Materialism and the Task of Anthroposophy

GA 204

29 April 1921, Dornach

Lecture X

In recent days, we have dealt with the development of European civilization and we shall try to add a number of considerations to what has been said. In this, it is always our intention to bring about an understanding of what plays into human life in the present age from the most diverse directions and leads to comprehension of the tasks posed by our time.

When you look at individual human life, it can indeed give you a picture of mankind's development. Nevertheless, you must naturally take into consideration here what has been mentioned in regard to the differences between the development of the individual and the overall development of humanity. I have repeatedly called attention to the fact that whereas the individual gets older and older, mankind as a whole becomes younger and younger, advancing, as it were, to the experience of younger periods of life. While keeping in mind that in this regard the life of the whole human community and that of the individual are direct opposites, at least for the sake of clarification, we can still say that individual human life can be a picture for us of the life of all humanity. If we then view the single human life in this way, we find that a quite specific sum of experiences belongs with each period of life. We cannot teach a six year-old child something we can teach a twelve-year-old; in turn, we cannot expect that the twelve-year-old approaches things with the same comprehension as a twenty-year-old. In a sense, the human being has to grow into what is compatible with individual periods in life. It is the same in the case of humanity as a whole.

True, the individual cultural epochs we have to point out based on insight into humanity's evolution—the old Indian, the old Persian, the Egypto-Chaldean, the Greco-Roman epoch and then the one to which we ourselves belong—have quite specific cultural contents and the whole of mankind has to grow into them. But just as the individual can fall behind his potential of development, so certain segments of mankind can do the same. This is a phenomenon that must be taken into consideration, particularly in our age, since humanity is now moving into the evolutionary state of freedom. It is, therefore, left up to mankind itself to find its way into what this and the following epoch put forward. It is, as it were, left up to human discretion to remain behind what is posed as goals. If an individual lags behind in this regard, he is confronted by others who do find their way properly into their tasks of evolution. They then have to carry him along, in a manner of speaking. Yet, in a certain sense, this can frequently signify a somewhat unpleasant destiny for such a person when he has to become aware that in a certain way he remains behind the others who do arrive at the goal of evolution.

This can also take place in the life of nations. It is possible that some nations achieve the goal and that others remain behind. As we have seen, the goals of the various nations also differ from each other. First of all, if one nation attains its goal and the other falls short of what it is supposed to accomplish, then something is lost that could only have been achieved by this laggard nation. On the other hand, this backsliding nation will adopt much that is really not suitable for it. It appropriates contents it receives by imitating other nations that do attain their goal. Such things do take place in the evolution of mankind, and it is of particular significance for the present age to pay attention to them.

Today, we shall summarize a number of things, familiar to us from other aspects, and throw light on them from a certain standpoint. We know that the time from the eighth pre-Christian century until the fifteenth century A.D. is the time of the development of the intellectual or rational soul among the civilized part of humanity. This development of the intellectual or rational soul begins in the eighth pre-Christian century in southern Europe and Asia Minor. We can trace it when we focus upon the beginnings of the historical development of the Greek people. The Greeks still possess much of what can be termed the development of the sentient soul that was particularly suited to the third post-Atlantean age, the Egypto-Chaldean epoch. That whole period was devoted to the development of the sentient soul.

During those times, human beings surrendered to the impressions of the external world, and through these impressions of the outer world they received at the same time everything they then valued as insights and that they let flow into the impulses of their will. With all their being people were in a condition where they experienced themselves as members of the whole cosmos. They questioned the stars and their movements when it was a matter of deciding what to do, and so on. This experiencing of the surrounding world, this seeing of the spiritual in all details of the outer world, was the distinguishing feature of the Egyptians at the height of their culture. This is what existed in Asia Minor and enjoyed a second flowering among the Greeks. The ancient Greeks certainly possessed this faculty of free surrender to the outer surroundings, and this was connected with a perception of the elemental spirit beings within the outer phenomena.

Then, however, something developed among the Greeks, which Greek philosophers call “nous,” namely, a general world intellect. This then remained the fundamental quality of human soul developments until the fifteenth century. It attained a kind of high point in the fourth Christian century and then diminished again. But this whole development from the eighth pre-Christian century up until the fifteenth century actually developed the intellect. However, if we speak of “intellect” in this period, we really have to disregard what we term “intellect” in our present age. For us, the intellect is something we carry within ourselves, something we develop within ourselves, by virtue of which we comprehend the world. This was not so in the case of the Greeks, and it was still not so in the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries, when people spoke about the intellect. Intellect was something objective; the intellect was an element that filled the world. The intellect arranged the individual world phenomena. People observed the world and its phenomena and told themselves: It is the universal intellect that makes one phenomenon follow the other, places the individual phenomena into a greater totality, and so forth. People attributed to the human brain no more than the fact that it shared in this general universal intelligence.

When we work out of modern physics and physiology and speak about light, we say that the light is within us. But even in his naive mind nobody would believe that light is only in our heads. Just as little as today's naive consciousness claims that it is dark outside and light exists only in the human head would a Greek or even a person of the eleventh or twelfth century have said that the intellect was only in his head. Such a person said, The intellect is outside, permeating the world and bestowing order on everything. Just as the human being becomes aware of light owing to his perceptions, so he becomes aware of the intellect. The intellect lights up in him, so to speak.

Something important was connected with this emergence of cosmic intelligence within the human cultural development. Earlier, when the cultural development ran its course under the influence of the sentient soul, people did not refer to a uniform principle encompassing the whole world. They spoke of the spirits of plants, of spirits that regulate the animal kingdom, of water spirits and spirits of the air, and so on. People referred to a multitude of spiritual entities. It was not merely polytheism, the folk religion, that spoke of this multitude. Even in those who were initiates, the awareness was definitely present that they were dealing with a multitude of actual beings in the world outside. Due to the dawn of the rational soul age, a sort of monism developed. Reason was viewed as something uniform that enveloped the whole world. It was not until then that the monotheistic character of religion developed, although a preliminary stage of it existed in the third post-Atlantean epoch. But what we should record scientifically concerning this era—from the eighth pre-Christian to the fifteenth century A.D.—is the fact that it is the period of the developing world intellect and that people had quite different thoughts about the intellect than we have nowadays.

Why did people think so differently about the intellect? People thought differently about the intellect because they also felt differently when they tried to grasp something by means of their intellect. People went through the world and perceived objects through their senses; but when they thought about them, they always experienced a kind of jolt. When they thought about something, it was as if they were experiencing a stronger awakening than they sensed in the process of ordinary waking. Thinking about something was a process still experienced as different from ordinary life. Above all, when people thought about something, they felt that they were involved in a process that was objective, not merely subjective. Even as late as the fifteenth century—and in its aftereffect even in still later times—people had a certain feeling in regard to the more profound thinking about things, a feeling people today do not have anymore. Nowadays human beings do not have the feeling that thinking about something should be carried out in a certain mood of soul. Up until the fifteenth century, people had the feeling that they produced only something evil if they were not morally good and yet engaged in thinking. In a sense, they reproached themselves for thinking even though they were bad persons. This is something we no longer experience properly. Nowadays people believe, In my soul I can be as bad as I want to be, but I can engage in thinking. Up to the fifteenth century, people did not believe that. They actually felt that it was a kind of insult to the divine cosmic intelligence to think about something while in an immoral soul condition. Hence, already in the act of thinking, they saw something real; in a manner of speaking, they viewed themselves as submerged with their soul in the overall cosmic intellect.

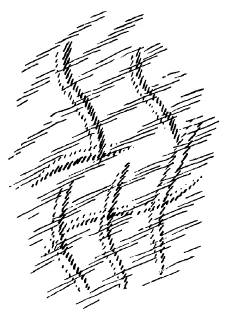

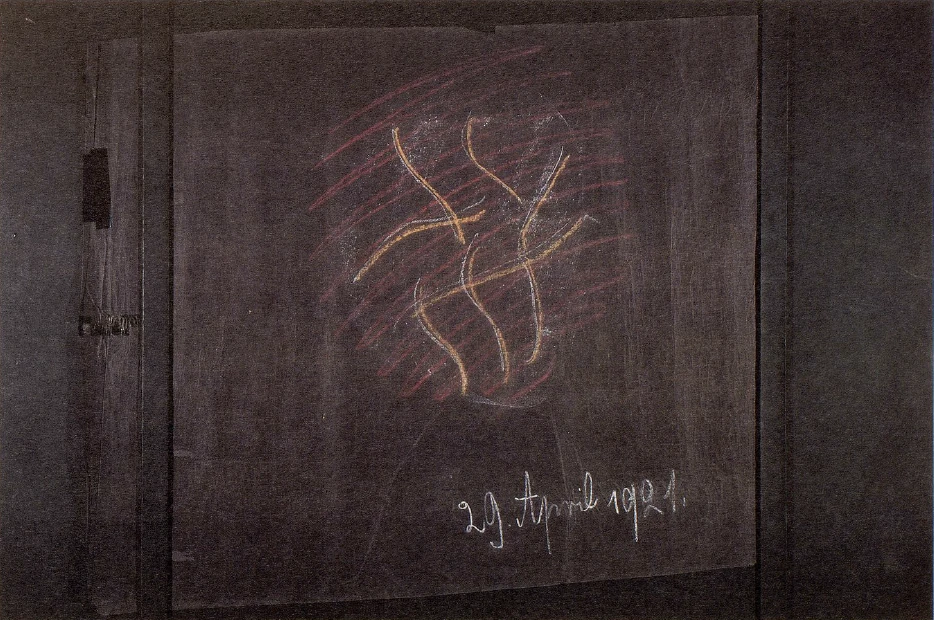

What was the reason for that? This came about because in this period from the eighth pre-Christian century to the fifteenth century A.D., and particularly in the fourth century, human beings predominantly employed their etheric body when they engaged in thinking. It was not that they decided to activate the ether body. But what they did sense—their whole soul mood—brought the etheric body into movement when thinking occurred. We can almost say: During that age, human beings thought with their etheric body. And the characteristic thing is that in the fifteenth century people began to think with their physical bodies. When we think, we do so with the forces the etheric body sends into the physical body. This is the great difference that becomes evident when we look at thinking before and after the fifteenth century. When we look at thinking prior to that time, it runs its course in the etheric body (see drawing, light-shaded crosshatching); in a sense, it gives the etheric body a certain structure. If we look at thinking now, it runs its course in the physical body (dark). Each such line of the ether body calls forth a replica of itself, and this replica is then found in the physical body.

Since that time, what occurs in human beings when they think is, as it were, an impression of the etheric activity as though of a seal on the physical body. The development from the fifteenth to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was mainly that human beings increasingly have taken their thinking out of the etheric body, that they adhere to this shadow image brought about in the physical body by the actual thought impulses originating in the etheric body. We therefore deal with the fact that in this fifth post-Atlantean epoch people really think with the physical body but that this is merely a shadow image of what was once cosmic thinking; hence, since that time, only a shadow image of cosmic thinking dwells in mankind.

You see, everything that has developed since the fifteenth century, all that developed as mathematics, as modern natural science and so on, is fundamentally a shadow image, a specter of former thinking; it no longer contains any life. People today actually have no idea of how much more alive an element thinking was in former times. In those ancient days, the human being actually felt refreshed while thinking. He was glad when he could think, for thinking was a refreshment of soul for him. In that age, the concept did not exist that thinking could also be something tiring. Human beings could become tired out by something else, but when they could truly think, they experienced this as a refreshment, an invigoration for the soul; when they could live in thoughts, they also experienced something of a sense of grace bestowed on them.

Now, this transition in the soul condition has occurred. In what appears as thinking in modern times, we are confronted with something shadowy. This is the reason for the difficulty in motivating a human being to any action through thinking—if I may put it like this. One can tell people all sorts of things based on thinking, but they will not feel inspired. Yet this is the very thing they must learn. Human beings must become aware of the fact that they possess shadow images in their current thinking. They have to realize that it must not be allowed to remain thus; that this shadow image, i.e. modern thinking, has to be enlivened so that it can turn into Imagination. It becomes evident, for example, in such books as my Theosophy or my An Outline of Occult Science that the attempt is always made to change modern thinking into Imagination, that pictures are driven everywhere into our thinking so that thinking can be aroused to Imagination, hence, to life. Otherwise, humanity would be laid waste completely. We can disseminate arid scholarliness far and wide, but this dry scholarliness will not become inflamed and rouse itself to will-filled action, if Imaginative life does not once more enter into this shadowy thinking, this ghost of thinking which has invaded mankind in recent times.

This is indeed the profound and fateful challenge for modern civilization, namely, that we should realize that, on the one hand, thinking tends to become a shadowy element into which human beings increasingly withdraw and that, on the other hand, what passes over into the will actually turns only into a form of surrender to human instincts. The less thinking is capable of taking in Imagination, the more will the full interest of what lives outside in society be abandoned to the instincts. Humanity of former times, at least in the epochs that bore the stamp of civilization—you have been able to deduce that from the previous lectures—possessed something, out of the whole human organism that was spiritual. Modern human beings only receive something spiritual from their heads; in regard to their will, they thus surrender to their impulses and instincts. The great danger is that human beings turn more and more into purely head-oriented creatures, that in regard to acting in the outer world out of their will, they abandon themselves to their instincts. This then naturally leads to the social conditions that are now spreading in the East of EuropeT1This is a reference to what was happening in Russia. and also infect us here everywhere. This comes about because thinking has become but a shadow image. One cannot stress these things often enough.

It is on the basis of precisely such profound insight that the significant strivings of anthroposophically oriented spiritual science will be understood. Its aim is the shadow image once again become a living being, so that something will be available again to mankind that can take hold of the whole human being. This, however, cannot take place if thinking remains a shadow image, if Imaginations do not enter into this thinking once more. Numbers, for example, will have to be imbued again with life in the way I outlined when I pointed to the sevenfold human being, who is actually a nine-membered being, where the second and the third, the sixth and the seventh parts unite in such a way as to become in each case a unity, and where seven is arrived at when one sums up the nine parts. It is this inner involvement of what was once bestowed on man from within that must be striven for. We have to take very seriously what is characterized in this regard by anthroposophically oriented spiritual science.

From a different direction, an awareness came about of the fact that thinking is becoming shadow like; for that reason, a method was created in Jesuitism that from a certain aspect, brings life into this thinking. The Jesuit exercises are designed to bring life into this thinking. But they accomplish this by renewing an ancient form of life, above all, not by moving in the direction of and working through Imagination, but through the will, which particularly in Jesuit exercises plays an important role. We should realize—yet realize it far too little—how in a community such as the Jesuit order all aspects of the life of soul become something radically different from what is true of ordinary people. Basically, all other human beings of the present possess a different condition of soul than those who become Jesuits. The Jesuits work out of a world will; that cannot be denied. Consequently, they are aware of certain existing interrelationships; at most, such interrelationships are noticed also by some other orders that in turn are fought tooth and nail by the Jesuits. But it is this significant element whereby reality enters into the shadowy thinking that turns a Jesuit into a different kind of person from the others in our modern civilization. These think merely in shadow images and therefore are actually asleep mentally, since thinking no longer takes hold of their organism and does not really permeate their nervous system.

Nobody, I believe, has ever seen a gifted Jesuit who is nervous, whereas those imbued with modern scholarliness and education increasingly suffer from nervousness. When do we become nervous? When the physical nerves make themselves felt. Something then makes itself felt that, from a physical standpoint, has no right at all to make itself felt, for it exists merely to transmit the spiritual. These matters are intimately connected with the wrongness of our modern education. And from a certain standpoint of imbuing thinking with life—a standpoint we must nevertheless definitely oppose—Jesuitism is something that goes along with the world, even though, like a crab, it goes backwards. But at least it moves, it does not stand still, whereas the form of science in vogue today basically does not comprehend the human being at all.

Here, I would like to draw your attention to something. I have already mentioned repeatedly that it is actually painful to witness again and again that modern human beings, who can think all sorts of things and are so very clever, do not stand in a living manner with a single fiber of their lives in the present age, that they do not see what is going on around them, indeed, that they are unaware of what is happening around them and do not wish to participate in it. That is different in the case of the Jesuit. The Jesuit who activates his whole being is well aware of what vibrates through the world today. As evidence, I would like to read to you a few lines from a current Jesuit pamphlet from which you can deduce what sort of life pulsates in it:

For all those who are serious about the fundamental Christian principles, those to whom the welfare of the people is truly a concern of the heart, whose soul was once profoundly touched by the words of the Savior, “Miseror super turbam,”T2Latin for “I have compassion on the crowd” (Matthew 15:32). for all those the time has now come when, borne by the ground swell of the Bolshevist storm tide, they can work with much greater success for the people and with the people. There is no room for timidity. Hence, as a matter of policy, we advocate the all out struggle against “capitalism,” against the exploitation of the people and profiteering at their expense, stricter emphasis on the duty to work even for the higher classes, the procurement of decent housing for millions of fellow citizens, even if such procurement necessitates making use of palaces and larger houses, utilization of natural resources and energy gained from water and air for the general welfare, not for trusts and syndicates, enhancement and education of the masses of people, participation by all segments of the people in government and administration, utilization of the concept of the system of soviets for the purpose of developing class representation having equal rights alongside parliamentary mass representation in order to prevent “the isolation of the masses from the state apparatus” as censured justifiably by Lenin ... God has given the goods of the earth to all human beings, not to a few so they can live on the fat of the land while millions languish in poverty, which is degrading both physically and morally ...1 “Bolshevism” in pamphlets of Stimmen der Zeit (“Voices of the Times”), 6, 3rd edition Freiburg i. Br., 1919 by Bernhard Duhr, S. J. (1852–1930), historian.

You see, this is the fiery mind that does sense something of what is happening. Here is a person who, in the rest of his book, sternly opposes Bolshevism and naturally wishes to have nothing to do with it. But, unlike somebody who has made himself comfortable in a chair today and is oblivious to the conflagration in the world all around him, he does not remain in such a position. Instead, he is aware of what is happening and knows what he wants because he sees what is going on.

People have gone so far as to merely think about the affairs of the world, and otherwise let things run their course. This is what has to be stressed again and again, namely, that the human being has more in him than mere thoughts with which to think about things while really not paying attention to the world's essential nature. As an example we need only indicate the Theosophical Society. It points to the great initiates who exist somewhere, and indeed, it can do so with justification. But it is not a matter of the initiates' existence; what is important is the manner in which those who refer to them speak of them. Theosophists imagine that the great initiates rule the world; in turn, they themselves sit down and produce good thoughts, which they let stream out in all directions. Then they talk of world rule, of world epochs, of world impulses. However, when the point is reached where something real, such as anthroposophy, has to live within the actual course of world events because it could not be otherwise, people find that uncomfortable since then they cannot really remain sitting on their chairs but have to experience what goes on in the world.

It must be strongly emphasized that the intellect has turned into a shadow in humanity, that it was earlier experienced in the etheric body and has now slipped, so to speak, into the physical body where it leads only a subjective existence. However, it can be brought to life through Imagination. Then it leads to the consciousness soul, and this consciousness soul can be grasped as a reality only when it senses the ego descends out of soul-spiritual worlds into incarnation and then passes through the gate of death into soul-spiritual worlds. When this inner soul-spiritual nature of the ego is comprehended, then the shadow image of the intellect can in fact be filled with reality. For it is through the ego that this has to be accomplished.

It is necessary to realize that living thinking exists. For what is it that people know since the fifteenth century? They know only logical thinking, not living thinking. This, too, I have pointed out repeatedly. What is living thinking? I shall take an example close at hand. In 1892, I wrote the The Philosophy of Freedom. This book has a certain content. In 1903, I wrote Theosophy; again, it has a certain content. In Theosophy, mention is made of the etheric body, the astral body, and so on. In Philosophy of Freedom, there is no mention of that. Now those who are only familiar with the logical, dead thinking come and say, Yes, I read the Philosophy of Freedom; from it, I cannot extract any concept of the etheric and astral body; it is impossible; I cannot find these concepts from the concepts contained in the book. But this is the same as if I were to take a small, five-year-old boy and fashioned him into a man of sixty by pulling him upwards and sideways to make him taller and wider!

I cannot put a mechanical, lifeless process in place of something living. But picture the Philosophy of Freedom as something alive—which indeed it is—and then imagine it growing. From it, then develops what only a person who tries to cull or pick out something from concepts will not figure out. All objections concerning contradictions are based on just this, namely, that people cannot understand the nature of living thinking as opposed to the dead thinking that dominates the whole world and all of civilization today. In the world of living things, everything develops from within, A formerly black-haired person who has white hair has acquired the latter not because the hair has been painted white; it has turned white from within. Things that grow and wane develop from within, and so it is also in the case of living thinking. Yet, today, people sit down and merely try to form conclusions, try to sense outward logic. What is logic? Logic is the anatomy of thinking, and one studies anatomy by means of corpses. Logic is acquired through the study of the corpse of thinking. It is certainly justified to study anatomy by means of corpses. It is just as justified to study logic through the corpses of thinking. But one will never comprehend life by means of what has been observed on the corpse!

This is what is important today and what really matters if we wish with all our soul to take part in a living way in what actually permeates and weaves through the world. This side of the matter has to be pointed out again and again, because insofar as the positive world development and evolution of mankind are concerned, we need to invigorate a thinking that has become shadowy. This process of thinking becoming shadow-like reached its culmination in the middle of the nineteenth. century. For that reason, the things that, so to say, beguiled humanity most of them fall into that period. Although in themselves these things were not great, if placed in the right location, they appear great.

Take the end of the 1850's. Darwin's Origin of the Species,2 Charles Darwin, 1809–1882, natural scientist. Karl Marx's The Principles of Political Economy,3 Karl Marx, 1818–1883. as well as Psycho-Physics by Gustav Theodor Fechner,4 Gustav Theodor Fechner, 180–1887, natural scientist and philosopher. a work in which the attempt is made to discover the psychic sphere by means of outward experiments, were published then. In the same year, the captivating discovery of spectral analysis by Kirchhoff5 Gustav Robert Kirchhoff, 1824–1887, physicist. and Bunsen6 Robert Wilhelm Bunsen, 1811–1899, chemist. is introduced; it demonstrates, as it were, that wherever one looks in the universe the same materiality is discovered. It is as if everything were being done in the middle of the nineteenth century to beguile human beings into believing that thinking must remain subjective and shadow-like, that it must not interfere in the world outside so that they could not possibly imagine that there might be reason, nous, in the cosmos, something that lives in the cosmos itself.

This is what caused this second half of the nineteenth century to be so unphilosophical. Basically, this is also what made it so devoid of deeds. This is what caused the economic relationships to become more and more complicated while commerce became enlarged into a world economy so that the whole earth in fact turned into one economic sphere, and particularly this shadow-like thinking was unable to grasp the increasingly complex and overwhelming reality. This is the tragedy of our modern age. The economic conditions have become more and more complex, weighty, and increasingly brutal; human thinking remained shadowy, and these shadows certainly could no longer penetrate into what goes on outside in the brutal economic reality.

This is what causes our present misery. Unfortunately, if a person actually believes that he is more delicately organized and has need of the spirit, he may possibly get into the habit of making a long face, of speaking in a falsetto voice and of talking about the fact that he has to elevate himself from brutal reality, since the spiritual basically can be grasped only in the mystical realm. Thinking has become so refined that it has to withdraw from reality, that it perishes right away in its shadowy existence if it tries to penetrate brutal reality. Reality in the meantime develops below in conformity with the instincts; it proliferates and brutalizes. Up above, we see the bloated ideas of mysticism, of world views and theosophies floating about; below, life brutally takes its course. This is something that must stop for the sake of mankind. Thinking must be enlivened; thought has to become so powerful that it need not withdraw from brutal reality but can enter into it, can live in it as spirit. Then reality will no longer be brutal. This has to be understood.

What is not yet understood in many different respects is that a thinking in which universal being dwells cannot but pour its force over everything. This should be something that goes without saying. But it appears as a sacrilege to this modern thinking if a form of thinking appears on the scene that cannot help but extend to all different areas. A properly serious attitude in life should be comprised of the realization: In thinking, we have been dealing with a shadow image, and rightly so, but the age has now arrived when life must be brought once again into this shadow image of thought in order that from this form of thought life, from this inner life of soul, the outer physical, sensory life can receive its social stimulus.

Tomorrow, we shall continue with this.

Zehnter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Wir haben uns in dieser Zeit beschäftigt mit der europäischen Zivilisationsentwickelung, und wir werden den Versuch machen, einiges zu dem Gesagten hinzuzufügen, immer mit der Absicht, dadurch ein Verständnis desjenigen herbeizuführen, was in der Gegenwart in das menschliche Leben von den verschiedensten Seiten her hereinspielt und was zum Ergreifen der Gegenwartsaufgaben führt. Wenn Sie das einzelne menschliche Leben betrachten, so kann Ihnen das ja ein Bild geben von der Entwickelung der Menschheit. Allein Sie müssen natürlich dabei berücksichtigen, was wir mit Bezug auf die Unterschiede der individuellen menschlichen Entwickelung und der menschlichen oder menschheitlichen Gesamtentwickelung gesagt haben. Ich habe ja wiederholt darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß, während der einzelne Mensch immer älter und älter wird, sich für die Gesamtheit eigentlich die Sache so stellt, daß sie immer jünger und jünger wird, gewissermaßen heraufrückt zum Erleben jüngerer Abschnitte. Wenn wir aber berücksichtigen, daß also in dieser Beziehung gewissermaßen Leben der Gesamtheit und Leben des einzelnen individuellen Menschen polarisch entgegengesetzt sind, so können wir aber dann doch, wenigstens zur Verdeutlichung, davon sprechen, wie uns das einzelne menschliche Leben ein Bild sein kann von dem Leben der Gesamtmenschheit. Und betrachten wir dann so das Leben des einzelnen Menschen, so finden wir, daß in jedes Lebensalter gewissermaßen etwas ganz Bestimmtes als Summe von Erlebnissen hineingehört. Wir können nicht, sagen wir, einem sechsjährigen Kinde beibringen, was wir einem zwölfjährigen beibringen können, und wir können nicht voraussetzen, daß wiederum das zwölfjährige Kind mit demselben Verständnis denjenigen Dingen entgegenkommt, die erst der zwanzigjährige Mensch begreift. Der Mensch muß gewissermaßen hineinwachsen in das, was für seine einzelnen Lebensepochen das Angemessene ist. So ist es auch mit der Gesamtmenschheit. Es ist schon einmal so, daß diese einzelnen Kulturepochen, die wir aus der Erkenntnis der Menschheitsentwickelung heraus anzugeben haben - urindisches, urpersisches, ägyptisch-chaldäisches, griechisch-lateinisches Zeitalter und dann das Zeitalter, dem wir selbst angehören -, daß diese Zeitalter ganz gewisse Zwvilisationsinhalte haben, und daß die Gesamtmenschheit in diese Zivilisationsinhalte hineinwachsen muß. Aber so wie der einzelne Mensch gewissermaßen hinter sich selbst, hinter seinen Entwickelungsmöglichkeiten zurückbleiben kann, so können das auch gewisse Teile der Gesamtmenschheit. Das ist eine Erscheinung, welche durchaus berücksichtigt werden muß, namentlich in unserer Zeit berücksichtigt werden muß, weil ja die Menschheit jetzt einrückt in das Entwickelungsstadium der Freiheit und ihr es also selbst überlassen ist, sich hineinzufinden in das, was ihr für dieses und das nächste Zeitalter vorgesetzt ist. Es liegt gewissermaßen in der menschlichen Willkür, zurückzubleiben hinter dem, was ihr vorgesetzt ist. Dem einzelnen Menschen, wenn er zurückbleibt in bezug auf das, was ihm vorgesetzt ist, stehen gegenüber andere, die sich hineinfinden in ihre richtigen Entwickelungsinhalte; diese anderen schleppen ihn dann gewissermaßen mit sich. Aber es bedeutet das auch in gewissem Sinne ein ihm oftmals nicht gerade behagliches Schicksal, wenn er empfinden muß, wie er da in einem gewissen Sinne zurückbleibt hinter den anderen, die das entsprechende Entwickelungsziel erreichen.

[ 2 ] Es kann auch so im großen Menschenleben geschehen; es kann geschehen, daß einzelne Völker das Ziel erreichen, andere zurückbleiben. Die Ziele der verschiedenen Völker sind ja, wie wir gesehen haben, auch voneinander verschieden. Wenn nun irgendein Volk sein Ziel erreicht, andere hinter ihrem Ziel zurückbleiben, so geht erstens etwas verloren, was nur gerade durch dieses zurückbleibende Volk hätte erreicht werden können, andererseits aber wird das zurückbleibende Volk sehr vieles annehmen, was ihm eigentlich gar nicht angemessen ist, und was es, ich möchte sagen, nachahmend von anderen Völkern, die ihre Ziele erreichen, dann aufnimmt.

[ 3 ] Solche Dinge geschehen eben in der Menschheitsentwickelung; sie zu beachten, ist in der Gegenwart von ganz besonderer Bedeutung. Nun werden wir zunächst heute einiges zusammenfassen und von einem bestimmten Gesichtspunkte aus beleuchten, was uns ja bekannt ist von anderen Seiten her. Wir wissen: Die Zeit vom 8. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert bis zum 15. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert ist die Zeit der Entwickelung der Verstandes- oder Gemütsseele bei dem eigentlichen zivilisierten Teil der Menschheit. Diese Entwickelung der Verstandes- oder Gemütsseele beginnt im 8. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert in Südeuropa, in Vorderasien, und wir können es verfolgen, wenn wir auf die Anfänge der geschichtlichen Entwickelung des griechischen Volkes hinschauen. Das griechische Volk hat ja durch aus noch sehr viel von dem in sich, was man nennen kann Entwickelung der Empfindungsseele, die insbesondere angemessen war dem dritten nachatlantischen Zeitalter, dem ägyptisch-chaldäischen Zeitalter. Da war alles Entwickelung der Empfindungsseele. Da gab sich der Mensch den Eindrücken der Außenwelt hin und in den Eindrücken der Außenwelt empfing er zugleich alles dasjenige, was er dann als seine Erkenntnisse schätzte, was er in seine Willensimpulse übergehen ließ. Der ganze Mensch war gewissermaßen so, daß er sich fühlte als ein Glied des ganzen Kosmos. Er befragte die Sterne und ihre Bewegungen, wenn es sich darum handelte, was er tun solle und so weiter. Dieses Miterleben der Außenwelt, dieses Sehen von Geistigem in allen Einzelheiten der Außenwelt, das war ja dasjenige, was die Ägypter in dem Höhenzeitalter ihrer Kultur auszeichnete, was in Vorderasien lebte und was bei den Griechen eine gewisse Nachblüte hatte. Die älteren Griechen hatten ja durchaus diese freie Hingabe der Seele an die äußere Umgebung, und mit diesem freien Hingeben der Seele an die äußere Umgebung war eben verknüpft ein Wahrnehmen des Elementar-Geistigen in den äußeren Erscheinungen. Aber es entwickelte sich dann bei den Griechen dasjenige heraus, was die griechischen Philosophen «Nus» nennen, was ein allgemeiner Weltverstand ist und dann eigentlich überhaupt die Grundeigenschaft der menschlichen Seelenentwickelungen bis ins 15. Jahrhundert hinein geblieben ist, im 4. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert eine Art Höhepunkt erlebte und dann wieder abflutete. Aber diese ganze Entwickelung vom 8. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert bis zum 15. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert entwickelt eigentlich dasjenige, was Verstand ist. Wenn wir aber in diesem Zeitalter von «Verstand» sprechen, so müssen wir absehen von dem, was wir jetzt in unserem Zeitalter eigentlich als Verstand ansprechen. Für uns ist der Verstand etwas, was wir eigentlich nur in uns tragen, was wir in uns entwickeln und wodurch wir die Welt begreifen. So war es nicht bei den Griechen und so war es auch noch nicht im 11.,12., 13. Jahrhundert, wenn von Verstand gesprochen wurde. Der Verstand war ein Objektives, der Verstand war etwas, was die Welt erfüllte. Der Verstand ordnete die einzelnen Welterscheinungen. Man betrachtete die Welt und ihre Erscheinungen und sagte sich: Dasjenige, was eine Erscheinung auf die andere folgen läßt, was hineinstellt die einzelnen Erscheinungen in ein größeres Ganzes und so weiter, das macht der Weltverstand. - Dem menschlichen Kopfe sprach man nur zu, daß er teilnehme an diesem allgemeinen Weltverstand.

[ 4 ] Wenn wir heute vom Lichte sprechen, dann sagen wir, wenn wit moderne Physik und Physiologie treiben wollen: Das Licht ist in uns. Aber mit dem naiven Bewußtsein wird kein Mensch glauben, daß das Licht nur in seinem Kopfe ist. Ebensowenig wie das naive Bewußtsein von heute sagt: Da draußen ist es ganz finster, das Licht ist nur in meinem Kopfe -, ebensowenig sagte der Grieche oder sagte noch der Mensch des 11., 12. nachchristlichen Jahrhunderts: Der Verstand ist nur in meinem Kopfe. - Er sagte: Der Verstand ist draußen, er erfüllt die Welt, er ordnet da alles. Geradeso wie der Mensch sich bewußt wird des Lichtes durch seine Wahrnehmung, so sagte er sich, wird er sich bewußt des Verstandes. Der Verstand leuchtet gewissermaßen in ihm auf.

[ 5 ] Es war ein Wichtiges verbunden mit diesem Heraufkommen des Weltverstandes in der menschlichen Kulturentwickelung. Vorher, als die Kulturentwickelung im Zeichen der Empfindungsseele verlief, da sprach man nicht von einem solchen die ganze Welt übergreifenden Einheitsprinzip, da sprach man von Geistern der Pflanzen, von Geistern, welche die Tierwelt regulieren, von Geistern des Flüssigen, von Geistern der Luft und so weiter. Es war eine Vielheit von geistigen Wesenheiten, von denen man sprach. Nicht nur war es der Polytheismus, die Volksreligion, welche von dieser Vielheit sprach, sondern es war durchaus auch in denjenigen, die Eingeweihte waren, das Bewußtsein vorhanden, daß sie es mit einer wesenhaften Vielheit draußen zu tun haben. Dadurch, daß das Verstandeszeitalter heraufrückte, entwickelte sich eine Art von Monismus. Der Verstand wurde als ein einziger, die ganze Welt umfassender angesehen; und dadurch entwickelte sich auch eigentlich erst der monotheistische Charakter der Religion, der allerdings schon im dritten nachatlantischen Zeitalter seine Vorstufe hatte. Aber das, was wir wissenschaftlich festhalten sollen von diesem Zeitalter - vom 8. vorchristlichen bis zum 15. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert -, das ist schon die Tatsache, daß es das Zeitalter der Entwickelung des Weltverstandes ist, und daß man ganz anders über den Verstand dachte, als wir heute denken.

[ 6 ] Woher kommt es nun, daß man anders über den Verstand dachte? Man dachte anders über den Verstand aus dem Grunde, weil man auch, indem man verständig war, indem man durch den Verstand etwas zu begreifen suchte, anders fühlte. Der Mensch ging durch die Welt, er sah die Dinge an durch seine Sinne; aber er empfand gewissermaßen immer, wenn er nachdachte, einen gewissen Ruck. Es war etwa so, wenn er nachdachte, wie wenn er etwas von stärkeren Aufwachen empfinde, als er empfand im gewöhnlichen Wachen. Das Nachdenken war noch etwas, was man unterschieden empfand von dem gewöhnlichen Leben. Vor allen Dingen empfand man im Nachdenken noch, daß man da in etwas drinnensteht, was objektiv ist, was nicht bloß subjektiv ist. Daher war es auch, daß bis in das 15. Jahrhundert, und in der Nachwirkung noch bis in spätere Zeiten, die Menschen ein gewisses Gefühl hatten gegenüber dem tieferen Nachdenken über die Dinge, ein Gefühl, das der Mensch heute gar nicht mehr hat. Heute hat der Mensch gar nicht das Gefühl, daß das Nachdenken in einer gewissen Seelenverfassung vollbracht werden sollte. Bis in das 15. Jahrhundert hatte der Mensch das Gefühl, daß er eigentlich nur etwas Schlechtes bewirkt in der Welt, wenn er nicht gut ist und doch nachdenklich wird. Er machte sich gewissermaßen einen Vorwurf, wenn er als ein schlechter Mensch nachdachte. Das ist etwas, was man gar nicht mehr so richtig gründlich empfindet. Heute denken die Menschen: Ich kann schlecht sein, wie ich will, in meiner Seele, ich denke halt nach. Das haben die Menschen bis zum 15. Jahrhundert nicht getan. Die haben es eigentlich als eine Art Beleidigung des göttlichen Weltenverstandes empfunden, wenn sie in einer schlechten Seelenverfassung nachgedacht haben; sie haben also in dem Akte des Nachdenkens schon etwas Reales gesehen, sie haben sich darinnen gewissermaßen mit der Seele schwimmend gesehen in dem allgemeinen Weltenverstande. Woher kommt das?

[ 7 ] Das kommt davon her, daß die Menschen eigentlich in diesem Zeitalter vom 8. vorchristlichen bis zum 15. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert, insbesondere im 4. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert, ausgesprochen ihren Ätherleib verwendeten, wenn sie nachdachten. Nicht als ob sie sich sagten: Jetzt, jetzt bringe ich den Ätherleib in Tätigkeit. Aber dasjenige, was sie empfanden, die ganze Seelenstimmung, die brachte der Ätherleib in Bewegung, wenn gedacht wurde. Man kann geradezu sagen: Die Menschen dachten in diesem Zeitalter mit dem Ätherleib. - Und das ist das Charakteristische, daß im 15. Jahrhundert angefangen wird, mit dem physischen Leib zu denken. Wir denken mit den Kräften, die der Ätherleib in den physischen Leib hineinsendet, wenn wir denken. Das ist also der große Unterschied, der sich ergibt, wenn man das Denken vor dem 15. Jahrhundert und nach dem 15. Jahrhundert betrachtet. Wenn man das Denken vor dem 15. Jahrhundert betrachtet, dann verläuft es im Ätherleib (siehe Zeichnung, helle Schraffierung), gewissermaßen gibt es dem Ätherleib eine gewisse Struktur. Wenn man das Denken jetzt betrachtet, verläuft es im physischen Leib (dunkel). Jede solche Linie des Ätherleibes ruft ein Abbild von sich hervor, und dieses Abbild ist dann im physischen Leib; es ist also gewissermaßen ein Siegelabdruck der ätherischen Tätigkeit im physischen Leibe, was seit jener Zeit in der Menschheit vor sich geht, wenn gedacht wird. Das war im wesentlichen die Entwickelung vom 15. bis ins 19., 20. Jahrhundert herein, daß der Mensch immer mehr und mehr sein Denken herausgeholt hat aus dem Ätherleib und daß er sich hält an dieses Schattenbild, das er im physischen Leib erhält von dem eigentlichen Gedankenursprung im Ätherleib. Es ist also wirklich das vorhanden, daß in diesem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum eigentlich gedacht wird mit dem physischen Leib, daß aber im Grunde genommen das nur ein Schattenbild ist desjenigen, was das Weltendenken einstmals war, daß also seit jener Zeit in der Menschheit nur ein Schattenbild des Weltendenkens lebt.

[ 8 ] Sehen Sie, im Grunde genommen ist all das, was da entstanden ist seit dem 15. Jahrhundert, was sich ausgebildet hat als neuere Mathematik, als neuere Naturwissenschaft und so weiter, Schattenbild, Gespenst des früheren Denkens; es hat kein Leben mehr. Die Menschheit macht sich heute eigentlich keinen Begriff davon, ein ‚wieviel lebendigeres Element das Denken vorher war. Der Mensch fühlte sich im Denken zu gleicher Zeit erfrischt in jener älteren Zeit, er war froh, wenn er denken konnte, denn das Denken war ein Labetrunk der Seele für ihn. Daß das Denken etwa auch ermüden könne, das war keine Ansicht jener Zeiten. Es konnte der Mensch gewissermaßen durch etwas anderes ermüden; aber wenn er wirklich denken konnte, so fühlte er dies als eine Erfrischung, als einen Labetrunk der Seele, er fühlte auch immer etwas von Begnadung, die ihm wurde, wenn er in Gedanken leben konnte.

[ 9 ] Dieser Umschwung in der Seelenverfassung ist einmal geschehen, und wir haben heute in dem, was als Denken der neueren Zeit auftritt, ein durchaus Schattenhaftes. Daher auch die große Schwierigkeit, durch das Denken - wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf - den Menschen überhaupt in irgendeinen Schwung zu bringen. Vom Denken aus kann man ja zu dem modernen Menschen alles mögliche reden, aber er kommt nicht in Schwung. Dennoch ist es das, was er lernen muß. Der Mensch muß sich bewußt werden, daß er in seinem modernen Denken ein Schattenbild hat, und daß dieses Schattenbild nicht Schattenbild bleiben darf, daß dieses Schattenbild, das das moderne Denken ist, belebt werden muß, damit es Imagination werden kann. Es ist immer ein Versuch, das moderne Denken zur Imagination zu machen, was zum Beispiel zutage tritt in einem solchen Buch wie in meiner «Theosophie» oder wie in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß», wo eben überall in das Denken hinein die Bilder getrieben werden, damit das Denken zur Imagination, also wiederum zum Leben aufgerufen werde. Es würde sonst die Menschheit vollständig veröden. Wir könnten vertrocknete Gelehrsamkeit weit verbreiten, aber diese vertrocknete Gelehrsamkeit würde nicht zum Wollen sich aufraffen und nicht entflammen können, wenn in dieses schattenhafte Denken, in dieses Denkgespenst, das in der neueren Zeit eben in die Menschheit hereingekommen ist, nicht wiederum das imaginative Leben einziehen würde.

[ 10 ] Das ist ja, ich möchte sagen, die große Schicksalsfrage der neueren Zivilisation, daß eingesehen werde, wie das Denken auf der einen Seite tendiert, ein Schattenwesen zu werden, wie die Menschen immer mehr und mehr sich in dieses Denken zurückziehen, einkapseln, und wie daneben dasjenige, was ins Wollen übergeht, eigentlich bloß eine Art Auslieferung an die menschlichen Instinkte wird. Je weniger das Denken wird Imagination aufnehmen können, desto mehr wird das volle Interesse desjenigen, was im äußeren sozialen Leben lebt, in die Instinkte übergehen. Die ältere Menschheit, wenigstens in denjenigen Zeiten, welche die Zivilisation trugen, bekam - das haben Sie aus den letzten Vorträgen entnehmen können - aus ihrem ganzen Organismus heraus etwas, was geistig war. Der moderne Mensch bekommt nur aus seinem Kopfe etwas heraus, was geistig ist, daher überläßt er sich in bezug auf den Willen seinen Trieben, seinen Instinkten. Das ist die große Gefahr, daß die Menschen immer mehr und mehr bloße Kopfmenschen werden und in bezug auf das Wollen in der Außenwelt sich ihren Instinkten überlassen, was dann selbstverständlich zu den sozialen Zuständen führt, die jetzt im Osten Europas Platz greifen und auch bei uns infizierend Platz greifen allüberall. Dadurch, daß das Denken Schattenbild geworden ist, dadurch kommt das auf. Man kann nicht oft genug auf diese Dinge hinweisen. Gerade aus solchen Untergründen heraus wird man das Bedeutsame begreifen, was anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft eigentlich will. Sie will, daß das Schattenbild wiederum ein lebendiges Wesen werde, daß wiederum unter Menschen herumgehe das, was ergreift den ganzen Menschen. Das kann aber nicht geschehen, wenn dasDenken Schattenbild bleibt, wenn nicht die Imaginationen in dieses Denken wieder einziehen, wenn nicht zum Beispiel die Zahl so belebt wird, wie ich es gezeigt habe, indem ich hingewiesen habe auf den siebengliedrigen Menschen, der eigentlich ein neungliedriger ist, wobei aber immer zweites und drittes, und sechstes und siebentes Glied, sich so zusammenschließen, daß sie jeweils eine Einheit werden, so daß gewissermaßen sieben herauskommt, wenn man neun Glieder summiert. Dieses innere Eingreifen desjenigen, was einmal dem Menschen von innen gegeben war, das ist dasjenige, was angestrebt werden muß. In dieser Beziehung muß man recht ernst nehmen, was durch Geisteswissenschaft, anthroposophisch orientiert, gerade von dieser Seite her charakterisiert wird.

[ 11 ] Von anderer Seite her ist gesehen worden, wie das Denken schattenhaft wird, und daher ist im Jesuitenorden eine Methode geschaffen worden, welche von einer gewissen Seite her Leben in dieses Denken hineinbringt. Die jesuitischen Exerzitien gehen darauf hinaus, Leben in dieses Denken hineinzubringen. Aber sie tun es, indem sie altes Leben wiederum erneuern, indem sie vor allen Dingen nicht auf die Imagination hin und dutch die Imagination arbeiten, sondern durch den Willen arbeiten, der ja insbesondere in den jesuitischen Exerzitien eine große Rolle spielt. Die Menschheit der Gegenwart sollte begreifen und begreift viel zuwenig, wie in einer solchen Gemeinschaft, wie es die jesuitische ist, alles Seelenleben etwas radikal anderes wird, als es bei den anderen Menschen ist. Die anderen Menschen der Gegenwart sind alle im Grunde genommen in anderer Seelenverfassung als diejenigen, die Jesuiten werden. Die Jesuiten arbeiten aus einem Weltenwillen heraus, das ist nicht zu leugnen. Sie sehen daher gewisse Zusammenhänge, die da sind, und höchstens werden solche Zusammenhänge von manchen anderen Orden noch gesehen, die wiederum von den Jesuiten bis aufs Messer bekämpft werden. Aber dieses Bedeutungsvolle, wodurch Realität hineinkommt in das schattenhafte Denken, das ist es, was den Jesuiten zu einem Menschen anderer Art macht, als es die modernen Zivilisationsmenschen sind, die überhaupt nurmehr in Schattenbildern denken und daher im Grunde genommen schlafen, weil das Denken nicht ergreift ihren Organismus, weil es nicht vibriert in ihrem Blute, weil es nicht eigentlich wirklich durchflutet ihr Nervensystem.

[ 12 ] Noch niemals wird jemand, wie ich glaube, einen begabten Jesuiten nervös gesehen haben, währenddem die moderne Gelehrsamkeit und die moderne Bildung immer mehr nervös werden. Wann wird man nervös? Wenn die physischen Nerven sich geltend machen. Dann macht sich etwas geltend, was eigentlich physisch gar keine Berechtigung hat, sich geltend zu machen, weil es bloß da ist, um das Geistige durchzuleiten. Diese Sachen hängen innig zusammen mit der Verkehrtheit unseres modernen Bildungswesens, und der Jesuitismus ist gewiß von einem Standpunkte aus, den wir entschieden bekämpfen müssen, aber eben von einem Standpunkte des Belebens des Denkens aus, etwas, was mit der Welt geht, wenn es auch wie ein Krebs zurückgeht. Aber es geht, es steht nicht still, während unsere Wissenschaft, wie sie heute gang und gäbe ist, im Grunde genommen den Menschen gar nicht ergreift.

[ 13 ] Wenn ich Sie da auf etwas hinweisen darf, so muß ich sagen: Ich habe ja schon öfters zum Ausdrucke gebracht, wie es einem eigentlich fortwährend immer wieder und wiederum Schmerz bereitet, daß dieser moderne Mensch, der ja alles mögliche denken kann, der so furchtbar gescheit ist, aber doch mit keiner Faser seines Lebens auch lebendig drinnensteht in der Gegenwart, nicht sieht, was um ihn herum vorgeht; er sieht es ja nicht, was um ihn herum vorgeht, er will nicht mitmachen. Das ist beim Jesuiten anders. Der Jesuit, der den vollen Menschen in Regsamkeit bringt, der sieht, was heute durch die Welt vibriert. Dafür möchte ich ein paar Worte aus einer Jesuitenflugschrift der Gegenwart vorlesen, aus der Sie sehen, was darinnen für ein Leben pulsiert:

<[ 14 ] «Für alle diejenigen, die es mit den christlichen Grundsätzen ernst nehmen, denen das Volkswohl wirklich Herzenssache ist, denen das Heilandswort ‹Misereor super turbam› einmal tief in die Seele gedrungen, für diese alle ist jetzt die Zeit gekommen, wo sie getragen von den Grundwellen der bolschewistischen Sturmflut, mit viel größerem Erfolg mit dem Volk und für das Volk arbeiten können. Und da nur nicht zu zaghaft sein. Also grundsätzliche und allseitige Bekämpfung des «Kapitalismus, der Ausbeutung und Auswucherung des Volkes, schärfere Betonung der Arbeitspflicht auch für die höheren Stände, Beschaffung menschenwürdiger Wohnungen für Millionen von Volksgenossen, auch wenn diese Beschaffung Inanspruchnahme der Paläste und größeren Wohnungen erfordert, Ausnutzung der Bodenschätze, Wasser- und Luftkräfte nicht für Trusts und Syndikate, sondern für das Gemeinwohl, Hebung und Bildung der Volksmassen, Beteiligung aller Volkskreise an Staatsverwaltung und Staatsleitung, Benutzung der Idee des Rätesystems zum Ausbau einer neben der parlamentarischen Massenvetretung einhergehenden und gleichberechtigten Ständevertretung, um die von Lenin mit Recht gerügte «Isolierung der Massen vom Staatsapparat» zu verhindern. ... Gott hat die Güter der Erde für alle Menschen gegeben, nicht daß einzelne in üppigem Überfluß schwelgen, Millionen aber in einer physisch und moralisch gleich verderblichen Armut schmachten. ...»

[ 15 ] Sehen Sie, das ist das Feuer, das allerdings etwas spürt von dem, was vorgeht. Das ist ein Mensch, der in seinem übrigen Buche den Bolschewismus streng bekämpft, der natürlich vom Bolschewismus nichts wissen will, der aber nicht sitzt wie irgend jemand, der heute sich schön auf einen Stuhl niedergelassen hat und ringsherum das Feuer der Welt nicht merkt, sondern der es merkt und der weiß, was er will, weil er sieht.

[ 16 ] Die Menschen haben es dazu gebracht, über die Dinge der Welt bloß nachzudenken und sie im übrigen laufen zu lassen, wie sie laufen. Das ist es, worauf man immer wieder hinweisen muß, daß der Mensch noch etwas anderes in sich hat als bloße Gedanken, durch die man eben nachdenkt, und sich nicht kümmert eigentlich um das Wesen der Welt. Da braucht man ja bloß hinzuweisen auf das, was zum Beispiel die Theosophische Gesellschaft ist. Die Theosophische Gesellschaft weist hin auf die großen Eingeweihten, die irgendwo sitzen; gewiß, das kann sie mit Recht. Aber es handelt sich nicht darum, daß die da sitzen, sondern es handelt sich darum, wie diejenigen, die von ihnen reden, auf sie hinweisen. Die Theosophen stellen sich vor, die großen Eingeweihten regieren die Welt; dann setzen sie sich selber nieder und haben gute Gedanken, die sie überallhin ausströmen lassen, und dann reden sie von Weltregierung, reden von Weltepochen, von Weltimpulsen. Wenn es aber wirklich einmal dahin kommt, daß eine reale Sache, wie Anthroposophie es ist, notwendigerweise, weil es nicht anders sein kann, drinnen leben muß im realen Gang der Welt, dann findet man das ungemütlich, weil man eigentlich dann nicht mehr auf dem Stuhl sitzenbleiben könnte, sondern miterleben müßte das, was in der Welt vorgeht.

[ 17 ] Scharf muß betont werden, wie das, was Verstand ist, in den Menschen geworden ist zum Schatten, weil es früher erlebt worden ist im ätherischen Leib und jetzt gewissermaßen hinuntergerutscht ist in den physischen Leib und da nur ein subjektives Dasein führt. Aber es kann durch die Imagination lebendig gemacht werden. Dann führt es zur Bewußtseinsseele, und diese Bewußtseinsseele kann nur als ein Reales erfaßt werden, wenn sie das Ich als das Ewige in sich fühlt, und wenn durchschaut wird, wie dieses Ich heruntersteigt zur Verkörperung aus geistig-seelischen Welten, wie es durch die Todespforte wiederum in geistig-seelische Welten geht. Wenn diese innerliche geistig-seelische Wesenheit des Ichs ergriffen wird, dann kann tatsächlich das Schattenbild des Verstandes mit Realität erfüllt werden. Denn vom Ich aus muß dieses Schattenbild des Verstandes mit Realität erfüllt werden.

[ 18 ] Es ist notwendig, daß gesehen werde, wie es ein lebendiges Denken gibt. Denn was kennt denn der Mensch seit dem 15. Jahrhundert? — Er kennt ja bloß das logische Denken, er kennt nicht das lebendige Denken. Auch darauf habe ich wiederholt aufmerksam gemacht. Was ist lebendiges Denken? - Ich will ein naheliegendes Beispiel nehmen. Ich habe 1892 die «Philosophie der Freiheit» geschrieben. Diese «Philosophie der Freiheit» hat einen bestimmten Inhalt. Ich habe 1903 geschrieben die «Theosophie», die hat wieder einen bestimmten Inhalt. In der «Theosophie» ist die Rede vom Ätherleib, Astralleib und so weiter. Davon ist in der «Philosophie der Freiheit» nicht die Rede. Da kommen nun diejenigen Menschen, die bloß das logisch Tote kennen, bloß den Leichnam des Denkens kennen, und sagen: Ja, ich lese die «Philosophie der Freiheit», ich kann aus ihr heraus keinen Begriff «herausmutzeln», keinen Begriff herausnehmen vom Ätherleib, Astralleib; das geht nicht, das bekomme ich nicht heraus aus den Begriffen, die dort sind. - Aber das wäre ja derselbe Vorgang, wie wenn ich einen kleinen fünfjährigen Knaben hätte und möchte einen Mann von sechzig Jahren aus ihm machen, und ich nehme ihn und ziehe ihn in die Höhe und möchte ihn in der Breite ausdehnen! Ich darf da nicht einen mechanisch-leblosen Vorgang an die Stelle des Lebendigen setzen. Aber stellen Sie sich die «Philosophie der Freiheit» als etwas Lebendiges vor, was sie wirklich ist, stellen Sie sich vor, daß sie wächst; dann wächst aus ihr das heraus, was nur derjenige, der aus den Begriffen etwas «herausmutzeln» will, nicht herausbekommt. Darauf beruhen eben alle die Einwände von Widersprüchen: daß man nicht verstehen kann, was lebendiges Denken ist, im Gegensatz zu dem toten Denken, das heute die ganze Welt, die ganze Zivilisation beherrscht. In der Welt des Lebendigen entwickeln sich die Dinge von innen heraus. Derjenige, der weiße Haare hat, der hat sie, wenn er früher schwarze gehabt hat, nicht dadurch bekommen, daß sie ihm weiß angestrichen worden sind, sondern er hat sie von innen heraus bekommen. Das Aufundabsteigende entwickelt sich von innen heraus, und so ist es auch mit dem lebendigen Denken. Heute aber setzt man sich hin und will bloß Konklusionen entwickeln, will bloß äußerliche Logik empfinden. Was ist Logik? - Logik ist Anatomie des Denkens, und Anatomie studiert man an Leichnamen, und Logik ist am Leichnam des Denkens studiert. Es ist ja gewiß berechtigt, Anatomie an den Leichnamen zu studieren. Ebenso berechtigt ist es, Logik an Leichnamen des Denkens zu studieren! Aber niemals kann man mit dem, was am Leichnam studiert ist, das Leben begreifen. Das ist dasjenige, worauf es ankommt, worauf es wirklich ankommt, wenn man heute lebendig Anteil nehmen will mit ganzer Seele an dem, was durch die Welt eigentlich wallt und webt. Man muß schon immer wiederum auf diese Seite der Sache hinweisen, weil wir im Sinne der guten Weltentwickelung, im Sinne der guten Merischenentwickelung eine Belebung brauchen des schattenhaft gewordenen Denkens. Dieses Schattenhaftwerden des Denkens, das hat seinen Höhepunkt in der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts erlebt. Daher fallen in diese Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts gerade diejenigen Dinge, welche, ich möchte sagen, die Menschheit am meisten berückt haben. Wenn auch diese Dinge als solche nicht groß gewesen sind: wenn sie an den richtigen Platz gestellt werden, erscheinen sie groß.

[ 19 ] Nehmen wir das Ende der fünfziger Jahre. Da erscheinen Darwins «Entstehung der Arten», Karl Marx «Die Prinzipien der politischen Ökonomie» sowie die «Psycho-Physik» von Gustav Theodor Fechner, in der versucht wird, das Psychische, das Seelische durch das äußere Experiment aufzudecken. In demselben Jahre wird der Menschheit die berückende Entdeckung der Kirchhoff- und Bunsenschen Spektralanalyse vorgeführt, wodurch gewissermaßen gezeigt wird, daß, wo man hinschauen mag im Weltenall, man dieselbe Stofflichkeit findet. Es wird gewissermaßen alles getan in dieser Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts, um die Menschen darin zu berücken, daß das Denken hier schon subjektiv zu bleiben hat, eben schattenhaft zu bleiben hat und ja nicht eingreifen darf in das Äußere, so daß man sich gar nicht vorstellen darf, daß in der Welt Verstand, Nus, irgend etwas im Kosmos selber Lebendes sei.

[ 20 ] Das ist es, was diese zweite Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts so unphilosophisch, aber auch im Grunde genommen so tatenlos machte und was bewirkte, daß während die wirtschaftlichen Verhältnisse immer komplizierter und komplizierter wurden, der Welthandel sich zur Weltwirtschaft ausdehnte, so daß tatsächlich die ganze Erde ein Wirtschaftsgebiet wurde, daß gerade dieses schattenhafte Denken die immer wuchtigere Wirklichkeit nicht erfassen konnte. Das ist die Tragik des allermodernsten Zeitalters. Die wirtschaftlichen Verhältnisse sind immer wuchtiger und wuchtiger, immer brutaler und brutaler geworden, das menschliche Denken blieb schattenhaft, und die Schatten konnten schon gar nicht mehr eindringen in das, was sich äußerlich in der brutalen wirtschaftlichen Wirklichkeit abspielte.

[ 21 ] Das ist es, was unsere gegenwärtige Misere ausmacht. Wenn ein Mensch nun wirklich einmal glaubt, feiner organisiert zu sein und Bedürfnis zu haben nach dem Geistigen, dann gewöhnt er sich womöglich an, ein langes Gesicht zu machen, in Fistelstimme zu sprechen und davon zu reden, wie man sich erheben müsse von der brutalen Wirklichkeit, denn nur im Mystischen könne im Grunde genommen das Geistige erfaßt werden. Das Denken ist so fein geworden, daß es weggehen muß von der Wirklichkeit, daß es in seinem Schattendasein ja gleich zugrunde geht, wenn es eindringen will in die brutale Wirklichkeit. Die Wirklichkeit entwickelt sich nach den Instinkten darunter, die wuchtet und brutalisiert. Wir sehen oben die fetten Eier der Mystiken und Weltanschauungen und Theosophien schwimmen und unten das Leben brutal ablaufen. Das ist etwas, was zum Heile der Menschheit eben aufhören muß. Das Denken muß belebt werden, und der Gedanke muß so mächtig werden, daß er sich nicht zurückzuziehen braucht vor der brutalen Wirklichkeit, sondern daß er in diese brutale Wirklichkeit untertauchen kann, leben kann als Geist in dieser brutalen Wirklichkeit; dann wird die Wirklichkeit nicht mehr brutal sein. Das muß man verstehen.

[ 22 ] Was nach allen möglichen Richtungen hin nicht verstanden wird, das ist, daß das Denken, wenn darinnen das Weltenwesen lebt, gar nicht anders sein kann, als daß es seine Kraft ausgießt über alles mögliche. Das ist doch eigentlich etwas ganz Selbstverständliches. Aber diesem modernen Denken gilt es als Sakrileg, wenn nur einmal auftritt so etwas wie ein Denken, das gar nicht anders kann, als seine Fäden zu ziehen nach den verschiedenen Gebieten hin. Was den Ernst des Lebens heute ausmachen soll, das ist, daß eingesehen werden soll: Wir haben in dem Denken, und zwar mit Recht, ein Schattenbild gehabt; es ist aber das Zeitalter angekommen, das in dieses Denk-Schattenbild hinein Leben bringen muß, damit von diesem Denk-Leben, von diesem inneren seelischen Leben das äußere physisch-sinnliche Leben seine soziale Anregung erhalten kann.

[ 23 ] Davon wollen wir dann morgen weiterreden.

Tenth lecture

[ 1 ] During this time, we have been dealing with the development of European civilization, and we will attempt to add a few things to what has been said, always with the intention of bringing about an understanding of what is influencing human life from various sides in the present and what leads to the grasping of the tasks of the present. If you consider the individual human life, this can give you a picture of the development of humanity. But of course you must take into account what we have said about the differences between individual human development and the overall development of humanity. I have repeatedly pointed out that while the individual human being grows older and older, the situation for the whole is actually such that it becomes younger and younger, in a sense moving up to experience younger stages. But if we take into account that, in this respect, the life of the whole and the life of the individual human being are, in a sense, polar opposites, we can then, at least for the sake of clarification, speak of how the individual human life can be a picture of the life of the whole of humanity. And when we look at the life of the individual human being in this way, we find that at every age of life there is, as it were, something very specific that belongs to it as the sum of experiences. We cannot, for example, teach a six-year-old child what we can teach a twelve-year-old, and we cannot assume that the twelve-year-old will have the same understanding of things that a twenty-year-old will have. Human beings must, in a sense, grow into what is appropriate for the individual stages of their lives. The same is true of humanity as a whole. It is already the case that these individual cultural epochs, which we can identify from our knowledge of human development—the ancient Indian, ancient Persian, Egyptian-Chaldean, Greek-Latin epochs, and then the epoch to which we ourselves belong — that these epochs have very specific civilizational content, and that humanity as a whole must grow into this civilizational content. But just as the individual human being can, in a sense, lag behind himself, behind his potential for development, so can certain parts of humanity as a whole. This is a phenomenon that must be taken into account, especially in our time, because humanity is now entering the stage of development of freedom and it is therefore up to humanity itself to find its way into what is set before it for this and the next age. It is, in a sense, up to human will to lag behind what is set before it. When an individual falls behind in relation to what is set before him, he is confronted by others who are finding their way into their proper stage of development; these others then carry him along with them, so to speak. But in a certain sense, this also means that he often has to endure an uncomfortable fate when he feels that he is lagging behind the others who are reaching the corresponding goal of development.

[ 2 ] This can also happen in the great life of humanity; it can happen that individual peoples reach the goal while others lag behind. As we have seen, the goals of different peoples are also different from one another. When one people reaches its goal and others lag behind, something is lost that could only have been achieved by the lagging people. On the other hand, the lagging people will adopt many things that are not really appropriate for them and which they imitate from other peoples who have reached their goals.

[ 3 ] Such things happen in the development of humanity; it is particularly important to bear them in mind at the present time. Now we will first summarize a few things and examine them from a certain point of view, which we are familiar with from other sources. We know that the period from the 8th century BC to the 15th century AD is the time of the development of the intellectual or emotional soul in the truly civilized part of humanity. This development of the intellectual or emotional soul began in the 8th century BC in Southern Europe and the Near East, and we can trace it if we look at the beginnings of the historical development of the Greek people. The Greek people still had a great deal of what can be called the development of the sentient soul, which was particularly appropriate for the third post-Atlantean age, the Egyptian-Chaldean age. Everything there was development of the sentient soul. Man surrendered himself to the impressions of the outer world, and in the impressions of the outer world he received at the same time everything that he then valued as his knowledge, which he allowed to pass into his will impulses. The whole human being was, in a sense, such that he felt himself to be a member of the whole cosmos. He consulted the stars and their movements when it came to what he should do and so on. This experience of the outer world, this seeing of the spiritual in all the details of the outer world, was what distinguished the Egyptians in the heyday of their culture, what lived in the Near East, and what had a certain revival among the Greeks. The older Greeks certainly had this free devotion of the soul to the external environment, and linked to this free devotion of the soul to the external environment was a perception of the elemental spiritual in external phenomena. But then the Greeks developed what the Greek philosophers call “nus,” which is a general understanding of the world and actually remained the fundamental characteristic of human soul development until the 15th century, reaching a kind of peak in the 4th century AD and then ebbing away again. But this entire development from the 8th century BC to the 15th century AD actually developed what is called the intellect. However, when we speak of the intellect in this age, we must disregard what we actually refer to as the intellect in our age. For us, the intellect is something we actually carry within us, something we develop within ourselves and through which we comprehend the world. This was not the case with the Greeks, nor was it the case in the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries when people spoke of the intellect. The intellect was something objective; the intellect was something that filled the world. The mind organized the individual phenomena of the world. People looked at the world and its phenomena and said to themselves: That which causes one phenomenon to follow another, which places the individual phenomena into a larger whole, and so on, is the world mind. The human mind was only said to participate in this general world mind.

[ 4 ] When we speak of light today, when we want to engage in modern physics and physiology, we say: Light is within us. But with naive consciousness, no one will believe that light is only in their head. Just as the naive consciousness of today does not say, “It is completely dark outside; light is only in my head,” neither did the Greeks or the people of the 11th and 12th centuries AD say, “The intellect is only in my head.” They said, “The intellect is outside; it fills the world; it orders everything there.” Just as man becomes conscious of light through his perception, so he said to himself, he becomes conscious of the intellect. The intellect shines within him, as it were.

[ 5 ] There was something important connected with this emergence of the world intellect in human cultural development. Previously, when cultural development was dominated by the sentient soul, people did not speak of such a unifying principle encompassing the whole world; they spoke of plant spirits, spirits that regulate the animal world, spirits of liquids, spirits of the air, and so on. There was a multitude of spiritual beings about which people spoke. It was not only polytheism, the religion of the people, that spoke of this multiplicity, but even those who were initiated were well aware that they were dealing with an essential multiplicity outside themselves. With the advent of the age of reason, a kind of monism developed. The mind came to be regarded as a single entity encompassing the whole world, and this was what actually gave rise to the monotheistic character of religion, which had already had its precursors in the third post-Atlantean age. But what we should scientifically note about this age—from the eighth century BC to the fifteenth century AD—is that it was the age of the development of world reason, and that people thought about reason in a completely different way than we do today.

[ 6 ] Where did this different way of thinking about the intellect come from? People thought differently about the intellect because, in being intelligent, in seeking to understand something through the intellect, they also felt differently. Man went through the world, he saw things through his senses; but when he thought, he always felt, as it were, a certain jolt. When he thought, it was as if he felt something stronger than what he felt in his ordinary waking state. Thinking was still something that was felt as distinct from ordinary life. Above all, when thinking, one still felt that one was standing inside something that was objective, not merely subjective. That is why, until the 15th century, and in its aftermath even into later times, people had a certain feeling toward deeper thinking about things, a feeling that people today no longer have at all. Today, people do not have the feeling that reflection should be accomplished in a certain state of mind. Until the 15th century, people had the feeling that they were actually only doing something bad in the world if they were not good and yet became thoughtful. They reproached themselves, as it were, if they thought as a bad person. This is something that is no longer really felt so deeply. Today, people think: I can be as bad as I want in my soul, I'm just thinking. People did not do that until the 15th century. They actually felt it was a kind of insult to the divine understanding of the world if they thought while in a bad state of mind; they saw something real in the act of thinking, they saw themselves, as it were, floating with their souls in the general understanding of the world. Where does that come from?

[ 7 ] This comes from the fact that people in this era, from the 8th century BC to the 15th century AD, especially in the 4th century AD, made pronounced use of their etheric body when they thought. It was not as if they said to themselves: Now, now I am activating my etheric body. But what they felt, the whole mood of the soul, was set in motion by the etheric body when they thought. One can say that in this age, people thought with their etheric body. And it is characteristic that in the 15th century, people began to think with their physical body. We think with the forces that the etheric body sends into the physical body when we think. This is the great difference that arises when we consider thinking before the 15th century and after the 15th century. When we consider thinking before the 15th century, it takes place in the etheric body (see drawing, light hatching), giving the etheric body a certain structure, so to speak. If we now consider thinking, it takes place in the physical body (dark). Each line of the etheric body produces an image of itself, and this image is then in the physical body; it is, so to speak, a seal impression of the etheric activity in the physical body, which has been going on in humanity since that time when thinking began. This was essentially the development from the 15th to the 19th and 20th centuries, that human beings increasingly brought their thinking out of the etheric body and clung to this shadow image, which they receive in the physical body from the actual source of thought in the etheric body. So it is really the case that in this fifth post-Atlantean period, thinking actually takes place with the physical body, but that this is basically only a shadow image of what world thinking once was, so that since that time only a shadow image of world thinking has lived in humanity.

[ 8 ] You see, basically everything that has come into being since the 15th century, everything that has developed as modern mathematics, modern natural science, and so on, is a shadow image, a ghost of earlier thinking; it no longer has any life. Humanity today has no idea how much more alive thinking used to be. In those older times, people felt refreshed when they thought; they were happy when they could think, because thinking was a balm for the soul. The idea that thinking could also be tiring was not a view held in those days. Man could, in a sense, tire of something else; but when he was truly able to think, he felt this as a refreshment, as a drink for the soul, and he always felt something of the blessing that came to him when he was able to live in his thoughts.

[ 9 ] This change in the state of mind happened once, and today we find something quite shadowy in what appears to be the thinking of modern times. Hence the great difficulty of using thinking—if I may express myself thus—to get people moving at all. From thinking, one can say all sorts of things to modern man, but he does not get into motion. Nevertheless, this is what he must learn. Man must become aware that he has a shadow image in his modern thinking, and that this shadow image must not remain a shadow image, that this shadow image, which is modern thinking, must be enlivened so that it can become imagination. It is always an attempt to turn modern thinking into imagination, which comes to light, for example, in a book such as my Theosophy or my Outline of Esoteric Science, where images are driven into thinking everywhere so that thinking is called upon to become imagination, that is, life again. Otherwise, humanity would become completely desolate. We could spread dry scholarship far and wide, but this dry scholarship would not be able to rouse itself to will and would not be able to ignite if imaginative life did not once again enter into this shadowy thinking, into this specter of thought that has entered into humanity in recent times.