Anthroposophy, An Introduction

GA 234

19 January 1924, Dornach

1. Anthroposophy as What Men Long for Today

In attempting to give a kind of introduction to Anthroposophy I shall try to indicate, as far as possible, the way it can be presented to the world today. Let me begin, however, with some preliminary remarks. We have usually not sufficient regard for the Spiritual as a living reality; and a living reality must be grasped in the fulness of life. Feeling ourselves members of the Anthroposophical Society and the bearers of the Movement, we ought not to act each day on the assumption that the Anthroposophical Movement has just begun. It has, in fact, existed for more than two decades, and the world has taken an attitude towards it. Therefore, in whatever way you come before the world as Anthroposophists, you must bear this in mind. The feeling that the world has already taken up an attitude towards Anthroposophy must be there in the background. If you have not this feeling and think you can simply present the subject in an absolute sense—as one might have done twenty years ago—you will find yourselves more and more presenting Anthroposophy in a false light. This has been done often enough, and it is time it stopped. Our Christmas meeting should mark a beginning in the opposite direction; it must not remain ineffective, as I have already indicated in many different directions.

Of course, we cannot expect every member of the Society to develop, in some way or other, fresh initiative, if he is not so constituted. I might put it this way: Everyone has the right to continue to be a passively interested member, content to receive what is given. But whoever would share, in any way, in putting Anthroposophy before the world, cannot ignore what I have just explained. From now on complete truth must rule in word and deed.

No doubt I shall often repeat such preliminary remarks. We shall now begin a kind of introduction to the anthroposophical view of the world.

Whoever decides to speak about Anthroposophy must assume, to begin with, that what he wants to say is really just what the heart of his listener is itself saying. Indeed, no science based on initiation has ever intended to utter anything except that which was really being spoken by the hearts of those who wished to hear. To meet the deepest needs of the hearts of those requiring Anthroposophy must be, in the fullest sense, the fundamental note of every presentation of it.

If we observe today those who get beyond the superficial aspect of life, we find that ancient feelings, present in every human soul from age to age, have revived. In their subconscious life the men and women of today harbour earnest questions. They cannot even express these in clear thoughts, much less find answers in what the civilised world can offer; but these questions are there, and a large number of people feel them deeply. In fact, these questions are present today in all who really think. But when we formulate them in words they appear, at first, far-fetched. Yet they are so near, so intimately near to the soul of every thinking man.

We can start with two questions chosen from all the riddles oppressing man today. The first presents itself to man's soul when he contemplates the world around him and his own human existence. He sees human beings enter earthly life through birth; he sees life running its course between birth (or conception) and physical death, and subject to the most manifold experiences, inner and outer; and he sees external nature with all the fullness of impressions that confront man and gradually fill his soul.

There is the human soul in a human body. It sees one thing before all others: that Nature receives into herself all the human soul perceives of physical, earthly existence. When man has passed through the gate of death, Nature receives the human body through one element or another (it makes little difference whether through burial or cremation). And what does Nature do with this physical body? She destroys it. We do not usually study the paths taken by the individual substances of the body. But if we make observations at places where a peculiar kind of burial has been practised, we deepen this impression made by a study of what Nature does with the physical, sensible part of man, when he has passed through the gate of death. You know there are subterranean vaults where human remains are kept isolated, but not from the air. They dry up. And what remains after a certain time? A distorted human form consisting of carbonate of lime, itself inwardly disintegrated. This mass of carbonate of lime still resembles, in a distorted form, the human body, but if you only shake it a little, it falls to dust.

This helps us to realise vividly the experience of the soul on seeing what happens to the physical instrument with which man does all things between birth and death. We then turn to Nature, to whom we owe all our knowledge and insight, and say: Nature, who produces from her womb the most wonderful crystal forms, who conjures forth each spring the sprouting, budding plants, who maintains for decades the trees with their bark, and covers the earth with animal species of the most diverse kinds, from the largest beasts to the tiniest bacilli, who lifts her waters to the clouds and upon whom the stars send down their mysterious rays—how is this realm of Nature related to what man, as part of her, carries with him between birth and death? She destroys it, reduces it to formless dust. For man, Nature with her laws is the destroyer. Here, on the one hand, is the human form; we study it in all its wonder. It is, indeed, wonderful, for it is more perfect than any other form. to be found on earth. There, on the other hand, is Nature with her stones, plants, animals, clouds, rivers and mountains, with all that rays down from the sea of stars, with all that streams down, as light and warmth, from the sun to the earth. Yet this Realm of Nature cannot suffer the human form within her own system of laws.1This sentence and the rest of the paragraph in which it occurs must of course be read in the context of the lecture as a whole. Taken by itself it may well arouse the objection: ‘The human form is as much within Nature's system of laws as those of the plants and animals. Certainly Nature destroys it after death; but does she not also bring it to birth?’ It may help to remind the reader that Dr. Steiner is at this stage merely putting into words a feeling, which, he expressly says, arises when we stand in the presence of death. Later on in the book, when he deals with the relation in which the human body stands to the world of nature, he shows how the human form in fact has an origin quite different from those of other living creatures. Editor. The human being before us is reduced to dust when given to her charge. We see all this. We do not form ideas about it, but it is deeply rooted in our feeling life. Whenever we stand in the presence of death, this feeling takes firm root in mind and heart. It is not from a merely selfish feeling nor from a merely superficial hope of survival, that a subconscious question takes shape in mind and heart—a question of infinite significance for the soul, determining its happiness and unhappiness, even when not expressed in words. All that makes, for our conscious life, the happiness or unhappiness of our earthly destiny, is trivial in comparison with the uncertainty of feeling engendered by the sight of death. For then the question takes shape: Whence comes this human form? I look at the wonderfully formed crystal, at the forms of plants and animals. I see the rivers winding their way over the earth, I see the mountains, and all that the clouds reveal and the stars send down to earth. I see all this—man says to himself—but the human form can come from none of these. These have only destructive forces for the human form, forces that turn it to dust.

In this way the anxious question presents itself to the human mind and heart: Where, then, is the world from which the human form comes? And at the sight of death, too, the anxious question arises: Where is the world, that other world, from which the human form comes?

Do not say, my dear friends, that you have not yet heard this question formulated in this way. If you only listen to what people put into words out of the consciousness of their heads, you will not hear it. But if you approach people and they put before you the complaints of their hearts, you can, if you understand the heart's language, hear it asking from its unconscious life: Where is the other world from which the human form comes?—for man, with his form, does not belong to this. People often reveal the complaints of their hearts by seizing on some triviality of life, considering it from various points of view and allowing such considerations to colour the whole question of their destiny.

Thus man is confronted by the world he sees, senses and studies, and about which he constructs his science. It provides him with the basis for his artistic activities and the grounds for his religious worship. It confronts him; and he stands on the earth, feeling in the depths of his soul: I do not belong to this world; there must be another from whose magic womb I have sprung in my present form. To what world do I belong? This sounds in men's hearts today. It is a comprehensive question; and if men are not satisfied with what the sciences give them, it is because this question is there and the sciences are far from touching it. Where is the world to which man really belongs?—for it is not the visible world.

My dear friends, I know quite well it is not I who have spoken these words. I have only formulated what human hearts are saying. That is the point. It is not a matter of bringing men something unknown to their own souls. A person who does this may work sensationally; but for us it can only be a matter of putting into words what human souls themselves are saying. What we perceive of our own bodies, or of another's, in so far as it is visible, has no proper place in the rest of the visible world. We might say: No finger of my body really belongs to the visible world, for this contains only destructive forces for every finger.

So, to begin with, man stands before the great Unknown, but must regard himself as a part of it. In respect of all that is not man, there is—spiritually—light around him; the moment he looks back upon himself, the whole world grows dark, and he gropes in the darkness, bearing with him the riddle of his own being. And it is the same when man regards himself from outside, finding himself an external being within Nature; he cannot, as a human being, contact this world.

Further: not our heads but the depths of our subconscious life put questions subsidiary to the general question I have just discussed. In contemplating his life in the physical world, which is his instrument between birth and death, man realises he could not live at all without borrowing continually from this visible world. Every bit of food I put into my mouth, every sip of water comes from the visible world to which I do not belong at all. I cannot live without this world; and yet, if I have just eaten a morsel of some substance (which must, of course, be a part of the visible world) and pass immediately afterwards through the gate of death, this morsel becomes at once part of the destructive forces of the visible world. It does not do so within me while I live; hence my own being must be preserving it therefrom. Yet my own being is nowhere to be found outside, in the visible world. What, then, do I do with the morsel of food, the drink of water, I take into my mouth? Who am I who receive the substances of Nature and transform them? Who am I? This is the second question and it arises from the first.

When I enter into relationship with the visible world I not only walk in darkness, I act in the dark without knowing who is acting, or who the being is that I designate as myself. I surrender to the visible world, yet I do not belong to it.

All this lifts man out of the visible world, letting him appear to himself as a member of a quite different one. But the great riddle, the anxious doubt confronts him: Where is the world to which I belong? The more human civilisation has advanced and men have learnt to think intensively, the more anxiously have they felt this question. It is deep-seated in men's hearts today, and divides the civilised world into two classes. There are those who repress this question, smother it, do not bring it to clarity within them. But they suffer from it nevertheless, as from a terrible longing to solve this riddle of man. Others deaden themselves in face of this question, doping themselves with all sorts of things in outer life. But in so deadening themselves they kill within them the secure feeling of their own being. Emptiness comes over their souls. This feeling of emptiness is present in the subconsciousness of countless human beings today.

This is one side—the one great question with the subsidiary question mentioned. It presents itself when man looks at himself from outside, and only dimly, subconsciously, perceives his relation, as a human being between birth and death, to the world.

The other question presents itself when man looks into his own inner being. Here is the other pole of human life. Thoughts are here, copying external Nature which man represents to himself through them. He develops sensations and feelings about the outer world and acts upon it through his will. In the first place, he looks back upon this inner being of his, and the surging waves of thinking, feeling and willing confront him. So he stands with his soul in the present. But, in addition, there are the memories of experiences undergone, memories of what he has seen earlier in his present life. All these fill his soul. But what are they? Well, man does not usually form clear ideas of what he thus retains within him, but his subconsciousness does form such ideas.

Now a single attack of migraine that dispels his thoughts, makes his inner being at once a riddle. His condition every time he sleeps, lying motionless and unable to relate himself, through his senses, to the outer world, makes his inner being a riddle again. Man feels his physical body must be active and then thoughts, feelings and impulses of will arise in his soul. I turn from the stone I have just been observing and which has, perhaps, this or that crystalline form; after a little time I turn to it again. It remains as it was. My thought, however, arises, appears as an image in my soul, and fades away. I feel it to be infinitely more valuable than the muscles or bones I bear in my body. Yet it is a mere fleeting image; nay, it is less than the picture on my wall, for this will persist for a time until its substance crumbles away My thought, however, flits past—a picture that continually comes and goes, content to be merely a picture. And when I look into the inner being of my soul, I find nothing but these pictures (or mental presentations). I must admit that my soul life consists of them.

I look at the stone again. It is out there in space; it persists. I picture it to myself now, in an hour's time, in two hours' time. In the meantime the thought disappears and must always be renewed. The stone, however, remains outside. What sustains the stone from hour to hour? What lets the thought of it fluctuate from hour to hour? What maintains the stone from hour to hour? What annihilates the thought again and again so that it must be kindled anew by outer perception? We say the stone ‘exists’; existence is to be ascribed to it. Existence, however, cannot be ascribed to the thought. Thought can grasp the colour and the form of the stone, but not that whereby the stone exists as a stone. That remains external to us, only the mere picture entering the soul.

It is the same with every single thing of external Nature in relation to the human soul. In his soul, which man can regard as his own inner being, the whole of Nature is reflected. Yet he has only fleeting pictures—skimmed off, as it were, from the surfaces of things; into these pictures the inner being of things does not enter. With my mental pictures (or presentations) I pass through the world, skimming everywhere the surfaces of things. What the things are, however, remains outside. The external world does not contact what is within me.

Now, when man, in the sight of death, confronts the world around him in this way he must say: My being does not belong to this world, for I cannot contact it as long as I live in a physical body. Moreover, when my body contacts this outer world after death, every step it takes means destruction. There, outside, is the world. If man enters it fully, he is destroyed; it does not suffer his inner being within it. Nor can the outer world enter man's soul. Thoughts are images and remain outside the real existence of things. The being of stones, the being of plants, of animals, stars and clouds—these do not enter the human soul Man is surrounded by a world which cannot enter his soul but remains outside.

On the one hand, man remains outside Nature. This becomes clear to him at the sight of death. On the other hand, Nature remains external to his soul.

Regarding himself as an object, man is confronted by the anxious question about another world. Contemplating what is most intimate in his own inner being—his thoughts, mental images, sensations, feelings and impulses of will—he sees that Nature, in whom he lives, remains external to them all. He does not possess her.

Here is the sharp boundary between Man and Nature. Man cannot approach Nature without being destroyed; Nature cannot enter the inner being of man without becoming a mere semblance. When man projects himself in thought into Nature, he is compelled to picture his own destruction; and when he looks into himself, asking: How is Nature related to my soul? he finds only the empty semblance of Nature.

Nevertheless, while man bears within him this semblance of the minerals, plants, animals, stars, suns, clouds, mountains and rivers, while he bears within his memory the semblance of the experiences he has undergone with these kingdoms of Nature, experiencing all this in his fluctuating inner world, his own sense of being emerges amid it all.

How is this? How does man experience this sense of his own existence? He experiences it somewhat as follows. Perhaps it can only be expressed in a picture:

Imagine we are looking at a wide ocean. The waves rise and fall. There is a wave here, a wave there; there are waves everywhere, due to the heaving water. One particular wave, however, holds our attention, for we see that something is living in it, that it is not merely surging water. Yet water surrounds this living something on all sides. We only know that something is living in this wave, though even here we can only see the enveloping water. This wave looks like the others; but the strength of its surging, the force with which it rises, gives an impression of something special living within. This wave disappears and reappears at another place; again the water conceals what is animating it from within. So it is with the soul life of man. Images, thoughts, feelings and impulses of will surge up; waves everywhere. One of the waves emerges in a thought, in a feeling, in an act of volition. The ego is within, but concealed by the thoughts, or feelings, or impulses of will, as the water conceals what is living in the wave. At the place where man can only say: ‘There my own self surges up,’ he is confronted by mere semblance; he does not know what he himself is. His true being is certainly there and is inwardly felt and experienced, but this ‘semblance’ in the soul conceals it, as the water of the wave the unknown living thing from the depths of the sea. Man feels his own true being hidden by the unreal images of his own soul. Moreover, it is as if he wanted continually to hold fast to his own existence, as if he would lay hold of it at some point, for he knows it is there. Yet, at the very moment when he would grasp it, it eludes him. Man is not able, within the fluctuating life of his soul, to grasp the real being he knows himself to be. And when he discovers that this surging, unreal life of his soul has something to do with that other world presented by nature, he is more than ever perplexed. The riddle of nature is, at least, one that is present in experience; the riddle of man's own soul is not present in experience because it is itself alive. It is, so to speak, a living riddle, for it answers man's constant question: ‘What am I?’ by putting a mere semblance before him.

On looking into his own inner being man receives the continual answer: I only show you a semblance of yourself; and if you ascribe a spiritual origin to yourself, I only show you a semblance of this spiritual existence within your soul life.

Thus, from two directions, searching questions confront man today. One of these questions arises when he becomes aware that:

Nature exists, but man can only approach her by letting her destroy him;

the other when he sees:

The human soul exists, but Nature can only approach this human soul by becoming mere semblance.

These two truths live in the subconsciousness of man today. On the one hand, we have the unknown world of Nature, the destroyer of man; on the other, the unreal image of the human soul which Nature cannot approach although man can only complete his physical existence by co-operating with her. Man stands, so to speak, in double darkness, and the question arises:

Where is the other world to which I belong?

Man turns, now, to historical tradition, to what has been handed down from ancient times and lives on. He learns that there was once a science that spoke of this unknown world. He looks to ancient times and feels deep reverence for what they tried to teach about the other world within the world of Nature. If one only knows how to deal with Nature in the right way, this other world is revealed to human gaze.

But modern consciousness has discarded this ancient knowledge. It is no longer regarded as valid. It has been handed down to us, but is no longer believed. Man can no longer feel sure that the knowledge acquired by the men of an ancient epoch as their science can answer today his own anxious question arising from the above subconscious facts.

So we turn to Art.

But here again we find something significant. The artistic treatment of physical material—spiritualisation of physical matter—comes down to us from ancient times. Much of this treatment has been retained and can be learnt from tradition. Nevertheless, it is just the man with a really artistic subconscious nature who feels most dissatisfied today; for he can no longer realise what Raphael could still conjure into the human earthly form—the reflection of another world to which man truly belongs. Where is the artist today who can handle earthly, physical substance in such an artistic way?

Thirdly, there is Religion. This, too, has been handed down through tradition from olden times. It directs man's feeling and devotion to that other world. It arose in a past age through man receiving the revelations of the realm of Nature which is really so foreign to him. For, if we turn our spiritual gaze backwards over thousands of years, we find human beings who also felt: Nature exists, but man can only approach her by letting her destroy him. Indeed, the men who lived thousands of years ago felt this in the depths of their souls. They looked at the corpse passing over into external Nature as into a vast Moloch, and saw it destroyed. But they also saw the human soul passing through the same portal beyond which the body is destroyed. Even the Egyptians saw this, or they would never have embalmed their dead. They saw the soul go further still. These men of ancient times felt that the soul grows greater and greater, and passes into the cosmos. And then they saw the soul, which had disappeared into the elements, return again from the cosmic spaces, from the stars. They saw the human soul vanish at death—at first through the gate of death, then on the way to the other world, then returning from the stars. Such was the ancient religion: a cosmic revelation—cosmic revelation from the hour of death, cosmic revelation from the hour of birth. The words have been retained; the belief has been retained, but has its content still any relation to the cosmos? It is preserved in religious literature, in religious tradition foreign to the world.

The man of our present civilisation can no longer see any relation between what religious tradition has handed down to him and the anxious question confronting him today. He looks at Nature and only sees the human physical body passing through the gate of death and falling a prey to destruction. He sees, more-over, the human form enter through the gate of birth, and is compelled to ask whence it comes. Wherever he looks, he cannot find the answer. He no longer sees it coming from the stars, as he is no longer able to see it after death. So religion has become an empty word.

Thus, in his civilisation, man has around him what ancient times possessed as science, art and religion. But the science of the ancients has been discarded, their art is no longer felt in its inwardness, and what takes its place today is something man is not able to lift above physical matter, making this a vehicle for the radiant expression of the spiritual.

The religious element has remained from olden times. It has, however, no point of contact with the world, for, in spite of it the above riddle of the relation of the world to man remains. Man looks into his inner being, and hears the voice of conscience; but in olden times this was the voice of that God who guided the soul through those regions in which the body is destroyed, and led it again to earthly life, giving it its appropriate form. It was this God who spoke in the soul as the voice of conscience. Today even the voice of conscience has become external, and moral laws are no longer traceable to divine impulses. Man surveys history, to begin with; he studies what has come down from olden times, and—at most—can dimly feel: The ancients experienced the two great riddles of existence differently from the way I feel them today. For this reason they could answer them in a certain way. I can no longer answer them. They hover before me and oppress my soul, for they only show me my destruction after death and the semblance of reality during life.

It is thus that man confronts the world today. From this mood of soul arise the questions Anthroposophy has to answer. Human hearts are speaking in the way we have described and asking where they can find that knowledge of the world which meets their needs.

Anthroposophy comes forward as such knowledge, and would speak about the world and man so that such knowledge may arise again—knowledge that can be understood by modern consciousness, as ancient science, art and religion were understood by ancient consciousness. Anthroposophy receives Its mighty task from the voice of the human heart itself, and is no more than what humanity is longing for today. Because of this, Anthroposophy will have to live. It answers to what man most fervidly longs for, both for his outer and inner life. ‘Can there be such a world-conception today?’ one may ask. The Anthroposophical Society has to supply the answer. It must find the way to let the hearts of men speak from out of their deepest longings; then they will experience the deepest longing for the answers.

Erster Vortrag

Meine lieben Freunde, wenn ich nun versuchen werde, eine Art von Einführung in die Anthroposophie selbst zu geben, so soll das so geschehen, daß darinnen womöglich eine Anleitung zugleich gegeben ist für die Art, wie man vor der Welt Anthroposophie heute vertreten kann. Aber ich will eben doch einige einleitende Worte der Sache noch vorausschicken. Es wird gewöhnlich nicht genügend berücksichtigt, daß das Geistige ein Lebendiges ist; und dasjenige, was lebt, muß auch im vollen Leben erfaßt werden. Wir dürfen einfach nicht, indem wir uns als die Träger der anthroposophischen Bewegung in der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft fühlen, gewissermaßen die Hypothese voraussetzen, jeden Tag beginne die anthroposophische Bewegung. Sie ist eben mehr als zwei Jahrzehnte da, und die Welt hat Stellung zu ihr genommen. Daher muß bei jeder Art, sich im anthroposophischen Sinne zur Welt zu verhalten, dies Gefühl stehen, daß man es zu tun hat mit etwas, wozu die Welt Stellung genommen hat; es muß im Hintergrunde stehen, dieses Gefühl. Hat man dieses Gefühl nicht und denkt, man vertritt einfach da im absoluten Sinne, wie man es auch vor zwei Jahrzehnten hätte machen können, Anthroposophie, dann wird man immer weiter und weiter darinnen fortfahren, diese Anthroposophie vor der Welt in ein schiefes Licht zu bringen. Und das ist ja gerade genug geschehen. Es sollte eben dem ein Ende gemacht werden auf der einen Seite, und es sollte auf der anderen Seite demgegenüber ein Anfang gegeben werden durch unsere Weihnachtstagung. Diese darf nicht ohne Auswirkung bleiben, wie ich schon nach den verschiedensten Richtungen hin angedeutet habe.

Gewiß, es kann nicht jedem Mitgliede der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft zugemutet werden, irgendwie sozusagen nun sich neue Impulse zu geben, wenn ihm das nicht seiner Seelenverfassung nach gegeben ist. Jeder hat das Recht, weiter, ich möchte sagen, ein teilnahmsvolles Mitglied zu sein, das die Dinge aufnimmt, und das sich damit begnügt, die Dinge aufzunehmen. Wer aber teilnehmen will an der Vertretung der Anthroposophie vor der Welt in irgendeiner Form, der kann nicht vorübergehen an dem, was ich auseinandergesetzt habe. In dieser Beziehung muß in die Zukunft hinein nicht nur in Worten, sondern im Tun die vollste Wahrheit herrschen.

Nun, meine lieben Freunde, ich werde noch öfter solche einleitenden Worte sprechen. Wollen wir nun damit beginnen, eine Art von Einführung in die anthroposophische Weltanschauung zu geben.

Wer über Anthroposophie etwas sprechen will, muß voraussetzen, daß zunächst dasjenige, was er sprechen will, eigentlich nichts anderes ist als im letzten Grunde das, was das Herz seines Zuhörers durch sich selber sagt. In aller Welt ist niemals durch irgendeine Initiations- oder Einweihungswissenschaft irgend etwas anderes beabsichtigt gewesen, als auszusprechen, was im Grunde genommen die Herzen derjenigen durch sich selbst sprechen, die das Betreffende hören wollen. So daß eigentlich das im allereminentesten Sinne der Grundton anthroposophischer Darstellung sein muß, aufzutreffen auf das, was das tiefste Herzensbedürfnis derjenigen Menschen ist, die Anthroposophie nötig haben.

Wenn man heute auf diejenigen Menschen hinschaut, die über die Oberfläche des Lebens hinauskommen, so sieht man, daß alte, durch die Zeiten gehende Empfindungen einer jeden Menschenseele sich erneuert haben. Man sieht, daß die Menschen heute in ihrem Unterbewußtsein schwere Fragen haben, Fragen, die nicht einmal in klare Gedanken gebracht werden können, geschweige denn durch dasjenige, was in der zivilisierten Welt vorhanden ist, eine Antwort finden können. Aber vorhanden sind diese Fragen. Und sie sind tief vorhanden bei einer großen Anzahl von Menschen. Sie sind eigentlich vorhanden bei allen wirklich denkenden Menschen der Gegenwart. Wenn man aber diese Fragen in Worte faßt, so scheint es zunächst, als ob sie weit hergeholt wären, und sie sind doch so nahe. Sie sind in aller unmittelbarster Nähe der Menschenseele, der denkenden Menschen.

Zwei Fragen kann man aus dem ganzen Umfang der Rätsel, die heute den Menschen bedrücken, zunächst stellen. Die eine Frage, sie ergibt sich für die Menschenseele dann, wenn diese Menschenseele auf das eigene menschliche Dasein schaut und auf die Weltumgebung. Die Menschenseele sieht den Menschen hereinkommen durch die Geburt in das irdische Dasein. Sie sieht das Leben verlaufen zwischen der Geburt oder Empfängnis und dem physischen Tode. Sie sieht dieses Leben verlaufen mit den mannigfaltigsten inneren und äußeren Erlebnissen. Und diese Menschenseele sieht auch draußen die Natur, all die Fülle der Eindrücke, die da an den Menschen herankommen, und die nach und nach die Menschenseele erfüllen.

Und da steht nun diese Menschenseele im Menschenleibe und schaut vor allen Dingen eines: Die Natur nimmt eigentlich alles dasjenige auf, was die Menschenseele vom physischen Erdendasein sieht. Wenn der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen ist, dann nimmt die Natur in ihren Kräften durch irgendein Element - feuerbestattet oder erdbestattet zu werden, ist ja kein so großer Unterschied -, es nimmt die Natur durch irgendein Element den menschlichen physischen Leib auf. Aber was tut sie mit diesem physischen Leib? Sie vernichtet ihn. Die Menschenseele schaut gewöhnlich nicht nach, welche Wege die einzelnen Substanzen dieses physischen Menschenleibes nehmen; aber wenn man an denjenigen Stätten, wo eine eigentümliche Art von Bestattung ist, einmal Betrachtungen anstellt, dann vertieft sich sozusagen dieses eindrucksvolle Nachsehen dessen, was die Natur mit alldem unternimmt, was am Menschen physisch-sinnlich ist, wenn der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen ist. Es gibt ja unterirdische Gewölbe, da werden die menschlichen Leichname aufbewahrt, abgeschlossen, aber an der Luft aufbewahrt. Sie vertrocknen. Und was hat man nach einiger Zeit? Man hat nach einiger Zeit an diesen Leichen die verzerrte menschliche Gestalt, bestehend aus schon in sich zerstäubtem kohlensaurem Kalk. Und wenn man nur ein wenig diese kohlensaure Kalkmasse, die in Verzerrung die menschliche Gestalt nachahmt, rüttelt, so zerfällt sie in Staub.

Das gibt einen tiefen Eindruck dessen, was die Seele überkommt, wenn sie nachsieht, was eigentlich geschieht mit dem, wodurch alles von dem Menschen verrichtet wird zwischen Geburt und Tod. Und der Mensch sieht dann auf die Natur hin, die ihm seine Erkenntnis liefert, aus der er alles, was er Einsichten nennt, eigentlich schöpft, und sagt sich: Diese Natur, die hervorsprießen läßt aus ihrem Schoße die wunderbarste Kristallisation, diese Natur, welche jeden Frühling aus sich hervorzaubert die sprießenden, sprossenden Pflanzen, diese Natur, welche die berindeten Bäume jahrzehntelang erhält, diese Natur, welche die Erde anfüllt mit den Tierreichen der mannigfaltigsten Art, von den größten Tieren bis zu den winzigsten Bazillen, diese Natur, welche hinaufschickt dasjenige, was sie als Wasser in sich trägt in die Wolken, diese Natur, auf die herunterstrahlt dasjenige, was doch in einer gewissen Unbekanntschaft von den Sternen herunterströmt, diese Natur, sie verhält sich zu dem, was der Mensch innerhalb ihrer zwischen Geburt und Tod an sich trägt, so, daß sie es bis in die vollständigste Verstäubung vernichtet. Für den Menschen ist die Natur mit ihren Gesetzen die Vernichterin. Man steht vor der menschlichen Gestalt; diese menschliche Gestalt, die man im Auge hat mit all dem Wunderbaren, das sie an sich trägt — und sie trägt das Wunderbare an sich, denn sie ist vollkommener als alle anderen Gestalten, welche auf der Erde auffindbar sind -, diese menschliche Gestalt, sie steht da. Und auf der anderen Seite steht die Natur mit ihren Steinen, mit ihren Pflanzen, mit ihren Tieren, mit ihren Wolken, mit Flüssen und Bergen, mit alledem, was aus dem Sternenmeere herabstrahlt, was von der Sonne auf die Erde herunterströmt an Licht und Wärme, und diese Natur, sie duldet in ihrer eigenen Gesetzmäßigkeit nicht die menschliche Gestalt. Dasjenige, was als Mensch dasteht, wenn es der Natur übergeben wird, wird zerstäubt. Das sieht der Mensch. Er bildet sich nicht Ideen darüber, aber in seinem Gemüte sitzt es tief. Jedesmal, wenn der Mensch vor dem Anblicke des Todes steht, setzt es sich tief in sein Gemüt hinein. Denn nicht aus bloßem egoistischem Gefühl heraus, nicht aus einer bloßen oberflächlichen Hoffnung, fortzuleben nach dem Tode, formt sich wiederum tief im Gemüte unterbewußt eine Frage, die unendlich bedeutungsvoll in der Seele sitzt, die Glück und Unglück der Seele bedeutet, auch wenn sie nicht formuliert wird. Und alles dasjenige, was für das Bewußtsein schicksalsmäßig beim Menschen auf Erden Glück und Unglück bedeuten mag, es ist im Grunde genommen ein Geringfügiges gegenüber dem, was sich an Unsicherheit des Fühlens formuliert aus dem Anblicke des Todes. Denn da formuliert sich die Frage also: Woher kommt diese menschliche Gestalt? Ich sehe hin zu dem wunderbar geformten Kristall, ich sehe hin zu den Gestalten der Pflanzen, ich sehe hin zu den Gestalten der Tiere, ich sehe hin, wie die Flüsse über die Erde rollen, ich sehe die Berge, ich sehe alles das, was aus den Wolken spricht, was von den Sternen herunter spricht. Ich sehe alles das, so sagt sich der Mensch, aber von alledem kann nicht die menschliche Gestalt kommen, denn alles das hat nur Vernichtungskräfte, Zerstäubekräfte für die menschliche Gestalt an sich.

Und da entsteht die bange Frage vor dem menschlichen Gemüte, vor dem menschlichen Herzen: Wo also ist die Welt, aus der die menschliche Gestalt kommt? Wo ist sie, diese Welt? — Aus dem Anblick des Todes geht die bange Frage hervor: Wo ist die Welt, diese andere Welt, aus der die menschliche Gestalt kommt?

Sagen Sie nicht, meine lieben Freunde, daß Sie diese Frage noch nicht in dieser Weise formuliert gehört haben. Wenn man hinhört auf das, was die Menschen aus ihrem Kopfe heraus der Sprache anvertrauen, hört man diese Frage nicht formuliert. Wenn man hintritt vor die Menschen, und die Menschen die Klagen ihrer Herzen vorbringen - sie bringen manchmal die Klagen ihrer Herzen vor, indem sie irgendeine Kleinigkeit des Lebens auffassen und über diese Kleinigkeit des Lebens allerlei Betrachtungen anstellen, die sie als Nuance in ihre ganze Schicksalsfrage einfügen -, wer diese Sprache des Herzens versteht, der hört das Herz sprechen aus dem Unterbewußten heraus: Welches ist die andere Welt, aus der die menschliche Gestalt kommt, da doch der Mensch dieser Welt mit seiner Gestalt nicht angehört?

Und so stellt sich vor den Menschen hin die Welt, die er erblickt, die er anschaut, die er wahrnimmt, über die er seine Wissenschaft formt, die Welt, die ihm die Unterlage gibt für die Wirkungen seiner Kunst, die Welt, die ihm die Gründe gibt für seine religiöse Verehrung, so stellt sich hin diese Welt, und der Mensch steht auf Erden und hat in den Tiefen seines Gemütes das Gefühl: Dieser Welt gehöre ich nicht an; es muß eine andere geben, die mich aus ihrem Schoße in meiner Gestalt hervorgezaubert hat. Welcher Welt gehöre ich an? — So tönt es aus den Herzen der Menschen der Gegenwart. Das ist die umfassende Frage. Und wenn die Menschen unbefriedigt sind in dem, was ihnen die heutigen Wissenschaften geben, so ist es aus dem Grunde, weil sie diese Frage in den Tiefen ihres Gemütes stellen und die Wissenschaften weit davon entfernt sind, irgendwie auch nur diese Frage zu berühren: Welches ist die Welt, der der Mensch eigentlich angehört? — denn die sichtbare Welt ist es nicht.

Meine lieben Freunde, ich weiß ganz gewiß: Das, was ich zu Ihnen gesprochen habe, nicht ich habe es gesprochen, ich habe nur dem, was die Herzen sprechen, Worte verliehen. Und darum handelt es sich. Denn nicht darum kann es sich handeln, an die Menschen irgend etwas heranzutragen, was den Menschenseelen selber unbekannt ist — das kann Sensation geben —, sondern darum handelt es sich, kann es sich allein handeln, dasjenige in Worte zu bringen, was die Menschenseelen durch sich selber sprechen. Was der Mensch auch von sich selber nur ansieht, was er von seinen Mitmenschen ansieht, soweit es sichtbar ist, es gehört nicht in die übrige sichtbare Welt hinein. Kein Finger - so kann sich der Mensch sagen -, den ich an mir habe, gehört in diese Welt der Sichtbarkeit herein, denn diese Welt der Sichtbarkeit trägt für jeden Finger bloß die Vernichtungskräfte in sich.

Und so steht der Mensch zunächst vor dem großen Unbekannten. Aber er steht vor diesem Unbekannten, indem er sich selber als einen Angehörigen dieses Unbekannten ansehen muß. Das heißt aber mit anderen Worten, in bezug auf alles dasjenige, was der Mensch nicht ist, ist es um ihn herum geistig licht; in dem Augenblicke, wo der Mensch auf sich selbst zurücksieht, verdunkelt sich die ganze Welt und es wird finster, und der Mensch tappt im Finsteren, indem er das Rätsel seines eigenen Wesens durch die Finsternis trägt. Und so ist es, wenn der Mensch sich von außen ansieht, wenn er sich drinnenstehen findet in der Natur als ein äußeres Wesen. Er kann als Mensch an diese Welt nicht heran.

Und wieder, nicht der Kopf, aber die Tiefen des Unbewußten formulieren sich Fragen, die Unterfragen sind dieser allgemeinen Frage, die ich eben erörtert habe. Indem der Mensch sein physisches Dasein, das sein Werkzeug ist zwischen Geburt und Tod, betrachtet, weiß er: Ohne diese physische Welt kann ich dieses Dasein zwischen Geburt und Tod gar nicht leben, denn ich muß fortwährend Anleihen machen bei diesem Dasein der sichtbaren Welt. Jeder Bissen, den ich in den Mund nehme, jeder Trunk Wasser ist aus dieser Welt der Sichtbarkeit, der ich ja gar nicht angehöre. Ich kann ohne sie im physischen Dasein nicht leben. Habe ich eben einen Bissen zu mir genommen aus einer Substanz, die ja dieser sichtbaren Welt angehören muß, und gehe ich unmittelbar, nachdem ich diesen Bissen zu mir genommen habe, durch die Pforte des Todes, in dem Augenblicke gehört dasjenige, was der Bissen in mir ist, den Vernichtungskräften dieser sichtbaren Welt an. Und daß er in mir selbst nicht den Vernichtungskräften angehört, davor muß ihn mein Wesen, mein eigenes Wesen bewahren. Aber nirgends draußen in der sichtbaren Welt ist dieses eigene Wesen zu finden. Was tue ich denn mit dem Bissen, den ich in den Mund nehme, was tue ich mit dem Trunk Wasser, den ich in den Mund nehme, durch mein eigenes Wesen? Wer bin ich denn, der die Substanzen der Natur empfängt und umwandelt? Wer bin ich denn? Das ist die zweite Frage, die Unterfrage, die aus der ersten entsteht.

Ich gehe nicht nur, indem ich mich in ein Verhältnis setze zu der Welt der Sichtbarkeit, durch die Finsternis, ich handle in der Finsternis, ohne zu wissen, wer handelt, ohne zu wissen, was das Wesen ist, das ich als mein Ich bezeichne. Ich bin ganz hingegeben an die sichtbare Welt; aber ich gehöre ihr nicht an.

Das hebt den Menschen heraus aus der sichtbaren Welt. Das läßt ihn sich selber erscheinen als Angehörigen einer ganz anderen Welt. Und die bange, die große Zweifelsfrage steht da: Wo ist die Welt, der ich angehöre? — Und je mehr die menschliche Zivilisation vorgeschritten ist, je mehr die Menschen intensiv denken gelernt haben, desto mehr ist diese Frage eine bange Frage geworden. Und sie sitzt heute in den Tiefen der Gemüter. Die Menschen teilen sich, insofern sie der zivilisierten Welt angehören, eigentlich nur in zwei Klassen in bezug auf diese Frage. Die einen drängen sie hinunter, würgen sie hinunter, bringen sie sich nicht zur Klarheit, aber leiden darunter, als unter einer furchtbaren Sehnsucht, dieses Menschenrätsel zu lösen; die anderen betäuben sich gegenüber dieser Frage, reden sich allerlei Dinge aus dem äußeren Dasein vor, um sich zu betäuben. Und in dem sie sich betäuben, tilgen sie in sich selber das feste Gefühl des eigenen Seins aus. Nichtigkeit befällt ihre Seele. Und dieses Gefühl der Nichtigkeit sitzt heute im Unterbewußten unzähliger Menschen.

Das ist die eine Seite, die eine große Frage mit der erwähnten Unterfrage. Sie ersprießt, wenn der Mensch sich von außen ansieht und sein Verhältnis als Mensch zwischen Geburt und Tod zur Welt auch nur ganz gedämpft, unterbewußt wahrnimmt.

Die andere Frage aber entsteht, wenn der Mensch in sein eigenes Inneres sieht. Da ist der andere Pol des menschlichen Daseins. Da drinnen sitzen die Gedanken. Sie bilden die äußere Natur ab. Der Mensch stellt durch seine Gedanken die äußere Natur vor. Der Mensch entwickelt Empfindungen, Gefühle über die äußere Natur. Der Mensch wirkt durch seinen Willen auf die äußere Natur. Der Mensch sieht zunächst auf sein eigenes Inneres zurück. Das wogende Denken, Fühlen und Wollen steht vor seiner Seele. So steht er mit seiner Seele in der Gegenwart darinnen. Dazu kommen die Erinnerungen an gehabte Erlebnisse, die Erinnerungen an Dinge, die man in früheren Zeiten des gegenwärtigen Erdendaseins gesehen hat. Das alles füllt die Seele aus. Was ist es?

Nun bildet sich der Mensch nicht klare Ideen über dasjenige, was er da eigentlich in sich drinnen behält; aber das Unterbewußte bildet diese Ideen. Eine einzige Migräne, die die Gedanken verscheucht, macht sogleich das Innere des Menschen zu einer Rätselfrage. Und jeder Schlafzustand macht es zu einer Rätselfrage, wenn der Mensch regungslos daliegt und ihm die Möglichkeit fehlt, durch seine Sinne sich in Korrespondenz mit der Außenwelt zu setzen. Der Mensch fühlt, sein physischer Leib muß rege sein, dann treten die Gedanken, die Gefühle, die Willensimpulse in seiner Seele auf. Aber der Stein, den ich soeben betrachtet habe, der vielleicht diese oder jene Kristallgestalt hat —- ich wende mich von ihm ab, nach einiger Zeit wende ich mich ihm wieder zu -, er ist so geblieben, wie er ist. Mein Gedanke, er steigt auf, er stellt sich als Bild in der Seele dar, er glimmt wieder hinunter. Er wird als unendlich viel wertvoller empfunden als die Muskeln, als die Knochen, die der Mensch in sich trägt, aber er ist etwas Verfliegendes, er ist ein bloßes Bild. Er ist weniger als ein Bild, das ich an der Wand hängen habe; denn das Bild, das ich an der Wand hängen habe, bleibt eine Zeitlang bestehen, bis es durch seine Substanz zerfällt. Der Gedanke fliegt vorüber. Der Gedanke ist ein Bild, das fortwährend entsteht und vergeht, ein fluktuierendes, ein kommendes und gehendes Bild, ein Bild, das in seinem Bilddasein sein Genügen hat. Und dennoch, blickt der Mensch in das Innere seiner Seele hinein, er hat nichts anderes als diese Vorstellungsbilder. Er kann nichts anderes sagen als: sein Seelisches besteht in diesen Vorstellungsbildern.

Noch einmal blicke ich auf den Stein hin. Er ist da draußen im Raume., Er bleibt. Ich stelle ihn jetzt vor, ich stelle ihn in einer Stunde vor, ich stelle ihn in zwei Stunden vor. Der Gedanke verschwindet immer wiederum dazwischen, er muß immer erneuert werden. Der Stein bleibt draußen. Was trägt den Stein von Stunde zu Stunde? Was läßt den Gedanken fluktuieren von Stunde zu Stunde? Was erhält und bewahrt den Stein von Stunde zu Stunde? Was vernichtet den Gedanken immer wiederum, so daß er neuerdings angefacht sein muß an dem äußeren Anblick? Was ist das, was den Stein erhält? Man sagt: Er ist. Das Sein kommt ihm zu. -— Dem Gedanken kommt nicht das Sein zu. Der Gedanke kann die Farbe des Steins erfassen, der Gedanke kann die Form des Steins erfassen; aber dasjenige, wodurch der Stein sich bewahrt, kann er nicht fassen. Das bleibt draußen. Das bloße Bild tritt in die Seele hinein.

Und so ist es mit jeglichen Dingen der äußeren Natur in dem Verhältnis zur Menschenseele. Der Mensch kann auf diese Menschenseele hinblicken auf sein eigenes Inneres. Die ganze Natur spiegelt sich in dieser Menschenseele. Aber seine Seele hat nur fluktuierende Bilder, die gewissermaßen die Oberflächen der Dinge abheben, aber das Innere der Dinge dringt nicht in diese Bilder hinein. Ich gehe mit meinen Vorstellungen durch die Welt. Ich hebe überall die Oberfläche von den Dingen ab, aber dasjenige, was die Dinge sind, bleibt draußen. Ich trage meine Seele durch diese Welt, die mich umgibt, aber diese Welt bleibt draußen. Und dasjenige, was drinnen ist, an das kommt die Außenwelt mit ihrem eigentlichen Sein nicht heran. Und wenn der Mensch im Anblicke des Todes vor der Welt, die ihn umgibt, so dasteht, muß er sich sagen: Dieser Welt gehöre ich nicht an, denn ich dringe an diese Welt nicht heran, mein Wesen gehört einer anderen Welt an; diese Welt, ich kann an sie nicht herandringen, solange ich im physischen Leibe lebe. Und dringt mein Leib nach meinem Tode an diese äußere Welt heran, so kann er nicht heran, denn dann ist jeder Schritt, den er macht, Vernichtung für ihn. Da draußen ist die Welt. Dringt der Mensch in sie hinein, sie vernichtet ihn, sie duldet ihn nicht in sich mit seiner Wesenheit. Will aber die äußere Welt in die Menschenseele hinein, so kann sie das auch nicht. Die Gedanken sind Bilder, die außerhalb des Wesens, des Seins der Dinge stehen. Das Sein der Steine, das Sein der Pflanzen, das Sein der Tiere, das Sein der Sterne, der Wolken, es kommt nicht herein in die Menschenseele. Eine Welt umgibt den Menschen, die nicht an seine Seele heran kann, die draußen bleibt.

Auf der einen Seite bleibt der Mensch - es wird ihm das klar im Anblicke des Todes — außerhalb der Natur. Auf der anderen Seite bleibt die Natur außerhalb seiner Seele. Der Mensch blickt sie als ein Äußeres an. Es muß ihm die bange Frage aufsteigen nach einer anderen Welt. Der Mensch blickt nach dem, was ihm am intimsten, am vertrautesten ist in seinem eigenen Inneren. Der Mensch blickt hin nach jedem Gedanken, nach jeder Vorstellung, nach jeder Empfindung, nach jedem Gefühl, nach jedem Willensimpuls: an nichts dringt die Natur, in der er lebt, heran; er hat sie nicht.

Da ist die scharfe Grenze zwischen dem Menschen und der Natur. Der Mensch kann nicht an die Natur heran, ohne daß er vernichtet wird. Die Natur kann nicht in das Innere des Menschen hinein, ohne daß sie zum Schein wird. Der Mensch hat, indem er sich selber in die Natur hineindenkt, die krasse Vernichtung allein, die er vorstellen muß. Der Mensch hat, indem er in sich hineinblickt und frägt: Wie steht die Natur zu meiner Seele? - nichts anderes als den wesenlosen Schein in seiner Seele von der Natur.

Aber indem der Mensch diesen Schein in sich trägt von Mineralien, Pflanzen, Tieren, Sternen, Sonnen, Wolken, Bergen, Flüssen, und indem er in sich trägt in seiner Erinnerung den Schein von all den Erlebnissen, die er durchgemacht hat mit diesen Reichen der äußeren Natur, hat der Mensch, indem er alles dieses als sein flutendes Inneres erlebt, aufsteigend in diesem Fluten sein eigenes Seinsgefühl.

Und wie ist es nun? Wie erlebt der Mensch dieses Seinsgefühl? Er erlebt es etwa in der folgenden Weise. Das kann man vielleicht nur durch ein Bild ausdrücken. Man schaue hin auf ein weites Meer. Die Wogen gehen auf und ab. Da eine Woge, dort eine Woge, überall Wogen, die von sich aufbäumendem Wasser herrühren. Da wird der Blick gefesselt durch eine besondere Woge. Denn diese eine besondere Woge zeigt, daß in ihr etwas lebt, daß das nicht bloß aufgepeitschtes Meer ist, daß hinter dieser Woge etwas lebt. Aber das Wasser umhüllt dieses Lebende von allen Seiten. Man weiß nur, daß etwas drinnen lebt in dieser Woge, aber man sieht auch in dieser Woge nichts anderes als das dieses Leben umhüllende Wasser. Die Woge sieht aus wie die anderen Wogen. Nur an der Stärke ihres Aufspringens, an der Kraft, mit der sie sich hinstellt, hat man das Gefühl, da lebt etwas Besonderes in ihr. Sie geht wieder hinunter, diese Woge. An einer anderen Stelle erscheint sie wiederum, wiederum verdeckt das Wasser der Woge dasjenige, was sie innerlich belebt. So ist es mit dem Seelenleben des Menschen. Da wogen auf Vorstellungen, Gedanken, da wogen auf Gefühle, da wogen auf Willensimpulse; überall Wogen. Eine der Wogen, die taucht herauf in einem Gedanken, in einem Willensentschluß, in einem Gefühl. Ich ist da drinnen. Aber die Gedanken oder die Gefühle oder die Willensimpulse, sie verdecken wie das Wasser in der Wasserwoge das Lebendige. Sie verdecken dasjenige, was als Ich drinnensteckt. Und der Mensch weiß nicht, was er selbst ist. Denn alles, was sich ihm zeigt an der Stelle, von der er nur weiß: da wogt mein Selbst herauf, da wogt mein eigenes Sein herauf, all dasjenige, was sich ihm zeigt, ist nur Schein. Der Schein in der Seele verdeckt das Sein, das ja ganz gewiß da ist, das der Mensch erfühlt, innerlich erlebt. Aber der Schein deckt es ihm zu, wie das Wasser der Wasserwoge ein Lebendiges zudeckt, das heraufkommt aus den Tiefen des Meeres, das man nicht kennt. Und der Mensch fühlt sein eigenes wahres Wesen verhüllt durch die Scheingebilde seiner eigenen Seele. Und es ist, als ob der Mensch sich fortwährend an sein Sein anklammern wollte, als ob er es irgendwo erfassen wollte. Er weiß, es ist da. Aber in dem Augenblicke, wo er es erfassen will, entschlüpft es ihm schon wieder, eilt von ihm fort. Der Mensch ist nicht imstande, das, was er weiß, was er ist, ein seiendes Wesen, in dem Gewoge seiner Seele zu erfassen. Und wenn dann der Mensch darauf kommt, daß dieses wogende Scheinleben der Seele etwas zu tun hat mit jener anderen Welt, die ihm vor die Vorstellung tritt, wenn er in die Natur hinausschaut, dann, dann tritt erst recht ein furchtbares Rätsel auf. Das Naturrätsel ist wenigstens ein solches, das sozusagen im Erleben vorhanden ist. Das Rätsel der eigenen Seele ist nicht im Erleben vorhanden, weil es selber lebt, weil es sozusagen lebendes Rätsel ist, weil es auf die fortdauernde Frage des Menschen: Was bin ich? — dasjenige vor ihn hinstellt, was bloßer Schein ist.

Indem der Mensch in das eigene Innere blickt, wird er gewahr, daß dieses Innere ihm fortwährend die Antwort gibt: Ich zeige dir von dir selbst nur einen Schein; und schreibst du dich von einem geistigen Dasein her, ich zeige dir in deinem Seelenleben von diesem geistigen Dasein einen Schein.

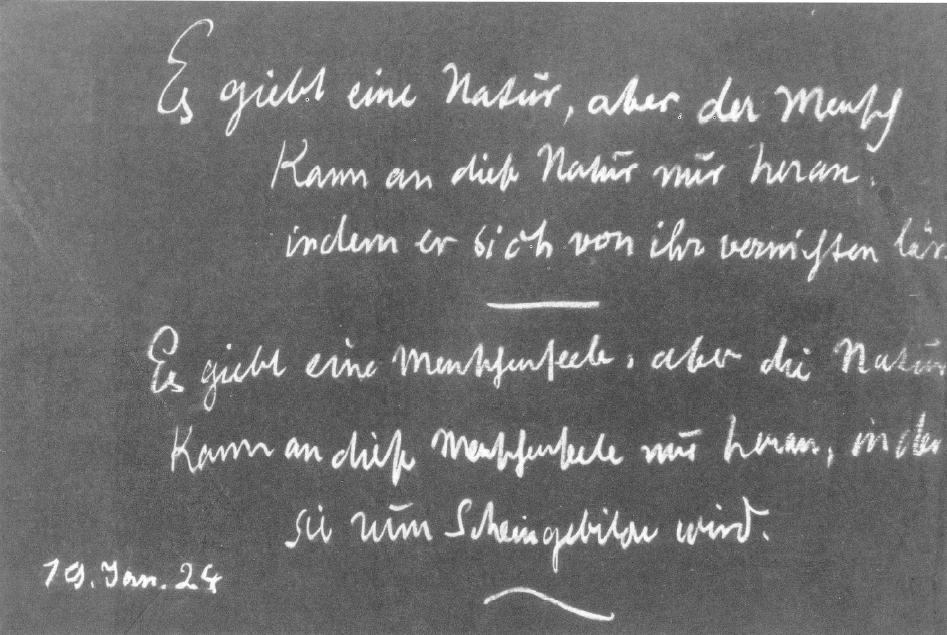

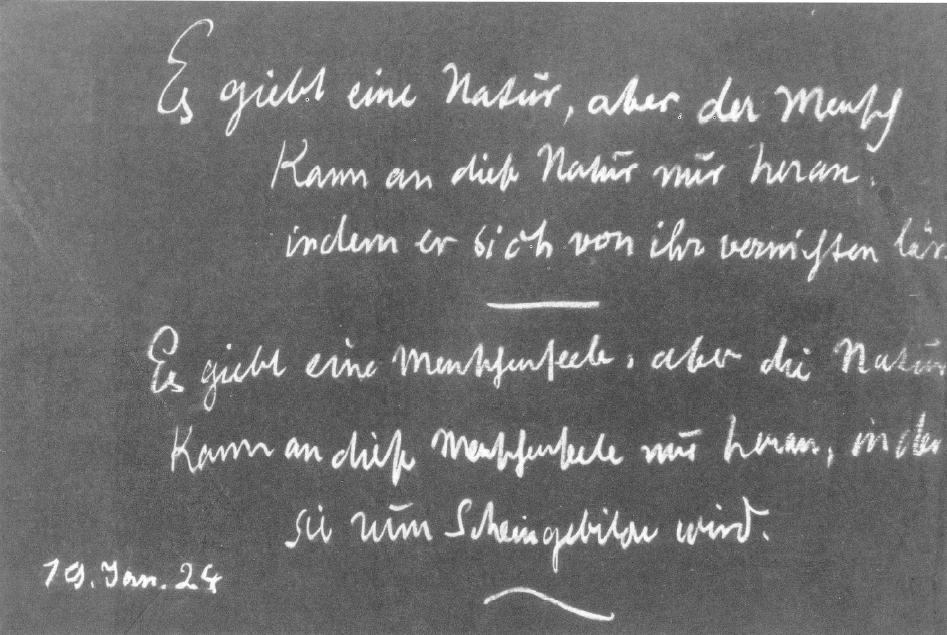

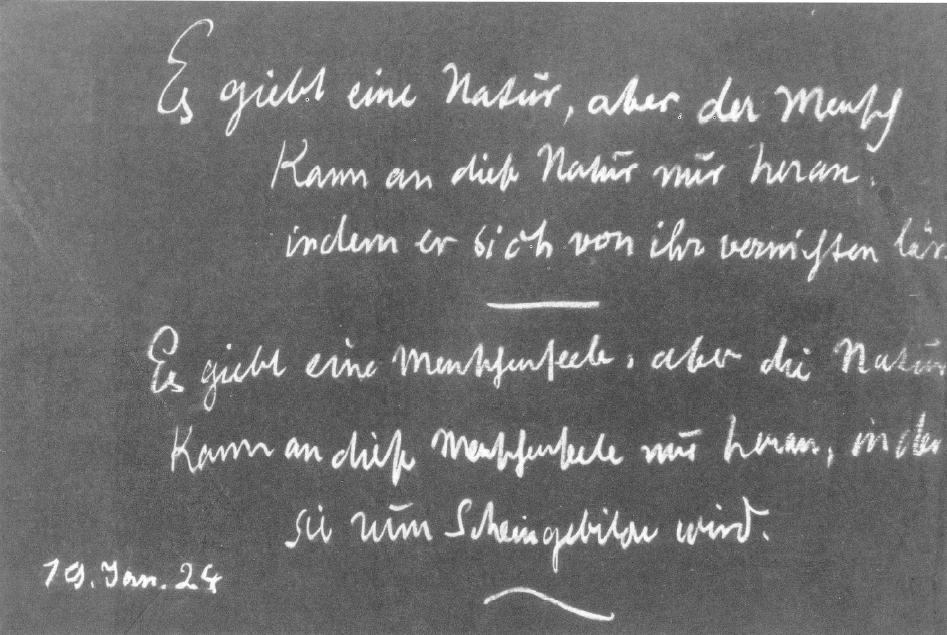

Und so treten prüfende Fragen von zwei Seiten an das Menschenleben heute heran. Die eine Frage, sie entsteht daraus, daß der Mensch gewahr wird (Tafelanschrift):

Es giebt eine Natur, aber der Mensch / kann an diese Natur nur heran, / indem er sich von ihr vernichten laßt.

Die andere (Tafelanschrift):

Es giebt eine Menschenseele, aber die Natur / kann an diese Menschenseele nur heran, indem / sie zum Scheingebilde wird.

Diese beiden Erkenntnisse leben in dem Unterbewußtsein des heutigen Menschen.

Und nun wendet sich der Mensch hin zu dem, was da lebt, aus alten Zeiten in unsere Gegenwart herein übertragen. Da steht die unbekannte Natur, die des Menschen Vernichterin ist; da steht das Scheingebilde der Menschenseele, an das diese Natur nicht herangebracht werden kann, obzwar der Mensch sein physisches Dasein nur unter den Anleihen an diese Natur vollenden kann. Da steht der Mensch sozusagen in einer doppelten Finsternis. Und die Frage taucht auf: Wo ist die andere Welt, der ich angehöre?

Und die geschichtliche Tradition steigt auf. Da gab es einmal eine Wissenschaft, die sprach von dieser unbekannten Welt. Man wendet sich zurück in alte Zeiten. Man bekommt große Ehrfurcht vor dem, was alte Zeiten wissenschaftlich bekunden wollten von dieser anderen Welt, die überall in der Natur drinnenliegt. Wenn man aber die Natur nur richtig zu behandeln weiß, enthüllt sich vor dem menschlichen Blick diese andere Welt.

Aber das neuere Bewußtsein hat diese alte Wissenschaft fallen gelassen. Sie gilt nicht mehr. Sie ist überliefert, aber sie gilt nicht mehr. Der Mensch kann nicht mehr das Vertrauen haben, daß ihm dasjenige, was einmal die Menschen in einer alten Zeit wissenschaftlich über die Welt erkundet haben, heute auf seine bange Frage, die aus diesen zwei unterbewußten Tatsachen sprießt, Antwort gibt. Da tut sich ein zweites vor dem Menschen kund: die Kunst.

Aber wiederum zeigt sich in der Kunst eines. In der Kunst zeigt sich, wie aus alten Zeiten Kunstbehandlung heraufkommt: Durchgeistigung des physischen Stoffes. Der Mensch kann durch Tradition manches von dem empfangen, was an alter künstlerischer Durchgeistigung erhalten geblieben ist. Aber gerade wenn in seinem Uhnterbewußtsein eine echte Künstlernatur sitzt, fühlt er sich heute unbefriedigt, weil er dasjenige nicht mehr handhaben kann, was selbst noch Raffael hineingezaubert hat in die menschliche irdische Gestalt als den Abglanz einer anderen Welt, der der Mensch mit seinem eigentlichen Sein angehört. Wo ist denn heute der Künstler, der die physisch-irdische Substanz in einer solchen Weise stilvoll zu behandeln weiß, daß diese physisch-irdische Substanz den Abglanz jener anderen Welt zeigt, der der Mensch eigentlich angehört?

Bleibt als drittes aus alten Zeiten traditionell erhalten die Religion. Sie weist die menschliche Empfindung, das menschliche Frommsein auf jene andere Welt hin. Einstmals ist diese Religion dadurch entstanden, daß der Mensch die Offenbarungen der Natur, die ihm eigentlich so fern steht, empfangen hat. Und wenn wir den geistigen Blick um Jahrtausende zurücksenden, dann treffen wir auf Menschen, die auch gefühlt haben: Es gibt eine Natur, aber der Mensch kann an diese Natur nur heran, indem er sich von ihr vernichten läßt. Ja, auch die Menschen vor Jahrtausenden haben das in den Tiefen ihrer Seele empfunden; aber sie blickten hin — noch bei den Agyptern war das so — auf den Leichnam, der gewissermaßen wie in eine Art Weltenmoloch hineingeht in die äußere Natur, als Leichnam vernichtet wird. Sie sahen nach; aber sie sahen: in dasselbe Tor, hinter dem der menschliche Leichnam vernichtet wird, geht auch die menschliche Seele. Niemals hätten diese Ägypter ihre Mumien gebildet, wenn der Mensch nicht, nachschauend in alten Zeiten der Seele, gesehen hätte: durch dasselbe Tor hindurch, durch das der Leichnam geht, hinter dem die Leichname vernichtet werden, geht auch die Seele. Aber die Seele geht weiter. Diese Menschen der alten Zeiten fühlten, wie diese Seele größer und größer wird und aufgeht in den Kosmos. Und dann sahen sie dasjenige, was in die Erde hinein verschwunden ist, in die Elemente hinein verschwunden ist, sie sahen es wie wiederum aus den Weltenweiten, aus den Sternen zurückkommen; sie sahen im Tode die Menschenseele verschwinden, zunächst hinter das Tor des Todes, dann hinter dem Tor des Todes sahen sie diese Menschenseele auf dem Wege zur anderen Welt, und sie sahen sie wieder zurückkommen aus den Sternen. Das war die alte Religion: Weltenoffenbarung. Weltenoffenbarung aus der Stunde des Todes, Weltenoffenbarung aus der Stunde der Geburt. Die Worte haben sich erhalten. Der Glaube hat sich erhalten. Aber dasjenige, was er enthält, hat es noch einen Bezug zur Welt?

Es ist in weltenfremder Literatur, religiöser weltenfremder Literatur und Tradition erhalten. Es steht ferne der Welt selbst. Und keine Beziehung mehr kann der Mensch der gegenwärtigen Zivilisation von dem, was ihm religiös überliefert ist, zu demjenigen erblicken, was jetzt die bange Frage ist. Denn er schaut in die Natur hinaus, sieht allein, indem er auf den Tod hinblickt, den menschlichen physischen Leib durch das Tor des Todes gehen und jenseits des Todes der Vernichtung anheimfallen. Dann sieht er hereinkommen durch die Geburt die menschliche Gestalt. Und er muß sich sagen: Woher kommt sie? Überall, wohin ich schaue, erblicke ich nichts, woher sie kommt. Denn aus den Sternen sieht er sie nicht mehr kommen, wie er nicht mehr den Blick dafür hat, sie jenseits der Pforte des Todes zu erblikken. Und Religion ist zum inhaltslosen Worte geworden. Der Mensch hat um sich herum in der Zivilisation dasjenige, was alte Zeiten als Wissenschaft, als Kunst, als Religion besessen haben. Aber die Wissenschaft der Alten ist fallengelassen worden. Die Kunst der Alten wird nicht mehr in ihrer Innerlichkeit empfunden, und was ihr als Ersatz entgegentritt, ist dasjenige, was der Mensch nicht aus der physischen Substanz heraufheben kann bis zum Erstrahlen des Geistigen in dem physischen Stoffe.

Und geblieben ist aus alten Zeiten das Religiöse, Aber das Religiöse knüpft nirgends an die Welt an. Trotz des Religiösen bleibt die Welt im Verhältnis zum Menschen jenes Rätsel. Dann blickt der Mensch in sein Inneres hinein. Er hört die Stimme des Gewissens sprechen. In alten Zeiten war die Stimme des Gewissens die Stimme desjenigen Gottes, der die Seele führte über die Regionen hin, in denen der Leichnam vernichtet wird, der die Seele führte und ihr die Gestalt gab zum irdischen Leben: Derselbe Gott war es, der dann in der Seele sprach als die Stimme des Gewissens. Jetzt ist auch die Stimme des Gewissens äußerlich geworden. Die Moralgesetze führen sich nicht mehr zurück auf die göttlichen Impulse. Der Mensch blickt zunächst auf das Historische. Der Mensch blickt auf dasjenige, was ihm aus alten Zeiten geblieben ist. Er kann nur die Ahnung haben: Die beiden großen Daseinsfragen haben die Alten in anderer Weise empfunden, als du sie heute empfindest; daher haben sie sich in einer gewissen Weise Antwort geben können. Du kannst dir nicht mehr Antwort geben. Die Rätsel schweben vor dir, vernichtend für dich, weil sie dir nach dem Tode nur deine Vernichtung, weil sie deiner Seele im Leben nur den Schein zeigen.

So steht einmal der Mensch heute vor der Welt. Und aus dieser Empfindung heraus entstehen jene Fragen, die Anthroposophie beantworten soll. Die Herzen sprechen aus diesen beiden Empfindungen heraus. Und die Herzen sprechen: Wo ist die Welterkenntnis, welche diesen Empfindungen gerecht wird?

Diese Welterkenntnis möchte Anthroposophie sein. Und sie möchte so über Welt und Menschen sprechen, daß wiederum etwas da sein kann, was verstanden werden kann mit dem modernen Bewußtsein, wie verstanden worden ist alte Wissenschaft, alte Kunst, alte Religion mit dem alten Bewußtsein. Anthroposophie hat durch die Stimme des menschlichen Herzens selber ihre gewaltige Aufgabe. Sie ist nichts anderes als Menschensehnsucht der Gegenwart. Sie wird leben müssen, weil sie die Menschensehnsucht der Gegenwart ist. Das, meine lieben Freunde, will Anthroposophie sein. Sie entspricht dem, was der Mensch am heißesten ersehnt für sein äußeres, für sein inneres Dasein. Und die Frage entsteht: Kann es heute eine solche Weltanschauung geben? Der Welt hat diese Antwort zu geben die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft. Die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft muß den Weg finden, die Herzen der Menschen aus ihren tiefsten Sehnsuchten heraus sprechen zu lassen. Dann werden diese menschlichen Herzen eben auch die tiefste Sehnsucht nach den Antworten empfinden.

First Lecture

My dear friends, if I now attempt to give a kind of introduction to anthroposophy itself, it will be done in such a way that it may also provide a guide to the way in which anthroposophy can be presented to the world today. But I would like to say a few introductory words beforehand. It is not usually sufficiently taken into account that the spiritual is a living thing; and that which is living must also be grasped in its full life. We simply must not, by feeling ourselves to be the bearers of the anthroposophical movement in the Anthroposophical Society, presuppose, as it were, the hypothesis that the anthroposophical movement begins every day. It has been around for more than two decades and the world has taken a stand on it. Therefore, in every way of relating to the world in the anthroposophical sense, there must be this feeling that one is dealing with something on which the world has taken a stand; this feeling must be in the background. If one does not have this feeling and thinks that one is simply representing anthroposophy in the absolute sense, as one could have done two decades ago, then one will continue to present this anthroposophy to the world in a false light. And that has happened just enough. An end should be put to this on the one hand, and on the other hand a beginning should be made through our Christmas conference. This must not remain without effect, as I have already indicated in various directions.

Certainly, not every member of the Anthroposophical Society can be expected to give himself new impulses, so to speak, if this is not given to him according to the constitution of his soul. Everyone has the right to continue to be, I would say, a participating member who takes things in and is content to take things in. But anyone who wants to take part in representing anthroposophy to the world in any form cannot ignore what I have set out. In this respect the fullest truth must prevail in the future, not only in words but in deeds.

Now, my dear friends, I will often speak such introductory words. Let us now begin by giving a kind of introduction to the anthroposophical world view.

Whoever wants to speak about anthroposophy must assume that what he wants to speak is really nothing other than what the heart of his listener says through itself. No initiation or initiatory science in the world has ever intended to say anything other than what the hearts of those who wish to hear it speak through themselves. So that actually, in the most essential sense, this must be the keynote of anthroposophical presentation, to meet what is the deepest need of the heart of those people who need anthroposophy.

If one looks today at those people who have gone beyond the surface of life, one sees that old feelings of every human soul that have passed through the ages have been renewed. You can see that people today have difficult questions in their subconscious, questions that cannot even be put into clear thoughts, let alone find an answer through what is available in the civilized world. But these questions are there. And they are deeply present in a large number of people. They are actually present in all truly thinking people of the present day. But if you put these questions into words, it seems at first as if they are far-fetched, and yet they are so close. They are very close to the human soul, to thinking people.

Two questions can be asked first of all from the whole range of riddles that oppress man today. One question arises for the human soul when this human soul looks at its own human existence and at the world around it. The human soul sees the human being coming into earthly existence through birth. It sees life passing between birth or conception and physical death. It sees this life passing with the most varied inner and outer experiences. And this human soul also sees nature outside, all the abundance of impressions that come to the human being and that gradually fill the human soul.

And there this human soul now stands in the human body and sees one thing above all: Nature actually takes in everything that the human soul sees from physical earth existence. When the human being has passed through the gate of death, then nature, in its powers, takes in the human physical body through some element - being buried in fire or in the ground is not such a great difference - nature takes in the human physical body through some element. But what does it do with this physical body? It destroys it. The human soul does not usually look to see which paths the individual substances of this physical human body take; but if one makes observations at those places where there is a peculiar kind of burial, then this impressive inspection of what nature does with everything that is physical-sensual in man deepens, so to speak, when man has passed through the gate of death. There are underground vaults where human corpses are kept, locked away, but exposed to the air. They dry out. And what do you have after a while? After some time, you have the distorted human form on these corpses, consisting of carbonated lime that has already been atomized. And if you shake this carbonated lime mass, which imitates the distorted human form, just a little, it disintegrates into dust.

This gives a deep impression of what overcomes the soul when it looks at what actually happens to what is done by man between birth and death. And man then looks at the nature that provides him with his knowledge, from which he actually draws everything he calls insight, and says to himself: This nature, which lets the most wonderful crystallization sprout forth from its bosom, this nature, which every spring conjures out of itself the sprouting, sprouting plants, this nature, which sustains the barked trees for decades, this nature, which fills the earth with the animal kingdoms of the most varied kind, from the largest animals to the tiniest bacilli, this nature, which sends up into the clouds that which it carries within itself as water, this nature, upon which shines down that which flows down from the stars in a certain unfamiliarity, this nature, it behaves towards that which man carries within himself between birth and death in such a way that it destroys it to the most complete atomization. For man, nature with its laws is the destroyer. One stands before the human form; this human form, which one has in mind with all the marvelous things it carries with it - and it carries the marvelous things with it, for it is more perfect than all other forms that can be found on earth - this human form, it stands there. And on the other side stands nature with its stones, with its plants, with its animals, with its clouds, with rivers and mountains, with everything that radiates down from the sea of stars, everything that streams down from the sun to the earth in light and warmth, and this nature, in its own lawfulness, does not tolerate the human form. That which stands there as man, when it is handed over to nature, is atomized. Man sees this. He does not form ideas about it, but it sits deep in his mind. Every time man stands before the sight of death, it settles deep into his mind. For it is not out of mere egoistic feeling, not out of a mere superficial hope of living on after death, that a question is subconsciously formed deep in the mind which is infinitely meaningful in the soul, which means happiness and unhappiness for the soul, even if it is not formulated. And all that which may mean happiness and unhappiness for the consciousness of man on earth in terms of fate, it is basically insignificant compared to the uncertainty of feeling that is formulated from the sight of death. For there the question is formulated: Where does this human form come from? I look at the wonderfully formed crystal, I look at the shapes of the plants, I look at the shapes of the animals, I look at how the rivers roll over the earth, I see the mountains, I see everything that speaks from the clouds, that speaks down from the stars. I see all this, man says to himself, but the human form cannot come from all this, for all this has only destructive powers, destructive powers for the human form itself.

And then the anxious question arises before the human mind, before the human heart: Where then is the world from which the human form comes? Where is it, this world? - From the sight of death arises the anxious question: Where is the world, this other world, from which the human form comes?

Do not say, my dear friends, that you have not yet heard this question formulated in this way. If you listen to what people entrust to language out of their heads, you will not hear this question formulated. When one goes before men, and men bring forward the lamentations of their hearts - they sometimes bring forward the lamentations of their hearts by grasping some trifle of life and making all kinds of reflections on this trifle of life, which they insert as a nuance into their whole question of destiny - he who understands this language of the heart hears the heart speaking from the subconscious: What is the other world from which the human form comes, since man does not belong to this world with his form?

And so the world which he sees, which he looks at, which he perceives, about which he forms his science, the world which gives him the basis for the effects of his art, the world which gives him the reasons for his religious worship, so this world presents itself, and man stands on earth and has the feeling in the depths of his mind: I do not belong to this world; there must be another which has conjured me out of its bosom in my form. To which world do I belong? - So it sounds from the hearts of people today. That is the all-encompassing question. And if people are unsatisfied with what today's sciences give them, it is because they ask this question in the depths of their minds and the sciences are far from even touching this question in any way: What is the world to which man actually belongs? - because it is not the visible world.

My dear friends, I know for certain that what I have spoken to you, I have not spoken it, I have only given words to what the heart speaks. And that is the point. For it cannot be a question of conveying to people anything that is unknown to the human souls themselves - that can cause sensation - but it is a question, it can only be a question of putting into words that which the human souls speak through themselves. Whatever man only sees of himself, whatever he sees of his fellow men, as far as it is visible, it does not belong in the rest of the visible world. No finger - so man can say to himself - that I have on me belongs in this world of visibility, for this world of visibility only carries the powers of destruction for every finger.

And so man initially stands before the great unknown. But he stands before this unknown in that he must regard himself as a member of this unknown. In other words, in relation to everything that man is not, it is spiritually light around him; the moment man looks back at himself, the whole world darkens and it becomes dark, and man gropes in the dark, carrying the riddle of his own being through the darkness. And so it is when man looks at himself from the outside, when he finds himself standing inside nature as an external being. He cannot approach this world as a human being.

And again, not the head, but the depths of the unconscious formulate questions that are sub-questions of this general question that I have just discussed. As man contemplates his physical existence, which is his instrument between birth and death, he knows: without this physical world I cannot live this existence between birth and death at all, for I must continually borrow from this existence of the visible world. Every bite I take into my mouth, every drink of water is from this world of visibility, to which I do not belong. I cannot live without it in my physical existence. If I have just taken a mouthful from a substance which must belong to this visible world, and if I pass through the gate of death immediately after I have taken this mouthful, at that moment that which the mouthful is in me belongs to the powers of destruction of this visible world. And that it does not belong to the forces of destruction in myself, my being, my own being, must protect it from this. But nowhere outside in the visible world is this own being to be found. What am I doing with the morsel I take into my mouth, what am I doing with the drink of water I take into my mouth, through my own being? Who am I that receives and transforms the substances of nature? Who am I then? This is the second question, the sub-question that arises from the first.

I not only walk through the darkness by placing myself in relation to the world of visibility, I act in the darkness without knowing who is acting, without knowing what the being is that I call my self. I am completely devoted to the visible world; but I do not belong to it.

This lifts man out of the visible world. It makes him appear to himself as a member of a completely different world. And the anxious, the great question of doubt is there: Where is the world to which I belong? - And the more human civilization has progressed, the more people have learned to think intensively, the more this question has become an anxious one. And today it sits in the depths of people's minds. Insofar as they belong to the civilized world, people are actually divided into two classes with regard to this question. Some push it down, choke it down, do not bring it to clarity, but suffer from it as from a terrible longing to solve this human riddle; others numb themselves to this question, talk themselves into all kinds of things from external existence in order to numb themselves. And by numbing themselves, they eradicate within themselves the solid feeling of their own being. Nothingness afflicts their souls. And this feeling of nothingness resides in the subconscious of countless people today.

This is one side, the one big question with the aforementioned sub-question. It sprouts up when man looks at himself from the outside and perceives his relationship to the world as a human being between birth and death in a very subdued, subconscious way.

The other question, however, arises when man looks into his own inner self. There is the other pole of human existence. In there are the thoughts. They represent the outer nature. Through his thoughts, man represents external nature. Man develops sensations, feelings about external nature. Man affects external nature through his will. Man first looks back at his own inner self. The surging thoughts, feelings and will are in front of his soul. Thus he stands with his soul in the present. Added to this are the memories of past experiences, the memories of things seen in earlier times of the present earthly existence. All this fills the soul. What is it?

Now man does not form clear ideas about that which he actually retains within himself; but the subconscious forms these ideas. A single migraine that scares away the thoughts immediately turns the inner being of man into a riddle. And every state of sleep makes it a question of riddles when man lies motionless and lacks the possibility of corresponding with the outside world through his senses. Man feels, his physical body must be active, then the thoughts, the feelings, the impulses of will arise in his soul. But the stone that I have just looked at, which perhaps has this or that crystal form - I turn away from it, after a while I turn towards it again - it has remained as it is. My thought, it rises up, it presents itself as an image in the soul, it glows down again. It is perceived as infinitely more valuable than the muscles, than the bones that man carries within him, but it is something that fades away, it is a mere image. It is less than a picture that I have hanging on the wall; for the picture that I have hanging on the wall remains for a time until it disintegrates through its substance. The thought flies by. Thought is an image that continually arises and passes away, a fluctuating image, an image that comes and goes, an image that is satisfied in its pictorial existence. And yet, if man looks into the interior of his soul, he has nothing other than these imaginary images. He can say nothing other than: his soul consists of these images.