Karma

GA 235

2 March 1924, Dornach

VI. The Threefold Man and the Hierarchies

In continuing our studies on karma, we are under the necessity, at the outset, of casting a glance at the manner in which karma intervenes in the evolution of man, how destiny, which intervenes with the free deeds of man, is really fashioned in its physical reflection out of the spiritual world.

To begin with, I shall have to tell you today a few things about that which is connected with the human being in as far as he lives on earth. This earthly man—during these lectures we have been studying him in regard to the various members of his being. We have distinguished in him the physical body, the ether body, the astral body, the ego organism. We can, however, by directing our gaze upon him, just as he stands before us in the physical world, perceive the membering of the human being in yet another way.

Today we intend—quite independently of what we have already been discussing—to consider a certain membering of the human being, and we shall try to build a bridge between what we discuss today and that which we already know.

If we consider the human being as he stands before us on the earth, simply according to his physical form, then this physical form has three clearly differentiated members. This differentiation is, however, not usually observed, because that which asserts itself as science nowadays really looks at things and facts in a merely superficial way. It has no sensibility for what reveals itself when things and facts are considered with a perception inwardly illumined.

We have, to begin with, the human head. Even outwardly considered, this human head shows itself as something quite different from the remainder of the human form. We need but turn our attention to the formation of the human being out of the human embryo. The first thing we can see developing in the body of the mother as human embryo is the head organization.

The whole human organization takes its start from the head, and everything else in the human being which afterwards flows into his configuration is, actually, an appendage-organ of the human embryo. As physical form, the human being is a head in the beginning. The rest are appendage-organs. And the functions which these appendage-organs assume in later life—such as breathing, circulation, nutrition—are, in the first period of the embryonic existence, activities proceeding not from within the embryo, but from without inward, out of the body of the mother, through organs which afterwards fall off, organs which are no longer present later in the human being.

The human being is, at the outset, entirely head. The rest is appendage-organ. We do not exaggerate in the following sentence: The human being is in the beginning head; the rest is, so to speak, appendage-organ. Since that which at first was appendage-organ later on grows and gains in importance for the human being, his head finally loses its sharp distinction from the rest of the organs.

But this gives only a superficial characterization of the human being. For in reality he is, also as physical form, a threefold being. All that which actually constitutes his first form—the head—remains throughout his earthly life a more or less individual member. We fail merely to recognize this; nevertheless, it is a fact.

You will say: Indeed, one ought not to divide the human being in such a way that we behead him, as it were, chop off his head. That this happens in Anthroposophy was only the belief of Professor “Blank” who reproached Anthroposophy for dividing men into head, chest organs, and limb organs. But this charge is not true; it is not at all a fact; for in what is outwardly head configuration, lies only the main outer expression of the head configuration. Man remains completely “head” throughout his whole life. The most important sense organs—the eyes, ears, the organs of smell, the organs of taste—are, to be sure, in the head, but the sense of warmth, for example, the sense of pressure, the sense of touch, are spread out over the whole human being. That is precisely because the three members of the human organism are not to be differentiated spatially, but only in such a way that the head formation mainly appears in the outwardly formed head, while in reality it permeates the entire human being. And this is true also for the rest of the members. The head is, throughout man's earthly life, in the big toe, in so far as the big toe possesses a sense of touch or a sense of warmth.

Thus we have characterized, to begin with, the one member of the human being's essential nature, that human nature which confronts us as something sensuous. In my books I have designated this organization also as the nerve-sense organism in order to characterize it more inwardly. This, then, is one member of the human being, the nerve-sense organism.

The second member of the essential nature of the human being is all that manifests in rhythmical activity. You cannot say of the nerve-sense system that it finds expression in rhythmic activity, for example, in the perception of the eye; for in that case you would have to perceive one thing at a certain moment, then another, then a third, then a fourth, and then return again to the first, and so on. In other words, there would have to be a rhythm in your sense perception. But that is not the case. Observe on the other hand the main characteristic of your breast organism. There you will find the rhythm of breathing, the rhythm of circulation, the rhythm of digestion, and so forth. There, everything is rhythm.

Rhythm, with its organs of rhythm, is the second thing to develop in the human being; and it also extends over the whole human being, though its chief external manifestation is in the organs of the breast. The whole human being, again, is a lung; yet lung and heart are localized, so to speak, in the organs so named. The whole human being, indeed, breathes; you breathe in every spot of your organism. People speak of skin respiration. Only, in the activity of the lung is respiration mainly concentrated.

The third human organism is that of the limbs—the limb organism. The limbs terminate in the breast organism. In the embryonic stage of existence, they appear as appendages. They are the latest to develop. They are, however, the organs which are chiefly connected with metabolism. The metabolic process finds its chief stimulus through the fact that these organs are put into motion, perform most of the work in the human being. We have thus characterized the three members that appear to us in the human form.

But these three members are intimately connected with the soul life of the human being. His soul life can be divided into thinking, feeling, and willing. Thinking finds its physical expression chiefly in the head. But it has its physical organism also in the entire human being, because the head exists, in the way I have just described, throughout the entire human being.

Feeling is connected with the rhythmic organism. It is a prejudice, indeed even a superstition on the part of modern science to assume that the nervous system has directly to do with feeling. The nervous system has nothing directly to do with feeling. The respiration and circulation rhythms are the organs of feeling, and the nerves only transmit the fact that we cognize our feelings, that we experience them. The feelings have their organism in the rhythmic system, but we should know nothing of our feelings if the nerves did not procure for us percepts of them. And because the nerves procure for us these percepts of our feelings, modern intellectualism creates the superstition that the nerves themselves are tin* organs of feeling. This is not the case.

But, when we consciously observe our feelings, as they arise out of our rhythmic organism, and compare them with the thoughts which an* bound to our head, to our nerve-sense organism, then—if we are able to observe at all—we shall perceive the same difference between our thoughts and our feelings that exists between our daytime thoughts which we have in waking life and our dreams. Our feelings have no greater intensity in consciousness than dreams. They only have a different form; they only make their appearance in a different way. When you dream in pictures, your consciousness lives in pictures. But these pictures, in their picture character, have the same significance—although in another form—as our feelings. Thus, we may say that we have the clearest consciousness, the most illumined consciousness in our visualizations, in our thoughts. We have a kind of dream consciousness in regard to our feelings. We only believe that we have a clear consciousness of our feelings; we have no clearer consciousness of our feelings than we have of our dreams. If on awaking from sleep we recollect our dreams and form of them wide-awake visualizations, we do not seize hold of the dream. The dream is far richer than our visualization of it afterwards. In like manner is the world of feeling infinitely richer than our mental pictures of it, which we make present to our consciousness.

And completely immersed in sleep is our willing. This willing is bound to the limb-metabolic organism, to the motor organism. All that we really know of our willing are the thoughts. I form the visualization: I shall take hold of this watch. Just try to think quite sincerely that you form the visualization: I shall take hold of this watch. Then you do take hold of it. What proceeds from your visualization, your thought, right down into the muscles and finally leads to something which again appears as a visualization—your taking hold of the watch, which is a continuation of the first visualization—what lies between the thought of the intention to act, and the thought of its fulfilment, what occurs in your organism, all these activities remain just as unconscious as your life in the deepest dreamless sleep.

We do at least dream of our feelings, but from our impulses of will we have nothing but what we have from our sleep. You may say: I have nothing at all from sleep. Well, I do not speak now from the physical standpoint; even from the physical standpoint it is, indeed, entirely senseless to say that you have nothing at all from sleep. But psychically, too, you have a great deal from your sleep. If you were never to sleep, you would never reach your ego consciousness.

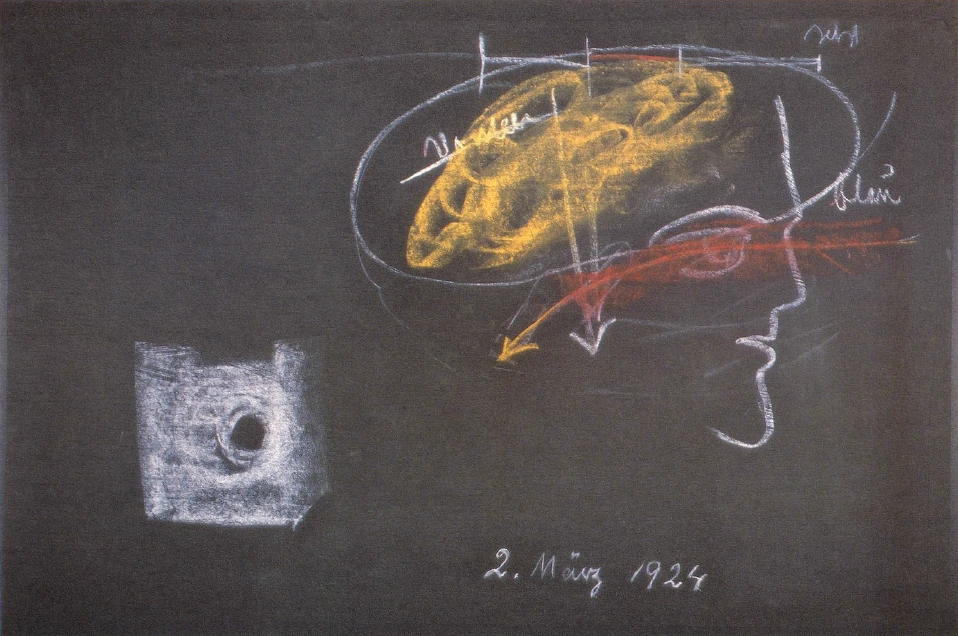

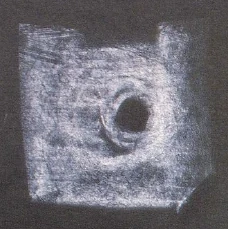

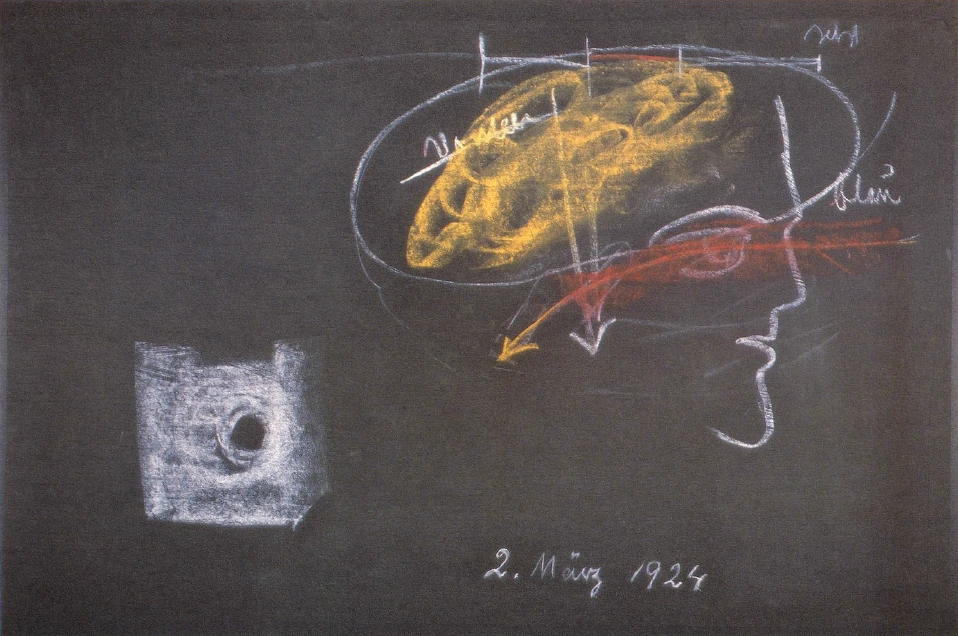

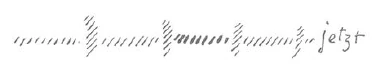

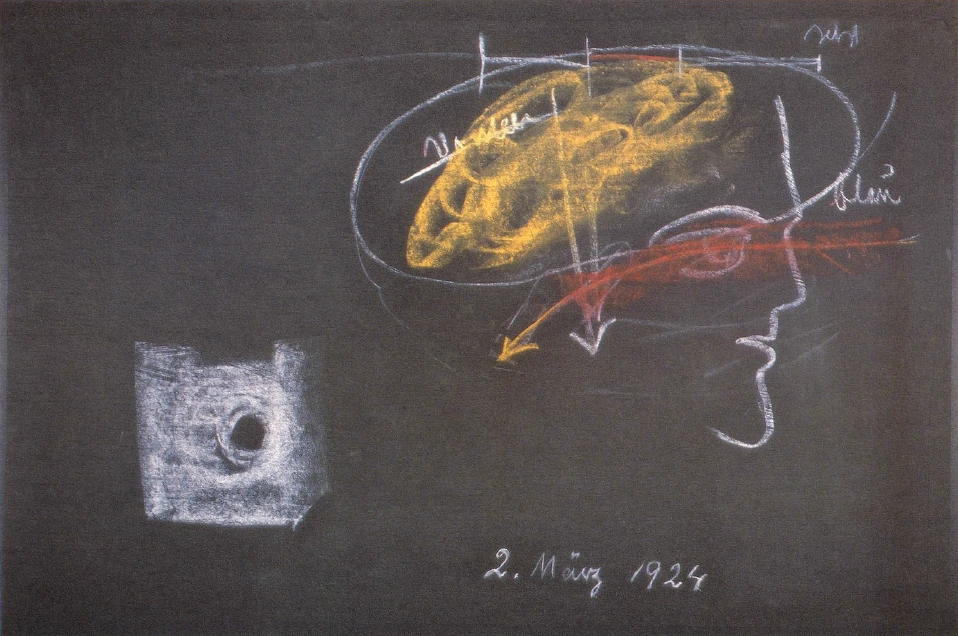

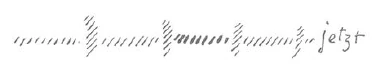

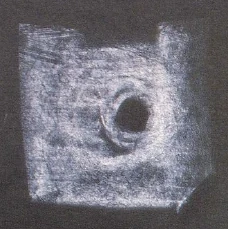

You need only realize the following: When you remember the experiences you have had, then you say that you are going back in time, that from the present you go further back in time. Indeed, you imagine that it is a fact that you go further back in time. But it is not so at all. In reality you only go back to the moment when you awoke from sleep the last time. (See Figure X.) Then you have fallen asleep. What lies there between is eliminated. And then in the interval from the last time you fell asleep back to the time before the last when you woke up, memory appears again. So the matter continues on, back in time. And by looking back, you must really always insert the periods of unconsciousness. In doing so we must insert unconsciousness for one third of our life. We do not pay attention to this. But it is just as if you had a white plane with a black hole in the center. (See Figure XI.) You see the black hole, in spite of the fact that there are no forces present. Thus, in looking back in memory, in spite of the fact that it contains nothing from life's reminiscences, you see, nevertheless, the blackness—the nights, through which you have slept. There your consciousness strikes against this blackness continually, and that impels you to call yourself an I, an ego.

If this really continued on and you were to knock against nothing, you would never gain an ego consciousness. Thus we can, indeed, say that we benefit from sleep. And just as we benefit from our sleep in the ordinary earth life, do we benefit from the sleep which rules in our willing. We sleep through that which really takes place in us with every act of will. But in it there lies the true ego. Just as we receive our ego consciousness through the black void (see Figure XI), so does our ego lie in that which sleeps in us during the act of will—the ego, however, which passed through our former earth lives.

That is where karma holds sway. Karma rules in our willing. In our willing all the impulses from our preceding earth life hold sway; only, even in the waking human being, they are sunk in sleep.

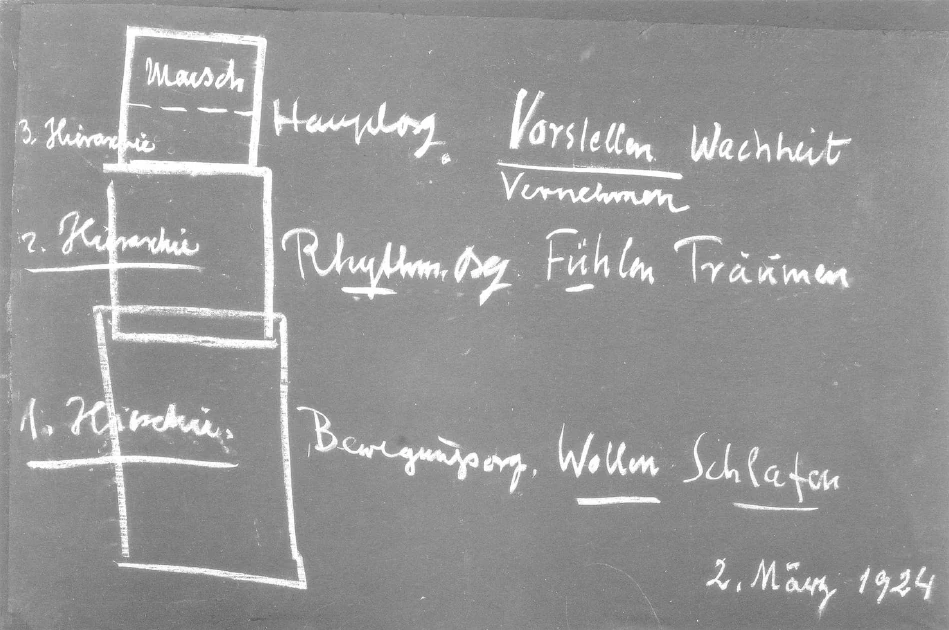

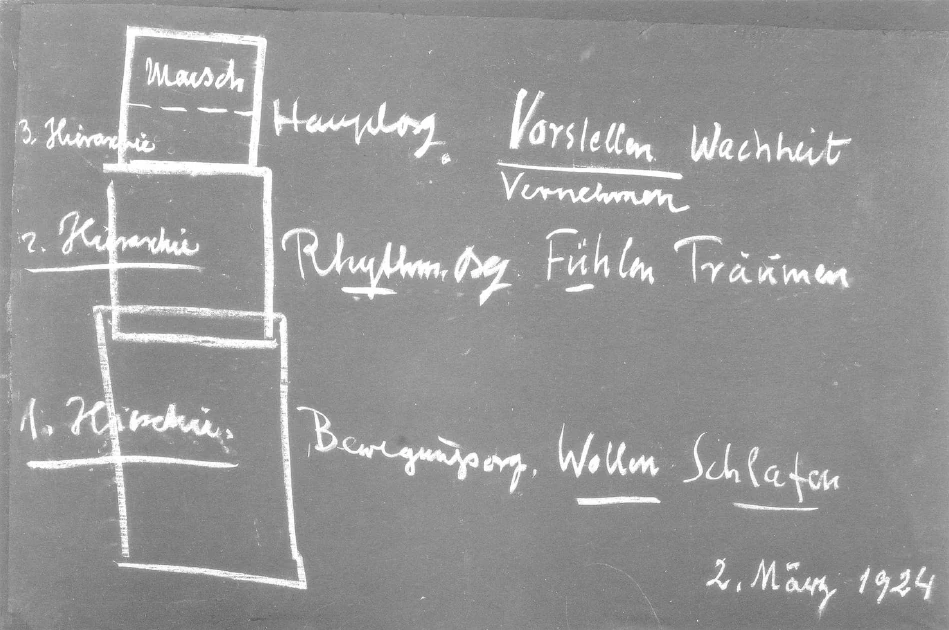

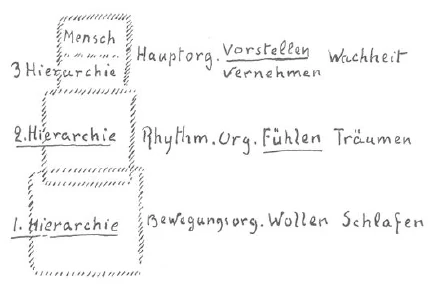

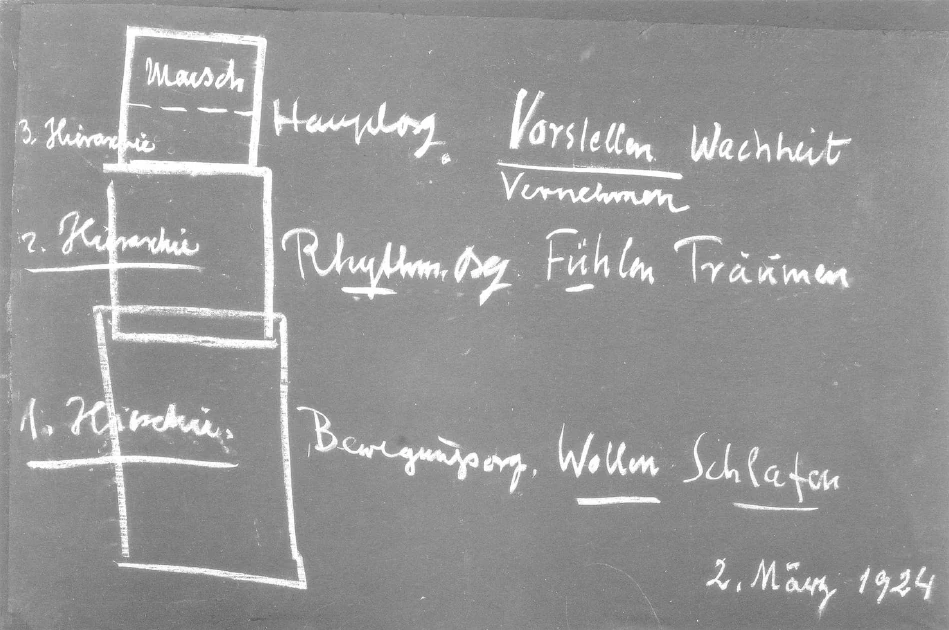

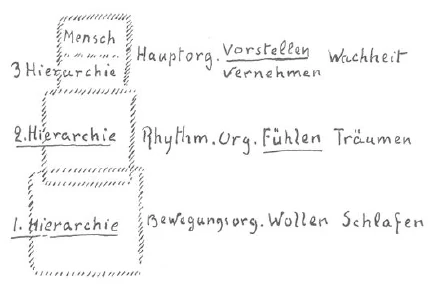

Thus, when we visualize the human being as he confronts us in earth life, a threefold membering of his organism is observable: the head organism, the rhythmic organism, and the motor organism. That is a schematic division. Each member belongs in turn to the whole man. Visualizing is bound to the head organism, feeling is bound to the rhythmic organism, and willing to the motor organism. Our state while visualizing is wakefulness, while feeling is dreaming. Our state in which willing, in which the will impulses take place is sleep, even during our waking life.

Now, in the head—that is, in our visualizing—we must distinguish two things; we must discover, as it were, a more subtle membering of the head. This more subtle membering leads us to distinguish what we have as momentary visualization by virtue of our having intercourse with the world, from what we have as memory.

You go through the world, constantly forming visualizations, mental images, according to the impressions you receive from the world. But it remains possible for you to call up these impressions again out of your memory. The visualizations you form in your intercourse with the world at present are not differentiated inwardly from the visualizations aroused to life when memory becomes active. In one case they come from without, and in the other from within. It is, indeed, a naive thought to imagine that memory works in the following way: I now confront a thing or event, form a visualization, a mental picture of it; this visualization sinks down into me somewhere, into some sort of pigeon-hole, and, when later I remember, I take it again out of the pigeon-hole. There are, indeed, whole philosophies which are able to describe how the visualizations sink down beneath the threshold of consciousness, then are fished out again in the act of recollecting. These are naive concepts.

There is, of course, no such pigeon-hole in which our visualizations lie when we remember them. Nor is there any such place in us where they are moving about and whence, when we remember them, they walk up again into our head. All these things are utterly non-existent, nor is there any explanation in their favor.

The facts are rather as follows, you need only to reflect on the following: When you wish to exercise your memory, you often do not work merely with your powers of visualizing, but you bring to your aid very different means. I have seen people memorizing who exercised their power to visualize just as little as possible, but carried on vehement outer movements accompanying their speech (arm movements) again and again:

And it undulates, surges, and roars and hisses

[Und es wallet und woget und brauset und zischt.

A well-known line of German poetry. (Tr.)]

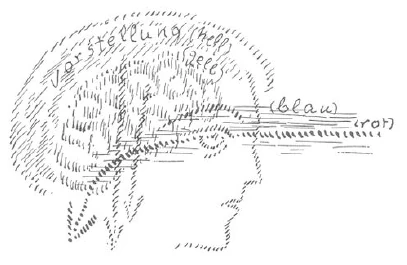

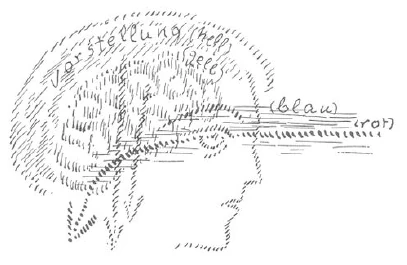

Thus, people memorize in this way, and in so doing the least possible thinking occurs. And in order to add a further stimulus—And it undulates, surges, and roars and hisses—they beat their forehead with their fists. Even this happens. It is definitely a fact that the visualizations we form as we occupy ourselves with the world are as evanescent as dreams. On the other hand, what emerges out of memory are not visualizations which have sunk below into us, but something quite different. Were I to give you some notion of it, I should have to draw it thus (see Figure XII). This is, naturally, only a kind of symbolic figure. Imagine the human being as a seeing being. He sees something. I shall not describe the process more exactly; that could be done, but for the moment we do not need it. The human being sees something. It passes through his eye (see Figure XII), through the optic nerve into the organs into which the optic nerve then merges.

We have two clearly distinct members of our brain: the more external brain, the gray matter; and, beneath it, the white matter. The white matter terminates in the sense organs, the gray matter lies within it; it is far less developed than the white mass. “Gray” and “white” are, of course, only approximate terms. But even thus crudely anatomically considered, the matter is as follows: The objects make an impression on us, pass through our eyes, and on into the processes that take place in the white matter of the brain.

On the other hand, our visualizations have their organs in the gray matter (see Figure XII) which, incidentally, has quite a different cell structure. Therein our visualizations glimmer and vanish like dreams. They glimmer, because the impressions are occurring underneath.

If you were dependent upon having the mental images sink down into you, and you then had to call them up again in memory, you would remember nothing at all, you would have no memory. The fact is like this: At the present moment, let us say, I see something. The impression of it—whatever it may be—sinks into me, the white matter of the brain acting as the medium. The gray matter functions by dreaming in its turn of the impressions, making pictures of them. These are only transitory pictures; they come and go. That which remains we do not visualize at all at this moment, but that goes down into our organism. And when we remember, we look within; down there below, the impression remains.

Thus, when you see something blue, then an impression of blue sinks down into you (below, in Figure XII), here (above, in Figure XII) you form the visualization of blue. It is transitory. Then, after three days, you

observe in your brain the impression which has remained. Now, by looking inward, you visualize the blue. The first time, when you saw the blue from without, you were stimulated from outside by the blue object. The second time, when you remember, you are stimulated from within, because the blueness portrayed itself within you. In both cases, the process is the same. It is always a perception. Memory, too, is a perception. So that our day-waking consciousness is actually to be found, as it were, in the visualizing process; but, beneath the visualizing, certain processes are going on which also rise into consciousness through visualizing, namely, through the memory visualizations. Below this visualizing lies perceiving, the actual perception, and only below this lies feeling. Thus, we can distinguish more intimately between the processes of visualizing and perceiving in our head organism, our thought organism. That which we have perceived we can then remember. But it remains, indeed, very unconscious; only in memory does it rise into consciousness. What really takes place in the human being is actually no longer experienced by him. When he perceives, he experiences the visualization. The effect of the perception penetrates him. Out of this effect he is able to awaken the memory. But then the unconscious has already begun.

In reality it is only here, in this region—where in waking-day consciousness we visualize—there only do we ourselves exist as human beings. There only are we really aware of ourselves as human beings (see Figure XIII). Where we do not reach down with our consciousness (we do not even reach the causes of our memories) there we are not aware of ourselves as human beings but are incorporated into the world. It is just as it is in the physical life. You inhale, the air you now have within yourself was a short while ago outside, it was the air of the outer atmosphere; it is now your air. After a short time, you give it back again to the world; you are one with the world. The air is now outside you, now inside you, now without, now within. You would not be a human being were you not united with the world in such a way that you possess not only that which is present within your skin, but that by means of which you yourself are connected with the whole surrounding atmosphere. And just as you are thus connected on your physical side, so are you connected on your spiritual side—the moment you descend into the nearest sub-conscious region, the region out of which memory arises—so are you connected with that which we call the third Hierarchy, Angeloi, Archangeloi, Archai. Just as you are connected through your breathing with the air, so are you connected through your head organism, the lower head organism, with the third Hierarchy. The outer lobes of the brain, consisting of gray matter, only and solely belong to the earth. What is beneath (the white matter) is connected with the third Hierarchy, Angeloi, Archangeloi, Archai.

Now let us descend into the region, psychologically speaking, of feeling; corporeally speaking, of the rhythmic organism, out of which the dreams of our feeling life arise. There we do not at all possess ourselves as human beings; there we are connected with what constitutes the second Hierarchy—the spiritual beings who do not incarnate in any kind of earthly body, but who remain in the spiritual world. They, however, send unceasingly their currents, their impulses, that which streams from them as forces, into the rhythmic organism of the human being. Exusiai, Dynamis, Kyriotetes—these are the beings whom we bear within our breast.

Just as we bear our human ego only in the outer lobes of our brain, so do we bear the Angeloi and Archangeloi, directly beneath this region, but still within the head organism. That is the scene of their earthly activities; there the starting-points of their activity are to be found.

In our breast we bear the second Hierarchy—Exusiai, and so forth; there in our breast are the starting-points of their activity. And if we now descend into the sphere of our motor organism, if we enter our movement organism, then in this sphere the beings of the first Hierarchy are active—Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones.

The transmuted food-stuffs, the food-stuffs we have eaten, circulate in our limbs, undergo there a process which is a living combustion process. For, if we take just a single step, there arises in us a living process of combustion, a burning up of that which was outside us. We are connected with it. Through our limb and metabolic organism, we are connected as human beings with the lowest, and yet it is precisely through the limb organism that we are connected with the highest. With the first Hierarchy, with the Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, we are connected by that which permeates us with spirit. Now the great question arises—it may sound trivial in that I clothe it in earthly words, but there is nothing else I can do—the question arises: With what are they occupied—these beings of the three successive Hierarchies, while they are among us—with what do they occupy themselves?

The third Hierarchy—Angeloi, Archangeloi, and so forth—concerns itself with that which has its physical organism in the head; this Hierarchy occupies itself with our thinking. Were it not concerned with our thinking, with that which takes place in our head, we would have no memory in ordinary earth life. The beings of this Hierarchy retain in us the impulses which we receive with our perceptions. They underlie the activity which manifests itself in our recollection, manifests itself in memory. They lead us through our earth life within this, our first unconscious region.

Now let us proceed to the beings of the second Hierarchy—Exusiai, and so forth. They are the beings we encounter when we have passed through the gate of death, in the life between death and a new birth. There we encounter the souls of the departed human beings who lived with us on earth; but we encounter there, above all, the spiritual beings of this second Hierarchy also, it is true, those of the third Hierarchy, but the second Hierarchy is more important. We work with them during the time between death and a new birth upon all that we have felt in our earth life, all that we have transplanted into our organism. In union with these beings of the second Hierarchy, we elaborate our next earth life.

When we stand here on the earth, we have the feeling that the spiritual beings of the divine world are in us. When we are there beyond in the sphere between death and a new birth, we have the reverse thought. The Angeloi, Archangeloi and so forth, who guide us through our earth life in the manner indicated, live on the same plane with us, so to speak, after our death. Directly underneath are the beings of the second Hierarchy. With them we work on the forming, the shaping, of our inner karma. And all that I told you yesterday about the karma of health and disease we elaborate with these beings, the beings of the second Hierarchy.

And if we look still deeper in the time between death and a new birth, that is, if we, as it were, look through the beings of the second Hierarchy, then below we discover the beings of the first Hierarchy, Cherubim, Seraphim, and Thrones. As earthly human beings, we seek the highest Gods above us. We seek as human beings between death and a new birth in the profoundest depths below us for the highest Divinity attainable by us. And while we are working with the beings of the second Hierarchy, dab- orating our inner karma between death and a new birth, that inner karma which afterwards appears reflected in the healthy or diseased constitution of our next earth life, while we are engaged in this work, while we work with ourselves and with other human beings upon the bodies which will then appear in our next earth life, the beings of the first Hierarchy are occupied below in a peculiar way. We behold that. They stand within a certain necessity in regard to their activity, in regard to a part, a small part, of their activity. They must imitate—for they are the creators of the earthly—that which the human being has molded during his earth life but imitate it in a quite definite way.

Think of the following: In his will, the human being performs certain deeds on earth. The will belongs to the first Hierarchy. Be these deeds good or bad, wise or foolish, the beings of the first Hierarchy—Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones—have to mold the counterparts of these deeds in their own sphere.

You know, my dear friends, we live together. No matter, whether the things we do together are good or evil, for all that is good, for all that is evil, the beings of the first Hierarchy must shape the corresponding counterparts. Among the first Hierarchy all things are judged, but also shaped and fashioned. While we work on our inner karma with the second Hierarchy and with the departed human souls, we behold between death and a new birth what Seraphim, Cherubim, and Thrones have experienced through our earthly deeds.

Indeed, my dear friends, here upon earth the blue sky with its cloud formations and sunshine arches overhead, and at night, as the starry heavens, it vaults above us. Between death and a new birth, the activity of the Seraphim, Cherubim, and Thrones vaults beneath us. And we gaze down upon these Seraphim, Cherubim, and Thrones just as we here look up to the clouds, to the blue heaven, to the star-strewn heaven. Beneath us we behold the heavens formed of the activity of Seraphim, Cherubim, and Thrones. But what kind of activity is it? While we live between death and a new birth, we behold the Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones performing the activity which results as the just and compensating activity from our own deeds on earth—our own and the earthly deeds lived through with other human beings. The Gods are obliged to exercise the compensating activity, and we behold it as our heavens which are now beneath us. In the deeds of the Gods we behold the consequences of our earthly deeds, whether good or bad, wise or foolish. And by looking downward we relate ourselves, between death and a new birth, to the reflection of our deeds in the same way as in earthly life we relate ourselves to the vaulting heaven above us.

We carry our inner karma into our inner organism. We bring it back with us onto the earth as our faculties and talents, our genius and our stupidity. What the Gods fashion there beneath us, what they must experience in consequence of our earth lives, confronts us in our next earth life as the facts of destiny which come to meet us from without. We may say that what we pass through to which we are asleep carries us into our destiny in our earth life. But in this lives what the Gods in question, those of the first Hierarchy, had to experience as the consequences of our deeds in their domain during the time between our death and a new birth.

One always feels the need of expressing such things in pictures. Let us imagine ourselves standing somewhere in the physical world. The sky is overcast; we behold the clouded sky. Soon thereafter, a rain begins to trickle down; the rain is falling. What previously hovered above us we now see on the dripping fields, on the dripping trees. If we look back, with the eye of the initiate, from human life into the time we passed through between our last death and our last birth, we then see therein, first of all, the forming of divine deeds, the consequences of our own deeds in our last earth life. We then see how this spiritually rains down and becomes our destiny.

If I meet a human being who has significance for me in earth life, who has a determining influence upon my destiny, what occurs with (his meeting of the other human being has been previously experienced by the Gods as a result of what I have had in common with him in a former earl h life. If I am transferred during my earth life to some locality important to me or placed in some important calling, all that comes to me thus as outer destiny is a likeness of what the Gods have experienced—Gods of the first Hierarchy—as a consequence of my former earth life, during the time when I was myself between death and a new birth.

Indeed, if you think abstractly, then you think: “There we have the former earth lives; the deeds of the former earth lives work across into the present. Previously they were causes; now they are effects.” With this we cannot think very far; we have actually little more than words when we make this statement. But behind what we thus describe as the law of karma lie the deeds of the Gods, experiences of the Gods; and behind all that lie the other facts.

If we human beings approach our destiny only through feeling, then we look up, according to our faith, either to the Gods or to some Providence, upon which we feel the course of our earth life depending. But the Gods—those whom we know as the beings of the first Hierarchy, Seraphim, Cherubim, and Thrones—have, as it were, a reverse religious confession. They feel their necessity lies with men on earth whose creators they arc. The aberrations human beings suffer, and the progress they enjoy, must be equalized by the Gods. And what the Gods prepare for us as our destiny in a subsequent life they have already lived through before us.

These truths must be found again through Anthroposophy. Out of a consciousness not fully developed, they were perceived by mankind in an erstwhile instinctive clairvoyance. The ancient wisdom contained such truths. Then only a dim feeling about them remained. In much that meets us in the spiritual life of mankind, there is still a dim feeling for these things. You need only remember the verse by Angelus Silesius which you will also find quoted elsewhere in my writings. To a narrow religious understanding it sounds like an impertinence:

Without me, God could not a moment live at most.

Came I to naught, must He from need give up the ghost.Ohn' mich könnt' Gott ein Nu nicht leben.

Würd' ich zunicht, müsst' er vor Not den Geist aufgeben.

Angelus Silesius went over to Roman Catholicism and as a Catholic wrote such verses. To him it was still clear that the Gods are dependent on the world, just as the world is dependent on the Gods, that this dependence is something mutual, and that the Gods must direct their life according to the life of human beings. But the divine life acts creatively and has its effect in turn in the destiny of human beings. Angelus Silesius, dimly feeling, but not knowing the exact truth, said:

Without me, God could not a moment live at most.

Came I to naught, must He from need give up the ghost.

World and Godhead depend on one another and work into one another. Today we have seen this interactivity in the example of human destiny, of karma.

Sechster Vortrag

Indem wir in unseren Betrachtungen über das Karma weiterschreiten, haben wir zunächst nötig, einen Blick auf die Art und Weise zu werfen, wie in der Menschenentwickelung das Karma eingreift; wie das Schicksal, das sich verwebt mit den freien Menschentaten, eigentlich aus der geistigen Welt heraus im physischen Abglanz gestaltet wird.

Da werde ich Ihnen heute einiges zu sagen haben über dasjenige, was mit dem Menschen, insofern er auf der Erde lebt, zusammenhängt. Dieser irdische Mensch, wir haben ihn ja in bezug auf seine Gliederung in diesen Vorträgen betrachtet. Wir haben an ihm den physischen Leib, den ätherischen Leib, den astralischen Leib, die Ich-Organisation unterschieden. Wir können aber, indem wir unseren Blick auf den Menschen, einfach wie er vor uns steht in der physischen Welt, wenden, die Gliederung des Menschen noch anders einsehen.

Wir wollen heute unabhängig von dem, was wir schon besprochen haben, an eine Gliederung des Menschen herantreten und dann versuchen, eine Verbindung zu schlagen zwischen dem, was wir heute besprechen, und dem, was wir schon kennen.

Wenn wir den Menschen, so wie er auf der Erde vor uns steht, einfach seiner physischen Gestalt nach betrachten, so hat ja diese physische Gestaltung drei deutlich voneinander unterschiedene Glieder. Man unterscheidet nur gewöhnlich diese Gliederung des Menschen nicht, weil alles dasjenige, was heute als Wissenschaft sich geltend macht, eigentlich nur oberflächlich auf die Dinge und Tatsachen hinschaut, keinen Sinn hat für dasjenige, was sich offenbart, wenn man mit innerlich aufgehelltem Blicke Dinge und Tatsachen betrachtet.

Da haben wir am Menschen zunächst das Haupt. Dieses Haupt des Menschen, schon äußerlich betrachtet, kann sich uns zeigen als von der übrigen menschlichen Gestalt ganz verschieden. Man braucht nur den Blick auf die Entstehung des Menschen aus dem Menschenkeim heraus zu wenden. Man wird als erstes, was sich im Leibe der Mutter bildet als Menschenkeim, eigentlich nur die Hauptes-, die Kopfesorganisation sehen können.

Die ganze menschliche Organisation geht vom Kopfe aus, und alles übrige, was am Menschen später in die Gestaltung einfließt, ist eigentlich Anhangsorgan am Menschenkeim. Erst ist der Mensch im Grunde genommen als physische Gestalt der Kopf; das andere ist Anhangsorgan. Und dasjenige, was dann diese Anhangsorgane im späteren Leben übernehmen, Ernährung, Atmung und so weiter, das wird in der ersten Embryonalzeit des Menschen gar nicht als Atmungs- oder Zirkulationsprozeß und so weiter von dem Inneren des Menschenkeimes aus besorgt, sondern von außen herein aus dem Leibe der Mutter durch Organe, die später abfallen, die später am Menschen gar nicht mehr vorhanden sind.

Dasjenige, was der Mensch zunächst ist, ist eben durchaus Haupt, ist durchaus Kopf. Das andere ist Anhangsorgan. Man übertreibt nicht, wenn man geradezu den Satz ausspricht: Der Mensch ist anfangs Kopf, das andere ist im Grunde genommen Anhangsorgan. Und da später dasjenige, was zuerst Anhangsorgan ist, heranwächst, Wichtigkeit gewinnt für den Menschen, unterscheidet man im späteren Leben das Haupt, den Kopf, nicht strenge von dem übrigen Organismus.

Aber damit ist nur eine oberflächliche Charakteristik des Menschen gegeben. In Wirklichkeit ist eben der Mensch auch als physische Gestalt ein dreigliedriges Wesen. Und alles dasjenige, was eigentlich seine erste Gestalt ist, das Haupt, das bleibt ein mehr oder weniger individuelles Glied am Menschen durch das ganze Erdenleben hindurch. Man beachtet das nur nicht, es ist aber so.

Sie werden sagen: Ja, man sollte den Menschen nicht so einteilen, daß man ihn gewissermaßen köpft, ihm das Haupt abschneidet. - Daß in der Anthroposophie dies geschehe, das war nur der Glaube von dem Professor, der der Anthroposophie vorgeworfen hat, daß sie den Menschen einteilt in Kopf, Brustorgane, Gliedmaßenorgane. Aber das ist nicht wahr, so ist es nicht; sondern in dem, was äußerlich Hauptesgestaltung ist, liegt nur der hauptsächlichste Ausdruck für die Kopfgestaltung. Der Mensch bleibt auch sein ganzes Leben hindurch ganz Kopf. Die wichtigsten Sinnesorgane, Augen, Ohren, Geruchsorgane, Geschmacksorgane, sind allerdings am Kopfe; aber zum Beispiel der Wärmesinn, der Drucksinn, der Tastsinn, sind über den ganzen Menschen ausgebreitet. Das ist deshalb, weil man nicht räumlich die drei Glieder voneinander unterscheiden soll, sondern nur so, daß die Kopfbildung hauptsächlich im äußerlich gestalteten Kopfe erscheint, aber eigentlich den Menschen ganz durchdringt. Und so ist es auch für die übrigen Glieder. Der Kopf ist während des ganzen Erdenlebens auch in der großen Zehe, insofern die große Zehe eine Tastempfindung hat oder eine Wärmeempfindung hat.

Sehen Sie, damit haben wir das eine Glied der menschlichen Wesenheit, jener menschlichen Wesenheit, die als sinnliche vor uns steht, zunächst charakterisiert. Diese Organisation habe ich in meinen Schriften auch die Nerven-Sinnesorganisation genannt, um sie mehr innerlich zu charakterisieren. Das ist das eine Glied der menschlichen Wesenheit, die Nerven-Sinnesorganisation.

Das zweite Glied der menschlichen Wesenheit ist alles dasjenige, was in rhythmischer Tätigkeit sich auslebt. Sie werden von der NervenSinnesorganisation nicht sagen können, daß sie in rhythmischer Tätigkeit sich auslebt, sonst müßten Sie zum Beispiel in der Augenwahrnehmung in einem bestimmten Augenblicke das eine wahrnehmen, dann das andere, dann das dritte, dann das vierte, dann wiederum auf das erste zurückkommen und so weiter. Es müßte ein Rhythmus in Ihrer Sinneswahrnehmung drinnen sein. Das ist nicht darinnen. Dagegen: gehen Sie auf das Hauptsächlichste Ihrer Brustorganisation, dann finden Sie da den Atmungsrhythmus, den Zirkulationsrhythmus, den Verdauungsrhythmus und so weiter. Das ist alles Rhythmus.

Und der Rhythmus mit seinen Rhythmusorganen ist das zweite, was sich in der menschlichen Wesenheit ausbildet, was sich nun wiederum verbreitet über den ganzen Menschen, aber hauptsächlich seine äußere Offenbarung in den Brustorganen hat. Der ganze Mensch ist wiederum Herz, ist wiederum Lunge; aber Lunge und Herz sind eben lokalisiert sozusagen in den Organen, die man gewöhnlich so nennt. Es atmet ja auch der ganze Mensch. Sie atmen an jeder Stelle Ihres Organismus. Man spricht von der Hautatmung. Nur hauptsächlich ist die Atmung konzentriert auf die Tätigkeit der Lunge.

Und das dritte ist dann dasjenige, was Gliedmaßenorganismus des Menschen ist. Die Gliedmaßen endigen in dem Brustorganismus. Sie treten im Embryonalstadium als Anhangsorgane auf. Sie bilden sich am spätesten aus. Sie sind aber diejenigen Organe, welche mit dem Stoffwechsel am meisten zusammenhängen. Dadurch, daß diese Organe in Bewegung kommen, dadurch, daß diese Organe vorzugsweise die Arbeit am Menschen verrichten, findet der Stoffwechsel die meiste Anregung. Dadurch haben wir die drei Glieder, die uns an der menschlichen Gestalt erscheinen, charakterisiert.

Aber diese drei Glieder hängen innig zusammen mit dem seelischen Leben des Menschen. Das seelische Leben des Menschen zerfällt in das Denken, in das Fühlen, in das Wollen. Das Denken findet seine physische Organisation vorzugsweise in der Hauptesorganisation. Es findet schon aber auch im ganzen Menschen seine physische Organisation, weil das Haupt in der Weise, wie ich es Ihnen eben erzählt habe, im ganzen Menschen eben ist.

Das Fühlen hängt mit der rhythmischen Organisation zusammen. Es ist ein Vorurteil, ja geradezu ein Aberglaube unserer heutigen Wissenschaft, daß das Nervensystem direkt mit dem Fühlen etwas zu tun hätte. Das Nervensystem hat direkt nichts mit dem Fühlen zu tun. Das Fühlen hat zu seinen Organen Atmungs- und Zirkulationsrhythmus, und die Nerven, die vermitteln nur das, daß wir vorstellen, daß wir unsere Gefühle haben. Die Gefühle haben ihre Organisation im rhythmischen Organismus, aber wir wüßten nichts von unseren Gefühlen, wenn nicht die Nerven uns Vorstellungen verschaffen würden von unseren Gefühlen. Und weil die Nerven uns Vorstellungen verschaffen von unseren Gefühlen, bildet sich der heutige Intellektualismus den Aberglauben, daß die Nerven auch die Organe für die Gefühle wären. Das ist nicht der Fall.

Aber wenn wir die Gefühle, wie sie aus unserem rhythmischen Organismus heraufkommen, in unserem Bewußtsein uns anschauen und sie vergleichen mit unseren Gedanken, die an unsere Hauptes-, an unsere Nerven-Sinnesorganisation gebunden sind, dann werden wir zwischen unseren Gedanken und unseren Gefühlen ganz den gleichen Unterschied wahrnehmen — wenn wir nur überhaupt beobachten können — wie zwischen unseren Tagesgedanken, die wir im Wachleben haben, und dem Träumen. Gefühle haben keine stärkere Intensität im Bewußtsein als die Träume. Sie haben nur eine andere Form. Sie kommen nur auf eine andere Weise zum Vorschein. Wenn Sie träumen in Bildern, lebt Ihr Bewußtsein eben in Bildern. Aber diese Bilder bedeuten in ihrer Bildform ganz dasselbe, was in einer anderen Form die Gefühle bedeuten. So daß wir sagen können: das hellste Bewußtsein, das durchleuchtetste Bewußtsein haben wir in unseren Vorstellungen, in unseren Gedanken. Eine Art Traumbewußtsein haben wir in bezug auf unser Fühlen. Wir glauben nur, wir hätten ein helles Bewußtsein von unserem Gefühl. Wir haben kein helleres Bewußtsein von unseren Gefühlen, als wir von unseren Träumen haben. Wenn wir, wachwerdend, uns erinnern und von den Träumen wache Vorstellungen bilden, da haben wir nicht den Traum erhascht. Der Traum ist viel reicher als dasjenige, was wir dann von ihm vorstellen. Ebenso ist die Gefühlswelt in sich unendlich viel reicher als dasjenige, was wir an Vorstellungen von dieser Gefühlswelt in uns präsent, gegenwärtig machen.

Und vollends in Schlaf getaucht ist das Wollen. Dieses Wollen ist an den Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganismus, an den Bewegungsorganismus gebunden. Von diesem Wollen kennen wir ja nur die Gedanken. Ich bilde mir die Vorstellung: Diese Uhr werde ich ergreifen. Versuchen Sie einmal sich ehrlich zu gestehen, Sie bilden sich die Vorstellung «diese Uhr werde ich ergreifen», und dann ergreifen Sie sie: Was da vorgeht von Ihrer Vorstellung hinunter in die Muskeln und zuletzt dazu führt, daß wiederum eine Vorstellung auftritt, das Ergreifen der Uhr, die die erste Vorstellung fortsetzt, dasjenige, was zwischen der Absichtsvorstellung und der Verwirklichungsvorstellung liegt, was in Ihrem Organismus vor sich geht, das bleibt so unbewußt, wie nur das Leben im tiefsten Schlaf, im traumlosen Schlaf unbewußt bleibt.

Von unseren Gefühlen träumen wir wenigstens. Von unseren Willensimpulsen haben wir nichts anderes, als was wir von unserem Schlafe haben. Sie können sagen: Vom Schlafe habe ich gar nichts. — Nun, ich rede jetzt nicht vom physischen Gesichtspunkte aus. Da ist es natürlich von vornherein schon ein Unsinn, zu sagen, vom Schlafe habe ich gar nichts; aber Sie haben auch seelisch sehr viel vom Schlafe. Wenn Sie nie schlafen würden, so kämen Sie nie zu Ihrem Ich-Bewußtsein.

Sie müssen sich nur das Folgende vergegenwärtigen. Wenn Sie sich erinnern an die Erlebnisse, die Sie gehabt haben, dann gehen Sie also zurück, von dem Jetzt weiter zurück. Ja, Sie meinen, das ist so: Sie gehen weiter zurück. — Aber so ist es ja nicht. Sie gehen nur zurück bis zu dem Momente, wo Sie das letzte Mal aufgewacht sind (siehe Zeichnung). Dann haben Sie geschlafen - was da dazwischenliegt, das schaltet sich aus -, und dann gliedert sich vom letzten Einschlafen bis zum vorletzten Aufwachen wirklich wiederum die Erinnerung an. Und so geht es zurück. Und indem Sie zurückschauen, müssen Sie eigentlich immer die Bewußtseinslosigkeit einschalten. Indem wir da zurückschauen, müssen wir ein Drittel unseres Lebens hindurch die Bewußtseinslosigkeit einschalten. Das beachten wir nicht. Aber das ist gerade so, wie wenn Sie eine weiße Fläche haben und in der Mitte ein schwarzes Loch. Sie sehen doch das schwarze Loch, trotzdem nichts dort ist von Kräften. So sehen Sie bei der Rückerinnerung, trotzdem nichts Inks drinnen ist von Lebensreminiszenzen, dennoch das Schwarze, die Nächte, die Sie verschlafen haben. Da stößt sich immer Ihr Bewußtsein. Das macht, daß Sie sich ein Ich nennen.

Wenn das wirklich immer fortginge und sich an nichts stoßen würde, kämen Sie gar nicht zu einem Ich-Bewußtsein. Also man kann schon sagen: Man hat etwas von dem Schlafe. Und geradeso wie man im gewöhnlichen Erdenleben etwas vom Schlafe hat, so hat man etwas von jenem Schlafe, der da in unserem Wollen waltet.

Man verschläft das, was eigentlich in einem vorgeht beim Willensakt. Aber darinnen liegt gerade das wahre Ich wiederum. So wie man das Ich-Bewußtsein durch das Schwarze erhält (siehe Zeichnung), so liegt in dem, was da schläft in uns während des Willensaktes, das Ich, aber das Ich durch die vorigen Erdenleben hindurch.

Ja, sehen Sie, da waltet das Karma. Im Wollen waltet das Karma. Im Wollen walten alle Impulse aus dem vorigen Erdenleben. Nur sind sie auch beim wachenden Menschen in Schlaf getaucht.

Wenn wir uns also den Menschen, so wie er uns im Erdenleben entgegentritt, vorstellen, dann tritt uns an ihm eine dreifache Gliederung entgegen: Die Hauptesorganisation, die rhythmische Organisation, die Bewegungsorganisation. Das ist schematisch abgeteilt; jedes Glied gehört wieder dem ganzen Menschen an. Gebunden an die Hauptesorganisation ist das Vorstellen, gebunden an die rhythmische Organisation ist das Fühlen, gebunden an die Bewegungsorganisation ist das Wollen. Der Zustand, in dem die Vorstellungen sind, ist die Wachheit. Der Zustand, in dem die Gefühle sind, ist das Träumen. Der Zustand, in dem das Wollen ist, die Willensimpulse, ist das Schlafen auch während des Wachens.

Nun müssen wir am Haupte, beziehungsweise am Vorstellen, zweierlei unterscheiden. Wir müssen noch einmal, ich möchte sagen, intimer das Haupt gliedern. Diese intimere Gliederung, die führt uns dazu, zu unterscheiden zwischen demjenigen, was wir als augenblickliche Vorstellung haben, indem wir mit der Welt umgehen, und dem, was wir als Erinnerung haben.

Sie gehen durch die Welt. Fortdauernd bilden Sie sich Vorstellungen nach Maßgabe der Eindrücke, die Sie von der Welt empfangen. Aber es bleibt Ihnen die Möglichkeit, diese Eindrücke später wiederum aus der Erinnerung heraufzuholen. Innerlich unterscheiden sich die Vorstellungen, die Sie sich gegenwärtig im Umgange mit der Welt bilden, nicht von den Vorstellungen, die dann erregt werden, wenn die Erinnerung spielt. Das eine Mal kommen die Vorstellungen von außen, das andere Mal kommen sie von innen. Es ist eben durchaus eine naive Vorstellung, wenn man sich denkt, daß das Gedächtnis so wirkt: Ich trete jetzt einem Ding oder Ereignis gegenüber, bilde mir eine Vorstellung, diese Vorstellung, die geht dann in mich irgendwie hinunter, in irgendeinen Kastenschrank, und wenn man sich erinnert, nimmt man sie aus dem Schrank wieder heraus. Es gibt ganze Philosophien, die beschreiben, wie die Vorstellungen, die hinuntergehen unter die Schwelle des Bewußtseins, dann wieder herausgefischt werden bei der Erinnerung. Es sind naive Vorstellungen.

Es ist natürlich gar kein solcher Kasten da, in dem die Vorstellungen darinnen liegen, wenn wir uns an sie erinnern. Es ist auch nichts in uns, wo sie spazierengehen und wieder heraufspazieren in den Kopf, wenn wir uns erinnern. Das alles gibt es nicht. Das alles hat ja aber auch gar keine Erklärung für sich. Der Tatbestand ist vielmehr der folgende.

Denken Sie nur, wenn Sie für Ihre Erinnerungen arbeiten wollen, dann arbeiten Sie oftmals nicht bloß mit dem Vorstellen, sondern Sie kommen sich mit ganz anderem zu Hilfe. Ich habe schon Leute memorieren sehen, die haben sich möglichst wenig vorgestellt, aber sie haben äußerlich vehemente Sprechbewegungen immer und immer wieder ausgeführt [Bewegungen mit den Armen]: «und es wallet und woget und brauset und zischt.» So memorieren ja viele, und dabei wird möglichst wenig gedacht. Und damit noch eine andere Anregung da ist: «und es wallet und woget und brauset und zischt», haben sie mit den Fäusten vor die Stirne gehämmert. Das gibt es auch. Es ist eben durchaus so: Die Vorstellungen, die wir uns bilden, wenn wir mit der Welt umgehen, verfliegen wie die Träume. Dagegen, was aus der Erinnerung herauftaucht, das sind nicht Vorstellungen, die hinuntergehen, sondern das ist etwas anderes. Wenn ich Ihnen davon eine Vorstellung bilden will, so müßte ich es so machen (siehe Zeichnung Seite 106). Das ist natürlich nur eine Art sinnbildlicher Zeichnung. Stellen Sie sich einmal den Menschen als sehendes Wesen vor. Er sieht etwas. Nun, ich will den Vorgang nicht genauer beschreiben, das könnte ja auch sein, aber das brauchen wir jetzt nicht. Er sieht etwas. Das geht durch sein Auge, durch den Sehnerv in die Organe, in die der Sehnerv dann übergeht.

Wir haben zwei deutlich unterschiedene Glieder unseres Gehirnes: das mehr äußere Gehirn, die graue Masse, darunterliegend die mehr weiße Masse. Die weiße Masse geht dann in die Sinnesorgane hinein; die graue Masse liegt darinnen, sie ist viel weniger entwickelt als die weiße Masse. Annähernd grau und weiß ist sie ja nur. Aber schon so grob anatomisch betrachtet, ist die Sache so: Da machen die Gegenstände auf uns einen Eindruck, gehen durch das Auge, gehen weiter zu Vorgängen in der weißen Masse des Gehirnes.

Dagegen unsere Vorstellungen haben ihr Organ in der grauen Masse (siehe Zeichnung), die dann eine ganz andere Zellenbildung hat. Da drinnen flimmern die Vorstellungen, die verschwinden wie die Träume. Sie flimmern, weil da unten dasjenige vor sich geht, was die Eindrücke sind.

Wenn Sie darauf angewiesen wären, daß die Vorstellungen hinuntergehen, und Sie in der Erinnerung sie wieder heraufholen sollen, dann würden Sie sich an gar nichts erinnern, dann hätten Sie überhaupt kein Gedächtnis. Die Sache ist so: In diesem Augenblicke, sagen wir, sehe ich irgend etwas. Der Eindruck von diesem Irgendetwas geht in mich hinein, vermittelt durch die weiße Gehirnmasse. Die graue Gehirnmasse wirkt, indem sie da ihrerseits träumt von den Eindrücken, Bilder entwirft von den Eindrücken. Die gehen vorüber. Dasjenige, was bleibt, das stellen wir gar nicht vor in diesem Augenblick, sondern das geht da unten in unsere Organisation hinein. Und wenn wir uns erinnern, so schauen wir hinein: da unten bleibt der Eindruck.

Wenn Sie also Blau gesehen haben, so geht von dem Blau ein Eindruck in Sie hinein (siehe Zeichnung, unten); hier (oben) bilden Sie sich die Vorstellung von Blau. Die geht vorüber. Nach drei Tagen beobachten Sie in Ihrem Gehirn den Eindruck, der geblieben ist. Und Sie stellen sich jetzt, indem Sie nach innen schauen, das Blau vor. Das erste Mal, wenn Sie das Blau von außen sehen, werden Sie von außen angeregt durch den Gegenstand, der blau ist. Das zweite Mal, wenn Sie sich erinnern, werden Sie von innen angeregt, weil die Blauheit in Ihnen sich abgebildet hat. Der Vorgang ist in beiden Fällen derselbe. Es ist immer ein Wahrnehmen, die Erinnerung ist auch ein Wahrnehmen. So daß eigentlich unser Tagesbewußtsein im Vorstellen sitzt; aber unter dem Vorstellen, da sind gewisse Vorgänge, die uns auch nur durch das Vorstellen heraufkommen, nämlich durch die Erinnerungsvorstellungen. Unter diesem Vorstellen liegt das Vernehmen, das eigentliche Wahrnehmen, und unter diesem erst das Fühlen. So daß wir intimer an der Hauptesorganisation, an der Denkorganisation das Vorstellen und das Wahrnehmen unterscheiden können. Das haben wir dann, was wir vernommen haben, an das können wir uns dann erinnern. Aber es bleibt eigentlich schon stark unbewußt. Es kommt nur herauf ins Bewußtsein in der Erinnerung. Was da eigentlich vorgeht im Menschen, das schon erlebt der Mensch eigentlich nicht mehr. Wenn er wahrnimmt, erlebt er die Vorstellung. Die Wirkung der Wahrnehmung geht in ihn hinein. Er kann aus dieser Wirkung die Erinnerung wachrufen. Aber da beginnt schon das Unbewußte.

Nun, sehen Sie: Wo wir im wachen Tagesbewußtsein vorstellen, nur da sind wir eigentlich selbst als Mensch, da haben wir uns als Mensch. (Siehe Zeichnung Seite 109.) Wo wir mit unserem Bewußtsein nicht hinreichen - nicht einmal zu den Ursachen der Erinnerungen reichen wir —, da haben wir uns nicht als Mensch, da sind wir in die Welt eingegliedert. Genau wie es im physischen Leben ist: Sie atmen ein, die Luft, die Sie jetzt in sich haben, war kurz vorher draußen, war Weltenluft; jetzt ist sie Ihre Luft. Nach kurzer Zeit übergeben Sie sie wieder der Welt: Sie sind mit der Welt eins. Die Luft ist bald draußen, bald drinnen, bald draußen, bald drinnen. Sie wären nicht Mensch, wenn Sie nicht so mit der Welt verbunden wären, daß Sie nicht nur das haben, was innerhalb Ihrer Haut ist, sondern dasjenige, womit Sie zusammenhängen mit der ganzen Atmosphäre. Ebenso wie Sie nach dem Physischen zusammenhängen, so hängen Sie in bezug auf Ihr Geistiges — in dem Augenblick, wo Sie ins nächste Unterbewußte herunterkommen, in diejenige Region, aus der die Erinnerung aufsteigt -, so hängen Sie da zusammen mit dem, was man die dritte Hierarchie nennt: Angeloi, Archangeloi, Archai. So wie Sie durch Ihr Atmen mit der Luft zusammenhängen, hängen Sie durch Ihre Hauptesorganisation, das heißt die untere Hauptesorganisation, die nur mit den äußeren Gehirnlappen bedeckt ist — die gehört einzig und allein der Erde an -, mit demjenigen, was darunter ist, mit der dritten Hierarchie zusammen, mit Angeloi, Archangeloi, Archai.

Gehen wir nun hinunter in die Region, seelisch gesprochen des Fühlens, körperlich gesprochen der rhythmischen Organisation, aus der ja nur die Träume des Gefühles heraufkommen, da haben wir uns erst recht nicht als Mensch. Da hängen wir mit dem, was die zweite Hierarchie ist, zusammen: geistige Wesenheiten, die nicht sich in irgendeinem Erdenleibe verkörpern, sondern die in der geistigen Welt bleiben, die aber ihre Strömungen, ihre Impulse, dasjenige, was von ihnen als Kräfte ausgeht, in die rhythmische Organisation des Menschen unaufhörlich hineinsenden. Exusiai, Dynamis, Kyriotetes, das sind die Wesenheiten, die wir in unserer Brust tragen.

Geradeso wie wir unser Menschen-Ich eigentlich nur in den äußeren Lappen unseres Gehirns tragen, tragen wir Angeloi, Archangeloi und so weiter unmittelbar darunter noch in unserer Hauptesorganisation. Da ist der Schauplatz ihres Wirkens auf Erden. Da sind die Angriffspunkte ihrer Tätigkeit.

In unserer Brust tragen wir die zweite Hierarchie, Exusiai und so weiter. Da in unserer Brust sind die Angriffspunkte ihrer Tätigkeit. Und gehen wir in unsere motorische Sphäre, gehen wir in unseren Bewegungsorganismus, so wirken in diesem die Wesenheiten der ersten Hierarchie: Seraphim, Cherubim, Throne.

In unseren Gliedmaßen zirkulieren die umgewandelten Nahrungsstoffe, die wir essen, machen dort einen Prozeß durch, der ein lebendiger Verbrennungsprozeß ist. Denn wenn wir einen Schritt machen, so entsteht in uns eine lebendige Verbrennung. Dasjenige, was außen ist, ist in uns. Wir stehen damit in Verbindung. Mit dem Niedrigsten stehen wir in Verbindung durch unseren Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganismus als physischer Mensch. Mit dem Höchsten stehen wir gerade durch unseren Gliedmaßenorganismus in Verbindung. Mit der ersten Hierarchie, mit Seraphim, Cherubim, Thronen stehen wir in Verbindung durch dasjenige, was uns durchgeistet.

Nun entsteht die große Frage - es sieht trivial aus, indem ich diese Frage in Erdenworte kleide, aber ich muß es ja tun -, die Frage: Womit beschäftigen sich, indem sie unter uns sind, diese Wesenheiten der drei aufeinanderfolgenden Hierarchien, womit beschäftigen sie sich?

Nun, die dritte Hierarchie, Angeloi, Archangeloi und so weiter, sie beschäftigt sich mit dem, was seine physische Organisation im Haupte hat, beschäftigt sich mit unserem Denken. Würde sie nicht sich mit unserem Denken beschäftigen, mit demjenigen, was in unserem Haupte vor sich geht, wir hätten keine Erinnerung im gewöhnlichen Erdenleben. Die Wesenheiten dieser Hierarchie halten die Impulse, die wir mit den Wahrnehmungen empfangen, in uns; sie liegen der Tätigkeit zugrunde, die in unserem Erinnern sich offenbart, im Gedächtnisse sich offenbart. Sie führen uns das Erdenleben hindurch, im ersten Gebiete, das wir haben als unterbewußtes, unbewußtes Gebiet.

Gehen wir zu den Wesenheiten der zweiten Hierarchie, Exusiai und so weiter. Sie treffen wir, diese Wesenheiten, wenn wir durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen sind, in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Da treffen wir die Seelen der abgeschiedenen Menschen, die mit uns auf der Erde gelebt haben, da treffen wir aber vor allen Dingen die geistigen Wesenheiten dieser zweiten Hierarchie; allerdings auch die dritte Hierarchie, aber wichtiger ist die zweite Hierarchie. Mit ihnen zusammen arbeiten wir in der Zeit zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt an allem dem, was wir im Erdenleben gefühlt haben, was wir da in unsere Organisation hineinverserzt haben. Wir arbeiten im Vereine mit den Wesenheiten dieser zweiten Hierarchie das nächste Erdenleben aus.

Wenn wir hier auf der Erde stehen, haben wir das Gefühl, die geistigen Wesenheiten der göttlichen Welt sind über uns. Wenn wir drüben sind in der Sphäre zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, hat man die umgekehrte Vorstellung. Die Angeloi, Archangeloi und so weiter, die uns durch das Erdenleben auf die angedeutete Art führen, die leben mit uns gewissermaßen in demselben Niveau nach dem Tode; darunter unmittelbar sind die Wesenheiten der zweiten Hierarchie. Mit denen arbeiten wir an der Formierung, der Gestaltung unseres inneren Karmas. Und was ich Ihnen gestern über das Karma der Gesundheit und Krankheit gesagt habe, das arbeiten wir mit diesen Wesenheiten aus, mit diesen Wesenheiten der zweiten Hierarchie.

Und wenn wir noch tiefer schauen in der Zeit zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, also wenn wir gewissermaßen durch die Wesenheiten der zweiten Hierarchie durchschauen, dann entdecken wir unten die Wesenheiten der ersten Hierarchie, Seraphim, Cherubim und Throne. Die höchsten Götter sucht man als Erdenmensch droben. Das höchste Göttliche, das uns zunächst erreichbar ist, sucht man als Mensch zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt zutiefst unten. Und während man mit den Wesenheiten der zweiten Hierarchie das innere Karma ausarbeitet zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, das dann im Abbilde erscheint im gesunden oder kranken Zustande des nächsten Erdenlebens, während man in dieser Arbeit steckt, während man also mit sich und den anderen Menschen arbeitet an den Leibern, die dann erscheinen im nächsten Erdenleben, betätigen sich die Wesenheiten der ersten Hierarchie unten in einer eigentümlichen Weise. Das sieht man. Sie stehen in bezug auf ihre Tätigkeit, in bezug auf einen Teil, einen kleinen Teil ihrer Tätigkeit in einer Notwendigkeit drinnen. Sie müssen nachbilden - denn sie sind die Schöpfer des Irdischen — dasjenige, was der Mensch im Erdenleben ausgestaltet hat, aber nachbilden in einer ganz bestimmten Weise.

Denken Sie sich, der Mensch vollbringt im Erdenleben in seinem Wollen - das gehört der ersten Hierarchie an — bestimmte Taten. Diese Taten sind gut oder böse, weise oder töricht. Die Wesenheiten der ersten Hierarchie, Seraphim, Cherubim und Throne, die müssen die Gegenbilder ausgestalten in ihrer eigenen Sphäre.

Sehen Sie, meine lieben Freunde, wir leben miteinander. Ob das nun gut oder böse ist, was wir miteinander treiben: Für alles Gute, für alles Böse müssen Gegenbilder ausgestalten die Wesenheiten der ersten Hierarchie. Alles wird unter der ersten Hierarchie beurteilt, aber auch ausgestaltet. Und während man an dem inneren Karma arbeitet mit der zweiten Hierarchie und mit den abgeschiedenen Menschenseelen, schaut man zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt dasjenige, was Seraphim, Cherubim und "Throne an unseren Erdentaten erlebt haben.

Ja, meine lieben Freunde, hier auf Erden wölbt sich über uns der blaue Himmel mit seinen Wolkengebilden, mit dem Sonnenschein und so weiter, wölbt sich als Sternenhimmel in nächtlicher Zeit über uns. Zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt wölbt sich unter uns das Tun der Seraphim, Cherubim und Throne. Und auf diese Seraphim, Cherubim und Throne schauen wir hin, wie wir hier hinaufschauen zu den Wolken, zum blauen Himmel, zum sternenbesäten Himmel. Wir sehen unter uns den Himmel, gebildet aus der Seraphim-, Cherubim- und Thronen-Tätigkeit. Aber in was für einer Tätigkeit? Indem wir zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt sind, sehen wir an den Seraphim, Cherubim und Thronen diejenige Tätigkeit, die sich als die gerechte ausgleichende Tätigkeit aus unseren eigenen und mit anderen Menschen verlebten Erdentaten ergibt. Die Götter müssen die ausgleichende Tätigkeit üben, und wir schauen sie als unseren Himmel, der jetzt unten ist. Wir schauen die Folgen unserer Erdentaten, ob irgend etwas gut oder böse ist, weise oder töricht ist, in den Taten der Götter. Wir verhalten uns zu dem Spiegelbilde unserer Taten zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, indem wir hinunterschauen, so, wie wir uns hier im Erdenleben zu dem über uns sich wölbenden Himmel verhalten. Unser inneres Karma tragen wir in unsere innere Organisation herein. Wir bringen es auf die Erde mit als unsere Fähigkeiten, unsere Talente, unser Genie, unsere Torheit. Das, was da unten die Götter formen, was sie erleben müssen infolge unserer Erdenleben, das tritt uns im nächsten Erdenleben als die Schicksalstatsachen entgegen, die an uns herankommen. Und wir können sagen: Dasjenige, was wir eigentlich verschlafen, das trägt uns in unserem Erdenleben in unser Schicksal. Aber in dem lebt dasjenige drinnen, was die entsprechenden Götter der ersten Hierarchie als die Folgen unserer Taten bei sich erleben mußten in der Zeit zwischen unserem 'Tode und einer neuen Geburt.

Man hat immer das Bedürfnis, solche Dinge in Bildern auszusprechen. Wir stehen irgendwo auf der physische Welt. Der Himmel ist bedeckt. Wir sehen den bedeckten Himmel. Gleich darauf rieselt Regen herunter. Regen fällt herunter. Was da noch über uns geschwebt hat, wir sehen es in den berieselten Feldern, in den berieselten Bäumen gleich nachher. Schaut man mit dem Blicke des Eingeweihten vom menschlichen Leben aus zurück in die Zeit, die man durchgemacht hat, bevor man herunterstieg ins Erdenleben, in die Zeit, die man durchgemacht hat zwischen dem letzten Tode und der letzten Geburt, so sieht man darinnen zunächst das Formen von Göttertaten, die Folge unserer Taten im letzten Erdenleben; dann sieht man, wie das geistig hereinrieselt und unser Schicksal wird.

Ob ich einen Menschen treffe, der für mich Bedeutung hat im Erdenleben, der für mich schicksalbestimmend ist: Dasjenige, was mit diesem Treffen des anderen Menschen geschieht, die Götter haben es vorgelebt als das Ergebnis dessen, was wir mit diesem Menschen in einem vorigen Erdenleben gehabt haben. Ob ich während meines Erdenlebens in eine Gegend versetzt werde, die für mich wichtig ist, in einen Beruf, der für mich wichtig ist, alles das, was da als äußeres Schicksal an mich herantritt, ist das Abbild desjenigen, was Götter erlebt haben, Götter der ersten Hierarchie, als Folgen meines früheren Erdenlebens in der Zeit, in der ich selber zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt gestanden habe,

Ja, sehen Sie, wenn man abstrakt denkt, so denkt man: Da sind die früheren Erdenleben, die Taten der früheren Erdenleben wirken herüber; damals waren die Ursachen, jetzt sind die Wirkungen. Man kann sich dabei nicht viel denken; man hat eigentlich nicht viel mehr als Worte, wenn man das ausspricht. Aber hinter dem, was man so als das Gesetz des Karmas schildert, liegen Göttertaten, Göttererlebnisse. Und hinter all dem liegt das andere.

Wenn wir Menschen nur der Empfindung nach an unser Schicksal herantreten, so schauen wir, je nach unserem Bekenntnis, zu Göttern hinauf oder zu irgendeiner Vorsehung, und fühlen davon den Verlauf unseres Erdenlebens abhängig. Aber die Götter, gerade diejenigen, die wir als die Wesenheiten der ersten Hierarchie anerkennen, Seraphim, Cherubim und Throne, sie haben gewissermaßen ein umgekehrtes religiöses Bekenntnis. Sie empfinden ihre Notwendigkeit bei den Menschen auf Erden, deren Schöpfer sie ja sind. Die Verirrungen und die Fördernisse, in die diese Menschen kommen, sie müssen von den Göttern ausgeglichen werden. Und was die Götter dann wiederum im späteren Leben für uns zubereiten als unser Schicksal, das haben sie zunächst uns vorgelebt.

Diese Dinge müssen wiederum durch Anthroposophie gefunden werden. Aus einem nicht voll entwickelten Bewußtsein heraus war das in einstigem instinktivem Hellsehen der Menschheit offenbar. Die alte Weisheit hatte solche Dinge in sich. Dann blieb nur ein dunkles Fühlen. Und in manchem, was uns im Geistesleben der Menschheit entgegentritt, ist noch ein dunkles Fühlen von diesen Dingen da. Erinnern Sie sich nur an den Vers des Angelus Silesins, den Sie ja auch in meinen Schriften finden, der für ein eingeschränktes religiöses Bewußtsein wie eine Frechheit aussieht:

Ich weiß, daß ohne mich Gott nicht ein Nu kann leben,

Werd’ ich zunicht, er muß von Not den Geist aufgeben.

Und Angelus Silesius ist zum Katholizismus übergetreten und hat als Katholik solche Sprüche geschrieben. Er war sich noch klar darüber, daß die Götter von der Welt abhängig sind, wie die Welt von den Göttern, daß die Abhängigkeit eine wechselweise ist, und daß die Götter ihr Leben nach dem Leben der Menschen richten müssen. Aber das göttliche Leben wirkt schöpferisch, wirkt sich wiederum aus im Schicksale der Menschen. Dunkel fühlend, nicht das Genaue wissend, hat Angelus Silesius gesagt:

Ich weiß, daß ohne mich Gott nicht ein Nu kann leben,

Werd’ ich zunicht, er muß von Not den Geist aufgeben.

Welt und Göttlichkeit sind voneinander abhängig, wirken ineinander.

Heute haben wir dieses Ineinanderwirken an dem Beispiel des menschlichen Schicksals, Karmas, gesehen. Ich mußte diese Betrachtungen einfügen in die Karmabetrachtungen.

Sixth Lecture

Before we go any further in our reflections on karma, we first need to take a look at the way in which karma intervenes in human development; how fate, which is interwoven with free human deeds, is actually shaped from the spiritual world in the physical reflection.

There I will have something to say to you today about that which is connected with the human being insofar as he lives on earth. We have looked at this earthly human being in terms of his structure in these lectures. We have distinguished between the physical body, the etheric body, the astral body and the ego organization. But by turning our gaze to the human being, simply as he stands before us in the physical world, we can see the structure of the human being still differently.

Today we want to approach the organization of the human being independently of what we have already discussed and then try to make a connection between what we are discussing today and what we already know.

If we look at the human being as he stands before us on earth, simply according to his physical form, then this physical form has three clearly differentiated limbs. This division of man is not usually distinguished because everything that is asserted today as science, which actually only looks superficially at things and facts, has no meaning for what is revealed when one looks at things and facts with an inwardly enlightened gaze.

There we have first of all the head of man. This head of the human being, even when viewed externally, can reveal itself to us as quite different from the rest of the human form. We need only look at the origin of man from the human germ. The first thing that forms in the womb of the mother as the human germ is actually only the head organization.

The entire human organization starts from the head, and everything else that later flows into the formation of the human being is actually an organ attached to the human germ. First, the human being as a physical form is basically the head; the rest is an appendage organ. And what these appendage organs then take over in later life, nutrition, respiration and so on, is not taken care of in the first embryonic period of the human being as a respiratory or circulatory process and so on from the inside of the human germ, but from the outside in from the womb of the mother through organs that later fall off, that are later no longer present in the human being.

What the human being is at first is definitely the head. The other is an appendage organ. It is no exaggeration to say that the human being is initially the head, the other is basically an appendage organ. And since later that which is first an appendage organ grows up and gains importance for the human being, in later life the head is not strictly distinguished from the rest of the organism.

But this is only a superficial characteristic of the human being. In reality, man as a physical form is also a tripartite being. And everything that is actually his first form, the head, remains a more or less individual part of man throughout his entire life on earth. You just don't pay attention to it, but it is like that.

You will say: Yes, one should not divide the human being in such a way that one beheads him, so to speak, cuts off his head. - That this happens in anthroposophy was only the belief of the professor who accused anthroposophy of dividing the human being into head, chest organs and limb organs. But this is not true, it is not so; but what is outwardly the main form of the head is only the most important expression of the form of the head. Throughout his whole life man remains entirely a head. The most important sensory organs, eyes, ears, organs of smell, organs of taste, are indeed at the head; but the sense of warmth, the sense of pressure, the sense of touch, for example, are spread over the whole human being. This is because the three limbs should not be distinguished from each other spatially, but only in such a way that the formation of the head appears mainly in the externally formed head, but actually permeates the human being completely. And it is the same for the other limbs. Throughout life on earth the head is also in the big toe, insofar as the big toe has a tactile sensation or a sensation of warmth.

You see, with this we have first characterized the one limb of the human being, that human being which stands before us as a sensual being. In my writings I have also called this organization the nerve-sense organization in order to characterize it more inwardly. This is one part of the human entity, the nervous-sensory organization.

The second part of the human being is everything that lives itself out in rhythmic activity. You will not be able to say of the nerve-sense organization that it lives itself out in rhythmic activity, otherwise you would have to perceive one thing in eye perception at a certain moment, then another, then the third, then the fourth, then come back to the first and so on. There would have to be a rhythm in your sensory perception. That is not there. On the other hand, if you go to the most important part of your chest organization, you will find the rhythm of breathing, the rhythm of circulation, the rhythm of digestion and so on. This is all rhythm.

And the rhythm with its rhythmic organs is the second thing that develops in the human being, which in turn spreads throughout the whole human being, but mainly has its outer manifestation in the chest organs. The whole human being is again the heart, is again the lungs; but the lungs and the heart are localized, so to speak, in the organs that are usually referred to as such. The whole person breathes. You breathe in every part of your organism. We speak of skin respiration. Breathing is mainly concentrated on the activity of the lungs.

And the third is that which is the human limb organism. The limbs end in the thoracic organism. They appear in the embryonic stage as appendages. They develop the latest. However, they are the organs that are most closely connected with the metabolism. The fact that these organs are set in motion, the fact that these organs preferentially carry out the work on the human being, means that the metabolism receives the most stimulation. Thus we have characterized the three limbs that appear to us in the human form.

But these three limbs are intimately connected with the spiritual life of the human being. The spiritual life of man is divided into thinking, feeling and willing. Thinking finds its physical organization preferably in the main organization. But it also finds its physical organization in the whole human being, because the head is in the whole human being in the way I have just told you.

Feeling is connected with the rhythmic organization. It is a prejudice, indeed a superstition of our science today, that the nervous system has anything directly to do with feeling. The nervous system has nothing directly to do with feeling. Feeling has respiratory and circulatory rhythms among its organs, and the nerves only convey that we imagine that we have our feelings. The feelings have their organization in the rhythmic organism, but we would know nothing of our feelings if the nerves did not provide us with ideas of our feelings. And because the nerves provide us with ideas about our feelings, today's intellectualism forms the superstition that the nerves are also the organs for the feelings. This is not the case.

But if we look at the feelings as they arise from our rhythmic organism in our consciousness and compare them with our thoughts, which are bound to our main nervous-sensory organization, then we will perceive quite the same difference between our thoughts and our feelings - if we can observe at all - as between our daily thoughts, which we have in waking life, and dreaming. Feelings have no greater intensity in consciousness than dreams. They just have a different form. They just appear in a different way. When you dream in images, your consciousness lives in images. But these images mean in their pictorial form quite the same thing that feelings mean in another form. So that we can say: we have the brightest consciousness, the most illuminated consciousness in our imaginations, in our thoughts. We have a kind of dream consciousness in relation to our feelings. We only believe that we have a bright consciousness of our feelings. We have no brighter awareness of our feelings than we have of our dreams. When, waking up, we remember and form waking images of the dreams, we have not caught the dream. The dream is much richer than what we then imagine of it. In the same way, the emotional world itself is infinitely richer than what we make present in us in terms of ideas of this emotional world.

And the will is completely immersed in sleep. This volition is bound to the metabolic organism of the limbs, to the organism of movement. Of this volition we only know the thoughts. I form the idea: I will seize this watch. Try to honestly admit to yourself that you form the idea “I will take hold of this watch”, and then you take hold of it: What goes on there from your imagination down into the muscles and finally leads to the appearance of another imagination, the seizing of the watch, which continues the first imagination, that which lies between the imagination of intention and the imagination of realization, that which goes on in your organism, that remains unconscious as only life remains unconscious in the deepest sleep, in dreamless sleep.

We at least dream of our feelings. Of our volitional impulses we have nothing other than what we have of our sleep. You can say: I have nothing at all from sleep. - Well, I am not talking from the physical point of view. It is of course nonsense from the outset to say that I get nothing at all from sleep; but you also get a great deal from sleep in your soul. If you never slept, you would never come to your ego-consciousness.

You only have to visualize the following. When you remember the experiences you have had, then you go back, further back from the present. Yes, you think that's the case: you go further back. - But it's not like that. You only go back to the moment when you last woke up (see drawing). Then you have slept - what lies in between is switched off - and then the memory is really structured from the last time you fell asleep to the last but one time you woke up. And so it goes back. And by looking back, you actually always have to switch on unconsciousness. By looking back, we have to switch on unconsciousness for a third of our lives. We don't pay attention to that. But it's just like when you have a white surface and a black hole in the middle. You can see the black hole, but there are no forces there. So when you remember back, even though there is nothing inside of life's reminiscences, you still see the black hole, the nights you slept through. Your consciousness always bumps into them. That's what makes you call yourself an ego.

If that really went on all the time and didn't bump into anything, you wouldn't have an ego consciousness at all. So you can already say that you have something of sleep. And just as one has something of sleep in ordinary earthly life, so one has something of the sleep that reigns in our will.

We sleep through what is actually going on in us in the act of will. But therein lies the true I again. Just as one receives the I-consciousness through the black (see drawing), so in that which sleeps in us during the act of will lies the I, but the I through the previous earth lives.

Yes, you see, that is where karma rules. Karma rules in the will. All the impulses from the previous life on earth are at work in the will. Only they are also immersed in sleep in the waking human being.

So if we imagine the human being as he appears to us in earthly life, then a threefold structure appears to us: The main organization, the rhythmic organization, the organization of movement. This is schematically subdivided; each member again belongs to the whole human being. Imagination is bound to the main organization, feeling is bound to the rhythmic organization, and volition is bound to the organization of movement. The state in which the imaginations are is alertness. The state in which the feelings are is dreaming. The state in which the will is, the impulses of the will, is sleeping even during wakefulness.