Impulses of Utility, Evil, Birth, Death, Happiness

GA 171

7 October 1916, Dornach

I. Western and Eastern Culture, H. P. Blavatsky

My dear friends, in the lectures which have been held here for some weeks I have endeavoured to show you some of the things which have lived in human evolution—certain things connected with various inner impulses which have entered into the modern development of humanity. We have had to go very far back to find the origin of these impulses. We have sought to understand how, from out of the Atlantean civilisation, there flowed the relics of an ancient Atlantean Mystery magic. We have shewn how, in a state of decadence, this Atlantean civilisation still lived on amongst those peoples who were re-discovered in Europe through the re-discovery of America. We then sought to study the relics of another branch of Atlantean magic which sent its rays and streams from Asia throughout Europe. And so, we have seen coming from Atlantis a co-operation in a certain sense between the Eastern and Western pole. From out of these impulses which have remained over from Atlantis, we then sought to deepen ourselves concerning the nature of the Graeco-Roman epoch, which as we know, was a copy to a certain extent, of Atlantean civilisation, though of course on a higher stage. And then we tried to understand the two poles of the IVth Post Atlantean Period. That is, the pole of Greece and the pole of Rome. We then attempted to follow at least partially, the various impulses which were further active in our European life of civilisation. We have especially considered that impulse which came into the spiritual stream of Europe through the fact that the Templars had to undergo a certain fate, and that this fate of the Templars which works so powerfully, so deeply on our own souls, evokes spiritual forces into existence which have continued to work on in a spiritual way; inspiring, impelling, initiating all of those things which have contributed to the external path of the history of the peoples of Europe. And then we have continued to trace how these impulses pass over into a recent material. And in the last lecture, we saw at the end of the 18th century, it gives a peculiar colouring to those ideas which at that time confused the world, the ideas of Brotherhood, Freedom and Equality. Many such impulses as have been born in the course of centuries and flowed into European development could be characterised, but that must be left over to a later time.

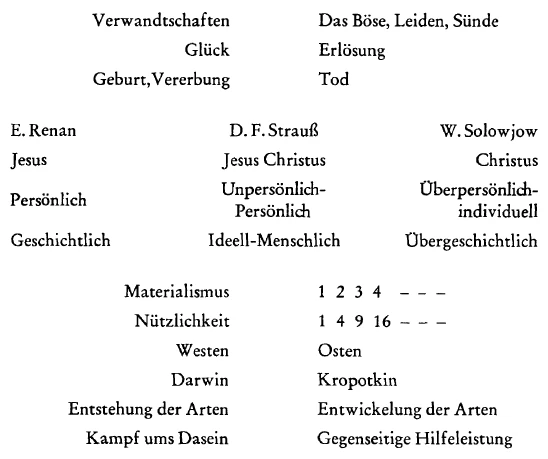

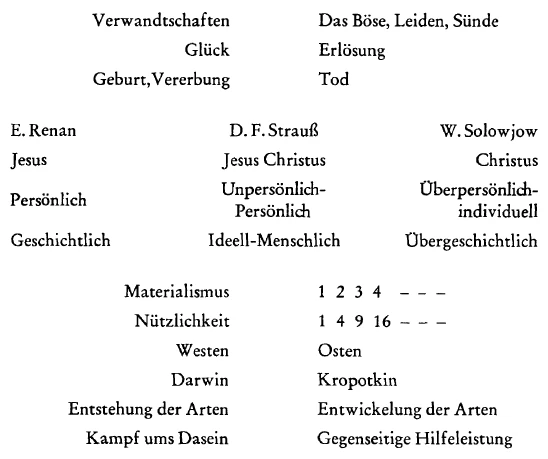

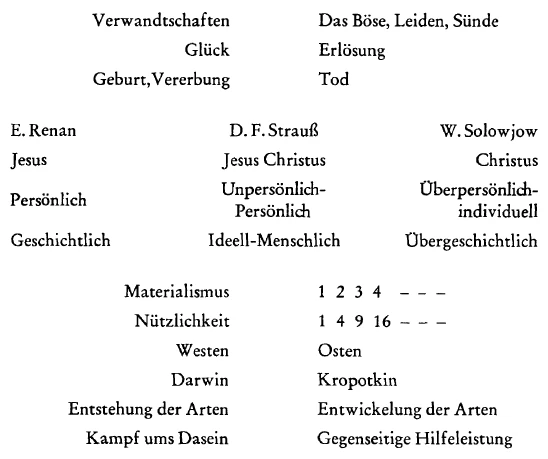

I should now like to characterise, through certain significant impulses, the path of our own European life of civilisation, because it is essential that through a Spiritual Scientific observation one should learn to know more and more thoroughly the peculiarities of our own age, the age in which we are standing to-day. It is important for us to know how our own time is determined by that special spiritual structure of the 19th century. In this 19th century all those impulses of which I have spoken to you have been more or less veiled, covered up to a certain extent. I have often drawn your attention to the fact that, as regards the evolution of modern civilisation, the middle of the 19th century was a most important time;—it was that time in which in the 5th Post Atlantean civilisation something was to become especially active something which man knows and learns to produce through his intellect in so far as that is bound to the physical plane. We must rake this quite clear to ourselves. With the 5th Post Atlantean civilisation something of the nature of forces comes into the Post Atlantean development which was absolutely different from what occurred in the Graeco-Latin age in the 4th Post Atlantean epoch. Naturally the Greeks had intellect (verstand) but that was of quite a different nature from our own - our own intellect,—which has gone through the 5th Post Atlantean epoch and which, in the middle of the 19th century, really entered upon a quite definite crisis. That intellect which was developed in ancient Greece, and which, for instance, radiated in all that the Greeks created artistically, which radiated in all that the Greeks created in their State arrangements (which were not really State arrangements at all),—that intellect which worked through the Philosophy of Plato and Aristotle, that intellect which then was drawn over into the political being of Rome was utterly different from the intellect which arose in our own 5th Post Atlantean epoch. One can even prove this philosophically, as I have attempted to do in the first volume of my “Riddles of Philosophy.” With the Greeks, their ideas were really so existing that they perceived them just as we to-day can see colours, hear sounds, and have sense perceptions: so they could experience ideas. Now with our modern humanity the intellect is separated from outer perception and it works in the inner being of man; but it works in such a way as it must do when it is to be activated through the brain or, in general, through the physical organism. This has gradually brought about a certain state of affairs:—and please bear in mind, that by reason of the whole meaning of our civilisation, it had to be so. The tendency was gradually brought about in the 15th century, through this intellectual development, of permeating human life more and more with purely materialistic cognition, and practical life with the principle of mere utility, Utilitarianism. We have gradually seen with what necessity these things developed, how in the civilisation of the West of Europe certain impulses arose, and in connection with these impulses questions were put in the sphere of cognition. We have seen how these questions differed from others which arose, for instance, in the East of Europe. We have seen, for instance, how the West, through a long preparation was driven in the sphere of knowledge and in the practical sphere of life, to urge the spirit into a configuration which gradually put certain questions above all else. We have seen how in the West there gradually rose the tendency to study what I must call the affinity of all beings; and, when it comes to man, of studying what relates to the Birth of man and to Heredity. One can best understand Western civilisation (when it is striving for cognition) if one knows that these questions concerning the affinity of beings, and of Birth and Heredity, were dominant in the life of the West. From this there arose in the Western world, in their science of chemistry and physics, the seeking of the affinity of different forces of Nature which were regarded as modifications of one particular force of Nature. This tendency then extended to other spheres; in the sphere of Biology it was the affinity of various animals and plants which was investigated; and out of all of this man himself was explained—man, as he was thought to have developed, from a purely animal existence. One must say: To understand the birth of man in its affinity with other creatures on the Earth, was the culmination of these questions in the West.

The Eastern sphere on the other hand, sought in the realm of knowledge other questions: “What is Evil? What is the meaning of suffering in the world?” Never so much as in the East of Europe was there so much thinking concerning Evil and Sin. Of course, in the other spheres this was also the case, but nowhere with the same intensity and with the same genius as in the East. All the literary production of the East stands under the influence of the question: “What is Evil?” And the pains which in the West we applied to the problems of Affinity, were in the East applied to the investigation of Sin. The same thought which was employed in the West to investigate the natural connections of physical man as he passes through birth into existence, was applied in the East to understand Death. That same effort is employed in the East to understand Death. “How does man maintain himself aright as a soul, as he passes through Death? What does Death signify in the whole connection of Life?” That announced itself as a question in the East, one just as important for the East as the question concerning the natural Affinity of Man and the Birth of Man is for the West. Just as in the Western World we can prove that these problems of Birth and Happiness lay at the basis of their thinking, so we can show that in the Eastern world, (for example, in Solovieff) we can say that all his thinking is directed to the question of Evil and of Death. The difference is only this—that in the West one has already travelled a long way in one's investigation, whereas in the East they are still more or less at the beginning. Then, as you know, all these things passed over into the sphere of practical life, into the arranging of social life,—those ideas which we seek to realise in everyday life,—and if to a certain extent we investigate the most intimate impulses in the life of the West, we see that we can refer these to the thoughts concerning the Happiness of Man.

Please just bear in mind how this thinking concerning the Happiness of Man begins with the “Utopia” of Lord Bacon and the “Utopia” of Sir Thomas More, and we see how this same trend of thought has developed into the most diverse social programmes which have found expression in the West. Of course, social programmes have also come to expression in the East, but one can easily prove that in the East they spring from quite different impulses than have the social programmes of the West. All these, as well as the idea of Freedom which came to us from the French Revolution, and all the social ideas of the 19th century, all have as their aim the Happiness of Man. In the East we find, (of course still in the beginning) how there, instead of Happiness it is Redemption which is sought for—the inner freeing of the soul of man. There the longing exists to know how the soul of man can develop towards the overcoming of life. One understands this extraordinary interplay of impulses if one keeps this in mind. And we have seen how even a consideration of a somewhat higher kind, of the Lives written of Christ Jesus, has received its colouring from what lies in these same impulses and tendencies. In the West, we have that most characteristic and clever observer of the Life of Jesus—Jesus considered only as Jesus—just as one can consider any other human being, born from a certain race, a certain climate, or a certain nation. I refer to the “Life of Jesus” by Ernest Renan. Now in the East Jesus is little spoken of, and when one speaks of Jesus it is simply as a path along which one can come to the Christ. You find this very strongly in Solovieff.

Between these two, as I have told you, (and if one only has an eye for these things, a sense for what Goethe calls the UR-phenomenon, one knows how these three names are chosen)—between these two, Renan and Solovieff, there stands—a far more original and far clever man than the other two—David Frederick Strauss. Ernest Renan considers only the Jesus, Solovieff considers only the Christ; Ernest Renan transformed Jesus into a simple man, a human, one can almost say an “all too human” man Now with Solovieff this human element is completely lost. Man's gaze is directed into the spiritual world by Solovieff, when he considers the Christ; and he only speaks of moral, spiritual impulses. Everything with Solovieff is forced into a super earthly sphere. The Christ has nothing earthly, although He pours His effects into an earthly sphere. Between these two stands David Frederick Strauss. He does not deny Jesus—he admits that such a personality lives; but, just as Ernest Renan simply and solely considers Jesus as man, so to David Frederick Strauss, Jesus is only of significance in so far as on this Jesus for the first time is suspended the idea of the whole of humanity. Everything which man can long for or ever has longed for, from out of the Mysteries of all ages as the Idea of All-humanity, is attached to the Jesus of David Frederick Strauss. D. F. Strauss does not very much consider the earthly Life of Jesus only as a means whereby to show how in the age when Jesus appears, humanity had the longing to bring together all the myths which refer to the sum total of humanity, and to concentrate them on that Figure. And so, that which in Ernest Renan's Life is so full of colour, with D. F. Strauss becomes a kingdom of shadow, which only seeks to show how the Myths of Centuries all flow together. With D. F. Strauss Christ is not a figure cut off as with Solovieff, but is the idea of that which lives on throughout the whole of humanity—that Christ Who for thousands of years has poured Himself into humanity and developed through humanity. With D. F. Strauss, therefore we find only an idea of Jesus, united with an idea of Christ. With Ernest Renan, we have a personal and historical Jesus. With Solovieff we have a Christ Who is super-personal yet individual, but at the same time super-historic. He is super-personal yet individual, because He is a Being shut off, included in Himself, although at the same time He is an individual but transcending personality. Between these two stands D. F. Strauss, who has not to do with a vision,—a perception of the personal element working in Christ Jesus,—for this personal element is only, as it were, a point of support for all those myths streaming through humanity.

If one only keeps in mind this scheme obtained from a spiritual observation of the history of Europe, one can almost read straight off the various spiritual connections. You see, with Ernest Renan, a man who pre-eminently arose out of the Western civilisation, it is a question the whole time, of understanding how a certain country, a certain race could give birth to Christ Jesus. It is a question of the birth of Jesus. With Solovieff the question is especially: “What does Christ signify for human evolution? And how can Christ save what is born in man as a soul, how can He lead that again through the Gate of Death?”

And so, in the middle of the 19th century, as I have told you, that which lives in this evolution and which belongs especially to our 19th century, reached a certain crisis. At that time, the most extreme point was reached which one can strive for through physical, intellectual performance. In the course of the 19th century, the striving after happiness was gradually transformed into the striving for mere utility,—Utilitarianism. That is something which appears especially in the middle of the 19th century, both in the sphere of knowledge as also in the sphere of life:—the striving after mere utility. And that is something which especially disturbed those who understand the real eternal needs of the human soul, it disturbed them especially that the 19th century should bring forth a striving especially concentrated on the principle of Utilitarianism. Thus, we meet Materialism in the sphere of Knowledge, and Utilitarianism in the sphere of Practical Life. And those two things belong absolutely together.

Now I am not bringing forward these things in order to criticise them, but because they are necessary points of transition for humanity. Man had to go through this materialistic principle in the sphere of Knowledge, as he had to pass through the principle of Utilitarianism in the sphere of Practical Life. It was a question of how humanity should be led in the 19th century in order to pass in the right way through those necessary points of its development. We will therefore begin the consideration of these things this evening from a certain point of view, and then, on a later occasion I shall hope to enter into them more thoroughly.

Knowledge, especially that which in the West is, ae we know, concentrated on the phenomena of Birth and the question of Heredity, and this was placed in the service of Materialism, of Utilitarianism. Now let us make clear to ourselves what really happened in thought. As you know, Darwinism arose, which studied the problem of the Birth of Man, that is, the Origin of Man from a sequence of organisms; and Darwinism attempted to make popular certain quite definite views. We know also that something far more spiritual than Darwinism already stands in Goethe's “Theory of Evolution,” but Goethe's theory had for the time to remain more esoteric. And so, in the first place, the more coarse, materialistic form had to be taken up by humanity. We know too that in the last decades the most intimate pupils of Darwinism have attempted to undermine Darwinism itself in its materialistic colouring. But Darwinism, as it really entered the world of the I9th century, did not enter the world because the investigations of Nature, because science itself made it necessary—not even the natural scientists would maintain that. Oscar Hertwig, the best pupil of Haeckel says, that because human beings only wanted to keep in man the social and mercantile principles of utility during the I9th century, therefore they carried these principles over even into the external world. They simply wanted a reflection of their own thinking, and it was no external facts of nature which forced a Darwinistic view on humanity. So, it is no wonder that, on a closer investigation, one no longer finds these views substantiated. But, as human beings, we have come now to the principle of Utility.

Now Darwin also lived in a certain stream which strove after the principle of Happiness, the Happiness of Human beings, but a stream which was absolutely materialistic. Darwin came very near to that stream which belongs to the doctrine of Malthus. The teaching of Malthus proceeded from a certain definite view, a view that on the Earth in a certain way the means of life increases. That means the fruitfulness of the Earth can increase. But, side by side with this increase in the fruitfulness of the Earth the Malthusians also regarded the increase in the population of the Earth, in such a way as one is only able to regard it, if one does not take into consideration the idea of reincarnation. And they came to see that the fruitfulness of the earth—that is, the means of nourishment,—did not increase at the same rate as the increase in population. They thought: the increase in the nourishment runs its course according to the number [sequence] 1, 2, 3, 4, and so on which we call arithmetical progression; whereas the increase in population happens according to the numbers 1, 2, 4, 8 and so on, which as you know, is geometrical progression. The disciples of Malthus, on the basis of this view, developed the ideas which they thought they had to develop, keeping in mind the Happiness of humanity on the earth. All the time they had in front of them their calculated increase in population, and on the other side an increasing lack in the means of nourishment. From this proceeded the so-called Malthusian ideal—that is, the ideal of the `two children' system. It was said: Since nature has the tendency to impel men forward geometrically and only to impel the means of nourishment forward arithmetically, therefore the population must be restricted, which can be done through the two children system. Now, concerning this special application of the principle of Happiness in the whole stream of Materialism which one gets simply by studying the sequences of Birth according to a materialistic principle (which of course has blinded humanity), we need not speak further now, but Darwin started from the certainty of the principle that for all beings who live on the Earth, the means of nourishment increase in arithmetical progression, whereas the population increases in geometrical progression, And so for him there resulted a certain consequence. He said: If things transpire so the means of nourishment increasing at the rate of 1, 2, 3, 4 and so on, whereas the population increases at the rate of 1, 2, 4, 8, then there will be amongst the beings of the Earth an inevitable struggle for existence, and the struggle for existence must be a really operative principle. So, upon Malthusianism,—that means something which was meant absolutely for practical life,—Darwin based his system. Please bear in mind that Darwin did not derive his system from an observation of Nature, but from a theory. It was not an observation of Nature based on Knowledge which gave Darwin his impulse, but simply this principle of utility which said that by regulating the births so that the rate of birth did not grow greater than the rate in the increase of nourishment—one could thereby maintain a balance. Of course, it was thought that one could find the struggle for existence everywhere in Nature, and so the Darwinians said: All beings live immersed in a struggle for existence whereby the unfit are removed and the fit remain over. That means the Darwinian `survival of the fittest.' And so, you see, no cosmic principle full of wisdom is required, because now everything runs on by itself through the survival of the fittest. How suitable for the humanity of the I9th century to strip off everything of a spiritual nature and to live as far as possible only in material existence! One has no need to think of ideals if one lives only under the principle of the survival of the fittest. Nature can then go on entirely without ideals. As a matter of fact, one might even work against the course of Nature if one attempts to realise any ideals, because through one's ideals one might even cause an unfit individual to survive;—an individual who would go under in the struggle for existence!

My dear friends, that principle lived in the humanity of the 19th century everywhere, and was uttered more or less clearly. One lived under the impulse of thinking along these lines, even if one did not always say it quite so clearly. In short, a View of the World arose which sought to satisfy the humanity of the I9th century in this special manner. I just wanted to show you in this where lies the true impulse of Darwinism, because in the beautiful scientific Unions or Scientific Societies in general, people have sought to spread a materialistically coloured Darwinism as a kind of Gospel throughout humanity, without knowing what real impulse lay at the back of them. You see, humanity has a far greater preference for ideas which deceive it than for those which explain the truth. We could go on to bring forward many, many things which would simply be an expression of the fact that in the middle of the 19th century our civilisation and culture had reached a certain crisis, and it was a question for those who knew that certain things must never he quite killed,—things that they knew were necessary for the progress of humanity,—it was a question for those who knew, how, m such an age of mere utility, one could still maintain a spiritual civilisation and culture. And so, it was no accident but something founded in the purpose of the whole of human development, that when that principle of utility brought European development to a crisis in the middle of the 19th century, a personality such as Time. Blavatsky appeared who, through her natural endowment, was capable of revealing to humanity an extraordinary amount from out of the spiritual world itself. if anyone who is an astrologer wanted to consider this matter, he could undertake the following pretty experiment. He could take the point of time of the strongest utilitarian crisis of the 19th century, and for that point of time set up a horoscope. He would get just the same horoscope if he calculates the horoscope of Time. Blavatsky! This is simply a symptom that the self-evolving Cosmic Spirit in the course of time wanted to place a personality in the world through whose soul the opposite of Utilitarianism should come to expression. That principle of utility is absolutely established in Western civilisation, and against all this the Eastern civilisation has always held itself erect. Therefore, we see this peculiar play that, whereas in the West right into the sphere of Knowledge this Western principle is striven for out of a materialistic Darwinism, where a struggle for existence inserts itself into scientific observation,—that brutal struggle for existence against which attacks have always been made by the Russian investigators, whose research work you find collected by Kropotkin in his book, wherein he says that it is not a struggle for existence which lies at the basis of all animal species, but what he calls Mutual Aid. And so, about the middle of the 19th century we have Darwin's “Origin of Species” appearing in the West through the struggle for existence, and in the East, we have brought together by Kropotkin, the labour of a whole series of Russian scientists in his book “Mutual Aid,” which characterises the evolution of species by showing that just those species develop best of all who help each other mutually. Thus, on the one side as it were, at the one pole of the newer spiritual civilisation men are taught that those species develop best who suppress each other most of all, and then from the East, from the other pole, we are taught that those species develop best, the members of which are so endowed that they support each other mutually. That is extraordinarily interesting. One might say, that just as Darwin from out of the milieu of the West works m the middle of the 19th century, so from out of the aura of the East there worked that which was laid down in the soul of Blavatsky, but which could not come fully to development because the time was not yet at hand

We have seen how the West has come forward in a certain way already, whereas the East still stands at the beginning of this development. And so, in Blavatsky there appears a kind of beginning, the announcement of a soul-development. This soul-development of Blavatsky appeared entirely out of a Russian aura, in spite of the fact that her origin was not in itself entirely Russian. This soul, in her mediumship, was developed in a Russian way, but, in the course of her life she was completely led into Western civilisation,—she was so utterly led into Western civilisation that, as you know, she wrote her books in the language of the West; even as far West as America, this figure of Blavatsky was interwoven with the civilisation of our recent age. One might say that in Blavatsky the attempt was made to see how these two things could be intermingled. From all that I have told you concerning the evolution of Blavatsky, you will know that certain things were attempted through her, but, as you also know all meaning, all sense was snatched away from these very exempts. The works of Blavatsky are even chaotic, giving out great significant truths, hut all hopelessly mixed up with the most extraordinary rubbish. Now what, in reality, has proceeded from that impulse which was attempted with Blavatsky? With Blavatsky, the attempt was made to take occultism, which is a merely traditional occultism, and to propagate that. And what has followed from this, after Blavatsky's death right on to our own age? That you have experienced for yourselves right up to the humbug with Alcyone, and what is now developing from Mrs. Besant herself.

Thus, you have this example before you—an attempt to unite occultism with utilitarianism. Now in the way in which it was attempted there, it could not go on any further. Through that peculiar intermingling of something which was born in the East with what existed in the West, Blavatsky, whose soul was of a mediumistic nature, was intended to incorporate the spirituality of the West with the principle of Utilitarianism An Ahrimanic attempt was begun; and that is a terrible, a horrible, but powerful example of how an Ahrimanic attempt inserts itself, which tries, not only to bring out a certain knowledge concerning the supersensible world, but to place it entirely in the service of utility, of Utilitarianism. Blavatsky was surrounded by personalities who strove to keep her entirely in their own hands, but that never quite succeeded because she always slipped away from them in a certain way. But a certain number of men in the Western world endeavoured to get Blavatsky entirely into their own hands, and if that had succeeded, if the ideal of uniting spirituality with the principle of utility had been Utterly realised, we should experience something quite different to-day from that Bureau of Julia (Stead's Bureau); for the Bureau of Julia is only a posthumous, an unsuccessful attempt to amalgamate the principle of utility with spiritualism. What was attempted with Blavatsky was simply only a caricature, but if that had succeeded, we should have everywhere to-day Bureaus where, through mediums, we could get all kinds of information concerning what numbers would win in a lottery, what lady one should marry, whether one should sell out or keep for a time certain stocks and shares. And all that would be arranged from the information to be got from the spiritual world, through mediumship. The spiritual life would be placed utterly at the service of utility. The tragedy of Blavatsky consists in this,—that she was driven to and fro, between both poles, and therefore her life is of such an extraordinary psychological character. In Blavatsky's life, certain doors had to be opened through which one could look into the spiritual world, and so we see this extraordinary phenomenon appearing, of the withdrawal of the Individuality who used Blavatsky as a means of bringing revelations into the world concerning the spirit, while in its place appears that individuality whom Olcott characterises as the reincarnated Sea-Pirate of the 16th century, John King. John King, who then occupied himself in materialising tea cups and things of that kind, when they were especially needed! Into these things there plays a conflict between the principle of Utility and that principle which must work with more Utilitarianism in the course of the further development of humanity,—not by removing utility out of the world, but by directing it spiritually into the right paths. Because, my dear friends, you must not think that any spiritual civilisation of the future will ever be at enmity with life. The task of any true spiritual Science should be to bring Utilitarianism into the right waters.

But of this we shall attempt to speak in the next lecture. We shall then attempt to show the relation between the principle of utility of the most practical life of our present age, and that which should be a spiritual life within this life of practise. And therewith we shall contact one of the most important questions of the life of our present age.

Zehnter Vortrag

In den Vorträgen, die hier in den letzten Wochen gehalten worden sind, habe ich mich bemüht, einiges von dem zu zeigen, was in der neueren Menschheitsentwickelung gelebt hat an verschiedenen inneren Impulsen, die eingegriffen haben in diese moderne Menschheitsentwickelung. Wir sind weit zurückgegangen. Wir haben zu verstehen gesucht, wie herüberspielen aus der atlantischen Kultur die Überreste, die stehengebliebenen Überreste alter atlantischer Mysterienmagie. Wir haben vor unsere Seele geführt, wie eine Seite dieser atlantischen Mysterienkultur in Dekadenzzuständen lebte bei den Völkern, die aufgefunden worden sind von den europäischen Völkern durch die Entdeckung Amerikas. Wir haben uns weiter etwas vertieft in die Überbleibsel des anderen Zweiges atlantischer Magie, der seine Strahlen und Strömungen hinübergesendet hat aus Asien nach Europa. Und so haben wir ein Zusammenwirken gewissermaßen eines westlichen und eines östlichen Poles bei den aus der Atlantis übriggebliebenen Impulsen kennengelernt. Wir haben uns dann etwas vertieft in die Eigentümlichkeit, in das Wesen der griechisch-lateinischen Kultur, die ja in gewissem Sinne eine Nachbildung, eine Art Wiederholung der atlantischen Kultur war, aber auf einer anderen Stufe. Und wir haben wiederum versucht, die beiden Pole der vierten nachatlantischen Kulturzeit, nämlich den griechischen Pol und den romanischen Pol, kennenzulernen. Wir haben dann auch versucht, die verschiedenen weiteren Impulse, wenigstens teilweise, zu erwähnen, welche im europäischen Kulturleben tätig waren. Wir haben insbesondere betrachtet jenen Impuls, der in den geistigen Strom der europäischen Kulturentwickelung gekommen ist dadurch, daß die Tempelherren ein gewisses Schicksal durchgemacht haben, und daß durch dieses so eindringliche, so gewaltig auf unsere Seele wirkende Schicksal der Tempelherren geistige Kräfte ins Dasein gerufen worden sind, welche fortgewirkt haben auf geistige Art, gewissermaßen inspirierend, impulsierend, initiierend dasjenige, was im äußeren Gang der Geschichte der europäischen Völker sich zugetragen hat. Und wir haben dann zu verfolgen versucht, wie diese sich fortentwickelnden Impulse in die neuere materialistische Zeitenkultur hereingeströmt sind. Wir haben am letzten Montag betrachtet, was sie bewirkt haben am Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts, wie sie eine eigentümliche Färbung verliehen haben — das suchten wir zu begreifen - den Ideen, die damals durch die Welt schwirrten, den Ideen von Brüderlichkeit, von Freiheit und Gleichheit. Es könnten noch viele solche Impulse, wie sie im Laufe der Jahrhunderte nach und nach geboren werden in der europäischen Entwickelung, charakterisiert werden; das kann aber einer späteren Zeit überlassen werden. Ich wollte an einigen bedeutungsvollen Impulsen charakterisieren, welcher Art der Gang des europäischen Kulturlebens war. Denn worauf es uns ja ganz besonders ankommen muß, das ist, in geisteswissenschaftlicher Art immer besser und besser zu verstehen, welches die Eigentümlichkeit des Zeitpunktes ist, in dem wir selber stehen, wie dieser Zeitpunkt bestimmt worden ist durch die besondere geistige Struktur des 19. Jahrhunderts. In diesem 19. Jahrhundert haben ja dann, mehr oder weniger verhüllt, alle diese Strömungen auf geistige Art gespielt, diese Kulturimpulse, von denen wir gesprochen haben.

Nun habe ich Sie auch schon öfter darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß in bezug auf die Entwickelung der neueren Kulturvölker die Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts ein wichtiger Zeitpunkt war. Es war der Zeitpunkt, in dem im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum dasjenige besonders bedeutsam werden sollte, was der Mensch erkennen und hervorbringen kann durch den Verstand, insofern dieser Verstand an das physische Gehirn gebunden ist. Denn das müssen wir uns nur ganz klarmachen: mit dem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum kommt etwas von Kräften in die nachatlantische Kulturentwickelung herein, was noch ganz anders war im griechisch-lateinischen Zeitraum, im vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum. Selbstverständlich hatten die Griechen auch Verstand, aber einen Verstand ganz anderer Art als derjenige ist, der durch den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum heraufgezogen ist und in der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts in eine ganz besondere Krisis eingetreten ist. Der Verstand, der sich im Griechentum ausgebildet hatte zum Beispiel, der durchstrahlt hat dasjenige, was das Griechentum künstlerisch geschaffen hat, der durchstrahlt hat dasjenige, was das Griechentum in seinen Städteeinrichtungen — nicht Staatseinrichtungen — geschaffen hat, der Verstand, der dann in der griechischen Philosophie Platos und Aristoteles’ gewirkt hat, der Verstand, der dann auch mit dem Römertum in das Staatswesen eingezogen ist, dieser Verstand war im vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum noch etwas ganz anderes, als er im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum geworden ist. Daß sich dies selbst philosophisch nachweisen läßt, das können Sie ja entnehmen aus dem ersten Band meiner «Rätsel der Philosophie», worinnen ich zu zeigen versuchte, wie anders der Grieche mit dem Begriffe, mit der Idee lebte, als der Mensch zum Beispiel des 19. Jahrhunderts. Beim Griechen war dieldee wirklich so vorhanden, daß er sie gewissermaßen wahrnahm, wie wir heute nur noch Farben oder Töne, Sinnesempfindungen wahrnehmen. Bei den modernen Menschen unserer Zeit ist der Verstand abgetrennt von der äußeren Wahrnehmung und wirkt im Innern des Menschen, aber doch so im Innern des Menschen, wie er wirken muß, wenn er sich betätigt durch das Gehirn, überhaupt durch den physischen Organismus.

Dies hatte allmählich — und es mußte durch den Sinn der neueren Geschichte so sein — im 19. Jahrhundert die Tendenz heraufgebracht, das menschliche Leben immer mehr und mehr zu durchziehen mit materialistischer Erkenntnis und mit dem bloßen Nützlichkeitsprinzip im praktischen Leben. Wir haben ja gesehen, mit welcher Notwendigkeit sich diese Dinge entwickelt haben. Wir haben gesehen, wie in den westlichen Kulturländern Europas gewisse Triebe zu Fragen aufgetaucht sind, wie da andere Fragen gestellt worden sind, oder, wenn wir so sagen wollen, wie gewisse große Menschheitsfragen anders gestellt worden sind als zum Beispiel im Osten. Wir haben gesehen, daß der Westen durch lange Vorbereitung dahin gedrängt worden ist, auf dem Erkenntnisgebiete und auch auf dem Gebiete des praktischen Lebens den Geist in eine gewisse Konfiguration hineinzudrängen. Wir haben gesehen, daß sich die Fragen allmählich zugespitzt haben. Ich werde heute die Ausdrücke gebrauchen, auf die ich schon hingewiesen habe, die aber heute so gebraucht werden sollen, daß sie besonders präzise dasjenige bezeichnen — wir haben es angeführt -, was im Westen hauptsächlich gefragt worden ist: die Verwandtschaften der Wesen und alles, was sich beim Menschen auf Geburt und Vererbung bezieht. Man kann im tiefsten Sinne die westliche Erkenntniskultur verstehen, wenn man weiß, daß diese Frage nach der Verwandtschaft der Wesen im Weltenall und nach Geburt und Vererbung tonangebend war. Damit, daß man im 19. Jahrhundert nach den Verwandtschaften fragte, wurde in der westlichen Welt begründet das, was Physik, was Chemie ist, und so weit gebracht, daß die Verwandtschaft der verschiedenen Naturkräfte erkannt werden wollte als Einheit der Naturkräfte auf chemischem Gebiete; daß die Verwandtschaft der verschiedenen Stoffe untersucht wurde chemisch, aber auch auf biologischem Gebiete, auf dem Gebiete der Lebenslehre; daß die einzelnen Formen der Tiere und Pflanzen untersucht wurden und ihre Verwandtschaft geprüft wurde. Das alles sollte dann dahin führen, daß begriffen werden sollte der Mensch, aber der Mensch so, wie er sich herausentwickelt aus dem rein tierisch-natürlichen Dasein, man kann sagen, die Geburt des Menschen zu begreifen, das heißt den sinnlichen Menschen zu verstehen in seiner Verwandtschaft mit den anderen sinnlichen Wesen der Erde. Dazu spitzte sich zu in der Geburts- und Vererbungsfrage dasjenige, was die westliche Welt suchte.

Die östliche Welt suchte auf dem erkenntnismäßigen Gebiete um andere Fragen sich zu bemühen. Und wenn wir diese wieder zusammenfassen wollen, so können wir sagen: Es ist das Böse, das Leiden in der Welt. - Nirgends ist so viel wie im Osten Europas gegen Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts zu nachgedacht worden, über nichts ist so viel nachgedacht worden, als über die Frage: Wie kommt das Böse, die Sünde könnten wir auch sagen, in die Welt herein? Gewiß, es ist auch in anderen Gegenden über die Sünde nachgedacht worden, aber, man möchte sagen, nicht mit soviel Begabung wie im Osten Europas. Die literarische Produktion, das philosophische Denken, sie stehen im Osten Europas, namentlich im russischen Geistesleben, ganz unter dem Impuls, das Böse zu erforschen. Und dieselben Mühen, die im Westen auf die Verwandtschaften der Wesen verwendet werden, die werden im Osten verwendet auf die Erforschung des Bösen, der Leiden, der Sünde. Dieselben Mühen, die im Westen verwendet werden auf den natürlichen Zusammenhang des Menschen, so daß der physische Mensch, wie er durch die Geburt ins Dasein tritt, begriffen werden soll, dieselben Mühen werden im Osten verwendet, den Tod zu begreifen. Wie der Mensch als Seele sich aufrechterhält im Tode, wie er durch die Pforte des Todes tritt als lebendige Seele, was der Tod im ganzen Lebenszusammenhange bedeutet, das kündigt sich im Osten an als eine Frage, die da ebenso wichtig ist für den Osten wie für den Westen, die Frage nach den natürlichen Verwandtschaften, nach dem, was zu der physischen Geburt des Menschen führt. Wie wir bei den westlichen Philosophen auch philosophisch nachweisen können, daß diese Fragen ihnen zugrunde liegen, so können wir bei dem größten, bei dem vorläufig größten östlichen Philosophen, bei Wladimir Solowjow, nachweisen, wie all sein Denken, all sein Sinnen beherrscht ist von den Fragen: Tod und das Böse, die Sünde.

Der Unterschied ist nur der, daß im Westen die Entwickelung verhältnismäßig weit fortgeschritten ist, daß man schon sehr weit gekommen ist in der Erforschung desjenigen, was mit den charakterisierten zwei Fragen zusammenhängt, während im Osten die Sachen mehr im Anfange stehen. Alle diese Dinge übertragen sich dann auf das praktische Gebiet, auf das Einrichten des sozialen Lebens, auf die Ideen, die man im Alltag verwirklichen will. Und wir haben ja gesehen, wenn wir den gewissermaßen intimsten Lebenstrieb des Westens suchten, wie er sich unter diesem Erkenntnisimpulse entwickelte. Wir können ihn bezeichnen als das Nachdenken über das Glück des Menschen. Bedenken Sie, wie das Nachdenken über das Glück des Menschen beginnt mit den Ütopisten Bacon, Thomas Morus und so weiter. Wie aber entwickelt sich dann dieses Nachdenken weiter in den verschiedensten sozialistischen Programmen, die im Westen zum Vorschein kommen? Gewiß, auch im Osten sind sozialistische Programme zum Vorschein gekommen. Wer aber einen Sinn hat für Differenzierung, der kann sehr leicht herausfinden, wie diese einem ganz anderen Impulse entspringen als die sozialistischen Ideen des Westens, die zu den neueren sozialistischen Ideen geführt haben. Das alles, sowohl die Freiheitsideen der Revolution wie die sozialistischen Ideen des 19. Jahrhunderts, sie haben, könnte man sagen, als ihr praktisches Ideal das Glück. Wenn wir nach dem Osten hinüberschauen — wir haben es schon vor einigen Wochen ausgesprochen -, so finden wir, allerdings hier auch wiederum mehr im Anfange, aber wir finden es deutlich: es wird gesucht, wie dort das Glück, so hier die Erlösung, die innere Befreiung des Menschen. Es ist die Sehnsucht vorhanden, kennenzulernen, wie das Leben der Seele mit Besiegung des physischen Lebens sich entfalten kann. Man versteht dasjenige, was im europäischen Leben merkwürdig durcheinanderspielt, wenn man dieses Durcheinanderspielen der Impulse, die sich so ausleben, ins Auge faßt. Und wir haben gesehen, wie selbst eine Erkenntnisbetrachtung höchster Art, die Betrachtung des Christus Jesus-Lebens, ihre Färbung erhält durch alles das, was in diesen Impulsen, in diesen Trieben liegt.

Hier im Westen betrachtet der charakteristischste und genialste Betrachter des Jesus-Lebens, Ernest Renan, den Jesus nur als Jesus. Er betrachtet ihn so, wie man einen anderen Menschen betrachtet, indem er ihn aus seinen natürlichen Bedingungen heraus entwickelt: wie Jesus herausgeboren ist aus seinem Volke, herausgeboren ist aus seinem Klima, seinem Land, seiner Nation. Im Osten spricht man wenig von dem Jesus, und wenn man von dem Jesus spricht, nur, um über ihn weg zu dem Christus zu kommen. Und insbesondere scharf ausgeprägt — aber nicht nur bei ihm, sondern auch bei anderen - können Sie dieses finden wiederum bei Solowjow. Mitten drinnen, habe ich schon gesagt, steht wenn man einen Sinn hat für das, was Goethe das Urphänomen nennt, so wird man, und das mit Recht, gerade diese drei Namen nennen -, origineller und genialer als alle anderen Jesus-Betrachter, David Friedrich Strauß.

Ernest Renan betrachtet, man könnte sagen, einzig den Jesus. Solowjow betrachtet einzig den Christus. Bei Ernest Renan wird Jesus zu einem bloßen Menschen, der menschlich, man könnte fast sagen, allzu menschlich von Ernest Renan betrachtet wird. Bei Solowjow verliert sich das Menschliche vollständig. Ein Aufstieg in die geistigen Welten wird von Solowjow immer gesucht, wenn er den Christus betrachtet, und nur von moralisch-geistigen Wirksamkeiten und Impulsen wird gesprochen, wenn er den Christus betrachtet. Alles ist in eine spirituelle Sphäre gerückt. Dieser Christus des Solowjow hat nichts Irdisches, obwohl er sein Wirken in das Irdische hereingießt. Mitten drinnen steht David Friedrich Strauß. Ich habe Ihnen schon charakterisiert, wie eigentümlich seine Christus Jesus-Betrachtung ist. Er leugnet den Jesus nicht, er gibt zu, daß solch eine Persönlichkeit gelebt hat, wie sie Ernest Renan einzig und allein als Mensch betrachtet. Aber dieser Jesus hat für David Friedrich Strauß nur insoferne eine Bedeutung, als in ihm zunächst die Idee der ganzen Menschheit aufgetaucht ist. Damit ist aufgetaucht durch Jesus alles dasjenige, was die Menschen ersehnt und erahnt haben in den Mythen aller Zeiten. Was in der Mythenbildung gelebt hat als die Idee der Gesamtmenschheit, das tritt in Jesus auf. David Friedrich Strauß betrachtet nicht das irdische Leben des Jesus. Es wird ihm dieses irdische Leben des Jesus nicht die Hauptsache, wie es das für Ernest Renan ist, sondern David Friedrich Strauß betrachtet das irdische Leben Jesu nur als ein Mittel, um zeigen zu können, wie in dem Zeitpunkt, da der Jesus auftritt, die Menschheit das Bedürfnis hat, alle die Mythen, die sich auf die Entwickelung der Gesamtmenschheit und auf die Ideale der Gesamtmenschheit immer bezogen, zusammenzufassen. So wird in der Betrachtung von David Friedrich Strauß dasjenige, was bei Ernest Renan farbenreich, menschlich farbenreich ist, das Leben Jesu, nur ein, man möchte sagen, Schattenleben, das gewissermaßen hineingestellt wird in die Welt der Entwickelung, um zeigen zu können, wie die Mythen von Jahrtausenden zusammenfließen. Und Christus ist bei David Friedrich Strauß nicht eine abgeschlossene Individualität, eine Wesenheit, wie bei Solowjow, die gewissermaßen persönlich hereinwirkte mit ihren Impulsen in das Menschheitsleben, sondern die Idee der Menschheit, dasjenige, was in jedem Menschen lebt, was in der ganzen Menschheit lebt, der Christus, der über die Jahrtausende der Menschheitsentwickelung ausgegossen ist, der sich mit der Menschheit selber entwickelt. Bei David Friedrich Strauß finden wir gewissermaßen nur die Idee des Jesus mit der Idee des Christus vereinigt. So daß wir bei Ernest Renan einen Jesus haben, der persönlich ist und der geschichtlich ist; bei Solowjow haben wir einen Christus, der überpersönlich ist, aber individuell, und der übergeschichtlich ist. Überpersönlich, aber individuell, ist er aus dem Grunde, weil er eine in sich abgeschlossene Wesenheit ist. So wie der Mensch eine physisch abgeschlossene Persönlichkeit ist, so ist der Christus des Solowjow eine in der Geistwelt, wenn auch im Erdenkreise lebende Persönlichkeit, also eine Überpersönlichkeit; und übergeschichtlich ist er, weil er nicht unter den geschichtlichen Persönlichkeiten lebt wie der Jesus des Ernest Renan, sondern weil er anders in die Geschichte eingreift, übergeschichtlich ist. Jede Persönlichkeit, die mit physischem Leibe begabt ist, würde geschichtlich eingreifen, außer dem Christus, der in dem physischen Leibe nur lebte, um seither immer zu leben mit der Erde, aber übergeschichtlich die Erde zu lenken durch die Impulse, die von ihm ausgehen. Dazwischen steht die Betrachtung des David Friedrich Strauß, der es nicht zu tun hat mit der Anschauung, daß das Persönliche bei Christus Jesus besonders in Betracht kommt. Diese Persönlichkeit trat nur auf, um gewissermaßen ein Konzentrationspunkt zu sein für die bei allen Völkern zerstreuten Mythen, die von einem ähnlichen Heiland sprachen.

So können wir sagen: Während bei Ernest Renan der Jesus persönlich, bei Solowjow überpersönlich ist, ist er bei David Friedrich Strauß mehr unpersönlich-persönlich. Unpersönlich-persönlich, dieser Widerspruch muß gebildet werden aus dem Grunde, weil zwar die Persönlichkeit vorliegt in der Betrachtung, aber auf die Persönlichkeit selbst nicht der Hauptwert gelegt wird. Dasjenige, was gewissermaßen der Weltenlauf in der Zwischenzeit vollbracht hat mit den verschiedenen Mythen, die sich da konzentriert haben, also das unpersönliche Wirken, das stellt David Friedrich Strauß in den Mittelpunkt. Und auch nicht geschichtlich und nicht übergeschichtlich ist dieses, sondern ideell-allmenschlich. Der Christus des David Friedrich Strauß ist, weil er im Grunde nur ideell ist, weniger konkret als der Christus des Solowjow; sein Jesus ist dafür mehr ideell als der Jesus des Ernest Renan, der nur eine Persönlichkeit ist. Und man kann fast ablesen, wenn man dieses aus der Geistesgeschichte Europas heraus gewonnene Schema nimmt, wie der Zusammenhang ist. Ernest Renan, einem im eminentesten Sinne aus der Westkultur hervorgegangenen Manne, handelt es sich vorzugsweise darum, zu begreifen: Wie konnte ein Land, eine Zeit, ein Volk, wie konnte ein gewisses Milieu gebären den persönlichen Jesus? — Auf die Geburt kam es Ernest Renan an. Für Solowjow handelte es sich vorzugsweise darum: Was bedeutet der Christus für die menschheitliche Entwickelung? Wie rettet der Christus dasjenige, was im Menschen geboren ist als Seelisches? Wie führt der Christus den Menschen durch den Tod hindurch?

Im 19. Jahrhundert nun erreichte namentlich dasjenige, was in dieser Entwickelung lebt - denn die letzten Ereignisse dieser Entwickelung gehören ja durchaus dem 19, Jahrhundert schon an -, eine gewisse Krisis. In der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts erreicht es eine gewisse Krisis. Es wurde gewissermaßen das Äußerste erreicht, was anstreben kann physische Verstandesleistung: das Streben nach dem Glück wurde allmählich im 19. Jahrhundert zum Streben nach der bloßen Nützlichkeit. Und das ist es, was insbesondere in der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts hervortritt: das Streben sowohl auf erkenntnismäßigem Gebiete wie auf dem Gebiete der bloßen Nützlichkeit. Das war dasjenige, was insbesondere beunruhigt hat diejenigen, welche die wahren, die ewigen Bedürfnisse der Menschheitsentwickelung verstehen: daß das 19. Jahrhundert eine Krisis bringen sollte in bezug auf das Nützlichkeitsprinzip. Materialismus auf dem Gebiete des Erkenntnislebens, Nützlichkeit auf dem Gebiete des praktischen Lebens sind zwei Dinge, die zusammengehören. Hier werden diese beiden Dinge nicht aufgezählt aus dem Grunde, um sie zukritisieren und gegen sie zu zetern, sondern sie werden aufgezählt, weil sie notwendige Durchgangspunkte für die Menschheit waren. Die Menschheit mußte durchgehen sowohl durch das Prinzip des Materialismus auf dem Erkenntnisgebiete wie durch das Prinzip der bloßen Nützlichkeit auf dem Gebiete des praktischen Lebens. Nur handelte es sich darum, wie nun in diesem 19. Jahrhundert die Menschheit geführt werden sollte, um durch diesen notwendigen Punkt ihrer Entwickelung durchzugehen. Und mit der Betrachtung darüber, mit der Betrachtung desjenigen, was heute schon betrachtbar ist aus dem 19. Jahrhundert, wollen wir heute beginnen, auf einige Gesichtspunkte aufmerksam zu machen, um sie dann am nächsten Samstag weiter auszuführen.

Die Erkenntnis gerade, die auf die Geburt hinging und auf die Vererbung, auf das Begreifen des Menschen als eines natürlichen Geschöpfes, diese Erkenntnis wurde nun in den Dienst des Materialismus, ja sogar als Erkenntnis in den Dienst des Nützlichkeitsprinzips gestellt. Das kann man auf den verschiedensten Gebieten nachweisen. Machen wir uns klar, was da eigentlich geschehen ist. Sie wissen alle, und ich habe es in den beiden öffentlichen Vorträgen in dieser Woche ja auch öffentlich hervorgehoben: Der Darwinismus ist heraufgekommen, der Darwinismus hat über das Problem der Geburt des Menschen, das heißt des Hervorgehens des Menschen aus der übrigen Organismenreihe ganz besondere Ideen heraufzubringen versucht. Wir wissen, daß alles dasjenige, was mehr spirituell, geistig ist am Darwinismus, schon in Goethes Metamorphosenlehre steckt; aber diese Goethesche Metamorphosenlehre solite zunächst, man möchte sagen, wie esoterisch bleiben. Die gröbere materialistische Form der Verwandelungslehre, die der Darwinismus gebracht hat, sollte zunächst unter die Menschheit kommen, sollte beliebt werden, sollte von den Menschen zu verstehen gesucht werden. Und wir haben ja im öffentlichen Vortrage gesehen, welche Schicksale der Darwinismus durchgemacht hat, wie die intimsten Schüler der Darwinisten im Laufe weniger Jahrzehnte dazu gekommen sind, diesen Darwinismus selbst, insofern er in seiner drastischen Färbung aufgetreten ist, in den Grund und Boden zu bohren. Aber dieser Darwinismus, ist er eigentlich in die Weltbetrachtungen des 19. Jahrhunderts eingezogen deshalb, weil irgendwelche Naturtatsachen dazu nötigen? Nicht einmal die Naturforscher selber, die denken, behaupten das heute mehr. Ich habe das gestern auseinandergesetzt. Oscar Hertwig sagt es ausdrücklich: Weil die Menschen in der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts auf dem Punkt angekommen waren, nur die äußeren Nützlichkeitsprinzipien gelten zu lassen, die merkantilen, die sozialen Nützlichkeitsprinzipien, haben sie diese Prinzipien auch übertragen auf die äußere Welt. Kein Wunder, daß die äußere Welt das nicht bewahrheitet hat, als man sie genauer betrachtete. Die Menschen wollten ein Spiegelbild ihres eigenen Denkens in der Natur sehen.

Aber wie ist Darwin eigentlich zu dieser Anschauungsweise gekommen? Das ganze Nützlichkeitsprinzip ist ja wiederum aus der Anschauung über das Glück, wie man dasGlück auf der Erde begründet, hervorgegangen. Es ist außerordentlich charakteristisch. Nun wurde Darwin aufmerksam in seiner Zeit auf eine gewisse Strömung, welche, man könnte sagen, in der denkbar materialistischsten Weise über das Glück der Menschen auf Erden nachdachte, darüber nachdachte, wie das Glück auf der Erde begründet werden solle. Darwin kam dem nahe und stellte sein Denken in den Dienst desjenigen, was man Malthusianismus nannte, die Lehre des Malthus. Was ist das? Diese Lehre des Malthus ging aus von der Anschauung, daß auf Erden die Lebensmittel sich vermehren dadurch, daß man die Fruchtbarkeit der Erde rationeller ausnützt, daß man also die Fruchtbarkeit der Erde vergrößern kann. Aber neben dieser Zunahme der Fruchtbarkeit der Erde betrachteten die Malthusianer auch die Zunahme in der Bevölkerung der Erde, wie sie das eben betrachten konnten. Alle Inkarnationsideen waren ja ausgeschaltet. Und da kamen sie darauf, daß in ungleicher Art die Fruchtbarkeit der Erde zunimmt, einerseits die Fruchtbarkeit in bezug auf die Nahrungsmittel, andererseits die Fruchtbarkeit in bezug auf die Bevölkerung. Sie dachten, die Zunahme der Nahrungsmittel geschieht etwa so: 1 2 3 4, wie man sagt, in arithmetischer Progression, die Zunahme der Bevölkerung dagegen 1 4 9 16 und so weiter in entsprechend langen Zeiträumen, wie man sagt, in geometrischer Progression. Die Anhänger des Malthus begründeten auf diese Anschauung eine Ansicht, die sie glaubten begründen zu müssen im Sinne der Glückseligkeit der Menschen auf Erden. Denn wohin soll es denn führen, wenn die Erde so übervölkert wird, wie sie übervölkert werden muß, wenn die Bevölkerung in geometrischer Progression steigt, während die vorhandenen Nahrungsmittel nur in arithmetischer Progression steigen? Daraus ging ein Prinzip hervor, das, ich möchte sagen, Gott sei Dank nur kurze Zeit wenige verblendet hat, es ging das Prinzip des sozialen Malthusianismus hervor, das Ideal des Zweikindersystems. Man sagte, da die Natur die Tendenz hat, die Menschenvermehrung geometrisch vorwärtszutreiben, muß Einhalt geschaffen werden durch das Zweikindersystem. Nun, über diese besondere Anwendung des Glückseligkeitsprinzipes im ganz materialistischen Sinne, daß man einfach die Geburtenfolge der Erde so bestimmt, wie man sich sie nur unter materiellen Voraussetzungen bestimmbar dachte, brauchen wir uns ja nicht weiter einzulassen. Aber Darwin stand ganz unter dem Einfluß dieses Prinzipes, und er sagte sich: Wie ist die Natur also eigentlich beschaffen, wenn sie solch ein Prinzip hat? - Er ging aus von der Gewißheit dieses Prinzipes, daß für alle Wesen, die leben, die Nahrungsmittelzunahme in arithmetischer Progression geschieht, die Zunahme an Individuen in geometrischer Progression. Daraus ergab sich ihm das Folgende, er sagte sich: Wenn die Nahrungsmittel nur zunehmen wie 1 2 3 4 5, die Vermehrung aber der einzelnen tierischen Wesen wie 1 4 9 16 25 und so weitet, dann muß notwendigerweise unter den Wesen der Kampf um die Nahrungsmittel, der Kampf ums Dasein ein wirksames Prinzip sein. Und aus dem Malthusianismus heraus, also aus etwas, was im Grunde genommen für das praktische Leben bestimmt war, hat Darwin sein Prinzip vom Kampf ums Dasein gebildet, nicht aus Beobachtung der Natur, sondern aus dem Malthusianismus heraus; der hat ihn angeregt, der hat ihn inspiriert. Kampf ums Dasein ist aus diesem Grunde da.

Wir sehen also: Erkenntnismäßige Naturbetrachtung war es nicht, was Darwin den Anstoß gegeben hat, sondern es war das Nützlichkeitsprinzip im Leben, das der Malthusianismus durch Geburtenregulierung gesucht hat. Dann hat man geglaubt, diesen Kampf ums Dasein in der Natur überall zu finden und hat sich gesagt: Alle Wesen leben im Kampf ums Dasein, das Unpassende wird besiegt, das Passende bleibt übrig im Kampf ums Dasein, — Auslese des Nützlichen. Jetzt brauchte man kein weisheitsvolles Prinzip, sondern man hatte an die Stelle der Weltenweisheit den Kampf ums Dasein gesetzt. Das Nützliche erhält sich, das Nutzlose geht verloren im Kampf ums Dasein: Auslese des Passendsten. Wie geeignet für die Menschen des 19. Jahrhunderts, die einen gewissen Trieb entwickelten, möglichst das Geistige abzustreifen und möglichst nur im Materiellen zu leben! Denn Ideale zu haben, daran brauchte man ja nicht zu denken, wenn man nur dem großen Prinzipe der Auslese des Passendsten leben konnte. Und man brauchte sich ja so wenig zu bemühen, Ideale zu verwirklichen, da die Natur ohnedies das Passendste ausliest, ja man könnte sogar der Natur entgegenarbeiten, wenn man Idealen sich hingäbe, denn die Natur findet in sich selber das Prinzip, das Passendste auszulesen. Man könnte, wenn man Ideale verwirklicht, sich vielleicht sogar zu einem unpassenden Individuum machen, das den Kampf ums Dasein in seinen Idealen zugrunde legen müßte! Das ist nicht etwas, was bloß ein einzelner empfindet, sondern was in den Menschen des 19. Jahrhunderts lebte und klar und deutlich ausgesprochen wurde überall. Aber außerdem, wie konnte man sich sozusagen die Finger ablecken, wenn man auf den Wegen des 19. Jahrhunderts es zu etwas gebracht hatte, wenn man, sagen wir zum Beispiel durch irgendwelche, seien es auch noch so fragwürdige Mittel, eine besondere Position im Leben erworben hat! Die Natur hat das allgemeine Prinzip, das Passendste auszuwählen; man war also der Passendste! Man genierte sich zwar, das immer auszusprechen, aber man wirkte doch unter dem Triebe, so zu denken. Wenn man sich ein möglichst großes Vermögen ergaunert hat, warum sollte man dies nicht gerechtfertigt finden, da die Natur immer das Passende auswählt? Man war also der Passendste. Kurz, dadurch kam eine Weltanschauung herauf, welche die Menschheit des 19. Jahrhunderts in einer ganz besonderen Weise betäuben mußte.

Ich wollte hauptsächlich zeigen, wo der wahre Antrieb, der wahre Impuls des Darwinismus liegt, weil in den schönen Vereinen, die sich heute als Monistenvereine kundgeben, oder in den Vereinen, die überhaupt heute Aufklärungen verbreiten, der materialistisch gefärbte Darwinismus wie ein Evangelium gelehrt wird, wenig aber gewußt wird, welche Impulse eigentlich in ihm leben, wie denn auf diesem Gebiete die Menschen überhaupt viel mehr geneigt sind, solche Begriffe und Ideen zu predigen und entgegenzunehmen, durch die sie sich über die Wahrheit betäuben, als solche, durch die sie sich über die Wahrheit etwa aufklären würden. So könnten wir noch vieles anführen, was ein Ausdruck dafür wäre, wie in der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts die Verstandeskultur in eine Krisis eingetreten war.

Nun handelte es sich für diejenigen, die da wissen, daß niemals eine der Strömungen, die notwendig sind zum Fortschritt der Menschheit, ganz getöter werden darf, darum, wie im Zeitalter der bloßen Nützlichkeit aufrechtzuerhalten war spirituelle Kultur. Es ist kein Zufall, sondern im Sinne der ganzen menschlichen Entwickelung begründet ich habe schon öfter darauf hingewiesen und ich will heute noch einmal darauf hinweisen —, daß, als das Nützlichkeitsprinzip in der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts die europäische Entwickelung in eine Krisis brachte, geboren wurde eine Persönlichkeit wie die Frau Blavatsky, welche durch natürliche Veranlagung fähig gewesen wäre, ganz besonders viel aus der geistigen Welt heraus der Menschheit zu offenbaren. Wenn jemand als Astrologe die Sache betrachten wollte, so könnte er folgendes schöne Experiment machen: Er könnte den Zeitpunkt der stärksten Nützlichkeitskrise in der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts untersuchen und der Nützlichkeitskrise im 19. Jahrhundert das Horoskop stellen. Er kann dasselbe Horoskop bekommen, wenn er das Geburtshoroskop der Blavatsky stellt! Es war dies einfach ein Symptom, daß der sich entwickelnde Weltengeist im Laufe der Zeit eine Persönlichkeit in die Welt stellen wollte, durch deren Seele das Gegenteil des Nützlichkeitsprinzipes zum Vorscheine kommen sollte.

Das Nützlichkeitsprinzip ist nun ganz und gar begründet in der Westkultur. Die Ostkultur aber hat immer Front gemacht gegen das Nützlichkeitsprinzip. Daher sehen wir auch das eigentümliche Schauspiel, daß im Westen bis in die Erkenntnis hinein das Nützlichkeitsprinzip getrieben wird im materialistischen Darwinismus, daß der Kampf ums Dasein einzieht in die wissenschaftliche Betrachtung, der brutale Kampf ums Dasein. Wissenschaftlich ist zuerst Front gemacht worden gegen den Kampf ums Dasein vom Osten her durch russische Forscher, deren emsige Geistesarbeit dann Kropotkin zusammengefaßt hat in seinem Buche, das zu lesen sehr nützlich ist, in dem er zeigt, wie nicht der Kampf ums Dasein in der Entwickelung der tierischen Arten lebt, sondern die gegenseitige Hilfeleistung. Und so haben wir um die Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts erscheinend Darwins «Entstehung der Arten», Entwickelung der Arten durch Kampf ums Dasein im Westen, im Osten haben wir bei Kropotkin den Gegenpol zusammengefaßt. Aber Kropotkin faßt eben nur eine ganze Reihe russischer Forschungen zusammen in dem Buche, das die Entwickelung der Lebewesen, die Entwickelung der Arten dadurch charakterisiert, daß gezeigt wird, wie diejenigen Arten am besten fortkommen, welche am meisten darauf veranlagt sind, daß sich ihre Individuen gegenseitig helfen. Diejenigen Tierarten entwickeln sich am besten weiter, welche am meisten zur gegenseitigen Hilfeleistung angelegte Individuen haben. Dem Kampf ums Dasein wird die gegenseitige Hilfeleistung gegenübergestellt.

So wird gelehrt auf der einen Seite, gewissermaßen am einen Pol der neueren Geisteskultur: Diejenigen Arten entwickeln sich am besten vorwärts, die am brutalsten bestehen im Kampfe ums Dasein, die die anderen am besten verdrängen können. Von Osten her, vom anderen Pole wird gelehrt: Diejenigen Arten entwickeln sich am besten, deren Individuen am meisten dafür angelegt sind, daß das eine dem anderen hilft. Es ist das außerordentlich interessant, und man möchte sagen: Wie Darwin um die Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts wirkt aus dem Milieu des Westens heraus, so wirkt aus der Aura des Ostens heraus dasjenige, was in der Seele der Blavatsky veranlagt war. Nur konnte es noch nicht, weil es noch nicht an der Zeit war, vollständig zur Entwickelung kommen. Wir haben ja gesehen, wie der Westen mit Bezug auf dasjenige, was er gerade anstrebt, schon in einer gewissen Weise vorwärtsgekommen ist, und wie der Osten am Anfange erst ist. Und so tritt denn auch ein Anfangs-Seelengebilde in der Seele der Blavatsky auf. Und ein merkwürdiges Schicksal erlebt dieses Anfangsgebilde der Blavatsky. Ganz herausgeboren ist diese Seele aus der russischen Aura, mit allen möglichen Eigenschaften einer russischen Seele ist Blavatsky trotz ihrer Abstammung, die ja nicht eine rein russische war, ausgestattet. Aber diese Seele, die bis in ihr visionäres Leben herauf, bis in ihre Genialität, die in so hohem Sinne bei der Blavatsky ausgebildet war, russisch ausgestattet ist, sie wird im Verlaufe ihres Lebens eigentlich ganz geführt in die Westkultur, sie wird so weit geführt in die Westkultur, daß sie in einer westlichen Sprache ihre Werke schreibt. Bis nach Amerika hinüber — ich habe ja die Schicksale der Blavatsky schon erzählt - wurde die Blavatsky verwoben mit der Westkultur der neueren Zeit. Man kann sagen, daß in ihr der Versuch gemacht wird, wie sich die beiden Dinge miteinander verschmelzen, durcheinanderorganisieren lassen. Ein außerordentlich interessanter Versuch. Aus all dem, was ich Ihnen dargestellt habe, und auch aus all dem, was Sie erlebt haben in der Entwickelung dessen, was sich an den Namen Blavatsky knüpft, werden Sie ja wissen, daß dasjenige, was mit der Blavatsky versucht worden ist, gescheitert ist, daß ihm gewissermaßen der Sinn entrissen worden ist. Denn schon die Werke der Blavatsky selber — ich habe es ja oft gesagt — sind chaotisch. Große, bedeutende Wahrheiten stehen in ihnen, vermischt mit konfusem Zeug, und nur derjenige, der solches sondern kann, ist gewachsen dem, was in den Büchern der Blavatsky steht.

Aber was ist dann aus diesem Impuls, der mit der Blavatsky versucht worden ist, hervorgegangen? Bei der Blavatsky selber schon ist der Versuch gemacht worden, den bloß traditionellen westlichen Okkultismus — ich habe das ja gerade hier in Vorträgen dargestellt zu propagieren. Und was dann weiter geworden ist nach dem Tode der Blavatsky bis in unsere Zeiten herein, das haben Sie ja erlebt bis zu jener Zeit des Humbugs mit dem Alcyone und bis zu dem, was aus Mrs. Besant geworden ist. So daß Sie das Beispiel haben eines, man möchte sagen, abgestumpften Versuches. Auf die Weise, wie es da versucht worden ist, konnte es nicht weitergehen. Und für denjenigen, der nun das prüft, was geblieben ist und auch bleiben wird aus dem, was in der Blavatsky steckte, der zu sondern weiß zwischen dem, was bleiben darf in diesem Chaos und was nicht bleiben darf, für den ist das Folgende ganz klar. Durch die eigentümliche Verschmelzung dessen, was im Osten geboren ist und nach Westen versetzt worden ist mit der Blavatsky, sollte die Blavatsky, die eine sehr mediale Natur war und die sich dadurch nicht auf ihre vollen Füße stellen konnte, ausgenützt werden, das Spirituelle, das durch sie in die Welt geführt wurde, im Sinne des Nützlichkeitsprinzips zu verwerten. Eine ahrimanische Bestrebung setzte ein. Und das ist’ein furchtbares, man möchte sagen, ein grausig gewaltiges Kapitel, wie eine ahrimanische Bestrebung da einsetzt, welche dahin geht, nicht nur gewisse Erkenntnisse über die übersinnliche Welt durch die Blavatsky heraufzubringen, die dann fruchtbar werden und langsam sich fortpflanzen könnten, die zunächst in der Erkenntnissphäre schweben konnten, sondern dem Nützlichkeitsprinzip sollte auch der Spiritualismus dienstbar gemacht werden! Und es lag der Wille vor, die Blavatsky mit Persönlichkeiten zu umgeben, die danach strebten, sie ganz in ihre Hände zu bekommen. Sie ist ihnen ja durch verschiedene Umstände vielfach entschlüpft, kam ihnen nur nahe und entschlüpfte ihnen immer wieder. Aber es bemühten sich gewisse Menschen der Westwelt, sie ganz in ihre Hände zu bekommen. Dann wäre dasjenige, was in der Blavatsky-Seele lebte, ganz in die Westwelt gekommen, es wäre das Ideal der Nützlichkeit mit Hilfe des Spiritualismus verwirklicht worden. Denn das «Büro Julia» ist nur ein nach Blavatsky auftretender mißglückter Versuch. Das «Büro Julia» wurde eingerichtet, um durch die « Julia» Auskünfte von der geistigen Welt zu erhalten, die dem gewöhnlichen physischen Nützlichkeitsleben dienen sollten. Das war eine Karikatur dessen, was im großen Stile mit Blavatsky hätte versucht werden sollen. Wäre mit Blavatsky voll gelungen, was versucht werden sollte, dann hätte man heute überall Einrichtungen, in denen man Auskünfte aus der geistigen Welt durch bestimmte Medien erlangen kann: Welche Nummern von Losen da oder dort in jener Ziehung gezogen werden, was man tun kann, um dieses oder jenes Mädchen zu heiraten, mit dem man am besten diese oder jene Persönlichkeit in die Welt setzen kann. Dann würde man durch allerlei Auskunftsstätten noch manches andere erzielen können, und Börsenpapiere würde man zur Hausse oder Baisse bringen nach den Auskünften, die man durch Medien aus der geistigen Welt heraus erhält! Das spirituelle Leben sollte in den Dienst der Nützlichkeit gestellt werden.

Blavatskys Tragik bestand darinnen, daß sie gewissermaßen zwischen den beiden Polen hin und her getrieben worden ist. Deshalb gewinnt dieses Leben etwas so psychologisch Merkwürdiges. Es mußte im Blavatsky-Leben gewissermaßen zur rechten Zeit zugemacht werden die Türe, die durch eine natürliche mediale Begabung sich ihr eröffnet hatte in die geistige Welt hinein. Und so sehen wir, wie diese merkwürdige Wandlung eintritt, daß eine Individualität, welche die Blavatsky wie ein Mittel betrachtet hat, um ihre Mitteilungen in die Welt des physischen Lebens zu bringen, sich zurückzieht, und an ihre Stelle jene Individualität tritt, die ich ja auch schon hier charakterisiert habe, und die Olcott selber charakterisiert als den wiedergeborenen Seeräuber aus dem 16. Jahrhundert, John King, der sich dann damit beschäftigt hat, allerlei Teetassen und dergleichen aus dem Nichts heraus zu schaffen, wenn sie gerade gebraucht wurden. In diese Dinge spielt hinein der Kampf des Nützlichkeitsprinzipes und desjenigen Prinzipes, welches dem bloßen Nützlichkeitsprinzipe im Verlaufe der neueren Menschheitskultur die Spitze abbrechen muß, indem nicht die Nützlichkeit aus der Welt geschafft wird, sondern die Nützlichkeit spirituell in die richtige Bahn gelenkt wird. Denn glauben Sie nur ja nicht, daß jemals eine spirituelle Kultur dem weiteren Leben feindlich werden könne, Die Nützlichkeit ist mit Berechtigung heraufgekommen im 19. Jahrhundert, sie hat nur noch nicht die Form gefunden, die sie im Leben finden muß, wie sie richtig sein muß im Leben. Und gerade die Nützlichkeit in das rechte Fahrwasser zu bringen, das wird die Aufgabe wahrer Geisteswissenschaft sein.

Doch da treten wir in ein so wichtiges Kapitel ein, daß wir es uns auf das nächste Mal verschieben werden. Wir werden dann sprechen über die Beziehungen zwischen dem Nützlichkeitsprinzip, dem allerpraktischsten Leben unserer Gegenwart und dem, was diesem praktischen Leben, diesem Nützlichkeitsleben das spirituelle Leben werden soll und werden kann. Eine der wichtigsten Lebensfragen der Gegenwart werden wir damit berühren.

[Am Ende des Vortrags stand folgendes an der Tafel:]

Tenth Lecture

In the lectures given here in recent weeks, I have endeavored to show some of what has been lived in the more recent evolution of humanity in various inner impulses that have intervened in this modern human evolution. We have gone far back. We have sought to understand how the remnants of ancient Atlantean mystery magic have carried over from Atlantean culture. We have brought before our souls how one aspect of this Atlantean mystery culture lived in a state of decadence among the peoples who were encountered by the European peoples through the discovery of America. We delved deeper into the remnants of the other branch of Atlantean magic, which sent its rays and currents from Asia to Europe. And so we came to know the interaction, so to speak, of a western and an eastern pole in the impulses left over from Atlantis. We then delved a little deeper into the peculiarity, into the essence of Greek-Latin culture, which was, in a certain sense, a replica, a kind of repetition of Atlantean culture, but on a different level. And we again tried to get to know the two poles of the fourth post-Atlantean cultural epoch, namely the Greek pole and the Roman pole. We then also attempted to mention, at least in part, the various other impulses that were active in European cultural life. We have considered in particular the impulse that entered the spiritual stream of European cultural development through the fact that the Knights Templar underwent a certain fate, and that through this fate of the Knights Templar, which had such a profound and powerful effect on our souls, spiritual forces were brought into existence which continued to work in a spiritual way, inspiring, impelling, and initiating what took place in the external course of the history of the European peoples. We then attempted to trace how these developing impulses flowed into the more recent materialistic culture of our time. Last Monday, we looked at what they brought about at the end of the 18th century, how they gave a peculiar coloring—that is what we sought to understand—to the ideas that were buzzing around the world at that time, the ideas of brotherhood, freedom, and equality. Many more such impulses, which gradually arose in the course of centuries in European development, could be characterized; but that can be left to a later time. I wanted to characterize the nature of European cultural life using a few significant impulses. For what is particularly important to us is to understand better and better, in a spiritual-scientific way, what is unique about the moment in which we ourselves stand, how this moment has been determined by the special spiritual structure of the 19th century. In the 19th century, all these currents played out in a spiritual way, more or less veiled, these cultural impulses we have been talking about.

Now, I have often pointed out to you that the middle of the 19th century was an important moment in the development of the newer cultural peoples. It was the moment in the fifth post-Atlantean epoch when what human beings can recognize and bring forth through the intellect, insofar as this intellect is bound to the physical brain, was to become particularly significant. For we must make it very clear to ourselves that with the fifth post-Atlantean period, something entered into post-Atlantean cultural development that was quite different from what existed in the Greek-Latin period, the fourth post-Atlantean period. Of course, the Greeks also had intellect, but it was of a completely different kind than that which emerged during the fifth post-Atlantean period and entered a very special crisis in the middle of the 19th century. The intellect that had developed in Greek culture, for example, permeated everything that Greek culture created artistically; it permeated everything what Greek culture created in its city institutions — not state institutions — the intellect that then worked in the Greek philosophy of Plato and Aristotle, the intellect that then also entered the state system with Roman culture, this intellect was something completely different in the fourth post-Atlantean period than it became in the fifth post-Atlantean period. That this can be proven philosophically can be seen in the first volume of my “Riddles of Philosophy,” in which I attempted to show how differently the Greeks lived with concepts and ideas than, for example, people in the 19th century. For the Greeks, the idea was so real that they perceived it in the same way that we today perceive colors or sounds, sensory impressions. In modern humans, the intellect is separated from external perception and works within the human being, but it works within the human being in the way it must work when it is active through the brain, through the physical organism in general.

This gradually led — and it had to be so, given the spirit of recent history — to a tendency in the 19th century to permeate human life more and more with materialistic knowledge and with the mere principle of utility in practical life. We have seen how necessary it was for these things to develop. We have seen how certain impulses have arisen in the Western cultural countries of Europe, how other questions have been asked, or, if we may say so, how certain great questions of humanity have been posed differently than, for example, in the East. We have seen that the West, through long preparation, has been driven to force the spirit into a certain configuration in the realm of knowledge and also in the realm of practical life. We have seen that these questions have gradually become more acute. Today I will use the expressions I have already mentioned, but they should be used today in such a way that they describe with particular precision what has been the main question in the West: the relationships between beings and everything that relates to birth and heredity in human beings. One can understand Western culture of knowledge in its deepest sense when one knows that this question of the relationship between beings in the universe and of birth and heredity was the dominant one. By asking about relationships in the 19th century, the Western world established what physics and chemistry are and brought to the point where the relationship between the various forces of nature was sought as a unity of natural forces in the chemical realm; where the relationship between different substances was investigated chemically, but also in the biological realm, in the realm of the study of life; where the individual forms of animals and plants were investigated and their relationship examined. All this was supposed to lead to an understanding of man, but man as he develops out of purely animal-natural existence; one might say, to an understanding of the birth of man, that is, to an understanding of the sensory human being in his relationship to the other sensory beings on earth. This was the focus of the Western world's search in the question of birth and heredity.

The Eastern world sought to address other questions in the realm of knowledge. And if we want to summarize these, we can say: It is evil, suffering in the world. Nowhere was there as much reflection as in Eastern Europe at the end of the 19th century, nowhere was there as much reflection as on the question: How did evil, or sin, come into the world? Certainly, sin has also been pondered in other regions, but one might say that this has not been done with as much talent as in Eastern Europe. Literary production and philosophical thought in Eastern Europe, particularly in Russian intellectual life, are entirely driven by the impulse to explore evil. And the same efforts that are devoted in the West to the relationships between beings are devoted in the East to the exploration of evil, suffering, and sin. The same efforts that are devoted in the West to the natural connection of human beings, so that the physical human being, as he comes into existence through birth, can be understood, are devoted in the East to understanding death. How the human being as soul maintains itself in death, how it passes through the gate of death as a living soul, what death means in the whole context of life, this is announced in the East as a question that is just as important for the East as for the West, the question of natural relationships, of what leads to the physical birth of the human being. Just as we can prove philosophically with Western philosophers that these questions are fundamental to them, so we can prove with the greatest, or at least the greatest Eastern philosopher to date, Vladimir Solovyov, how all his thinking, all his thinking is dominated by the questions of death and evil, of sin.