The Driving Force of Spiritual Powers in World History

GA 222

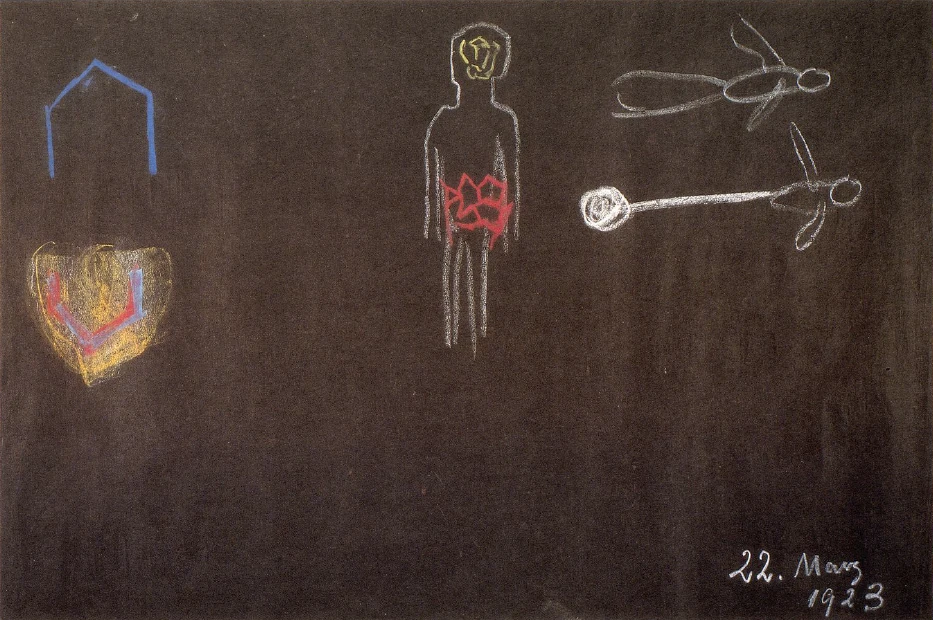

22 March 1923, Dornach

Lecture VI

To begin with today we will remind ourselves of the indications I have given you concerning the real nature of human thinking. In the present age, since the well-known point of time in the 15th century, our thinking has become essentially abstract, devoid of pictures and imagery. People take pride in this kind of thinking which as we know, did not begin to be general until the above-mentioned epoch; previously to that, thinking had been pictorial and was therefore a living thinking in the real sense.

Let us remind ourselves of the essential character of thinking as it is today. The living essence of thinking was within us during the period between death and rebirth, before we descended from the spiritual into the physical world. This living essence was then cast off and today, as men of the Fifth postAtlantean epoch, our thinking is the corpse of that living thinking between death and a new birth. It is just because our thinking now is devoid of life that our ordinary-level consciousness as modern men makes it so easy for us to be satisfied with comprehending the lifeless and we have no aptitude for understanding the living nature of the world around us.

True, we have thereby acquired our freedom, our self dependence as human beings but we have also shut ourselves off entirely from what is involved in a perpetual process of ‘becoming’. We observe the things around us in which no such process is operating, which are incapable of germination and have a present existence only. It may be objected that man observes the germinating force in plants and animals, but actually he is deceiving himself. He observes this germinating force only in so far as it is the bearer of dead substances; moreover he observes the germinating force itself as something that is dead.

The essential characteristic of this kind of perception is indicated by the following: In earlier epochs of evolution men perceived an active germinal force everywhere in their environment, whereas nowadays they have eyes only for what is dead; they hope somehow to grasp the nature of life too, merely by observing what is dead. Hence they do not grasp it at all!

Therewith, however, man has entered into a quite remarkable epoch of his evolution. Nowadays, when he observes the sense world, thoughts are no longer given to him in the way that applies to sounds and colours. From what I say in the book Riddles of Philosophy, you know that thoughts were given to the Greeks just as sounds and colours present themselves to us today. We say that a rose is red ; the Greek perceived not only the redness of a rose but also the thought of the rose, that is to say, he perceived something spiritual. And this perception of the purely spiritual has gradually died away with the rise of the abstract, lifeless thinking that is only a corpse of what thinking was in us before our earthly life.

But now the question arises: If we want to understand Nature, if we want to form a world-conception for ourselves, how are the sense-world outside us and the dead thinking within us to be related to each other? We must be quite clear that when man confronts the world today, he confronts it with lifeless thinking. But then, is there death also outside in the world? There ought at least to be an inkling today that there is not. In the colours, in the sounds, at the very least, life seems to proclaim its presence everywhere! To one who understands the real nature of the senses the remarkable fact becomes clear that although modern man invariably directs his attention to the sense-world alone, he cannot grasp this sense-world by means of thinking, because dead thoughts are simply not applicable to the living sense-world.

Make this quite clear to yourselves.—Man confronts the sense-world today and believes that he should not allow himself to look beyond it. But what does this mean for modern man—not to be willing to look beyond the sense-world? It actually means renouncing all vision and all knowledge. For neither colour, nor sound, nor warmth, can be grasped at all by dead thinking. Man thinks, then, in an element quite other than that in which he actually lives.

Hence it is a remarkable fact that although we enter the earthly world at birth, our thinking is the corpse of what it was before our earthly existence. And today man wants to bring the two together ; he wants to apply the residue from his pre-earthly existence to his earthly existence.

And it is this fact which since the 15th century has constantly asserted itself in the sphere of thinking and knowledge in the form of doubt of every kind. This is the cause of the great confusion prevailing at the present time; it is this that has allowed scepticism and doubt to creep into every possible mode of thinking; it is this that is responsible for the fact that men today no longer have the remotest concept of what knowledge really is. There is indeed nothing more unsatisfactory than to examine theories of knowledge in their modern form. Most scientists abstain from this and leave it to the philosophers. And in this field one can have remarkable experiences.

In Berlin, in the year 1889, I was once visiting the philosopher Eduard von Hartmann, now long since dead. We spoke about questions connected with theories of knowledge. In the course of conversation he said that one should not allow questions connected with theories of knowledge to be printed; they should at most be duplicated by some machine or in some other way, for in the whole of Germany there were at most sixty individuals capable of occupying themselves usefully with such questions.

Just think of it—one in every million! Naturally, among a million human beings there is more than one scientist or, at least, more than one highly educated individual. But as regards real insight into questions connected with theories of knowledge, Eduard von Hartmann was probably right; for apart from the handbooks which candidates at the Universities have to skim through for certain examinations, not many readers will be found for works on the theory of knowledge, if written in the modern style and based on the modern way of thinking.

And so things jog along in the same old grooves. People study anatomy, physiology, biology, history and the rest, unconcerned as to whether these sciences bring them knowledge of reality; they go on at the same jog-trot. But a time will come when men will have to be clear about the fundamental fact that because their thinking is abstract it is full of light and therefore embraces something in the highest sense super-earthly, whereas in their life on Earth they have around them only what is earthly. The two sets of facts simply do not harmonize.

You may ask: did the thought-pictures current in days of old accord more fully with man's nature when his thinking was full of life? The answer is, Yes—and I will indicate the reason to you.

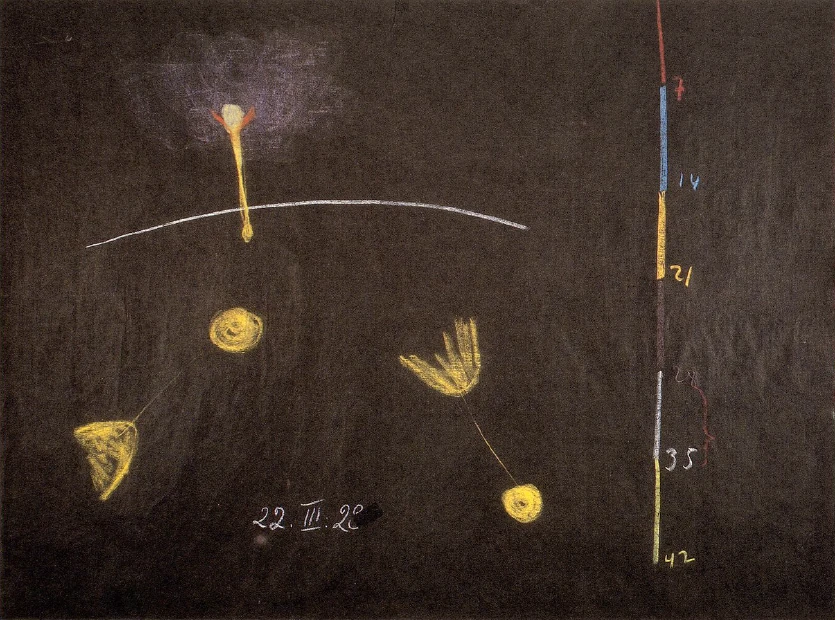

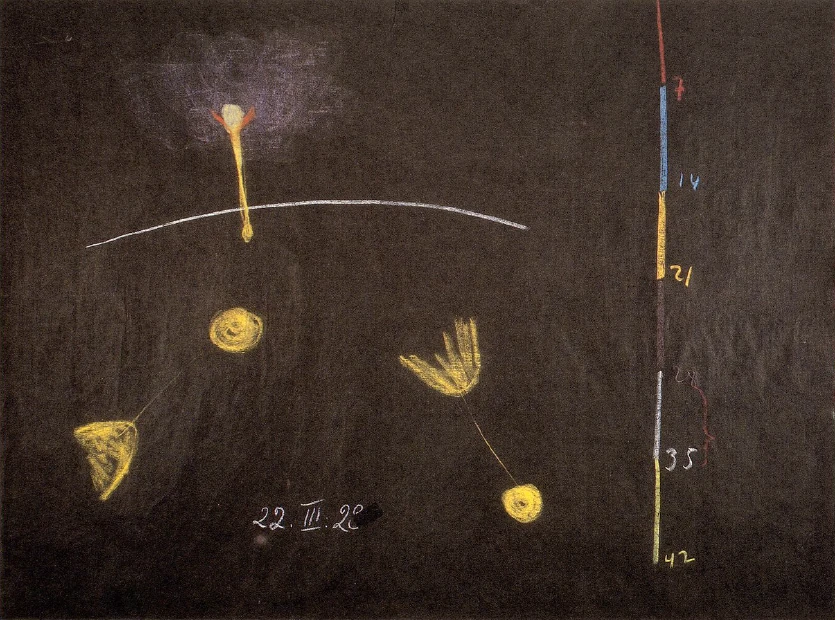

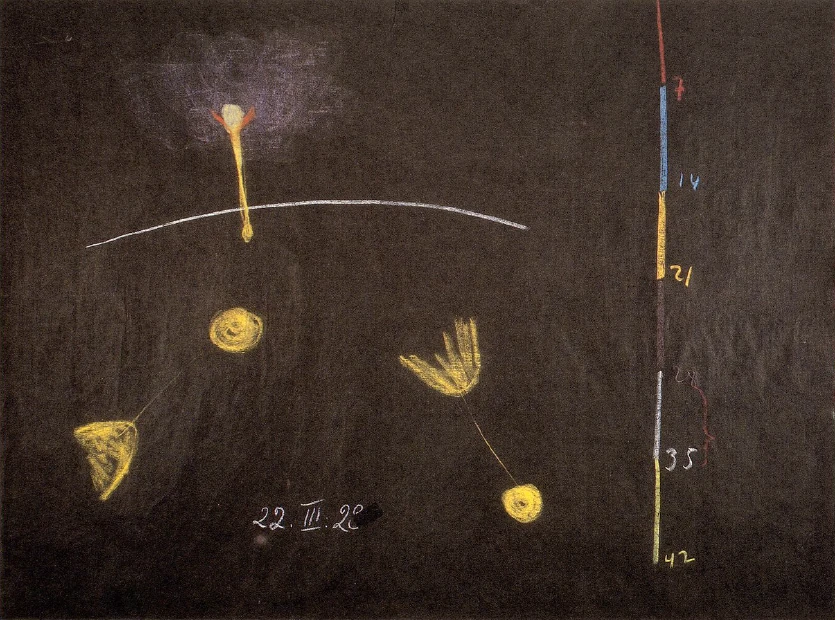

The human being of today is engrossed from his birth to his seventh year in developing his physical body; then comes the point where he is able to develop his etheric body as well—this takes place from the seventh to the fourteenth year. Then from the fourteenth to the twenty-first year he develops his astral body; until his twenty-eighth year the sentient soul; until his thirty-fifth year the intellectual or mind-soul; and after that the consciousness-soul. It can then no longer be said that he develops but that he himself is being developed, for the Spirit Self which will evolve only in future ages, already participates to some extent in his development from his forty-second year onwards. And so the process continues.

Now the period from the twenty-eighth to the thirty-fifth year in human life is extremely important. Conditions during this period have altered essentially since the 15th century. Until then, influences had continued to come to man from the surrounding cosmic ether. Because this is no longer the case today, it is difficult to imagine how man could have been influenced by the surrounding ether. Nevertheless it was so. Between their twenty-eighth and thirty-fifth years, human beings experienced a kind of inner revival. It was as though something within them was given new life. These experiences were connected with the fact that in his twenty-eighth year a man was raised to the degree of ‘Master’ in his trade; it was not until that age that he experienced a revival—of course not in a crude but in a delicate form. He was given a new impulse. This was because the all-encompassing ether-world worked upon him—the ether-world which, as well as the physical world, is all around us.

In the first seven years of life the ether-world worked through the processes operating in the physical body of the human being but it did not work directly upon him until his twenty-eighth year when the period of the development of the sentient soul was over. But then, when he entered into the period of the intellectual or mind-soul at that time, the ether worked upon him with a vivifying effect.

This no longer takes place and man would never have achieved independence today as an individual and a personality, had the process continued. This also has to do with the fact that the whole inner disposition of the human soul has changed since those days.

You must now accept a concept that may be extremely difficult for modern thinking to grasp but is nevertheless very important.

In physical life it is quite clear to us that what is going to take place only in the future, is not yet here. In etheric life, however, this is not so. In etheric life, time is, as it were, a kind of space and what will some day be present already has an effect upon what precedes it, as well as upon what will follow. But this should not be a matter for wonder; it is the same in the physical world too.

If we really understand Goethe's theory of Metamorphosis, we shall say to ourselves that the blossom of the plant is already working in the root. And that is indeed so. It is the case too with everything in the ether-world: the future is already working in what has gone before. Thus the fact that man was open to the influences of the ether-world had an effect upon the preceding life back to his birth, chiefly upon his world of thoughts. As a result his world of thoughts was different from the one that is his in the epoch in which we are living today, when the doorway between the twenty-eighth and thirty-fifth years is no longer open, when it is closed. There was a time when men's thoughts were truly alive. They made him unfree but at the same time they gave him a feeling of being connected with his whole environment; he felt himself to be a living member of the world.

Today man feels that he exists only in a dead world. This feeling is inevitable because if the living world were working upon him, it would make him unfree. Only because the dead world requires nothing of us, can determine nothing in us, can give rise to nothing in us—only because it is a dead world that is working in upon us are we free men.

But an the other side we must also understand clearly that precisely because of what man has within him now in complete freedom, precisely through his thoughts, which are dead, he can acquire no understanding of the life round about him; he can understand the death around him—and only that.

Now if there were to be no change in the attitude and mood of man's soul, the discordance in culture and civilization which is becoming more and more apparent, would inevitably increase and the inner assurance and resoluteness of the soul would progressively diminish. This would be even more apparent if men were to pay real attention to the knowledge they glean today from what is said to be irrefutable. But they still do not pay attention. They still content themselves with traditional religious ideas which they no longer understand but which have been propagated. Even in the sciences people content themselves with these ideas. When a man pursues any particular science he generally has no idea, when he begins really to grasp it, that he is still clinging to the old traditions, while the modern ideas which are only dead, abstract thoughts, do not even approach the sphere of the living.

In earlier times, because the ether worked in him, man could also come in touch with the living nature of the sense-world. When he still believed in the reality of the spiritual world, he could also grasp the essential nature of the world of the senses. Today, when he believes only in the world of the senses, the strange thing is that his thoughts, although dead, are now spiritual in the very highest degree! Here there is dead spirit. But man is not conscious of the fact that today he Looks into the world with the heritage of what was his before his earthly life. If his thoughts were still living, vivified by the surrounding ether, he could look into the living world of his environment. As, however, nothing comes to him from his environment and he has to rely only on what he has inherited from a spiritual world, he can no longer understand the physical world around him.

This is apparently paradoxical but for all that an extraordinarily important fact. It provides the answer to the question: Why are modern men materialists? They are materialists because they are too spiritual! They would be able to understand matter everywhere if they could comprehend the life that is present in all matter. But because they confront the life with their dead thinking, men make this life itself into something that is dead and see lifeless substance everywhere. It is because they are too spiritual, because they have within them only what was theirs before their birth, that they become materialists. A man does not become a materialist through knowledge of substance—in point of fact he has no real knowledge—but he becomes a materialist because he does not live on the Earth in the real sense.

And if you ask why hardened materialists, such as Büchner, Vogt and the rest, have become such out-and-out materialists, the answer is: because they were too spiritual, because they had nothing within them that connected them with earthly life, but only what they had experienced before their life on Earth—and this was dead. This remarkable phenomenon in human civilization, this materialism, is in truth a profound mystery.

Now in the present epoch, because his thoughts are no longer imbued with life from without, from the ether, man can transcend his dead thoughts only by instilling life into them himself. And the only possibility of doing this is by instilling life as conceived in Anthroposophy into his world of thoughts, by imbuing his thoughts with life and then penetrating into the life inherent in the world of the senses. He must therefore vivify himself inwardly. He must himself impart life to dead thoughts through inner activity of soul, and then he will overcome materialism. He will begin to judge everything around him differently. And from this very platform you have heard a great deal about the many possibilities of such judgments.

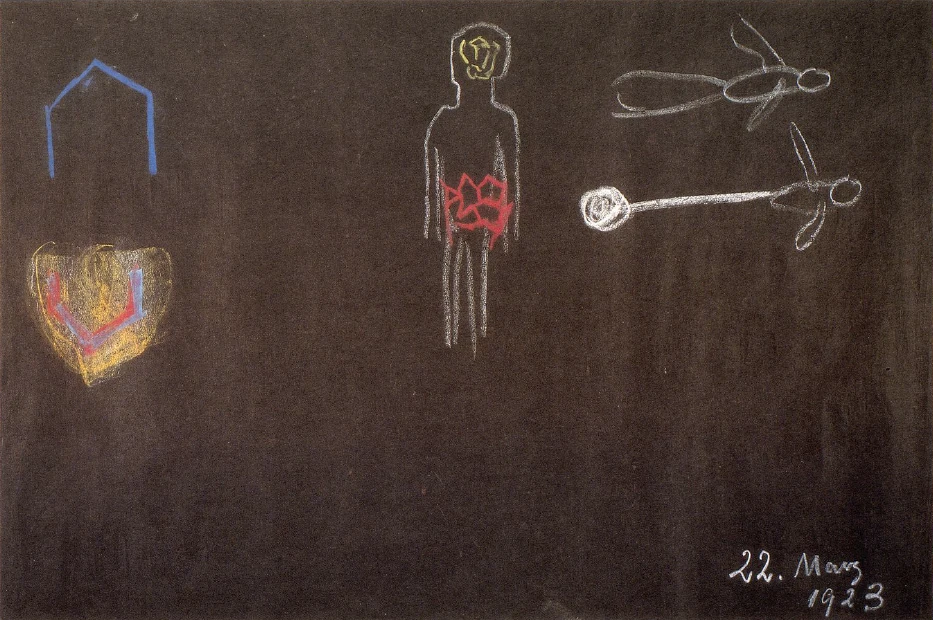

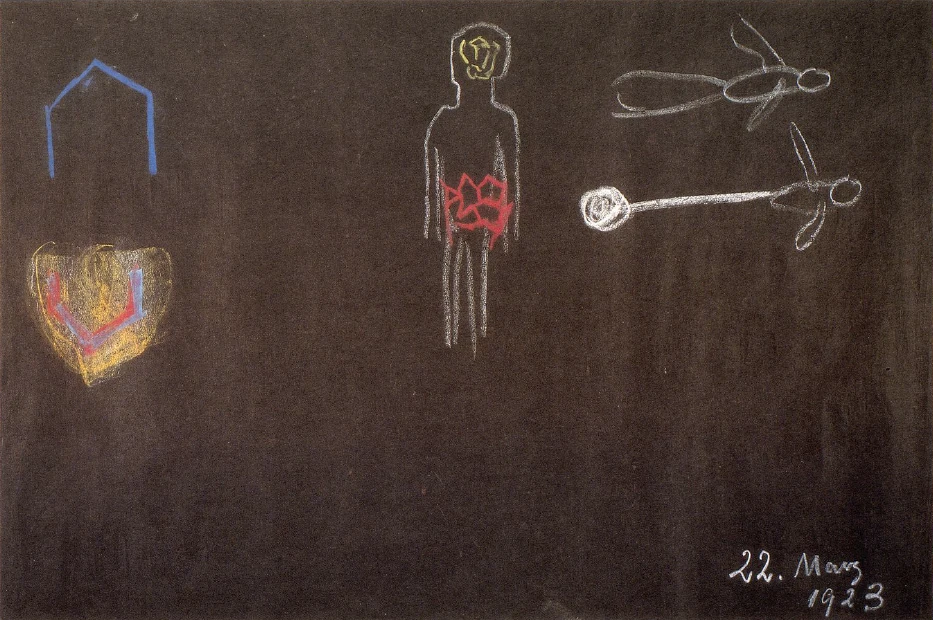

Let us focus our attention today on a particular subject: the plant-kingdom in our environment. We know that many plants are consumed as foodstuffs by animals and human beings and are worked upon in the processes of nourishment and digestion. In the way generally indicated they can be assimilated into the animal and human organisms. And now we suddenly come across a poisonous plant, let us say henbane or belladonna. What have we there? Suddenly, among the other vegetation, we find something that does not combine with the animal and human organisms as do other plants.

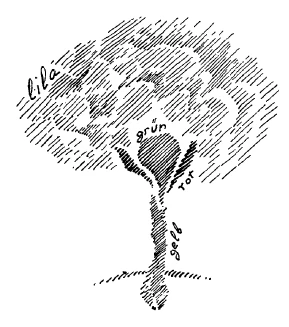

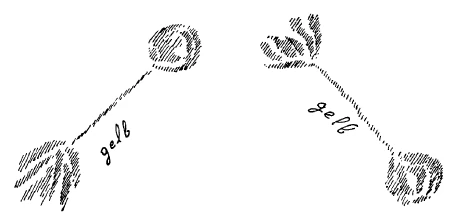

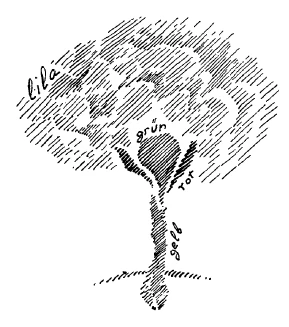

Let us be clear in our minds about the basis of plant-life. I have often spoken about this. Let us picture the surface of the Earth and the plants growing out of it. We know that the physical organization of the plant is permeated by its ether body. But as I have often pointed out, the plant would not be able to unfold if the all-pervading astrality did not contact it from above by way of the blossom (lilac).

The plant has no astral body within it but the astrality touches it from above. As a rule the plant does not absorb the astrality but only allows itself to be touched by it. The plant does not assimilate the astrality but towards the blossom and the fruit there is interplay with the astrality which does not, as a rule, combine with the ether-body or physical body of the plant.

In a poisonous plant, however, it is different. In a poisonous plant the astrality penetrates into the actual substance of the plant and combines with it. A plant such as belladonna or, let us say, henbane, hyoscyamus, sucks in the astrality either strongly or more moderately and so bears astrality within itself—in an uncoordinated state, of course, for if it were coordinated the plant would have to become an animal. It does not become an animal; the astrality within it is in a compressed state.

As a result, interaction takes place between what is present in a plant saturated with astrality and the processes of assimilation in the animal and human organisms. If we eat plants that are not poisonous, we absorb not only those constituents of the plant which the chemist works up in the laboratory, not only the actual substance of the plant but also the etheric life forces ; but we must, as I have said here before, destroy the substance completely during the process of nutrition. In feeding on what is living, man must kill it within himself. That is to say, within his own organism he must expel the etheric from the plant-substance.

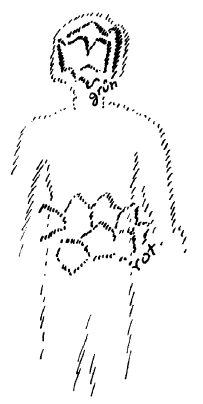

In the lower man, in the metabolic system, the following remarkable process takes place. When we eat plants, that is to say, vegetable substance—the same also applies to cooked foodstuffs but it is specially marked when we eat raw pears, or raw apples, or raw berries—we force out the etheric and absorb into our own ether-body the dynamic structure which underlies the plant. The plant has a definite form, a definite structure. It is revealed to clairvoyant consciousness that the structure we thus take into ourselves is not always identical with the form we see externally. It is something different. The plant-structure rises up within us and adapts itself to the organism in a remarkable way.

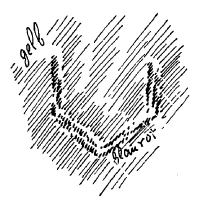

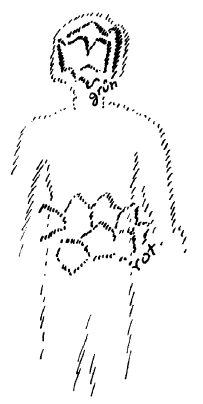

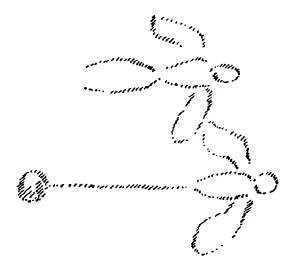

And now something very strange occurs. Just suppose—I must speak rather paradoxically here but it is exactly how things are—suppose you have eaten some cabbage. A definite form (blue in diagram) becomes visible in the lower man as a result, and activity is generated there.

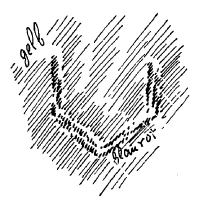

To the extent to which this activity is generated in the lower man through the eating of cabbage, the actual negative of the process makes its appearance in the upper man, the head-man. So having sketched the form which appears in the lower part of the organism, I now sketch in the upper man a hollow form (blue, red).

It is actually the case that the eating of the cabbage produces in us a definite form or structure and that the negative of it appears in our head.

And into this negative we now receive the impressions of the external world. This is possible because we have the hollow space within us—I am of course speaking approximately—and all nutritive plants have this effect.

If we have eaten something that is usually known as a foodstuff, the cohesiveness of its form is only strong enough to persist for twenty-four hours, in the course of which we must continually be dissolving it; one period of waking and sleeping dissolves it and it must again and again be formed anew. This is what happens when we have eaten nutritive plants—plants which have a physical body and an etheric body in their natural growth and do not allow the astrality to do more than play around them.

But now let us suppose that we drink the juice of henbane. Henbane is a plant that has sucked astrality into itself and consequently has a much more strongly cohesive form. In the lower man, therefore, there is a much firmer form which cannot easily be dissolved and which actually asserts its independence! Consequently the corresponding negative is more pronounced.Now suppose some human being has a brain with a structure that is not properly maintained. He tends to lapse into clouded, somnolent states because his astral body is not established firmly enough in the physical body of his brain. He drinks the juice of henbane and that produces in him a firm plant-form which in turn gives rise to a strong negative. And so by energizing the etheric body of his lower body and bringing into it a firm form through the taking of henbane, clearly defined thoughts may arise in a person whose brain was, so to speak, too soft, and the clouded state may pass away. Then, if in the rest of his organism he is strong enough—he may often be ordered this medicine for his condition—if he is strong enough to rouse the corresponding life-forces into activity and his brain is again in order, a poison such as this may help him to overcome his tendency to lapse into somnolent states.

Belladonna, for example, has a similar effect. Let me indicate in a sketch the effect it produces.

By taking belladonna the etheric body is reinforced by strong ‘scaffolding’. Hence when belladonna is taken in a suitable dosage which the patient can stand—after all, one can be cured by a remedy only if one can stand it—then a strong scaffolding is built, as it were, within the etheric body of the lower man. This strong scaffolding produces its negative in the head. And upon this reciprocal action of positive and negative depends the healing process we expect from belladonna.

You must, however, be clear that when dealing with such effects, the factor of spatial distance can be ignored. The man of today, with his lifeless but massive intellect, imagines that if something is going on in his stomach it can get into his brain only if it visibly streams upwards. This, however, is not the case; processes in the lower body generate processes in the head as their counterpart and spatial distance does not come into consideration. If one is able to observe the etheric body, it can be seen distinctly how a form lights up in the etheric body of the lower body (red in diagram), while in the etheric body of the head, now darkened, the form is reproduced in negative.

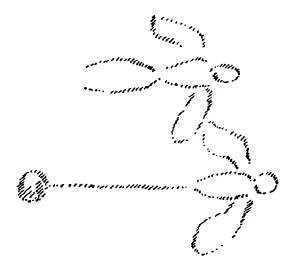

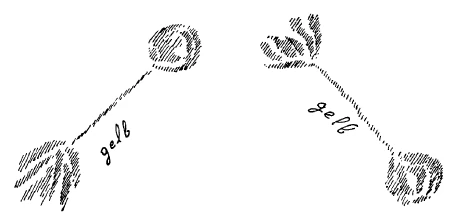

You can perceive for yourselves that Nature everywhere tends to produce such phenomena. You know that a properly formed wasp has a kind of head in front, a kind of hind-quarter, and wings. That is a properly formed wasp.

But there are also wasps which look like this (lower form in diagram). They have a sting and drag their hind-quarters after them: the gall-flies. And even in the physical sphere, this appendage between the front part of the body and the hind-quarter is reduced to a minimum; the sting is greatly reduced.

As soon as one enters the spiritual realm, no visible sting is necessary any longer. And when you come across certain beings in the elemental world—you remember that I spoke to you not long ago about the elemental kingdoms—you may see, for example, some being ... then there is nothing ... far away there is a different being. And gradually it dawns on you that the beings belong together; where the one goes the other also goes. So you may find yourself in the remarkable position—in the elemental world it can indeed be so—of discovering that here there is one part of an elemental-etheric organism, and there the other part; then one part may have turned round, but when this happened the other part cannot move directly to a new position but must follow the path taken by the first.

So you see, for those substances which neither the human nor the animal organism can immediately destroy, which produce a stronger and more lasting scaffolding, it is a matter of finding a connection with what, in a quite different part of the human organism, can also work constructively and with healing effects.

This gives you a vista of how the world can again become living and be revealed as such to man. Today, having only a heritage from the spiritual world, man has no possibility of approaching the living environment. He will, however, one day understand it again, he will again perceive how physical thinking is related to the whole universe. Then the universe will help him to discover why things are connected in this way or in that, why, let us say, the relation of a non-poisonous plant to the human and animal body is different from that of a poisonous plant. Only in this way is a re-vitalizing of the whole of human existence possible.

Now this may cause the modern comfort-lover to say: the men of old were far better off than we are, for the surrounding ether still worked upon them and they had living thoughts; they still understood such matters as the essential difference between poisonous and non-poisonous plants.—You know, of course, that animals still understand this difference, for they have no abstract thoughts to detach them from the world. Hence the animals are able through instinct to distinguish poisonous from non-poisonous plants.

Yes, but it must be emphasized over and over again that under such conditions man would never have been able to exercise his freedom. For what keeps us inwardly living—even in our thoughts—robs us of freedom. However paradoxical it may seem, with respect to the thoughts belonging to earlier earthly lives, we must each become an empty nothingness; then we can be free. And we become a nothingness when we receive into ourselves as corpses the living thoughts which were ours in pre-earthly existence, receive them into ourselves, that is to say, in their condition of ‘non-being’. Therefore with our dead thoughts we really go about as blanks in our waking life on Earth as far as our soul-life is concerned. And only out of this state of blankness or nothingness can our freedom become reality.

This is quite comprehensible. But we can understand nothing truly if we have nothing living within us. We can understand what is dead, but that will not bring us a single step further in our living relation to the world. And so, while safeguarding our freedom in face of the interruption in understanding that has come about, we must achieve new understanding by beginning now, in earthly existence, to give life to our thoughts by the power of our will. At every moment we can distinguish between living and dead thoughts. When we rise to the level of pure thinking—I have spoken of this in the book, The Philosophy of Freedom—we can be free men. If we fill our thoughts with feeling we shall, it is true, leave freedom aside, but in compensation we shall renew our connection with the environment. We participate in freedom through the consciousness that we are always capable of approaching nearer and nearer to pure thought, and in acts of moral intuition draw from it moral impulses.

Thereby we become free men; but we must first regulate our inner life of soul, the inner disposition of our soul, through our own deeds on Earth. Then we can take the results of those deeds with us through the gate of death into the spiritual world. For what has been achieved by individual effort does not go to waste in the universe.

I may have demanded difficult thoughts from you today but you will realize on reflection that we come nearer to understanding the world by learning to understand man, and especially the relation of physical man—the apparently physical man for he is really not a physical man alone, being permeated always by the higher members of his organism—to the other aspects of the physically manifested world, as we have learnt to know it from the example of poisonous plants.

Sechster Vortrag

Heute wollen wir uns zunächst einmal an die Angaben erinnern, die ich Ihnen über die eigentliche Natur, über die Wesenheit des menschlichen Denkens gemacht habe. Wir haben ja in dieser Gegenwart, seit dem so oftmals angeführten Zeitpunkte im 15. Jahrhundert, ein wesentlich abstraktes Denken, ein bildloses Denken, und die Menschheit ist ja stolz auf dieses bildlose Denken. Wir wissen, daß dieses bildlose Denken erst eingetreten ist in dem angedeuteten Zeitraume, daß früher ein bildhaftes und damit ein lebendiges Denken vorhanden war.

Nun wollen wir uns heute daran erinnern, was eigentlich die Natur und Wesenheit dieses Denkens ist, wie wir es heute haben. Wir konnten sagen: Die lebendige Wesenheit dieses Denkens lebte in uns in der Zeit zwischen dem Tode und der Geburt, durch die wir heruntergestiegen sind aus den geistigen Welten in die physische Welt. Da ist gewissermaßen die Lebendigkeit, die Wesenhaftigkeit des Denkens abgestreift worden, und wir tragen heute als Menschen des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraumes eigentlich ein totes Denken in uns, den Leichnam jenes lebendigen, wesenhaften Denkens, das uns eigen ist zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. Gerade dadurch, daß wir dieses tote, dieses unlebendige Denken in uns tragen, gerade dadurch sind wir ja als heutige Menschen durch das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein so stark in die Möglichkeit versetzt, das Leblose zu unserer Befriedigung zu begreifen, während wir als heutige Menschen keine Anlage haben, die Welt unserer Umgebung als lebendig zu erfassen.

Damit haben wir zwar als Menschen unsere Freiheit, unsere Selbständigkeit errungen, aber wir haben uns gewissermaßen auch gegenüber demjenigen in der Welt, was das fortlaufend Werdende ist, ganz abgeschlossen. Wir beobachten die Dinge um uns herum, die eigentlich nicht das fortlaufend Werdende sind, die nicht keimkräftig sind, sondern die eigentlich nur eine Gegenwart haben. Gewiß, man kann einwenden, daß der Mensch am Pflanzlichen, am Tierischen das Keimkräftige betrachtet; aber da täuscht er sich nur. Er betrachtet dieses Keimkräftige auch nur, insofern es erfüllt ist von abgestorbenen Stoffen, er betrachtet auch das Keimkräftige nur wie ein Totes.

Wenn wir das besonders Eigentümliche dieser Anschauungsweise uns vor die Seele stellen wollen, so ist es eben dieses, daß in früheren Zeiträumen der Menschheitsentwickelung die Menschen überall in ihrer Umgebung ein Lebendiges, Keimkräftiges wahrgenommen haben, während sie heute überall nur das Tote aufsuchen und das Leben eigentlich auch nur aus dem Toten irgendwie begreifen wollen. Sie begreifen es ja doch nicht.

Damit aber ist der Mensch eingetreten in eine ganz merkwürdige Epoche seiner Entwickelung. Der Mensch betrachtet ja heute die Sinneswelt, ohne daß ihm - so wie ihm Farben, wie ihm Töne in der Sinneswelt gegeben sind - in ihr auch Gedanken gegeben wären. Sie wissen schon aus der Darstellung meiner «Rätsel der Philosophie», daß dem Griechen ebenso Gedanken gegeben waren, wie uns heute die Töne, die Farben. Wir nennen eine Rose rot; der Grieche nahm nicht nur die Röte der Rose wahr, sondern er nahm auch den Gedanken der Rose wahr, ein rein Geistiges nahm er wahr. Und dieses Wahrnehmen des rein Geistigen ist allmählich eben hingestorben mit dem Heraufkommen des abstrakten, des toten Denkens, das nur ein Leichnam ist des lebendigen Denkens, welches wir vor unserem Erdenleben gehabt haben.

Nun aber frägt es sich: Wie kommen eigentlich diese zwei Dinge zusammen? Wie kommen sie zusammen, wenn wir die Natur auffassen wollen, wenn wir uns eine Weltanschauung bilden wollen: draußen die Sinneswelt, in uns das tote Denken? — Das muß man sich nur einmal ganz klarmachen, daß wenn heute der Mensch der Welt gegenübersteht, er ihr mit einem toten Denken gegenübersteht. Aber ist denn der Tod auch draußen in der Welt? Wenigstens ahnungsvoll müßte sich der Mensch heute sagen: Der Tod ist ja gar nicht draußen in der Welt, in den Farben, in den Tönen scheint ja zum mindesten überall Lebendiges sich anzukündigen! — So daß für denjenigen, der die Sinne durchschaut, sich das ganz Merkwürdige herausstellt, daß ja der heutige Mensch, trotzdem er immerfort nur seine Aufmerksamkeit auf die Sinneswelt richtet, diese Sinneswelt denkend gar nicht begreifen kann, weil die toten Gedanken auf die lebendige Sinneswelt gar nicht anwendbar sind.

Machen Sie sich das nur einmal restlos klar. Der Mensch steht heute vor der Sinneswelt und glaubt, nicht über die Sinneswelt hinausgehen zu sollen mit seinen Ansichten. Aber was heißt denn das überhaupt für den heutigen Menschen, nicht über die Sinneswelt hinausgehen zu wollen? Das heißt, überhaupt verzichten auf alles Anschauen und alles Erkennen. Denn das Rote, das Tönende, das Wärmende wird ja gar nicht begriffen durch den toten Gedanken. Der Mensch denkt also in einem ganz andern Elemente, als in demjenigen, worinnen er eigentlich lebt.

Und so ist es merkwürdig, daß wir mit unserer Geburt in die Erdenwelt eintreten, aber ein Denken haben, das der Leichnam dessen ist, was wir vor dem irdischen Dasein hatten. Und die zwei Dinge will heute der Mensch zusammenbringen: er will den Rest, das Übriggelassene des vorirdischen Lebens anwenden auf das irdische Leben.

Und das ist es, was seit dem 15. Jahrhundert fortwährend als alle möglichen Denk- und Erkenntniszweifel heraufgestiegen ist. Das ist es, was die großen Verirrungen der Gegenwart ausmacht, das ist es, was den Skeptizismus, die Zweifelsucht in alle möglichen menschlichen Denkweisen hat einziehen lassen; das ist es, was macht, daß heute der Mensch überhaupt nicht mehr einen Begriff vom Erkennen hat. Es gibt ja nichts Unbefriedigenderes, als wenn wir im heutigen Stile gehaltene Erkenntnistheorien durchschauen. Die meisten Wissenschafter tun das gar nicht; sie überlassen das den einzelnen Philosophen. Da kann man ganz merkwürdige Erfahrungen machen.

Ich besuchte einmal — es war im Jahre 1889 in Berlin — den jetzt schon lange verstorbenen Philosophen Eduard von Hartmann, und wir sprachen über erkenntnistheoretische Fragen. Im Verlauf des Gespräches sagte er: Erkenntnistheoretische Fragen sollte man nicht drucken lassen, die sollte man überhaupt nur höchstens mit der Maschine vervielfältigen oder auf irgendeine andere Weise vervielfältigen, denn es gibt in Deutschland überhaupt höchstens sechzig Menschen, die mit erkenntnistheoretischen Fragen sich sachgemäß beschäftigen können.

Also denken Sie sich: unter jeder Million einen! Natürlich sind unter einer Million Menschen mehr als ein Wissenschafter oder wenigstens mehr als ein gebildeter Mensch. Aber mit Bezug auf das wirkliche Eingehen auf erkenntnistheoretische Fragen wird wahrscheinlich Eduard von Hartmann schon recht gehabt haben, denn wenn man absieht von den Kompendien, welche die Kandidaten an den Universitäten rasch durchhecheln müssen zu gewissen Prüfungen, so wird man nicht viele Leser für erkenntnistheoretische Schriften finden, wenn sie im heutigen Stile, aus der heutigen Denkweise heraus geschrieben sind.

Und so wird eben, möchte man sagen, fortgewurstelt. Man treibt Anatomie, Physiologie, Biologie, Geschichte und so weiter, kümmert sich nicht darum, ob man durch diese Wissenschaften auch wirklich das Reale erkennt, sondern man geht eben in dem Trott fort. Aber diese fundamentale Tatsache, die müßte eigentlich einmal der Menschheit ganz klarwerden: daß der Mensch in dem Denken, das gerade das abstrakte Denken ist, weil er es so lichtvoll hat, etwas im höchsten Sinne Überirdisches in sich trägt, während er im Erdenleben immer nur das Irdische um sich hat. Beide Dinge passen gar nicht zusammen.

Nun können Sie die Frage aufwerfen: Paßten denn die Gedankenbilder, die sich die Menschen früher gemacht haben, besser zu dem, was der Mensch innerlich hatte, wo er noch ein lebendiges Denken hatte? Und da muß man sagen: Ja. — Und dafür will ich Ihnen den Grund angeben.

Bei dem heutigen Menschen ist es doch so, daß er von seiner Geburt bis zum siebenten Jahre in dem Ausgestalten seines physischen Leibes lebt, daß er dann, indem er in dem Ausgestalten seines physischen Leibes lebt, bis zum siebenten Jahre dahin gekommen ist, nun auch seinen Ätherleib immer mehr und mehr auszugestalten; das geschieht vom siebenten bis zum vierzehnten Jahre. Dann gestaltet der Mensch seinen astralischen Leib aus, das geschieht vom vierzehnten bis einundzwanzigsten Jahre. Dann gestaltet er seine Empfindungsseele aus bis zum achtundzwanzigsten Jahre, dann bis zum fünfunddreißigsten Jahre die Verstandes- oder Gemütsseele, dann die Bewußtseinsseele. Dann kann man nicht mehr sagen, er gestaltet aus, aber er wird ausgestaltet, indem das Geistselbst, das ja erst in zukünftigen Zeiten entwickelt wird, aber dennoch an seiner Entwickelung jetzt schon Teil hat, vom zweiundvierzigsten Jahre an ausgebildet wird. Und dann geht es so weiter.

Nun ist dies ein außerordentlich wichtiger Zeitraum, vom achtundzwanzigsten bis fünfunddreißigsten Lebensjahr. Dieser Zeitraum hat sich für das menschliche Leben seit dem 15. Jahrhundert ganz wesentlich geändert. Bis zum 15. Jahrhundert haben die Menschen in dieser Zeit immer noch Einflüsse von dem umgebenden Weltenäther gehabt. Man kann sich heute schwer vorstellen — weil es eben ganz und gar nicht mehr der Fall ist —, wie die Menschen Einflüsse von dem umgebenden Weltenäther hatten. Sie hatten sie aber. Die Menschen machten gewissermaßen zwischen dem achtundzwanzigsten und fünfunddreißigsten Jahre, ich möchte sagen, eine Art Auflebe-Erfahrung in sich durch. Es war wie etwas, was sich neu belebte in ihnen. Mit diesen Wahrnehmungen hing ja das zusammen, daß man eigentlich in diesen älteren Zeiten den Menschen im achtundzwanzigsten Jahre zur Meisterschaft kommen ließ in irgendeinem Fache, weil er mit diesem achtundzwanzigsten Jahre erst in einer besonderen Weise — wenn auch natürlich nicht stark, aber in einer besonderen, schwachen Weise — wiederum auflebte. Er bekam einen neuen Impuls. Das ist deshalb gewesen, weil die ganze universelle, umfassende Atherwelt, die ja uns alle außer der physischen Welt umgibt, auf den Menschen wirkte.

In den ersten sieben Lebensjahren, da wirkte sie durch die Vorgänge, die sich im physischen Leibe abspielten, hindurch, nicht direkt wirkte sie auf den Menschen. Und so wirkte sie auch noch nicht bis zum vierzehnten Jahre direkt, ja, nicht bis zum achtundzwanzigsten Jahre, wo sie noch das Empfindungsleben zu passieren hatte. Aber als der Mensch dann in das Verstandes- oder Bewußtseinsleben der damaligen Zeit eintrat, da wirkte der Äther neu belebend auf ihn.

Das haben wir verloren. Wir wären auch niemals zu der heutigen Selbständigkeit des individuell-persönlichen Menschen gekommen, wenn wir dieses nicht verloren hätten. Und mit diesem hängt es zusammen, daß die ganze innere Seelenverfassung des Menschen seit jener Zeit eben eine andere geworden ist.

Da müssen Sie schon einen Begriff aufnehmen, der vielleicht für das heutige Denken außerordentlich schwierig ist, aber der trotzdem auch wiederum außerordentlich wichtig ist.

Nicht wahr, im physischen Leben, da sind wir uns ganz klar darüber: Dasjenige, was erst in der Zukunft geschieht, das ist heute noch nicht da. Das ist aber im ätherischen Leben nicht so. Im ätherischen Leben ist die Zeit gewissermaßen eine Art Raum, und das, was einmal da sein wird, wirkt auch schon auf das Vorhergehende, wie auch auf das Nachfolgende. Aber das ist nicht wunderbar, denn das tut es im Physischen auch.

Wenn man die Goethesche Metamorphosenlehre wirklich versteht, so wird man sich sagen: In der Wurzel wirkt schon die Blüte der Pflanze. — Das tut sie auch. Und so ist es für alles, was im Ätherischen ist. Da wirkt das Zukünftige schon im Vorhergehenden. So ist es, daß dieses Offensein des Menschen gegenüber der ätherischen Welt schon im Vorhergehenden, zurück bis zur Geburt noch, vorzugsweise auf die menschliche Gedankenwelt wirkt. Dadurch hatte der Mensch wirklich eine andere Gedankenwelt, als er sie in demjenigen Zeitraum hat, der der unsrige ist, wo eben nicht mehr dieses Tor zwischen dem achtundzwanzigsten und fünfunddreißigsten Jahre offen ist, wo dieses Tor geschlossen ist. Der Mensch hatte lebendige Gedanken. Die machten ihn unfrei, aber sie machten zu gleicher Zeit, daß er in einer gewissen Weise mit seiner ganzen Umgebung zusammenhing, daß er sich lebendig in der Welt fühlte.

Heute fühlt sich der Mensch eigentlich nur in der toten Welt. Er muß sich in der toten Welt fühlen, weil die lebendige Welt, wenn sie in ihn hereinwirken würde, ihn unfrei machte. Nur dadurch, daß die tote Welt, die nichts in uns will, nichts in uns bestimmen kann, nichts in uns verursachen kann, in uns hereinwirkt, sind wir freie Menschen.

Aber auf der andern Seite muß man sich auch darüber klar sein, daß der Mensch gerade durch dasjenige, was er jetzt in voller Freiheit in seinem Inneren hat, durch seine Gedanken, die aber tot sind, kein Verständnis für das umliegende Leben gewinnen kann, sondern nur für den umliegenden Tod.

Wenn nun in dieser Seelenverfassung keine Veränderung eintreten würde, dann würde die Kultur- und Zivilisationsmißstimmung, die ja so deutlich immer mehr und mehr heraufzieht, immer größer und größer werden müssen, und der Mensch würde eigentlich in bezug auf die innere Sicherheit und Festigkeit seiner Seelenverfassung immer mehr und mehr verflachen müssen. Das würde sich schon viel mehr zeigen, wenn die Menschen unmittelbar auf dasjenige achteten, was sie heute aus dem heraus wissen können, wovon man sagt, daß es sicher ist. Aber sie achten noch nicht darauf. Sie beruhigen sich noch mit alten, traditionellen religiösen Vorstellungen, die sie nicht mehr verstehen, die sich aber fortgepflanzt haben. Bis in die Wissenschaften hinein beruhigen sich die Menschen mit solchen Vorstellungen. Gewöhnlich weiß man gar nicht, wenn man irgendeine Wissenschaft treibt, wie man im Grunde genommen da, wo man anfängt zu begreifen, noch an den alten, traditionellen Vorstellungen festhält, während die neueren Vorstellungen, die nur abstrakte, tote Gedanken sind, überhaupt an das Lebendige gar nicht mehr herankommen.

Der Mensch ist in der Tat früher dadurch, daß der Äther in ihn hereingewirkt hat, auch mit dem Lebendigen der Sinneswelt in Beziehung gekommen. In derjenigen Zeit, wo der Mensch noch an die geistige Welt geglaubt hat, konnte er auch die Sinneswelt begreifen. Heute, wo er nur mehr an die Sinneswelt glaubt, ist gerade das Eigentümliche, daß seine Gedanken am allergeistigsten sind, wenn auch tot. Es ist eben toter Geist. Aber der Mensch ist sich dessen nicht bewußt, daß er eigentlich heute mit der Erbschaft dessen, was er vor dem irdischen Leben hatte, in die Welt hineinschaut. Hätte er noch lebendige Gedanken, durch den Äther ringsherum belebt, so könnte er in das Lebendige seiner Umgebung hineinschauen. Da er aber von seiner Umgebung nichts mehr empfängt, sondern nur das hat, was er aus einer geistigen Welt geerbt hat, kann er die umliegende physische Welt nicht mehr verstehen.

Das ist wirklich eine scheinbar paradoxe, aber außerordentlich wichtige Tatsache, die auf die Frage antwortet: Warum sind denn die heutigen Menschen Materialisten? — Sie sind deshalb Materialisten, weil sie zu geistig sind. Sie würden überall die Materie verstehen können, wenn sie das Lebendige, das in aller Materie lebt, erfassen könnten. Da sie aber mit ihrem toten Denken dem Lebendigen gegenüberstehen, machen die Menschen dieses Lebendige selbst zum Toten, sehen überall den toten Stoff; und weil sie zu geistig sind, weil sie in sich nur das haben, was sie vor ihrer Geburt hatten, deshalb werden sie Materialisten. Man wird nicht Materialist, weil man den Stoff erkennt - man erkennt ihn eben nicht -—, sondern man wird Materialist, weil man eigentlich gar nicht auf der Erde lebt.

Und wenn Sie sich fragen: Warum sind diese ausgepichten Materialisten wie Büchner, der dicke Vogt und so weiter, warum sind die so starke Materialisten geworden? — Weil sie zu geistig waren, weil sie eigentlich gar nichts, was sie mit dem Erdenleben verband, in sich gehabt haben, sondern nur das in sich gehabt haben, was sie vor ihrem Erdenleben erlebt hatten, aber erstorben. Es ist wirklich ein tiefes Geheimnis, diese merkwürdige Erscheinung der Menschheitszivilisation, dieser Materialismus.

Nun kann der Mensch in diesem Zeitraum nicht anders über die toten Gedanken hinüberkommen - weil sie ihm nicht mehr von außen, von dem Äther belebt werden - als dadurch, daß er sie selber belebt. Und das kann er nur tun, indem er das Lebendige, wie es in der Anthroposophie gemeint ist, in seine Gedankenwelt aufnimmt, die Gedanken belebt, und wiederum unabhängig untertaucht in das Lebendige gerade der Sinneswelt. Also der Mensch muß sich innerlich selber beleben. Die toten Gedanken muß er durch innerliche Seelenarbeit beleben, und er wird über den Materialismus hinauswachsen.

Dann wird der Mensch anfangen, überhaupt die Dinge seiner Umgebung in einer andern Weise zu beurteilen. Und von solchen Beurteilungsmöglichkeiten haben Sie ja auch von diesem Orte aus hier schon das Verschiedenste gehört.

Wollen wir uns einmal heute ein besonderes Kapitel vor Augen stellen. Da sehen wir in unserer Umgebung, sagen wir, die Pflanzenwelt. Wir wissen von einem großen Teile der Pflanzenwelt: Tiere und Menschen können diese Pflanzen genießen; sie werden in ihnen durch die Ernährung, durch die Verdauung verarbeitet. Sie können sich in der Weise, wie man das gewöhnlich andeutet, mit der tierischen, mit der menschlichen Organisation vereinigen. Nun treffen wir plötzlich auf eine Giftpflanze, sagen wir, auf das Gift, das im Bilsenkraut oder in der Belladonna ist. Wir müssen uns fragen: Was liegt denn da eigentlich vor? Da treffen wir plötzlich mitten in dem andern Pflanzenwachstum etwas, was sich nicht mit der tierischen und menschlichen Organisation so vereinigt, wie das andere, das im Pflanzenleben wirkt.

Machen wir uns einmal klar, worauf denn das Pflanzliche beruht. Ich habe ja das schon öfter angedeutet. Wir stellen uns die Erdoberfläche vor. Die Pflanze wächst aus der Erdoberfläche heraus. Wir wissen, die Pflanze hat ihre physische Organisation. Sie ist von ihrem Ätherleib durchdrungen. Aber die Pflanze würde sich nicht entfalten können, wenn sie nicht, wie ich das öfter schon dargestellt habe, von oben herunter zur Blüte hin berührt würde von dem astralischen Elemente, das überall ausgebreitet ist (siehe Zeichnung, lila). Die Pflanze hat nicht einen astralischen Leib in sich, aber das Astralische berührt überall die Pflanze. Die Pflanze nimmt in der Regel das Astralische nicht in sich auf, sie läßt sich nur berührt werden davon. Sie verarbeitet in sich das Astralische nicht. Sie lebt nur in einer Wechselwirkung; nach oben, nach dem Blühenden und Fruchtenden zu lebt sie in einer Wechselwirkung mit dem Astralischen. Das Astralische verbindet sich nicht mit dem Ätherleib oder mit dem physischen Leib der Pflanze, in der Regel.

Bei der Giftpflanze ist es anders. Bei der Giftpflanze liegt das Eigentümliche vor, daß das Astralische in das Pflanzliche eindringt und sich mit dem Pflanzlichen verbindet. So daß, wenn wir die Belladonna haben, oder sagen wir das Bilsenkraut, Hyoscyamus, dann saugt gewissermaßen solch eine Pflanze das Astralische stärker oder schwächer auf und trägt ein Astralisches in sich; natürlich auf eine ungeordnete Weise, denn trüge sie es in geordneter Weise in sich, müßte sie ja Tier werden. Sie wird nicht Tier, sie trägt das Astralische in einer Art gepreßten Zustandes in sich.

Dadurch stellt sich ein besonderes Wechselverhältnis ein zwischen dem, was da in einer astralisch gesättigten Pflanze und in dem tierischen und menschlichen Organismus vorhanden ist. Essen wir Pflanzen, die nicht giftig sind, wie man sagt, so nehmen wir nicht nur das von der Pflanze auf, was, ich möchte sagen, der Chemiker im Laboratorium von der Pflanze verarbeitet, wir nehmen nicht bloß das Stoffliche auf, wir nehmen auch das Ätherische, Lebenskräftige auf, müssen es allerdings, wie ich ja auch hier einmal ausgeführt habe, gerade während unseres Ernährungsprozesses zur vollständigen Tötung bringen. Das ist ja notwendig, daß der Mensch, indem er sich nährt aus dem Lebendigen, das Lebendige dann in sich selber zur vollständigen Tötung bringt. Er muß also in sich das Ätherische aus dem Pflanzlichen herausarbeiten.

Nun haben wir im unteren Menschen, in dem Stoffwechselmenschen, diesen merkwürdigen Prozeß: Wir genießen die Pflanze, das Pflanzlich-Stoffliche — es ist auch noch beim Gekochten das der Fall, aber insbesondere stark der Fall, wenn wir rohe Birnen oder rohe Apfel oder rohe Beeren essen -, wir pressen das Ätherische heraus und nehmen in unseren eigenen Ätherleib das Kraftgebilde auf, welches der Pflanze zugrunde liegt. Die Pflanze hat ja eine bestimmte Form, eine bestimmte Gestalt. Diese Gestalt, die wir da aufnehmen — das zeigt sich dem hellseherischen Bewußtsein —, die ist sogar nicht immer gleich der Gestalt, die wir äußerlich sehen. Es ist etwas Verschiedenes. Es quillt die Gestalt der Pflanze in uns auf, und sie paßt sich in einer merkwürdigen Weise dem menschlichen Organismus an.

Nun tritt etwas sehr Eigentümliches auf. Denken Sie sich also — man muß natürlich dabei etwas paradox reden, aber die Dinge sind doch so richtig —, nehmen Sie an, Sie essen Kohl, so ist da im unteren Menschen ein ganz bestimmtes Gebilde zunächst aufleuchtend (blau). Es besteht eine Tätigkeit im Stoffwechselmenschen, im unteren Menschen, die die Folge ist davon, daß der Mensch diesen Kohl gegessen hat.

In demselben Maße, in dem diese Tätigkeit im unteren Menschen auftritt durch das Kohlessen, entsteht im oberen Menschen, im Kopfmenschen, das Negativ davon, ich möchte sagen, der leere Raum, der dem entspricht, ein Abbild, ein richtiges Negativ. Wenn ich also, sagen wir, die Form, die da unten entsteht, so zeichne, dann entsteht im oberen Menschen ein Abbild (blau, rot), ein Hohlgebilde. Es ist tatsächlich so, der Kohl erzeugt in uns eine bestimmte Form, und das Negativ davon, das entsteht in unserem Kopf.

Und in dieses, ich möchte sagen, Negativ des Kohles nehmen wir nun die äußere Welt auf. Die kann uns ihre Eindrücke hereingeben, weil wir so gewissermaßen den leeren Raum in uns tragen - es ist natürlich alles nur approximativ ausgedrückt —, und so wirken alle Pflanzen, die Nährmittel sind, in uns. Nehmen Sie an, wir haben das, was man gewöhnlich Nährmittel nennt, aufgenommen, so besteht der Zusammenhang ihrer Form nur insoweit intensiv, daß wir ihn fortwährend im Laufe von vierundzwanzig Stunden auflösen müssen. Einmal Wachen und Schlafen löst ihn auf. Er muß immer wieder neu gebildet werden. Das ist bei denjenigen Pflanzen der Fall, die in ihrem natürlichen Wachstum physischen Leib und Ätherleib haben und sich gewissermaßen von dem Astralischen nur umspülen lassen.

Nehmen wir aber an, wir nehmen den Saft des Bilsenkrautes zu uns. Da haben wir eine Pflanze, die in sich das Astralische aufgesaugt hat, und die dadurch, daß sie das Astralische aufgesaugt hat, einen viel stärkeren Formzusammenhang hat, so daß da unten eine viel festere Form entsteht, die wir nicht so leicht verarbeiten können, die sich sogar als selbständig geltend macht. Dadurch entsteht ein ausgesprocheneres, intensiver wirkendes Negativ.

Und nehmen wir jetzt an, irgendein Mensch hat ein seine Struktur nicht ordentlich aufrechterhaltendes Gehirn, er neigt zu Dämmerzuständen, weil sein astralischer Leib nicht fest genug im physischen Leib des Gehirnes drinnen ist. Er nimmt den Saft des Bilsenkrautes zu sich; dadurch entsteht eine intensive Pflanzenform, die ein starkes Negativ bildet. Und so können in dem Menschen, dessen Gehirn gewissermaßen zu weich ist, dadurch, daß man den Ätherleib seines Unterleibes verstärkt, eine starke Form durch das Bilsenkraut da hineinbringt, deutliche Gedanken in ihm entstehen, der Dämmerzustand kann abdämmern. Ist er dann in seiner übrigen Organisation stark genug, um — wenn er das öfter gegen seine Dämmerzustände als Arznei verordnet bekommt - seine entsprechenden Lebenskräfte aufzurufen, so daß diese dadurch wieder reger gemacht werden und sein Gehirn wieder in Ordnung kommt, dann kann er durch ein solches Gift eben über seine Neigung zu Dämmerzuständen wieder hinausgebracht werden.

In einer ganz ähnlichen Weise wirkt zum Beispiel die Belladonna auf den Menschen. Die Belladonna wirkt durchaus so, daß folgendes eintritt. Ich möchte es schematisch zeichnen. Durch den Belladonnagenuß — der ja kein «Genuß» ist natürlich — wird der Ätherleib von einem starken Gerüste durchzogen. Wenn sie also in einer entsprechenden Dosis genommen wird, so daß der Mensch sie vertragen kann aber man kann ja überhaupt nur durch eine Arznei geheilt werden, wenn man sie ertragen kann -, so wird also gewissermaßen dem Ätherleib des Unterleibes ein starkes Gerüste eingebaut. Dieses starke Gerüste erzeugt richtig sein Negativ im Kopfe. Und auf dieser Wechselwirkung des Positivs und Negativs beruht der Heilungsprozeß, auf den man bei der Belladonna rechnet.

Sie müssen sich nur darüber klar sein, daß, wenn man zu solchen Wirkungen kommt, man die räumliche Verteilung nicht mehr braucht. Der heutige Mensch mit seinem toten, aber massiven Verstande, kann sich nur denken: wenn in seinem Bauch etwas vorgeht, dann kann es nur dadurch ins Gehirn kommen, daß es sichtbarlich hinauffließt. Das ist aber nicht der Fall, sondern Prozesse des Unterleibes rufen als ihr Gegenbild Prozesse des Kopfes hervor, ohne daß eine räumliche Verteilung da ist. Man kann es durchaus, wenn man den Ätherleib zu beobachten vermag, sehen, wie es im Ätherleib des Unterleibes hell wird, hell aufglänzt in regelmäßiger Gestalt (rot), wie es im Kopfe dunkel wird (grün), aber die Form nachgebildet wird als Negativ, ohne daß eine räumlich-physische Verteilung da ist.

Daß die Natur überall nach solchen Dingen strebt, das können Sie sich ja versinnbildlichen. Sie wissen, nicht wahr, eine anständige Wespe hat vorn eine Art Kopf, dann eine Art Hinterleib und die Flügel. Das ist eine anständige Wespe. Aber es gibt auch Wespen, Sandwespen, welche so ausschauen (Zeichnung unten):

Sie haben hier einen Stiel und schleppen dahinten ihren Hinterleib nach. Da ist schon im Physischen diese Verbindung zwischen dem Vorderleib und dem Hinterleib auf ein Minimum reduziert; dieser Stiel ist sehr reduziert.

Sobald man ins Geistige hineinkommt, braucht es gar keines so sichtbaren Stieles. Und wenn Sie zu gewissen Elementarwesen in der elementarischen Welt kommen — Sie wissen, ich habe ja neulich von den Elementarreichen gesprochen -, da sehen Sie zum Beispiel irgendein Wesen, dann ist nichts da, weit weg ist etwas anderes, und nach und nach kommen Sie erst darauf: die gehören zusammen; wo das eine hingeht, geht das andere hin. So daß Sie also da in die ganz merkwürdige Lage kommen - in der elementarischen Welt kann es so sein —, da haben Sie irgendwo ein Stück eines elementar-ätherischen Organismus, und hier das andere Stück, jetzt einen nächsten Zustand (siehe Zeichnung unten) zum Beispiel so: der hat sich umgedreht, aber da ist nicht ein Stiel oder ähnliches und das ist nicht etwa so, daß wenn das eine Stück sich umdreht, das andere einfach direkt daherlaufen könnte, sondern es muß den Weg machen, den das andere gemacht hat.

Sie sehen also, es handelt sich darum, daß man in der Tat einen Zusammenhang finden kann für diejenigen Stoffe, die der menschliche und tierische Organismus nicht unmittelbar zerstören kann, die intensivere, bleibendere - wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf — Gerüste erzeugen, daß man einen Zusammenhang finden kann mit dem, was dann an einem ganz andern Ort des menschlichen Organismus wiederum Struktur hervorrufend, organisierend, gesundend mit andern Worten, wirken kann.

Das gibt Ihnen nun einen Ausblick, wie die Welt wiederum belebt werden kann für die Beobachtung des Menschen. Der Mensch hat dadurch, daß er nur die Erbschaft aus der geistigen Welt heute hat, keine Möglichkeit, an die lebendige Umgebung heranzukommen. Gerade die Sinneswelt begreift er eigentlich nicht. Er wird sie wieder begreifen, er wird wiederum hinschauen auf dasjenige, was das sinnliche Denken in bezug auf das ganze Weltenall ist. Dann wird er aus dem ganzen Weltenall heraus finden, warum die Dinge in diesem oder jenem Zusammenhang stehen, warum also eine giftlose Pflanze zum menschlichen und tierischen Leibe in einem andern Zusammenhang steht als eine giftige Pflanze. Eine Belebung des ganzen menschlichen Daseins ist nur auf diese Weise möglich.

Nun kann es ja dem heutigen Bequemling so vorkommen, daß er sagt: Die früheren Menschen haben es doch besser gehabt, auf die hat noch die Umgebung des Äthers gewirkt, die haben lebendige Gedanken gehabt, die haben noch so etwas begriffen, wie den wirklichen Unterschied zwischen giftigen und giftlosen Pflanzen. — Sie wissen, die Tiere tun das heute noch, denn bei denen kommen nicht abstrakte Gedanken, die sie von der Welt loslösen können. Daher unterscheiden die Tiere, wie man sagt, aus ihrem Instinkte heraus die giftigen von den giftlosen Pflanzen.

Ja, aber der Mensch wäre — das muß immer wieder und wieder betont werden — nicht zum Gebrauche seiner Freiheit gekommen. Denn dasjenige, was uns in uns lebendig hält bis zum Gedanken hin, beraubt uns der Freiheit. Wir müssen, so paradox das klingt, in bezug auf die Gedanken früherer Erdenleben geradezu ein Nichts werden, dann können wir frei werden. Und wir werden ein Nichts, wenn wir die lebendigen Gedankenwesen, die wir im vorirdischen Dasein hatten, nur als Leichname in uns hereinkriegen, das heißt in ihrem Nichtdasein in uns hereinkriegen. Wir gehen also eigentlich herum mit unseren abgestorbenen Gedanken in bezug auf unser Seelisches in unserem wachen Erdenzustande als Nichtse. Und aus den Nichtsen heraus wird im Grunde erst unsere Freiheit.

Die läßt sich schon verstehen. Aber wir können nichts erkennen, wenn wir kein Lebendiges in uns tragen. Wir können das Tote erkennen, aber das Tote bringt uns ja keinen Schritt weiter in unserem lebendigen Verhältnis zur Welt. Und so müssen wir gegenüber der Unterbrechung im Erkennen, die eingetreten ist, unsere Freiheit bewahrend wiederum zu einem Erkennen kommen, indem wir nun im irdischen Leben beginnen, durch menschliches Wollen wiederum unsere Gedanken zu beleben. Dann können wir jeden Moment unterscheiden: dies sind lebendige, das sind tote Gedanken. Wenn wir zu den reinen Gedanken aufsteigen — das habe ich in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» beschrieben —, können wir freie Menschen sein. Wenn wir die Gedanken erfühlen, werden wir zwar aus der Freiheit heraustreten, aber dafür auch mit der Umgebung wiederum in Zusammenhang kommen. Wir werden der Freiheit teilhaftig durch das Bewußtsein, daß wir fähig sind, zum reinen Gedanken immer mehr hinzugehen, aus ihm in moralischer Intuition die moralischen Impulse zu entnehmen.

Wir werden dadurch freie Menschen, müssen aber dadurch auch unser inneres Seelenleben, unsere Seelenverfassung uns erst durch unsere eigene irdische Tat einrichten. Dann können wir allerdings die Folgen dieser irdischen Tat durch die Pforte des Todes in die geistige Welt hineinnehmen. Denn was individuell erarbeitet ist, geht eben im Weltenall nicht verloren.

Nun, meine lieben Freunde, ich habe Ihnen vielleicht heute einiges Schwierige zugemutet, aber Sie sehen ja aus der Betrachtung auch, daß wir in der Tat der Welt dadurch näherkommen, daß wir den Menschen verstehen lernen, und namentlich die Verhältnisse auch des physischen Menschen - des scheinbar physischen Menschen, denn er ist ja nicht ein physischer Mensch, er ist immer durchdrungen von den höheren Gliedern des Organismus — zu dem andern der sich physisch offenbarenden Welt, wie wir das an den Giftpflanzen kennengelernt haben.

Nun ist es doch so gekommen, daß ich morgen noch da sein muß, und daher kann ich für diejenigen, die das hören wollen, auch noch morgen abends um acht Uhr einen Vortrag halten.

Sixth Lecture

Today we shall first of all recall the information I have given you about the actual nature, the essence of human thinking. In this present age, since the 15th century, which has been mentioned so often, we have an essentially abstract thinking, a thinking without images, and humanity is proud of this thinking without images. We know that this imageless thinking only came about in the period indicated, that earlier there was a pictorial and thus a living thinking.

Now let us remember today what the nature and essence of this thinking as we have it today actually is. We could say: The living essence of this thinking lived in us in the time between death and birth, through which we descended from the spiritual worlds into the physical world. There the vitality, the essential nature of thinking was, so to speak, stripped away, and today, as human beings of the fifth post-Atlantean period, we actually carry a dead thinking within us, the corpse of that living, essential thinking which is our own between death and a new birth. Precisely because we carry this dead, this inanimate thinking within us, it is precisely because of this that we as human beings today are so strongly enabled by ordinary consciousness to comprehend the inanimate for our satisfaction, whereas we as human beings today have no capacity to comprehend the world around us as living.

Thus we as human beings have achieved our freedom, our independence, but we have to a certain extent also completely closed ourselves off from that in the world which is continuously becoming. We observe the things around us, which are not actually that which is continuously becoming, which are not germinative, but which actually only have a presence. Certainly, one can object that man observes the germinal force in the vegetable, in the animal; but there he is only deceiving himself. He only looks at this germinal substance insofar as it is filled with dead matter; he also only looks at the germinal substance as if it were dead.

If we want to place the particularly peculiar aspect of this way of looking at things before our souls, it is precisely this, that in earlier periods of human development people perceived a living, germinal substance everywhere in their surroundings, whereas today they only seek out the dead everywhere and actually only want to somehow understand life from the dead. They do not understand it after all.

With this, however, man has entered a very strange epoch in his development. Today man observes the world of the senses without being given thoughts in it, just as he is given colors and sounds in the world of the senses. You already know from the presentation of my “Riddles of Philosophy” that thoughts were given to the Greeks just as sounds and colors are given to us today. We call a rose red; the Greek not only perceived the redness of the rose, but he also perceived the thought of the rose, he perceived something purely spiritual. And this perception of the purely spiritual has gradually died with the emergence of abstract, dead thinking, which is only a corpse of the living thinking we had before our life on earth.

But now the question arises: How do these two things actually come together? How do they come together if we want to comprehend nature, if we want to form a world view: outside the sense world, inside us the dead thinking? - We only have to realize that when man faces the world today, he faces it with dead thinking. But is death also outside in the world? Today man should say to himself at least forebodingly: Death is not outside in the world at all, in the colors, in the sounds, at least living things seem to announce themselves everywhere! - So that for those who see through the senses, the very strange thing turns out to be that today's man, although he constantly directs his attention only to the sensory world, cannot comprehend this sensory world by thinking, because dead thoughts cannot be applied to the living sensory world at all.

Make this completely clear to yourself just once. Man today stands before the world of the senses and believes that he should not go beyond the world of the senses with his views. But what does it actually mean for people today not to want to go beyond the world of the senses? It means renouncing everything that we look at and everything that we recognize. For the red, the sounding, the warming is not grasped at all through the dead thought. Man therefore thinks in a completely different element than that in which he actually lives.

And so it is strange that we enter the earthly world with our birth but have a thinking that is the corpse of what we had before the earthly existence. And today man wants to bring the two things together: he wants to apply the rest, what is left of pre-earthly life to earthly life.

And that is what has continually arisen since the 15th century as all kinds of doubts of thought and knowledge. That is what constitutes the great aberrations of the present, that is what has allowed skepticism, the addiction to doubt, to enter into all possible human ways of thinking; that is what makes it so that today man no longer has any concept of knowledge at all. There is nothing more unsatisfactory than to see through theories of knowledge held in today's style. Most scientists do not do this at all; they leave it to individual philosophers. You can have some very strange experiences.

I once visited the now long-deceased philosopher Eduard von Hartmann - it was in Berlin in 1889 - and we talked about epistemological questions. In the course of the conversation, he said: epistemological questions should not be printed, they should only be reproduced by machine or in some other way, because there are at most sixty people in Germany who can deal with epistemological questions properly.

So think of it: one in every million! Of course, there is more than one scientist or at least more than one educated person in a million. But Eduard von Hartmann will probably have been right when it comes to really dealing with epistemological questions, because if you disregard the compendiums that university candidates have to rush through for certain exams, you won't find many readers for epistemological writings if they are written in today's style, from today's way of thinking.

And so, one might say, we muddle along. One pursues anatomy, physiology, biology, history and so on, not caring whether one really recognizes the real through these sciences, but one continues in the same rut. But this fundamental fact should actually become quite clear to mankind: that in thinking, which is precisely abstract thinking, because he has it so full of light, man carries something supernatural in the highest sense, while in earthly life he always has only the earthly around him. The two things do not go together at all.

Now you can raise the question: Did the mental images that people used to make for themselves fit better with what man had inwardly, where he still had a living mind? And you have to say: Yes - and I will give you the reason why.

With today's man it is so that he lives from his birth until the seventh year in the shaping of his physical body, that he then, while living in the shaping of his physical body, has come to the point until the seventh year to now also shape his etheric body more and more; this happens from the seventh to the fourteenth year. Then the human being develops his astral body, which takes place from the fourteenth to the twenty-first year. Then he forms his sentient soul until the twenty-eighth year, then the intellectual or emotional soul until the thirty-fifth year, then the consciousness soul. Then it can no longer be said that it forms, but it is formed, in that the spirit soul, which will only be developed in future times, but which nevertheless already takes part in its development now, is formed from the forty-second year onwards. And then it goes on like this.

Now this is an extraordinarily important period, from the twenty-eighth to the thirty-fifth year of life. This period has changed considerably for human life since the 15th century. Until the 15th century, people still had influences from the surrounding world ether during this time. It is difficult to imagine today - because it is no longer the case at all - how people were influenced by the surrounding world ether. But they had them. Between the ages of twenty-eight and thirty-five people underwent, I would say, a kind of revival experience within themselves. It was like something that revived within them. It was connected with these perceptions that in these older times man was actually allowed to attain mastery in some subject in his twenty-eighth year, because it was only in this twenty-eighth year that he revived in a special way - though of course not strongly, but in a special, weak way. He received a new impulse. This was because the whole universal, comprehensive etheric world, which surrounds us all apart from the physical world, had an effect on the human being.

In the first seven years of life, it worked through the processes that took place in the physical body, not directly on the human being. And so it did not have a direct effect until the fourteenth year, indeed not until the twenty-eighth year, when it still had to pass through the sentient life. But when man then entered the intellectual or conscious life of that time, the ether had a revitalizing effect on him.

We have lost that. We would never have come to the present independence of the individual-personal human being if we had not lost this. And it is connected with this that the whole inner constitution of the human soul has changed since that time.

There you have to include a concept that is perhaps extremely difficult for today's thinking, but which is nevertheless extremely important.

Not true, in physical life we are quite clear about this: That which will only happen in the future is not yet here today. But that is not the case in etheric life. In etheric life, time is a kind of space, so to speak, and what will one day be there already has an effect on what has gone before, as well as on what will follow. But that is not wonderful, because it also does this in the physical world.

If you really understand Goethe's theory of metamorphosis, you will say to yourself: the blossom of the plant is already at work in the root. - It does that too. And so it is for everything that is in the etheric. There the future is already at work in the previous. So it is that this openness of the human being to the etheric world already has an effect on the human world of thought in the preceding, back to birth. Thus man really had a different world of thoughts than he has in the period that is ours, where this gate is no longer open between the twenty-eighth and thirty-fifth year, where this gate is closed. Man had living thoughts. They made him unfree, but at the same time they made him connected in a certain way with his whole environment, made him feel alive in the world.

Today man actually only feels himself in the dead world. He must feel himself in the dead world because the living world, if it were to work its way into him, would make him unfree. Only because the dead world, which wants nothing in us, can determine nothing in us, can cause nothing in us, works in us, are we free people.

But on the other hand one must also be clear about the fact that man cannot gain an understanding of the surrounding life, but only of the surrounding death, precisely through that which he now has in full freedom within himself, through his thoughts, which however are dead.

If no change were to occur in this constitution of the soul, then the cultural and civilizational discord, which is so clearly becoming more and more prevalent, would have to become greater and greater, and man would actually have to become more and more flat in terms of the inner security and stability of his soul constitution. This would already become much more apparent if people paid direct attention to what they can know today from what is said to be certain. But they do not yet pay attention to it. They still reassure themselves with old, traditional religious ideas which they no longer understand but which have been perpetuated. Even in the sciences, people reassure themselves with such ideas. Usually, when you do any kind of science, you don't even know how, basically, where you begin to understand, you still hold on to the old, traditional ideas, while the newer ideas, which are only abstract, dead thoughts, no longer come close to the living at all.

In the past, man did indeed come into contact with the living of the sensory world through the ether working into him. At the time when man still believed in the spiritual world, he was also able to comprehend the sensory world. Today, when he only believes in the sense world, the peculiar thing is that his thoughts are most spiritual, even if dead. It is just dead spirit. But man is not aware of the fact that he actually looks into the world today with the inheritance of what he had before earthly life. If he still had living thoughts, animated by the ether all around him, he could look into the living things in his surroundings. However, since he no longer receives anything from his surroundings, but only has what he has inherited from a spiritual world, he can no longer understand the surrounding physical world.

This really is a seemingly paradoxical but extremely important fact that answers the question: Why are people today materialists? - They are materialists because they are too spiritual. They would be able to understand matter everywhere if they could grasp the living that lives in all matter. But since they are confronted with the living with their dead thinking, people turn this living into dead matter themselves, see dead matter everywhere; and because they are too spiritual, because they only have in themselves what they had before they were born, that is why they become materialists. One does not become a materialist because one recognizes matter - one does not recognize it - but one becomes a materialist because one does not actually live on earth.

And if you ask yourself: Why did these pompous materialists like Büchner, the fat Vogt and so on, why did they become such strong materialists? - Because they were too spiritual, because they didn't really have anything in them that connected them to life on earth, they only had in them what they had experienced before their life on earth, but which had died. It really is a deep mystery, this strange phenomenon of human civilization, this materialism.

Now man cannot get over the dead thoughts in this period in any other way - because they are no longer enlivened for him from outside, from the ether - than by enlivening them himself. And he can only do this by absorbing the living, as it is meant in anthroposophy, into his world of thoughts, by enlivening the thoughts, and again by immersing himself independently in the living of the sense world. Thus man must inwardly animate himself. He must enliven the dead thoughts through inner soul work, and he will grow beyond materialism.

Then man will begin to judge the things of his surroundings in a different way. And you have already heard the most diverse things about such possibilities of judgment from this place.

Let's look at a particular chapter today. In our surroundings we see, let us say, the plant world. We know about a large part of the plant world: animals and humans can enjoy these plants; they are processed in them through nutrition, through digestion. They can unite with the animal, with the human organization in the way that is usually implied. Now we suddenly come across a poisonous plant, let us say, the poison in henbane or belladonna. We have to ask ourselves: What is actually going on here? In the midst of the other plant growth, we suddenly encounter something that does not unite with the animal and human organization in the same way as the other things that work in plant life.

Let us realize what the plant life is based on. I have already hinted at this several times. Let us imagine the surface of the earth. The plant grows out of the surface of the earth. We know that the plant has its physical organization. It is permeated by its etheric body. But the plant would not be able to unfold if it were not, as I have often shown, touched from above down to the blossom by the astral element that is spread everywhere (see drawing, purple). The plant does not have an astral body within itself, but the astral element touches the plant everywhere. As a rule, the plant does not take the astral into itself, it only allows itself to be touched by it. It does not process the astral within itself. It lives only in an interaction; upwards, towards the flowering and fruiting, it lives in an interaction with the astral. The astral does not connect with the etheric body or with the physical body of the plant, as a rule.

The poisonous plant is different. The poisonous plant has the peculiarity that the astral penetrates the plant and connects with the plant. So that when we have Belladonna, or let us say the henbane, Hyoscyamus, then in a way such a plant absorbs the astral stronger or weaker and carries an astral within itself; of course in a disordered way, because if it carried it in an ordered way, it would have to become an animal. It does not become an animal, it carries the astral within itself in a kind of pressed state.

This creates a special interrelationship between what is present in an astrally saturated plant and in the animal and human organism. If we eat plants that are not poisonous, as they say, we not only take in from the plant what, I would like to say, the chemist in the laboratory processes from the plant, we not only take in the material, we also take in the etheric, vital force, but, as I have also explained here, we must bring it to complete death precisely during our nourishment process. It is necessary that the human being, by nourishing himself from the living, then brings the living within himself to complete death. He must therefore work out the etheric from the vegetable within himself.

Now in the lower man, in the metabolic man, we have this strange process: We enjoy the plant, the vegetable material - it is also still the case with cooked food, but especially strongly the case when we eat raw pears or raw apples or raw berries - we press out the etheric and absorb into our own etheric body the power structure that underlies the plant. The plant has a certain form, a certain shape. This form that we absorb - this is revealed to the clairvoyant consciousness - is not always the same as the form that we see externally. It is something different. The form of the plant wells up within us, and it adapts itself to the human organism in a strange way.

Now something very peculiar occurs. If you think of it - of course you have to speak somewhat paradoxically, but things are nevertheless correct - suppose you eat cabbage, then a very specific structure will first light up (blue) in the lower human being. There is an activity in the metabolic human being, in the lower human being, which is the result of the human being having eaten this cabbage.