The New Spirituality

and the Christ Experience of the Twentieth Century

GA 200

23 October 1920, Dornach

Lecture III

Yesterday I drew attention again, but from a different point of view to the one we have taken for some time in the past, to the differentiation that exists among the peoples of the present civilized world. I indicated how the individualization of the human being in the fifth post-Atlantean epoch is guided by spiritual beings: how, on the one side, certain beings interfere through individuals of the West—beings that have progressed in an irregular way, that are more advanced than humanity, but for their own interests incarnate into human beings in order to work against the true impulse of the present, the impulse of the threefolding of the social organism.

I also drew attention to how, in a different way, we find in the East that certain beings, that had their real significance in the far distant past, but wish now to work into and to influence human lives, assert themselves; not, indeed, through human beings themselves, but by appearing to them. We spoke of how these beings influence Eastern human beings, be it more or less consciously, by virtue of the particular soul-configuration of the people living in the Orient; by working as imaginations into the consciousness of certain human beings of the East—perhaps by working during sleep into the human 'I' and astral body—and then asserting themselves, without the people realizing it, in the after-effects during waking. And in this way they bring in everything they wish to pit against the normal progress of humanity in the East. Thus we can say: For a long time in the West a kind of earth-boundness has, in a certain sense, been prepared in such human beings as I described yesterday, who are dispersed there, and who take leading positions, particularly in sects and in secret societies and the like. In the East there are also certain leading personalities who, under the influence of beings from the past who appear to them in imaginations, put into practice in present cultural development what these beings introduce. If one wants to understand how the human beings of the European Centre are wedged in, as it were, between the West and the East one must look more closely into the underlying spiritual conditions and at everything in the physical-sense world that expresses itself out of these spiritual conditions.

I have drawn your attention, from the most varied points of view, to how the life of the ancient Orient was, in the main, a spiritual life; how the human being of the ancient Orient had a highly developed spiritual life that flowed from a direct perception of the spiritual worlds; how this spiritual life then lived on as a heritage; how it existed in Greece, primarily as artistic beauty but also as a certain insight; and how already in Greece there mingled in with it what then became Aristotelianism, what was already intellectual, dialectical thinking. So what came from oriental wisdom penetrated then into Western civilization, and, with the exception of what stems from natural science and what can stem from the modern anthroposophically-oriented spiritual science, everything that exists in Western civilization as spiritual life is basically an inheritance from the ancient Orient. But this spiritual life is, in fact, completely decadent. This spiritual life is of such a nature that it lacks strength, lacks impetus. The human being is, to be sure, guided to the spiritual world through it, but can no longer find a link between what he believes about the spiritual world and what happens here on earth. This shows itself most strongly in Anglo-Saxon Puritanism, in which a faith, completely estranged from the world, has secured itself a place alongside worldly activities. It is directed towards entirely abstract spiritual regions, and basically does not take the trouble to confront and come to terms with the external physical world of the senses.

In the Orient even completely worldly aspirations—aspirations of the social life—take on such a spiritual character that they have the appearance of religious movements. And the momentum of Bolshevism in the East, for example, is to be traced to the fact that it is actually conceived by the people of the East, even by the Russian people, as a religious movement. The impetus of this social movement in the East lies not so much in the abstract concepts of Marxism, but essentially in the fact that its bearers are regarded as new Saviours, as the continuers so to speak, of earlier religious-spiritual striving and life.

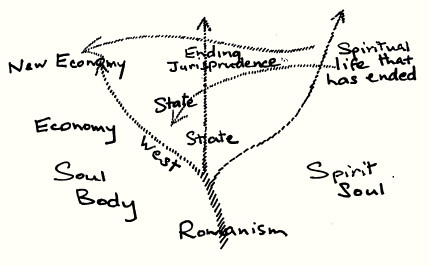

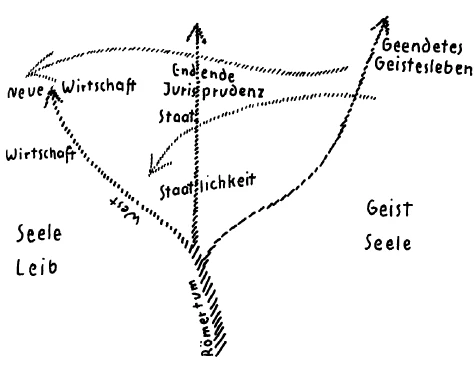

From the Roman culture, and even already from the Hellenistic culture there developed, as we know, what took hold of the human beings of the Centre most of all—the dialectical element, the element of political-legal-militaristic thinking. And one can only understand the role played by what then developed out of the Roman culture when one considers at first that all three branches of human experience—the experience of the spiritual, the experience of economics, the experience of the civic-political in which Rome developed to particular splendour and in which the Roman Empire arose—were mixed up and at cross-purposes in much the same way that is the case today over basically the whole civilized world. Rome ended in complete decadence, brought about essentially by the fact that in the Roman Empire the untenable situation arose which always arises when these three human activities—spiritual life, political life and economic life—get mixed up chaotically with one another. It can truly be said that the Roman Empire and particularly the Byzantine Empire were a kind of symbol of the decay of the fourth post-Atlantean epoch, the Graeco-Roman epoch. We need only consider that of 107 Eastern Roman Emperors only 34 died in their beds! The others were either poisoned or maimed and died in prison, or left prison to join monasteries or the like. And out of the decline of the Roman world in Southern Europe developed something which then streamed northwards in three branches (see diagram).

Here, to begin with, we have the Western branch. I shall not go today into the historical details of what developed throughout the Middle Ages out of the older development of humanity, but I should like to draw your attention to a few things. The characteristic phenomenon of Western development, of development in the more southerly Western regions to begin with, is that Roman culture spreads as a sum-total of people towards Spain, over present-day France, and also over a part of Britain. These were Roman people who developed in this direction. But all this was interpenetrated by what entered into these Roman peoples through the migrations of Germanic tribes of various kinds.

And here we find a singular phenomenon. We find that Germanic peoples force their way into the Roman element and that something then arises there which can only be characterized by saying: Human beings of Germanic nature penetrated into the Roman element. Rome as such, the Roman human being, went under. But what remained of the Roman culture—what took shape, that is, through the intersection of these two lines (see diagram) and formed the Spanish, the French and also a part of the British population—is essentially Germanic blood overlain by the Roman language-element. It can only really be understood by looking at it in this way. This human being, as regards his soul-configuration, his direction of perceiving, feeling and willing, is descended from what, as the Germanic element, moved in the stream of the migrations from East to West. But it is a peculiarity of this Germanic element that when it comes up against a foreign language element—and there is always a culture embodied in a language—it dissolves into it, assumes it. It grows into this foreign language as though, if I may put it so, into a garment of civilization. What lives in the West of Europe as the Latin race has, fundamentally, nothing in it of Latin blood. But it, has grown into what, embodied in the language, has streamed up to it there. For it lay in the nature of the Latin, of the Roman, element to assert itself beyond the purely human in the course of world evolution. This is why the concept of one's will and testament first arose in Rome—the assertion of egoism beyond death. The wish to extend one's will beyond death led to the concept of the will and testament. Thus, too, the continuance of the language worked an beyond the continuance of the human element in the people.

And other things, too, were preserved apart from the language. Thus, in this stream here (see diagram), there was preserved for the West the ancient traditions of the different secret societies, (the significance of which I have frequently referred to in the course of the past years). These are traditions stemming from the fourth post-Atlantean epoch, from the Graeco-Roman times, which, to be sure, are borrowings from the East—from manuscripts—but have passed thoroughly through the Roman, the Latin, culture. Thus, in a certain respect, in so far as Western humanity is submerged in the Roman language-element that has endured beyond the actual Roman people, one finds the human being in the cloak of a foreign civilization. One also has the human being in a foreign cloak in as much as in the ancient Mystery truths—which have become abstract and which, in the ceremonies and ritual of the Western societies, have become more or less empty forms—one has something in which the human element is submerged and which is capable of touching it.

Now, if other conditions are particularly favourable, then this situation [of the human being being penetrated from without by everything that arises from language] provides a foothold for beings of the kind I described yesterday, enabling them to incarnate into the human being. But particularly favourable for this incarnating process is the Anglo-Saxon element. This is because it was a thoroughly Germanic people that moved across to the West and because the Germanic element has been strongly preserved in these human beings who have permeated themselves to a lesser degree with the Roman element than have those whom we call the Latin peoples. Thus there is a far more malleable balance present here in the Anglo-Saxon race, and because of this those beings which incarnate here have far greater freedom of action, far greater room to move in as it were. In the Latin countries proper they would be extremely constricted. Above all, however, one must be clear that what can then manifest in individual, personalities depends an configurations of folk psychology such as these. Although Puritanism certainly represented an abstract sphere of belief, this freer element was pre-eminently suited to adopting and Anglo-Saxon developing natural-scientific thinking and to forming a concept of the world and of life based upon it. The whole humanity of the human being, certainly, is not engaged here—only part of man's being is engaged through the incorporation of languages, through the incorporation of other elements of the human being—which makes it possible for such beings as I described yesterday to incarnate in these people.

Let me state expressly that what I am talking about at the moment concerns only certain single individuals who are scattered amongst the mass of other human beings. It does not refer to nations; it does not refer to the vast masses of people but only to single individuals who, however, have an extraordinarily strong position of leadership in those regions I have mentioned. What is primarily taken hold of in the West by these beings, who then secure for the human body in which they incarnate a certain position of leadership, is the body and soul—not the spirit to which less attention is paid.

Where, for example, does the whole magnificent but one-sided elaboration of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution come from?1 Charles Darwin (1809–1882). It comes from the fact that, in Charles Darwin, body and soul, and not the spirit, were particularly dominant. He, therefore, also considers the human being only according to body and soul and ignores the spirit and that which lives into the soul from the spirit. Anyone who looks without prejudice at the results of Darwin's research will understand that something was present there which was unwilling to consider the human being from the aspect of his spirit. 'Spirit' was only taken from more recent science—which is international. But what coloured his whole conception of the human being was the emphasis put on body and soul and the disregard for the spirit. In fact, the most faithful pupils of the Ecumenical Council of 8692 In the year 869, the 8th Ecumenical Council of Constantinople under Pope Hadrian II, decreed, against Photios, that the human being has a rational and intellectual soul—unam animam rationabilem et intellectualem—so that it was no longer permitted to speak of a separate spiritual principle in the human being. The spiritual was henceforth seen more as a quality of the soul. were the people of the West. Initially they left the spirit out of consideration, taking body and soul in the way they are represented particularly in Darwin's descriptions and simply put an artificial head on top as spirit, in the materialistic way of thinking that arises out of science. And because people were ashamed, as it were, to make a universal religion out of natural science, there remained, as an external appendage, leading an abstract existence of its own, what lived on as Puritanism and the like but which had no connection with the real world culture. We see how here, in a certain sense, body and soul are overwhelmed by an abstract scientific spirit which we can clearly observe even into the present.

But let us suppose that something else happened. Let us suppose that what lives on in language—what lives on in the spiritual world of forms of the fourth post-Atlantean epoch—were to be stronger. What would arise then? There would arise a strong fanatical rejection of the modern spirit; and rather than emphasizing that an 'artificial head' of natural-scientific concepts be superimposed on the bodily-soul element, the old traditions would be superimposed: in fact only the physical and the soul element would really be cultivated. We could then imagine that, in such a crude way, some individual might work on everything that is only body and soul and devise a doctrine that wished only to consider body and soul; which outwardly did not use science for this but rather the external part of a revelation from an earlier time carried over into a later one. And then we have Jesuitism, we have Ignatius of Loyola.3 Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556), the founder of the Jesuit Order in 1534. We may say that, just as minds like Darwin arose of necessity from Anglo-Saxondom, so from later Romanism there arose Ignatius of Loyola.

The characteristic of the human beings of the West, of whom we have to speak here, is that through them those spiritual beings I described yesterday make themselves felt in the world. In the East this is different. A different stream moves towards the East (see diagram). But we will first look at something that goes out from ancient Rome as a second stream—which does not carry the language but which carries the whole trend of the soul-constitution, the trend of thought. The language goes more to the West and, through this we get all the phenomena of which I have just spoken. The direction of thought, on the other hand, moves more towards the centre of Europe. But it unites there with what lies there with the essential Germanic element; namely, a certain wish to be one with the language. But it is possible to maintain this wish to be one with the language only as long as the people who live in that language remain together. When the Goths, the Vandals and so on moved westwards they were immersed in the Latin element. This 'being one with the language' only remained in the centre of Europe. This means that in Central Europe the language is indeed not bound particularly strongly to human beings but is nevertheless bound more strongly than was the case in the Roman people, who are now lost but who have passed their language on. The Germanic people would not be able to pass on their language. The Germanic people have their language as something living in them and would never be able to leave it behind as a heritage. This language can only continue to live as long as it is bound together with the human being. This is connected with the whole nature of the human constitution of those peoples who have gradually asserted themselves in the centre of Europe. This has the effect that human beings came to the fore in Central Europe who were not suitable for such beings to incarnate into, as was the case in the West. But they could nevertheless be taken hold of. It was quite possible for the beings of the three types I described yesterday to assert themselves in the leaders of the people of Central Europe. But this also makes it possible for those people to be accessible to the phenomena which appear to the people of the Orient as imaginations. But in the people of the Centre these imaginations remain so pale during the day that they appear only as concepts, as ideas. The same applies also to what has its origin in those beings who incarnate in human beings and who play such a great role in individuals of the West. They cannot have the same effect here, but nevertheless give the whole human being a certain tendency. It is particularly the case in human beings of the Centre that over the course of centuries it was barely possible for any individual who attained to any sort of significance to save himself from the embodiment of the spirits of the West on the one side, and from the spirits of the East on the other. This always caused a kind of schism in these people.

To describe these human beings [of the Centre] in their true nature we can say: When they were awake there was working in them something of the attacks of the spirits of the West which influenced their desires, their instincts, lived in their will, and crippled it. When these individuals slept, when the astral body and the 'I' were separated, beings asserted themselves in them of the kind that often worked unconsciously on human beings of the Orient, appearing in imaginations. And one only needs to choose a highly characteristic personality from the civilization of the Centre and one will be able to touch—almost, as it were, with one's bare hands—the fact that this is as I have described it. One only needs to take Goethe. Take everything that lived in Goethe from the attacks of the spirits of the West that asserted themselves in his will, that surged particularly in the young Goethe and which one senses strongly when one reads the scenes, which gushed from Goethe in his youth, of Faust or The Wandering Jew. And then you see how, on the other hand, Goethe reached calm inner clarity—for the element of the Orient that tends merely to the spirit and soul was mastered in him, was permeated with this will element. You see how in old age he turns, in Part Two of Faust, more towards imaginations. But a cleft is nevertheless there. It is difficult to find a bridge between the style of Part One of Faust and the style of Part Two.

And look at the living Goethe himself, who grows from the impulses of the West; who, as it were, is tormented by the spirits of the West and who, as a young man, comforts himself with what after all also contains a great deal of the West: the Gothic style. But here there emerges a striving towards the spirits of the past, to those spirits which were at work in Greece—and also, most especially, in the Gothic style—but which nonetheless were basically the successors of those spirits which once inspired the oriental at the time when he came to his great ancient wisdom. And coming to the 1780s we see how he can no longer bear the spirits of the West, how they torment him. And he tries to balance this by moving to the South in order to absorb there what can come from the other side. This is just what gives the leading personalities of the Centre—and the other human beings, of course, follow these leaders—their characteristic stamp. The human beings of the Centre were thereby particularly prepared for the coming to prominence of the one thing that is important for the whole evolution of humanity. One can observe this best in a mind such as Hegel. If you take Hegel's philosophy, you find—I have often mentioned this here—that this philosophy develops in every respect towards the spirit. Yet nowhere in Hegel do you find anything which goes beyond the physical-sense life. Instead of a real teaching on the spirit you find logical dialectics as the first part of his philosophy. His philosophy of nature is merely a sum of abstractions of what lives in the human being himself; and you find what is supposed to be treated by psychology presented in the third part of Hegel's philosophy. But what comes out of it is nothing other than what the human being lives through between birth and death, which is then compressed into history. Nowhere in Hegel is it a matter of the eternal in the human being entering into an existence before birth or after death. Nor can its justification be found anywhere.

This is the one thing that the human beings, the most outstanding human beings, of the Centre give weight to: the fact that the human being, as he lives here between birth and death, consists of body, soul and spirit. For the human beings of the sense-world—for our physical world—soul and spirit should be made manifest by these people of the Centre.

As soon as we move to the East we find that soul and spirit predominate, just as, in the West, it is primarily body and soul. Thus, this rising up to imaginations is natural and, even if they do not come to consciousness, they nevertheless still work into the consciousness. The whole disposition Anlage) of thinking in the human being of the East is such that it tends towards imaginations: even if, at times, these imaginations are taken hold of in abstract concepts, as in Soloviev.4 Vladimir Sergeyevich Soloviev (1853–1900), Russian philosopher and poet.

And a third branch extends from Rome towards the North and into the East via Byzantium (see diagram). What was together, though chaotically, in Rome now divides to a certain extent into three separate branches. It diverges and moves to the West where a new element of economics establishes itself as something especially appropriate for the new age, finding dose affinity with natural science. It moves also to the East and progresses from the ancient primal wisdom into decadence. There develops that which is the spiritual, in religious form. All this happens, of course, in parallel. And towards the Centre there develops what is political-militaristic, civic-judicial, which also naturally spreads into different areas. But we must keep the characteristic branches in mind.

The further eastward we go, the more do we see how the people of the East are not bound up with their language in the same way that the Germanic peoples are. The Germanic peoples really live in their language as long as they have it. Just study the strange course of the Germanic humanity of Central Europe. Look at the two branches of Germanic population which moved, for example, towards Hungary into the Zipser region; as Swabians down into the Banat; as Siebenbürger Saxons towards Transylvania. In all these places it is, if I may put it so, rather like a fading away of the actual language element. Everywhere these people allow themselves to be absorbed by the [foreign] language into which they merge. It would be a most interesting ethnological study to see how, in a relatively short time during the last two-thirds of the nineteenth century, the German element in the area around Vienna has withdrawn, has been swamped. This would be tangibly apparent if one looked at this matter with understanding. One saw how the German element evolved into the Magyar in an artificial way and into the Slavonic in a natural way.

In the East the human being is intimately bound up with his language. There the spirit-soul element lives in the language. This is often disregarded. The human being of the West lives in language in a completely different way—in a radically different way—from the human being of the East. The human being of the West lives in his language as though in a garment; the human being of the East lives in his language as though in himself. This is why the human being of the West could adopt the natural-scientific view of life, could pour it into his language, which is only a vessel. The scientific world-view of the West will never find a foothold in the Orient because it simply cannot get into the oriental languages. The languages of the Orient reject it; they do not adopt the world-view of science. You can sense this if you let the—albeit rather coquettish—writings of Rabindranath Tagore5 Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), Indian philosopher and poet. work on you. Even though, in Tagore, it is all permeated with coquetry, one nevertheless sees how the whole nature of his existence consists in an experience of the forceful impact of the Western world-view, and then, through living in the language, an immediate rejection of it.

The human being of the Centre was thrown into all this. He had to take in everything he experienced in the West but did not absorb it as deeply as the Westerner; he suffused it with what also came from the East. Hence the more malleable equilibrium in the Centre; but hence also the inner strife, the duality in the individualization of the souls of human beings of the Centre. The striving to find a harmony, a balancing out of this duality—which is so classicially, so magnificently, portrayed in Schiller's Letters an Aesthetic Education in which two driving forces that are to be united—that of Nature and that of Reason—points clearly to this duality. But one can point to something much deeper. You see, when one looks to the West one finds primarily a certain inclination in the whole people to adopt the natural-scientific way of thinking, which is so exceptionally suited to the economic life. I have shown you how this scientific way of thinking has entered even into psychology. It has been adopted there completely. And it is there that Puritanism lived like an abstract appendage (Einschlag), like something that has nothing to do with real outer life—something that one locks away, as it were, in one's soul house—something one does not allow to be touched by outer culture.

The nature of what is developing in the West is such that we can say: There is a tendency here to take into oneself everything that is accessible to human reason in as much as this is bound to body and soul. Everything else—Puritanism—is only the Sunday coat of what is the body, what is accessible to reason. Hence the deism—that squeezed lemon of a religious world-view—in which there is nothing more of God than the fairy tale of a generalized, completely abstract, cosmic first cause. Reason, bound to body and soul, is what is asserting itself here.

If you go to the East there is no understanding at all for a rationality of this kind. This already begins in Russia. For, has the Russian any understanding at all for what is called rational in the West? Let us be under no illusion here. The Russian has not the slightest understanding for what, in the West, one calls rationality. The Russian is open to what one could call revelation. Fundamentally, he takes up as the content of his soul everything that comes to him by virtue of a kind of revelation. Reason—even when he says the word, copying it from Western human beings—is something of which he understands nothing; that is, he does not feel in this word what Western people feel. But what can be felt when one speaks of revelations, of the descent of truths from the supersensible worlds into human beings—this he understands well. Through the nature of what is spoken of in the West—and Puritanism is indeed good proof of this—one sees that there is by nature not the slightest understanding for what one must refer to as the relation of the Russian—and even more so of the oriental, of the Asiatic human being—of the relation in general of the human being to the spiritual world. In the West there is not the slightest understanding for this. For this is something quite different from what is given through reason. It is something which, going out from the spirit, takes hold of the human being and permeates him in a living way.

And in the human being of Central Europe the situation is this: as the fifth post-Atlantean epoch was approaching—around the tenth, eleventh and twelfth centuries (it came then in the fifteenth century)—the outstanding spirits of Central Europe were faced with an immense question, a question that was set them as human beings placed between West and East—a West that pulled them towards reason and an East that pulled them towards revelation. Just study later Scholasticism, the brilliant age of medieval spiritual development, from this point of view. Just study, from this standpoint, such spirits as Albertus Magnus,6 Albertus Magnus (1193–1280), Scholastic philosopher, called 'Doctor Universalis'. Thomas Aquinas,7 Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), Scholastic and pupil of Albertus Magnus; called Doctor Angelicus. Canonized in 1323. Duns Scotus8 Johannes Duns Scotus (1266–1294), Scholastic. and so on. Compare them with such spirits as Roger Bacon9 Roger Bacon (1214–1294), Franciscan, taught at Oxford University.—I mean the elder, who was more orientated towards the West—and you will see that a great question arose for the spirits of later Central-European Scholasticism, from the working together of what pressed from the West as reason and what pressed in from the East as revelation. This pressure came, on the one hand, from those spirits who wished to take hold of the human body and soul through the will and from those spirits, on the other hand, who, in the East, wished to take hold of spirit and soul through imaginations. It is from this that the tenet of Scholastic teaching arose that both were valid: reason on the one side and revelation on the other. Reason for everything on the earth which can be acquired through the senses and revelation for the supersensible truths which can be drawn only from the Bible and from the traditions of Christianity. One comprehends the Christian Scholasticism of the Middle Ages when one perceives its most outstanding spirits as being those in whom reason from the West and revelation from the East came together. Both influences were working in the human being and in the Middle Ages people could only bring them together by feeling the split, the duality in themselves.

In that place high up in the small cupola,10In the first Goetheanum. A presentation of the individual motifs of the small cupola can be found in Der Baugedanhe des Goetheanum (The Architectural Concept of the Goetheanum), Dornach, 1952. where the Germanic element is meant to be shown with its dualism, you see the elements of this duality clashing against one another in the red-yellow and the black-brown—the red-yellow of revelation and the black-brown of reason. You see there, felt in colour, revealed through colour, what has inspired and worked through different human cultures and has thus come to the human being.

Thus we could say that what we have now, spread over the civilized world, is taken hold of in the West by economic life—the element that has actually arisen only in modern times. For economic life was never such a topical question in earlier epochs as it is today. It is actually appropriate to our times. In contrast, matters of state and politics are already fading. And what was founded in the last third of the nineteenth century as the German Empire took into itself just this fading element of ancient Rome and fell to pieces because of it. This was already so at the beginning in the way it was structured but even more so in the way it then developed. Fundamentally, this German Empire was nothing but a continuation of the civic-judicial, the political element, which excelled in organizing everything—indeed, had great geniuses of organization. But it wanted to also take over the economic life without having economic thinking. For everything that the economy did in this Empire wanted more and more to creep under the umbrella of the State. Militarism, for example, which basically orginated in France and also in Switzerland but which had quite different forms, was 'politicized' (verstaatlicht), as it were, in Central Europe. Central Europe could therefore take up neither an economic life nor a spiritual life truly alive in itself and arising out of its own roots. The anti-spirituality that has been organized in Central Europe in recent times is of the most terrible kind! We see everything pertaining to the spiritual life becoming more and more part of a political State. And so it came about that in Central Europe in the second decade of the twentieth century there was not a single individual left who wrote about history or similar things except as a 'party-political man'. Everything which came out of the universities was not objective history but party-wisdom, distinctly politically coloured. And even more decadent is the spiritual life which originates in very ancient times in the Orient. It mingled with the deluge from the West, from the Centre, in the measures of Peter the Great with the native spirituality that was already in a state of decadence, expressing itself in Pan-Slavism, in Slavophilism. And it led finally to the creation of the present conditions from which a new spirit wishes to arise, for the old is completely decadent.

Thus we see, spread out over the world, a new economy, jurisprudence and political life coming to an end, and a spiritual life which has come to an end.

In the West we see how the political element has been completely absorbed by the economy and that the spiritual element, if one disregards the unreality of Puritanism, exists only in the form of natural science. In the Centre we have had an already aging State which tried to absorb both economy and spiritual life and was therefore unable to survive. And in the East we have nothing but—the dying spirit of ancient times which the West tries to galvanize through all manner of measures. No matter whether tried by Peter the Great or by Lenin, what wishes to come from the West galvanizes the corpse of the Eastern spirit. Salvation lies in clearly seeing that a new spirit must permeate humanity.

This new spirit, which cannot be found in the Orient but only in the Occident, must put economic life, political life and spiritual life side by side, quite distinct from one another. Then the economic life of the West, for which the West is particularly organized through its natural qualities, can be complemented by the political and the spiritual life. Then the Centre can take up beside its political life—which will be improved through quite different principles than were there in the past if it is anthroposophically-oriented—an economic and spiritual life. And then the Orient can be re-fructified. The Orient will understand the spiritual life that blossoms in the Occident only if one introduces it in the right way. As soon as artificial barriers are no longer created, which do not allow the movement of the truly anthroposophically-oriented spiritual life of the Occident; as soon as this is allowed to cross into the Orient, it will be understood there, even if it enters at first through such coquettish spirits as Rabindranath Tagore or others. The point is that natural science as such is rejected by the Orient. But that science which is illumined by true spirituality, which we have wanted to present here in our courses of the Free School of Spiritual Science, will also be taken up in the Orient with great eagerness. The Orient will then have a great deal of understanding for an independent spiritual life. And it will also take up an independent civic-political life and an independent economic life which it will be able to run in independence. Thus, in this threefold form of the social organism, there is a fulfillment of that which, from a rational but at the same time also spiritual view, represents the development of the European and Asiatic world since the decline of Rome.

Dritter Vortrag

Ich habe gestern wiederum von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte aus, als dies schon durch längere Zeiten hindurch geschehen ist, auf die Differenzierung aufmerksam gemacht, die unter den Völkern der gegenwärtigen zivilisierten Welt besteht. Ich habe darauf hingewiesen, wie die Individualisierung des Menschen im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum von den geistigen Welten her gelenkt wird, wie eingreifen auf der einen Seite im Westen durch die Menschen selber gewisse Wesenheiten, welche in einer unregelmäßigen Weise vorgerückt sind, welche weiter sind als die Menschheit, aber aus gewissen Interessen heraus sich in Menschen verkörpern, um den wahren Impulsen der Gegenwart entgegenzuwirken, den Impulsen der Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus.

Ich habe auch darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie in anderer Art im Osten sich die Tatsache geltend macht, daß zwar nicht durch die Menschen selber, wohl aber durch ihr Erscheinen gegenüber den Menschen sich gewisse Wesenheiten geltend machen, Wesenheiten, die ihre eigentliche Bedeutung in ferner Vergangenheit hatten, die aber jetzt ins Menschenleben hereinwirken wollen; wie diese durch die besondere Seelenverfassung der im Orient Lebenden auf diese Menschen wirken, sei es mehr oder weniger bewußt, indem sie als Imagination hereinwirken in das Bewußtsein einiger Menschen des Ostens, sei es, daß sie während des Schlafes hineinwirken in das menschliche Ich, in den astralischen Leib und sich dann geltend machen, ohne daß die Menschen es wissen, in den Nachwirkungen während des Wachens und auf diese Weise alles das hereintragen, was sich gegen einen regelmäßigen Fortschritt der Menschheit im Osten auftürmen will. So daß wir sagen können: Im Westen hat sich seit langem vorbereitet in einer gewissen Weise eine Art Erdgebundenheit bei solchen Menschen, wie ich sie gestern geschildert habe, die da eingestreut sind, die insbesondere in Sekten Führerstellungen einnehmen, die auch in Geheimgesellschaften Führerstellungen einnehmen und dergleichen. Im Osten finden sich auch gewisse führende Persönlichkeiten, welche eben unter dem Eindrucke solcher durch Imagination erscheinenden Wesen der Vorzeit dasjenige ausüben, was sie eben in die gegenwärtige Kulturentwickelung hereinbringen. Wenn man verstehen will, wie die Menschen der europäischen Mitte zwischen dem Westen und dem Osten gewissermaßen eingekeilt sind, so muß man genauer hinschauen gerade auf die geistigen Bedingungen, die da zugrunde liegen, und auf alles das, was sich ausspricht in der physisch-sinnlichen Welt aus diesen geistigen Bedingungen heraus.

Ich habe Sie ja eben von den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten aus darauf aufmerksam gemacht, wie in der Hauptsache das Leben des uralten Orients ein Geistesleben war, wie der Mensch des uralten Orients ein hochentwickeltes Geistesleben hatte, ein Geistesleben, das aus unmittelbarer Anschauung der geistigen Welten herausströmte; wie dann dieses Geistesleben eigentlich als Erbstück weiter fortlebte, wie es im Griechentum als schöne Künstlerschaft zunächst vorhanden war, aber auch noch als eine gewisse Einsicht; wie aber auch schon im Griechentum sich hineinmischte dasjenige, was dann der Aristotelismus war, was bereits verstandesmäßiges, dialektisches Denken war. Aber es drang dann das, was von orientalischer Weisheit kam, eben in die Zivilisation des Abendlandes hinein, und mit Ausnahme dessen, was aus der Naturwissenschaft stammt, und was stammen kann aus der modernen anthroposophisch orientierten Geisteswissenschaft, ist im Grunde genommen alles, was in der abendländischen Zivilisation an Geistesleben vorhanden ist, altes orientalisches Erbgut. Aber dieses Geistesleben ist eben durchaus dekadent. Dieses Geistesleben ist so, daß ihm die eigentliche Tragkraft fehlt, daß der Mensch zwar noch eine gewisse Hinlenkung zur geistigen Welt hat, aber dies, was er von der geistigen Welt glaubt, nicht mehr verbinden kann mit dem, was hier in der physischen Welt geschieht.

Es zeigt sich das am stärksten, wenn im angelsächsischen Puritanertum ein, ich möchte sagen, ganz weltfremdes, neben dem weltlichen Treiben einhergehendes weltfremdes Glauben Platz gegriffen hat, das nach ganz abstrakten geistigen Regionen hinzielt, das im Grunde genommen gar nicht sich die Mühe gibt, sich auseinanderzusetzen mit der äußeren physisch-sinnlichen Welt.

Im Orient nehmen selbst ganz weltliche Bestrebungen, Bestrebungen des sozialen Lebens, einen so geistigen Charakter an, daß sie sich wie religiöse Bewegungen ausnehmen. Und im Osten ist zum Beispiel die Tragkraft des Bolschewismus darauf zurückzuführen, daß er eigentlich von den Menschen des Ostens, schon vom russischen Volke, wie eine Religionsbewegung aufgefaßt wird. Nicht so sehr auf den abstrakten Vorstellungen des Marxismus beruht die Tragkraft dieser sozialen Bewegung des Ostens, sondern sie beruht im wesentlichen darauf, daß die Träger wie neue Heilande angesehen werden, gewissermaßen wie die Fortsetzer früheren religiös-geistigen Strebens und Lebens.

Aus dem Römertum heraus, auch schon aus späterem Griechentum heraus hat sich dann, wie wir wissen, dasjenige entwickelt, was die Menschen der Mitte am allermeisten ergriffen hat, das dialektische Element, das Element des juristischen, des politischen, des militärischen Denkens.

Und welche Rolle das dann später spielte, was da aus dem Römertum heraus sich entwickelte, das kann man nur verstehen, wenn man zunächst bedenkt, daß alle drei Zweige des menschlichen Erlebens, das geistige Erleben, das wirtschaftliche Erleben, das staatlich-politische Erleben in den Zeiten, in denen das Römertum sich zu besonderem Glanze entwickelte, in denen das römische Kaisertum aufkam, in einer ähnlichen Weise verknäuelt waren, durcheinanderstrebten, wie das im Grunde über die ganze zivilisierte Welt hin in der gegenwärtigen Zeit der Fall ist. Das Römertum lief durchaus in eine Dekadenz aus, welche im wesentlichen dadurch bedingt war, daß im römischen Weltreiche die Unmöglichkeit wirkte, die immer daraus hervorgeht, daß die drei menschlichen Betätigungen — Geistesleben, Staatsleben, Wirtschaftsleben — chaotisch ineinandergreifen. Man kann ja wirklich sagen, das römische und insbesondere das byzantinische Kaisertum ist eine Art Symbolum gewesen für den Verfall der vierten nachatlantischen Zeit, der griechisch-lateinischen Zeit. Man braucht ja nur zu bedenken, daß von einhundertsieben oströmischen Kaisern bloß vierunddreißig in ihrem Bette gestorben sind. Von einhundertsieben Kaisern sind bloß vierunddreißig in ihrem Bette gestorben! Die anderen sind entweder vergiftet oder verstümmelt worden und im Kerker gestorben, sind aus dem Kerker ins Mönchsleben übergegangen und dergleichen. Und aus dem, was da im Süden Europas (siehe Zeichnung) als die romanische Welt ihrem Niedergange entgegenging, aus dem entwickelte sich dasjenige heraus, was dann, ich möchte sagen, in drei Ästen nach Norden heraufströmte.

Da haben wir zunächst den westlichsten Ast. Ich will heute nicht darauf eingehen, was sich in geschichtlichen Einzelheiten entwickelte durch das hindurch, was als das Mittelalter aus der alten Menschheitsentwickelung hervorging; aber ich will auf einiges aufmerksam machen. Die charakteristische Erscheinung der westlichen, zunächst der mehr südwärts gelegenen westlichen Entwickelung ist ja diese, daß das Römertum, ich möchte sagen, auch als eine Summe von Menschen zunächst sich ausdehnt nach Spanien, über das heutige Frankreich, auch über einen Teil von Britannien hin. Römische Menschen waren es, die da hinein sich entwickelten. Aber alles das wurde durchsetzt von dem, was als germanische Stämme der verschiedensten Art durch die Völkerwanderung gerade in diese Bevölkerungen von römischen Menschen hineindrang.

Und eine eigentümliche Erscheinung finden wir da. Die Erscheinung finden wir, daß germanische Menschen in das Römertum sich hineinzwängen, in das Römertum sich hineinstoßen, und daß da etwas entsteht, was nur so charakterisiert werden kann, daß man sagt: Es war Menschenwesen germanischer Art eingedrungen in das Römertum; das Römertum als solches ging im Grunde genommen als Menschenwesen unter; was aber erhalten blieb von dem Römertum, also dasjenige, was, ich möchte sagen, durch diese Kreuzung (siehe Zeichnung S. 50) der beiden Linien hier sich bildete, was sich da bildete als spanische Bevölkerung, als französische Bevölkerung, zum Teil auch als britannische Bevölkerung, das ist im wesentlichen germanisches Blut, übertönt von dem romanischen Sprachelemente. Nicht anders kann in Wirklichkeit verstanden werden, um was es sich da handelt, als wenn man es so anschaut. Dieses Menschenwesen ist durchaus seiner Seelenkonfiguration nach, seiner Empfindungs-, Gefühls- und Willensrichtung nach hervorgegangen aus dem, was sich als germanisches Element im Strom der Völkerwanderung vom Osten nach dem Westen bewegt hat. Aber es ist eine Eigentümlichkeit dieses germanischen Elementes, daß, wenn es zusammenstößt mit einem fremden Sprachelemente — und in der Sprache ist immer eine Kultur, möchte ich sagen, verkörpert -, es in diesem fremden Sprachelemente aufgeht, diese Sprache annimmt. Es wächst hinein in diese fremde Sprache, ich möchte sagen, wie in ein Zivilisationskleid. Was im Westen von Europa lebt als lateinische Rasse, das hat im Grunde genommen nichts von lateinischem Blute in sich. Das ist aber hineingewachsen in dasjenige, was da heraufgeströmt ist, verkörpert durch die Sprache. Denn es lag im Wesen des lateinischen, des römischen Elementes, sich selber über das Menschentum hinaus im Weltenentwickelungsgang zu behaupten. Deshalb ist ja in Rom zuerst das Testament aufgekommen, die Behauptung des Egoismus über den Tod hinaus. Daß der Wille über den Tod hinausreiche, das hat dazu geführt, den Gedanken des Testamentes zu fassen. So auch wirkte der Bestand der Sprache über den Bestand des Menschlichen im Volkstum hinaus.

Und anderes als die Sprache wurde erhalten. So wurden erhalten für diesen Westen auf dieser Strömung hier (siehe Zeichnung S. 50) die alten Traditionen der verschiedenen Geheimgesellschaften, von deren Bedeutung ich Ihnen ja im Laufe der letzten Jahre Mannigfaltiges erzählt habe, durchaus Traditionen, die aus der vierten nachatlantischen Zeit, aus der griechisch-lateinischen Zeit stammen, die allerdings Entlehnungen sind aus dem Orient — namentlich aber aus Handschriften -, die aber durchaus durch das Römertum, durch das Lateinertum durchgegangen sind. So daß man in einer gewissen Beziehung in dem westlichen Menschentum, insofern es untergetaucht ist in dem römischen Sprachelemente, das sich über das Volkstum hinaus erhalten hat, den Menschen in einem fremden Zivilisationskleide hat. Man hat auch den Menschen in einem fremden Kleide, indem man in den alten Mysterienwahrheiten, die schon abstrakt geworden sind, die namentlich in den Zeremonien und in dem Kultus der westlichen Gesellschaften mehr oder weniger leere Formeln geworden sind, etwas hat, worin das Menschentum untergetaucht ist und worin es als in etwas lebt, wovon es ergriffen werden kann.

Sind nun andere Verhältnisse besonders günstig, dann bietet gerade dieses, ich möchte sagen, mehr von außen Durchdrungenwerden des Menschen mit alledem, was aus der Sprache herauskommt, einen Anhaltspunkt dafür, daß sich solche Wesen, wie ich es gestern geschildert habe, in diesen Menschen verkörpern können. Aber besonders günstig ist für dieses Verkörpern gerade das angelsächsische Element aus dem Grunde, weil da auch durchaus germanisches Menschenwesen nach dem Westen hinübergekommen ist, weil sich stark das germanische Menschenwesen erhalten hat, und in einem geringeren Maße als das eigentlich lateinische Element sich durchdrungen hat mit dem römischen Elemente. So daß da ein viel labileres Gleichgewicht in der angelsächsischen Rasse vorhanden ist, und durch dieses labilere Gleichgewicht jene Wesen, die sich da verkörpern, eine viel größere Willkür des Wirkens, einen viel größeren Spielraum haben. In eigentlich romanischen Ländern würden sie außerordentlich gebunden sein. Vor allen Dingen aber muß man sich klar sein darüber, daß von solchen volkspsychologischen Konfigurationen dasjenige abhängt, was sich dann in einzelnen Persönlichkeiten äußern kann. Durch dieses freiere Element im Angelsachsentum ist es möglich geworden, daß, während allerdings das Puritanertum eine abstrakte Glaubenssphäre darstellt, dieses angelsächsische Element im höchsten Grade geeignet war, das naturwissenschaftliche Denken auch als Welt- und Lebensanschauung aufzunehmen und auszugestalten. Es wird allerdings nicht das volle Menschentum ergriffen, aber es wird gerade derjenige Teil des Menschenwesens ergriffen, welcher durch die Eingliederung von Sprachen, durch die Eingliederung von anderen Elementen des Menschenwesens es möglich macht, daß sich solche Wesen, wie ich es gestern geschildert habe, in diesen Menschen verkörpern.

Ich bemerke ausdrücklich, daß bei alledem, was ich jetzt bespreche, es sich nur um solche einzelne Menschen handelt, die unter der Menge der übrigen Menschen zerstreut sind. Es betrifft nicht die Nationen, es betrifft nicht irgendwie die große Masse der Menschen, es betrifft die einzelnen Menschen, die aber außerordentlich starke Führerstellungen in den Regionen haben, von denen ich gesprochen habe. Was nun da im Westen vorzugsweise ergriffen wird von solchen Wesen, die dann dem Menschenleib, in welchem sie sich verkörpern, eine gewisse Führerstellung sichern, das ist hauptsächlich Leib und Seele, nicht der Geist, für den man sich daher weniger interessiert.

Woher kommt zum Beispiel die ganz grandiose, aber einseitige Ausgestaltung der Deszendenzlehre durch Charles Darwin? Sie kommt daher, daß bei Charles Darwin tatsächlich besonders dominierend waren Leib und Seele, nicht der Geist. Daher betrachtet er den Menschen auch nur nach Leib und Seele, sieht ab von dem Geiste und von dem, was aus dem Geiste in das Seelische sich hereinlebt. Wer unbefangen auf die Ergebnisse der Forschungen Darwins sieht, der wird sie verstehen von dem Gesichtspunkte aus, daß da etwas lebte, was den Menschen nicht betrachten wollte seinem Geiste nach. «Geist» nahm man nur von der neueren naturwissenschaftlichen Richtung, die international ist; dasjenige aber, was die ganze Anschauung über das Menschenwesen färbte, nuancierte, das war die Hinneigung zu Leib und Seele, mit Außerachtlassung des Geistes. Ich möchte sagen, die treuesten Schüler des ökumenischen Konzils vom Jahre 869 waren die Menschen des Westens. Sie haben den Geist zunächst unberücksichtigt gelassen, Leib und Seele genommen, wie sie besonders in der Schilderung Darwins zum Vorschein kommen, und nur einen künstlichen Kopf aufgesetzt als Geist mit materialistischer Denkungsweise, wie er aus der Naturwissenschaft hervorkommt. Und weil man sich gewissermaßen schämte, aus der Naturwissenschaft eine Universalreligion zu machen, blieb als äußerliches Nebenwerk, das ein abstraktes Dasein führte, dasjenige, was als Puritanismus und dergleichen weiterlebt, was aber mit der eigentlichen Weltkultur hier keinen Zusammenhang hat. Da sehen wir, wie in einer gewissen Weise überwältigt wird Leib und Seele von einem abstrakt naturwissenschaftlichen Geist, den wir bis in die Gegenwart herauf klar beobachten können.

Aber man nehme an, das andere geschähe. Es würde stärker sein dasjenige, was in der Sprache weiterlebt, was in der ganzen geistigen Formenwelt der vierten nachatlantischen Zeit weiterlebt, was würde da herauskommen? Da würde ein strenges fanatisches Abweisen des modernen Geistes herauskommen; und es würde nicht betont werden, daß aus naturwissenschaftlichen Begriffen ein künstlicher Kopf aufgesetzt werde dem Leiblich-Seelischen, sondern es würden die alten Traditionen aufgesetzt werden, aber es würden doch nur das Leibliche und Seelische eigentlich gepflegt werden. Da könnten wir uns denken, daß irgendein Mensch in ebenso brutaler Weise alles das, was nur Leib und Seele ist, ausbildet und eine Lehre erfindet, die nur auf Leib und Seele hinsehen will und als Äußeres dazu nicht die Naturwissenschaft hat, sondern einen wiederum nur noch äußerlich gebliebenen Teil von einer aus früherer Zeit in spätere Zeit hineingetragenen Offenbarung: Und dann haben wir den Jesuitismus, dann haben wir Ignaz von Loyola. Ich möchte sagen, ebenso wie mit Notwendigkeit Geister wie Darwin hervorgingen aus dem Angelsachsentum, ebenso ging aus dem Spätromanismus Ignaz von Loyola hervor.

Das Eigentümliche der Menschen, von denen wir hier in bezug auf den Westen zu sprechen haben, ist, daß sich durch sie der Welt bemerklich machen jene geistigen Wesen, die ich gestern charakterisiert habe, daß sie durch sie in der Welt wirken. Im Osten ist das anders. Nach dem Osten geht eben eine andere Strömung (siehe Zeichnung S. 50). Wir werden zunächst aber etwas betrachten, was als eine zweite Strömung von dem alten Römertum ausgeht, was nun nicht die Sprache auch hinaufträgt, wohl aber die ganze Richtung der Seelenverfassung hinaufträgt, was die Gedankenrichtung hinaufträgt. Nach dem Westen geht mehr die Sprache. Dadurch kommen alle diejenigen Erscheinungen, von denen ich eben gesprochen habe. Nach der europäischen Mitte geht dasjenige, was mehr die Gedankenrichtung ist. Aber es vereinigt sich mit dem, was in dem Germanentum veranlagt ist, und in dem Germanentum ist veranlagt ein gewisses Verwachsen-seinWollen mit der Sprache. Aber man kann dieses Verwachsen-sein-Wollen mit der Sprache nur erhalten, solange die Menschen, die in dieser Sprache leben, zusammen sind. Als die Goten, die Vandalen und so weiter nach dem Westen zogen, tauchten sie unter in das lateinische Element. Es blieb das Verwachsensein mit der Sprache nur in der europäischen Mitte vorhanden. Dies bedeutet, daß in dieser europäischen Mitte die Sprache zwar nicht in einer besonders starken Weise an dem Menschen haftet, aber doch stärker haftet, als sie in den römischen Menschen war, die als solche sich verloren haben, aber die Sprache selber abgegeben haben. Die germanischen Menschen würden ihre Sprache nicht abgeben können. Die germanischen Menschen haben ihre Sprache als ein Lebendigeres in sich. Sie würden es nicht als Erbstück hinterlassen können. Sie kann sich nur so lange erhalten, diese Sprache, als sie mit dem Menschen verbunden ist. Das hängt zusammen mit der ganzen Art und Weise der menschlichen Verfassung dieser Völker, die in Europas Mitte sich nach und nach geltend gemacht haben. Das bedingt, daß in dieser europäischen Mitte sich Menschen geltend gemacht haben, die nicht gerade geeignet waren, starke Möglichkeiten für die Verkörperung solcher Wesen zu bieten, wie es im Westen der Fall war. Aber ergriffen konnten sie doch auch werden. Bei diesen Menschen der europäischen Mitte war es durchaus möglich, daß in den Führergestalten sich solche Wesen der dreifachen Gattung geltend machten, wie ich sie gestern geschildert habe. Aber das bewirkt immer, daß auf der anderen Seite auch eine gewisse Zugänglichkeit bei diesen Menschen vorhanden ist für jene Erscheinungen, die den Menschen des Orients sich als Imagination entgegenstellen. Nur bleiben diese Imaginationen bei den Menschen der Mitte während des Tagwachens so blaß, daß sie eben nur als Begriffe, als Vorstellungen erscheinen. In derselben Weise wirkt dasjenige, was von jenen Wesen herrührt, die sich durch die Menschen verkörpern und eine so große Rolle bei einzelnen Menschen des Westens spielen. Dadurch können diese durchaus nicht eine solche Wirkung hervorbringen, aber doch dem ganzen Menschen eine gewisse Richtung geben. Es ist insbesondere bei den Menschen dieser Mitte so, daß es durch Jahrhunderte hindurch kaum möglich gewesen ist, daß diejenigen Menschen, die irgendeine Bedeutung erhielten, sich retten konnten vor der Einkörperung auf der einen Seite der Geister des Westens und auf der anderen Seite der Geister des Ostens. Das bewirkte immer eine Art Zwiespältigkeit dieser Menschen.

Man könnte sagen, wenn man sie ihrer wahren Realität nach schildert: Wenn diese Menschen wachten, so war etwas von den Attacken der Geister des Westens in ihnen, das ihre Triebe, ihr Instinktleben beeinflußte, das in ihrem Willen lebte, das ihren Willen lähmte. Wenn diese Menschen schliefen, wenn der astralische Leib und das Ich gesondert waren, da machten sich auf sie solche Geister geltend wie diejenigen, die auf die Menschen des Orients als Erscheinungen in Imaginationen oft unbewußt wirkten. Und man braucht nur eine ganz charakteristische Persönlichkeit aus der Zivilisation der Mitte herauszunehmen, und man wird, ich möchte sagen, mit Händen greifen können, daß das so ist, wie ich es geschildert habe. Man braucht nur Goethe herauszunehmen. Nehmen Sie all das, was in Goethe von den Attacken der Geister des Westens lebte, was in seinem Willen sich geltend machte, was insbesondere in dem jungen Goethe wühlte, was man wohl fühlt, wenn man die in der Jugend hingewühlten Szenen des «Faust» oder des «Ewigen Juden» liest; und dann sehen Sie, wie Goethe auf der anderen Seite abgeklärt war — weil das bloß nach dem Geistig-Seelischen hintendierende Element des Orients in ihm gebändigt war, durchströmt war von diesem Willenselement -, wie er im Alter sich mehr zu Imaginationen hinwendet im zweiten Teil seines «Faust». Aber eine Kluft ist doch vorhanden. Sie kommen nicht recht herüber vor allen Dingen aus dem Stil des ersten Teiles des «Faust» in den Stil des zweiten Teiles des «Faust».

Und betrachten Sie den lebendigen Goethe selbst, der herauswächst aus den Impulsen des Westens, der, ich möchte sagen, gepeinigt wird von den Geistern des Westens, der sich als junger Mensch tröstet mit dem, was ja schließlich auch viel Westliches in sich enthält: mit der Gotik, womit aber auftaucht das Streben zu den Geistern der Vergangenheit, zu jenen Geistern, die im Griechentum, die auch ganz besonders in der Gotik tätig waren, die aber doch im Grunde genommen die Nachkommen jener Geister waren, die einstmals den Orientalen inspirierten, als er zu seiner großen Urweisheit kam. Und so sehen wir, als es in die achtziger Jahre hereingeht, wie er es nicht aushält mit den Geistern des Westens, wie sie ihn quälen. Er will das ausgleichen, indem er nach dem Süden zieht, um aufzunehmen, was von der anderen Seite kommen kann. Das gibt den Menschen der Mitte gerade in ihren hervorragenden Führern — und die anderen folgen ja diesen Führern — ihr charakteristisches Gepräge. Die Menschen der Mitte waren dadurch besonders vorgebildet zur Geltendmachung des einen, was wichtig ist in der ganzen Menschheitsentwickelung. Man kann es am besten bei einem solchen Geiste wie Hegel beobachten. Wenn Sie Hegels Philosophie nehmen - ich habe das schon öfter hier erwähnt -, finden Sie überall diese Philosophie hinentwickelt bis zum Geiste. Aber nirgends finden Sie irgend etwas bei Hegel, was über das physisch-sinnliche Leben hinausragt. Statt einer eigentlichen Geistlehre finden Sie eine logische Dialektik als ersten Teil der Philosophie; die Naturphilosophie finden Sie bloß als eine Summe von Abstraktionen dessen, was im Menschen wesen selber lebt; was durch die Psychologie ergriffen werden soll, das finden Sie dargestellt im dritten Teil von Hegels Philosophie. Aber es kommt nichts anderes heraus als das, was der Mensch auslebt zwischen Geburt und Tod, was sich dann zusammendrängt in der Geschichte. Von irgendeinem Hineingehen des Ewigen im Menschen in ein vorgeburtliches, in ein nachtodliches Dasein ist ja bei Hegel nirgends die Rede; es kann auch gar nicht geltend gemacht werden.

Das eine ist es, was die Menschen, die hervorragendsten Menschen der Mitte geltend machen, daß in dem Menschen, wie er hier lebt zwischen Geburt und Tod, Leib, Seele und Geist vorhanden sind. Für den Menschen der Sinneswelt, für unsere physische Welt sollte durch diese Menschen der Mitte der Geist und das Seelische sich darstellen.

Sobald wir nach dem Osten gehen, finden wir, daß — ebenso wie wir im Westen sagen müssen, es lebe vorzugsweise Leib, Seele — im Osten vorzugsweise Seele und Geist lebt. Daher das Hinaufheben zu den Imaginationen ja natürlich ist, und wenn diese Imaginationen auch nicht zum Bewußtsein kommen, so wirken sie in das Bewußtsein hinein. Die ganze Anlage des Denkens ist beim Menschen des Ostens so, daß sie nach Imaginationen hintendiert, wenn auch diese Imaginationen zuweilen, wie bei Solowjow, in abstrakte Begriffe gefaßt werden.

Und ein dritter Ast geht von dem Römertum nach dem Norden über Byzanz in den Osten hinein (siehe Zeichnung S. 50). Es spaltet sich gewissermaßen dasjenige, was im Römertum chaotisch beisammen war, in drei Zweige. Es strebt auseinander, kommt zum Westen, wo ein neues Element des Wirtschaftlichen sich geltend macht als dasjenige, was der Neuzeit besonders angemessen war, und was sich mit der Naturwissenschaft verbindet. Es kommt zum Osten und kommt aus der alten Urweisheit in die Dekadenz hinein; es entwickelt sich da hinüber dasjenige, was in religiöser Form das Geistige ist. Das alles geht natürlich parallel. Es entwickelt sich nach der Mitte hin dasjenige, was Politisch-Militärisches, Staatlich- Juristisches ist, was natürlich nach den verschiedenen Seiten sich ausbreitet; aber wir müssen die charakteristischen Äste ins Auge fassen. Je weiter wir nach dem Osten kommen, desto mehr sehen wir, wie diese Menschen des Ostens mit ihrer Sprache nicht in derselben Art verwachsen sind wie die germanischen Völker. Die germanischen Völker leben in ihrer Sprache, solange sie sie haben. Studieren Sie einmal diesen merkwürdigen Gang gerade der germanischen Menschheit Mitteleuropas. Studieren Sie diese Zweige der germanischen Bevölkerung, die sich zum Beispiel nach Ungarn hinüber in die Zipser Gegend, als Schwaben hinunter ins Banat, nach Siebenbürgen als die Siebenbürgener Sachsen bewegt haben. Überall ist es, ich möchte sagen, etwas wie ein Abglimmen des eigentlich sprachlichen Elementes. Diese Menschen gehen überall in der Sprache auf, in die sie untertauchen. Und eine der allerinteressantesten ethnographischen Studien wäre es, zu sehen, wie um Wien herum in verhältnismäßig kurzer Zeit, im Laufe der letzten zwei Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts, das Deutschtum zurückgegangen ist, überflutet worden ist. Man könnte das mit Händen greifen, wenn man diese Sache verständig ansähe. Man sah, wie in das Magyarentum hinein auf künstliche Weise, aber namentlich in das Slawentum hinein auf natürliche Weise, sich das germanische Element entwickelte. Im Osten ist der Mensch mit seiner Sprache aber ganz verwachsen. Da lebt das Geistig-Seelische, lebt in der Sprache. Das ist etwas, was man oftmals gar nicht berücksichtigt. Der Mensch des Westens lebt ja in der Sprache in einer ganz anderen Art, in einer radikal anderen Art als der Mensch des Ostens. Der Mensch des Westens lebt in seiner Sprache wie in einem Kleide; der Mensch des Ostens lebt in seiner Sprache wie in sich selbst. Daher konnte der Mensch des Westens die naturwissenschaftliche Lebensauffassung annehmen, hineingießen in seine Sprache, die ja nur ein Gefäß ist. Im Orient wird die naturwissenschaftliche Weltanschauung des Westens niemals Fuß fassen, denn sie kann gar nicht untertauchen in die Sprachen des Orients. Die Sprachen des Orients weisen sie zurück, die naturwissenschaftliche Weltanschauung nehmen sie gar nicht auf.

Das können Sie schon verspüren, wenn Sie die allerdings heute noch koketten Auseinandersetzungen des Rabindranath Tagore auf sich wirken lassen; wenn auch das bei Rabindranath Tagore von Koketterie durchwirkt ist, so sieht man doch, wie sein ganzes Sich-Darleben besteht im Erleben eines Anpralles der westlichen Weltanschauung, aber sofort — durch das Leben in der Sprache - ein Zurückwerfen dieser Weltanschauung des Westens.

In dieses Ganze war der Mensch der Mitte hineingeworfen. Er mußte alles das aufnehmen, was er im Westen erlebte. Er nahm es nicht so tief auf wie der Westen, er durchtränkte es mit dem, was auch der Osten hatte. Daher das labilere Gleichgewicht in der Mitte, dadurch aber auch die Zerrissenheit, die Zweiheit der Individualisierung der Seelen der Menschen der Mitte, dieses Streben, eine Harmonie, einen Ausgleich in der Zweiheit zu finden, wie es sich so klassisch, so großartig darlebt in Schillers Briefen über die ästhetische Erziehung, wo zwei Triebe — der Naturtrieb und der Vernunfttrieb -, die vereinigt werden sollen, deutlich hinweisen auf diese Zweiheit. Aber man kann noch auf viel Tieferes deuten.

Sehen Sie, wenn man nach dem Westen hinblickt, so finder man, daß da vorzugsweise eine gewisse Geneigtheit im ganzen Volkstum ist, die naturwissenschaftliche Denkweise aufzunehmen, die sich für das Wirtschaftsleben so außerordentlich eignet. Ich habe Ihnen gezeigt, wie die naturwissenschaftliche Denkweise sich bis in die Psychologie, bis in die Seelenkunde hineingelebt hat. Da nimmt man sie auf, da nimmt man sie restlos auf, diese naturwissenschaftliche Anschauungsweise. Und das Puritanertum lebte eben dort wie ein abstrakter Einschlag, wie etwas, das mit dem eigentlichen äußeren Leben nichts zu tun hat, das man auch gewissermaßen in sein Seelenhaus einsperrt, das man nicht berührt werden läßt von der äußeren Kultur.

Das, was da im Westen sich entwickelt, ist so, daß man sagen kann: Es ist eine Neigung vorhanden, alles in sich aufzunehmen, was der menschlichen Vernunft zugänglich ist, insofern sie gebunden ist an Leib und Seele. Das andere, der Puritanismus, ist ja nur ein Sonntagskleid dessen, was Leib ist, was zugänglich ist der Vernunft. Daher der Deismus, diese ausgepreßte Zitrone einer religiösen Weltanschauung, wo von Gott nichts mehr vorhanden ist als ein Märchen einer allgemeinen, ganz abstrakten Weltursache; die Vernunft, wie sie an Leib und Seele gebunden ist, die macht sich da geltend.

Wenn Sie nach dem Osten gehen, da ist gar kein Verständnis für eine solche Vernünftigkeit. Schon in Rußland fängt es an. Hat denn der Russe überhaupt Verständnis für das, was man im Westen Vernünftigkeit nennt? Man gebe sich nur keiner Täuschung hin; nicht das geringste Verständnis hat der Russe schon für das, was man im Westen Vernünftigkeit nennt. Der Russe ist zugänglich für dasjenige, was man Offenbarung nennen könnte. Er nimmt im Grunde genommen alles das auf als seinen Seeleninhalt, was er einer Art Offenbarung verdankt. Vernünftigkeit, wenn er auch das Wort den westlichen Menschen nachsagt, so versteht er doch nichts davon, das heißt, er fühlt nicht das, was die westlichen Menschen dabei fühlen. Aber was nachgefühlt werden kann, wenn man von Offenbarung, von dem Herabkommen von Wahrheiten aus der übersinnlichen Welt in den Menschen herein spricht, das versteht er gut. Dasjenige aber, wovon man im Westen so redet — und dafür ist ja gerade das Puritanertum ein Beweis —, ist so, daß man sieht: In diesem Westen ist selbstverständlich nicht das geringste Verständnis da für dasjenige, was man eigentlich als das Verhältnis des russischen Menschen und gar erst des Orientalen, des asiatischen Menschen, was man überhaupt als das Verhältnis des Menschen zur geistigen Welt ansprechen muß. Dafür ist im Westen nicht das geringste Verständnis. Denn das ist etwas ganz anderes als das, was durch Vernunft vermittelt wird; das ist etwas, was, vom Geistigen ausgehend, den Menschen ergreift und den Menschen lebendig durchdringt.

Und bei den Menschen der europäischen Mitte, nun, da ist es so: Als der fünfte nachatlantische Zeitraum sich schon nahte, so im 10., 11., 12. Jahrhundert — er kam ja dann in der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts —, da standen die hervorragendsten Geister der europäischen Mitte vor einer ungeheuren Frage, vor einer Frage, die ihnen aufgegeben war als Menschen, die drinnenstanden zwischen dem Westen und dem Osten, und es drängte in ihnen der Westen nach Vernunft, und es drängte in ihnen der Osten nach Offenbarung. Und man studiere einmal von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus die Hochscholastik, die Glanzepoche mittelalterlicher Geistesentwickelung, man studiere von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus solche Geister, wie Albertus Magnus, Thomas von Aquino, Duns Scotus und so weiter; man vergleiche sie mit solchen Geistern wie Roger Bacon — ich meine den Älteren, der mehr westwärts orientiert war —, und man wird sehen: Eine große Frage entstand bei den Geistern der mitteleuropäischen Hochscholastik aus dem Zusammenwirken von dem, was vom Westen her als Vernunft, vom Osten her als Offenbarung drängte. Ihre Bedrängnis war die, die auf der einen Seite von den Geistern herrührte, die durch den Willen den menschlichen Leib und die menschliche Seele ergreifen wollten, auf der anderen Seite von den Geistern herrührte, die von der Imagination aus Geist und Seele im Osten ergreifen wollten. Daher entstand die scholastische Lehre, daß alles beides gilt: Vernunft auf der einen Seite, Offenbarung auf der anderen Seite, Vernunft für alles dasjenige, was auf der Erde mit den Sinnen zu erreichen ist, Offenbarung für die übersinnlichen Wahrheiten, die nur aus der Bibel und aus der Tradition des Christentums geschöpft werden können. Man begreift so richtig die christliche Scholastik des Mittelalters, wenn man ihre hervorragendsten Geister auffaßt als diejenigen, in denen zusammenströmte Vernünftigkeit von Westen, Offenbarung von Osten. Da wirkten in den Menschen beide Richtungen, und im Mittelalter konnte man sie nicht anders zusammenbringen als dadurch, daß man gewissermaßen in sich selber den Zwiespalt empfand.

An jener Stelle unserer kleinen Kuppel, drüben im kleinen Kuppelraum, wo das germanische Element zur Darstellung kommen sollte mit seinem Dualismus, sehen Sie daher auch in dem Bräunlich-Schwärzlichen und dem Rötlich-Gelblichen aneinanderstoßen diese Zweiheit: das Rot-Gelbliche der Offenbarung, das Schwärzlich-Bräunliche des Vernünftigen; wie dort überhaupt inspirierend das gewirkt hat, was durch die verschiedenen Menschheitskulturen hindurch an die Menschen herangetreten ist; nur ist es dort in Farben und in den Offenbarungen der Farben empfunden.

So, möchte man sagen, ist das, was wir jetzt haben über die zivilisierte Welt hin, im Westen ergriffen von dem eigentlichen, erst in der Neuzeit heraufgekommenen Element, von dem Wirtschaftsleben; denn dieses Wirtschaftsleben selbst war in keiner früheren Epoche eine solche Zeitfrage, wie es jetzt geworden ist. Es ist eigentlich zeitgemäß. Dagegen ist dasjenige, was in Staat und Politik ist, schon im Abglimmen begriffen. Und was dann im letzten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts als Deutsches Reich begründet worden ist, das nahm eben in sich auf dieses abglimmende Element des alten Römertums und ging daran zugrunde. Schon wie es sich aufgebaut hat, war es so, aber insbesondere, wie es dann sich ausgestaltet hat. Im Grunde genommen gab es innerhalb dieses Deutschen Reiches nur die Fortsetzung des juristischstaatlichen, politischen Elementes, das organisierte, das ja große Genies des Organisierens hatte; aber das wollte sich einverleiben die Wirtschaft, ohne daß man das wirtschaftliche Denken hatte. Denn alles, was die Wirtschaft innerhalb dieses Gebietes trieb, das wollte immer mehr und mehr unter das Staatssystem unterkriechen. Der Militarismus zum Beispiel, der im Grunde genommen von Frankreich oder auch der Schweiz ausgegangen ist, der aber ja noch andere Formen hatte, wurde verstaatlicht, möchte man sagen, in Mitteleuropa. So daß dieses Mitteleuropa weder aufnehmen konnte das wirtschaftliche Leben, noch aufnehmen konnte ein wirklich in sich selbst lebendiges, aus seinen Wurzeln heraus treibendes Geistesleben. Was organisiert wurde an Widergeistigkeit in der letzten Zeit gerade in Mitteleuropa, das ist ja das Allerfurchtbarste! Wir sehen alles, was Geistesleben ist, immer mehr und mehr hineinwachsen in die Form des politischen Staates. Und so kam es, daß es im zweiten Jahrzehnt des 20. Jahrhunderts in Mitteleuropa keinen Menschen mehr gab, der über Geschichte oder über ähnliche Dinge anders schrieb denn als politischer Parteimann. Alles, was von den Universitäten ausging, ist nicht objektive Geschichte, ist Parteiweisheit, ist durchaus politisch gefärbt. Und noch mehr in der Dekadenz ist das geistige Leben, das aus Urzeiten aus dem Orient stammt. Es wuchs hinein in eine Überschwemmung aus dem Westen, aus der Mitte, in den Maßnahmen Peters des Großen, die noch durchdrungen waren von einem urwüchsigen Geistigen, das aber eben in der Dekadenz ist, das sich im Panslawismus, im Slawophilentum auslebt. Und es führte endlich dazu, daß die heutigen Zustände geschaffen wurden, aus denen heraus will ein neuer Geist, denn der alte ist ja ganz in der Dekadenz.

So sehen wir über die Welt verbreitet die neue Wirtschaft, die endende Jurisprudenz und Staatlichkeit und das geendete Geistesleben.

Im Westen sehen wir, von der Wirtschaft ganz aufgesogen, das Staatselement, und das Geistige ist ja nur in der Form der Naturwissenschaft da, wenn man eben absieht von dem unwahren Puritanertum. In der Mitte haben wir einen schon alternden Staat gehabt, der Wirtschaft und Geistesleben aufsaugen wollte und deshalb nicht leben konnte. Und im Osten haben wir nichts anderes als den ersterbenden Geist der alten Zeit, der galvanisiert werden soll durch allerlei Maßnahmen des Westens; gleichgültig, ob es Peter der Große ist, ob es Lenin ist, dasjenige, was vom Westen kommen will, galvanisiert den Leichnam des östlichen Geistes. Die Rettung besteht darinnen, daß man klar einsieht: Ein neuer Geist muß die Menschen durchziehen.

Dieser neue Geist, der nun nicht im Orient, der im Abendlande selber gefunden werden kann, dieser neue Geist muß reinlich nebeneinander hinstellen Wirtschaftsleben, staatlich-politisches Leben, Geistesleben. Dann kann zu dem Wirtschaftsleben des Westens, wozu der Westen besonders durch seine Natureigenschaften organisiert ist, auch das staatliche und geistige Leben treten. Dann kann die Mitte neben dem staatlichen Leben, das, wenn es anthroposophisch orientiert wird, aus ganz anderen Grundsätzen heraus aufgebessert wird, als früher da waren, dann kann die Mitte wirklich ein Wirtschafts- und ein Geistesleben aufnehmen. Und dann kann der Orient wiederum befruchtet werden. Das Geistesleben, das im Abendlande blüht, das wird der Orient verstehen, wenn man es ihm nur in der richtigen Weise bringt. Sobald nicht mehr künstliche Grenzen geschaffen sind, über die nicht hinübergelassen wird, was an wirklichem anthroposophisch orientierten Geistesleben im Abendlande lebt, sobald das hinübergelassen wird nach dem Orient, wird man es verstehen, wenn es auch zunächst durch so kokette Geister dringt wie Rabindranath Tagore oder andere. Es handelt sich darum, daß die Naturwissenschaft als solche zurückgewiesen wird von dem Orient. Aber jene Naturwissenschaft, welche durchleuchtet ist von wirklicher Geistigkeit, wie wir sie ja darstellen wollten in unseren Hochschulkursen hier, die wird mit allem Eifer auch vom Orient aufgenommen werden. Dann wird der Orient sehr viel Verständnis für ein selbständiges Geistesleben haben. Und er wird auch aufnehmen das selbständige staatlich-politische Leben, er wird aufnehmen können das Wirtschaftsleben, es in Unabhängigkeit treiben können. So daß wirklich in dieser Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus sich auch dasjenige erfüllt, was sich aus einer vernünftigen und zu gleicher Zeit geistigen Betrachtung als Entwickelung der europäischen und asiatischen Welt seit dem untergehenden Römertum darstellt.

Third Lecture

Yesterday, I drew attention once again, from a different perspective than I have done for some time now, to the differentiation that exists among the peoples of the present civilized world. I pointed out how the individualization of human beings in the fifth post-Atlantean epoch is guided by the spiritual worlds, how, on the one hand, certain beings that have advanced in an irregular manner and are further than humanity intervene in the West through human beings themselves, embodying themselves in humans out of certain interests in order to counteract the true impulses of the present, the impulses of the threefold social organism.

I have also pointed out how, in a different way in the East, the fact asserts itself that certain beings assert themselves, not through human beings themselves, but through their appearance to human beings, beings who had their real significance in the distant past but now want to influence human life; how these beings, through the special soul constitution of those living in the East, influence these people, whether more or less consciously, by entering the consciousness of some people in the East as imagination, or by entering the human ego during sleep, into the astral body, and then asserting themselves without people knowing it, in the after-effects during waking life, and in this way bringing in everything that wants to pile up against the regular progress of humanity in the East. So we can say that in the West, a kind of earthbound condition has long been developing in certain people, as I described yesterday, who are scattered here and there and who occupy leadership positions, especially in sects, secret societies, and the like. In the East, there are also certain leading personalities who, under the influence of such beings of the past appearing through imagination, carry out what they bring into the present cultural development. If we want to understand how the people of the European center are, in a sense, wedged between the West and the East, we must take a closer look at the spiritual conditions that underlie this and at everything that is expressed in the physical-sensory world out of these spiritual conditions.

I have just pointed out to you from various points of view how the life of the ancient Orient was essentially a spiritual life, how the people of the ancient Orient had a highly developed spiritual life, a spiritual life that flowed out of their direct perception of the spiritual worlds; how this spiritual life actually lived on as a legacy, how it was initially present in Greek culture as beautiful artistry, but also as a certain insight; how, however, even in Greek culture, something began to creep in that later became Aristotelianism, which was already intellectual, dialectical thinking. But then what came from Oriental wisdom penetrated into Western civilization, and with the exception of what comes from natural science and what can come from modern anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, everything that exists in Western civilization in terms of spiritual life is basically old Oriental heritage. But this spiritual life is thoroughly decadent. This spiritual life is such that it lacks real substance, so that although human beings still have a certain inclination toward the spiritual world, they can no longer connect what they believe about the spiritual world with what happens here in the physical world.