The New Spirituality

and the Christ Experience of the Twentieth Century

GA 200

24 October 1920, Dornach

Lecture IV

As early as 1891 I drew attention1 See Rudolf Steiner's own review (GA 51) of his lecture to the Vienna Goethe Association (Wiener Goetheverein) on 27 November 1891 entitled Über das Geheimnis in Goethes Rätselmarchen in den 'Unterhaltu deutscher Ausgewanderter' (On the Secret in Goethe's Enigmatic Fairy Tale in 'Conversations of German Emigrants) in Literarisches Frühhwerk, Vol III, Book IV, Dornach, 1942. See also Goethe's Standard of the Soul (Goethes Geistesart in ihrer Offenbarung durch seine 'Faust' und durch sein 'Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der Lilie') (GA 22). to the relation between Schiller's Aesthetic Letters2 See On the Aesthetic Education of Man published in 1795 in the Die Horen. This work arose from letters sent by Schiller to the Duke of Augustenburg between 1793 and 1795. and Goethe's Fairy-tale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily.3 Published in the Die Horen in 1795 as the close to the short story Conversations of German Emigrants. I would like today to point to a certain connection between what I gave yesterday as the characteristic of the civilization of the Central-European countries in contrast to the Western and Eastern ones and what arises in quite a unique way in Goethe and Schiller. I characterized, on the one hand, the seizure of the human corporality by the spirits of the West and, on the other hand, the feeling of those spiritual beings who, as imaginations, as spirits of the East, work inspiringly into Eastern civilization. And one can notice both these aspects in the leading personalities of Goethe and Schiller. I will only point out in addition how in Schiller's Aesthetic Letters he seeks to characterize a human soul-constitution which shows a certain middle mood between one possibility in the human being—his being completely given over to instincts, to the sensible-physical—and the other possibility—that of being given over to the logical world of reason. Schiller holds that, in both cases, the human being cannot come to freedom. For if he has completely surrendered himself to the world of the senses, to the world of instincts, of desires, he is given over to his bodily-physical nature and is unfree. But he is also unfree when he surrenders himself completely to the necessity of reason, to logical necessity; for then he is coerced under the tyranny of the laws of logic. But Schiller wants to point to a middle state in which the human being has spiritualized his instincts to such a degree that he can give himself up to them without their dragging him down, without their enslaving him, and in which, on the other hand, logical necessity is taken up into sense perception (sinnliche Anschauen), taken up into personal desires (Triebe), so that these logical necessities do not also enslave the human being.

Schiller finds this middle state in the condition of aesthetic enjoyment and aesthetic creation, in which the human being can come to true freedom.

It is an extremely important fact that Schiller's whole treatise arose out of the same European mood as did the French Revolution. The same thing which, in the West, expressed itself tumultuously as a large political movement orientated towards external upheaval and change also moved Schiller—but moved him in such a way that he sought to answer the question: What must the human being do in himself in order to become a truly free being? In the West they asked: How must the external social conditions be changed so that the human being can become free? Schiller asked: What must the human being become in himself so that, in his constitution of soul, he can live in (darleben) freedom? And he sees that if human beings are educated to this middle mood they will also represent a social community governed by freedom. Schiller thus wishes to realize a social community in such a way that free conditions are created through [the inner nature of] human beings and not through outer measures.

Schiller came to this composition of his Aesthetic Letters through his schooling in Kantian philosophy. His was indeed a highly artistic nature, but in the 1780s and the beginning of the 1790s he was strongly influenced by Kant and tried to answer such questions for himself in a Kantian way (im Kantischen Sinne). Now the Aesthetic Letters were written just at the time when Goethe and Schiller were founding the magazine Die Horen (The Hours) and Schiller lays the Aesthetic Letters before Goethe.

Now we know that Goethe's soul-configuration was quite different from Schiller's. It was precisely because of the difference of their soul-constitutions that these two became so close. Each could give to the other just that which the other lacked. Goethe now received Schiller's Aesthetic Letters in which Schiller wished to answer the question: How can the human being come inwardly to a free inner constitution of soul and outwardly to free social conditions? Goethe could not make much of Schiller's philosophical treatise. This way of presenting concepts, of developing ideas, was not unfamiliar to him. Anyone who, like myself, has seen how Goethe's own copy of Kant's Critique of Pure Reason is filled with underlinings and marginal comments knows how Goethe had really studied this work of Kant's which was abstract, but in a completely different sense. And just as he seems to have been able to take works such as these purely as study material, so, of course, he could also have taken Schiller's Aesthetic Letters. But this was not the point. For Goethe this whole construction of the human being—on the one hand logical necessity and on the other the senses with their sensual needs, as Schiller said, and the third, the middle condition—for Goethe this was all far too cut and dried, far too simplistic. He felt that one could not picture the human being so simply, or present human development so simply, and thus he wrote to Schiller that he did not want to treat the problem, this whole riddle, in such a philosophical, intellectual form, but more pictorially. Goethe then treated this same problem in picture form—as reply, as it were, to Schiller's Aesthetic Letters—in his Fairy-tale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily by presenting the two realms on this and on the far side of the river, in a pictorial, rich and concrete way; the same thing that Schiller presents as sense-life and the life of reason. And what Schiller characterizes abstractly as the middle condition, Goethe portrays in the building of the temple in which rule the King of Wisdom (the Golden King), the King of Semblance (the Silver King), the King of Power (the Copper King) and in which the Mixed King falls to pieces. Goethe wanted to deal with this in a pictorial way. And we have, in a certain sense, an indication—but in the Goethean way—of the fact that the outer structure of human society must not be monolithic but must be a threefoldness if the human being is to thrive in it. What in a later epoch had to emerge as the threefold social order is given here by Goethe still in the form of an image. Of course, the threefold social order does not yet exist but Goethe gives the form he would like to ascribe to it in these three kings; in the Golden, the Silver, and the Copper King. And what cannot hold together he gives in the Mixed King.

But it is no longer possible to give things in this way. I have shown this in my first Mystery Drama4 See The Portal of Initiation—A Rosicrucian Mystery, 1910, in Four Mystery Dramas, (GA 14). which, in essence, deals with the same theme but in the way required by the beginning of the twentieth century, whereas Goethe wrote his Fairy-tale at the end of the eighteenth century.

Now, however, it is already possible to indicate in a certain way—even though Goethe had not himself yet done so—how the Golden King would correspond to that aspect of the social organism which we call the spiritual aspect: how the King of Semblance, the Silver King, would correspond to the political State: how the King of Power, the Copper King, would correspond to the economic aspect, and how the Mixed King, who disintegrates, represents the 'Uniform State' which can have no permanence in itself.

This was how, in images, Goethe pointed to what would have to arise as the threefold social order. Goethe thus said, as it were, when he received Schiller's Aesthetic Letters: One cannot do it like this. You, dear friend, picture the human being far too simplistically. You picture three forces. This is not how it is with the human being. If one wishes to look at the richly differentiated inner nature of the human being, one finds about twenty forces—which Goethe then presents in his twenty archetypal fairy-tale figures—and one must then portray the interplay and interaction of these twenty forces in a much less abstract way.

Thus at the end of the eighteenth century we have two presentations of the same thing. One by Schiller, from the intellect as it were, though not in the usual way that people do things from the intellect, but such that the intellect is permeated here with feeling and soul, is permeated by the whole human being. Now there is a difference between some dry, average, professional philistine presenting something on the human being in psychological terms, where only the head thinks about the matter, and Schiller, out of an experience of the whole human being, forming for himself the ideal of a human constitution of soul and thereby only transforming into intellectual concepts what he actually feels.

It would be impossible to go further on the path taken by Schiller using logic or intellectual analysis without becoming philistine and abstract. In every line of these Aesthetic Letters there is still the full feeling and sensibility of Schiller. It is not the stiff Königsberg approach of Immanuel Kant with dry concepts; it is profundity in intellectual form transformed into ideas. But should one take it just one step further one would come into the intellectual mechanism that is realized in the usual science of today in which, basically, behind what is structured and developed intellectually, the human being has no more significance. It thus becomes a matter of no importance whether Professor A or D or X deals with the subject because what is presented does not arise from the whole human being. In Schiller everything still has a totally personal (urpersönlich) nature, even into the intellect. Schiller lives there in a phase—indeed, in an evolutionary point of the modern development of humanity which is of essential importance—because Schiller stops just short of something into which humanity later fell completely.

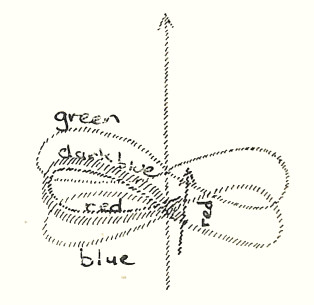

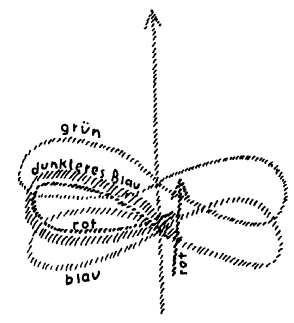

Let us show diagramatically what might be meant here. One could say: This is the general tendency of human evolution (arrow pointing upwards). Yet it cannot go [straight] like this—portrayed only schematically—but loops round into a lemniscate (blue). But it cannot go on like that—there must, if evolution takes this course, be continually new impulses Antriebe) which move the lemniscates up along the line.

Schiller, having arrived at this point here (see diagram), would have gone into a dark blue, as it were, of mere abstraction, of intellectuality, had he proceeded further in objectifying what he felt inwardly. But he drew a halt and paused with his forms of reasoning just at that point at which the personality is not lost. Thus, this did not become blue but, on a higher level of the Personality—which I will colour with red (see diagram)—was turned into green.

Thus one can say: Schiller held back with his intellectuality just before that point at which intellectuality tries to emerge in its purity. Otherwise he would have fallen into the usual intellect of the nineteenth century. Goethe expressed the same thing in images, in wonderful images, in his Fairy-tale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily. But he, too, stopped at the images. He could not bear these pictures to be in any way criticized because, for him, what he perceived and felt about the individual human element and the social life, did simply present itself in such pictures. But he was allowed to go no further than these images. For had he, from his standpoint, tried to go further he would have come into wild, fantastic daydreams. The subject would no longer have had definite contours; it would no longer have been applicable to real life but would have risen above and beyond it. It would have become rapturous fantasy. One could say that Goethe had to avoid the other chasm, in which he would have come completely into a fantastic red. Thus he adds that element which is non-personal—that which keeps the pictures in the realm of the imaginative—and thereby came also to the green.

Expressing it schematically, Schiller had, as it were, avoided the blue, the Ahrimanic-intellectuality; Goethe had avoided the red, excessive rapturousness, and kept to concrete imaginative pictures.

As a human being of Central Europe, Schiller had con-fronted the spirits of the West. They wanted to lead him astray into the solely intellectual. Kant had succumbed to this. I spoke about this recently5 See Lecture One of this volume. and indicated how Kant had succumbed to the intellectuality of the West through David Hume. Schiller had managed to work himself clear of this even though he allowed himself to be taught by Kant. He stayed at the point that is not mere intellectuality.

Goethe had to do battle with the other spirits, with the spirits of the East, who pulled him towards imaginations. Because at that time spiritual science was not yet present on the earth he could not go further than to the web of imaginations in the Fairy-tale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily. But even here he managed to remain within firm contours. He did not go off into wild fantasy or ecstasies. He gave himself a new and fruitful stimulus through his journey to the South where much of the legacy from the Orient was still preserved. He learnt how the spirits of the East still worked here as a late blossoming of oriental culture; in Greek art as he construed this for himself from Italian works of art. It can therefore be said that there was something quite unique in this bond of friendship between Schiller and Goethe. Schiller had to battle with the spirits of the West; he did not yield to them but held back and did not fall into mere intellectuality. Goethe had to battle with the spirits of the East; they tried to pull him into ecstatic reveries zum Schwärmerischen). He, too, held back; he kept to the images which he gives in his Fairy-tale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily. Goethe would have had either to succumb to rapturous daydreams (Schwärmerei) or to take up oriental revelation. Schiller would have had either to become completely intellectual or would have had to take seriously what he became—it is well known that he was made a 'French citizen' by the revolutionary government but that he did not take the matter very seriously.

We see here how, at an important point of European development, these two soul-constitutions, which I have characterized for you, stand side by side. They live anyway, so to speak, in every significant Central-European individuality but in Schiller and Goethe they stand in a certain way simultaneously side by side. Schiller and Goethe remained, as it were, at this point, for it just required the intercession of spiritual science to raise the curve of the lemniscate (see diagram) to a higher level.

And thus, in a strange way, in Schiller's three conditions—the condition of the necessity of reason, the condition of the necessity of instincts and that of the free aesthetic mood—and in Goethe's three kings—the Golden King, the Silver King, and the Copper King—we see a prefiguration of everything that we must find through spiritual science concerning the threefold nature of the human being as well as the threefold differentiation of the social community representing, as these do, the most immediate and essential aims and problems of the individual human being and of the way human beings live together.

These things direct us indeed to the fact that this threefolding of the social organism is not brought to the surface arbitrarily but that even the finest spirits of modern human evolution have already moved in this direction. But if there were only the ideas about the social questions such as those in Goethe's Fairy-tale and nothing more one would never come to an impetus for actual outer action. Goethe was at the point of overcoming mere revelations. In Rome he did not become a Catholic but raised himself up to his imaginations. But he stopped there, with just pictures. And Schiller did not become a revolutionary but a teacher of the inner human being. He stopped at the point where intellect is still suffused with the personality.

Thus, in a later phase of European culture, there was still something at work which can be perceived also in ancient times and most clearly, for modern people, in the culture of ancient Greece. Goethe also strove towards this Greek element. In Greece one can see how the social element is presented in myth—that is, also in picture form. But the Greek myth, basically, Is image in the same way that Goethe's Fairy-tale is image. It is not possible with these images to work into the social organism in a reforming way. One can only describe as an idealist, as it were, what ought to take shape. But the images are too frail a structure to enable one to act strongly and effectively in the shaping of the social organism. For this very reason the Greeks did not believe that their social questions were met by remaining in the images of the myths. And it is here, when one follows this line of investigation, that one comes to an important point in Greek development.

One could put it like this: for everyday life, where things go on in the usual way, the Greeks considered themselves dependant on their gods, on the spirits of their myths. When, however, it was a matter of deciding something of great importance, then the Greeks said: Here it is not those gods who work into imaginations and are the gods of the myths that can determine the matter; here something real must come to light. And so the Oracle arose. The gods were not pictured here merely imaginatively but were called upon (veranlasst) really to inspire people. And it was with the sayings of the Oracle that the Greeks concerned themselves when they wanted to receive social impulses. Here they ascended from imagination to inspiration, but an inspiration which they attained by means of outer nature. We modern human beings must certainly also endeavour to lift ourselves up to inspiration; an inspiration, however, that does not call upon outer nature in oracles but which rises to the spirit in order to be inspired in the sphere of the spirit. But just as the Greeks turned to reality in matters of the social sphere—just as they did not stop at imaginations but ascended to inspirations—so we, too, cannot stop at imaginations but must rise up to inspirations if we are to find anything for the well-being of human society in the modern age.

And we come here to another point which is important to look at. Why did Schiller and Goethe both stop at a certain point—the one on the path towards the intellectual (Verstandiges) and the other on the path to the imaginative? Neither of them had spiritual science; otherwise Schiller would have been able to advance to the point of permeating his concepts in a spiritual-scientific way and he would then have found: something much more real in his three soul-conditions than the three abstractions in his Aesthetic Letters. Goethe would have filled imagination with what speaks out in all reality from the spiritual world and would have been able to penetrate to the forms of the social life which wish to be put into effect from the spiritual world—to the spiritual element in the social organism, the Golden King; to the political element in the social organism, the Silver King; and to the economic element, the Bronze, the Copper, King.

The age in which Goethe and Schiller pressed forward to these insights—the one in the Aesthetic Letters and the other in the Fairy-tale—was not yet able to go any further. For, in order to penetrate further, there is something quite definite that must first be realized. People have to see what becomes of the world if one continues along Schiller's path up to the full elaboration (Ausgestaltung) of the impersonally intellectual. The nineteenth century developed it to being with in natural science and the second half of the nineteenth century already began to try to realize it in outer public affairs. There is a significant secret here. In the human organism what is ingested is also finally destroyed. We cannot simply go on eating but must also excrete; the substance we take in has to meet with destruction, has to be destroyed, and has then to leave the organism. And the intellectual is that which—and here comes a complication—as soon as it gets hold of the economic life in the uniform State, in the Mixed King, destroys that economic life.

But we are now living in the time in which the intellect must evolve. We could not come to the development of the consciousness-soul in the fifth post-Atlantean epoch without developing the intellect. And it is the Western peoples that have just this task of bringing the intellect into the economic life. What does this mean? We cannot order modern economic life imaginatively, in the way that Goethe did in his Fairy-tale, because we have to shape it through the intellect (verständig). Because in economics we cannot but help to go further along the path which Schiller took, though in his case he went only as far as the still-personal outbreathing of the intellect. We have to establish an economic life which, because it has to come from the intellect, of necessity works destructively in the fifth post-Atlantean epoch. In the present age there is no economic life that could be run imaginatively like that of the Orient or the economy of medieval Europe. Since the middle of the fifteenth century we have only had the possibility of an economic life which, whether existing alone or mixed with the other limbs of the social organism, works destructively. There is no other way. Let us therefore look on this economic life as the side of the scales that would sink far down and therefore has to work destructively. But there also has to be a balance. For this reason we must have an economic life that is one part of the social organism, and a spiritual life which holds the balance, which builds up again. If one clings today to the uniform State, the economic life will absorb this uniform State together with the spiritual life, and uniform States like these must of necessity lead to destruction. And when, like Lenin and Trotsky, one founds a State purely out of the intellect it must lead to destruction because the intellect is directed solely to the economic life.

This was felt by Schiller as he thought out his social conditions. Schiller felt: If I go further in the power of the intellect (verständesmassiges Können) I will come into the economic life and will have to apply the intellect to it. I will not then be portraying what grows and thrives but what lives in destruction. Schiller shrank back before the destruction. He stopped just at the point where destruction would break in. People of today invent all sorts of social economic systems but are not aware, because they lack the sensitivity of feeling for it, that every economic system like this that they think up leads to destruction; leads definitely to destruction if it is not constantly renewed by an independent, developing spiritual life which ever and ever again works as a constructive element in relation to the destruction, the excretion, of the economic life. The working together of the spiritual limb of the social organism with the economic element is described in this sense in my Towards Social Renewal (Kernpunkte der Sozialen Frage).6 See Towards Social Renewal, 1919, (GA 23). For what follows on here, see Chapter Two.

If, with the modern intellectuality of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch, people were to hold on to capital even when they themselves could no longer manage it, the economic life itself would cause it to circulate. Destruction would inevitably have to come. This is where the spiritual life has to intervene; capital must be transferred via the spiritual life to those who are engaged in its administration. This is the inner meaning of the threefolding of the social organism; namely that, in a properly thought out threefold social organism, one should be under no illusion that the economic thinking of the present is a destructive element which must, therefore, be continually counterbalanced by the constructive element of the spiritual limb of the social organism.

In every generation, in the children whom we teach at school, something is given to us; something is sent down from the spiritual world. We take hold of this in education—this is something spiritual—and incorporate it into the economic life and thereby ward off its destruction. For the economic life, if it runs its own course, destroys itself. This is how we must look at things. Thus we must see how at the end of the eighteenth century there stood Goethe and Schiller. Schiller said to himself: I must pull back, I must not describe a social system which calls merely on the personal intellect. I must keep the intellect within the personality, otherwise I would describe economic destruction. And Goethe: I want sharply contoured images, not excessive vague ones. For if I were to go any further along that path I would come into a condition that is not on the earth, that does not take hold with any effect on life itself. I would leave the economic life below me like something lifeless and would found a spiritual life that is incapable of reaching into the immediate circumstances of life.

Thus we are living in true Goetheanism when we do not stop at Goethe but also share the development in which Goethe himself took part since 1832. I have indicated this fact—that the economic life today continually works towards its own destruction and that this destruction must be continually counterbalanced. I have indicated this in a particular place in my Towards Social Renewal. But people do not read things properly. They think that this book is written in the same way most books are written today—that one can just read it through. Every sentence in a book such as this, written out of practical insight, requires to be thoroughly thought through!

But if one takes these two things [Goethe's Fairy-tale and Schiller's Aesthetic Letters], Schiller's Aesthetic Letters were little understood in the time that followed them. I have often spoken about this. People gave them little attention. Otherwise the study of Schiller's Aesthetic Letters would have been a good way of coming into what you find in my Knowledge of the Higher Worlds—How is it Achieved? Schiller's Aesthetic Letters would be a good preparation for this. And likewise, Goethe's Fairy-tale could also be the preparation for acquiring that configuration of thinking (Geisteskonfiguration) which can arise not merely from the intellect but from still deeper forces, and which would be really able to understand something like Towards Social Renewal. For both Schiller and Goethe sensed something of the tragedy of Central European civilization—certainly not consciously, but they sensed it nevertheless. Both felt—and one can read this everywhere in Goethe's conversations with Eckermann, with Chancellor von Müller7 See, for example, the conversation with Chancellor von Müller on 8 June 1830 and that with Eckermann on 11 March 1832., and in numerous other comments by Goethe—that if something like a new impulse from the spirit did not arise, like a new comprehension of Christianity, then everything must go into decline. A great deal of the resignation which Goethe felt in his later years is based, without doubt, on this mood.

And those who, without spiritual science, have become Goetheanists feel how, in the very nature of German Central Europe, this singular working side by side of the spirits of the West and the spirits of the East is particularly evident. I said yesterday that in Central European civilization the balance sought by later Scholasticism between rational knowledge and revelation is attributable to the working of the spirits of the West and the spirits of the East. We have seen today how this shows itself in Goethe and Schiller. But, fundamentally, the whole of Central European civilization wavers in the whirlpool in which East and West swirl and interpenetrate one another. From the East the sphere of the Golden King; from the West the sphere of the Copper King. From the East, Wisdom; from the West, Power. And in the middle is what Goethe represented in the Silver King, in Semblance; that which imbues itself with reality only with great difficulty. It was this semblance-nature of Central European civilization which lay as the tragic mood at the bottom of Goethe's soul. And Herman Grimm, who also did not know spiritual science, gave in a beautiful way, out of his sensitive feeling for Goethe whom he studied, a fine characterization of Central-European civilization. He saw how it had the peculiarity of being drawn into the whirlpool of the spirits of the East and the spirits of the West. This was the effect of preventing the will from coming into its own and leads to the constantly vacillating mood of German history. Herman Grimm8 Herman Grimm (1828–1902). The quotations are from his essay Heinrich von Treitschke's German History (Heinrich von Treitschhes Deutsche Geschichte) in Contributions to German Cultural History, (Beitrage zur Deutschen Kultur-geschichte) Berlin, 1897, page. 5 puts it beautifully when he says: 'To Treitschke German history is the incessant striving towards spiritual and political unity and, on the path towards this, the incessent interference by our own deepest inherent peculiarities.' This is what Herman Grimm says, experiencing himself as a German. And he describes this further as 'Always the same way in our nature to oppose where we should give way and to give way where resistance is called for. The remarkable forgetting of what has just past. Suddenly no longer wanting what, a moment ago, was vigorously striven for. A disdain for the present, but strong, indefinite hope. Added to this the tendency to give ourselves over to the foreigner and, no sooner having done so, then exercising an unconscious, determining (massgebende) influence on the foreigners to whom we had subjected ourselves.'

When, today, one has to do with Central European civilization and would like to arrive at something through it, one is everywhere met by the breath of this tragic element which is betrayed by the whole history of the German, the Central European element, between East and West. It is everywhere still so today that, with Herman Grimm, one can say: There is the urge to resist where one should give way and to give way where resistance is needed.

This is what arises from the vacillating human beings of the Centre; from what, between economics and the reconstructing spirit-life, stands in the middle as the rhythmical oscillating to and fro of the political. Because the civic-political element has celebrated its triumph in these central countries, it is here that a semblance lives which can easily become illusion. Schiller, in writing his Aesthetic Letters, did not want to abandon semblance. He knew that where one deals purely with the intellect, one comes into the destruction of the economic life. In the eighteenth century that part was destroyed which could be destroyed by the French Revolution; in the nineteenth century it would be much worse. Goethe knew that he must not go into wild fantasies but keep to true imagination. But in the vacillation between the two sides of this duality, which arises in the swirling, to and fro movement of the spirits of the West and of the East, there is easily generated an atmosphere of illusion. It does not matter whether this illusionary atmosphere emerges in religion, in politics or in militarism; in the end it is all the same whether the ecstatic enthusiast produces some sort of mysticism or enthuses in the way Ludendorff9 Erich Ludendorff (1865–1937), German general. did without standing on the ground of reality. And, finally, one an also meet it in a pleasing way. For the same place in Herman Grimm which I just read out continues as follows: 'You can see it today: no one seemed to be so completely severed from their homeland as the Germans who became Americans, and yet American life, into which our emigrants dissolved, stands today under the influence of the German spirit.'

Thus writes the brilliant Herman Grimm in 1895 when it was only out of the worst illusion that one could believe that the Germans who went to America would give American life a German colouring. For already, long before this, there had been prepared what then emerged in the second decade of the twentieth century: that the American element completely submerged what little the Germans had been able to bring in.

And the illusionary nature of this remark by Herman Grimm becomes all the greater when one finally bears in mind the following. Herman Grimm makes this comment from a Goethean way of thinking (Gesinnung), for he had modelled himself fully on Goethe. But he had a certain other quality. Anyone who knows Herman Grimm more closely knows that in his style, in his whole way of expressing himself, in his way of thinking, he had absorbed a great deal of Goethe, but not Goethe's real and penetrating quality—for Grimm's descriptions are such that what he actually portrays are shadow pictures, not real human beings. But he has something else in him, not just Goethe. And what is it that Herman Grimm has in himself? Americanism! For what he had in his style, in his thought-forms, apart from Goethe he has from early readings of Emerson. Even his sentence structure, his train of thought, is copied from the American, Emerson.10Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), American writer and philosopher.

Thus, Herman Grimm is under this double illusion, in the realm of the Silver King of Semblance. At a time when all German influence has been expunged from America he fondly believes that America has been Germanized, when in fact he himself has quite a strong vein of Americanism in him.

Thus there is often expressed in a smaller, more intimate context what exists in a less refined form in external culture at large. A crude Darwinism, a crude economic thinking, has spread out there and would in the end, if the threefolding of the social organism fails to come, lead to ruin—for an economic life constructed purely intellectually must of necessity lead to ruin. And anyone who, like Oswald Spengler,11Reference is made here to Oswald Spengler (1880–1936) and his work Der Untergang des Abendlandes (The Decline and Fall of the Occident), the first part of which was published in 1918. thinks in the terms of this economic life can prove scientifically that at the beginning of the third millenium the modern civilized world—which today is actually no longer so very civilized—will have had to sink into the most desolate barbarity. For Spengler knows nothing of what the world must receive as an impulse, as a spiritual impulse.

But the spiritual science and the spiritual-scientific culture which not only wishes to enter, but must enter, the world today still has an extremely difficult task getting through. And everywhere those who wish to prevent this spiritual science from arising assert themselves. And, basically, there are only a few energetic workers in the field of spiritual science whereas the Others, who lead into the works of destruction, are full of energy.

One only has to see how people of today are actually completely at a loss in the face of what comes up in the life of Present civilization. It is characteristic, for instance, how a newspaper of Eastern Switzerland carried articles on my lectures on The Boundaries of Natural Science during the course at the School of Spiritual Science. And now, in the town where the newspaper is published, Arthur Drews12Arthur Drews (1865–1935), Professor of Philosophy at the Technical University at Karlsruhe, spoke on 10 October 1920 in lectures organized by the free religious congregation at Konstanz on 'Rudolf Steiner's Anthroposophy'. He repeated this lecture on 19 November in Mainz. His articles opposing Anthroposophy were published as a collection under the title Metaphysik and Anthropasophie in ihrer Stellung zur Erkenrunis des Obersinnlichen (Metaphysics and Anthropasophy in their Position Regarding Knowledge of the Supersensible), Berlin, 1922., the copy-cat of Eduard von Hartmann, holds lectures in which he has never done anything more than rehash Eduard von Hartmann, the philosopher of the unconscious.13Eduard von Hartmann (1842–1906), Philosophie des Unbewucsten: Versuch einer Weltanschauung (Philosophy of the Unconscious: An Attempt at a World-View), Berlin, 1869. In the case of Hartmann it is interesting. In the case of the rehasher it is, of course, highly superfluous. And this philosophical hollow-headedness working at Karlsruhe University is now busying itself with anthroposophically-orientated spiritual science.

And how does the modern human being—I would particularly like to emphasize this—confront these things? Well, we have listened to one person, we now go and listen to someone else. This means that, for the modern human being, it is all a matter of indifference, and this is a terrible thing. Whether the rehasher of Eduard von Hartmann, Arthur Drews, has something against Anthroposophy or not is not the important point—for what the man can have against Anthroposophy can be fully construed beforehand from his books, not a single sentence need be left out. The significant thing is that people's standpoint is that one hears something, makes a note of it, and then it is over and done with, finished! All that is needed to come to the right path is that people really go into the matter. But people today do not want to be taken up with having to go into something properly. This is the really terrible and awful thing; this is what has already pushed people so far that they are no longer able to distinguish between what is speaking of realities and what writes whole books, like those of Count Hermann Von Keyserling,14Count Hermann Keyserling (1880–1946). Compare, for example, the chapter 'Für and wider die Theosophie' ('For and Against Theosophy') in Philosophic als Kunst (Philosophy as an Art), Darmstadt, 1920. in which there is not one single thought, just jumbled-together words. And when one longs for something to be taken up enthusiastically—which would, of itself, lead to this hollow word-skirmishing being distinguished from what is based on genuine spiritual research—one finds no one who rouses himself, makes a stout effort and is able to be taken hold of by that which has substance. This is what people have forgotten—and forgotten thoroughly—in this age in which truth is not decided according to truth itself, but in which the great lie walks among men so that in recent years individual nations have only found to be true what comes from them and have found what comes from other nations to be false. The disgusting way that people lie to each other has fundamentally become the stamp of the public spirit. Whenever something came from another nation it was deemed untrue. If it came from one's own nation it was true. This still echoes on today; it has already become a habit of thought. In contrast, a genuine, unprejudiced devotion to truth leads to spiritualization. But this is basically still a matter of indifference for modern human beings.

Until a sufficiently large number of people are willing to engage themselves absolutely whole-heartedly for spiritual science, nothing beneficial will come from the present chaos. People should not believe that one can somehow progress by galvanizing the old. This 'old' founds 'Schools of Wisdom' on purely hollow words. It has furnished university philosophy with the Arthur Drews's who, however, are actually represented everywhere, and yet humanity will not take a stand. Until it makes a stand in all three spheres of life—in the spiritual, the political and the economic spheres—no cure can come out of the present-day chaos. It must sink ever deeper!

Vierter Vortrag

Ich habe bereits im Jahre 1891 aufmerksam gemacht auf die Beziehung, welche besteht zwischen Schillers «Ästhetischen Briefen» und Goethes «Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der schönen Lilie». Heute möchte ich darauf hinweisen, daß ein gewisser Zusammenhang besteht zwischen dem, was ich gestern als Charakteristik der mittelländischen Zivilisation im Gegensatze zu der westlichen und der östlichen gegeben habe, und dem, was ja in ganz eigenartiger Weise bei Schiller und bei Goethe auftritt. Man kann dieses ganze Streben, wie ich es gestern charakterisiert habe — auf der einen Seite das Ergriffensein der menschlichen Leiblichkeit von den Geistern des Westens und auf der anderen Seite das Fühlen jener geistigen Wesenheiten, die als Imaginationen, als Geister des Ostens inspirierend wirken auf die östliche Zivilisation —, man kann beides gerade bei diesen führenden Geistern, bei Schiller und bei Goethe, merken. Ich mache nur noch darauf aufmerksam, wie in Schillers «Ästhetischen Briefen» gesucht wird, eine Seelenverfassung des Menschen zu charakterisieren, die eine gewisse mittlere Stimmung darstellt zwischen dem einen, das der Mensch auch haben kann, dem Hingegebensein an die Instinkte, an das Sinnlich-Physische, und dem anderen, das er haben kann, wenn er an die logische Vernunftwelt hingegeben ist. Schiller meint, daß der Mensch in beiden Fällen nicht zur Freiheit kommen könne. In dem Falle nicht, wenn er ganz der Sinnenwelt, der Welt der Instinkte, der Triebe hingegeben ist; da ist er seiner leiblich-physischen Wesenheit unfrei hingegeben. Aber er ist auch nicht frei, wenn er der Vernunftnotwendigkeit, der logischen Notwendigkeit ganz hingegeben ist, denn da zwingen ihn eben die logischen Gesetze unter ihre Tyrannei. Aber Schiller will hinweisen auf einen mittleren Zustand, wo der Mensch seine Instinkte so weit vergeistigt hat, daß er sich ihnen überlassen kann, daß sie ihn nicht hinunterziehen, daß sie ihn nicht versklaven, und wo auf der anderen Seite die logische Notwendigkeit aufgenommen ist in das sinnliche Anschauen, aufgenommen ist in die persönlichen Triebe, so daß auch diese logische Notwendigkeit den Menschen nicht versklavt.

Schiller findet allerdings dann in dem Zustand des ästhetischen Genießens und des ästhetischen Schaffens jenen mittleren Zustand, in dem der Mensch zur wahren Freiheit kommen kann.

Es ist von großer Wichtigkeit, daß diese ganze Abhandlung Schillers hervorgegangen ist aus derselben europäischen Stimmung, aus der die Französische Revolution hervorgegangen ist. Dasselbe, was sich tumultuarisch im Westen geäußert hat als große politische Bewegung mit der Hinorientierung auf äußere Umwälzungen, das bewegte Schiller, und es bewegte ihn so, daß er suchte die Frage zu beantworten: Was muß der Mensch an sich selbst tun, um zu einem wahrhaft freien Wesen zu werden? — Im Westen stellte man die Frage: Wie müssen die äußeren sozialen Zustände werden, damit der Mensch in ihnen frei werden könne? — Schiller frägt: Wie muß der Mensch selbst in sich werden, damit er in seiner Seelenverfassung die Freiheit darleben könne? — Und Schiller stellt sich vor, daß, wenn die Menschen zu einer solchen mittleren Stimmung erzogen werden, sie auch ein soziales Gemeinwesen darstellen werden, in dem Freiheit herrscht; also auch ein soziales Gemeinwesen will Schiller auf die Weise verwirklichen, daß durch die Menschen die freien Zustände geschaffen werden, nicht durch äußere Maßnahmen.

Schiller ist zu dieser Fassung seiner « Ästhetischen Briefe» durch seine Kant-Schulung gekommen. Er war ja bis zu einem hohen Grade eine künstlerische Natur, allein er hat sich gerade am Ende der achtziger Jahre und im Beginne der neunziger Jahre des 18. Jahrhunderts von Kant stark beeinflussen lassen und versuchte, im Kantischen Sinne sich solche Fragen zu beantworten. Die Abfassung der «Ästhetischen Briefe» fällt nun gerade in die Zeit, in der Goethe und Schiller zusammen die Zeitschrift «Die Horen» gründen, und Schiller legt die «Ästhetischen Briefe» Goethe vor.

Nun wissen wir ja, wie Goethes Seelenverfassung eine ganz andere war als die Schillers. Gerade durch die Verschiedenheit dieser Seelenverfassung kamen sich die beiden so nahe. Sie konnten, jeder dem anderen, das geben, was eben dieser andere nicht hatte. Nun bekam also Goethe Schillers «Ästhetische Briefe», in denen Schiller die Antwort geben wollte auf die Frage: Wie kommt der Mensch innerlich zu einer innerlich freien Seelenverfassung und äußerlich zu sozial freien Zuständen? Goethe konnte aus der philosophischen Abhandlung Schillers nicht viel machen. Diese Art der Begriffsführung, der Ideenentwickelung war Goethe nicht etwa fremd gewesen, denn derjenige, der, wie ich, gesehen hat, wie Kants «Kritik der reinen Vernunft» in Goethes eigenem Exemplar mit Unterstreichungen und Randbemerkungen versehen ist, der weiß, wie Goethe dieses noch in ganz anderem Sinne abstrakte Werk Kants wirklich studiert hat. Und wie er sie als solche Werke durchaus hätte hinnehmen können, so hätte er natürlich als Studiumwerk auch Schillers «Ästhetische Briefe» hinnehmen können. Aber darum handelte es sich gar nicht, sondern für Goethe war diese ganze Konstruktion des Menschen, auf der einen Seite der Vernunfttrieb mit seiner logischen Notwendigkeit, auf der anderen Seite der Sinnestrieb mit seiner sinnlichen Notdurft, wie Schiller sagte, und der dritte, mittlere Zustand, das war für Goethe etwas viel zu Gradliniges, zu Einfaches. Er empfand: So einfach kann man sich den Menschen nicht vorstellen, so einfach kann man auch die menschliche Entwickelung nicht darstellen, und deshalb schrieb er an Schiller, er wolle das ganze Problem, das ganze Rätsel nicht in einer solchen philosophisch verstandesmäßigen Form behandeln, sondern bildmäßig. Bildmäßig hat Goethe denn auch dieses selbe Problem, gewissermaßen als die Antwort auf die Zusendung der «Ästhetischen Briefe» Schillers, in seinem Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der schönen Lilie behandelt, indem er in den beiden Reichen, diesseits und jenseits des Flusses, aber in bildhafter, mannigfaltiger, konkreter Weise dasselbe hingestellt hat, was Schiller als Sinnlichkeit und als Vernunftmäßigkeit auf der anderen Seite hinstellte. Und das, was Schiller bloß abstrakt als den mittleren Zustand charakterisiert, das hat Goethe dann in der Aufrichtung des Tempels, in dem da herrscht der König der Weisheit, der goldene König, der König des Scheines, der silberne König, der König der Gewalt, der eherne, der kupferne König, und in dem zerfällt der gemischte König; das hat Goethe in bildhafter Weise behandeln wollen. Und wir haben gewissermaßen eine Hindeutung, aber eben noch in der Goetheschen Weise eine Hindeutung auf die Tatsache, daß die äußere Gliederung der menschlichen Gesellschaft nicht eine Einheit sein dürfe, sondern eine Dreiheit sein müsse, wenn der Mensch darinnen gedeihen solle.

Dasjenige, was dann entsprechend einer späteren Epoche als die Dreigliederung herauskommen mußte, das gibt Goethe noch im Bilde; natürlich ist noch nicht die Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus da, aber Goethe gibt eben die Gestalt, die er dem sozialen Organismus anweisen will, in diesen drei Königen, in dem goldenen, dem silbernen und dem kupfernen König; und das, was zerfällt, gibt er in dem gemischten König.

Man kann heute nicht mehr so diese Dinge geben. Das habe ich gezeigt in meinem ersten Mysterium, wo im Grunde genommen dasselbe Motiv behandelt ist, wo es aber so ist, wie man es behandeln mußte im Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts, während Goethe sein Märchen schrieb am Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts.

Nun kann man aber in einer gewissen Weise schon hindeuten darauf, wenn das auch Goethe selber noch nicht getan hat, wie der goldene König entsprechen würde demjenigen sozialen Gliede, das wir als das geistige Glied des sozialen Organismus bezeichnen; wie der König des Scheines, der silberne König, entsprechen würde dem politischen Staate; wie der König der Gewalt, der kupferne König, entsprechen würde dem wirtschaftlichen Gliede des sozialen Organismus; und wie der gemischte König, der in sich selber zerfällt, den Einheitsstaat darstellt, der in sich selber eben keinen Bestand haben kann.

Das ist gewissermaßen Goethes bildhafte Hindeutung auf das, was einmal herauskommen mußte als die Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus. Goethe hat also gewissermaßen gesagt, als er Schillers «Ästhetische Briefe» bekam: So kann man das nicht machen ; Sie, lieber Freund, stellen sich den Menschen viel zu einfach vor. Sie stellen sich drei Kräfte vor. So ist es beim Menschen nicht. Wenn man dieses ganze reichgegliederte Innere des Menschen nehmen und anschauen will, so bekommt man so ungefähr zwanzig Kräfte - die Goethe dann in seinen zwanzig Märchengestalten bildhaft dargestellt hat —-, und man muß dann das Spielen und Ineinanderwirken dieser etwa zwanzig Kräfte auch in einer wesentlich weniger abstrakten Weise darstellen.

So haben wir am Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts zwei Darstellungen ein und derselben Sache, eine von Schiller, man möchte sagen aus dem Verstande heraus, aber nicht so, wie die Menschen gewöhnlich aus dem Verstande heraus etwas machen, sondern doch so, daß der Verstand durchdrungen ist von Empfindung und Seele, von dem ganzen Menschen. Nur ist es ein Unterschied, ob irgendein steifer durchschnittsprofessionaler Philister irgendeine Sache über den Menschen psychologisch darstellt, wo nur der Kopf über die Sache denkt, oder ob hier Schiller aus dem Erleben des vollen Menschen heraus sich das Ideal einer menschlichen Seelenverfassung konstruiert und gewissermaßen das, was er empfindet, nur in Verstandesbegriffe umwandelt.

Man könnte nicht weiter nach dem Logisieren, nach dem verstandesmäßßigen Analysieren hin gehen auf dem Wege, auf dem Schiller gegangen ist, ohne daß man philiströs und abstrakt würde. Es ist noch das volle Fühlen und Empfinden Schillers in jeder Zeile dieser «Ästhetischen Briefe». Es ist nicht die steife Königsbergerität Immanuel Kants mit den trockenen Begriffen, es ist Tiefsinn in Verstandesform, in Ideen hinein gestaltet. Aber würde man einen Schritt weitergehen, dann würde man eben in das verstandesmäßige Getriebe hineinkommen, das verwirklicht ist in der heutigen gewöhnlichen Wissenschaft, wo ja im Grunde genommen hinter dem, was verstandesmäßig ausgestaltet ist, der Mensch nichts mehr bedeutet, wo es gleichgültig ist, ob der Professor A oder D oder X die Sache ausgestaltet, weil die Dinge eben dargestellt werden, ohne aus dem ganzen Menschen heraus genommen zu sein. Bei Schiller ist noch alles urpersönlich, aber bis in den Verstand heraufgehoben. Da lebt Schiller in einer Phase, ja geradezu in einem Entwickelungspunkt der modernen Menschheitsentfaltung, der wichtig und wesentlich ist, weil Schiller gerade haltmacht vor dem, in das dann später die Menschheit vollständig hinein verfallen ist.

Wollen wir einmal graphisch darstellen, wie etwa die Sache gemeint sein könnte. Man könnte sagen: Das ist im allgemeinen die Tendenz der Menschheitsentwickelung (Pfeil aufwärts). Sie geht aber nicht so vor sich, diese Menschheitsentwickelung - es ist dies nur schematisch, graphisch dargestellt —, sondern sie geht so vor sich, daß sich die Entwickelung (blau) in einer Lemniskate herumschlängelt; aber sie kann nicht so gehen, sondern es muß fortwährend, wenn die Entwickelung diesen Gang nimmt, neue Antriebe geben, die im Sinne dieser Linie die Lemniskate heraufheben. Schiller würde, angekommen an diesem Punkte hier (siehe Zeichnung), gewissermaßen in ein dunkleres Blau der bloßen Abstraktion, des bloßen Verstandesmäßigen hineingekommen sein, wenn er weiter fortgefahren hätte im Selbständigmachen desjenigen, was er innerlich fühlte. Er machte halt, und gerade noch hielt er mit dem verständigen Gestalten inne an dem Punkt, wo man die Persönlichkeit nicht verliert, sondern in dem verständigen Gestalten noch die Persönlichkeit drinnen hat. Daher wurde das nicht blau, sondern es wurde auf einer höheren Stufe der Persönlichkeit, die ich hier (siehe Zeichnung) mit Rot durchziehen will, grün gemacht. So daß man sagen kann: Schiller hielt zurück gerade im Verstandesmäßigen vor dem, wo das Verstandesmäßige in seiner Reinheit heraus will. Sonst wäre er in den gewöhnlichen Verstand des 19. Jahrhunderts hineinverfallen. Goethe drückte dasselbe aus in Bildern, in wunderbaren Bildern, in dem «Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der schönen Lilie»; aber er blieb auch stehen bei diesen Bildern; er konnte gar nicht leiden, daß man irgendwie an diesen Bildern etwas herummäkelte, denn für ihn ergab sich das, was er über das Individuell-Menschliche und über das soziale Leben empfand, eben in solchen Bildern. Aber weiter durfte er nicht gehen als bis zu diesen Bildern. Denn würde er nun weiterzugehen versucht haben von seinem Standpunkte aus, er wäre in das Schwärmerische, in die Phantastik hineingekommen. Die Sache würde nicht mehr Konturen gehabt haben; sie würde nicht mehr anwendbar gewesen sein für das Leben, sie würde das Leben überschritten haben, sich über das Leben hinaus erhoben haben. Es würde schwärmerische Phantastik geworden sein. Man möchte sagen: Goethe war genötigt, die andere Klippe zu vermeiden, wo er ganz ins PhantastischRote hineingekommen wäre. Darum hat er beigemischt das, was das Unpersönliche ist, dasjenige, was die Bilder in der Region des Imaginativen hielt, und ist dadurch auch auf das Grün gekommen.

Schiller hat gewissermaßen, wenn ich mich schematisch ausdrücken soll, das Blau vermieden, das Ahrimanisch-Verstandesmäßige; Goethe hat vermieden das Rot, das Schwärmerische, und ist beim konkreten imaginativen Bilde geblieben.

Schiller hat sich auseinandergesetzt als mittelländischer Mensch mit den Geistern des Westens. Die wollten ihn verleiten zu dem ganz Verstandesmäßigen. Kant ist dem unterlegen. Ich habe es dargestellt, indem ich vor kurzer Zeit hier darauf hingewiesen habe, wie Kant durch David Hume unterlegen ist dem Verstandesmäßigen des Westens. Schiller hat sich herausgearbeitet, obwohl er von Kant sich schulen ließ. Er ist geblieben bei dem, das nicht bloß das Verstandesmäßige ist.

Goethe hatte mit den anderen Geistern, den Geistern des Ostens zu kämpfen, die ihn nach der Imagination trieben. Er konnte zu seiner Zeit, weil Geisteswissenschaft noch nicht vorhanden war, nicht weiter gehen als bis zu dem Gewebe der Imagination in dem «Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der schönen Lilie». Aber auch da blieb er innerhalb der festen Konturen. Er ging nicht bis ins Phantastische, Schwärmerische hinauf. Er befruchtete sich, indem er nach Süden zog, wo noch viel erhalten war von dem Erbgute des Orients. Er lernte kennen, wie die Geister des Orients da noch wirkten in der Nachblüte orientalischer Kultur, der griechischen Künste, wie er sie sich konstruierte aus den italienischen Kunstwerken. So daß man sagen kann: Es ist etwas Eigentümliches in diesem Freundschaftsbunde zwischen Schiller und Goethe. Schiller hat zu kämpfen mit den Geistern des Westens; er ergibt sich ihnen nicht, er hält zurück, er verfällt nicht in den bloßen Verstand. Goethe hat zu kämpfen mit den Geistern des Ostens; sie wollen ihn zum Schwärmerischen treiben. Er hält zurück; er bleibt bei den Bildern, die er im «Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der schönen Lilie» gegeben hat. Goethe hätte entweder in die Schwärmerei verfallen oder die orientalische Offenbarung annehmen müssen. Schiller hätte entweder ganz verstandesmäßig werden müssen, oder er hätte das, was er geworden ist, ernst nehmen müssen; bekanntlich ist er ja von der Revolutionsregierung zum «französischen Bürger» ernannt worden, aber er hat die Sache nicht sehr ernst genommen.

Da sehen wir, wie in einem wichtigen Punkte europäischer Entwickelung diese zwei Seelenverfassungen nebeneinanderstehen, die ich Ihnen charakterisiert habe. Sie leben sonst ja auch, man möchte sagen in jeder einzelnen bedeutsamen mitteleuropäischen Individualität, aber in Schiller und Goethe stehen sie zu gleicher Zeit in einer gewissen Weise nebeneinander. Es mußte, während Schiller und Goethe gewissermaßen noch auf jenem Punkte geblieben sind, erst der Einschlag der Geisteswissenschaft kommen, der diese Lemniskatenkurve (siehe Zeichnung) heraufhebt, so daß sie auf einer höheren Stufe dann erscheint.

Und so sehen wir denn in einer eigentümlichen Weise in Schillers drei Zuständen, dem Zustand der Vernunftnotwendigkeit, dem der Instinktnotwendigkeit und dem der freien ästhetischen Stimmung, und in Goethes drei Königen, dem goldenen, dem silbernen, dem kupfernen, vorgebildet alles das, was wir sowohl über die Dreigliederung des Menschen, wie über die Dreigliederung des sozialen Gemeinwesens zu finden haben durch Geisteswissenschaft als die nächsten notwendigen Ziele und Rätselfragen des einzelnen Menschen und des menschlichen Zusammenlebens.

Diese Dinge weisen uns doch wohl darauf hin, daß nicht durch eine Willkür diese Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus an die Oberfläche getragen worden ist, sondern daß schon beste Geister der neueren Menschheitsentwickelung darauf hintendiert haben, solches zu bringen. Aber wenn es nichts anderes gäbe als ein solches Denken über das Soziale, wie es Goethes «Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der schönen Lilie» ist, so würde man nicht zur Schlagkraft des äußeren Wirkens kommen können. Goethe stand an dem Punkt, die bloße Offenbarung zu überwinden. Er ist ja auch in Rom nicht zum Katholiken geworden. Er erhob sich eben zu seinen Imaginationen. Aber er blieb doch beim bloßen Bilde stehen. Und Schiller ist nicht zum Revolutionär geworden, sondern zum Erzieher des inneren Menschen. Er blieb stehen bei dem Punkte, wo noch Persönlichkeit in der Verstandesgestaltung drinnen ist.

So wirkte sich in einer späteren Phase mitteleuropäischer Kultur etwas aus, was schon seit älteren Zeiten zu bemerken ist, am klarsten für den modernen Menschen noch im Griechentum. Nach dem Griechentum strebte ja auch Goethe. Im Griechentum ist zu bemerken, wie das Soziale im Mythus dargestellt wird, also auch im Bilde. Aber im Grunde genommen ist der griechische Mythus so Bild, wie auch Goethes «Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der schönen Lilie» Bild ist. Man kann nicht mit diesen Bildern nun etwa reformatorisch wirken im sozialen Organismus. Man kann gewissermaßen nur als Idealist etwas sagen, was sich bilden müßte. Aber die Bilder sind ein zu leichtes Gebäude, als daß man wirklich schlagkräftig eingreifen könnte in die Gestaltung des sozialen Organismus. Daher haben die Griechen auch nicht geglaubt, mit ihrem Stehenbleiben in den Mythenbildern auch das Soziale zu treffen. Und da kommt man, wenn man diese Linie des Forschens verfolgt, an einen wichtigen Punkt der griechischen Entwickelung.

Man möchte sagen: Für das Alltagsleben, wo sich die Dinge gewohnheitsmäßig abspielen, da dachten sich die Griechen abhängig von ihren Mythengöttern, Mythengeistern. Dann aber, wenn es sich darum handelte, Großes zu entscheiden, da sagten sich die Griechen: Ja, da machen es diejenigen Götter nicht aus, welche in die Imagination hereinwirken und eben die Mythengötter sind; da muß etwas Reales zutage treten. Und da trat das Orakel zutage. Da wurden die Götter nicht bloß imaginativ vorgestellt, da wurden sie veranlaßt, die Menschen wirklich zu inspirieren. Und mit den Orakelsprüchen befaßten sich die Griechen, wenn sie soziale Impulse haben wollten. Da stiegen sie auf von der Imagination zur Inspiration, aber zu einer Inspiration, zu welcher sie die äußere Natur herbeiriefen. Wir modernen Menschen müssen allerdings auch versuchen, uns zur Inspiration zu erheben, aber dann zu einer Inspiration, die nicht die äußere Natur in den Orakeln herbeiruft, sondern die zum Geiste aufsteigt, um in der Sphäre des Geistigen sich inspirieren zu lassen. Aber so wie die Griechen zum Realen griffen, wenn es sich um Soziales handelte, wie sie nicht bei Imaginationen geblieben sind, sondern zu den Inspirationen aufstiegen, so können wir auch nicht bei den bloßen Imaginationen bleiben, sondern müssen zu den Inspirationen aufsteigen, wenn wir irgend etwas zum sozialen Heile finden wollen in der neueren Zeit.

Und hier kommen wir an einen anderen Punkt, der wichtig ist zu beachten. Warum sind denn eigentlich Schiller und Goethe stehengeblieben, der eine auf dem Wege nach dem Verständigen, der andere auf dem Wege nach dem Imaginativen? Geisteswissenschaft hatten sie beide nicht, sonst hätte Schiller fortschreiten können dazu, seine Begriffe geisteswissenschaftlich zu durchdringen, und er würde dann etwas viel Realeres in seinen drei Seelenzuständen gefunden haben als die drei Abstraktionen, die er in den «Ästhetischen Briefen» hat. Goethe würde die Imagination ausgefüllt haben mit dem, was real aus der geistigen Welt herein spricht, und er hätte vordringen können zu den Gestaltungen des sozialen Lebens, die da bewirkt sein wollen aus der geistigen Welt herein, dem geistigen Glied des sozialen Organismus, dem goldenen König; dem staatlichen Glied des sozialen Organismus, dem silbernen König, dem König des Scheins; dem wirtschaftlichen Gliede, dem ehernen, dem kupfernen König.

Die Zeit, in der Schiller und Goethe zu diesen Einsichten, der eine in den «Ästhetischen Briefen», der andere im «Märchen», vorgedrungen sind, diese Zeit war noch nicht dazu angetan, weiterzudringen; denn um weiterzudringen muß man etwas ganz Bestimmtes einsehen. Man muß das einsehen, was eigentlich aus der Welt würde, wenn man den Weg Schillers nun weitergehen würde bis zur vollen Ausgestaltung des Unpersönlich-Verstandesmäßigen. Das 19. Jahrhundert hat es ja zunächst in der Naturwissenschaft ausgebildet, dieses Unpersönlich-Verstandesmäßige, und die zweite Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts hat angefangen, es in den äußeren öffentlichen Angelegenheiten verwirklichen zu wollen. Da liegt aber ein bedeutsames Geheimnis vor. Im menschlichen Organismus wird fortwährend das, was aufgenommen wird, auch zur Zerstörung geführt. Wir können nicht fortwährend bloß essen, wir müssen auch ausscheiden, es muß das, was wir als Stoff aufnehmen, auch einem Niedergang entgegengehen, das muß auch zerstört werden, muß wiederum heraus aus dem Organismus. Und das Verstandesmäßige ist dasjenige, welches, sobald es - und hier kommt eine Komplikation — das wirtschaftliche Leben ergreift, im Einheitsstaat, im gemischten König, dieses Wirtschaftsleben zerstört.

Nun leben wir aber in der Zeit, in der sich der Verstand entwickeln muß. Wir können nicht im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum zur Entwickelung der Bewußtseinsseele kommen, ohne den Verstand zu entwickeln. Und die westlichen Völker haben ja gerade die Aufgabe, den Verstand in das Wirtschaftsleben hineinzutragen. Was bedeutet das? Wir können das moderne Wirtschaftsleben, weil wir es verständig gestalten müssen, nicht imaginativ gestalten, wie Goethe es in seinem «Märchen» gestaltet hat. Weil wir im Wirtschaftlichen den Weg weiter machen müssen, den Schiller nur getrieben hat bis zu dem noch persönlichen Aushauchen des Verstandesmäßigen, müssen wir ein Wirtschaftsleben gründen, das als Wirtschaftsleben, weil es eben verständig sein muß, im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum notwendig zerstörend wirkt. Es gibt im heutigen Zeitraum kein Wirtschaftsleben, das etwa imaginativ geführt werden könnte wie das Wirtschaftsleben des Orients oder noch das Wirtschaften des europäischen Mittelalters, sondern seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts haben wir nur die Möglichkeit, ein solches Wirtschaftsleben zu haben, das, wenn es allein da wäre oder mit den anderen Gliedern des sozialen Organismus vermengt ist, zerstörend wirkt. Es geht nicht anders. Daher betrachten wir dieses Wirtschaftsleben als die eine Waagschale, die tief heruntersinken würde und dadurch zerstörend wirken muß; es muß ein Gleichgewicht da sein. Daher müssen wir ein Wirtschaftsleben haben als das eine Glied des sozialen Organismus, und ein Geistesleben, welches jetzt eben das Gleichgewicht hält, immer wieder aufbaut. Hält man heute an dem Einheitsstaat fest, dann wird das Wirtschaftsleben, wie es im Westen der Fall ist, diesen Einheitsstaat mit dem Geistesleben aufsaugen, dann müssen aber solche Einheitsstaaten notwendig zur Zerstörung führen. Und wenn man bloß aus dem Verstande heraus wie Lenin und Trotzkij, einen Staat begründet, er muß zur Zerstörung führen, weil sich der Verstand bloß auf das Wirtschaftsleben richtet.

Das fühlte Schiller, indem er seinen sozialen Zustand ausdachte. Schiller fühlte: Gehe ich weiter in dem verstandesmäßigen Können, komme ich ins Wirtschaftsleben hinein, so muß ich den Verstand auf das Wirtschaftsleben anwenden. Dann schildere ich nicht dasjenige, was wächst und gedeiht, dann schildere ich dasjenige, was in der Zerstörung lebt. - Schiller zuckte zurück vor der Zerstörung. Er hielt gerade an dem Punkt, wo die Zerstörung anbrechen würde, an; da blieb er stehen. Die Neueren denken alle möglichen sozialen wirtschaftlichen Systeme aus, wissen nur nicht, weil sie ein zu grobes Gefühl dazu haben, daß jedes wirtschaftliche System, das sie so ausdenken, zur Zerstörung führt, unbedingt zur Zerstörung führt, wenn es nicht jederzeit wiederum erneuert wird durch das selbständige, sich entwickeinde Geistesleben, das immer wieder und wiederum sich zu dem Zerstören, zu dem Ausscheiden des Wirtschaftslebens verhält wie das Aufbauende. In diesem Sinne ist auch in meinen «Kernpunkten» das Zusammenwirken des geistigen Gliedes des sozialen Organismus mit dem Wirtschaftlichen geschildert.

Würde unter der modernen Verständigkeit des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraums das Kapital bleiben bei den Menschen, auch dann, wenn sie nicht mehr es selber verwalten können, dann würde das Wirtschaftsleben selber den Kreislauf des Kapitals bewirken; Zerstörung müßte kommen. Da muß das geistige Leben eingreifen, da muß über das geistige Leben hinüber das Kapital an denjenigen gebracht werden, der wieder bei seiner Verwaltung dabei ist. Das ist der innere Sinn der Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus, daß auch in dem richtig gedachten dreigliedrigen sozialen Organismus man sich keiner Illusion hingibt, daß das wirtschaftliche Denken in der modernen Zeit ein zerstörendes Element ist, und daß daher fortwährend ihm entgegengesetzt werden muß das aufbauende Element des geistigen Gliedes des sozialen Organismus.

Mit jeder neuen Generation, mit den Kindern, die wir in der Schule unterrichten, wird uns von der geistigen Welt etwas gegeben, etwas heruntergeschickt; das fangen wir auf in der Erziehung, das ist etwas Geistiges, das einverleiben wir wiederum dem Wirtschaftsleben und verhüten dessen Zerstörung; denn das Wirtschaftsleben, durch sich selbst seinen Gang gehend, zerstört sich. So muß man hineinsehen in das Getriebe. So muß man sehen, wie am Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts Goethe und Schiller dastanden, Schiller sich sagte: Ich muß zurückzucken, ich darf keinen sozialen Zustand schildern, der bloß an den persönlichen Verstand appelliert, ich muß mit dem Verstand innerhalb des Persönlichen bleiben, sonst würde ich die wirtschaftliche Vernichtung schildern -, Goethe: Ich will nicht die schwärmerischen, ich will die scharf konturierten Bilder; denn würde ich eine Strecke weitergehen, ich käme hinein in einen Zustand, der nicht auf der Erde ist, der nicht eingreift schlagkräftig in das Leben selber; ich würde wie etwas Unlebendiges das Wirtschaftsleben unter mir lassen, würde ein Geistesleben begründen, das nicht eingreifen kann in die Tatsachen des unmittelbaren Lebens.

So sehen wir, daß wir im richtigen Goetheanismus leben, wenn wir nirgends bei Goethe stehenbleiben, sondern überall mitmachen die Entwickelung, die ja wohl Goethe selber mitgemacht hat seit dem Jahre 1832. Ich habe auch dieses, daß das Wirtschaftsleben fortwährend heute in seine eigene Zerstörung hineinarbeitet und fortwährend der eigenen Zerstörung entgegengearbeitet werden muß, wie der Zerstörung des Menschen durch das Essen entgegengearbeitet werden muß, ich habe auch das an einer bestimmten Stelle in meinen «Kernpunkten der sozialen Frage» angedeutet. Nur liest man die Sachen nicht ordentlich, sondern man denkt, dieses Buch sei auch so geschrieben, wie etwa heute die meisten Bücher geschrieben sind, daß man, nun ja, einfach so durchlesen kann. Es will eben jeder Satz bei einem solchen, aus dem Praktischen heraus geschriebenen Buche durchaus bedacht sein.

Aber wenn man diese beiden Dinge nimmt: Schillers «Ästhetische Briefe» sind wenig verstanden worden in der Folgezeit, ich habe davon öfter gesprochen, man hat sich wenig mit ihnen beschäftigt; es würde sonst dasStudium der Schillerschen «Ästhetischen Briefe» ein guter Weg sein zum Hineinmünden in das, was Sie finden in meiner Schrift «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?»; dazu könnten Schillers «Ästhetische Briefe» die Vorbereitung sein. Und wiederum könnte Goethes «Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der schönen Lilie» die Vorbereitung sein, um jene Art der Geisteskonfiguration sich anzueignen, die nicht aus dem bloßen Verstande, sondern aus tieferen Kräften heraus kommen kann, und die dann so etwas wie die «Kernpunkte der sozialen Frage» wirklich verstehen könnte. Denn sowohl Schiller wie Goethe empfanden das Tragische der mitteleuropäischen Zivilisation. Gewiß, die Dinge waren ihnen nicht bewußt, aber sie empfanden sie. Beide empfanden — man kann das nachlesen bei Goethe überall in den Gesprächen mit Eckermann, mit dem Kanzler von Müller, in den zahlreichen anderen Andeutungen Goethes -: Wenn nicht etwas heraufkommt wie ein neuer Einschlag aus dem Geistigen, wie ein neues Begreifen des Christentums, dann muß es abwärts gehen. — Vieles, was Goethe an Resignation in seinen späteren Jahrzehnten dargelebt hat, beruht zweifellos auf dieser Stimmung.

Und diejenigen, die ohne die Geisteswissenschaft Goetheaner geworden sind, die fühlen, wie namentlich aus dem deutschen mitteleuropäischen Wesen gerade dieses eigentümliche Nebeneinanderwirken der Geister des Westens und der Geister des Ostens ersichtlich ist. Ich habe gestern gesagt: Innerhalb der mitteleuropäischen Zivilisation ist jener Ausgleich, den die Hochscholastik gesucht hat zwischen Vernunftwissenschaft und Offenbarung, auch zurückzuführen auf die Wirkungen der Geister des Westens und der Geister des Ostens. Wie das bei Schiller und Goethe zum Vorschein kommt, wir haben es heute gesehen. Aber im Grunde genommen schwankt die ganze mitteleuropäische Zivilisation in diesem Wirbel drinnen, in dem der Osten und der Westen durcheinanderwirbeln; vom Osten herüber die Sphäre des goldenen Königs, vom Westen herüber die Sphäre des kupfernen, vom Osten herüber die Weisheit, vom Westen herüber die Gewalt und in der Mitte dasjenige, was Goethe im silbernen König darstellt, der Schein, der sich nur schwer durchdringt mit Wirklichkeit. Das Scheinhafte der mitteleuropäischen Zivilisation, es lag als tragische Stimmung auf dem Untergrunde der Goetheschen Seele. Und Herman Grimm hat in schöner Weise aus seinem Goethe-Empfinden heraus - er hat ja als ein Mensch, der eben auch von der Geisteswissenschaft unberührt war, Goethe angesehen -, er hat als ein solcher Geist charakterisiert, wie diese mitteleuropäische Zivilisation in sich hat dieses Hineingetriebensein in den Wirbel der Geister des Ostens und der Geister des Westens, was dazu führt, den Willen nicht zu seinem Rechte kommen zu lassen, und was zu der ewig schwankenden Stimmung der deutschen Geschichte geführt hat. Schön sagt Herman Grimm gerade über diese Dinge: «Die deutsche Geschichte ist für Treitschke das unablässige Streben nach geistiger und staatlicher Einheit und auf dem Wege zu ihr das unablässige Dazwischentreten unserer eigensten angeborenen Eigenschaften.» So sagt Herman Grimm, sich selber als Deutscher fühlend. Er sagt weiter: «Immer dieselbe Art unserer Natur, sich zu widersetzen, wo man nachgeben sollte, und nachzugeben, wo Widerstand nötig war. Das wunderbare Vergessen des eben erst Vergangenen, das plötzliche Nichtmehrwollen des eben noch heftig Erstrebten, die Mißachtung der Gegenwart, aber die feste, doch unbestimmte Hoffnung. Dazu der Hang, sich dem Fremden hinzugeben und, wenn dies einmal geschah, zugleich dann aber der unbewußte, maßgebende Einfluß auf die Ausländer, denen man sich doch unterwarf.»

Wenn man es heute mit mitteleuropäischer Zivilisation zu tun hat und mit ihr etwas erreichen möchte, so weht einem überall diese Tragik entgegen, die die ganze Geschichte dieses Deutschen, Mitteleuropäischen, zwischen dem Westen und Osten verrät. Auch heute ist es überall noch so, daß man mit Herman Grimm sagen könnte: Der Drang, sich zu widersetzen, wo man nachgeben sollte, und nachzugeben, wo Widerstand nötig ist.

Das ist dasjenige, was von dem schwankenden Mittleren herrührt, von dem, was zwischen Wirtschaft und aufbauendem Geistesleben als das rhythmische Hin- und Herschwanken des Staatlichen mitten drinnensteht. Weil in diesen Mittelländern gerade das staatlich-politische Element seine Triumphe gefeiert hat, deshalb lebt der Schein, der leicht zur Illusion werden kann. Schiller will nicht den Schein verlassen, indem er seine «Ästhetischen Briefe» hinschreibt. Er weiß, wenn es mit dem bloßen Verstande zu tun hat, dann kommt man in die Zerstörung des Wirtschaftslebens hinein; im 18. Jahrhundert wurde der Teil zerstört, der durch die Französische Revolution zerstört werden konnte; im 19. Jahrhundert würde es viel schlimmer werden. Goethe wußte, er darf nicht bis zum Schwärmerischen gehen, er muß im Imaginativen stehenbleiben. Aber es erzeugt sich auch sehr leicht bei diesem Schwanken zwischen dem einen und dem anderen in dieser Zweiheit, die in der wirbelnden Hin- und Herbewegung der Geister des Westens und des Ostens sich vollzieht, es erzeugt sich leicht eine illusionäre Stimmung. Es ist gleichgültig, ob diese illusionäre Stimmung im Religiösen, ob sie im Politischen, im Militärischen herauskommt, es ist schließlich ganz gleichgültig, ob der Schwärmer irgendwelche Mystik ausschwärmt, oder ob er so schwärmt, wie Ludendorff geschwärmt hat, ohne auf dem Boden der Wirklichkeit zu stehen. Und schließlich, auch in einer liebenswürdigen Weise kann einem das entgegentreten. Denn dieselbe Stelle von Herman Grimm, die ich Ihnen vorgelesen habe, fährt fort: «Man sehe doch heute: Niemand schien so völlig vom Vaterlande losgetrennt als der Deutsche, der zum Amerikaner geworden war, und heute steht das amerikanische Leben, in dem das unserer Auswanderer aufging, unter dem Einflusse des deutschen Geistes.»

So schreibt Herman Grimm, der geistvolle Mann, im Jahre 1895, wo man wirklich nur aus der schlimmsten Illusion heraus glauben konnte, daß die Deutschen, die nach Amerika gekommen sind, das amerikanische Leben deutsch nuancieren würden. Denn längst bereitete sich das vor, was dann im zweiten Jahrzehnt des 20. Jahrhunderts herauskam: daß eben das Amerikanische völlig überflutet hat das Wenige, was die Deutschen hineinbringen konnten.

Und schließlich, noch größer wird das Illusionshafte dieses Herman Grimmschen Ausspruches, wenn man folgendes ins Auge faßt. Herman Grimm tut diesen Ausspruch aus Goethescher Gesinnung heraus, denn er hat sich ganz an Goethe herangebildet. Nur, einen Einschlag hat er gehabt. Wer Herman Grimm genau kennt, seinem Stil nach, seiner ganzen Ausdrucksform nach, seiner Denkweise nach, der weiß, Herman Grimm hat sehr viel von Goethe angenommen, nicht das Reale, Durchdringende Goethes; denn er schildert ja so, daß er eigentlich Schattenbilder schildert, nicht wirkliche Menschen. Aber er hat doch etwas anderes noch in sich, nicht bloß Goethe. Und was hat Herman Grimm in sich? Amerikanismus, denn dasjenige, was er in seinem Stile, seinen Gedankenformen außer von Goethe in sich hat, das hat er durch eine frühe Lektüre Emersons bekommen; und sogar seine Satzbildung, seine Gedankenführung ist dem Amerikaner Emerson nachgebildet.

So findet sich also Herman Grimm in dieser doppelten Illusion, in diesem Reiche des silbernen Königs des Scheins. Er wähnt, als schon alles herausgeworfen wird, was in Amerika deutscher Einfluß ist, daß Amerika germanisiert würde, während er einen guten Einschlag von Amerikanismus in sich trägt.

So drückt sich oftmals intim aus, was dann in der äußeren Kultur grob da ist. Da hat sich der grobe Darwinismus, die grobe wirtschaftliche Denkweise ausgebreitet, und würde schließlich, wenn nicht die Dreigliederung des sozialen Organismus kommt — weil eben das bloß verstandesmäßig konstruierte Wirtschaftsleben notwendig zum Ruin führen muß -, zum Ruin führen. Und derjenige, der aus diesem Wirtschaftsleben heraus denkt wie Oswald Spengler, der kann wissenschaftlich beweisen, daß mit dem Beginn des 3. Jahrtausends die heutige zivilisierte Welt — sie ist ja eigentlich heute nicht mehr so stark zivilisiert — in die wüsteste Barbarei wird versunken sein müssen. Denn Spengler weiß nichts von demjenigen, was diese Welt als Einschlag erhalten muß, von dem geistigen Einschlag.

Aber doch hat sich recht schwer durchzukämpfen, was als Geisteswissenschaft und als geisteswissenschaftliche Kultur vor die Welt heute nicht hintreten will, sondern hintreten muß. Und überall machen sich diejenigen geltend, die gerade diese Geisteswissenschaft nicht aufkommen lassen wollen. Und wenig tatkräftige Arbeiter sind im Grunde genommen noch auf diesem Boden der Geisteswissenschaft da, während die anderen, die in das Werk der Zerstörung hineinführen, durchaus tatkräftig sind.

Man braucht nur zu sehen, wie eigentlich der heutige Mensch schon ganz ratlos ist gegenüber dem, was im heutigen Zivilisationsleben auftritt. Es ist zum Beispiel charakteristisch, wie eine Zeitung der Ostschweiz Berichte gebracht hat über meine Vorträge über die Grenzen des Naturerkennens während des Hochschulkurses. Und jetzt hält in dem Ort, in dem die Zeitung erscheint, der Nachgackerer Eduard von Hartmanns, Arthur Drews, Vorträge, der niemals etwas anderes zustande gebracht hat, als daß er nachgegackert hat dem Eduard von Hartmann, dem Philosophen des Unbewußten. Bei dem ist es interessant. Bei dem Nachgackerer ist es natürlich etwas höchst Überflüssiges. Und diese an der Karlsruher Hochschule wirkende philosophische Hohlköpfigkeit, die macht sich jetzt auch über dasjenige her, was anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft ist!