Spiritual Relation in the Configuration of the Human Organism

GA 218

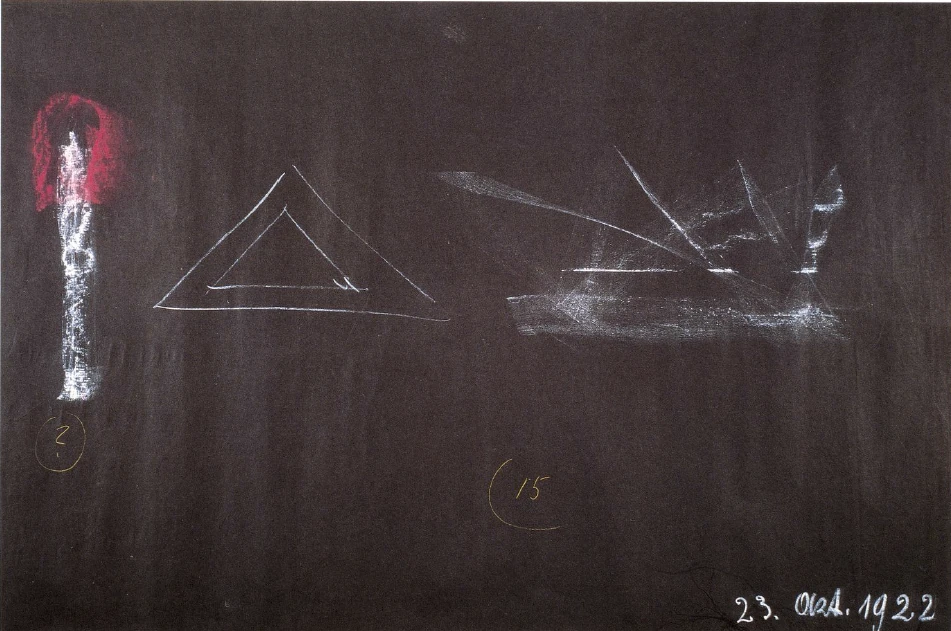

23 October 1922, Dornach

Lecture III

You will have seen from several earlier contemplations, that I do not like the phrase: “We live in a time of transition”, because every age is a time of transition—a transition from the earlier time to the later one. It is only a question of in how far a time is the time of transition—and just what is changing?

For the person who can see into the spiritual world, ours is indeed the time of an important transition.The wisdom of oldest time has always pointed to this important transition. During the epochs in which a spiritual world was still spoken of truthfully—if only out of dreamlike knowing—it was always said: after a certain time had passed, the so-called Dark Age will come to an end and a light-filled age would begin. If one now examines the words of the old wise men and takes them seriously, one indeed comes to realize that they meant that the transition from the Dark to the Light Age would occur around the turn of the 19th and 20th century—the time in which we now live. But we do not have to go through Anthroposophy to a renewal of the old dreamlike wisdom. I often have said that this is not the case, that with Anthroposophy it is the question of what one can acquire as knowledge in our time through spiritual research. Anthroposophy shall therefore not be the renewal of any kind of old wisdom, but a present-day mode of cognition. But as regards the transition from the Dark Age into the Light Age, present cognition has to completely concur with the old wisdom.

Although one can hardly say that we as mankind, especially as civilized European mankind, enter from worse conditions into better ones, what the old wisdom had in mind regarding the passing over into the light age, and what we also must think today, is nevertheless true. Only we must understand matters in the right way. I would like to make clear, with the help of an example, what the difference is between a Light Age—meant in this way—and a Dark Age.

Those people who once—in about the 5th pre-Christian millennium—spoke about such Dark and Light Ages, looked at this dark age as at the continuation of an earlier Light Age, and they expressed the opinion that, after the Dark Age had lasted for some time, a Light Age would come again. It would be instructive to look back and see how—mainly in human affairs—the Light Age, which once existed (approximately in the 7th or 8th millennium) was different from the later Dark Age, out of which we as mankind shall now emerge.

I would like to make that clear by an example—as I said—through the example of healing. The example of healing is very suitable in this respect, because one can see much by it. Namely, during that Light, or illuminated age, we did not look to the physical human body. One did not think of that at all. Altogether, one did not speak during that old Light Age of illness in the manner that one still speaks today of illness, but will speak no longer in the future. Of course one had in those olden times also the phenomenon that a person experienced the decay of his organs in this or that direction, that he simple was not healthy. However, one did not speak of illness, but said right out: Death exists and He takes hold of man. One saw something like a struggle between life and death in the situation where we would say today: this person is ill. So in those olden times one did not speak of illness and health when a person had become ill in the sense we understand, but one spoke about it in this way: in him death is fighting. And making well one regarded as combating, as driving out death in this way. Illness was only a special case of death, one might say, "a little dying", and health was life.

Why did one speak that way? One spoke that way because healing was then done entirely from the etheric body of man. One did not pay attention to the physical body; instead one was healing altogether in relation to the etheric body.

How was this done? Let us assume now, that a human being had become ill of something we would call pneumonia today. The form of illness in case of pneumonia was of a somewhat different type at that time, but one can nevertheless speak of this type of illness. One then said to oneself: this person has become too dependent on the region of the earth where he lives. This took place in times when migrations of people, when the moving away from places, was more unusual than today. People—at least the majority of people--mostly spent all their life at the same place. Nevertheless in such a case one said: this person has become too dependent upon the earthly spot where he was born. In those olden times one knew very specifically: man has already had a pre-earthly existence; through the survey, so to speak,through his destiny, he had decided about the place on earth himself. Therefore one said to oneself if a person has been taken ill before his 40th year or earlier by pneumonia, then he simply has not chosen his place on earth in quite the right way. He does not quite fit on this place on earth. In short, one derived the illness from the relation his human organization had to the spot on earth on which he was.

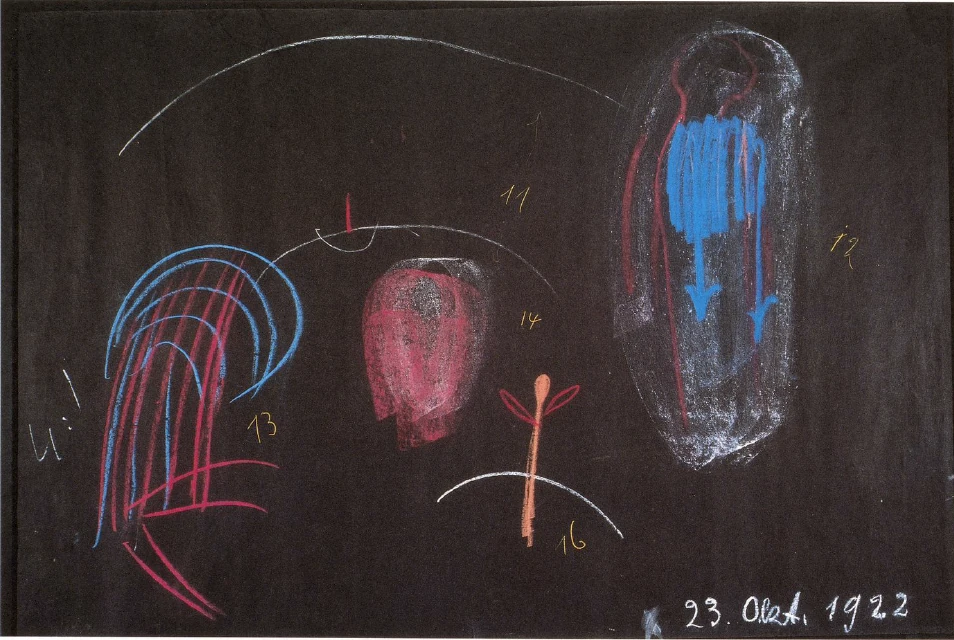

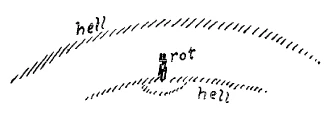

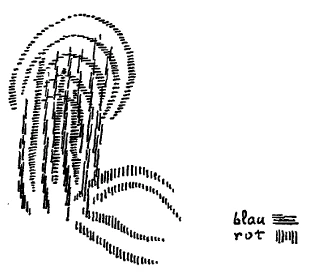

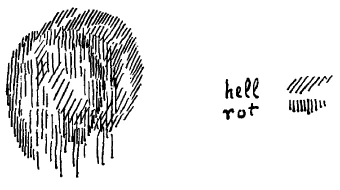

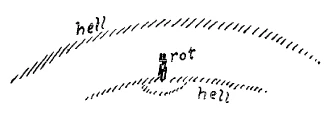

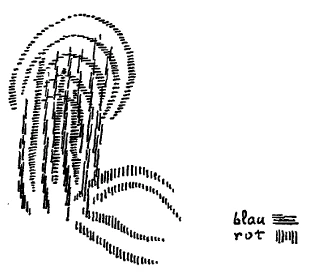

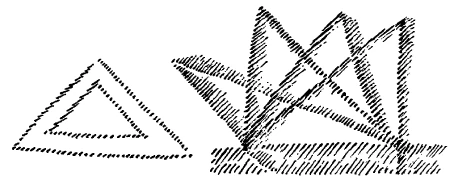

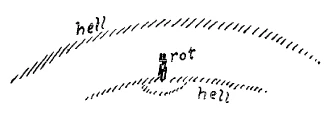

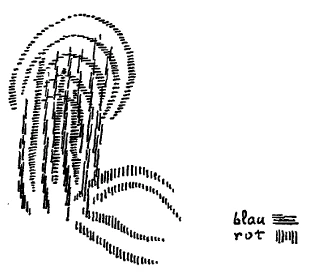

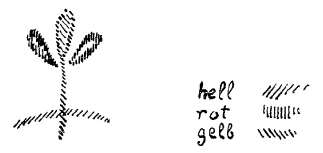

If I would sketch this, it would be this way: (diagram 1). If one imagined the earth this way, one said to oneself: if the person lives there, then he is too strongly dependent upon this particular spot on earth. One has to heal him by freeing him inwardly from the outer dependence on this earthly spot. One can do this by bringing him into connection with the surrounding cosmos to the outer heavenly cosmos. Heaven is that which had been man's home before he came down to earth. He does not quite fit into the earthly surroundings. One has to heal him in bringing him into the right relationship to the cosmos. One did this in such a way that one said: since this person has too many effects of the earth in himself—because there is too much gravity, and what is connected with gravity, in him, one has to give him relief—one has to bring super-earthly forces into him. One said to oneself: In these or other plant-blossoms, super-earthly forces are working. Therefore one prepared these or other plants by extracting their juice. One said to oneself: this plant is blossoming at a certain season, it is blossoming at this season through the influence of the cosmos. One investigated now, how far this person is influenced by this season in particular. In olden times the dependence of a person upon the cosmic forces was investigated through a kind of horoscope. One gave then as medication something that brought his ether-body into a general vibration. One expressed it to oneself in the following way: If this is a man (diagram 2, red), then this will be his ether body. He became ill of pneumonia because his ether body in the region of the lung is too much inclined towards the earth (blue) and because the forces of the earth have too great an influence on him. Mow one simply imparts to him juices from plant blossoms, which will work in him and help him to overcome these forces (Yellow). In this way one imparted forces to him which brought him into connection with the cosmos. One was striving through this treatment to place the whole ether body into the right vibration to balance the different single incorrect vibrations. So one always was asking: what does one have to do regarding the ether body?

Altogether, how could one proceed in such a way? One could do that, because one had a distinct picture of the human ether body. One did not only see the physical human body in those old times, but one saw the physical human body luminous, one saw the ether body. Man was a being of light, and as one judges today by a person's complexion, e.g., if someone is pale, that he is ill—in the same way one formed an opinion about his state of health by his ether body, by the color, if it became red, or blue or green. On what did one base one's knowledge of the human being in those times? On the light, on that which was Light in man. One has to take it quite literally: it was the Light Age, it was the age in which one really saw what was living in man as Light.

If you look at man from today's point of view in regard to health and illness, you will find that today, also, it must be said: light has a tremendous strong influence on human health. People have to take care that they receive the right quantity of light into their organism. We know that children who at a delicate age suffer from lack of light, will contract rickets or other illnesses ,which are throughout related to a lack of light. Of course these are related to other factors, too—an illness can never be derived from only one cause—but such cases as rickets, can connected throughout with lack of light. One can relate with certainty how frequently rickets occurs among children who live in city apartments, where little light enters, and how little children are inclined to rickets—approximately, of course—who can be exposed to light in the proper way. So we can rightly say today as well that the human being takes light into himself.

But the light that man receives today is—if I may express myself that way—mineral light. Man takes up that light which is radiated onto the earth, onto the minerals, and is radiated back to him, or else the light which he receives directly from the sun. It is mineral light. The light that falls on the meadows and on the trees is also conveyed to us in a mineral way. It is dead light that we absorb through our skin, throughout our whole human being. During that old light-filled age, which preceded our dark age, men were conscious that this dead light was of no meaning to them.

The research historian of today, as well as the cultural historian know absolutely nothing about such things. The light that we appreciate so much today was not considered worthy of appreciation by men of olden times. They differentiated between the light they appreciated and the light that is so much esteemed today. For example—we sit down at the table and have plates and forks and knives, and on the plate some kind of cake or something else that is edible. We then eat the cake; naturally, we also appreciate knives and forks, but we don't eat them, they are just there. What we value as light stood in relation to what the ancients valued as light much as the utensils stand in relation to the cake. But what they regarded as light comes from the plant kingdom. This we do not take up at all any more, as it was taken up in the old light ages. We enjoy ourselves today when we can walk in the sun. The man of old enjoyed himself when he walked over a meadow, or through the woods, because he absorbed into himself—through his skin—the light that the woods had first absorbed, which had been enlivened in the woods, enlivened on the meadow. The other, the dead light—that was an addition, “trimmings,” as it were. For us, the trimmings have become the main thing. The man of old lived in the light, which the flowers, the trees of the woods gave to him. For him that was a source of being quickened inwardly with light, with inner living light and not with dead light. With our abstract joy of the woods, with our abstract joy about flowers, with all that, we have, basically, what I might call philistinism, in the cosmic sense. It may still be very beautiful, but it is philistine in contrast to what was existing in the old people as inner jubilation of the soul in face of the wood, of the meadow, in face of all that was living outside. The man of old felt himself related with his trees, with all that was for him precisely the suitable plant. He felt sympathy and antipathy in the most animated way with this or that plant. We, for example, walk across such meadows as those around the Goetheanum in autumn. We judge in a philistine way: the meadow saffron, the colchium autumnale might perhaps be beautiful. The man of old passed by these plants and became sad, so that even his skin seemed to become somewhat dry. He even sensed something like his hair becoming limp. While, when he passed—let us say, by red blooming plants, they might be such plants as the poppy is today, his hair became downy, soft. Thus he experienced the light of the plants in an absolute way. It was the light-filled age, and his whole cultural life was directed accordingly. Accordingly it was also directed that he could heal—that is, could combat death—through observation and treatment of the ether body.

This remained effective for a long time and we still see, when we go back to the older Greek medicine, to Hippocrates, how one spoke then of the “humors” of man, of a black or light bile, of blood and of phlegm. This was really thought about as remembrances of the old light age. Phlegm was essentially taken to mean the ether body and blood, those vibrations which the astral body effects in the ether body, and so on, So these after-effects were still there, and basically only at the time of Galen did one start to rely on the mere physical world, including the remaining human cultural life. The conception of man, in as far as it should be the foundation for processes of healing, received a physical character. One looked at the physical body.

But it was in fact only at the great turn in the first half of the 15th century that one did not know anything at all any more of the human ether body, not even how it expresses itself in the temperaments; that one began to look more and more only at the physical body of man. The older physical medicine was still something else than it was to become later, mainly in the 18 and 19th centuries. The old physical medicine always had traditions, at least, of the earlier healing through the ether body. One really has the impression that in this older European medicine, one had retained old principles and had only carried them over into the physical. In a certain way the physical human organism still continued to be seen as under the influence of the etheric organism. Only in more recent times—in the time of Copernicus and Galileo—did one begin to observe more and more merely the physical human body and cease to know something the earlier times had known in an exact way. Today one thinks: if man eats this or that substance, which one finds out there in nature, it will stay basically the same inside the human organism. But that is not true. Only the salts remain approximately the same. But all that is there in the animal and plant kingdom becomes something entirely different in the human organism. The human organism changes it completely. One knew that the human physical organism “is not from this world” in its inner consistency and one knew fundamentally that becoming ill is nothing else than a continuation of what happens through eating. In fact there was a time, especially among the Arabian physicians, when one regarded every digestion as a partial process of illness, where one looked at digestion in a way that.was not really wrong; when man has eaten, he has brought something foreign into himself and that he really is “sick”. He must first, through his inner organism, through inner organic functions, overcome the illness. So that one continuously lives in a state of being “a little bit sick,” and “a little bit overcoming the illness.” One eats oneself sick and one digests oneself well again. This was in fact for some time, especially among Arabian physicians, a point of view which is altogether—if I may express myself that way—something quite healthy, because there exists no real borderline between what one calls today “eating oneself well” and “eating oneself ill.” Just think how easy it is to get one's stomach in disorder, something that—as one says—could normally still be overcome, quickly goes over into something one cannot overcome any more. Then one is simply sick. But the borderline is really not to be drawn at all.

It is just as difficult to draw a borderline regarding confusions between something that still can be evened out in a completely natural way and something where one has to come and give help through a process of healing. So once one correctly saw illness as a continuation of eating—eating that was not done correctly. One studied the daily process of digestion, that is: digesting oneself into health; this one studied.

In this respect it is quite a good practice if one person or another who cannot tolerate this or that food unsalted, adds more salt for himself. Somebody else even has to add pepper, others add paprika—isn't that so? Because he cannot digest the things just as they are, he adjusts them to his needs. There again is no borderline, if somebody needs pepper or paprika as a healing factor; there again is no borderline, if one gives more pepper or paprika, so one can digest oneself well, or if, when things get worse, one takes something out of the mineral kingdom. It does not matter if one then gives that as addition to the food, or as medicine. There again things flow into each other, there is again no borderline.

What was therefore known in a precise way was that if man takes something completely from the outer world, this will injure his inner organism and he must by all means overcome it. If finally I push a rusty nail into myself and my organism has to fester it out, or if I bring something into my stomach, which must not be allowed to stay that way, and my organism has to go through all these processes so it can assimilate this—these are only gradations of difference. But the knowledge that the human organism is not of this earth, and that it can sustain itself on this earth only if it is continuously stimulated to overcome the forces of this earth—this knowledge did exist. Namely, we do not eat to get this or that food into oneself, but we eat so that we can develop the forces inwardly which can overcome this food. We eat to bring forth resistance to this earth, and we live on this earth in order to bring forth resistance.

But this was gradually forgotten. One just took the whole matter in a materialistic way and finally one only still tried to see if this or that substance in these or other plants might give help. Yes, you see that is what was once meant, and what we again must have in mind regarding the dark age. Everything has simply become dark. In earlier times one looked at the light ether-body, and regarded this as man. Now one does not see anything of this light any more. One perceives only where there is matter, and one holds on to the dead light. But this dead light gives man only abstract conceptions, it has brought forth only intellectualism. But today we stand in a transition to the necessity to recognize the light again in a new way. Before, man knew within himself: he had this light ether body. Now we must increasingly develop such knowledge, and recognize the etheric in the outer world, especially in the plant kingdom.

Goethe made a beginning with this in his theory of metamorphosis, although he still put the whole into abstract conceptions. This must develop more and more into Imaginations. And we must be clear that we simply must reach the point of perceiving the being of the plant in luminous pictures. While man himself was luminous in the earlier light age, in the future nature around us, as far as it is plant-world, has to become aglow in the most manifold Imaginations of plant forms. And just with the help of these plant forms, luminously shining forth, will we be able to find new remedies in the plants. This necessity confronts us. While man in the earlier light age saw an inner light, people of the present age have the obligation of “seeing” in the outer world, to behold again a light, this light in the outer world.

This light can be kindled, if one deepens more and more the study of spiritual science. You may say: spiritual science, Anthroposophy—there also I read only concepts, and finally, if I read Occult Science, I also find only concepts there; that does not give me an occasion to really “perceive.” Yet, my dear friends, this Occult Science does have a twofold goal. The first is that one learns to know what is related there; but that is not the whole. If you have read my Occult Science like another book, then you will know only the match. But if you want to have fire, you must not say: this match is no fire! It is nonsense to say, if he gives me a match, that he gives me fire, it does not look like fire! Occult Science does not look like clairvoyance; that is like saying the match does not look like fire. Yet it will look like fire if you will but strike the match. And if it does not work the first time, you will strike another time, and so on. That is how it is with Occult Science. If you have read it like another book, then it is simply only “the match,” but if you have rubbed it in the right way in your whole human being, then you will see, it kindles! It has kindled only a little! But it does kindle, my dear friends. And the person who says: this remains far away from what one is striving for, namely clairvoyance, he will only look at the match and not strike it. But the fact is, one must first know the match, otherwise one will give oneself up to the illusion that one could kindle it with a pin. Of course, you cannot kindle it with a pin—that is, with modern science—you can do it only with a real match.

The human race is confronted precisely by this necessity and it may be especially shown in something such as medical knowledge and medical ability. If one will find the transition from a mere looking at the darkness in substances—in the way that one somehow looks at a plant blossom, as it is done today—to an imaginative way of looking, by “striking the match”—then one acquires the knowledge of how this or the other substance will affect the human being. And if one now thinks over the matter a little, one has to say to oneself: today's mankind is confronted with that: out of the darkness it should enter again into the light, it should learn to judge in a light-filled way.

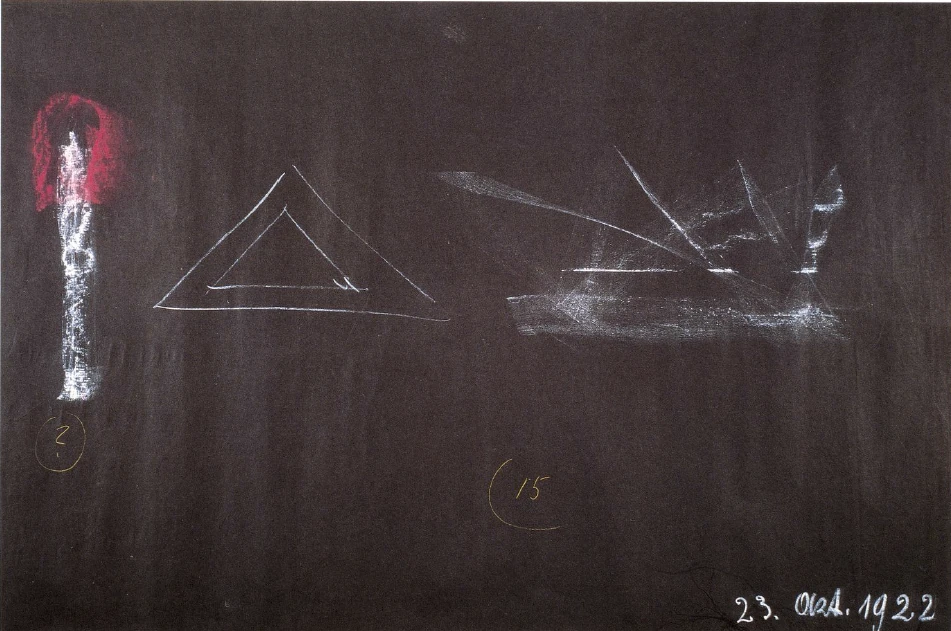

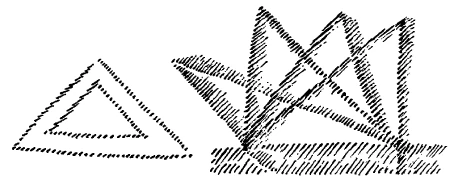

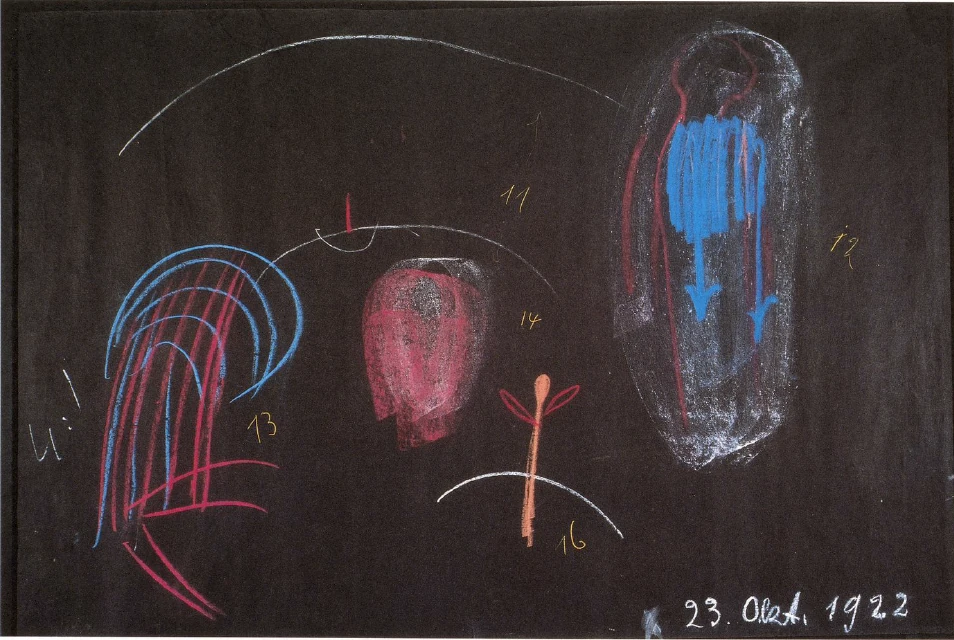

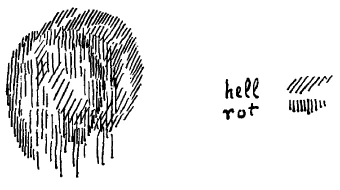

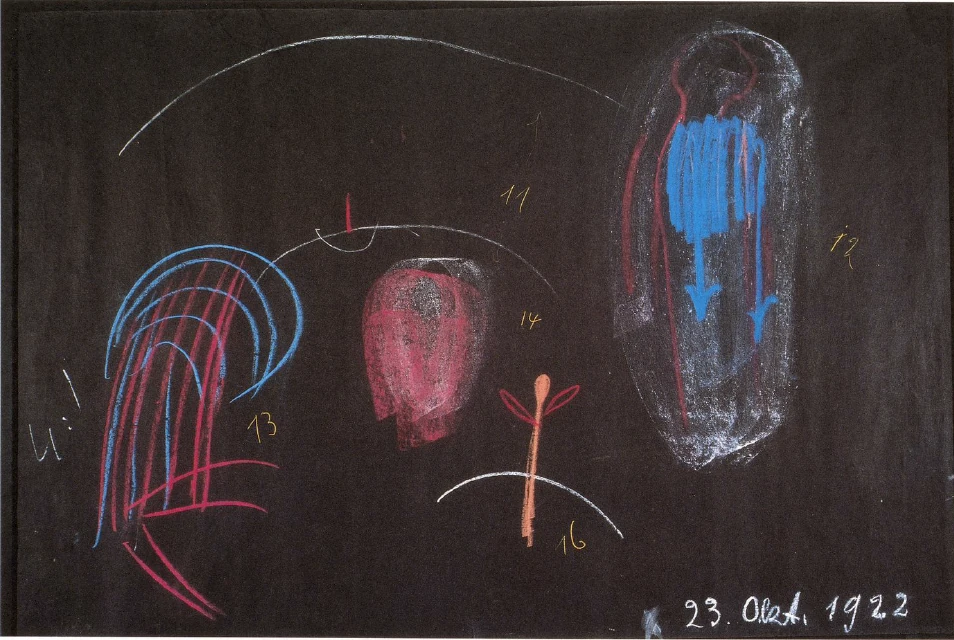

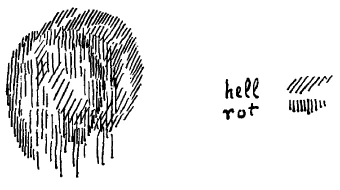

I want to make this clear once more by an example. Let us assume that a physician of today is making a diagnosis of, let us say, an enlargement of the heart. He does it the way it is done today. One cannot do much with such a diagnosis. Perhaps one has tried if this or that can help here. But the fact is that one does not have any comprehensive connections. One does not have anything comprehensive because one does not look through the whole matter. A real penetration of the whole would result in the following: Assume once that the human being, as I have, presented him quite often, renews his organism after seven years. But I also mentioned last time how this renewal comes about. There are always unfinished substances in a way sent upwards or also forwards or downwards by the kidneys' system. From the head the rounding off is done (diagram 3) so that continuously such waves (blue) are coming from the head-system, which give form, and that through the kidney-system such effects take place—four times faster—which are broken off and formed by the waves (red) as I described.

Take an organ such as the heart (orange). There too such an exchange takes place in every human after 7 or 8 years. The heart is being renewed. It is made anew. What you see at the fingernails, that they grow outwards and always grow again after one cuts them off, that is also the case with the whole human being: he renews the material substance from the center. Now assume once that the rhythmic man might not be in order, that it might be so for his organization, that the rays from the kidney system burst forth much too rapidly, so that the right relation of 4 to 2 is not there. That varies for the individual—every person is an individuality in this respect—but it is the case in regard to his whole construction as a human being. Assume then, that this is not in order, that the radiation from the kidney-system is pushing too fast. What will happen thereby?

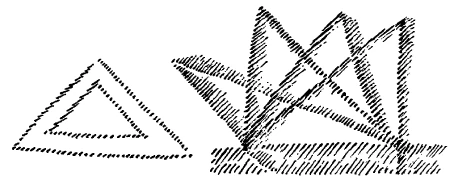

The following can happen. The process of renewal is indeed happening continuously; let us then imagine that the new heart moved in (red) before the old heart is completely ejected (diagram 4, light). Then it goes too fast. If the renewal goes on too fast, such phenomena as an enlargement of the heart occurs. First and foremost you can detect in the beginning of an enlargement of the heart that something is not in order in the activity of the kidney. Just where you take this matter of a renewal of the human being in 7-8 years seriously you will see: if that which will come as renewed substance is already there after 6 years, that which is there as the old heart has not yet been removed sufficiently and the organ expands, or tries at least to expand itself. That is how one must learn to look at things; one must learn to see things in living movement. That is what confronts us. One must see most of all what one always has seen in fixed limits. How does the physician today make a diagnosis?

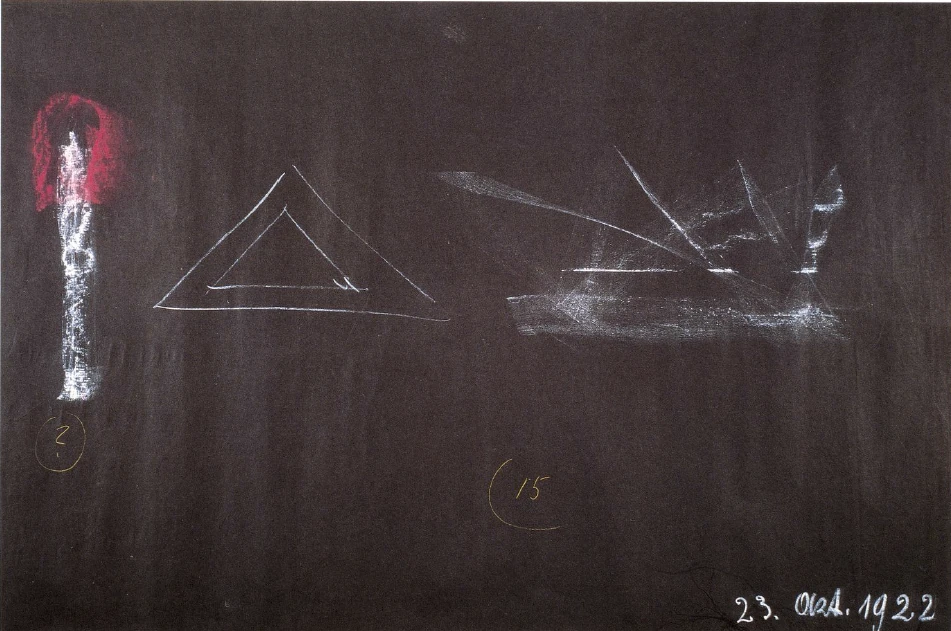

The physician of today comes to a diagnosis in such a way that he likes best to trace down the contours of the heart to what it is as a finished organ. It is not so much the question of looking at what the finished organ is, since it simply is an organ that is always floating away and getting pushed back again. In this going away and pushing back there is something inwardly mobile. If I lay hold of it, it is essentially as if I were to lay hold of lightning—it is constantly in movement, Therefore if I want to comprehend man, I have to grasp him in his liveliness. This liveliness I understand and find today only if I understand the whole world, and man out of the world and cosmos. This is what we are confronted with: every thing has to pass over into knowledge that is flexible. It is something dreadful if we keep the children in school immobile. For example, it is always quite grievous for me to see the children use any kind of finished triangle, with which they make all sorts of things. This fixed object is really nothing. One should really have a kind in which the triangle can be shifted. This is the point: that the children get the conception in the right way that everything should be grasped in movement. (diagram 5).

It is, of course, dreadfully difficult to get an understanding in regard to these things with such people who want their peace and quiet, who are already angry, when children are making a row—and now the tools for instruction are making a row! It is, of course, something dreadful: but it is so, we have to change over to liveliness. All this taken together results in the challenge to move upward into the light, luminous

age. Out of the dark age we must enter into the light luminous age.

And because people can not do it—that is, they imagine that they cannot do it—because people do not want it, because people cling to the old, and don't want to step into the new, and because the old does not fit any more—it is because of this that we experience the terrible catastrophes in our present time. And we will experience them still more if people don't want to take the trouble to enter into the new.

What occurs as catastrophe is the reaction of the dark age, which does not belong in our time. But it is, of course, terribly difficult to come to an understanding. At best something like an inkling appears in the contrasting attitude between the old people and youth today, like an inkling of the new light: filled age. Young people say as a rule: oh, the old people are philistines. This also has its forerunners. The great German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte had something of an inkling beforehand of this in making the classical declaration, that one really should kill all people at the age of thirty because man is only a decent human being up to his 30th year. This is a famous sentence of Fichte and since Goethe at the time that Fichte made this sentence was already considerably older, he was terribly annoyed and has ridiculed this whole theory in the second part of his Faust. It was really provoking for Goethe, of course! So one finds that youth agrees that the old people are philistines, but up to now no serious results have come about in this matter, because young people declare this up to a certain age and then become even greater philistines than the old ones have been. Even this side must be looked upon from an inner vantage point.

What I mean is the question that we already know: either Spenglerism—that is, the decline of the West—or taking the trouble to adjust ourselves to the new appearance of the light age in contrast to darkness, during which men were “earthworms” in regard to the cosmos. It cannot be different. But for a while in the course of history man had to he an earthworm because otherwise he would have been taken up completely by the light. He could strive to gain his freedom only during the dark age, and most of all during the termination of the dark age, in the more recent times. He could acquire his freedom only because the light left him unmolested so that he could lead an earthworm existence.

But now I tell you: men of the light ages preferred to receive the light of the plant world. The plants were, so to speak, drinking the cosmos light and man in turn drank the light out of the cup the plants presented to him.

Today we have only the dead light. But on the rays of the dead light Christ has come and has achieved the Mystery of Golgotha. That is the great cosmic Mystery of the newer time. Though we have the dead light—the dead light that cannot make us blessed—yet on this dead light's rays has Christ entered the earth and achieved the Mystery of Golgotha. And though outwardly we have around us the dead light we can bring the Christ in us to life. And with Christ in us in the right way we will enliven all of the light on earth around us—we will carry life into the dead light, we ourselves will have a reviving effect on the light. This means we must enter the new age with the right Christ impulse. The denial of the Christ-impulse is the basis of all that keeps men away from seeing rightfully how a dark age transits into the light age.

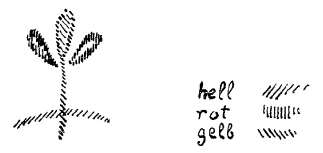

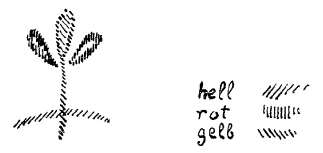

It is really so. Where the plant grows out of the earth (diagram 6) it develops the seed bud—as I have shown you already—still through the forces of the previous year; only the petals grow out of this year's light. What pulls the plant out of the earth really comes from the previous year. So it was actually conserved light which the plants once gave to man during the old light age. We have to find the possibility to comprehend the dead light with the mind and heart that is engendered in us if we receive the strength of Christ in the living perception of the Mystery of Golgotha. Then we will revive the light as I have indicated. But we can do that only if we learn to try to look at all things in the way I have tried to describe to you in these lectures.

Geistige Zusammenhänge In Der Gestaltung Des Menschlichen Organismus III

[ 1 ] Sie werden schon aus allerlei früheren Betrachtungen ersehen haben, daß ich nicht die Phrase gerne gebrauche: Wir leben in einer Übergangszeit —, denn jede Zeit ist eine Übergangszeit, nämlich vom Früheren zum Späteren, und es handelt sich immer nur darum: inwiefern ist irgendeine Zeit eine Übergangszeit, was geht über?

[ 2 ] Nun, in unserer Zeit ist tatsächlich für denjenigen, der hineinschauen kann in die geistige Welt, ein sehr wichtiger Übergang vorhanden, und auf diesen wichtigen Übergang hat ja die Weisheit ältester Zeiten immer hingewiesen. In den Epochen, in denen von einer geistigen Welt in Wahrheit noch die Rede war, wenn auch nur aus alten traumhaften Erkenntnissen heraus, ist immer gesagt worden, nach Ablauf einer gewissen Zeit werde das sogenannte finstere Zeitalter zu Ende gehen und ein lichtes Zeitalter beginnen. Nun, wenn man die Worte der alten Weisen prüft und ernst nimmt, so kommt man ja wirklich darauf, daß sie gemeint haben, um die Wende des 19. zum 20. Jahrhundert, in der wir eben jetzt leben, sei dieser Übergang von dem finsteren in das lichte Zeitalter. Wir brauchen uns aber nicht etwa darauf einzulassen, durch Anthroposophie die alte traumhafte Weisheit zu erneuern. Ich habe oftmals gesagt, daß das durchaus nicht der Fall ist, sondern daß es sich bei Anthroposophie um dasjenige handelt, was man gegenwärtig durch geistige Forschung erkennen kann. Anthroposophie soll also nicht die Erneuerung irgendwelcher alter Weisheit sein, sondern eine gegenwärtige Erkenntnis. Aber in dieser Sache, bezüglich des Obergange: aus dem finsteren Zeitalter in das lichte Zeitalter, muß die gegenwärtige Erkenntnis eben der alten Weisheit durchaus zustimmen.

[ 3 ] So wenig man auch, wenn man gerade die Ereignisse der Gegenwart ins Auge faßt, vom Äußerlichen her sagen kann, wir treten als Menschheit, namentlich als zivilisierte Menschheit Europas etwa aus schlimmeren in bessere Zustände ein, so wahr ist auf der anderen Seite aber dennoch dasjenige, was schon die alte Weisheit gemeint hat mit dem Übertritt in das lichte Zeitalter, und was wir heute wieder meinen müssen. Wir müssen die Dinge nur in der richtigen Weise verstehen. Ich möchte zunächst an einem Beispiele klarmachen, wie der Unterschied eines in diesem Sinne gemeinten lichten Zeitalters und eines finsteren Zeitalters ist.

[ 4 ] Die Menschen, die einstmals, etwa im 5. vorchristlichen Jahrtausend, von einem solchen finsteren und lichten Zeitalter gesprochen haben, die haben dieses finstere Zeitalter als die Folge von einem früheren lichten Zeitalter angesehen und haben die Meinung ausgesprochen, daß, nachdem das finstere Zeitalter eine Weile gedauert haben werde, wiederum ein lichtes Zeitalter kommen werde. Es wird also lehrreich sein, zurückzublicken, wodurch sich in wesentlichen menschlichen Angelegenheiten das lichte Zeitalter, das einmal vorhanden war, das etwa da war im 7. oder 8. vorchristlichen Jahrtausend, wodurch sich dieses lichte Zeitalter von dem späteren finsteren Zeitalter, aus dem wir Menschen nun heraustreten sollen, unterschieden hat.

[ 5 ] Ich möchte das, wie gesagt, an einem Beispiel klarmachen, an dem Beispiel des Heilens. Das Beispiel des Heilens ist sehr gut anwendbar dabei, denn man kann daran sehr vieles sehen. In jenem alten hellen oder lichten Zeitalter heilte man nämlich nicht dadurch, daß man hinblickte auf den physischen Menschenleib. Daran hat man gar nicht gedacht. Man hat überhaupt in jenem alten lichten Zeitalter nicht in dem Sinne von Krankheit gesprochen, wie man heute noch von Krankheit spricht, wie man aber aufhören wird in der Zukunft zu sprechen. Man hat in jenen alten Zeiten natürlich auch die Erscheinung gehabt, daß ein Mensch nach dieser oder jener Richtung einen Verfall seiner Organe erlebte, daß er nach dieser oder jener Richtung eben nicht gesund war, aber man hat nicht von Krankheit gesprochen, sondern man hat geradezu gesagt: Es gibt einen Tod, und der bemächtigt sich des Menschen. — Und man sah eine Art von Kampf zwischen Leben und Tod in dem Falle, wo wir heute sagen, der Mensch ist krank. Also in jenen älteren Zeiten sprach man nicht von Krankheit und Gesundheit, sondern man sprach davon, wenn ein Mensch in unserem Sinn krank geworden war: in dem kämpft der Tod. Und das Gesundmachen sah man als ein Bekämpfen, ein Austreiben des Todes an. Man sprach also eigentlich von Leben und Tod. Und Krankheit war nur ein spezieller Fall des Todes, möchte ich sagen, ein kleines Sterben; Gesundheit war das Leben.

[ 6 ] Warum sprach man so? Man sprach aus dem Grunde so, weil man dazumal ganz vom ätherischen Leib des Menschen aus heilte. Man kümmerte sich sozusagen damals nicht um den physischen Leib des Menschen, sondern man heilte ganz und gar vom ätherischen Leib des Menschen aus.

[ 7 ] Wie machte man das? Nun, sagen wir, der Mensch wäre dazumal von so etwas befallen worden, was wir heute eine Lungenentzündung, Pneumonie nennen. Die Krankheitsform der Lungenentzündung hatte einen etwas anderen Typus dazumal, aber man kann immerhin von dieser Krankheitsform sprechen. Da sagte man sich dazumal: Dieser Mensch ist zu stark abhängig geworden von der Erdengegend, in der er lebt. - Es war ja das in den Zeiten, wo Menschenwanderungen, wo das Verlassen der Orte seltener waren als heute. Die Menschen blieben zumeist, wenigstens die Mehrzahl der Menschen, ihr ganzes Leben an dem Orte, wo sie waren. Dennoch, man sagte in einem solchen Falle: Der Mensch ist zu stark abhängig geworden von dem Erdenflecke, auf dem er geboren ist. - Man wußte in jenen älteren Zeiten ganz genau: der Mensch hatte schon ein vorirdisches Dasein, er hat sozusagen durch die Überschau, durch sein Schicksal sich im vorirdischen Dasein seinen Erdenort selber bestimmt. So also sagte man sich: Wenn ein Mensch etwa vor dem vierzigsten Jahre oder noch früher von einer Lungenentzündung, von Pneumonie befallen wird, dann hat er sich seinen Erdenort eben nicht ganz richtig gewählt. Er paßt nicht recht zu seinem irdischen Aufenthalte. - Kurz, man leitete die Krankheit ab von dem Verhältnis seiner menschlichen Organisation zum Erdenflecke, auf dem der Mensch war.

[ 8 ] Wenn ich das aufzeichnen will, so wäre also das so (siehe Zeichnung Seite 91), wenn man sich so die Erde vorstellte, so sagte man sich, wenn da der Mensch lebt, so ist er zu stark abhängig von diesem Erdenfleck, und man muß den Menschen dadurch heilen, daß man ihn innerlich befreit von der äußerlichen Abhängigkeit von diesem Erdenfleck. Das kann man dadurch, daß man ihn in Beziehung bringt zu dem umliegenden Kosmos, zu der äußeren Himmelswelt. Man sagte: Der Himmel ist dasjenige, was des Menschen Heimat war, bevor er hier auf der Erde war. Er paßt nicht recht auf die Erde herein. Man muß ihn heifen dadurch, daß man ihn in die richtige Beziehung zum Kosmos bringt. —- Und das tat man dann etwa in der Weise, daß man sagte: Man muß also den Menschen, weil zuviel Erdenwirkungen in ihm sind, weil gewissermaßen zuviel Schwerkraft und das, was mit der Schwerkraft zusammenhängt, in ihm ist, man muß ihn erleichtern; man muß die überirdischen Kräfte in ihn hineinbringen. — Man sagte sich: Überirdische Kräfte wirken in diesen oder jenen Pflanzenblüten. Also man bearbeitete diese oder jene Pflanzenblüten, indem man ihren Saft gewann. Man sagte sich; Diese Pflanze, die blüht zu einer gewissen Jahreszeit; sie blüht durch die Einflüsse des Kosmos zu dieser Jahreszeit. — Man erforschte nun, inwiefern der Mensch gerade durch diese Jahreszeit beeinflußt wird. Zu diesem Zwecke wurden ja in älteren Zeiten die Abhängigkeiten des Menschen von den Himmelserscheinungen in einer horoskopartigen Weise gesucht. Und man gab dann als Arzneien dem Menschen dasjenige, was seinen Ätherleib in eine allgemeine Schwingung brachte. Man sagte sich so: Wenn das der Mensch ist (siehe Zeichnung $. 93, rot), dann ist das sein Ätherleib (hell), und er ist an Pneumonie erkrankt aus dem Grunde, weil sein Ätherleib in der Gegend der Lunge zu stark der Erde zuneigt (blau), und weil die Erdenkräfte auf ihn zu großen Einfluß haben. Jetzt bringt man ihm eben Säfte von Pflanzenblüten bei, welche in ihn hineinwirken und welche diese Kräfte überwinden (gelb). Man führte ihm also Kräfte zu, die ihn in Zusammenhang brachten mit dem Kosmos. Dadurch strebte man an, den ganzen Ätherleib in richtige Schwingungen zu versetzen, damit die unrichtigen einzelnen Schwingungen ausgeglichen werden. Also man fragte sich immer: Was muß man mit dem Ätherleib tun?

[ 9 ] Nun, warum konnte man denn überhaupt in dieser Weise vorgehen? Man konnte das aus dem Grunde, weil man eine deutliche Vorstellung vom menschlichen Ätherleib hatte. In jenen älteren Zeiten sah man nicht bloß den physischen Menschenleib, sondern man sah den physischen Menschenleib leuchten, man sah den Ätherleib. Der Mensch war ein Lichtwesen, und wie man heute am Inkarnat beurteilt, wenn zum Beispiel einer blaß ist, daß er krank ist, so beurteilte man seinen Gesundheitszustand an dem Ätherleib, an der Färbung, wenn er zum Beispiel rot oder blau oder grün wurde. Worauf gründete man also seine Menschenkenntnis in der damaligen Zeit? Auf das Licht, auf dasjenige, was im Menschen Licht war. Es ist ganz wörtlich zu nehmen: es war das lichte Zeitalter, es war das Zeitalter, in dem man das, was im Menschen als Licht lebte, wirklich sah.

[ 10 ] Wenn Sie vom heutigen Gesichtspunkte aus den Menschen nach Gesundheit und Krankheit betrachten, so werden Sie ja finden, daß auch heute gesagt werden muß: das Licht hat einen ungeheuer starken Einfluß auf die menschliche Gesundheit. Der Mensch muß darnach trachten, daß er die richtigen Quantitäten von Licht in seinen Organismus hereinbekommt. Wir wissen ja, wie Kinder, die im zarten Alter an Lichtmangel leiden, der Rachitis verfallen oder anderen Krankheiten, die eben durchaus mit dem Lichtmangel zusammenhängen — natürlich auch mit anderen Dingen, niemals ist eine Krankheit nur aus einer Ursache abzuleiten —, aber solche Dinge, wie Rachitis zum Beispiel, hängen durchaus mit Lichtmangel zusammen. Man kann durchaus konstatieren, wie sehr, sagen wir, die Kinder der Rachitis ausgesetzt sind, die in der Stadt in Wohnungen sind, wo wenig Licht hineinkommt, und wie wenig Kinder zu Rachitis neigen - im Durchschnitt natürlich -, die in gehöriger Weise dem Licht exponiert werden können. Also auch heute können wir durchaus sagen, daß der Mensch Licht in sich aufnimmt.

[ 11 ] Aber das Licht, das heute der Mensch in sich aufnimmt, das ist, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, mineralisches Licht. Der Mensch nimmt dasjenige Licht auf, was auf die Erde, auf die Mineralien gestrahlt und zu ihm zurückgestrahlt wird, oder was er direkt von der Sonne bekommt. Es ist mineralisches Licht. Auch das Licht, das auf die Wiesen, das auf den Baum fällt, wird in mineralischer Weise zu uns geleitet. Es ist totes Licht, das wir heute einsaugen durch unsere Haut, durch unseren ganzen Menschen. In jenem alten lichten Zeitalter, das dem finsteren Zeitalter vorangegangen ist, da waren sich die Menschen bewußt, daß dieses tote Licht eigentlich für sie keine Bedeutung hatte.

[ 12 ] Solche Dinge weiß der heutige Geschichtsforscher, auch der Kulturhistoriker, gar nicht. Das Licht, das wir heute so sehr schätzen, das war für jene alten Menschen gar nicht etwas so Schätzenswertes. Ungefähr so unterschieden sie zwischen dem Lichte, das sie schätzten, und diesem heute von uns geschätzten Lichte, wie, sagen wir, wenn wir uns zu Tisch setzen und Teller und Löffel und Gabel haben, auf dem Teller irgendeinen Kuchen oder irgend etwas anderes Eßbares. Da essen wir den Kuchen; wir schätzen auch natürlich Messer und Gabel, aber wir essen sie nicht, sie sind dabei. So war für die Alten bei dem, was sie als Licht schätzten, das dabei, was wir heute vorzugsweise als Licht schätzen. Aber das, was sie als Licht schätzten, das kommt vom Pflanzenreich. Das nehmen wir heute gar nicht mehr in der Weise auf, wie es in alten lichten Zeiten aufgenommen worden ist. Wir erfreuen uns heute, wenn wir in die Sonne gehen können. Der alte Mensch erfreute sich, wenn er über eine Wiese, durch einen Wald ging, weil er in sich, durch seine Haut hereinsaugte das Licht, das zunächst der Wald aufgesogen hatte, das belebt war im Walde, belebt war auf der Wiese. Und das andere, das tote Licht, das war die Zutat. Für uns ist die Zutat die Hauptsache geworden. Der alte Mensch lebte in dem Lichte, das ihm die Blumen, das ihm die Bäume des Waldes gaben. Für ihn war das ein Quell innerlichen Durchlebtwerdens mit Licht, mit innerlichem lebendigem Licht, und nicht mit totem Licht. Wir haben gar keine Vorstellung davon mit unserer abstrakten Freude am Walde, mit unserer abstrakten Freude an den Blumen, mit alldem, was im Grunde genommen, ich möchte sagen, im kosmischen Sinne philiströs ist. Es mag noch immer sehr schön sein, aber es ist philiströs im Gegensatz zu dem, was an innerlichem seelischem Jauchzen vorhanden war bei den alten Menschen im Angesichte des Waldes, der Wiese, im Angesichte überhaupt dessen, was da draußen lebte. Der alte Mensch fühlte sich verbunden mit seinen Bäumen, mit dem, was gerade die für ihn geeignete Pflanze war. Der alte Mensch fühlte Sympathie und Antipathie in der lebendigsten Weise mit dieser oder jener Pflanze. Wir gehen zum Beispiel über solche Wiesen, wie sie um das Goetheanum herum im Herbste sind. Wir urteilen philiströs, die Herbstzeitlose, das Colchicum autumnale sei vielleicht schön. Der alte Mensch ging an diesen Pflanzen so vorbei, daß er traurig wurde, daß seine Haut sogar sich etwas trocknete, während er an dem Colchicum autumnale vorbeiging. Er empfand sogar etwas von Schlaffwerden der Haare. Während, wenn er vorbeiging, sagen wir, an rot blühenden Pflanzen, meinetwillen an solchen Pflanzen, wie der heutige Mohn es ist, seine Haare flaumig, weich wurden. Also er erlebte das Licht der Pflanzenwelt absolut mit. Es war das lichte Zeitalter und darnach richtete sich sein ganzes Kulturleben, darnach richtete sich auch, daß er heilen konnte, das heißt, daß er den Tod bekämpfen konnte durch die Beobachtung und durch die Behandlung des Ätherleibes.

[ 14 ] Das wirkte lange nach, und wir sehen zum Beispiel noch, wenn wir zu der älteren griechischen Medizin zurückgehen, zu Hippokrates, wie gesprochen wird von den Säften des Menschen, von schwarzer und heller Galle, von Blut und von Schleim. Damit waren eigentlich noch immer Erinnerungen an das alte lichte Zeitalter gemeint. Der Schleim war im Grunde genommen für den Ätherleib gemeint und zum Beispiel das Blut für jene Schwingungen, die der astralische Leib im Ätherleib bewirkt und so weiter. Also diese Nachwirkungen waren noch da, und im Grunde genommen bekam erst in der Zeit des Galen, als auch schon für das andere menschliche Kulturleben das Rechnen mit der bloßen physischen Welt heraufkam, auch die Anschauung des Menschen, insofern sie die Grundlage von Heilprozessen sein sollte, einen physischen Charakter. Man sah auf den menschlichen physischen Leib hin.

[ 15 ] Aber so richtig war das doch erst an der großen Wende im 15. Jahrhundert, in der ersten Hälfte des 15. Jahrhunderts, daß man gar nichts mehr wußte vom menschlichen Ätherleib, nicht einmal, wie er sich in den Temperamenten ausdrückt, daß man anfing, immer mehr und mehr bloß auf den physischen Leib des Menschen hinzuschauen. Es war auch die ältere physische Medizin noch etwas anderes, als sie später, namentlich im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert geworden ist. Die alte physische Medizin hatte noch immer Traditionen, wenigstens von dem früheren Heilen durch den Ätherleib, und man hat eigentlich den Eindruck von jener älteren, auch europäischen Medizin, daß man alte Grundsätze behalten hatte und sie nur auf das Physische übertragen hatte. Es wurde gewissermaßen der physische Menschenorganismus doch fortwährend unter dem Einfluß des ätherischen Organismus gesehen. Erst in der neueren Zeit, in der kopernikanischen Zeit, in der Galilei-Zeit, fing man an, immer mehr bloß den physischen Menschenleib zu betrachten, und man hörte auf, etwas zu wissen, was die früheren Zeiten ganz genau gewußt haben. Man denkt ja heute: Wenn der Mensch diesen oder jenen Stoff, den man da draußen in der Natur findet, ißt, so bleibt er im menschlichen Organismus im Grunde genommen dasselbe. Das ist aber nicht wahr. Annähernd dasselbe bleiben nur etwa die Salze; aber alles das — ich habe es ja gestern gesagt —, was im Tier- und Pflanzenreich ist, wird im menschlichen Organismus etwas ganz anderes. Der menschliche Organismus ändert es völlig. Man wußte, daß der physische Menschenorganismus in seiner inneren Zusammensetzung «nicht von dieser Welt ist», und man wußte, daß im Grunde genommen Krankwerden nichts anderes ist als eine Fortsetzung dessen, was durch das menschliche Essen geschieht. Und es gab tatsächlich eine Zeit, insbesondere unter den arabischen Ärzten, wo man jede Verdauung als einen partiellen Krankheitsprozeß ansah, wo man über die Verdauung die Ansicht hatte, die durchaus nicht etwa unrichug ist: hat der Mensch gegessen, so hat er etwas Fremdes in sich hinein gebracht und er ist eigentlich krank. Er muß erst durch seinen inneren Organismus, durch die innere organische Funktion die Krankheit überwinden. So daß man eigentlich fortwährend in einem «Ein-bißchenKranksein», «Ein-bißchen-die-Krankheit-Überwinden», «Ein-bißchenHeilen» lebt. Man ißt sich krank und verdaut sich gesund. Das war tatsächlich eine Zeitlang, namentlich unter arabischen Ärzten, eine Anschauung, die durchaus — wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf — etwas sehr Gesundes hat, denn es gibt eigentlich keine Grenze zwischen dem, was man heute Sich-gesund-Essen nennt und dem Sich-krank-Essen. Denken Sie sich doch nur einmal, wie leicht es möglich ist, daß man sich beim Essen verdirbt. Da geht gleich dasjenige, was man gerade noch, wie man sagt, normal überwinden kann, über in das, was man nicht mehr überwinden kann. Dann ist man eben krank. Aber die Grenze ist wirklich gar nicht zu ziehen.

[ 16 ] Ebensowenig ist sonst selbst bei Quetschungen zum Beispiel auch die Grenze zwischen dem, was noch auf eine ganz naturgemäße Weise ausgeglichen wird, und dem, wo man zu Hilfe kommen muß durch einen Heilprozeß, gar nicht so ohne weiteres zu ziehen. So daß man also einmal in dem innerlich Krankwerden mit Recht eine Fortsetzung des Essens sah, ein nicht ganz richtiges Essen. Und so studierte man den täglichen Verdauungsprozeß, also das Sich-gesund-Verdauen; das studierte man.

[ 17 ] So ist es auch eine ganz gute Sitte, daß der eine oder andere, der dies oder jenes nicht so ungesalzen vertragen kann, es sich weiter salzt; mancher muß es sich sogar pfeffern, mancher paprizieren, nicht wahr. Weil er die Dinge nicht so ohne weiteres vertragen kann, richtet er es sich zu. Da ist wiederum keine Grenze, wenn einer Pfeffer oder Paprika braucht als Heilmittel; da ist wieder keine Grenze, ob man nun Pfeffer oder Paprika gibt, damit man sich gesund verdauen kann, oder ob, wenn die Sache ärger wird, man etwas aus dem Mineralreich nimmt. Ob man das nun als Speisezusatz oder als Medizin gibt, darauf kommt es nicht an. Da ist wiederum ein Ineinanderlaufen, da ist wiederum keine Grenze.

[ 18 ] Also das, was man genau wußte, das ist: wenn der Mensch überhaupt irgend etwas aus der äußeren Welt zu sich nimmt, so beeinträchtigt das seinen inneren Organismus, und er muß es unbedingt überwinden. Ob ich mir schließlich einen rostigen Nagel einstoße und mein Organismus ihn herausschwären muß, oder ob ich in meinen Magen etwas hineinbringe, was so nicht bleiben darf, und mein Organismus alle diese Prozesse durchmachen muß, damit er es assimiliert, das hat nur Gradunterschiede. Aber diese Erkenntnis, daß der menschliche Organismus nicht von dieser Erde ist, daß er auf dieser Erde sich nur erhalten kann, wenn er fortwährend angeregt wird, die Kräfte dieser Erde zu überwinden, die war vorhanden. Wir essen nämlich nicht, damit wir diese oder jene Speise in uns bekommen, sondern wir essen aus dem Grunde, damit wir die Kräfte innerlich entwickeln, die diese Speise überwinden. Wir essen, um Widerstand zu leisten gegen die Kräfte dieser Erde, und wir leben auf dieser Erde dadurch, daß wir Widerstand leisten.

[ 19 ] Aber es wurde das allmählich vergessen. Man nahm die ganze Sache eben materialistisch, und man probierte schließlich nur noch, ob dieses oder jenes Substantielle in diesen oder jenen Pflanzen eine Hilfe gewährt. Ja, sehen Sie, das ist dasjenige, was man einmal gemeint hat und was wir heute wieder meinen müssen mit dem finsteren Zeitalter. Es ist ja alles finster geworden. Man hat früher auf den hellen Ätherleib hingeschaut; der war einem der Mensch. Jetzt sieht man nichts mehr von diesem Licht. Man nimmt nur wahr, wo Stoffe sind, und man hält sich an das tote Licht. Aber dieses tote Licht hat für den Menschen zunächst nur abstrakte Begriffe, hat nur den Intellektualismus hergegeben. Heute stehen wir aber im Übergange zu der Notwendigkeit, in neuer Weise das Licht wiederum zu erkennen. Früher hat der Mensch in sich gewußt: er hat diesen lichten Ätherleib. Jetzt müssen wir immer mehr ausbilden das Erkennen, das ätherische Erkennen in der äußeren Welt, namentlich in der Pflanzenwelt.

[ 20 ] Goethe hat damit den Anfang gemacht in seiner Metamorphosenlehre. Er hat allerdings das Ganze auch noch intellektualistisch abstrakt in Begriffe gefaßt. Das muß immer mehr und mehr zu Bildern werden. Und wir müssen uns klar sein darüber, daß wir eben dahin kommen müssen, das Pflanzliche in leuchtenden Bildern zu sehen. Während der Mensch geglänzt hat im früheren lichten Zeitalter, muß in Zukunft die Natur um uns herum, insofern sie Pflanzenwelt ist, in den mannigfaltigsten Imaginationen der Pflanzenformen erglänzen. Dann werden wir auch gerade durch dieses Erglänzen der Pflanzenformen in den Pflanzen wiederum die Heilmittel finden. Diese Notwendigkeit steht vor uns. Während ein inneres Licht geschaut haben die Menschen des früheren lichten Zeitalters, obliegt den Menschen der Gegenwart das Schauen in der äußeren Welt, wiederum ein Licht zu schauen, dieses Licht in der äußeren Welt.

[ 21 ] Und dieses Licht kann angefacht werden, wenn man sich mehr und mehr in die Geisteswissenschaft vertieft. Sie können sagen: Geisteswissenschaft, Anthroposophie — da lese ich doch auch nur Begriffe, und schließlich, wenn ich die «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß» lese, dann sind da auch Begriffe drinnen; da habe ich doch nicht den Anlaß, nun auch wirklich zu schauen. — Doch, meine lieben Freunde! Diese «Geheimwissenschaft» hat ja ein doppeltes Ziel: Zunächst, daß man das kennenlernt, was drinnen steht; aber das ist noch nicht das Ganze. Wenn Sie meine «Geheimwissenschaft» so gelesen haben wie ein anderes Buch, dann kennen Sie nämlich erst das Zündhölzchen. Wenn Sie aber Feuer haben wollen, so dürfen Sie nicht sagen: Dieses Zündhölzel ist doch kein Feuer! Es ist doch Unsinn, zu sagen, wenn der mir ein Zündhölzel gibt, daß er mir Feuer gibt, es sieht doch nicht aus wie Feuer. Geheimwissenschaft schaut doch nicht aus wie Heilsehen! Das wäre gerade so, wie wenn Sie sagen würden: Das Zündhölzel schaut doch nicht aus wie Feuer. — Es wird schon aussehen wie Feuer, wenn Sie das Zündhölzel erst anreiben. Und wenn es das erste Mal nicht geht, reiben Sie ein zweites Mal und so weiter. So ist es mit der «Geheimwissenschaft», Wenn Sie es so gelesen haben wie ein anderes Buch, dann ist es eben erst das Zündhölzel; aber wenn Sie es richtig verrieben haben in Ihrem ganzen menschlichen Wesen, da werden Sie schon sehen, da zündet es. Es hat nur noch wenig gezündet! Aber es zündet, meine lieben Freunde. Und derjenige, der sagt: Das steht dem, was man eigentlich anstrebt, dem Hellsehen, ganz fern -, der will eben das Zündholz bloß angucken, nicht anzünden. Aber es wird nie ein Feuer, wenn Sie das Zündhölzel bloß angucken. Also es ist tatsächlich so: man muß schon erst das Zündholz kennen, sonst wird man sich dem Wahn hingeben können, daß man mit der Stecknadel anzünden könnte. Sie können natürlich mit der Stecknadel — das heißt mit der modernen Wissenschaft - nicht anzünden; Sie können es nur mit dem Zündhölzel, mit dem wirklichen Zündhölzel anzünden; aber es ist so, man kann es anzünden!

[ 22 ] Vor dieser Notwendigkeit steht eben das Menschengeschlecht heute, und vielleicht wird sich am meisten gerade an so etwas, wie es das medizinische Wissen und Können ist, zeigen, ob man den Übergang finden wird von dem bloßen Anschauen des Finsteren im Stofflichen — so daß man irgendwie anschaut eine Pflanzenblüte, so wie man es heute tut —, zu dem imaginativ bildhaften Anschauen durch Anzünden des Zündhölzels, um von da aus dann zu erkennen, wie dies oder jenes auf den Menschen wirkt. Und derjenige, welcher sich die Sache jetzt ein wenig überlegt, der wird sich sagen müssen: Das steht vor der heutigen Menschheit, sie soll aus der Finsternis wiederum ins Licht eintreten, sie soll lichtvoll urteilen lernen.

[ 23 ] Ich will das noch einmal an einem Beispiel klarlegen. Nehmen wir einmal an, der heutige Arzt diagnostiziert meinetwillen Herzerweiterung. Er macht das in der Weise, wie man das heute macht, und er findet die Herzerweiterung. Man kann nicht viel anfangen mit einer solchen Diagnose. Man hat vielleicht probiert, ob dieses oder jenes da helfend wirken kann, aber man weiß ja keinen Zusammenhang. Man weiß keinen Zusammenhang, weil man die ganze Sache nicht durchschaut. Ein richtiges Durchschauen aber wird folgendes ergeben. Nehmen Sie einmal an, daß, wie ich Ihnen öfter auseinandergesetzt habe, der Mensch doch eigentlich seinen Organismus immer nach sieben Jahren erneuert. Ich habe Ihnen aber auch das letzte Mal gesagt, wie diese Erneuerung geschieht. Da werden immerfort vom Nierensystem aus die unverarbeiteten Stoffe gewissermaßen nach aufwärts oder auch nach vorne oder nach unten geschickt. Vom Kopfsystem aus wird die Abrundung vollzogen (siehe Zeichnung), so daß fortwährend vom Kopfsystem aus solche Wellen gehen (blau), welche die Form bewirken, und vom Nierensystem aus solche Wirkungen stattfinden, die durch die Wellen abgebrochen und geformt werden (rot), viermal schneller, habe ich gesagt.

<

[ 24 ] Nehmen Sie ein solches Organ wie das Herz (siehe Zeichnung Seite 102, hell}. Auch da findet ungefähr nach sieben, acht Jahren bei jedem Menschen ein solcher Austausch statt. Das Herz wird erneuert. Es wird neu gemacht. Dasjenige, was Sie an den Fingernägeln sehen, daß sie nach außen hin wachsen, immer nachwachsen, wenn man sie abschneidet, das ist auch beim ganzen Menschen so: daß er vom Mittelpunkte her die Materie immer erneuert. Nun denken Sie aber einmal, es sei der rhythmische Mensch nicht in Ordnung, es sei so, daß für seine Organisation viel zu schnell diese Strahlen vom Nierensystem herschießen, daß also nicht das richtige Verhältnis von vier zu eins besteht. Das variiert für jeden Menschen, jeder Mensch ist in dieser Beziehung eine Individualität, aber es ist das mit Bezug auf seine ganze Menschheitskonstruktion der Fall. Nehmen Sie also an, es sei das nicht in Ordnung, es schlage ein zu schnelles Strahlen vom Nierensystem her. Was wird dadurch geschehen?

[ 25 ] Dadurch kann nämlich das Folgende geschehen. Der Erneuerungsprozeß geschieht ja fortwährend — nehmen wir also an, bevor das alte Herz ganz heraußen ist, ganz weggeworfen ist (siehe Zeichnung, hell), ist das neue schon hineingeschoben (rot). Da geht es zu schnell. Wenn die Erneuerung zu schnell geht, so kommen solche Erscheinungen wie die Herzerweiterung. Am allerersten werden Sie an der beginnenden Herzerweiterung nachweisen können, daß an der Nierentätigkeit etwas nicht in Ordnung ist. Gerade wenn Sie diese Dinge ernst nehmen von der Erneuerung des Menschen in sieben, acht Jahren, da werden Sie sehen: wenn das schon nach sechs Jahren fertig ist, was erneuert werden soll, so ist das Alte noch nicht genügend fortgeschoben, und das Organ dehnt sich, oder strebt wenigstens darnach, sich zu dehnen. So muß man die Dinge anschauen lernen, in lebendiger Bewegung anschauen lernen. Das steht vor uns. Wir müssen vor allen Dingen dasjenige sehen, was man immer nur abgegrenzt hat. Wie diagnostiziert denn heute der Arzt?

[ 26 ] Der heutige Arzt diagnostiziert so, daß er am liebsten außen aufzeichnet die Konturen des Herzens, so recht eben dasjenige, was fertiges Organ ist. Es kommt gar nicht so sehr darauf an, hinzuschauen, wie das fertige Organ ist, denn es ist eben ein Organ, das immer wegflutet und wieder nachgeschoben wird. Und in diesem Weggehen und Nachschieben ist ein innerlich Beweglicheres, und wenn ich es aufzeichne, so ist es im Grunde genommen so, wie wenn ich den Blitz aufzeichne; es ist in einer fortwährenden Beweglichkeit. Ich muß also, wenn ich den Menschen erfassen will, ihn in seiner Lebendigkeit erfassen. Und diese Lebendigkeit, die finde ich heute nur, wenn ich die ganze Welt verstehe und den Menschen aus der Welt heraus.

[ 27 ] Das steht vor uns: es muß alles in bewegliches Erkennen übergehen. Vor allen Dingen müssen wir eigentlich schon in der Schule anfangen mit der Beweglichkeit. Es ist etwas Fürchterliches, wenn wir die Kinder im Unbeweglichen halten in der Schule. Es ist zum Beispiel mir immer schon etwas Schweres, daß die Kinder, sagen wir, irgendein fertiges Dreieck haben, mit dem sie alle möglichen Sachen machen. Dieses Stillstehende ist eigentlich nichts. Man müßte im Grunde genommen so etwas haben, wo das Dreieck verschiebbar ist. Darauf kommt es an, daß das Kind richtig die Vorstellung bekommt, daß das alles nur in Bewegung erfaßt werden soll (siehe Zeichnung).

[ 28 ] Es ist natürlich furchtbar schwer, sich über diese Dinge mit denjenigen, die am liebsten ihren Frieden haben wollen und nur ja nicht so irgend etwas haben möchten, wo man als Mensch tätig sein muß, es ist schwer, sich mit solchen Menschen zu verständigen, die ihre Ruhe und ihren Frieden haben möchten, und die auch schon bös sind, wenn die Kinder spektakulieren, und nun auch noch die Unterrichtswerkzeuge spektakulieren sollen. Es ist etwas Furchtbares natürlich: aber es ist so, wir müssen zum Lebendigen übergehen. Und das alles zusammengefaßt, ergibt eben die Forderung, ins helle, lichte Zeitalter hinaufzukommen. Wir müssen eintreten aus dem finsteren ins helle lichte Zeitalter.

[ 29 ] Und weil die Menschen es nicht können - das heißt, sie reden sich ein, daß sie es nicht können -, weil die Menschen nicht wollen, weil die Menschen an dem Alten hängen und nicht eintreten wollen ins Neue, und weil das Alte nicht mehr hereinpaßt, deshalb ist es, daß wir die schrecklichen Katastrophen in der Gegenwart erleben. Und wir werden sie noch mehr erleben, wenn die Menschen sich nicht bequemen, ins Neue einzutreten.

[ 30 ] Das, was als Katastrophe auftritt, das ist ja die Reaktion des finsteren Zeitalters, das nicht mehr in die Gegenwart hereingehört. Aber da ist es natürlich furchtbar schwer, Verständnis zu finden, weil höchstens in dem Gegensatz zwischen dem Alter und der Jugend heute so etwas auftritt wie eine Ahnung von dem neuen lichten Zeitalter. Die Jugend sagt in der Regel: Ach, die Alten sind Philister. —- Auch das hat ja seine Vorgänger. Der große deutsche Philosoph Johann Gottlieb Fichte hat ja das schon vorgeahnt, indem er den klassischen Ausspruch tat, daß man eigentlich alle Dreißigjährigen totschlagen sollte, weil der Mensch eigentlich nur bis zu seinem dreißigsten Jahre anständig ist. Das ist ja ein berühmter Fichtescher Ausspruch, und da Goethe, als Fichte ihn getan hat, schon wesentlich älter war, so hat er sich furchtbar geärgert und hat dann diese ganze Lehre in seinem «Faust» im zweiten Teile verspottet. Es war ja auch ärgerlich, nicht wahr, für Goethe. So findet man, daß die Jugend ja schon damit einverstanden ist, daß die Alten Philister sind, aber bis jetzt ist es eben noch nicht zu großem Ernst gekommen mit solchen Dingen, weil die Jugend das bis zu einem gewissen Lebensalter macht, und dann in der Regel sogar ein noch größerer Philister wird, als die Alten es gewesen sind. Es geht ganz hübsch in das Philisterium über. Die Dinge müssen eben auch von dieser Seite aus innerlich genommen werden.

[ 31 ] Ich meine also, daß es sich schon darum handelt, daß wir nun wissen: entweder Spenglerismus, das heißt Niedergang des Abendlandes, oder Sich-Anbequemen dem neu auftretenden Zeitalter des Lichtes gegenüber der Finsternis, in welcher die Menschen dem Kosmos gegenüber Regenwürmer waren. Das ist nicht anders. Aber es mußte in der Geschichte eine Zeitlang der Mensch Regenwurm sein, weil er sonst von dem Lichte ganz hingenommen wäre. Er konnte seine Freiheit nur erringen im finsteren Zeitalter, und zwar erst eigentlich am Ausgange des finsteren Zeitalters, in der neueren Zeit. Er konnte seine Freiheit nur dadurch erringen, daß das Licht ihn ungeschoren ließ, daß er ein Regenwurmdasein führen konnte.

[ 32 ] Nun aber sagte ich Ihnen, die Menschen des älteren lichten Zeitalters haben vorzugsweise das Licht der Pflanzenwelt empfangen. Die Pflanzen tranken gewissermaßen das kosmische Licht, und der Mensch trank wiederum aus dem Becher das Licht, das ihm die Pflanzen darreichten.

[ 33 ] Wir haben heute nur das tote Licht. Aber auf den Strahlen dieses toten Lichtes ist einstmals der Christus hereingezogen und hat das Mysterium von Golgatha vollbracht. Das ist das große Weltengeheimnis der neuen Zeit. Zwar haben wir das tote Licht. Das tote Licht kann uns nicht selig machen. Aber auf den Strahlen des toten Lichtes ist der Christus auf die Erde hereingezogen, hat das Mysterium von Golgatha vollbracht. Und wenn wir außer uns auch heute das tote Licht haben, dann können wir in uns den Christus beleben. Und mit dem Christus in richtiger Weise in uns, beleben wir alles Licht auf Erden um uns herum, tragen Leben in das tote Licht hinein, wirken selber belebend auf das Licht. Das heißt, wir müssen mit dem richtigen Christus-Impuls in das neue Zeitalter des Lichtes eintreten. Und die Verleugnung des Christus-Impulses ist es im Grunde genommen, welche die Menschen davon abhält, richtig zu sehen, wie ein finsteres Zeitalter in das lichte Zeitalter hinübergeht.

[ 34 ] Es ist schon so. Wenn die Pflanze herauswächst aus der Erde (siehe Zeichnung S. 105), so entwickelt sie, wie ich Ihnen schon gezeigt habe, den Fruchtknoten oben noch mit den Kräften aus dem vorigen Jahre; nur die Blütenblätter wachsen aus dem Lichte dieses Jahres heraus. Dasjenige, was die Pflanze aus der Erde herauszieht, ist eigentlich vom vorigen Jahre. So daß es ein recht konserviertes Licht war, was die Pflanzen den Menschen einstmals im alten lichten Zeitalter gegeben haben. Wir müssen eben die Möglichkeit finden, das tote Licht mit demjenigen Gemüte in der Welt aufzufassen, das in uns erzeugt wird, indem wir die Kraft des Christus in der lebendigen Anschauung des Mysteriums von Golgatha aufnehmen. Dann beleben wir, wie ich es dargestellt habe, das Licht. Das können wir aber nur, wenn wir alle Dinge versuchen lernen so anzuschauen, wie ich das eben gerade in diesen Vorträgen versuchte, vor Ihnen auseinanderzusetzen.

Spiritual Connections in the Formation of the Human Organism III

[ 1 ] You will already have seen from all sorts of earlier observations that I do not like to use the phrase: We live in a transitional time -, for every time is a transitional time, namely from the earlier to the later, and it is always only a question of: in what way is any time a transitional time, what passes over?

[ 2 ] Now, in our time there is indeed a very important transition for those who can see into the spiritual world, and the wisdom of the oldest times has always pointed to this important transition. In the epochs in which there was still talk of a spiritual world in truth, even if only from old dreamlike insights, it was always said that after a certain time the so-called dark age would come to an end and an age of light would begin. Now, if one examines the words of the old wise men and takes them seriously, one really comes to the conclusion that they meant that this transition from the dark to the light age would take place at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century, in which we are now living. We do not, however, need to engage in renewing the old dreamlike wisdom through anthroposophy. I have often said that this is by no means the case, but that anthroposophy is about that which can be recognized at present through spiritual research. Anthroposophy should therefore not be the renewal of some ancient wisdom, but a present realization. But in this matter, with regard to the transition from the dark age to the light age, the present knowledge must certainly agree with the old wisdom.

[ 3 ] As little as one can say from the outward appearance, if one considers the events of the present, that we as mankind, namely as the civilized mankind of Europe, are entering from worse into better conditions, so true is, on the other hand, that which the ancient wisdom already meant by the passage into the light age, and which we must mean again today. We only have to understand things in the right way. I would first like to give an example to illustrate the difference between an age of light meant in this sense and an age of darkness.

[ 4 ] The people who once, in about the 5th millennium BC, spoke of such a dark and light age, regarded this dark age as the consequence of an earlier light age and expressed the opinion that, after the dark age had lasted a while, a light age would come again. It will therefore be instructive to look back to see how, in essential human affairs, the light age that once existed, which was there in about the 7th or 8th millennium before Christ, differed from the later dark age from which we humans are now to emerge.

[ 5 ] As I said, I would like to illustrate this with an example, the example of healing. The example of healing is very applicable here, because you can see a great deal from it. In that old bright or light age, healing was not done by looking at the physical human body. That was not even considered. In those old bright ages, illness was not spoken of in the same sense as it is still spoken of today, but as it will cease to be spoken of in the future. In those ancient times, of course, there was also the phenomenon that a person experienced a deterioration of his organs in this or that direction, that he was not healthy in this or that direction, but one did not speak of illness, but one actually said: There is a death, and it takes possession of man. - And they saw a kind of struggle between life and death in the case where today we say that a person is ill. So in those older times, people did not speak of illness and health, but they spoke of when a person had become ill in our sense: death is fighting in him. And getting well was seen as fighting death, driving it out. So we were actually talking about life and death. And illness was only a special case of death, I would say, a small death; health was life.

[ 6 ] Why did they speak like that? They spoke this way because in those days they healed entirely from the etheric body of the human being. In those days they did not concern themselves with the physical body of man, so to speak, but healed entirely from the etheric body of man.

[ 7 ] How was this done? Well, let's say a person back then was afflicted with what we today call pneumonia. Pneumonia was a slightly different type of disease back then, but we can still talk about this form of illness. In those days, people said to themselves: This person has become too dependent on the area of the earth in which he lives. - It was in times when human migration, when leaving places was rarer than it is today. For the most part, at least the majority of people stayed in the place where they were for their entire lives. Nevertheless, in such cases it was said that man had become too dependent on the spot on earth where he was born. - In those older times it was well known that man had already had a pre-earthly existence, that he had, so to speak, determined his own place on earth in his pre-earthly existence by means of his fate. So it was said: If a person is attacked by pneumonia before the age of forty or even earlier, then he has not chosen his place on earth quite rightly. It does not quite fit in with his earthly sojourn. - In short, the disease is derived from the relationship of his human organization to the spot on earth where he was.

[ 8 ] If I want to draw this, it would be like this (see drawing on page 91), if one imagined the earth in this way, one would say to oneself, if the human being lives there, he is too strongly dependent on this earth spot, and one must heal the human being by freeing him inwardly from the outward dependence on this earth spot. This can be done by relating him to the surrounding cosmos, to the outer heavenly world. It has been said that heaven is that which was man's home before he was here on earth. It does not quite fit in with the earth. One must heal it by bringing it into the right relationship to the cosmos. -- And this was then done in such a way that one said: One must therefore lighten man, because there are too many earthly effects in him, because there is, so to speak, too much gravity and that which is connected with gravity in him; one must bring the supernatural forces into him. - One said to oneself: supernatural forces are at work in these or those plant blossoms. So one worked on these or those plant blossoms by extracting their juice. One said to oneself: This plant blooms at a certain time of year; it blooms at this time of year due to the influences of the cosmos. - Research was then carried out into the extent to which man is influenced by this particular season. For this purpose, in older times, the dependencies of man on the celestial phenomena were sought in a horoscope-like manner. And the remedies given to man were those which brought his etheric body into a general vibration. It was said: If this is the human being (see drawing $. 93, red), then this is his etheric body (light), and he is ill with pneumonia for the reason that his etheric body in the region of the lungs leans too strongly towards the earth (blue), and because the earth forces have too great an influence on him. Now he is given juices from plant blossoms which work into him and overcome these forces (yellow). He was thus given forces that brought him into connection with the cosmos. The aim was to set the whole etheric body into the right vibrations so that the incorrect individual vibrations could be balanced out. So the question was always: What must be done with the etheric body?

[ 9 ] Now, why was it possible to proceed in this way at all? It was possible because we had a clear idea of the human etheric body. In those older times one did not merely see the physical human body, but one saw the physical human body shining, one saw the etheric body. The human being was a being of light, and just as we judge today by his incarnation, for example, if he is pale, that he is ill, so we judged his state of health by the etheric body, by the coloring, for example, if he became red or blue or green. So what did people base their knowledge of human nature on in those days? On the light, on what was light in man. It is to be taken quite literally: it was the age of light, it was the age in which people really saw what lived in man as light.

[ 10 ] If you look at man today from the point of view of health and illness, you will find that even today it must be said that light has a tremendously strong influence on human health. Man must strive to get the right amount of light into his organism. We know how children who suffer from a lack of light at a tender age fall prey to rickets or other diseases that are definitely connected with a lack of light - of course also with other things, a disease can never be derived from just one cause - but such things as rickets, for example, are definitely connected with a lack of light. We can certainly state how much, let's say, children are exposed to rickets who live in the city in homes where there is little light, and how few children are prone to rickets - on average, of course - who can be properly exposed to light. So even today we can certainly say that man absorbs light.

[ 11 ] But the light that man absorbs today is, if I may put it this way, mineral light. Man absorbs that light which is shone upon the earth, upon the minerals, and is reflected back to him, or which he receives directly from the sun. It is mineral light. The light that falls on the meadows, that falls on the tree, is also transmitted to us in a mineral way. It is dead light that we absorb today through our skin, through our whole being. In that old age of light that preceded the dark age, people were aware that this dead light had no real meaning for them.

[ 12 ] Today's historians, including cultural historians, do not even know such things. The light that we value so much today was not something so precious to those ancient people. They distinguished between the light they valued and the light we value today in much the same way as, say, when we sit down at table and have a plate and a spoon and a fork, there is some cake or something else edible on the plate. We eat the cake; we also appreciate the knife and fork, of course, but we don't eat them, they are there. So for the ancients, what they valued as light included what we today prefer to value as light. But what they valued as light came from the plant kingdom. Today we no longer receive it in the same way as it was received in the old, bright times. Today we rejoice when we can go out into the sun. The old man rejoiced when he walked across a meadow, through a forest, because he absorbed through his skin the light that the forest had first absorbed, that was animate in the forest, animate in the meadow. And the other, the dead light, that was the ingredient. For us, the ingredient has become the main thing. The old man lived in the light that the flowers and the trees of the forest gave him. For him, this was a source of inner living with light, with inner living light, and not with dead light. We have no idea of this with our abstract joy in the forest, with our abstract joy in the flowers, with everything that is basically, I would like to say, philistine in a cosmic sense. It may still be very beautiful, but it is philistine in contrast to the inner spiritual exultation that was present in the old people in the face of the forest, the meadow, in the face of everything that lived out there. The old man felt connected with his trees, with whatever plant was suitable for him. The old man felt sympathy and antipathy in the most vivid way with this or that plant. For example, we walk across meadows such as those around the Goetheanum in autumn. We make the philistine judgment that the autumn crocus, the Colchicum autumnale, is perhaps beautiful. The old man walked past these plants in such a way that he became sad, that his skin even dried a little as he walked past the Colchicum autumnale. He even felt something of limpness in his hair. Whereas when he passed, let us say, red-flowering plants, in my opinion plants like the poppy today, his hair became downy and soft. So he absolutely experienced the light of the plant world. It was the age of light and his whole cultural life was based on it, and it was also based on it that he could heal, that is, that he could fight death by observing and treating the etheric body.

[ 14 ] This had a long-lasting effect, and we still see, for example, when we go back to the older Greek medicine, to Hippocrates, how the juices of man, black and white bile, blood and phlegm are spoken of. These were actually still reminders of the old light age. The mucus was basically meant for the etheric body and, for example, the blood for those vibrations that the astral body causes in the etheric body and so on. So these after-effects were still there, and basically it was only in the time of Galen, when the reckoning with the mere physical world also came up for the other human cultural life, that the view of the human being, insofar as it was to be the basis of healing processes, also acquired a physical character. One looked at the human physical body.