The Bridge Between Universal Spirituality and the Physical Constitution of Man

GA 202

19 December 1920, Dornach

Translator Unknown

III. The Path to Freedom and Love and Their Significance in World-Events

Man stands in the world as thinking, contemplative being on the one hand, and as a doer, a being of action, on the other; with his feelings he lives within both these spheres. With his feeling he responds, on the one side, to what is presented to his observation; on the other side, feeling enters into his actions, his deeds. We need only consider how a man may be satisfied or dissatisfied with the success or lack of success of our deeds, how in truth all action is accompanied by impulses of feeling, and we shall see that feeling links the two poles of our being: the pole of thinking and the pole of deed, of action. Only through the fact that we are thinking beings are we Man in the truest sense. Consider too, how everything that gives us the consciousness of our essential manhood is connected with the fact that we can inwardly picture the world around us; we live in this world and can contemplate it. To imagine that we cannot contemplate the world would entail forfeiting our essential manhood. As doers, as men of action, we have our place in social life and fundamentally speaking, everything we accomplish between birth and death has a certain significance in this social life.

In so far as we are contemplative beings, thought operates in us; in so far as we are doers, that is to say, social beings, will operates in us. It is not the case in human nature, nor is it ever so, that things can simply be thought of intellectually side by side with one another; the truth is that whatever is an active factor in life can be characterized from one aspect or another; the forces of the world interpenetrate, flow into each other. Mentally, we can picture ourselves as beings of thought, also as beings of will. But even when we are entirely engrossed in contemplation, when the outer world is completely stilled, the will is continually active. And again, when we are performing deeds, thought is active in us. It is inconceivable that anything should proceed from us in the way of actions or deeds—which may also take effect in the realm of social life—without our identifying ourselves in thought with what thus takes place. In everything that is of the nature of will, the element of thought is contained; and in everything that is of the nature of thought, will is present. It is essential to be quite clear about what is involved here if we seriously want to build the bridge between the moral-spiritual world-order and natural-physical world-order.

Imagine that you are living for a time purely in reflection as usually understood, that you are engaging in no kind of outward activity at all, but are wholly engrossed in thought. You must realize, however, that in this life of thought, will is also active; will is then at work in your inner being, raying out its forces into the realm of thought. When we picture the thinking human being in this way, when we realize that the will is radiating all the time into his thoughts, something will certainly strike us concerning life and its realities. If we review all the thoughts we have formulated, we shall find in every case that they are linked with something in our environment, something that we ourselves have experienced. Between birth and death we have, in a certain respect, no thoughts other than those brought to us by life. If our life has been rich in experiences we have a rich thought-content; if our life experiences have been meagre, we have a meagre thought-content. The thought-content represents our inner destiny—to a certain extent. But within this life of thought there is something that is inherently our own; what is inherently our own is how we connect thoughts with one another and dissociate them again, how we elaborate them inwardly, how we arrive at judgments and draw conclusions, how we orientate ourselves in the life of thought—all this is inherently our own. The will in our life of thought is our own.

If we study this life of thought in careful self-examination we shall certainly realize that thoughts, as far as their actual content is concerned, come to us from outside, but that it is we ourselves who elaborate these thoughts.—Fundamentally speaking, therefore, in respect of our world of thought we are entirely dependent upon the experiences brought to us by our birth, by our destiny. But through the will, which rays out from the depths of the soul, we carry into what thus comes to us from the outer world, something that is inherently our own. For the fulfillment of what self-knowledge demands of us it is highly important to keep separate in our minds how, on the one side, the thought content comes to us from the surrounding world and how, on the other, the force of the will, coming from within our being, rays into the world of thought.

How, in reality, do we become inwardly more and more spiritual?—Not by taking in as many thoughts as possible from the surrounding world, for these thoughts merely reproduce in pictures this outer world, which is a physical, material world. Constantly to be running in pursuit of sensations does not make us more spiritual. We become more spiritual through the inner, will-permeated work we carry out in our thoughts. This is why meditation, too, consists in not indulging in haphazard thoughts but in holding certain easily envisaged thoughts in the very centre of our consciousness, drawing them there with a strong effort of will. And the greater the strength and intensity of this inner radiation of will into the sphere of thinking, the more spiritual we become. When we take in thoughts from the outer material world—and between birth and death we can take in only such thoughts—we become, as you can easily realize, unfree; for we are given over to the concatenations of things and events in the external world; as far as the actual content of the thoughts is concerned, we are obliged to think as the external world prescribes; only when we elaborate the thoughts do we become free in the real sense.

Now it is possible to attain complete freedom of our inner life if we increasingly efface and exclude the actual thought content, in so far as this comes from outside, and kindle into greater activity the element of will which streams through our thoughts when we form judgments, draw conclusions and the like. Thereby, however, our thinking becomes what I have called in my Philosophy of Spiritual Activity: purethinking. We think, but in our thinking there is nothing but will. I have laid particular emphasis on this in the new edition of the book (1918). What is thus within us lies in the sphere of thinking. But pure thinking may equally be called pure will. Thus from the realm of thinking we reach the realm of will, when we become inwardly free; our thinking attains such maturity that it is entirely irradiated by will; it no longer takes anything in from outside, but its very life is of the nature of will. By progressively strengthening the impulse of will in our thinking we prepare ourselves for what I have called in the Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, "Moral Imagination." Moral Imagination rises to the Moral Intuitions which then pervade and illuminate our will that has now become thought, or our thinking that has now become will. In this way we raise ourselves above the sway of the ‘necessity’ prevailing in the material world, permeate ourselves with the force that is inherently our own, and prepare for Moral Intuition. And everything that can stream into man from the spiritual world has its foundation, primarily, in these Moral Intuitions. Therefore freedom dawns when we enable the will to become an ever mightier and mightier force in our thinking.

Now let us consider the human being from the opposite pole, that of the will. When does the will present itself with particular clarity through what we do?—When we sneeze, let us say, we are also doing something, but we cannot, surely, ascribe to ourselves any definite impulse of will when we sneeze! When we speak, we are doing something in which will is undoubtedly contained. But think how, in speaking, deliberate intent and absence of intent, volition and absence of volition, intermingle. You have to learn to speak, and in such a way that you are no longer obliged to formulate each single word by dint of an effort of will; an element of instinct enters into speech. In ordinary life at least, it is so, and it is emphatically so in the case of those who do not strive for spirituality. Garrulous people, who are always opening their mouths in order to say something or other in which very little thought is contained, give others an opportunity of noticing—they themselves, of course, do not notice—how much there is in speech that is instinctive and involuntary. But the more we go out beyond our organic life and pass over to activity that is liberated, as it were, from organic processes, the more do we carry thoughts into our actions and deeds. Sneezing is still entirely a matter of organic life; speaking is largely connected with organic life; walking really very little; what we do with the hands, also very little. And so we come by degrees to actions which are more and more emancipated from our organic life. We accompany such actions with our thoughts, although we do not know how the will streams into these thoughts. If we are not somnambulists and do not go about in this condition, our actions will always be accompanied by our thoughts. We carry our thoughts into our actions, and the more our actions evolve towards perfection, the more are our thoughts being carried into them.

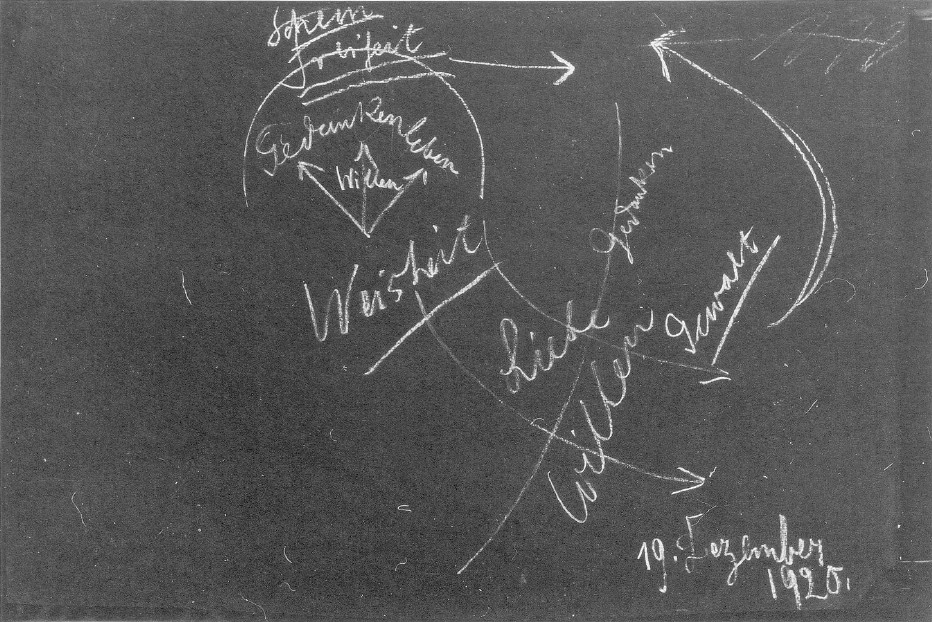

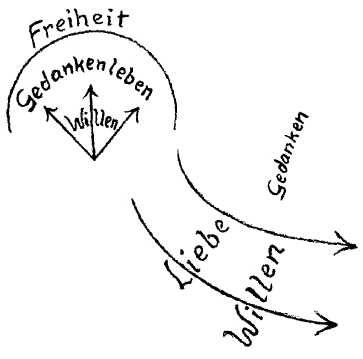

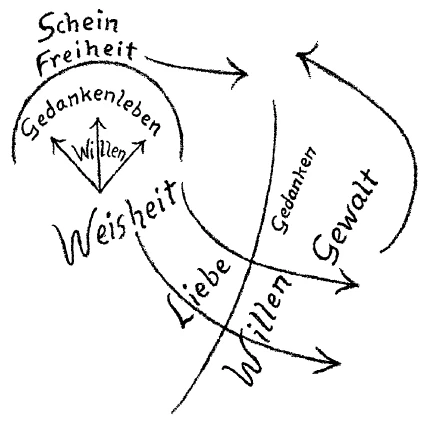

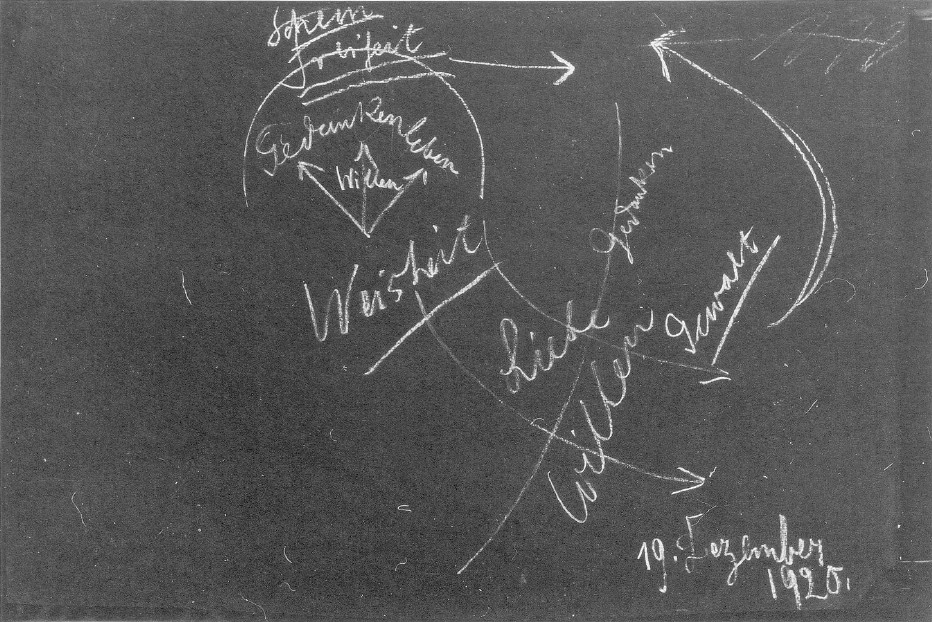

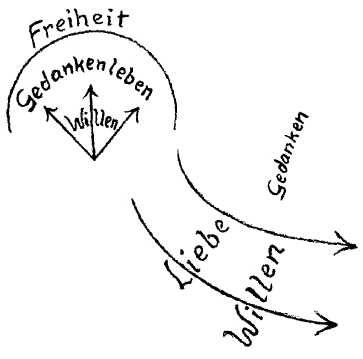

Our inner life is constantly deepened when we send will—our own inherent force—into our thinking, when we permeate our thinking with will. We bring will into thinking and thereby attain freedom. As we gradually perfect our actions we finally succeed in sending thoughts into these actions; we irradiate our actions—which proceed from our will—with thoughts. On the one side (inwards) we live a life of thought; we permeate this with the will and thus find freedom. On the other side (outwards) our actions stream forth from our will, and we permeate them with our thoughts. (Diagram IX)

But by what means do our actions evolve to greater perfection? To use an invariably controversial expression—How do we achieve greater perfection in our actions? We achieve this by developing in ourselves the force which can only be designated by the words: devotion to the outer world.—The more our devotion to the outer world grows and intensifies, the more does this outer world stir us to action. But it is just through unfolding devotion to the outer world that we succeed in permeating our actions with thoughts. What, in reality, is devotion to the outer world? Devotion to the outer world, which pervades our actions with thoughts, is nothing else than love.

Just as we attain freedom by irradiating the life of thought with will, so do we attain love by permeating the life of will with thoughts. We unfold love in our actions by letting thoughts radiate into the realm of the will; we develop freedom in our thinking by letting what is of the nature of will radiate into our thoughts. And because, as man, we are a unified whole, when we reach the point where we find freedom in the life of thought and love in the life of will, there will be freedom in our actions and love in our thinking. Each irradiates the other: action filled with thought is wrought in love; thinking that is permeated with will gives rise to actions and deeds that are truly free.

Thus you see how in the human being the two great ideals, freedom and love, grow together. Freedom and love are also that which man, standing in the world, can bring to realization in himself in such a way that, through him, the one unites with the other for the good of the world.

We must now ask: How is the ideal, the highest ideal, to be attained in the will-permeated life of thought?—Now if the life of thought were something that represented material processes, the will could never penetrate fully into the realm of the thoughts and increasingly take root there. The will would at most be able to ray into these material processes as an organizing force. Will can take real effect only if the life of thought is something that has no outer, physical reality. What, then, must it be?

You will be able to envisage what it must be if you take a picture as a starting-point. If you have here a mirror and here an object, the object is reflected in the mirror; if you then go behind the mirror, you find nothing. In other words, you have a picture—nothing more. Our thoughts are pictures in this same sense. (Diagram X) How is this to be explained?—In a previous lecture I said that the life of thought as such is in truth not a reality of the immediate moment. The life of thought rays in from our existence before birth, or rather, before conception. The life of thought has its reality between death and a new birth. And just as here the object stands before the mirror and what it presents is a picture—only that and nothing more—so what we unfold as the life of thought is lived through in the real sense between death and a new birth, and merely rays into our life since birth. As thinking beings, we have within us a mirror-reality only. Because this is so, the other reality which, as you know, rays up from the metabolic process, can permeate the mirror-pictures of the life of thought. If, as is very rarely the case today, we make sincere endeavors to develop unbiased thinking, it will be clear to us that the life of thought consists of mirror-pictures if we turn to thinking in its purest form—in mathematics. Mathematical thinking streams up entirely from our inner being, but it has a mirror-existence only. Through mathematics the make-up of external objects can, it is true, be analyzed and determined; but the mathematical thoughts in themselves are only thoughts, they exist merely as pictures. They have not been acquired from any outer reality.

Abstract thinkers such as Kant also employ an abstract expression. They say: mathematical concepts are a priori.—A priori, apriority, means "from what is before." But why are mathematical concepts a priori? Because they stream in from the existence preceding birth, or rather, preceding conception. It is this that constitutes their ‘apriority.’ And the reason why they appear real to our consciousness is because they are irradiated by the will. This is what makes them real. Just think how abstract modern thinking has become when it uses abstract words for something which, in its reality, is not understood! Men such as Kant had a dim inkling that we bring mathematics with us from our existence before birth, and therefore they called the findings of mathematics ‘a priori.’ But the term ‘a priori’ really tells us nothing, for it points to no reality, it points to something merely formal.

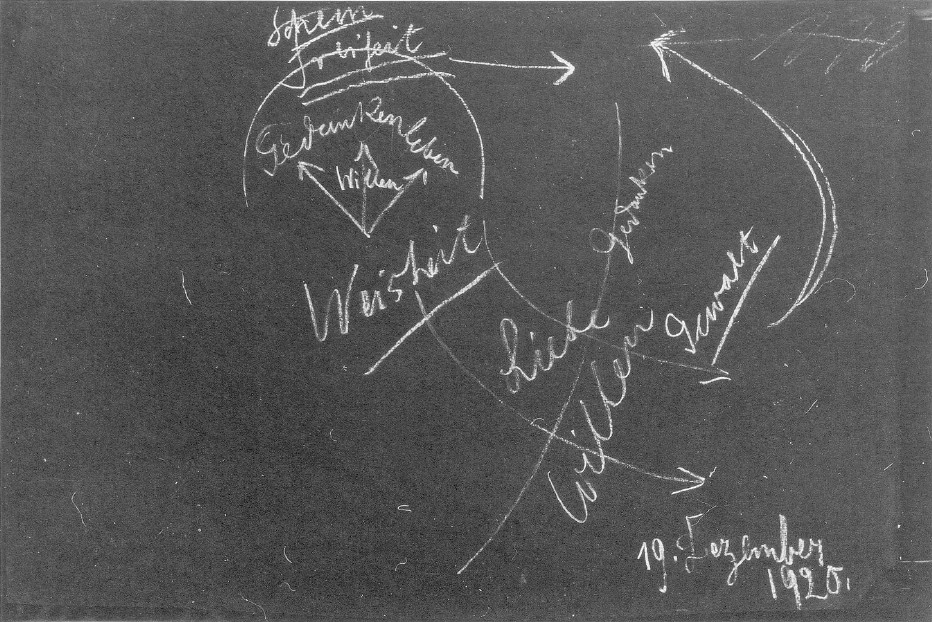

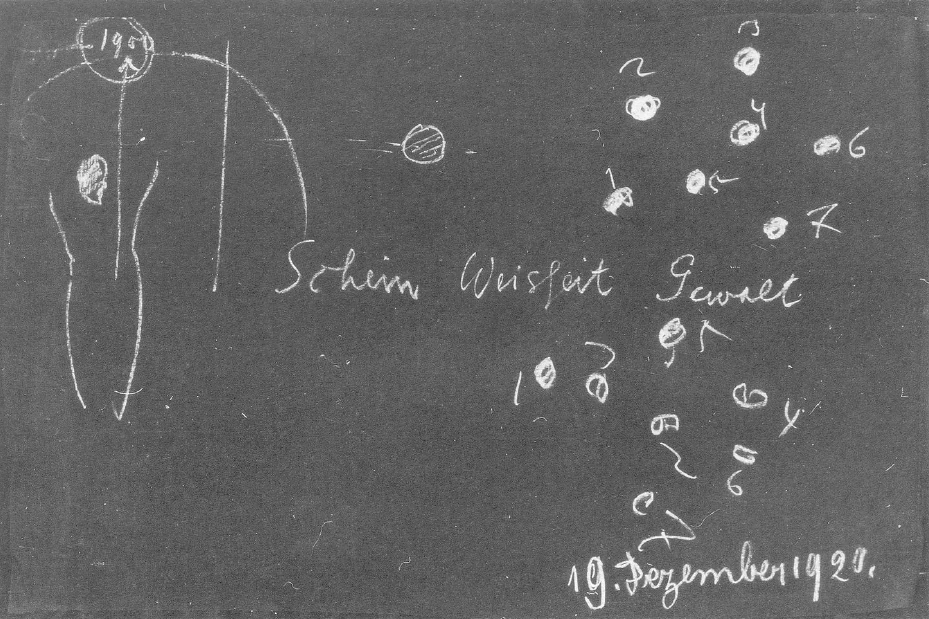

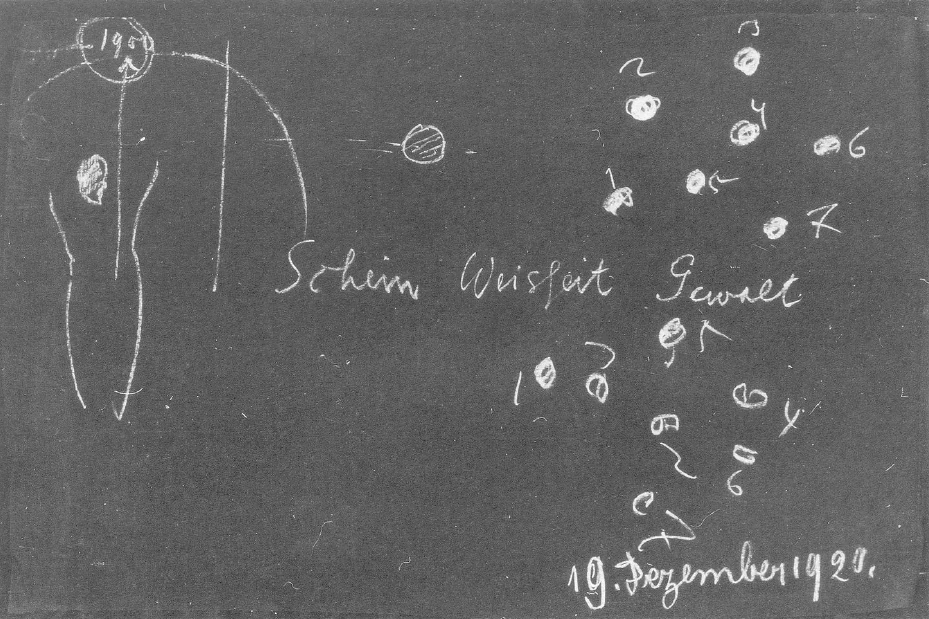

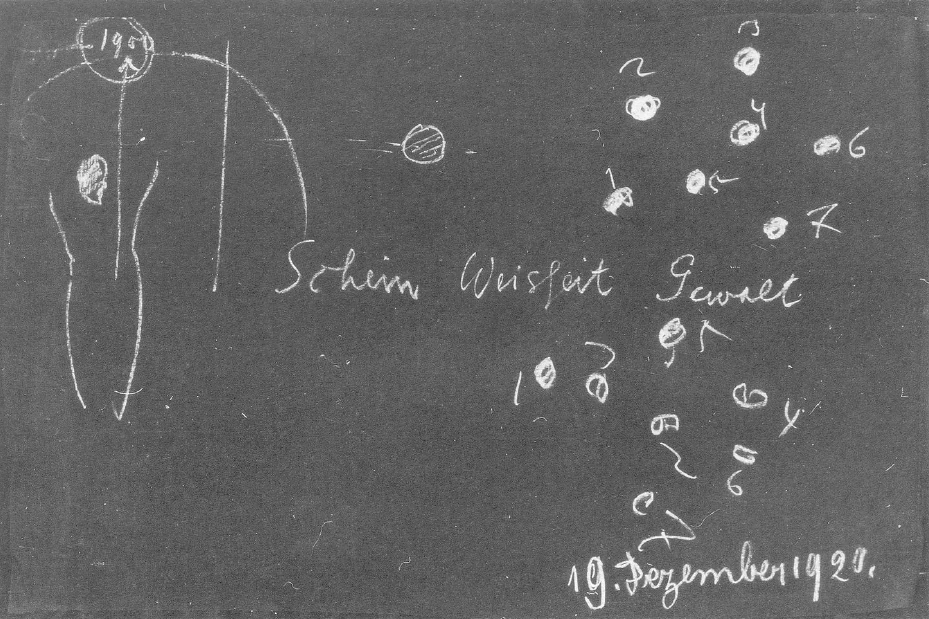

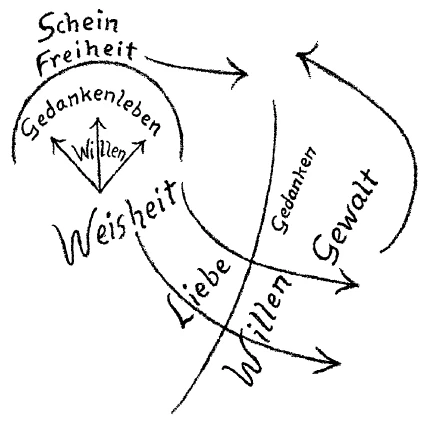

In regard to the life of thought, which with its mirror-existence must be irradiated by the will in order to become reality, ancient traditions speak of Semblance. (Diagram XI, Schein.)

Let us now consider the other pole of man's nature, where the thoughts stream down towards the sphere of will, where deeds are performed in love. Here our consciousness is, so to speak, held at bay, it rebounds from reality. We cannot look into that realm of darkness—a realm of darkness for our consciousness—where the will unfolds whenever we raise an arm or turn the head, unless we take super-sensible conceptions to our aid. We move an arm; but the complicated process in operation there remains just as hidden from ordinary consciousness as what takes place in deep sleep, in dreamless sleep. We perceive our arm; we perceive how our hand grasps some object. This is because we permeate the action with thoughts. But the thoughts themselves that are in our consciousness are still only semblance. We live in what is real, but it does not ray into our ordinary consciousness. Ancient traditions spoke here of Power (Gewalt), because the reality in which we are living is indeed permeated by thought, but thought has nevertheless rebounded from it in a certain sense, during the life between birth and death. (Diagram XI.)

Between these two poles lies the balancing factor that unites the two—unites the will that rays towards the head with the thoughts which, as they flow into deeds wrought with love, are, so to say, felt with the heart. This means of union is the life of feeling, which is able to direct itself towards the will as well as towards the thoughts. In our ordinary consciousness we live in an element by means of which we grasp, on the one side, what comes to expression in our will-permeated thought with its predisposition to freedom, while on the other side, we try to ensure that what passes over into our deeds is filled more and more with thoughts. And what forms the bridge connecting both has since ancient times been called Wisdom. (Diagram XI.)

In his fairy-tale, The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily, Goethe has given indications of these ancient traditions in the figures of the Golden King, the Silver King, and the Brazen King. We have already shown from other points of view how these three elements must come to life again, but in an entirely different form—these three elements to which ancient instinctive knowledge pointed and which can come to life again only if man acquires the knowledge yielded by Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition.

But what is it that is actually taking place as man unfolds his life of thought?—Reality is becoming semblance! It is very important to be clear about this. We carry about with us our head, which with its hard skull and tendency to ossification, presents, even outwardly, a picture of what is dead, in contrast to the rest of the living organism. Between birth and death we bear in our head that which, from an earlier time when it was reality, comes into us as semblance, and from the rest of our organism we pervade this semblance with the element issuing from our metabolic processes, we permeate it with the real element of the will. There we have within us a seed, a germinating entity which, first and foremost, is part of our manhood, but also means something in the cosmos. Think of it—a man is born in a particular year; before then he was in the spiritual world. When he passes out of the spiritual world, thought which there is reality, becomes semblance, and he leads over into this semblance the forces of his will which come from an entirely different direction, rising up from parts of his organism other than the head. That is how the past, dying away into semblance, is kindled again to become reality of the future.

Let us understand this rightly. What happens when man rises to pure thinking, to thinking that is irradiated by will?—On the foundation of the past that has dissolved into semblance, through fructification by the will which rises up from his egohood, there unfolds within him a new reality leading into the future. He is the bearer of the seed into the future. The thoughts of the past, as realities, are as it were the mother-soil; into this mother-soil is laid that which comes from the individual egohood, and the seed is sent on into the future for future life.

On the other side, man evolves by permeating his deeds and actions, his will-nature, with thoughts; deeds are performed in love. Such deeds detach themselves from him. Our deeds do not remain confined to ourselves. They become world-happenings; and if they are permeated by love, then love goes with them. As far as the cosmos is concerned, an egotistical action is different from an action permeated by love. When, out of semblance, through fructification by the will, we unfold that which proceeds from our inmost being, then what streams forth into the world from our head encounters our thought-permeated deeds. Just as when a plant unfolds it contains in its blossom the seed to which the light of the sun, the air outside, and so on, must come, to which something must be brought from the cosmos in order that it may grow, so what is unfolded through freedom must find an element in which to grow through the love that lives in our deeds.

Thus does man stand within the great process of world-evolution, and what takes place inside the boundary of his skin and flows out beyond his skin in the form of deeds, has significance not only for him but for the world, the universe. He has his place in the arena of cosmic happenings, world-happenings. In that what was reality in earlier times becomes semblance in man, reality is ever and again dissolved, and in that his semblance is quickened again by the will, new reality arises. Here we have—as if spiritually we could put our very finger upon it—what has also been spoken of from other points of view.—There is no eternal conservation of matter! Matter is transformed into semblance and semblance is transformed to reality by the will. The law of the conservation of matter and energy affirmed by physics is a delusion, because account is taken of the natural world only. The truth is that matter is continually passing away in that it is transformed into semblance; and a new creation takes place in that through Man, who stands before us as the supreme achievement of the cosmos, semblance is again transformed into Being (Sein.)

We can also see this if we look at the other pole—only there it is not so easy to perceive. The processes which finally lead to freedom can certainly be grasped by unbiased thinking. But to see rightly in the case of this other pole needs a certain degree of spiritual-scientific development. For here, to begin with, ordinary consciousness rebounds when confronted by what ancient traditions called Power. What is living itself out as Power, as Force, is indeed permeated by thoughts; but the ordinary consciousness does not perceive that just as more and more will, a greater and greater faculty of judgment, comes into the world of thought, so, when we bring thoughts into the will-nature, when we overcome the element of Power more and more completely, we also pervade what is merely Power with the light of thought. At the one pole of man's being we see the overcoming of matter; at the other pole, the new birth of matter.

As I have indicated briefly in my book, Riddles of the Soul, man is a threefold being: as nerve-and-sense man he is the bearer of the life of thought, of perception; as rhythmic being (breathing, circulating blood), he is the bearer of the life of feeling; as metabolic being, he is the bearer of the life of will. But how, then, does the metabolic process operate in man when will is ever more and more unfolded in love? It operates in that, as man performs such deeds, matter is continually overcome.—And what is it that unfolds in man when, as a free being, he finds his way into pure thinking, which is, however, really of the nature of will?—Matter is born!—We behold the coming-into-being of matter! We bear in ourselves that which brings matter to birth: our head; and we bear in ourselves that which destroys matter, where we can see how matter is destroyed: our limb-and-metabolic organism.

This is the way in which to study the whole man. We see how what consciousness conceives of in abstractions is an actual factor in the process of World-Becoming; and we see how that which is contained in this process of World-Becoming and to which the ordinary consciousness clings so firmly that it can do no other than conceive it to be reality—we see how this is dissolved away to nullity. It is reality for the ordinary consciousness, and when it obviously does not tally with outer realities, then recourse has to be taken to the atoms, which are considered to be firmly fixed realities. And because man cannot free himself in his thoughts from these firmly fixed realities, one lets them mingle with each other, now in this way, now in that. At one time they mingle to form hydrogen, at another, oxygen; they are merely differently grouped. This is simply because people are incapable of any other belief than that what has once been firmly fixed in thought must also be as firmly fixed in reality.

It is nothing else than feebleness of thought into which one lapses when he accepts the existence of fixed, ever-enduring atoms. What reveals itself to us through thinking that is in accordance with reality is that matter is continually dissolved away to nullity and continually rebuilt out of nullity. It is only because whenever matter dies away, new matter comes into being, that people speak of the conservation of matter. They fall into the same error into which they would fall, let us say, if a number of documents were carried into a house, copied there, but the originals burned and the copies brought out again, and then they were to believe that what was carried in had been carried out—that it is the same thing. The reality is that the old documents have been burned and new ones written. It is the same with what comes into being in the world, and it is important for our knowledge to advance to this point. For in that realm of man's being, where matter dies away into semblance and new matter arises, there lies the possibility of freedom, and there lies the possibility of love. And freedom and love belong together, as I have already indicated in my Philosophy of Spiritual Activity.

Those who on the basis of some particular conception of the world speak of the imperishability of matter, annul freedom on the one side and the full development of love on the other. For only through the fact that in man the past dies away, becomes semblance, and the future is a new creation in the condition of a seed, does there arise in us the feeling of love—devotion to something to which we are not coerced by the past—and freedom—action that is not predetermined. Freedom and love are, in reality, comprehensible only to a spiritual-scientific conception of the world, not to any other. Those who are conversant with the picture of the world that has appeared in the course of the last few centuries will be able to assess the difficulties that will have to be overcome before the habits of thought prevailing in modern humanity can be induced to give way to this unbiased, spiritual-scientific thinking. For in the picture of the world existing in natural science there are really no points from which we can go forward to a true understanding of freedom and love.

How the natural-scientific picture of the world on the one side, and on the other, the ancient, traditional picture of the world, are related to a truly progressive, spiritual-scientific development of humanity—of this we will speak on some other occasion.

Zwolfter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Der Mensch steht da in der Welt auf der einen Seite als ein Betrachtender, auf der anderen Seite als ein Handelnder, zwischen drinnen steht er mit seinem Fühlen. Er ist auf der einen Seite mit seinem Fühlen hingegeben an dasjenige, was sich seiner Betrachtung ergibt, auf der anderen Seite ist er mit seinem Fühlen wiederum beteiligt an seinem Handeln. Man braucht ja nur darüber nachzudenken, wie der Mensch befriedigt oder unbefriedigt sein kann von dem, was ihm als Handelnder gelingt oder nicht gelingt; man braucht nur daran zu denken, wie schließlich alles Handeln begleitet ist von Gefühlsimpulsen, und man wird sehen, daß in der Tat unser gefühlsmäßiges Wesen verbindet die beiden entgegengesetzten Pole: das betrachtende Element in uns und das handelnde Element in uns. Nur dadurch, daß wir betrachtende Wesen sind, werden wir im vollsten Sinne des Wortes eigentlich Mensch. Sie brauchen sich nur zu überlegen, wie alles, was Ihnen schließlich das Bewußtsein gibt, daß Sie Mensch sind, damit zusammenhängt, daß Sie die Welt, die Sie umgibt, in der Sie leben, innerlich gewissermaßen abbilden können, betrachten können. Zu denken, daß wir die Welt nicht betrachten können, würde bedeuten, daß wir unser ganzes Menschsein von uns abtun müssen. Als handelnde Menschen stehen wir drinnen im sozialen Leben. Und im Grunde genommen hat alles das, was wir zwischen Geburt und Tod vollbringen, eine gewisse soziale Bedeutung.

[ 2 ] Nun wissen Sie, daß, insofern wir betrachtende Wesen sind, in uns der Gedanke lebt, insofern wir handelnde Wesen sind, also auch insofern wir soziale Wesen sind, in uns der Wille lebt. Es ist aber nicht so in der menschlichen Natur, wie es überhaupt in der Wirklichkeit nicht so ist, daß man verstandesmäßig die Dinge nebeneinanderstellen kann, sondern, was wirksam ist im Sein, das kann man nach der einen oder anderen Seite charakterisieren; die Dinge fließen ineinander, die Kräfte der Welt fließen ineinander. Wir können uns denkend vorstellen, daß wir ein Gedankenwesen sind, wir können uns denkend auch vorstellen, daß wir ein Willenswesen sind. Aber auch wenn wir kontemplativ, bei völliger äußerer Ruhe in Gedanken leben, so ist der Wille in uns dennoch fortwährend tätig. Und wiederum, wenn wir Handelnde sind, so ist in uns der Gedanke tätig. Es ist undenkbar, daß irgend etwas als Handlung von uns ausgeht, daß irgend etwas in das soziale Leben auch überspringe, ohne daß wir uns gedanklich mit dem, was so geschieht, identifizieren. In allem Willensartigen lebt das Gedankenartige, in allem Gedanklichen lebt das Willensartige. Und es ist durchaus notwendig, daß man gerade über die hier in Frage kommenden Dinge sich klar werde, wenn man jene Brücke, von der ich hier jetzt schon so oft gesprochen habe, im Ernste bauen will, die Brücke zwischen der moralisch-geistigen Weltordnung und der physisch-natürlichen Ordnung.

[ 3 ] Denken Sie sich einmal, Sie lebten im Sinne der gewöhnlichen Wissenschaften für eine Weile rein nachdenklich, Sie regten sich gar nicht, Sie sähen ganz ab von allem Handeln, Sie lebten eben ein Vorstellungsleben. Sie müssen sich aber klar sein, daß dann in diesem Vorstellungsleben Wille tätig ist, Wille, der allerdings dann in Ihrem Inneren sich betätigt, der im Bereiche des Vorstellens seine Kräfte ausbreitet. Gerade wenn wir so den denkenden Menschen betrachten, wie er fortwährend den Willen hineinstrahlt in seine Gedanken, dann muß uns eigentlich eines gegenüber dem wirklichen Leben auffallen. Die Gedanken, die wir also fassen, wenn wir sie alle durchgehen — wir werden immer finden, daß sie an irgend etwas anknüpfen, was in unserer Umgebung, was unter unseren Erlebnissen ist. Wir haben zwischen Geburt und Tod gewissermaßen keine anderen Gedanken als diejenigen, die uns das Leben bringt. Ist unsere Erfahrung reich, so haben wir auch einen reichen Gedankeninhalt; ist unsere Erfahrung arm, so haben wir einen armen Gedankeninhalt. Der Gedankeninhalt ist gewissermaßen unser innerliches Schicksal. Aber innerhalb dieses Denk-Erlebens ist eines ganz uns eigen: Die Art und Weise, wie wir die Gedanken verknüpfen und voneinander lösen, die Art und Weise, wie wir innerlich die Gedanken verarbeiten, wie wir urteilen, wie wir Schlüsse ziehen, wie wir uns überhaupt im Gedankenleben orientieren, das ist unser, ist uns eigen. Der Wille in unserem Gedankenleben ist unser eigener.

[ 4 ] Wenn wir auf dieses Gedankenleben hinblicken, so müssen wir uns gerade bei einer sorgfältigen Selbstprüfung sagen, und Sie werden schon sehen, daß das so bei einer sorgfältigen Selbstprüfung ist: Die Gedanken kommen uns von außen ihrem Inhalte nach, die Bearbeitung der Gedanken, die geht von uns aus. — Wir sind daher im Grunde genommen in bezug auf unsere Gedankenwelt ganz abhängig von dem, was wir erleben können durch die Geburt, in die wir schicksalsmäßig versetzt sind, durch die Erlebnisse, die uns werden können. Aber in dasjenige, was uns da von der Außenwelt kommt, tragen wir hinein gerade durch den Willen, der aus der Seelentiefe ausstrahlt, unser Eigenes. Es ist für die Erfüllung dessen, was Selbsterkenntnis von uns Menschen will, im hohen Grade bedeutsam, wenn wir auseinanderhalten, wie auf der einen Seite uns von der Umwelt der Gedankeninhalt kommt, wie auf der anderen Seite aus unserem Inneren in die Gedankenwelt einstrahlt die Kraft des Willens, die von innen kommt.

[ 5 ] Wie wird man eigentlich innerlich immer geistiger und geistiger? Man wird nicht dadurch geistiger, daß man möglichst viele Gedanken aus der Umwelt aufnimmt, denn diese Gedanken geben ja doch nur, ich möchte sagen, die Außenwelt, die eine sinnlich-physische ist, in Bildern wieder. Dadurch, daß man möglichst den Sensationen des Lebens nachläuft, dadurch wird man nicht geistiger. Geistiger wird man durch die innere willensgemäße Arbeit innerhalb der Gedanken. Daher besteht auch Meditieren darinnen, daß man sich nicht einem beliebigen Gedankenspiel hingibt, sondern daß man wenige, leicht überschaubare, leicht prüfbare Gedanken in den Mittelpunkt seines Bewußtseins rückt, aber mit einem starken Willen diese Gedanken in den Mittelpunkt seines Bewußtseins rückt. Und je stärker, je intensiver dieses innere Willensstrahlen wird in dem Elemente, wo eben die Gedanken sind, desto geistiger werden wir. Wenn wir Gedanken von der äußeren physisch-sinnlichen Welt aufnehmen — und wir können ja nur solche aufnehmen zwischen Geburt und Tod -, dann werden wir dadurch, wie Sie leicht einsehen können, unfrei, denn wir werden hingegeben an die Zusammenhänge der äußeren Welt; wir müssen dann so denken, wie es uns die äußere Welt vorschreibt, insofern wir nur den Gedankeninhalt ins Auge fassen; erst in der inneren Verarbeitung werden wir frei.

[ 6 ] Nun gibt es eine Möglichkeit, ganz frei zu werden, frei zu werden in seinem inneren Leben, wenn man den Gedankeninhalt, insofern er von außen kommt, möglichst ausschließt, immer mehr und mehr ausschließt, und das Willenselement, das im Urteilen, im Schlüsseziehen unsere Gedanken durchstrahlt, in besondere Regsamkeit versetzt. Dadurch aber wird unser Denken in denjenigen Zustand versetzt, den ich in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» genannt habe das reine Denken. Wir denken, aber im Denken lebt nur Wille. Ich habe das besonders scharf betont in der Neuauflage der «Philosophie der Freiheit» 1918. Dasjenige, was da in uns lebt, lebt in der Sphäre des Denkens. Aber wenn es reines Denken geworden ist, ist es eigentlich ebensogut als reiner Wille anzusprechen. So daß wir aufsteigen dazu, uns vom Denken zum Willen zu erheben, wenn wir innerlich frei werden, daß wir gewissermaßen unser Denken so reif machen, daß es ganz und gar durchstrahlt wird vom Willen, nicht mehr von außen aufnimmt, sondern eben im Willen lebt. Gerade dadurch aber, daß wir immer mehr und mehr den Willen im Denken stärken, bereiten wir uns vor für das, was ich in der «Philosophie der Freiheit» die moralische Phantasie genannt habe, was aber aufsteigt zu den moralischen Intuitionen, die dann unseren gedankegewordenen Willen oder willegewordenen Gedanken durchstrahlen, durchsetzen. Auf diese Weise heben wir uns heraus aus der physisch-sinnlichen Notwendigkeit, durchstrahlen uns mit dem, was uns eigen ist und bereiten uns vor für die moralische Intuition. Und auf solchen moralischen Intuitionen beruht doch alles das, was den Menschen von der geistigen Welt aus zunächst erfüllen kann. Es lebt also auf dasjenige, was Freiheit ist, dann, wenn wir gerade in unserem Denken immer mächtiger und mächtiger werden lassen den Willen.

[ 7 ] Betrachten wir den Menschen von dem anderen Pol aus, von dem Willenspol. Der Wille, wann tritt er durch unser Handeln uns besonders klar vor das Seelenauge? Nun, wenn wir niesen, so tun wir ja auch etwas sozusagen, aber wir werden nicht in der Lage sein, uns einen besonderen Willensimpuls dabei zuzuschreiben, wenn wir niesen. Wenn wir sprechen, dann tun wir schon etwas, wo in einer gewissen Weise der Wille drinnen liegt. Aber bedenken Sie nur einmal, wie im Sprechen Willentliches und Unwillentliches, Willensgemäßes und Unwillensgemäßes ineinanderlaufen! Sie müssen sprechen lernen und müssen es gerade so lernen, daß Sie nicht mehr jedes einzelne Wort willensgemäß formen müssen, daß gewissermaßen etwas Instinktives hineinkommt in das Sprechen. Für das gewöhnliche Leben ist es wenigstens so, und im Grunde genommen ist es so gerade für diejenigen Menschen, die wenig nach Geistigkeit streben. Schwätzer, die gewissermaßen fortwährend ihren Mund offen haben müssen, um das oder jenes zu sagen, in das nicht viel Gedankliches hineingesandt wird, die lassen den anderen merken - sie selber merken es allerdings nicht -, wieviel Instinktives, Unwillensgemäßes im Sprechen liegt. Aber je mehr wir aus unserem Organischen herausgehen und übergehen zur Tätigkeit, die vom Organischen gewissermaßen losgelöst ist, desto mehr tragen wir in unser Handeln die Gedanken hinein. Das Niesen steckt noch ganz im Organischen drinnen, das Sprechen steckt zum großen Teil im Organischen drinnen, das Gehen schon sehr wenig, dasjenige, was wir mit den Händen vollziehen, auch sehr wenig. Und so geht es allmählich über in immer mehr und mehr vom Organischen in uns losgelöste Handlungen. Diese Handlungen, die verfolgen wir mit unseren Gedanken, wenn wir auch nicht wissen, wie der Wille in diese Handlungen hineinschießt. Und wenn wir nicht gerade Nachtwandler sind und in diesem Zustande uns betätigen, dann werden unsere Handlungen stets von unseren Gedanken begleitet sein. Wir tragen in unser Handeln die Gedanken hinein, und je mehr sich unser Handeln ausbildet, desto mehr tragen wir die Gedanken in unser Handeln hinein.

[ 8 ] Sie sehen, wir werden immer innerlicher und innerlicher, indem wir unsere Eigenkraft als Wille in das Denken hineinschicken, das Denken gewissermaßen ganz vom Willen durchstrahlen lassen. Wir bringen den Willen in das Denken hinein und gelangen dadurch zur Freiheit. Wir gelangen dazu, indem wir immer mehr und mehr unser Handeln ausbilden, in dieses Handeln die Gedanken hineinzutragen. Wir durchstrahlen unser Handeln, das ja aus unserem Willen hervorgeht, mit unseren Gedanken. Auf der einen Seite, nach innen, leben wir ein Gedankenleben; das durchstrahlen wir mit dem Willen und finden so die Freiheit. Auf der anderen Seite, nach außen, fließen unsere Handlungen von uns aus dem Willen heraus; wir durchsetzen sie mit unseren Gedanken.

[ 9 ] Aber wodurch werden denn unsere Handlungen immer ausgebildeter? Wodurch, wenn wir den allerdings anzufechtenden Ausdruck gebrauchen wollen, kommen wir denn zu einem immer vollkommeneren Handeln? - Wir kommen zu einem immer vollkommeneren Handeln eigentlich dadurch, daß wir diejenige Kraft in uns ausbilden, die man nicht anders nennen kann als Hingabe an die Außenwelt. Je mehr unsere Hingabe an die Außenwelt wächst, desto mehr regt uns diese Außenwelt an zum Handeln. Dadurch aber gerade, daß wir den Weg finden, um hingegeben zu sein an die Außenwelt, gelangen wir dazu, dasjenige, was in unserem Handeln liegt, mit Gedanken zu durchdringen. Was ist Hingabe an die Außenwelt? Hingabe an die Außenwelt, die uns durchdringt, die unser Handeln mit den Gedanken durchdringt, ist nichts anderes als Liebe.

[ 10 ] Geradeso wie wir zur Freiheit kommen durch die Durchstrahlung des Gedankenlebens mit dem Willen, so kommen wir zur Liebe durch die Durchsetzung des Willenslebens mit Gedanken. Wir entwickeln in unserem Handeln Liebe dadurch, daß wir die Gedanken hineinstrahlen lassen in das Willensgemäße; wir entwickeln in unserem Denken Freiheit dadurch, daß wir das Willensgemäße hineinstrahlen lassen in die Gedanken. Und da wir als Mensch eine Ganzheit, eine Totalität sind, so wird, wenn wir dazu kommen, in dem Gedankenleben die Freiheit und in dem Willensleben die Liebe zu finden, in unserem Handeln die Freiheit, in unserem Denken die Liebe mitwirken. Sie durchstrahlen einander, und wir vollziehen ein Handeln, ein gedankenvolles Handeln in Liebe, ein willensdurchsetztes Denken, aus dem wiederum das Handlungsgemäße in Freiheit entspringt.

[ 11 ] Sie sehen, wie im Menschen die zwei größten Ideale zusammenwachsen, Freiheit und Liebe. Und Freiheit und Liebe sind auch dasjenige, was eben der Mensch, indem er dasteht in der Welt, in sich so verwirklichen kann, daß gewissermaßen das eine mit dem anderen sich gerade durch den Menschen für die Welt verbindet.

[ 12 ] Man wird nun fragen müssen: Wodurch ist denn das Ideal, das höchste, in diesem willensdurchstrahlten Gedankenleben zu erreichen? Ja, wenn das Gedankenleben etwas wäre, das materielle Vorgänge darstellte, dann könnte das eigentlich gar nie eintreten, daß der Wille ganz in die Sphäre der Gedanken gewissermaßen hineinträte und in der Sphäre des Gedankens das Willensmäßige immer mehr und mehr Platz griffe. Stellen Sie sich vor, da wären materielle Vorgänge — der Wille könnte in diese materiellen Vorgänge höchstens organisierend hineinstrahlen. Nur dann kann der Wille wirksam sein, wenn das Gedankenleben als solches keine äußere physische Realität hat, wenn das Gedankenleben etwas ist, was der äußeren physischen Realität bar ist. Was muß es also sein?

[ 13 ] Nun, Sie werden sich klarmachen können, was es sein muß, wenn Sie von einem Bilde ausgehen. Wenn Sie hier einen Spiegel haben und hier einen Gegenstand, der Gegenstand im Spiegel sich spiegelt, dann können Sie hinter den Spiegel gehen, Sie finden nichts. Sie haben eben ein Bild. Solches Bilddasein haben unsere Gedanken. Wodurch haben sie ein solches Bilddasein? Nun, Sie brauchen sich nur zu erinnern, was ich Ihnen über das Gedankenleben gesagt habe. Es ist ja eigentlich als solches gar nicht im gegenwärtigen Augenblick Realität. Das Gedankenleben strahlt herein aus unserem Vorgeburtlichen, oder sagen wir aus dem Dasein vor der Empfängnis. Das Gedankenleben hat seine Realität zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. Und geradeso wie hier der Gegenstand vor dem Spiegel steht und aus dem Spiegel nur Bilder kommen, so ist dasjenige, was wir als Gedankenleben entwickeln, im Grunde genommen ganz real durchlebt zwischen dem Tode und der neuen Geburt und strahlt nur herein in dieses Leben, das wir seit der Geburt vollbringen. Als denkende Wesen haben wir in uns nur eine Spiegelbild-Realität. Dadurch kann die andere Realität, die gerade aus unserem Stoffwechsel, wie Sie wissen, aufstrahlt, die bloße Spiegelbild-Realität des Gedankenlebens durchdringen. Man sieht am klarsten, wenn man überhaupt unbefangenes Denken entfalten will, was heute in dieser Beziehung allerdings sehr selten ist, daß das Gedankenleben ein Spiegelbilddasein hat, wenn man das reinste Gedankenleben ins Auge faßt, das mathematische. Dieses mathematische Gedankenleben fließt ganz aus unserem Inneren herauf. Aber es hat nur ein Spiegeldasein. Sie können allerdings durch die Mathematik alle äußeren Gegenstände bestimmen; aber die mathematischen Gedanken selber sind eben nur Gedanken und sie haben bloß ein Bilddasein. Sie sind etwas, was nicht aus irgendeiner äußeren Realität gewonnen ist.

[ 14 ] Abstraktlinge wie Kant gebrauchen auch ein abstraktes Wort. Sie sagen: Die mathematischen Vorstellungen sind a priori. — A priori, das heißt: bevor etwas anderes da ist. Aber warum sind mathematische Vorstellungen a priori? Weil sie hereinstrahlen aus dem vorgeburtlichen beziehungsweise vor der Empfängnis liegenden Dasein; das macht ihre Apriorität aus. Und daß sie uns für unser Bewußtsein als real erscheinen, das rührt davon her, daß sie vom Willen durchstrahlt sind. Diese Durchstrahlung des Willens macht sie real. Bedenken Sie einmal, wie abstrakt das moderne Denken geworden ist, indem es abstrakte Worte gebraucht für etwas, was man seiner Realität nach eben nicht durchschaut. Daß wir uns die Mathematik mitbringen aus unserem vorgeburtlichen Dasein, das spürte gewissermaßen ein Kant und nannte deshalb die mathematischen Urteile a priori. Aber mit a priori ist weiter nichts gesagt, denn es ist auf keine Realität hingedeutet, es ist auf etwas bloß Formales hingedeutet.

[ 15 ] Alte Traditionen sprechen gerade hier bei dem, was Gedankenleben ist, was in seinem Bilddasein angewiesen ist, vom Willen durchstrahlt zu werden, um zur Realität zu werden - alte Vorstellungen sprechen hier von Schein (siehe Zeichnung Seite 209).

[ 16 ] Sehen wir uns den anderen Pol des Menschen an, wo die Gedanken nach dem Willensmäßigen hinstrahlen, wo in Liebe die Dinge vollbracht werden: da prallt gewissermaßen unser Bewußtsein an der Realität ab. Sie können nicht hineinschauen in jenes Reich der Finsternis — für das Bewußtsein das Reich der Finsternis -, wo der Wille sich entfaltet, indem Sie auch nur Ihren Arm erheben oder Ihren Kopf drehen, wenn Sie nicht zu übersinnlichen Vorstellungen greifen. Sie bewegen Ihren Arm; aber was da Kompliziertes vorgeht, das bleibt dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein geradeso unbewußt wie die Dinge des tiefen Schlafes, der traumlos ist. Wir sehen unseren Arm an, wir sehen, wie unsere Hand greifen kann. Das alles ist, weil wir die Sache mit Vorstellungen, mit Gedanken durchsetzen. Aber die Gedanken selber, die in unserem Bewußtsein sind, sie bleiben auch hier Schein. Das Reale aber ist es, in dem wir leben, und das nicht ins gewöhnliche Bewußtsein heraufstrahlt. Alte Traditionen sprachen hier von Gewalt, weil dasjenige, in dem wir als Realität leben, zwar von dem Gedanken durchsetzt wird, aber der Gedanke doch in einer gewissen Weise in dem Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod davon abgeprallt ist (siehe Zeichnung).

[ 17 ] Zwischen beiden drinnen liegt der Ausgleich, liegt dasjenige, was den Willen, der gewissermaßen nach dem Haupte strahlt, die Gedanken, die sozusagen mit dem Herzen, in unserem Handeln in Liebe erfühlt werden, was diese beiden miteinander verbindet: das gefühlsmäßige Leben, das sowohl nach dem Willensmäßigen hinzielen kann, wie nach dem Gedanken hinzielen kann. Wir leben in einem Elemente im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein, wodurch wir auf der einen Seite dasjenige erfassen, was in unserem zur Freiheit hinneigenden, willensdurchsetzten Denken zum Ausdruck kommt, auf der anderen Seite, wo wir versuchen, immer gedankenvoller dasjenige zu haben, was in unser Handeln übergeht. Und was die Verbindungsbrücke zwischen beiden bildet, das nannte man von alten Zeiten her die Weisheit (siehe Zeichnung).

[ 18 ] Goethe hat in seinem Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der schönen Lili ein den drei Königen, dem goldenden König, dem silbernen König, dem ehernen König, hingewiesen auf diese alten Traditionen. Wir haben ja auch schon von anderen Gesichtspunkten aus gezeigt, wie wiederum aufleben müssen, aber in einer ganz anderen Form, diese drei Elemente, auf die eine alte, instinktive Erkenntnis hinweisen konnte, und die nur wieder aufleben können, wenn der Mensch die Erkenntnisse der Imagination, der Intuition, der Inspiration aufnimmt.

[ 19 ] Was aber geht denn eigentlich vor, indem der Mensch sein Gedankenleben entwickelt? Eine Realität wird zum Schein. Das ist sehr wichtig, daß man sich darüber klar werde. Wir tragen unser Haupt, das in seiner Verknöcherung und in seiner Neigung zum Verknöchern bildhaft ja schon äußerlich das Erstorbene gegenüber der anderen, frischen Körperorganisation zeigt. Wir tragen in unserem Haupte zwischen Geburt und Tod dasjenige, was aus einer Vorzeit, wo es Realität war, hereinragt als Schein, und wir durchstrahlen von unserem übrigen Organismus den Schein mit dem realen Elemente, das aus unserem Stoffwechsel kommt, mit dem realen Elemente des Willens. Da haben wir eine Keimbildung, die zunächst in unserem Menschentum abläuft, die aber eine kosmische Bedeutung hat. Denken Sie sich, ein Mensch ist geboren in irgendeinem Jahre, vorher war er in der geistigen Welt; er geht aus der geistigen Welt heraus, indem dasjenige, was da als Gedanke Realität war, in ihm zum Schein wird, und er überführt in diesen Schein die Willenstätigkeit, die aus einer ganz anderen Richtung herkommt, die aus seinem übrigen, nichthauptlichen Organismus aufsteigt. Das ist dasjenige, wodurch die in den Schein ersterbende Vergangenheit wiederum angeregt wird durch das, was im Willen erstrahlt, zur Realität der Zukunft.

[ 20 ] Verstehen wir recht: Was geschieht, wenn der Mensch sich zum reinen, das heißt, willensdurchstrahlten Denken erhebt? In ihm entwickelt sich auf Grundlage dessen, was der Schein aufgelöst hat der Vergangenheit —, durch die Befruchtung mit dem Willen, der aus seiner Ichheit aufsteigt, eine neue Realität in die Zukunft hin. Er ist der Träger des Keimes in die Zukunft. Der Mutterboden gewissermaßen sind die realen Gedanken der Vergangenheit, und in diesen Mutterboden wird versenkt dasjenige, was aus dem Individuellen kommt, und der Keim wird in die Zukunft geschickt zum zukünftigen Leben.

[ 21 ] Und auf der anderen Seite entwickelt der Mensch, indem er seine Handlungen, sein Willensgemäßes mit Gedanken durchsetzt, dasjenige, was er in Liebe vollbringt. Es löst sich von ihm los. Unsere Handlungen bleiben nicht bei uns. Sie werden Weltgeschehen; wenn sie von Liebe durchsetzt sind, dann geht die Liebe mit ihnen. Eine egoistische Handlung ist kosmisch etwas anderes als eine liebedurchsetzte Handlung. Indem wir aus dem Schein durch die Befruchtung des Willens dasjenige entwickeln, was aus unserem Inneren hervorgeht, trifft das, was da gewissermaßen aus unserem Kopfe fortströmt in die Welt, auf unsere gedankendurchsetzten Handlungen auf. Geradeso wie wenn eine Pflanze sich entwickelt, in ihrer Blüte der Keim ist, den außen das Licht der Sonne treffen muß, den außen die Luft treffen muß und so weiter, dem etwas entgegenkommen muß aus dem Kosmos, damit er wachsen kann, so muß dasjenige, was durch die Freiheit entwickelt wird, durch die entgegenkommende, in den Handlungen lebende Liebe ein Wachstumselement finden (siehe Zeichnung Seite 209).

[ 22 ] So steht der Mensch tatsächlich drinnen in dem Weltenwerden, und was innerhalb seiner Haut geschieht, und was aus seiner Haut ausfließt als Handlungen, das hat nicht bloß eine Bedeutung an ihm, das ist Weltgeschehen. Er ist hineingestellt in das kosmische, in das Weltgeschehen. Indem dasjenige, was in der Vorzeit real war, zum Schein im Menschen wird, löst sich fortwährend Realität auf, und indem dieser Schein wiederum befruchtet wird durch den Willen, entsteht neue Realität. Da haben Sie, ich möchte sagen, wie geistig zu greifen dasjenige, was wir auch von anderen Gesichtspunkten heraus gesagt haben: Es gibt keine Konstanz des Stoffes. Der verwandelt . sich in Schein, und der Schein wird vom Willen des Menschen wiederum in die Realität erhoben. Ein Truggebilde ist es, was als das Gesetz der Erhaltung des Stoffes und der Kraft in die physikalische Weltanschauung gebracht ist, weil man eben nur das natürliche Weltbild ansieht. In Wahrheit vergeht fortwährend Stoff, indem er sich in Schein verwandelt, und Neues entsteht, indem gerade durch das, was zunächst als höchstes Gebilde des Kosmos vor uns steht, durch den Menschen, der Schein wiederum in Sein verwandelt wird.

[ 23 ] An dem anderen Pol können wir es auch sehen, nur ist dieses Sehen nicht so leicht wie das andere, denn die Vorgänge, die schließlich zur Freiheit führen, sind im Grunde genommen für ein unbefangenes Denken wirklich zu durchschauen; aber um hier richtig zu sehen, dazu gehört schon einige geisteswissenschaftliche Entwickelung. Denn zunächst prallt das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein an der Gewalt ab. Es durchsetzt ja allerdings dasjenige, was an der Gewalt, an der Kraft sich auslebt, mit Gedanken; aber das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein sieht nicht, daß geradeso wie hier immer mehr und mehr Wille, Urteilsschluß in die Gedankenwelt hineinkommt, daß, wenn wir die Gedanken in das Willensmäßige hineinbringen, wenn wir eben immer mehr und mehr die Gewalt ausrotten, wir immer mehr dasjenige, was bloß Gewalt ist, durchdringen mit dem Lichte des Gedankens. Da, an dem einen Pol des Menschen, sieht man die Überwindung des Stoffes, da, an dem anderen Pol, sieht man die Neuerstehung des Stoffes.

[ 24 ] Wir wissen ja, ich habe es wenigstens andeutungsweise ausgeführt in meinem Buche «Von Seelenrätseln», daß der Mensch ein dreigliedriges Wesen ist: als Nerven-Sinnesmensch Träger des Gedankenlebens, des Wahrnehmungslebens, als rhythmischer Mensch — Atmung, Blutzirkulation — Träger des Gefühlslebens, als Stoffwechselmensch Träger des Willenslebens. Aber wie entfaltet sich denn, wenn der Wille immer mehr und mehr in Liebe entwickelt wird, im Menschen der Stoffwechsel? Indem der Mensch ein Handelnder ist, so, daß eigentlich der Stoff fortwährend überwunden wird. Und was entfaltet sich im Menschen, indem er sich als freies Wesen in das reine Denken, das aber eigentlich willensmäßiger Natur ist, hineinentwickelt? Es entsteht der Stoff. Wir sehen hinein in Stoffentstehung. Wir tragen selbst in uns dasjenige, was den Stoff entstehen macht: unseren Kopf; und wir tragen in uns das, was den Stoff vernichtet, wo wir es sehen können, wie der Stoff vernichtet wird: unseren Gliedmaßen-, unseren Stoffwechselorganismus.

[ 25 ] Das heißt den Menschen in seiner Ganzheit betrachten. Wir sehen, wie dasjenige, was sonst nur innerhalb des menschlichen Bewußstseins zumeist in Abstraktionen aufgefaßt wird, wie das als reales Element sich am Weltenwerden beteiligt; und wie das, was im Weltenwerden darinnensteht und woran das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein so haftet, daß es sich gar nicht etwas anderes vorstellen kann, als daß es eine Realität ist, wie das bis in die Null hinein aufgelöst wird. Das ist eben eine Realität für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein, und wenn es schon nicht geht mit den äußeren Realitäten, so müssen es wenigstens die Atome sein, die starre Realitäten sind. Und weil man nicht mit seinen Gedanken loskommen kann von diesen starren Realitäten, so läßt man sie einfach durcheinandermischen, einmal so, einmal so. Das eine Mal wird es Wasserstoff, das andere Mal Sauerstoff, sie sind anders gruppiert, eben weil man nicht anders kann, als das, was man einmal in Gedanken festgehalten hat, auch festgehalten zu denken in der Realität.

[ 26 ] Es ist nichts anderes als eine Gedankenschwäche, der sich der Mensch hingibt, wenn er starre, ewige Atome annimmt. Was sich uns aus dem Wirklichkeitsdenken ergibt, das ist, daß fortwährend aufgelöst wird bis in die Null hinein das Stoffliche. Nur weil, wenn Stoff vergeht, fortwährend neuer Stoff entsteht, redet der Mensch von einer Konstanz des Stoffes. Er gibt sich demselben Irrtum hin, dem er sich hingeben würde, sagen wir, wenn eine Anzahl von Dokumenten in ein Haus hineingetragen, drinnen abgeschrieben. würden, aber als solche verbrannt würden, und die Abschriften wieder herauskommen, und er, weil er dasselbe herauskommen sieht, was hineingetragen ist, denken würde, es sei dasselbe. In Wirklichkeit sind die alten verbrannt worden und neue sind geschrieben worden. So ist es auch mit dem Werden in der Welt, und es ist wichtig, daß man bis zu diesem Punkte mit seinem Erkennen vordringt. Denn da, wo im Menschen Stoff vergeht, zum Scheine wird und neuer Stoff entsteht, da sitzt die Möglichkeit der Freiheit und da sitzt die Möglichkeit der Liebe. Und Freiheit und Liebe gehören zusammen, wie ich schon in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» angedeutet habe.

[ 27 ] Derjenige, der durch irgendeine Weltanschauung von der Unvergänglichkeit des Stoffes redet, der vertilgt sowohl die Freiheit nach der einen Seite wie die völlig ausgebildete Liebe nach der anderen Seite. Denn nur dadurch, daß im Menschen Vergangenes ganz vergeht, zum Scheine wird und Zukünftiges neu entsteht, ganz Keim ist, entsteht in ihm sowohl das Gefühl der Liebe, die Hingabe ist an etwas, wozu man nicht gestoßen wird durch das Vergangene, als auch die Freiheit, die ein Handeln ist aus dem, was nicht vorbedingt ist. Freiheit und Liebe sind in Wirklichkeit nur begreifbar für geisteswissenschaftliche Weltanschauung, nicht für eine andere. Wer sich hineingelebt hat in dasjenige, was als Weltenbild im Laufe der letzten Jahrhunderte heraufgekommen ist, der wird auch ermessen können, welche Schwierigkeiten zu überwinden sind gegenüber dem gewohnheitsmäßigen Denken der neueren Menschheit, um mit diesem unbefangenen geisteswissenschaftlichen Denken durchzudringen. Denn es sind in dem modernen naturwissenschaftlichen Weltbilde sozusagen gar keine Anhaltspunkte da, um so weit zu kommen, daß man Freiheit und Liebe wirklich begreifen kann.

[ 28 ] Wie sich nun verhalten müssen gegenüber einer wirklich fortschreitenden geisteswissenschaftlichen Entwickelung der Menschheit auf der einen Seite das naturwissenschaftliche Weltbild, auf der anderen Seite die alten traditionellen Weltenbilder, davon wollen wir dann ein anderes Mal sprechen.

Twelfth lecture

[ 1 ] Human beings stand in the world on the one hand as observers, on the other hand as actors, and in between they stand with their feelings. On the one hand, they are devoted with their feelings to what their observation reveals, and on the other hand, they are involved in their actions with their feelings. One need only think about how human beings can be satisfied or dissatisfied with what they achieve or fail to achieve as actors; one need only think about how all actions are ultimately accompanied by emotional impulses, and one will see that our emotional nature actually connects the two opposing poles: the observing element in us and the acting element in us. It is only because we are contemplative beings that we become human beings in the fullest sense of the word. You need only consider how everything that ultimately gives you the awareness that you are human is connected with the fact that you can, in a sense, reproduce the world that surrounds you and in which you live, that you can contemplate it. To think that we cannot contemplate the world would mean that we would have to reject our entire humanity. As acting human beings, we are part of social life. And basically, everything we accomplish between birth and death has a certain social significance.

[ 2 ] Now you know that, insofar as we are contemplative beings, the thought lives within us, and insofar as we are active beings, that is, insofar as we are social beings, the will lives within us. However, it is not in human nature, nor is it in reality, that things can be placed side by side intellectually. Rather, what is effective in being can be characterized in one way or another; things flow into one another, the forces of the world flow into one another. We can imagine that we are beings of thought, and we can also imagine that we are beings of will. But even when we live contemplatively, in complete external calm, the will is nevertheless constantly active within us. And again, when we are active, thought is active within us. It is unthinkable that anything should proceed from us as an action, that anything should spill over into social life without our identifying ourselves mentally with what is happening. In everything volitional, the thought-like lives; in everything thought-like, the volitional lives. And it is absolutely necessary to be clear about the things in question here if one seriously wants to build the bridge I have spoken of so often, the bridge between the moral-spiritual world order and the physical-natural order.

[ 3 ] Imagine for a moment that you lived for a while purely in a contemplative manner, in accordance with the ordinary sciences. You did not stir yourself at all, you refrained from all action, you lived a purely imaginative life. But you must be clear that in this life of imagination, the will is at work, a will that is indeed active within you, spreading its powers in the realm of imagination. Precisely when we consider the thinking human being in this way, as he continually radiates his will into his thoughts, then something must strike us in contrast to real life. The thoughts we form, when we go through them all, always connect to something in our environment, to our experiences. Between birth and death, we have, in a sense, no other thoughts than those that life brings us. If our experience is rich, we also have a rich content of thoughts; if our experience is poor, we have a poor content of thoughts. The content of our thoughts is, in a sense, our inner destiny. But within this experience of thinking, one thing is entirely our own: the way we connect and separate thoughts, the way we process thoughts internally, how we judge, how we draw conclusions, how we orient ourselves in our thought life in general—that is ours, it is unique to us. The will in our thought life is our own.

[ 4 ] When we look at this thought life, we must say to ourselves, especially in careful self-examination, and you will see that this is so in careful self-examination: Thoughts come to us from outside in terms of their content, but the processing of thoughts comes from within us. — We are therefore, in relation to our world of thoughts, completely dependent on what we can experience through the birth into which we have been placed by fate, through the experiences that can happen to us. But into what comes to us from the outside world, we carry our own selves precisely through the will that radiates from the depths of our souls. It is highly significant for the fulfillment of what self-knowledge demands of us as human beings that we distinguish between, on the one hand, the content of thoughts coming to us from the environment and, on the other hand, the power of the will, which comes from within, radiating into the world of thoughts.

[ 5 ] How does one actually become more and more spiritual within oneself? One does not become more spiritual by absorbing as many thoughts as possible from the environment, for these thoughts only reflect, I would say, the external world, which is sensory and physical, in images. One does not become more spiritual by pursuing the sensations of life as much as possible. One becomes more spiritual through inner work in accordance with one's will within one's thoughts. That is why meditation consists in not indulging in random mental games, but in placing a few easily comprehensible, easily verifiable thoughts at the center of one's consciousness, and doing so with a strong will. And the stronger, the more intense this inner ray of will becomes in the element where the thoughts are, the more spiritual we become. When we take in thoughts from the external physical-sensory world—and we can only take in such thoughts between birth and death—then, as you can easily see, we become unfree, because we are given over to the connections of the external world; we must then think as the external world dictates to us, insofar as we only consider the content of the thoughts; only in the inner processing do we become free.

[ 6 ] Now there is a way to become completely free, to become free in one's inner life, if one excludes as much as possible the content of thoughts insofar as they come from outside, excludes them more and more, and sets the element of will that permeates our thoughts in judging and drawing conclusions into particular activity. This, however, puts our thinking into the state I have called pure thinking in my Philosophy of Freedom. We think, but only the will lives in thinking. I emphasized this particularly sharply in the new edition of Philosophy of Freedom in 1918. That which lives in us lives in the sphere of thinking. But when it has become pure thinking, it is actually just as good to address it as pure will. So that we rise to this, to elevate ourselves from thinking to will, when we become inwardly free, when we, so to speak, mature our thinking to such an extent that it is completely permeated by the will, no longer taking in from outside, but living in the will itself. But precisely by strengthening the will in our thinking more and more, we prepare ourselves for what I have called moral imagination in The Philosophy of Freedom, which rises to moral intuitions that then permeate and prevail over our will that has become thought or our thoughts that have become will. In this way, we lift ourselves out of physical and sensory necessity, permeate ourselves with what is our own, and prepare ourselves for moral intuition. And it is on such moral intuitions that everything that can initially fulfill human beings from the spiritual world is based. So what is freedom lives on when we allow the will to become more and more powerful in our thinking.

[ 7 ] Let us consider human beings from the other pole, from the pole of the will. When does the will become particularly clear to the mind's eye through our actions? Well, when we sneeze, we are also doing something, so to speak, but we are not able to attribute a particular impulse of the will to ourselves when we sneeze. When we speak, we are already doing something that involves the will in a certain way. But just consider how the voluntary and the involuntary, the willful and the unwilling, intertwine in speech! You have to learn to speak, and you have to learn it in such a way that you no longer have to form every single word willfully, that something instinctive enters into speech, so to speak. This is at least the case in ordinary life, and basically it is especially true for people who do not strive for spirituality. Chatterboxes, who have to keep their mouths open all the time to say this or that, without putting much thought into it, let others notice — although they themselves do not notice it — how much instinctive and involuntary there is in their speech. But the more we move out of our organic nature and into activity that is, so to speak, detached from the organic, the more we bring our thoughts into our actions. Sneezing is still entirely organic, speaking is largely organic, walking is only very slightly organic, and what we do with our hands is also very slightly organic. And so it gradually passes into actions that are increasingly detached from the organic in us. We follow these actions with our thoughts, even if we do not know how the will enters into these actions. And unless we are sleepwalkers and act in this state, our actions will always be accompanied by our thoughts. We carry our thoughts into our actions, and the more our actions develop, the more we carry our thoughts into our actions.

[ 8 ] You see, we become more and more inward by sending our own power as will into our thinking, allowing our thinking to be completely permeated by the will, so to speak. We bring the will into our thinking and thereby attain freedom. We attain this by developing our actions more and more and carrying our thoughts into these actions. We permeate our actions, which arise from our will, with our thoughts. On the one hand, inwardly, we live a life of thought; we permeate this with the will and thus find freedom. On the other hand, outwardly, our actions flow from us out of our will; we carry them out with our thoughts.

[ 9 ] But how do our actions become more and more refined? How, if we want to use this somewhat questionable expression, do we arrive at increasingly perfect actions? We arrive at increasingly perfect actions by developing within ourselves a force that can only be called devotion to the external world. The more our devotion to the external world grows, the more this external world stimulates us to act. But it is precisely by finding the way to be devoted to the external world that we come to permeate our actions with thought. What is devotion to the external world? Devotion to the external world, which permeates us and permeates our actions with thought, is nothing other than love.

[ 10 ] Just as we attain freedom through the permeation of our thought life with the will, so we attain love through the permeation of our will life with thoughts. We develop love in our actions by allowing thoughts to radiate into what is in accordance with the will; we develop freedom in our thinking by allowing what is in accordance with the will to radiate into our thoughts. And since we as human beings are a whole, a totality, when we come to find freedom in our thought life and love in our will life, freedom will be at work in our actions and love in our thinking. They radiate into each other, and we carry out actions, thoughtful actions in love, willful thinking, from which in turn actions in accordance with our will spring forth in freedom.

[ 11 ] You see how the two greatest ideals, freedom and love, grow together in human beings. And freedom and love are also what human beings, standing there in the world, can realize within themselves in such a way that, in a sense, the one connects with the other for the world precisely through human beings.

[ 12 ] One must now ask: How can the highest ideal be achieved in this will-filled life of thought? Yes, if the life of thought were something that represented material processes, then it could never actually happen that the will would enter completely into the sphere of thought, so to speak, and that the volitional would take up more and more space in the sphere of thought. Imagine that there were material processes — the will could at most shine into these material processes in an organizing way. The will can only be effective if the life of thought as such has no external physical reality, if the life of thought is something that is devoid of external physical reality. So what must it be?

[ 13 ] Well, you will be able to see what it must be if you start from an image. If you have a mirror here and an object here, and the object is reflected in the mirror, then you can go behind the mirror and find nothing. You have an image. Our thoughts have this kind of image existence. How do they have such an image existence? Well, you only need to remember what I told you about the life of thoughts. It is not actually reality as such in the present moment. The life of thoughts radiates in from our pre-birth, or let us say from our existence before conception. The life of thought has its reality between death and a new birth. And just as the object stands here in front of the mirror and only images come out of the mirror, so what we develop as the life of thought is, in essence, lived through quite realistically between death and the new birth and only radiates into this life that we have been living since birth. As thinking beings, we have only a mirror image reality within us. This allows the other reality, which, as you know, radiates from our metabolism, to penetrate the mere mirror image reality of thought life. If one wants to develop completely unbiased thinking, which is very rare today, one can see most clearly that thought life has a mirror image existence when one considers the purest form of thought life, namely mathematical thought. This mathematical thought life flows entirely from within us. But it only has a mirror existence. You can, of course, determine all external objects through mathematics; but mathematical thoughts themselves are just thoughts and they only have an image existence. They are something that is not derived from any external reality.

[ 14 ] Abstract thinkers like Kant also use an abstract word. They say: Mathematical ideas are a priori. — A priori means: before anything else exists. But why are mathematical ideas a priori? Because they shine in from pre-birth or pre-conception existence; that is what makes them a priori. And the fact that they appear real to our consciousness stems from the fact that they are permeated by the will. This permeation by the will makes them real. Consider how abstract modern thinking has become by using abstract words for something whose reality we cannot see through. Kant sensed, in a sense, that we bring mathematics with us from our pre-birth existence, and therefore called mathematical judgments a priori. But a priori says nothing more, because it does not refer to any reality, it refers only to something formal.

[ 15 ] Old traditions speak precisely here, in relation to what thought life is, which in its pictorial existence is dependent on being permeated by the will in order to become reality – old ideas speak here of appearance (see drawing on page 209).

[ 16 ] Let us look at the other pole of the human being, where thoughts radiate toward the will, where things are accomplished in love: here, our consciousness rebounding, as it were, against reality. You cannot look into that realm of darkness — the realm of darkness for consciousness — where the will unfolds, even when you raise your arm or turn your head, unless you resort to supersensible ideas. You move your arm, but what is going on there in all its complexity remains just as unconscious to ordinary consciousness as the things that happen during deep, dreamless sleep. We look at our arm, we see how our hand can grasp things. All this is because we fill the thing with ideas, with thoughts. But the thoughts themselves, which are in our consciousness, remain mere appearances. But what is real is that in which we live, and that does not shine up into ordinary consciousness. Old traditions spoke of violence here, because that in which we live as reality is indeed permeated by thought, but thought has nevertheless rebounded in a certain way in the life between birth and death (see drawing).

[ 17 ] Between the two lies the balance, that which connects the will, which shines, as it were, from the head, with the thoughts, which are felt with the heart, so to speak, in our actions in love: the emotional life, which can aim both toward the will and toward the thoughts. We live in an element in ordinary consciousness, through which we grasp, on the one hand, what is expressed in our thinking, which tends toward freedom and is determined by the will, and on the other hand, where we try to have, in an increasingly thoughtful way, what passes into our actions. And what forms the connecting bridge between the two has been called wisdom since ancient times (see drawing).

[ 18 ] In his fairy tale of the green snake and the beautiful Lili, Goethe referred to these ancient traditions in connection with the three kings, the golden king, the silver king, and the bronze king. We have already shown from other points of view how these three elements, to which an ancient, instinctive knowledge could point, must be revived, but in a completely different form, and that they can only be revived if human beings take up the insights of imagination, intuition, and inspiration.

[ 19 ] But what actually happens when human beings develop their life of thought? A reality becomes an illusion. It is very important to understand this clearly. We carry our head, which in its ossification and tendency to ossify already shows outwardly the deadness of the other, fresh body organization. Between birth and death, we carry in our head that which protrudes from a past time when it was reality as an illusion, and we radiate from our remaining organism the illusion with the real element that comes from our metabolism, with the real element of the will. Here we have a germ formation that initially takes place in our humanity, but which has a cosmic significance. Imagine that a human being is born in a certain year; before that, he was in the spiritual world; he leaves the spiritual world when what was reality there as thought becomes an illusion in him, and he transfers into this illusion the activity of the will, which comes from a completely different direction, rising from his remaining, non-essential organism. This is what causes the past, which is dying in appearance, to be stimulated again by what shines in the will and becomes the reality of the future.

[ 20 ] Let us understand correctly: What happens when a person rises to pure, that is, will-pervaded thinking? On the basis of what the appearance has dissolved of the past — through fertilization with the will that rises from his ego — a new reality develops within him toward the future. He is the bearer of the seed into the future. The real thoughts of the past are, so to speak, the mother soil, and into this mother soil is sunk that which comes from the individual, and the seed is sent into the future for future life.

[ 21 ] And on the other hand, by infusing his actions, his will, with thoughts, man develops what he accomplishes in love. It detaches itself from him. Our actions do not remain with us. They become world events; if they are infused with love, then love goes with them. An egoistic action is cosmically different from an action imbued with love. By developing what emerges from within us through the fertilization of the will, what flows out of our minds, so to speak, encounters our actions imbued with thought. Just as when a plant develops, the seed is in its blossom, which must be exposed to the light of the sun, to the air, and so on, and something must come to meet it from the cosmos so that it can grow, so what is developed through freedom must find an element of growth through the love that comes to meet it and lives in actions (see drawing on page 209).

[ 22 ] Thus, human beings actually stand within the becoming of the world, and what happens within their skin and flows out of their skin as actions does not merely have meaning for them; it is world events. They are placed within the cosmic, within world events. As what was real in the past becomes an appearance in human beings, reality is continually dissolved, and as this appearance is in turn fertilized by the will, new reality arises. Here you have, I would say, a way of grasping spiritually what we have also said from other points of view: there is no constancy of matter. It transforms into appearance, and appearance is in turn raised to reality by the will of human beings. It is an illusion that has been introduced into the physical worldview as the law of conservation of matter and energy, because one looks only at the natural world. In truth, matter is constantly passing away by transforming itself into appearance, and something new arises precisely through that which initially stands before us as the highest structure of the cosmos, through human beings, who transform appearance back into being.

[ 23 ] We can also see this at the other pole, but this vision is not as easy as the other, because the processes that ultimately lead to freedom are, in essence, truly transparent to unbiased thinking; but in order to see correctly here, some spiritual scientific development is already necessary. For at first, ordinary consciousness collides with violence. It does, of course, permeate with thoughts that which is expressed in violence, in force; but ordinary consciousness does not see that just as more and more will and judgment enter into the world of thoughts, so too, when we bring thoughts into the realm of the will, when we eradicate violence more and more, we increasingly permeate that which is merely violence with the light of thought. There, at one pole of the human being, we see the overcoming of matter; there, at the other pole, we see the rebirth of matter.