The Riddle of Humanity

GA 170

5 August 1916, Dornach

Lecture IV

If we set out to compare the way in which people of today speak about matters of the soul and of the body, with how the Greeks once spoke of these things, we will discover a time, not very long ago, when the Greeks were much more aware of the relationship between body and soul than is the case today. In so doing, it is extraordinarily important for us to be clear that, given the Greeks' view of the world, a materialistic explanation of the connections between body and soul would have been out of the question. Today, when someone says that this or that convolution of the brain is the speech centre, he is thinking about the location of the faculty in a very materialistic way. For the most part, such a person is only thinking of how the speech sounds might be produced, purely mechanically, at some particular place in the brain. Even if he is not explicitly a materialist, at the very least he will think that anyone who wants to understand the real connections must conceive of the act of speaking in more or less materialistic terms. The Greeks could speak much more extensively about the inner connections between body and soul without arousing any materialistic assumptions, for they still felt that the things of the external world could be seen as revelations and manifestations of the spirit.

Today it does not occur to someone who is speaking about the speech centre in the brain that this speech centre is, in the first instance, built in the spirit. Nor does he think of what is there materially as being a sign or symbol or likeness of the spirit that is behind it and exists quite independently of those spiritual events that are played out in the human soul. The Greeks always saw the entire, physically existing human being as a likeness and a symbol of the super-sensible, spiritual reality that stands behind him. It must be conceded that most people of today would not find such a conception at all easy, for even though we may not want them, many materialistic notions have adhered to our souls. Just consider what was said in the last lecture about how a person's head has actually been formed in the spiritual world, how its source is in the spiritual world, and how, essentially, it was prepared in the spiritual world in the time between the previous death and this birth. These days, it would be astonishing to meet someone who does not say, ‘We know for certain that the head is formed in the mother's body during the time of pregnancy; it is mad to say that it is really formed during the long period between the last death and this birth or conception.’ Anyone who thinks in wholly materialistic terms—‘thinks naturally’, one is almost bound to say—must view these aforementioned assertions as a form of madness.

But, as you shall see, if you picture matters in the manner of what follows, it will nevertheless be possible for you to arrive at the appropriate thoughts.

Naturally, prior to conception everything to do with the head is invisible. No meteor descends from the heights of heaven to lodge in the mother's body—of course not. But the forces required for the human head, namely, the forces that form and shape it, are active during the time between death and a new conception. Think of it as a more or less invisible, but already shaped, head. Of course, when I use lines to draw it, they represent something invisible. Only forces are present. (See drawing.)

Nor should these forces be imagined as having the shape of the physical head. But they are the forces that cause the physical shape of the head—bring it about. And these begin to work on matter during the time in the mother's body; the matter takes on form in accordance with these forces. The form of the head is not made there, but the head that is built there is built according to the form that has moved into the mother's body from out of the expanses of the cosmos. That is the real truth. Of course it is only when physical matter comes into this form that it becomes visible for the first time. The physical matter crystallises more or less within the field of certain invisible formative forces. The forces connected with inheritance also play into this, but the principal formative forces of the head are of cosmic origin. In the mother's body, matter is drawn into the field of these forces, which I would like to describe as forces of crystallisation.

Thus, one must keep in mind that what is visible is extraneous material that has, so to speak, been shot into a field of forces. The lines of force originate in the cosmos. Thus you can see how the material part of the head really can he pictured as analogous to iron filings within a magnetic field. The iron filings align themselves in accordance with the magnet's invisible lines of force. The form of the head is to be imagined as radiating in from the cosmos, invisibly, like the force-field emitted by a magnet. What the mother contributes is incorporated into the head in accordance with the cosmic patterns, like iron filings in a magnetic field.

Picturing things in this way will help you to fashion the concepts you need for understanding how the human head is shaped during the period between death and a new birth, and how the formative forces that shape the rest of the organism—not totally, but more or less, as in the previous case—originate in the earthly sphere, in the stream of inheritance passed through the generations. By origin, a human being is both cosmic and earthly: cosmic with respect to the principal source of the head, earthly with respect to the rest of the body. These things are manifestations of the most profound mysteries, so one always has to limit oneself to speaking only about particular aspects. They are unimaginably far-reaching mysteries which contain keys to understanding the origins not only of humanity, but of the whole cosmos. The mysteries at work here actually are keys to understanding the whole cosmos.

So, from this point of view, we can already conceive of man as a being with a dual nature. Because humanity has this dual nature, it is necessary to our studies that we draw a sharp distinction between everything that is a part of the head, or is connected with it, and what is a part of the rest of the organism, or is connected with that.

This brings us to a subject that a contemporary mind finds particularly difficult to understand, for people of today like to explain everything in the same way, to stuff everything into one pigeon-hole. One cannot do this if one keeps the realities in view, but keeping realities in view is the last thing our modern science does! The whole body except for the head—everything to do with the human body with the exception of head—must be seen as a pictorial representation of the spiritual forces standing behind it. What is related to the head, however, is not a pictorial representation in the same sense, but is more like the kind of representation you have in a drawing. A picture resembles its subject more closely than a mere drawing. The painter and the sculptor try to reproduce certain aspects of the original; someone writing a description of a thing uses letters that have very little similarity to the original. Letters are the most extreme example of drawings; paintings and works of sculpture are pictures and resemble their originals much more closely.

Now the difference we are considering here is not so great as the difference between a picture and a written description, but the situation is similar. The rest of the body, excluding the head, is a picture of what stands behind it; the head and all that concerns it is more like a drawing. The head we see with our physical eyes has less resemblance to what stands behind it than does the rest of the body; the body our physical eyes see is more like what stands behind it. The discrepancy is already very pronounced if you observe the etheric body; it is even more pronounced when you observe the astral body—not to mention the ego. Thus, as regards the head—its shape, expression, and so on—we are dealing with something that is more like a drawing; when we look at the rest of the body with our physical eyes we are seeing something that more closely resembles what stands behind it spiritually—it is a closer copy of the super-sensible, invisible forces in which it originated. We must maintain this distinction, for today there is a tendency to observe these two things in the same way. People are fond of reminding themselves of the old saying, ‘Everything transitory is but a likeness.’ And that is rightly said—but there are different degrees of likeness. I want to consider the whole human being as a likeness of the super-sensible, but in such a way that the body is a likeness in the manner of a picture, whereas the head is a likeness in an even higher sense. This follows from the way the rest of the body is formed by the forces in whose midst we live during the period between birth and death, while the head is more the product of the forces in whose midst we live during the period between death and a new birth, or conception. If we want to consider the human being as a whole, both as the being who goes through the life between death and a new birth as well as the being who lives between birth and death, we cannot leave the parts of the human being that remain strictly super-sensible—even when he is here in the physical world—out of our considerations.

I would like to use three words to describe the part of the human being that always remains strictly super-sensible—words that have been particularly significant since time immemorial. During certain periods they have degenerated into mere phrases, as have many such words, but they need not be taken as mere phrases if one gives them their full meaning. In the course of his development, a person comes into contact with truth, beauty and goodness. Truth, Beauty and Goodness are the three concepts to which I refer and which have been spoken about since time immemorial. Even a superficial examination begins to reveal something of these ideas to us. What is normally called truth is related to the life of thought, what one calls beautiful is related to the life of feeling, and what one calls good is related to the life of the will. One can also say: the life of the will brings us into a relationship with morality. Everything to do with aesthetic enjoyment and creativity is related to the life of the feelings. All matters of truth are related to the life of thought.

Naturally, these things are always meant to be taken in a restricted sense. One thing plays over into the other. So is it always with the significant truths. A person develops here on the physical plane by participating in the moral life, in the aesthetic life, and in the life that is concerned with truth. But only the most crass of materialist could believe that the ideas of morality, of aesthetic worth, and of truth, refer to a concrete physical thing. Even for the man living here in the physical world, these three things point to the super-sensible.

Now, in this respect, it is instructive to become acquainted with the spiritual-scientific results that come to light when one addresses the questions: What is the origin of the truth for which man strives? What is the origin of that for which he strives in his artistic, aesthetic enjoyment or in his creative artistic and aesthetic efforts? And what is the source of the morality for which he strives? For you see, in the physical world, everything to do with truth is related to the forces that are developed by means of the physical head. Indeed, it is related in such a way that matters of truth depend on the interaction between the physical head and the external, earthly world—extended, obviously, to include the cosmos, but the earthly, external world all the same. Thus, one can say: Matters of truth involve a relationship between our head and the outer world.

What do we observe when we turn to matters of beauty, to the aesthetic? All these things rest on interactions and relationships. If truth is based on the relationship of the head to the external world, then what relationship provides the basis for aesthetic experience, for artistic experience? In the one case, our experience depends on the relation between the head and the rest of the body. It is very important to be entirely clear about this. Consider how here, in this world, a total, unqualified, absolutely awake consciousness is necessary for grasping the truth. Anyone who without further ado accepts a dream as truth,—truth in the same sense that we acknowledge it on the physical plane—is ill, is he not? Thus, in matters of thorough-going waking consciousness, our head is the organ that comes into consideration. And the consciousness of truth that we develop here on earth, or need to develop, is based primarily on the interaction between our head and the outer world. Of course this includes the spiritual parts of the external world in so far as we can come into contact with them, but they, also, belong to the world that surrounds us. With aesthetic experience, what comes into consideration is what lives in the head and in the rest of the organism, for aesthetic experience arises either when the head dreams about what is going on in the rest of the organism, or when the rest of the organism dreams about what is going on in the head. These are interactions that involve more than can be contained in our normal life of ideas. The roots of these experiences reach beneath the conscious levels and they depend on the inward, more unconscious way our body and head interact when we enjoy something beautiful. The same elements that we are otherwise aware of in dreams surge back and forth, back and forth. This is the primary thing with aesthetic enjoyment: either the head is dreaming about the contents of the rest of the body, or the rest of the body is dreaming about the contents of the head. And then, afterwards, we bring this back from our inner world into waking consciousness. The waking consciousness comes second. The occult basis of all aesthetic and artistic enjoyment is this surging and weaving back and forth between the head and the rest of the organism. In the case of lesser aesthetic pleasures, the head is dreaming of the body; with the higher and highest aesthetic pleasures, the body is dreaming about the head.

What I have just been explaining to you is the source of much of what I would like to call—if you will forgive the barbaric expression—the extensive spread of Botocudianism,8Botocudian: The Botocudos are an Indian tribe of eastern Brazil. According to Chamber's Encyclopaedia of 1901 (Vol. 11, pp., 356-7), they are ‘the most barbarous of the Indian tribes of Brazil’. The tenor of the description that follows suggests how ‘botocudian’ could have become synonymous with extreme barbarism. The article concludes with the comment, ‘Ungovernably passionate, they often commit outrageous cruelties; but through systematically cruel treatment they have been almost annihilated, and now number not more than 4,000.’ of the botocudian attitude people have regarding aesthetic matters. Everyone strives for truth, do they not, and also to do the good and follow the dictates of conscience, but when it comes to the aesthetic sphere we find botocudian attitudes in many circles. The feeling for beauty is not regarded as being necessary for a human being here in the physical world in the same way that truth and goodness are regarded as necessary. A person who does not strive for truth displays a human defect; a person who opposes the good also displays a human defect; but a person who is unable to understand the Sistine Madonna would not be seen as humanly defective because of this—and you will have to agree that there are many people who are unable to approach the artistic side of such a work of art. This is because the aesthetic sphere is something very inward, it involves something that must be done within oneself; it involves an interaction between our two parts, the head and the rest of the body, and in this we are answerable to no one but ourselves. A person without regard for the truth is harmful to others; a person who has no regard for the good is harmful to others, as well as to the spiritual world, as we know. But a person who is a Botocudian in his attitude to the sense of beauty deprives himself without harming the rest of mankind—except for those few who find it distinctly not beautiful for there to be so few who can respond openly to beauty.

Actually, our materialistic age has a false conception of the good, for it is assumed that the good approaches us in the same way as truth approaches us. But that is utter nonsense. The good signifies an interaction between the human body and the outer world, but in this case the body includes the head.

So these things are naturally interwoven! When we speak of the striving for truth, we are talking about the head in relation to the external world. When we speak of the striving for beauty, we are talking about the head in relation to the body. And when we speak of morality, we are talking about the relation of the body to the rest of the world. But in this case we are including the head as part of the body, so that we are talking about the relation of the entire human being to an external world—and, indeed, in this case a purely spiritual outer world. Morality is concerned with the relation of the entire human being to the external world—not, however, to the physical external world, but rather to the spiritual forces and powers that surround us.

My dear friends, you know that when I speak of materialistic science I am speaking of something that has its rightful place, not of something that has no justification for existing. I have given many lectures here about the rightful place of materialism in the external sciences provided it remains within its own borders. But for a long time it has been impossible for scientific materialism to speak correctly about the relation of morality to humanity. It has not been possible for the simple reason that our materialistic science has long been suffering—and still suffers—from a fundamental disease and it will not be able to speak until the illness has been removed. I have mentioned this fundamental illness frequently, but when one, speaks of it our scientifically-minded people regard one as a thorough-going dilettante.

You will be aware of the fact that present-day science talks about two kinds of nerves: the so-called sensory nerves that serve feeling and perception, and the nerves connected with the motor system which are supposed to serve human will impulses and acts of will. The sensory nerves are said to connect the periphery with the inner parts, the motor nerves to connect the inner parts with the periphery. A nerve that issues from the brain and mediates the lifting of my hand is called a motor nerve; whereas it is a sensory nerve that is supposed to be involved when I touch something and feel that it is warm or smooth. Thus, the anatomy and physiology of today assumes there are two kinds of nerves. This is utter nonsense. But it will be a long time before it is recognised as nonsense. Even though it is known that there is no anatomical difference between the motor and the sensory nerves, it will be a long time before people admit that there is only one kind of nerve and that the motor nerves are not different from the sensory nerves. Actually, arousal of the will does not depend on these motor nerves, which serve rather for perception of the processes brought about by the will. For in order to be fully conscious when I lift my hand, I must be able to perceive the movement of my hand. The only thing this involves is an inner sensory nerve which perceives the movements of the hand. I am of course very well aware of all the objections that one can raise against this, based on diseases of the spinal cord, and so on; but when these cases are properly understood they do not furnish contrary evidence, but rather are proof for what I am saying.

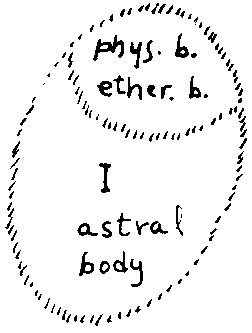

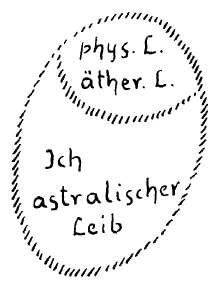

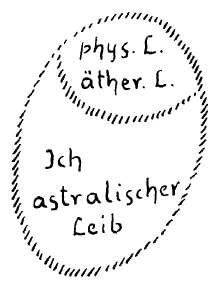

Therefore, there is only one kind of nerve, not the two kinds that haunt today's materialistic science. The so-called motor nerves are only there to serve our perception of movement. They also serve perception. They are internally situated nerves of perception which reach towards the periphery of the body for the purpose of perception. But, as I said, this will only gradually come to be recognised, and only when it has been recognised will it be possible to have some understanding for the connection between morality and the will, or for the direct connection between morality and the entire human being. For morality really works directly on what we call the I. Working down from there, it affects the astral body, the etheric body and, finally, the physical body. Therefore, if a moral act is committed, the moral impulse radiates, so to speak, from the I into the astral body, then into the etheric body, and then into the physical body. Now it becomes movement, becomes something that happens outwardly; and it is only at this stage that it can be perceived by means of the so-called motor nerves.

Morality is truly something that works into humanity directly from the spiritual world. It comes more directly out of the spiritual world than, for example, beauty and truth. In the case of truth, truths have to be approached in a sphere where physical truths, as well as the pure spiritual truths, have a say. In order to enter us, spiritual truths have to make the same detour through the head that is necessary for ordinary physical perceptions mediated by the senses. Moral impulses involve the entire human being, even when we take hold of them in a purely spiritual fashion as moral ideas. That is the fact to keep sight of: they affect the entire human being.

In order to understand this matter more fully we must look further into the way the difference between the head and the rest of the body is revealed. As regards our uppermost part, the head, the things that most come into consideration are the parts we refer to as the physical body and the etheric body. These are revealed distinctly, here in the physical plane, by the head. When I have a physical head before me, I must say to myself: ‘Yes, here I have something expressed like in a drawing. There is a physical shape, the physical body, and the etheric body. But there is already less of the astral body present. And as for the I, it is almost entirely absent; it cannot come very strongly at all into the formative forces of the head. Its presence there is almost entirely restricted to the soul level.’ Thus, the presence of the I in the head is very much on the soul level; although it saturates the head with its soul forces, it remains fairly independent of it. This is not the case with the rest of the body. There—paradoxical and strange though it may seem—there the physical body and etheric body are much less physically, bodily present. There the astral body and I are more strongly active. The I is active in the circulation of the blood. Everything else that lives in the body is a strong expression of the astral. On the other hand, the parts of the physical body that are actually physical cannot even be directly observed. (I refer to, as physical, those parts that are governed by physical forces, those subject to physical forces.)

Naturally, it is terribly easy to deceive oneself in this regard. Anyone who accepts materialistic criteria will say that breathing is a physical process in the human being: a person takes in air and then, as a consequence of the breath, certain processes occur in the blood, and so on, all of this being physical processes. Of course these all are physical processes, but the forces on which the chemical processes of the blood are based come from the I. It is precisely in the human body that what is really physical is less involved. For example, physical forces are expressed in the human body when a child begins to crawl and then to assume an upright position. That is a kind of victory over gravity. These extraordinary relationships with balance and with the effects of weight are always present, but they are not physically visible. They are what spiritual science refers to as the physical body: they are physical forces, to be sure, but they are, essentially, forces that cannot be observed. It is like having a balance on a stand; in the middle is the hypomochlion; forces are acting on one side because of the weight that is there; other forces are working on the other side where another weight is hanging. The strings by which the weights are attached are not identical with the forces at work there; even though the forces are physical, they are invisible. This is the sense in which parts of the human body can be called physical—for the most part, they are to be thought of as forces.

When we come to the etheric sphere, there is still a considerable amount that remains unobservable. There are physical processes that are brought into play by sense perceptions, as when perception of taste affects the taste-nerves. All of these, however, are basically very subtle processes.

Then we come to what happens in the muscles, and so on. Although the muscles provide us with a likeness, a picture that we can physically perceive, this picture depends on astral forces. The processes that occur in the nerves also depend on the astral.

And then we come to the circulation of the blood, to the forces of the I. The forces of the I and the astral body are at work in everything associated with the processes of inheritance through the succession of the generations. But astral body and I do not work in the same way in the human head, especially not the I. You could say that the I is very active in man's head when he is awake, but it never brings about any inner processes there in the way it does in the rest of the body, in the blood. The blood that goes to the head is dependent on the rest of the body—that is the kind of thing I meant when I said that one cannot separate things absolutely. One thing plays over into the other. Although blood flows to the head, the actual impulse of the blood does not originate in the head; the blood is pressed into the head. To the extent that this is a bodily process it originates in the I.

Thus, one really can say that when we look at a person's head, the most prominent and most important things to be seen are those that have been pressed outward into the physical and etheric bodies. If we look at the rest of the body, the most important things are the impulses and forces that are at work in it. These originate in the I and the astral body. Therefore, when you contrast the head, on the one hand, with the rest of the body on the other, it is the physical and etheric bodies that are relatively prominent in the head, whereas the astral body and the I that flow through it remain relatively independent. With the rest of the body it is the I and the astral body that are directly at work in the physical processes, whereas the remaining members are only present as the basis of an invisible framework—a physical and etheric framework that is not normally even considered. The place where the I is really present is in the circulation of the blood.

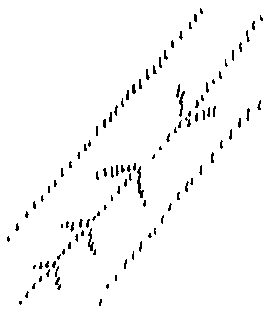

And now, what about the part we could call the moral-etheric aura? First of all, this part works on the entire human being. But it works on the I and the I works on the bodily part of man—for example in the blood. As we saw, the most important thing in the blood is the I. Morality affects the blood. You should not concentrate too much on the physical aspects of the blood; the physical blood is only there to occupy, so to speak, a position in space where the forces of the I can work. Instead, consider the blood in the light of what I have described. Morality, therefore, affects the I. In the blood, the forces of the I encounter the forces of morality. This is true for the man who stands here in the physical world: there is a spiritual encounter between what pulses in his blood and the moral forces that radiate into it. In the course of this encounter, the really moral impulses drive out what otherwise would emanate from the blood. Picture this as the bloodstream: the I flows in it and morality is at work there, too. (See the drawing.) Morality, then, has to counter the initial stream of the I. Therefore it must be a counter-force to this flowing force of the I. And so it is. When someone has the impulse to take a strong moral stand, this moral impulse has a direct effect on his blood. This effect even precedes the perception, mediated by the head, of the moral event and the moral process. This is what led Aristotle to make a wonderful observation. (Aristotle always took note of these things, both the physical and the moral, with an exacting eye.) He said that morality depends on a skill and that actual moral practice is the child of something further—it is the child of intellectual judgement.

To put it radically, the head is a spectator. And so, as we move about here on the physical plane, the forces of the I that are the basis of the circulation of the blood interact with moral impulses pressing in upon us from out of the spiritual world. Essentially, this interaction is based on the fact that we occupy our entire body with our waking consciousness. The I really does have to be present as conscious ego in the pulsing of the blood. Perhaps you are wanting to say—I will slip this in parenthetically—Yes, but the I and the astral body are outside of the physical body and etheric body when one is sleeping. How can the I and the astral body be the prime active forces here, since the shapes and movements still persist during sleep, during the time the astral body and I are absent! To be sure, the essential parts are outside the body, but, as I have often emphasised, this withdrawal from the body only applies essentially to one part of it, the head. I have said explicitly that the interaction of the I and astral body with the rest of the organism is all the more intensive when these are not at work in the head. That has often been said here. The I and the astral body are not separated from the rest of the organism in the same way as they are from the head.

But it is through the head that morality pours in when it encounters the ego forces in the blood. That is why I said earlier that the head must be included here as part of the entire body. For moral impulses cannot pour into the body directly, but have to enter by way of the head. This implies that the person must be awake. If a man is asleep and his I and his astral body have withdrawn from his head, morality would have to pour into the head and body by way of the physical and etheric, rather than spiritually. But this is not possible, for these have nothing to do with morality.

Now, if you will be entirely honest with yourself, there is a simple thing that will convince you of the truth of what I am saying. Just ask yourself how moral you are in your sleep or in your dreams—assuming that morality is not just a reminiscence of physical life! Now and then morality and everything to do with morals has rather a bad time in the world of dreams, does it not? Things can be quite amoral there; the criteria of morality are no more applicable there than they are in the world of plants. As such, moral impulses can only be applied to waking life. So you can see that morality involves a direct influence of our spiritual environment on the forces within us radiating from the I.

Now let us turn to beauty and to the things that have aesthetic effect. We already know that this depends on an interaction between the head and the rest of the body. The head dreams about the rest of the body, the rest of the body dreams about the head. If one investigates what lies behind this, one discovers that everything aesthetic originates in certain impulses that come from the spiritual world and stimulate that interaction. Those representatives of botocudianism to whom I earlier referred are less susceptible to these impulses; they do not allow themselves to be inwardly moved by the impulses that summon up such interactions. These impulses, however, do not affect the I. They work directly on the astral body, as distinguished from moral impulses, which work directly on the I. And that lack of consciousness associated with morality, that half-unconscious quality of conscience, is a result of the way morality must pass through the head—to which the I is not so intimately bound—and thence into the more subconscious realm of the body, seizing the whole person. The aesthetic sphere works directly on the astral body. There it brings about that extraordinary interplay between the part of the astral body that is intensively connected with wakefulness, whether it be wakefulness of the nerves or wakefulness in the muscles of the body, and the part of the astral body that is connected with the head and has less to do with wakefulness in the nerves or muscles of the body. For the head and the rest of the body are related in different ways to the astral body. This is why there are two kinds of human astrality; the more or less free astrality associated with the head, and the astrality that is bound to the physical processes in the rest of the body. The aesthetic impulse causes the free and the bound parts of the astral to interact and play into one another. They weave and surge, back and forth, through one another.

And when we enter the realm of truth, we find that truth, also, is something super-sensible. But it affects the head directly. Truth as such is directly connected with the activities and processes of the head. But the most curious thing about truth is that a human being grasps it in such a way—and truth affects him in such a way—that it flows directly into the etheric body. You may infer this from our numerous discussions of the past. In so far as truth lives in human thoughts, it lives in the etheric body. As I have often said, truth lives with thoughts in the etheric body. Truth enters the etheric part of the head directly. From there, naturally, it is passed on, as truth, to the physical part of the head.

This, you see, is the human being as he is when he is possessed by truth, beauty and goodness—by knowledge, by the aesthetic, by morality. When a person is in the grip of knowledge, or perception, or truth, the external world flows directly into his etheric body from outside-flowing through the I and the astral body in so far as the head is involved in the process. And because a person is not able to submerge himself consciously in his etheric body, the truth appears to him as a thing that is already complete in itself. One of the overwhelming and surprising experiences of initiation comes when one begins to experience truth as a free impulse that resides in the etheric body, in the same way as one experiences morality or beauty in the astral body. This is overwhelming and surprising because the one who goes through an initiation enters into a much freer relationship to truth and, as a consequence, into a much more responsible relationship with truth. As long as we remain unaware of truth as it enters us, it appears as something already completed. Then we simply say, applying the normal logic: this is true, that is false. As long as this remains the case, one has much less of a sense of responsibility towards the truth than one has after discovering that the truth is just as dependent on deeply-rooted feelings of sympathy and antipathy as are morality and beauty. Then one begins to relate to truth in freedom.

At this point we touch on yet another mystery, an important mystery of the subjective life. It manifests itself in the fact that the feeling for truth of some who approach initiation in an improper, unworthy way does not increase. They do not develop a greater sense of responsibility toward the truth. Instead, they cease to feel responsible about violating the truth and come under the influence of a certain element of untruth. Oh, herein lies much of significance regarding mankind's evolution towards spiritual truth, which in its purest form is wisdom. To the extent that it flows into the I and the astral body, truth directly enters the etheric, the human etheric. Beauty affects the human astral body; morality penetrates to the I—it is admitted into the ego. Thus, when truth pours into us from out of the cosmos it still remains for it to work on into the physical body. It must still imprint itself on the physical body—in other words, on the physical brain. There, in the physical realm it becomes perception. When beauty streams into our astral body from out of the cosmos, it still has to work its way into the etheric body and thence into the physical body. The good works into the I, and must imprint itself so strongly on the I that its vibrations are able to penetrate the astral body, the etheric body and, finally, the physical body. Only there, in the physical body, can it finally become effective.

Thus is mankind related to the true, the good and the beautiful.

In truth, man opens his etheric body directly to the cosmos—initially, it is the etheric part of the head. In beauty, he opens his astral body directly to the cosmos. In the sphere of morality, he opens his I directly to the cosmos. Of these, truth is the one that has been in preparation for mankind for the longest time. We will speak further about these things tomorrow and see how they are related to the laws that govern life between death and a new birth, as well as life between birth and death. Relatively speaking, beauty has been in preparation for a shorter time. Morality is something that is only now in its first earthly stages. What lives in the truth and, in its purified state, becomes wisdom, underwent its first stages during the Sun stage of human evolution. It achieved its highest point during the Moon stage, lives further during the Earth stage, and will essentially have reached completion by the period that we call the Jupiter stage of evolution. By then, mankind will have more or less completed the aspects of its development that have to do with the contents of wisdom. Beauty—which is a very inward thing for man—had its first beginnings during Moon evolution. It continues to develop now, during Earth evolution, and it will reach its final completion during Venus—during what we call the Venus stage of evolution. In all these cases where we have had recourse to the occult in assigning names to things, there are good reasons for choosing the names. It is not for nothing that I call one stage of development ‘the Venus stage’; it is so named to correspond with what will then be the dominant process.

During the Moon stage of development there was nothing that could be called morality. At that time, the bonds of necessity, of what was virtually a natural necessity, connected human beings to their acts. Morality could only begin on Earth. It will reach its culmination during the Vulcan stage when the purified I—the I that has been purified by morality and entirely moulded by it—will be the only thing that pulsates in the fiery processes of the blood. Then the forces of the human ego and the forces of morality will have become one and the same thing. Then the blood of mankind—in other words, the warmth of the blood, for matter is just an external sign of this warmth—will have become the holy fire of Vulcan.

Tomorrow we will speak further about these things.

Vierter Vortrag

Wenn wir die Art, wie heute der Mensch über Seelisches und Leibliches spricht, vergleichen mit der Art, sagen wir nur, wie in Griechenland darüber gesprochen worden ist - wir brauchen gar nicht weiter zurückzugehen -, so finden wir, daß in Griechenland der Beziehung zwischen dem Seelischen und dem Leiblichen weit mehr noch Rechnung getragen ist als in unserer Zeit, wobei es außerordentlich wichtig ist, sich klarzumachen, daß innerhalb der griechischen Weltanschauung von einem materialistischen Ausdeuten des Zusammenhanges zwischen Seelischem und Leiblichem nicht die Rede sein konnte. Wenn heute jemand davon spricht, daß diese oder jene Stirnwindung Sprachzentrum ist, so deutet er sich die Sachlage recht materialistisch. Zumeist denkt er überhaupt, daß an der betreffenden Stelle des Gehirns der Sprachlaut mehr oder weniger erzeugt wird, rein mechanisch. Oder wenigstens denkt er, auch wenn er nicht direkt Materialist ist, sich doch den Zusammenhang so, daß derjenige, der den wahren Zusammenhang kennt, die Aussage als mehr oder weniger materialistisch auffassen muß. Der Grieche hat viel weitergehend von der innigen Beziehung zwischen dem Seelischen und Leiblichen gesprochen, ohne materialistische Nebenempfindungen dabei zu haben, weil er noch ein lebendiges Gefühl davon hatte, daß, wenn wir von den Dingen der Außenwelt sprechen, wir von diesen Dingen so sprechen, daß sie Offenbarungen, Manifestationen des Geistigen sind. Der heutige Mensch, der vom Sprachzentrum im Gehirn spricht, denkt nicht daran, daß aus irgendeinem Geistigen heraus dieses Sprachzentrum erst aufgebaut ist, daß dasjenige, was materiell da ist, nur wie ein Zeichen, wie ein Symbol, wie ein Gleichnis eines dahinterstehenden Geistigen ist, ganz abgesehen von dem, was sich in der menschlichen Seele als Geistiges abspielt. Daran hat der Grieche immer gedacht: den ganzen Menschen, wie er dasteht in der physischen Welt, als ein Gleichnis anzusehen, als ein Symbol des ÜbersinnlichGeistigen, das dahintersteht. Es ist ja durchaus zuzugeben, daß diese Vorstellung heute den meisten Menschen nicht ganz leicht wird, weil die Seele, selbst wenn sie es nicht will, heute schon stark an materialistischen Vorstellungen haftet. Nehmen Sie nur einmal an, was ja schon, wenigstens andeutungsweise, in dem letzten Vortrage gesagt worden ist: Der Kopf des Menschen wird eigentlich in der geistigen Welt gebildet, in der geistigen Welt veranlagt; zwischen dem letzten Tode und dieser Geburt ist der Kopf im wesentlichen gebildet worden. Nicht wahr, man möchte sozusagen den Menschen in der Gegenwart kennen, der nun nicht sagen wird: Man weiß doch ganz genau, daß der Kopf im Leibe der Mutter während der Zeit der Schwangerschaft entsteht, und es ist doch eine Verrücktheit, zu sagen, daß er hauptsächlich in der langen Zeit gebildet wird, die zwischen dem letzten Tode und dieser Geburt oder Empfängnis liegt. - Wer heute ganz materialistisch denkt, und, man möchte fast sagen, naturgemäß so denkt, der muß die eben angeführte Behauptung mehr oder weniger als eine Art Verrücktheit ansehen.

Aber, sehen Sie, Sie kommen, wenn Sie sich die Sache in der folgenden Art vorstellen, schon zu der Möglichkeit, einen entsprechenden Gedanken zu gewinnen.

Natürlich, vor der Empfängnis ist alles das, um was es sich handelt am menschlichen Kopf, unsichtbar; es fährt natürlich kein Meteor aus Himmelshöhen in den Leib der Mutter hinein. Aber die Kräfte, die in Betracht kommen, namentlich auch die Formungskräfte, die gestaltenden Kräfte des menschlichen Hauptes, die sind tätig in der Zeit zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Empfängnis. Denken Sie sich gewissermaßen eine unsichtbare Form des Kopfes ausgebildet, die man nur sichtbar zeichnet, also die Linien, die ich jetzt hier andeute, die sind natürlich dann unsichtbar. Das alles sind nur Kräfte (siehe Zeichnung Seite 58).

Diese Kräfte muß man sich auch nicht so vorstellen, daß sie die physische Form des Kopfes haben. Aber es sind Kräfte vorhanden, welche diese physische Form des Kopfes bewirken, bedingen. Und während der Vorbereitungszeit des menschlichen Hauptes im Mutterleibe setzt sich die Materie an diese Kräfte an; im Sinne dieser Kräfte setzt sich die Materie an. Nicht die Form des Kopfes wird gebildet, sondern nach der Form, die aus kosmischen Weiten in den Mutterleib versetzt ist, wird der Kopf gebildet. Das ist schon einmal wahr. An diese Formen setzt sich die physische Materie an, und dann wird es natürlich erst sichtbar. Es kristallisiert sich die Materie gewissermaßen um bestimmte unsichtbare Bildekräfte. Gewiß, es spielen noch die mit der Vererbung zusammenhängenden Kräfte hinein, aber die hauptsächlichsten Bildekräfte des Kopfes sind kosmischen Ursprungs, sind gewisse Kristallisationskräfte, möchte ich sagen, an die sich die Materie im Mutterleib ansetzt.

Also das muß man schon festhalten, daß das, was man sieht, gewissermaßen angeschossen ist, angeschossene Materie. Die Kraftlinien, die sind aus dem Kosmos. Sehen Sie, das Materielle des Hauptes können Sie sich wirklich so vorstellen wie etwa, wenn Sie einen Magneten haben, und sich nach bestimmten Kraftlinien Eisenfeilspäne anordnen; ja, die Eisenfeilspäne ordnen sich nach den unsichtbaren Kraftlinien des Magneten an. So unsichtbar wie der Magnet seine Strahlen aussendet, müssen Sie sich auch die Form des Kopfes vorstellen, wie sie aus dem Kosmos hereinwirkt. Und wie sich die Eisenfeilspäne nach Maßgabe der magnetischen Linie ordnen, so ordnet sich das, was die Mutter hergibt, nach Maßgabe der kosmischen Formen, die dem Haupte eingegliedert sind.

Wenn Sie diese Vorstellung zu Hilfe nehmen, dann werden Sie sich schon einen entsprechenden Gedanken bilden können davon, daß an dem menschlichen Haupt gearbeitet wird während der Zeit zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, und daß die Bildekräfte für den übrigen Organismus — aber auch wiederum nur mehr oder weniger, nicht vollständig — angesetzt werden vom Irdischen aus, von dem, was in den Vererbungsverhältnissen durch die Generationen liegt. Insoferne ist der Mensch irdischen und kosmischen Ursprungs, kosmischen Ursprungs in bezug auf seinen Hauptesteil in der Hauptsache, irdischen Ursprungs in bezug auf seinen übrigen Leib. In diesen Sachen spielen die allertiefsten Mysterien, und man kann immer nur einzelne Dinge daraus besprechen; ungeheuer tiefgehende Geheimnisse, die aufschlußgebend sind nicht nur für die Menschheitsentstehung, sondern eigentlich für den ganzen Kosmos, für das Verständnis des ganzen Kosmos, spielen da hinein.

So können wir den Menschen von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus schon als eine Art Doppelwesen auffassen. Und weil er ein solches Doppelwesen ist, muß man beim Studium scharf unterscheiden zwischen all dem, was zum Haupt gehört und mit dem Haupt zusammenhängend ist, und dem, was zum übrigen Organismus gehört und mit ihm zusammenhängt.

Und da kommen wir zu einer Sache, die insbesondere für unsere jetzige Zeit dem Verständnis außerordentlich große Schwierigkeiten macht. Denn heute will man eigentlich alles in gleicher Weise erklären, alles über einen Leisten schlagen. Das kann man nicht, wenn man Realitäten ins Auge faßt, und die materialistische Wissenschaft faßt am wenigsten Realitäten ins Auge! Alles, was zum menschlichen Leibe gehört, mit Ausschluß des Hauptes, muß so betrachtet werden, daß dieser menschliche Leib — abgesehen vom Haupt - eine bildhafte, gleichnishafte Darstellung dessen ist, was an geistigen Kräften dahintersteht. Alles, was mit dem Haupt zusammenhängt, ist nicht in demselben Sinne eine bildhafte Darstellung, sondern mehr eine zeichenhafte Darstellung. Beim Bilde hat das, was im Bilde ist, noch mehr Ähnlichkeit mit dem, was zugrunde liegt, als beim bloßen Zeichen. Der Maler, der Bildhauer versucht in den Bildern gewisse Ähnlichkeiten mit dem Originale wiederzugeben; derjenige, der etwas schreibt, gibt in den Buchstaben sehr wenig Ähnlichkeit mit dem Original. Buchstaben sind im äußersten Falle Zeichen; Gemälde, Bildhauerwerke sind Bilder, die haben noch sehr viel zu tun mit dem Original.

Nun ist der Unterschied, den wir hier ins Auge fassen, nicht so groß wie der zwischen einem Bild und einem Geschriebenen, aber ähnlich liegen die Dinge. Der übrige Leib, also außer dem Haupte, ist mehr Bild; alles, was am Haupte ist, ist mehr Zeichen für das, was zugrunde liegt. Es ist zwischen dem, was wir mit physischen Augen am Haupte sehen, und dem, was dem Haupte zugrunde liegt, eine geringere Ähnlichkeit als zwischen dem, was wir mit physischen Augen sehen beim übrigen Leib und dem, was ihm zugrunde liegt. Das drückt sich schon bei der Betrachtung des Ätherleibes sehr stark aus; noch mehr bei der Betrachtung des astralischen Leibes oder gar des Ich. Also beim Haupt haben wir es mehr mit Zeichen zu tun in den Formen, im Ausdruck und so weiter; beim übrigen Leib haben wir es mehr mit Abbildung zu tun, mit einer größeren Ähnlichkeit zwischen dem, was unsere physischen Augen sehen, und dem, was geistig zugrunde liegt an Kräften, an übersinnlichen und unsichtbaren Kräften. Diesen Unterschied muß man machen; denn heute liegt die Tendenz vor, beides in gleicher Weise zu betrachten. Der Mensch bekennt sich am liebsten dazu, daß er sagt: «Alles Vergängliche ist nur ein Gleichnis.» Das ist ja richtig — aber in verschiedenem Grade ein Gleichnis. Ich möchte den ganzen Menschen als ein Gleichnis des Übersinnlichen betrachten, aber so: ein bildhaftes Gleichnis ist der Leib; aber im höheren Sinne sogar Gleichnis ist das Haupt. Und das hängt damit zusammen, daß der übrige Leib mehr gebildet wird durch die irdischen Kräfte, in deren Mitte wir zwischen Geburt und Tod leben, und das Haupt mehr bestimmt wird durch diejenigen Kräfte, in deren Mitte wir zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt leben beziehungsweise einer neuen Empfängnis. Wollen wir aber den vollständigen Menschen betrachten mit Bezug auf sein Durchgehen einerseits durch das Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod, und andererseits durch das Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, dann müssen wir allerdings auch noch etwas ins Auge fassen, was ja am Menschen immer, auch hier in der physischen Welt, streng übersinnlich bleibt.

Das, was dem Menschen eigen ist und an ihm streng übersinnlich bleibt, das bezeichnet man ja, ich möchte sagen, seit relativen Urzeiten mit drei Worten, denen man immer eine große typische Bedeutung beigelegt hat, die auch zuweilen, wie viele solche Worte, zu Phrasen werden, aber eben nicht Phrasen sein müssen, wenn man sie ihrer vollen Bedeutung nach nimmt: Der Mensch lebt innerhalb seiner Entwickelung sich ein in die Wahrheit, in die Schönheit, in die Güte. Das Wahre, Schöne, Gute, das sind ja die drei Begriffe, von denen, wie gesagt, seit relativen Urzeiten viel gesprochen wird. Schon eine oberflächliche Betrachtungsweise kann Ihnen einen gewissen Zusammenhang mit Bezug auf diese drei Ideen enthüllen. Das, was man gewöhnlich als Wahrheit bezeichnet, hängt mit dem Vorstellungsleben zusammen, was man als Schönheit bezeichnet, mit dem Gefühlsleben, was man als Güte bezeichnet, mit dem Willensleben. Man kann auch sagen: mit dem Willensleben steht im Zusammenhang die Moralität. Alles ästhetische Genießen oder ästhetische Hervorbringen, also alles Ästhetische steht im Zusammenhang mit dem Gefühlsleben. Alles Wahrheitsmäßige steht im Zusammenhang mit dem Vorstellungsleben.

Die Dinge sind natürlich immer wieder im engeren Sinne gemeint. Eines spielt ja ins andere hinüber. Es sind nur immer die signifikanten Dinge der Wahrheit. Indem sich der Mensch einlebt in das moralische Leben, in das ästhetische Leben, in das Wahrheitsleben, entwickelt er sich hier auf dem physischen Plane. Aber nur ein ganz krasser Materialist könnte den Glauben haben, daß mit dem, was eigentlich durch die Ideen: Moralität, Ästhetisches, Wahrheitsgemäßes gemeint ist, irgend etwas physisch Greifbares angedeutet werden könnte. Es weisen diese drei Dinge durchaus auf ein Übersinnliches hin, in dem der Mensch hier in der physischen Welt lebt.

Nun, von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus ist es bedeutsam, das geisteswissenschaftliche Ergebnis kennenzulernen, das zutage tritt, wenn man sich frägt: Wie kommt dasjenige zustande, was der Mensch als Wahrheit erstrebt, wie das, was der Mensch als künstlerisches, ästhetisches Genießen oder als künstlerisches ästhetisches Schaffen erstrebt, wie das, was er als Moralität erstreben muß? Sehen Sie, alles Wahrheitsgemäße hängt zunächst hier für die physische Welt mit den Kräften zusammen, die durch das physische Haupt entwickelt werden. Und zwar so, daß das Wahrheitsmäßige auf der Wechselwirkung zwischen dem physischen Haupte und der irdischen Außenwelt beruht; selbstverständlich in den Kosmos hinein, aber der irdischen Außenwelt. Also man kann sagen: Beim Wahrheitsgemäßen liegt ein Verhältnis unseres Kopfes zur Außenwelt vor.

Wie ist es da, wo das Schönheitsmäßige, das Ästhetische in Betracht kommt? Alle solche Dinge beruhen nämlich auf Verhältnissen, auf Beziehungen; das Wahrheitsmäßige auf der Beziehung des Kopfes zur Außenwelt. Was für ein Verhältnis kommt nun in Frage beim Ästhetischen, beim Künstlerischen? Da kommt in Frage das Verhältnis zwischen dem Haupt und dem übrigen Leibe. Das ist sehr wichtig, sich das in entsprechender Weise einmal klarzumachen. Sehen Sie, vollständiges, unbedingtes, absolutes Wachbewußtsein ist ja notwendig zur Erfassung der Wahrheit hier in der physischen Welt. Derjenige, der Träume ohne weiteres für wahr hält, in demselben Sinne, wie wir Wahrheit hier auf dem physischen Plan anerkennen, der ist ungesund, nicht wahr? Also für das vollständige Wachbewußtsein kommt unser Haupt in Betracht, unser Haupt als Organ. Und dasjenige, was für das Wahrheitsbewußtsein und was an Wahrheitsbewußtsein entwickelt werden muß, beruht zunächst hier auf Erden auf dem Wechselverhältnis zwischen dem Haupt und der Außenwelt, natürlich namentlich auch dem Geistigen der Außenwelt, das wir erreichen können, aber es ist eben die uns umgebende Welt. Für das Ästhetische kommt in Betracht das, was im Kopfe lebt und das, was im übrigen Organismus lebt; denn das Ästhetische kommt dadurch zustande, daß entweder unser Kopf träumt von dem, was im übrigen Organismus vorgeht, oder unser übriger Organismus träumt von dem, was im Kopfe vorgeht. Es ist ein Wechselverhältnis, das sich nicht vollständig im gewöhnlichen Vorstellungsleben erschöpft, sondern dem schon etwas Unterbewußtes zugrunde liegt; was eben darauf beruht, daß eigentlich, wenn wir Schönes genießen, unser Leib in einem innerlichen, mehr unterbewußten Wechselverhältnis mit unserem Haupt steht. Das wogt hin und her; das ist ein Hin- und Herwogen desselben Elementes, was wir sonst im Traum vor uns haben. Und das ist die Hauptsache beim ästhetischen Genuß: das Träumen des Kopfes vom Inhalte des übrigen Leibes, oder das Träumen des übrigen Leibes vom Inhalte des Kopfes. Und dann bringen wir uns das aus unserem Innern heraus wieder zum Wachbewußtsein. Dieses Wachbewußtsein ist erst das Zweite. Das, was jedem Leben im ästhetischen Genuß, im Künstlerischen okkult zugrunde liegt, ist dieses Wogen, dieses Weben zwischen dem Kopf und dem übrigen Organismus. Bei den niederen ästhetischen Genüssen ist es so, daß der Kopf träumt vom Leib, und bei den höheren und höchsten ästhetischen Genüssen ist es so, daß der Leib träumt vom Kopfe.

Auf dieser Tatsache, die ich Ihnen jetzt vorgeführt habe, beruht vieles von dem, was ich nennen möchte - verzeihen Sie die barbarische Wortbildung — den so weitverbreiteten Botokudismus, das Botokudenmäßige der Menschen in bezug auf das Ästhetische. Nicht wahr, nach Wahrheit streben schon die Menschen alle; nach dem Gewissenhaften, dem Guten auch; aber in bezug auf das Ästhetische ist in weiten Kreisen viel botokudenmäßige Gesinnung vorhanden. Schönheitsgefühl betrachtet man nicht in demselben Maße als notwendig für den Menschen hier in der physischen Welt wie das Wahre und Gute. Einer, der nicht die Wahrheit erstrebt, hat einen menschlichen Defekt; einer, der sich gegen das Gute sträubt, hat auch einen menschlichen Defekt. Aber nicht ohne weiteres werden Sie einen Menschen, der nichts von der Sixtinischen Madonna versteht — und Sie werden mir zugeben, daß es viele Menschen gibt, die nicht auf das Künstlerische eines solchen Kunstwerks eingehen können -, als mit einem menschlichen Defekt behaftet ansehen. Es ist allgemeines menschliches Bewußtsein, daß man das nicht tut. Aber das beruht eben darauf, daß im Grunde genommen das Ästhetische ein recht Innerliches ist, dadurch, daß es etwas ist, was der Mensch mit sich selber abmacht, ein Wechselverhältnis zwischen seinem Hauptesteil und seinem übrigen Leibesteil, und daß der Mensch gewissermaßen mit Bezug auf das Ästhetische dadurch nur sich selbst gegenüber verantwortlich ist und niemand anderem. Einer, der nichts auf die Wahrheit hält, wird schädlich der übrigen Menschheit; einer, der nichts auf das Gute hält, wird schädlich der übrigen Menschheit, und, wir wissen, auch für die geistige Welt. Einer, der nur ein Botokude ist in bezug auf den Schönheitssinn, der verliert für sich etwas, aber er schadet der übrigen Menschheit nicht — außer den wenigen, die selber es als etwas Unschönes empfinden, daß so wenige Menschen für die Schönheit ein offenes Organ haben.

Von dem Guten hat unsere materialistische Zeit eigentlich die allerunrichtigste Vorstellung; denn das Gute betrachtet man ungefähr so, als ob es in derselben Weise an den Menschen herankäme wie das Wahre. Aber das ist ein völliger Unsinn. Das Gute bedeutet ein Wechselverhältnis zwischen dem Leib des Menschen und der Außenwelt, nur daß jetzt zum ganzen Leib der Kopf hinzugehört.

Also, hier gehen die Dinge natürlich ineinander! Wenn wir von dem Wahrheitsstreben reden, so haben wir den Kopf im Verhältnis zur Außenwelt; wenn wir von dem Schönheitsstreben reden, so haben wir den Kopf im Verhältnis zum Leibe; und wenn wir von Moralität sprechen, haben wir den Leib im Verhältnis zur Außenwelt, aber so, daß der Kopf jetzt mitgerechnet ist zum Leibe, also den ganzen Menschen in einem Verhältnis zu einer, und zwar jetzt nur geistigen Außenwelt. Alles Moralische beruht auf einem Verhältnis des Gesamtmenschen zur Außenwelt; nicht zur physischen Außenwelt, sondern zu dem, was uns an geistigen Kräften und Mächten umgibt.

Meine lieben Freunde, Sie wissen, wenn ich von materialistischer Wissenschaft rede, rede ich von etwas Berechtigtem, nicht von etwas Unberechtigtem; ich habe hier viele Vorträge darüber gehalten, wie berechtigt der Materialismus in der äußeren Wissenschaft ist, wenn er seine Grenzen einhält. Aber von jener Beziehung, die die Moralität hat zum Menschen, wird dieser Materialismus in der Wissenschaft noch lange nicht das Richtige sagen können aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil ja unsere materialistische Wissenschaft an einer Grundkrankheit heute noch leidet, die erst behoben werden muß. Ich habe ja diese Grundkrankheit öfter erwähnt; aber wenn man von ihr spricht, so ist es für den heutigen Wissenschafter schon so, als ob man als ein blutiger Dilettant reden würde.

Sie wissen, daß die heutige Wissenschaft davon spricht, daß der Mensch zweierlei Nerven hat: sogenannte sensitive Nerven, die zur Empfindung, zur Wahrnehmung da sind, und motorische Nerven, die die Willensregungen, die Willenshandlungen des Menschen vermitteln sollen. Sensitive Nerven, die von der Peripherie hineingehen in das Innere des Menschen, motorische Nerven, die von dem Innern des Menschen nach der Peripherie gehen. Und es würde also ein Nerv, der von dem Gehirn aus vermittelt, daß ich dieHand hebe, ein motorischer Nerv sein; wenn ich etwas berühre, es als warm empfinde oder als glatt, so würde es ein sensitiver Nerv sein. Also zweierlei Nerven gibt es, so nimmt der heutige Anatomie-Physiologe an. Dies ist ein völliger Unsinn. Aber man wird das noch lange nicht als einen Unsinn erkennen. Obwohl man weiß, anatomisch weiß, daß es einen Unterschied zwischen motorischen und sensitiven Nerven nicht gibt, wird man doch noch lange nicht gelten lassen, daß es nur eine Art von Nerven gibt, und daß auch die motorischen Nerven nichts anderes sind als sensitive Nerven. Die motorischen Nerven dienen nämlich nicht zur Erregung des Willens, sondern sie dienen dazu, den Vorgang, der durch den Willen ausgelöst wird, wahrzunehmen. Also, wenn ich eine Hand bewege, so muß ich, damit ich mein volles Bewußtsein habe, die Handbewegung wahrnehmen. Es handelt sich nur um einen inneren sensitiven Nerv, der die Handbewegung wahrnimmt. Ich kenne natürlich ganz gut alles das, was dagegen einwendbar ist, wie es ist bei Rückenmarkskranken und dergleichen; aber wenn man die Dinge in der entsprechenden Weise versteht, so sind sie keine Einwände, sondern gerade Beweise für das, was ich jetzt sage.

Also es gibt nicht diese zweierlei Nerven, die heute in der materialistischen Wissenschaft spuken, sondern nur einerlei Nerven. Die sogenannten motorischen Nerven sind nur da, damit dieBewegung wahrgenommen werden kann; sie sind auch Wahrnehmungsnerven, indem innerlich gelegene Wahrnehmungsnerven sich nach der Peripherie des Körpers hin erstrecken, um wahrzunehmen. Doch, wie gesagt, das wird man erst nach und nach erkennen; und dann erst wird man das Verhältnis einsehen können, in dem die Moralität zum Willen und unmittelbar zum ganzen Menschen steht, weil die Moralität wirklich unmittelbar auf das wirkt, was wir das Ich nennen. Von da aus wirkt es dann herunter in den Astralleib, in den Ätherleib, und von da in den physischen Leib. Wenn also aus Moralität eine Handlung begangen wird, so strahlt gewissermaßen der Moralitätsimpuls in das Ich, von da in den Astralleib, von da in den Ätherleib, von da in den physischen Leib. Da wird er Bewegung, da wird er dasjenige, was der Mensch äußerlich tut, was erst wahrgenommen werden kann durch die sogenannten motorischen Nerven.

Moralität ist wirklich etwas, was unmittelbar aus der geistigen Welt in den Menschen hereinwirkt, was stärker aus der geistigen Welt heraus wirkt, als zum Beispiel Schönheit und Wahrheit. Bei der Wahrheit liegt die Sache so, daß wir die rein geistigen Wahrheiten hineingestellt finden in eine Sphäre, in der auch die physischen Wahrheiten mitsprechen müssen. In einer ähnlichen Weise, wie die gewöhnliche physische Wahrnehmung durch die Sinne vermittelt wird, kommen auf dem Umwege durch den Kopf die geistigen Wahrheiten in uns herein. Die moralischen Impulse, auch wenn wir sie ganz geistig fassen als moralische Ideen, kommen nicht auf dem Umwege des Kopfes, sondern die berühren den ganzen Menschen. Das ist als Tatsache festzuhalten: die wirken auf den ganzen Menschen.

Um diese Sache voll zu verstehen, ist es sehr wichtig, daß Sie ins Auge fassen, wie sich nun weiter die Verschiedenheit zwischen dem Haupte und dem übrigen Leib des Menschen ausdrückt. Der Kopf des Menschen, das Haupt ist so, daß bei ihm am meisten in Betracht kommt das, was wir physischen Leib nennen und Ätherleib; die sind so recht ausgeprägt hier auf dem physischen Plan im Haupte. Wenn ich so ein Haupt auf dem physischen Plan vor mir habe, so muß ich sagen: Ja, das drückt mir aus als Zeichen: physische Form, physischer Leib, Ätherleib; aber Astralleib schon weniger, und Ich - das bleibt fast heraußen, das ist fast ganz bloß seelisch für das Haupt, das kann nicht sehr stark hinein in die Bildekräfte des Hauptes. Also beim Kopf ist das Ich eigentlich sehr seelisch; es durchtränkt, durchkraftet seelisch das Haupt, aber es ist als Seelisches ziemlich selbständig. Beim übrigen Leib ist das nicht so. Da ist eigentlich — so paradox, so sonderbar das klingt, aber wahr ist es doch -, da ist eigentlich das Physische und Ätherische viel weniger anwesend im physischen Leib, da ist mehr das Ich und der astralische Leib wirksam; das Ich in der Zirkulation des Blutes. Alle diese Kräfte, die in der Zirkulation des Blutes regelnd da sind, sind eigentlich ein äußerer Ausdruck des Ich. Und alles, was sonst im Leib lebt, ist sehr stark ein Ausdruck des Astralischen, während eigentlich das, was am physischen Leib physisch ist — ich meine, was von physischen Kräften beherrscht ist, was physischen Kräften unterliegt —, auch das, was von Ätherkräften beherrscht wird, so unmittelbar gar nicht wahrgenommen werden kann.

In dieser Beziehung wird man sich natürlich furchtbar täuschen. Wenn man die materialistischen Maßstäbe nimmt, so wird jeder sagen: Wenn der Mensch atmet, so ist das doch ein physischer Vorgang; die Luft geht in ihn hinein; infolge der Atmung findet ein gewisser Prozeß im Blute statt und so weiter, alles physische Vorgänge. Selbstverständlich, alles physische Vorgänge, aber die Kräfte, die zugrunde liegen, sind in den chemischen Blutvorgängen vom Ich kommend. Das eigentlich Physische wird gerade beim Leibe des Menschen viel weniger beachtet. Physische Kräfte drücken sich beim Leibe des Menschen aus, wenn er zum Beispiel als Kind zuerst kriecht und dann allmählich in die Vertikalstellung übergeht. Das ist die eine Art von Überwindung der Schwere; diese eigentümlichen Gleichgewichts- und Schwerewirkungsverhältnisse sind immer in ihm. Aber das ist eigentlich nicht physisch sichtbar, es ist das, was wir in der Geisteswissenschaft den physischen Leib nennen: Es sind zwar physische Kräfte, aber es sind als solche im Grunde genommen unsichtbare Kräfte. So, wie wenn wir eine Waage haben und einen Hebel: in der Mitte das Hypomochlion, auf der einen Seite eine Kraft, die infolge eines Gewichts wirkt, und auf der andern Seite wieder eine Kraft, die infolge eines Gewichts wirkt. Die Kräfte, die da wirken, sind nicht die Schnüre, an denen die Gewichte hängen, sondern die sind unsichtbar, sind aber doch physische Kräfte. So müssen wir das, was wir beim physischen Leib des Menschen physisch nennen, uns zum großen Teil als Kräfte denken.

Und wenn wir ins Ätherische kommen, da ist auch noch ziemlich viel, was unbeachtet bleibt - denn das sind physische Vorgänge, die im Ätherleib spielen, die sich abspielen, wenn die Sinneswahrnehmung wirkt, wenn der Geschmack wirkt in den Geschmacksnerven. Aber das alles sind im Grunde genommen sehr feine Vorgänge.

Dann kommen wir zu dem, was sich in Muskeln und so weiter abspielt, was äußerlich als Gleichnis, als Bild physisch wahrzunehmen ist, was aber von astralischen Kräften abhängt. Auch das, was in den Nerven sich abspielt, ist vom Astralischen abhängig.

Und dann kommen wir zur Blutzirkulation, zu den Ich-Kräften. So, wie das Ich und der astralische Leib wirksam sind bei all dem, was wir durch die Vererbung in der Generationenfolge haben, in der gleichen Weise sind sie nicht wirksam im Kopf des Menschen - vor allem nicht das Ich. Man kann sagen, das Ich ist sehr tätig im Kopf, wenn der Mensch wacht; aber es ist eigentlich niemals so, daß es im Kopfe eine solche innerliche Tätigkeit verrichtet wie im übrigen Leib, im Blute, und das Blut, das zum Kopf geht, ist ja auch vom übrigen Leib abhängig. Deshalb, sagte ich, kann man die Dinge nicht so trennen. Es spielt eines in das andere hinein. Aber dasjenige, was der Impuls des Blutes ist, kommt eben nicht aus dem Kopf, sondern es wird in den Kopf hineingedrängt. Das geht von dem Ich aus, insoferne es vom Leib abhängig ist.

So daß man wirklich sagen kann: Sehen wir uns den Kopf eines Menschen an, so ist das Hervorstechendste, das Wichtigste das, was herausgepreßt ist in den physischen Leib und in den Ätherleib. Sehen wir uns den übrigen Leib an, so ist das wichtigste das, was in ihm pulsiert und ihn erkraftet, das, was vom Ich kommt und vom astralischen Leib. Also, wenn Sie diesen Gegensatz nehmen, einerseits den Kopf und andererseits den übrigen Leib, so würden wir im Kopf hervorstechend haben: physischen Leib und AÄtherleib, und relativ selbständig, das durchflutend, astralischen Leib und Ich. Im übrigen Leib würden wir Ich und astralischen Leib haben, die geradezu in den physischen Vorgängen drinnen wirken; und das übrige liegt eigentlich als unsichtbares Gerüst, als physisches und ätherisches Gerüst, das gewöhnlich gar nicht beachtet wird, zugrunde. Es ist wirklich das Ich physisch in unserer Blutzirkulation.

Dasjenige nun, was wir gewissermaßen die moralisch-ätherische Aura nennen, wie wirkt denn die auf uns? Sie wirkt zunächst auf den ganzen Menschen. Aber sie wirkt auf das Ich, und das Ich wirkt eigentlich im ganzen übrigen Leib, sagen wir zum Beispiel im Blut. Nicht wahr, es ist ja das Ich das Hauptsächlichste im Blute. Die Moralität wirkt auf das Blut. Sie müssen nicht so sehr das physische Blut ins Auge fassen, das eigentlich nur da ist, ich möchte sagen, um die Stelle im Raum auszufüllen, wo die Ich-Kräfte wirken, sondern das Blut im Sinne dessen auffassen, was ich gesagt habe. Also die Moralität wirkt auf das Ich. Es begegnet sich gleichsam dasjenige, was in unserem Blute wirkt als Ich-Kräfte, mit den Kräften der Moralität. Wenn der Mensch hier in der physischen Welt steht, so ist es schon so: was in seinem Blute pulsiert, begegnet sich geistig mit den Kräften, die aus der moralischen Sphäre hereinspielen, und zwar so, daß der eigentlich moralische Impuls dasjenige, was gewissermaßen aufsteigt aus dem Blute, heraustreibt. Also stellen Sie sich vor, wir hätten hier einen Blutstrom, und da strömt das Ich und wirkt die Moralität (siehe Zeichnung $.69). Dann muß die Moralität entgegenwirken dem zunächst strömenden Ich, muß die Gegenkraft zu diesem strömenden Ich sein. Das ist auch der Fall. Wenn jemand unter einem starken moralischen Impuls steht, so ist eine unmittelbare Wirkung des moralischen Impulses auf das Blut vorhanden. Die geht voran selbst der Wahrnehmung des moralischen Vorganges, des moralischen Prozesses durch den Kopf. Daher hat Aristoteles, der diese Dinge immer noch genauer gesehen hat, nicht nur die physischen, sondern auch die moralischen Dinge, ein wunderbares Wort gesagt: daß die Moralität auf einer Fertigkeit beruht, das heißt entbunden ist in bezug auf ihre eigentliche Tätigkeit, entbunden ist dem intellektuellen Urteil.

Der Kopf schaut zu, radikal gesprochen. Also wir haben, indem wir hier auf dem physischen Plan herumgehen, eine Wechselwirkung zwischen gewissen Kräften, die als Ich zugrunde liegen unserer Blutpulsation, und den moralischen Impulsen, die aus einer geistigen Welt in uns hereindringen. Diese Wechselwirkung beruht im wesentlichen darauf, daß wir mit unserem ganzen Leib im Wachbewußtsein sind; das gehört schon dazu, daß wir im Wachbewußtsein sind. Es muß das Ich wirklich pulsieren als bewußtes Ich im Blute. Sie werden vielleicht sagen das will ich gewissermaßen in Parenthese einschalten -: Ja, aber im Schlafe, da ist doch das Ich und der astralische Leib heraußen, die sind heraußen aus dem physischen Leib und Ätherleib. Wenn hier hauptsächlich das Ich und der astralische Leib wirksam sind, dann ist Ja nichts mehr drinnen von dem Ich und dem astralischen Leib im Schlafe. Aber die Formen und Bewegungen bleiben doch! - Gewiß ist das Wesentliche draußen, aber eigentlich - ich habe es öfters betont —: das Heraussein bezieht sich wesentlich auf den Kopfteil. Ich habe ausdrücklich gesagt, die Wechselwirkung zwischen dem Ich und dem astralischen Leib, wenn sie nicht auf den Kopf wirkt, ist um so intensiver in bezug auf den übrigen Organismus. Das ist oftmals hier gesagt worden. Beim übrigen Organismus ist das Ich und der astralische Leib nicht so getrennt.

Aber wenn nun auch die Moralität sich in unserer Blutsphäre mit den Ich-Kräften begegnet, so strömt sie doch so ein, daß sie durch den Kopf geht. Deshalb habe ich früher auch gesagt: Hier gehört der dazu, zum ganzen Leib dazu. Sie muß durch den Kopf gehen, sie darf nicht direkt in den Leib einströmen. Das heißt, der Mensch muß wach sein. Denn würde der Mensch schlafen und das Ich und der astralische Leib aus dem Kopf heraußen sein, so könnte die Moralität nicht durch das Geistige, sondern müßte durch das Physische und Ätherische, womit sie gar nichts zu tun hat, in den Kopf, in den physischen Leib einströmen. Das würde unmöglich sein.

Sie können sich von dem, was ich jetzt sage, wenn Sie ganz ehrlich sind gegen sich, durch etwas sehr Einfaches überzeugen. Fragen Sie sich einmal, ob Sie im Schlafe oder im Traum so durchaus moralisch sind — wenn die Moralität nicht eine Reminiszenz aus dem physischen Leben ist! Mit der Moralität im Traum, mit dem, was man Moralität nennt, steht es zuweilen recht schlimm, nicht wahr? Es kann ja etwas amoralisch sein, das heißt, daß der Maßstab des Moralischen gar nicht anwendbar ist, wie es bei der Pflanzenwelt der Fall ist. Aber der moralische Impuls als solcher kann nur für das Wachbewußtsein gelten. So sehen Sie, wie wir in der Moralität eine Wirkung unserer geistigen Umwelt haben unmittelbar auf diejenigen Kräfte, die in uns Ich-Strahlung sind.

Gehen wir jetzt zur Schönheit, zu dem, was ästhetisch wirkt. Wir wissen schon: es beruht auf einer Wechselwirkung des Kopfteiles und des übrigen Leibes. Es ist so, daß der Kopf träumt von dem übrigen Leib, und der übrige Leib träumt von dem Kopf. Untersucht man das, was zugrunde liegt, so findet man, daß alles Ästhetische auch aus gewissen Impulsen der geistigen Umwelt kommt, welche diese Wechselwirkung in uns anregt. Diejenigen, von welchen ich vorhin gesagt habe, daß sie das botokudische Element darstellen, die sind für diese Impulse wenig empfänglich; die lassen sich nicht anregen durch dasjenige, was im Innern diese Wechselwirkung hervorruft. Aber diese Impulse wirken nun nicht auf das Ich, sondern sie wirken unmittelbar auf den astralischen Leib, während die moralischen Impulse unmittelbar auf das Ich wirken. Und jenes Unbewußte, welches im Moralischen liegt, das den Charakter des unbewußten, halb unterbewußten Gewissens ausmacht, das beruht eben darauf, daß das Moralische durch den Kopf durchgeht, und - da das Ich nicht so intensiv mit dem Kopf verbunden ist - in das mehr Unterbewußte des Leibes eintritt, den ganzen Menschen ergreift. Dasjenige, was aus einer ästhetischen Sphäre kommt, wirkt nun unmittelbar auf den astralischen Leib. Und es wirkt so, daß eben jenes eigentümliche Spiel entsteht zwischen dem astralischen Leib, der intensiv verbunden ist mit aller Regsamkeit, sei es Nerven-, sei es Muskelregsamkeit des Leibes, und dem astralischen Leib, der weniger intensiv mit der Muskel- und Nervenregsamkeit des Kopfes verbunden ist. Der astralische Leib steht eben in einem andern Verhältnis zum Kopfe als zum übrigen Leib. Dadurch hat der Mensch diese zwei Astralitäten: eine gewissermaßen freiere Astralität im Kopfteil, und eine an die physischen Vorgänge gebundene Astralität im übrigen Leib. Und diese gebundene und freie Astralität, die spielen ineinander durch die ästhetischen Impulse. Das ist ein Durcheinanderwogen und Durcheinanderweben.

Und wenn wir ins Gebiet der Wahrheit kommen: Wahrheit ist auch etwas Übersinnliches, wirkt aber in den Kopf direkt hinein. Wahrheit als solche hat es unmittelbar mit den Tätigkeiten, mit den Prozessen des Kopfes zu tun. Aber das Eigentümliche alles dessen, was Wahrheit ist, das ist,daß es so wirkt auf den Menschen, und daher so erfaßt wird, daß es unmittelbar in den ätherischen Leib einströmt. Aus vielen Auseinandersetzungen, die gepflogen worden sind, können Sie das entnehmen. Indem die Wahrheit in Form der Gedanken im Menschen lebt, lebt sie im ätherischen Leib — das habe ich ja oft gesagt -, lebt mit den Gedanken im ätherischen Leib. Wahrheit erfaßt unmittelbar den Ätherteil des Kopfes und überträgt sich da natürlich als Wahrheit auf den physischen Teil des Kopfes.

Sehen Sie, so ist das Ergriffenwerden des Menschen von Wahrheit, Schönheit, Güte, von Erkenntnis, von Ästhetik, von Moralität. Erkenntnis, Wahrnehmung, Wahrheit erfaßt den Menschen so, daß die äußere Welt unmittelbar — durch das Ich und den astralischen Leib hindurchströmend, insofern die am Kopfteil teilnehmen - bis in den Ätherleib hinein von außen her wirkt. Da wird unmittelbar der Ätherleib ergriffen. Und weil der Mensch mit seinem Bewußtsein nicht so untertaucht in seinen Ätherleib, kommt ihm die Wahrheit als etwas Fertiges vor. Das ist gerade das Bestürzende, das Überraschende der Initiation, daß man beginnt, die Wahrheit, wie sie da hineinpulst in den Ätherleib, als etwas ebenso Freies zu empfinden, wie man sonst das Hereinpulsieren der Moralität empfindet oder der Schönheit in den astralischen Leib. Das ist dieses Bestürzende, Überraschende aus dem Grunde, weil es den Menschen, der irgendeine Initiation durchgemacht hat, in ein viel freieres Verhältnis zur Wahrheit bringt, und dadurch in ein viel verantwortungsvolleres Verhältnis zur Wahrheit. Tritt die Wahrheit ganz unbewußt in uns herein, dann ist sie fertig, und dann sagen wir einfach mit der gewöhnlichen Logik: das ist wahr, das ist unwahr. Dann hat man ein viel geringeres Verantwortlichkeitsgefühl gegenüber der Wahrheit, als wenn man weiß, daß die Wahrheit geradeso im Grunde abhängig ist von tiefliegenden Sympathie- und Antipathiegefühlen wie die Moralität und wie die Schönheit, so daß man ein gewisses freies Verhältnis zur Wahrheit hat.

Hier liegt wiederum ein Mysterium, und zwar jetzt ein bedeutsames subjektives Mysterium vor, das sich darin äußert, daß manche, die nicht in richtiger, würdiger Weise sich dem Erlebnis der Initiation nähern, an ihrem Wahrheitsgefühl nicht so gewinnen, daß sie ein größeres Verantwortlichkeitsgefühl entwickeln, sondern daß sie das Verantwortlichkeitsgefühl, das sie gegenüber der aufgezwungenen Wahrheit haben, verlieren und in ein gewisses unwahres Element hineinkommen. Oh, hier liegen sehr viele bedeutungsvolle Dinge in der menschlichen Entwickelung zur spirituellen Wahrheit, die dann in ihrer höchsten Läuterung Weisheit ist. Indem sie gewissermaßen durchströmt durch das Ich und den astralischen Leib, wirkt sie unmittelbar in das Ätherische, in den Ätherleib des Menschen. Das Schöne wirkt in den astralischen Leib des Menschen herein; das Ich durchdringt das Moralische; der moralische Impuls wirkt in das Ich herein. Das Wahre hat also nur noch, indem es aus dem Kosmos, aus dem Universum in uns einströmt, auf den physischen Leib zu wirken, hat sich nur noch im physischen Leib abzudrücken, das heißt im physischen Gehirn; es wird im Physischen Wahrnehmung. Das Schöne muß, indem es von außen, vom Universum in unser Astralisches einströmt, noch in den Ätherleib hineinwirken, und dann in den physischen Leib. Das Gute, der Impuls des Guten wirkt auf das Ich, und muß so stark auf das Ich wirken, daß das wieder weitervibriert in den astralischen Leib, Ätherleib und physischen Leib hinein, wo es dann erst wirksam werden kann in dem physischen Leib.