The Driving Force of Spiritual Powers in World History

GA 222

23 March 1923, Dornach

Lecture VII

The essential characteristic of our present age in evolution is to be recognized in the fact that the thoughts of man on Earth are abstract and dead, persisting in us as a residue of the living nature of the soul in pre-earthly existence.

This stage of development leading to abstract, that is to say, to dead thoughts is connected with the acquisition of consciousness of freedom within the process of evolution. We will give special attention today to this aspect of the subject by studying the course taken by evolution in the post-Atlantean era.

You know that after the great Atlantean catastrophe, the gradual distribution of the continents on the Earth as we know them today took place and that on the dry land, or within the areas of the dry land, five successive civilization- or culture epochs have evolved, epochs which in my book Occult Science: an Outline I have called the ancient Indian, ancient Persian, Egypto-Chaldean, Graeco-Latin and our present Fifth culture epoch.

These five epochs are distinguished by the fact that the constitution of man, in the general sense, is different in each of them. If we go back to the very early culture-epochs this constitution is also expressed in the whole outer appearance of man, in his bodily features. And the nearer we come to our own epoch, the more clearly is the progress of humanity expressed in the natural tendencies of the soul. Matters relating to this subject have often been described but today I will speak about them from a point of view to which less attention has hitherto been paid.

If we go back to the first, the ancient Indian civilization-epoch which was still partly a direct outcome of the Atlantean catastrophe, we find that in those days a man felt himself to be far rather a citizen of the Cosmos beyond the Earth than a citizen of the Earth itself. And if we study the details of life at that time which, as I have often pointed out, takes us back to the seventh/eighth millennium B.C., it must be emphasised that, not out of intellectual observation—for that was unknown in those days—but out of deep, instinctive perception in that remote past, great importance was attached to the outer appearance, the external aspect of a man. Not that the people of those days engaged in any kind of study of physiognomy—that, of course, was utterly foreign to them. Such a practice belongs to much later epochs, when intellectualism, although not yet fully developed, was already dawning. These men, however, had a sensitive feeling for physiognomy. They felt deeply that if someone had this or that facial expression it indicated certain musical talents. They attached great importance to divining the musical gifts of an individual from his facial expression but also from his gestures and movements, his whole appearance as a human being. In those olden days men did not strive for any more definite knowledge of human nature in general. At that time, if anyone had come to them saying that something should be ‘proved’, they simply would not have known what was meant. It would have troubled them, would almost have given them physical pain; indeed in still earlier times there would have been actual physical pain. To ‘prove’—that would be like carving someone with knives ... so these men would have said. Why should anything have to be proved? We do not need to know anything so certain about the world that it must first be proved.

This is connected with the very vivid feeling these people still had of having come from pre-earthly existence, from the spiritual world. In the spiritual world there is no such thing as ‘proving’. There it is known that proving is a matter that has meaning on the Earth but not in the spiritual world. The wish to prove something in the spiritual world would seem to indicate a definite norm of measurement : the height of a human being must be such and such ... and then, as in the Procrustean myth, something is cut off from one who is too tall and someone too short is stretched! This is more or less what ‘proving’ would be in the spiritual world. Things there do not allow themselves to be manoeuvred into proofs ; things there are inwardly mobile, inwardly fluid.

To an Indian belonging to the ancient Indian epoch with his vivid consciousness of having descended from the spiritual world, of having simply enveloped himself in this external human nature—to such an Indian it would have seemed highly curious if anyone had demanded of him that something should be ‘proved’. These people much preferred what we today should call ‘divining’ because they wanted to be attentive to what was revealed in their environment. And in this activity of ‘divining’ they found a certain inner satisfaction.

Moreover a certain instinct enabled them to infer cleverness in a man from a face of this or that type; from another face they inferred stupidity; from the stature they inferred a phlegmatic temperament, and so on. In that epoch, divining took the place of what we today would call explanatory knowledge. And in human intercourse the aim of reciprocal behaviour was to be able to infer the moral quality of a man from his attitude of soul; from his movements and gestures, his stature.

In the earliest epoch of ancient Indian existence there was no such thing as division into castes—that came later. In connection with the Mysteries of ancient India there was actually a kind of social classification of men according to their physiognomies and their gestures. This was possible in early epochs of evolution, for a certain instinct prompted men to accept such classifications. What later arose within Indian civilization as the caste system was a kind of schematic arrangement of what had been a far more individual classification based upon an instinctive feeling for physiognomy. And in those olden days men did not feel outraged if they were ranked here or there according to their physiognomy; for they felt themselves to be God-given beings of Earth. And the authority of those from the Mysteries who were responsible for this classification, was absolute.

It was not until the later post-Atlantean civilization-epochs that the caste system gradually developed from antecedents of which I have spoken in other lectures. In the epoch of ancient India there was a deep and strong feeling that the basis of man's being was a divine IMAGINATION.

I have told you a great deal about the existence of a primordial, instinctive clairvoyance, a dreamlike clairvoyance. But in remotely distant times of the post-Atlantean era men not only spoke of seeing dreamlike Imaginations, but they said : In the particular configuration of the physical body of man when he enters Earth-existence there is present a divine Imagination. A divine Imagination becomes the basis of the being who descends to the Earth as man, and in accordance with it he forms his physiognomy and the whole physical expression of his manhood, from childhood onwards.

And so men not only looked instinctively, as I have indicated, at the physiognomy of an individual; they also saw there the Imagination of the Gods. They said to themselves : The Gods have Imaginations and they imprint these Imaginations in the physical human being.—That was the very first conception of what man is on the Earth, as a being sent by the Gods.

Then came the second post-Atlantean epoch, the ancient Persian. The instinctive feeling for physiognomy was no longer as strong as it had been in earlier times. Now men no longer looked upwards to Imaginations of the Gods but to THOUGHTS of the Gods. Formerly it had been assumed that an actual picture of man exists in certain divine Beings before a man comes down to the Earth. Afterwards, the conception was that Thoughts, Thoughts which together formed the Logos—the expression subsequently used—were the basis of the individual human being.

In this second post-Atlantean epoch—strange though it seems, it was so—great importance was attached to whether a human being was born during fine weather, whether he was born by night or by day, during the winter or the summer. There was nothing resembling intellectual reasoning but men had the feeling: whatever heavenly constellation is approved by the Gods, whether fine weather or blizzard, whether day or night, when they send a human being down to the Earth, this constellation gives expression to their Thoughts, to their divine Thoughts. And if a child was born perhaps during a storm or during some other unusual weather conditions, that was regarded by the laity as the expression of the divine Thought allocated to the child.

This was so among the laity. Among the priesthood, which in turn was dependent on the Mysteries, and kept the official register, so to speak, of the births—but this is not to be understood in the modern bureaucratic sense—these aspects of weather, time of day, season of the year and so forth, indicated under what conditions the divine Thought was allocated to a human being. This was in the second post-Atlantean epoch, the ancient Persian epoch.

Very little of this has persisted into our own time. Nowadays something extremely boring is suggested if it is said that a person talks about the weather. It is considered derogatory to say of anyone nowadays that he is a bore, he can talk of nothing but the weather.—In the days of ancient Persia such a remark would not have been understood ; it was someone who had nothing interesting to say about the weather who would have been regarded as exceedingly boring! And in point of fact it is true that we have lifted ourselves right out of the natural environment if no connection can be felt between human life and meteorological phenomena. In the ancient Persian epoch an intense feeling of participation in the cosmic environment expressed itself in the fact that men thought of events—and the birth of a human being was an important event—in connection with what was taking place in the Universe.

It would be a definite advance if men—they need not merely talk about the weather being good or bad, for that is very abstract—if men were again to reach the stage of not forgetting, when they are relating some incident, to say what kind of weather was experienced, what natural phenomena were connected with it.

It is extremely interesting when, here or there, striking phenomena are still mentioned, as, for instance was the case in connection with the death of Kaspar Hauser. Because it was a striking phenomenon, mention is made of the fact that the sun was setting on the one side while the moon was rising on the other, and so forth.

And so we can come to understand human nature as it was in the second post-Atlantean epoch.

In the third post-Atlantean epoch this instinct in men had very largely already died out—the instinct for perceiving the spiritual, for perceiving divine Thoughts in the phenomena of weather—and then men began gradually to calculate, to compute. Calculation of stellar constellations replaced the intuitive grasp of the divine Thoughts of man in the natural order; and when a child was born into the world they calculated the positions of the stars, of the fixed stars and the planets. It was essentially in the third, the Egypto-Chaldean epoch that the greatest importance was attached to the capacity to reckon from the stellar constellations the conditions under which a human being had passed from the pre-earthly into the earthly life.

So there was still consciousness of the fact that man's earthly life was determined by conditions of the extra-terrestrial environment. But now it was necessarily a matter of calculation; the time had come when the connection of the human being with the divine-spiritual Beings was no longer directly perceptible.

You need only consider how the whole mental process is really external when it is a matter of calculation. Most certainly I am not going to speak in support of the laziness of youth or of the later indifference to arithmetic shown by grown men. But it is a very different matter to give precedence to external modes of thinking which have very little to do with the whole being of man, and are simply arithmetical methods. These methods of calculation were introduced in all domains of life during the third post-Atlantean epoch. But, after all, the calculations were concerned with super-earthly conditions in which Man was at least reckoned to have his rightful abode. Whatever was calculated had been permeated through and through with feeling. But calculations today are sometimes thought out, sometimes not even thought out but arrived at simply by the application of method; calculation today is often unconcerned with content, being simply a matter of method. And the absence of content that is sometimes obvious in mathematics because method alone has been followed, is really appalling—I do not say this out of ill-will—but it is terrible. In the Egypto-Chaldean epoch there was still something thoroughly human in calculations.

Then came the Graeco-Latin epoch. This was the first postAtlantean civilization-epoch in which man felt that he was living entirely on the Earth, that he was completely united with the Earth-forces. His connection with the phenomena of weather had already become a matter of mythology. The spiritual reality with which he had still felt vitally linked in the second post-Atlantean epoch, that of ancient Persia, had become the world of the Gods. Men no longer stressed the significance of climbing Olympus and plunging their heads in the mist veiling the summit; they now left it to the Gods, to Zeus, to Apollo, to plunge their heads in this Olympic cloud. Anyone who follows the myths belonging to this Graeco-Latin culture-epoch will even now have the impression that at one time men felt a relationship with the clouds and with phenomena of the heavens, but that later on they transferred this relationship to their Gods. Now it was Zeus who lived with the clouds, or Hera who created havoc among them. In earlier times man was involved with his own soul in all this. The Greek exiled Zeus—this cannot be stated in drastic terms but it does indicate how things were—the Greek had exiled Zeus to the region of the clouds, to the region of light.

The man of the ancient Persian epoch felt that together with his soul he still lived in that region. He could not have said, ‘Zeus lives in the clouds or in the light’—but because he felt his soul to be at home in the realm of the clouds, in the realm of the air, he would have said: ‘Zeus lives in me.’ The Greek was the first man in the post-Atlantean epoch who felt himself to be wholly a citizen of the Earth, and this attitude too developed only slowly and by degrees. Hence it was in the Graeco-Latin epoch that the feeling of connection with pre-earthly existence first died away. In all the three earlier post-Atlantean civilization-epochs men were keenly aware of their connection with the pre-earthly existence. No-one could have confronted them with a dogma denying pre-existence. In any case such dogmas can be formulated only if there is some prospect of their being accepted. One must be sensible enough to lay down as a dogma only that for which a number of people are prepared through evolution. The Greeks, however, had lost all awareness of pre-earthly existence and they felt themselves to be entirely men of the Earth—so much so that although they felt themselves to be still permeated by the divine-spiritual, yet they were thoroughly at one with all that belongs exclusively to the Earth.

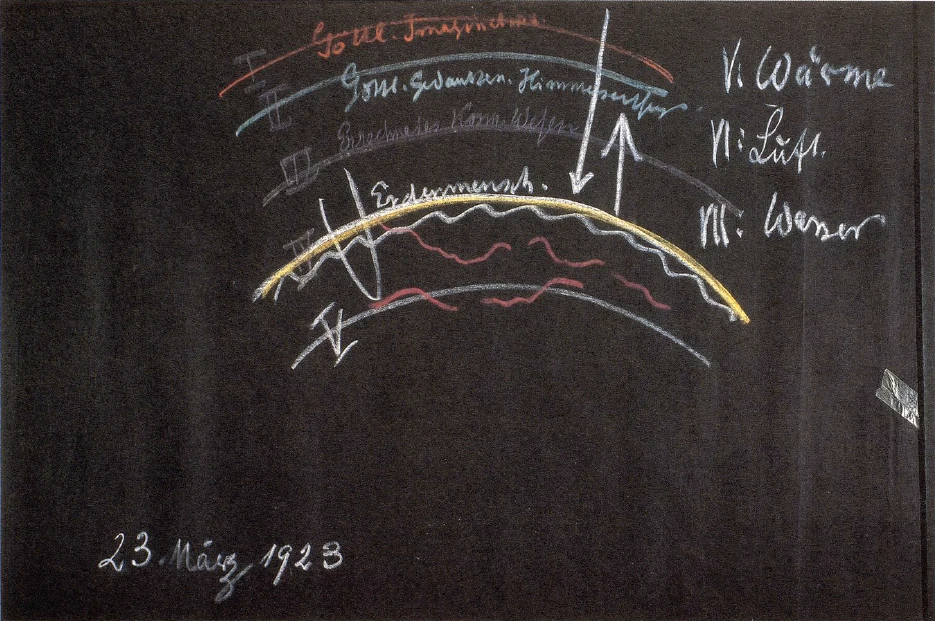

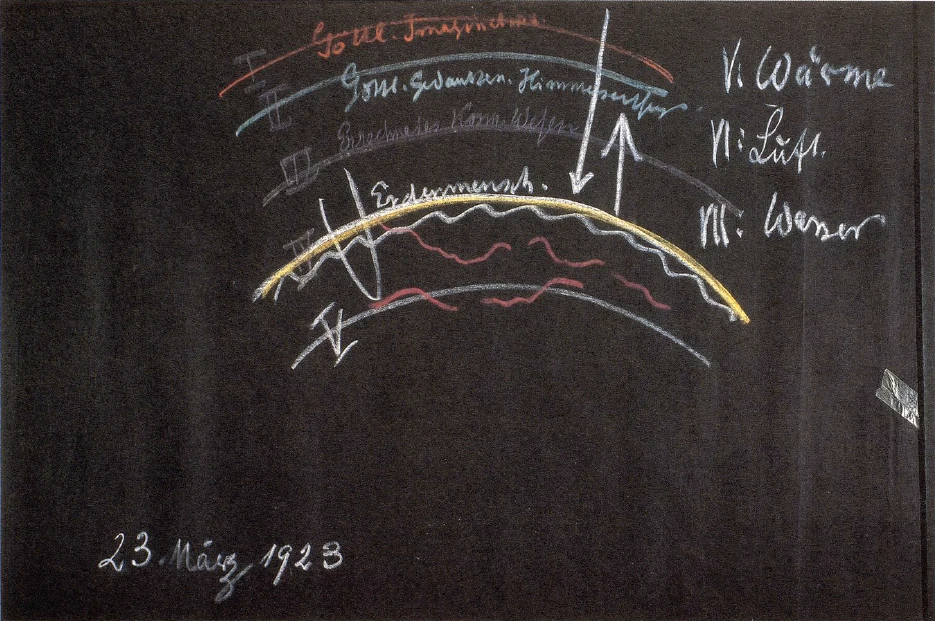

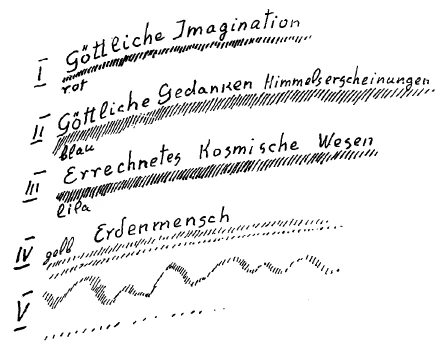

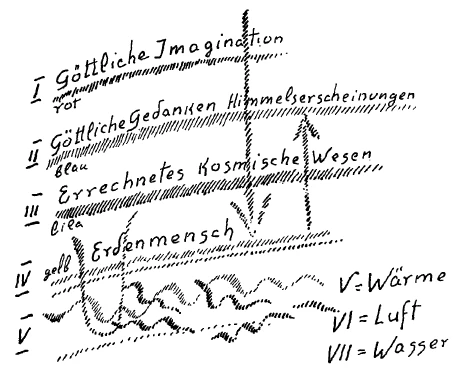

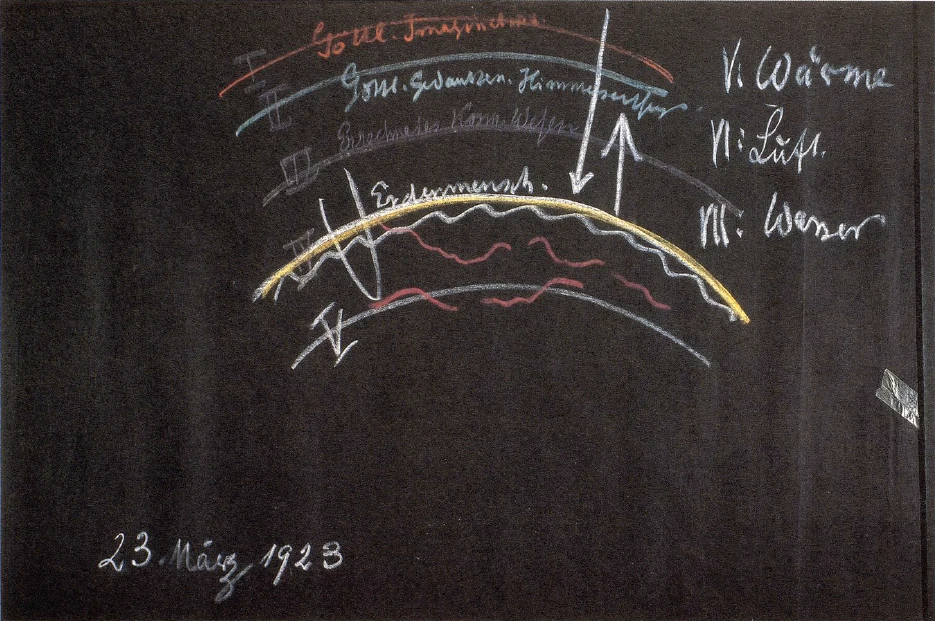

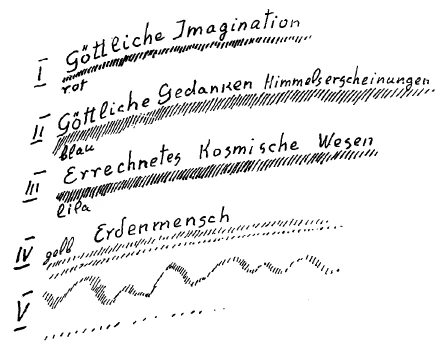

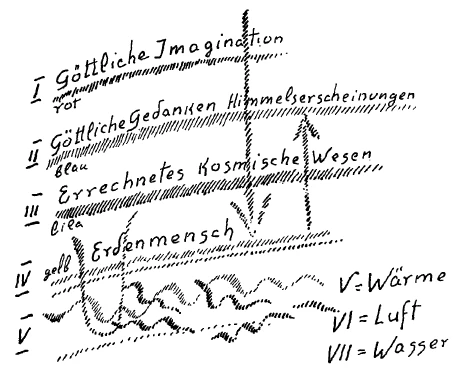

One must have a feeling for the reason why such mythology could be evolved for the first time in the Greek period, after the connection of man's own soul with super-earthly phenomena had been lost. In the first post-Atlantean epoch man felt himself to be the product of divine Imagination which he conceived as being present in the sphere of soul and spirit (diagram). Later he felt himself to be the product of divine Thoughts manifesting in the phenomena of the heavens, in wind and weather, and so forth. Then he gradually lost the consciousness which once led him into the cosmic expanse but had narrowed more and more into the confines of the Earth. Then came the Egypto-Chaldean epoch, when through calculation man was recognized as a cosmic being. And then came the fourth epoch, the Graeco-Latin epoch, when man became wholly a citizen of the Earth.

If we look back once again into the third post-Atlantean epoch, we come to a time when, although men calculated the conditions of their heavenly existence, at the same time they still had very strong feelings about where they were born on Earth. This is a particularly interesting fact. Except for calculation, men had forgotten their heavenly existence and in any case the calculation had first to be made. It was the age of astrological calculations. But a man who perhaps had no data at all for the time of his birth, nevertheless felt the effects of calculation. One who was born in the far south felt in what he could experience there, the effects of the calculation; he attached more importance to this than to the calculation itself. The calculation was different for one who was born in the north. The astrologers of course could work out the calculation itself but the man felt the effects of it. And how did he feel these effects?

He felt them because the whole natural tendency of his soul and Body was bound up with the place of his birth and its geographical and climatic characteristics ; for in this third postAtlantean culture-epoch man felt himself to be primarily a creature of breath. His breathing in the south was not the same as it was in the north. He was a being of breath. Of course, outer civilization was not advanced enough to enable such feelings to be expressed ; but what was living in the human soul was a product of the breathing-process; and the breathing process in turn was a product of the place on Earth where a man was born, where he lived.

This was no longer so among the Greeks. In the Greek age it was not the breathing-process or the connection with the locality on Earth that was the determining factor. In the Greek age it was the tie of blood, the tribal feeling and sentiment that gave rise to the group-soul consciousness. In the third postAtlantean epoch, group-souls were felt to be connected with the earthly locality. In that epoch men pictured to themselves wherever there is a holy place, the God who represents the group soul is within it; the God was attached to the locality. This ceased during the Greek period. Then, together with the Earth-consciousness, with the attitude of soul bound to the Earth through man's feelings, sentient experiences and instincts, there began the feeling for kinship in the blood. Man had been brought right down to the Earth. His consciousness no longer led him to Look beyond the Earth; he felt that he belonged to his tribe, to his race, through his blood.

And what is our own position in this fifth post-Atlantean epoch? This is almost obvious from the diagram I have sketched in accordance with the facts. Yes, we have crept into the Earth. We have been deprived of the super-earthly forces; we no longer live and should no longer live, with the purely earthly forces which are astir in the blood; we have become dependent upon subterranean forces, sub-earthly forces.

That there are indeed such forces you may learn from what is done with potatoes. You know, of course, that in the winter the peasants bury their potatoes in trenches; then they keep alive, otherwise they would perish. Conditions under the Earth are different; there the summer warmth is maintained during the winter.

Now the life of plants in general can only be understood when we know that up to the flower the plant is a product of the previous year. It grows out of the Earth-forces; it is only the flower that needs the actual sunlight.

What, then, does it signify for us as human beings that we become dependent upon sub-earthly forces? It is not the same for us as for potatoes. We are not laid in trenches in order that we may thrive during the winter. Our dependence upon sub-earthly forces signifies something quite different, namely, that the Earth takes away from us the influence of the super-earthly. We are deprived of this influence by the Earth. In his consciousness, man was first a divine Imagination, then a divine Thought, then the result of calculation, then Earth-man. The Greek felt himself to be a man belonging altogether to the Earth, living in the blood. We, therefore, must learn to feel ourselves independent of the super-earthly ; but independent, too, of what lies in our blood.

This has come about because we no longer live through the period between our twenty-first and twenty-eighth years in the same way as men did in earlier times; we no longer have the second experience described yesterday, we no longer have living thoughts as the result of consciousness influenced by the super-earthly, but we have thoughts which have no inner vitality at all and are therefore dead. It is the Earth itself, with its inner forces, which kills our thoughts when we become Earth-men.

And a remarkable vista ensues: as Earth-men we bury what is left of man in the physical sphere; we give over the corpse to the Earth-elements. The Earth is also active in the process of cremation; decay is only a slow process of burning. As to our thoughts—and this is the striking characteristic of the Fifth post-Atlantean period—when we are born, when we are sent down to the Earth, the Gods give over our thoughts to the Earth. Our thoughts are buried, actually buried, when we become men of Earth. This has been so since the beginning of the Fifth post-Atlantean epoch. To be possessed of intellect means to have a soul with thoughts from which the heavenly impulses have been taken away by the Earth-forces.

The characteristic of our manhood today is that in our inmost soul, precisely through our thinking, we have united with the Earth. On the other hand, as a result of this, it is only now, in the Fifth post-Atlantean culture-epoch that it is possible for us to send back to the Cosmos the thoughts which we imbue with life through our earthly deeds in the way described at the end of yesterday's lecture.

Evolutionary impulses of this nature lie at the very roots of the significant products of human culture. And our feelings cannot but be profoundly stirred by the fact that at the time when European humanity was approaching this Fifth postAtlantean epoch, poetic works such as Wolfram von Eschenbach's ‘Parsifal’ appeared. We have often studied this work as such but today we will direct our eyes of soul to something that is to be found there as a majestic sign of the times. Think of the remarkable characteristic that now becomes evident, not only in Wolfram, but wherever the poetic gift comes to expression in men of that period.

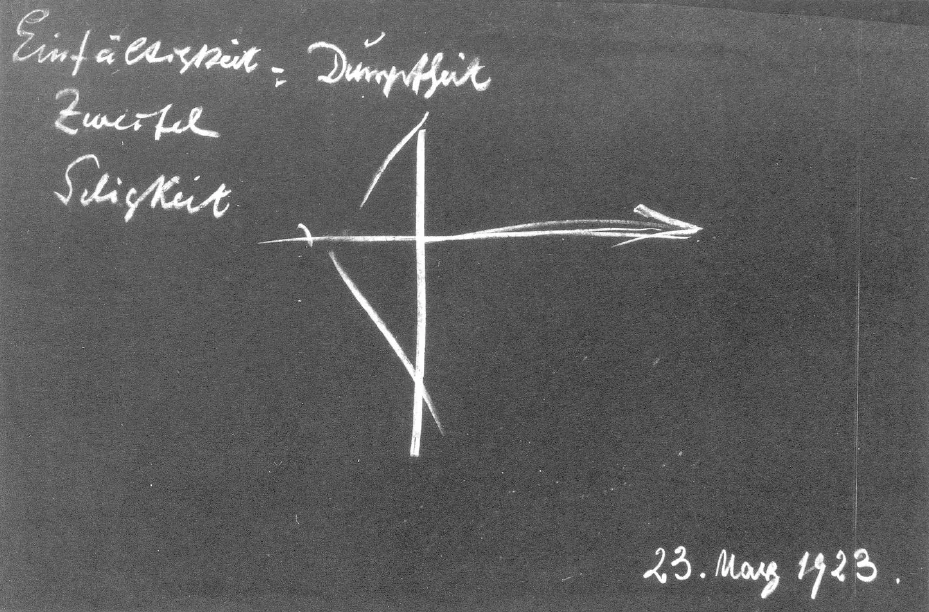

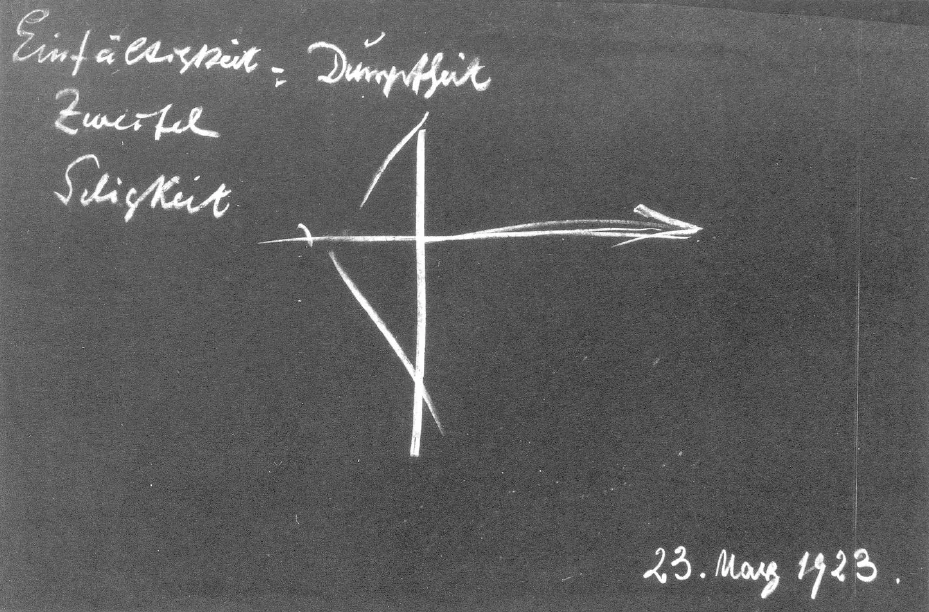

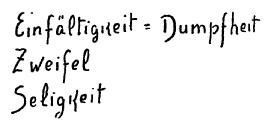

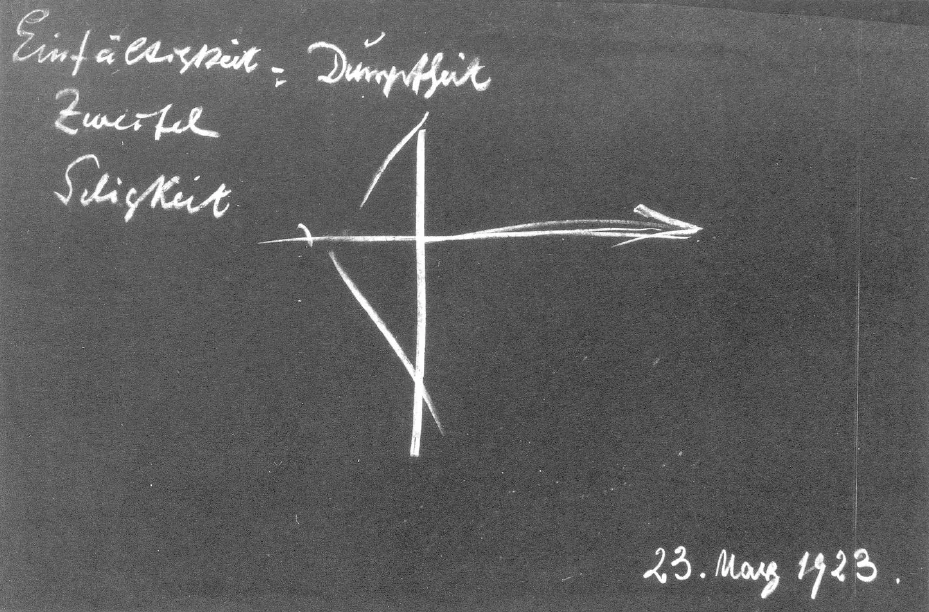

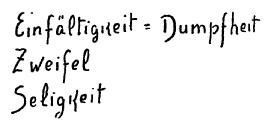

A certain uneasiness is perceptible concerning three stages in the evolution of the human soul. The first trait to be observed in a human being when he comes into this world, when he submits himself to this life and is living in a naive connection with the world—the first trait to be observed is simplicity, dullness.

The second, however, is doubt. And precisely at the time of the approaching Fifth post-Atlantean epoch, doubt is graphically described. If doubt is close to the heart, a man's life (or soul) must have a hard time1With a slight variation Dr Steiner was quoting the opening couplet of Wolfram von Eschenbach's ‘Parsifal’. In the original the lines are as follows:

Ist zwîfel herzen nâchgebûr.—such was the feeling prevailing in those days. But there was also the feeling: man must wrestle his way through doubt to blessedness. And blessedness was the word used for the condition created when man has brought divine life again into thoughts that have become ungodly, into dead thoughts that have become completely earthly. Man's submergence in the earthly realm—this was felt to be the cause of the condition of doubt; and blessedness was felt to be a break from earthly things through the vitalizing of thoughts.

SIMPLICITY—DULLNESS

DOUBT

BLESSEDNESS

This was the gist of the mood prevailing in the poetic works of the 12th, 13th and 14th centuries, when man was struggling onwards to the Fifth post-Atlantean epoch. The dawn of this epoch was felt more intensely at the time than it is today, when men are weary of thinking about these things, when they have become mentally too lazy. But they will have to begin again to think deeply about such matters and to set their feelings astir, otherwise the ascent of mankind would not be possible. And what does that really mean? The Earth acts as a mirror for man; he is not intended to reach a sub-earthly level. But his lifeless thoughts penetrate into the Earth and apprehend death, which pertains to the Earth-element only. However, the nature of man himself is such that when he imbues his thoughts with life he sends them out into the Cosmos as mirror-pictures. And so all the living thoughts that arise in man are seen by the Gods glittering back from evolving humanity. When man is urged to make his thoughts come alive he is being called upon to be a co-creator in the Universe. For these thoughts are reflected by the Earth and stream out again into the Universe, must make their way again out into the Universe.

Hence when we grasp the meaning of the evolution of mankind and the world, we feel that in a way we are led back again to the epochs that have already been lived through. In the Egypto-Chaldean epoch, man's status an Earth was arrived at by means of calculation; but for all that he was always brought by this means into connection with the surrounding world of stars. Today we proceed historically, starting from man; man becomes the starting-point for a study which you will find presented in the book, Occult Science: an Outline, where we have actually sent out living human thoughts and noted what they have become when we follow them in the cosmic environment as they speed away from us, when we learn to live with these living thoughts in the cosmic expanse.

These processes indicate the deep significance of the fact that man has come to the stage of having dead thoughts, that he is, so to speak, in danger of uniting completely with the Earth.

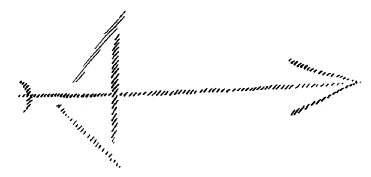

Let us follow the picture further. Genuine Imaginations make this possible. It is only deliberately thought-out Imaginations that lead us no further. Think for a moment of a mirror. We say that it throws the light back. The expression is not quite accurate, but in any case the light must not get behind the mirror. There is only one way in which this could happen and that would be if the mirror were broken. And indeed, if man does not vitalize his thoughts, if he persists in harbouring merely intellectualistic thoughts, dead thoughts, he must destroy the Earth.

Admittedly, the destruction begins with the most highly rarefied element: warmth. And in the Fifth post-Atlantean epoch man has no opportunity of ruining anything other than the warmth-atmosphere of the Earth through the ever-increasing development of purely intellectualistic thoughts. But then comes the Sixth post-Atlantean epoch. If by that time man has not been converted from intellectualism to Imagination, destruction would begin, not only of the warmth-atmosphere but also of the air-atmosphere, and if their thoughts were to remain purely intellectualistic, men would poison the air, ruining, in the first place, all vegetation.

In the Seventh post-Atlantean epoch it will be possible for man to contaminate the water, and if his exudations were to be the outcome of purely intellectualistic thoughts, they would pass over into the universal fluidity of the Earth. Through this universal fluidity of the Earth, the mineral element of the Earth would, in the first place, lose cohesion. And if man did not vitalize his thoughts, thereby giving back to the Cosmos what he has received from it, he would have every opportunity of shattering the Earth.

Thus the life of soul in man is intimately connected with natural existence. Intellectualistic knowledge today is a purely Ahrimanic product, aiming at blinding humanity to these things If a man is persuaded that his thoughts are merely thoughts and have nothing to do with happenings in the Universe, he is being deluded into believing that he can have no influence upon the evolution of the Earth, and that either with or without his collaboration the Earth will at some time come to an end in some such way as foretold by physical science.

But the Earth will not come to a purely physical end; its end will come in the way brought about by mankind itself.

Here again is one of the points where we are shown how Anthroposophy connects the moral world of soul with the physical world of the senses, whereas today no such connection exists and modern theology even considers it preferable to regard the moral sphere as being entirely independent of the physical. And philosophers today who drag themselves about, panting and puffing, with backs bent under the burden of the findings of science, are happy when they can say : Yes, for the world of nature there is science; but philosophy must extend to the Categorical Imperative, to that about which man can know nothing.

These things today are often confined to the schools and universities. But they will take effect in life itself if mankind does not become conscious of how soul-and-spirit is creative in the physical-material realm and of how the future of the physical material realm will depend upon what man resolves to develop in the realm of soul-and-spirit. With these basic principles we can become conscious on the one side of the infinite importance of the soul-life of mankind, and on the other side of the fact that man is not merely a creature wandering fortuitously over the Earth, but that he belongs to the whole Universe.

But, my dear friends, right Imaginations give rise to what is right. If man does not vitalize his thoughts, but is more and more apt to allow them to die, then his thoughts will creep into the Earth and, in the end, he will become an earthworm in the Universe, because his thoughts seek out the habitations of the earthworms. That too is a valid Imagination.

Human civilization should avoid the possibility of man becoming an earthworm, for should that happen the Earth will be shattered and the cosmic goal that is quite clearly within the scope of human capacities, will not be reached. There are things which we should not merely take into our theories, into our abstract speculations, but deeply into our hearts, for Anthroposophy is a concern of the heart. And the more clearly it is grasped as a concern of the heart, the better it is understood.

Siebenter Vortrag

Als das Wesentliche unserer Gegenwart innerhalb der Menschheitsentwickelung hat sich uns ergeben der Besitz des Erdenmenschen an abstrakten Gedanken, das heißt für uns toten Gedanken, an Gedanken, die in uns so ihr Dasein führen, daß sie eigentlich die Überbleibsel sind des lebendigen Wesens der Seele im vorirdischen Dasein.

Mit dieser Entwickelungsstufe der Menschheit zu abstrakten, das heißt toten Gedanken hin, ist verknüpft — wie ich des öfteren auseinandergesetzt habe — das Erringen des Freiheitsbewußtseins innerhalb der Menschheitsentwickelung. Wollen wir heute einmal gerade auf diese Seite der Sache ein besonderes Augenmerk wenden. Wir können das, indem wir den ganzen Hergang der Menschheitsentwickelung in der nachatlantischen Zeit ein wenig betrachten.

Sie wissen, daß nach der großen atlantischen Katastrophe sich nach und nach die Gliederung der Erdenkontinente ergeben hat, wie wir sie heute kennen, und daß sich auf dieser Verteilung des festen Landes auf der Erde oder innerhalb der Verteilung des festen Landes auf der Erde nach und nach fünf aufeinanderfolgende Kultur- oder Zivilisationsperioden entwickelt haben, die ich in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß» die urindische, die urpersische, die ägyptisch-chaldäische, die griechisch-lateinische und unsere gegenwärtige fünfte Zivilisationsepoche genannt habe.

Diese fünf Zivilisationsepochen unterscheiden sich ja dadurch, daß der Mensch als Gesamtwesen in jeder von ihnen in einer andern Verfassung ist. Wenn wir auf die älteren Zivilisationsepochen zurückgehen, so drückt sich diese Verfassung auch im ganzen Äußeren des Menschen aus, in den, ich möchte sagen, körperlichen Offenbarungen des Menschen. Und je mehr wir in die spätere Zeit, also näher unserer Zivilisationsepoche kommen, um so mehr drückt sich das, was wir den Fortschritt der Menschheit nennen können, in der Seelenverfassung aus. Wir haben ja das, was hierauf bezüglich ist, öfter geschildert. Ich will es heute von einem bisher weniger berücksichtigten Gesichtspunkte aus schildern.

Wenn wir in die erste, urindische Zivilisationsepoche zurückgehen, die sich, ich möchte sagen, noch halb aus der atlantischen Katastrophe heraus ergeben hat, so finden wir, daß der Mensch sich in dieser Zeit viel mehr als ein Bürger des außerirdischen Kosmos fühlt, denn als ein Erdenbürger. Und wenn wir auf Einzelheiten des damaligen Lebens eingehen, das ja, wie ich Ihnen schon öfter angedeutet habe, in das 7., 8. Jahrtausend der vorchristlichen Zeit zurückführt, so müssen wir namentlich das betonen, daß nicht aus einer intellektuellen Betrachtung — die gab es ja natürlich damals nicht-, aber aus einem tief instinktiven Empfinden heraus in diesen sehr alten Zeiten der Menschheitsentwickelung ein großer Wert gelegt wurde auf das Äußere, auf das Exterieur des Menschen. Nicht als ob diese Leute der alten Zeit etwa physiognomische Studien getrieben hätten; das lag ihnen natürlich ganz ferne. So etwas gehört erst Zeitaltern an, in denen der Intellektualismus, wenn auch noch nicht vollkommen ist, doch schon heraufdämmert. Aber sie haben ein feines physiognomisches Empfinden gehabt. Sie haben tief gefühlt, diese Menschen: Wenn einer den oder jenen Gesichtsausdruck hat, so deutet das darauf hin, daß er auch diese oder jene musikalischen Eigenschaften hat. Sie gaben sehr viel darauf, die musikalische Wesenheit des Menschen aus seinem Gesichtsausdruck, aber auch aus seinen Gesten, aus seiner ganzen Menschenoffenbarung heraus, ich möchte fast sagen, zu erraten. Nach einer bestimmteren Art des Erkennens strebte man ja für das allgemein Menschliche in jener alten Zeit nicht. Gar kein Verständnis hätten die Menschen damals gehabt, wenn man ihnen gekommen wäre damit, irgend etwas solle bewiesen werden. Das hätte sie geniert, das hätte ihnen fast physisch wehe getan, ja, in älteren Zeiten wirklich physisch wehe getan. Beweisen, das ist so, wie wenn einen jemand mit Messern bearbeiten will -, so hätten diese Menschen gesagt. Warum soll man denn beweisen? Man braucht ja nichts so Sicheres über die Welt zu wissen, das man erst bewiesen haben muß.

Das hängt damit zusammen, daß diese Menschen noch das lebendigste Empfinden hatten, sie kommen alle vom vorirdischen Dasein aus der geistigen Welt heraus. In der geistigen Welt, wenn man drinnen ist, beweist man nicht. Da weiß man: Das Beweisen ist eine Angelegenheit, die auf Erden ja ihren guten Sinn hat, aber in der Welt des Geistigen beweist man nicht. Da würde es einem so vorkommen, wenn man beweisen wollte, als ob man, sagen wir, ein bestimmtes Maß hätte: ein Mensch darf so oder so lang sein —, und man macht es dann so, wie nach der Prokrustes-Sage: Demjenigen, der zu lang ist, schneidet man etwas ab, und denjenigen, der zu kurz ist, den dehnt man etwas aus. So etwa würde im ganzen Zusammenhang der geistigen Welt das Beweisen sein. Da sind die Dinge nicht so, daß sie sich schnitzeln lassen in Beweise hinein. Da sind die Dinge innerlich beweglich, innerlich flüssig.

Und einem Inder der urindischen Zeit mit seinem starken Bewußtsein: Ich bin herabgestiegen aus der geistigen Welt, ich habe dieses äußere menschliche Wesen nur um mich herumgelegt —, einem solchen Inder würde es ganz kurios vorgekommen sein, wenn man an ihn irgendwie die Zumutung gestellt hätte, etwas solle bewiesen werden. Diese Leute haben: vielmehr das, was wir heute «Erraten» nennen, geliebt. Sie haben es deshalb geliebt, weil sie auf dasjenige aufmerksam sein wollten, was sich in ihrer Umgebung zeigte. Und in dieser Tätigkeit des Erratens haben sie eine gewisse innere Befriedigung gefunden.

Und ebenso haben sie einen gewissen Instinkt gehabt, aus diesem oder jenem Gesicht auf einen klugen Menschen, aus einem andern Gesicht auf einen törichten Menschen zu schließen, aus einer Statur zu raten auf, sagen wir, Phlegma und dergleichen. Das Erraten war dasjenige, was man dazumal hatte an Stelle dessen, was wir heute beweisendes Erkennen nennen. Und im menschlichen Verkehr lief das ganze gegenseitige Verhalten darauf hinaus, aus dem Seelischen, aus der Geste, aus der Statur des Menschen, aus der Art und Weise wie er ging, darauf zu schließen, was er eigentlich für eine moralische Qualität hatte.

In der ersten Epoche des urindischen Wesens gab es ja das nicht, was später Kasteneinteilung war. Da gab es im Zusammenhange mit dem urindischen Mysterienwesen durchaus sogar eine Art sozialer Gliederung der Menschen nach den Physiognomien, nach den Gesten. Diese Dinge waren in älteren Zeiten der Menschheitsentwickelung eben möglich, denn die Menschen hatten auch einen gewissen Instinkt, solchen Gliederungen zu folgen. Das, was später innerhalb der indischen Zivilisation sich als Kastenbildung ergeben hat, das war, ich möchte sagen, schon eine Art schematischer Einteilung einer viel individuelleren Gliederung, die man ursprünglich nach der instinktiv gefühlten Physiognomie hatte. Und die Menschen fühlten sich in jenen alten Zeiten nicht verletzt, wenn sie — wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf — nach ihrem Gesichte da oder dort hingestellt wurden, denn sie fühlten sich eben durchaus als gottgegebene Erdenwesen. Und die Autorität, die denen zukam, die aus den Mysterien heraus solch eine Gliederung besorgten, diese Autorität war eine ungeheure.

Erst in den späteren nachatlantischen Zivilisationsepochen hat sich allmählich dann das Kastenwesen herausgebildet aus Voraussetzungen, die ich in andern Vorträgen auch schon angegeben habe. Man hatte eben in jener älteren Zeit, in jener urindischen Epoche, ein starkes Gefühl davon, daß der Mensch zugrunde liegend hat eine göttliche Imagination.

Ich habe Ihnen viel erzählt von dem, wie es ursprünglich eine Art instinktiven Hellsehens, traumhaften Hellsehens gegeben hat. Aber wenn wir in ganz alte Zeiten der nachatlantischen Periode zurückgehen, dann sagten die Menschen nicht nur, sie sehen traumhafte Imaginationen, sondern sie sagten: In der besonderen Konfiguration, die der physische Leib des Menschen hat, wenn der Mensch das Erdendasein betritt, lebt eine göttliche Imagination. Dem Menschen, der auf die Erde herabsteigt, wird eine göttliche Imagination zugrunde gelegt. Danach bildete er dann von der Kindheit auf seine Physiognomie, danach bildete er überhaupt den ganzen physischen Ausdruck seines Menschen.

Also man sah nicht nur instinktiv, wie ich es eben angedeutet habe, auf das Physiognomische hin, sondern man sah in dem Physiognomischen die Imagination der Götter. Man sagte sich: Die Götter haben Imaginationen, und diese Imaginationen prägen sie aus in dem physischen Menschenwesen. — Das war die allererste Anschauung über das, was der Mensch als gottgesandtes Wesen auf der Erde ist.

Dann kam die zweite nachatlantische Kulturperiode, die urpersische. Da hatte man nicht mehr jenes instinktive Gefühl für das Physiognomische so stark wie früher. Da schaute man nicht auf Imaginationen der Götter, sondern auf Gedanken der Götter. Vorher war es eigentlich so, daß man vorausgesetzt hat: In irgendwelchen göttlichen Wesenheiten lebt, bevor ein Mensch auf die Erde herabsteigt, ein wirkliches Menschenbild. Nachher war die Vorstellung, daß eben Gedanken, Gedanken, die dann zusammen den Logos bildeten — wie man es später nannte —, dem einzelnen Menschenwesen zugrunde liegen.

Man hat großen Wert darauf gelegt in dieser zweiten nachatlantischen Periode, ob der Mensch geboren wurde — so paradox uns das heute erscheint, es ist so — bei freundlichem Wetter, ob der Mensch etwa geboren wurde bei Nacht oder bei Tag, zur Winterszeit oder zur Sommerszeit. Intellektuelles gab es nicht, aber man hatte die Empfindung: Was die Götter für eine Himmelskonstellation sein lassen, ob schönes Wetter oder Schneegestöber, ob Tag oder Nacht, wenn sie einen Menschen auf die Erde herunterschicken, das drückt ihre Gedanken aus, das drückt diese göttlichen Gedanken aus. Und wenn etwa gerade zur Gewitterszeit oder sonst irgendwie bei merkwürdigen Wetterkonstellationen ein Kind geboren wurde, so betrachtete man das im laienhaften Leben als den Ausdruck für diese oder jene dem Kinde gegebenen göttlichen Gedanken.

Wenn das im Laienhaften der Fall war, so war es auf der andern Seite da, wo die Priesterschaft, die wiederum abhängig war von den Mysterien, sozusagen Protokoll führte über die Geburten — aber das ist nicht im bürokratischen Sinne von heute zu verstehen —, durchaus so, daß man aus diesen Konstellationen von Wetter, Tageszeit, Jahreszeit und so weiter darauf sah, wie dem Menschen seine göttliche Gedankengabe mitgegeben war. Das war in der zweiten nachatlantischen Periode, in der urpersischen Periode.

Solche Dinge haben sich in unsere Zeit herein sehr wenig erhalten. In unserer Zeit gilt es als etwas außerordentlich Langweiliges, wenn man von jemandem sagen muß: Der redet vom Wetter. — Denken Sie nur, das gilt als etwas Abträgliches, wenn man von jemandem heute sagt: Der ist ein langweiliger Mensch, da er von nichts anderem zu reden weiß als vom Wetter. — Das hätten die Leute in der urpersischen Zeit nicht verstanden, sie hätten den Menschen ungemein langweilig gefunden, der nichts Interessantes über das Wetter zu sagen wußte. Denn in der Tat, es heißt schon, sich ganz herausgehoben haben aus der natürlichen Umgebung, wenn man nicht mehr etwas richtig Menschliches empfindet gegenüber den Wettererscheinungen. Es war ein intensives Miterleben der kosmischen Umgebung, das sich darinnen ausdrückte, daß man überhaupt Ereignisse — und die Geburt eines Menschen war eben ein wichtigstes Ereignis — in Zusammenhang dachte mit dem, was nun vorgeht in der Welt.

Es würde durchaus ein Fortschritt sein, wenn die Menschen - sie brauchen ja nicht bloß zu der Redensart zu kommen: es ist gutes und schlechtes Wetter, das ist sehr abstrakt -, wenn die Menschen wiederum dazu kommen würden, indem sie das oder jenes sich erzählen, nicht zu vergessen, was bei diesem oder jenem Ereignis, das erlebt worden ist, für Wetter war, für Erscheinungen überhaupt in der Natur waren.

Es ist dies außerordentlich interessant, wenn bei auffälligen Erscheinungen dies noch da oder dort erwähnt wird, wie das zum Beispiel für den Tod des Kaspar Hauser erwähnt wird, weil es eine auffällige Erscheinung war, daß auf der einen Seite die Sonne unterging, während auf der andern Seite der Mond aufging, und so weiter.

So können wir uns also hineinfühlen in menschliches Wesen dieser zweiten nachatlantischen Periode.

In der dritten nachatlantischen Periode, da war für die Menschen zum großen Teil dieser Instinkt schon verflogen, Geistiges zu sehen, göttliche Gedanken zu sehen im Wetter, und da fing man allmählich an zu rechnen. Da kam dann auf anstelle des intuitiven Erfassens der göttlichen Menschengedanken in der Naturkonfiguration das Errechnen der Sternkonstellationen, und man berechnete eben für einen Menschen, wenn er in die Welt kam, die Sterne, die Fixstern-Planetenkonstellation. Das war im wesentlichen dann die dritte, die chaldäisch-ägyptische Periode, in der man den allergrößten Wert darauf legte, nun aus den Sternkonstellationen errechnen zu können, wie der Mensch aus dem vorirdischen Leben in das irdische Leben hereingetreten war.

Da also war immerhin noch ein Bewußtsein vorhanden, daß des Menschen Erdenleben aus der außerirdischen Umgebung gegeben ist. Nur, wenn es ans Rechnen kommt, dann kommt auch schon die Zeit, wo wir die Verbundenheit des menschlichen Wesens mit den göttlich-geistigen Wesenheiten nicht mehr so recht haben.

Sie brauchen nur zu berücksichtigen, wie der ganze Geistesvorgang des Menschen eigentlich äußerlich ist, wenn es ans Rechnen kommt. Ich will ganz gewiß nicht der jugendlichen Faulenzerei oder meinetwillen auch der späteren Unaufmerksamkeit der Menschen mit Bezug auf das Rechnen das Wort reden. Das soll nicht geschehen. Aber es ist natürlich ein großer Unterschied, wenn man jene äußerlichen Denkmethoden in den Vordergrund stellt, die eigentlich mit dem ganzen Menschen wenig mehr zu tun haben, und die rechnerische Methoden sind. Diese rechnerischen Methoden wurden überhaupt in alles Leben hineingeführt in dieser dritten nachatlantischen Periode. Aber immerhin errechnete man dasjenige, was außerirdisch war, und man stellte den Menschen wenigstens durch die Rechnung ins Außerirdische hinein. So abstrakt wie wir haben die Ägypter und Chaldäer nicht gerechnet; was man errechnete, war durchaus Durchgefühltes. Heute ist alles Errechnete manchmal durchgedacht, manchmal nicht einmal durchgedacht, sondern durchmethodisiert. Man rechnet ja heute oftmals nicht mehr mit Inhalten, sondern nur mit Methoden. Und was in der Mathematik zuweilen geleistet wird an Abgelegenheit des Inhaltes, der nur auf methodenhafte Weise erreicht wird, das ist heute im Grunde genommen, ich meine es nicht schlimm, aber es ist fürchterlich. Es war durchaus in dieser chaldäisch-ägyptischen Periode im Errechnen noch etwas Menschliches drinnen.

Dann kam die griechisch-lateinische Zeit. Das war die erste nachatlantische Zivilisationsepoche, in welcher der Mensch eigentlich das Gefühl hatte, er lebt ganz auf der Erde, er ist ganz verbunden mit den Erdenkräften. Der Zusammenhang des Menschen mit den Wettererscheinungen hatte sich bereits zurückgezogen in das Erzählen der Mythen. Dasjenige, womit sich der Mensch in der zweiten nachatlantischen Zeit, in der urpersischen Kulturepoche, noch lebendig verbunden gefühlt hat, das hatte sich zurückgezogen als die Götterwelt. Der Mensch selbst hielt nicht mehr darauf, ob es etwas bedeutete, wenn er den Olymp bestieg und seinen Kopf in der Höhe in den Nebel hineinsteckte; den Kopf in diese olympische Wolke hineinstecken ließ er jetzt seine Götter, den Zeus, den Apollo. Wer die Mythen verfolgt in dieser griechisch-lateinischen Kulturperiode, wird noch ein Nachgefühl davon haben, daß die Menschheit sich einstmals verbunden fühlte mit den Wolken und Himmelserscheinungen, daß aber die Menschen das abgeschoben haben an die Götter. Zeus ist es jetzt, der mit den Wolken sich bewegt, oder Hera ist es, die da mit den Wolken herumwirtschaftet. Das hat der Mensch mit seiner eigenen Seele früher getan. Der Grieche hatte den Zeus — man kann ja so was nicht sagen, aber es gibt doch den Tatbestand wieder -, der Grieche hatte den Zeus in die Wolkenregion, in die Lichtregion hinein verbannt.

Der urpersische Mensch fühlte sich mit seiner eigenen Seele noch dadrinnen. Der hätte nicht sagen können: Der Zeus lebt in den Wolken oder im Lichte -, sondern er hätte gesagt: Der Zeus lebt in mir -, weil er seine Seele im Bereiche der Wolken, im Bereiche der Lüfte fühlte. Der Grieche war der erste Mensch in der nachatlantischen Zeit, der sich ganz — und es kam das auch erst langsam und allmählich heran - als Erdenmensch fühlte: Daher ging in der griechisch-lateinischen Zeit auch zuerst zugrunde das Sich-Zusammenfühlen mit dem vorirdischen Dasein. In allen drei älteren nachatlantischen Zivilisationsepochen haben die Menschen stark ihren Zusammenhang mit dem vorirdischen Dasein gefühlt. Da hätte man ihnen kein Dogma machen dürfen darüber, daß es keine Präexistenz gibt. Man kann auch solche Dogmen nur machen, wenn man Aussicht darauf hat, daß die Menschen sie annehmen. Man muß dann nur so klug sein, dasjenige gerade als Dogma aufzustellen, wofür eine Menge von Menschen durch die menschliche Entwickelung präpariert sind. Aber die Griechen haben allmählich aus dem menschlichen Fühlen und Empfinden heraus das vorirdische Dasein verloren, und sie fühlten sich ganz als Erdenmenschen. Sie fühlten sich allerdings so als Erdenmenschen, wie ich das in früheren Vorträgen beschrieben habe, daß sie sich noch durchsetzt fühlten von GöttlichGeistigem, aber doch eben durchaus in Verbindung mit alldem, was auf Erden allein lebt.

Man muß schon ein Gefühl dafür haben, wie eine solche Mythologie in der Griechenzeit durchaus sich erst entwickeln konnte, nachdem man den Zusammenhang der eigenen Seele mit den überirdischen Er 115 scheinungen verloren hatte. So daß wir sagen können: Wenn hier die Erde ist - ich zeichne schematisch -, so fühlte sich der Mensch in der ersten nachatlantischen Periode als das Ergebnis göttlicher Imagination, die er ganz im Geistig-Seelischen suchte. Dann fühlte er sich als das Ergebnis göttlicher Gedanken, die er in den Himmelserscheinungen und so weiter, in Wind und Wetter suchte. Es verlor dann der Mensch immer mehr und mehr das in die Weiten hinausgehende Bewußtsein; er engte dieses Bewußtsein immer mehr und mehr gegen die Erde herzu ein. Dann kam die Periode der ägyptisch-chaldäischen Zeit, wo wir den Menschen haben als errechnetes kosmisches Wesen. Und dann kam die vierte, die griechisch-lateinische Zeit, wo der Mensch ganz und gar Erdenmensch ist (siehe Zeichnung).

Wenn wir noch einmal in den dritten nachatlantischen Zeitraum zurückgehen, so stoßen wir auf eine Zeit, in der die Menschen auch noch stark fühlten, trotzdem sie sich ihr Himmelsdasein errechneten, wo sie auf der Erde geboren wurden. Das ist eine besonders interessante Tatsache. Das Himmelsdasein hatte man bis auf die Rechnung hin vergessen; man mußte es eben erst errechnen. Es war die Zeit der astrologischen Rechnungen. Aber irgendein Mensch, der vielleicht gar keine Rechnung hatte für sein Geburtsdatum, fühlte dennoch das Ergebnis dieser Rechnung. Einer, der ganz im Süden geboren war, fühlte in dem, wie er sich ausleben konnte im Süden, das Ergebnis der Rechnung; auf das gab er viel mehr, als auf die Rechnung selbst. Einer, der im Norden geboren war, war unter einer andern Rechnung geboren. Nun ja, die Astrologen konnten das ausrechnen, aber der Mensch fühlte das Ergebnis dieser Rechnung. Und wie fühlte er es?

Er fühlte es dadurch, daß eigentlich seine ganze menschliche Seelen- und Körperverfassung mit dem Orte seiner Geburt und den geographischen, klimatischen Eigentümlichkeiten seiner Geburt zusammenhingen, weil der Mensch in dieser dritten nachatlantischen Zivilisationsperiode sich vorzugsweise als ein Atmungsgeschöpf fühlte. Man atmet anders im Süden als im Norden. Der Mensch war ein Atmungsmensch. Natürlich war die äußere Zivilisation nicht so weit, daß man solche Dinge aussprechen konnte; aber das, was in der menschlichen Seele lebte, das war ein Ergebnis des Atmungsprozesses, und der Atmungsprozeß war ein Ergebnis des Erdenortes, auf dem man geboren war, auf dem man lebte.

Das hörte bei den Griechen auf. In der Griechenzeit ist nicht mehr der Atmungsprozeß und der Zusammenhang mit dem Irdischen das Maßgebende, sondern der Zusammenhang des Blutes, das Stammesgefühl, die Stammesempfindung ist dasjenige, was das Bewußtsein der Gruppenseelenhaftigkeit ergibt. Gruppenseelen fühlte man in der dritten nachatlantischen Zeit im Zusammenhang mit dem Erdenorte. Man stellte sich ja geradezu auch vor in dieser dritten nachatlantischen Zeit: Wenn da oder dort ein Heiligtum ist, so ist der Gott darin, der die Gruppenseele darstellt -, der war an den Ort gebunden. Das hörte auf während der Griechenzeit. Da begann mit dem Erdenbewußtsein, mit der ganzen Verfassung, die an die Erde mit allem menschlichen Fühlen und Empfinden im ganzen menschlichen Instinktleben gebunden war, dieses Gefühl für die Zusammengehörigkeit im Blute. So daß der Mensch dann ganz auf die Erde herunter versetzt war. Er sah nicht mehr mit seinem Bewußtsein über die Erde hinaus, sondern fühlte sich mit seinem Stamm, mit seinem Volk zusammengehörig im Blute. Und wie steht es mit uns in der fünften nachatlantischen Periode? Es ergibt sich fast aus dem Schematismus, den ich da ganz sachgemäß entworfen habe. Ja, wir sind in die Erde hereingekrochen. Wir sind bar geworden der außerirdischen Kräfte, wir leben auch nicht mehr und sollen nicht mehr leben mit den bloßen Erdenkräften, die im Blute vibrieren, sondern wir sind abhängig geworden von Kräften, die unter der Erde sind.

Daß sich unter der Erde auch Kräfte befinden, die eine Bedeutung haben, das können Sie von den Kartoffeln lernen. Sie wissen ja, daß die Bauern ihre Kartoffeln im Winter in Gruben hineintun; da kommen sie fort, während sie sonst verderben würden. Es ist eben unter der Erde anders. Da lebt die Sommerwärme während des Winters fort.

Es ist ja auch durchaus das Leben der Pflanzen nur dann zu verstehen, wenn man weiß, daß das Leben der Pflanze bis zur Blüte ein Ergebnis des jeweiligen vorigen Jahres ist. Es kommt aus den Erdenkräften heraus. Erst die Blüte ist dasjenige, was an der Sonne gedeiht. Nun, das habe ich einmal hier auseinandergesetzt.

Was bedeutet es denn für uns Menschen, daß wir abhängig werden von Kräften unter der Erde? Dasselbe wie bei den Kartoffeln bedeutet es nicht, wir werden ja auch im Winter nicht in die Gruben hineingelegt, damit wir da den Winter über besser gedeihen können. Es bedeutet eben etwas ganz anderes, es bedeutet gerade, daß die Erde den Einfluß des Überirdischen von uns wegnimmt. Wir werden durch die Erde des Einflusses des Überirdischen beraubt. Der Mensch war zuerst in seinem Bewußtsein göttliche Imagination, dann göttlicher Gedanke, dann Errechnungsresultat und dann Erdenmensch. Der Grieche fühlte sich durchaus als Erdenmensch und lebend im Blute. Wir also müssen lernen, uns als unabhängig von demjenigen zu fühlen, was überirdisch ist, unabhängig aber auch von dem, was bloß in unserem Blute liegt. Dazu ist es gekommen dadurch, daß wir eben zwischen dem einundzwanzigsten und achtundzwanzigsten Jahr anders leben, als früher gelebt worden ist: daß wir nicht mehr aufwachen zu dem gestern charakterisierten zweiten Erlebnis, daß wir nicht mehr lebendige Gedanken als die Resultate des vom Überirdischen beeinflußten Bewußtseins haben, sondern daß wir Gedanken haben, die ganz frei geworden sind von innerer Lebendigkeit, die deshalb auch tot sind. Es ist schon die Erde mit ihren Innenkräften, die unsere Gedanken, indem wir Erdenmenschen werden, ertötet.

Und ein merkwürdiges Bild ergibt sich: Als Erdenmenschen begraben wir dasjenige, was im Physischen vom Menschen übrigbleibt, wir übergeben den Leichnam den Erdenelementen. Die Erde wird auch bei verbrannten Menschen tätig, Verwesung ist nur eine langsame Verbrennung. Mit unseren Gedanken geht es so — das ist ja das Merkwürdige der fünften nachatlantischen Periode -, daß die Götter, indem wir geboren werden, indem wir auf die Erde heruntergeschickt werden, unsere Gedanken der Erde übergeben. Begraben, richtig begraben werden unsere Gedanken, indem wir Erdenmenschen werden. Das ist so seit dem Beginn des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraumes. Intellektualistischer Mensch sein, heißt: eine Seele haben mit in der Erde begrabenen Gedanken, das heißt, mit Gedanken, denen die Erdenkräfte die Himmelsimpulse nehmen.

Das ist eigentlich das Charakteristische für unser gegenwärtiges Menschsein, daß wir mit der Erde in unserem innersten Seelenwesen gerade durch unser Denken zusammenwachsen. Dadurch aber haben wir andererseits auch erst jetzt, in der fünften nachatlantischen Kulturperiode, die Möglichkeit, dem Kosmos die Gedanken zurückzusenden, die wir auf die gestern am Schlusse erwähnte Weise in uns lebendig machen durch unser Erdenleben.

Solche Entwickelungsimpulse ruhen tief in den bedeutsamen Kulturergebnissen der Menschheit. Und es erweckt in uns gewiß ein tiefes Gefühl, wenn in der Zeit, in der sich die europäische Menschheit nähert diesem fünften nachatlantischen Kulturzeitraum, solche Dichtungen heraufkommen, wie die des Wolfram von Eschenbach, der «Parzival». Wir haben die Dichtung als solche oftmals betrachtet, aber wir wollen heute ein Auge haben, ein Seelenauge haben für etwas, was uns da als ein grandioses Merkzeichen der Zeit entgegentritt. Sehen Sie sich die merkwürdige Charakteristik an, die nun, nicht nur bei Wolfram, sondern überhaupt bei den Menschen dieser Zeit, indem in ihnen die Dichterkraft aufgeht, heraufkommit.

Da sieht man, ich möchte sagen, sich beunruhigt durch drei Entwickelungsstadien der menschlichen Seele. Das erste, was man an dem Menschen wahrnimmt, wenn er in die Welt hereintritt, wenn er sich seinem Leben überläßt, wenn er in naiver Weise im Zusammenhang mit der Welt lebt, das erste, was man wahrnimmt, ist die Einfältigkeit, Dumpfheit.

Das zweite aber, das ist der Zweifel. Und gerade in dieser Zeit des herannahenden fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraumes wird der Zweifel lebendig geschildert. Ist Zweifel des Herzens Angebinde, so muß dem Menschen das Leben sauer werden: das ist die Empfindung in jener Zeit. Aber die Empfindung ist auch da: Der Mensch muß sich durchringen durch den Zweifel zur Saelde, zur Seligkeit. - Und Seligkeit nennt man dann dasjenige, wo der Mensch in die ungöttlich gewordenen Gedanken, in die ganz irdisch gewordenen, toten Gedanken nun wiederum das göttliche Leben hereinbringt. Als den Zustand des Zweifels empfindet man dieses Untertauchen des Menschen mit seinen Gedanken in den irdischen Bereich. Und die Saelde, die Seligkeit, empfindet man wie ein Losreißen von dem Irdischen dadurch, daß man die Gedanken wiederum lebendig macht.

Das ist gerade als ein Stimmungsgehalt der Dichtungen in diesem 12., 13., 14. Jahrhundert vorhanden, wo man sich heraufringt in den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum. Ich möchte sagen, die erste Morgenröte dieses fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraumes wurde lebendiger von den Menschen empfunden als heute, wo die Menschen müde sind, über diese Dinge nachzudenken, wo sie zu bequem geworden sind. Aber sie werden wieder beginnen müssen, über diese Dinge tief nachzudenken, und namentlich nachzufühlen. Sonst würde eben der Aufstieg der Menschheit nicht möglich sein. Und was tritt da eigentlich ein?

Es ist ein Hinunterbewegen des Menschen von dem Himmlischen zu dem Irdischen, bis der Mensch ganz auf der Erde ist. Aber wie ist es mit dem Menschen? Ja, es ist so, wie wenn die Erde für den Menschen ein Spiegel wäre. Der Mensch soll nicht bloß bis unter die Erde hineinwachsen. Die Gedanken in ihrem toten Elemente dringen in die Erde hinein, begreifen das Tote, das nur dem Erdenelemente angehört. Aber der Mensch selbst ist so, daß er, wenn er seine Gedanken belebt, sie wie Spiegelbilder hinaussendet in den Kosmos. So daß alles, was an lebendigen Gedanken in dem Menschen entsteht, dasjenige ist, was die Götter zurückglänzen sehen von dem sich entwickelnden Menschen. Der Mensch wird aufgerufen zum Mitschöpfer am Weltenall, indem ihm zugemutet wird, daß er seine Gedanken belebt. Denn diese Gedanken spiegeln sich an der Erde und gehen wiederum in das Weltenall hinaus, müssen den Weg wiederum nehmen in das Weltenall hinaus.

Daher ist es ja so, wenn wir den ganzen Sinn der Menschen- und Weltenentwickelung in uns aufnehmen, daß wir schon fühlen: In einer Art kommen wir wiederum zu den Epochen zurück, die durchgemacht worden sind. In der ägyptisch-chaldäischen Zeit hat man gerechnet, wie es mit dem Menschen ist auf der Erde; man hat immerhin durch die Rechnung den Menschen in Zusammenhang gebracht mit der umliegenden Sternenwelt. Heute machen wir es historisch, indem wir vom Menschen ausgehen, und der Mensch uns der Ausgangspunkt wird für eine Betrachtung, wie Sie sie angestellt finden in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft», wo wir tatsächlich die belebten menschlichen Gedanken wiederum hinaussenden und achtgeben, wie sie werden, wenn wir sie in der kosmischen Umgebung als von uns wegeilend verfolgen, wenn wir lernen, mit den lebendigen Gedanken in den kosmischen Weiten zu leben.

Das sind Zusammenhänge, die da zeigen, welche tiefe Bedeutung es hat, daß der Mensch zu toten Gedanken gekommen ist, daß er sozusagen in die Gefahr gekommen ist, ganz mit der Erde sich zu verbinden.

Und verfolgen wir das Bild weiter. Gültige Imaginationen lassen sich weiter verfolgen. Nur ausgedachte Imaginationen lassen sich nicht weiter verfolgen. Denken Sie sich einmal, hier wäre ein Spiegel (es wird gezeichnet). Man sagt, er wirft das Licht zurück; die Ausdrucksweise ist nicht ganz richtig, das Licht darf aber jedenfalls nicht hinter den Spiegel kommen. Wodurch nur allein kann das Licht hinter den Spiegel kommen? Dadurch, daß der Spiegel zerbrochen wird. Und in der Tat, wenn der Mensch seine Gedanken nicht belebt, wenn der Mensch stehenbleibt bei den bloß intellektualistischen, toten Gedanken, muß er die Erde zerbrechen.

Das Zerbrechen beginnt allerdings bei dem dünnsten Elemente, bei der Wärme. Und im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum hat man nur die Gelegenheit, durch weiteres, immer weiteres Ausbilden der bloßen intellektualistischen Gedanken die Wärmeatmosphäre der Erde zu verderben.

Dann aber kommt die sechste nachatlantische Periode. Würde die Menschheit nicht bis dahin bekehrt sein vom Intellektualismus zur Imagination, dann würde die Verderbnis nicht nur der Wärmeatmosphäre, sondern der Luftatmosphäre beginnen, und die Menschen würden mit den bloß intellektualistischen Gedanken die Luft vergiften. Und die vergiftete Luft würde auf die Erde zurückwirken, das heißt, zunächst das Vegetabilische verderben (siehe Zeichnung Seite 123).

Und im siebenten nachatlantischen Zeitraum hat der Mensch schon Gelegenheit, das Wasser zu verderben, und seine Ausdünstungen würden übergehen, wenn sie die Ergebnisse bloß intellektualistischer Gedanken wären, in das allgemeine Flüssigkeitselement der Erde. Aus dem allgemeinen Flüssigkeitselement der Erde heraus würde zunächst das mineralische Element der Erde entformt werden. Und der Mensch hat durchaus Gelegenheit, wenn er seine Gedanken nicht belebt und damit dem Kosmos dasjenige zurückgibt, was er vom Kosmos empfangen hat, die Erde zu zersplittern.

So hängt das, was im Menschen seelisch ist, mit dem natürlichen Dasein zusammen. Und das bloß intellektualistische Wissen heute ist lediglich ein ahrimanisches Produkt, um den Menschen hinwegzutäuschen über diese Dinge. Indem man dem Menschen weismacht, daß seine Gedanken bloße Gedanken sind, die mit dem Weltgeschehen nichts zu tun haben, macht man ihm einen Nebel vor, als ob er keinen Einfluß haben könnte auf die Erdenentwickelung, und als ob ohne oder mit seinem Zutun einmal das Erdenende so oder so kommen wird, wie es eben die bloße Physik vorschreibt.

Aber es wird nicht ein bloß physikalisches Erdenende kommen, sondern dasjenige Erdenende, das die Menschheit selber wird herbeigeführt haben.

Hier ist wieder einer der Punkte, wo sich uns zeigt, wie Anthroposophie die moralisch-seelische Welt zusammenführt mit der physischsinnlichen Welt, während heute gar kein solcher Zusammenhang vorhanden ist und die neuere Theologie sogar etwas Vorzügliches darinnen sieht, das Moralische ganz unabhängig zu machen von dem Physischen. Und Philosophen, die da heute keuchend, gebückt, mit krummen Rücken unter der Bürde der naturwissenschaftlichen Ergebnisse sich dahinschleppen, die sind froh, wenn sie sagen können: Ja, in der Natur, da gibt es Wissenschaft; aber die Philosophie, die muß sich auf den kategorischen Imperativ, auf dasjenige, worüber man nichts wissen kann, erstrecken.

Diese Dinge sind heute oftmals nur innerhalb der Schulen spielend. Sie werden aber das Leben ergreifen, wenn die Menschheit sich nicht dessen bewußt wird, wie das Seelisch-Geistige mitschöpferisch ist im Physisch-Sinnlichen, und wie die Zukunft des Physisch-Sinnlichen davon abhängen wird, was der Mensch im Seelisch-Geistigen auszubilden sich entschließt. Aus solchen Untergründen heraus kann man schon auf der einen Seite das Bewußtsein bekommen von der unendlichen Wichtigkeit des seelischen Lebens der Menschheit, auf der andern Seite kann man allerdings auch wiederum ein Bewußtsein davon bekommen, daß der Mensch nicht nur ein auf der Erde beliebig herumwandelndes Geschöpf ist, sondern dem ganzen Weltenall angehört.

Aber, meine lieben Freunde, richtige Imaginationen geben schon das Richtige. Wenn der Mensch nämlich nun nicht seine Gedanken belebt, sondern sie immer weiter und weiter sterben läßt, dann kriechen eben die Gedanken in die Erde hinein, und der Mensch wird zuletzt gegenüber dem Weltenall ein Regenwurm, weil seine Gedanken sich die Lokalitäten der Regenwürmer aufsuchen. Das ist auch etwas, was eine ganz gültige Imagination ist.

Die menschliche Zivilisation sollte es vermeiden, daß der Mensch Regenwurm werden kann, denn sonst wird die Erde zerbrochen, und das Weltenziel, das in den menschlichen Anlagen ganz deutlich ausgesprochen ist, wird nicht erreicht. Das sind Dinge, die wir nicht bloß in unsere Theorien, in unsere Abstraktionen, sondern tief in unsere Herzen aufnehmen sollen, denn Anthroposophie ist eine Herzenssache. Je mehr sie als eine Herzenssache gefaßt wird, desto besser wird sie verstanden.

Seventh Lecture

The essential aspect of our present time within the development of mankind has turned out to be the possession of the earthly human being of abstract thoughts, that is, for us dead thoughts, thoughts that lead their existence in us in such a way that they are actually the remnants of the living being of the soul in pre-earthly existence.

With this stage of development of mankind towards abstract, i.e. dead thoughts, is linked - as I have often explained - the attainment of freedom consciousness within the development of mankind. Let us turn our attention today to this side of the matter in particular. We can do this by looking a little at the whole course of human development in the post-Atlantean period.

You know that after the great Atlantean catastrophe the division of the earth continents as we know them today gradually developed, and that on this distribution of solid land on earth, or within the distribution of solid land on earth, five successive periods of culture or civilization gradually developed, which I have called in my “Secret Science in Outline” the primeval Indian, the primeval Persian, the Egyptian-Chaldean, the Greek-Latin and our present fifth epoch of civilization.

These five epochs of civilization differ in that the human being as a whole is in a different condition in each of them. If we go back to the older epochs of civilization, this constitution is also expressed in the whole outward appearance of man, in what I would call the physical manifestations of man. And the more we come to the later period, that is, closer to our epoch of civilization, the more that which we can call the progress of mankind expresses itself in the constitution of the soul. We have often described what is related to this. Today I want to describe it from a point of view that has been less considered so far.

If we go back to the first, primeval Indian epoch of civilization, which, I would like to say, still half emerged from the Atlantean catastrophe, we find that man at that time felt much more as a citizen of the extraterrestrial cosmos than as a citizen of the earth. And when we go into the details of life at that time, which, as I have often indicated to you, goes back to the 7th, 8th millennium of pre-Christian times, we must emphasize in particular that great importance was attached to the appearance, to the exterior of man, not out of an intellectual consideration - which of course did not exist at that time - but out of a deeply instinctive feeling in these very old times of human development. Not as if these people of ancient times had engaged in physiognomic studies; that was of course quite remote from them. Such things only belong to an age in which intellectualism, though not yet perfect, is already dawning. But they had a fine physiognomic sense. They felt deeply, these people: If someone has this or that facial expression, it indicates that he also has these or those musical qualities. They put a lot of effort into guessing, I would almost say, the musical nature of a person from his facial expression, but also from his gestures, from his whole human revelation. In those ancient times, people did not strive for a more specific way of recognizing what was generally human. People would have had no understanding at all if they had been told that something was to be proven. It would have embarrassed them, it would have almost physically hurt them, indeed, in older times it would have really physically hurt them. Proving, that's like someone trying to cut you with knives - that's what these people would have said. Why should you have to prove it? You don't need to know anything so certain about the world that you first have to prove it.

This has to do with the fact that these people still had the most vivid feeling, they all come from the pre-earthly existence out of the spiritual world. In the spiritual world, when one is inside, one does not prove. There one knows: Proving is a matter that has its good sense on earth, but in the world of the spiritual one does not prove. It would seem to you if you wanted to prove as if you had, let's say, a certain measure: a person may be this or that length - and then you do it like the Procrustean legend: To him who is too long you cut something off, and to him who is too short you stretch him out a little. In the whole context of the spiritual world, proof would be something like this. Things are not such that they can be carved into evidence. There, things are inwardly mobile, inwardly fluid.

And an Indian of the primeval Indian time with his strong consciousness: I have descended from the spiritual world, I have only placed this outer human being around me - to such an Indian it would have seemed quite strange if he had somehow been asked to prove something. Rather, these people loved what we call “guessing” today. They loved it because they wanted to pay attention to what was happening around them. And they found a certain inner satisfaction in this activity of guessing.

And they also had a certain instinct to deduce a clever person from this or that face, a foolish person from another face, to guess at, say, phlegm and the like from a stature. Guessing was what people had in those days instead of what we today call proving knowledge. And in human intercourse, all mutual behavior amounted to deducing from the soul, from the gesture, from the stature of the person, from the way he walked, what he actually had for a moral quality.

In the first epoch of the primeval Indian being there was no such thing as caste division. In connection with the primeval Indian mystery system, there was even a kind of social division of people according to physiognomy and gestures. These things were possible in earlier times of human development because people also had a certain instinct to follow such classifications. What later emerged within Indian civilization as the formation of castes was, I would say, already a kind of schematic division of a much more individual classification that was originally based on instinctively felt physiognomy. And in those ancient times, people did not feel offended if they were - if I may put it this way - placed here or there according to their face, because they felt themselves to be God-given earthly beings. And the authority vested in those who, out of the Mysteries, provided such a classification was immense.

It was only in the later post-Atlantean epochs of civilization that the caste system gradually emerged from preconditions that I have already mentioned in other lectures. In those older times, in that primeval Indian epoch, there was a strong feeling that man had an underlying divine imagination.

I have told you a lot about how there was originally a kind of instinctive clairvoyance, dreamlike clairvoyance. But if we go back to very ancient times of the post-Atlantean period, then people not only said that they saw dreamlike imaginations, but they also said that a divine imagination lives in the particular configuration that the physical body of man has when man enters earthly existence. The human being who descends to earth is based on a divine imagination. He then formed his physiognomy from childhood onwards, after which he formed the entire physical expression of his human being.

So one not only looked instinctively, as I have just indicated, at the physiognomic, but one saw in the physiognomic the imagination of the gods. One said to oneself: The gods have imaginations, and they shape these imaginations in the physical human being. - That was the very first view of what man is on earth as a being sent by God.

Then came the second post-Atlantean cultural period, the Urperian. People no longer had the same instinctive feeling for the physiognomic as before. People did not look at the imaginations of the gods, but at the thoughts of the gods. Before, it was actually the case that one assumed: Before a human being descends to earth, a real human image lives in some divine beings. Afterwards, the idea was that thoughts, thoughts that together formed the Logos - as it was later called - underlay the individual human being.

In this second post-Atlantean period, great importance was attached to whether man was born - as paradoxical as this may seem to us today, it is true - in good weather, whether man was born at night or during the day, in winter or summer. There was nothing intellectual, but there was a feeling: What the gods let be for a celestial constellation, whether nice weather or snow flurries, whether day or night, when they send a person down to earth, that expresses their thoughts, that expresses these divine thoughts. And if a child was born at the time of a thunderstorm or other strange weather constellations, this was regarded in lay life as the expression of these or those divine thoughts given to the child.

If this was the case in lay life, then on the other hand, where the priesthood, which in turn was dependent on the Mysteries, kept a record of births, so to speak - but this is not to be understood in the bureaucratic sense of today - it was certainly the case that one saw from these constellations of weather, time of day, season and so on how the human being had been given his divine gift of thought. That was in the second post-Atlantean period, in the Urpersian period.

Such things have survived very little into our time. In our time it is regarded as something extraordinarily boring if you have to say of someone: He talks about the weather. - Just think how detrimental it is to say of someone today: He is a boring person because he knows nothing else to talk about than the weather. - People in the Urperian period would not have understood that, they would have found a person who knew nothing interesting to say about the weather extremely boring. Because in fact, it does mean that you are completely removed from your natural surroundings if you no longer feel anything truly human about weather phenomena. It was an intense co-experience of the cosmic environment, which expressed itself in the fact that one thought of events - and the birth of a human being was one of the most important events - in connection with what was happening in the world.

It would certainly be a step forward if people - they don't just have to come to the saying: there is good and bad weather, that is very abstract - if people would again come to the conclusion, by telling each other this or that, not to forget what the weather was like at this or that event that was experienced, what phenomena were in nature in general.

It is extraordinarily interesting when this is mentioned here or there in the case of striking phenomena, as is mentioned, for example, for the death of Kaspar Hauser, because it was a striking phenomenon that on one side the sun set while on the other side the moon rose, and so on.

So we can feel our way into the human nature of this second post-Atlantean period.

In the third post-Atlantean period, this instinct to see the spiritual, to see divine thoughts in the weather, had for the most part already faded, and people gradually began to calculate. Instead of intuitively grasping the divine human thoughts in the configuration of nature, people began to calculate the constellations of the stars, and when a person came into the world, they calculated the stars, the fixed star-planet constellation. This was essentially the third, the Chaldean-Egyptian period, in which the greatest importance was attached to being able to calculate from the star constellations how man had entered earthly life from pre-earthly life.

There was still an awareness that man's earthly life was given from the extraterrestrial environment. Only, when it comes to calculating, then the time comes when we no longer really have the connection of the human being with the divine-spiritual entities.

You only need to consider how the whole spiritual process of man is actually external when it comes to arithmetic. I certainly do not want to speak of youthful laziness or, for my part, of people's later inattention to arithmetic. That should not happen. But there is, of course, a big difference when one emphasizes those external methods of thinking that actually have little more to do with the human being as a whole, and which are arithmetical methods. These mathematical methods were introduced into all life in this third post-Atlantean period. But at least they calculated that which was extraterrestrial, and they at least placed man into the extraterrestrial through calculation. The Egyptians and Chaldeans did not calculate as abstractly as we do; what they calculated was definitely felt. Today, everything calculated is sometimes thought through, sometimes not even thought through, but methodized. Today we often no longer calculate with content, but only with methods. And what is sometimes achieved in mathematics in terms of the remoteness of the content, which is only achieved in a methodical way, is today basically, I don't mean it badly, but it is terrible. In this Chaldean-Egyptian period, there was still something human in calculation.