Historical Necessity and Freewill

GA 179

15 December 1917, Dornach

5. The Members of Man's Being and the Periods of His Life

If we wish to understand what lies at the foundation of the two impulses that penetrate so deeply into human life—that of the so-called free will and of the so-called necessity—then we must add still other thoughts to the various ideas already gained as a foundation. This I will do today, in order that tomorrow we may be in a position to draw the conclusion, or inference, in regard to the concept of free will and necessity in the social, ethical-moral, and historical processes of human life. In discussing such things it becomes more and more evident that people—especially modern people—strive to embrace the highest, most important and significant things with the most primitive kinds of thoughts. It is taken for granted (I have often mentioned this) that certain things must be known in order to understand a clock; someone who has not the slightest idea of how the wheels of a clock work together, etc., will hardly attempt to explain, on the spur of the moment, the details of a clock's mechanism. Yet we wish to be competent judges of free will and necessity in all situations of life without having learned anything fundamental about these things. We prefer to remain ignorant concerning the most important and most essential things, which can only be understood if we consider their whole relationship to human nature, and we wish to know and judge everything imaginable of our own accord. This is particularly the desire of our times. When it is shown that the human being is a complicated being, organized in manifold ways, a being that penetrates deeply, on the one hand, into all that is connected with the physical plane, and on the other, into all that is connected with the spiritual world, then people often object that such things are dry and intellectual, and that the most important and essential things must be grasped in quite another way.

The world will have to learn (perhaps just the present catastrophic events may teach us something) how much lies hidden in man and in his relationship with the course of the world's evolution. For years we have emphasized that we can differentiate roughly in man what we may call his physical nature, or his physical body; his etheric body, or the body of formatives forces, as I have called it; his astral body, which is already psychic; and the actual ego.

We have emphasized recently from the most varied points of view that—in reality—man, as he lives between waking and sleeping, in his usual waking day-consciousness, has some knowledge only of the impressions given to him by his senses, and of his thoughts; but he dreams away the real contents of his life of feeling, and sleeps away the real contents of his life of the will. Dream and sleep stretch into the world of waking life; during our usual waking consciousness, our feeling life is hardly more than a dream, and the real contents of our will reach our consciousness just as little as a dreamless sleep. Through our feelings, through the contents of our will, we dive down into the world (we have pointed this out specially during these considerations) in which we live together with the dead, in the midst of the Beings of the higher Hierarchies, the Angeloi, the Archangeloi, Archai, etc. As soon as we live in a feeling—and we live constantly in feelings—all that lives in the kingdom of the dead lives with us in the sphere, or in the realm of feeling.

Now something else must be added to this. In the life of ordinary waking consciousness we speak of our ego. But in reality we can only speak of this ego in a very unreal sense as far as our usual waking consciousness is concerned. For what is the real nature and being of this ego? The usual waking consciousness cannot gain knowledge of this. When the clairvoyant dives down consciously into the true being of the ego, he will find that the true ego of man is of a will-like nature. What man possesses in his everyday consciousness is only an idea of the ego. This is why it is so easy for the scientific psychologists to do away entirely with this ego although, on the other hand, this is really nonsense. These scientists and psychologists say that the ego develops gradually and that the human being acquires this ego in the course of his individual development. In this way he does not acquire the ego itself, but only the idea of the ego. It is easy to eliminate the ego, because for the everyday consciousness it is merely a thought, a reflection of the true, genuine ego. The real ego lives in the world in which the true reality of our will also lives. And what we call our astral body, what we designate as the actual soul life, lives in the same sphere as our life of feelings. If you bear in mind the things that we have thus considered, you will see that we dive down with our ego and our astral body into the same region that we share with the dead. When we penetrate clairvoyantly into our true ego, we are also among the egos of the dead, as well as among the egos of the so-called living.

We must realize such things quite clearly, in order to grasp to what an extent man lives, with his everyday consciousness, in the so-called world of appearance, or in Maya, as it is called by a oriental term. We are consciously awake in the world of our senses, in the world of our thoughts; but the sense impulses give us only that portion of the world that is spread out as Nature. And our world of thoughts gives us only that which is in us and corresponds to our own nature between birth and death. That which is our eternal nature remains in the world that we share with the dead. When we enter the life of the physical plane through incarnation, it remains indeed in the world in which also the dead live.

In order to understand these things fully we must grasp thoughts which are not so easy to digest (but these things must be said because they are so)—thoughts that cost us an effort to think out. Man has no such thoughts in the course of his everyday waking consciousness. He prefers to limit his knowledge to that which is stretched out in space and that which takes its course in Time. A frequent pathological symptom is this one: to imagine even the spiritual world spatially, although these thoughts may be nebulous, thin and misty; yet we somehow wish to imagine is spatially; we wish to think of souls flying about in space, and so on. We must go beyond the ideas of space and time to more complicated ideas, if we really wish to penetrate into these things. Today I wish to draw your attention to something that is very important for the understanding of the whole of human life.

Let us bear in mind once more the fact that—roughly speaking—we possess this four-fold nature—the physical body, the body of formative forces or etheric body, the astral body, and the ego.

Now, when someone speaks from the standpoint of the usual waking consciousness, he may ask:—How old is a person—How old is a certain person A? Someone may give his age, let us say 35, and he may believe that he has made an important statement. In stating that a certain person is 35 years old he has, in fact, said something of importance for the physical plane and for the usual waking consciousness; but for the spiritual world, in other words, for the etheric being of man, this implies only a part of the reality. When you say: I am 35 years old—you only say this in regard to your physical body. You must say: My physical body is 35 years old—then this will be correct. But these words express nothing at all as far as the etheric body, or the body of formative forces is concerned, and nothing at all as far as the other members of the human being are concerned. For it is an illusion, it is indeed quite fantastic to think that your ego, for instance, is 35 years old, when your physical body is 35 years old. You see, here we must bear in mind different speeds, different rapidities in the development of the various members.

The following figures will make you realize this. A human being is, let us say, 7 years old; this means nothing less than this:--his physical body has reached the age of 7 years. His etheric body, his body of formative forces, is not yet 7 years old, for his body of formative forces does not maintain the same speed as the physical body and has not yet reached this age. We are not aware of such things just because we imagine time as one continuous stream, and thus we cannot form the thought that different things maintain different speeds within the course of time. This physical body that is 7 years old has developed according to a certain speed. The etheric body develops more slowly, the astral body still more slowly, and slowest of all, the ego. The etheric body is only 5 years and 3 months old when the physical body is 7 years old, because it develops more slowly. The astral body is 3 years and 6 months old, and the ego, 1 year and 9 months. Thus you must say to yourself—when a child is 7 years old, its ego is only 1 year and 9 months old. This ego undergoes a slower development on the physical plane. On the physical plane this ego develops at a slower pace; it is a slower pace, the same pace that we find in our life with the dead. Why do we not grasp what takes place in the stream of the experiences of the dead? Because we do not grow accustomed to the slower pace of the dead, and do not admit this into our thoughts and especially into our feelings, in order to hold them fast.

Hence, if someone is 28 years old as far as his physical body is concerned, then his ego is only 7 years old. As far as your ego is concerned, which is the essential part of your being, you thus maintain a much slower pace in the course of development than that of the physical body. You see, the difficulty consists in the fact that, generally, we consider speed, or velocities, merely as outer velocities. When things move one beside another, we say that one thing moves more quickly and the other one more slowly because we use Time as a comparison. But here the speed within Time is different. Without this insight into the fact that the different members of the human being have different speeds in their development, it is impossible to grasp the connections with the true deeper being of man.

From this you will see how in everyday consciousness people simply throw together entirely different things contained in human nature.

Man consists of this four-fold being, and the four members of this being are so different from one another that they even have different ages. But man is under a great illusion in making everything depend on his physical body. He says something that has absolutely no meaning whatever for the spiritual world, in stating that his ego is 28 years old, when he is 28 according to his physical body. His statement would only have a meaning if he would say:—My ego is 7 years old—in the case of the ego, a year is naturally four times as long as in the case of the physical body. One might also say that the age of the four different members of the human being must be reckoned according to four entirely different measurements of time; for the ego, a year is simply four times as long as for the physical body.

Pictorially you might conceive this as a projection from the physical plane—for instance, one human being may normally become 28 years old, while another child may grow more slowly and after 28 years be like a child of 7. Thus the whole matter appears at first like an abstract truth. But it is a fundamental reality in man. Just consider that our ego is the bearer of what we call our understanding, or our thinking consciousness of self. When our understanding and our conscious thinking are within our ego, then this understanding and conscious thinking are really essentially younger than we ourselves apparently are, according to our physical body. This is indeed so.

But this will show you that when a human being of 28 gives the impression of one whose understanding has developed to the age of 28, only one fourth of this understanding is really his own. It cannot be helped; when we have a certain quantity of understanding at 28, only a quarter of this is our own; the rest belongs to the universe, to the world in which we are submerged through our astral body, through our etheric body, and through our physical body. But we only know directly something of these bodies through ideas, through sense perceptions, in other words, again within the ego. This means that during our development as human beings between birth and death we are indeed mere apparitions of a reality. We make the impression of being four times as clever as we really are. This is true. All we possess, in addition to this one fourth, we owe to what holds sway in the historical, social, and moral processes within that world we dream away and sleep away. Dream and sleep impulses, which we have in common with the universe, seethe up, above the horizon of our being and fructify this fourth part of our understanding and soul, and make it four times as strong as it really is.

You see at this point arises the illusion concerning the freedom of man. Man is a free being; he is, indeed. But only the real, true man is a free being. That fourth part, of which I have just spoken, is a free being. Other beings play into the remaining three fourths; these cannot be free. This gives rise to the delusion in regard to freedom so that we continually ask:—Is man free or is he not free? Man is free when he connects this idea of freedom with the one fourth of his being, in the sense in which I have just explained it. If the human being wishes to have this freedom as an impulse of his own, then he must develop this fourth part in a corresponding, independent way. In usual life, this fourth part cannot assert itself, for the simple reason that it is overpowered by the other three fourths. In the remaining three fourths is active all that man calls his desires, his appetites, his emotions and passions. These slay his freedom, for what is contained in the universe in the form of impulses works through these desires, emotions and passions.

Now the question arises:—What shall we do to make this one fourth of our soul-life, which is a reality within us, really free? We must place this one fourth in relationship with that which is independent of the remaining three fourths.

I have tried to answer this question philosophically in my The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, by attempting to show how man can only realize the impulse of freedom within himself, when he places his actions, his deeds, entirely under the influence of pure thought, when he reaches the point of transforming impulses of pure thought into impulses of action, into impulses which are not in any way dependent upon the outer world for their development. All that which is developed out of the outer world does not allow us to realize freedom. Only that which develops in our thinking, independently of the outer world, as the motive of our actions, enables us to realize freedom.

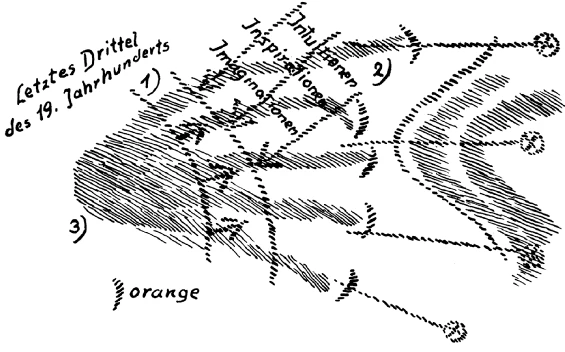

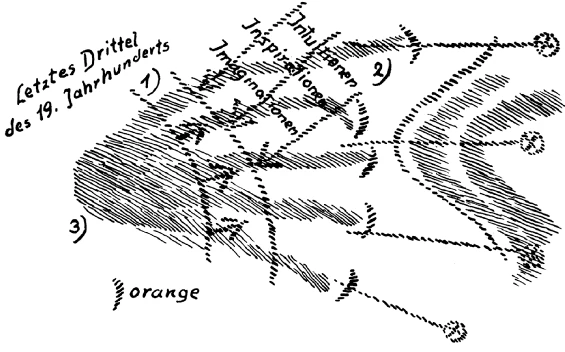

Where do such motives come from? Where does that which does not come from the outer world come from? It comes out of the spiritual world. The human being need not be clairvoyantly conscious in every situation of life of how these impulses come from the spiritual world; they may nevertheless be within him all the same. But he will necessarily conceive these impulses in a somewhat different way than they must be conceived in reality. When we rise in clairvoyant consciousness to the first stage of the spiritual world, we come to the imaginative world; the second stage is the world of inspiration, as you know; the third stage, the world of intuition. Instead of allowing the impulses of our will or of our actions to rise out of our physical body, our astral body, and etheric body, we can receive them as imaginations, behind which stand inspirations and intuitions. That is, if we receive no impulses from our bodies, but only from the spiritual world. This does not need to be the conscious clairvoyant perception: “Now I will something and behind this stand intuition, inspiration, and imagination.”—but, instead, the result appears as an idea, as a pure thought, and has the appearance of an idea created within the element of fantasy. Because this is so, because such an idea, which lies at the foundation of free actions must appear to everyday consciousness as an idea created out of the element of fantasy, I call it moral fantasy in my The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity. (That which lies at the foundation of free actions.) What, then, is this moral fantasy? This moral fantasy is the reverse of a mirrored reflection. What lies spread out around us as the outer physical reality is a mirrored reflection; physical reality sends us reflections of things. Moral fantasy is the image, through which we do not see. For this reason, things appear to us as fantasy. Behind them, however, stand the real impulses—imagination, inspiration, intuition—which are active. When we do not know that they are active, but only receive the influences into our usual consciousness, then this appears as fantasy. And these results of moral fantasy, these incentives to action, which do not lie in desires, passions and emotions—are free. But how can we attain them?

Moral fantasy can also be developed by a human being who is not clairvoyant. Everything that implies a real progress for humanity has always been born out of moral fantasy, insofar as this progress lay within the ethical sphere. The point in question is that man first develops a feeling, and then an enhanced feeling (we shall hear immediately, what is to be understood exactly by “enhanced feeling”)—that he is not merely here on this earth in order to accomplish things which concern him personally, or individually, but in order to accomplish things through which the will of the Time Spirits can be realized.

It appears as if something quite special were implied when one says: Man must realize the will of the Time Spirits. But a time will come when people will understand this much better than now. And a time will come when the contents of human teaching will not be that of the present. At present only ideas dealing with nature can be conveyed even to the most educated people; for what is imparted to people in regard to ethical and social life is in most cases an unreal, schematic abstraction; indeed, the greatest abstraction.

In this connection we have not yet attained what earlier ages already possessed. Only with great difficulty can a modern man immerse himself in earlier times. Earlier times possessed myths—myths that were connected with the vital life of the people, myths that penetrated into poetry, into art, into all manner of things. In Greece one spoke of Oedipus, of Hercules, and of other heroes, one tried to emulate those who had done things which were exemplary deeds, and first deeds, and one wished to tread in their footprints. Everyone wished to tread in these footprints. The thread of ideas, the thread of thought and feeling, led backwards. One felt at one with those long dead. What went out as an impulse from those who had died was told in myths; and these men lived in experiencing, in becoming one with the impulses of these myths.

Something similar must again be created and will be created if the impulses of spiritual science are rightly understood. Except that, in the future, souls will gaze forward much more than backward. The contents of public teaching must be that which binds human beings together with the creative activity of the Time, and above all, with the impulses of the Time Spirit, the corresponding Being from the Hierarchy of the Archai, concerning whom I have said, in an earlier description, that the so-called dead, as well as the living, are connected with him. People will learn in the public teaching of the future the meaning of such a period of culture as the one that began in the 15th century and closed the Greco-Latin period; in this fifth post-Atlantean period people will learn to know the real intentions of the universal World-All. They will take up the impulses of this fifth post-Atlantean period and they will know:—This must be realized between the 15th century and one of the centuries in a coming millennium. They will know: We belong to our period of culture in such a way that the impulses of this coming age stream through us. In future, even the children, as they learn to name the flowers and the stars (they do this less today—but it is at least something outwardly real) will learn to take up the real, spiritual impulses of the period. First they must be educated to do this. What is told as “history” today must first cease to be called “history.” In not too distant a future, instead of speaking of all the things contained in history as it is told today, people will speak of the spiritual impulses standing behind the historical evolution, impulses which are dreamed by human beings. These are the spiritual impulses that call man to freedom, and make him free, because they raise him to the world from which intuition, inspiration, and imagination come. For what happens outwardly on the physical plane, what constitutes outer history (I have explained this even in public lectures) loses its meaning as soon as it has occurred; in reality it does not justify our saying that the former event is always the cause of the latter. There is nothing more senseless than to recount history by describing, for instance, the deeds of Napoleon at the beginning of the 19th century, and then assuming that the events after Napoleon's exile are the consequence of Napoleon's actions. Nothing is more senseless than this! Descriptions of Napoleon imply exactly the same, as far as reality is concerned, as the description of a human corpse three days after death, as far as the dead man's life is concerned. What is now called “history” is a “corpse-history” compared with reality, even though this “corpse-history” has a great importance in the minds of many people.

What happens outwardly becomes a reality only when it is revealed in its development from spiritual impulses. Then it will be seen clearly that a human being's deeds, let us say, in a certain decade of a certain century, are the consequence of what he experienced before entering into his incarnation on earth; they are in no sense the consequence of events that occurred in the course of decades of physical experience on the earth, and so on. Spiritual Science, in the meaning of Anthroposophy, will have to bring more depth and more life—especially in regard to historical, social, and moral life—into the sphere of history above all. When this knowledge of the spiritual impulses will have become one of the essential demands of our time—it will then correspond to the living reality of the myths in ancient times—it will permeate human beings with impulses leading them to deeds and actions that will make them free. These things must first be understood; they will indeed influence real life when this understanding spreads over an ever-wider sphere.

But these considerations will show you something else besides. You will realize that the impulses of feeling, the impulses of will, which place us within the same sphere of life as the so-called dead, are a higher and more intensive reality than the one we know through our waking consciousness, in the form of ideas and sense impressions. For this reason, what has just been brought forward as a demand of our age, as something that must become an object of public teaching, can only be truly fruitful when it is grasped not merely with the understanding, but goes over into the impulses of feeling and into the impulses of will.

This can only come about when spiritual science is really seen as a reality, and not simply as a teaching. spiritual science is easily looked upon merely as a teaching, as a theory; but spiritual science is not a mere teaching, a mere theory, spiritual science is a living Word. For what is given out as spiritual science is the revelation from the world which we share with the higher Hierarchies and with the so-called dead. This very world speaks to us through spiritual science. And he who really understands spiritual science knows that the soul music of the spiritual world continues to resound in spiritual science. What we read, not from the dead letters, but from the real happenings in the spiritual world, can indeed permeate our feeling with true life, when we grasp spiritual science in this sense, as something which speaks to our inner being from out the spiritual world. I have emphasized at different times how the matter stands, when I described how, on the one hand, since 1879, spiritual life has the opportunity of streaming down to the physical plane in an entirely new way, and how, on the other hand, it must indeed face an opponent in the Spirits of Darkness, of whom we have spoken. Everything must still be achieved, before the content of spiritual science really enters the life of our feeling and will. And this can be achieved when certain things change fundamentally, in regard to which modern man has reached a cultural blind alley.

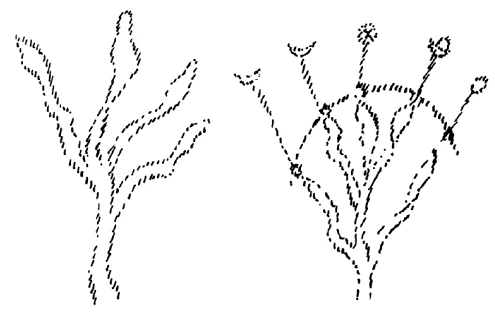

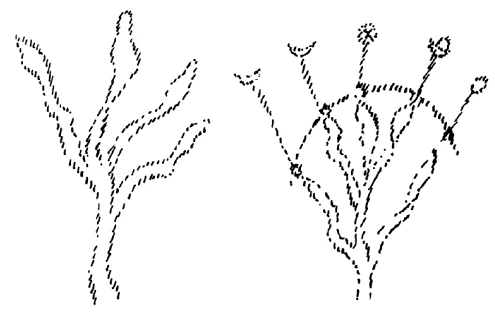

Something else must also work its way through; namely, evolution must develop in such a way that, on the one hand, the events of history may be compared to a growing tree (I have already used this picture during these considerations): but when the leaves have grown as far as the periphery, the tree ceases to grow. Here the dying process begins. It is the same with historical events. A certain group of events takes shape—let us describe it quite schematically:—Certain historical events have their roots. A definitive group of historical events may have their roots in the last third of the 18th century. I shall speak of this more clearly tomorrow. Other influences are added to these in the course of the 19th century, and so on. But you see, these historical events expand and reach their extreme boundaries. In this case the boundary is not the same as in the case of a tree or a plant, which does not grow beyond its periphery; but here a new root of historical events must begin. For decades, already, we have been living in a time in which such new historical events must spring out of direct intuition. But in the historical life of man, illusion can easily spread also over these things. To be sure, you can watch the growth of a plant, which grows according to its inner laws until it reaches a certain periphery and cannot grow beyond it. But now you can call forth an illusion—you can take wires, hang paper leaves on them, and give yourself the illusion that the plant continues to grow up to this point.

Such wires do indeed exist where historical events are concerned. While historical events should long ago have adopted another course, such wires are there instead; except that in historical evolution these wires are human prejudices, human indolence, which continue to maintain, on dead wires, what has died long ago. Certain people place themselves at the ends of these dead wires—in other words, at the outermost ends of human prejudice—and these people are often considered historical personalities; indeed, the true historical personalities. And people do not realize to what an extent these personalities sit on the wires of human prejudice. One of the most important tasks of the present is to begin to understand how certain personalities who are looked upon as “great” are, in reality, merely hanging on the wires of human prejudice; this is indeed one of the chief tasks of the present.

Fünfter Vortrag

Wenn wir dasjenige durchdringen wollen, was den beiden in das Menschenleben eingreifenden Impulsen, der sogenannten Freiheit und der sogenannten Notwendigkeit, zugrunde liegt, dann müssen wir zu den mancherlei Voraussetzungen, die wir schon geschaffen haben, einige andere noch hinzufügen. Und das will ich heute tun, damit wir dann morgen in der Lage sind, gewissermaßen die Konklusion, den Schluß in bezug auf den Freiheits-- und Notwendigkeitsbegriff im menschlichen, sozialen, sittlichen und geschichtlichen Wirken zu ziehen. Wenn man solche Dinge bespricht, dann kommt eigentlich immer mehr in Betracht, daß die Menschen, und namentlich die Menschen der Gegenwart danach streben, die höchsten, die wichtigsten, die bedeutsamsten Dinge mit den allereinfachsten Begriffen und Vorstellungen zu umfassen. Um eine Uhr zu begreifen - ich habe das öfters schon erwähnt -, dazu hält man mancherlei Kenntnisse für notwendig, und man wird nicht ohne einen Schimmer davon zu haben, wie Räder zusammenwirken oder dergleichen, aus dem Stegreif heraus den Gang einer Uhr im einzelnen erklären wollen. Ein Sachverständiger über Freiheit und Notwendigkeit will man eigentlich in jeder Lage des Lebens sein, ohne über diese Dinge etwas zugrunde Liegendes gelernt zu haben. Über die allerwichtigsten, allerwesentlichsten Dinge, die nur eingesehen werden können im ganzen Zusammenhange mit der Menschennatur, möchte man sich am liebsten nicht unterrichten und alles mögliche wie von selbst wissen und beurteilen. Das ist insbesondere so die Sehnsucht unserer Zeit. Wenn geltend gemacht wird, daß der Mensch eine komplizierte, eine mannigfaltigst zusammengesetzte Wesenheit ist, eine Wesenheit, die auf der einen Seite tief eintaucht in alles das, was mit dem physischen Plane zusammenhängt, auf der andern Seite wiederum seelisch tief eintaucht in all das, was mit den geistigen Welten zusammenhängt, dann wird gar leicht erwidert, daß solche Dinge trocken, verstandesmäßig seien, daß man die allerwichtigsten und wesentlichsten Dinge in einer ganz andern Weise auffassen müsse.

Die Welt wird kennenlernen müssen - sie lernt es vielleicht doch gerade durch die gegenwärtigen katastrophalen Ereignisse schon ein wenig —, was alles im Menschen und in seinem Zusammenhange mit dem Gang der Weltenentwickelung Verborgenes liegt. Wir haben seit Jahren betont, daß wir dasjenige im Rohen unterscheiden können im Menschen, was man seine physische Natur nennt, seinen physischen Leib, seinen Ätherleib, den Bildekräfteleib, wie ich ihn nenne, seinen astralischen Leib, der schon Seelisches ist, und das eigentliche Ich.

Wir haben nun in den letzten Zeiten von den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten her betont, daß der Mensch, so wie er lebt vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen, also im gewöhnlichen wachen Tagesbewußtsein, eigentlich in Wirklichkeit nur etwas weiß von den Eindrücken seiner Sinneswahrnehmungen und noch von seinen Vorstellungen, daß er aber den eigentlichen Inhalt seines Gefühlslebens verträumt, und den eigentlichen Inhalt seines Willenslebens verschläft. Traum und Schlaf dehnen sich herein in die gewöhnliche Welt des Wachens, und mehr bewußt als eines’ Traumes sind wir uns auch unseres Gefühlslebens nicht im gewöhnlichen Wachbewußtsein. Mehr bewußt als im traumlosen Schlafe ist sich der Mensch seines wirklichen Willensinhaltes nicht. Denn durch unsere Gefühle, durch unseren Willensinhalt tauchen wir in dieselbe Welt hinein — das haben wir in diesen Betrachtungen betont -, in welcher wir gemeinschaftlich mit den Toten unter den Wesenheiten der höheren Hierarchien, der Angeloi, Archangeloi, Archai und so weiter leben. Sobald wir in einem Gefühle leben - und wir leben ja fortwährend in Gefühlen -, lebt in der Sphäre, in dem Gebiete dieses Fühlens alles dasjenige mit, was im Reiche der Toten ist.

Nun kommt ein anderes dazu. Wir sprechen im gewöhnlichen wachen Bewußtseinsleben von unserem Ich. Aber von diesem Ich können wir eigentlich mit dem gewöhnlichen Wachbewußtsein nur in recht uneigentlichem Sinne sprechen. Denn welche Natur und Wesenheit hat eigentlich dieses Ich? Es kann nicht erkannt werden im gewöhnlichen Wachbewußtsein. Taucht das schauende Bewußtsein in das wahre Wesen des Ich ein, dann ist das wahre Ich des Menschen willensartiger Natur. Das, was der Mensch im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein hat, ist nur die Vorstellung des Ich. Daher wird es dem naturforscherischen Psychologen leicht, dieses Ich überhaupt wegzuleugnen, obwohl andererseits dieses Wegleugnen ein wirklicher Unsinn ist. Solche Naturforscher und Psychologen sprechen davon, daß das Ich sich eigentlich nach und nach heranbilde, daß der Mensch im Verlauf seiner individuellen Entwickelung zu diesem Ich komme. Er kommt nicht zu dem Ich, sondern zu der Ich-Vorstellung auf diese Art. Und es ist leicht hinwegzuleugnen, weil es eben im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein nur eine Vorstellung, ein Spiegelbild des wirklichen, wahren, echten Ich ist. Das echte Ich lebt in derselben Weltensphäre, in der die wahre Wirklichkeit unseres Willens lebt. Und das, was wir den astralischen Leib nennen, was wir als das eigentliche Seelenleben bezeichnen können, das wiederum lebt in derselben Sphäre, in der da lebt unser Gefühlsleben. Wenn Sie die beiden Dinge zusammennehmen, die wir so betrachtet haben, können Sie daraus wiederum ersehen, daß wir mit unserem Ich und mit unserem astralischen Leib untertauchen in dasselbe Gebiet, das wir mit den Toten gemeinschaftlich haben. In dem Augenblicke, wo wir hellseherisch in unser wahres Ich hinuntersteigen, sind wir ebenso unter den Ichen der Toten wie unter den Ichen der sogenannten Lebendigen.

So etwas muß man sich nur ganz klarmachen, um voll einzusehen, wie sehr der Mensch mit seinem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein in der sogenannten Scheinwelt, oder wie man es mit einem orientalischen Ausdrucke nennt, in der Maja lebt. Wir leben wachbewußt in unserer Sinnes- und in unserer Vorstellungswelt. Aber die Sinnesimpulse, die geben uns nur den Teil der Welt, der als Natur sich ausbreitet. Und unsere Vorstellungswelt gibt uns auch nichts anderes als dasjenige in uns, was unserer Natur angemessen ist, aber zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode. Dasjenige, was unsere ewige Natur ist, das tritt im Grunde gar nicht aus der Welt heraus, die wir mit den Toten gemeinschaftlich haben. Das verbleibt im Grunde genommen in der Welt, in der die Toten auch sind, wenn wir durch die Verkörperung in das Leben des physischen Planes eintreten.

Um aber diese Dinge voll zu verstehen, haben wir nötig, gewisse Begriffe aufzunehmen, die - man kann schon nichts dafür, das sagen zu müssen, weil die Dinge eben so sind — nicht ganz leicht zu durchdenken sind, bei denen man sich, um sie zu durchdenken, Mühe geben muß. Solche Begriffe hat zunächst der Mensch im Verlaufe seines gewöhnlichen wachen Bewußtseins nicht. Der Mensch kennt im gewöhnlichen wachen Bewußtsein das, was räumlich ausgedehnt ist, was in der Zeit verläuft. Und er möchte eigentlich mit dem zufrieden sein, was räumlich ausgedehnt ist und was in der Zeit verläuft. Krankt ja sogar der Mensch vielfach daran, sich auch dasjenige, was in der geistigen Welt enthalten ist, möglichst räumlich zu denken, wenn auch nebulos, wenn auch dünn und nebelhaft, aber er möchte es doch irgendwie sich räumlich denken: räumlich herumfliegende Seelen und dergleichen möchte er sich denken. Man muß über die Begriffe von Raum und Zeit hinausgehen zu komplizierteren Begriffen, wenn man in diese Dinge wirklich eindringen will. Und da möchte ich Ihnen denn heute etwas andeuten, was wichtig ist zur Erfassung des menschlichen Gesamtlebens.

Fassen wir noch einmal ins Auge — wie gesagt, im Rohen -, daß wir diese vierfache Natur zunächst haben: den physischen Leib, den Bildekräfte- oder Ätherleib, den astralischen Leib und das Ich. Wenn man so vom Standpunkte des gewöhnlichen wachen Bewußtseins aus redet und frägt: Wie alt ist eigentlich ein Mensch, dieser bestimmte Mensch A, wie alt ist er? - Nun, da wird irgend jemand sein Alter angeben, sagen wir fünfunddreißig Jahre, und er glaubt, damit etwas Ernsthaftes gesagt zu haben. Er hat auch für den physischen Plan und das gewöhnliche Wachbewußtsein etwas Ernsthaftes damit gesagt, daß er fünfunddreißig Jahre alt sei. Aber für die geistige Welt, also für die Gesamtwesenheit des Menschen, ist damit nur teilweise etwas gesagt. Denn Sie können eigentlich, wenn Sie sagen, ich bin fünfunddreißig Jahre alt, dies nur für Ihren physischen Leib sagen. Sie müßten sagen: Mein physischer Leib ist fünfunddreißig Jahre alt - dann würde die Sache stimmen. Für den ätherischen oder Bildekräfteleib, für die andern Glieder der menschlichen Wesenheit haben Sie aber damit noch gar nichts gesagt. Denn daß Ihr Ich zum Beispiel auch fünfunddreißig Jahre alt sein soll, wenn Ihr physischer Leib fünfunddreißig Jahre alt ist, das ist eine bloße Illusion, das ist sogar eine reine Phantasterei. Denn sehen Sie, hier tritt auf der Begriff verschieden geschwinder, verschieden schneller Entwickelung der verschiedenen Glieder der menschlichen Natur.

Das können Sie sich durch folgende Zahlen klarmachen. Der Mensch wird, sagen wir sieben Jahre alt; das heißt aber nichts anderes als: sein physischer Leib ist sieben Jahre alt geworden. Dann ist deshalb sein Ätherleib, sein Bildekräfteleib noch nicht sieben Jahre alt, sondern sein Bildekräfteleib macht nicht so schnell mit; der ist noch nicht so alt geworden. Man kommt auf diese Dinge nur deshalb nicht, weil man die Zeit sich eben so als einen einheitlich dahinlaufenden Strom vorstellt und man sich gar nicht denken kann, daß innerhalb der Zeit verschiedenes mit verschiedener Geschwindigkeit vorwärtsgeht. Dieser physische Leib, der sieben Jahre ist, der hat sich mit einer gewissen Geschwindigkeit entwickelt. Langsamer hat sich entwickelt der Ätherleib, noch langsamer der astralische Leib, und am langsamsten das Ich. Dieser Ätherleib ist erst fünf Jahre drei Monate alt, wenn der physische Leib sieben Jahre alt ist, weil er ein langsameres Tempo durchmacht. Der astralische Leib ist drei Jahre sechs Monate alt. Und das Ich ist ein Jahr neun Monate alt. So daß Sie sich sagen müssen, wenn ein Kind sieben Jahre alt ist, so ist sein Ich erst ein Jahr neun Monate alt. Es macht dieses Ich eine langsamere Entwickelung durch auf dem physischen Plane. Es geht dieses Ich auf dem physischen Plane ein langsameres Tempo, jenes langsamere Tempo, welches auch das Tempo ist, das man gemeinschaftlich mit den Toten durchleben kann. Warum faßt denn der Mensch dasjenige, was im Strom des Erlebens der Toten stattfindet, nicht auf? Weil er sich nicht angewöhnt, das langsamere Tempo einzuschlagen im Halten von Gedanken, im Halten von Gefühlen namentlich, in dem die Toten verharren.

Ist also ein Mensch achtundzwanzig Jahre alt seinem physischen Leibe nach, so ist sein Ich erst sieben Jahre alt. Sie können also nur den Anspruch darauf machen, daß Sie in bezug auf Ihr Ich, was das Eigentliche Ihrer Wesenheit ist, ein viel langsameres Tempo einhalten in der Entwickelung als in bezug auf den physischen Leib. Die Schwierigkeit besteht darinnen, daß man sonst Geschwindigkeiten nur als äußere Geschwindigkeiten auffaßt. Wenn die Dinge nebeneinander hinlaufen, so sagt man: Eines geht schneller und das andere geht langsamer - weil man die Zeit zum Vergleich hat. Aber hier ist die Geschwindigkeit in der Zeit verschieden. Ohne diese Einsicht aber, daß die verschiedenen Glieder der menschlichen Natur verschiedenes Tempo haben zu ihrer Entwickelung, ist es unmöglich, dasjenige einzusehen, was mit der eigentlichen tieferen Wesenheit des Menschen zusammenhängt.

Sie sehen aber daraus, wie man im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein eigentlich ganz verschiedene Dinge, die in der menschlichen Natur sind, einfach zusammenwirft. Der Mensch hat diese viergliederige Wesenheit, und die vier Glieder dieser Wesenheit sind so voneinander verschieden, daß sie sogar verschiedenes Alter haben. Der Mensch aber gibt sich dadurch einer beträchtlichen Illusion hin, daß er alles auf seinen physischen Leib bezieht. Er sagt etwas, was schlechterdings vor der geistigen Welt gar keinen Sinn hat, wenn er behauptet, sein Ich sei achtundzwanzig Jahre alt, wenn er seinem physischen Leibe nach achtundzwanzig Jahre alt ist. Es hätte nur einen Sinn, wenn er dann sagen würde: Mein Ich ist sieben Jahre alt - wobei aber dann ein Jahr selbstverständlich viermal so lang ist.

Man könnte die Sache auch so ausdrücken: die vier verschiedenen Glieder der menschlichen Wesenheit rechnen nach ganz verschiedenen Zeitmaßen. Das Ich rechnet einfach ein Jahr viermal so lang als der physische Leib. Und bildhaft könnten Sie sich das so vorstellen, wenn Sie es sich projizieren wollten auf den physischen Plan heraus. Während zum Beispiel ein Mensch normal wächst, achtundzwanzig Jahre alt wird, wachse ein Kind langsamer und sei nach achtundzwanzig Jahren ein siebenjähriges Kind. So zunächst erscheint die ganze Sache wie eine abstrakte Wahrheit, aber es ist im Menschen eine gründliche Wirklichkeit. Denn denken Sie doch, daß wir in unserem Ich dasjenige tragen, was wir unseren Verstand, unser selbstbewußtes Denken nennen. Wenn wir in unserem Ich unseren Verstand, unser selbstbewußtes Denken haben, dann sind unser Verstand und unser selbstbewußtes Denken eigentlich wesentlich jünger, als wir scheinbar unserem physischen Leibe nach sind. Das sind sie auch, das sind sie wirklich!

Ja, da kommen Sie aber darauf, einzusehen: wenn ein solcher Mensch achtundzwanzig Jahre alt ist und den Eindruck eines achtundzwanzigjährig entwickelten Verstandes macht, so ist das, was sein Eigen ist von diesem Verstand, den er hat, nur ein Viertel. Es hilft nichts: wenn wir mit achtundzwanzig Jahren eine gewisse Summe von Verstand haben uns eigen ist nur ein Viertel davon, das andere gehört der allgemeinen Welt an; das andere gehört der Welt an, in die wir eingetaucht sind durch unseren astralischen Leib, durch unseren ÄÄtherleib, durch unseren physischen Leib. Aber von denen wissen wir ja unmittelbar nur durch Vorstellungen, durch Sinneswahrnehmungen etwas, also auch wiederum im Ich. Das heißt, wenn wir als Menschen uns entwickeln zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode, so sind wir eigentlich rechte Scheinwesen der Wirklichkeit. Wir machen den Eindruck von viermal so gescheiten Wesen, als wir in Wirklichkeit sind. Das ist wahr! Alles, was wir außer jenem Viertel haben, das verdanken wir dem, was da waltet im historischen, im sozialen, im moralischen Wirken jener Welt, die wir verträumen, die wir verschlafen. Träume, Schlafimpulse, die wir mit der Allgemeinheit gemein haben, brodeln herauf über den Horizont unseres Daseins und befruchten unser Verstandes- und Seelenviertel und machen es viermal so stark, als es in Wirklichkeit ist.

Hier ist der Punkt, wo die Täuschung entsteht in bezug auf die Freiheit des Menschen. Der Mensch ist ein freies Wesen; das ist er schon. Aber nur der wahre Mensch ist ein freies Wesen — jenes Viertel, von dem ich eben gesprochen habe, das ist ein freies Wesen. Die andern drei Viertel, in die spielen andere Wesenheiten herein; die können nicht frei sein. Und dadurch entsteht die Täuschung in bezug auf die Freiheit, daß man immer frägt: Ist der Mensch frei oder ist er nicht frei? Frei ist der Mensch, wenn er diesen Begriff der Freiheit bezieht auf das eine Viertel seines Wesens in dem Sinne, wie ich das jetzt auseinandergeserzt habe. Will der Mensch diese Freiheit als einen eigenen Impuls haben, dann muß er allerdings dieses Viertel in entsprechend selbständiger Weise entwickeln. Im gewöhnlichen Leben kann dieses Viertel nicht zu seinem Rechte kommen, aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil es von den übrigen drei Vierteln überwältigt wird. In den übrigen drei Vierteln wirkt alles dasjenige, was der Mensch in sich trägt als seine Triebe, seine Begierden, seine Affekte, seine Leidenschaften. Die ertöten seine Freiheit, denn durch die Triebe, durch die Affekte, durch die Leidenschaften wirkt dasjenige hindurch, was an Impulsen in der Allgemeinheit ist.

Nun entsteht die Frage: Was wollen wir tun, um das eine Viertel von Seelenleben, das in uns Realität ist, wirklich zur Freiheit zu bringen? Wir müssen es in Beziehung setzen, dieses Viertel, zu dem, was unabhängig ist von dem übrigen Dreiviertel.

Philosophisch habe ich eben versucht, diese Frage zu beantworten in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit», indem ich damals zu zeigen bestrebt war, wie der Mensch nur dadurch in sich den Impuls der Freiheit realisieren kann, wenn er sein Handeln, sein Tun ganz unter den Einfluß des reinen Denkens stellt, wenn er dazu kommt, reine Gedankenimpulse zu seinen Handlungsimpulsen machen zu können, Impulse, die gar nicht herausentwickelt sind aus der äußeren Welt. Denn alles das, was aus der äußeren Welt entwickelt ist, läßt uns nicht Freiheit realisieren. Freiheit realisieren läßt uns nur dasjenige, was sich unabhängig von der äußeren Welt in unserem Denken als Antrieb unseres Handelns entwickelt.

Woher kommen solche Antriebe? Woher kommt das, was nicht aus der äußeren Welt kommt? Nun, es kommt aus der geistigen Welt. Der Mensch braucht sich nicht in jeder Lage seines Lebens hellseherisch bewußt zu sein, wie diese Impulse aus der geistigen Welt kommen, aber sie können in ihm doch da sein. Nur wird er sie notwendigerweise etwas anders auffassen müssen. Wenn wir uns im schauenden Bewußtsein zur ersten Stufe der geistigen Welt erheben, so ist das die imaginative Welt; die zweite Stufe ist die inspirierte Welt, wie Sie wissen; die dritte Stufe die intuitive Welt. Statt daß wir also die Impulse unseres Wollens, unseres Handelns aufsteigen lassen aus unserem physischen, aus unserem astralischen, aus unserem ätherischen Leib, können wir, wenn wir von dieser Seite her keine Impulse empfangen, sondern sie aus der geistigen Welt empfangen, sie nur entgegennehmen als Imaginationen, hinter denen Inspirationen, hinter denen Intuitionen stehen. Aber das braucht nicht bewußt als hellseherisches Bewußtsein erlebt zu werden: Jetzt will ich dieses, dahinter stehen Intuitionen, Inspirationen, Imaginationen -, sondern das Resultat davon tritt auf als ein Begriff, als ein reines Denken, sieht so aus, wie ein in der Phantasie geschaffener Begriff. Weil das so ist, weil ein solcher Begriff, der dem freien Handeln zugrunde liegt, für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein wie ein aus der Phantasie heraus geschaffener Begriff erscheinen muß, nannte ich das, was dem freien Handeln zugrunde liegt, in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» die moralische Phantasie. Was ist also diese moralische Phantasie? Diese moralische Phantasie ist, ich möchte sagen, das Gegenteil eines Spiegelbildes. Dasjenige, was wir um uns herum als die äußere physische Wirklichkeit ausgebreitet haben, das ist ein Spiegelbild, da werden uns die Dinge zurückgespiegelt. Die moralische Phantasie ist das Tableau, durch das wir nicht durchsehen. Daher erscheinen uns die Dinge als Phantasie. Hinter ihnen stehen aber die eigentlichen Impulse: Imaginationen, Inspirationen, Intuitionen, die wirken (siehe Zeichnung S. 102). Wenn man nicht weiß, daß diese wirken, sondern nur das, was sie bewirken, ins Bewußtsein, ins gewöhnliche Bewußtsein hereinbekommt, so sieht es wie eine Phantasie aus. Und diese Ergebnisse der moralischen Phantasie, diese nicht aus Trieben, Leidenschaften, Affekten geholten Antriebe des Handelns, sie sind freie Antriebe.

Wie soll man aber zu ihnen kommen? Würde man sich ohne weiteres zum hellseherischen Bewußtsein erheben, dann würde man durch das Hellsehen bewußt dazu kommen. Aber das braucht man gar nicht. Moralische Phantasie kann auch der Mensch entwickeln, der nicht hellseherisch ist. Alles dasjenige, was den wirklichen Fortschritt der Menschheit bedeutet hat, ist immer aus moralischer Phantasie hervorgegangen, insoferne dieser Fortschritt auf ethischem Gebiete lag. Es handelt sich nur darum, daß der Mensch zuerst ein Gefühl entwickelt, und dann ein gesteigertes Gefühl - wir werden gleich deutlicher hören, was unter diesem gesteigerten Gefühl zu verstehen ist -, daß er hier auf dieser Erde da ist, um Dinge zu tun, welche nicht bloß seine Persönlichkeit, seine Individualität angehen, sondern um Dinge zu tun, durch die dasjenige verwirklicht wird, was die Zeitgeister wollen.

Es scheint zunächst, als ob etwas ganz Besonderes dahinter stecke, wenn man sagt, der Mensch soll dasjenige realisieren, was die Zeitgeister wollen. Es wird eine Zeit kommen, wo man dies aber viel besser verstehen wird als in der Gegenwart. Und es wird eine Zeit kommen, wo man anderes zu Inhalten des menschlichen Lehrens machen wird, als es die Gegenwart macht, wo selbst den Allergebildetsten nur Begriffe beigebracht werden, die auf die Natur gehen. Denn was beigebracht wird den Leuten mit Bezug auf das ethische, mit Bezug auf das soziale Leben, das sind zumeist wesenlose, schemenhafte Abstraktionen, das sind äußerste Abstraktionen.

In dieser Beziehung haben wir dasjenige noch nicht erreicht, was frühere Zeiten hatten. Nur kann sich der Mensch jetzt sehr schwer in frühere Zeiten hineindenken. Frühere Zeiten hatten Mythen - Mythen, die mit dem lebendigen Leben des Volkes zusammenhingen, Mythen, die in Dichtung, in Kunst, in alles mögliche hineinwirkten. Und womit beschäftigten sich diese Mythen? Man redete im Griechischen von Odipus, von Herkules, von andern Heroen, denen man nachstrebte, die etwas getan hatten, was die Einleitung von Taten war, in deren Fußstapfen man treten wollte. Jeder einzelne wollte in ihre Fußstapfen treten. Nach rückwärts leitete der Faden des Vorstellens, der Faden des Denkens, der Faden des Empfindens. Man fühlte sich eins mit längst Verstorbenen. Dasjenige, was von den Verstorbenen als ein Impuls ausgegangen ist, das wurde erzählt im Mythus, und im Durchleben des Mythus, im Sich-Einswissen mit den Impulsen des Mythus lebten diese Menschen.

Etwas Ähnliches muß wieder geschaffen werden, wird geschaffen werden, wenn die Impulse der Geisteswissenschaft richtig verstanden werden. Nur werden allerdings die Seelenblicke der Zukunft weniger nach rückwärts als nach vorwärts gerichtet sein. Aber was Inhalt des öffentlichen Unterrichts werden muß, das ist das, was den Menschen zusammenbindet mit dem Werden der Zeit, und damit mit den Impulsen vor allem des Zeitgeistes, des entsprechenden Wesens aus der Hierarchie der Archai, von dem ich in einer früheren Betrachtung gesagt habe, daß ihm ebenso die sogenannten Toten gegenüberstehen wie die Lebendigen. Lernen wird man im öffentlichen Unterricht in der Zukunft, was der Inhalt eines solchen Zeitalters ist wie desjenigen, das mit dem 15. Jahrhundert begonnen und zugleich das griechisch-lateinische Zeitalter abgeschlossen hat; lernen wird man, was das allgemeine Weltenall in diesem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum eigentlich will. Die Impulse dieses fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums wird man aufnehmen. Man wird wissen: das muß sich realisieren zwischen dem 15. Jahrhundert und einem Jahrhundert in einem folgenden Jahrtausend. Und man wird wissen: man gehört seinem Zeitalter so an, daß durch einen hindurchströmen die Impulse dieses bestehenden Zeitalters. Die Kinder schon werden es in der Zukunft lernen, wie sie Blumen benennen, wie sie Sterne benennen lernen - das tun sie ja heute wieder weniger, aber das ist wenigstens etwas Außerlich-Reales -, so werden sie lernen, die wirklichen geistigen Impulse des Zeitalters aufzunehmen. Dazu müssen sie allerdings erst erzogen werden, dazu muß erst aufhören, dasjenige Geschichte zu heißen, was jetzt als Geschichte erzählt wird. Statt all der Dinge, von denen heute die Geschichte erzählt, wird man in einer nicht zu fernen Zukunft von den geistigen Impulsen, die hinter dem geschichtlichen Werden stehen und die von den Menschen geträumt werden, sprechen. Denn diese geistigen Impulse sind dasjenige, was den Menschen aufruft zur Freiheit und ihn frei macht, weil es ihn erhebt zu der Welt, aus der die Intuitionen, Inspirationen, Imaginationen kommen. Denn dasjenige, was äußerlich auf dem physischen Plane geschieht, was äußerlich Geschichte ist - ich habe das selbst in öffentlichen Vorträgen auseinandergesetzt -, das hat schon seine Bedeutung verloren, wenn es vorüber ist; das hat in Wirklichkeit nicht die Bedeutung, daß man sagen kann: Das Vorhergehende ist immer die Ursache des Nachfolgenden. — Es gibt nichts Unsinnigeres, als Geschichte etwa so zu erzählen, daß man die Taten Napoleons im Beginn des 19. Jahrhunderts erzählt und dann glaubt, dasjenige, was später geschehen ist, nachdem Napoleon verbannt worden ist, sei die Folge desjenigen, was Napoleon zu seiner Zeit getan hat. Nichts Unsinnigeres gibt es als das! Denn das, was man von Napoleon erzählen kann, bedeutet für die Wirklichkeit genau dasselbe, was es für das Leben eines Menschen bedeutet, wenn ich drei Tage nach seinem Tode seinen Leichnam beschreibe. Dasjenige, was jetzt Geschichte genannt wird, ist gegenüber der Wirklichkeit des geschichtlichen Werdens Kadavergeschehen, wenn auch die Erzählung dieses Kadavergeschehens im Bewußtsein mancher Menschen außerordentlich viel bedeutet.

Was äußerlich geschehen ist, wird erst eine Wirklichkeit, wenn es aufgezeigt wird in seinem Hervorsprießen aus den geistigen Impulsen. Dann wird man vielfach sehen, daß das, was ein Mensch tut, sagen wir in irgendeinem bestimmten Jahrzehnt eines Jahrhunderts, die Folge von etwas ist, was er erfahren hat, bevor er zu seiner eigenen Erdeninkarnation gegangen ist, gar nicht die Folge von dem, was vor Jahrzehnten im Verlauf des physischen Erlebens auf der Erde sich zugetragen hat und so weiter. Gerade mit Bezug auf das geschichtliche, mit Bezug auf das soziale und sittliche Leben wird die anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft vertiefend, befruchtend wirken müssen, namentlich auf dem Gebiete der Geschichte. Dieses Wissen der geistigen Impulse, das, zu den Forderungen unserer Zeit erhoben, etwas ähnliches sein wird, wie für die alten Zeiten das Drinnenstehen im lebendigen Mythus es war, das wird die Menschen erfüllen mit solchen Impulsen für ihr Tun und Handeln, die sie frei machen. Diese Dinge müssen zuerst verstanden werden, dann werden sie, wenn sich das Verständnis immer mehr und mehr ausbreitet, schon eingreifen in das wirkliche Leben.

Aber noch ein anderes geht Ihnen ja gerade aus diesen Betrachtungen hervor. Es geht Ihnen daraus hervor, daß die Gefühlsimpulse, die Willensimpulse, mit denen wir in derselben Lebenssphäre drinnenstehen, in der auch die sogenannten Toten drinnenstehen, dann eine höhere, eine intensivere Wirklichkeit sind als dasjenige,was wir mit dem wachen Bewußtsein als Vorstellungen und als Sinnesempfindungen kennen. Daher kann das, was jetzt eben so gefordert worden ist, daß es auch ein Gegenstand der öffentlichen Belehrung werden muß, nur recht fruchtbar werden, wenn es nicht nur mit dem Verstande aufgefaßt wird, sondern wenn es übergeht in die Impulse des Fühlens, in die Impulse des Wollens.

Das kann nur geschehen, wenn in Geisteswissenschaft eine reale Wirklichkeit gesehen wird, und nicht eine bloße Lehre. Es wird leicht in Geisteswissenschaft eine bloße Lehre gesehen, eine Theorie. Aber Geisteswissenschaft ist nicht eine bloße Lehre, ist nicht eine bloße Theorie, Geisteswissenschaft ist ein lebendiges Wort. Denn was als Geisteswissenschaft verkündet wird, ist die Offenbarung aus den Welten, die wir gemeinschaftlich haben mit den höheren Hierarchien und mit der Welt der sogenannten Toten. Diese Welt selbst spricht zu uns durch Geisteswissenschaft. Und der, welcher wirklich Geisteswissenschaft versteht, der weiß, daß in der Geisteswissenschaft forttönt das, was Seelenmusik der geistigen Welt ist. Dasjenige, was herausgelesen wird aber jetzt nicht aus toten Buchstaben, sondern aus wirklichem Geschehen der geistigen Welt —, es kann schon unser Gefühl durchdringen mit lebendigem Leben, wenn wir Geisteswissenschaft in diesem Sinne als etwas auffassen, was aus der geistigen Welt zu uns hereinspricht.

Ich habe betont, wie das der Fall ist, als ich besprach, wie seit dem Jahre 1879 auf der einen Seite die Gelegenheit gegeben ist, daß in der Art, wie es früher nicht vorhanden war, Geistesleben herunterfließe auf den physischen Plan, auf der andern Seite allerdings es seine Gegner findet in den Geistern der Finsternis, von denen wir gesprochen haben. Und gerade mit Bezug auf dieses Einleben des geisteswissenschaftlichen Inhaltes in Gefühl und Wille muß gewissermaßen noch alles, alles geschehen. Und dieses kann nur geschehen, wenn gewisse Dinge, mit Bezug auf welche die Menschen gegenwärtig geradezu in einer Kultursackgasse angelangt sind, sich gründlich ändern.

Und durchdringen muß man sich damit: Auf der einen Seite schreitet die Entwickelung so fort, daß allerdings die Ereignisse der Geschichte sich vergleichen lassen mit einem Baum, der wächst; aber wenn sich die Blätter bis zu seiner äußeren Peripherie entwickelt haben, wächst er nicht weiter, da beginnt das Absterben. So ist es mit den geschichtlichen Ereignissen. Bleiben wir bei dem Bilde, das ich in diesen Betrachtungen schon früher gebraucht habe: Es gibt eine ganz bestimmte Summe von geschichtlichen Ereignissen, die haben ihre Wurzeln im letzten Drittel des 18. Jahrhunderts - davon werde ich dann morgen deutlicher sprechen -, dazu kommen andere Einflüsse im Lauf des 19. Jahrhunderts und so weiter. Und sehen Sie, diese historischen Ereignisse, die breiten sich aus und erreichen äußerste Grenzen (Siehe Zeichnung). Aber jene Grenzen sind nicht so wie bei einem Baum oder bei einer Pflanze, wo es an der Peripherie einfach nicht weiterwächst, sondern es muß eine neue Wurzel geschichtlicher Ereignisse beginnen. Wir leben im eminentesten Sinne seit Jahrzehnten schon in einer Zeit, in der solche neuen geschichtlichen Ereignisse aus unmittelbaren Intuitionen heraus beginnen müssen (rechte Hälfte der Zeichnung). Nur ist es im geschichtlichen Leben der Menschen so, daß auch über diese Dinge leicht Illusionen sich ausbreiten. Sie können ja eine Pflanze, die durch ihr inneres Gesetz bis zu einer gewissen Peripherie wächst, naturgemäß wachsend ansehen nur bis zu dieser Peripherie. Jetzt aber könnten Sie eine Illusion hervorrufen: Sie könnten Drähte anbringen, Papierblätter an die Drähte anhängen und könnten sich der Illusion hingeben, daß dann die Pflanze bis dahin gehe.

Solche Drähte gibt es allerdings bei geschichtlichen Ereignissen! Während längst ein anderer Duktus des geschichtlichen Ereignisses da sein sollte, gibt es solche Drähte. Nur sind im geschichtlichen Werden diese Drähte die menschlichen Vorurteile, die menschlichen Bequemlichkeiten, die das, was längst abgestorben ist, eben in toten Drähten fortsetzen. Dann setzen sich gewisse Leute an das Ende dieser toten Drähte, und die Menschen, die sich dann an das Ende dieser toten Drähte setzen, das heißt, an die äußersten Ranken der menschlichen Vorurteile, die werden oftmals auch als historische Persönlichkeiten aufgefaßt, ja oftmals als die richtigen historischen Persönlichkeiten. Und man ahnt gar nicht, inwiefern diese Persönlichkeiten an solchen Drähten menschlicher Vorurteile sitzen! Ein wenig sich ein Urteil zu bilden, wieviel Persönlichkeiten, die in der Gegenwart als «große» angesehen werden, an solchen Drähten menschlicher Vorurteile pendeln, das gehört schon zu den wichtigen Aufgaben der Gegenwart.

Fifth Lecture

If we want to penetrate what lies at the basis of the two impulses that intervene in human life, the so-called freedom and the so-called necessity, then we must add a few more to the various prerequisites we have already established. And that is what I want to do today, so that tomorrow we will be in a position to draw, as it were, the conclusion regarding the concepts of freedom and necessity in human, social, moral, and historical activity. When discussing such things, it becomes increasingly apparent that people, and especially people of the present day, strive to comprehend the highest, most important, and most significant things with the simplest concepts and ideas. In order to understand a clock—I have mentioned this often—one considers various kinds of knowledge necessary, and one will not, without having some idea of how wheels work together or the like, attempt to explain the workings of a clock in detail off the cuff. One wants to be an expert on freedom and necessity in every situation in life, without having learned anything fundamental about these things. When it comes to the most important, most essential things, which can only be understood in their entire context with human nature, we would prefer not to be taught and to know and judge everything possible as if by ourselves. This is particularly true of the longing of our time. When it is asserted that the human being is a complicated, multifaceted entity, an entity which on the one hand is deeply immersed in everything connected with the physical plane, and on the other hand is deeply immersed in everything connected with the spiritual worlds, it is very easy to reply that such things are dry and intellectual, that the most important and essential things must be understood in a completely different way.

The world will have to learn — perhaps it is already learning a little through the present catastrophic events — what lies hidden in human beings and in their connection with the course of world evolution. For years we have emphasized that we can distinguish in the human being, in its raw state, what is called its physical nature, its physical body, its etheric body, the form-forming body, as I call it, its astral body, which is already soul, and the actual I.We have now emphasized from various points of view that the human being, as he lives from waking to falling asleep, that is, in ordinary waking consciousness, actually knows only something of the impressions of his sense perceptions and of his ideas, but that he sleeps through the actual content of his feeling life and sleeps through the actual content of his will life. Dream and sleep extend into the ordinary world of waking, and we are no more conscious of our emotional life in ordinary waking consciousness than we are of a dream. Human beings are no more conscious of the actual content of their will than they are in dreamless sleep. For through our feelings, through the content of our will, we immerse ourselves in the same world—as we have emphasized in these considerations—in which we live together with the dead among the beings of the higher hierarchies, the angeloi, archangeloi, archai, and so on. As soon as we live in a feeling — and we live continuously in feelings — everything that is in the realm of the dead lives along with us in the sphere, in the realm of this feeling.

Now something else comes into play. In our ordinary waking consciousness, we speak of our I. But in reality, we can only speak of this I in a very impersonal sense with our ordinary waking consciousness. For what is the nature and essence of this I? It cannot be recognized in ordinary waking consciousness. When the contemplative consciousness plunges into the true essence of the I, then the true I of the human being is of a volitional nature. What the human being has in ordinary consciousness is only the idea of the I. Therefore, it is easy for the natural scientist-psychologist to deny this I altogether, although on the other hand this denial is utter nonsense. Such natural scientists and psychologists speak of the ego gradually developing, of the human being arriving at this ego in the course of his individual development. He does not arrive at the ego, but at the idea of the ego in this way. And it is easy to deny this because, in ordinary consciousness, it is only an idea, a mirror image of the real, true, genuine ego. The real I lives in the same sphere of the world in which the true reality of our will lives. And what we call the astral body, what we can describe as the actual soul life, lives in the same sphere in which our emotional life lives. If you take the two things we have considered together, you can see that with our ego and our astral body we descend into the same realm that we share with the dead. At the moment when we descend clairvoyantly into our true ego, we are just as much among the egos of the dead as among the egos of the so-called living.

One only has to make this clear to oneself in order to fully understand how much human beings live with their ordinary consciousness in the so-called illusory world, or, as it is called in Eastern terminology, in Maya. We live consciously in our sensory and imaginative world. But the sensory impulses only give us that part of the world that extends as nature. And our world of imagination gives us nothing more than what is appropriate to our nature, but between birth and death. That which is our eternal nature does not, in essence, leave the world we share with the dead. It basically remains in the world where the dead are, when we enter the life of the physical plane through embodiment.

However, in order to fully understand these things, we need to take up certain concepts which — one cannot help saying, because that is simply the way things are — are not easy to think through and require some effort on our part. Such concepts are not initially available to human beings in the course of their ordinary waking consciousness. In ordinary waking consciousness, human beings know what is spatially extended and what passes in time. And they would actually like to be satisfied with what is spatially extended and what passes in time. In fact, human beings often suffer from trying to think of what is contained in the spiritual world in as spatial terms as possible, even if these are nebulous, thin, and foggy, but they still want to think of it spatially: they want to think of souls flying around in space and the like. One must go beyond the concepts of space and time to more complicated concepts if one really wants to penetrate these things. And here I would like to suggest something to you today that is important for understanding the whole of human life.

Let us once again consider — as I said, in rough terms — that we initially have this fourfold nature: the physical body, the formative forces or etheric body, the astral body, and the I. If one speaks and asks from the standpoint of ordinary waking consciousness: How old is a human being, this particular human being A, how old is he? Well, someone will give his age, say thirty-five, and believe that he has said something serious. He has also said something serious for the physical plane and ordinary waking consciousness when he says that he is thirty-five years old. But for the spiritual world, that is, for the whole being of the human being, this only says something partial. For when you say, “I am thirty-five years old,” you can only say this about your physical body. You would have to say, “My physical body is thirty-five years old” — then the statement would be correct. But you have not said anything at all about the etheric or form-force body, about the other members of the human being. For to say that your I, for example, is also thirty-five years old when your physical body is thirty-five years old is a mere illusion, it is even pure fantasy. For you see, here the concept of different speeds, different rates of development of the various members of human nature comes into play.

You can clarify this with the following figures. Let us say that a human being reaches the age of seven; this means nothing other than that his physical body has reached the age of seven. Therefore, his etheric body, his formative body, is not yet seven years old, but his formative body does not develop as quickly; it has not yet grown that old. We do not come to these conclusions simply because we imagine time as a uniform stream flowing along, and we cannot conceive that within time, different things progress at different speeds. This physical body, which is seven years old, has developed at a certain speed. The etheric body has developed more slowly, the astral body even more slowly, and the I is the slowest. This etheric body is only five years and three months old when the physical body is seven years old, because it develops at a slower pace. The astral body is three years and six months old. And the ego is one year and nine months old. So you must say to yourself that when a child is seven years old, its ego is only one year and nine months old. This ego undergoes a slower development on the physical plane. This ego moves at a slower pace on the physical plane, the slower pace that is also the pace at which one can live together with the dead. Why does the human being not grasp what takes place in the stream of the dead's experience? Because he does not accustom himself to the slower pace of holding thoughts, especially of holding feelings, in which the dead remain.

So if a person is twenty-eight years old in terms of their physical body, their ego is only seven years old. You can therefore only claim that, in relation to your ego, which is the essence of your being, you are developing at a much slower pace than in relation to your physical body. The difficulty lies in the fact that we otherwise understand speeds only as external speeds. When things run side by side, we say that one goes faster and the other slower — because we have time to compare them. But here the speed in time is different. Without this insight, however, that the different members of human nature have different speeds of development, it is impossible to understand what is connected with the actual deeper essence of the human being.

You can see from this how, in ordinary consciousness, things that are actually quite different in human nature are simply thrown together. Man has this fourfold nature, and the four members of this nature are so different from each other that they even have different ages. But man indulges in a considerable illusion by relating everything to his physical body. They say something that makes no sense at all in the spiritual world when they claim that their ego is twenty-eight years old if their physical body is twenty-eight years old. It would only make sense if they said: My ego is seven years old — in which case, of course, one year is four times as long.

One could also express the matter in this way: the four different members of the human being reckon according to completely different measures of time. The ego simply reckons a year to be four times as long as the physical body. And you could imagine this pictorially if you wanted to project it onto the physical plane. For example, while a person grows normally and reaches the age of twenty-eight, a child grows more slowly and is a seven-year-old child after twenty-eight years. At first, the whole thing seems like an abstract truth, but it is a fundamental reality in human beings. Just think about it: in our ego we carry what we call our mind, our self-conscious thinking. If we have our intellect, our self-conscious thinking, in our ego, then our intellect and our self-conscious thinking are actually much younger than we appear to be in our physical body. They are, they really are!

Yes, but then you come to realize that if such a person is twenty-eight years old and gives the impression of having a mind developed to the level of a twenty-eight-year-old, then only a quarter of what he has is his own. It is of no use: when we have a certain amount of mind at the age of twenty-eight, only a quarter of it belongs to us; the rest belongs to the general world; the rest belongs to the world in which we are immersed through our astral body, through our etheric body, through our physical body. But we know about these only indirectly through ideas, through sense perceptions, and thus again in the I. This means that when we develop as human beings between birth and death, we are actually mere illusions of reality. We give the impression of being four times as intelligent as we really are. That is true! Everything we have apart from that quarter, we owe to what prevails in the historical, social, and moral activity of that world which we dream away, which we sleep through. Dreams and sleep impulses, which we have in common with the general public, bubble up above the horizon of our existence and fertilize the quarter of our mind and soul, making it four times stronger than it really is.

This is where the deception arises with regard to human freedom. Man is a free being; that he already is. But only the true man is a free being — that quarter I just spoke of is a free being. The other three quarters are played in by other entities; they cannot be free. And this gives rise to the illusion regarding freedom, that one always asks: Is man free or is he not free? Man is free when he applies this concept of freedom to the one quarter of his being in the sense I have just explained. If man wants to have this freedom as his own impulse, then he must develop this quarter in a correspondingly independent manner. In ordinary life, this quarter cannot come into its own, for the simple reason that it is overwhelmed by the other three quarters. In the remaining three quarters, everything that man carries within himself acts as his instincts, his desires, his emotions, his passions. These kill his freedom, because through the instincts, through the emotions, through the passions, that which is in the general nature acts through him.

Now the question arises: What do we want to do to truly bring the one quarter of our soul life that is reality within us to freedom? We must relate this quarter to that which is independent of the remaining three quarters.

Philosophically, I have just attempted to answer this question in my Philosophy of Freedom, in which I endeavored to show how human beings can only realize the impulse of freedom within themselves if they place their actions, their deeds, entirely under the influence of pure thinking, if they come to be able to turn pure thought impulses into impulses for action, impulses that have not developed from the external world. For everything that has developed from the external world does not allow us to realize freedom. Only that which develops independently of the external world in our thinking as the driving force of our actions allows us to realize freedom.

Where do such impulses come from? Where does that which does not come from the external world come from? Well, it comes from the spiritual world. Man does not need to be clairvoyantly aware in every situation of his life of how these impulses come from the spiritual world, but they can nevertheless be present in him. Only, they will necessarily have to perceive them somewhat differently. When we rise in our conscious awareness to the first stage of the spiritual world, we enter the imaginative world; the second stage is the inspired world, as you know; the third stage is the intuitive world. So instead of allowing the impulses of our will and our actions to rise up from our physical, astral, and etheric bodies, if we do not receive impulses from this side but receive them from the spiritual world, we can only accept them as imaginations, behind which stand inspirations and intuitions. But this does not need to be consciously experienced as clairvoyant consciousness: now I want this, behind it are intuitions, inspirations, imaginations — but the result of this appears as a concept, as pure thinking, looking like a concept created in the imagination. Because this is so, because such a concept, which underlies free action, must appear to ordinary consciousness as a concept created out of the imagination, I called what underlies free action the moral imagination in my Philosophy of Freedom. So what is this moral imagination? This moral imagination is, I would say, the opposite of a mirror image. What we have spread out around us as external physical reality is a mirror image, in which things are reflected back to us. Moral imagination is the tableau through which we cannot see. That is why things appear to us as fantasy. Behind them, however, are the actual impulses: imaginations, inspirations, intuitions that are at work (see drawing on p. 102). If one does not know that these are at work, but only what they bring about, then it appears to be fantasy. And these results of moral fantasy, these impulses to act that are not derived from drives, passions, or emotions, are free impulses.

But how can we attain them? If one were to rise to clairvoyant consciousness without further ado, then one would arrive at them consciously through clairvoyance. But that is not necessary. Moral imagination can also be developed by people who are not clairvoyant. Everything that has meant real progress for humanity has always emerged from moral imagination, insofar as this progress was in the ethical realm. It is simply a matter of human beings first developing a feeling, and then a heightened feeling—we will hear more clearly in a moment what is meant by this heightened feeling—that they are here on this earth to do things that do not merely concern their personality, their individuality, but to do things through which what the spirits of the times want is realized.

At first glance, it seems as if there is something very special behind the statement that human beings should realize what the spirit of the times wants. However, a time will come when this will be much better understood than it is today. And a time will come when the content of human teaching will be different from what it is today, where even the most educated are taught only concepts that relate to nature. For what is taught to people with regard to ethics and social life is mostly insubstantial, shadowy abstractions, extreme abstractions.

In this respect, we have not yet achieved what earlier times had. However, it is very difficult for people today to imagine what life was like in earlier times. Earlier times had myths—myths that were connected with the living life of the people, myths that influenced poetry, art, and everything else. And what were these myths about? In Greek, people spoke of Oedipus, Hercules, and other heroes whom they aspired to emulate, who had done something that was the beginning of deeds they wanted to follow in their footsteps. Each individual wanted to follow in their footsteps. The thread of imagination, the thread of thought, the thread of feeling led backward. People felt at one with those who had long since died. What had emanated from the dead as an impulse was recounted in the myth, and in living through the myth, in identifying with the impulses of the myth, these people lived.