Man—Hieroglyph of the Universe

GA 201

2 May 1920, Dornach

Lecture Eleven

I drew attention yesterday to the fact that what is present in man points to something correspondingly present in the Cosmos outside him. What we have now to notice especially in man is the relation of the head to a world beyond the Earth—a world that lies outside the world upon which the rest of the human organism is dependent. The head points clearly to the world through which we passed between death and rebirth, its whole organisation being so modeled that it forms a distinct echo of our sojourn in the spiritual world. Now let us look for the corresponding phenomenon in the Cosmos.

We need only compare the behaviour of Saturn, who stands far out in the Universe, with that of the Earth, to notice a certain difference. Astronomy recognises this difference by saying that Saturn goes round the Sun in 30 years, the Earth in one year. We will not now stop to discuss whether these assertions are correct or whether they show a superficial view. We will only point to the fact that the observation which can be gained by following Saturn in cosmic space and comparing the rapidity of his progress with that of the Earth, brings us to the conclusion that according to the astronomical system of Copernicus and Kepler, Saturn needs 30 years and the Earth only one year, in which to go round the Sun. Looking at Jupiter, we assign to him a revolution lasting 12 years. Much shorter is that of Mars. And when we come to the other planets, Venus and Mercury, we find that they have even shorter periods of rotation than the Earth. All these conclusions are obviously well thought out, worked out on the basis of observations made in one way or another.

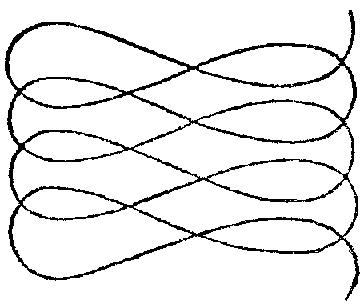

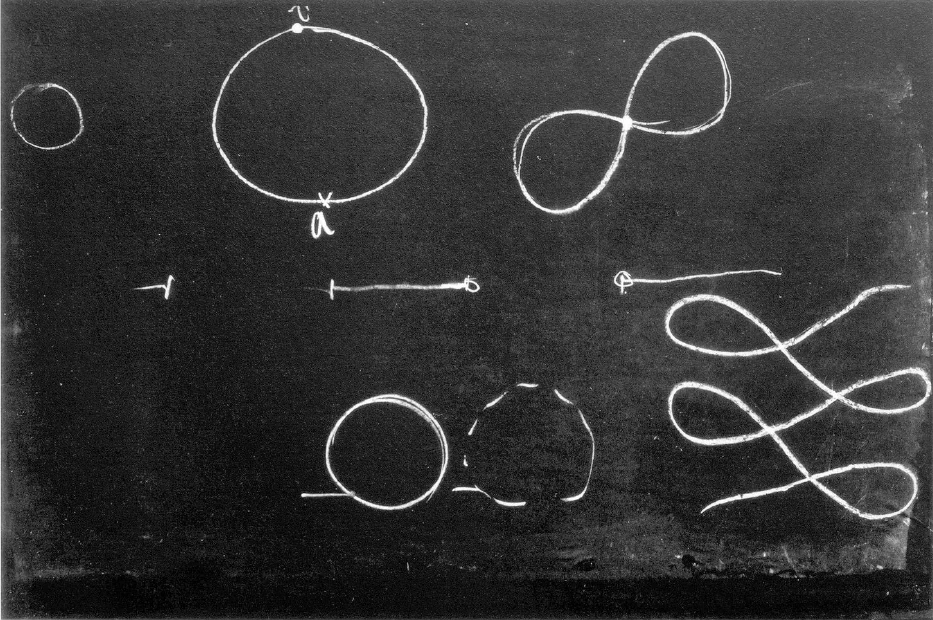

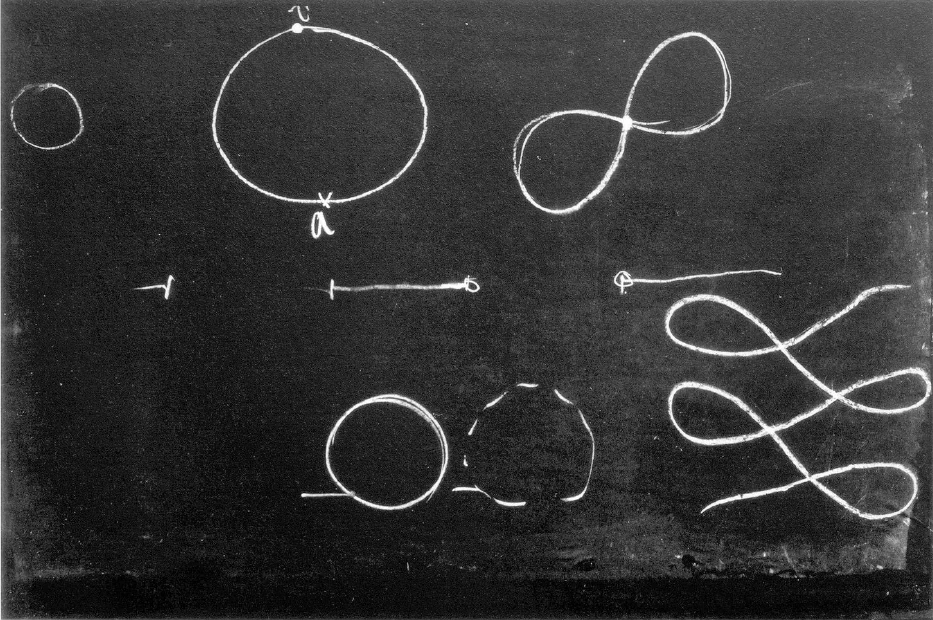

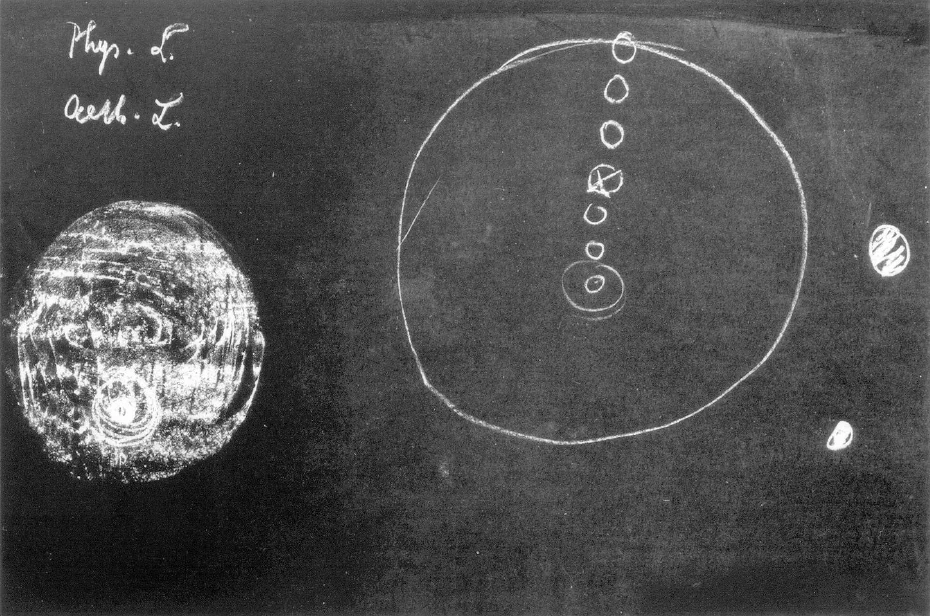

I have pointed out that we only gain a clear insight into these things by comparing what takes place in the far distances of cosmic space with what goes on within the boundary of our skin, in our own organism. Reflect for a moment and you will find that what is called the period of rotation of the Earth round the Sun, corresponds to something in yourself. In the foregoing lecture we showed that in order to represent the daily series of events, we have to use a certain curve, a certain line that turns back upon itself. In a similar way must the curved line corresponding to the yearly motion of the Earth be imagined. It is quite immaterial whether man's view is that the movement of the Earth is at the same time a movement round the Sun or no; for what have we here? Let us think. We have our own daily cycle of life, which we will consider now, not in its correspondence to the Cosmos, but as it presents itself in man, so that we can also include those whose sleeping and waking do not correspond with the alternation of day and night—idlers as well as all those who do not live by rule! Let us consider this daily round of man on the basis already established, that is to say, representing it in thought as a line in which the points of sleeping and waking lie upon one another, as I have pointed out. There are many reasons, but one will suffice for an unprejudiced judgement to understand that we are bound to place the point of waking over that of falling asleep. Consider the remarkable fact that when we look back over our life, it appears to us as an unbroken stream. We do not feel compelled to regard life in such a way as to say: Today I have lived and have been conscious of my environment from the moment of waking; before that all was darkness; before that again, my falling asleep of yesterday was preceded by life, I lived again, back to the moment of waking; but then darkness again. You do not picture the stream of memory like this, you picture it so that the moment of awaking and the moment of falling asleep really unite in your conscious recollection. That is a plain fact. This fact can be expressed in that the curve representing the daily round in man comes out as a spiral, with the point of awaking always crossing the point of falling asleep. If the curve were an ellipse or a circle, then awaking and falling asleep would have to be separate, they could not possibly be joined. In this way alone therefore can we picture the daily round of man.

Now let us try to see exactly what this means in man himself. Your waking time runs from your awaking to your falling asleep. During that time you are a physical human being, and you are moreover a complete human being, possessing physical body, etheric body, astral body and Ego. Now consider your condition from falling asleep until awaking. Then you have only physical body and etheric body. You are physical man, but you are not man; you have only physical body and etheric body. Strictly speaking, such a thing should not be. Your physical body and etheric body become really an untruth, for a being so composed should be a plant. It is the remainder of the whole man, left behind when the Ego and astral body have gone away; and only by virtue of the fact that these will return before the physical and etheric bodies can actually reach the plant stage—it is only because of this that you do not die every night.

Now let us examine what is left lying on the bed. What happens with it? It suddenly becomes of the nature of the plant. Its life is comparable to what takes place on Earth from the moment when plants sprout in spring until the autumn, when they die down. The plant-nature springs up and puts forth leaf in man, so to say, from falling asleep to awaking. He is then like the Earth in summer; and when the Ego and astral body return and man awakes, he becomes like the Earth in winter. So that we may say that the time between awaking and falling asleep is our winter, and that between falling asleep and awaking is our summer. For the year of the Cosmos—in so far as the Earth is part of it—corresponds with man's day. The Earth wakes in winter and sleeps in summer. The summer is the Earth's sleeping time, the winter her waking time. Outer perception obviously gives a false analogy, presenting summer as the Earth's waking time and winter as her time of sleeping. The reverse is the case, for during sleep we resemble the blossoming, sprouting plant-life; like the Earth in summer. When our Ego and astral body re-enter our physical and etheric bodies, it is as though the summer sun withdrew from the plant-laden Earth and the winter sun began to work. Thus the whole year is at different times represented in any one part of the Earth's surface. The case of the Earth is different from that of the individual man, but only apparently so. In respect to the Earth, in whichever part of it we may dwell, a year's course corresponds to the daily course of the individual man. The course of a year in the Cosmos corresponds to a man's day.

Thus we have the direct fact that when we look up to the Cosmos, we have to say: A year—that is for the Cosmos sleeping and waking; and if our Earth is the head of the Cosmos, it expresses in winter the waking of the Cosmos, and in summer its sleeping. If we now consider the Cosmos, which as we see manifests waking and sleeping—for the plant-covering of the Earth is an outcome of cosmic working—we shall find that we have to think of it as a great organism. We must think of what takes place in its members as organically fitted into the whole Cosmos, just as what takes place in one of our own members is fitted into our organism. And here we come to the significance of the difference expressed by astronomy in the shorter periods of Venus' and Mercury's revolutions as compared with the longer periods of Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. When we consider the so-called outer planets, Saturn, Jupiter and Mars, then the Sun, Mercury, Venus and the Earth, we find this apparently long period of revolution in the case of the outer planets stretching beyond a year, thus beyond the mere waking time. Let us consider Saturn with his 30-year period, the apparent time of his revolution round the Sun; how can we express his 30 years in the language of the Cosmos according to which its daily revolution is a year? If a year is the daily revolution of the Cosmos, then the so-called period of Saturn's revolution is approximately 30 days, a cosmic month, a cosmic four weeks. Thus we may say that if we regard Saturn as the outermost planet (the other two, Uranus and Neptune, regarded today as of equal standing with Saturn, are really fugitives that have wandered in), then we must say that Saturn bounds our Cosmos; and, in his apparent slowness, in his limping behind the Earth, we behold the life of the Cosmos in 4 weeks or a month, as compared to the life it displays in the course of the year, which for the Cosmos is like a falling asleep and awaking.

From this it may be seen that Saturn, if his apparent path is regarded as the outermost limit of our planetary system, is inwardly related to it in a different way from, let us say Mercury; Mercury needing less than 100 days for his apparent revolution, moves quickly, he is active inwardly, he has a certain celerity; whereas Saturn moves slowly.

To what exactly does this correspond? In the movement of Saturn you have something comparatively slow, in that of Mercury something that is very much quicker, an inner activity of the cosmic organism, something that stirs the Cosmos inwardly. It is as if you had, let us say, a kind of living, mucilaginous organism, itself revolving, but having besides within it an organ which is revolving more quickly. Mercury separates itself from the movement of the whole by its quicker revolution. It is, as it were, an enclosed member; so too is the movement of Venus. Here we have something analogous to the relation of the head in man to the rest of his organism. The head separates itself off from the movements of the rest of the organism. Venus and Mercury emancipate themselves from the movement set by Saturn. They go their own way; they vibrate in the whole system. What does this signify? They have something extra as compared with the whole system; their more rapid movement shows this. What is the corresponding thing to this extra in our head? Our head has something extra, namely its co-ordination to the super-sensible world; only, our head is at rest in our organism, just as we are at rest in a coach or a railway carriage, while it is moving. Venus and Mercury act differently; they do the exact opposite as regards their emancipation. Whereas our head is quiescent, like we are when we sit still in a railway carriage, Venus and Mercury emancipate themselves from the whole planetary system in the opposite way. It is as though we, sitting in the railway carriage, were impelled by something to move all the time much faster than the railway train itself. This is due to the fact that Venus and Mercury, which show a much quicker apparent movement, are related on their past not to space alone, but to that to which our head is also related; only these relations take opposite courses—our head being brought to rest, Venus and Mercury on the other hand becoming more active. They are the two planets through which our planetary system has a relation to the super-sensible world. They incorporate our planetary system into the Cosmos in a different way than do Jupiter and Saturn. Our planetary system is spiritualised through Venus and Mercury, more intimately adapted to the spiritual Powers than happens through Jupiter and Saturn.

Things that are real often appear quite differently when studied in accordance with true reality instead of in accordance with generally received opinion. Just as, when we judge externally, we call winter the sleeping time of the Earth, and summer her waking time, whereas it is the reverse; in the same way, judging externally, Saturn and Jupiter might be regarded as more spiritual than Venus and Mercury. This is not the case; for Venus and Mercury stand in more intimate relation to something behind the whole Cosmos than do Jupiter and Saturn. Thus we may say that in Venus and Mercury we have something which places us outwardly, as a member of the planetary system, in relation to a super-sensible world. Here, while we live, we are brought into connection with a super-sensible world through Venus and Mercury. We might say: When we are incorporated by birth into the physical world, we are carried into it by Saturn and Jupiter; while we live from birth to death, Venus and Mercury work within us and prepare us to carry our super-sensible part back again through death into the super-sensible world. In fact, Mercury and Venus have just as much share in our immortality after death as Jupiter and Saturn have in our life before death. It is really so, we have to see something in the Cosmos which corresponds to the relation between the comparatively more spiritual organisation of the head and the rest of the human organisation.

Now let us suppose that Saturn pursues his movement also in a like curve (lemniscate)—only, of course, his path is different through cosmic space—with the 30 times less rapid movement than the Earth; if we picture these two curves, we must realise that each Cosmic body which follows such a path (lemniscate) is obviously moved in this path by forces, but each one by forces of a different kind. Then we come to an idea which is extremely important and which, if taken rightly, will probably at once strike you as true. If it does not, it is only because, under the influence of the materialism of the last centuries, people are not accustomed to connect such things with the facts of the Universe.

To the modern materialistic view of the Cosmos, Saturn is observed merely as a body moving about in cosmic space; and the same with the other planets. This is not the case; for if we take Saturn, the outermost Planet of our Universe, we must represent him as the leader of our planetary system in cosmic space. He directs our system in space. He is the body for the outermost force which leads us round in the lemniscate in cosmic space. He is the driver and the horse at the same time. Saturn is thus the force in the outermost periphery. Were he alone to work, we should continually move in a lemniscate. But there are other forces in our planetary system which show a more intimate adjustment to the spiritual world—the forces that we find in Mercury and Venus. Through these forces our path is continually raised. Thus, when we look upon the path from above, we have the lemniscate, but when we look at it from the other side, we obtain lines which are continually rising upwards; there is a progression.

This progression corresponds in man to the fact that during sleep what we have taken into us, though it may not pass over at once into consciousness, is elaborated; during sleep we work upon it. It is principally during sleep that we work on what we have absorbed through our life, our training and education. During sleep Mercury and Venus communicate that to us. They are our most important night-planets, as Jupiter and Saturn are our most important day-planets. Hence the old instinctive atavistic wisdom was right in connecting Jupiter and Saturn with the formation of the human head, Mercury and Venus with the formation of the human trunk, with the rest of the organism. These things arose from an intimate knowledge of the connection between man and the Universe.

Now I will ask you carefully to consider the following. It is first of all necessary to understand from inner grounds the movement of the Earth. We must recognise the influence upon it of the Venus and Mercury forces, which themselves bear the lemniscate on further, so that it progresses, and its axis becomes itself a lemniscate. We have thus for the Earth an extremely complicated movement. And now I come to what I wish to point out. Suppose we have to draw this movement. Astronomy tries to do so. Astronomy wants to have a planetary system; it wants to draw the solar system and explain it by calculation. Planets such as Venus and Mercury, however, have relation to the extra-spatial, the super-sensible, the spiritual, to that which does not originally belong in space, but has, as it were, come into it. Thus if you have the paths of Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, and, in the same space, draw in also the paths of Mercury and Venus, you will get at most a projection of the Mercury or of the Venus orbit, but in no sense the orbits themselves. If we employ the three-dimensional space to sketch in the orbits of Jupiter, Saturn and Mars, we come at most to a boundary, where we get something like a path of the Sun. But if we wish to draw the others, we can no longer do so in the three-dimensional space, we can only get shadow-pictures of these other movements in it; we cannot draw the path of Venus and that of Saturn in the same space. From this we see that all delineations of the solar system where the same space is used for Saturn as for Venus, are only approximate, they do not suffice for a solar system. Such drawings are as little possible as it would be to explain the whole being of man according to purely natural forces only. This shows why no solar system is adequate. A non-astronomer such as Johannes Schlaf could easily prove to quite well-established astronomers the impossibility of their solar system by very simple facts, pointing out that if the Sun and the Earth are so related that the latter revolves round the former, the Sun-spots could not show themselves as they do, the Earth being at one time behind the Sun, at another in front, and then going round it again. That, however, is in no wise the case. No drawing of our solar system that is inscribed into one space of the ordinary three dimensions will be right. We must understand this. Just as in the case of man, in order to understand him as a whole we must pass from physical to super-sensible forces; so in the same way, to understand the solar-system, we must pass from the three dimensions into other dimensions. That is to say, we cannot delineate the ordinary solar system in the three-dimensional space. Planetary ‘globes’ and so forth we have to look at in this way: If here we have Saturn on the globe and there Mercury, then it is not the true Mercury but its shadow only, its projection.

These are things that must be brought to light by Spiritual Science. They have quite disappeared. About six or seven centuries before the Christian era, the ancient primeval wisdom began gradually to disappear, until replaced by Philosophy from the middle of the fifteenth century. But men such as Pythagoras, for instance, still knew so much of the ancient wisdom that they could say: We dwell on the Earth, we belong through the Earth to a cosmic system, to which Jupiter and Saturn also belong; but if we remain in these three dimensions, then we shall not belong in the same way to Venus and Mercury. We cannot belong to the two latter directly, as we do to Saturn and Jupiter; but if our Earth is in one space with Saturn and Jupiter, there must be a ‘counter-Earth’ which is in another space with Venus and Mercury. Hence ancient astronomers spoke of the Earth and the counter-Earth. Of course the modern materialist would say: “Counter-Earth? I see nothing of that!” He is like a person who weighs a man, having first charged him to think about nothing, and weighs him again when he has charged him to think a specially clever thought, and then says: I have weighed him, but I have not found the weight of his thought. Materialism rejects what has no weight or cannot be seen. Remarkable things however shine out of the atavistic primeval wisdom to which we can return by the inner vision of Spiritual Science. It is of urgent necessity that we should work our way through now to that which is entirely new and which has yet been on Earth all the time, and has only now in these days to be acquired in full consciousness. Unless we do, this we shall lose the very possibility of thinking.

I called attention yesterday to the fact that in social thought men strive for mono-metalism for the sake of free trade-and Protection comes! No true social order will arise out of what is being striven for on the foundation the thinking man possesses To-day; a true social order can only come about through a thinking trained in a science which does not draw a planisphere showing Saturn and Venus in the same space. For the view of the Universe which we are giving here does not merely mean that we hold something up before us, but also that, in a sense, we learn to think. What exactly does this mean?

Remember what I have said: When our bodily organisation is remodeled in the next incarnation, it not only goes through a change, but is turned inside out; as a glove is turned from a left-hand to a right-hand glove by turning it inside out so too what is now inside—liver, heart, kidneys—becomes the outer sense-organs, eye, ear and so on. It is all turned inside out. This corresponds to another turning inside out: Saturn on the one side, and wholly outside his space, Venus and Mercury. A reversal in itself. If we do not observe this, what happens? It is the same, when we do not observe the turning inside out in the case of the human head, or when we do not observe the Universe under this law of reversal; we do something very peculiar. We do not in that case think with our head at all. And this is something to which the fifth post-Atlantean epoch is tending, in so far as it is descending and not seeking to ascend again by means of Spiritual Science. Man would like to wrest his head free and think only with the rest of the organism; that mode of thought is abstract. He wants to set free the head. He has no desire to lay claim to what has resulted from the foregoing incarnations. He wants to reckon only with the present one. Not only do men wish to deny the theory of successive Earth-lives, but carrying their head as it were with external dignity, they would like to set it as lord over the rest of the organism, they would have it like a man riding in a carriage. And they do not take that rider in the carriage in earnest; they carry him about with them, but make no claim upon his innate capacities. They make no practical use of their repeated Earth-lives.

This tendency has virtually been developing ever since the beginning of the 5th post-Atlantean epoch, and we can only oppose it by adopting Spiritual Science. One might even define Spiritual Science as that which brings man to take his head in earnest once more! From one point of view the essential part in Spiritual Science is really that it takes the human head in earnest, not merely regarding it as an addition to the rest of the organism. Europe especially, as it so rapidly approaches barbarism, would like to free the head. Spiritual Science must disturb this sleep. It must make its appeal to humanity: ‘Use your heads!’ This can only be done by taking the belief in repeated Earth-lives seriously.

One cannot talk of Spiritual Science in the way that is usually done, if one takes it in earnest. One must say what is; and to what is belongs something which appears as sheer madness, belongs the fact that men disown their heads. They would rather not believe this, they prefer to regard truth as madness. This has always been so. Things in human evolution come about in such a way that men are taken unawares by the new.

And so they must of course be shocked and astonished by this emphasis on the necessity for using the head. Lenin and Trotsky say: Do not use your head, act for the rest of your organism. The rest of the organism is the vehicle of the instincts. Men are to be led by instincts alone. And they carry it out. It is their practice that nothing that arises from the human head should enter the modern Marxist theories. These things are very serious—how serious they are has to be emphasised again and again.

Elfter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Ich habe gestern aufmerksam darauf gemacht, wie dasjenige, was im Menschen vorhanden ist, auf etwas hinweist, was entsprechend im außermenschlichen Weltall vorhanden ist, insofern ein bestimmtes Verhältnis des Menschen zum außermenschlichen Weltall besteht. Worauf wir nun besonders hinzuweisen haben als im Menschen vorhanden, das ist die Hinordnung des menschlichen Hauptes auf eine außerirdische Welt, auf eine Welt, welche außerhalb derjenigen liegt, von der der übrige Organismus des Menschen abhängig ist. Unser Haupt weist noch deutlich in diejenige Welt hinein, die wir durchgemacht haben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. Die ganze Organisation unseres Hauptes ist so gebildet, daß sie den deutlichen Nachklang bildet unseres Aufenthaltes in den geistigen Welten. Nun müssen wir das Entsprechende suchen im Kosmos.

[ 2 ] Da brauchen Sie ja nur einmal zu vergleichen das Verhalten, sagen wir, des weit im Weltenall draußen stehenden Saturn mit dem Verhalten der Erde selbst, und Sie werden einen gewissen Unterschied wahrnehmen. Dieser Unterschied ist dadurch für die Astronomie zur Geltung gekommen, daß man sagt, der Saturn kreise um die Sonne in 30 Jahren, die Erde in einem Jahre. Wir wollen uns jetzt einmal nicht kümmern, ob diese Dinge richtig oder falsch sind, ob sie eine Einseitigkeit darstellen oder nicht, wir wollen nur auf das hinweisen, daß eben die Beobachtungen, die man gewinnen kann dadurch, daß man den Saturn im Weltenraume verfolgt und die Geschwindigkeit seiner Bewegung vergleicht mit dem, was man der Erde als eine gewisse Geschwindigkeit zuschreibt, daß man dadurch unter Voraussetzung des kopernikanisch-keplerischen Weltsystems zu der Anschauung kommt, daß der Saturn 30 Jahre braucht, um die Sonne zu umkreisen, die Erde ein Jahr. Und wenn wir dann auf den Jupiter hinschauen, so spricht man ihm eine Umlaufszeit von 12 Jahren zu. Viel kürzer ist die Umlaufszeit des Mars. Aber nun kommen wir, wenn wit die anderen Planeten uns ansehen, die Venus, den Merkur, zu Umlaufszeiten, die kleiner sind als die der Erde, oder sagen wir, von denen gesagt wird, daß sie kleiner sind als die Umlaufszeit der Erde. Alle diese Dinge sind ja selbstverständlich ausgedacht, sind ausgedacht auf Grundlage der Beobachtungen, die in der einen oder in der anderen Weise gemacht werden.

[ 3 ] Nun habe ich ja darauf hingewiesen, daß wir eigentlich eine wahre Einsicht in diese Dinge nur gewinnen, wenn wir gewissermaßen das, was da in den Weiten des Weltenraumes vor sich geht, vergleichen mit dem, was zugeordnet vor sich geht innerhalb der Grenzen unserer Haut, in unserem eigenen Organismus. Bedenken Sie einmal, daß dem, was man Umlaufszeit der Erde um die Sonne nennt, ja irgend etwas entspricht. Wir haben gestern darauf hingewiesen, daß auch für die tägliche Tatsachenreihe hinzuweisen ist auf eine gewisse Kurve, auf eine gewisse Linie, die sich selber schneidet. In einer ähnlichen Weise wird auch vorzustellen sein diejenige Kurve, diejenige krumme Linie, welche der jährlichen Bewegung der Erde entspricht, ganz gleichgültig, ob man nun der Anschauung ist, daß diese Bewegung der Erde zugleich eine Bewegung um die Sonne ist oder nicht. Denn was haben wir da eigentlich vor uns? Bedenken Sie einmal: Wir haben in unserem eigenen Tageskreislauf, den wir jetzt nicht so nehmen wollen, wie er dem Kosmos entspricht, sondern wie er im Menschen auftritt, so daß wir auch diejenigen, deren Schlafens- und Wachenszeit nicht zusammenfällt mit dem Wechsel von Tag und Nacht, daß wir also auch die Bummler und unregelmäßig Lebenden fassen können. Wir wollen diesen Tageskreislauf im Menschen so betrachten, daß wir ihn aus dem Grunde, den wir gestern schon angeführt haben, uns repräsentiert denken durch solch eine Linie (Tafel 20, rechts oben), wobei die Punkte des Einschlafens und Aufwachens übereinanderfallen. Ich habe gestern schon bemerkt, daß man diese Punkte des Einschlafens und Aufwachens übereinanderfallend denken muß. Es gibt viele Gründe, aber es genügt ein Grund, um vor unbefangenem Urteil einzusehen, daß wir den Punkt des Aufwachens über den Punkt des Einschlafens zu legen haben. Denn nehmen Sie einmal die auffälligste Tatsache: Wenn Sie zurückblicken auf Ihr Leben, so erscheint Ihnen dieses Leben wie eine geschlossene Strömung. Sie sind nicht veranlaßt, dieses Leben so vorzustellen (die unterbrochene Gerade in mittlerer Höhe, von rechts nach links): Heute habe ich gelebt und die Umgebung gewußt bis zum Aufwachen; dann kommt Dunkelheit; dann gestern, da bin ich eingeschlafen, da habe ich wiederum gelebt bis zum Aufwachen; folgt wiederum Dunkelheit. So stellen Sie sich die Erinnerungsströmung nicht vor, sondern Sie stellen sich die Erinnerungsströmung so vor, daß in der Tat der Moment des Aufwachens und der Moment des Einschlafens wirklich zusammenfallen in Ihrem erinnernden Bewußtsein. Das ist eine einfache Tatsache. Diese Tatsache läßt sich nur so zeichnen, daß man die den Tageslauf im Menschen repräsentierende Kurve als eine Schleifenlinie zeichnet, wo dann der Punkt des Aufwachens über den Punkt des Einschlafens fällt. Wäre eine Kurve richtig, die eine Ellipse oder ein Kreis wäre, dann müßte das Einschlafen und das Aufwachen deutlich voneinander getrennt sein; es könnte nicht sich anschließen unmittelbar das Aufwachen an das Einschlafen. So also müssen wir den Tageslauf des Menschen uns vorstellen.

[ 4 ] Versuchen Sie einmal, sich im Menschen selbst ordentlich zurechtzulegen, was das eigentlich ist: Sie leben wachend vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen. Da sind Sie, indem Sie physischer Mensch sind, zugleich der ganze Mensch, da haben Sie in sich Ihren physischen Leib, Ihren Ätherleib, Ihren astralischen Leib, Ihr Ich. Jetzt nehmen Sie den physischen Menschen vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen. Da haben Sie nur den physischen Leib und den Ätherleib. Als physischer Mensch sind Sie nicht Mensch, sondern Sie haben den physischen Leib und den Ätherleib; das liegt im Bette. Das sollte im Grunde genommen gar nicht sein. Das besteht im Grunde genommen zu Unrecht, denn das sollte eine Pflanze sein. Das ist nur der liegengebliebene Rest des vollständigen Menschen, von dem fort sind das Ich und der astralische Leib, und nur unter dem Einflusse der Tatsache, daß Ich und astralischer Leib wiederum zurückkehren können, bevor der physische Leib und der Ätherleib ihrem Pflanzenziel nachgehen können, nur diese Tatsache macht es, daß wir nicht jede Nacht sterben.

[ 5 ] Nun sehen wir auf das hin, was da eigentlich im Bette liegt. Was ist denn das, was da im Bette liegt? Das wird plötzlich zu der Natur des Pflanzenreiches. Das müssen Sie sehen als ähnlich dem, was auf der Erde vorgeht von dem Moment an, wo im Frühling die Pflanzen hervorsprießen bis zum Herbst, wo die Pflanzen wiederum hinuntergehen. Da schießt im Menschen das Pflanzensein ins Kraut, möchte man sagen, vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen. Da wird er so, wie die Erde zur Sommertszeit ist. Und wenn wiederum das Ich und der astralische Leib zurückkehren, wenn der Mensch aufwacht, dann wird er so, wie die Erde zur Winterszeit ist. So daß wir sagen können: der Wachzustand des Menschen, die Zeit vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen ist der persönliche Winter, die Zeit vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen ist der persönliche Sommer. Für den Kosmos, insofern die Erde ja auch zu diesem Kosmos gehört, ist das Jahr das Entsprechende. Die Erde wacht in der Winterszeit, schläft in der Sommerszeit. Die Sommertszeit ist die Schlafzeit der Erde, die Winterszeit ist die Wachzeit der Erde. Äußerlich verglichen gibt es selbstverständlich eine falsche Analogie; da glaubt man, daß die Sommerszeit die Wachzeit der Erde ist und die Winterszeit die Schlafenszeit der Erde ist. Umgekehrt ist es das Richtige; denn wir werden ja während unserer Schlafenszeit dem blühenden, sprossenden Pflanzenleben ähnlich, werden also da so wie die Erde während der Sommerszeit. Und wenn unser Ich und unser astralischer Leib in unsern physischen Leib und in unsern Ätherleib hineingehen, so ist es so, wie wenn für die pflanzentragende Erde die Sommersonne sich zurückzieht und die Wintersonne wirkt. Doch ist eine Jahreszeit jeweilig für irgendeinen Teil der Erdoberfläche. Bei der Erde ist es also anders wie beim einzelnen Menschen, aber auch nur scheinbar, übrigens; bei der Erde, insofern wir sie auf irgendeinem Teile bewohnen, ist es so, daß ein Jahreslauf dem Tageskreislauf des Menschen entspricht. Ein Jahreskreislauf im Kosmos entspricht dem Tageskreislauf des Menschen.

[ 6 ] Nun haben Sie dadurch ja unmittelbar die Tatsache gegeben, daß wenn Sie auf den Kosmos hinschauen, Sie sich sagen müssen: ein Jahr, das ist für ihn Schlafen und Wachen. Und wenn unsere Erde einfach der Kopf des Kosmos ist, dann drückt sich im Wintersein das Wachen des Kosmos eben aus, im Sommersein das Schlafen des Kosmos. Nehmen wir jetzt diesen Kosmos, der ja hervorbringt Wachen und Schlafen, denn die Pflanzendecke auf der Erde ist ja das Ergebnis des Kosmos, nehmen wir jetzt diesen Kosmos, dann müssen wir ihn auch ansehen als einen großen Organismus. Wir müssen dasjenige, was in seinen Gliedern vorgeht, uns so organisch dem ganzen Kosmos eingefügt denken, wie wir uns organisch eingefügt denken müssen das, was in einem unserer Organe vorgeht, unserem Organismus. Da kommen wir auf Bedeutungen jener Unterschiede, die sich sonst für die Astronomie ausdrücken in den kürzeren Umlaufszeiten von Venus und Merkur gegenüber den längeren Umlaufszeiten - länger als eine sogenannte Umlaufszeit der Erde bei Mars, Jupiter und Saturn namentlich. Wenn wir die sogenannten äußeren Planeten nehmen, Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, so haben diese scheinbar eine lange Umlaufszeit, die über ein Jahr hinauswächst, die also über das bloße Wachen hinauswachsen. Nehmen wir den Saturn, seine 30 Jahre, die ja die scheinbare Umlaufszeit um die Sonne sind (Tafel 20, links oben); seine 30 Jahre, wie können wir sie denn ausdrücken, wenn wit die ordentliche Sprache des Kosmos sprechen, daß ein Jahr sein Tageskreislauf ist? Wenn ein Jahr der Tageskreislauf des Kosmos ist, dann ist die sogenannte Umlaufszeit des Saturn ungefähr 30 Tage, ein kosmischer Monat, kosmische 4 Wochen. So daß Sie sich sagen können: Wenn man den Saturn - die anderen zwei Planeten, Uranus und Neptun, die man heute als gleichberechtigt ansieht, sind ja zugeflogene -, wenn man den Saturn als den äußersten Planeten ansieht, dann muß man sagen: der Saturn begrenzt unseren Kosmos, und in dem scheinbaren Langsamgehen, in dem Nachhinken des Saturn hinter der Erde zeigt sich das Leben des Kosmos in vier Wochen, in einem Monat, gegenüber jenem Leben, das der Kosmos zeigt im Jahreslauf, und das für ihn ein Einschlafen und Aufwachen ist.

[ 7 ] Daraus aber ersehen Sie, daß der Saturn, wenn wit gewissermaßen seine scheinbare Bahn als die äußerste Grenze unsetes Planetensystems ansehen, in einer anderen Weise sich innerhalb dieses Planetensystems verhält als zum Beispiel der Merkur. Der Merkur, der nicht einmal 100 Tage zu einem sogenannten scheinbaren Umlauf braucht, der bewegt sich schnell herum, der ist regsam da im Innern, hat eine gewisse Geschwindigkeit, während sich der Saturn langsam bewegt.

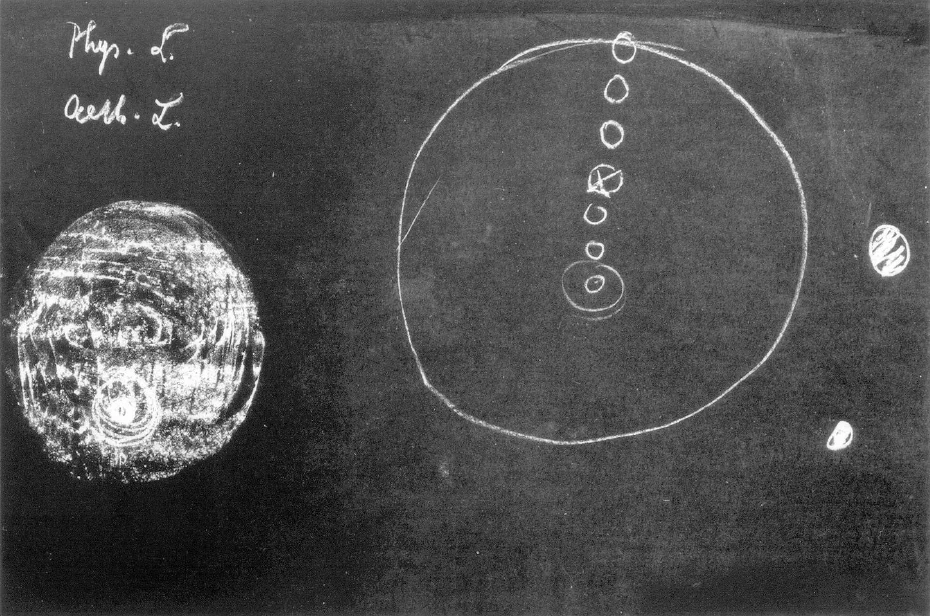

[ 8 ] Wem entspricht denn das eigentlich? Wenn Sie diese Bewegung des Saturn nehmen, so ist also verhältnismäßig etwas Langsames da; die Bewegung des Merkur ist etwas, was gegenüber der Bewegung des Saturn etwas sehr Schnelles ist, eine innere Regsamkeit des Organismus Kosmos, etwas, was innerlich den Kosmos bewegt. Es ist so, wie wenn Sie sich meinetwillen eine Art lebendigen Schleimorganismus denken, (Tafel 21, links), der sich als solcher dreht, und da extra drinnen ein Organ, das wiederum schneller sich um sich dreht. Es sondert sich dieser Merkur da in seiner Bewegung dutch sein schnelleres Drehen aus von dem ganzen Drehen, von der ganzen Bewegung. Es ist wie ein eingeschlossenes Glied, ebenso ist das Bewegen der Venus wie ein eingeschlossenes Glied. Da haben Sie etwas, was im Menschen dem Verhalten des Hauptes zum übrigen Organismus entspricht. Das Haupt schließt sich aus von den Bewegungen des übrigen Organismus. Venus und Merkur emanzipieren sich von der Bewegung, die der Saturn angibt. Sie gehen ihren eigenen Weg. Sie erzittern in dem ganzen System drinnen. Was bedeutet denn das? Sie haben etwas extra da in dem ganzen System. Ihre schnellere Regsamkeit deutet darauf, daß sie etwas extra da drinnen haben. Was ist denn das Entsprechende dieses Extra? Nun, in unserem Haupte ist das, was das Haupt extra hat, die Zuordnung zu der übersinnlichen Welt; nur — unser Haupt wird ruhig an unserem Organismus, so wie wir in einer Kutsche oder im Eisenbahnzug drinnen ruhig sind, trotzdem der Eisenbahnzug weitergeht. Venus und Merkur machen es anders; sie machen das Entgegengesetzte in bezug auf ihr Emanzipieren. Während unser Haupt ruhig ist, wie wenn wir uns ganz ruhig in die Kutsche oder in die Eisenbahn setzen und darinnen ruhig sind, emanzipieren sich in der entgegengesetzten Art von dem ganzen Planetensystem Venus und Merkur. Es ist so, wie wenn wit, indem wir uns in den Eisenbahnwagen setzen, durch etwas angeregt, noch extra da drinnen immerfort schneller uns bewegen würden als der Eisenbahnzug selber.

[ 9 ] Sehen Sie, das rührt davon her, daß eben Venus und Merkur, die die schnellere scheinbare Bewegung zeigen, nicht bloß zum Raume draußen, zum Räumlichen eine Beziehung haben, sondern ihrerseits auch Beziehungen haben zu dem, wozu unser Haupt Beziehungen hat. Nur gehen sie diese Beziehungen in der entgegengesetzten Art ein, unser Haupt durch Beruhigtwerden, Venus und Merkur durch Regsamwerden. Aber Venus und Merkur sind diejenigen Planeten, durch die unser Planetensystem zu der übersinnlichen Welt eine Beziehung hat. Venus und Merkur gliedern unser Planetensystem in anderer Art in den Kosmos ein als Saturn und Jupiter. Vergeistigt wird unser Planetensystem durch Venus und Merkur, vergeistigt, zugeordnet den geistigen Mächten in einer intimeren Weise, als das etwa durch Jupiter und Saturn geschieht.

[ 10 ] Die Dinge, die wirklich sind, nehmen sich eben oftmals ganz anders aus, wenn man sie wirklichkeitsgemäß studiert, als wenn man sie nach dem naheliegenden Urteile faßt. Geradeso wie der Mensch, wenn er äußerlich urteilt, die Winterszeit die Schlafenszeit der Erde nennt, und die Sommerszeit die Wachenszeit, während es umgekehrt ist, so könnte man äußerlich urteilend auch versucht sein, Saturn und Jupiter als geistiger zu denken denn Venus und Merkur. Aber so ist es nicht, sondern gerade Venus und Merkur stehen in intimerer Beziehung zu etwas, was hinter dem ganzen Kosmos ist, als Jupiter und Saturn. So daß wir sagen können: In Venus und Merkur haben wir etwas gegeben, was uns äußerlich, insofern wir ein Glied unseres Planetensystems sind, in Beziehung setzt zu einer übersinnlichen Welt. Indem wir hier leben, werden wir durch Merkur und Venus zu einer übersinnlichen Welt in Beziehung gesetzt. Man könnte sagen: Indem wir uns durch die Geburt in der physischen Welt verkörpern, werden wir durch Saturn und Jupiter in diese physische Welt hereingetragen; indem wir von der Geburt bis zum Tode hin leben, wirken Venus und Merkur in uns und bereiten uns vor, durch den Tod wiederum unser Übersinnliches in die übersinnliche Welt hinauszutragen. In der Tat haben Merkur und Venus ebensoviel Anteil an unserer Unsterblichkeit nach dem Tode, wie Jupiter und Saturn Anteil haben an unserer Unsterblichkeit vor dem Tode. Aber es ist so, daß wir wirklich auch im Kosmos so etwas sehen müssen, was da entspricht der verhältnismäßig geistigeren Organisation des Hauptes im Vergleich zu der Organisation des übrigen menschlichen Organismus.

[ 11 ] Nun, wenn wir uns vorstellen, daß der Saturn seinerseits auch seine Bewegung in einer solchen Kurve (Lemniskate, Tafel 20) hat, die nur selbstverständlich anders gezogen wird im Weltenraum, wie die durch eine 30mal schnellere Bewegung bewirkte Kurve der Erde, wenn wir uns diese Kurve so vorstellen beim Saturn und auch bei der Erde, dann müssen wir uns ja vorstellen, daß jeder Weltenkörper, der in einer solchen Bahn kreist, dutch Kräfte selbstverständlich in dieser Bahn bewegt wird, aber er wird durch Kräfte verschiedener Art bewegt. Und da kommen wir zu einer Vorstellung, die außerordentlich bedeutsam ist und die, wenn Sie sie einmal in Wirklichkeit aufnehmen, Ihnen wahrscheinlich sofort einleuchten wird als eine gültige. Sie leuchtet den Menschen nur deshalb nicht ein als eine gültige, weil die Menschen unter dem Einflusse des Materialismus der letzten Jahrhunderte eben gar nicht gewöhnt sind, solche Dinge mit den Tatsachen des Weltenalls zu verbinden.

[ 12 ] Für die heutige materialistische Weltanschauung ist eben der Saturn, der sich da im Weltenraume findet, nur ein Körper, der da im Weltenraum herumgondelt, und die anderen Planeten auch. Aber so ist es nicht; sondern wenn wir diesen äußersten Planeten unseres Planetensystems, den Saturn nehmen, dann müssen wir ihn uns vorstellen - und ich werde jetzt etwas wiederum gewissermaßen referierend angeben müssen, was wir erst später erläutern —, wir müssen ihn uns vorstellen als den Führer unseres Planetensystems im Weltenraume. Er zieht unser Planetensystem im Weltenraume. Er ist der Körper für die äußerste Kraft, die uns da in der Lemniskate im Weltenraume herumführt. Er kutschiert und zieht zugleich. Er ist also die Kraft in der äußersten Peripherie. Würde er nur wirken, so würden wir uns in der Lemniskate bewegen. Aber nun sind in unserem Planetensystem eben diese anderen Kräfte, die eine intimere Vermittelung darstellen zur geistigen Welt, die wir im Merkur und in der Venus finden. Durch diese Kräfte wird fortwährend die Bahn gehoben. So daß wir, wenn wir diese Bahn von oben anschauen, wir diese Lemniskate bekommen (die vorige Kurve); wenn wir sie aber von der Seite anschauen, bekommen wir Linien, die sich fortwährend heben, fortschreiten (Tafel 20, rechts unten). Dieses Fortschreiten, das entspricht im Menschen der Tatsache, daß wir, während wir schlafen, das verarbeiten, was wir in uns aufgenommen haben; wenn es auch nicht gleich ins Bewußtsein übergeht, wir verarbeiten es. Wir verarbeiten, was wir durch unsere Erziehung, durch unser Leben aufnehmen, eigentlich hauptsächlich während des Schlafens. Und während des Schlafes vermitteln uns das Merkur und Venus. Sie sind unsere wichtigsten Nachtplaneten, während Jupiter und Saturn unsere wichtigsten Tagesplaneten sind. Daher hat mit vollem Rechte eine ältere instinktive atavistische Weisheit Jupiter und Saturn mit der menschlichen Hauptesbildung zusammengebracht, Merkur und Venus mit der menschlichen Rumpfesbildung, also mit dem übrigen Organismus. Aus der intimen Erkenntnis des Verhältnisses zwischen Mensch und Weltenall sind diese Dinge entstanden.

[ 13 ] Nun bitte ich Sie aber folgendes zu beachten. Wir haben nötig, zunächst einmal aus inneren Gründen die Bewegung der Erde lemniskatisch aufzufassen, außerdem als wirkend auf die Bewegung der Erde die Venus- und Merkurkräfte, die die Lemniskate selber wiederum weitertragen, so daß eigentlich die Lemniskate fortschreitet und ihre Achse selber dann wiederum eine Lemniskate wird. Wir haben eine außerordentlich komplizierte Bewegung für die Erde selber. Und nun kommt das, worauf ich Sie eigentlich hinweisen will. Es strebt die Astronomie danach, diese Bewegungen zu zeichnen. Man will ein Planetensystem haben. Man will das Sonnensystem zeichnen und rechnerisch erklären. Aber solche Planeten wie Venus und Merkur, die haben auch Beziehungen zu dem Außerräumlichen, zu dem Übersinnlichen, zu dem Geistigen, zu dem, was gar nicht in den Raum hineingehört. Wollen Sie also die Bahn des Saturn, die Bahn des Jupiter, die Bahn des Mars erfassen und in denselben Raum hineinzeichnen auch die Bahn von Venus und Merkur, so kriegen Sie da hinein höchstens eine Projektion der Venus- und Merkurbahn, aber keineswegs die Venus- und Merkurbahn selbst. Wenn Sie den dreidimensionalen Raum verwenden, um hineinzuzeichnen die Bahn von Jupiter, Saturn und Mars, so kommen Sie höchstens noch an eine Grenze; da kriegen Sie so etwas wie eine Bahn der Sonne. Wollen Sie aber jetzt das andere zeichnen, was da noch kommt, dann können Sie das nicht mehr in den dreidimensionalen Raum hineinzeichnen, sondern Sie können nur Schattenbilder für diese anderen Bewegungen in den dreidimensionalen Raum hineinkriegen. Sie können nicht in denselben Raum hineinzeichnen die Bahn der Venus und die Bahn des Saturn. Daraus ersehen Sie, daß alles Zeichnen des Sonnensystems, indem man sich dabei desselben Raumes bedient für den Saturn wie für die Venus, daß das alles nur Annäherungen sind, daß es gar nicht geht, ein Sonnensystem zu zeichnen. Das geht ebensowenig, wie Sie einen Menschen seiner Gesamtwesenheit nach aus den bloß natürlichen Kräften erklären können. Und jetzt werden Sie einsehen, warum kein Sonnensystem genügt. Leicht konnte ein Gar-nicht-Astronom wie Johannes Schlaf den Leuten, die ganz feste Astronomen sind, die Unmöglichkeit ihres Sonnensystems zeigen an sehr einfachen Tatsachen, indem er einfach zum Beispiel darauf hinwies, daß wenn die Sonne und die Erde sich so verhielten, daß die Erde herumginge um die Sonne, müßten sich Sonnenflecken nicht so zeigen, wie sie sich eben zeigen, denn einmal ist man hinten und dann ist man vorn und dann geht man herum. Das ist aber alles nicht der Fall. Es stimmt nichts von dem, was in einen Raum von den gewöhnlichen drei abstrakten Dimensionen von unserem Sonnensystem hineingezeichnet wird. Man muß sich durchaus klar sein, daß man, ebenso wie beim Menschen, sich sagen muß: Will man den Menschen als ganzen Menschen begreifen, so muß man von den physischen Kräften zu den übersinnlichen Kräften gehen. Ebenso muß man, will man ein Sonnensystem begreifen, über die drei Dimensionen hinausgehen in andere Dimensionalität hinein. Das heißt, man kann nicht ein gewöhnliches Sonnensystem zeichnen im dreidimensionalen Raum (Tafel 21, Mitte). Alle diese Planiglobien und so weiter, die haben wir so aufzufassen, daß wir sagen: Da, wo in einem solchen Planiglobium der Saturn ist, da ist, wenn wir nach unserm gewöhnlichen schematischen Sonnensystem irgendwo Merkur haben, nicht der wirkliche Merkur, sondern sein Schatten, seine bloße Projektion.

[ 14 ] Das sind solche Dinge, die erst wieder von der Geisteswissenschaft ans Tageslicht gebracht werden müssen. Nicht wahr, sie sind verschwunden. Ungefähr sechs, sieben Jahrhunderte vor der christlichen Zeitrechnung hat die Urweisheit begonnen zu verschwinden. Dann ist sie allmählich hinuntergegangen, bis sie durch die Philosophie ersetzt worden ist von der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts ab. Aber Menschen wie zum Beispiel Pythagoras haben aus der alten Urweisheit noch so viel gewußt, daß sie zum Beispiel sagen konnten, oder wenigstens Zeitgenossen des Pythagoras sagen konnten: Ja, wir wohnen auf der Erde, wir gehören dutch diese Erde einem Weltsystem an, dem Saturn und Jupiter angehören; aber wenn wir in dieser Dimensionalität drinnenbleiben, dann finden wir da drinnen nicht ein ebensolches Zugehören zu Venus und Merkur. Und wenn wir zu Venus und Merkur gehören wollen, dann können wir nicht so unmittelbar dazugehören, wie wir zu Saturn und Jupiter gehören, sondern wenn unsere Erde in einem gemeinschaftlichen Raum ist mit Saturn und Jupiter (Tafel 20, Mitte unten), so gibt es eine Gegenerde, die ist dann in dem anderen gemeinschaftlichen Raum mit Merkur und Venus. — Daher sprechen diese alten Astronomen von der Erde und der Gegenerde. Selbstverständlich kommt nun der moderne Materialist und sagt: Gegenerde? Ich sehe nichts davon. Er gleicht dem, der einen Menschen abwiegt, dem er erst befohlen hat, nichts zu denken, und ihn dann abwiegt, wenn er ihm befohlen hat, einen besonders gescheiten Gedanken zu denken, und dann sagt: Ich habe gewogen, aber ich habe die Schwere der Gedanken nicht gefunden. - Nicht wahr, der Materialismus lehnt alles ab, was nicht schwer ist oder was nicht gesehen werden kann. Aber es leuchten merkwürdige Dinge aus der Urweisheit, aus der atavistischen Urweisheit der Menschen herauf, auf die wir wiederum aus ganz innerem Schauen, aus innerem Anschauen aus der Geisteswissenschaft kommen. Und dieses Sich-wieder-Durcharbeiten zu einem absolut Neuen, das aber eigentlich auf der Erde schon einmal da war, jetzt nur errungen werden soll aus dem vollen Bewußtsein der Menschen heraus, das ist eben etwas, was dieser Menschheit jetzt dringend notwendig ist aus dem Grunde, weil die Menschen sonst ja die ganze Möglichkeit ihres Denkens verlieren.

[ 15 ] Ich habe Sie doch gestern darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß für das soziale Denken die Menschen Mono-Metallismus anstreben wegen des Freihandels, und — der Schutzzoll kommt. Aus dem, was angestrebt wird auf Grundlage des Denkens, das die Menschheit heute hat, wird auf der Erde niemals eine wirkliche soziale Ordnung entstehen - einzig und allein aus jenem Denken heraus, das geschult ist an solcher Wissenschaft, die nicht Planiglobien zeichnet, in denen Saturn und Venus in demselben Raume sind. Denn dieses anthroposophische Anschauen der Welt bedeutet nicht nur, daß wir uns etwas vorhalten, sondern es bedeutet auch, daß wir in einer gewissen Weise denken lernen. Was ist es denn nun eigentlich, wenn wir so denken lernen, wie wir heute denken lernen? Nun, erinnern Sie sich, was ich gesagt habe. Indem unsere Leibesorganisation zur nächsten Inkarnation metamorphosisch sich umbildet, da macht sie nicht nur eine Umwandelung durch, sondern eine Umstülpung. So, wie wenn ich den Handschuh der linken Hand zur rechten Hand richtig umstülpe, daß das Innere nach außen kommt, so geht dasjenige, was jetzt nach innen geht, Leber, Herz, Niere und so weiter, in der nächsten Inkarnation nach außen, wird die Sinnesorganisation, wird Auge, wird Ohr und so weiter. Es stülpt sich um. Dieses Umstülpen im Menschen entspricht diesem anderen Umstülpen: Saturn auf der einen Seite, dann ganz draußen aus diesem Raume Venus und Merkur. Ein Umstülpen in sich selber. Beachten wir es nicht, was tun wir denn dann? Wir tun ganz dasselbe, als wenn wir das Umstülpen beim menschlichen Haupt nicht beachten. Wenn wir die Welt gar nicht betrachten unter diesem Umstülpegesetz, tun wir etwas sehr Eigentümliches. Wir denken nämlich dann gar nicht mit unserem Kopfe. Und das ist dasjenige, wohin der fünfte nachatlantische Zeitraum, insofern er sich abwärts bewegt, und nicht durch Geisteswissenschaft wiederum einen Aufstieg sucht, wohin dieser fünfte nachatlantische Zeitraum tendiert. Die Menschen möchten ihren Kopf loskriegen und bloß mit dem übrigen Organismus denken. Abstraktion ist das Denken mit dem übrigen Organismus. Den Kopf möchten sie loskriegen. Sie möchten keinen Anspruch machen auf dasjenige, was ihnen aus der vorigen Inkarnation sich ergeben hat. Sie möchten nur mit der gegenwärtigen Inkarnation rechnen. Nicht nur theoretisch möchten die Menschen die aufeinanderfolgenden Erdenleben leugnen, sondern sie tragen ihren Kopf, wenn ich so sagen darf, mit äußerer Würde, weil sich der Herr auf ihren übrigen Organismus setzt, wie sich der Mensch in eine Kutsche setzt. Und sie ‚nehmen den Kurschenbewohner nicht ernst. Sie tragen ihn mit sich herum, machen aber auf seine eigenen Fähigkeiten keine rechten Ansprüche. Sie machen auch praktisch keinen Gebrauch von den wiederholten Erdenleben.

[ 16 ] Das ist die Tendenz, die sich im wesentlichen seit dem Beginn der fünften nachatlantischen Zeit entwickelt und der nur begegnet werden kann dadurch, daß in der Tat zur Geisteswissenschaft gegriffen wird. Geisteswissenschaft könnte man auch so definieren, daß man sagt, sie bringt den Menschen dazu, seinen Kopf wiederum ernst zu nehmen. Das ist eigentlich das Wesentliche der Geisteswissenschaft von einer gewissen Seite aus, daß der menschliche Kopf wiederum ernst genommen wird, daß er nicht wie eine bloße Beigabe zu dem übrigen Organismus genommen wird. Europa insbesondere möchte, indem es rasch der Barbarei entgegengeht, die Menschenköpfe loskriegen. Geisteswissenschaft muß schon diesen Schlaf stören. Sie muß appellieren an die Menschheit: Gebraucht eure Köpfe! Das kann man nicht anders, als indem man die wiederholten Erdenleben ernst nimmt.

[ 17 ] Sie sehen, man kann nicht in der gewöhnlichen Weise über Geisteswissenschaft reden, wenn man diese Geisteswissenschaft ernst nimmt. Man muß sagen was ist. Und zu dem, was ist, gehört etwas, was den Leuten wie ein Wahnsinn erscheint; zu dem, was ist, gehört, daß die Menschen ihre Köpfe verleugnen. Sie entschließen sich nicht gern, die Menschen, das zu glauben. Sie sehen selbstverständlich lieber solch eine Wahrheit als einen Wahnsinn an. Aber schließlich war es ja immer so. Es mußten die Dinge in die Menschheitsentwickelung so hereintreten, daß die Menschen von dem Neuen gewissermaßen überrascht werden. So müssen die Menschen natürlich auch überrascht werden von jener Notwendigkeit, daß ihnen betont wird, ihre Köpfe zu gebrauchen. Lenin und Trotzki sagen: Macht ja keinen Gebrauch von euren Köpfen, geht nur aus von dem übrigen Organismus. Der ist Träger der Instinkte. - Da soll man bloß auf Instinkte rechnen. Sehen Sie, das ist die Praxis. Die Praxis ist ja: Nichts von dem, was aus dem menschlichen Haupte entspringt, soll eingehen in die moderne marxistische Theorie. Das sind sehr ernste Dinge, und immer wieder muß betont werden, wie ernst diese Dinge sind.

Eleventh Lecture

[ 1 ] Yesterday, I drew attention to how that which is present in human beings points to something that is correspondingly present in the non-human universe, insofar as there is a certain relationship between human beings and the non-human universe. What we must now point out in particular as existing in human beings is the orientation of the human head toward an extraterrestrial world, toward a world that lies outside the one on which the rest of the human organism depends. Our head still points clearly to the world we passed through between death and a new birth. The entire organization of our head is formed in such a way that it forms a clear echo of our stay in the spiritual worlds. Now we must seek the corresponding in the cosmos.

[ 2 ] You need only compare the behavior of, say, Saturn, which is far out in the universe, with the behavior of the Earth itself, and you will perceive a certain difference. This difference has become apparent to astronomy in that it is said that Saturn revolves around the Sun in 30 years and the Earth in one year. Let us not concern ourselves here with whether these things are right or wrong, whether they represent a one-sided view or not; we only want to point out that the observations that can be made by tracking Saturn in space and comparing the speed of its movement with what is attributed to the Earth as a certain speed, that, assuming the Copernican-Keplerian world system, one arrives at the view that Saturn takes 30 years to orbit the Sun and the Earth one year. And when we then look at Jupiter, it is said to have an orbital period of 12 years. The orbital period of Mars is much shorter. But now, when we look at the other planets, Venus and Mercury, we find orbital periods that are shorter than that of the Earth, or let us say, that are said to be shorter than the orbital period of the Earth. All these things are, of course, imagined, imagined on the basis of observations made in one way or another.

[ 3 ] Now, I have pointed out that we can only gain true insight into these things if we compare what is happening in the vastness of space with what is happening within the limits of our skin, in our own organism. Consider that what we call the Earth's orbit around the Sun corresponds to something. Yesterday we pointed out that the daily sequence of events also points to a certain curve, a certain line that intersects itself. In a similar way, we can imagine the curve, the crooked line, that corresponds to the Earth's annual movement, regardless of whether we believe that this movement of the Earth is also a movement around the Sun or not. For what do we actually have before us? Consider this: we have our own daily cycle, which we do not want to take as it corresponds to the cosmos, but as it appears in human beings, so that we can also include those whose sleeping and waking hours do not coincide with the change of day and night, that is, we can also include those who dawdle and live irregularly. We want to consider this daily cycle in humans in such a way that, for the reason we already mentioned yesterday, we think of it as represented by such a line (plate 20, top right), with the points of falling asleep and waking up coinciding. I already noted yesterday that these points of falling asleep and waking up must be thought of as coinciding. There are many reasons for this, but one reason is sufficient to see, without prejudice, that we must place the point of waking above the point of falling asleep. For take the most striking fact: when you look back on your life, it appears to you as a continuous flow. You are not inclined to imagine this life in this way (the interrupted straight line in the middle, from right to left): Today I lived and was aware of my surroundings until I woke up; then came darkness; then yesterday, when I fell asleep, I lived again until I woke up; then darkness followed again. That is not how you imagine the stream of memory, but rather you imagine the stream of memory in such a way that the moment of waking up and the moment of falling asleep actually coincide in your remembering consciousness. That is a simple fact. This fact can only be drawn by drawing the curve representing the course of the day in a human being as a looped line, where the point of waking up falls above the point of falling asleep. If a curve that was an ellipse or a circle were correct, then falling asleep and waking up would have to be clearly separated from each other; waking up could not immediately follow falling asleep. This is how we must imagine the course of a human day.

[ 4 ] Try to figure out for yourself what this actually means: You live awake from the moment you wake up until you fall asleep. As a physical human being, you are the whole human being, you have your physical body, your etheric body, your astral body, and your I within you. Now take the physical human being from falling asleep to waking up. There you have only the physical body and the etheric body. As a physical human being, you are not a human being, but you have the physical body and the etheric body; that lies in bed. That should not really be there at all. It basically exists unjustly, because it should be a plant. It is only the remnant of the complete human being, from which the ego and the astral body have departed, and only under the influence of the fact that the ego and the astral body can return before the physical body and the etheric body can pursue their plant destiny, only this fact prevents us from dying every night.

[ 5 ] Now let us look at what is actually lying in the bed. What is it that lies there? It suddenly becomes the nature of the plant kingdom. You must see this as similar to what happens on earth from the moment when plants sprout in spring until autumn, when the plants die back again. In humans, the plant nature shoots up, one might say, from falling asleep to waking up. They become like the earth in summer. And when the ego and the astral body return, when humans wake up, they become like the earth in winter. So we can say that the waking state of human beings, the time from waking up to falling asleep, is personal winter, and the time from falling asleep to waking up is personal summer. For the cosmos, insofar as the earth also belongs to this cosmos, the year is the equivalent. The earth wakes up in winter and sleeps in summer. Summer is the earth's sleeping time, winter is the earth's waking time. Outwardly, there is of course a false analogy; one believes that summer is the earth's waking time and winter is the earth's sleeping time. The opposite is true, because during our sleeping time we become similar to blossoming, sprouting plant life, and thus become like the Earth during summertime. And when our ego and our astral body enter our physical body and our etheric body, it is as if the summer sun withdraws and the winter sun takes effect on the plant-bearing earth. However, a season is always for a certain part of the earth's surface. So it is different with the earth than with the individual human being, but only apparently so, by the way; with the earth, insofar as we inhabit any part of it, it is so that a year corresponds to the daily cycle of the human being. A year in the cosmos corresponds to the daily cycle of the human being.

[ 6 ] Now you have immediately established the fact that when you look at the cosmos, you must say to yourself: a year is for it a period of sleeping and waking. And if our Earth is simply the head of the cosmos, then winter expresses the waking of the cosmos, and summer the sleeping of the cosmos. Let us now take this cosmos, which brings forth waking and sleeping, for the plant cover on the earth is the result of the cosmos. Let us now take this cosmos, then we must also view it as a large organism. We must think of what is happening in its limbs as being as organically integrated into the whole cosmos as we must think of what is happening in one of our organs as being organically integrated into our organism. This brings us to the significance of those differences which are otherwise expressed in astronomy in the shorter orbital periods of Venus and Mercury compared to the longer orbital periods—longer than a so-called orbital period of the Earth—of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn in particular. If we take the so-called outer planets, Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, these apparently have a long orbital period that extends beyond a year, that is, beyond mere waking life. Take Saturn, for example, with its 30 years, which are its apparent orbital period around the Sun (plate 20, top left); how can we express its 30 years if we speak the proper language of the cosmos, which is that a year is its daily cycle? If a year is the daily cycle of the cosmos, then Saturn's so-called orbital period is approximately 30 days, a cosmic month, cosmic 4 weeks. So you can say: if you consider Saturn—the other two planets, Uranus and Neptune, which are now regarded as equal, have flown in—if you consider Saturn to be the outermost planet, then you must say: Saturn limits our cosmos, and in its apparent slow movement, in Saturn's lagging behind the Earth, the life of the cosmos is revealed in four weeks, in one month, as opposed to the life that the cosmos reveals in the course of a year, which for it is a falling asleep and waking up.

[ 7 ] From this you can see that Saturn, if we consider its apparent orbit as the outermost boundary of our planetary system, behaves differently within this planetary system than Mercury, for example. Mercury, which does not even need 100 days for a so-called apparent orbit, moves quickly, is active within, has a certain speed, while Saturn moves slowly.

[ 8 ] What does this actually correspond to? If you take the movement of Saturn, there is something relatively slow; the movement of Mercury is something that is very fast compared to the movement of Saturn, an inner liveliness of the cosmic organism, something that moves the cosmos internally. It is as if you were to imagine a kind of living slime organism (plate 21, left), which rotates as such, and inside it there is an organ that rotates faster around itself. In its movement, Mercury separates itself from the whole rotation, from the whole movement, through its faster rotation. It is like an enclosed limb, just as the movement of Venus is like an enclosed limb. Here you have something that corresponds to the behavior of the head in relation to the rest of the organism in humans. The head excludes itself from the movements of the rest of the organism. Venus and Mercury emancipate themselves from the movement indicated by Saturn. They go their own way. They tremble within the whole system. What does that mean? They have something extra in the whole system. Their faster activity indicates that they have something extra inside. What is the equivalent of this extra? Well, in our head, what the head has extra is the connection to the supersensible world; only—our head is calm in our organism, just as we are calm inside a carriage or a train, even though the train is moving. Venus and Mercury do it differently; they do the opposite in relation to their emancipation. While our head is calm, as when we sit quite calmly in the carriage or on the train and are calm inside, Venus and Mercury emancipate themselves in the opposite way from the entire planetary system. It is as if, when we sit in the train carriage, stimulated by something, we would continue to move faster inside than the train itself.

[ 9 ] You see, this stems from the fact that Venus and Mercury, which appear to move faster, are not only related to the space outside, to the spatial, but also have relationships to that to which our head is related. Only these relationships are of an opposite nature, our head being calmed and Venus and Mercury becoming more active. But Venus and Mercury are the planets through which our planetary system has a relationship to the supersensible world. Venus and Mercury integrate our planetary system into the cosmos in a different way than Saturn and Jupiter. Our planetary system is spiritualized by Venus and Mercury, spiritualized, assigned to the spiritual powers in a more intimate way than is the case with Jupiter and Saturn, for example.

[ 10 ] Things that are real often appear quite different when studied realistically than when judged according to obvious criteria. Just as humans, when judging externally, call winter the sleeping time of the earth and summer the waking time, when in fact it is the other way around, so too, judging externally, one might be tempted to think of Saturn and Jupiter as more spiritual than Venus and Mercury. But this is not the case. Venus and Mercury are in fact more intimately related to something that lies behind the entire cosmos than Jupiter and Saturn. So we can say that in Venus and Mercury we have something that, insofar as we are members of our planetary system, connects us externally to a supersensible world. By living here, we are connected to a supersensible world through Mercury and Venus. One could say: by incarnating ourselves in the physical world through birth, we are carried into this physical world by Saturn and Jupiter; by living from birth to death, Venus and Mercury work within us and prepare us to carry our supersensible nature out into the supersensible world through death. In fact, Mercury and Venus have just as much to do with our immortality after death as Jupiter and Saturn have to do with our immortality before death. But it is so that we really must see something in the cosmos that corresponds to the relatively more spiritual organization of the head in comparison with the organization of the rest of the human organism.

[ 11 ] Now, if we imagine that Saturn also moves in such a curve (lemniscate, plate 20) which is of course drawn differently in space than the curve of the Earth caused by a movement 30 times faster, if we imagine this curve for Saturn and also for the Earth, then we must imagine that every world body that revolves in such a path is of course moved by forces in this path, but it is moved by forces of different kinds. And this brings us to an idea that is extremely significant and which, once you have accepted it as reality, will probably immediately strike you as valid. The only reason it does not strike people as valid is because, under the influence of the materialism of recent centuries, they are simply not accustomed to connecting such things with the facts of the universe.

[ 12 ] For today's materialistic worldview, Saturn, which is found in outer space, is just a body floating around in outer space, and so are the other planets. But this is not the case; rather, if we take Saturn, the outermost planet of our planetary system, we must imagine it—and I will now have to refer again to something that we will explain later—we must imagine it as the leader of our planetary system in the universe. It pulls our planetary system through space. It is the body for the outermost force that guides us around in the lemniscate in space. It drives and pulls at the same time. It is therefore the force in the outermost periphery. If he were only acting, we would be moving in the lemniscate. But now there are these other forces in our planetary system, which represent a more intimate connection to the spiritual world, which we find in Mercury and Venus. These forces continuously raise the orbit. So that when we look at this orbit from above, we see this lemniscate (the previous curve); but when we look at it from the side, we see lines that continuously rise and progress (plate 20, bottom right). This progression corresponds in humans to the fact that while we sleep, we process what we have taken in; even if it does not immediately enter our consciousness, we process it. We process what we take in through our education and our lives, mainly during sleep. And during sleep, Mercury and Venus mediate this to us. They are our most important night planets, while Jupiter and Saturn are our most important day planets. Therefore, an older instinctive atavistic wisdom has rightly associated Jupiter and Saturn with the formation of the human head, and Mercury and Venus with the formation of the human trunk, that is, with the rest of the organism. These things have arisen from an intimate knowledge of the relationship between the human being and the universe.

[ 13 ] Now, however, I ask you to note the following. First of all, for inner reasons, we need to understand the movement of the Earth as lemniscate, and furthermore as being influenced by the forces of Venus and Mercury, which in turn carry the lemniscate forward, so that the lemniscate actually progresses and its axis itself then becomes a lemniscate. We have an extremely complicated movement for the Earth itself. And now comes what I actually want to point out to you. Astronomy strives to draw these movements. We want to have a planetary system. We want to draw the solar system and explain it mathematically. But planets such as Venus and Mercury also have relationships to the extra-spatial, to the supersensible, to the spiritual, to that which does not belong in space at all. So if you want to capture the orbit of Saturn, the orbit of Jupiter, the orbit of Mars, and draw the orbits of Venus and Mercury into the same space, you will at best get a projection of the orbits of Venus and Mercury, but by no means the orbits of Venus and Mercury themselves. If you use three-dimensional space to draw the orbits of Jupiter, Saturn, and Mars, you will at best reach a boundary; there you will get something like the orbit of the sun. But if you now want to draw the other things that come after that, you can no longer draw them in three-dimensional space; you can only get shadow images of these other movements into three-dimensional space. You cannot draw the orbit of Venus and the orbit of Saturn in the same space. From this you can see that all drawings of the solar system, using the same space for Saturn as for Venus, are only approximations, that it is impossible to draw a solar system. This is just as impossible as explaining the totality of a human being in terms of natural forces alone. And now you will understand why no solar system is sufficient. A non-astronomer like Johannes Schlaf could easily show people who are staunch astronomers the impossibility of their solar system using very simple facts, for example by simply pointing out that that if the sun and the earth behaved in such a way that the earth revolved around the sun, sunspots would not appear as they do, because once you are behind, then you are in front, and then you go around. But none of this is the case. Nothing that is drawn into a space of the usual three abstract dimensions of our solar system is true. One must be quite clear that, just as with human beings, one must say: if one wants to understand the human being as a whole, one must go from the physical forces to the supersensible forces. Similarly, if you want to understand a solar system, you have to go beyond the three dimensions into other dimensions. This means that you cannot draw an ordinary solar system in three-dimensional space (plate 21, center). All these flat globes and so on must be understood in such a way that we say: Where Saturn is in such a flat globe, if we have Mercury somewhere in our ordinary schematic solar system, it is not the real Mercury, but its shadow, its mere projection.

[ 14 ] These are things that must first be brought to light again by spiritual science. They have disappeared, haven't they? About six or seven centuries before the Christian era, the ancient wisdom began to disappear. Then it gradually declined until it was replaced by philosophy from the middle of the 15th century onwards. But people like Pythagoras, for example, still knew so much from the ancient primordial wisdom that they could say, or at least Pythagoras' contemporaries could say: Yes, we live on Earth, we belong to this Earth, which is part of a world system to which Saturn and Jupiter belong; but if we remain within this dimension, we do not find the same belonging to Venus and Mercury. And if we want to belong to Venus and Mercury, then we cannot belong to them as directly as we belong to Saturn and Jupiter, but if our Earth is in a communal space with Saturn and Jupiter (plate 20, bottom center), then there is a counter-Earth, which is then in the other communal space with Mercury and Venus. — That is why these ancient astronomers speak of the Earth and the counter-Earth. Of course, the modern materialist comes along and says: Counter-Earth? I don't see anything of the sort. He is like someone who weighs a person, first telling him not to think anything, and then weighing him again after telling him to think a particularly clever thought, and then saying: I have weighed him, but I have not found the weight of his thoughts. Materialism rejects everything that is not heavy or cannot be seen. But strange things shine forth from the primordial wisdom, from the atavistic primordial wisdom of human beings, which we in turn arrive at through inner contemplation, through inner observation from spiritual science. And this working through again to something absolutely new, which has actually already been here on earth, but now has to be achieved out of the full consciousness of human beings, is precisely what humanity urgently needs now, because otherwise human beings will lose the whole possibility of their thinking.

[ 15 ] I pointed out to you yesterday that, for social thinking, people strive for mono-metallism because of free trade, and — protective tariffs come in. From what is being strived for on the basis of the thinking that humanity has today, a real social order will never arise on earth — solely out of that thinking which is trained in such science that does not draw flat globes in which Saturn and Venus are in the same space. For this anthroposophical view of the world does not only mean that we hold something up before ourselves, but it also means that we learn to think in a certain way. What is it, then, when we learn to think as we learn to think today? Well, remember what I said. As our bodily organization undergoes metamorphic transformation for the next incarnation, it does not merely undergo a conversion, but a reversal. Just as when I turn my left glove inside out so that the inside comes out, so too does that which is now inside—the liver, heart, kidneys, and so on—go outside in the next incarnation, becoming the sensory organization, the eye, the ear, and so on. It turns inside out. This turning inside out in humans corresponds to this other turning inside out: Saturn on one side, then completely outside this space, Venus and Mercury. A turning inside out within itself. If we do not pay attention to this, what do we do then? We do exactly the same as if we did not pay attention to the turning inside out in the human head. If we do not view the world at all under this law of turning inside out, we do something very peculiar. For then we are not thinking with our heads at all. And that is where the fifth post-Atlantean period, insofar as it moves downward and does not seek an ascent through spiritual science, tends to go. People want to get rid of their heads and think only with the rest of their organism. Abstraction is thinking with the rest of the organism. They want to get rid of their heads. They do not want to lay claim to what has come to them from their previous incarnation. They only want to reckon with their present incarnation. Not only do people want to deny successive earth lives in theory, but they carry their heads, if I may say so, with outward dignity, because the Lord sits on their remaining organism, just as a person sits in a carriage. And they do not take the inhabitants of the course seriously. They carry them around with them, but do not make any real demands on their abilities. They also make practically no use of their repeated lives on earth.

[ 16 ] This is the tendency that has essentially developed since the beginning of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch and can only be countered by actually turning to spiritual science. Spiritual science could also be defined as something that causes people to take their heads seriously again. From a certain point of view, this is actually the essence of spiritual science: that the human head is taken seriously again, that it is not regarded as a mere appendage to the rest of the organism. Europe in particular, in its rapid descent into barbarism, wants to rid itself of human heads. Spiritual science must disturb this slumber. It must appeal to humanity: Use your heads! This can only be done by taking repeated lives on earth seriously.

[ 17 ] You see, one cannot talk about spiritual science in the usual way if one takes this spiritual science seriously. One must say what is. And what is includes something that seems like madness to people; what is includes the fact that human beings deny their heads. People do not readily decide to believe this. They naturally prefer to regard such a truth as madness. But after all, it has always been this way. Things had to come about in human evolution in such a way that people would be surprised, so to speak, by the new. So people must naturally also be surprised by the necessity of being told to use their heads. Lenin and Trotsky say: Don't use your heads, just proceed from the rest of the organism. That is the carrier of instincts. - One should rely solely on instincts. You see, that is the practice. The practice is that nothing that springs from the human mind should enter into modern Marxist theory. These are very serious matters, and it must be emphasized again and again how serious they are.