Meditation and Concentration:

Three Kinds of Clairvoyance

GA 161

1 May 1915, Dornach

Translator Unknown

Lecture II

Through all that we have recently been discussing here there runs a basic theme. This basic theme is an expression of how at the present time, within the whole cultural development of mankind, the necessity may be seen for a new impulse—that is, a spiritual impulse, an impulse towards spiritual knowledge.

In these recent lectures it was intended to show from the most varied points of view that we have been passing through an age with a quite distinct character and that now a new age must begin. The age that has been running its course is the time when thinking and perceiving have reached their most pronounced form of materialism, the time when throughout the centuries materialistic thinking and perceiving have increasingly taken hold of the inner life of the human soul. But just as a pendulum that has swung to one side has then to swing in the opposite direction, we are now faced by an age when the human soul must once more come to the perception that in everything having to do with the senses, in everything material, spiritual impulses, spiritual forces, are experience of the spiritual forces behind material sense phenomena—spiritual forces to which for centuries mankind has been able to give but little attention and but little interest.

Now we all know how in our day the assertion that it is possible for the human soul to enter spiritual worlds is decried and considered heretical. We know how a multiplicity of factors in life—either conscious or unconscious—are directed against the coming of such a stream in world-conception as that of spiritual science. It is easy to see how at the present time what spiritual science must offer, for the ordering of life and the facts of life, would appear absolutely absurd, foolish, and fantastic. When, however, we enter into what is maintained even now by men of insight, out of a deeper impulse in life, all that has just been described: takes on a different aspect.

I should like first to point out to you that among men of deeper insight today there does not always exist antagonism against what spiritual science maintains—antagonism to spiritual science itself is certainly there but not so much against what it stands for. Many, very many, examples of this might be quoted; today I will give you a characteristic one connected with a recent philosopher of repute—Otto Liebmann, who died a short while ago.

Most of you will not even know his name; that will not matter. But I should like to say that Otto Liebmann was one of the most clear-sighted of those who have recently analysed. Man’s life of thought—that he thoroughly ploughed the ground of epistemology, always putting the question: How much reality is human thought capable of grasping?

I should like to read you a short passage from Otto Liebmann’s philosophical writings because it is characteristic of a man who throughout his life made great efforts to fathom the nature of human thought and what at the present time can be said about it in the light of the results of modern science. This is what Otto Liebmann said: “Someone might hit on the idea that there is not just albumen and yolk in a hen’s egg, but besides these something of a ghostly nature - an invisible spirit. This spirit materializes itself and when it has completed this materialisation it bursts open the egg-shell with the sharp beak, darts upon the grain and pecks it up.”

It might occur to one, he says, that a spirit was in the egg and that when the egg-shell was broken this spirit came out and pecked up the grain. .. What will those people say who are building up a world-conception founded on present-day science? They will tell you: If anyone says that a spirit is working in a hen's egg, he is a fool.—That is how the clever people of today will speak and their remark will apply to those who call themselves theosophists or anthroposophists. But what says the philosopher who has been at such infinite pains to analyse man’s present thinking? He says: The only thing to be said against this assertion is that the preposition "in" is nonsense when used in a physical sense, but in a metaphysical is quite right. It is true that we get nowhere by conceiving the spirit to be within the egg spatially; when, however, this is taken metaphysically no objection can be made; it is only that the preposition cannot be used in its ordinary sense.

We are therefore faced with the fact that a philosopher who has written an intelligent book, "The Analysis of Reality", and another on "Thoughts and Facts” (what is said about the "invisible spirit" comes in the second part of the 1899 "Naturerkenntnis")—that this philosopher owns that, in reality, it is possible to stand at the pinnacle of modern philosophy and yet be unable to do other than admit that an invisible spirit lies hidden in the egg of a hen.

It goes without saying that Otto Liebmann would have scorned to recognise the reasonable nature of spiritual science. We might ask why this is. Why would he—or anyone who thinks in the way he does—not pursue the matter further and perceive in spiritual science what would make him say: Strictly speaking, this spiritual science is merely wanting to confirm that in the hen’s egg there is actually an invisible spirit!—The name is not of importance; with us it would be called the etheric body, which for its part is permeated by the astral body. The spiritual scientist indeed says what it is that is hidden within as invisible spirit; thus spiritual scientist says nothing but what others are saying—yet there is this difficulty in turning to spiritual science. It is said to be foolish and fantastic in spite of being urgently needed for the science and the thinking of the day.

Now how far is it from the assertion that an invisible spirit is concealed in the hen’s egg to the other statement that in the human physical body too—anatomy and physiology examine only the physical—something invisible is hidden? If we could clear up the difficulty about the use of the preposition "in” (dwelt upon by the philosopher); we should come to the point of indicating what spiritual science says, namely, that what is "within" consists of etheric body, astral body and ego. Thus, spiritual science does nothing for which there is no ample proof that it is really demanded by all that has to do with present-day though and culture. Spiritual Science however, obviously has to go farther, for it cannot stop short at the vague idea that an invisible spirit is concealed in a hen's egg—especially when this same idea is applied to man. There we have to be clear that what is thus hidden in man is possessed of certain qualities, certain inner factors of reality. Whereas in the case of the hen's egg our conception can be what we might almost call of a ghostly nature—"an unknown spirit is concealed there"—if we go on to man we have to recognise that, when living in the physical body, he develops consciousness and does so for the very reason that the physical body is such a complicated apparatus. Thereby we sense that what has here been called invisible spirit must be recognised as underlying the visible. Now, if what is external has consciousness we have to take for granted that there is consciousness also in what is within, and that what is within cannot be deemed unconscious.

Science will lead to the perception of something like what spiritual science assumes, namely, that in the physical body there lives a spiritual man. It is the nature of this spiritual man’s consciousness to which our attention is directed by spiritual science.

Today we know—have known for some -time how to give an answer about the precise qualities of the invisible spirit underlying man. If we take, to begin with, what today is offered us by philosophy, we shall admit that at the basis of man, too, there lies an invisible spirit. We now ask: Is it possible to know anything about this spirit? Most certainly it is. Just as man can acquire knowledge about the world outside through sense perception and the thoughts connected with the brain, this knowledge can go further; for in the spirit there lives Imagination—what has been described as Imaginative knowledge. We should then be able to see that it is not only in the hen’s egg that there lies an invisible spirit, but that in man is hidden an etheric body which, given the possibility (this is also mentioned in our writings), frees itself from the physical body and develops Imaginative knowledge—knowledge that works, in the world in Imaginations, standing before the soul in fluctuating Imaginations.

We must here ask: What is the reason for spiritual science meeting with so much opposition today, the fact that people who do not understand it arrived at, and give indications of, what is said by spiritual science?

My dear friends, here something must be said that it is dangerous to put into words—or in any case not without danger. Why would Otto Liebmann, had he picked up a book on spiritual science, have certainly said: I find this really foolish, ridiculous—while standing himself at the very gates of the spiritual world? Why was he living in such strange self-deception—standing before the gates but, the door being opened to him, saying: No, I am not entering—why? It is certainly not very reasonable!

Sometimes comparisons throw light, therefore it is with a comparison that I should like to answer the question: Why among the finest men today are there those who shy away from spiritual science?

I should like at the same time to draw your attention to something of which we have already spoken, namely, what I said about sleep and fatigue. There is much talk today about the reason for people having to sleep and it is said to because they are tired—so that tiredness is considered the essential cause of sleep. This is what is said today. Now from the most ordinary experience in life everyone knows that any leisured person who comes to a lecture, out of politeness shall we say, will often fall asleep when the lecture has hardly begun even if he isn’t tired—so that we may all come to the conclusion that fatigue is not entirely the cause of sleep. On the contrary, we should be nearer the truth in saying, not that we go to sleep because we are tired, but that we feel tired because we want to sleep. This would be more correct.

The essential nature of sleep consists in a man going with his ego and his astral body out of the physical and etheric bodies, thus feeding upon his physical body and etheric body from outside—we might even say feeding upon and digesting them; whereas when he is within his physical and etheric bodies he lives with his consciousness in the external world. Note well what is actually said here. If with ego and astral body we are outside our physical and etheric bodies, we apply all our will, all our desires, to these physical and etheric bodies; we feed on and digest physical body and etheric body from outside; whereas when we are within these bodes the outside world makes its impressions upon us.

Now everything in the world depends like the pendulum upon periodicity. When the pendulum has swung up to a certain point it descends again and then rises up to the same height on the opposite side through the force it acquires in its descent. In the same way that the pendulum can go not only up to here but has to return to the level it reached before it descended are sleeping and waking opposed to one another. Roughly it may be expressed thus.

Let us suppose that from waking to falling asleep we have been interested in the outside world and what has passed there. This absorbing of the outside world can be likened to the swing of the pendulum in one direction. When we have sufficiently absorbed the world outside then by reason of the satiety this causes there develops the satisfaction formerly provided by the outside world—and we go to sleep. When we have exhausted this enjoyment of ourselves we are able to wake up again. It is a swinging to and fro, a periodicity, which takes its regular course in the same way as in ordinary mechanics. Lucifer and Ahriman can, however, lift a man out of the whole course of nature. Thus the man who goes to a lecture or concert from sheer courtesy and not because he wants to listen, can be lifted out of himself so that he loses all interest. He withdraws from himself, feeds on himself, finding this more interesting than what is going on around him.

Thus we can see that whoever falls asleep in an abnormal way simply has no interest in his environment and what is going on there. We find exactly the same thing among those, of whom I have spoken, who have had their attention turned to what spiritual science offers. In the sphere of spiritual science Otto Liebmann is just like a man who goes out of courtesy to a concert or lecture and at once falls asleep. He goes, yet is not actually willing to take in what he is offered there.

On a higher level we can say the same of men who are like Otto Liebmann. They come to philosophy, to the land of the spirit through conditions holding good in our world. Someone writes a thesis, a book, is then sent as teacher to a grammar school and, when proving himself to be a thinker, he is sent on to a university. Philosophising is world-courtesy, just world-courtesy—and there is no need for any call to the land of the spirit. One goes to the door, even goes inside, and then falls asleep; not immediately like the satiated concert-goer, who sleeps without even being tired, through lack of interested consciousness in the subject—but the philosopher cannot wake up to Imaginative consciousness. If it is impossible for people to awake to Imaginative consciousness then the moment anything is said about the spiritual world they fall asleep. In other words, it is too difficult for them to take in anything about spiritual science. It is therefore not without danger to make this assertion, for people will say: So you are the people who are making a study of what to other men, to men of consequence, is so difficult!—Since we are conscious of the difficulty, however, we shall not be too arrogant. For we shall know that the very points about which we ought to agree will be attacked by the world because people refuse to embark upon so difficult an affair—for the very reason that they find it too difficult.

Now let us examine these difficulties rather more closely. We will point the way by asking: What does ordinary human thinking consist in from the time of waking to that of failing asleep? In what does it consist? How whoever thinks in a grossly materialistic way holds the following opinion—that men have a brain that is of extraordinarily delicate construction, that in this brain processes go on and because they do so thinking arises. Thinking is a consequence of this brain-process; so he says.

I have already pointed out that this is just as if someone were to say: I go along a street where there are footprints and the tracks of wheels. Whence come these—tracks? It is the earth beneath which must have made them; the earth itself has made the traces of feet and wheels appear. Logically this is on a par with thinking that it is the brain that makes these impressions. When someone goes out, sees all kinds of tracks along the street and says: Aha—then it is the earth that is inwardly permeated by a variety of forces which make these tracks—the same as when the physiologist, examining the human brain, and substantiating the fact that all manner of processes are going on there, says: It is the brain that is doing all this. There is just as little reason for saying that it is the earth itself that makes the tracks which are really made by the men and vehicles moving around upon it as there is for saying that what the anatomists and physiologists discover is by the brain, when it is far rather the work of forces in movement in the etheric body.

By this you will be able to see in what the deceptive nature of materialist consists. There is nothing in everyday life that does not make an impression on the brain. Just as every step makes an impression on the earth, and you can prove that each of your steps has made its impression, you can also prove that all that is willed and thought makes its impression, has its influence, on the brain. But that is only the trace, it is only what is left behind of the thinking. Thinking takes place indeed in the etheric body; in reality everything you perceive as thinking is nothing but the etheric body's inner activity. So long as we remain in the physical body we need this physical body for thinking. It is very easy to see why the materialist does not arrive at the true. The materialist says: For heaven sake, can’t you see that you must have a brain if you are to think? And if you see this, you can also see that it is your brain which actually does the thinking. And if you see this, you can also see that it is your brain which actually does the thinking. This conclusion is about as clever as to say: I can prove that this track on the road has been made by the ground itself. I shall remove part of the ground and you will see that without it you are unable to walk. The ground is indeed a necessity—it is also necessary to have a brain to be able, when in the physical body, to think.

It is necessary for us to be clear about these things for it is only then that that we learn under what illusion present day thinking labours, with what a host of illusions this thinking fools itself, and how the only cure for this must be effected through that knowledge so difficult to acquire which, we trust, does not fail to take the physical body into consideration. For when going about in the physical body we must have solid earth beneath our feet: When thinking in the physical world we must have support for our thinking; we must have a nervous system. When, however, we change the place of our thinking activity to our astral body, the etheric body will become for us what the physical body is when we think with the etheric body.

If we progress to Imaginative thinking we then think in the astral and the etheric body retains the traces as formerly, when thinking took place in the etheric body, the traces were retained by the physical body. When after death we are outside the physical body and have also laid aside the etheric body—in the way often described—then our support is the outer life—ether and what is developed by the astral body and later by the ego we write into the whole cosmic ether.

This, therefore, is the process we go through during what is called the first stage of initiation. The process consists in our removing our thinking (it is no longer thinking, only the activity of thinking) from the etheric body to the astral body, getting over to the more volatile etheric body the retention of the traces which formerly the physical body held. This is the essential feature of the first stage in initiation. It is essential that the activity formerly carried on by the etheric body should be handed over to the astral body.

Thus we see that while living in Imaginative knowledge we, as it were, withdraw from the physical body to the etheric body, imprinting no further traces into the physical body. Through this it comes about that, for anyone who makes this first step in initiation, the physical body from which he withdraws becomes objective and is then outside his astral body and ego. Formerly it was within, now it is outside. He thinks, feels and wills in the astral body. He has an influence on the etheric body, leaves traces in it, but he no longer influences the physical body and looks upon it as something external.

This is approximately the normal course when it is a question of the first step in initiation—the normal course. It finds expression in a quite definite way in subjective experience.

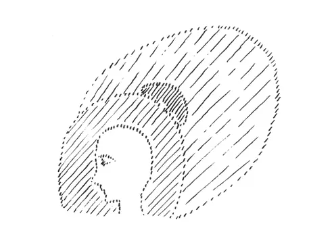

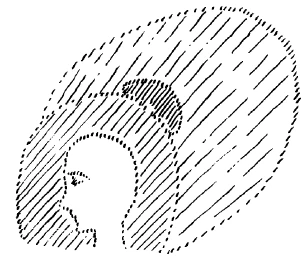

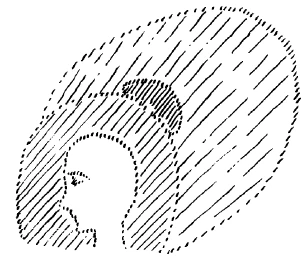

By means of a diagram I will now make clear in what this first stage of initiation consists. Let us assume that this is the human physical head—and all around the human physical head we have the etheric body. When a man begins to develop what I have been speaking about, when he begins to develop Imaginative knowledge, then the etheric body grows in this way larger, and what is characteristic of this is that parallel with it goes on naturally what has been described as the cultivation of the lotus flowers. The man grows etherically out of himself and the strange thing is that, while he is doing so, something develops out of his body which I would call a kind of etheric heart.

As [a] physical human being we have our physical heart, and we all know how to appreciate the difference between a dry, abstract man who develops his thoughts in a machine-like way and a man who goes with his heart into everything that he experiences—with his physical heart, that is; we can all appreciate this distinction. From the man who slouches around without any interest in life and whose heart plays no part in the experiences of his soul, we do not expect much on the physical plane in the way of real cosmic knowledge. A kind of spiritual heart develops outside our physical body, parallel to the phenomena I have described in “Knowledge of the Higher Worlds”, just as the blood-system develops and has its center in the heart. The blood-system goes outside the body and outside the body we feel ourselves in our heart bound up with what we know in the way of spiritual science. Only we must not look to enter into the knowledge of spiritual science with the heart that is in our body but with the heart outside it, for it is with this heart that we enter into what we know of spiritual science.

On reading what is written in the sphere of spiritual science it is possible to say: But this too is scientifically dry—this is science—here we have to go back to school again! We must in any case do enough learning in life, and now we are supposed to learn what spiritual science has to say. There is no heart in that.—One will discover the heart in it when going into things deeply enough.

It is true that many people say: Theosophy must consist above all in a man in his ego becoming one with the whole world.—This “becoming one", this “development in man of the divine man", this "discovery of the divine ego”, and so on—these are the pet phrases of those who want to be theosophists without having any knowledge of theosophy. This all springs from lack of desire to develop warmth of heart even when no longer sustained by the living warmth of the physical heart. Just as Lichtenberg said: “When a head and a book collide and there is a hollow sound, the book is not to be blamed”, we might say: If a man comes up against spiritual science and finds no warmth of heart in it, it is not spiritual science that is to blame. All that I have just been describing as the normal path to clairvoyance consists in man lifting out from his physical body, his etheric body and also the higher members of his organization, and providing himself with a heart outside the limits of his physical body.

What then do ordinary thoughts rest upon? A thought of this kind is actually only developed in the etheric body; it then comes up against the physical body and there makes impressions all over the brain. If we call up before our souls the essential feature of everyday thinking we can say: It rests on our thinking in the etheric body, and on what is thus thought sinking into the nervous system of the brain; there it makes impressions which do not, however, go very deep but rebound. In this way the thinking is reflected and thus enters our consciousness. A thought therefore consists above all in our having it in our soul as far as the etheric body; it then makes an impression on the physical brain, but cannot enter it and has to rebound. These reflected thoughts we perceive. Then physiology comes along and points to the traces which have appeared in the physical brain.

Now how would it be were the thought not reflected back, were it to enter the brain and there merely to cause processes? Were the thought not reflected back we should not be able to perceive it; then it would go into the brain and be the cause simply of processes. It would be conceivable that the thought, instead of being thrown back, might enter the brain; then we should not be conscious of it, for it is only by the thought being reflected that consciousness arises.

There is, however, an activity of the soul which does enter the body and that is the will. Willing differs from thinking because thinking is thrown back from the bodily organization and perceived as a mirrored image—whereas willing is not. The willing enters into the bodily organization; thereby a physical bodily process is called into being. This brings it about that we walk, move our hands, and so on. Actual willing arises in quite a different way from thinking: which does so by being thrown back. But willing enters into the bodily organization, is not thrown back, but within the bodily organization brings about definite processes. Nevertheless in one part of our bodily organization there is the possibility for what thus sinks down being thrown back.

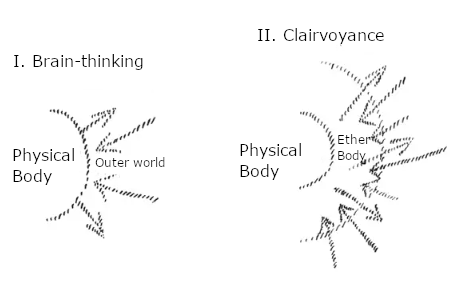

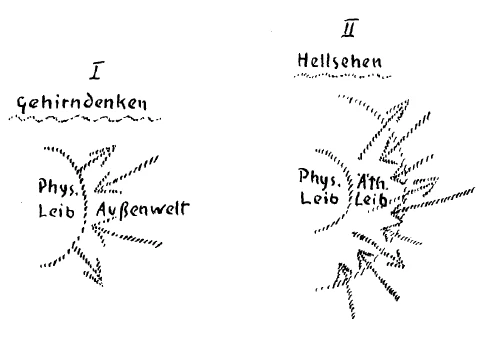

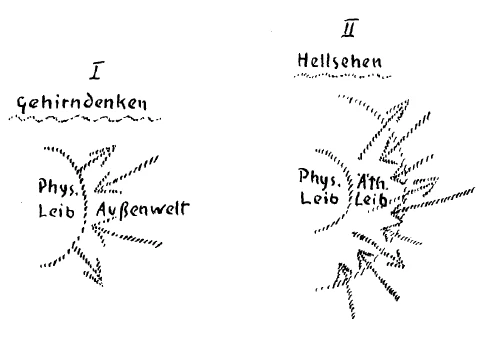

Follow carefully what I am about to say. The procedure in brain-thinking is this—thought-activity develops in the etheric brain, rebounds against the physical nervous system, thus bringing our thoughts into consciousness. In the case of clairvoyance we, as it were, thrust the brain back; we think with the astral body and the thinking is thrown back to us by the etheric body.

Here (1 in diagram) is the outer world, here the physical body (when brain thinking is in question). Here (2 in diagram) for clairvoyance, is the outer world, what we work upon with our astral body; we let the etheric body throw this back and we altogether exclude the physical body.

Here (I), however, when we will, the activity of the soul goes down into the physical body. Hence when we walk, when we move our hand, this is done by the soul; but the activity of the soul has to bring about inner organic, material processes, upon which the activity of the soul expends itself. It might be put thus—that the will consists in the activity of the soul being exhausted by its material work in the body.

Let us now ask in what way we actually live when living in our thinking. My answer would be that in our thinking we are living close to the boundary of eternity. The moment we exclude the physical body and let our thoughts be rayed back from the etheric body we live in what we carry through the gate of death. As long as we let the physical body ray back the thoughts, we are living in all that is between birth and death; when we will, our will belongs entirely to our physical body. Our physical body is there to promote activity. Whereas our thinking stands at the very gate of eternity, our willing is organized for the physical body.

Remember how I said in one of the lectures that our willing is the baby and when it is older it will become thinking. This is absolutely in accordance with what from another point of view we can develop today. Willing is under the ban of the temporal, and only because a man develops, becomes wiser and wiser and permeates his willing by thought, does he raise what is inherent in willing out of time into the sphere of eternity, and free his willing from his body.

But in a certain part of our body there is something inserted, namely, the secondary nervous system, the glandular system, the nervous system of the abdomen—part of which is often called the solar plexus. As developed in a man at present this nervous system is an unfinished organ; it exists only in an embryonic state. It will develop itself later. But just as of a child we know that he has qualities which can still go on developing as he grows up, we can know that this nervous system, today in the service of organic activity, will also develop further. This nervous system which works side-by-side with the systems of brain and spine and with the nerves that branch-out into the limbs, this abdominal nervous system is not so far developed today that it would be able to do what it will do when man has once reached Jupiter. By that time brain and spine will have lost ground and the abdominal nervous system will have progressed to something quite different from what it is today. It will then be placed on the surface of a man; for all that to begin with was within a man will later have its place on his surface.

For this reason for ordinary life between birth and death we make no direct use of this nervous system, letting it remain in the subconscious. Through abnormal conditions, however, it may happen that what a man has in his will and his capacity for desire enters his organism, and through these abnormal conditions—about which we shall speak presently—is thrown back by the abdominal nervous system in the same way as the thought is thrown back by the brain. The will goes into the glandular system but instead of becoming active it is thrown back by the glandular system and something arises in man that usually takes place in his brain—a process which may be characterized as follows.

When we bear in mind the transition from the ordinary waking state to clairvoyance, you can see how within us thinking, feeling and willing reflect themselves in the ordinary nervous system—feeling and willing, that is, to the extent that they are thoughts—and we let what is our willing sink down into our organization. In clairvoyance we form by these means—outside the space occupied by the body—a higher organ over against the brain. As the ordinary brain is connected with our physical heart, what develops as thought outside (in the astral body) is connected with the etheric heart. This is the higher clairvoyance—clairvoyance of the head.

A man can, however, take the reverse path. He can go into the organization with the baby-willing in such a way that willing becomes thinking, whereas otherwise he made thinking into will. This is the deeper distinction between what a little time ago I described here as head-clairvoyance and abdominal clairvoyance {See lecture 1}. In the case of head-clairvoyance we form a new etheric organ in which we are independent of the bodily organization we have in ordinary life. Where abdominal clairvoyance is concerned appeal is made to the glandular system, to what otherwise remains unnoticed. Hence the results of abdominal clairvoyance are more fleeting than ordinary waking experience; they have no significance for the soul when passing through the gate of death; whereas even for those souls who have gone through the gate of death, everything gained by head-clairvoyance has spiritual, lasting significance—greater significance than waking day-experience. What is acquired through abdominal clairvoyance has even less significance for life after death than ordinary waking day-knowledge. All somnambulistic clairvoyance is below waking day-consciousness—not above.

This is certainly not to say that all manner of positional and other qualities cannot be developed through abdominal clairvoyance; because the moment abdominal clairvoyance arises it is really the glands which always send the willing particularly, there arises one of the main forces of opposition against spiritual science which strives in all directions after clearness.

Spiritual science must everywhere have real sympathy and love for consistent, complete thoughts, not for those that are incomplete. It must not be content with the vague and obscure, but on all sides press on towards what does not narrowly shed the mere semblance of light but spreads true light throughout the wide spaces of the world. In this connection, we still have much, very much, to overcome.

These are the things I wanted to make objects of our study, in order to show how through Ahriman, in the course of the centuries, thoughts have given rise to the denial of the spiritual world, but how the spiritual world itself has worked in the thoughts of those who deny it because—the time has come.

“The time has come.” Appropriate here are these words from Goethe’s “Fairy Tale”.

This must very soon receive confirmation.

Zwölfter Vortrag

Durch alle die Besprechungen, die in der letzten Zeit hier gepflogen worden sind, ging ein Grundzug. Dieser Grundzug enthielt den Ausdruck dafür, daß wir in unserer Gegenwart in der Tat innerhalb der ganzen Kulturentwickelung der Menschheit beobachten können die Notwendigkeit eines neuen Impulses, nämlich eines spirituellen Impulses, eines Impulses geistiger Erkenntnis.

Es sollte in diesen Vorträgen von den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten aus eben gezeigt werden, daß gewissermaßen eine Zeit abgelaufen ist, die einen ganz bestimmten Charakter hatte, und daß eine neue Zeit beginnen muß. Die Zeit, die abgelaufen ist, ist gewissermaßen die Zeit der intensivsten materialistischen Denk- und Empfindungsweise, die Zeit, in welcher das materialistische Denken und Empfinden immer mehr und mehr durch Jahrhunderte hindurch Platz gegriffen hat im inneren Leben der Menschenseele. Aber ebenso wie das Pendel, wenn es nach der einen Seite ausgeschlagen hat, wiederum nach der anderen Seite, in der entgegengesetzten Richtung ausschlagen muß, so stehen wir vor einer Zeit, in welcher die Menschenseele wieder ergriffen werden muß von der Empfindung, daß in allem Sinnlichen, in allem Materiellen, geistige Impulse verborgen sind, geistige Kräfte verborgen sind, und die Geisteswissenschaft soll ja im wesentlichen vermitteln die Erkenntnis und das Erleben dieser geistigen Kräfte hinter den sinnlichen und materiellen Erscheinungen und Erlebnissen, der geistigen Kräfte, auf welche die Menschheit durch Jahrhunderte hindurch weniger Aufmerksamkeit, weniger Interesse hat verwenden können.

Nun wissen wir alle, wie in unserer Zeit angeschwärzt, verketzert wird allein schon die Geltendmachung dessen, daß es der Menschenseele möglich ist, in geistige Welten hineinzutreten. Wir wissen, wie die mannigfaltigsten Faktoren des Lebens, bewußt oder unbewußt, sich gegen das Heraufkommen einer solchen Weltanschauungsströmung, wie es die geisteswissenschaftliche ist, wenden. Man könnte glauben, daß es in unserer Gegenwart ganz und gar absurd, töricht, phantastisch erscheinen würde, was die Geisteswissenschaft von sich aus zur Regelung des Lebens und seiner Tatsachen darbieten muß; wenn man aber auf dasjenige eingeht, was immerhin, ich möchte sagen, auch jetzt schon einsichtigere Menschen, aus etwas gründlicheren Lebensimpulsen heraus, geltend machen, so sieht das eben Geschilderte doch wieder anders aus.

Ich möchte Sie zuerst heute hinweisen darauf, daß bei einsichtigeren Menschen der Gegenwart doch nicht überall ein solches Verschließen vorhanden ist gegenüber dem, was die Geisteswissenschaft geltend machen will, obzwar das Verschließen gegen die Geisteswissenschaft wohl da ist, aber nicht so sehr das Verschließen gegen das, was die Geisteswissenschaft geltend macht. Viele, viele Beispiele nach dieser Richtung wären da anzuführen. Ich will ein charakteristisches Beispiel einmal herausheben heute, das sich bezieht auf einen immerhin bedeutenderen Philosophen der jüngst verflossenen Zeit, auf den vor nicht langer Zeit verstorbenen Otto Liebmann.

Die meisten von Ihnen werden den Namen Otto Liebmann gar nicht kennen, und das macht auch nichts. Aber ich möchte doch sagen, daß Otto Liebmann einer der scharfsinnigsten Zergliederer des menschlichen Gedankenlebens in der neueren Zeit gewesen ist, daß er dasjenige, was man Erkenntnistheorie nennen kann, nach allen Seiten hin durchgeackert hat, daß er sich überall die Frage vorgelegt hat: Was kann der menschliche Gedanke erfassen von der Wirklichkeit?

Eine kleine Stelle aus den philosophischen Schriften Otto Liebmanns möchte ich Ihnen vorlesen, weil sie charakteristisch ist für einen Mann, der sein ganzes Leben hindurch sich abgemüht hat, zu ergründen, was der menschliche Gedanke ist, was die Gegenwart von ihm zu sagen vermag, wenn er sich stützt auf alle wissenschaftlichen Ergebnisse dieser unserer Gegenwart. Da sagt also Otto Liebmann: Es könnte jemand auf den Gedanken verfallen, in dem Hühnerei stecke nicht bloß Eiweiß und Dotter, sondern außerdem ein unsichtbares Gespenst darinnen; dieses Gespenst vermaterialisiere sich, und wenn es mit seiner Materialisierung fertig ist, sprenge es die Eischale mit dem spitzen Schnabel, laufe auf die Körner zu und picke sie auf.

Zunächst, sagt er, könnte einem einfallen, daß in dem Ei ein Gespenst wäre, und wenn dann die Eischale aufgepickt ist, käme das Gespenst heraus und könne die Körner aufpicken. Wie werden sich diejenigen äußern, die auf dem Standpunkte stehen, sich aus der gegenwärtigen Wissenschaft eine Weltanschauung aufzubauen? Die werden es folgendermaßen tun: Wenn einer sagt, im Hühnerei darinnen steckt ein Gespenst, so ist er eben ein Narr. - So werden die gescheiten Leute der Gegenwart sprechen. Nur wendet man das bloß auf diejenigen an, die sich Theosophen oder Anthroposophen nennen! Was sagt aber der Philosoph, der sich um die Zergliederung des menschlichen Denkens in der Gegenwart so viel Mühe gegeben hat? Er sagt: Gegen diese Behauptung läßt sich nichts anderes einwenden, als daß die Präposition «im» Unsinn ist, wenn sie im physischen Sinne gebraucht wird; im metaphysischen Sinne ist sie ganz richtig. Daß man mit der Vorstellung, das Gespenst sitzt räumlich darinnen, nichts anfangen kann, ist ganz richtig; aber wenn man sie metaphysisch versteht, so läßt sich gegen sie nichts einwenden. Es ist die Präposition nur nicht im gewöhnlichen Sinne zu gebrauchen.

Also die Tatsache liegt vor, daß ein Philosoph, der ein geistvolles Buch geschrieben hat «Analysis der Wirklichkeit» und ein Buch «Gedanken und Tatsachen» — im zweiten Heft 1899 der «Naturerkenntnis» steht dies von dem unsichtbaren Gespenst -, zugibt, daß man im Grunde genommen ganz auf dem Höhepunkte der heutigen Philosophie stehen kann und gar nicht anders kann, als zuzugeben, daß im Hühnerei darinnen wirklich ein unsichtbares Gespenst stecke.

Selbstverständlich würde Otto Liebmann nie sich herbeilassen, in der Geisteswissenschaft etwas Vernünftiges zu sehen. Man könnte die Frage aufwerfen: Warum tut er denn das nicht? Warum würde er oder jemand, der so denkt wie er, nicht herangehen und sich einmal diese Geisteswissenschaft ansehen, um zu dem Urteil zu kommen: Ja, diese Geisteswissenschaft will ja im Grunde genommen gar nichts anderes, als in Wirklichkeit konstatieren, daß dieses unsichtbare Gespenst im Hühnerei wirklich darinnen ist! - Auf den Namen kommt es ja nicht an; es würde eben bei uns Ätherleib genannt werden, der wiederum von dem astralischen Leib durchsetzt ist. Der Geisteswissenschafter beschreibt eben, was da drinnen ist als unsichtbares Gespenst; der Geisteswissenschafter sagt also nichts anderes, als was die anderen sagen. Dennoch wird man sich nicht zur Geisteswissenschaft so leicht wenden. Man wird sie eine "Narretei, eine Phantasterei schelten, trotzdem sie von der Wissenschaft und von der Gedankenarbeit der Gegenwart energisch gefordert wird.

Wie weit ist es nun von der Behauptung, daß im Hühnerei ein unsichtbares Gespenst steckt, zu der anderen, daß im menschlichen physischen Leib - die Anatomie und Physiologie untersuchen nur das Physische - auch etwas Unsichtbares darinnen steckt? Und wenn man sich hinweghelfen würde über die Anwendung der Präposition «im» darauf kommt es dem Philosophen ja an -, dann wäre man schon daran, auf etwas hinzuweisen, wovon die Geisteswissenschaft sagt, daß es in dem Ätherleibe, dem Astralleibe und dem Ich besteht. Die Geisteswissenschaft tut also nichts, wovon sich nicht streng nachweisen läßt, daß es wirklich gefordert wird von dem ganzen Gedanken- und Kulturprozesse der Gegenwart. Nur muß selbstverständlich die Geisteswissenschaft etwas weitergehen, denn bei der Ahnung kann es nicht bleiben: im Hühnerei steckt ein unsichtbares Gespenst -, insbesondere, wenn man damit zum Menschen übergeht. Da muß es klar sein, daß dasjenige, was unsichtbar im Menschen darinnen steckt, gewisse Eigenschaften, gewisse innere Wirklichkeitsfaktoren hat. Während man sich beim Hühnerei, ich möchte fast sagen, gespenstisch vorstellen kann: da steckt ein unbekanntes Gespenst darinnen -, muß man, wenn man zum Menschen vorschreitet, sich klar sein, daß der Mensch, wenn er im physischen Leibe wohnt, Bewußtsein entwickelt, dadurch Bewufßtsein entwickelt, daß der physische Leib ein so komplizierter Apparat ist. Dadurch ahnt man, daß das, was man hier unsichtbares Gespenst genannt hat, doch gelten muß als etwas, was dem Sichtbaren zugrunde liegt. Wenn nun das Äußere schon Bewußtsein hat, so muß man doch als selbstverständlich annehmen, daß auch das Innere Bewußtsein hat, daß man es nicht «bewußtlos» glauben kann.

Die Wissenschaft wird darauf hinführen, einzusehen so etwas wie dasjenige, was die Geisteswissenschaft annimmt: daß es in dem physischen Leibe einen geistigen Menschen gibt. Und die Art des Bewußtseins dieses geistigen Menschen ist es ja, auf die uns die Geisteswissenschaft hinweist.

Wir wissen heute schon, seit längerer Zeit schon, eine Antwort zu geben über die genauen Eigenschaften dieses dem Menschen zugrunde liegenden, unsichtbaren Gespenstes. Nehmen wir zunächst diese philosophischen Darbietungen der Gegenwart, so werden wir zugeben, es liegt auch dem Menschen ein unsichtbares Gespenst zugrunde. Wir fragen uns nun: Können wir über dieses unsichtbare Gespenst etwas wissen? — Jawohl; so wie der Mensch durch die sinnlichen Wahrnehmungen und durch die Gedanken, die an das Gehirn gebunden sind, Erkenntnisse über die äußere Welt erwirbt, erweitert auch dieses Wissen sich: denn in dem Gespenste leben die Imaginationen, lebt dasjenige, was wir beschrieben haben als imaginative Erkenntnis. Wir würden sehen können: nicht nur dem Hühnerei liegt ein unsichtbares Gespenst zugrunde, sondern im Menschen steckt der ätherische Leib darinnen, der, wenn ihm die Möglichkeit gegeben wird - es ist dies in unseren Schriften schon ausgesprochen -, sich vom physischen Leibe frei macht und eine imaginative Erkenntnis entwickelt, eine Erkenntnis, die in Imaginationen in der Welt arbeitet, die in bewegten Imaginationen vor der Seele steht.

Es muß schon einmal die Frage vorgelegt werden: Worauf beruht es eigentlich, daß die Geisteswissenschaft heute so viele Gegner findet, trotzdem im Grunde die Leute, die sich selber nicht verstehen, auf das kommen und auf das hinweisen, was die Geisteswissenschaft sagt?

Meine lieben Freunde, da muß etwas gesagt werden, was, ich möchte sagen, gefährlich ist auszusprechen, jedenfalls nicht ungefährlich. Warum würde Otto Liebmann zweifellos, wenn er ein geisteswissenschaftliches Buch in die Hand bekäme, sagen: Das ist mir zu töricht, zu närrisch —, während er doch sozusagen selber vor der Pforte der geistigen Welt steht? Warum lebt er in dieser sonderbaren Selbsttäuschung, daß er zwar vor der Pforte steht, aber wenn jemand kommt und ihm das Tor aufmachen will, sagen würde: Nein, da gehe ich nicht hinein. - Warum? Das ist doch nicht besonders vernünftig!

Manchmal erreicht man doch etwas durch Vergleiche, und deshalb möchte ich mit einem Vergleich die Frage beantworten: Warum gibt es unter den Besten der Gegenwart solche vor der Geisteswissenschaft zurückschreckende Menschen?

Ich möchte da ebenfalls auf etwas aufmerksam machen, worüber wir schon gesprochen haben: auf das, was ich schon gesagt habe über den Schlaf und die Ermüdung. Man redet heute vielfach darüber, wie es kommt, daß die Menschen schlafen müssen, und man sagt sich: weil sie ermüdet sind. So daß die Ermüdung im wesentlichen als die Ursache des Schlafes angesehen wird. So redet man heute vielfach. Nun weiß zwar jeder aus der gewöhnlichsten Erfahrung des Lebens, daß irgendein Rentier, der, sagen wir, aus Courtoisie einen schönen Vortrag besucht, oftmals, kaum nachdem der Vortrag begonnen hat, sogleich einschläft, auch wenn er nicht ermüdet ist, woraus jeder den Schluß ziehen könnte, daß die Ermüdung durchaus nicht die Ursache des Schlafes ist. Im Gegenteil, die Sache würde richtiger ausgedrückt werden, wenn wir nicht sagen würden: Wir schlafen, weil wir ermüdet sind -, sondern sagen würden: Wir fühlen uns ermüdet, weil wir schlafen wollen. - Das würde der richtigere Ausdruck sein.

Das Schlafen besteht nämlich im wesentlichen darin, daß der Mensch, indem er mit seinem Ich und seinem astralischen Leibe aus dem physischen Leibe und dem Ätherleibe herausgeht, seinen physischen Leib und seinen Ätherleib von außen genießt, man möchte sogar sagen, nicht nur genießt, sondern verdaut; während, wenn er im physischen Leib und im Ätherleib darinnen ist, er mit seinem Bewußtsein in der äußeren Welt lebt. Merken Sie wohl, was damit eigentlich gesagt ist. Sind wir außerhalb unseres physischen Leibes und Ätherleibes mit unserem Ich und unserem Astralleibe, so wenden wir allen Willen und alle Begehrlichkeit nach dem physischen Leibe und dem Ätherleibe hin, wir genießen und verdauen den physischen Leib und den Ätherleib von außen; während die äußere Welt Eindrücke macht auf uns, wenn wir im Ätherleibe und im physischen Leibe darinnen stecken.

Nun beruht alles, was in der Welt ist, auf Periodizität, geradeso wie es beim Pendel ist. Wenn das Pendel nach der einen Seite bis zu einem gewissen Punkte hinaufgegangen ist, so geht es wieder hinunter und auf der anderen Seite hinauf bis zu derselben Höhe, durch die Kraft, die es sich beim Herunterfallen erworben hat. So wie das Pendel nicht nur bis hierher gehen kann, sondern dann wieder zurück muß und hinauf bis zu dem Punkte, den es erreicht hatte bevor es heruntergegangen war, so sind Schlafen und Wachen einander entgegengesetzt. Im gröbsten Sinne laßt es sich so sagen.

Nehmen wir an, wir haben vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen uns interessiert für die äußere Welt und deren Ablauf. Dieses Aufnehmen der äußeren Welt war so, wie das Pendel nach der einen Seite ausschlägt. Wenn wir das, was äußere Welt ist, genügend aufgenommen haben, dann entwickelt sich durch die Übersättigung, durch das Genughaben von der äußeren Welt, das normale Bedürfnis, auch uns selber wieder zu genießen, von uns selber den Genuß zu haben, den wir sonst in der äußeren Welt haben: wir schlafen ein. Und haben wir mit diesem Genuß genügend uns aus uns herausgepreßt, dann können wir auch wieder aufwachen. Es ist ein Hin- und Herschlagen, eine Periodizität, die, wie draußen im Mechanismus, regelmäßig ablaufen wird. Aber den Menschen kann Luzifer und Ahriman wirklich herausheben aus dem ganzen Naturlaufe. So kann der Mensch, wenn er zu einem Vortrage oder zu einem Konzerte aus Courtoisie gegangen ist, nicht weil er zuhören will, herausgehen und kann sein Interesse ablenken. Er geht heraus und genießt sich, weil er sich interessanter findet als dasjenige, was äußerlich um ihn herum abläuft.

So kann man sehen: Derjenige, welcher in anormaler Weise in Schlaf verfällt, hat einfach kein Interesse an der Umwelt, an dem, was in der Umwelt vorgeht. Nichts anderes liegt aber vor bei solchen Menschen, von denen ich gesprochen habe, die eigentlich hingewiesen werden auf dasjenige, was die Geisteswissenschaft darbietet. Otto Liebmann ist auf geisteswissenschaftlichem Gebiete ein solcher Mann, wie der, welcher aus Courtoisie ein Konzert oder einen Vortrag besucht und gleich einschläft. Er geht hin, aber eigentlich will er doch nicht dasjenige aufnehmen, was darinnen geboten wird.

In einem höheren Stile kann man dasselbe sagen von Menschen wie Otto Liebmann. Sie kommen zur Philosophie, ins Land des Geistes durch Zusammenhänge, die in unserer Welt sind. Man schreibt eine Dissertation, ein Buch, dann wird man als Dozent auf das Gymnasium geschickt; man erweist sich als guter Denker und wird dann auf die Universität geschickt. Das Philosophische ist maskierte Weltcourtoisie. Man braucht nicht den inneren Ruf nach dem Lande des Geistes zu haben, Weltcourtoisie ist das. Man geht bis zum Tore, geht auch hinein, und schläft ein; schläft nicht gleich - wie der satte Rentier, der zum Konzert geführt wird, schläft, auch wenn er gar nicht ermüdet ist —, man schläft ein wie durch einen Mangel an Interesse für das Gegenstandsbewußtsein; aber man kann nicht aufwachen für das imaginative Bewußtsein. Ist es einem unmöglich aufzuwachen für das imaginative Bewußtsein, so schläft man sogleich ein in dem Augenblicke, wo etwas erzählt wird von der geistigen Welt. Mit anderen Worten: es ist den Leuten zu schwer, von der Geisteswissenschaft etwas aufzunehmen. Und es ist deshalb nicht so ganz ungefährlich das festzustellen, weil die Menschen nun sagen: Also seid Ihr diejenigen, die das betreiben, was anderen Menschen, bedeutenden Menschen so beschwerlich ist! - Wir werden aber, da wir uns der Schwierigkeit bewußt sind, nicht gerade hochmütig werden. Aber wir werden auch wissen, daß dasjenige, worin wir uns begegnen müssen, deshalb von der Welt bekämpft wird, weil die Menschen sich nicht einlassen wollen auf so schwierige Sachen, eben weil sie ihnen zu schwierig sind.

Nun wollen wir noch etwas genauer auf die Schwierigkeiten achten,

die da bestehen. Wir wollen darauf hinweisen, indem wir fragen: Worin besteht das gewöhnliche Denken der Menschen vom Aufwachen bis ‚zum Einschlafen? Worin besteht es? Nun, der grobmaterialistische Denker meint: es besteht darinnen, daß der Mensch ein Gehirn mit außerordentlich feiner Struktur hat, daß in diesem Gehirn Prozesse vor sich gehen, und daß, weil diese Prozesse vor sich gehen, das Denken eintritt. Das Denken ist eine Konsequenz dieser Gehirnprozesse -, meint er.

Ich habe Sie schon darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß das so ist, wie wenn jemand sagte: Ich gehe über die Straße; da sind Fuß- und Räderspuren. Woher sind diese Räderspuren gekommen? Die Erde unten, die hat das wohl gemacht, die Erde hat die Fuß- und Räderspuren selbst hervorgetrieben. - Logisch ganz auf derselben Stufe steht der, welcher denkt, das Gehirn macht durch sich selber solche Eindrücke. Ganz dasselbe ist es, wenn einer auf der Straße geht, auf der Straße allerlei Spuren sieht und dann sagt: Aha, da ist diese Erde da, die ist innerlich mit allerlei Kräften fein durchzogen, mit Kräften, die solche Spuren machen. - Ganz dasselbe ist es, wenn der Physiologe kommt und das menschliche Gehirn anschaut und darin alle möglichen Vorgänge konstatiert und sagt: Das macht alles das Gehirn. - So wenig diese Spuren am Erdboden bewirkt werden durch den Erdboden selber, sondern durch die Menschen und Wagen, die sich auf dem Wege fortbewegen, so wenig wird das, was der Anatom und der Physiologe entdecken, bewirkt durch das Gehirn, sondern vielmehr durch die Kräfte, die sich im Ätherleibe bewegen.

Dadurch werden Sie darauf kommen, worin die Täuschung des Materialismus besteht. Es gibt nichts im alltäglichen Leben, was nicht auf das Gehirn einen Eindruck machte. Geradeso wie jeder Schritt einen Eindruck in die Erde macht, und wie Sie nachweisen können, daß jeder Ihrer Schritte einen Eindruck erzeugt hat, so können Sie nachweisen, daß das, was da gewollt und gedacht wird, einen Eindruck, eine Wirkung auf das Gehirn ausübt. Aber das ist nur die Spur davon, das ist nur das, was zurückgelassen ist von dem Denken. Das Denken geht nämlich im Ätherleibe vor sich, und in Wahrheit ist alles das, was Sie als Denken empfinden, nichts als innere Tätigkeit des Ätherleibes. Solange wir im physischen Leibe sind, brauchen wir den physischen Leib für das Denken. Auch das ist sehr leicht einzusehen, warum der Materialist auf die Wahrheit nicht kommt. Der Materialist sagt: Um Gottes willen, da siehst du ja doch, daß du ein Gehirn haben mußt, sonst kannst du ja nicht denken! Also siehst du auch, daß dein Gehirn eigentlich das Denken macht. - Dieser Schluß ist gerade so gescheit, wie wenn einer sagte: Ich kann dir beweisen, daß diese Spur da auf dem Wege von dem Boden selber gemacht worden ist. Ich werde ein Stück von dem Boden wegräumen, und du wirst sehen, daß du ohne ihn nicht gehen kannst. Der Boden ist notwendig; so ist es auch notwendig, daß wir ein Gehirn haben, damit wir im physischen Leibe denken können.

Es ist notwendig, daß man sich diese Dinge klarmacht, denn man lernt da erst erkennen, unter welchen ungeheuren Irrtümern das Denken der Gegenwart leidet, mit welcher Summe von Irrtümern sich dieses Denken der Gegenwart selber narrt, und wie eine Gesundung stattfinden muß durch jenes schwierigere Wissen, welches nicht etwa keine Rücksicht nimmt auf den physischen Leib: wenn wir mit dem physischen Leibe gehen, müssen wir den Boden unter unseren Füßen haben; wenn wir in der physischen Welt denken, so müssen wir eine Widerlage als Boden für das Denken haben: das Nervensystem. Wenn wir aber unsere Denkarbeit zurückverlegen in unseren astralischen Leib, dann wird für uns der Ätherleib dasselbe, was dann, wenn wir im Ätherleibe denken, der physische Leib ist.

Schreiten wir zum imaginativen Denken fort, dann denken wir im astralischen Leibe, und der ätherische Leib behält dann die Spuren, wie sonst, wenn im Ätherleibe gedacht wird, der physische Leib die Spuren behält. Und wenn wir nach dem Tode außerhalb des physischen Leibes sind und auch den Ätherleib abgelegt haben, wie das oftmals beschrieben worden ist, dann ist unsere Widerlage der äußere Lebensäther, dann schreiben wir dasjenige, was der Astralleib und später das Ich entwickelt, in den ganzen Weltenäther ein.

So also ist der Vorgang, den wir durchmachen bei dem, was man die erste Stufe der Initiation nennt. Dieser Vorgang ist der, daß wir unser Denken zurückverlegen - es bleibt nicht Denken, es ist nur die Tätigkeit des Denkens -, daß wir unser Denken zurückverlegen vom Ätherleib in den Astralleib, und die Aufbewahrung der Spuren, die früher dem physischen Leibe obgelegen hat, dem flüchtigeren Ätherleibe auferlegen. Das ist das Wesentliche des ersten Schrittes der Initiation: die Zurückverlegung dieser Tätigkeit, die vorher der Ätherleib ausgeführt hat, auf den astralischen Leib.

So sehen wir, daß wir, während wir in imaginativen Erkenntnissen leben, uns gewissermaßen zurückziehen von dem physischen Leibe auf den Ätherleib, und dann keine weiteren Spuren in den physischen Leib eingraben. Dadurch geschieht es, daß für den, der diese ersten Schritte der Initiation durchmacht, dieser physische Leib, von dem er sich zurückzieht, objektiv wird, daß er ihn jetzt außerhalb seines astralischen Leibes und Ichs hat. Früher hat er darinnen gesteckt; jetzt ist er außerhalb. Er denkt, fühlt und will im astralischen Leibe. Den Ätherleib beeinflußt er, macht Spuren darin; aber den physischen Leib beeinflußt er nicht mehr, den sieht er jetzt wie etwas Äußeres.

Das ist gewissermaßen der normale Gang in bezug auf die ersten Schritte in der Initiation. Er spricht sich im subjektiven Erleben in einer ganz bestimmten Weise aus.

Nun will ich Ihnen zuerst durch eine Art schematischer Zeichnung klarmachen, worin diese ersten Schritte der Initiation bestehen. Nehmen wir an, das sei das menschliche physische Haupt, so sei der Ätherleib um dieses menschliche physische Haupt herum. Wenn nun der Mensch anfängt, dasjenige zu entwickeln, wovon ich gesprochen habe, wenn er anfängt, imaginative Erkenntnisse zu entwickeln, dann vergrößert sich der Ätherleib in dieser Weise, und das Eigenartige ist dabei, daß natürlich dem parallel gehen die Erscheinungen, die wir beschrieben haben als die Ausbildung der Lotusblumen. Der Mensch wächst gleichsam ätherisch aus sich heraus, und das Eigentümliche ist, daß der Mensch, indem er ätherisch also aus sich herauswächst, außerhalb seines Leibes etwas ähnliches entwickelt, möchte ich sagen, wie eine Art Ätherherz.

Als physische Menschen haben wir unser physisches Herz, und wir wissen alle zu schätzen den Unterschied zwischen einem trockenen, abstrakten Menschen, der wie eine richtige Maschine seine Gedanken entwickelt, und einem Menschen, der mit seinem Herzen bei alledem ist, was er erlebt; ich meine, mit seinem physischen Herzen dabei ist. Diesen Unterschied wissen wir alle zu schätzen. Dem trockenen Schleicher, der mit seinem Herzen nicht ist bei dem, was er in der Seele erlebt, muten wir nicht viel zu in bezug auf wirkliche Welterkenntnis auf dem physischen Plan. Eine Art geistiges Herz, das außerhalb unseres physischen Leibes ist, bildet sich aus, parallel all den Erscheinungen, die ich beschrieben habe in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?», so wie sich das Blutnetz bildet und im Herzen sein Zentrum hat. Dieses Netz geht außerhalb des Leibes, und wir fühlen uns außerhalb des Leibes dann herzlich verbunden mit demjenigen, was wir geisteswissenschaftlich erkennen. Nur muß man nicht verlangen, daß der Mensch sozusagen mit dem Herzen, das er im Leibe hat, bei dem geisteswissenschaftlichen Erkennen dabei ist, sondern mit dem Herzen, das ihm außerhalb des Leibes wird; mit dem ist er herzlich bei dem, was er geisteswissenschaftlich erkennt.

Man kann gewiß auch sagen, wenn man so dasjenige durchliest, was auf dem Gebiete der Geisteswissenschaft geschrieben ist: Das ist wiederum nun wissenschaftlich trocken, das ist Wissenschaft. Da muß man ja wieder lernen! Man muß schon sowieso genug im Leben lernen und nun soll man noch das, was die Geisteswissenschaft sagt, lernen! Da ist ja kein Herz darinnen. - Man wird das Herz schon darinnen entdecken, wenn man nur genügend tief hineingeht in die Dinge.

Gewiß, viele Leute sagen: Ach, die Theosophie muß darinnen bestehen, daß der Mensch vor allen Dingen in seinem Ich eins wird mit der ganzen Welt. - Dieses «Einswerden», dieses «Entwickeln des Gottmenschen im Menschen», diese «Auffindung des göttlichen Ich» und so weiter sind beliebte Phrasen von solchen, die Theosophen sein wollen, ohne die Theosophie zu kennen. Das alles entspringt nur daraus, daß man sich nicht einlassen will auf die Entwickelung von Herzenswärme, auch wenn man nicht mehr unterstützt wird durch die Lebenswärme des physischen Herzens. Geradeso wie Lichtenberg gesagt hat: «Wenn ein Kopf und ein Buch zusammenstoßen, und es klingt hohl, so muß nicht gerade das Buch daran schuld sein», könnte man sagen: Wenn ein Mensch mit Geisteswissenschaft zusammenkommt, und er findet darin eben die Herzenswärme nicht, so muß ja nicht die Geisteswissenschaft daran schuld sein. - Alles das, was ich jetzt als normalen Gang zum Hellsehertum beschrieben habe, besteht darinnen, daß der Mensch seinen Ätherleib, ja selbst auch die höheren Glieder der Organisation, heraushebt aus dem physischen Leibe, daß er sich ein Herz eingliedert außerhalb des Umfangs des physischen Leibes.

Worauf beruhen denn die gewöhnlichen Gedanken? Sehen Sie, solch ein Gedanke wird wirklich im Ätherleibe nur entwickelt; aber nun stößt er an den physischen Leib an, er macht überall im Gehirn darinnen Eindrücke. Wenn man das Wesentliche, worauf es ankommt bei dem Denken des Alltags, sich vor die Seele führt, so kann man sagen: Es beruht darauf, daß man denkt im Ätherleibe, und daß das Gedachte auf das Nervensystem des Gehirns fällt; es macht da Eindrücke, aber diese Eindrücke gehen nicht tief, sondern sie prallen zurück. Und dadurch spiegelt sich das Denken, dadurch kommt es uns zum Bewußtsein. Also ein Gedanke besteht zunächst darinnen, daß wir ihn in der Seele haben bis zum Ätherleibe hin; dann macht er einen Eindruck auf das physische Gehirn, da kann er aber nicht hinein und muß daher zurück. Diese zurückgeprallten Gedanken nehmen wir wahr. Und da kommt die Physiologie her und zeigt die Spuren, die im physischen Gehirn darinnen entstanden sind.

Was wäre es denn nun, wenn der Gedanke nicht zurückprallte, sondern wenn er ins Gehirn hineinginge und darinnen bloß Prozesse verursachen würde? Wenn er nicht zurückprallte, könnten wir ihn nicht wahrnehmen; dann würde er ins Gehirn hineingehen und da einfach Prozesse verursachen. Es wäre denkbar, daß der Gedanke, statt zurückgeworfen zu werden, ins Gehirn hineinginge. Da würden wir kein Bewußtsein haben, denn das Bewußtsein entsteht erst, indem der Gedanke reflektiert wird.

Es gibt aber eine solche Tätigkeit der Seele, die in den Leib hineingeht: das ist das Wollen. Das Wollen unterscheidet sich dadurch vom Denken, daß das Denken zurückprallt an der Leibesorganisation und im Spiegelbilde wahrgenommen wird, das Wollen aber nicht. Bei ihm ist es so, daß es in die Leibesorganisation hineingeht, und es wird dann ein physischer Leibesprozeß hervorgerufen. Das bewirkt, daß wir gehen oder die Hände bewegen und so weiter. Das eigentliche Wollen entsteht auf ganz andere Weise als der Gedanke. Der entsteht dadurch, daß er zurückprallt. Das Wollen aber geht in die Leibesorganisation hinein, wird nicht zurückgeworfen, sondern bewirkt in der Leibesorganisation bestimmte Prozesse.

Nun gibt es aber in einem Teile unserer Leibesorganisation doch noch die Möglichkeit, daß so etwas, was da untertaucht, wiederum zurückprallt. Verfolgen Sie wohl dasjenige, was ich sagen werde. Bei unserem Gehirndenken geht das so vor sich, daß die Gedankentätigkeit sich entwickelt in dem ätherischen Gehirn, an dem physischen Nervensystem zurückprallt, und daß uns dadurch die Gedanken zum Bewußtsein kommen. Beim Hellsehen stoßen wir gleichsam das Gehirn zurück. Wir denken mit dem astralischen Leibe, und es wird uns schon das Denken zurückgeworfen durch den Ätherleib.

Hier (siehe Zeichnung I) ist Außenwelt, hier der physische Leib (beim Gehirndenken); hier beim Hellsehen die Außenwelt, dasjenige was wir verarbeiten mit dem astralischen Leibe (siehe Zeichnung II); den Ätherleib lassen wir das zurückwerfen, und den physischen Leib lassen wir ganz ausgeschaltet.

Hier (siehe Zeichnung I), wenn wir wollen, taucht aber die Tätigkeit der Seele in den physischen Leib hinein. Daher, wenn wir gehen, die Hand bewegen, ist es die Seele, die das tut. Aber ihre Tätigkeit muß innere, organische, materielle Prozesse bewirken, und in denen lebt sich die Tätigkeit der Seele aus. Ich möchte sagen: der Wille besteht darinnen, daß die Tätigkeit der Seele erstirbt in der materiellen Betätigung im Leibe.

Fragen Sie sich jetzt: Wie leben wir eigentlich, wenn wir in unserem Denken leben? Ich möchte sagen, in unserem Denken leben wir hart an der Grenze der Ewigkeit. In dem Augenblicke, wo wir den physischen Leib ausschalten und von dem Ätherleibe unsere Gedanken zurückstrahlen lassen, leben wir in dem, was wir durch die Pforte des Todes tragen. Solange wir von dem physischen Leibe die Gedanken zurückstrahlen lassen, leben wir in dem, was zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode da ist. Wenn wir aber wollen, so gehört unser Wollen lediglich unserem physischen Leibe an. Unser physischer Leib ist da, damit er Tätigkeit entwickle. Während das Denken sozusagen schon an der Pforte der Ewigkeit steht, ist das Wollen für den physischen Leib gestiftet.

Erinnern Sie sich, daß ich in einem der Vorträge gesagt habe: Das Wollen ist das Baby, und wenn es älter wird, dann wird es zum Denken. Das stimmt überein mit dem, was wir heute von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte aus entwickeln können. Das Wollen ist in die Zeitlichkeit hineingebannt, und nur dadurch, daß der Mensch sich entwickelt, daß er immer weiser und weiser wird, immer mehr mit Gedanken sein Wollen durchdringt, erhebt er das, was geboren wird im Wollen, aus der Zeitlichkeit in die Sphäre der Ewigkeit hinauf, erlöst er sein Wollen aus seinem Leibe.

Aber in einem Teile seines Leibes ist etwas eingeschaltet: das untergeordnete Nervensystem, das Gangliensystem, das Bauchnervensystem; das Sonnengeflecht wird oftmals auch ein Teil desselben genannt. Dieses Nervensystem ist so, wie es sich jetzt im Menschen entwickelt, ein unvollkommenes Organ; es ist erst in den allerersten Anlagen vorhanden. Später wird es sich weiter ausbilden. Aber geradeso wie man von einem Kinde weiß, daß es noch die Eigenschaften entwickeln kann, die man als Erwachsener entwickelt, so kann man wissen, daß dieses Nervensystem, das heute dazu dient, organische Tätigkeiten zu versorgen, sich noch entwickeln wird. Dieses Nervensystem, das neben dem eigentlichen Gehirn und Rückenmarksystem und neben den in den Gliedmaßen verzweigten Nerven hergeht, dieses Bauchnervensystem ist heute noch nicht so entwickelt, daß es dasjenige tun könnte, was es tun wird, wenn der Mensch einmal auf dem Jupiter sein wird. Da werden das Gehirn und das Rückenmark zurückgebildet sein, und das Bauchnervensystem wird eine ganz andere Ausbildung haben, als es heute hat. Dann wird es an der Oberfläche des Menschen gelagert sein. Denn alles das, was zuerst darinnen ist in dem Menschen, lagert sich später an der Oberfläche des Menschen ab.

Dafür aber benützen wir auch für das gewöhnliche Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod dieses Nervensystem nicht direkt, wir lassen es im Unterbewußten liegen. Aber es kann eintreten durch abnorme Verhältnisse, daß dasjenige, was im menschlichen Willen und Begehrungsvermögen liegt, hineingeht in den menschlichen Organismus, und daß es durch abnorme Verhältnisse, über die wir noch sprechen werden, zurückgeworfen wird vom Bauchnervensystem, so wie sonst der Gedanke vom Gehirn zurückgeworfen wird. Der Wille geht hinein ins Gangliensystem, aber, statt daß er Tätigkeit wird, wird er zurückgeworfen von dem Gangliensystem, und es entsteht im Menschen etwas, was sonst im Gehirn entsteht. Es entsteht ein Prozeß im Menschen, den man auch so charakterisieren kann: Wenn Sie den Übergang vom gewöhnlichen Wachzustande zum Hellsehen ins Auge fassen, so können Sie sehen, wie in uns im gewöhnlichen Nervensystem unser Denken, Fühlen und Wollen sich spiegeln - Fühlen und Wollen insofern sie Gedanken sind -, dasjenige aber, was Wollen ist, lassen wir untertauchen in die Organisation.

Im Hellsehen bilden wir uns - außerhalb des Leibesraumes sozusagen — damit aber auch ein gegenüber dem Gehirn höheres Organ. Wie unser gewöhnliches Gehirn mit unserem physischen Herzen zusammenhängt, so hängt dasjenige, was draußen, im Astralleibe, als Gedanke sich entwickelt, mit diesem Ätherherzen zusammen. Das ist höheres Hellsehen: Kopfhellsehen.

Aber es kann der Mensch auch den umgekehrten Weg machen. Er kann mit dem, was in dem «Baby» Wollen steckt, in die Organisation so hineingehen, daß das Wollen zu einem Denken wird, während er sonst das Denken zum Wollen gemacht hat. Das ist die tiefere Begründung von dem, was ich vor einiger Zeit hier angeführt habe als den Unterschied zwischen Kopfhellschen und Bauchhellsehen. Beim Kopfhellsehen wird ein neues Ätherorgan gebildet, in dem man unabhängig wird von der Leibesorganisation. Beim Bauchhellsehen appelliert man an das Gangliensystem, appelliert man an dasjenige, was sonst unberücksichtigt bleibt. Daher sind die Ergebnisse des Bauchhellsehens flüchtiger als die gewöhnlichen Wacherlebnisse, sie haben keine Bedeutung für die Seelen, wenn diese durch die Pforte des Todes gehen. Alles was durch Kopfhellsehen gewonnen ist, hat eine geistige, dauernde Bedeutung auch für die ‚Seelen, welche durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen sind, hat mehr Bedeutung als das wache Tageserleben. Das, was durch Bauchhellsehen gewonnen wird, hat sogar eine noch geringere Bedeutung für das Leben nach dem Tode als das alltägliche wache Wissen. Jedes somnambule Hellsehen steht unter dem wachen Tagesbewußtsein, nicht darüber. Dagegen spricht gar nicht, daß allerlei poetische und sonstige Eigenschaften entwickelt werden können durch das Bauchhellsehen; weil in dem Augenblicke, wo dieses Bauchhellsehen eintritt, es wirklich die Gänglien sind, welche stets das Wollen in den physischen Leib hineingeben. Dadurch wird in den Ganglien die Tätigkeit des Ätherleibes zurückgehalten und strahlt zurück, und dadurch nimmt man dann wahr dasjenige, was man nicht durch das Gehirn wahrnehmen kann. Man kann dadurch Gedanken wahrnehmen, die man sonst durch das Gehirn nicht wahrnimmt; aber es bleibt doch eine untergeordnete Tätigkeit. Sie sehen, daß man scharf unterscheiden kann zwischen dem, was man als Kopf- und was man als Bauchhellsehen bezeichnet. Nun können Sie fragen: Wie unterscheide ich, ob ich Kopfhellsehen oder Bauchhellsehen entwickele? - Man kann nur sagen: Kopfhellsehen wird sich immer dann bilden, wenn man in unserem Menschheits-Zeitenzyklus dieses Hellsehen wirklich sucht auf dem Wege, wie er angegeben wird, durch Meditation und Konzentration, und wenn man alles ausbildet, was sich auf dem Wege der Meditation und Konzentration ergibt. Das Bauchhellsehen ist etwas, was sich nicht auf dem Wege der Meditation und der Konzentration ergibt. Das Bauchheilsehen beruht darauf, daß das Gangliensystem empfunden wird, und das kann durch die verschiedensten abnormen Verhältnisse des Lebens geschehen. Es ist bequemer, Bauchhellseher zu sein, weil es in gewissem Sinne von selbst kommt, während das Kopfhellsehen im strengsten Sinne des Wortes erworben werden muß. Darum ist es das beste, sich nicht zu sagen, wenn ein Hellsehen von selbst auftritt, man sei ein gottbegnadeter Mensch, dem etwas gegeben wird, was er nicht erworben hat; denn da ist es das beste, mißtrauisch zu sein. Man kann an einzelnen Beispielen zeigen, wie Bauchhellsehen entstehen kann. Kopfhellsehen wird auf keine andere Weise entstehen, als indem man fleißig und regelmäßig durch Meditation und Konzentration sich auf gewisse Stufen der Initiationsentwickelung bringt. Bezüglich des Bauchhellsehens will ich, weil es in einem etwas anderen Sinne als dies vorhin der Fall war, nicht ungefährlich ist, von diesen Dingen zu sprechen, einen der harmlosesten Fälle anführen, wodurch einer Bauchhellseher werden kann.

Nehmen wir an, ein Mensch wächst unter solchen Bedingungen auf, daß sich in seiner Seele früh die Begierde entwickelt, sagen wir, im äußeren physischen Leben ein möglichst «hohes Tier» zu werden, wie Geheimrat, Hofrat, Staatsrat, wo es solche gibt. Nehmen wir also an, es wächst früh die Begierde: man will so ein Geheimer Hofrat oder Regierungsrat und so weiter werden. Daß man so etwas werden will, heißt: ehrgeizig sein. Dieser Ehrgeiz lebt in der Begierdennatur, kann brennen, furchtbar, in der Begierdennatur. Der Mensch macht sich nicht klar: Du willst Geheimer Hofrat werden; aber es brennt ihn seine Begierde, und er geht mit dieser brennenden Begierde durch die Welt und wächst heran mit seiner Begierde. Daher geschieht es, daß seine Begierde nicht immer regulär hineingeht in die physische Organisation. Etwas stört. Wenn einer Geheimer Hofrat wird, so wird er kein Bauchhellseher. Wenn er aber Geheimer Hofrat werden will und es nicht wird und mit dem brennenden Ehrgeize durch die Welt geht, der an ihm frißt und frißt, dann kann er es werden. Diese Begierde muß aber sehr stark sein. Da unter uns niemand ist, der Geheimer Hofrat werden will, so kann ich das alles wohl sagen. Wenn diese Begierde frißt und frißt, dann bleibt sie stecken im Organismus, und dann gewöhnt sich das Gangliensystem daran, zurückzuwerfen die Begierde, und es ist möglich, mit den zurückgespiegelten Begierden so Hellseher zu werden. Dadurch ist es dann möglich, daß, wenn er zum Beispiel wohnt in Berlin in Schönhauserallee 25, und ein anderer, der in Schönhauserallee 23 wohnt, Hofrat wird, er dieses Ereignis gerade durch das besonders ausgebildete Hellsehen wahrnimmt. Das rührt davon her, daß sein Gangliensystem besonders empfänglich gemacht worden ist durch die ihm innewohnende Begierde, Geheimer Hofrat zu werden. Und wenn ein anderer etwas anderes wird, was auch ungefähr in dieser Richtung liegt, so wird er gerade für solche Dinge ein feines, intensives Hellsehen entwickeln können.

Ein solches Hellsehen entwickelt sich gewöhnlich auf einem bestimmten Gebiete. Da Sie wissen, daß es auch andere Begierden im Leben gibt, als die von mir harmlos gewählten, so werden Sie sehen, durch welche Begierden die verschiedenen Formen und Gebiete dieses Hellsehens geweckt werden können. Denn sie strömen im Organismus, diese Begierden, weil sie unbefriedigt bleiben im physischen Leben, während sie doch da sind. Sie werden also sehen, durch welche Begierden Bauchhellsehen gezüchtet werden kann; es wird immer durch Begierde gezüchtet, man sieht es nur nicht immer ein. In der brennenden Begierde, die zurückgespiegelt wird, spiegeln sich auch die Ereignisse, die dann wahrgenommen werden können im Ätherleibe. Sie haben jetzt einen genaueren Blick tun können in den tieferen Zusammenhang des Kopf- und des Bauchhellsehens. Wir brauchen diese Dinge, weil sie zusammenhängen mit dem, was ich morgen entwickeln werde.

Twelfth Lecture

A fundamental theme ran through all the discussions that have taken place here recently. This theme expressed the fact that in our present time we can indeed observe, within the entire cultural development of humanity, the necessity for a new impulse, namely a spiritual impulse, an impulse of spiritual knowledge.

The aim of these lectures was to show from various points of view that a period of a very specific character has come to an end and that a new period must begin. The time that has passed is, in a sense, the time of the most intense materialistic way of thinking and feeling, the time in which materialistic thinking and feeling have increasingly taken hold in the inner life of the human soul over the centuries. But just as a pendulum, when it has swung to one side, must swing back to the other side, in the opposite direction, so we are now facing a time in which the human soul must once again be seized by the feeling that spiritual impulses are hidden in everything sensual, in everything material, that spiritual forces are hidden, and spiritual science is essentially intended to convey the knowledge and experience of these spiritual forces behind the sensory and material phenomena and experiences, the spiritual forces to which humanity has been able to devote less attention and less interest throughout the centuries.

Now we all know how, in our time, the mere assertion that it is possible for the human soul to enter spiritual worlds is denounced and condemned. We know how the most diverse factors of life, consciously or unconsciously, oppose the emergence of a worldview such as that offered by spiritual science. One might think that what spiritual science has to offer for the regulation of life and its facts would appear completely absurd, foolish, and fantastical in our time; but if one considers what, I would say, even now more discerning people are asserting out of more profound impulses of life, then what has just been described appears in a different light.

I would first like to point out to you today that even among more discerning people of the present day, there is not everywhere such a closed attitude toward what spiritual science seeks to assert, although there is certainly a closed attitude toward spiritual science, but not so much a closed attitude toward what spiritual science asserts. Many, many examples of this could be cited. I would like to highlight one characteristic example today, which relates to a philosopher of the recent past who was nevertheless significant, Otto Liebmann, who died not long ago.

Most of you will not be familiar with the name Otto Liebmann, and that does not matter. But I would like to say that Otto Liebmann was one of the most astute analysts of human thought in recent times, that he thoroughly examined what can be called epistemology from all angles, that he asked himself the question everywhere: What can human thought grasp of reality?

I would like to read you a short passage from Otto Liebmann's philosophical writings because it is characteristic of a man who struggled throughout his entire life to fathom what human thought is and what it can say about the present when it draws on all the scientific findings of our time. Otto Liebmann says: Someone might think that a chicken egg contains not only egg white and yolk, but also an invisible ghost; this ghost materializes, and when it has finished materializing, it breaks the eggshell with its sharp beak, runs toward the grains, and pecks them up.

First of all, he says, one might think that there is a ghost in the egg, and when the eggshell is pecked open, the ghost comes out and can peck at the grains. How will those who take the position of building a worldview based on current science respond? They will do so as follows: If someone says that there is a ghost inside a chicken egg, he is simply a fool. That is how the clever people of today will speak. But this is only applied to those who call themselves theosophists or anthroposophists! But what does the philosopher say who has taken so much trouble to dissect human thinking in the present day? He says: Nothing can be objected to this assertion except that the preposition “in” is nonsense when used in the physical sense; in the metaphysical sense it is quite correct. It is quite right that nothing can be made of the idea that the ghost is sitting spatially inside; but if it is understood metaphysically, nothing can be objected to it. The preposition is simply not to be used in the usual sense.

So the fact is that a philosopher who wrote a witty book entitled “Analysis of Reality” and a book entitled “Thoughts and Facts” — in the second issue of Naturerkenntnis in 1899, this is written about the invisible ghost — admits that, when it comes down to it, one can stand at the very pinnacle of contemporary philosophy and cannot help but admit that there really is an invisible ghost inside a chicken egg.

Of course, Otto Liebmann would never stoop to seeing anything reasonable in spiritual science. One might ask: Why doesn't he do that? Why wouldn't he, or anyone who thinks like him, approach this spiritual science and take a look at it in order to come to the conclusion: Yes, this spiritual science basically wants nothing more than to state that this invisible ghost is really inside the chicken egg! The name is irrelevant; we would simply call it the etheric body, which in turn is permeated by the astral body. The spiritual scientist simply describes what is inside as an invisible ghost; the spiritual scientist therefore says nothing other than what others say. Nevertheless, one will not turn to spiritual science so easily. One will rebuke it as “foolery, fantasy,” even though it is energetically demanded by science and the intellectual work of the present day.