Spiritual Ground of Education

GA 305

21 August 1922, Oxford

V. How Knowledge Can Be Nurture

If the process of the change of teeth in a child is gradual even more gradual is that great transformation in the bodily, psychic and spiritual organism of which I have already spoken. Hence, in education it is important to remember that the child is gradually changing from an imitative being into one who looks to the authority of an educator, of a teacher. Thus we should make no abrupt transition in the treatment of a child in its seventh year or so—at the age, that is, at which we receive it for education in the primary school. Anything further that is said here on primary school education must be understood in the light of this proviso.

In the art of education with which we are here concerned the main thing is to foster the development of the child's inherent capacities. Hence all instruction must be at the service of education. The task is, properly speaking, to educate; and instruction is made use of as a means of educating.

This educational principle demands that the child shall develop the appropriate relation to life at the appropriate age. But this can only be done satisfactorily when the child is not required at the very outset to do something which is foreign to its nature.

Now it is a thoroughly unnatural thing to require a child in its sixth or seventh year to copy without more ado the signs which we now, in this advanced stage of civilisation, use for reading and writing.

If you consider the letters we now use for reading and writing, you will realise that there is no connection between what a seven-year old child is naturally disposed to do—and these letters. Remember, that when men first began to write they used painted or drawn signs which copied things or happenings in the surrounding world; or else men wrote from out of will impulses, so that the forms of writing gave expression to processes of the will, as for example in cuneiform. The entirely abstract forms of letters which the eye must gaze at nowadays, or the hand form, arose from out of picture writing. If we confront a young child with these letters we are bringing to him an alien thing, a thing which in no wise conforms to his nature. Let us be clear what this ‘pushing’ of a foreign body into a child's organism really means. It is just as if we habituated the child from his earliest years to wearing very small clothes, which do not fit and which therefore damage his organism. Nowadays when observation tends to be superficial, people do not even perceive what damage is done to the organism by the mere fact of introducing reading and writing to the child in a wrong way. An art of education founded in a knowledge of man does truly proceed by drawing out all that is in the child. It does not merely say: the individuality must be developed, it really does it. And this is achieved firstly by not taking reading as the starting point. For with a child the first things are movements, gestures, expressions of will, not perception or observation. These come later. Hence it is necessary to begin, not with reading, but with writing—but a writing which shall come naturally from man's whole being.

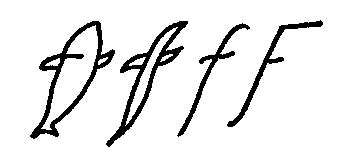

Hence, we begin with writing lessons, not reading lessons, and we endeavour to lead over what the child does of its own accord out of imitation, through its will, through its hands, into writing. Let me make it clear to you by an example: We ask the child to say the word “fish,” for instance, and while doing so, show him the form of the fish in a simple sketch; then ask him to copy it;—thus we get the child to experience the word “fish.” From “fish” we pass to f (F), and from the form of the fish we can gradually evolve the letter f. Thus we derive the form of the letter by an artistic activity which carries over what is observed into what is willed:

By this means we avoid introducing an utterly alien F, a thing which would affect the child like a demon, something foreign thrust into his body; and instead we call forth from him the thing he has seen himself in the market place. And this we transform little by little into ‘ f .’

In this way we come near to the way writing originated, for it arose in a manner similar to this. But there is no need for the teacher to make a study of antiquity and exactly reproduce the way picture writing arose so as to give it in the same manner to the child. What is necessary is to give the rein to living fantasy and to produce afresh whatever can lead over from the object, from immediate life, to the letter forms. You will then find the most manifold ways of deriving the letter form for the child from life itself. While you say M let him feel how the M vibrates on the lips, then get him to see the shape of the lips as form, then you will be able to pass over gradually from the M that vibrates on the lips to M.

In this way, if you proceed spiritually, imaginatively, and not intellectually, you will gradually be able to derive from the child's own activity, all that leads to his learning to write. He will learn to write later and more slowly than children commonly do to-day. But when parents come and say: My child is eight, or nine years old, and cannot yet write properly, we must always answer: What is learned more slowly at any given age is more surely and healthily absorbed by the organism, than what is crammed into it.

Along these lines, moreover, there is scope for the individuality of the teacher, and this is an important con-sideration. As we now have many children in the Waldorf School we have had to start parallel classes—thus we have two first classes, two second classes and so on. If you go into one of the first classes you will find writing being taught by way of painting and drawing. You observe how the teacher is doing it. For instance, it might be just as we have been describing here. Then you go into the other Class I., Class I. B; and you find another teacher teaching the same subject. But you see something quite different. You find the teacher letting the children run round in a kind of eurhythmy, and getting them to experience the form from out of their own bodily movements. Then what the child runs is retained as the form of the letter. And it is possible to do it in yet a third and a fourth manner. You will find the same subject taught in the most varied ways in the different parallel classes. Why? Well, because it is not a matter of indifference whether the teacher who has to take a lesson has one temperament or another. The lesson can only be harmonious when there is the right contact between the teacher and the whole class. Hence every teacher must give his lesson in his own way. And just as life appears in manifold variety so can a teaching founded in life take the most varied forms.

Usually, when pedagogic principles are laid down it is expected that they shall be carried out. They are written down in a book. The good teacher is he who carries them out punctiliously, 1, 2, 3, etc. Now I am convinced that if a dozen men, or even fewer, sit down together they can produce the most wonderful programme for what should take place in education; firstly, secondly, thirdly, etc. People are so wonderfully intelligent nowadays;—I am not being sarcastic, I really mean it—one can think out the most splendid things in the abstract. But whether it is possible to put into practice what one has thought out is quite another matter. That is a concern of Life. And when we have to deal with life,—I ask you now, life is in all of you, natural life, you are all human beings, yet you all look different. No one man's hair is like another's. Life displays its variety in the manifold varieties of form. Each man has a different face. If you lay down abstract principles, you expect to find the same thing done in every class room. If your principles are taken from life, you know that life is various, and that the same thing can be done in the most varied ways. You see, for instance, that Negroes must be regarded as human beings, and in them the human form appears quite differently. In the same way when the art of education is held as a living art, all pedantry and also every kind of formalism must be avoided. And education will be true when it is really made into an art, and when the teacher is made into an artist. It is thus possible for us in the Waldorf School to teach writing by means of art. Then reading can be learned afterwards almost as a matter of course, without effort. It comes rather later than is customary, but it comes almost of itself.

While we are concerned on the one hand in bringing the pictorial element to the child—(and during the next few days I shall be showing you something of the paintings of the Waldorf School children)—while we are engaged with the pictorial element, we must also see to it that the musical element is appreciated as early as possible. For the musical element will give a good foundation for a strong energetic will, especially when attention is paid—at this stage—not so much to musical content as to the rhythm and beat of the music, the experience of rhythm and beat; and especially when it is treated in the right manner at the beginning of the elementary school period. I have already said in the introduction to the eurhythmy demonstration that we also introduce eurhythmy into children's education. I shall be speaking further of eurhythmy, and in particular of eurhythmy in education, in a later lecture. For the moment I wished to show more by one or two examples how early instruction serves the purpose of education in so far as it is called out of the nature of the human being.

But we must bear in mind that in the first part of the stage between the change of teeth and puberty a child can by no means distinguish between what is inwardly human and what is external nature. For him up to his eighth or ninth year these two things are still merged into one. Inwardly the child feels a certain impression, outwardly he may see a certain phenomenon, for instance a sunrise. The forces he feels in himself when he suffers unhappiness or pain; he supposes to be in sun or moon, in tree or plant. We should not reason the child out of this. We must transpose ourselves into the child's stage of life and conduct everything within education as if no boundary existed as yet between inner man and outer nature. This we can only do when we form the instruction as imaginatively as possible, when we let the plants act in a human manner—converse with other plants, and so on,—when we introduce humanity everywhere. People have a horror nowadays of Anthropomorphism, as it is called. But the child who has not experienced anthropomorphism in its relation to the world will be lacking in humanity in later years. And the teacher must be willing to enter into his environment with his full spirit and soul so that the child can go along with him on the strength of this living experience.

Now all this implies that a great deal shall have happened to the teacher before he enters the classroom. The carrying through of the educational principles of which we have been speaking makes great demands on the preparation the teachers have to do. One must do as much as one possibly can before-hand when one is a teacher, in order to make the best use of the time in the class room. This is a thing which the teacher learns to do only gradually, and in course of time. And only through this slow and gradual learning can one come really to have a true regard for the child's individuality.

May I mention a personal experience in this connection, Years before my connection with the Waldorf School I had to concern myself with many different forms of education. Thus it happened that when I was still young myself I had corded to me the education of a boy of eleven years old who was exceedingly backward in his development. Up to that time he had lied nothing at all. In proof of his attainment I was shown an exercise book containing the results of the latest examination he had been pushed into. All that was to be seen in it was an enormous hole that he had scrubbed with the india-rubber; nothing else. Added to this the boy's domestic habits were of a pathological nature. The whole family was unhappy on his account, for they could not bring themselves to abandon him to a manual occupation—a social prejudice, if you like, but these prejudices have to be reckoned with. So the whole family was unhappy. The family doctor was quite explicit that nothing could be made of the boy. I was now given four children of this family to educate. The others were normal, and I was to educate this one along with them. I said: I will try—in a case like this one can make no promises that this or the other result will be achieved,—but I would do everything that lay within my power, only I must be left complete freedom in the matter of the education. So now I undertook this education. The mother was the only member of the family who understood my stipulation for freedom, so that the education had to be fought for him in the teeth of the others. But finally the instruction of the boy was confided to me. It was necessary that the time spent in immediate instruction of the boy should be as brief as possible. Thus if I had, say, to be engaged in teaching the boy for about half-an-hour, I had to do three hours' work in preparation so as to make the most economical use of the time. Moreover, I had to make careful note of the time of the music lesson, for example. For if the boy were overtaxed he turned pale and his health deteriorated. But because one understood the boy's whole pathological condition, because one knew what was to be set down to hydrocephalus, it was possible to make such progress with the boy—and not psychical progress only,—that a year and a half after he had shown up merely a hole rubbed in his exercise book, he was able to enter the Gymnasium. (Name given to the Scientific and Technical School as distinct from the Classical.) And I was further able to help him throughout the classes of the Gymnasium and follow up the work with him until near the end of his time there, Under the influence of this education, and also because everything was spiritually directed, the boy's head became smaller. I know a doctor might say perhaps his head would have become smaller in any case. Certainly, but the right nurture of spirit and soul had to go with this process of getting smaller. The person referred to subsequently became an excellent doctor. He died during the war in the exercise of his profession, but only when he was nearly forty years old.

It was particularly important here to achieve the greatest economy in the time of instruction by means of suitable preparation beforehand. Now this must become a general principle. And in the art of education of which I am here speaking this is striven for. Now, when it is a question of describing what we have to tell the children in such a way as to arouse life and liveliness in their whole being, we mast master the subject thoroughly beforehand and be so at home with the matter that we can turn all our attention and individual power to the form in which we shall present it to the child. And then we shall discover as a matter of course that all the stuff of teaching must become pictorial if a child is to grasp it not only with his intellect but with his whole being. Hence we mostly begin with tales such as fairy tales, but also with other invented stories which relate to Nature. We do not at first teach either language or any other “subject,” but we simply unfold the world itself in vivid and pictorial form before the child. And such instruction is the best preparation for the writing and reading which is to be derived imaginatively.

Thus between his ninth and tenth year the child comes to be able to express himself in writing, and also to read as far as is healthy for him at this age, and now we have reached that important point in a child's life, between his ninth and tenth year, to which I have already referred. Now you must realise that this important point in the child's life has also an outward manifestation. At this time quite a remarkable change takes place, a remarkable differentiation, between girls and boys. Of the particular significance of this in a co-educational school such as the Waldorf School, I shall be speaking later. In the meantime we must be aware that such a differentiation between boys and girls does take place. Thus, round about the tenth year girls begin to grow at a quicker rate than the boys. Growth in boys is held back. Girls overtake the boys in growth. When the boys and girls reach puberty the boys once more catch up with the girls in their growth. Thus just at that stage the boys grow more rapidly.

Between the tenth and fifteenth year the outward differentiation between girls and boys is in itself a sign that a significant period of life has been reached. What appears inwardly is the clear distinction between oneself and the world. Before this time there was no such thing as a plant, only a green thing with red flowers in which there is a little spirit just as there is a little spirit in ourselves. As for a “plant,” such a thing only makes sense for a child about its tenth year. And here we must be able to follow his feeling. Thus, only when a child reaches this age is it right to teach him of an external world of our surroundings.

One can make a beginning for instance with botany—that great stand-by of schools. But it is just in the case of botany that I can demonstrate how a formal education—in the best sense of the word—should be conducted. If we start by showing a child a single plant we do a thoroughly unnatural thing, for that is not a whole. A plant especially when it is rooted up, is not a whole thing. In our realistic and materialistic age people have little sense for what is material and natural otherwise they would feel what I have just said. Is a plant a whole thing? No, when we have pulled it up and fetched it here it very soon withers. It is not natural to it to be pulled up. Its nature is to be in the earth, to belong with the soil. A stone is a totality by itself. It can lie about anywhere and it makes no difference. But I cannot carry a plant about all over the place; it will not remain the same. Its nature is only complete in conjunction with the soil, with the forces that spring from the earth, and with all the forces of the sun which fall upon this particular portion of the earth. Together with these the plant makes a totality. To look upon a plant in isolation is as absurd as if we were to pull out a hair of our head and regard the hair as a thing in itself. The hair only arises in connection with an organism and cannot be understood apart from the organism. Therefore: In the teaching of botany we must take our start, not from the plant, or the plant family but from the landscape, the geographical region: from an understanding of what the earth is in a particular place. And the nature of plants must be treated in relation to the whole earth.

When we speak of the earth we speak as physicists, or at most as geologists. We assume that the earth is a totality of physical forces, mineral forces, self-enclosed, and that it could exist equally well if there were no plants at all upon it, no animals at all, no men at all. But this is an abstraction. The earth as viewed by the physicist, by the geologist, is an abstraction. There is in reality no such thing. In reality there is only the earth which is covered with plants. We must be aware when we are describing from a geological aspect that, purely for the convenience of our intelligence, we are describing a non-existent abstraction. But we must not start by giving a child an idea of this non-existent abstraction, we must give the child a realisation of the earth as a living organism, beginning naturally with the district which the child knows. And then, just as we should show him an animal with hair growing upon it, and not produce a hair for it to see before it knew anything of the animal—so must we first give him a vivid realisation of the earth as a living organism and after that show him how plants live and grow upon the earth.

Thus the study of plants arises naturally from introducing the earth to the child as a living thing, as an organism—beginning with a particular region. To consider one part of the earth at a time, however, is an abstraction, for no region of the earth can exist apart from the other regions; and we should be conscious that we take our start from something incomplete. Nevertheless, if, once more we teach pictorially and appeal to the wholeness of the imagination the child will be alive to what we tell him about the plants. And in this way we gradually introduce him to the external world. The child acquires a sense of the concept “objectivity.” He begins to live into reality. And this we achieve by introducing the child in this natural manner to the plant kingdom.

The introduction to the animal kingdom is entirely different—it comes somewhat later. Once more, to describe the single animals is quite inorganic. For actually one could almost say: It is sheer chance that a lion is a lion and a camel a camel. A lion presented to a child's contemplation will seem an arbitrary object however well it may be described, or even if it is seen in a menagerie. So will a camel. Observation alone makes no sense in the domain of life.

How are we to regard the animals? Now, anyone who can contemplate the animals with imaginative vision, instead of with the abstract intellect, will find each animal to be a portion of the human being. In one animal the development of the legs will predominate—whereas in man they are at the service of the whole organism. In another animal the sense organs, or one particular sense organ, is developed in an extreme manner. One animal will be specially adapted for snouting and routing (snuffling), another creature is specially gifted for seeing, when aloft in the air. And when we take the whole animal kingdom together we find that what outwardly constitutes the abstract divisions of the animal kingdom is comprised in its totality in man. All the animals taken together, synthetically, give one the human being. Each capacity or group of faculties in the human being is expressed in a one-sided form in some animal species. When we study the lion—there is no need to explain this to the child, we can show it to him in simple pictures—when we study the lion we find in the lion a particular over-development of what in the human being are the chest organs, the heart organ. The cow shows a one-sided development of what in man is the digestive system. And when I examine the white corpuscles in the human blood I see the indication of the earliest, most primitive creatures. The whole animal kingdom together makes up man, synthetically, not symptomatically, but synthetically woven and interwoven.

All this I can expound to the child in quite a simple, primitive way. Indeed I can make the thing very vivid when speaking, for instance, of the lion's nature and showing how it needs to be calmed and subdued by the individuality of man. Or one can take the moral and psychic characteristics of the camel and show how what the camel presents in a lower form is to be found in human nature. So that man is a synthesis of lion, eagle, ape, of camel, cow and all the rest. We view the whole animal kingdom as human nature separated out and spread abroad.

This, then, is the other side which the child gets when he is in his eleventh or twelfth year. After he has learned to separate himself from the plant world, to experience its objectivity and its connection with an objective earth, he then learns the close connection between the animals and man, the subjective side. Thus the universe is once more brought into connection with man, by way of the feelings. And this is educating the child by contact with life in the world.

Then we shall find that the requirements we always make are met spontaneously. In theory we can keep on saying: You must not overload the memory. It is not a good thing to burden the child's memory. Anyone can see that in the abstract. It is less easy for people to see clearly what effect the overburdening of memory has on a man's life. It means this, that later in life we shall find him suffering from rheumatism and gout—it is a pity that medical observation does not cover the whole span of a man's life, but indeed we shall find many people afflicted with rheumatism and gout, to which they had no predisposition; or else what was a very slight predisposition has been in-creased because the memory was overtaxed, because one had learned too much from memory. But, on the other hand, the memory must not be neglected. For if the memory is not exercised enough inflammatory conditions of the physical organs will be prone to arise, more particularly between the 16th and 24th years.

And how are we to hold the balance between burdening the memory too much or too little? When we teach pictorially and imaginatively, as I have described, the child takes as much of the instruction as it can bear. A relationship arises like that between eating and being satisfied. This means that we shall have some children further advanced than others, and this we must deal with, without relegating less advanced children to a class below. One may have a comparatively large class and yet a child will not eat more than it can bear—spiritually speaking—because its organism spontaneously rejects what it cannot bear. Thus we take account of life here, just as we draw our teaching from life.

A child is able to take in the elements of Arithmetic at quite an early age. But in arithmetic we observe how very easily an intellectual element can be given the child too soon. Mathematics as such is alien to no man at any age. It arises in human nature; the operations of mathematics are not foreign to human faculty in the way letters are foreign in a succeeding civilisation. But it is exceedingly important that the child should be introduced to arithmetic and mathematics in the right way. And what this is can really only be decided by one who is enabled to overlook the whole of human life from a certain spiritual standpoint.

There are two things which in logic seem very far removed from one another: arithmetic and moral principles. It is not usual to hitch arithmetic on to moral principles because there seems no obvious logical connection between them. But it is apparent to one who looks at the matter, not logically, but livingly, that the child who has a right introduction to arithmetic will have quite a different feeling of moral responsibility from the child who has not. And—this may seem extremely paradoxical to you, but since I am speaking of realities and not of the illusions current in our age, I will not be afraid of seeming paradoxical, for in this age truth often seems paradoxical.—If, then, men had known how to permeate the soul with mathematics in the right way during these past years we should not now have bolshevism in Eastern Europe. This it is that one perceives: what forces connect the faculty used in arithmetic with the springs of morality in man.

Now, you will understand this better probably if I give you a very small illustration of the principles of arithmetic teaching. It is common nowadays to start arithmetic by the adding of one thing to another. But just consider how foreign a thing it is to the human mind to add one pea to another and at each addition to name a new name. The transition from one to two, and then to three,—this counting is quite an arbitrary activity for the human being. But it is possible to count in another way. And this we find when we go back a little in human history. For originally people did not count by putting one pea to another and hence deriving a new thing which, for the soul at all events, had little connection with what went before. No, men counted more or less in the following way: They would say: What we get in life is always a whole, something to be grasped as a whole; and the most diverse things can constitute a unity. If I have a number of people in front of me, that can be a unity at first sight. Or if I have a single man in front of me, he then is a unity. A unity, in reality, is a purely relative thing. And I keep this in mind if I count in the following way: One | = | two | = | = | three | = | = | = | four | = | = | =| = | and so on, that is, when I have an organic whole (a whole consisting of members): because then I am starting with unity, and in the unity, viewed as a multiplicity, I seek the parts. This indeed was the original view of number. Unity was always a totality, and in the totality one sought for the parts. One did not think of numbers as arising by the addition of one and one and one, one conceived of the numbers as belonging to the whole, and proceeding organically from the whole.

When we apply this to the teaching of arithmetic we get the following: Instead of placing one bean after another beside the child, we throw him a whole heap of beans. The bean heap constitutes the whole. And from this we make our start. And now we can explain to the child: I have a heap of beans—or if you like, so that it may the better appeal to the child's imagination: a heap of apples,—and three children of different ages who need different amounts to eat, and we want to do something which applies to actual life. What shall we do? Now we can for instance, divide the heap of apples in such a way as to give a certain heap on the one hand and portions, together equal to the first heap, on the other. The heap represents the sum. Here we have the heap of apples, and we say: Here are three parts, and we get the child to see that the sum is the same as the three parts. The sum = the three parts. That is to say, in addition we do not go from the parts to arrive at the sum, but we start with the sum and proceed to the parts. Thus to get a living understanding of addition we start with the whole and proceed to the addenda, to the parts. For addition is concerned essentially with the sum and its parts, the members which are contained, in one way or another, within the sum.

In this way we get the child to enter into life with the ability to grasp a whole, not always to proceed from the less to the greater. And this has an extraordinarily strong influence upon the child's whole soul and mind. When a child has acquired the habit of adding things together we get a disposition which tends to be desirous and craving. In proceeding from the whole to the parts, and in treating multiplication similarly, the child has less tendency to acquisitiveness, rather it tends to develop what, in the Platonic sense, the noblest sense of the word, can be called considerateness, moderation. And one's moral likes and dislikes are intimately bound up with the manner in which one has learned to deal with number. At first sight there seems to be no logical connection between the treatment of numbers and moral ideas, so little indeed that one who will only regard things from the intellectual point of view, may well laugh at the idea of any connection. It may seem to him absurd. We can also well understand that people may laugh at the idea of proceeding in addition from the sum instead of from the parts. But when one sees the true connections in life one knows that things which are logic-ally most remote are often in reality exceedingly near.

Thus what comes to pass in the child's soul by working with numbers will very greatly affect the way he will meet us when we want to give him moral examples, deeds and actions for his liking or disliking, sympathy with the good, antipathy with the evil. We shall have before us a child susceptible to goodness when we have dealt with him in the teaching of numbers in the way described.

Die Erziehung der jüngeren Kinder: Der Lehrer als Erziehungskünstler I

Wie sich der Zahnwechsel beim Kinde um das 7. Jahr herum allmählich vollzieht, so ist das auch in einem noch höheren Grade mit dem großen Umschwung im körperlichen, seelischen und geistigen Organismus, von dem ich in dieser Darstellung gesprochen habe. Und daher muß auch bei Erziehung und Unterricht darauf Rücksicht genommen werden, daß das Kind aus einem nachahmenden Wesen allmählich ein solches wird, das auf die Autorität des Erziehenden, des Unterrichtenden hin sich heranbildet. Deshalb darf auch nicht ein schroffer Übergang gemacht werden in der Behandlung des Kindes um das 7. Jahr herum, also in dem Lebensalter, in dem man es zum Erziehen in die elementare Schule bekommt. Das weiter hier über den Anfang der Erziehung in der Elementarschule Gesagte muß in diesem Sinne aufgefaßt werden.

In der Erziehungskunst, von der hier die Rede ist, soll alles darauf angelegt sein, dasjenige in seiner Entwickelung zu pflegen, was im Kinde veranlagt ist. Daher muß aller Unterricht in den Dienst der Erziehung gestellt sein. Eigentlich erzieht man, und den Unterricht benützt man gewissermaßen, um zu erziehen.

Das hier vertretene Erziehungsprinzip erfordert, daß das Kind im richtigen Lebensalter die richtige Orientierung im Leben ausbildet. Allein das ist nur in befriedigender Weise möglich, wenn man das Kind nicht von vornherein zu etwas Unnatürlichem in seiner Betätigung veranlaßt.

Es ist aber in einem gewissen Sinne etwas durchaus Unnatürliches, wenn man in der gegenwärtigen Zeit auf einer vorgerückten Zivilisationsstufe der Menschheit das Kind in seinem 6. oder 7. Lebensjahre unmittelbar veranlaßt, die Formen der Lesezeichen und des Schreibens nachzubilden, die üblich sind.

Wenn man dasjenige in Betracht zieht, was man heute als Buchstaben hat für das Lesen und Schreiben, so muß man sich sagen, daß kein Zusammenhang besteht zwischen demjenigen, was das Kind in seinem 7. Jahre aus seiner Veranlagung heraus gestalten will, und diesen Buchstaben. Man bedenke, daß die Menschheit, als sie angefangen hat zu schreiben, sich malerischer Zeichen bedient hat, die eine Sache oder einen Vorgang der Außenwelt nachahmten; oder es wurde aus dem Willen heraus geschrieben so, daß die Schriftformen Willensvorgänge zum Ausdruck brachten, wie zum Beispiel bei der Keilschrift. Aus dem, was als Bilderschrift entstanden ist, entwickelten sich erst die ganz abstrakten Buchstabenformen, auf die heute das Auge geheftet wird oder die aus der schreibenden Hand heraus sich formen.

Bringen wir dem ganz jungen Kinde diese Buchstaben bei, so fügen wir ihm etwas ganz Fremdes zu, was gar nicht seiner Natur entspricht. Wir müssen uns aber klar sein darüber, was das bedeutet, wenn wir etwas Fremdes in dasKind, in den ganzen kindlichen Organismus einfach hineinschieben. Es ist so, wie wenn wir das Kind frühzeitig daran gewöhnen würden, ganz enge Kleider zu tragen, die ihm nicht passen, und die dann seinen Organismus ruinieren. Heute, wo man, ich möchte sagen, nur oberflächlich beobachtet, sieht man eben nicht ein, was im späteren Alter an Hemmungen im eigenen Organismus da ist, einfach aus dem Grunde, weil man in falscher Weise mit dem Lesen und Schreiben an das Kind herangekommen ist.

Erziehungskunst, die auf Menschenerkenntnis beruht, geht so vor, daß sie wirklich alles aus dem Kinde heraus entwickelt, nicht bloß sagt, es soll die Individualität entwickelt werden, sondern es auch wirklich tut. Das erreicht man dadurch, daß man zunächst überhaupt nicht vom Lesen ausgeht. Das Kind geht auch vom Zappeln aus, von Willensäußerungen, nicht vom Anschauen. Das Anschauen kommt erst später. Und so ist es nötig, nicht vom Lesen auszugehen, sondern vom Schreiben, aber das Schreiben auch so zu betreiben, daß es aus der ganzen Menschenwesenheit als etwas Selbstverständliches herauskommt. Daher beginnen wir mit dem Schreibunterricht, nicht mit dem Leseunterricht, und versuchen allmählich dasjenige, was das Kind in der Nachahmung selber entwickeln will durch seinen Willen, durch seine Hände, auch hinzuleiten zum Schreiben.

Ich möchte es Ihnen anschaulich machen an einem Beispiel. Denken Sie sich, wir veranlassen das Kind dazu, das Wort «Fisch» zu sagen, und indem wir es dazu veranlassen, das Wort zu sagen, versuchen wir, mit ganz einfachen Linien die Form des Fisches ihm vor Augen zu führen, etwa so (es wird gezeichnet), daß wir in einfacher Weise so etwas dem Kinde vormalen, was die Form des Fisches imitiert, und dann auch versuchen, das von dem Kinde nachmalen zu lassen. Und dann bringen wir das Kind dazu, zu empfinden vom Wort «Fisch», das F. Vom «Fisch» gehen wir über zu F, und wir haben aus der Form des Fisches die Möglichkeit, nach und nach das F zu gestalten. Wir lassen also künstlerisch aus demjenigen, was aus der Anschauung in den Willen hineingeht, die Buchstabenform entstehen.

Auf diese Weise bringen wir nicht ein fremdes F; das ist ein Dämon für das Kind, das ist etwas, was als ganz Fremdes in seinen Leib hineingestopft wird; wir bringen dasjenige, was das Kind auf dem Markte gesehen hat, aus dem Kinde heraus. Wir verwandeln das nach und nach in das F.

Wir kommen dadurch nahe der Entstehung der Schrift, denn so, in ähnlicher Weise, ist auch die Schrift entstanden. Aber es ist nicht nötig, daß der Lehrer antiquarische Studien macht und gleichsam wiederholt dasjenige, wie die Bilderschrift entstanden ist, um nun wiederum das dem Kinde beizubringen. Das, um was es sich handelt, ist, eine lebendige Phantasie walten zu lassen, und das heute noch entstehen zu lassen, was vom Gegenstand, vom unmittelbaren Leben in die Buchstabenformen hineinführt. Sie werden da jede mögliche Gelegenheit haben, dem Kinde Buchstabenformen aus dem Leben heraus abzuleiten. Lassen Sie es M sprechen, lassen Sie es fühlen, wie das M auf den Lippen vibriert, und versuchen Sie ihm dann die Form der Lippe als Form beizubringen, dann werden Sie von dem M, das auf der Lippe vibriert, übergehen können nach und nach zu dem ZeichenM. Und so werden Sie, wenn Sie nicht intellektualistisch, sondern spirituell, imaginativ vorzugehen versuchen, alles aus dem Kinde herausholen können, was nach und nach dazu führt, daß das Kind schreiben lernt. Es lernt langsamer schreiben, als es heute oftmals schreiben lernt. Aber wenn dann die Eltern kommen und sagen: Mein Kind ist acht Jahre alt, neun Jahre alt, und kann noch nicht gut schreiben! — so müssen wir ihnen immer sagen: Alles dasjenige, was langsamer gelernt wird in einem gewissen Lebensalter, das lebt sich sicherer und gesunder in den Lebensorganismus hinein, als was hineingepfropft wird.

Wichtig ist dabei, daß auf diese Weise durchaus auch die Individualität des Lehrers zum Ausdrucke kommt. Da wir in der Waldorfschule schon viele Schüler haben, mußten wir Parallelklassen errichten, wir haben zwei 1. Klassen, zwei 2. und so weiter. Sie können, wenn Sie in die eine 1. Klasse kommen, sehen, wie da der Schreibunterricht aus dem Malen, aus dem Zeichnen herausgeholt wird, Sie können da sehen, wie die Lehrkraft das in einer gewissen Weise macht. Sagen wir, in der einen Klasse finden Sie, daß das gerade so gemacht wird, wie hier jetzt gezeigt worden ist. Sie gehen in die andere Klasse, in die 1. Klasse B hinein; Sie finden eine andere Lehrkraft; da wird derselbe Unterricht erteilt, Sie sehen aber etwas ganz anderes. Sie sehen, daß da die Lehrkraft die Kinder in einer Art eurythmischer Bewegung herumlaufen läßt, aus der eigenen Körperbewegung heraus die Form entstehen läßt. Und dasjenige, was das Kind abläuft, das wird dann als Buchstabe fixiert. Und so ist eine dritte Art, eine vierte Art und so weiter möglich. Sie können denselben Unterricht in den verschiedenen Parallelklassen in der verschiedensten Weise erteilt sehen. Warum? Ja, weil es nicht gleichgültig ist, ob eine Lehrkraft mit diesem "Temperament und eine andere Lehrkraft mit einem anderen Temperament den Unterricht erteilt. Nur dann, wenn der richtige Kontakt ist zwischen der Lehrkraft und der ganzen Klasse, kann der Unterricht heilsam sein. Daher muß jede Lehrkraft so, wie es ihr entspricht, den Unterricht erteilen. Aber so, wie das Leben in den verschiedensten Formen erscheinen kann, so kann auch ein Unterricht, eine Erziehung, die auf das Leben gebaut ist, in den verschiedensten Formen erscheinen.

Wenn man pädagogische Grundsätze aufstellt, dann verlangt man, sie sollen befolgt werden. Man schreibt sie in ein Buch. Und derjenige ist ein guter Lehrer, der diese Grundsätze: 1, 2, 3 und so weiter befolgt. Nun, ich bin ganz davon überzeugt, wenn sich heute 12 oder sonst eine Anzahl von Menschen eben zusammensetzen — die Menschen sind heute alle furchtbar gescheit und klug -, sie bringen das wunderbarste Programm zusammen über dasjenige, was in der Erziehung geschehen soll: 1.,2.,3. und so weiter. Ich spreche nicht Hohn aus, ich meine das wirklich; man kann in abstrakten Grundsätzen das Wunderbarste ausdenken. Aber ob man dieses, was man ausgedacht hat, auch verwirklichen kann, das ist eine ganz andere Frage. Da kommt es auf das Leben an. Und beim Leben - ich frage Sie, in Ihnen allen ist Leben, Sie sind alle Menschen, aber Sie sehen doch alle anders aus. Keiner gleicht aufs Haar dem anderen. Das Leben vermannigfaltigt sich in der mannigfaltigsten Gestalt. Jeder trägt ein anderes Antlitz. Wenn man abstrakte Grundsätze aufstellt, geht man in die Schulklasse hinein, und überall möchte man wünschen, daß dasselbe gemacht werde. Wenn man aus dem Leben heraus Grundsätze aufstellt, weiß man, wie das Leben mannigfaltig ist, wie sich das eine in der allerverschiedensten Weise verwirklicht. Denn selbst die Neger müssen wir als Menschen ansehen, und in ihnen ist ja die menschliche Gestalt in einer ganz anderen Weise verwirklicht als in uns, zum Beispiel. Und so handelt es sich darum, daß jede Art von Pedanterie, aber auch jede Art von Schematismus ferngehalten werden muß, wenn Erziehungskunst als etwas Lebendiges aufgefaßt wird, was eben dadurch unterstützt wird, daß die Erziehungskunst zu einer wirklichen Kunst gemacht wird, der Lehrer zu einem Künstler gemacht wird. So sind wir in der Waldorfschule in der Lage, aus dem Künstlerischen heraus das Schreiben zu lehren. Dann läßt sich das Lesen nachher wie von selbst lernen. Es kommt etwas später als gewöhnlich, aber es läßt sich wie von selbst lernen.

Ist man unmittelbar so darinnen — und ich werde in den nächsten Tagen etwas von den Malereien unserer Kinder in der Waldorfschule zu zeigen haben -, ist man so darinnen, einerseits das bildnerische Element an das Kind heranzubringen, so handelt es sich für uns darum, nun auch möglichst früh das musikalische Element im Unterricht zu verwerten. Denn das musikalische Element, namentlich wenn weniger auf das Inhaltliche der Musik, als auf Rhythmus und Takt, und das Erfühlen von Rhythmus und Takt gesehen wird, wird eine gute Grundlage für die Stärke, für die Energie des Willens geben, namentlich wenn es im Beginne der Elementarschule schon in der richtigen Weise gepflegt wird. Und ich habe in der Einleitung zu der Eurythmievorstellung ja gesagt, daß wir auch die Eurythmie im Kindesunterricht einführen. Davon, gerade von der Eurythmie im Unterrichte, werde ich noch in einem späteren Vortrage zu sprechen haben. Zunächst wollte ich dieses mehr im einzelnen zeigen, wie der erste Unterricht als Erziehung herausgeholt wird auf künstlerische Weise, aus der Natur des Menschen selbst.

Wir müssen berücksichtigen, daß das Kind in der ersten Zeit seiner Lebensepoche zwischen dem Zahnwechsel und der Geschlechtsreife vor allen Dingen noch nicht unterscheiden kann zwischen dem, was innerlich Mensch ist und demjenigen, was äußerlich Umgebung, Natur ist. Beides wächst noch für das Kind bis zum 9., 10. Jahre in eines zusammen. Das Kind fühlt innerlich dieses oder jenes. Es schaut äußerlich, sagen wir, einen Vorgang, die Sonne aufgehen oder dergleichen. Dieselben Kräfte, die es in sich vermutet, wenn ihm Unlust, Schmerz bereitet wird, vermutet es auch in Sonne und Mond, in Baum und Pflanze. Wir sollen dem Kinde das nicht ausreden. Wir sollen uns hineinversetzen in das kindliche Lebensalter, und ebenso in der Erziehung vor dem 9. Jahre alles behandeln, wie wenn eine Grenze noch nicht gezogen wäre zwischen dem Menschen-Inneren und dem Natur-Außen. Das können wir nur, wenn wir den Unterricht möglichst bildhaft gestalten, wenn wir die Pflanzen menschlich handeln lassen, sie mit der anderen Pflanze menschlich sprechen lassen, wenn wir die Sonne mit dem Mond sprechen lassen, wenn wir überall hinein das Menschliche versetzen. Man hat heute eine wahre Scheu vor dem sogenannten Anthropomorphismus. Aber dasjenige Kind, das den Anthropomorphismus in seinem Verhältnis zu der Umwelt nicht erlebt hat, dem fehlt ein Teil vom Menschsein im späteren Alter, und der Lehrer muß eine Neigung haben, sich nun auch so in die ganze Umgebung lebendig geistig-seelisch hineinzuversetzen, daß das Kind durchaus mitgehen kann vermöge dessen, was in ihm vorhanden ist.

Das allerdings setzt voraus, daß für den Lehrer ungeheuer viel geschehen ist, bevor er die Klasse betritt. Auf die Vorbereitung, die der Lehrer zu leisten hat, wird große Anforderung gestellt unter dem Einfluß des Erziehungsprinzipes, von dem wir gesprochen haben. Man muß möglichst viel vorher tun als Lehrer, um nachher möglichst die Zeit ausnützen zu können, in der man in der Klasse ist. Das lernt sich auch für den Lehrer nur langsam und allmählich. Und nur durch dieses langsame und allmähliche Lernen gelangt man dahin, die Individualität des Kindes wirklich zu berücksichtigen.

Vielleicht darf ich dafür ein persönliches Beispiel anführen, Ich habe mich ja, bevor ich mich mit der Waldorfschule zu befassen hatte, lange Zeit früher mit allerlei Erziehungen befassen müssen. So wurde mir einmal, als ich selber noch jung war, ein Knabe zur Erziehung übertragen, der gegen sein 11. Jahr hin im Grunde genommen noch ganz unentwickelt war. Er hatte noch gar nichts gelernt. Als Probe für dasjenige, was er gelernt hatte, wurde mir ein Schulheft gegeben, in dem gezeigt wurde, was der Knabe beim letzten Examen, zu dem man ihn getrieben hatte, geleistet hatte. Darinnen war nur zu sehen ein großes Loch, das er mit dem Radiergummi ausradiert hatte, sonst nichts. Dabei hatte der Knabe wirklich pathologische Lebensgewohnheiten. Die ganze Familie, die nicht darauf angelegt war, den Knaben dem Handwerk zu übergeben — das mag ein Vorurteil sein, aber mit diesen Vorurteilen hat man ja natürlich im sozialen Leben zu rechnen -, die ganze Familie war unglücklich. Der Hausarzt war sich klar, aus dem Knaben könne nichts werden. Nun, ich bekam vier Kinder in dieser Familie zu erziehen. Die übrigen waren normal — diesen Knaben sollte ich miterziehen. Ich sagte: Ich werde den Versuch machen. Versprechen, daß dies oder jenes geschehe, kann man in einem solchen Falle ja nicht, aber es wird alles getan werden, was getan werden kann, nur muß man mir die Erziehung ganz vollständig in Freiheit überlassen. Allein die Mutter hatte ein Verständnis für diese Freiheit, die ich beanspruchte, so daß sogar der ganze Unterricht durchgekämpft werden mußte gegen die übrige Familie, außer der Mutter. Ich bekam aber schließlich den Unterricht. Und ich hatte nun nötig, möglichst wenig Zeit unmittelbar auf den Unterricht bei dem Knaben zu verwenden. Sagen wir, wenn ich etwa eine halbe Stunde unterrichtlich mich mit dem Knaben beschäftigen sollte, mußte ich mich drei Stunden vorher beschäftigen, um möglichst ökonomisch viel in den Unterricht hineinzuschieben. Ich mußte aber außerdem genau berechnen, in welche Tageszeit der Musikunterricht zum Beispiel geschoben wurde. Wenn das Kind überanstrengt wurde, wurde es gleich blaß, und man sah, wie seine Gesundheit herunterging. Aber, indem man die ganze pathologische Eigentümlichkeit des Kindes verstand, indem man wußte, was da auf die Hydrocephalie zu schieben war, war es möglich, nicht nur das Seelische des Kindes zu fördern, sondern es so weit vorwärts zu bringen, daß der Knabe nach einem und einem halben Jahre, nachdem er vorher nichts anderes gekonnt hatte, als ein großes Loch ausradieren in seinem Schulheft, das Gymnasium besuchen konnte. Und ich konnte ihm noch durch die Gymnasialklassen helfen, konnte ihn verfolgen bis ziemlich zum Ende des Gymnasiums. Unter dem Einflusse dieser Erziehung, dadurch also, daß man spirituell die Sache leitete, wurde der Kopf kleiner. Ich weiß, daß der Arzt vielleicht sagen wird: Der Kopf wäre auch so kleiner geworden. Gewiß, aber im Kleinerwerden mußte das Richtige seelisch und geistig geschehen. Der Betreffende ist dann ein ganz tüchtiger Arzt geworden. Er ist während des Krieges dann in seiner ärztlichen Tätigkeit gestorben, aber erst, nachdem er schon das 40. Jahr nahezu erreicht hatte.

Es handelte sich eben da ganz besonders darum, durch eine genügende Vorbereitung für das Erziehen die Ökonomie des Unterrichts zu erreichen. Nun, das muß ein allgemeines Prinzip werden. Das wird innerhalb derjenigen Erziehungskunst angestrebt, von der ich hier sprechen will. Da hat man allerdings nötig, wenn in einem leben soll dasjenige, was dann auf das Kind übergehen soll in einer solchen Beschreibung, daß die ganze Natur lebendig wird, da hat man nötig, zuerst alles, was man vorbringt, so durcharbeitet zu haben, daß man gar keinen Kampf mehr mit dem Stoff hat, daß man alles darauf verwenden kann, durch die Kraft der eigenen Persönlichkeit das zu gestalten, was man an das Kind heranbringt. Und da wird man dann schon von selbst dazu kommen, daß einem aller Unterrichtsstoff bildhaft wird, so daß das Kind sich nicht bloß mit seinem Verstande, sondern mit seinem ganzen Menschen in den Unterrichtsstoff hineinlebt.

Daher gehen wir hauptsächlich aus vom märchenhaften Erzählen, aber auch von erfundenen Erzählungen, die sich auf die Natur beziehen. Wir unterrichten eigentlich zunächst weder Sprache noch irgendeinen anderen Gegenstand, sondern wir lassen einfach die Welt vor dem Kinde bildhaft lebendig werden. Und solch ein Unterricht schließt sich in der besten Weise dann an dasjenige an, was nun auch aus der Bildhaftigkeit heraus zum Schreiben und zum Lesen führt.

So bringen wir das Kind ungefähr zwischen dem 9. und 10. Jahre dazu, daß es sich schreibend ausdrücken kann, daß es auch lesen kann, soviel es heilsam ist für dieses Lebensalter, und wir erreichen damit jenen wichtigen Punkt im Leben des Kindes, auf den ich schon hingedeutet habe, der so zwischen dem 9. und 10. Jahre liegt.

Dieser wichtige Punkt im Leben des Kindes offenbart sich ja auch im Äußeren des Menschen. Da tritt ein merkwürdiger Unterschied, eine merkwürdige Differenzierung zwischen Knaben und Mädchen ein. Ich werde noch davon zu sprechen haben, was das für eine Bedeutung hat in einer Schule, die Knaben und Mädchen untereinander hat, wie das die Waldorfschule hat. Man muß wissen, daß eine wichtige Differenzierung zwischen Knaben und Mädchen eintritt. So gegen das 10. Jahr hin fangen die Mädchen an, verhältnismäßig schneller zu wachsen als die Knaben. Die Knaben bleiben im Wachstum zurück. Die Mädchen überholen die Knaben im Wachstum. Wenn dann die Mädchen und die Knaben geschlechtsreif geworden sind, dann beginnen die Knaben wiederum die Mädchen zu überwachsen. Sie wachsen dann schneller sozusagen gerade in diesem Lebensalter.

Zwischen dem 9. und 10. Lebensjahr ist schon in der äußeren Differenzierung zwischen Knaben und Mädchen gezeigt, daß man da an einem wichtigen Lebensabschnitt ankommt. Der drückt sich darinnen aus, daß das Kind überhaupt unterscheiden lernt zwischen sich und der Natur. Vorher gibt es eigentlich gar keine Pflanze, sondern ein Wesen, das grün ist und rote Blumen hat, und in dem ein kleiner Geist drinnen ist, wie in ihm selber ein kleiner Geist drinnen ist. Pflanze, dieses Wesen, bekommt erst einen Sinn für das Kind gegen das 10. Jahr hin. Das muß man ihm nur nachfühlen können. Daher darf man den Unterricht erst gegen dieses Jahr hin so gestalten, daß man wie von einer äußeren Welt von der Umgebung spricht.

Dann kann man anfangen mit dem, was man gewöhnlich als die Schulgegenstände ansieht, zum Beispiel Pflanzenlehre. Aber gerade an der Pflanzenlehre kann ich veranschaulichen, wie man realistisch im besten Sinne des Wortes beim gestalteten Erziehen vorgehen muß. Wenn wir eine einzelne Pflanze zunächst einem Kinde vorführen, so handeln wir da ganz unnatürlich, denn das ist nichts Ganzes. Eine Pflanze, insbesondere wenn sie ausgerissen ist, ist nichts Ganzes. Die Menschen haben in unserer Zeit des Realismus, des Materialismus, wenig materiellen und naturalistischen Sinn, sonst würden sie das fühlen, was ich eben jetzt gesagt habe. Ist eine Pflanze ein Ganzes? Nein, wenn wir sie ausgerissen haben und hierher legen, so geht sie sehr bald zugrunde. Es ist nicht ihre Natur, ausgerissen zu sein. Sie ist nur etwas in dem Erdboden drinnen, mit dem Erdboden zusammen. Ein Stein ist etwas Ganzes für sich. Den kann ich überall hinlegen, er ist dasselbe. Eine Pflanze kann ich nicht überall hintragen; sie ist nicht mehr dasselbe. Sie ist nur unmittelbar dasjenige, was sie ist, mit dem Stammboden, mit den Kräften zusammen, die aus dem Boden heraussprießen, und mit all den Sonnenkräften, die gerade auf diesen Teil der Erde auffallen, da ist die Pflanze ein Ganzes. Eine Pflanze für sich zu betrachten, ist geradeso absurd, wie wenn wir ein Haar ausreißen und das Haar für sich betrachten, als ob es ein Ding für sich wäre. Das Haar entsteht ja gar nicht anders, als an einem Organismus und kann nur verstanden werden im Zusammenhang mit einem Organismus. Das heißt, man kann bei der Pflanzenlehre nicht ausgehen von der einzelnen Pflanze, namentlich nicht von der Pflanzenwesenheit, sondern von der Landschaft, dem Geographischen, von demjenigen, was die Erde an einem bestimmten Ort ist. Und im Zusammenhang mit der ganzen Erde muß Pflanzliches behandelt werden.

Wenn wir von der Erde sprechen, sprechen wir als Physiker, höchstens noch als Geologen. Wir stellen uns vor: Die Erde ist eine abgeschlossene Totalität von physischen Kräften, mineralischen Kräften, und sie könnte auch existieren, wenn gar keine Pflanze, gar keine Tiere und gar keine Menschen darauf wären. Das ist aber ein Abstraktum. Die Erde, die der Physiker, der Geologe im Auge hat, die ist ein Abstraktum. Die gibt es eigentlich gar nicht in Wirklichkeit. Es gibt nur diejenige Erde, die überall bedeckt ist von Pflanzen. Wir müssen uns bewußt sein, wenn wir eben das Geologische beschreiben, daß wir ein wesenloses Abstraktum nur zur Bequemlichkeit unserer Intelligenz beschreiben. Dem Kinde soll man aber nicht von Anfang an dieses wesenlose Abstraktum beibringen, sondern den Kindern soll man die Erde als einen Organismus lebendig machen. Zunächst natürlich die Landschaft, die das Kind kennt; und dann, wie man ihm ein Tier zeigt, auf dem Haare sind, und man nicht, wenn es gar nichts von dem Tier wüßte, ihm ein Haar verständlich machen könnte, so muß man ihm die Erde als einen lebendigen Organismus auch lebendig machen und dann zeigen, wie auf der Erde die Pflanze west und webt. So also wird man Pflanzenlehre beibringen, indem man die Erde als ein Lebendiges, als einen Organismus ihm vorführt, zunächst das Stück Landschaft, das es kennt. Dadurch hat man natürlich auch ein Abstraktum, denn eine Landschaft ist nicht möglich ohne eine andere auf der Erde; aber man muß sich dann bewußt sein, daß man auch von etwas Mangelhaftem ausgehen muß. Aber trotzdem kann man nach und nach erwecken bei dem Kinde nun wiederum aus der ganzen Bildhaftigkeit heraus dasjenige, was man nötig hat, ihm die Pflanze beizubringen.

Dadurch bringt man das Kind allmählich heran an die Außenwelt. Es bekommt das Kind ein Gefühl für den Begriff «Objektivität». Es lebt sich in das Irdische hinein. Das erreicht man am besten, wenn man das Kind in dieser natürlichen Art an die Pflanzenwelt heranführt.

Ganz anders muß es, und zwar etwas später, an die Tierwelt herangeführt werden. Wiederum, die einzelnen Tiere beschreiben, das ist etwas, was ganz unorganisch ist. Denn schließlich, man könnte doch fast sagen: Es ist ein reiner Zufall, daß ein Löwe ein Löwe, ein Kamel ein Kamel ist. Ja, an der Beobachtung des Löwen, wenn man ihn noch so gut abbildet oder sogar in der Menagerie dem Kinde vorführt, hat das Kind doch nur eine Zufallsbeobachtung; ebenso an dem Kamel. Diese Beobachtung hat gar keinen Sinn zunächst, wenn man auf das Lebendige ausgeht. Wie ist es mit dem Tiere? Nun, derjenige, der nun nicht mit abstrakter Intellektualität an das Tier herantritt, sondern mit bildhafter Anschauung, der findet in jedem Tiere ein Stück Mensch. Das eine Tier hat besonders stark die Beine ausgebildet, die beim Menschen dem Ganzen dienen. Das andere Tier hat die Sinnesorgane, ein Sinnesorgan im Extrem ausgebildet. Das eine Tier schnüffelt besonders; das andere Tier ist, wenn es in den Lüften ist, für die Augen besonders veranlagt. Und wenn wir die ganze Tierwelt zusammennehmen, so finden wir in Abstraktionen draußen verteilt als Tierwelt dasjenige, was in der Zusammenfassung den Menschen gibt. Wenn ich alle Tiere synthetisch zusammenfasse, so bekomme ich den Menschen. Irgendeine Eigenschaft, eine Fähigkeitsgruppe des Menschen ist einseitig äußerlich ausgebildet in einer Tierart. Wenn wir den Löwen studieren — wir brauchen das dem Kinde nicht so vorzuführen, wir können es ihm in einfachen Bildern vorführen -, so finden wir, daß insbesondere dasjenige, was im Menschen Brustorgane sind, Herzorgane, einseitig im Löwen ausgebildet ist. In der Kuh ist dasjenige, was im Menschen Verdauungsorgane sind, einseitig ausgebildet, und wenn ich dasjenige betrachte, was zum Beispiel in unserem Blute als weiße Blutkörperchen herumschwimmt, so bin ich auf die einfachsten, primitivsten Tiere gewiesen. Das ganze Tierreich bildet zusammen den Menschen, synthetisch, nicht summiert, aber synthetisch ineinander verwoben.

Das ist etwas, was ich durchaus in primitiver, in einfacher Weise vor dem Kinde entwickeln kann. Selbst in sehr lebendiger Form kann ich dem Kinde so etwas bringen, indem ich auf die Eigenschaften des Löwen hinweise, wie sie kalmiert sein müssen, untertauchen müssen in das, was beim Menschen eine Individualität ist. Ja selbst was moralisch und seelisch beim Kamel lebt, kann man so bringen, daß man zeigt, wie das, was im Kamel lebt, untergeordnet sich in die Menschennatur hineinfügt. So daß der Mensch eine Synthese ist von Löwe, Adler, Affe, von Kamel, von Kuh und von allem. Das ganze Tierreich betrachtet man als auseinandergelegte Menschennatur.

Das ist die andere Seite, die das Kind dann im 11., 12. Jahre in sich aufnimmt. Nachdem es die Pflanzenwelt von sich abgesondert hat, die Empfindung des Objektiven der Pflanzenwelt, das Zusammenhängen der Pflanzenwelt mit der objektiven Erde in seiner Seele hat wirken lassen, lernt es die enge Beziehung der Tierwelt zum Menschen kennen, das Subjektive. Und so wird das Universum auf eine empfindungsgemäße Weise mit dem Menschen wiederum zusammengebracht. Das Unterscheidungsvermögen wird gerade dadurch in der richtigen Weise veranlagt. Das heißt, aus dem Lebendigen der Welt heraus das Kind erziehen.

Dann werden wir sehen, daß sich dasjenige, das wir immer als Forderungen stellen, wie von selbst ergibt. Man kann lange in der abstrakten Pädagogik fordern: Du sollst das Gedächtnis des Kindes nicht überlasten. Es ist nicht gut, das Gedächtnis des Kindes zu überlasten. Das kann jeder aus der Abstraktion einsehen. Weniger klar sieht man aber ein, was Überlastung des Gedächtnisses bedeutet für das Leben des Menschen: dies, daß man im späteren Leben ihn mit Rheumatismus, Gicht beobachten kann. — Man dehnt das medizinische Beobachten leider nicht über den ganzen Lebenslauf des Menschen aus. Man kann manche Menschen mit Rheumatismus, mit Gicht beobachten, wozu sie gar nicht die Anlage hatten; man hat etwas, was als eine ganz spärliche Anlage vorhanden war, vielleicht nur dadurch heranerzogen, daß man das Gedächtnis viel überlastet hat, daß man zuviel hat erinnern müssen. Aber auch nicht zu wenig darf man das Gedächtnis belasten. Denn wenn man wieder zu wenig das Gedächtnis belastet, dann entstehen sehr leicht, namentlich schon zwischen dem 16. und 24. Jahre, empfindliche Zustände in dem physischen Organismus.

Und wie soll man die Waage halten zwischen zuviel und zuwenig an Gedächtnisbelastung? Indem man in der Weise, wie ich es geschildert habe, anschaulich bildhaft erzieht, nimmt sich nämlich das Kind so viel aus dem Unterricht, als es vertragen kann. Es entsteht ein Verhältnis wie zwischen dem Essen und Sattsein. Dadurch bekommt man allerdings verschieden fortgeschrittene Kinder, und man muß mit ihnen wiederum fertig werden, ohne daß man sie immer in dem Unterricht eine Klasse sitzen läßt. Aber man kann eine verhältnismäßig große Klasse vor sich haben, und das Kind ißt nicht mehr geistig, als es vertragen kann, wenn ich so sagen darf, weil der Organismus von selbst dasjenige zurückweist, was es nicht vertragen kann. Man rechnet also auf das Leben, so wie man auch aus dem Leben heraus selber unterrichtet und erzieht.

Früh ist das Kind bereits veranlagt für die ersten Elemente der Rechenkunst. Aber gerade bei der Rechenkunst kann man beobachten, wie nur allzuleicht ein intellektualistisches Element zu früh in das Kind hineinkommt. Rechnen als solches ist ja keinem Menschen in keinem Lebensalter ganz fremd. Es entwickelt sich aus der menschlichen Natur heraus, und es kann nicht eine solche Fremdheit zwischen den menschlichen Fähigkeiten und den Rechenoperationen eintreten wie zwischen diesen Fähigkeiten und den Buchstaben in einer folgenden Kultur. Aber dennoch, gerade darauf kommt ungeheuer viel an, daß der Rechenunterricht in richtiger Weise an das Kind herangebracht wird. Das kann im Grunde genommen nur derjenige beurteilen, der aus einer gewissen spirituellen Grundlage heraus das gesamte menschliche Leben beobachten kann.

Zwei Dinge liegen logisch scheinbar einander recht fern: Rechenunterricht und moralische Prinzipien. Man rückt gewöhnlich gar nicht den Rechenunterricht an die moralischen Prinzipien heran, weil man keinen logischen Zusammenhang zunächst findet. Aber für den, der nun nicht bloß logisch, sondern lebensvoll betrachtet, für den stellt sich die Sache so, daß das eine Kind, das in der richtigen Weise an das Rechnen herangebracht worden ist, ein ganz anderes moralisches Verantwortungsgefühl im späteren Alter hat, als dasjenige Kind, das nicht in der richtigen Weise an das Rechnen herangebracht worden ist. Und, es wird Ihnen vielleicht außerordentlich paradox erscheinen, aber da ich über Wirklichkeiten spreche, und nicht über dasjenige, was sich unser Zeitalter einbildet, so möchte ich, da die Wahrheit unserem Zeitalter oftmals paradox erscheint, auch nicht zurückschrecken vor solchen Paradoxien. Wenn wir nämlich verstanden hätten als Menschen, in den verflossenen Jahrzehnten die menschliche Seele in der richtigen Weise in den Rechenunterricht tauchen zu lassen, hätten wir heute keinen Bolschewismus im Osten von Europa. Das ist dasjenige, was sich ergibt, was man innerlich sieht: mit welchen Kräften diejenige Fähigkeit, die im Rechnen sich auslebt, sich verbindet mit dem, was auch das Moralische im Menschen ergreift.

Nun werden Sie vielleicht mich noch besser verstehen, wenn ich ein klein wenig das Prinzip des Rechenunterrichts Ihnen darlege. Heute geht doch vielfach das Rechnen davon aus, daß wir zunächst damit beginnen, daß wir eins zum anderen hinzufügen. Allein bedenken Sie, welche fremde Betätigung das für die menschliche Seele ist, daß man eine Erbse zu den anderen hinzufügt, und immer wenn etwas hinzugefügt ist, man wieder einen neuen Namen gibt. Der Übergang von eins zu zwei, dann wiederum zu drei, dieses Zählen ist ja etwas, was ganz wie willkürlich im Menschen als Tätigkeit sich vollzieht. Aber es gibt eine andere Möglichkeit, zu zählen. Wir finden diese Möglichkeit, wenn wir etwas in der menschlichen Kulturgeschichte zurückgehen. Denn ursprünglich wurde gar nicht so gezählt, daß man eine Erbse zu der anderen legte, Einheit zu Einheit hinzulegte, und dadurch etwas Neues entstand, was wenigstens zunächst für das Seelenleben außerordentlich wenig mit dem Vorhergehenden zu tun hat. Aber man zählte etwa in der folgenden Weise. Man sagte sich: Was man im Leben hat, ist immer ein Ganzes, das man als Ganzes aufzufassen hat, und es kann das Verschiedenste eben eine Einheit sein. Wenn ich einen Volkshaufen vor mir habe, so ist er zunächst eine Einheit. Wenn ich einen einzelnen Menschen vor mir habe, ist er auch eine Einheit. Die Einheit ist im Grunde genommen etwas ganz Relatives. Das berücksichtige ich, wenn ich nicht zähle 1, 2, 3, 4 und so fort, sondern wenn ich in der folgenden Weise zähle: und so weiter, wenn ich das Ganze gliedere, weil ich also von der Einheit ausgehe, und in der Einheit als Mannigfaltigkeit die Teile suche. Das ist auch die ursprüngliche Anschauung vom Zählen. Die Einheit war immer das Ganze, und in der Einheit suchte man erst die Zahlen. Man dachte sich nicht die Zahlen entstehend als 1 zu 1 hinzugefügt, sondern man dachte sich die Zahlen alle als in einer Einheit darinnen, aus der Einheit organisch hervorgehend.

Das, angewendet auf den ganzen Rechenunterricht, gibt das Folgende: Sie werfen, statt daß Sie Erbse zu Erbse hinzulegen, einen Erbsenhaufen dem Kinde hin. (Es wird gezeichnet.) Der Erbsenhaufe ist das Ganze. Von dem geht man aus. Und jetzt bringt man etwa dem Kinde bei: Ich habe den Erbsenhaufen, oder, sagen wir, damit es für das Kind empfindlich anschaulich wird, einen Haufen von Äpfeln und 3 Kinder, vielleicht 3 Kinder von verschiedenem Alter, die verschieden stark zu essen haben, und wir wollen etwas tun, was mit dem Leben zusammenhängt. Was können wir da tun? Nun, wir können das tun, daß wir den Äpfelhaufen in einer gewissen Weise teilen, und daß wir dann den ganzen Haufen als Summe betrachten gleich den einzelnen Teilen, in die wir ihn aufgeteilt haben. Wir haben den Äpfelhaufen dort, und wir sagen: Wir haben 3 Teile, und bringen so dem Kinde bei, daß die Summe gleich ist den 3 Teilen. Summe = 3 Teile. Das heißt, wir gehen bei der Addition nicht von den einzelnen Teilen aus und haben nachher die Summe, sondern wir nehmen zuerst dieSumme und gehen zu den Teilen über. So gehen wir von dem Ganzen aus, und gehen zu den Addenden, zu den Teilen über, um auf diese Weise ein lebendiges Erfassen der Addition zu haben. Denn dasjenige, worauf es in der Addition ankommt, das ist immer die Summe, und die Teile, die Glieder sind dasjenige, was in der Summe in einer gewissen Weise drinnen sein muß.

So ist man in der Lage, das Kind heranzubringen an das Leben in der Art, daß es sich hineinfügt, Ganzheiten zu erfassen, nicht immer von dem Wenigen zu dem Mehr überzugehen. Und das übt einen außerordentlich starken Einfluß auf das ganze Seelenleben des Kindes. Wenn das Kind daran gewöhnt wird, hinzuzufügen, dann entsteht eben jene moralische Anlage, die vorzugsweise ausbildet das nach dem Begehrlichen Hingehen. Wenn von dem Ganzen zu den Teilen übergegangen wird, und wenn entsprechend so auch die Multiplikation ausgebildet wird, so bekommt das Kind die Neigung, nicht das Begehrliche so stark zu entwickeln, sondern es entwickelt dasjenige, was im Sinne der platonischen Weltanschauung genannt werden kann die Besonnenheit, die Mäßigkeit im edelsten Sinne des Wortes. Und es hängt innig zusammen dasjenige, was einem im Moralischen gefällt und mißfällt, mit der Art und Weise, wie man mit den Zahlen umzugehen gelernt hat. Zwischen dem Umgehen mit den Zahlen und den moralischen Ideen, Impulsen, scheint ja zunächst kein logischer Zusammenhang, so wenig, daß derjenige, der nur intellektualistisch denken will, darüber höhnen kann, wenn man davon spricht. Es kann ihm lächerlich vorkommen. Man begreift es auch ganz gut, wenn jemand lachen kann darüber, daß man beim Addieren von der Summe ausgehen soll, und nicht von dem Addenden. Aber wenn man die wirklichen Zusammenhänge im Leben ins Auge faßt, dann weiß man, daß die logisch entferntesten Dinge im wirklichen Dasein einander oftmals sehr nahe stehen.

So ist dasjenige, was sich herausarbeitet in der kindlichen Seele durch die Behandlung mit den Zahlen, von ungeheurer Wichtigkeit für die Art und Weise, wie das Kind uns dann entgegenkommt, wenn wir ihm moralische Beispiele vor die Seele führen wollen, an denen es Gefallen oder Mißfallen, Antipathie oder Sympathie mit dem Guten oder Bösen entwickeln soll. Wir werden ein Kind vorfinden, das empfänglichen Sinn hat für das Gute, wenn wir das Kind in der entsprechenden Weise behandelt haben, mit den Zahlen umzugehen.

The education of younger children: The teacher as an educational artist I

Just as children's teeth gradually change around the age of 7, so too does a major transformation take place in their physical, emotional, and mental organisms, as I have discussed in this presentation. Therefore, education and teaching must take into account that the child gradually develops from an imitative being into one who is shaped by the authority of the educator and teacher. For this reason, there should be no abrupt transition in the treatment of the child around the age of 7, i.e., the age at which they enter elementary school for their education. What is said here about the beginning of education in elementary school must be understood in this sense.

In the art of education discussed here, everything should be designed to nurture what is inherent in the child's development. Therefore, all teaching must be placed at the service of education. In fact, one educates, and one uses teaching, so to speak, to educate.

The educational principle advocated here requires that the child develop the right orientation in life at the right age. However, this is only possible in a satisfactory way if the child is not encouraged from the outset to do something unnatural in its activities.

However, in a certain sense, it is quite unnatural in the present age, at an advanced stage of civilization, to immediately encourage children in their sixth or seventh year of life to reproduce the usual forms of reading and writing.

When one considers what we have today as letters for reading and writing, one must say that there is no connection between what the child wants to create in its seventh year based on its predisposition and these letters. It should be remembered that when humanity began to write, it used pictorial signs that imitated a thing or a process in the outside world; or it was written out of the will in such a way that the forms of writing expressed processes of the will, as in cuneiform writing, for example. From what emerged as pictorial writing, the completely abstract letter forms developed, which today catch the eye or are formed by the writing hand.

When we teach these letters to very young children, we are adding something completely foreign to them, something that does not correspond to their nature at all. But we must be clear about what it means when we simply push something foreign into the child, into the whole child's organism. It is like getting the child used to wearing very tight clothes at an early age, clothes that do not fit and then ruin their organism. Today, when people only observe superficially, they do not realize what inhibitions will be present in their own organism later in life, simply because they approached the child in the wrong way with reading and writing.

The art of education based on knowledge of human nature proceeds in such a way that it truly develops everything in the child, not merely saying that individuality should be developed, but actually doing so. This is achieved by not starting with reading at all. The child also starts with fidgeting, with expressions of will, not with looking. Looking comes later. And so it is necessary not to start with reading, but with writing, but to practice writing in such a way that it emerges from the whole human being as something natural. Therefore, we begin with writing lessons, not reading lessons, and gradually try to guide what the child wants to develop in imitation through its own will, through its hands, towards writing.

I would like to illustrate this with an example. Imagine we encourage the child to say the word “fish,” and by encouraging them to say the word, we try to show them the shape of the fish with very simple lines, something like this (it is drawn), so that we simply draw something for the child that imitates the shape of the fish, and then we also try to get the child to copy it. And then we get the child to feel the word “fish,” the F. From “fish” we move on to F, and we have the opportunity to gradually form the F from the shape of the fish. So we artistically let the letter form arise from what enters the will from the observation.

In this way, we do not introduce a foreign F; that is a demon for the child, something that is stuffed into its body as something completely foreign; we bring out of the child what it has seen at the market. We gradually transform this into the F.

This brings us close to the origin of writing, because writing came into being in a similar way. But it is not necessary for the teacher to engage in antiquarian studies and repeat, as it were, how pictorial writing came into being in order to teach this to the child. What is important is to allow a lively imagination to prevail and to let what leads from the object, from immediate life, into the forms of letters arise today. You will have every opportunity to derive letter forms from life for the child. Let them say M, let them feel how the M vibrates on their lips, and then try to teach them the shape of the lip as a form, then you will be able to move gradually from the M vibrating on the lip to the sign M. And so, if you try to proceed not intellectually but spiritually and imaginatively, you will be able to bring out everything in the child that will gradually lead to the child learning to write. It will learn to write more slowly than it often learns to write today. But when the parents come and say, "My child is eight years old, nine years old, and still can't write well! — we always have to tell them: Everything that is learned more slowly at a certain age is integrated more securely and healthily into the organism of life than what is grafted onto it.

It is important that the individuality of the teacher is also expressed in this way. Since we already have many students at the Waldorf school, we had to set up parallel classes; we have two first grades, two second grades, and so on. When you come to one of the first grades, you can see how writing lessons are derived from painting and drawing; you can see how the teacher does this in a certain way. Let's say that in one class you find that this is done exactly as has just been shown here. You go into the other class, first grade B, and you find a different teacher; the same lesson is being taught, but you see something completely different. You see that the teacher has the children running around in a kind of eurythmic movement, allowing the form to emerge from their own body movements. And what the child runs out is then fixed as a letter. And so a third way, a fourth way, and so on, is possible. You can see the same lesson being taught in different ways in different parallel classes. Why? Because it is not irrelevant whether one teacher with this temperament and another teacher with a different temperament teaches the lesson. Only when there is the right contact between the teacher and the whole class can the lesson be beneficial. Therefore, every teacher must teach in the way that suits them. But just as life can appear in many different forms, so too can a lesson, an education based on life, appear in many different forms.

When you establish educational principles, you demand that they be followed. You write them down in a book. And a good teacher is one who follows these principles: 1, 2, 3, and so on. Well, I am quite convinced that if 12 or any other number of people get together today—people today are all terribly clever and intelligent—they will come up with the most wonderful program for what should happen in education: 1, 2, 3, and so on. I am not being sarcastic, I really mean it; one can come up with the most wonderful things in abstract principles. But whether what one has come up with can also be realized is a completely different question. That depends on life. And when it comes to life—I ask you, there is life in all of you, you are all human beings, but you all look different. No two are exactly alike. Life manifests itself in the most diverse forms. Everyone has a different face. When you establish abstract principles, you go into the classroom and want everyone to do the same thing. When you establish principles based on life, you know how diverse life is, how one thing can be realized in the most diverse ways. For even Negroes must be regarded as human beings, and in them the human form is realized in a completely different way than in us, for example. And so it is important that any kind of pedantry, but also any kind of schematism, must be kept at bay if the art of education is to be understood as something alive, which is supported by the fact that the art of education is made into a real art, and the teacher is made into an artist. Thus, in the Waldorf school, we are in a position to teach writing from an artistic perspective. Then reading can be learned afterwards as if by itself. It comes a little later than usual, but it can be learned as if by itself.

Once you are directly involved in this – and in the next few days I will be showing some of the paintings by our children at the Waldorf school – once you are involved in introducing the child to the visual element, it is important for us to also make use of the musical element in teaching as early as possible. For the musical element, especially when less attention is paid to the content of the music than to rhythm and beat, and to the feeling of rhythm and beat, will provide a good foundation for strength, for the energy of the will, especially if it is cultivated in the right way at the beginning of elementary school. And in the introduction to the eurythmy presentation, I said that we also introduce eurythmy into children's lessons. I will talk more about this, specifically about eurythmy in lessons, in a later lecture. First, I wanted to show in more detail how the first lessons are brought out in an artistic way, from the nature of the human being itself.