Meditation and Concentration:

Three Kinds of Clairvoyance

GA 161

2 May 1915, Dornach

Translator Unknown

Lecture III

Yesterday I drew attention to the way in which a man is able with the higher members of his being - his etheric body, astral body and ego—to leave his physical body; and I pointed out how, having left his physical body, he then makes his first steps in initiation, and learns that what we call man's spiritual activity does not come only with initiation but, in reality, is there all the time in everyday life.

We had particularly to emphasize that the activity which enters our consciousness through our thoughts actually takes its course in man's etheric body, and that this activity taking its course in man's etheric body, this activity underlying the thought-pictures, enters our consciousness by reflecting itself in the physical body. As activity it is carried on in soul and spirit, so that a man when he is in the physical world and just thinks—but really thinks, is carrying out a spiritual activity. It may be said, however, that it does not enter consciousness as a spiritual activity. Just as when we stand in front of a mirror it is not our face that enters our consciousness out of the mirror but the image of our face, so in everyday life it is not the thinking but its reflection that as thought-content is rayed back into consciousness from the mirror of the physical body. In the case of the will it is different.

Let us keep this well in mind—that what finds expression in thinking is an activity which actually does not enter our physical organism at all, but runs its course entirely outside it, being reflected back by the physical organism. Let us remember that as men we are actually in our soul-spiritual being all the time.

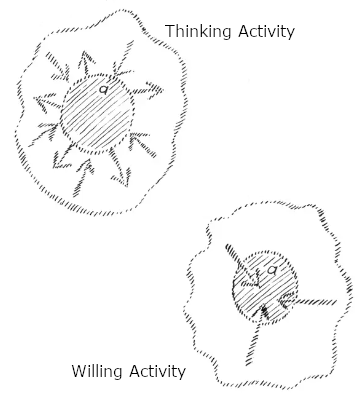

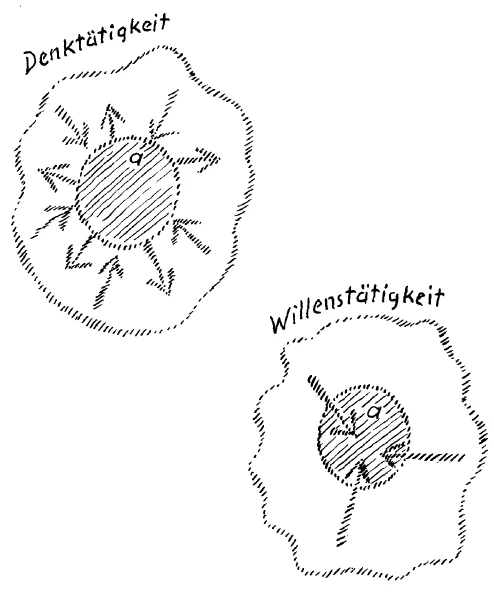

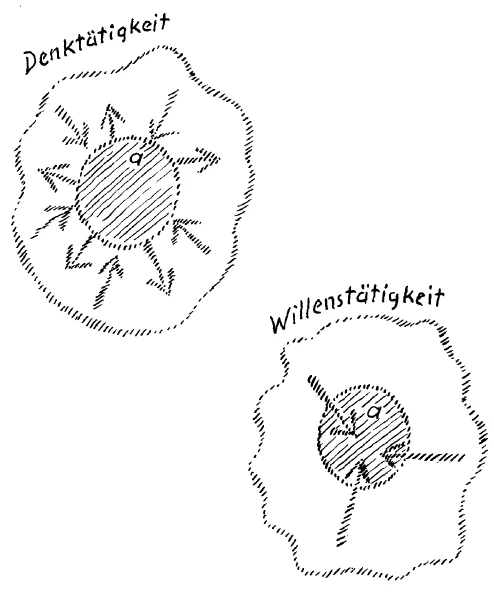

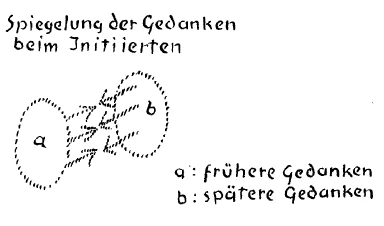

Now this is how it might be represented diagrammatically. If this (a) represents man's bodily being, in actual fact his thinking goes on outside it, and what we perceive as thoughts is thrown back. Thus, with our thinking we are always outside our physical body; in reality spiritual knowledge consists in our recognizing that we are outside the physical body with our thinking.

It is different with what we call will-activity. This goes right into the physical body. What we call will-activity enters into the physical body everywhere and there brings about processes; and the effect of these processes in man is what is brought about by the will as movement.

We can thus say: While living as man in the physical world there rays out of the spiritual into our organism the essential force of the will and carries out certain activities in the organism enclosed within the skin. Between birth and death we are therefore permeated by will-forces; whereas the thoughts do not go on within our organism but outside it. From this you may conclude that everything to do with the will is intimately connected with what a man is between birth and death by reason of his bodily organization. The will is really closely bound up with us and all expressions of the will are in close connection with our organization, with our physical being as man between birth and death. This is why thinking really has a certain character of detachment from the human being, a certain independent character, never attainable by the will.

Now for a moment try to concentrate on the great difference existing in human life between thinking and what belongs to the will. It is just spiritual science that is capable from this point of view of throwing the most penetrating side-lights on certain problems in life. Do we not all find that what can be known through spiritual science really confronts us in life in the form of questions which somehow have to be answered? Now think what happens when anyone goes to a solicitor about some matter. The solicitor hears all about the case and institutes proceedings for the client in question. He will look into all possible ingenious grounds—puts into this all the ingenuity of which he is capable—to win the case for his client. To win the case he will summon up all his powers of intelligence and reasoning.

What do you think would have happened (life will certainly give you the answer) had his opponent outrun the client mentioned and come a few hours before to the same solicitor? What I am assuming hypothetically often happens in reality. The solicitor would have listened to the opponent's case and put all his ingenuity into the grounds for the defense of this client—grounds for getting the better of the other man. I don't think anyone will feel inclined to deny the possibility of my hypothesis being realized. What does it show however?

It shows how little connection a man has in reality with his intelligence and his reason with all that is his force of thought, that in a certain case he can put them at the service of one side just as well as of the other. Think how different this is when man's will-nature is in question, in a matter where man’s feelings and desires are engaged. Try to get a clear idea of whether it would be possible for a man whose will-nature was implicated to act in the same way. On the contrary, if he did so we should consider him mentally unsound. A man is intimately bound up with his will—most intimately; for the will streams into his physical organism and in this human physical organism, induces processes directly related to the personality.

We can therefore say: It is just into these facts of life which, when we think about life at all, confront us so enigmatically, that light is thrown by all we gain through spiritual science. Ever more fully can spiritual science enlighten men about what happens in everyday life, because everything that happens has supersensible causes. The most mundane events are dependent on the supersensible, and are comprehensible only when these supersensible causes are open to our view.

But now let us take the case of a man going with his soul through the gate of death. We must here ask: What happens to his force of thinking and to his will-force? After death the thinking force can no longer be reflected by an organism such as we bear with us between birth and death. For the significant fact here is that after death this organism, everything present in us lying beneath the surface of our skin, is cast off. Therefore, when we have gone through the gate of death, the thinking cannot be reflected by an organism no longer there, neither can an organism no longer there induce inner processes. What the thinking force is continues to exist—just as a man is still there when after passing a mirror he is no longer able to see his reflection. During the time he is passing it his face will be reflected to him; had he passed by earlier the reflection would have appeared to him earlier. The thinking force is reflected in the life of the organism as long as we are on earth, but it is still there even though we have left our physical organism behind.

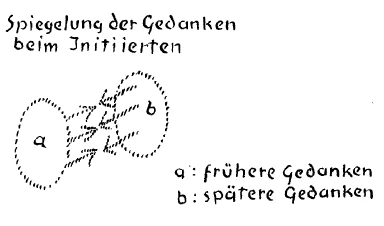

What happens then? What constitutes the thinking force cannot, in itself be perceived; just as the eye is incapable of seeing itself so also is the thinking, for it has to be reflected-back by something—and the bodily organism is no longer there. When a man has discarded his physical organism what will then throw back the thinking force for whatever the thinking force develops in itself as process? Here something occurs that is not obvious to human physical intelligence; but it must, be considered if we really want to understand the life between death and rebirth. This can be under stood through initiates' teachings. An initiate knows that even during life in the body knowledge does not come to him through the mirror of his body but outside it, that he goes out of his body and receives knowledge without it, that therefore he dispenses with his bodily mirrors. Whoever cultivates in himself this kind of knowledge sees that what constitutes the thinking force henceforward enters his consciousness outside the body; it enters consciousness by the later thoughts being reflected by those that have gone before.

Thus, bear this well in mind—when an initiate leaves his body, and is outside it, he does not perceive by something being reflected by his body, he perceives by the thinking force he now sends out being reflected by what he has previously thought. You must therefore imagine that what has been thought previously—not only because it was thought previously—mirrors back the forces developed by the thinking, when this development takes place outside the body.

I can perhaps put it still more clearly. Let us suppose that someone today becomes an initiate. In this state of initiation how can he perceive anything through the force of his thinking? He does this by encountering, with the thinking forces he sends out, what, for instance, he thought the day before. What he thought the day before remains inscribed in the universal cosmic chronicle—which you know as the Akashic record—and what his thinking force develops today is reflected by what he thought yesterday.

From this you may see that the thinking must be qualified to make the thought of yesterday as strong as possible, so that it can reflect effectively. This is done by the rigorous concentration of one's thought and by various kinds of meditation, in the way described from time to time in lectures about knowledge of the higher worlds. Then the thought that otherwise is of a fleeting nature is so densified in a man, so strengthened, that he is able to bring about the reflection of his thinking force in these previously strengthened and densified thoughts.

This is how it is also with the consciousness men develop after death. What a man has lived through between birth and death is indeed inscribed spiritually into the great chronicle of time. Just as in this physical world we are unable to hear without ears, after death we are unable to perceive unless there is inscribed into the world our life, with all that we have lived through between birth and death. This is the reflecting apparatus.

I drew attention to these facts in my last Vienna cycle.1see..{"The Inner Nature of Man and Life between Death and Rebirth." Our life itself, in the way we go through it between birth and death, becomes our sense-organ for the higher worlds. You do not see your eye nor do you hear your ear, but you see with your eye, you hear with your ear. When you want to perceive anything to do with your eye you must do so in the way of ordinary science. It is the same in the case of your ear. The forces a man develops between death and rebirth have the quality of always raying back to the past earth-life, so as to be reflected by it; then they spread themselves out and are perceived by a man in the life between death and rebirth.

From this it can be seen what nonsense it is to speak of life on earth as if it were a punishment, or some other superfluous factor in man’s life as a whole. A man has to make himself part of this earthly life, for in the spiritual world in life after death it becomes his sense-organ.

The difficulty of this conception consists in this that when you imagine a sense-organ you conceive it as something in space. Space, however, ceases as soon as we go either through the gate of death or through initiation; space has significance only for the world of the senses. What we afterwards meet with is time, and, just as here we make use of ears and eyes that are spatial, there we need temporal processes. These processes are those carried out between birth and death, by which the ones developed after death are reflected back. In life between birth and death everything is perceptible to us in space; after death everything takes its course in time, whereas formerly it was in space that we perceived it.

The particular difficulty in speaking about the facts of spiritual science is that, as soon as we turn our gaze to the spiritual worlds, we have really to renounce the whole outlook we have developed for existence in space; we must entirely give up this spatial conception and realize that there space no longer exists, everything running its course in time—that there even the organs are temporal processes. If we would find our way about among the events in spiritual life, we have not only to transform our way of learning; we must entirely transform ourselves, re-model ourselves, acquire fresh life, in such a way that we adopt quite a different method of conception. Here lies the difficulty referred to yesterday, which so many people shun, however ingenious for the physical plane their philosophy may be. People indeed are wedded to their spatial conceptions and cannot find their bearings in a life that runs its course entirely in time.

I know quite well that there may be many souls who say: But I just cannot conceive that when I enter the spiritual world this spiritual world is not to be there in a spatial sense.—That may be, but if we wish to enter the spiritual world the most necessary thing of all is for us to make every effort to grow beyond forming our conceptions as we do on the physical plane. If in forming our conceptions of the higher worlds we never take for our standards and models any but those of the physical world, we shall never attain to real thoughts about the higher worlds—at best picture thoughts.

It is thus where thinking is concerned. After death thinking takes its course in such a way that it reflects itself in what we have lived through, what we were, in physical earthly life between birth and death. All the occurrences we have experienced constitute after death our eyes and our ears. Try by meditating to make real to yourselves all that is contained in the significant sentence: Your life between birth and death will become eye and ear for you, it will constitute your organs between death and rebirth.

Now how do matters stand with the will forces? The will-forces bring about in us the life-processes within the limits of our body—it is our life-processes which they bring about. The body is no longer there when a man has gone through the gate of death, but the whole spiritual environment is there. True as it is that the will with its forces works into the physical organism, it is just as true that after death the will has the desire to go out from the man in all directions; it pours itself into the whole environment, in the opposite way to physical life when the will works into man. You gain some conception of this out—pouring of the will into the surrounding world, if you consider what you have to acquire in the way of inner cultivation of the will in meditation, when you are really anxious to make progress in the sphere of spiritual knowledge.

The man who is willing to be satisfied with recognizing the world as a merely physical one sees, for example, the color blue, sees somewhere a blue surface, or perhaps a yellow surface; and this satisfies the man who is content to stop short at the physical world. We have already discussed how, even through a true conception of art, we must get beyond this mere grasping of the matter in accordance with the senses; how when we must experience blue as if we let our will, our force of heart, stream out into space, and as if from us out into space there could shine forth towards what shines forth to us as blue something we feel like a complete surrender—as if we could pour ourselves out into space. Our own being streams into the blue, flows away into it. Where there is yellow, however, the being, the being of the will, has no wish to enter—here it is repulsed; it feels that the will cannot get through, and that it is thrown back on itself.

Whoever wishes to prepare himself to develop in his soul those forces which lead him into the spiritual world, must be able in his life of soul to connect something real with what I have just been saying. For instance, he must in all reality connect the fact that he is looking at a blue surface with saying: This blue surface takes me to itself in a kindly way; it lets my soul with its forces flow out into the illimitable. But the surface here, this yellow surface, repels me, and my soul-forces return upon my soul like the pricks of a needle. It is the same with everything perceived by the senses; it all has these differences of color. Our will, in its soul-nature, pours itself out into the world and can either thus pour itself out or be thrust back. This can be cultivated by giving the forces of our soul a training in color or in some other impression of the physical world. You will discover in my book "Knowledge of the Higher Worlds" how this may be done.

When, however, this has been developed, when we know that if the forces of the soul float away, become blue (becoming blue and floating away are one and the same thing), this means to be taken up with sympathy whereas becoming yellow is to be repelled and is identical with antipathy—well, then we have forces such as these within us. Let us say that we have experienced this coloring of the soul when we are taken up sympathetically and that we do not, in this case, confront a physical being at all, but that it is possible through our developed soul-forces for a spiritual being with whom we are in sympathy to flow into us. This is the way in which we can perceive the Beings of the Higher Hierarchies and the beings of the elemental world.

I will give you an example, one that is not meant to be personal but should be taken quite objectively. We need not develop merely through the forces in our color-sense, it is possible to do so through any forces of the soul. Imagine that we arouse in our self-knowledge a feeling of how it appears to our soul when we are really stupid or foolish. In everyday life we take no notice of such things, we do not bring them into consciousness; but if we wish to develop the soul we must learn to feel within us what is experienced when something foolish is done. Then we notice that when this foolish action occurs will-forces of the soul stream forth which can be thrown back from outside. They are, however, thrown back in such a way that on noticing the repulsion we feel we are being mocked at and scorned. This is a very special experience. When we are really stupid and are alive to what is happening spiritually we feel looked down upon, provoked. A feeling can then follow of being provoked from out of the spiritual world. If we then go to someplace where there are the nature-spirits we call gnomes, we then have the power to perceive them. This power is acquired only when we perceive in ourselves the feeling I have just described. The gnomes carry-on in a way that is provoking, making all manner of gestures and grimaces, laughing, and so on. This is perceptible to us only if when we are stupid we observe ourselves. It is important that we should acquire inward forces through these exercises, that with our will forces we should delve deeply into the world surrounding us; then this surrounding world will come alive, really and truly alive.

Thus we see while our life between birth and death becomes an organ, an organ of perception, within the spiritual organism that we bear between death and rebirth, our will becomes a participator in our whole spiritual environment. We see how the will rays back in initiates (in the seeing of gnomes, for example) and in those who are dead. When gnomes are seen it is an example of this, out of the elemental world.

Now consider how there once lived a philosopher who in the second half of the nineteenth century had a great influence on many people, namely, Schopenhauer. As you know, he exercised a great influence both on Nietzsche and Richard Wagner. Schopenhauer derived the world—as others have derived it from other causes—from what he called conception, or representation, and will. He said: Representation and will are what constitutes the foundation of the world.

But—obsessed by Kant’s method of thinking—he goes on to say that representation are never more than dream-pictures and that it is impossible ever to come to reality through them. It is only through the will that we can penetrate into the reality of things—this is done by the will. Now Schopenhauer philosophises in an impressive manner about representation and will; and, if one may say so—he does this indeed rather well. He is, however, one of those who I have likened to a man standing in front of a door and refusing to go through it. When we take his words literally—the world is representation, the world is a mere dream-picture—we have to forgo all knowledge of the world through representation and can then pass on to knowledge of the representations themselves, pass on to doing something in one's own soul with the representations—in other words to meditate, to concentrate. Had Schopenhauer gone a step further he would have reached the point of saying: "I must renounce representations! If a representation is something produced within me, I must put it to an inward use.’ Had he made this step he would have been driven to cultivate his representations, to work upon them in meditation and concentration.

When he says: The world is will—when, as in his clever treatise on the "Will in Nature", he goes on to describe this will in nature, he does not take his own proposition in earnest. In describing the will we seek the help of representations and he denies those all possibility of knowledge. This reminds us of Munchausen who to pull himself out of a bog catches hold of his own pigtail. What would Schopenhauer have been obliged to be if had taken in earnest his own words—the world is will? He would have had to say: Then we ought to pour out our will into the world; we must use our will to creep inside things. We must delve right into the world, send into it cur will, no longer taking the color blue as mere representation, but trying to perceive how the will sinks down into it; no longer thinking of our stupidity as a representation, but realizing what can be experienced through that stupidity.

You can see that here too it is possible to arrive at a description which needs only to be taken in earnest. Had Schopenhauer gone further he would have had to say: If the representation is really only a picture we represent to ourselves, then we must work upon it; if the will is really in the things, then we must go with it right into the things, not just describe how things have the will within them.

You see here another example of how a renowned Philosopher of the nineteenth century takes men to the very gates of initiation, right up to spiritual science; and how this philosopher then does everything he can to close these gates to men. Where people really take hold of life they are shown on all sides that the time is ripe for picking the fruits of spiritual science—only things must be taken in earnest, deeply in earnest. Above all we must understand how to take people at their word. For it is not required of spiritual science to stand on its own defense. For the most part this is actually done by others, by its opponents, though they do not know this, have no notion of it.

Now consider a certain class of human beings to which very many in the nineteenth century belonged—the atomistic philosophers, those who conceived the idea that atoms in movement were at the basis of all the phenomena of life. They had the idea that behind this entire visible and audible world there was a world of atoms in movement, and through this movement arose processes perceived by us as what appears in our surroundings. Nothing spiritual is there, the spiritual is merely a product of atomic movement, and all—prevailing atomic activity.

Now how has the thought of these whirling atoms arisen? Has anyone seen them? Has anyone discovered them through what they have experienced or come to know empirically? Were this the case they would not be what they are supposed to be, for they are supposed to be concealed behind empirical knowledge. Had they any reality, by what means would they have to be discovered? Suppose the movement of atoms were there—the understanding cannot discover them in what is sense-perceptible. What would a man have to be in order to possess the right to speak of this world of atoms? He would have to be clairvoyant; the whole of this atom-world would have to be a product of inner vision, of clairvoyance. The only thing we can say to the people who have appeared as the materialists of the nineteenth century is: There is no need for us to prove that there are clairvoyants for either you must be silent about all your theories, or you must admit that to perceive these things you are possessed of clairvoyant vision—at least to the point of being able to perceive atoms behind the world of the senses. For if there is no such things as clairvoyance it is senseless to speak of this material world of atoms. If you find it a necessity to have moving atoms you prove to us that there are clairvoyant human beings.

Thus we take these people seriously, although they do not take themselves seriously when they say things of this kind. If Schopenhauer is taken in earnest we must come to this conclusion—“If you say the world is will and what we have in the way of representation is only pictures, you ought to penetrate into the world with your will, and penetrate into your thinking through meditation and concentration. We take you seriously but you do not take yourselves so.” Strictly speaking, it is the same with everything that comes into question.

This is what is so profoundly significant in the world—conception of spiritual science, that it takes in all earnest what is not so taken by the others—what they skim over in a superficial way. Proofs are always to be found among the opponents of spiritual science. But people never notice that in their assertions, in what they think, at bottom they are at the same time setting at naught what they think. For the materialistic atomist, and Schopenhauer too, set a naught what they themselves maintain.

Schopenhauer nullifies his own system when he asserts: Everything is will and representation. The moment he is not willing to stop there, however, he is obliged to lead men onto the development of spiritual science. It is not we who form the world-conception of spiritual science; how then does this world-conception come into being? It enters the world of itself—is there, everywhere, in the world. It enters life through unfamiliar doors and windows; and even when others do not take it in earnest, it finds its way into men’s cultural life.

But there is still something else we can recognize if, through considerations of this kind we really have our attention drawn to how superficially men approach their own spiritual processes, and how little in a deeper sense they take themselves seriously—even when they are clever and profound philosophers. They weave as it were a conceptual web, but with it they shy away from really fulfilling the inner life’s work that would lead them to experience the forces upon which the world is founded. Hence we see that the centuries referred to yesterday, during which ordinary natural science has seen its great triumphs, have also been the centuries to develop in human beings the superficial thinking. The more glorious the development of science, the more superficial has become investigation into the sources of existence.

We can point to really shining examples of what has just been touched upon here. Suppose we have the following experience—a man, who has never shown any interest in the spiritual world undergoes a sudden change, begins to concern himself about the spiritual world and longs to know something about it. Let us suppose we have this experience after having found our way into spiritual science. What will become a necessity for us when we experience how a man, who has never worried about the spiritual world, having been immersed in everyday affairs, now finds himself at one of the crossroads of life and turns to the spiritual world? As spiritual scientists we shall interest ourselves about what has been going on in this man’s soul. We shall try as often as possible to enter into the soul of such a man, and it will then be useful for us to know what has often been stressed here, namely, that the saying in constant use about nature making no sudden jumps is absolutely untrue. Nature does make sudden jumps. She makes a jump when the green leaf becomes the colourful petal, and when she so changes a man who has never troubled himself about the spiritual world that he begins to interest himself in it, this too is like a sudden jump; and for this we shall seek the cause. We shall make certain discoveries about the various spiritual sources of which we have spoken here, and see how anything of this kind takes place.

When doing this we shall ask: How old was the man? We know that every seven years something new is born in the human being: From the seventh year on, the etheric body; from the fourteenth year on, the astral body, and so on. We shall gather up all that we know about the etheric and astral bodies, taking this particularly from an inner, not an outer, point of view. Then we shall be able to gain a good deal of information about what is going on in a human soul such as this.

It is also possible to proceed in another way. We can become interested in the fact that men in ordinary life suddenly go over to a life concerned with spiritual truths, and the profundities of religion. Some men may look upon spiritual science as a foolish phantasy, and when we examine into what is going on in the depths of his soul it is possible for us to discover what makes him find it foolish. But we can then do the following. We write, let us say 192, or even more, letters to people whom we have heard about as having gone through a change of this kind. We send these letters to a whole continent, in order to learn in reply what it was that brought about this change in their life.—We then receive answers of the most diverse kind….someone writes: When I was fourteen my life led me into all manner of bad habits. That made my father very angry and he gave me a good thrashing; this it was which induced in me a feeling for the spiritual world.—Others assert that they have seen a man die, and so on. Suppose then that we get 192 answers and proceed to arrange them in piles—one pile for the letters in which the writers say that they have been changed by their fear of death or of hell; a second pile in which it is stated that the writers come across good men, or imitated them; a third pile—and so on. In piles such as these matters easily become involved and then we make an extra pile for other, egocentric motives. Then we arrive at the following. We have sorted the 192 letters into piles and have counted how many letters go into each one; then we are able to make a simple calculation of the percentage of letters in each pile. We can discover, for example, that 14 per cent of the changes come about through fear, either of death or of hell; 6 per cent come from egocentric motives; 5 per cent because altruistic feelings have arisen in the writers; 17 per cent of them are striving after some moral ideal—supposedly those belonging to an ethical society; 16 percent through pangs of conscience, 10 per cent by following teachings concerning what is good, 13 per cent through imitating other men considered to be religious, 19 per cent by reason of social pressure, the pressure of necessity and so forth.

Thus, we can proceed by trying with love to delve into the soul who confesses to a change of this kind; we can try to discover what is within the soul; and for this we have need of spiritual science. Or we can do what I have just been describing. One who has done this is a certain Starbuck who has written about these matters a book which has aroused a good deal of attention. This is the most superficial exposition and the very opposite of all we must perceive in spiritual science. Spiritual science seeks everywhere to go to the very root of things. A tendency that has arisen to the materialistic character of the times is to apply even to the religious life this famous popular science of statistics. For, as it has clearly pointed out, this means of research is incontrovertible. It has one quality particularly beloved by those people who are unwilling to enter the doors of spiritual science—it can truly be called easy, very easy.

Yesterday we dwelt on the reason for so many people being unwilling to accept spiritual science, mainly, its difficulty. But we can say of statistics that it is easy, in truth very easy. Now today people go in for an experimental science of the soul; I should have to talk about this science at great length to give you a concept of it. It is called experimental psychology; outwardly a great deal is expected from it. I am going just to describe the beginning that has been made with these experiments. We take, let us say, ten children and give these ten children a written sentence—perhaps like this: M… is g… by st… We then look at our watch and say to one of the children: “Tell me what you make of that sentence.” The child doesn’t know; it thinks hard and finally comes out with “Much is gained by striving.” Then it is at once noted down how much time it took the child to complete the sentence. Obviously there must be several sentences for effort has to be made to read them; gradually this will be done in a shorter space of time. Note is then made of the number of seconds taken by the various children to complete one of these sentences, and the percentages among the children are calculated and treated further statistically. In this way the faculty of adaption to outer circumstance and other matters, are tested. This method of experimental psychology has a grand-sounding name, it is called “intelligence tests”; whereas the other method is said to be the testing by experiment of man’s religious nature.

My dear friends, what I have given you here in a few words is no laughing matter. For where philosophy is propounded today these experimental tests are looked upon as the future science of the soul to a far greater extent than any serious feeling is shown, not for what we subscribe to here, but for what was formerly discovered by inner observation of the soul. Today people are all for experiment.

These are examples of people’s experiments today and these methods have many supporters in the world. Physical and chemical laboratories are set up for the purpose of these experiments and there is a vast literature on the subject. We can even experience what I will just touch upon in passing. A friend of ours, chairman of one of our groups, a group in the North, had been preparing his doctorate thesis. It goes without saying that he went to a great deal of trouble (when talking to children one goes to a great deal of trouble to speak on a level with their understanding) to leave out of his thesis anything learnt from spiritual science. All that was left out. Now among the examiners of the thesis there was one who was an expert in these matters, who therefore was thoroughly briefed in these methods; this man absolutely refused to accept the thesis. (The case was even discussed in the Norwegian Parliament.) Anyone who is an experimental psychologist is firmly convinced that his science of the soul is founded on modern science and will continue to hold good for the future.

There is no intention here of saying anything particular against experimental psychology. For why should it not be interesting once in a way to learn about it? Certainly one can do so and it is all very interesting. But the important thing is the place such things are given in life, and whether they are made use of to injure what is true spiritual science, what is genuine knowledge of the soul. It must repeatedly be emphasized that it is not we who wish to turn our back on what is done by people who in accordance with their capacities investigate the soul—the people who investigate what has to do with the senses, and like to make records after the fashion of those 192 replies. This indeed is in keeping, with men's capacities; but we must take into consideration what kind of world it is today in which spiritual science takes its place. We must be very clear about that.

I know very well that there are those who may say: Here is this man, now, abusing experimental psychology—absolutely tearing it to shreds! People may seek thus just as they said: At Easter you ran down Goethe's "Faust" here and roundly criticized Goethe. These people cannot understand the difference between a description of something and a criticism in the superficial sense; they always misunderstand such things. By characterizing them I am wanting to give them their place in the whole sphere of human life. Spiritual Science is not called upon to play the critic, neither can what has been said be criticism.

Men who are not scientists should behave in a Christian way towards true spiritual science.

Another thing is to have clear vision. Thus when we look at science we see how superficially it takes all human striving, how even in the case of religious conversion it does not turn to the inner aspect but looks upon human beings from the outside.

In practical life men are not particularly credulous. The statisticians of the insurance companies—I have referred to this before—calculate about when a man will die. It can be calculated, for instance, about when an 18-year-old will die, because he belongs to a group of people a certain number of whom will die at a certain age. According to this the insurance quota is reckoned and correctly assigned. This all works quite well. If people in ordinary life, however, wanted to prepare for death in the year reckoned as that of their probable death by the insurance company, they would be taken for lunatics. The system does not determine a man’s the length of life. Statistics have just as little to do with his conversion.

We must look deeply into all these things. Through them we strive for a feeling which has within it intuitive knowledge. It will be particularly difficult to bring to the world-culture of today what I would call the crown of spiritual science—knowledge of the Christ. Christ-knowledge is that to which—as the purest, highest and most holy—we are led by all that we receive through spiritual science. In many lectures I have tried to make it clear how it is just at this point of time that the Christ-impulse, which has come into the world through the Mystery of Golgotha, has to be made accessible to the souls of men through the instrument of spiritual science. In diverse ways I tried to point out clearly the way in which the Christ-impulse has worked. Remember the lectures about Joan of Arc, about Constantine, and so on. In many different ways I tried to make clear how in these past centuries the Christ-impulse has been drawn more into the unconscious, but how we are now living at a time when the Christ-impulse must enter more consciously into the life of man, and when there must come a real knowledge of the Mystery of Golgotha. We shall never learn to know about this Mystery of Golgotha if we are not ready to accept conceptions of the kind touched upon at Eastertide2(*see Festivals of the Seasons)—about Christ in connection with Lucifer and Ahriman—and if we do not permeate these conceptions with spiritual science.

We are living in a terribly hard time, a time of suffering and sorrow. You know that for reasons previously mentioned I am not able to characterize this time; neither do I want to do so but from a quite different angle I will just touch upon something connected with our present studies.

This time of suffering and sorrow has wakened many things in human souls, and anyone living through this time, anyone who concerns himself about what is going on, will notice that today, in a certain direction, a great deepening is taking place in the souls of men. These human souls involved in present events were formerly very far from anything to do with religion, their perceptions and feelings were thoroughly materialistic. Today we can repeatedly find in their letters, for one thing, how because of having been involved in all the sorrowful events of the present time they have recovered their feeling for religion. The remarkable thing is that they begin to speak of God and of a divine ordering when formerly such words never passed their lips. On this point today among those people who are in the thick of events we really experience a very great religious deepening.

But one fact has justly been brought before us which is quite as evident as what I have now been saying. Take the most characteristic thing, in the letters written from the front, in which can be seen this religious deepening. Much is said of how God has been found again but almost nothing, almost nothing at all—this has been little noticed—of Christ. We hear of God but nothing of Christ.

This is a very significant fact—that in this present time of heavy trial and great suffering many people have their religious feeling aroused in the abstract form of the idea of God. Of a similar deepening of men's perception of the Christ we can hardly speak at all. I say “hardly", for naturally it is to be met with here and there, but generally speaking things are as I have described. You can see from this, however, that today, when it behooves the souls of men to look for renewed connection with the spiritual world, it is difficult to find the way to what we call the Christ-impulse, the Mystery of Golgotha.

For this, it is necessary for the human soul to rise to a conception of mankind as one great whole. It is necessary for us not merely to foster mutual interest with those amongst whom we are living just for a time; We should extend our spiritual gaze to all times and beings, to how as souls we have gone through various lives on earth and thorough various ages. Then there gradually arises in the soul an urgent need to learn how there exists in man a deepening and then an ascending evolution. In the evolution of Time we must feel one with all mankind; we must look back to how the earth came originally into being, focus our gaze on this ascending and descending evolution, in the centre point of which the Mystery of Golgotha stands; we must feel ourselves bound up with the whole of humanity, feel ourselves bound up with the Mystery of Golgotha. Today the souls of men are nearer the cosmos spatially than they are temporally, that is, to what has been unfolded in the successive evolutionary stages. We shall be led to this, however, when with the aid of spiritual science we feel ourselves part of man's whole course of evolution. For then we cannot do other than recognize that there was a point of time when something entered the evolution of mankind which had nothing to do with human force. It entered man's evolution because into it an impulse made its way from the spiritual world through a human body—an impulse present in the beginning of the Christian era. It was a meeting of heaven with the earth.

Here we touch upon something which must be embodied into the religious life through spiritual-science. We shall touch upon how spiritual science has to sink down into human feeling so that men come into a real connection with the Mystery of Golgotha, and find the Christ-impulse in such a way that it can always be present in them not only as a vague feeling but also in clear consciousness. Spiritual science will work. We have recognized and repeatedly stressed the necessity for this work. In reality, the fact of your sitting there is proof that all of you in this Movement for spiritual science are willing to put your whole heart into working together. When in the future hard times fall again upon mankind, may spiritual science have already found the opportunity to unite the deepening of men's souls not only with an abstract consciousness of God but with the concrete, historical consciousness of Christ.

This is the time, my dear friends, when perceptions, feelings, of a serious nature can be aroused in us and they should not avoid arousing in ourselves these serious, one might say solemn, feelings. This is how those within our movement for spiritual science should be distinguished from the people who, by reason of their karma, have not yet found their way into this Movement—that the adherents of spiritual science take everything that goes on in the world—the most superficial as also the profoundest—in thorough earnest.

Just consider how important it is in everyday life to see that with our ordinary understanding bound up with our brain and with our reason we are outside what mostly interests us in ordinary physical experience, and that hence—as is the case with our hypothetical solicitor—we are strangers to our own thinking, strangers to ourselves. When we enter spiritual science, however, we develop a heart outside our body, as we said yesterday, and what we thoroughly reflect upon will once more be permeated by what is full of inner depth and soul. We can make use both of the understanding bound up with our body and of our reason, in various directions, only if we do not draw upon what unites us most deeply with the spheres in which we live with our thinking. Through spiritual science we shall draw upon this, and in what we think we shall become, with our understanding and with our reason, men of truth, men wedded to the truth; and life has need of such men. What we let shine upon us from the sun of spiritual science grows together with us because we grow together with the Beings of the Higher Hierarchies. Then our thinking is not so constituted that like that solicitor we can apply it to either party in a legal case. We shall be men of truth by becoming one with those who are spiritual truth itself. By discovering how to grasp hold of our will in the way described today, we shall find our path into the very depths of things. This will not be by speaking of the will in nature as Schopenhauer did, but by living ourselves into things, developing our forces in them.

Here we touch upon something terribly lacking at the present time, namely, going deeply and with love into the being of things. This is missing today to such a terrible degree. I might say that over and over again one has to face, the bitter-experience in life of how the inclination to sink the will into the being of things is lacking among men.

What on the ground of spiritual science has to be over-come is the falsifying of objective facts; and this falsifying of objective facts is just what is so widespread at the present time. Those who know nothing of previous happenings are so ready to make assertions which can be proved false.

When a thing of his kind is said, my dear friends, is to be taken as an illustration, not as a detail without importance. But this detail is a symptom for us to ponder in order to come to ever greater depth in the whole depth that is to be penetrated by our spiritual movement. This spiritual movement of ours will throw light into our souls quite particularly when we become familiar with what today cannot yet be found even by those whose hearts are moved by the most grievous events of the times in which they are living, and who seek after the values of the spiritual world. Spiritual science must gradually build up for us the stages leading to an understanding of the Mystery of Golgotha—an understanding never again to be lost. This Mystery of Golgotha is the very meaning of the earth. To understand what this meaning of the earth is, must constitute the noblest endeavor of anyone finding his way step by step into spiritual science.

Dreizehnter Vortrag

Ich habe gestern aufmerksam gemacht auf die Art und Weise, wie der Mensch auf der einen Seite mit den höheren Gliedern seiner Wesenheit, mit dem ätherischen Leibe, mit dem astralischen Leibe und dem Ich seinen physischen Leib verlassen kann, und wie er dann, wenn er seinen physischen Leib verläßt, die ersten Schritte in der Initiation macht und darauf kommt, daß dasjenige, was wir geistige Tätigkeit des Menschen nennen, nicht etwa erst da ist, wenn der Mensch in die Initiation eintritt, sondern im Grunde genommen im alltäglichen Leben schon immer vorhanden ist.

Wir haben besonders betonen müssen, daß die Tätigkeit, die uns durch die Gedanken zum Bewußtsein kommt, eigentlich verläuft im ätherischen Leibe des Menschen, und daß diese im ätherischen Leib verlaufende Tätigkeit, also die Tätigkeit, die dem Gedankenbilde zugrunde liegt, uns zum Bewußtsein kommt durch ihre Abspiegelung im physischen Leibe. Aber verrichtet wird sie im Seelisch-Geistigen, so daß der Mensch, wenn er in der physischen Welt darinnen steht und nur denkt - aber wirklich denkt -, eine geistige Tätigkeit verrichtet. Man kann sagen, daß sie ihm nur nicht zum Bewußtsein kommt als geistige Tätigkeit. So wie uns, wenn wir vor einem Spiegel stehen, nicht unser Gesicht, sondern dessen Abbild aus dem Spiegel heraus zum Bewußtsein kommt, so kommt uns im alltäglichen Leben nicht das Denken, sondern dessen Spiegelbild, als Gedankeninhalt, von dem physischen Leibesspiegel zurückgestrahlt, zum Bewußtsein. Anders ist es beim Willen.

Also bedenken wir wohl: Dasjenige, was sich im Denken ausspricht, ist eine Tätigkeit, die eigentlich gar nicht in unseren physischen Organismus hineingeht, die ganz außerhalb unseres physischen Organismus verläuft, die nur zurückgespiegelt wird von unserem physischen Organismus. Bedenken wir, daß wir als Menschen eigentlich immer in unserem geistig-seelischen Wesen sind. Wenn man es schematisch darstellen wollte, so könnte man es so darstellen:

Wenn das (a) das leibliche Wesen des Menschen darstellt, so verläuft das Denken in Wahrheit außerhalb des leiblichen Wesens des Menschen, und das, was wir als Gedanken wahrnehmen, wird zurückgeworfen. Also mit unserem Denken sind wir stets außerhalb unseres physischen Leibes, und da besteht im Grunde genommen die Geisteserkenntnis nur darinnen, daß wir das einsehen: wir sind mit unserem Denken außerhalb unseres physischen Leibes.

Anders ist es mit dem, was wir als die Willenstätigkeit bezeichnen. Die geht wirklich in den physischen Leib (a) hinein. Das, was wir als Willenstätigkeit bezeichnen, geht überall in unseren physischen Leib hinein und bewirkt darinnen Prozesse, Vorgänge. Und die Wirkung dieser Vorgänge ist dasjenige, was als Bewegung durch den Willen beim Menschen zustande gebracht wird.

Wir können also sagen: indem wir als Mensch in der physischen Welt darinnenstehen, strahlt die Grundkraft des Willens aus der Geistigkeit in unseren Organismus hinein und verrichtet gewisse Tätigkeiten in dem Organismus, der innerhalb der Haut beschlossen ist. Wir sind also in der Zeit zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode von den Willenskräften durchdrungen, während der Gedankeninhalt nicht innerhalb unseres Organismus vor sich geht, sondern außerhalb des Organismus. Daraus können Sie den Schluß ziehen, daß alles, was den Willen betrifft, innig zusammenhängt mit dem, was der Mensch in seiner physischen Existenz zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode durch seine Leibesorganisation ist. Der Wille hängt wirklich innig mit uns zusammen, und alle Äußerungen des Willens sind eng mit unserer Organisation, mit unserem physischen Menschenwesen, solange wir zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode stehen, verbunden. Davon rührt es her, daß das Denken wirklich einen gewissen Charakter des Losgelöstseins vom Menschen hat, einen gewissen selbständigen Charakter gegenüber dem Menschen, den der Wille niemals haben kann.

Versuchen Sie einmal gründlich nachzudenken über den großen Unterschied, der besteht im menschlichen Leben zwischen dem Denken und dem, was zum Willen gehört. Gerade die Geisteswissenschaft ist geeignet, von einem solchen Gesichtspunkte aus die allerintensivsten Streiflichter auf gewisse Rätselfragen des Lebens zu werfen. Sehen wir nicht alle, daß das, was wir so durch die Geisteswissenschaft erkennen können, im Grunde genommen im Leben vor uns steht wie Frageformen, die wir uns doch beantworten müssen?

Denken Sie einmal: es kommt doch vor, daß irgend jemand zu einem Rechtsanwalt geht mit irgendeiner Sache. Der Rechtsanwalt läßt sich die Sache erzählen, und er macht den Prozeß für den betreffenden Klienten. Der Rechtsanwalt wird alle möglichen scharfsinnigen Gründe hervorsuchen, wird so scharfsinnig sein, als er nur sein kann, um den Prozeß für den betreffenden Klienten zu gewinnen; er wird alles dasjenige, was er an Verstand und Vernunft hat, zusammennehmen, um den Prozeß zu gewinnen.

Was würde geschehen sein - glauben Sie, das Leben wird Ihnen gewiß darüber Aufschluß geben -, wenn es dem Gegner gelungen wäre, ich möchte sagen, dem anderen den Rang abzulaufen, wenn der Gegner ein paar Stunden früher zu demselben Rechtsanwalt gekommen wäre? Es geschieht das, was ich hypothetisch da annehme, sehr oft. Der Rechtsanwalt würde sich den Fall des Gegners haben erzählen lassen und würde mit dem Scharfsinne, der ihm zur Verfügung steht, alle Gründe zur Verteidigung eben dieses anderen Klienten vorbringen, Gründe, die geeignet sind, den ersteren hineinzulegen, wie man sagen kann. Ich glaube nicht, daß jemand geneigt ist, in Abrede zu stellen, daß eine solche Hypothese Wirklichkeit sein könnte. Aber was beweist uns diese Annahme?

Sie beweist uns, wie wenig im Grunde genommen der Mensch zusammenhängt mit dem, was sein Verstand und seine Vernunft ist, mit dem, was seine Denkkraft ist, da er sie in dem gleichen Falle sowohl in den Dienst des einen, als auch in den Dienst des anderen stellen kann. Vergleichen Sie, wie das anders ist bei alledem, wo die Willensnatur des Menschen in Betracht kommt, wo der Mensch mit seinen Gefühlen und Begierden engagiert ist bei einer Sache. Versuchen Sie sich klarzumachen, ob einem Menschen, der aus der Willensnatur heraus für eine Sache eintritt, das gleiche möglich wäre, wenn er in derselben Weise verführe. Wir würden im Gegenteil ihn geistig für nicht ganz gesund halten, wenn es so wäre. Mit dem Willen ist der Mensch intim verbunden, ganz intim verbunden, weil das Wollen hereinstrahlt in den physischen Organismus und unmittelbar zur Persönlichkeit gehörende Prozesse auslöst im menschlichen physischen Organismus.

Also wir können sagen: gerade in diese Tatsachen des Lebens, die so rätselvoll vor unserer Seele stehen müssen, wenn wir über das Leben überhaupt nur nachdenken, leuchtet hinein, was wir durch die Geisteswissenschaft gewinnen können. Immer tiefer und tiefer wird die Geisteswissenschaft die Menschheit aufklären können über dasjenige, was im alltäglichen Leben geschieht, weil alles, was geschieht, abhängig ist von übersinnlichen Ursachen. Das Alleralltäglichste, was geschieht, ist so abhängig vom Übersinnlichen und kann nur erkannt werden, wenn wir zu den übersinnlichen Ursachen aufblicken können.

Nun aber setzen wir einmal den Fall, der Mensch tritt mit seiner Seele durch die Pforte des Todes. Da müssen wir uns fragen: Wie ist es nun mit der Denkkraft, wie mit der Willenskraft? - Nachdem der Tod eingetreten ist, kann die Denkkraft nicht von einem solchen Organismus zurückgespiegelt werden, wie wir ihn sonst an uns tragen zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode. Denn das ist das Bedeutsame dabei, daß dieser Organismus, alles dasjenige, was in uns vorhanden ist als innerhalb der Hautoberfläche liegend, nach dem Tode von uns abgeworfen wird. Also die Denkkraft kann nicht zurückgespiegelt werden von einem Organismus, aber auch innerliche Prozesse können nicht ausgelöst werden von einem Organismus, der, wenn man durch die Pforte des Todes getreten ist, nicht mehr da ist. Das aber, was die Denkkraft ist, bleibt vorhanden; geradeso wie der Mensch vorhanden bleibt, wenn er vor dem Spiegel vorübergeht, in der Zeit, wo er sich nicht mehr im Spiegel sehen kann. In der Zeit, wo er vor dem Spiegel vorübergeht, wird ihm sein Antlitz zurückgeworfen; wäre er früher vorübergegangen, so würde ihm sein Spiegelbild früher zurückgeworfen worden sein. Die Denkkraft spiegelt sich so lange, als wir im Leben, im Leben des Organismus stehen; sie ist aber auch dann da, wenn der Mensch den physischen Organismus verlassen hat.

Was tritt nun ein? Dasjenige, was Denkkraft ist, kann nicht in sich selbst wahrgenommen werden. So wenig als das Auge sich selber sehen . kann, kann die Denkkraft sich selber wahrnehmen; sie muß von irgend etwas zurückgespiegelt werden. Der Leibesorganismus ist aber nicht mehr da. Wovon wird nun die Denkkraft, respektive dasjenige, was die Denkkraft in sich als Prozeß entwickelt, zurückgeworfen, wenn der Mensch seinen physischen Organismus abgelegt hat? Hier tritt etwas ein, was dem menschlichen physischen Verständnisse nicht ganz nahe liegt, was aber eingesehen werden muß, wenn wir wirklich das Leben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt begreifen wollen. Begreifen kann man das durch die Lehren der Initiation. In der initiierten Erkenntnis ist es während des Leibeslebens schon so, daß der Mensch nicht in der Spiegelung seines Leibes erkennt, sondern außerhalb seines Leibes, daß er aus dem Leibe herausgeht und ohne den Leib erkennt, daß er also seinen Leibesspiegel ausschaltet. Da sieht derjenige, der solche Erkenntnisse in sich ausbildet, wie das, was Denkkraft ist, nunmehr außerhalb des Leibes zum Bewußtsein kommt. Es kommt dadurch zum Bewußtsein, daß die Spiegelung des Späteren bewirkt wird durch das Frühere.

Also merken Sie wohl: wenn derjenige, der initiiert ist, seinen Leib verläßt und außerhalb seines Leibes ist, dann nimmt er nicht dadurch wahr, daß ihm sein Leib etwas spiegelt, sondern er nimmt wahr dadurch, ‘ daß sich seine Denkkraft, die er jetzt aussendet, spiegelt an demjenigen, was er früher gedacht hat. Sie müssen sich also vorstellen: dasjenige, was früher gedacht worden ist, das spiegelt wieder zurück die durch das Denken entfalteten Kräfte, wenn diese Entfaltung außerhalb des Leibes geschieht.

Also, ich kann es vielleicht noch genauer sagen: Nehmen wir an, irgend jemand tritt heute in den Zustand der Initiation. Wodurch kann er in diesem Zustande der Initiation durch seine Denkkraft etwas wahrnehmen? Dadurch, daß er mit seinen Denkkräften, die er aussendet, auftrifft auf das, was er zum Beispiel gestern gedacht hat. Das, was er gestern gedacht hat, bleibt in der allgemeinen Weltenchronik, die Sie kennen als die Akasha-Chronik, eingeschrieben, und das, was heute seine Denkkraft entwickelt, spiegelt sich in dem gestern Gedachten.

Daraus können Sie ersehen, daß das Bestreben eine Berechtigung haben muß, so stark wie möglich das gestern Gedachte zu machen, damit es wirklich richtig spiegeln kann. Und dieses wird bewirkt durch die strenge Konzentration der Gedanken und durch Meditationen verschiedener Art, wie wir sie gelegentlich solcher Vorträge, die über die Erkenntnis höherer Welten gehalten worden sind, beschrieben haben. Da wird gleichsam der Gedanke, der sonst flüchtig bleibt, in dem Menschen so verdichtet, so verstärkt, daß der Mensch dann dazu kommen kann, daß sich die Denkkraft spiegelt an den vorher verstärkt gemachten, verdichteten Gedanken.

Und so ist es auch beschaffen mit dem Bewußtsein, das die Menschen entwickeln nach dem Tode. Dasjenige, was der Mensch durchlebt hat zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode, das ist wohl eingeschrieben in die große Chronik der Zeit in geistiger Weise. Und so wie wir nicht hören können ohne Ohren hier in der physischen Welt, so können wir nicht wahrnehmen nach dem Tode, ohne daß da ist, in der Welt eingeschrieben, unser Leben mit alledem, was wir durchlebt haben zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode. Das ist der Spiegelungsapparat.

Ich habe schon einmal, in meinem letzten Wiener Zyklus, auf diese Tatsache aufmerksam gemacht. Unser Leben selber, das wir hier so führen zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode, wird zum Sinnesorgan für die höheren Welten. Sie sehen Ihr Auge nicht, Sie hören Ihr Ohr nicht, Sie sehen aber durch Ihr Auge und Sie hören durch Ihr Ohr. Wenn Sie von dem Auge etwas wahrnehmen wollen, so müssen Sie dies auf dem Wege der äußeren Wissenschaft tun. So ist es auch mit dem Ohr. Diejenigen Kräfte, die der Mensch entwickelt zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, sind dazu veranlagt, immerdar zurückzustrahlen zu dem Erdenleben, das wir verlebt haben, durch dieses gespiegelt zu werden, um dann sich auszubreiten und. wieder wahrgenommen zu werden von dem Menschen, der in dem Leben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt ist.

Daraus ersehen Sie, wie unsinnig es ist, von dem irdischen Leben nur so zu sprechen, als ob dieses irdische Leben eine Strafe oder irgend sonst etwas Überflüssiges in bezug auf das gesamte Leben des Menschen ist. Es ist durchaus notwendig, um wahrzunehmen, sozusagen Auge und Ohr zu haben zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt. In dieses irdische Leben muß sich der Mensch einfügen, weil es ihm zum Sinnesorgan wird in der geistigen Welt im Leben nach dem Tode.

Die Schwierigkeit des Vorstellens besteht nun darin, daß wenn Sie sich ein Sinnesorgan denken, Sie sich etwas Räumliches vorstellen. Der Raum hört aber auf, sobald man durch die Pforte des Todes oder durch die Initiation geht. Der Raum hat nur Bedeutung für die sinnliche Welt. Dasjenige, was wir betreten, ist die Zeit, und so wie wir hier Raumesohren und Raumesaugen gebrauchen, so gebrauchen wir dort zeitliche Vorgänge. Das sind eben die Vorgänge, die sich zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode vollziehen, durch die zurückgestrahlt werden diejenigen, die wir nach dem Tode entwickeln. In dem Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod liegt alles vor uns wahrnehmbar im Raume. Nach dem: Tode verläuft alles in der Zeit, während sonst alles für uns wahrnehmbar im Raume lebt.

Die besondere Schwierigkeit über die Dinge der Geisteswissenschaft zu sprechen, liegt darin, daß wir uns, sobald wir den Blick hinaufwenden in die geistigen Welten, wirklich die ganze Anschauung abgewöhnen müssen, die wir hier entwickeln für das Raumesdasein; daß wir uns ganz abgewöhnen müssen die Raumesanschauung und wissen müssen, daß es Raum da nicht gibt, daß alles in der Zeit verläuft, und daß sogar die Organe da zeitliche Vorgänge sind. Man muß nicht nur umlernen, wenn man sich hineinfinden will in die Ereignisse des geistigen Lebens, sondern man muß auch in der Weise sich ganz umwandeln, ummodellieren, umlebendigen, daß man sich eine ganz andere Vorstellungsart aneignet. Und darinnen besteht das Schwierige, auf das gestern hingewiesen worden ist und das viele so sehr scheuen, selbst wenn sie eine noch so scharfsinnige Philosophie für den physischen Plan betreiben. Die Leute hängen eben an der Raumesvorstellung und können sich nicht hineinfinden, in bezug auf die Vorstellungen, in ein Leben, das lediglich in der Zeit verläuft.

Ich weiß wohl, daß manche Seele da sein kann, die sich sagt: Aber ich kann mir gar nicht vorstellen, wenn ich mich in die geistige Welt hineinversetze, daß diese geistige Welt nicht räumlich ausgedehnt sein soll. - Gewiß, aber viel mehr als irgend etwas anderes ist notwendig, daß wir uns bemühen, gerade über die Vorstellungsarten des physischen Planes hinauszukommen, wenn wir in die geistige Welt hinein wollen. Wenn wir immer wieder und wieder alle höheren Welten nur nach dem Maßstabe, Musterbilde der physisch-räumlichen Welt vorstellen wollen, dann können wir wirkliche Gedanken über die höheren Welten doch nicht gewinnen, sondern höchstens bildhafte Gedanken.

So ist es mit Bezug auf das Denken. Das Denken also verläuft nach dem Tode so, daß es sich spiegelt an demjenigen, was wir durchlebt haben, an dem, was wir waren im physischen Erdenleben zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode. Diese Vorgänge, die wir da durchlebt haben, sind gewissermaßen unsere Augen und unsere Ohren nach dem Tode. Versuchen Sie durch Meditationen sich nahezubringen, was der bedeutungsvolle Satz eigentlich enthält: Dein Leben zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode wird dir als Auge und Ohr eingesetzt sein, es wird dir diejenigen Organe geben, die du tragen wirst zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt.

Wie ist es nun aber mit dem, was Willenskräfte sind? Die Willenskräfte, sie bewirken ja Lebensvorgänge in uns, die innerhalb der Grenzen unseres Leibes liegen. Lebensvorgänge bewirken sie in uns. Der Leib ist nicht da, wenn der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes geschritten ist, aber die ganze geistige Umwelt ist da. So wahr der Wille mit seinen Kräften in den physischen Organismus hineinwirkt, so wahr will dieser Wille nach dem Tode überall aus dem Menschen heraus; er ergießt sich in die ganze Umwelt, umgekehrt als im physischen Leben, wo der Wille ja in den Menschen hinein wirkt. Sie bekommen eine Vorstellung von diesem Ergießen des Willens in die ganze Umwelt, wenn Sie darüber nachdenken, was Sie schon durch Meditation sich aneignen müssen an innerer Willenskultur, wenn Sie wirklich vorwärtskommen wollen auf dem Gebiete der geistigen Erkenntnis.

Derjenige Mensch, der sich begnügen will, die Welt bloß sinnlich zu erkennen, der sieht zum Beispiel eine blaue Farbe, sieht irgendwo eine blaue Fläche, oder er sieht irgendwo eine gelbe Fläche. Damit begnügt sich derjenige Mensch, der in der physischen Welt stehenbleiben will. Wir haben auch darüber schon gesprochen, wie wir, selbst bei einer wirklichen Kunstanschauung, über diese bloß sinnliche Auffassung der Sache hinauskommen müssen: wie wir zum Beispiel üben müssen, Blau so zu erleben, als ob unser Wille, unsere Gemütskraft, hineingelassen würde in den Raum, und als ob von uns entgegenstrahlen könnte in den Raum dem, was uns als Blau entgegenstrahlt, etwas wie wenn wir ein Hingebungsvolles empfinden, als ob wir uns in den Raum hineinergießen könnten. Da strömt das eigene Wesen hinein, wo Blau ist, da fließt es fort. Da aber, wo Gelb ist, da will das eigene Wesen nicht hinein, das Willenswesen; da wird es zurückgestoßen. Da fühlt es, daß der Wille nicht durch kann und in sich selber zurückgestoßen wird.

Derjenige, der wirklich sich dazu vorbereiten will, die Kräfte seiner - Seele zu entwickeln, die ihn in die geistige Welt hineinführen, der muß mit dem, was ich eben gesagt habe, etwas Reales in seinem Seelenleben verbinden können. Er muß zum Beispiel real verbinden die Tatsache, daß er hier eine blaue Fläche sieht, damit, daß er sagt: Die nimmt mich. freundlich auf, die läßt meine Seele mit ihren Kräften in unbestimmte Fernen ziehen. Aber die Fläche hier, die gelbe, stößt mich zurück; da kommen die Kräfte meiner Seele gleichsam als Nadelstiche in meine eigene Seele zurück. - Aber so ist es mit alledem, was man sinnlich wahrnimmt. Alles hat solche Nuancen. Unser seelisches Willenswesen ergießt sich in die Welt, wird entweder zurückgestoßen oder kann sich ergießen über die Welt. Entwickelt kann das werden, indem man an Farben oder sonstigen Eindrücken der physischen Welt seine seelischen Kräfte schult. Wie man das kann, finden Sie geschildert in dem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?».

Aber wenn man das entwickelt hat, wenn man weiß, wie es ist, wenn die Kräfte der Seele fortschwingen, blau werden - blau werden und fortschreiten ist ein und dasselbe, ist: sympathisch aufgenommen werden; gelb werden ist dasselbe wie zurückgestoßen werden, identisch mit Antipathie -, dann hat man diese Kräfte in sich. Sagen wir, man habe erfahren wie eine solche Seelennuance ist: sympathisch aufgenommen zu werden, und man stellt sich jetzt gar nicht einem physischen Wesen gegenüber, sondern es kann so sein, daß man ein geistiges Wesen, dem wir sympathisch sind, in sich einfließen läßt durch so entwickelte . Seelenkräfte. Wir nehmen so die Wesen der oberen Hierarchien und der elementarischen Welt wahr.

Ich will Ihnen ein Beispiel geben, ein Beispiel, das wirklich nicht anzüglich sein soll, sondern als ganz objektiv gefaßt gelten soll. Man braucht nicht bloß an dem Farbensinn Kräfte entwickeln; man kann an allem Seelenkräfte entwickeln. Denken Sie sich, man bemüht sich, in Selbsterkenntnis zu fühlen, wie sich das in der eigenen Seele ausnimmt, wenn man so recht dumm oder töricht ist. Im alltäglichen Leben geht man über solche Empfindungen hinweg, man bringt sie sich nicht zum Bewußtsein. Aber wenn man die Seele entwickeln will, muß man ein Gefühl haben davon, wie es sich innerlich erlebt, wenn man erwas recht Törichtes tut. Und da merkt man, daß, wenn man etwas Törichtes tut, solche Seelen-Willenskräfte ausstrahlen, und die können von etwas draußen zurückgeworfen werden. Aber sie werden so zurückgeworfen, daß, indem wir das Zurückwerfen verspüren, wir uns selbst verspottet, verhöhnt fühlen. Das ist ein eigentümliches Erlebnis. Gibt man acht, wenn man recht dumm ist, was da geistig um einen vorgeht, so fühlt man sich verhöhnt, geneckt; und nun kann man das Gefühl entwickeln, wie wenn man aus der geistigen Welt heraus geneckt würde. Geht man dann in eine Gegend, wo es Naturgeister gibt, die man als Gnomen bezeichnet, dann hat man die Kraft, sie wahrzunehmen. Man erwirbt sich die Kraft, sie wahrzunehmen nur, wenn man das Gefühl in sich entwickelt, das ich eben beschrieben habe. Die Gnomen benehmen sich so, daß sie necken, allerlei Gesten und Grimassen machen, einen auslachen und so weiter. Das kann man aber nur wahrnehmen, wenn man sich beim Dummsein beobachtet. Es handelt sich darum, daß wir durch diese Übungen intime Kräfte uns aneignen, daß wir selber mit dem Willen untertauchen in die Umwelt. Dann wird die ganze Umwelt belebt, wirklich belebt.

So kann man sagen: Während unser Leben zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode Organ, Wahrnehmungsorgan wird in unserem geistigen Organismus, den wir tragen zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, wird unser Wille Teilnehmer an der ganzen geistigen Umgebung, in der wir sind. $o sehen wir, wie der Wille zurückstrahlt beim Inittierten, beim Gnomen-Sehen zum Beispiel, und beim Toten. Und wenn man Gnomen sieht, so ist das ein Beispiel dafür aus der elementarischen Welt.

Denken Sie sich, daß es einen Philosophen gegeben hat, der in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts einen großen Eindruck auf viele Menschen gemacht hat: Schopenhauer. Der hat auch, wie Sie wissen, einen großen Einfluß auf Nietzsche und Richard Wagner gehabt. Schopenhauer hat - wie andere die Welt zurückführen auf andere Ursachen die Welt zurückgeführt auf das, was er Vorstellung und Wille nennt. Er sagte: Vorstellung und Wille sind dasjenige, was der Welt zugrunde liegt.

Nun findet er aber, angefressen von Kantscher Denkweise, daß die Vorstellungen immer ein Traumgebilde bleiben, daß man durch die Vorstellungen niemals in die Wirklichkeit hineindringen kann. Nur durch den Willen kann man in die Wirklichkeit hineindringen, der Wille führt uns in die Realität der Dinge hinein. Nun philosophiert Schopenhauer in eindrucksvoller Weise über Vorstellung und Wille. Er ist, wenn man so sagen darf, gar nicht einmal auf unebenem Wege. Aber nun ist er auch einer von denen, die ich verglichen habe mit den Leuten, die bis zum Tore gehen, aber am Tore stehenbleiben und nicht hinein wollen. Wenn man ihn nämlich beim Wort nimmt, die Welt sei Vorstellung und die Welt sei bloß Traumbild, dann kann man darauf verzichten, durch die Vorstellung die Welt zu erkennen, und man kann dann dazu übergehen, die Vorstellungen in sich zu erkennen, mit der Vorstellung etwas zu machen in der eigenen Seele, das heißt: Meditieren, Konzentrieren. Hätte Schopenhauer einen Schritt weiter gemacht, so wäre er darauf gekommen sich zu sagen: Ich muß verzichten auf die Vorstellung! Wenn die Vorstellung nur ein Produkt meines Inneren ist, so muß ich sie innerlich verwenden. — Hätte Schopenhauer diesen Schritt gemacht, dann würde er fortgetrieben worden sein dazu, die Vorstellung zu kultivieren, sie zu Konzentration und Meditation zu verarbeiten.

Und wenn er sagt: Die Welt ist Wille -, ja, wenn er zu beschreiben anfängt, wie er das in der geistvollen Abhandlung über den «Willen in der Natur» tut, wenn er zu beschreiben anfängt den Willen in der Natur, so nimmt er seinen eigenen Satz nicht ernst. Wenn man den Willen beschreibt, dann nimmt man die Vorstellungen zur Hilfe, und denen hat er ja alle Erkenntniskraft abgesprochen. Daraus wird dann wirklich eine Münchhauseniade, die derjenigen gleicht, sich selber am Schopf zu fassen, um sich aus dem Sumpfe herauszuziehen. Was hätte er tun müssen, wenn er seinen eigenen Satz: Die Welt ist Wille - ernst genommen hätte? Er hätte sich dann sagen müssen: Also müßte man den Willen in die Welt hinausergießen. Man muß den Willen gebrauchen, um in die Dinge hineinzukriechen. Man muß untertauchen in die Welt, und den Willen hineinsenden in die Welt, so daß man die blaue Farbe nicht als Vorstellung nimmt, sondern versucht zu empfinden, wie der Wille untertaucht in sie; daß man seine Dummheit nicht nimmt als Vorstellung, sondern das nimmt, was man im Vorgange der eigenen Dummheit erleben kann.

Sie sehen wiederum: man kann so auf ein geistreiches Aperçu kommen, auf ein Aperçu, das nur ernst genommen zu werden braucht. Wenn Schopenhauer weitergegangen wäre, dann hätte er sich sagen müssen: Wenn die Vorstellung wirklich nur das von uns vorgestellte Bild ist, dann muß man sie in sich verarbeiten; wenn der Wille wirklich in den Dingen ist, dann muß man mit dem Willen in die Dinge untertauchen, nicht bloß beschreiben, wie der Wille in den Dingen ist.

Sie sehen wieder ein Beispiel dafür, wie ein bedeutsamer Philosoph des 19. Jahrhunderts die Menschen vor die Pforte der Einweihung, vor die Geisteswissenschaft bringt, und wie dieser Philosoph dann alles tut, um den Menschen dann diese Pforte zu verschließen. Wo man das Leben anfaßt, überall zeigt es sich, daß unsere Zeit reif ist, die Früchte der Geisteswissenschaft zu pflücken. Man muß nur wirklich die Dinge ernst, tief ernst nehmen. Vor allen Dingen muß man verstehen, die Leute beim Wort zu nehmen; denn die Geisteswissenschaft ist gar nicht darauf angewiesen, daß sie selber ihr Recht verteidigt. Das tun eigentlich die anderen, ihre Gegner, am allermeisten. Aber sie wissen es nicht, sie haben keine Ahnung davon.

Nehmen Sie eine gewisse Sorte Menschen, die es im 19. Jahrhundert so vielfach gegeben hat: die atomistischen Materialisten, diejenigen Menschen, die sich vorgestellt haben, allen Erscheinungen des Lebens liegen Bewegungen der Atome zugrunde, so daß sie sich vorgestellt haben, hinter all dieser sichtbaren und hörbaren Welt ist eine Welt der Atome in Bewegung, und durch diese Bewegung entstehen die Prozesse, die wir als den Schein, der da ist, wahrnehmen. Nichts Geistiges ist vorhanden, das Geistige ist bloß ein Produkt der Atombewegung. Atomwirkungen also allüberall.

Ja, wie entstehen denn die Gedanken von den Atomwirbeln? Hat sie jemand gesehen? Hat sie jemand durch seine Erlebnisse, durch seine Erfahrungen gefunden? Wäre das der Fall, dann wären sie nicht dasjenige, was sie sein sollen: sie sollen ja hinter der Erfahrung stehen. Wenn sie eine Realität hätten, durch was müßten sie gefunden werden? Nehmen wir an, die Atombewegungen wären da. Der Verstand kann sie aus den Sinneswahrnehmungen nicht herausschälen. Was müßte der Mensch haben, damit er von dieser Atomwelt reden könnte? Hellsehen müßte er haben. Die ganze Atomwelt müßte ein Produkt des inneren Schauens, der Hellseherkraft sein. Und man kann nur den Leuten, die als Materialisten des 19. Jahrhunderts aufgetreten sind, sagen: Wir brauchen nicht zu beweisen, daß es Hellseher gibt, denn entweder müßt ihr von all euren Theorien schweigen oder ihr müßt zugeben, daß ihr Hellseher seid, um diese Dinge wahrzunehmen, wenigstens in dem Grade, daß ihr hinter der Sinnenwelt die Atome wahrnehmen könnt. Denn es hat keinen Sinn, von der materialistischen Atomwelt zu sprechen, wenn es nicht Hellseherkräfte gibt. Wenn ihr eine Notwendigkeit findet, es müsse eine Atombewegung geben, dann beweist ihr uns, daß es Hellseher gibt.

So nimmt man die Leute ernst, obgleich sie sich selber nicht ernst nehmen, wenn sie so etwas sagen. Wenn man Schopenhauer ernst nimmt, so folgert man: Wenn du sagst, die Welt ist Wille, und das, was wir als Vorstellung haben, sind nur Bilder, so müßtest du in die Welt mit dem Willen hinunterdringen, und durch Meditation und Konzentration in das Denken hinunterdringen. Wir nehmen dich ernst; du nimmst dich aber nicht ernst. — So ist es im Grunde mit all den Dingen, die in dieser Richtung in Betracht kommen.

Darinnen liegt das tief Bedeutsame der geisteswissenschaftlichen Weltanschauung, daß sie dasjenige, was die anderen nicht ernst nehmen, über das sie oberflächlich hinweggehen, ernst nimmt. Die Beweise sind immer bei dem Gegner der Geisteswissenschaft zu finden. Aber die Menschen merken gar nicht, daß sie mit ihren Behauptungen, mit dem, was sie denken, im Grunde genommen das, was sie denken, zugleich vernichten. Denn der materialistische Atomist und auch Schopenhauer vernichten dasjenige, was sie behaupten, durch ihre eigene Behauptung.

Schopenhauer vernichtet sein eigenes System mit der Behauptung: Alles ist Wille und Vorstellung. - In dem Augenblicke aber, wo er nicht stehenbleiben will, muß er die Menschen zu der geisteswissenschaftlichen Entwickelung führen. Nicht wir machen die geisteswissenschaftliche Weltanschauung. Wie macht sich in der Welt die geisteswissenschaftliche Weltanschauung? Sie tritt herein, ist überall in der Welt da. Sie tritt durch unbekannte Pforten und Fenster in das Leben herein, und sie wird, auch wenn die anderen sie nicht ernstlich wahrnehmen, den Weg in das Kulturleben der Menschheit hinein finden.

Aber etwas anderes kann noch erkannt werden, wenn man wirklich durch solche Betrachtungen hingewiesen wird darauf, wie wenig tief die Menschen in ihre eigenen geistigen Prozesse hinuntersteigen, wie wenig die Menschen im tieferen Sinne sich selber ernst nehmen, selbst wenn sie geistvolle, tiefe Philosophen sind. Die Menschen weben gleichsam ein Vorstellungsgewebe; aber sie scheuen davor zurück, mit diesem Vorstellungsgewebe wirklich eine innere Lebensarbeit zu vollbringen, die sie weiterführt im Erleben desjenigen, was die Grundkräfte der Welt sind. So sehen wir, daß die Jahrhunderte, auf die gestern wieder hingedeutet worden ist, in denen die äußere Naturwissenschaft ihre großen Triumphe gefeiert hat, zugleich diejenigen sind, die den Menschen in ein oberflächliches Denken hineingebracht haben. Je glorreicher die Entwickelung der Naturwissenschaft ist, desto oberflächlicher ist das in die Quellen des Daseins eindringende Forschen geworden.