The Value of Thinking for Satisfying our Quest for Knowledge

GA 164

18 September 1915, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

The Value of Thinking II

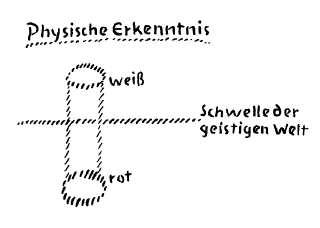

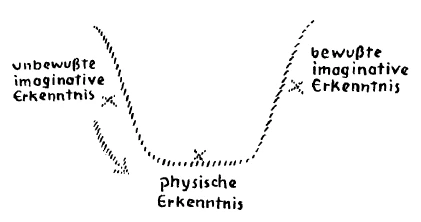

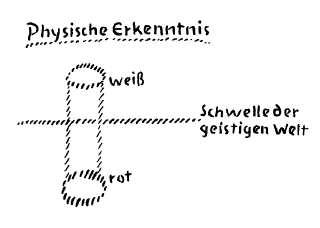

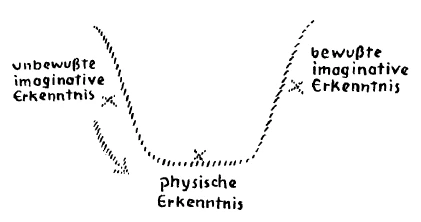

Yesterday I spoke about a kind of ascending movement that is rooted in human nature. And basically, by contemplating this ascending movement, we have rediscovered everything we already know, namely, at the lowest level, knowledge that is applicable only to the facts of the physical plane, physical knowledge, which is called objective knowledge in “How to Know Higher Worlds”. So today I will call it physical knowledge. We then came to know the next higher stage of knowledge, the so-called imaginative knowledge; but we considered it as archetypally conscious imaginative knowledge; conscious imaginative knowledge can only be present in the human being who tries to work his way up to it in the way described in the book “How to Know Higher Worlds”. The words “physical knowledge”, “unconscious imaginative knowledge”, “conscious imaginative knowledge” were written on the blackboard; see diagram.

But the fact is that the content of imaginative knowledge, that is, imaginations, are in every human being. So that the development of the human soul in this respect is nothing more than an expansion of consciousness to include a realm that is always present in the human soul. We may say, then, that the situation with imaginative knowledge is no different than it would be with objects in a dark room. For in the depths of the human soul all the imaginations that come into question for the human being are present just as the objects of a dark room are. And just as the objects in a dark room are not increased in number when light is brought into the room, but remain as they are, only illuminated, so, after the consciousness for imaginative knowledge has been awakened, there is no different content in the soul than there was before; they are only illuminated by the light of consciousness. So, in a sense, by struggling to the imaginative level of knowledge, we experience nothing other than what has long been present in our soul as a sum of imaginations.

If we look back again at what we were able to understand yesterday, we know that when our perceptions of the objects around us through our physical senses descend into the realm of memory, that is, into the unconscious, , so that we are in a position to be unaware of them for some time, but they have not been lost, but can be brought up again from the soul, then we have to say that we are sinking down into the unconscious that which we have in ordinary physical consciousness. Thus the world of representations that we gain through physical knowledge of the external world is constantly being taken up by our spiritual, by the supersensible; it continually slips into the supersensible. Every moment we gain representations of the external world through physical perceptions, and these representations are handed over to our supersensible nature. It will not be difficult for you to consider this in the light of everything that has been said over the years, because this is the most superficial supersensible process imaginable, a process that takes place continuously: the transition from ordinary perceptions to perceptions that we can remember. So it seems obvious, and this is also true according to spiritual research, that everything that takes place when we perceive the external world is a process of the physical plane. Even when we form ideas about the physical external world, this is still a process of the physical plane. But in the moment when we let the ideas sink down into the unconscious, we are already standing at the entrance to the supersensible world.

This is even a very important point to be taken into account by anyone who, not through all kinds of occult chatter but through serious human soul-searching, wants to gain an understanding of the occult world. For there is a very important fact hidden in the saying I have just applied: When we as human beings face the things of the external world and form ideas, it is a process of the physical plane. At the moment when the idea sinks down into the unconscious and is stored there until it is brought up again by a memory, a supersensible process takes place, a real supersensible process. So that you can say to yourself: If one is able to follow this process, which consists in the fact that a thought that is up in the consciousness sinks down into the subconscious and is present there as an image, one can, in other words, follow an idea as it is down in the subconscious, then one actually begins to glide into the realm of the supersensible. Just think: when you go through the usual process of remembering, the idea must first come up into consciousness, and you perceive it up here in consciousness, never down in the unconscious. You must distinguish between ordinary remembering and pursuing the ideas down into the unconscious. What takes place in remembering can be compared to a swimmer sinking under the water, whom you see until he is completely submerged. Now he is down and you no longer see him. When he comes up again, you see him again! [It was drawn.] It is the same with human perceptions: you have them as long as they are on the physical plane; when they go down, you have forgotten them; when you remember them again, they come up again like the float. But the process I am talking about, which already points to imaginative knowledge, could be compared to you diving under yourself and thereby being able to see the swimmer down in the water, so that he does not disappear when he submerges.

But from this follows nothing less than that the line I drew earlier, the level surface, as it were, below which the imagination sinks into the unconscious, into the realm of memory, is the threshold of the spiritual world itself, the first threshold of the spiritual world. This follows with absolute necessity. It is the first threshold of the spiritual world! Just think how close the human being is to this threshold of the spiritual world. [The words 'threshold of the spiritual world' were written next to the diagram.]

And now take a process by which one can try to really get down there, to submerge. The process would be to try to follow ideas down into the unconscious. This can actually only be done by trial and error. It can be done by doing something like the following. You have formed an idea about the outside world; you try to artificially evoke the process of remembering independently of the outside world. Think of how it is recommended in “How to Know Higher Worlds”, where the very ordinary rule of looking back at the events of the day is given. When one looks back at the experiences of the day, one trains oneself to enter into the paths that the imagination itself takes by descending below the threshold and then ascending again. So the whole process of remembering is designed to follow the images that have sunk below the threshold of consciousness.

But in addition, it is said in “How to Know Higher Worlds” that one does well to trace the ideas one has formed in reverse order, that is, from the end back to the beginning; and if one wants to survey the day, to follow the stream of events backwards from evening to morning. In doing so, one must make a different effort than is made in the way of ordinary recollections. And this different effort of will brings one to grasp, as it were below the threshold of consciousness, what one has had as an experiential image. And in the course of trying, one comes to feel, to experience inwardly, how one runs after the images, runs after them below this threshold of consciousness. It is really a process of inner experiential probing that comes into play here. But it is important to do this review really seriously, not in a way that after a while you lose the seriousness of the matter. But then, if you do this process of looking back for a long time, or in general do the process of bringing up an experience from memory, an experienced world of ideas, so that you imagine the matter in reverse, thus applying a greater force than you when you remember in the usual sequence, then you also experience that you are no longer able to grasp the idea from a certain point on in the same way as you would have grasped it in ordinary life on the physical plane.

On the physical plane, memory expresses itself in such a way – and it is best for memory on the physical plane to express itself in this way – that if one brings up the image that one wants or is supposed to remember, one does so in a way that is true to the context of one's life, one brings it up in the way one has formed it on the physical plane. But if, through the suggested trial, one gradually gets used to chasing the ideas, as it were, under the threshold of consciousness, one does not discover them down there as they are in life. That is the mistake people always make when they believe that they will find a copy of what is in the physical world in the spiritual world. They have to assume that the ideas will look different down there. In reality, they look like this below the threshold of consciousness: they have stripped away everything that is characteristic of the physical plane. Down there they become entirely images; and they become so completely that we feel life in them. We feel life in them. It is very important to keep this sentence in mind: we feel life in them. You can only be convinced that you have really followed an idea down below the threshold of consciousness when you have the feeling that the idea is beginning to live, to stir. When I compared the ascent to imaginative knowledge with sticking one's head into an anthill, I explained it from a different point of view. I said: everything begins to stir, everything becomes active.

Now, for example, let us say you have had an ordinary experience during the day – I will take that – sat at a table and held a book in your hand. Now, at some time in the evening, you vividly imagine what it was like: the table, the book, you sitting there, as if you were outside of yourself. And it is always good to visualize the whole thing pictorially from the outset, not in abstract thoughts, because abstraction, the ability to abstract, has no significance at all for the imaginative world. So you imagine this picture: sitting at a table, with a book in your hand. - With table and book I simply want to say, imagine as vividly as possible some detail from everyday life. Then, if you really let your soul gaze upon this image, if you really imagine it intensely in meditation, then from a certain moment on you will feel differently than usual; yes, I will say comparatively, it is similar to when you would take a living being in your hand.

When you pick up an inanimate object, you have the feeling that the object is still, it does not tingle or crawl in your hand. Even if you have a moving dead object in your hand, you calm down when you feel that this life does not come from the object, but is mechanically assigned to it. It is a different matter if you happen to have a living object, let's say a mouse, in your hand. Let's say, for example, that you reached into a cupboard and thought you were taking some object in your hand and discovered that you had a mouse in your hand. And then, you feel the crawling and tingling of the mouse in your hand! There are people who start screaming at the top of their lungs when they suddenly feel a mouse in their hand. And the screaming is no less when they cannot yet see what is crawling and tingling in their hand. So there is a difference between having a dead or a living object in your hand. You have to get used to the living object first in order to tolerate it to a certain extent. Isn't it true that people are accustomed to touching dogs and cats, but they have to get used to it first. But if you put a living being in someone's hand in the middle of the night, in the dark of night, without their knowing it, they will also be shocked.

You have to realize this difference you feel between touching a dead and a living object. When you touch a dead object, you have a different feeling than when you touch a living one. Now, when you have an idea on the physical plane, you have a feeling that you can compare to touching a dead object. But as soon as you really go below the threshold of consciousness, that changes; so that you get the feeling: the thought has life within, begins to stir. It is the same discovery you have – as a comparison for the feeling of the soul – as when you have grasped a mouse: the thought tingles and crawls.

It is very important that we pay attention to this feeling if we are to get an idea of imaginative knowledge; for we are in the imaginative world at the moment when the thoughts that we bring up from the subconscious begin to tingle and crawl, begin to behave in such a way that we have the feeling: down there, under the threshold, everything is actually swirling and churning. And while it is very quiet up there in the attic and thoughts can be controlled so nicely, just as machines can be controlled, down there one thought follows another, the thoughts tingle and crawl, they churn and roll, down there they suddenly become a very active world. It is important to appropriate this feeling, because at that moment, when you begin to feel the life of the world of thought, you are in the imaginative or elementary world. That is where you are! And one can enter so easily if only one follows the very simplest rules given in “How to Know Higher Worlds”, if only one refrains from trying to enter by the way of all kinds of “practices” hinted at in recent days. One can really enter so easily. Just think that one of the very first things clearly stated in the book “How to Know Higher Worlds” is that one should try to follow the life of a plant, for example: how it gradually grows and gradually fades away. Yes, if you really follow this, you have to go through the life of the plant in your thoughts. First you have the thought of the very small seed, and if you do not make the thought flexible, you will not be able to follow the plant as it grows. You have to make the thought flexible. And then again, when you think of the plant shedding its leaves, gradually dying, withering, you have to think of shrinking and wrinkling. As soon as you begin to think in terms of living things, you have to make the thought itself mobile. The thought must begin to acquire inner mobility through your own power.

There are two beautiful poems by Goethe. One is called “The Metamorphosis of Plants” and the other “The Metamorphosis of Animals”. These two poems can be read, you can find them beautiful, but you can also do the following. You can try to really think the thoughts in these poems as Goethe thought them, from the first line to the last, and then you will find that if you go through with it, the thought can move inwardly from beginning to end. And anyone who does not follow the thought of these poems in this way has not understood the metamorphosis. But anyone who follows the thought in this way and then lets it sink down into the unconscious, and then, after having done this several times, remembers precisely this thought of the metamorphosis – for this is no different from the thinking that you are supposed to follow in 'How to Know Higher Worlds' Knowledge of Higher Worlds?», will sink into the unconscious, and will then, after he has done this often, remember precisely this thought of the metamorphosis. So he who carries this out, who sinks this thought down and then makes the effort to do it fifty, sixty, a hundred times, and a hundred and one times it will perhaps take, will one day bring it up. But then this thought, which he has practiced in this way, will be a mobile one. You will see that it does not come up like a small machine, but forgive me for using this example again, like a small mouse; you will see how it is an inwardly mobile, living element.

I said that it is so easy to delve into this elemental world if you just tear yourself away from the human tendency towards abstract thought. This tendency to have limited, abstract thoughts instead of inwardly mobile thoughts is so terribly great. Isn't it true that people are so eager to say what this or that is and what is meant by it, and are so satisfied when they can say that this or that is meant by it, because it gives them a thought that does not move like a machine. And people become so terribly impatient in their ordinary lives when you try by all means to convey to them flexible and not such abstract boxed thoughts. Because all outer life of the physical plan and all life of outer science consists of such dead boxed thoughts, of nested thoughts. How often have I had to experience that people asked me about this or that: Yes, what about it? What is that? They wanted a complete, rounded thought that they could write down and then read again, repeating it as often as they liked. But the aim should be to have a thought that is flexible within, a thought that lives on, really lives on.

But you see, there is also a very serious side to the mouse. Why do some people scream when they discover that they have reached into a cupboard and are holding a mouse in their hand? Because they are afraid! And this feeling really does arise at the moment when you realize, really realize: the thought is alive! Then you start to be afraid too! And that is precisely what good preparation for the matter consists of: unlearning to be afraid of the living thought. The materialists do not want to come to such living thoughts, I have emphasized this often. Why? Because they are afraid. Yes, the master of materialism, Ahriman, appears once in the Mystery Drama with the expression “fear”. There you have the passage in the Mysteries where it is indicated how one feels when thoughts begin to become mobile. But now, all the indications in “How to Know Higher Worlds”, if followed, lead to getting rid of this fear of the mobile, of the living thought.

So you see, you enter into a completely different world, a world at whose threshold you must truly discard abstract thinking, which dominates the entire physical plane. The endeavor of people who want to enter the occult world with a certain degree of comfort always consists of wanting to take with them the ordinary thinking of the physical plane. You cannot do that. You cannot take ordinary physical thinking into the occult world. You have to take mobile thinking into it. All thinking must become agile and mobile. If you do not feel this within you – and as I said, you are not doing it right if you do not feel it relatively soon – if you do not pay attention to what I have just said, then it is very easy not to grasp the peculiarity of the spiritual world. And one should grasp it if one wants to deal with the spiritual world at all.

You see, it is so difficult to struggle with human abstractness in this field; because once you have grasped this flexibility of thought, you will also understand that a flexible thought cannot occur in any old way, here or there. You cannot, for example, find a land animal in the water; you cannot accustom a bird, which is suited to the air, to live deep down in the water. If you go to the living, you cannot do otherwise than to accept the idea that one must not take it out of its element. You have to keep that in mind.

I once tried, in a very strict way, initially in a small area – I always try to do it this way, but I will just mention it now as an example – with a very important idea, to show vividly, precisely with an example, how things must be when one takes into account the inner life of the thought. In Copenhagen I gave a small lecture cycle on 'The Spiritual Guidance of the Human Being and of Humanity', which is also available in print. At a certain point in this lecture cycle, I drew attention to the mystery of the two Jesus children. Now take it as it is presented there. We have a lecture cycle that begins in a certain way. It draws attention to how man can already acquire certain insights if he tries to look at the first years of a child's development, tries to look back at these things. The whole thing is designed. Then it continues. The part of the hierarchies in human progress is presented - the book is printed, it is probably in everyone's hands, so I am talking about something very well known - then there is a certain connection, at a very specific point, about the two Jesus children. It is part of the discussion of the two Jesus children that it happens at a certain point. And anyone who says, “Well, why shouldn't we be able to take this discussion of the two Jesus children and present it exoterically, even though it has been taken out of context?” is asking the same question as someone who asks, “Why does the hand have to be on the arm, on this part of the body?” They could even say, “Why isn't the hand on the knee?” It could perhaps be there too. He does not understand the whole organism as a living being, he believes that the hand could also be somewhere else, right? The hand cannot be anywhere other than on the arm! So in this context, the thought of the two Jesus children cannot be in a different place because it is tempting to develop the matter in such a way that the living thought is included in the presentation.

Now someone comes along and writes a piece of writing and takes this thought in a crude way and puts it in context with other thoughts that have nothing to do with it! But that means nothing other than: he puts his hand on his knee! What does someone do who puts his hand on his knee? Yes, you can't do it to an organism, but you could draw it. Paper is patient, you could just draw a human figure, supported here, and the two knees so that hands grow out of them. [This drawing has not been handed down.] Not true, you could draw that, but then you would have drawn an impossible organism; you would have proved that you understand nothing of real life! One could also use the comparison: he has placed the eagle, the bird that is meant for the air, in the depths of the sea or something similar.

What did such a person try to do? Yes, you see, what he tried can be done with all things that relate only to knowledge of the physical plane. One professor can write a book by starting with one, another can start with another, and it does not matter so much there: things can be taken out and so on. But there one is not dealing with living beings, but with thought machines. That is the essential point.

A person who does something like this, who tears something out of context and puts it into an impossible context, has proved that he is completely ignorant of the essence that has been the driving force and inspiration of our entire spiritual scientific movement since its inception, because he is trying to apply the very ordinary materialistic scheme to the spiritual as well. This is very essential. It is very important to face these things squarely, otherwise one does not understand the inner significance of higher knowledge. One cannot say everything at any given point. And it is really true with regard to the exoteric, which borders on the esoteric, that Hegel has already said that a thought belongs in its place in context. I hinted at this recently when I tried to make some suggestions in this direction on Hegel's birthday. In this way, one achieves nothing less than to submerge into life with thinking, whereas otherwise one always lives in the dead; one submerges into life.

But through this, something also reveals itself that could not be recognized at all before and that cannot be examined at all on the physical plane, namely, arising and ceasing. You can also see this from “How to Know Higher Worlds.” On the physical plane, nothing else can be observed than what has come into being. The arising cannot be observed at all; only what has come into being can be observed on the physical plane. The passing away cannot be observed either, because when the object passes into the passing away, it is no longer on the physical plane, or at least it moves away from the physical plane.

So one cannot observe arising and ceasing on the physical plane. The consequence of this is that we can say: we enter into a completely new world element when we discover the movable thought, namely into the world of life and that is the world of arising and ceasing.

Occultly speaking, this could also be expressed in the following way: During the old moon time, man was - albeit only in the dream consciousness - in the world of becoming and passing away. It was not that he saw with his senses what was arising, for he had not yet developed the senses to perceive with, but was still immersed in things. He imagined in a dream-like way, but the images that he imagined in a dream-like way allowed him to really follow the arising and passing away. And that is what he must first strive for again by developing mobile thoughts. So the ascent to imaginative knowledge is at the same time a return, only a return to the level of consciousness. We return to something we have outgrown; we return properly.

So that we can say: This imaginative knowledge is the return to the world of becoming and passing away. We discover becoming and passing away when we return. And we cannot learn anything about becoming and passing away if we do not come to imaginative knowledge. It is quite impossible to discern anything about becoming and passing away without coming to imaginative knowledge.

That is why what Goethe wrote about the metamorphosis of plants and animals is so infinitely meaningful, because Goethe really wrote it from the point of view of imaginative knowledge. And that is why people could not understand what was actually meant when I wrote my comments on “Goethe's Scientific Writings”, which, in the most diverse turns of phrase, repeatedly express that it does not depend on the current scientific but to delve into Goethe's scientific knowledge and to see something tremendously outstanding in it, something quite different from current scientific knowledge. That is why I referred to a sentence that Goethe expressed so beautifully and in which he indicates what is important to him. Goethe made the Italian Journey and followed not only art but also nature with interest. When reading the 'Italian Journey', one can see how he gradually immersed himself in everything that the mineral, plant and so on could offer him. And then, when he had arrived in Sicily, he said that, after what he had observed there, he now wanted to make a journey to India, not to discover anything new, but to look at what had already been discovered by others in his way. In other words, to look at it with flexible concepts! That is what is important: to look at what others have discovered with flexible concepts. That is the tremendously significant fact that Goethe introduced these flexible concepts into scientific life.

Therefore, for those who understand occultism, the following is a fact that is otherwise misunderstood. Ernst Haeckel and other materialistic, or as they are also called, monistic scholars, have spoken very appreciatively about Goethe's Metamorphosis of Plants and Animals. But the fact that they were able to express their appreciation is based on a very strange process, which I will also make clear to you through a comparison.

Imagine you have a plant in a flowerpot in front of you, or even better, outside in the garden, and you want to enjoy this plant. You go out into the garden to enjoy it, to enter into a relationship with it. And now imagine that there is a person who cannot do anything with the plant. And if you ask yourself why, you discover: He is actually disturbed by life! And so he makes a cast of the plant very finely, so that the plant is now like the real one, but in papier-mâché. He puts it in his room and now he enjoys it. Life disturbed him; only now does he enjoy it!

I cannot tell you what torments I suffered as a boy when comparing, which is also characteristic of the attitude of people, I often had to hear as a boy that someone wanted to emphasize the beauty of a rose particularly by saying: Truly, as if made of wax! - It's enough to make you want to tear your hair out! But it does exist. It really does exist that someone emphasizes the excellence of a living thing by saying, in his phrase, that it is like a dead thing. It really does exist. For those who have a sense for the matter, it is something terrible. But if you don't have such feelings, you really can't develop according to reality.

Now, the following happened with Ernst Haeckel. Goethe wrote “The Metamorphosis of Plants” and “The Metamorphosis of Animals”, Haeckel reads them and Ahriman transforms what is alive that Goethe has written into mock-ups, into something that is actually made of papier-mâché, and Haeckel grasps that. He actually likes it. So that in what he praises, he has not praised what Goethe really meant, but Haeckel has only translated it into the mechanistic. Ahriman steps between Goethe and Haeckel, transforming the living into a dead one.

Now, as I said, this conscious upward leap to imaginative knowledge is a return. I said at the beginning of the lecture: the imaginations are actually already within us, they have been within us since the time of the moon, and the development on earth consists in the fact that we have covered them with the ordinary layers of consciousness. Now we are returning through what we have acquired in our ordinary earthly consciousness. It is a real return.

And now one can ask: how can one describe the whole thing? One can now say: it is a descent and a re-ascent. Only now is there any justification for drawing this line at all [the words on the blackboard are connected by a line, see diagram]; there would be no sense in drawing it from the outset. And only now can we say: on the level of ordinary physical cognition, there we are below; here is unconscious imaginative cognition, which now sits below in our nature and has to do with the forces of becoming and passing away; and on the other side, in the ascent, is conscious imaginative cognition. [Both were marked on the blackboard.]

If we take Goethe as an obvious example – I will only look at him as an example – we can say that in Goethe's later works, the point has been reached where the outer development of humanity embraces imaginative knowledge, where it is actually introduced into science.

Now one may ask: Now one can study whether or not very strange things are associated with it? Yes, they are associated with it, because basically the whole of Goethe's way of thinking is quite different from that of other people. And Schiller, who was unable to develop this way of thinking, was only able to understand Goethe with the greatest effort, as you can see from the correspondence between Schiller and Goethe at the point I have often quoted, where Schiller writes to Goethe on August 23, 1794:

”...For a long time now, although from a considerable distance, I have observed the course of your mind and noted the path you have mapped out with ever-renewed admiration. You seek what is necessary in nature, but you seek it by the most difficult route, which any weaker force would do well to avoid. You take all of nature together to get light on the individual; in the totality of its manifestations you seek the explanation for the individual. From the simple organization you ascend, step by step, to the more complicated, to finally build the most complicated of all, the human being, genetically from the materials of the whole of nature. By recreating it, as it were, you seek to penetrate its hidden technology. A great and truly heroic idea, which shows sufficiently how much your mind holds the rich totality of its ideas together in a beautiful unity. You could never have hoped that your life would be enough for such a goal, but even just to embark on such a path is worth more than any other ending, and you have chosen, like Achilles in the Iliad between Phthia and immortality. If you had been born a Greek, or even an Italian, and had been surrounded from your cradle by a refined nature and idealizing art, your path would have been infinitely shortened, perhaps even made superfluous. You would have absorbed the form of the necessary into your first view of things, and the great style would have developed in you with your first experiences. Now that you have been born a German, since your Greek spirit has been thrown into this Nordic creation, you had no choice but to either become a Nordic artist yourself or to replace what reality withheld from your imagination by the help of your thinking power, and thus to give birth to a Greece from within and in a rational way, so to speak. In that period of your life when the soul forms its inner world from the outer world, surrounded by imperfect forms, you had already absorbed a wild and Nordic nature into yourself, when your victorious genius, superior to its material, discovered this defect from within, and from without it was confirmed by your acquaintance with Greek nature. Now you had to correct the old, inferior nature, which had already been forced upon your imagination, according to the better model that your creative mind created for itself, and this could not, of course, be done otherwise than according to guiding concepts. But this logical direction, which the mind is compelled to take in reflection, does not go well with the aesthetic one, through which alone it forms. So you had more work to do, because just as you went from intuition to abstraction, you now had to convert concepts back into intuitions, and transform thoughts into feelings, because only through these can the genius bring forth... “

He considers him to be a Greek transplanted to the Nordic world, and so on. Yes, there you see the whole difficulty Schiller had in understanding Goethe! Some people could learn something from this who believe they can understand Goethe in the twinkling of an eye and thereby elevate themselves above Schiller, even though Schiller was not exactly a fool when it came to those people who believe they can understand Goethe so readily!

But the peculiar thing that can be discovered is that Goethe also has a very peculiar and different view in relation to other areas, for example in relation to the ethical development of the human being, namely in the way of thinking about what the human being deserves or does not deserve as reward or punishment.

It is impossible to understand Goethe's work from the very beginning if you do not consider his, I would say his entire environment's, divergent way of thinking about reward and punishment. Read the poem “Prometheus,” where he even rebels against the gods. Prometheus, that is of course a revolt against the way people think about rewards and punishments. For Goethe there is the possibility of forming very special ideas about rewards and punishments. And in his “Wilhelm Meister” he really did try to present this, I would say, in a wonderfully probing way in the secrets of the world. You don't understand “Wilhelm Meister” if you don't consider that.

But where does that come from? It comes from the fact that in the realm of physical knowledge one cannot form any idea at all of what punishment or reward is to be applied to anything human in relation to the world, because that can only arise in the realm of imagination. That is why the occultists always said: When you ascend to imaginative knowledge, you experience not only the elemental world, but also - as they put it - “the world of wrath and punishment”. So it is not only a return to the world of becoming and passing away, but at the same time a climbing up to the world of wrath and punishment. The words “return to the world of becoming and passing away” and “world of wrath and punishment” were written on the blackboard. ]

Therefore, only spiritual science can truly illuminate the peculiar chain of cause and effect between what a person is worthy and unworthy of in relation to the universe. All other “justifications” in the world are preparatory to this.

We have now reached an important point, and I will continue with this tomorrow.

Zweiter Vortrag

Ich habe gestern über eine Art aufsteigender Bewegung, die in der Menschennatur begründet ist, gesprochen. Und im Grunde haben wir durch die Betrachtung dieser aufsteigenden Bewegung alles dasjenige wiedergefunden, was wir schon kennen, nämlich auf der untersten Stufe die Erkenntnis, die nur für die Tatsachen des physischen Planes anwendbar ist, die physische Erkenntnis, die in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» die gegenständliche Erkenntnis genannt ist. Also Physische Erkenntnis will ich sie heute nennen. Wir haben dann die nächsthöhere Stufe der Erkenntnis kennengelernt, die sogenannte imaginative Erkenntnis; aber wir haben sie betrachtet als urbewußte imaginative Erkenntnis; bewußte imaginative Erkenntnis kann ja nur vorhanden sein bei dem Menschen, der versucht, sich zu ihr durchzuringen auf die in dem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» angegebene Weise. [Die Worte «physische Erkenntnis», «unbewußte imaginative Erkenntnis», «bewußte imaginative Erkenntnis» wurden an die Tafel geschrieben, siehe Schema.]

Aber als Tatsache ist der Inhalt der imaginativen Erkenntnis, das heißt, sind Imaginationen in jedem Menschen. So daß eigentlich die Entwickelung der Menschenseele in dieser Beziehung nichts anderes ist als ein Ausdehnen des Bewußtseins auf ein Gebiet, das immer in der Menschenseele drinnen ist. Man kann also sagen: Mit dieser imaginativen Erkenntnis verhält es sich nicht anders, als es sich etwa verhalten würde mit Gegenständen, welche in einem zunächst finsteren Zimmer sind. Denn in den Tiefen der Menschenseele sind alle Imaginationen, die für den Menschen zunächst in Betracht kommen, genauso vorhanden, wie die Gegenstände eines finsteren Zimmers. Und wie diese um keinen einzigen vermehrt werden, wenn man Licht in das Zimmer hineinbringt, sondern wie alle bleiben, wie sie sind, nur daß sie beleuchtet sind, ebenso sind, nachdem das Bewußtsein für die imaginative Erkenntnis erwacht ist, in der Seele keine anderen Inhalte da, als schon vorher da waren; sie werden nur von dem Licht des Bewußtseins erleuchtet. Also wir erfahren gewissermaßen durch das Sich-Hinaufringen zur imaginativen Erkenntnisstufe nichts anderes, als was längst vorher in unserer Seele als eine Summe von Imaginationen vorhanden ist.

Blicken wir noch einmal zurück auf dasjenige, was uns gestern hat klar werden können, so wissen wir ja: Wenn unsere Vorstellungen, die wir an den Gegenständen ringsherum durch unsere physischen Wahrnehmungen gewinnen, hinuntertauchen in das Gebiet der Erinnerungsmöglichkeiten, also ins Unbewußte hinunterversenkt werden, so daß wir in die Lage kommen, einige Zeit nichts von ihnen zu wissen, aber sie doch nicht verloren haben, sondern sie wieder heraufbringen können aus der Seele, dann müssen wir sagen, daß wir in das Unbewußte hinunterversenken dasjenige, was wir im gewöhnlichen physischen Bewußtsein haben. Es wird also die Welt der Vorstellungen, die wir durch die physische Erkenntnis an der Außenwelt gewinnen, ja immerfort von unserem Geistigen, von dem Übersinnlichen aufgenommen; sie schlüpft fortwährend in das Übersinnliche hinein. In jedem Moment ist es so, daß wir an der Außenwelt durch die physischen Wahrnehmungen Vorstellungen gewinnen, und diese Vorstellungen unserer übersinnlichen Natur übergeben werden. Es wird Ihnen nicht schwierig sein, dieses zu überdenken nach alle dem, was im Laufe der Jahre gesprochen worden ist, weil das ja gerade der alleroberflächlichste übersinnliche Prozeß ist, der nur denkbar ist, ein Prozeß, der sich fortwährend abspielt: der Übergang der gewöhnlichen Vorstellungen in Vorstellungen, an die wir uns erinnern können. So liegt es nahe, zu denken, was auch wahr ist gemäß der Geistesforschung, daß alles dasjenige, was sich abspielt, indem wir die äußere Welt wahrnehmen, ein Vorgang des physischen Planes ist. Auch dann, wenn wit an der physischen Außenwelt uns Vorstellungen bilden, ist das noch ein Vorgang des physischen Planes. In dem Augenblicke aber, wo wir die Vorstellungen hinuntersinken lassen ins Unbewußte, da stehen wir bereits beim Eingange in die übersinnliche Welt.

Das ist sogar ein sehr wichtiger Punkt, der berücksichtigt werden muß von dem, welcher nicht durch allerlei okkultistisches Geschwätz, sondern durch ernstliche menschliche Seelenanstrengung ein Verständnis der okkulten Welt erlangen will. Denn es liegt schon eine ganz wesentliche Tatsache verborgen in dem Ausspruch, den ich eben angewendet habe: Wenn wir als Menschen den Dingen der Außenwelt gegenüberstehen und uns Vorstellungen bilden, so ist das ein Vorgang des physischen Planes. In dem Augenblick, wo die Vorstellung hinuntersinkt ins Unbewußte und dort aufbewahrt wird, bis sie wieder einmal heraufgeholt wird durch eine Erinnerung, vollzieht sich ein übersinnlicher Vorgang, ein richtiger übersinnlicher Vorgang. So daß Sie sich sagen können: Ist man imstande, diesen Vorgang zu verfolgen, der darinnen besteht, daß ein Gedanke, der oben im Bewußtsein ist, hinuntersinkt ins Unterbewußte und da unten als ein Bild vorhanden ist, kann man, mit anderen Worten, eine Vorstellung verfolgen, wie sie unten im Unbewußten ist, dann beginnt man eigentlich schon in das Gebiet des Übersinnlichen hineinzugleiten. Denn denken Sie doch nur einmal: Wenn Sie den gewöhnlichen Prozeß der Erinnerung vollziehen, so muß ja erst die Vorstellung in das Bewußtsein heraufkommen, und Sie gewahren sie dann heroben im Bewußtsein, niemals unten im Unbewußten. Sie müssen das gewöhnliche Erinnern unterscheiden von dem Verfolgen der Vorstellungen bis hinunter ins Unbewußte. Das, was im Erinnern stattfindet, können Sie vergleichen mit einem Schwimmer, der unter das Wasser sinkt und den Sie so lange sehen, bis er ganz untergetaucht ist. Jetzt ist er unten, und Sie sehen ihn nicht mehr. Wenn er wieder heraufkommit, sehen Sie ihn wieder! [Es wurde gezeichnet.] Ebenso ist es mit den menschlichen Vorstellungen: Sie haben sie, solange sie auf dem physischen Plan sind; gehen sie hinunter, so haben Sie sie vergessen; erinnern Sie sich wieder, dann kommen sie wieder wie der Schwimmer herauf. Aber dieser Prozeß, den ich jetzt meine, der also schon in die imaginative Erkenntnis hineinweist, der würde damit zu vergleichen sein, daß Sie selber untertauchen und dadurch den Schwimmer auch unten im Wasser sehen können, so daß er Ihnen nicht entschwindet, wenn er untertaucht.

Daraus aber folgt nichts Geringeres, als daß die Linie, die ich vorhin gezeichnet habe, gleichsam die Niveaufläche - unter welche hinuntersinkt die Vorstellung ins Unbewußte, in die Erinnerungsmöglichkeit -, die Schwelle der geistigen Welt selber ist, die erste Schwelle der geistigen Welt. Das folgt daraus mit absoluter Notwendigkeit. Es ist die erste Schwelle der geistigen Welt! Denken Sie nur einmal, wie nahe der Mensch dieser Schwelle der geistigen Welt steht. [Die Worte «Schwelle der geistigen Welt» wurden neben das Schema geschrieben.]

Und nun nehmen Sie einmal einen Vorgang, durch den man versuchen kann, richtig da hinunterzukommen, unterzutauchen. Der Vorgang würde der sein, daß Sie sich bemühen, Vorstellungen zu verfolgen bis hinunter ins Unbewußte. Das kann eigentlich nur durch Probieren geschehen. Es kann dadurch geschehen, daß man etwa folgendes macht. Man hat sich eine Vorstellung an der Außenwelt gebildet; man versucht unabhängig von der Außenwelt künstlich den Prozeß der Erinnerung hervorzurufen. Denken Sie, wie das empfohlen wird in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?», indem die ganz gewöhnliche Regel des Rückschauens auf die Tagesereignisse angegeben wird. Wenn man rückschaut auf die Tageserlebnisse, dann übt man sich darin, gleichsam in die Wege hineinzukommen, welche die Vorstellung selber macht, indem sie untergetaucht ist und wiederum aufsteigt. Also der ganze Prozeß der Rückerinnerung ist darauf angelegt, nachzugehen den Vorstellungen, die unter die Schwelle des Bewußtseins hinuntergesunken sind.

Aber außerdem wird dort in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» gesagt, daß man gut tut, die Vorstellungen, die man sich gebildet hat, umgekehrt, also von dem Ende nach dem Anfang zurückzuverfolgen; und wenn man den Tag überschauen will, den Strom der Ereignisse vom Abend zum Morgen hin rückwärts verlaufend zu verfolgen. Dadurch muß man eine andere Kraftanstrengung machen, als sie gemacht wird auf dem Wege der gewöhnlichen Erinnerungen. Und diese andere Kraftanstrengung bringt einen dahin, gewissermaßen unter der Schwelle des Bewußtseins das zu erfassen, was man als Erlebnisvorstellung gehabt hat. Und im Laufe des Probierens kommt man darauf, zu empfinden, innerlich zu erleben, wie man da den Vorstellungen nachläuft, ihnen unter diese Schwelle des Bewußtseins hinunter nachläuft. Es ist wirklich hier ein Vorgang des inneren erlebnismäßigen Probierens, der in Betracht kommt. Doch handelt es sich darum, daß man diese Rückschau wirklich ernsthaftig macht, nicht so macht, daß man nach einiger Zeit in bezug auf den Ernst der Sache erlahmt. Dann aber, wenn man diesen Prozeß des Rückschauens längere Zeit macht, oder überhaupt den Prozeß des Heraufholens eines Erlebnisses aus der Erinnerung, einer erlebten Vorstellungswelt macht, so daß man die Sache umgekehrt vorstellt, also eine größere Kraft anwendet, als man anwenden muß, wenn man sich in der gewöhnlichen Folge erinnert, dann erlebt man nun auch, daß man nicht mehr in der Lage ist, die Vorstellung von einem gewissen Punkte an so aufzufassen, wie man sie im gewöhnlichen Leben eben auf dem physischen Plan aufgefaßt hat.

Auf dem physischen Plan lebt sich ja die Erinnerung so aus - und es ist für die Erinnerung auf dem physischen Plan das Beste, wenn sie sich so auslebt -, daß, wenn man die Vorstellung, die man erinnern will oder erinnern soll, dem Lebenszusammenhang nach treu heraufbekommt, man sie so heraufbekommt, wie man sie eben auf dem physischen Plan sich gebildet hat. Wenn man aber allmählich durch das angedeutete Probieren sich daran gewöhnt, den Vorstellungen gleichsam nachzulaufen unter die Schwelle des Bewußtseins, so entdeckt man sie da unten nicht so, wie sie im Leben sind. Das ist ja der Fehler, den die Menschen immer machen, wenn sie glauben, sie finden in der geistigen Welt einen Abklatsch dessen, was in der physischen Welt ist. Sie müssen voraussetzen, daß die Vorstellungen da unten anders aussehen werden. In Wirklichkeit schen sie unter der Schwelle des Bewußtseins so aus, daß sie alles dasjenige, was sie gerade als Charakteristisches auf dem physischen Plane haben, abgestreift haben. Da unten werden sie ganz und gar zu Bildern; und sie werden ganz und gar so, daß wir in ihnen Leben spüren. Leben spüren wir in ihnen. Das ist sehr wesentlich, gerade diesen Satz ins Auge zu fassen: Leben spüren wir in ihnen. Sie können sich erst dann überzeugt haben, daß Sie einer Vorstellung da unter der Schwelle des Bewußtseins wirklich nachgelaufen sind, wenn Sie das Gefühl haben: die Vorstellung beginnt zu leben, sich zu regen. Ich habe ja, als ich das Hinaufsteigen zur imaginativen Erkenntnis mit dem Hineinstecken des Kopfes in einen Ameisenhaufen verglichen habe, von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte aus das erklärt. Ich habe gesagt: es beginnt sich alles zu regen, alles regsam zu werden.

Nehmen Sie also zum Beispiel an, Sie haben während des Tages ich will ein ganz gewöhnliches Erlebnis nehmen - an einem Tische gesessen und ein Buch in der Hand gehabt. Jetzt, zu irgendeiner Zeit am Abend, da stellen Sie sich lebhaft vor, wie das war: den Tisch, das Buch, Sie dabeisitzend, wie wenn Sie außerhalb Ihrer wären. Und es ist dabei immer gut, sich die ganze Sache von vornherein bildhaft, nicht in abstrakten Gedanken vorzustellen, weil die Abstraktion, das Abstraktionsvermögen gar keine Bedeutung hat für die imaginative Welt. Also Sie stellen sich dieses Bild vor: sich sitzend an einem Tisch, mit einem Buch in der Hand. - Mit Tisch und Buch will ich einfach sagen, stellen Sie sich so lebhaft als nur möglich, irgendeinen Ausschnitt aus dem täglichen Leben vor. Dann, wenn Sie wirklich den Seelenblick auf diesem Bild ruhen lassen, wenn Sie wirklich intensiv meditierend das vorstellen, dann werden Sie von einem gewissen Moment ab anders als sonst fühlen; ja, ich will vergleichsweise sagen, so ähnlich, wie wenn Sie ein lebendiges Wesen in die Hand nehmen würden.

Wenn Sie einen toten Gegenstand in die Hand nehmen, dann haben Sie das Gefühl: der Gegenstand ist ruhig, der kribbelt und krabbelt nicht in Ihrer Hand. Selbst wenn Sie einen bewegten toten Gegenstand in der Hand haben, so beruhigen Sie sich durch das Gefühl, daß das Leben eben ein solches ist, das nicht von dem Gegenstand ausgeht, sondern ihm mechanisch zugeteilt ist. Etwas anderes ist es, wenn Sie einen lebendigen Gegenstand, sagen wir eine Maus, zufällig in der Hand haben. Nehmen wir zum Beispiel an, Sie haben in einen Schrank hineingegriffen und glauben, irgendeinen Gegenstand in die Hand zu nehmen und entdecken, Sie haben eine Maus in die Hand bekommen. Und dann, nicht wahr, dann fühlen Sie das Krabbeln und Kribbeln der Maus in Ihrer Hand! Es gibt Leute, die fangen ein ganz riesiges Geschrei an, wenn sie plötzlich eine Maus in ihrer Hand fühlen. Und das Geschrei ist nicht kleiner, wenn sie noch nicht sehen, was da krabbelt und kribbelt in der Hand. Es ist also ein Unterschied, ob man einen toten oder einen lebendigen Gegenstand in der Hand hat. Man muß sich erst an den lebendigen Gegenstand gewöhnen, um ihn in gewisser Weise zu ertragen. Nicht wahr, die Menschen sind gewöhnt, Hunde und Katzen zu berühren; aber sie müssen sich erst daran gewöhnen. Wenn man aber in der Nacht, in finsterer Nacht, jemandem ein lebendiges Wesen in die Hand gibt, ohne daß er es weiß, so findet er sich auch schockiert.

Diesen Unterschied, den Sie fühlen zwischen dem Berühren eines toten und eines lebendigen Gegenstandes, den müssen Sie sich klarmachen. Wenn Sie einen toten Gegenstand anfassen, haben Sie ein anderes Gefühl, als wenn Sie einen lebendigen anfassen. Wenn Sie nun eine Vorstellung haben auf dem physischen Plan, so haben Sie ein Gefühl, das Sie vergleichen können mit dem Anfassen eines toten Gegenstandes. Aber sobald Sie wirklich hinunterkommen unter die Schwelle des Bewußtseins, ändert sich das; so daß Sie das Gefühl bekommen: Der Gedanke hat innerlich Leben, beginnt sich zu regen. Es ist die gleiche Entdeckung, die Sie haben - als Vergleich für das seelische Gefühl -, wie wenn Sie meinetwillen eine Maus erfaßt haben: es kribbelt und krabbelt der Gedanke.

Es ist sehr wichtig, daß wir auf dieses Gefühl achtgeben, wenn wit einen Begriff von der imaginativen Erkenntnis bekommen sollen; denn wir sind in der imaginativen Welt in dem Augenblicke, wo die Gedanken, die wir heraufholen aus dem Unterbewußten, anfangen zu kribbeln und zu krabbeln, anfangen so sich zu benehmen, daß wir das Gefühl haben: da unten, unter der Schwelle, da quirlt und wurlt ja eigentlich alles. Und während es da oben im Oberstübchen ganz ruhig ist und die Gedanken sich so hübsch beherrschen lassen, so wie Maschinen sich behertschen lassen, läuft da unten ein Gedanke dem anderen nach, da kribbeln und krabbeln, da quirlen und wurlen die Gedanken, da unten werden sie plötzlich eine ganz regsame Welt. Es ist wichtig, daß man sich dieses Gefühl aneignet, denn in diesem Augenblick, wenn man das Leben der Gedankenwelt zu fühlen anfängt, ist man in der imaginativen oder elementarischen Welt drinnen. Da ist man drinnen! Und man kann so leicht hineinkommen, wenn man nur die aller-, allereinfachsten Regeln befolgt, welche in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» gegeben sind; wenn man nur nicht versucht, auf dem Wege von allerlei in den letzten Tagen ja angedeuteten «Praktiken» hineinzukommen. Man kann wirklich so leicht hineinkommen. Denken Sie sich doch nur, daß als etwas vom allerersten in dem Buch «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» klar angegeben ist, man solle zum Beispiel versuchen, das Leben einer Pflanze zu verfolgen: wie sie nach und nach wächst, wie sie nach und nach wiederum vergeht. Ja, wenn Sie das wirklich verfolgen, so müssen Sie ja in Gedanken dieses Leben der Pflanze durchmachen. Da haben Sie zuerst den Gedanken des ganz kleinen Samenkorns und wenn Sie den Gedanken nicht beweglich machen, so kommen Sie ja der Pflanze nicht nach in ihrem Wachsen. Sie müssen den Gedanken beweglich machen. Und dann wiederum, wenn Sie die Pflanze sich entblättern, allmählich absterbend, abwelkend denken, dann müssen Sie sich wiederum das Zusammenschrumpfen, das Zusammenrunzeln denken. Sobald Sie anfangen, das Lebendige zu denken, müssen Sie den Gedanken selber beweglich machen. Der Gedanke muß durch Ihre eigene Kraft anfangen, innere Beweglichkeit zu bekommen.

Es gibt zwei schöne Gedichte von Goethe. Das eine heißt «Die Metamorphose der Pflanzen», das andere «Die Metamorphose der Tiere». Diese zwei Gedichte kann man lesen, man kann sie schön finden, aber man kann auch folgendes machen. Man kann versuchen, den Gedanken in diesen Gedichten wirklich so zu denken, wie ihn Goethe gedacht hat, von der ersten Zeile bis zur letzten und dann wird man finden: wenn man das durchmacht, kann sich der Gedanke innerlich bewegen vom Anfang bis zum Ende. Und wer den Gedanken dieser Gedichte nicht so verfolgt, hat die Metamorphose nicht verstanden. Wer aber den Gedanken so verfolgt und ihn dann hinuntersinken läßt ins Unbewußte, und sich wiederum, nachdem er das öfters gemacht hat, erinnert gerade an diesen Gedanken der Metamorphose - denn es ist dies kein anderes Denken, als wie Sie es in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» verfolgen sollen -, wer also das ausführt, wer diesen Gedanken hinuntersenkt und dann sich bemüht, dies fünfzig-, sechzig-, hundertmal zu machen, und hundertundeinmal wird es vielleicht brauchen, der wird ihn einmal heraufkriegen. Dann aber wird dieser Gedanke, den er so praktiziert hat, ein beweglicher sein. Man wird erleben, daß er nicht so heraufkommt, wie etwa eine kleine Maschine, sondern verzeihen Sie nochmals das Beispiel - wie eine kleine Maus; man wird erleben, wie er selber ein innerlich bewegliches, lebendiges Element ist.

Ich sagte, man kann so leicht hinuntertauchen in diese elementatische Welt, wenn man sich nur ein wenig losreißt von dem Hang aller Menschen nach abstrakten Gedanken. Dieser Hang, begrenzte, abstrakte Gedanken zu haben statt innerlich bewegliche Gedanken, der ist ja so furchtbar groß. Nicht wahr, die Menschen gehen so darauf aus, bei allem zu sagen, was das oder jenes ist und was damit gemeint ist, und sind so zufrieden, wenn sie sagen können, das oder jenes ist damit gemeint, weil ihnen das einen Gedanken gibt, der wie eine Maschine sich nicht regt. Und die Menschen werden im gewöhnlichen Leben so furchtbar ungeduldig, wenn man mit allen Mitteln versucht, ihnen bewegliche und nicht solche abstrakte Schachtelgedanken zu übermitteln. Denn alles äußere Leben des physischen Planes und alles Leben der äußeren Wissenschaft besteht aus solchen toten Schachtelgedanken, aus eingeschachtelten Gedanken. Wie oft habe ich es erleben müssen, daß Menschen mich bei dem oder jenem fragten: Ja, wie ist es denn? Was ist das? — Sie wollten einen abgeschlossenen, abgerundeten Gedanken, den sie sich aufschreiben können, um ihn dann wieder ablesen, ihn wiederholen zu können, so oft sie wollen, während das Bestreben sein muß, einen innerlich beweglichen Gedanken zu haben, einen Gedanken, der fortlebt, richtig fortlebt.

Aber sehen Sie, die Sache mit der Maus hat doch auch ihre ganz ernste Seite. Denn warum schreien manche Menschen, wenn sie entdecken, sie haben in einen Schrank hineingegriffen und eine Maus in der Hand? Weil sie sich fürchten! Und dieses Gefühl tritt wirklich auch auf in dem Moment, wo man merkt, richtig merkt: der Gedanke lebt! Da fängt man auch an, sich zu fürchten! Und darin besteht eben die gute Vorbereitung für die Sache, daß man sich die Furcht vor dem lebendigen Gedanken abgewöhnt. Die Materialisten wollen zu solch lebendigen Gedanken nicht kommen, ich habe das oft betont. Warum? Weil sie Furcht haben. Ja, der Meister des Materialismus, Ahriman, erscheint einmal im Mysteriendrama mit dem Ausdruck «Furcht». Da haben Sie die Stelle in den Mysterien, wo das angedeutet ist, wie man empfindet, wenn die Gedanken beginnen, beweglich zu werden. Nun aber sind ja alle Angaben in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?», wenn sie befolgt werden, eben dahin bringend, daß man sich diese Furcht vor dem beweglichen, vor dem lebendigen Gedanken abgewöhnt, richtig abgewöhnt.

Sie sehen also, man kommt in eine ganz andere Welt hinein, in eine Welt, an deren Schwelle man das abstrakte Denken, das den ganzen physischen Plan beherrscht, richtig ablegen muß. Das Bestreben der Menschen, die mit einer gewissen Bequemlichkeit in die okkulte Welt hineinkommen wollen, besteht immer darin, daß sie das gewöhnliche Denken des physischen Planes da hinein mitnehmen wollen. Das kann man nicht. Man kann nicht in die okkulte Welt das gewöhnliche physische Denken hineinnehmen. Man muß das bewegliche Denken hineinnehmen. Das ganze Denken muß regsam, beweglich werden. Wenn man dies nicht spürt in sich - und wie gesagt, man macht es nur nicht richtig, wenn man es nicht verhältnismäßig bald spürt -, wenn man das nicht beachtet, was ich jetzt gesagt habe, dann kommt man sehr leicht dazu, eben nicht die Eigentümlichkeit der geistigen Welt zu erfassen. Und man sollte sie erfassen, wenn man sich überhaupt mit der geistigen Welt beschäftigen will.

Sehen Sie, es ist so schwierig, auf diesem Gebiet zu kämpfen mit der menschlichen Abstraktheit; denn wenn Sie dies Bewegliche des Gedankens erfaßt haben, dann werden Sie auch begreifen, daß ein beweglicher Gedanke nicht in beliebiger Weise da und dort auftreten kann. Sie können zum Beispiel ein Landtier nicht im Wasser finden; Sie können dem Vogel, der für die Luft geeignet ist, nicht angewöhnen, tief unten im Wasser zu leben. Sie können, wenn Sie auf das Lebendige gehen, nicht anders, als zu der Vorstellung sich bequemen, daß man es aus seinem Element nicht herausnehmen darf. Das muß man beachten.

Ich habe einmal in einer ganz strikten Weise, zunächst auf einem kleinen Gebiet - ich versuche es immer so zu machen, aber ich will es jetzt nur als Beispiel anführen - mit einem sehr wichtigen Gedanken versucht, gerade an einem Beispiel anschaulich zu zeigen, wie die Dinge sein müssen, wenn man mit diesem innerlichen Leben des Gedankens rechnet. Ich habe in Kopenhagen einen kleinen Vortragszyklus gehalten über «Die geistige Führung des Menschen und der Menschheit», der auch gedruckt vorliegt. An einer bestimmten Stelle dieses Vortragszyklus habe ich aufmerksam gemacht auf das Geheimnis von den zwei Jesusknaben. Nun nehmen Sie es einmal, wie die Sache dort dargestellt ist. Wir haben einen Vortragszyklus, der in einer gewissen Weise beginnt. Es wird da aufmerksam gemacht, wie der Mensch sich schon gewisse Erkenntnisse aneignen kann, wenn er hinzublicken versucht auf die ersten Entwickelungsjahre des Kindes, zurückzublicken versucht auf diese Dinge. Das Ganze ist gestaltet. Dann geht es weiter. Es wird der Anteil der Hierarchien an dem Menschheitsfortschritt dargestellt - das Buch ist ja gedruckt, es ist wahrscheinlich in aller Hände, ich spreche also von etwas ganz Bekanntem -, dann wird in einem gewissen Zusammenhange, an einer ganz bestimmten Stelle, von den zwei Jesusknaben gesprochen. Das gehört zu der Besprechung der zwei Jesusknaben, daß es an der bestimmten Stelle geschieht. Und wer sagt: Ja, warum soll man denn nicht das herausnehmen können, diese Besprechung der zwei Jesusknaben, und sie auch so herausgerissen exoterisch vortragen? — der tut dieselbe Frage, wie einer, der frägt: Warum muß denn die Hand just hier am Arm sitzen, an diesem Teil des Körpers? Er könnte ja sogar sagen: Warum sitzt die Hand nicht am Knie? Da könnte sie ja vielleicht auch sein. - Der versteht den ganzen Organismus nicht als Lebewesen, der glaubt, die Hand könnte auch woanders sitzen, nicht wahr? Die Hand kann nirgends anders als am Arm sitzen! So kann in diesem Zusammenhang der Gedanke von den zwei Jesusknaben nicht an einer anderen Stelle sein, weil versucht ist, die Sache so auszubilden, daß der lebendige Gedanke in der Darstellung drinnen liegt.

Nun kommt einer und schreibt eine Schrift und nimmt diesen Gedanken grobklotzig heraus und setzt ihn mit anderen Gedanken in Zusammenhang, mit denen er gar nichts zu tun hat! Das heißt aber nichts anderes als: er setzt die Hand ans Knie! Was tut einer, der die Hand ans Knie setzt? Ja, an einem Organismus wird man es nicht machen können, aber man könnte es ja zeichnen. Das Papier ist geduldig, es könnte einer einfach eine menschliche Figur aufzeichnen, hier abgestutzt, und die beiden Knie so, daß Hände daraus herauswachsen. [Diese Zeichnung ist nicht überliefert.] Nicht wahr, das könnte einer zeichnen, dann hätte er aber einen unmöglichen Organismus gezeichnet; er hätte bewiesen, daß er vom wirklichen Leben nichts versteht! Man könnte ja auch den Vergleich gebrauchen: er hat den Adler, den Vogel, der für die Luft bestimmt ist, in die Tiefe des Meeres hinunterversetzt oder dergleichen.

Was hat ein solcher denn versucht? Ja, sehen Sie, dasjenige, was er versucht hat, kann man mit allen Dingen, die sich nur auf Erkenntnisse des physischen Planes beziehen, ruhig tun. Da kann der eine Professor ein Buch schreiben, indem er mit dem einen anfängt, der andere kann mit dem anderen anfangen, und da kommt es nicht so darauf an: da kann man die Dinge herausnehmen und so weiter. Aber da hat man es nicht mit lebendigen Wesen zu tun, sondern mit Gedankenmaschinen. Das ist das Wesentliche.

Es hat also ein Mensch, der so etwas macht, indem er eine solche Sache aus dem Zusammenhang herausreißt und in einen unmöglichen Zusammenhang hineinversetzt, bewiesen, daß er ganz und gar nicht bekannt ist mit dem Wesen, das unsere ganze geisteswissenschaftliche Strömung seit ihrem Anbeginne durchfeuert und durchglüht, weil er versucht, nach dem ganz gewöhnlichen materialistischen Schema auch das Geistige zu behandeln. Das ist sehr wesentlich. Es ist sehr wichtig, daß man diese Dinge ins Auge faßt, sonst versteht man nicht von innen her den Nerv der höheren Erkenntnisse. Man kann nicht an jeder beliebigen Stelle alles sagen. Und es ist wirklich in bezug auf das Exoterische, das etwas an das Esoterische anstößt, von Hegel schon ausgesprochen worden, daß ein Gedanke an seine Stelle gehört im Zusammenhang. Ich habe das neulich einmal angedeutet, als ich am Geburtstag Hegels einige Andeutungen nach dieser Richtung hin zu machen versuchte. Man kommt also zu nichts Geringerem auf diese Weise, als daß man mit dem Denken ins Leben untertaucht, während man sonst immer im Toten lebt; man taucht ins Leben unter.

Dadurch aber enthüllt sich einem auch etwas, was man vorher überhaupt nicht hat erkennen können und was auf dem physischen Plane gar nicht zu prüfen ist, nämlich das Entstehen und Vergehen. Auch das können Sie schon aus «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» ersehen. Auf dem physischen Plane ist ja nichts anderes zu beobachten als das, was entstanden ist. Das Entstehen kann gar nicht beobachtet werden, nur was entstanden ist, kann auf dem physischen Plan beobachtet werden. Auch das Vergehen kann nicht beobachtet werden, denn wenn der Gegenstand ins Vergehen übergeht, ist er nicht mehr auf dem physischen Plan, oder er geht wenigstens weg vom physischen Plan.

Man kann also das Entstehen und Vergehen auf dem physischen Plan nicht beobachten. Die Folge davon ist, daß wir sagen können: Wir treten in ein ganz neues Weltenelement ein, wenn wir den beweglichen Gedanken entdecken, nämlich in die Welt des Lebens und das ist die Welt des Entstehens und Vergehens.

Okkultistisch gesprochen würde das auch in der folgenden Weise ausgedrückt werden können: Der Mensch war während der alten Mondenzeit - allerdings nur im Traumbewufßtsein - in der Welt des Entstehens und Vergehens darinnen. Da war es nicht so, daß der Mensch erst das Entstandene mit den Sinnen gesehen hat, denn er hat ja die Sinne noch nicht zur Sinnenanschauung ausgebildet gehabt, sondern steckte noch in den Dingen drinnen. Er stellte zwar traumhaft vor, aber die Bilder, welche er traumhaft vorstellte, die ließen ihn wirklich das Entstehen und Vergehen verfolgen. Und das ist es, wozu er sich erst wiederum aufschwingen muß, indem er zu beweglichen Gedanken kommt. So ist das Aufsteigen zur imaginativen Erkenntnis zugleich eine Rückkehr, nur eine Rückkehr auf der Stufe des Bewußtseins. Wir kehren zurück zu etwas, aus dem wir herausgewachsen sind; wir kehren richtig zurück.

So daß wir sagen können: Diese imaginative Erkenntnis ist die Rückkehr in die Welt des Entstehens und Vergehens. Entstehen und Vergehen entdecken wir, wenn wir also zurückkehren. Und wir können gar nicht etwas erfahren über Entstehen und Vergehen, wenn wir nicht zur imaginativen Erkenntnis kommen. Es ist ganz unmöglich, etwas über Entstehen und Vergehen auszumachen, ohne zur imaginativen Erkenntnis zu kommen.

Daher ist ja das, was Goethe über die Metamorphose der Pflanzen und der Tiere geschrieben hat, so unendlich bedeutungsvoll, weil Goethe das wirklich vom Standpunkte der imaginativen Erkenntnis aus geschrieben hat. Und deshalb konnten die Leute nicht verstehen, was eigentlich gemeint war, als ich meine Kommentare schrieb zu «Goethes Naturwissenschaftlichen Schriften», die in den verschiedensten Wendungen immer wieder ausdrücken, daß es gar nicht darauf ankomme, an den gegenwärtigen naturwissenschaftlichen Erkenntnissen diejenigen Goethes zu bemessen, sondern sich in diese naturwissenschaftlichen Erkenntnisse Goethes selbst zu vertiefen und in ihnen etwas ungeheuer Überragendes zu sehen, etwas ganz anderes als die gegenwärtigen Naturwissenschaftserkenntnisse zu sehen. Deshalb habe ich hingewiesen auf einen Satz, den Goethe so wunderschön ausgesprochen hat und in dem er andeutet, worauf es bei ihm ankommt. Goethe machte die Italienische Reise und verfolgte dabei mit Interesse nicht nur die Kunst, sondern auch die Natur. Man sieht, wenn man die «Italienische Reise» liest, wie er Schritt für Schritt sich in alles das, was ihm Mineralisches, Pflanzliches und so weiter bieten konnte, vertiefte. Und dann, als er in Sizilien angekommen war, da sagte er, nach dem, was er da beobachtet hatte, nun möchte er eine Reise nach Indien machen, nicht um Neues zu entdecken, sondern um das Entdeckte, das schon von anderen Entdeckte, in seiner Art anzuschauen. Das heißt mit anderen Worten: mit beweglichen Begriffen anzuschauen! Das ist es, worauf es ankommt: Das, was andere entdeckt haben, mit beweglichen Begriffen anzuschauen. Das ist das so ungeheuer Bedeutungsvolle, daß Goethe diese beweglichen Begriffe eingeführt hat in das wissenschaftliche Leben.

Daher ist für den, der okkultistisch begreift, das Folgende ein Faktum, das sonst verkannt wird. Ernst Haeckel und andere materialistische, oder wie man auch sagt, monistische Gelehrte, haben sich sehr anerkennend über Goethes Metamorphose der Pflanzen und der Tiere ausgesprochen. Aber daß sie sich anerkennend aussprechen konnten, das beruht auf einem sehr merkwürdigen Prozesse, den ich Ihnen auch durch einen Vergleich klarmachen will.

Nehmen Sie an, Sie haben eine Pflanze in einem Blumentopf vor sich, oder gar, was noch besser ist, draußen im Garten, und Sie wollen diese Pflanze genießen. Sie gehen hinaus in den Garten, um sie zu genießen, um sich in ein Verhältnis zu ihr zu bringen. Und nun denken Sie sich, es gäbe einen Menschen, der mit der Pflanze gar nichts anfangen kann. Und wenn man sich fragt, warum, dann entdeckt man: Den stört ja eigentlich das Leben! Und darum macht er einen Abguß der Pflanze ganz fein nach, so daß die Pflanze jetzt so ist wie die wirkliche, aber in Papiermaché. Das stellt er sich ins Zimmer und jetzt hat er seine Freude daran. Das Leben hat ihn gestört; er hat erst jetzt seine Freude daran!

Ich kann Ihnen nicht sagen, welche Qualen ich als Bub ausgestanden habe bei dem Vergleich, der auch charakterisierend ist für die Gesinnung der Menschen, ich habe oftmals hören müssen als Knabe, daß jemand das Schöne einer Rose dadurch besonders hervorheben wollte, daß er sagte: Wahrhaftig, wie aus Wachs! - Es ist zum Aus-der-Haut-Fahren! Aber es gibt das. Es gibt das wirklich, daß jemand das Vorzügliche eines Lebendigen dadurch hervorhebt, indem er in seiner Redewendung sagt, es wäre wie ein Totes. Das gibt es wirklich. Für den, der eine Empfindung für die Sache hat, ist das etwas Furchtbares. Aber wenn man nicht solche Empfindungen hat, so kann man sich wirklich nicht der Realität gemäß weiter entwickeln.

Nun also, bei Ernst Haeckel ist folgendes passiert. Goethe hat «Die Metamorphose der Pflanzen» und «Die Metamorphose der Tiere» geschrieben, Haeckel liest sie und Ahriman verwandelt ihm das Lebendige, das Goethe geschrieben hat, in Attrappen, in etwas, was aus Papiermaché eigentlich ist, und das begreift er. Das gefällt ihm eigentlich. So daß man in dem, was er lobt, gar nicht das gelobt hat, was Goethe wirklich gemeint hat, sondern Haeckel hat es erst ins Mechanistische umgesetzt. Da tritt eben zwischen Goethe und Haeckel der Ahriman, der das Lebendige in ein Totes verwandelt.

Nun ist, wie ich gesagt habe, dieses sich zur imaginativen Erkenntnis bewußt Hinaufschwingen ein Rückkehren. Ich habe schon im Anfang des Vortrages gesagt: eigentlich sind die Imaginationen schon in uns, sie sind in uns seit der Mondenzeit, und die Erdenentwickelung besteht darinnen, daß wir die gewöhnlichen Bewußtseinsschichten darübergelegt haben. Jetzt kehren wir durch das, was wir uns im gewöhnlichen Erdenbewußtsein angeeignet haben, wiederum zurück. Es ist eine wirkliche Rückkehr.

Und nun kann man sich fragen: Wie kann man denn das Ganze bezeichnen? Man kann jetzt sagen: Es ist ein Hinuntersteigen und ein Wiederaufsteigen. Jetzt hat man erst eine Berechtigung, überhaupt diese Linie hinzuzeichnen [die an der Tafel stehenden Worte werden durch eine Linie verbunden, siehe Schema]; sie von vornherein hinzuzeichnen hätte keinen Sinn. Und jetzt kann man erst sagen: Auf der Stufe des gewöhnlichen physischen Erkennens, da ist man unten, Hier ist das unbewußte imaginative Erkennen, das jetzt unten in unserer Natur sitzt, das zu tun hat mit den Kräften des Entstehens und Vergehens; und auf der anderen Seite, bei dem Hinaufstieg, ist das bewußte imaginative Erkennen. [Beides wurde an der Tafel angekreuzt.]

Wenn man nun gerade Goethe als ein naheliegendes Beispiel nimmt - ich will ihn nur als ein Beispiel ansehen -, so kann man sagen: Bei Goethe ist in der neueren Epoche der Punkt gekommen, wo die äußere Entwickelung der Menschheit das imaginative Erkennen erfaßt, wo es wirklich in die Wissenschaft eingeführt wird.

Nun kann man sich fragen: Jetzt kann man studieren, ob nicht ganz merkwürdige Dinge damit verknüpft sind? Ja, sie sind damit verknüpft, denn im Grunde genommen ist die ganze Goethesche Denkweise eine durchaus andere als die anderer Menschen. Und Schiller, der eben diese Denkweise nicht entwickeln konnte, der konnte deshalb Goethe doch nur aus äußerster Anstrengung verstehen, wie Sie aus dem Briefwechsel zwischen Schiller und Goethe ersehen können an der Stelle, die ich öfters anführte, wo Schiller an Goethe schreibt am 23. August 1794:

«...Lange schon habe ich, obgleich aus ziemlicher Ferne, dem Gang Ihres Geistes zugesehen, und den Weg, den Sie sich vorgezeichnet haben, mit immer erneuter Bewunderung bemerkt. Sie suchen das Notwendige der Natur, aber Sie suchen es auf dem schwersten Wege, vor welchem jede schwächere Kraft sich wohl hüten wird. Sie nehmen die ganze Natur zusammen, um über das Einzelne Licht zu bekommen; in der Allheit ihrer Erscheinungsarten suchen Sie den Erklärungsgrund für das Individuum auf. Von der einfachen Organisation steigen Sie, Schritt vor Schritt, zu der mehr verwickelten hinauf, um endlich die verwickeltste von allen, den Menschen, genetisch aus den Materialien des ganzen Naturgebäudes zu erbauen. Dadurch, daß Sie ihn der Natur gleichsam nacherschaffen, suchen Sie in seine verborgene Technik einzudringen. Eine große und wahrhaft heldenmäßige Idee, die zur Genüge zeigt, wie sehr Ihr Geist das reiche Ganze seiner Vorstellungen in einer schönen Einheit “ zusammenhält. Sie können niemals gehofft haben, daß Ihr Leben zu einem solchen Ziele zureichen werde, aber einen solchen Weg auch nur einzuschlagen, ist mehr wert als jeden anderen zu endigen, und Sie haben gewählt, wie Achill in der Ilias zwischen Phthia und der Unsterblichkeit. Wären Sie als ein Grieche, ja nur als ein Italiener geboren worden und hätten schon von der Wiege an eine auserlesene Natur und eine idealisierende Kunst Sie umgeben, so wäre Ihr Weg unendlich verkürzt, vielleicht ganz überflüssig gemacht worden. Schon in die erste Anschauung der Dinge hätten Sie dann die Form des Notwendigen aufgenommen und mit Ihren ersten Erfahrungen hätte sich der große Stil in Ihnen entwickelt. Nun, da Sie ein Deutscher geboren sind, da Ihr griechischer Geist in diese nordische Schöpfung geworfen wurde, so blieb Ihnen keine andere Wahl, als entweder selbst zum nordischen Künstler zu werden, oder Ihrer Imagination das, was ihr die Wirklichkeit vorenthielt, durch Nachhilfe der Denkkraft zu ersetzen, und so gleichsam von innen heraus und auf einem rationalen Wege ein Griechenland zu gebären. In derjenigen Lebensepoche, wo die Seele sich aus der äußeren Welt ihre innere bildet, von mangelhaften Gestalten umringt, hatten Sie schon eine wilde und nordische Natur in sich aufgenommen, als Ihr siegendes, seinem Material überlegenes Genie diesen Mangel von innen entdeckte, und von außen her dutch die Bekanntschaft mit der griechischen Natur davon vergewissert wurde. Jetzt mußten Sie die alte, Ihrer Einbildungskraft schon aufgedrungene schlechtere Natur nach dem besseren Muster, das Ihr bildender Geist sich erschuf, korrigieren, und das kann nun freilich nicht anders als nach leitenden Begriffen vonstatten gehen. Aber diese logische Richtung, welche der Geist bei der Reflexion zu nehmen genötigt ist, verträgt sich nicht wohl mit der ästhetischen, durch welche allein er bildet. Sie hatten also eine Arbeit mehr, denn so wie Sie von der Anschauung zur Abstraktion übergingen, so mußten Sie nun rückwärts Begriffe wieder in Intuitionen umsetzen, und Gedanken in Gefühle verwandeln, weil nur durch diese das Genie hervorbringen kann...»

Er hält ihn für einen in die nordische Welt versetzten Griechen, und so weiter. Ja, da sehen Sie die ganze Schwierigkeit Schillers, Goethe zu verstehen! Manche Leute könnten daraus etwas lernen, die glauben, im Handumdrehen Goethe verstehen zu können und sich dadurch über Schiller zu erheben, trotzdem Schiller auch nicht gerade ein Tor war gegenüber denjenigen Menschen, die da glauben, Goethe so ohne weiteres zu verstehen!

Aber das Eigentümliche, das man entdecken kann, das ist das, daß Goethe auch in bezug auf andere Gebiete eine ganz eigentümlich abweichende Anschauung hat, zum Beispiel in bezug auf die ethische Entwickelung des Menschen, namentlich in der Art zu denken, was der Mensch als Belohnung oder Strafe verdient oder nicht.

Man kann Goethe schon von Anfang an in seinem Wirken nicht verstehen, wenn man nicht seine, ich möchte sagen, von seiner ganzen Umgebung abweichende Art, über den Menschen in bezug auf Belohnung und Strafe zu denken, ins Auge faßt. Lesen Sie das Gedicht «Prometheus», wo er sich sogar gegen die Götter auflehnt. Prometheus, das ist natürlich ein Auflehnen gegen die Denkweise der Menschen über Belohnen und Strafen. Für Goethe existiert die Möglichkeit, sich ganz besondere Begriffe zu machen über Belohnen und Strafen. Und in seinem «Wilhelm Meister» hat er das ja wirklich, ich möchte sagen, wunderbar schürfend in den Geheimnissen der Welt, darzustellen versucht. Man versteht den «Wilhelm Meister» nicht, wenn man das nicht ins Auge faßt.

Woher kommt denn das? Das kommt daher, weil man auf dem Gebiet des physischen Erkennens überhaupt nicht sich eine Vorstellung machen kann, welche Strafe oder welche Belohnung in bezug auf die Welt für irgend etwas Menschliches anzusetzen ist, denn das kann erst aufgehen auf dem Gebiet der Imagination. Die Okkultisten haben daher immer auch gesagt: Wenn man hinaufkommt in die imaginative Erkenntnis, erlebt man nicht nur die elementarische Welt, sondern auch - wie sie sich ausdrückten - «die Welt des Zornes und der Strafe». Also nicht nur ist es hier eine Rückkehr in die Welt des Entstehens und Vergehens, sondern zu gleicher Zeit ein Hinaufklettern zur Welt des Zornes und der Strafe. |Die Worte «Rückkehr in die Welt des Entstehens und Vergehens» und «Welt des Zornes und der Strafe» wurden an die Tafel geschrieben. ]

Darum wird die eigentümliche Verkettungsmöglichkeit zwischen dem, was der Mensch wert ist und nicht wert ist mit Bezug auf das Universum erst eine richtige Beleuchtung durch die Geisteswissenschaft erfahren können. Alles andere «Justifizieren» in der Welt ist vorbereitend dazu.

Hier stehen wir an einem wichtigen Punkt, wo ich dann morgen fortfahren will.