The Riddle of Humanity

GA 170

12 August 1916, Dornach

Lecture VII

When we speak of the great world and the small world, of the macrocosm and the microcosm, we are referring to the whole universe and to the human being. Goethe, for example, spoke in these terms in Faust. He called the whole cosmos ‘the great world’, and the human being ‘the small world.’ We have already had many occasions to observe how manifold and complicated are the relationships between man and the cosmos. Today I would like to remind you of some of the things we have spoken about at various times, connecting these with a consideration of humanity's relationship to the cosmos. You will remember that when we spoke of the senses and of what man, as the possessor of his senses, is, we said that the senses lead us back to the ancient Saturn phase of evolution. That is where we find the first impulses for the development of the senses, the first seeds of the senses. You will find these things described again and again in previous lecture cycles. Now, obviously, the early seed-like phases of the senses during the Saturn period are not to be imagined as if they already resembled the senses as we know them today. That would be foolish. As a matter of fact, it is extremely difficult to imagine what the senses were like during ancient Saturn development. It is already difficult enough to picture the senses as they were during the ancient Moon period. Even that far back in time they were thoroughly different from the senses we know now. Today I would like to throw some light on what the senses were like during the ancient Moon phase of evolution. By that time they were already in their third phase of development—Saturn, Sun, Moon.

As regards their form, the senses of today are much more dead than were the senses of Old Moon. At that period the sense organs were much livelier, much more full of life. Because of this they were not suited to provide the foundations for fully conscious human life, but were only suited to the dreamy clairvoyance of Moon man. Such clairvoyance excluded the possibility of freedom. There was no freedom to act or to follow impulses and desires. Humanity had to wait for the Earth phase of evolution before it could develop the impulse to freedom. Thus, the senses during Old Moon were not the basis for the kind of consciousness we now have, but rather for a consciousness that was both more dull and more imaginative than ours. As I have often explained, it was much more like today's dream consciousness. People generally assume that we have five senses. We know, however, that this is not justified, but that, in truth, we must distinguish twelve human senses. There are seven further senses that must be included with the usual five, since they are equally relevant to earthly, human existence. You know the usual list of the senses: sense of sight, sense of hearing, sense of taste, sense of smell, and sense of feeling. The last of these is often called the sense of touch and is mixed together with the sense of warmth, although more recently there are some who distinguish the one from the other. In earlier times these two completely distinct senses were mixed together, confusedly, as a single sense. The sense of touch tells whether something is hard or soft, which has nothing to do with the sense of warmth. And so, if one really has a sense—if I may use that word—for the way humanity relates to the rest of the world, one will have to distinguish twelve senses. Today I would like, once again, to describe these twelve senses.

The sense of touch is the sense that relates us to the most material aspect of the external world. With our sense of touch we, so to speak, bump into the external world; through touch we are continually involved in a coarse kind of exchange with the external world. Nevertheless, the process of touching takes place within the boundaries of our skin. Our skin collides with an object. What then happens to give us a perception of the object must, as a matter of course, take place within the boundaries of our skin, within our body. Thus, what happens in touching, in the process of touch, happens inside us—

The sense that we shall call the sense of life involves processes that lie still more deeply embedded in the human organism. This sense exists within us, but we are accustomed to ignore it, for the life sense manifests itself indistinctly from within the human organism. Nevertheless, throughout all our daily waking hours, the harmonious collaboration of all the bodily organs expresses itself through the life sense, through the state of life in us. We usually pay no attention to it because we expect it as our natural right. We expect to be filled with a certain feeling of well-being, with the feeling of being alive. If our feeling of alive-ness is diminished, we try to recover a little so that our feeling of life is refreshed again. This vital enlivening or damping down is something we are aware of, but generally we are too accustomed to the feeling of being alive to be constantly aware of it. The life sense, however, is a distinct sense in its own right. Through it we feel the life in us, precisely as we see what is around us with our eyes. We sense ourselves through the life sense just as we see with our eyes. Without this internal sense of life we would know nothing about our own vital state.

What can be called the sense of movement is still more inward, more physically inward, more bodily inward. Through feelings of well-being or of discontent the life sense makes us conscious of the state of the whole organism. Having a sense of movement, on the other hand, means being able to be aware of the way parts of the body move with respect to each another. I do not refer here to movements of the whole person—that is something else. I am referring to movements such as the bending of an arm or leg, or the movements of the larynx when you speak. The sense of movement makes you aware of all these inner movements that entail changes in the position of separate parts of the organism.

A further sense that must be distinguished is the sense we will call balance. We do not normally pay any attention to it. If we get dizzy and fall, or if we feel faint, it is because the sense of balance has been interrupted. This is exactly analogous to the way the sense of sight is interrupted when we close our eyes. When we relate ourselves to the world, orientating ourselves with respect to above and below and to right and left so that we feel upright, we are employing our sense of balance, just as we employ the sense of movement when we are aware of internal changes of position. Our sense of balance, therefore, is due to a distinct sense. Balance is a proper sense in its own right.

The senses mentioned so far involve processes that remain within the bounds of the organism. If you touch something, you have collided with an external object, it is true, but you do not get inside it. If you come up against a needle you will notice that it is pointed, but of course you do not get inside the point. Instead, you prick yourself, and that no longer has anything to do with touching. Everything that happens, happens within the boundaries of your organism. You can touch an object, to be sure, but everything you experience through touch takes place within your skin. Thus, experiences of touch are internal to the body. What you experience through the life sense is likewise internal to the body. It does not show you what is going on somewhere outside you; it lets you look within. Equally internal is the sense of movement: it is not concerned with how I can walk about in the world, but with the internal movements I make when I move part of myself or when I speak. When I move about externally there is also internal movement. But the two things must be distinguished from one another: on the one hand there is my forward movement, on the other, there is the movement of parts of me, which is internal. So the sense of movement gives us internal perceptions, as do the senses of life and balance. In balance, too, you perceive nothing external—rather, you perceive yourself in your state of balance.

The first sense to take you outside yourself is the sense of smell. With smell you already come into contact with the external world. But you will have the feeling that smell does not take you very far outside yourself. You do not experience much about the external world through the sense of smell. Furthermore, people do not want to have anything to do with the intimate connection with the world that a developed sense of smell can give. Dogs are much more interested. People are willing to use the sense of smell to perceive the world, but they do not want the world to come very close. It is not a sense through which people want to get very involved with the outer world.

With the sense of taste we get more deeply involved with the world. When we taste sugar or salt, the experience of its qualities is already very inward. What is external is taken inward—more so than with smell. So there is already more of a connection established between inner world and outer world.

The sense of sight involves us even more with the external world. In seeing we take into ourselves more of the properties of the external world than we do with the sense of smell. And we take yet more into ourselves with the sense of warmth. What we see, what we perceive through the sense of sight, remains more foreign to us than what we perceive through the sense of warmth. The relationship to the outer world perceived through the sense of warmth is already a very intimate one. When we are aware of the warmth or the coldness of an object we also experience this warmth or coldness—we experience it along with the object. On the other hand, in experiencing the sweetness of sugar, for example, one is not so involved with the object. In the case of sugar we are interested in what it becomes as we taste it, not in what it is out there in the world. Such a distinction ceases to be possible with the sense of warmth. With warmth we are already participating in what is within the object perceived.

When we turn to the sense of hearing, the relation to the external world acquires another degree of intimacy. A sound tells us very much indeed about the inner structure of an object—more than what the sense of warmth can tell, and very much more than what sight reveals. Sight only gives us pictures, so to speak, pictures of the outer surface. But when a metal resonates it tells us what is going on within it. The sense of warmth also reaches into the object. When I take hold of something, a piece of ice, say, I am sure that the ice is cold through and through, not just on its outer surface. When I look at something, I can see only the colours at its outer limits, on its surface; but when I make an object resonate, the sounds bring me into a particular relationship with what is within it.

And the intimacy is greater still if the sounds contain meaning. Thus we arrive at the sense of tone: perhaps it would be better to call it the sense of speech or the sense of word. It is simply nonsense to think that perception of words is the same as perception of sounds. The two are as distinct and different from one another as are taste and sight. To be sure, sounds open the inner world of objects to our perception, but these sounds must become much more inward before they can become meaningful words. Therefore it is a step into a deeper intimacy with the world when we proceed from perceiving sounds through the sense of hearing to perceiving meaning through the sense of the word. And yet, when I perceive a mere word I am still not so intimately connected with the object, with the external thing, as I am connected with it when I perceive the thoughts behind the words. At this stage, most people cease to make any distinctions. But there is a distinction between merely perceiving words and actually perceiving the thoughts behind the words. After all, you still can perceive words when a phonograph—or writing, for that matter—has separated them from their thinker. But a sense that goes deeper than the usual word sense must come into play before I can come into a living relationship with the being that is forming the words, before I can enter through the words and transpose myself directly into the being that is doing the thinking and forming the concepts. That further step calls for the sense I would like to call the sense of thought. And there is another sense that gives an even more intimate sense of the outer world than the sense of thought. It is the sense that enables you to feel another being as yourself and that makes it possible to be aware of yourself while at one with another being. That is what happens if one turns one's thinking, one's living thinking, towards the being of another. Through living thinking one can behold the I of this being: the sense of the I.

You see, it really is necessary to distinguish between the ego sense, which makes you aware of the I of another person, and the awareness of yourself. The difference is not just that in one case you are aware of your own I and, in the other, of someone else's I. The two perceptions come from different sources. The seeds of our ability to distinguish one another were sown on Old Saturn. The beginnings of this sense were implanted in us then. The basis of your being able to perceive another person as an I was established on Old Saturn. But it was not until the Earth stage of evolution that you obtained your own I; so the ego sense is not to be identified with the I that ensouls you from within. The two must be strictly distinguished from one another. When we speak of the ego sense, we are referring to the ability of one person to be aware of the I of another.

As you know, I have never spoken of materialistic science without acknowledging its truth and its greatness. I have given lectures here that were for the express purpose of appreciating materialistic science fully. But, having appreciated it, one must deepen one's knowledge of materialistic science so lovingly that one also can hold up its shadow side with a loving hand. The materialistic science of today is just beginning to bring its thoughts about the senses into some kind of order. The physiologists are finally recognising and distinguishing the senses of life, of movement and of balance from one another, and they have begun to treat the senses of warmth and touch separately. The other senses about which we have been speaking are not recognised by our externally-orientated, material science. And so I ask you to carefully distinguish the ability to be aware of another I from the ability you could call the consciousness of self. With respect to this distinction, my deep love of material science forces me to make an observation, for a deep love of material science also enables one to see what is going on: today's material science is afflicted with stupidity. It turns stupid when it tries to describe what happens when someone uses his ego sense. Our material science would have us believe that when one person meets another he unconsciously deduces from the other's gestures, facial expressions, and the like, that there is another I present—that the awareness of another I is really a subconscious deduction. This is utter nonsense! In truth, when we meet someone and perceive their I we perceive it just as directly as we perceive a colour. It really is thick-headed to believe that the presence of another I is deduced from bodily perceptions, for this obscures the truth that humans have a special, higher sense for perceiving the I of another.

The I of another is perceived directly by the ego sense, just as brightness and darkness and colours are perceived through the eyes. It is a particular sense that relates us to another I. This is something that has to be experienced. Just as a colour affects me directly through my eyes, so another person's I affects me directly through my ego sense. At the appropriate time we will discuss the sense organ for the ego sense in the same way that we could discuss the sense organs of seeing, of sight. With sight it is simply easier to refer to material manifestations than it is in the case of the ego sense, but each sense has its own particular organ.

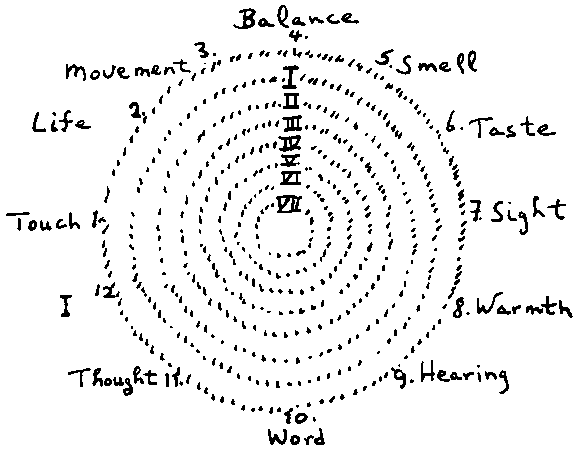

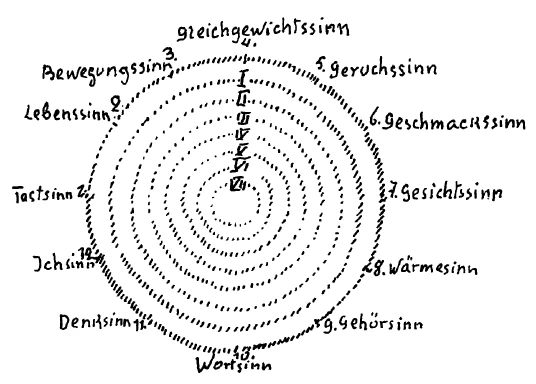

If you view your senses from a certain perspective you can say: each sense particularises and differentiates my organism. There is a real differentiation, for seeing is not the same as perception of tone, perception of tone is different from hearing, hearing is not the same as perception of thought, perception of thought is not touching. Each of these senses demarcates a separate and particular region of the human being. It is this separation of each into its special sphere to which I want you to pay especially close attention, for it is this separation that makes it possible to picture the senses as a circle divided into twelve distinct regions. (See diagram.)

The situation of these powers of perception is different from the situation of forces that could be said to reside more deeply embedded within us. Seeing is bound up with the eyes and these constitute a particular region of a human being. Hearing is bound up with the organs of hearing, at least principally so, but it needs more besides—hearing involves much more of the organism than just the ear, which is what is normally thought of as the region of hearing. And life flows equally through each of these regions of the senses. The eye is alive, the ear is alive, that which is the foundation of all the senses is alive; the basis of touch is alive—all of it is alive. Life resides in all the senses; it flows through all the regions of the senses.

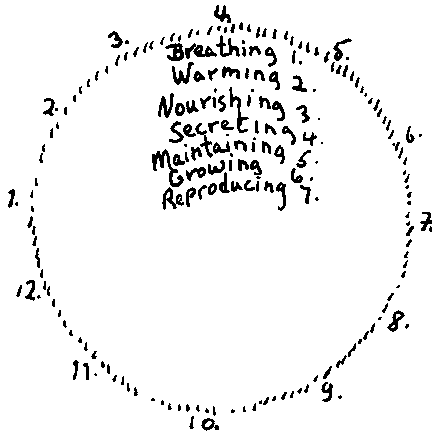

If we look more closely at this life, it also proves to be differentiated. There is not just one life process. And you must also distinguish what we have been calling the sense of life, through which we perceive our own vital state, from the subject of our present discussion. What I am talking about now is the very life that flows through us. That life also differentiates itself within us. It does so in the following manner (see diagram). The twelve regions of the twelve senses are to be pictured as being static, at rest within the organism. But life pulsates through the whole organism, and this life is manifested in various ways. First of all there is breathing, a manifestation of life necessary to all living things. Every living organism must enter into a breathing relationship with the external world. Today I cannot go into the details of how this differs for animals, plants and human beings, but will only point out that every living thing must have its way of breathing. The breathing of a human being is perpetually being renewed by what he takes in from the outer world, and this benefits all the regions associated with the senses. The sense of smell could not manifest itself—neither sight, nor the sense of tone—if the benefits of breathing did not enliven it. Thus, I must assign ‘breathing’ to every sense. We breathe—that is one process—but the benefits of that process of breathing flow to all the senses.

The second process we can distinguish is warming. This occurs along with breathing, but it is a separate process. Warming, the inner process of warming something through, is the second of the life-sustaining processes. The third process that sustains life is nourishment. So here we have three ways in which life comes to us from without: breathing, warming, nourishing. The outer world is part of each of these. Something must be there to be breathed—in the case of humans, and also animals, that substance is air. Warming requires a certain amount of warmth in the surroundings; we interact with it. Just think how impossible it would be for you to maintain proper inner warmth if the temperature of your surroundings were much hotter or much colder. If it were one hundred degrees lower your warmth processes would cease, they would not be possible; at one hundred degrees hotter you would do more than just sweat! Similarly, we need food to nourish us as long as we are considering the life processes in their earthly aspects.

At this stage, the life processes take us deeper into the internal world. We now find processes that re-form what has been taken in from outside—processes that transform and internalise it. To characterise this re-forming, I would like to use the same expressions that we have used on previous occasions. Our scientists are not yet aware of these things and therefore have no names for them, so we must formulate our own. The purely inner process that is the basis of the re-forming of what we take in from outside us can be seen to be fourfold. Following the process of nourishing, the first internal process is the process of secretion, of elimination. When the nourishment we have taken in is distributed to our body, this is already the process of secretion; through the process of secretion it becomes part of our organism. The process of elimination does not just work outward, it also separates out that part of our nourishment that is to be absorbed into us. Excretion and absorption are two sides of the processes by which organs of secretion deal with our nourishment. One part of the secretion performed by organs of digestion separates out nutriments by sending them into the organism. Whatever is thus secreted into the organism must remain connected with the life processes, and this involves a further process which we will call maintaining. But for there to be life, it is not enough for what is taken in to be maintained, there also must be growth. Every living thing depends on a process of inner growth: a process of growth, taken in the widest sense. Growth processes are part of life; both nourishment and growth are part of life.

And, finally, life on earth includes reproducing the whole being; the process of growth only requires that one part produce another part. Reproduction produces the whole individual being and is a higher process than mere growth.

There are no further life processes beyond these seven. Life divides into seven definite processes. But, since they serve all twelve of the sense zones, we cannot assign definite regions to these-the seven life processes enliven all the sense zones. Therefore, when we look at the way the seven relate to the twelve we see that we have 1. Breathing, 2. Warming, 3. Nourishing, 4. Secretion, 5. Maintaining, 6. Growth, 7. Reproduction. These are distinct processes, but all of them relate to each of the senses and flow through each of the senses: their relationship with the senses is a mobile one. (See drawing.) The human being, the living human being, must be pictured as having twelve separate sense-zones through which a sevenfold life is pulsing, a mobile, sevenfold life. If you ascribe the signs of the zodiac to the twelve zones, then you have a picture of the macrocosm; if you ascribe a sense to each zone, you have the microcosm. If you assign a planet to each of the life processes, you have a picture of the macrocosm; as the life processes, they embody the microcosm. And the mobile life processes are related to the fixed zones of the senses in the same way that, in the macrocosm, the planets are related to the zones of the zodiac—they move unceasingly through them, they flow through them. And so you see another sense in which man is a macrocosm.

Now, someone who is thoroughly versed in contemporary physiology and knows how physiology is pursued today could well say to us: ‘This is all just clever tricks; it is always possible to find relations between things. And if a person has divided up the senses so as to come out with twelve, of course he can relate them to the twelve signs of the zodiac; and the same goes for distinguishing seven life processes which can then be related to the seven planets.’ To put it bluntly, such a person might believe that all this is the product of fantasy. But this is truly not the case, for the human being of today is the result of a slow process of unfolding and development. During Old Moon, the human senses were not as they are today. As I said, they provided the basis for the ancient, dreamlike clairvoyance of Old Moon existence. Today's senses are more dead than those of Old Moon. They are less united into a single whole and are more separated from the sevenfold unity of the life processes. The senses of Old Moon were themselves more akin to the life processes. Today, seeing and hearing are quite dead, they involve processes that occur at the periphery of our being.

Perception, however, was not nearly so dead on Old Moon. Take any of the senses, the sense of taste, for example. I imagine all of you know what that is like on Earth. During the Moon era it was rather different. At that time a person was not so separated from his outer surroundings as he is nowadays. For us, sugar is something out there: to connect with it we have to lick something and then inner processes have to take place. There is a clear distinction between the subjective and the objective. It was not like this during Old Moon. Then, the process was much more filled with life and there was not such a clear distinction between subjective and objective. The process of tasting was more like a life process, more like—say—breathing. When we breathe, something real happens in us. We breathe in air but, in so doing, all the blood-forming processes in us are affected-all these processes are part of breathing, which is one of the seven life processes and does not permit of such clear distinctions between subject and object. In this case, what is outside and what is within must be taken together: air outside, air within. And something real happens through the process of breathing, much more real than what happens when we taste something. When we taste, enough happens to provide a basis for the typical consciousness of today, but on Old Moon tasting was much more similar to the dreamlike process that breathing is for us today. We are not nearly so aware of ourselves in our breathing as we are when we taste something. But on Old Moon, tasting was like breathing is for us now. Man on ancient Moon experienced no more of his tasting than we experience of our breathing, nor did he feel a need for it to be otherwise. The human being had not yet become a gourmet, nor could he become one, for tasting depended on certain internal happenings that were connected with his processes of maintenance, with his continued existence on Old Moon.

Sight, the process of seeing, was also different on Old Moon. Then one did not simply look at external objects, perceiving the colour as something outside oneself. Instead, the eye penetrated into the colour and the colour entered through the eyes, helping to maintain the life of the viewer. The eye was a kind of organ for breathing colour. The state of our life was affected by how we related to the outer world through our eyes and by the perceptual processes of the eyes. On Old Moon, we expanded upon entering a blue region and contracted if we ventured into a red region: expanding-contracting, expanding-contracting. Colour affected us that much. Similarly, all the other senses also had a more living connection, both with the outer world and with the inner world of the perceiver, a connection such as the life processes have today.

And what was the sense of another ego like on Old Moon? There could not have been any such sense on Old Moon, for it is only since the Earth stage of development that the I has begun to dwell within us. The sense of thought, of living thought as I previously described it, is also connected with Earth consciousness. Our sense of thought did not yet exist on Old Moon. Neither did humanity speak. And since there was nothing like our perception of each other's speech, the sense of word was also absent. In earlier times the word lived as the Logos which streamed through the whole world, including humanity. It had significance to man, but was not perceived by him. The sense of hearing was already developing, though, and was much more filled with life than the hearing of today. That sense has, so to speak, now come to rest on Earth, to a standstill. When we listen, we stay quite still, at least as a rule. Unless a sound does something of the order of bursting an eardrum, hearing does not change anything in our organism. We remain at rest within ourselves and perceive the sounds, the tones. This is not how things were during Old Moon. Then the tones really came close. They were heard, but that hearing involved being inwardly pervaded by the tones, it involved inwardly vibrating with the sounds and actively participating in their creation. Man participated actively in the production of what we call the Cosmic Word, but he was not aware of it. Thus we cannot call it a sense, properly speaking, although Moon man participated in a living fashion in the sounds that are the basis of today's hearing. If what we hear today as music had been played on Old Moon, there would have been more than just an outward dancing! If that had happened, all the internal organs, with few exceptions, would have reacted the way my larynx: and related organs react when I use them to produce a tone. Thus, it was not a conscious process, but a life process in which one actively participated, for the whole inner man was brought into vibration. These vibrations were harmonious or dissonant, and the vibration was perceived in the tones.

The sense of warmth was also a life process. Today we are comparatively calm when we regard our surroundings; we just notice that it is warm or cold outside. Of course we experience it to a mild degree, but not as during Old Moon, when a rise or fall in temperature was experienced so intensely that one's whole sense of life changed. In other words, the participation was much more intense: just as one vibrated with a tone, one experienced oneself getting inwardly cooler or warmer.

I already have described what the sense of sight was like on Old Moon. There was a living involvement with colours. Some colours caused us to enlarge our body, others to contract it. Today we can only experience this symbolically, if at all. We no longer collapse when confronted with red, nor do we inflate when surrounded by blue—but we did do this on Old Moon. The sense of taste has also been described already.

The sense of smell was intimately bound up with the life processes on Old Moon. There was also a sense of balance, it was already needed. And the sense of movement was much livelier. Today we have more or less come to rest in ourselves—we are more or less dead. We move our limbs, but not much of us actually vibrates. But just imagine all the movement there was to be aware of on Old Moon when tones generated inner movement.

Now, as for the sense of life, you will gather from what I have been saying that no sense analogous to our sense of life could have been present on Old Moon. At that time one was altogether immersed in life, in life as a whole. The skin was not the boundary of inner life. Life was something in which one swam. There was no need for a special sense of life since all the organs that today are sense organs were organs of life in those times—they were alive and they provided consciousness of that life. So there was no need for a special sense of life on Old Moon.

The sense of touch came into being along with the mineral world, which is a result of Earth evolution. On Old Moon there was nothing analogous to the sense of touch that we have developed here on Earth in conjunction with the mineral realm. There was no such sense on Old Moon where it was no more needed than was a sense of life.

If we count how many of our senses were already to be found on Old Moon as organs of life, we find there were seven. Manifestations of life are always sevenfold. The five senses unique to Earth evolution fall away when we consider Moon man. They join the other seven later, during our Earth evolution, to make up the twelve senses, because the Earth-senses have become fixed zones as have the regions of the zodiac. There were only seven senses on Old Moon, for then the senses were still mobile and full of life. Thus there was a sevenfold life on Old Moon, a life in which the senses were still immersed.

This account is the result of living observations of a super-sensible world which—initially—is beyond the limits of earthly perception. What has been said is just a small, an elementary part of all that needs to be said to show that our account is not the product of arbitrary whims. The more one presses on and achieves a vision of cosmic secrets, the more one sees that all this talk about the relation of seven to twelve is not just a game. This relationship really can be traced through all the manifestations of life. The relation of the fixed stars to the planets is a necessary outer expression of it and reveals one of the mysteries of number that underlie the cosmos. And the relationship of the number twelve to the number seven expresses one of the mysteries of existence, the mystery of how man, as bearer of the senses and faculties of perception, is related to man as the bearer of life. The number twelve is connected with the mystery of how we are able to carry an I. The establishment of twelve senses, each at rest in its own proper region, provided a basis for earthly self-awareness. The fact that the senses of Old Moon were still organs of life meant that Moon man could possess an astral body, but not an I; for then the seven senses were still organs of life and only provided the basis for the astral body. The number seven is concerned with the mysteries of the astral body just as the number twelve is concerned with the mysteries of the human I.

Siebenter Vortrag

Wenn man, wie zum Beispiel auch Goethe im «Faust», von der großen und kleinen Welt spricht, vom Makrokosmos und Mikrokosmos, dann meint man ja das ganze Universum und den Menschen: das ganze Universum als die große Welt und den Menschen als die kleine Welt. Die Beziehungen zwischen dem Kosmos und dem Menschen sind ja, wie wir jetzt schon aus vielem gesehen haben, sehr mannigfaltig, sehr kompliziert. Ich möchte heute an einiges erinnern, das wir im Laufe der Zeiten schon besprochen haben, und dies Erinnerte anknüpfen an eine Betrachtung über das Verhältnis des Menschen zum Universum. Sie erinnern sich, daß, wenn wir von unseren Sinnen sprechen, von dem, was der Mensch als Besitzer seiner Sinne ist, wir sagen: Diese Sinne haben ihren ersten Anstoß, ihre ersten Keime während der alten Saturnentwickelung erhalten. Das finden Sie ja auch in Zyklen ausgeführt und immer wieder angegeben. Nun, selbstverständlich darf man sich nicht vorstellen, daß die Sinne, wie sie im ersten Anlauf, im ersten Keim während der Saturnzeit aufgetreten sind, schon so waren, wie sie heute sind. Das wäre natürlich eine Torheit. Es ist sogar außerordentlich schwierig, sich die Gestalt der Sinne vorzustellen, die zur Zeit der alten Saturnentwickelung vorhanden war. Denn es ist schon schwierig, sich vorzustellen, wie die Sinne des Menschen waren während der alten Mondenentwickelung. Da waren sie noch ganz anders als heute. Und darauf möchte ich jetzt einiges Licht werfen, wie diese Sinne, die ja während der alten Mondenentwickelung schon sozusagen ihr drittes Entwickelungsstadium durchmachten — Saturn, Sonne, Mond -, zur Zeit der alten Mondenentwickelung waren.

Die Gestalt, die die menschlichen Sinne heute haben, ist gegenüber der Art, wie sie zur Zeit der alten Mondenentwickelung vorhanden waren, eine viel totere. Die Sinne waren damals viel lebendigere, viel lebensvollere Organe. Dafür aber waren sie nicht geeignet, Grundlagen zu bilden für das vollbewußte Leben des Menschen; sie waren nur geeignet für das alte traumhafte Hellsehen des Mondenmenschen, das dieser Mondenmensch vollzogen hat mit Ausschluß jeder Freiheit, jedes freien Handlungs- oder Begehrungsimpulses. Die Freiheit konnte sich erst während der Erdenentwickelung im Menschen als ein Impuls entwickeln. Also die Sinne waren noch nicht Grundlage für ein solches Bewußtsein, wie wir es während der Erdenzeit haben; sie waren Grundlage nur für ein Bewußtsein, das dumpfer, auch imaginativer war als das heutige Erdenbewußtsein, und das, wie wir das öfter auseinandergesetzt haben, dem heutigen Traumesbewußtsein glich. Der Mensch, so wie er heute ist, nimmt fünf Sinne an. Wir wissen aber, daß das unberechtigt ist, denn in Wahrheit müssen wir zwölf menschliche Sinne unterscheiden. Alle anderen sieben Sinne, die außer den fünf gewöhnlichen Sinnen noch genannt werden müssen, sind genau ebenso berechtigte Sinne hier für die Erdenzeit, wie es die fünf Sinne sind, die immer aufgezählt werden. Sie wissen, man zählt auf: Gesichtssinn, Hörsinn, Geschmackssinn, Geruchssinn und Gefühlssinn. — Letzteren nennt man oft Tastsinn, wobei man schon beim Tasten nicht recht unterscheidet, was in der neueren Zeit einige nun doch schon unterscheiden wollen, den eigentlichen Tastsinn von dem Wärmesinn. Tastsinn und Wärmesinn hat eine ältere Zeit noch ganz durcheinandergeworfen. Diese beiden Sinne sind natürlich völlig voneinander verschieden. Durch den Tastsinn nehmen wir wahr, ob etwas hart oder weich ist; der Wärmesinn ist etwas ganz anderes. Aber wenn man wirklich einen Sinn hat, wenn ich das Wort so gebrauchen darf, für das Verhältnis des Menschen zur übrigen Welt, dann hat man zwölf Sinne zu unterscheiden. Wir wollen sie heute noch einmal aufzählen, diese zwölf Sinne.

Tastsinn ist gewissermaßen derjenige Sinn, durch den der Mensch in ein Verhältnis zur materiellsten Art der Außenwelt tritt. Durch den Tastsinn stößt gewissermaßen der Mensch an die Außenwelt, fortwährend verkehrt der Mensch durch den Tastsinn in der gröbsten Weise mit der Außenwelt. Aber trotzdem spielt sich der Vorgang, der beim Tasten stattfindet, innerhalb der Haut des Menschen ab. Der Mensch stößt mit seiner Haut an den Gegenstand. Das, was sich abspielt, daß er eine Wahrnehmung hat von dem Gegenstand, an den er stößt, das geschieht selbstverständlich innerhalb der Haut, innerhalb des Leibes. Also der Prozeß, der Vorgang des Tastens geschieht innerhalb des Menschen.

Schon mehr innerhalb des menschlichen Organismus als der Vorgang des Tastsinns liegt dasjenige, was wir nennen können den Lebenssinn. Es ist ein Sinn innerhalb des Organismus, an den der Mensch sich heute kaum gewöhnt zu denken, weil dieser Lebenssinn, ich möchte sagen, dumpf im Organismus wirkt. Wenn irgend etwas im Organismus gestört ist, dann empfindet man die Störung. Aber jenes harmonische Zusammenwirken aller Organe, das sich in dem alltäglich und immer im Wachzustande vorhandenen Lebensgefühl, in dieser Lebensverfassung ausdrückt, das beachtet man gewöhnlich nicht, weil man es als sein gutes Recht fordert. Es ist dieses: sich mit einem gewissen Wohlgefühl durchdrungen wissen, mit dem Lebensgefühl. Man sucht, wenn das Lebensgefühl herabgedämpft ist, sich ein bißchen zu erholen, daß das Lebensgefühl wieder frischer wird. Diese Erfrischung und Herabdämpfung des Lebensgefühles, die spürt man, nur ist man im allgemeinen zu sehr an sein Lebensgefühl gewöhnt, als daß man es immer spüren würde. Aber es ist ein deutlicher Sinn vorhanden, der Lebenssinn, durch den wir das Lebende in uns geradeso fühlen, wie wir irgend etwas mit dem Auge sehen, was ringsherum ist. Wir fühlen uns mit dem Lebenssinn, wie wir mit dem Auge sehen. Wir wüßten nichts von unserem Lebensverlaufe, wenn wir nicht diesen inneren Lebenssinn hätten.

Schon noch mehr innerlich, körperlich-innerlich, leiblich-innerlich als der Lebenssinn ist das, was man nennen kann Bewegungssinn. Der Lebenssinn verspürt gewissermaßen den Gesamtzustand des Organismus als ein Wohlgefühl oder auch als ein Mißbehagen. Aber Bewegungssinn haben, heißt: Die Glieder unseres Organismus bewegen sich gegeneinander, und das können wir wahrnehmen. Hier meine ich nicht, wenn sich der ganze Mensch bewegt - das ist etwas anderes -, sondern wenn Sie einen Arm beugen, ein Bein beugen; wenn Sie sprechen, bewegt sich der Kehlkopf; das alles, dieses Wahrnehmen der innerlichen Bewegungen, der Lageveränderungen der einzelnen Glieder des Organismus, das nimmt man mit dem Bewegungssinn wahr.

Weiter müssen wir wahrnehmen dasjenige, was wir nennen können unser Gleichgewicht. Wir achten auch darauf eigentlich nicht. Wenn wir sogenannten Schwindel bekommen und umfallen, ohnmächtig werden, dann ist der Gleichgewichtssinn unterbrochen, genau ebenso, wie der Sehsinn unterbrochen ist, wenn wir die Augen zumachen. Ebenso wie wir unsere innere Lageveränderung wahrnehmen, so nehmen wir unser Gleichgewicht wahr, wenn wir einfach uns in ein Verhältnis bringen zu oben und unten, links und rechts, und uns so einordnen in die Welt, daß wir uns drinnen fühlen; daß wir fühlen, wir stehen jetzt aufrecht. Also dieses Gleichgewichtsgefühl wird wahrgenommen von uns durch den Gleichgewichtssinn. Der ist ein wirklicher Sinn.

Diese Sinne verlaufen in ihren Prozessen so, daß eigentlich alles innerhalb des Organismus bleibt, was vorgeht. Wenn Sie tasten, stoßen Sie zwar an den äußeren Gegenstand, aber Sie kommen nicht hinein in den äußeren Gegenstand. Wenn Sie an einer Nadel sich stoßen, so sagen Sie, die Nadel ist spitz, Sie kommen selbstverständlich nicht hinein in die Spitze, wenn Sie bloß tasten, sonst stechen Sie sich, aber das ist ja nicht mehr Tasten. Aber alles das kann nur in Ihrem Organismus selbst vorgehen. Sie stoßen zwar an den Gegenstand, aber das, was Sie als Tastmensch erleben, vollzieht sich innerhalb der Grenzen Ihrer Haut. Also das ist leiblich-innerlich, was Sie da im Tastsinn erleben. Ebenso ist leiblich-innerlich, was Sie im Lebenssinn erleben. Sie erleben nicht, wie der Verlauf da oder dort ist, außer sich, sondern was in Ihnen ist. Ebenso im Bewegungssinn: nicht die Bewegung, daß man hin und her gehen kann, ist gemeint, sondern diejenigen Bewegungen, wenn ich an mir meine Glieder bewege, oder aber wenn ich spreche, also die innerlichen Bewegungen, die sind mit dem Bewegungssinn gemeint. Wenn ich außer mir mich bewege, bewege ich mich auch innerlich. Sie müssen da die zwei Dinge unterscheiden: meine Vorwärtsbewegung und die Lage der Glieder, das Innerliche. Der Bewegungssinn also wird innerlich wahrgenommen, wie der Lebenssinn und auch der Gleichgewichtssinn. Nichts nehmen Sie da äußerlich wahr, sondern Sie nehmen sich selbst in einem Gleichgewicht wahr.

Jetzt gehen Sie zunächst aus sich heraus im Geruchssinn. Da kommen Sie schon in das Verhältnis zur Außenwelt. Aber Sie werden das Gefühl haben, daß Sie da im Geruchssinn noch wenig nach außen kommen. Sie erfahren wenig durch den Geruchssinn von der Außenwelt. Der Mensch will das auch gar nicht wissen, was man durch einen intimeren Geruchssinn von der Außenwelt erfahren kann. Der Hund will es schon mehr wissen. Es ist so, daß der Mensch die Außenwelt durch den Geruchssinn nur zunächst wahrnehmen will, aber wenig mit der Außenwelt in Berührung kommt. Es ist kein Sinn, durch den sich der Mensch so sehr tief mit der Außenwelt einlassen will.

Schon mehr will sich der Mensch mit der Außenwelt einlassen im Geschmackssinn. Man erlebt das, was Eigenschaft ist des Zuckers, des Salzes, indem man es schmeckt, schon sehr innerlich. Das Äußere wird schon sehr innerlich, mehr als im Geruchssinn. Also es ist schon mehr Verhältnis zu Außenwelt und Innenwelt.

Noch mehr ist es im Sehsinn, im Gesichtssinn. Sie nehmen viel mehr von den Eigenschaften der Außenwelt im Gesichtssinn herein als im Geschmackssinn. Und noch mehr nehmen Sie im Wärmesinn herein. Das, was Sie durch den Sehsinn, durch den Gesichtssinn wahrnehmen, bleibt Ihnen doch noch fremder, als was Sie durch den Wärmesinn wahrnehmen. Durch den Wärmesinn treten Sie eigentlich schon in ein sehr intimes Verhältnis zu der Außenwelt. Ob man einen Gegenstand als warm oder kalt empfindet, das erlebt man stark mit, und man erlebt es mit dem Gegenstande mit. Die Süßigkeit des Zuckers zum Beispiel erlebt man weniger mit dem Gegenstande mit. Denn schließlich kommt es Ihnen beim Zucker auf das an,was er durch Ihren Geschmack erst wird, weniger auf das, was da draußen ist. Beim Wärmesinn können Sie das nicht mehr unterscheiden. Da erleben Sie schon das Innere dessen, was Sie wahrnehmen, stark mit.

Noch intimer setzen Sie sich mit dem Inneren der Außenwelt durch den Gehörsinn in Beziehung. Der Ton verrät uns schon sehr viel von dem inneren Gefüge des Äußeren, viel mehr noch als die Wärme, und sehr viel mehr als der Gesichtssinn. Der Gesichtssinn gibt uns sozusagen nur Bilder von der Oberfläche. Der Hörsinn verrät uns, indem das Metall anfängt zu tönen, wie es in seinem eigenen Innern ist. Der Wärmesinn geht schon auch in das Innere hinein. Wenn ich irgend etwas, zum Beispiel ein Stück Eis anfasse, so bin ich überzeugt: Nicht bloß die Oberfläche ist kalt, sondern es ist durch und durch kalt. Wenn ich etwas anschaue, sehe ich nur die Farbe der Grenze, der Oberfläche; aber wenn ich etwas zum Tönen bringe, dann nehme ich gewissermaßen von dem Tönenden das Innere intim wahr.

Und noch intimer nimmt man wahr, wenn das Tönende Sinn enthält. Also Tonsinn: Sprachsinn, Wortsinn könnten wir vielleicht besser sagen. Es ist einfach unsinnig, wenn man glaubt, daß die Wahrnehmung des Wortes dasselbe ist wie die Wahrnehmung des Tones. Sie sind ebenso voneinander verschieden wie Geschmack und Gesicht. Im Ton nehmen wir zwar sehr das Innere der Außenwelt wahr, aber dieses Innere der Außenwelt muß sich noch mehr verinnerlichen, wenn der Ton sinnvoll zum Worte werden soll. Also noch intimer in die Außenwelt leben wir uns ein, wenn wir nicht bloß Tönendes durch den Hörsinn wahrnehmen, sondern wenn wir Sinnvolles durch den Wortsinn wahrnehmen. Aber wiederum, wenn ich das Wort wahrnehme, so lebe ich mich nicht so intim in das Objekt, in das äußere Wesen hinein, als wenn ich durch das Wort den Gedanken wahrnehme. Da unterscheiden die meisten Menschen schon nicht mehr. Aber es ist ein Unterschied zwischen dem Wahrnehmen des bloßen Wortes, des sinnvoll Tönenden, und dem realen Wahrnehmen des Gedankens hinter dem Worte. Das Wort nehmen Sie schließlich auch wahr, wenn es gelöst wird von dem Denker durch den Phonographen, oder selbst durch das Geschriebene. Aber im lebendigen Zusammenhange mit dem Wesen, das das Wort bildet, unmittelbar durch das Wort in das Wesen, in das denkende, vorstellende Wesen mich hineinversetzen, das erfordert noch einen tieferen Sinn als den gewöhnlichen Wortsinn, das erfordert den Denksinn, wie ich es nennen möchte. Und ein noch intimeres Verhältnis zur Außenwelt als der Denksinn gibt uns derjenige Sinn, der es uns möglich macht, mit einem anderen Wesen so zu fühlen, sich eins zu wissen, daß man es wie sich selbst empfindet. Das ist, wenn man durch das Denken, durch das lebendige Denken, das einem das Wesen zuwendet, das Ich dieses Wesens wahrnimmt — der Ichsinn.

Sehen Sie, man muß wirklich unterscheiden zwischen dem Ichsinn, der das Ich des anderen wahrnimmt, und dem Wahrnehmen des eigenen Ich. Das ist nicht nur deshalb verschieden, weil man das eine Mal das eigene Ich wahrnimmt, und das andere Mal das Ich des anderen, sondern es ist auch verschieden hinsichtlich des Herkommens. Die Keimanlage, das, was jeder vom anderen wissen kann, wahrnehmen zu können, die wurde schon auf dem alten Saturn uns eingepflanzt mit den Sinnesanlagen. Also, daß Sie einen anderen als ein Ich wahrnehmen können, das wurde Ihnen schon mit den Sinnesanlagen auf dem alten Saturn eingepflanzt. Ihr Ich haben Sie aber überhaupt erst während der Erdenentwickelung erlangt; dieses innerlich Sie beseelende Ich ist nicht das gleiche wie der Ichsinn. Die beiden Dinge müssen streng voneinander unterschieden werden. Wenn wir vom Ichsinn reden, so reden wir von der Fähigkeit des Menschen, ein anderes Ich wahrzunehmen. Sie wissen, ich habe nie anders als voll anerkennend über das Wahre und Große der materialistischen Wissenschaft gesprochen. Ich habe hier Vorträge gehalten, um diese materialistische Wissenschaft voll anzuerkennen; aber man muß dann wirklich so liebevoll sich in diese materialistische Wissenschaft vertiefen, daß man sie auch in ihren Schattenseiten liebevoll anfaßt. Wie diese materialistische Wissenschaft von den Sinnen denkt, das kommt erst heute in eine gewisse Ordnung. Erst heute fangen die Physiologen an, wenigstens Lebenssinn, Bewegungssinn, Gleichgewichtssinn zu unterscheiden, und den Wärmesinn vom Tastsinn zu trennen. Das andere, was hier noch angeführt ist, das unterscheidet die äußere materialistische Wissenschaft nicht, Also, was Sie Erleben Ihres eigenen Ichs nennen, das bitte ich Sie sehr zu unterscheiden von der Fähigkeit, ein anderes Ich wahrzunehmen. Bezüglich dieser Wahrnehmung des anderen Ich durch den Ichsinn ist nun — das sage ich aus tiefer Liebe zur materialistischen Wissenschaft, weil diese tiefe Liebe zur materialistischen Wissenschaft einen befähigt, die Sache wirklich zu durchschauen — die materialistische Wissenschaft heute geradezu behaftet mit Blödsinnigkeit. Sie wird blödsinnig, wenn sie von der Art redet, wie sich der Mensch verhält, wenn er den Ichsinn in Bewegung setzt, denn sie redet Ihnen vor, diese materialistische Wissenschaft, daß eigentlich der Mensch, wenn er einem Menschen entgegentritt, aus den Gesten, die der andere Mensch macht, aus seinen Mienen und aus allerlei anderem unbewußt auf das Ich schließt, daß es ein unbewußter Schluß wäre auf das Ich des anderen, Das ist ein völliger Unsinn! Wahrhaftig, so unmittelbar wie wir eine Farbe wahrnehmen, nehmen wir das Ich des anderen wahr, indem wir ihm entgegentreten. Zu glauben, daß wir erst aus der körperlichen Wahrnehmung auf das Ich schließen, ist eigentlich vollständig stumpfsinnig, weil es abstumpft gegen die wahre Tatsache, daß im Menschen ein tiefer Sinn vorhanden ist, das andere Ich aufzufassen. So wie durch das Auge Hell und Dunkel und Farben wahrgenommen werden, so werden durch den Ichsinn die anderen Iche unmittelbar wahrgenommen. Es ist ein Sinnenverhältnis zu dem anderen Ich. Das muß man erleben. Und ebenso, wie die Farbe durch das Auge auf mich wirkt, so wirkt das andere Ich durch den Ichsinn. Wir werden, wenn die Zeit dazu gekommen sein sollte, auch ebenso von dem Sinnesorgan für den Ichsinn sprechen, wie man von den Sinnesorganen für den Sehsinn, für den Gesichtssinn sprechen kann. Es ist da nur leichter, eine materielle Manifestation anzugeben, als für den Ichsinn. Aber vorhanden ist das alles.

Wenn Sie gewissermaßen sich besinnen auf diese Sinne, so können Sie sagen: In diesen Sinnen spezifiziert sich oder differenziert sich Ihr Organismus. Er differenziert sich wirklich, denn Sehen ist nicht TöneWahrnehmen, Tonwahrnehmung ist nicht Hören, Hören ist wiederum nicht Denken-Wahrnehmen, Denken-Wahrnehmen ist nicht Tasten. Das sind gesonderte Gebiete des menschlichen Wesens. Zwölf gesonderte Gebiete des menschlichen Organismus haben wir in diesen Sinnesgebieten. Die Sonderung, daß jedes für sich ein Gebiet ist, das bitte ich Sie besonders festzuhalten; denn wegen dieser Sonderung kann man diese ganze Zwölfheit in einen Kreis einzeichnen, und man kann zwölf getrennte Gebiete in diesem Kreise unterscheiden. (Siehe Zeichnung Seite 113.)

Das ist anders, als es nun mit den Kräften steht, die gewissermaßen tiefer im Menschen liegen als diese Sinneskräfte. Der Sehsinn ist an das Auge gebunden, ist ein gewisser Bezirk im menschlichen Organismus. Der Hörsinn ist an den Hörorganismus gebunden, wenigstens in der Hauptsache; er braucht ihn aber nicht allein; es wird mit viel mehr im Organismus gearbeitet, es wird mit einem viel weiteren Bezirk gehört als durch das Ohr; aber das Ohr ist der normalste Hörbezirk. Alle diese Sinnesbezirke werden von dem Leben gleichmäßig durchflossen. Das Auge lebt, das Ohr lebt, das, was dem Ganzen zugrunde liegt, lebt; was dem Tastsinn zugrunde liegt, lebt — alles lebt. Das Leben wohnt in allen Sinnen, es geht durch alle Sinnesbezirke durch.

Wenn wir dieses Leben weiter betrachten, so stellt es sich wiederum differenziert heraus. Es gibt nicht nur eine Kraft des Lebens. Sie müssen schon unterscheiden, es ist etwas anderes der Lebenssinn, durch den wir das Leben wahrnehmen, als das, was ich jetzt bespreche, Ich bespreche jetzt das Leben selber, wie es durch uns flutet; das differenziert sich in uns selber wiederum, und zwar in der folgenden Weise (siehe Zeichnung). Die zwölf Sinnesbezirke müssen wir uns gleichsam ruhend denken im Organismus. Das Leben aber pulsiert durch den ganzen Organismus, und das Leben ist wiederum differenziert. Da haben wir zunächst etwas, was in einer gewissen Weise in allem Lebendigen sein muß: die Atmung. Jenes Verhältnis zur Außenwelt, das die Atmung ist, muß gewissermaßen in jedem Lebendigen sein. Ich kann mich jetzt nicht im einzelnen darauf einlassen, wie es wiederum für die Tiere, Pflanzen und Menschen differenziert ist; aber in jedem Lebendigen ist in einer gewissen Weise die Atmung. Die Atmung des Menschen wird immer wieder erneuert durch etwas, was er von der Außenwelt aufnimmt; das kommt allen Sinnesbezirken zugute. Es kann nicht der Geruchssinn walten, der Sehsinn walten, der Tonsinn walten, wenn nicht das, was das Leben von der Atmung hat, allen Sinnen zugute kommt. Ich müßte also zu jedem Sinn «Atmung» dazuschreiben. Nicht wahr, es wird geatmet; aber was durch die Atmung als Lebensprozeß geleistet wird, das kommt allen Sinnen zugute.

Als zweites können wir unterscheiden die Wärmung. Sie tritt ein mit der Atmung; aber sie ist etwas anderes als die Atmung. Die Wärmung, die innerliche Durchwärmung ist eine zweite Art, das Leben zu unterhalten. Eine dritte Art, das Leben zu unterhalten, ist die Ernährung. Da haben wir die drei Arten, dem Leben von außen mit Lebensprozessen entgegenzukommen: Atmung, Wärmung, Ernährung. Zu alledem gehört die Außenwelt. Atmung setzt voraus einen Stoff, beim Menschen die Luft, beim Tier auch die Luft. Wärmung setzt voraus eine ganz bestimmte Wärme der Umgebung, zu der wir uns in eine Beziehung setzen. Denken Sie sich nur einmal, wie Sie unmöglich innerlich mit der richtigen Wärme leben könnten, wenn die Temperatur in ‚Ihrer Umgebung höher oder tiefer wäre! Denken Sie sie sich um hundert Grad tiefer: Ihre Wärmung wäre nicht mehr möglich, Ihre Wärmung hörte auf; oder um hundert Grad höher: Sie würden nicht bloß schwitzen! Ebenso ist die Ernährung notwendig, insoweit wir den Lebensprozeß als Erdenprozeß betrachten.

Jetzt kommen wir mit den Lebensprozessen mehr ins Innere. Da haben wir den nächsten Prozeß, der schon mehr dem Inneren angehört, das, was man nennen könnte die Umformung, die Verinnerlichung dessen, was aufgenommen worden ist von außen, die Umwandlung, die Verwandlung des von außen Aufgenommenen. Ich möchte, konform mit der Art, wie wir das einmal früher benannt haben, diese Umformung wiederum mit denselben Ausdrücken bezeichnen. Es gibt in der Wissenschaft noch keine Ausdrücke dafür; man muß sie erst prägen, weil man alle diese Dinge noch nicht unterscheidet. Diese innerliche Umformung dessen, was von außen aufgenommen wird, die also rein inneren Prozessen unterliegt, die können wir wiederum uns vierfach vorstellen. Das erste, was innerlich auftritt nach der Ernährung, ist die innere Absonderung. Absonderung ist es schon, wenn nur das aufgenommene Nahrungsmittel dem Körper mitgeteilt wird, wenn es ein Glied im Organismus wird. Es ist nicht nur die Absonderung nach außen, sondern die Mitteilung desjenigen, was durch die Nahrungsmittelsubstanz aufgenommen wird, im Inneren. Die Absonderung besteht zum Teil in Abgabe nach außen oder aber in der Aufnahme der Nahrungsmittel. Das ist eine Absonderung durch diejenigen Organe, die eben der Nahrung dienen: Absonderung in den Organismus hinein. Was so abgesondert ist in den Organismus hinein, das muß erhalten werden im Lebensprozeß, das ist wiederum ein besonderer Lebensvorgang für sich, den wir als Erhaltung bezeichnen müssen. Damit aber das Leben bestehen kann, muß es nicht nur das, was es aufnimmt, erhalten, sondern es muß es vergrößern. Jedes Lebendige unterliegt einer innerlichen Vermehrung: Wachstumsprozeß im weitesten Sinne; Wachstumsprozeß gehört zum Leben, Erhaltung und Wachstum.

Und dann gehört zum Leben hier auf Erden die Hervorbringung des Ganzen; der Wachstumsprozeß erfordert nur, daß ein Glied das andere hervorbringt. Reproduktion ist ein Prozeß, der höher ist als das bloße Wachstum, der das gleiche Individuum hervorbringt.

Außer diesen sieben Prozessen gibt es keinen weiteren Lebensprozeß mehr innerlich, In sieben Prozesse zerfällt das Leben. Aber wir können das nicht Bezirke nennen, sondern diese sieben kommen allen zwölf Bezirken zugute, diese sieben Lebensprozesse beleben alles. Wir müssen daher, wenn wir das Verhältnis dieser sieben zu den zwölf ins Auge fassen, sagen: Wir haben 1. Atmung, 2. Wärmung, 3. Ernährung, 4. Absonderung, 5. Erhaltung, 6. Wachstum, 7. Reproduktion, aber so, daß sie doch zu allen Sinnen in einem Verhältnis stehen, daß das durch alle Sinne gewissermaßen strömt, daß das Bewegung ist. (Siehe Zeichnung 5.115.) Wir müssen gewissermaßen den Menschen, insofern er ein lebender Mensch ist, so darstellen, daß er zwölf getrennte Sinnesbezirke hat, und daß durch diese das siebenfältige Leben pulst, das in sich bewegte siebenfältige Leben. — Schreiben Sie zu den zwölf Bezirken die Tierkreiszeichen dazu, dann haben Sie den Makrokosmos; schreiben Sie dazu die Sinnesbezirke, dann haben Sie den Mikrokosmos. Schreiben Sie zu den sieben Lebensprozessen die Zeichen der Planeten, so haben Sie den Makrokosmos; schreiben Sie die Namen für die sieben Lebensprozesse, so haben Sie den Mikrokosmos. Und wie sich im Makrokosmos die Planeten in ihren Bewegungen verhalten zu den Tierkreisbildern, durch die sie durchgehen, so geht der lebendige Lebensprozeß durch die ruhenden Sinnesbezirke immer hindurch, durchströmt sie. Sie sehen, noch in mancher Beziehung ist der Mensch ein Mikrokosmos.

Wenn nun jemand kommen würde, der ein gründlicher Kenner der gegenwärtigen Physiologie und auch schon, wie man sie heute auffaßt, der experimentellen Psychologie ist, so wird er sagen: So etwas ist ja eine niedliche Spielerei; denn Beziehungen kann man zwischen allem finden. Und wenn man es gerade so einrichtet, daß man die Sinnesbezirke als zwölf annimmt, kriegt man die zwölf Tierkreiszeichen heraus; wenn man den Lebensprozeß in sieben Teile teilt, bekommt man die sieben Planeten heraus. - Kurz, man kann glauben, daß das durch irgendeine Phantastik so eingerichtet sei. Das ist es aber nicht, das ist es wahrhaftig nicht; sondern das, was heute am Menschen ist, das hat sich langsam heran- und herausgebildet. So, wie die Sinne heute im Menschen sind, waren sie nicht während der alten Mondenzeit. Ich sagte, sie waren viel, viel lebendiger. Sie waren die Grundlage für das alte traumhafte Hellsehen während der Mondenzeit. Heute sind die Sinne mehr tot als sie während der alten Mondenzeit waren, sie sind mehr getrennt von dem Einheitlichen, von dem siebengliedrigen und in seiner Siebengliedrigkeit einheitlichen Lebensprozeß. Die Sinnesprozesse waren während der alten Mondenzeit noch selbst mehr Lebensprozesse. Wenn wir heute sehen oder hören, so ist das schon ein ziemlich toter Prozeß, ein sehr peripherischer Prozeß. So tot war die Wahrnehmung während der alten Mondenzeit gar nicht. Greifen wir einen Sinn heraus, zum Beispiel den Geschmackssinn. Wie er auf der Erde ist, ich denke, Sie wissen es alle. Während der Mondenzeit war er etwas anderes. Da war das Schmecken ein Prozeß, in dem der Mensch sich nicht so von der Außenwelt abtrennte wie jetzt. Jetzt ist der Zucker draußen, der Mensch muß erst daran lecken und einen inneren Prozeß vollziehen. Da ist sehr genau zwischen Subjektivem und Objektivem zu unterscheiden. So lag es nicht während der Mondenzeit. Da war das ein viel lebendigerer Prozeß, und das Subjektive und Objektive unterschied sich nicht so stark. Der Schmeckprozeß war noch viel mehr ein Lebensprozeß, meinetwillen ähnlich dem Atmungsprozeß. Indem wir atmen, geht etwas Reales in uns vor. Wir atmen die Luft ein, aber indem wir die Luft einatmen, geht mit unserer ganzen Blutbildung etwas vor in uns; denn das gehört ja alles zur Atmung hinzu, insofern die Atmung einer der sieben Lebensprozesse ist, da kann man nicht so unterscheiden. Also da gehören Außen und Innen zusammen: Luft draußen, Luft drinnen, und indem der Atmungsprozeß sich vollzieht, vollzieht sich ein realer Prozeß. Das ist viel realer, als wenn wir schmecken. Da haben wir allerdings eine Grundlage für unser heutiges Bewußtsein; aber das Schmecken auf dem Mond war viel mehr ein Traumprozeß, so wie es heute für uns der Atmungsprozeß ist. Im Atmungsprozeß sind wir uns nicht so bewußt wie im heutigen Schmeckprozeß. Aber der Schmeckprozeß war auf dem Mond so, wie heute der Atmungsprozeß für uns ist. Der Mensch hatte auf dem Mond auch nicht mehr vom Schmecken als wir heute vom Atmen, er wollte auch nichts anderes haben. Ein Feinschmecker war der Mensch noch nicht und konnte es auch nicht sein, denn er konnte seinen Schmeckprozeß nur vollziehen, insoferne durch das Schmecken in ihm selber etwas bewirkt wurde, was mit seiner Erhaltung zusammenhing, mit seinem Bestehen als Mondes-Lebewesen.

Und so war es zum Beispiel mit dem Sehprozeß, mit dem Gesichtsprozeß während der Mondenzeit. Da war das nicht so, daß man äußerlich einen Gegenstand anschaute, äußerlich Farbe wahrnahm, sondern da lebte das Auge in der Farbe drinnen, und das Leben wurde unterhalten durch die Farben, die durch das Auge kamen. Das Auge war eine Art Farbenatmungsorgan. Die Lebensverfassung hing zusammen mit der Beziehung, die man mit der Außenwelt durch das Auge in dem Wahrnehmungsprozeß des Auges einging. Man dehnte sich aus während des Mondes, wurde breit, wenn man ins Blaue hineinkam, man drückte sich zusammen, wenn man sich ins Rot hineinwagte: auseinander — zusammen, auseinander — zusammen. Das hing mit dem Wahrnehmen von Farben zusammen. Und so hatten alle Sinne noch ein lebendigeres Verhältnis zur Außenwelt und zur Innenwelt, wie es heute die Lebensprozesse haben.

Der Ichsinn — wie war er auf dem Monde? Das Ich kam in den Menschen erst auf der Erde hinein, konnte also auf dem Mond gar keinen «Sinn» haben; man konnte kein Ich wahrnehmen, der Ichsinn konnte überhaupt noch nicht da sein. - Auch das Denken, wie wir es heute wahrnehmen, wie ich es vorher geschildert habe, das lebendige Denken, das ist mit unserem Erdenbewußtsein in Zusammenhang. Der Denksinn, wie er heute ist, war auf dem Monde noch nicht da. Redende Menschen gab es auch nicht. In dem Sinne, wie wir heute die Sprache des andern wahrnehmen, gab es das auf dem Monde noch nicht, es gab also auch den Wortsinn nicht. Das Wort lebte erst als Logos, durchtönend die ganze Welt, und ging auch durch das damalige Menschenwesen hindurch. Es bedeutete etwas für den Menschen, aber der Mensch nahm es noch nicht als Wort wahr am anderen Wesen. Der Gehörsinn war allerdings schon da, aber viel lebendiger, als wir ihn jetzt haben. Jetzt ist er gewissermaßen als Gehörsinn zum Stehen gekommen auf der Erde. Wir bleiben ganz ruhig, in der Regel wenigstens, wenn wir hören. Wenn nicht gerade das Trommelfell platzt durch irgendeinen Ton, wird in unserem Organismus nicht etwas substantiell geändert durch das Hören. Wir in unserem Organismus bleiben stehen; wir nehmen den Ton wahr, das Tönen. So war es nicht während der Mondenzeit. Da kam der Ton heran. Gehört wurde er; aber es war jedes Hören mit einem innerlichen Durchbebtsein verbunden, mit einem Vibrieren im Innern, man machte den Ton lebendig mit. Das, was man das Weltenwort nennt, das machte man auch lebendig mit; aber man nahm es nicht wahr. Man kann also nicht von einem Sinn sprechen, aber der Mondenmensch machte dieses Tönen, das heute dem Hörsinn zugrunde liegt, lebendig mit. Wenn das, was wir heute als Musik hören, auf dem Monde erklungen wäre, so würde nicht nur äußerer Tanz möglich gewesen sein, sondern auch noch innerer Tanz; da hätten sich die inneren Organe alle mit wenigen Ausnahmen so verhalten, wie sich heute mein Kehlkopf und das, was mit ihm zusammenhängt, innerlich bewegend verhält, wenn ich den Ton hindurchsende. Der ganze Mensch war innerlich bebend, harmonisch oder disharmonisch, und wahrnehmend dieses Beben durch den Ton. Also wirklich ein Prozeß, den man wahrnahm, aber den man lebendig mitmachte, ein Lebensprozeß.

Ebenso war der Wärmesinn ein Lebensprozeß. Heute sind wir verhältnismäßig ruhig gegenüber unserer Umgebung: es kommt uns warm oder kalt vor. Wir erleben das zwar leise mit, auf dem Monde aber wurde es so miterlebt, daß immer die ganze Lebensverfassung anders wurde, wenn die Wärme hinauf- oder herunterging. Also ein viel stärkeres Mitleben; wie man mit dem Ton mitbebte, so wärmte und kühlte man im Innern und empfand dieses Wärmen und Kühlen.

Sehsinn, Gesichtssinn: Ich habe schon beschrieben, wie er auf dem Monde war. Man lebte mit den Farben. Gewisse Farben verursachten, daß man seine Gestalt vergrößerte, andere, daß man sie zusammenzog. Heute empfinden wir so etwas höchstens symbolisch. Wir schrumpfen nicht mehr zusammen gegenüber dem Rot und blasen uns nicht mehr auf gegenüber dem Blau; aber auf dem Mond taten wir es. Den Geschmackssinn habe ich schon beschrieben. Geruchssinn war auf dem Monde innig verbunden mit dem Lebensprozesse. Gleichgewichtssinn war auf dem Monde vorhanden, den brauchte man auch schon. Bewegungssinn war sogar viel lebendiger. Heute vibriert man nur wenig, bewegt seine Glieder, es ist alles mehr oder weniger zur Ruhe gekommen, tot geworden. Aber denken Sie, was dieser Bewegungssinn wahrzunehmen hatte, wenn alle diese Bewegungen stattfanden wie das Erbeben durch den Ton. Es wurde der Ton wahrgenommen, mitgebebt, aber dieses innere Beben, das mußte erst wiederum durch den Bewegungssinn wahrgenommen werden, wenn der Mensch es selber hervorrief, und er ahmte nach dasjenige, was der Hörsinn in ihm erweckte.

Lebenssinn: Nun, aus dem, was ich beschrieben habe, können Sie ersehen, daß der Lebenssinn in demselben Sinne, wie er auf der Erde ist, nicht vorhanden gewesen sein kann auf dem Monde. Das Leben muß man viel mehr als ein allgemeines mitgemacht haben. Man lebte viel mehr im Allgemeinen drinnen. Das innere Leben grenzte sich nicht so durch die Haut ab. Man schwamm im Leben drinnen. Indem alle Organe, alle heutigen Sinnesorgane dazumal Lebensorgane waren, brauchte man nicht einen besonderen Lebenssinn, sondern alle waren Lebensorgane und lebten und nahmen sich gewissermaßen selber wahr. Lebenssinn brauchte man nicht auf dem Monde. Der Tastsinn entstand erst mit dem Mineralreich, das Mineralreich ist aber ein Ergebnis der Erdenentwickelung. In demselben Sinne, wie wir auf der Erde den Tastsiinn durch das Mineralreich entwickelt haben, gab es ihn auf dem Monde nicht, der hatte dort ebensowenig einen Sinn wie der Lebenssinn.

Zählen wir, wieviel Sinne uns übrigbleiben, die nun in Lebensorgane verwandelt sind: sieben. Das Leben ist immer siebengliedrig. Die fünf, die auf der Erde dazukommen und zwölf machen, weil sie ruhige Bezirke werden, wie die Tierkreisbezirke, die fallen beim Monde weg. Sieben bleiben nur übrig für den Mond, wo die Sinne noch in Bewegung sind, wo sie selber noch lebendig sind. Es gliedert sich also auf dem Mond das Leben, in das die Sinne noch hineingetaucht sind, in sieben Glieder.

Das ist nur ein kleiner elementarer Teil dessen, was man sagen muß, um zu zeigen, daß da nicht Willkür zugrunde liegt, sondern lebendige Beobachtung der übersinnlichen Tatsachenwelt, die während des Erdenseins zunächst nicht in die Sinne der Menschen fällt. Je weiter man vordringt und je weiter man sich wirklich auf die Betrachtung der Weltengeheimnisse einläßt, desto mehr sieht man, wie so etwas nicht eine Spielerei ist, dieses Verhältnis von zwölf zu sieben, sondern wie es wirklich durch alles Sein durchgeht, und wie die Tatsache, daß es draußen ausgedrückt werden muß durch das Verhältnis der ruhenden Sternbilder zu den bewegten Planeten, auch ein Ergebnis ist eines Teiles des großen Zahlengeheimnisses im Weltendasein. Und das Verhältnis der Zwölfzahl zur Siebenzahl drückt ein tiefes Geheimnis des Daseins aus, drückt das Geheimnis aus, in dem der Mensch steht als Sinneswesen zum Lebewesen, zu sich als Lebewesen. Die Zwölfzahl enthält das Geheimnis, daß wir ein Ich aufnehmen können. Indem unsere Sinne zwölf geworden sind, zwölf ruhige Bezirke, sind sie die Grundlage des Ich-Bewußtseins der Erde. Indem diese Sinne noch Lebensorgane waren während der Mondenzeit, konnte der Mensch nur den astralischen Leib haben; da waren diese sieben noch Lebensorgane bildenden Sinnesorgane die Grundlage des astralischen Leibes. Die Siebenzahl wird so geheimnisvoll zugrunde gelegt dem astralischen Leib, wie die Zwölfzahl geheimnisvoll zugrunde liegt der Ich-Natur, dem Ich des Menschen.

Seventh Lecture

When one speaks, as Goethe does in Faust, for example, of the large and small worlds, of the macrocosm and microcosm, one means the entire universe and human beings: the entire universe as the large world and human beings as the small world. The relationships between the cosmos and human beings are, as we have already seen from many sources, very diverse and very complicated. Today I would like to recall some things we have already discussed in the course of time and link these recollections to a consideration of the relationship between human beings and the universe. You will remember that when we speak of our senses, of what human beings are as possessors of their senses, we say: these senses received their first impulse, their first seeds, during the ancient Saturn evolution. You will find this explained in detail in the cycles and mentioned again and again. Now, of course, one must not imagine that the senses, as they appeared in their first attempt, in their first germ during the Saturn period, were already as they are today. That would be foolish, of course. It is even extremely difficult to imagine the form of the senses that existed at the time of the ancient Saturn evolution. For it is already difficult to imagine what the human senses were like during the ancient lunar evolution. They were quite different from what they are today. And I would now like to shed some light on how these senses, which had already undergone their third stage of development during the ancient lunar evolution — Saturn, Sun, Moon — were at the time of the ancient lunar evolution.

The form that the human senses have today is much more dead compared to the way they existed during the ancient lunar evolution. At that time, the senses were much more lively, much more vital organs. However, they were not suitable for forming the basis of fully conscious human life; they were only suitable for the old dreamlike clairvoyance of the lunar human being, which this lunar human being carried out with the exclusion of all freedom, all free impulses of action or desire. Freedom could only develop as an impulse in human beings during the Earth's evolution. So the senses were not yet the basis for such consciousness as we have during the Earth period; they were only the basis for a consciousness that was duller and more imaginative than today's Earth consciousness and, as we have often explained, resembled today's dream consciousness. Human beings as they are today assume that they have five senses. But we know that this is not justified, for in truth we must distinguish between twelve human senses. All the other seven senses that must be mentioned in addition to the five ordinary senses are just as valid senses here for the earthly period as the five senses that are always listed. You know, we count: sight, hearing, taste, smell, and feeling. The latter is often called touch, although even when touching, we do not really distinguish between what some people in recent times want to distinguish, namely the actual sense of touch and the sense of warmth. In earlier times, the senses of touch and warmth were completely confused. These two senses are, of course, completely different from each other. Through the sense of touch, we perceive whether something is hard or soft; the sense of warmth is something completely different. But if one really has a sense, if I may use the word in this way, for the relationship between human beings and the rest of the world, then one has to distinguish between twelve senses. Let us list these twelve senses again today.

The sense of touch is, in a sense, the sense through which human beings enter into a relationship with the most material aspect of the external world. Through the sense of touch, human beings come into contact with the external world, so to speak; through the sense of touch, human beings interact with the external world in the crudest way. Nevertheless, the process that takes place during touch occurs within the human skin. Humans come into contact with objects through their skin. What happens, namely that they have a perception of the object they come into contact with, naturally takes place within the skin, within the body. So the process, the act of touching, takes place within the human being.

Even more within the human organism than the process of the sense of touch lies what we can call the sense of life. It is a sense within the organism that people today are hardly accustomed to thinking about because this sense of life, I would say, has a dull effect on the organism. When something in the organism is disturbed, we feel the disturbance. But we do not usually pay attention to the harmonious interaction of all organs, which is expressed in the everyday feeling of being alive, in this state of life, because we demand it as our right. It is this: to know oneself to be imbued with a certain feeling of well-being, with the feeling of being alive. When the feeling of being alive is dampened, one seeks to recover a little so that the feeling of being alive becomes fresher again. One senses this refreshing and dampening of the feeling of being alive, but one is generally too accustomed to one's feeling of being alive to always notice it. But there is a clear meaning, the meaning of life, through which we feel the living within us just as we see something with our eyes that is around us. We feel with the meaning of life as we see with our eyes. We would know nothing of the course of our lives if we did not have this inner meaning of life.

Even more internal, physically internal, bodily internal than the meaning of life is what can be called the sense of movement. The meaning of life senses, as it were, the overall state of the organism as a feeling of well-being or discomfort. But to have a sense of movement means that the limbs of our organism move against each other, and we can perceive this. I don't mean when the whole person moves—that's something else—but when you bend an arm or a leg; when you speak, your larynx moves; all of this, this perception of internal movements, of changes in the position of the individual limbs of the organism, is perceived with the sense of movement.

Furthermore, we must perceive what we can call our balance. We do not really pay attention to this either. When we feel dizzy and fall over, or faint, our sense of balance is interrupted, just as our sense of sight is interrupted when we close our eyes. Just as we perceive our internal positional changes, we perceive our balance when we simply relate ourselves to up and down, left and right, and thus orient ourselves in the world in such a way that we feel we are inside it; that we feel we are now standing upright. This sense of balance is perceived by us through our sense of balance. It is a real sense.

These senses function in such a way that everything that happens remains within the organism. When you touch something, you bump into the external object, but you do not enter into it. If you bump into a needle, you say that the needle is sharp. Of course, you do not enter into the tip when you merely touch it, otherwise you would prick yourself, but that is no longer touching. But all of this can only take place within your organism itself. You do bump into the object, but what you experience as a person with sense of touch takes place within the boundaries of your skin. So what you experience in your sense of touch is physical and internal. What you experience in your sense of life is also physical and internal. You do not experience how things are here or there, outside of yourself, but rather what is within you. The same applies to the sense of movement: it is not the movement of being able to go back and forth that is meant, but rather those movements when I move my limbs or when I speak, i.e., the inner movements are meant by the sense of movement. When I move outside myself, I also move inwardly. You have to distinguish between two things here: my forward movement and the position of my limbs, the inner aspect. The sense of movement is therefore perceived inwardly, like the sense of life and also the sense of balance. You do not perceive anything externally, but you perceive yourself in a state of balance.

Now, first step outside yourself with your sense of smell. This brings you into relationship with the outside world. But you will have the feeling that you are still not reaching very far outside yourself with your sense of smell. You experience little of the outside world through your sense of smell. Human beings do not really want to know what can be experienced of the outside world through a more intimate sense of smell. Dogs want to know more. It is the case that human beings initially only want to perceive the outside world through their sense of smell, but come into little contact with it. It is not a sense through which human beings want to engage so deeply with the outside world.

Humans want to engage more with the outside world through their sense of taste. We experience the properties of sugar and salt very internally when we taste them. The external becomes very internal, more so than with the sense of smell. So there is already more of a relationship between the outside world and the inner world.

This is even more so in the sense of sight, in the sense of vision. You take in much more of the properties of the outside world through your sense of sight than through your sense of taste. And you take in even more through your sense of warmth. What you perceive through your sense of sight, through your sense of vision, remains more foreign to you than what you perceive through your sense of warmth. Through the sense of warmth, you actually enter into a very intimate relationship with the outside world. Whether you perceive an object as warm or cold, you experience this very strongly, and you experience it together with the object. The sweetness of sugar, for example, is less experienced together with the object. After all, what matters to you about sugar is what it becomes through your sense of taste, rather than what is out there. With the sense of warmth, you can no longer distinguish between the two. You experience the inside of what you perceive very strongly.