The Spiritual Background of the Social Question

GA 190

13 April 1919, Dornach

Translated by Dorothy Osmond

Lecture V

This lecture appeared in The Golden Blade, 1954.

From the two preceding lectures you will have realised that in finding it necessary to speak at the present time of the threefold social order, anthroposophical spiritual science is not actuated by any subjective views or aims. The purpose of the lecture yesterday was to point to impulses deeply rooted in the life of the peoples of the civilised world—the world as it is in this Fifth Post-Atlantean Epoch. I tried to show how, from about the year 1200 A.D. onwards, there awakened in Middle Europe an impulse leading to the growth of what may be called the civic social order, but that this civic social life of the middle classes was infiltrated by the remains of a life of soul belonging to earlier centuries—by those decadent Nibelung traits which appeared particularly among the ruling strata in the mid-European countries.

I laid special stress upon the existence of a radical contrast in mid-European life from the thirteenth until the twentieth centuries, culminating in the terrible death-throes of social life that have come upon Middle Europe. This incisive contrast was between the inner, soul-life of the widespread middle-class, and that of the descendants of the old knighthood, of the feudal overlords, of those in whom vestiges of the old Nibelung characteristics still survived. These latter were the people who really created the political life of Middle Europe, whereas the bulk of the middle class remained non-political, a-political. If one desires to be a spiritual scientist from the practical point of view, serious study must be given to this difference of soul-life between the so-called educated bourgeoisie and all those who held any kind of ruling positions in Middle Europe at that time. I spoke of this in the lecture yesterday.

We will now consider in rather greater detail why it was that the really brilliant spiritual movement which lasted from the time of Walter von der Vogelweide until that of Goetheanism, and then abruptly collapsed, failed to gain any influence over social life or to produce any thoughts which could have been fruitful in that sphere. Even Goethe, with all his power to unfold great, all-embracing ideas in many domains of life, was really only able to give a few indications—concerning which one may venture to say that even he was not quite clear about them—as to what must come into being as a new social order in civilised humanity. Fundamentally speaking, the tendency towards the threefold membering of a healthy social organism was already present in human beings, subconsciously, by the end of the eighteenth century. The demands for freedom, equality and fraternity, which can have meaning only when the threefold social order becomes reality, testified to the existence of this subconscious longing. Why did it never really come to the surface?

This is connected with the whole inherent character of mid-European spiritual life. At the end of the lecture yesterday I spoke of a strange phenomenon. I said that Hermann Grimm—for whom I have always had such high regard and whose ideas were able to shed light upon so many aspects of art and general human interest of bygone times—succumbed to the extraordinary fallacy of admiring such an out-and-out phrasemonger as Wildenbruch! In the course of years I have often mentioned an incident which listeners may have thought trivial, but which can be deeply indicative for those who study life in its symptomatological aspect. Among the many conversations I had with Hermann Grimm while I was in personal contact with him, there was one in which I spoke from my own point of view about many things that need to be understood in the spiritual sense. In telling this story I have always stressed the fact that Hermann Grimm's only response to such mention of the spiritual was to make a warding-off gesture with his hand, indicating that this was a realm he was not willing to enter. A supremely true utterance, consisting of a gesture of the hand, was made at that moment. It was true inasmuch as Hermann Grimm, for all his penetration into many things connected with the so-called spiritual evolution of mankind, into art, into matters of universal human concern, had not the faintest inkling of what ‘spirit’ must signify for men of the Fifth Post-Atlantean epoch of culture. He simply did not know what spirit really is from the standpoint of a man of this epoch. In speaking of such matters one must keep bluntly to the truth: until it came to the spirit, there was truth in a man like Hermann Grimm. He made a parrying gesture because he had no notion of how to think about the spirit. Had he been one of the phrasemongers going about masked as prophets today endeavouring to better the lot of mankind, he would have believed that he too could speak about the spirit; he would have believed that by reiterating Spirit, spirit, spirit! something is expressed that has been nurtured in one's own soul.

Among those who of recent years have been talking a great deal about the spirit, without a notion of its real nature, are the theosophists—the majority of them at any rate. For it can truly be said that of all the vapid nonsense that has been uttered of late, the theosophical brand has been the most regrettable and also in a certain respect the most harmful in its effects. But a statement like the one I have made about Hermann Grimm—not thinking of him as a personality but as a typical representative of the times—raises the question: how comes it that such a true representative of Middle European life has no inkling of how to think about the spiritual, about the spirit? It is just this that makes Hermann Grimm the typical representative of Middle European civilisation. For when we envisage this brilliant culture of the townsfolk, which has its start about the year 1200 and lasts right on into the period of Goetheanism, we shall certainly perceive as its essential characteristic—but without valuing it less highly on this account—that it is impregnated in the best sense with soul but empty of anything that can be called spirit. That is the fact we have to grasp, with a due sense of the tragedy of it: this brilliant culture was devoid of spirit. What is meant here, of course, is spirit as one learns to apprehend it through anthroposophical spiritual science.

Again and again I return to Hermann Grimm as a representative personality, for the thinking of thousands and thousands of scholarly men in Middle Europe was similar to his. Hermann Grimm wrote an excellent book about Goethe, containing the substance of lectures he gave at the University of Berlin in the seventies of the last century. Taking it all in all, what Hermann Grimm said about Goethe is really the best that has been said at this level of scholarship. From the vantage-point of a rich life of soul, Hermann Grimm derived his gift not only for portraying individual men but for accurately discerning and assessing their most characteristic traits. He was brilliant in hitting upon words for such characterisations. Take a simple example. In the nature of things, Hermann Grimm was one of those who misunderstood the character of the wild Nibelung people. He was an ardent admirer of Frederick the Great and pictured him as a Germanic hero. Now Macaulay, the English historian and man of letters, wrote about Frederick the Great, naturally from the English point of view. In an essay on Macaulay, Hermann Grimm set out to show that in reality only a German possessed of sound insight is capable of understanding and presenting a true picture of Frederick the Great. Hermann Grimm describes Macaulay's picture of Frederick the Great in the very apt words: Macaulay makes of Frederick the Great a distorted figure of an English Lord, with snuff in his nose.

To hit upon such a characterisation indicates real ability to shape ideas and mental images in such a way that they have plasticity, mobility. Many similar examples could be found of Hermann Grimm's flair for apt characterisation. And other kindred minds, belonging to the whole period of Middle European culture of which I spoke yesterday, were endowed with the same gift. But if, with all the good-will born of a true appreciation of Hermann Grimm, we study his monograph on Goethe—what is our experience then? We feel: this is an extraordinarily good, a really splendid piece of writing—only it is not Goethe! In reality it gives only a shadow-picture of Goethe, as if out of a three-dimensional figure one were to make a two-dimensional shadow-picture, thrown on the screen. Goethe seems to wander through the chapters like a ghost from the year 1749 to the year 1832. What is described is a spectral Goethe—not what Goethe was, what he thought, what he desired.

Goethe himself did not succeed in lifting to the level of spiritual consciousness all that was alive within his soul. Indeed, the great ‘Goethe problem’ today is precisely this: to raise into consciousness in a truly spiritual way what was spiritually alive in Goethe. He himself was not capable of this, for culture in his day could give expression only to a rich life of the soul, not of the spirit. Therefore Hermann Grimm, too, firmly rooted as he was in the Goethean tradition, could depict only a shadow, a spectre, when he wanted to speak of Goethe's spirit. It is thoroughly characteristic that the best modern exposition of Goethe and Goetheanism should produce nothing but a spectre of Goethe.

Why is it that through the whole development of this brilliant phase of culture there is no real grasp of the spirit, no experience of it or feeling for it? Men such as Troxler, and Schelling too at times, pointed gropingly to the spirit. But speaking quite objectively, it must be said that this culture was empty of spirit. And because of this, men were also ignorant of the needs, the conditions, that are essential for the life of the spirit. Here too there is something which may well up as a feeling of tragedy from contemplation of this stream of culture: men were unable to perceive, to divine, the conditions necessary for the life of the spirit, above all in the social sphere; For the reason why the social life of Middle Europe has developed through the centuries to the condition in which it finds itself today is that it had no real experience of the spirit, nor felt the need to meet the fundamental requirement of the spiritual life by emancipating it, making it independent of and separate from the political sphere. Because men had no understanding of the spirit, they allowed it to be merged with the political life of the State, where it could unfold only in shackles. I am speaking here only of Middle Europe; in other regions of the modern civilised world it was the same, although the causes were different.

And then, in the inmost soul, a reaction can set in. Then a man can experience how in his study of nature the spirit remains dumb, silent, uncommunicative. Then the soul rebels, gathers its forces and strives to bring the spirit to birth from its own inmost being! This can happen only in an epoch when scientific thinking impinges on a culture which has no innate disposition towards spirituality. For if men are not inwardly dead, if they are inwardly alive, the impulse of the spirit begins of itself to stir within them. We must recognise that since the middle of the 15th century the spirit has to be brought to birth through encountering what is dead if it is to penetrate into man's life of soul. The only persons who can gain satisfaction from inwardly experiencing the spiritualised soul-life of the Greeks are those who, with their classical scholarship, live in that afterglow of Greek culture which enables the soul-quality of the spirit to pulsate through a man's own soul. But men who are impelled to live earnestly with natural science and to discern what is deathly, corpse-like in it—they will make it possible for the spirit itself to come alive in their souls.

If a man is to have real and immediate experience of the spirit in this modern age, he must not only have smelt the fumes of prussic acid or ammonia in laboratories, or have studied specimens extracted from corpses in the dissecting room, but out of the whole trend and direction of natural scientific thinking he must have known the odour of death in order that through this experience he may be led to the light of the spirit! This is an impulse which must take effect in our times; it is also one of the testings which men of the modern age must undergo. Natural science exists far more for the purpose of educating man than for communicating truths about nature. Only a naive mind could believe that any natural law discovered by learned scientists enshrines an essential, inner truth. Indeed it does not! The purpose of natural science, devoid of spirit as it is, is the education of men. This is one of the paradoxes implicit in the historic evolution of humanity.

And so it was only in the very recent past, in the era after Goetheanism, that the spirit glimmered forth; for it was then, for the first time, that the essentially corpse-like quality in the findings of natural science came to the fore; then and not until then could the spirit ray forth—for those, of course, who were willing to receive its light. Until the time of Goethe, men protected themselves against the sorry effects of a spiritual life shackled in State-imposed restrictions by cultivating a form of spiritual life fundamentally alien to them, namely the spiritual life of ancient Greece; this was outside the purview of the modern State for the very reason that it had nothing to do with modern times. A makeshift separation of the spiritual life from the political sphere was provided by the adoption of an alien form of culture. This Greek culture was a cover for the spiritual emptiness of Middle European life and of modern Europe in general.

On the other hand, the need to separate the economic sphere from the Rights-sphere, from the political life of the State proper, was not perceived. And why not? When all is said and done, nobody can detach himself from the economic field. To speak trivially, the stomach sees to that! In the economic sphere it is impossible for men to live unconcernedly through such cataclysms as are allowed to occur, all unnoticed, in the political and spiritual spheres. Economic activity was going on all the time, and it developed in a perfectly straightforward way. The transformation of the old impenetrable forests into meadows and cornfields, with all the ensuing economic consequences, went steadily ahead. But into economic life, too, there came an alien intrusion, one that had actually found a footing in the souls of men in Middle Europe earlier than that of Greece, namely the Latin-Roman influence. Everything pertaining to the State, to the Rights-life, to political life, derives from this Latin-Roman influence. And here again is something that will have to be stressed by history in the future but has been overlooked by the conventional, tendentious historiography of the immediate past, with its bias towards materialism—the strangely incongruous fact that certain economic ideas and procedures are a direct development from social relationships described, for example, by Tacitus, as prevailing in the Germanic world during the first centuries after the founding of Christianity.

But that is not all. These trends in economic thinking did not go forward unhampered. The Roman view of rights, Roman political thinking, seeped into the economic usages and methods originally prevailing in Europe, infiltrated them through and through and caused a sharp cleavage between the economic sphere and the political sphere. Thus the economic sphere and the political sphere, the former coloured by the old Germanic way of life and the latter by the Latin-Roman influence, remained separate on the surface but without any organic distinction consistent with the threefold membering of the body social: the distinction was merely superficial, a mask. Two heterogeneous strata were intermingled; it was felt that they did not belong together, in spite of external unification. Inwardly, however, people were content, because in their souls they experienced the two spheres as separate and distinct.

One need only study mediaeval and modern history in the right way and it will be clear that this mediaeval history is really the story of perpetual rebellion, self-defense, on the part of the economic relationships surviving from olden times against the political State, against the Roman order of life. Imaginative study of these things shows unmistakably how Roman influences in the form of jurisprudence penetrate into men via the heads of the administrators. A great deal of the Roman element had even found its way into the wild Nibelung men in their period of decline. “Graf” is connected with “grapho”—writing. One can picture how the peasants, thinking in terms of husbandry, rise up in rebellion against this Roman juridical order, with fists clenched in their pockets, or with flails. Naturally, this is not always so outwardly perceptible. But when one observes history truly, these factors are present in the whole moral trend and impulse of those times. And so—I am merely characterising, not criticising, for everything that happened has also brought blessings and was necessary for the historic evolution of Middle Europe—all that developed from the seeds planted in mid-European civilisation was permeated through and through by the juristic-political influences of the Roman world and the humanism of Greece, by the Greek way of conceiving spirit in the guise of soul.

On the other hand, directly economic life acquired its modern, international character, the old order was doomed. A man might have had a very good classical education and be an ignoramus in respect of modern natural science, but then he was inwardly on a retrograde path. A man of classical education could not keep abreast of his times unless he penetrated to some extent into what modern natural scientific education had to offer. And again, if a man were schooled in natural science, if he acquired some knowledge of modern natural science and of what had come out of the old Roman juristic system in the period of which I have spoken, he could not help suffering from an infantile disease, from ‘culture scarlet fever’, ‘culture measles’, in a manner of speaking. In the old Imperium Romanum a juristic culture was fitting and appropriate. Then this same juristic principle, the res publica (i.e. the conception of it), was transplanted from ancient Rome into the sphere of Middle European culture, together with the element of Nibelung barbarism on the other side. One really gets ‘culture scarlet fever’, ‘culture measles’, if one does not merely think of jurisprudence in the abstract, but, with sound natural scientific concepts, delves into the stuff that figures as modern jurisprudence in literature and in science.

We can see that this state of things had reached a certain climax when we find a really gifted man such as Rudolf von Ihering at an utter loss to know how to deal with the pitiable notions of jurisprudence current in the modern age. The book written by Ihering on the aim of justice (Der Zweck im Recht) was a grotesque production, for here was a man who had made a little headway in natural scientific thinking endeavouring to apply the concepts he had acquired to jurisprudence—the result being a monstrosity of human thinking. To study modern literature on law is a veritable martyrdom for sound thinking; one feels all the time as though so many worms were crawling through the brain. This is the actual experience—I am simply describing it pictorially.

We must be courageous enough to face these things fairly and squarely, and then it will be clear that we have arrived at the point of time when not only certain established usages and institutions, but men's very habits of thought, must be metamorphosed, re-cast; when men must begin to think about many things in a different way. Only then will the social institutions in the external world be able, under the influence of human thinking and feeling, to take the form that is called for by these ominous and alarming facts.

A fundamental change in the mental approach to certain matters of the highest importance is essential. But because between 1200 and the days of Goetheanism, modern humanity, especially in Middle Europe, absorbed all unwittingly thoughts that wriggled through the brain like worms, there crept over thinking the lazy passivity that is characteristic of the modern age. It comes to expression in the absence of will from the life of thought. Men allow their thoughts to take possession of them; they yield to these thoughts; they prefer to have them in the form of instinct. But in this manner no headway can be made towards the spirit. The spirit can be reached only by genuinely putting the will into thinking, so that thinking becomes an act like any other, like hewing wood. Do modern men feel that thinking tires them? They do not, because thinking for them is not activity at all. But the fact that anyone who thinks with thoughts, not with words, will get just the same fatigue as he gets from hewing wood, and actually in a shorter time, so that he simply has to stop—that is quite outside their experience. Nevertheless, this is what will have to be experienced, for otherwise modern mankind as a community will be incapable of achieving the transition from the sense-world into the super-sensible world of which I spoke in the two preceding lectures. Only by entering thus into the super-sensible world, with understanding for what is seen and apprehended in the spirit, will human souls find harmony again.

The year 1200 is the time of Walter von der Vogelweide, the time when the spiritual life of Middle Europe is astir with powerful imaginations of which conventional history has little to say. Then it flows on through the centuries, but from the 15th and 16th centuries onwards takes into itself the germs of decline with the founding of the Universities of Prague, Ingolstadt, Freiburg, Heidelberg, Restock, Wurzburg and the rest. The founding of these Universities throughout Middle Europe occurred almost without exception in a single century. The kind of life and thinking emanating from the Universities started the trend towards abstraction—towards what was subsequently to be idolised and venerated as the pure, natural scientific thinking which today invades the customary ways of thought with such devastating results.

Fundamentally speaking, this gave a definite stamp to the whole mentality of the educated middle class. Naturally, many individuals were not deeply influenced, but all the same the effect was universal. Of salient importance during this period was the increasing receptiveness of people to a form of soul-life entirely foreign to them. Side by side with what was developed through those who were the bearers of this middle-class culture, which reached its culmination in Goethe, Herder and Schiller, alien elements and impulses were at work.

I am speaking here of something profoundly characteristic. In their souls, the bearers of this culture were seeking for the spirit without a notion of what the spirit is. And where did they seek it? In the realm of Greek culture! They learnt Greek in their intermediate schools, and what was instilled into them by way of spiritual substance was Greek in tenor and content. To speak truly of the spirit as conceived in Middle Europe from the thirteenth right on into the twentieth century, one would have to say: spirit, as conveyed by the inculcation of Greek culture. No spiritual life belonging intrinsically and innately to the people came into being. Greek culture did not really belong to the epoch beginning in the middle of the 15th century, which we call the epoch of the evolution of self-consciousness. And so the bourgeoisie in Middle Europe were imbued with an outworn form of Greek culture, and this was the source of all that they were capable of feeling and experiencing in regard to the spirit.

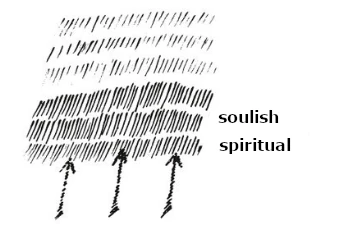

But what the Greek experienced of the spirit was merely its expression in the life of soul (Seelenseite das Geistes). What gave profundity to the culture of ancient Greece was that the Greek rose to perception of the highest manifestation of soul-life. That was what he called ‘spirit’. True, the spirit shines down from the heights, pulsing through the realm of soul; but when the gaze is directed upwards, it finds, to begin with, only the expression of the spirit in the realm of soul.

Man's task in the Fifth Post-Atlantean epoch, however, is to lift himself into the very essence of the spirit—an attainment still beyond his reach in the days of Greece. This is of far greater significance than is usually supposed, for it sheds light upon the whole way in which medieval, neo-medieval culture apprehended the spirit.

What, then, was required in order to reach a concept, an inward experience, of the spirit appropriate for the modern age? It is precisely by studying a representative figure like Hermann Grimm that we can discover this. It is something of which a man such as Hermann Grimm, steeped in classical lore, had not the faintest inkling—namely, the strivings of natural science and the scientific mode of thinking. This thinking is devoid of spirit; precisely where it is great it contains no trace of spirit, not an iota of spirituality. All the concepts of natural science, all its notions of laws of nature, are devoid of spirit, are mere shadow-pictures of spirit; while men are investigating the laws of nature, no trace of the spirit is present in their consciousness.

Two ways are open here. Either a man can give himself up to natural science, contenting himself—as often happens today—with what natural science has to offer; then he will certainly equip his mind with a number of scientific laws and ideas concerning nature—but he loses the spirit. Along this path it is possible to become a truly great investigator, but at the cost of losing all spirituality. That is the one way. The other is to be inwardly aware of the tragic element arising from the lack of spirituality in natural science, precisely where science appears in all its greatness. Man immerses his soul in the scientific lore of nature, in the abstract, unspiritual laws of chemistry, physics, biology, which, having been discovered at the dissecting table, indicate by this very fact that from the living they yield only the dead. The soul delves into what natural science has to impart concerning the laws of human evolution. When a man allows all this to stream into him, when he endeavours not to pride himself on his knowledge, but asks: ‘What does this really give to the human soul?’—then he experiences something true; then spirit is not absent. Herein, too, lies the tragic problem of Nietzsche, whose life of soul was torn asunder by the realisation that modern scientific learning is devoid of spirituality.

As you know, insight into the super-sensible world does not depend upon clairvoyance; all that is required is to apprehend by the exercise of healthy human reason what clairvoyance can discover. It is not essential for the whole of mankind to become clairvoyant; but what is essential, and moreover within the reach of every human being, is to develop insight into the spiritual world through the healthy human intelligence. Only thus can harmony enter into souls of the modern age: for the loss of this harmony is due to the conditions of evolution in our time. The development of Europe, with her American affinities on the one hand and the Asiatic frontier on the other, has reached a parting of the ways. Spiritual Beings of higher worlds are bringing to a decisive issue the overwhelming difference between former ages and modern times as regards the living side-by-side of diverse populations on the earth.

How were the peoples of remote antiquity distributed and arranged over the globe? Up to a certain point of time, not long before the Mystery of Golgotha, the configuration of peoples on earth was determined from above downwards, inasmuch as the souls simply descended from the spiritual world into the physical bodies dwelling in some particular territory. Owing to physiological, geographical, climatic conditions in early times, certain kinds of human bodies were to be found in Greece, and similarly on the peninsula of Italy. The souls came from above, were predestined entirely from above, and took very deep root in man's whole constitution, in his outer, bodily physiognomy.

Then came the great migrations of the peoples. Men wandered over the earth in different streams. Races and peoples began to intermix, thus enhancing the importance of the element of heredity in earthly life. A population inhabiting a particular region of the earth moved to another; for example the Angles and Saxons who were living in certain districts of the Continent migrated to the British Isles. That is one such migration. But in respect of physical heredity, the descendants of the Angles and Saxons are dependent upon what had developed previously on the Continent; this was a determining factor in their bodily appearance, their practices, and so forth. Thus there came into the evolutionary process a factor working in and conditioned by the horizontal. Whereas the distribution of human beings over the earth had formerly depended entirely upon the way in which the souls incarnated as they came down from above, the wanderings and movements of men over the earth now also began to have an effect.

At the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, however, a new cosmic historic impulse came into operation. For a period of time a certain sympathy existed between the souls descending from the spiritual world and the bodies on the earth below. Speaking concretely: souls who were sympathetically attracted by the bodily form and constitution of the descendants of the Angles and Saxons, now living in the British Isles, incarnated in those regions. In the 15th century this sympathy began to wane, and since then the souls have no longer been guided by racial characteristics, but once again by geographical conditions, the kind of climate, and so forth, on the earth below, and also by whether a certain region of the earth is flat or mountainous. Since the 15th century, souls have been less and less concerned with racial traits; once again they are guided more by the existing geographical conditions. Hence a kind of chasm is spreading through the whole of mankind today between the elements of heredity and race and the soul-element coming from the spiritual world. And if men of our time were able to lift more of their subconsciousness into consciousness, very few of them would—to use a trivial expression—feel comfortable in their skins. The majority would say: I came down to the earth in order to live on flat ground, among green things or upon verdant soil, in this or that kind of climate, and whether I have Roman or Germanic features is of no particular importance to me.

It certainly seems paradoxical when these things, which are of paramount importance for human life, are concretely described. Men who preach sound principles, saying that one should abjure materialism and turn towards the spirit—they too talk just like the pantheists, of spirit, spirit, spirit. People are not shocked by this today; but when anyone speaks concretely about the spirit they simply cannot take it. That is how things are. And harmony must again be sought between, shall I say, geographical predestination and the racial element that is spread over the earth. The leanings towards internationalism in our time are due to the fact that souls no longer concern themselves with the element of race.

A figure of speech I once used is relevant here. I compared what is happening now to a ‘vertical’ migration of peoples, whereas in earlier times what took place was a ‘horizontal’ migration. This comparison is no mere analogy, but is founded upon facts of the spiritual life.

To all this must be added that, precisely through the spiritual evolution of modern times, man is becoming more and more spiritual in the sphere of his subconsciousness, and the materialistic trend in his upper consciousness is more and more sharply at variance with the impulses that are astir in his subconsciousness. In order to understand this, we must consider once more the threefold membering of the human being.

When the man of the present age, whose attention is directed only to the material and the physical, thinks of this threefold membering, he says to himself: I perceive through my senses: they are indeed distributed over the whole body but are really centralised in the head; acts of perception, therefore, belong to the life of the nerves and senses—and there he stops. Further observation will, of course, enable him to describe how the human being breathes, and how the life passes over from the breath into the movement of the heart and the pulsation of the blood. But that is about as far as a he gets today. Metabolism is studied [in] all detail, but not as one of the three members of threefold man: actually it is taken to be the whole man. One need not, of course, go to the lengths of the scientific thinker who said: man is what he eats (Der Mensch ist, was er isst)—but, broadly speaking, science is pretty strongly convinced that it is so. In Middle Europe at the present time it looks as if he will soon be what he does not eat!

This threefold membering of the human being, which will ultimately find expression in a threefold social order because its factual reality is becoming more and more evident, manifests in different forms over the earth. Truly, man is not simply the being he appears outwardly to be, enclosed within his skin. It was in accordance with a deep feeling and perception when in my Mystery Play, “The Portal of Initiation”, in connection with the characters of Capesius and Strader, I drew attention to the fact that whatever is done by men on earth has its echo in cosmic happenings out yonder in the universe. With every thought we harbour, with every movement of the hand, with everything we say, whether we are walking or standing, whatever we do—something happens in the cosmos.

The faculties for perceiving and experiencing these things are lacking in man today. He does not know—nor can it be expected of him and it is paradoxical to speak as I am speaking now—he does not know how what is happening here on the earth would appear if seen, for example, from the Moon. If he could look from the Moon he would see that the life of the nerves and senses is altogether different from what can be known of it in physical existence. The nerves-and-senses life, everything that transpires while you see, hear, smell, taste, is light in the cosmos, the radiation of light into the cosmos. From your seeing, from your feeling, from your hearing, the earth shines out into the cosmos.

Different again is the effect produced by what is rhythmic in the human being: breathing, heart movement, blood pulsation. This activity manifests in the universe in great and powerful rhythms which can be heard by the appropriate organs of hearing. And the process of metabolism in man radiates out into cosmic space as life streaming from the earth. You cannot perceive, hear, see, smell or feel without shining out into the cosmos. Whenever your blood circulates, you resound into universal space, and whenever metabolism takes place within you, this is seen from out yonder as the life of the whole earth.

But there are great differences in respect of all this—for example, between Asia and Europe. Seen from outside, the thinking peculiar to the Asiatics would appear—even now, when a great proportion of them have lost all spirituality—as bright, shining light raying out into the spiritual space of the universe. But the further we go towards the West, the dimmer and darker does this radiance become. On the other hand, more and more life surges out into cosmic space the further we go towards the West. Only from this vista can there arise in the human soul what may be called perception of the cosmic aspect of the earth—with the human beings belonging to it.

Such conceptions will be needed if mankind is to go forward to a propitious and not an ominous future. The idiocy that is gradually being bred in human beings who are made to learn from the sketchy maps of modern geography: Here is the Danube, here the Rhine, here Reuss, here Aare, here Bern, Basle, Zürich, and so forth—all this external delineation which merely adds material details to the globe—this kind of education will be the ruin of humanity. It is necessary as a foundation and not to be scoffed at; but nevertheless it will lead gradually to man's downfall. The globe of the future will have to indicate: here the earth shines because spirituality is contained in the heads of men: there the earth radiates out more life into cosmic space because of the characteristics of the human beings inhabiting this particular territory.

Something I once said here is connected with this. (One must always illumine one fact by another). I told you that Europeans who settle in America develop hands resembling those of the Red Indians; they begin to resemble the Indian type. This is because the souls coming down into human bodies today are directed more by geographical conditions, as they were in the olden days. In our own time, the souls are directed, not by racial considerations, not by what develops out of the blood, but by geographical conditions, as in the past. But it will be necessary to get at the roots of what is going on in humanity. This can be done only when men accustom themselves to concepts of greater flexibility, capable of penetrating matters of this kind. These concepts, however, can be developed only on the foundation of spiritual science. And such a foundation is available when the spirit can be brought to birth in the human soul. For this, man needs a free spiritual life, emancipated from the political life of the State.

I have now given you one or two indications of what is astir in humanity, and of the need to strive for a new ordering of social life. Social demands cannot nowadays be advanced in terms of the trivial concepts commonly employed. Men must have insight into the nature of present-day humanity; they must make good what they have neglected in the study of modern mankind.

Elfter Vortrag

Aus den beiden Vorträgen von vorgestern und gestern werden Sie ersehen haben, daß wahrhaftig nicht aus irgendeiner subjektiven Meinung, aus irgendeinem subjektiven Wollen heraus von seiten anthroposophisch orientierter Geisteswissenschaft gegenwärtig gesprochen werden muß von jener sozialen Dreigliederung, von der wir ja jetzt so oft gesprochen haben und die auch zum Gegenstande öffentlicher Darstellungen gemacht worden ist. Was besonders die Auseinandersetzungen von gestern betrifft, so ist darüber zu sagen, daß ich dabei die Absicht haben mußte, darauf hinzuweisen, welche tiefgehenden Impulse in dem Völkerleben der gegenwärtigen zivilisierten Welt, also der Welt der fünften nachatlantischen Zeit herrschen. Ich versuchte zu zeigen, wie ungefähr vom Jahre 1200 ab in Mitteleuropa ein Impuls erwacht, der in diesem Mitteleuropa eigentlich bedeutete den Aufstieg desjenigen, was man nennen kann die bürgerliche soziale Ordnung, daß aber sich hineinmischte in dieses bürgerlich soziale Leben Mitteleuropas wie zurückgebliebenes Seelenleben aus früheren Jahrhunderten, verfallendes Nibelungentum, jenes verfallene Nibelungentum, welches als Seelenleben sich ausgestaltete, namentlich in den verwaltenden und regierenden Oberschichten der mitteleuropäischen Länder. Und ich betonte ganz besonders, welch ein einschneidender Kontrast in diesem mitteleuropäischen Leben vorhanden war vom 13. bis ins 20. Jahrhundert herein, wo er eben dann geführt hat zu jenem furchtbaren sozialen Röcheln, das auch über Mitteleuropa hereingebrochen ist. Ich versuchte darauf hinzuweisen, welch ein einschneidender Kontrast vorhanden war zwischen dem inneren seelischen Erleben der breiten bürgerlichen Bevölkerung und denjenigen Leuten, welche, hervorkommend aus dem alten Rittertum, aus den alten Lehensträgern, aus alldem, was eben Überbleibsel war in seelischer Beziehung des alten Nibelungentums, im Grunde die Politik dieses Mitteleuropa machten, während die breite Masse des Bürgertums unpolitisch, apolitisch blieb. Man muß sich schon einmal ganz ernsthaftig, gerade wenn man von praktischen Gesichtspunkten aus Geisteswissenschafter sein will, hineinversetzen in diesen Seelenunterschied, der da besteht oder bestanden hat, namentlich zwischen dem sogenannten gebildeten Bürgertum und seinen Angehörigen und zwischen alldem, was auf irgendwie gearteten Regierungssesseln in Mitteleuropa gesessen hat. Das habe ich gestern charakterisiert.

Nun wollen wir ein wenig näher ins Auge fassen, warum eigentlich diese im Grunde doch großartige Geistesbewegung, die da geht von Walther von der Vogelweide bis herauf zum Goetheanismus, während sie nach dem Goetheanismus einen jähen Absturz erfährt, warum denn diese Geistesbewegung so gar nicht dahin gekommen ist, das soziale Leben irgendwie zu bewältigen, in dem sozialen Leben irgendwie Gedanken zu fassen. Man bedenke doch nur, daß selbst Goethe, der über vieles in der Welt die umfassendsten Ideen zu entwickeln verstand, eigentlich nur in gewissen Andeutungen, von denen man dreist sagen kann, daß sie ihm selber nicht ganz klar waren, zu sprechen verstand über dasjenige, was da als eine neue soziale Ordnung über die zivilisierte Menschheit heraufkommen muß. Im Grunde war schon die Tendenz nach der Dreigliederung des gesunden sozialen Organismus seit dem Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts in dem Unterbewußtsein der Menschen vorhanden. Und die Rufe nach Freiheit, Gleichheit, Brüderlichkeit, die nur dann Sinn bekommen werden, wenn einmal die Dreigliederung sich verwirklicht, sie bezeugten, daß diese unterbewußte Sehnsucht nach der Dreigliederung vorhanden war. Warum eigentlich kam sie nicht ans Tageslicht?

Das hängt mit der ganzen Artung des Geisteslebens Mitteleuropas zusammen. Ich habe gestern am Schlusse hingewiesen auf eine eigentümliche Erscheinung, ich habe gesagt: Der von mir so hoch verehrte Herman Grimm, der mit seinen Ideen in so manches hineinleuchten konnte, was Künstlerisches, was Allgemein-Menschliches ist, was die Antike betrifft, er verfiel in die merkwürdige Unwahrheit, einen bloRen Wortphraseur wie Wildenbruch zu bewundern. Ich habe öfter im Lauf der Jahre - gestatten Sie diese persönliche Bemerkung - auf etwas hingewiesen, was, wenn man es so erzählt, recht unbedeutend dem Zuhörer erscheinen könnte, was aber für den, der das Leben symptomatologisch betrachtet, eine große, tiefgehende Bedeutung haben kann. Ich hatte unter manchen anderen Gesprächen, die ich führen durfte in der Zeit, als ich mit Herman Grimm persönlichen Verkehr hatte, auch einmal ein Gespräch mit ihm, im Verlauf dessen ich von meinem Gesichtspunkte aus auf manches hinwies, was geistig zu verstehen ist. Und wenn ich dies erzählt habe, habe ich immer darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß Herman Grimm für eine solche Rede über das Geistige nur eine abwehrende Handbewegung hatte; er meinte, das ist etwas, worauf er sich nicht einläßt. Es war in diesem Momente eine ungeheuer wahre Bemerkung, die in dieser Handbewegung bestand. Inwiefern war diese Bemerkung ungeheuer wahr? Wahr war sie insofern, als Herman Grimm bei allem seinem Eingehen auf manches in der sogenannten geistigen Entwickelung der Menschheit, in der Kunst, in der Darlebung des ‚Allgemein-Menschlichen, auch nicht die geringste Ahnung hatte von dem, was eigentlich Geist sein muß dem Menschen des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitalters. Herman Grimm wußte einfach nicht vom Gesichtspunkte aus eines Menschen des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums, was Geist ist. Wenn man solch eine Sache bespricht, dann ist es schon nötig, daß man nicht schroff sich auf den Gesichtspunkt der Wahrheit stellt; wenigstens bis zum Geiste hin war ein solcher Mensch wie Herman Grimm wahr -: weil er nichts wußte von der Art, wieman über den Geist denkt, machte er eine abwehrende Bewegung. Wäre er einer gewesen von den Phraseuren, die heute wieder als Propheten maskiert herumgehen und die Menschen bessern wollen, dann würde er geglaubt haben, er könne über den Geist mitreden, dann würde er geglaubt haben, wenn man sagt: Geist, Geist, Geist -, dann wäre damit irgend etwas gesagt, was auch entsprechen würde einem Inhalt, den man in seiner eigenen Seele hegt.

Unter denjenigen, die auch viel vom Geiste gesprochen haben in den letzten Jahrzehnten, ohne eine Ahnung zu haben von dem, was Geist ist, sind ja auch die Majorität der Theosophen zu verzeichnen. Denn eigentlich kann man schon sagen, daß unter allen geistlosen Schwätzereien, die in der neuesten Zeit gepflogen worden sind, die theosophischen die betrübendsten waren, auch die schlimmsten Früchte zum Teil getragen haben. Wenn man aber so etwas ausspricht wie dasjenige, was ich eben in bezug auf Herman Grimm gesagt habe, den ich dabei nicht als Persönlichkeit, sondern als Repräsentanten, als Typus unserer Zeit ins Auge fassen möchte, dann kann man doch die Frage stellen, wie es denn eigentlich möglich ist, daß ein solcher, das mitteleuropäische Leben ganz und gar repräsentierender Mensch keine Ahnung davon hat, wie man denken muß, wenn man über den Geist denkt. Damit ist nämlich Herman Grimm wirklich nur der Repräsentant für mitteleuropäisches Leben. Denn fassen wir eben gerade diejenige Kultur ins Auge, die ich gestern charakterisiert habe, die als die Kultur des Bürgertums, sagen wir im Jahre 1200 - approximativ natürlich — aufgeht und dann bis in den Goetheanismus hinein sich erstreckt, fassen wir gerade diese Kultur, diese glanzvolle Kultur ins Auge, dann muß uns als das Charakteristische dieser Kultur, die ja deshalb nicht geringer geschätzt zu werden braucht, erscheinen, daß sie im schönsten Sinne von demjenigen durchpulst ist, was man Seele nennt, daß ihr aber ganz und gar dasjenige fehlt, was man Geist nennen kann. Das muß man nur mit all der dazu nötigen tragischen Empfindung ins Auge fassen können, daß gerade dieser glanzvollen Kultur dasjenige fehlt, was man Geist nennen könnte. Nur muß man natürlich den Geist in dem Sinne nehmen, wie man den Geist zu nehmen lernt durch die anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft.

Ich komme immer wiederum auf diese repräsentative Persönlichkeit, Herman Grimm, zurück, denn so, wie er gedacht hat, so haben Tausende und aber Tausende von Gebildeten Mitteleuropas gedacht. Herman Grimm hat ein ausgezeichnetes Buch über Goethe geschrieben, das zusammenfaßt Vorlesungen, die er in den siebziger Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts an der Berliner Universität gehalten hat. Mit Bezug auf all dasjenige, was Herman Grimm über Goethe gesagt hat, ist es richtig, daß er eigentlich das Beste gesagt hat, was in umfassender Weise aus dieser Bildungsschicht heraus über Goethe gesagt worden ist. Und Herman Grimm hatte von seinem seelenvollen Standpunkte aus die Gabe, Menschen zu charakterisieren, aber auch die Gabe, Menschencharakteristiken in richtiger Weise aufzufassen, in richtiger Weise zu taxieren. In dieser Beziehung war er glänzend im Auffinden der Worte, um irgend etwas zu charakterisieren. Ich möchte nur an eines erinnern. Herman Grimm gehörte natürlich auch zu den Menschen, von denen ich gestern gesprochen habe, die mit Bezug auf die Nibelungenwildlinge in der Unwahrheit drinnen waren. Er war begeistert für Friedrich den Großen und hatte in seiner Seele eine ganz bestimmte Vorstellung, wie er sich Friedrich den Großen als einen germanisch-deutschen Helden vorzustellen habe. Nun hat der englische Historiker und Schriftsteller Macaulay eine Charakteristik Friedrichs des Großen gegeben, die selbstverständlich vom englischen Gesichtspunkte aus geschrieben ist. Herman Grimm wollte in einem Aufsatz über Macaulay klarmachen, wie eigentlich nur ein richtig empfindender Deutscher Friedrich den Großen verstehen und die Linien ziehen kann, durch die dieser Charakter gezeichnet wird, und die Macaulaysche Zeichnung von Friedrich dem Großen charakterisierte er sehr treffend, indem er sagte: Macaulay macht aus Friedrich dem Großen ein verzwicktes englisches Lordsgesicht mit Schnupftabak auf der Nase.

Nun, solch eine Charakteristik zu finden, das ist etwas, das bedeutet etwas, nämlich, daß man runden kann seine Ideen, seine Vorstellungen, daß diese Vorstellungen plastisch werden können. Solche Beispiele, aus denen anschaulich wird, wie solch ein Geist wie Herman Grimm treffend charakterisieren kann, könnte man viele geben, aber auch von anderen ähnlichen Geistern aus der ganzen Kulturzeit Mitteleuropas, die ich gestern charakterisiert habe. Aber sieht man gerade mit diesem guten Willen, der aus einer solchen Anerkennung Herman Grimms hervorgeht, seine Goethe-Monographie an, die weitaus die beste ist von denen, die geschrieben worden sind, was hat man dann für eine Empfindung? Man hat die Empfindung: Das ist etwas sehr Schönes, etwas außerordentlich Gutes - aber Goethe ist es nicht! Von Goethe ist eigentlich im Grunde genommen nur ein Schattenbild da, wie wenn man von einem Gebilde, das drei Dimensionen hat, nur ein Schattenbild, das auf die Wand geworfen wird und zwei Dimensionen hat, macht. Ich möchte sagen: Kapitel für Kapitel wandelt Goethe wie ein Gespenst vom Jahre 1749 bis 1832. Ein gespenstiger Goethe wird geschildert, nicht dasjenige, was Goethe war, was Goethe dachte, was Goethe fühlte, was Goethe wollte, sondern dasjenige, was wie ein Gespenst durch die Jahrzehnte, auf die ich eben gedeutet habe, hinwanderte und -wandelte.

Goethe selber hat nicht alles von dem, was in seiner Seele lebte, was in seiner Seele namentlich geistig lebte, auch geistig sich zum Bewußtsein gebracht. Das ist gerade heute das große Problem Goethe, dasjenige, was in Goethe geistig lebte, wirklich auf geistige Art ins Bewußtsein heraufzuholen, was Goethe noch nicht konnte, denn es war dazumal nicht möglich, etwas anderes als eine seelenvolle, nicht eine geistige Kultur zu haben. So hat auch Herman Grimm, der ganz in der Goethe-Tradition drinnen fußt, wenn er von dem Geist Goethes reden sollte, nur einen Schatten, ein Gespenst, ein Schema. Und es ist schon eine charakteristische Erscheinung, daß dasjenige, was man aus der heutigen Kultur hervorgehend als das Beste über Goethe und den Goetheanismus bezeichnen muß, nur ein Gespenst von Goethe gibt. Das ist schon eine bezeichnende Erscheinung.

Ja, woher rührt es denn aber, daß durch diese ganze glanzvolle Kulturentwickelung hindurch der Begriff, das Erleben, das Erfühlen des eigentlichen Geistes fehlt? Tastend haben Leute wie Troxler, wie auch manchmal Schelling, hingewiesen auf den Geist. Aber rein objektiv gesehen, muß man sagen: In dieser ganzen Kultur fehlt der Geist. Und weil der Geist fehlte, kannte man auch nicht die Bedürfnisse des Geistes, kannte man nicht die Lebensbedingungen des Geistes. Das ist wiederum etwas, was als tragische Empfindung hervorquellen kann aus der Wahrnehmung dieser Kulturströmung, daß man innerhalb ihrer die Lebensbedingungen des Geistes, auch die sozialen Lebensbedingungen des Geistes nicht wahrzunehmen, nicht zu empfinden vermochte. Daran liegt es aber, daß sich das mitteleuropäische soziale Leben durch die Jahrhunderte herauf entwickeln konnte und, weil es kein eigentliches Erlebnis vom Geiste hatte, auch nicht das Bedürfnis bekam, die Grundbedingungen dieses Geisteslebens dadurch zu erfüllen, daß man das Geistesleben emanzipiert, auf sich selber stellt und von dem Staatsleben absondert. Weil man den Geist nicht kannte, kannte man auch nicht die innersten Lebensbedingungen des Geistes, empfand daher nicht die Notwendigkeit - ich rede immer nur von diesen Gebieten, bei den anderen Gebieten der gegenwärtigen zivilisierten Welt empfand man es auch nicht, aber aus anderen Gründen -, den Geist auf sich selbst zu stellen, sondern ließ ihn verschmelzen mit dem, worinnen er sich nur in Fesseln entwickeln konnte: mit dem Staatswesen. 1200, sagte ich, ist der Zeitpunkt, in dem auch die Tätigkeit Walthers von der Vogelweide verzeichnet werden kann, der Zeitpunkt, in dem das geistige Leben Mitteleuropas in mächtigen Imaginationen dahinpulste, von denen die konventionelle Geschichte wenig verzeichnet. Dann gleitet dieses Geistesleben durch die Jahrhunderte weiter, nimmt aber eigentlich schon vom 15., 16. Jahrhundert an die Keime des Niedergangs in sich auf, und es stellt sich hinein in dieses Geistesleben Mitteleuropas die Begründung der Universitäten Prag, Ingolstadt, Freiburg, Heidelberg, Rostock, Würzburg und so weiter. Die Begründung dieser Universitäten, die sich so aussäen über das mitteleuropäische Leben, fällt fast ganz in ein Jahrhundert hinein. Mit diesem Denken, mit diesem Leben, das von den Universitäten ausstrahlte, wurde die Tendenz gebracht nach dem Abstrakten, nach demjenigen, das dann als das rein naturwissenschaftliche Denken vergöttert und verehrt wurde - vergöttert kann man natürlich nur vergleichsweise sagen und das heute so verheerend in die Denkgewohnheiten der Menschen eingreift.

Und mit diesem Leben wurde im Grunde genommen der ganzen gebildeten Bürgerwelt die Nuance gegeben. Wie war denn diese Nuance der ganzen gebildeten Bürgerwelt? Natürlich spricht da vieles mit, was nicht in jedem einzelnen, ich möchte sagen, quellenhaft wirkte, aber dessen Wirkung auf jeden einzelnen überging. Es wirkte das mit, daß ja in dieser Zeit immer mehr und mehr heraufkam die Empfänglichkeit für ein ganz fremdes Seelenleben, das gebildet wurde durch Träger der Bildung in diesem Bürgertum, das dann in Goethe und Herder und Schiller kulminierte. Das entwickelte ja außer dem, was in der eigenen Seele lag, im wesentlichen fremde Elemente, fremde Impulse.

Damit weise ich auf eine ungeheuer charakteristische Erscheinung hin. Die Seelen dieser Leute, die Träger des Bürgertums waren, sie suchten ja nach dem Geiste, dessen Begriff sie nicht einmal hatten. Aber wo suchten sie nach dem Geiste? In der griechischen Bildung. Sie lernten in ihren Mittelschulen griechisch, und was als Geistesinhalt in die Seelen floß, war griechischer Inhalt. Wenn man vom 13. Jahrhundert bis ins 20. Jahrhundert in Mitteleuropa vom Geist sprach, hätte man immer sagen müssen: Dasjenige, was einem die eingeimpfte griechische Bildung über den Geist beibrachte. Es entstand da kein eigenes Leben über den Geist. Griechische Bildung aber über den Geist war noch nicht die Bildung desjenigen Zeitraumes in der Menschheitsentwickelung, den wir den Zeitraum der Bewußtseinsentwickelung nennen. Der beginnt erst mit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts. So trug dieses Bürgertum in sich veraltete Bildung, griechische Bildung, und die gab ihm allein dasjenige, was der Grieche vom Geiste eigentlich fühlte und empfand.

Dasjenige aber, was der Grieche vom Geiste empfand, das war durchaus bloß die Seelenseite des Geistes. Darin liegt ja die Tiefe des Griechentums, daß der Grieche gewissermaßen gerade hinaufgelangte bis zur Empfindung des höchsten Seelischen. Das nannte er Geist. Gewiß, der Geist erglänzt herunter aus den Höhen. So wie ich ihn hier zeichne, erglänzt er aus den Höhen herunter, durchpulst das Seelische. Aber wenn man den Blick hinaufrichtet, so hat man das Seelische des Geistes.

Aber es wurde die Aufgabe des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums, sich zu erheben in den Geist selbst. Das konnte diese Kulturentwickelung noch nicht. Das ist viel wichtiger, als man gewöhnlich denkt. Denn das klärt auf über die ganze Art, wie neuzeitlich-mittelalterliche Bildung von dem Geist Besitz ergreifen konnte.

Was war denn notwendig, um zu einem Begriff des Geistes, zu einem inneren Erleben des Geistes im neuzeitlichen Sinne zu kommen? Gerade an einer solchen repräsentativen Erscheinung wie Herman Grimm ist es möglich zu studieren, was notwendig war, um in der neueren Zeit sich durchzuarbeiten zum inneren Erleben des Geistes. Dazu ist nämlich notwendig gewesen, wovon gerade ein so klassisch gebildeter Mensch wie Herman Grimm keine Ahnung hatte: naturwissenschaftliches Streben, naturwissenschaftliche Denkweise. Warum? Die naturwissenschaftliche Denkweise ist geistlos. Die naturwissenschaftliche Denkweise enthält gerade, wenn sie groß ist, nicht ein Stückchen Geist, gar nichts Geistiges. Alle naturwissenschaftlichen Begriffe, alle Begriffe von Naturgesetzen sind geistlos, weil sie nur Schattenbilder vom Geiste sind, weil im Bewußtsein, wenn man etwas weiß von Naturgesetzen, nichts vom Geist anwesend ist. Man kann dann zwei Wege gehen. Man kann sich der Naturwissenschaft hingeben, wie viele sich ihr heute hingeben, kann stehenbleiben bei dem, was die Naturwissenschaft gibt; dann wird man geistlos. Man kann gerade dadurch ein großer Naturforscher sein, aber man muß geistlos sein. Das ist der eine Weg.

Der andere Weg ist der, daß man die Geistlosigkeit der Naturwissenschaft gerade da, wo sie in ihrer Größe aufgetreten ist, innerlich tragisch erlebt, daß man mit seiner Seele untertaucht in das Naturwissen. Wenn man mit seiner Seele untertaucht in dasjenige, was an abstrakten Naturgesetzen, die sehr interessant sind und in manches hineinleuchten, gefunden wurde, die aber geistlos sind, wenn man untertaucht in die Naturgesetze der Chemie, der Physik, der Biologie, die am Seziertisch gewonnen werden und schon dadurch andeuten, wie sie von dem Lebendigen nur das Tote geben, wenn man versucht, mit dem nicht nur in menschlichem Hochmut als einer Erkenntnis zu leben, sondern wenn man versucht zu fragen: Was gibt das der menschlichen Seele? - dann ist es erlebt! Das gibt nichts von Geistlosigkeit. Das ist ja auch das tragische Problem Nietzsche, der gerade an dem Empfinden der Geistlosigkeit der modernen naturwissenschaftlichen Bildung in seinem Seelenleben zerklüftet und zerrissen wird.

Und dann kann die Reaktion eintreten im Inneren der Seele. Dann kann man erleben, wie im Anschauen der Natur der Geist ganz stumm, ganz schweigsam bleibt, nichts sagt. Die Seele bäumt sich auf, nimmt ihre Kraft zusammen, sucht dann aus dem Inneren heraus den Geist zu gebären. Das kann nur in dem Zeitalter geschehen, in dem die unmittelbare Naturanlage bei solchen Menschen wie denen der mitteleuropäischen bürgerlichen Bildung nicht vorhanden sind, und an die herantritt naturwissenschaftliche Kultur. Dann, wenn sie nicht innerlich tot sind, wenn sie innerlich lebendig sind, dann rafft sich in ihrem Inneren der Impuls des Geistes selbst auf. An dem Toten muß seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts der Geist geboren werden, wenn der Geist in das menschliche Seelenleben überhaupt hereintreten soll. Daher werden diejenigen, die nur mit der klassischen Bildung jenen Nachduft des Griechischen ausleben, der das Seelenhafte des Geistes durch des Menschen eigene Seele durchpulsieren läßt, noch befriedigt sein können in dem inneren Erleben, das ihnen gibt die Empfindung dieses griechischen Seelen-Geistes, dieser griechischen Geistes-Seele. Diejenigen aber, die genötigt sind, mit der Naturwissenschaft innerlich lebendig Ernst zu machen und ihren Tod, ihr Leichnamhaftes zu empfinden, die werden dann den Geist in ihrer Seele erstehen lassen.

Man muß schon, um in der neueren Zeit ein wirkliches unmittelbares Erlebnis vom Geist zu haben, nicht nur in Laboratorien gewesen sein und dort Zyansäure oder Ammoniak gerochen oder im Seziersaal gewesen sein und die frischen Präparate der Leichen angeschaut haben, man muß aus der ganzen naturwissenschaftlichen Richtung heraus den Leichenduft verspürt haben, um aus dieser Empfindung heraus zu dem Licht des Geistes zu kommen. Das ist ein Impuls, der in neuerer Zeit aufleben muß. Das ist eine der Prüfungen, die die Menschen durchmachen müssen in der neueren Zeit. Die Naturwissenschaft ist viel mehr dazu da, die Menschen zu erziehen, als Wahrheiten über die Natur zu vermitteln. Nur der naive Mensch kann glauben, daß in irgendeinem Naturgesetz, das die gelehrten Naturwissenschafter verzeichnen, eine innerliche Wahrheit ist. Nein, die ist nicht drinnen; aber zur Erziehung der Menschen zum Geiste ist gerade die geistlose Naturwissenschaft da. Das ist eine von jenen Paradoxien der weltgeschichtlichen Entwickelung der Menschheit.

So leuchtete erst in der neuesten Zeit - in der Zeit, die den Goetheanismus ablöste, denn da kam erst die eigentliche Leichenhaftigkeit, das eigentliche Tote der Naturwissenschaft herauf — der Geist, allerdings nur für diejenigen Menschen, die sein Licht empfangen wollten. Und so schützten sich die Menschen bis zur Goethe-Zeit und noch Goethe selber gegen das Verheerende eines in den Staatszwang hineingefesselten Geisteslebens dadurch, daß sie im Grunde genommen das griechische Geistesleben verarbeiten, das ja dem modernen Staate nicht angehörte, weil es überhaupt der modernen Zeit nicht angehörte. Die Abtrennung des Geisteslebens von dem Staatsleben wurde surrogativ dadurch besorgt, daß man ein fremdes Geistesleben, das griechische, in sich aufnahm. Dieses griechische Geistesleben, das war es eben, welches die innere Geistleerheit der neueren europäischen Welt überhaupt zudeckt. Das war auf der einen Seite.

Auf der anderen Seite empfand man aber auch nicht die Notwendigkeit der Trennung des Wirtschaftslebens von dem Rechtsleben, von dem Leben des eigentlichen politischen Staates. Warum nicht? Dem Wirtschaftsleben kann sich ja der Mensch niemals entziehen. Dafür sorgt, trivial ausgedrückt, eben der Magen. Es ist nicht möglich, daß die Menschen solche Kataklysmen auf dem Gebiete des Wirtschaftslebens unbemerkt erleben, wie sie unbemerkt erlebt werden auf dem Gebiete des Rechtslebens und des Geisteslebens. Das Wirtschaften war also da, und dieses Wirtschaften entwickelte sich auch in einer sehr geraden Linie. Das, was ich gestern angedeutet habe, die Verwandlung der alten, undurchdringlichen Wälder in Wiesen und Kornfelder mit alldem, was als wirtschaftliche Konsequenz davon dasteht, das entwickelte sich in sehr gerader, regulärer Linie. Das war eine sehr gerade Strömung. Aber es fiel in das Erleben dieses Wirtschaftlichen hinein wiederum ein Fremdes, das eigentlich schon länger stark war in der mitteleuropäischen Seele als das Griechische: Es fiel hinein das Lateinisch-Romanische. Und aus dem Lateinisch-Romanischen stammt alles, was sich auf Staats- und Rechtsleben, auf Politik bezieht. Und das ist ja diese merkwürdige Inkongruenz, wiederum etwas, was von der Geschichte der Zukunft scharf wird betont werden müssen, was aber übersehen wird von der parteiischen, für den Materialismus namentlich parteiischen konventionellen Geschichtsschreibung der unmittelbaren Vergangenheit: daß gewisse wirtschaftliche Vorstellungen, gewisse wirtschaftliche Hantierungen des Lebens, ein gewisses Nehmen des Wirtschaftens im Leben sich in gerader Linie aus den sozialen Verhältnissen fortentwickelte, die Tacitus beschreibt für das erste Jahrhundert der germanischen Welt nach der Begründung des Christentums. Aber diese wirtschaftlichen Denkgewohnheiten haben sich nicht ungehindert fortentwickelt. Da schlug die politische Denkart des Romanisch-Lateinischen hinein und infizierte sie ganz und gar und hielt auseinander die ursprünglichen europäischen Wirtschaftsgewohnheiten und das politische Rechtsleben. Und so waren künstlich nebeneinander, scheinbar geteilt, so daß die Teilung eine Maske war, Wirtschaftsleben und politisches Leben, weil das politische Leben die Nuance des Lateinisch-Romanischen und das Wirtschaftsleben die Nuance des Altgermanischen hatte. Weil zwei einander fremde Schichtungen ineinanderlebten, empfand man, daß das nicht zusammengehörte und schmolz äußerlich ineinander, aber man war zufrieden, weil man es ja doch innerlich, seelisch, als getrennt erlebte. Man muß nur einmal die Geschichte des Mittelalters und der neueren Zeit studieren, dann wird man sehen, wie eigentlich diese Geschichte in Wahrheit in Mitteleuropa ein fortwährendes Aufmucken, ein fortwährendes Sich-Wehren, eine fortwährende Opposition ist der wirtschaftlichen Verhältnisse, die aus den alten Zeiten heraufgebracht worden sind, gegen das Staatswesen, gegen den juristischen Romanismus. Man sieht förmlich, wenn man die Dinge bildlich sieht, wie durch die Köpfe der Verwaltungsbeamten der Romanismus als Jurisprudenz eindringt in die Menschen. Da dringt auch viel vom Romanismus gerade in die verfallenden Nibelungenwildlinge hinein. «Graf» hängt mit grapho, schreiben zusammen, das habe ich schon einmal gesagt. Da dringt der Romanismus hinein. Wie ich sagte: man kann es förmlich im Bilde sehen, wie die Bauern, die erfüllt sind von diesem wirtschaftsorientierten Denken, entweder die Fäuste in den Taschen ballen oder mit den Dreschflegeln sich gegen dieses Romanische, Juristische aufbäumen. Das geschieht natürlich nicht immer so äußerlich habhaft. Aber im ganzen moralischen Treiben, wenn man die Geschichte wirklich betrachtet, ist es schon so. So war das, was aus den Keimen der mitteleuropäischen Welt sich heraufentwickelte, durchsetzt — ich charakterisiere bloß, kritisiere nicht, denn alles, was da sich vollzogen hat, hat auch seinen Segen gebracht und war notwendig, war in der historischen Entwickelung in Mitteleuropa nicht zu umgehen -, es war durchsetzt, infiziert von dem juristisch-politischen Romanismus und dem griechischen Humanismus, von dem griechischen Geist-Seele-Begriff, Seelen-Geist-Begriff. Und erst als einschlug das moderne internationale wirtschaftliche Element mit allem, was es im Gefolge hatte, da war es eigentlich nicht mehr möglich, die alten Dinge aufrechtzuerhalten. Man konnte sehr gut klassisch gebildet sein und ein Ignorant sein in bezug auf die naturwissenschaftliche Bildung der neueren Zeit, aber man war dann eben trotzdem innerlich-seelisch ein Rückschrittler. Man konnte nicht mit seiner Zeit gehen, wenn man bloß klassisch gebildet war, wenn man nicht eindrang in dasjenige, was die naturwissenschaftliche Bildung der neueren Zeit gab. Und war man naturwissenschaftlich gebildet, war man vertraut mit dem, was die Naturwissenschaft der neueren Zeit bringen wollte, so konnte man wahrhaftig nur Kulturkrankheiten, Kulturscharlach, Kulturmasern durchmachen, wenn man sich bekanntmachte mit dem, was innerhalb des Zeitraumes, von dem ich Ihnen gesprochen habe, aus dem alten juristischen Romanismus geworden war. Im alten Imperium Romanum war dieser juristische Romanismus am Platze. Dann hatte sich dieses romanische Juristentum, die Res publica, beziehungsweise die Anschauungen darüber, vom alten Romanismus her, ebenso wie auf der anderen Seite die Nibelungenwildheit, durch die mitteleuropäische Bildung hindurch fortgepflanzt.

Ja, meine lieben Freunde, Kulturscharlach, Kulturmasern bekommt man, wenn man die Jurisprudenz nicht bloß abstrakt denkt, sondern mit gesunden naturwissenschaftlichen Begriffen durchtränkt sich einläßt auf dieses Etwas, das als moderne Juristerei in der Literatur und in der Wissenschaft figuriert.

Einen gewissen Höhepunkt hat das erreicht, als einer, der eigentlich geistreich war, wie Rudolf von Ihering, schon gar nicht mehr wußte, wie er zurechtkommen sollte mit diesen Jammerbegriffen von Jurisprudenz der neueren Zeit. Grotesk wurde das Buch, das Ihering schrieb über den «Zweck im Recht», weil ein Mensch, der ein bißchen sich hineingefunden hatte in naturwissenschaftliches Denken, diese sprachlichen Begriffe, die er hatte, nun auf die Jurisprudenz anwenden wollte, so daß ein Wechselbalg des menschlichen Denkens herauskam. Es ist tatsächlich ein Martyrium für ein gesundes Denken, sich in die neuere juristische Literatur einzulassen, denn man hat alle Augenblicke das Gefühl: das geht wie Regenwürmer durch das Gehirn. Es ist schon so, ich schildere nur die imaginativen Wahrnehmungen.

Man muß den Mut haben, auch diese Dinge gehörig ins Auge zu fassen, um einzusehen, daß wir an dem Zeitpunkt angekommen sind, wo nicht nur gewisse Einrichtungen, sondern wo die Denkgewohnheiten der Menschen metamorphosiert, umgestaltet werden müssen, wo die Menschen beginnen müssen, über manche Dinge anders zu denken. Dann erst werden die sozialen Einrichtungen in der Außenwelt unter dem Einfluß der menschlichen Denkgewohnheiten und Empfindungsgewohnheiten so werden können, wie es diese furchtbaren, schreckhaft sprechenden Tatsachen fordern.

Es ist schon ein gründliches Umlernen mit Bezug auf allerwichtigste Dinge der modernen Menschheit notwendig. Weil aber diese moderne Menschheit insbesondere in der Zeit, von der ich gestern sprach, 1200 anfangend, mit dem Goetheanismus schließend, solche wie Regenwürmer durch das Gehirn ziehende Gedanken in sich aufnahm und das nicht bemerkte, geschah es, daß jene Lässigkeit, jene Passivität des Denkens eintrat, die eine charakteristische Erscheinung der neueren Zeit ist. Diese charakteristische Erscheinung der neueren Zeit ist ja das Nichtvorhandensein des Willens im Element des Denkens. Die Menschen lassen ihre Gedanken über sich kommen, sie geben sich ihnen hin, sie haben die Gedanken am liebsten als Instinkt. Auf diese Weise kann man niemals zum Geiste dringen. Man kann nur zum Geiste dringen, wenn man wahrhaft objektiv den Willen in das Denken hineinlegt, so daß das Denken eine Handlung wird wie irgendeine andere Handlung, wie Holzhacken. Haben denn die modernen Menschen wirklich das Gefühl, daß man beim Denken ermüdet? Das haben sie nicht, weil das Denken für sie keine Tätigkeit ist. Die modernen Menschen haben das Gefühl, daß man beim Holzhacken ermüdet. Daß aber für den, der nicht mit Worten, sondern mit Gedanken denkt, ebenso nach kürzerer Zeit als beim Holzhacken jene Ermüdung kommt, die ganz genau ebenso ist wie beim Holzhacken, daß man nicht weiter kann, das haben die modernen Menschen nicht, das erleben die modernen Menschen nicht. Das muß erlebt werden, sonst wird nicht von der modernen Menschheit in ihrem Zusammenleben jener Durchgang vollbracht werden können, von dem ich nun gestern und vorgestern sprach, jener Durchgang von der sinnlichen in die übersinnliche Welt. Sie wissen, man braucht nicht hellsehend zu werden, um in die übersinnliche Welt überzugehen, sondern man braucht nur durch den gesunden Menschenverstand zu begreifen, was aus der übersinnlichen Welt heraus erforscht werden kann durch einen Hellseherweg. Nicht ist notwendig, daß die ganze Menschheit hellsehend wird, aber notwendig ist, was für jeden Menschen möglich ist: mit dem gesunden Menschenverstand die Einsichten in die geistige Welt zu bekommen. Nur auf diesem Wege kann Harmonie in die moderne Seele hineinkommen, denn diese Harmonie in den modernen Seelen geht gerade aus den Bedingungen der Zeitentwickelung heraus verloren. Wir sind heute einmal an einem Punkt, namentlich der europäischen Entwickelung mit ihrem amerikanischen Anhange und ihren asiatischen Vorposten, angekommen, in der von den Geistern der überirdischen Welt real das Fazit gezogen wird zwischen dem, was in älteren Zeiten gang und gäbe war mit Bezug auf das Nebeneinander der Bevölkerungen auf der Erde, und dem, was in späterer Zeit gang und gäbe geworden ist.

Wie waren in ältester Zeit die Völker auf der Erdkugel angeordnet? Bis zu einem gewissen Zeitpunkte, der eigentlich nicht weit vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha zurückliegt, da war alles, was an Völkerkonfiguration auf der Erde bewirkt worden ist, von oben herunter bedingt, dadurch bedingt, daß die Seelen sich einfach senkten aus dem Kosmos, aus der geistigen Welt in die Körper, welche an einem bestimmten Territorium lebendig waren in der physischen Menschheitsentwickelung. So waren in Griechenland in den älteren Zeiten aus den physiologischen, geographischen, klimatischen Verhältnissen heraus gewisse Menschenleiber da, auf der italischen Halbinsel gewisse Menschenleiber da. Die Eltern brachten zwar die Kinder zur Welt, doch kamen die Seelen von oben, waren nur ganz von oben bestimmt und griffen sehr tief in die ganze Konfiguration des Menschen, in seine äußere körperliche Physiognomie ein.

Dann kamen die großen Völkerwanderungen. Menschen wanderten in verschiedenen Strömungen über die Erde. Die Rassenmischungen traten ein, Völkermischungen traten ein. Dadurch kam in ausgiebigem Maße das Vererbungselement im irdischen Leben zur Geltung. Da lebte an einem bestimmten Orte der Erde eine Bevölkerung, die wanderte an einen anderen Ort; so lebten in gewissen Gegenden des Kontinents die Angeln und die Sachsen, die wanderten nach den englischen Inseln aus. Das ist solch eine Völkerwanderung. Nun sind doch die Nachkommen der Angeln und der Sachsen in physischer Vererbung abhängig von dem, was sich vorher auf dem Kontinente entwickelte; sie sehen so aus in bezug auf ihre Physiognomie, mit Bezug auf ihre Hantierungen und so weiter. Dadurch kommt etwas hinein in die Entwickelung der Menschheit, was horizontal abhängig ist. Während früher die Verteilungen der Menschen über die Erde nur abhängig waren von der Art und Weise, wie sich die Seelen inkarnierten, heruntersenkten, wurde jetzt mitbestimmend dasjenige, was an Wanderungen, an Strömungen auftrat. Aber mit Bezug darauf ist gerade um die Wende des 14. zum 15. Jahrhundert ein neues kosmisch-geschichtliches Element aufgetreten, ein neuer kosmisch-geschichtlicher Impuls. Es war eine Zeit hindurch so, daß eine gewisse Sympathie bestand zwischen den Seelen, die herunterkamen aus der geistigen Welt, und den Körpern, die unten waren. Also konkret gesprochen: Auf den englischen Inseln, über den englischen Inseln senkten sich Seelen, die sympathisch berührt waren von der Gestaltung der Leiber, die als Nachkommen der Angeln und der Sachsen auf der britischen Insel lebten. Diese Sympathie hörte mit dem 15. Jahrhundert immer mehr und mehr auf, und die Seelen richten sich seit diesem 15. Jahrhundert nicht mehr nach den Rasseneigentümlichkeiten, sondern wiederum nach den geographischen Verhältnissen, nach dem Klima, nach dem, ob da unten Ebene, ob da Gebirge ist. Die Seelen kümmern sich seit dem 15. Jahrhundert immer weniger darum, wie die Menschen rassengemäß aussehen; sie richten sich mehr nach den geographischen Verhältnissen. So daß es heute in der über die Erde hin ausgebreiteten Menschheit etwas gibt, wie einen Zwiespalt zwischen dem angeerbten Rassenmäßigen und dem Seelischen, das aus der geistigen Welt kommt. Und würden die heutigen Menschen mehr ihr Unterbewußtes wirklich ins Bewußtsein bringen können, dann würden sich heute die wenigsten Menschen - wenn ich mich trivial ausdrücken darf - in ihrer Haut wohlfühlen. Die meisten Menschen würden heute sagen: Ich bin doch heruntergestiegen auf die Erde, um in der Ebene zu leben, unter Grünem oder über Grünem, um dieses oder jenes Klima zu haben, und im Grunde genommen ist es mir gar nicht so besonders wichtig, daß ich ein romanisch oder ein germanisch aussehendes Gesicht trage.

Ja, es sieht schon einmal paradox aus, wenn man diese Dinge, die von eminentester Wichtigkeit sind für das Menschenleben heute, im Konkreten schildert. Pantheistisch von Geist, Geist, Geist reden auch die Menschen, die gute Lehren geben, die sagen, man solle sich vom Materialismus abwenden und wiederum dem Geiste zuwenden; das schockiert die Leute heute nicht. Aber wenn man in dieser Konkretheit spricht über den Geist, dann lassen sich das die Leute heute noch nicht recht gefallen. Aber so ist es schon. Und Harmonie muß wiederum gesucht werden zwischen, ich möchte sagen, einer geographischen Prädestination und einem Rassenelemente, das sich über die Erde hin breitet. Daher kommen die internationalen Neigungen in unserer Zeit, daß die Seelen sich nicht kümmern mehr um das Rassenmäßige.

Ich habe dasjenige, was jetzt geschieht, einmal verglichen mit einer vertikalen Völkerwanderung, während früher eine horizontale Völkerwanderung war. Der Vergleich ist nicht bloß eine Analogie, der Vergleich ist auf Grund der Tatsachen des geistigen Lebens ausgesprochen.

Zu alldem muß hinzugenommen werden, daß der Mensch einfach durch die geistige Entwickelung der neueren Zeit im Unterbewußten immer geistiger wird, und daß eigentlich jene materialistische Gesinnung, die im Oberbewußtsein auftritt, immer mehr widerspricht dem, was der Mensch in seinem Unterbewußtsein hat. Um das einzusehen, dazu ist allerdings notwendig, auf die dreifache Gliederung des Menschen selbst noch einmal einzugehen.

Diese dreifache Gliederung empfindet zunächst der heute nur dem Sinnlich-Physischen zugewendete Mensch so, daß er sich sagt: Ich nehme wahr durch meine Sinne, die sind durch den ganzen Körper verteilt, aber hauptsächlich im Kopfe zentralisiert; ich habe im Wahrnehmen das Nerven-Sinnesleben. Aber weiter kommt der Mensch heute nicht. Er kann dann allenfalls beschreiben, daß der Mensch atmet, und daß das Leben von dem Atmen in die Herzbewegung, in die Blutpulsation übergeht. Aber viel weiter kommt der Mensch nicht. Den Stoffwechsel studiert man ja sehr genau, aber nicht als ein Glied des dreigliedrigen Menschen; man betrachtet ihn eigentlich als den ganzen Menschen. Man braucht ja nicht so weit zu gehen, wie jener naturwissenschaftliche Denker, der gesagt hat: Der Mensch ist, was er ißt -, aber im Ganzen ist die naturwissenschaftliche Gesinnung ziemlich stark davon durchdrungen, daß der Mensch ist, was er ißt. In Mitteleuropa wird er ja bald dasjenige sein, was er nicht ißt!

Diese Dreigliederung des Menschen, die sich hineinfinden will in eine soziale Dreigliederung, weil sie immer deutlicher und deutlicher auftritt, die tritt auch differenziert über die Erde hin auf. Der Mensch ist wahrhaftig nicht bloß dasjenige, was innerhalb seiner Haut eingeschlossen ist. Es entsprach schon einer tiefen Empfindung, als ich in meinem ersten Mysterium «Die Pforte der Einweihung» Capesius und Strader allerlei Dinge verrichten ließ und darauf aufmerksam machte, daß das, was da auf der Erde hantiert wird von den Menschen, entspricht kosmischen Vorgängen draußen im Weltenall. Bei jedem Gedanken, den wir fassen, jeder Handbewegung, die wir tun, bei allem, was wir sagen, ob wir gehen, stehen, oder was wir sonst vollbringen, da geht immer etwas im Kosmos vor. Um diese Dinge wirklich zu durchleben, fehlen dem heutigen Menschen die Wahrnehmungsmöglichkeiten. Der Mensch weiß heute nicht - man kann es auch nicht verlangen, und es ist paradox, so zu reden, wie ich jetzt rede -, wie er sich ausnehmen würde, wenn er nur vom Monde aus meinetwillen beobachten würde, wie es auf der Erde hier zugeht. Da würde er sehen, daß das Nerven-Sinnesleben noch etwas ganz anderes ist, als dasjenige, was man davon weiß im physisch-sinnlichen Dasein. Das Nerven-Sinnesleben, also dasjenige, was vorgeht während Sie sehen, während Sie hören, riechen, tasten, das ist Licht im Kosmos, das Ausstrahlen von Licht in den Kosmos. Von Ihrem Schauen, von Ihrem Fühlen, von Ihrem Hören erglänzt die Erde in den Kosmos hinaus.