The Riddle of Humanity

GA 170

2 September 1916, Dornach

Lecture XIV

Recently we have had repeated occasion to cite a result of spiritual-scientific investigation that, in fact, is of most far-reaching significance. You will remember how we described the relationship of the human head and the rest of the human body to the whole cosmos, and how this then shows the way the head is related to the rest of the body. We said that the shape and structure of the human head and all that pertains to it is a transformation, a metamorphosis. The head is a transformation and reconstruction of the entire body from the previous incarnation. So, when we observe the entire body of the present incarnation, we can see how it contains forces that are capable of transforming it into nothing but a head, a head with all that pertains to it: with the twelve pairs of nerves that originate in it, and so on. And this head that is developed from our entire body will be the head we bear in our next incarnation. The body of our next incarnation and everything to do with it, on the other hand, will be produced during the time after our present life is over, the time between death and the birth which begins our next incarnation. In part it will be produced during the time between death and a new birth from the forces of the spiritual world, and in part from forces of the physical world during the time between our conception and birth into the next incarnation.

These facts should be viewed as truths that testify to their own inherent validity, truths that point to connections of major significance; they should not be treated like the truths of everyday life or of normal science. The truths of everyday life consist more or less in descriptions of ourselves and our surroundings; but truths like those we have just mentioned provide us with the light by which we are able to read the cosmic significance of our surroundings and ourselves. The truths of ordinary life and ordinary science are like descriptions of how the shapes of a row of letters are combined into words or, at most, they are like a clarification based on grammatical laws. But understanding the kind of truths we have been describing is comparable to reading without first having to resort to a special description of the shapes of the letters or to a grammatical consideration of how they are combined into words. Just consider how different is the content of what we read from what our eyes see written upon the page. And so it is that, when we cite truths such as those we have just been discussing, we have before our eyes not only what is now being said, but also the whole, far-reaching significance of such things for the role of humanity in the cosmos. Thereby we are, so to speak, able to read profound, living, spiritual truths that have nothing to do with the shape of the body or the head as it is studied by an anatomist or physiologist, or as one refers to it in ordinary life. It is not enough to describe the human being in the manner of ordinary life and ordinary science; only if one can read man can he be understood.

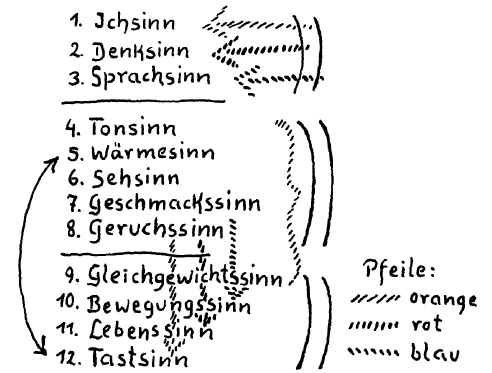

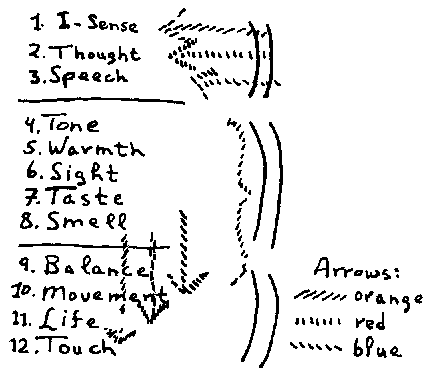

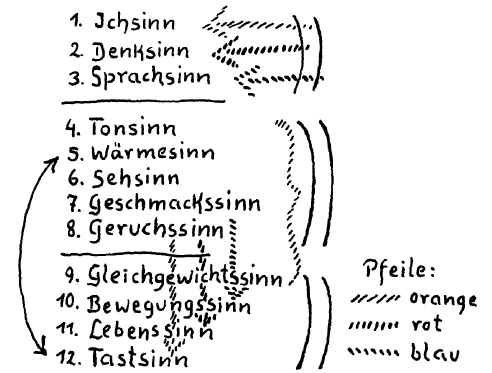

In the light of the foregoing considerations, and in the sense they indicate, I want to turn yet again to what we have been considering during the past few weeks. I want to direct your attention to the twelve senses of man.30The twelve senses: Compare with this lecture the lecture given by Rudolf Steiner on 8 August 1920 in Dornach, ‘Man's Twelve Senses in their relation to Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition’. (See Spiritual Science as a Foundation for Social Forms—Lecture 3) Let us once more allow these twelve senses to pass in review before us.

The I sense: Again I ask you to remember what has been said about this sense of the I. The sense of I does not refer to our capacity to be aware of our own I. This sense is not for perceiving our own I, that I which we first received on Earth; it is for perceiving the I of other men. What this sense perceives is everything that is contained in our encounters with another I in the physical world.

Second, comes the sense of thought: Similarly, the sense of thought has nothing to do with the formation of our own thoughts. Something entirely different is involved when we ourselves are thinking; this thinking is not an activity of our sense of thought. That still remains to be discussed. Our sense of thought is what gives us the ability to understand and perceive the thoughts of others. Thus this sense of thought does not, primarily, have anything to do with the formation of our own thoughts.

The sense of speech: Once again, this sense has nothing primarily to do with the formation of our own speech or with our ability to speak. It is the sense that enables us to understand what others say to us.

The sense of hearing, or tone: This sense cannot be misunderstood.

The senses of warmth, sight, taste, smell and balance: I have already characterised these senses on previous occasions, as well as in this course of lectures.

The senses of movement, life and touch.

Those are the twelve senses, the senses that enable us to perceive the external world while we are here in the physical world. As you know, materialistic thinking speaks of only five senses, for it only distinguishes the sense of hearing, the sense of warmth—which it throws together with the sense of touch—the sense of sight, the sense of taste and the sense of smell. But it must be said that the physiology of our more recent science has now added the senses of balance, movement and life, and also distinguishes between the senses of warmth and touch. But the physiology of our ordinary science still does not refer to a special sense of speech, or to a special sense of thinking—or thought. Nor, because of the nature of the thinking it employs today, is it able to speak of a special ego sense. Materialistic thinking is happy to restrict its view of the world to only those things that can be perceived by the senses. Of course, there is a certain contradiction in saying ‘perceived by the senses’, because the realm of the sensibly perceptible has been arbitrarily restricted—namely to what can be perceived by the five senses. But all of you know what is meant when one says, ‘Only what can be perceived by the senses is valid according to the ordinary materialistic point of view, so it also investigates the organs of perception that belong to these senses.’ Since there are no apparent organs to be found for perception of another's I, or for thought or speech,—nothing, for example, that would correspond to them as the ear corresponds to the sense of hearing or the eye to the sense of sight—it makes no mention of the sense of another I, the sense of thought or of the sense of speech. For us, however, a question arises: Is there really an organ for the I sense, for the sense of thought and for the sense of speech? Today I would like to investigate these matters more exactly.

So the I sense gives us the ability to perceive the I of others. One of the especially restricted and inadequate views of modern thinking is the view that we always more or less deduce the existence of another ego, but do not ever perceive it directly. According to this line of thought, we deduce that something we encounter is the bearer of an I: We see it walking upright on two legs, putting one leg after the other or placing one next to the other; we see that these two legs support a trunk which has, hanging from it, two arms which move in various ways and carry out certain actions. Upon this trunk is placed a head which produces sounds, which speaks and changes expression. On the basis of these observations—so goes the materialistic line of thought—we deduce that what is approaching us is the bearer of an I. But this is utter nonsense; it is really pure nonsense. The truth is that we actually perceive the I of another just as we see colours with our eyes and hear sounds with our ears. Without a doubt, we perceive it. Furthermore, this perception is independent. The perception of another I is a direct reality, a self-sufficient truth that we arrive at independently of seeing or hearing the person; it does not depend on our drawing any conclusions, any more than seeing or hearing depend on drawing conclusions. Apart from the fact that we hear someone speak, that we see the colour of his skin, that we are affected by his gestures—apart from all of these things—we are directly aware of his I. The ego sense has no more to do with the senses of sight or sound, or with any other sense, than the sense of sight has to do with the sense of sound. The perception of another I is independent. The science of the senses will not rest on solid foundations until this has been understood.

So now the question arises: What is the organ for perceiving another I? What is our organ for perceiving an I, as the eyes perceive colours and the ears perceive tones? What organ perceives the I of another? There is indeed an organ for perceiving an I, just as there are organs for perceiving colours and tones. But the organ for perceiving an I only originates in the head; from there it spreads out into the entire body, in so far as the body is appended to the head, making of the entire body an organ of perception. So the whole perceptible, physical form of a human being really does function as an organ of perception, the organ for perceiving the I of another. In a certain sense you could also say that the head, in so far as the rest of the body is appended to it and in so far as it sends its ability to perceive another I through the whole human being, is the organ for perceiving another's I. The entire, immobile human being is the organ for perceiving an I—the whole of the human form at rest, with the head as a kind of central point. The organ for perceiving another I is thus the largest of our organs of perception; we ourselves, as physical human beings, constitute the largest of our organs of perception.

Now we come to the sense of thought. What is the organ for perceiving the thoughts of others? Everything that we are, in so far as we are aware of the stirrings of life within us, is our organ for perceiving others' thoughts. Think of yourself, not with regard to your form, but with regard to the life you bear within you. Your whole organism is permeated with life. This life is a unity. In so far as the life of our entire organism is expressed physically, it is the organ for perceiving thoughts that come toward us from without. We would not be able to perceive the I of another if we were not shaped the way we are; we would not be able to perceive the thoughts of another if we did not bear life in the way that we do. Here I am not talking about the sense of life. What is in question here is not the inner perception of our general vital state of being—and that is what the sense of life gives us—rather is it the extent to which we are bearers of life. And it is the life we bear within us, the physical organism that bears the life within us, that is the organ by which we perceive the thoughts that others share with us.

Furthermore, we are able to initiate movement from within ourselves. We have the power to express all the movements of our inner nature through movement—through hand movements, for example, or by the way we turn our head or move it up and down. Now, the basis for our ability to bring our bodies into movement is provided by the physical organism. This is not the physical organism of life, but the physical organism that provides us with the ability to move. And it is also the organ for perceiving speech, for perceiving the words which others address to us. We would not be able to understand a single word if we did not possess the physical apparatus of movement. It is really true: in sending out nerves for apprehending the whole process of movement, our central nervous system also provides us with the sensory apparatus for perceiving the words that are spoken to us. The sense organs are specialised in this fashion. The whole man: sense organ for the I; the physical basis of life: sense organ for thought; man, in so far as he is capable of movement: sense organ for the word.

The sense of tone is even more specialised. Even though the apparatus for hearing includes more than physiology usually includes, it is nevertheless more specialised. It is not necessary for me to discuss the sense of tone. You only need to lay your hands on a normal textbook on the physiology of the senses to find a description of the organ on which the sense of tone is based. But today it is still difficult to find a description of the organ for the sense of warmth because, as I mentioned, it is still confused with the sense of touch. But the sense of warmth is actually a very specialised sense. Whereas the sense of touch is really spread over the whole organism, the sense of warmth only appears to be spread over the whole organism. Naturally, the entire organism is sensitive to the influence of warmth, but the sense for perceiving warmth is very much concentrated in the breast portion of the human body. As for the specialised organs of sight, taste and smell, these are, of course, generally known to normal observation, and can be found in what ordinary science has to say.

Now it is possible to make a real distinction between the middle part, the upper part, and the lower part of our sense life, and today I would like to include some special observations with regard to this distinction. Let us begin by observing the sense of speech. I said that our organism of movement is what enables us to perceive words. It provides the basis for our sense of speech. But not only are we able to perceive and understand the words of others; it is also possible for us to speak: we are able to speak, too. And it is interesting and important to understand the connection between our ability to speak and our ability to understand the speech of others. Please note that I am not speaking about our ability to hear the tones, but about our ability to understand speech. The senses of tone and speech must be clearly distinguished from one another. Not only can we hear the words another speaks, we ourselves can speak. How, then, is one of these related to the other? How is speaking related to understanding speech?

If we use spiritual-scientific means to investigate the human being, we discover that the things on which the capacity to speak and the capacity for understanding speech are based are very closely related to one other. If we want to look at what furnishes the basis of speech, we can start by tracing it back to where every reasonable person will agree its beginnings must undeniably be, namely, to experiences of the human soul. Speaking originates in the realm of the soul; the will kindles speech in the soul. Naturally, no words would ever be spoken if our will were not active, if we did not develop will impulses. Observing a person spiritually-scientifically, we can see that what happens in him when he speaks is similar to what happens when he understands something that is being spoken. But what happens when a person himself speaks involves a much smaller portion of the organism, much less of the organism of movement. Remember that the entire organism of movement must be taken into account in the case of the sense of speech, the sense of word—the entire organism of movement is also the organ for apprehending speech. A part of it, a part of the movement organism, is isolated and brought into motion when we speak. The larynx is the principal organ of this isolated portion of the organism of movement, and speaking occurs when will impulses rouse the larynx into motion. When we ourselves speak, what happens in our larynx happens because impulses of will originating in our soul bring the part of our movement organism that is concentrated in the larynx into motion. The entire movement organism, however, is the sense organ for understanding speech; but we keep it still while we are perceiving words. And it is precisely for this reason, precisely because we keep the movement organism still, that we are able to perceive words and understand them. In a certain respect everyone knows this instinctively, for every now and then everyone does something that shows he unconsciously understands what I have just been discussing. I will speak in very broad outlines. Suppose I make a movement like this (a hand raised in a gesture of holding off). Now, even the smallest of movements is not just localised in one part of the movement organism, but comes from the entire movement organism. And when you consider this motion as coming from the entire movement organism, it has a very particular effect. When another person expresses something in words, I am doing what I need to do to understand it by not making this gesture. Because I do not make this gesture, but repress it instead, I am able to understand what someone else is saying; my movement organism wakes up right to the tips of my fingers, but I hold back the motion, delay it, block it. By blocking this motion, I am enabled to understand what is being said. When one does not wish to hear something, one will often make such a gesture to show that one wants to repress one's hearing. This shows that there is an instinctive understanding for what it means to hold back such a motion.

Now, according to the original plan of the human constitution, it is the whole of the organism of movement—which is at the same time the organism of the sense of word—that belongs in the rightful course of human evolution. At one time, in the Lemurian period, when we were being released from our connection with the whole of the cosmos, we were given a constitution that enabled us to understand words. But that constitution did not enable us to speak words. You will find it strange that we should be constituted so that we could understand words, but not be able to speak words. But it only seems strange, for our organism of movement is not so exactly constituted for hearing the words of others, for understanding other men's words—rather is it adapted to understanding various other things. Originally, we had a much greater gift for understanding the elemental language of nature and for perceiving how certain elemental beings rule over the external world. That ability has been lost; in exchange for it we have received our own capacity to speak. This happened because, during the Atlantean period, the ahrimanic powers set about altering the organism of movement that had originally been given to us. We have the ahrimanic powers to thank for the fact that we can speak; they gave us the gift of speech. So we have to say that the way in which a human being perceives speech now is different from the way we were originally intended to understand it. Such a long time has passed since the Atlantean period that we have grown accustomed to what has happened, and we find it extraordinary to think that our gift of understanding speech was originally for perceiving more or less the whole of the other human being: it gave us the ability to perceive the silent expression in the gestures and bearing of other men, and, without using a physically perceptible speech, to communicate by imitating it, using our own apparatus of movement. Our original way of communicating was much more spiritual. But Ahriman took hold of this original, more spiritual way of communicating. He specialised a part of our organism, creating the larynx, which is designed to produce sounding words. And he designed the part of the larynx that is not used to produce words, so that it would enable us to understand words; that is also a gift of Ahriman.

We are able to perceive the thoughts of others in so far as our organism is alive. Once again, our present ability to understand others' thoughts is much less spiritual than the gift we originally possessed. Our original gift enabled us to feel another's thoughts inwardly, to resonate with their life, simply by being in their presence. The way in which we perceive each other's thoughts today is a coarse physical reflection of the way it once was, and only through the detour of speech is it possible at all. At most, we can experience an echo of the kind of perception that was originally intended for us by training ourselves to attend to others' gestures, to the play of their features, and to their physiognomy. We were once able to perceive the whole direction of another's thinking and to live in it, simply by being in his presence, and the particular thoughts were expressed in his particular gestures and in the play of his features. And it is once again thanks to Ahriman that this more spiritual manner of perceiving another's thoughts has, in the course of human evolution, become more and more concentrated in external speech.

We do not have to look very far back in the development of humanity to find a period when there was still a very highly developed understanding for the way the life of thought was expressed through the physiognomy, through the gestures, even through the posture—through the whole manner in which one human being presents himself to another. There is no need to speak of Old India: we only have to go back to the period before the Greco-Roman period, to the Egypto-Chaldean period. There we still find a highly-developed understanding of the life of thought. Humanity has lost this understanding. Less and less of it has been retained, until now there are very few who understand how the art and manner in which a person meets us can enable us to listen in on the inner secrets of his thinking. What a man says to us through the words we hear is almost the only thing we listen to any more—what these tell us about his thoughts, about their content and their purpose. But, because this has happened, we have been able to retain the ability to use our organism of life and the apparatus of life as an instrument for thinking. If there had been no ahrimanic intervention, if the things I have been describing had never happened, we would not possess the gift of thought. So you can see that, in a certain sense, our present ability to speak is related to the sense of speech, to the sense of the word. But it is related because of an ahrimanic deviation. And again because of an ahrimanic deviation, our present ability to think is related to the sense of thought.

We were constituted, furthermore, so as to be able to be conscious of another's I in a more subtle manner—so that we would not merely experience it, but would perceive it inwardly—for our entire human form is the organ of the sense of the ego. Ahriman is still hard at work today, specialising the ego sense just as he has specialised and remodelled the senses of speech and thought. In fact, that is happening now, as is revealed by an extraordinary, related tendency that is coming towards humanity. In order to talk about what I am referring to, one is forced to say something quite paradoxical. As yet, only the early stages of it are showing themselves, mainly in a philosophical way. Today there are already philosophers who entirely deny the inner capacity to perceive the I: Mach,31Ernst Mach (1838 – 1916): philosopher. for example, as well as others. I have spoken about them in a recent lecture concerned with philosophy. These men really have to be described as holding the view that man is not able to perceive the I inwardly, and that the awareness of the I is based on the perception of other things. There is a tendency to think along the following lines—I will give you a grotesque example of it. People are getting to the point where they say to themselves, in the way I described earlier, ‘I encounter others who walk about on two limb-like appendages and from this I conclude that there is an I within them. And, since I look just like them, I apply this conclusion to myself and decide that I must also possess an I.’ According to this, one derives the existence of one's own I from the existence of the I of others. This is implied by many of the assertions of those about whom I am speaking, when they come to describe how the ego is supposed to develop as the result of our evolution during the interval between the birth and death of a single incarnation. If you read our current psychologists, you will already find descriptions of how our sense of our own I is derived from other persons. We do not have it to begin with, as children, but we are supposed to have watched others and applied what we see them doing to ourselves. In any event, our capacity to come to conclusions about ourselves on the basis of other people seems to be growing ever greater! Just as the capacity to think gradually developed out of the sense of thought, and the capacity to speak out of the sense of speech, so the capacity to experience oneself as belonging to the whole of the world is increasingly developing alongside the ability to perceive another's I. We are talking about fine distinctions, but they must be grasped. To this end, Ahriman is very busy working alongside humanity—he is very much involved.

Let us look at the human being from the other side. There we find the sense of touch. As I have said, the sense of touch is an internal sense. When you touch something like a table, it exerts pressure on you, but what you actually perceive is an inner experience. If you bump into it, it is what happens within you that is the content of the perceptual experience. In such an event, what you experience through your sense of touch is entirely contained within you. Thus, fundamentally the sense of touch can only reach as far as the outermost periphery of the skin: we experience touching something because the external world pushes against the periphery formed by the skin, because inner experiences arise when the external world pushes against us or otherwise comes into contact with us. So the sense of touch is fundamentally an internal sense, even though it is the most peripheral of these. The apparatus for touching is found mainly at the periphery. From there it sends only delicate branches inward, and our external scientific physiology has not been able to isolate these systematically because it has not systematically distinguished the sense of touch from the sense of warmth.

Our organ of touch is spread like a network over the whole outer surface of our body; it sends delicate branches inward. What is this network, really? (If I may use this word, for ‘network’ is inexact.) What was its original purpose? Our attention is immediately caught by the fact that the sense of touch makes us aware of inner experiences, even though it is now used to perceive how we come into contact with the external world. This fact is as undeniable as it is noteworthy and exceptional. And, as spiritual science shows us, it is connected with the fact that the sense of touch was not originally destined for perception of the external world. The sense of touch has undergone a metamorphosis—it was not originally intended to be used, as it is today, to perceive the external world. The sense of touch was really intended for an entirely spiritual perception, for perceiving how our I, the fourth member of our organism, spiritually permeates our entire body. What the organs of touch really gave us, originally, was an inner feeling for our own I, an inner feeling of the I.

So now we have come to the inner perception of the I. Here you must make a clear distinction. The I that is within us and extends to the surface of the sense of touch, really exists in its own right; it is a substantial, spiritual being. And when the I extends itself and comes into contact with the surface created by the sense of touch, this produces a perception of the I. If the sense of touch had remained in its original form, the nature of which I have just indicated, it would not provide us with the kind of perceptions it now provides. Certainly, we would still bump into the things of the external world, but this would be a matter of total indifference to us. We would not experience the collisions through touch; nor, for that matter, would the sense of touch be involved when we run our fingertips over things, as we are fond of doing. We would experience our I through such contacts with the external world; we would experience our I, but would not speak of perceiving the external world. In order for the organ which generated an inner perception of the I to become an organ of touch, capable of perceiving the external world through touch, it has been necessary for our organism to undergo a series of alterations. These began in the Lemurian period and are to be attributed to luciferic influences. They are deeds of Lucifer. Through them, our sense of I was specialised so that we could experience the external world through touch, but our inner experience of the I, of course, was thereby clouded. If, as we go about the world, it were not necessary for us to pay constant heed to the things that bump into us and press against us, to what is rough and what is smooth, and so on, we would have an entirely different experience of the I.

In other words, by re-shaping the sense of touch, luciferic influences were introduced into the experience of the I. In this case, what is most inward has been adulterated by something external, just as, in the sense of speech, what is external has been adulterated by something internal. The sense of speech was designed for the perception of words—a sense perception, but not one that depended on anything being expressed in sounds. Then the inner activity of speaking was intermixed with this. So, in this case, the original perception was internal, and external perception has been added to it.

The sense of life: Luciferic influence has accomplished a similar alteration in the organs of the sense of life. For these organs, organs which enable us to experience our inner structure and inner condition, were originally meant only for the perception of our astral body as it works within our living organism. Now, however, the ability to experience the internal condition of the body in feelings of well-being or feelings of being ill has been intermixed with it. A luciferic impulse has been mixed in with it. Here the astral body has been linked to the feelings of well-being or illness that show the condition of our body, just as the I has been linked to the sense of touch.

And, again, our organism of movement was originally designed so that we would only experience the interactions between our etheric body and our organism of movement. The capacity to perceive and experience our inner mobility, which is the sense of movement, properly speaking, has been added to this. Once more, a luciferic impulse. Thus, alterations in the fundamental nature of the human being are due to influences from two sides, the luciferic side and the ahrimanic side. The sense of the I, the sense of thought, and the sense of speech have been altered by ahrimanic influences from the form which was actually intended for the physical plane. Only through these changes and through the changes wrought by luciferic influences on the senses of touch, life and movement, have we become what, on the physical plane, we now are. And there remains to us, free from these influences, only an intermediate area. This, then, is a more exact, more detailed presentation of our human organism.

It would be a good idea to consider what has been said thus far, so I will wait until tomorrow before pursuing these matters any further. Tomorrow we will see how fruitful these considerations are. We will see how they expand that great and significant truth that is the key to so many things: the truth about the relation of our head to the body of our previous incarnation, the relation of the body of our present incarnation to the head of our next incarnation, and what follows from this regarding our relationship to the cosmos.

We can already see how necessary it is to pay attention to that state of balance which needs to be established between the luciferic and the ahrimanic forces in the world. This is the most essential and significant thing. Just consider how the human I is involved in the extremes of both sides: here, the I without and, in the sense of touch, the I within. (See the orange arrows in the drawing.) Similarly, the astral body is involved both in thinking, and also, from within, in the life organism. (Red arrows.) The etheric body is involved here, as long as speech does not occur, but is also involved from within in the sense of movement. (Blue arrows.) And, holding the middle, like the unmoving hypomochlion at the centre of a pair of scales, we have a sphere that is not so involved in the ‘I touch—I think—I live—I speak—I move.’ The more closely one approaches this centre, the more immobile the arm of the scales becomes. To either side, it is deflected. Thus there is a kind of state of balance at the middle.

Here we see how the being of man is subject to significant influences from two sides. In order to understand present-day human activity, and the structure of the human being, it is necessary to have the correct view of Lucifer and Ahriman.

Vierzehnter Vortrag

Das Ergebnis aus geisteswissenschaftlichen Betrachtungen, das wir in der letzten Zeit sogar wiederholt angeführt haben, von der Beziehung des menschlichen Hauptes und des menschlichen übrigen Leibes — wobei dann das Haupt einbezogen ist in den übrigen Leib — zu dem Weltganzen, dieses Ergebnis ist in der Tat von weittragendster Bedeutung. Sie wissen ja, wie wir es angeführt haben. Wir haben gesagt: Dasjenige, was der Mensch als sein Haupt trägt mit alldem, was dazu gehört, ist eine umgewandelte Form, eine umgewandelte Gestalt, eine Metamorphose, und dasjenige, woraus sich dieses Haupt umgewandelt, umgebildet hat, das ist der Gesamtleib der vorhergehenden Inkarnation. Also wenn wir hinblicken auf den Gesamtleib unserer jetzigen Inkarnation, dann sehen wir, wie er in sich trägt die Kräfte, die ihn umwandeln können so, daß er nur ein Haupt wird, ein Kopf mit dem, was dazugehört, mit zwölf aus ihm entspringenden Nervenpaaren und so weiter. Und diesen Kopf, der sich aus unserem Gesamtleib entwickelt, wir werden ihn tragen in unserer nächsten Inkarnation. Dagegen wird in der Zeit zwischen unserem Tode, nach unserem jetzigen Leben und unserer Geburt in der nächsten Inkarnation, teils aus den Kräften der geistigen Welt, soweit die Zeit in Betracht kommt zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, teils aus den Kräften der physischen Welt, soweit die Zeit in Betracht kommt von unserer Empfängnis bis zu unserer Geburt in der nächsten Inkarnation, unser Leib, also alles das, was zu unserem Leibe gehört, für die nächste Inkarnation herausgearbeitet.

Solche Wahrheiten muß man nur nicht so nehmen wie die Wahrheiten des gewöhnlichen Lebens oder der gewöhnlichen Wissenschaft, sondern man muß sie nehmen als Wahrheiten, die Bedeutungen in sich tragen, als Wahrheiten, die hinweisen auf große Zusammenhänge. Bezüglich der Wahrheiten im gewöhnlichen Leben beschreiben wir gewissermaßen uns und unsere Umgebung; bezüglich solcher Wahrheiten wie die angeführten lesen wir unsere Umgebung und uns selber im Weltenzusammenhange. Die Wahrheiten des gewöhnlichen Lebens und der gewöhnlichen Wissenschaft sind da wirklich so, wie wenn wir die Formen der einzelnen Buchstaben beschreiben, die auf einer Seite stehen, oder höchstens noch grammatikalisch die Gesetze erklären, wie sie sich zu Worten zusammenfügen. Dasjenige aber, was mit solchen Wahrheiten gemeint ist, wie die angeführten, das läßt sich vergleichen mit dem Lesen, ohne erst auf die Buchstabenformen eine besondere Beschreibung zu verwenden und auf das Grammatikalische zu sehen und darauf, wie sich diese Buchstabenformen zu Worten zusammenfügen. Denken Sie doch, wie ganz anders das aussieht, der Inhalt dessen, was wir lesen, und dasjenige, was auf der Seite für die Augen daraufsteht. So haben wir auch, wenn wir eine solche Wahrheit anführen wie die eben angeführte, nicht das, was wir nun aussagen, allein im Auge, sondern wir haben die ganze weittragende Bedeutung einer solchen Sache für die Stellung des Menschen im Weltenall im Auge. Wir lesen gewissermaßen dadurch tief lebendige geistige Wahrheiten, die nichts zu tun haben mit den Formen des Kopfes oder des Leibes, welche die Anatomie, die Physiologie studiert oder die man im gewöhnlichen Leben vor sich hat, wenn man von der menschlichen Form spricht. Den Menschen kann man eben nur verstehen, wenn man ihn nicht nur beschreibt, wie das gewöhnliche Leben und die Wissenschaft es tut, sondern wenn man ihn liest.

Nach dieser Voraussetzung und im Sinne derselben wollen wir noch einmal unseren Blick wenden auf das, was wir auch in den Zusammenhängen der letzten Wochen ausgeführt haben. Wir wollen unseren Sinn wenden auf die zwölf Sinne des Menschen. Führen wir uns sie noch einmal vor, diese zwölf Sinne des Menschen.

Ichsinn: Ich bitte Sie, noch einmal ins Auge zu fassen dasjenige, was ich in bezug auf diesen Ichsinn gesagt habe. Dieser Ichsinn ist nicht gemeint mit Bezug auf die Fähigkeit unseres eigenen Ich-Wahrnehmens. Mit diesem Ichsinn nehmen wir nicht unser eigenes Ich wahr, jenes Ich, das uns auf der Erde erst zugekommen ist, sondern mit diesem Ichsinn nehmen wir die Iche der anderen Menschen wahr. Also alles dasjenige, was uns mit einem Ich behaftet entgegentritt in der physischen Welt, das nehmen wir mit diesem Ichsinn wahr.

Das zweite ist der Denksinn. Der Denksinn hat wiederum nichts zu tun mit unseren eigenen Gedankenbildungen. Wenn wir selber denken, so ist dieses Denken nicht eine Tätigkeit des Denksinns, sondern das ist etwas ganz anderes. Wir werden davon noch sprechen. Der Denksinn bezieht sich darauf, daß wir die Fähigkeit haben, die Gedanken der anderen Menschen zu verstehen, wahrzunehmen. Also mit unseren eigenen Gedankenbildungen hat dieser Denksinn zunächst nichts zu tun.

Sprachsinn: Der hat wiederum nichts zu tun mit der Bildung unserer eigenen Sprache, nichts zu tun zunächst mit der Fähigkeit, die dem eigenen Sprechen zugrunde liegt, sondern er ist der Sinn für das Verständnis dessen, was zu uns gesprochen wird von dem anderen Menschen.

Hörsinn oder Tonsinn: Das kann ja nicht mißverstanden werden.

Wärmesinn, Sehsinn, Geschmackssinn, Geruchssinn, Gleichgewichtssinn: Ich habe ja diese Sinne öfter schon und auch in diesen Betrachtungen wieder erklärt.

Bewegungssinn, Lebenssinn, Tastsinn.

Das sind die zwölf Sinne, durch die wir hier in der physischen Welt die Außenwelt wahrnehmen. Das materialistische Denken verzeichnet ja, wie Sie wissen, von diesen Sinnen nur den Tonsinn, den Wärmesinn — wobei sie den aber zusammenwirft mit dem Tastsinn —, Sehsinn, Geschmackssinn, Geruchssinn, und spricht infolgedessen von fünf Sinnen. Allerdings, die neuere Wissenschaft, die neuere Physiologie, Sinnesphysiologie, fügt schon dazu den Gleichgewichtssinn, Bewegungssinn, Lebenssinn, und unterscheidet auch zwischen dem Tastsinn und Wärmesinn. Von einem besonderen Sprachsinn, von einem besonderen Denksinn — Gedankensinn könnte man auch sagen - und von einem besonderen Ichsinn spricht die gewöhnliche Wissenschaft, die gewöhnliche Physiologie nicht, weil sie aus der Art ihres Denkens heraus heute auch noch nicht davon sprechen kann. Das materialistische Denken und Anschauen der Welt beschränkt sich ja gern auf alles dasjenige, was sinnlich wahrnehmbar ist. Es liegt zwar ein gewisser Widersinn darinnen, zu sagen «sinnlich wahrnehmbar», weil man nur willkürlich abgrenzt das sinnlich Wahrnehmbare, nämlich das durch die fünf Sinne Wahrnehmbare; aber Sie wissen ja alle, was damit gemeint ist, wenn man sagt: Die gewöhnliche materialistische Anschauung läßt gelten dasjenige, was sinnlich wahrnehmbar ist, und sie sucht deshalb auch für die Sinne die Wahrnehmungsorgane. Weil ihr so gar nichts vorliegt als ein Wahrnehmungsorgan für den Ichsinn, den Gedankensinn und den Sprachsinn, weil ihr so gar nichts dafür vorliegt, was sie vergleichen könnte zum Beispiel mit dem Ohre für den Tonsinn oder mit dem Auge für den Sehsinn, so spricht sie nicht von diesen Sinnen: Ichsinn, Gedankensinn, Sprachsinn. Für uns entsteht aber die Frage: Gibt es wirklich keine Organe für den Ichsinn, den Gedankensinn, den Sprachsinn? Wir wollen heute einmal auf die genaueren Untersuchungen dieser Dinge eingehen.

Also mit dem Ichsinn ist gemeint unsere Fähigkeit, die Iche der anderen Menschen wahrzunehmen. Eine besonders ungenügende und unzulängliche Aussage des modernen Denkens ist die, daß man eigentlich das Ich des anderen Menschen gar nicht wahrnehme, sondern auf das Ich des anderen Menschen immer mehr oder weniger nur schließen würde. Wir sehen so etwas auf uns zukommen - so nimmt diese Denkweise an —, welches aufrecht auf zwei Beinen geht, ein Bein immer an dem anderen vorbeiführt oder eines neben das andere hinsetzt, gestützt von diesen Beinen einen Rumpf hat, daran pendeln zwei Arme, die verschiedene Bewegungen ausführen zu verschiedenen Zwecken; dann sitzt weiter darauf ein Haupt, welches Töne äußert, spricht, Gesten äußert. Und wenn so etwas, wie ich es jetzt beschrieben habe, uns entgegentritt, so schließen wir: Das ist der Träger eines Ich. — So meint die materialistische Anschauung. Dies ist ein vollständiger Unsinn, ein wirklicher, echter Unsinn; denn die Wahrheit ist, daß ebenso wie wir mit den Augen Farben sehen, wie wir mit dem Ohre Töne hören, wir auch das Ich des anderen wirklich wahrnehmen. Ganz ohne Zweifel, wir nehmen es wahr. Und diese Wahrnehmung ist eine selbständige. So wie das Sehen nicht auf einem Schluß beruht, wie das Hören nicht auf einem Schluß beruht, so beruht das Wahrnehmen des Ich des anderen nicht auf einem Schluß, sondern ist eine unmittelbar wirkliche, selbständige Wahrheit, die unabhängig gewonnen wird davon, daß wir den andern sehen, daß wir seine Töne hören. Abgesehen davon, daß wir seine Sprache vernehmen, daß wir sein Inkarnat sehen, daß wir seine Gesten auf uns wirken lassen, abgesehen von alledem nehmen wir unmittelbar das Ich des andern wahr. Und so wenig der Sehsinn mit dem Tonsinn zu tun hat, so wenig hat die Ich-Wahrnehmung mit dem Sehsinn oder mit dem Tonsinn oder mit irgendeinem anderen Sinne zu tun. Es ist eine selbständige Ich-Wahrnehmung. Ehe das nicht eingesehen wird, ruht die Wissenschaft von den Sinnen nicht auf soliden Grundlagen.

Nun entsteht die Frage: Was ist das Organ für die Wahrnehmung des anderen Ich? Was nimmt in uns das andere Ich wahr, so wie wir mit dem Sehorgan Farben oder Hell und Dunkel wahrnehmen, so wie wir mit den Ohren Töne wahrnehmen? Was nimmt das Ich des andern wahr? Die Ich-Wahrnehmung hat ebenso nun ihr Organ, wie die Sehwahrnehmung oder die Tonwahrnehmung. Nur ist das Organ der IchWahrnehmung gewissermaßen so gestaltet, daß sein Ausgangspunkt im Haupte liegt, aber das ganze Gebiet des übrigen Leibes, insoferne es vom Haupte abhängig ist, Organ bildet für die Ich-Wahrnehmung des andern. Wirklich, der ganze Mensch als Wahrnehmungsorgan gefaßt, insoferne er hier sinnlich-physisch gestaltet ist, ist Wahrnehmungsorgan für das Ich des andern. Gewissermaßen könnte man auch sagen: Wahrnehmungsorgan für das Ich des andern ist der Kopf, insoferne er den ganzen Menschen an sich anhängen hat und seine Wahrnehmungsfähigkeit für das Ich durch den ganzen Menschen durchstrahlt. Der Mensch, insofern er ruhig ist, insoferne er die ruhige Menschengestalt ist gewissermaßen mit dem Kopf als Mittelpunkt, ist Wahrnehmungsorgan für das Ich des andern Menschen. So ist das Wahrnehmungsorgan für das Ich des andern Menschen das größte Wahrnehmungsorgan, das wir haben, und wir sind selbst als physischer Mensch das größte Wahrnehmungsorgan, das wir haben.

Nun kommen wir zum Gedankensinn. Was ist Wahrnehmungsorgan für die Gedanken des anderen? Wahrnehmungsorgan für die Gedanken des anderen ist alles dasjenige, was wir sind, insoferne wir in uns Regsamkeit, Leben verspüren. Wenn Sie sich also denken, daß Sie in Ihrem ganzen Organismus Leben haben und dieses Leben eine Einheit ist — also nicht insoferne Sie gestaltet sind, sondern insoferne Sie Leben in sich tragen -, so ist dieses in Ihnen getragene Leben des gesamten Organismus, insofern es sich ausdrückt im Physischen, Organ für die Gedanken, die uns von außen entgegenkommen. Wären wir nicht so gestaltet, wie wir sind, könnten wir nicht das Ich des andern wahrnehmen; würden wir nicht so belebt sein, wie wir sind, könnten wir nicht die Gedanken des andern wahrnehmen. Das ist nicht der Lebenssinn, von dem ich hier spreche. Nicht daß wir unsere Gesamtlebensverfassung innerlich wahrnehmen, ist hier in Frage — das gehört zum Lebenssinn -, sondern insofern wir das Leben in uns tragen. Und dieses Lebendige in uns, alles das, was in uns physischer Organismus des Lebens ist, das ist Wahrnehmungsorgan für die Gedanken, die der andere uns zuwendet.

Und insofern wir Kraft haben, uns zu bewegen, ausführen zu können alles das, was wir durch unser Inneres an Bewegungen haben, zum Beispiel wenn wir die Hände bewegen, wenn wir das Haupt drehen oder von oben nach unten bewegen, führen wir von innen heraus Bewegungen aus. Also insofern wir diese Kräfte haben, den Körper in Bewegung zu versetzen, liegt dieser Bewegbarkeit in uns ein physischer Organismus zugrunde. Das ist nicht der physische Organismus des Lebens, das ist der physische Organismus der Bewegungsfähigkeit. Der ist nun zugleich das Wahrnehmungsorgan für die Sprache, für die Worte, die uns der andere zusendet. Wir könnten keine Worte verstehen, wenn wir nicht in uns einen physischen Bewegungsapparat hätten. Wahrhaftig, insofern von unserem Zentralnervensystem die Nerven zu unserem gesamten Bewegungsvorgang ausgehen, liegt darinnen auch der Sinnesapparat für die Worte, die zu uns gesprochen werden. So spezialisieren sich die Sinnesorgane. Der ganze Mensch: Sinnesorgan für das Ich; das Lebendige, das dem Physischen zugrunde liegt: Sinnesorgan für das Denken; der in sich bewegbare Mensch: Sinnesorgan für die Worte.

Noch mehr spezialisiert ist nun der Tonsinn. Obwohl auch mehr als dasjenige, was gewöhnlich die Physiologie zum Gehörapparat rechnet, dazugehört, so ist doch schon der 'Tonsinn mehr spezialisiert. Nun, über den Tonsinn brauche ich nicht zu sprechen. Da können Sie ja, wenn Sie ein gewöhnliches Lehrbuch der Sinnesphysiologie in dieHand nehmen, den Tonsinn, das Organ des Tonsinns beschrieben finden. Schwieriger wird es einem heute noch, das Organ für den Wärmesinn beschrieben zu finden, weil der, wie gesagt, mit dem Tastsinn zusammengeworfen wird. Aber der Wärmesinn ist eigentlich ein sehr spezialisierter Sinn. Während der Tastsinn über den ganzen Organismus verbreitet ist, ist der Wärmesinn nur scheinbar über den ganzen Organismus verbreitet. Natürlich sind wir für Wärmeeinflüsse am ganzen Organismus zugänglich, aber als Sinn, als Wahrnehmung der Wärme, ist der Wärmesinn sehr konzentriert in dem Rumpf des Menschen, in dem Brustteil. — Die Spezialisierung dann in bezug auf die Organe für den Sehsinn, Geschmackssinn, Geruchssinn, sind ja natürlich bekannt aus der gewöhnlichen Beobachtung oder aus dem, was die gewöhnliche Wissenschaft zu sagen weiß.

Nun können wir wirklich in einer gewissen Weise die mittlere Partie, die untere Partie und die obere Partie unseres Sinneslebens voneinander unterscheiden und wir wollen heute eine besondere Betrachtung noch anstellen mit Bezug auf diese Unterscheidung. Gehen wir dabei aus von dem Sprachsinn und betrachten wir den Sprachsinn. Ich sagte: Insofern wir Bewegungsorganik in uns tragen, können wir die Worte wahrnehmen. Das liegt also dem Sprachsinn zugrunde. Wir können aber nicht nur die Worte des andern wahrnehmen, verstehen, wir haben also nicht nur einen Sprachsinn, sondern wir haben auch eine Sprachfähigkeit, eine Sprachmöglichkeit; wir sprechen selber. Und das ist nun interessant und wichtig, welches das Verhältnis ist zwischen unserer Fähigkeit, zu sprechen, und unserer Fähigkeit, die Sprache zu verstehen; also jetzt nicht die Töne zu hören, bitte unterscheiden Sie das, sondern die Sprache zu verstehen. Tonsinn und Sprachsinn muß da genau unterschieden werden. Also wir können nicht nur die Worte des andern verstehen, sondern wir können selber sprechen. Wie verhält sich das eine zum anderen, das Sprechen zum Sprache-Verstehen?

Wenn wir den Menschen untersuchen mit den Mitteln der Geisteswissenschaft, so finden wir, daß dasjenige, was dem Worte-Verstehen zugrunde liegt und was dem Sprechen zugrunde liegt, sehr verwandt ist miteinander. Wenn wir auf das blicken wollen, was eigentlich dem Sprechen zugrunde liegt, so können wir zunächst zurückgehen bis zum menschlichen seelischen Leben, in dem ja für jeden, der vernünftig ist, unleugbar der Ausgang des Sprechens liegt. Das Sprechen stammt aus dem Seelischen, wird angefacht durch den Willen im Seelischen. Ohne daß wir wollen, also einen Willensimpuls entwickeln, kommt natürlich kein gesprochenes Wort zustande. Beobachtet man nun geisteswissenschaftlich den Menschen, wenn er spricht, so geschieht etwas ähnliches in ihm, wie da geschieht, wenn er das Gesprochene versteht. Aber das, was geschieht, wenn der Mensch selber spricht, umfaßt einen viel kleineren Teil des Organismus, viel weniger vom Bewegungsorganismus. Das heißt, der ganze Bewegungsorganismus kommt in Betracht als Sprachsinn, als Wortesinn; der ganze Bewegungsorganismus ist Sprachsinn zugleich. Ein Teil ist herausgehoben und wird in Bewegung versetzt durch die Seele, wenn wir sprechen, - ein Teil dieses Bewegungsorganismus. Und dieser herausgegriffene Teil des Bewegungsorganismus, der hat eben sein hauptsächliches Organ im Kehlkopf, und das Sprechen ist Erregung der Bewegungen im Kehlkopf durch die Impulse des Willens. Was im Kehlkopf vorgeht beim eigenen Sprechen, kommt so zustande, daß aus dem Seelischen heraus die Willensimpulse kommen und den im Kehlkopfsystem konzentrierten Bewegungsorganismus in Bewegung versetzen, während unser gesamter Bewegungsorganismus Sinnesorganismus ist für die Wortewahrnehmung. Nur, daß wir diesen Bewegungsorganismus, indem wir Worte wahrnehmen, in Ruhe halten. Gerade dadurch, daß wir ihn in Ruhe halten, gerade dadurch nehmen wir die Worte wahr und verstehen die Worte. Instinktiv weiß das in einer gewissen Beziehung jeder Mensch; denn jeder Mensch tut etwas Instinktives zuweilen, wodurch er andeutet, daß er das weiß in seinem Unterbewußtsein, was ich jetzt eben auseinandergesetzt habe. Ich will ganz im Groben sprechen. Denken Sie, ich mache diese Bewegung (zur Abwehr erhobene Hand). Die Fähigkeit, diese Bewegung zu machen, insofern sie aus meinem ganzen Bewegungsorganismus kommt — denn jede kleinste Bewegung ist nicht bloß in einem Teile lokalisiert, sondern kommt aus dem ganzen Bewegungsorganismus des Menschen -, bewirkt etwas ganz Bestimmtes. Indem ich diese Bewegung nicht mache, mache ich dasjenige, was ich haben muß, damit ich irgend etwas Bestimmtes verstehe, was in Worten ausgedrückt wird durch einen anderen Menschen. Ich verstehe, was der andere sagt, dadurch, daß ich, wenn er spricht, diese Bewegung nicht ausführe, sondern sie unterdrücke, daß ich in mir den Bewegungsorganismus nur gewissermaßen bis in die Fingerspitzen errege, aber zurückhalte die Bewegung, also anhalte, staue. Indem ich dieselbe Bewegung staue, begreife ich etwas, was gesprochen wird. Will man etwas nicht hören, macht man oftmals diese Bewegung — womit man andeuten will, daß man unterdrücken will das Hören. Das ist das instinktive Wissen von dem, was dieses Stauen der Bewegung bedeutet.

Nun ist der Mensch ursprünglich so veranlagt, daß der gesamte Bewegungsorganismus, der zugleich der Wortesinn-Organismus ist, gewissermaßen das in der regelrecht fortlaufenden Evolution des Menschen Gelegene ist. So wie wir einstmals in der lemurischen Zeit entlassen worden sind aus unserem Zusammenhang mit dem Weltenganzen, sind wir veranlagt, Worte zu verstehen. Aber wir sind damals noch nicht veranlagt gewesen, Worte zu sprechen. Es wird Ihnen das kurios vorkommen, daß wir veranlagt sein konnten, Worte zu verstehen, aber nicht veranlagt gewesen sind, Worte zu sprechen. Es ist aber nur scheinbar etwas Kurioses; denn so ganz genau ist unser Bewegungsorganismus nicht veranlagt, die Worte des anderen zu hören, zu verstehen, die Worte des andern Menschen zu verstehen, sondern — verschiedenes andere zu verstehen. Wir waren ursprünglich viel mehr dazu veranlagt, die elementarische Sprache der Natur zu verstehen, das Walten gewisser elementarischer Wesenheiten in der Außenwelt wahrzunehmen. Das haben wir verlernt; dafür haben wir einzutauschen gehabt die Fähigkeit des eigenen Sprechens. Das ist dadurch gekommen, daß mit unserem uns ursprünglich verliehenen Bewegungsorganismus die ahrimanische Macht während der atlantischen Zeit eine Veränderung vorgenommen hat. Die ahrimanische Macht ist es, der wir verdanken, daß wir sprechen können, daß wir die Gabe der Sprache haben. So daß wir sagen müssen: Wir sind eigentlich als Menschen wirklich ursprünglich veranlagt gewesen, anders Sprache wahrzunehmen, als wir jetzt wahrnehmen. Wir sind so veranlagt gewesen, Sprache wahrzunehmen, daß wir eigentlich dem andern gegenübergetreten wären — und so sonderbar uns das jetzt vorkommt, aber man gewöhnt sich ja natürlich, besonders im Laufe so langer Zeiten, wie es seit den atlantischen Zeiten her ist, an das, was eben geschehen ist -, wir sind veranlagt gewesen, mehr oder weniger den ganzen anderen Menschen wahrzunehmen in Gebärden und Gesten, in stummen Ausdrucksmitteln, und diese selbst mit unserem eigenen Bewegungsapparat nachzuahmen und uns so ohne die physisch hörbare Sprache zu verständigen. Viel geistiger uns zu verständigen waren wir veranlagt. In diese mehr geistige Verständigungsart hat Ahriman eingegriffen, hat unseren Organismus spezialisiert, das Kehlkopfsystem geeignet gemacht, tönende Worte hervorzubringen. Und das, was dann übriggeblieben ist vom Kehlkopfsystem, geeignet gemacht zu haben, tönende Worte zu verstehen, das ist also eine ahrimanische Gabe.

Insofern wir ein Lebensorganismus sind, können wir wahrnehmen die Gedanken des andern. Wiederum sind wir dazu veranlagt gewesen, viel geistiger die Gedanken des andern wahrzunehmen, als wir sie eigentlich jetzt wahrnehmen. Gewissermaßen im einfachen Demandern-Gegenübertreten sind wir veranlagt gewesen, seine Gedanken innerlich nachzufühlen, sie nachzuleben. Es ist ein grober physischer Abglanz, wie wir heute die Gedanken des andern ja sogar nur auf dem Umweg der Sprache wahrnehmen. Und höchstens, wenn wir uns ein wenig dressieren auf die Gestikulationen und auf das Mienenspiel und auf die Physiognomie des andern, können wir noch einen Nachklang von dem wahrnehmen, wozu wir veranlagt waren. Die ganze Denkdisposition eines Menschen wahrzunehmen, waren wir veranlagt, indem wir ihm gegenübertraten, sie nachzuleben und die einzelnen Denkäußerungen aus den einzelnen Gesten, einzelnen Mienen wahrzunehmen. Wiederum ist es eine ahrimanische Gabe, durch welche umgewandelt worden ist diese mehr geistige Art der Wahrnehmungen der Gedankenwelt, die sich sogar im Verlaufe der Menschheitsevolution immer mehr und mehr auf die äußere Sprache konzentriert hat.

Wir brauchten gar nicht so sehr weit zurückzugehen in der Menschheitsentwickelung, nur bis in die ägyptisch-chaldäische Zeit, von der indischen gar nicht zu sprechen, wo das noch in höchstem Maße ausgebildet war — wir brauchten nur hinter die griechisch-lateinische Zeit zurückzugehen, da finden wir noch ein feines Verständnis bei der Menschheit für das Gedankenleben, insofern es sich ausgedrückt hat in den unausgesprochenen Worten, in dem, was durch Physiognomie, durch Gesten, selbst durch Stellungen, durch die ganze Art des Gegenübertretens des einen Menschen zum anderen, zum Ausdrucke gekommen ist. Dafür hat der Mensch sein Verständnis verloren. Immer weniger und weniger ist von dem erhalten geblieben, und heute ist schon recht wenig Verständnis dafür vorhanden, die inneren Gedankengeheimnisse des Menschen zu erlauschen aus der Art und Weise, wie er uns entgegentritt. Wir hören fast nur mehr auf dasjenige,was von seinen Gedanken, in seinen Gedanken, an seinen Gedanken dadurch zu uns kommt, daß er es uns durch die hörbaren Worte mitteilt. Dadurch aber, daß dies geschehen ist, haben wir die Fähigkeit erhalten, unseren Lebensapparat, unseren Lebensorganismus selbst zum Denkapparat zu machen. Wir würden nicht die Gabe des Denkens haben, wenn das nicht geschehen wäre, was ich gesagt habe, wenn nicht jener ahrimanische Einfluß gekommen wäre, von dem ich gesprochen habe. So sehen Sie, daß in einer gewissen Beziehung zusammenhängt unsere heutige Fähigkeit, zu sprechen, mit dem Wortesinn, Sprachsinn, aber auf dem Umwege durch ahrimanische Einflüsse; daß unsere heutige Fähigkeit, zu denken, zusammenhängt mit unserem Gedankensinn, wiederum auf dem Umwege durch ahrimanische Einflüsse.

Dann waren wir veranlagt, in feiner Weise das Ich des anderen Menschen zu verspüren, es nicht nur zu erleben, sondern innerlich wahrzunehmen; denn unser ganzer Mensch ist Ichsinn-Organ. Es arbeitet Ahriman heute noch immer sehr stark daran, auch diesen Ichsinn zu spezialisieren, wie er den Sprachsinn und den Gedankensinn spezialisiert, umgeändert hat. Das ist sogar im Werden, und das drückt sich darin aus, daß mit Bezug darauf die Menschheit einer merk würdigen Tendenz entgegengeht. Man muß etwas ganz Paradoxes sagen, wenn man von dem spricht, was eigentlich nun hier gemeint ist. Es drückt sich heute nur in den allerersten Anfängen aus, eigentlich noch mehr auf philosophische Weise. Es gibt heute schon Philosophen, welche die Fähigkeit, innerlich das Ich zu erleben, ganz leugnen: zum Beispiel Mach und andere; ich habe davon in dem philosophischen Vortrag, den ich neulich gehalten habe, gesprochen. Diese Menschen müßten eigentlich der Ansicht sein, daß man keine Fähigkeit hat, innerlich das Ich wahrzunehmen, sondern daß man das Ich wahrnimmt dadurch, daß man andere wahrnimmt. Und die Tendenz geht dahin, so zu denken, wie ich es jetzt grotesk andeuten will. Die Menschen würden dahin kommen, sich zu sagen: Da treten mir andere entgegen, die auf zwei Beinen pendelnd herumwandeln, wie ich es vorhin beschrieben habe, und daraus schließe ich, daß da innerlich ein Ich ist. Und weil ich geradeso ausschaue wie der, so schließe ich zurück, daß auch ich ein Ich habe. - Da würde man von den Ichs der anderen auf das eigene Ich schließen. Das liegt schon in dem Wesen von vielen Behauptungen, die heute aufgestellt werden, namentlich, wenn von der Seite, die ich eben meine, beschrieben wird, wie das Ich sich eigentlich während unserer einzelnen Evolution zwischen Geburt und Tod entwickelt. Lesen Sie in den heutigen Psychologien nach, da werden Sie schon beschrieben finden, wie diese Ich-Erfassung sich entwickelt an dem anderen. Dadurch, daß wir sie zuerst als Kind nicht haben, aber die anderen wahrnehmen, dadurch übertragen wir, was wir an den anderen sehen, auch auf uns selber. Die Fähigkeit, von dem anderen auf uns zu schließen, die wird allerdings immer größer und größer werden. Geradeso, wie sich nach und nach die Fähigkeit des Denkens entwickelt hat aus der Fähigkeit des Denksinns, die Fähigkeit der Sprache aus der Fähigkeit des Sprachsinns, so wird die Fähigkeit, an der ganzen Welt sich mitzuerleben, immer mehr entwickelt, neben der Fähigkeit, die anderen Iche wahrzunehmen. Wir haben es da mit feineren Unterscheidungen zu tun, aber man muß diese schon erfassen. So arbeitet gewissermaßen an diesem Ende des Menschen das Ahrimanische sehr mit — sehr, sehr mit.

Betrachten wir den Menschen jetzt von der anderen Seite. Da haben wir den Tastsinn. Ich sagte Ihnen: der Tastsinn ist eigentlich im Grunde ein innerer Sinn. Denn wenn Sie etwas antasten, etwa den Tisch, so übt das auf Sie einen Druck aus; aber das, was Sie wahrnehmen, ist eigentlich ein inneres Erlebnis. Das, was in Ihnen bewirkt wird beim Anstoß, das ist das, was eigentlich das Wahrnehme-Erlebnis ist. Was Sie da erleben, bleibt ganz in Ihrem Inneren beim Tastsinn. Es ist also der Tastsinn doch etwas, was im Grunde genommen nur bis zu der äußersten Peripherie der Haut geht; und weil die Außenwelt an diese Peripherie der Haut stößt, und wir nach diesem Anstoßen oder nach anderen Berührungen mit der Außenwelt Innenerlebnisse haben, haben wir die Erlebnisse des Tastsinns. Der Tastsinn ist also der am meisten peripherische Sinn und doch im Grunde ein innerer Sinn. Der Apparat für das Tasten ist am meisten ausgebildet an der Peripherie und schickt nur seine feinen Verzweigungen nach dem Innern, die nur deshalb nicht ordentlich bloßgelegt sind von der äußeren wissenschaftlichen Physiologie, weil diese nicht ordentlich den Tastsinn vom Wärmesinn unterscheidet.

Wir tragen auch ein Organ des Tastsinns mit, das gewissermaßen wie ein Geflecht auf unserer ganzen Oberfläche ausgebreitet ist und feine Verzweigungen nach dem Innern schickt. Dieses Geflecht, wenn ich es so nennen darf - es ist grob bezeichnet —, was ist es denn eigentlich? Wozu ist denn das ursprünglich dagewesen? Es ist eben das von vornherein eine auffällige Tatsache, daß dieser Tastsinn, trotzdem er jetzt verwendet wird, um durch Berührung die räumliche Außenwelt wahrzunehmen, in seinen Erlebnissen uns die inneren Erlebnisse gibt. Das ist eine ebensowenig zu leugnende, wie auf der anderen Seite bedeutungsvolle, merkwürdige Tatsache. Und sie hängt damit zusammen — das ergibt sich ja aus der Geisteswissenschaft —, daß dieser Tastsinn wiederum ursprünglich nicht eigentlich zum Wahrnehmen der Außenwelt bestimmt war, so wie er heute ist, gar nicht zum Wahrnehmen der physischen Außenwelt bestimmt war, sondern eine Metamorphose durchgemacht hat. Dieser Tastsinn ist eigentlich dazu bestimmt, daß wir unser Ich, ganz geistig gefaßt, das vierte Glied unseres Organismus, geistig ausstrecken durch unsern ganzen Körper. Und die Organe, welche die Organe des Tastsinns sind, geben uns eigentlich ursprünglich im inneren Erleben unser Ich-Gefühl, unsere innerliche Ich-Wahrnehmung.

Jetzt sind wir bei der innerlichen Ich-Wahrnehmung. Also unterscheiden Sie wohl: Das Wesen des Ich, das ist ein wirkliches Wesen, ein geistig substantielles Wesen, das sich in uns befindet, das sich in uns dehnt bis zu dem Geflecht des Tastsinns hin; und das, was das Geflecht des Tastsinns ist, das innerlich berührt wird vom sich erstreckenden Ich, gibt die Wahrnehmung des Ich. Würde es bei der ursprünglichen Bestimmung geblieben sein, deren Wesen ich jetzt angedeutet habe, dann würden wir durch den Tastsinn nicht solche Wahrnehmungen haben, wie wir sie jetzt haben. Wir würden ja gewiß dann auch auf die Dinge der Außenwelt stoßen, aber das würde uns höchst gleichgültig lassen. Wir würden dieses Stoßen oder meinetwillen das Darüberfahren mit den Fingerspitzen über die Sachen, nicht als Tasten haben. Wir würden also solche Zusammenstöße mit der Außenwelt so empfinden, daß wir unser Ich dabei empfinden, unser Ich dabei erleben, aber nicht von der Wahrnehmung der Außenwelt sprechen. Es mußte seit unserer Entwickelung von der lemurischen Zeit an unser Organismus umgewandelt werden, daß er aus einem Wahrnehmungserreger für das innere Ich Tastorgan wurde, fähig, die Außenwelt durch Tasten wahrzunehmen. Und das ist eine luziferische Tat, das ist einem luziferischen Einfluß zuzuschreiben. Dadurch ist unser Ich-Erlebnis so spezialisiert worden, daß wir die Außenwelt tastend erleben, dadurch natürlich auch unser Ich-Erlebnis getrübt haben. Wir würden das IchErlebnis ganz anders haben, wenn wir durch die Welt gingen und nicht immer zu achten hätten, was uns stößt oder drückt, oder ob etwas rauh oder glatt ist und so weiter.

Es mischt sich also das Luziferische, das den Tastsinn gestaltet hat, in das Ich-Erlebnis da hinein. Da ist also ein Innerlichstes mit einem Außerlichen vermischt, wie beim Sprachsinn ein Äußeres mit einem Inneren vermischt ist. Der Sprachsinn ist dazu bestimmt gewesen, nur Worte wahrzunehmen, die dann nicht zu tönen brauchen, also Sinnwahrnehmen. Sprechen als Innerliches hat sich dazu hineingemischt. Hier war es ein Innerliches, und ein Äußerliches ist dazugekommen, die Wahrnehmung draußen.

Lebenssinn: Das, was Organ des Lebenssinns ist, wodurch wir unsere innern Gebilde, unsere innere Verfassung erlebend wahrnehmen, das ist nun in ähnlicher Weise umgestaltet worden durch einen luziferischen Einfluß; denn ursprünglich waren wir in dieser Beziehung nur bestimmt, daß sich unser astralischer Leib innerlich wahrnimmt, erlebt an unserm Lebensorganismus. Nun ist aber hineingemischt worden die Fähigkeit, die innere Leibesverfassung, die innere Verfassung des Menschen als Wohlgefühl oder Mißgefühl zu erleben. Das ist luziferischer Impuls, der dort hineingemischt ist. Wie hier das Ich zusammengespannt wird mit dem Tasten, so wird hier der astralische Leib mit dem Wohl- oder Mißgefühl unserer Lebensverfassung zusammengespannt.

Und wiederum, unser Bewegungsorganismus ist ursprünglich so hergerichtet gewesen, daß wir nur die Wechselwirkung unseres Ätherleibes mit unserem Bewegungsorganismus erleben würden. Dazu ist gekommen die Fähigkeit, unsere innere Beweglichkeit wahrzunehmen und zu erleben, eben der Bewegungssinn selber. Wieder ein luziferischer Impuls. Wir verdanken also von zwei Seiten her luziferischen und ahrimanischen Einflüssen Umgestaltungen unseres ganzen Menschenwesens. Die eigentlich für den physischen Plan bestimmten Sinne, Ichsinn, Denksinn, Sprachsinn, sind ahrimanisch umgestaltet. Und nur dadurch sind wir das geworden, was wir als Menschen auf dem physischen Plan sind, daß Tastsinn, Lebenssinn, Bewegungssinn luziferisch umgestaltet sind. Und nur ein mittleres Gebiet haben wir, das gewissermaßen sich bewahrt hat vor diesen Einflüssen. Das ist die genauere, detaillierte Darstellung dieses unseres Organismus.

Ich will in dieser Betrachtung heute nicht weiter gehen, sondern sie morgen fortsetzen, weil es schon gut ist, wenn man sich das überlegt. Denn wir werden morgen sehen, wie fruchtbar das ist, was wir eben auseinandergesetzt haben, um zu erweitern die große, bedeutungsvolle und so vieles aufschließende Wahrheit von der Beziehung unseres Hauptes, unseres Kopfes, zu unserem Leib der vorigen Inkarnation, des Leibes der gegenwärtigen Inkarnation wieder zum Haupte der folgenden Inkarnation, und dessen, was daraus folgt für unser ganzes Verhältnis zum Kosmos.

Wir sehen da, wie es schon notwendig ist, das Augenmerk zu richten auf jenen Gleichgewichtszustand, der das Wesentliche, das Bedeutungsvolle ist, der hergestellt werden muß zwischen Ahrimanischem und Luziferischem in der Welt. Denken Sie, daß gewissermaßen an den äußersten Enden das Ich des Menschen beteiligt ist, hier gewissermaßen das Ich von außen, am Tastsinn das Ich von innen. (Siehe Zeichnung, orange Pfeile.) Ebenso ist der astralische Leib am Denken beteiligt, aber am Lebensorganismus wiederum von innen beteiligt (rote Pfeile). Der Ätherleib ist beteiligt hier, wenn das Sprechen nicht geschieht, aber ebenso beteiligt am Bewegungssinn von innen (blaue Pfeile). In der Mitte haben wir gewissermaßen dasjenige, woran «ich taste denke — lebe — spreche — bewege», weniger beteiligt sind, eine Art Hypomochlion, wie es die Waage hat in der Mitte, wo sie ruht. Je mehr man gegen die Mitte kommt, desto mehr bleibt der Waagebalken ruhig. An den Seiten schlägt er aus. So hätten wir in der Mitte eine Art Ruheverhältnis.

Da enthüllt sich uns schon die menschliche Wesenheit, in einer bedeutungsvollen Weise von zwei Seiten her beeinflußt. Und es ist notwendig, daß das Ahrimanische und das Luziferische in der rechten Art ins Auge gefaßt wird, wenn man den Menschen verstehen will in seinem Aufbau, wie auch in seiner heutigen Betätigung.

Fourteenth Lecture

The result of spiritual scientific observations, which we have repeatedly mentioned recently, concerning the relationship of the human head and the rest of the human body — whereby the head is included in the rest of the body — to the whole world, this result is indeed of the most far-reaching significance. You know how we have explained it. We have said that what the human being carries as his head, with everything that belongs to it, is a transformed form, a transformed shape, a metamorphosis, and that what this head has transformed itself from, what it has been transformed into, is the entire body of the previous incarnation. So when we look at the entire body of our present incarnation, we see how it carries within itself the forces that can transform it so that it becomes only a head, a head with all that belongs to it, with twelve pairs of nerves springing from it, and so on. And this head, which develops from our entire body, we will carry in our next incarnation. In contrast, in the time between our death, after our present life, and our birth in the next incarnation, partly from the forces of the spiritual world, insofar as the time between death and a new birth is taken into account, and partly from the forces of the physical world, insofar as the time from our conception to our birth in the next incarnation is taken into account, our body, that is, everything that belongs to our body, is worked out for the next incarnation.

Such truths must not be taken as truths of ordinary life or ordinary science, but as truths that carry meaning within themselves, as truths that point to great connections. With regard to the truths of ordinary life, we describe ourselves and our environment, so to speak; with regard to truths such as those mentioned above, we read our environment and ourselves in the context of the world. The truths of ordinary life and ordinary science are really like describing the shapes of individual letters on a page, or at most explaining the grammatical rules by which they are combined to form words. But what is meant by truths such as those mentioned above can be compared to reading without first using a special description of the shapes of the letters and looking at the grammar and how these letter shapes combine to form words. Think how completely different the content of what we read is from what is written on the page for our eyes to see. Similarly, when we cite a truth such as the one just mentioned, we do not have only what we are saying in mind, but we have in mind the whole far-reaching significance of such a thing for the position of human beings in the universe. In a sense, we read deeply living spiritual truths that have nothing to do with the forms of the head or the body that anatomy and physiology study or that we encounter in everyday life when we speak of the human form. One can only understand human beings if one does not merely describe them as everyday life and science do, but if one reads them.

Based on this premise and in accordance with it, let us once again turn our attention to what we have discussed in the context of the last few weeks. Let us turn our attention to the twelve senses of the human being. Let us review these twelve senses of the human being.

Sense of self: I ask you to consider once again what I have said about this sense of self. This sense of self does not refer to our ability to perceive our own self. With this sense of self, we do not perceive our own self, the self that first came to us on earth, but rather we perceive the selves of other people. In other words, we perceive everything in the physical world that confronts us with a self.

The second is the sense of thinking. The sense of thinking, in turn, has nothing to do with our own thought formations. When we think for ourselves, this thinking is not an activity of the sense of thinking, but something completely different. We will talk about this later. The sense of thinking refers to our ability to understand and perceive the thoughts of other people. So this sense of thinking has nothing to do with our own thoughts.

Sense of language: This, in turn, has nothing to do with the formation of our own language, nothing to do with the ability that underlies our own speech, but is rather the sense for understanding what is said to us by other people.

Hearing sense or sound sense: This cannot be misunderstood.

Sense of warmth, sense of sight, sense of taste, sense of smell, sense of balance: I have already explained these senses several times, including in these reflections.

Sense of movement, sense of life, sense of touch.

These are the twelve senses through which we perceive the outside world here in the physical world. As you know, materialistic thinking only recognizes the sense of sound, the sense of warmth — which it conflates with the sense of touch —, the sense of sight, the sense of taste, and the sense of smell, and therefore speaks of five senses. However, newer science, newer physiology, sensory physiology, adds to this the sense of balance, the sense of movement, the sense of life, and also distinguishes between the sense of touch and the sense of warmth. Ordinary science and ordinary physiology do not speak of a special sense of language, a special sense of thought — one could also say a sense of thought — and a special sense of self, because the nature of their thinking does not yet allow them to do so. Materialistic thinking and viewing of the world tend to limit themselves to everything that is perceptible to the senses. There is a certain absurdity in saying “perceptible to the senses,” because one arbitrarily delimits what is perceptible to the senses, namely what is perceptible through the five senses; but you all know what is meant when one says: The ordinary materialistic view accepts as valid that which is perceptible to the senses, and therefore seeks the organs of perception for the senses. Because it has nothing at all to offer as an organ of perception for the sense of self, the sense of thought, and the sense of language, because it has nothing at all that it can compare, for example, with the ear for the sense of hearing or with the eye for the sense of sight, it does not speak of these senses: sense of self, sense of thought, sense of language. But for us the question arises: Are there really no organs for the sense of self, the sense of thought, the sense of speech? Today we want to examine these things in more detail.

The sense of self refers to our ability to perceive the selves of other people. A particularly inadequate and insufficient statement of modern thinking is that we do not actually perceive the self of another person, but rather always infer the self of another person to a greater or lesser extent. We see something coming toward us—so this way of thinking assumes—that walks upright on two legs, one leg always passing the other or one sitting down next to the other, supported by these legs, with a torso from which two arms swing, performing various movements for various purposes; then a head sits on top, which utters sounds, speaks, and makes gestures. And when something like what I have just described comes towards us, we conclude: That is the bearer of an I. — That is the materialistic view. This is complete nonsense, real, genuine nonsense; for the truth is that just as we see colors with our eyes and hear sounds with our ears, we also truly perceive the I of another person. Without a doubt, we perceive it. And this perception is independent. Just as seeing is not based on a conclusion, just as hearing is not based on a conclusion, so the perception of the ego of another is not based on a conclusion, but is an immediately real, independent truth that is gained independently of our seeing the other, of our hearing his sounds. Apart from the fact that we hear his language, that we see his incarnate form, that we allow his gestures to affect us, apart from all that, we perceive the other's ego directly. And just as little as the sense of sight has to do with the sense of hearing, so little does the perception of the ego have to do with the sense of sight or with the sense of hearing or with any other sense. It is an independent perception of the self. Until this is understood, the science of the senses does not rest on solid foundations.

Now the question arises: What is the organ for the perception of the other ego? What perceives the other ego in us, just as we perceive colors or light and dark with the organ of sight, just as we perceive sounds with the ears? What does the ego of the other perceive? The perception of the ego has its organ just as the perception of sight or sound has its organ. Only the organ of ego-perception is, so to speak, so constituted that its starting point lies in the head, but the whole area of the rest of the body, insofar as it is dependent on the head, forms an organ for the ego-perception of the other. Indeed, the whole human being, understood as an organ of perception, insofar as it is sensually and physically formed, is an organ of perception for the ego of another. In a sense, one could also say that the organ of perception for the ego of another is the head, insofar as it is attached to the whole human being and its capacity for perception of the ego radiates through the whole human being. The human being, insofar as he is calm, insofar as he is the calm human form with the head as its center, is an organ of perception for the ego of another human being. Thus, the organ of perception for the ego of another human being is the greatest organ of perception we have, and we ourselves, as physical human beings, are the greatest organ of perception we have.

Now we come to the meaning of thought. What is the organ of perception for the thoughts of others? The organ of perception for the thoughts of others is everything that we are, insofar as we feel activity and life within ourselves. So if you think that you have life in your entire organism and that this life is a unity—not insofar as you are formed, but insofar as you carry life within you—then this life carried within you by your entire organism, insofar as it expresses itself in the physical, is the organ for the thoughts that come to us from outside. If we were not shaped as we are, we could not perceive the I of another; if we were not as animated as we are, we could not perceive the thoughts of another. That is not the meaning of life I am talking about here. It is not a question here of our inner perception of our overall condition of life—that belongs to the meaning of life—but rather of the extent to which we carry life within us. And this living thing within us, everything that is the physical organism of life within us, is the organ of perception for the thoughts that others direct toward us.