Practical Course for Teachers

GA 294

26 August 1919, Stuttgart

V. Writing and Reading—Spelling

In the last lecture we spoke of how the first school-lesson should be conducted. Naturally I cannot go on to describe every step separately, but I should like to indicate the essential course of the teaching, so that you are able to make something of it in practice.

You have seen that we have considered as most important: first, the child's consciousness of why he has actually come to school; then the transition by which he becomes conscious that he has hands; and then, after making him conscious of this, that a kind of drawing should be embarked on, and even a kind of transition to painting, from which the sense of the beautiful and the less beautiful can be developed. We have seen that this emerging sense can be observed in hearing, too, and that the first elements of the musical experience of beauty and the less beautiful will be linked up with it.

Let us now suppose that you have pursued such exercises with pencil and with colour for some time. It is absolutely a condition of well-founded teaching that a certain intimacy with drawing should precede the learning to write, so that, in a sense, writing is derived from drawing. And a further condition is that the reading of printed characters should only be developed from the reading of handwriting. We shall then try to find the transition from drawing to handwriting, from writing to the reading of handwriting, and from the reading of handwriting to the reading of print. I assume for this purpose that you have succeeded, through the element of drawing, in giving the child a certain mastery of the round and straight-lined forms which he will need for writing. Then from this point we would again seek the transition to what we have already mentioned as the foundation of teaching in reading and writing. To-day I will first try to show you by a few examples how this can be done.

We assume, then, that the child has already come to the point at which he can master straight-lined and round forms with his little hand. We began with the fish and the F. You do not need to proceed alphabetically; I am only doing it now so that you have it in encyclopaedic form. Let us see what success we have in beginning to evolve writing and reading on the lines of your own free imagination. I should first say to the child at this point: “You know what a bath is”—and here I will say in parenthesis that much depends in teaching on being able to make use of any situation in a rational way, that is, on always having between the lines of the lesson anything that may help your purpose. It is well to use the word “bath” for what I now intend to do, so that the child remembers, in connection with being at school, baths, washing, and cleanliness. It is well to have something like this in the background, without having to moralize or give orders. It is well to select your examples so that the child is compelled to think of something which contributes at the same time to a moral-aesthetic attitude. Then go on to say: “Look; when the grown-ups want to write down what a bath is, they write it like this: BATH. So this is the picture of what you mean when you say Bath and when you give a name to it.” Then, again, I simply let a number of children write this after me, so that whenever they come to something of this kind they get it into their little hand; they do not merely look at it, but they grasp it with their whole being. Now I shall say: “Watch yourself beginning to say ‘bath.’ We will just get the beginning clear: ‘B.’” The child must be guided from saying the whole word “bath” to breathing the first sound, as I illustrated with “fish.” And now it must be made clear to the child that just as Bath is the sign for the whole bath, “B” is the sign for the beginning of the word “bath.”

Then I draw the child's attention to the presence in other words of a similar beginning. I say: “When you say ‘band’ you begin just the same way; when you say ‘bow,’ which many women wear on their heads, a bow of ribbon, you begin just the same way; and perhaps, too, you have seen a bear at the zoo; for that, too, you begin to breathe the same way; each of these words begins with the same breathing out.” In this way I try to pass with the child from the whole of the word to the initial letter, to lead him to nothing but the single sound, to the letter, always to develop the initial letter from the word.

Now the problem for you is to try, let us say, first to evolve the initial letter yourself in the same visualizing way from drawing. You will be able to do this easily if you simply call your imagination to your aid and say to yourselves:

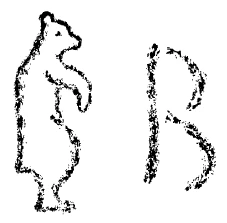

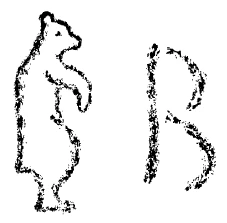

“The people who first saw animals which begin with B, like beaver, bear, etc., portrayed the back of the animal, the feet on which it sits and the lifted fore-feet; they drew an animal in the act of rising, standing on its hind legs, and the drawing became the B. You will find in every word—” and here you can give full rein to your imagination; there is no need to go into histories of civilizations, which are incomplete in any case—you will find that the initial letter is pictorial, representing the form of an animal or plant or even an external object. This is historically the fact: if you go back to the most ancient forms of the Egyptian writing, which was still hieroglyphic, you find that everywhere the letters are imitations of such things. And not until the transition from the Egyptian civilization to the Phoenician was the process completed which we can call a development from the “picture” to the “sign” to represent a sound. Let the child follow the same line. It leads to the following:

In the earliest periods of the evolution of writing in Egypt, literally every detail which had to be written down was written down in picture-writing, was drawn—indeed, was so drawn that it became necessary to learn the easiest possible way of making the drawings. Anyone who made a mistake, when he was appointed to copy these hieroglyphics, if, for instance, the error occurred in a sacred word, was condemned to death. In ancient Egypt, then, matters of writing were taken very, very seriously. But all writing which existed was picture-writing of the kind I have described. Then civilization passed over to the Phoenicians, who lived more in the world outside them. Here the initial image was always retained and transferred to the sound. As an example I will show you from a word where the process is most easily paralleled in our language (though we cannot here study Egyptian) and is also true of the Egyptian language. The Egyptians saw that the sound M could be best shown by watching chiefly the upper lip. So they took the sign for M from the picture of the upper lip. From this sign there then evolved the letter which we have for the beginning of the word Mouth and which then remained for every similar beginning, for everything beginning with M. The picture of the word was taken over. Thus transferring the picture of the word to the initial letter one came to the sign for the sound.

This principle, which is contained in the history of the evolution of writing, can also be very well applied to teaching, and now is the moment to apply it. That is: we shall try to arrive at the letter from the drawing: just as we get from the “fish” with his two fins to F, we get from the bear, dancing, standing up, to B. We get from the upper lip to the mouth, to the M, and we try with our imagination to trace for the child a path like this from drawing to writing. I said that you have no need to study the history of writing in civilized life and refer to it for what you need. For what you look up in this research is of far less value to you in teaching than are the discoveries of your own soul's making, of your own imagination. The activity which you apply to the study of the history of writing deadens you so that your influence on your pupil is far less living than when you think out for yourself something like the Ð’ from the picture of the bear. This thinking out for yourself refreshes you so that what you want to convey to your pupil is much more living than when you embark on excursions into the history of civilizations to discover something for your lesson. And from these two points of view both life and teaching must be considered. For you must ask yourself: “What is more important, to have learnt an historical, most elaborately ascertained fact and incorporated it painfully into your teaching—or to feel yourself so astir in your soul that you transmit to the child with your own enthusiasm the discovery you make?” You will always feel joy, even if it is a quite calm joy, in transferring to letters the form of some animal or some plant which you have found yourself. And this joy which you yourself feel will live in what you make of your pupil.

Then you go on to draw the child's attention to the fact that the letter which he has seen at the beginning of a word occurs in the middle of words too. You go on to say to him: “Let us see; you know what grows outside in the fields or on the hills, what is gathered in autumn and what wine is made from: the vine? (Rebe). The grown-ups write Rebe like this: REBE. Now just think, when you say Rebe quite slowly there is the same sound in the middle as there was at the beginning of Bear.” Then always write it up first in big letters so that the child sees the resemblance with the picture. Like this we teach him that what he has learnt for the beginning of a word is found, too, in the middle of words. We go on to split the whole into its atoms.

You see the important thing for us who wish to achieve living teaching as opposed to dead: all depends on starting from the whole. As in arithmetic we start with the sum, not with the addenda, and analyse the sum, here, too, we go from the whole to the part. This has the great advantage for education and teaching that we succeed in leading the child into the world in a fully living way; for the world is a whole, and the child lives in enduring intimacy with the living whole when we proceed as I have suggested. When you let the child learn the separate letters from their pictures he enters into a relation with living reality. But you must never omit to write up the letter forms so that they are seen to emerge from an image, and you must always be careful to explain the accompanying sounds, the consonants, as

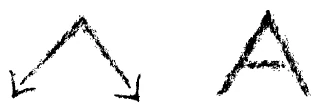

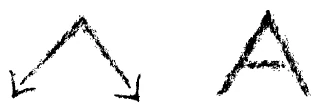

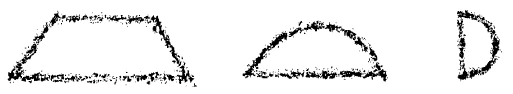

drawings of external things—but never the vowels. The vowels must always be made to render the human inner being and its relation to the outside world. When, for instance, you try to teach the child a, you will say to him: “Now just think of the sun which you see in the morning. Can any of you remember what you did when the sun rose in the morning?” Then perhaps one child or another will remember what he did. If he does not, if nobody remembers, you must refresh the child's memory a little to bring back to him what he did: how he must have stood, what he must have said if the sunrise was very beautiful: “Ah!” You must let this echo of emotion resound; you must try to derive the resonance, which we hear in the vowel, from emotion. And then you must try to say: “When you stood like that and said ‘Ah!’ it was as if a sunbeam had streamed out of your mouth in the shape of an opening angle. When you see the sunrise you let the life inside you stream out like this (Fig. 1) and you reveal it when you say ‘Ah!’ But you do not let it all stream out; you hold some of it back and that becomes this sign (Fig. 2).” You can try some time to clothe in picture-form the essence of the breath in a vowel. In this way you get drawings which can represent to you in images the process by which the vowel-signs arose. Vowels, you remember, are also rare in the primitive civilizations known to-day. The languages of primitive races are very rich in consonants; much more is expressed in the accompanying sounds, in the consonants, than we know. They sometimes literally click their tongues, they have all kinds of refined resources for pronouncing complicated consonants, and the vowel only vibrates in an undertone between them. Among the African races you find sounds which are like the cracking of a whip, etc.; on the other hand, the vowels are only faintly heard, and the European travellers who meet with such races usually sound the vowels much more than the natives do.

We can always derive the vowels from drawing. If, for instance, you succeed in making the child imagine—by appealing to his feeling—that he is in a situation like this: “Your brother or your sister is coming to you. They tell you something, but you don't understand them. Then there comes a moment when it begins to dawn on you. What sound do you make, then, to show that it is dawning?” Then, again, a child will discover, or the other children will be drawn on until one of them says: “i, i, i” (English ee, ee, ee). The pictorial form of the sound ee then expresses the pointing to something that has been understood. In Eurhythmy it is more clearly expressed. The simple stroke, then, which ought to be thicker at the bottom and thinner at the top, is turned into “i;” the stroke alone is made, and the vanishing at the top is expressed by the smaller sign above it. In this way all the vowels can be extracted from the shape assumed by the breath, from the shape of the breath.

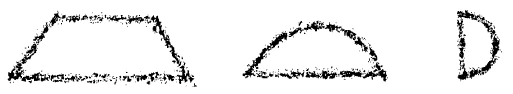

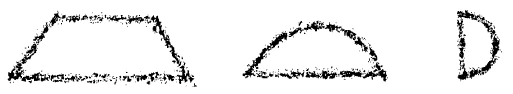

In this way you teach the child first of all a kind of picture-writing. Then you need not be at all shy of calling to your aid ideas which evoke real experiences of past history. You can teach the child this: you can say to him: “Just look at the top of the house; what do you say for that? ‘Dach!’ (roof). But then you ought to make a  like this; that is awkward. So people changed it round: D.” Such ideas lie concealed in writing and you can utilize them by all means. But then people did not want to write so complicatedly; instead, they wanted to make writing simpler. So from the sign D, which should really be

like this; that is awkward. So people changed it round: D.” Such ideas lie concealed in writing and you can utilize them by all means. But then people did not want to write so complicatedly; instead, they wanted to make writing simpler. So from the sign D, which should really be  (and here you pass on to small letters) there grew this sign, the little d. You can derive the existing letter-forms like this without exception from figures which you have taught to the child pictorially.

(and here you pass on to small letters) there grew this sign, the little d. You can derive the existing letter-forms like this without exception from figures which you have taught to the child pictorially.

In this way, always explaining the transition from one form to another, you bring the child on, never by mere abstract teaching, but so that he discovers the real transition from the form first derived from drawing to the form which the modern written letter actually takes.

These facts, of course, have already been observed by individual people; very few in number, it is true. There are educationists who have already drawn attention to the fact that writing should spring from drawing. But they proceed on different lines from those laid down here. They more or less anticipate letters in their final forms; they take a letter in its present form and do not come to the B from the drawing of the sitting or dancing bear, but they take the B as it is now, divide it up into its separate strokes and lines:  , and try to lead the child in this way from drawing to writing. They do abstractly what we are attempting to do concretely. That is, several educationists have already rightly observed the practicability of deriving writing from drawing, but people are too firmly rooted in the dead husks of civilized life to be able to conceive of the living process clearly.

, and try to lead the child in this way from drawing to writing. They do abstractly what we are attempting to do concretely. That is, several educationists have already rightly observed the practicability of deriving writing from drawing, but people are too firmly rooted in the dead husks of civilized life to be able to conceive of the living process clearly.

Here, too, I should not like to forget to warn you of being led astray by many modern attempts. Don't say: here, this has already been attempted: and there, something else. For you will see that the attempt has not been very profoundly and firmly willed. Humanity continually feels the urge to realize such aims, but it will not be able to carry them out until it has taken spiritual science into its culture.

Thus we can always link up with man and his relation to the world around him by writing organically and teaching reading from the reading of what is written.

Now it is natural to teaching—and we should not leave this out of account—that there should be a certain yearning to be completely free. And notice how freedom inspires this discussion of the preparation of lessons. Our discussion has an inner relation to freedom. For I draw your attention to the fact that you are not to enslave yourself by cramming yourself with the knowledge of how writing evolved from Egyptians to Phoenicians, but you are to look to developing yourself the capacities of your own soul. Positively the same results can be achieved by one teacher in this way, by another teacher in that. Not everyone can make use of a dancing bear; perhaps someone else will make use of something much better for the same point. The ultimate aim can be secured just as well by one teacher as by another. But every teacher puts himself into his teaching, and thus it is that his freedom is perfectly preserved. The more the staff wish to preserve their freedom in this respect, the more they will be able to put into their teaching, to devote themselves to it. This fact has been almost completely lost sight of in recent times. You can see this in a certain phenomenon.

A few years ago there was some agitation—the younger among you have perhaps not had the experience, but it caused the older ones, who had an understanding of such things, a good deal of annoyance—in favour of imposing in spiritual things something similar to the famous “Imperial German State-Gravy” in the material sphere. As you know, it was frequently insisted that a uniform sauce or gravy should be made for all the inns which did not depend entirely on foreign visitors, but rather on Germans. It was called “Imperial German State-Gravy;” people wanted to organize things uniformly. In the same way the attempt was made to make spelling, orthography, uniform. Now people have a quite extraordinary attitude to this question. You can study it in concrete examples. German spiritual life contains a very beautiful, tender relationship between Novalis and a woman. This relationship is so beautiful because Novalis, after her death, still continued to live with her consciously. He speaks of this, following her, in his meditation, into the spiritual world. It is one of the most beautiful, most intimate things which you can read in the history of German literature—this relationship of Novalis to a woman. Now there is a very intelligent, even very interesting (from the point of view I have mentioned), severely philological treatise by a German scholar on the relation between Novalis and his beloved. The delicate, lovely relationship is “put in its proper light,” for it can be proved that the beloved died before she could spell properly. She made spelling mistakes in her letters! In short, the portrait of this personality in its relation to Novalis is shown up in a thoroughly trivial light—in accordance with quite strict scholarship. The method of this scholarship is so good that everyone who writes an essay in which he follows this method deserves to get full marks for it. I only want to remind you that people have already forgotten that Goethe could never spell properly, that in reality he made mistakes all his life, especially in his youth. In spite of this, however, he could rise to Goethean greatness! Not to mention the people who knew him, whom he valued very much—whose letters, in the facsimiles now made, would leave a schoolmaster's hand literally scored with red ink! They would get a thoroughly bad mark!

This absurdity is connected with an utter lack of freedom in our common life, which should play no part in teaching and in education. But a few decades ago it was so pronounced that the enlightened minds among the teachers were seriously annoyed by it. A uniform German orthography was to be set up—the famous “Puttkammer” orthography. That is, in the very school itself the State did not merely exercise a right of supervision, it did not merely control administration, but it laid down even the spelling by law. It looks like it, too! For through this Puttkammer orthography we have really lost much that might still awaken us to-day to some of the intimacies of the German language. Because nowadays they are given an abstract kind of writing, people lose much of the quality which used to live in the German language; the so-called standard language (Schriftsprache) suffers loss.

Now the thing that matters in such a case is, above all, to have the right attitude. Obviously we cannot let any sort of orthography run riot, but we can at least know the extreme ways of dealing with this question. If, after learning to write, people could write what they hear from others, or from themselves, just as they hear it, they would write very variously; they would have very varied fashions of orthography; they would be very individualistic. It would be extraordinarily interesting, but it would obstruct intercourse. On the other hand, our task is to develop not only our individuality in human intercourse, but also our social impulses and social feelings. Many things which we would develop as individuals must be sacrificed where we have to meet others. But we should feel that this is the position, and the feeling should be educated with us, that we do such and such a thing only for social reasons. When you come with your writing-lessons to orthography you will have to start with a certain definite feeling-complex. You will have to draw the child's attention again and again—I have already mentioned this fact from another point of view—to the necessity for reverence, respect for grown-up people, to the fact that he is growing up to an already finished life, which is to receive him, that therefore he must respect what is already there. From this point of view, too, we must try to introduce the child to a thing like orthography. Along with the spelling we must cultivate in him the feeling of respect, of reverence, for what our forefathers have settled. And we must not try to teach spelling from some abstraction, for instance as if orthography had been created by a “divine”—for some, а “Puttkammer” law, as though it came from the Absolute—but you must develop in the child the feeling that the grown-ups, whom one must respect, write like this, therefore their example should be followed. There will result, indeed, a certain variety in spelling, but it will not run riot; instead, it will represent the adjustment of the growing child to the grown-up people about him. And we should reckon with this kind of adaptability: we ought not to want to produce the belief: that is right, and that is wrong; but we ought only to encourage the belief: that is how the grown-ups write; that is, you build here, too, on a living authority.

That is what I meant when I said: “The transition must be found from the child's first period up to the change of teeth, to his second period up to puberty, that is from the principle of imitation to that of authority.” What I meant by this must everywhere be realized in concrete detail, not by inculcating authority in the child, but by proceeding so that the sensitiveness to authority arises of itself, that is by basing the teaching of spelling and the whole orthographic form of writing on so-called authority in the way I have just described.

Fünfter Vortrag

Wir haben gestern von der Art gesprochen, wie die erste Schulstunde angehen sollte. Ich kann selbstverständlich nicht jeden einzelnen Schritt weiter charakterisieren, möchte Ihnen aber doch im wesentlichen den Gang des Unterrichtes so angeben, daß Sie im Praktischen etwas daraus machen können.

Sie haben gesehen, wir haben den Hauptwert darauf gelegt, daß zunächst das Kind sich bewußt werde, warum es eigentlich in die Schule kommt, daß dann übergegangen werde dazu, daß das Kind sich bewußt werde, daß es Hände hat; und nachdem wir ihm dies zum Bewußtsein gebracht haben, sollte ein gewisses Zeichnen angehen und sogar ein gewisses Übergehen zu etwas Malerischem, an dem dann die Empfindung des Schönen und des weniger Schönen entwickelt werden kann. Wir haben gesehen, daß dies, was sich da ausbildet, auch beobachtet werden kann beim Hören, und daß die ersten Elemente des musikalichen Empfindens im Schönen und weniger Schönen sich daran anschließen werden.

Wir wollen nun nach der Seite des Nächstfolgenden den Unterricht ein wenig verfolgen. Ich nehme dabei an, daß Sie solche Übungen mit dem Stift und mit der Farbe eine Zeitlang fortgesetzt haben. Es ist durchaus ein Erfordernis eines auf guten Grundlagen ruhenden Unterrichtes, daß dem Schreibenlernen vorangehe ein gewisses Eingehen auf ein Zeichnerisches, so daß gewissermaßen das Schreiben herausgeholt werde aus dem Zeichnen. Und es ist ein weiteres Erfordernis, daß dann wiederum aus dem Lesen des Geschriebenen erst herausgeholt werde das Lesen des Gedruckten. Also werden wir versuchen, von dem Zeichnen den Übergang zu finden zu dem Schreiben, vom Schreiben zum Lesen des Geschriebenen und vom Lesen des Geschriebenen zum Lesen des Gedruckten. Ich setze dabei voraus, daß Sie es dahin gebracht haben, daß das Kind durch das zeichnerische Element schon ein wenig darinnensteht, runde und geradlinige Formen, die es im Schreiben braucht, zu beherrschen. Dann würden wir von da aus wieder den Übergang versuchen zu dem, was wir schon besprochen haben als die Grundlage des Schreibe-Leseunterrichtes. Ich werde Ihnen heute zunächst in einigem zu zeigen versuchen, wie Sie da vorgehen können.

Also angenommen, das Kind habe es schon dazu gebracht, daß es geradlinige Formen und runde Formen beherrschen kann mit dem Händchen. Dann versuchen Sie, das Kind zunächst darauf hinzuweisen, daß es eine Reihe von Buchstaben gibt. Wir haben begonnen mit dem Fisch und dem f, die Reihenfolge ist dabei gleichgültig. Sie brauchen nicht alphabetisch vorzugehen, ich tue es jetzt nur, damit Sie etwas Enzyklopädisches haben. Wir wollen sehen, wie wir zu Rande kommen, wenn wir so vorgehen, das Schreiben und Lesen so zu entwickeln, wie es aus Ihrer eigenen, freien imaginativen Phantasie folgt. Da würde ich zunächst dem Kinde sagen: Du weißt, was ein Bad ist - und dabei will ich eine Zwischenbemerkung machen: es kommt im Unterrichten sehr darauf an, daß man in rationeller Weise schlau ist, das heißt, daß man immer hinter den Kulissen auch etwas hat, was wieder zur Erziehung und zum Unterrichte beiträgt. Es ist gut, wenn Sie zu dem, was ich jetzt entwickeln werde, gerade das Wort Bad verwenden, damit das Kind dadurch, daß es jetzt in der Schule ist, sich an ein Bad, an das Waschen überhaupt erinnert, an die Reinlichkeit. So etwas immer im Hintergrunde zu haben, ohne daß man es ausgesprochen charakterisiert und in Ermahnungen kleidet, das ist gut. Seine Beispiele so wählen, daß das Kind gezwungen ist, an etwas zu denken, was zu gleicher Zeit zu einer moralisch-ästhetischen Haltung beitragen kann, das ist gut. Dann gehen Sie dazu über zu sagen: Sieh, wenn die Großen das, was das Bad ist, niederschreiben wollen, so schreiben sie das folgendermaßen nieder: BAD. Dies also ist das Bild desjenigen, das du aussprichst, indem du «Bad» sagst, das Bad bezeichnest. — Jetzt lasse ich wieder eine Anzahl von Schülern einfach dieses nachschreiben, damit die Kinder jedesmal, wenn sie so etwas bekommen, die Sache auch schon in das Händchen hineinbekommen, daß sie es nicht bloß mit dem Anschauen, sondern mit dem ganzen Menschen auffassen, Jetzt werde ich sagen: Sieh, du fängst an «Bad» zu sagen. Wir wollen jetzt einmal den Anfang uns klarmachen: B. - Das Kind muß geführt werden von dem Aussprechen des ganzen Wortes BAD zu dem Aushauchen des Anfangslautes, wie ich es für den Fisch gezeigt habe. Und nun muß dem Kinde klargemacht werden: Wie dies BAD das Zeichen ist für das ganze Bad, so ist das B das Zeichen für den Anfang des Wortes BAD.

Jetzt mache ich das Kind darauf aufmerksam, daß solch ein Anfang auch noch bei andern Worten vorhanden ist. Ich sage: Wenn du sprichst Band, so fängst du geradeso an; wenn du sprichst Bund, was manche Frauen auf dem Kopf tragen, einen Kopfbund, so fängst du es ebenso an. Dann hast du vielleicht im Tiergarten schon einen Bären gesehen: da fängst du ebenso an zu hauchen; jedes dieser Worte fängt mit demselben Hauch an. — Auf diese Weise versuche ich beim Kinde überzugehen von dem Ganzen des Wortes zu dem Anfange des Wortes, es überzuführen zu dem bloßen Laut beziehungsweise zum Buchstaben; immer aus dem Worte heraus einen Anfangsbuchstaben zu entwickeln.

Nun handelt es sich darum, daß Sie vielleicht versuchen, den Anfangsbuchstaben selber zuerst auch sinnvoll aus dem Zeichnerischen heraus zu entwickeln. Das werden Sie gut können, wenn Sie einfach Ihre Phantasie zu Hilfe nehmen und sich sagen: Diejenigen Menschen, die zuerst solche Tiere gesehen haben, die mit B anfangen, wie Biber, Bär und dergleichen, die zeichneten den Rücken des Tieres, die Füße, die aufsitzen und die Vorderpfoten, die sich erheben; ein sich aufrichtendes Tier zeichneten sie, und die Zeichnung ging über in das B. Bei einem Worte werden Sie immer finden - und da können Sie ihre phantasievollen Imaginationen eben spielen lassen, brauchen gar nicht auf Kulturgeschichten, die doch nicht vollständig sind, einzugehen -, daß der Anfangsbuchstabe eine Zeichnung ist, eine Tier- oder Pflanzenform oder auch ein äußerer Gegenstand. Historisch ist das so: Wenn Sie zurückgehen auf die ältesten Formen der ägyptischen Schrift, die noch eine Zeichenschrift war, so finden Sie überall in den Buchstaben Nachahmungen von solchen Dingen. Und im Übergange von der ägyptischen Kultur in die phönizische hat sich das erst vollzogen, was man nennen kann: Entwickelung von dem Bilde zu dem Zeichen für den Laut. Diesen Übergang muß man das Kind nachmachen lassen. Machen wir ihn uns für unsere Information einmal theoretisch klar.

In den ersten Zeiten der Schriftentwickelung war es in Ägypten so, daß einfach alles einzelne, was niedergeschrieben werden sollte, durch Bilderschrift niedergeschrieben, gezeichnet wurde, allerdings so gezeichnet wurde, daß man lernen mußte, die Zeichnung möglichst einfach zu machen. Wer Fehler machte, wenn er zum Abschreiben dieser Bilderschrift angestellt war, der wurde zum Beispiel, wenn ein heiliges Wort verfehlt worden war, zum Tode verurteilt. Also im alten Ägypten nahm man diese Dinge, die mit dem Schreiben zusammenhingen, sehr, sehr ernst. Da war aber auch alles, was Schrift war, in der angedeuteten Weise Bild. Dann ging die Kultur über auf die mehr in der Außenwelt lebenden Phönizier. Da behielt man dann immer das Anfangsbild bei und übertrug dieses Anfangsbild auf den Laut. So zum Beispiel will ich Ihnen das, was auch für das Ägyptische gilt — weil wir ja hier nicht ägyptische Sprachen treiben können -, bei einem Worte zeigen, wo es sich am leichtesten in unserer Sprache nachbilden läßt. Die Ägypter wurden sich darüber klar, daß dasjenige, was der Laut M ist, dadurch bezeichnet werden konnte, daß man hauptsächlich auf die Oberlippe sieht. Daher nahmen sie das Zeichen für das M aus dem Bilde für die Oberlippe. Aus diesem Zeichen ging dann derjenige Buchstabe hervor, den wir für den Anfang des Wortes Mund haben, der dann blieb für jeden solchen Anfang, für alles, was mit M anfing. Dadurch wurde die bildhafte Wortbezeichnung - indem man immer das Bild von dem Anfang des Wortes nahm — zur Lautbezeichnung.

Dieses Prinzip, das in der Geschichte der Schriftentwickelung eingehalten worden ist, ist auch sehr gut im Unterricht zu verwenden, und wir verwenden es hier. Das heißt, wir werden versuchen, aus dem Zeichnerischen heraus zum Buchstaben zu kommen: Wie wir aus dem Fisch mit seinen zwei Flossen zu dem f kommen, so kommen wir vom Bären, der tanzt, der aufgestellt ist, zum B; wir kommen von der Oberlippe zum Mund, zum M und versuchen uns durch unsere Imagination auf diese Weise für das Kind einen Weg zu bahnen vom Zeichnen zum Schreiben. - Ich sagte, es ist nicht nötig, daß Sie Kulturgeschichte des Schriftwesens treiben und sich dort aufsuchen, was Sie brauchen. Denn was Sie sich dort aufsuchen, das dient Ihnen viel weniger im Unterricht als das, was Sie durch Ihre eigene Seelentätigkeit, durch Ihre eigene Phantasie finden. Die Tätigkeit, die Sie anwenden im Studium der Kulturgeschichte der Schrift, die macht Sie so tot, daß Sie viel weniger lebendig auf Ihren Zögling wirken, als wenn Sie sich so etwas wie das B aus dem Bilde des Bären selbst ausdenken. Dieses Selbstausdenken erfrischt Sie so, daß auf den Zögling das, was Sie ihm mitteilen wollen, viel lebendiger wirkt, als wenn Sie erst kulturhistorische Exkurse anstellen, um etwas für den Unterricht zu gewinnen. Und auf diese zwei Dinge hin muß man das Leben und den Unterricht betrachten. Denn Sie müssen sich fragen: Was ist wichtiger, eine kulturhistorische, mit aller Mühe zusammengestellte Tatsache aufgenommen zu haben und sie mühselig in den Unterricht hineingetragen zu haben, oder in der Seele selber so regsam zu sein, daß man die Erfindung, die man macht, im eigenen Enthusiasmus auf das Kind überträgt? — Freude werden Sie immer haben, wenn es auch eine recht stille Freude ist, wenn Sie von irgendeinem Tier oder einer Pflanze die Form, die Sie selbst gefunden haben, auf den Buchstaben übertragen. Und diese Freude, die Sie selbst haben, wird in dem leben, was Sie aus Ihrem Zögling machen werden.

Dann geht man dazu über, das Kind darauf aufmerksam zu machen, daß das, was es so für den Anfang eines Wortes angeschaut hat, auch in der Mitte der Worte vorkommt. Also gehe man dazu über, zu dem Kinde zu sagen: Sieh einmal, du kennst das, was draußen auf den Feldern oder Bergen wächst, was im Herbst eingeerntet wird und aus dem der Wein bereitet wird: die Rebe. Die Rebe schreiben die Großen so: REBE. Jetzt überlege dir einmal, wenn du ganz langsam sprichst: Rebe, da ist in der Mitte dasselbe drinnen, was bei BAR am Anfang war. — Man schreibt es immer zunächst groß auf, damit das Kind die Ähnlichkeit des Bildes hat. Dadurch bringt man ihm bei, wie das, was es für den Anfang eines Wortes gelernt hat, auch in der Mitte der Worte zu finden ist. Man atomisiert ihm weiter das Ganze.

Sie sehen, worauf es uns, die wir einen lebendigen Unterricht - im Gegensatz zu einem toten — erzielen wollen, ankommt: daß wir immer von dem Ganzen ausgehen. Wie wir im Rechnen von der Summe ausgehen, nicht von den Addenden, und die Summe zergliedern, so gehen wir auch hier von dem Ganzen ins Einzelne. Das hat den großen Vorteil für die Erziehung und den Unterricht, daß wir es erreichen, das Kind wirklich auch lebendig in die Welt hineinzustellen; denn die Welt ist ein Ganzes, und das Kind bleibt in fortwährender Verbindung mit dem lebendigen Ganzen, wenn wir so vorgehen, wie ich es angedeutet habe. Wenn Sie es die einzelnen Buchstaben aus dem Bilde heraus lernen lassen, so hat das Kind eine Beziehung zur lebendigen Wirklichkeit. Aber Sie dürfen nie versäumen, die Buchstabenformen so aufzuschreiben, wie sie sich aus einem Bilde ergeben, und Sie müssen immer Rücksicht darauf nehmen, daß Sie die Mitlaute, die Konsonanten, als Zeichnung von äußeren Dingen erklären - nie aber die Selbstlaute, die Vokale. Bei den Selbstlauten gehen Sie immer davon aus, daß sie wiedergeben das menschliche Innere und seine Beziehung zur Außenwelt. Wenn Sie also zum Beispiel versuchen, dem Kinde das A beizubringen, werden Ste ihm sagen: Nun stelle dir einmal die Sonne vor, die du morgens siehst. Kann sich keines von euch erinnern, was es da getan hat, wenn die Sonne morgens aufgegangen ist? - Nun wird sich vielleicht das eine oder andere Kind an das erinnern, was es getan hat. Wenn es nicht dazu kommt, wenn sich keines erinnert, so muß man dem Kinde in der Erinnerung etwas nachhelfen, was es getan hat, wie es sich hingestellt haben wird, gesagt haben wird, wenn der Sonnenaufgang sehr schön war: Ah! - Man muß diese Wiedergabe eines Gefühles anschlagen lassen, man muß versuchen, die Resonanz, die im Selbstlaut ertönt, aus dem Gefühl herauszuholen. Und dann muß man versuchen, zunächst zu sagen: Wenn du dich so hingestellt hast und Ah! gesagt hast, da ist das so, wie wenn von deinem Inneren hinausgegangen wäre wie in einem Winkel aus deinem Mund der Sonnenstrahl. Was in deinem Inneren lebt, wenn du den Sonnenaufgang siehst, das läßt du so (siehe Zeichnung links) ausströmen aus dir und bringst es hervor, indem du A sagst. Du läßt es aber nicht ganz ausströmen, du hältst etwas davon zurück, und da wird das dann zu diesem Zeichen (siehe Zeichnung rechts). Sie können einmal den Versuch machen, das, was beim Selbstlaut im Hauch liegt, in zeichnerische Formen zu kleiden. Dadurch bekommen Sie Zeichnungen, die Ihnen im Bilde darstellen können, wie die Zeichen für die Selbstlaute entstanden sind. Die Selbstlaute sind ja auch bei primitiven Kulturen wenig vorhanden, auch bei den heutigen primitiven Kulturen. Die Sprachen der primitiven Kulturen sind sehr reich an Mitlauten, sie sind so, daß die Leute noch viel anderes in den Mitlauten, in den Konsonanten, zum Ausdruck bringen, als wir kennen. Sie schnalzen manchmal direkt, sie haben allerlei Raffiniertheiten, um komplizierte Konsonanten zum Ausdruck zu bringen, und dazwischen tönt nur so leise an der Vokal. Bei den afrikanischen Völkerschaften finden Sie Laute, die so sind, wie wenn man mit der Peitsche schnalzen würde und so weiter, dagegen klingen die Vokale bei ihnen nur leise an, und die europäischen Reisenden, die zu solchen Völkern kommen, lassen gewöhnlich viel mehr die Vokale ertönen, als sie bei diesen Völkern ertönen.

Wir können also immer aus dem Zeichnerischen die Selbstlaute herausholen. Wenn Sie zum Beispiel das Kind dahin bringen, ihm klarzumachen - indem Sie sich an sein Gefühl wenden -, daß es in einer solchen Situation ist wie zum Beispiel der folgenden: Sieh mal, es kommt dein Bruder oder deine Schwester zu dir. Sie sagen dir etwas, du verstehst sie nicht gleich. Dann kommt ein Augenblick, da fängst du an, sie zu verstehen. Wie drückst denn du das aus? - dann wird sich wieder ein Kind finden oder es werden sich die Kinder dahin bringen lassen, daß eines sagt iii. In dem Hinweis auf das, was verstanden worden ist, liegt die zeichnerische Gestalt des Lautes I, die ja selbst grob in dem Hinweisen zum Ausdruck kommt. In der Eurythmie haben Sie es in klarerer Weise ausgedrückt. Es wird also der einfache Strich zum i, der einfache Strich, der unten dicker, oben dünner sein müßte; statt dessen macht man nur den Strich und drückt dann das Dünnwerden durch das kleinere Zeichen darüber aus. So kann man alle Selbstlaute herausholen aus der Gestalt des Hauches, aus der Gestalt des Atems.

Auf diese Weise bekommen Sie es fertig, dem Kinde zunächst eine Art Zeichenschrift beizubringen. Dann brauchen Sie sich gar nicht genieren, gewisse Vorstellungen zu Hilfe zu rufen, welche auch in der Empfindung etwas hervorrufen von dem, was ja in der Kulturentwikkelung wirklich gelebt hat. So können Sie dem Kinde das Folgende beibringen. Sie sagen ihm: Sieh einmal das Obere des Hauses: Wie drückst du es aus? Dach! D! - Aber man müßte dann das D so machen:  , das ist unbequem, daher haben die Leute es umgestellt:

, das ist unbequem, daher haben die Leute es umgestellt:  . Solche Vorstellungen liegen in der Schrift, und Sie können sie durchaus benutzen.

. Solche Vorstellungen liegen in der Schrift, und Sie können sie durchaus benutzen.

Dann aber haben die Menschen nicht so kompliziert schreiben wollen, sondern sie haben es sich einfacher machen wollen. Daher ist aus diesem Zeichen:  , das eigentlich so sein sollte

, das eigentlich so sein sollte  - indem Sie jetzt übergehen zur kleinen Schrift, dieses Zeichen, das kleine d geworden. — Sie können durchaus die bestehenden Buchstabenformen in dieser Weise aus solchen Figuren heraus entwickeln, die Sie als zeichnerisch dem Kinde beigebracht haben. Auf diese Weise werden Sie, immer den Übergang von Form zu Form besprechend, niemals bloß abstrakt lehrend, das Kind vorwärtsbringen, so daß es den wirklichen Übergang findet von der zuerst aus dem Zeichnen herausgeholten Form zu jener Form, die nun der heutige Buchstabe, wenn er geschrieben wird, wirklich hat.

- indem Sie jetzt übergehen zur kleinen Schrift, dieses Zeichen, das kleine d geworden. — Sie können durchaus die bestehenden Buchstabenformen in dieser Weise aus solchen Figuren heraus entwickeln, die Sie als zeichnerisch dem Kinde beigebracht haben. Auf diese Weise werden Sie, immer den Übergang von Form zu Form besprechend, niemals bloß abstrakt lehrend, das Kind vorwärtsbringen, so daß es den wirklichen Übergang findet von der zuerst aus dem Zeichnen herausgeholten Form zu jener Form, die nun der heutige Buchstabe, wenn er geschrieben wird, wirklich hat.

Solche Dinge sind ja von einzelnen, allerdings recht wenigen Leuten heute schon bemerkt worden. Es gibt Pädagogen, die schon darauf aufmerksam gemacht haben: Man sollte das Schreiben aus dem Zeichnen herausholen. Aber sie machen es anders, als es hier gefordert wird. Sie nehmen gewissermaßen gleich die Formen in Aussicht, wie sie zuletzt entstanden sind; sie nehmen eine Form, wie sie jetzt schon ist, so daß sie nicht aus dem Zeichen des sitzenden oder des tanzenden Bären zu dem B kommen, sondern sie nehmen das B wie es jetzt ist, zerlegen es in einzelne Striche und Linien:  und wollen auf diese Weise das Kind vom Zeichnen zum Schreiben bringen. Sie machen das in abstracto, was wir im Konkreten versuchen. Also das Praktische des Hervorgehenlassens des Schreibens aus dem Zeichnen haben einige Pädagogen richtig bemerkt, aber die Menschen stecken zu sehr in dem Abgelebten der Kultur drinnen, als daß sie ganz klar auf das Lebendige kämen.

und wollen auf diese Weise das Kind vom Zeichnen zum Schreiben bringen. Sie machen das in abstracto, was wir im Konkreten versuchen. Also das Praktische des Hervorgehenlassens des Schreibens aus dem Zeichnen haben einige Pädagogen richtig bemerkt, aber die Menschen stecken zu sehr in dem Abgelebten der Kultur drinnen, als daß sie ganz klar auf das Lebendige kämen.

Ich möchte auch hierbei nicht versäumen, Sie darauf hinzuweisen, daß Sie sich nicht beirren lassen, indem Sie auf allerlei Bestrebungen in der Gegenwart sehen und sagen: Da ist dies schon gewollt, dort ist jenes schon gewollt. Denn Sie werden immer sehen: Aus sehr starken Tiefen heraus ist das nicht gewollt. Aber es drängt die Menschheit immer dahin, solche Dinge durchzuführen. Sie wird sie jedoch nicht durchführen können, bevor sie nicht die Geisteswissenschaft in die Kultur aufgenommen haben wird.

So können wir immer anknüpfen an den Menschen und seine Beziehung zur Umwelt, indem wir organisch schreiben und mit dem Lesen des Geschriebenen auch Lesen lehren.

Nun gehört zu dem Unterricht dazu - und wir sollten das nicht außer acht lassen — eine gewisse Sehnsucht, völlig frei zu sein. Und merken Sie, wie die Freiheit in diese Besprechung der Vorbereitung des Unterrichtes hineinfließt. Sie hat innerlich etwas zu tun mit der Freiheit. Denn ich mache Sie darauf aufmerksam, daß Sie sich nicht unfrei machen sollen, indem Sie nun ochsen sollen, wie die Schrift entstanden ist im Übergange von den Ägyptern zu den Phöniziern, sondern daß Sie danach sehen sollen, Ihre eigene Seelenfähigkeit selber zu entwickeln. Was dabei gemacht werden kann, das kann durchaus von dem einen Lehrer in dieser Weise, von dem andern in jener Weise gemacht werden. Es kann nicht jeder einen tanzenden Bären verwenden; es verwendet einer vielleicht etwas viel Besseres für dieselbe Sache. Was zuletzt erreicht wird, kann von dem einen Lehrer ebenso erreicht werden wie von dem andern. Aber jeder gibt sich selbst hin, indem er unterrichtet. Es wird seine Freiheit dabei völlig gewahrt. — Je mehr die Lehrerschaft in dieser Beziehung ihre Freiheit wird wahren wollen, desto mehr wird sie sich hineinlegen können in den Unterricht, wird sich hingeben können an den Unterricht. Das ist etwas, was in den letzten Zeiten fast völlig verlorengegangen ist. Sie können es an einer Erscheinung sehen.

Es hat sich vor einiger Zeit darum gehandelt - die Jüngeren unter Ihnen haben es vielleicht nicht miterlebt, den Älteren aber, die verständig waren, hat es Ärger genug gemacht -, auf geistigem Gebiete etwas Ähnliches zustande zu bringen wie die berühmte kaiserlich deutsche Reichstunke auf materiellem Gebiet. Sie wissen, man hat oft betont, daß für alle Wirtshäuser, die nicht auf besonderen Fremdenbesuch rechneten, sondern nur auf Deutsche, eine einheitliche Soße oder Tunke gemacht werden sollte. Kaiserlich deutsche Reichssoße nannte man es, man wollte einheitlich gestalten. So wollte man auch die Rechtschreibung, die Orthographie, einheitlich gestalten. Nun sind mit Bezug auf diesen Gegenstand die Leute von ganz merkwürdiger Gesinnung. Man kann an konkreten Beispielen diese Gesinnung studieren. Da gibt es ein sehr schönes zartes Verhältnis innerhalb des deutschen Geisteslebens, das zwischen Novalis und einer weiblichen Gestalt. Dieses Verhältnis ist deshalb so schön, weil Novalis, als die betreffende weibliche Gestalt weggestorben war, noch immer ganz bewußt mit ihr zusammenlebte, als sie schon in der geistigen Welt war, und von diesem Zusammenleben mit ihr auch spricht, in dem er der Gestorbenen in einer inneren meditativen Seelentätigkeit nachstirbt. Es gehört zu den schönsten, intimsten Sachen, die man in der deutschen Literaturgeschichte lesen kann, wenn man auf dieses Verhältnis von Novalis zu dieser weiblichen Gestalt kommt. Nun gibt es eine sehr geistvolle, von dem betreffenden Standpunkte aus auch interessante, streng philologische Abhandlung eines deutschen Gelehrten über das Verhältnis zwischen Novalis und seiner Geliebten. Darin wird «richtig gestellt» das zarte, schöne Verhältnis; denn es könne nachgewiesen werden, daß diese weibliche Persönlichkeit eher gestorben ist, als sie orthographisch richtig schreiben konnte. Sie hat in ihren Briefen Schreibfehler gemacht! Kurz, es wird das Bild dieser Persönlichkeit, die zu Novalis in Beziehung gestanden hat, in einer recht banausischen Weise gezeigt — alles nach ganz strenger Wissenschaftlichkeit. Die Methode dieser Wissenschaft ist so gut, daß jeder, der eine Dissertation macht, worin er diese Methode befolgt, diese Dissertation nach dem ersten Grade zensiert zu bekommen verdient! — Ich will nur darauf hinweisen, daß die Leute schon vergessen haben, daß Goethe ja niemals hat orthographisch schreiben können, daß er in Wirklichkeit sein ganzes Leben hindurch Fehler gemacht hat, insbesondere in seiner Jugend. Trotzdem aber konnte er zu der Goetheschen Größe emporsteigen! Und dann erst Personen, die mit ihm in Beziehung waren, auf die er sehr viel gegeben hat - ja, deren Briefe, wie sie jetzt manchmal faksimiliert werden, würden aus der Hand eines Schulmeisters mit lauter roten Strichen versehen hervorgehen! Sie würden einen recht abfälligen Grad in der Zensur bekommen.

Das hängt mit einer recht unfreien Nuance unseres Lebens zusammen, die im Unterricht und in der Erziehung nicht spielen dürfte. Sie hat aber vor einigen Jahrzehnten so gespielt, daß die Verständigen unter der Lehrerschaft sie als recht ärgerlich empfanden. Es sollte eine einheitliche deutsche Orthographie erstellt werden, die berühmte Puttkamersche Orthographie. Das heißt, es wurde vom Staate aus bis in die Schule hinein nicht nur ein Aufsichtsrecht ausgeübt, nicht nur die Verwaltung ausgeübt, sondern auch die Orthographie gesetzlich festgestellt. Sie ist auch darnach! Denn im Grunde genommen haben wir durch diese Puttkamersche Orthographie vieles verloren, was uns heute noch aufmerksam machen könnte auf gewisse Intimitäten der deutschen Sprache. Dadurch, daß die Menschen heute ein abstraktes Geschreibe vor sich haben, geht ihnen vieles verloren von dem, was früher leben konnte in der deutschen Sprache; es geht verloren für die sogenannte Schriftsprache.

Nun handelt es sich darum, in bezug auf eine solche Sache vor allem die richtige Gesinnung zu haben. Man kann ja selbstverständlich nicht eine beliebige Orthographie wuchern lassen, aber man kann wenigstens wissen, wie in bezug auf diesen Gegenstand der eine und der andere Pol sich verhalte. Würden die Leute schreiben können, nachdem sie Schreiben gelernt haben, was sie hören an andern oder an sich selbst, so wie sie es hören, so würden sie sehr verschieden schreiben. Sie würden eine sehr verschiedene Orthographie haben, würden sehr stark individualisieren. Das würde außerordentlich interessant sein, aber es würde den Verkehr erschweren. Auf der andern Seite liegt das vor für uns, daß wir nicht nur unsere Individualität im menschlichen Zusammenleben entwickeln, sondern auch die sozialen Triebe und die sozialen Gefühle. Da handelt es sich darum, daß wir einfach vieles von dem, was in unserer Individualität sich offenbaren könnte, abschleifen an dem, was wir um des Zusammenlebens willen mit den andern entwickeln sollen. Aber wir sollten von dieser Tatsache ein Gefühl haben, und dieses Gefühl sollte mit uns heranerzogen werden, daß wir so etwas nur tun aus sozialen Gründen. Daher werden Sie, indem Sie den Schreibunterricht hindirigieren zum Orthographieunterricht, ausgehen müssen von einem ganz bestimmten Gefühlskomplex. Sie werden das Kind immer wieder und wieder darauf aufmerksam machen müssen — ich habe das schon von einem andern Gesichtspunkt aus erwähnt -, daß es Achtung, Respekt haben soll vor den Großen, daß es hineinwächst in ein schon fertiges Leben, von dem es aufgenommen werden soll, daß es daher das zu beachten hat, was schon da ist. Von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus muß man versuchen, das Kind auch in so etwas einzuführen, wie es die Orthographie ist. Man muß mit dem Orthographieunterricht parallelgehend ihm entwickeln das Gefühl des Respektes, des Achtens desjenigen, was die Alten festgesetzt haben. Und man muß Orthographie nicht lehren wollen aus irgendeiner Abstraktion heraus, etwa wie wenn die Orthographie durch eine göttliche — für andere Puttkamersche Gesetzmäßigkeit da wäre gleichsam aus dem Absoluten heraus, sondern Sie müssen in dem Kinde das Gefühl entwickeln: Die Großen, vor denen man Respekt haben soll, die schreiben so, man muß sich nach ihnen richten. — Dadurch wird man allerdings eine gewisse Variabilität in die Rechtschreibung hineinbringen; aber das wird nicht überwuchern, sondern es wird eine Anpassung des heranwachsenden Kindes an die Erwachsenen da sein. Und mit dieser Anpassung sollte man rechnen. Man sollte gar nicht den Glauben hervorrufen wollen: So ist es richtig, und so ist es falsch -, sondern man sollte nur den Glauben erwecken: So pflegen die Großen zu schreiben -, also auch da auf die lebendige Autorität bauen.

Das habe ich gemeint, wenn ich sagte: Übergegangen muß werden von dem Kinde bis zum Zahnwechsel zu dem Kinde bis zur Geschlechtsreife als von dem Nachahmen zur Autorität. Was ich damit meinte, muß im einzelnen überall konkret durchgeführt werden, nicht indem man dem Kinde Autorität eindtessiert, sondern indem man so handelt, daß das Autoritätsgefühl entsteht, also indem man beim Orthographieunterricht so handelt, daß man das ganze orthographische Schreiben auf die sogenannte Autorität stellt, wie ich es jetzt auseinandergesetzt habe.

Fifth Lecture

Yesterday we discussed how the first school lesson should be approached. Of course, I cannot characterize every single step in detail, but I would like to outline the basic structure of the lesson so that you can put it into practice.

You have seen we have placed the main emphasis on the child first becoming aware of why they are actually coming to school, then moving on to the child becoming aware that they have hands; and after we have made them aware of this, a certain amount of drawing should be done and even a certain transition to something painterly, where the sense of beauty and less beauty can then be developed. We have seen that what develops here can also be observed in listening, and that the first elements of musical feeling in the beautiful and the less beautiful will follow on from this.

Let us now follow the lesson a little further. I assume that you have continued with such exercises with pen and paint for some time. It is absolutely essential for teaching based on sound principles that learning to write be preceded by a certain amount of drawing, so that writing is, in a sense, derived from drawing. And it is a further requirement that reading the printed word be derived from reading the written word. So we will try to find the transition from drawing to writing, from writing to reading what has been written, and from reading what has been written to reading what has been printed. I assume that you have already brought the child to the point where, through the element of drawing, they have already mastered some of the round and straight forms that they need for writing. Then, from there, we would try again to make the transition to what we have already discussed as the basis of writing and reading instruction. Today, I will first try to show you in a few ways how you can proceed.

So, let's assume that the child has already mastered straight and round shapes with their little hand. Then try to point out to the child that there is a series of letters. We started with the fish and the f; the order is irrelevant. You don't need to proceed alphabetically; I'm only doing so now to give you something encyclopedic. Let's see how we get on if we proceed in this way, developing writing and reading as it follows from your own free imaginative fantasy. I would first say to the child: You know what a bath is – and here I would like to make an aside: in teaching, it is very important to be clever in a rational way, that is, to always have something behind the scenes that contributes to education and teaching. It is good if you use the word “bath” in what I am about to develop, so that the child, now that it is in school, remembers bathing, washing in general, cleanliness. It is good to always have something like this in the background, without explicitly characterizing it and dressing it up in admonitions. It is good to choose examples in such a way that the child is forced to think about something that can at the same time contribute to a moral and aesthetic attitude. Then move on to saying: Look, when grown-ups want to write down what a bath is, they write it down like this: BATH. So this is the image of what you express when you say “bath,” when you refer to the bath. Now I will again have a number of pupils simply write this down, so that every time the children are given something like this, they already have it in their hands, so that they grasp it not only with their eyes, but with their whole being. Now I will say: Look, you begin to say “bath.” Let's first clarify the beginning: B. The child must be guided from pronouncing the whole word BAD to exhaling the initial sound, as I showed for the fish. And now it must be made clear to the child: just as BAD is the sign for the whole bath, so B is the sign for the beginning of the word BAD.

Now I draw the child's attention to the fact that such a beginning is also present in other words. I say: When you say “band,” you begin in exactly the same way; when you say “bund,” which some women wear on their heads, a headband, you begin in exactly the same way. Then you may have seen a bear in the zoo: you start to breathe in the same way; each of these words begins with the same breath. — In this way, I try to move the child from the whole word to the beginning of the word, to transfer it to the mere sound or letter; always developing an initial letter from the word.

Now it is a matter of you perhaps trying to develop the initial letter yourself first in a meaningful way from the drawing. You will be able to do this well if you simply use your imagination and say to yourself: Those people who first saw animals beginning with B, such as beavers, bears, and the like, drew the back of the animal, the feet that sit on it, and the front paws that rise up; they drew an animal standing upright, and the drawing turned into the letter B. In a word, you will always find—and here you can let your imagination run wild, without having to delve into cultural histories, which are incomplete anyway—that the initial letter is a drawing, an animal or plant form, or even an external object. Historically, this is the case: if you go back to the oldest forms of Egyptian writing, which was still a pictographic script, you will find imitations of such things everywhere in the letters. And in the transition from Egyptian culture to Phoenician culture, what can be called the development from the image to the sign for the sound took place. Children must be allowed to imitate this transition. Let us clarify this theoretically for our own information.

In the early days of the development of writing in Egypt, everything that was to be written down was simply written down or drawn using pictographic writing, but it was drawn in such a way that one had to learn to make the drawing as simple as possible. Anyone who made a mistake when copying this pictographic writing was sentenced to death, for example, if a sacred word was missed. So in ancient Egypt, things related to writing were taken very, very seriously. But everything that was writing was also pictorial in the manner indicated. Then the culture passed on to the Phoenicians, who lived more in the outside world. There, the initial image was always retained and transferred to the sound. For example, I will show you what also applies to Egyptian—because we cannot use Egyptian languages here—with a word that can be most easily reproduced in our language. The Egyptians realized that the sound M could be represented by looking mainly at the upper lip. Therefore, they took the sign for M from the image of the upper lip. From this sign emerged the letter that we have for the beginning of the word mouth, which then remained for every such beginning, for everything that began with M. In this way, the pictorial word designation—by always taking the image from the beginning of the word—became the sound designation.

This principle, which has been adhered to throughout the history of the development of writing, is also very useful in teaching, and we use it here. That is, we will try to arrive at the letter from the drawing: just as we arrive at the letter f from the fish with its two fins, so we arrive at the letter B from the bear that is dancing, that is standing upright; we move from the upper lip to the mouth, to the M, and in this way we try to use our imagination to pave the way for the child from drawing to writing. I said that it is not necessary for you to study the cultural history of writing and search there for what you need. For what you find there is much less useful to you in teaching than what you find through your own soul activity, through your own imagination. The activity you engage in when studying the cultural history of writing makes you so dead that you have much less of a lively effect on your pupil than if you think up something like the B from the image of the bear yourself. This self-thinking refreshes you so much that what you want to communicate to your pupils has a much more lively effect than if you first make cultural-historical digressions in order to gain something for your teaching. And it is in terms of these two things that one must view life and teaching. For you must ask yourself: What is more important, to have absorbed a cultural-historical fact that has been painstakingly compiled and laboriously incorporated into your teaching, or to be so lively in your soul that you transfer the invention you make to the child through your own enthusiasm? — You will always have joy, even if it is a quiet joy, when you transfer the shape you have found yourself from an animal or a plant to the letter. And this joy that you yourself have will live on in what you make of your pupil.

Then you move on to pointing out to the child that what they saw at the beginning of a word also occurs in the middle of words. So you move on to saying to the child: Look, you know what grows outside in the fields or mountains, what is harvested in autumn and used to make wine: the vine. Grown-ups write the vine like this: REBE. Now think about it, if you say it very slowly: Rebe, there is the same thing in the middle as there was at the beginning of BAR. — You always write it in capital letters first, so that the child has the similarity of the image. In this way, you teach them how what they have learned at the beginning of a word can also be found in the middle of words. We continue to break down the whole for them.

You can see what is important to us, who want to achieve lively teaching — as opposed to dead teaching —: that we always start from the whole. Just as in arithmetic we start from the sum, not from the addends, and break down the sum, so here too we start from the whole and move on to the details. This has the great advantage for education and teaching that we succeed in really placing the child alive in the world; for the world is a whole, and the child remains in constant connection with the living whole if we proceed as I have indicated. If you let the child learn the individual letters from the picture, the child has a relationship to living reality. But you must never fail to write down the letter forms as they appear in a picture, and you must always take care to explain the consonants as drawings of external things—but never the vowels. With the vowels, always assume that they reflect the human inner world and its relationship to the outside world. So, for example, if you are trying to teach the child the letter A, you will say to him: Now imagine the sun that you see in the morning as a mental image. Can any of you remember what you were doing when the sun rose in the morning?“ Perhaps one or two children will remember what they were doing. If this is not the case, if no one remembers, then you have to help the child remember what they were doing, how they stood, what they said when the sunrise was very beautiful: ”Ah!" You have to let this reproduction of a feeling strike a chord; you have to try to draw out the resonance that sounds in the vowel from the feeling. And then you have to try to say first: When you stood there and said Ah!, it was as if the sunbeam had come out of your inner self, as if from a corner of your mouth. What lives within you when you see the sunrise, you let it flow out of you like this (see drawing on the left) and bring it forth by saying A. But you don't let it flow out completely, you hold some of it back, and then it becomes this sign (see drawing on the right). You can try to clothe what lies in the breath of the vowel in graphic forms. This will give you drawings that can show you how the signs for the vowels came into being. Vowels are also rare in primitive cultures, even in today's primitive cultures. The languages of primitive cultures are very rich in consonants, and people use them to express much more than we are familiar with. They sometimes click directly, they have all kinds of refinements to express complicated consonants, and in between, the vowels sound only very softly. Among African peoples, you find sounds that are like the crack of a whip and so on, whereas their vowels are only faintly audible, and European travelers who come to such peoples usually pronounce the vowels much more loudly than they do among these peoples.

So we can always extract the vowels from the drawings. For example, if you make the child understand—by appealing to their feelings—that they are in a situation such as the following: Look, your brother or sister is coming to you. They say something to you, but you don't understand them right away. Then there comes a moment when you begin to understand them. How do you express that? – then another child will come forward, or the children will be led to the point where one of them says iii. The reference to what has been understood contains the graphic form of the sound I, which is itself roughly expressed in the reference. In eurythmy, you have expressed it more clearly. So the simple line becomes the i, the simple line that should be thicker at the bottom and thinner at the top; instead, you just make the line and then express the thinning by the smaller sign above it. In this way, you can bring out all the vowels from the form of the breath, from the form of the breath.

In this way, you will be able to teach the child a kind of sign language at first. Then you need not hesitate to call upon certain mental images that also evoke something in the senses of what has actually been experienced in cultural development. In this way, you can teach the child the following. You say to him: Look at the top of the house: How do you express it? Dach! D! — But then you would have to write the D like this:  , which is inconvenient, so people changed it to:

, which is inconvenient, so people changed it to:  . Such mental images are found in the script, and you can certainly use them.

. Such mental images are found in the script, and you can certainly use them.

But then people didn't want to write in such a complicated way; they wanted to make it easier for themselves. That's why this character:  , which should actually be

, which should actually be  — by now switching to small print, this symbol has become the small d. — You can certainly develop the existing letter forms in this way from such figures that you have taught the child to draw. In this way, always discussing the transition from form to form, never teaching abstractly, you will help the child progress so that it finds the real transition from the form first drawn from the drawing to the form that today's letter actually has when it is written.

— by now switching to small print, this symbol has become the small d. — You can certainly develop the existing letter forms in this way from such figures that you have taught the child to draw. In this way, always discussing the transition from form to form, never teaching abstractly, you will help the child progress so that it finds the real transition from the form first drawn from the drawing to the form that today's letter actually has when it is written.

Such things have already been noticed by a few individuals today. There are educators who have already pointed out that writing should be derived from drawing. But they do it differently than is required here. They take, as it were, the forms as they have finally emerged; they take a form as it already is, so that they do not arrive at the B from the sign of the sitting or dancing bear, but take the B as it is now, break it down into individual strokes and lines:  and in this way they want to bring the child from drawing to writing. They do in abstracto what we try to do in concreto. So some educators have correctly noticed the practicality of letting writing emerge from drawing, but people are too stuck in the deadness of culture to see the living clearly./p>

and in this way they want to bring the child from drawing to writing. They do in abstracto what we try to do in concreto. So some educators have correctly noticed the practicality of letting writing emerge from drawing, but people are too stuck in the deadness of culture to see the living clearly./p>

I would also like to take this opportunity to point out that you should not be misled by looking at all kinds of current endeavors and saying: this is already wanted here, that is already wanted there. For you will always see that from very deep down, this is not wanted. But humanity is always pushing to carry out such things. However, it will not be able to carry them out until it has incorporated spiritual science into its culture.

I would also like to take this opportunity to point out that you should not be misled by looking at all kinds of efforts in the present and saying: this is already wanted here, that is already wanted there. For you will always see that from very deep down, this is not wanted. But humanity is always pushing to carry out such things. However, it will not be able to carry them out until it has incorporated spiritual science into its culture.

In this way, we can always connect with people and their relationship to the environment by writing organically and teaching reading by reading what has been written.

Now, part of teaching—and we should not ignore this—is a certain longing to be completely free. And notice how freedom flows into this discussion of lesson preparation. It has something to do with inner freedom. For I would like to point out that you should not make yourselves unfree by having to plod through how writing came into being in the transition from the Egyptians to the Phoenicians, but that you should seek to develop your own soul capacity. What can be done in this regard can certainly be done by one teacher in this way and by another in that way. Not everyone can use a dancing bear; one may use something much better for the same purpose. What is ultimately achieved can be achieved by one teacher as well as by another. But everyone gives themselves to teaching. Their freedom is completely preserved in the process. The more teachers want to preserve their freedom in this respect, the more they will be able to put themselves into their teaching, to devote themselves to it. This is something that has been almost completely lost in recent times. You can see it in one phenomenon.

Some time ago, there was a debate—the younger ones among you may not have witnessed it, but it caused enough trouble for the older ones who were knowledgeable—about achieving something in the spiritual realm similar to the famous imperial German Reich sauce in the material realm. You know, it was often emphasized that a uniform sauce or dip should be made for all restaurants that did not expect special visitors from abroad, but only Germans. It was called the Imperial German Reich Sauce, and the aim was to create uniformity. In the same way, there was a desire to standardize spelling and orthography. Now, people have a very strange attitude toward this subject. This attitude can be studied using concrete examples. There is a very beautiful, delicate relationship within German intellectual life, that between Novalis and a female figure. This relationship is so beautiful because Novalis, when the female figure in question had passed away, still consciously lived with her, even though she was already in the spiritual world, and he also speaks of this life with her, in which he dies after her in an inner meditative activity of the soul. This relationship between Novalis and this female figure is one of the most beautiful and intimate things one can read about in German literary history. Now there is a very witty, and from the relevant point of view also interesting, strictly philological treatise by a German scholar on the relationship between Novalis and his beloved. In it, the tender, beautiful relationship is “corrected,” because it can be proven that this female personality died before she could spell correctly. She made spelling mistakes in her letters! In short, the image of this personality, who had a relationship with Novalis, is presented in a rather philistine manner—all according to very strict scientific principles. The method of this science is so good that anyone who writes a dissertation in which he follows this method deserves to have his dissertation graded with the highest mark! — I would just like to point out that people have already forgotten that Goethe was never able to write orthographically, that he actually made mistakes throughout his entire life, especially in his youth. Nevertheless, he was able to rise to Goethean greatness! And then there are the people who were related to him, to whom he gave a great deal — indeed, their letters, as they are now sometimes reproduced in facsimile, would come out of the hands of a schoolmaster covered with red marks! They would receive a rather derogatory grade in the censorship.

This has to do with a rather restrictive aspect of our lives that should not play a role in teaching and education. However, a few decades ago, it did play such a role that the more sensible members of the teaching profession found it quite annoying. The aim was to create a uniform German orthography, the famous Puttkamer orthography. This means that the state not only exercised supervisory authority and administration in schools, but also established spelling rules by law. And that's how it is! Because, basically, this Puttkamersche spelling system has caused us to lose much of what could still draw our attention today to certain intricacies of the German language. Because people today are faced with abstract writing, they lose much of what used to be alive in the German language; it is lost to the so-called written language.

Now, when it comes to such a matter, it is above all important to have the right attitude. Of course, one cannot allow any spelling to proliferate, but one can at least know how the two extremes relate to each other in this matter. If, after learning to write, people were able to write what they hear from others or from themselves as they hear it, they would write very differently. They would have very different spellings and would individualize very strongly. That would be extremely interesting, but it would make communication more difficult. On the other hand, we are faced with the fact that we not only develop our individuality in human coexistence, but also our social instincts and social feelings. The point is that we simply polish away much of what could reveal itself in our individuality in favor of what we should develop for the sake of coexisting with others. But we should be aware of this fact, and this awareness should be cultivated in us, that we do such things only for social reasons. Therefore, when you direct writing instruction toward spelling instruction, you will have to start from a very specific set of feelings. You will have to draw the child's attention to this again and again — I have already mentioned this from another point of view — that they should have respect for adults, that they are growing into an already established life from which they are to be accepted, and that they must therefore pay attention to what is already there. From this point of view, one must try to introduce the child to something like spelling. Parallel to spelling lessons, one must develop in them a feeling of respect and esteem for what the elders have established. And one must not try to teach spelling from some kind of abstraction, as if spelling were a divine law – for others, Puttkamer's law – as if it came from the absolute, but rather one must develop in the child the feeling that the grown-ups, whom one should respect, write this way, and one must follow their example. — This will, of course, introduce a certain variability into spelling, but this will not become excessive; rather, there will be an adaptation of the growing child to the adults. And this adaptation should be expected. One should not try to instill the belief that “this is right and that is wrong,” but rather one should only awaken the belief that This is how grown-ups write — thus building on living authority in this area as well.

This is what I meant when I said: We must transition from the child until the change of teeth to the child until sexual maturity, from imitation to authority. What I meant by this must be implemented in detail everywhere, not by instilling authority in the child, but by acting in such a way that a sense of authority arises, that is, by teaching spelling in such a way that the whole of orthographic writing is based on so-called authority, as I have now explained.