den Satz, den wir hingeschrieben haben, zergliedern wir, und die andern Buchstabenformen, die wir noch nicht aus ihren Elementen herausgeholt haben, zeigen wir durch Atomisieren der Worte, gehen von dem Ganzen zu dem Einzelnen. Zum Beispiel: hier steht KOPF. Jetzt lernt das Kind zuerst «KOPF» schreiben, malt es einfach nach. Und nun spalten wir das KOPF in K,O, P, F, holen die einzelnen Buchstaben aus dem Worte heraus; wir gehen also von dem Ganzen ins Einzelne.

Dieses Von-dem-Ganzen-ins-Einzelne-Gehen setzen wir überhaupt durch den ganzen Unterricht fort. Wir machen es so, daß wir vielleicht zu einer andern Zeit ein Stück Papier in eine Anzahl von kleinen Papierschnitzeln zerspalten. Wir zählen dann diese Papierschnitzel; sagen wir, es sind 24. Wir sagen dann dem Kinde: Sieh einmal, diese Papierschnitzel bezeichne ich mit dem, was ich da aufgeschrieben habe und nenne es: 24 Papierschnitzel. — Es könnten natürlich auch Bohnen sein. — Jetzt wirst du dir das merken. Nun nehme ich eine Anzahl Papierschnitzel weg, die gebe ich auf ein Häufchen, dort mache ich ein anderes Häufchen, dort ein drittes und hier ein viertes; jetzt habe ich aus den 24 Papierschnitzeln vier Häufchen gemacht. Nun sieh: jetzt zähle ich, das kannst du noch nicht, ich kann es, und das, was da auf dem einen Häufchen liegt, nenne ich 9, was auf dem zweiten liegt, nenne ich 5 Papierschnitzel, was auf dem dritten liegt, nenne ich 7 Papierschnitzel, und was auf dem vierten Häufchen liegt, nenne ich 3 Papierschnitzel. Siehst du, früher hatte ich einen einzigen Haufen: 24 Papierschnitzel; jetzt habe ich vier Häufchen: 9, 5, 7, 3 Papierschnitzel. Das ist ganz dasselbe Papier. Das eine Mal, wenn ich es zusammen habe, nenne ich es 24; jetzt habe ich es in vier Häufchen abgeteilt und nenne es das eine Mal 9, dann 5, dann 7 und dann 3 Papierschnitzel. — Jetzt sage ich: 24 Papierschnitzel sind zusammen 9 und 5 und 7 und 3. - Jetzt habe ich dem Kinde das Addieren gelehrt. Das heißt, ich bin nicht ausgegangen von den einzelnen Addenden und habe dann die Summe herausgebildet; das ist niemals der ursprünglichen Menschennatur entsprechend - ich verweise dabei auf meine «Erkenntnistheorie der Goetheschen Weltanschauung» -, sondern das Umgekehrte entspricht der Menschennatur: die Summe ist zuerst ins Auge zu fassen, und die ist dann zu spalten in die einzelnen Addenden. So daß wir das Addieren dem Kinde umgekehrt beibringen müssen, als es gewöhnlich gemacht wird: von der Summe ausgehend, zu den Addenden übergehend. Dann wird das Kind den Begriff des «Zusammens» besser begreifen, als wenn wir in der bisherigen Weise das einzelne zusammenklauben. Dadurch werden wir unseren Unterricht von dem bisherigen unterscheiden müssen, daß wir gewissermaßen umgekehrt dem Kinde das beibringen müssen, was Summe ist im Gegensatz zu den Addenden. Dann können wir darauf rechnen, daß ein ganz anderes Verständnis uns entgegengebracht wird, als wenn wir umgekehrt vorgehen. Das Wichtigste daran werden Sie eigentlich erst durch die Praxis durchschauen. Denn Sie werden ein ganz anderes Eingehen in die Sache, eine ganz andere Aufnahmefähigkeit des Kindes bemerken, wenn Sie den gekennzeichneten Weg einschlagen.

Den umgekehrten Weg können Sie dann im weiteren Rechnen durchführen. Sie können sagen: Jetzt werfe ich diese Papierschnitzel alle wieder zusammen; nun nehme ich eine Anzahl davon wieder weg, mache zwei Häufchen, und ich nenne das Häufchen, das mir da abgesondert geblieben ist, 3. Wodurch habe ich diese 3 erhalten? Dadurch, daß ich sie von dem andern weggenommen habe. Wie es noch zusammen war, nannte ich es 24; jetzt habe ich 3 weggenommen und nenne nun das, was da zurückgeblieben ist, 21. - Auf diese Weise gehen Sie über zu dem Begriff des Subtrahierens. Das heißt, Sie gehen wieder nicht aus von Minuend und Subtrahend, sondern von dem Rest, der geblieben ist, und gehen von diesem über zu dem, woraus der Rest entstanden ist. Sie machen auch da den umgekehrten Weg. Und so können Sie es— wie wir in der speziellen Methodik noch sehen werden über die ganze Kunst des Rechnens ausdehnen, daß sie immer aus dem Ganzen ins Einzelne gehen. In dieser Beziehung werden wir uns schon angewöhnen müssen, einen ganz andern Lehrgang einzuhalten, als wir gewohnt sind. Wir gehen da so vor, daß wir mit der Anschauung - die wir durchaus nicht vernachlässigen dürfen, die aber heute einseitig herausgehoben wird — zugleich das Autoritätsgefühl pflegen. Denn wir sagen ja fortwährend: Das nenne ich 24, das nenne ich 9. — Indem ich in den anthroposophischen Vorträgen hervorhebe: zwischen dem 7. und dem 14. Jahre solle das Autoritätsgefühl gepflegt werden, soll man nicht denken an ein Abrichten zum Autoritätsgefühl, sondern was nötig ist, kann schon hineinfließen in die Methodik des Unterrichtes. Das waltet da wie ein Unterton. Das Kind hört: Aha, das nennt er 9, das nennt er 24 und so weiter. — Es gehorcht von selbst. Durch dieses Hinhören auf den, der diese Methode handhabt, infiltriert sich das Kind mit dem, was dann als das Autoritätsgefühl herauskommen soll. Das ist das Geheimnis. Jedes künstliche Abrichten zum Autoritätsgefühl soll durch das Methodische selbst ausgeschlossen werden.

Dann müssen wir uns ganz klar sein, daß wir immer zusammenwirken lassen wollen: Wollen, Fühlen und Denken. Indem wir so unterrichten, wirken Wollen, Fühlen und Denken schon zusammen. Es handelt sich nur darum, daß wir das Wollen nie durch falsche Mittel in die verkehrte Richtung bringen, sondern daß wir die Erstarkung des Wollens durch künstlerische Mittel richtig zum Ausdruck bringen. Dazu soll von Anfang an malerische, künstlerische Unterweisung dienen und auch musikalische. Wir werden dabei bemerken, daß gerade in der ersten Zeit der zweiten Lebensepoche das Kind für die autoritative Unterweisung durch das Künstlerische am allerempfänglichsten ist und daß wir da am meisten mit ihm erreichen können. Es wird wie von selbst hereinwachsen in das, was wir ihm übertragen wollen, und es wird seine denkbar größte Freude haben, wenn es zeichnerisch oder sogar malerisch dieses oder jenes auf das Papier bringen wird, wobei wir nur absehen müssen von allem bloß äußerlichen Nachahmen. Auch da werden wir uns im Unterrichten erinnern müssen, daß wir gewissermaßen das Kind zurückversetzen müssen in frühere Kulturepochen, aber daß wir nicht so verfahren können wie diese früheren Kulturepochen. Da waren die Menschen eben anders. Sie werden jetzt mit ganz anderem Seelen- und Geistesgestimmtsein das Kind in frühere Kulturepochen zurückversetzen. Daher werden wir im Zeichnen nicht darauf ausgehen, du sollst dieses oder jenes nachahmen, sondern wir werden ihm ursprüngliche Formen im Zeichnen beibringen, werden ihm beibringen, einen Winkel so zu machen, einen andern so; wir werden versuchen, ihm den Kreis, die Spirale beizubringen. Wir werden also von den in sich geschlossenen Formen ausgehen, nicht davon, ob die Form dieses oder jenes nachahmt, sondern wir werden sein Interesse an der Form selbst zu erwecken versuchen, — Erinnern Sie sich an den Vortrag, in welchem ich versucht habe, ein Gefühl zu erwecken für die Entstehung des Akanthusblattes. Ich habe darin ausgeführt, daß der Gedanke, man habe dabei das Blatt der Akanthuspflanze nachgeahmt in der Form, wie er in der Legende auftritt, ganz falsch ist, sondern das Akanthusblatt ist einfach entstanden aus einer inneren Formgebung heraus, und man hat nachträglich gefühlt: das sieht der Natur ähnlich. Man hat also nicht die Natur nachgeahmt. — Das werden wir beim zeichnerischen und malerischen Element zu berücksichtigen haben. Dann wird endlich das Furchtbare aufhören, was so sehr die Gemüter der Menschen verwüstet. Wenn ihnen etwas vom Menschen Gebildetes entgegentritt, dann sagen sie: Das ist natürlich, das ist unnatürlich. — Es kommt gar nicht darauf an, das Urteil zu fällen: Dies ist richtig nachgeahmt und so weiter. — Diese Ähnlichkeit mit der Außenwelt muß erst als ein Sekundäres aufleuchten. Was im Menschen leben muß, muß das innere Verwachsensein mit den Formen selbst sein. Also man muß, selbst wenn man eine Nase zeichnet, ein inneres Verwachsensein mit der Nasenform haben, und nachher erst stellt sich die Ähnlichkeit mit der Nase heraus. Das Gefühl für innere Gesetzmäßigkeit wird in der Zeit vom 7. bis zum 14. Jahre nie durch äußerliches Nachahmen erweckt. Denn dessen muß man sich bewußt sein: Was man zwischen dem 7. und dem 14. Jahre entwickeln kann, das kann man später nicht mehr entwickeln. Die Kräfte, die da walten, sterben dann ab; später kann man nur noch ein Surrogat davon haben, wenn nicht gerade eine solche Umgestaltung des Menschen zustande kommt, die man eine Einweihung nennt, natürlich oder unnatürlich.

Ich werde jetzt etwas Aufßergewöhnliches sagen, aber wir müssen auf die Prinzipien der Menschennatur zurückgehen, wenn wir heute im richtigen Sinne Unterrichter sein wollen. Es gibt Ausnahmefälle, wo im späteren Lebensalter der Mensch noch etwas nachholen kann. Dann muß er aber durch eine schwere Krankheit durchgegangen sein, oder er muß sonstwie Deformationen erlitten haben, muß etwa ein Bein gebrochen haben, das dann nicht mehr richtig eingerenkt ist, muß also eine gewisse Loslösung des ätherischen Leibes vom physischen Leibe erlitten haben. Das ist natürlich eine gefährliche Sache. Wenn sie durch das Karma eintritt, muß man sie hinnehmen. Aber man kann nicht damit rechnen und eine gewisse Vorschrift geben für das öffentliche Leben, daß einer etwas Versäumtes auf diese Weise nachholen könnte — von andern Dingen gar nicht zu sprechen. Es ist dieEntwickelung des Menschen eine geheimnisvolle Sache, und was durch Unterricht und Erziehung angestrebt werden soll, darf nie mit dem Abnormen rechnen, sondern muß immer mit dem Normalen rechnen. Daher ist das Unterrichten immer eine soziale Sache. Daher muß immer damit gerechnet werden: In welches Lebensalter muß die Ausbildung gewisser Kräfte hineinfallen, damit diese Ausbildung den Menschen in der richtigen Art ins Leben hineinstellen kann? Wir müssen also damit rechnen, daß gewisse Fähigkeiten nur zwischen dem 7. und dem 14. Lebensjahre des Menschen so entwickelt werden können, daß der Mensch später den Lebenskampf bestehen kann. Würde man diese Fähigkeiten in dieser Zeit nicht ausbilden, so würden die Menschen später dem Lebenskampf nicht gewachsen sein, sondern ihm unterliegen müssen, was heute bei den meisten Menschen der Fall ist.

Diese Art, künstlerisch sich ins Weltengetriebe zu stellen, die ist es, welche wir als Erzieher dem Kinde angedeihen lassen müssen. Da werden wir bemerken, daß die Natur des Menschen so ist, daß er gewissermaßen als Musiker geboren ist. Würden die Menschen die richtige Leichtigkeit dazu haben, so würden sie mit allen kleinen Kindern tanzen, würden sich mit allen kleinen Kindern irgendwie bewegen. Der Mensch wird in die Welt so hereingeboren, daß er seine eigene Leiblichkeit in musikalischen Rhythmus, in musikalischen Zusammenhang mit der Welt bringen will, und am meisten ist diese innere musikalische Fähigkeit zwischen dem 3. und dem 4. Lebensjahre bei den Kindern vorhanden. Ungeheuer viel könnten Eltern tun, wenn sie dieses bemerkten und dann weniger an das äußere musikalische Gestimmtsein anknüpften, sondern an das Bestimmtsein des eigenen Leibes, an das Tänzerische. Und gerade in diesem Lebensalter könnte man durch das Durchdringen des Kinderleibes mit elementarer Eurythmie unendlich viel erreichen. Wenn die Eltern lernen würden, sich eurythmisch mit dem Kinde zu beschäftigen, so würde etwas ganz anderes in den Kindern entstehen, als es sonst der Fall ist. Sie würden eine gewisseSchwere, die in den Gliedern lebt, überwinden. Alle Menschen haben heute eine solche Schwere in ihren Gliedern; die würde überwunden werden. Und was dann übrigbliebe, wenn es zum Zahnwechsel kommt, das ist die Veranlagung für das gesamte Musikalische. Die einzelnen Sinne, das musikalisch gestimmte Ohr, das plastisch gestimmte Auge entstehen erst aus diesem Musikalischen; das ist eine Spezifizierung des ganzen musikalischen Menschen, was man das musikalische Ohr oder das zeichnerisch-plastische Auge nennt. Daher wird man den Gedanken durchaus hegen müssen, daß man gewissermaßen das, was im ganzen Menschen veranlagt ist, in den oberen Menschen, in den Nerven-Sinnesmenschen hineinnimmt, indem man zum Künstlerischen geht. Sie tragen die Empfindung in das Intellektuelle hinauf, indem Sie entweder des Mittels des Musikalischen oder des Mittels des Zeichnerisch-Plastischen sich bedienen. Das muß in der richtigen Weise geschehen. Heute schwimmt alles durcheinander, insbesondere wenn das Künstlerische gepflegt wird. Wir zeichnen mit der Hand und wir plastizieren auch mit der Hand — und dennoch ist beides völlig verschieden. Das kann insbesondere dann zum Ausdruck kommen, wenn wir Kinder in das Künstlerische hineinbringen. Wir müssen, wenn wir Kinder ins Plastische hineinbringen, möglichst darauf sehen, daß sie die Formen des Plastischen mit der Hand verfolgen. Indem das Kind sein eigenes Formen fühlt, indem es dieHand bewegt und zeichnerisch irgend etwas macht, können wir es dahin bringen, daß es mit dem Auge, aber mit dem durch das Auge gehenden Willen die Formen verfolgt. Es ist durchaus nicht etwas die Naivität des Kindes Verletzendes, wenn wir das Kind anweisen, selbst mit der hohlen Hand die Körperformen nachzufühlen, wenn wir es aufmerksam machen auf das Auge, indem es die Wendungen des Kreises zum Beispiel verfolgt, und ihm sagen: Du machst ja selbst mit deinem Auge einen Kreis. Das ist nicht eine Verletzung der Naivität des Kindes, sondern es ist ein Inanspruchnehmen des Interesses des ganzen Menschen. Daher müssen wir uns bewußt sein, daß wir das Untere des Menschen hinauftragen in das Obere, in das Nerven-Sinneswesen.

So werden wir ein gewisses methodisches Grundgefühl gewinnen, das wir in uns ausbilden müssen als Erzieher und Unterrichter und das wir auf niemanden so unmittelbar übertragen können. Denken Sie, wir haben einen Menschen, den wir zu unterrichten und zu erziehen haben, also ein Kind vor uns. Heute verschwindet in der Erziehung ganz die Anschauung des werdenden Menschen, es geht alles durcheinander. Wir müssen uns aber angewöhnen, in der Anschauung dieses Kindes zu differenzieren. Wir müssen gewissermaßen das, was wir unterrichtend und erziehend tun, begleiten mit inneren Empfindungen, mit inneren Gefühlen, auch mit inneren Willensregungen, die gewissermaßen in einer unteren Oktave nur mitklingen, die nicht ausgeführt werden. Wir müssen uns bewußt werden: In dem werdenden Kinde entwickeln sich nach und nach das Ich und der astralische Leib; durch die Vererbung steht schon da der ätherische Leib und der physische Leib. Jetzt ist es gut, daß wir uns denken: Der physische Leib und der ätherische Leib sind etwas, was immer besonders gepflegt wird von dem Kopfe nach unten. Der Kopf strahlt aus, was den physischen Menschen eigentlich schafft. Machen wir die richtigen Erziehungsund Unterrichtsprozeduren mit dem Kopfe, dann dienen wir der Wachstumsorganisation am besten. Unterrichten wir das Kind so, daß wir aus dem ganzen Menschen das Kopfelement herausholen, dann geht das Richtige vom Kopfe in seine Glieder über: Der Mensch wächst besser, er lernt besser gehen und so weiter. Und so können wir sagen: Es strömt nach unten in das Physische und das Ätherische, wenn wir in sachgemäßer Weise alles, was sich auf den oberen Menschen bezieht, ausbilden. Haben wir das Gefühl, indem wir in mehr intellektueller Weise Lesen und Schreiben ausbilden, daß das Kind uns entgegenkommt, indem es das aufnimmt, was wir ihm beibringen, so werden wir das vom Kopfe aus in den übrigen Leib hineinschicken. Ich und astralischer Leib wird aber von unten herauf ausgebildet, wenn der ganze Mensch in die Erziehung hineingestellt wird. Ein kräftiges Ichgefühl würde zum Beispiel dann entstehen, wenn man zwischen dem 3. und 4. Lebensjahre elementare Eurythmie an das Kind heranbringen würde. Dann würde der Mensch davon in Anspruch genommen, und es würde ein rechtes Ichgefühl hineinstoßen in sein Wesen. Und wenn er viel erzählt bekommt, woran er sich freut oder auch woran er Schmerzen hat, dann bildet das von dem unteren Menschen aus den astralischen Leib aus. Bitte, reflektieren Sie da einmal auf Ihre eigenen Erlebnisse etwas intimer. Ich glaube, Sie werden alle eine Erfahrung gemacht haben: Wenn Sie auf der Straße gegangen sind und durch irgend etwas erschrocken sind, dann sind Sie nicht nur mit dem Kopfe und mit dem Herzen erschrocken, sondern dann sind Sie auch mit den Gliedern erschrocken und haben in ihnen den Schreck nachgefühlt. Daraus werden Sie den Schluß ziehen können, daß die Hingabe an etwas, was Gefühle und Affekte auslöst, den ganzen Menschen ergreift, nicht bloß Herz und Kopf.

Das ist eine Wahrheit, die der Erziehende und Unterrichtende ganz besonders ins Auge fassen muß. Er muß darauf sehen, daß der ganze Mensch ergriffen werden muß. Daher denken Sie von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus ans Legenden- und Märchenerzählen, und haben Sie ein richtiges Gefühl dafür, so daß Sie aus Ihrer eigenen Stimmung heraus dem Kinde Märchen erzählen, dann werden Sie so erzählen, daß das Kind etwas nachfühlt an dem Erzählten im ganzen Leibe. Sie wenden sich dann wirklich dabei an den astralischen Leib des Kindes. Von dem astralischen Leib strahlt etwas herauf in den Kopf, was das Kind dort erfühlen soll. Man muß das Gefühl haben, das ganze Kind zu ergreifen und daß erst aus den Gefühlen, aus den Affekten, die man erregt, das Verständnis für das Erzählte kommen müsse. Betrachten Sie es daher als ein Ideal, daß Sie, wenn Sie dem Kinde Märchen oder Legenden erzählen, oder wenn Sie mit ihm Malerisches, Zeichnerisches treiben, daß Sie dann nicht erklären, daß Sie nicht begriffsmäßig wirken, sondern den ganzen Menschen ergreifen lassen, und daß dann das Kind von Ihnen weggeht und erst nachher von sich selbst aus zum Verstehen der Dinge kommt. Versuchen Sie also, das Ich und den astralischen Leib von unten herauf zu erziehen, so daß dann Kopf und Herz erst nachkommen. Versuchen Sie nie so zu erzählen, daß Sie auf Kopf und Verstand reflektieren, sondern so zu erzählen, daß Sie in dem Kinde gewisse stille Schauer - in gewissen Grenzen — hervorrufen, daß Sie den ganzen Menschen ergreifende Lüste oder Unlüste hervorrufen, daß dies noch nachklingt, wenn das Kind weggegangen ist und daß es dann zu dem Verständnisse davon und zu dem Interesse daran erst übergeht. Versuchen Sie zu wirken durch Ihr ganzes Verbundensein mit den Kindern. Versuchen Sie nicht künstlich das Interesse zu erregen, indem Sie auf die Sensationen rechnen, sondern versuchen Sie dadurch, daß Sie eine innere Verbindung zu den Kindern herstellen, das Interesse aus der eigenen Wesenheit des Kindes entstehen zu lassen.

Wie kann man das mit einer ganzen Klasse machen? Mit einem einzelnen Kinde geht es verhältnismäßig leicht. Man braucht es nur gern zu haben, braucht nur das, was man mit ihm ausübt, in Liebe mit ihm zu vollbringen, dann ergreift es den ganzen Menschen, nicht bloß Herz und Kopf. Bei einer ganzen Klasse ist es nicht schwieriger, wenn man selbst von den Dingen ergriffen ist, wenn man nicht selbst bloß im Herzen und Kopfe ergriffen ist. Nehmen Sie das einfache Beispiel: Das Weiterleben der Seele nach dem Tode will ich dem Kinde klarmachen. Ich mache es dem Kinde nie klar, sondern täusche mir nur darüber etwas vor, indem ich ihm darüber Theorien beibringe. Keine Art von Begriff kann dem Kinde vor dem 14. Lebensjahre etwas beibringen über die Unsterblichkeit. Aber ich kann ihm sagen: Sieh dir einmal diese Schmetterlingspuppe an. Da ist nichts drinnen. Da war der Schmetterling drinnen, aber der ist herausgekrochen. — Ich kann ihm auch den Vorgang zeigen, und es ist gut, solche Metamorphosen dem Kinde vorzuführen. Ich kann nun den Vergleich ziehen: Denke dir, du bist jetzt selbst eine solche Puppe. Deine Seele ist in dir, die dringt später heraus, wird dann so herausdringen wie der Schmetterling aus der Puppe. — Das ist allerdings naiv gesprochen. Nun können Sie lange darüber reden. Wenn Sie aber nicht selbst daran glauben, daß der Schmetterling die Seele des Menschen darstellt, so werden Sie beim Kinde nicht viel mit einem solchen Vergleich erreichen. Sie werden auch nicht jene reine Unwahrheit hineinbringen dürfen, daß Sie die Sache nur als einen menschlich gemachten Vergleich ansehen. Es ist kein solcher Vergleich, sondern es ist eine von der göttlichen Weltenordnung hingestellte Tatsache. Die beiden Dinge sind nicht durch unseren Intellekt gemacht. Und wenn wir uns den Dingen gegenüber richtig verhalten, so lernen wir glauben an die Tatsache, daß die Natur überall Vergleiche für das Geistig-Seelische hat. Wenn wir eins werden mit dem, was wir dem Kinde beibringen, dann ergreift unser Wirken das ganze Kind. Das Nicht-mehr-mit-dem-Kinde-fühlen-Können, sondern glauben an das Nur-Umsetzen in irgendeine Ratio, an die wir selber nicht glauben, das macht es, daß wir dem Kinde so wenig beibringen. Wir müssen mit unserer eigenen Auffassung so zu den Tatsachen stehen, daß wir zum Beispiel mit dem Auskriechen des Schmetterlings aus der Puppe nicht ein willkürliches Bild, sondern ein von uns begriffenes und geglaubtes, von den göttlichen Weltenmächten gesetztes Beispiel in die Kinderseele hineinbringen. Das Kind muß nicht von Ohr zu Ohr, sondern von Seele zu Seele verstehen. Wenn Sie das beachten, werden Sie damit weiterkommen.

First Lecture

My dear friends, we will have to divide the lectures that we want to include in this course into those that are generally educational and those that are more specifically methodological and didactic. I would also like to give a kind of introduction to these lectures, because even in the actual method we have to use, we will have to differ, in all modesty, from the methods that have developed today from completely different premises than those we have to use. Truly, the methods we use will differ from those that have been used up to now, not because we stubbornly want something new or different, but because we must recognize from the tasks of our particular age how teaching will have to proceed for humanity if it is to correspond in the future to the developmental impulses prescribed for it by the general world order.

Above all, in applying the method, we will have to be aware that we will be dealing with a harmonization, so to speak, of the higher human being, the spirit-soul human being, with the physical human being, with the lower human being. You will not have to use the subjects in the same way as they have been used up to now. You will have to use them, as it were, as a means of developing the soul and body forces of the human being in the right way. Therefore, it will not be a matter of passing on knowledge as such, but of using this knowledge to develop human abilities. Above all, you will have to distinguish between knowledge that is actually based on convention, on human agreement — even if this is not expressed very precisely and clearly — and knowledge that is based on an understanding of general human nature.

Consider only superficially, when you teach children to read and write today, how reading and writing actually fit into general culture. We read, but the art of reading has developed in the course of cultural evolution. The shapes of letters that have emerged, the connection between letter shapes, all of this is based on convention. By teaching children to read in today's form, we are teaching them something that, as soon as we disregard the fact that human beings live within a very specific culture, has no meaning whatsoever for the human being. We must be aware that what we practice in our physical culture has no immediate significance whatsoever for superphysical humanity, for the superphysical world. It is quite incorrect when some people, especially in spiritualist circles, believe that spirits write human script in order to bring it into the physical world. Human writing has come about through human activity and convention on the physical plane. Spirits have no interest whatsoever in conforming to this physical convention. Even if the spirits' communication is correct, it is a special translation through the mediumistic activity of humans; it is not something that the spirit does directly itself by introducing what lives within it into this form of writing or reading. So what you teach the child as reading and writing is based on convention; it is something that has arisen within physical life.

It is quite different when you teach a child arithmetic. You will feel that the main thing here is not the numerical forms, but what lives in the numerical forms of reality. And this life has more meaning for the spiritual world than what lives in reading and writing. And when we go so far as to teach the child certain activities that can be called artistic, we enter a sphere that has an eternal significance, one that reaches up into the spiritual-soul activity of the human being. We teach in the realm of the most physical when we teach children to read and write; we teach less physically when we teach arithmetic, and we actually teach the soul spirit or the spirit soul when we teach children music, drawing, and the like.

Now, however, in rationally conducted teaching, we can combine these three impulses of the superphysical in art, the semi-superphysical in arithmetic, and the wholly physical in reading and writing, and it is precisely through this that we will bring about the harmonization of the human being. Consider, for example — today is just an introduction, where only individual aphorisms are to be presented — that we approach the child by saying: You have already seen a fish. Think about what you saw as a fish. When I show you this (see drawing on the left), it looks very much like a fish. What you saw as a fish looks something like what you see on the board. Now imagine you are saying the word fish. What you say when you say fish is contained in this sign (see drawing on the left). Now try not to say fish, but just to start saying fish. We now try to teach the child that it should only start to say fish: F-f-f-f-. — Look, now you have started to say fish; and now consider that people have gradually come to make what you see there simpler (see drawing on the right). By starting to say fish, F-f-f-f-, you express this by writing it down, by making this sign. And people call this sign f. So you have learned that what you pronounce in the fish begins with f - and now you write it down as f. You always breathe F-f-f- with your breath when you start to write fish. So you learn the sign for saying fish in the beginning.

When you begin to appeal to the nature of the child in this way, you are actually transporting the child back to earlier cultural epochs, because this is how writing originally came into being. Later, the process became merely a convention, so that today we no longer recognize the connection between the abstract letter forms and the images that emerged purely from drawing, from observation and from imitation of observation. All letter forms originated from such image forms. And now think about it: if you only teach the child the convention: You should do it this way! — then you are teaching them something completely derivative, removed from the human context. Then writing is removed from what it originated from: from the artistic. And therefore, when we teach writing, we must begin with the artistic drawing of forms, the sound-letter forms, if we want to go back far enough that the child is moved by the differences in the forms. It is not enough to simply tell the child this with our mouths, because that is what has made people what they have become today. By lifting the written form out of what is now convention and showing where it sprang from, we capture the whole person and make them into something completely different from what we would make them into if we merely appealed to their intellect. Therefore, we must not think merely in abstracto: we must teach art in drawing and so on, we must teach the soul in arithmetic, and we must teach convention in reading and writing in an artistic way; we must permeate the whole of teaching with an artistic element. Therefore, from the very beginning, we will have to attach great importance to cultivating the artistic in the child. Artistic expression has a particularly strong effect on the human will. In this way, we penetrate something that is connected with the whole human being, whereas what is connected with convention has to do only with the intellectual human being. Therefore, we will proceed in such a way that we let every child cultivate something of the artistic and something of the painterly. We will begin with drawing and drawing and painting in the simplest way. But we will also begin with music, so that the child becomes accustomed from the very beginning to handling an instrument, thereby enlivening the child's artistic sensibility. Then the child will also develop a feeling for something that comes from the whole human being, something that is otherwise only conventional.

In our methodology, it will be our task to always engage the whole person. We would not be able to do this if we did not focus our attention on developing the artistic feeling inherent in human beings. In this way, we will also make people inclined to develop an interest in the whole world according to their whole being. The fundamental mistake up to now has always been that people have only engaged with the world with their heads; they have merely dragged the other parts along behind. And the result is that the other parts now follow their animal instincts and live out their emotions — as we are now experiencing in what is spreading in such a remarkable way from Eastern Europe. This occurs because the whole human being has not been cultivated. But not only must the artistic be cultivated, the whole of education must be drawn out of the artistic. All methodology must be immersed in the artistic. Education and teaching must become a real art. Knowledge must also be the basis here.

So we will first extract the written forms of letters from the element of drawing, then the printed forms. We will build reading on drawing. In this way, you will see that we are striking a chord with which the child's soul will gladly resonate, because the child then has more than just an external interest, because, for example, it sees what it has in its breath actually expressed in reading and writing.

Then we will have to reverse some things in our teaching. You will see that we cannot, of course, build up what we want to achieve today in reading and writing entirely in the way we have indicated here, but we will only be able to awaken the forces for such a development. For if we wanted to structure all teaching in today's life in such a way that we wanted to extract reading and writing from drawing, we would need until the age of 20 to do so; we would not be able to manage it in the school years. So we can only carry this out in principle at first and then have to move on, but remain within the artistic element. So when we have singled out individual aspects of the whole human being in this way for a while, we must then move on to making the child understand that when grown-ups see these peculiar forms, they discover a meaning in them. As the child continues to develop what it has learned in detail, we move on to writing down sentences, regardless of whether the child understands the individual letters or not. In these sentences, the child will then notice forms such as the one it has learned here as f on the fish. It will then notice other forms alongside it, which we cannot bring out now due to lack of time. We will then proceed to draw on the blackboard what the individual letter looks like in print, and one day we will write a long sentence on the blackboard and say to the child: This is what the grown-ups have in front of them, having developed everything we have discussed, such as the f in fish and so on. — Then we will teach the child to copy it. We will insist that what they see is transferred to their hands, so that they not only read with their eyes, but also form the letters with their hands, and that they know: everything they have on the blackboard, they can also form themselves in this way and that way. So they will not learn to read without forming what they see with their hands, including the printed letters. In this way, we achieve the extremely important goal of never reading with the naked eye, but rather, in a mysterious way, transferring the activity of the eyes to the entire limb activity of the human being. The children then unconsciously feel in their legs what they would otherwise only see with their eyes. The interest of the whole human being in this activity is what we must strive for.

Then we take the opposite approach: we break down the sentence we have written down, and we show the other letter forms that we have not yet extracted from their elements by atomizing the words, moving from the whole to the individual. For example: here we have KOPF (head). Now the child first learns to write “KOPF,” simply copying it. And now we split KOPF into K, O, P, F, extracting the individual letters from the word; in other words, we move from the whole to the individual.