The Bridge Between Universal Spirituality and the Physical Constitution of Man

GA 202

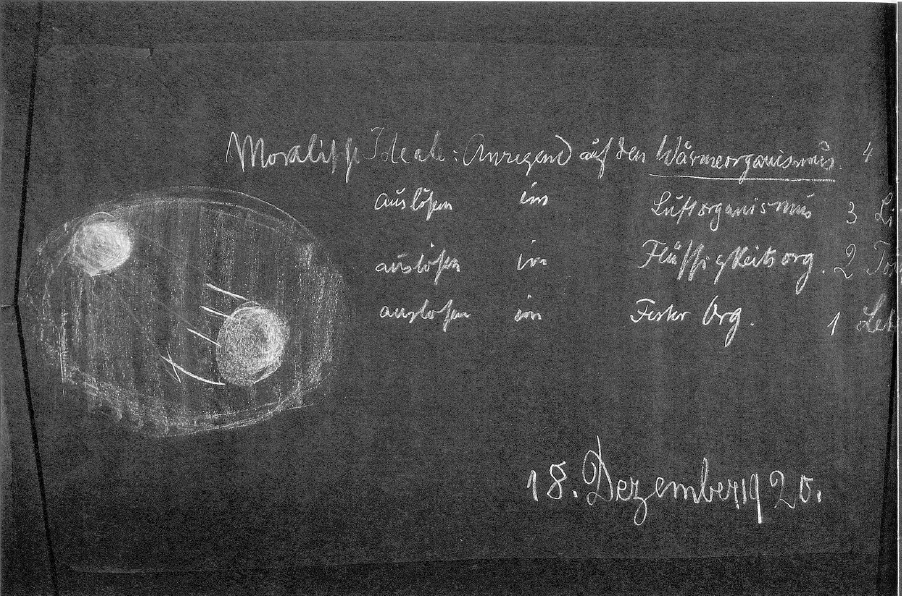

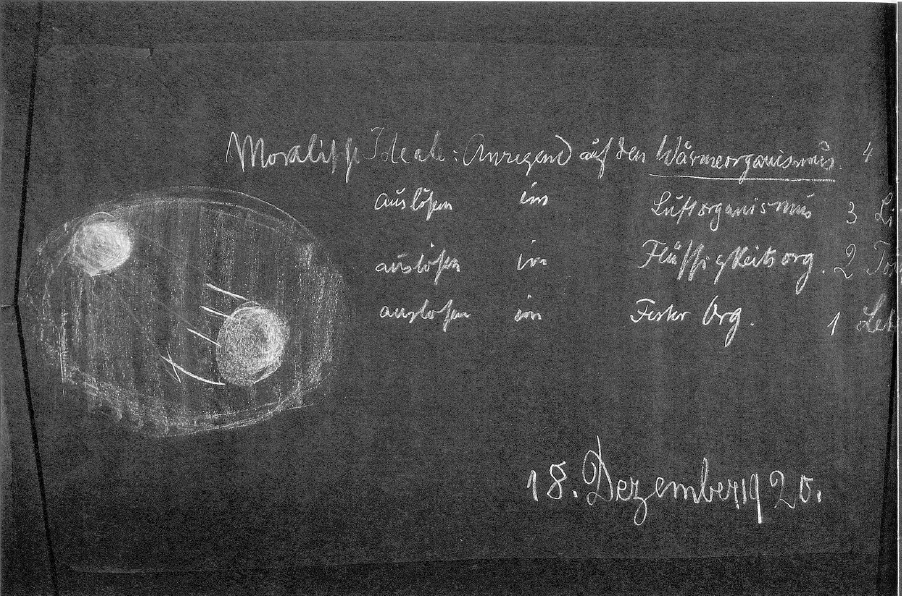

18 December 1920, Dornach

Translator Unknown

II. Moral as the Source of World-Creative Power

I tried yesterday to give certain indications about the constitution of man, and at the end it was possible to show that a really penetrating study of human nature is able to build a bridge between man's external constitution and what it unfolds, through self-consciousness, in his inner life. As a rule no such bridge is built, or only very inadequately built, particularly in the science current today. It became clear to us that in order to build this bridge we must know how man's constitution is to be regarded. We saw that the solid or solid fluid organism—which is the sole object of study today and is alone recognized by modern science as organic in the real sense—we saw that this must be regarded as only one of the organisms in the human constitution; that the existence of a fluid organism, an aeriform organism, and a warmth-organism must also be recognized. This makes it possible for us also to perceive how those members of man's nature which we are accustomed to regard as such, penetrate into this delicately organized constitution. Naturally, up to the warmth-organism itself, everything is to be conceived as physical body. But it is paramountly the etheric body that takes hold of the fluid body, of everything that is fluid in the human organism; in everything aeriform, the astral body is paramountly active, and in the warmth-organism, the Ego. By recognizing this we can as it were remain in the physical but at the same time reach up to the spiritual.

We also studied consciousness at its different levels. As I said yesterday, it is usual to take account only of the consciousness known to us in waking life from the moment of waking to the moment of falling asleep. We perceive the objects around us, reason about these perceptions with our intellect; we also have feelings in connection with these perceptions, and we have our will-impulses. But we experience this whole nexus of consciousness as something which, in its qualities, differs completely from the physical which alone is taken account of by ordinary science. It is not possible, without further ado, to build a bridge from these imponderable, incorporeal experiences in the domain of consciousness to the other objects of perception studied in physiology or physical anatomy. But in regard to consciousness too, we know from ordinary life that in addition to the waking consciousness, there is dream-consciousness, and we heard yesterday that dreams are essentially pictures or symbols of inner organic processes. Something is going on within us all the time, and in our dreams it comes to expression in pictures. I said that we may dream of coiling snakes when we have some intestinal disorder, or we may dream of an excessively hot stove and wake up with palpitations of the heart. The overheated stove symbolized irregular beating of the heart, the snakes symbolized the intestines, and so forth. Dreams point us to our organism; the consciousness of dreamless sleep is, as it were, an experience of nullity, of the void. But I explained that this experience of the void is necessary in order that man shall feel himself connected with his bodily nature. As an Ego he would feel no connection with his body if he did not leave it during sleep and seek for it again on waking. It is through the deprivation undergone between falling asleep and waking that he is able to feel himself united with the body. So from the ordinary consciousness which has really nothing to do with our own essential being beyond the fact that it enables us to have perceptions and ideas, we are led to the dream-consciousness which has to do with actual bodily processes. We are therefore led to the body. And we are led to the body even more strongly when we pass into the consciousness of dreamless sleep. Thus we can say: On the one hand our conception of the life of soul is such that it leads us to the body. And our conception of the bodily constitution, comprising as it does the fluid organism, the aeriform organism, the warmth-organism and thus becoming by degrees more rarefied, leads us to the realm of soul. It is absolutely necessary to take these things into consideration if we are to reach a view of the world that can really satisfy us.

The great question with which we have been concerning ourselves for weeks, the cardinal question in man's conception of the world, is this: How is the moral world-order connected with the physical world-order? As has been said so often, the prevailing world-view—which relies entirely upon natural science for knowledge of the outer physical world and can only resort to earlier religious beliefs when it is a matter of any comprehensive understanding of the life of soul, for in modern psychology there really is no longer any such understanding—this world-view is unable to build a bridge. There, on the one side, is the physical world. According to the modern world view, this is a conglomeration from a primeval nebula, and everything will eventually become a kind of slag-heap in the universe. This is the picture of the evolutionary process presented to us by the science of today, and it is the one and only picture in which a really honest modern scientist can find reality.

Within this picture a moral world-order has no place. It is there on its own. Man receives the moral impulses into himself as impulses of soul. But if the assertions of natural science are true, everything that is astir with life, and finally man himself came out of the primeval nebula and the moral ideals well up in him. And when, as is alleged, the world becomes a slag-heap, this will also be the graveyard of all moral ideals. They will have vanished.—No bridge can possibly be built, and what is worse, modern science cannot, without being inconsistent, admit the existence of morality in the world-order. Only if modern science is inconsistent can it accept the moral world-order as valid. It cannot do so if it is consistent. The root of all this is that the only kind of anatomy in existence is concerned exclusively with the solid organism, and no account is taken of the fact that man also has within him a fluid organism, an aeriform organism, and a warmth-organism. If you picture to yourselves that as well as the solid organism with its configuration into bones, muscles, nerve-fibres and so forth, you also have a fluid organism and an aeriform organism—though these are of course fluctuating and inwardly mobile—and a warmth-organism, if you picture this you will more easily understand what I shall now have to say on the basis of spiritual-scientific observation.

Think of a person whose soul is fired with enthusiasm for a high moral ideal, for the ideal of generosity, of freedom, of goodness, of love, or whatever it may be. He may also feel enthusiasm for examples of the practical expression of these ideals. But nobody can conceive that the enthusiasm which fires the soul penetrates into the bones and muscles as described by modern physiology or anatomy. If you really take counsel with yourself, however, you will find it quite possible to conceive that when one has enthusiasm for a high moral ideal, this enthusiasm has an effect upon the warmth organism.—There, you see, we have come from the realm of soul into the physical!

Taking this as an example, we may say: Moral ideals come to expression in an enhancement of warmth in the warmth-organism. Not only is man warmed in soul through what he experiences in the way of moral ideals, but he becomes organically warmer as well—though this is not so easy to prove with physical instruments. Moral ideals, then, have a stimulating, invigorating effect upon the warmth-organism.

You must think of this as a real and concrete happening: enthusiasm for a moral ideal—stimulation of the warmth-organism. There is more vigorous activity in the warmth-organism when the soul is fired by a moral ideal. Neither does this remain without effect upon the rest of one's constitution. As well as the warmth-organism he also has the air-organism. He inhales and exhales the air; but during the inbreathing and outbreathing process the air is within him. It is of course inwardly in movement, in fluctuation, but equally with the warmth-organism it is an actual air-organism in man. Warmth, quickened by a moral ideal, works in turn upon the air-organism, because warmth pervades the whole human organism, pervades every part of it. The effect upon the air-organism is not that of warming only, for when the warmth, stimulated by the warmth-organism, works upon the air-organism, it imparts to it something that I can only call a source of light. Sources of light, as it were, are imparted to the air-organism, so that moral ideals which have a stimulating effect upon the warmth-organism produce sources of light in the air-organism. To external perception and for ordinary consciousness these sources of light are not in themselves luminous, but they manifest in man's astral body. To begin with, they are curbed—if I may use this expression—through the air that is within man. They are, so to speak, still dark light, in the sense that the seed of a plant is not yet the developed plant. Nevertheless man has a source of light within him through the fact that he can be fired with enthusiasm for moral ideals, for moral impulses.

We also have within us the fluid organism. Warmth, stimulated in the warmth organism by moral ideals, produces in the air-organism what may be called a source of light which remains, to begin with, curbed and hidden. Within the fluid organism—because everything in the human constitution interpenetrates—a process takes place which I said yesterday actually underlies the outer tone conveyed in the air. I said that the air is only the body of the tone, and anyone who regards the essential reality of tone as a matter of vibrations of the air, speaks of tones just as he would speak of a man as having nothing except the outwardly visible physical body. The air with its vibrating waves is nothing but the outer body of the tone. In the human being this tone, this spiritual tone, is not produced in the air-organism through the moral ideal, but in the fluid organism. The sources of tone, therefore, arise in the fluid organism.

We regard the solid organism as the densest of all, as the one that supports and bears all the others. Within it, too, something is produced as in the case of the other organisms. In the solid organism there is produced what we call a seed of life—but it is an etheric, not a physical seed of life such as issues from the female organism at a birth. This etheric seed which lies in the deepest levels of subconsciousness is actually the primal source of tone and, in a certain sense, even the source of light. This is entirely hidden from ordinary consciousness, but it is there within the human being.

Think of all the experiences in your life that came from aspiration for moral ideas—be it that they attracted you merely as ideas, or that you saw them coming to expression in others, or that you felt inwardly satisfied by having put such impulses into practice, by letting your deeds be fired by moral ideals ... all this goes down into the air-organism as a source of light, into the fluid organism as a source of tone, into the solid organism as a source of life.

These processes are withdrawn from the field of man's consciousness but they operate within him nevertheless. They become free when he lays aside his physical body at death. What is thus produced in us through moral ideals, or through the loftiest and purest ideas, does not bear immediate fruit. For during the life between birth and death, moral ideas as such become fruitful only in so far as we remain in the life of ideas, and in so far as we feel a certain satisfaction in moral deeds performed. But this is merely a matter of remembrance, and has nothing to do with what actually penetrates down into the different organisms as the result of enthusiasm for moral ideals.

So we see that our whole constitution, beginning with the warmth-organism, is, in very fact, permeated by moral ideals. And when at death the etheric body, the astral body, and the Ego emerge from the physical body, these higher members of our human nature are filled with all the impressions we have had. Our Ego was living in the warmth-organism when it was quickened by moral ideas. We were living in our air-organism, into which were implanted sources of light which now, after death, go forth into the cosmos together with us. In our fluid organism, tone was kindled which now becomes part of the Music of the Spheres, resounding from us into the cosmos. And we bring life with us when we pass out into the cosmos through the portal of death.

You will now begin to have an inkling of what the life that pervades the universe really is. Where are the sources of life? They lie in that which quickens those moral ideals which fire man with enthusiasm. We come to the point of saying to ourselves that if today we allow ourselves to be inspired by moral ideals, these will carry forth life, tone and light into the universe and will become world-creative. We carry out into the universe world-creative power, and the source of this power is the moral element.

So when we study the whole man we find a bridge between moral ideals and what works as life-giving force in the physical world, even in the chemical sense. For tone works in the chemical sense by assembling substances and dispersing them again. Light in the world has its source in the moral stimuli, in the warmth-organisms of men. Thus we look into the future—new worlds take shape. And as in the case of the plant we must go back to the seed, so in the case of these future worlds that will come into being, we must go back to the seeds which lie in us as moral ideals.

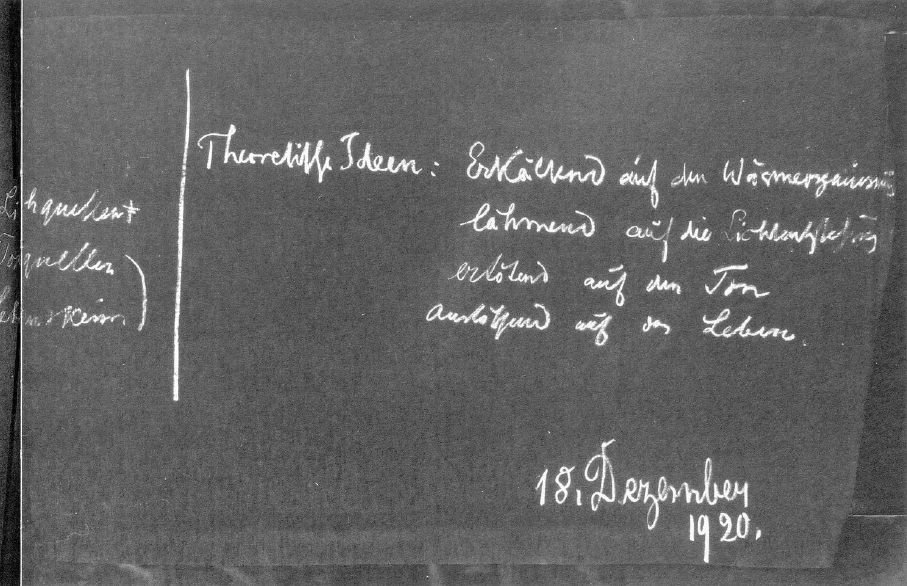

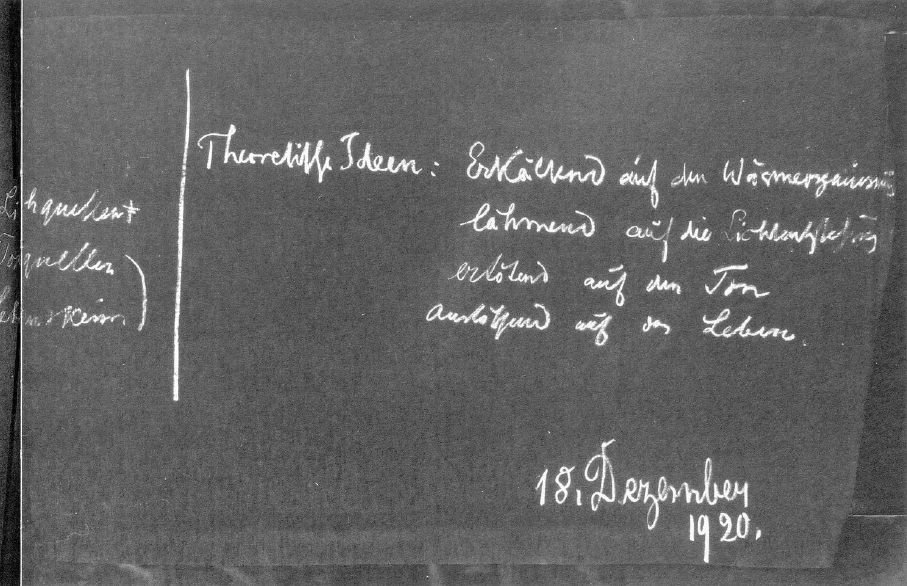

And now think of theoretical ideas in contrast to moral ideals. In the case of theoretical ideas everything is different, no matter how significant these ideas may be, for theoretical ideas produce the very opposite effect to that of stimulus. They cool down the warmth-organism—that is the difference.

Moral ideas, or ideas of a moral-religious character, which fire us with enthusiasm and become impulses for deeds, work as world-creative powers. Theoretical ideas and speculation's have a cooling, subduing effect upon the warmth-organism. Because this is so, they also have a paralyzing effect upon the air-organism and upon the source of light within it; they have a deadening effect upon tone, and an extinguishing effect upon life. In our theoretical ideas the creations of the pre-existing world come to their end. When we formulate theoretical ideas a universe dies in them. Thus do we bear within us the death of a universe and the dawn of a universe.

Here we come to the point where he who is initiated into the secrets of the universe cannot speak, as so many speak today, of the conservation of energy or the conservation of matter. [e.Ed: The law propounded by Julius Robert Mayer (1814-1878)]. It is simply not true that matter is conserved forever. Matter dies to the point of nullity, to a zero-point. In our own organism, energy dies to the point of nullity through the fact that we formulate theoretical thoughts. But if we did not do so, if the universe did not continually die in us, we should not be man in the true sense. Because the universe dies in us, we are endowed with self-consciousness and are able to think about the universe. But these thoughts are the corpse of the universe. We become conscious of the universe as a corpse only, and it is this that makes us Man.

A past world dies within us, down to its very matter and energy. It is only because a new universe at once begins to dawn that we do not notice this dying of matter and its immediate rebirth. Through man's theoretical thinking, matter—substantiality—is brought to its end; through his moral thinking, matter and cosmic energy are imbued with new life. Thus what goes on inside the boundary of the human skin is connected with the dying and birth of worlds. This is how the moral order and the natural order are connected. The natural world dies away in man; in the realm of the moral a new natural world comes to birth.

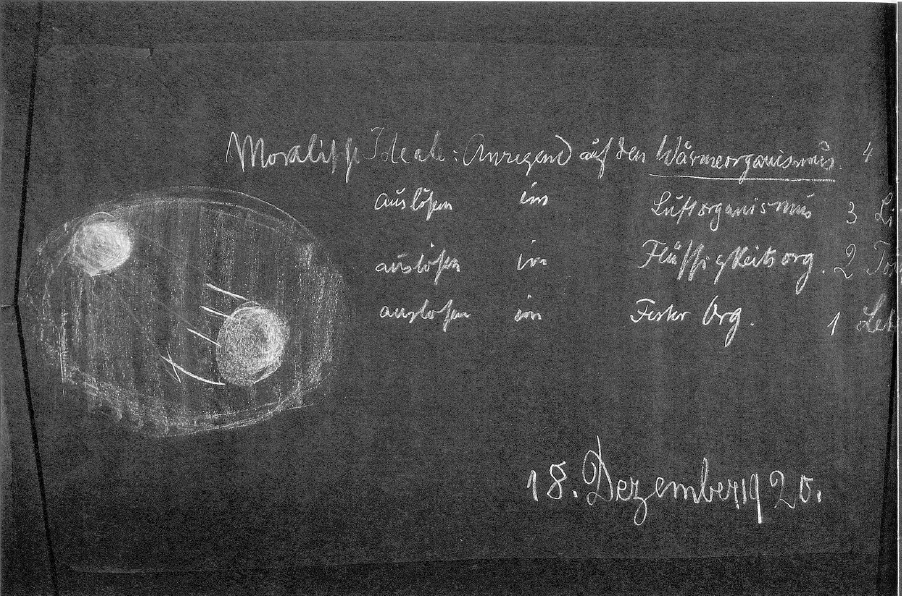

Moral Ideals:

stimulate the warmth-organism.

producing in the air organism—sources of Light.

producing in the fluid organism—sources of Tone.

producing in the solid organism—seeds of Life. (etheric)

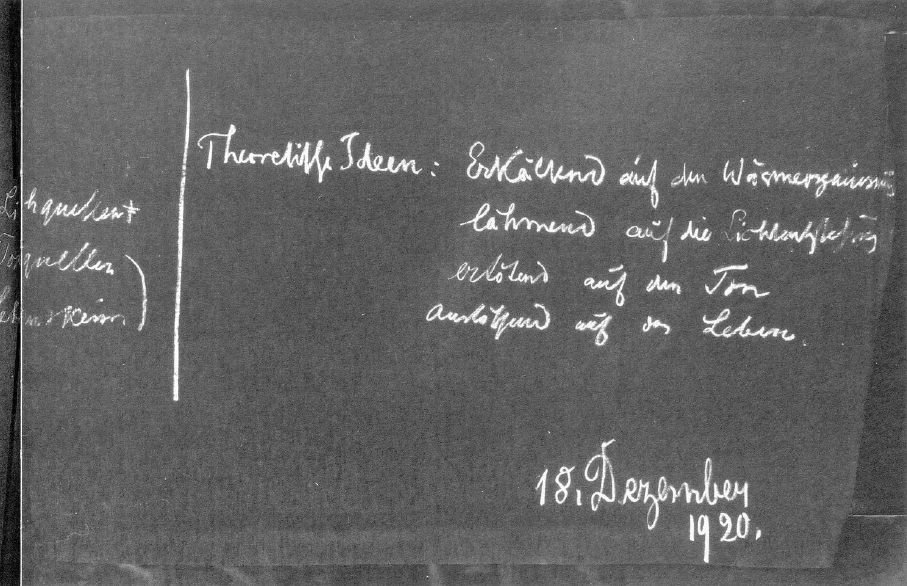

Theoretical thoughts:

cool down the warmth organism.

paralyze the sources of Light.

deaden the sources of Tone.

extinguish Life.

Because of unwillingness to consider these things, the ideas of the imperishability of matter and energy were invented. If energy were imperishable and matter were imperishable there would be no moral world-order. But today it is desired to keep this truth concealed and modern thought has every reason to do so, because otherwise it would have to eliminate the moral world-order—which in actual fact it does by speaking of the law of the conservation of matter and energy. If matter is conserved, or energy is conserved, the moral world order is nothing but an illusion, a mirage. We can understand the course of the world's development only if we grasp how out of this ‘illusory’ moral world-order—for so it is when it is grasped in thoughts—new worlds come into being.

Nothing of this can be grasped if we study only the solid component of man's constitution. To understand it we must pass from the solid organism through the fluid and aeriform organisms to the warmth-organism. Man's connection with the universe can be understood only if the physical is traced upwards to that rarefied state wherein the soul can be directly active in the rarefied physical element, as for example in warmth. Then it is possible to find the connection between body and soul.

However many treatises on psychology may be written—if they are based upon what is studied today in anatomy and physiology it will not be possible to find any transition to the life of soul from this solid, or solid-fluid bodily constitution. The life of soul will not be revealed as such. But if the bodily substance is traced back to warmth, a bridge can be built from what exists in the body as warmth to what works from out of the soul into the warmth in the human organism. There is warmth both without and within the human organism. As we have heard, in man's constitution warmth is an organism; the soul, the soul-and-spirit, takes hold of this warmth-organism and by way of the warmth all that becomes active which we inwardly experience as the moral. By the ‘moral’ I do not of course mean what philistines mean by it, but I mean the moral in its totality, that is to say, all those impulses that come to us, for example when we contemplate the majesty of the universe, when we say to ourselves: We are born out of the cosmos and we are responsible for what goes on in the world.—I mean the impulses that come to us when the knowledge yielded by Spiritual Science inspires us to work for the sake of the future. When we regard Spiritual Science itself as a source of the moral, this, more than anything else, can fill us with enthusiasm for the moral, and this enthusiasm, born of spiritual-scientific knowledge, becomes in itself a source of morality in the higher sense. But what is generally called ‘moral’ represents no more than a subordinate sphere of the moral in the universal sense.—All the ideas we evolve about the external world, about Nature in her finished array, are theoretical ideas. No matter with what exactitude we envisage a machine in terms of mathematics and the principles of mechanics, or the universe in the sense of the Copernican system—this is nothing but theoretical thinking, and the ideas thus formulated constitute a force of death within us; a corpse of the universe is within us in the form of thoughts, of ideas.

These matters create deeper and deeper insight into the universe in its totality. There are not two orders, a natural order and a moral order in juxtaposition, but the two are one. This is a truth that must be realized by the man of today. Otherwise he must ever and again be asking himself: How can my moral impulses take effect in a world in which a natural order alone prevails?—This indeed was the terrible problem that weighed upon men in the nineteenth century and early twentieth century: How is it possible to conceive of any transition from the natural world into the moral world, from the moral world into the natural world?—The fact is that nothing can help to solve this perplexing, fateful problem except spiritual-scientific insight into Nature on the one side and Spirit on the other.

With the premises yielded by this knowledge we shall also be able to get to the root of something that is presented as a branch of science today and has already penetrated into the general consciousness of men. Our world-view today is based upon Copernicanism. Until the year 1827 the Copernican conception of the universe which was elaborated by Kepler and then diluted into theory by Newton, was tabooed by the Roman Catholic Church. No orthodox Catholic was allowed to believe it. Since that year the prohibition has been lifted and the Copernican view of the universe has taken root so strongly in the general consciousness that anyone who does not base his own world-view upon it is regarded as a fool.

What is this Copernican picture of the universe?—It is in reality a picture built up purely on the basis of mathematical principles, mathematical-mechanical principles. The rudiments of it began, very gradually, to be unfolded in Greece, [e.Ed: Particularly by Aristarchos of Samos, the Greek astronomer, circa 250 B.C.] where, however, echoes of earlier thought—for example in the Ptolemaic view of the universe—still persisted. And in course of time this developed into the Copernican system that is taught nowadays to every child.

We can look back from this world-conception to ancient times when man's picture of the universe was very different. All that has remained of it are those traditions which in the form in which they exist today—in astrology and the like—are sheer dilettantism. That is what has remained of ancient astronomy, and it has also remained, ossified and paralyzed, in the symbols of certain secret societies, Masonic societies and the like. There is usually complete ignorance of the fact that these things are relics of an ancient astronomy. This ancient astronomy was quite different from that of today, for it was based, not upon mathematical principles but upon ancient clairvoyant vision.

Entirely false ideas prevail today of how an earlier humanity acquired its astronomical-astrological knowledge. This was acquired through an instinctive-clairvoyant vision of the universe. The earliest Post-Atlantean peoples saw the heavenly bodies as spirit forms, spirit entities, whereas we today regard them merely as physical structures. When the ancient peoples spoke of the celestial bodies, of the planets or of the fixed stars, they were speaking of spiritual beings. Today, the sun is pictured as a globe of burning gas which radiates light into the universe. But for the men of ancient times the sun was a living Being and they regarded the sun, which their eyes beheld, simply as the outward manifestation of this Spirit Being at the place where the sun stands in the universe; and it was the same in regard to the other heavenly bodies—they were seen as Spirit Beings. We must think of an age which came to an end long before the time of the Mystery of Golgotha, when the sun out yonder in the universe and everything in the stars was conceived of as living spirit reality, living Being. Then came an intermediary period when people no longer had this vision, when they regarded the planets, at any rate, as physical, but still thought of them as pervaded by living souls. In times when it was no longer known how the physical passes over by stages into what is of the soul, how what is of the soul passes over by stages into the physical, how in reality the two are united, men postulated physical existence on the one side and soul existence on the other. They thought of the correspondences between these two realms just as most psychologists today—if they admit the existence of a soul at all—still think, namely that the soul and the physical nature of the man are identical. This, of course, leads thought to absurdity; or there is the so-called ‘psycho-physical parallelism,’ which again is nothing else than a stupid way of formulating something that is not understood.

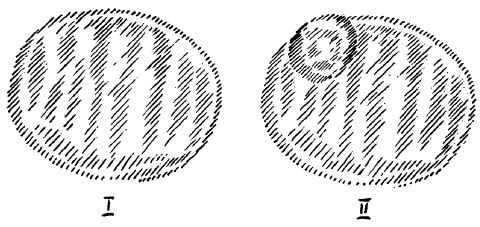

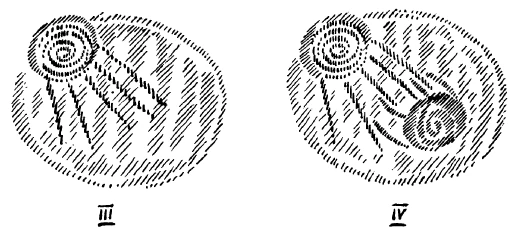

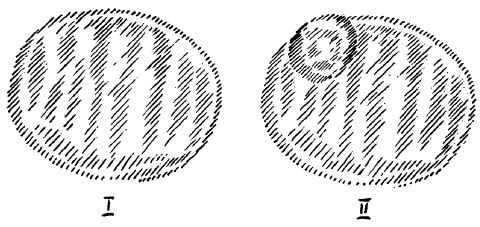

Then came the age when the heavenly bodies were regarded as physical structures, circling or stationary, attracting or repelling one another in accordance with mathematical laws. To be sure, in every epoch there existed a knowledge—in earlier times a more instinctive knowledge—of how things are in reality. But in the present age this instinctive knowledge no longer suffices; what in earlier times was known instinctively must now be acquired by conscious effort. And if we enquire how those who were able to view the universe in its totality—that is to say, in its physical, psychical and spiritual aspects—if we enquire how these men pictured the sun, we must say: They pictured it first and foremost as a Spirit-Being. Those who were initiated conceived of this Spirit-Being as the source of the moral. In my Philosophy of Spiritual Activity I have said that ‘moral intuitions’ are drawn from this source—but drawn from it in the earthly world, for the moral intuitions shine forth from man, from what can live in him as enthusiasm for the moral.

Think of how greatly our responsibility is increased when we realize: If here on the earth there were no soul capable of being with enthusiasm for true and genuine morality, for the spiritual moral order in general, nothing could be contributed towards the progress of our world, towards a new creation; our world would be led towards its death.

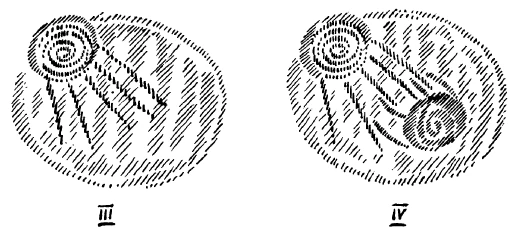

This force of light that is on the earth (Diagram VII) rays out into the universe. This is, to begin with, imperceptible to ordinary vision; we do not perceive how human moral impulses in man ray out from the earth into the universe. If a grievous age were to dawn over the earth, an age when millions and millions of men would perish through lack of spirituality—spirituality conceived of here as including the moral, which indeed it does—if there were only a dozen men filled with moral enthusiasm, the earth would still ray out a spiritual, sun-like force! This force rays out only to a certain distance. At this point it mirrors itself, as it were, in itself, so that here (Diagram VIII) there arises the reflection of what radiates from man. And in every epoch the initiates regarded this reflection as the sun. For as I have so often said, there is nothing physical here. Where ordinary astronomy speaks of the existence of an incandescent globe of gas, there is merely the reflection of a spiritual reality in physical appearance.

You see, therefore, how great is the distance separating the Copernican view of the world, and even the old astrology, from what was the inmost secret of Initiation. The best illustration of these things is provided by the fact that in an epoch when great power was vested in the hands of groups of men, who, as they declared, considered that such truths were dangerous for the masses and did not wish them to be communicated, one who was an idealist—the Emperor Julian (called for this reason ‘the Apostate’)—wanted to impart these truths to the world and was then brought to his death by cunning means. There are reasons which induce certain occult societies to withhold vital secrets of world-existence, because by so doing they are able to wield a certain power. If in the days of the Emperor Julian certain occult societies guarded their secrets so strictly that they acquiesced in his murder, it need not surprise us if those who are the custodians of certain secrets today do not reveal them but want to withhold them from the masses in order to enhance their power—it need not surprise us if such people hate to realize that at least the beginnings of such secrets are being unveiled. And now you will understand some of the deeper reasons for the bitter hatred that is leveled against Spiritual Science, against what Spiritual Science feels it a duty to bring to mankind at the present time. But we are living in an age when either earthly civilization will be doomed to perish, or certain secrets will be restored to mankind—truths which hitherto have in a certain way been guarded as secrets, which were once revealed to people through instinctive clairvoyance but must now be reacquired by fully conscious vision, not only of the physical but also of the spiritual that is within the physical.

What was the real aim of Julian the Apostate?—He wished to make clear to the people: ‘You are becoming more and more accustomed to look only at the physical sun; but there is a spiritual Sun of which the physical sun is only the mirror-image!’ In his own way he wished to communicate the Christ-Secret to the world. But in our age it is desired that the connection of Christ, the spiritual Sun, with the physical sun, shall be kept hidden. That is why certain authorities rage most violently of all when we speak of the Christ Mystery in connection with the Sun Mystery. All kinds of calumnies are then spread abroad.—But Spiritual Science is assuredly a matter of importance in the present age, and those alone who regard it as such view it with the earnestness that is its due.

Elfter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Ich habe gestern versucht, einiges vorzubringen über die gesamte Konstitution des Menschen, so daß es möglich war, am Schlusse darauf aufmerksam zu machen. wie durch eine sachgemäße Totalbetrachtung der menschlichen Natur eine Brücke gebaut werden kann zwischen dem, was wir im Menschen als äußere Organisation finden, und demjenigen, was wir durch das Selbstbewußtsein in unserem Inneren entwickeln. Diese Brücke wird ja gewöhnlich nicht oder nur in sehr mangelhafter Weise, insbesondere mangelhaft von der gegenwärtigen äußeren Wissenschaft, geschaffen. Und wir haben gesehen, daß, um diese Brücke zu bauen, man sich klar sein muß, wie man die menschliche Organisation zu betrachten hat. Wir sahen, daß wir alles, was eigentlich einzig und allein heute betrachtet wird, wenigstens was von der äußeren Wissenschaft ernsthaft betrachtet wird als organisiert, das Feste oder Fest-flüssige, nur als den einen Organismus betrachten dürfen; daß wir aber ebenso eine flüssige Organisation, eine luftförmige Organisation und eine Wärmeorganisation anerkennen müssen. Wir erlangen dadurch die Möglichkeit, auch einzusehen, wie in diese feinere Organisation eingreifen diejenigen Glieder der menschlichen Wesenheit, die wir eben gewöhnt sind, als solche zu betrachten. Natürlich ist alles bis zur Wärme hinauf physischer Leib. Aber in den Flüssigkeitsleib, in all das, was im Organismus als Flüssigkeit organisiert ist, greift der Ätherleib vorzugsweise ein; in all das, was als Luft organisiert ist, greift der astralische Leib ein, und in all das, was als Wärme organisiert ist, greift das Ich vorzugsweise ein. Dadurch gelangen wir dazu, gewissermaßen im Physischen stehenzubleiben, aber innerhalb dieses Physischen bis herauf ins Geistige zu kommen.

[ 2 ] Auf der anderen Seite haben wir das Bewußtsein betrachtet. Gewöhnlich sieht man nur, sagte ich gestern, auf dasjenige Bewußtsein hin, das wir aus dem Zustande heraus kennen, den wir durchmachen vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen. Da nehmen wir die Gegenstände um uns herum wahr, kombinieren sie mit unserem Verstande, fühlen auch wohl über sie, leben in unseren Willensimpulsen; aber wir erleben diesen ganzen Bewußtseinskomplex als etwas, was seinen Eigenschaften nach ganz verschieden ist von all dem Physischen, das die äußere physische Wissenschaft ganz allein betrachtet. Und es läßt sich nicht ohne weiteres eine Brücke schaffen zwischen diesen ganz unkörperlichen Erlebnissen, die man im Bewußtsein hat, und den anderen Anschauungen, den anderen Wahrnehmungsobjekten, die man durch physische Physiologie oder physische Anatomie betrachtet. Aber auch in bezug auf das Bewußtsein kennen wir ja schon im gewöhnlichen Leben außer dem gewöhnlichen Tagesbewußtsein das Traumbewußtsein, und wir haben gestern ausgeführt, wie die Träume im wesentlichen Bilder oder Sinnbilder sind von inneren organischen Vorgängen. Es geht immer in uns etwas vor, und bildhaft drückt sich das, was da vorgeht, aus in den Träumen. Wir träumen, sagte ich, von Schlangen, die sich winden, wenn wir irgendwelche Schmerzen in den Gedärmen haben; wir träumen von einem kochenden Ofen, wachen nachher mit Herzklopfen auf; der kochende Ofen hat uns das unregelmäßig gehende Herz symbolisiert, die Schlangen haben uns die Gedärme symbolisiert und so weiter. Es weist uns der Traum in unseren Organismus hinunter, und das Bewußtsein im Schlafe, es ist dumpf, es ist sozusagen für den Menschen eigentlich ein Null-Erlebnis. Aber ich habe gestern ausgeführt, wie man dieses Null-Erlebnis haben muß, um gerade sich verbunden zu fühlen mit seiner Körperlichkeit. Man würde sich nicht als Ich verbunden fühlen mit seiner Körperlichkeit, wenn man nicht den Körper verließe, ihn wiederum aufsuchte beim Aufwachen und auf diese Weise gerade aus dem Entbehren, das man erlebt zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen, sich als eins mit seinem Körper fühlte. Da werden wir von dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein, das ja nichts mit uns selber zu tun hat, als daß es uns die Wahrnehmung, die Vorstellung gibt, in das Traumbewußtsein geführt, welches mit dem zu tun hat, was nun schon im Leibe ist. Wir werden also zum Leibe hingeführt. Und wir werden noch mehr zum Leibe hingeführt, wenn wir in das traumlose Schlafbewußtsein eindringen. So also können wir sagen: Wir betrachten auf der einen Seite das Seelische so, daß es uns zum Leibe hinführt. Und wir betrachten das Leibliche so, daß es, indem es durch die Organisation des Flüssigen, die Organisation des Luftförmigen, die Organisation der Wärme auftritt, indem sich die Organisation also immer mehr verfeinert, uns zum Seelischen hinführt. — Diese Dinge muß man durchaus in Erwägung ziehen, wenn man zu einer wirklich den Menschen befriedigenden Weltanschauung kommen will.

[ 3 ] Die große Frage, die uns nun seit Wochen beschäftigt, sie ist ja, wie wir wiederholt versuchten zu erkennen, die Kardinalfrage der menschlichen Weltanschauung zunächst: Wie hängt das Moralische, die moralische Weltordnung zusammen mit der physischen Weltordnung? Wir haben es oft gesagt: Die gegenwärtige Weltanschauung, die sich für die äußere Sinneswelt auf die Naturwissenschaft stützt, die, wenn es um ein umfassendes Seelisches geht — denn die Psychologie enthält ein solches nicht mehr -, nur zu den älteren religiösen Bekenntnissen Zuflucht nehmen kann, diese Weltanschauung enthält keine Brücke. Da ist auf der einen Seite die physische Welt. Sie ist hervorgegangen nach dieser Weltanschauung aus einem Urnebel. Aus dem hat sich alles herausgeballt; zu einer Art Weltenschlacke wird das alles wieder zurückkehren. Das ist, was uns als äußeres Bild durch die gegenwärtige wissenschaftliche Richtung vorgehalten wird innerhalb dieses ganzen Werdens, das ja schließlich, wenn man ehrlich ist als Wissenschafter der heutigen Zeit, als das allein Reale erscheinen kann. Innerhalb dieses Bildes hat das Moralische, die moralische Weltordnung keinen Platz. Sie steht dann für sich da. Der Mensch empfängt in seiner Seele die moralischen Impulse als Seelenimpulse. Aber wenn das so ist, wie es die Naturwissenschaft sagt, dann ist eben aus dem Urnebel hervorgegangen alles das, was sich regt und lebt, und zuletzt der Mensch, und dem Menschen steigen auf die moralischen Ideale. Und wenn einmal die Welt zurückgekehrt sein soll zum Schlackenzustand, dann wird das der große Friedhof sein auch für alle moralischen Ideale. Sie werden verschwunden sein. Eine Brücke kann gar nicht geschaffen werden, und was noch schlimmer ist, es kann nicht einmal, wenn der Mensch nicht inkonsequent wird, die wirkliche Moralität der Weltenordnung von seiten der heutigen Wissenschaft zugegeben werden. Nur wenn diese Wissenschaft inkonsequent ist, läßt sie die moralische Weltenordnung gelten. Aber wenn sie konsequent ist, kann sie das eigentlich nicht. Das alles rührt davon her, daß man eben auf der einen Seite im Grunde genommen nur eine Art Anatomie des Festen hat, daß man nicht berücksichtigt, daß der Mensch auch in sich trägt eine Organisation des Flüssigen, eine Organisation des Luftförmigen, ja auch eine Organisation des Wärmehaften. Wenn Sie sich vorstellen, daß, ebenso wie Sie in sich, meinetwillen zu den Knochen, zu den Muskeln, zu den Nervensträngen konfiguriert, die Organisation des Festen haben, Sie auch eine Organisation des Flüssigen, des Luftförmigen haben, allerdings fluktuierend, in sich beweglich, dann wieder eine Wärmeorganisation haben, so werden Sie das schon eher verstehen, was ich nun aus geisteswissenschaftlichen Beobachtungen vorzubringen habe.

[ 4 ] Stellen wir uns einmal vor, der Mensch wird begeistert von einem hohen moralischen Ideal. Der Mensch kann sich wirklich innerlich seelisch begeistern für ein moralisches Ideal, für das Ideal des Wohlwollens, für das Ideal der Freiheit, das Ideal der Güte, der Liebe und so weiter. Er kann sich begeistern in konkreten Fällen für dasjenige, was durch diese Ideale angedeutet ist. Daß aber das, was da in der Seele als Begeisterung vor sich geht, in die Knochen oder in die Muskeln fährt, so wie Knochen oder Muskeln von der heutigen Physiologie oder heutigen Anatomie betrachtet werden, das kann sich natürlich niemand vorstellen. Aber Sie werden darauf kommen, wenn Sie nur mit sich selbst innerlich ordentlich zu Rate gehen, daß Sie sich sehr wohl vorstellen können - und es ist auch so —, daß, wenn der Mensch begeistert ist für ein hohes moralisches Ideal, dann ein Einfluß ausgeübt wird von dieser inneren Begeisterung auf den Wärmeorganismus. Und dann ist man schon im Physischen drinnen vom Seelischen aus! So daß man sagen kann, wenn wir dieses Beispiel herausgreifen: Moralische Ideale drücken sich aus durch eine Erhöhung der Wärme im Wärmeorganismus. — Der Mensch wird nicht nur seelisch wärmer, der Mensch — wenn das auch nicht so leicht mit irgendeinem physikalischen Instrument nachweisbar ist — wird wirklich durch dasjenige, was er erlebt an moralischen Idealen, innerlich wärmer. Also es wirkt anregend auf den Wärmeorganismus.

[ 5 ] Das müssen Sie sich nun als einen konkreten Vorgang vorstellen: Begeisterung für ein moralisches Ideal: Belebung des Wärmeorganismus. — Es geht im Wärmeorganismus lebhafter zu, wenn ein moralisches Ideal die Seele durchglüht. Aber es bleibt auch für die übrige Organisation des Menschen nicht ohne Wirkung. Außer dem Wärmeorganismus, der gewissermaßen sein höchster physischer Organismus ist, hat ja der Mensch den Luftorganismus. Er atmet die Luft ein, er atmet die Luft aus; aber während des Ein- und Ausatmens ist die Luft in ihm. Sie ist allerdings innerlich in Bewegung, in Fluktuation; aber das ist auch eine Organisation, das ist ein wirklicher Luftorganismus, der in ihm lebt, geradeso wie der Wärmeorganismus. Indem nun durch ein moralisches Ideal die Wärme belebt wird, wirkt sie, weil ja die Wärme im ganzen Organismus, in allen Organismen wirksam ist, wiederum auf den Luftorganismus. Diese Wirkung auf den Luftorganismus ist aber nicht bloß eine erwärmende, sondern wenn die Wärme, welche regsam wird im Wärmeorganismus, auf den menschlichen Luftorganismus wirkt, so teilt sie ihm all dasjenige mit, was ich nicht anders benennen kann als eine Lichtquelle. Gewissermaßen Keime des Leuchtens teilen sich dem Luftorganismus mit, so daß also moralische Ideale, die auf den Wärmeorganismus anregend wirken, im Luftorganismus Lichtquellen auslösen. Diese Lichtquellen werden für das äußere Bewußtsein, für die äußere Wahrnehmung allerdings nicht leuchtend, aber in dem menschlichen astralischen Leib erscheinen diese Lichtquellen. Sie sind zunächst gebunden, wenn ich mich dieses physikalischen Ausdruckes bedienen darf, durch die Luft selber, die der Mensch in sich trägt. Sie sind gewissermaßen noch dunkles Licht, wie ja der Pflanzenkeim auch noch nicht die ausgebildete Pflanze ist. Aber der Mensch trägt dadurch, daß er sich begeistern kann für moralische Ideale oder für moralische Vorgänge, einen Lichtquell in sich.

[ 6 ] Als weiteren Organismus haben wir in uns den Flüssigkeitsorganismus. Indem die Wärme im Wärmeorganismus wirkt und, vom moralischen Ideal ausgehend, im Luftorganismus dasjenige auslöst, was man eine Lichtquelle nennen kann, die zunächst gebunden bleibt, verborgen bleibt, löst sich im Flüssigkeitsorganismus, weil sich alles in der menschlichen Organisation, wie gesagt, mitteilt, dasjenige aus, wovon ich gestern gesprochen habe, daß es eigentlich dem äußeren Lufttönen zugrunde liegt. Die Luft ist ja nur der Körper des Tones, sagte ich gestern, und wer etwa das Wesen des Tones in den Luftschwingungen sucht und von nichts weiter spricht, der spricht vom Tönen so, wie man vom Menschen spricht, wenn man nur vom äußeren sichtbaren Leibe spricht. Die Luft mit ihren schwingenden Wellen ist nichts anderes als der äußere Körper für den Ton. Im Menschen wird dieser Ton nicht im Luftorganismus ausgelöst, dieser geistige Ton, sondern er wird gerade im Flüssigkeitsorganismus ausgelöst durch das moralische Ideal. Also hier werden die Tonquellen ausgelöst. Und gewissermaßen als den festesten Organismus, als den, der alle übrigen Organismen stützt und trägt, betrachten wir den festen Organismus. Auch in ihm wird etwas ausgelöst, so wie in den anderen Organisationen; nur wird in dem festen Organismus dasjenige ausgelöst, was wir Lebenskeim nennen können, aber ätherischen Lebenskeim, nicht physischen Lebenskeim, wie er sich dann durch die Geburt loslöst von der menschlichen weiblichen Organisation, sondern es wird der ätherische Lebenskeim losgelöst. Das, was da als ätherischer Lebenskeim lebt, es ist ja im tiefsten Unterbewußtsein unten; schon dasjenige, was die Tonquellen sind, ja in gewissem Sinne sogar das, was Lichtquelle ist. Das ist für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein verborgen, aber es ist im Menschen.

[ 7 ] Stellen Sie sich alles vor, was Sie im Leben durchlebt haben an Hinwendungen Ihrer Seele an die moralischen Ideen, sei es, daß Sie diese moralischen Impulse sympathisch gefunden haben, indem Sie sie bloß als Ideen erfaßten, sei es, daß Sie sie gesehen haben an anderen, sei es, daß Sie in der Ausführung in einer gewissen Weise innerlich befriedigt sein konnten mit Ihrem eigenen Tun, indem Sie dieses Tun durchglüht sein lassen von den moralischen Idealen, all das geht hinunter in die Luftorganisation als Lichtquelle, in die Flüssigkeitsorganisation als Tonquelle, in die feste Organisation als Lebensquelle. All das löst sich in einer gewissen Weise von dem, was im Menschen bewußt ist, ab. Aber der Mensch trägt es in sich. Es wird frei, wenn der Mensch seine physische Organisation mit dem Tode ablegt. Was so durch unsere moralischen Ideale, was gerade durch die reinsten Ideen in unserer Organisation ausgelöst wird, das wird zunächst nicht fruchtbar. Für das Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod fruchtbar werden eben die moralischen Ideen selber, insofern wir im Ideenleben bleiben und indem wir eine gewisse Genugtuung haben über dasjenige, was wir moralisch vollbracht haben. Das hat aber lediglich mit der Erinnerung zu tun, das hat nichts zu tun mit dem, was hinuntergedrängt wird in die Organisation dadurch, daß wir moralische Ideale sympatisch finden.

[ 8 ] Wir sehen also hier, wie tatsächlich unsere ganze Organisation, ausgehend von unserem Wärmeorganismus, durchdrungen wird von den moralischen Idealen. Und wenn wir mit dem Tod herauslösen aus unserer physischen Organisation unseren ätherischen Leib, unseren astralischen Leib, unser Ich, dann sind wir in diesen höheren Gliedern der Menschennatur durchdrungen von Eindrücken, die wir gehabt haben. Wir waren mit unserem Ich in unserem Wärmeorganismus, indem die moralischen Ideale belebt haben unsere eigene Wärmeorganisation. Wir waren in unserem Luftorganismus, wo Lichtquellen gepflanzt worden sind, die nun nach unserem Tod in den Kosmos mit uns hinausgehen. Wir haben in unserem Flüssigkeitsorganismus den Ton angeregt, der zur Sphärenmusik wird, mit der wir hinaustönen in den Kosmos. Wir bringen Leben hinaus, indem wir durch die Pforte des Todes gehen.

[ 9 ] Sie ahnen an dieser Stelle, was das Leben, das ausgegossen ist in der Welt, eigentlich ist. Wo liegen die Quellen des Lebens? Sie liegen in dem, was die moralischen Ideale anregt, die im Menschen begeisternd wirken. Wir kommen darauf, uns sagen zu müssen, daß, wenn wir heute uns durchglüht sein lassen von moralischen Idealen, diese Leben und Ton und Licht hinaustragen und weltenschöpferisch werden. Wir tragen das Weltenschöpferische hinaus, und der Quell des Weltenschöpferischen ist das Moralische.

[ 10 ] Sie sehen, wir finden eine Brücke, wenn wir den ganzen Menschen betrachten, zwischen den moralischen Idealen und demjenigen, was draußen in der physischen Welt belebend, auch chemisch wirkt. Denn der Ton ist es, der chemisch wirkt, der die Stoffe zusammenbringt und auseinanderanalysiert. Und das Leuchtende in der Welt, es hat seinen Quell in den moralischen Erregungen, in den Wärmeorganismen der Menschen. Wir blicken in die Zukunft hinein, da bilden sich Weltgestalten. Und wie wir bei der Pflanze zurückgehen müssen auf den Keim, so müssen wir bei den zukünftigen Welten, die sich gestalten werden, zurückgehen auf die Keime, die als moralische Ideale in uns selber liegen.

[ 11 ] Betrachten Sie jetzt theoretische Ideen im Gegensatz zu moralischen Idealen. Mit theoretischen Ideen, und wenn sie auch noch so bedeutsam sind, verhält es sich ganz anders. Bei theoretischen Ideen haben wir tatsächlich eine Abregung, eine Erkühlung des Wärmeorganismus zu verzeichnen. So daß wir also sagen müssen: Theoretische Ideen wirken erkältend auf den Wärmeorganismus. — Das ist der Unterschied in der Wirkung auf die menschliche Organisation. Moralische oder nach dem Moralisch-Religiösen hingeordnete Ideen, diejenigen, die uns in Begeisterung versetzen, indem sie Impulse unseres Handelns werden, sie wirken in dieser Weise weltschöpferisch. Theoretische Ideen wirken zunächst abregend, erkältend auf den Wärmeorganismus. Dadurch, daß sie erkältend auf den Wärmeorganismus wirken, wirken sie auch lähmend auf den Luftorganismus und wirken lähmend auf die Lichtquelle, auf die Lichtentstehung. Sie wirken weiter ertötend auf den Weltenton, und sie wirken auslöschend auf das Leben. Es kommt zu Ende dasjenige, was in der Vorwelt geschaffen worden ist, in unseren theoretischen Ideen. Indem wir theoretische Ideen fassen, erstirbt in ihnen ein Weltenall. Wir tragen in uns das Ersterben eines Weltenalls, wir tragen in uns das Aufgehen eines Weltenalls.

Moralische Ideale: Theoretische Ideen:

anregend auf den Wärmeorganismus (4) erkältend auf den Wärmeorganismus

auslösend im Luftorganismus (3) lähmend auf die Lichtentstehung Lichtquellen

auslösend im Flüssigkeitsorganismus (2) ertötend auf den Ton Tonquellen

auslösend im festen Organismus Lebenskeime (ätherisch) (1) auslöschend auf das Leben

[ 12 ] Hier ist auch der Punkt, wo derjenige, der in die Weltengeheimnisse eingeweiht ist, nicht sprechen kann, wie heute so viele sprechen, von der Konstanz der Kraft oder der Konstanz des Stoffes. Das ist einfach nicht wahr, daß der Stoff konstant bleibt. Der Stoff vergeht bis zum Nullpunkt hin. Die Kraft vergeht bis zum Nullpunkt in unserem eigenen Organismus dadurch, daß wir theoretisch denken. Und wir wären ja nicht Menschen, wenn wir nicht theoretisch denken würden, wenn nicht das Weltenall fortwährend in uns erstürbe. Durch das Ersterben des Weltenalls sind wir eigentlich selbstbewußte Menschen, die zu Gedanken über das Weltenall kommen können. Aber indem das Weltenall sich in uns denkt, ist es schon Leiche. Der Gedanke über das Weltenall ist die Leiche des Weltenalls. Erst als Leiche wird uns das Weltenall bewußt und macht uns zum Menschen. Eine vergangene Welt also erstirbt in uns bis zum Stoff, bis zur Kraft. Und nur weil gleich wiederum eine neue aufgeht, merken wir nicht, daß der Stoff vergeht und wieder entsteht. Im Menschen wird zu Ende geführt die Stofflichkeit durch sein theoretisches Denken; es wird neu belebt die Stofflichkeit und die Weltenkraft durch sein moralisches Denken. So greift dasjenige, was innerhalb der menschlichen Haut geschieht, in Weltenvergehen und Weltenentstehen ein. So gliedern sich zusammen Moralisches und Natürliches. Das Natürliche vergeht im Menschen; im Moralischen entsteht neues Natürliches.

[ 13 ] Weil man auf diese Dinge nicht hinschauen wollte, erfand man die Ideen von der Unvergänglichkeit des Stoffes und der Kraft. Wenn die Kraft unvergänglich wäre, wenn der Stoff unvergänglich wäre, gäbe es keine moralische Weltordnung. Das will man nur heute verdecken, und die heutige Weltanschauung hat alle Ursache, das zu verdecken, denn sie müßte eigentlich die moralische Weltordnung auslöschen, und sie wird ausgelöscht, wenn man von dem Gesetz der Erhaltung des Stoffes und der Kraft spricht. Denn erhält sich irgendwie der Stoff, erhält sich irgendwie die Kraft, dann ist die moralische Weltordnung nichts weiter als eine Illusion, ein Scheingebilde. Erst dadurch kommt man dazu, den gesamten Gang der Welt zu verstehen, daß man einsieht, wie aus diesem «Scheingebilde» — das ist es ja zunächst, weil es in Gedanken lebt — der moralischen Weltordnung neue Welten erstehen. Das alles aber ergibt sich nicht, wenn man nur die festen Bestandteile der menschlichen Organisation betrachtet, sondern wenn man hinausgeht durch den Flüssigkeits- und Luftorganismus bis zum Wärmeorganismus. Den Zusammenhang des Menschen mit der Welt, man wird ihn nur verstehen, wenn man gewissermaßen das Physische bis zu jener Verfeinerung, Verdünnung verfolgt, wo unmittelbar das Seelische in dieses verdünnte Physische, wie bei der Wärme, eingreifen kann. Dann findet man den Zusammenhang zwischen dem Körperlichen und dem Seelischen. Noch so viele Psychologien, Seelenlehren können geschrieben werden: Wenn sie ausgehen von dem, was heute durch die Anatomie und Physiologie betrachtet wird, so wird man bei diesen festen oder fest-flüssigen, weich-fest gedachten Körpern keinen Übergang finden können zum Seelischen, das überhaupt nicht seelisch erscheint. Wenn man aber das Körperliche bis zur Wärme verfolgt, dann wird man eine Brücke schlagen können von dem, was in den Körpern als Wärme existiert, zu demjenigen, was von der Seele aus in die Wärme des eigenen menschlichen Organismus hineinwirkt.

[ 14 ] Wärme ist äußerlich in den Körpern, Wärme ist innerlich im menschlichen Organismus, und indem die Wärme selbst im Menschen organisiert ist, greift die Seele, das Seelisch-Geistige, in diesen Wärmeorganismus ein, und auf dem Umwege durch die Wärme greift ein alles das, was wir innerlich moralisch erleben. Ich meine jetzt natürlich mit dem Moralischen nicht nur, was sich der Philister unter moralisch allein vorstellt, sondern ich meine die Gesamtheit alles Moralischen, also auch diejenigen Impulse, die wir zum Beispiel gewinnen, wenn wir die Herrlichkeit des Kosmos betrachten, wenn wir uns sagen: Wir sind aus dem Kosmos heraus geboren, wir sind verantwortlich für das, was in der Welt vorgeht, wenn wir uns begeistern lassen, in die Zukunft hineinzuwirken aus den Erkenntnissen der Geisteswissenschaft heraus. — Und wenn wir die Geisteswissenschaft selber als einen Quell des Moralischen betrachten, dann können wir am meisten begeistert sein für dasjenige, was moralisch ist, dann wird solche Begeisterung, die aus geisteswissenschaftlicher Erkenntnis wirkt, zu gleicher Zeit ein Quell des im höheren Sinne Moralischen sein. Aber, was man gewöhnlich moralisch nennt, ist nur eine Unterabteilung des Moralischen im allgemeinen. Alle diejenigen Ideen, die wir uns über die äußere Welt machen, über fertige Naturanordnungen, sind theoretische Ideen. Wir können uns noch so stark mathematisch-mechanisch eine Maschine vorstellen, noch so stark mathematisch-mechanisch uns das Weltenall im Sinne des kopernikanischen Systems vorstellen, was wir so als theoretische Ideen gewinnen, ist Sterbekraft in uns, ist dasjenige, was Leiche des gesamten Weltalls in uns ist als Gedanke, als Vorstellung.

[ 15 ] Diese Dinge schaffen immer mehr und mehr eine Einsicht in die Gesamtheit, in die totale Welt. Und es stehen nicht zwei Ordnungen, eine Naturordnung und eine moralische Ordnung, nebeneinander, sondern beide sind eines, und das ist es, was der Mensch der Gegenwart braucht, sonst wird er immer dastehen und sagen: Was mache ich mit meinen moralischen Impulsen in einer Welt, die doch nur eine natürliche Ordnung hat? — Das war ja die auf den Gemütern des 19. Jahrhunderts, des beginnenden 20. Jahrhunderts furchtbar lastende Frage: Wie ist ein Übergang denkbar von dem Natürlichen ins Moralische, von dem Moralischen ins Natürliche? - Nichts anderes wird zur Lösung dieser bangen schicksalsschweren Frage beitragen können, als allein das geisteswissenschaftliche Durchschauen sowohl der Natur auf der einen Seite wie des Geistes auf der anderen Seite.

[ 16 ] Wenn man die Voraussetzungen hat, die aus solchen Erkenntnissen kommen, dann wird man mit ihnen nun sich auch entgegenstellen können dem, was einem auf gewissen Gebieten als äußere Wissenschaft erscheint, und was ja auch heute schon in das populäre Bewußtsein hinübergegangen ist. Wir haben als eine Grundlage unseres Weltbildes heute die kopernikanische Weltanschauung anzusehen. Diese kopernikanische Weltanschauung, die dann Kepler weiter ausgebildet, Newton vertheoretisiert hat, sie wurde ja allerdings verpönt bis zum Jahre 1827 von der katholischen Kirche. Kein rechtgläubiger Katholik durfte sie bis dahin glauben. Seither ist es ihm erlaubt, sie zu glauben. Aber sie ist so sehr in das populäre Bewußtsein übergegangen, daß natürlich heute jemand als ein Tropf gelten würde, der nicht die Welt im Sinne dieses kopernikanischen Weltbildes anschauen würde.

[ 17 ] Was ist dieses kopernikanische Weltenbild? Es ist eigentlich etwas, was nur nach mathematischen Grundsätzen, nach mathematischen Prinzipien und Anschauungen ausgebildet ist, nach mathematisch-mechanischen Anschauungen, können wir sagen. Und wir können dann vergleichen dieses Weltenbild, das sich ja langsam innerhalb der griechischen Weltanschauung vorbereitet hat, die noch immer die Reste früherer Gedankenrichtungen, zum Beispiel im ptolemäischen Weltenbilde gehabt hat, dann aber sich weiter ausgebildet hat zu dem, was eben heute jedem Kinde gelehrt wird als kopernikanisches Weltbild; wir können von diesem Weltbild zurückschauen in alte Zeiten der Menschheit. Da haben wir ein anderes Weltbild. Von dem ist nur zurückgeblieben, was heute jene Traditionen bewahren, die ja auch auf recht dilettantischer Basis stehen, so wie sie heute unter den Menschen figurieren, was als Astrologie und dergleichen existiert. Das ist als Reste alter Astronomie zurückgeblieben, oder es ist wohl auch zurückgeblieben dasjenige, was verknöchert, erstarrt gewisse Geheimgesellschaften, Freimaurergesellschaften und dergleichen in ihren Symbolen haben. Die Leute wissen gemeiniglich nicht, daß das Reste alter Astronomie sind. Aber es war eine andere Astronomie, es war eine Astronomie, welche nicht in demselben Sinne auf bloß mathematischen Prinzipien aufgebaut war, wie es die heutige Astronomie ist, sondern diese alte Astronomie war aus alten hellseherischen Anschauungen heraus entstanden. Man macht sich heute ganz falsche Vorstellungen von der Art und Weise, wie die ältere Menschheit zu ihren astronomischastrologischen Vorstellungen gekommen ist. Sie kam durch gewisse instinktiv-hellseherische Anschauungen des Weltenalls dazu. Es nahmen die ältesten nachatlantischen Völker ebenso Geistgebilde, Geistwesen in den Weltenkörpern wahr, wie heute der Mensch in den Weltenkörpern bloße physische Gebilde sieht. Wenn unter alten Völkern von Weltenkörpern, von Planeten oder Fixsternen gesprochen wurde, wurde von Geistwesen gesprochen. Heute stellt man sich vor, daß die Sonne irgendein brennender Gasball ist, daß sie Licht in die Welt hinausstrahlt, weil sie ein brennender Gasball ist. Die alten Völker haben sich vorgestellt, daß die Sonne ein lebendiges Wesen ist, und sie sahen in dem, was ihren Augen als Sonne erschien, im Grunde genommen nur den äußeren leiblichen Ausdruck für dieses Geistwesen, das sie da draußen, wo die Sonne steht, vermuteten; ebenso für die anderen Himmelskörper. Geistwesen sahen sie. Wir müssen uns vorstellen, daß es eine Zeit gab, welche ziemlich lange vor dem Eintreten des Mysteriums von Golgatha schon zu Ende gegangen ist, wo alles dasjenige, was da draußen im Weltenall eine Sonne, was in den Sternen war, als Geistwesen vorgestellt worden ist; daß dann, ich möchte sagen, eine Zwischenzeit war, wo man nicht recht wußte, wie man sich das vorzustellen habe, wo man auf der einen Seite allerdings die Planeten, die da sind, schon wie etwas Physisches ansah, sie aber doch sich belebt dachte von Seelen. In diesen Zeiten, in denen man nicht mehr gewußt hat, wie das Physische nach und nach in das Seelische übergeht, wie das Seelische nach und nach in das Physische übergeht, wie im Grunde genommen beides eines ist, statuierte man auf der einen Seite ein Physisches, auf der anderen Seite ein Seelisches. Und man dachte es sich ebenso zusammen, wie sich heute die meisten Psychologen noch, wenn sie überhaupt ein Seelisches annehmen, das Seelische und das Physische im Menschen zusammendenken, was ja natürlich zu nichts anderem als zu einem absurden Denken führt; oder wie der psychophysische Parallelismus es annimmt, was ja wiederum nichts anderes ist als ein törichtes Auskunftsmittel über etwas, was man nicht weiß.

[ 18 ] Dann kam die Zeit, in der man die Weltenkörper als physische Wesenheiten ansah, die nach mathematischen Gesetzen kreisen oder stillstehen, sich anziehen und abstoßen und so weiter. Allerdings, es ging durch alle Zeiten, in den älteren Zeiten mehr instinktiv, ein Wissen davon, wie die Dinge wirklich sind. Jetzt kommt es so, daß das instinktive Wissen nicht ausreicht, daß mit vollständigem Bewußtsein dasselbe errungen werden muß, was früher instinktiv gewußt wurde. Und wenn wir anfragen, wie diejenigen, die nun in totaler Anschauung, das heißt, in physischer, seelischer und geistiger Anschauung das Weltenall erkennen konnten, sich vorstellten die Sonne, so können wir etwa folgendes sagen: Sie stellten sich die Sonne zunächst als Geistwesen vor (Zeichnung I). Dieses Geistwesen, das dachten sich die Initiierten als den Quell alles Moralischen. Dasjenige also, wovon ich in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» sagte, daß die moralischen Intuitionen aus diesem Quell herausgenommen werden, sie werden innerhalb der Erde herausgenommen; von den Menschen erglänzen sie, von dem, was in den Menschen als moralische Begeisterung leben kann (II).

[ 19 ] Denken Sie einmal, wie unsere Verantwortlichkeit erhöht wird, wenn wir wissen: Wäre niemand auf der Erde, der für wahrhafte, echte Moral oder überhaupt geistige Ideale erglühen kann in seiner Seele, so würden wir nicht beitragen zu einem Fortgange unserer Welt, zu einer Neuschöpfung, sondern zu einem Absterben unserer Welt. Diese Leuchtekraft (Zeichnung III), die hier auf der Erde ist, wirkt ins Weltenall hinaus. Das ist allerdings eben für das gewöhnliche menschliche Wahrnehmen zunächst unwahrnehmbar, wie da hinausstrahlt von der Erde, was in dem Menschen Moralisches lebt. Ja, wenn über die ganze Erde heraufziehen würde ein trauriges Zeitalter, in dem Millionen und aber Millionen von Menschen nur in Ungeistigkeit vergehen würden — das Geistige zu gleicher Zeit hier einschließlich des Moralischen gedacht, denn so ist es ja auch -, dann würde, wenn nur ein Dutzend Menschen mit heller moralisch-geistiger Begeisterung da wären, doch die Erde erstrahlen geistig-sonnenhaft. Dasjenige, was da ausstrahlt, das strahlt nur bis zu einer gewissen Entfernung. In dieser Entfernung spiegelt es sich gewissermaßen in sich selbst, und es entsteht hier die Spiegelung desjenigen, was von dem Menschen ausstrahlt. Und diese Spiegelung, die sahen die Initiierten aller Zeiten als die Sonne an. Denn da ist nichts Physisches, ich habe es oft gesagt. Wo die äußere Astronomie davon redet, daß ein glühender Gasball ist, da ist nur die Widerspiegelung eines Geistigen, das physisch erscheint (IV).

[ 20 ] Sie sehen, wie weit die kopernikanische Weltanschauung und schließlich auch die alte Astrologie entfernt sind von dem, was nun wiederum das Geheimnis der Initiation war. Wie diese Dinge zusammenhängen, das spricht sich wohl am besten darin aus, daß in einer Zeit, in der diejenigen Menschengruppen schon sehr starke Macht hatten, die solche Wahrheiten, wie sie sagten, für die Menge gefährlich fanden und sie ihr nicht mitteilen wollten, daß in einer solchen Zeit ein Idealist wie Julian, den man deshalb den «Abtrünnigen» genannt hat, das der Welt mitteilen wollte und dann auf einem Umwege getötet worden ist. Es gibt eben durchaus Gründe, welche gewisse Geheimgesellschaften dazu veranlassen, die durchdringenden Geheimnisse der Welt nicht mitzuteilen, weil sie dadurch eine gewisse Macht ausüben können. Wenn zu Kaiser Julians Zeiten gewisse Geheimgesellschaften so stark ihre Geheimnisse hüreten, daß sie Julian töten ließen, dann brauchen wir uns nicht zu verwundern, wenn die Behüter gewisser Geheimnisse, die sie aber nicht herausgeben, sondern auch zur Ausgestaltung ihrer Macht vor der Menge hüten wollen, es hassen, wenn nun wenigstens die Anfänge gewisser Geheimnisse enthüllt werden. Und Sie sehen hier wohl etwas von den tieferen Gründen, warum sich in der Welt ein so furchtbares Hassen erhebt gegen dasjenige, was Geisteswissenschaft sich verpflichtet fühlt, in der gegenwärtigen Zeit an die Menschheit heranzubringen. Wir leben aber in einer Zeit, in der entweder die Erdenzivilisation zugrunde gehen wird, oder die Menschheit der Erde gewisse Geheimnisse ausgeliefert bekommt: diese Dinge, die in einer gewissen Weise bisher als Geheimnisse gehütet worden sind, die einmal der Menschheit zugekommen sind. durch instinktives Hellsehen, die jetzt aber wiederum errungen werden müssen durch vollbewußtes Schauen nicht nur des Physischen, sondern auch des Geistigen, das in ihm ist! Was wollte schließlich Julian der Abtrünnige? Er wollte den Leuten begreiflich machen: Ihr gewöhnt euch immer mehr und mehr an, nur die physische Sonne zu sehen; aber es gibt eine geistige Sonne, von der die physische nur der Spiegel ist! — Er wollte auf seine Art das Christus-Geheimnis der Welt mitteilen. Aber man will die Zusammenhänge des Christus, der geistigen Sonne, mit der physischen Sonne verdecken. Daher werden gewisse Machthaber am wütendsten, wenn von dem Christus-Geheimnis im Zusammenhange mit dem Sonnengeheimnis gesprochen wird. Da werden alle möglichen Verleumdungen dann vorgeführt. Aber Sie sehen, Geisteswissenschaft ist in der gegenwärtigen Zeit eine wichtige Angelegenheit. Nur wer sie als wichtige Angelegenheit betrachtet, betrachtet sie in dem vollen Ernste, der ihr gebührt.

Eleventh Lecture

[ 1 ] Yesterday, I attempted to present some ideas about the overall constitution of the human being, so that it would be possible to draw attention to this at the end. how, through a proper overall view of human nature, a bridge can be built between what we find in humans as an external organization and what we develop within ourselves through self-consciousness. This bridge is usually not built, or only in a very inadequate manner, especially by contemporary external science. And we have seen that in order to build this bridge, one must be clear about how to view the human organization. We saw that everything that is actually considered today, at least what is seriously considered by external science as organized, the solid or solid-liquid, can only be regarded as one organism; but that we must also recognize a liquid organization, an air-like organization, and a heat organization. This enables us to see how those members of the human being that we are accustomed to regard as such intervene in this finer organization. Of course, everything up to heat is physical body. But the etheric body intervenes preferentially in the fluid body, in everything that is organized as fluid in the organism; the astral body intervenes in everything that is organized as air, and the I intervenes preferentially in everything that is organized as heat. This enables us, as it were, to remain in the physical realm, but to reach up into the spiritual realm within this physical realm.

[ 2 ] On the other hand, we have considered consciousness. I said yesterday that we usually only see the consciousness that we know from the state we go through from waking up to falling asleep. We perceive the objects around us, combine them with our intellect, feel about them, live in our impulses of will; but we experience this whole complex of consciousness as something whose properties are completely different from all the physical phenomena that external physical science considers. And it is not easy to build a bridge between these entirely incorporeal experiences that we have in consciousness and the other perceptions, the other objects of perception that we observe through physical physiology or physical anatomy. But even in relation to consciousness, we already know in ordinary life, apart from ordinary daytime consciousness, dream consciousness, and yesterday we explained how dreams are essentially images or symbols of inner organic processes. Something is always going on within us, and what is going on is expressed pictorially in dreams. I said that we dream of snakes writhing when we have some kind of pain in our intestines; we dream of a boiling stove and wake up afterwards with our heart pounding; the boiling stove symbolizes our irregular heartbeat, the snakes symbolize our intestines, and so on. The dream points us down to our organism, and consciousness in sleep is dull; it is, so to speak, a zero experience for humans. But yesterday I explained how we must have this zero experience in order to feel connected to our physicality. We would not feel connected to our physicality as ourselves if we did not leave our bodies, seek them out again when we wake up, and in this way, precisely through the deprivation we experience between falling asleep and waking up, feel ourselves to be one with our bodies. There we are led by ordinary consciousness, which has nothing to do with us except that it gives us perception and imagination, into dream consciousness, which has to do with what is already in the body. We are thus led to the body. And we are led even more to the body when we enter dreamless sleep consciousness. So we can say that, on the one hand, we regard the soul as leading us to the body. And we view the physical in such a way that, by appearing through the organization of the liquid, the organization of the gaseous, the organization of heat, by means of which the organization becomes increasingly refined, it leads us to the soul. — These things must be taken into consideration if we want to arrive at a worldview that truly satisfies human beings.

[ 3 ] The big question that has been occupying us for weeks now is, as we have repeatedly tried to recognize, the cardinal question of the human worldview: How are morality and the moral world order connected with the physical world order? We have often said that the current worldview, which is based on natural science for the external sensory world and, when it comes to a comprehensive soul, can only resort to older religious creeds—because psychology no longer contains such a thing—this worldview contains no bridge. On the one hand, there is the physical world. According to this worldview, it emerged from a primordial nebula. Everything emerged from this nebula and will return to it in the form of a kind of world slag. This is what is presented to us as an external image by the current scientific trend within this whole process of becoming, which, if we are honest as scientists of today, can ultimately appear as the only reality. Within this picture, morality, the moral world order, has no place. It stands alone. Human beings receive moral impulses in their souls as soul impulses. But if this is the case, as natural science says, then everything that moves and lives, and ultimately human beings, emerged from the primordial nebula, and moral ideals arise in human beings. And once the world has returned to its state of slag, it will be the great graveyard for all moral ideals. They will have disappeared. A bridge cannot be built, and what is worse, unless humans become inconsistent, the real morality of the world order cannot even be admitted by today's science. Only if this science is inconsistent will it allow the moral world order to prevail. But if it is consistent, it cannot actually do so. All this stems from the fact that, on the one hand, we basically only have a kind of anatomy of the solid, that we do not take into account that human beings also carry within themselves an organization of the fluid, an organization of the gaseous, and even an organization of the warm. If you imagine that, just as you have within you, for my sake, the configuration of bones, muscles, and nerve strands, you also have an organization of the solid, of the liquid, of the gaseous, albeit fluctuating, moving within you, and then again an organization of warmth, then you will understand more easily what I now have to say based on observations from the spiritual sciences.

[ 4 ] Let us imagine that a person becomes enthusiastic about a high moral ideal. A person can truly become enthusiastic in their soul for a moral ideal, for the ideal of benevolence, for the ideal of freedom, the ideal of goodness, love, and so on. They can be enthusiastic in specific cases for what these ideals imply. But no one can imagine that what is going on in the soul as enthusiasm goes into the bones or muscles, as bones and muscles are viewed by modern physiology or anatomy. But if you consult your inner self properly, you will come to realize that you can very well imagine — and it is indeed so — that when a person is enthusiastic about a high moral ideal, this inner enthusiasm exerts an influence on the warmth organism. And then you are already inside the physical realm from the soul realm! So that we can say, if we take this example: Moral ideals express themselves through an increase in warmth in the heat organism. — The human being not only becomes warmer in the soul, but — even if this is not so easily demonstrable with any physical instrument — the human being really does become warmer inwardly through what he experiences in moral ideals. So it has a stimulating effect on the heat organism.

[ 5 ] You must now imagine this as a concrete process: enthusiasm for a moral ideal: stimulation of the heat organism. — The heat organism becomes more lively when a moral ideal glows through the soul. But it also has an effect on the rest of the human organism. In addition to the heat organism, which is, in a sense, the highest physical organism, the human being also has an air organism. He breathes air in and out, but during inhalation and exhalation, the air is inside him. It is, of course, in internal motion, in fluctuation; but that is also an organization, a real air organism that lives within him, just like the heat organism. Now, when heat is enlivened by a moral ideal, it has an effect on the air organism because heat is effective in the entire organism, in all organisms. This effect on the air organism is not merely a warming one, however. When the heat that becomes active in the heat organism acts on the human air organism, it communicates to it everything that I can only describe as a source of light. In a sense, germs of light are communicated to the air organism, so that moral ideals, which have a stimulating effect on the heat organism, trigger sources of light in the air organism. These sources of light do not appear luminous to the external consciousness, to external perception, but they do appear in the human astral body. They are initially bound, if I may use this physical expression, by the air itself that humans carry within themselves. They are, in a sense, still dark light, just as the plant seed is not yet the developed plant. But because humans are capable of enthusiasm for moral ideals or moral processes, they carry a source of light within themselves.

[ 6 ] We have another organism within us: the fluid organism. As the warmth in the warmth organism acts and, starting from the moral ideal, triggers in the air organism what can be called a source of light, which initially remains bound, remains hidden, it dissolves in the fluid organism because, as I said, everything in the human organism communicates with everything else, that which I spoke of yesterday, which actually underlies the external sounds of the air. Air is only the body of sound, I said yesterday, and anyone who seeks the essence of sound in air vibrations and speaks of nothing else is speaking of sound in the same way as one speaks of human beings when one speaks only of the outer visible body. Air with its vibrating waves is nothing other than the outer body for sound. In humans, this sound, this spiritual sound, is not triggered in the air organism, but rather in the fluid organism through the moral ideal. So this is where the sources of sound are triggered. And we consider the solid organism to be, in a sense, the most solid organism, the one that supports and carries all other organisms. Something is also triggered in it, just as in the other organisms; only in the solid organism is that triggered which we can call the germ of life, but not the physical germ of life, as it then detaches itself from the human female organism through birth, but rather the etheric germ of life is detached. That which lives there as the etheric germ of life is in the deepest subconscious; it is already that which is the source of sound, and in a certain sense even that which is the source of light. This is hidden from ordinary consciousness, but it is within the human being.

[ 7 ] Imagine everything you have experienced in life in terms of your soul's turning toward moral ideas, whether you found these moral impulses appealing by merely grasping them as ideas, whether you saw them in others, or whether in the execution of them in a certain way that you were able to feel inner satisfaction with your own actions, by allowing these actions to be imbued with moral ideals. All of this goes down into the air organization as a source of light, into the fluid organization as a source of sound, and into the solid organization as a source of life. All of this detaches itself in a certain way from what is conscious in human beings. But human beings carry it within themselves. It becomes free when the human being sheds his physical organization at death. What is triggered in this way by our moral ideals, by the purest ideas in our organization, does not initially bear fruit. It is the moral ideas themselves that become fruitful for life between birth and death, insofar as we remain in the life of ideas and insofar as we have a certain satisfaction with what we have accomplished morally. But this has to do only with memory; it has nothing to do with what is pushed down into the organization by our finding moral ideals sympathetic.

[ 8 ] We see here, then, how our entire organization, starting from our heat organism, is permeated by moral ideals. And when we detach our etheric body, our astral body, our ego from our physical organization through death, we are permeated in these higher members of human nature by the impressions we have had. We were with our ego in our warmth organism, where moral ideals enlivened our own warmth organization. We were in our air organism, where sources of light had been planted, which now go out into the cosmos with us after our death. In our fluid organism, we stimulated the sound that becomes the music of the spheres, with which we sound out into the cosmos. We bring life out by passing through the gate of death.

[ 9 ] At this point, you can guess what the life that is poured out into the world actually is. Where are the sources of life? They lie in what inspires moral ideals, which have an inspiring effect on human beings. We come to the conclusion that when we allow ourselves to be imbued with moral ideals today, these carry out life, sound, and light and become world-creating. We carry out the world-creating, and the source of the world-creating is the moral.

[ 10 ] You see, when we consider the whole human being, we find a bridge between moral ideals and that which has a vivifying, even chemical effect in the physical world outside. For it is sound that has a chemical effect, that brings substances together and analyzes them. And the light in the world has its source in moral emotions, in the warmth of human beings. We look into the future and see world forms taking shape. And just as we must go back to the seed in the case of plants, so we must go back to the seeds that lie within ourselves as moral ideals in the case of the future worlds that will take shape.

[ 11 ] Now consider theoretical ideas in contrast to moral ideals. With theoretical ideas, no matter how significant they may be, the situation is quite different. With theoretical ideas, we actually observe a dampening, a cooling of the warmth organism. So we must say that theoretical ideas have a cooling effect on the warmth organism. That is the difference in their effect on the human organism. Moral ideas, or ideas based on morality and religion, those that inspire us by becoming impulses for our actions, have a world-creating effect in this way. Theoretical ideas initially have a dampening, cooling effect on the warmth organism. By cooling the warmth organism, they also have a paralyzing effect on the air organism and on the source of light, on the creation of light. They continue to have a deadening effect on the world tone, and they have an extinguishing effect on life. That which was created in the pre-world comes to an end in our theoretical ideas. When we grasp theoretical ideas, a universe dies in them. We carry within us the death of a universe; we carry within us the emergence of a universe.

Moral ideals: Theoretical ideas:

stimulating to the heat organism (4) cooling to the heat organism

triggering in the air organism (3) paralyzing to the creation of light light sources

triggering in the fluid organism (2) killing the sound sound sources

triggering in the solid organism life germs (ethereal) (1) extinguishing life