The Tree of Life and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil

GA 162

7 August 1915, Dornach

5. Tree of Knowledge I

My dear friends, I should like to put together various things today which will give us the possibility of going into some important matters that we will speak of in connection with our present subject.

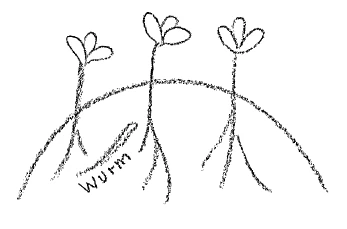

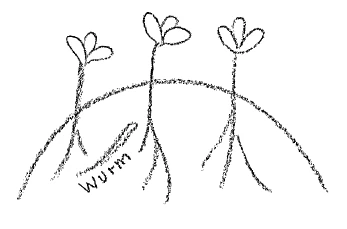

Let us suppose that here were the surface of the earth—arable land, meadow, or what you will (a drawing was made), and plants, any kind of plants grew in this meadow. And suppose that here were a worm or some little creature, that lives and burrows under the earth and has its home under the earth and never comes above the surface. This little grub or caterpillar, or whatever it is, creeps about inside and learns by its creeping about to know the roots of these plants. Naturally, as this creature never comes out above the surface of the earth, it only learns to know the roots of the plants, it learns to know nothing else; it creeps about and learns to recognise the roots. And what will happen is the following, is it not?

When a certain time comes in this creeping about of the caterpillar, processes are going on up above in the plants, in the whole plant nature; real processes are going on which are dependent on the sunshine, on the sun's giving out a certain warmth. The processes which the plants are undergoing naturally also bring about changes in the roots. When the plant above begins to put out fresh shoots and to bear blossoms, changes occur similarly in the roots. All the roots processes are affected when something occurs above. So we can say: when this worm is creeping about underneath, up above, caused by sun-activities, shoots, leaves, fruits are called forth, and processes are then brought about in the roots. But the caterpillar only crawls about in the earth; it creeps from root to root.

Now let us for once suppose—hypothetically we can accept it—that this caterpillar or grub were a worm-philosopher or a caterpillar-philosopher, and evolved a world-conception. Thus it creeps about there down below the earth and makes itself a world-conception. In the picture that it devises as world-conception, there can naturally never play a role, the fact that the sun comes and the shoots spring forth—for the caterpillar can know nothing of this; it creeps around, this caterpillar, this worm, and studies the changes in the roots, and notices quite clearly that something is going on, that the roots become different, and also that in the part of the earth lying round something is happening, and he now expresses all he knows, this worm. He expresses all of this, but in the picture of the world which he makes for himself, never a word is to be found about the existence of the sun, the coming forth of the plants; this indeed is self-evident. That is to say, a world-conception arisen in this worm-philosopher which will give a proper picture of the condition under the earth, whether it becomes damper, becomes warmer ... To be sure he does not know, this worm, whence this warmth comes ... That it becomes warmer, that all sorts of processes go on in the roots, all that he comprehends. And let us suppose the worm were not an ordinary worm-philosopher but was inspired by some modern philosopher of the opinion so current today, that all depends on cause and effect, everything is subjected to causality, as it is expressed in a scientifically philosophical-technical way. Then this worm will creep about down below and will call one thing a cause and another an effect and say: Now the earth becomes somewhat warmer from above downwards; that causes alterations in the roots. With the further processes he will represent the one as cause and the further processes in the roots as effects, and so on ... and a consistent picture will emerge, which classifies all the processes under the earth as cause and effect. But it would not include that fact that the sun shines, and the plants come out, and through this the processes in the roots are changed. Still, the worm's world-picture would be quite a consistent one. It could be a genuine picture of causality, there need be nothing lacking in the chain of cause and effect.

Now you see, it is quite clear to you, I think, that this worm-philosophy represents a one-sided world-conception which is quite correct ... except that it lacks what man considers the most important of all. That is, that the sun comes with its warmth and light and brings about what the worm actually observes down there below; it is clear, indeed, how in fact his whole causality only depends on the fact that he does not come up above the surface of the earth.

You see, as a matter of fact, such worms are the people who philosophize today on the chain of causality, of causes and effects. The image is completely opposite: men makes researches into what their senses see; and move about in what—well, not in what is shut off spatially from above—but in what is shut off through sense observation, and they simply do not perceive the spiritual extended everywhere, that causes the causes. They do not distinguish the spiritual which is behind cause and effect. It is really an exact analogy.

Now if the worm should suddenly come out and see the sun, he could discover that the cause of all he has puzzled out down below is, as a matter of fact, what other beings up above are seeing, and that his world-conception simply does not hold good. He would have to realize that what he himself underneath has had as perceptions of differences, is up above. It is just the same when one raises oneself from ordinary human sight to spiritual sight, for one notes how then something comes into the sense-world which cannot be perceived under ordinary circumstances.

You also see from this how the much vaunted inner completeness of a world-conception means nothing for its correctness. One who can set himself genuinely with his whole heart and soul into this worm-existence can give the assurance that nothing at all in this worm-conception need rest on a logical error. Hence all logic can be correct and complete in itself, there need be no logical error in it, it can be a world-conception completely tenable inwardly. You will realize from this, however, that it is in no way a question of being able or not able to prove something with the instruments of the world in which man is. I have often referred to this from other aspects. This we are not concerned with, whether or not a man can prove something with the means offered by the world in which he dwells. World-conceptions can have ever such fine proofs in themselves, they still remain—well—let us say: worm-world-conceptions. When we let this really work upon our soul, we see what stands behind of great importance: we note how—when we once guess that there are yet other worlds—a kind of general world -the duty arises of entering into those other worlds. For no matter how complete in itself is a world-conception, it does not follow that it gives one any knowledge of the actual events and processes. And this is truly what one finds with the majority of the philosophies of today and the immediate past; they are worm-conceptions. They are complete in themselves in a really extraordinarily logical way, they have an immense amount of value for the worlds in which man dwells; but they are only constructed with the means of the worlds in which man dwells. You see from this that you cannot rely on so-called proofs, unless you first come to understand where these proofs originate. For our time, it is truly a matter of getting a feeling for the way other worlds permeate our world, for the way other worlds allow themselves to become manifest. Certainly, this is difficult. For truly, conditions for the worm are such that he lives underground; the worm would not endure well up above, if he were forced to go out there; first he would have to adapt himself to the new conditions. Thus it is also difficult for the human being, when he detaches himself as soul from his bodily nature, to adapt himself to the new conditions.

Now you can raise a question, my dear friends, you can say: ‘Fine, you have now compared the world in which the human being lives with his senses to the world under the earth. Show us something, anything at all, that limits, truly limits our ordinary sense-world conception in any such way.’ One can raise this point quite seriously. In the course of the process of consecutive formation of Saturn, Sun and Moon, Time (during the Moon-existence) and Space (during the Earth-existence) first entered into humanity's world conception. When we speak of Saturn, Sun and Moon, and use spatial conceptions to aid is that description, we actually speak only in Imaginations, and we must remain conscious throughout of the fact that when we speak of these three worlds in spatial conceptions, these space-conceptions have only as much to do with what was brought to completion in those worlds as ... well, let us say, as the forms of the letters of the alphabet have to do with the meanings of the words. We must not take contemporary conceptions as they are, but rather as signs, as images of these worlds. For Space only has meaning for that which evolves within the span of Earth-existence, and Time has actually only become meaningful since the separation of the Old Moon from the Sun; that is the strict point in which the Old Moon separated from the Sun. Then for the first time it is possible to speak of events occurring in time, as we speak today.

Since, however, we have our mental concepts in time and space—for everything external that we conceive is in space, everything that we bring to consciousness and let arise within, runs its course in time—we are thereby between birth and death, but only between birth and death, shut in by space and time, as the worm dwells down there in its earth. Space and time are our boundaries, just as the earth substance is the worm's boundary. We are worms of space and worms of time; we are so, truly, in a quite high, in a quite exact sense. For as incarnated men we move about in space; we observe things in space, and that which observes is our soul, which itself lives in the concepts (Vorstellungen). Between birth and death time goes on, from falling asleep to awakening time goes on. The comparison is by no means a bad one, when one sees the reality. Insofar as our soul is enclosed in the body, as regards the world-picture it forms, it is truly a worm, who creeps about in space and who, if it wishes to arrive at realities, must come out of space. Then it must also get accustomed to viewing things not merely under time-conditions, but under conditions, for which that which takes its course in time is nothing but an outer sign, like a letter of the alphabet.

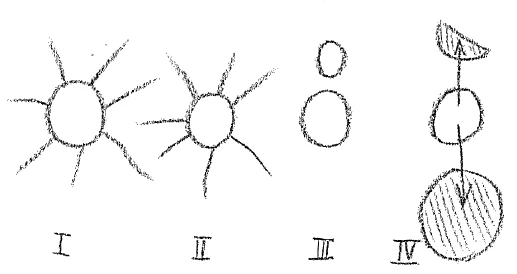

Now after I have called attention to this, I will lead these studies over to the realm of soul and spirit. Just as the coming plant is already actually contained in the seed, so, naturally, there was already contained in an earlier germinal state, what has developed for man today on earth in perceptions of space and time. I have already pointed out here in one connection that rudiments were already contained in Saturn, Sun, Moon. So that when here on earth we assign a certain meaning to what goes on around us, we must as it were see this meaning already present, in the old evolution of the Moon, the Sun, etc. With the forming of time and the forming of space, the meaning of life on earth must in some way have prepared itself. The forming of space and time must have so come about that then the meaning of the earth-life was added to it like a kind of flower. Now we can picture these processes—Saturn, Sun and Moon in the following way. We can say: We have an Old Saturn existence which is surrounded by the cosmos; we have an Old Sun-existence, again surrounded by the cosmos; we have an Old Moon-existence but already developing out of it a sort of neighbouring planet (you may read this in my Occult Science and we have then learnt to know that the Earth separates from the Sun and again from the Moon.

If the man of materialistic thought (I will suppose what is most favourable for our Spiritual Science) could prevail on himself to believe in these developments, he would still have to overcome the next step, which consists fundamentally in the fact that the whole evolution (origin of Saturn, of the Sun, further development to Moon, separation of the Moon, separation of Earth, Sun and Moon) all really occurs in order to make Man possible, as he is on earth. Just as the processes of a plant's root- and leaf-building happen in order to make possible the blossom and the fruit, so do all these processes, these macrocosmic processes, happen in order to make possible our life on earth; they arise so that we may live on earth in the way we do. One could also say: These processes are the roots of our earth-life; this life is there so that we can develop on Earth as we do. Let us be quite clear that we have to do with the separation of the Sun on the one hand, the separation of the Moon on the other hand—that we have to do with separations so that our Earth could come into existence as Earth. That is to say, we were left behind on the Earth planet, and Sun and Moon separated from us and work on the earth from outside. That had to come about, otherwise nothing could have developed in us as it does on earth. For everything to develop on Earth in the way it does it was necessary that once in primeval times Sun and Moon were united with the earth and that then they separated, and now let their activity shine in from outside upon the earth. That is absolutely necessary.

Now I should like to show that our inner soul life has taken on quite distinct configurations through the fact that this has taken place. Among the very varied ideas which we have—I could adduce many as examples—and which play a certain role in the whole state of our earth existence, is the idea of ‘possessing something,’ ‘having something.’ This implies that our own person unites itself with something which is outside the personality. We speak in the rarest cases of possessing our arm and our nose, for most people experience their arm or nose as so much belonging to them that they do not speak of a possession. But what could be separated and then belongs to us we describe purely in the legal sense as a possession, a genuine possession. Now the concept of possessing something which is outside could not be formed in us at all, if there had not arisen the separation of what had formerly belonged to the earth, and the being drawn in again of the Sun and Moon to the earth. Our life was quite different on the Old Sun. There Sun and Moon were united as Sun with what were processes of Earth; they were inwardly united with the whole human existence. There the human being could say: ‘Sun activity in me,’ ‘I Sun activity’ (if he could have said ‘I’ already, as the archangels could) ‘I Sun activity’; not ‘the sun shines on me, Sun activity comes toward me.’ This Planet or Fixed Star Sun had to be separated so that we as earth men could develop this special configuration of the possession-concept.

Now this is connected with something else. Imagine an Archangel on the old Sun-existence; he says: ‘I Sun.’ That we see something rests upon the fact that the sun's rays or other light-rays shine on the object and are thrown back to us. Were the sun to shine from the midst of the earth, we should see nothing of the objects which are upon the earth. We should then say: ‘I Sun,’ ‘I Light,’ but we should not separate the individual objects, we should not see them. Thus something else still is connected with this. In the Earth's evolution from Saturn, Sun, Moon to Earth, we have for the first time, through this macrocosmic constellation, the possibility of seeing and perceiving objects as we do now. Such perceptions were naturally not present during the Sun-existence. Although the first rudiments of our sense-organs had already been prepared on Old Saturn, they were only opened upon the Earth, only there were they made organs of perception. These rudiments on Saturn were blind and unperceiving sense-organs. The sense-organs were first opened by the separation of the Sun and the departure of the Moon from the earth. You see from this that two processes go parallel—the activity of our sense-perceptions and the sight of external objects, and running parallel with this, the possession-concept. For how do we come to the concept of possession? You could not imagine that an Archangel during the Sun-existence wished to possess anything. He does not behold things; he is everything. If all objects and beings of the earth were like this, they would never have the urge to want to possess anything. With this development of the senses develops for the first time the possession-concept, the possession-concept is not separable from the development of the senses; these two things run parallel. The senses were on the one side, and something like the possession-concept on the other side. Other concepts can also be taken.

And when we consider in a more comprehensive sense what stands in the religious records, in the Bible (for in such records as the Bible very many things lie concealed)—then we can say: What is given at the beginning of the Bible about the Luciferic temptation is connected with the promise of Lucifer to man that his senses shall be developed: ‘Your eyes shall be opened.’ He means that all senses shall be opened—the eyes only stand for the senses as a whole. In this way he has guided the senses to external things and at the same time called forth the concept of possession. If we wished to relate somewhat more in detail what Lucifer promised to the woman we should have to say: You will become as gods, your senses will be opened; you will distinguish between what pleases you and does not please you, what you call good and evil, and you will wish to possess all that pleases you, that you call good.—One must connect all this with the Luciferic temptation.

Now we must reflect about something, if we wish to grasp aright such a conception as I have now developed. Here is one of the points where it is necessary in a lecture on Spiritual Science to call upon the reflection and meditation of each individual who wants to assimilate what is given. One must reflect upon something; In developing for you the arising of the senses, the perception of objects, and the evolution of the possession-concept, we have not been obliged to introduce any concept of space or time. To be sure, if a man wants to picture these things to himself, if he sketches them on a board, he avails himself of the assistance of the space and time idea. But in order to grasp what this means: 'the senses are opened' or 'the possession-concept is developed' one does not need the idea of space and time. These things are independent of space and time. You do not need to think you are spatially distant from something when you want to possess it; nor do you need to call on the time-processes. I have said, here one must summon self-reflection, for everyone can object: ‘I cannot do it’ ... But if he makes sufficient effort, he can imagine such things without the aid of space and time concept. Indeed, something else is true: when you try to bring such concepts clearly to consciousness, that is, to meditate them as I have just done with you, you gradually come out beyond the idea of space and time. You come out into a world where space and time really do not-play the eminent role in your experience that they play in everyday life.

Now there exists in the evolution of humanity a peculiar longing. Wherever in history we meet with the human race in its innermost striving, we come upon a certain longing. And that is the longing to have concepts which are independent of space and time, which have nothing to do with space and time. Historical events are transformed into myths, or in the historical presentation there is an indication of the spiritual in order to make it possible to show how historical events take a mythical form. And the further we look back in history, for instance, the more we find as historical traditions, the historical facts veiled in the myth. Only reflect how already in ancient Greek history all is veiled in myth and in regard to earlier mid-European history all is enveloped in myth and legend! The further one goes back the more one is removed from the external, merely physical feeling of facts, and the presentation plunges into symbolism. When you study myths you will remark that in the arising of myths there is clearly to be seen the desire to work oneself out of space and time. Not only that fairy tales—the most elementary myths—often depict how some human being (I am thinking of the Sleeping Beauty) passes out of time and enters the timeless, but when you examine myths you will see that you do not rightly know which facts are meant to be spiritual. Something that lies centuries earlier may be related later. Sometimes, too, facts which lie hundreds of years apart in history are welded together in a myth. The myth seeks to lift itself above space and time. This means that there lives in man's existence the longing to rise above this space-condition which makes us think and visualise in space and time. There is a longing to live in such concepts as depict, free of space and time, those realities which rule as the eternal things in the succession of events in our space and time existence, or, if they have once been formed, remain as the eternal things.

You see, if you take what I have just said together with something which I said last time you will see a wonderful connection. I said that if a Luciferic quality was not active in us, we should see that our world of concepts is really in the Old Moon. But now it follows from this that the Old Moon is actually present, has remained, and that it is only Lucifer who bewitches us into thinking that our concept is now in ourself. Thus time becomes there a means of deception and illusion for Lucifer. The ancient Moon-existence endures and so also do things that arise, endure. Our possession-concepts are enduring. This means that what earthly man develops as social earthly-order, by reason of his possession-concept, this remains, this will also still be in existence when the Jupiter and Venus conditions are one day there. And then if corresponding temptations do not come as Luciferic and Ahrimanic temptations, one will see how social orders were formed on earth through the possession-idea. They will then present something like physical orders. For that is a part of Maya-existence, of illusion—the idea that things pass away; in reality they are enduring, in reality they go on subsisting. And already, if one understands things aright, one finds the enduring behind the actual past. You can grasp it to some extent in what I have just related.

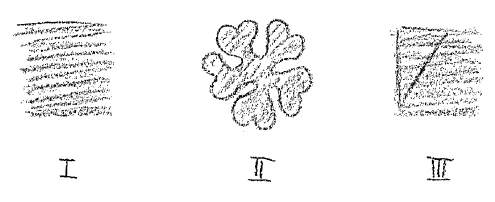

But now, if we truly grasp what I have said, we are really looking into profoundly important foundations of our whole earth-existence. For do we not see how beneath the spatial and temporal earth-existence the eternally enduring earth-existence, or existence in general, is veritably spread out? How we have a spatial, a temporal-spatial condition on the surface, and within, the condition of duration. And now comes our mode of viewing things when it takes its course in space and time, our views and concepts that live in space and time. Just consider, how one can picture that concretely in detail, think for once ... nowadays men no longer grasp this thoroughly ... but somewhere or somehow, think simply 'red.’ In order to think 'red' you need no space and you need no time; you can think 'red' to yourself anywhere; it does not have to be there in time or space, because it is thought of just as quality. (red was put on the board.) It is difficult nowadays for a man to picture it because he wants to give the red a boundary. It was not difficult like this for the angels on the Old Moon for they had no desire to distribute red over separate objects. They had time already, but not space. Actually they pictured, that is they experienced 'red' or 'green' or any other colour as flowing current. Try to conceive this vividly: blue = flowing current; red = flowing current; conceive, too, of the other sense-experiences in the same way—streaming, but only in time, letting no real spatial concept, intermingle ... we can say: at the transition from Moon- to Earth-existence one can feel how the mere time-quality was yoked into the spatial. What then actually determines the essential nature of earth existence, that a 'red' is in this way given a boundary and yoked in? On the Moon it would have been impossible to see an enclosed 'red,’ on Earth it is possible to see red enclosed in a boundary. (A sketch of a flower was drawn.) This, however, is connected, inwardly connected, with the separation of the sun from the earth, and with the falling of the sun's rays from outside upon the earth. So that in a true sense I can say: the sunbeam falls on earth from outside. That already shows you that our present existence is inconceivable without the space-concept. Yes, for our present perception and life, this external position of the sun betokens something real.

Now from what I have brought forward you can easily gather that we can really say: colours are harnesses into space. In ‘Theosophy’ I have called that which lives in man after death ‘flowing sensitivity,’ since there he is not bound to space. I therefore spoke of the first world through which he lives as the ‘world of flowing sensitivity.’ For the sun's must first come in from outside, must harness sense-perceptions into space. With this is connected, as I have explained, the fact that man evolves ideas of possession; for in a world of flowing sensitivity a person can never think of possession -time at most is present there—and he would soon see the futility of it if he were to think of possession. It would be rather like thinking of possessing a piece of water, flowing along in a brook. This only arises inasmuch as the sun, separating from the earth, brings the sense-perceptions into the framework of space.

You see, something like this that I have just expounded must be transformed into an experience, a feeling; one cannot leave it as a mere theoretical concept. One must change it into a feeling, one must really get an inner living sensation how as man, as microcosm, one is placed into the macrocosm, and how this very yearning, i.e. to possess something, is connected with the whole development of the macrocosm, with the course of events through which sense observation has developed. When one feels this rightly, when one begins, so to say, to feel cosmically how, for instance, the simple concept: thou wouldst like to possess what thou seest and what pleases thy sight ... how this is born out of the macrocosm, then for the first time one really gets the truly living idea that the human soul nature is dependent on the whole cosmos. Then one gets a strong and vividly living feeling of how in every concept of ordinary life one is connected with the macrocosm, and how actually in all that we picture and conceive and experience in the soul, the macrocosm lives in us. And there exists a continual longing in man to experience such hidden connections as actually exist in life, and to express the experience. This exists—this longing in the human soul, in the heart of man. And let us imagine that there arose in a human soul a vivid feeling and sensation ( I wish to express the cosmic connection of this single soul experience): ‘My eye falls there on an external object; I want to possess it; I will appropriate it’ ... then from such a feeling, one can experience what I might call—the tragedy of Nature. I say 'the tragedy of the world of nature.’ We really take from a whole world,—extending to the Moon and still present as the basis of our world,—we take from it what we wish to possess. What we desire to possess we take away from this world which rests on the basis of our natural world. That we take away. And this it is which must be consistently felt by a human soul felt by a human soul that is really sensitive to nature: that there, in the background of Nature, lies something which she must continually submit to; namely, that man contests Nature, who will give all to all, and says: ‘This belongs to me!’ And now consider with full human feeling this gainsaying of Nature, who gives all to all: This I will have for myself, and that I will have it for myself is induced by the fact that my senses find it good or less good for me, sympathetic or antipathetic. Here one can enter deeply with one's own soul into natural existence, can feel with Nature how something is taken away from her. And it is taken away because the human being, under the impression of his senses, forms the thought that he wants to have for himself what Nature wishes to give to all.

I once felt in my soul, my dear friends, suddenly and with special profoundness, how one can experience this whole relationship that I have just sought to characterize. How one can learn to feel with Nature when she says: Protect myself as I will, world evolution has gone so far that the human being declares that my things are his things. Yes, in a certain moment years ago, I felt that experience most warmly and intimately in my soul. It was years ago in a society where there was to be a programme of Recitations. And as it happens from time to time, especially in Recitation programmes, that the persons concerned are prevented from coming and excuse themselves; so it happened here too, a lady reciter sent her excuses and at once a substitute had been found. And now one may think as one will about the value of the declamation that followed and about the substitute—I will not go into that now,—but he was of a quite particular kind, namely, there was found ready to recite the programme in place of the actress who had fallen out, one of the purest, noblest Catholic priests that I have ever come to know in the world. And one had then, or could have, a quite specially significant experience, which in effect condensed for me into what I just now expressed to you.

For this grave and earnest priest—with all that Catholicism brings with it for the really true and upright priest—had according to the programme to recite the ‘Heidenröslein’ of Goethe. And in this recitation one could really experience something, for the man was not only a priest in the ordinary sense, but he, was so learned and so purely given up to spiritual studies, that many said: ‘This man (I will not mention his name) knows the whole world ... and in addition, three villages ...’ for they found him so wise and experienced in things one can know. Now although the recitation was not particularly good, there actually lay in the whole mode and manner in which he gave the ‘Heidenröslein,’ something immensely significant, since one could feel that his whole perception of the world was derived, one might say, from a perception that had been turned away from everything of a sense nature. One could feel how, precisely through the fact that a priest came forward instead of an actress, the whole cosmic power, the immense cosmic power and fineness that lies in this unique poem ‘Das Heidenröslein’ (see end of lecture for poem and translation) came into the recitation. This poem has, indeed, what one might call a prelude; it is an old folksong. And I have already said that men have ever the longing to experience what lives cosmically in the subsoil of existence. And precisely in this poem ‘Das Heidenr&öslein’ there enters something of this quite grandly sublime cosmic subsoil in infinitely simple images. Therefore one must count ‘Das Heidenröslein’ among the very finest pearls of poetry that ever have been given to the world. Years ago I have also heard of people who have attributed something or other, I know not what, of everyday human, all-too-human, connexions to ‘Das Heidenröslein’; that merely comes from a perverted condition of mind. If people can do that—interpret anything which is not quite pure into the ‘Heidenröslein,’ this appertains to a mind that from its sense-exhalations likes continually to revel in all sorts of ‘sacred love.’ One can indeed revel continuously in ‘sacred love’ from sensations of sense-exhalations but that which underlies as cosmic foundations such a poem as ‘Das Heidenröslein’ can only be felt with pure, with chaste heart, and every misconstruction would show a complete desolation and emptiness of mind.

For let us take the wonderful thing which this ‘Heidenröslein’ has actually become as it has been given us by Goethe, and through the fact that the folk song passed over into the youthful lyric depths of his art. Something quite remarkable it has become: in every line always the very thing that ought to be there! Consider for a moment that one felt what lies in the activity of sense-perceptions and how they have developed throughout cosmic evolution ... and that one wished to describe this. How could one do it better than by taking the red in an object, eliminating the space-boundary and letting echo: ‘Röslein, Röslein, Röslein rot’ ... ‘rot’ (red) echoing in ‘Röslein,Röslein,Röslein rot.’ Immediately there confronts us the whole mystery as it is set before us out of the cosmos. The sense-world stands there: ‘Röslein,Röslein,Röslein rot,’ in the continuous ‘Röslein,Röslein,Röslein rot.’ Now in the first line we are shown at once that we are concerned with this mystery—this being able to look out from the senses,’sah ein Knab' ein Röslein stehn, Röslein auf der Heiden.’ Now already in the next line in a wonderful enhancement, which is rarely so beautiful in poetry, a nuance is brought out that now the little red rose begins to become sympathetic—‘War so Jung undmorgenschön’ ... it thus already becomes something which warrants sympathy with what is revealed from the senses. So the next line is inserted with precisely what belongs to it: ‘lief er schnell, es nah zu sehn’: there you have the whole correspondence of the senses with what is presented to them: he runs to see it close to! And now the next line, again an enhancement, but this time in himself; to begin with, the intensification was outside,—‘Röslein auf der Heiden,’—simply the object; then ‘was so young and morning-fair,’ the enhancement outside, and in him ‘ran he fast, it near to see’ ... inasmuch as he ran fast to see it near, ‘Sah's mit vielen Freuden’ (saw it with much joy). You see how the outer corresponds with the inner. Now comes the refrain, ‘Röslein, Röslein, Röslein rot, Röslein auf der Heiden,’ in order to show us quite particularly how the correspondence is between him and that which appears outside as the object ‘red.’ And the mysterious connection with possession: ‘Knabe sprach: ich breche dich.’ He wants to possess it, he wants to pluck the little rose, he wants to take it home with him. There is nothing else in it, but what is in it is of wonderful cosmic depth.‘Knabe sprach: ich breche dich, Röslein auf der Heiden. Röslein sprach: ich steche dich ...’We can see in this sentence, ‘ich steche dich’ (I prick thee) the whole mystery of Nature, who wants to protect herself from man's assertion: ‘I will take thy things home.’ She, Nature, would like to do with all her objects as she would have done with the little rose ‘ leave it for all to see who pass by. For in this ‘Röslein sprach: ich steche dich’ is indeed uniquely contained what I have described as a feeling that shares in the tragedy of Nature. ‘bass du ewig denkst an mich’ (that thou must think of me eternally); he must think of Nature forever, for he transforms her permanence into something fleeting, he brings the possession-relation into what has first arisen in space and time. The human being must atone for his having come out of permanence and must therefore at least think of it eternally, it must be perpetuated, made eternal; the untruth must not persist that it is not perpetuated. Then again: ‘und ich will's nicht leiden’ (and I will not suffer it). The little rose simply stands as the representative of the whole of Nature—every natural object actually says this when one wants to possess it. And again, so that attention may be fully fixed on the real subject, ‘Röslein, Röslein, Röslein rot, Röslein auf der Heiden...’ And the next verse again shows a wonderful enhancement: he will not let himself be held back—‘und der wilde Knabe brach's Röslein auf der Heiden’—thus he nevertheless determines to possess it! ‘Röslein wehrte sich und stack’ ’¦ Again as the representative of the whole of Nature. ‘Half ihm dock kein Weh und Ach’—this is the general experience of Nature, and we feel that tragedy which expresses itself like a mood in Nature when man wishes to possess her: ‘Musst' es eben leiden’ (she must after all permit, suffer it.) Infinitely profound are these words ‘musst' es eben leiden!’

But this microcosmic mystery has in fact a macro-cosmic counterpart, and if one now leaves the microcosm for the macrocosm one may say—who then in the macrocosm is the wild boy who plucks the little rose on the heath? It is the sunbeam, which separated from the earth with the Sun and which now falls on earth from outside. It actually calls forth on the one hand the little rose on the heath, but then when it sees it, when it is there, quickly gathers it again, makes it wither and fade.

Thus it is in nature everywhere. Nature still gives us a memory of the ‘Musst’ es eben leiden’: next to the rose the thorns, the shrivelled thorns which are a token that Nature nevertheless remembers how the sunbeam takes from her what she possesses. But when we do not merely observe as the materialist does, but include the whole cosmic feeling, the thorn near the rose is also the expression of the grief of nature in contrast to Nature's great joy; the jubilation of nature when the rosebush stands there with all its roses, the grief when the wild boy, the sun-ray comes and makes the roses wither. That is the Goethe-poem in the macrocosm: and one can only say: if anything is fitted to stimulate esoteric feelings, it is such poems, where there is no need to think and attribute all sorts of dry allegories to them, but where one only needs to remember a great truth:—when the true poet goes beyond nature it is because he seeks to put into words what can be felt behind the surface of facts, and beyond space and time.

And when a poet produces something in such simple incidents as a boy's plucking a rose on the heath, which yet speaks so deeply to our hearts, it is because this heart of ours received its rudiments when we ourselves were not yet united with the earth, when we were still united with the ancient Sun existence—and were able to feel with the whole world. Although through the Luciferic-Ahrimanic illusion we now ascribe our feelings to ourselves as I have shown, yet all the same they arise out of the cosmos, and on this rests the fact that we can so inwardly accompany the true poet although he describes the simplest incident of the plucking of a rose. For into what arises from the human soul in the simplest events, the whole cosmos is placed. And we need not make assertions and think it out, but we feel it, when we let such a marvellously delicate poem as ‘Das Heidenrösslein’ work upon us. We feel that the whole world is secreted in it, world mysteries are laid within it,—so that the secrets of art too gradually reveal themselves to us. They unfold as we ascend from the perception and experiencing of objects in a purely external way to an inward perception, as we ascend from microcosmos to macrocosmos and seek gradually to learn the hidden but active mysteries in our souls.Das Heidenröslein—1 ‘rosebud’ is not strictly ‘Röslein,’ but is used for the sake of the metre. (Translator)

| The Little Rose on the Heath | Das Heidenröslein |

|---|---|

Saw a boy a rosebud there, Boy declared: I'm picking thee, And the wild young boy did pick |

Sah ein Knab' ein Röslein stehn, Knabe sprach: ich breche dich, Und der wilde Knabe brach's |

Zwölfter Vortrag

Heute möchte ich Verschiedenes zusammenstellen, das uns die Möglichkeit bieten wird, morgen auf einiges Bedeutungsvolle einzugehen, das wir in unserm jetzigen Zusammenhang besprechen wollen.

Nehmen wir einmal an, hier wäre etwa die Oberfläche der Erde, ein Stück Acker oder irgendwie ein Stück Wiese, oder was es immer ist (siehe Zeichnung), und in dieser Wiese wurzelten Pflanzen, irgendwelche Pflanzen, und hier sei etwa ein Wurm oder irgendein kleines Tier, das eben da unter der Erde lebt und wühlt, und das seinen Aufenthalt so unter der Erde hat, daß es niemals über die Erde hinaufkommt, also immer innerhalb der Erde lebt. Diese, sagen wir, Made, Raupe, oder was es sonst ist, die kriecht also da drinnen herum und lernt bei ihrem Herumkriechen die Wurzeln dieser Pflanzen kennen. Selbstverständlich, da dieses Tier niemals über die Oberfläche der Erde herauskommt, lernt es immer nur kennen die Wurzeln der Pflanzen, nichts anderes, kriecht herum und lernt nur die Wurzeln der Pflanzen kennen. Und dasjenige, was geschehen wird, nicht wahr, das ist ja das Folgende.

Es werden - wenn es gerade die richtige Zeit ist, in der diese Raupe da herumkriecht - da droben in den Pflanzen, überhaupt in den ganzen Pflanzen, Vorgänge vor sich gehen, die abhängig sind davon, daß die Sonne scheint, daß die Sonne eine gewisse Wärme ausbreitet. Diese Vorgänge, die da mit den Pflanzen vorgehen, die werden selbstverständlich auch bewirken, daß in den Wurzeln drinnen Veränderungen vor sich gehen. Wenn die Pflanze oben anfängt, frische Triebe zu bekommen, anfängt, Blüten zu tragen, so gehen unten in den Wurzeln auch Veränderungen vor sich, selbstverständlich. Es werden alle Vorgänge in den Wurzeln veranlaßt, anders vor sich zu gehen, wenn da oben irgendwie etwas vor sich geht. Wir können also sagen: Wenn da dieser Wurm unten herumkriecht, so geschieht mittlerweile das, daß da oben durch dasjenige, was dieSonne bewirkt, hervorgeholt werden Triebe, Blätter, Früchte; und dann werden dadurch auch Vorgänge bewirkt in den Wurzeln. Die Raupe kriecht aber nur herum in der Erde; sie kriecht von Wurzel zu Wurzel.

Nun nehmen wir einmal an - hypothetisch können wir das ja annehmen -, diese Raupe oder Made sei ein Wurm- oder ein Raupenphilosoph und bilde sich eine Weltanschauung. Also sie kriecht herum da unten unter der Erde und bildet sich eine Weltanschauung. In dem Bilde, das sie sich da als Weltanschauung zurechtmacht, kann selbstverständlich niemals das eine Rolle spielen, was da durch den Einfluß der Sonne kommt und die Triebe hervorlockt; denn davon kann ja die Raupe nichts wissen; sie kriecht herum, diese Raupe, dieser Wurm, und studiert die Veränderungen an den Wurzeln, und merkt ganz gut, daß da etwas vor sich geht, daß die Wurzeln anders werden, und auch in dem umliegenden Erdreich etwas vor sich geht. Und dieser Wurm drückt jetzt alles aus in seiner Weltanschauung, was er weiß. Das drückt er alles aus, aber es kommt niemals in dem Weltbild, das sich dieser Wurm macht, davon etwas vor, daß die Sonne hervorkommt, die Pflanzen hervorkommen. Das ist ja ganz selbstverständlich. Das heißt, es entsteht in diesem Wurmphilosophen eine Weltanschauung, welche ein entsprechendes Bild geben wird über den Zusammenhang der Tatsachen, ob da unten die Erde feuchter wird, wärmer wird und so weiter. Er weiß zwar nicht, der Wurm, woher diese Wärme kommt; daß es wärmer wird, daß in den Wurzeln allerlei Vorgänge vor sich gehen, das alles faßt er zusammen.

Und nehmen wir nun an, der Wurm wäre nicht ein gewöhnlicher Wurmphilosoph, sondern er wäre sogar inspiriert von irgendeinem modernen Philosophen mit der heute ja so gangbaren Anschauung, daß alles zusammenhängt nach Ursache und Wirkung, alles der Kausalität unterstellt ist, wie man das wissenschaftlich philosophisch-technisch ausdrückt: Da wird dieser Wurm da unten herumkriechen und wird das eine die Ursache nennen, das andere die Wirkung, und wird also sagen: Nun, die Erde wird von oben herunter etwas wärmer; das bewirkt, daß die Wurzeln sich verändern. - Er wird dann die weiteren Vorgänge in den Wurzeln darstellen, und es wird ein zusammenhängendes Bild entstehen, welches alle die Vorgänge unter der Erde nach Ursache und Wirkung gliedert. Aber nichts wird darin stehen davon, daß die Sonne scheint und die Pflanzen herauslockt, und damit die Vorgänge in den Wurzeln sich ändern. Aber das Weltbild dieses Wurmphilosophen wird ein ganz zusammenhängendes sein. Es wird ein richtiges Kausalitätsbild sein können; nirgends wird etwas in der Kette von Ursache und Wirkung zu fehlen brauchen.

Nun sehen Sie, es ist Ihnen ganz klar, glaube ich, daß diese Wurmphilosophie ein einheitliches Weltbild hat, das ganz richtig ist, aber daß ihm eben dasjenige fehlt, was wir Menschen als das Wichtigste anschauen müssen, nämlich daß die Sonne mit ihrer Wärme, ihrem Licht kommt, und das bewirkt, was der Wurm da unten beobachtet. Seine ganze Kausalität hängt eben nur davon ab, daß er nicht über die Oberfläche der Erde heraufkommt und daher nicht wissen kann, was über der Erde vor sich geht.

Sehen Sie, solche Würmer sind im Grunde genommen doch die Menschen, welche an der Kette der Kausalität, der Ursachen und Wirkungen, heute Philosophien machen. Das Bild ist ein vollkommen zutreffendes: die Menschen untersuchen das, was ihre Sinne sehen; sie gehen herum unter den Dingen und bewegen sich eben in dem, was ja jetzt nicht räumlich nach oben abgeschlossen ist, aber was durch die Sinnesanschauung begrenzt ist, und nehmen einfach das Geistige nicht wahr, das sich um sie ausbreitet, und das in Wirklichkeit die Vorgänge bewirkt, die sie der Kette von Ursache und Wirkung zuschreiben. Es ist wirklich vergleichsweise genau dasselbe.

Wenn der Wurm nun plötzlich herausgezogen würde, die Sonne sehen könnte, und merken könnte, daß alles, was er da unten ausgeklügelt hat, im Grunde genommen nicht die Ursache, sondern die Wirkung von dem ist, was die andern Wesen da oben sehen und was da als Sonne, Licht, Wärme, Luft, Wasser existiert: er müßte wahrnehmen, daß sein Weltbild einfach nicht gilt; er müßte erkennen, daß oben die Ursache für dasjenige ist, was er selber unten wahrgenommen hat. Gerade dasselbe ist es, wenn man sich erhebt von der gewöhnlichen Menschenanschauung zu Geistesanschauungen; denn man merkt, wie da dasjenige in die Sinnenwelt hereinkommt, was eben unter gewöhnlichen Umständen nicht wahrgenommen werden kann.

Sie sehen daraus auch, daß die viel gerühmte innere Geschlossenheit einer Weltanschauung nichts bedeutet für deren Richtigkeit. Derjenige, der sich so richtig mit ganzem Herzen und mit ganzer Seele in dieses Wurmdasein hinein zu versetzen vermag, der kann die Versicherung abgeben, daß nichts irgendwie in diesen Wurmanschauungen auf einem logischen Fehler beruhen muß. Da kann alles logisch in sich richtig und geschlossen sein, da braucht gar kein logischer Fehler drinnen zu sein, das kann eine vollständig innerlich haltbare Weltanschauung sein. Daraus aber ersehen Sie, daß es gar nicht darauf ankommt, ob man irgend etwas eben mit den Mitteln der Welt, in der man ist, beweisen kann oder nicht. Ich habe das öfter von anderen Gesichtspunkten aus erwähnt. Es kann sich da nicht darum handeln, ob man etwas mit den Mitteln der Welt, innerhalb welcher man sich aufhält, beweisen kann oder nicht. Weltanschauungen können noch so schöne Beweise für sich haben, sie bleiben eben doch, sagen wir, Wurmanschauungen.

Wenn man dies wirklich auf seine Seele wirken läßt, so merkt man, was dahinter sehr bedeutsam steht: man merkt, wie, wenn man nur einmal ahnt, daß es noch andere Welten gibt, eine Art allgemeiner Weltenverpflichtung entsteht, sich einzulassen auf diese anderen Welten. Denn man braucht ja eben, wenn man eine noch so geschlossene Weltanschauung hat, über die wirklichen Vorgänge mit dieser geschlossenen Weltanschauung gar nichts zu wissen. Und das ist esin der Tat, was man zumeist bei den Philosophien der Gegenwart und der unmittelbaren Vergangenheit hat: sie sind Wurmanschauungen. Sie sind wirklich außerordentlich logisch in sich geschlossen, sie haben für die Welten, in denen man sich aufhält, außerordentlich viel für sich; aber sie sind eben aufgebaut mit den Mitteln der Welten, in denen man sich aufhält.

Sie sehen daraus, daß Sie nichts geben können auf sogenannte Beweise, sondern daß Sie erst darauf sehen müssen, woher diese Beweise genommen sind. Für unsere Gegenwart handelt es sich wirklich darum, ein Gefühl zu bekommen für das Sich-Aufgehen-Lassen von anderen Welten, für das Offenbar-Werden-Lassen von anderen Welten. Gewiß, schwierig ist dieses. Denn, nicht wahr, des Wurmes Bedingungen sind, unter der Erde zu wohnen; so wird er es oben nicht gut aushalten, wenn er heraufgedrängt wird; er müßte sich erst an die neuen Bedingungen anpassen. So ist es natürlich auch schwierig für den Menschen, wenn er sich als Seele abtrennt von seinem Leiblichen, sich anzupassen an die neuen Bedingungen.

Nun können Sie eine Frage aufwerfen, meine lieben Freunde. Sie können sagen: Na schön, du hast uns jetzt die Welt, in der der Mensch mit seinen Sinnen ist, verglichen mit dem, was da unter der Erde ist. Zeige uns irgend etwas, was unsere gewöhnlichen Sinnesanschauungen eben in irgendeiner Weise begrenzt, richtig begrenzt. Darauf kann man auch strenge hinweisen. Dadurch daß die Aufeinanderfolge des Werdens von Saturn, Sonne, Mond vor sich gegangen ist, ist eigentlich erst eingetreten, und zwar während des Mondendaseins, die Zeit in die Anschauungen, die der Mensch hat, und während des Erdendaseins eigentlich erst der Raum. Wenn wir von Saturn, Sonne und Mond sprechen, und dabei räumliche Vorstellungen zu Hilfe nehmen, so reden wir wirklich nur bildlich, nur in Imaginationen, und wir müssen uns durchaus bewußt sein, daß, wenn wir von diesen drei Welten in Raumesvorstellungen sprechen, diese Raumesvorstellungen so viel zu tun haben mit dem, was da früher sich vollzogen hat, sagen wir, wie die Formen unserer Buchstaben mit dem Sinn des Wortes. Wir dürfen nicht die heutigen Vorstellungen als solche nehmen, sondern müssen sie als Zeichen, als Bilder nehmen für dasjenige, was daraus folgt. Denn der Raum hat nur eine Bedeutung für das, was sich innerhalb des Erdendaseins entwickelt, und die Zeit hat eigentlich erst eine Bedeutung seit der Loslösung des alten Mondes von der Sonne. Das ist der strikte Punkt, in welchem sich ablöst der Mond, der alte, von der Sonne. Da erst ist es möglich, von solchen in der Zeit verlaufenden Vorgängen zu sprechen, wie wir heute davon sprechen.

Damit aber, daß wir unsere geistigen Vorstellungen im Raum und in der Zeit haben - denn nicht wahr, alles Äußerliche, was wir vorstellen, ist im Raum, alles Innerliche, was wir zum Bewußtsein bringen, innerlich aufleben lassen, verläuft in der Zeit -, dadurch sind wir gewissermaßen zwischen Geburt und Tod, aber eben nur zwischen Geburt und Tod, in Raum und Zeit eingeschlossen, wie der Wurm da unten in seiner Erde wohnt. Raum und Zeit grenzen uns ebenso ein, wie diesen Wurm die Erdensubstanz eingrenzt. Wir sind Würmer des Raumes und Würmer der Zeit; wir sind es wirklich in einem ganz hohen, in einem ganz richtigen Sinne. Denn wir bewegen uns, so wie wir sind als inkarnierte Menschen, im Raume, schauen die Dinge im Raume an; und dasjenige, was anschaut, ist unsere Seele, die selber in der Zeit lebt. Zwischen Geburt und Tod geht Zeit vor sich, vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen geht Zeit vor sich. Der Vergleich ist gar nicht einmal ein so schlechter, wenn man auf die Realität selbst schaut. Insofern unsere Seele im Leibe eingeschlossen ist, ist sie mit ihrem Bilden eines Weltbildes so richtig ein Wurm, der im Raume kriecht und der, wenn er zu den Realitäten kommen will, aus dem Raume heraus muß; dann sich auch daran ge- : wöhnen muß, nicht mehr bloß unter den Bedingungen der Zeit die Dinge anzuschauen, sondern unter solchen Bedingungen, für die das, was in der Zeit verläuft, eben nur ein äußeres Zeichen ist, gleichsam ein Buchstabe.

Nun will ich, nachdem ich auf dieses aufmerksam gemacht habe, diese Betrachtungen überleiten auf das geistig-seelische Gebiet. Wie wirklich in dem Keime schon die folgende Pflanze enthalten ist, so war natürlich dasjenige, was sich heute auf Erden in Raum- und Zeitwahrnehmungen entwickelt, für den Menschen entwickelt, im Keim schon enthalten in den früheren Zuständen. Ich habe darauf schon in einem Zusammenhange hier aufmerksam gemacht, daß in Saturn, Sonne und Mond eben schon Keime enthalten sind. So daß, wenn wir hier auf der Erde dem, was um uns herum geschieht, einen gewissen Sinn beilegen, wir diesen Sinn gewissermaßen in den alten Vorgängen des Mondes, der Sonne, des Saturns schon drinnen sehen müssen. Mit der Bildung der Zeit und der Bildung des Raumes muß sich in irgendeiner Weise der Sinn des Lebens auf unserer Erde zubereitet haben. Es muß gleichsam das Bilden von Zeit und Raum so geschehen sein, daß dann wie eine Art von Blüte dazu gekommen ist der Sinn des Erdenlebens.

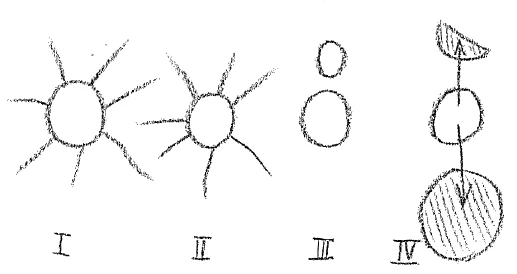

Nun können wir uns ja von diesen Vorgängen auf Saturn, Sonne und Mond folgendes Bild machen. Wir können sagen: Wir haben ein altes Saturndasein (I), das ist umgeben von dem Kosmos; wir haben ein altes Sonnendasein (II), wiederum umgeben von dem Kosmos; wir haben ein altes Mondendasein (III), aber aus dem Mondendasein heraus sich schon entwickelnd eine Art Nebenplanet - das brauchen Sie ja nur in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft» nachzulesen -; und wir haben dann das Erdendasein (IV) so kennen gelernt, daß sich die Erde abtrennt vom Sonnendasein, und wiederum abtrennt vom Mondendasein.

Wenn ein materialistisch denkender Mensch - ich will das Günstigste für unsere Geisteswissenschaft annehmen - selbst sich überwinden könnte, an diese Vorgänge zu glauben, so würde er aber noch immer den nächsten Schritt zu überwinden haben, der darin besteht, sich zu überzeugen, daß im Grunde genommen die ganzen Vorgänge - Saturnentstehung, Sonnenentwickelung, dann Heranentwickelung zum Mond, Abtrennung des Mondes, Abtrennung von Erde, Sonne und Mond -, daß alle diese Vorgänge eigentlich geschehen, um den Menschen möglich zu machen, so wie er auf der Erde ist. So wie bei einer Pflanze die Vorgänge in den Wurzeln, in den Blättern geschehen, um die Blüte, die Frucht möglich zu machen, so geschehen alle diese Vorgänge, ich möchte sagen, diese makrokosmischen Vorgänge, um unser Leben auf der Erde möglich zu machen; sie geschehen, damit wir auf Erden gerade so leben können, wie wir eben leben. Man könnte auch sagen: Diese Vorgänge sind die Wurzeln unseres Lebens auf Erden; das ist deshalb da, damit wir so, wie wir auf Erden uns entwickeln, uns entwickeln können.

Fassen wir genau ins Auge, daß wir es zu tun haben mit der Abtrennung der Sonne auf der einen Seite, der Abtrennung des Mondes auf der andern Seite, daß wir es also zu tun haben - damit unsere Erde als Erde zustandekomme - mit Trennungen. Das heißt, wir werden zurückgelassen auf dem Erdenplaneten, und abgetrennt haben sich von uns Sonne und Mond, und wirken nun von außen auf die Erde herein. Das mußte sich so ereignen, sonst könnte sich nichts in uns so entwickeln, wie es sich auf Erden entwickelt. Daß alles sich so entwickelt, wie es sich auf Erden entwickelt, dazu ist nötig, daß einmal in Urzeiten Sonne und Mond mit der Erde verbunden waren, und daß sie sich dann getrennt haben und von außen nun ihre Wirkungen hereinscheinen lassen auf die Erde. Das ist durchaus notwendig.

Nun möchte ich darauf hinweisen, daß unser inneres seelisches Leben ganz bestimmte Konfigurationen angenommen hat dadurch, daß dies geschehen ist. Unter den mannigfaltigsten Begriffen, die wir haben - ich könnte ja viele Begriffe als Beispiel anführen - und die im ganzen Zusammenhang unseres Erdendaseins eine gewisse Rolle spielen, ist auch der Begriff des «Etwas-Besitzens», des «Etwas-Habens», was zusammenhängt damit, daß sich unsere Person mit etwas verbindet, was ebensogut außerhalb der Person ist. Wir sprechen in den seltensten Fällen davon, daß wir unsern Arm oder unsere Nase besitzen, denn nicht wahr, die meisten Menschen empfinden ihren Arm oder ihre Nase so sehr zu sich gehörig, daß sie da nicht von einem Besitz sprechen. Aber dasjenige, was auch getrennt sein könnte, und was dann zu uns gehört, bezeichnen wir lediglich im juristischen Sinne als einen Besitz, als einen richtigen Besitz.

Nun könnte sich in uns das gar nicht bilden, was wir die VorstelJung nennen: etwas von dem besitzen, was da draußen ist -, wenn nicht eingetreten wäre die Trennung desjenigen, was früher zur Erde gehört hat, und das Wiederbezogenwerden von Sonne und Mond zur Erde. Unser Leben noch auf der alten Sonne war ganz anders. Da waren Sonne und Mond eben mit dem, was Vorgänge der Erde waren, als Sonne verbunden; da waren sie mit dem ganzen Menschendasein innig verbunden. Da konnte der Mensch sagen: «Sonnenwirkung in mir», oder «Ich-Sonnenwirkung» - wenn er dazumal schon hätte «Ich» sagen können, die Erzengel konnten es aber - «Ich Sonnenwirkung»; nicht: die Sonne bescheint mich, es kommt das an mich heran, was Sonnenwirkung ist. - Das mußte vor sich gehen, daß abgetrennt wurde dieser Planet oder dieser Fixstern Sonne, damit wir als Erdenmenschen eben diese besondere Konfiguration der Besitzesvorstellung entwickeln konnten.

Nun hängt das noch mit etwas anderem zusammen. Stellen Sie sich vor, noch auf dem alten Sonnendasein sagte der Erzengel: Ich Sonne. - Daß wir etwas sehen, das beruht darauf, daß die Sonnenstrahlen oder Lichtstrahlen auf den Gegenstand scheinen und zu uns zurückgeworfen werden. Würde die Sonne mitten in der Erde scheinen, so würden wir nichts sehen von den Gegenständen, die auf der Erde sind. Wir würden dann zwar sagen: Ich Sonne, Ich Licht, aber wir würden nicht die einzelnen Gegenstände unterscheiden, wir würden nicht die Gegenstände sehen. Also, Sie sehen, noch weiteres hängt damit zusammen. Während die Erde sich entwickelt von Saturn, Sonne, Mond zur Erde herüber, entsteht erst durch die Konstellation im Makrokosmos die Möglichkeit, die Gegenstände so zu sehen und wahrzunehmen, wie wir sie jetzt wahrnehmen. Solche Wahrnehmungen, die gab es natürlich während des Sonnendaseins nicht; wenn auch die ersten Anlagen unserer Sinnesorgane auf dem alten Saturn schon vorbereitet worden sind, aufgeschlossen wurden sie erst auf der Erde, erst da wurden sie zu Wahrnehmungsorganen gemacht. Diese Anlagen auf dem alten Saturn, das waren, ich möchte sagen, blinde und unwahrnehmende Sinnesorgane. Aufgeschlossen wurden diese Sinnesorgane erst dadurch, daß die Sonne ausschied, und der Mond aus der Erde herausgegangen ist.

Damit sehen Sie, daß zwei Vorgänge parallel gehen: Wir bilden unsere Sinneswahrnehmungen und sehen draußen eine Welt; und damit parallel gehend entwickeln wir die Besitzesvorstellung. Denn wie kommen wir zu der Besitzesvorstellung? Sie könnten während des alten Sonnendaseins sich nicht denken, daß irgendein Erzengel etwas besitzen will. Er sieht ja auf nichts; er ist ja alles. Wären alle Gegenstände und Wesen der Erde so, würden sie niemals den Drang bekommen, etwas besitzen zu wollen. Mit der Entwickelung der Sinne entwickelt sich erst die Besitzesvorstellung; die Besitzesvorstellung ist nicht trennbar von der Entwickelung der Sinne; diese beiden Dinge gehen parallel. Die Sinne waren auf der einen Seite, und so etwas wie die Besitzesvorstellung auf der andern Seite. Es können auch andere Vorstellungen genommen werden.

Und wenn wir in umfassenderem Sinne bedenken dasjenige, was in der religiösen Urkunde, der Bibel, steht - denn hinter solchen Dingen, wie sie in den religiösen Urkunden stehen, liegt immer noch sehr vieles verborgen -, so können wir sagen: Das, was im Anfang der Bibel steht von der luziferischen Verführung, hängt damit zusammen, daß Luzifer dem Menschen verheißen hat seine Sinnesentwickelung: «Die Augen werden euch aufgeschlossen», -— damit meint er, überhaupt alle Sinne werden aufgeschlossen. Das Aufschließen der Augen steht nur für die Sinne im allgemeinen. Damit hat er die Seele hingelenkt auf die äußeren Dinge und damit zu gleicher Zeit die Besitzesvorstellung hervorgerufen. Wollten wir das etwas ausführlicher sagen, was da Luzifer dem Weibe verheißen hart, so müßten wir sagen: «Ihr werdet Gott-gleich sein» heißt soviel wie: Eure Sinne werden aufgeschlossen sein. Ihr werdet unterscheiden zwischen demjenigen, was euch gefällt und was nicht gefällt, was ihr Gut, was ihr Böse nennt, und ihr werdet das alles besitzen wollen, was euch gefällt, was ihr gut nennt. - Das müßte man alles verbinden mit dieser luziferischen Verheißung.

Nun müssen wir allerdings, wenn wir solch eine Vorstellung, wie ich sie eben jetzt entwickelt habe, so recht erfassen wollen, uns auf etwas besinnen. Da ist einer der Punkte, wo es notwendig ist, daß man im geisteswissenschaftlichen Vortrag appelliert an die Selbstbesinnung jedes Einzelnen, der die Dinge aufnehmen will. Man muß sich auf etwas besinnen: Indem ich Ihnen dieses entwickelt habe von der Entstehung der Sinne, von dem Wahrnehmen der Dinge und von der Entwickelung der Besitzesvorstellung, haben wir nicht nötig gehabt, irgendwo eine Raumes- oder eine Zeitvorstellung einzufügen. Gewiß, wenn sich der Mensch diese Dinge versinnlichen will, wie ich es auch getan habe, indem ich sie auf die Tafel gezeichnet habe, so nimmt man Raum- und Zeitvorstellungen zu Hilfe. Aber um zu begreifen, was es heißt: die Sinne werden aufgeschlossen -, und um zu begreifen, was es heißt: die Besitzesvorstellung entwickelt sich -, dazu braucht man nicht Raum- und Zeitvorstellungen. Diese Dinge sind unabhängig von Raum und Zeit. Sie haben nicht nötig daran zu denken, daß ich raumgemäß von irgendeiner Sache entfernt bin, wenn ich sie besitzen will; auch an die Zeitvorgänge brauchen Sie nicht zu appellieren. Wie gesagt, hier muß man an die Selbstbesinnung appellieren. Denn es kann jeder einwenden: ich kann’s nicht -, aber wenn er sich genügend zusammennimmt, so kann er solche Dinge sich vorstellen: daß er keine Raum- und Zeitvorstellung zu Hilfe nimmt. Ja, noch etwas anderes ist richtig: wenn Sie versuchen, solche Vorstellungen sich klar zum Bewußtsein zu bringen, also darüber zu meditieren, wie ich jetzt gleichsam mit Ihnen meditiert habe, so kommen Sie allmählich hinaus über das Raumes- und Zeitvorstellen. Sie kommen hinaus in eine Welt, wo Raum und Zeit in Ihren Erlebnissen wirklich nicht mehr die eminente Rolle spielen, die sie im Alltagsleben spielen.

Nun besteht in der Menschheitsentwickelung eine eigentümliche Sehnsucht. Überall, wo wir das Menschengeschlecht in seinem innersten Streben in der Geschichte antreffen, treffen wir eine bestimmte Sehnsucht schon an; und das ist die Sehnsucht, auch Vorstellungen zu haben, die von Raum und Zeit unabhängig sind, die nichts zu tun haben mit Raum und Zeit. Geschichtliche Vorgänge werden in Mythen verwandelt, oder es wird in dem geschichtlichen Vorgang auf das hineingedeutet, was das Geistige ist, um möglich zu machen, daß man auf dem Hintergrunde von geschichtlichen Vorgängen Mythen sich gestalten sieht. Und je weiter wir in der Geschichte zurückblicken, desto mehr finden wir als geschichtliche Überlieferungen die geschichtlichen Tatsachen in den Mythus gehüllt. Denken Sie sich, wie schon in bezug auf die ältere griechische Geschichte alles in den Mythus gehüllt ist; auch viel von der älteren mitteleuropäischen Geschichte ist in den Mythus gehüllt. Je weiter man zurückgeht, desto mehr wird man entfernt von dem äußeren, rein sinnlichen Fühlen der Tatsachen, und es taucht ein die Darstellung in ein sinnvolles Erfassen. Wenn Sie Mythen studieren, da werden Sie ganz deutlich sehen, daé man bei der Entstehung der Mythen, sich aus Raum und Zeit herausarbeiten will. Nicht nur, daß schon, ich möchte sagen, die elementarsten Mythen, die Märchen oftmals darstellen, wie irgendein menschliches Wesen - ich erinnere nur an Dornröschen - aus der Zeit herausgeht und ins Zeitlose hineingeht, sondern wenn Sie bei den Mythen nachschauen, so werden Sie sehen: Sie wissen nicht recht, welche geschichtlichen Tatsachen gemeint sind. Es kann etwas, was Jahrhundertelang früher liegt, als etwas Späteres erzählt werden. Manchmal werden auch Tatsachen, die in der historischen Entwickelung Jahrhunderte auseinanderliegen, zusammengeschmiedet im Mythus. Der Mythus sucht über Raum und Zeit sich zu erheben. Das heißt, es lebt im Menschendasein die Sehnsucht, sich über diese Alltäglichkeit hinaus, die uns anweist, im Raum und in der Zeit zu denken und vorzustellen, auch sich hineinzuleben in solche Vorstellungen, welche raumlos und zeitlos diejenigen Realitäten darstellen, die jenseits des Nebeneinander und des Hintereinander unseres Raumes- und Zeitendaseins als die ewigen Dinge walten, oder wenn sie sich einmal gebildet haben, als die ewigen Dinge bleiben.

Wenn Sie das, was ich jetzt gesagt habe, zusammennehmen mit etwas, was ich das letzte Mal gesagt habe, so wird sich Ihnen eine schöne Verbindung ergeben. Ich habe gesagt, wir sollten sehen: wenn nicht ein Luziferisches in uns wirkte, wäre unsere Vorstellungswelt eigentlich im alten Monde drinnen. — Daraus geht aber nun hervor, daß eigentlich dieser alte Mond noch da ist, geblieben ist, und daß nur Luzifer uns vorzaubert, unsere Vorstellung sei jetzt in uns drinnen. Also die Zeit wird da zu einem Mittel des Truges, der Täuschung für Luzifer. Das alte Mondendasein ist dauernd, und so sind auch die Dinge dauernd, die entstehen. Unsere Besitzesvorstellungen sind etwas Dauerndes, das heißt, dasjenige, was der Erdenmensch durch seine Besitzesvorstellung als soziale Erdenordnung entwickelt, das bleibt, das wird auch noch bestehen, wenn der Jupiter- und der Venuszustand einmal da sind. Und wenn dann nicht entsprechende Verführungen als luziferische und ahrimanische Verführungen kommen, so wird man sehen, wie auf Erden durch den Besitzesbegriff soziale Ordnungen sich gebildet haben. Die werden dann etwas wie physische Ordnungen darstellen. Denn das gehört zum Maja-Sein, zu der Täuschung, daß die Dinge vorübergehen; in Wirklichkeit sind sie dauernd, in Wirklichkeit bestehen sie. Und schon, wenn man richtig das Dasein versteht, findet man hinter dem eigentlich Vergangenen das Dauernde. Sie können es gleichsam erfassen in dem, was ich jetzt erzählt habe.

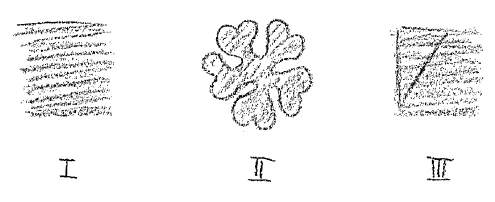

Nun aber blicken wir, wenn wir das so recht erfassen, was ich gesagt habe, eigentlich in tief bedeutsame Untergründe unseres ganzen Erdendaseins hinein. Sehen wir denn nicht, wie unter dem zeitlichräumlichen Erdendasein das ewig dauernde Erdendasein oder Dasein überhaupt sich förmlich ausbreitet? Wie einen Schleier haben wir das Zeitlich-Räumliche oben, und darunter die Dauerverhältnisse, die Verhältnisse der Dauer. Und nun kommt unsere Anschauung, wenn sie im Raum und der Zeit verläuft, unsere Anschauung, die in Raum und Zeit lebt. Denken Sie nur einmal, wie man das, ich möchte sagen, konkret im einzelnen sich vorstellen kann. Denken Sie einmal bloß - heute fassen das die Menschen gar nicht mehr ordentlich -, denken Sie sich irgendwo, irgendwie «rot». Um «rot» zu denken, brauchen Sie keinen Raum, brauchen Sie keine Zeit; Sie können sich «rot» irgendwie denken; es braucht nicht im Raum, nicht in der Zeit zu sein, weil es bloß als Eigenschaft gedacht ist (D. Es ist dies schwer für den Menschen, weil er das Rot durchaus räumlich begrenzen will. So schwer war es nicht auf dem alten Mond für die Engel, denn die hatten keine Sehnsucht, das Rot auf einzelne Gegenstände zu verteilen. Die Zeit hatten sie schon, aber räumlich stellten sie nicht vor. Zeitlich stellten sie vor; daher empfanden sie «rot» oder «grün» oder irgendeine Farbe als fließenden Strom. Wenn Sie sich das lebhaft vorstellen: Blau als fließenden Strom, Rot als fließenden Strom, wenn Sie auch die anderen Sinnesempfindungen strömend vorstellen, aber nur zeitlich, ohne daß eine richtige Raumesvorstellung sich hineinmengt, so können wir sagen: Da kann man empfinden beim Übergang vom Monden- zum Erdendasein, wie das bloß Zeitliche hereingespannt wird in das Räumliche. Was macht denn eigentlich das Wesentliche des Erdendaseins aus? Daß so ein Rot abgegrenzt wird und hereingespannt wird. Auf dem Monde wäre es unmöglich gewesen, ein abgegrenztes «Rot» zu sehen: auf der Erde ist es uns möglich, abgegrenztes «Rot» zu sehen (ID). Das aber hängt zusammen, innig zusammen mit der Abtrennung der Sonne von der Erde, und mit dem Hereinfallen des Sonnenstrahls von außen. Schon daß ich sagen kann im wirklichen Sinne: der Sonnenstrahl fällt von außen herein -, schon das weist Sie darauf hin, daß unser jetziges Dasein ohne die Raumesvorstellung nicht zu denken ist. Ja, für dieses unser jetziges Wahrnehmen und Leben bedeutet dieses Außerhalb-Stehen der Sonne etwas Reales.

Nun werden Sie leicht aus dem, was ich vorgebracht habe, entnehmen können, daß wir wirklich sagen könnten: die Farben sind in den Raum hereingespannt, und die anderen Sinneswahrnehmungen auch. «Fließenden Reiz» habe ich in der «Theosophie» dasjenige genannt, was nach dem Tode in dem Menschen lebt, weil er da nicht in den Raum eingespannt ist. Daher sprach ich schon von der ersten Welt, die er durchlebt, als «fließender Reizeswelt». Da sind die Sinneswahrnehmungen nicht in den Raum hereingespannt. Auf der Erde sind sie das. Hier muß der Sonnenstrahl von außen kommen, muß die Sinneswahrnehmungen in den Raum hereinspannen (III). Damit hängt zusammen - wie ich auseinandergesetzt habe -, daß der Mensch Besitzesvorstellungen entwickelt; denn niemals kann der Mensch in einer Welt des fließenden Reizes an Besitz denken; da ist höchstens Zeit vorhanden, und da würde er schon das Vergebliche einsehen, wenn er an Besitz denken wollte. Es wäre da ungefähr so, wie wenn er an den Besitz eines Stücks Wasser denken würde, das im Bach dahinfließt. Diese Vorstellung entsteht also erst, indem die aus der Erde herausgehende Sonne die Sinneswahrnehmungen in den Raum hineinspannt.

Sehen Sie, so etwas, wie ich jetzt auseinandergesetzt habe, muß man in eine Empfindung, in ein Gefühl verwandeln. Man kommt nicht zurecht, wenn man bei einer bloß theoretischen Vorstellung bleibt; man muß sie in ein Gefühl, in eine Empfindung verwandeln, man muß wirklich eine innerlich lebendige Empfindung davon bekommen, wie man als Mensch, als Mikrokosmos, in den Makrokosmos hineingestellt ist, und wie selbst dieses Sich-sehnen, etwas zu besitzen, zusammenhängt mit der ganzen Entwickelung des Makrokosmos, mit dem Hergange, wie sich die sinnliche Anschauung entwickelt hat. Wenn man das so recht fühlt, wenn man beginnt, ich möchte sagen, kosmisch zu fühlen, wenn man beginnt, zu fühlen, wie so etwas, wie die einfache Vorstellung: du möchtest dies besitzen, was du siehst und was dir im Anschauen gefällt -, wie das aus dem Makrokosmos herausgeboren ist: dann bekommt man wirklich erst die recht lebendige Vorstellung, daß zusammenhängt das menschlich Seelische mit dem ganzen Makrokosmos; dann geht einem ein innerlich lebendiges, ein ernst lebendiges Gefühl auf, wie man in dem einzelnen, was man im alltäglichen Leben vorstellt, mit dem Makrokosmos zusammenhängt, und wie eigentlich in allem, was wir so vorstellen, was wir in der Seele erleben, der Makrokosmos in uns lebt. Und in dem Menschen besteht eine fortwährende Sehnsucht, solche wirklich auf dem Grund des Lebens ruhende geheime Zusammenhänge zu empfinden, und die Empfindung auszudrücken. Diese Sehnsucht besteht in den Menschenseelen, in den Menschenherzen.

Und so denken wir uns einmal, es entstünde in einer Menschenseele so recht das Gefühl, so recht das Empfinden, ich will den kosmischen Zusammenhang dieses Einzelseelenerlebnisses ausdrücken: «Da fällt mein Auge auf einen äußeren Gegenstand; ich will ihn besitzen; ich will ihn mir aneignen», dann wird man, ich möchte sagen, die Tragik des Naturdaseins von einer solchen Empfindung aus erfühlen können. Die Tragik des Naturdaseins, sage ich. Wir nehmen ja im Grunde genommen einer ganzen Welt, die bis zum Monde geht, und die ja noch in unserer Welt als Grundlage vorhanden ist, wir nehmen ihr wirklich dasjenige, was wir besitzen wollen. Was wir zu besitzen streben, nehmen wir weg dieser Welt, die auf dem Grund unserer natürlichen Welt ruht. Das nehmen wir von ihr weg. Und das ist es, was die wirklich mit der Natur empfindende Menschenseele fortwährend fühlen muß: daß da auf dem Untergrund der Natur wirklich etwas enthalten ist, was fortwährend dulden muß; daß der Mensch dieser Natur, die allen Alles geben will, widerspricht und sagt: Dies gehört mir. - Und denken Sie sich jetzt hinein in diesen Widerspruch zwischen der Natur, die allen Alles geben will, und dem ganzen menschlichen Fühlen: Dies will ich für mich haben, und daß ich es für mich haben will, ist hervorgerufen dadurch, daß meine Sinne es als für mich gut oder weniger gut, sympathisch oder antipathisch empfinden können. - Da kann man seine eigene Seele hineinvertiefen in das Naturdasein, kann mit der Natur mitfühlen, wie ihr etwas weggenommen wird; schon dadurch weggenommen wird, daß der Mensch den Gedanken faßt, unter dem Eindruck seiner Sinne den Gedanken faßt: er will das haben, was die Natur allen geben will.

Ich habe einmal, ich möchte sagen, ganz besonders gründlich plötzlich in meiner Seele gefühlt, wie man dieses ganze Verhältnis, das ich jetzt zu charakterisieren versuchte, durchempfinden kann, wie man lernen kann mitzufühlen mit der Natur, die da sagt: Ich mag mich wehren, wie ich will, die Weltentwickelung ist soweit gekommen, daß der Mensch erklärt, meine Dinge seien seine Dinge. Ich sage, ich habe das in einem besonderen Augenblicke in der Seele vor Jahren einmal so recht warm und innig auch fühlend empfunden, als einmal in einer Gesellschaft - es war vor vielen Jahren - eine Rezitation gepflegt werden sollte, ein Rezitationsprogramm war. Und wie es ja zuweilen vorkommt, besonders bei Rezitationsprogrammen, daß die betreffenden Persönlichkeiten verhindert sind, absagen lassen, so war es auch hier: eine Rezitatorin mußte absagen lassen. Es mußte also ein Ersatz gefunden werden und er hatte sich auch gefunden. Man mag nun über den Wert der Deklamation, die nun folgte, über diesen Ersatz denken wie man will - darauf will ich jetzt nicht eingehen -, aber der Ersatz war von ganz besonderer Art. Es fand sich nämlich einer der reinsten katholischen, edelsten katholischen Priester, die ich jemals in der Welt kennengelernt habe, bereit, das Programm zu rezitieren, welches die betreffende Schauspielerin wegen ihres Verhindertseins nicht rezitieren konnte. Und man hatte da ein ganz besonders Bedeutsames, man konnte ein besonders bedeutsames Erlebnis haben, das sich für mich verdichtete zu dem, was ich Ihnen eben aussprach.

Denn dieser, wirklich seine Katholizität mit allem, was für den wirklich wahren und aufrichtigen Priester die Katholizität mit sich bringt, ernst nehmende Priester hatte dem Programm gemäß zu rezitieren das «Heidenröslein» von Goethe. Und man konnte an dieser Rezitation wirklich etwas erleben, weil der Mann nicht nur eben ein Priester im gewöhnlichen Sinne war, sondern so gelehrt war und so rein nur hingegeben geistigen Betrachtungen, daß viele sagten: der Betreffende - ich will jetzt seinen Namen nicht nennen - kennt die ganze Welt und außerdem noch drei Dörfer. So weise und erfahren in den Dingen, die man wissen kann, empfand man ihn. Nun war die Rezitation nicht besonders gut, trotzdem aber lag in der Art und Weise, wie er das «Heidenröslein» vorbrachte, etwas so ungeheuer Bedeutsames, weil man fühlen konnte, daß seine Empfindung der Welt aus seinem, ich möchte sagen, allem Sinnlichen abgekehrten Empfinden der Welt her kam; man konnte fühlen, wie gerade durch diesen Vorgang, daß eben ein Priester statt einer Schauspielerin eintrat, die ganze kosmische Gewalt, die ungeheure kosmische Gewalt: dieses einzigartigen Gedichtes das «Heidenröslein» in den Vortrag hereinkam, und die ungeheure Feinheit, die in diesem Gedichte liegt.