Anthroposophy, An Introduction

GA 234

20 January 1924, Dornach

2. Meditation

Yesterday I had to show how we can observe ourselves in two ways, and how the riddle of the world and of man confronts us from both directions. If we look once more at what we found yesterday, we see, on the one hand, the human physical body, perceived—at first—in the same way as the external, physical world. We call it the physical body because it stands before our physical senses just as the external, physical world. At the same time, however, we must call to mind the great difference between the two. Indeed, yesterday we had to recognise this great difference from the fact that man, on passing through the gate of death, must surrender his physical body to the elements of the external, physical world; and these destroy it. The action of external Nature upon the human physical body is destructive, not constructive. So we must look quite outside the physical world for what gives the human physical body its shape between birth (or conception) and death. We must speak, to begin with, of another world which builds up this human body that external, physical Nature can only destroy.

On the other hand there are two considerations which show the close relationship between the human physical body and Nature. In the first place, the body requires substances—building materials in a sense—although this is not strictly accurate. Let us say, it has need of the substances of external nature, or, at least, needs to take them in.

Again: when we observe the external manifestations of the physical body—whether it be its excretions, or the whole body as seen after death—it is nevertheless substances of the external, physical world that we observe. We always find the same substances as in the external, physical world—whether we are studying the separate excretions or the whole physical body cast off at death.

So we are compelled to say: Whatever the inner processes going on in the human body may be, their beginning and end are related to the external, physical world.

Materialistic science, however, draws from this fact a conclusion that cannot be drawn at all. Though we see how man, through eating, drinking and breathing, takes in substances from the external physical world and gives these same substances back again, in expiration, in excretion or at death, we can only say that we have here to do with a beginning and an end. We have not determined the intermediary processes within the physical body.

We speak so glibly of the blood man bears within him; but has anyone ever investigated the blood within the living human organism itself? This cannot be done with physical means at all. We have no right to draw the materialistic conclusion that what enters the body and leaves it again was also within it.

In any case, we see an immediate transformation when external, physical substances are taken in—let us say, by the mouth. We need only put a small grain of salt in the mouth and it is at once dissolved. The transformation is immediate. The physical body of man is not the same, in its inner nature, as the external world; it transforms what it takes in, and then transforms it back again. Thus we must seek for something within the human organism that is, at first, similar to external nature and, on excretion, becomes so again. It is what lies between these two stages that we must first discover.

Try to picture this that I have said: On the one hand, we have what the organism takes in; on the other, what it gives of including even the physical body as a whole. Between these are the processes within the organism itself. From the study of what the human physical organism takes in we can say nothing at all about the relation of man to external nature. We might put it this way: Though external physical nature does destroy man's corpse, dissolving and dissipating it, man does, with his organism, ‘get even’ with Nature. He dissolves everything he receives from her. Thus, when we commence with man's organs of assimilation, we find no relationship to external nature, for this is destroyed by them. We only find such a relationship when we turn to what man excretes. In relation to the form man bears into physical life, Nature is a destroyer; in regard to what man casts off, Nature receives what the human organism provides. Thus the human physical organism comes eventually to be very unlike itself and to resemble external Nature very much. It does this through excretion.

If you think this over you will say to yourself: There, outside, are the substances of the different kingdoms of Nature. They are, today, just what they have become; but they have certainly not always been as they are. Even physical science admits that past conditions of the earth were very different from those of today. What we see around us in the kingdoms of Nature has only gradually become what it is. And when we look at man's physical body we see it destroys—or transforms—what it takes in. (We shall see that it really destroys, but for the moment we will say ‘transforms’.) At any rate, what is taken in must be reduced to a certain condition from which it can be led back again to present physical Nature. In other words: If you think of a beginning somewhere in the human organism, where the sub-stances begin to develop in the direction of excretions, and then think of the earth, you are led to trace it back to a similar condition in which it once was. You have to say: At some past time the whole earth must have been in the condition in which some-thing within man is today; and in the short space of time during which something incorporated into the human organism is transformed into excretory products, the inner processes of the organism recapitulate what the earth itself has accomplished in the course of long ages.

Thus we look at external Nature today and see that it was once something very different. But when we try to find something similar to its former condition we have to look into our own organism. The beginning of the earth is still there. Every time we eat, the substances of our food are transformed into a condition in which the whole earth once was. The earth has developed further in the course of long periods of time and become what it is today; our food substances, in developing to the point of excretion, give a brief recapitulation of the whole earth-process.

Now, you can look at the vernal point of the zodiac, where the sun rises every spring. This point is not stationary; it is advancing. In the Egyptian epoch, for example, it was in the constellation of Taurus. It has advanced through Taurus and Aries, and is today in the constellation of Pisces; and it is still advancing. It moves in a circle and will return after a certain time. Though this point where the sun rises in spring describes a complete circle in the heavens in 25,920 years, the sun describes this circle every day. It rises and sets, thereby describing the same path as the vernal point. Let us contemplate, on the one hand, the long epoch of 25,920 years, which is the time taken by the vernal point to complete its path; and on the other hand, the short period of twenty-four hours in which the sun rises, sets and rises again at the same point. The sun describes the same circle. It is similar with the human physical organism. Through long periods the earth consisted of substances like those within us at a certain stage of digestion—the stage midway between ingestion and egestion, when the former passes over into the latter. Here we carry within us the beginning of the earth. In a short period of time we reach the excretory stage, in which we resemble the earth; we hand over substances to the earth in the form they have today. In our digestive processes we do in the physical body something similar to what the sun does in its diurnal round with respect to the vernal point. Thus we may survey the physical globe and say: Today this physical globe has reached a condition in which its laws destroy the form of our physical organism. But this earth must once have been in a condition in which it was subjected to other laws—laws which, today, bring our physical organism into the condition of food-stuffs midway between ingestion and egestion. That is to say, we bear within us the laws of the earth's beginning; we recapitulate what was once on the earth.

You see, we may regard our physical organism as organised for taking in external substances—present-day substances—and excreting them again as such; but it bears within it something that was present in the beginning of the earth but which the earth no longer has. This has disappeared from the earth leaving only the final products, not the initial substances. Thus we bear within us something to be sought for in very ancient times within the constitution of the earth. It is what we thus bear within us, and the earth as a whole has not got, that raises us above physical, earthly life. It leads man to say: I have preserved within me the beginning of the earth. Through entering physical existence through birth, I have ever within me something the earth had millions of years ago, but has no longer.

From this you see that, in calling man a microcosm, we cannot merely take account of the world around us today. We must go beyond its present condition and consider past stages of its evolution. To understand man we must study primeval conditions of the earth.

What the earth no longer possesses but man still has in this way, can become an object of observation. We must have recourse to what may be called meditation. We are accustomed merely to allow the ‘ideas’ or, mental presentations [Vorstellungen], whereby we perceive the world, to arise within us—merely to represent the outer world to ourselves with the help of such ideas. And for the last few centuries man has become so accustomed to copy merely the outer world in his ideas, that he does not realise his power of also forming ideas freely from within. To do this is to meditate; it is to fill one's consciousness with ideas not derived from external Nature, but called up from within. In doing so we pay special attention to the inner activity involved. In this way one comes to feel that there is really a ‘second man’ within, that there is something in man that can really be inwardly felt and experienced just as, for example, the force of the muscles when we stretch out an arm. We experience this muscular force; but when we think we ordinarily experience nothing. Through meditation, however, it is possible so to strengthen our power of thinking—the power whereby we form thoughts—that we experience this power inwardly, even as we experience the force of our muscles on stretching out an arm. Our meditation is successful when we are at length able to say: In my ordinary thinking I am really quite passive. I allow something to happen to me; I let Nature fill me with thoughts. But I will no longer let myself be filled with thoughts, I will place in my consciousness the thoughts I want to have, and will only pass from one thought to another through the force of inner thinking itself. In this way our thinking becomes stronger and stronger, just as the force of our muscles grows stronger if we use our arms. At length we notice that this thinking activity is a ‘tension’, a ‘touching’, an inner experience, like the experience of our own muscular force. When we have so strengthened ourselves within that our thinking has this character, we are at once confronted in our consciousness by what we carry within us as a repetition of an ancient condition of the earth. We learn to know the force that transforms food substances within the body and retransforms them again. And in experiencing this higher man within, who is as real as the physical man himself, we come, at the same time, to perceive with our strengthened thinking the external things of the world.

Suppose, my dear friends, I look at a stone with such strengthened thinking. Let us say it is a crystal of salt or of quartz. It seems to me like meeting a man I have already seen. I am reminded of experiences I had with him ten or twenty years ago. In the mean-time he may have been in Australia, or anywhere, but the man before me now conjures up the experience I had with him ten or twenty years ago. So, if I look at a crystal of salt or of quartz with this strengthened thinking, there immediately comes before my mind the past state of the crystal, like the memory of a primeval condition of the earth. At that time the crystal of salt was not hexahedral, i.e. six-faced, for it was all part of a surging, weaving, cosmic sea of rock. The primeval condition of the earth comes before me, as a memory is evoked by present objects.

I now look again at man, and the very same impression that the primeval condition of the earth made upon me, is now made by the ‘second human being’ man carries within him. Further: the very same impression is made upon me when I behold, not stones, but plants. Thus I am led to speak, with some justification, of an ‘etheric body’ as well as the physical. Once the earth was ether; out of this ether it has become what it is today in its inorganic, lifeless constituents. The plants, however, still bear within them the former primeval condition of the earth. And I myself bear within me, as a second man, the human ‘etheric body’.

All that I am describing to you can become an object of study for strengthened thinking. So we may say that, if a man takes trouble to develop such thinking he perceives, besides the physical, the etheric in himself, in plants and in the memory of primeval ages evoked by minerals.

Now, what do we learn from this higher kind of observation? We learn that the earth was once in an etheric condition, that the ether has remained and still permeates the plants, the animals—for we can perceive it in them too—and the human being.

But now something further is revealed. We see the minerals free from ether, and the plants endowed with it. At the same time, however, we learn to see ether everywhere. It is still there today, filling cosmic space. In the external, mineral kingdom alone it plays no part; still, it is everywhere. When I simply lift this piece of chalk, I observe all sorts of things happening in the ether. Indeed, lifting a piece of chalk is a complicated process. My hand develops a certain force, but this force is only present in me in the waking state, not when I am asleep. If I follow what the ether does in transmuting food-stuffs, I find this going on during both waking and sleeping states. One might doubt this in the case of man, if one were superficial, but not in the case of snakes; they sleep in order to digest. But what takes place through my raising an arm can only take place in the waking state. The etheric body gives no help here. Nevertheless if I only lift the chalk I must overcome etheric forces—I must work upon the ether. My own etheric body cannot do this. I must bear within me a ‘third man’ who can.

Now this third man who can move, who can lift things, including his own limbs is not to be found—to begin with—in anything similar in external Nature. Nevertheless external Nature, which is everywhere permeated by ether, enters into relation with this ‘force-man’—let us call him—into whom man himself pours the force of his will.

At first it is only in inner experience that we can become aware of this inner unfolding of forces. If, however, we pursue meditation further, not only forming our ideas ourselves, and passing from one idea to another in order to strengthen our thinking, but eliminating again the strengthened thinking so acquired—i.e. emptying our consciousness—we attain something special. Of course, if one frees oneself of ordinary thoughts passively acquired, one falls asleep. The moment one ceases to perceive or think, sleep ensues, for ordinary consciousness is passively acquired. If, however, we develop the forces whereby the etheric is perceived, we have a strengthened man within us; we feel our own thinking forces as we usually feel our muscular forces. And now, when we deliberately eliminate, ‘suggest away’ this strengthened man we do not fall asleep, but expose our empty consciousness to the world. What we dimly feel when we move our arms, or walk, when we unfold our will, enters us objectively. The forces at work here are nowhere to be found in the world of space; but they enter space when we produce empty consciousness in the way described. We then discover, objectively, this third man within us. Looking now at external Nature we observe that men, animals and plants have etheric bodies, while minerals have not. The latter only remind us of the original ‘ether’ of the earth. Nevertheless there is ether wherever we turn, though it does not always reveal itself as such.

You see, if you confront plants with the ‘meditative’ consciousness I described at first, you perceive an etheric image; likewise if you confront a human being. But if you confront the universal ether it is as if you were swimming in the sea. There is only ether everywhere. It gives you no ‘picture.’ But the moment I merely lift this piece of chalk there appears an image in the etheric where my third man is unfolding his forces.

Picture this to yourselves: The chalk is, at first, there. My hand now takes hold of the chalk and lifts it up. (I could represent the whole process in a series of snapshots.) All this, however, has its counterpart in the ether, though this cannot be seen until I am able to perceive by means of ‘empty consciousness’—i.e. until I am able to perceive the third man, not the second. That is to say, the universal ether does not act as ether, but in the way the third man acts.

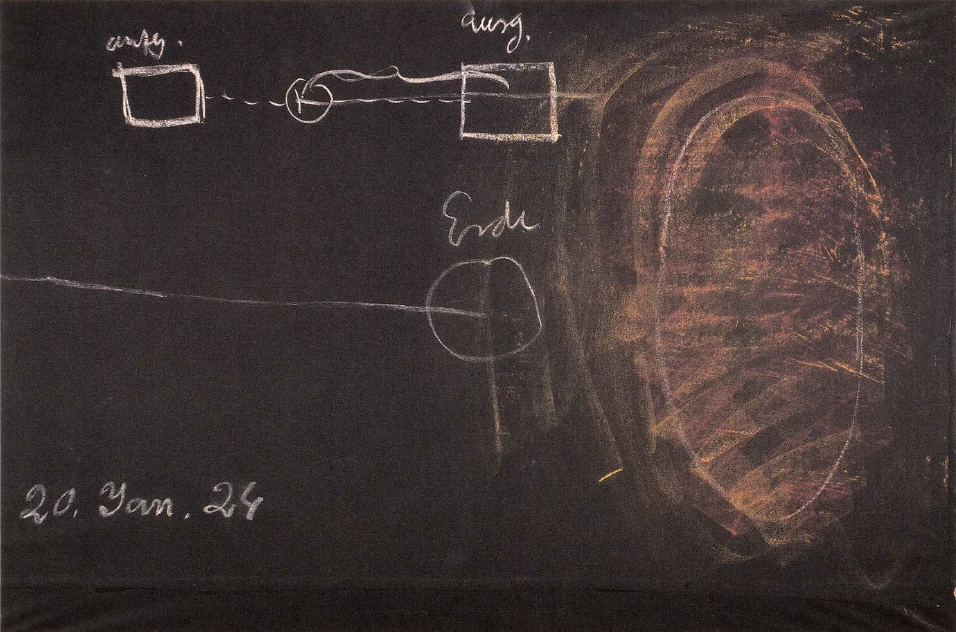

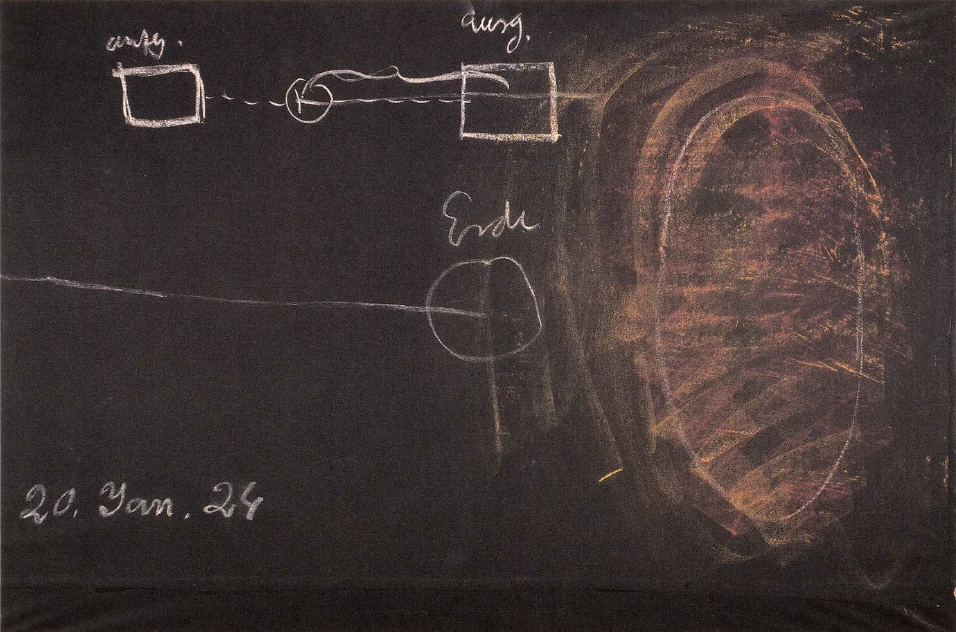

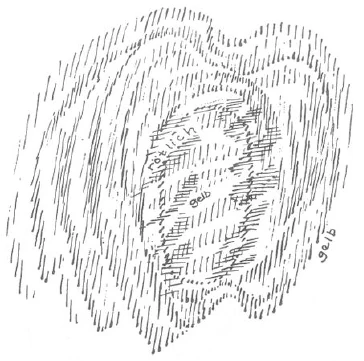

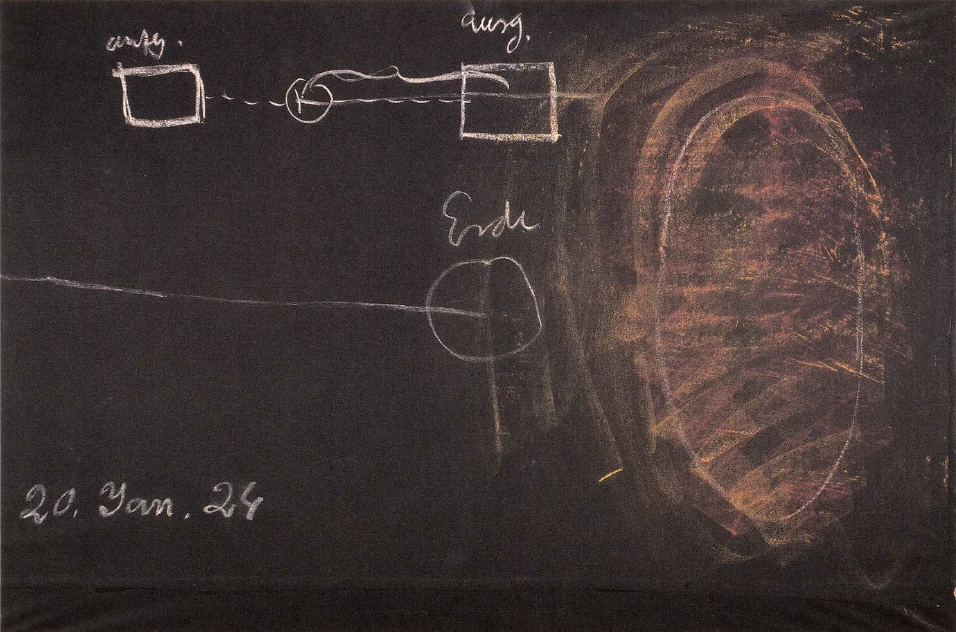

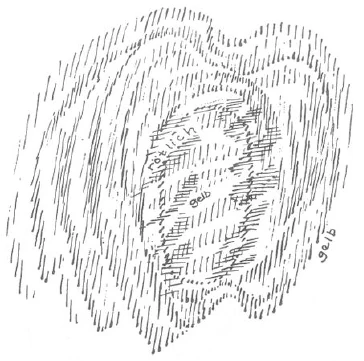

Thus I may say: I have first my physical body (oval),1The drawings in this volume are reconstructions of those freely drawn by Rudolf Steiner in coloured chalks on the blackboard. Some were made progressively but as depicted here they are from the completed sketches. Reproduction in colour is impracticable. then my etheric body, perceived in ‘meditative’ consciousness (yellow), then the third man, which I will call the ‘astral’ man (red). Everywhere around me I have what we found to be the second thing in the universe—the universal ether (yellow). This, to begin with, is like an indefinite sea of ether.

Now the moment I radiate into this ether anything that proceeds from this third man within me, it responds; this ether responds as if it were like the third man within me, i.e. not etherically, but ‘astrally’. Thus I release through my own activity something within this wide sea of ether that is similar to my own ‘third man’. What is this that acts in the ether as a counter-image? I lift the chalk; any hand moves from below upwards. The etheric picture, however, moves from above downwards; it is an exact counter-image. It is really an astral picture, a mere picture. Nevertheless, it is through the real, present-day man that this picture is evoked. Now, if I learn, by means of what I have already described, to look backwards in earth-evolution—if I learn to apply to cosmic evolution what is briefly recapitulated in the way described—I discover the following:

Here is the present condition of the earth. I go back to an etheric earth. I do not find there, as yet, what has been released through me in the surrounding ether. I must go farther back to a still earlier condition of the earth in which the earth resembled my own astral body. The earth was then astral—a being like my third man. I must look for this being in times long past, in times long anterior to those in which the earth was etheric. Going back-wards in time is really no different from seeing a distant object—a light, let us say—that shines as far as this. It is over there, but shines as far as here; it sends images to us here. Now put time instead of space: That which is of like nature with my own astral body was there in primeval times. Time has not ceased to be; it is still there. Just as, in space, light can shine as far as here, so that which lies in a long gone past works on into the present. Fundamentally speaking, the whole time-evolution is still there. What-ever was once there—and is of like nature with that which, in the outer ether, resembles my own astral body—has not disappeared.

Here I touch on something that, spiritually, is actively present and makes time into space. It is really no different from communicating over a long distance with the help of a telegraph. In lifting the chalk I evoke a picture in the ether and communicate with what, for outer perception, has long passed away.

We see how man is placed in the world in a quite different way from what appears at first. And we understand, too, why cosmic riddles present themselves to him. He feels within that he has an etheric body, though he does not realise it clearly: even science does not realise it clearly today. He feels that this etheric body transforms his food-stuffs and transforms them back again. He does not find this in stones, though the stones were already there, in primeval times which he discovers, there as general ether. But in this ether a still more remote past is active. Thus man bears within him an ancient past in a twofold way; a more recent past in his etheric body and a more ancient past in his astral body.

When man confronts Nature today he usually only studies what is lifeless. Even what is living in plants is only studied by applying to them the laws of substances as discovered in his laboratory. He omits to study growth; he neglects the life in his plants. Present-day science really studies plants as one who picks up a book and observes the forms of the letters, but does not read. Science, today, studies all things in this way.

Indeed, if you open a book but cannot read, the forms must appear very puzzling. You cannot really understand why there is here a form like this: ‘b’, then ‘a’, then ‘l’, then ‘d’, i.e. bald. What are these forms doing side by side? That is, indeed, a riddle. The way of regarding things that I have put before you is really learning to read in the world and in man. By ‘learning to read’ we come gradually near to the solution of our riddles.

You see, my dear friends, I wanted to put before you merely a general path for human thinking along which one can escape from the condition of despair in which man finds himself and which I described at the outset. We shall proceed to study how one can advance farther and farther in reading the phenomena in the outer world and in man.

In doing this, however, we are led along paths of thought with which man is quite unfamiliar today. And what usually happens? People say: I don't understand that. But what does this mean? It only means that this does not agree with what was taught them at school, and they have become accustomed to think in the way they were trained. ‘But do not our schools take their stand on genuine science?’ Yes, but what does that mean? My dear friends, I will give you just one example of this genuine science.—One who is no longer young has experienced many things like this. One learnt, for example, that various substances are necessary for the process referred to today—the taking in of foodstuffs and their transformation within the human organism. Albumens (proteins), fats, water, salts, sugar and starch products were cited as necessary for men. Then experiments were made.

If we go back twenty years, we find that experiments showed man to require at least one hundred and twenty grammes of protein a day; otherwise he could not live. That was ‘science’ twenty years ago. What is ‘science’ today? Today twenty to fifty grammes are sufficient. At that time it was ‘science’ that one would become ill—under-nourished—if one did not get these one hundred and twenty grammes of protein. Today science says it is injurious to one's health to take more than fifty grammes at the most; one can get along quite well with twenty grammes. If one takes more, putrefying substances form in the intestines and auto-intoxication, self-poisoning, is set up. Thus it is harmful to take more than fifty grammes of protein. That is science today.

This, however, is not merely a scientific question, it has a bearing on life. Just think: twenty years ago, when it was scientific to believe that one must have one hundred and twenty grammes of protein, people were told to choose their diet accordingly. One had to assume that a man could pay for all this. So the question touched the economic sphere. It was proved carefully that it is impossible to obtain these one hundred and twenty grammes of protein from plants. Today we know that man gets the requisite amount of protein from any kind of diet. If he simply eats sufficient potatoes—he need not eat many—along with a little butter, he obtains the requisite amount of protein. Today it is scientifically certain that this is so. Moreover, it is a fact that a man who fills himself with one hundred and twenty grammes of protein acquires a very uncertain appetite. If, on the other hand, he keeps to a diet which provides him with twenty grammes of protein, and happens, once in a while, to take food with less, and which would therefore under-nourish him, he turns from it. His instinct in regard to food becomes reliable. Of course, there are still under-nourished people, but this has other causes and certainly does not come from a deficiency of protein. On the other hand, there are certainly numerous people suffering from auto-intoxication and many other things because they are over-fed with protein.

I do not want to speak now of infectious diseases, but will just mention that people are most susceptible to so-called infection when they take one hundred and twenty grammes of protein [a day]. They are then most likely to get diphtheria, or even small-pox. If they only take twenty grammes, they will only be infected with great difficulty.

Thus it was once scientific to say that one requires so much protein as to poison oneself and be exposed to every kind of infection. That was ‘science’ twenty years ago! All this is a part of science; but when we see what was scientific in regard to very important matters but a short time ago, our confidence in such science is radically shaken.

This, too, is something one must bear in mind when we encounter a study like Anthroposophy that gives to our thinking, our whole mood of soul, a different direction from that customary today. I only wanted to point, so to speak, to what is put forward—in the first place—as preliminary instruction in the attainment of another kind of thinking, another way of contemplating the world.

Zweiter Vortrag

Gestern hatte ich darauf hinzuweisen, wie der Mensch nach zwei Seiten hin sich betrachten kann, und wie nach diesen zwei Seiten hin an den Menschen das Welten- und das Menschenrätsel herantritt. Wenn wir noch einmal hinblicken auf dasjenige, was sich uns gestern ergeben hat, so sehen wir auf der einen Seite das, was zunächst auf dieselbe Weise wahrgenommen wird wie die äußere physische Welt. Wir sehen den menschlichen physischen Leib. Wir nennen ihn deshalb physischen Leib, weil er für unsere physischen Sinne so vor uns dasteht wie die äußere physische Welt. Aber wir müssen zugleich gedenken des gewaltigen Unterschiedes gerade dieses physischen Menschenleibes von der äußeren physischen Welt. Und wir haben diesen gewaltigen Unterschied gestern daran wahrzunehmen gehabt, daß in dem Augenblicke, wo der Mensch, durch die Pforte des Todes tretend, den physischen Leib den Elementen der äußeren physischen Welt übergeben muß, daß in diesem Augenblicke dieser physische Leib von der äußeren Natur vernichtet wird. Die äußere Natur hat also nicht in ihren Aufbaukräften, sondern in ihren Zerstörungskräften dasjenige, womit sie den menschlichen physischen Leib behandelt. Und wir müssen daher das, was dem menschlichen physischen Leib seine Gestalt gibt von der Geburt oder von der Empfängnis bis zum Tode, ganz außerhalb der physischen Welt suchen. Wir müssen von einer zunächst anderen Welt sprechen, die diesen physischen Menschenleib aufbaut, denn die äußere physische Natur kann ihn nicht aufbauen, sie kann ihn nur vernichten.

Aber auf der anderen Seite sind zwei Dinge da, welche diesen physischen Menschenleib in ein ganz nahes Verhältnis zur Natur bringen. Auf der einen Seite bedarf dieser physische Menschenleib der Substanzen für seinen Aufbau, gewissermaßen als seiner Baumaterialien, obwohl das im uneigentlichen Sinne gesprochen ist, er bedarf der Substanzen der äußeren Natur, oder wenigstens können wir sagen, er bedarf der Aufnahme der Substanzen der äußeren Natur.

Und doch, wenn wir, sei es in den Ausscheidungen, die sich ergeben, sei es, daß der ganze physische Leib des Menschen uns nach dem Tode als Leichnam entgegentritt, wenn wir das betrachten, was dieser physische Leib nach außen offenbart, so sind es doch wiederum die Substanzen der äußeren physischen Welt; denn wo wir auch diesen physischen Leib betrachten, seien es die einzelnen Ausscheidungen, sei es die Abscheidung des ganzen physischen Leibes mit dem Tode, er stellt sich uns dar als offenbarend dieselben Substanzen, die wir auch in der äußeren physischen Welt finden. So daß wir sagen müssen: Was auch immer in diesem Wesen des Menschen vor sich geht, Anfang und Ende der inneren Prozesse, der inneren Vorgänge sind verwandt der äußeren physischen Welt.

Aber die materialistische Wissenschaft zieht aus der eben erwähnten Tatsache einen Schluß, der ganz und gar nicht gezogen werden kann. Wenn wir auf der einen Seite sehen, daß der Mensch durch Essen oder Trinken oder durch Atmen die Substanzen der äußeren physischen Welt in sich aufnimmt, daß er durch Ausatmen, Ausscheiden oder im Tode diese Substanzen wiederum an die äußere Welt abgibt als solche Substanzen, die mit denen der äußeren Welt übereinstimmen, so können wir doch nur sagen, daß wir es da mit einem Anfang und mit einem Ende zu tun haben. Was dazwischen im menschlichen physischen Leibe vor sich geht, das ist damit nicht ausgemacht.

Man spricht so leichten Herzens von dem Blute, das der Mensch in sich trägt. Aber hat jemals ein Mensch dieses Blut im lebenden menschlichen Organismus selber untersucht? Das kann man ja gar nicht mit physischen Mitteln. So daß also nicht ohne weiteres der materialistische Schluß gezogen werden darf: dasjenige, was in den Körper hineingeht und was wieder aus ihm herausgeht, das ist auch in dem menschlichen Organismus drinnen.

Aber jedenfalls sehen wir, schon wenn die Aufnahme von äußeren physischen Substanzen, sagen wir zum Beispiel im Munde beginnt, daß sogleich eine Verwandelung eintritt. Wir brauchen ja nur ein Körnchen Salz in den Mund zu nehmen, sofort muß es aufgelöst werden. Es tritt sofort eine Verwandelung ein. Der menschliche physische Leib in seinem Inneren ist nicht gleich der äußeren Natur. Er verwandelt dasjenige, was er aufnimmt und verwandelt es wiederum zurück. So daß wir im menschlichen physischen Organismus etwas zu suchen haben, was in seinem Anfange bei der Aufnahme der physischen Substanzen ähnlich ist der äußeren Natur, was bei seiner Ausgabe ähnlich ist der äußeren Natur. Dazwischen aber liegt dasjenige, was eben erst erkannt werden muß im Menschenwesen.

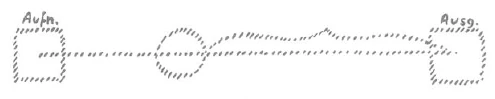

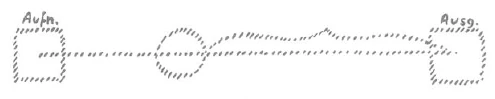

Stellen Sie sich einmal dasjenige schematisch vor, was ich gesagt habe (siehe Zeichnung). Wir haben das, was der menschliche physische Organismus aufnimmt, und wir haben das, was er ausgibt, auch als seinen ganzen Leib ausgibt. Dazwischen liegen die Vorgänge, die im menschlichen Organismus vor sich gehen zwischen der Aufnahme und der Ausgabe. Wir können gar nicht bei dem, was der menschliche physische Organismus aufnimmt, irgend etwas über das Verhältnis des Menschen zur äußeren Natur sagen. Denn man möchte das aussprechen: Wenn es schon so ist, daß die äußere physische Natur den Leichnam des Menschen vernichtet, auflöst, zerstäubt, der Mensch zahlt der äußeren Natur in bezug auf seinen eigenen Organismus das wiederum zurück. Er löst auch alles auf, was er von der äußeren Natur empfängt. Also wenn wir bei denjenigen Organen beginnen, durch die der Mensch Physisches aufnimmt, kommen wir zu keinem Verhältnis zur äußeren Natur, denn die vernichten die äußere Natur. Wir kommen allein zu einem Verhältnis des Menschen zur äußeren Natur, wenn wir auf das hinschauen, was der Mensch ausscheidet. Mit Bezug auf die Gestalt, die der Mensch ins physische Leben hereinträgt, ist die Natur eine Zerstörerin; in bezug auf dasjenige, was er ausscheidet, nimmt sie das auf, was der menschliche Organismus liefert. So daß der menschliche physische Organismus an seinem Ende sich selber ganz ungleich, aber der äußeren Natur sehr ähnlich wird. Der menschliche physische Organismus macht sich der äußeren Natur erst ähnlich, indem er ausscheidet.

Wenn Sie dies bedenken, dann werden Sie sich sagen: Draußen in der Natur sind die Substanzen der verschiedenen Naturreiche. Sie sind heute nun einmal, wie sie eben geworden sind; aber sie sind ganz gewiß nicht immer so gewesen. Das gibt selbst die physische Wissenschaft zu, daß, wenn man zurückgeht im Zeitenverlaufe und man zu alten Zuständen des Irdischen kommt, diese ganz anders sind als heute; also dasjenige, was uns draußen in den Reichen der Natur umgibt, ist erst zu dem geworden, was es heute ist. Und wenn man auf den menschlichen physischen Leib hinsieht, so muß man sich sagen: Der menschliche physische Leib vernichtet, was er aufnimmt, zunächst in sich, verwandelt es - wir werden schon darauf kommen, daß er es in Wirklichkeit vernichtet, aber sagen wir zunächst verwandelt -, jedenfalls muß er es zu einem gewissen Zustande bringen, aus dem heraus er es dann weiterführen kann bis zu der heutigen physischen Natur. Das heißt, wenn Sie sich auf der einen Seite irgendwo im menschlichen Organismus einen Anfang denken, wo die Substanzen beginnen sich bis zu den Ausscheidungen hin zu entwickeln, und dann die Erde sich denken (siehe Zeichnung), so muß die Erde nur in einer langen Zeit irgendwo irgendwie zurückgehen zu einem Zustande, in dem sie einmal war, und in dem heute das Innere des menschlichen physischen Organismus ist. Sie müssen sagen: Es muß irgendwo in der Vergangenheit die ganze Erde in einem Zustande gewesen sein, worin heute irgendetwas im Inneren des Menschen ist. Und in der kurzen Spanne Zeit, in der sich im menschlichen Organismus ein in ihm organisch Verwobenes in die Ausscheidungen verwandelt, in dieser kurzen Zeit wiederholen die inneren Vorgänge des menschlichen Organismus dasjenige, was im Laufe langer Zeiträume von der Erde selber vollzogen worden ist.

Wir schauen daher auf die äußere Natur und sagen uns: Dasjenige, was heute äußere Natur ist, es war einmal ganz anders. Aber wenn wir auf den Zustand, in dem diese äußere Natur einmal war, hinschauen und etwas ähnliches finden wollen, dann müssen wir in unseren eigenen Organismus hineinschauen. Da ist noch der Erdenanfang drinnen. Jedesmal, wenn wir essen, kommen die Eßmaterialien im Inneren durch die Verwandelung, die sie durchmachen, in einen Zustand, in dem die ganze Erde einmal war. Und die Erde hat im Laufe langer Zeiträume sich weiter entwickelt, ist das geworden, was sie heute ist. Wir haben dasjenige, was im Menschen vorhanden ist als ein Zustand seiner verzehrten Nahrungsmittel, die sich entwickeln bis zu den Ausscheidungen. In dieser Entwickelung eines kurzen Zeitraumes liegt, kurz wiederholt, der ganze Erdenprozeß.

Sehen Sie, man kann auf den Frühlingspunkt blicken, in dem jährlich im Frühling die Sonne aufgeht. Er verschiebt sich, er schreitet vorwärts. In alten Zeiten, sagen wir im ägyptischen Zeitraum, war der Frühlingspunkt im Sternbilde des Stieres. Er ist fortgeschritten durch das Sternbild des Stieres, des Widders, steht heute im Sternbild der Fische. Und dieser Frühlingspunkt läuft immer weiter und weiter. Er läuft im Kreise herum. Er muß nach einiger Zeit wiederum zurückkommen. Der Sonnenaufgangspunkt durchläuft einen Himmelskreis in 25920 Jahren. Die Sonne durchläuft diesen Kreis jeden Tag. Sie geht auf, sie geht unter und durchläuft dabei dieselbe Bahn, die der Frühlingspunkt durchläuft. Wir blicken auf den langen Zeitraum von 25920 Jahren als der Umlaufszeit des Frühlingspunktes. Wir blicken auf den kurzen Zeitraum eines Sonnenauf- und -unterganges bis zum Zurückkommen wiederum zum Aufgangspunkte - auf einen vierundzwanzigstündigen Zeitraum blicken wir. Da durchläuft die Sonne denselben Kreis in kurzer Zeit.

So ist es mit dem menschlichen physischen Organismus. Im Laufe längerer Jahre hat die Erde aus Substanzen bestanden, die gleich denen sind, die wir in uns tragen, wenn wir einen gewissen Grad der Verdauung erreicht haben, gerade den Zwischenpunkt zwischen der Aufnahme und der Ausscheidung, wo sich die Aufnahme in die Ausscheidung verwandelt; da tragen wir in uns den Erdenanfang. In kurzer Zeit bringen wir es bis zu der Ausscheidung. Da sind wir der Erde ähnlich. Da werden die Stoffe in der Form, wie sie heute sind, der Erde übergeben. Wir tun mit unserem Ernährungsprozeß im physischen Leib etwas ähnliches, wie es die Sonne tut bei ihrem Umgang gegenüber dem Frühlingspunkte. Wir dürfen daher hinausschauen auf das physische Erdenrund und dürfen sagen: Heute ist dieses physische Erdenrund bei Gesetzen angekommen, welche die Gestalt unseres physischen Organismus auflösen. Aber diese Erde muß einmal in einem Zustande gewesen sein, wo auf sie Gesetze wirkten, die heute unseren physischen Organismus dahin bringen, wo eben die Nahrungsmittel sind, wenn sie zwischen Aufnahme und Ausscheidung in der Mitte drinnenstehen. Das heißt, wir tragen die Gesetze des Erdenanfangs in uns. Wir wiederholen dasjenige, was einmal auf der Erde da war.

Nun, so können wir sagen: Wenn wir unseren physischen Organismus ansehen als dasjenige, das die äußeren Stoffe aufnimmt und sie wiederum abschiebt in der Form von äußeren Stoffen, so ist dieser physische Organismus in einem gewissen Sinne also hinorganisiert auf die Aufnahme und Ausscheidung der heutigen Substanzen; aber in sich trägt er etwas, was im Erdenanfange vorhanden war, was heute die Erde nicht mehr hat, was aus ihr verschwunden ist, denn die Erde hat die Endprodukte, nicht aber die Anfangsprodukte. Wir tragen also etwas in uns, was wir suchen müssen in sehr, sehr alten Zeiten innerhalb der Konstitution der Erde. Und was wir so in uns tragen, was zunächst die Erde als Ganzes nicht hat, das ist dasjenige, das den Menschen hinaushebt über das physische Erdendasein. Das ist dasjenige, was den Menschen dazu bringt, sich zu sagen: Ich habe in mir den Erdenanfang bewahrt. Ich trage, indem ich durch die Geburt ins physische Dasein hereintrete, immer etwas in mir, was die Erde heute nicht hat, aber vor Jahrmillionen gehabt hat.

Sie sehen daraus, daß wir, wenn wir den Menschen eine kleine Welt nennen, nicht bloß Rücksicht darauf nehmen können, wie die Welt um uns herum heute ist, sondern daß wir über den heutigen Zustand in die Entwickelungszeiten hineingehen müssen, daß wir, um den Menschen zu verstehen, uralte Erdenzustände ins Auge fassen müssen.

Dasjenige, was auf diese Art an dem Menschen noch vorhanden ist, was die Erde nicht mehr hat, kann aber dennoch vor der menschlichen Beobachtung auftreten. Und das geschieht dadurch, daß der Mensch zu dem greift, was man meditieren nennen kann. Man ist gewöhnt, die Vorstellungen, durch die man die äußere Welt wahrnimmt, einfach in sich entstehen zu lassen, die äußere Welt durch diese Vorstellungen abzubilden. Und in den letzten Jahrhunderten hat sich der Mensch so stark gewöhnt, nur die äußere Welt abzubilden, daß er gar nicht dazu kommt, sich innerlich bewußt zu werden, daß er auch selber Vorstellungen von innen heraus frei bilden kann. Solche Vorstellungen von innen heraus frei bilden, heißt meditieren: sich im Bewußtsein durchdringen mit Vorstellungen, die nicht von der äußeren Natur kommen, mit Vorstellungen, welche aus dem Inneren herausgeholt werden, wobei man vorzugsweise aufmerksam ist auf diejenige Kraft, die diese Vorstellungen heraustreibt. Man kommt dann dazu, zu fühlen, wie wirklich im Menschen ein zweiter Mensch steckt, wie wirklich im Menschen etwas innerlich fühlbar werden kann, was man so erlebt, wie zum Beispiel die Muskelkraft, mit der man einen Arm ausstreckt — man erlebt diese Muskelkraft am Menschen. Wenn man denkt, erlebt man gewöhnlich nichts; aber durch das Meditieren ist es möglich, die Gedankenkraft, die Kraft, durch die man die Gedanken bildet, in einer solchen Weise zu verstärken, daß man sie innerlich so erlebt wie die Muskelkraft, wenn man den Arm ausstreckt. Und das Meditieren hat einen Erfolg, wenn man sich zuletzt sagen kann: Ich bin eigentlich in meinem gewöhnlichen Denken ganz passiv. Ich lasse mit mir etwas geschehen. Ich lasse mich von der Natur ausstopfen mit Gedanken. Aber ich will mich nicht weiter ausstopfen lassen mit Gedanken, sondern ich versetze in mein Bewußtsein hinein diejenigen Gedanken, die ich haben will, und ich gehe von einem Gedanken zu dem anderen über nur durch die Kraft des inneren Denkens selber. - Da wird das Denken immer stärker und stärker, wie die Muskelkraft stärker wird, wenn man den Arm gebraucht. Da merkt man zuletzt, daß dieses Denken ebenso ein Spannen, ein Tasten, ein innerliches Erleben ist wie das Erleben der Muskelkraft. Hat der Mensch sich so innerlich erlebt, daß er sein Denken in sich fühlt, wie man sonst nur die innere Muskelkraft fühlt, dann tritt sofort dasjenige vor sein Bewußtsein, was er zunächst in sich trägt als Wiederholung eines alten Erdenzustandes. Er lernt erkennen diejenige Kraft, welche die von ihm genossenen Speisen im physischen Leibe umwandelt und wiederum zurückverwandelt. Und indem er dazu kommt, in sich diesen höheren Menschen zu erleben, der so real ist, wie nur der physische Mensch ist, kommt er zugleich dazu, die äußeren Dinge der Welt nun auch mit diesem erkrafteten Denken anzuschauen.

Nun, meine lieben Freunde, denken Sie sich: mit einem solchen erkrafteten Denken schaue ich auf einen Stein, meinetwillen auf einen Salzwürfel oder auf einen Quarzkristall. Ich schaue mit dieser innerlichen Erkraftung auf einen Stein. Da ist es so, daß es mir vorkommt, wie wenn ich einem Menschen begegne: den habe ich doch schon gesehen? Ich erinnere mich dadurch, daß ich ihn wieder vor mir sehe, an Erlebnisse, die ich vor zehn, zwanzig Jahren mit ihm gehabt habe. Mittlerweile war er meinetwillen in Australien oder irgendwo. Dasjenige, was jetzt als Mensch vor mich hintritt, zaubert mir herauf das Erlebnis, das ich mit ihm vor zehn oder zwanzig Jahren gehabt habe. Schaue ich einen Salzwürfel, schaue ich einen Quarzkristall an mit dem erkrafteten Denken, sofort steht vor mir, wie dieser Salzwürfel, dieser Quarzkristall einmal war, wie wenn die Erinnerung an einen Urzustand der Erde aufgehen würde. Damals aber war dieser Salzwürfel nicht hexaedrisch, also nicht sechsflächig, sondern alles war in einem welligen, webenden Steinweltenmeer. Der Urzustand der Erde geht so auf, wie an den gegenwärtigen Gegenständen eben eine Erinnerung aufgeht.

Und dann blicke ich zum Menschen zurück, und ganz derselbe Eindruck, den ich sonst vom Urzustand der Erde habe, stellt sich mir dar in einem zweiten Menschen, den der Mensch in sich trägt. Und ganz derselbe Eindruck stellt sich mir dar, wenn ich nun nicht Steine ansehe, sondern wenn ich Pflanzen ansehe. Und ich komme dazu, mit einem gewissen Recht neben dem physischen Leib von einem Ätherleib zu sprechen. Die Erde war einstmals Äther. Sie ist aus dem Äther das geworden, was sie heute ist in ihren unorganischen, in ihren leblosen Dingen. Die Pflanze trägt noch dasjenige in sich, was ein uralter Zustand der Erde war. Und ich selber auch: als einen zweiten Menschen, als den Ätherleib des Menschen.

Das alles, was ich Ihnen schildere, kann Beobachtungsgegenstand des erkrafteten Denkens werden. So daß wir sagen können: Gibt sich der Mensch Mühe, das erkraftete Denken zu haben, dann schaut er an sich, an der Pflanze, und indem er auf die Mineralien sieht, in Erinnerung an uralte Zeiten, die die Mineralien wachrufen, außer dem Physischen Ätherisches. Nun aber, was weiß man denn aus dem, was einem so in einer höheren Beobachtung entgegentritt? Man weiß daraus, daß die Erde einmal in einem ätherischen Zustande war, daß der Äther geblieben ist, daß er heute noch die Pflanzen durchsetzt, die Tiere durchsetzt, denn auch an ihnen nimmt man ihn wahr, daß er den Menschen durchsetzt.

Aber nun tritt ein weiteres auf. Die Mineralien erblicken wir ätherfrei. Die Pflanzen erblicken wir mit Äther begabt. Aber wir lernen zu gleicher Zeit den Äther überall sehen. Er ist heute noch da. Er füllt den Weltenraum aus. Er nimmt nur nicht teil an der äußeren mineralischen Natur. Er ist überall da. Und wenn ich nur die Kreide aufhebe, da merke ich, in dem Äther geht allerlei vor. Oh, das ist ein verwickelter Prozeß, ein verwickelter Vorgang, wenn ich die Kreide aufhebe. Mein Arm und meine Hand heben die Kreide auf. Dasjenige, was da meine Hand tut, das ist die Entwickelung einer Kraft in mir. Diese Kraft in mir ist während des wachen Zustandes vorhanden; während des schlafenden Zustandes ist sie nicht vorhanden. Wenn ich das, was der Äther tut, verfolge, die geschilderte Verwandlung der Nahrungsmittel, so ist das durch den Wach- und durch den Schlafzustand hindurch vorhanden. Das könnte man zunächst, wenn man oberflächlich wäre, beim Menschen bezweifeln, aber bei den Schlangen nicht, denn die schlafen, um zu verdauen. Aber dasjenige was dadurch geschieht, daß ich den Arm hebe, das kann nur im wachen Zustand geschehen. Der Ätherleib hilft mir nichts zu diesem Heben. Aber dennoch, wenn ich nur die Kreide hebe, muß ich Ätherkräfte überwinden, muß ich in den Äther hineinwirken. Aber der eigene Ätherleib kann das nicht. Ich muß also einen dritten Menschen in mir tragen, der das kann.

Diesen dritten Menschen, ihn finde ich nicht in irgend etwas ähnlichem draußen in der Natur zunächst. Diesen dritten Menschen, der sich bewegen kann, der Dinge heben kann, der seine eigenen Glieder heben kann, ihn finde ich nicht in der äußeren Natur. Aber die äußere Natur, in der überall Äther ist, die tritt ja in Beziehung zu diesem, sagen wir, Kräftemenschen, zu diesem Menschen, in den der Mensch selber die Kraft seines Willens hineingießt.

Zunächst kann man diese innere Kräfte-Entfaltung nur wahrnehmen an sich selber durch ein inneres Erleben. Wenn man aber die Meditation weiter treibt, wenn man nicht nur das innerlich tut, daß man Vorstellungen selber schafft, von einer Vorstellung zur anderen übergeht, um so das Denken zu erkraften, sondern wenn man, nachdem man ein solches kraftvolles Denken sich errungen hat, es innerlich wieder abschafft, sich ganz leer im Bewußtsein macht, dann erreicht man etwas Besonderes. Ja, wenn man sich von den gewöhnlichen Gedanken, die man passiv erwirbt, freimacht, schläft man ein. In dem Augenblick, wo der Mensch nicht mehr wahrnimmt, nicht mehr denkt, schläft er ein, weil das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein eben passiv erworben ist. Ist es nicht da, schläft er ein. Aber wenn man die Kräfte entwickelt, durch die man das Ätherische sieht, hat man einen innerlich erstarkten Menschen. Man fühlt die Gedankenkräfte, wie man sonst die Muskelkräfte fühlt. Wenn man diesen erstarkten Menschen wiederum wegsuggeriert, dann schläft man nicht ein, dann exponiert man sein leeres Bewußtsein der Welt. Dann tritt dasjenige objektiv in den Menschen herein, was der Mensch spürt, indem er seine Arme bewegt, indem er geht, indem er seinen Willen entfaltet. In der Welt des Raumes ist dasjenige nirgends zu finden, was da als Kräfte im Menschen wirkt. Aber es tritt in den Raum herein, wenn man in der Weise, wie ich es geschildert habe, leeres Bewußtsein erzeugt. Dann entdeckt man auch objektiv diesen dritten Menschen im Menschen. Schaut man dann wiederum in die äußere Natur hinaus, dann merkt man: Ja, der Mensch hat einen Ätherleib, die Tiere haben einen Ätherleib, die Pflanzen haben einen Ätherleib. Die Mineralien haben keinen. Die erinnern nur an den ursprünglichen Erdenäther. Aber überall ist Äther. Wo man hinschaut, hingeht, überall ist Äther. Aber er verleugnet sich. Warum? Weil er sich nicht als Äther gibt.

Sehen Sie, wenn Sie mit dem meditativen Bewußtsein, wie ich es zunächst geschildert habe, an die Pflanzen herantreten, so haben Sie ein Ätherbild. Treten Sie an den Menschen heran, Sie haben ein Ätherbild. Wenn Sie aber an den allgemeinen Äther in der Welt herantreten, dann sind Sie so, wie wenn Sie im Meere schwimmen würden: Überall ist nur der Äther. Er gibt kein Bild; aber er gibt in dem Momente ein Bild, wo ich nur die Kreide erhebe: da erscheint im Ätherischen ein Bild, wo mein dritter Mensch seine Kraft entwickelt.

Stellen Sie sich dieses Bild vor: Die Kreide liegt da zunächst, meine Hand ergreift die Kreide, hebt sie auf. Das Ganze kann ich ja meinetwillen nachbilden in Augenblicksaufnahmen. Das, was sich da entwickelt, das hat im Äther ein Gegenbild. Aber dieses Gegenbild im Äther wird erst in dem Momente gesehen, wo ich durch das leere Bewußtsein wahrnehmen kann, wo ich den dritten Menschen wahrnehmen kann, nicht den zweiten ätherischen Menschen, sondern wo ich den dritten Menschen wahrnehmen kann. Das heißt, der allgemeine Weltenäther wirkt nicht als Äther, er wirkt so wie der dritte Mensch.

Und ich kann sagen: Ich habe zunächst den physischen Leib (Oval), dann den ätherischen Leib, den ich wahrnehme durch das meditative Bewußtsein (gelb), dann den dritten Menschen, ich nenne ihn den astralischen Menschen (rötlich). Ringsherum überall habe ich aber dasjenige, was hier das zweite war in der Welt, den Weltenäther (gelb). Dieser Weltenäther, er ist zunächst wie ein unbestimmtes Äthermeer. Nun, in dem Moment, wo ich irgend etwas, was von meinem dritten Menschen kommt, in diesen Äther hineinstrahle, da antwortet er mir, wie wenn er gleich wäre meinem dritten Menschen; da antwortet er mir nicht ätherisch, da antwortet er mir astral. So daß ich überall im weiten Äthermeere durch meine eigene Tätigkeit etwas entfessele, was meinem eigenen dritten Menschen ähnlich ist.

Wenn ich mich nun frage: Was ist denn das, was ich da entfessele? Was ist denn das, was da sonst im Ätherischen als ein Gegenbild ist? Ich hebe die Kreide auf, meine Hand geht von unten nach oben. Das Ätherbild geht von oben nach unten. Es ist das richtige Gegenbild. Es ist eigentlich ein astralisches Bild, aber es ist ein bloßes Bild. Aber dasjenige, durch das dieses Bild hervorgerufen wird, ist der heutige reale Mensch. Lerne ich nun durch dasjenige, was ich früher gesagt habe, zurückschauen in der Erdenentwickelung, lerne ich dasjenige, was kurz wiederholt wird auf die Art, wie ich es beschrieben habe, anwenden auf die große Entwickelung, da stellt sich mir dann das Folgende heraus:

Ich habe den heutigen Erdenzustand (siehe Zeichnung). Ich gehe zurück zu einer Äthererde. In der finde ich noch nicht dasjenige, was da durch mich entfesselt wird im umliegenden Äther. Ich muß noch weiter zurückgehen und komme zu einem noch früheren Erdenzustand, in dem die Erde gleich meinem eigenen Astralleib war, in dem die Erde astralisch war, in dem die Erde ein Wesen war, wie mein dritter Mensch selber ist. Und dieses Wesen, ich muß es suchen in längst vergangenen Zeiten, in viel mehr vergangenen Zeiten, als diejenigen sind, in denen die Erde eine Äthererde war. Aber indem ich da weit zurückgehe in der Zeitenentwickelung, ist es wirklich nicht anders, als wenn ich im Raume einen fernen Gegenstand sehe, meinetwillen ein Licht, das bis hierher leuchtet. (Es wird gezeichnet.) Es ist dort, es leuchtet bis hierher, entwickelt Bilder, geht bis hierher. Hier habe ich es verlassen; hier habe ich für den Raum nur die Zeit. Dasjenige, was meinem eigenen Astralleib gleich ist, war in uralten Zeiten vorhanden, aber es ist immer noch da. Die Zeit hat nicht aufgehört zu sein, sie ist noch da. Und wie im Raume das Licht bis hierher leuchtet, so wirkt dasjenige, was in einer längst vergangenen Zeit liegt, in die heutige Gegenwart herein. Es ist also im Grunde genommen die ganze Zeitentwickelung noch da. Es ist nicht verschwunden, was einmal da war, wenn es so etwas ist, wie dasjenige, was im äußeren Äther meinem eigenen astralischen Leibe ähnlich ist.

Ich komme da also zu etwas, was im Geiste vorhanden ist und die Zeit zum Raume macht. Und es ist nicht anders, als wenn ich meinetwillen durch einen Telegraphen weithin korrespondiere; so korrespondiere ich, indem ich die Kreide aufhebe und ein Bild im Äther erzeuge, mit demjenigen, was für die äußere Anschauung längst vergangen ist.

Wir sehen, wie der Mensch in die Welt hineingestellt wird in einer ganz anderen Weise, als ihm das zunächst erscheint. Aber wir begreifen auch, warum für den Menschen Welträtsel auftauchen. Der Mensch fühlt in sich, wenn er sich das auch nicht klarmacht - heute macht es ja nicht einmal die Wissenschaft sich klar -, der Mensch fühlt in sich, daß er ein Ätherisches hat, das die Speisen umwandelt und wiederum zurückverwandelt. Er findet das in den Steinen nicht, sondern die Steine waren in uralten Zeiten noch vorhanden als allgemeiner Äther. Aber in diesem allgemeinen Äther ist wirksam dasjenige, was noch weiter zurückliegt. Der Mensch trägt also eine uralte Vergangenheit schon, wie wir sehen, in zweifacher Weise in sich: eine spätere Vergangenheit in seinem Ätherleib und eine noch weiter zurückreichende Vergangenheit in seinem Astralleibe.

Wenn der Mensch sich heute der Natur gegenüberstellt, betrachtet er eigentlich gewöhnlich nur das Leblose. Das Lebendige selbst in den Pflanzen betrachtet er nur dadurch, daß er die Substanzen und die Gesetze in den Substanzen, die er im Laboratorium erkundet hat, dann auf die Pflanzen anwendet. Das Wachsen läßt er aus, er kümmert sich nicht um das Wachsen, um das Leben in den Pflanzen. Die heutige Wissenschaft betrachtet ja schon die Pflanzen so wie einer, der ein Buch in die Hand nimmt und bloß die Buchstabenformen anschaut und nicht liest. So betrachtet die heutige Wissenschaft alle Dinge der Welt.

Ja, im Grunde genommen, wenn man so ein Buch aufschlägt und nicht lesen kann, müssen einem die Formen sehr rätselhaft erscheinen. Man kann doch wirklich nicht begreifen, warum da eine Form ist, die just so ausschaut: b, a, dann eine solche: l, und eine solche: d bald. Was tut das nebeneinander? Es ist ja rätselhaft. Das ist ja ein Welträtsel. - Das, was ich Ihnen dargelegt habe als eine Betrachtungsart, ist ein Lesenlernen in der Welt und im Menschen. Und durch das Lesenlernen kommt man allmählich der Lösung der Rätsel nahe.

Sehen Sie, meine lieben Freunde, ich wollte Ihnen heute nur einen allgemeinen Gang des Menschensinnens geben, durch den man hinausgelangen kann aus dem verzweiflungsvollen Zustand, in dem der Mensch sich befindet, und den ich Ihnen gestern geschildert habe. Wir werden aufsteigend betrachten, wie man im Lesen der Erscheinungen draußen in der Welt und im Lesen der Erscheinungen im Menschen immer weiter und weiter dringen kann.

Damit aber macht man schließlich Gedankengänge durch, die dem heutigen Menschen ganz ungewohnt sind. Und was ist das Gewöhnliche? Das Gewöhnliche ist, daß nun die Menschen sagen: Das verstehe ich nicht. — Aber was heißt denn das: Das verstehe ich nicht? Das heißt nichts anderes als: es stimmt mit demjenigen, was mir in der Schule beigebracht worden ist, nicht überein, und ich bin gewöhnt worden, so zu denken, wie ich in der Schule angeleitet worden bin.

Aber die Schule baut doch auf der richtigen Wissenschaft auf. Ja, aber diese richtige Wissenschaft! Wer ein bißchen alt geworden ist wie ich, hat mancherlei da miterlebt. So erlebte man zum Beispiel, daß für jenen Prozeß, den ich hier ja auch heute angedeutet habe, Aufnahme von Nahrungsmitteln, Verwandlung von Nahrungsmitteln im menschlichen Organismus, verschiedenerlei notwendig ist. Man zählt auf: Eiweißstoffe, Zucker und Stärkeprodukte, Fette, Wasser und Salze, das ist für den Menschen notwendig. Nun experimentiert man.

Wenn man so etwa zwanzig Jahre zurückgeht, da haben die Experimente ergeben, daß der Mensch im Tag mindestens 120 Gramm Eiweiß zu sich nehmen müsse, sonst könne er nicht leben. Das war vor zwanzig Jahren Wissenschaft. Was ist heute Wissenschaft? Heute ist Wissenschaft, daß man mit 20 bis 50 Gramm ausreicht. Das ist heute Wissenschaft. Dazumal war es Wissenschaft, daß man, wenn man die 120 Gramm nicht hat, ein kranker Mensch wird, unterernährt wird. Heute ist Wissenschaft, daß es nicht zuträglich ist, mehr als höchstens 50 Gramm zu haben, man reicht aber auch mit 20 aus. Und wenn man mehr genießt, so bilden sich im Darm faulige Substanzen, die den Körper mit einer Art von Selbstvergiftung behandeln. Es ist also schädlich, mehr als 50 Gramm Eiweiß aufzunehmen. Das ist heute Wissenschaft.

Aber das ist ja nicht nur Wissenschaft, das ist zu gleicher Zeit Leben. Denn denken Sie sich nur einmal, vor zwanzig Jahren, als es wissenschaftlich war, daß man mindestens 120 Gramm Eiweiß haben muß, wurde den Menschen gesagt: Ihr müßt halt solche Nahrungsmittel zu euch nehmen, wobei ihr 120 Gramm Eiweiß in euch bekommt. -— Man müßte dann bei dem Menschen auch voraussetzen, daß er das alles bezahlen kann. Das geht in die Nationalökonomie hinein, Man hat sorgfältig dazumal beschrieben, wie es unmöglich ist, durch Pflanzenkost zum Beispiel diese 120 Gramm Eiweiß aufzunehmen. Heute weiß man, daß die nötige Eiweißmenge bei jeder Nahrung in den Menschen kommt; denn wenn er einfach genügend Kartoffeln ißt, er braucht nicht einmal viel zu essen, wenn er Kartoffeln ißt mit etwas Butter, so gibt das die nötige Menge Eiweißstoff. Es ist heute ganz absolut wissenschaftlich sicher, daß das so ist. Und dabei ist die Sache noch so: Wenn der Mensch sich anfüllt mit den 120 Gramm Eiweiß, wird sein Appetit höchst unsicher. Wenn er aber bei einer Nahrung bleibt, die ihm die 20 Gramm Eiweiß liefert, und es passiert ihm wirklich einmal, daß er eine Nahrung zu sich nimmt, die nicht die 20 Gramm hat, durch die er also unterernährt würde, so schmeckt es ihm nicht mehr. Sein Instinkt wird wiederum sicher. Nun ja, dabei gibt es natürlich immer noch unterernährte Menschen. Das kommt von anderen Dingen, das kommt dann jedenfalls nicht von zu geringem Eiweiß. Aber es gibt ganz sicher zahllose Menschen, die, weil sie mit Eiweiß sich überfüttern, Selbstvergiftungen durchmachen und allerlei andere Dinge.

Ich will jetzt nicht sprechen über die Natur der Infektionskrankheiten, aber am leichtesten ist der Mensch zugänglich für die sogenannte Infektion, wenn er 120 Gramm Eiweiß zu sich nimmt. Da kriegt er am leichtesten Diphtherie oder selbst Pocken. Wenn er nur 20 Gramm zu sich nimmt, wird er sehr schwer angesteckt.

Es war also einmal wissenschaftlich: Man braucht soviel Eiweiß, daß man sich damit selbst vergiftet und daß man sich jeder möglichen Ansteckung dadurch aussetzt. Das war vor zwanzig Jahren Wissenschaft! Ja, sehen Sie, was man so denkt, das liegt in der Richtung des Wissenschaftlichen; aber wenn man anschaut, was in ganz wichtigen Dingen vor ganz kurzer Zeit wissenschaftlich war und was heute wissenschaftlich ist, dann kommt man doch zu einer wesentlichen Erschütterung dieses Wissenschaftlichen.

Das ist etwas, was man auch als ein Gefühl aufnehmen muß, wenn jetzt etwas auftritt wie die Anthroposophie, die das Denken, das ganze Sinnen des Menschen, die ganze Seelenverfassung eben in eine andere Richtung bringt, als diejenige ist, die nun eben gang und gäbe ist. Ich wollte also nur sozusagen auf etwas hinweisen, was zunächst wie eine Anleitung erscheint, in ein anderes Sinnen und in ein anderes Denken hineinzukommen.

Second Lecture

Yesterday I pointed out how man can look at himself from two sides, and how man is approached from these two sides by the riddle of the world and the riddle of man. If we look again at what we saw yesterday, we see on the one side what is initially perceived in the same way as the outer physical world. We see the human physical body. We call it the physical body because for our physical senses it stands before us in the same way as the outer physical world. But at the same time we must remember the enormous difference between this physical human body and the outer physical world. And we had to perceive this enormous difference yesterday in the fact that at the moment when man, passing through the gate of death, has to hand over the physical body to the elements of the outer physical world, that at this moment this physical body is destroyed by outer nature. So it is not in its constructive powers but in its destructive powers that external nature has that with which it treats the human physical body. And we must therefore look for that which gives the human physical body its form from birth or from conception to death entirely outside the physical world. We must speak of an initially different world that builds up this physical human body, because external physical nature cannot build it up, it can only destroy it.

But on the other hand there are two things that bring this physical human body into a very close relationship with nature. On the one hand, this physical human body needs substances for its construction, so to speak as its building materials, although this is spoken of in a non-actual sense, it needs the substances of external nature, or at least we can say that it needs to absorb the substances of external nature.

And yet, when we look at what this physical body reveals to the outside world, be it in the excretions that arise, be it that the whole physical body of man confronts us as a corpse after death, it is again the substances of the outer physical world; for wherever we look at this physical body, be it the individual excretions, be it the separation of the whole physical body with death, it presents itself to us as revealing the same substances that we also find in the outer physical world. So that we must say: Whatever is going on in this being of man, the beginning and end of the inner processes, the inner processes are related to the outer physical world.

But materialistic science draws a conclusion from the fact just mentioned which cannot be drawn at all. If, on the one hand, we see that man takes into himself the substances of the outer physical world through eating or drinking or through breathing, and that through exhalation, excretion or death he gives these substances back to the outer world as substances that correspond to those of the outer world, then we can only say that we are dealing with a beginning and an end. What happens in between in the human physical body is not clear from this.

One speaks so lightly of the blood that man carries within himself. But has anyone ever examined this blood in the living human organism itself? This cannot be done by physical means. So that the materialistic conclusion cannot be drawn without further ado: that which goes into the body and that which comes out of it is also inside the human organism.

But in any case, we can already see when the absorption of external physical substances begins, for example in the mouth, that a transformation occurs immediately. We only need to take a grain of salt into our mouth, it must be dissolved immediately. A transformation occurs immediately. The human physical body in its inner being is not like the outer nature. It transforms what it takes in and transforms it back again. So that we have to look for something in the human physical organism which in its beginning is similar to external nature in its intake of physical substances, and which is similar to external nature in its output. But in between lies that which must first be recognized in the human being.

Imagine schematically what I have said (see drawing). We have what the human physical organism takes in, and we have what it gives out, also gives out as its whole body. In between are the processes that take place in the human organism between intake and output. We cannot say anything about the relationship of the human being to external nature with regard to what the human physical organism takes in. For one would like to express this: If it is already the case that external physical nature destroys, dissolves, atomizes the corpse of man, man in turn pays this back to external nature in relation to his own organism. He also dissolves everything he receives from external nature. So if we begin with those organs through which man absorbs the physical, we do not arrive at any relationship to external nature, for they destroy external nature. We only arrive at a relationship between man and external nature if we look at what man excretes. With regard to the form that man brings into physical life, nature is a destroyer; with regard to that which he excretes, it absorbs what the human organism provides. So that the human physical organism at its end becomes quite unlike itself, but very similar to external nature. The human physical organism only makes itself similar to external nature by excreting.

If you consider this, then you will say to yourself: Outside in nature are the substances of the various kingdoms of nature. They are today as they have just become; but they have certainly not always been so. Even physical science admits that if you go back in the course of time and come to old states of the earthly, they are quite different from what they are today; in other words, that which surrounds us outside in the realms of nature has only become what it is today. And if you look at the human physical body, you must say to yourself: the human physical body first destroys what it takes in, transforms it - we will come to the conclusion that it actually destroys it, but let us say first transforms it - at any rate it must bring it to a certain state from which it can then carry it on to the present physical nature. In other words, if you think of a beginning somewhere in the human organism, where the substances begin to develop up to the excretions, and then think of the earth (see drawing), then the earth only has to go back somewhere in a long time to a state in which it once was, and in which the interior of the human physical organism is today. You must say: somewhere in the past the whole earth must have been in a state in which something is inside the human being today. And in the short span of time in which something organically interwoven in the human organism is transformed into the excretions, in this short time the inner processes of the human organism repeat that which has been carried out by the earth itself in the course of long periods of time.

We therefore look at external nature and say to ourselves: That which is external nature today was once quite different. But if we want to look at the state in which this external nature once was and find something similar, then we have to look into our own organism. The beginning of the earth is still there. Every time we eat, the food inside us is transformed into a state that the whole earth was once in. And the earth has evolved over long periods of time, becoming what it is today. We have that which is present in man as a state of his consumed food, which develops up to the excretions. In this development of a short period of time lies, briefly repeated, the whole earth process.

You see, you can look at the vernal equinox, where the sun rises every spring. It shifts, it moves forward. In ancient times, let's say in the Egyptian period, the vernal equinox was in the constellation of Taurus. It has progressed through the constellation of Taurus, Aries, today it is in the constellation of Pisces. And this vernal equinox goes on and on. It goes around in circles. It must come back again after some time. The sunrise point passes through a celestial circle in 25920 years. The sun passes through this circle every day. It rises, it sets and in doing so it follows the same path as the vernal equinox. We are looking at the long period of 25920 years as the orbital period of the vernal equinox. We are looking at the short period of a sunrise and sunset until it returns again to the rising point - we are looking at a twenty-four hour period. The sun passes through the same circle in a short time.

So it is with the human physical organism. In the course of long years the earth has consisted of substances similar to those which we carry within us, when we have reached a certain degree of digestion, just the intermediate point between absorption and excretion, where absorption turns into excretion; then we carry within us the beginning of the earth. In a short time we reach excretion. There we are similar to the earth. There the substances are handed over to the earth in the form in which they are today. With our nourishment process in the physical body we do something similar to what the sun does in its dealings with the vernal equinox. We may therefore look out over the physical earth and say: Today this physical earth has arrived at laws which dissolve the form of our physical organism. But this earth must once have been in a state where laws acted upon it which today bring our physical organism to the point where food is, when it is in the middle between absorption and excretion. This means that we carry the laws of the beginning of the earth within us. We repeat what was once there on earth.

Now, we can say: If we regard our physical organism as that which absorbs the external substances and in turn expels them in the form of external substances, then this physical organism is in a certain sense organized towards the absorption and excretion of today's substances; but it carries within itself something that was present in the beginning of the earth, which today the earth no longer has, which has disappeared from it, for the earth has the end products, but not the initial products. So we carry something within us that we have to look for in very, very old times within the constitution of the earth. And what we carry within us, which the earth as a whole does not have at first, is that which lifts the human being beyond the physical earthly existence. It is that which makes man say to himself: I have preserved within me the beginning of the earth. By entering physical existence through birth, I always carry something within me that the earth does not have today, but had millions of years ago.

You can see from this that if we call man a small world, we cannot merely take into consideration what the world around us is like today, but that we must go beyond the present state into the times of development, that in order to understand man we must consider ancient earthly states.

That which is still present in man in this way, which the earth no longer has, can nevertheless appear before human observation. And this happens when man resorts to what can be called meditation. We are accustomed to simply allowing the ideas through which we perceive the outer world to arise within us, to depict the outer world through these ideas. And in the last centuries man has become so accustomed to depicting only the outer world that he does not even come to realize inwardly that he can also freely form ideas from within. To form such ideas freely from within means to meditate: to penetrate oneself in consciousness with ideas that do not come from external nature, with ideas that are drawn from within, whereby one is preferably attentive to the force that drives out these ideas. One then comes to feel how there really is a second human being in the human being, how something can really be felt in the human being that one experiences in this way, such as the muscular strength with which one stretches out an arm - one experiences this muscular strength in the human being. When one thinks, one usually experiences nothing; but through meditation it is possible to strengthen the power of thought, the power through which one forms thoughts, in such a way that one experiences it inwardly in the same way as the muscular power when one stretches out one's arm. And meditation is successful when you can finally say to yourself: I am actually quite passive in my ordinary thinking. I let something happen to me. I let nature stuff me with thoughts. But I don't want to let myself continue to be stuffed with thoughts, but I put into my consciousness those thoughts that I want to have, and I pass from one thought to another only through the power of inner thinking itself. - Thinking becomes stronger and stronger, just as muscle strength becomes stronger when you use your arm. Then one finally realizes that this thinking is just as much a tensing, a feeling, an inner experience as the experience of muscular strength. When man has experienced himself inwardly in such a way that he feels his thinking within himself, as one otherwise only feels the inner muscular strength, then that which he initially carries within himself as a repetition of an old earthly state immediately comes before his consciousness. He learns to recognize that power which transforms the food he has enjoyed in the physical body and transforms it back again. And by coming to experience within himself this higher man, who is as real as only the physical man is, he comes at the same time to look at the outer things of the world with this strengthened thinking.

Now, my dear friends, think to yourself: I look at a stone, a cube of salt or a quartz crystal for my sake, with this kind of enlightened thinking. I look at a stone with this inner power. It seems to me as if I were meeting a person: I have already seen him, haven't I? When I see him again, I remember experiences I had with him ten or twenty years ago. In the meantime, for my sake, he was in Australia or somewhere. That which now stands before me as a human being conjures up the experience I had with him ten or twenty years ago. If I look at a cube of salt, if I look at a quartz crystal with an enlightened mind, I immediately see before me what this cube of salt, this quartz crystal was once like, as if the memory of a primordial state of the earth were to arise. At that time, however, this salt cube was not hexahedral, i.e. not hexahedral, but everything was in an undulating, weaving sea of stone worlds. The primordial state of the earth emerges in the same way as a memory emerges in the present objects.

And then I look back to the human being, and quite the same impression that I otherwise have of the original state of the earth presents itself to me in a second human being that the human being carries within himself. And I get exactly the same impression when I look not at stones, but at plants. And I am justified in speaking of an etheric body alongside the physical body. The earth was once ether. From the ether it has become what it is today in its inorganic, lifeless things. The plant still carries within itself that which was an ancient state of the earth. And I myself too: as a second human being, as the etheric body of the human being.

All that which I am describing to you can become the object of observation of enlightened thinking. So that we can say: If the human being makes an effort to have an enlightened thinking, then he looks at himself, at the plant, and by looking at the minerals, in memory of ancient times, which the minerals evoke, apart from the physical, the etheric. But what do we know from what we encounter in this higher observation? We know from it that the earth was once in an etheric state, that the ether has remained, that it still permeates the plants today, permeates the animals, for we also perceive it in them, that it permeates the human being.

But now another one appears. We see the minerals without ether. We see plants endowed with ether. But at the same time we learn to see the ether everywhere. It is still there today. It fills the world space. It just does not take part in the outer mineral nature. It is everywhere. And if I just pick up the chalk, I realize that all kinds of things are going on in the ether. Oh, it's a complicated process, a complicated process, when I pick up the chalk. My arm and my hand pick up the chalk. What my hand is doing is the development of a force within me. This power is present in me during the waking state; it is not present during the sleeping state. If I follow what the ether does, the described transformation of the food, it is present through the waking and sleeping states. At first, if one were superficial, one could doubt this in humans, but not in snakes, for they sleep in order to digest. But what happens when I raise my arm can only happen when I am awake. The etheric body helps me nothing in this lifting. But still, if I only lift the chalk, I have to overcome etheric forces, I have to work into the ether. But my own etheric body cannot do this. I must therefore carry a third person within me who can do this.

This third person, I do not find him in anything similar outside in nature at first. I do not find this third human being, who can move, who can lift things, who can lift his own limbs, in outer nature. But the outer nature, in which ether is everywhere, enters into a relationship with this, let us say, power-man, with this man into whom man himself pours the power of his will.

At first you can only perceive this inner unfolding of forces in yourself through an inner experience. But if you take meditation further, if you not only do this inwardly, that you create ideas yourself, move from one idea to another in order to strengthen your thinking, but if, after you have acquired such powerful thinking, you inwardly abolish it again, make yourself completely empty in consciousness, then you achieve something special. Indeed, when one frees oneself from the ordinary thoughts that one passively acquires, one falls asleep. The moment a person no longer perceives, no longer thinks, he falls asleep, because ordinary consciousness is passively acquired. If it is not there, he falls asleep. But if one develops the powers through which one sees the etheric, one has an inwardly strengthened human being. You feel the powers of thought as you would otherwise feel the powers of muscle. If this strengthened human being is once again sucked away, then one does not fall asleep, then one exposes one's empty consciousness to the world. Then that which the human being senses by moving his arms, by walking, by developing his will, enters into him objectively. In the world of space there is nowhere to be found that which works as forces in man. But it enters into space when empty consciousness is created in the way I have described. Then one also objectively discovers this third person in the human being. If you then look out again into external nature, you realize: Yes, man has an etheric body, the animals have an etheric body, the plants have an etheric body. The minerals have none. They only remind us of the original earth ether. But ether is everywhere. Wherever you look, wherever you go, there is ether. But it denies itself. Why? Because it does not present itself as ether.