The Riddle of Humanity

GA 170

21 August 1916, Dornach

Lecture X

What I would like to give you today is a thoroughly undemanding analysis of some recent directions in recent philosophical thinking. I want to take some well-known currents of thought from the surface of recent intellectual life as my point of departure. Later—very soon, if not in the next lecture—we will have time to consider some of the details and the special ramifications of contemporary thought. I would like to describe a certain tendency that is fundamental to some of the most recent of contemporary schools of thought. The whole direction taken by certain schools of thought is marked by the loss of a sense for how to orient oneself in reality, and by the loss of a sense for truth in so far as ‘the truth’ refers to an agreement between our knowledge and something that is objective. Just observe what difficulties the adherents of some recent schools of thought find themselves in when they need to decide whether a judgement about reality—about some aspect of reality or other—is right or wrong. They have difficulty in finding valid epistemological grounds, valid scientific or philosophical grounds, for their decision. There is no trace of a principle or—to use a more scientific expression—of a criterion for deciding whether particular judgements are true judgements; that is, there is no way of deciding whether they have been made with regard for reality. Certain of the old criteria have been lost and it is quite evident that nothing has come along to take their place in recent times.

I would like to take as my point of departure a thinker who died very recently. Initially, the physical sciences were his field. He turned from them to a kind of inductive philosophy in which he attempted to find something to replace the old concepts of truth, the feeling for which has been lost. I am speaking of Ernst Mach. Today I can only give you an outline of his ideas. Ernst Mach was sceptical about all the concepts produced by the thinking that preceded his time-all the thinking up to the last third of the nineteenth century. Although it approached its concepts more or less critically, this earlier thinking still spoke of the world and man under the assumption that man perceives the world through his senses—processes his sense perceptions with the help of concepts, and thereby arrives at certain pictures and ideas about the world. This assumes—and, as I said, I cannot go into all kinds of epistemological considerations today—that the impressions of colour, sound, warmth, pressure, and so on, originate in something objective. It assumes that the impressions are made on our senses by something objective, something objectively out there in external space and, in general, external to our soul life. It assumes that these impressions create sense experiences which then are further digested. And it also assumes that the human I is the true agent which is actively at work in the whole process of knowledge, and forms the basis of the entire life process. This I was acknowledged in one form or another and there was much speculation about it. People said: There exists something which one is justified in seeing as a kind of I. It is active and it is what ultimately shapes sense experiences into concepts and ideas.

Ernst Mach looked around our given world and said, more or less: None of these concepts are justified—neither the concept of subjectivity and of the I which is the subject of knowledge, nor the concept of the object that is the basis of sense impressions. What are we really given? he asked. What does the world really put before us? Fundamentally, all that is given are our sensations. We perceive colours, we perceive sounds, we have sensations of smell, and so on; but beyond these sensations, nothing at all is given to us. If we review the whole world, everything is some [form] of sensation, and beyond the sensations nothing objective is to be found. The entire world around us actually resolves into sensations. The multiplicity of sensations is all that there is. And if we can say that nothing exists beyond sensations, then we cannot say that there is some kind of I active within us. For what is given to us in the sphere of the soul? Again, only sensations. When we observe what is within us, the only thing given is the succession of sensations. These are strung together as on a thread: yesterday we had sensations; today we have sensations; tomorrow we will have sensations. They connect like the links of a chain. But everywhere, nothing is there but sensations; there is no active I. An I only appears to be there because groups of sensations are associated with one another and thus are separated out from the total world of impressions. We call this group of impressions ‘I’. They belong to us and are a part of what we perceived yesterday and the day before yesterday and half a year before that. We have found a group of sensations that belong together, so we use the expression ‘I’ as a common designator to apply to them all. Thus both the I and the object of knowledge fall away; the manifold of sensations is all that a human being can talk about. At first we relate to the world naively but, if we observe reality, all that is really there is a multiplicity of variously-grouped colours, variously-grouped sounds, variously-grouped experiences of temperature, variously-grouped experiences of pressure, and so on. And that is all.

Now along comes science. Science discovers laws. In other words it does not simply describe sensations—here I see this sensation, there I see that sensation, and so on—it discovers laws, laws of nature. Why should men need to establish natural laws if all they ever experience is a multiplicity of sensations? Merely watching the multiplicity of sensations never leads to judgements. It is only when we have more or less achieved laws that we arrive at judgements. What have our Judgements to do with the world of experience, which is really nothing more than a chaotic multiplicity? What guides one in forming judgements? Sensations are all that one has to go on-and Mach maintains that one sensation cannot even be measured against another. If that is so, what is the source of criteria for passing judgements, establishing laws and arriving at the laws of nature? To this Ernst Mach replies that it is merely a matter of economy of thought. By devising certain laws we are enabled to follow particular sensations and hold them together in our thought. What we call a law of nature is a method of associating sensations. It is the method we feel is the most economical for our thinking, the one that requires the least amount of thought.

We see a stone fall to earth. This involves a collection of sensations—one here, one there, and so on—nothing but sensations. The law of weight, of gravitation, gives us a way of combining these sensations. But there is no further reality in the law of gravitation; the sensations are the real content.

But why should we ever think out the law of gravity in the first place? Because we find it convenient: it is economical to have a concise way of referring to a special group of sensations. It gives us a kind of comfortable overview of the world of sensations. And the ways of thinking that we find most comfortable—these are the ones we call laws. What we accept as valid laws are the thoughts that give us the most convenient overview of some group of sensations. Laws provide us with certain useful expressions. Through them we know—so to speak—that when one set of conditions (that is, some collection of sensations) is repeated, then others will again be found to follow them. It is convenient for me to use the law of gravity to gather together the sensations aroused by a falling stone, for then I know: If this is a law, one thing will fall to earth like another. Thus I can think about the future in terms of the past. That is economy of thought. It is the law upon which Ernst Mach says the whole business of science is founded—the law of economy of thought, the law of the application of the least energy, which says that the greatest possible sum of sensations should be thought with the least possible number of thoughts.

You can see that no one will ever arrive at reality in this way. For, collecting together groups of sensations in the most comfortable manner possible serves nothing beyond making one's life more comfortable. The expressions to which one is led by the principle of economy of thought tell one nothing about the real basis of the sensations. The thoughts merely serve to give us a comfortable orientation in the world. The only fundamental reason for a thought is that we find it comfortable; that is why we connect certain sensations as we do. Thus you see that we have here a criterion of truth that quite deliberately tries to avoid establishing any sort of objectivity. Its only purpose is to support man's capacity to orient himself by means of sensations.

Richard Wahle16Richard Wahle (b. 1857): Das ganze der Philosophie und ihr Ende. Ihre Vermachtnisse an die Theologie, Aesthetik und Staatspedagogik, Vienna and Leipzig, 1894. was a thinker who based his ideas on similar considerations. Richard Wahle also said: People think that one thing is a cause, that another thing is an effect; that an I lives within us, that objects live outside us. But that is all nonsense. (I use approximately the same expressions as those he used.) In truth, the only things in the world that are known to us are these: that here I see the occurrence of a colour, that there a sound occurs. The world, says Wahle, consists in such occurrences and nothing more. We have already gone too far if we name these occurrences ‘sensations’, as Mach called them, for the word ‘sensation’ already contains the hidden implication that there is someone present who is doing the sensing. But how could one possibly know that the occurrence of which one is presently aware is a sensation? Out there is an occurrence of colour, an occurrence of sound, an occurrence of pressure, an occurrence of warmth; within is an occurrence of pain, an occurrence of joy, an occurrence of repletion, an occurrence of hunger. Or within is an occurrence in which someone thinks, ‘There is a God.’ But nothing more is present there than the occurrence in which someone thinks, ‘There is a God.’ Having the idea that God exists is just like having a pain. Both are only occurrences. Wahle believes, to be sure, that one must distinguish between two kinds of occurrence, the primary ones, and the so-called miniatures: Primary occurrences are those that come with an original sharpness, such as occurrences of colour, occurrences of sound, occurrences of pressure, occurrences of warmth, occurrences of pain, occurrences of joy, occurrences of hunger, occurrences of repletion, and so on. Miniatures are fantasies, intentions and, in short, everything that appears as a shadowy picture of primary occurrences. But when one takes the sum of all primary occurrences and all miniatures, that is all the world has to offer us. Fundamentally, everything else is poetry—it has been written-in without justification. Such is the case, Wahle believes, when, instead of restricting themselves to saying, ‘Three years ago there were certain occurrences, then there were others’, people are blinded by the fact that these occurrences follow one another and make the further assumption that the occurrences are collected together in an I. But where is this I? There is nothing there but occurrences, occurrences that are arranged in sequence, series of occurrences. Nowhere is an I to be found. And then others come along and claim to have discovered laws that connect occurrences, natural laws. But these laws, too, present us with nothing more than series of occurrences. And it is absolutely impossible to come to any decision as to why the series of occurrences are as they are. When men think they know something because they have strung together occurrences in a particular way, that knowledge is just so much folderol. Such knowledge, according to Wahle, is neither valid nor is it especially lofty—it is just a sign that someone has had to think something out because he has had difficulty in relating to his own occurrences. The I is the most curious of all mankind's inventions. For nowhere in the sum total of occurrences is such a thing as an I to be found. Some unknown factors seem to lurk behind the manner in which occurrences follow one another, since it does not seem arbitrary. But—and I am using the words that Wahle would use—it is entirely beyond the capacities of human judgement to ascertain what kind of unknown factors might be at work there. There is nothing one can say about them. All that a human being can know is that occurrences occur and that the factors directing them are unknown. Physics, physiology, biology, sociology—they all falter about in the dark, seeking for the director-in-charge. But this faltering about merely helps us to live with the occurrences. It will never lead us to knowledge about the unknown factors at play in the succession of occurrences. It is human folly, therefore, when people believe they can arrive at a philosophy which teaches us something about why the occurrences are as they are. Humanity has devoted itself to this folly for a time; it is high time they gave it up. One of Wahle's most important books bore the title The End of all Philosophy. Its Legacy to Theology, Physiology, Aesthetics and National Policy (Das Ganze der Philosophie und ihr Ende. Ihre Vermachtnisse an die Theologie, Physiologie. Aesthetik und Staatspedagogik). In order to teach about this ‘end of philosophy’, and in order to teach that philosophy is nonsense, Richard Wahle became a professor of philosophy!

Above all else, we can see that a total helplessness regarding the criteria of truth lies at the root of such an approach. All impulse to come to any decisions regarding knowledge has been lost. What this is based on could be characterised in the following way. Imagine someone who has a book which he has been reading for a long time. He has read it again and again and certain information contained in the book has become a part of the way he lives. Then one day he thinks to himself: Yes, here I have this book before me and I have always assumed that it gives me information about certain things. But when I take a really good look at it, the pages contain nothing but letters, letters, and more letters. I have really been an ass to believe that information about things that are not even in the book could somehow flow to me from it. For nothing is there but letters. I have been living in the mad expectation that if I let these letters affect me and if I enter into a relationship with them, they could give me something. But nothing is there but rows of the letters of the alphabet—just letters. So I must finally release myself from the insane notion that these letters describe something, or that they could somehow relate to one another, or that they could group into meaningful words, or such like. That really is a picture of the kind of thinking on which Wahle's non-philosophy, his un-philosophy, is based. For his great discovery consists in this: Men have been foolish asses, he says, to believe that they could read in the book of nature and explain how occurrences are connected! They witness occurrences, but there is nothing there beyond the unconnected occurrences. At the very most, there might be some further, unknown factors at work which are responsible for the special groupings of the letters.

This is how Wahle fails to identify with the impulse to decide about the truth of judgements and to make discoveries about the nature of the world. Human knowledge has lost the power to formulate any criterion of truth. In earlier times one believed in the human capacity to arrive at truths by means of judgements based on inner experience.

This belief has slipped from one's grasp. Hence the way philosophers wander about in this area, philosophising. By way of these two examples I wanted to demonstrate how a criterion of truth and a feeling for one's capacity to produce the truth have been lost.

A contemporary school of thought called Pragmatism demonstrates the loss of the older understanding for a criterion of truth. In Pragmatism you have a large-scale, calculated version of this loss. William James17William James (1842 – 1910): American philosopher and psychologist. is the most prominent, if not the most significant, proponent of Pragmatism. The following is a brief characterisation of the principle of Pragmatism as it has recently appeared.

Men pass judgements and they want them to express something about reality. But no human being can possibly generate anything within himself that will enable him to pass a true judgement about reality. There is nothing in man that, in and of itself, leads to the decision: that is true and the other is false. In other words, there is a feeling that one is powerless to find any original, self-sufficient criterion for whether something is true or false. And yet, because they live in a real world, men feel it is necessary to make judgements. And the sciences are full of judgements. But if one reviews the entire spectrum of the sciences with all their judgements, do they contain anything about anything that is in a higher sense true, true in the sense in which the old schools of philosophy spoke of truth and falsehood? No! According to what William James says, for example, any line of thought which asks whether something is true or false is a totally impossible way of thinking. One makes judgements. If certain judgements are passed, then one can use them to get along in life. They prove to be useful and applicable to living—they enhance one's life. If other judgements were passed, one would soon cease to come to terms with life, one's life would cease to progress. They would not be useful, they would harm life. This applies to even the most unsophisticated judgements. One cannot even say, reasonably, that the sun will rise again in the morning, for no criterion of truth is available. But we have formed the judgement: The sun rises every morning. If someone came along, maintaining that the sun would only rise for the first two thirds of the month, but not during the last third, this judgement would not bring him forward in life; he would run into trouble in the last third of the month. The judgements we form are useful. But there can be no talk of whether they are true or false. All that can be said is that one judgement helps us to get on in the world, enhances life, and that the contrary is the case with another, which gets in the way of life. There is no independent criterion of truth and falsehood: what enhances life we call true, and what hinders life, false. Thus everything to do with the question of whether or not we should pass a certain judgement is reduced to external matters of practical living. None of the impulses one once believed one possessed are valid.

Now, this line of thought is not the arbitrary product of one or the other school. One of the most extraordinary things about the line of thinking I have just described is that it has spread to practically the whole of our earth's intellectual community. It makes its appearance, independently, in one place and then in another, because present-day humanity is organised so as to fall into this way of thinking. The following interesting example demonstrates this. In the 1870s, in America, Pierce18Charles Sanders Pierce (1839 – 1914): American philosopher. wrote the first book about Pragmatic Philosophy. This was taken up by William James and, in England, by Schiller,19F. C. S. Schiller (1864 – 1937): English philosopher. and these and others continued to develop it. Now, at the very same time that Pierce was publishing his initial treatment of the ideas of pragmatic philosophy in America, a German thinker published the book The Philosophy of As If (Philosophie des Als Ob). It was a parallel occurrence. The philosopher in question was Hans Vaihinger.20Hans Vaihinger (1852 – 1933): Philosophie des Als Ob, System der theoreticshen, praktischen und religiosen Fiktionen der Menschheit auf Grund eines idealistischen Positivismus, 2nd edition, Berlin, 1913. What is this Philosophy of As If all about? It begins with the thought that human beings are actually incapable of forming true or false concepts in the way they used to do, although they still persist in forming them. The atom is a well-known example of this. The concept of the atom is, of course, wholly absurd. For our thinking attributes all sorts of qualities to the atom, qualities that will not stand up when, they are put to the test of the senses. And yet sense impressions are thought of as the effects of atomic activity. So the concept is contradictory. It is a concept of something that is totally unobservable. The atom, as Vaihinger says, is a fiction. We create many such fictions. All the higher concepts we form about reality are, fundamentally, fictions of this sort. Since there is no criterion of truth or falsehood, the reasonable man of the present needs to be clear that he is dealing in fictions. One must be fully conscious about making fictions. One must be clear that the atom is nothing but a fiction and that it cannot really exist. But one can observe the various things that are manifest in the world as if they were ruled by the life and movements of atoms—as if. For this fiction is useful. Establishing such fictions makes it possible to connect the appearances in certain ways. The I is also a fiction, but it is a fiction one has to create. For it is much more comfortable to treat the appearances that come together as if an I were active within them than it is to get along without the fiction of the I ... even though one can rest assured that it is a fiction. Thus we live according to fictions. There is no philosophy of reality, only a “Philosophy of As If”. The world humours us by appearing as if it agreed with the fictions we have made about it.

As a whole, in its tendencies and also in the way it presents individual arguments, the philosophy of Pragmatism is very similar to the “Philosophy of As If”. As I said, it was written down during the same period, the 1870s, when Pierce was writing his treatise on ‘Pragmatic Philosophy’. But an objective criterion of truth was still possible for the humanity of the 1870s. They still possessed enough rudiments of the old beliefs for their science not to have to consist of fictions. The 1870s were an awkward time for someone who wanted to become a professor of philosophy to publish a ‘Philosophy of As If’. It was not yet possible to get away with it. So Vaihinger looked for a way out. At first he acted as one has to act (has one not?). He left the Philosophy of As If lying in his desk while he went about his teaching. When the time came, he accepted his pension. Then he published the Philosophy of As If, which has now appeared in numerous editions. I simply tell the story; I am not pointing my finger, I am not judging, I am only telling the story.

So we see that there was a tendency for the old criteria of truth to break down and for truth to be measured against life. Formerly it was believed that life should be shaped in accordance with the truth, so life was put in the service of truth. What one meant by truth in the old sense did not include fictions, not even useful fictions. But, according to the extraordinary definition of the Philosophy of As If, truth is the most comfortable form of error. For, although there is nothing else but error, some errors are more agreeable and others less agreeable. The fact that what we call truths are simply the more agreeable errors is something we must clearly understand.

Thus, an impulse to do away with the concept of truth as it had been understood in older theories of knowledge really has been developing in the more recent schools of thought. One must ask oneself, ‘What is this all about?’ Naturally, there would be much to tell if I were to give you a comprehensive account of the matter. But to begin with we will take only one from among the many possible examples. In recent times, a boundless flood of empirical knowledge has become available to mankind. At the same time, men's thinking has become increasingly powerless. Thinking has lost its sovereignty over this inexhaustible richness of empirical observation and empirical knowledge; it cannot hold them together.

The way in which people have become more and more accustomed to abstract thinking is another factor. One did not think so much in earlier times, but one tried to keep one's thinking connected to the external world and to actual experience. It was felt that thinking needed to be connected with something and that it could not progress if it were wholly isolated. But along with the extensive cultivation of thinking, one has also learned to think abstractly—has become accustomed to abstract thinking and has become fond of it. To this must be added other harmful characteristics of our age, above all, the view that anyone who wants to become even so much as a lecturer must produce some kind of elevated thinking or research, and that those who want to become professors must do something quite immense! A kind of hypertrophy of thinking, so to speak, has been thus created. Thinking is set loose on its own; it begins to arrive at forms of thought that, as such, are merely internally logical. I will show you one of these internally logical thought-forms.

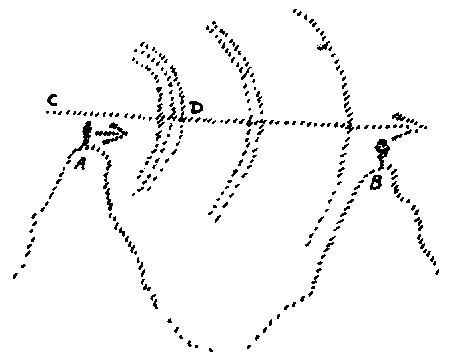

Just picture the following: Here is a mountain. On this mountain (A) a shot is fired. After a while, say two minutes, two more shots are fired. Then, after a further two minutes, three shots are fired.

And now, over here (B) there is someone who is listening. I will not say that he is wounded, but he is listening. What he hears would be, first a single shot, then after a certain period, two shots, and then, after another pause, three shots. But now let us assume that matters are not so simple, with one, two, and then three shots being fired here, and over here someone who hears the shots—first one, then two, then three. Let us assume that someone (C) moves from this mountain (left) towards this other one (right). Assume that he flies at a certain speed and that he moves very fast. You know from elementary physics that sound requires a certain time to get from here (see drawing) to there. Therefore, when a shot is fired here (A), a certain period of time will elapse before it will be heard by a person who is listening over here (B) ... then the sound of the single shot will arrive. Two minutes later, the pair of shots will arrive and, after a further two minutes, the three shots. But let us assume that this other person (C) moves faster than the speed of sound. As he passes this mountain, moving towards the other, he is already moving faster than the speed of sound. The first shot is fired ... then two shots ... then three ... After the three shots have been fired, he arrives at this other mountain and flies on at the same speed until he overtakes the three shots—that is, he flies past the sound of the three shots—flying quickly past them, for he is moving faster. Eventually, the sound of the three shots will arrive here (D). He is flying after them. He hears them as he overtakes them and continues onward, flying towards the two shots that had been fired earlier. These he also hears as he overtakes them. Then he overtakes the single shot and hears it. Therefore, someone who is flying faster than sound would hear the shots in reverse order: three shots ... two shots ... one shot. If one is living in circumstances usual for an ordinary human being on the ordinary earth, and thus has the usual relationship to the speed of sound, one would hear one shot at this point, two shots here, three here. But if one does not behave like an ordinary human being on the ordinary earth, but instead is a being who can fly faster than the speed of sound, one would hear the events in reverse order: three shots, two shots, one shot. All that is required is that one practise the minor skill of chasing after the sounds while flying faster than the sounds of the shots are moving.

Now, this is unquestionably as logical as it could be. There is not the slightest logical objection to be brought against it. Thanks to certain things that have emerged recently in the sciences, the example I have just been describing to you—in which someone flies in pursuit of sounds and hears them in reverse order—has been used to introduce countless lectures. Again and yet again, lectures begin with this so-called example. For this is supposed to demonstrate that the way in which one perceives things is a result of the situation in which one is living. The only reason that we hear as we do, rather than in reverse, is that we move at a snail's pace in comparison with the speed of sound. I cannot describe here all that is derived from this train of thought, but I wanted to acquaint you with it, since for many it is the basis of a widespread, acutely discerning theory, the so-called theory of relativity.

I have only described the most obvious parts to you. But you can see from what I have described that everything here is logical—very, very logical. Now, these days one finds countless judgements—the philosophical literature is teeming with them—all of which are derived from the same assumptions about thought. It is as though thinking has been torn away from reality. One thinks only about certain isolated conditions of reality and then constructs further thoughts from them.

It is scarcely possible to reply to such things, for the naturally expected reply would be a logical reply. But there can be no logical reply. It was for this reason that I introduced a certain idea in my last book, On the Riddles of Humanity (Vom Menschenratsel). This is the idea that if one wants to arrive at the truth, it is not sufficient just to form a logical concept, or a logical idea. There is the further requirement that the concept or idea must be in accordance with reality. Now, a very lengthy discussion would be required if I were to show you that the whole of the theory of relativity does not agree with reality, even though it is logical—wonderfully logical. We could show how the concept that is constructed regarding the series of one, two and three shots is completely logical and that, nevertheless, it is not a concept that would be formed by someone who thinks in accordance with reality. One cannot disprove the theory, one can only refrain from using it! And someone who has understood the criterion of being in accord with reality would refrain from using such concepts.

The empirical phenomena that Lorentz,21Hendrik Antoon Lorentz (1853 – 1929): Dutch physicist; founder of the theory of electrons. Einstein, and others are trying to understand by means of this theory of relativity must be approached in an entirely different manner, not along the lines in which they and the others are thinking.

What I have been describing to you here is only one current in the ongoing stream of recent thought. Naturally, remnants of earlier thought are always being intermixed with the more recent thinking. But the ultimate and radical consequences of the assumptions on which almost all recent thinking is based are already contained in what I have been describing to you. We can see one distinctive peculiarity. A self-sufficient criterion of truth and falsehood has been lost—or, better said, the feeling for such a criterion has been lost. The resulting emancipation of abstract thinking has led to the formation of concepts which, being logical, are indisputable. In a certain sense they even accord with reality. But they remain merely formal concepts, for they are not suitable for saying something real about reality. They swim on the surface of reality without penetrating to the actual impulses at work in reality.

The following is an example of a theory that stays on the surface of reality and does not want to submerge in reality: Consider how, within the sphere of human reality one can distinguish the mineral realm, the plant realm, the animal realm and the human realm. And men live within a social order, as well—one could call it a sociological order. Perhaps other, higher, orders could be found, but we are not presently concerned with those. Now, in the middle of the nineteenth century, when a materialistic concept of reality held sway, the fashion in which people pictured these superimposed realms was one that must seem simplistic to us. Basically, only the mineral realm was taken into account. One said to oneself: Now, plants consist of the same things that are to be found in the mineral realm; they are simply organised in a more complicated way. The animal realm is again just a matter of further complication, and the human realm is more complicated still ... and so we reach the higher levels. Mind you, when one proceeds further, to the social order, it is no longer possible to discover more complicated atomic movements. Certain patterns of movement correspond to the mineral realm—that is how people pictured things. The movements become more complicated in the plant realm—this one knew, although it was not possible to observe the atoms. Still more complicated movements correspond to the animal realm, and even more complicated ones to the human realm. All was built up in this way. But, of course, when one comes to the social order it is not so easy to continue thinking in terms of atoms, for no atomic movements are there to be observed.

It was left to a thinker of the final third of the nineteenth century to at last accomplish the wonder of reducing sociology to biological concepts. He treated social structures, such as families, like cells. These then group themselves, do they not, into regional communities—or whatever we shall call them?—which are the beginnings of tissues. Then the theory goes further—countries are complete organs ... and so on. The person who created this way of thinking.22Albert Schaffle (1831 – 1903): Die Aussichtslosigkeit der Sozialdemokratie. Drei Briefe an einen Staatsmann zur Erganzung der ‘Quintessenz des Sozialismus’, Tubingen, 1885. Schaffle then wrote a book Social Democracy's Empty Future. (Die Aussichtslosigkeit der, Sozialdemokratie), which drew on these theories for support. Hermann Bahr,23Hermann Bahr (1863 – 1934): Die Einsichtslosigkeit des Herm Schaffle. Drei Breife an einen Volksmann als Antwort auf ‘Die Aussichtslosigkeit der Sozialdemokratie’, Zurich, 1886. the Viennese writer, was still a young, but very talented, whipper-snapper in those days. He wrote a reply to Schaffle's Social Democracy's Empty Future and called it, Herr Schaffle's Empty lnsights (Die Einsichtslosigkeit des Herm Schaffle). This outstandingly-written book has since been forgotten.

Thus, as I was saying, the old materialists conceived of reality in terms of ever more complicated structures. In doing so, they naturally had to introduce certain concepts, concepts, say, about how the movements of the atoms, which in a mineral are fixed, become more labile and seek to achieve a balanced form in plants, and so on. In short, various theories were constructed in which it was attempted to derive one thing from another. Once materialism had been active for long enough, it was possible to think back and see how little fruit it had borne and how poorly its idea of reality had stood up to exacting tests. And so people came to the idea: Yes, to be sure, there is the mineral realm, and after that comes the plant realm. Mineral substance is contained within the plant, and the laws applying to minerals even apply there; the salts and other substances contained in the plant function in accordance with their own physiological-chemical laws. But the plant realm can never arise out of the mineral realm. Something further is required, some creative element. When one proceeds from the mineral realm to the plant realm, something creative has to be added to it. This creative element—the first creative element—works creatively in the realm of the minerals. Then a second creative element manifests itself in the mineral realm and the animal realm arises. So the animal sphere must take hold of the plant and mineral realms. Then a fourth creative element appears and takes hold of the three lower realms—takes them into the human sphere. Then, when we come to the social order, a further creative element again takes hold of the subordinate realms. A veritable hierarchy of creative elements! Of course there is nothing objectionable in the logic of this thinking. As thought, it is correct thought. But you will certainly have to think differently about these matters if you call to mind some of the concepts of spiritual science—concepts which we shall not be discussing today. These reflections remain stuck in abstractions; they never arrive at a concrete picture. Some details are mentioned, of course, but when one sets about thinking in this fashion one is stuck with an abstract concept of creativity. All the thinking remains stuck at the level of abstractions. And yet it is an attempt to use clear, formal thinking to overcome an unadorned materialism. One arrives at something higher, but only as an abstract concept.

Boutroux's24Emile Boutroux (1845 – 1921): French philosopher. philosophy is an attempt to overcome unadorned materialism. He makes use of a formal thinking derived from the unprejudiced observation of the hierarchy of the realms of nature. He seeks the concept of an ascending creative scale in what could be called the hierarchy of the sciences. This leads to interesting conclusions. But the whole attempt remains stuck in abstractions. It is easy to show this by examining the details of Boutroux's philosophy. To begin with, I will only describe the line of thought he takes; perhaps the rest can be introduced later. Here we have an attempt to capture reality by applying abstractions to a more or less superficial observation of reality. But it is not thus to be captured. He does not want a mere ‘Philosophy of As If’, nor does he want to found some sort of mere pragmatism, or to restrict himself to an unreal enumeration of occurrences. But he cannot arrive at the sort of concreteness needed for reading the external world and for discovering what lies behind it. He cannot help us to look at the external world as one looks at the letters in a book to discover what is behind them; he only shows us some abstractions. These are supposed to express what it is that lives in the realms of reality. Whereas it was the criterion of reality that was missing in the other philosophical lines of thought I have been describing, what has been lost here is the power to take hold of reality concretely. One is no longer able to submerge in the inner impulses that are at work in reality, but only to skim along the top.

This shows us another fundamental tendency of modern life. I mentioned that thinking has emancipated itself in a particular way Torn from reality. Once emancipated from reality, it proceeds in abstractions.

If you will observe all the various recent schools of thought, you will perceive how the ability to plunge into reality has been lost. The ability to grasp reality in its true shape is becoming weaker and weaker. For a classic example of this follow the development of thought that leads from Maine de Biran25Francois Pierre Gauthier Maine de Biran (1766 – 1824): French philosopher. to Bergson.26Henri Bergson (1859 – 1941): French philosopher. Whereas Biran, living in the first third of the nineteenth century, still pursued a line of thought whose important psychological concepts enabled him to submerge in the real sphere of the human being, Bergson strikes out on a curious path that is wholly characteristic of the particular tendencies at work in recent thought. Bergson notices, on the one hand, that it is not possible to submerge in an immediate, living reality by means of the usual abstract thinking nor with the help of anything offered by scientific thinking as it is currently practised and as it is embodied in various scientific conclusions. He saw that this thinking is fundamentally unable to connect with reality—that it will always remain more or less on the surface of reality. For this reason he wishes to grasp reality by means of a kind of intuition. At present, I can only give you the broadest outlines of this intuition at the moment. It is an inner mode of experience; it contrasts with an approach which tries to capture reality in external structures of its own devising. This leads Bergson to some odd conclusions regarding the theory of knowledge and psychology. I will omit the intermediate steps and proceed to the summit from whence he points to the materialistic view that memories and other higher manifestations of soul life—manifestations involving complicated inner forms or movements—are dependent on structures in the brain. He says, to the contrary, that the shaping of these complicated forms has nothing at all to do with the purpose of the brain. What happens, rather, is that the soul acts and comes into relationships with reality which are then expressed in sensations, perceptions, in practical engagement with life, and in the way we move our body. These things are beyond the reach of abstract thinking and must be grasped by intuition, by inner experience. The function of the inner structures that are dependent on the brain extends no further than to their effects on perception and on the promotion and arrangement of life. Memory is not the result of formations in the brain; memory functions with an intensity that is independent of the brain.

This is an attempt to overcome a materialistic concept of knowledge. It is a curious attempt in that what it brings to light is the opposite of reality. For memory depends precisely upon the support of the physical body, the physical brain and the whole physical system.

Memory could never be established in the soul life if the soul were not able to extend its development into the physical body and establish within it the things necessary for exercising the faculty—the ability—to remember. So here we have a theory in which the drive to overcome materialism leads to conclusions that are precisely the opposite of the right ones. The truth of the matter is that memory needs to be annexed to the soul—it is among the capacities that the human soul needs to acquire. Therefore, memory, with the help of the physical body, needs to be annexed to the soul. But Bergson arrives at a contrary view—the view that the physical body does not participate in the development of memory. I am not describing these things in order to say something in particular about Bergsonian philosophy, but merely to show you this curious manifestation in contemporary thinking. Proceeding in an entirely logical fashion, one arrives at the opposite of what is correct.

We could start, therefore, with those more epistemologically orientated philosophies which speak of the inability to arrive at a criterion of truth and falsehood, and then proceed to the philosophies that are more concerned to arrive at the truth. What we would find, throughout, is that they all arrive at exactly the wrong conclusions because of their helplessness in dealing with the truth. Thus does contemporary thinking lean towards the very things that are incorrect and false. This phenomenon is connected with the way in which mankind has developed a tendency towards abstractions and an ability to work with abstractions, for this has made man a stranger to reality. Mankind is detached from reality and cannot finds its way back into reality. You can read about this in detail in my book, The Riddles of Philosophy (Die Ratsel der Philosophie). If one separates oneself from reality and lives in abstractions, the way back to reality is not to be found. But a counter-tendency is beginning to make itself felt. People are beginning to discover in themselves a kind of longing for spiritual concepts. But the helplessness persists; there is still an inability to arrive at the spirit. Significant and instructive things are to be observed happening in contemporary attempts to find a path that leads out of this absolute helplessness, a path leading to spiritual truths. And we have just looked at an example in which thinking that has been emancipated from reality seeks for the truth and arrives at the opposite of the truth.

The philosophy of Eucken27Rudolf Eucken (1846 – 1926): German philosopher. is a characteristic example of someone who is seeking for the spirit without having the slightest ability to grasp even so much as the shirt-tail of anything spiritual. Although Eucken speaks of nothing but the spirit, he does so only in words. He never actually says anything about the spirit. Because his words are wholly incapable of capturing anything truly spiritual, he speaks unceasingly of the spirit. He has already written countless books. To read through his books is a genuine torture, for they all say the same thing. There you will always find ... that one must discover how to grasp one's own being with thinking that exists in itself, that takes hold of itself without any dependence on anything external or on any external resistance, that beholds itself within itself, that proceeds entirely within itself and in so doing enters into itself and then recreates itself from out of itself. If you hear Eucken deliver a series of lectures about Greek philosophy, or read one of his books about it, you will find the development of Greek philosophy presented in this manner: At first thinking tries a little to take hold of itself, but it cannot yet do so ... Or you can hear how Paracelsus is gradually beginning to take hold of the inner world ... Or you can read a book about the development of Christianity-everywhere you will find the same things; everywhere the same! Yet our modern philistines find this philosophy so infinitely important; they rejoice to hear someone speaking about the spirit and theorising about the spirit as long as they are not required to know anything about the spirit or to actually enter into anything spiritual. This is why many say that Eucken's philosophy is the reawakening of Idealism, the reawakening of the life of the spirit, and is the right philosophy for creating a cultural ferment that will again enliven today's deathly, exhausted spiritual life, and so on. And yet anyone who has a feeling for what pulses, or ought to pulse, through a philosophy, and who reads or listens to Eucken, will have the lively impression that he is supposed to take hold of his own hair and drag himself into the heights, and then drag himself higher still, and higher still again. For such is the self-consistent logic of Eucken's philosophy. I have tried to give a totally objective account of these things in my Riddles of Philosophy. Anyone is capable of saying what I have just said, for it is not necessary to embark on critical analysis—merely acquainting oneself with the concepts as they are is enough.

Thus we see how certain contemporary streams of thought flow from a helplessness in the face of truth; we see how it is even possible to construct philosophies out of such helplessness in the face of reality. If one were not concerned about life, this might not seem so terrible. But terrible it is. And now and again it is necessary to enter into what lives and weaves in contemporary intellectual life in order to develop a feeling for what might overcome these things.

I have only described to you a few of the currents of thought that have been important to the intellectual life in the most varied places, places where philosophical views of the world are presented in lectures and are taught. Over the last years, the various streams of thought have been developing similar tendencies, so that a common structure of thought exists overall. I touched on this when I showed you how the ‘Philosophy of As If’ and Pragmatism arose at the same time, independently of one another.

But the thinkers have also borrowed various things from one another. The exchange of thoughts is always an active business. Vaihinger was wholly independent of Pierce; the two, one in Germany, the other over there in America, arrived at this approach to life independently of one another. Indeed, one finds many such echoes between personalities in one culture and personalities in another. Only by observing these in detail does one obtain a true picture of what is really going on in the spiritual life. And an unbelievable amount is written and thought and considered along these lines today, but the speculations pay no attention, to some of the simplest of things. Certain connections are ignored because the present day has not preserved a sense for reality. And this sense for reality is something that must be learned. As a sort of appendix to today's lecture let me state: This sense for reality is a thing that has to be learned.

If I may be allowed to mention something personal, I should like to say that I have always attempted—even in external scientific matters—to develop the sense for reality, the sense for how to keep on the trail of reality. This consists not only in being able to judge what is really there, but also in being able to find ways of applying real measures and real comparisons to reality. Perhaps you are acquainted with the so-called doctrine of the eternal return—the return of the same things—that is to be found in Nietzsche. According to this doctrine, we have already sat together countless times before in just the way we are sitting now. And we will sit together in this way countless times again. This is not a doctrine of reincarnation, but a doctrine about the repetition of the same things. At the moment I am not concerned to criticise the doctrine of the eternal return. This doctrine of eternal return is derived from a quite definite picture of how the world was formed. Out of this other, prior, view of the world Nietzsche developed some impossible ideas.

I was once present with other scholars at the Nietzsche Archive. The doctrine of the eternal return was being discussed and people were interested to know how Nietzsche might have arrived at this idea. Now, just think of the marvellous possibilities there! Anyone who is acquainted with academic circumstances will see what beautiful opportunities there are for writing the greatest possible number of dissertations and books about how Nietzsche originally came upon the idea of the doctrine of the eternal return. Naturally, one can come up with the boldest of theories to explain it. One can find all kinds of things; one only has to look for them. After the discussion had gone on for a while, I said to the gathering: Nietzsche often arrived at an idea by formulating the contradictory of some idea he encountered in another person. Thus I was trying to approach his ideas realistically. To my knowledge, I said, the contrary of this idea of his is to be found in another philosopher, Duhring, who said that the original configuration of the earth made it impossible that anything should ever repeat itself. And I said that, to the best of my knowledge, Nietzsche had read Duhring. So I suggested that the simplest thing would be to go into Nietzsche's library, which has been preserved, take down the books by Duhring, and look at the passages where the counter-theory is to be found. We then went to his library and located the books. We found them the relevant passages—with which I was quite familiar—and found heavy markings in Nietzsche's own hand and some characteristic words. When he came to passages where he intended to formulate a contradictory idea—I am no longer sure exactly which word he used in this particular case—Nietzsche would write something like ‘ass’ or ‘nonsense’ or ‘meaningless’. There was such a characteristic word written in the margin at this place. Thus the idea for ‘the doctrine of the eternal return’ was born in Nietzsche's spirit when he read this passage and formulated the contradictory idea! Here it was just a matter of looking in the right place. For when he met certain ideas, Nietzsche really did tend to formulate the contradictory idea.

Here we have another characteristic manifestation of the powerlessness of the modern criterion of reality. I have been showing you some of the things that originate in this powerlessness. We have another example in this use of contradiction to confront a stated truth or a pre-existing judgement when one is unable to arrive at any independent criterion of truth of one's own. But one must not generalise about such things. It would naturally be absurd to take this example and come to the abstract judgement that Nietzsche arrived at his entire philosophy in this manner, for at times he was entirely positive and simply extended an idea while remaining completely faithful to its original spirit. This, for example, is how the whole of what we encounter in Nietzsche's Beyond Good and Evil (Jenseits von Gut und Bose) came into being. This can be demonstrated in all particulars. Once again, all one has to do is go to Nietzsche's library. There one will find a book on morality by Guyau.28Marie Jean Guyau (1854 – 1888): French poet and philosopher. Esquisse d'une morale sans obligation ni sanction, Paris, 1884. Read all the passages where Nietzsche has made notes in the margins—you can then find them again, summarised, in Beyond Good and Evil. Beyond Good and Evil is already contained in Guyau's treatment of morality. These days it is necessary to pay attention to such connections. Otherwise one can arrive at entirely false impressions about what kind of person this or that thinker was.

Today I wanted to share with you some perspectives on the modern intellectual life. I have restricted myself to what is most familiar and straightforward. If circumstances permit, we can return to these matters in the near future and examine them in greater detail.

Zehnter Vortrag

Was ich heute geben will, soll eine ganz anspruchslose Auseinandersetzung sein über einige in der neueren Zeit heraufgekommene philosophische Gedankenrichtungen. Ich werde an sehr bekannte Gedankenrichtungen anknüpfen, sozusagen an die an der Oberfläche des Gedankenlebens der letzten Zeit sich befindlichen. Später, in der nächsten oder in der allernächsten Zeit, können wir uns ja einmal auf Einzelheiten und spezielle Ausgestaltungen gegenwärtiger Gedanken einlassen. Ich möchte einen gewissen Grundzug in einigen Gedankenrichtungen der Gegenwart, der jüngsten Zeit, charakterisieren. Dieser Grundzug besteht darin, daß die ganze Richtung gewisser Gedankenströmungen uns zeigt, man könnte sagen, ein Abhandenkommen eines Orientierungsgefühles für die Wirklichkeit, für die Wahrheit, insofern man die Zusammenstimmung unserer Erkenntnisse mit einem Objektiven «die Wahrheit» nennen kann. Man merkt gewissen Gedankenströmungen der jüngsten Zeit an, daß sich die Denker so schwer zurechtfinden, wenn sie aus erkenntnistheoretischen Gründen heraus, aus Gründen heraus, die sie philosophisch oder wissenschaftlich gelten lassen können, eine Entscheidung treffen sollen darüber, ob ein Urteil über die Wirklichkeit, diese oder jene Form der Wirklichkeit richtig oder unrichtig ist. Es ist nicht in dem Denken ein Prinzip oder — wenn ich mich wissenschaftlich ausdrücken sollte — ein Kriterium zu verspüren, das den Impuls darstellte, sich zu entscheiden bei gewissen Urteilen, ob sie wahre Urteile, das heißt auf Wirklichkeit bezügliche Urteile sind. Gewisse ältere Kriterien sind abhanden gekommen. Und das ist deutlich zu merken, daß an die Stelle dieser alten Wahrheitskriterien eigentlich nichts Rechtes tritt in der letzten Zeit.

Ich möchte dabei ausgehen von einem in der allerjüngsten Zeit verstorbenen Denker, der von physikalischen Studien ausgegangen ist und sich dann einer Art induktiver Philosophie zugewendet hat, und der versucht hat, etwas zu setzen an die Stelle der alten Wahrheitsbegriffe, für die allmählich das Gefühl verlorengegangen ist. Ich meine Ernst Mach zunächst. Ernst Mach - ich kann nur Grundlinien der Begriffe heute anführen - ist skeptisch gegenüber allen Begriffen, welche das vorhergehende Denken, das Denken bis in das letzte Drittel des neunzehnten Jahrhunderts hinein, hervorgebracht hat. Dieses Denken sprach ja, indem es mehr oder weniger kritisch sich zu diesen Begriffen verhält, sie mehr oder weniger ausarbeitete, doch so über die Welt und den Menschen, daß man annahm: Der Mensch nimmt durch seine Sinne die Welt wahr, verarbeitet die Sinnesempfindungen durch Begriffe und kommt dann zu gewissen Vorstellungen, zu Ideen über die Welt. Dabei setzt man voraus — wie gesagt, auf allerlei weitere erkenntnistheoretische Dinge kann ich mich heute nicht einlassen -, daß dasjenige, was empfunden wird: Farben, Töne, Wärme, Druckempfindungen und so weiter, herkommt von irgendeiner Objektivität, von irgend etwas Objektivem, das sich draußen im Raum oder überhaupt draußen außerhalb unseres Seelischen befindet, durch die Sinne einen Eindruck macht, welcher Eindruck dann Sinnesempfindung ist, welche Sinnesempfindung dann wieder weiterverarbeitet wird. Und als das Agens, das eigentlich Tätige, das Aktive in diesem ganzen Erkenntnisprozeß, der nun wiederum zugrunde liegt dem ganzen Lebensprozeß, sah man das Ich des Menschen an, über das man ja viel spekulierte, theoretisierte, das man aber in der einen oder in der anderen Form so gelten ließ, daß man sagte: Es gibt eben so etwas, das man berechtigt ist, als eine Art Ich anzusehen, das aktiv ist und das die verschiedenen Sinnesempfindungen zuletzt zu Begriffen, Ideen formt.

Ernst Mach sieht sich gewissermaßen um in unserer gegebenen Welt und sagt: Alle diese Begriffe — vom Ich, also von dem Erkenntnissubjekt, von der Subjektivität; von dem Objekt, das den Sinnesempfindungen zugrunde liegt -, alle diese Begriffe sind eigentlich unberechtigt. Er sagt: Was haben wir eigentlich gegeben? Was ist eigentlich vorliegend in der Welt? Nur Empfindungen sind im Grunde genommen vorliegend. Wir nehmen Farben wahr, wir nehmen Töne wahr, wir nehmen Geruchsempfindungen wahr und so weiter; aber irgend etwas außerhalb dieser Empfindungen ist uns ja gar nicht gegeben. Wenn wir richtig Umschau halten in der Welt, so ist alles irgendwie Empfindung, und jenseits der Empfindungen findet man nirgends ein Objektives. Alle Welt, die uns vorliegt, löst sich eigentlich auf in Empfindungen. Alles sind nur mannigfaltige Empfindungen. Und wenn wir so sagen können: Nichts ist da außer Empfindungen - so kann man auch nicht sagen: Da drinnen in uns ist ein besonderes Ich, ein Aktives. Denn was ist uns denn in unserer Seele gegeben? Wiederum nur Empfindungen. Wenn wir da hineinschauen in uns, ist uns nur ein Verlauf von Empfindungen gegeben; diese Empfindungen sind gleichsam an einem Faden aufgerollt: gestern haben wir Empfindungen gehabt, heute haben wir Empfindungen, morgen werden wir Empfindungen haben. Die gliedern sich so zusammen wie die Kettenglieder. Aber überall nur Empfindung; nirgends ein aktives Ich. Es ist nur ein Schein von einem Ich da, weil aus der allgemeinen Empfindungswelt eine Gruppe von Empfindungen herausgeholt wird, die sich zusammengruppieren. Und diese Gruppierungen nennen wir Ich, sie gehören uns, sie gehören zu dem, was wir gestern und vorgestern und vor einem halben Jahre wahrgenommen haben. Weil wir solch eine Gruppe von zusammengehörenden Empfindungen finden, bezeichnen wir sie mit dem gemeinsamen Worte «Ich». — Also das Ich fällt auch weg, das Erkenntnisobjekt fällt auch weg, alles, wovon der Mensch sprechen kann, ist nur eine Mannigfaltigkeit von Empfindungen. Stehen wir also zunächst naiv der Welt gegenüber, betrachten wir das Wirkliche, so ist wirklich eine unendliche Mannigfaltigkeit verschieden gruppierter Farben, verschieden gruppierter Töne, verschieden gruppierter Temperaturempfindungen, verschieden gruppierter Druckempfindungen und so weiter vorhanden; aber das ist alles.

Nun kommt aber auch die Wissenschaft. Die Wissenschaft findet Gesetze. Das heißt, sie beschreibt nicht einfach: Ich sehe hier diese Empfindung, ich sehe dort jene Empfindung und so weiter, sondern sie findet Gesetze, Naturgesetze. Was nötigt denn den Menschen, Naturgesetze aufzustellen, da er doch nur eine Mannigfaltigkeit von Empfindungen hat? Bloß hinzuschauen auf die Mannigfaltigkeit der Empfindungen gibt kein Urteil. Erst indem wir mehr oder weniger zu Gesetzen aufsteigen, kommen wir zum Urteil. Was wollen wir denn eigentlich mit dem Urteil in der Empfindungswelt, die doch eigentlich nur eine chaotische Mannigfaltigkeit ist? Wonach richtet man sich denn, indem man Urteile bildet? Ja, wenn nichts da ist als nur Empfindungen —- man kann doch nicht, meint Mach, eine Empfindung an der anderen messen. Also, was gibt denn ein Kriterium her, Urteile zu bilden, Gesetze aufzustellen, zu Naturgesetzen zu kommen? — Da sagt Ernst Mach: lediglich die Denkökonomie führt dazu. Wenn wir gewisse Gesetze ausdenken, so können wir an der Hand dieser Gesetze gewisse Empfindungen verfolgen, zusammenhalten gleichsam im Denken. Und wenn wir fühlen, daß wir bei irgendeiner Art, die Empfindungen zusammenzuhalten, mit dem kleinsten Maß des Denkens messen können, am Ökonomischsten denken, so nennen wir das ein Naturgesetz. Wir sehen, daß ein Stein zur Erde fällt. Es ist eine Summe von Empfindungen, hier eine Empfindung, dort eine Empfindung und so weiter — lauter Empfindungen. Wir fassen das zusammen unter dem Gesetz der Schwere, der Gravitation. Aber das Gesetz der Schwere ist weiter keine Wirklichkeit, denn Wirklichkeit sind nur die Empfindungen. Also warum denken wir dann überhaupt das Gesetz der Schwere aus? Weil es unsbequem ist; es ist denkökonomisch, einegewisse Gruppe von Empfindungen mit einem kurzen Ausdruck zusammenzufassen. Wir gewinnen dadurch gewissermaßen einen bequemen Überblick über die Empfindungswelt. Und dasjenige Gedachte, was uns den bequemsten Überblick über irgendeine Gruppe von Empfindungen gibt, so daß wir diesen Ausdruck gebrauchen können, indem wir gewissermaßen wissen, wenn wir den Ausdruck haben und gewisse Bedingungen wiederum hergestellt sind, das heißt, gewisse Empfindungen wieder auftreten werden, dann werden in ihrer Folge wieder andere auftreten — das gilt uns als Gesetz. Wenn ich die Empfindungen, die hervorgerufen werden durch einen fallenden Stein, in das Gesetz der Schwere zusammenfasse, so ist das für mich bequem, denn ich weiß: wenn ich dieses Gesetz habe, dann wird einer auf die Erde fallen wie ein anderer. Ich kann also von der Vergangenheit in die Zukunft herein denken. Es ist Denkökonomie. Das Gesetz der Denkökonomie, das Gesetz des kleinsten Kraftmaßes, das heißt, mit der kleinsten Summe von Gedanken die größte Zahl von Empfindungen zu umfassen, das ist dasjenige, was Ernst Mach zugrunde legt dem ganzen wissenschaftlichen Betrieb.

Sie sehen daraus: Zu etwas Wirklichem kommt man dadurch nicht. Denn dadurch, daß man in der bequemsten Weise Gruppen von Empfindungen zusammenfaßt, dient man nur der eigenen Bequemlichkeit des Lebens. Aber das, was man als Ausdrücke bekommt durch das Prinzip der Denkökonomie, das sagt nichts aus über das, was den Empfindungen zugrunde liegt. Es ist nur zu unserer eigenen bequemsten Orientierung in der Welt. Es ist nur, weil wir es im Grunde genommen so bequem finden; deshalb fassen wir die Empfindungen in einer gewissen Weise zusammen. Sie sehen also, hier handelt es sich um ein Wahrheitskriterium, das ganz absichtlich absieht davon, zu irgendeiner Objektivität zu kommen, das kein anderes Ziel verfolgt, als dem ‚menschlichen Orientierungsvermögen durch die Empfindung hindurch zu dienen.

Ein Denker, der auf ähnlichen Erwägungen seine Ideen aufgebaut hat, ist Richard Wahle. Richard Wahle sagt auch: Da reden die Menschen davon, das eine ist Ursache, das andere ist Wirkung; da lebe im Innern ein Ich, draußen leben Objekte. Aber das ist alles Unsinn — ich gebrauche ungefähr die Ausdrücke, die er auch gebraucht -, in Wahrheit ist uns nichts in der Welt vorliegend, als: wir sehen da ein Farbenvorkommnis, da ein Tonvorkommnis; die Welt besteht nur, wie Wahle sagt, aus Vorkommnissen. Wenn wir diese Vorkommnisse Empfindung nennen, wie das Mach tut, so gehen wir eigentlich schon zu weit; denn in dem Worte «Empfindung» liegt schon eine geheime Hindeutung, daß jemand da ist, der empfindet. Aber woher soll man denn wissen, daß das, was als Vorkommnis auftritt, eine Empfindung ist? Vorkommnisse sind da. Da draußen ist ein Farbenvorkommnis, ein Tonvorkommnis, ein Druckvorkommnis, ein Wärmevorkommnis; da drinnen ist ein Schmerzvorkommnis, ein Freudenvorkommnis, da ist das Vorkommnis der Sättigung, das Vorkommnis des Hungers, da ist das Vorkommnis, daß sich einer vorstellt: einen Gott gebe es. Aber es liegt eigentlich nichts vor, als daß einer sich vorstellt: einen Gott gibt es. So wie einer einen Schmerz hat, so stellt er sich vor: einen Gott gibt es. Alles ist nur Vorkommnis. Zwar meint Wahle, man muß unterscheiden zwischen zweierlei Arten von Vorkommnissen, den primären Vorkommnissen und den sogenannten Miniaturen. Die primären Vorkommnisse, das sind diejenigen, die mit ihrer ursprünglichen Schärfe auftreten, Farbenvorkommnisse, Tonvorkommnisse, Druckvorkommnisse, Wärmevorkommnisse, Schmerzvorkommnisse, Freudenvorkommnisse, Hungervorkommnisse, Sättigungsvorkommnisse und so weiter. Miniaturen sind Phantasiebilder, Absichten, kurz, alles dasjenige, was wie in Abschattung, wie in Schattenbildern der primären Vorkommnisse auftritt. Aber wenn man die Summe aller primären Vorkommnisse und aller sekundären Vorkommnisse, der sogenannten Miniaturen, nimmt, dann hat man auch alles, was die Welt uns bietet. Alles übrige ist im Grunde genommen hinzugedichtet, ohne Berechtigung hinzugedichtet. Da, meint Wahle, sagen sich die Menschen: Vor drei Jahren sind diese Vorkommnisse dagewesen, dann sind die anderen Vorkommnisse gekommen, und weil gewisse Vorkommnisse so aufeinanderfolgen, so blendet das die Menschen, und sie fassen das zusammen als ein Ich. Aber wo ist ein solches Ich? Vorkommnisse sind nur da, die aneinandergereiht sind, Reihen von Vorkommnissen. Aber nirgends ist ein Ich da. Und dann kommen die Menschen und sagen, sie hätten Gesetze gefunden, welche diese Vorkommnisse verbinden — Naturgesetze. Aber diese Gesetze stellen auch nichts anderes dar, als daß sie Vorkommnisse aneinanderreihen. Und warum sie sich so aneinanderreihen, darüber etwas zu entscheiden, das ist schlechterdings unmöglich. Und wenn die Menschen das Wissen nennen, wenn sie die Vorkommnisse in einer gewissen Weise auffädeln, so ist dieses Wissen eben Firlefanzerei. Dieses Wissen, meint Wahle, sei weder etwas Gültiges noch etwas besonders Erhabenes, sondern es stellt nur dar, daß der Mensch eigentlich nicht recht die Möglichkeit findet, sich zu seinen Vorkommnissen in ein Verhältnis zu setzen und sich etwas ausdenkt. Das Ich ist die kurioseste Erfindung. Denn nirgends ist in der Summe der Vorkommnisse so etwas wie ein Ich wirklich aufzufinden. So wie die Vorkommnisse aufeinander folgen, muß man annehmen, daß unbekannte Faktoren im Spiele sind; denn es scheint, daß die Vorkommnisse nicht willkürlich aufeinander folgen. Aber was für unbekannte Faktoren - ich gebrauche dieselben Worte, die Wahle gebraucht — im Spiele sind, das entzieht sich vollkommen der menschlichen Beurteilung, darüber kann man überhaupt nichts aussagen. Alles, was der Mensch wissen kann, ist, daß Vorkommnisse vorhanden sind, und daß diese Vorkommnisse dirigiert werden von ganz unbekannten Faktoren. An der Direktion tappen Physik, Physiologie, Biologie, Soziologie herum. Aber das ist eben nur ein Herumtappen, so daß man mit den Vorkommnissen leben kann. Das führt niemals dazu, über die im Spiele befindlichen unbekannten Faktoren etwas zu wissen. Daher ist alle Meinung, daß man zu einer Philosophie kommen könnte, die etwas enthielte über die Gründe, warum die Vorkommnisse so und so auftreten, ein menschlicher Wahnsinn, dem sich die Menschheit eine Zeitlang hingegeben hat und demgegenüber es hoch an der Zeit ist, ihn aufzugeben. — Eines der wichtigsten Bücher von Richard Wahle heißt: «Das Ganze der Philosophie und ihr Ende. Ihre Vermächtnisse an die Theologie, Physiologie, Ästhetik und Staatspädagogik.» Um dieses Ende der Philosophie zu lehren, um zu lehren, daß die Philosophie ein Wahnsinn ist, ist Richard Wahle Professor der Philosophie geworden!

Wir sehen, daß vor allen Dingen solchen Erwägungen zugrunde liegt eine vollständige Ohnmacht gegenüber Wahrheitskriterien. Man empfindet keinen Impuls mehr, eine Entscheidung in der Erkenntnis herbeizuführen. Was zugrunde liegt, könnte man etwa in der folgenden Weise charakterisieren. Denken Sie sich, jemand hat ein Buch und hat darinnen lange gelesen; immer wieder liest er und immer wieder liest er und lebt der Anschauung, daß er durch dieses Buch Mitteilungen empfangen hat über gewisse Dinge, über die das Buch eben Mitteilungen enthält. Nun überlegt er sich einmal: Ja, da liegt nun dieses Buch vor mir, da habe ich mir immer eingebildet, durch dieses Buch habe ich Mitteilungen über das oder jenes; aber wenn ich dieses Buch so recht ansehe: da sind immer auf den Seiten nur Buchstaben, Buchstaben, Buchstaben. Ich bin also eigentlich ein Esel gewesen, daß ich geglaubt habe, aus diesem Buche können mir Mitteilungen über allerlei Dinge, die gar nicht in dem Buch drinnen sind, zufließen, denn es sind ja doch nur Buchstaben. Ich habe immer nur in dem Wahn gelebt, diese Buchstaben so auf mich wirken zu lassen, in Wechselwirkungen, daß sie mir etwas geben sollen; aber Buchstaben sind immer nur da, folgen immer nur aufeinander — Lettern. Also muß man endlich sich von dem Wahn befreien, daß diese Buchstaben irgend etwas beschreiben, daß sie sich irgendwie aufeinander beziehen könnten, sich gruppieren könnten zu bedeutsamen Worten oder dergleichen. - Es ist wirklich ein Bild, das man gebrauchen kann für die Art des Denkens, die dieser Wahleschen Nichtphilosophie, Unphilosophie zugrunde liegt. Denn seine große Entdeckung besteht darinnen, daß er sagt: Die Menschen haben bisher geglaubt, sie sehen Vorkommnisse; aber die Vorkommnisse deuten sie in ihrem Zusammenhange, sie lesen gleichsam die Natur. Aber wie törichte Esel waren doch die Menschen! Es gibt ja nur unzusammenhängende Vorkommnisse, und höchstens sind noch unbekannte Faktoren im Spiele, wie vielleicht etwas Unbekanntes im Spiele ist, was nun die Buchstaben so sonderbar gruppiert.

Also das Sich-Hineinleben in den Impuls fehlt, in den Impuls, eine Entscheidung zu treffen über den Wahrheitswert eines Urteils, das eben gewonnen wird auf Grundlage der Welt. Ohnmächtig ist die menschliche Erkenntnis geworden in bezug auf ein Wahrheitskriterium. In älteren Zeiten hat man geglaubt, der Mensch habe in sich so etwas wie die Fähigkeit, aus dem inneren Erleben desjenigen, was im Urteile ist, zu Wahrheiten zu kommen. Das konnte man nicht festhalten. Und so philosophiert man in einer solchen Richtung herum. - Ich wollte gerade durch diese zwei Beispiele klarmachen dieses Abhandenkommen des Wahrheitskriteriums, dieses Sich-nicht-mehr-drinnenstehend-Fühlen in der Erzeugung der Wahrheit.

In groß angelegter Weise sehen wir dieses Abhandenkommen eines im alten Stile zu nehmenden Wahrheitskriteriums bei derjenigen Denkrichtung der Gegenwart, die man als Pragmatismus bezeichnet. Und wenn auch vielleicht nicht der bedeutendste, so ist doch der bekannteste Vertreter des Pragmatismus William James. Wenn wir uns in Kürze das Prinzip des Pragmatismus klarmachen wollen, wie er in der jüngsten Zeit aufgetreten ist, so kann man ihn annähernd auch etwa in der folgenden Weise charakterisieren.

Die Menschen fällen Urteile, durch die sie etwas aussagen wollen über die Wirklichkeit. Allein der Mensch hat keine Möglichkeit, in sich etwas aufzutreiben, das ihn dazu bringen könnte, über die Wirklichkeit ein wahres Urteil zu fällen. Es gibt nicht so etwas im Menschen, was entscheiden würde, für sich entscheiden würde, an sich entscheiden würde: das ist wahr, das ist falsch. - Also man fühlt sich ohnmächtig, ein ursprüngliches, an sich bestehendes Kriterium darüber zu finden, ob dies wahr, ob dies falsch ist. Dennoch fühlt sich der Mensch gezwungen, indem er in der Wirklichkeit lebt, Urteile zu fällen. Und die Wissenschaften sind ja voller Urteile. Wenn man nun den ganzen Umfang der Wissenschaften ansieht mit allen ihren Urteilen — sagen sie etwas aus über irgend etwas, was in einem höheren Sinne, im Sinne der alten Philosophenschulmeinungen wahr oder falsch ist? Nein! Das ist überhaupt im Sinne zum Beispiel von William James eine ganz unmögliche Denkweise, sich zu fragen, ob an sich irgend etwas wahr oder falsch sein kann. Man fällt Urteile. Wenn man gewisse Urteile fällt, so kann man mit diesen Urteilen leben. Sie erweisen sich als nützlich und anwendbar im Leben, als das Leben fördernd. Würde man andere Urteile fällen, so würde man bald mit dem Leben nicht zurechtkommen, würde man nicht vorwärtskommen im Leben. Sie wären unnützlich, lebensschädigend. Selbst für die gröbsten Urteile kann man das anwenden. Man kann nicht einmal vernünftigerweise sagen, morgen werde wieder die Sonne aufgehen; denn ein Wahrheitskriterium gibt es gar nicht. Aber wir haben uns einmal das Urteil gebildet: Jeden Morgen geht die Sonne auf. - Wenn einer kommen wollte und würde sagen: Nur die zwei Drittel vom Monat geht die Sonne auf und im letzten Drittel nicht mehr, - so würde er mit diesem Urteile im Leben nicht vorwärtskommen, denn er würde immer anstoßen im letzten Drittel des Monats. Das Urteil, das wir uns bilden, ist nützlich. Aber von wahr oder falsch kann nicht in einem anderen Sinne die Rede sein, als daß ein Urteil uns durch die Welt durchführt, daß es das Leben fördert, und daß ein anderes Urteil, das ein entgegengesetztes ist, das Leben schädigt. Es gibt nicht ein an sich bestehendes Kriterium für wahr und falsch, sondern das Leben-Fördernde nennen wir wahr, das Leben-Schädigende nennen wir falsch. - Da ist also alles hinausgetrieben in die Lebenspraxis, was entscheiden soll darüber, ob wir ein Urteil fällen oder nicht. Und alle die Impulse, die man früher geglaubt hat zu besitzen, die werden nicht gelten gelassen.

Solch eine Denkrichtung ist nun nicht etwa das willkürliche Erzeugnis eines einzelnen oder einer Schule. Sondern das Eigentümliche gerade solcher Denkrichtungen, wie ich sie heute anführte, ist, daß sie fast über das Ganze der, sagen wir, denkerischen Erdenkultur ausgebreitet sind, daß sie wie unabhängig voneinander da und dort auftreten, weil die Menschheit der Gegenwart darauf hinorganisiert ist, in solche Denkrichtungen hineinzukommen. Es liegt zum Beispiel folgende interessante Erscheinung vor. Während Peirce in Amerika in den siebziger Jahren das erste Buch geschrieben hat über «pragmatische Philosophie», die dann bei William James, in England bei Schiller und bei anderen immer mehr ausgebildet worden ist, während also Peirce in Amerika seine erste Abhandlung über die pragmatische Philosophie hat erscheinen lassen, die in dieser Gedankenrichtung liegt, schrieb ein Denker in Deutschland seine «Philosophie des Als Ob». Das ist also eine Parallelerscheinung. Vaihinger heißt der Betreffende, der die «Philosophie des Als Ob» dazumal geschrieben hat. Was will diese «Philosophie des Als Ob»? Sie geht von dem Gedanken aus, daß der Mensch eigentlich unfähig ist, im alten Sinn wahre oder falsche Ideen oder Begriffe zu bilden, aber doch Ideen und Begriffe bildet, so zum Beispiel — nehmen wir einen bekannten Begriff — den des Atoms. Das Atom ist natürlich ein ganz absurder Begriff. Denn das Atom wird im Denken mit allerlei Qualitäten ausgestattet, die in die Sinne fallen müßten, wenn sie wirklich bestehen würden. Dennoch aber werden die Sinnesempfindungen als Wirkungen von Atomtätigkeit aufgefaßt. Also ist es ein widerspruchsvoller Begriff, ein Begriff für ein vollständig Unauffindbares. Es ist, wie Vaihinger sagt, das Atom eine Fiktion. Wir bilden uns viele solche Fiktionen, und im Grunde genommen sind alle höheren Begriffe, die wir uns über die Wirklichkeit bilden, solche Fiktionen. Da es ein Kriterium für das Wahre oder Falsche nicht gibt, so muß man eigentlich als vernünftiger Mensch der Gegenwart sich klar sein darüber, daß man es mit Fiktionen zu tun hat. Und man muß vollbewußt sich Fiktionen machen. Man muß sich klar sein darüber, daß das Atom eine bloße Fiktion ist, daß das Atom nicht da sein kann. Aber man betrachtet die Welterscheinungen so, als ob die Welt von den Bewegungen oder dem Leben der Atome beherrscht wäre - als ob -, und dadurch ist es nützlich, sich diese Fiktion zu bilden. Man kommt zu einem gewissen Zusammenhang der Erscheinungen, wenn man solche Fiktionen aufstellt. Ein Ich ist eine Fiktion; aber man muß diese Fiktion bilden. Denn wenn man gewisse Erscheinungen, die miteinander auftreten, so betrachtet, als ob ein Ich in ihnen tätig wäre, von dem man ganz gewiß weiß, daß es nur eine Fiktion ist, so betrachten sie sich bequemer, als wenn man sie nicht unter der Fiktion des Ich betrachten würde. Und so lebt man eigentlich von lauter Fiktionen. Es gibt nicht eine Philosophie der Wirklichkeit, sondern eine «Philosophie des Als Ob». Die Welt gaukelt uns vor, als ob das wäre, was wir als Fiktionen haben.

Im Ganzen, in der Anlage und auch in den einzelnen Durchführungen, ist die Philosophie des Pragmatismus sehr ähnlich der «Philosophie des Als Ob». Ich sagte: In derselben Zeit, als Peirce seine pragmatische Philosophie als Abhandlung geschrieben hat, in den siebziger Jahren, hat Vaihinger die «Philosophie des Als Ob» niedergeschrieben. Aber so wie die Menschen damals waren, in den siebziger Jahren, hatten sie noch so viele Rudimente des alten Glaubens, daß es doch noch ein objektives Kriterium der Wahrheit geben könnte, und daß die Wissenschaften nicht bloß aus Fiktionen bestehen könnten, daß es eine mißliche Sache gewesen wäre, diese «Philosophie des Als Ob» just in den siebziger Jahren zu veröffentlichen, wenn man Professor hat werden wollen. Dazumal ging es noch nicht. Da hat denn Vaihinger einen Ausweg gesucht. Er hat zunächst die «Philosophie des Als Ob» im Schreibtisch liegenlassen, hat so, wie es heute notwendig ist, nicht wahr, gelehrt, und als die Zeit herangekommen war, wo er sich pensionieren lassen konnte, da hat er sich pensionieren lassen und die «Philosophie des Als Ob» veröffentlicht, die jetzt schon in mehreren Auflagen erschienen ist. — Ich erzähle nur; ich richte nicht, urteile nicht, kritisiere nicht, erzähle nur.