Spiritual Ground of Education

GA 305

22 August 1922, Oxford

VI. The Teacher as Artist in Education

The importance for the educator of knowing man as a whole is seen particularly clearly when we observe the development of boys and girls between their eleventh and twelfth years. Usually only what we might call the grosser changes are observed, the grosser metamorphoses of human nature, and we have no eye for the finer changes. Hence we believe we can benefit the child simply by thinking: what bodily movements should the child make to become physically strong P But if we want to make the child's body strong, capable and free from cramping repressions we must reach the body during childhood by way of the soul and spirit.

Between the 11th and 12th year a very great change takes place in the human being. The rhythmic system—breathing system and system of blood circulation—is dominant between the change of teeth and puberty. When the child is nearly ten years old the beat and rhythm of the blood circulation and breathing system begin to develop and pass into the muscular system. The muscles become saturate with blood and the blood pulses through the muscles in intimate response to man's inner nature—to his own heart. So that between his 9th and 11th years the human being builds up his own rhythmic system in the way which corresponds to its inner disposition. When the 11th or 12th year is reached, then what is within the rhythmic system and muscular system passes over into the bone system, into the whole skeleton. Up to the 11th year the bone system is entirely embedded in the muscular system. It conforms to the muscular system. Between the 11th and 12th years the skeleton adapts itself to the outer world. A mechanic and dynamic which is independent of the human being passes into the skeleton. We must accustom ourselves to treating the skeleton as though it were an entirely objective thing, not concerned with man.

If you observe children under eleven years old you will see that all their movements still come out of their inner being. If you observe children of over 12 years old you will see from the way they step how they are trying to find their balance, how they are inwardly adapting themselves to the leverage and balance, to the mechanical nature of the skeletal system. This means: Between the 11th and 12th year the soul and spirit nature reaches as far as the bone-.system. Before this the soul and spirit nature is much more inward. And only now that he has taken hold on that remotest part of his humanity, the bone-system, does man's adaptation to the outer world become complete. Only now is man a true child of the world, only now must he live with the mechanic and dynamic of the world, only now does he experience what is called Causality in life. Before his 11th year a human being has in reality no understanding of cause and effect. He hears the words used. We think he under-stands them. But he does not, because he is controlling his bone system from out of his muscular system. Later, after the 12th year, the bone system, which is adjusting itself to the outer world, dominates the muscular system, and through it, influences spirit and soul. And in consequence man now gets an understanding of cause and effect based on inner experience,—an understanding of force, and of his own experience of the perpendicular, the horizontal, etc.

For this reason, you see, when we teach the child mineralogy, physics, chemistry, mechanics before his 11th year in too intellectual a way we harm his development, for he cannot as yet have a corresponding experience of the mechanical and dynamical within his whole being. Neither, before his 11th year can he inwardly participate in thy causal connections in history.

Now this enlightens us as to how we should treat the soul in children, before the bone system has awakened. While the child still dwells in his muscular system, through the intermediary of his blood system, he can inwardly experience biography; he can always participate when we bring before him some definite historical picture which can please or displease him, and with which he can feel sympathy or antipathy. Or when we give him a picture of the earth in the manner I described yesterday. He can grasp in picture everything that belongs to the plant kingdom, because his muscular system is plastic, is inwardly mobile. Or if we show him what I said of the animal kingdom, and how it dwells in man—the child can go along with it because his muscular system is soft. But if before his 11th year we teach the child the principle of the lever or of the steam engine he can experience nothing of it inwardly because as yet he has no dynamic or mechanic in his own body, in his physical nature. When we begin physics, mechanics and dynamics at the right time with the child, namely about his 11th or 12th year, what we present to him in thought goes into his head and it is met by what comes from his inner being,—the experience the child has of his own bone-system. And what we say to the child unites with the impulse and experience which comes from the child's body. Thus there arises, not an abstract, intellectual understanding, but a psychic understanding, an understanding in the soul. And it is this we must aim at.

But what of the teacher who has to make this endeavour? What must he be like? Suppose for example, a teacher knows from his anatomy and physiology that “the muscle is in that place, the bones here; the nerve cells look like this”:—it is all very fine, put it is intellectual; all this leaves the child out of account, the child is, as it were, impermeable to our vision. The child is like black coal, untransparent. We know what muscles and nerves are there; we know all that. But we do not know how the circulation system plays into the blood system, into the bone-system. To know that, our conception of the build of a human being, of man's inner configuration must be that of an artist. And the teacher must be in a position to experience the child artistically, to see him as an artist would. Everything within the child must be inwardly mobile to him.

Now, the philosopher will come and say: “Well, if a thing is to be known it must be logical.” Quite right, but logical after the manner of a work of art, which can be an inner artistic representation of the world we have before us. We must accept such an inward artistic conceiving—we must not dogmatise: The world shall only be conceived logically. All the teacher's ideas and feelings must be go mobile that he can realise: If I give the child ideas of dynamics and mechanics before his 11th year they clog his brain, they congest, and make the brain hard, so that it develops migraine in the latter years of youth, and later still will harden;—if I give the child separate historical pictures or stories before his 11th year, if I give him pictures of the plant kingdom which shows the plants in connection with the country-side where they grow, these ideas go into his brain, but they go in by way of the rest of his nervous system into his whole body. They unite with the whole body, with the soft muscular system. I build up lovingly what is at work within the child. The teacher now sees into the child, what to one who only knows anatomy and physiology is opaque black coal now becomes transparent. The teacher sees everything, sees what goes on in the rows of children facing him at their desks, what goes on in the single child. He does not need to cogitate and have recourse to some didactic rule or other, the child himself shows him what needs to be done with it. The child leans back in his chair when something has been done which is unsuitable to him; he becomes inattentive. When you do something right for the child he becomes lively.

Nevertheless one will sometimes have great trouble in controlling the children's liveliness. You will succeed in controlling it if you possess a thing not sufficiently appreciated in this connection, namely humour. The teacher must bring humour into the class room as he enters the door. Some-times children can be very naughty. A teacher in the Waldorf School found a class of older children, children over 12 years old, suddenly become inattentive to the lesson and begin writing to one another under their desks. Now a teacher without humour might get cross at this, mightn't he? There would be a great scene. But what did our Waldorf School teacher do? He went along with the children, and explained to them the nature of—the postal service. And the children saw that he understood them. He entered right into this matter of their mutual correspondence. They felt slightly ashamed, and order was restored.

The fact is, no art of any kind can be mastered without humour, especially the art of dealing with human beings. This means that part of the art of education is the elimination of ill-humour and crossness from the teachers, and the development of friendliness and a love full of humour and fantasy for the children, so that the children may not see portrayed in their teacher the very thing he is forbidding them to be. On no account must it happen in a class that when a child breaks out in anger the teacher says: I will beat this anger out of you! That is a most terrible thing! And he seizes the inkpot and hurls it to the ground where it smashes. This is not a way to remove anger from a child. Only when you show the child that his anger is a mere object, that for you it hardly exists, it is a thing to be treated with humour, then only will you be acting educationally.

Up till now I have been describing how the human being is to be understood in general by the teacher or educator. But man is not only something in general. And even if we can enter into the human being in such detail that the very activity of the muscular system before the 11th year is transparent to us, and that of the bone system after the 11th year, there will yet remain something else—a thing of extraordinary vitality where education is an art—namely the human individuality. Every child is a different being, and what I have hitherto described only constitutes the very first step in the artistic comprehension and knowledge of the child.

We must be able to enter more and more into what is personal and individual. We are helped provisionally by the fact that the children we have to educate are differentiated according to temperaments. A true understanding of temperaments has, from the very first, held a most important place in the education I am here describing, the education practised at the Waldorf School.

Let us take to begin with the melancholic child; a particular human type. What is he like? He appears externally a quiet, withdrawn child. But these outward characteristics are not much help to us. We only begin to comprehend the child with a disposition to melancholy when we realise that the melancholic child is most powerfully affected by its purely bodily, physical nature; when we know that the melancholy is due to an intense depositing of salt in the organism. This causes the child of melancholic temperament to feel weighed down in his physical organism. For a melancholic child to raise a leg or an arm is quite a different matter than for another child. There are hindrances, impediments to this raising of the leg or arm. A feeling of weight opposes the intention of the soul. Thus it gradually comes about that the child of melancholic disposition turns inward and does not take to the outside world with any pleasure, because his body obtrudes upon his attention, because he is so much concerned with his own body. We only gain the right approach to a melancholic child when we know how his soul which would soar, and his spirit which would range are burdened by bodily deposits continuously secreted by the glands, which permeate his other bodily movements and encumber his body. We can only help him when we rightly understand this encroaching heaviness of the body which takes the attention prisoner.

It is often said: Well, a melancholic child broods inwardly, he is quiet and moves little. And so one purposely urges him to take in lively ideas. One seeks to heal a thing by its opposite. One's treatment of the melancholic is to try and enliven him by telling him all sorts of amusing things. This is a completely false method. We can never reach the melancholic child in this way.

We must be able, through our sympathy and sympathetic comprehension of his bodily gravity, to approach the child m the mood which is his own. Thus we must give him, not lively and, comical ideas, but serious ideas like those which he produces himself. We must give him many things which are in harmony with the tone of his own weighted organism.

Further, in an education such as this, we must have patience; the effect is not seen from one day to the next, but it takes years. And the way it works is that when the child is given from outside what he has within himself he arouses in himself healing powers of resistance. If we bring him something quite alien, if we bring comic things to a serious child—he will remain indifferent to the comic things. But if we confront him outwardly with his own sorrow and trouble and care he perceives from this outward meeting what he has in himself. And this calls out the inner action, the opposite. And we heal pedagogically by following in modern form the ancient golden rule: Not only can like be known by like, like can be treated and healed by like.

Now when we consider the child of a more phlegmatic temperament we must realise: this child of more phlegmatic temperament dwells less in his physical body and more in what I have called, in my descriptions here, the etheric body, a more volatile body. He dwells in his etheric body. It may seem a strange thing to say about the phlegmatic child that he dwells in his etheric body, but so it is. The etheric body prevents the processes of man's organic functions, his digestion, and growth, from coming into his head. It is not in the power of the phlegmatic child to get ideas of what is going on in his body. His head becomes inactive. His body becomes ever more and more active by virtue of the volatile element which tends to scatter his functions abroad in the world. A phlegmatic child is entirely given up to the world. He is absorbed into the world. He lives very little in himself hence he meets what we try to do with him with a certain indifference. We cannot reach the child because immediate access to him must be through the' senses. The principle senses are in the head. The phlegmatic child can make little use of his head. The rest of his organism functions through interplay with the outer world.

Once again, as in the case of the melancholic child, we can only reach the phlegmatic child when we can turn ourselves into phlegmatics of some sort at his side, when we can transpose ourselves, as artists, into his phlegmatic mood. Then the child has at his side what he is in himself, and in good time what he has beside him seems too boring. Even the phlegmatic finds it too boring to have a phlegmatic for a teacher at his side! And if we have patience we shall presently see how something lights up in the phlegmatic child if we give him ideas steeped in phlegma, and tell him phlegmatically of indifferent events.

Now the sanguine child is particularly difficult to handle. The sanguine child is one in whom the activity of the rhythmic system predominates in a marked degree. The rhythmic system, which is the dominant factor between the change of teeth and puberty, exercises too great a dominion over the sanguine child. Hence the sanguine child always wants to hasten from impression to impression. His blood circulation is hampered if the impressions do not change quickly. He feels inwardly cramped if impressions do not quickly pass and give way to others. So we can say: The sanguine child feels an inner constriction when he has to attend long to anything; he feels he cannot dwell on it, he turns away to quite other thoughts. It is hard to hold him.

Once more the treatment of the sanguine child is similar to that of the others: one must not try to heal the sanguine child by forcing him to dwell a long time on one impression, one must do the opposite. Meet the sanguine nature, change impressions vigorously and see to it that the child has to take in impression after impression in rapid succession. Once again, a reaction will be called into play. And this cannot fail to take the form of antipathy to the hurrying impressions, for the system of circulation here dominates entirely. With the result that the child himself is slowed down.

The choleric child has to be treated in yet a different way. The characteristic of the choleric child is that he is a stage behind the normal in his development. This may seem strange. Let us take an illustration. A normal child of 8 or 9 of any type moves his limbs quickly or slowly in response to outer impressions. But compare the 8 or 9-year old child with a child of 3 or 4 years. The 3- or 4-year old child still trips and dances through life, he controls his movements far less. He still retains something of the baby within him. A baby does not control its movements at all, it kicks—its mental powers are not developed. But if tiny babies all had a vigorous mental development you would find them all to be cholerics. Kicking babies—and the healthier they are the more they kick—kicking babies are all choleric. A choleric child comes from a body made restless by choler.

Now the choleric child still retains something of the rompings and ragings of a tiny baby. Hence the baby lives on in the choleric child of 8 or 9, the choleric boy or girl. This is the reason the child is choleric and we must treat the child by trying gradually to subdue the “baby” within him.

In the doing of this, humour is essential. For when we confront a real choleric of 8, 9, 10 years or even older, we shall affect nothing with him by admonition. But if I get him to re-tell me a story I have told him, which requires a show of great choler and much pantomime, so that he feels the baby in himself, this will have [For further descriptions of the alternation between sympathy and antipathy in children and its place in education see Steiner's educational writings passim.] the effect little by little of calming this “tiny baby.” He adapts it to the stage of his own mind. And when I act the choleric towards the choleric child—naturally, of course, with humour and complete self-control—the choleric child at my side will grow calmer. When the teacher begins to dance—but please do not misunderstand me—the raging of the child near him gradually subsides. But one must avoid having either a red face or a long face when dealing with a choleric child, one must enter into this inner raging by means of artistic sensibility. You will see the child will become quieter and quieter. This utterly subdues the inner raging.

But there must be nothing artificial in all this. If there is anything forced or inartistic in what the teacher gives the child it will have no result. The teacher must indeed have artist's blood in him so that what he enacts in front of the child shall have verisimilitude and can be accepted unquestioningly; otherwise it is a false thing in the teacher, and that must not be. The teacher's relation to the child must be absolutely true and genuine.

Now when we enter into the temperaments in this manner it helps us also to keep a class in order, even quite a large one. The Waldorf teacher studies the temperaments of the children confided to him. He knows: I have melancholies, phlegmatics, sanguines and cholerics. He places the melancholies together, unobtrusively, without its being noticed of course. He knows he has them in this corner. Now he places the cholerics together, he knows he has them in that corner; similarly with the sanguinis and the phlegmatics. By means of this social treatment those of like temperament rub each other's corners off reciprocally. For example the melancholic becomes cheerful when he sits among melancholies. As for the cholerics, they heal each other thoroughly, for it is the very best thing to let the cholerics work off their choler upon one another. If bruises are received, mutually it has an exceedingly sobering effect. So that by a right social treatment the—shall we say—hidden relationship between man and man can be brought into a healthy solution.

And if we have enough sense of humour to send out a boy when he is overwrought and in a rage—into the garden, and see to it that he climbs trees and scrambles about until he is colossally tired,—when he comes in again he will have worked off his choleric temper on himself and in company with nature. When he has worked off what is in him by overcoming obstacles, he will come back to us, after a little while, calmed down.

Now the point is, you see, to come by way of the temperaments into ever closer and closer touch with the individuality of the child, his personality. To-day many people say you must educate individually. Yes, but first you must discover the individual. First you must know man; next you must know the melancholic—Actually the melancholic is never a pure melancholic, the temperaments are always mixed. One temperament is dominant—But only when you rightly understand the temperament can you find your way to the individuality.

Now this shows you indeed that the art of education is a thing that must be learned intimately. People to-day do not start criticising a clock—at least I have not heard it—they do not set up to criticise the works of a clock. Why? Because they do not understand it, they do not know the inner working of a clock. Thus you seldom hear criticism of the working of a clock in ordinary conversation. But criticism of education—you hear it on all hands. And frequently it is as though people were to talk of the works of a clock of which they haven't the slightest inkling. But people do not believe that education must be intimately learned, and that it is not enough to say in the abstract: we must educate the individuality. We must erst be able to find the individuality by going intimately through a knowledge of man and a knowledge of the different dispositions and temperaments. Then gradually we shall draw near to what is entirely individual in man. And this must become a principle of life, particularly for the artist teacher or educator.

Everything depends upon the contact between teacher and child being permeated by an artistic element. This will bring it about that much that a teacher has to do at any moment with an individual child comes to him intuitively, almost instinctively. Let us take a concrete illustration for the sake of clarity. Suppose we find difficulty in educating a certain child because all the images we bring to him, the impressions we seek to arouse, the ideas we would impart, set up so strong a circulation in his head system and cause such a disturbance to his nervous system that what we give him cannot escape from the head into the rest of his organism. The physical organism of his head becomes in a way partially melancholic. The child finds it difficult to lead over what he sees, feels or otherwise experiences, from his head to the rest of his organism. What is learned gets stuck, as it were, in the head. It cannot penetrate down into the rest of the organism. An artist in educating will instinctively keep such a thing in view in all his specifically artistic work with the child. If I have such a child I shall use colours and paint with him in quite a different way than with other children. Because it is of such importance, special attention is given to the element of colour in the Waldorf School from the very beginning. I have already explained the principle of the painting; but within' the painting lesson one can treat each child individually. We have an opportunity of working individually with the child because he has to do everything himself.

Now suppose I have by me such a child as I described. I am taking the painting lesson. If there is the right artistic contact between teacher and child—under my guidance this child will produce quite a different painting from another child.

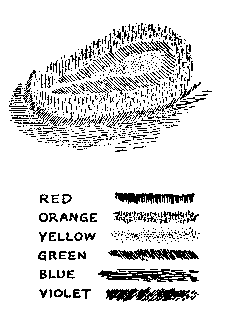

I will draw you roughly on the black-board what should come on the paper painted on by the child whose ideas are stuck in his head. Something of this sort should arise:

Here a spot of this colour (yellow), then further on a spot of some such colour as this (orange), for we have to keep in mind the harmony of colours. Next comes a transition (violet), the transition may be further differentiated, and in order to make an outer limit the whole may be enclosed with blue. This is what we shall get on the paper of a child whose ideas are congested in his head.

Now suppose I have another child whose ideas, far from sticking in his head, sift through his head as through a sieve; where everything goes into the body, and the child grasps nothing because his head is like a sieve—it has holes, it lets things through. It sifts everything down. One must be able to feel that in the case of this child the circulation system of the other part of the organism wants to suck everything into itself.

Then instinctively, intuitively, it will occur to one to get the child to do something quite different. In the case of such a child you will get something of this sort on the painting paper; You will observe how much less the colours go into curves, or rounded forms; rather you will find the colours tend to be drawn out, painting is approximating to drawing, we get loops which are proper to drawing. You will also notice that the colours are not much differentiated; here (in the first drawing) they are strongly differentiated: here in this one they are very little differentiated.

If one carries this out with real colours—and not with the nauseating substance of chalk, which cannot give an idea of the whole thing—then through the experience of pure colour in the one case, and of more formed colour in the other, one will be able to work back upon the characteristics of the child which I described.

Similarly when you go into the gymnasium with a boy or girl whose ideas stick in his head and will not come out of it, your aim will be different from that with which yon would go into it with a child whose head is like a sieve, who lets everything through into the rest of his body and into the circulation of the rest of his body. You take both kinds of children into the gymnasium with you. You get the one kind,—whose heads are like a sieve, where everything falls through—to alternate their gymnastic exercises with recitation or singing. The other gymnastic—group—those whose ideas are stuck fast in their heads—should be got to do their movements as far as possible in silence. Thus you make a bridge between bodily training and psychic characteristics from out the very nature of the child himself. A child which has stockish ideas must be got to do gymnastics differently from the child whose ideas go through his head like a sieve.

Such a thing as this shows how enormously important it is to compose the education as a whole. It is a horrible thing when first the teacher instructs the children in class and then they are sent off to the gymnasium—and the gymnastic teacher knows nothing of what has gone on in class and follows his own scheme in the gymnastic lesson. The gymnastic lesson must follow absolutely and entirely upon what one has experienced with the children in class. So that actually in the Waldorf School the endeavour has been as far as possible to entrust to one teacher even supplementary lessons in the lower classes, and certainly everything which concerns the general development of the human being.

This makes very great demands upon the staff, especially where art teaching is concerned; it demands, also, the most willing and loving devotion. But in no other way can we attain a wholesome, healing human development.

Now, in the following lectures I shall show you on the one hand certain plastic, painted figures made in the studio at Dornach, so as to acquaint you better with Eurhythmy—that art of movement which is so intimately connected with the whole of man. The figures bring out the colours and forms of eurhythmy and something of its inner nature. On the other hand I shall speak tomorrow upon the painting and other artistic work done by the younger and older children in the Waldorf School.

Die Erziehung der jüngeren Kinder: Der Lehrer als Erziehungskünstler II

Wie sehr es nötig ist, für die Erziehung und den erziehenden Unterricht den ganzen Menschen zu kennen, das zeigt sich ganz besonders, wenn man beobachtet, welche Entwickelung der Knabe und das Mädchen zwischen dem 11. und 12. Lebensjahre durchmachen. Man beobachtet ja gewöhnlich nur, ich möchte sagen, die gröbere Verwandlung, die gröbere Metamorphose der menschlichen Natur, und man hat kein Auge für die feineren Verwandlungen. Aus diesem Grunde glaubt man, daß man dem Kinde etwas Gutes tut, wenn man nur ausdenkt: Was für körperliche Bewegungen muß das Kind machen, um körperlich stark zu werden. Gerade um das Kind körperlich stark, kräftig und ohne Hemmungen zu machen, muß man im kindlichen Alter den Körper auf dem Umwege der Seele und des Geistes finden.

Zwischen dem 11. und 12. Jahre geht innerlich im Menschen eine große Verwandlung vor sich. Das rhythmische System, Atmungssystem, Blutzirkulationssystem ist das Herrschende, das Dominierende zwischen dem Zahnwechsel und der Geschlechtsreife. Wenn das Kind gegen das 10. Jahr kommt, dann entwickelt sich dasjenige, was im Atmungs- und im Blutzirkulationssystem drinnen waltet; der Takt, der Rhythmus, der da drinnen ist, die entwickeln sich in das Muskelsystem hinein. Die Muskeln werden vom Blut versorgt, und das Blut vibriert in die Muskeln so hinein, wie der Mensch innerlich ist. So daß der Mensch zwischen dem 9. und 11. Jahre sein Muskelsystem so ausbildet, wie es seinen innerlichen rhythmischen Anlagen gemäß ist. Wenn das 11.,12. Jahr herankommt, dann strahlt dasjenige, was im rhythmischen System und im Muskelsystem ist, in das Knochensystem, in das ganze Skelett hinein. Das Skelett ist bis zum 11. Jahre ganz eingeschaltet in das Muskelsystem. Es folgt dem Muskelsystem. Zwischen dem 11., 12. Jahre wird das Skelett so, daß es sich an die Außenwelt anpaßt, Mechanik, Dynamik, die vom Menschen unabhängig ist, geht in das Skelett hinein. Wir müssen uns bequemen, das Skelett so zu behandeln, wie wenn es objektiv wäre, gar nicht am Menschen wäre.

Wenn Sie Kinder beobachten unter 11 Jahren, Sie werden sehen, daß alle Bewegungen noch aus dem Inneren herauskommen. Wenn Sie Kinder beobachten nach dem 12. Jahre, Sie werden beobachten, daß sie auf ihre Füße so treten, daß sie immer versuchen das Gleichgewicht zu finden, daß sie das Hebel-Gleichgewicht, das Maschinelle des Skelettsystems innerlich fühlen. Das heißt, zwischen dem 11. und 12. Jahre breitet sich das Geistig-Seelische bis in das Knochensystem hinein aus. Das Geistig-Seelische ist viel innerlicher vorher. Nachher gewinnt der Mensch erst seine völlige Anpassung an die Außenwelt, indem er dasjenige, was er am wenigsten menschlich erlebt, das Knochensystem, erfaßt.

Jetzt wird der Mensch eigentlich erst ein richtiges Weltkind. Jetzt muß er erst mit der Mechanik, mit der Dynamik der Welt rechnen. Jetzt erlebt er erst innerlich dasjenige, was man im Leben die Kausalität nennt. In Wirklichkeit hat der Mensch vor dem 11. Jahre gar kein Verständnis für Ursache und Wirkung. Er hört die Worte. Wir glauben, daß der Mensch ein Verständnis hat. Er hat es nicht, weil er vom Muskelsystem aus sein Knochensystem beherrscht. Später, nach dem 12. Jahre, beherrscht das Knochensystem, das sich in die äußere Welt hineinstellt, das Muskelsystem und von da aus Geist und Seele. Und die Folge davon ist, daß der Mensch jetzt ein innerliches, erlebtes Verständnis bekommt von Ursache und Wirkung, von Kraft und von demjenigen, was als Aufrechtes gefühlt wird, was als Horizontales gefühlt wird und so weiter.

Sehen Sie, aus diesem Grunde ist es, daß, wenn wir Mineralogie, Physik, Chemie, Mechanik dem Kinde in einer zu intellektuellen Form vor dem 11. Jahre beibringen, wir es in seiner Entwickelung schädigen, denn es kann in seinem ganzen Menschen das Mechanische, das Dynamische noch nicht miterleben. Ebensowenig kann es miterleben vor dem 11. Jahre dasjenige, was in der Geschichte, in der Historie Kausalzusammenhänge sind.

Sehen Sie, das gibt einem ein Licht, wie man die Kinder behandeln soll, bevor das Knochensystem seelisch erwacht ist. Solange das Kind von seinem Blutsystem aus noch in seinem Muskelsystem lebt, kann es innerlich erleben die Biographie, kann innerlich erleben, wenn wir ihm beibringen ein abgeschlossenes Geschichtsbild, das ihm gefällt oder mißfällt, mit dem es Sympathie oder Antipathie haben kann, wenn wir ihm beibringen ein Bild von der Erde, wie ich es gestern geschildert habe. Alles das, was Pflanzenwelt ist, kann es als Bild erfassen, weil das Muskelsystem plastisch, innerlich beweglich ist; wenn wir ihm das beibringen, was ich von der Tierwelt gesagt habe, wie die im Menschen lebt, so fühlt das das Kind nach, weil das Muskelsystem weich ist. Wenn wir dem Kinde vor dem 11. Jahre beibringen das Prinzip des Hebels, das Prinzip der Dampfmaschine, dann kann es innerlich nichts davon erleben, weil es Dynamik, Mechanik noch nicht in seinem Leibe, in seinem Körper hat. Wenn wir zur rechten Zeit beginnen mit Physik, Mechanik, Dynamik gegen das 11. und 12. Jahr, da stellen wir im Denken etwas vor das Kind hin, das in seinen Kopf hineingeht, und von dem Inneren des Menschen kommt dem entgegen dasjenige, was das Kind vom Knochensystem aus erlebt. Und es verbindet sich das, was wir dem Kinde sagen, mit dem, was aus dem Körper des Kindes heraus will. So entsteht nicht ein abstraktes, intellektualistisches, sondern ein lebendiges Seelenverständnis. Das ist es, was wir anstreben müssen.

Aber wie muß der Lehrer sein, wenn er so etwas anstreben will? Bedenken Sie einmal, wenn der Lehrer aus Anatomie und Physiologie weiß: Dort an der Stelle sitzt der Muskel, dort der Knochen; die Nervenzellen sehen so und so aus - es ist das alles recht sehr schön, aber es ist intellektualistisch; das alles stellt das Kind neben uns hin, so daß das Kind wie undurchsichtig ist. Es ist wie schwarze Kohle, das Kind, wie undurchsichtig. Wir wissen, was da für Muskeln, für Nerven drinnen sind; das wissen wir alles. Aber wir wissen nicht, wie das Zirkulationssystem in das Muskelsystem, in das Knochensystem hineinspielt. Um das zu verstehen, muß unsere Auffassung von dem Bau des Menschen, von der inneren Gestaltung des Menschen eine künstlerische sein. Und der Lehrer muß imstande sein, das Kind künstlerisch, als Artist zu erleben. Ihm muß alles im Kinde innerlich beweglich sein.

Da wird die Philosophie kommen und wird sagen: Ja, aber wenn man etwas erkennen will, dann muß eben die Sache logisch sein. Ganz richtig, aber so, wie das Kunstwerk logisch sein muß, wenn wir die Welt vor uns haben, und die Welt kann durch künstlerisches Erfassen repräsentiert werden im Inneren. So müssen wir uns eben zu solchem künstlerischen Erfassen bequemen, müssen nicht dogmatisch diktieren: Die Welt muß allein logisch ergriffen werden. Nur wenn der Lehrer seine eigenen Empfindungen, Vorstellungen und Gefühle so innerlich beweglich hat, daß er sieht: Wenn ich dem Kinde dynamische, mechanische Vorstellungen beibringe vor dem 11. Jahre, da stocken diese Vorstellungen im Gehirn, da sammeln sie sich an, da machen sie das Gehirn hart, so daß es später in jugendlichen Jahren zur Migräne wird und noch später sich verhärtet. Wenn ich ihm abgeschlossene Geschichtsbilder beibringe vor dem 11. Jahre, wenn ich ihm Bilder aus der landschaftlichen Pflanzenwelt beibringe, dann gehen die Vorstellungen in das Gehirn hinein, aber durch das übrige Nervensystem in den ganzen Leib hinein. Sie verbinden sich mit dem ganzen Leib, mit dem weichen Muskelsystem. Ich baue mir das, was im Kinde geschieht, liebevoll auf. Die Kohle, die das Kind sonst ist, wenn man nur die tote Anatomie und die Physiologie kennt, wird so durchsichtig. Der Lehrer sieht überall, was in den Bänken vor ihm sitzt, was in dem einzelnen Kinde vor sich geht. Er braucht nicht nachzudenken nach diesen oder jenen didaktischen Grundsätzen, sondern das Kind sagt ihm selber, was mit ihm zu geschehen hat, indem es in seinen Stuhl zurücksinkt, wenn man etwas tut, was dem Kinde nicht angepaßt ist: es wird unaufmerksam. Tut man etwas, was dem Kinde angepaßt ist: es wird lebendig.

Allerdings, man hat ja manchmal rechte Mühe, die Lebendigkeit der Kinder etwas zu bewältigen. Aber man bewältigt sie, wenn man etwas hat von dem, was heute in der Welt weniger anerkannt wird: Humor. Der Lehrer muß durch die Türe der Klasse Humor in die Klasse hineintragen. Die Kinder können ja zuweilen recht ungezogen werden. Einer unserer Lehrer in der Waldorfschule, der erlebte es an seinen größeren Kindern gerade, die über das 12. Jahr hinaus waren, daß sie plötzlich anfingen, weniger Interesse zu haben am Unterricht und sich gegenseitig Briefe schrieben unter der Bank. Nun, nicht wahr, ein Lehrer, der nicht Humor hat, der wird griesgrämig. Es wird eine schreckliche Szene geben. Was hat unser Lehrer in der Waldorfschule getan? Er ging hin zu den Kindern und erklärte ihnen - das Postwesen. Und die Kinder sahen, er versteht sie. Er ging ein auf ihr gegenseitiges Briefschreiben. Sie bekamen ein leises Schamgefühl, und die Sache war wieder hergestellt.

Es handelt sich darum, daß man tatsächlich Kunst, und insbesondere Menschenkunst ohne Humor nicht bewältigen kann. Das heißt, die pädagogische Kunst besteht auch darinnen, aus der Lehrerschaft das Griesgrämige wegzubringen, und eben starke Freundlichkeit, humoristische, humorvolle Liebe zu den Kindern zu entwickeln, damit nicht die Kinder in dem Lehrer das Bild desjenigen sehen, was er ihnen eigentlich verbietet. Jedenfalls darf das in der Klasse nicht geschehen, daß, wenn das Kind zornig wird und seinen Zorn zum Ausdrucke bringt, der Lehrer geht und sagt: Ich will dir diesen Zorn austreiben! Das ist etwas Furchtbares! - Und er nimmt das Tintenfaß und wirft es auf den Boden, daß es zersplittert. Dadurch bringt man den Zorn nicht aus dem Kinde heraus; nur wenn man dem Kinde zeigen kann, daß sein Zorn Objekt ist, daß er für einen gar nicht da ist, daß man es mit Humor auffaßt, dann erzieht man erst richtig.

Ich habe zunächst geschildert, wie der Mensch im allgemeinen von dem Uhnterrichtenden und Erziehenden erfaßt werden muß. Aber der Mensch ist nicht nur so etwas im allgemeinen. Und selbst wenn man schon so genau auf den Menschen eingehen kann, daß er einem durchsichtig wird bis auf die Betätigung des Muskelsystems vor dem 11. Jahre, des Knochensystems nach dem 12, Jahre, so bleibt noch immer das übrig, was ja für eine künstlerisch gemeinte Erziehung und einen künstlerisch gemeinten Unterricht außerordentlich notwendig ist, die Individualität des Menschen. Jedes Kind ist ein anderes Wesen, und es kann nur der allererste Schritt sein zum künstlerisch erkennenden Auffassen des Kindes, wenn man so vorgeht, wie ich es bis jetzt beschrieben habe.

Man muß immer mehr und mehr in das Persönliche, in das Individuelle hineingehen können. Da bieten sich zunächst Anhaltspunkte dadurch, daß wir die Kinder, die uns zur Erziehung und zum Unterricht übergeben werden, nach dem 'Temperamente verschieden haben. Die Temperamente wirklich innerlich zu durchschauen, das ist etwas, was innerhalb derjenigen Erziehungskunst, von der ich hier spreche, und die in der Waldorfschule geübt wird, vom Anfange an die allerstärkste Bedeutung bekam.

Da haben wir zunächst das melancholische Kind; ein besonderer Menschentypus. Wie tritt es uns entgegen? Es tritt uns zunächst äußerlich als ein stilles, in sich gezogenes Kind entgegen. Aber mit dieser äußerlichen Charakteristik ist nicht viel anzufangen. Wir kommen dem Kinde, das melancholische Anlagen hat, erst nahe, wenn wir sehen, wie gerade beim melancholischen Kinde die rein physische Körperlichkeit den allerstärksten Einfluß ausübt, wenn wir wissen, daß die Melancholie darauf beruht, daß starke Salzablagerungen im Organismus stattfinden, so daß das Kind, das melancholische Anlagen hat, sich schwer fühlt in seinem ganzen physischen Organismus. Ganz anders ist es beim melancholischen Kinde als bei einem anderen, wenn es nur ein Bein heben soll, oder einen Arm heben soll. Da sind Hindernisse, Hemmungen des Beinhebens, des Armhebens da. Es ist ein Gefühl der Schwere, das der seelischen Intention entgegentritt. Das bringt es allmählich dazu, daß das Kind mit der melancholischen Anlage nach innen schaut und nicht freundlich nach außen schaut, weil sein Körper sich so stark bemerklich macht, weil es so viel zu tun hat mit seinem Körper. Erst wenn wir wissen, wie die Seele, die hinauf will, der Geist, der in die Weite will, beschwert werden bei einem melancholischen Kinde durch die körperlichen Einlagerungen, die fortwährend aus den Drüsen heraus, den Körper beschwerend, in das übrige Körpergewebe hineinleben, erst wenn wir dieses Schwerwerden und dadurch Gefangennehmen der Aufmerksamkeit von seiten des Körperlichen richtig verstehen, dann erst kommen wir dem melancholischen Kinde bei.

Sehr häufig sagt man: Nun ja, das melancholische Kind brütet in sich hinein, ist still, bewegt sich wenig. Und wir veranlassen es dazu, nun gerade recht lebendige Vorstellungen aufzunehmen. Wir wollen es mit seinem Gegenteil heilen. Wir wollen dem melancholischen Kind so beikommen, daß wir es aufmuntern durch allerlei Lustiges, das wir an es heranbringen. Das ist die ganz falsche Methode. Da kommen wir dem melancholischen Kinde gar nicht bei.

Wir müssen die Möglichkeit haben, durch Mitgefühl und Mitempfindung mit seiner körperlichen Schwere gerade in der Art an das Kind heranzutreten, wie es selber ist. Wir müssen gerade versuchen, an das melancholische Kind nicht lustige, komische Vorstellungen heranzubringen, sondern ernste Vorstellungen heranzubringen, diejenigen, die es selber aus sich herausholt. Wir müssen ihm viel von der Art beibringen, was anklingt an seinen eigenen schweren Organismus.

Dann werden wir allerdings Geduld haben müssen mit einer solchen Erziehung; denn die wirkt nicht von heute auf morgen, aber sie wirkt durch Jahre hindurch. Sie wirkt so, daß das Kind, indem ihm von außen entgegengebracht wird, was es in sich hat, Heilkräfte dagegen in sich aufnimmt. Wenn wir ihm von außen etwas ganz Fremdes entgegenbringen, wenn wir dem ernsten Kinde das Lustige entgegenbringen, bleibt es gleichgültig gegen das Lustige. Aber wenn wir ihm seine eigene Trauer, Kummer, Sorge entgegenbringen, dann nimmt es von außen das wahr, was es im Inneren selbst hat. Dadurch wird im Inneren die Reaktion, das Gegenteil aufgerufen, und wir heilen gerade pädagogisch, indem wir in einer modernen Form den alten goldenen Grundsatz befolgen: Gleiches wird nicht nur von Gleichem erkannt, sondern Gleiches wird auch durch Gleiches richtig behandelt, geheilt.

Dann aber, wenn das Kind ein mehr phlegmatisches Temperament hat, dann müssen wir uns klar sein darüber: dieses Kind, das ein mehr phlegmatisches Temperament hat, das lebt weniger in seinem physischen Leib, mehr in dem, was ich in diesen Tagen den Ätherleib genannt habe, den Leib, der flüchtiger ist. Es lebt in dem Ätherischen. Es sieht sonderbar aus, wenn man vom phlegmatischen Kinde sagt: es lebt im Ätherischen, aber es ist so. Das Ätherische, das läßt dasjenige, was in den menschlichen organischen Funktionen vorgeht, das Verdauen, das Wachsen, das läßt es nicht zum Kopfe kommen. Das phlegmatische Kind hat es nicht in seiner Gewalt, Vorstellungen von dem zu bekommen, was in seinem Leib vorgeht. Der Kopf wird untätig. Der Leib wird immer mehr und mehr tätig durch das flüchtige Element, das seine Funktionen in alle Welt zerstreuen möchte. Das phlegmatische Kind ist ganz hingegeben der Welt. Es geht in der Welt auf. Es lebt wenig in sich. Dadurch bringt es uns eine gewisse Gleichgültigkeit entgegen gegenüber dem, was wir mit ihm unternehmen wollen. Wir können nicht an das Kind heran, weil wir ja doch zuletzt durch die Sinne heran müssen. Die hauptsächlichsten Sinne sind im Kopfe. Das phlegmatische Kind kann den Kopf wenig gebrauchen. Der übrige Organismus wird von der Außenwelt in Funktion erhalten.

Wir kommen dem phlegmatischen Kind nur bei, wenn wir nun wiederum, geradeso wie beim melancholischen Kinde, selber zu einer Art Phlegmatiker werden neben ihm, wenn wir uns künstlerisch in seine phlegmatische Stimmung hinein zu versetzen vermögen. Da hat dann das Kind das, was es selber ist, neben sich, und es wird ihm schließlich dasjenige, was es da neben sich hat, zu langweilig. Selbst dem Phlegmatiker wird das zu langweilig, wenn er einen Phlegmatiker als Lehrer neben sich hat! Und wenn wir wieder Geduld haben, so werden wir bemerken, daß sich da irgend etwas entzündet, wenn wir dem phlegmatischen Kind in Phlegma getauchte Vorstellungen, in Phlegma getauchte Vorgänge auch vorführen.

Besonders schwierig zu behandeln ist das sanguinische Kind. Das sanguinische Kind ist dasjenige, bei dem ganz besonders der rhythmische Organismus in einer dominierenden Tätigkeit ist. Der rhythmische Organismus, der ja zwischen dem Zahnwechsel und der Geschlechtsreife an sich im Menschen das Dominierende ist, der kommt zu einer zu großen Herrschaft, zu einer zu großen Domination bei dem sanguinischen Kinde. Daher will das sanguinische Kind von Eindruck zu Eindruck eilen. Es stockt seine Blutzirkulation, wenn die Eindrücke nicht schnell wechseln. Es fühlt sich innerlich beengt, wenn die Eindrücke nicht schnell vorübergehen und andere kommen. Und so kann man sagen: Das sanguinische Kind, das fühlt eine innerliche Beklemmung, wenn es lange seine Aufmerksamkeit auf etwas heften soll; es fühlt, daß es nicht dabei bleiben kann, wendet sich weg, bekommt fremde Gedanken. Es kann schwer gefesselt werden.

Wiederum muß ich ein ähnliches sagen für die Behandlung des sanguinischen Kindes: Man versuche, das sanguinische Kind nicht dadurch zu heilen, daß man es nun zwingt, recht lange bei einem Eindrucke zu verweilen, sondern man mache das Gegenteil. Man komme dem Sanguinismus entgegen und wechsle die Eindrücke recht stark, zwinge das Kind gerade dazu, rasch hintereinander Eindrücke aufzunehmen. Wiederum ist es die Reaktion, die sich geltend macht. Dann kann, weil ja das Zirkulationssystem ganz dominierend ist, dann kann es nicht anders als in Antipathie gegen die beschleunigten Eindrücke sich ausleben. Und die Folge davon ist, daß das Kind selber zum Retardieren kommt.

In einer noch anderen Weise ist das cholerische Kind zu behandeln. Das cholerische Kind hat die Eigentümlichkeit, daß es immer ein Stück hinter der normalen Menschenentwickelung zurückgeblieben ist. Es sieht das sonderbar aus. Aber nehmen Sie das folgende Bild. Ein acht-, neunjähriges Kind ist als normaler Mensch von einer bestimmten Art, seine Glieder zu bewegen, schnell und langsam, je nach den äußeren Eindrücken. Vergleichen Sie das acht-, neunjährige Kind mit dem drei-, vierjährigen Kind. Das drei-, vierjährige Kind tänzelt noch durchs Leben, beherrscht viel weniger seine Bewegungen. Es hat noch etwas von dem an sich, was das ganz kleine Kind hat. Das beherrscht gar nicht seine Bewegungen, das zappelt, das hat das Seelische noch nicht entwickelt. Aber wenn Säuglinge das Seelische stark entwickelt hätten, dann würden Sie die Säuglinge alle cholerisch finden. Die Säuglinge mit ihrem Zappeln - gerade wenn sie gesund sind, so zappeln sie viel - sind alle cholerisch.

Das cholerische Kind aber behält etwas zurück von dem Toben und Wüten des ganz kleinen Kindes. Dadurch lebt in dem cholerischen Kinde, dem acht-, neunjährigen Knaben oder Mädchen, drinnen noch der kleine Säugling weiter. Dadurch ist dieses Kind cholerisch, und man muß versuchen, dieses cholerische Kind dadurch zu behandeln, daß man das «kleine Kind», das darinnen ist, allmählich zur Ablähmung bringt.

Das muß nun ganz besonders, ich möchte sagen, mit Humor behandelt werden. Denn hat man so einen richtigen Choleriker mit 8, 9, 10 Jahren, auch noch im späteren Lebensalter vor sich, so kommt man ihm nicht bei, wenn man ihn ermahnt; das macht gar keinen Eindruck, wenn man ihn ermahnt. Aber wenn ich ihn dazu veranlasse, daß er mir eine Erzählung machen muß, die ich selber zuerst vorerzähle, und er muß mir dann recht cholerisch voragieren die Erzählung, er muß mimen, er muß sich nun in seinen kleinen Menschen hineinleben, dann kommt er allmählich dazu, diesen kleinen Menschen in sich zu beruhigen. Er paßt ihn dem Seelischen an. Und indem ich selber seelisch mit dem cholerischen Kind cholerisch werde, aber natürlich, indem ich mich humorvoll immer in der Hand habe, werde ich erreichen, daß das cholerische Kind neben mir ruhiger wird. Wenn der Lehrer zu tanzen beginnt - aber ich bitte, das nicht im schlimmen Sinne aufzufassen —, so hört das Toben des Kindes neben ihm nämlich nach und nach auf. Man muß nur die Fähigkeit haben, einem cholerischen Kinde gegenüber nicht einen roten Kopf zu bekommen, den Kopf nicht lang werden zu lassen, aber in eine Art von künstlerischem Nachempfinden dieses innerlichen Tobens zu kommen. Sie werden sehen, das Kind wird immer stiller und stiller. Es lähmt das innerliche Toben ganz ab.

Aber es muß etwas nicht Gemachtes darinnen liegen. Wenn beim Lehrer etwas Gemachtes, Unkünstlerisches in dem, was er da dem Kinde gibt, liegt, dann wird die Sache eben durchaus keinen Erfolg haben. Der Lehrer muß tatsächlich Künstlerblut in sich haben, damit er das, was er da dem Kinde vormacht, damit er das in einer glaubhaften Weise dem Kinde gegenüber leben läßt; sonst ist es vom Lehrer aus verlogen, und das darf es nicht sein. Es muß durch und durch das Verhältnis des Lehrers zum Kinde wahr sein.

Sehen Sie, man kann aber auch dadurch, daß man überhaupt eingeht auf die Temperamente, die Klasse, auch wenn sie etwas groß sein muß, in einer gewissen Weise ordentlich halten. Der Waldorflehrer studiert die Temperamente der Kinder, die ihm übergeben werden. Nun weiß er: Ich habe die Melancholiker, die Phlegmatiker, die Sanguiniker, die Choleriker. Er setzt, womöglich ganz unvermerkt, ohne daß das natürlich bemerkt wird, die Melancholiker zusammen. Er weiß, er hat sie in dieser einen Ecke. Da setzt er die Choleriker zusammen; er weiß, er hat sie in jener Ecke, und so die Sanguiniker, und so die Phlegmatiker. Durch diese Art sozialer Behandlung schleifen sich die Temperamente an ihresgleichen gegenseitig ab. Der Melancholiker wird nämlich munter, wenn er unter Melancholikern sitzt. Und die Choleriker, nun, die heilen sich gründlich, denn es ist am allerbesten, wenn man die tobenden Choleriker sich aneinander ausleben läßt. Wenn sie dann blaue Flecken haben gegenseitig, dann wirkt das ungeheuer kalmierend. So daß man dasjenige, was als, ich möchte sagen, Geheimnisvolles von Mensch zu Mensch wirkt, gerade durch die richtige soziale Behandlung in ein heilsames Fahrwasser bringen kann.

Und wenn man gar noch den Humor hat, wenn ein Junge ganz besonders cholerisch aufgeregt wird, ihn in den Schulgarten zu schicken, und darauf sieht, daß er die Bäume hinauf- und hinabklettert und endlich dadurch ungeheuer müde wird - wenn er wiederum hineinkommit, hat er sein cholerisches Temperament an sich selber ausgelebt, mit der Natur ausgelebt. Wenn er sich durch Überwindung der Hindernisse ausgelebt hat, dann bekommt man ihn kalmiert nach einiger Zeit zurück.

So, sehen Sie, handelt es sich darum, daß man nun immer mehr und mehr den Weg findet, durch die Temperamente hindurch ganz ins Individuelle des Kindes, in das Persönliche hineinzukommen. Heute sagen sehr viele Leute, man muß individuell erziehen. Ja, aber das Individuum muß man erst finden. Zuerst muß man den Menschen kennen, dann muß man den Melancholiker kennen. Der Melancholiker ist nun nie ein reiner Melancholiker, die Temperamente sind immer vermischt. Ein Temperament ist dominierend. Aber nur, wenn man das einzelne Temperament richtig kennt, findet man den Weg in die Individualität hinein.

Das zeigt doch wirklich, daß Erziehungskunst etwas ist, was in intimer Weise gelernt sein will. Die Menschen der Gegenwart - ich habe das noch nicht gehört — fangen ja nicht an, eine Uhr zu kritisieren, wie eine Uhr sein soll dem Werke nach innerlich. Warum? Weil sie das nicht wissen, weil sie nicht wissen, wie die Uhr innerlich wirkt. Kritik über den Gang der Uhr hört man sehr wenig so im gewöhnlichen Gespräch. Kritiken über die Erziehung — man hört sie allerorten. Aber es ist gerade so oftmals, wie wenn die Menschen reden würden über ein Uhrwerk, von dem sie keine Ahnung haben. Man glaubt nur nicht, daß das Erziehen auch intim gelernt sein muß, und daß es nicht genügt, im Abstrakten zu sagen: man muß die Individualität erziehen. Man muß die Individualität erst finden können, indem man den intimen Weg macht durch die Menschenerkenntnis, durch die Erkenntnis der Art und Temperamente. Dann kommt man allmählich an das ganz Individuelle des Menschen heran. Das muß ein Lebensprinzip werden gerade bei dem artistisch gearteten Lehrer und Erzieher.

Es kommt ganz darauf an, daß der Kontakt zwischen dem Lehrer und dem Kinde durchaus in ein künstlerisches Element getaucht ist. Dadurch wird eben in dem Lehrer selber vieles eine Art intuitiven, instinktiven Charakter annehmen, was er in bezug auf die Individualität des Kindes im gegebenen Momente zu tun hat. Nehmen wir, um uns darüber zu verständigen, die Sache möglichst konkret. Stellen wir uns vor, wir haben ein Kind vor uns, das Erziehungsschwierigkeiten dadurch macht, daß wir bemerken: die Anschauungen, die wir ihm vorführen, die Empfindungen, die wir erregen wollen, die Vorstellungen, die wir ihm mitteilen wollen, sie bringen in dem Kopfsystem eine so starke Zirkulation und eine so starke Nervenerregung zustande, daß gewissermaßen das, was ich dem Kinde beibringe, nicht durchkommen kann vom Kopfe aus zu dem übrigen Organismus. Die physische Organisation des Kopfes wird gewissermaßen partiell melancholisch. Das Kind hat Schwierigkeiten, dasjenige, was es sieht, was es empfindet, auch was ihm durch andere Impulse beigebracht wird, vom Kopfe zu seinem übrigen Organismus zu leiten. Es bleibt gewissermaßen das Gelernte im Kopfe stecken. Es kann nicht hinunterdringen in den übrigen Organismus. Wenn man mit künstlerischem Sinn das Kind unterrichtet, dann wird man gerade alles dasjenige, was in der Erziehung und dem Unterricht an künstlerischem waltet, ganz instinktiv danach einrichten. Habe ich ein solches Kind vor mir, so werde ich in ganz anderer Weise ihm das Arbeiten in der Farbe beibringen, das malerische Element, als einem anderen Kinde. Und deshalb, weil das so wichtig ist, wird bei uns in der Waldorfschule von Anbeginne an das malerische Element berücksichtigt. Ich habe ja auseinandergesetzt, wie das Schreiben selbst aus dem Malerischen herausgeholt wird; aber innerhalb dieses Malerischen wiederum kann man individualisieren von Kind zu Kind. Denn da hat man ja gerade Gelegenheit zu individualisieren, indem das Kind selber alles machen muß.

Nun nehmen wir an, ich habe ein solches Kind vor mir, wie ich es eben geschildert habe. Ich übe die Malerziehung. Da wird, wenn der richtige künstlerische, artistische Kontakt ist zwischen Lehrer und Schüler, auf dem Blatt Papier, auf dem das Kind mit den Farben arbeitet, durch meine Anleitung etwas anderes entstehen, als bei einem anderen Kinde.

Ich will Ihnen ungefähr schematisch auf die Tafel aufzeichnen, was bei einem solchen Kinde, bei dem gewissermaßen die Empfindungen, die Vorstellungen im Kopfe stocken, auf dem Blatt Papier, auf dem es malt, entstehen muß. Da muß ungefähr so etwas entstehen: da wird solch ein Farbenfleck sein (gelb), dann wird weitergehend solch ein Farbenfleck irgendwie sein (lila), denn auf die Harmonik der Farben kommt es an. Dann wird ein Übergang sein (orange), der Übergang wird noch weiter verteilt sein, und das Ganze wird vielleicht, um nach außen einen Abschluß zu bekommen, etwa so nach außen schließen (blau). So wird es auf dem Blatte aussehen bei dem Kinde, bei dem gewissermaßen die Vorstellungen in dem Kopfe stocken.

Nehmen Sie an, ich habe ein anderes Kind, bei dem ich sehe, daß die Vorstellungen gar nicht im Kopfe stocken, sondern daß sie gewissermaßen durch den Kopf wie durch ein Sieb durchsickern und alles in den Leib hineingeht, daß das Kind nicht fassen kann, weil sein Kopf ein Sieb ist. Er hat Löcher, er ist durchlässig. Es sickert alles hinunter. Das muß man eben empfinden, daß das beim Kind so ist, daß das Zirkulationssystem des anderen Organismus alles in sich hereinsaugen will. Dann kommt man eben instinktiv, intuitiv dazu, dem Kinde die Anleitung zu geben zu etwas, das nun etwas ganz anderes ist. Bei einem solchen Kinde werden Sie etwa folgendes auf dem Papier sehen (es wird gezeichnet): Da werden Sie sehen, wie weniger die Farben ineinander sich gestalten, rund; Sie werden mehr sehen, daß die Farben in die Länge gehen, daß das Farbige in das Zeichnerische übergeht, daß Schlingen eintreten, die auf das Zeichnen hinweisen. Sie werden auch sehen, daß die Farben nicht sehr differenziert sind; hier (bei der ersten Zeichnung) sind sie stark differenziert; hier, bei der zweiten Zeichnung, sind sie weniger differenziert.

Wenn man das dann ausführt mit wirklichen Farben — nicht mit dem ekelhaften Material der Kreide, was das Ganze nicht wiedergeben kann -, dann wird man gerade von diesem Erleben des rein Farbigen auf der einen Seite und des formhaften Farbigen auf der anderen Seite wohltätig heilend zurückwirken auf diejenigen Eigenschaften des Kindes, von denen ich gesprochen habe.

Ebenso werden Sie, wenn Sie, sagen wir, einen Knaben oder ein Mädchen haben, das die Vorstellung stocken hat im Kopfe, das sie nicht hinunterbringt, mit diesem Knaben oder mit diesem Mädchen mit anderen Absichten in die Turnhalle gehen, als mit einem Kinde, das den Kopf wie ein Sieb hat, wo alles hinuntergeht in den übrigen Körper und in die Zirkulation des übrigen Körpers hinein. Sie gehen mit den beiden Kindergruppen in die Turnhalle. Die einen Kinder, bei denen alles wie ein Sieb ist, alles hinuntergeht, die lassen Sie so turnen, daß sie abwechselnd die Turnbewegungen machen und dann etwas rezitieren oder singen. Die andere Turngruppe, wo alles in dem Kopfe stockt, die lassen Sie möglichst so die Bewegungen machen, daß die Kinder schweigen müssen dabei. Und so können Sie ganz aus der Natur des Kindes heraus den Übergang bilden zwischen der körperlichen Erziehung und der seelischen Eigentümlichkeit. Sie müssen in anderer Weise turnen lassen ein Kind, das stockende Vorstellungen hat und in anderer Weise ein Kind, das Vorstellungen hat, die wie ein Sieb durch den Kopf durchgehen.

Das ist dasjenige, woran man sieht, wie ungeheuer bedeutungsvoll es ist, den Unterricht als Ganzes gestalten zu können. Es ist etwas Furchtbares, wenn auf der einen Seite in der Klasse der Lehrer den Unterricht erteilt, und dann die Kinder in die Turnschule geschickt werden. Der Turnlehrer weiß gar nichts von dem, was in der Klasse vor sich geht, und er hält nun nach einem Schema den Turnunterricht. Der Turnunterricht muß ganz und gar ein Ergebnis desjenigen sein, was man mit den Kindern in der Klasse erfahren hat. So daß eben in der Waldorfschule angestrebt wird, möglichst, soweit es geht, bis in die Nebenfächer in den unteren Klassen alles, wenigstens all dasjenige, was zur Menschenbildung führen soll, nur einer Lehrkraft zu übergeben.

Dadurch wird gerade eben in bezug auf das Artistische allerdings von dieser Lehrkraft das Höchste gefordert, und auch die willigste, liebevollste Hingabe gefordert. Aber man erreicht auf eine andere Weise kein Heilsames für die Menschheitsentwickelung.

The education of younger children: The teacher as an educational artist II

The importance of understanding the whole person for education and teaching becomes particularly apparent when observing the development that boys and girls undergo between the ages of 11 and 12. Usually, one only observes I would say, the coarser transformation, the coarser metamorphosis of human nature, and one has no eye for the finer transformations. For this reason, one believes that one is doing something good for the child if one only thinks about what physical movements the child must do in order to become physically strong. In order to make the child physically strong, vigorous, and uninhibited, one must find the body in childhood through the detour of the soul and the spirit.

Between the ages of 11 and 12, a great transformation takes place within the human being. The rhythmic system, the respiratory system, and the blood circulation system are the dominant forces between the change of teeth and sexual maturity. When the child reaches the age of 10, what prevails in the respiratory and blood circulation systems develops; the rhythm that is within them develops into the muscular system. The muscles are supplied with blood, and the blood vibrates into the muscles in accordance with the inner nature of the person. Thus, between the ages of 9 and 11, the person develops their muscular system in accordance with their inner rhythmic predispositions. When the 11th and 12th years approach, what is in the rhythmic system and the muscular system radiates into the skeletal system, into the entire skeleton. Until the age of 11, the skeleton is completely integrated into the muscular system. It follows the muscular system. Between the ages of 11 and 12, the skeleton becomes adapted to the outside world, and mechanics and dynamics that are independent of the human being enter into the skeleton. We must be prepared to treat the skeleton as if it were objective, not part of the human being at all.

If you observe children under the age of 11, you will see that all their movements still come from within. If you observe children after the age of 12, you will see that they step on their feet in such a way that they are always trying to find their balance, that they feel the lever balance, the mechanics of the skeletal system, internally. This means that between the ages of 11 and 12, the spiritual-soul aspect spreads into the skeletal system. The spiritual-soul aspect is much more internal before this. Afterwards, the human being only gains complete adaptation to the outside world by grasping that which he experiences as least human, the skeletal system.

Now the human being actually becomes a true child of the world. Now they must reckon with the mechanics, with the dynamics of the world. Now they experience internally what is called causality in life. In reality, before the age of 11, human beings have no understanding of cause and effect. They hear the words. We believe that human beings have an understanding. They do not, because their muscular system controls their skeletal system. Later, after the age of 12, the skeletal system, which is positioned in the outer world, controls the muscular system and, from there, the mind and soul. The result of this is that the human being now gains an inner, experiential understanding of cause and effect, of force and of what is felt as upright, what is felt as horizontal, and so on.

You see, it is for this reason that if we teach mineralogy, physics, chemistry, and mechanics to children in an overly intellectual form before the age of 11, we damage their development, because they cannot yet experience the mechanical and dynamic aspects in their whole being. Nor can it experience, before the age of 11, what are causal relationships in history.

You see, this sheds light on how children should be treated before their skeletal system has awakened spiritually. As long as the child still lives in its muscular system from its blood system, it can experience the biography internally, it can experience internally when we teach it a complete picture of history that it likes or dislikes, with which it can have sympathy or antipathy, when we teach it a picture of the earth as I described yesterday. It can grasp everything that is the plant world as an image because the muscular system is plastic, internally mobile; when we teach it what I have said about the animal world, how it lives in human beings, the child feels this because the muscular system is soft. If we teach children under the age of 11 the principle of the lever, the principle of the steam engine, they cannot experience any of this internally because they do not yet have dynamics and mechanics in their bodies. If we begin with physics, mechanics, and dynamics at the right time, around the age of 11 or 12, we present something to the child's thinking that enters their head, and from within the human being comes that which the child experiences from their skeletal system. And what we tell the child connects with what wants to come out of the child's body. This creates not an abstract, intellectual understanding, but a living understanding of the soul. That is what we must strive for.

But what must the teacher be like if he wants to strive for something like this? Consider this: if the teacher knows from anatomy and physiology that the muscle is located here, the bone there, and the nerve cells look like this or that – that's all very well, but it's intellectual; it places the child beside us, so that the child is like an opaque object. The child is like black coal, so opaque. We know what muscles and nerves are inside; we know all that. But we do not know how the circulatory system interacts with the muscular system and the skeletal system. To understand this, our conception of the human structure, of the inner constitution of the human being, must be an artistic one. And the teacher must be able to experience the child artistically, as an artist. Everything within the child must be internally mobile for him.

Philosophy will come along and say: Yes, but if you want to recognize something, then the thing must be logical. Quite right, but just as a work of art must be logical when we have the world before us, and the world can be represented internally through artistic perception. So we must simply allow ourselves to have such artistic perception, and not dogmatically dictate that the world must be grasped logically alone. Only when the teacher has his own sensations, ideas, and feelings so internally flexible that he sees: If I teach the child dynamic, mechanical ideas before the age of 11, these ideas stagnate in the brain, they accumulate there, they make the brain hard, so that later in adolescence it leads to migraines and even later it hardens. If I teach them closed historical images before the age of 11, if I teach them images from the landscape and plant world, then the ideas enter the brain, but through the rest of the nervous system they enter the whole body. They connect with the whole body, with the soft muscle system. I lovingly build up what is happening in the child. The coal that the child otherwise is, if one only knows dead anatomy and physiology, becomes transparent. The teacher sees everywhere what is sitting in the desks in front of him, what is going on in each individual child. They do not need to think about this or that didactic principle, but the child tells them themselves what needs to be done with them by sinking back into their chair when something is done that is not suited to the child: they become inattentive. If something is done that is suited to the child, they become lively.

Of course, it can sometimes be quite difficult to cope with the liveliness of children. But you can cope with it if you have something that is less recognized in today's world: humor. The teacher must bring humor into the classroom through the door. Children can sometimes be quite naughty. One of our teachers at the Waldorf school experienced this with his older children, who were over 12 years old, when they suddenly began to lose interest in the lessons and wrote letters to each other under the desk. Well, isn't it true that a teacher who has no sense of humor becomes grumpy? There will be a terrible scene. What did our teacher at the Waldorf school do? He went to the children and explained the postal system to them. And the children saw that he understood them. He responded to their writing letters to each other. They felt a slight sense of shame, and the situation was restored.

The point is that art, and especially human art, cannot be mastered without humor. This means that the art of teaching also consists in removing grumpiness from the teaching staff and developing strong friendliness, humorous, humorous love for the children, so that the children do not see in the teacher the image of what he actually forbids them to do. In any case, it must not happen in the classroom that when a child becomes angry and expresses his anger, the teacher goes and says: I will drive this anger out of you! That is a terrible thing! - And he takes the inkwell and throws it on the floor so that it shatters. This does not drive the anger out of the child; only if you can show the child that his anger is an object, that it is not there for you at all, that you take it with humor, then you are educating him properly.

I have first described how the human being in general must be understood by the teacher and educator. But human beings are not just something general. And even if one can understand human beings so precisely that they become transparent to one, down to the activity of the muscular system before the age of 11 and the skeletal system after the age of 12, there still remains something that is extremely necessary for an artistically oriented education and artistically oriented teaching: the individuality of the human being. Every child is a different being, and proceeding as I have described so far can only be the very first step toward an artistically perceptive understanding of the child.

One must be able to delve more and more into the personal, into the individual. The first clues are provided by the fact that the children entrusted to us for education and teaching have different temperaments. Really understanding these temperaments from within is something that has been of the utmost importance from the very beginning in the art of education I am talking about here, which is practiced in Waldorf schools.

First, we have the melancholic child, a special type of person. How do they appear to us? Outwardly, they appear to us as a quiet, withdrawn child. But this outward characteristic is not very helpful. We can only get close to a child with melancholic tendencies when we see how, in melancholic children in particular, pure physicality exerts the strongest influence, when we know that melancholy is based on strong salt deposits in the organism, so that children with melancholic tendencies feel heavy in their entire physical organism. It is quite different for a melancholic child than for another child when it comes to lifting a leg or an arm. There are obstacles, inhibitions to lifting the leg or arm. There is a feeling of heaviness that opposes the soul's intention. This gradually causes the child with melancholic tendencies to look inward and not look outward in a friendly way, because their body makes itself so strongly felt, because they have so much to do with their body. Only when we know how the soul that wants to ascend, the spirit that wants to expand, is weighed down in a melancholic child by the physical deposits that continually flow out of the glands, weighing down the body, into the rest of the body tissue, only when we correctly understand this heaviness and the resulting capture of attention on the part of the physical body, only then can we reach the melancholic child.

Very often people say: Well, the melancholic child broods within itself, is quiet, moves little. And we encourage it to take in precisely lively ideas. We want to cure it with its opposite. We want to reach the melancholic child by cheering it up with all kinds of funny things that we bring to it. This is completely the wrong method. We are not reaching the melancholic child at all.

We must have the opportunity to approach the child through compassion and empathy with its physical heaviness, just as it is. We must try not to present the melancholic child with funny, comical ideas, but rather with serious ideas, those that it draws out of itself. We must teach it a lot of things that resonate with its own heavy organism.

Then, of course, we will have to be patient with such an education, for it does not work overnight, but over the course of years. It works in such a way that when the child is confronted with what it has within itself, it absorbs healing powers to counteract it. If we confront it with something completely foreign, if we confront the serious child with something funny, it remains indifferent to the funny. But if we confront it with its own sadness, grief, and worry, then it perceives from outside what it has inside itself. This evokes the opposite reaction inside, and we heal pedagogically by following the old golden principle in a modern form: like is not only recognized by like, but like is also treated and healed correctly by like.

But then, if the child has a more phlegmatic temperament, we must be clear about this: this child, who has a more phlegmatic temperament, lives less in its physical body and more in what I have called these days the etheric body, the body that is more fleeting. It lives in the etheric. It seems strange to say of a phlegmatic child that it lives in the etheric, but it is so. The etheric does not allow what goes on in the human organic functions, digestion, growth, to reach the head. The phlegmatic child has no power to form ideas about what is going on in its body. The head becomes inactive. The body becomes more and more active through the volatile element, which wants to scatter its functions throughout the world. The phlegmatic child is completely devoted to the world. It is absorbed in the world. It lives little within itself. As a result, it shows a certain indifference towards what we want to do with it. We cannot reach the child because, ultimately, we have to reach it through the senses. The main senses are in the head. The phlegmatic child can make little use of its head. The rest of the organism is kept functioning by the outside world.

We can only reach the phlegmatic child if, just as with the melancholic child, we ourselves become a kind of phlegmatic person beside them, if we are able to artistically put ourselves in their phlegmatic mood. Then the child has what it is itself beside it, and eventually what it has beside it becomes too boring for it. Even the phlegmatic child will find it too boring if he has a phlegmatic teacher beside him! And if we are patient again, we will notice that something is ignited when we present the phlegmatic child with ideas and processes steeped in phlegm.

The sanguine child is particularly difficult to deal with. The sanguine child is one in whom the rhythmic organism is particularly dominant. The rhythmic organism, which is dominant in humans between the change of teeth and sexual maturity, becomes too dominant in the sanguine child. Therefore, the sanguine child wants to rush from one impression to the next. Its blood circulation stagnates if the impressions do not change quickly. It feels constricted internally if the impressions do not pass quickly and others come. And so one can say: the sanguine child feels an inner anxiety when it has to focus its attention on something for a long time; it feels that it cannot stay with it, turns away, and gets strange thoughts. It can be difficult to keep its attention.

Again, I must say something similar about the treatment of the sanguine child: one should not try to cure the sanguine child by forcing it to dwell on one impression for a long time, but rather do the opposite. One should accommodate the sanguine nature and change impressions quite rapidly, forcing the child to take in impressions in quick succession. Again, it is the reaction that asserts itself. Then, because the circulatory system is completely dominant, it cannot help but express itself in antipathy towards the accelerated impressions. And the result of this is that the child itself becomes retarded.

The choleric child must be treated in yet another way. The choleric child has the peculiarity of always lagging a little behind normal human development. This seems strange. But consider the following image. An eight- or nine-year-old child is a normal human being with a certain way of moving its limbs, quickly and slowly, depending on external impressions. Compare the eight- or nine-year-old child with the three- or four-year-old child. The three- or four-year-old child still prances through life, has much less control over its movements. It still has something of the very small child about it. It has no control over its movements, it fidgets, its soul is not yet developed. But if infants had a highly developed soul, you would find them all to be choleric. Infants, with their fidgeting—especially when they are healthy, they fidget a lot—are all choleric.

The choleric child, however, retains something of the raging and raving of the very young child. As a result, the little infant still lives on inside the choleric child, the eight- or nine-year-old boy or girl. This is why this child is choleric, and one must try to treat this choleric child by gradually bringing the “little child” inside them to a standstill.

This must be treated with humor, I would say. Because if you have a real choleric child at the age of 8, 9, or 10, or even later in life, you will not get through to them by admonishing them; admonishing them will have no effect whatsoever. But if I get them to tell me a story that I tell them first, and they have to act out the story in a really angry way, they have to mime, they have to get into the role of their little person, then they gradually get to calm this little person inside them. They adapt them to their soul. And by becoming angry myself in my soul with the angry child, but of course, by always keeping myself under control with humor, I will achieve that the angry child next to me becomes calmer. When the teacher begins to dance—but please don't take that in a bad way—the raging of the child next to him gradually stops. One must simply have the ability not to get red in the face when dealing with a choleric child, not to let one's head get carried away, but to enter into a kind of artistic empathy with this inner raging. You will see that the child becomes quieter and quieter. It completely paralyzes the inner raging.

But there must be something uncontrived in it. If there is something artificial, unartistic in what the teacher gives the child, then the whole thing will be completely unsuccessful. The teacher must actually have artistic blood in him, so that he can demonstrate what he is showing the child and let the child experience it in a credible way; otherwise it is dishonest on the part of the teacher, and that must not be the case. The relationship between the teacher and the child must be true through and through.